자기조절학습 SRL : 신념, 테크닉, 환상 (Annu Rev Psychol, 2013)

Self-Regulated Learning: Beliefs, Techniques, and Illusions

Robert A. Bjork,1 John Dunlosky,2 and Nate Kornell3

1Department of Psychology, University of California, Los Angeles, California 90095, 2Department of Psychology, Kent State University, Kent, Ohio 44242, 3Department of Psychology, Williams College, Williamstown, Massachusetts 01267;

email: rabjork@psych.ucla.edu, jdunlosk@kent.edu, nkornell@gmail.com

도입

INTRODUCTION

이 검토에서 우리는 다음에 대한 최근의 연구를 요약한다.

사람들이 학습 활동에 대해 무엇을 이해하고 이해하지 못하는지,

그리고 이해, 보존 및 전송을 촉진하는 프로세스

In this review we summarize recent research on what people do and do not understand about the learning activities and processes that promote comprehension, retention, and transfer.

사람들은 우리의 직관과 실천이 "매일의 삶과 학습에서 벌어지는 실수와 오류"로부터 향상되리라 예상할 수도 있지만, 실제로는 그렇지 않은 것으로 보인다.

One might expect that our intuitions and practices would be informed by what Bjork (2011) has called the “trials and errors of everyday living and learning,” but that appears not to be the case.

어떤 사회적 태도와 가정은 또한 우리가 [최대한 효과적인 학습자가 되는 방법]을 배우지 않는 데에도 역할을 하는 것처럼 보인다. 그러한 가정 중 하나는 아이들과 성인들이 그들의 학습 활동을 관리하는 방법을 배울 필요가 없다는 것 같다. 예를 들어 코넬 & 비요크(2007)와 하트비히 & 던로스키(2012년)의 대학생들을 대상으로 한 설문조사에서 약 65%에서 80%의 학생들이 "누군가가 알려준 학습법대로 공부하느냐"는 질문에 대해 "아니오"라고 대답했다(반대로 20~35%가 "그렇다"라고 대답하는 것도 중요하다.)

Certain societal attitudes and assumptions also seem to play a role in our not learning how to become maximally effective learners. One such assumption seems to be that children and adults do not need to be taught how to manage their learning activities. In surveys of college students by Kornell & Bjork (2007) and Hartwig & Dunlosky (2012), for example, about 65% to 80% of students answered “no” to the question “Do you study the way you do because somebody taught you to study that way?” (Whether the 20%to 35%who said “yes” had been taught in a way that is consistent with research findings is, of course, another important question.)

학습 방법에 대한 지침의 부재는 정말로 사람들이 스스로 점차적으로 학습 능력을 습득할 것이라는 가정을 반영하는 것 같다.

It seems likely that the absence of instruction on how to learn does indeed reflect an assumption that people will gradually acquire learning skills on their own

예를 들어 사람마다 자신의 학습 스타일을 가지고 있다는 개념은 모든 개인에게 적용되는 학습 방법에 대한 교육을 제안하는 것이 불가능하다는 생각을 암묵적/명시적으로 하게 만든다. (학습 스타일 개념과 증거에 대한 검토는 Pashler et al.을 참조)

The notion that individuals have their own styles of learning, for example, may lead, implicitly or explicitly, to the idea that it is not possible to come up with training on how to learn that is applicable to all individuals (for a review of the learning-styles concept and evidence, see Pashler et al. 2009).

학습자로서 정교해지는 법

BECOMING SOPHISTICATED AS A LEARNER

우리의 관점에서는, 진짜 효과적인 학습을 하려면 다음이 필요하다

(a) 인간의 학습과 기억을 특징짓는 기능 아키텍처의 주요 측면을 이해하는 것

(b) 습득해야 할 정보 및 절차의 저장 및 후속 검색을 강화하는 이해 활동 및 기법

(c) 이러한 모니터링에 대응하여 학습 상태를 모니터링하고 학습 활동을 제어하는 방법을 알고 있어야 한다.

(d ) 후기의 회상 및 전이를 지원할 학습이 달성되었는지 여부에 대한 판단을 저해할 수 있는 특정 편견을 이해하는 것.

In our view, as we sketch below, becoming truly effective as a learner entails

(a) understanding key aspects of the functional architecture that characterizes human learning and memory,

(b) knowing activities and techniques that enhance the storage and subsequent retrieval of to-be-learned information and procedures,

(c) knowing how to monitor the state of one’s learning and to control one’s learning activities in response to such monitoring, and

(d ) understanding certain biases that can impair judgments of whether learning has been achieved that will support later recall and transfer.

1. 인간 기억의 관련 특성 이해

Understanding Relevant Peculiarities of Human Memory

학습자로서 최대의 효과를 얻기 위해서는 부분적으로 비요크 & 비요크(1992)가 인간의 학습과 기억력을 특징짓는 저장과 인출 과정의 "중요한 특성"이라고 규정한 것을 이해해야 한다.

To become maximally effective as a learner requires, in part, understanding what Bjork & Bjork (1992) labeled “important peculiarities” of the storage and retrieval processes that characterize human learning and memory.

예를 들어, 사람은 정보를 문자 그대로 기록함으로써 장기 기억 속에 정보를 저장하지 않고, 대신에 이미 알고 있는 것과 새로운 정보를 연관시킴으로써 정보를 저장한다는 것을 이해하는 것이 중요하다. 우리는 이미 기억 속에 존재하는 정보에 대한 관계선 및 의미적 연관성에 의해 정의된 바와 같이, 새로운 정보를 그 의미 면에서 저장한다. 그것은 무엇보다도, 우리가 단순히 녹음하는 것이 아니라, 해석, 연결, 상호 관계, 그리고 정교하게 함으로써, 학습 과정에 적극적인 참여자를 끌어들여야 한다는 것을 의미한다. 기본적으로, 정보는 우리의 기억에 저절로 각인되지 않을 것이다.

It is important to understand, for example, that we do not store information in our long-term memories by making any kind of literal recording of that information, but, instead, we do so by relating new information to what we already know. We store new information in terms of its meaning to us, as defined by its relation-ships and semantic associations to information that already exists in our memories. What that means, among other things, is that we have tobean active participant in the learning process—by interpreting, connecting, interrelating, and elaborating, not simply recording. Basically, information will not write itself on our memories.

또한 배워야 하는 정보나 절차를 저장할 수 있는 우리의 능력은 본질적으로 무한하다는 것을 이해할 필요가 있다. 사실, 정보를 기억에 저장하는 것은 용량을 창출create하는 것으로 보인다. 즉, 기억공간을 써버리는 것이 아니라 추가 연결과 저장 기회를 창출한다. 기존의 지식과 장기 기억으로 상호 연관되어 한때 저장되었던 정보는, 반드시 접근 가능하지는 않더라도 저장되어 있는 경향이 있다는 것도 이해하는 것이 중요하다. 그러한 지식은 다시 쉽게 접근할 수 있게 되어 새로운 학문의 자원이 된다.

We need to understand, too, that our capacity for storing to-be-learned information or procedures is essentially unlimited. In fact, storing information in human memory appears to create capacity—that is, opportunities for additional linkages and storage—rather than use it up. It is also important to understand that information, once stored by virtue of having been interrelated with existing knowledge in long-term memory, tends to remain stored, if not necessarily accessible. Such knowledge is readily made accessible again and becomes a resource for new learning.

또한, 특정한 단서가 주어진다면 기억 속에 저장된 정보에 접근하는 것이 일반적인 기록 장치처럼 기록된 내용의 literal한 "재생"에 해당하지 않는다는 점을 이해하는 것도 필요하다. 저장된 정보나 절차를 인간의 기억에서 검색하는 것은 literal한 과정이 아니라, 추론과 재구성을 하는 fallible한 과정이다. 바틀렛(1932)의 고전적 연구로 거슬러 올라가는 연구는 종종 자신감에 차서 우리가 어떤 이전 에피소드를 회상하는 것이 실제로 에피소드의 특징들이 에피소드 자체에서가 아니라 우리의 가정, 목표 또는 이전 경험에서 파생된 특징들과 결합되거나 대체될 수 있다는 것을 반복적으로 보여주었다. 우리가 과거를 기억할 때, 우리는 의식적이지는 않더라도 우리의 기억들이 우리의 배경 지식, 우리의 기대, 그리고 현재의 맥락에 맞도록 불러온다.

To be sophisticated as a learner also requires understanding that accessing information stored in our memories, given certain cues, does not correspond to the “playback” of a typical recording device. The retrieval of stored information or procedures from human memory is a fallible process that is inferential and reconstructive—not literal. Research dating back to a classic study by Bartlett (1932) has demonstrated repeatedly that what we recall of some prior episode, often confidently, can actually be features of the episode combined with, or replaced by, features that derive from our assumptions, goals, or prior experience, rather than from the episode itself. When we remember the past, we are driven, if not consciously, to make our recollections fit our background knowledge, our expectations, and the current context.

중요한 것은, 인출도 신호cue에 의존한다는 것이다. 학습 과정 중에 (일부 학습해야 할) 정보가 쉽게 호출될 수 있다는 사실이 학습 과정이 끝난 후 반드시 다른 시간과 장소에서도 비슷하게 쉽게 호출할 수 있다는 것을 의미하지는 않는다.

Importantly, retrieval is also cue dependent. The fact that some to-be-learned information is readily recallable during the learning process does not necessarily mean it will be re-callable in another time and place, after the learning process has ended.

학습자가 우리의 기억에서 정보를 검색하는 것에 따르는 결과가 발생한다는 것을 이해하는 것도 중요하다. 컴팩트 디스크와 같은 일부 인공 장치로부터 정보를 재생하는 것과는 대조적으로, 인간의 기억에서 정보를 검색하는 것은 "기억 변조활동"이다(Bjork 1975). 검색된 정보는, 동일한 상태로 남겨지기 보다는, 접근하지 않았을 때보다, 미래에 더 손쉽게 인출할 수 있게 된다. 실제로 학습 이벤트로서, 특히 장기적 리콜을 용이하게 한다는 관점에서, 정보를 인출하는 연습는 반복 학습보다 상당히 강력하다(학습 이벤트로써의 검색에 관한 연구의 리뷰는 Roediger & Butler 2011, Roediger & Karpicke 2006 참조).

It is critical, too, for a learner to understand that retrieving information from our memories has consequences. In contrast to the playback of information from some man-made device, such as a compact disk, retrieving information from human memory is a “memory modifier” (Bjork 1975): The retrieved information, rather than being left in the same state, becomes more recallable in the future than it would have been without having been accessed. In fact, as a learning event, the act of retrieving information is considerably more potent than is an additional study opportunity, particularly in terms of facilitating long-term recall (for reviews of research on retrieval as a learning event, see Roediger & Butler 2011, Roediger &Karpicke 2006).

포괄적으로 말해서, 정교한 학습자가 되기 위해서는 학습할 정보에 대한 지속적이고 유연한durable and flexible 접근을 만드는 것은 [부분적으로 그 정보의 의미 있는 인코딩을 달성하는 문제]이고 [부분적으로 검색 프로세스를 연습하는 문제]라는 것을 이해해야 한다.

Broadly, then, to be a sophisticated learner requires understanding that creating durable and flexible access to to-be-learned information is partly a matter of achieving a meaningful encoding of that information and partly a matter of exercising the retrieval process.

On the encoding side, the goal is to achieve an encoding that is part of a broader framework of interrelated concepts and ideas.

On the retrieval side, practicing the retrieval process is crucial.

비요크(1994)가 예를 든 것처럼,

응급 상황에서 실제로 그 절차를 정확하게 수행할 수 있는 가능성 측면에서,

부풀릴 수 있는 구명 조끼를 실제로 착용, 고정 및 팽창할 수 있는 한 번의 기회는

보다 자주 비행기를 자주 타서 승무원이 그 과정을 수행하는 것을 지켜보는 것보다 더 큰 가치가 있을 것이다.

To repeat an example provided by Bjork (1994), one chance to actually put on, fasten, and inflate an inflatable life vest would be of more value— in terms of the likelihood that one could actually perform that procedure correctly in an emergency—than the multitude of times any frequent flier has sat on an airplane and been shown the process by a flight attendant.

2. 저장 및 인출 기능을 향상시키는 활동 및 기법 파악

Knowing Activities and Techniques that Enhance Storage and Retrieval

인간의 학습과 기억을 특징짓는 저장 및 검색 프로세스에 대한 일반적인 이해를 달성하는 것 외에, 진정으로 효과적인 학습자는 새로운 정보의 저장과 그 정보에 대한 후속 접근을 촉진하는 활동에 참여할 필요가 있다.

Beyond achieving a general understanding of the storage and retrieval processes that characterize human learning and memory, a truly effective learner needs to engage in activities that foster storage of new information and subsequent access to that information.

학습자로서 정교해지는 것은 또한 자신의 학습 조건을 관리하는 것을 포함한다.

Becoming sophisticated as a learner also involves learning to manage the conditions of one’s own learning.

따라서 예를 들어, 학습해야 할 주제에 대해 간격을 둔 연습은 몰아치는 공부보다 학습 효과를 높일 수 있다(예: Cepeda et al. 2006). 마찬가지로, [학습의 환경적 맥락을 일정하고 예측 가능한 상태로 유지하는 것]보다는 [자신의 학습 조건을 스스로 변화시켜야 한다는 것을 아는 것]도 더 효과적인 학습자로 만들어준다. 또한 정보 또는 프로시저를 단순히 찾아보기look up만 하는 것보다, 정보를 능동적으로 생성하고자generate 시도해야 한다는 것도 마찬가지다.

Thus, for example, knowing that one should space, rather than mass, one’s study sessions on some to-be-learned topic can increase one’s effectiveness as a learner, as can knowing that one should interleave, rather than block, successive study or practice sessions on separate to-be-learned tasks or topics (see, e.g., Cepeda et al. 2006). Similarly, knowing that one should vary the conditions of one’s own learning, even, perhaps, the environmental context of studying (Smith et al 1978, Smith & Rothkopf 1984), versus keeping those conditions constant and predictable, can make one a more effective learner, as can knowing that one should test one’s self and attempt to generate information or procedures rather than looking them up (e.g., Jacoby 1978).

그러한 정교함을 획득하는 것을 어렵게 만드는 것은 (간격, 변동, 인터리빙, 생성과 같은 조작을 도입함으로써 얻는) 단기적 결과는 결코 유익하지 않은 것으로 보일 수 있다는 점이다. 그러한 조작은 학습자에게 어려움과 도전을 초래하며 현재의 수행으로 측정했을 때 학습 속도를 늦추는 것으로 보일 수 있다. 그들은 종종 학습할 정보와 절차의 장기 보존과 전송을 향상시키기 때문에 바람직한 어려움으로 불려왔지만(Bjork 1994), 그럼에도 불구하고 학습자에게 난이도감과 느린 진행을 만들어 낼 수 있다.

What makes acquiring such sophistication difficult is that the short-term consequences of introducing manipulations such as spacing, variation, interleaving, and generating can seem far from beneficial. Such manipulations introduce difficulties and challenges for learners and can appear to slow the rate of learning, as measured by current performance. Because they often enhance long-term retention and transfer of to-be-learned information and procedures, they have been labeled desirable difficulties (Bjork 1994), but they nonetheless can create a sense of difficulty and slow progress for the learner.

