피드백을 효과적으로 만드는 것은 무엇인가? 학생과 교수의 관점(Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education, 2018)

What makes for effective feedback: staff and student perspectives

Phillip Dawsona , Michael Hendersonb , Paige Mahoneya, Michael Phillipsb ,

Tracii Ryanb , David Bouda and Elizabeth Molloyc

소개

Introduction

피드백은 학생 학습에 가장 강력한 영향 중 하나가 될 수 있다. 연구 문헌에는 효과적인 것으로 간주되는 피드백 접근법에 대한 수많은 연구가 포함되어 있으며, 이는 여러 검토 연구(Hattie and Timperley 2007; Shute 2008)에서 통합되었다. 피드백에 대한 증거 기반은 피드백이 수행되어야 하는 방법에 대한 이해에 영향을 미친 몇 가지 개념 모델을 개발하는 데에도 사용되었다(Carless et al. 2011; Boud and Molloy 2013). 따라서 피드백이 더 효과적으로 만들어질 수 있는 방법에 대한 실질적인 조언을 얻을 수 있다.

Feedback can be one of the most powerful influences on student learning (Hattie and Timperley 2007). The research literature contains numerous studies on feedback approaches that are regarded as effective, and these have been synthesised in several review studies (Hattie and Timperley 2007; Shute 2008). The evidence base on feedback has also been used to develop several conceptual models that have been influential in our understandings of how feedback should be done (Carless et al. 2011; Boud and Molloy 2013). Substantial advice is thus available on how feedback might be made more effective.

문헌에 설명된 효과적인 피드백 가능성과는 달리, 학생들은 일반적으로 고등교육에서 피드백이 다른 측면과 비교하여 잘 수행되지 않는다고 조사에서 보고한다(Carroll 2014; 영국 고등교육 기금 지원 위원회; Bell and Brooks committee for England committee for higher Education funding 2014; Bell and brooks comks 곧 발표). 그러나 학생 만족도 조사(특히 영국 전국 학생 조사 및 호주 등가물)의 실질적인 문제는 피드백에 대한 구시대적인 이해에 기초한다는 것이다. 질문은 학생들이 교육자(윈스톤과 피트 2017)로부터 받은 코멘트의 양과 질에 대해 만족하는지 묻는 경향이 있다. 이는 지난 10년 동안 추가적인 학습으로 이어지는 과정으로서 피드백에 대한 이해를 지향하는 문헌의 강한 변화와는 대조적이다(Sadler 2010; Carless et al. 2011; Molloy 20).13).

In contrast to the effective feedback possibilities expounded in the literature, students generally report in surveys that feedback is done poorly in higher education, compared with other aspects of their studies (Carroll 2014; Higher Education Funding Council for England 2014; Bell and Brooks forthcoming). However, a substantial problem with student satisfaction surveys (particularly the UK’s National Student Survey and its Australian equivalent) is that they are based on an outmoded understanding of feedback. Questions tend to ask if students are happy with the volume or quality of comments they receive from their educators (Winstone and Pitt 2017); this contrasts with a strong shift in the literature over the past decade towards understandings of feedback as a process that leads to further learning (Sadler 2010; Carless et al. 2011; Molloy and Boud 2013).

평가 및 피드백 분야에서 다양한 용어의 의미는 최근 수십 년 동안 변화했다(Cookson). 2010년대 초에는 피드백에 대한 이해가 [학생들에게 '주어지는' 것]에서 [학생들이 능동적인 역할을 수행하는 과정]으로 변화하였다. 슈트(2008)의 피드백 검토는 '학습자에게 전달된 정보'에 초점을 맞추고, 해티와 팀펄리(2007)는 '에이전트가 제공한 정보'에 초점을 맞춘 반면, 보다 최근의 이해는 피드백을 생물학 또는 공학에 대한 개념적 근간을 두고, [작업의 개선으로 이어지는 과정]으로 피드백을 재배치한다(Boud and Moloy 2013). 피드백이 이해되는 방법의 이러한 변화는 교육자부터 학생까지의 '희망적으로 유용한' 의견 제공보다 피드백의 특징에 더 많은 중점을 둔다. 현재 문헌에서 두드러지는 피드백의 개념화에서는 전체 피드백 프로세스를 고려한다. 즉, 교육자보다는 [학생에 의해 주도]되고 [다수의 참여자가 참여]하며, 그리고 필수적으로 [학생이 변화를 일으키기 위해 정보를 사용하는 것]이다. 따라서 문헌은 피드백을 이해하는 방식으로 발전해 왔지만 피드백에 관련된 사람들이 피드백과 함께 참여했는지는 명확하지 않다.

The meanings of various terms in the field of assessment and feedback have changed over recent decades (Cookson forthcoming). The early 2010s marked a shift in how feedback was positioned within the literature, with understandings of feedback moving from something ‘given’ to students towards feedback as a process in which students have an active role to play. Where Shute’s (2008) review of feedback focused on ‘information communicated to the learner’, and Hattie and Timperley (2007) focused on ‘information provided by an agent’, more recent understandings reposition feedback within its conceptual roots in biology or engineering, as a process leading to improved work (Boud and Molloy 2013). This shift in how feedback is understood places emphasis on many more features of feedback than just the provision of ‘hopefully useful’ comments from educators to students. The conceptualisations of feedback currently prominent in the literature consider the entire feedback process, driven by the student rather than the educator, involving a multitude of players, and necessarily involving the student making use of information to effect change. The literature has thus moved forward in how it understands feedback – but it is not clear if those involved in feedback have been brought along with it.

2010년대 초 이러한 변화 이전에는 피드백에 대한 직원과 학생의 인식에 대한 다양한 연구가 있었다. 몇몇은 학생들이 생각하는 것에만 집중했습니다. 예를 들어, Poulos와 Mahony(2008)는 호주의 한 대학의 보건 학생들이 형식과 시기적절함뿐만 아니라 피드백 출처의 신뢰도에도 관심이 있다는 것을 발견했다. 직원과 학생의 관점을 모두 고려한 연구에서 피드백 실천에 대한 학생과 교육자의 인식 사이에는 일반적으로 불일치가 있었다. 예를 들어, 홍콩의 한 연구에서 교육자들은 피드백에 대한 비슷한 질문을 받았을 때 학생들보다 훨씬 더 긍정적인 그림을 보고하는 경향이 있었다(Carless 2006). 호주의 한 연구에서는 교육자들의 지지된 피드백 이론과 실습이 실제 피드백 행동과 유사한 불일치를 보였으며, 실제 실습은 종종 개인의 이상에 미치지 못한다는 것을 발견했다(Orrell 2006). 일반적으로 보면, 실제 실습, 교육자 관점 및 학생 관점 사이의 불일치가 있는 것으로 보인다(Li 및 De Luca 2014).

Prior to this shift in the early 2010s, there had been a range of studies about staff and student perceptions of feedback. Some focused only on what students thought. For example, Poulos and Mahony (2008) found that health students at an Australian university were interested not just in modality and timeliness, but also the credibility of the feedback source. In studies that considered both staff and student perspectives, there were generally discrepancies between student and educator perceptions of feedback practices. For example, in one Hong Kong study, educators tended to report a much more positive picture than students when both were asked similar questions about feedback (Carless 2006). An Australian study found a similar mismatch between educators’ espoused feedback theories and practices and their actual feedback behaviours, with actual practices often falling short of individuals’ ideals (Orrell 2006). The general message appears to be one of inconsistencies between understandings of actual practices, educator perspectives and student perspectives (Li and De Luca 2014).

그러나 2010년대 초반 연구자 및 전문가 피드백 이해도가 변화한 이후 직원과 학생들이 효과적인 피드백으로 경험하는 것에 대한 연구는 부족했다. 특히 다양한 제도적·징계적 맥락의 교직원과 학생이 모두 포함된 공부가 부족했다. 피드백에 대한 인식에 대한 일반적인 2010년 이후의 연구는 단일 기관의 단일 분야에 초점을 맞추고 있으며, 학생 연구 참여자는 200명 미만이고 직원 참여자는 없다(예: Dowden et al. 2013; Robinson, Pope and Holyoak 2013; Bayerlein 2014; Pitt and Norton 2017). 소수의 직원 또는 여러 분야(예: Orsmond and Merry 2011; Sanchez and Dunworth 2015; Mulliner and Tucker 2017)를 포함하는 소수의 연구가 있었지만, 이들은 여전히 특정 성별에 치우쳐 있고 제한된 분야 그룹에 집중된 공동 조직 연구였다. 피드백 연구를 일반화할 때 주의해야 할 필요성에 대한 새들러(2010)의 주의를 고려할 때, 학문, 제도, 연도 수준, 성별 및 기타 특성 측면에서 더 포괄적이고 포괄적인 연구가 필요하다.

However, since the shift in researcher and expert understandings of feedback in the early 2010s, there has been a dearth of studies on what staff and students experience as effective feedback. In particular, there has been a lack of studies that include both staff and students from a range of institutional and disciplinary contexts. The typical post-2010 study on perceptions of feedback focuses on a single discipline at a single institution, with a convenience sample of less than 200 student research participants and no staff participants (e.g. Dowden et al. 2013; Robinson, Pope, and Holyoak 2013; Bayerlein 2014; Pitt and Norton 2017). While there have been a handful of studies that also include a small number of staff or several disciplines (e.g. Orsmond and Merry 2011; Sanchez and Dunworth 2015; Mulliner and Tucker 2017), these have still largely been single-institution studies with cohorts skewed toward particular genders and concentrated in limited discipline groups. Given Sadler’s (2010) caution about the need to be careful when generalising in feedback research, there is a need for studies that are more inclusive and comprehensive in terms of disciplines, institutions, year levels, gender and other characteristics.

피드백에 대한 직원과 학생의 인식에 대한 광범위한 연구가 부족한 것은 문제가 되는데, [문헌에서 일어나는 피드백에 대한 이해의 변화]와 함께 [직원과 학생의 변화]가 어느 정도까지 오게 되었는지 알 수 없기 때문이다. 평가에서 교육자는 학생들이 무엇을 할 것으로 예상되는지를 설계하는 사람들이며, [무엇이 효과적인지에 대한 그들의 의견]은 [무엇이 일어나는지에 대한 연구 증거]보다 더 영향력이 있을 수 있다(Bearman et al. 2017). 마찬가지로, 프로세스 중심의 피드백 개념화에서 학생들은 주요 행위자(Boud and Molloy 2013)이며, 피드백이 무엇에 적합한지, 무엇을 효과적으로 만드는지에 대한 그들의 이해는 정교한 디자인을 구현하기 위해 필요하다.

The lack of broader studies on staff and student perceptions of feedback is problematic, because we do not know to what extent staff and students have been brought along with the changing understandings of feedback occurring in the literature. In assessment more broadly, educators are the people who design what students are expected to do, and their opinions about what is effective may be more influential than research evidence about what occurs (Bearman et al. 2017). Similarly, in a process-oriented conceptualisation of feedback, students are the main actors (Boud and Molloy 2013), and their understandings of what feedback is for and what makes it effective are necessary to implement sophisticated designs.

본 논문은 대규모 피드백 설문조사의 의도적인 샘플에 대한 정성적 분석을 통해 교육자와 학생들이 피드백이 무엇에 대한 것이라고 생각하고 효과적인 피드백을 위해 무엇을 만드는지에 대한 이해의 격차를 해소한다. 특히 다음과 같은 연구 질문을 다룬다.

This paper addresses a gap in our understanding around what educators and students think feedback is for, and what they think makes for effective feedback, through qualitative analysis of a purposive sample from a large-scale feedback survey. In particular, it addresses the following research questions:

RQ1: 직원과 학생들은 피드백의 목적이 무엇이라고 생각하나요?

RQ1: What do staff and students think is the purpose of feedback?

RQ2: 직원과 학생들은 무엇이 효과적인 피드백을 만든다고 생각하는가?

RQ2: What do staff and students think makes for effective feedback?

방법

Method

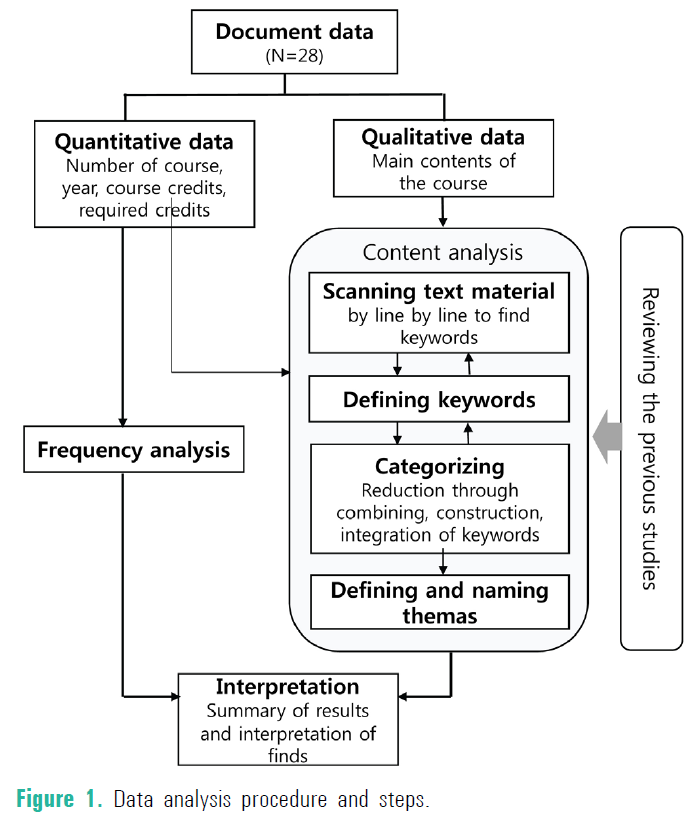

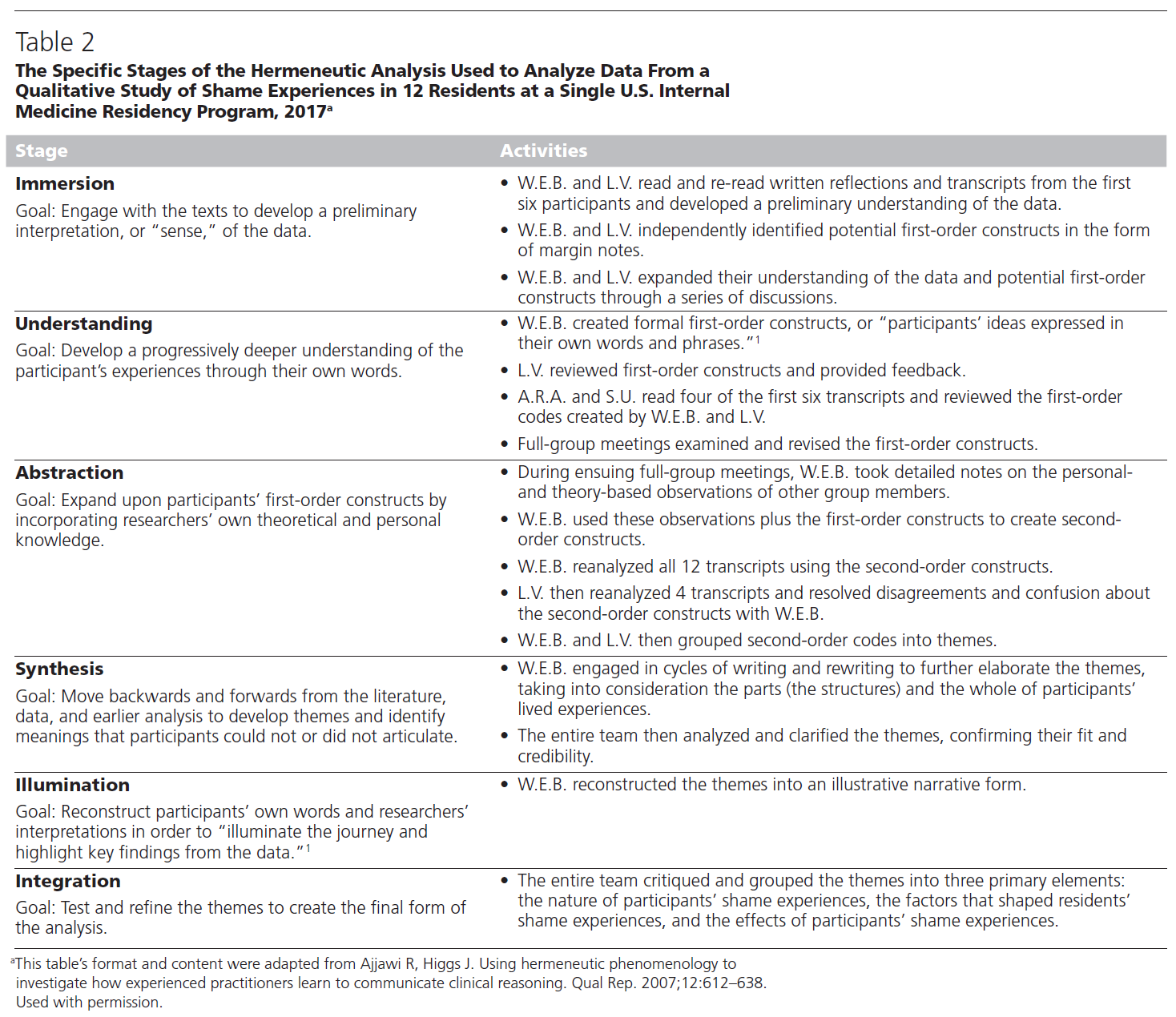

우리는 2016-2017년에 호주 2개 대학의 직원과 학생들을 대상으로 피드백에 대한 대규모 설문조사를 실시했습니다. Creative Commons ShareAlike 4.0 International License에 따라 무료로 사용할 수 있습니다. 4514명의 학생과 406명의 직원으로부터 유효한 답변을 받았습니다. 설문조사는 주로 양적이었지만, 공개 응답 항목도 소수 포함되어 있었다. 본 논문은 평가 책임이 있는 직원(즉, 교육자)과 학생들이 피드백이 무엇에 대한 것이라고 생각하는지, 무엇을 효과적인 피드백으로 구성한다고 생각하는지, 경험했던 효과적인 피드백의 예를 제공하는 공개 응답 데이터의 하위 집합에 대한 정성적 분석에 대해 보고한다.

We administered a large-scale survey about feedback to staff and students at two Australian universities in 2016–2017. The survey instrument is available at www.feedbackforlearning.org/wp-content/uploads/Feedback_for_Learning_Survey.pdf and is free to use under a Creative Commons ShareAlike 4.0 International Licence. Valid responses were received from 4514 students and 406 staff. The survey was primarily quantitative, but it also included a small number of open response items. This paper reports on our qualitative analysis of a subset of the open response data where staff with assessment responsibilities (i.e. educators) and students discussed what they thought feedback was for, what they thought constituted effective feedback, and gave examples of effective feedback they had experienced.

이 조사 데이터는 호주 정부 학습 및 교육 사무소가 자금을 지원하는 연구 프로젝트의 첫 번째 단계의 일부로 수집되었으며 두 개의 호주 대학이 수행했다. 이 프로젝트는 코스워크 학생과 대학 직원(학술 및 전문직 모두)의 피드백 경험과 실천을 이해하는 데 광범위한 초점을 맞췄다. 모든 데이터를 수집하기 전에 두 대학의 인간 연구 윤리 위원회로부터 승인을 받았다. 설문 참여는 자발적이었고, 참가자들은 작은 인센티브를 위해 경품 추첨에 들어갈 수 있는 기회가 제공되었다. 우리는 연구의 옵트인 성격과 인센티브가 모집된 참가자의 대표성에 영향을 미칠 수 있다는 것을 인정한다.

The survey data were collected as part of the first phase of a research project funded by the Australian government Office for Learning and Teaching and undertaken by two Australian universities. The project had the broad focus of seeking to understand the feedback experiences and practices of coursework students and university staff (both academic and professional). Approval was received from the Human Research Ethics Committees of both universities prior to all data collection. Participation in the survey was voluntary, and participants were offered the opportunity to go into a prize draw for a small incentive. We acknowledge that both the opt-in nature of the study and the incentive may affect the representativeness of the participants recruited.

샘플

Sample

리소스 제약으로 인해 심층적인 정성 분석을 수행하기 위해 데이터를 샘플링해야 했습니다. 따라서 성별, 국제/학생 등록, 온라인/학생 등록 및 교수진 측면에서 전체 모집단의 특성을 대표하는 각 기관의 학생 응답 표본 200개(총 N = 400)를 선택했다. 교육자의 전체 데이터 세트가 비슷한 크기(n = 323명 참가자)였기 때문에 샘플 대신 교육 직원의 모든 데이터를 사용하기로 결정했습니다.

Resource constraints dictated that we needed to sample the data in order to conduct in-depth qualitative analysis. We therefore opted for a sample of 200 student responses from each institution (total N = 400) that was representative of the characteristics of the overall populations in terms of gender, international/domestic enrolment, online/on-campus enrolment, and faculty. As the entire data-set of educators was of comparable size (n = 323 participants) we opted to use all data from teaching staff rather than a sample.

분석.

