상상해보자: 의학교육의 새 패러다임 (Acad Med, 2013)

Just Imagine: New Paradigms for Medical Education

Neil B. Mehta, MBBS, MS, Alan L. Hull, MD, PhD, James B. Young, MD, and James K. Stoller, MD, MS

위대한 돌파구는 필사적으로 필요로 했던 것이 어느 순간 갑자기 달성되면서 생겨난다

Big breakthroughs happen when what is suddenly possible meets what is desperately necessary.

—Thomas L. Friedman, “Come the Revolution,” New York Times, May 15, 2002

2010년 'Educating Physicians: A Call for Reform of Medical School and Residency는 두 번째 플렉스너 보고서라고도 불리며, 의학교육이 오늘날 마주한 중대한 도전을 지적한다.

The 2010 publication Educating Physicians: A Call for Reform of Medical School and Residency,1 often referred to as the “second Flexner Report,” points out the substantial challenges facing medical education today.

현재 의학교육 모델의 한계

Shortcomings of the Current Model of Medical Education비효율성, 비유연성, 학습자-중심 결여

A stark inventory of the shortcomings of the current model of medical education includes inefficiency, inflexibility, and lack of learner-centeredness.

지금의 성적은 효과적인 의사가 되기 위해 필요한 진정한 스킬/행동/특성을 반영하지 못한다. 교수가 학생을 평가하는 것은 무척 variable하며, 종종 문제해결능력 또는 비판적 사고능력이 아니라 대인관계의 특성을 반영한다.

Thus, these grades likely do not reflect true skills, behaviors, and attributes needed to be an effective physician. Faculty assessments of students are highly variable and often reflect interpersonal characteristics2 rather than problem- solving and critical thinking skills.

또한, 현대 임상환경은 교수가 교육에 헌신하기 힘들게 한다. 많은 학생들이 임상실습동안 병력청취나 신체검진에 대해서 observed 되지도 못한 채 실습을 마친다.

Also, realities of the modern academic clinical environment can challenge faculty’s commitment to recruitment and teaching. Strikingly, many students go through the required clinical rotations without once being observed taking a history or examining a patient.3

GME도 문제이긴 마찬가지이다. 동료peer to peer 교육의 질은 GME에서 중요한 요소인데, 레지던트의 교육 스킬을 향상시키는데 관심을 두지 않고, 교육병원은 진료와 교육에 대한 의무mission의 균형을 맞추지 못하고 있다. 최종적으로 로테이션 동안에 임상경험은 '운에 맡기는' 상황이다. 이러한 갭은 전공의 근무시간 제한으로 인해서 더 악화된다.

Graduate medical education (GME) is challenged as well. For example, the quality of peer-to-peer teaching, an important element of GME, is compromised by inattention to improving residents’ teaching skills and an unfavorable imbalance between the service and education missions of the teaching hospital.2 Finally, clinical exposure during rotations can be “hit-or- miss,” leaving gaps in trainees’ exposure. These gaps may be exacerbated by limitations on clinical exposure due to resident duty hours restrictions.

의학교육은 사회로부터도 도전을 받고 있다. 의사 부족에 대비하여 더 많은 의사를 양성하라는 요구가 있지만 달성되지 못하고 있다. 또한 의과대학 졸업생의 부채가 $150,000를 넘어서면서 일차의료 전공을 하려는 학생이 줄고 있다.

Medical education faces challenges at a societal level as well. There is a clear but unmet need to train more physicians to meet a massive projected physician shortage.4 Because the debt level of most students graduating from medical schools exceeds $150,000,5 choices to pursue primary care specialties may be undermined by the need to seek more remunerative specialties to pay off debt.6

의학교육의 개혁

Reforming Medical Education

이상적인 상태에서는 모든 학생은 필수적인 입원환자 경험과 외래환자 경험을 쌓을 수 있어야 한다. 환자를 보는 것에 대한 감독을 받아야 하며, 환자를 본 것에 대한 형성적 피드백을 받고, 스스로의 지식, 기술을 쌓고 전문직의 사회화 과정에 활용해야 한다.