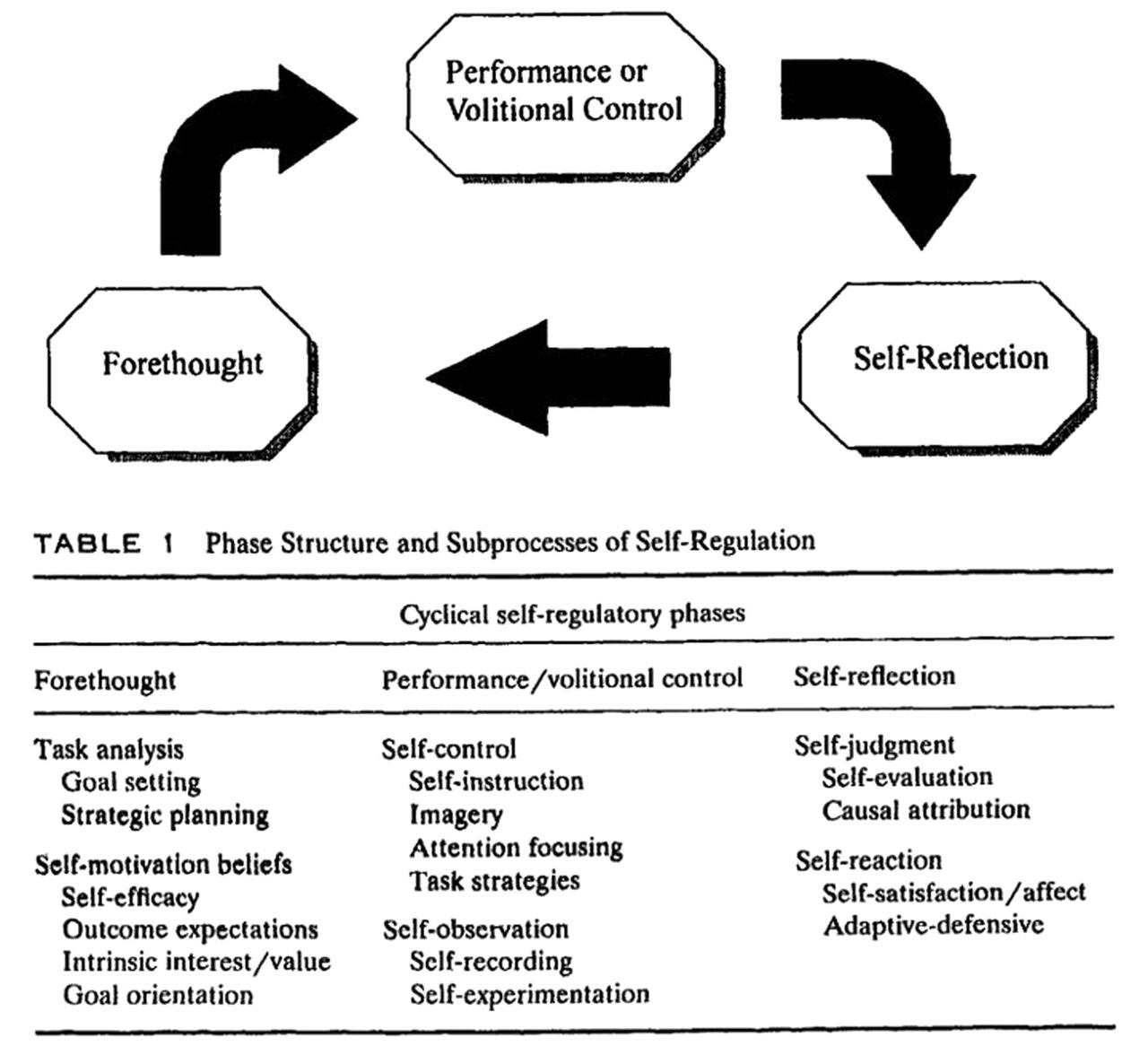

3. 학습을 모니터링하고 학습 활동을 효과적으로 제어

Monitoring One’s Learning and Controlling One’s Learning Activities Effectively

기본적으로 학습과정은 다음과 같은 지속적인 평가와 결정을 수반한다.

다음에 무엇을 학습해야 하고 어떻게 학습해야 하는지,

어떤 정보, 개념 또는 절차에 대한 향후 access을 지원하는 학습이 달성되었는지 여부,

회상한 것이 정확한지 등

Basically, the learning process involves making continual assessments and decisions, such as

what should be studied next and how it should be studied,

whether the learning that will support later access to some information, concept, or procedure has been achieved,

whether what one has recalled is correct, and on and on.

