HPE에서 데이터 사이언스와 머신러닝의 역할: 실용적 적용, 이론적 기여, 인식론적 신념(Adv Health Sci Educ Theory Pract. 2020)

The role of data science and machine learning in Health Professions Education: practical applications, theoretical contributions, and epistemic beliefs

Martin G. Tolsgaard1,2 · Christy K. Boscardin3 · Yoon Soo Park4,5 · Monica M. Cuddy6 · Stefanie S. Sebok‑Syer7

서론

Introduction

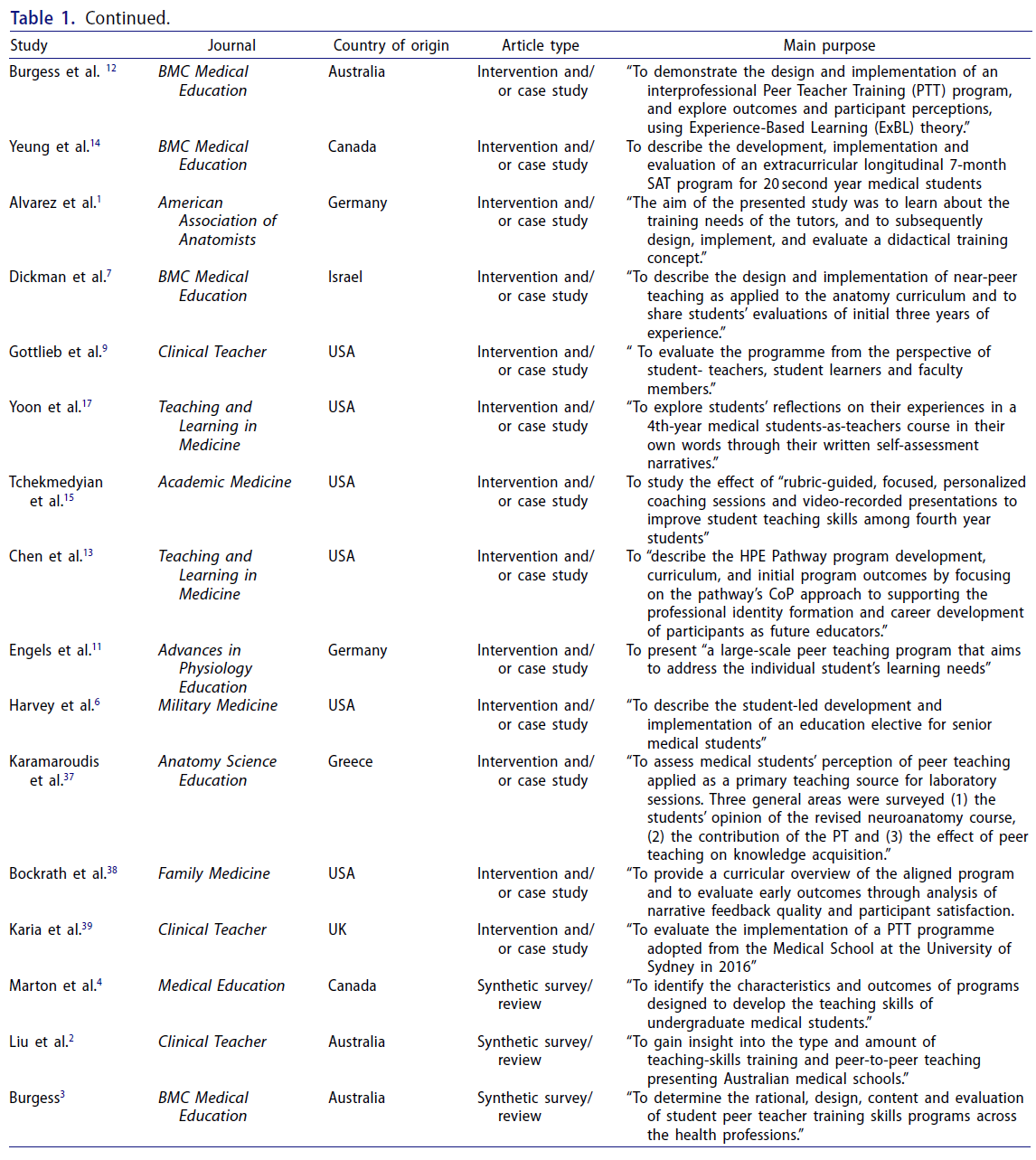

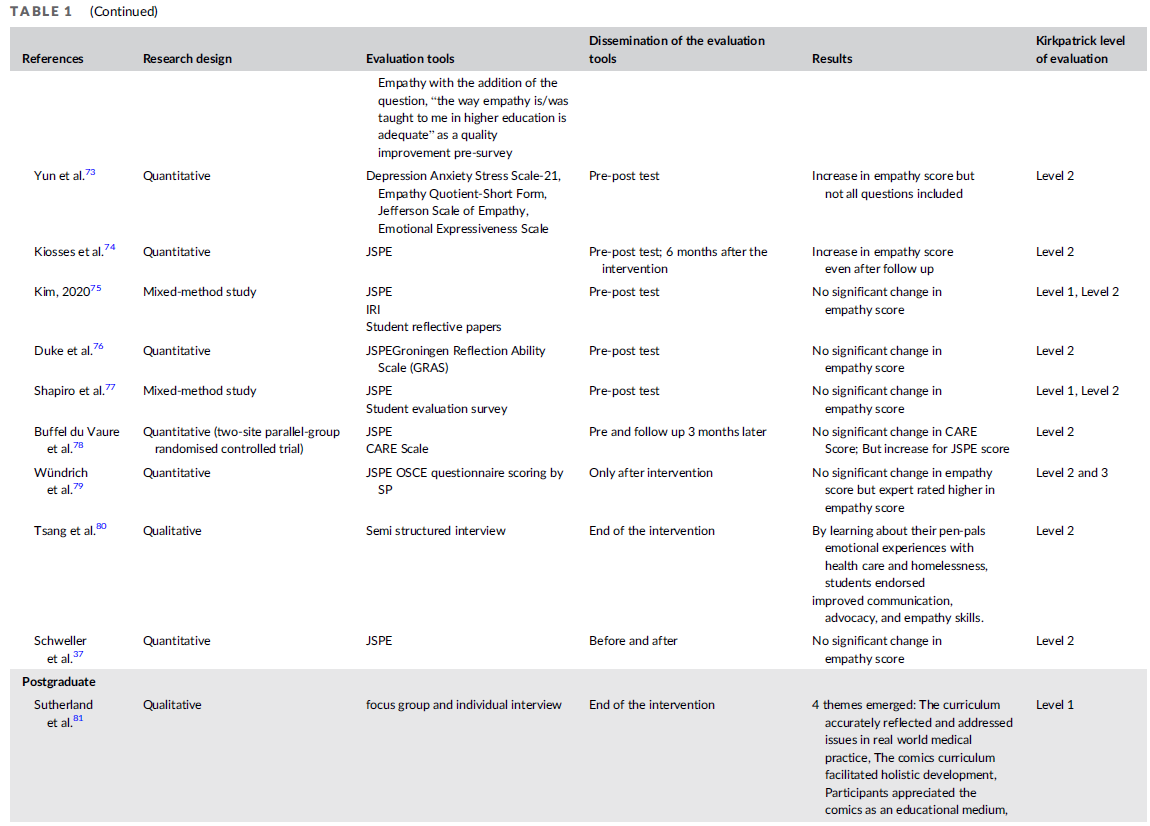

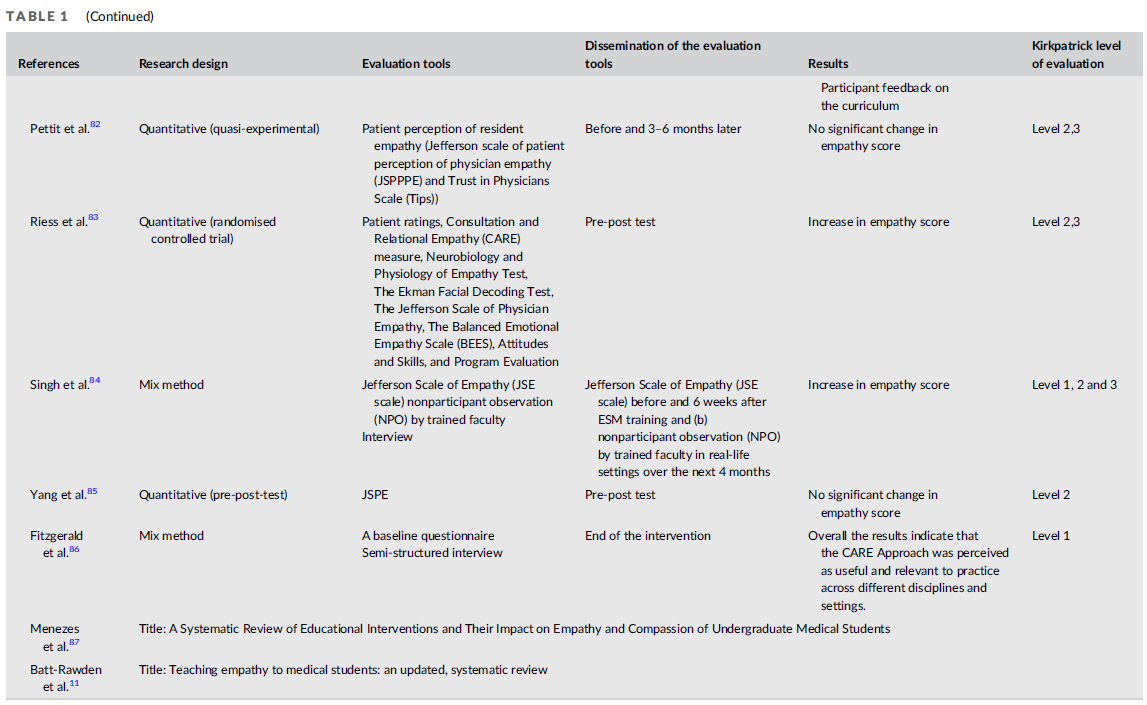

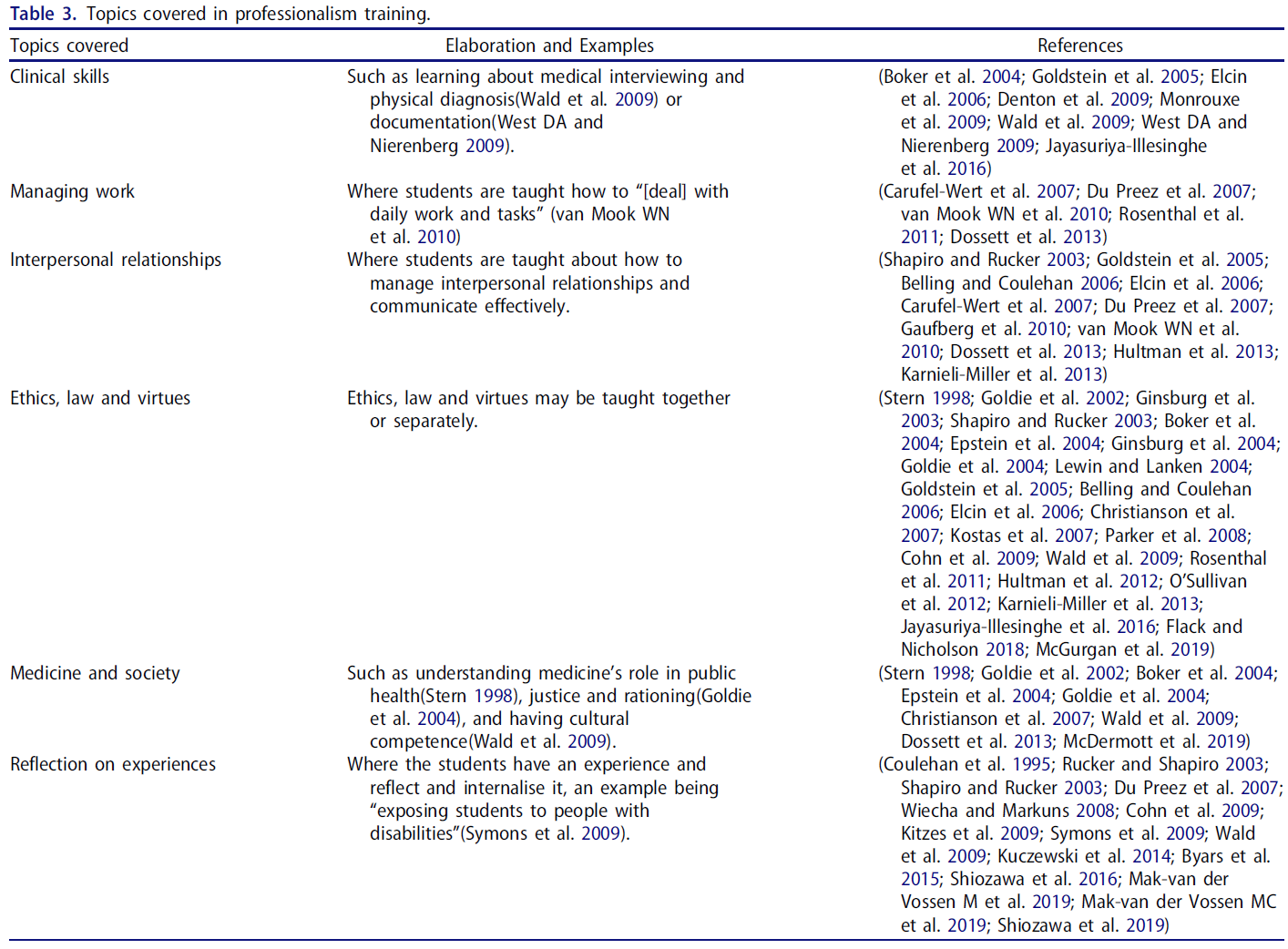

거의 10년 전, 제프 노먼은 왓슨의 상업적 성공을 사설화한 "의학자가 기계를 만난다"라는 제목의 글을 썼고, 왓슨은 인공지능(AI)이 미래에 의학에 어떻게 영향을 미칠 수 있는지를 보여주는 것이라고 주장했다(노먼 2011). 그 이후로 건강 전문 교육(HPE) 분야의 학자들이 증가하고 있으며, 데이터 과학 분야에 뿌리를 둔 AI가 교육, 학습 및 평가에 혁명을 일으킬 가능성을 선전하고 있다. 미국 통계 협회(van Dyk et al. 2015)에 따르면, [데이터 과학의 학제간 분야]는 다음을 활용하는 것을 목표로 한다.

- (1) 데이터에서 지식을 추출하기 위한 통계, 인공지능(AI), 머신러닝(ML) 등.

- (2) 데이터 구성, 관리 및 저장을 위한 데이터베이스 관리,

- (3) 복잡한 데이터 분석을 수행하는 데 필요한 계산 인프라를 제공하기 위한 시스템 엔지니어링.

Almost a decade ago, Geoff Norman wrote a piece entitled, “Medicine man meets machine” where he editorialized the commercial success of Watson, arguing that Watson was a demonstration of how Artificial Intelligence (AI) may influence medicine in the future (Norman 2011). Since then, a growing body of scholarship in health professions education (HPE) has touted the potential for AI, rooted in the field of data science, to revolutionize instruction, learning, and assessment (Masters 2019; Chahine et al. 2018; Murdoch and Detsky 2013; Gruppen 2012). According to the American Statistical Association (van Dyk et al. 2015), the interdisciplinary field of data science aims to utilize:

- (1) statistics, artificial intelligence (AI), and machine learning (ML) to extract knowledge from data,

- (2) database management to organize, manage, and store data, and

- (3) systems engineering to provide the computational infrastructure needed to conduct complex data analyses.