In an ideal future state, all students would experience every essential inpatient and ambulatory clinical experience, would be observed during these encounters, and would receive formative feedback on such interactions to guide them in improving their knowledge, skills, and socialization to the profession.

의학교육의 수준을 올리기 위해서 플렉스너는 최소한의 입학요건을 제안하였고, 모든 의과대학이 대학에 affiliation되어야 한다고 권고했다. 플렉스너는 일방적 강의를 비판하고 학생이 learn by doing 해야 한다고 했다. 또한 교육과정이 유연하여 공식적 학습formal learning을 임상경험과 연구와 통합시킬 수 있게 해야한다고 주장했다.

To improve the standards of medical education, Flexner recommended that minimum admission standards should be established and that all medical schools should be affiliated with a university. Flexner criticized didactic teaching in lecture halls and wanted students to learn by doing. He believed that curricula should be flexible and should allow for integration of formal learning with clinical experiences and research.

플렉스너는 이러한 제안이 '현재와 가까운 미래, 길어봐야 한 세대'를 위한 것이다 라고 인식했다.

Flexner realized that his recommendations were for “the present and the near future—a generation at most.”8

현재, 의학교육을 재구조화 하고 향상시키려는 노력이 다시 한 차례 이뤄지고 있다. ACGME는 시간-기반 수련모델을 역량-기반 모델로 바꾸고자 한다.

Today, efforts are under way to reframe and enhance medical education once again. The Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) Milestone Project is attempting to move from a time-based to a competence-based framework for progression through medical training.

2007년 ten Cate와 Scheele는 EPA개념과 STAR를 주장하며, 현재의 역량 프레임워크와 실제 임상 진료행위의 갭을 연결시키고자 했다.

In 2007, ten Cate and Scheele10 proposed the concept of entrustable professional activities (EPAs) and statements of awarded responsibilities (STARs) to bridge the gap between the competency framework and practical clinical practice.

AAMC와 NBME는 다른 기관과 협력하여 의학교육과 진료행위의 연속체에 걸쳐 학습을 추적하는 도구를 개발중이다.

The Association of American Medical Colleges (AAMC) and National Board of Medical Examiners are working with other accrediting agencies to develop a tool for tracking learning across the continuum of medical training and practice.11,12

파괴적 혁신

Disruptive Innovations

이러한 것들 모두 종합하면, 현재의 과제는 '파괴적 혁신'이라 불리는 급진적인 새로운 패러다임을 받아들이는 것이다. 구체적으로 Bower와 Clayton은 '어떻게 새로운 급진적 패러다임이 현재 산업리더 industrial leader로부터 소외받아온 소비자들에게 더 단순하고 더 편리하고 더 맞춤화되고 더 저렴한 방식으로 이득이 되게 할 수 있는가'로 파과적 혁신을 주창했다.

Taken together, current challenges invite radical new paradigms, which have been dubbed “disruptive innovations.” Specifically, Bower and Clayton have introduced the concept of disruptive innovations to describe how new radical paradigms can produce simpler, more convenient, more customizable, or cheaper ways of benefiting consumers who are currently being ignored by industry leaders.13

대학의학은 국가적 문제 해결을 위한 의학교육 개혁의 급박한 필요성을 인정해야 한다. sound한 교육모델에 기반한 혁신은 더 광범위한 보건의료인력을 더 낮은 비용으로 양성할 수 있을 것이다. 이러한 맥락에서 Willliam Bennett은 "테크놀로지 대학의 메카라 할 수 있는 실리콘벨리는 대학과 교육자들이 할 수 없는, 아니 하지 않으려고 하는 방향으로의 고등교육 혁신을 진행중에 있다"라고 지적했다.

Academic medicine must recognize the urgent need for medical education reform that will help solve the nation’s problems. Innovations must be rooted in sound pedagogic models that can help create a larger health care workforce at a lower cost. In this context, William Bennett,14 the former U.S. secretary of education, has pointed out that the “mecca of the technology universe (Silicon Valley) is in the process of revolutionizing higher education in a way that educators, colleges and universities cannot, or will not.”