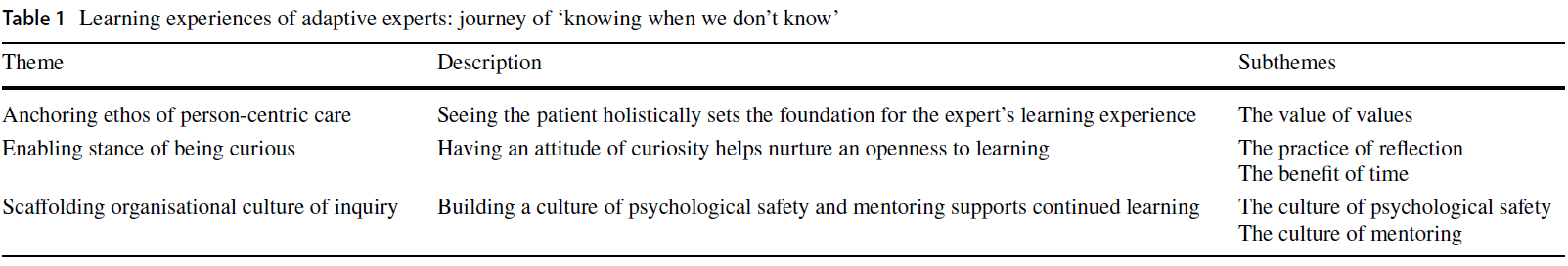

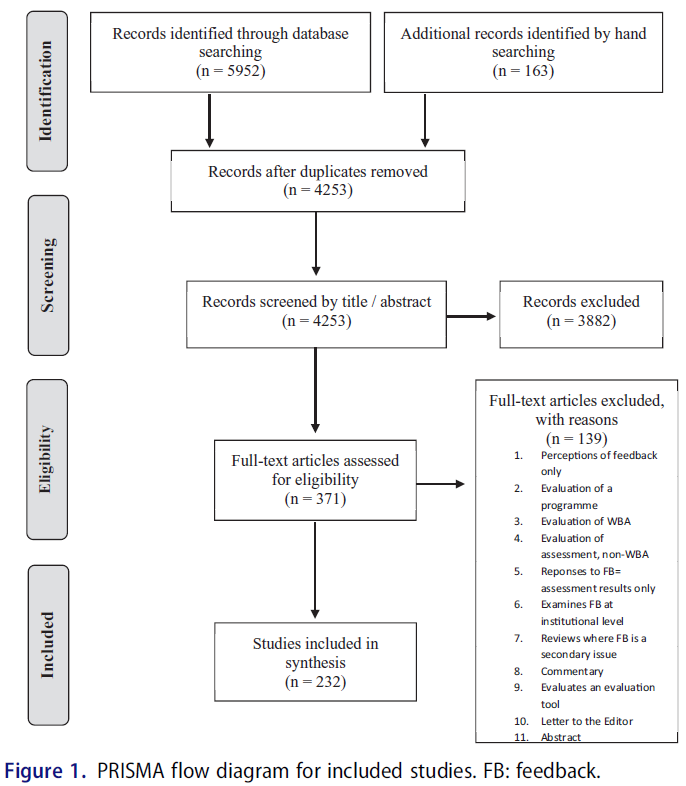

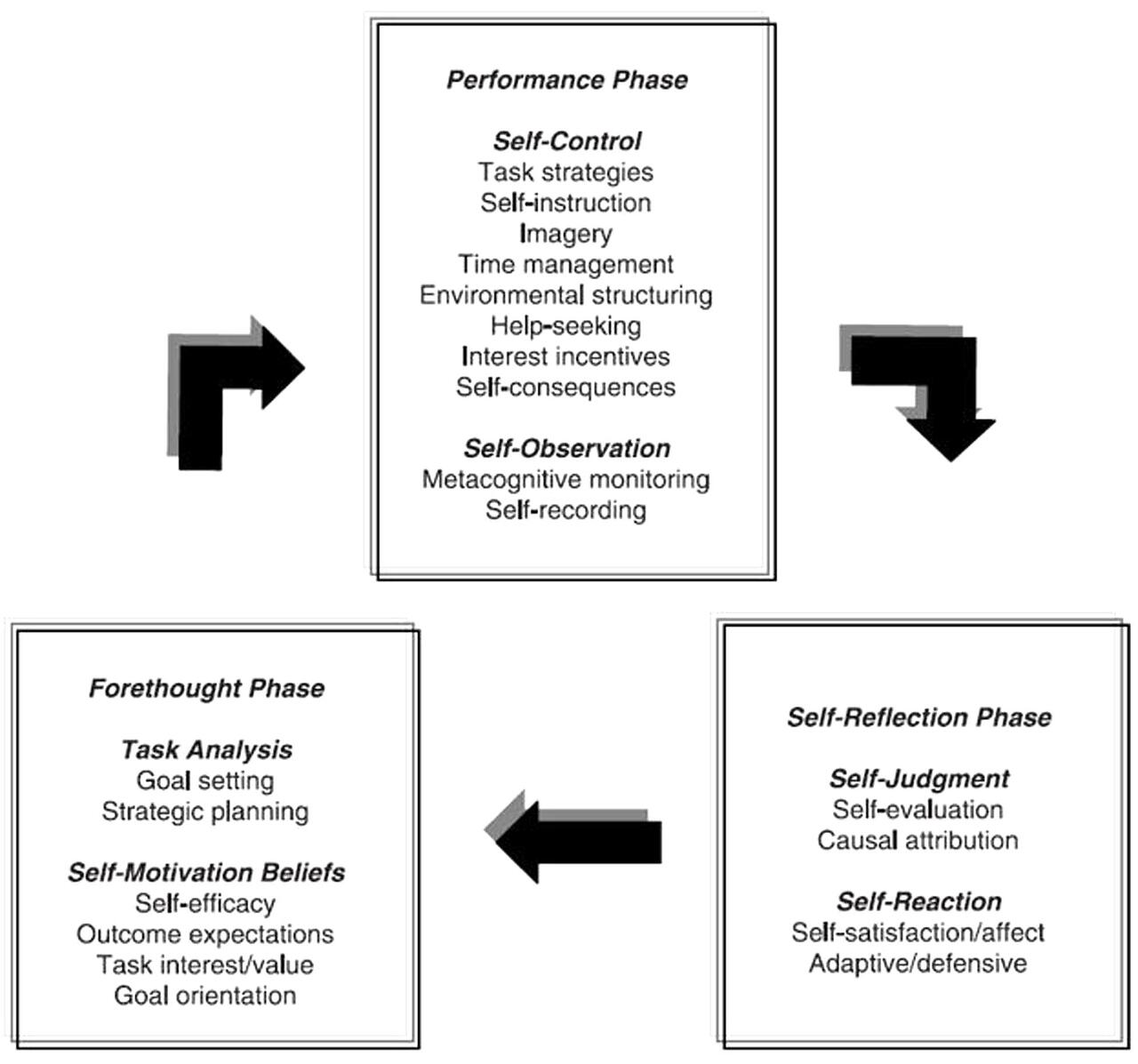

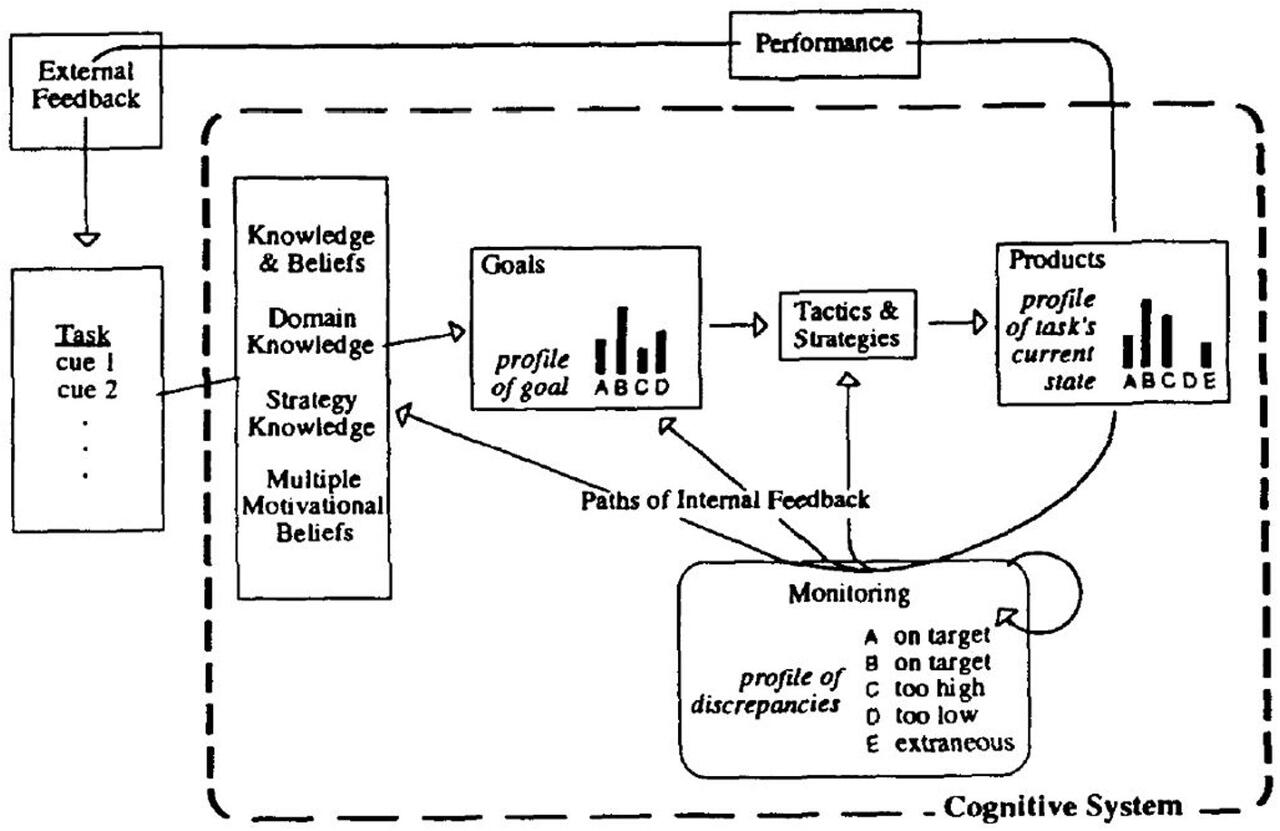

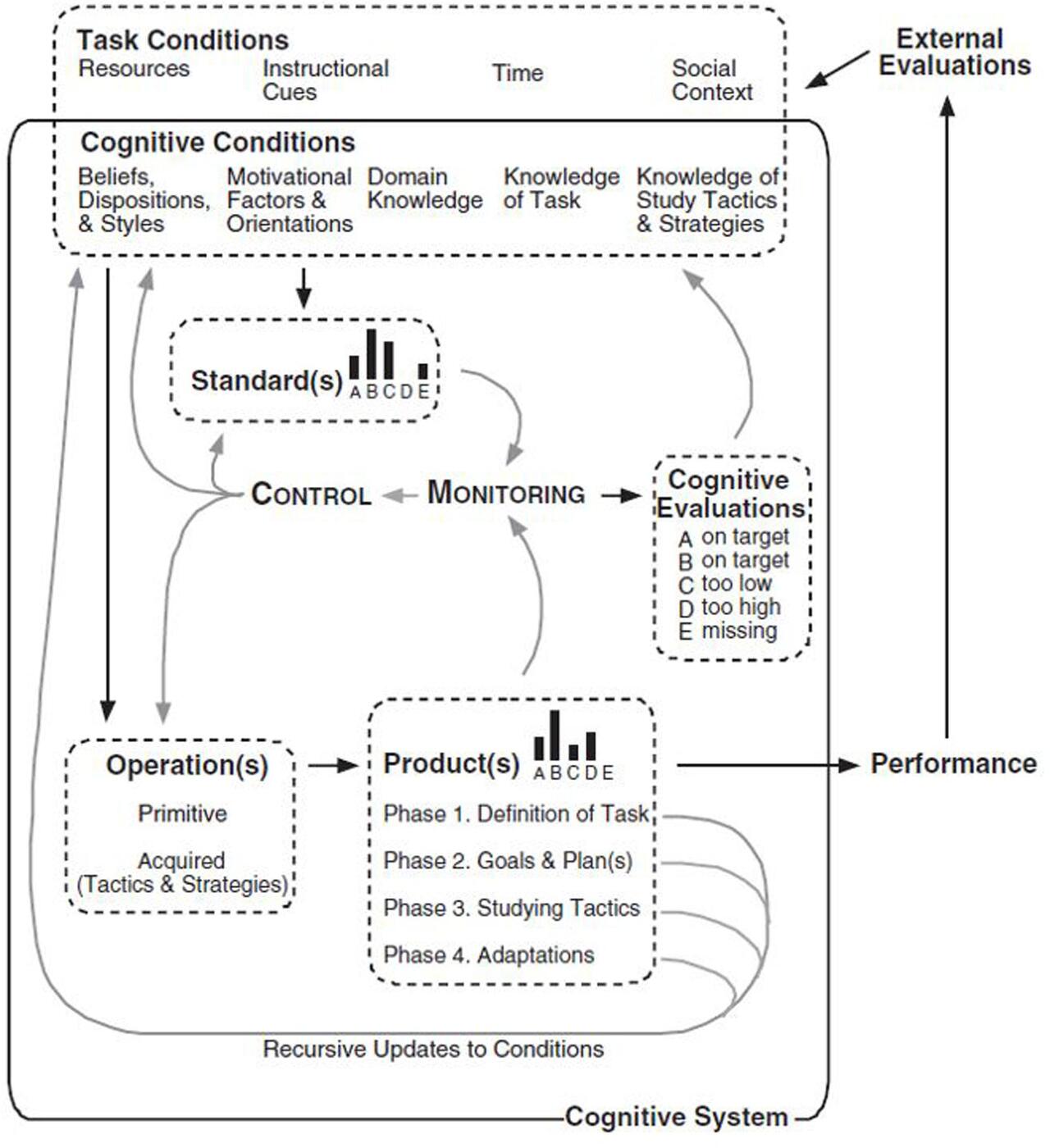

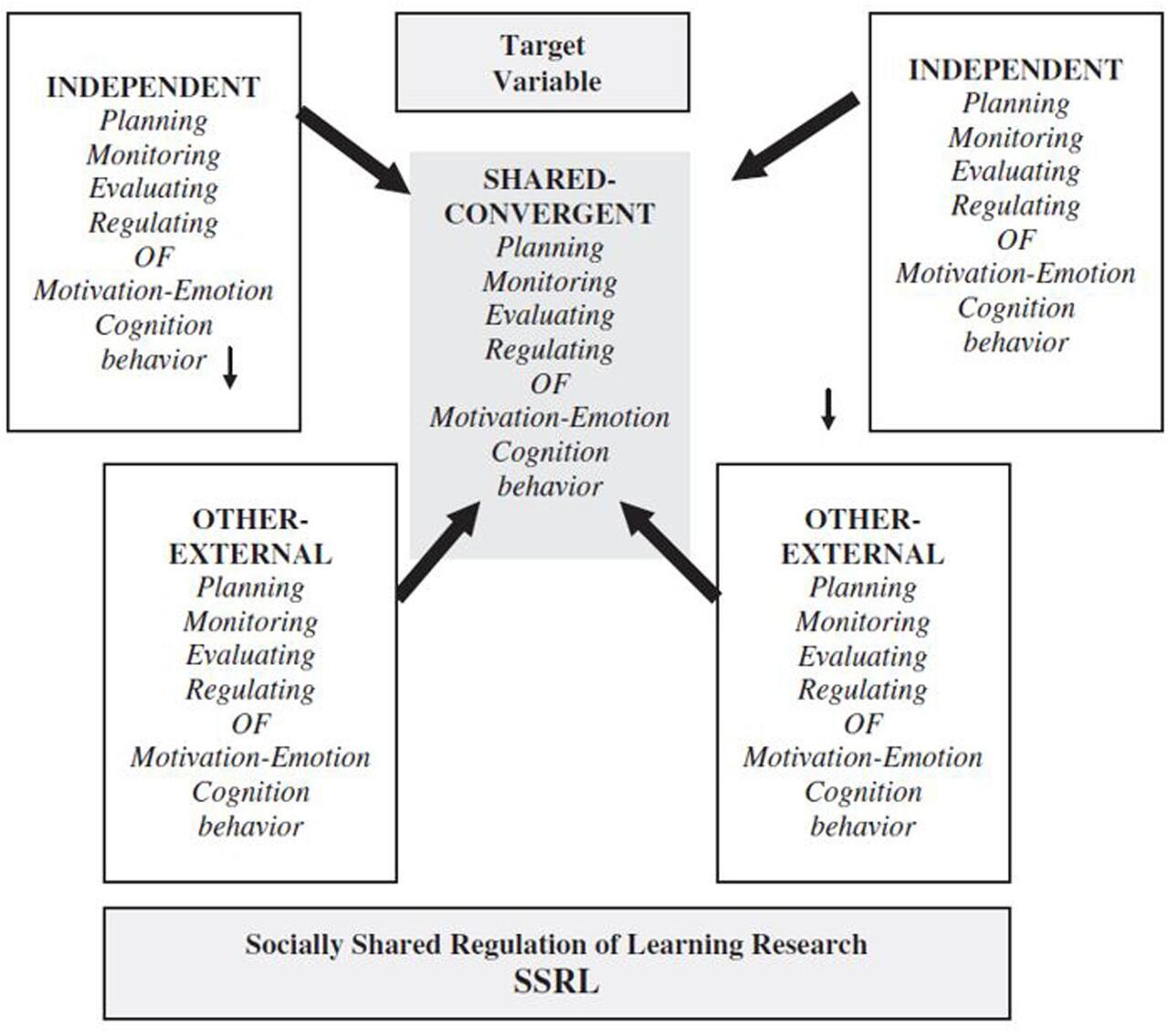

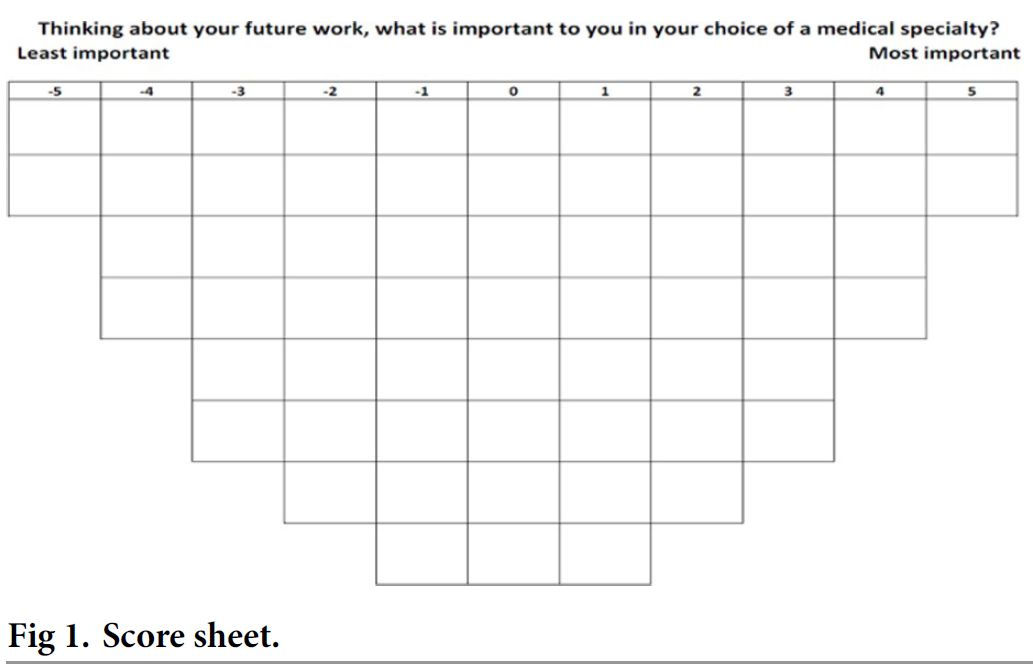

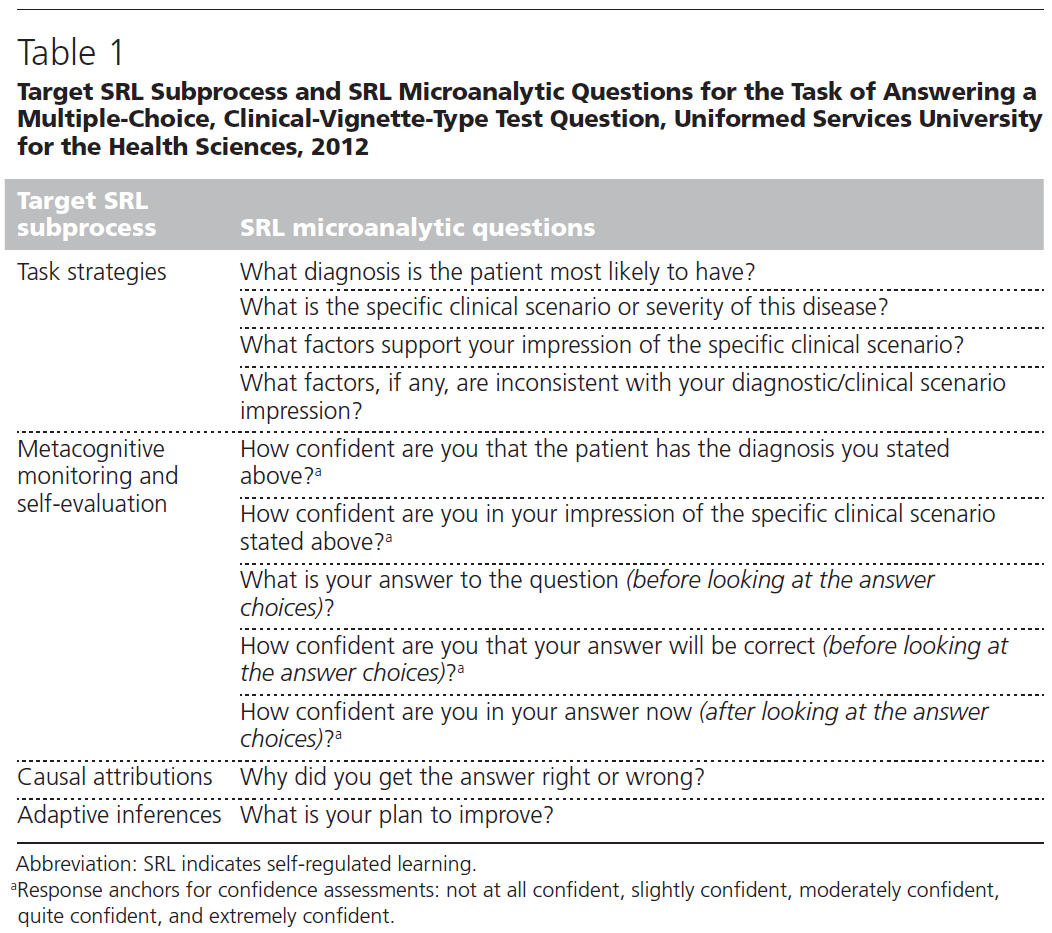

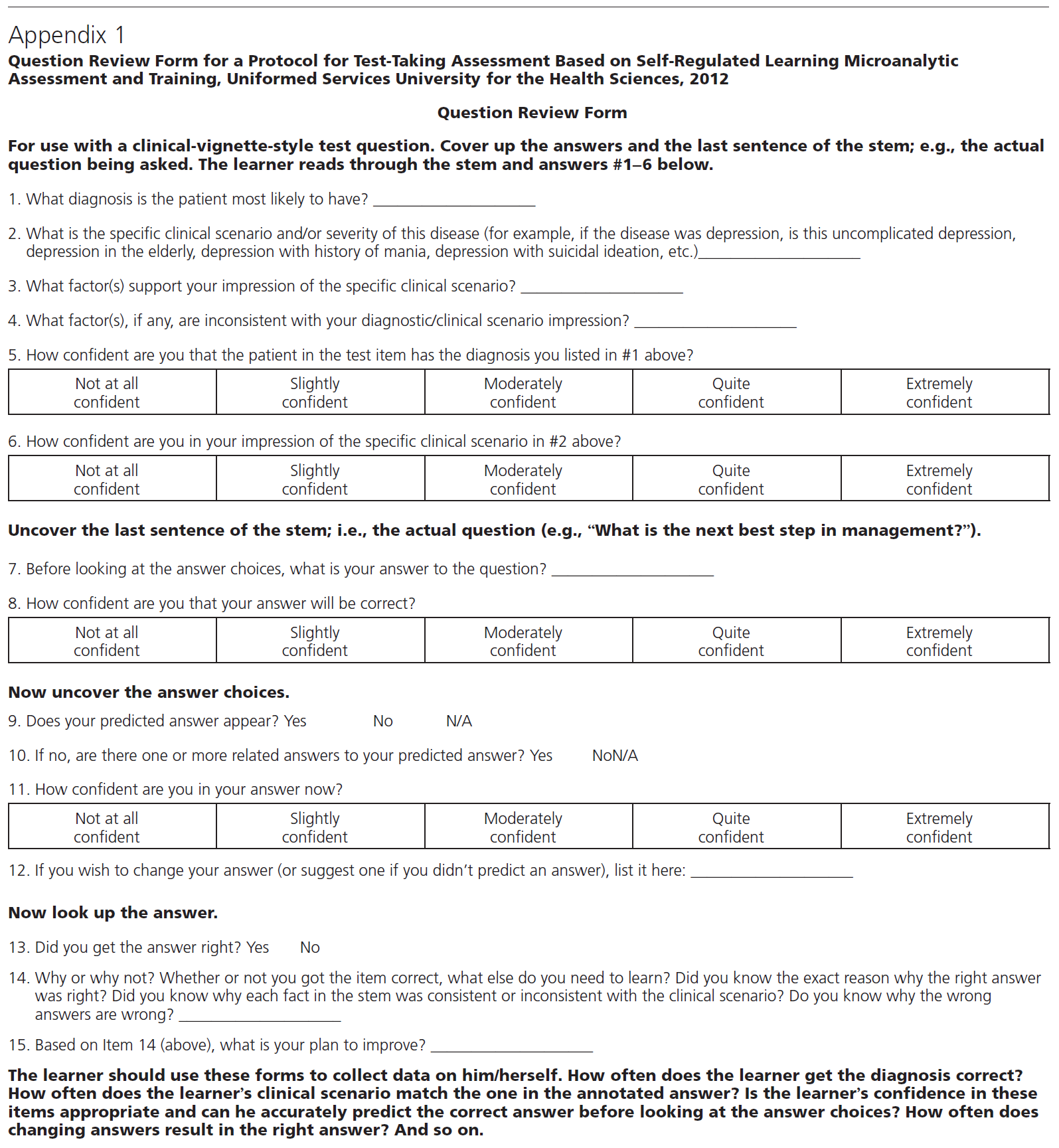

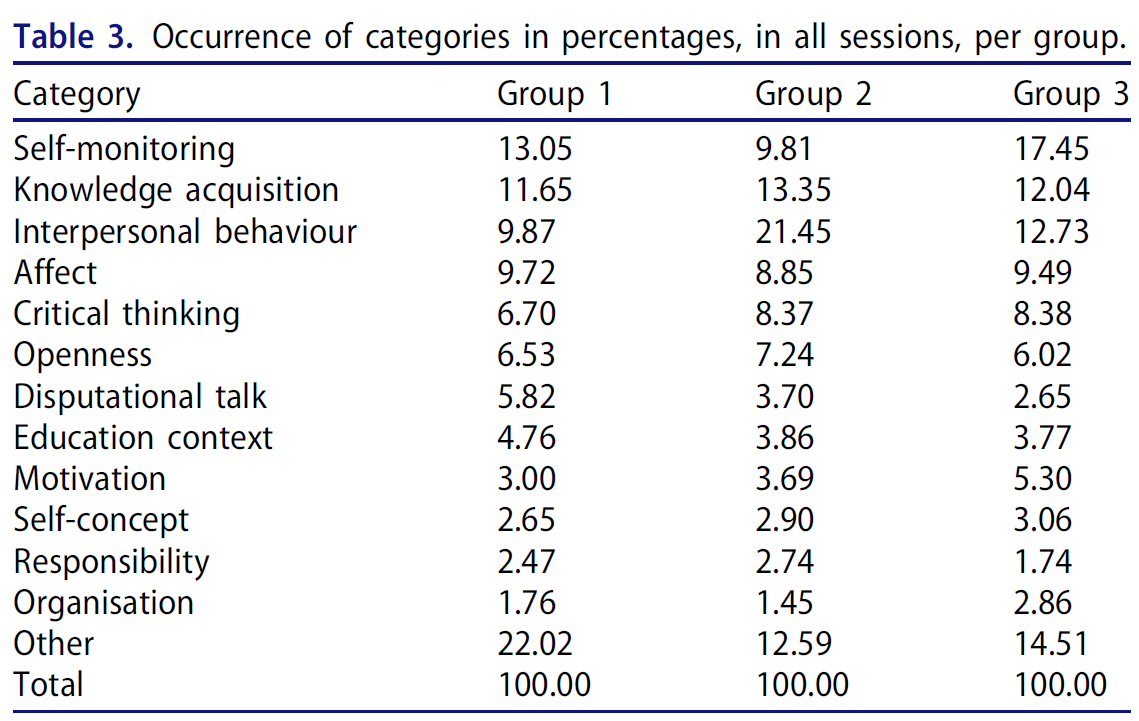

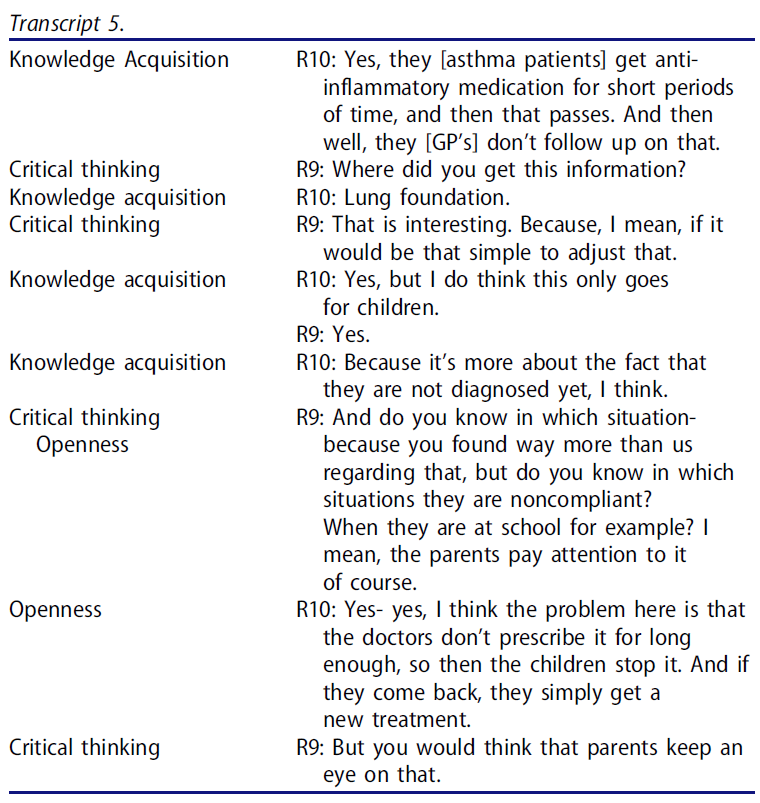

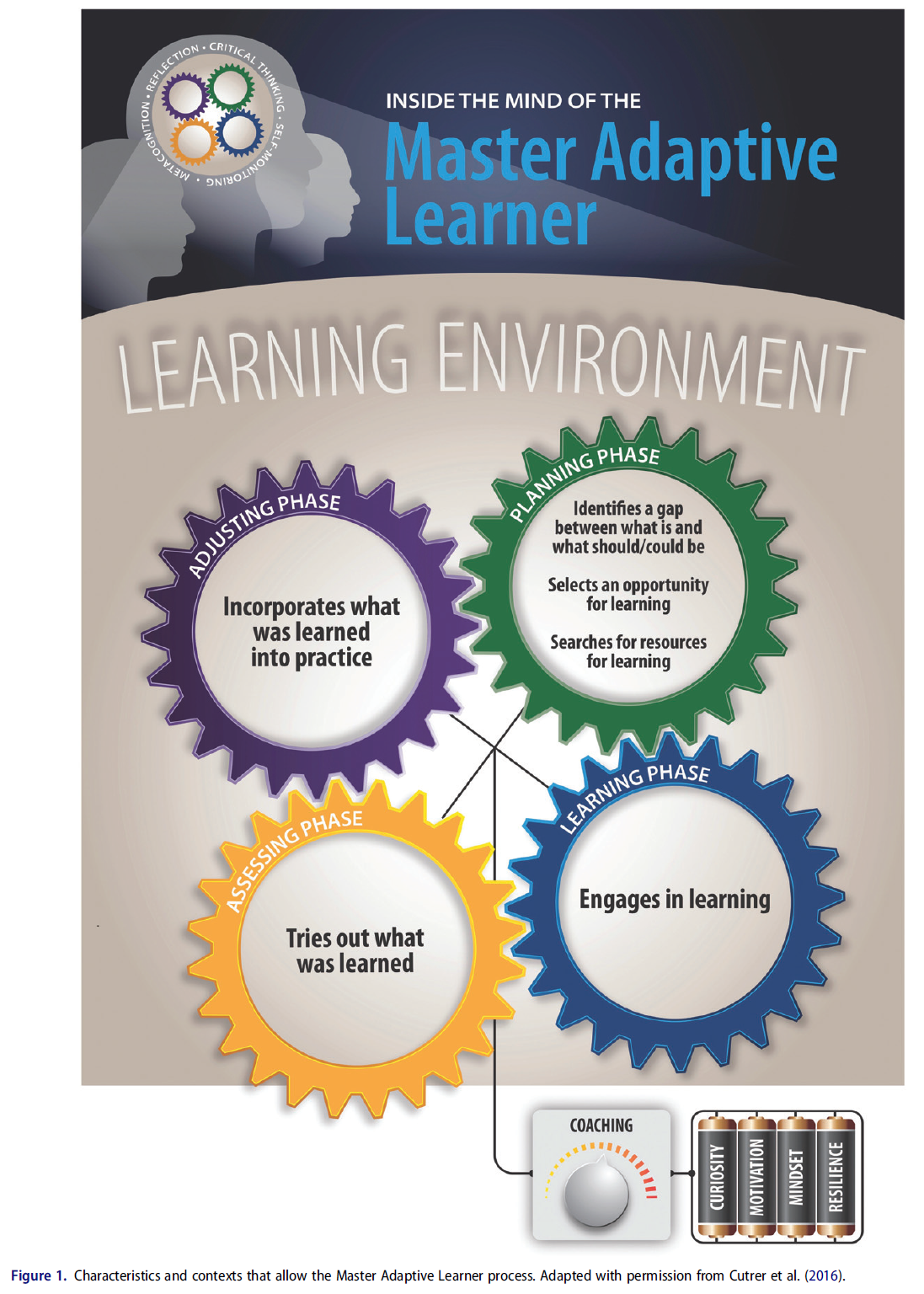

그림 1에서 포착한 바와 같이 감시와 통제 사이에는 중요한 상호작용이 있다. 학습자로서 정교하고 효과적으로 되기 위해서는

As captured in Figure 1, there is an important back and forth between monitoring and control. To become sophisticated and effective as a learner requires not only being able to assess, accurately, the state of one’s learning (as illustrated by the monitoring judgments listed in the top of the figure), but also being able to control one’s learning processes and activities in response to such monitoring (as illustrated by the control decisions).

(a) 학습자는 학습이 달성되었는지에 대해 쉽게 오해할 수 있으며, 일반적으로 과신(과신)을 야기할 수 있다.

(b) 사람들이 학습에 효과적이거나 효과적이지 않은 활동에 대해 믿는 경향이 있는 것은 종종 현실과 상충된다.

(a) learners can easily be misled as to whether learning has been achieved, typically resulting in overconfidence, and

(b) what people tend to believe about activities that are and are not effective for learning is often at odds with reality.

학습의 상태를 평가하는 것이 어려운 이유는, 현재의 성과나 습득한 정보를 인코딩하거나 검색하는 데 있어서 친숙함이나 유창함 같은 평가의 기초가 될 수 있는 객관적이고 주관적인 지표가 학습이 달성되었는지와 무관한 요인을 반영할 수 있기 때문이다. 현재의 성과—그리고 주관적인 회수 유창함은 학습 중에 존재하지만 나중에 나타나지 않을 재조명, 예측 가능성, 단서 등의 요인에 의해 크게 영향을 받을 수 있으며, 친숙함 또는 지각성 독감의 주관적인 감각은 학습의 유효한 척도가 되기 보다는 프라이밍과 같은 요인을 반영할 수 있다.

Assessing the state of one’s learning is difficult because the objective and subjective indices on which one might base such assessments, such as current performance or the sense of familiarity or fluency in encoding or retrieving to-be-learned information, can reflect factors unrelated to whether learning has been achieved. Current performance—and the subjective sense of retrieval fluency, can be heavily influenced by factors such as recency,predictability, and cues that are present during learning but will not be present later, and the subjective sense of familiarity or perceptual fluency can reflect factors such as priming rather than being a valid measure of learning.

마지막으로, 자신의 학습을 평가하는 데 효과적이 되기 위해서는 우리가 나중에 배울 정보를 생산할 수 있을지를 판단하는 데 있어 사후 판단 편향과 선견지명 편향의 대상이 된다는 것을 알아야 한다.

Finally, to be effective in assessing one’s own learning requires being aware that we are subject to both hindsight and foresight biases in judging whether we will be able to produce to-be-learned information at some later time.

Hindsight bias (Fischhoff 1975) refers to the tendency we have, once information is made available to us, to think that we knew it all along.

Foresight bias (Koriat &Bjork 2005), on the other hand, rather than reflecting a knew-it-all-along tendency, reflects a will-know-it-in-the-future tendency.

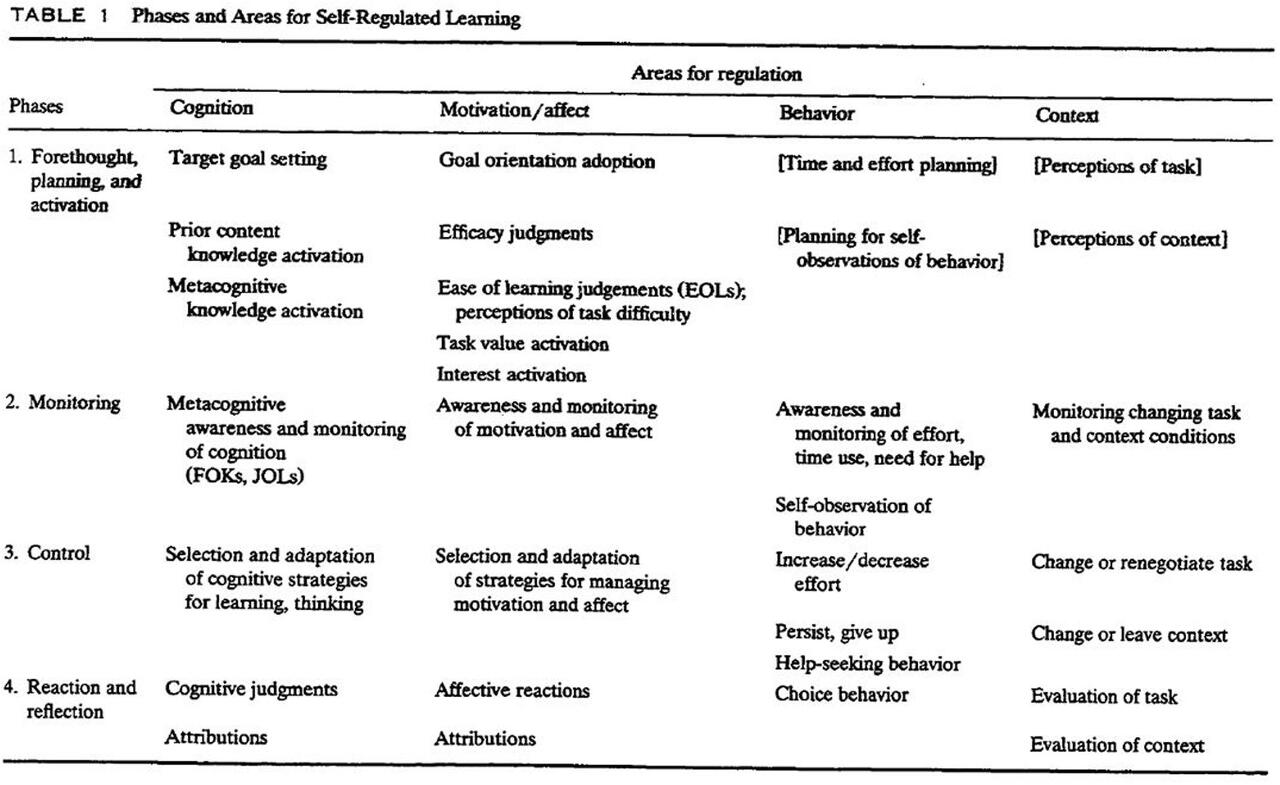

학생들은 '어떻게 배우는지'에 대해 무엇을 믿는가?

WHAT DO STUDENTS BELIEVE ABOUT HOW TO LEARN?

학생들의 학습전략 이용실태와 공부에 대한 믿음

Surveys of Students’ Strategy Use and Beliefs About Studying

가장 자주 사용되는 학생 자율 규제의 평가 중 하나는 학습 설문지를 위한 동기식 전략이다(MSLQ; Pintrich 등 1993).

One of the most frequently used assessments of student self-regulation is the Motivated Strategies for Learning Questionnaire (MSLQ; Pintrich et al. 1993).

