사회적 책무성을 갖춘 의과대학 만들기(AMEE Guide No. 109) (Med Teach, 2016)

Producing a socially accountable medical school: AMEE Guide No. 109

Charles Boelena, David Pearsonb, Arthur Kaufmanc, James Rourked, Robert Woollarde, David C. Marshf and Trevor Gibbsg

도입 Introduction

"21세기는 의료 서비스 제공의 품질, 형평성, 목적적합성 및 효과 개선, 사회적 우선 순위와의 불일치 감소, 보건 전문가의 역할 재정의 및 국민의 건강 상태에 미치는 영향의 증거 제공 등 의과대학에 다양한 과제를 제시한다." (GCSA 2010)

“The 21st century presents medical schools with a different set of challenges: improving quality, equity, relevance and effectiveness in health care delivery; reducing the mis-match with societal priorities; redefining roles of health professionals and providing evidence of the impact on people’s health status.” (GCSA 2010)

(의학교육에는) 교육, 학습 및 평가 방법론에 변화가 일어났으며, 주로 의학교육 연구와 기초 교육 이론에 대한 비판적 평가에 의해 촉진되었다(Eva 2008; Gibbs et al. 2011). 컨텍스트, 교육 환경 및 학습 공간의 적용 가능성은 모두 "목적에 맞는" 의료 전문가를 양성하기 위한 목적으로, 학습을 위한 새로운 기술과 병행하여 발전하였다(Ross et al. 2014).

Changes have occurred in teaching, learning, and assessment methodologies, mainly facilitated by a critical appraisal of medical education research and the underlying theories of education (Eva 2008; Gibbs et al. 2011). The importance of context, the educational environment and the applicability of learning space have developed in parallel with new technologies for learning, all with a purpose of developing a “fit for purpose” healthcare professional (Ross et al. 2014).

20세기에 의학과 그것의 교육 시스템의 발전의 두드러진 특징은 전문화, 기술, 그리고 동반자 자격주의attendant credentialism에 대한 상대적으로 무비판적인 사랑이었다. 이것은 개인에게 [의료]와 [교육]의 실제 전달에 많은 매우 긍정적인 영향을 끼쳤지만, 동시에 두 시스템의 분리를 초래했고, 다른 시스템과의 분리를 가져왔다. 따라서 사회는 매우 유능한 실무자와 교육자를 통해 축복받았지만, 특히 가장 소외된 인구의 건강 요구에 대한 그들의 집단적 영향은 필요한 것보다 훨씬 적었다. 20세기 말까지, 직업교육의 근본적 사상가들 중 한 명은 다음과 같이 말했다:

A salient feature of the development of medicine and its educational systems in the twentieth century has been a relatively uncritical love affair with specialization, technology, and attendant credentialism. While this has had many very positive effects on the actual delivery of health care and education to individuals, it has simultaneously led to a fractionation of both systems and their separation one from the other. Society has thus been blessed with highly competent practitioners and educators but their collective impact on the health needs of the populations, most particularly the most marginalized, has been far less than is needed. By the end of the twentieth century Ernest Boyer, one of the seminal thinkers in professional education was led to observe:

"우리 시대의 위기는 기술적 역량이 아니라 사회적, 역사적 관점의 상실과 관련이 있다. 양심과 역량의 비참한 이혼이다."(Boyer 1997)

“The crisis of our time relates not to technical competence, but to a loss of the social and historical perspective, to the disastrous divorce of competence from conscience.” (Boyer 1997)

세계가 건강의 사회적 결정요소를 더 비판적으로 바라보기 시작하면서 매우 가슴 아픈 의문이 생겼다: "사람들의 병을 치료한 뒤, 그들을 병들게 한 곳으로 돌려보내는 것이 무슨 도움이 되는가?"

As the world began to look more critically at the social determinants of health there arose a very poignant question: “What good does it do to treat people’s illness and then send them back to the conditions that made them sick?”

사회적 책무에 관한 시책들이 구체화되기 시작한 21세기 초의 맥락이다. 활동은 Francophone 의과대학 이니셔티브와 같은 집단을 통해 필리핀 시골에서 GCSA로 대표되는 진정한 글로벌인 것에 이르기까지 다양한 규모로 일어나고 있었다.

This was the context at the dawn of the twenty-first century when initiatives around social accountability began to take shape. Activities were occurring at a range of scales from the very local in rural Philippines through collectives such as the Francophone medical schools initiative to the truly global as represented by the Global Consensus for Social Accountability.

이 모든 것은 [의료계와 학계]가 [다음과 같은 모호하지 않은 의무가 있다는 중심 전제]에 토대를 두고 있다.

All were predicated on the central premise that the medical profession and its academic community have an unambiguous obligation:

"…교육, 연구 및 서비스 활동을 지역사회, 지역 및/또는 국가의 우선적인 건강 문제를 해결하기 위해 지시direct합니다."

“…to direct their education, research and service activities towards addressing the priority health concerns of the community, region and/or nation they have the mandate to serve.”

우선적인 건강 문제는 정부, 의료 기관, 보건 전문가 및 대중이 공동으로 확인해야 한다(WHO 1995).

The priority health concerns are to be identified jointly by governments, health care organisations, health professionals and the public, (WHO 1995).

GCSA는 높은 자원과 낮은 자원 상황에서 세계의 모든 지역을 끌어들여 기관, 조직 및 인증 시스템이 실제로 이 간단해 보이는 아이디어를 애니메이션화하려고 시도함에 따라 정확히 어떤 영향을 미치는지 보다 세밀하게 이해하게 되었다. 대부분의 국가에서 보건과 교육을 위한 정치 시스템은 도움 없이 서로 거리를 두고 있다는 것이 점점 분명해졌다. Lancet Commission 보고서(Frenk et al. 2010)에 의해 우아하게 요약된 이 분리와 각 시스템 내의 분리는 증가하는 비용 효과, 목적적합성, 품질 영향 또는 건강의 형평성에 의해 일치하지 않는 건강 시스템에 기여했다는 것이 명백하다. 간단히 말해서, 이 시스템은 그들이 추정적으로 복무해야 할 사회에 대해 책임을 지지 않고 있었다.

The GCSA drew upon all regions of the world in both high and low resource situations to reach a more refined understanding of what exactly the implications were as institutions, organisations, and systems of accreditation attempted to actually animate this seemingly straight-forward idea. It became increasingly evident that, in most nations, the political systems for health and for education were unhelpfully distanced one from the other. Outlined elegantly by the Lancet Commission report Health Professions for a New Century (Frenk et al. 2010) it is apparent that this separation and the fractionation within each of the systems contributed to health systems whose increasing expense was not matched by an increasing cost effectiveness, relevance, quality impact, or equity in health. In short, the systems were not being held accountable to the societies they putatively served.

더 많은 개인과 조직이 (사회적 목적적합성, 사회적 책임에 대한 사회적 대응성 및 그 너머 사회적 책임에 대한 우리의 현재 활동을 어떻게 변화시킬 것인가를) 노력한 끝에 많은 작업, 증거 및 경험을 얻었다

a great deal of work, evidence, and experience has been gained as increasing numbers of individuals and organisations have wrestled with how to change our current activities towards

- social relevance,

- social responsiveness to

- social responsibility, and beyond that to

- social accountability.

이것은 단순히 좋은 의도를 넘어, 여러 부문에 걸쳐서 다음을 위하는 것으로 나아가고자 하는 포부를 수반한다.

- 필요한 전문인력의 종류를 개념화합니다.

- 그것을 생산하고

- 그들이 사회의 건강 요구를 해결하는데 있어 가장 높고 최선의 목적에 익숙해져 있는지 확인한다.

This carries with it the aspiration to move beyond good intentions to working across sectors to

- conceptualize the kind of professionals needed,

- produce them and

- ensure that they are used to their highest and best purpose in addressing the health needs of their societies.

이는 건강 우선순위에 미치는 영향을 [평가할 수 있다]는 것을 의미합니다.

This means being able to assess their impact on health priorities.

사회적 책임 정의

Defining social accountability

지난 20년 동안, 보건 직업 학교 및 기타 의료 교육 제공자의 사회적 책임 개념은 특히 1995년(Boelen & Heck 1995)의 첫 정의 이후 탄력을 받았다. 사회적 책임에 대한 현재의 정의는 이 날부터 인정되며, 현재 다음과 같이 인정된다.

Over the last two decades, the concept of social accountability of health professions schools and other healthcare educational providers has gained momentum, notably since its first definition in 1995 (Boelen & Heck 1995). The present day definition of social accountability is accepted from this date and is now recognized as:

"…의과대학이 의무적으로 교육, 연구 및 서비스 활동을 지역사회, 지역 및/또는 국가의 우선적인 건강 요구를 해결하도록 지시해야 합니다. 우선적인 건강 요구 사항은 정부, 의료 기관, 보건 전문가 및 대중이 공동으로 파악해야 합니다."

“…the obligation of medical schools to direct their education, research and service activities towards addressing the priority health needs of the community, region, and/or nation they have a mandate to serve. The priority health needs are to be identified jointly by governments, healthcare organisations, health professionals and the public.”

이 정의는 이제 진화하는 문헌에 포함되었고 전 세계의 많은 학교와 기관에 의해 채택되었다. 의과대학의 사회적 책임에 대한 글로벌 컨센서스(GCSA 2010)는 이러한 정의를 재확인하고 나중에 사회적 책임과 대응성의 구체적인 정의를 용어집에 추가하였다.;

- 사회적 책임이 사회적 인식 범위 내에서 진실되고, 목적적이며, 측정 가능한 활동을 반영한다는 것을 인식하는 것

- 사회적 책임에서 사회적 책무까지

This definition has now become embedded in the evolving literature and has been adopted by many schools and organisations around the world. The Global Consensus for the Social Accountability of Medical Schools (GCSA 2010) reaffirmed this definition and later added the specific definitions of social responsibility and responsiveness into their terminology;

- recognizing that social accountability reflects a true, purposeful, and measureable activity within the spectrum of social awareness;

- from social responsibility to social accountability;

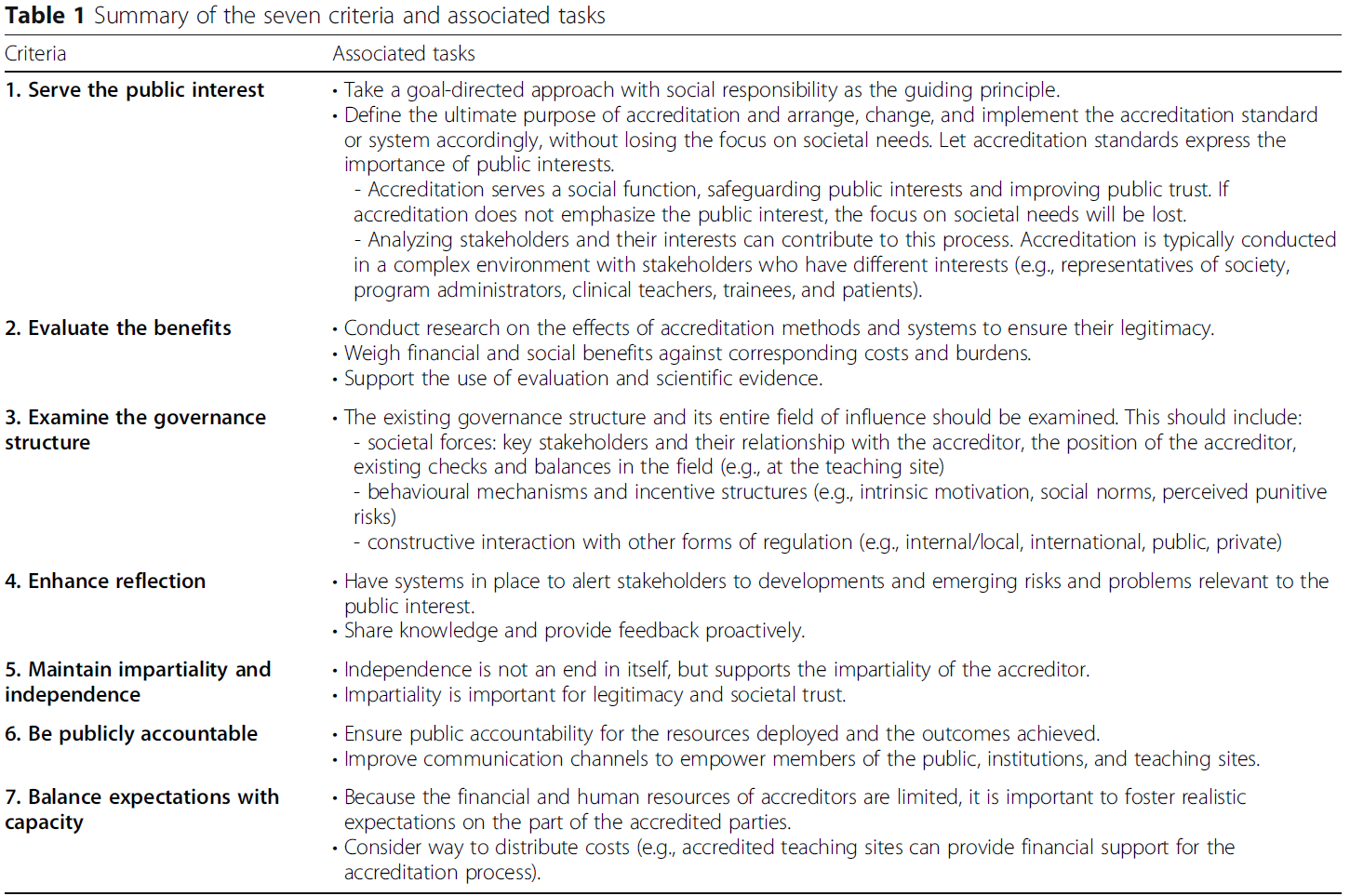

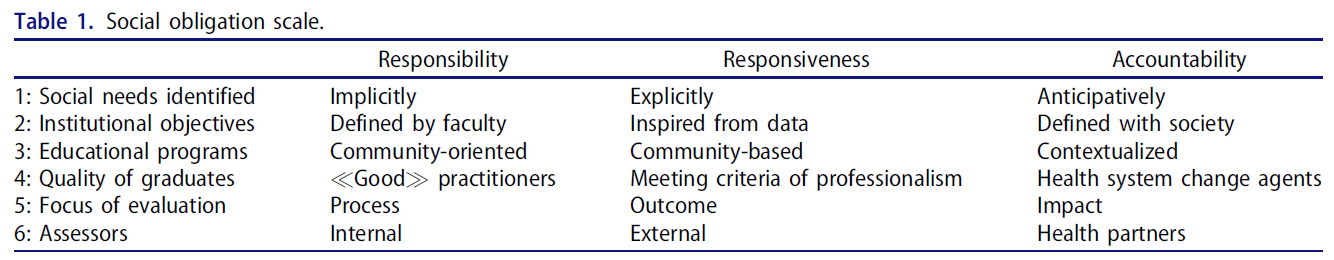

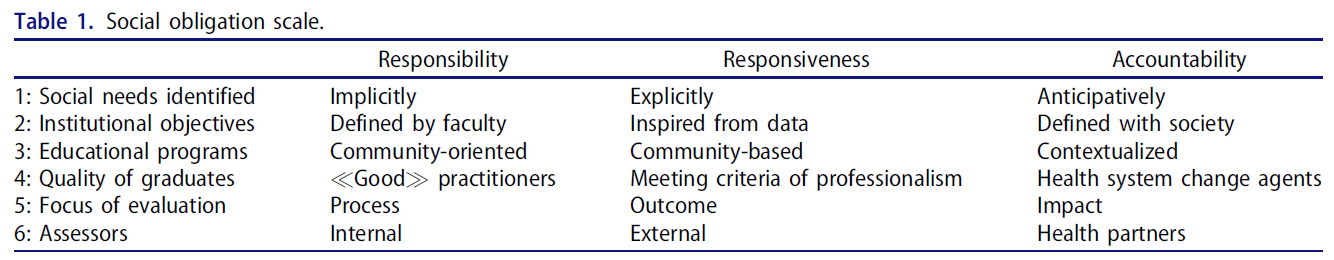

Boelen과 동료들은 나중에 이 주제를 명확히 했다(Boelen & Woollard 2011; Boelen et al. 2013). (표 1)

Boelen and colleagues later clarified this topic (Boelen & Woollard 2011; Boelen et al. 2013) (Table 1).