거꾸로 교실과 MOOC

Flipped classrooms and massive open online courses

의학교육 외 분야에서 다수의 강력한 파괴적 변화가 이미 일어나고 있다. Khan Academy 등

In nonmedical education, a number of powerful disruptive changes already under way are changing the educational landscape. For example, the Khan Academy15 started in 2006

Open access online courses는 이미 20년 전에 가능했으나 MOOC이란 개념은 2008년 “Connectivism and Connected Knowledge” 에 관한 강의가 전 세계 2300명의 지원자를 모집하며 유명해졌다. 이후 MOOC은 Sebastian Thurn 가 2012년 1월 스탠포드 대학의 테뉴어를 반납하고 Udacity를 시작한 것을 계기로 세계를 매료시켰다.

Open access online courses have been available for at least two decades,18,19 but the concept of massive open online courses (MOOCs) was popularized by a group of learning researchers when a course on “Connectivism and Connected Knowledge” in 2008 attracted over 2,300 worldwide participants.20 However, MOOCs did not take the world by storm until Sebastian Thurn ceded his tenured position at Stanford University in January 2012 to start Udacity, a start-up offering MOOCs at low or no cost.21

Khan Academy and Udacity로 인해서 전통적인 교육 역할을 잃을까 두려웠던 대학들은 이제 무료 온라인 코스를 제공하기 위해 협력하고 있다. Udacity가 런칭되고 얼마 지나지 않아 Coursera가 설립되었다. Coursera의 초기 파트너는 Stanford, the University of Pennsylvania, the University of Michigan, and Princeton University였으며, 이제는 190개국에서 150만명 이상이 Coursera의 198개 MOOC(33개 대학)을 수강중이다 이후 하버드와 MIT는 edX collaboration을 발표했다.

Stimulated and possibly threatened by the fear of losing their traditional role in education by initiatives like the Khan Academy and Udacity, universities are now collaborating to offer free online courses. Shortly after Udacity launched, Coursera22 was founded by two Stanford faculty members with expertise in machine learning and artificial intelligence and their application to biomedical sciences. Coursera’s first university partners were Stanford, the University of Pennsylvania, the University of Michigan, and Princeton University. Currently, over 1.5 million students from 190 countries are enrolled through Coursera in 198 MOOCs from 33 universities.23 Soon after Coursera began, Harvard University and the Massachusetts Institute of Technology announced their edX collaboration,24 which will offer free content from the two universities to anyone in the world. Both Coursera and edX will offer certificates of mastery.

이전 세대의 learning management systems 와 달리 새로운 시스템은 학생-중심적이며 타당한 교육적 이론에 기반을 두고 있다.

Although previous generations of learning management systems faltered because they focused more on tracking and managing instruction and content, these new systems are student-centered and are based on sound pedagogic principles. They aim to

- promote active, retrieval-based learning;

- customized feedback based on analysis of vast amounts of data created by students’ performance;

- real-time collaboration; and

- peer learning while also creating an experience mimicking one-on-one tutoring.

디지털 배지

Digital badges

디지털 배지는 또 다른 파괴적 혁신이다. 디지털 배지는 학습자에게 수여되는 전자 이미지로서, 지원서나 레쥬메에 포함될 수 있고 웹사이트나 블로그에 들어갈 수도 있다. 이 개념은 2010년 바로셀로나 컨퍼런스에서 처음 시작되었는데, 다양한 formal and informal 학습공간에서의 학습을 capture하는 것을 도와준다. 이후 곧 디지털배지는 MacArthur Foundation 로부터 2백만달러의 투자를 받게 된다.