Analysis

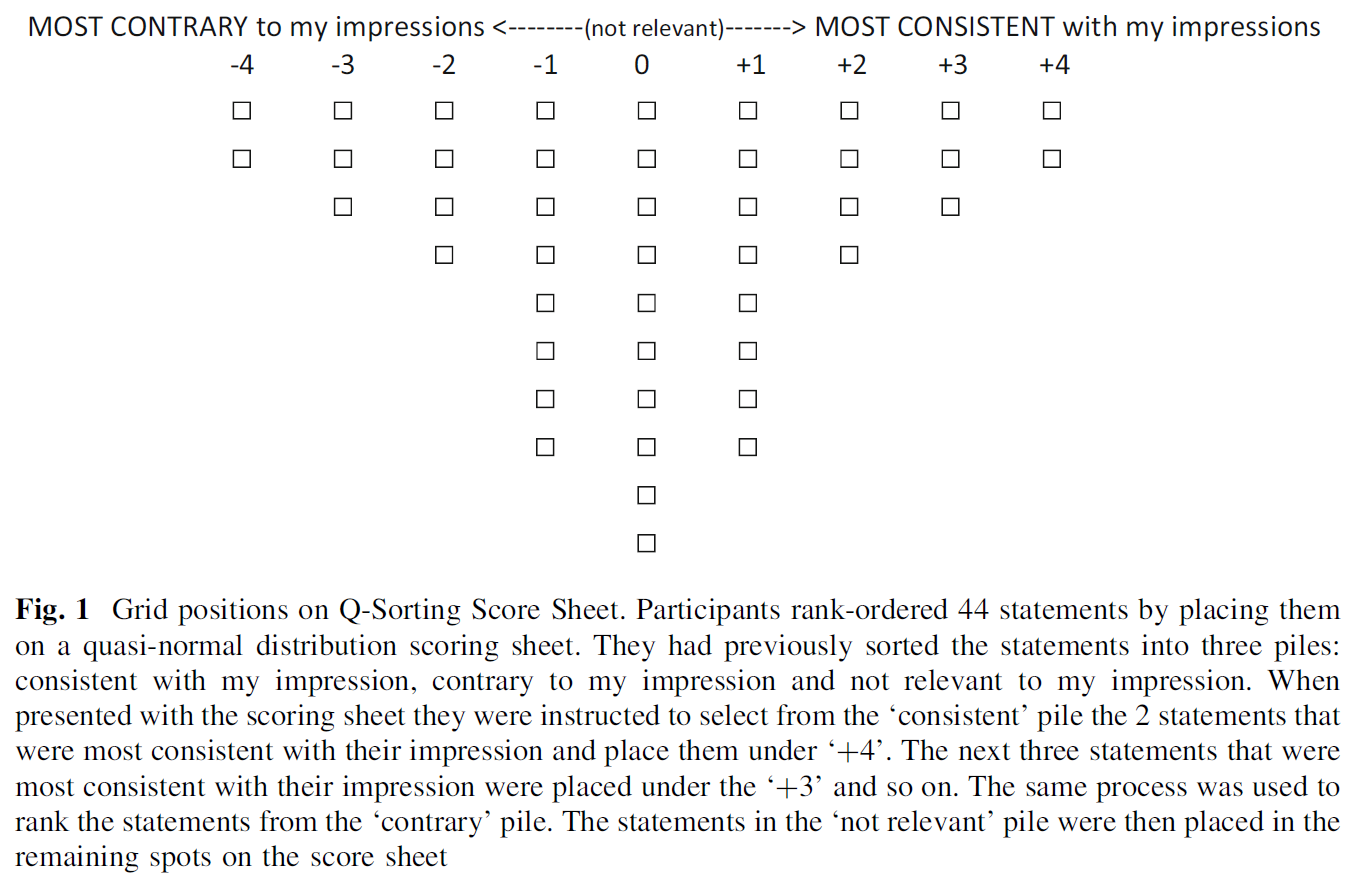

이 논문에서 분석은 두 개의 개방형 응답 질문의 하위 집합에 초점을 맞췄다. 평가 책임이 있는 학생과 교직원은

- (a) 피드백의 목적으로 본 것을 진술하고,

- (b) 최근 스스로 선택한 피드백 사례가 효과적이었다고 생각하는 이유를 진술하도록 요청받았다.

For this paper, analysis focused on a subset of two open-response questions. Students and staff with assessment responsibilities were asked to:

- (a) state what they saw as the purpose of feedback; and

- (b) state why they considered a recent, self-selected instance of feedback had been effective.

브라운과 클라크(2006)가 설명한 프로세스와 유사한 데이터의 주제 분석을 실시했다. 다른 주제 분석과 마찬가지로, 개발된 주제와 분석 결과를 형성하는 연구 설계 동안 일련의 선택이 이루어졌다. 존재론적으로 이 연구는 광범위하게 현실주의에 기초한다(Maxwell 2012). 우리는 참가자들이 피드백을 실제처럼 경험하며, 교육자와 학생들이 동일한 피드백 현실에서 매우 다른 경험을 할 수 있다고 생각한다. 우리는 피드백 연구자로서 일련의 도메인 이론을 주제에 가져오고, 데이터로부터 수동적으로 'emerge'되도록 하기보다는 적극적으로 주제를 구성한다는 것을 인정하여 귀납적 분석을 수행했다(Varpio 등 2017). 잠재된 의미를 식별하는 것보다 참가자들이 명시적으로 쓴 내용에 더 관심이 있었기 때문에 우리는 '의미적' 주제(Braun과 Clarke 2006)를 개발했다. 개방형 질적 조사 질문에 대한 응답은 종종 더 깊은 형태의 분석을 지원하기에는 너무 '얇은' 경향이 있다.

We conducted a thematic analysis of the data similar to the process described by Braun and Clarke (2006). As with any thematic analysis, a series of choices were made during the research design that shaped the themes developed and the outcomes of the analysis. Ontologically, the study is broadly based in realism (Maxwell 2012); we think the participants experience feedback as a real thing, and it is possible for educators and students to have very different experiences of the same feedback reality. We undertook an inductive analysis, with the acknowledgement that as feedback researchers we bring a set of domain theory to the topic, and that we actively construct themes rather than have them passively ‘emerge’ from the data (Varpio et al. 2017). We developed ‘semantic’ themes (Braun and Clarke 2006), because we were more interested in what our participants explicitly wrote than we were in identifying latent meanings; responses to open-ended qualitative survey questions often tend to be too ‘thin’ to support deeper forms of analysis (LaDonna, Taylor, and Lingard 2018).

우리의 코딩 프레임워크는 데이터의 하위 세트를 읽고, 노트를 공유하고, 예비 코드를 테스트하는 반복적인 프로세스를 통해 개발되었다. 이 과정에는 4명의 연구원(MH, PD, MP, TR)이 5번의 주요 반복 과정을 거쳤다. 이 과정을 통해 예비 프레임워크가 개발되면, 개발(PM)에 관여하지 않은 다른 연구원과 코드북으로 공유되었고, 연구팀의 두 구성원(PD, MH)과 협의하여 코드를 수정하기 전에 50명의 참가자의 데이터를 코드화했다. 최종 프레임워크는 전체 샘플에 적용되었습니다.

Our coding framework was developed through an iterative process of reading subsets of the data, sharing notes and testing preliminary codes. This process involved four researchers (MH, PD, MP, TR) going through five major iterations. Once a preliminary framework was developed through this process it was shared as a codebook with another researcher not involved in its development (PM), who then coded data from 50 participants before making minor amendments to the codes in consultation with two members of the research team (PD, MH). The final framework was then applied to the entire sample.

결과 및 토론.

Results and discussion

RQ1: 직원과 학생들은 피드백의 목적이 무엇이라고 생각하나요?

RQ1: What do staff and students think is the purpose of feedback?