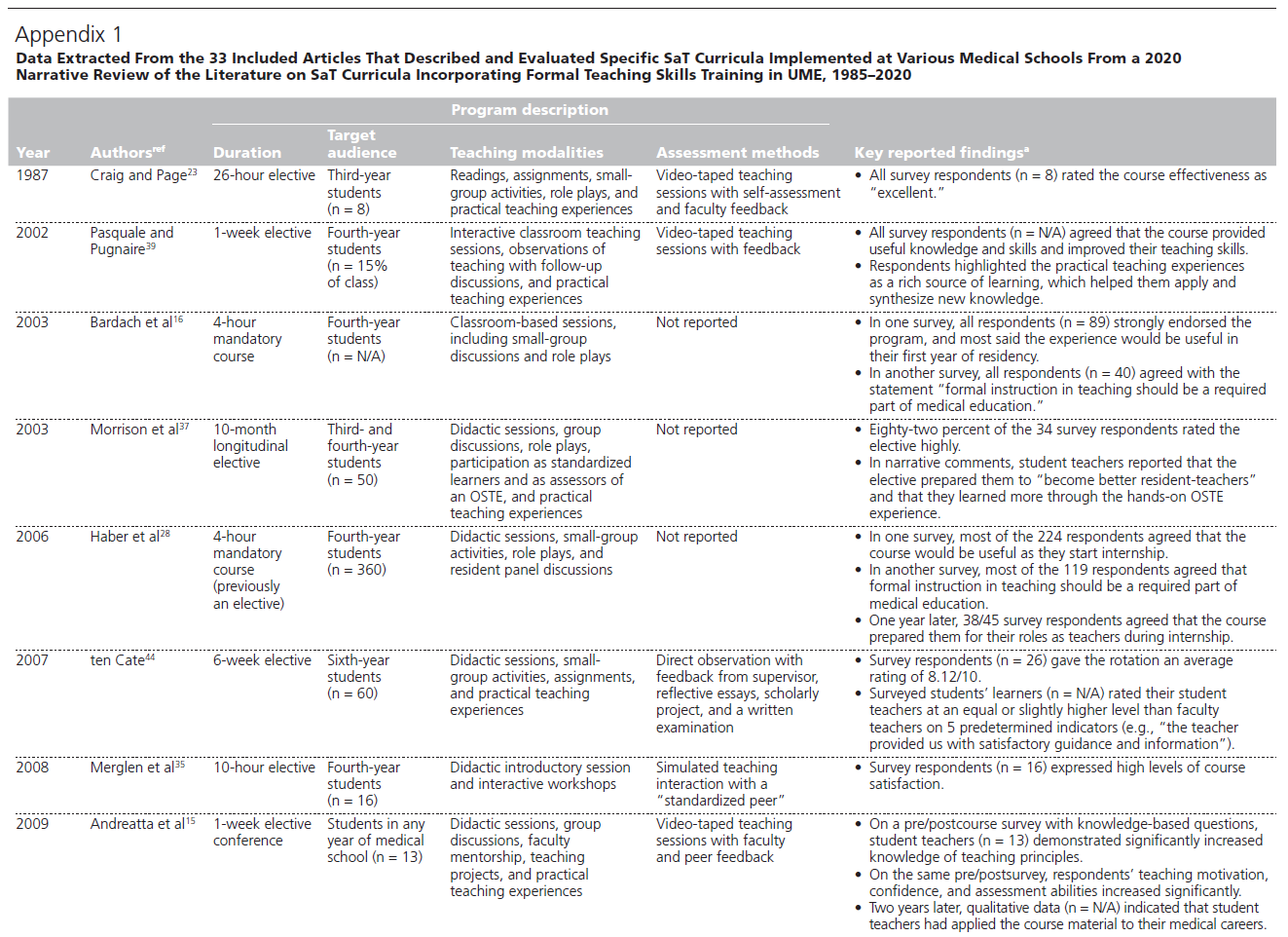

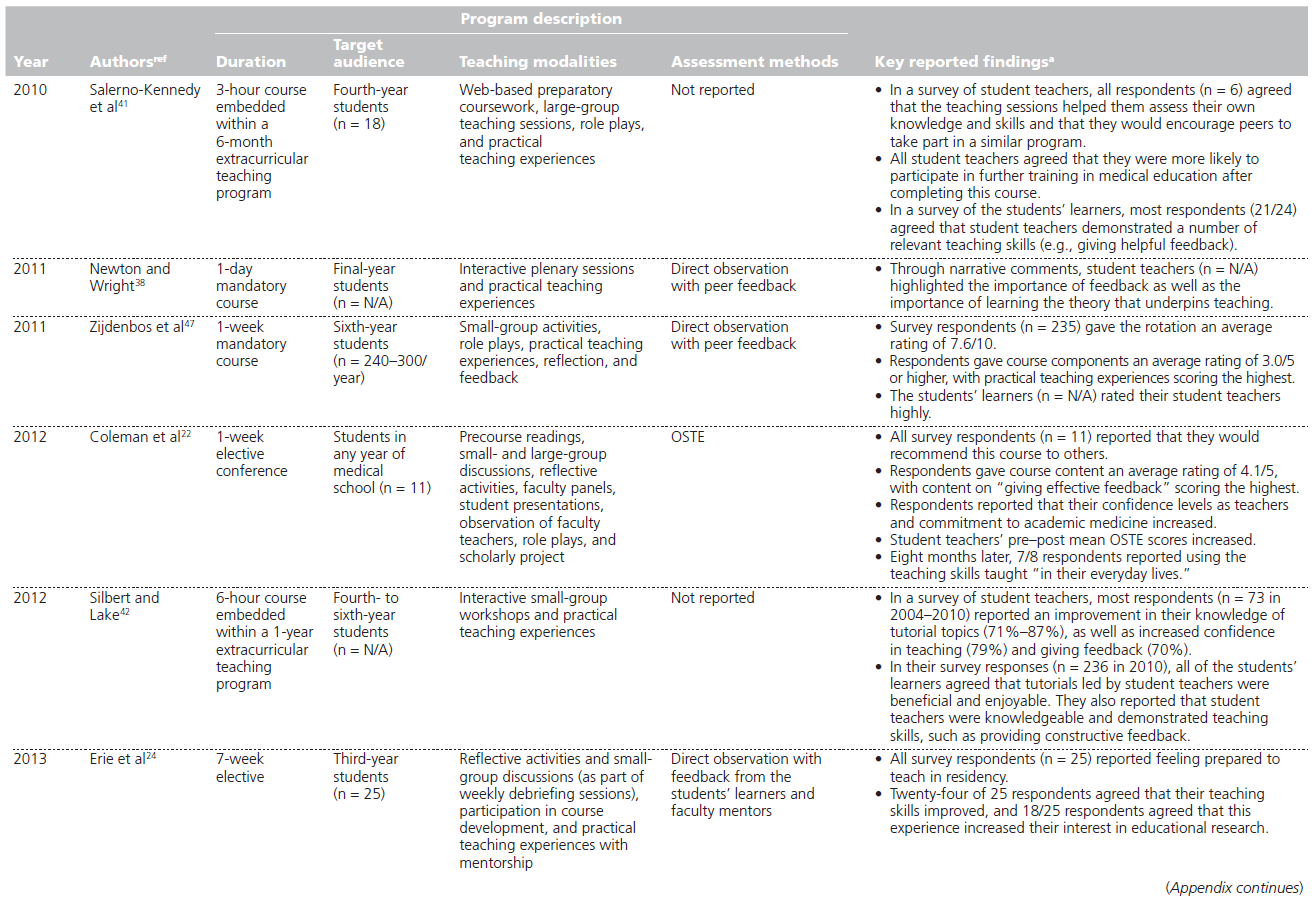

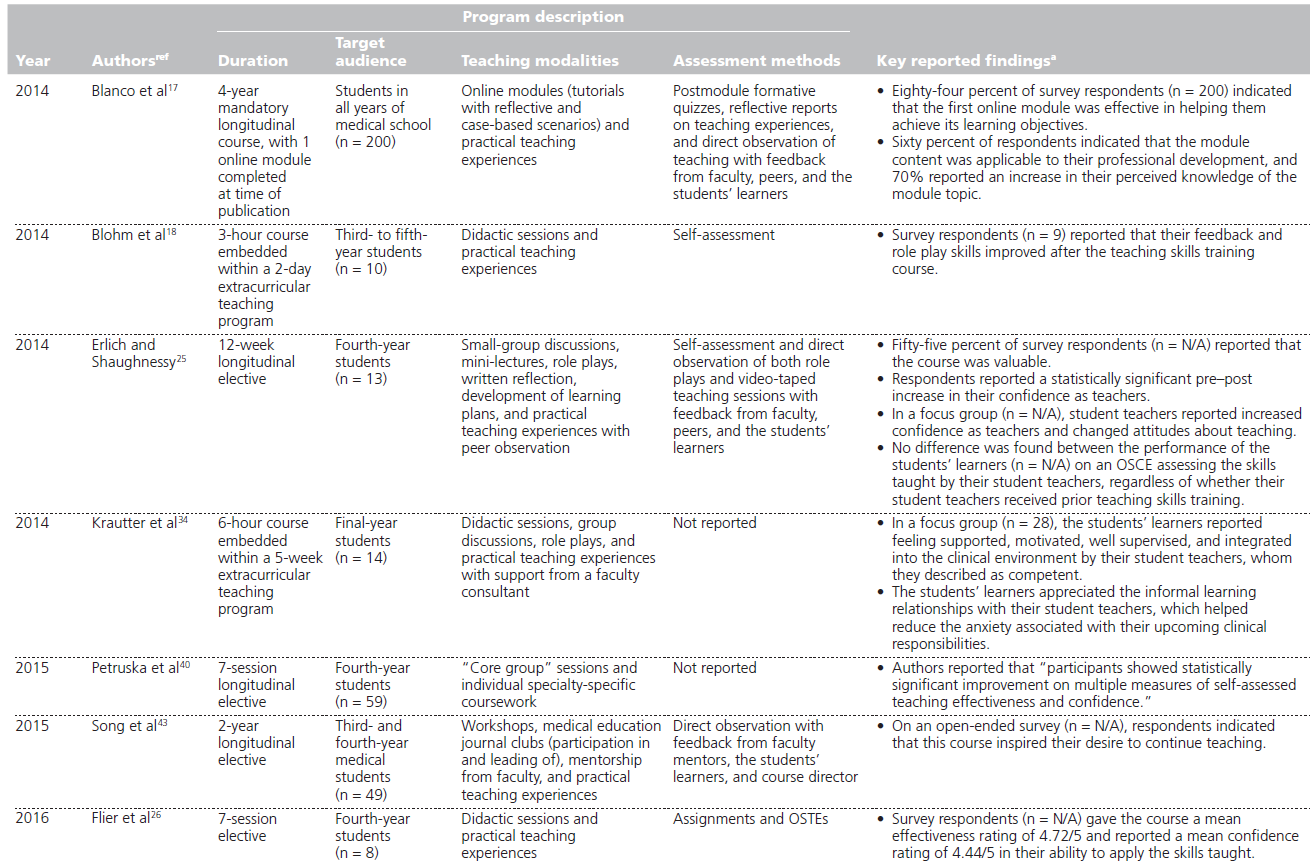

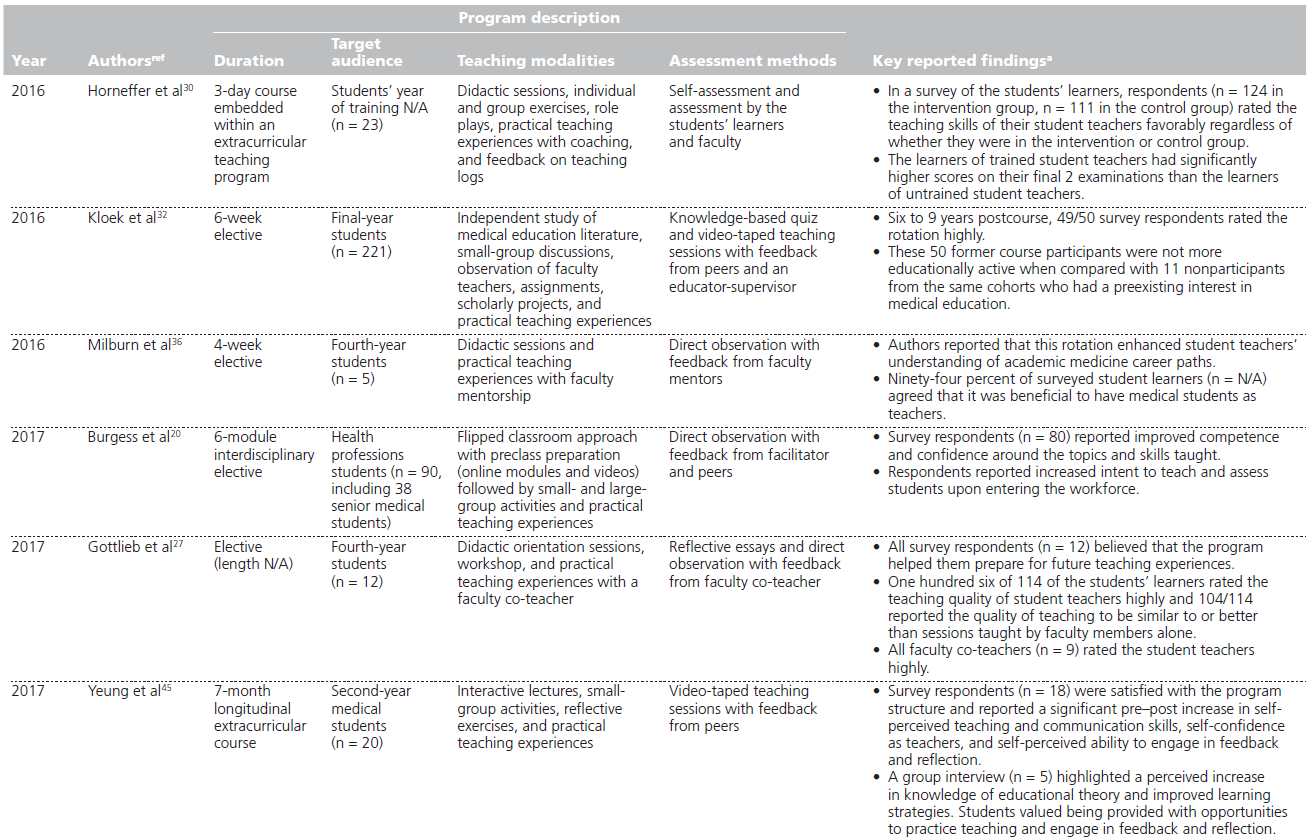

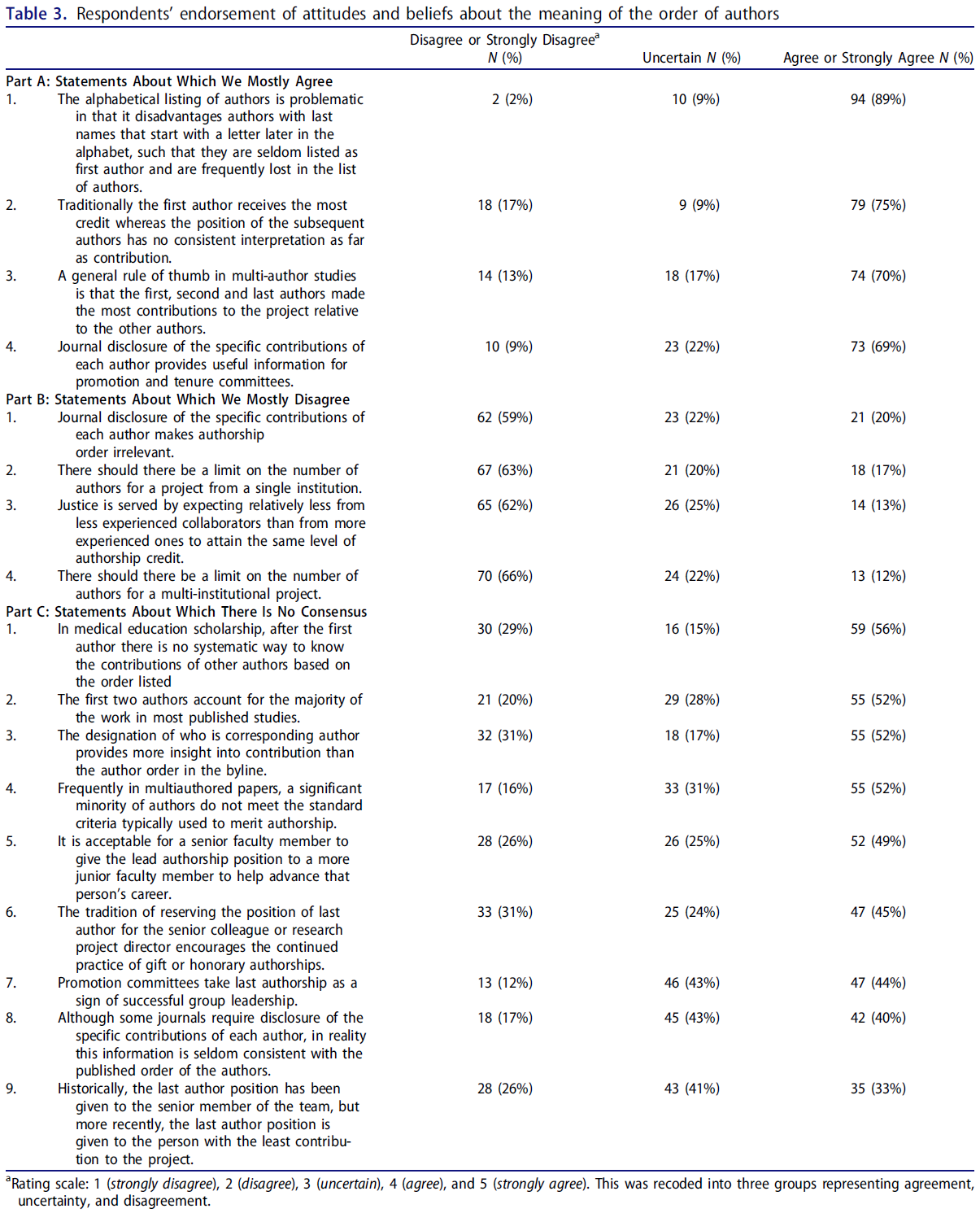

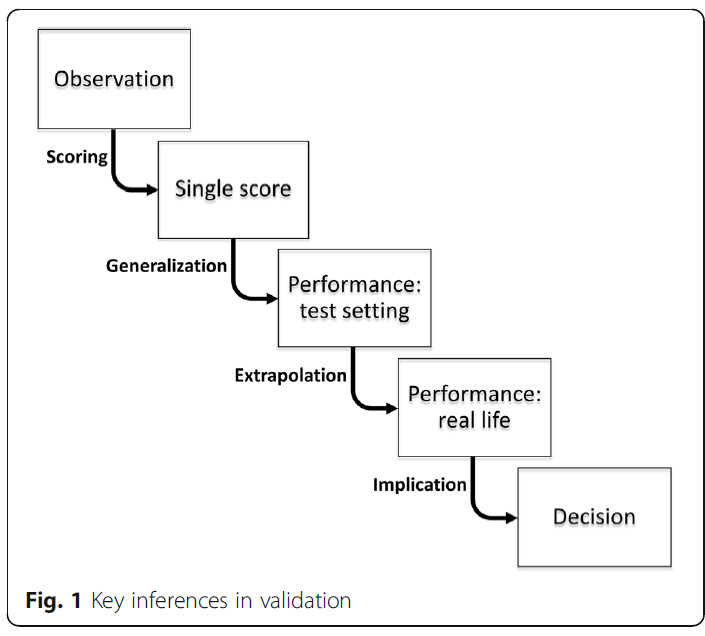

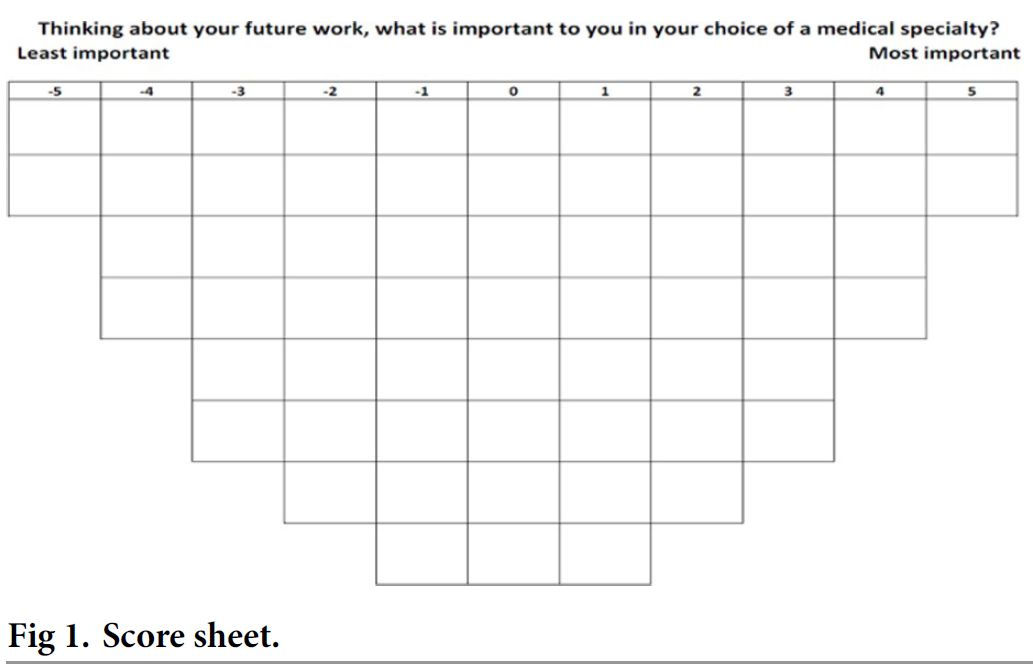

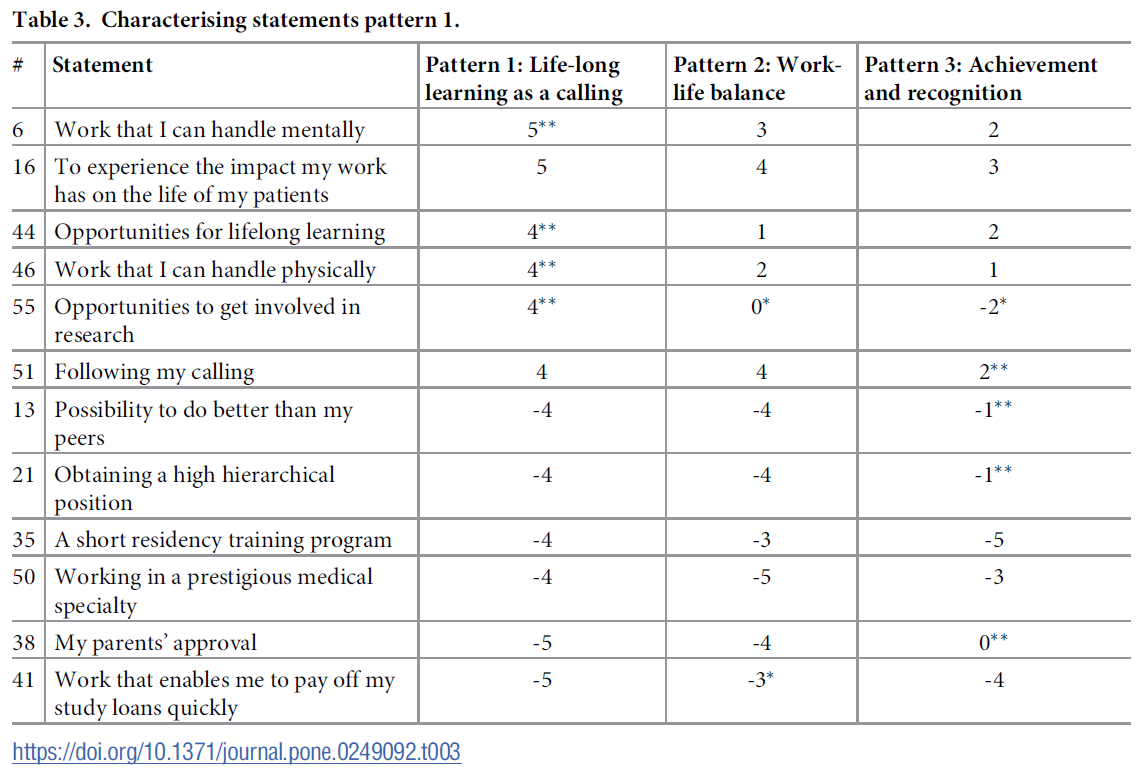

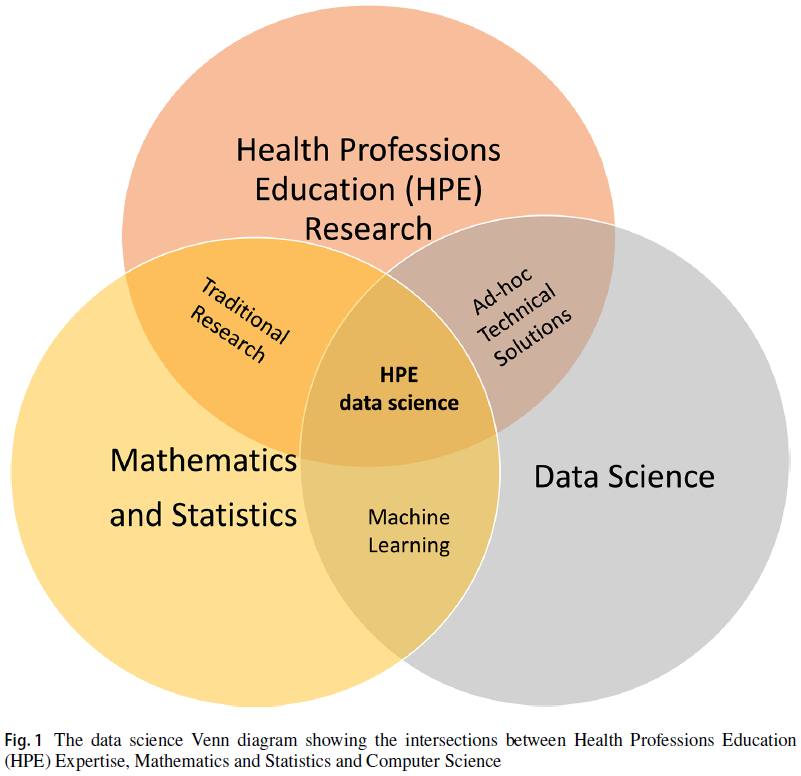

본 논문에서는 컴퓨터 알고리즘과 수학적 모델이 HPE의 맥락에서 데이터와 그 응용에 대한 이해를 어떻게 형성했는지 강조하기 위해 데이터 과학의 ML 측면(그림 1 참조)에 초점을 맞춘다. 우리가 HPE 연구 내에서 데이터 과학과 ML의 존재 증가를 예상함에 따라, 건강 과학 교육의 발전은 데이터 과학과 HPE의 교차 분야 내에서 지식 확산을 촉진하고 중요한 대화를 가능하게 하는 데 중요한 역할을 할 수 있다.

In this paper, we focus on the ML aspect of data science (see Fig. 1) to highlight how computer algorithms and mathematical models have shaped our understanding of data and its applications in the context of HPE. As we anticipate an increasing presence of data science and ML within HPE research, Advances in Health Sciences Education can play an important role in facilitating knowledge dissemination and enabling critical conversations within the intersecting fields of data science and HPE.

용어가 익숙하지 않을 수 있는 사람들을 위해, ML은 통계를 사용하여 기계가 특정 동작을 수행하도록 프로그래밍되지 않고 데이터를 기반으로 학습하고 적응적 예측을 할 수 있도록 하는 AI의 하위 집합이다(Thakur 2020). 많은 ML 접근 방식의 기본 원칙은 [기계의 데이터 해석 능력을 지속적으로 개선하는, 반복적이고 적응적인 알고리듬을 통해, 데이터 내의 패턴을 자동으로 찾는 것]이다. 딥 러닝(DL)은 신경망 또는 노드(뇌에서 뉴런이 작동하는 방식과 유사)를 사용하여 빅데이터를 활용하여 복잡한 문제를 이해하고 해결하는 ML 기술의 새로운 하위 집합이다(MIT 2020). 자연어 처리(NLP)는 많은 양의 언어 또는 텍스트 데이터를 처리하고 분석하는 데 사용되는 일반적인 DL 접근법이다.

For those who may be unfamiliar with the terms, ML is a subset of AI that uses statistics to enable machines to learn and make adaptive predictions based on data without being programmed to perform specific actions (Thakur 2020). The fundamental principle of many ML approaches is to automatically find patterns within data through iterative and adaptive algorithms that continuously refine the machine’s ability to interpret data. Deep learning (DL) is a newer subset of ML techniques that uses neural networks or nodes (similar to the way neurons work in the human brain) to leverage big data to understand and solve complex problems (MIT 2020). Natural language processing (NLP) is a common DL approach used to process and analyze large amounts of language or text data.