MSLQ 척도와 학생 성적 사이의 관계는 낮았고 때로는 유의하지 않았다.

The relationships between these subscales and student grades were low and sometimes non-significant.

이러한 낮은 상관관계는 여러 가지 이유로 발생할 수 있다. 그 관계는 선형적이지 않을 수 있으며, 몇몇 전략은 평균적인 학생들이 주로 사용하고 있다. 게다가, 이러한 일반적인 전략은 모든 종류의 시험에 효과적이지 않을 것이다; 다른 제한은 척도의 일반적인 문구가 모든 학생들에 의해 같은 방식으로 해석되지 않을 수 있다는 것이다(Crede & Phillips 2011).

these low relationships may arise for multiple reasons. The relationships may not be linear, with some strategies being used largely by average students. Moreover, these general strategies will not be effective for all kinds of exams; Other limitations are that the general wording of the scale items may not be interpreted the same way by all students (Cred´e & Phillips 2011),

자가 테스트는 많은 학생들이 (하트위그 & 던로스키 2012, 카피크 외)를 사용하여 보고하는 플래시 카드의 사용에 내재되어 있다. 2009년) 그러나 학생들은 플래시카드를 효과적으로 사용하는가?

Self-testing is intrinsic to the use of flashcards that many students report using (Hartwig & Dunlosky 2012, Karpicke et al. 2009), but do students use them effectively?

거의 모든 학생들이 시험을 위한 자료를 배우기 위해 플래시카드를 한 번 이상 사용할 것이라고 보고했지만, 그들은 또한 사용하는 날이 시험 하루나 이틀 전에 대부분 제한되어 있다고 보고했다. 이러한 종류의 주입식 주입구는 인기가 있으며(Taraban et al. 1999) 학생들이 학습에 효과적인 방법이라고 믿음에도 불구하고 확실히 보존을 최적화하지 않는다(Kornell 2009).

Almost all the students reported that they would use flashcards more than once to learn materials for an exam, but they also reported that such use was largely limited to just a day or two before the exam. This kind of cramming is popular (Taraban et al. 1999) and certainly does not optimize retention, although students believe it is an effective way to learn (Kornell 2009).

학습 관리를 위한 결정의 지표가 되는 학생들의 믿음

Students’ Beliefs as Indexed by Decisions They Make in Managing Their Learning

셋째, 학생들은 학습 시간을 할당하기 위한 안건, 즉 학습계획을 개발하며, 때로는 이러한 학습계획은 discrepancy-reduction 모델과는 반대로 가장 학습이 어려운 내용에 우선순위를 두지 않는다(아리엘 외). 2009).

Third, students develop agendas—that is, plans—for the allocation of their study time, and sometimes these agendas, in contrast to the discrepancy-reduction model, do not prioritize the most difficult items for study (Ariel et al. 2009).

마찬가지로 메트칼페(2009, Kornell & Metcalfe 2006)는 어떤 조건에서는 학생들이 가장 공부하기 쉬운 아이템을 먼저 선택하고 가장 쉬운 아이템을 공부하는 데 더 많은 시간을 보낸다고 보고했다. 쉬운 항목에 우선 초점을 맞추는 것은 메탈프가 "proximal learning지역의 학습"이라고 부르는 것으로서, 학생들이 학습 시간을 할당하기 위해 개발할 수 있는 많은 의제 중 하나이며, 그렇게 하는 것은 심지어 학습을 증진시킬 수 있다(Atkinson 1972, Kornell & Metcalfe 2006).

Similarly, Metcalfe (2009, Kornell &Metcalfe 2006) reported that under some conditions students choose the easiest items first for study and spend more time studying the easiest items. Focusing on the easier items first (which Metcalfe calls studying within the region of proximal learning) is one of many agendas that students can develop to allocate their study time, and doing so can even boost their learning (Atkinson 1972, Kornell & Metcalfe 2006).

습관적인 편견은 효과적인 공부 시간 할당을 저해할 수 있다. 따라서, 예를 들어, 시험을 준비하는 학생은 단순히 교과서를 열고, 그들의 공부를 이끌 수 있는 어떤 종류의 공격 계획을 가지고 있는 것과 대조적으로, 할당된 내용만 읽어나갈 수 있다. 이러한 수동적 reading은, 심지어 그것을 반복해서 읽더라도, 자가 설명 또는 자가 테스트와 같은 능동적 처리보다 훨씬 덜 효과적이다.

habitual biases can undermine the development of effective agendas for study time allocation. Thus, for example, a student preparing for a test might simply open a textbook and read through the assigned pages versus having any kind of plan of attack that might guide their studying. Such passive reading— and even rereading—is much less effective than active processing, such as self-explanation or self-testing.

