모두에게 맞는 사이즈는 없다: 보건전문직교육 연구에서 개인-중심 분석(Perspect Med Educ, 2020)

‘One size does not fit all’: The value of person-centred analysis in health professions education research

Rashmi A. Kusurkar · Marianne Mak-van der Vossen · Joyce Kors · Jan-Willem Grijpma · Stéphanie M. E. van der Burgt · Andries S. Koster · Anne de la Croix

도입

Introduction

의료 교육 저널을 빠르게 스캔한 결과, 보건 직업 교육(HPE)에서 수행된 연구는 주로 변수-중심 분석variable-centred analysis [1]이라고 할 수 있는 것을 채택하고 있음을 알 수 있습니다. [주어진 표본에서 두 개 이상의 변수 간의 관계]를 조사하는 이러한 유형의 분석은 HPE 연구의 변수가 서로 어떤 영향을 미칠 수 있는지를 이해하는 데 중요합니다. 그러나 [많은 연구가 단지 몇 가지 변수에만 초점을 맞추고 있지만, 교육적 실천은 복잡하고 상황에 의존적이며 지저분할 수 있기 때문에], 교육자는 그러한 분석에 근거하여 실천 방식을 적용하거나 바꾸기가 어려울 수 있다.

A quick scan of medical education journals shows that the research conducted in health professions education (HPE) predominantly employs what can be called variable-centred analysis [1]. This type of analysis, which investigates the relationships between two or more variables in a given sample, is important in understanding how variables in HPE research can influence one another. However, it can be hard for educators to adapt or change their practice on the basis of such analysis, as many studies focus only on a few variables and educational practice can be complex, context-dependent and messy.

[사람 중심 분석]은 하위집단subgroup 전체에 걸쳐 변수가 서로 어떻게 관련되는지를 기반으로 [개인의 하위집단subgroup이 어떻게 만들어질 수 있는지]를 조사하는 추가 접근법입니다 [1]. 개인 중심 분석은 교육자에게 개인별 실천 이니셔티브를 위한 도구를 제공할 수 있는 결과를 생성합니다.

Person-centred analysis is an additional approach, which investigates how subgroups of individuals can be made based on how variables are related to each other across sub-groups [1]. Person-centred analysis generates findings that could provide educators with tools to personalize practice initiatives.

사람 중심 분석이란 무엇입니까?

What is person-centred analysis?

주어진 데이터 집합에서 [독립 변수에 대해 유사한 특성 또는 유사한 점수를 가진 사람들이 함께 군집화]하는 방식으로 [사람 그룹groups of people]을 만들 수 있다 [2]. 이는 [사례 기반 분석case-based analysis]의 한 유형으로, 즉 유사한 특성을 가진 개인 또는 사례에 대한 분석입니다. 이를 위해 일반적으로 변수 중심 분석에 사용하는 것과 다른 유형의 파일을 만들 필요가 없습니다. 유일한 차이점은 분석이 수행되는 방식입니다.

In a given dataset we can create groups of people in such a way that people with similar characteristics or similar scores on the independent variables are clustered together [2]. This is a type of case-based analysis, i.e. analysis of individuals or cases with similar characteristics. For this, we do not need to create a different type of file than what we would normally use for a variable-centred analysis. The only difference is the way the analysis is carried out.

종속 변수와의 연관성을 독립 변수로 간주하여 계산한다면, 특정 특성(예: 높은 공감과 높은 복원력)을 가진 그룹 1이 종속 변수(학업 성과)와 어떤 연관성을 가지는지를 보여주고, 그룹 2(예: 낮은 공감과 높은 복원력)가 보이는 종속 변수(학업성적)와의 연관성이 (그룹1과) 다르거나 유사하다는 것을 보여줍니다.

If the associations with the dependent variables are computed by considering group membership as the independent variable, we demonstrate that group 1 with certain characteristics (e.g. high empathy and high resilience) shows a certain type of association with the dependent variables (academic performance), group 2 (e.g. low empathy and high resilience) shows a different or similar association with the dependent variables (academic performance), and so on.

[사람 중심 분석]에서는 데이터의 패턴을 기반으로 '덜 명확한' 범주를 찾으려고 시도합니다. 통계적으로 말하면, 우리는 총 변동성을 '군간' 변동성과 '군내' 변동성‘between-group’ variability and ‘within-group’ variability으로 나누고 그룹 간의 차이를 해석하는 데 더 집중함으로써 데이터의 '잡음'을 줄이려고 합니다. 그런 다음 이러한 연구 결과에서 도출된 실제적인 의미는 특정 요구에 따라 [서로 다른 그룹에 맞게 커스터마이징]될 수 있습니다.

In person-centred analysis, the attempt is to find the ‘less obvious’ categories on the basis of patterns in the data. Statistically speaking we try to reduce the ‘noise’ in the data by splitting the total variability into ‘between-group’ variability and ‘within-group’ variability, and further concentrating on interpreting the differences between groups. The practical implications derived fromthese research findings can then be customized for the different groups as per their specific needs.

[사람 중심 분석]은 [[전체 표본] 또는 [인구통계학적 특성에 기반한 표본의 부분군]에 대해서 변수 간의 연관성을 찾는 변수 중심 분석]을 보완합니다.

Person-centred analysis complements variable-centred analysis, in which we look for associations between variables for the entire sample or subgroups in the sample made on the basis of demographic characteristics.