최근의 연구는 ML이 HPE를 개선하고 환자 관리를 개선할 수 있는 가능성을 보여주었다. 현재 검토 기사에서 Topol(2019)은 방사선사와 병리학자가 ML을 사용하여 의료 영상(예: 흉부 X선, 심전도, 피부 병변, 망막 영상)을 진단하는 전문가 수준의 성능을 보여주는 방법을 강조했다. 예를 들어, Haensle et al.(2018)은 알려진 결과를 가진 24,000개의 피부 병변 이미지에 대해 훈련된 신경망이 흑색종 진단 시 민감도와 특이성 측면에서 대부분의 인간 피부과 의사보다 우수하다는 것을 입증했다. 또한, 의학에서 NLP의 적용에는 전자 건강 기록 및 임상 기록의 데이터를 사용하여 환자 정보를 효율적으로 분류하고 요약하는 음성 인식 및 감정 분석이 포함된다.

Recent research showcased the potential for ML to enhance HPE and improve patient care. In a current review article, Topol (2019) highlighted how radiologists and pathologists use ML to display expert-level performance in diagnosing medical images (e.g., chest X-rays, electrocardiograms, skin lesions, retinal images). For instance, Haenssle et al. (2018) demonstrated that a neural network trained on 24,000 skin lesion images with known outcomes outperformed most human dermatologists in terms of sensitivity and specificity when diagnosing melanomas. Furthermore, applications of NLP in medicine include speech recognition and sentiment analyses that use data from electronic health records and clinical notes to efficiently classify and summarize patient information (Koleck et al. 2019).

이러한 예에서 알 수 있듯이, 의료 분야의 ML은 주로 분류 및 예측 목적으로 사용되어 왔다. 어떤 사람들은 그것이 그것을 [서포트]하기보다는, 의사들이 하는 일을 [모방]하는 경향이 있다고 주장한다. ML 기술은 의사 성과를 대체하는 대신 개선하는 데 중점을 두기 때문에, [HPE에 상당한 가치를 추가할 수 있는 잠재력]을 가지고 있다. 일반적으로 ML은 보건 전문가의 교육, 학습 및 평가를 지원하기 위해 대량의 임상 및 교육 데이터를 자동화, 관리 및 결합하는 데 적합할 수 있다(Chan 및 Zary 2019).

As these examples suggest, ML in healthcare has been used primarily for classification and/or prediction purposes. Some argue that it tends to mimic the work being done by physicians rather than support it (Masters 2019). With a focus on improving physician performances as opposed to replacing them, ML techniques have the potential to add substantial value in HPE. In general, ML may be well-suited for automating, managing, and combining large amounts of clinical and educational data to support the instruction, learning, and assessment of health professionals (Chan and Zary 2019).

그러나 이 약속은 데이터 과학과 ML이 보건 분야의 연구와 실무에 미치는 장기적인 영향에 대한 우려가 커짐에 따라 완화될 수 있다. 교육 과학자들은 ML 기술이 HPE의 맥락적 뉘앙스를 인식하지 못할 수 있기 때문에 "복잡한 문제에 대한 포괄적인 해결책"으로 홍보하는 것을 경계했다. 일반 교육 문헌에서 제기된 한 가지 구체적인 우려는, 데이터 과학과 ML의 초기 적용은, 주로 [특정한 과학적 사고 방식에 뿌리를 둔 학문]인, [인지 심리학과 신경 과학]에서 비롯되었다는 것이다. 얼리 어답터로서, 이러한 특정 분야는 일반적으로 교육 및 특히 HPE 내에서 데이터 과학과 ML의 현재 사용을 알리는 이론적 입장과 인식론적 믿음에 과도하게 영향을 미쳤을 수 있다. 이러한 유형의 영역 영향은 HPE 연구에서 이러한 새로운 분석 접근법의 범위와 유용성을 제한할 수 있다.

This promise, however, may be tempered by growing concerns about the long-term impact of data science and ML on research and practice in the health professions (van der Niet and Bleakley 2020; Imran and Jawaid 2020; Wartman and Combs 2019). Education scientists have cautioned against promoting ML technology as an “all-encompassing answer to complex problems” as it might fail to recognize the contextual nuances of HPE (van der Niet and Bleakley, 2020). One specific concern raised in the general education literature is that early applications of data science and ML stemmed primarily from cognitive psychology and neuroscience, disciplines rooted in certain scientific ways of thinking (Williamson 2017). As early adopters, these specific disciplines may have unduly affected the theoretical positions and epistemic beliefs that inform the current use of data science and ML within education in general and HPE specifically. This type of domain influence has the potential to limit the scope and utility of these new analytic approaches in HPE research.

지난 10년간 데이터 과학과 ML의 발전은 교육 연구에서 [가설 검증에서 이론의 관련성과 사용에 대한 논의]를 이끌었다. 일부 학자들은 데이터 과학과 ML의 출현을 인간의 주관성과 편견의 영향 없이 데이터가 "스스로를 대변"할 수 있게 했다고 칭찬한다(Kitch 2014). 이러한 프레임워크는 교육에서 확립된 많은 전통적인 연구 관행에서 벗어난다. 전통적 연구 관행에서는 [이론의 사용]이 지식 생성을 위한 [가설 생성과 검증에 중심적인 역할]을 하기 때문이다. 교육 및 HPE에서 데이터 과학과 ML을 사용하는 이론 중심 접근법이 아직 충분히 구체화되지 않았지만(Kitch in 2014), [데이터 과학]은 [경험적 증거], [과학 이론], [계산 과학]에 합류하여 과학에서 네 번째 패러다임으로 언급되었다. 그러나 데이터 과학이 개념적으로나 운영적으로 과학적 패러다임으로서 어떻게 작동할지는 불분명하다. 이는 HPE에서 ML을 사용하는 경우에도 마찬가지입니다. 이러한 논의를 고려하여, 우리는 HPE 문헌 내에서 ML과 관련된 연구의 실제 적용, 이론적 기여 및 인식론적 믿음을 비판적으로 평가했다.

Advances in data science and ML over the past decade have led to discussions regarding the relevance and use of theory in hypothesis testing in educational research (Williamson 2017; Kitchin 2014). Some scholars praise the emergence of data science and ML for allowing data to “speak for itself” without the influence of human subjectivity and bias (Kitchin 2014). Such a framework strays from many traditional research practices established in education, where the use of theory takes a central role in hypothesis generation and testing for the purpose of knowledge generation (Laksov et al., 2017). Although a theory-driven approach to using data science and ML in education and HPE has not been sufficiently articulated yet (Kitchin 2014), data science has been referred to as the fourth paradigm in science, joining empirical evidence, scientific theory, and computational science (Hey et al. 2009). Yet, it is unclear how data science might operate as a scientific paradigm both conceptually and operationally. This is also true for the use of ML in HPE. In light of these discussions, we critically evaluated the practical applications, theoretical contributions, and epistemic beliefs of studies involving ML within the HPE literature.

방법들

Methods

연구설계

Study design

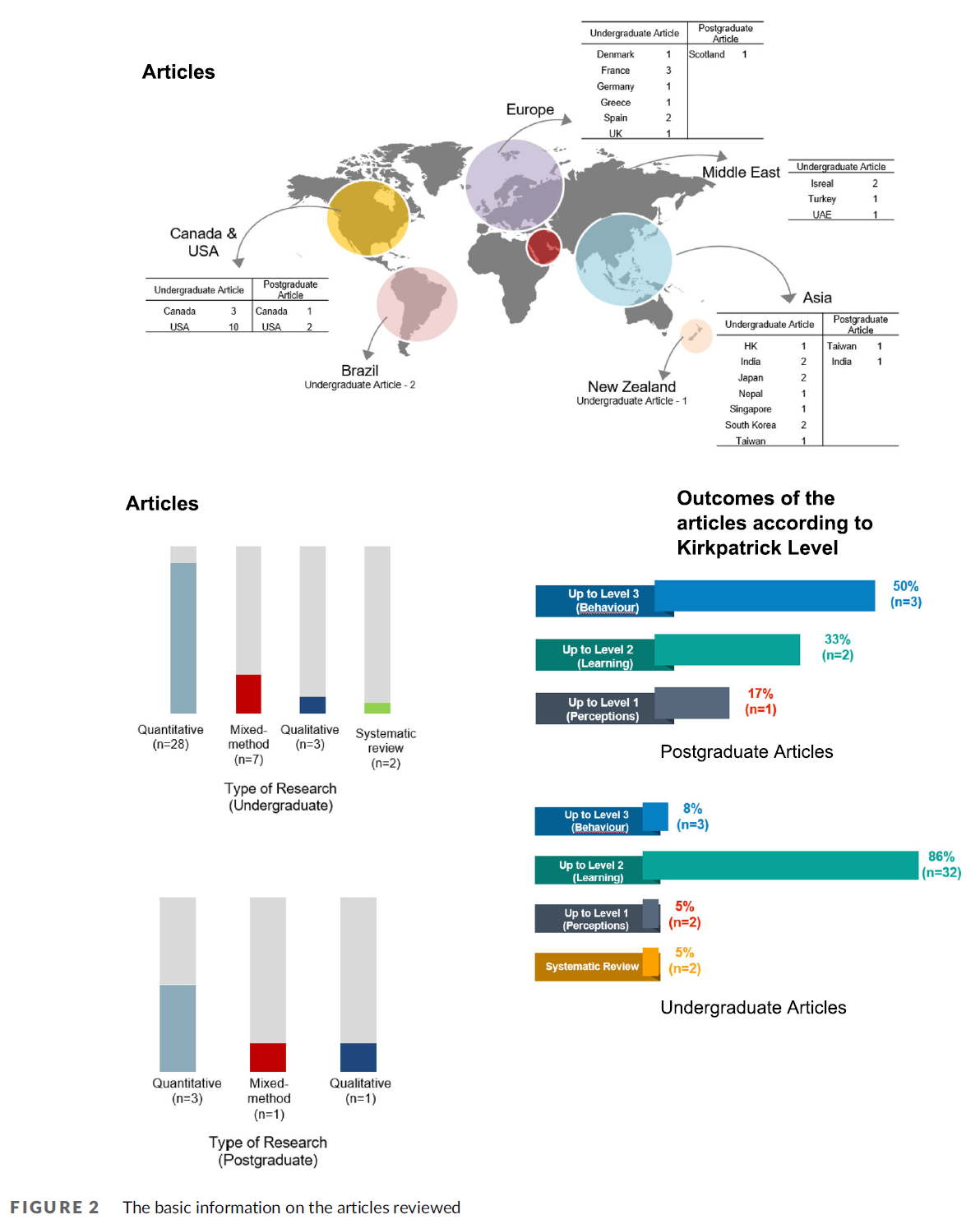

우리는 HPE 내에서 데이터 과학과 ML 연구를 분류하기 위해 비판적 검토 방법론(Grant and Booth 2009)을 사용했다. 우리는 실제 적용, 이론적 기여 및 인식론적 기반과 관련하여 선택된 연구의 속성을 비판적으로 평가했다. [비판적 검토]는 체계적인 검토를 위해 설계된 것은 아니지만, 우리의 목적과 잘 일치하는 문헌의 개념적 기여에 대한 평가를 지원하는 과정을 제공한다. 우리의 목적은 [HPE에서 데이터 과학 및 ML의 사용에 inform하는 핵심 또는 영향력 있는 작업의 개요를 제공하는 것]이다.

We employed critical review methodology (Grant and Booth 2009) to classify data science and ML research within HPE. We critically appraised attributes of selected studies with respect to their practical applications, theoretical contributions, and epistemic underpinnings. Although a critical review is not designed to systematically review a body of work, it offers a process that supports an evaluation of the conceptual contributions of the literature (Grant and Booth 2009), which aligns nicely with our purpose: to provide an overview of key or influential work that informs the use of data science and ML in HPE.

분류 과정을 안내하기 위해 Stokes의 프레임워크를 사용하여 각 연구 논문을 분류했다(Stokes 1997). [Stokes의 프레임워크]를 채택한 것은 연구자들이 HPE에서 데이터 과학과 ML을 활용하는 방식에 대한 분류를 기반으로 하는 공통 언어를 제공했다. 또한, 이 프레임워크는 비평적 렌즈를 사용하여 문헌을 탐구할 수 있게 해주었는데, 이는 일부 연구가 이론이나 개념적 프레임워크를 참조하는 방법과 이유를 설명하는 데 도움이 되었고, 다른 연구들은 그렇지 않았다.

To help guide our classification process, we used Stokes’ framework to categorize each research article (Stokes 1997). Employing Stokes’ framework provided a common language upon which to base our classifications of the ways that researchers utilized data science and ML in HPE. Furthermore, this framework allowed us to explore the literature with a critical lens, which helped explain how and why some studies referenced a theory or conceptual framework, while others did not.

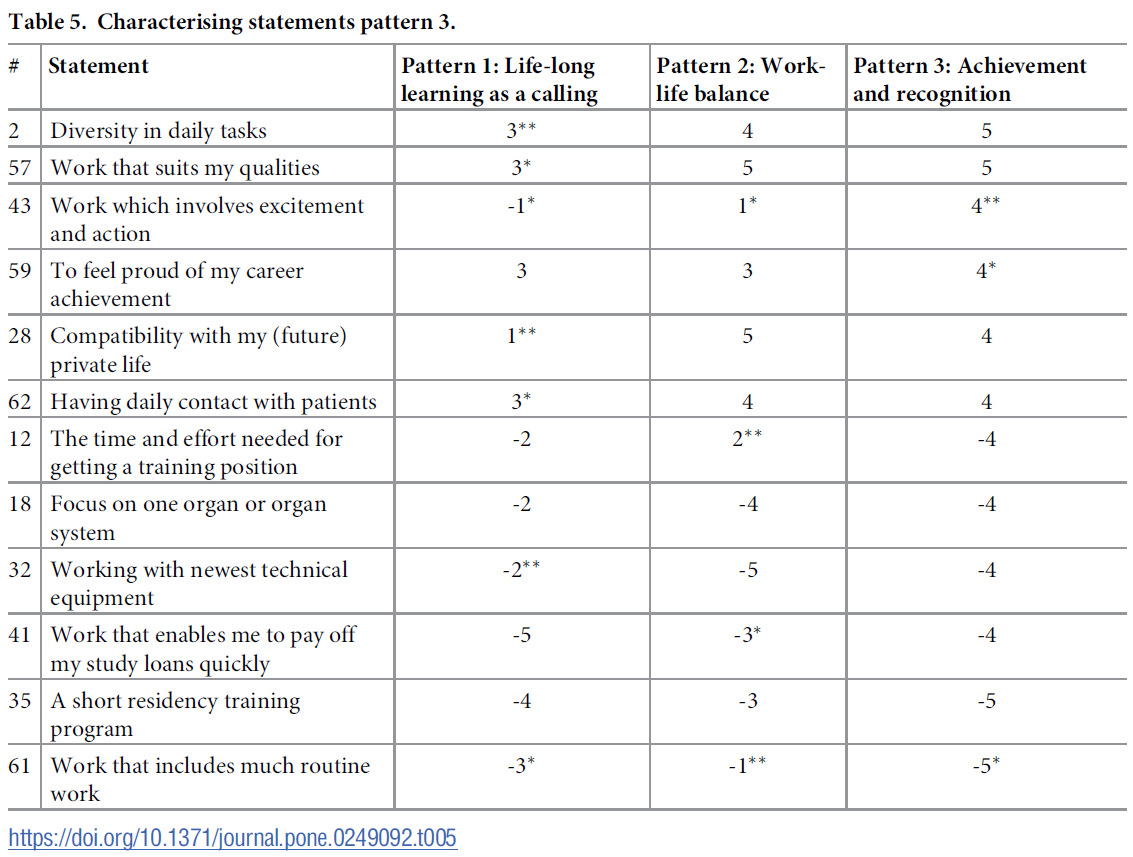

Stokes의 프레임워크(Stokes 1997)는 [두 가지 차원]에 따라 연구를 검토한다.

- (1) 근원적 이해

- (2) 실제 사용을 고려

그것은 네 가지 유형의 연구 결과를 낳는다.

- [이론적 이해]에 정보를 주기 위해서만 이루어지며, [실제적인 함의를 고려하지 않는 연구]를 '순수 기초 연구'라고 한다.

- [이론적 이해]뿐만 아니라 그러한 [작업의 활용을 고려]하는 연구를 "사용에 영감을 받은 기초 연구"라고 한다.

- 특정 과학 분야의 이론적 지식을 발전시키려 하지 않고, [오로지 실질적인 문제를 해결하거나 특정한 목표를 달성하]기 위해 행해지는 연구를 '순수 응용 연구'라고 한다.

- 마지막으로 [이론적 이해를 알리거나 실용화를 고려하지 않는 연구]는 '예측적, 탐색적, 평가적'으로 분류할 수 있다.

Stokes’ framework (Stokes 1997) examines research along two dimensions:

- (1) quest for fundamental understanding and (2) consideration of practical use.

It results in four types of research.

- First, research that is done solely to inform theoretical understandings, but does not consider any practical implications, is labelled “Pure Basic Research.”

- Research that seeks to further not only theoretical understanding, but also considers the applications of such work is called “Use-inspired Basic Research” and

- research that is done solely to solve practical problems or achieve specific goals without attempting to advance theoretical knowledge in a particular scientific area is called “Pure Applied Research.”

- Finally, research that does not seek to inform theoretical understandings or consider practical use can be classified as “Predictive, Exploratory, or Evaluative.”

검색 전략

Search strategy

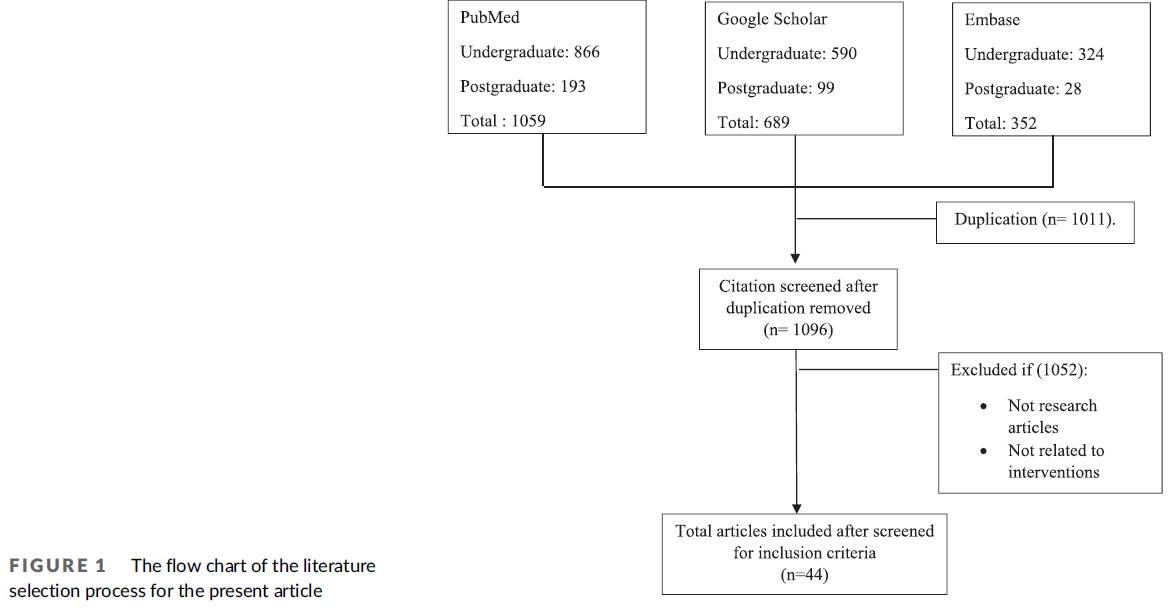

우리는 주요 용어에 대해 Medline, Scopus, Eric, Web of Science, Google Scholar를 검색했습니다. 이 용어는 데이터 과학(데이터 과학, "인공지능", "딥 러닝", "빅 데이터 분석", "기계 학습", "자연 언어 처리", "신경 네트워크"), HPE(보건 전문 교육", "의학 교육", "시뮬레이션 기반 의료 교육", "학습 평가", "성과 평가", "컴포지트")와 관련이 있다.의학적 교육("Etentency-based medical dev 또한, 우리는 스노우볼 기법을 사용하여 주요 논문의 참조 목록을 검색했습니다. 주요 포함 기준은 본 논문에서 HPE 맥락에서 일부 데이터 과학 기술을 활용했다는 것이다. 우리는 다양한 실제 적용, 이론적 관점 및 인식론적 믿음을 강조하기 위해 독창적인 연구, 입장 논문, 사설 및 주석을 포함했다.

We searched Medline, Scopus, Eric, Web of Science, and Google Scholar for key terms. These terms related to data science (“data science”, “artificial intelligence”, “deep learning”, “big data analytics”, “machine learning”, “natural language processing”, “neural networks”) and HPE (“health professions education”, “medical education”, “simulation-based medical education”, “assessment of learning”, “assessment of performance,” “competency-based medical education”). In addition, we searched reference lists of key papers using a snowball technique. The main inclusion criterion was that the paper utilized some data science technique in an HPE context. We included original research, position papers, editorials, and commentaries to highlight a diversity of practical applications, theoretical perspectives, and epistemic beliefs.

검토 프로세스

Review process

모든 저자들은 선별된 논문들을 검토하고 토론하는데 기여했다. Stokes의 프레임워크에 따라 논문을 분류하기 위해, 우리는 연구의 명시된 목표, 결과의 프레임 및 토론의 초점을 기반으로 지식을 발전시키거나 실제 문제를 해결하거나 둘 다로 코딩했다. 우리는 2020년 4월 16일부터 2020년 7월 29일까지 매주 만나 새로운 주제에 대해 논의했습니다.

All authors contributed to reviewing and discussing selected papers. To categorize the papers according to Stokes’ framework, we coded them as either advancing knowledge, solving practical problems, or both based on the stated goals of the study, framing of the results, and focus of the discussion. We met weekly from April 16, 2020 to July 29, 2020 to discuss emerging themes.

결과.

Results

HPE 연구에서 데이터 과학 및 ML의 실용적 적용

Practical applications of data science and ML in HPE research

HPE에서 데이터 과학과 ML을 사용한 연구의 대부분은 [실제 문제]를 해결하는 것을 목표로 했으며, 이론적 이해를 증진시키기 위한 몇 가지 연구만 명시적으로 시작했다. 확인된 다수의 논문은 기술적 효율성을 입증한 "정당화" 연구 또는 [개념 증명]으로 분류될 수 있으며, 이는 "순수 응용 연구" 범주와 일치한다. 이것은 어떤 것이 어떻게, 누구를 위해, 왜 작동하는지에 대한 질문을 던지는 [명확화 연구]와 구별된다.

The majority of research using data science and ML in HPE aimed to solve practical problems, with only a few studies explicitly setting out to advance theoretical understanding. A large number of papers identified (Dias et al. 2019; Masters 2019; van der Niet and Bleakley 2020; Chan and Zary 2019; Topol 2019) could be classified as “justification” studies that demonstrated technological efficiency or a proof-of-concept (Cook et al. 2008), which coincides with the “Pure Applied Research” category. This is distinct from clarification research (Cook et al. 2008), which asks questions about how, for whom and why something works.