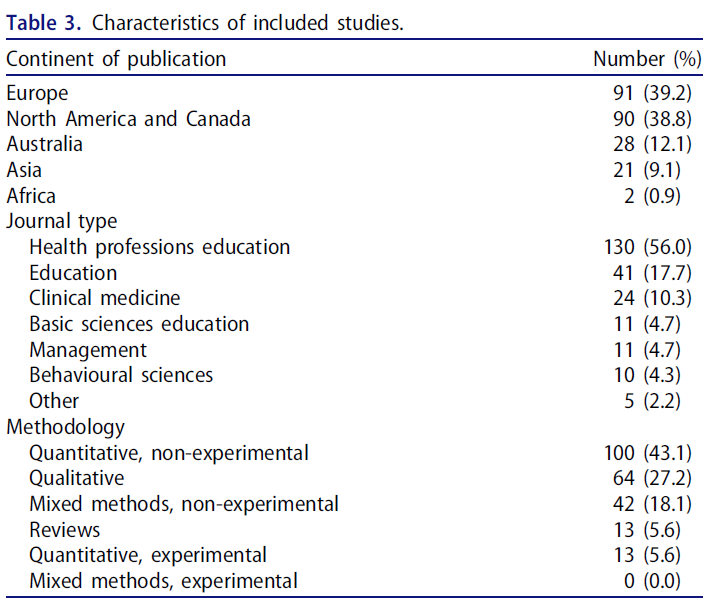

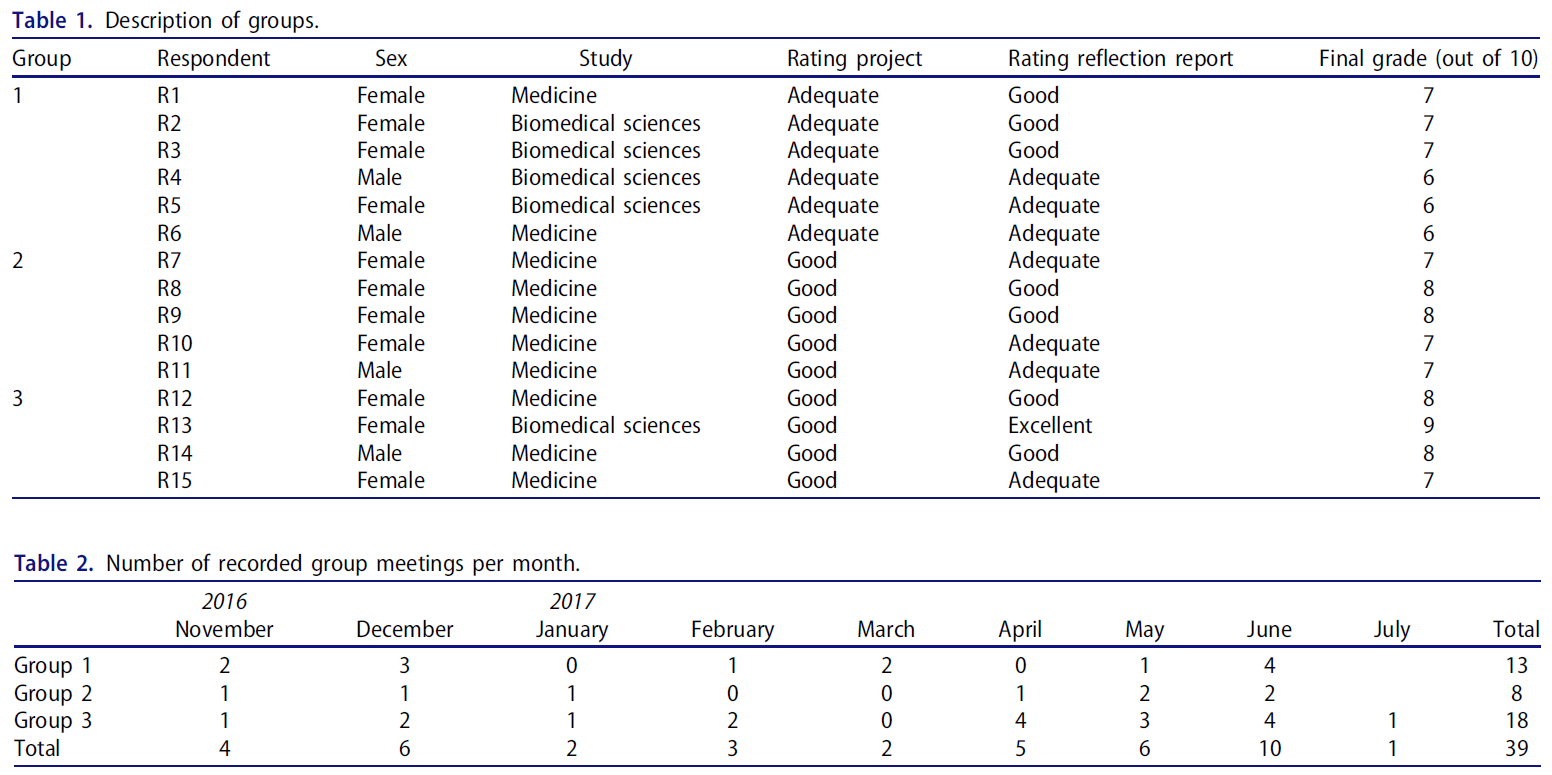

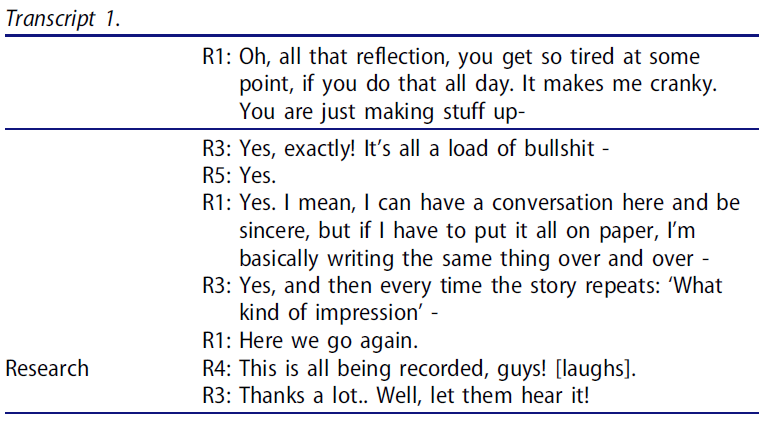

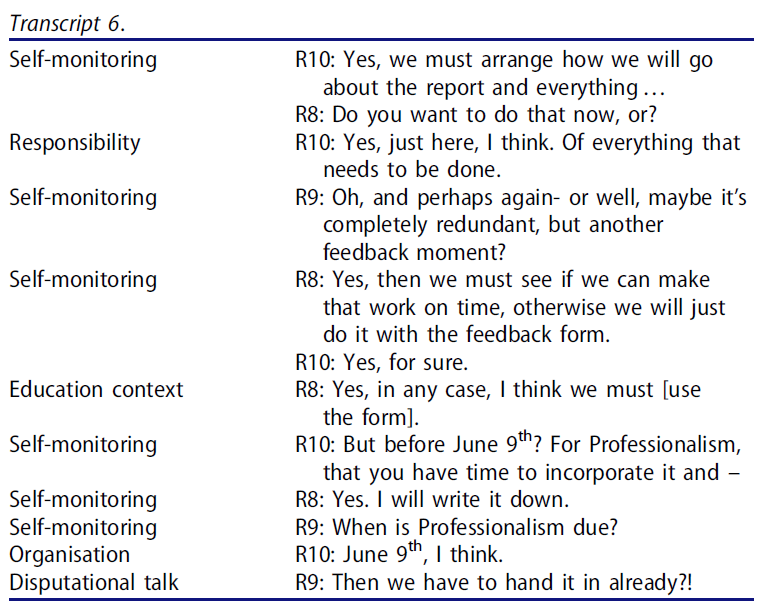

학생들이 새에 대한 공부를 마쳤을 때, 그림 2에 묘사된 인터페이스가 제시되었다. 자율 학습 단계 동안 참가자들은 최종 테스트에서 새 새를 분류하는 데 가장 도움이 되는 순서로 새를 연구하도록 지시 받았다. 평균적으로, 참가자들은 57마리의 새를 다시 연구하기로 선택했고, 상당수의 참가자들이 인터리브(또는 공간) 대신 블록(또는 몰아치기)을 선호했다.

when they finished studying this bird, the interface depicted in Figure 2 (see color insert) was presented. During the self-paced phase, the participants were instructed to study the birds in an order that would best help themto classify new birds on the final test. On average, participants chose to restudy 57 birds, and a sizable majority of participants (75%) preferred to block (or mass) instead of interleave (or space).

요약하자면, 학생들은 자기 테스트와 같은 학습을 위한 몇 가지 효과적인 전략을 사용하여 지지하며, 때때로 실험실 실험에서는 시간을 어떻게 관리해야 하는지에 대해 좋은 결정을 내린다. 그럼에도 불구하고, 다른 결과는 학생들이 이러한 효과적인 전략의 이점을 충분히 얻지 못한다는 것을 암시한다. 시험과 관련하여, 많은 학생들은 재독서의 장점이 기껏해야 미미하지만(Dunloskey et al. 2012, Fritz et al.) 재독은 시험보다 우수한 전략이라고 믿는다. 2000년, Rawson & Kintsch 2005). 더욱이 대부분의 학생들은 학습을 평가하기 위해 시험을 사용하므로 학습을 향상시키기 위한 전략으로 더 광범위하게 사용하지 않을 수 있다. 간격 연습과 관련하여, 비록 학생들이 때때로 실험실 실험에서 간격을 둔 학습를 선호하지만, 그러한 간격은 단일 세션 내에서만 발생한다. 안타깝게도, 학생들이 주입식 교육을 지지하고 그렇게 하는 것이 효과적이라고 믿는다면, 그들은 여러 세션에서 간격 연습이 일어날 때 발생하는 장기적인 혜택을 얻지 못할 것이다(예: Bahrick 1979, Rawson &Dunlosky 2011).

In summary, students do endorse using some effective strategies for learning, such as self-testing, and they sometimes make good decisions about how to manage their time in laboratory experiments. Nevertheless, other outcomes suggest that students do not fully reap the benefits of these effective strategies. With respect to testing, many students believe that rereading is a superior strategy to testing (McCabe 2010), even though the benefits of rereading are modest at best (Dunloskey et al. 2012, Fritz et al. 2000, Rawson & Kintsch 2005). Moreover, most students use testing to evaluate their learning and hence may not use it more broadly as a strategy to enhance their learning. With respect to spaced practice, even though students sometimes prefer to space study in laboratory experiments, such spacing occurs within a single session. Unfortunately, given that students endorse cramming and believe doing so is effective, they will not obtain the long-term benefits that arise when spacing practice occurs across multiple sessions (e.g., Bahrick 1979, Rawson &Dunlosky 2011).

왜 학생들은 효과적인 전략을 잘 사용하지 않고 비효율적인 것이 실제로 효과적이라고 생각하는가? 그들이 효과적인 전략을 충분히 사용하지 못할 수 있는 한 가지 이유는 아마도 아이들과 어른들이 학습전략 같은 것은 가르칠 필요가 없다고 사회적 태도를 갖고 가정하기 때문일 것이다. 맥나마라(2010년)가 지적한 바와 같이, "우리 교육 시스템에는 "학생들에게 전달해야 할 가장 중요한 것은 내용"이라고 하는 압도적인 가정이 있다"(원본 341쪽, 이탤릭체). 실제로, 대부분의 대학생들은 어떻게 공부하느냐가 교사나 다른 사람들에게 어떻게 공부해야 하는지를 배운 결과물이 아니라고 보고한다(K

Why might students underuse effective strategies and believe that ineffective ones are actually effective? One reason why they may underuse effective strategies is that many students are not formally trained (or even told) about howto use effective strategies, perhaps because societal attitudes and assumptions indicate that children and adults do not need to be taught them. As noted by McNamara (2010), “there is an overwhelming assumption in our educational system that the most important thing to deliver to students is content” (p. 341, italics in original). Indeed, most college students report that how they study is not a consequence of having been taught howto study by teachers or others (Kornell &Bjork 2007).

아마도 더 나쁜 것은, 학생들이 전략을 사용한 경험이 때때로 비효율적인 기술이 실제로 더 효과적인 것이라고 믿게 할 수도 있다(예: 코넬 & 비요크 2008a, 사이먼 & 비요크 2001). 예를 들어, 여러 실험에서, 코넬(2009)은 대학생 참가자의 90%가 매스작업보다 간격을 두고 더 나은 성과를 보였다고 보고했다. 그러나, 연구 세션이 끝났을 때, 참가자의 72%가 간격보다 질량이 더 효과적이라고 보고했다. 이러한 인지적 착각은 연구 중 처리가 간격보다 질량화를 위해 더 쉬우거나 더 유창하기 때문에 발생할 수 있으며, 일반적으로 사람들은 더 쉬운 처리가 더 나은 처리를 의미한다고 믿는 경향이 있다(Alter &Oppenhemer 2009). 불행하게도, 다음 절에서 자세히 설명하듯이, 이러한 인지적 환상은 학생들에게 나쁜 전략이 오히려 좋다고 믿게끔 속일 수 있고, 그 자체가 잘못된 자기 조절과 낮은 수준의 성취로 이어질 수 있다.

Perhaps even worse, students’ experience in using strategies may sometimes lead them to believe that ineffective techniques are actually the more effective ones (e.g., Kornell & Bjork 2008a, Simon & Bjork 2001). For instance, across multiple experiments, Kornell (2009) reported that 90%of the college student participants had better performance after spacing than massing practice. When the study sessions were over, however, 72%of the participants reported that massing was more effective than spacing. This metacognitive illusion may arise because processing during study is easier (or more fluent) for massing than spacing, and people in general tend to believe that easier processing means better processing(Alter &Oppenheimer 2009). Unfortunately, as the next section explains in more detail, these metacognitive illusions can trick students into believing that a bad strategy is rather good, which itself may lead to poor self-regulation and lower levels of achievement.

학습에 대한 학습자의 판단에 어떤 영향을 주며, 미래 수행능력을 어떻게 예측하는가?

WHAT INFLUENCES LEARNERS’ JUDGMENTS OF LEARNING AND PREDICTIONS OF FUTURE PERFORMANCE?

올바른 학습 결정을 내리는 것은 성공적인 학습자가 되기 위한 전제 조건이다. 이러한 결정은 학생들이 자신이 공부하는 자료를 얼마나 잘 알고 있는지에 대한 학생들의 판단에 달려 있다. 학생들은 종종 그들이 받아들일 수 있는 수준의 지식에 도달할 때까지 공부한다. 2009년, Kornell & Metcalfe 2006, Thiede & Dunlosky 1999)—예를 들어, 그들은 3장을 다 이해할 때까지 공부한다. 그들은 다가오는 시험에서 그것이 무엇을 다루는지 기억하고 나서 4장으로 돌아간다.

Making sound study decisions is a precondition of being a successful learner. These decisions depend on students’ judgments of how well they know the material they are studying. Students often study until they have reached what they deem to be an acceptable level of knowledge (Ariel et al. 2009, Kornell & Metcalfe 2006, Thiede & Dunlosky 1999)—for example, they study chapter 3 until they judge that they will remember what it covers on an upcoming test, then turn to chapter 4, and so forth.

학습의 판단(JOL)이라는 용어는 미래의 기억 성능에 대한 그러한 예측을 설명하기 위해 사용된다. 일반적인 JOL 과제에서 참가자들은 다가오는 시험에서 공부하고 있는 정보를 기억할 확률을 판단한다. JOL의 정확성은 어떻게 적응적(또는 부적응적) 학습 결정이 내려지는지에 큰 역할을 할 수 있다(Kornell & Metcalfe 2006, Nelson & Narens 1990).

The term judgment of learning ( JOL) is used to describe such predictions of future memory performance. In a typical JOL task, participants judge the probability that they will remember the information they are studying on an upcoming test. The accuracy of JOLs can play a large role in determining how adaptive (or maladaptive) study decisions end up being (Kornell & Metcalfe 2006, Nelson & Narens 1990).

믿음 기반 VS 경험 기반 판단 및 예측

Belief-Based Versus Experience-Based Judgments and Predictions

학습의 판단은 단서에 근거한 추론이지만, 어떤 단서일까? 믿음과 경험이라는 두 가지 광범위한 범주의 단서가 있는 것으로 보인다. (Jacoby & Kelley 1987, Koriat 1997).

Judgments of learning are inferences based on cues, but what cues? There appear to be two broad categories of cues—beliefs and experiences ( Jacoby & Kelley 1987, Koriat 1997).

믿음 기반 단서(이론 기반 또는 지식 기반 단서라고도 함)는 "공부함으로써 배운다"와 같이 기억력에 대해 의식적으로 믿는 것을 말한다.

경험 기반 단서에는 답이 얼마나 친숙해 보이는지, 화자가 얼마나 큰 소리를 내고 있는지, 단어가 얼마나 발음 가능한지 등 학습자가 직접 경험할 수 있는 모든 것이 포함된다.

Belief-based cues (which are also known as theory-based or knowledge-based cues) refer to what one consciously believes about memory, such as “I learn by studying.”

Experience-based cues include anything learners can directly experience, including how familiar an answer seems, how loud a speaker is talking, how pronounceable a word is, and so forth.

경험 기반과 신념 기반 단서 간의 경쟁과 상호작용.

