비판적 성찰과 비판적 반영의 발산과 수렴: 보건의료전문직교육에의 함의(Acad Med, 2019)

The Divergence and Convergence of Critical Reflection and Critical Reflexivity: Implications for Health Professions Education

Stella L. Ng, PhD, Sarah R. Wright, PhD, and Ayelet Kuper, MD, DPhil

보건전문교육(HPE)은 사회과학 및 인문과학(SS&H)을 교과 내용, 디자인, 교육학에 활용해야 한다는 요구에 부응하기 시작했다. 보건 전문가는 역량 프레임워크에 의해 증명된 바와 같이 사회적, 인문학적 역할과 활동을 수행해야 한다. 따라서 SS&H는 HPE에 분명한 이점을 제공한다. 그러나 정보에 입각한 방법으로 HPE에 SS&H 방법을 적용하는 것은 어려울 수 있다. 한편으로 SS&H 접근방식은 HPE에서 의미 있고 효과적이려면 신중한 적응이 필요하다. 한편, SS&H의 내용과 방법을 보건 전문직 훈련 프로그램에 적용하려는 의도는 좋지만 정보에 입각하지 않은 많은 사례들이 있다. HPE에 SS&H의 도입이 두드러지고, SS&H와 관련된 목표, 역할, 환자 중심의 관리, 건강 옹호, 포트폴리오 코스 등의 활동의 인기가 높아짐에 따라 잘못된 적용은 더욱 확산될 위험이 있다. 잘못 적용하면 잠재적으로 유용한 개념이 배제되고 더 많은 정보를 가진 애플리케이션을 통해 실현될 수 있는 것보다 더 낮은 교육 결과가 초래될 수 있습니다.

Health professions education (HPE) has begun to answer calls to draw on the social sciences and humanities (SS&H) for curricular content, design, and pedagogy.1–8 Health professionals must—as evidenced by competency frameworks—perform social and humanistic roles and activities9,10; thus, SS&H offers clear benefits to HPE. However, applying SS&H methods in HPE in an informed manner can prove challenging.11 On the one hand, SS&H approaches often require thoughtful adaptation if they are to be meaningful and effective in HPE.11,12 On the other hand, many examples abound of well-intentioned yet ill-informed attempts at applying SS&H content and methods to health professions training programs.13–16 As incorporation of SS&H rises in prominence in HPE,17 and as the popularity of SS&H-related goals, roles, and activities such as patient-centered care, health advocacy, and portfolio courses surges, misapplication risks becoming even more widespread. Misapplication may result in dismissal of potentially useful concepts and in poorer educational outcomes than could be realized with more informed applications.

HPE에서 일반적으로 오해되고 잘못 적용된 SS&H 접근법 두 가지는 비판적 성찰과 비판적 성찰성이다. 겹치지만 다른 지적 전통에서 비롯된 이러한 개념은 유사점을 공유하지만 교육학 및 평가에 대해 뚜렷한 의미, 사용 및 시사점을 가지고 있습니다. 하지만, 우리는 그들이 공통적인 몇 가지 기본적인 생각을 가지고 있거나, 아마도 비슷하게 들리기 때문에, 종종 혼동되거나 서로 결합된다는 것을 알아차렸다. HPE에서 SS&H 지식과 접근법의 잠재력을 실현하기 위해서는 기초 지식과 방법의 견고한 기반이 필요하기 때문에 이러한 혼란은 교육자에게도 영향을 미칠 수 있다.

Two commonly misunderstood and misapplied SS&H approaches in HPE are critical reflection14,18,19 and critical reflexivity.20–23 Arising from overlapping yet different intellectual traditions, these concepts share similarities but have distinct meanings, uses, and implications for pedagogy and assessment. However, we have noticed that, perhaps because they have some foundational ideas in common, or perhaps because they sound similar, they are often confused and/or conflated with each other. This confusion should concern educators because a solid foundation in the underlying knowledge and methods is required to realize the potential of SS&H knowledge and approaches in HPE.

학자들은 (성찰의 감시로서 사용하는 것을 포함하여) 성찰과 성찰성의 서투른 적용으로 인한 부정적인 결과에 주목하고 있으며, 우리는 '성찰 피로reflection fatigue'를 초래할 정도로 성찰이 남용되는 것에 주목하고 있다. 이러한 결과는 자금과 자원의 감소와 함께 설명 책임과 복잡성이 증가하는 시기에 심각합니다. 우리는 교육 접근방식의 부실하거나 비효율적인 구현에 시간과 자원을 낭비하거나 낭비할 수 없습니다. 그러나 우리는 "아기를 목욕물과 함께 내던져서는 안 된다" 즉, 성찰적 접근의 실행 실패가 성찰과 성찰성의 실패로 오해되어서는 안 된다. 우리는 비판적 성찰과 성찰성의 세부사항을 이해하는 것이 그들의 더 미묘한, 따라서 효과적인 연구와 응용을 지원할 수 있다고 주장한다.

Scholars have noted negative consequences from clumsy applications of reflection and reflexivity in medical education, including the use of reflection as surveillance,24,25 and we have noticed its overuse to the point of driving “reflection fatigue.” These consequences are serious at a time of increased accountability and complexity alongside decreased funding and resources. We cannot spend or waste time and resources on poor or ineffective implementations of education approaches. Yet we should not “throw the baby out with the bathwater”; that is, the failings of implementations of reflective approaches should not be mistaken for the failings of reflection and reflexivity. We argue that understanding the details of both critical reflection and reflexivity can support their more nuanced and thus effective study and application.

이 기사에서는 HPE 분야의 비판적 성찰과 비판적 반사성을 위한 견고한 기반을 명확히 하기 시작한다. 우선 각 항목을 차례로 정의하는 것부터 시작합니다(정의의 개요는 표 1 참조). 우리는 독자들이 그들의 지향과 목표를 이해하도록 돕기 위해 각각의 지적 맥락 안에 위치를 정하고, 그들 사이의 유사점과 차이점을 명확히 한다. 그런 다음 비판적 성찰과 비판적 반사성에 적합한 교육 및 평가 방법의 유형을 설명합니다. 공간 제약으로 인해 기술자 "critical"에 포함된 개념을 상세하게 검토하지 않습니다(본 문서에서 사용되는 이 용어 및 기타 용어의 간단한 정의는 박스 1 참조).

간단히 말해서, 성찰 또는 성찰성이라는 단어를 앞에서 한정하는qualifier "비판적critical"이라는 단어는 관련된 성찰적reflective 또는 성찰성적reflexive 활동이 특히 가정, 권력 관계, 구조, 시스템적 효과와 실천에 대한 제약에 도전/질문하는 것을 의미한다.

In this article, we begin to articulate a solid base for both critical reflection and critical reflexivity for the HPE field. We start with defining each in turn (see Table 1 for a summary of their definitions). We locate each in their intellectual contexts to help readers make sense of their orientations and goals, and we clarify the similarities and differences between them. We then delineate the types of teaching and assessment methods that fit with critical reflection versus critical reflexivity. Because of space constraints, we do not explore in depth the concepts embedded in the descriptor “critical” (see Box 1 for a brief definition of this and other terms used in this article); put simply, as a qualifier before reflection or reflexivity, “critical” means that the associated reflective or reflexive activities specifically challenge/question assumptions, power relations, and structural or systemic effects and constraints on practice.26–28

크리티컬 리플렉션/비판적 성찰

Critical Reflection

비판적 성찰은 [가정(즉, 개인 및 사회적 신념과 가치)과 권력 관계, 그리고 이러한 가정과 관계가 어떻게 실천을 형성하는지를 조사하는 프로세스]로 정의할 수 있다. 가정이 [유해한 실천]으로 이어질 경우, 비판적으로 성찰하는 실천자practitioner는 가정과 관행에 도전하고 변경하는 것을 목표로 합니다. 따라서 비판적 성찰의 목표는 프락시스이다: 사회 개선을 이끄는 [비판적 이론과 실천]의 균형잡힌 융합을 말한다.