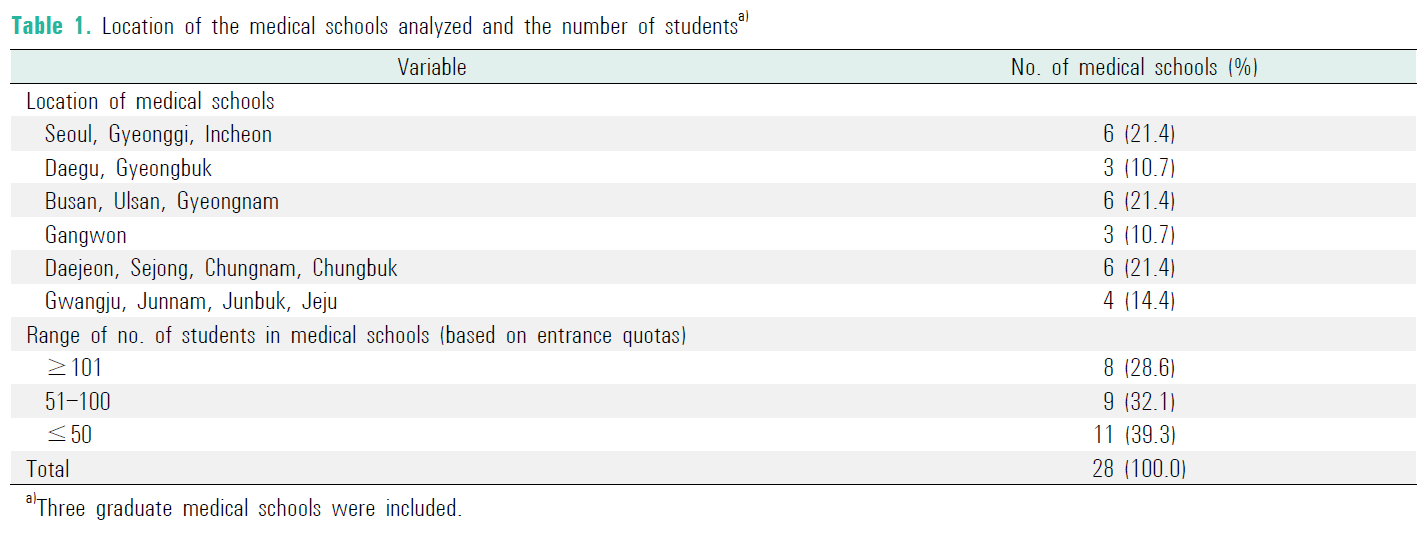

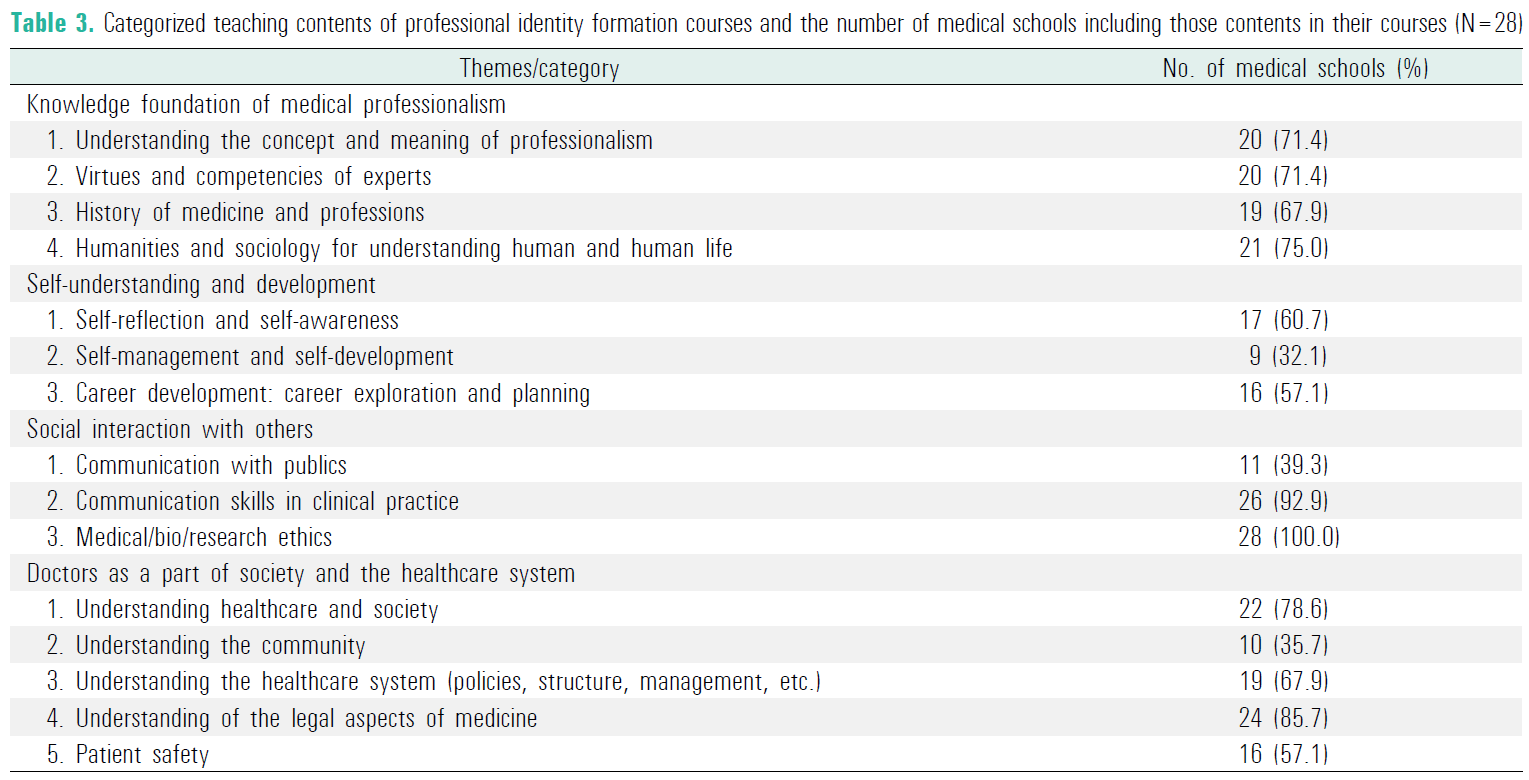

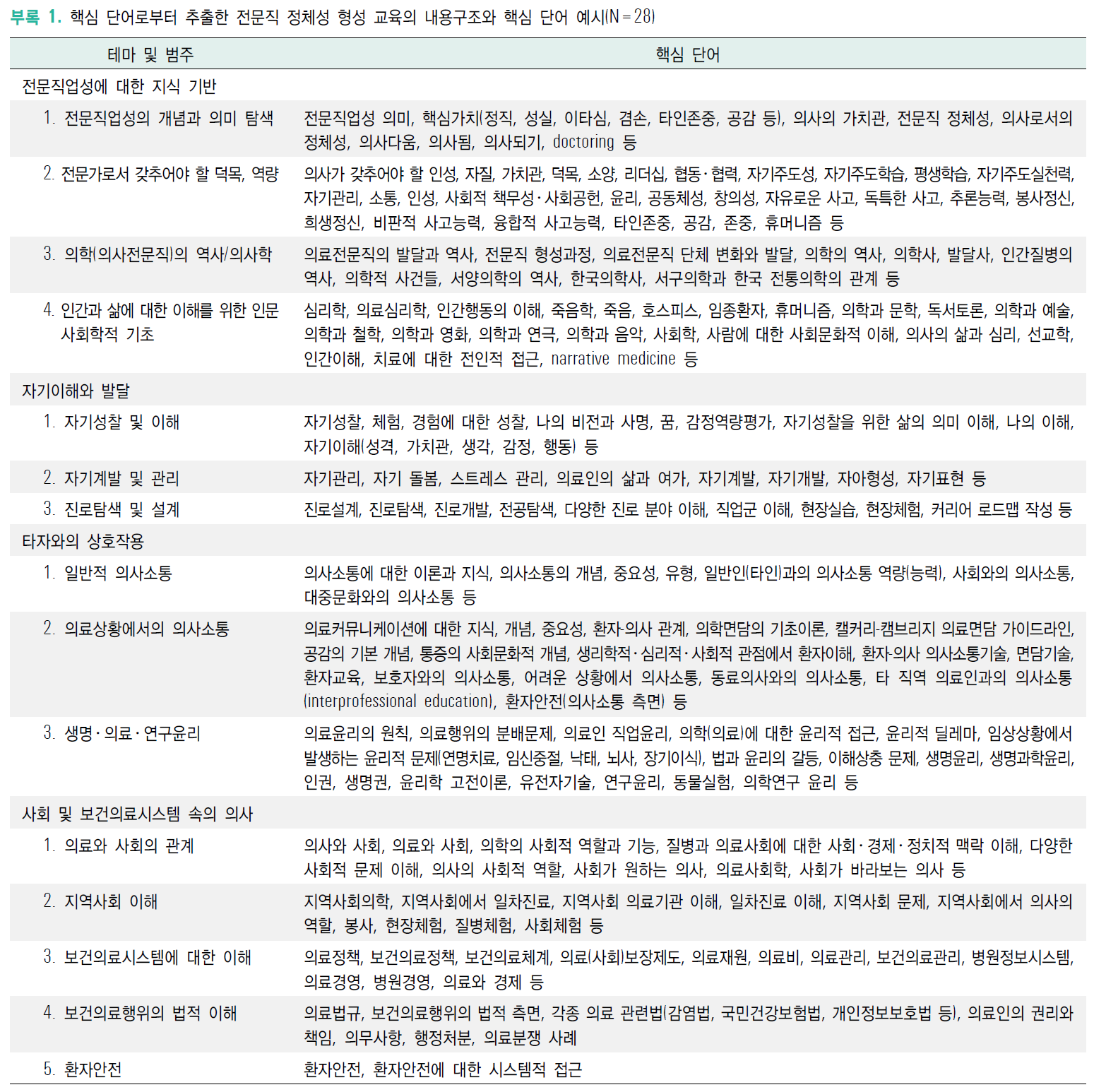

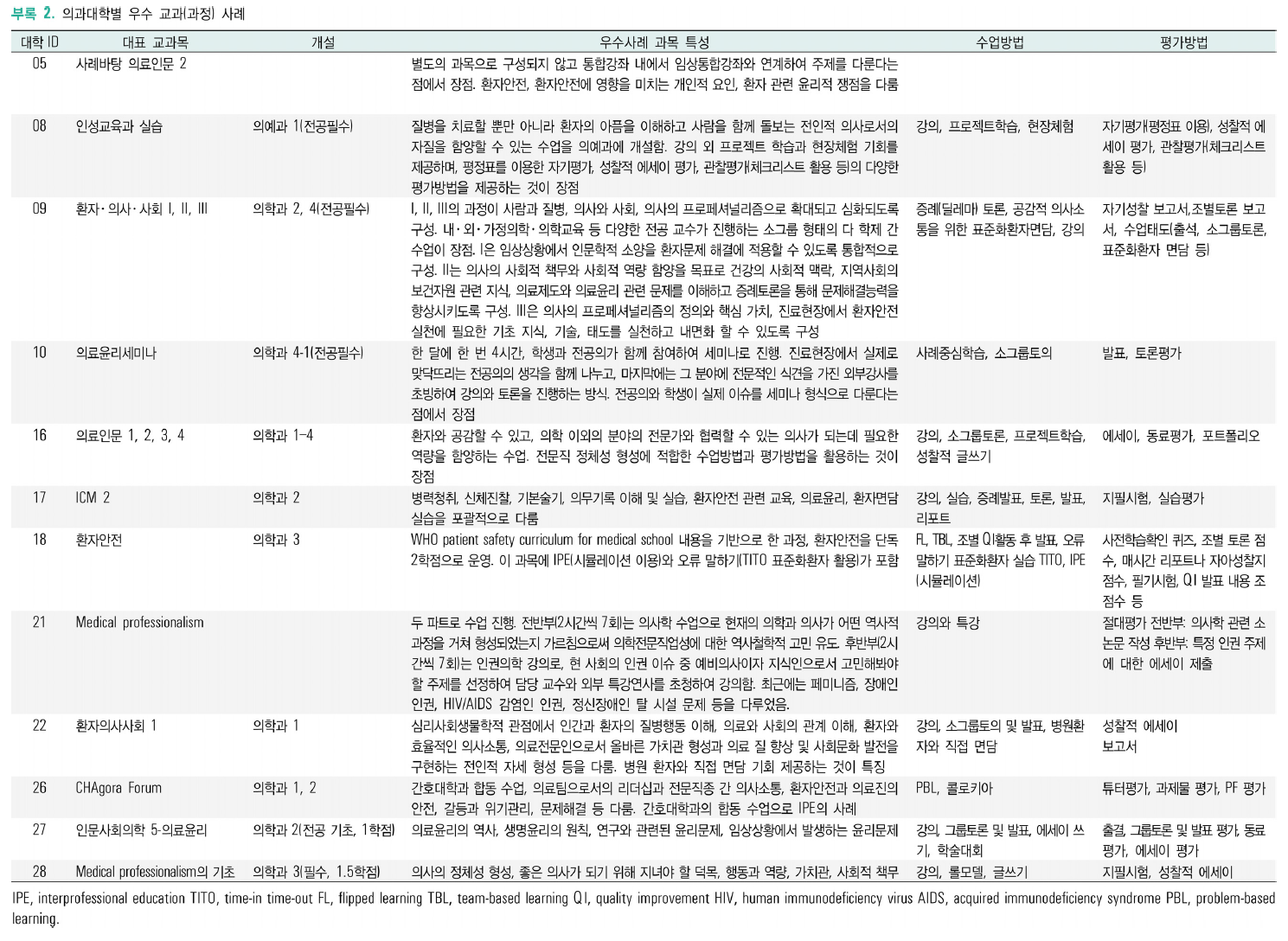

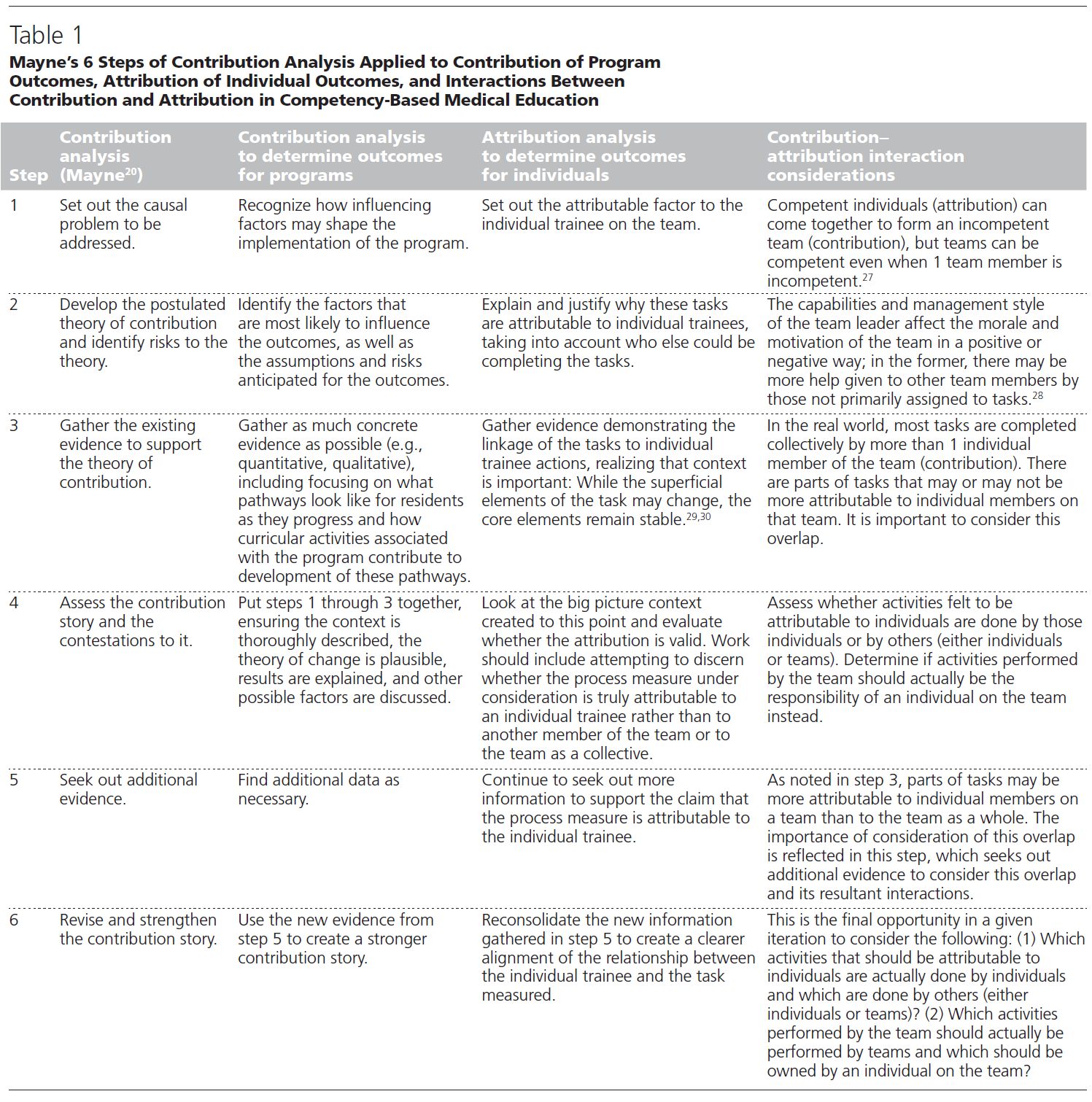

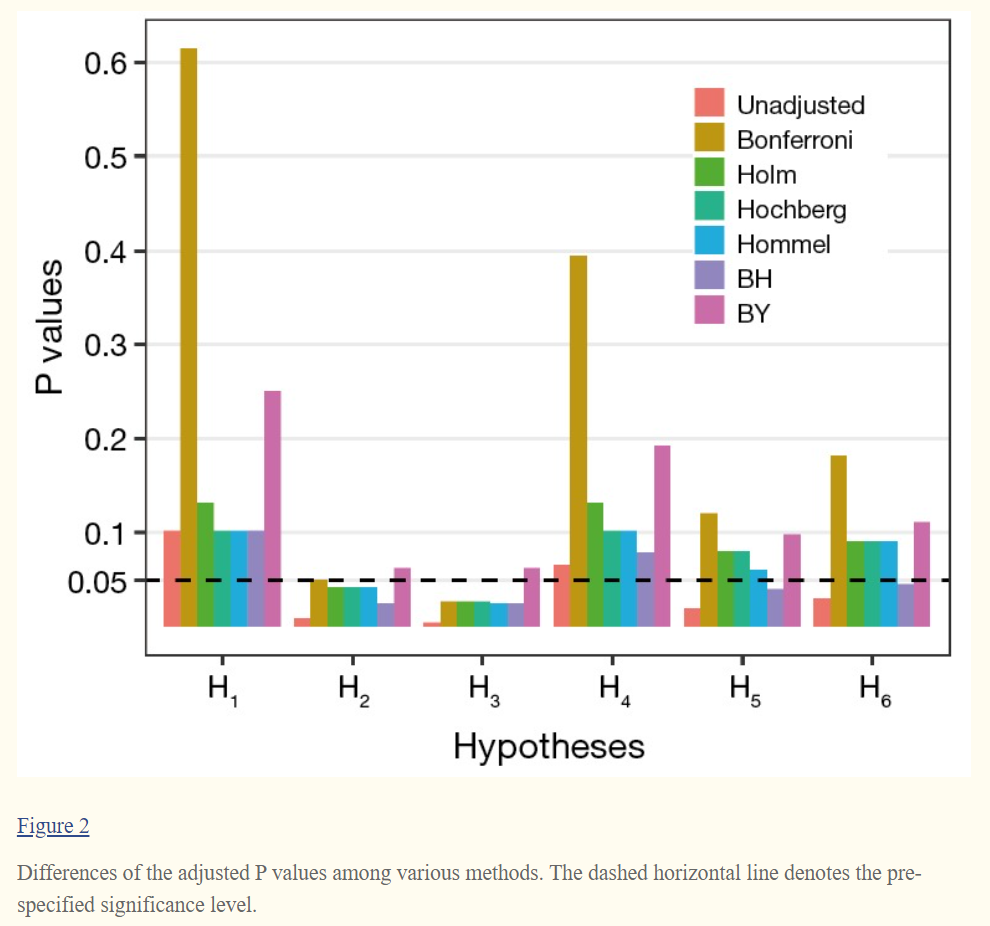

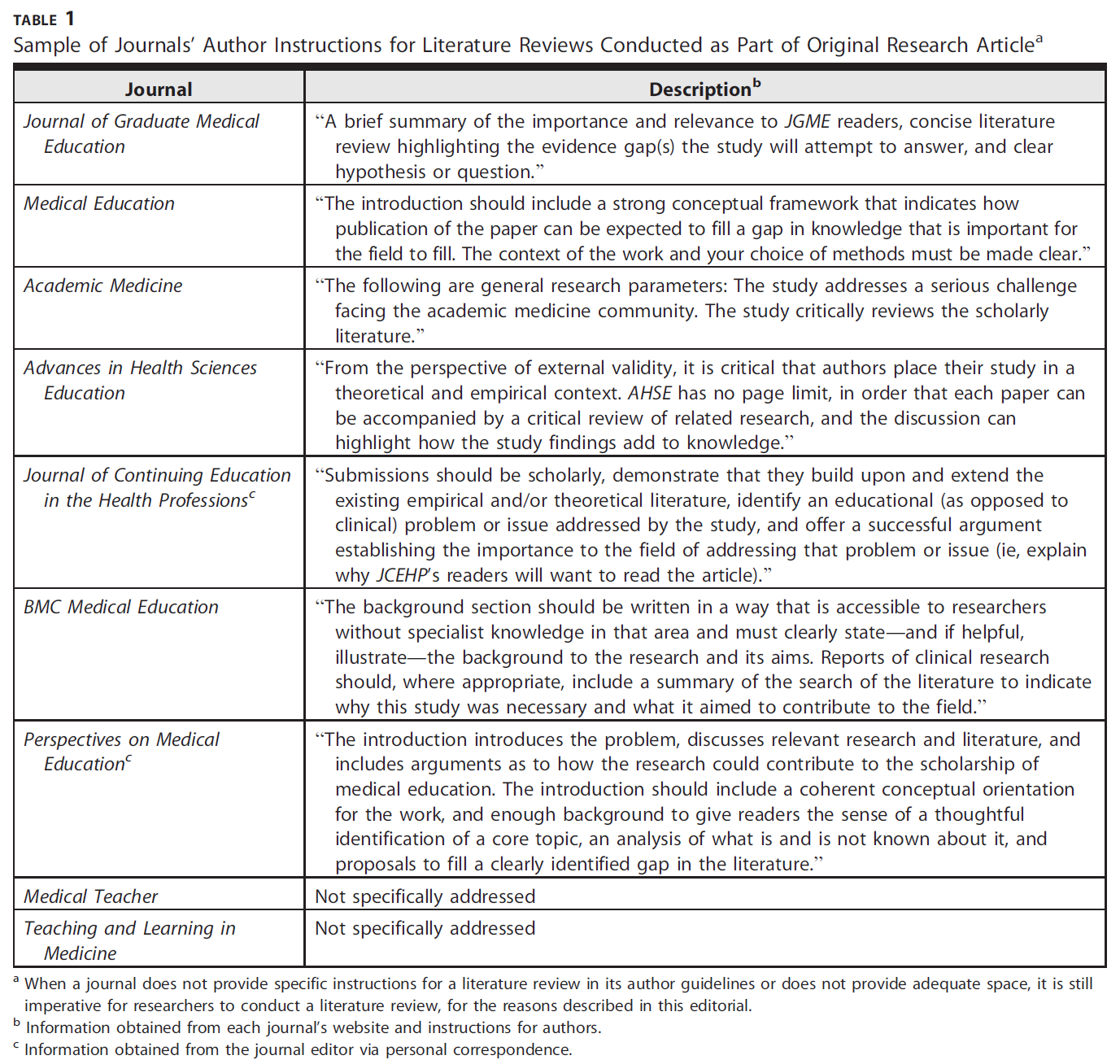

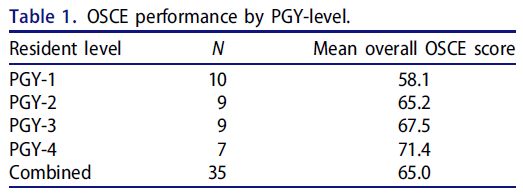

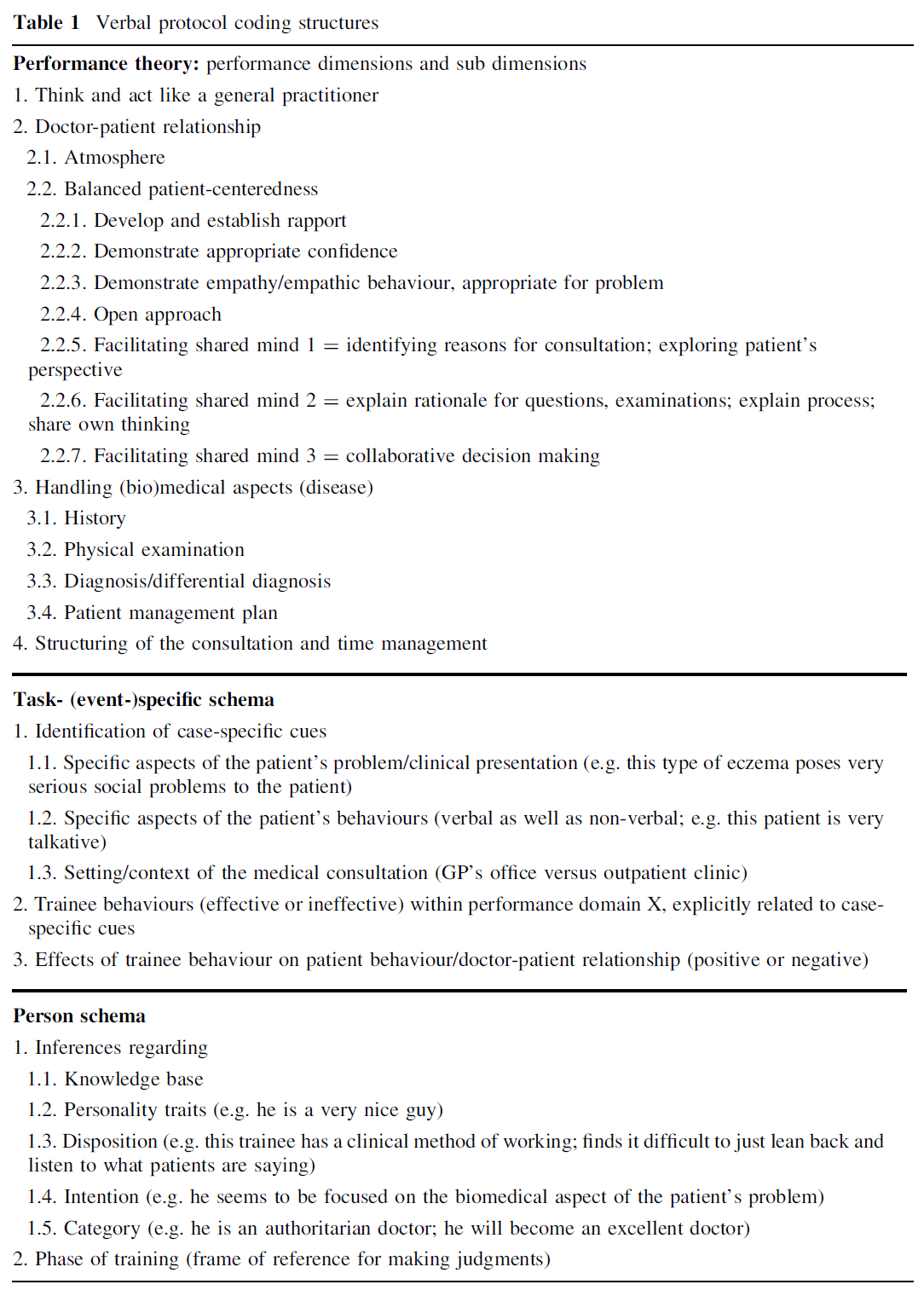

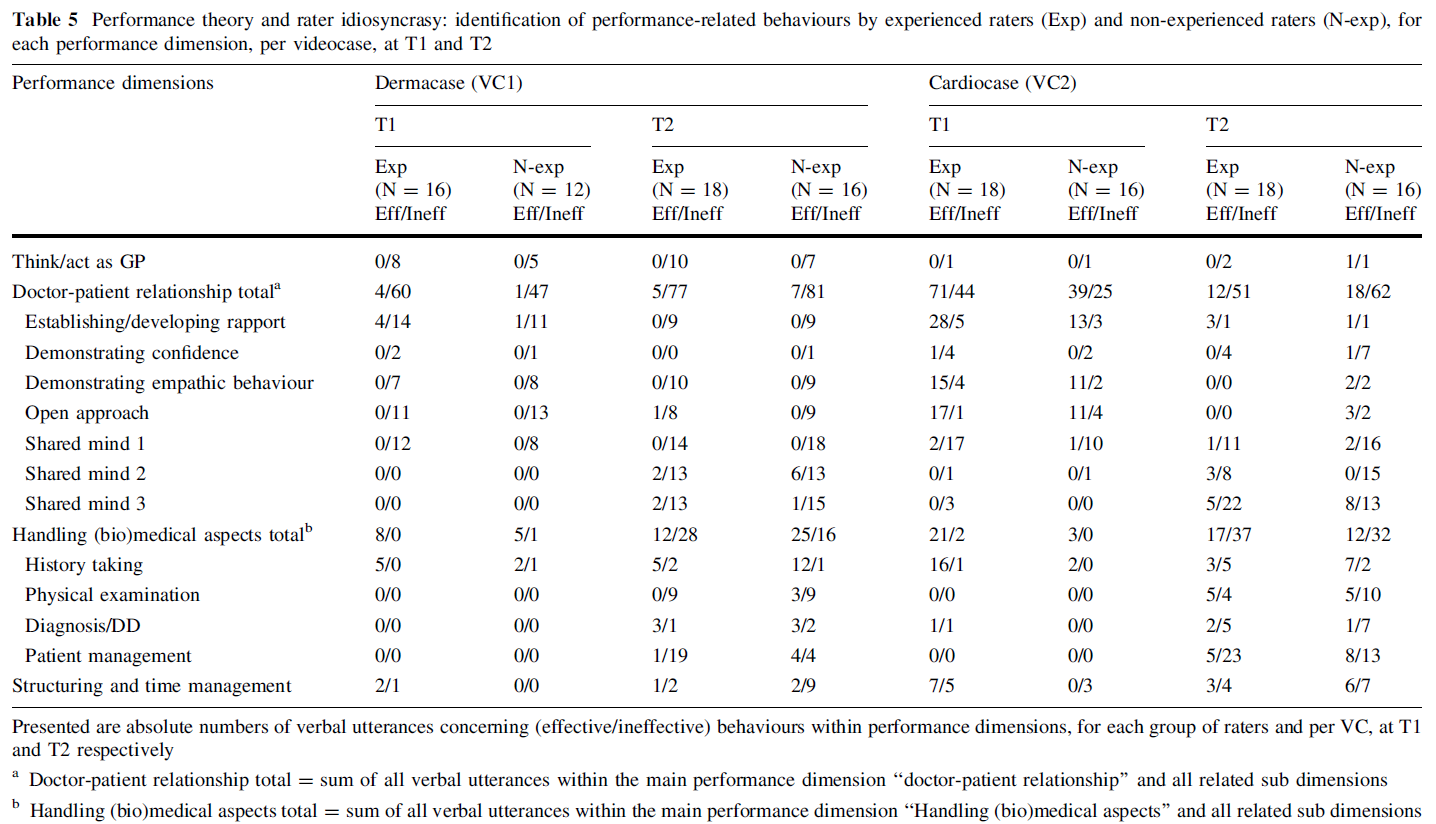

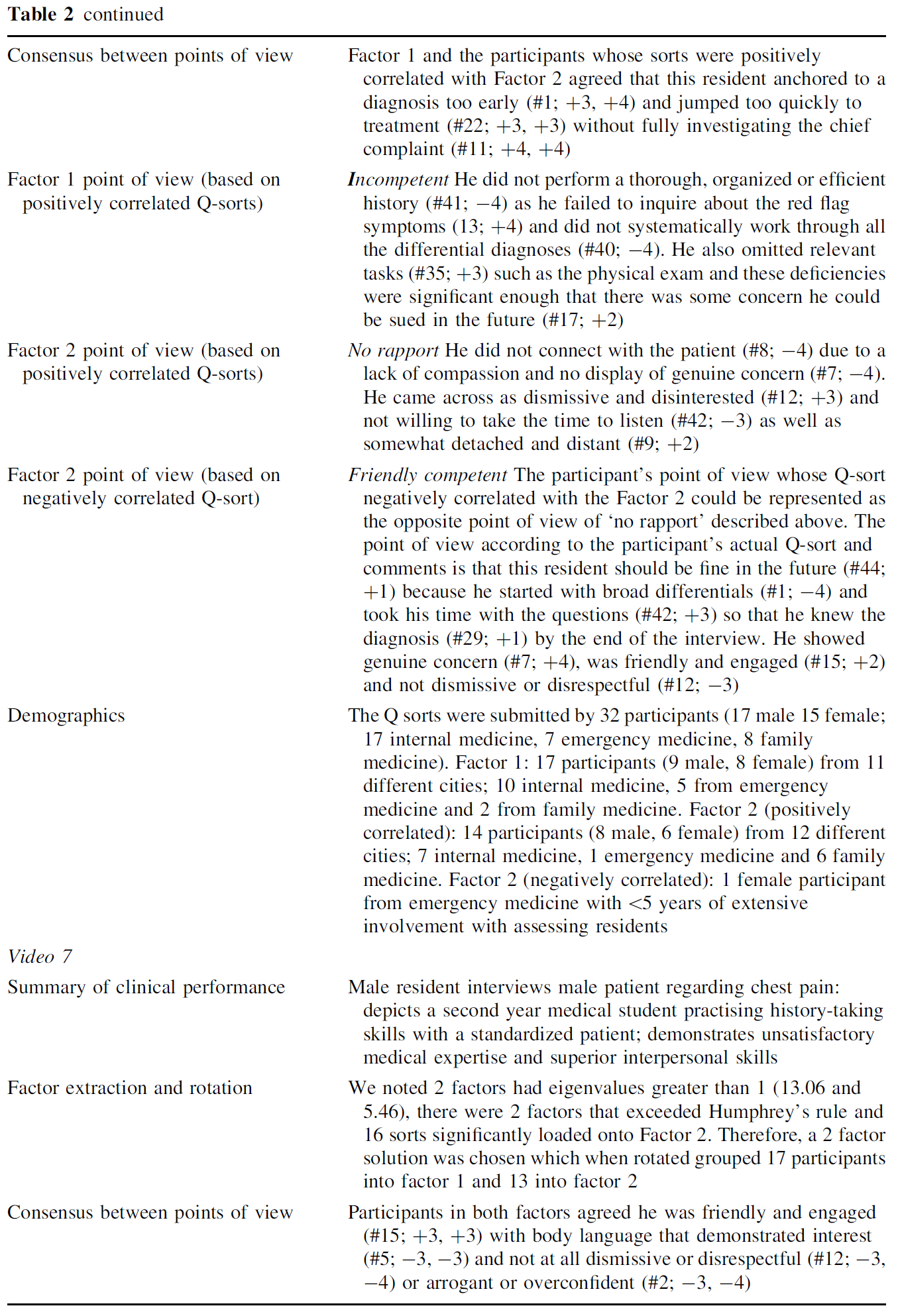

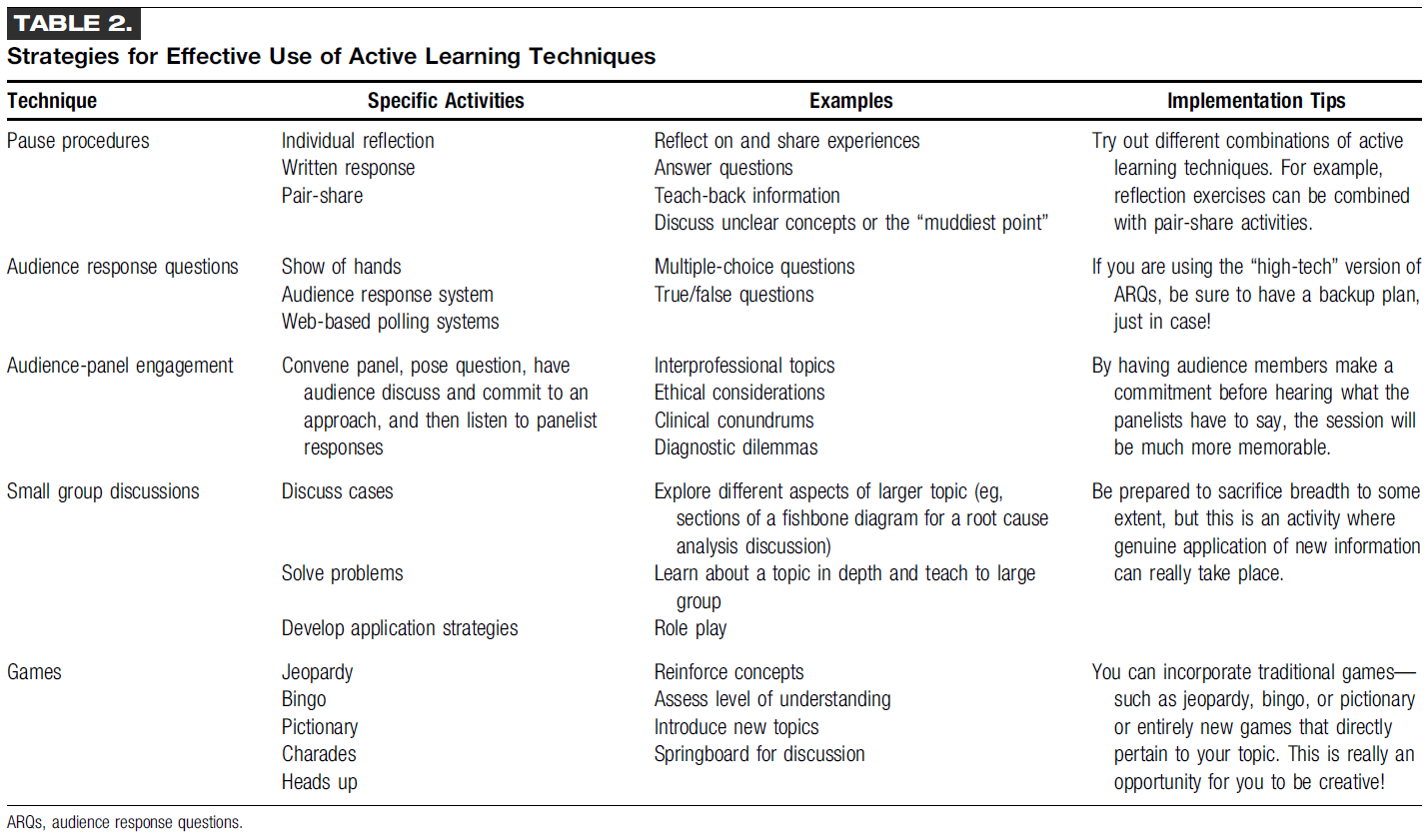

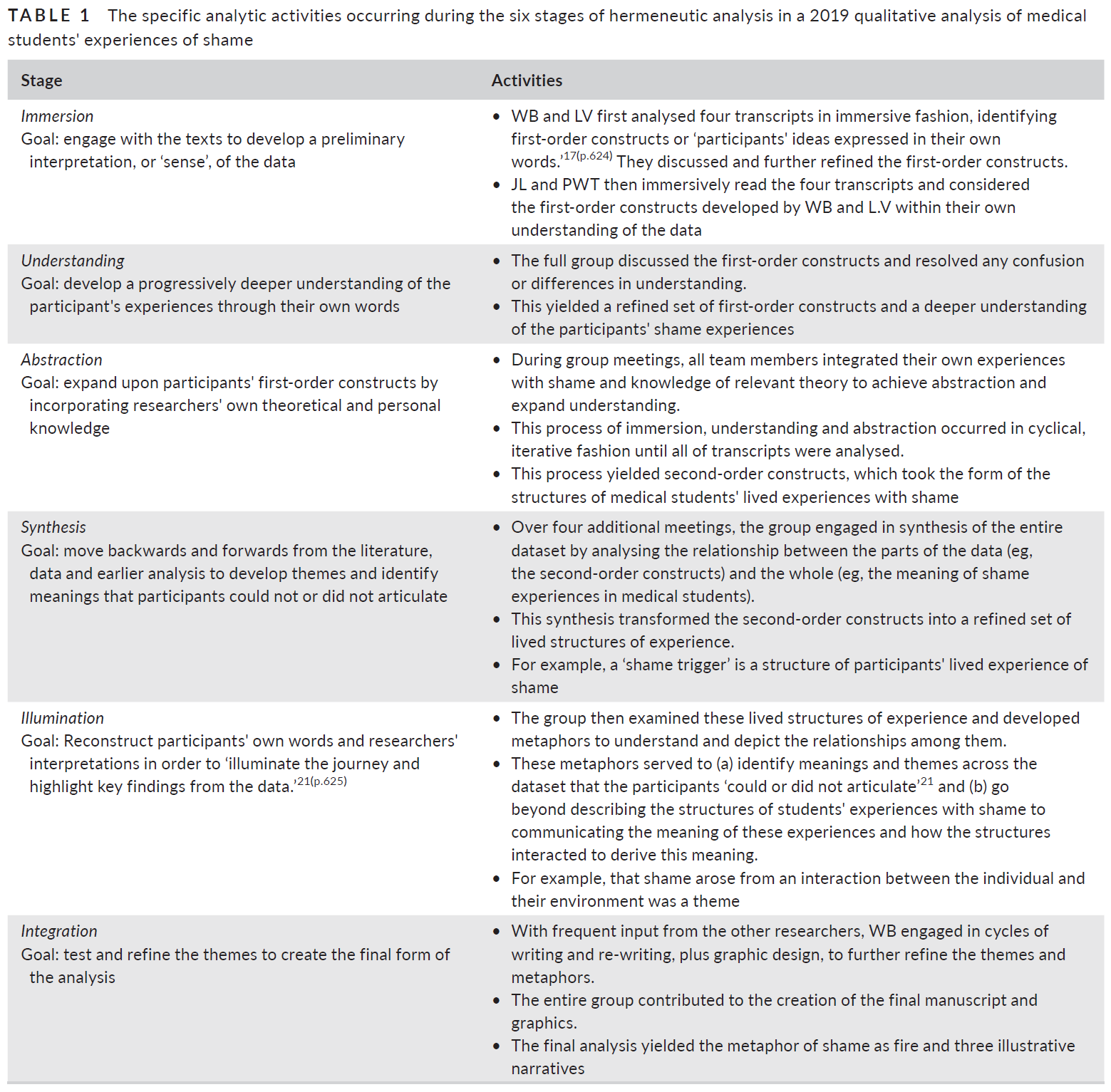

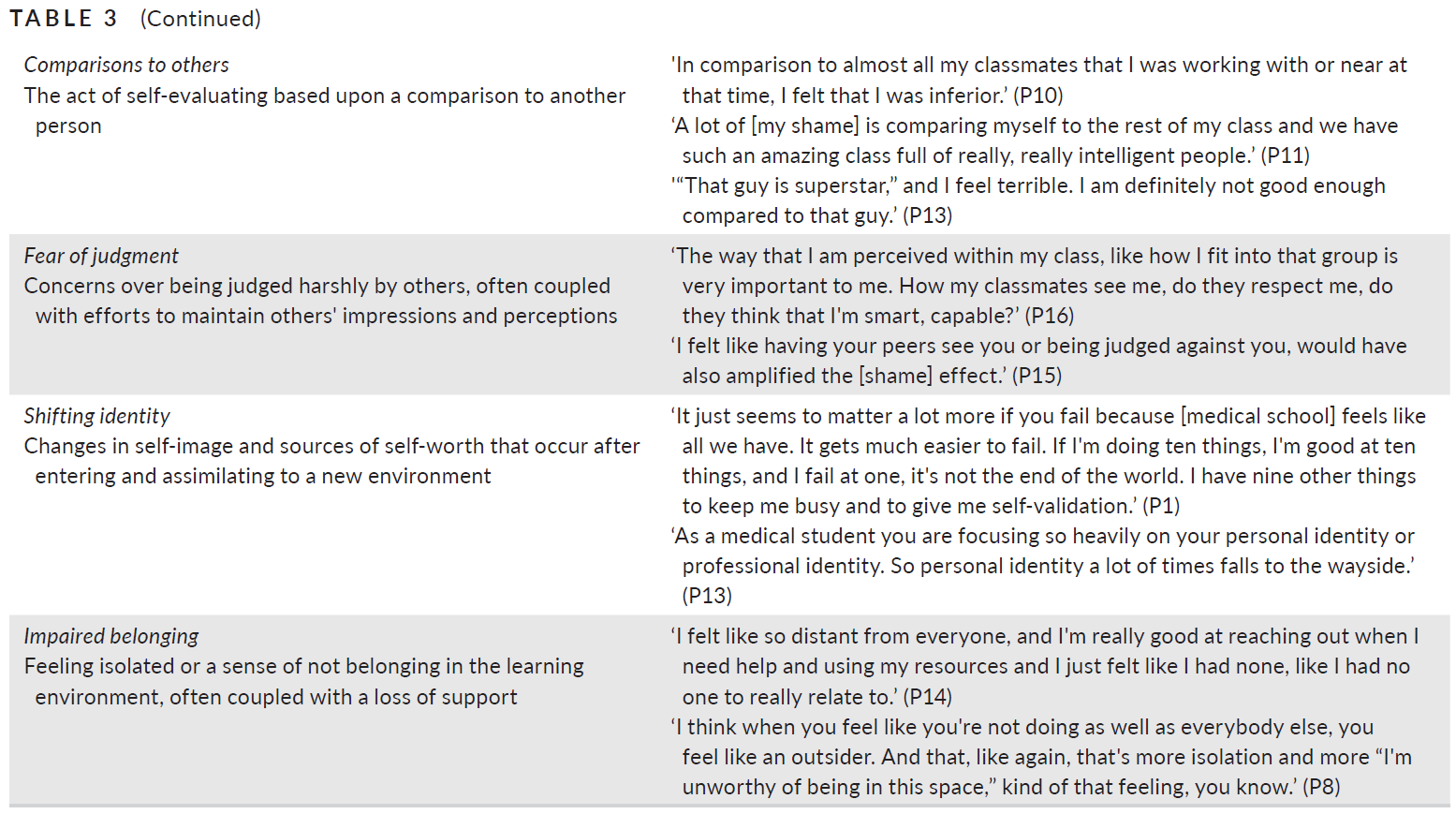

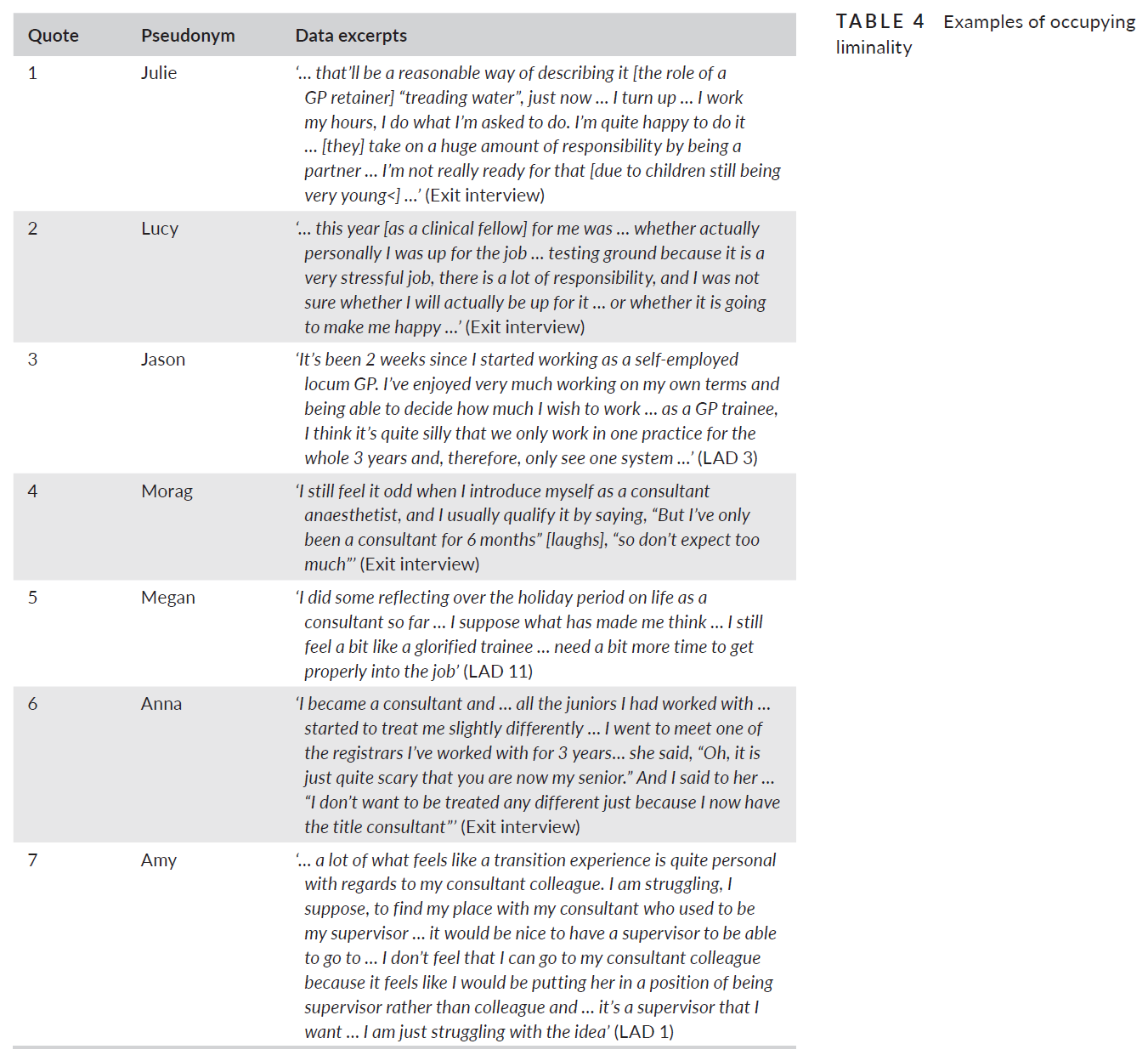

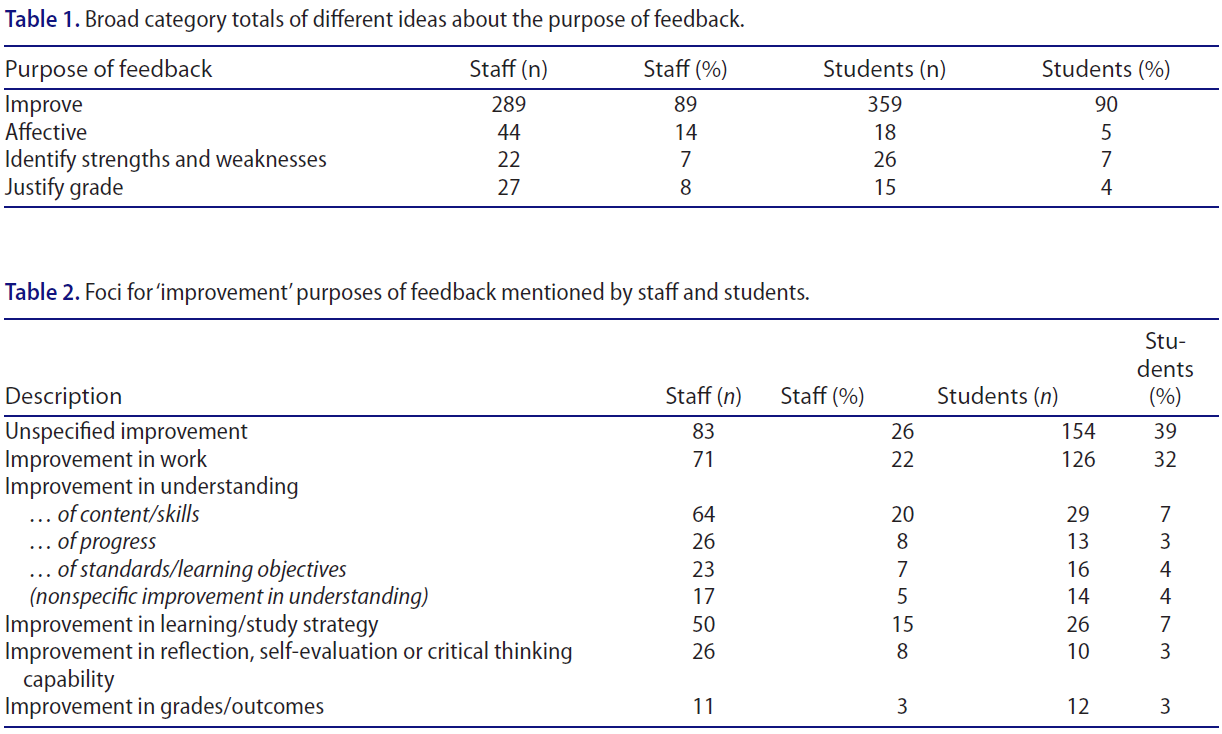

참가자들은 피드백의 네 가지 주요 목적을 나타냈다: 성적 정당화, 일의 장단점 확인, 개선, 정서적 목적. 이러한 목적의 확산은 우리가 관찰한 하위 주제와 함께 표 1에 제시되어 있다. 개별 참가자의 데이터가 여러 테마로 코딩되었을 수 있기 때문에 표에 제시된 데이터가 100% 이상 추가될 수 있다는 점에 유의해야 한다.

Participants indicated four main purposes of feedback:

- justifying grades;

- identifying strengths and weaknesses of work;

- improvement; and

- affective purposes.

The prevalence of each of these purposes is presented in Table 1, along with subthemes where we observed them. It should be noted that data presented in tables may add up to more than 100% because individual participants’ data may have been coded in multiple themes.

피드백은 성적 향상에 대한 것인가, 아니면 성적을 정당화하는 것인가?

Is feedback about improvement, or justifying a grade?

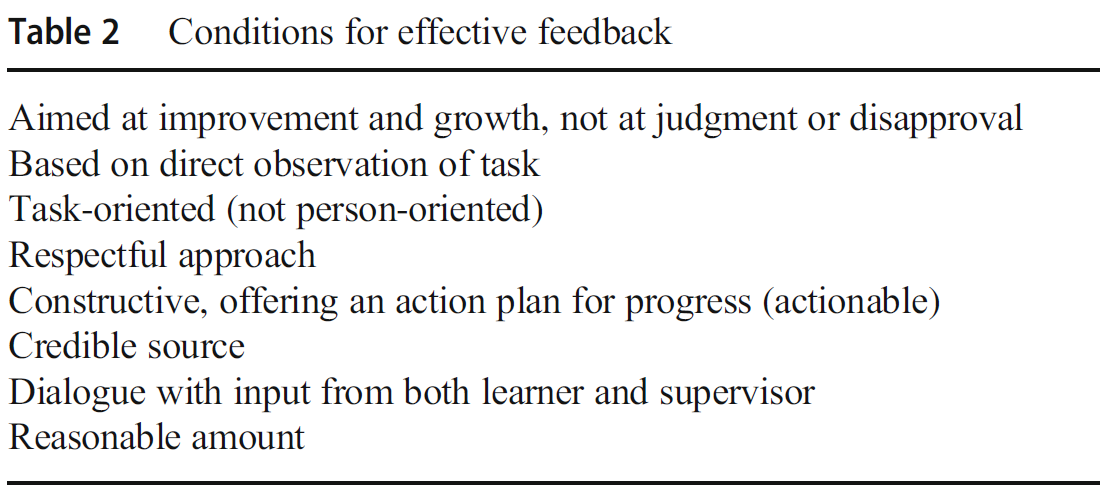

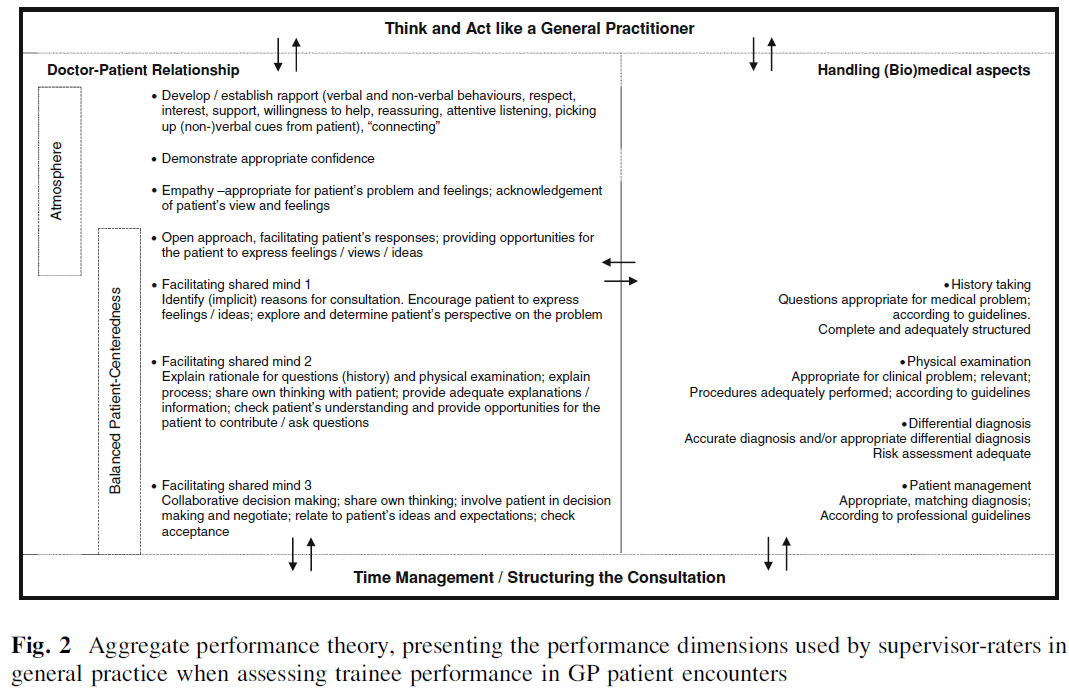

대다수의 응답자가 피드백의 목적으로 학생 90%, 교직원 89%가 일종의 개선을 언급할 정도로 피드백은 개선에 관한 것이라고 표현했다. 직원의 경우 피드백의 개선 목적이 성적 정당화 목적보다 10배 우세했고, 학생의 경우 개선 목적이 정당화 목적보다 20배 이상 우세했다. 일부 참여자들은 개선을 피드백의 '명백한' 목적이라고 여겼는데, 이는 이 주제가 널리 퍼지고 있다는 점을 고려할 때 놀라운 일이 아닐 수 있다. Carless 등(2011), Sadler(2010), Boud and Molloy(2013)가 제안한 의견과 같은 대중적인 피드백 아이디어의 기본 요소이기 때문에 개선 가능성이 높은 것은 고무적이다. 그러나 학생과 교직원이 개선에 대해 글을 쓸 때 표 2에 요약된 것처럼 개선 대상으로 간주하는 부분에서 현저한 차이가 있었다.