사회적 의무의 이러한 스펙트럼을 구조화함에 있어

In structuring this spectrum of social obligation,

사회적 책임은 "사회의 요구에 대응하는 의무의 인식 상태"로 정의된다.

- 즉, 지역사회가 헬스케어의 정의에 관여한다는 인식이다. 의료 교육에서 이는 공공 보건 정책과 보건 결정 요인을 설명하는 특정 강의에서 지역사회와 공공 보건 요구에 대한 인식을 높이는 과정에 자주 반영된다.

social responsibility is defined as: “a state of awareness of duties to respond to society’s needs” – recognition that the community plays a part in defining healthcare. In healthcare education this is frequently reflected in courses that raise awareness of community and public health needs, of specific lectures describing public health policies and health determinants.

사회적 반응성이라는 용어를 갖게 되는데, 이는 다음과 같이 정의된다: 사회의 요구를 다루는 행동의 과정course of action이다.

- 실용적이거나 교육적인 측면에서 이것은 학생들이 지역사회 내에서 배우고, 학생들이 지역사회에서 시간을 보내고, 관찰하고, 때로는 건강과 관련된 공동체 활동을 수행하는 것으로 보여진다.

social responsiveness, defined as: a course of actions addressing society’s needs. In practical or educational terms, this is seen as students learning within the community, students spending time in the community, observing and sometimes partaking of community activities related to health.

사회적 책무는 이 스펙트럼의 끝에 나타난다.

- 이러한 행위가 [어떻게 영향을 미치거나 결과로 전환되는지를 측정하는 척도]를 가지고, [특정 조치action가 "졸업생들의 직무, 보건 시스템 성과 및 모집단의 건강 상태"에 가장 큰 영향을 미칠 수 있는 기회]를 갖게끔 하겠다는 [지역사회와의 약속]이다. 따라서 이는 측정 가능한 활동이며, 이것이 사회적 책무에서 가장 중요한 요소이다

Social accountability then emerges at the end of this spectrum as an engagement with communities to ensure that actions have the greatest chance to achieve the desired effects upon graduates’ work, on health system performance and population’s health status together with a measure of how these actions affect or transition into results – it is therefore a measurable activity; a most important element within social accountability.

GCSA 문서는 130개의 유사한 사고 조직과 개별 지도자로 구성된 국제 참조 그룹을 통해 개발된 주요 사업이었다. GCSA는 델파이(Delphi)와 중재(Mediated) 과정을 사용하여 전 세계 모든 지역의 대표가 10개의 행동 영역을 정의했으며, 이를 처리하면 학교가 사회적으로 책임을 질 수 있게 된다. 이 [10가지 행동 영역]은 [사회에 대한 학교의 책임]의 네 가지 특정 요소에서 파생되었으며, 학교의 능력은 다음과 같다.

- 사회의 현재 및 미래의 건강 요구와 과제에 대응한다.

- (건강 요구에 따라) 교육, 연구 및 서비스 우선순위를 재조정한다.

- 다른 이해당사자와의 거버넌스 및 파트너십 강화

- 평가와 인증을 사용하여 성과와 영향을 평가한다.

The GCSA document was a major undertaking developed through an international reference group of 130 similarly thinking organisations and individual leaders. The GCSA used a Delphi and mediated process, with representation from all regions of the world, to define 10 action areas, that if processed would enable the schools to become socially accountable. These 10 action areas were derived from four specific components of a school’s responsibility to society, notable the school’s ability to:

- respond to current and future health needs and challenges in society;

- reorientate their education, research and service priorities accordingly;

- strengthen governance and partnerships with other stakeholders;

- use evaluation and accreditation to assess their performance and impact.

Boelen and Woollard(2009)의 획기적인 논문은 다음과 같다.

The landmark paper by Boelen and Woollard (2009) notes:

… 수월성excellence은 [자기자신의 행동이 사람들의 복지에 변화를 가져오는 것]을 증명하는 교육기관의 것이어야 한다. 이들이 배출하는 졸업생은 시민과 사회의 건강 증진을 위해 바람직한 모든 역량을 갖추어야 할 뿐만 아니라, 전문직업적 실천을 위하여 그 역량을 활용해야 한다. 세계보건기구(WHO)가 제시한 네 가지 원칙은 개인과 집단적 관점에서 사람들이 권리를 갖는 의료의 유형, 즉 질, 형평성, 목적적합성 및 효과성을 가리킨다. 따라서 건강의 사회적, 경제적, 문화적, 환경적 결정요인은 교육기관의 전략적 발전을 이끌어야 한다.

… excellence should be reserved for educational institutions which verify that their actions make a difference to people’s well-being. The graduates they produce should not only possess all of the competencies desirable to improve the health of citizens and society, but should also use them in their professional practice. Four principles enunciated by the World Health Organisation refer to the type of health care to which people have a right, from both an individual and a collective standpoint: quality, equity, relevance and effectiveness. Therefore, social, economic, cultural and environmental determinants of health must guide the strategic development of an educational institution.

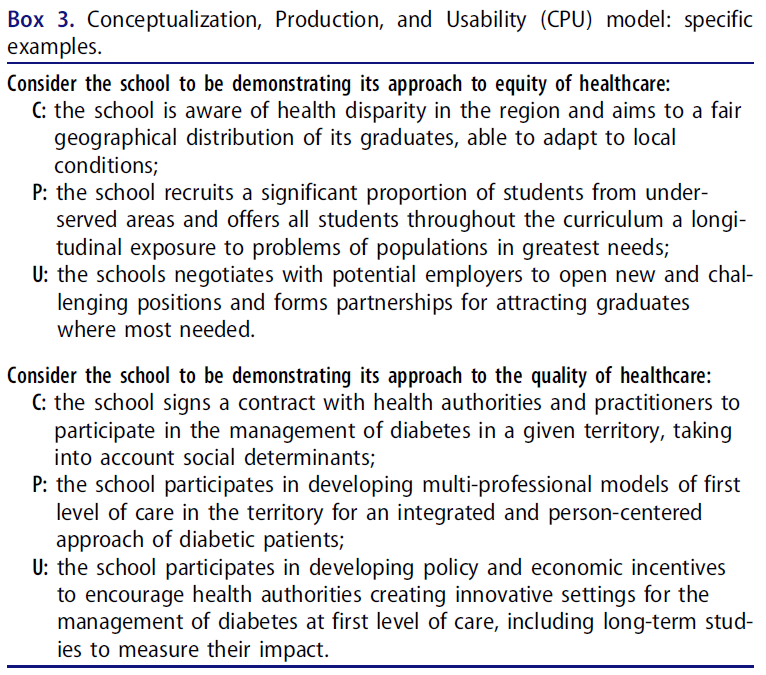

Boelen과 Woollard는 또한 사회적 책무에는 교육 및 학습 조직이 단순이 아닌 활동의 효과를 입증할 수 있도록, 사회적 책무를 평가하기 위해 CPU 모델을 개발한 기관의 개념화, 생산 활동 및 졸업생의 사용성이 포함되어야 한다고 언급했다.전위를 상술하다

Boelen and Woollard also noted that social accountability should include the institution’s Conceptualization, Production activities, and Usability of graduates, from which they developed the CPU model to assess social accountability, in order that teaching and learning organisations could demonstrate the effects of their activities, rather than simplistically describe a potential.

"완전한 사회적 책무를 지기 위해, 기관은 자신의 '제품'(졸업생, 서비스 모델 또는 연구 결과)이 공공의 이익을 위해 사용되고 있는지에 대한 의문을 제기할 권리를 보장할 필요가 있다."(Boelen & Woollard 2009).

“To be fully socially accountable, an institution needs to claim the right to question whether its ‘products’ (graduates, service models or research findings) are being used in the best interest of the public” (Boelen & Woollard 2009).

[의과대학의 사회적 책무의 본질]은 [우선적인 건강 요구]를 해결하기 위해 [지역사회/지역/국가]와 관여하고 대응하며 영향을 미치는 것으로 간주할 수 있다. 여기에는 지역사회, 지역 보건 서비스 기관 및 정부를 포함한 주요 이해 관계자들과 협력하여 건강을 개선하고 공정하고 효과적인 의료 서비스를 제공하는 것이 포함됩니다.

The essence of social accountability of medical schools can be considered to be engaging with, responding to and impacting on their community/region/nation to address their priority health needs. This involves working in partnership with key stakeholders including communities, regional health service organisations, and governments towards improving health and providing equitable and effective health care.

왜 우리가 사회적 책임을 져야 하는가?

Why do we need to be socially accountable?

사회적 책임의 초점인 사회적 결정요인과 건강

Social determinants and health a focus of social accountability

[안전한 이웃, 생활 가능한 소득, 교육적 성취, 적절한 영양 섭취, 기초 보건 및 사회 서비스에 대한 접근, 그리고 사회적 포함과 같은] 사회적 결정 요소는 국가의 어떤 의료 시스템보다 건강에 더 큰 역할을 한다(Marmot 2005).

- 예를 들어, 미국의 모든 사람들이 중등학교를 졸업한다면, 미국의 모든 흡연자들이 담배를 끊을 때보다 더 많은 생명을 구할 수 있다는 최근의 연구 결과가 나왔다(Krueger et al. 2015).

- 미국 남서부 뉴멕시코 주의 토착민들은 당뇨병에 대한 최상의 검사와 치료법을 가지고 있지만, 그 질환으로 인한 사망률이 가장 높다.

- high quality care가 poor outcome을 막아줄 수는 없습니다. (건강에 약 10%만 기여하는) 의료 시스템에 들어가는 엄청난 자금이 [우리 인구의 질병의 기저에 있는 것을 방치하는 것]을 보충할 수 없다. 그리고 (질병의 기저에는) 사회적 결정요인이 있다.

- 북미 원주민 인구는 가장 높은 비만율, 낮은 교육적 성취도, 열악한 식생활 및 사회적 소외로 인해 어려움을 겪고 있습니다.

Social determinants such as safe neighborhoods, liveable income, educational attainment, adequate nutrition, access to basic health and social services, and social inclusion play a greater role in health than does any country’s healthcare system (Marmot 2005).

- For example, a recent study revealed that if all people in the United States graduated from secondary school, more lives would be saved than if all smokers in the country stopped smoking (Krueger et al. 2015).

- In New Mexico in the south-western United States, the indigenous population has some of the best screening and treatment for diabetes, but has the highest death rate from that condition.

- High quality care cannot protect against poor outcomes. The heavy funding of the healthcare system (which contributes to only about 10% of what makes people healthy) cannot make up for the neglect of what underlies illness in our population—the social determinants,

- and the indigenous population in North America among all groups suffers from the highest rates of obesity, low educational attainment, poor diet, and social marginalization.

의료 사업자 및 사회적 책임

Health care providers and social accountability

대부분의 국가에서, [AMC에서 생산한 보건 인력 졸업자의 배경 및 전문성]과 [국가와 지역사회 졸업자가 봉사해야 할 우선적인 보건 인력 요구] 사이에는 상당한 단절이 있다.

- 가난한 나라에서 부유한 나라로 의사들이 떠나가는 것은 여전히 높은 수준을 유지하고 있다. 그 결과 의사를 "기부"하는 국가에서는 투자 수익이 거의 나지 않는다.

- 한 국가에 대해 적절하고 지리적으로 분포된 보건 인력을 생산하는 것은 사회 책임의 주요 요소로서, 인구의 진료 접근성 측면뿐만 아니라 지역적으로 접근하기 쉬운 적절한 의료 인력에 의해 생성된 지역사회에 대한 경제적, 사회적 편익 측면에서도 중요하다(Frenk et al. 2010).

In most countries, there is a substantial disconnect between the background and specialties of health workforce graduates produced by our academic centers and the priority health workforce needs of the country and communities graduates are to serve.

- Physician migration from poorer to richer countries remains at high levels leaving the “donor” country with little return on their investment.

- Producing the appropriate and geographically distributed health workforce for a nation is a major element in social accountability, both in terms of a population’s access to care but also in terms of the economic and social benefits to communities generated by an appropriate, locally accessible health workforce (Frenk et al. 2010).

또한 의료 서비스 제공이 상당한 공공 자원을 소비하는 사실에도 불구하고, 의료 서비스 제공의 사회적 사명에는 거의 관심을 기울이지 않는다. 이유는 많지만, 종종 학교는 [급여가 적지만 더 건강을 촉진하는 외래 환자 및 예방 서비스] 대신에 [비싸고, 높은 강도의 절차 지향적인 입원 서비스]에 집중하도록 incentivize된다.

In addition, despite the fact that healthcare provision consumes substantial public resources, little of their attention is devoted to their social mission. Reasons are many, but often schools are incentivized to focus upon expensive, high intensity, procedurally oriented inpatient service instead of upon the lesser paid but more health promoting outpatient and preventive services.

기관이 사회적 임무를 수행하는 데 있어 추가적인 장벽은 학교 자체(부서 간, 대학 간, 미션 간)의 많은 사일로(교육, 임상 관리 및 연구)입니다. 기관의 사회적 책무를 적절히 표현하기 위해, 이러한 임무는 지역사회 건강에서 측정 가능한 개선을 보여주면서 목표가 외부로 향하는 곳에 상호 보완적이고 상호적으로 재강화하는 것mutually re-enforcing이어야 한다.

A further barrier to institutions fulfilling their social mission is the many silos within the school itself—between departments, between colleges and between missions—education, clinical care, and research. To adequately express the institution’s social accountability, these missions must be complementary and mutually re-enforcing where the goal is outward facing, showing a measurable improvement in community health.

아마도 가장 큰 장벽은 [기관들이 행동하도록 동기를 부여받는 전통적인 방식]일 것이다. 예방에 대한 투자는 보상이 좋지 않으며, 1차 진료와 협업 치료를 실천하는 데는 충분한 위신이 없습니다. 사회적 책임의 또 다른 핵심 요소인 사회의 다른 이해당사자 및 부문과의 공동체 참여는 소수의 교수들이 기술을 가지고 있거나 투자를 위해 충분한 시간을 허용하는 느린 과정이다. 직업들은 아마도 가장 자격이 있는 보건 분야에 대해 자율적으로 규제하는 경향이 있다. 따라서 [외부 규제]와 [기관의 책무]와 [우선순위 요구에 관한 지역사회가 창출한 조언과 방향]에 대한 근본적인 불편이 있다.

Perhaps the greatest barrier is the traditional manner in which institutions are incentivized to behave. Investment in prevention is poorly rewarded, and practicing primary and collaborative care lacks sufficient prestige. Community engagement with other stakeholders and sectors in society, another key component of social accountability, is a slow process in which few faculty have skills or are allowed sufficient time for investment. Professions tend to be self-regulating with the health sector perhaps the most entitled. So there is an underlying discomfort with external regulation and community-generated advice and direction regarding priority needs and accountability of the institution.

