체면을 차리기 위한 헷징: ITER의 서술형 코멘트의 언어학적 분석(Adv in Health Sci Educ, 2015)

Hedging to save face: a linguistic analysis of written comments on in-training evaluation reports

Shiphra Ginsburg1,5 • Cees van der Vleuten2 • Kevin W. Eva3 • Lorelei Lingard4

도입

Introduction

교육 내 평가 보고서(ITERs)와 같은 업무 기반 평가에 대해 교수진이 작성한 논평이 어려움에 처한 학생을 식별하고(Cohen et al. 1993), 순위/정렬 훈련생(Ginsburg et al. 2013), 성공 또는 실패를 예측하는 데 유용할 수 있다는 증거가 증가하고 있다(Guerasio et al. 2012). 그러나, 최근의 연구는 쓰여진 코멘트가 상당부분 모호하고 '습관적dispositional' 언어를 포함하고 있음을 시사한다(Ginsburg et al. 2011). 교수진은 이를 "행간 읽기"로 해독한다(Ginsburg et al. 2015). 교육생에 대한 [교수진의 모호한 논평]이 어제오늘 일이 아님에도 불구하고, 우리는 교수진이 왜 이러한 발언을 하는지, 다른 교수진이 어떻게 그러한 발언을 디코딩할 수 있는지, 교육생에게 미치는 영향이 무엇인지 아직 이해하지 못하고 있다(Watling et al. 2008).

There is growing evidence that comments written by faculty on work-based assessments such as in-training evaluation reports (ITERs) can be useful for identifying students in difficulty (Cohen et al. 1993), for ranking/sorting trainees (Ginsburg et al. 2013) and for predicting success or failure (Guerrasio et al. 2012). However, recent work suggests that written comments contain a prevalence of vague and ‘dispositional’ language (Ginsburg et al. 2011), which faculty decode by ‘‘reading between the lines’’ (Ginsburg et al. 2015). Despite a well-established tradition of vague comments in faculty evaluation of trainees (Kiefer et al. 2010; Lye et al. 2001), we don’t yet understand why faculty do this, how other faculty are able to decode such comments, or what their implications are for trainees (Watling et al. 2008).

[글에 막연한 언어가 있는 것]은 그 문장을 해석하려는 독자들에게 좌절의 원인이 될 수 있다. 예를 들어, '함께 일하기 좋은 사람'(Lye et al. 2001)과 같은 의견이나 전공의가 얼마나 열심히 일했는지를 반영하는 의견(Ginsburg et al. 2011)은 매우 일반적이지만, 학습자의 성과를 판단하는 데 특히 도움이 되지 않는다고 한 연구 참가자가 지적한 바 있다(Ginsburg et al.. 2015). 이러한 코멘트에 대한 한 가지 가능한 설명은 교직원들이 교육생들을 잘 알지 못할 수 있기 때문에 "누구에 대해서나 써먹을 수 있는" 코멘트에 의존한다는 것이다(Ginsburg et al. 2015). 또 다른 설명은 모호한 언어를 의도적으로 사용한다는 것이다. 예를 들어, 교수진들은 "좋은 말을 할 수 없다면 아무 말도 하지 말라"는 원칙을 준수하기 위한 실제적 결핍에 대한 언급을 회피할 수 있다(Ginsburg et al. 2015). 막연한 논평에 대한 또 다른 잠재적 이유는 (특히 수련생의 수행능력이 안 좋을 경우) 평가가 어렵고, [애매한 언어를 사용하는 것]이 ITER의 양쪽 모두에게 부정적인 영향을 끼치지 않도록 보호하는 데 도움이 된다는 현실과 관련이 있습니다(Ilott 및 Murphy 1997).

The presence of vague language in written comments can be a source of frustration to readers who try to interpret them. For example, comments such as ‘‘pleasant to work with’’ (Lye et al. 2001), or those that reflect how hard a resident worked (Ginsburg et al. 2011), are extremely common, yet are considered particularly unhelpful for judging learners’ performance—as a participant in one study noted, ‘‘if you’re a good person you get those’’ comments (Ginsburg et al. 2015). One potential explanation for such comments is that faculty may not know their trainees very well, so they resort to comments that ‘‘you could say about anyone’’ (Ginsburg et al. 2015). Another explanation is that vague language is used deliberately. For example, faculty may avoid commenting on an actual deficiency to abide by the principle that ‘‘if you can’t say anything nice, don’t say anything at all’’ (Ginsburg et al. 2015). Another potential reason for vague comments relates to the reality that evaluation is difficult—especially when a trainee is not performing well—and that the use of vague language helps guard against negative consequences for individuals on both sides of the ITER (Ilott and Murphy 1997).

ITER에서 모호한 언어의 현상을 체계적으로 탐구하기 위해 실용적 의사소통을 위해 언어가 어떻게 사용되는지 고민하는 실용주의라는 언어학의 한 분야로 눈을 돌렸다. [언어적 실용론Linguistic pragmatics]은 우리가 일상에서 사용하는 언어의 많은 부분이 문자 그대로 해석되는 것이 아니라고 주장한다. 아이러니, 빈정거림, 은유를 표현하는 언어는 이 전제를 쉽게 식별할 수 있는 예이다. 또한 [비문자적 표현Non-literal language]는 관습적인 간접성(Brown and Levinson 1987)의 개념을 포함하는데, 여기서 '좋은' 또는 '기대치를 충족'과 같은 단어와 구절은 (관습적으로) 평균 이하를 의미할 수 있다(Kiefer et al. 2010). 최근의 한 연구에서는 필기 ITER 코멘트에서 비문자적 표현Non-literal language 사용 사례가 많이 보고되었지만(Ginsburg et al. 2015), 교수진들은 그러한 코멘트만을 사용하여 높은 신뢰성으로 전공의의 순위를 매길 수 있는 것으로 밝혀졌다(Ginsburg et al. 2013). 서술적 평가 논평에 언어적 프레임워크linguistic frameworks를 적용하는 것은 모호해 보이는 언어가 어떻게 신뢰성 있게 해석될 수 있는지를 설명하는 데 도움이 될 수 있다.

To systematically explore the phenomenon of vague language in ITERs in more depth we turned to the branch of linguistics called pragmatics, which is concerned with how language is used for practical communication. Linguistic pragmatics argues that much of the language we use in day to day practice is not meant to be interpreted literally. Language expressing irony, sarcasmand metaphors are readily identifiable illustrations of this premise (Akmajian et al. 2010). Non-literal language also includes the concept of conventional indirectness (Brown and Levinson 1987), whereby words and phrases such as ‘good’ or ‘meets expectations’ can—by virtue of convention—come to mean below average (Kiefer et al. 2010). A recent study reported many examples of non-literal language use in written ITER comments (Ginsburg et al. 2015), but it was also found that faculty were able to rankorder residents using such comments alone with a high degree of reliability (Ginsburg et al. 2013). The application of linguistic frameworks to narrative assessment comments may help to explain how language that seems vague can be reliably interpreted.

실용주의 안에서, [예의 이론theory of politeness] 은 평가 맥락에 특정한 목적적합성과 적용가능성을 가지고 있다. 1970년대 브라운과 레빈슨(Brown and Levinson 1987)에 의해 처음 개발되었으나, 새로운 이론과 제안된 변경에도 불구하고 여전히 영향력이 있다(Fraser 1990; Mills 2003). 브라운과 레빈슨의 프레임워크는 사회학에서 처음 설명한 것처럼 '체면'이라는 개념에 기반을 두고 있다. '체면'의 개념이 시간이 지나면서 다른 의미를 띠었지만, 브라운과 레빈슨의 관점에서 볼 때, [체면]은 [개인이 보호하려는 공적의 자기 이미지]이다.

- 긍정적인 체면은 사람이 자신에 대해 가지고 있는 긍정적인 이미지(자존심)입니다.

- 부정적인 체면은 자신의 행동을 방해받지 않으려는 욕망(행동의 자유)입니다.

Within pragmatics, the theory of politeness has particular relevance and applicability to an evaluation context. Originally developed by Brown and Levinson in the 1970s (Brown and Levinson 1987), it remains influential in spite of newer theories and suggested modifications (Fraser 1990; Mills 2003). Brown and Levinson’s framework is based on the idea of ‘face’, as first described in sociology (Bakker 2007).The concept of face has taken on different meanings over time but from Brown and Levinson’s perspective, in essence, face is the public self-image that individuals try to protect.

- Positive face is the positive image a person has of him/herself (self-esteem);

- negative face is the desire to not have one’s actions impeded (freedom to act).

[체면 위협 행위(FTA)]의 상황에서, 우리는 종종 [말하는 사람과 듣는 사람 모두를 위해] 체면 상실을 완화하기 위해 언어 전략을 사용한다(이론으로 사용되는 용어는 대부분 구술 언어에 근거하여 개발되었다). 체면을 위협하는 행동의 흔한 예는 동료에게 부탁을 하는 것이다. 거절당하거나, 청취자에게 은혜를 입히거나, 궁핍한 사람으로 비칠 가능성이 있기 때문이다. 따라서 [부탁을 하는 사람]은 잠재적으로 체면을 위협받을 수 있다. 그것은 또한 [부탁을 받는 사람]에게도 위협적인 면인데, 그녀가 말하는 사람을 불쾌하게 하거나 그녀의 명성에 도움이 되는 것으로 영향을 미치지 않는 방식으로 반응해야 하기 때문이다. 이런 부탁을 하기 위해 발화자speaker는 동료에게 먼저 칭찬(최근 교직상이나 보조금 대회에서의 성공)을 할 수 있는데, 이는 동료의 이미지를 높여 (동료의) 긍정적인 체면을 구제redress해주고, 도움을 청할 수 있는 이유를 설명해줌으로써 자신의 체면을 구제redress해준다.