Competition and interactions between experience-based and belief-based cues.

깊은 심리적 차이는 믿음과 경험을 나누는 것으로 나타난다. 비록 사람들은 그들의 기억력에 대해 확실히 믿음을 가지고 있지만, 그들은 종종 JOLs를 내릴 때, 즉 그들은 심지어 (특히 아마도) 믿음 기반 단서에 무감각하고, 동시에 경험 기반 단서에 매우 민감하다(예: Kelley & Jacoby 1996 참조).

A deep psychological difference appears to divide beliefs from experience. Although people clearly hold beliefs about their memories, they frequently fail to apply those beliefs when making JOLs—that is, they are insensitive to belief-based cues even (and perhaps especially) when they are, at the same time, highly sensitive to experience-based cues (see, e.g., Kelley & Jacoby 1996).

사람들은 경험 기반 단서에 민감하며, 그 반대가 옳은 상황에서도 믿음 기반 단서에 민감하지 않다.

people are sensitive to experience-based cues and not belief-based cues, even in a situation where the opposite should be true.

안정성 편견의 증거.

Evidence of a stability bias.

미래의 공부가 자신의 지식에 영향을 미칠 것이라고 예측하지 못하는 것은 Kornell & Bjork(2009)가 메모리의 안정성 편향, 즉, 기억력이 미래에 변하지 않는 것이라고 생각하는 편견의 한 예다(Kornell 2011, 2012 참조). 코넬과 비요크는 참가자들이 단어 쌍 목록을 한 번 연구한 다음 0~3번의 추가 연구 시험 후 최종 시험 성과를 예측하도록 요청했을 때, 미래에 학습 능력이 부족하여 안정성 편향을 보여주지만 동시에 현재의 지식 수준에서도 과신임을 알게 되었다. 이 패턴은 최적의 방식으로 공부하지 않는 두 가지 이유를 동시에 제공하는 것으로 보이기 때문에 문제가 된다.

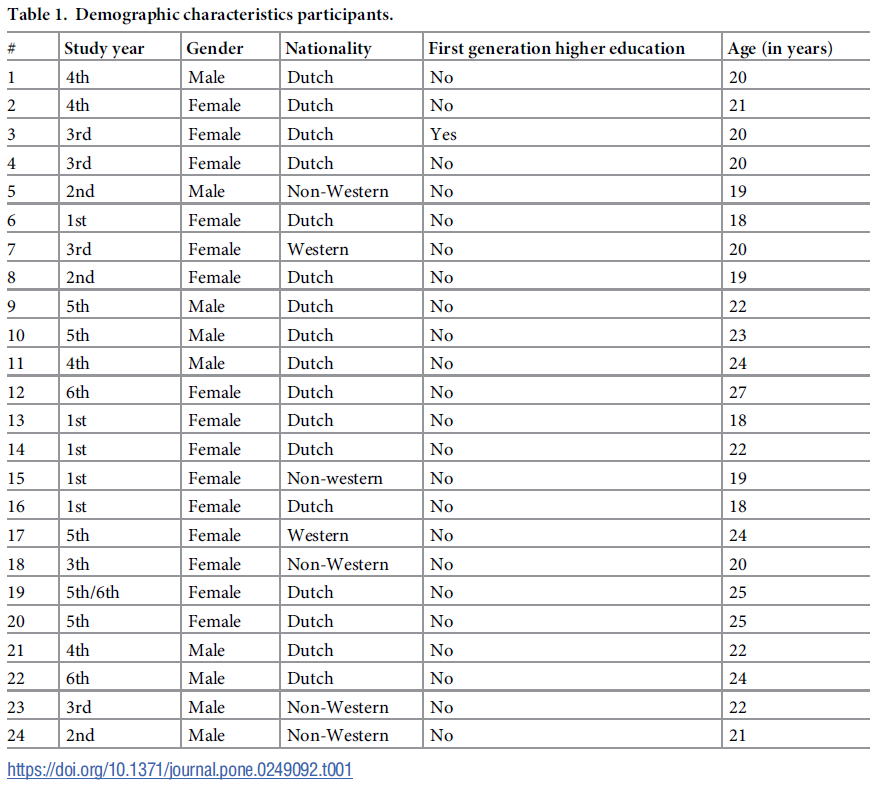

Failing to predict that future studying will affect one’s knowledge is an example of what Kornell & Bjork (2009) labeled a stability bias in memory—that is, a bias to act as though one’s memory will not change in the future (see also Kornell 2011, 2012). Kornell and Bjork found that participants, when asked to study a list of word pairs once and then to predict their final test performance after 0– 3 additional study trials, were underconfident in their ability to learn in the future, demonstrating a stability bias, but were also, at the same time, overconfident in their current level of knowledge. This pattern is troubling because it appears to provide dual reasons not to study as much as would be optimal.

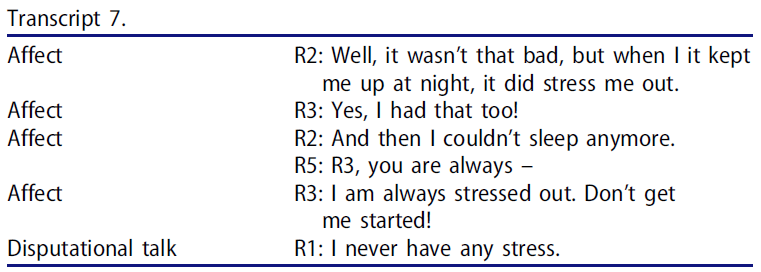

안정성 편견은 골치 아픈 의미를 가지고 있다. 학생들이 어려운 상황에서도 공부에 굴복하지 않는 한 가지 이유는 궁극적으로는 그들이 발전할 것이라고 생각하기 때문이다. [공부로 얼마나 발전할 수 있는지]를 과소평가하는 학생들은 포기하기 이를 때에조차 희망을 포기할 수도 있다. 망각을 무시하는 것도 위험하다. 학생들은 무의식적으로 만약 오늘날 무언가를 안다면, 다음 주나 다음 달에도 그것을 알 것이라고 생각할 수도 있다(꼭 그렇지는 않다). 그리고 그 결과 조기에 공부를 중단할 수도 있다. (교사들은 학생들의 지식을 판단할 때 같은 오류에 취약하다.) 사실, 망각하는 것을 고려하지 못하는 것은 엄청난 양의 장기적인 과신( over神)을 낳을 수 있다(Kornell 2011). 과신 및 저신뢰에 대한 안정성 편견의 효과는 그림 3에 나타나 있다.

The stability bias has troubling implications. One reason students donot give upon studying, even in the face of difficulty, is the knowledge that eventually they will improve. Students who underestimate how much they can improve by studying may give up hope when they should not. Ignoring forgetting is also dangerous. Students may unconsciously assume that if they know something today, they will know it next week or next month—which is not necessarily true—and stop studying prematurely. (Teachers are vulnerable to the same error when judging their students’ knowledge.) Indeed, failing to account for forgetting can produce extreme amounts of long-term over-confidence (Kornell 2011). The effects of the stability bias on over and under-confidence are illustrated in Figure 3.

따라서, 사람들은 [공부가 배움을 낳고], [망각은 시간에 걸쳐 발생한다]는 믿음과 같이 가장 분명한 인지적 믿음조차도 무시 할 수 있는 것으로 보인다. 믿음에 기초한 단서가 무시되는 이유는 일반적으로 현재의 경험에 영향을 미치지 않는 단서 범주에 속하기 때문인 것으로 보인다. 선견지명 편향, 즉 앞에서 논의했던 자신의 기억을 어떻게 시험할 것인지를 고려하지 못한 것도 이 범주에 속한다. [미래의 시험]이라는 것은 현재의 경험에 영향을 미치지 않는다.

Thus, it appears that people can ignore even the most obvious of metacognitive beliefs, such as the beliefs that studying produces learning and forgetting happens over time. The reason belief-based cues are ignored appears to be that, in general, they fall into the category of cues that do not impact one’s current experience. The foresight bias—that is, the failure to take into account how one’s memory will be tested, which was discussed previously—falls into this category as well. The form taken by a future test does not affect current experience.

현재 수행능력의 목표 지표 해석: 휴리스틱스 및 일루시스

Interpreting Objective Indices of Current Performance: Heuristics and Illusions

반응 정확도.

Response accuracy.

답을 떠올릴 수 있느냐가 JOLs에 강력한 영향을 미친다는 것은 분명하다. 지금까지 제시된 증거에 비추어 볼 때 현재의 경험이 JOLs에 대한 독점적인 지배력을 가지고 있어 보인다. 즉, 과거의 사건은 현재의 경험에 영향을 미칠 수 있지만, 현재의 경험만이 JOLs에 영향을 미친다. 그러나 핀&메트칼프(2007, 2008년)가 보여준 바와 같이(King et al. 1980도 참조), 과거에 시험이 있었고 그 사이에 추가 연구 시험이 발생했더라도, 사람들은 가장 최근의 테스트를 기초로 JOL을 판단하는 경향이 있다. 이러한 판단 전략은 과거 시험 휴리스틱에 대한 기억이라고 한다. 따라서 경험이 JOL을 제어하는 것으로 보이며, 그 경험이 꼭 현재의 경험은 아닌 경우도 있다.

It is clear that whether one can recall an answer has a powerful influence on JOLs. It seems possible, given the evidence presented thus far, that current experience has exclusive control over JOLs. That is, past events can influence current experience, but only current experience influences JOLs. As Finn & Metcalfe (2007, 2008) have shown (also see King et al. 1980), however, people tend to base their JOLs on their most recent test, even if the test occurred in the past and additional study trials have occurred in the meantime. This judgment strategy is referred to as the memory for past test heuristic. Thus, it appears that experiences, not necessarily current experiences, control JOLs.

응답 시간.

Response time.

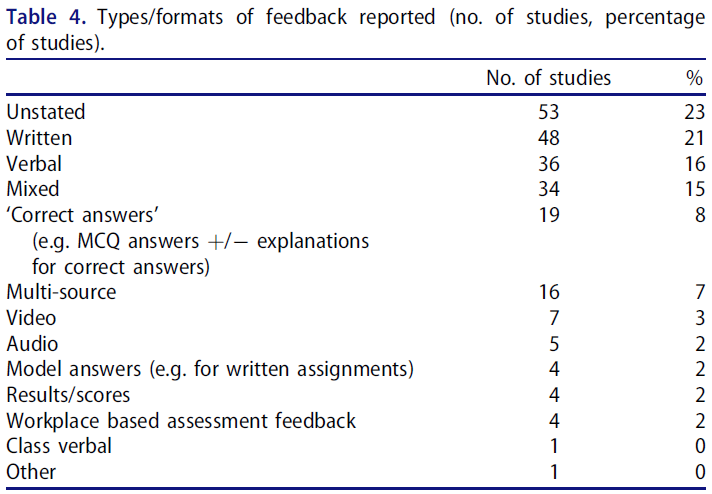

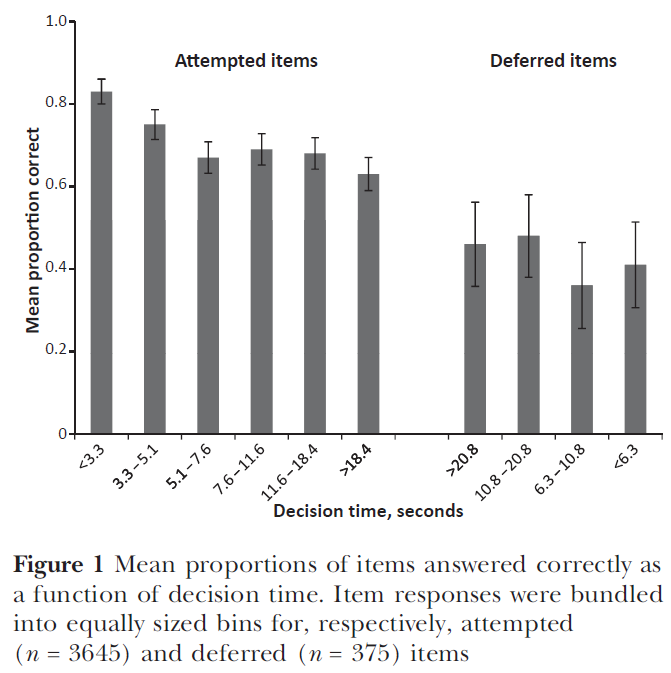

질문에 대답할 수 있는 능력처럼, 답이 떠오르는 속도는 JOLs에 중요한 경험에 기초한 영향을 미친다. 벤자민 외 연구진(1998)은 이 주장에 대한 뚜렷한 증거를 발견했다.

Like the ability to answer a question, the speed with which an answer comes to mind has an important experiencebased influence on JOLs. Benjamin et al. (1998) uncovered striking evidence for this claim.

결과는 놀라웠다. 자신이 있는 참가자들일수록 답을 떠올릴 가능성이 낮았다. 이 결과는 참가자들이 빠르게 대답하는 질문에 더 높은 JOL을 주었기 때문에 발생했지만, 그들은 오랫동안 생각한 문제에 대해서 답을 free-recall할 가능성이 가장 높았다(그림 4 참조).

The results were surprising: The more confident participants were that they would recall an answer, the less likely they were to recall it. This outcome occurred because participants gave higher JOLs to questions that they answered quickly, but they were most likely to free-recall answers that they had thought about for a long time (see Figure 4).

주관적 성과 지표 해석: 휴리스틱스 및 일루젼

Interpreting Subjective Indices of Performance: Heuristics and Illusions

응답 시간과 검색 성공은 객관적으로 측정할 수 있는 단서지만, JOL은 보다 주관적인 근거인 유창함과 밀접한 관련이 있다.

정보를 처리하거나 정보를 검색할 때 주관적인 유창함은 경험 기반 단서 범주에 속하기 때문에 유창함은 인지적 판단에 강력한 영향을 미친다.

Response time and retrieval success are objectively measurable cues, but they are closely related to a more subjective basis for judgments: fluency.

Fluency during the perceptual processing of information is the sense of ease or speed of processing;

fluency during the retrieval of information is the sense of how readily information “comes to mind.”

Because the subjective sense of fluency, either in processing information or in retrieving information, falls squarely in the category of experience-based cues, fluency has powerful effects on metacognitive judgments

인출 유창성.

Retrieval fluency.

인출 유창성은 메모리에서 정보를 검색하는 것이 쉽고 빠른 것이다.

Retrieval fluency, as mentioned above, is the ease and speed with which information is retrieved from memory

일반적으로 인출 유창함은 어떤 것이 얼마나 잘 알려져 있는지를 판단하는 측면에서 유용한 휴리스틱스지만, 그것이 priming과 같이 학습 정도와 관계없는 요인에 의한 결과일 때 [아는 것에 대한 환상]을 불러일으킬 수 있다.

In general, retrieval fluency is a useful heuristic in terms of judging how well something is known, but it can be misleading and create illusions of knowing when it is the product of factors unrelated to degree of learning, such as priming.

정보가 유창하게 떠오를수록 학생들은 그것을 알고 있다고 판단하고, 따라서 공부를 중단하게 된다.

The more fluently information comes to mind, the more likely students are to decide they know it, and therefore put it aside and stop studying.

인코딩 유창성

Encoding fluency.

인코딩 유창성(즉, 정보를 배우기가 쉽거나 어렵다는 주관적 느낌)은 공부에 관한 결정에 대한 또 다른 중요한 영향이다(예: Miele et al. 2011).

Encoding fluency—that is, the subjective feeling that it is easy or difficult to learn a piece of information—is another important influence on decisions about studying (e.g., Miele et al. 2011).

그러나 인코딩 유창성은 recall이 fluency와 상관관계가 없기 때문에 문제의 소지가 있다(Castel et al. 2007 참조). 따라서 인출 유창성과 마찬가지로 인코딩 유창성은 오해의 소지가 있지만 높은 인코딩 유창성은 학생이 해당 항목을 다시 학습할 가능성을 감소시킬 수 있다.

Yet, encoding fluency was misleading (see also Castel et al. 2007) because recall was not correlated with fluency. Thus, like retrieval fluency, encoding fluency can be misleading, but high encoding fluency may decrease the chance that a student will restudy the item.

지각 유창성

Perceptual fluency.

인지적 판단은 지각적 유창성이 더 큰 항목, 즉 주관적으로 지각적 수준에서 처리하기 쉬운 항목의 경우 더 높은 경향이 있다.

Metacognitive judgments tend to be higher for items with greater perceptual fluency—that is, items that are subjectively easier to process at a perceptual level.