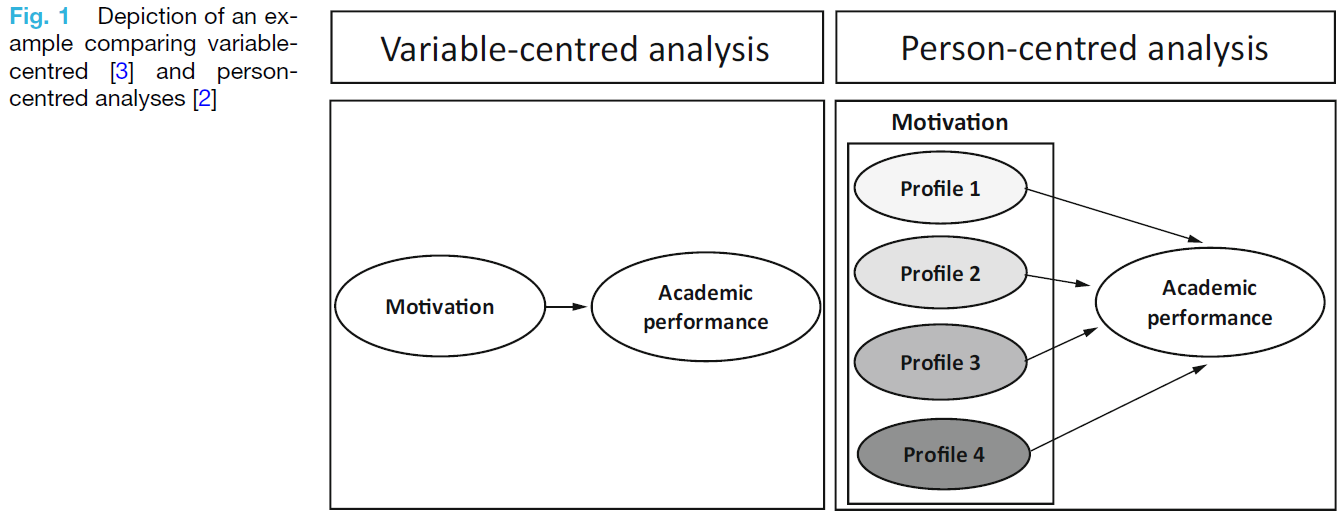

변수 중심 분석 [3]과 사람 중심 분석 [2]을 비교하는 예는 그림 1을 참조하십시오.

See Fig. 1 for an example comparing variablecentred [3] and person-centred analyses [2].

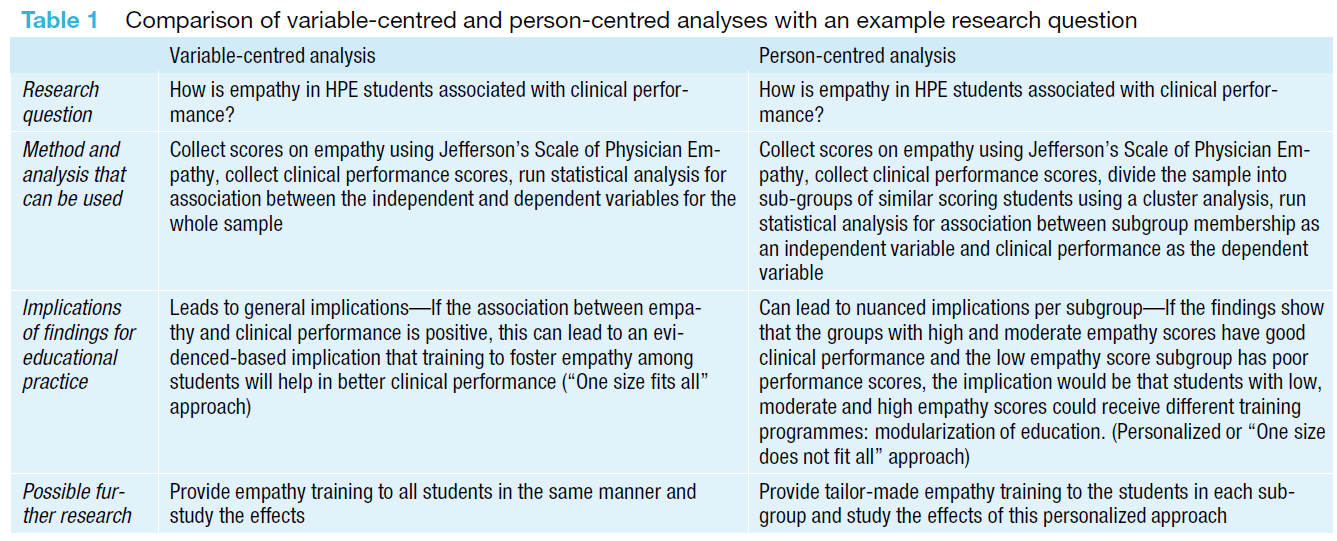

표 1은 예제 연구 질문에 대한 변수 중심 분석과 사람 중심 분석이 서로 어떻게 비교되고 보완되는지를 보여준다.

Tab. 1 illustrates how variable and person-centred analyses for an example research question compare with as well as complement each other.

문헌의 구체적인 사례를 포함한 사람 중심 분석 수행 방법

How to conduct person-centred analysis including concrete examples fromthe literature

전자 보완 자료에서 찾을 수 있는 본 문서의 부록에는 이 세 가지 방법, 이 방법을 사용한 분석 수행 방법에 대한 실제 단계 및 분석 결과를 해석하는 방법에 대한 세부 사항이 포함되어 있습니다. 자세한 내용에 관심이 있는 독자는 온라인 부록을 참조하시기 바랍니다.

In the Appendix of this paper, which can be found in the Electronic Supplementary Material, we have included details on these three methods, practical steps on how to conduct analyses using these methods, and how to interpret the findings of such analyses. We encourage the readers who are interested in more details to consult the online Appendix.

군집 분석

Cluster analysis

군집 분석 [4]은 [두 개 이상의 변수의 조합]에 대한 점수 또는 결과에 따라 연구 참가자를 함께 그룹화하는 방법입니다. 이 방법은 모든 종류의 샘플 크기에 사용할 수 있습니다. 이는 '그룹 내' 변동성을 줄이고 '그룹 간' 변동성을 극대화하여 데이터의 노이즈를 줄이려고 합니다.