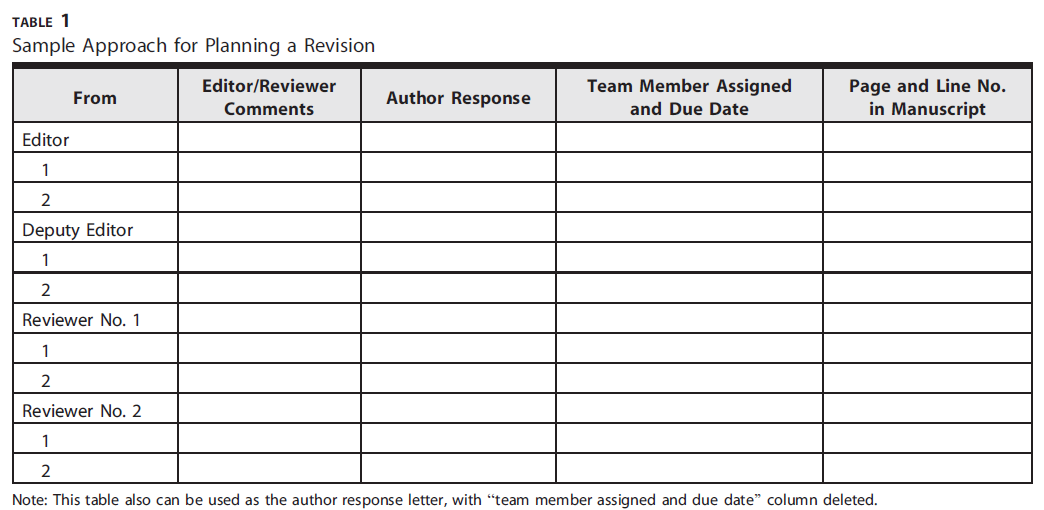

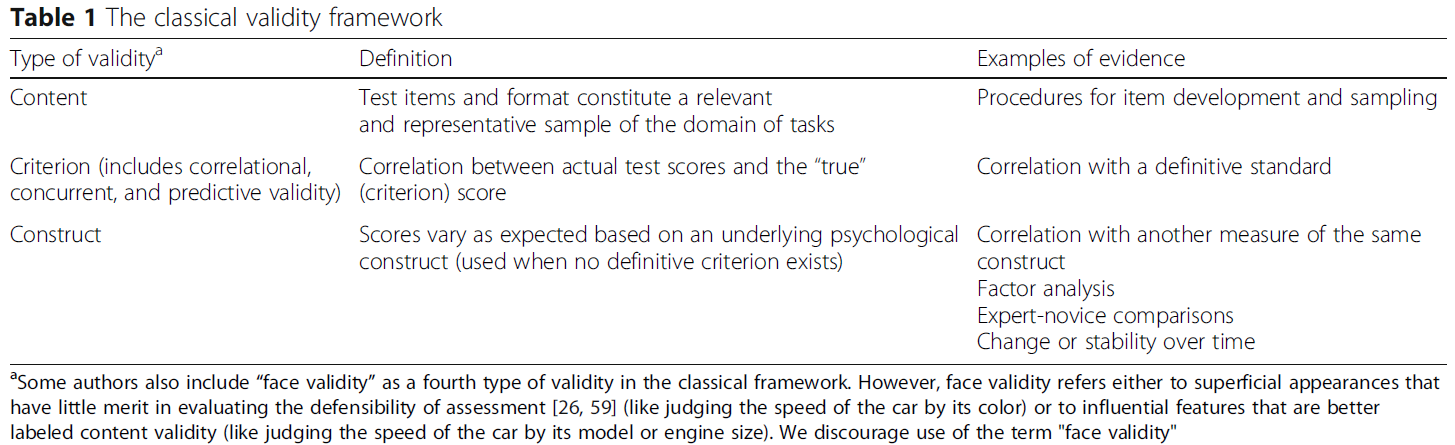

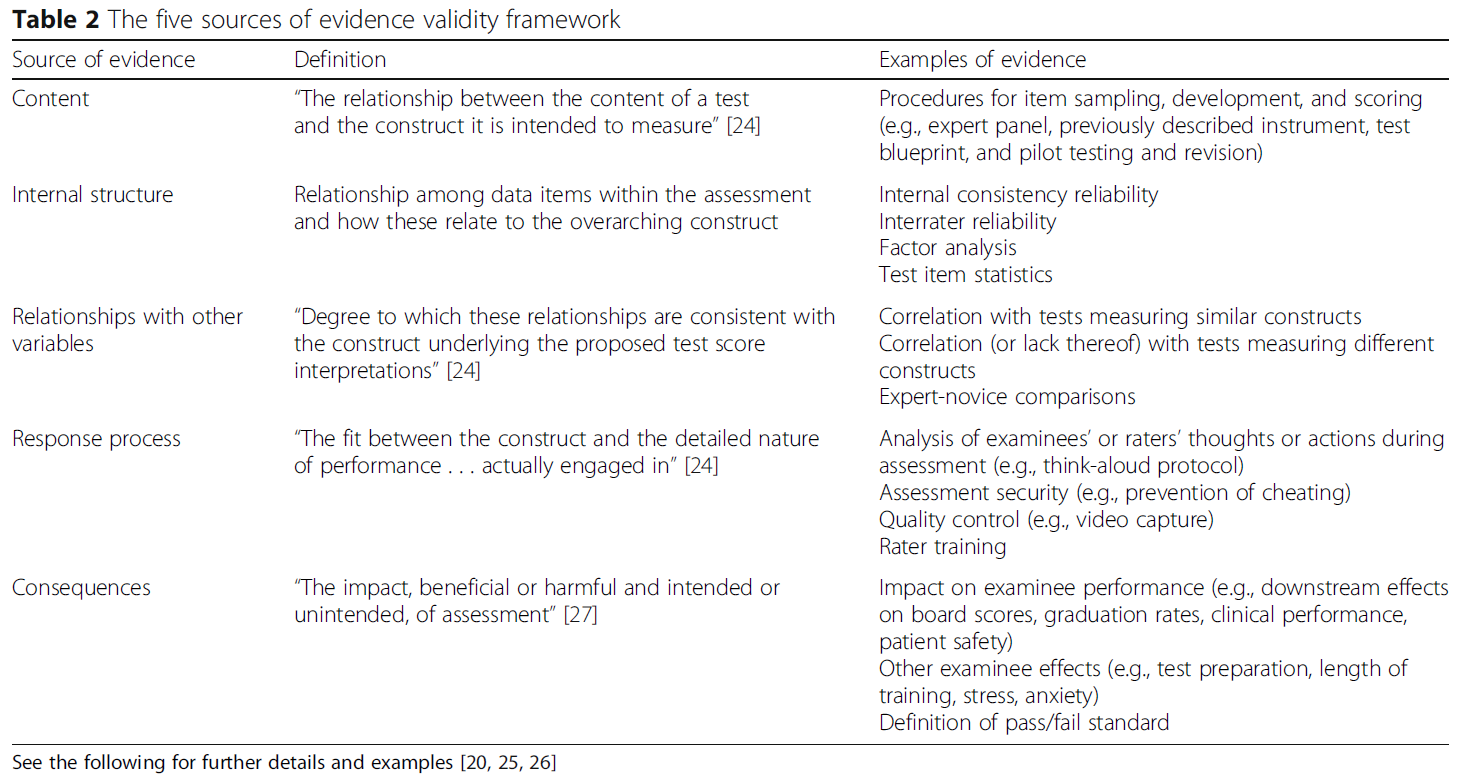

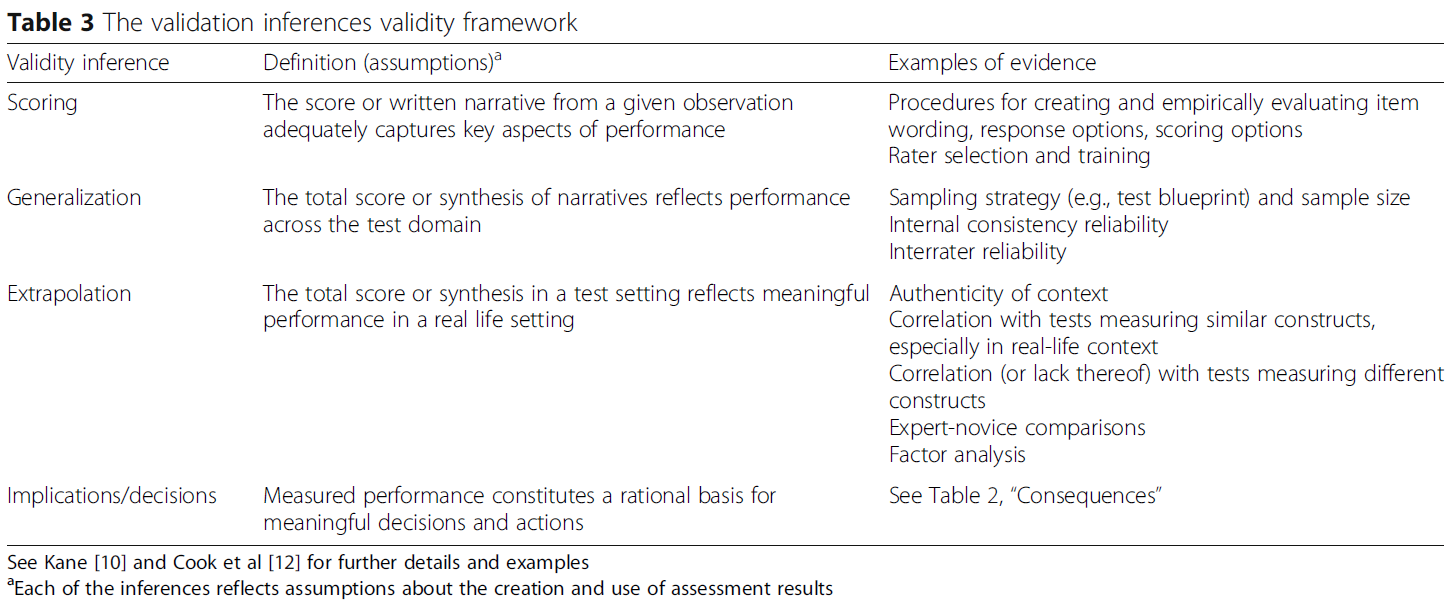

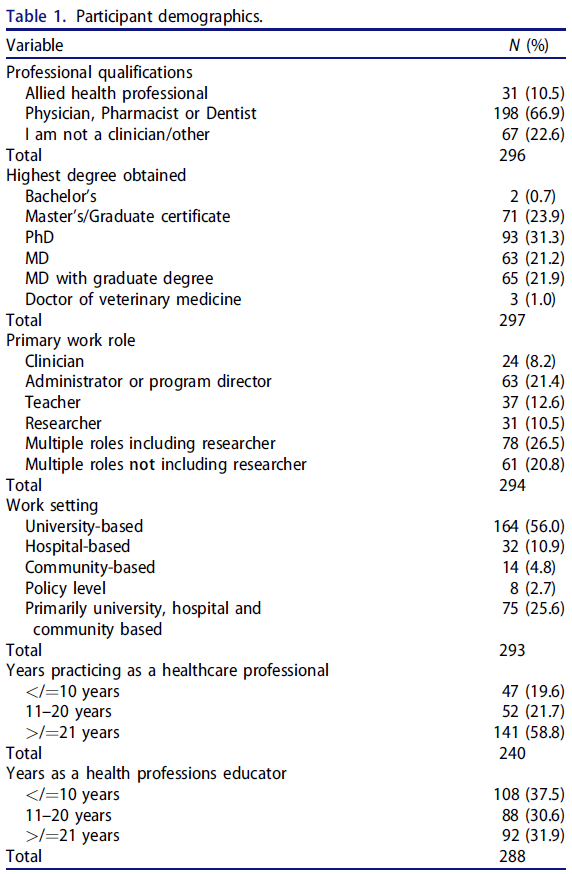

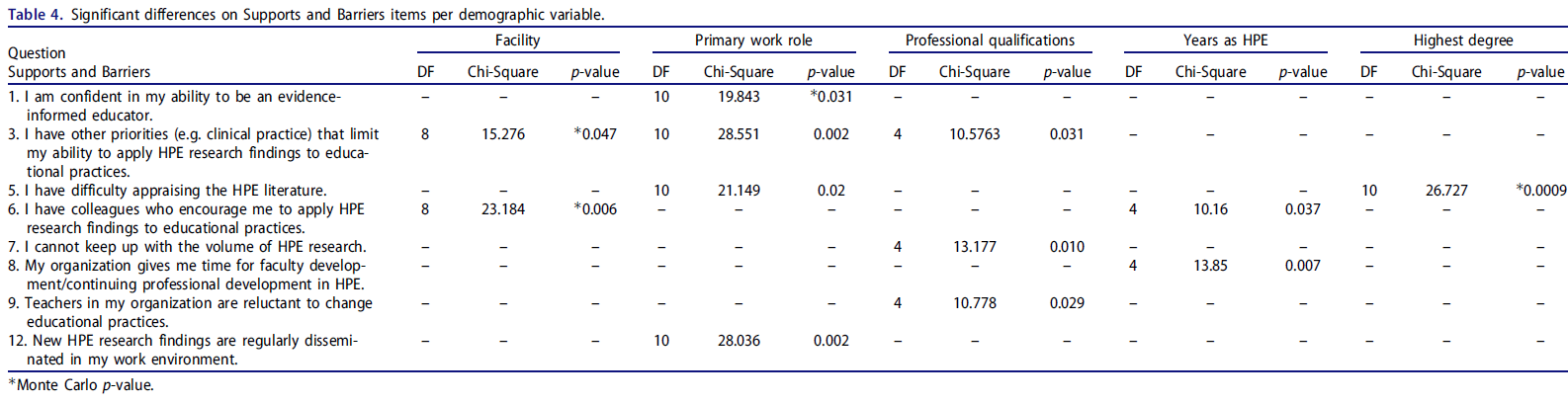

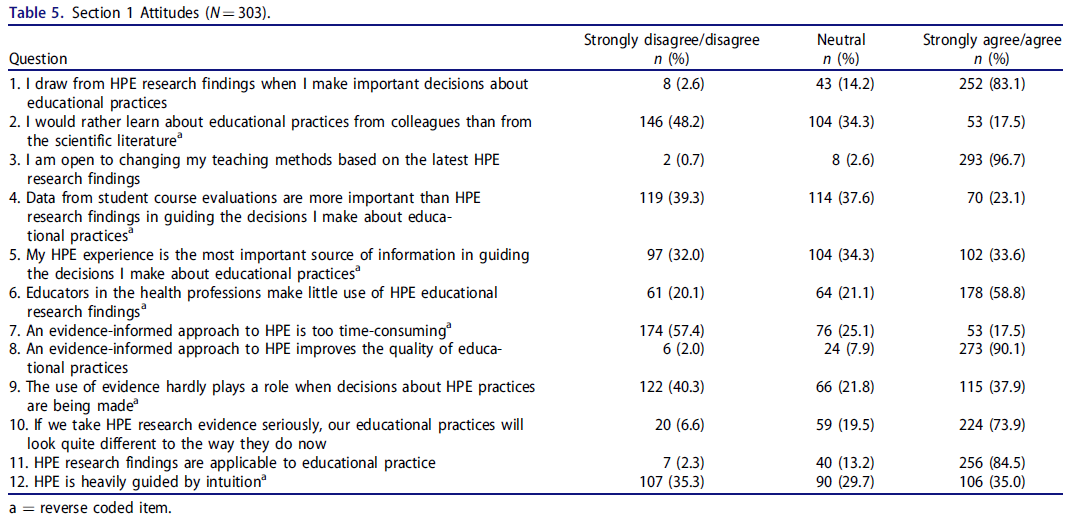

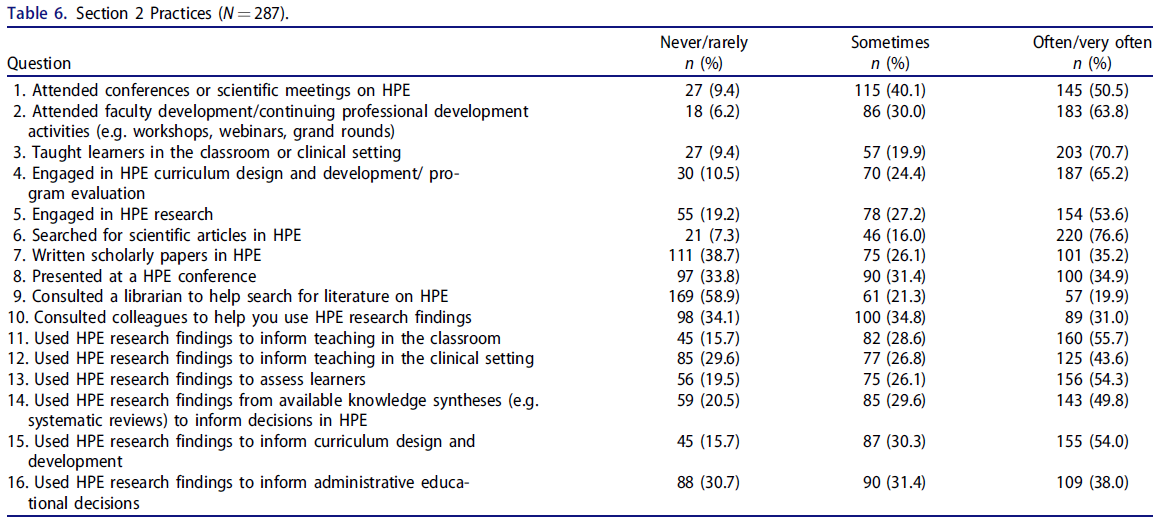

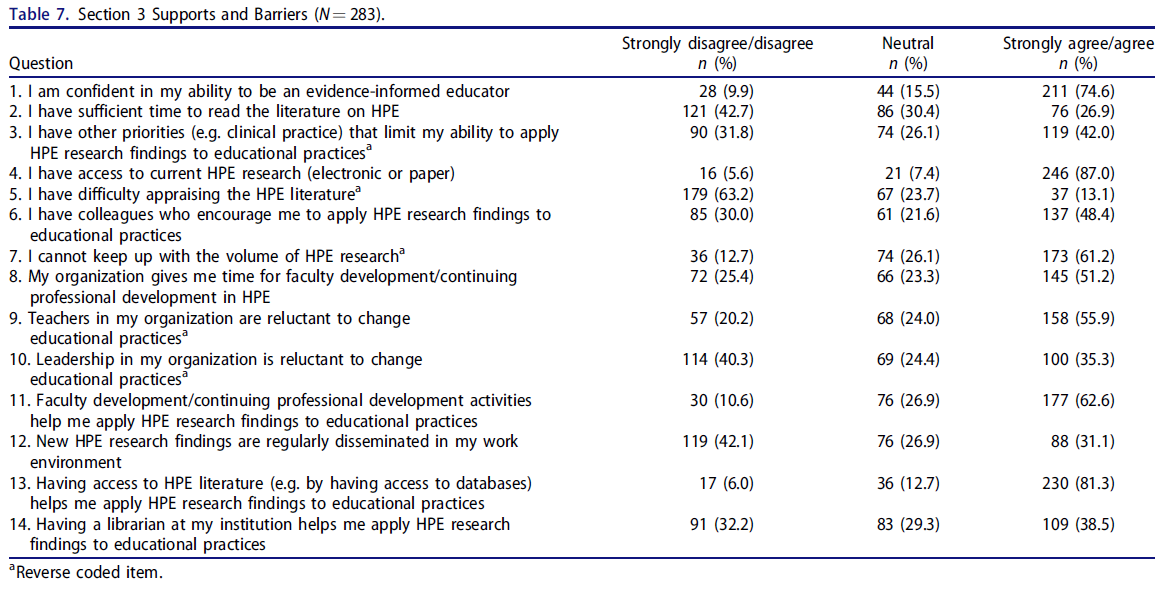

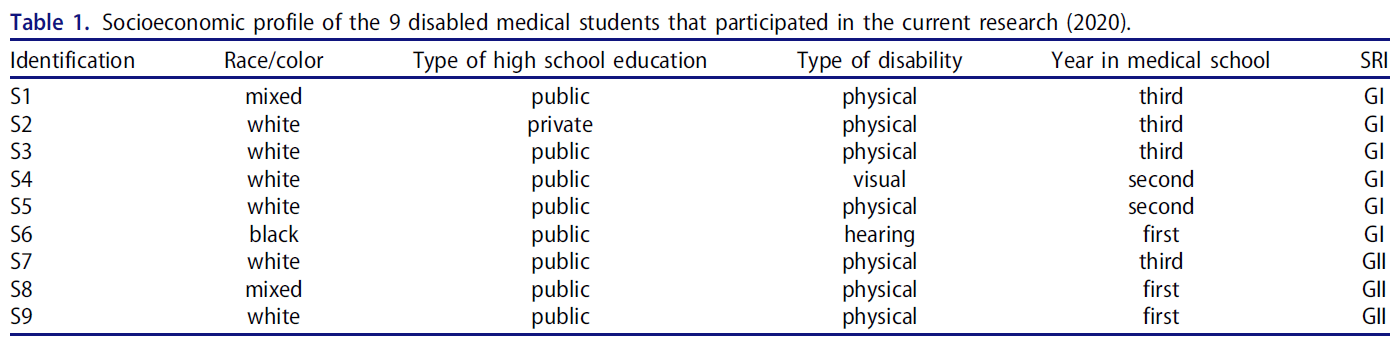

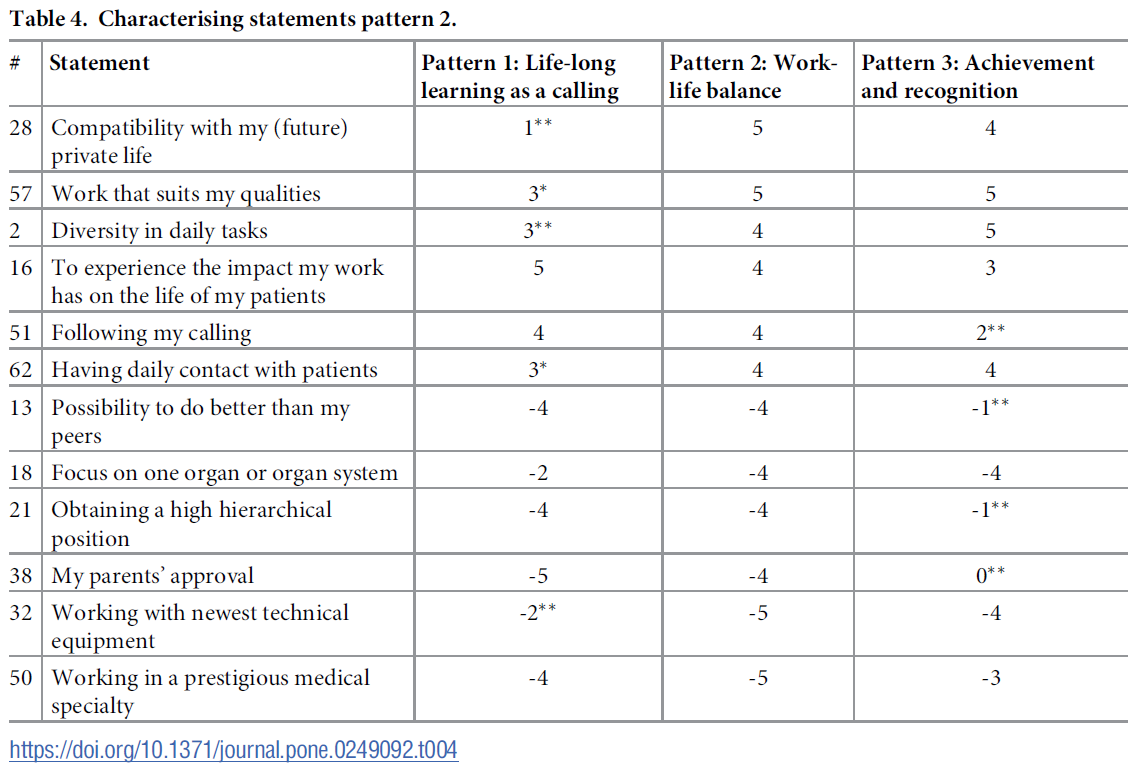

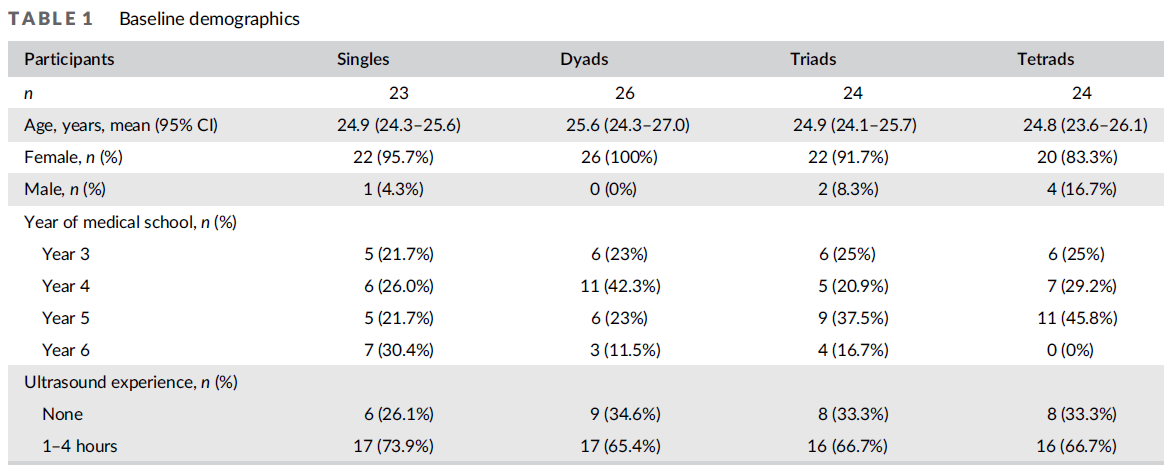

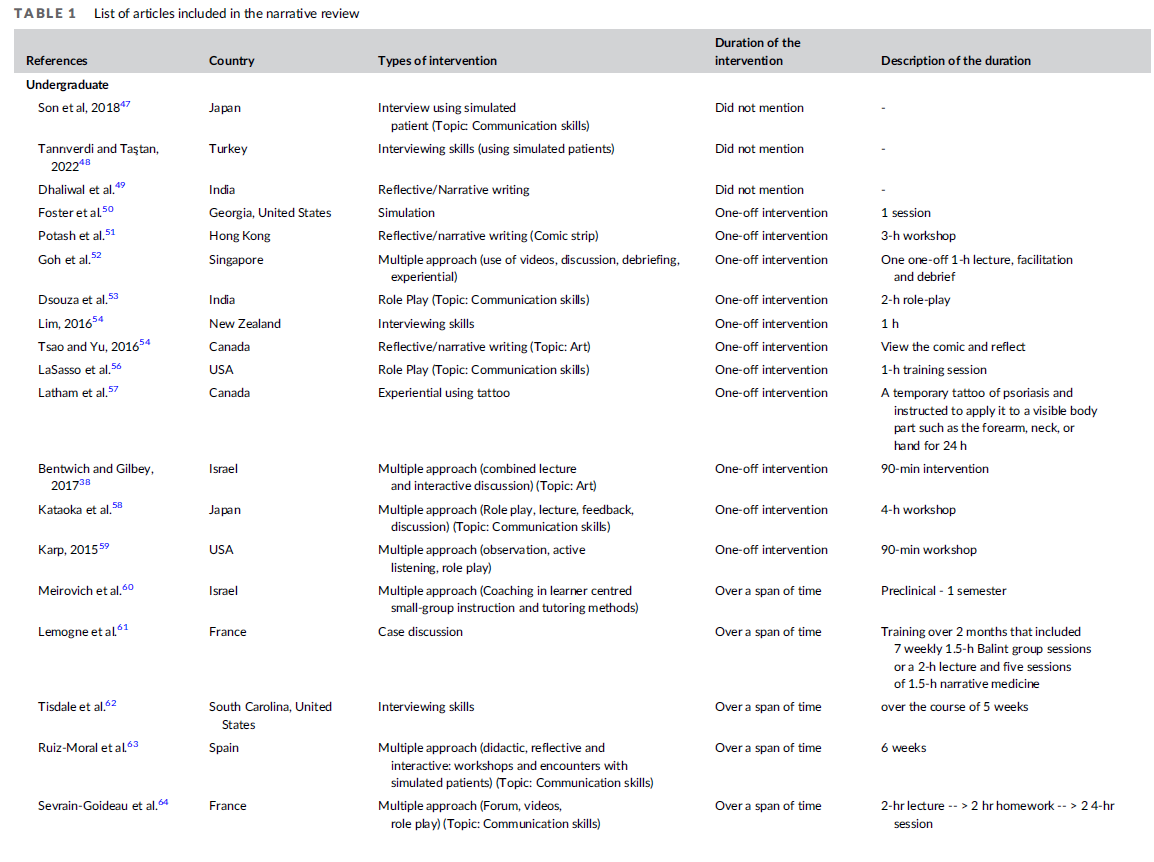

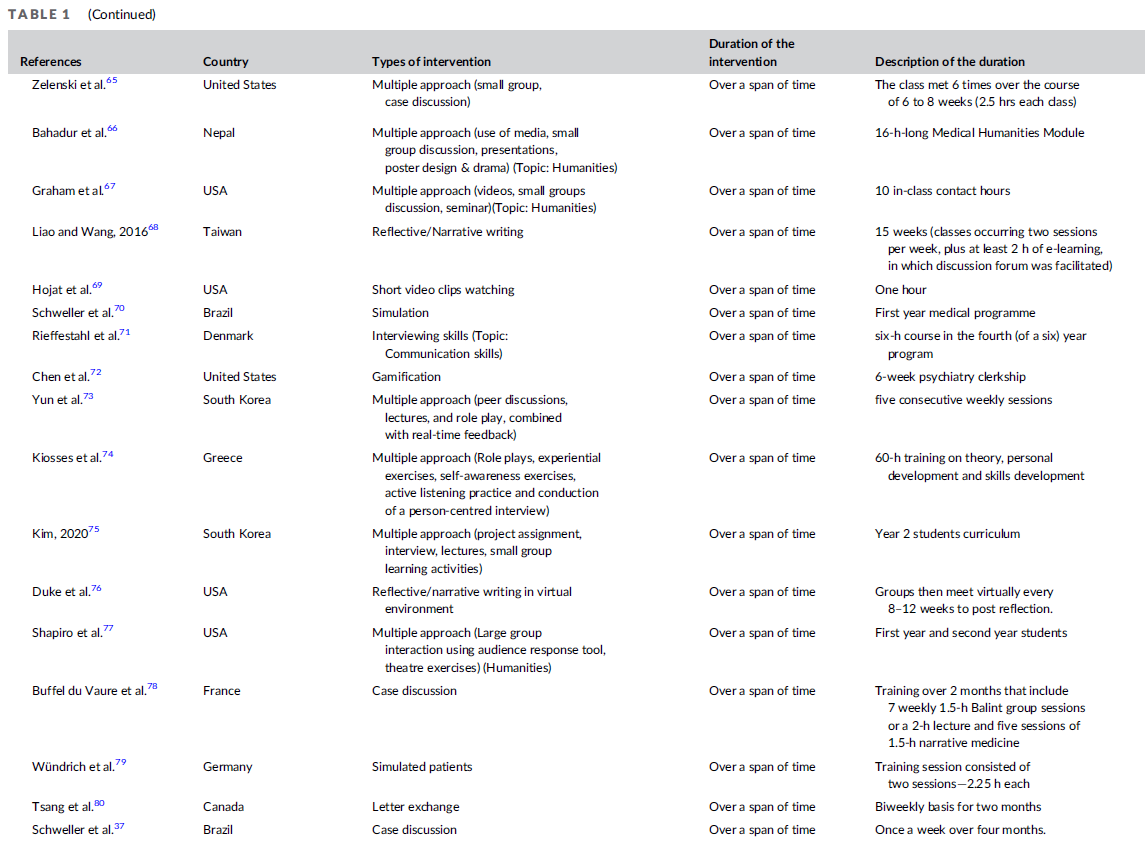

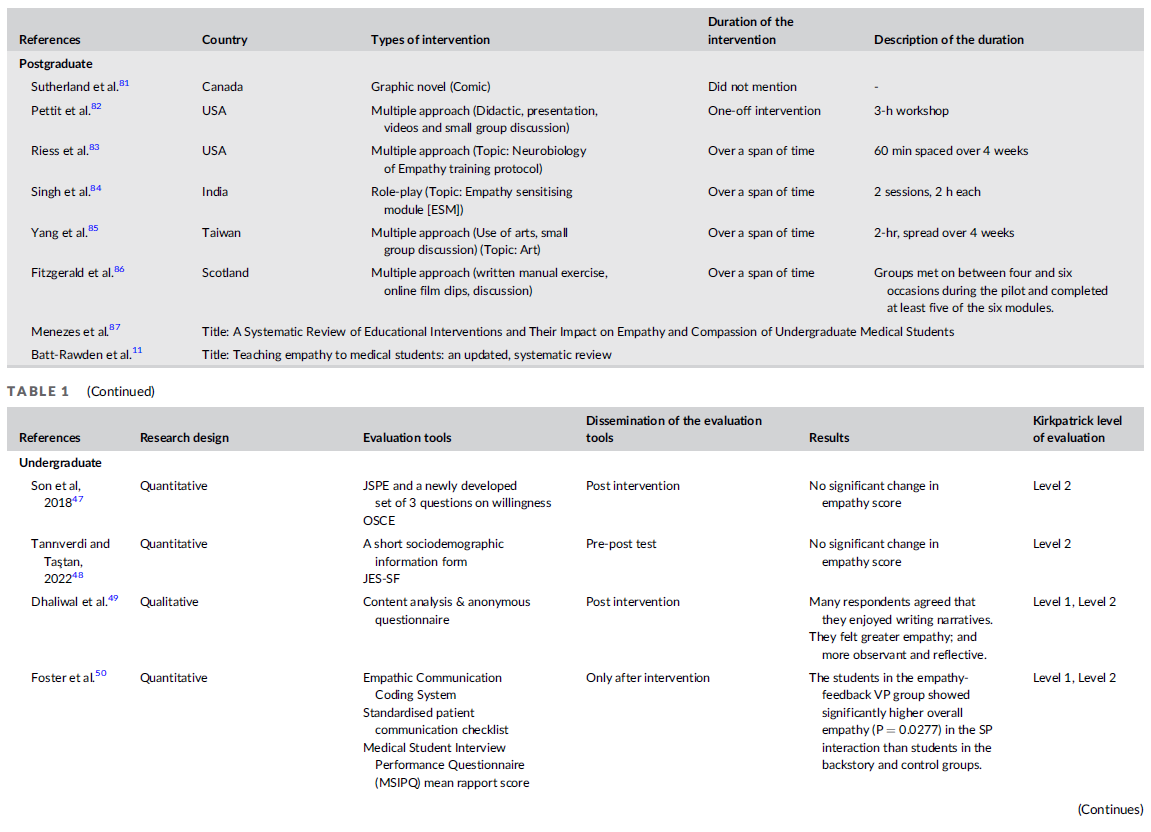

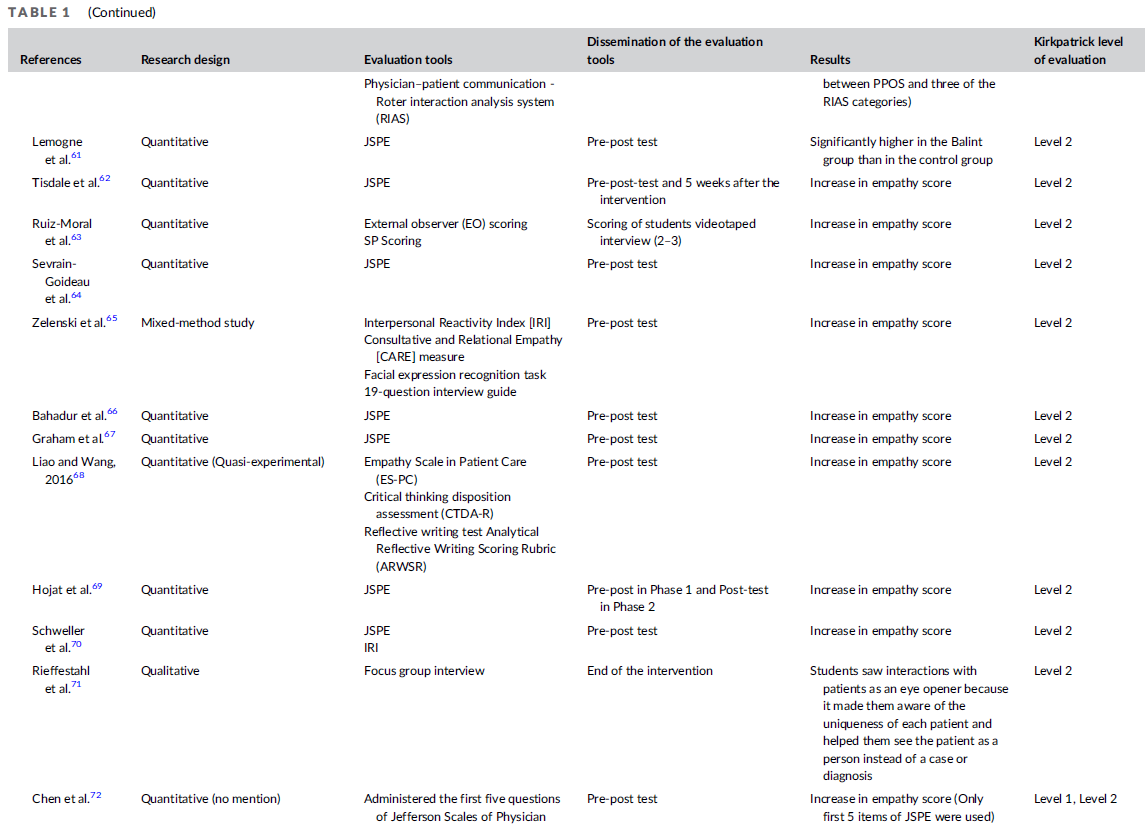

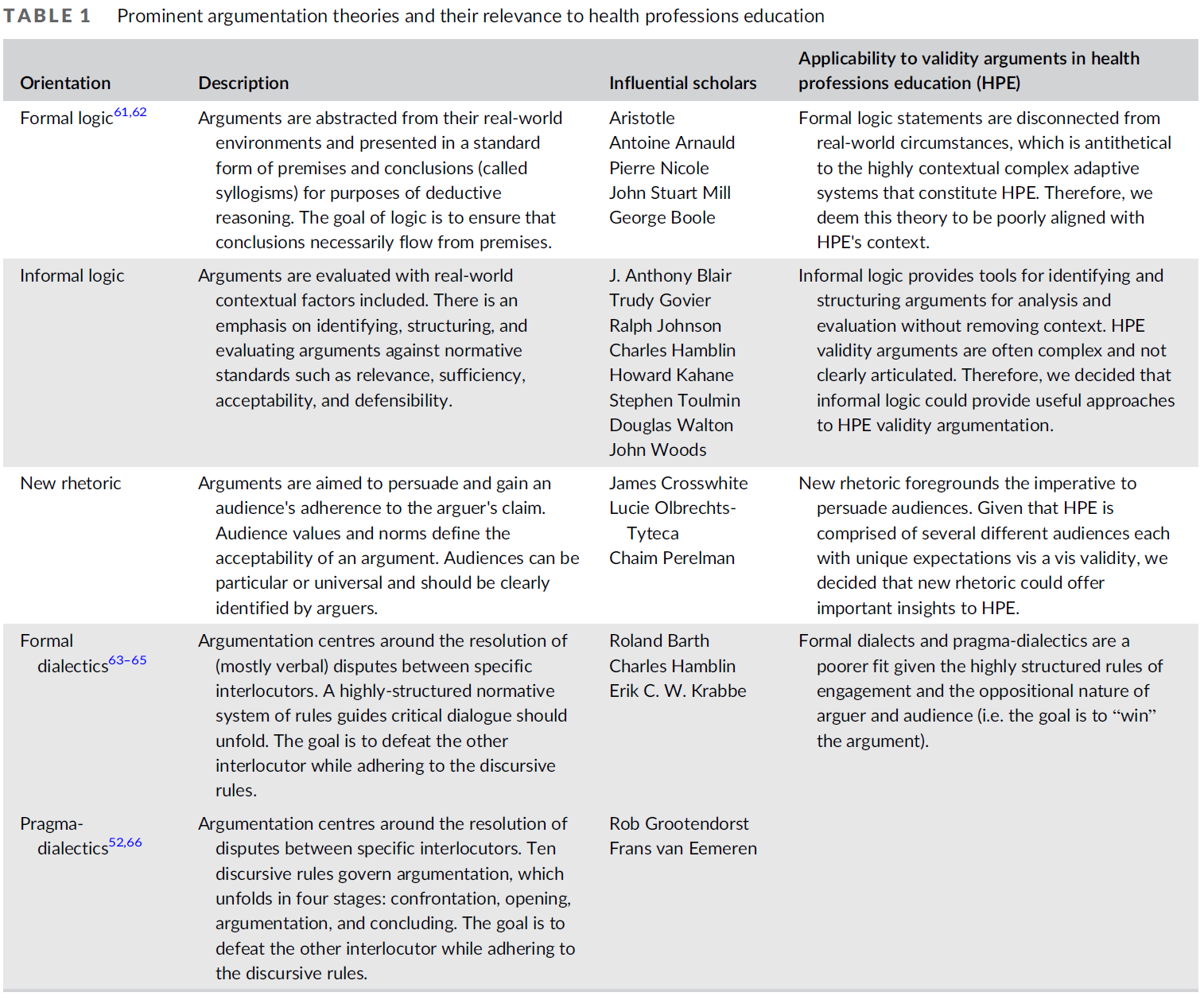

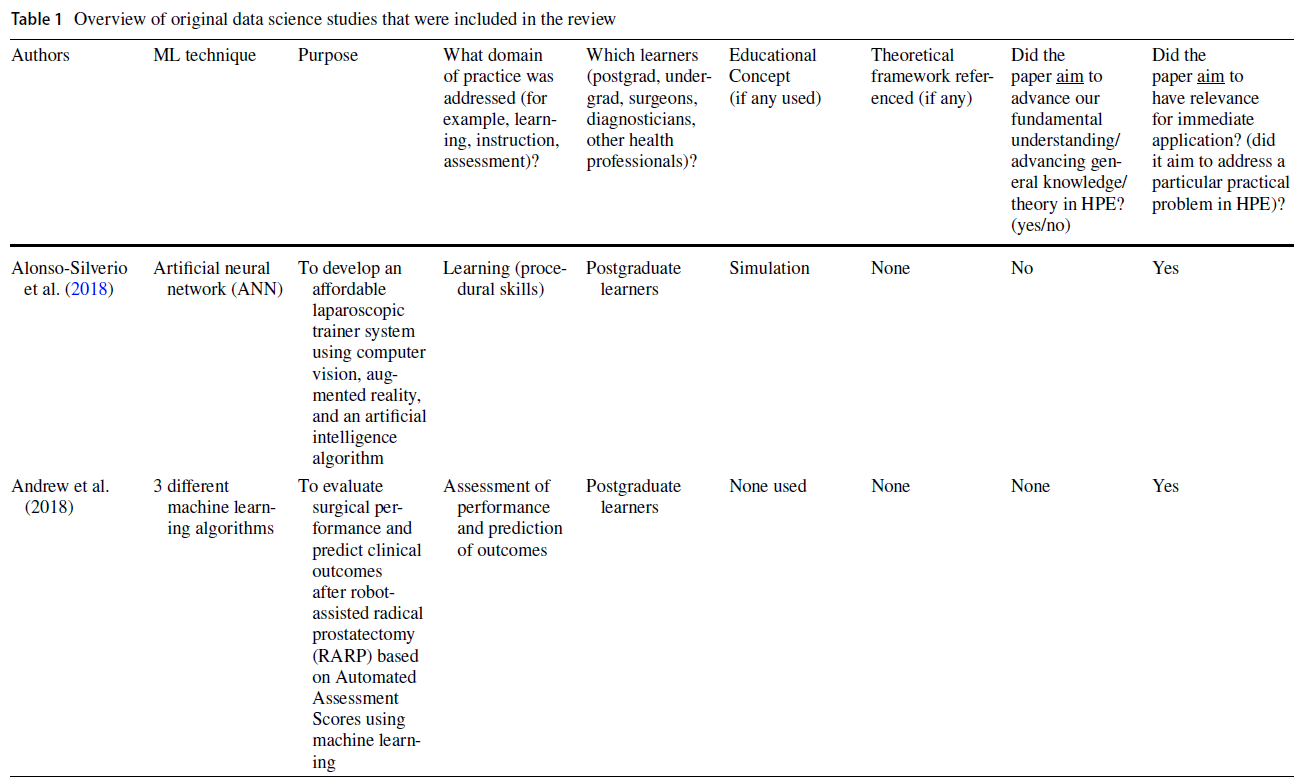

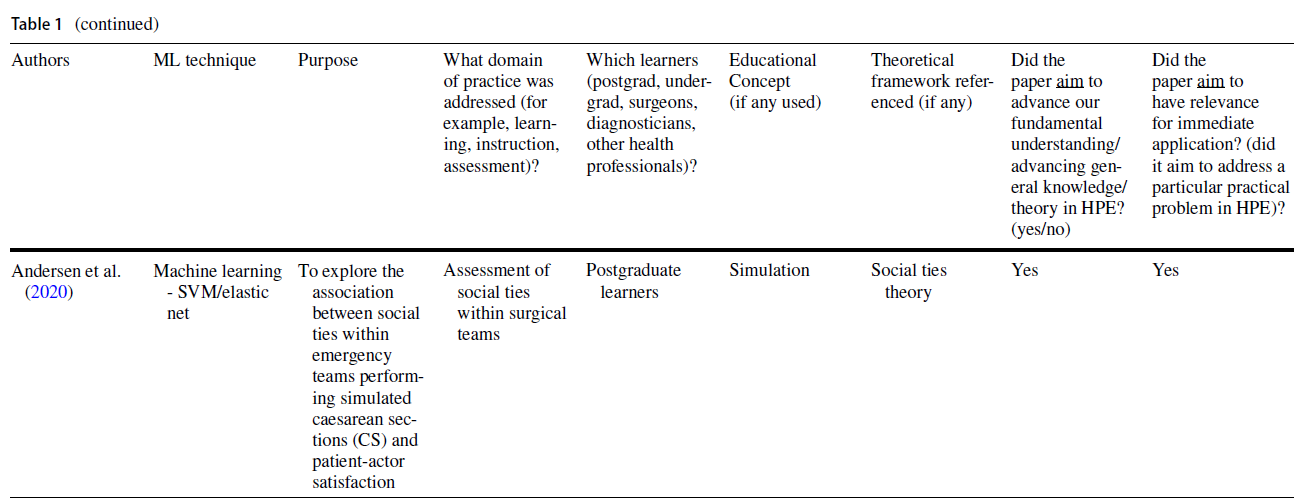

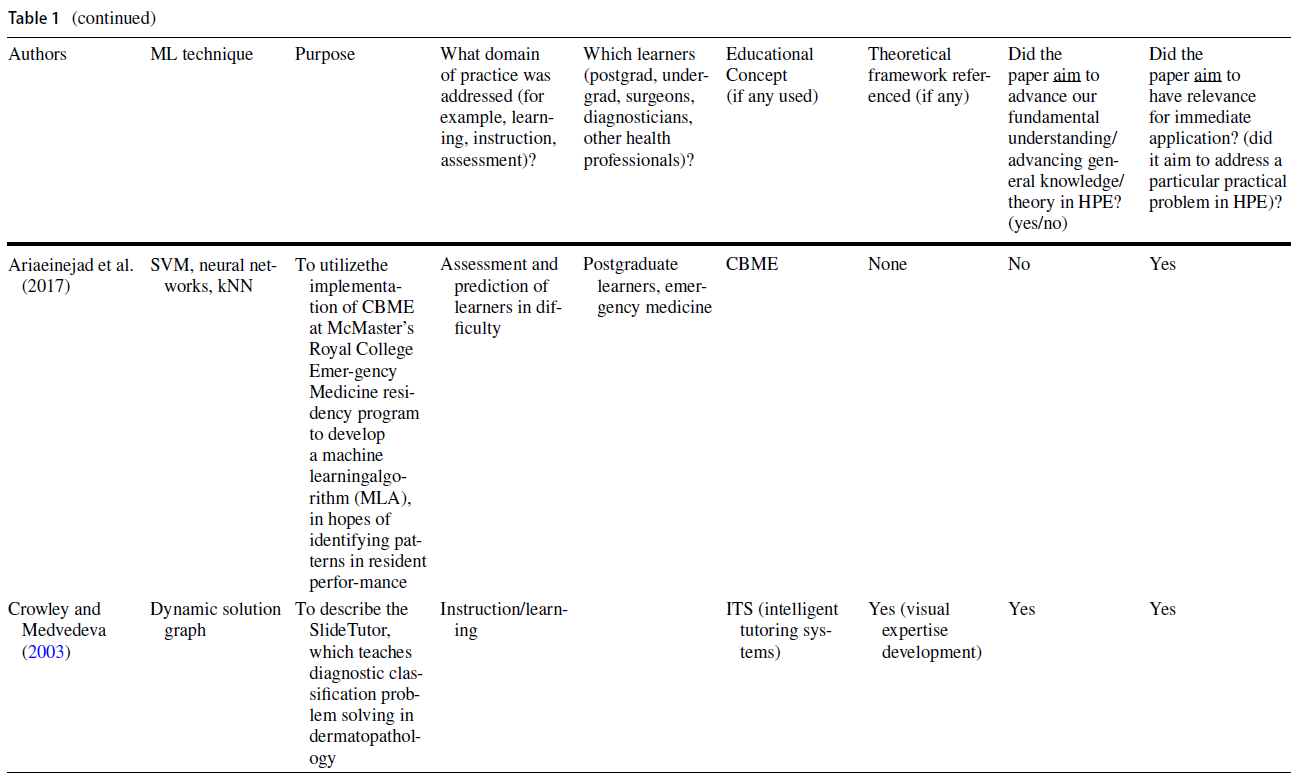

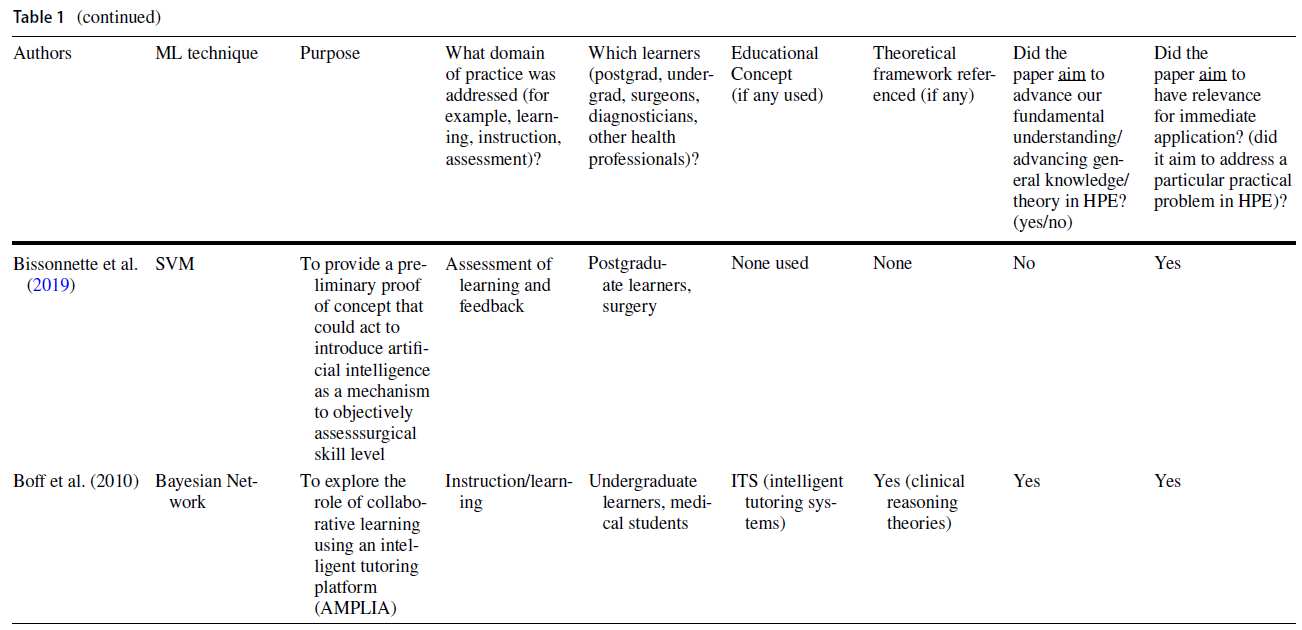

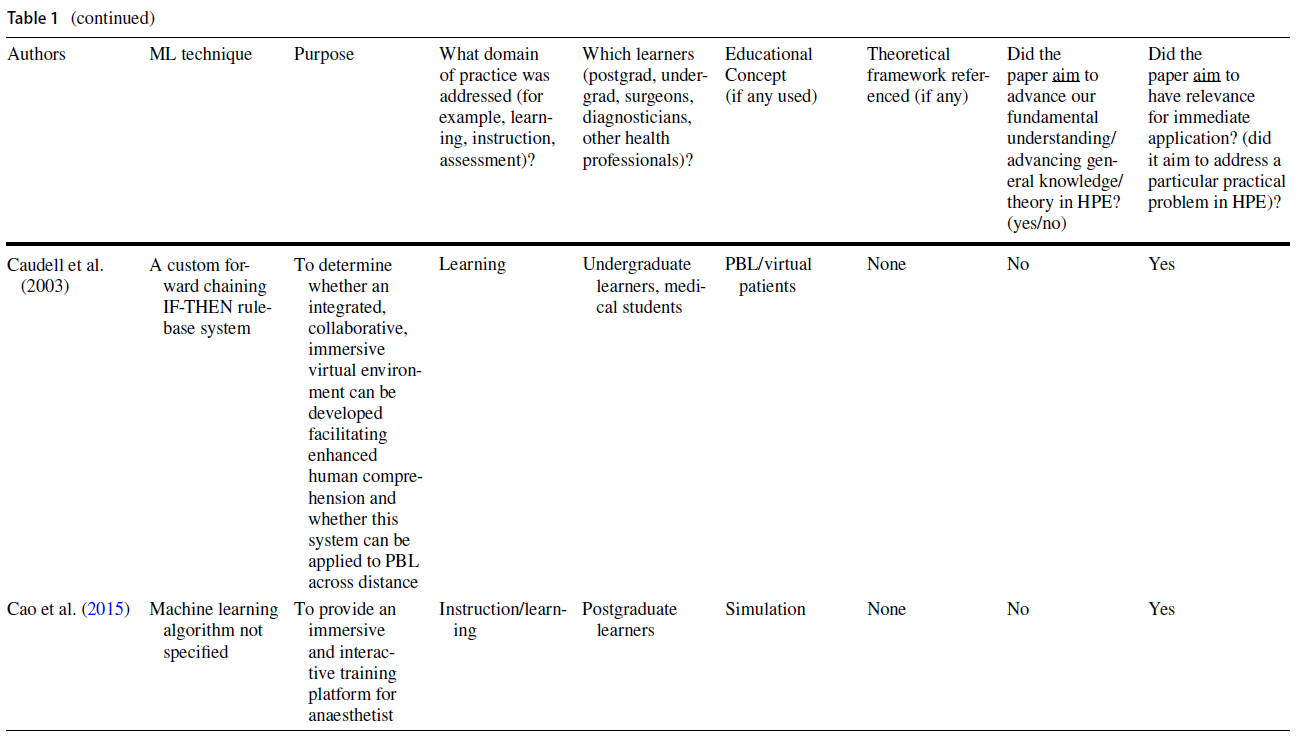

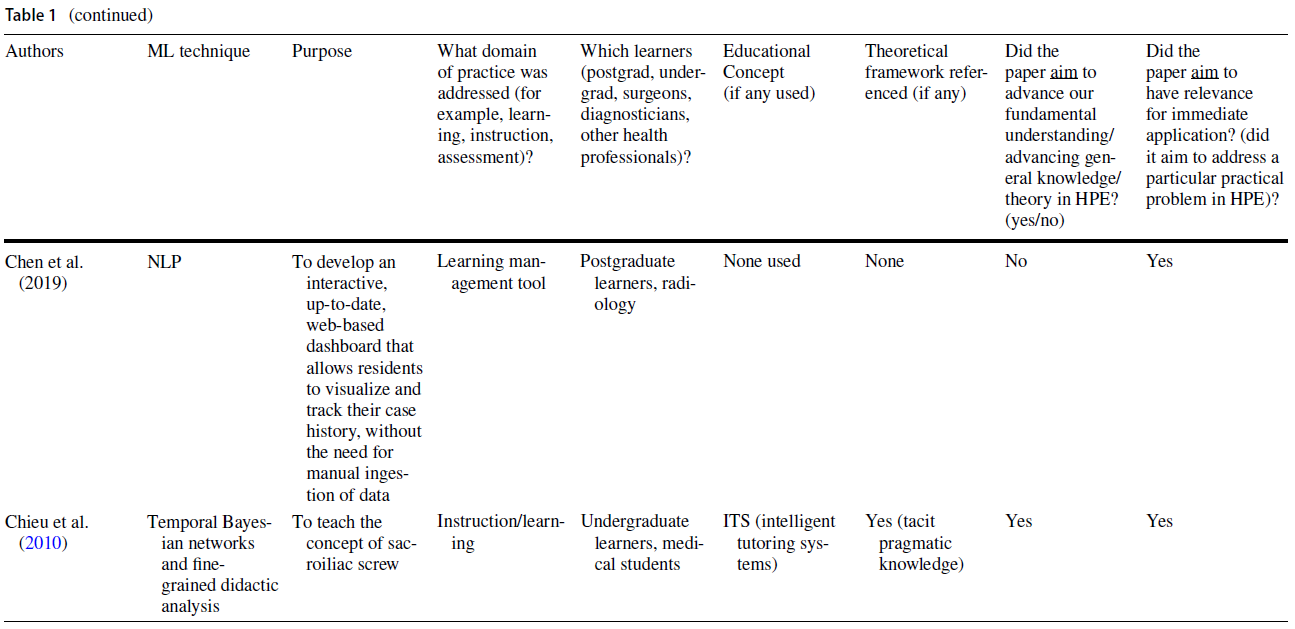

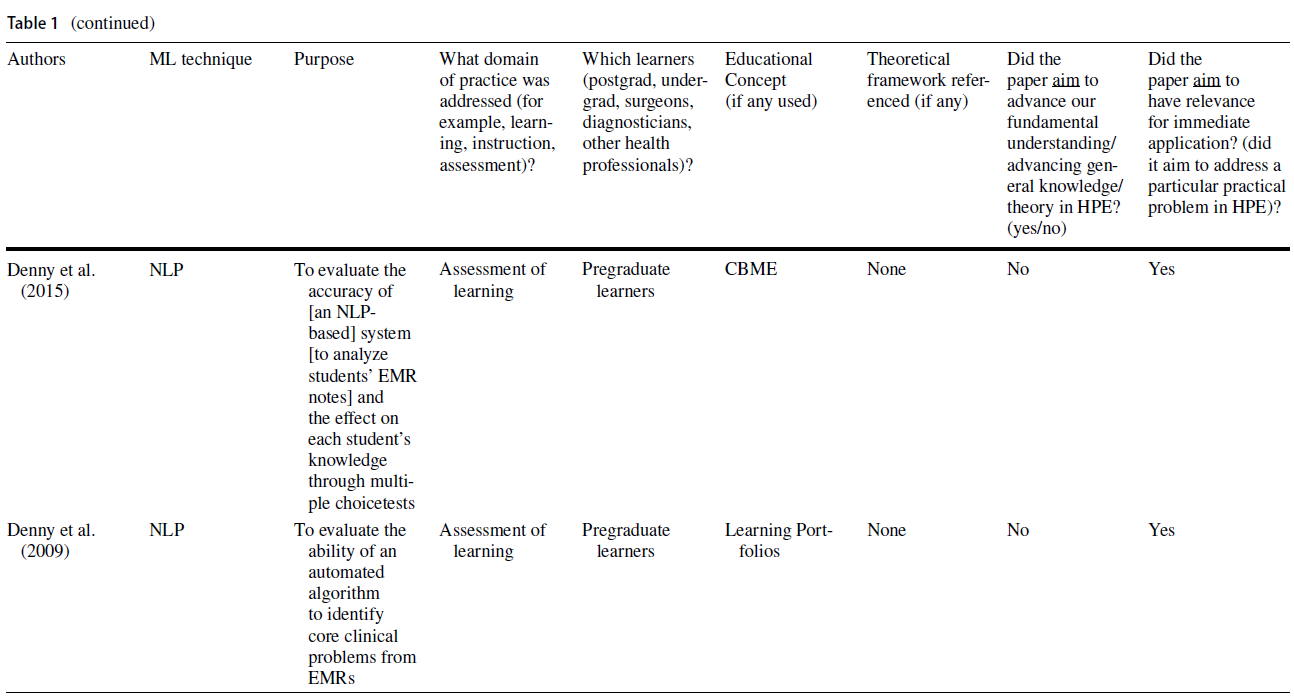

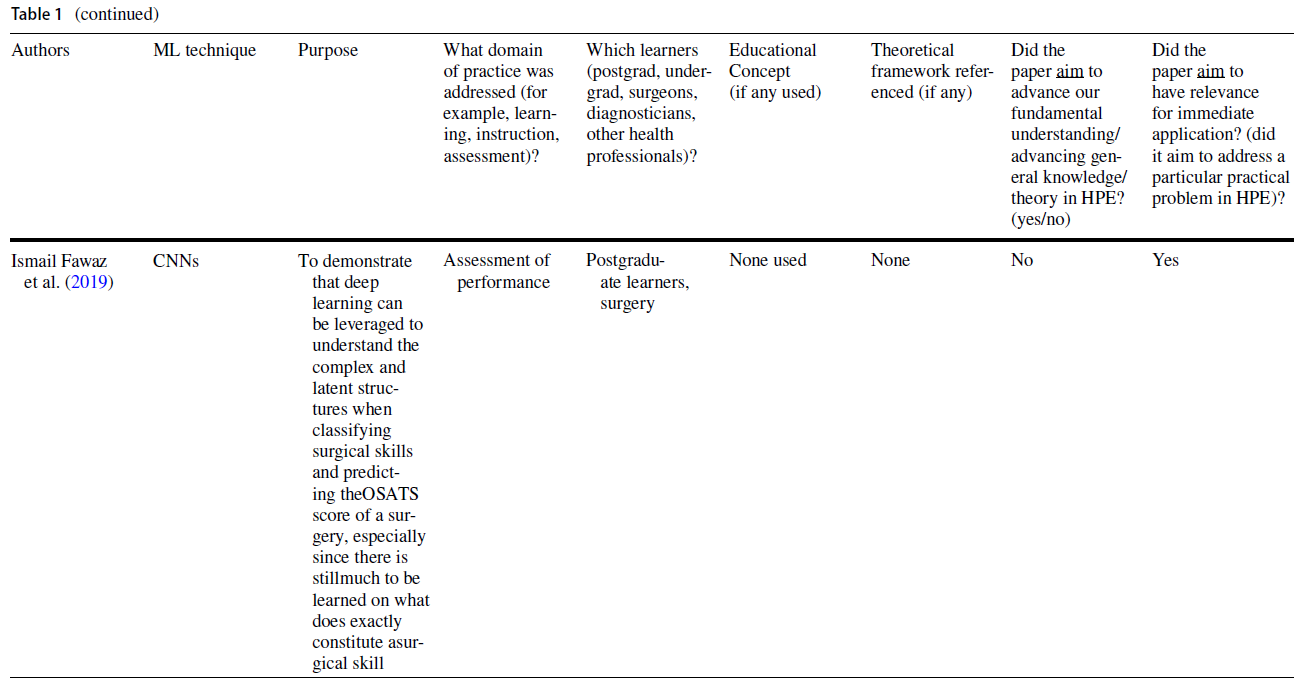

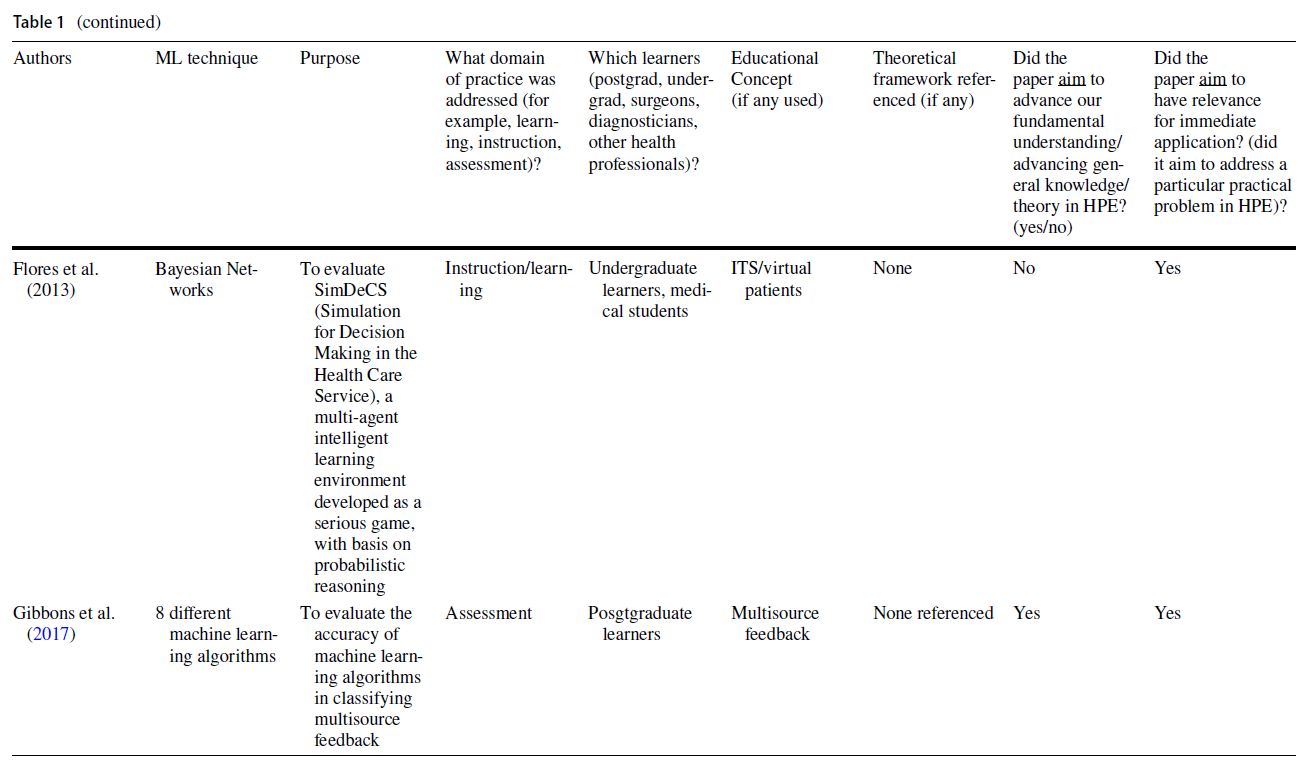