예를 들어, 레더(1987년)는 질문에 핵심 단어를 미리 노출하는 것(골프 1언더파를 치는 용어의 용어는 무엇인가?)이 주어진 질문에 대한 답을 만들어낼 수 있을 것이라는 피실험자들의 자신감을 높인다는 것을 발견했다. 또한 앞에서 언급한 바와 같이 더 큰 글꼴로 표시된 단어가 더 기억에 남는다고 잘못 판단되었다(Kornell et al. 2011, Rodes & Castel 2008). 더 큰 음량으로 제시된 단어들도 더 기억에 남는 것으로 잘못 평가되었다(Roades & Castel 2009). 최근의 한 연구는 지각적 유창함이 학습을 감소시킬 수 있다고 제안하기도 했다. 학생들은 같은 PowerPoint 프레젠테이션과 유인물을 유창성을 감소시키는 글꼴로 변환했을 때 더 많은 것을 배웠다(Diemand-Yauman et al. 2011). 정보가 더 유창해 보일 때 학생들이 더 많이 배웠다고 판단하는 것을 감안하면 걱정스러운 결과다.

Reder (1987), for example, found that simply pre-exposing key words in a question (such as the words “golf ” and “par” in the question “What is the term in golf for scoring one under par?”) increased subjects’ confidence that they would be able to produce the answer to a given question. Also, as mentioned previously, words presented in larger fonts have been incorrectly judged to be more memorable (Kornell et al. 2011, Rhodes & Castel 2008). Words presented at a louder volume were also incorrectly rated as more memorable (Rhodes & Castel 2009). A recent study even suggested that perceptual fluency can decrease learning: Students learned more when in-class PowerPoint presentations and handouts were converted to fonts that decreased fluency (Diemand-Yauman et al. 2011). This is a worrying outcome given that students judge that they have learned more when information seems more fluent.

귀납 유창성

Fluency of induction.

자기 규제 학습은 한 가지 유형의 학습에만 국한되지 않는다. 많은 연구들은 암기 자료들을 포함하고 있지만, 그러한 자료들은 귀납적 학습을 포착하지 못한다. 귀납적 학습이란 사례를 관찰함으로써 개념이나 범주를 배우는 것이다. 예를 들어 느릅나무를 오크나무와 단풍나무와 구별하는 것을 배우는 것은 각 종류의 나무의 예를 볼 필요가 있다.

Self-regulated learning is not limited to one type of learning. Most of the research on the topic involves materials that can be memorized, but such materials do not capture inductive learning—learning a concept or category by observing examples. For example, learning to differentiate elm trees from oaks and maples requires seeing examples of each kind of tree.

블록 학습으로 인해 특정 예술가의 그림에서 유사성을 쉽게 알아차릴 수 있었을 수 있지만, 인터리빙의 가치는 적어도 부분적으로는 범주 간의 차이를 강조하는데 있어 있는 것으로 보인다(Kang & Pashler 2012, Wahlheim et al. 2011). 인터리빙의 이점은 비유동적 학습(예: 세페다 외, 2006, 뎀프스터 1996)에서 간격적 연습의 이점에 관한 많은 문헌과 일치한다(인터리빙이 학습을 강화시키는 이유? 참조).

Blocking may have made it easier to notice similarities within a given artist’s paintings, whereas the value of interleaving appears to lie, at least in part, in highlighting differences between categories (Kang & Pashler 2012, Wahlheim et al. 2011). The benefit of interleaving is consistent with a large literature on the benefits of spaced practice in noninductive learning (e.g., Cepeda et al. 2006, Dempster 1996) (see sidebar Why Does Interleaving Enhance Learning?).

그림 5(컬러 삽입 참조)에서 알 수 있듯이, 코넬 & 비요크(2008a) 참가자의 대다수는 블록 학습이 인터리빙 학습보다 더 효과적이었다고 잘못 믿었다(비슷한 결과는 코넬 외, 2010, Wahlheimet al. 2011, Zulkiply 외, 2012 참조).

As Figure 5(see color insert) shows, the majority of Kornell &Bjork’s (2008a) participants incorrectly believed that blocking had been more effective than interleaving (for similar results, see Kornell et al. 2010, Wahlheimet al. 2011, Zulkiply et al. 2012).

블록 스케줄에서, 방금 제시된 범주의 이전 예는 매우 유창하지만, 인터리브 스케줄에서는 그렇지 않다. 따라서 블록으로 학습하는 것이 인터리빙보다 더 효과적인 것으로 평가된다. 이러한 인지적 오류는 비유인적 학습에서도 발생한다(Dunlosky &Nelson 1994, Kornell 2009, Simon &Bjork 2001, Zechmeister & Shaughnessy 1980).

In a blocked schedule, the previous example of a category, which was just presented, is highly fluent, whereas it is not in an interleaved schedule. Thus blocked studyingis ratedas more effective than interleaving. This metacognitive error occurs in noninductive learning as well (Dunlosky &Nelson 1994, Kornell 2009, Simon &Bjork 2001, Zechmeister & Shaughnessy 1980), although, as mentioned previously, students do tend to space their studying at least to some degree (see Son & Kornell 2009 and section What Do Students Believe About How to Learn?).

주관적인 경험이 예측의 가장 좋은 근거일 때.

When subjective experience is the best basis for predictions.

왜 교차연습이 학습을 향상시키는가?

WHY DOES INTERLEAVING ENHANCE LEARNING?

별도의 학습 주제 또는 절차에 대한 학습 세션 인터리빙은 주어진 주제 또는 절차에 대한 스터디 또는 연습 세션의 간격을 도입하지만 lnterleaving의 이점은 spacing의 이점 이상인가? 인터리빙은 학습해야 할 별도의 주제 또는 절차 사이의 간섭(검토의 경우, Lee 2012 참조)을 도입하고, 모터 기술 영역에서, 몇 번의 스트로크처럼 학습해야 할 별도의 기술에 대한 인터리빙 연습이 모터에게 요구된다는 생각에 대한 상당한 지원이 있다. 이러한 기술에 대응한 프로그램은 반복적으로 반복해서 실행되지 않고 다시 로드되며, 이는 학습 이점이 있다.

Interleaving study sessions on separate to-be-learned topics or procedures introduces spacing of the study or practice sessions on a given topic or procedure, but do the benefits of interleaving go beyond the benefits of spacing? Interleaving introduces contextual interference, that is, interference among the separate topics or procedures to be learned (for a review, see Lee 2012), and in the domain of motor skills there is substantial support for the idea that interleaving practice on separate skills to be learned, such as the several strokes in tennis, requires that motor programs corresponding to those skills be repeatedly reloaded, rather than executed over and over again, which has learning benefits.

그러나 다른 연구결과는, 특히 학습개념과 범주의 영역에서, 상호작용에 의해 도입된 상황적 간섭이 비교와 대조를 촉발하여, 다른 개념이나 범주가 서로 어떻게 관련되는지 상위 순서로 정신적 표현을 하게 하고, 그 결과 보존과 전이가 촉진된다는 것을 시사한다. 그러한 관점에서 interleaving의 이점은 실제로 spacing의 이점을 넘어서지만, 문제는 현재의 관심사와 연구 문제로 남아 있다(예: 강앤파슬러 2012, 테일러 & 로어 2010 참조).

Other findings, though, especially in the domain of learning concepts and categories, suggest that contextual interference introduced by interleaving triggers comparisons and contrasts that result in a higher-order mental representation of how different concepts or categories relate to each other, which then fosters retention and transfer. In that view, the benefits of interleaving indeed go beyond the benefits of spacing per se, but the issue remains a matter of current interest and research (see, e.g., Kang &Pashler 2012, Taylor &Rohrer 2010).

바람직한 어려움에 대한 학습 성과 및 직관적이지 않은 이점

Learning Versus Performance and the Unintuitive Benefits of Desirable Difficulties

사람들은 공부하는 동시에 공부에 대한 결정을 내리기 때문에, 그들은 공부하는 동안 최고의 성과로 이어지는 기술에 끌리는 경향이 있다. 예를 들어, 몰아치기 학습을 통해 스터디 활동을 더 쉽게 하는 것은 더 잘 배우고 있다는 판단을유도하는 경향이 있는데, 이는 학습을 더 편안하게 만드는 조건이 실제로 장기 학습을 감소시킬 수 있기 때문에 문제가 될 수 있다. 간격과 인터리빙, 답안 생성, 자기 시험, 학습 조건 변경과 같은 활동은 바람직한 어려움으로 알려져 있다(Bjork 1994, Bjork & Bjork 2011). 그들은 습득하는 동안 성과, 따라서 명백한 학습을 손상시키지만 장기 학습을 강화한다. 연구 결정의 기초로 유창성을 사용하는 것의 근본적인 문제는 학습자들이 종종 높은 유창성을 실제로, 어떤 상황에서는, 그 반대의 신호를 보낼 수 있을 때 높은 개선율을 나타내는 것으로 해석한다는 것이다.

Because people make study decisions while they are studying, they tend to be drawn to techniques that lead to the best performance during study. Making study activities easier—by, for example, massing practice—tends to increase judgments of learning, which is problematic because conditions that make learning seem easier can actually decrease long-term learning. Activities such as spacing and interleaving, generating answers, testing oneself, and varying the conditions of learning are known as desirable difficulties (Bjork 1994, Bjork & Bjork 2011). They impair performance—and, hence, apparent learning—during acquisition, but enhance long-term learning. The fundamental problem with using fluency as a basis for study decisions is that learners often interpret high fluency as signaling a high rate of improvement when it can actually, under some circumstances, signal just the opposite.

자기조절학습을 손상시킬 수 있는 태도와 가정들

ATTITUDES AND ASSUMPTIONS THAT CAN IMPAIR SELF-REGULATED LEARNING

[오류와 실수]의 의미와 역할 오해

Misunderstanding the Meaning and Role of Errors and Mistakes

오류와 실수는 일반적으로 학습 과정 중에 피해야 할 것으로 간주되며, 이는 부분적으로 학습자로서 자신의 부족함을 문서화하는 것으로 해석될 것을 우려하기 때문이다.

Errors and mistakes are typically viewed as something to avoid during the learning process,in part out of fear that they will be interpreted as documenting our inadequacies as a learner

이와는 대조적으로, 다양한 연구 결과는 오류를 만드는 것이 종종 효율적인 학습의 필수적인 요소라는 것을 암시한다.

A variety of research findings suggest, by contrast, that making errors is often an essential component of efficient learning.

반대로 오류를 제거하는 조작은 종종 배움을 없앨 수 있다. 따라서, 예를 들어, 습득해야 할 정보의 검색이 수선, 강력한 신호 지원 또는 다른 요인에 의해 성공을 보장할 정도로 쉽게 이루어질 때, 학습 이벤트로서의 그러한 retrieval의 이점은 대부분 또는 완전히 제거되는 경향이 있다(예: Landauer & Bjork 1978, Rawson & Kintsch 2005, Whitten & Bjork 1977).

Conversely, manipulations that eliminate errors can often eliminate learning. Thus, for example, when retrieval of to-be-learned information is made so easy as to insure success, by virtue of recency, strong cue support, or some other factor, the benefits of such retrieval as a learning event tend to be mostly or entirely eliminated (e.g., Landauer & Bjork 1978, Rawson & Kintsch 2005, Whitten & Bjork 1977).

오류를 범하는 것은 학습의 기회를 창출하는 것으로 보이며, 놀랍게도 높은 자신감과 오류가 동반될 때 특히 그러하다. 버터필드 & 메트칼프(2001)는 높은 자신감 상태에서의 오류와 낮은 자신감 상태에서의 오류를 비교하여, 높은 자신감 상태에서 뒤따를 때 특히 효과적이라는 것을 발견하고 이를 hypercorrection effect라고 불렀다. 교육적으로 현실적일 만큼 긴 보존 간격을 포함하여 현재 여러 번(예: Butler et al. 2011, Metcalfe & Pin 2011) 복제된 효과다.

Making errors appears to create opportunities for learning and, surprisingly, that seems particularly true when errors are made with high confidence. Butterfield &Metcalfe (2001) found that feedback was especially effective when it followed errors made with high confidence versus errors made with low confidence, a finding they labeled a hypercorrection effect. It is an effect that has now been replicated many times (e.g., Butler et al. 2011, Metcalfe & Finn 2011), including at retention intervals long enough to be educationally realistic.

기본적 메시지는, 정교한 학습자가 되기 위해서는, 단순히 낙담하기보다는, 오류를 범하고 고군분투하는 것도 학습의 중요한 기회로 보아야 한다는 것이다.

From the standpoint of becoming sophisticated as a learner, the basic message is that making errors and struggling, rather than being simply discouraging, should also be viewed as important opportunities for learning.

성능의 차이를 과대평가하여 능력의 차이점 식별

Overattributing Differences in Performance to Innate Differences in Ability

우리의 견해에 따르면, 우리 사회에는 무엇을 배울 수 있고 얼마나 배울 수 있는지를 결정함에 있어, [개인들 사이의 선천적인 차이]의 역할을 과대평가하는 경향이 있으며, 이러한 과대평가는 훈련, 실천, 경험의 힘에 대한 과소평가와 결합되어 있다. 타고난 차이를 과대평가하고, 노력과 실천의 역할을 과소평가하는 이러한 조합은 개인들로 하여금 그들이 배울 수 있는 것에 일정한 한계가 있다고 가정하게 하고, 결과적으로 그들 자신의 학습 능력을 과소평가하게 할 수 있다. 기본적으로 듀크의 (2006) 용어를 사용하기 위해서는 학습자가 고정된 사고방식이 아니라 성장형 마인드를 가질 필요가 있다.

There is, in our view, an overappreciation in our society of the role played by innate differences between individuals in determining what can be learned and how much can be learned, and that overappreciation is coupled with an underappreciation of the power of training, practice, and experience. This combination of overappreciating innate differences and underappreciating the roles of effort and practice can lead individuals to assume that there are certain limits on what they can learn, resulting in an underestimation of their own capacity to learn. Basically, to use Dweck’s (2006) terms, learners need to have a growth mindset, not a fixed mindset.

개인간의 차이는 중요하지만, 이것은 주로 new learning은 old learning에 바탕을 두고 있기 때문이다. old learning의 수준은 new learning에 필요한 것으로서 정말로 중요한 것이며, 개개인의 가정과 문화적 역사는 학습에 관한 개개인의 열망과 기대에 깊은 영향을 미치기 때문이다.

Differences between individuals do matter, but mostly because new learning builds on old learning, so the level of old learning an individual brings to new learning really matters, and because our personal family and cultural histories have a profound effect on our aspirations and expectations with respect to learning.

학습이 쉬워야 한다고 가정하는 것

Assuming That Learning Should Be Easy

마지막으로, 역효과를 낼 수 있는 또 다른 일반적인 가정은 배움이란 쉬운 것이고, 쉬워야 한다는 것이다. 그러한 가정은

다양한 "made-easy" 핸드북,

교실 내에서의 성과를 높이는 것이 중요하다는 일반적인 가정(그렇게 하는 것이 실제로 장기 학습을 손상시킬 수 있음에도),

그리고 우리 각자가 자신만의 학습 스타일을 가지고 있다는 생각에 의해 부채질된다.

Finally, another common assumption that can be counterproductive is that learning can be, and should be, easy. Such an assumption is fueled by various “made-easy” self-help books, by the common assumption that it important to increase performance in classrooms (when doing so can actually damage long-term learning), and by the idea that we each have our own style of learning.

매우 영향력 있는 학습스타일이라는 아이디어는 패슬러가 meshing hypothesis라고 이름붙인 것으로, 학습자가 학습 스타일과 맞물리는 방식으로 자료를 제시하면 학습이 효과적이고 쉬울 것이라는 가설이다. 기존의 증거를 검토하는 과정에서, 파슬러 등은 meshing hypothesis에 대한 지지를 찾을 수 없었고, 심지어 정반대를 시사하는 몇 가지 증거까지 발견하였다(예를 들어 시각/공간적 능력 점수가 높은 사람은 언어적 가르침에서 가장 많은 이익을 얻을 수 있는 반면, 대화자는 언어적 완화를 위해 높은 시험하는 개인에게는 진실일 수 있다).

The very influential styles-of-learning idea involves what Pashler et al. (2009) labeled a meshing hypothesis—namely, that learning will be effective and easy if material is presented to the learner in a way that meshes with his or her learning style. In their review of the existing evidence, Pashler et al. could find no support for the meshing hypothesis and even found some evidence that suggests the opposite—that, for example, someone with high visual/spatial ability scores may profit most from verbal instruction, whereas the converse may be true for individuals testing high for verbal abilities.

우리의 리뷰는 효과적인 배움이 재미있을 수 있고, 보람을 줄 수 있고, 시간을 절약할 수 있지만, 좀처럼 쉽지 않다는 것을 암시한다. 가장 효과적인 인지 과정에는 학습자가 연결과 연결, 예제 및 백표 작성, 생성 및 검색 등의 노력을 기울이는 것이 포함된다. 요컨대 효과적인 학습은 학습자의 적극적인 참여를 필요로 한다.