Cluster analysis [4] is a method in which study participants are grouped together based on their scores or results on a combination of two or more variables. This method can be used with all kinds of sample sizes. It tries to reduce noise in the data by reducing ‘within-group’ variability and maximizing ‘betweengroup’ variability.

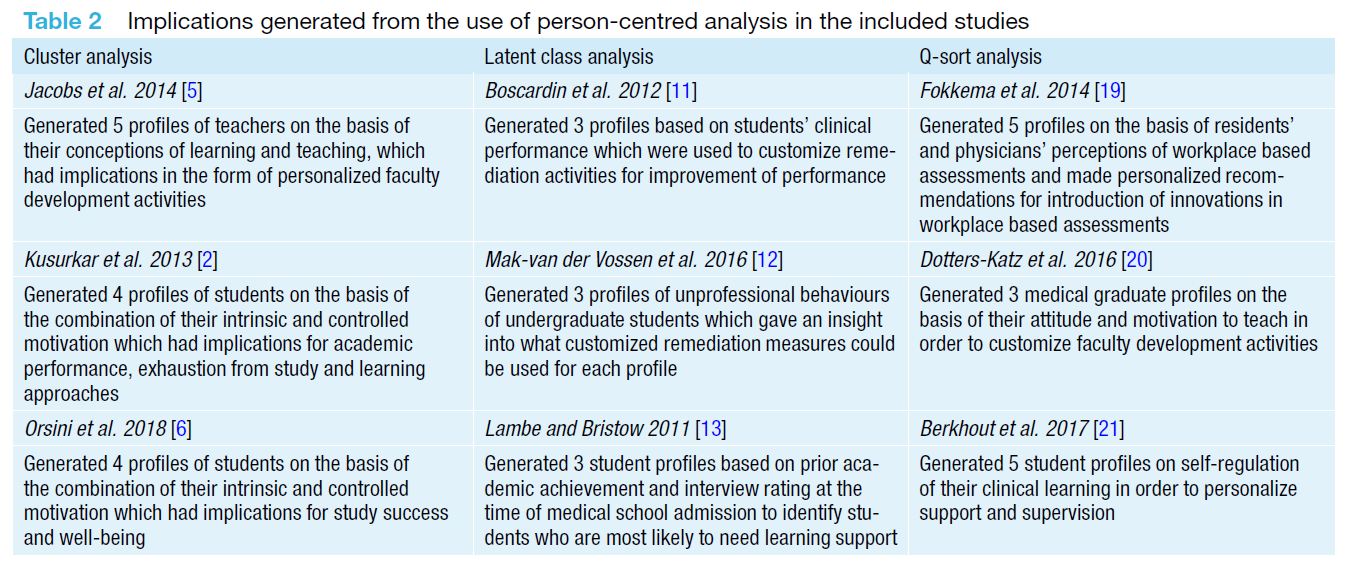

제이콥스 외 연구진[5] 이 연구의 목적은 COLT(학습 및 교육에 대한 교사 개념) 사이의 패턴을 탐구하는 것이었다. 저자들은 COLT의 3가지 차원 즉 교사 중심, 능동적 학습의 감사, 전문적 실무에 대한 오리엔테이션에 대한 참가자들의 점수를 이용하여 클러스터 분석을 실시했다. 이들은 5개의 클러스터로 구성된 클러스터 솔루션을 수용했습니다. 이러한 5가지 COLT 프로파일은 전송기, 조직자, 중간자, 촉진자 및 개념 변경 에이전트로 분류되었습니다.

Jacobs et al. 2014 [5] The aimof this study was to explore patterns among teachers’ conceptions for learning and teaching (COLT). The authors ran a cluster analysis using the participants’ scores on the three dimensions of the COLT: teacher-centredness, appreciation of active learning and orientationto professional practice. They accepted a cluster solution comprising five clusters. These five COLT profiles were labelled as transmitters, organizers, intermediates, facilitators and conceptual change agents.

Kusurkar et al. 2013 [2] 본 연구는 학생들의 [동기 부여와 성과] 사이의 관계를 조사하는 것을 목표로 하였다. 본 연구에서는 1~6학년 의대생들의 내적 및 통제된 동기 부여에 대한 점수를 바탕으로 프로필을 만들었다. 고유 저조 제어, 고유 고조 제어, 저 고유 고조 제어 및 저 고유 저조 제어로 분류된 네 가지 프로파일이 발견되었습니다. 그런 다음 이러한 프로파일과 학습 및 성과 결과의 연관성을 조사했습니다. 이러한 프로파일 각각은 이러한 결과와 서로 다른 연관성을 가지고 있었으며, [높은 내인성 낮은 통제] 프로파일은 더 많은 학습 시간, 심층 학습 전략, 우수한 학업 성과 및 낮은 학업 피로 측면에서 최상의 결과를 나타냈다. 사실 [높은 내인성 낮은 통제] 프로파일은 학업으로부터의 높은 소모와 연관지어 [높은 내인성 높은 통제] 프로파일과 차이가 있을 뿐이었고, 이는 연구 결과에 중요한 뉘앙스였다. 이러한 프로필은 모니터링 및 멘토링의 다른 방법이 필요하다는 권고 사항이었습니다.

Kusurkar et al. 2013 [2] This study aimed to investigate the relationship between student motivation and performance. In this study, profiles of medical students fromyear 1-6 were created on the basis of their scores on intrinsic and controlled motivation. Four profiles were found which were labelled as high-intrinsic low-controlled, high-intrinsic high-controlled, low-intrinsic high-controlled and low-intrinsic low-controlled. The associations of these profiles with learning and performance outcomes were then explored. Each of these profiles had different associations with these outcomes and the high intrinsic low controlled profile had the best outcomes in terms of more study hours, deep learning strategy, good academic performance and low-exhaustion from study. In fact the high intrinsic low controlled profile only differed from the high intrinsic high controlled profile in its association with higher exhaustion from study, which was an important nuance in our findings. Recommendations were that these profiles would need different ways of monitoring and mentoring.