Digital badges are another disruptive innovation in the education world27 with implications for medical education. Digital badges are electronic images that follow learners through their lifetimes and can be included in applications and resumes or displayed on Web sites and blogs. The concept originated in 2010 at a conference in Barcelona, Spain, to help capture learning that occurs in multiple formal and informal learning spaces. Soon thereafter, digital badges received a substantial endorsement when the MacArthur Foundation funded a $2 million “Badges for Lifelong Learning Competition.”28

베지에는 메타데이터가 들어있어서 수여자의 이름, 수여 기관, 수여기관의 정보, 수여자가 이 배지를 받기 위해서 해야 했던 것들, 이 배지를 받기 위하여 수여자가 충족시킨 기준의 근거 등이 포함된다. 따라서 디지털 배지는 스킬/성취/퀄리티를 더 섬세한granular 방식으로 보여준다. 디지털 배지는 실제 상황에서의 스킬을 마스터했다는 것을 보여주는 것으로, 고용주에게는 (일반적으로 학위에서는 잘 드러나지 않는) 전문성의 근거가 될 수 있다. 디지털배지를 수집하고 보여주는 것은 테크놀로지 세대에 있어서 동기부여 요인이 될 수 있다. 표준화된 온라인 플랫폼이 개발된 바 있다.

Badges encode metadata containing information such as the badge recipient’s name, the institution (or individual) awarding the badge, information about the endorser (i.e., the organization that certifies or approves the badge or the badge provider), information about what the recipient had to do to get the badge, and evidence that the recipient met the criteria to earn the badge. Thus, digital badges can provide concrete evidence of skills, achievements, and qualities in a more granular manner than traditional grades and degrees. They reflect mastery of real-life skills and are valued by employers looking for evidence of expertise not often reflected by college degrees.28 Collecting and displaying electronic badges can be motivating for a generation that has grown up with technology. Standardized online platforms have been developed (e.g., Openbadges.org) for badge sponsors, badge issuers, and badge earners, allowing the issuing, collection, management, and sharing of badges across multiple Web sites and learning management systems.