The vast majority of responses expressed that feedback is about improvement, with 90% of students and 89% of staff mentioning some sort of improvement as a purpose of feedback. For staff, an improvement purpose of feedback was ten times as prevalent as a grade justification purpose; for students, improvement was more than twenty times as prevalent as justification. Improvement was regarded by some participants as an ‘obvious’ purpose of feedback, which is perhaps unsurprising given the prevalence of this theme. It is heartening to see such a high prevalence for improvement, as it is the fundamental element of popular feedback ideas such as those proposed by Carless et al. (2011), Sadler (2010) and Boud and Molloy (2013). However, when students and staff wrote about improvement, there was a marked difference in what they regarded as the object of improvement, as outlined in Table 2.

참석자들이 가장 많이 응답한 내용은 피드백의 목적이 개선이지만 개선의 대상을 밝히지 않았다는 것이었다. 특정되지 않은 개선을 언급한 참여자들은 암묵적으로 개선의 일부 기본 초점을 가정하였거나 전반적인 일반적인 개선을 가정했을 수 있다.

The most common response by participants was that the purpose of feedback was improvement but they did not state an object of the improvement. Those participants who referred to unspecified improvement may have implicitly assumed some default focus of improvement or an overall, general improvement.

참가자들이 개선을 위해 특별히 초점을 맞춘다면, 그것은 보통 학생들의 공부, 이해의 향상 또는 학습이나 공부 전략의 향상이었다. Boud and Molloy(2013)의 연구를 바탕으로 Carless(2015)는 피드백을 '학습자가 다양한 출처의 정보를 이해하고 이를 활용하여 작업이나 학습 전략의 질을 높이는 대화 과정'으로 정의했다.(192쪽) 데이터의 작업 전략과 학습 전략 모두에 대한 개선이 널리 퍼진다는 것은 일부 교육자와 학생이 피드백의 목적에 대한 우리의 이해를 공유한다는 것을 시사한다. 또한 해티와 팀펄리(2007)가 피드백이 자율성 향상에 초점을 맞춰야 한다고 권고한 일부 측면이 교육자와 학생의 이해로 나타날 수 있음을 시사한다.

Where participants did specify a particular focus for improvement, it was usually improvements to students’ work, improvements in understanding, or improvements in learning or study strategies. Building on work by Boud and Molloy (2013), Carless (2015) defined feedback as ‘a dialogic process in which learners make sense of information from varied sources and use it to enhance the quality of their work or learning strategies.’ (p. 192). The prevalence of improvements to both work and learning strategies in the data suggests that some educators and students share our own understanding of the purpose of feedback. It also suggests that some aspects of Hattie and Timperley’s (2007) recommendation that feedback should focus on improving self-regulation may be represented in the understandings of educators and students.