Orsini et al. 2018 [6] 이 연구의 목적은 치과 학생들의 동기 부여와 그 학업 결과를 조사하는 것이었다. 저자들은 학생들의 본질적이고 통제된 동기를 바탕으로 프로필을 만들었습니다.

Orsini et al. 2018 [6] The purpose of this study was to investigate dental students’ motivation and its academic outcomes. The authors created profiles of students on the basis of their intrinsic and controlled motivation.

잠재 클래스 분석

Latent class analysis

잠재 클래스 분석[10](LCA)은 연구에 포함된 표본의 부분군(클래스, 클러스터)을 구성하는 것을 목표로 하는 [탐색적 통계 기법]이며, 이러한 표본의 관측된 지표를 기반으로 합니다. LCA는 범주형 데이터와 함께 사용할 수 있습니다. LCA의 출력output은 [지표의 조합에 기초한 가설적 그룹화hypothesized grouping]입니다.

Latent class analysis [10] (LCA) is an exploratory, statistical technique that aims at forming subgroups (classes, clusters) of the samples included in a study, based on observed indicators of these samples. LCA can be used with categorical data. The output of LCA is a hypothesized grouping based on a combination of indicators.

보스카딘 외 연구진[11] 이 연구는 교정조치에 대한 학생을 식별하고 교정조치에 대한 최선의 방법론적 접근법에 대한 합의에 기여하는 것을 목표로 했다. LCA는 임상성과검사에서 의대생 147명의 점수를 분석하는 데 사용되었다. 성능이 낮은 두 개의 하위 그룹을 포함하여 세 가지 뚜렷한 성능 프로파일이 식별되었습니다. [낮은 성과 부분군]을 두 그룹으로 구분하는 것은 의미가 있었는데, 이 두 그룹이 보여준 [성과 지표 집합]이 달랐기 때문이다. 첫 번째 하위그룹은 임상지식과 [모든 종류의 임상기술]에서 모두 결손이 나타났고, 두 번째 하위그룹은 주로 [의사소통 능력]에서 결손이 나타났다.

Boscardin et al. 2012 [11] This study aimed to identify students for remediation and to contribute to consensus about the best methodological approach for remediation. LCA was used to analyze scores of 147 medical students on the Clinical Performance Examination. Three distinct performance profiles were identified, including two low performing subgroups. Distinguishing two different low performing subgroups had significant implications, as the two groups had low scores on contrasting sets of performance indicators. The first subgroup of students showed deficits in both clinical knowledge and all kinds of clinical skills, while the second subgroup mainly displayed a deficit in communication skills.

Mak-Van der Vossen et al. 2016 [12] 본 연구의 목적은 의과대학에서 만족스럽지 못한 전문적 행동 평가를 받은 의대생들의 행동 패턴을 식별하고 이러한 패턴의 분류에 사용할 수 있는 변수를 정의하는 것이었다. 잠재적 그룹의 수에 대한 다양한 선택권을 가진 잠재 클래스 모형이 반응 데이터에 적합되었습니다. 이 경우, 응답 데이터는 앞서 문헌 검토에 기초한 템플릿에 요약된 바와 같이 109개의 비전문적 행동 각각을 학생 평가 보고서에서 '관찰됨' 또는 '관찰되지 않음'으로 기술했는지 여부를 나타냈다. LCA는 불만족스러운 전문 행동 보고서를 받은 학생 중 '신뢰성 저하', '신뢰성 저하 및 통찰력 저하', '신뢰성 저하, 통찰력 저하 및 적응성 저하' 등 3개 계층classes을 발표했다.

Mak-van der Vossen et al. 2016 [12] The purpose of this study was to identify patterns in the behaviours of medical students who received an unsatisfactory professional behaviour evaluation in medical school, and to define a variable that could be used for the categorization of these patterns. A latent class model with various choices for the number of latent groups was fitted to the response data. In this case, the response data indicated whether each of 109 unprofessional behaviours, as earlier summarized in a template based on a literature review, was described as ‘observed’ or ‘not observed’ in student evaluation reports. LCA yielded three classes of students who received unsatisfactory professional behaviour reports: ‘poor reliability’, ‘poor reliability and poor insight’, and ‘poor reliability, poor insight and poor adaptability’.

Lambe & Bristow 2011 [13] 이 연구의 초점은 학생 수행의 '유형학' 모델을 식별하는 것이었다. LCA는 선행 학업성취도 측정, 의과대학 입학 당시 면접등급, 과정 전반의 후속 성과 측정치를 바탕으로 학생 하위그룹을 만드는 데 사용되었다. LCA는 학생 시험 성과의 '유형'을 나타내는 구별되는 하위집단의 세 가지 클래스 모델을 식별했다.

Lambe & Bristow 2011 [13] The focus of this study was to identify a model of ‘typologies’ of student performance. LCA was used to make subgroups of students based on measures of

- prior academic achievement,

- interview rating at the time of medical school admission and

- outcome measures of subsequent performance across the course.

LCA identified a three class model of distinct subgroups representing ‘typologies’ of student examination performance.

Q-정렬 분석

Q-sort analysis

Q 방법론은 [주관성] 연구(예: 관점, 아이디어 및 의견)에 적합하다[16–18]. 참가자가 동의에 따라 순서를 매겨야 하는 자극(일반적으로 진술 형식)을 사용한다. 요인 분석의 특별한 형태를 사용하여 연구 대상 주제에 대해 비슷하게 생각하는 참가자를 그룹화한다.