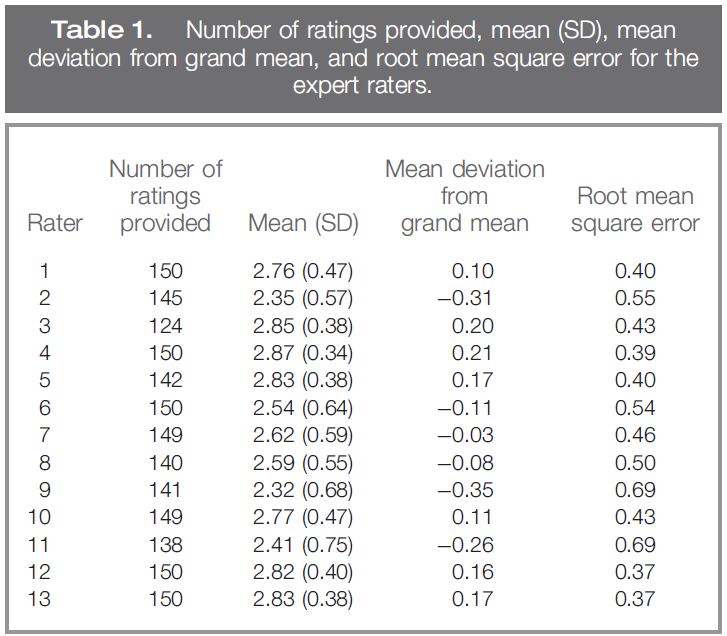

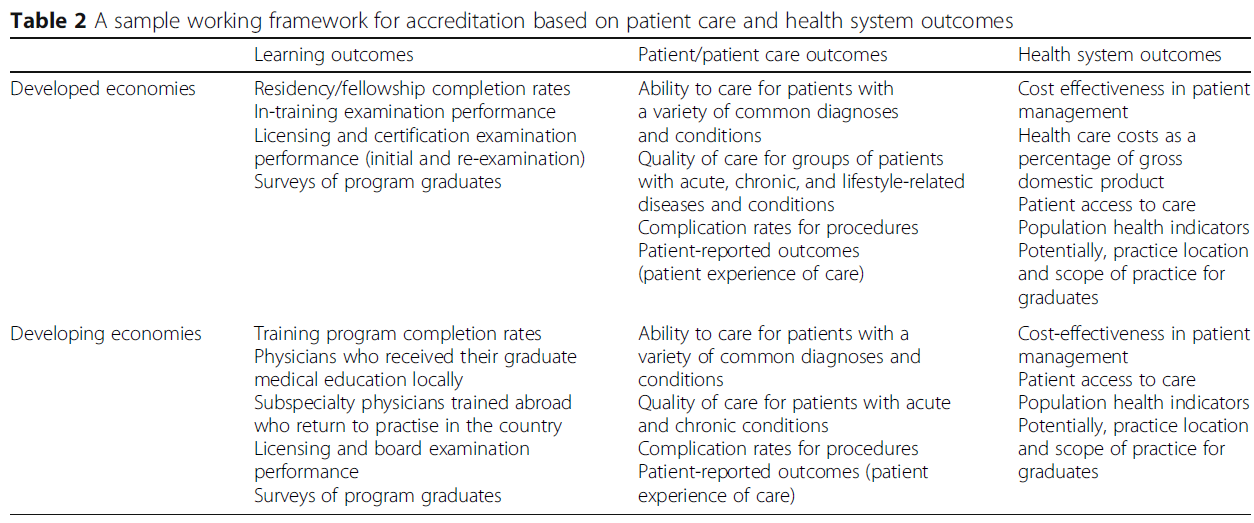

의료 사업자와 사회적 책임의 필요성 사이의 관계는 Rourke(2013)가 제시한 수치로 가장 잘 설명될 수 있다(그림 1).

The relationship between healthcare providers and the need for social accountability may best be described by the figure presented by Rourke (2013) (Figure 1).

변화가 오고 있다.

Change is coming

[지역사회 건강 요구를 해결하기 위해 대학, 병원, 미션 및 지역사회 참여의 통합을 위한 학술 기관의 총체적인 약속]은 매우 중요한 요구이며 대두되고 있다(Kaufman et al. 2015). 사회적 책임을 promoting하는 세력이 커지고 있다. 하나는 세계적으로 영향을 미치고 있는 "증거 기반 실천" 운동이다(Sackett et al. 1996). 한 나라의 1인당 지출은 그 인구의 건강과 잘 관계가 없다.

- 예를 들어, 미국은 1인당 다른 어떤 나라보다도 의료 서비스에 지출하는 나라가 많습니다. 이는 국내총생산의 18%에 해당합니다. 그러나 WHO는 품질에서 37위를 기록하고 있다(데이비스 외 2014). 원인은 많지만 전문의에 비해 1차 진료비 지원 부족, 인구 내 높은 사회경제적 격차, 사회안전망 지원 부족 등이 있다. 새로운 Affordable Care Act("Obamacare")는 이러한 적자를 여러 가지 방법으로 해결합니다(미국 의회 2010).

A total commitment by the academic institution to merge its colleges, hospitals, missions, and community engagement to address community health needs is a critical need and is emerging (Kaufman et al. 2015). Forces promoting social accountability are growing. One is the “evidence-based practice” movement, which is having a global impact (Sackett et al. 1996). The expenditure per person in a country correlates poorly with the health of that population. For example, the United States spends more than any other country per capita on healthcare (double the next highest spender); 18% of the gross domestic product. Yet, the WHO ranks it 37th in quality (Davis et al. 2014). The reasons are many, but include poor funding of primary care compared to specialists, high socioeconomic disparities within the population and poor support for the social safety net. The new Affordable Care Act (“Obamacare”) addresses these deficits in many ways (US Congress 2010).

변화의 또 다른 중요한 힘은 의료 서비스 및 정부 간의 가치, 글로벌 예산 및 "capitation"으로의 이동입니다. 즉, 보험 회사나 제공자 집단은 (서비스 항목별로 '서비스 수수료'를 받거나 비용을 지불하는 대신) 가입자의 건강을 관리하기 위해 정해진 금액을 받는다. 이 시나리오에서는 환자가 응급실에 가거나 예방 가능한 질환으로 입원하거나 과다한 양의 약을 복용할 때마다 진료비나 보험사, 실습단의 지원금을 적게 받는다. 대신, 이 약정에서, 그들은 사람들을 건강하게 하고, 건강의 사회적 결정요인을 검사하고 다루는 것을 수반함으로써 이익을 얻는다. 이것은 사회적 책임에 대한 "business case"의 한 예이다.

Another important force for change is the movement among payers of healthcare services and governments toward value, global budgets, and “capitation.” In other words instead of getting a “fee for service” or pay for each item of service, an insurance company or provider group receives a fixed amount of money to manage the health of an enrolled population. Under this scenario, every time a patients goes to the emergency room, becomes hospitalized for a preventable condition or takes an excessive amount of drugs, the payers of care or insurance companies or practice group receives less funding. Instead, in this arrangement, they profit by keeping people healthy and that entails screening for and addressing the social determinants of health. This is an example of the “business case” for social accountability.

Academic institution은 이제 [졸업생들이 사회적 사명을 다하기 위하여] 건강지향적이고 다전문적인 건강관리 환경, 지역사회 현장에서 교육함으로써 [이러한 새로운 현실에 대비]해야 한다. 의사 및 기타 의료 전문가의 사회적 책임 역할을 확대하기 위해, 북미 지역의 점점 더 많은 기관들이 Health Extension agents를 교육, 고용 및 배치하고 있습니다. 개발도상국에서 출발하여 농업 부문(Kaufman et al. 2010)과 지역사회 보건 종사자(Pittman et al. 2015)의 예를 사용하는 이 모델은, [지역사회 참여 교육의 서비스 학습 모델]을 활용한다.

- 배울 필요가 있는 사람들에게 일선 서비스를 제공하는 것,

- 문화적, 언어적 능력의 혼합, 그리고

- 참여자가 속한 지역사회와 더 큰 신뢰를 형성한다(Ellaway et al. 2016).

Academic institutions have now to prepare graduates for this new reality by educating them in health-oriented, multi-professional healthcare settings, and community sites if they are to fulfill their social mission. To expand the role of physicians and other health professionals in being socially accountable, a growing number of institutions in North American are training, hiring, and deploying Health Extension agents. Originating from developing countries and using examples from the agricultural sector (Kaufman et al. 2010) and Community Health Workers (Pittman et al. 2015), this model utilizes a service learning model of community-engaged education; combining the skills of those

- providing a front line service with those needing to learn,

- blending cultural and linguistic ability, and

- creating a greater trust with the communities served and from which the participants come (Ellaway et al. 2016).

국내외 운동

National and international movements

사회적 책임의 중요성에 대한 인식은 또한 새롭게 부상하고 지지하고 있는 국가 및 지역 운동으로부터 힘을 얻고 있다. 캐나다 의과대학은 국가적으로 일련의 사회적 책임 원칙(Capon et al. 2001)의 지침을 따르고 있다. 북미에서는 학업자원과 지역사회 보건의 우선적 요구를 연계하는 건강확장 운동을 확대하고, 학술기관 간 사회적 사명 성장을 촉진하는 비욘드 플렉스너 운동에 동참하는 학술기관이 늘고 있다. 명시적인 사회적 책임 권한을 가진 보건 전문학교의 국제 연합인 The Training for Health Equity Network는 사회적 책임에 대한 기관의 방향을 평가하기 위한 프레임워크에 협력했다(Larkins et al. 2013).

The acknowledgement of the importance of social accountability is also getting a boost from emerging, supportive national, and regional movements. Canadian medical schools nationally are taking guidance from a set of social accountability principles (Cappon et al. 2001). In North America, a growing number of academic institutions are expanding the Health Extension movement to link academic resources with priority community health needs (www.healthextensiontoolkit.or) and a growing number are joining the Beyond Flexner movement which promotes the growth of social mission among the academic institutions (www.beyondflexner.org). An international association of health professional schools with an explicit social accountability mandate, The Training for Health Equity Network, has collaborated on a framework for assessing an institution’s orientation towards social accountability (Larkins et al. 2013).

마지막으로 지역사회 대응형 보건 직업 교육 및 서비스를 위해 헌신하는 가장 오래 생존한 국제 조직 중 하나는 The Network: Towards Unity for Health이다. 1979년 WHO의 지원을 받아 설립된 이 기구는 WHO와의 공식 관계에서 비정부기구(NGO)가 되었다. 그것은 그것의 시작부터 전세계의 학문적 보건 기관들을 국가와 지역사회의 우선적 요구에 연계시키는 프로그램과 전략을 보급해야 하는 중대한 필요성에 대응했다. 사회적 책임 운동은 이 네트워크에서 견고하고 국제적인 파트너를 찾았습니다.

Finally, one of the longest surviving, international organisations devoted to community-responsive health professions education and service is The Network: Towards Unity for Health. Founded in 1979 with support from the WHO, it became a Non-Governmental Organisation (NGO) in its official relations with the WHO. It responded from its inception to the critical need to disseminate programs and strategies that tied academic health institutions from around the world to the priority needs of their nations and communities. The social accountability movement has found a solid, international partner in this Network (www.the-networktufh.org).

사회적 책임을 보건 직업 교육에 어떻게 적용합니까?

How is social accountability applied to health professions education?

의과대학에 대한 사회적 의무의 개념은 북미와 캐나다의 의과대학에 대한 Flexner의 주요 보고서에서 이미 인지할 수 있었다. 그는 미래의 의사 준비에서 높은 기준을 채택하는 것을 강력히 옹호했으며, 의사의 기능이 "개인적이고 치료적인 것이 아니라 사회적이고 예방적인 것"이 될 것이라는 큰 희망을 품었다. 그는 의과대학이 '공공 서비스 기업'이 되어야 한다는 상념과 함께 사회적 필요의 개념을 소개했다. 안타깝게도 플렉스너의 보고서의 경우, 그가 의대의 거의 50%를 폐쇄한 결과 많은 학교들이 문을 닫게 되었고, 폐교된 학교들은 실제로는 가난한 사람들을 위한 것이었다.

The concept of a social obligation for medical schools was already perceptible in Flexner’s seminal report of North American and Canadian medical schools (Flexner 1910). He was a strong advocate for the adoption of high standards in the preparation of future physicians and held great hopes that the physician’s function would become “social and preventive, rather than individual and curative”. He introduced the concept of social need, with the corollary that a medical school should be “a public service corporation”. Sadly in the case of Flexner’s report, his closure of almost 50% of the medical schools resulted in many schools closing which indeed were catering for the under-served populations.

"사회적"이라는 용어는 다른 문화에서 다른 의미를 가질 수 있다. 예를 들어 서유럽 국가에서는 국가 규제 기구에 의해 보증된 연대를 불러일으킬 수 있는 반면 미국에서는 개인의 권리에 대한 간섭과 자율성에 대한 위협을 암시할 수 있다. 본 가이드의 맥락에서 "사회적"은 라틴어 어원을 가리킨다. '소시에우스'란 동맹이란 뜻이다. 사회는 공동의 이익을 위해 헌신하는 개인과 기관들 사이의 완전하고 조정된 상호작용으로 보여진다. 저명한 역사학자 아놀드 토인비는 이렇게 말했다.

The term “social” may carry a different meaning in different cultures. In Western European countries, for instance, it may evoke solidarity, warranted by national regulatory bodies, while in the United States it may allude to interference with individual rights and threat to autonomy. In the context of this Guide, “social” refers to its Latin etymology: “socius”, meaning an ally. Society is seen as the complete and coordinated interactions amongst individuals and institutions committed to a common good. The noted historian Arnold Toynbee put it thus:

"사회는 인간 사이의 관계의 총체적 네트워크입니다. 그러므로 사회의 구성 요소는 인간이 아니라 그들 사이의 관계이다. 사회 구조에서 개인은 단지 관계의 네트워크의 foci일 뿐이다……. 눈에 보이고 눈에 띄는 사람들의 집합은 사회가 아니라 군중이다. 군중은 사회와 달리 집결하거나 분산하거나 사진을 찍거나 학살할 수 있다.(토인비 1947년)

“Society is the total network of relations between human beings. The components of society are thus not human beings but the relations between them. In a social structure individuals are merely the foci in the network of relationships…….a visible and palpable collection of people is not a society; it is a crowd. A crowd, unlike a society, can be assembled, dispersed, photographed, or massacred.” (Toynbee 1947)

따라서 (의과대학은) 현재와 미래의 건강 요구와 사회의 도전을 탐색하고, 가능한 한 효율적으로 이에 대처하며, 개입이 사회에 가장 큰 영향을 미칠 수 있도록 보장할 의무가 있다.

The commitment therefore is to explore current and future health needs and challenges in society, to act on them as efficiently as possible, and to ensure interventions have the highest possible impact on society.

1995년 WHO의 사회적 책임에 대한 정의는

- "신체적, 정신적, 사회적 행복의 완전한 상태"로서 건강에 대한 동일한 조직의 정의와 일치하며,

- 개인 및 집단적으로 사람들의 건강에 긍정적이거나 부정적인 영향을 미칠 수 있는 다양한 직접 및 간접적 원인(즉, 정치, 인구학적, 역학, 환경적, 문화적, 경제적)으로 "건강의 사회적 결정적 요인"의 정의와 일치한다.

The 1995 WHO definition of social accountability (WHO 1995) is consistent with

- the same organization’s definition for health as “a complete state of physical, mental and social wellbeing”, and of

- “social determinants of health” as a wide spectrum of direct and indirect causes, i.e. political, demographic, epidemiological, environmental, cultural, or economical, that can positively or negatively influence people’s health, both individually and collectively (WHO 1946).

최근 몇 년 동안, 일련의 주요 검토와 보고서들은 [보건전문직 교육기관의 사명]을 '사회의 인구학적, 경제적, 문화적 변화뿐만 아니라 사람들의 건강 요구와 명시적으로 연결]시키라는 권고안을 제시하였다. 이러한 보고서는 영국 일반의학위원회(GMC 2015), 캐나다 의학부 협회(AFC 2010), 랜싯 글로벌 독립 위원회(Frenk et al. 2011), 그리고 의과대학의 사회적 책임에 대한 글로벌 컨센서스(GCSA 2010)에서 나왔다. 이러한 모든 보고서에서 공통적인 주제는 사회적 요구에 맞는 의료 서비스를 제공하는 기술과 욕망을 가진 졸업생 건강 전문가들에게 초점을 맞추는 것이다. 이 보고서는 학교가 주요 이해 관계자들과 협력하여 교육, 연구 및 서비스 제공 분야에서 잠재력을 더 잘 활용하고 보건 분야의 전반적인 성과를 개선하는 데 더 중요한 역할을 할 수 있는 방법을 강조합니다. 그러한 사회적 책무에 대한 접근법이 의대를 [사회 정의를 증진하기 위한 더 넓은 운동] 안에 둘 수 있다는 주장이 제기되었다(Ritz et al. 2014).