In the setting of a face threatening act (FTA), we often invoke linguistic strategies to mitigate against potential loss of face, for both the speaker and hearer (the terminology used as the theory was developed based mostly on oral language). One common example of a face threatening act is asking a colleague for a favour. It is potentially face-threatening for the person asking as there is a possibility that he may be turned down, become indebted to the hearer, or be seen as needy. It is also face threatening to the hearer, as she is imposed upon and must respond in a way that does not offend the speaker or affect her reputation as being helpful. To make such a request, the speaker may choose to compliment his colleague on something first (her recent teaching award or success at a grant competition), which redresses her positive face by enhancing her self-image and redresses his face by explaining why one might seek her assistance.

우리가 더 흔히 접하는 듣는이hearer의 '부정적인 체면'을 구제하는 방법은, '귀찮게 해드려서 정말 죄송합니다' 또는 '당신이 얼마나 바쁜지 알아요'와 같은 문구를 사용하는 것이다. 브라운과 레빈슨(1987)은 이러한 언어 전략이 말하는 사람과 듣는 사람에게 미치는 영향과 함께 체면을 구제하기 위해 사용되는 언어의 종류를 이해하기 위한 명확한 틀을 개발했다. 예의 전략이 사용되는 정도와 채택된 전략의 유형은 행위가 위협적인 상황에 직면해 있다고 간주되는 정도를 반영한다.

More commonly we redress hearers’ so-called ‘negative face’ by using phrases such as ‘‘I’m so sorry to bother you’’, or ‘‘I know how busy you are’’, which addresses their desire to not be interfered with. Brown and Levinson (1987) developed an explicit framework for understanding the types of language used to redress face along with the effects that these linguistic strategies have on the speaker and hearer (or writer and reader). The degree to which politeness strategies are used—and the types of strategies employed—reflect the degree to which an act is considered to be face threatening.

[헷징hedging]은 이러한 예의체계 안에 있는 체면상실을 완화하기 위해 사용되는 매우 일반적인 전략 중 하나이다. 브라운과 레빈슨은 헤지(hedge)를 "멤버십 정도를 수정하는 단어 또는 구절"로 정의하며, 멤버십 정도가 "일부적"이거나 특정 측면에서만 진실이라고 말한다(브라운과 레빈슨 1987, 페이지 145). 의사-의사 담론의 위험회피에 대해 연구한 Prince를 포함한 다른 연구자들은 위험회피에 대해 추가로 정의하고 분류하였다(Prince et al. 1982, 페이지 93).

Hedging is one very common strategy used to mitigate against loss of face that sits within this politeness framework. Brown and Levinson define a hedge as a ‘‘word or phrase that modifies the degree of membership … in a set’’; it says that the membership is ‘‘partial, or true only in certain respects’’ (Brown and Levinson 1987, p. 145). Other researchers have further defined and categorized hedges, including Prince, who studied hedging in physician–physician discourse (Prince et al. 1982, p. 93).

Prince는 두 가지 주요 유형의 헷지를 보고했다: 근사치와 방패.

- 근사치는 두 가지 방법 중 하나로 명제의 '진실 조건'에 영향을 미친다.

- 어댑터는 용어를 비전형적non-prototypical 상황(예: ''환자의 발이 약간 파랗다'')에 적응시키고,

- 라운더는 항이 숫자의 반올림 표현(예: ''혈압은 약 120/80'')임을 나타낸다.

Prince reported two main types of hedges: approximators and shields.

- Approximators affect the ‘truth conditions’ of a proposition in one of two ways:

- adaptors adapt a term to a non-prototypical situation (e.g., ‘‘the patient’s feet were a little bit blue’’) and

- rounders indicate that a term is a rounded-off representation of a number (e.g., ‘‘the blood pressure was about 120 over 80’’).

- 방패는 명제의 '진실 조건'에 영향을 미치지 않는다. 오히려 발언자가 "실제로 얻어진 것affairs의 관련성 상태에 대한 믿음"에 완전히 전념하지 않는다는 것을 암시한다(Prince et al. 1982, 페이지 89).

- 귀속 방패는 진술을 작성자가 아닌 다른 사람에게 귀속시키는 역할을 하는 반면,

- 개연성 방패는 발표자/작가가 진술의 진실에 전적으로 헌신하지 않는다는 것을 표시함으로써 의심의 요소를 도입한다(예: 전공의와의 짧은 만남 중…).

- Shields do not affect the ‘truth conditions’ of their propositions; rather they implicate that the speaker ‘‘is not fully committed to the belief that the relevant state of affairs actually obtains’’ (Prince et al. 1982, p. 89).

- Attribution shields serve to attribute the statement to someone other than the writer, whereas

- plausibility shields introduce an element of doubt, by allowing the speaker/writer to indicate that s/he is less than fully committed to the truth of the statement (e.g., ‘‘during my brief encounters with the resident…’’).

이는 보다 최근에 Fraser가 제안한 헷징 개념화와 유사하며, Fraser는 헷징이 [언어적 장치]를 사용하여 발표자가 말한 것에 대한 [약속commitment이 없음]을 표시함으로써, 체면을 세울 수 있는 수사적 전략이라고 언급한다(Fraser 2010) . 우리의 맥락에서 위험회피에 대해 이해하기 위해, 전공의의 지식 기반이 "평균보다 약간 낮은" 것처럼 보인다는 주치의의 서면 의견을 생각해보자. 브라운과 레빈슨에 따르면, Prince와 Fraser 모두에게 이 진술은 '헷징'이다.

- '어댑터'(전공의가 평균 이하의 범주에 완전히 포함되지 않음을 나타냄)로 간주될 수도 있고

- '방패'(전공의가 평균 미만이라는 주장을 전적으로 약속하지 않음을 나타냄)로 간주될 수 있다.

This is similar to a more recent conceptualization of hedging by Fraser, who states that hedging is a rhetorical strategy by which a speaker, using a linguistic device, can save face (for himself or others) by signalling a lack of commitment to what is said (Fraser 2010). To understand hedging in our context, consider an attending’s written comment that a resident’s knowledge base seems ‘‘a little below average’’. According to Brown and Levinson, as well as to both Prince and Fraser, this statement is hedged.

- It could be considered an ‘adaptor’ (indicating the resident isn’t fully in the category of below average) or

- it could be a ‘shield’ (indicating that the attending isn’t fully committed to the assertion that the resident is below average).

헷지는 [표현의 의미적 범주에 대한 완전한 확약을 나타내지 않는 것]을 뜻하며, 일종의, 거의, 대략 등의 문구로 나타낼 수 있다. 헷지의 또 다른 방법은 speech가 표현하는 힘에 전적으로 전념하지 않는 것입니다. 예를 들어 I suppose, maybe, 또는 I think와 같은 문구를 사용하는 것입니다.

Hedges that indicate less than full commitment to the semantic category of an expression can be represented by phrases such as sort of, almost,or like. Another way to hedge is by not commi tting fully to the force of the speech being expressed, by using phrases such as I suppose, perhaps, or I think.

요약하자면, 서면 평가는 의학 교육의 중요성이 높아질 가능성이 높지만, 종종 모호하고 해독하기 어려울 수 있습니다. 언어적 실용주의, 특히 예의 이론과 헷징은 평가 언어의 모호함을 이해하고 이해하는 데 도움이 될 수 있습니다.

To summarize, written assessments will likely take on increasing importance in medical education, yet are often vague and can be frustrating to decode. Linguistic pragmatics—in particular, politeness theory and hedging—might help us understand and make sense of some of the vagueness in assessment language.

방법 및 분석

Methods and analysis

우리는 토론토 대학교 내과과 1학년 레지던트(PGY1)의 단일 코호트에 대한 ITER 양식을 취합했습니다(n = 63). 이 프로그램의 각 전공의는 평균 9번의 로테이션을 완료하며, 이 회전을 위해 ITER가 생성됩니다. 매 로테이션이 끝날 때마다 담당의사가 평가 대상 레지던트에 대한 단일 ITER를 완료합니다.

We compiled ITER forms for a single cohort of first year residents (PGY1’s) in Internal Medicine at the University of Toronto (n = 63). Each resident in this program completes an average of nine rotations for which ITERs are generated. The attending physician at the end of every rotation completes a single ITER for the resident being assessed.