Q-methodology is suitable for the study of subjectivity (e.g. viewpoints, ideas and opinions) [16–18]. It uses stimuli (usually in the form of statements) that participants need to rank order according to agreement. A special form of factor analysis is used to group participants who think similarly about the topic under study.

Fokkema et al. 2014 [19] 이 연구는 산부인과 레지던트 및 담당 의사의 작업장 기반 평가에 대한 인식을 결정하는 것을 목표로 했다. 36개의 진술과 65명의 참가자들이 있었다. 저자들은 열정, 규정 준수, 노력, 중립성, 회의의 다섯 가지 유형의 인식을 발견했습니다. 이 다섯 가지 프로파일의 기본 문제는 혁신의 의도된 목표, 적용 가능성 및 실제 영향에 대한 아이디어였습니다. 그들은 이 연구가 '동료들이 혁신에 대한 서로의 반응을 이해하는 데 도움이 될 수 있다'고 느꼈다.

Fokkema et al. 2014 [19] This study aimed to determine the perceptions of obstetrics-gynaecology residents and attending physicians about workplacebased assessment. There were 36 statements and 65 participants. The authors found five types of perceptions: enthusiasm, compliance, effort, neutrality, and scepticism. The issues underlying these five profiles were ideas about intended goals of the innovation, its applicability, and actual impact. They felt that the study ‘may help colleagues understand one another’s responses to an innovation’.

Dotters-Katz et al. 2016 [20] 본 연구는 미국 의대 졸업생들의 교육 태도와 동기 부여에 초점을 맞췄다. 47개의 문장이 사용되었다. 편의 표본추출을 통해 '다양한 전문분야 및 대학원생 수준의 전공의 107명'이 연구에 참여했으며, Q 정렬과 사후면접은 디지털 방식으로 진행됐다. 이들의 분석 결과 열정, 거부감, 보상이라는 세 가지 프로파일이 나왔습니다. 이러한 연구결과는 '교육을 촉진하고 교육생들의 교육 동기를 개선하는 태도 강화 및 장려'를 위한 교사로서의 레지던트 프로그램 설계 변경 사항을 알리기 위해 사용되었다.

Dotters-Katz et al. 2016 [20] This study focused on US medical graduates’ attitudes and motivation for teaching. Forty-seven statements were used. Through convenience sampling, 107 residents ‘from a wide variety of specialties and postgraduate year levels’ joined the study, and the Q-sorting and post-interview were done digitally. Their analysis yielded three profiles: enthusiasm, reluctance and rewarded. These findings were used to inform modifications in the design of resident-as-teacher programmes that ‘reinforce and encourage attitudes that promote teaching as well as improve trainees’ motivation to teach’,

Berkhout 등[21] Berkhout 및 동료들은 임상 환경에서 학생들의 자기조절 학습 행동 패턴을 찾는 것을 목표로 했다. 그들은 이론과 학생 인터뷰를 통해 52개의 진술문를 만들었습니다. 서로 다른 병원의 11개 임상실습에 속해 있는 4명의 학생이 진술서를 분류했다. 온라인 데이터 수집 절차를 사용했으며 '실시간' 분류후post-sorting 면접은 없었다. 그들의 분석은 참여적이고, 비판적으로 기회주의적이며, 불확실하고, 절제되고, 노력적인 다섯 가지 학습 패턴으로 이어졌다.

Berkhout et al. 2017 [21] Berkhout and colleagues aimed to find patterns in students’ self-regulated learning behaviours in the clinical environment. They created 52 statements from theory and student interviews. Four students in 11 different clinical clerkships, in different hospitals, sortedthe statements. An online data collection procedure was used and there was no ‘live’ post-sorting interview. Their analysis led to five patterns of self-regulated learning behaviour, which they called engaged, critically opportunistic, uncertain, restrained and effortful.

사람 중심 분석을 위한 세 가지 방법의 비교, 장점 및 단점

Comparisons, advantages and disadvantages of the three methods for person-centred analysis