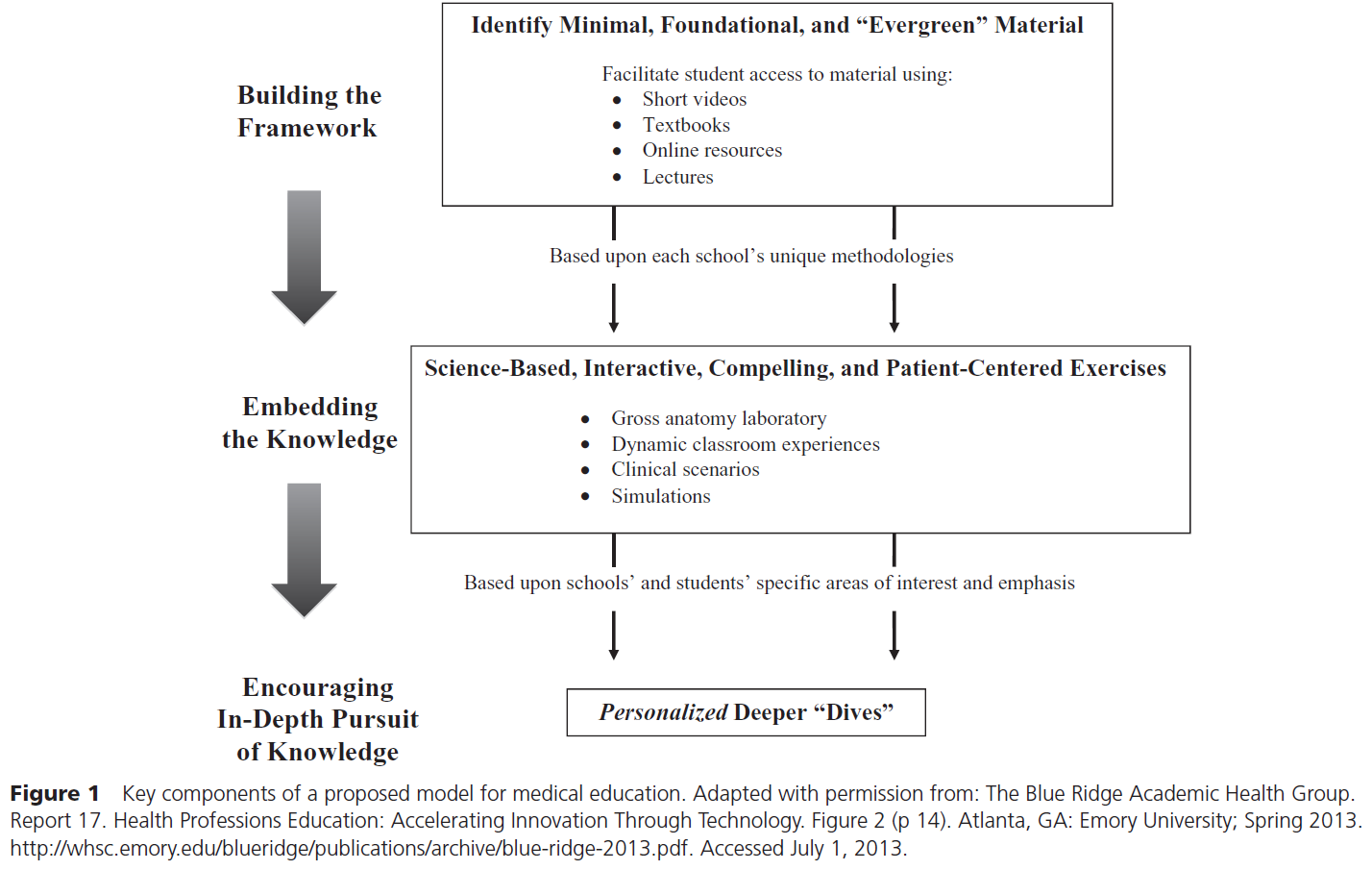

의학교육의 새로운 모델을 위한 비전

Vision for a New Model for Medical Education

우리는 협력적 온라인 학습환경을 위한 central environment를 만들 수 있다.

We could develop a central online collaborative learning environment

우리는 다학제간 협력을 구축할 수 있다. MOOC을 수강하는 무수한 학생은 가상의, 다학제적, 협력적 환경을 언제나 제공받을 수 있을 것이다.

We could ensure multidisciplinary collaboration by building communities of learning. The vast numbers of students in these MOOCs would ensure that they would always have other students online at the same time helping to build a virtual, and most likely multidisciplinary, collaborative environment.

MOOC은 교수들의 교육방식도 바꿔놓을 것이다. 예를 들어 교수들은 단순 강의를 제공하는 역할에서 벗어나, 면대면, 온라인 소그룹, 온라인 일대일 토론을 제공할 수도 있다. 이는 "거꾸로 교실"의 한 형태이며, 학생들은 기본적 학습 자료를 스스로 수업 전후에 공부하고, 아주 귀중한 (그리고 비싼) 교수들의 시간은 문제해결을 위한 협력적 학습에 사용될 수 있을 것이다.

Massive online learning could also affect faculty practices. For example, faculty members freed from providing didactic sessions could be available for face- to-face, online small-group, or online one-on-one discussion. This would “flip the classroom”—that is, students could learn basic didactic material on their own before and after class, and valuable (and expensive) faculty time could be used for collaborative learning or problem- solving.29

학생들은 배지 공급자를 선택할 수 있고, 의과대학과 궁극적으로는 인증기구가 설정한 파라미터에 따라서 스스로의 스케줄을 결정할 수 있다.

Students could choose their badge providers and schedule their advancement through the curriculum guided by the parameters set by the medical school and ultimately by the accreditation bodies.

임상실습 스케줄은 학생들이 house staff, allied health personnel, and faculty 들과 더 많은 시간을 보내게끔 바뀔 수 있으며, 이들이 로테이션동안의 학습목표에 대한 배지수여자가 된다. 의과대학의 역할은 철저한 교육훈련이 확실히 이뤄지게끔 하고, 배지수여자들에 대한 교수개발을 하고, 교육과정동안 학생의 모니터링과 자문 역할을 하는 것이다.

The clerkship schedules would be modified to ensure that students spend more time with house staff, allied health personnel, and faculty who are certified badge providers for the learning objectives of the rotation. The role of the medical school would be to ensure rigorous training, certification, and continuing faculty development for the badge providers as well as close monitoring and advising of students throughout the curriculum.

디지털 배지는 EPA로 정의된 특정 기술을 마스터했음을 보여주눈데 사용될 수 있으며, 디지털 STAR이다.

Digital badges could be used to record and display mastery of specific skills as defined in EPAs and thus would be the digital equivalents of the STARs.