Critical reflection can be defined as a process of examining assumptions (i.e., individual and societal beliefs and values) and power relations, and how these assumptions and relations shape practice. When assumptions lead to harmful practices, the critically reflective practitioner aims to challenge and change assumptions and practices. The goal of critical reflection is thus praxis: a balanced fusion of critical theory and practice that leads to social improvement.29

[비판적 성찰]은 practitioner로 하여금 [유해한 가정이 갖는 물질적 영향(박스 1 참조)에 대해 의문을 갖고 이에 대해 행동]하도록 지시합니다. 예를 들어, 가정의사는 장애인이 지원이나 자원에 접근할 수 있도록 작성하는 서류 등 [실제로 사용되는 일부 물질material object]에 내장된 [유해한 효과]를 발견할 수 있습니다. 환자의 특정 지원을 받기 위해 환자의 장애 정도를 "평가"해야 하는 경우가 많습니다. [장애를 평가하는 과정]은 보통 지나치게 단순하고, 사람을 잘못 표현하기 쉬우며, 제대로 논의하지 않으면 환자의 자기 이미지와 환자와의 관계에 해를 끼칠 수 있다. 만약 주치의가 비판적 성찰을 통해 이러한 잠재적 위해를 인식한다면, 환자와의 관계에서 [자신이 수행하는 평가의 필요성과 한계]를 인식할 것이다. 비판적 성찰이 이끄는 행동을 함으로써, 이 가정의사는 Praxis를 보여주고 있다. 또한 시간이 지남에 따라 정책 및 프로토콜 형성 관행을 개선하기 위해 노력할 수도 있습니다. 그녀는 정규 교육 및/또는 연습과 개인적 경험을 통해 이러한 방식으로 연습하는 법을 배웠을 수 있습니다.

Critical reflection orients practitioners to question and act on the material (see Box 1) effects of harmful assumptions. For example, a family doctor may notice harmful effects built into some of the material objects used in practice, such as the paperwork she completes for persons with disabilities to access supports and resources.30 To garner access to certain supports for her patients, she is often required to “rate” their level of disability. The process of rating disability is usually overly simplistic and prone to misrepresenting the person31 and can be damaging to the self-image of patients and to her relationship with them if left undiscussed.31 Because she recognizes this potential harm—through critical reflection—the family doctor ensures that in the relationship she builds with her patients, they appreciate the necessity and limitations of the rating she has to conduct. By engaging in action informed by critical reflection, this family doctor is demonstrating praxis. She may also work to improve the policies and protocols shaping practice, over time. She may have learned to practice this way through formal education and/or learning in and through practice and personal experience.

박스 1

Box 1

이 문서에서 사용된 용어집(중요한 반사 및 반사성 관련 용어집)

Glossary of Terms Used in This Article as They Relate to Critical Reflection and Reflexivity

행위자성: 사회에 대한 행동 능력.사회 규범과 가치관이 사회의 구조에 의해 어떻게 형성되어 왔는지를 알 수 있는 능력을 필요로 한다.

Agency: The capacity to act on the world, requiring the ability to see how social norms and values have come to be shaped by the structures of society.45

비판적: 성찰, 반사성 또는 이론보다 앞선 한정자 또는 형용사로서, '비판적'이란 의미는 가정, 이념, 시스템, 구조 및 권력 관계를 포함한 현재의 사회 규범에 대한 비판에 초점을 맞춘다는 것을 의미합니다.

Critical: As a qualifier or adjective preceding reflection, reflexivity, or theory, critical means that there is a focus on a critique of current societal norms including assumptions, ideology, systems, structures, and power relations.28,34,62

담론(형용사: 담론적): 사회적 구성 및 영속적인 언어 기반 의미 체계로서, 이것은 어떤 생각, 말, 행동 방식이 (불)가능한지를 형성한다. 예:

- [한 사람 내에 존재하는 기능 손상으로서의 장애]라는 지배적 담론은 사람들이 "기능"을 회복하도록 돕기 위해 재활을 생각하고 실천한다. 반면

- [사회가 부과하는 한계로서의 장애]라는 대안적 담론은 변화에 대한 부담의 일부를 사회에 이전시키고, 우리가 세상을 기능하고 살 수 있는 다양한 방법에 대한 개념을 넓힐 것을 간청한다.

Discourse (as an adjective: discursive): A socially-constructed and perpetuated, language-based system of meaning shaping (im)possible ways of thinking, speaking, and acting; e.g.

- the dominant discourse of disability as impairment of function within an individual means we think about and practice rehabilitation to help people regain “typical” function.

- An alternative discourse of disability as limitations imposed by society would move some of the burden of change to society, and implore us to broaden our conceptions of different ways of being able to function and live in the world.73–75

인식론: 우리가 알고 있는 것을 어떻게 알게 되는가에 대한 철학. (의견이 아니라) 지식을 개발하거나 습득하는 타당한 방법을 포함한다.

Epistemology: The philosophy of how we come to know what we know, including the methods considered to be valid ways of developing or gaining knowledge (as opposed to opinion).8,12,76–78

형평성Equity: 무엇이 정의롭고 공정한지에 대한 사고방식이며, 종종 평등equality과 대조된다.

- [평등]은 모든 사람이 같거나 동등한 기회와 지원을 받을 수 있는 것을 말한다(예: 의대에 입학하는 모든 학생이 동일한 수업료를 지불한다)

- [형평]은 누군가를 애초에 기회에서 배제시킬 수 있는 낮은 사회경제적 지위의 영향과 같은 장벽을 제거하는 것을 목표로 할 수 있다(예: 의대 진학에 필요한 학업기준에 부합하지만 등록금 재원이 부족한 학생에게 학비보조금을 제공한다.)

Equity: A way of thinking about what is just and fair, often contrasted with equality. Rather than

- equality in which all people would be given the same, or equal, opportunities and supports (e.g., all students entering into medical school pay the same tuition fee), an

- equitable approach might aim to remove barriers such as the effects of the lower socioeconomic status of a student that might preclude them from an opportunity (e.g., offering bursaries to students who meet the academic standards for entry to the medical school but lack the economic resources for tuition).79

물질: 사회와 문화가 구성하고, 사회와 문화를 구성하는 물리적 대상 및 측면과 관련된다. 예: 의료 차트, 증거 기반 진료 지침.

Material: Relating to the physical objects and aspects constituting and constituted by society and culture,80 e.g., medical charts, evidence-based practice guidelines.

교육학: 가르침의 이론과 실제.

Pedagogy: The theory and practice of teaching.

프락시스: 비판적으로 성찰하는 생각과 행동의 융합.

Praxis: The fusion of critically reflective thought and action.29

교육에서 [성찰]은 일반적으로 "어떤 믿음이나 가정된 형태의 지식에 대한 적극적이고 지속적이며 신중한 고려이다. [믿음이나 가정을 뒷받침하는 근거]와 [그것이 궁극적으로 지향하는 결론]에 비추어 고려하는 것이다"로 정의된다. 종종 성찰에 [비판적 차원]을 추가하는 것으로 알려진 하버마스는, 여기에 [성찰 과정에 비판적 렌즈를 적용하지 않는 한, 지식은 지식이 창조된 사회적 조건에 의해 제약을 받는다]는 것을 추가했다.