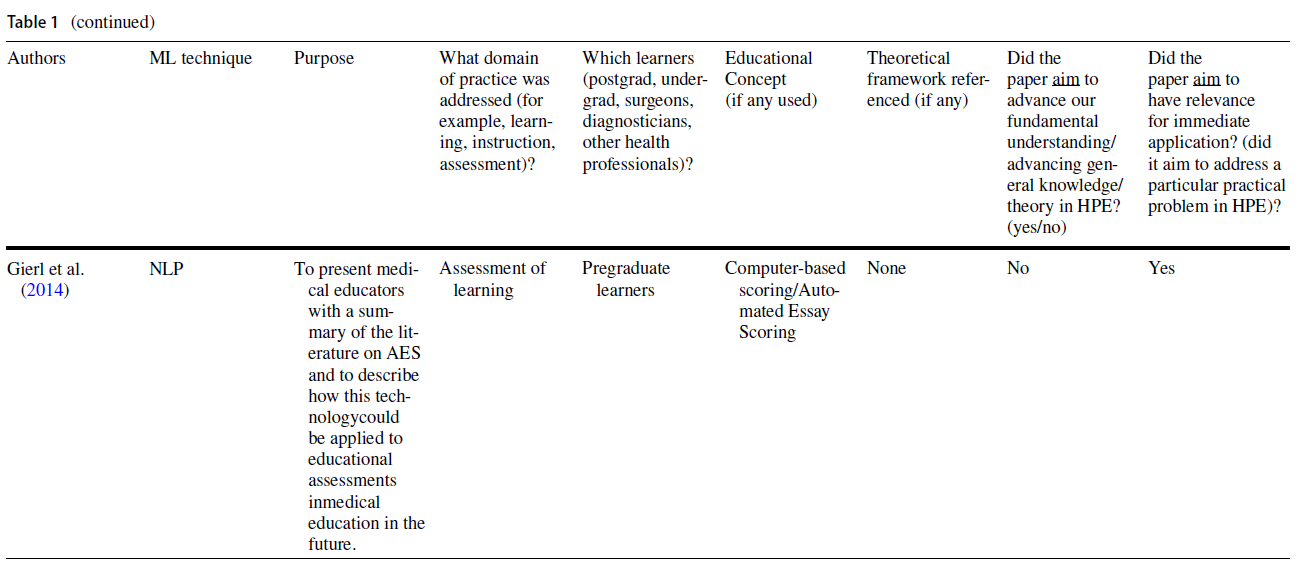

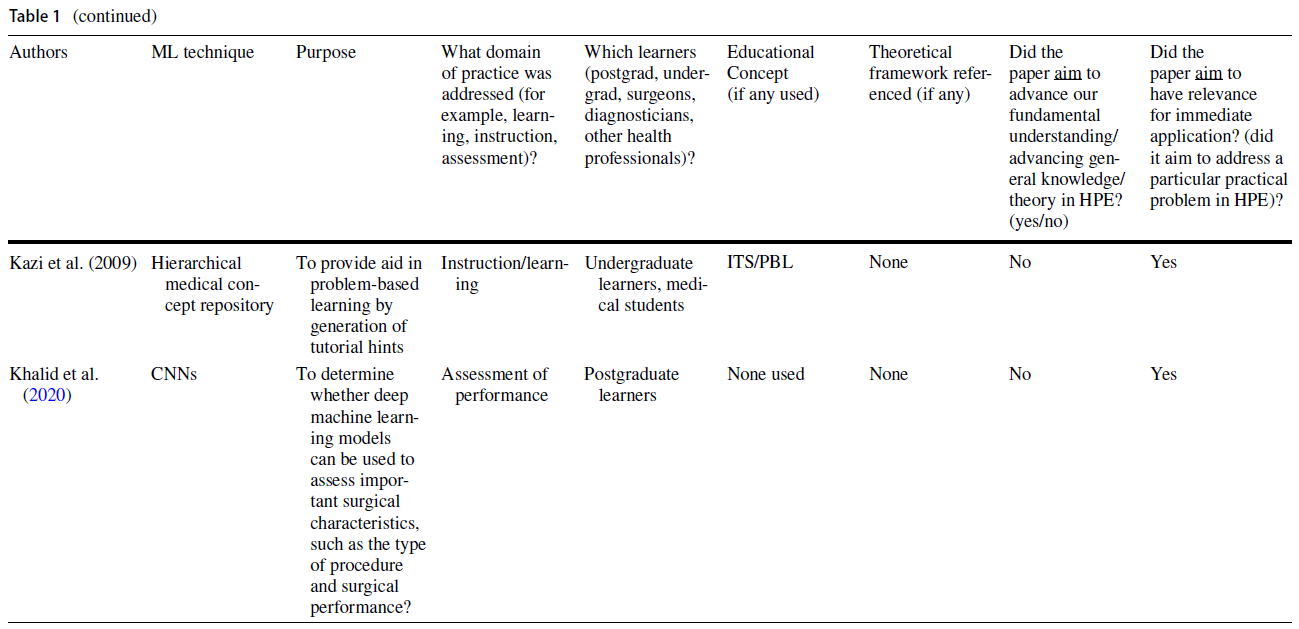

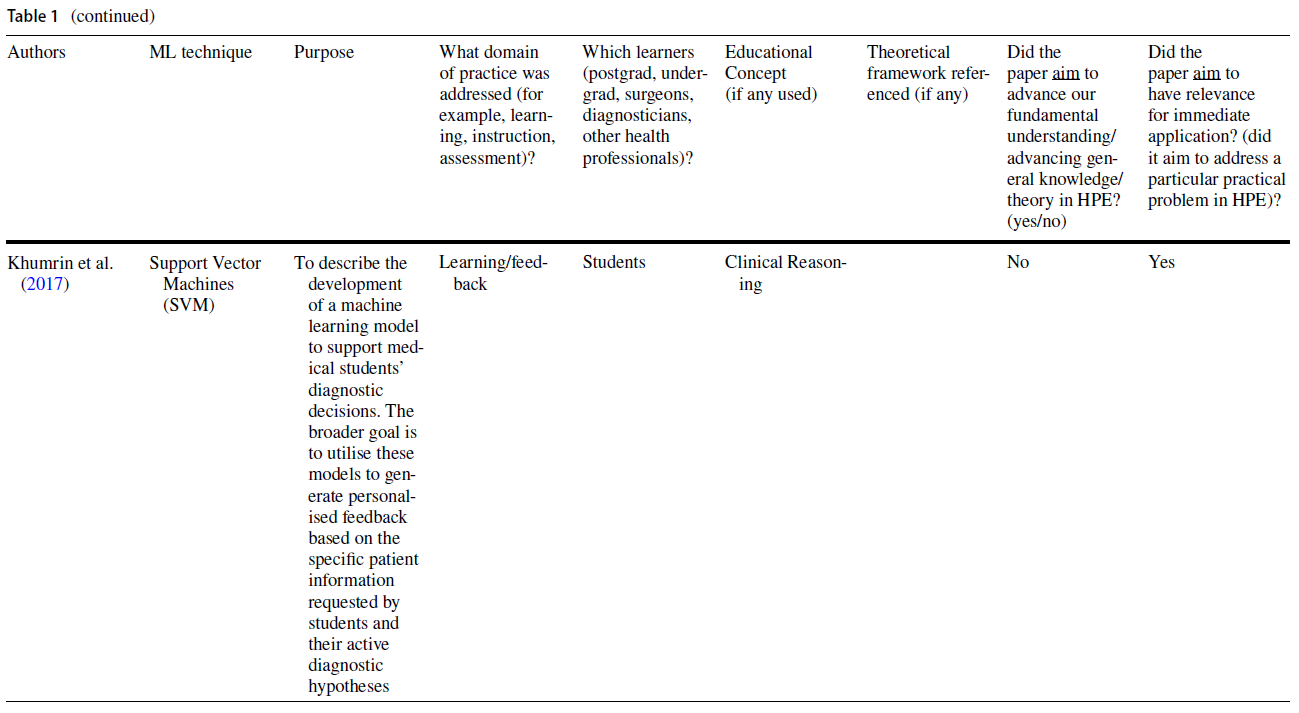

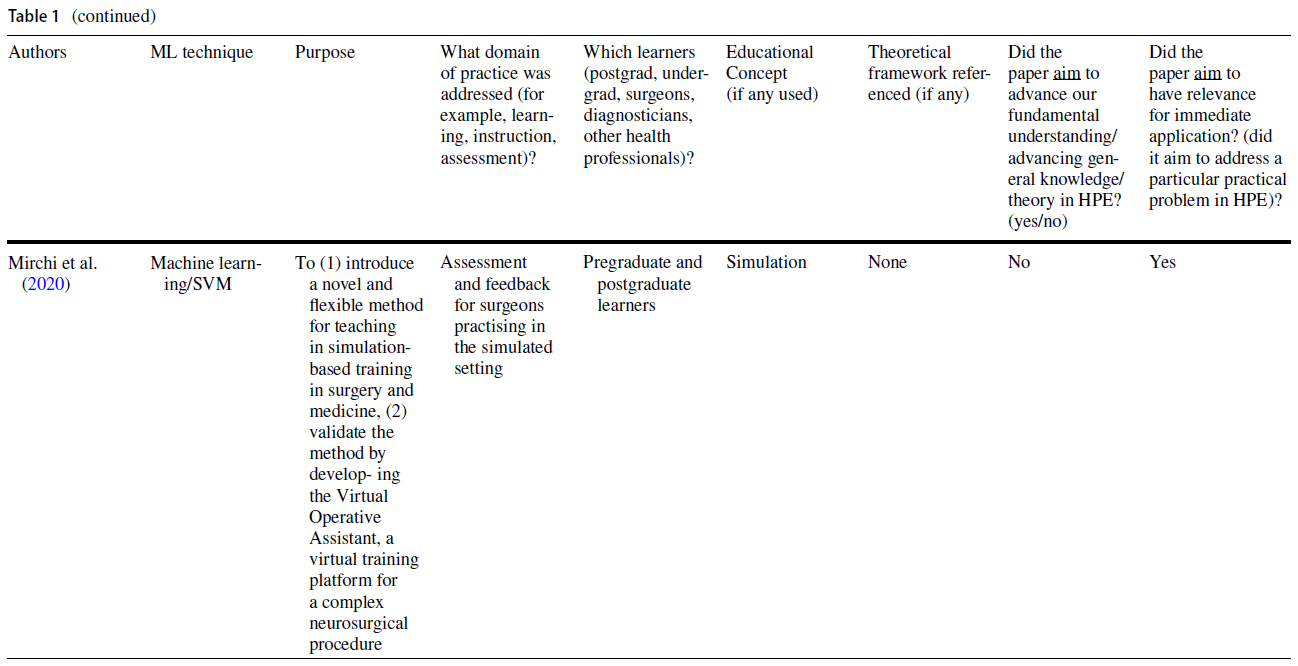

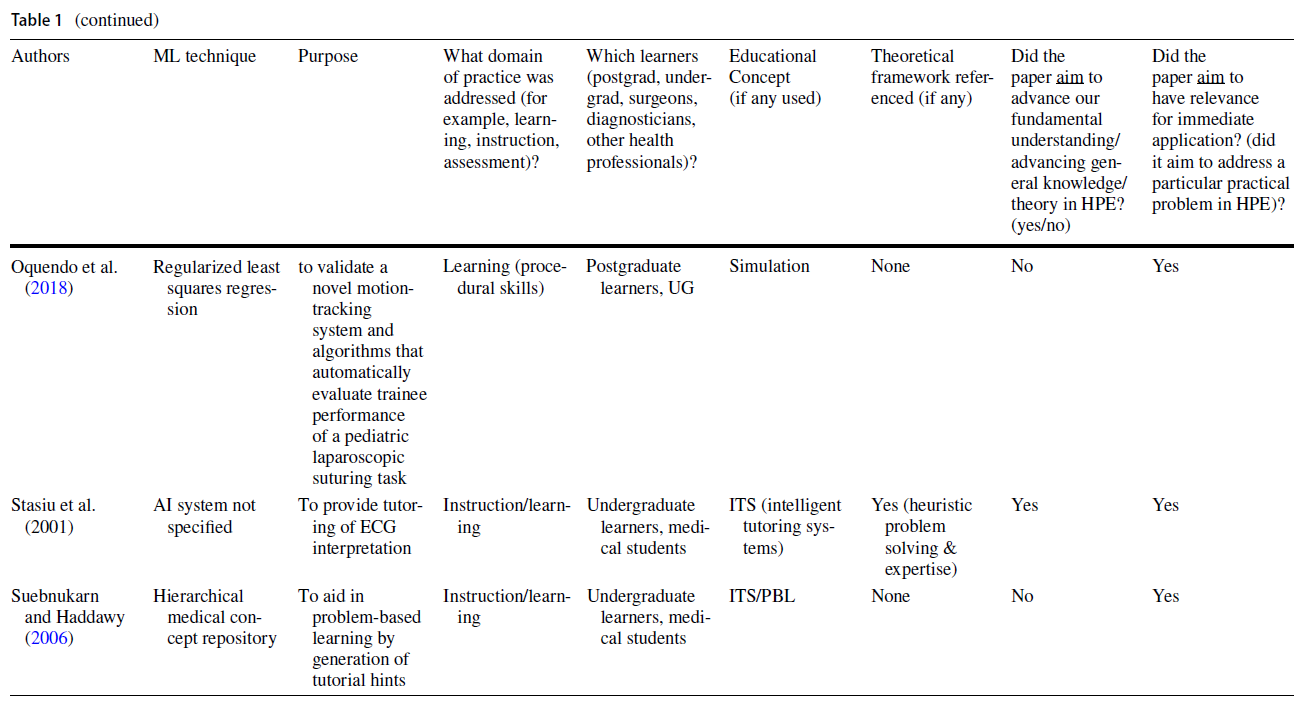

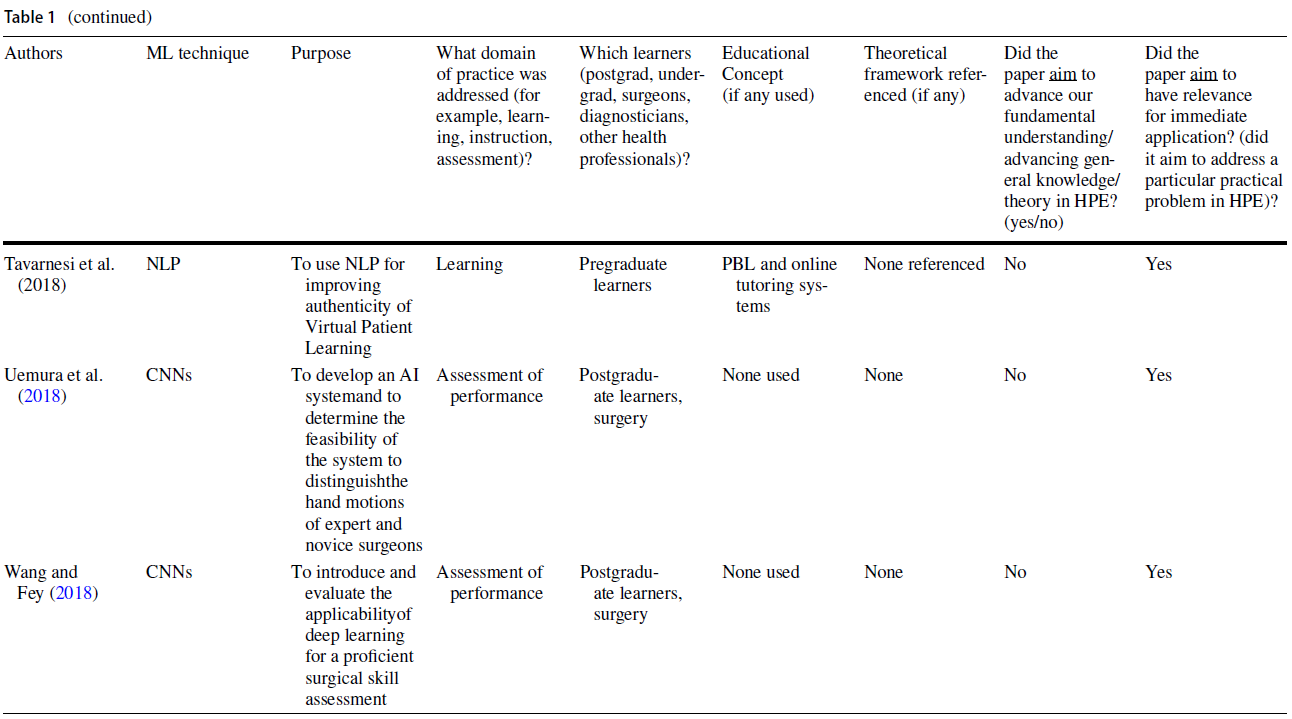

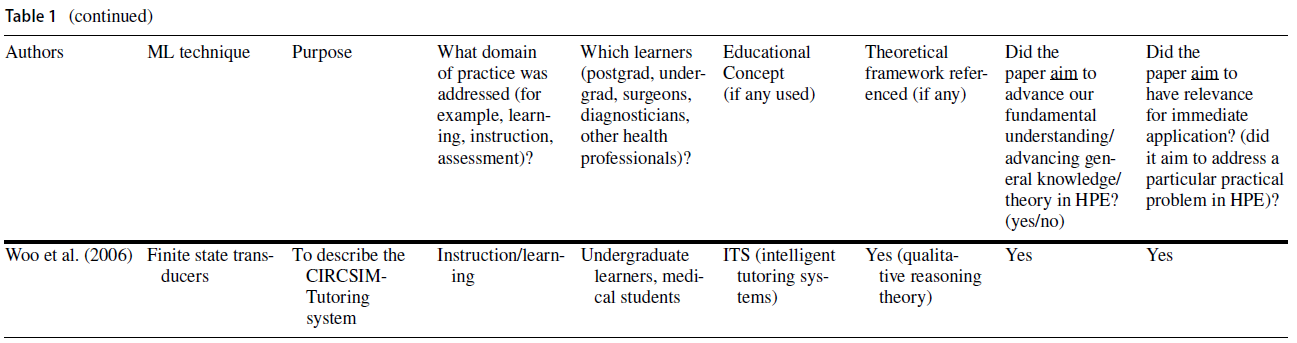

시뮬레이션 및 의료 영상과 같은 영역은 주로 성능 평가 자동화, 피드백 제공 및 환자 결과 예측을 위해 ML의 실용적인 응용 프로그램을 사용했다(표 1 참조). 많은 경우, 저자는 ML 접근 방식을 사용하는 이유로 기존 한계(예: 전문가 인간 평가자의 직접 관찰과 피드백에 의존하는 간헐적이고 무작위적인 작업장 기반 평가)를 해결할 수 있는 능력을 인용했다(Oquendo et al. 2018). 실제로, 여러 연구는 [평가자 기반 점수]를 [ML 기반 예측]으로 대체하여, 수술 기술 평가의 효율성을 향상시키기 위해 ML 알고리듬을 사용하는 방법을 설명했다. 예를 들어, 한 연구는 외과의사의 경험 수준을 사용하여 ML 알고리즘을 훈련시켜 서로 다른 수준의 수술 기술을 구별했습니다.

Areas such as simulation and medical imaging predominantly used practical applications of ML for automating performance assessment, providing feedback, and predicting patient outcomes (see Table 1). In many cases, authors cited the ability to address existing limitations (e.g., infrequent and haphazard workplace-based assessments that rely on direct observation and feedback by expert human raters) as the rationale for