이 분석에서는 극단적 집단이 특이하거나 표준과 다르기 때문에 더 "정보가 풍부"할 수 있고, 비교의 유용한 근거를 제공할 수 있기 때문에 [최고 등급]과 [최저 등급]의 전공의를 포함하기로 결정했다. (Patton 2002)

For this analysis we chose to include the highest and lowest rated residents, as extreme groups can be more ‘‘information rich’’ because they are unusual or differ from the norm, and can provide a useful basis for comparison. (Patton 2002)

코딩은 Brown과 Levinson의 예의 프레임워크을 사용하여 (아래에 자세히 설명된 바와 같이) 각 주석 상자에 대한 한 줄씩 접근하는 것으로 시작되었습니다. 프레임워크는 이러한 목적을 위한 두 가지 관련 섹션으로 구성되어 있다:

- 긍정적인 체면을 다루는 전략 (작성자가 독자가 원하는 것을 표시함으로써)

- 부정적인 체면을 다루는 전략 (본질적으로 "[작성자]가 수취인의 행동의 자유를 방해하지 않을 것임을 보증하는 것 … 자기 만족, 격식 및 구속"

Coding began with a line-by-line approach to each comment box (as described in more detail below) using Brown and Levinson’s politeness framework. The framework has two relevant sections for this purpose:

- strategies addressing positive face (by indicating that the writer wants what the reader wants) and

- strategies addressing negative face (which essentially ‘‘consist in assurances that the [writer] will not interfere with the addressee’s freedom of action …self-effacement, formality, and restraint’’ (Brown and Levinson 1987, p. 70).

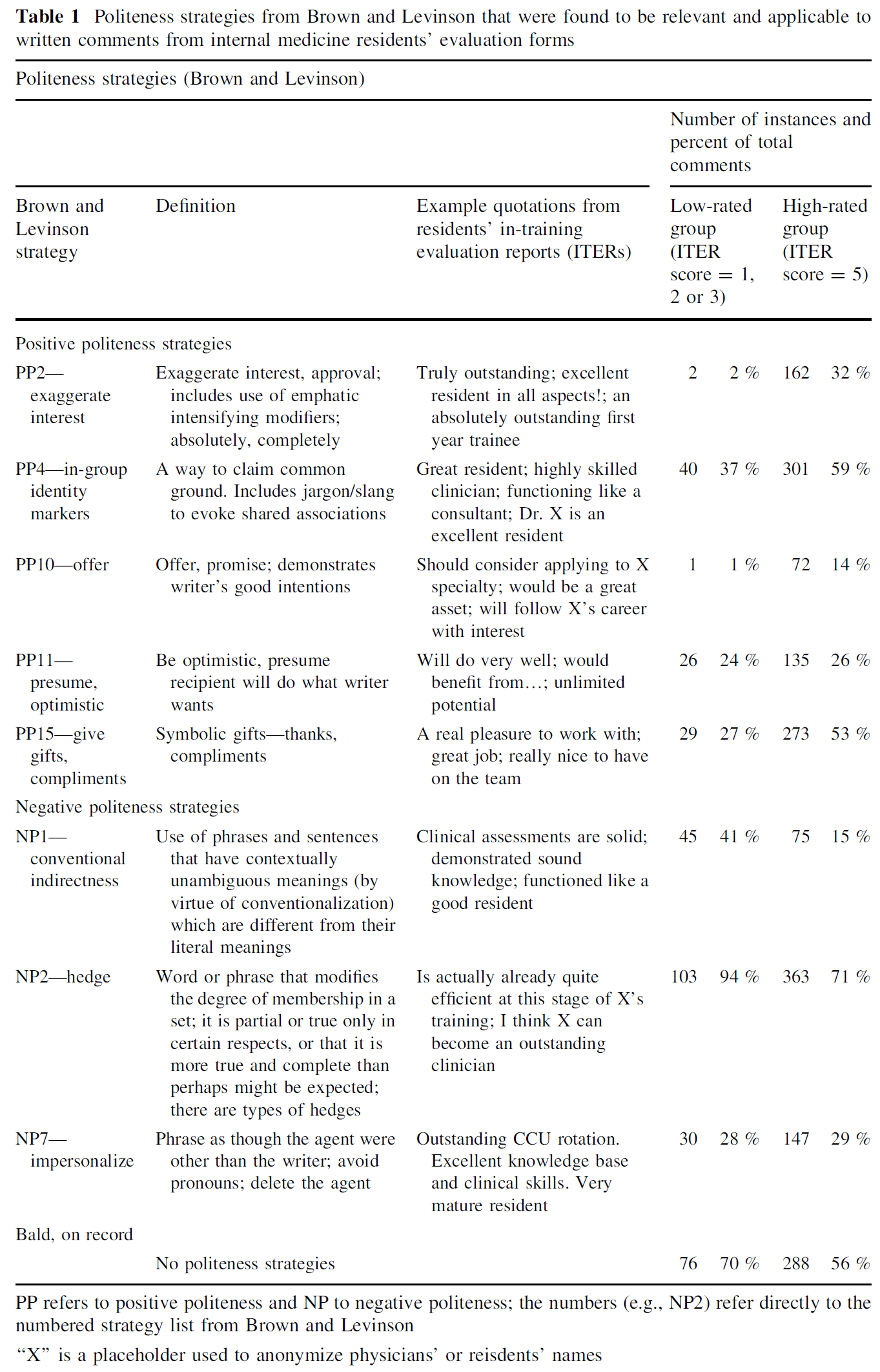

표 1은 우리의 데이터와 관련된 전략의 정의와 대표적인 인용문을 포함하고 있다.

Table 1 contains definitions of the strategies that were relevant to our data, along with representative quotations.

반복적인 읽기 및 분석에서 우리는 헷징이 만연하다는 것을 발견하였고, 도입부에서 간략히 언급한 Prince et al.(1982)가 제안한 보다 상세한 개념화를 사용하여 이를 코드화하였다. 저자에 따르면 헷징은 일반적으로 두 개의 부분집합을 갖는 '방패'의 형태로 표현된다.

On iterative reading and analysis we discovered that Hedging was pervasive so we coded it further by using the more detailed conceptualization proposed by Prince et al. (1982) that was briefly mentioned in the introduction. According to the authors, hedging is commonly expressed in the form of ‘shields’, which have two subsets.

- [귀인 방패]는 문장을 작성자가 아닌 다른 사람에게 귀속시키는 역할을 합니다. 그들은 전달된 진술이 때로는 특정되고 때로는 그렇지 않은 다른 누군가에게 귀속되어야 한다는 것을 암시한다. 일반적인 예로는 'A의 가르침에 대해 하우스 스태프가 정말 고마워했다' 또는 'B의 수행에 대해 수많은 의견을 받았다'와 같은 문구들이 있다. '분명히 노력한다' 또는 '명백하게 뛰어난 의사소통 능력을 가지고 있다'와 같은 진술도 누구나 또는 모두가 같은 결론에 도달한다는 것을 암시하기 때문에, 이러한 진술도 반드시 작가 자신의 신념에 관한 것은 아니다. 즉, 진술서에 대한 "저자 자신의 헌신commit의 정도"는 쓰여진 내용에서 간접적으로 추론가능할 뿐이다. (Prince et al. 1982)

Attribution shields serve to attribute the statement to someone other than the writer. They imply that the statement conveyed is to be attributed to someone else, sometimes specified and sometimes not. Common examples are phrases such as, ‘‘the housestaff really appreciated A’s teaching’’, or ‘‘I received numerous comments about B’s performance’’. Statements such as ‘‘Clearly making an effort’’ or ‘‘Obviously has excellent communication skills’’ are also attribution shields as they imply that anyone – or everyone – would come to the same conclusion and thus these statements are not necessarily about the writer’s own beliefs. That is, the writer’s ‘‘own degree of commitment to the statement is only indirectly inferable’’ from what is written. (Prince et al. 1982) - [개연성 방패]는 스피커/작성자가 자신의 진술의 진실에 완전히 충실하지 못함을 표시함으로써 의심의 요소를 유발합니다. 화자가 [그럴듯한 이유를 근거로 주장]을 하고 있기 때문에 그것들은 [개연성 방패]라고 불립니다. 일반적인 예로는 ‘‘I believe’’, ‘‘I think’’, ‘‘it is possible’’, ‘‘right now’’ 등의 구절이 있습니다. 작성자가 의식적이든 아니든 이러한 문제에 대해 자신의 의견을 해석할 수 있는 그럴듯한 근거로서 주의를 끌기 때문에, [훈련 단계 또는 연중 시기] 를 표시하는 방식으로 서술된 진술도 개연성 방패로 간주될 수 있다.

Plausibility shields introduce an element of doubt by allowing the speaker/writer to indicate that s/he is less than fully committed to the truth of the statement. They are called Plausibility shields because the speaker is making an assertion based on plausible reasons. Common examples are phrases such as, ‘‘I believe’’, ‘‘I think’’, ‘‘it is possible’’, ‘‘right now’’, etc. Statements that are marked by notation of stage of training or time of year may also be considered plausibility shields as the writer is – consciously or not – drawing our attention to these issues as a plausible basis on which to interpret their comments.

일차 코딩은 SG에 의해 수행되었으며, SG와 LL은 함께 프레임워크의 새로운 이해와 적용을 논의했다. SG와 LL은 데이터의 특정 예시와 함께 문헌의 사례를 사용하여 코드의 정의에 대한 이해를 도전하고 확장하며 세분화했다. 익명이기 때문에 우리는 그들의 언어 사용 이면에 있는 작가들의 의도를 파악할 수 없었습니다. 따라서 다른 연구자들과 함께, 우리는 논평이 진심이며, 이 맥락에서 사용되는 언어가 다른 서면 또는 구어 텍스트와 같은 방식으로 해석될 수 있다는 특정한 가정을 가지고 프레임워크를 적용했다.