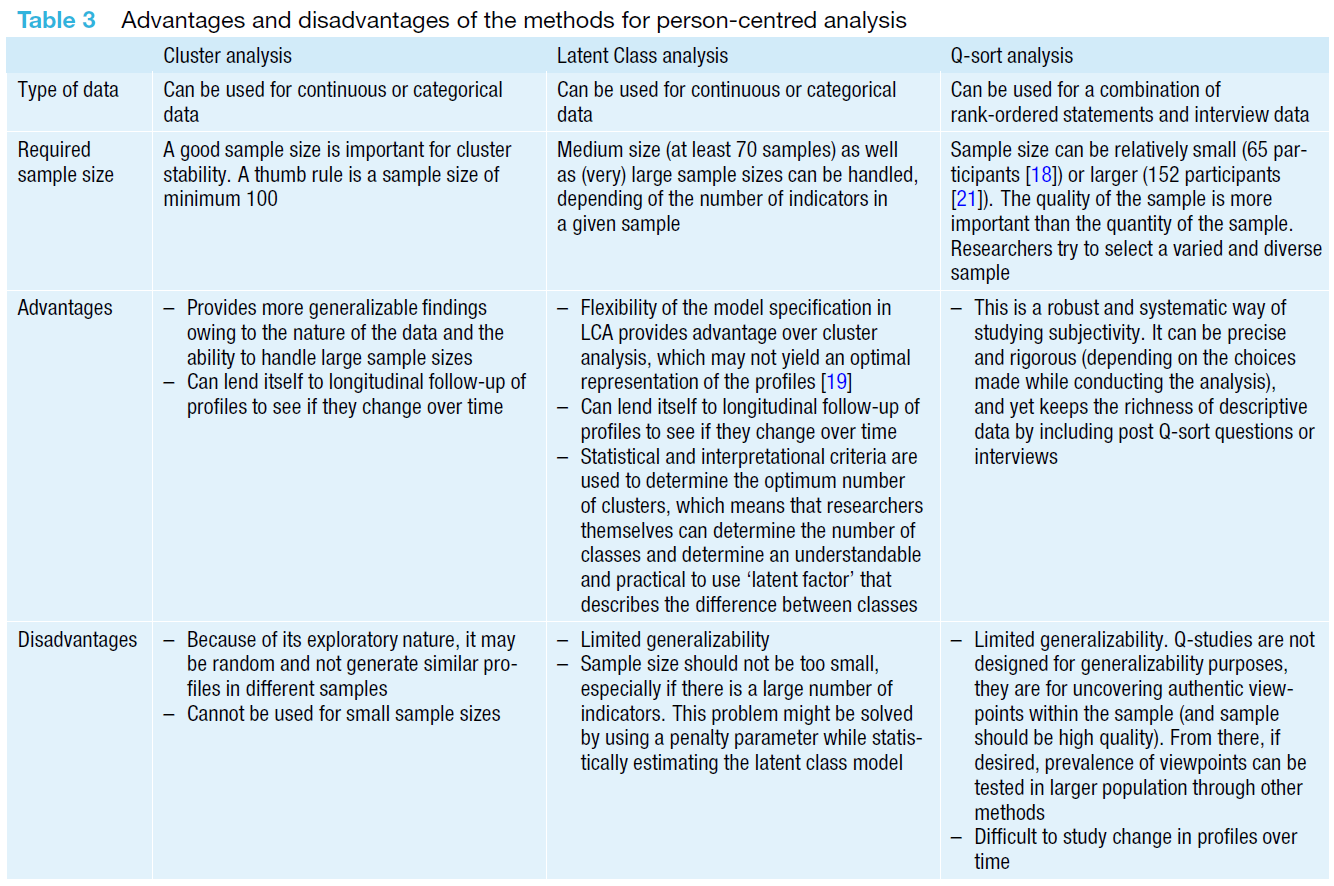

세 가지 분석 방법의 구체적인 장점과 단점은 표 3에 비교 요약되어 있다.

The specific advantages and disadvantages of the threeanalysismethodsarecomparedandsummarized in Tab. 3.

개인 중심 분석의 한계 및 윤리적 고려 사항

Limitations and ethical considerations of personcentred analysis

표본에서 발견되는 부분군은 [문화적으로 민감하고 맥락 의존적culturally sensitive and context-dependent]일 수 있습니다. 따라서 이 분석의 프로파일과 결과는 다른 모집단으로 일반화하기가 어려울 수 있다. 실제 개입을 설계하는 데 사람 중심 분석 결과를 사용하려면 [지역 대상 모집단local target population]의 프로파일 구조를 조사하는 것이 좋습니다. 사람 중심 분석은 변수 중심 분석을 대체하는 것이 아니라 보완 분석입니다. [특정 집단에 대한 오명stigmatization]을 남길 수 있다는 게 사람 중심 분석의 위험이다. 이러한 위험을 최소화하려면 다음과 같은 것이 중요합니다.

Subgroups found in samples may be culturally sensitive and context-dependent. The profiles and findings from this analysis could thus be difficult to generalize to other populations. To use the results of personcentred analyses for designing practical interventions, it is better to investigate the profile structure in the local target population. A person-centred analysis is not a replacement for variable-centred analysis, but a complementary analysis. A risk of person-centred analysis is that it can lead to stigmatization of certain groups. To minimize this risk, it is important that:

A. 개인 중심 분석을 사용하는 연구원들은 윤리 승인을 신청하고 연구 결과를 발표하는 경우 다음 작업을 수행합니다.

A. Researchers using person-centred analysis always do the following while applying for ethical approval and publishing their research:

– 이러한 분석을 수행한 배경과 근거를 설명합니다.

– Explain the background and rationale for conducting such an analysis;

– 분석 결과를 어떻게 해석해야 하는지 설명하며, 특히 상황에 유의해야 합니다.

– Explain how the results of this analysis should be interpreted, especially keeping in mind its context; and

– 이러한 연구 결과는 특정 그룹에 오명을 남기지 않고 사용자 개입을 맞춤화하는 건설적인 방법으로 사용되어야 한다고 선언합니다.

– Make a declaration that the results of such research should be used in a constructive way to customize interventions and not to stigmatize certain groups.

B. 윤리검토위원회는 항상 다음 사항을 고려한다.

B. Ethical Review Boards always consider the following:

– 연구진이 사람 중심 분석을 사용할 수 있는 충분한 근거를 제시했습니까?

– Have the researchers provideda goodrationale for using person-centred analysis?

– 연구자들이 실제로 생성된 프로파일을 맞춤형 또는 맞춤형 개입에 사용하고 있습니까?

– Are the researchers actually using the generated profiles for tailor-made or personalized interventions?

– 연구원들은 이 분석 결과를 어떻게 처리할 것인지 명확히 설명했습니까?

– How have the researchers clarified how they will treat the findings from this analysis?

Methodological details of cluster, latent class and Q-sort analyses

Cluster analysis1 - This analysis can be done quite easily using SPSS. Two ways of conducting this analysis are K-means clustering and hierarchical clustering. In SPSS, an additional ‘Two Step’ clustering procedure can be used to suggest an optimal cluster number.

K-means clustering is the most commonly used data clustering method. The methods sorts cases in a predefined number of clusters. The number of clusters can be based on theoretical (existing literature) or practical (applicability) considerations. Initial k-cluster centers are selected and then iteratively refined assigning each data point to its closest cluster-center and updating each cluster-center to be the mean of its constituent data points. An acceptable cluster solution should explain at least 50% of the variance in the variable scores and have an incremental effect over the cluster solution with (k-1) groups.