In recent years, a series of major reviews and reports presented their recommendations to explicitly link the missions of health professional schools to people’s health needs as well as to demographic, economic, and cultural changes in societies. Such reports emanated from the UK General Medical Council (GMC 2015), the Association of Faculties of Medicine of Canada (AFMC 2010), the Lancet Global Independent Commission (Frenk et al. 2011) and the Global Consensus for Social Accountability of Medical Schools (GCSA 2010). A common theme in all of these reports is the focus on graduating health professionals who have the skills and desire to provide health care that meets societal needs. They highlight ways for schools to partner with key stakeholders to better use their potential in education, research, and service provision and play a more prominent role in improving the overall performance of the health sector. It has been argued that such an approach to social accountability can place medical schools within a broader movement to promote social justice (Ritz et al. 2014).

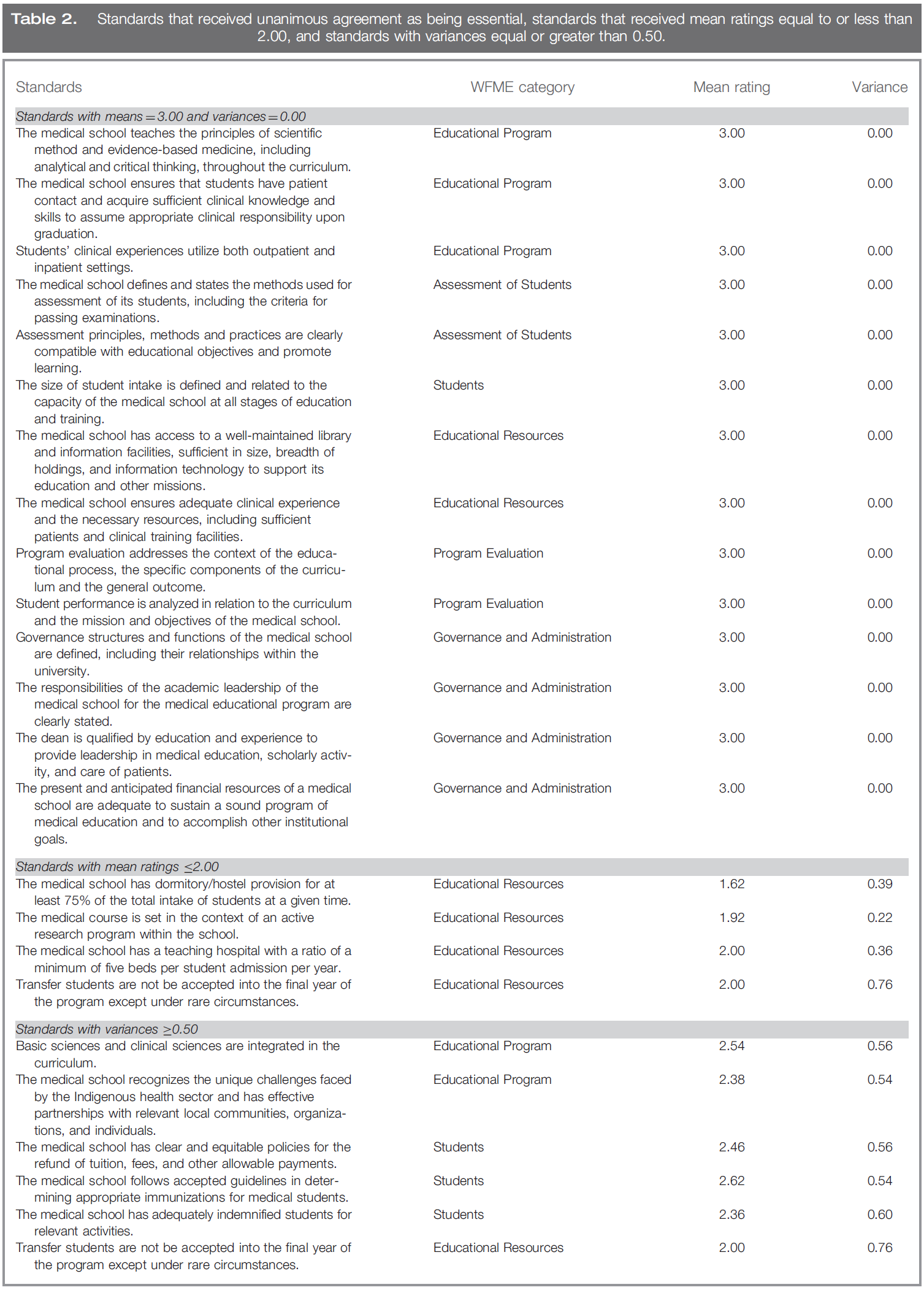

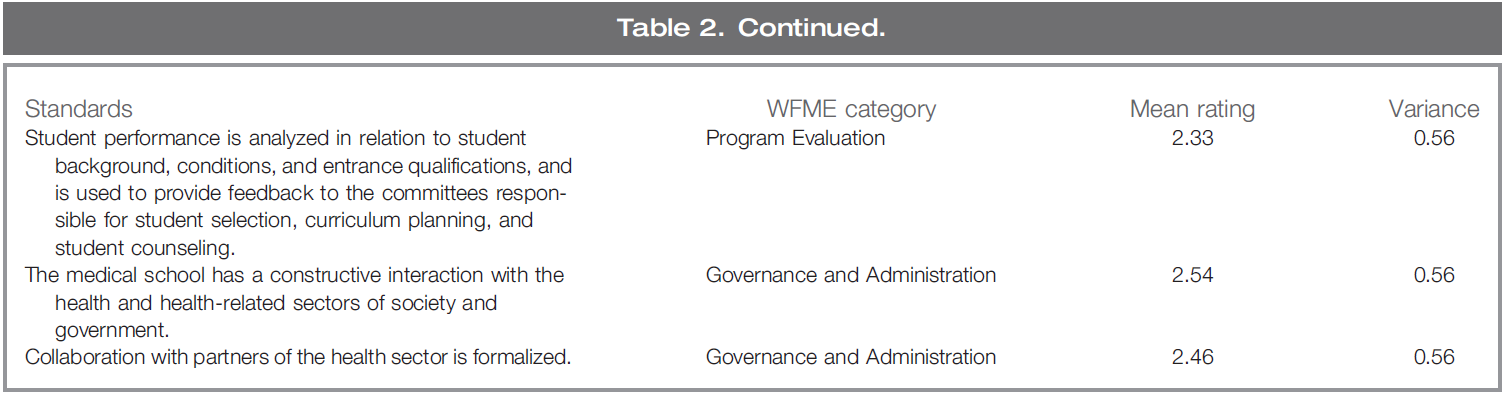

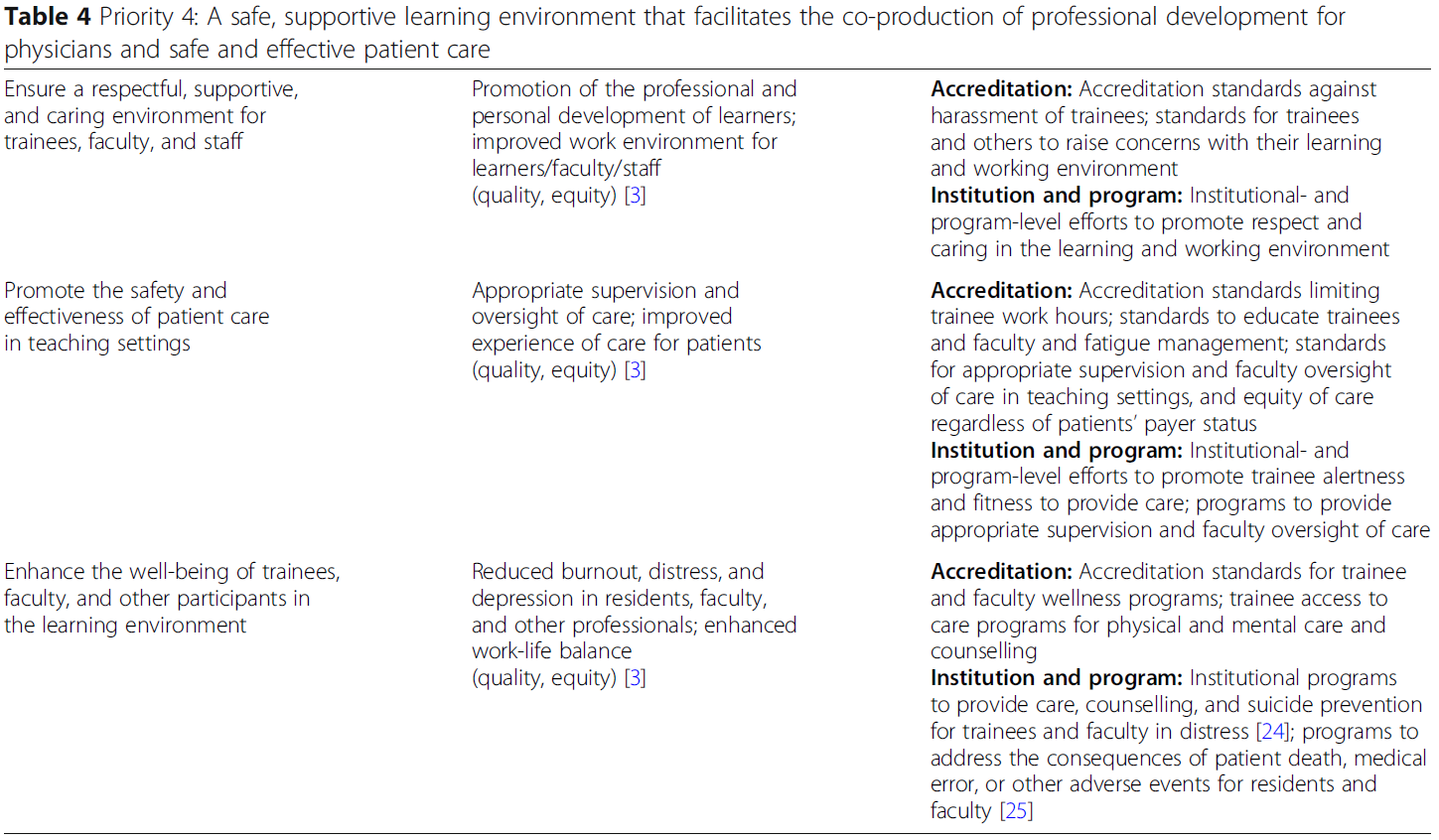

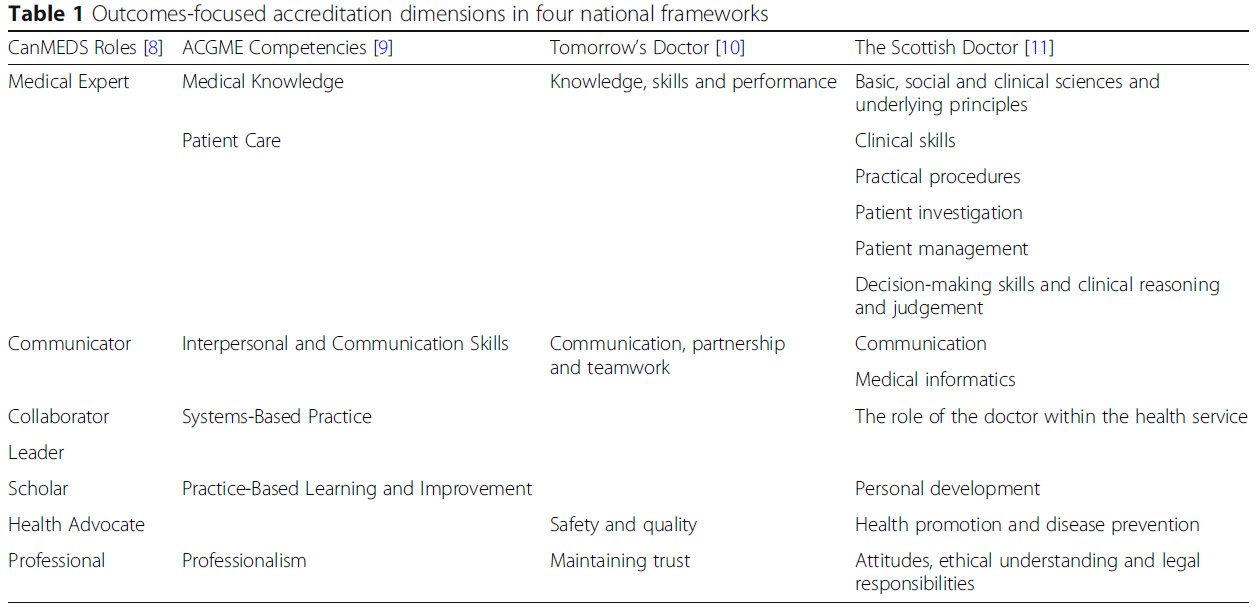

글로벌 컨센서스 문서(GCSA 2010)는 사람들의 건강 상태에 가장 잘 영향을 미치는 의과대학이 기대하는 변화를 탐구한다. 의대를 대상으로 하는 동안, 그것이 권장하는 10가지 전략적 방향은 모든 건강 전문 학교 또는 건강 행위자에게 적용된다(표 2).

The Global Consensus document (GCSA 2010) explores the transformation expected of a medical school to make the best impact on peoples’ health status. While targeting medical schools, the 10 strategic directions that it recommends are applicable to any health professional school or health actor (Table 2).

| 표 2. 글로벌 컨센서스 그룹의 10가지 전략적 방향 (GCSA 2010) Table 2. Ten strategic directions of the Global Consensus Group. (GCSA 2010) 1. 사회의 건강 요구 예측 2. 보건 시스템 및 기타 이해관계자와의 협력 3. 의사 및 기타 보건 전문가의 역할 변화에 적응 4. 성과 기반 교육 강화 5. 의과대학의 대응적이고 책임감 있는 거버넌스 구축 6. 교육, 연구, 서비스 제공 기준의 범위 정비 7. 교육, 연구, 서비스 제공의 지속적인 품질 개선 지원 8. 인가를 위한 의무적인 메커니즘의 확립 9. 글로벌 원칙과 컨텍스트 특수성의 균형 조정 10. 사회의 역할 정의 1. Anticipating society’s health needs 2. Partnering with the health system and other stakeholders 3. Adapting to the evolving roles of doctors and other health professionals 4. Fostering outcomes-based education 5. Creating responsive and responsible governance of the medical school 6. Refining the scope of standards for education, research and service delivery 7. Supporting continuous quality improvement in education, research and service delivery 8. Establishing mandated mechanisms for accreditation 9. Balancing global principles with context specificity 10. Defining the role of society |

10가지 전략적 방향의 목록은 논리적 순서를 반영한다.

- 사회적 맥락에 대한 이해, 건강상의 도전과 필요의 확인, 효율적으로 행동할 수 있는 관계의 창출에서 출발 (영역 1과 영역 2).

- 건강 요구를 해결하기 위해 필요한 보건 인력의 스펙트럼 중,

- 의사의 예상 역할과 역량이 설명된다(영역 3)

- 일관된 연구 및 서비스 전략과 함께 의과대학이 구현하기 위해 부르는 교육 전략(영역 4).

- 국가 당국이 인식해야 할 수준(영역 8)의 높은 우수성(영역 6, 7)을 향하도록 하기 위해서는 표준이 필요하다.

- 사회적 책임은 보편적 가치(영역 9)이지만, 지역 사회는 궁극적인 성과 평가자(영역 10)가 될 것이다.

The list of the 10 strategic directions reflects this logical sequence,

- starting with an understanding of the social context, an identification of health challenges and needs and the creation of relationships to act efficiently (Areas 1 and 2).