Primary coding was done by SG, who discussed the emerging understanding and application of the framework with LL. SGand LLworked together to challenge, expand and refine their understanding of the codes’ definitions as they apply to our narrative data using examples from the literature along with specific exemplars from our data. Because the comments were anonymized, we could not determine the writers’ intentions behind their language use. In keeping with other researchers, we therefore applied the frameworks with certain assumptions: that the comments were meant to be sincere and that the language used in this context would be interpretable in the same way as other written or spoken text.

성찰성

Reflexivity

결과

Results

브라운과 레빈슨의 예의 틀의 몇 가지 요소들은 우리의 데이터에 쉽게 적용될 수 있었습니다. 구어에도 상당 부분 적용되는 틀이 꽤 구체적이기 때문에 모든 예의 전략이 관련 있는 것은 아니다.

Several elements of the politeness framework from Brown and Levinson were easily applicable to our data. As the framework is quite detailed, with much of it applying to spoken language, not every politeness strategy was relevant.

긍정적 체면을 다루기 위한 전략

Strategies to address positive face

브라운과 레빈슨에 따르면 긍정적 체면을 다루기 위해 사용되는 가장 일반적인 전략은 "과장적 관심"이라고 불린다(브라운과 레빈슨 1987, 페이지 104). 이 전략을 통해 작가는 그들의 관심과 찬성을 과장하기 위해 강조 강화적인 수식어를 사용한다. 여기에는 '절대 탁월함', '슈퍼스타', '매우 철저하고 꼼꼼함' 등의 문구가 포함되었습니다. 또한, "모든 면에서 우수한 레지던트!"와 같이 느낌표를 포함한 작가들이 여기에 모두 코드화 된 사례도 있다. 비록 '과장exaggerate'이라는 용어는 주치의가 레지던트를 실제 모습보다 더 나은 것처럼 보이려고 노력한다는 것을 의미할 수 있지만, 이러한 종류의 언어에서 보이는 극단적extreme인 말은 주치의 의견의 진실된 반영일 수도 있다. 고평가군의 약 3분의 1에서 exaggerated interest가 나타났지만, 저평가군의 경우는 2%에 불과했다.

The most common strategy used to address positive face, according to Brown and Levinson, is called ‘‘exaggerate interest’’ (Brown and Levinson 1987, p. 104), by which the writer uses emphatic intensifying modifiers to exaggerate their interest and approval. This included phrases such as ‘‘Absolutely outstanding’’, ‘‘superstar’’ and ‘‘extremely thorough and meticulous’’. In addition, instances in which writers included exclamation marks were all coded here, such as, ‘‘Excellent resident in all respects!’’ Although the term ‘exaggerate’ may imply that the attending is trying to make the resident seem better than they were, it is possible that the extremes seen in this sort of language may actually be sincere reflections of an attending’s opinion. Exaggerated interest was seen in about a third of the high-rated group but only in 2 % of the low-rated.

두 번째 전략은 "그룹 내 정체성 표식기"를 저자와 수령자(전공의) 사이의 공통점을 주장하는 방법으로 사용하는 것이다(브라운과 레빈슨 1987, 페이지 107). 레지던트, 수련생, 임상의, 컨설턴트 또는 의사, 또는 존댓말 '닥터'가 포함된 문구가 여기에 포함되었다. 비록 우리 데이터의 맥락(전공의 평가)에 따라 그룹 내 표지를 예상할 수 있지만, 이 용어들은 낮은 등급(59 대 37%; v2 = 17, p\0.001)과 비교하여 높은 등급 그룹에서 더 자주 사용되었음을 주목하는 것이 흥미롭다.

A second strategy is to use ‘‘in-group identity markers’’ as a way to claim common ground between the writer and recipient (Brown and Levinson 1987, p. 107). Phrases that include the word resident, trainee, clinician, consultant or doctor, or the honorific ‘‘Dr.’’ were included here. Although in-group markers can be expected given the context of our data (evaluation of residents) it is interesting to note that these terms were used more often in the high-rated group compared to the low-rated (59 vs. 37 %; v2 = 17, p\0.001).

세 번째 공통 전략은 비록 상징적으로 레지던트가 ''함께 일하는 것이 정말 즐겁다'' 또는 ''훌륭한 일'' 또는 ''팀으로부터 좋은 호감을 받았다''고 써서 "선물이나 칭찬을 하는 것"이다(브와 레빈슨 1987, 페이지 129이다. 다시 말하지만, 이러한 현상은 낮은 등급(53 대 27%, v2 = 25, p\0.001)보다 높은 등급 그룹에서 더 흔했습니다.

A third common strategy is to ‘‘Give gifts or compliments’’ (Brown and Levinson 1987, p. 129), albeit symbolically, by writing that a resident is ‘‘a real pleasure to work with’’, or did ‘‘a great job’’ or was ‘‘well-liked by the team’’. Again these were more common in the high-rated group than the low-rated (53 vs. 27 %; v2 = 25, p\0.001).

부정적 체면을 해결하기 위한 전략

Strategies to address negative face

부정적 체면을 다루기 위해 일반적으로 사용되는 하나의 언어 전략은 '관습적 간접성'이라고 불리며, 관습상 [문자 그대로의 의미와 다른] [모호하지 않은 의미]를 띠게 된 단어나 구를 사용하는 것이다(브라운과 레빈슨 1987, 페이지 132). 보건 전문 교육 맥락에서 전형적인 예는 '좋은'이라는 단어를 사용하는 것이다. 이 단어는 '평균 미만'의 코드 단어로 이해된다(Kiefer et al. 2010). 다른 관례적인 간접 문구로는 "안정적solid"과 "기대 충족"이 있습니다. 이러한 전략은 높은 등급의 그룹(41 대 15%, v2 = 38, p\0.001)보다 낮은 등급의 그룹에서 더 일반적이었다.

One linguistic strategy commonly used to address negative face is called ‘‘conventional indirectness’’, which is the use of words or phrases that, by virtue of convention, have come to take on unambiguous meanings that are different from their literal meanings (Brown and Levinson 1987, p. 132). A classic example in the health professional education context is the use of the word ‘‘good’’, which is understood to be a code word for ‘‘below average’’ (Kiefer et al. 2010). Other conventionally indirect phrases include ‘‘solid’’ and ‘‘met expectations’’. These strategies were more common in the low-rated than the highrated group (41 vs. 15 %; v2 = 38, p\0.001).

브라운과 레빈슨이 보고한 두 번째 공통 전략은 작가가 [자신의 주장] 또는 [수신자(전공의)]로부터 거리를 두기 위해 이름과 대명사를 생략함으로써 '비인간화impersonalize'하는 것이다(브라운과 레빈슨 1987, 페이지 190). 다음 예를 고려해 보십시오.

A second common strategy, reported by Brown and Levinson, is to ‘‘impersonalize’’ by leaving out names and pronouns to distance the writer from the assertions made or from the recipient (Brown and Levinson 1987, p. 190). Consider the following example:

매우 유능한 팀 리더이자 팀 플레이어입니다. 하급 직원들이 존경했다. 좋은 선생님. 환자, 가족 및 기타 의료 전문가에 대해 매우 전문적이고 존중합니다. 매우 열심히 일하며 환자/가족과 함께 많은 시간을 할애하여 문제를 해결하고자 합니다. 철저한 평가 및 퇴원 계획.

Very competent teamleader and teamplayer. Looked up to by junior housestaff. Great teacher. Very professional and respectful of patients, families, and other health professionals. Very hard working and willing to spend a lot of time with patients/families ensuring issues are addressed. Thorough assessments and discharge plans.