Hierarchical clustering is an approach in which all data points are clustered hierarchically until only one cluster is left. The optimal cluster solution is decided on the basis of a hierarchical diagram called a dendrogram, a taxonomy or hierarchy of data point. This is a convenient representation which answers questions such as: ‘How many useful groups are present in this data?’ and ‘What salient interrelationships are present?’.2

Hierarchical clustering techniques are fundamentally different from K-means clustering. K-means tries to find compact clusters, where cluster members are similar (as far as possible). Hierarchical clustering leads to a tree of clustering, where it remains arbitrary at what level you want to set the borders between clusters.

After using one of the cluster methods, the cluster solutions can be tested for stability using a double split cross validation procedure in which the sample is divided into two and the cluster solution with the same cluster centers is tested in each sample. For a stable cluster solution, the Cohen’s kappa values, derived from this procedure, should be as close to 1 as possible.3

For use on categorical data, this data needs to be treated first (e.g. with Homogeneity analysis using alternating least squares - HOMALS).4

| Practical steps for K-means cluster analysis: - Prepare your data file in SPSS just like for any other analysis. - Compute standardized scores (z-scores) for the variable which you would like to use to make the clusters. - Exclude outliers from the data as cluster analysis is sensitive to outliers. - Use the command “Classify” and enter the number of clusters (“n”)that you would like to test (start with 2 and then go on with 3 and more), choose “save assigned cluster”. - Then repeat the process with “n+1”, “n+2”, “n+3” clusters. - Check for the percentage of variance explained by the 2-cluster, 3-cluster, 4-cluster, etc. solutions. Using a benchmark of at least 50% variance explained, choose the cluster that explains a significant amount of variance The optimal number of clusters can be selected on the basis of statistical parameters and interpretability. - Once you have chosen a cluster solution, create two new files splitting your sample into two random subsamples. Run the clustering analysis on each subsample and see if you get similar clusters in both. Compute the Cohen’s kappa for checking the stability of the cluster solution. - Use cluster membership as the independent variable and run t-tests or Analysis of Variance or Multiple Analysis of Variance for the dependent variables of interests to see the relationship of the different clusters with the outcome measures. Interpretation of findings: - Try to understand the meaning of the clusters based on your hypothesis, theoretical framework and the scores on the variables used for clustering. - If possible label the clusters (without being judgemental) and provide a description of each cluster so that your interpretation becomes clear to the readers or practitioners. - Try to understand how the cluster characteristics are associated with outcome variables. - Before ascribing any meaning to the clusters, it is important to establish the cluster stability mentioned above. - Be cautious in projecting your findings to other contexts and cultures. |

Latent Class Analysis5 – This is also called Latent Partition Analysis (LPA). This is done in a manner that the samples in the study are homogeneous within, and heterogeneous between the formed subgroups. It is a flexible method, as the best fitting model is established by testing several combinations of numbers of classes. This can be done using the software programmes R6 or Latent Gold7.

LCA can be used if there exists a still-unknown, so called ‘latent’ variable that can be used to make subgroups of the samples under investigation. This newly emerging variable can be identified as a distinguishing factor for the content of the subgroups. The researchers then determine if the distinguishing factor has practical relevance, and attribute a meaningful description and name to it.

LCA has an advantage over other clustering methods because it can reveal patterns, i.e. combinations of indicators within a sample, that cannot easily be detected by other methods. LCA is a probabilistic method. It means that there is no one-to-one relationship between a class and the occurrence of an indicator within that class, but each class is composed of a subgroup that is more likely to display a certain pattern than the subgroup belonging to a different class. A similar classification process is applied in diagnosing a disease: The presence or absence of a certain symptom in a patient (indicator in a sample) does not always lead to one specific diagnosis (class), but a certain combination of symptoms (pattern) makes this diagnosis more likely. Thus, instead of making a black-and-white decision on the subgroups of samples as cluster analysis does, LCA defines the probability of certain patterns in the samples, and thus sketches a more attenuated picture.

LCA has the possibility of defining ‘prototypes’ in each subgroup. To achieve this, LCA specifies for each class a probability of a sample belonging to that class. The probabilistic statement indicates the certainty of the assignment of a sample, based on a certain combination of indicators, to that class. In particular, samples that have a high, say >90%, probability of belonging to a certain class could be considered as prototypes of that class.

| Practical steps for Latent Class Analysis: - Conduct thematic or content analysis of your descriptive data. - Convert the categorical data into binary response data, e.g. presence/absence of the indicator in each sample (SSPS or Excel file). - Put your binary data into one of the abovementioned software programmes. - Test different numbers and properties of classes. - Determine the best fit for the number and properties of classes by considering the following: · the statistical information indicating between class differences and within class homogeneity. · the practical relevance of the content of the classes. · the number of cases per class. - Define prototypes for each class by taking the samples that have the highest probability to belong to that class (e.g. the top 10). - Provide the prototypes of each class with narrative information from your descriptive data to generate profile descriptions for each class. Interpretation of findings: - Try to understand the meaning of the classes based on the practical relevance of the content of the classes and the descriptions of the prototypes. - Identify the latent variable that distinguishes the classes from each other, and give this variable a meaningful name. - Be aware that the samples are clustered into hypothetical patterns (the classes) based on the chance that they display a combination of indicators. - Be cautious in projecting your findings to other contexts and cultures. |

Q-sort analysis8-10- Although there is considerable flexibility in Q-methodology, there are some common practices. A Q-methodological study starts with the development of a set of statements on a topic (the Q-set). This set of statements can be created as a result of interviewing stakeholders, looking at teaching evaluations, theories and literature, focus groups, etc. This initial Q-set is often piloted and refined before use in a study.