- Among the spectrum of required health workforce to address health needs,

- the anticipated role and competencies of the doctor are described (Area 3)

- serving as a guide to the education strategy (Area 4),

- which the medical school, along with consistent research and service strategies, is called to implement (Area 5).

- Standards are required to steer the institution towards a high level of excellence (Areas 6 and 7),

- which national authorities need to recognize (Area 8).

- While social accountability is a universal value (Area 9),

- local societies will be the ultimate appraisers of achievements (Area 10).

사회적 의무의 구배

Gradients of social obligation

어떤 의과대학이든 사회적 의무를 염두에 두어야 하는 것은 맞지만, 이 의무가 실제로 무엇을 의미하는지에 대한 혼란은 끊이지 않고 있다. 명확한 WHO 정의에도 불구하고(ibid), 사회적 책임은 지역사회가 완전히 참여하는 교육보다는 지역사회 기반 또는 지향적 교육 및 학습에서와 같이 지역사회와의 상호작용에 동화되는 경우가 많다(Ellaway et al. 2016). 또한, 서비스와 연구 활동에 대한 관심이 적은 학교의 교육적 임무에 너무 자주 제한을 받는다. 지난 몇 년 동안 저자들은 사회적 책임, 사회적 대응성, 사회적 책무의 세 가지 구분을 구별해야 하는 사회적 의무의 정의를 확장해 왔다(Boelen & Woollard 2011).

While any medical school is or should be mindful of its social obligation, there has been constant confusion on what this obligation really implies. Despite the clear WHO definition (ibid), social accountability is often assimilated to interaction with the community, as in community-based or orientated teaching and learning rather than education in which the community is fully engaged (Ellaway et al. 2016). Also, too often is it restricted to the educational mission of a school, with less attention to service and research activities. Over the last few years, authors have expanded the definition of social obligation to distinguish three gradients: social responsibility, social responsiveness, and social accountability (Boelen & Woollard 2011).

[사회적 책임]은 기관이 사회의 우선적인 건강 필요와 과제에 대한 암묵적인 인식을 가지고 있으며, 주로 직감이나 이를 해결하기 위한 자연스러운 성향에 의해 유도되는 상태로 간주된다. 이 경우, 학교는 학교의 우선적인 조치가 무엇이어야 하는지 그리고 교육, 연구, 서비스 프로그램의 결과가 사람들의 건강에 의미 있는 방식으로 영향을 미치는지에 대해 다른 건강 이해 관계자들과 상의할 필요를 느끼지 않을 수 있다.

- 예를 들어, 의료 커리큘럼은 현장 경험에 대한 노출을 포함하여 건강 결정 요인 및 공중 보건과 관련된 다양한 분야에서 충분한 학습 기회를 제공할 수 있지만, 졸업생이 공정하고 [효율적인 서비스를 제공하도록 설계된 보건 시스템에 최적으로 적합하도록 획득해야 하는 주요 역량]에 기초하지 않는다. 대표적인 예로는 건강의 사회적 결정요인, 공중보건, 건강시스템 등에 대한 강의가 있다.

Social responsibility is seen as the state by which an institution has an implicit awareness of society’s priority health needs and challenges and is mainly guided by intuition or a natural inclination to address them. In this case, a school may not feel the need to consult other health stakeholders of what the school’s priority actions should be and whether the outputs of its education, research, and service programs affect people’s health in a meaningful way. For instance, a medical curriculum may provide ample learning opportunities in a variety of disciplines related to health determinants and public health, including an exposure to field experiences, but is not built on key competences graduates should acquire to optimally fit into a health system designed to deliver equitable and efficient services. A typical example would be a lecture course on social determinants of health, what is public health, the health system, etc.

[사회적 대응성]은 사실에 대한 비판적 평가에 의한 건강 요구의 명시적 식별과 우선 순위를 의미한다. 이 경우, 학교는 이러한 우선순위 요구를 해결하기 위한 임무와 행동 프로그램을 결정할 수 있고, 명확하게 식별된 결과에 더 의미 있게 자원을 streamline할 수 있다.

- 예를 들어, 학교는 현재의 보건 시스템과 보건 인력의 장단점을 분석하고 효율적이고 공정한 보건 서비스를 제공하기 위한 전략으로 일차 의료의 강력한 옹호자가 될 수 있다. 따라서 교육 프로그램의 기대 결과는 첫 번째 진료 제공자로서의 실무에 관련된 능력을 보유한 충분한 수의 졸업생의 생산이다.

- 따라서, 학생들은 지역사회 활동을 관찰하고 참여하기 위해 다양한 시간 및 발전 단계별로 지역사회로 보내진다. 커뮤니티의 규모, 구조 및 맥락에 대한 정의는 각 학교에 따라 다릅니다. 마찬가지로 교육 내용과 예상 학습 성과도 학교마다 다릅니다.

Further along the social obligation spectrum, and at a higher level on the scale is “social responsiveness”, which implies an explicit identification and prioritization of health needs by a critical appraisal of facts. In this case, a school is able to determine its mission and action programs to address those priority needs, and streamline its resources more meaningfully to clearly identified outcomes.

- For instance, a school may have analyzed strengths and weaknesses of the current health system and health workforce, and be a strong advocate for primary health care as a strategy to provide efficient and equitable health services. Hence an expected outcome of its educational programs is the production of sufficient number of graduates possessing relevant competences to practice as the first line of care providers.

- Hence, students are sent out to the community for varying lengths of time and at different stages of their development to observe and participate in community activities. The definition of the size, structure, and context of the community varies with each school; similarly the educational content and expected learning outcomes varies from school to school.

["사회적 책임"]은 스펙트럼의 마지막 단계인 사다리의 가장 높은 단계로 간주된다. 여기에는 제품, 졸업생, 연구 결과 또는 의료 모델, 의료 시스템의 성능 및 사람들의 건강 상태에 미치는 영향을 최대한 활용할 수 있도록 지역사회 내 주요 이해 관계자들과의 적극적인 참여와 파트너십이 포함됩니다.

- 예를 들어, 학교는 졸업생이 가장 필요한 분야에서 일하도록 장려하는 전략을 개발할 것이다. 졸업자는 지역사회에서 필요하고 잘 대표되지 않는 전문 분야로 장려된다. 연구는 지역사회에 직접적인 영향을 미치는 문제에 특별히 초점을 맞춘다(Straser et al. 2015). 사회적 책무는 이러한 변화의 영향을 평가하고 측정할 필요성을 내포하고 있다(표 1).

“Social accountability” is seen as the highest step on the ladder, the final stage in the spectrum. It involves active engagement and partnering with key stakeholders, including those within the community, to ensure the best use is made of how its products, be graduates, research findings or health care models, impact upon health systems’ performance and people’s health status.

- For instance, the school would develop a strategy whereby graduates are encouraged to work in areas where they are most needed; graduates are encouraged into specialties that are needed and poorly represented in the community; research is specifically orientated towards issues that are directly impacting upon the community (Strasser et al. 2015). Social Accountability, most importantly, also implies a necessity to evaluate and measure the effect of such change (Table 1).

세계 각지의 의과대학에 대한 관찰은 많은 학교가 사회적 책임의 기준을 만족하고 부분적으로는 사회적 대응성을 달성하지 못했으나 사회적 책임의 수준을 달성하지 못한 것을 보여주는 경향이 있다(또는 그러한 성과를 입증하기 위한 연구 전문지식이나 지원을 받지 못한 것일 수 있다). 표 1의 요소 5와 6은 이러한 차이를 특징으로 한다.

Observations of medical schools from various parts of the world tend to show that many schools satisfy the criteria of social responsibility and in part social responsiveness, but have not achieved the level of social accountability (or perhaps have not had the research expertise or support to demonstrate such achievements). Elements 5 and 6 of Table 1 feature those differences.

사회적으로 책임 있는 학교의 경우

- 평가의 초점은 효율적인 관리가 성공적인 규정 준수와 동등한 범위의 프로세스에 있습니다.

- 외부 환경에 대한 제한적인 협의와 학계에 의해 본질적으로 설계된 규칙과 함께.

In the case of a socially responsible school,

- the focus of evaluation is on process with scope that efficient management equates with successful compliance,

- with rules essentially designed by the academic community and with limited consultation of the external environment.

사회적으로 반응하는 학교의 경우

- (평가의) 초점은 다른 보건 이해당사자들과 협의하여 확인된 (사회 우선 건강 요구와의 일치에 의해) 증명되는 결과에 있다. 이러한 결과는 다음과 같습니다.

- 사회가 필요로 하는 보건 전문가의 질과 양,

- 우선적인 건강 문제를 다루는 연구 의제

- 사람 중심의 관리를 제공하는 health setting의 모델.

In the case of a socially responsive school,

- the focus is on outcome evidenced by congruence with society priority health needs identified in consultation with other health stakeholders.

- Those outcomes may be: quality and quantity of health professionals needed by society, a research agenda addressing priority health issues or models of health settings delivering person-centered care.

사회적으로 책임 있는 학교의 경우,

- 평가의 초점은 사람들의 건강 상태에 미치는 영향에 있다. 이는 학교가 그들의 제품이 궁극적으로 어떻게 사용되는지 추적하기를 열망한다는 것을 의미한다.

- 졸업생들의 성과,

- 연구 결과가 어떻게 실천으로 전환되는지,

- 효율적이고 공정한 의료 서비스가 목표 집단에 제공되는지 여부.

- 사회적으로 책임 있는 학교는 그 행동의 장기적인 결과에 대한 책임을 받아들인다.

In the case of a socially accountable school,

- the focus of evaluation is on the impact on people’s health status, which implies that the school is keen to follow-up how its products are ultimately used: how graduates perform, how research findings are translated into practice, and whether efficient and equitable health services are delivered for a target population. A socially accountable school accepts the responsibility for long-term consequence of its actions.

학교성적을 평가하는 평가자 선택에서도 차이가 두드러진다.

- 사회적 책임의 경우 지역 학계에 속하거나

- 사회적 대응의 경우 외부일 수 있다.

- 두 경우 모두 평가자는 동료인 반면 사회적 책무의 경우 평가자는 다양한 의료 파트너로부터 제공되며, 주로 보건 기관, 보건 직업, 서비스 사용자 및 일반 대중을 대표한다.

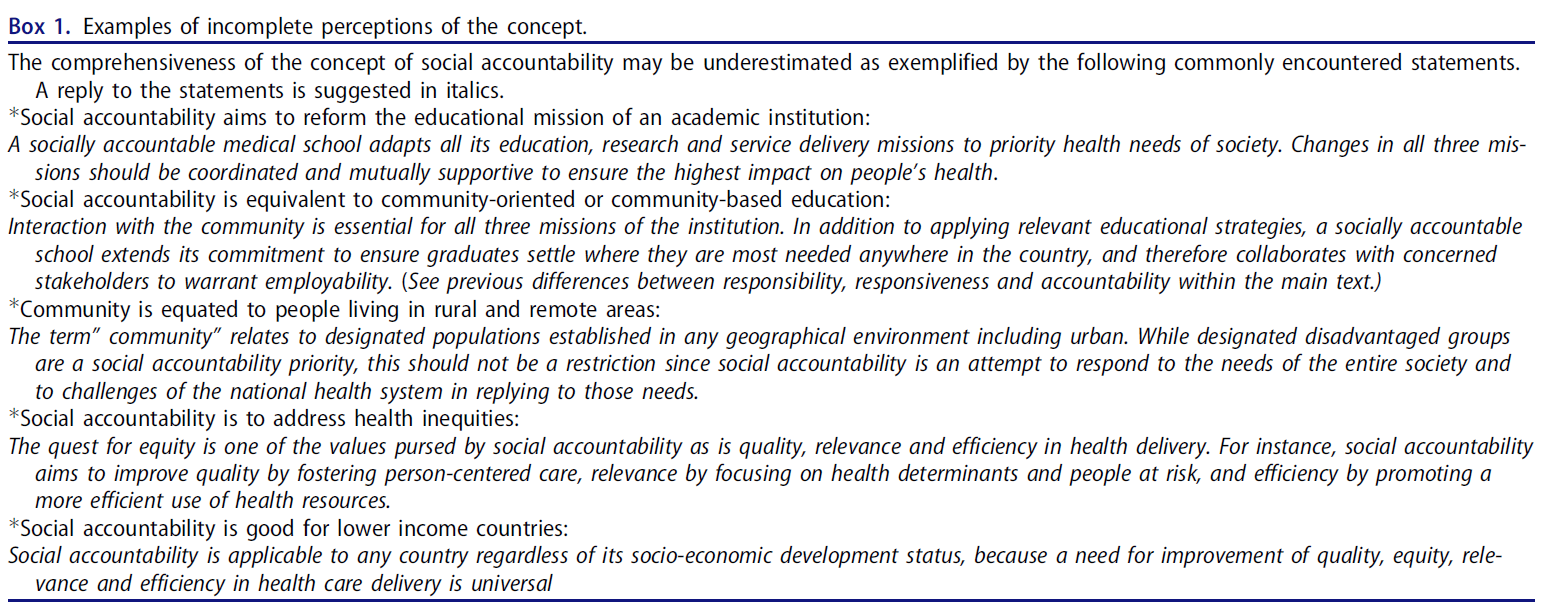

Difference is also notable in the choice of assessors in evaluating the school performance. They may belong to the local academic community in case of social responsibility, or be external in case of social responsiveness. In both instances, assessors are peers while in the case of social accountability, assessors are provided from a wider array of health partners, principally representing those the school is committed to serve, i.e. the health organisations, health professions, the users of the service, and the public at large. Box 1 demonstrates some examples of variability in defining social accountability.

사회적 책임을 어떻게 평가합니까?

How is social accountability assessed?

의과대학의 사회적 책임을 위한 글로벌 컨센서스는 사회적 책임을 지는 학교를 다음과 같은 것으로 묘사했다.

- 현재와 미래의 보건 요구 및 사회 과제에 대응한다.

- 이에 따라 교육, 연구 및 서비스 우선 순위를 재조정한다.

- 거버넌스와 다른 이해관계자와의 파트너십을 강화한다.

- 평가와 인증을 사용하여 성능과 영향을 평가한다(GCSA 2010).

The Global Consensus for Social Accountability of medical schools has pictured a socially accountable school as one that:

- responds to current and future health needs and challenges in society;

- reorients its education, research and service priorities accordingly;

- strengthens its governance and partnerships with other stakeholders;

- uses evaluation and accreditation to assess performance and impact (GCSA 2010).

학교가 사회적으로 책임을 지려면 선언된 의도, 프로그램 실행, 결과 및 영향 사이의 일관성을 입증해야 한다.

- 예를 들어, 학교가 건강 이견을 해소하기 위해 전념할 경우,

- 그것은 그러한 불균형을 개선할 수 있는 방법으로 봉사하기 위해 적절한 능력을 가진 졸업생들을 준비하기 위한 교육 프로그램을 설계할 것이다.

- 필요한 경우 지역 당국과 협력하여 일자리 기회를 열거나 창출할 것입니다.

- 그것은 새로운 졸업생들에게 매력적인 1차 진료와 다른 전문지식을 전달하기 위한 최선의 방법을 개선하기 위해 그것의 연구 능력을 사용할 것이다.

- 시간 경과에 따른 건강 상태 변화를 평가하고 적절한 의사 결정 수준에서 최종 개선 조치를 제안할 것이다.

For a school to be socially accountable, it needs to demonstrate consistency between declared intentions, program implementation, outcome, and impact.

- For instance, if a school is committed to address health disparities,

- it will design education programs to prepare graduates with appropriate competences to serve in a way that will improve those disparities,

- it will collaborate with local authorities to open or create job opportunities where required,

- it will use its research capacity to improve the best ways to deliver primary care and other specialties that are attractive to new graduates,

- it will assess health status changes overtime and suggest eventual remedial actions at appropriate decision levels.