헤징

Hedging

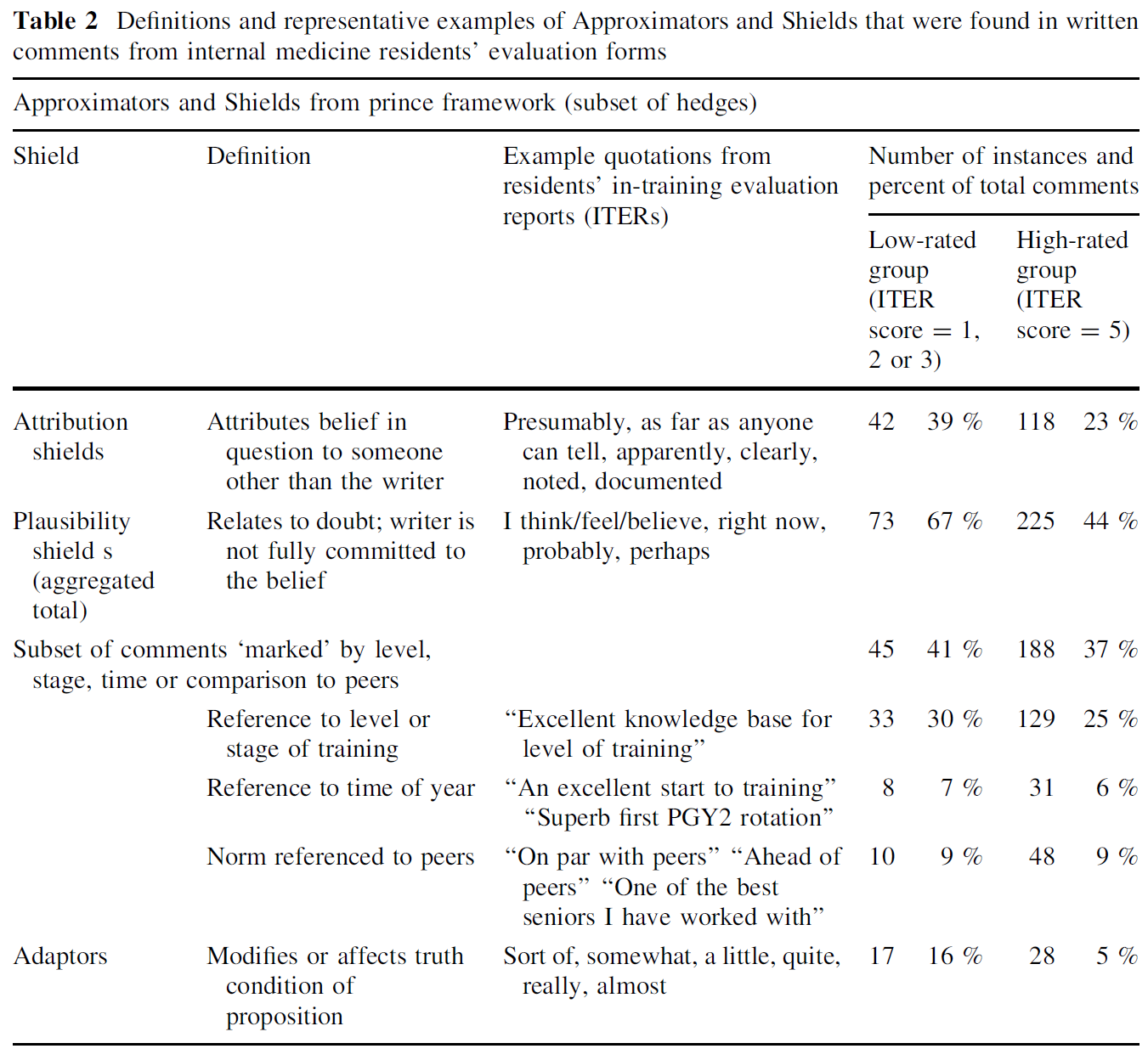

"약 2주 동안만 그와 교류했지만"이라는 문구 또한 데이터에서 발견한 가장 일반적인 언어 전략을 처음으로 보여줍니다. 데이터에 만연했던 헷징은 저성과 전공의의 의견 94%와 고성능 전공의의 의견 71%에 포함되었다(v2 = 27, p\ 0.001). 일반적인 헷징의 몇 가지 예로는 "진료/진료 차트를 시작하는 데 있어 좀 더 빠르게 진행될 수 있었을 것" 또는 "꽤 독립적으로 잘 작동될 것"과 같은 문구들이 있다. ''could have', ''little more', ''fairy'라는 단어는 [진술의 '진실 상태']나 저자의 [주장에 대한 헌신]에 영향을 미치기 때문에 헷지이다. 첫 번째 경우, 주치의가 ''클리닉을 시작할 때 더 빨리 시작했어야 했다"라고 썼다면 모호함의 여지가 없었을 것이다. 대부분의 위험회피는 [귀인 방패] 또는 [개연성 방패]로 추가로 분류할 수 있었다. 표 2에는 근사치와 보호막을 포함한 하위 유형의 위험회피에 대한 추가 정의와 예가 포함되어 있다.

The phrase ‘‘Although I only interacted with himfor about 2 weeks’’ also offers a first look at the most common linguistic strategy we found in our data: Hedging, which was pervasive in our data, being present in 94 % of comments from low-performing residents and in 71 % of comments from high-performing residents (v2 = 27, p\0.001). Some examples of general hedging include phrases such as ‘‘could have been a little more rapid in starting the clinic/picking up charts to get going’’ or ‘‘works well, fairly independently’’. The words ‘‘could have’’, ‘‘a little more’’, and ‘‘fairly’’ are hedges because they affect either the ‘truth condition’ of the statement or the writer’s commitment to the assertions made—in the first instance the attending could instead have written ‘‘should have been more rapid in starting the clinic’’ which would leave no room for doubt. Most hedges were further classifiable as either Attribution or Plausibility Shields. Table 2 contains further definitions and examples of subtypes of hedging including Approximators and Shields.

문장을 작성자가 아닌 다른 사람에게 귀속시키는 [귀인 방패]는 높은 등급의 그룹(39 대 23%, v2 = 12, p = 0.001)보다 낮은 등급의 그룹에서 더 일반적이었다. 어떤 경우는, 명시적인 대상을 포함했다(예: "하급 housestaff들에 의해" 또는 "복수의 직원이 제안하는 …"). 또는 암묵적인 경우도 있어서 (예: "관심 없음" 또는 "약점이 식별되지 않음" 등)은 어떤 사람도 구체적으로 명시하지 않았다. 종종 'X가 훌륭한 컨설턴트가 될 것이라고 확신한다' 또는 '모두가 우수 레지던트가 될 것으로 느낀다'와 같은 속성이 공유되었다. 따라서 귀속 방패는 글쓴이 자신의 주장을 숨김으로써 글쓴이를 보호하는 역할을 한다.

Attribution shields, which attribute statements to someone other than the writer, were more common in the low-rated than the high-rated group (39 vs. 23 %; v2 = 12, p\0.001) and included instances in which attribution was explicit (e.g., ‘‘looked up to by junior housestaff’’, or ‘‘comments from multiple staff suggest …’’) or implicit, such as ‘‘no concerns’’ or ‘‘no weaknesses were identified’’, without specifying by whom. Often the attribution was shared, e.g., ‘‘We are all confident that X will be an excellent consultant’’, or ‘‘Felt by all to be an outstanding resident’’. Attribution shields thus serve to protect the writer by obscuring his or her own contribution to the assertion.

의심 요소를 도입하는 [신뢰성 방패]는 높은 등급의 그룹 의견 44%보다 낮은 등급 그룹의 의견 67%에서 (v2 = 20, p\0.001)에 더 흔했다. 이러한 의견의 다수는 '나는 믿는다' 또는 '나는 생각한다'와 같은 구절을 포함했는데, 이는 작가가 그럴듯한 이유, 즉 그들 자신의 신념과 관찰에 근거하고 있다는 것을 나타낸다.

Plausibility shields, which introduce an element of doubt, were more common, being present in 67 % of comments from the low-rated group and 44 % of the high-rated group comments (v2 = 20, p\0.001). Many of these comments included phrases such as ‘‘I believe’’, or ‘‘I think’’, which indicate that the writer is basing the assertions that follow on plausible reasons—their own beliefs and observations.

글쓴이는 '내가 관찰할 수 있는 한'이라는 오프닝 문구를 사용하여 그들이 지금 말하려는 것을 그들이 본 것 이상의 것을 알고 있다는 주장을 하지 않고 있음을 표시함으로써 회피한다. 이것은 전공의에 대해 (아마 다른 관찰에 근거하여) 다른 결론에 도달했을 수 있는 타인의 정당한 의견 불일치 또는 비판에 개방함으로써 작가와 전공의recipient의 체면을 보호합니다. 글쓴이는 자신이 주장하는 것에 대해 [그럴듯한 의심을 불러일으키기 위한 헷지]를 사용했기 때문에 정말로 "틀릴" 수 없다. 이 의견에는 귀인 방패(타인으로부터 받은 피드-포워드)도 포함되어 있습니다.

By using the opening phrase ‘‘as far as I have been able to observe’’, the writer hedges what they are about to state by indicating that they are not making claims to know anything beyond what they’ve seen. This protects the writer’s and the recipient’s face, by leaving it open to legitimate disagreement or critique by others, who may have come to different conclusions about that resident (perhaps based on different observations). The writer can’t really be ‘‘wrong’’ because she used a hedge to create plausible doubt about what she asserted. Note that this comment also includes an attribution shield (the feed-forward received from others).

많은 [개연성 방패]들은 전공의의 훈련 단계나 연도를 나타내는 언어로 표시되었다. 예를 들어, '훈련 단계에 비해 우수한 지식 기반 보유' 또는 '훈련 단계에 비해 판단력 우수' 또는 'PGY2 레벨에서 수행할 수 있는 최고의 성과' 등이 있습니다. 이러한 진술은 전공의의 훈련 단계에 주목함으로써 자격을 갖췄거나 '표시'되었기 때문에 [개연성 방패]이며, 따라서 주장에 대한 그럴듯한 이유가 된다. '우수한 첫 달 레지던트', 또는 '훌륭한 시작'과 같은 비슷한 진술이 일년 중 시기에 이루어졌다. 이 작가들은 아마도 무의식적으로 그들의 논평이 조심스럽게 받아들여질 것이라는 것을 암시하고 있으며 해가 갈수록 상황이 변할 가능성에 대해 스스로 열어두고 있다.

Many of the plausibility shields were marked by language denoting a resident’s stage of training or the time of year. For example, ‘‘Has an excellent knowledge base for his level of training’’, or ‘‘good judgment for level of training’’, or ‘‘as good as you can perform at the PGY2 level’’. These statements are plausibility shields because they are qualified, or ‘marked’, by noting the resident’s stage of training, and thus serve as plausible reasons for the assertion. Similar statements were made about the time of the year, such as ‘‘excellent first month of residency’’, or ‘‘excellent start’’. These writers may be implying—perhaps unconsciously—that their comments are meant to be taken cautiously, and are leaving themselves open to the possibility that things will change as the year progresses.