using a ML approach (Oquendo et al. 2018). Indeed, several studies described how ML algorithms could be used to improve the efficiency of assessing surgical skills by replacing rater-based scores with ML-based predictions (Winkler-Schwartz et al. 2019; Alonso-Silverio et al. 2018; Oquendo et al. 2018; Ismail Fawaz et al. 2019; Wang and Fey 2018; Uemura et al. 2018; Bissonnette et al. 2019; Khalid et al. 2020; Andrew et al. 2018). For example, one study used surgeons’ experience levels to train a ML algorithm to distinguish between different levels of operative skills (Uemura et al. 2018).

전통적인 교육 방법을 보강하는 지능형 튜터링 시스템(ITS)은 HPE 내에서 ML의 실용적인 유용성을 입증한 문헌의 또 다른 영역을 대표했다. 한 연구에서는 복통 임상사례 208건을 바탕으로 임상추리력을 높이는 이러닝 툴을 개발하기 위해 ML 기법을 사용하였다. 이 도구를 사용하여 학생들은 가상 환자와 상호작용하고 학습자가 요청한 특정 환자 정보를 기반으로 개인화된 피드백을 받았다(Khumrin et al. 2017). 또 다른 연구에서는 ML 기술을 사용하여 임상 데이터를 수집하고 실제 임상 환경을 시뮬레이션하는 마취에서 몰입적이고 대화형 가상 훈련 플랫폼을 만들었다. 마지막으로 ML 기반 평가의 타당성을 탐구하는 대다수의 연구는 교육적 프레임워크가 없거나 시대에 뒤떨어진 타당성 프레임워크를 사용했다(Dias et al. 일반적으로, 이 연구의 하위 집합은 평가와 교육 내에서 실질적인 교육 문제를 다루었지만, 교육 이론이나 인식론에 대한 제한된 고려나 참고를 제공했다.

Intelligent tutoring systems (ITS) augmenting traditional instruction methods represented another area in the literature that demonstrated the practical utility of ML within HPE. In one study, ML techniques were used to develop an e-learning tool that increased clinical reasoning skills based on 208 clinical cases of abdominal pain. Using this tool, students interacted with a virtual patient and received personalized feedback based on the specific patient information requested by the learner (Khumrin et al. 2017). In another study, ML techniques were employed to collect clinical data and create an immersive and interactive virtual training platform in anesthesia that simulated an authentic clinical environment (Cao et al. 2015). Lastly, the majority of studies exploring the validity of ML-based assessments, either used no educational framework or outdated validity frameworks (Dias et al. 2019). In general, this subset of studies addressed practical educational problems within assessment and instruction, but offered limited consideration or reference to educational theory or epistemology.