사회적 책임 개념은 과학적으로 타당한sound 개념이다. 건강, 건강 시스템, 건강 파트너, 학교 거버넌스, 학교의 행동과 같은 요소들을 명시적으로 정의하고, 이들 요소들 사이의 더 나은 관계가 건강에 더 큰 영향을 줄 수 있다는 증거를 찾기 때문이다.

The social accountability concept is a scientifically sound one as it explicitly defines elements such as: health, health system, health partners, school governance, and school’s actions, and seeks evidence that a better relationship between these elements can make a greater impact on health.

사회적으로 책임 있는 학교는 [사회를 위해 공개적으로 약속한 것을 사회에 보고]해야 한다.

- 예를 들어, 벤치마크는 의료 학교가 특정 모집단의 건강 우선 순위를 다루기 위해 보건 당국과 어떻게 관계를 형성하는지 탐구할 것이다.

- 보다 효율적인 보건 서비스를 위해 의료와 공공의 건강을 통합하는 방법을 설계하고, 보건 전문가들 사이에서 보다 효율적인 업무 할당을 제안한다.

- 가장 필요한 모집단에 대한 졸업생의 공정한 지리적 분포를 보장하고 보편적 보장을 위해 보건 이해 관계자와 협력한다.

A socially accountable school should report back to society what it had publicly engaged to do for society,

- e.g. benchmarks will explore how a medical school creates a relationship with health authorities to address health priorities in a given population,

- suggests a more efficient allocation of tasks among health professionals, experiments, and designs ways to integrate medicine and public health for more efficient health service,

- ensures a fair geographical distribution of graduates for population in greatest need and partners with health stakeholders for universal coverage.

이것은 [동료들]뿐만 아니라, 함께 봉사하고 일하고자 하는 사람들(보건 당국, 보건 전문가, 시민 사회의 대표들(환자 및 고용주))에 의해서도 평가되는 학교의 사회적 책무로 발전할 수 있다. 이러한 대표자들이 유사한 사회적 책임 원칙을 채택한다면 이는 실현 가능할 것이다.

This may develop in the future to the social accountability of a school being assessed not only by peers, but also by those it intends to serve and work with, i.e. representatives of health authorities, health professionals, and civil society (patients and employers). This would be feasible if these representatives would adopt similar social accountability principles.

개념화-생산-이용성의 약자인 CPU 모델과 같은 사회적 책임에 대한 평가 도구가 등장하기 시작하고 있다. 우선순위의 건강 요구와 관련된 조치를 계획하고, 그러한 조치를 구현하고, 사회에 예상되는 영향을 초래하는 조치를 보장하기 위해 학교 약속을 탐구하는 일련의 매개 변수로 구성된다(Boelen & Woollard 2009). 상자 2와 3은 CPU 모델이 어떻게 구조화되고 특정 결과에 적용되는지를 보여준다.

Evaluation instruments of social accountability are beginning to emerge, such as the CPU model, an acronym for “Conceptualization-Production-Usability”, made up of a sequence of parameters exploring respectively the school commitments in planning actions relevant to priority health needs, in implementing those actions and in ensuring actions produced the anticipated affects on society (Boelen & Woollard 2009). Boxes 2 and 3 demonstrate how the CPU model is structured and applied to specific outcomes.

THEnet(Training for Health Equality Network)은 호주, 캐나다, 남아프리카 및 필리핀의 의과대학 샘플에서 테스트한 CPU 모델과 현장에서 파생된 벤치마크로 [평가 프레임워크]를 설계했다

- 이러한 각 학교는 이 프레임워크가 건강 결과와 보건 시스템 성과에 긍정적으로 영향을 미치는 학교의 능력에 영향을 미치는 주요 요인을 식별하고, 학생, 직원 및 이해 관계자들 사이에서 문제에 대한 인식을 높이는 데 효과적이라는 것을 발견했다.

- 그것은 각 학교가 사회적 책임 임무, 비전, 목표를 검토하고 강점, 약점 및 격차를 식별할 수 있게 했다(Larkins et al. 2012).

- 또한 THEnet은 이러한 벤치마크를 더 잘 달성할 수 있도록 참여 의과대학에 지원과 공유 경험을 제공했다.

The Training for Health Equity Network (THEnet) has designed an evaluation framework with benchmarks derived from the CPU model and field tested in a sample of medical schools in Australia, Canada, South Africa, and The Philippines (The Training for Health Equity Network 2011).

- Each of these schools found the framework effective to identify key factors that affect a school’s ability to positively influence health outcomes and health systems performance, also to raise awareness of the issue among students, staff, and stakeholders.

- It allowed each school to review their social accountability mission, vision and goals and identify strengths, weaknesses and gaps (Larkins et al. 2012).

- THEnet has also offered participating medical schools the support and shared experience to better achieve these benchmarks.

ASPIRE 이니셔티브는 유럽 의료 교육 협회(AMEE) 활동이며, 의학, 치과 및 수의과 학교(AMEE 2012)의 연구와 교육의 우수성을 인정하기 위해 고안되었다. 이 이니셔티브의 한 요소는 사회적 책무이다.

The ASPIRE initiative is an Association for Medical Education in Europe (AMEE) activity that was designed to recognize excellence in education as well as research within medical, dental, and veterinary schools (AMEE 2012). One element of the initiative allows schools to demonstrate a level of excellence in social accountability,

의과대학이 사회적 책임을 핵심 가치와 지침 원칙으로서 수용해야 하는 점점 더 강제적인 이유를 더하는 많은 [부수적 편익]이 있으며, 이는 또한 평가 기준에 추가될 수 있다.

- 비용 증가와 의료 수요 증가로 인해 의료 자원을 최선으로 활용해야 하는 필요성

- 의료 시스템의 성능 향상을 통해 시민의 건강을 증진시키기 위한 학술적 연구 잠재력의 초점 향상. 개인 진료 및 인구 건강 영향에 초점.

- 사람들의 건강에 가장 큰 영향을 미치는 실행 행동의 우선순위를 정하고 입증할 필요성(사회적 책임의 증거 기반)

- 변화하는 인구 통계 및 의료 수요에 대응하기 위한 새로운 역할의 흥분과 보건 인력진 내 과제의 재분배

- 당국과 공공이 추구하는 기관의 투명성 제고 필요성

- 모든 보건 시스템은 아이디어, 접근 방식, 증거 및 영향을 지속적으로 진화해야 한다.

There are a number of ancillary benefits that add to an increasingly compelling reason for medical schools to embrace social accountability as a core value and guiding principle, which may also add to the assessment criteria:

- the need to make the highest and best use of health resources, due to the rising costs and increased demands of healthcare;

- the better focus of academic research potential to improve the health of citizens through better performance of health systems, focused on personal care and coordinated population health impact;

- the need to prioritize and demonstrate performed actions that have the greatest impact on people’s health—a feature of the evidence base of social accountability;

- the excitement of new roles and reallocation of tasks within the health workforce to respond to changing demographics and health care demands;

- the need for greater transparency of performance of institutions as sought by authorities and the public alike;

- all health systems require an on-going evolution of ideas, approaches, evidence and impact;

사회적 책임을 지는 학교를 개발하기 위한 실질적인 조언

Practical tips for developing a socially accountable school

현재 위치 점검, 자체 평가

Benchmarking the current position, self-assessment

모든 학교는 사회적 요구에 대응하기 위해 노력하는 자신의 권리를 주장할 수 있다. 사회적으로 책임 있는 학교를 발전시키기 위한 보편적인 전략은 없지만, 가능한 해결책으로 다양한 상황에 맞는 몇 가지 시나리오를 상상할 수 있다.

Every school can claim in its own right it endeavors to respond to societal needs. While there is no universal strategy to develop a socially accountable school, several scenarios could be imagined to fit different situations, with possible solutions:

- 시나리오 1: 학교는 알지 못합니다.

- 사회의 우선적인 건강 요구를 충족시키기 위해 학교가 상대적으로 외진 것을 모르고 있는 '아이보리 타워' 상황이다.

- 개별 학과의 연구업무가 우수하고 업무의 질과 관련성을 확신하며 학교 전체의 사회공헌을 고려하도록 조직되지 않은 것으로 유명하다.

- 학교에서 옹호자가 되기 위해 헌신하는 한 명 또는 소수의 교수들은 사회적 책임을 중요한 개념으로 인식했다.

- 수석 교수진 또는 주요 이해 당사자는 (특히 글로벌 야망이 지역 또는 지역 야심을 무색하게 하는) 사회적 책임 개념에 의문을 제기할 수 있다.

- 우수성은 "최첨단의" 연구 성과와 동일시될 수 있으며, 소수의 지지자들만이 우수성이 사회 전체의 건강 증진에 기여하는 능력에 의해 측정되어야 한다고 주장해야 할 것이다.

- Scenario 1: School unaware.

- The “ivory tower” situation where the school is unaware of its relative remoteness to fulfill society’s priority health needs. It is noted for excellence in the research work of individual departments, confident of the quality and relevance of its work and is not organized to consider the contribution to society of the whole school. One or a few faculty members who are committed to be advocates in their school have perceived social accountability as an important concept. Senior faculty or key stakeholders may question concepts of social accountability, particularly where global ambitions overshadow regional or local ones. Excellence may be equated with achievement in “cutting-edge” research, the challenge for the few advocates will be to argue that excellence should be measured by the capacity to contribute to health improvement for society as a whole (both local, regional, and global).

- 시나리오 2: 학교는 의지가 있다, 단...

- 교수들은 학교가 복무하는 사회에 대한 책임을 인식하고, 사회적 요구를 더 잘 충족시키기 위해 임무와 프로그램을 재조정하겠다는 의지를 표명할 것입니다. 일부 고립된 프로그램은 지역사회 조정과 참여를 포함하여 좋은 실천을 보여줄 것이다.

- 학교는 필요한 변화를 간절히 원할 수 있지만 자원 부족 및/또는 제한된 외부 및 이해관계자 지원으로 인해 그렇게 할 수 없다.

- 이 학교는 다른 우선 순위를 요구할 수도 있는 상급 기관의 정치적 의지(&재정적 지원)에 의존할 수도 있다. 사회적 책임을 인정하고 촉진하는 국가 이니셔티브는 학계와 보건계의 저명한 구성원들이 참여하는 환영할 것이다.

- Scenario 2: School willing to, if only ………

- Faculty of the school will be aware of its responsibilities to the society it serves, and express a willingness to readjust its missions and programs to better meet societal needs. Some isolated programs will demonstrate good practice including community alignment and involvement. School may be keen to make necessary changes but is not be able to do so due to lack of resources and/or limited external and stakeholder support. The school may rely on a political will (& financial backing) from higher authorities, which may demand different priorities. National initiatives to recognize and promote social accountability would be welcome, involving the academic community and prominent members of the health community.

- 시나리오 3: 학교는 인지하고 있고 기꺼이 하려고 하지만…….

- 이러한 맥락에서 학교는 어떤 우선순위 조치가 필요한지 알고 있으며 지역사회와 상호작용하는 중요한 경험을 가지고 있다. 교육 프로그램은 졸업생들이 필요한 역량을 습득할 수 있도록 설계되었으며, 연구 의제 및 보건소 네트워크에 대한 서비스 분야에서 건강 결정 요인을 다루겠다는 의지가 있다.

- 그러나 학교는 [졸업생의 관행, 보건 시스템 관리 스타일 및 모집단 건강 지표의 변화에 미치는 스스로의 영향(또는 영향의 증거)]이 제한적이라는 것을 알고 있다. 학교 지도부는 보다 효율적이고 공정한 의료 제공 시스템에 대한 기여도를 최적화하기 위해 주요 보건 이해 관계자들과 보다 강력한 파트너십을 구축하기로 결정했습니다.

- 이는 "결국, 우리가 책임져야 할 환자와 인구가 더 높은 수준의 건강을 달성했다는 것을 증명할 수 있을 때에만 우리는 우리의 변혁적인 노력에 성공했다고 말할 수 있을 것이다"라는 학장의 말로 대표된다.

- 학교는 [건강 결과에 대한 영향의 증거를 얻는데 필요한, 복잡한 연구를 위한 전문 지식과 능력을 제공하는 측면에서] 지원이 필요할 수 있다.

- Scenario 3: School aware and willing, but…….

- In this context the school is aware of which priority actions are needed and has a significant experience interacting with the community. Educational programs are designed for graduates to acquire required competences and there is commitment to address health determinants in the research agenda and in services to a network of health centers.

- However, the school is aware of its limited impact (or evidence of impact) in changing graduates practice, health system management style and population health indicators. The leadership of the school is determined to create a stronger partnership with key health stakeholders to optimize its contribution to a more efficient and equitable health care delivery system.

- This is exemplified by the words of their Dean: “Ultimately, we will have succeeded in our transformational efforts only when we can demonstrate that the patients and populations for which we are responsible have achieved a higher level of health”

- The school may need support in terms of providing expertise and capacity for the complex research that allows evidence of impact on health outcomes.

- 시나리오 4: 학교, 의식, 의지, 그리고 궤도에 오른다.

- 드문 경우이긴 하지만, 이 학교는 동료들에게 인정받고 외부 벤치마킹을 통해 사회적 책임 분야에서 인정받는 리더가 될 것입니다. 그것은 비전과 전략을 지역사회 이해관계자들과 함께 설계하고 통제하며, 전략과 연계된 프로그램과 프로젝트를 가질 것이며, 그것이 봉사하는 모든 인구에서 건강 시스템과 건강 결과에 대한 개선을 보여줄 수 있는 능력을 가질 것이다.

- 다른 좋은 학교나 팀과 마찬가지로, 그것은 그 영예에 안주하지 않을 것이다. 더 많은 일을 하고 더 높은 목표를 세우고 더 멀리 도달하기 위해서는 강력한 지도 연합과 추진력이 여전히 필요하다.

- Scenario 4: School, aware, willing and on track….

- In rare cases the School would be a recognized leader in the field of social accountability – recognized by its peers and through external benchmarking. It will have vision and strategy designed and governed with its community stakeholders, it will have programs and projects aligned to strategy and will have the ability to demonstrate an improvement to health systems and health outcomes across all of the population it serves.

- Like any good school or team it won’t be resting on its laurels – a strong guiding coalition and driving force is still needed to do more and aim higher and reach further.

문화의 변화, 생각의 변화: 변화를 주도한다.

Changing culture, changing minds: leading change

시나리오 1과 2를 택한다면 변화를 전달하고 사회적으로 더 책임감 있는 학교를 세우려는 사람들은 다양한 리더십 기술과 전략이 필요할 것이다. 그들은 학교가 외부적으로 확립된 프레임워크에 반대했던 곳을 벤치마킹하는 것이 좋을 것이다. – 아마도 사회적 책임을 위한 TENet 또는 ASPIRE 프레임워크로부터 시작할 것이다(Ross et al. 2014). 이로부터, 학교의 이전을 시작하기 위한 변화-관리 전략이 필요하다.

- 학교는 이미 사회적 책임 원칙과 관련된 일을 하고 있는가?

- 또 뭘 해야 하죠? 무엇이 바뀌어야 합니까?

- 왜 변화가 이해관계자들에게 유익할까요?

- 어떻게 변화가 학교가 새로운 자금이나 지원을 유치하는 데 도움이 될까요?

- (예: 한 지역의 건강 격차를 줄이기 위한 다른 보건 행위자와의 파트너십, 환자 중심의 관리 및 인구 보건 조치를 통합한 다중 전문 일차 의료 센터 실험, 연구 우선 순위 설정에 대한 지역사회 및 환자 참여, 탄소 발자국에 대한 인식 및 활동의 환경 영향)

If we take Scenarios 1 and 2, those who seek to deliver change and build a more socially accountable school will need a range of leadership skills and strategies. They would do well to benchmark where the school was against external established frameworks – perhaps starting with the THENet or the ASPIRE frameworks for social accountability (Ross et al. 2014). From this, a change-management strategy is needed to start a repositioning of the school:

- What is the school already doing pertinent to social accountability principles?

- What else should it do? What needs to change?

- Why would change be beneficial to stakeholders?

- How would change help the school attract new funding or support?