Each participant sorts statements in a Grid (the Q-sort), with most statements placed in the middle, and the fewest placed at the edges (i.e. bell-curve shaped). These edges have 'strongly agree' or 'very important' on one side, and 'strongly disagree' or 'not at all important' on the other. This ranking process is called ‘Q-sorting’ and forces participants to make choices based on their own opinions and experiences. Usually the Q-sorting procedure is followed by a post-sorting interview or survey questions. In this post-sorting (often semi-structured) interview, or in some open survey questions, the participant elaborates on the reasons and stories behind the Q-sort, to enrich the data collected from the Q-sort.

Q-sorts are then compared to identify groups of individuals (profiles) who have similar attitudes on the subject of interest. This is often done using using Q-sort analysis software called PQmethod.11 The ranking scores are analysed statistically to lead to different factors10 using Q-sort analysis software. The number of profiles are dependent on how the participant scores 'load' onto a specific profile, similar to factor analysis. The qualitative data can aid the decision for the number of factors/profiles. The profiles are finalized through a combination of statistical, methodological and qualitative data analysis from a post Q-sort interview or survey questions. A description of the prototype of each profile is constructed by the researchers while constantly consulting the data.

| Practical steps for Q-sort analysis: - Develop a set of statements from the literature and pilot them with some study participants, refine them and your Q-set will be ready. - Select participants using theoretical sampling strategies, in order to include participants with diverse viewpoints. - Ask participants to sort the statements into the Q-grid, and ask participants to elaborate on their choices. - Enter the Q-sort of each participant into the abovementioned software and run the Q-sort analysis. - Check the different solutions for predetermined statistical criteria. At the minimal , you should take into account the percentage of variance explained by different solutions, eigenvalues, and number of Q-sorts per factor, total number of Q-sorts loading significantly on one factor, and Q-sorts loading on more than one factor or no factor at all. - Check the different solutions for methodological criteria: are the factors coherent, differentiated and recognizable? - Check if the qualitative data (from post-sorting interview) corroborates the factor solution. Interpretation of findings: - Try to understand the meaning of the profiles based on your research question and theoretical framework. - Combine the result from the factor analysis with the answers the post-sorting questions to create a rich and accurate profile description. - Label the profiles to capture their essence and improve the reader’s capability of comparing and contrasting the findings. |

10. Vermunt JK, Magidson J. Latent class cluster analysis. In: HagenaarsJ,McCutcheonA,editors. Appliedlatentclass analysis. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 2002. pp. 89–106.

Perspect Med Educ. 2021 Aug;10(4):245-251.

doi: 10.1007/s40037-020-00633-w. Epub 2020 Dec 7.

'One size does not fit all': The value of person-centred analysis in health professions education research

Rashmi A Kusurkar 1 2, Marianne Mak-van der Vossen 3 4, Joyce Kors 3 4, Jan-Willem Grijpma 3 4 5, Stéphanie M E van der Burgt 6, Andries S Koster 7, Anne de la Croix 3 4

Affiliations collapse

Affiliations

- 1Amsterdam UMC, Faculty of Medicine, Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam, Research in Education, Amsterdam, The Netherlands. R.Kusurkar@amsterdamumc.nl.

- 2LEARN! Research Institute for Learning and Education, Faculty of Psychology and Education, Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam, Amsterdam, The Netherlands. R.Kusurkar@amsterdamumc.nl.

- 3Amsterdam UMC, Faculty of Medicine, Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam, Research in Education, Amsterdam, The Netherlands.

- 4LEARN! Research Institute for Learning and Education, Faculty of Psychology and Education, Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam, Amsterdam, The Netherlands.

- 5LEARN! Academy, Faculty of Behavioural and Movement Sciences, Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam, Amsterdam, The Netherlands.

- 6Center for Evidence Based Education, Amsterdam UMC-location AMC, Amsterdam, The Netherlands.

- 7Department of Pharmaceutical Sciences, Utrecht University, Utrecht, The Netherlands.

- PMID: 33284407

- DOI: 10.1007/s40037-020-00633-wAbstractKeywords: Person-centred analysis; Personalized approach; Research method.

- Health professions education (HPE) research is dominated by variable-centred analysis, which enables the exploration of relationships between different independent and dependent variables in a study. Although the results of such analysis are interesting, an effort to conduct a more person-centred analysis in HPE research can help us in generating a more nuanced interpretation of the data on the variables involved in teaching and learning. The added value of using person-centred analysis, next to variable-centred analysis, lies in what it can bring to the applications of the research findings in educational practice. Research findings of person-centred analysis can facilitate the development of more personalized learning or remediation pathways and customization of teaching and supervision efforts. Making the research findings more recognizable in practice can make it easier for teachers and supervisors to understand and deal with students. The aim of this article is to compare and contrast different methods that can be used for person-centred analysis and show the incremental value of such analysis in HPE research. We describe three methods for conducting person-centred analysis: cluster, latent class and Q‑sort analyses, along with their advantages and disadvantage with three concrete examples for each method from HPE research studies.

- © 2020. The Author(s).

'Articles (Medical Education) > 의학교육연구(Research)' 카테고리의 다른 글

| 다중 비교에 관한 팩트와 픽션(J Grad Med Educ, 2021) (0) | 2021.10.22 |

|---|---|

| 통계학개론 (Adv Health Sci Educ Theory Pract. 2019) (0) | 2021.10.22 |

| 이론을 명시적으로 만들기: 의학교육 연구자는 이론과의 연계성을 어떻게 기술하는가(BMC Med Educ, 2017) (0) | 2021.08.25 |

| 문헌고찰: 양질의 의학교육연구를 위한 초석(J Grad Med Educ. 2016) (0) | 2021.08.25 |

| The Green Lumber Fallacy, Jingle-Jangle Fallacies (0) | 2021.05.13 |