- 위의 예에서, 만약 가정의사가 장애 서류 작업을 하는 동안 성찰적인 태도를 보였다면, 그녀는 실제로 환자 자신의 희망에 대한 자신의 가정에 의문을 제기했을 수 있으며, 그녀가 인간 중심적이고 사려 깊은 방식으로 연습하고 있는지 확인할 수 있습니다.

- 하지만, 그녀는 비판적인 성찰을 통해 드러난 서류 처리 과정의 잠재적인, 더 음흉한 피해를 인식하지 못했거나 완화하려고 노력하지 않았을 수 있습니다. 또한, (서류에 서명함으로써 궁극적으로 환자의 자원 접근을 허가 또는 불허하게 만드는) 자신의 위치와 더 큰 기관 복합체 내에서의 상대적인 위치에 대해 덜 의식했을 수도 있다.

[비판적 성찰]은 (이 경우 의사의 관점을 변화시킴으로써) 기존의 관점과 권력 관계를 영속화하기보다는 변화를 목표로 하기 때문에, 따라서 [해방적 지식]을 생산할 수 있다.

In education, reflection is commonly defined as “active, persistent, and careful consideration of any belief or supposed form of knowledge in the light of the grounds that support it and further conclusions to which it tends.”32(p6) Habermas,33 often credited with adding a critical dimension to reflection, added to this definition that knowledge remains constrained by the social conditions in which it was created, unless a critical lens is applied to the reflective process.

- In the example above, if the family doctor was reflective while working on the disability paperwork, she may indeed have questioned her own assumptions about the patient’s wishes, to ensure that she was practicing in a person-centered and thoughtful manner.

- However, she may not have recognized or tried to mitigate the potential, more insidious harms of the paperwork process, which were brought to light through critical reflection. She would also be less aware of the position she holds by virtue of being the signatory on this paperwork, which ultimately grants/denies the patient’s access to resources, and her position relative to the larger institutional complex.

Critical reflection can thus produce emancipatory knowledge, as it aims to transform rather than perpetuate existing perspectives and power relations (in this case, by transforming the perspective of the physician).33

비판적 성찰 이론을 발전시킨 현대 작가로는 브룩필드, 켐미스, 킨셀라, 그린 등이 있다. 의학 교육에서 비판적 성찰에 관한 이론을 도입한 학자는 프리레와 하버마스의 작품과 그 적용 방법에 특히 초점을 맞춘 쿠마가이이다. Kumagai와 Lypson은 이러한 지식에 대한 이해를 학생들을 문화적 역량 밖으로 이동시키기 위한 노력과 같은 교육 혁신에 적용했습니다. 그들은 학생들이 특정 환자와 상호작용하는 ["올바른" 또는 "최상의" 방법을 기억하는 체크리스트 접근법]에서 벗어나서, [권력 관계에 대한 더 넓은 인식과 사회적 불평등을 완화하려는 욕구]로 옮겨갈 필요성을 분명히 강조한다. 따라서, 이 접근방식에 따르면, 모든 환자에게 좋은 돌봄을 제공하기 위해서는 [바람직한 기술을 수행하는 특정 방법을 습득할 때 [존재의 방식에 대한 비판적 성찰]이 동반되어야 한다. [존재의 방식]이란 관점과 덕성virtue를 체화하고, 집행하고, 문화화하는 방식을 의미한다. 이렇듯, [비판적 성찰]은 [사고 과정]이다. 비판적 성찰의 실천은 이 과정에 자주 또는 항상 관여engage하는 존재와 실천의 한 방법이다.

Contemporary authors who advance theories of critical reflection include Brookfield, Kemmis, Kinsella, and Greene26–28,34–37 (see Table 1). In medical education, a scholar who has taken up theories related to critical reflection is Kumagai,4,38 who has focused particularly on the works of Freire and Habermas and how they can be applied in medical education. Kumagai and Lypson4 have applied these understandings of knowledge to educational innovations such as efforts to move students beyond cultural competence. They articulate a need to move from checklist approaches, wherein students memorize the “right” or “best” way to interact with a particular patient, toward a broader awareness of power relations and a desire to mitigate social inequity.4 This approach thus suggests that, to provide good care for all patients, acquiring particular ways of performing desired skills must be accompanied by critically reflective ways of being—by which we mean embodied, enacted, enculturated views and virtues. Critical reflection is a thought process; critically reflective practice is a way of being and practicing that engages this process often or always.26,39

(비판적) 성찰성

(Critical) Reflexivity

[성찰성]은 [[자기의 지식의 한계를 더 잘 이해]하고 [다른 사람들의 사회적 현실을 더 잘 인식]하기 위해, 세상world 내에서 자신의 위치position를 인식하는 것]으로 정의될 수 있다. 따라서 모든 성찰성은, 무엇보다 [권력관계]에 주의를 기울이는 것을 포함하기에, 정의상 비판적이다. 그러나 일부 저자들은 [권력에 대한 주의를 명시적으로 우선시]하고자, "비판적 성찰성critical reflexivity"이라는 더 긴 용어를 사용하기로 선택한다. [성찰성적reflexive 실천가]는 그녀의 인식론적 가정과 합법적인 지식, 사회적 규범, 그리고 가치의 개념에 영향을 미치는 [사회적, 담론적 요소]에 도전할 것입니다. [성찰성]과 [비판적 성찰]은 사회적 개선이라는 목표를 공유하지만, [성찰성]은 [담론적으로 이해된contrued 사회적 세계가 누가, 어떻게, 어떤 지식과 사회적 규범의 구축에 어떻게 영향을 미치는지] 강조한다.36. 따라서 성찰성적 접근으로 제시된 해결책은 종종 [구조와 제도를 바꾸는 것]을 포함할 것이다. 예를 들어, 장애에 대한 성찰성적 접근법은

- 현재의 정의에 의문을 제기하다. (예: 장애를 개인 안의 것으로 보는 정의)

- 정의에 따른 실천에서 누가 권력을 얻거나 유지할지(예: 현재 장애가 없는 자, 재활 전문가 등), 이 담론에 의해 권력적 약자가 되는 사람은 누구인지(예: 장애인 등)에 대한 인식을 높인다.

- 이러한 권력 불균형을 만들고 유지하는 구조와 프로세스의 변화를 모색한다.

Reflexivity can be defined as recognizing one’s own position in the world both to better understand the limitations of one’s own knowing and to better appreciate the social realities of others. All reflexivity is thus by definition critical, as it specifically involves paying heed to power relations; however, some authors choose to use the longer term “critical reflexivity,” which explicitly foregrounds their attentiveness to power. A reflexive practitioner would challenge her epistemological assumptions (how we know what we know) and the social and discursive factors that influence conceptions of legitimate knowledge, social norms, and values. Although reflexivity and critical reflection share goals of social improvement, reflexivity emphasizes how the discursively construed social world influences what, how, and by whom knowledge and social norms are constructed,36 and so the solutions put forward in a reflexive approach will often involve changing structures and institutions. For example, a reflexive approach to disability may

- call into question its current definition (e.g., as an impairment within an individual),

- raise awareness of who stands to gain or maintain power from the ensuing practices of this definition (e.g., people currently without disabilities, rehabilitation professionals) and who is rendered less powerful by this discourse (e.g., people with disabilities), and

- seek to change the structures and processes that create and maintain this power imbalance.40

[자신의 사회적 지위를 인식하는 것]은 [다른 사람들의 경험에 대한 이해]를 넓힐 수 있다. 성찰성에 참여하려면, 먼저 이러한 믿음과 가정이 [우리가 자라나고 훈련받거나 현재 살고 일하는 사회문화 구조에 어떻게 내재되어 있는지]를 인식함으로써, [무엇이 진실되고 정상적인지에 대한 우리 자신의 믿음과 가정에 도전]해야 합니다. 예를 들어, 성찰성적 가정의사는 자신이 [장애인이 아닌 사람을 "정상"이라고 가정하는 건강 시스템] 내에서 기능하고 있다는 것을 알게 될 것이다.