예의 전략이 없는 논평

Comments without politeness strategies

위에서 설명한 많은 예의 전략과 대조적으로, 우리는 또한 "Bald, on record (돌직구)"인 많은 논평의 예를 발견했는데, 이는 예의 언어가 전혀 포함되어 있지 않다는 것을 의미한다(브라운과 레빈슨 1987, 페이지 94).

By contrast to the many politeness strategies described above, we also found many examples of comments that are ‘‘Bald, on record’’, meaning they include no politeness language at all (Brown and Levinson 1987, p. 94).

이 언어는 코멘트 전체에 흩어져 있지만 전체 코멘트 상자가 "Bald" 문장만 포함하는 경우는 드물었다(총 12개).

Although this language could be found scattered throughout the comments it was rare for an entire comment box to contain only ‘‘bald’’ statements (12 in total).

고찰

Discussion

이러한 연구결과는 ITER 의견을 작성하는 것이 체면을 위협하는 행위라는 개념을 뒷받침한다. 다만 수신자의 체면만 위협하는 것은 아니다. 즉, '방패' 형태의 헷징의 반복적인 사용은 작성자가 자신의 체면을 보호하고 있었다는 것을 시사한다.

These findings support the notion that writing ITER comments is a face-threatening act, but not just for the recipient—the recurrent use of hedging in the form of ‘shields’ suggests that writers were also protecting their own face.

주치의가 전공의에 대한 서면 코멘트를 하는 것이 왜 체면을 위협하는지 생각해 보는 것이 흥미롭다. 브라운과 레빈슨은 FTA의 가중치를 계산하기 위한 공식을 개발했다: 가중치 = D + P + R. 여기서

- D는 distance로서 말하는 사람과 듣는 사람 사이의 사회적 거리(대칭 관계),

- P는 power로서 듣는 사람이 말하는 사람에 대해 갖는 권력의 척도이다(브라운과 레빈슨 1987, 페이지 76).

- R은 rank로서 특정 상황이나 문화에서 부담imposition의 정도 또는 '순위'이다.

It is interesting to consider why it is face-threatening for an attending to provide written comments about residents. Brown and Levinson developed a formula for calculating the weightiness of a FTA: Weightiness = D x P x R, where

- D is the social distance between the speaker and hearer (a symmetrical relationship) and

- P is a measure of the power that the hearer has over the speaker (an asymmetrical relationship; Brown and Levinson 1987, p. 76).

- R is the ‘rank’ or degree of imposition of the act in a particular context or culture.

이 공식에서 참석자/연설자가 우월한 위치에 있기 때문에 상주자/청취자가 큰 힘을 갖지 못하고 FTA의 비중이 낮다고 가정할 수 있다. 그러나 Brown과 Levinson의 다음 예를 생각해 보십시오. 같은 회의보다 임금 인상을 원하는 직원과 은행장 회의를 하는데 직원이 총을 들고 있다. —청취자에게 갑자기 유리한 힘의 차이가 뒤집히고, 요구의 사회적 거리 및 순위가 동일하더라도 직면 위협(및 그 결과)은 매우 높아진다. 이는 극단적인 예이지만, 권력 차이power differential가 중요한 고려 사항이라는 점을 보여준다.

From this formula one might assume that since the attending/speaker is in the superior position, the resident/hearer doesn’t have much power and the weight of the FTA is low. But consider the following example from Brown and Levinson: a bank manager meeting with an employee who wants a raise versus the same meeting but this time the employee is holding a gun—the power differential suddenly is flipped in favour of the hearer and the threat to face (and its consequences) are now very high, even with the same social distance and rank of the request. Although this is an extreme example, it illustrates the point that the power differential is an important consideration.

ITER 시스템에서, 전공의는 [(전공의의) 교사에 대한 평가]가 이들의 승진, 미래의 교육 및 감독 기회, 재정적 보상 또는 벌금의 계산 등 중요한 결과를 초래하기 때문에 중요한 권한을 가지고 있습니다. 이것은 우리 교수들은 종종 이해의 상충의 입장에 놓이며, 따라서 건설적인 피드백을 제공할 때 조심해야 하다고 제안했다.

And in the ITER system, residents do have important power because their assessments of their teachers carry significant consequences, including the ability to affect promotion, future educational and supervisory opportunities, and the calculation of financial rewards or penalties. This suggests that our faculty are often in a position of conflict of interest and must tread carefully when giving constructive feedback.

헷징 및 기타 예의 전략도 일상적인 커뮤니케이션을 통해 전파된다. 인간은 사회적 존재이며 공손함은 관계를 형성하고 유지하는데 도움을 줍니다. 일렌이 예절 이론의 분석과 통합에서 설명했듯이, 브라운과 레빈슨은 예절을 "사회적 관계의 표현을 구성하고, [사회적 필요 및 지위와 상충되는 의사소통 의도에서 발생하는 대인관계 긴장을 해소]할 언어적 방법을 제공한다는 점에서, 예절은 사회생활과 사회의 구조에 매우 중요하다. "고 이야기한다.

Hedging and other politeness strategies also pervade regular day-to-day communication. Human beings are social creatures and politeness helps build and maintain relationships. As Eelen explains in an analysis and integration of theories of politeness, Brown and Levinson consider politeness to be ‘‘fundamental to the very structure of social life and society, in that it constitutes the expression of social relationships and provides a verbal way to relieve the interpersonal tension arising fromcommunicative intentions that conflict with social needs and statuses’’ (Eelen 2014).

교사, 코치, 멘토, 평가자, 심판 등 여러 가지 역할과 교육생과의 관계를 고려했을 때, 그리고 ITER의 여러 가지 동시 목적을 고려할 때, Elen이 설명한 갈등의 종류를 쉽게 상상할 수 있습니다. 그렇다면 피드백을 전달할 때 약간의 예의가 도움이 될 수 있고, 교수진이 덜 긍정적인 메시지를 전달해야 할 때 위험회피가 특히 흔하다는 것은 놀랄 일이 아니다. [귀인 방패]를 사용하면 특히 좋지 않은 뉴스의 요소가 있는 경우 발화자/저자가 자신의 [진술에 대한 책임을 회피]할 수 있습니다. 이러한 회피 동기는 낮은 등급low-rated의 전공의에 대한 언급을 할 때 거의 모든 곳에서 위험회피가 사용되는 원인이 될 수 있다.

Given the multiple roles and relationships we have with our trainees—teacher, coach, mentor, assessor, judge—and the multiple,simultaneous purposes of ITERs in the first place, we can easily envision the kinds ofconflicts that Eelen describes. It should not be surprising then to see that a little politenesscan go a long way when delivering feedback, and that hedging is particularly commonwhen faculty must convey a less positive message. The use of attribution shields can allowthe speaker/writer to evade responsibility for their statements, especially if there is some element of bad news. This motive of evasion may be responsible for the near ubiquitous use of hedging when commenting on low-rated residents.

하지만, 이것은 [왜 그것이 높은 등급의 전공의들에게 그렇게 흔한지] 설명하지 못한다. 이 연결실체에서 위험회피에 대한 잠재적 설명 중 하나는 공손함politeness이 원활하고 조화로운 관계를 보장하기 위한 [사회생활의 기본]이라는 개념과 관련된다. 이러한 관점에서 볼 때, 헷징이 필수적인 사회적 기능을 한다는 점에서, 그 자체를 근본적인 문제로 간주하여서는 안 된다.

However, this doesn’t explain why it would be so common in high-rated residents. One potential explanation for hedging in this group relates to the notion that politeness is fundamental to social life for ensuring smooth, harmonious relationships. Considered in this light, hedging should not be deemed as fundamentally problematic as it serves an essential social function.

앞 단락의 설명에서는 서면 의견의 [주요 수신자]가 전공의라고 가정하지만, ITER는 프로그램 책임자와 기타 참석자를 포함한 [여러 대상자]에게 [다양한 용도]로 사용됩니다. 이러한 다른 대상자들이 야기하는 표면적 위협은 다른 상황에서 위험회피의 만연성을 고려한다면 더 잘 이해할 수 있을 것이다. 예를 들어, 일부 언어학자들은 과학적 담론의 위험회피에 대해 연구하였고 특히 연구 문헌(Myers 1989; Salager-Meyer 1994)에서 위험회피가 일반적이라는 것을 발견했다. 예를 들어, 성가신 문제나 질병의 "원인"에 대한 "해답"을 찾았다고 주장하는 연구자들을 보기 힘들다. 대신에 연구자들은 "A, B 또는 C가 X, Y, Z의 원인이 될 수 있는 요인일 수 있다는 증거를 발견했다"고 진술할 가능성이 훨씬 더 높다.

The explanations in the preceding paragraph assume that the main recipient of the written comments is the resident, yet we know that the ITER serves multiple purposes for multiple audiences, including program directors and other attendings. The face-threat created by these other audiences may be better understood by considering the pervasiveness of hedging in other situations. For example, some linguists have studied hedging in scientific discourse and have found that it is the norm especially in the research literature (Myers 1989; Salager-Meyer 1994). For example, one rarely sees authors claiming to have found ‘‘the answer’’ to a vexing problem or ‘‘the cause’’ of a disease. Instead, researchers are far more likely to state that they ‘‘have found evidence that suggests that A, B or C may be factors that could be responsible for X, Y or Z’’.