평가 및 피드백 문헌은 최근 '평가적 판단evaluative judgement'으로 알려진 품질에 대한 학생들의 이해와 양질의 작업에 대한 의사 결정 능력 개발에 초점을 맞추고 있다. 소수의 참여자들은 평가 판단과 관련된 개선 사항(예: 자기 평가 개선 또는 기준 이해 향상)에 대해 썼다. 그러나, 중요한 능력으로서의 평가적 판단은 데이터 세트에 비중있는 존재는 아니었다. 교육자들과 학생들은 주로 일의 개선과 일의 생산 능력 향상에 초점을 맞추었고, 학생들의 업무 평가 능력 향상은 아니었다.

The assessment and feedback literature has recently increased its focus on the development of students’ understandings of quality and their ability to make decisions about quality work, known as ‘evaluative judgement’ (Tai et al. forthcoming). A small set of participants wrote about improvements related to evaluative judgement, such as improved self-evaluation or improved understanding of standards. However, evaluative judgement as an overarching capability was not a substantive presence in the data-set. Educators and students were predominantly focused on improvements to work, and an improvement in the ability to produce work, not on an improvement in the ability of students to evaluate work.

장점과 단점을 지적하는 것

Pointing out strengths and weaknesses

학생 작업의 강점과 약점을 식별하는 것은 때때로 개선을 위한 정보의 사용에 대한 언급 없이 참여자들에 의해 보고되었다. 이것은 피드백의 목적에 대한 [비교적 오래된 정보 중심의 이해]와 일치할 수 있는데, 피드백은 학생들에게 일의 좋은 점과 나쁜 점을 알려주는 것이지만, 학생들에게 그것을 개선하는 방법을 알려주거나 학생들에게 그 정보를 개선을 위해 사용하는 것에 대한 것이 아니다. 이 주제에 대한 전형적인 표현은 한 교육자에 의해 만들어졌는데, 한 교육자는 피드백의 목적이 '학생들이 그 과제에 대한 자신의 장단점이 어디에 있는지 알 수 있게 하는 것'이라고 말했다.

The identification of strengths and weaknesses in student work was sometimes reported by participants without mention of the use of that information for improvement. This perhaps corresponds to older, information-centric understandings of the purpose of feedback, such that feedback is about telling students what is good and bad about their work, but not about telling students how to improve it or students using the information for improvement. A typical expression of this theme was made by one educator, who said the purpose of feedback was ‘to allow the student to see where their strengths and weaknesses for that task lie.’

학생들의 기분을 좋게 만들고 동기를 부여하는 피드백

Feedback to motivate and make students feel good

소수의 직원과 소수의 학생들이 피드백을 위해 정서적인 목적을 언급했습니다. 이러한 참가자들에게 피드백의 목적 중 하나는 학생들이 일을 더 잘하도록 동기를 부여하고, 학생들의 노력을 인정하거나, 학생들을 격려하거나, 그들의 일에 대해 좋게 느끼도록 하는 것이었다. 한 학생은 그것이 피드백의 주된 목적은 아니지만, 정서적인 목적이 결과에 반영되지 않으면 상처를 입을 수 있다고 언급했다.

A small number of staff, and a smaller number of students, mentioned affective purposes for feedback. For these participants, one of the purposes of feedback was to motivate students to do better work, to acknowledge student effort, to encourage students, or to make them feel good about their work. One student noted that although it is not the primary purpose of feedback, if affective purposes are not attended to the results can be hurtful:

[피드백의 목적은] 주로 미래의 개선을 위한 것이지만, 또한 칭찬과 동기를 부여하고 노력한 시간과 노력을 긍정적으로 강화하는 것입니다. 평가자가 아무런 긍정도 없이 트집잡고 비판만 할 때 그것은 완전히 산산조각이 납니다.

[The purpose of feedback is] primarily to improve in future, but also to compliment and motivate and provide positive reinforcement to the effort and time put in. It’s absolutely shattering when the assessor does nothing but nit-pick and criticise with no positivity at all.

이것은 영향을 피드백의 목적으로서 고려하는 다소 일반적인 방법이었다.

This was a somewhat common way of considering affect as a purpose of feedback: as a secondary but essential purpose.

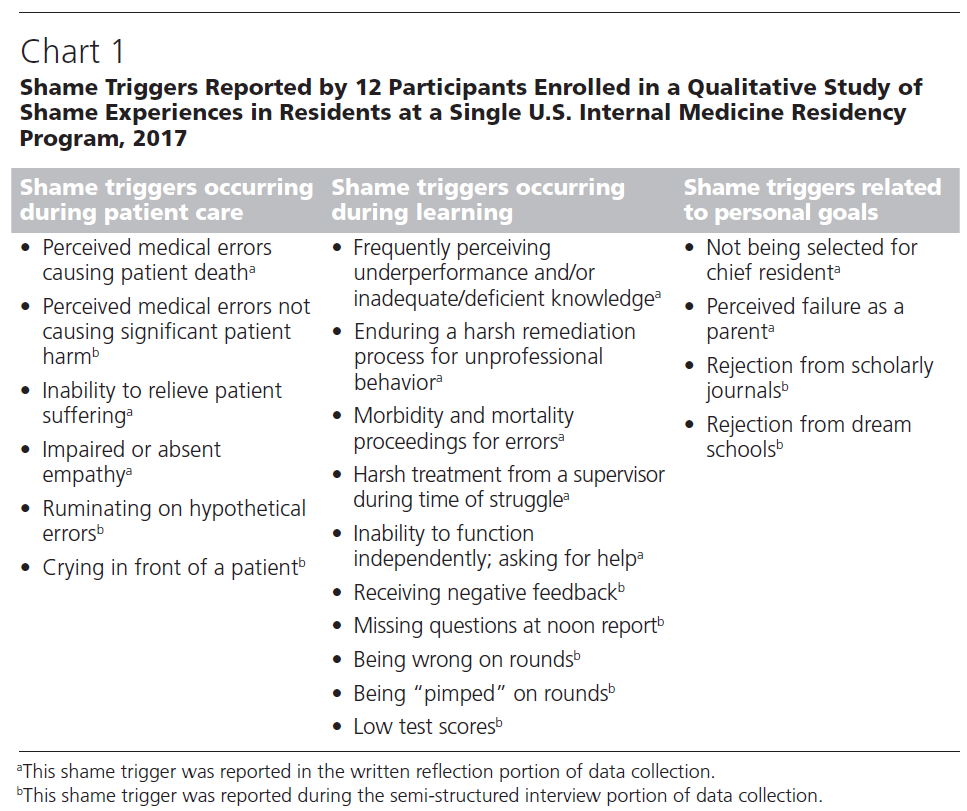

RQ2: 직원과 학생들은 무엇이 효과적인 피드백을 만든다고 생각하는가?

RQ2: What do staff and students think makes for effective feedback?