- (e.g. partnership with other health actors to reduce health disparity in a territory; experimenting a multi-professional primary health care center integrating patient centered care and population health actions; community and patient involvement in setting research priorities; an awareness of carbon footprint and environmental impact of activity.)

그 결과 변경 대리인 또는 리더는 사회적 책임 행사를 주최하거나 워크숍을 통해 변화를 유발하고 주요 이해관계자를 초청하여 참여 학교로부터 모범 사례와 그것이 가져다 주는 이점을 들을 수 있다.

In turn the change agent or leader might seek to provoke change through hosting a social accountability event, or workshop and invite key stakeholders to hear good practice from participating schools and the advantages it brings.

사회적 책임 원칙을 지키고자 하는 사람들을 위한 세 가지 핵심 전략이 있다.

- 첫째, 사회적으로 진행 중인 작업의 우수성과 장점을 학교에 보여주십시오.

- 좋은 홍보,

- 수상,

- 연구에 대한 환자/공공의 참여(grant에 필수적인 경우가 많음),

- 국가 교육 또는 정책(잠재적으로 자금을 확보함)과의 정렬

- 둘째, 무정부 상태가 아니라 비전과 일치하는 곳에서만 파트너십과 변화를 달성할 수 있기 때문에 (비전을 수립하는 이해 당사자인) 연합을 다시 활성화하고 참여시켜야 합니다. 비전은 기관의 우수성임을 기억하십시오. 학교의 정신을 이끄는 사회적 책임을 포함한 모든 측면에서 우수성을 목표로 합니다.

- 셋째, 국가적으로나 세계적으로 로비를 합니다. 우리 모두는 국제 및 국가 문화가 우리와 일치할 때 지역적으로, 우리의 기관과 지역사회에서 변화를 성취하는 것이 최선이다. 사회 정의와 사회 변혁을 위한 이 광범위한 운동을 형성하도록 돕습니다.

There are three key strategies for those wishing to uphold the principles of social accountability.

- First, to demonstrate excellence and advantage to the Schools from the work going on with and for society –

- advantages from good publicity,

- prizes,

- patient/public involvement in research (often essential for grants),

- alignment with national educational, or policy drivers (potentially unlocking funding).

- Second, to reinvigorate and involve the guiding coalition – the stakeholders who build the vision – not to be anarchic but because partnership matters and change can only be achieved where vision aligns with visions. Remember the vision is excellence of an institution– aim for that in all facets, including the social accountability driving the ethos of the school.

- Third, lobby, both nationally and globally. We all best achieve change locally, in our institutions and communities, when the international and national culture is aligned to ours. Help shape this wider movement for social justice and social transformation.

프로세스, 활동, 커리큘럼 및 기여 변경: 변경 관리

Changing processes, activities, curriculum, and contribution: managing change

학교가 변화의 과정을 따라 더 나아가고 있는 곳에서는 필요성은 모멘텀을 유지하고, 명확한 목표를 세우고, 성공을 축하하고, 안일함을 피하는 것에 관한 것일 수 있다. 교육과정 이니셔티브는 쉬운 승리이고, 지역사회 참여와 진정한 책무를 덜 필요로 할지도 모르지만, 교육과정 이니셔티브는 더 깊고 깊은 변화를 자극하기 위한 좋은 출발점으로 남아 있다.

- 예를 들어, 학생, 의대 직원, 보건 전문가가 참여하는 혁신적인 커뮤니티 프로젝트 만들기, 커뮤니티 프로젝트에 대한 평가가 학교에서 제시될 때 커뮤니티 대표가 참석하여 교류하도록 초대하는 것이다. 학교는 변화를 가속화하기 위해 그러한 계획들을 어떻게 활용하고 있는가?

Where the School is further along the process of change the need may be more about sustaining momentum, setting clear goals, celebrating successes, and avoiding complacency. Although curriculum initiatives may be easy wins, needing less community involvement, and true accountability, they remain good starting points to stimulate further and deeper changes.

- For instance, the creation of innovative community projects involving students, medical school staff, and health professionals from the field; the invitation of community representatives to attend and interact when evaluation of community projects are presented at the school. How does the school capitalize on such initiatives to accelerate change?

학교의 원래 비전과 전략이 더 넓은 지도적 연대guiding coalition를 바탕으로 한 강력한 기반에 바탕을 둔다면 학교가 봉사하는 지역사회에 대한 기여도에 상당한 변화가 일어날 가능성이 더 높다.

- 학교가 복무하는 지역 사회와의 관계 본질을 바꾸려고 노력하는 과정이 정체되고 있다면, 이 지도 연합의 문화와 헌법을 재검토하고 다시 활성화할 필요가 있을 것이다.

- 아마도 한가한 날을 위한 시간, 회의, 학교 재집중하기 위한 외부적으로 촉진되는 행사, 목표를 재검토하고 이러한 마지막 단계를 만드는 데 있어 장애물을 다시 한 번 살펴보아야 할 것이다.

- 빠른 승리는 도움이 될 수 있지만, 혁신적 변화는 강점과 약점, 기회와 제약, 나아가야 할 집단적 결정에 대한 도전적인 대화가 필요합니다.

Significant change in a school’s contribution for and with the community it serves is more likely to happen if the school’s original vision and strategy is based on strong foundations with a wider guiding coalition.

- If progress is stalling as a school seeks to change the nature of its relationship with the communities it serves then the culture and constitution of this guiding coalition may need to be revisited and reinvigorated.

- Time perhaps for an away day, a conference, an externally facilitated event to refocus the school, re-examine the goal and look again at barriers to making these last steps.

- Building the quick wins may help – but transformative change needs challenging conversations on strengths and weaknesses, on opportunities and constraints, collective decisions to move forward.

변화에 대한 장벽 및 저항

Barriers and resistance to change

사회적으로 책임 있는 의대를 개발하는 것이 항상 쉬운 일은 아니다. 학교의 철학과 조직 구조에 상당한 변화가 필요하다. 상대적으로 새로운 개념은 흔히 어려운 작업이다. 사회적 책임은 학교가 통제하려는 열망과 열망을 저해하고 변화에 대한 거부감과 빈번한 거부감으로 맞서는 경우가 많기 때문에 학교는 패러다임을 구현하기 위한 장벽을 의식해야 한다.

Developing a socially accountable medical school is not always easy; a relatively new concept, which requires significant change in the schools’ philosophy, and organizational structure, is frequently a daunting task. Schools must be conscious of the barriers to implement the paradigm, since social accountability impinges upon an eagerness and desire of the school to control and is frequently countered by unwillingness and frequent disincentives to change.

마찬가지로, 개업의는 대개 치료를 제공하지만 환자의 사회적 요구를 항상 인식하거나 고려하지 않으며, 다른 보건 전문가에게 업무를 위임하는 것을 꺼린다. 연구자들은 커뮤니티와 관련된 질문을 자주 피하거나 커뮤니티에 이익이 되는 질문을 피한다. 왜냐하면 그러한 연구는 종종 낮은 중요도, 발표되기 어렵고, 재정적인 지원을 얻기 어렵고, 그리고 종종 추진 위원회들의 눈에 낮은 위치를 차지하기 때문이다.

Similarly, practicing doctors usually provide care, not always recognizing or taking into account the patients’ social needs or are reluctant to delegate tasks to other health professionals; researchers frequently avoid questions related to the community or which will benefit the community, since the research produced is often seen of low importance, difficult to get published, hard to obtain financial support, and frequently occupies a lowly position in the eyes of the promotion committees.

교수진은 종종 "사회적 책무"와 같은 개념을 진정한 생물 의학이 아닌 "부드러운" 개념으로 폄하하고, 학생들이 그 개념을 진지하게 받아들이도록 하지 않는다. "사회적 책무"의 공간에서 일하면 사람들은 그들이 통제하는 영역인 편안한 영역에서 벗어나 다른 사람들로부터 배우고 신용을 공유해야 하는 영역으로 이동하게 된다. 학교는 다른 방향으로 찢어질 것이다. 지역사회와 협력하고 그 지역사회의 입학 허가를 넓히려는 의지가 진보적인 학교가 원하는 것보다 더 좁게 정의된 우수성을 보상하기 위해 국가 운전자들(그리고 재정적 인센티브)과 충돌할 수 있다.

Faculty often denigrates concepts like “social accountability” as “soft”, not true bio-medical science, whilst discouraging students to take the concept seriously. Working in the “social accountability” space moves people out of the comfort zone, a zone they control, into an arena where they have to learn from others and share credit. Schools will be torn in differing directions – a willingness to work with communities and widen access to admissions from that community may clash with national drivers (and financial incentives) to reward excellence as defined more narrowly than the progressive school may wish.

긴장은 실제한다. 긴장을 극복하는 첫 번째 방법은 긴장을 인식하고 학교의 의사 결정 기관이 모든 이해 관계자들과 정직한 정보에 입각한 토론을 하도록 하는 것입니다. 보수적 세력이 투명성 제고, 기관의 지배구조 개선, 부족한 자원의 보다 효율적인 사용을 위해 정부, 납세자 및 시민 모두가 환영하는 사회적 책임에 대한 전세계적인 모멘텀의 존재를 깨닫기 시작하면 변화에 대한 저항은 최소화될 수 있다.

The tensions are real – the first way to overcome them is to recognize them and ensure decision-making bodies in the school engage in honest informed debate with all stakeholders. Resistance to change may be minimized if conservative forces begin to realize the existence of a worldwide momentum towards greater social accountability welcome by governments, taxpayers, and citizens alike for greater transparency, better governance of institutions, and more efficient use of scarce resources.

빈번한 과제와 이에 접근하는 방법

Frequent challenges and how to approach them

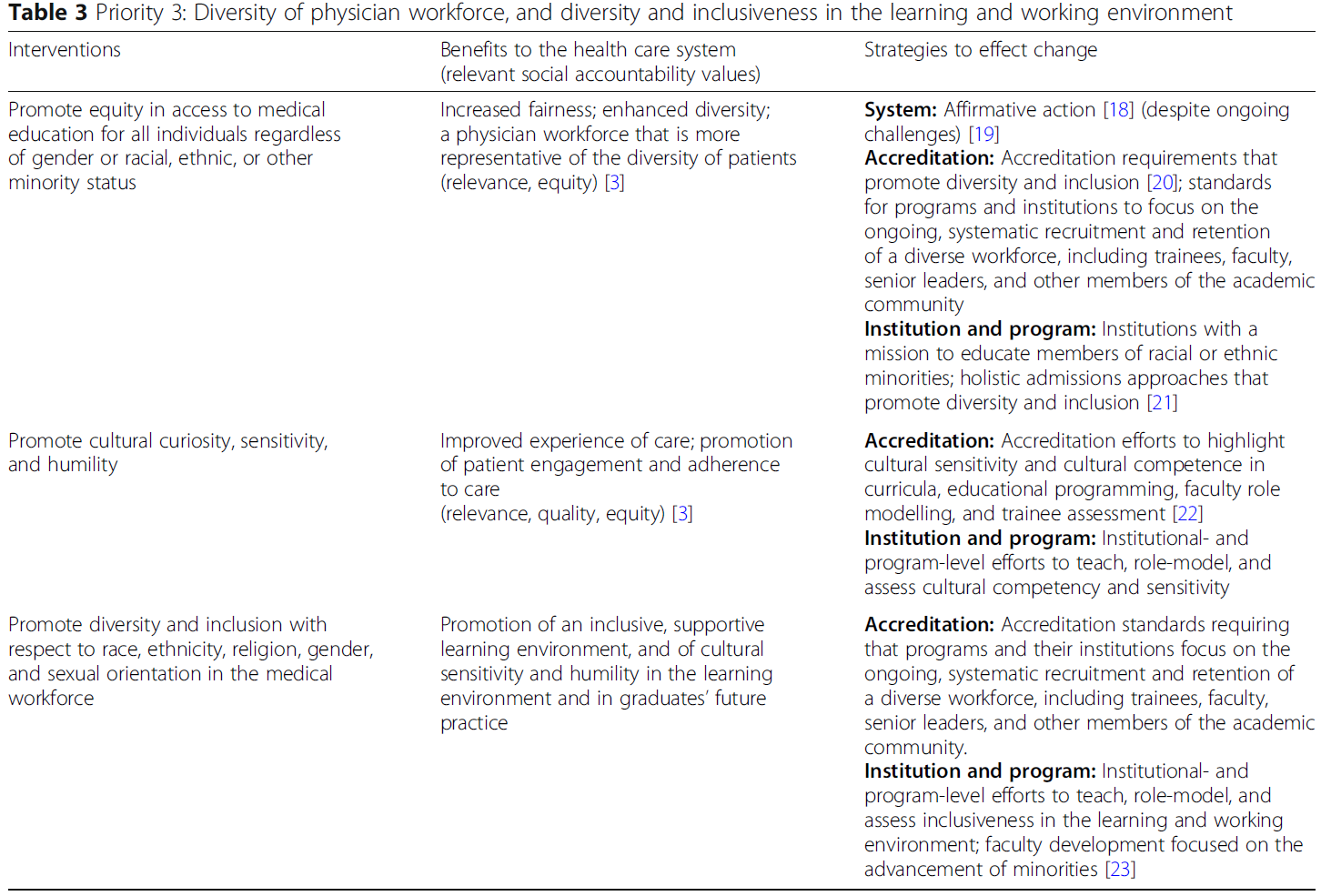

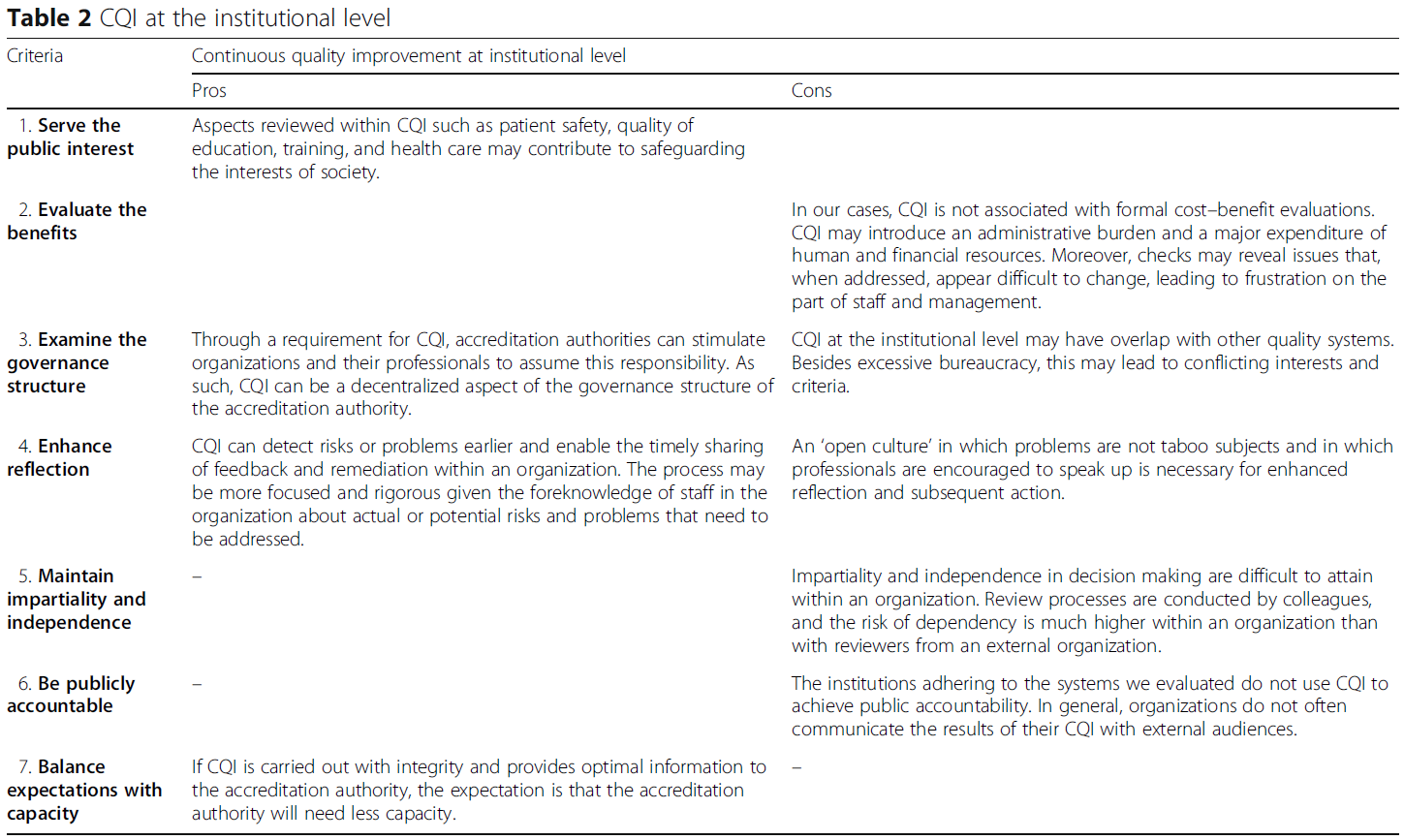

진정한 사회적 책임에 대한 사회적 의무의 스펙트럼을 따라 진행되기 위해서는 수많은 과제를 해결하고 극복해야 한다. 표 3은 전 세계의 실제 사례에서 가져온 몇 가지 빈번한 도전 사례와 몇 가지 해결책을 제시한다.