Our review suggests that effective learning can be fun, it can be rewarding, and it can save time, but it is seldom easy. The most effective cognitive processes involve some effort by the learner—to notice connections and linkages, to come up with examples and counterexamples, to generate and retrieve, and so forth. In short, effective learning requires the active participation of the learner.

어떻게 공부해야 하는가에 대한 FAQ

CONCLUDING COMMENTS ON SOME FREQUENTLY ASKED HOW-TO-STUDY QUESTIONS

"앞으로 있을 시험의 형식은 무엇인가요?"

“What Is the Format of the Upcoming Test?”

이것은 아마도 학생들이 가장 많이 하는 질문일 것이다. 그것은 "저것이 시험에 나올 것인가?"라는 질문과 유사하게 내용에 관한 것이 아니기 때문에 교사들을 짜증나게 할 수 있다. 그러나 이것은 학생이 자신의 학습을 규제하기를 원한다는 것을 의미하기 때문에 스스로 규제하는 학습의 관점에서 통찰력 있는 질문이며, 예를 들어 시험이 객관식 대 논술 형식을 가질 것인가에 따라 아마도 다르게 공부할 것으로 추측된다. 전자의 경우 단순히 관련 자료를 생략하기로 결정할 수 있는 반면 후자의 경우 논술을 반영하기 때문에 연습 시험을 시도할 수 있다.

This may be the most common question students ask. It can annoy teachers because it is not about content, similar to the question “Will that be on the test?” It is, however, an insightful question from the standpoint of self-regulated learning because it implies that the student wants to regulate his or her own learning—and will presumably study differently depending on whether the test will have, say, a multiple-choice versus an essay format. For the former, they may decide to simply skim the relevant materials, whereas for the latter, they may attempt practice testing because doing so reflects essay writing.

불행하게도, 이런 방식으로 제기된 질문은 학생들이 학습에 대해 가지고 있는 잘못된 인식을 더욱 부각시킨다. 왜냐하면 시험이 객관적 선택인지 에세이인지에 상관없이, 학생들은 학습할 자료를 elaborating하고, self-testing을 사용함으로써, 적극적으로 학습에 참여한다면, 원하는 정보를 더 잘 보존retain할 것이기 때문이다. (물론 어떤 유형의 시험이 있을지를 알면 성적이 더 높아지긴 한다; Lundeberg & Fox 1991).

Unfortunately, the question posed in this manner further highlights misconceptions students have about learning, because regardless of whether the test is multiple choice or essay, the students will retain the sought after information better if they actively participate in learning, such as by elaborating on the to-be-learned material and by using self-testing (although knowing what type of test to expect can increase students’ grades; Lundeberg & Fox 1991).

따라서 우리가 흔히 하는 대답은, 만약 시험이 당신이 '진정으로 이해했는지'를 확인하는 것이라고 가정한다면 당신은 최선의 결과를 얻을 것이다. 당신은 더 잘 기억해낼 수 있을 것이고, 필요한 정보를 생각해낼 것이다. 이는 시험문제가 사실의 회상에 대한 것이든, 이해했는지를 확인하는 문제이든, 문제를 해결하는 것이든 무관하다.

Thus, the answer we often give is that you will do best if you assume the exam will require that you truly understand, and can produce from memory, the sought-after information, whether doing so involves recalling facts, answering comprehension questions, or solving problems.

"나는 노트를 복사하여 공부한다. 그거 좋은 생각이야?"

“I Study by Copying My Notes. Is That a Good Idea?”

이 질문에 대한 답은 복사가 무엇을 의미하느냐에 달려 있다. 들은 그대로 copying하는 것은 수동적인 과정이기 때문에, 또한 그다지 효과적이지 않다. 그러나 노트를 다시 쓰거나 재편성하는 것은 적극적인 조직적이고 정교한 처리를 행하는데, 모든 입문 심리학 학생들은 교과서에서 알아야 할 가치가 있다(예: Schacter et al. 2011). 자신의 노트를 공부하고 나서 노트를 보지 않은 상태에서 재생산reproduce하려고 하는 것은 또 다른 능동적인 과정이며, 검색 연습의 학습 편익을 이용한다. 따라서 이 질문에 대한 대답은 해당 학생들이 노트를 복사할 때 정확히 무엇을 하는지 알아내야 한다.

The answer to this question depends on what is meant by copying. Because verbatim copying is a passive process, it is also not very effective. Rewriting one’s notes, however, or reorganizing them, exercises active organizational and elaborative processing, which all introductory psychology students should know from their textbook is valuable (e.g., Schacter et al. 2011). Studying one’s notes and then trying to reproduce them without the notes being visible is another active process and takes advantage of the learning benefits of retrieval practice. The answer to this question, therefore, requires finding out exactly what the students in question do when they copy their notes.

"벼락치기는 효과가 있나?"

“Does Cramming Work?”

반사적인 "아니오"는 이 질문에 대한 올바른 대답처럼 보이지만, 이 경우에도 대답은 그렇게 간단하지 않다. 우선, 만약 그 학생이 시험 전날 그 자료를 모른다면, 벼락치기는 벼락치기를 하지 않는 것보다 더 좋은 결과를 낼 것이다. 이 질문에 대한 가장 좋은 대답은 아마도 "무엇을 위해 일하는가?"일 것이다. 만약 그 학생의 목표가 다가오는 시험에 합격할 충분한 정보를 얻는 것이라면, 벼락치기 시험은 잘 볼 수 있을 것이다. 심지어 자주 벼락치기를 하면서도 학교에서 잘 하는 학생들도 있다(예: 하트비히 & 던로스키 2012). 장기적으로는 나쁘지만 벼락치기massing study session를 하는 것은, 단기적으로는 양호한 회수율을 얻을 수 있으며, 어떤 상황에서는 간격 학습 세션보다 훨씬 더 좋다(예: Rawson & Kintsch 2005).

A reflexive “no” seems the right answer to this question, but even in this case the answer is not so straightforward. For one thing, if the student doesn’t know the material the day before the exam, cramming will produce a better outcome than will not cramming. The best answer to this question is probably “Work for what?” If the student’s goal is merely to obtain enough information to pass (or even do well on) an upcoming test, then cramming may work fine. There is even a subset of students who do well in school who frequently cram for tests (e.g., Hartwig &Dunlosky 2012). Massing study sessions, though bad in the long-term, can yield good recall at a short retention interval, even better than spacing study sessions under some circumstances (e.g., Rawson & Kintsch 2005).

그러나, 만약 학생의 목표가 그들이 배우는 것을 더 오랜 기간 동안 유지하는 것이라면(예를 들어, 같은 주제에 대해 더 진보된 과정을 밟을 때까지), 벼락치기는 다른 기술에 비해 매우 효과적이지 않다. 다가오는 시험에서 좋은 성적을 내고 좋은 장기 유지가 목표라면, 학생들은 미리 공부를 하고 며칠에 걸쳐 학습 시간을 확보한 다음, 시험 전날 밤에 공부해야 한다(예: Kornell 2009, Rawson &Dunlosky 2011). 물론 교사들은 숙제, 주간 시험, 종합 기말고사를 이용하여 그러한 간격을 두고 공부하는 것을 장려할 수 있다.

If, however, a student’s goal is to retain what they learn for a longer period of time (e.g., until they take a more advanced course on the same topic), cramming is very ineffective compared to other techniques. If good performance on an upcoming test and good long-term retention is the goal, then students should study ahead of time and space their learning sessions across days, and then study the night before the exam (e.g., Kornell 2009, Rawson &Dunlosky 2011). Teachers, of course, can use homework assignments, weekly exams, and comprehensive finals to encourage such spaced studying.

"나는 내가 예상했던 것보다 훨씬 더 성적이 나빴다. 어떻게 된 거야?"

“I Did So Much Worse Than I Expected. What Happened?”

학습을 과대평가하는 많은 방법들이 있으며, 어떤 사람들은 시험 준비 상태를 일관되게 과대평가한다. 앞서 이 검토에서 논의한 바와 같이, 그러한 과대평가로 가는 두 가지 경로는

사후판단 편향으로서, 시험 대상 자료를 보고 그것을 이미 알고있었다고 생각하는 것과

선견지명 편향이며, 해답이 존재하지 않고 시험에 요구될 때 다른 가능한 해답이 떠오를 것이라는 것을 알지 못하는 것이다.

As summarized in our review, there are many ways to overestimate one’s learning, and some of us consistently overestimate our preparedness for exams. Two routes to such overestimation, as discussed previously in this review, are hindsight bias, looking at to-be-tested material and thinking that it was known all along, and foresight bias, not being aware that when the answer is not present and required on the test other possible answers will come to mind.

아마도 이 질문에 대한 가장 좋은 대답은 간단하다. 완전히 알 때까지 정답을 확인하지 않고 의미 있는 자가 테스트를 수행하십시오. 그래야만 정보를 알고 있다는 확신을 가질 수 있다(그리고 그때도 망각은 여전히 일어날 수 있다).

Perhaps the best answer to this question is a simple one: Take a meaningful self-test without checking the answers until you are done. Only then can you be confident that you know the information (and even then, forgetting can still occur).

“How Much Time Should I Spend Studying?”

이것은 사실 학생들이 결코 하지 않는 질문이지만, 아마도 이런 질문도 해야 할 것이다. 단순히 공부에 많은 시간을 보내는 것만으로는 충분하지 않다. 왜냐하면 그 시간은 매우 생산적이지 않게 소비될 수 있기 때문이다. 하지만 학생들은 효과적인 공부와 그렇게 하는 데 충분한 시간을 소비하지 않고는 뛰어날 수 없기 때문이다. 상황을 더 어렵게 만드는 것은, 자신의 학습 시간을 모니터링하는 것 자체가 어렵다는 사실이다. 왜냐하면 학습 세션, 심지어 수업에 출석하는 것조차 이메일, 온라인 쇼핑, 소셜 네트워크, 유튜브 등에 쓰는 시간도 포함할 수 있기 때문이다.

This is actually a question students never ask, but perhaps should. Simply spending a lot of time studying is not enough, because that time can be spent very unproductively, but students cannot excel without both (a) studying effectively and (b) spending enough time doing so. Compounding the problem, it is difficult to monitor one’s own study time—because study sessions, even attending class, can include email, online shopping, social networks, YouTube, and so on.

"좋은 성적을 받고 학교에서 성공하기 위해서는 어떻게 공부해야 할까?"

“How Should I Study To Get Good Grades and Succeed in School?”

이 질문은 정말 기본이고 대답에 할 말이 많다. 비록 단 한 가지 대답도 없다. 자가 테스트와 연습 간격과 같은 일부 전략은 일반적으로 광범위한 자료와 맥락에서 효과적이라 보이지만, 많은 전략은 그렇게 광범위하게 효과적이지 않으며 항상 유용하지는 않을 것이다. 예를 들어, 어떤 사람이 읽고 있는 것을 요약하는 것이 타당하지만, 필기 요약은 항상 학습과 이해에 도움이 되지 않으며 요약 작성에 어려움을 겪는 학생들에게 덜 효과적이다(Dunlosky et al. 2012). 더욱이 물리학 문제 집합을 요약하는 것은 적절하지 않을 수 있다.

This question is truly basic and there is much to say in response, though not any single answer. Some strategies, such as self-testing and spacing of practice, do seem generally effective across a broad set of materials and contexts, but many strategies are not so broadly effective and will not always be useful. It makes sense to summarize what one is reading, for example, yet writing summaries does not always benefit learning and comprehension and is less effective for students who have difficulty writing summaries (Dunlosky et al. 2012). Moreover, summarizing a physics problem set may not be appropriate.

다른 학생들과 함께 공부하는 것은 잘 되면 효과적일 수 있지만(예: 학생들이 교대로 서로 시험하고 피드백을 제공한다면) 그러한 세션이 사회적 사건social event으로 바뀌거나 한 그룹 구성원이 앞장서서 다른 모든 사람들이 수동적인 관찰자가 된다면 분명 잘 되지 않을 것이다.

Studying with other students may be effective if done well (e.g., if students take turns testing one another and providing feedback), but certainly will not work well if such a session turns into a social event or one group member takes the lead and everyone else becomes a passive observer.

배움에 대해 배울 것이 많다.

There is much to learn about learning.

요약

SUMMARY POINTS

1. 우리의 복잡하고 급변하는 세계는 점점 더 자기 주도적이고 자기 관리적인 학습을 요구하는데, 이는 단순히 공식적인 학교 교육과 관련된 몇 년 동안만이 아니라, 평생에 걸친 것이다.

1. Our complex and rapidly changing world increasingly requires self-initiated and self-managed learning, not simply during the years associated with formal schooling, but across the lifespan.

2. 배우는 법을 배우는 것은 그러므로 중요한 생존 도구지만, 학습자, 기억, 인지 과정에 대한 연구는 학습자가 학습자로서 그들의 효과를 향상시키기 보다는 손상시킬 수 있는 학습에 대한 직관과 믿음을 갖기 쉽다는 것을 보여주었다.

2. Learning how to learn is, therefore, a critical survival tool, but research on learning, memory, and metacognitive processes has demonstrated that learners are prone to intuitions and beliefs about learning that can impair, rather than enhance, their effectiveness as learners.

3. 학습자로서 정교해지는 것은 저장소의 특성과 학습할 지식 및 절차에 대한 후속 접근을 특징짓는 인코딩 및 검색 프로세스에 대한 기본적인 이해뿐만 아니라, 어떤 학습 활동과 기법이 장기적인 보존과 전송을 지원하는지를 알아야 한다.

3. Becoming sophisticated as a learner requires not only acquiring a basic understanding of the encoding and retrieval processes that characterize the storage and subsequent access to the to-be-learned-knowledge and procedures, but also knowing what learning activities and techniques support long-term retention and transfer.

4. 진행 중인 학습을 효과적으로 관리하려면 학습이 달성된 정도에 대한 정확한 모니터링이 필요하며, 그 모니터링에 대응한 학습 활동의 적절한 선택과 제어와 결합되어야 한다.

4. Managing one’s ongoing learning effectively requires accurate monitoring of the degree to which learning has been achieved, coupled with appropriate selection and control of one’s learning activities in response to that monitoring.

5. 학습 중 성과를 높이는 조건이 장기 보유와 전이를 지원하지 못할 수 있는 반면, 어려움을 일으키고 획득 과정을 늦추는 것으로 보이는 다른 조건들은 장기 보유와 전이를 향상시킬 수 있기 때문에 배움의 달성 여부를 평가하는 것은 어렵다.

5. Assessing whether learning has been achieved is difficult because conditions that enhance performance during learning can fail to support long-term retention and transfer, whereas other conditions that appear to create difficulties and slow the acquisition process can enhance long-term retention and transfer.

6. 학습자 자신의 학습 정도에 대한 판단도 학습자가 습득한 정보를 인지하거나 상기하는 유창함 같은 주관적 지수의 영향을 받지만, 그러한 유창함은 학습이 달성되었는지 여부와 무관한 낮은 수준의 프라이밍과 기타 요인의 산물이 될 수 있다.

6. Learners’ judgments of their own degree of learning are also influenced by subjective indices, such as the sense of fluency in perceiving or recalling to-be-learned information, but such fluency can be a product of low-level priming and other factors that are unrelated to whether learning has been achieved.

7. 학습자로서 최대의 효과를 거두기 위해서는 오류와 실수를 학습자로서의 자신의 부족함을 반영하는 것이 아니라 효과적인 학습의 필수 요소로서 해석해야 한다.

7. Becoming maximally effective as a learner requires interpreting errors and mistakes as an essential component of effective learning rather than as a reflection of one’s inadequacies as a learner.

8. 최대의 효과를 거두기 위해서는 인간이 배워야 할 믿을 수 없는 능력에 대한 감상도 필요하며, 자신의 학습 능력이 고정되어 있다는 사고방식을 피해야 한다.

8. To be maximally effective also requires an appreciation of the incredible capacity humans have to learn and avoiding the mindset that one’s learning abilities are fixed.

Annu Rev Psychol. 2013;64:417-44. doi: 10.1146/annurev-psych-113011-143823. Epub 2012 Sep 27.

Self-regulated learning: beliefs, techniques, and illusions.

- 1

- Department of Psychology, University of California, Los Angeles, California 90095, USA. rabjork@psych.ucla.edu

Abstract

Knowing how to manage one's own learning has become increasingly important in recent years, as both the need and the opportunities for individuals to learn on their own outside of formal classroom settings have grown. During that same period, however, research on learning, memory, and metacognitive processes has provided evidence that people often have a faulty mental model of how they learn and remember, making them prone to both misassessing and mismanaging their own learning. After a discussion of what learners need to understand in order to become effective stewards of their own learning, we first review research on what people believe about how they learn and then review research on how people's ongoing assessments of their own learning are influenced by current performance and the subjective sense of fluency. We conclude with a discussion of societal assumptions and attitudes that can be counterproductive in terms of individuals becoming maximally effective learners.