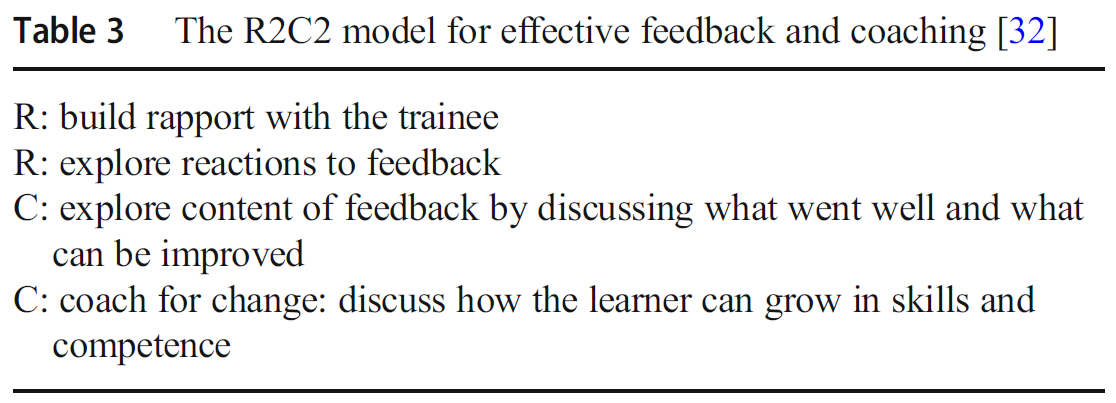

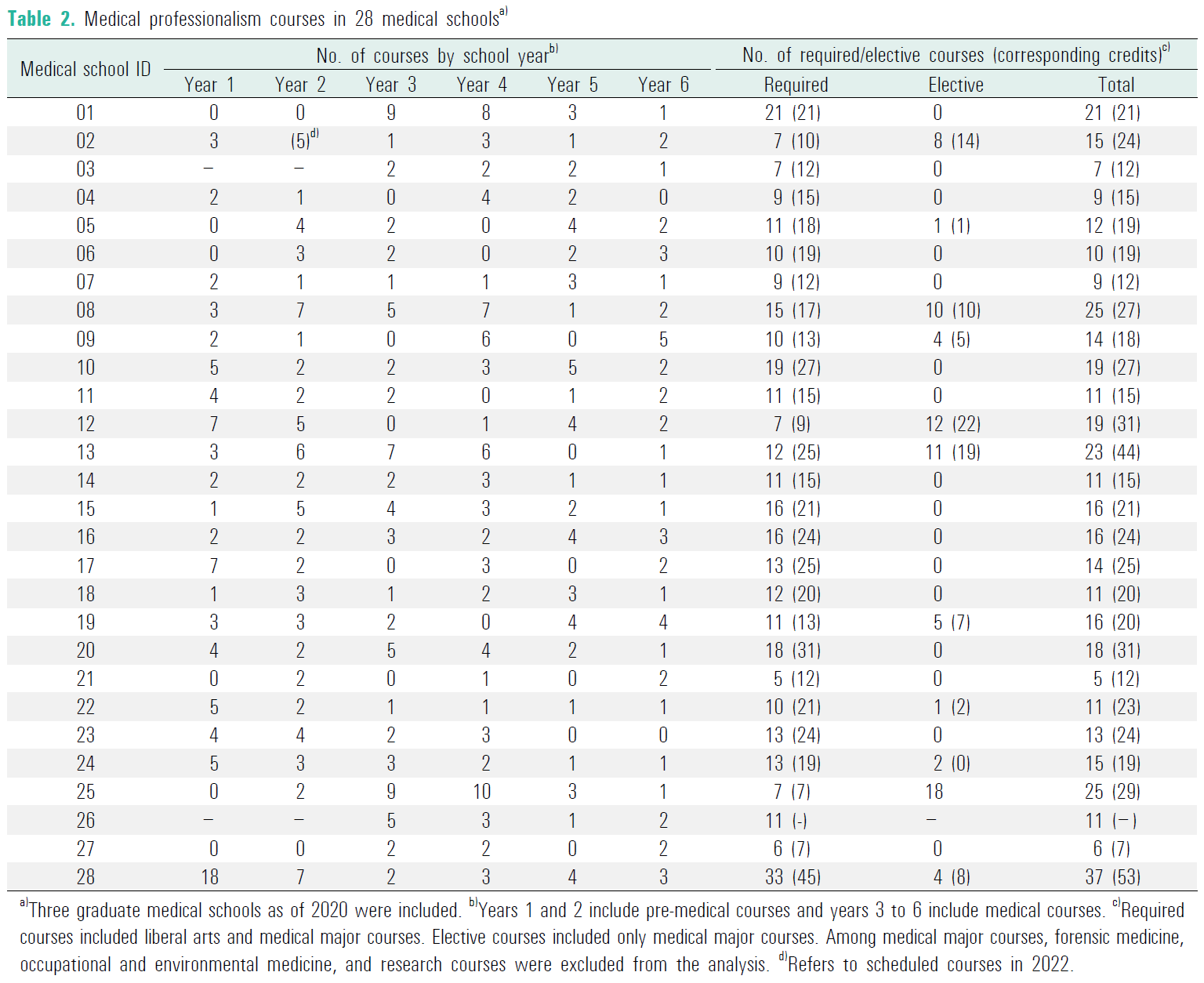

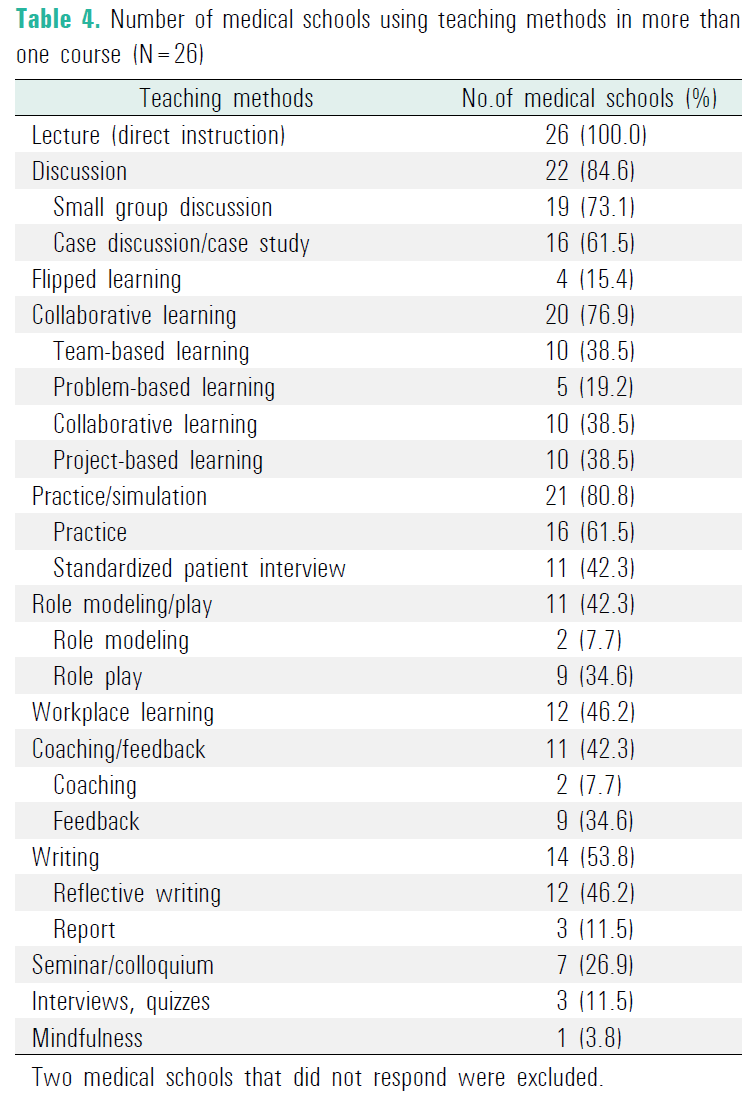

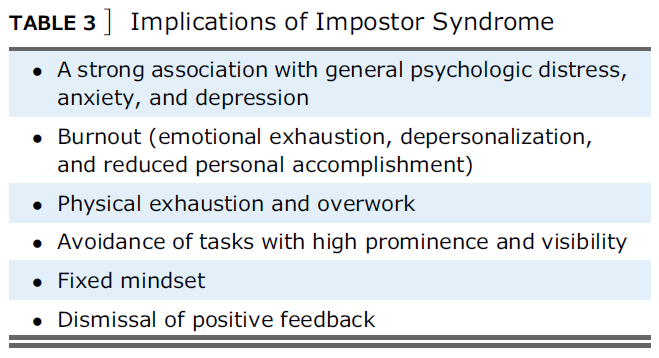

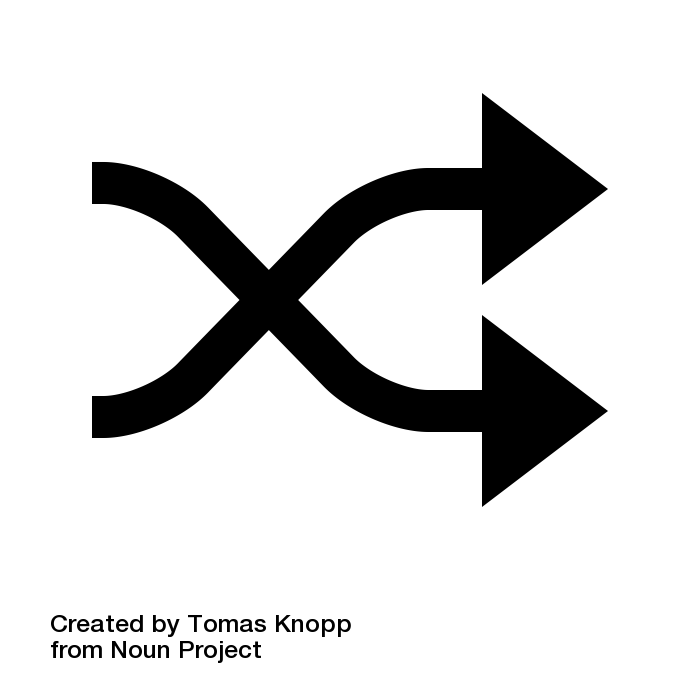

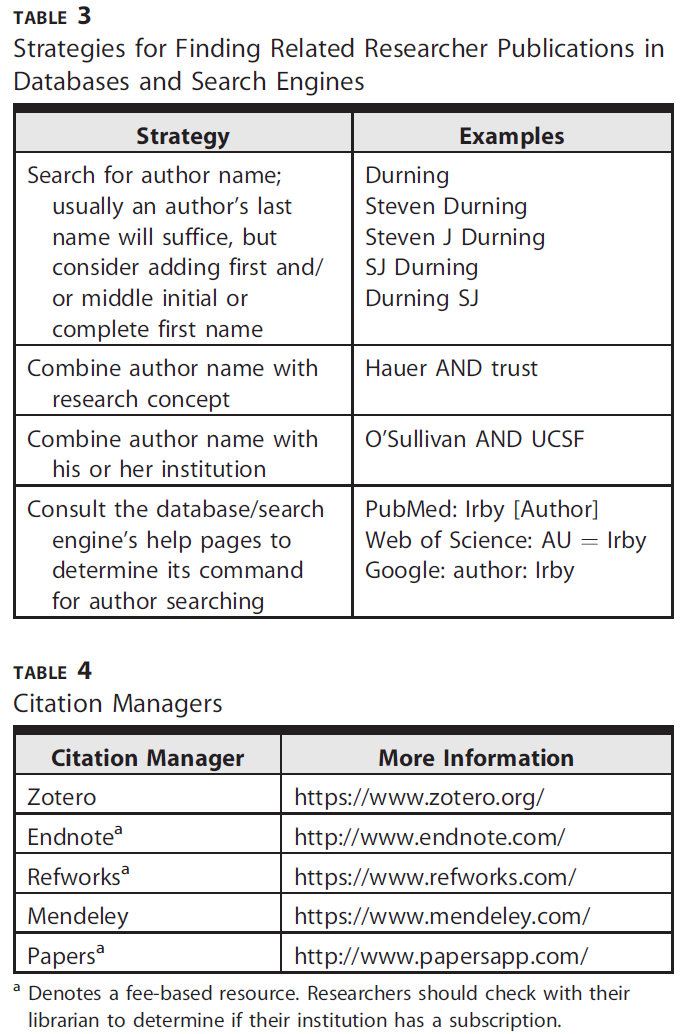

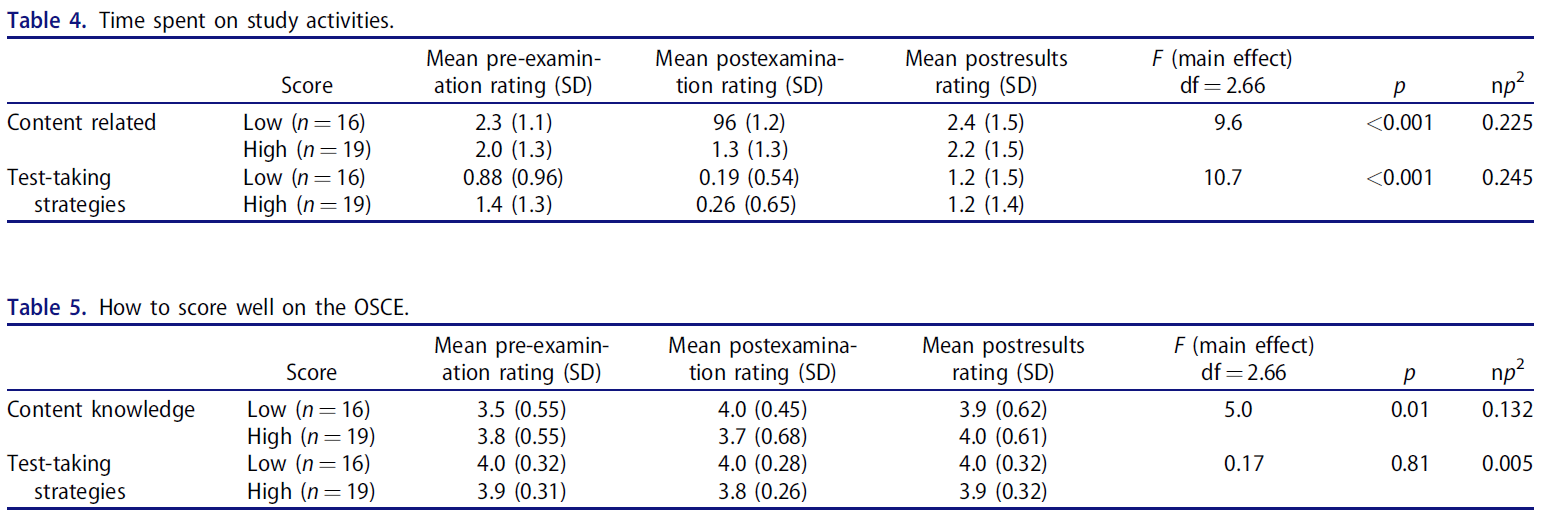

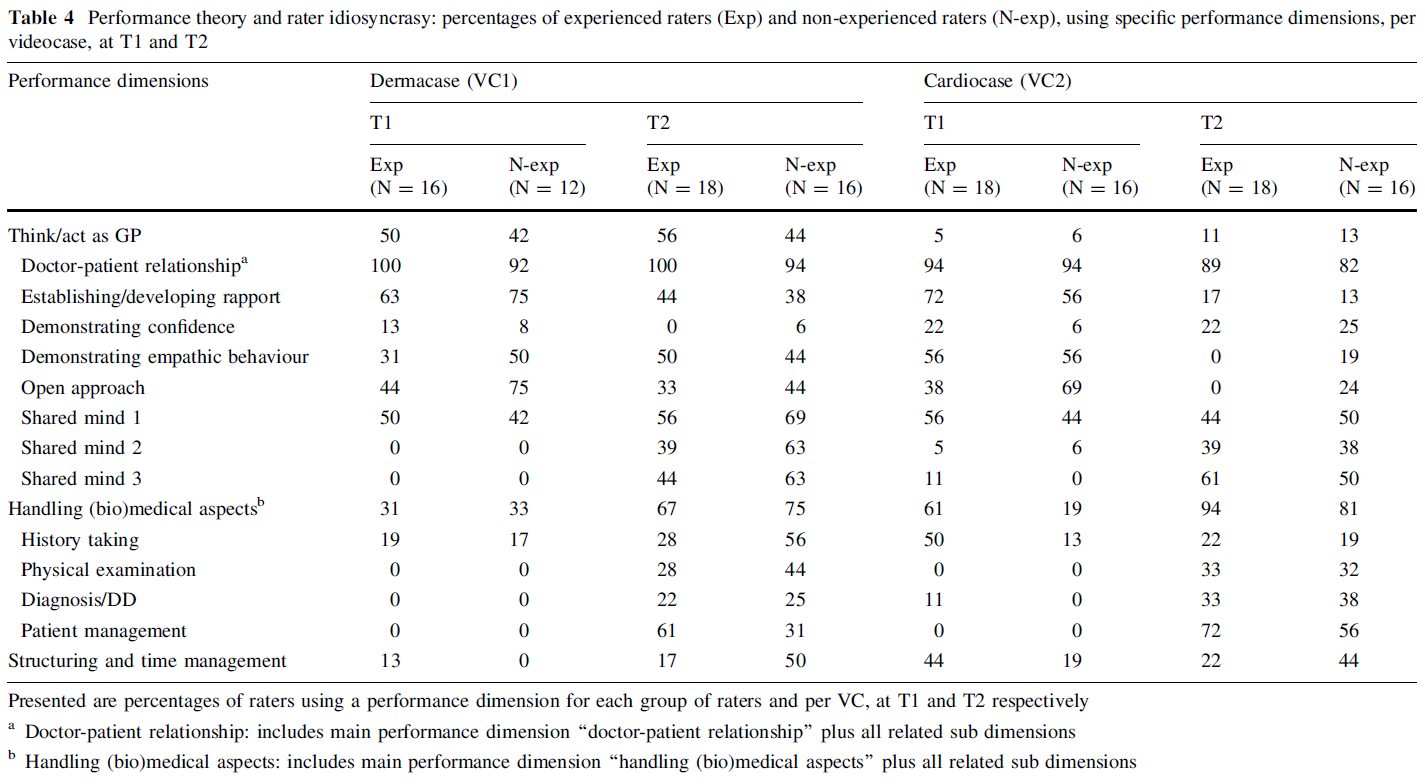

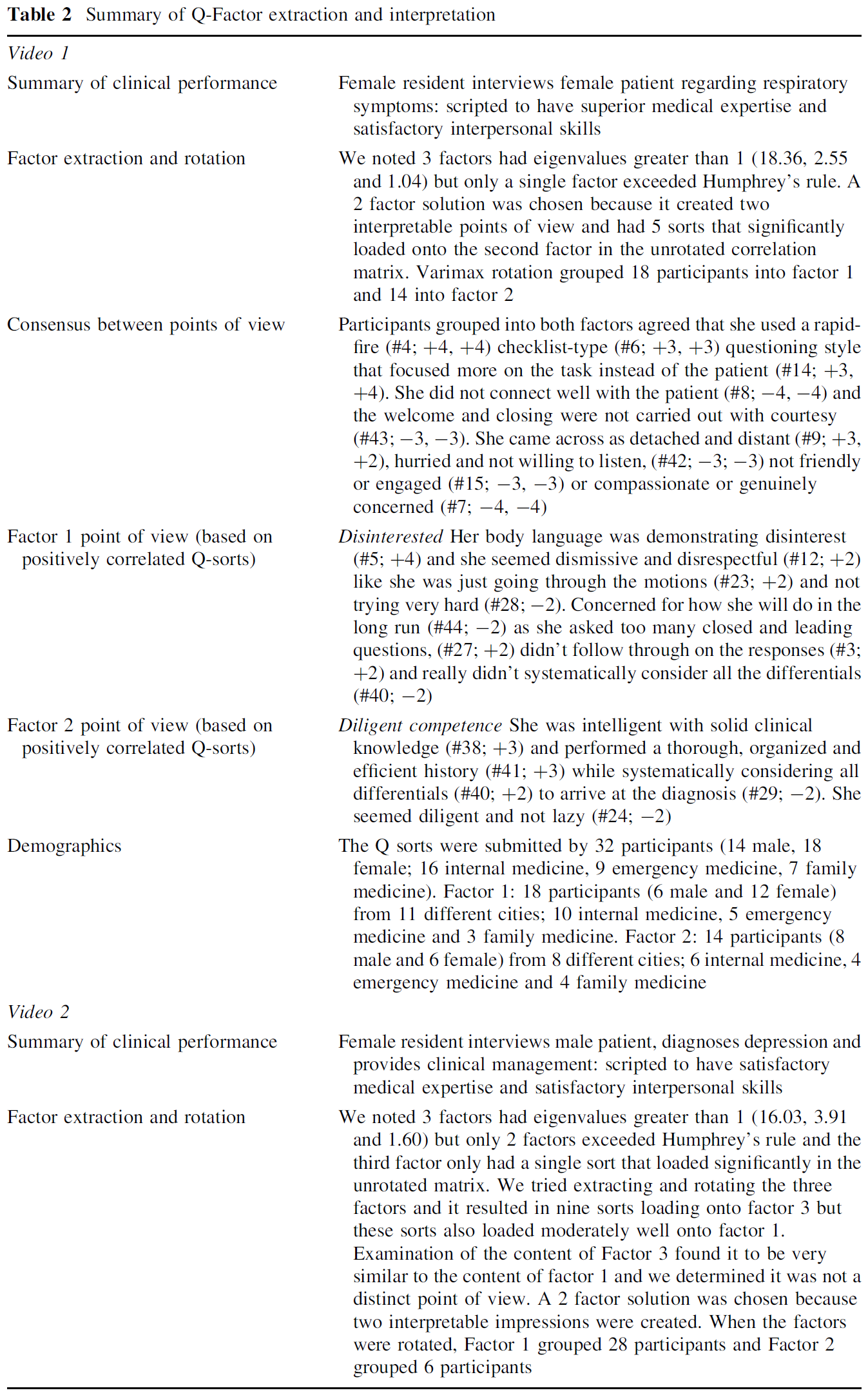

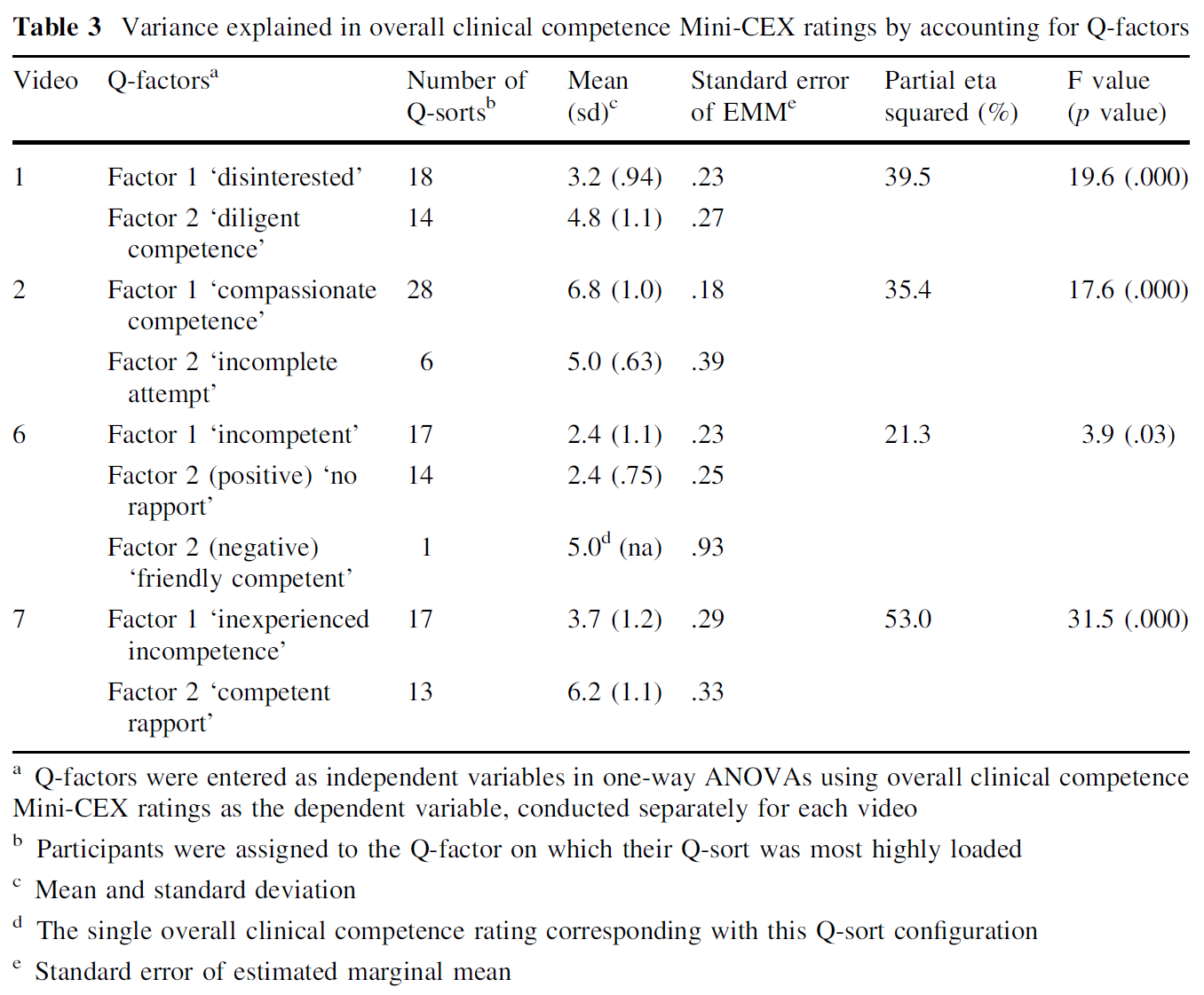

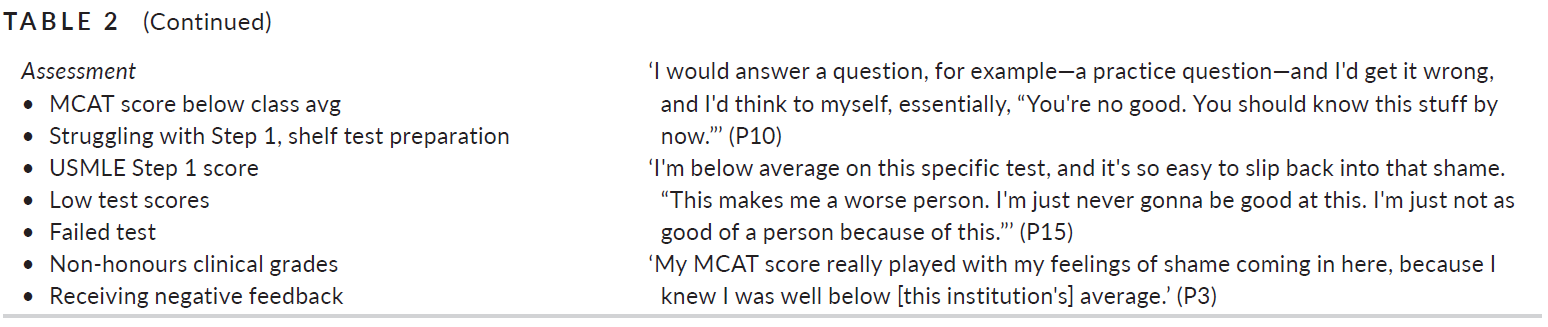

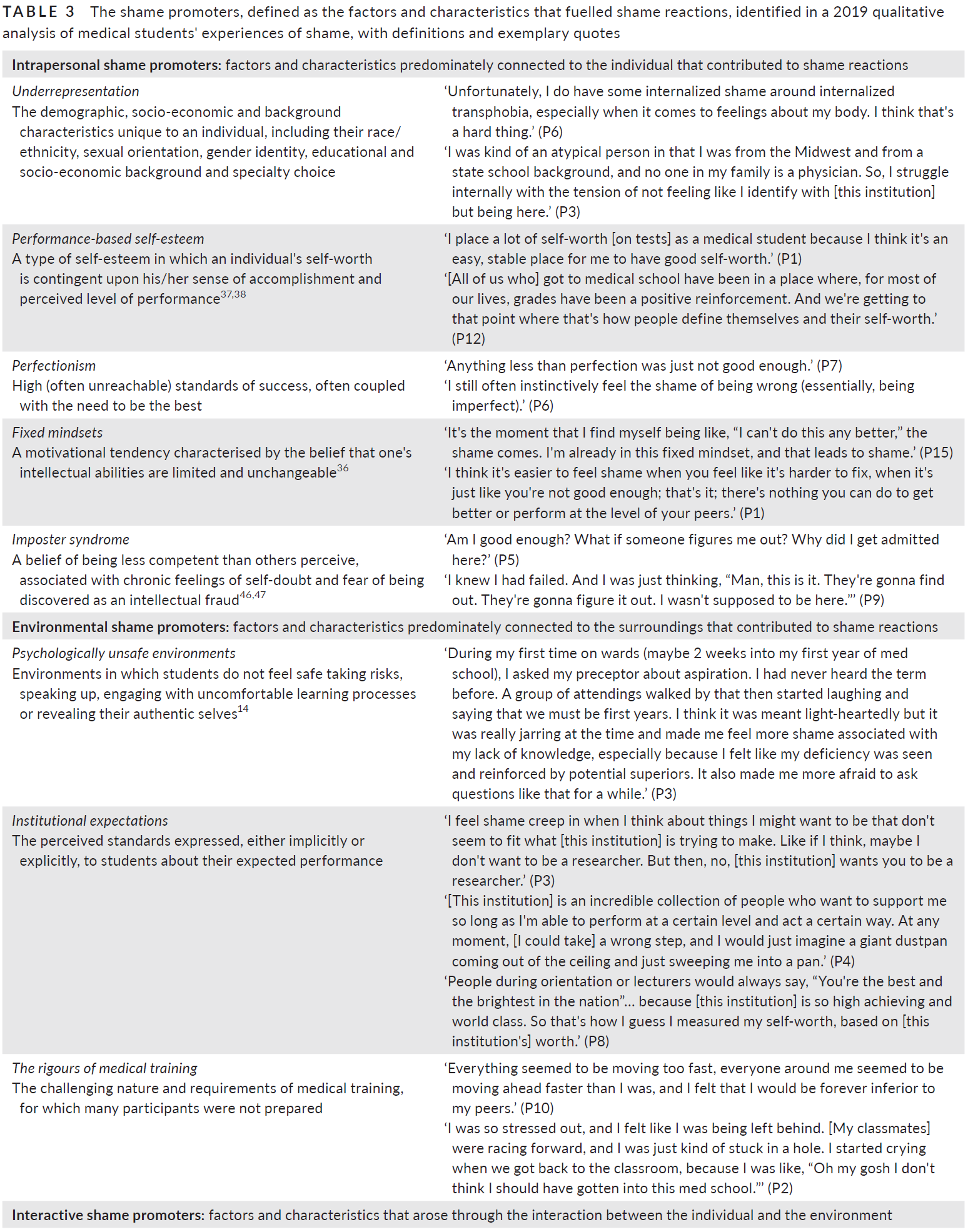

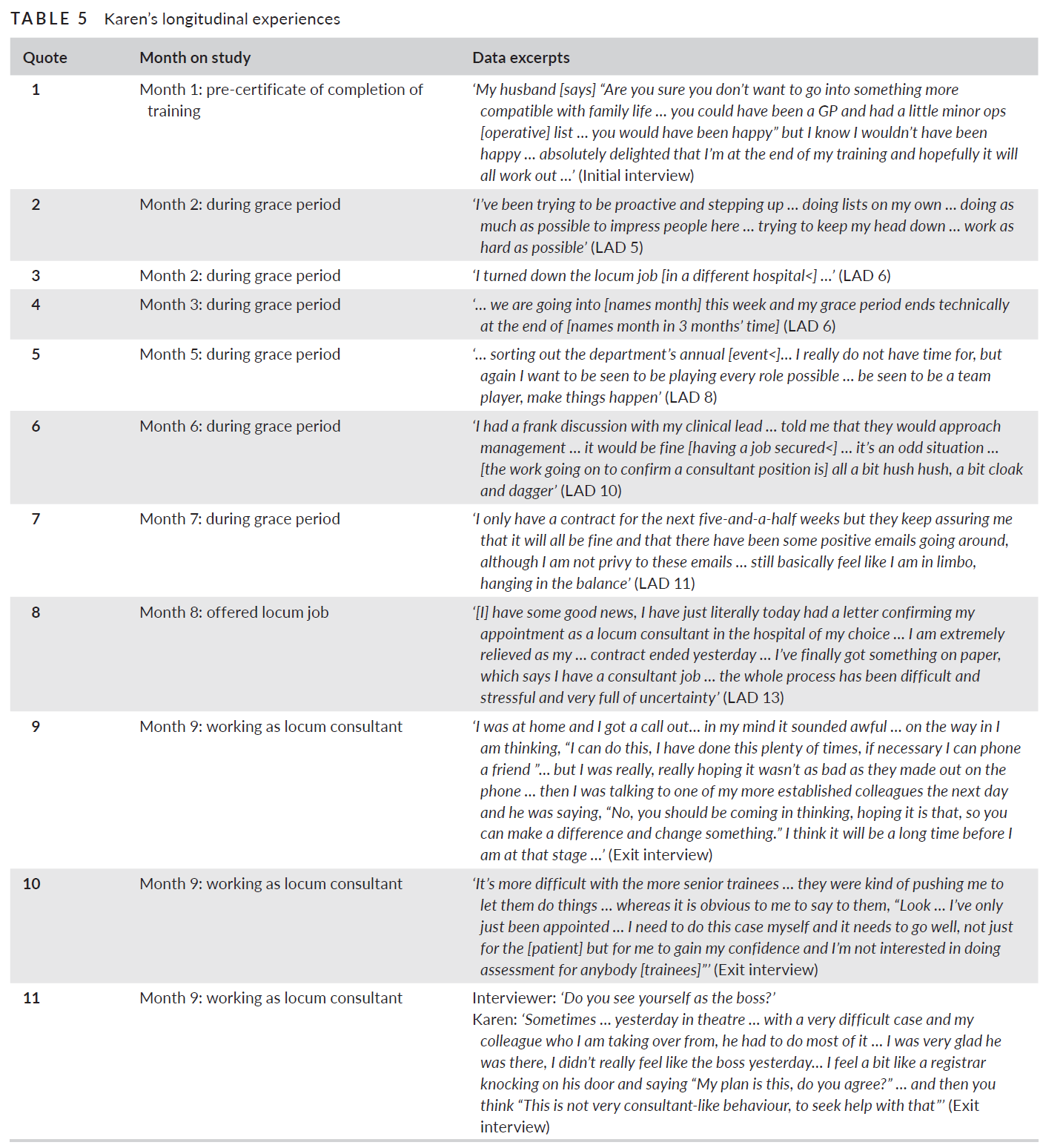

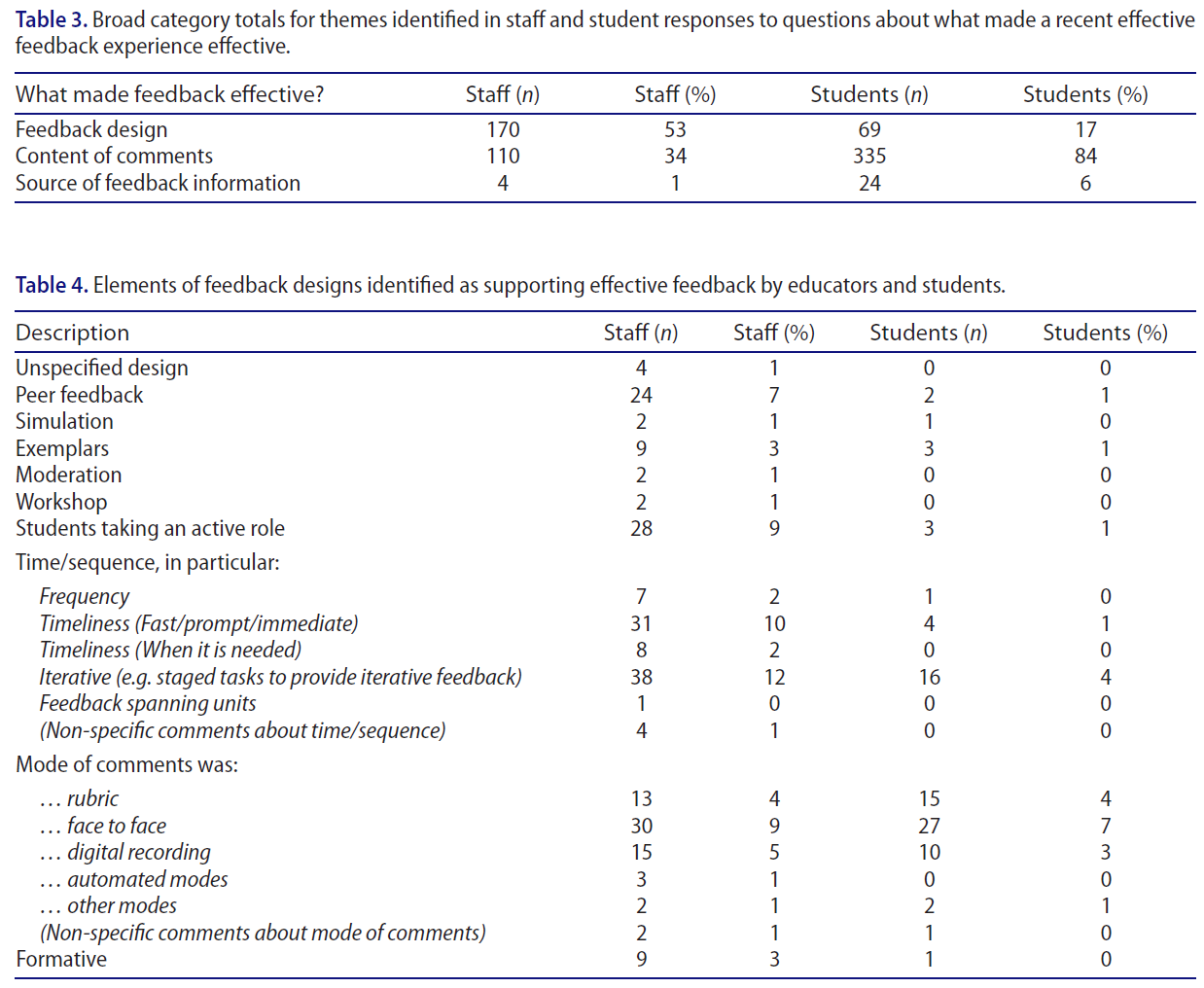

피드백의 목적보다 효과적인 피드백을 위해 무엇이 만들어지는지에 대해 직원과 학생이 더 의견이 갈렸습니다. 직원과 학생들이 피드백 경험을 효과적으로 만드는 것을 설명할 때, 눈에 띄는 주제는 의견의 내용, 피드백 설계의 측면 및 피드백 정보의 출처였다. 이러한 각 최상위 테마의 분포는 표 3에 나와 있습니다.