'''제시되는 증거''', ''아마도'' 및 ''아마도''라는 문구는 [개연성 방패]이다. 이러한 종류의 위험회피의 한 가지 이유는 작성자의 주장이 후속적으로 신용이 떨어지거나 재현할 수 없는 경우에 대비하여 연구자 본인의 체면을 보호하기 위함이다. 그것은 또한 다른 결과나 의견을 발표했을 수 있는 다른 연구자들의 체면을 보호해줍니다. 이 전략은 또한 전문지식과 연공서열이 다른 (그리고 종종 알려지지 않은) 많은 독자들이 있을 수 있다는 것을 고려한다.; 헷징은 [부정적인 예의 전략]으로서, 작가를 겸손하게 묘사함으로써 넓고 다양한 독자들에게 존경을 표한다.

The phrases ‘‘evidence that suggests’’, ‘‘may be’’ and ‘‘could be’’ are plausibility shields. One reason for this sort of hedging is to protect the face of the author in case his or her claims are subsequently discredited or not reproducible. It also protects the face of other researchers who may have published differing results or opinions. This strategy also takes into account that there may be many different (and often unknown) readers with differing levels of expertise and seniority; hedging, as a negative politeness strategy, pays deference to a broad and diverse audience, by portraying the writer as humble.

ITER 의견에도 동일한 논리가 적용된다. 작성자(즉, 담당 의사)는 작성자와 비교했을 때 전문성의 수준이나 지식의 수준이 다른 여러 유형의 독자(전공의, 프로그램 감독, 역량 또는 항소 위원회 등)가 있을 것이라고 가정한다. 한 주치의가 다른 주치의보다 특정 전공의를 다소 높거나 낮게 평가하는 것이 이상치outlier일 수도 있고, 레지던트에 대한 그들의 의견이 잘못되었을 가능성도 꽤 있다. 특히 [귀인 방패]와 [개연성 방패]를 사용하여 헷징함으로써, 작성자는 [자신이 잘못될 수 있다는 인식]과 [타당한 근거에 기초한 의견]이라는 인식을 함축imply하는 것이다.

The same logic applies to ITER comments—writers (i.e., attending physicians) assume there will be different types of readers (residents, program directors, competency or appeals committees, etc.), with different levels of expertise and knowledge relative to the writer. It is also quite possible that an attending might be found to be an outlier, or erroneous in their opinion of a resident, having rated them more or less highly than other attendings. By hedging—especially by using attribution and plausibility shields—the writer implies their awareness that they may turn out to be wrong and that their comments are opinions based on plausible evidence.

교육생들을 위한 헷징의 교육적 의미는 무엇입니까? 전공의들이 이 발언을 어떻게 읽거나 해석하는지는 아직 알 수 없지만, 여기에 제시된 이론적 틀을 바탕으로 예의 전략이 의도된 메시지를 모호하게 할 수 있다. [간접 언어indirect language]가 많을수록 오해를 받을 가능성이 높다(Bonnefon et al. 2011). 실제로 우리가 예의어를 사용하는 이유 중 하나는 직설성을 피하고 해석적 유연성을 만들기 위해서입니다.

What are the educational implications of hedging for trainees? We don’t yet know how residents read or interpret these comments but, based on the theoretical frameworks presented here, it is possible that politeness strategies obscure the intended message. The more indirect language is, the more likely it is to be misunderstood (Bonnefon et al. 2011). Indeed, one reason that we use politeness language is to avoid directness and create interpretive flexibility.

반대로, 전공의는 ITER 문맥에 정통한 사회 구성원으로서 ITER 논평에서 위험회피 및 기타 언어적 예의 전략을 식별하고 디코딩할 수 있습니다. 만약 그렇다면, 이러한 행위는 정중함 전략에도 불구하고 체면을 위협하는 특징을 여전히 유지할 것이며, 더 나아가 전공의들은 헷징을 읽어내어서, 직접 언급하지 않는 '더 나쁜' 것이 있다는 표시로 해석할 수 있다. 브라운과 레빈슨의 설명처럼, 작가가 FTA가 실제로 위험성이 높지 않을 때 고위험high-risk FTA에 적합한 전략을 쓴다면, 독자는 FTA가 예전보다 더 컸다고 추정할 것이다(브라운과 레빈슨 1987, 페이지 74). 따라서 잘못된 전략이나 너무 많은 예의 바른 언어를 사용함으로써 우리는 우리가 의도하는 것보다 받는 사람이 더 나쁘다는 인상을 줄 수 있습니다.

It is also possible that residents, as savvy social members of the ITER context, are able to discern and decode the hedging and other linguistic politeness strategies in ITER comments. If so, these acts will retain their face-threatening quality despite the politeness strategies and, furthermore, residents may read hedging as an indication that there is something ‘worse’ that is not being said. As Brown and Levinson explain, if a writer uses a strategy appropriate to a high-risk FTA when the FTA is actually not high risk, the reader will assume the FTA was greater than it was (Brown and Levinson 1987, p. 74). Therefore, by using the wrong strategy or too much politeness language, we may give the impression that things are worse for the recipient than we really intend.

우리 전공의 중 상당수가 영어가 모국어가 아니며, 특히 [문자 그대로의 뜻을 의미하지 않는non-literal 언어]가 오해를 살 수 있다는 문헌도 있다(Danesi 1993). 이러한 우려에도 불구하고, 컴퓨터 기반 과외에 관한 흥미로운 일련의 연구는 언어가 직접적인 것일 때보다 의도적으로 공손할 때 학생들이 실제로 더 많은 것을 배울 수 있다는 것을 시사한다. 이러한 '예절 효과'는 학생이 초보자인지 아니면 더 고급인지에 따라 달라질 수 있으며(McLaren et al. 2011), 온라인 학습 및 시뮬레이션 설정과 같은 의학교육 맥락에서 추가 탐구할 가치가 있을 수 있다.

Another issue to consider is that for many of our residents English is not the native language, and there is literature suggesting that non-literal language can be particularly prone to misunderstanding (Danesi 1993). Despite these concerns, an intriguing line of research in computer-based tutoring suggests that students may actually learn more when language is deliberately polite than when it is direct (Wang et al. 2008). This ‘politeness effect’ may depend on whether students are novices or more advanced (McLaren et al. 2011) and may be worthy of further exploration in medical education contexts such as online learning and simulation settings.

목적과 해석 방식에 따라 거의 모든 것을 헷지로 사용할 수 있다(Fraser 2010). 해석은 맥락, 의미적 의미, 사용된 특정 위험회피, 수취인의 신념 체계에 따라 달라진다. 본 연구에서는 익명의 기존 데이터 세트를 사용했기 때문에, 익명성 문제를 무시할 수 없으며, 의도성intentionality에 대한 주장도 할 수 없습니다. 즉, 특정 주치의가 특정 코멘트에 의해 의도된 것이 무엇인지 확실히 알 수 없으며, 우리의 분석은 (불가피하게) 이러한 맥락이 없는 코멘트의 해석을 요구한다. 그러나 이전 연구를 통해 임상 감독자는 친절하고 자신의 코멘트로 인해 다른 사람의 기분을 상하게 하지 않으려는 강한 욕구를 가지고 있다는 것을 알고 있다(Ginsburg et al. 2015; Ilott and Murphy 1997).

Nearly anything can be used as a hedge depending on how it is intended and interpreted (Fraser 2010). Interpretation depends on the context, the semantic meaning, the particular hedge used, and the belief system of the recipient. Because we used a pre-existing and anonymized data set for this study, we are unable to tease apart these issues and nor can we make claims regarding intentionality. That is, we cannot know for certain what a particular attending intended by any particular comment, and our analyses have, by necessity, required interpretation of these decontextualized comments. However, we do know from previous research that clinical supervisors have a strong desire to be nice and to not offend anyone with their comments (Ginsburg et al. 2015; Ilott and Murphy 1997).

게다가 밀스가 예의 이론에 대한 비판에서 지적했듯이, "예의는 [의도적이고 의식적인 언어적 선택]에서부터 [무의식적인 규칙이나 대본의 적용]에 이르기까지 모든 범위에 걸쳐 있다." (밀스 2003, 페이지 74)

Further, as Mills points out in her critique of politeness theories, ‘‘politeness spans the full range from deliberate, conscious linguistic choices to the unconscious application of rules or scripts’’ (Mills 2003, p. 74).

항상 의도적인 선택이라기 보다는, 일부 [공손함 언어politeness language]는 "주어진 [주어진] 문맥과 관련된 규범에 적합하게 결정될 수 있다(Mills 2003, 페이지 67)". 우리의 맥락에서 이 언어선택의 일부는 상대적으로 무의식적인 것일 수 있으며, 이는 우리의 과학출판 문화처럼 일반적으로 우리의 평가 문화가 정중하고 회피적인 언어를 선호하고 촉진한다는 것을 시사할 수 있다.

Rather than always being a deliberate choice, some politeness language may be ‘‘determined by conformity to the norms associated with the [given] context (Mills 2003, p. 67)’’. In our context it may be that some of this language choice is relatively unconscious, which might suggest that our culture of assessment in general prefers and promotes polite, hedging language, just as our culture of scientific publishing does.