A host of challenges have to be addressed and overcome to progress along the spectrum of social obligation to true social accountability. Table 3 notes some frequent examples of challenges, taken from real examples around the world, and some solutions.

향후 과제

Future challenges

우리는 의과대학이 사회적 책임을 지려면 미래에 환경적으로 책임을 져야 한다고 제안한다. 즉, 두 학교는 불가분의 관계에 있다.

We suggest medical schools should in future be environmentally accountable if they are to be socially accountable – the two are inextricably interlinked.

의과대학에 환경적으로 책임질 수 있는 것은 어떤 모습일까요? 그리고 어떻게 측정될 수 있을까요?

What would being environmentally accountable look like to a medical school, and how might it be measured?

첫째, 의과대학은 환경적으로 책임져야 한다.

- 즉, 우리가 사회로서 직면한 지구 환경 문제에 대한 인식과 이것이 미래의 학생과 직원, 그리고 학교에 의해 지역적으로 봉사되는 인구에 어떤 영향을 미칠 것인지에 대한 인식을 보여야 한다.

- 그러한 책임에는 학교와 학교 활동의 탄소 발자국의 계산과 직원, 학생 및 활동의 다른 환경 영향(예: 물과 자원 사용)에 대한 인식이 포함될 수 있다.

Firstly medical schools should be environmentally responsible;

- showing an awareness of the global environmental challenges we face as a society – and recognition of how these will impact on future students and staff, and the populations served locally by the school.

- Such responsibility may include a calculation of the carbon footprint of the school and its activities, and recognition about other environmental impact of staff, students, and activities (e.g. water and resource use).

둘째로, 학교는 환경적으로 대응해야 한다:

- 기후와 다른 자원 사용 측면에서, 지역 환경과 지구 환경에 미치는 영향을 완화하기 위해 필요한 조치들에 대한 인식을 입증해야 한다. 사실상, "지상에서 더 가볍게 여행하는" 방법에 대한 인식을 보여줍니다.

- 여기에는 물, 원자재, 에너지 절약 정책(건축 및 여행 정책 수정 포함)을 위한 정책과 우선순위가 포함될 수 있으며, 이를 통해 재활용을 줄이고 지속 가능한 개발을 옹호하는 이니셔티브를 장려할 수 있다.

Secondly, schools should be environmentally responsive:

- demonstrating an awareness of the steps needed to alleviate their impact on the local and global environment, both in terms of climate and other resource use. In effect, to demonstrate an awareness of how to “tread more lightly on the earth”.

- This may include policies and priorities for saving water, raw materials, and energy (including amendments to building and travel policies), to reduce and recycle and to encourage initiatives that champion sustainable development.

셋째, 사회적 책임을 지는 모든 학교는 그러나 환경적으로 책임져야 한다:

- 인식과 대응성을 입증된 명확한 실천 계획과 연계하고, 학교와 봉사된 지역사회가 환경에 미치는 영향을 줄이고, 피해가 불가피할 경우에는 피해를 완화할 수 있는 방법에 초점을 맞추기 위해 지역 사회와 협력해야 한다.

- 그러한 활동은 환경적 책임을 지기 위한 접근 방식에서뿐만 아니라 측정 가능한 결과에서도 나타날 수 있다.

Thirdly, any socially accountable school should however be environmentally accountable:

- linking the awareness and responsiveness to the challenges highlighted with a proven clear plan of action; working with local communities to focus on how the school and its served communities can reduce its impact on the environment and mitigate damage to it where impact is inevitable.

- Such activity may be manifest both in the approach to being environmental accountable but also in measurable outcomes.

[환경적으로 책무성을 갖는 학교]는 환경적 영향을 줄이고 미래 세대를 위해 건강 시스템이 점점 더 지속 가능하게 하기 위해 교육, 연구 및 서비스를 통해 일을 하는 명확하고 효과적인 정책을 가질 것이다. 이는 여행, 운송 및 에너지 사용에 대한 효과적인 정책에서부터 가정 의료에 더 가까운 곳에 대한 연구, 진단, 치료 및 관리에서 원자재 사용을 줄이는 것에 이르기까지 다양할 수 있다. 또한 졸업생들이 자신과 자신의 직업이 환경에 미치는 영향을 이해하게 되어 지역 및 글로벌 생태계에 미치는 영향을 완화할 수 있는 기술을 갖추게 될 것이다. 이를 통해, 의과대학, 그들의 직원들과 졸업생들은 그들이 책임지고 있는 의료서비스가 그들이 봉사하는 지역 사회와 그들이 속한 행성의 장기적인 건강을 증진시킬 수 있도록 도울 수 있다. 환경 책임 학교는 자원을 더 효율적으로 사용하고, 예방에 초점을 맞추고, 폐기물 및 저평가 절차를 피하고, 가능한 경우 저탄소 기술을 선택하고, 환자 자율성을 강화하여 자신의 진료를 관리하는 [지속 가능한 의료 시스템]을 평가하고 촉진할 것이다(Mortimer 2010).

An environmentally accountable school would have clear and effective policies to reduce its environmental impact and work through education, research, and service to ensure health systems are increasingly sustainable for future generations. This may range from effective policies on travel, transport, and energy use to research into closer to home health care, to reduced use of raw materials in diagnostics, therapeutics, and care. It would also have as outcomes graduates who understood the impact of themselves and their profession on the environment, so they are equipped with the skills to mitigate their impact on the local and global ecosystem. Through this, medical schools, their staff and graduates, can help ensure that the health services they are responsible for will promote the long term health of the communities they serve, and the planet they form part of. Environmentally accountable schools will evaluate and promote sustainable healthcare systems which use resources more efficiently, focus on prevention, avoid waste and low value procedures, chooses low-carbon technologies wherever possible and foster patient autonomy to manage their own care (Mortimer 2010).

사회적 책임을 지는 의대의 실제 사례

Practical examples of socially accountable medical schools

좋은 교육실천 공유하기

Sharing good practice in education

교육 및 사회적 책임: 영국 헐 요크 의과대학

Education and social accountability: Hull York Medical School, UK

헐 요크 의과대학은 2003년에 설립되었는데, 이전에 검진받았던 지역의 의료 서비스 제공을 개선하기 위해 설립되었다. HYMS는 이러한 목표를 향한 노력의 공로로, 특히 고품질 초등 및 지역사회 관리를 장려한 데 대한 지원으로 2013년에 ASPIRE – 사회적 책임 상을 수상하였다.

Hull York Medical School, situated within the Yorkshire and Humber region of east England, was established in 2003 to help improve health care provision in a previously under doctored area. HYMS was awarded the ASPIRE – Social Accountability Award in 2013 in recognition of its work towards this aim, particularly for its support in promoting high quality primary and community care.

초등돌봄 및 지역사회 기반 학부 교육

Primary care and community based undergraduate education

지역 대학원 교육 및 서비스 제공 지원

Support for postgraduate education and service provision in the region

사회적 책임 및 연구

Social accountability and research

캐나다 뉴펀들랜드 메모리얼 대학교

Memorial University of Newfoundland, Canada

사회적으로 책임이 있는 의과대학은 지역사회와 지역의 우선적인 건강 요구에 영감을 받아 이에 대응하는 연구를 수행한다. 여기에는 생물 의학 발견에서 임상 연구, 인구 건강 연구에 이르기까지 다양한 주제가 포함될 수 있다. 의과대학은 연구 및 지식번역/동원/응용에 대한 의제개발, 제휴, 참여 등 연구에 지역사회를 적극 참여시킨다. 연구는 지역 사회/지역에 유익한 영향을 주는 활동에 우선 순위를 두고 있으며, 여기에는 의료 서비스 및 서비스 인구의 건강에 긍정적인 영향이 포함된다(AMEE 2012).

Medical schools that are socially accountable perform research that is inspired by and responds to their community and region’s priority health needs. This may include a range of topics, from biomedical discovery to clinical research to population health research. The medical school actively engages the community in research including developing the agenda, partnering and participating in research and knowledge translation/mobilization/application. The research gives priority to activities that create beneficial effects upon its community/region including a positive impact on the health care for and the health of the population served (AMEE 2012).

사회적 책임 및 서비스 개발

Social accountability and service development

캐나다 북부 온타리오 의과대학

Northern Ontario School of Medicine, Canada

북부 온타리오 의과대학(Northern Ontario School of Medicine, NOSM)은 캐나다에서 가장 최신의 의과대학으로 2002년에 설립되었으며, 사회적 책임에 대한 명시적 권한을 가지고 있다. 지리적으로 방대한(>800,000 평방 킬로미터) 인구와 인구가 희박한(80,000명의 인구) 지역의 인구를 위해, NOSM은 지역사회가 참여하는 의료 교육의 고유한 모델을 개발했다(Straser et al. 2013). 북부 온타리오 주의 건강 결과는 전체적으로 지방 평균 이하이며, 특히 시골과 외딴 지역에 사는 인구의 40%와 원주민과 프랑코폰 인구의 상당한 소수민족에 대해 그러하다. NOSM은 교육 프로그램의 설계와 전달에 능동적인 파트너로서 지역사회를 참여시켰고, 인구의 우선적인 건강 요구에 커리큘럼 내용을 집중시켰으며, 역사적으로 서비스가 부족한 설정과 임상 배치 기회를 구체적으로 조정했다. 포괄적 커뮤니티 사무직은 MD 프로그램의 중요한 종적 측면으로, 의대생들에게 1차 진료 환경에서 고품질 학습을 제공하고 졸업 시 유사한 요구 사항이 높은 시골 환경에서 실습할 수 있도록 준비한다(Straser et al. 2015). 교육학에 대한 비판적 접근 방식은 NOSM의 사회적 책임 의무와 관련이 있기 때문에 교육 활동에 대한 지속적인 평가에 기초하며, 예를 들어 4년 MD 프로그램 전반에 걸쳐 인구 및 공공 보건에 대한 과정을 포함시켰으며, 실제 Northern Ontario community에 설정된 시나리오가 있는 사례 기반 학습이다.건강의 사회적 결정요인에 대한 명시적 논의와 시골, 북부, 원주민, 프랑코폰 출신 학생을 선발하는 입학전형(Ross et al. 2014)이다.

The Northern Ontario School of Medicine (NOSM) is the newest medical school in Canada and was established in 2002 with an explicit social accountability mandate. Serving the population of a geographically vast (>800,000 sq. km.) and sparsely populated (population of 800,000) region, NOSM has developed a unique model of distributed community-engaged medical education (Strasser et al. 2013). Health outcomes in Northern Ontario are below the provincial average as a whole and particularly so for the 40% of the population living in rural and remote communities and the significant minority populations of Indigenous and Francophone people. NOSM has engaged communities as active partners in the design and delivery of educational programs, focused the curricular content on the priority health needs of the population and specifically aligned clinical placement opportunities with settings that have been historically under-served. The Comprehensive Community Clerkship is a critical longitudinal aspect of the MD Program that provides medical students with high quality learning within a primary care setting and prepares them to practice in similar high-needs rural settings upon graduation (Strasser et al. 2015). A critical approach to pedagogy underlies continual evaluation of the teaching activities as they relate to the social accountability mandate of NOSM and has led, for example, to the inclusion of a course on Population and Public Health throughout the four-year MD program, case-based learning with scenarios set in real-life Northern Ontario communities, explicit discussion of the social determinants of health and an admissions process that favors selection of students from rural, northern, Indigenous, and Francophone backgrounds (Ross et al. 2014).

결론들

Conclusions

의과대학으로서 사회적 책임으로 나아간다는 것은 의과대학이 보건시스템의 change agent로 바뀐다는 것을 의미한다. 그것은 항상 새로운 건강관리 졸업생과 직접적인 관계를 가진 모든 사람들과의 변화와 긴밀한 협력을 포함한다. 그들 중 많은 사람들은 역사적으로 학교와 어떠한 직접적인 접촉도 한 적이 없었다. 그것은 진정한 지역사회 참여, 효과적인 의사소통에 대한 헌신, 그리고 상호 존중을 포함한다. 우수한 커뮤니티 프로젝트를 개발하고 제공하는 개인에 의해 주도되는 변화는 헤드라인을 장식할 수 있지만, 전략적, 재정적, 관리 등 모든 수준에서 사회적 책임을 포함하려는 학교 전체의 지원 약속에서 비롯된 것이 아니라면 이러한 변화는 여전히 고립되고 피상적인 것으로 남을 것이다.

Moving towards social accountability as a medical school means changing a medical school into a health system change agent. It always involves change and close working with all who have a direct relationship with the new healthcare graduate, many of whom have never historically had any previous direct contact with the school. It involves genuine community involvement, commitment to effective communication, and mutual respect. Whilst change led by individuals in developing and delivering excellent community projects may get headlines, such change will remain isolated and superficial if it does not flow from a supported commitment across the school to embed social accountability at all levels – strategic, financial, and managerial.

사회적 책임은 또한 인증 기관을 포함하여 국가 당국, 정치 및 학계의 지원을 필요로 한다. 힘들기는 하지만, 근본적인 아이디어에는 논란이 없고, 가장 전통적인 학교에 실질적인 이익을 가져다 줄 수 있기 때문에 달성될 수 있다. (연구와 혁신 자금 지원의 해제를 통해, 비록 지역사회와 환자가 기금 모금과 교육 또는 연구 프로젝트에 대한 지원으로 밀접하게 참여하지만).

Social accountability also requires support from national authorities, political, and academic, including accrediting bodies. Whilst tough, this can be achieved, simply because the underlying ideas are not controversial and can bring real benefit to the most traditional school (through unlocking research and innovation funding, though close community and patient engagement with fund raising and support for education or research projects).

Med Teach. 2016 Nov;38(11):1078-1091.

doi: 10.1080/0142159X.2016.1219029. Epub 2016 Sep 9.

Producing a socially accountable medical school: AMEE Guide No. 109

Charles Boelen 1, David Pearson 2, Arthur Kaufman 3, James Rourke 4, Robert Woollard 5, David C Marsh 6, Trevor Gibbs 7

Affiliations collapse

Affiliations

- 1a WHO Headquarters, Sciez-sur-Léman , France.

- 2b Hull York Medical School , Hull , UK.

- 3c University of New Mexico , Albuquerque , NM , USA.

- 4d Memorial University of Newfoundland , St. John's , NL , Canada.

- 5e University of British Columbia , Vancouver , BC , Canada.

- 6f Northern Ontario School of Medicine , Sudbury , ON , Canada.

- 7g AMEE , Dundee , Scotland.

- PMID: 27608933

- DOI: 10.1080/0142159X.2016.1219029Abstract