Staff and students diverged more on what makes for effective feedback than they did for the purpose of feedback. When staff and students were describing what made a feedback experience effective, the prominent themes were the content of the comments, aspects of the feedback design and the source of the feedback information. The prevalence of each of these top-level themes is shown in Table 3.

피드백 설계

Feedback design

앞에서 논의한 바와 같이, 피드백 문헌은 학생에게 더 나은 정보를 제공하는 것(예: 학생 업무에 대한 피드백 의견)의 초점에서 학생이 참여하는 과제와 활동의 설계(예: 학생이 두 번째 과제에서 피드백 의견을 사용하도록 요구하는 것)로 이동했다. 교육자 중 많은 수가 그들의 수업에서 피드백을 효과적으로 만드는 것으로 디자인을 언급했지만, 상대적으로 적은 수의 학생들이 디자인을 언급했습니다. 구체적인 특징은 표 4에 요약되어 있다.

As discussed earlier, the feedback literature has moved from a focus on providing better information to students (e.g. feedback comments on student work) to also consider designing the tasks and activities in which students engage (e.g. requiring students to use feedback comments from their first assignment in their second assignment). A slight majority of educators mentioned design as what made feedback in their classes effective; however, relatively few students mentioned design at all. The specific features are summarised in Table 4.

학생들과 비교했을 때, 더 많은 비율의 직원들이 디자인을 그들이 논의한 스스로 선택한 효과적인 피드백 사례를 뒷받침한다고 생각했다. 이것은 일반적으로 디자인에 적용되었고 피드백 설계의 거의 모든 특정 특징에 적용되었다. 이에 대한 한 가지 가능한 설명은 교육자들이 학생들보다 디자인에 대해 더 잘 알고 있을 수 있다는 것이다. 피드백 디자인은 교육자들에게 상당한 시간과 고려가 필요한 반면, 학생들은 디자인을 알아차리지 못하고 대신 디자인에서 만들어진 제품product에 초점을 맞출 수 있다(예: 코멘트).

Compared with students, a higher proportion of staff thought design was what supported the self-selected effective feedback instance they discussed. This was true for design in general, and for almost all specific features of feedback design. One possible explanation for this is that educators may be more aware of design than students; feedback design can take educators significant time and consideration, whereas students may not notice the design and instead focus on the products of the design (e.g. comments).

학생들은 종종 더 시기적절한 피드백을 원하는 것으로 간주되며(Li와 De Luca 2014), 교육기관에서는 특정 기간 내에 피드백 코멘트를 학생들에게 제공하도록 요구하는 것이 일반적이다. 피드백의 신속한 제공turnaround은 소수의 학생들, 그리고 10%의 교육자들에 의해 언급되었다. 그러나 피드백의 즉각적인 전환은 실제로 2차 관심사라고 주장할 수 있다. 시기적절성에 대한 가장 중요한 우려는 학생들이 다음 과제를 수행할 때 제때 피드백 정보를 이용할 수 있다는 것이다. 피드백 정보를 학생이 필요로 할 때 이용할 수 있는 형태의 적시성은 학생들에 의해 언급되지 않았고, 매우 적은 수의 직원들에 의해 언급되었다. 우리는 후속 작업을 위한 피드백 코멘트의 적시 제공 여부를 피드백이 전혀 발생하지 않는 근본적인 요구 사항으로 간주할 것이며, 이 테마의 상대적 희소성은 이 견해를 많은 학생과 교육자가 보유하고 있지 않거나, 애초에 언급할 가치가 없다고 간주함을 시사한다.

Students are often regarded as wanting more timely feedback (Li and De Luca 2014), and it is common for institutions to require feedback comments be provided to students within a particular timeframe. Prompt turnaround of feedback was mentioned by a very small number of students, and 10% of educators. However, we would argue that prompt turnaround of feedback is actually a second-order concern; the most important concern for timeliness is that feedback information is available to students in time for them to undertake the next task. Timeliness in the form of feedback information being available when the student needs it was not mentioned by students, and was mentioned by a very small number of staff. We would regard the availability of feedback comments in time to do subsequent work as a fundamental requirement for feedback to occur at all, and the relative scarcity of this theme suggests this view is either not held by many students and educators, or it is perhaps so taken-for-granted that it was not considered worth mentioning.

피드백의 또 다른 당연시되는 특징은 피드백이 반복적이거나 연결되어야 한다는 것이다. 학생들은 한 과제에서 다음 과제로 개선을 입증할 수 있는 방식으로 구성된 과제를 가져야 한다(Boud and Molloy 2013). 효과적인 피드백의 특징으로 이를 언급한 교육자와 학생은 거의 없었다. 학생들이 이 주제를 언급할 때, 그들은 피드백이 동일한 과제에 대한 반복적인 시도, 유사한 과제에 대한 반복적인 시도, 과제들을 조각으로 나누어 피드백이 산재된 것, 또는 개선된 제출에 대한 피드백에 따른 피드백에 의해 효과적으로 만들어졌다고 말했다. 그러나 상대적으로 적은 수의 학생들에 의해 언급되었음에도 불구하고, 그 학생들 중 몇 명은 그들의 특정한 피드백 사례를 효과적으로 만드는 유일한 특징으로 이것을 언급했다. 마찬가지로, 수업에서 효과적인 피드백의 특징으로 반복적이거나 연결된 과제를 언급한 많은 직원의 경우, 데이터에서 이 주제가 유일한 주제였다.

Another potentially taken for granted feature of feedback is that it needs to be iterative or connected; students need to have tasks structured in such a way that they can demonstrate their improvement from one task to the next (Boud and Molloy 2013). Few educators and fewer students mentioned this as a feature of effective feedback. Where students mentioned this theme, they said feedback was made effective either by repeated attempts at the same task, repeated attempts at similar tasks, tasks split into pieces and interspersed with feedback, or in-class feedback followed by feedback on an improved submission. However, despite being mentioned by relatively few students, several of those students mentioned this as the only feature that made their specific instance of feedback effective. Similarly, for many of the staff who mentioned iterative or connected tasks as a feature of effective feedback in their classes, this was the only theme found in their data.

일부 특정 피드백 설계 기능은 최근 몇 년 동안 피드백 문헌에서 인기를 끌었다. 특히 동료 피드백, 예시 및 피드백 조정의 사용 등이 그것이다. [동료 피드백의 거의 부재]는 우리의 맥락 내에서 동료 피드백을 일부 사용하는 것을 알고 있지만 학생과 교육자의 이러한 접근 방식에 대한 저항도 알고 있기 때문에 잠재적으로 놀랍지 않다. (Liu 및 Carless 2006; Tai 외 2016; Adachi, Tai 및 Dawson 2018) [모범적 접근법]의 부재는 교육자와 학생들이 피드백 프로세스의 일부로 보지 않는 모범적 접근법으로 설명될 수 있다. 모범적 접근법은 피드백 마크 2(Boud and Molloy 2013)와 같은 모델과 호환되지만, 일상적인 교육자나 학생의 피드백 정의에는 맞지 않을 수 있다. [피드백 조정]에 대한 코멘트가 부족한 것은 이 과정이 학생들에게 거의 보이지 않거나 상대적으로 니치 프락티스이기 때문일 수 있다.

Some specific feedback design features have gained popularity in feedback literature over recent years; in particular peer feedback, the use of exemplars and feedback moderation. The near absence of peer feedback is potentially unsurprising, as although we are aware of some use of peer feedback within our contexts, we are also aware of resistance to these approaches from students and educators (Liu and Carless 2006; Tai et al. 2016; Adachi, Tai, and Dawson 2018). The absence of exemplar approaches may be explained by exemplars not being viewed by educators and students as part of feedback processes; although exemplars are compatible with models like Feedback Mark 2 (Boud and Molloy 2013), they may not fit within everyday educator or student definitions of feedback. We suspect the lack of comments about feedback moderation (the review of educator feedback comments by other educators, as described in Broadbent, Panadero, and Boud 2018) may be due to this process being largely nonvisible to students, or it being a relatively niche practice.

학생들이 가장 많이 언급한 설계 요소는 양식, 즉 피드백 정보가 제공되는 형태와 관련이 있습니다. 이러한 논평은 특정 양식의 인식된 수용성과 관련된 경향이 있었다. 즉,

- 루브릭스는 '정확한' 또는 '상세적인' 것으로 기록되었고,

- 디지털 녹음은 '이해하기 쉬운' 또는 더 많은 양이었으며,

- 대면 피드백은 개인화되고 철저했다.

자동화된 소스(예: 형성적 객관식 퀴즈)에 대한 학생들의 의견 부족은 아마도 놀랍다. 그러나, 이것은 이러한 소스가 효과적이지 않다는 것을 의미하는 것이 아니다. 그것은 단지 그것들이 이러한 학생들에게 가장 효과적인 최근 피드백 경험의 일부가 아니었다는 것을 의미한다(또는 잠재적으로 피드백으로 간주되지 않는다).

The design elements most mentioned by students related to modalities – that is, the forms in which feedback information was provided. These comments tended to relate to the perceived affordances of particular modalities:

- rubrics were noted as ‘accurate’ or ‘detailed’;

- digital recordings were ‘easy to understand’ or more voluminous;

- face-to-face feedback was personalised and thorough.

The lack of comments from students around automated sources (e.g. formative multiple-choice quizzes) is perhaps surprising. However, this does not imply these sources are ineffective; it merely implies they were not a part of the most effective recent feedback experience for these students (or, potentially, are not considered to be feedback as such).

본 논문에서 채택된 피드백의 개념화 내에서, 코멘트는 학생들이 적극적으로 사용할 때까지 '데이터를 물고 늘어지는 것'(Sadler 1989, 페이지 121)이다. 피드백을 효과적으로 만드는 것 중 직접적으로 [학생들의 역할]을 언급한 교육자와 학생은 매우 소수였다. 예를 들어, 한 교육자는 이러한 디자인의 측면이 피드백을 효과적으로 만드는 것이라고 말했다.

Within the conceptualisation of feedback adopted in this paper, comments are ‘dangling data’ (per Sadler 1989, p. 121) until they are actively used by students. A small number of educators and a very small number of students directly referred to students taking an active role as what had made feedback effective. For example, one educator said that this aspect of design was what made feedback effective:

학생들은 에세이 초안에 대해 매우 상세한 코멘트를 받았다. 그들은 최종 초안과 초안에 대한 의견을 설명/정당하게 하는 성찰적인 내용을 작성해야 했다.

Students were given very detailed comments on an essay draft. They were required to produce a final draft, and a reflective piece that explained/justified their response to comments on their draft.

피드백 루프를 완료하여 피드백의 자격을 갖추기 위해 피드백을 제정해야 한다는 것이 점점 더 받아들여질 수 있지만, 학생들을 피드백의 행위자로 만든 설계의 상대적 부족은 다소 놀라웠다. 또한, 이 테마의 데이터가 학생들이 활동적인 것을 반영했지만, 일반적으로 피드백 추구와 같은 대리인, 학생 주도적인 관행을 설명하지는 않았다.

While it may be increasingly accepted that feedback needs to be enacted in order to complete the feedback loop and thus qualify as feedback, the relative scarcity of designs that made students the actors in feedback was somewhat surprising. In addition, although data in this theme reflected students as active, it did not usually describe agentic, student-driven practices such as feedback-seeking.

피드백 코멘트

Feedback comments

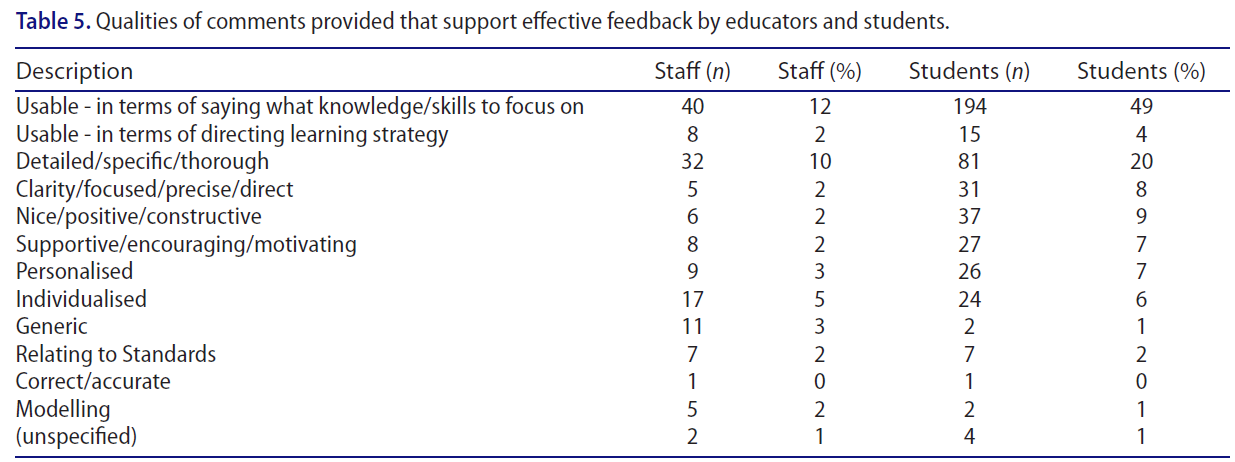

학생 응답에서 확인된 가장 일반적인 최상위 테마는 [양질의 '피드백 정보']가 효과적인 피드백의 일부라는 것이었다. 이는 학생들이 가장 원하는 피드백의 특징 중 일부가 '개인적이고, 설명할 수 있고, 준거-참조적이고, 객관적이고, 추가 개선에 적용할 수 있다'는 점에 주목한 Li와 De Luca의 2014년 체계적 검토 결과와 일치한다(390쪽). 하지만, 우리는 상대적으로 적은 수의 교육자들이 피드백 정보의 질을 언급하는 것을 보고 놀랐습니다. 교육자와 학생이 언급한 피드백 코멘트의 구체적인 특징은 표 5에 요약되어 있다.

By far the most common top-level theme identified in student responses was that high-quality ‘feedback information’ is part of effective feedback. This aligns with findings from Li and De Luca’s (2014) systematic review that noted some of the features of feedback most desired by students were that it was ‘personal, explicable, criteria-referenced, objective, and applicable to further improvement’ (p. 390). However, we were surprised to see that the quality of feedback information was mentioned by proportionally fewer educators. The specific features of feedback comments noted by educators and students are summarised in Table 5.

코멘트에 대한 데이터에서 가장 두드러진 주제는 학생들은 '사용가능한' 코멘트를 효과적으로 보았다는 것이다. 본 논문에서 채택된 피드백의 개념화를 고려할 때, 그러한 진술은 근본적이거나 심지어 동조적으로 들릴 수 있다. 그러나 그 보급률을 감안할 때, 학생의 관점에서 효과적인 피드백에 있어 가장 일반적인 활성화 요소는 [개선되어야 할 사항을 전달하는 것]이었다는 것을 강조할 필요가 있다. 이것은 보통 학생들의 공부나 이해도 향상으로 표현되지만, 일부 학생들은 학습 전략 향상에 초점을 맞춘 피드백도 효과적이었다고 언급했다.

The most prominent theme in the data about comments is that students found usable comments effective. Given the conceptualisation of feedback adopted in this paper, such a statement may sound fundamental or even tautological. However, given its prevalence, it is worth emphasising that the most common active ingredient in effective feedback from the student perspective was communicating what needs to be improved. While this was usually expressed in terms of improvements to the students’ work or understanding, some students also mentioned that feedback which focused on improvements to learning strategy was also effective.

그 다음으로 학생들이 가장 많이 생각하는 코멘트 내용은 피드백이 상세하고 구체적이거나 철저해야 한다는 것이었다. '자세한 피드백'을 언급한 많은 학생들에게는, 이것이 피드백을 효과적으로 만드는 유일한 특징이었다. 관련되어있지만, 덜 흔한 주제는 피드백이 명확하고, 집중적이고, 정확해야 하며, 직접적이어야 한다는 것이었다.

The next most prevalent theme for students in terms of the content of comments was that feedback needs to be detailed, specific or thorough. For many students who mentioned detail, it was the sole feature that made their instance of feedback effective. A related, less common theme was that feedback needed to be clear, focused, precise or direct.

일부 학생들은 자신의 피드백 경험이 개인화되거나 개인화됨으로써 효과적이라고 언급했다. 이러한 설명은 용어의 의미에 대한 설명 없이 '개인화'와 같은 용어를 자주 사용했기 때문에 분석하기 어려운 것으로 밝혀졌다. 이 설문 조사의 일부 응답을 명확히 하기 위해 수행된 탐색적 포커스 그룹에서 우리는 학생들에게 '개인화'라는 용어가 무엇을 의미하는지 물었고, 우리는 학생들이 평가자가 실제로 자신의 과제물을 읽고, 이에 대해 구체적으로 언급할 때 피드백을 개인화했다고 생각하는 일관된 응답을 받았다. 코호트의 작업에 대한 일반적인 피드백 정보를 받는 것에 반대된다. 이를 바탕으로, 우리는 개별화된 주제와 개인화된 주제를 분리할 수 없는 것으로 간주한다. 그러나 우리는 그것이 조사 데이터에서 독립적인 것으로 보았기 때문에 여기서 그것들을 구별되는 코드로 보고한다. 대조적으로, 일반적인 피드백 의견(개인화된 피드백의 반대)이 효과적이라는 것을 발견한 소수의 학생과 교직원도 있었다.

Some students mentioned that their feedback experience was made effective by being personalised or individualised. These descriptions proved difficult to analyse as they often used a term like ‘personalised’ without explanation of what the term meant. In exploratory focus groups conducted to clarify some responses from this survey, we asked students (n = 28) what the term ‘personalised’ meant to them, and we received the consistent response that students thought feedback was personalised when they felt the assessor had actually read their work and was making comments specifically about it – as opposed to receiving generic feedback information about the cohort’s work. Based on this, we consider the individualised and personalised themes to be perhaps inseparable; however, we report them as distinct codes here because that was what we saw in the survey data as standalone. In contrast, there was also a small set of students and staff who found generic feedback comments (the opposite of personalised feedback) effective.

소수의 학생들은 자신의 작품에 대한 코멘트가 친절하고 긍정적이거나 건설적이거나 지지적이거나 격려적이거나 동기부여가 되는 광범위한 감성적인 특징 덕분에 최근의 효과적인 피드백 경험이 효과적이라고 말했다. 이 두 가지 주제를 논의한 소수의 학생들에게는 이 주제만이 언급되었지만, 대부분의 학생들에게는 이 주제들이 다른 특징들과 함께 언급되었다.

A small number of students indicated that their recent effective feedback experience was made effective thanks to broadly affective features of the comments made about their work: the comments were nice, positive or constructive, or supportive, encouraging or motivating. For a substantial minority of students who discussed either of these themes it was the only theme mentioned; however, for most students these themes were mentioned alongside other features.

Li와 De Luca(2014)의 검토와 평가 판단에 대한 최근 작업(Tai 등)을 바탕으로, 우리는 스태프와 그보다 덜한 범위의 학생들이 표준이나 기준을 참조하는 의견을 가치 있게 여길 것으로 예상했다. 다른 질적 연구의 학생 참여자(예: Poulos와 Mahony 2008)는 종종 피드백의 효과적인 기준점으로 '준거criteria'를 언급했다. 놀랍게도, 우리 연구에서 이러한 특징을 언급한 직원이나 학생은 매우 적었고, 피드백 설계에서 루빅 양식 하위 테마를 다시 확인했을 때도 표준이나 기준에 대한 명시적인 언급이 거의 없었다. 지속 가능한 피드백(Carless et al. 2011) 또는 피드백 마크 2(Boud and Molloy 2013)와 같은 정교한 피드백 모델은 [해당 표준에 대한 학생의 이해를 높이기 위해 표준을 명시적으로 참조하는 피드백]에 일부 의존한다. '기준Standard'이 많은 직원과 학생들에게 효과적인 피드백 경험의 특징이 아니었다는 것은 우려스럽다. 대부분의 학생들은 개선 방법을 식별한 코멘트를 언급했지만, 그러한 개선의 기준점을 언급한 학생은 거의 없었다.

Based on Li and De Luca’s (2014) review, as well as recent work on evaluative judgement (Tai et al. forthcoming), we expected that staff, and to a lesser extent students, would value comments that made reference to standards or criteria. Student participants in other qualitative studies (e.g. Poulos and Mahony 2008) often mentioned criteria as an effective reference point for feedback. To our surprise, very few staff or students in our study mentioned these features, and even when we re-checked the rubric modality subtheme from feedback design, there was little explicit mention of standards or criteria. Sophisticated feedback models like sustainable feedback (Carless et al. 2011) or Feedback Mark 2 (Boud and Molloy 2013) are dependent in some part on feedback that makes explicit reference to standards, in order to develop student understanding of those standards; it is concerning that standards were not a feature of effective feedback experiences for many staff and students. Most students mentioned comments that identified how to improve, but few mentioned the reference point for those improvements.