Watling(2008)이 지적한 바와 같이, ITER 프로세스 개선을 위한 교수진 개발 노력은 실망스러웠습니다. 부분적으로는 피드백을 전달하는 데 있어 교수진의 기술을 향상시키는 데 중점을 두고 있으며, 이에 대한 전공의들의 수용성을 방치하고 있기 때문입니다.

As Watling (2008) noted, faculty development efforts to improve the ITER process have been disappointing, in part because they focus largely on enhancing faculty skill in delivering feedback and they neglect residents’ receptivity to it.

예를 들어, 완료된 ITER의 품질을 평가하는 두데크 외 연구진(2008)은 "Excellent하게 작성된 ITER은 어떤 모습인가"에 대한 교수진의 인식을 반영한다. 흥미롭게도, ITER 품질 체크리스트의 9개 항목 중 7개 항목이 숫자 점수가 아닌 작성된 코멘트에 초점을 맞추고 있었고, 이는 교수 감독관들은 '코멘트'가 양식에서 매우 중요한 부분이라고 느끼고 있음을 시사합니다.

For example, Dudek et al.’s (2008) work on evaluating the quality of completed ITERs reflects their faculty participants’ perceptions of how ‘‘excellent’’ completed ITERs should look. Interestingly, seven of the nine items on their ITER quality checklist focus on the written comments rather than the numeric scores, strongly suggesting that faculty supervisors feel the comments are a critically important part of the form.

피드백의 내용에 초점을 맞춘 "더 나은" 코멘트를 작성하도록 교수진을 훈련시키려는 노력이 일어났다(Dudek et al. 2013). 예를 들면,

- 강점과 약점을 모두 포함하는 "균형 잡힌" 코멘트를 제공한다.

- '지지적 방식''으로 피드백을 제공한다.

- 피드백 또는 교정조치에 대한 수습생의 반응을 문서화합니다.

Efforts have arisen to train faculty to write ‘‘better’’ comments (Dudek et al. 2013), which focus closely on the content of the feedback, including instructions for faculty

- to provide ‘‘balanced’’ comments that include both strengths and weaknesses,

- to provide feedback in ‘‘a supportive manner’’ and

- to document the trainee’s response to feedback or remediation.

안타깝게도, 교수진을 훈련시키는 것은 원하는 효과를 거두지 못했다(Dudek et al. 2013).

Unfortunately, training faculty has not had the desired effect (Dudek et al. 2013).

우리의 연구 결과가 그 이유를 설명하는 데 도움이 될 수 있습니다. 첫째, "균형 잡힌" 코멘트는 비교적 열악한 전공의 성과를 나타내는 신호로 해석되는 경우가 많다(Ginsburg et al. 2015). 아마도 평가와 피드백의 개념이 ITER에 통합되기 때문에 좋은 "피드백" 관행이 이 맥락에서 완전히 적용되지 않을 수 있기 때문일 것이다. 둘째, '지원적' 방식으로 서면 피드백을 제공하려는 시도는 역설적으로 감독자가 덜 비판적으로 보이는 방법으로 더 많은 헷징과 간접 언어를 포함하도록 유도할 수 있다.

Our findings may help to explain why. First, ‘‘balanced’’ comments are often interpreted as signalling relatively poor resident performance (Ginsburg et al. 2015), perhaps because concepts of assessment and feedback are conflated on an ITER, so that good ‘‘feedback’’ practice may not fully apply in this context. Second, the attempt to provide written feedback in ‘‘a supportive manner’’ may, paradoxically, lead supervisors to include more hedging and indirect language as a way to appear less critical.

우리가 연구에서 제시한 바와 같이, 그러한 헷징은 다른 교수들에게 [희미한 칭찬을 사용한 비판]으로 인식될 수 있다. ITER에 대한 교수진의 서면 의견을 개선하기 위한 현재의 접근방식은 역설적으로 교수진의 메시지가 왜곡될 수 있다는 점을 인식하고 신중하게 고려해야 합니다. 최소한, 우리의 결과는 어떻게 그것을 고칠지는 고사하고 서면 논평에서 어떤 것이 '고정fixed'되어야 하는지가 완전히 명확하지 않다는 것을 보여준다.

Such hedging, as we’ve suggested in our study, may be perceived by other faculty as damning by faint praise. That current approaches to improve faculty’s written comments on ITERs may, paradoxically, distort their messages should be acknowledged and considered carefully. At a minimum, our results reveal that it is not entirely clear what (if anything) needs to be ‘‘fixed’’ in written comments, let alone how to fix it.

[예의 이론]은 서술적 평가 코멘트를 작성할 때 교수진의 모호하고 겉보기에 도움이 되지 않는 언어의 사용에 바탕을 둔 중요한 사회적 동기를 드러냅니다. 헷징과 같은 전략은 [낮은 등급의 전공의]에게 널리 사용되고, [높은 등급의 전공의]에게도 놀라운 빈도로 사용된다. 이는 교수진이 어려운 사회 평가 맥락에서 자신뿐만 아니라 전공의들을 위해 '체면 유지' 작업을 하고 있을 수 있음을 시사한다. 일반적으로 언어의 사회적 기능과 특히 예의는 필수적이고 중요하며 반드시 교정이 필요한 것으로 여겨져서는 안 된다. 어텐딩들에게 그들의 언어에 더 직접적으로 대해 달라고 부탁하는 것은 의도하지 않은 부정적인 결과를 초래할 수 있으며, 이는 코멘트 작성을 "개선"하기 위한 교수진 개발 이니셔티브에서 고려되어야 한다.

Politeness theory reveals important social motives underlying faculty’s use of vague and seemingly unhelpful language when writing narrative assessment comments. Strategies such as hedging are used pervasively in low-rated residents and with surprising frequency in high-rated residents as well. This suggests that faculty attendings may be working to ‘‘save face’’ for themselves as well as for their residents in the difficult social context of assessment. The social function of language in general and politeness in particular are essential and important and should not necessarily be viewed as something in need of remediation. Asking attendings to be more direct in their language may have unintended adverse consequences which should be considered in faculty development initiatives to ‘‘improve’’ comment writing.

Adv Health Sci Educ Theory Pract. 2016 Mar;21(1):175-88.

doi: 10.1007/s10459-015-9622-0. Epub 2015 Jul 17.

Hedging to save face: a linguistic analysis of written comments on in-training evaluation reports

Shiphra Ginsburg 1 2, Cees van der Vleuten 3, Kevin W Eva 4, Lorelei Lingard 5

Affiliations collapse

Affiliations

- 1Department of Medicine and Wilson Centre for Research in Education, University of Toronto, Toronto, ON, Canada. shiphra.ginsburg@utoronto.ca.

- 2Mount Sinai Hospital, 600 University Ave, Ste. 433, Toronto, ON, M5G1X5, Canada. shiphra.ginsburg@utoronto.ca.

- 3School for Health Professions Education, Maastricht University, Maastricht, Netherlands.

- 4Faculty of Medicine, Centre for Health Education Scholarship, University of British Columbia, Vancouver, BC, Canada.

- 5Centre for Education Research and Innovation, Schulich School of Medicine and Dentistry, Western University, London, ON, Canada.

- PMID: 26184115

- DOI: 10.1007/s10459-015-9622-0AbstractKeywords: Assessment; Competence; Linguistics; Qualitative.

- Written comments on residents' evaluations can be useful, yet the literature suggests that the language used by assessors is often vague and indirect. The branch of linguistics called pragmatics argues that much of our day to day language is not meant to be interpreted literally. Within pragmatics, the theory of 'politeness' suggests that non-literal language and other strategies are employed in order to 'save face'. We conducted a rigorous, in-depth analysis of a set of written in-training evaluation report (ITER) comments using Brown and Levinson's influential theory of 'politeness' to shed light on the phenomenon of vague language use in assessment. We coded text from 637 comment boxes from first year residents in internal medicine at one institution according to politeness theory. Non-literal language use was common and 'hedging', a key politeness strategy, was pervasive in comments about both high and low rated residents, suggesting that faculty may be working to 'save face' for themselves and their residents. Hedging and other politeness strategies are considered essential to smooth social functioning; their prevalence in our ITERs may reflect the difficult social context in which written assessments occur. This research raises questions regarding the 'optimal' construction of written comments by faculty.

'Articles (Medical Education) > 평가법 (Portfolio 등)' 카테고리의 다른 글

| 원하는 것을 측정하기 위한 OSCE 개발을 위한 12가지 팁(Med Teach, 2017) (0) | 2021.08.19 |

|---|---|

| OSCE의 퀄리티 측정하기: 계량적 방법 검토 (AMEE Guide no. 49) (Med Teach) (0) | 2021.08.19 |

| WBA이해하기: 옳은 질문을, 옳은 방식으로, 옳은 것에 대해서, 옳은 사람에게 (Med Educ, 2012) (0) | 2021.08.15 |

| 근무지기반평가: 평가자의 수행능력이론과 구인(Adv in Health Sci Educ, 2013) (0) | 2021.08.13 |

| 상호 불일치로서 평가자간 변동: 평가자의 발산적 관점 식별(Adv in Health Sci Educ, 2017) (0) | 2021.08.13 |