그렇게 함으로써 그 의사는 [장애에 대한 현재의 담론]을 문제 삼을 것이다. 왜냐하면 이 담론에서는 "문제"는 '장애를 가진 사람'에게 존재하는 것이지, 장애를 가진 사람이 적응하고자 노력하고 있는 '시스템'에 존재하는 것이 아니기 때문이다.

Recognizing one’s own social position may broaden one’s understanding of the experiences of others. Engaging in reflexivity requires challenging our own beliefs and assumptions about what is true and normal by first recognizing how these beliefs and assumptions are embedded in the social and cultural structures in which we were raised and trained and/or currently live and work. Continuing our example, a reflexive family doctor would, for example, notice that she was functioning within a health system that assumes that people who are not disabled are “normal”; in so doing she would problematize the current discourse of disability, in which the “problem” is located with the “disabled” patient rather than with the system to which they have to try to fit in.40

이와 같은 (현재의) 문제적 담론은 [포용적인 환경을 만들려는 사회의 책임]을 회피하고, 대신 [인식된 규범에서 벗어난 사람들]에게 "적합해지기 위해 노력하라fit in"는 부담을 전가한다. [우리 모두가 억압적인 권력의 당사자]라는 성찰성의 내재적 의미는, 자신의 [특권적 지위]가 [지배적인 문화 또는 사회 집단]에 속함으로써 얻어지는 것임에 주의하게 만들기 때문에, 성찰성을 상당히 어렵게 만들 수 있다. 예를 들어, Rowland와 Kuper가 환자 경험을 하게 된 의료 전문가들을 대상으로 실시한 연구에서, 참가자들은 그들의 경험 중 [가장 고통스러웠던 부분] 중 하나는 환자의 입장에서 부정적으로 경험했던 [구조와 과정에 자기 자신이 (보건의료제공자로서) 어떻게 기여하고 있었는지에 대한 성찰적인 깨달음]이었다고 언급했다.

This problematic discourse defers responsibility from society to create an environment that is inclusive, instead shifting the burden onto those who fall outside the perceived norm to “fit in.” An inherent implication of reflexivity—that we are all (as part of society) party to oppressive forces—can make reflexivity quite difficult, particularly when it calls attention to one’s own privileged position derived from belonging to a dominant cultural or social group.41 For example, in Rowland and Kuper’s42 study of health care professionals who have also been patients, participants noted that one of the most painful parts of their experience was their reflexive realization of the ways in which they themselves (as health care providers) had contributed to the structures and processes that they then experienced so negatively as patients.

머튼은 성찰성을 [옳든 그르든, 상황의 결과와 그 믿음을 실현하기 위해 개인이나 집단이 어떻게 행동하는지에 영향을 미치는 자기충족적 예언]으로 묘사했다. 논쟁의 여지가 있지만, 그와 다른 초기 이론가들은 성찰성을 문제가 있다고 생각했다. 즉, 사회적 세계에 영향을 받지 않는 어떠한 행동도 취할 수 없고, 이는 다시 사회적 세계에 영향을 준다. 하지만, 더 최근에는 이론가들은 성찰성을 구조(사회가 개인의 신념과 행동에 영향을 주는가?) 대 개인(개인의 신념과 행동과 행위가 사회에 영향을 주는가?) 이라는 오랜 인식론적 문제를 극복하는 해결책으로 제시한다.

In one of the earliest uses of the term, Merton43 described reflexivity as a self-fulfilling prophecy, in which a belief or expectation, whether correct or incorrect, affects the outcome of the situation and how individuals or groups behave to make that belief come true. Arguably, he and other early theorists conceived of reflexivity as problematic: that no action can be taken that is not influenced by the social world, which in turn influences the social world. More recent theorists, however, present reflexivity as the solution to overcoming the long-standing epistemological problem of structure (does society influence individual beliefs and behaviors?) versus agency (do individual beliefs, behaviors, and actions influence society?).44

예를 들어,

- Bourdieu는 사회과학은 본질적으로 우리의 선입견preconception에 의해 제약을 받는다고 주장했다; 이러한 한계를 극복하기 위해, 우리는 우리의 사회적, 문화적 기원, 현장에서의 우리의 위치, 그리고 우리의 지식 주장을 질문함으로써 우리 자신의 입장을 더 잘 이해하려고 노력해야 한다.

- 비슷하게, Foucault46은 역사가 현재 지식을 구조화하고 체계화한다고 제안했다; 무엇을 생각할 수 있고 알 수 있는지는 우리가 사용하는 담론을 통해 형성되며, 담론이 우리의 사고를 어떻게 제약하는지를 고려하는 것이 반드시 필요하다.

- Bourdieu, for example, argued that the social sciences are inherently constrained by our preconceptions; to overcome these limitations, we should seek to better understand our own positions by interrogating our social and cultural origins, our position in the field, and our knowledge claims.45

- Similarly, Foucault46 proposed that history structures and organizes knowledge in the present; what is thinkable and knowable is shaped through the discourses we use, making it imperative that we consider the ways in which this constrains our thinking.

부르디우와 푸코는 둘 다 보통 당연하게 여겨졌던 사회의 특성, 어떻게 그러한 특성을 갖게 되었고, 결과적으로 누가 이득을 보고 손해를 보는지에 대해 이의를 제기했다. 또, 다음과 같은 권력의 문제에 초점을 맞췄습니다. 푸코는 [담론]이 우리의 사고와 실천을 함정에 빠뜨린다고 보았고, 부르디우는 [사회 구조]가 사회적 불평등을 재현한다고 보았. [비판적 성찰성]은 이렇게 ["자연스러워" 보이는 힘forces]을 인식하는 것이다. 즉, 우리가 힘forces을 어떻게 생산하고 재생산하는지, 힘forces이 우리에게 어떻게 영향을 미치는지, 우리가 힘forces에 어떻게 영향을 미치는지를 인식하는 것이고, 이것이 변화하는 역동적인 과정이라는 것을 인식하는 것이다.

Bourdieu and Foucault both challenged the properties of society normally taken for granted, how they came to be, how they were naturalized, and who ends up benefiting and losing as a result. They also focused on issues of power: Foucault46 sees discourses as trapping our thinking and practice, and Bourdieu44 sees social structures as reproductive of social inequities. Critical reflexivity is about recognizing these “natural”-seeming forces, how we are implicated in producing and reproducing them, how they affect us, how we affect them, and that this is a dynamic process subject to change.

더 많은 현대 학자들이 (성별, 인종, 식민지 경험, 능력과 같은) 특정한 사회적 구조(및 이들의 교차점)와 관련하여 [비판적 성찰성]의 개념을 탐구해 왔다. 예를 들어,

- 패트리샤 힐 콜린스는 아카데미에서 흑인 여성으로서의 그녀의 "외계인" 지위가 그녀가 정상적이고 자연스러워 보이는 "내부인"들에게 주목받지 못하는 현상을 알아차릴 수 있도록 하는 방법을 탐구했다.