결론

Conclusion

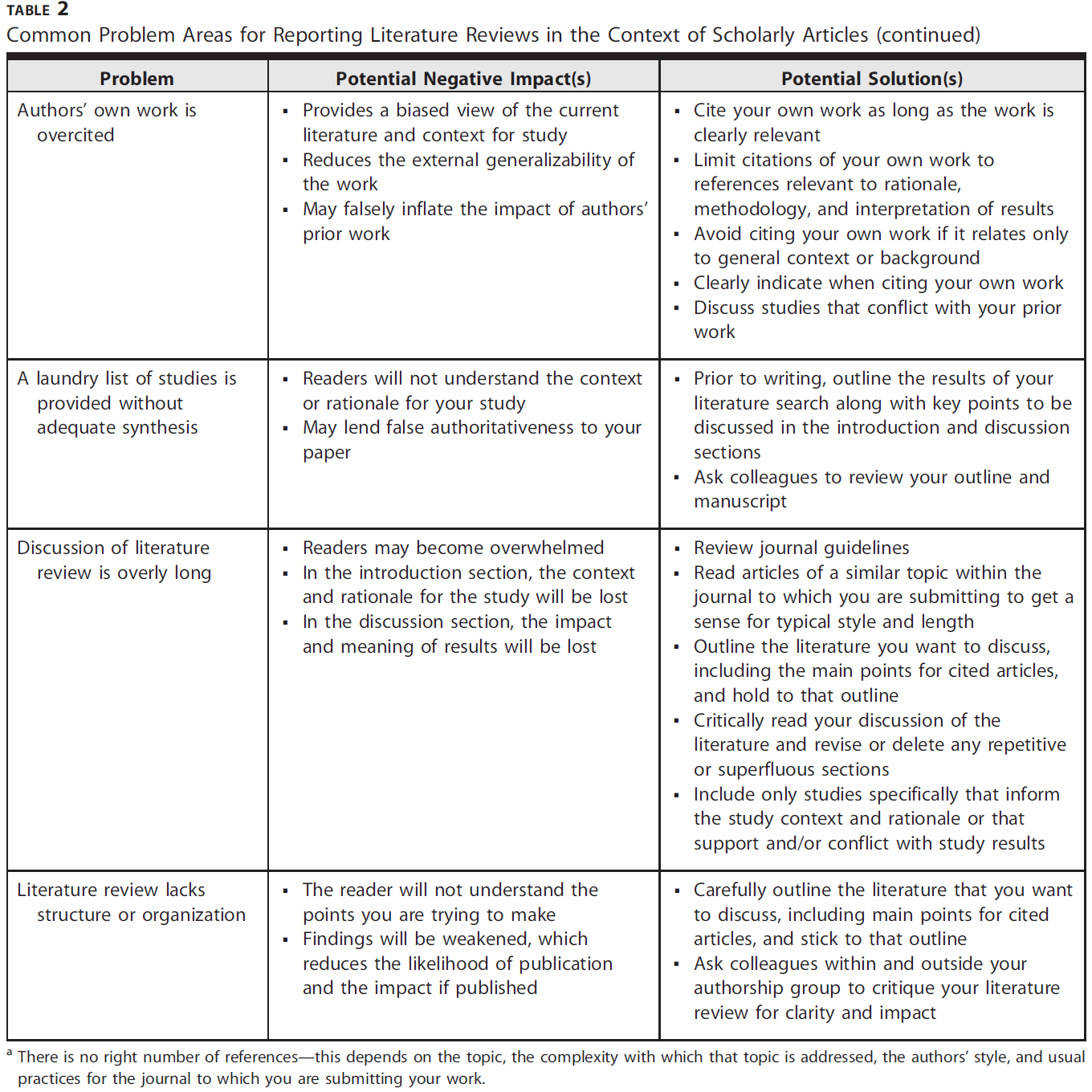

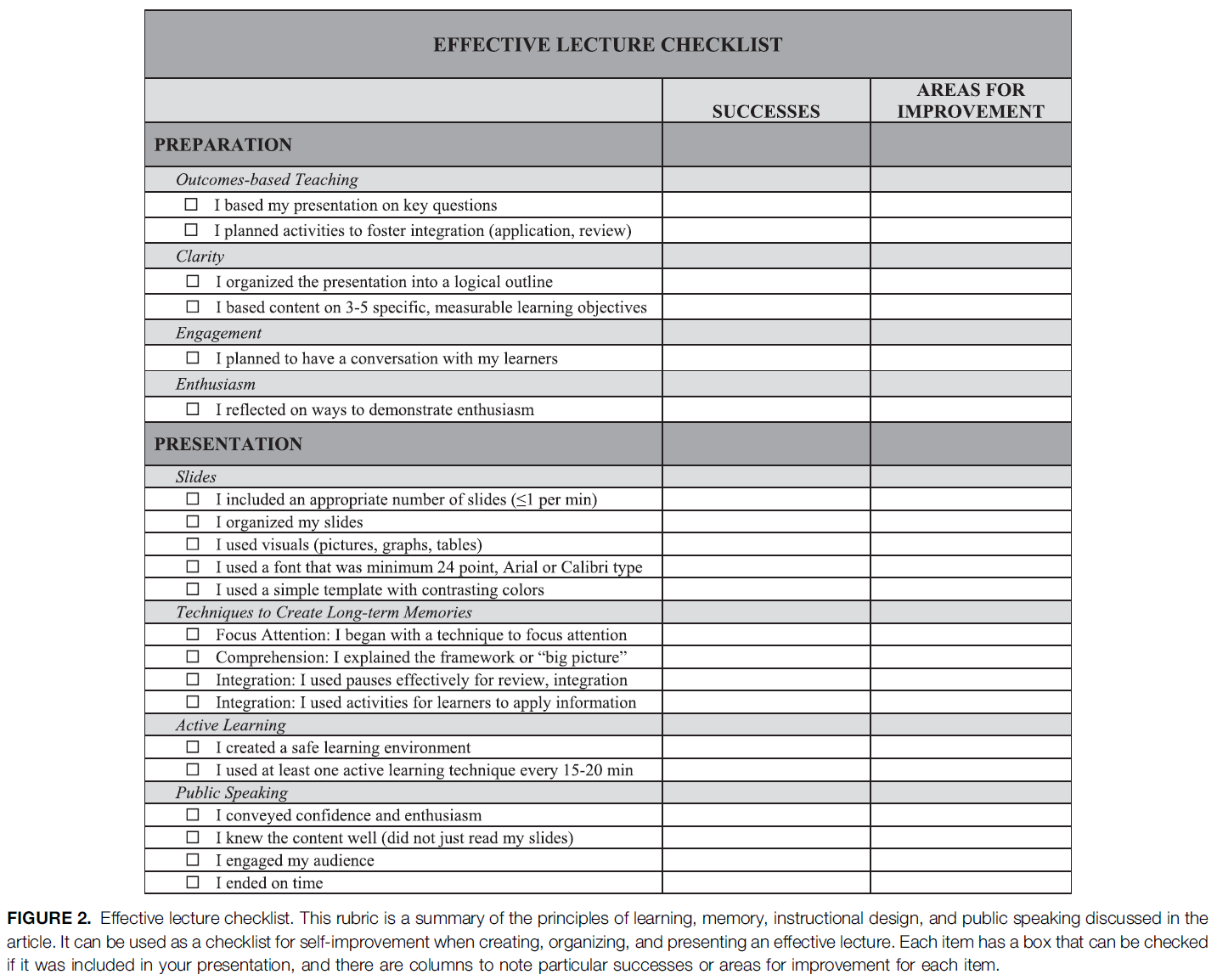

본 연구의 연구 질문으로 돌아가서, 우리는 대체로 직원과 학생들이 피드백의 목적이 개선이라고 생각한다는 것을 발견했습니다.

- 직원의 관점에서 피드백은 주로 타이밍, 방식, 연결된 작업과 같은 [설계 관련 문제]를 통해 효과적으로 만들어졌습니다.

- 학생 입장에서 피드백은 [사용가능하고, 충분히 상세하고, 감정에 신경쓰고, 자신의 과제와 관련있는 듯 보이는 양질의 코멘트]일 때 효과적이었다.

Returning to the research questions for this study, we have found that, broadly speaking, staff and students think the purpose of feedback is improvement.

- From the staff perspective, feedback was made effective primarily through design concerns like timing, modalities and connected tasks.

- From the student perspective, feedback was made effective through high-quality comments which were usable, sufficiently detailed, attended to affect and appeared to be about the student’s own work.

그러나, 효과적인 피드백에 대해서 종종 서로 모순되는 듯한 의견도 있었다. 예를 들어, 많은 학생들이 자신에게 맞춘 피드백 정보를 효과적인 피드백 경험이라고 언급한 한 반면, 다른 학생들은 일반적인 의견을 높이 평가하였다. 여기서 직원과 학생들의 경험은 새들러(2010)가 피드백에 대한 4개의 리뷰 연구에서 관찰한 것과 일치하는 것으로 보인다.

However, we were also very interested to find other, sometimes seemingly incongruous experiences of effective feedback. For example, while many students had effective feedback experiences involving feedback information tailored to them, some others appreciated generic comments. Here, the experiences of staff and students seem to concur with what Sadler (2010) observed from four review studies on feedback:

피드백에 대해 알려진 것의 복잡성을 얼버무릴 위험을 무릅쓰고, 일반적인 그림은 형태, 시기 및 효과 사이의 관계가 복잡하고 가변적이라서, 마법의 공식이란 없다는 것이다. (Sadler 2010, 페이지 536)

At the risk of glossing over the complexities of what is known about feedback, the general picture is that the relationship between its form, timing and effectiveness is complex and variable, with no magic formulas. (Sadler 2010, p. 536)

교수는 [피드백 설계]에 초점을 맞추고, 학생은 [피드백 코멘트]에 초점을 맞추면 직원과 학생이 가장 쉽게 알아볼 수 있는 피드백 프로세스 요소를 반영할 수 있습니다. 피드백을 개선함에 있어 학생들이 학습에 도움이 되는 디자인 요소에 집중하고 성찰하는 것이 도움이 될 수 있다. 피드백 설계에 대한 더 나은 이해는 Winstone 등(2017)이 피드백에 대한 더 많은 에이전트 참여를 지지하는 것으로 발견한 '평가 문해력' 피드백 수신자 프로세스의 요소이다. 또한, '더 나은 피드백 코멘트'가 아니라 '더 나은 피드백 디자인'으로 학생들의 요구가 바뀐다면, 피드백 방식을 바꾸기를 원하는 교육자들을 지원할 수 있습니다.

The staff focus on feedback designs and the student focus on feedback comments may reflect the elements of feedback processes that are most readily noticeable to staff and students. In improving feedback, it may be helpful for students to attend to and reflect on the design elements that support their learning. Better understandings of feedback designs are an element of the ‘assessment literacy’ feedback recipience process that Winstone et al. (2017) find to be supportive of more agentic engagement in feedback. In addition, student demand for better feedback designs – rather than just better feedback comments – may support educators who wish to change how they do feedback.

직원들과 학생들은 때때로 피드백에 대한 퇴행적인 관점을 가지고 있다는 편견이 있는데, 우리는 우리의 샘플 대부분이 그렇지 않다는 것을 알고 용기를 얻었습니다. 우리의 참가자들은 특히 그 목적에 관하여 우리가 상대적으로 긍정적이고 정교한 피드백의 관점을 가지고 있었다. 그러나 피드백에 대해 더 많이 생각하는 교육자와 학생들이 잠재적으로 주제에 대한 설문조사를 완료할 가능성이 더 높기 때문에 선택 편향의 결과일 수 있음을 경고한다.

Staff and students are sometimes stereotyped as holding regressive views of feedback, and we were heartened to find that this was not the case with most of our sample. Our participants held what we would regard as relatively positive and sophisticated views of feedback, especially with respect to its purpose. However, we caution that this could be a result of selection bias, with educators and students who think more about feedback potentially more likely to complete a survey on the topic.

그러나 이러한 정교함에도 불구하고, 우리의 참여자들에 대한 최근 효과적인 피드백 경험에 포함되지 않은 피드백에 대한 몇 가지 주제들이 여전히 존재한다. 평가적 판단, 동료 피드백, 예시 및 피드백 조정은 연구자들에 의해 보유 메리트로 간주되는 개념 또는 실천이다(Liu와 Carless 2006; Carless와 Chan 2016; Broadbent, Panadero, Boud 2018; Tai 등). 그러나 참가자들에 의해 가장 효과적인 것으로 인식되거나 경험 또는 우선순위화되지 않았다.

However, despite this sophistication there are still several frontier topics in feedback that have not featured in recent effective feedback experiences for our participants. Evaluative judgement, peer feedback, exemplars and feedback moderation are concepts or practices that are regarded as holding merit by researchers (Liu and Carless 2006; Carless and Chan 2016; Broadbent, Panadero, and Boud 2018; Tai et al. forthcoming), but either weren’t noticed, experienced or prioritised as most effective by our participants.

이 연구는 연구원과 학술 개발자들이 그들의 노력에 다시 집중할 수 있도록 도울 수 있다. 예를 들어, 피드백이 [학점을 정당화하는 것]이 아니라 [향상에 관한 것]이라는 것을 교육자와 학생들의 표본에 납득시키기 위한 개입은 거만한 것처럼 보일 수 있다. 그러나, 학생들에게 '코멘트의 질'에 초점을 맞추는 것에서 '그들이 그 코멘트로 무엇을 하는지'에 초점을 바꾸도록 하는 개입은 좋은 평가를 받을 수 있다. 왜냐하면, 학생들이 코멘트의 품질에 중점을 두었지만, 효과적인 코멘트의 가장 일반적으로 확인된 특징은 사용 가능하다는 것이었기 때문이다. 이 연구에서는 정서적, 관계적 문제가 크게 부각되지 않았다. 그러나, 우리는 다른 연구를 통해 이러한 문제들이 결정적이고 학생들의 다른 신체에 다르게 영향을 미친다는 것을 알고 있다. 이러한 교육자들과 학생들과의 정서적 문제에 대한 발전을 목표로 하는 것은 가치가 있을 수 있다.

This study may assist researchers and academic developers in refocusing their efforts. For example, interventions to convince this sample of educators and students that feedback is about improvement rather than justifying a grade may seem patronising. However, interventions to shift students from a focus on the quality of comments towards what they do with those comments may be well received, as, although there was a strong focus on the quality of comments, the most commonly identified feature of effective feedback comments was that they were usable. Affective and relational matters did not feature strongly in this study; however, we know from other research that these matters are crucial and impact different bodies of students differently (Telio, Ajjawi, and Regehr 2015; Ryan and Henderson forthcoming). It may be worthwhile to target development around affective matters with these educators and students.

본 연구의 분석은 피드백이 무엇인지에 대한 현대적인 이해에 바탕을 두고 있다. 즉, 피드백이란 [교육자가 설계하고 학습자가 수행하는 프로세스로서, 필연적으로 개선에 관한 것]이다. 피드백 연구 분야가 이러한 종류의 피드백 개념화를 적절하게 채택하려면, 이 프레임워크 내에서 해당 분야의 기본적인 발견과 가정을 재검토할 필요가 있을 수 있다. 비록 귀납적 접근법을 취했지만, 우리는 최근 몇 년간의 주요 개념적 주장을 무시할 수 없었다. 다른 귀납적 분석은 이 프레임 내에서 수행될 경우 피드백의 직원과 학생 경험에 대한 새로운 통찰력을 제공할 수 있다. 실용적인 관점에서도 제도적, 국가적 조사를 피드백의 보다 현대적이고 정교한 개념화로 옮겨갈 필요성이 크다(윈스톤과 피트 2017).

The analysis in this study was informed by a modern understanding of what feedback is: a process, designed by educators, undertaken by learners, which is necessarily about improvement. If the field of feedback research is to properly adopt this sort of conceptualisation of feedback, there may be a need to re-examine some of the fundamental findings and assumptions of the field within this framework. Although we took an inductive approach, we were unable to ignore key conceptual arguments from recent years; other inductive analyses may similarly yield new insights on the staff and student experience of feedback if conducted within this frame. From a practical perspective, there is also a great need to move institutional and national surveys toward more modern and sophisticated conceptualisations of feedback (Winstone and Pitt 2017).

그러나 우리의 현대적인 틀에도 불구하고, 우리는 몇몇 구식의 생각들이 여전히 널리 퍼져있다는 것을 발견했다. 예를 들어, 학생들은 피드백을 효과적으로 만든 것에 대해 '코멘트의 내용'에 압도적으로 집중했는데, 이는 언뜻 피드백 마크 2(Boud and Molloy 2013)와 같은 모델과 배치되는 것으로 보인다. 그러나 이에 비해 학생들의 관점에서 효과적인 코멘트의 가장 일반적인 특징은 '사용가능한 코멘트'였다.

Despite our modern framing, however, we found that some old-fashioned ideas remain prevalent. For example, students had an overwhelming focus on the content of comments as what had made feedback effective, which at first glance appears to run counter to models like Feedback Mark 2 (Boud and Molloy 2013). However, balanced against this, the most common feature of comments that made them effective from the student perspective was that they were usable.

이 연구는 교육자들과 학생들이 때때로 그들이 인정받는 것보다 더 정교한 피드백의 관점을 가질 수 있다는 것을 증명했다. 그러나 효과적인 피드백을 만드는 것에 대한 직원과 학생의 차이에도 불구하고, 피드백 연구자로서 피드백의 목적과 효과성을 고려하는 참여자와 저자의 차이가 가장 극명했다. 학생과 교직원은 코멘트를 '제공'하는 데 있다고 계속 믿고 있었고, 이는 피드백이 개선으로 이어질거라는 (종종 모호한) 생각과 관련된다. 그러나 그러한 믿음은 우리가 양질의 입력(정보 제공)이 어떤 모습인지에 대한 명확한 감각을 가지고 있다는 생각을 지나치게 강조한다. 대신, 우리는 피드백이 [학생들이 그들의 일에 대한 정보로 무엇을 하는지], 그리고 [이것이 그들의 일과 학습 전략에 어떻게 입증 가능한 개선으로 귀결되는지]를 보고 판단해야 한다고 주장한다. 즉, 효과적인 피드백은 효과를 입증할 필요가 있습니다. 그렇게 함으로써 우리는 의견의 형태를 포함한 전체 피드백 시스템을 가장 잘 판단하고 그에 따라 조정할 수 있습니다.

This study has demonstrated that educators and students may hold more sophisticated views of feedback than they are sometimes credited with. But despite the differences between staff and students around what makes for effective feedback, the starkest differences were between the participants and what we the authors, as feedback researchers, regard as the purpose of feedback and what makes it effective. Students and staff continue to believe the purpose of feedback is largely to ‘provide’ comments with (often vague) notions that it leads to improvement. However, such beliefs overemphasise the idea that we have a clear sense of what quality input (provision of information) looks like. Instead, we argue that feedback should be judged by looking at what students do with information about their work, and how this results in demonstrable improvements to their work and learning strategies. In other words, effective feedback needs to demonstrate an effect. In doing so we can best judge, and adapt accordingly, the entire feedback system, including the form of comments.

Abstract

Since the early 2010s the literature has shifted to view feedback as a process that students do where they make sense of information about work they have done, and use it to improve the quality of their subsequent work. In this view, effective feedback needs to demonstrate effects. However, it is unclear if educators and students share this understanding of feedback. This paper reports a qualitative investigation of what educators and students think the purpose of feedback is, and what they think makes feedback effective. We administered a survey on feedback that was completed by 406 staff and 4514 students from two Australian universities. Inductive thematic analysis was conducted on data from a sample of 323 staff with assessment responsibilities and 400 students. Staff and students largely thought the purpose of feedback was improvement. With respect to what makes feedback effective, staff mostly discussed feedback design matters like timing, modalities and connected tasks. In contrast, students mostly wrote that high-quality feedback comments make feedback effective – especially comments that are usable, detailed, considerate of affect and personalised to the student’s own work. This study may assist researchers, educators and academic developers in refocusing their efforts in improving feedback.

'Articles (Medical Education) > 교수법 (소그룹, TBL, PBL 등)' 카테고리의 다른 글

| 고르디우스의 매듭 풀기: 의과대학에서 재교육이 필요한 재교육 문제(BMC Med Educ, 2018) (0) | 2022.03.04 |

|---|---|

| 의과대학생 사이에서 학업적 어려움의 영향: 스코핑 리뷰(Med Educ, 2021) (0) | 2022.03.04 |

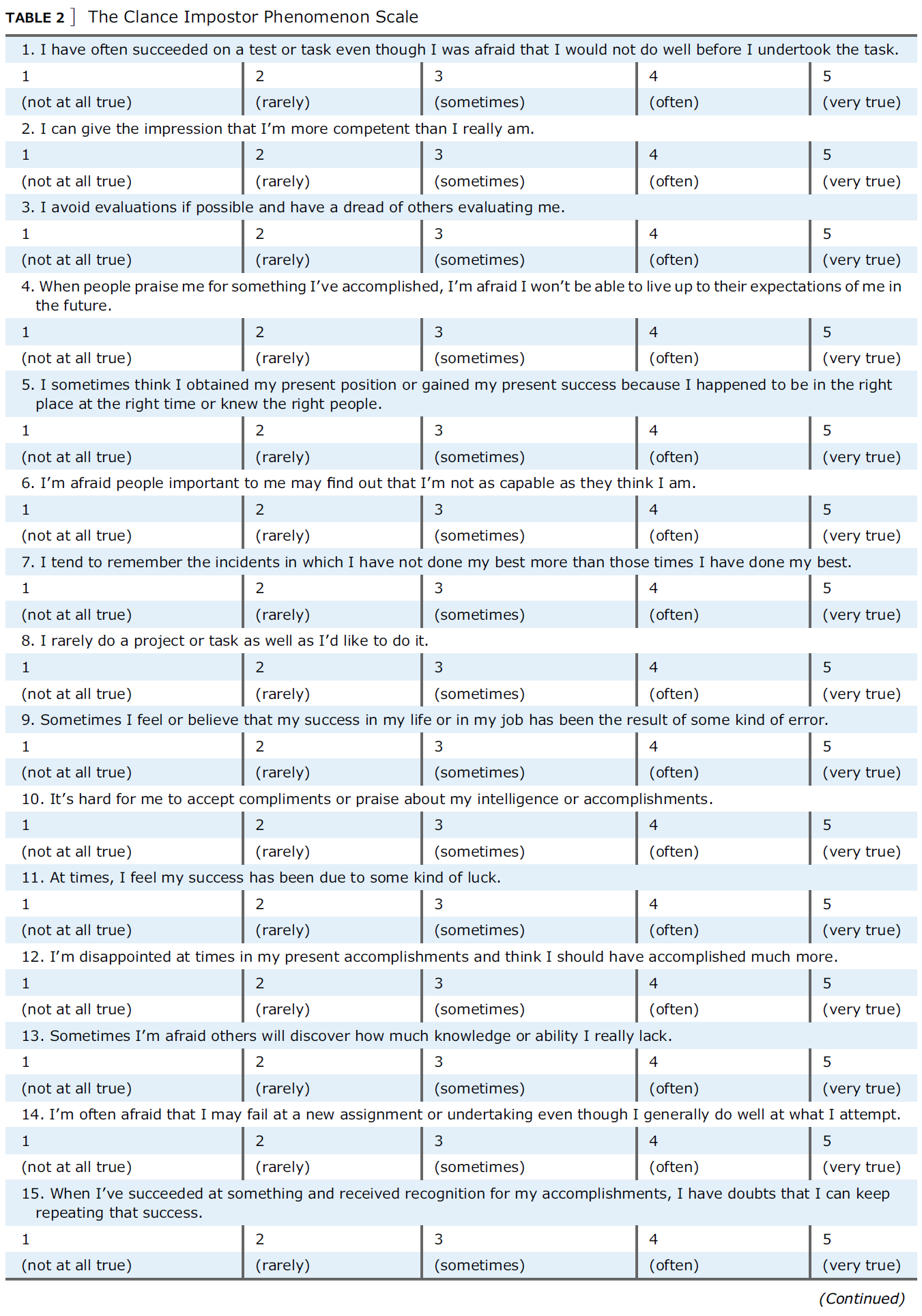

| 임포스터 신드롬: 당신 또는 당신의 멘티를 억누르고 있는가? (CHEST, 2019) (0) | 2022.01.07 |

| 의사소통 (스킬) 교육의 센스와 넌센스 (Patient Educ Couns. 2021) (0) | 2022.01.07 |

| 의학교육의 신화 폭로하기: 반증의 과학(Med Educ, 2019) (0) | 2021.08.29 |