스킬의 유지를 위해서 배지는 유효기간이 설정될 수 있다. 또한 새로운 프로세스와 절차procedure가 진료의 새로운 기준이 될 수 있는 것처럼, 배지가 추가적으로 업데이트 될 수 있다.

To support maintenance of skills, the specific badges could carry expiration dates. Also, as new processes and procedures become standard of care, the certification in women’s health would be updated with a need for additional badges.

학생은 MOOC과 디지털배지의 데이터를 바탕으로 전자 포트폴리오를 유지한다. 이는 고용주, 대학, 동료, 환자, 면허기관과 공유된다. 교수자-중심에서 학생-중심으로, 선형적, 시간-기반 교육에서 숙달-기반mastery-based 진전progression으로 바뀐다.

Students could maintain an electronic portfolio with data from MOOCs and digital badges they earn during their medical training. They would share this with employers, privileging hospitals, colleagues, patients, and state licensing boards. The focus would shift from teacher-centered to student-centered learning and from linear, temporal-based teaching to mastery-based progression.

파킨슨병을 위한 온라인 학습 커뮤니티가 ParkinsonNet이라는 이름으로 네덜란드에 만들어진 바 있다. 아홉 단계 프로세스로서 지역 커뮤니티를 통해 저비용으로 파킨슨병 환자를 지원한다.

A model for establishing an online learning community focused on Parkinson disease has been set up in the Netherlands.30 The program, called ParkinsonNet, is a nine-step process to help provide multidisciplinary care for patients with Parkinson disease in a cost-effective regional community network.

the AAMC, the Khan Academy, and the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation 는 MCAT준비를 위한 무료 온라인 교육비디오를 만들고 있다.

In a visionary move, the AAMC, the Khan Academy, and the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation are collaborating to create videos as a free online resource for students preparing for the Medical College Admission Test. This is an effort to help students from diverse and economically and educationally challenged backgrounds to enter the medical profession.31

가능성을 상상하라

Imagine the Possibilities

두 번째 플렉스너 리포트는 네 가지 감탄할 만한 목표를 제시한다.

The “second Flexner Report” identifies four laudable goals to improve medical education:

(1) standardization of learning outcomes and individualization of the learning process,

(2) integration of formal knowledge and clinical experience,

(3) development of habits of inquiry and innovation, and

(4) focus on professional identity formation.1

8 Ludmerer KM. Commentary: Understanding the Flexner Report. Acad Med. 2010;85: 193–196.

Just imagine: new paradigms for medical education.

Author information

- 1Dr. Mehta is associate professor of medicine and director of education technology, Cleveland Clinic Lerner College of Medicine of Case Western Reserve University, Cleveland, Ohio. Dr. Hull is professor of medicine and associate dean for curricular affairs, Cleveland Clinic Lerner College of Medicine of Case Western Reserve University, Cleveland, Ohio. Dr. Young is professor of medicine and executive dean, Cleveland Clinic Lerner College of Medicine of Case Western Reserve University, Cleveland, Ohio. Dr. Stoller is Jean Wall Bennett Professor of Medicine and Chairman,Education Institute, Cleveland Clinic, Cleveland, Ohio.

Abstract

- PMID:

- 23969368

- [PubMed - indexed for MEDLINE]

'Articles (Medical Education) > ⓧ교수법, 피드백, 멘토링 (From Misc.)' 카테고리의 다른 글

| 의과대학 2학년 학생의 동기부여신념, 정서, 성취(Med Educ, 2010) (0) | 2016.04.08 |

|---|---|

| 재교육의 어려움: 이론적 방법론적 통찰 (Med Educ, 2013) (0) | 2016.03.10 |

| 의학교육에 대한 새로운 상상: 행동할 때 (Acad Med, 2013) (0) | 2016.01.27 |

| "내가 의대에 적합한걸까?" 1학년 학생들의 확신결여 현상에 대한 이해(Med Teach, 2015) (0) | 2015.12.10 |

| 비공식적 학습용 웹사이트 분석(IJSDL, 2014) (0) | 2015.10.26 |