- 마찬가지로, 사이드는 유럽과 북미의 학자들이 아시아, 중동, 그리고 아프리카에서 온 사람들을 "미스터리한 다른 사람"으로 구성하면서 그들의 목소리와 힘을 식민지화의 더 큰 현상의 일부로서 감소시키는 방식을 문제화했다.

- Crenshaw58은 이러한 다른 사회적 범주가 중복될 수 있는 방법의 복잡성과 권력과 지식에 미치는 영향을 강조하기 위해 "교차성"이라는 용어를 도입했습니다.

이 저자들은 각기 다른 사회 집단의 경험을 강조하고 있지만, 집합적으로 우리가 ["자연적"이고 "정상적"으로 보이지만 실제로 변화하기 쉬운 구조와 과정을 유지하는 우리의 역할]을 깨닫는 데 도움이 되며, 따라서 우리가 공유된 사회 세계를 개선하기 위해 행동하도록 영감을 준다.

More contemporary scholars have explored the notion of critical reflexivity in relation to specific social constructs such as gender,47–50 race,51,52 experience of colonization,53–55 and ability40,56,57 (among others), as well as to the intersections between them.

- Patricia Hill Collins,52 for example, has explored the ways in which her “outsider” status as a black woman in the academy enables her to notice (and seek to address) phenomena that go unremarked to those “insiders” for whom they seem normal and natural.

- Similarly, Said53 has problematized the ways in which European and North American academics constructed people from Asia, the Middle East, and Africa as a “mysterious other,” diminishing their voices and their power as part of the larger phenomenon of colonization.

- Crenshaw58 introduced the term “intersectionality” to highlight the complexity of the ways in which these different social categories can overlap and the implications that has for power and knowledge.

Although the experiences of the social groups highlighted by these writers differ, collectively their work helps us to identify our roles in maintaining structures and processes that seem “natural” and “normal” but may actually be amenable to change, and thus inspires us to act to improve our shared social world.

교육 및 평가에 미치는 영향

Implications for Teaching and Assessment

교육적 접근 방식을 알려주는 학문적 전통을 사용하는 교육 및 평가 방법에 맞추는 것은 교육 노력의 질과 의미에 있어 중요합니다. 비판적 성찰과 비판적 성찰성은 특정한 약속을 공유한다. 둘 다 [사회 개선을 위해 노력]하고 [기존의 권력 구조에 도전]합니다. 따라서 우리는 차이점뿐만 아니라 비판적 성찰과 반사성을 교육, 평가 및 평가하기 위한 공통 과제와 전략도 탐구할 것이다.

Aligning the academic traditions informing an educational approach with the teaching and assessment methods used is key to the quality and meaning of the educational efforts being employed.59 Critical reflection and critical reflexivity share certain commitments; they both strive for social improvement and challenge existing power structures. We will thus explore not only the differences but also the common challenges and strategies for teaching, assessing, and evaluating critical reflection and reflexivity.

비판적 성찰에 대한 교육 및 평가

Teaching and assessing for critical reflection

HPE에서 비판적 성찰을 가르치는 사람들의 경우, 이론 문헌과 일치하는 전반적인 목표는 학생들이 임상 작업에 대해 일종의 [프락시스]로서 접근하는 것을 가르치는 것이다. 위의 장애 정책과 관련하여 일하는 가정의사의 예에서 언급한 바와 같이, Praxis는 [비판적 이론에 입각한 행동]이다. 그것은 [성찰]과 [행동], 특히 [비판적 성찰]과 [행동]의 융합이다.

- 조직 차원에서는 [비판적으로 성찰하는 의대]라면, [이론적인 조사에 근거해, 불평등하다고 보여지는 척도를 제거하는 방향으로 입학 기준을 바꿀 수]도 있다.

- [비판적으로 성찰하는 교수와 프로그램]은 학생들을 프락시스 지향의 문화(프락시스 지향의 입학은 좋은 시작이다)속에서 사회화하고, 학생들이 실천과 환자에 대해 자신이 가지고 있는 가정에 대해 지속적으로 의문을 던지도록 하는 것을 목표로 할 것이다.

- [(비판적으로 성찰하는) 학생들]은 자신의 실천과 프로토콜에 포함된 가정과 유해한 관계에 적극적으로 도전함으로써 자신의 실천 컨텍스트에서 점진적으로 매일 개선을 도모하는 것을 목표로 할 것이다.

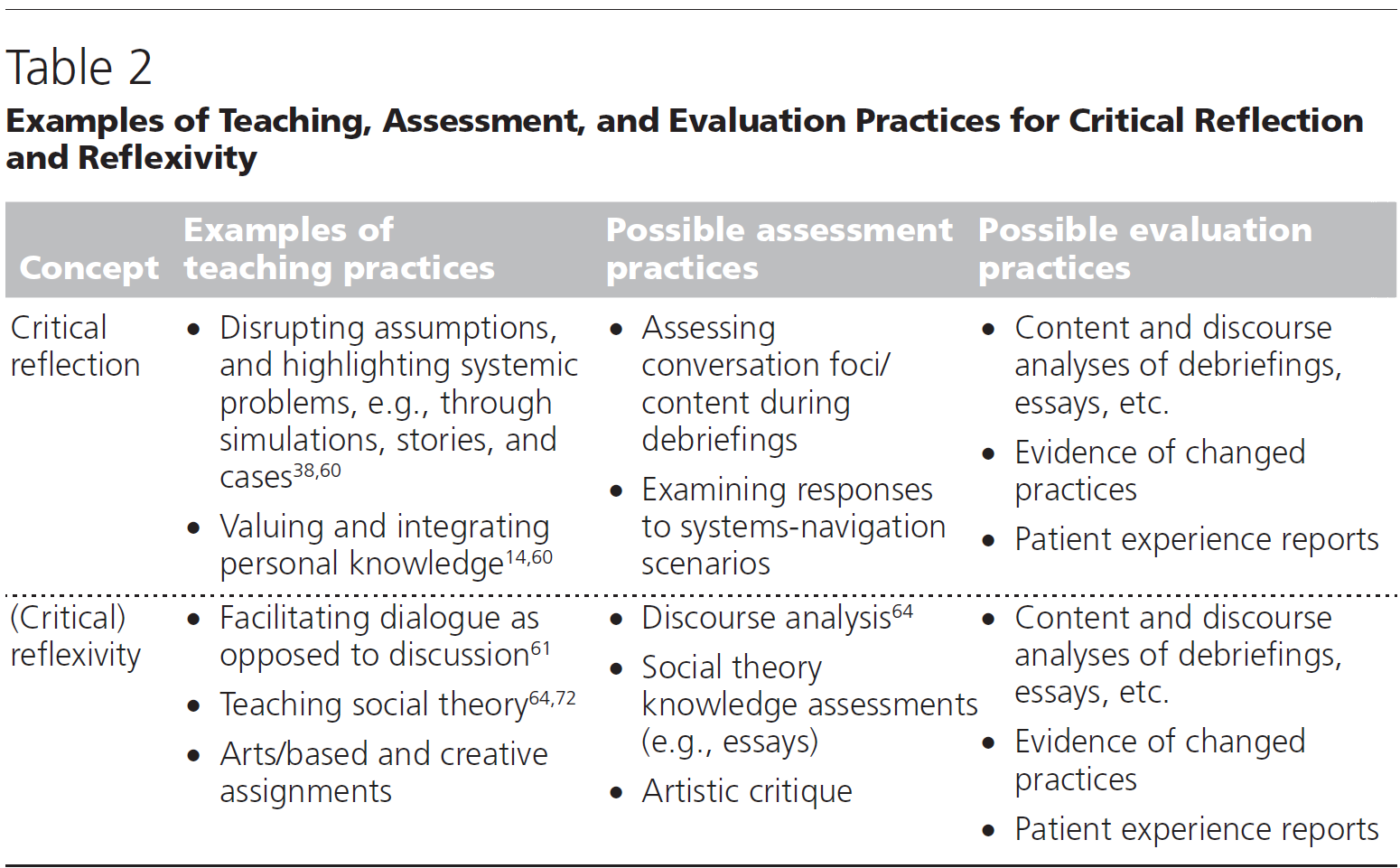

Baker 등, Halman 등, Kumagai 및 Lypson에 의해, 이러한 목표에 맞춘 교육 관행의 개요가 설명되고 있으며, 표 2에 몇 가지 예가 있다.

For those teaching critical reflection in HPE, the overall goal congruent with the theoretical literature would be to teach students to approach their clinical work as a form of praxis. As noted above in our example of the family doctor working in relation to disability policies, praxis is critical theory–informed action. It is a fusion of reflection and action, specifically critical reflection and action.29

- At the organizational level, a critically reflective medical school might change its admissions criteria by removing a measure shown to be inequitable, based on theory-informed investigation.

- Critically reflective faculty and programs would aim to socialize students in a praxis-oriented culture (a praxis-oriented admissions process being a good start) and to orient them toward continually questioning their own assumptions about their practices and about their patients.

- Students would also be oriented toward creating incremental everyday improvements in their own practice contexts by actively challenging the assumptions and harmful relations embedded in their practices and protocols.

Pedagogical practices aligned with these goals have been outlined by Baker et al,59 Halman et al,60 and Kumagai and Lypson,4 and we share some examples in Table 2.

비판적 성찰의 커리큘럼 목표는 [합의된 "콘텐츠" 지식 기반]을 구축하는 것이 아니라, [특정한(지속적으로 질문하는) 시각과 존재 방식]을 학생들에게 고취하는 데 초점을 맞추고 있습니다. 따라서 비판적 성찰의 핵심 개념(예: 확립된 권력관계를 인식하고 때로는 도전하는 것)은 단순히 특정 강의나 과목에서 가르치는 것이 아니라, 공식적이고 숨겨진 커리큘럼 전체에 통합될 필요가 있다. 마찬가지로 교수는 내용지식을 주로 전달하는 교사가 아니라, 학생들과 함께 배우고 도전하는 역할 모델 및 멘토 역할을 합니다. 구체적인 커리큘럼 내용은 사고와 존재 방식을 형성하는 수단이 될 것이다.

Curricular objectives for critical reflection focus on imbuing students with a particular, constantly questioning, way of seeing and being, rather than on building an agreed-upon “content” knowledge base. As such, notions that are key to critical reflection (such as recognizing and, at times, challenging established power relations) would need to be integrated throughout the formal and hidden curricula rather than simply taught in a particular lecture or course.29 Similarly, faculty members would serve as role models and mentors who learn with and challenge students rather than as teachers who primarily transmit content knowledge; the specific curriculum content would be a vehicle for shaping ways of thinking and being.4,38,61

비판적 성찰의 평가는 또한 그것의 철학적, 이론적 기원과 일치해야 한다. 성찰 학자들은 성찰 활동을 평가하거나 의무화할 때 잠재적 위험에 주목했다. 일부에서는 성찰적 사고의 표현을 서면으로 의무적으로 제출하게 만들면, 성찰이 [일종의 감시]가 된다고 주장한다. 다른 이들은 성찰을 지나치게 환원주의적으로 평가하는 접근법은 [핵심point을 놓치고], 대신 [토큰주의적이거나 조작된 반성을 유도한다]고 주장한다. 이러한 크리틱은 일반적으로 (비판적 성찰이 아니라) 성찰에 대한 것이다. 성찰과 반사성에 대한 [비판성criticality]를 더할 때 [사회적 가정, 규범 및 가치가 강조된다는 점]을 고려할 때, 우리는 주의를 기울여야 할 이유를 더 확장할 수 있다.

Assessment of critical reflection must also align with its philosophical and theoretical origins. Scholars of reflection have noted potential dangers in assessing or mandating reflective activities. Some have argued that through mandated submission of written representations of reflective thought, reflection becomes a form of surveillance; others argue that overly reductionistic approaches to assessing reflection miss the point and instead drive tokenistic or fabricated reflection.14,24,62 These critiques have typically been levied at reflection (not critical reflection); given the emphasis on societal assumptions, norms, and values that adding criticality to reflection and reflexivity brings, we extend the cause for caution even further.

[모든 평가는 통제의 한 형태]라는 주장이 종종 제기되어 왔지만, [점수grading]을 통해 사회 세계를 바라보는 특정한 방식을 명시적으로 강요하는 것은 현대 교육자들 사이에서 불편함을 야기할 것임을 쉽게 상상할 수 있다. 그러나 윤리적으로 덜 까다로울 수 있는 다른 옵션이 적어도 두 가지가 있다.

- 의료 분야에서는 실무 환경에서 직업의 일원으로 일하는 모든 실무자에게 요구되는 가치와 규범(종종 전문직 윤리강령으로 기술됨)이라는 오랜 역사가 있습니다. 그러한 가치의 현대적 예는 [동정심과 정직성]을 포함할 수 있습니다. 따라서 직장 내에서 이러한 직업별, 합의된 가치를 집행enact하거나 수행하는 학생들의 능력을 평가할 수 있다.

- 또한 비판적 성찰이 [환자 치료를 개선할 것으로 기대되는 특정 가치]를 옹호하고 모델링하는 [기관적 전환shift]의 일부로 받아들여진다면, [그러한 가치들을 기관적 차원에서 집행enact하는 학교의 성공]과 [환자 치료에 대한 그러한 조치의 효과]를 둘 다 평가하는 것이 적절할 것이다. 그러나 이러한 영향은 비판적 성찰과 일치하는 방식으로 평가해야 한다.

Although it has often been argued that all assessment is a form of control,63 one could easily imagine that explicitly enforcing—through grading—particular ways of viewing the social world might cause discomfort amongst contemporary educators. However, there are at least two other options that might be less ethically fraught.

- There is a long history in the health professions of identifying values and norms (often delineated in codes of professional ethics) required of all practitioners while working as a member of the profession in the practice setting; contemporary examples of such values might include compassion and honesty. One could, therefore, assess students’ abilities to enact or perform these profession-specific, agreed-upon values within the workplace.

- In addition, if critical reflection is taken up as part of an institutional shift to espousing and modeling particular values that are thought to improve patient care, then it would be appropriate to evaluate both the success of the school in enacting those values at the institutional level and the effect of those actions on patient care. However, these effects would need to be assessed in ways aligned with critical reflection.

비판적 성찰과 연계된 평가는 주로 추가 연구의 영역으로 남아있지만, 관점과 가치의 변화를 측정하기 위한 [체크리스트 접근방식]은 비판적 성찰의 기본 원칙과 일치하지 않을 수 있다. 대신 시뮬레이션 디브리핑 중 대화 분석을 포함하여 개인의 시프트된 관점을 평가하기 위한 접근방식을 모색하기 시작했습니다. 학자들은 최근 성찰성에 대한 학습을 평가하기 위해 담론 분석 접근법을 사용했으며, 우리는 비판적 성찰에도 같은 것이 이루어질 수 있다고 제안한다.

Although assessment aligned with critical reflection largely remains an area for further research,59 a checklist approach to measuring a shift in perspective and values would likely not be congruent with the underlying principles of critical reflection. Instead, we have begun to explore approaches to assessing a person’s shifted perspective, including, for example, analyzing conversations during simulation debriefings. Scholars have recently used discursive analysis approaches to assess learning about reflexivity, and we suggest that the same could be done for critical reflection.64

비판적 성찰성 교육 및 평가

Teaching and assessing for critical reflexivity

[비판적 성찰]을 가르치는 전반적인 목표가 [프락시스Praxis를 자극하는 것]이라면, [비판적 성찰성]을 가르치는 전반적인 목표는 [갱신된 행위자성renewed agency을 자극하는 것]이다. 행위자성은 [사회에 대해 행동할 수 있는 것]을 의미하며, 그것은 우리의 현재 행동 방식의 한계를 벗어나 더 나은, 더 윤리적 세상을 생각하는 것으로 시작해야 한다. [현재의 사고방식과 지식의 한계를 넘어 생각]할 수 있어야 하기 때문에, 진정한 에이전시를 갖기 위해서는 성찰성적이어야 한다. 위의 예를 계속하여, 만약 우리가 개인의 수준에서 [비판적 반성]을 평가하고 싶다면, 우리는 먼저 현재의 평가 정의를 재고하는 사람들을 반사적으로 생각하고 평가하는 방법을 제정할 필요가 있을 것이다. (즉, 평가의 다른 전제조건/이해에 의해 통지되는 새로운 평가 개념을 만드는 것). 여기서 우리는 [비판적 성찰과 비판적 성찰성 사이의 중첩]을 발견합니다. 즉, 평가를 완전히 다르게 상상함으로써 새로운 재료 평가 접근법을 만듭니다.

While the overall goal of teaching critical reflection is to stimulate praxis, the overall goal for teaching critical reflexivity in HPE is to stimulate renewed agency. Agency means being able to act on society, which must begin with thinking of a better, more ethical world, outside the confines of our current ways of doing things.44 One must be reflexive to have true agency as one must be able to think beyond the confines of current ways of thinking and knowing.44 Continuing with the example above, if we wanted to assess critical reflection at the individual level, we would need to first reflexively conceive of and enact a way of assessing people that rethinks current definitions of assessment (i.e., creating a new conception of assessment informed by different assumptions/understandings of assessment). Here we see a point of overlap between critical reflection and reflexivity—creating new material assessment approaches by imagining assessment completely differently.

[성찰성]을 가르치기 위해서는, 학생들에게 [자기 자신]뿐만 아니라, [자신의 위치나 존재 방식] 등에 대해서도 암묵적인 가정을 보다 폭넓게 질문하는 방법을 가르쳐야 합니다. 학생들은 [(일상적으로 정상으로 보이지만) 실제로는 역사와 우연의 산물인 사회적 현상을 "낯설게make strange" 만드는 방법]을 배울 필요가 있을 것이다.65 이러한 사고방식은 사회과학 전공에서 일상적으로 가르치고 있으며, HPE는 이러한 접근법에서 차용될 수 있다.8 예를 들어,

- 학생들은 특정한 개념(즉, 형평성, 권력)을 정의하도록, 그리고 중요한 이론적 프레임워크를 선택해서 작업하도록 배울 필요가 있을 것이다.

- 그들은 또한 식민주의, 동성애 혐오증, 인종차별, 또는 환자들이 직면할 수 있는 다른 유사한 형태의 차별과 같은 주제에 대해 교육받을 필요가 있을 것이다.

- 교수들은 학생들이 이 지식을 습득할 수 있도록 하고 모든 지식 주장의 기초가 되는 가정에 대한 추가 질문의 기초로 사용할 수 있도록 해야 합니다.

To teach reflexivity, students would need to be shown how to question their tacit assumptions not only about themselves—their own position and ways of being—but also about societal norms more broadly. They would need to learn how to “make strange” social phenomena that are routinely seen as normal but are actually socially constructed products of history and happenstance (e.g., definitions of family, competence, or disability).65 These ways of thinking are routinely taught in social science faculties; HPE could borrow from these approaches.8 For example,

- students would need to be taught to define specific concepts (i.e., equity, power) and work with a selection of important theoretical frameworks.

- They would also need to be educated about such topics as colonialism, homophobia, racism, and/or other similar forms of discrimination that might be faced by their patients.

- Faculty members would need to enable students both to acquire this knowledge and to use it as the basis for further questioning the assumptions underlying all knowledge claims.

이 사회과학 지식에 대한 평가는 학생들이 토론, 서면, 그리고 실제에서 어떻게 주요 개념을 적용하는지에 초점을 맞출 수 있다. 여기서 중요하지만 미묘한 차이점에 주목하십시오.

- [비판적 성찰]은 프락시스 지향의 전통에서 비롯됩니다. 그것은 [보는 방법과 존재하는 방법ways of seeing and being]에 더 초점을 맞추고 있기 때문에, 학습과 성과를 평가하는 [전통적인 학문적 방식]에 덜 적합합니다. 따라서 비판적 반성은 평가에 대한 더 실무에 기초한 접근법practice-based에 도움이 될 수 있다.

- 한편, [비판적 성찰성]은 학습자가 기억력, 이해력 및 적용 측면에서 시험할 수 있는 [사회과학 이론 세트]를 명확하게 포함하고 있다는 점에서, 약간 더 "전통적인" 것으로 생각될 수 있다. 즉, [비판적 성찰성적 이론의 이해]가 아니라, [비판적 반사성의 집행enact]에 대한 평가는 위에서 언급한 것처럼 [비판적 성찰]과 유사한 평가 접근법을 필요로 할 것이다.

비판적 성찰과 반사성의 궁극적인 목표는 겹치므로, 평가 접근법은 결국 관점과 관행이 어떻게 변화했는지를 결정하는 데 수렴될 수 있다.

Assessment of this social scientific knowledge could focus on how students apply key concepts in discussion, in writing, and in practice. Note here a key, yet subtle, difference.

- Critical reflection derives from praxis-oriented traditions; it is more focused on ways of seeing and being and thus fits less neatly into our traditional academic ways of assessing learning and performance. Critical reflection may therefore lend itself to more practice-based approaches to assessment.

- Meanwhile, critical reflexivity could be conceived of as being slightly more “traditional” in that it contains clearly agreed-upon sets of social science theory that learners could be tested on in terms of memory, understanding, and application. This said, the enactment of critical reflexivity as opposed to the understanding of critically reflexive bodies of theory would require similar assessment approaches to critical reflection such as those mentioned above.

The ultimate goals of critical reflection and reflexivity overlap, so the assessment approaches might eventually converge around determining how perspectives and practices have shifted.59

비판성을 위한 공간 확보

Making Space for Criticality

비판적 성찰과 반사성을 가르치고, 평가하고, 평가하는 위의 어떤 제안도 생명과학에서 일반적인 것 이상의 것을 알 수 있는 철학적, 물리적 공간 없이는 가능하지 않습니다. 다른 학자들이 이를 탐구했고, 우리는 독자들에게 이 작품들을 살펴보라고 권한다.

None of the above suggestions for teaching, assessing, and evaluating critical reflection and reflexivity are possible without a philosophical and physical space for ways of knowing beyond those common in bioscience. Other scholarship has explored this, and we direct readers to these works.38,61,66,67

이 기사에서는 비판적 성찰과 비판적 성찰성의 개념을 보다 정밀하고 뉘앙스로 도입하고, 사회과학이나 인문학의 개념을 HPE에 적용하는 이 접근방식을 채택할 기회를 제시한다. 그러나 우리는 비판적 성찰 및 비판적 성찰성을 (지속적으로 적용하는 과정에서 진화하지 않는) 완전하거나 정적인 개념으로 포지셔닝할 의도가 없다. 사실, 브룩필드는 우리가 궁극적으로 비판적 성찰의 과정을 그 자체로 되돌릴 것을 옹호한다. 우리는 비판적 성찰과 비판적 성찰성 자체를 문제화해야 한다고 주장한다. 이러한 개념이 더 대중화되면, 그것들은 또한 더 희석되어 의미가 "증발"되고, 궁극적으로 물화reified된다. 그렇게 되면, 이 개념은 [원래 그것이 기원한 맥락]을 훨씬 넘어, [담론의 수준]으로 올라감을 의미한다. 우리는 이미 비판적 성찰에서 피난evacuation의 징후를 볼 수 있다(비판적 성찰을 가르치고 육성한다고 주장하는 수많은 과제와 포트폴리오).

This article sets forth an opportunity to engage the concepts of critical reflection and reflexivity with more precision and nuance, and to take this approach to applying any social science or humanities concept to HPE. However, we do not intend to position critical reflection and reflexivity as infallible or static concepts, unable to evolve as they are continually applied. In fact, Brookfield26 advocates that we ultimately turn the critically reflective process back on itself. We argue that we must problematize both critical reflection and reflexivity themselves. As these concepts become more popular, they also become more diluted, becoming “evacuated” of meaning (wherein the concepts mean everything and thus nothing) and ultimately reified, which means the concepts can become raised to a level of discourse well beyond their original contexts of origin. We can already see signs of evacuation of critical reflection (with countless assignments and portfolios claiming to teach and foster critical reflection but meaning vastly different things).

브룩필드는 또한 우리가 비판적 성찰을 홍보하는 것에 너무 빠져든 나머지, 그것을 [배제의 메커니즘]으로 사용하고, [권력을 얻기 위한 수단]으로 사용할 수 있다고 경고한다. 우리는 (마치 비판적 성찰을 위해 사용하고 가르치는 교육자들이 점점 더 나은 교육자가 되어 억압을 뿌리뽑을 수 있다는 것과 같은) "선형적인 진보"를 목격할 것이며, 또 그래야만 한다는 생각을 버려야 한다. 브룩필드는 "지배적 문화적 가치가 다수보다 소수의 이익에 기여하는 방식을 분석하는 데 적용한 것과 동일한 [합리적 회의론]을 우리 자신의 입장에 적용해야 한다"고 결론지었다. 또한, 우리 자신의 실천에 대해 비판적으로 성찰하는 입장은 [건강한 아이러니]이다. 이것은 우리가 좋은 관행에 대한 하나의 보편적인 진실을 포착했다는 믿음에 대한 필요한 대비책hedge이다. 또한 [비판적 성찰 프로토콜]을 [무비판적 개발하고 물화하는 것]을 방지하는 데에도 도움이 된다."라고 말하였다.

Brookfield further cautions that we can get so caught up in our own promotion of critical reflection that we use it as a mechanism of exclusion and means to gain power. We also need to let go of the notion that we can and should see “linear progress,” as if educators using and teaching for critical reflection become increasingly better educators, eradicating oppression one day at a time. Brookfield concludes that we must “apply the same rational skepticism to our own position that we apply to analyzing how dominant cultural values serve the interests of the few over the many. A critically reflective stance towards our practice is healthily ironic, a necessary hedge against the belief that we have captured the one universal truth about good practice. It also works against uncritical development, and reification, of protocols of critical reflection.”26(p47)

우리는 Brookfield의 현명한 말을 반복하고, 모든 과학적이고 SS&H의 개념과 방법은 원래 분야와 HPE 양쪽에서 지속적인 정밀 조사를 받아야 한다고 강조한다. 비판적 성찰과 비판적 성찰성의 경우, 지속적인 연구는 학습 방법, 학습 방법 및 학습 방법, 평가 방법 및 평가 방법, 결정적 성찰 또는 반사성의 교육 및 평가가 정렬되고 의미 있는 영향에 대해 어떻게 평가될 수 있는지에 초점을 맞출 필요가 있다. [비판적 성찰과 비판적 성찰성]의 목적은 (유일하고 고정적이며 올바른 존재, 시각, 사고방식으로 이어지는 것이 아니라), 자신의 존재, 시각, 사고방식의 기초가 되는 가정에 대한 지속적인 의문을 불러일으키는 것이다. 이러한 접근방식을 보다 신중하게 실장하는 방향으로 나아가면 평가 접근방식도 조정되고 적절해야 합니다. 이러한 지속적 질문과 일치된 평가는 HPE 분야의 지속적인 발전과 보건 전문가의 사고 및 실천의 핵심이다.

We echo Brookfield’s wise words, and stress that all scientific and SS&H concepts and methods be subject to continued scrutiny both from within their originating disciplines and in HPE. For critical reflection and reflexivity, continued research needs to focus on how they are learned, how they can and should be taught, how they can and should be assessed, and how the teaching and assessing of critical reflection or reflexivity might be evaluated for aligned and meaningful impacts. The purposes of critical reflection and reflexivity are not to lead to a singular, fixed, right way of being, seeing, and thinking but, rather, to inspire continual questioning of the assumptions underlying one’s ways of being, seeing, and thinking. As we move toward implementing these approaches more thoughtfully, evaluation approaches must also be aligned and appropriate. This continued questioning and aligned evaluation are core to both the ongoing development of the HPE field and that of health professionals’ thinking and practice.

doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000002724.

The Divergence and Convergence of Critical Reflection and Critical Reflexivity: Implications for Health Professions Education

PMID: 30920447

Abstract

As a field, health professions education (HPE) has begun to answer calls to draw on social sciences and humanities (SS&H) knowledge and approaches for curricular content, design, and pedagogy. Two commonly used SS&H concepts in HPE are critical reflection and critical reflexivity. But these are often conflated, misunderstood, and misapplied. Improved clarity of these concepts may positively affect both the education and practice of health professionals. Thus, the authors seek to clarify the origins of each, identify the similarities and differences between them, and delineate the types of teaching and assessment methods that fit with critical reflection and/or critical reflexivity. Common to both concepts is an ultimate goal of social improvement. Key differences include the material emphasis of critical reflection and the discursive emphasis of critical reflexivity. These similarities and differences result in some different and some similar teaching and assessment approaches, which are highlighted through examples. The authors stress that all scientific and social scientific concepts and methods imported into HPE must be subject to continued scrutiny both from within their originating disciplines and in HPE. This continued questioning is core to the ongoing development of the HPE field and also to health professionals' thinking and practice.

'Articles (Medical Education) > 전문직업성(Professionalism)' 카테고리의 다른 글

| 성격은 무엇인가? 두 개의 미신과 하나의 정의(New Ideas in Psychology, 2020) (1) | 2022.03.21 |

|---|---|

| 복잡성 해결하려고 노력하기: 전문직정체성 발달의 창으로서 의과대학생의 환자 조우 성찰적 글쓰기(Med Teach, 2018) (0) | 2022.03.16 |

| 전문직 정체성 형성을 위한 의학교육 현장의 과제 (KMER, 2021) (0) | 2022.02.23 |

| 우리나라 의학전문직업성 교육과정에서의 ‘전문직 정체성 형성’ 교육 현황 (KMER, 2021) (0) | 2022.02.23 |

| 전문직 정체성 형성 및 촉진을 위한 의학교육 현황과 고려점(KMER, 2021) (0) | 2022.02.23 |