HPE 연구에서 데이터 과학과 ML의 이론적 기여

Theoretical contributions of data science and ML in HPE research

이번 심사를 위해 선정된 논문의 대다수가 '순수응용연구' 범주에 속하지만 모두 이론적이 없는 것은 아니었다. 통계이론, 계산이론, 방법론적 고려사항 측면에서 데이터 과학이론을 충분히 활용한 연구가 몇 개 있었는데, 이는 ML 모델을 선택하고 활용하는 방법을 안내하였다. 예를 들어, [설명 가능한 AI]의 개념은 모델이 특정 결과에 도달하는 방법이 불분명한 ML 연구에서 '블랙박스' 문제를 해결하기 위한 이론으로 도입되었다. 이러한 연구는 "사용에 영감을 받은 기초 연구" 범주에 속합니다.

Although the majority of papers selected for this review fall into the “Pure Applied Research” category, not all of them were atheoretical. There were a few studies with sufficient use of data science theory, in terms of statistical theory, computational theory, and methodological considerations, which guided how ML models were selected and utilized (Bisonette et al. 2019; Uemura et al. 2018; Wang and Fey 2018). For example, the concept of Explainable AI was introduced as a theory (Winkler-Schwartz et al. 2019) to address the ‘black box’ problem in ML research, where it is unclear how a model arrives at a certain result. These studies fell into the “Use-inspired Basic Research” category.

또한 역량 또는 성과 평가를 다루는 몇 개의 논문은 [이론이 데이터 분석 및 해석을 가이드하는 데 어떻게 사용되는지]를 보여주었다.

- 특별수술팀 구성원 간의 사회적 유대가 환자 만족도에 어떤 영향을 미치는지 탐구하기 위한 연구에서, 앤더슨 외 연구진(2020)은 ML 분석을 사용하여 기존의 통계로는 불가능했을 몇 가지 이론 기반 가설을 탐구했다. 소셜 네트워크 이론을 기반으로, 저자들은 수술팀의 서로 다른 하위 그룹을 대표하는 노드로 구성된 네트워크를 사용하여 환자 만족도의 예측 변수로서 하위 팀 간의 정서적, 전문적, 개인적 유대를 해부했다.

- 또 다른 연구에서, 기븐스 외 연구진(2017)은 가설 유도 코딩을 사용하고 의사의 성과에 대한 핵심 지표로 다중 소스 피드백을 기반으로 실행 가능한 통찰력을 수집하는 ML 알고리듬을 훈련시켰다. 이 두 연구에서, 저자들은 크고 복잡한 데이터 세트를 탐구하기 위해 이론 기반 접근 방식을 사용했다.

- 마지막으로, ITS에 초점을 맞춘 연구는 이러한 시스템이 도메인 모델에 그러한 통찰력을 포함하도록 설계되었기 때문에 학습 이론의 중요성을 강조했다. 예를 들어, Crowley와 Medbedeva(2003)는 병리학 슬라이드의 분류를 평가하는 연구에서 자신의 도메인 모델의 설계를 알리기 위해 시각적 전문지식을 개발하기 위해 이론적 프레임워크인 통합 문제 해결 방법을 사용했다.

Additionally, a few papers dealing with assessment of competence or performance demonstrated how theory was used to guide data analysis and interpretation.

- In a study aimed at exploring how social ties between members of ad hoc surgical teams influenced patient satisfaction, Andersen et al. (2020) used ML analytics to explore several theory-based hypotheses, which would not have been possible using traditional statistics. Building on social network theory, the authors dissected affective, professional, and personal ties between sub-teams as predictors of patient satisfaction using a network consisting of nodes representing different sub-groups of the surgical team.

- In another study, Gibbons et al. (2017) used hypotheses-guided coding and trained a ML algorithm that gleaned actionable insights based on multi-source feedback as key indicators of physicians’ performance. In both of these studies, the authors used theory-based approaches to explore large and complex datasets.

- Lastly, studies that focused on ITS stressed the importance of learning theory, as these systems were engineered to include such insights in their domain model. For example, Crowley and Medvedeva (2003) used a theoretical framework, the unified problem-solving method, for developing visual expertise to inform the design of their domain model in a study evaluating the classification of pathology slides.

위에서 예시한 바와 같이, 우리가 확인한 대부분의 연구는 "순수 응용 연구" 범주에 속하며, 몇 가지 예외는 "사용에 영감을 받은 기초 연구" 그룹에 속하는 것으로 분류되었다. 우리는 오로지 이론적 연구의 부족과 패턴 이해에만 초점을 맞춘 연구의 부족을 반영하여 "순수 기초 연구" 또는 "예측, 탐색적 또는 평가" 범주에서 0개의 연구를 분류했다.

As exemplified above, most of the studies we identified fell into the “Pure Applied Research” category, with a few exceptions classified as belonging in the “Use-inspired Basic Research” group. We classified zero studies in either the “Pure Basic Research” or “Predictive, Exploratory, or Evaluative” categories, reflecting a dearth of solely theoretical work and a lack of studies focused exclusively on understanding patterns.

데이터 과학 및 ML 기반 HPE 연구에 대한 인식론적 신념

Epistemic beliefs in data science and ML driven HPE research

HPE 문헌에서 교육 이론의 일반적인 부재는 데이터 과학과 ML이 역사적으로 등장한 분야를 반영할 수 있다. 여기에는 [이론 구축과 테스트]보다는 [실제 적용과 문제 해결에 중점]을 두는 경향이 있는 컴퓨터 과학, 통계 및 공학이 포함된다(Pea 2014). 같은 이유로, [교육 데이터 과학]은 기술자, 도구자, 기능주의자로 인식되어 왔다. 이러한 생각은 "과학적인 관점에서 학습을 정량화, 측정, 실행이 가능하고, 따라서 최적화가 가능하다고 보는 과학적 사고방식"라는 표현에서 잘 드러난다.

To some degree, the general absence of educational theory in HPE literature may reflect the disciplines from which data science and ML emerged historically (Pea 2014). These include computer science, statistics, and engineering which tend to focus on practical applications and problem solving rather than theory building and testing (Pea 2014). For the same reasons, educational data science has been perceived as technicist, instrumentalist, and functionalist (Kitchin 2014) as it reflects “a scientific style of thinking that views learning in scientific terms as quantifiable, measurable, actionable, and therefore optimizable” (Williamson 2017).

이러한 프레임으로, 일부 일반 교육 학자들은 데이터 과학과 ML에서 비롯된 새로운 [경험주의 인식론]의 출현은, [이론을 불필요하게 만들고, 지식 생산을 인간 편향의 영향으로부터 자유로운 상황으로 만들 수 있다]고 제안했다. 예를 들어, 앤더슨(2008)은 "과학은 모델, 통일된 이론, 또는 정말로 어떠한 기계론적 설명 없이도 진보할 수 있다"고 주장하면서 "이론의 종말"을 선언했다. HPE 연구에 대한 우리의 검토에서, 일부 학자들은 교육, 학습 및 평가를 진전시키기 위한 데이터 과학과 ML의 잠재적인 사용에 대해 논의할 때 유사한 인식론적 신념의 목소리를 냈다.

- 예를 들어 쇼텐 외 연구진(2018)은 의사의 기술력 향상을 위한 ML의 잠재적 사용을 요약하고 다음과 같이 주장했다. "[...] 환자 수준의 관찰은, 기계 학습 알고리즘을 통해 데이터가 스스로 말할 수 있도록 함으로써, 고품질 또는 낮은 품질의 성능(효율 및 오류 회피)과 임상 결과를 예측하고 평가할 수 있는 수단을 제공합니다."

- Uemura et al(2018)의 또 다른 연구는 외과의사의 전문성 수준 분류를 위한 신경망의 사용을 조사했고 "분류 중 인간의 개입은 없었으며, 이는 이 결과가 객관적이고 양적으로 간주될 수 있음을 의미한다"고 강조했다.

- 비슷한 맥락에서 솔트 외 연구진(2019)은 USMLE 2단계 임상 기술 점수를 평가하기 위해 NLP를 사용할 수 있는 방법을 연구했고 다음과 같이 진술했다. "잘 설계된 컴퓨터 기반 채점 시스템은 피로나 인간의 편견의 영향을 받지 않기 때문에 일관성, 객관성 및 효율성에 있어 인간의 판단보다 우수하다."

따라서 일부 연구자의 경우 HPE에서 데이터 과학과 ML의 사용을 지원하는 가치 제안에서 [객관성에 대한 강조]와 [인간 편향이 없는 것]이 높은 우선 순위를 갖는 것으로 보였다.

With this framing, some general education scholars suggested that the emergence of a new empiricist epistemology stemming from data science and ML may render theory unnecessary and situate knowledge production as free from the influence of human bias (Kitchin 2014). For instance, Anderson (2008) proclaimed the “end of theory” arguing that “science can advance even without models, unified theories, or really any mechanistic explanation at all.” In our review of HPE research, some scholars voiced similar epistemic beliefs when discussing the potential uses of data science and ML for advancing instruction, learning, and assessment.

- Shorten et al. (2018), for example, summarized potential uses of ML for improving physicians’ technical skills and argued that “by letting the data speak for themselves through a machine-learning algorithm, [...] patient level observations offer a means to predict and assess high- or low-quality performance (efficiency and error avoidance) and clinical outcome.”

- Another study by Uemura et al. (2018) examined the use of neural networks for classification of surgeons’ expertise levels and highlighted that “there were no human interventions during classification, meaning that this result can be considered objective and quantitative.”

- On a similar note, Salt et al. (2019) explored how NLP can be used to assess USMLE Step 2 Clinical Skills scores and stated that a “well-designed computer-based scoring system is superior to human judgment with respect to consistency, objectivity, and efficiency because it is not susceptible to the effects of fatigue or human biases.”

Hence, for some researchers, the emphasis on objectivity and perceived lack of human bias seemed to have high priority in the value proposition supporting the use of data science and ML in HPE.

[인간 편향의 감소를 통한 객관성 달성에 관한 이러한 인식론적 믿음]에 대해서나, [맥락의 역할]에 대해서 반대 의견이 없는 것은 아니다.

- Salt et al(2019)에 대한 답변에서, Spadafore와 Monrad(2019)는 ML의 알고리듬이 본질적으로 훈련하기 위해 선택한 데이터 유형에 따라 편향되기 때문에 [점수 매김의 일관성]과 [객관성]을 동일시하는 개념에 대해 우려를 제기했다.

- 솔트 외 연구진(2019)도 이것을 인정했지만, 그들은 다음과 같이 언급했다. "자동 채점 시스템은 이상적인 인간 평가자보다 우수할 수 없겠지만, 실제 일반적인 인간 평가자보다 사전 정의된 채점 기준을 따를 수는 있다."

- 솔트 외 연구진(2019)도 이것을 인정했지만, 그들은 다음과 같이 언급했다. "자동 채점 시스템은 이상적인 인간 평가자보다 우수할 수 없겠지만, 실제 일반적인 인간 평가자보다 사전 정의된 채점 기준을 따를 수는 있다."

- 여기에 더하여 지얼 외 연구진(2014)은 NLP 기반 점수가 신뢰성 측면에서 인간 평가자가 산출한 것과 같거나 그 이상이라고 강조했다. 그러나 그들은 또한 점수가 매겨지는 구조에 의미를 부여하고 시험의 비인간화를 피할 수 있는 방법을 제공하기 위해 [전문가의 판단을 통합할 필요]가 있다고 강조했다.

- 엘라웨이(2014)는 "의학과 의학 교육의 기술은 [인간으로부터 벗어나는 것]으로 보여서는 안 된다. [인간이 되는 것]은 [기술을 사용하는 것]이다. "

마지막으로, Bijker(1997)는 다음과 같이 말했다. "[하나는] 기술 아티팩트 또는 기술 시스템의 의미가 [기술 자체에 존재하는 것]으로 간주해서는 안 됩니다. 대신, 테크놀로지가 어떻게 형성되는지 연구하고, 사회적 상호 작용의 이질성 속에서 그 의미를 획득해야 한다."

These emerging epistemic beliefs around achievement of objectivity through reduction of human bias, and the role of context are not unopposed.

- In a reply to Salt et al. (2019), Spadafore and Monrad (2019) raised concerns about the notion of equating consistency in scoring with objectivity, as algorithms in ML are inherently biased based on the type of data we choose to train them with.

- Although this was acknowledged in a reply by Salt et al. (2019), they noted that “while an automated scoring system cannot be superior to the ideal human rater, it can be more adherent to predefined scoring rubrics than the typical human rater in practice”.

- Adding to this, Gierl et al. (2014) emphasized that NLP-based scorings were equal to (or better than) those produced by human raters in terms of their reliability; however, they also stressed the need for incorporating expert judgments to provide meaning to the constructs being scored as well as a way to avoid dehumanization of examinations.

- Another view offered by Ellaway (2014) argued that “technology in medicine and medical education should not be seen as a distraction or deviation from being human; to be human is to use technology”.

- Finally, Bijker (1997) stated that, “[one] should never take the meaning of a technical artifact or technical system as residing in the technology itself. Instead, one must study how the technologies are shaped and acquire their meaning in the heterogeneity of social interactions.”

논의

Discussion

데이터 과학과 ML은 HPE 분야에서 점점 더 많이 사용되고 있으며, 이는 미래에 교육, 학습 및 평가에 혁명을 일으킬 가능성이 높다. 검토한 연구에서, 우리는 주로 [이론을 생성하거나 테스트하기]보다는 [실제 문제를 해결]하기 위해 데이터 과학과 ML을 사용하는 데 초점을 맞추고 있다는 것을 발견했다. [프로시져 기술을 평가]하거나 [한정된 속성을 가진 임상 시나리오를 가르치는 것]은 데이터 과학 및 ML 기술을 사용하여 해결할 수 있는 [잘 정의된 문제]의 일부 예이다. 이러한 유형의 성공적인 응용 프로그램을 염두에 두고, HPE의 비판자들은 기술자 및 도구주의 방식으로 데이터 과학과 ML을 사용하면 콘텐츠 전문가가 개발 및 실행 활동에 포함되지 않는 한 효과적인 교육, 학습 및 평가에 지장을 줄 수 있다고 주장한다. 데이터 과학은 특히 ML 영역에서 새로운 가능성을 제공하지만, HPE에서도 몇 가지 고유한 과제를 안고 있다. 예를 들어, HPE는 사회과학에 의해 많이 알려진 분야인 반면, 데이터 과학과 ML은 기초과학 전통에 뿌리를 두고 있다. 과학을 조사하는 이러한 뚜렷한 사고 패턴과 철학은 HPE 내에서 데이터 과학과 ML 연구를 가이드하는 근원적 인식론적 믿음뿐만 아니라 연구를 설계하고 결과를 해석하는 데 이론의 사용에 영향을 미친다.

Data science and ML are increasingly used within the field of HPE and this likely will revolutionize instruction, learning, and assessment in the future (Rowe 2019; Wartman and Combs 2018). In the studies reviewed, we primarily found a focus on using data science and ML to solve practical problems, rather than generating or testing theories. Assessing procedural skills and teaching clinical scenarios with finite attributes are some examples of well-defined problems that can be addressed using data science and ML techniques. With these types of successful applications in mind, criticisms in HPE argue that the use of data science and ML in a technicist and instrumentalist way may disrupt effective instruction, learning, and assessment unless content experts are included in development and execution activities (van der Niet and Bleakley 2020). While data science offers new possibilities, especially in the area of ML, it also bears some inherent challenges in HPE. For example, HPE is a field that is heavily informed by the social sciences, whereas data science and ML are rooted in basic science traditions. These distinct thought patterns and philosophies of examining science have implications for not only the underlying epistemic beliefs guiding data science and ML studies within HPE, but also the use of theory in designing studies and interpreting results.

HPE 연구는 종종 [학습]이란, [학습이 이루어지는 학습 또는 의료 기관의 사회적 상호작용 및 맥락과는 동떨어진], [배타적인 인지 과정]이 아니라는 것을 인정한다. 학습과 평가를 이유나 작동 방식을 고려하지 않고 작동하는 무언가에 대한 간단한 시연으로 줄이는 것은 기술적 해결책으로 이어질 수 있지만, 의미 있는 방법으로 지식을 발전시키지 못할 수 있다. 그럼에도 불구하고, HPE의 많은 데이터 과학과 ML 연구는 '데이터가 스스로 말할 수 있도록' 하는 그들의 요구에서 이러한 유형의 [이론적 불가지론theoretical agnosticism]을 보여주는 것으로 보였다. 이 접근법에는 [두 가지 문제]가 있다.

- 첫째, [모델]에는 인간이 해야 할 선택과 판단이 항상 존재하기 때문에, 결코 가치가 없거나 인식론적 믿음에서 자유롭지 않다.

- 둘째, [기존의 어떤 신념과 이론적 렌즈]에 전혀 영향을 받지 않으면서, 자료에서 절대적인 진실이나 지식이 나타날 것이라는 견해는 오류이다.

HPE research often acknowledges that learning is not exclusively a cognitive process, separate from the social interactions and context of learning or healthcare organizations where learning takes place (e.g., Berkhout et al. 2018). Reducing learning and assessments to simple demonstrations of something working, without consideration of why or how it works, can lead to technical solutions, but may not advance knowledge in meaningful ways. Nonetheless, a number of data science and ML studies in HPE appeared to exhibit this type of theoretical agnosticism in their calls for letting ‘data speak for themselves’. There are two problems with this approach.

- First, models are never value-free or free from epistemic beliefs as there are always choices and judgments that need to be made by humans (Spadafore and Monrad 2019; Kitchin 2014; Diekmann and Peterson 2013; Norman 2011).

- Second, the view that an absolute truth or knowledge will emerge from data without being influenced by any pre-existing beliefs and theoretical lenses is a fallacy.

명백히, 데이터를 해석하는 렌즈는 언제나 있다(Bordage 2009). 문제는 렌즈가 어느 정도까지 식별되고 인식되는가 하는 것이다. 개념적 프레임워크의 사용은 HPE의 연구에 대한 두 가지 관점을 체계화한 Albert et al(2007)에 의해 강조된 연구 범위에 따라 달라지는 것으로 보인다. 동료 과학자를 위한 [지식과 이론을 생성하려는 의도]인지, 아니면 [교육의 실질적인 문제를 해결하려는 의도]인지에 따라 생산자를 위한 생산(PP)과 사용자를 위한 생산(PU)이 달라진다. 이전의 사고방식은 사회과학자들이, 후자는 임상의들이 지배하고 있는 것으로 생각된다. 현재 데이터 과학 문헌은 본 검토에서 설명한 바와 같이 PU 관점(또는 "순수 적용 연구")을 지향하는 것으로 보인다.

Certainly, there is always a lens, through which data are interpreted (Bordage 2009); the question is to what extent is the lens identified and acknowledged. The use of conceptual frameworks seems to depend on the scope of studies as highlighted by Albert et al. (2007), who framed two perspectives on research in HPE: Production for Producers (PP) and Production for Users (PU) as depending on whether the authors intended to generate knowledge and theory for fellow scientists or to solve practical problems in education. The former way of thinking is thought to be dominated by social scientists and the latter by clinicians (Albert et al. 2007). The current data science literature seems oriented towards the PU perspective (or “Pure Applied Research”) as illustrated in this review.

[무이론적이면서, 응용에 초점을 둔 작업]을 과도하게 강조하는 것의 한 가지 특별한 문제는 '블랙박스' 문제이다. ML 알고리듬은 알고리듬이 문제를 어떻게 해결했는지에 대한 정보를 제공하지 않고, 크고 지저분한 데이터 세트의 새로운 솔루션과 정밀한 분류를 제공한다(Topol 2019). 이에 대한 이유 중 일부는 일반적으로 사용되는 많은 ML 기법을 지원하는 통계 모델을 구성하는 노드 계층의 복잡성 때문이다. 모델이 [특정 결론에 도달한 이유 또는 방법을 설명할 수 없는 것]은 데이터 과학과 ML 접근법의 결과를 해석하기 위해 [이론을 사용하려는 노력]을 더욱 복잡하게 만든다. 이 문제를 기술적 차원에서 다루기 위한 노력이 이루어지고 있지만, 개념적, 이론적 차원에서 ML 모델에서 통찰력을 얻는 방법을 배우기 위해서는 여전히 해야 할 일이 많다.

One particular problem of a potential overemphasis on atheoretical, applied work is the ‘black box’ issue: ML algorithms provide novel solutions and precise classifications of large and messy data sets without providing any information about how the algorithm solved the problem (Topol 2019). Part of the reason for this is due to the complexity of the layers of nodes that make up the statistical model supporting many ML techniques commonly used. The inability to explain why or how a model arrived at a certain conclusion further complicates any efforts to use theory to interpret the results of data science and ML approaches. Efforts are being made to handle this problem on a technical level, but there is still much work to do to learn how to gain insights from ML models on a conceptual and theoretical level.

ML 결과를 학습자를 위한 실행 가능한 통찰력으로 변환하는 데 도움이 될 수 있는 기술적 솔루션의 유망한 예는 의료 이미지에서 '히트맵'을 사용하는 것이다. 히트 맵은 의료 이미지 분류에서 신경망에 특히 중요한 픽셀을 강조하기 위해 사용될 수 있으며, 이는 이미지가 원래대로 분류된 이유에 대한 통찰력을 제공할 수 있다. 피드백과 학습 목적에 유용한 것 외에도, 이러한 방법과 기술은 HPE 연구에 영향을 미칠 수 있으며, 과학자들은 방법이 효과가 있다는 것을 증명하는 것 보다 지시, 학습 및 평가를 위해 작동하는 이유를 설명하는 데 주로 관심이 있다. 이와 관련하여 통계 또는 계산 전문지식을 갖춘 HPE 학자들은 HPE 연구에서 데이터 과학과 ML의 미래 사용자들에게 맥락과 설명을 제공함으로써 번역자 역할을 할 수 있는 독특한 위치에 있다.

A promising example of technical solutions that can help translate ML findings to actionable insights for learners is the use of ‘heat maps’ in medical images (Miller and Brown 2019). Heat maps can be used to highlight the pixels that are particularly important for a neural network in the classification of medical images, which can provide insights into why images were classified as they were. Besides being useful for feedback and learning purposes, these methods and techniques may impact HPE research, where scientists are primarily concerned with explaining why methods work for instruction, learning, and/or assessment rather than merely demonstrating that they work. In this regard, HPE scholars with statistical or computational expertise are in unique positions to act as translators by providing context and explanation for future users of data science and ML in HPE research (Miller et al. 2017).

HPE에서 데이터 과학과 ML의 사용이 증가함에 따라, 더 많은 학제적 협력([데이터 과학자, 정량적 연구자 및 교육 과학자]들 사이)이 HPE에서 이론의 지속적인 발전을 보장하기 위해 필요할 수 있다. NLP의 유용성을 입증하는 연구는 학제간 접근법이 교육 이론, 질적 연구 방법, ML, 통계 및 데이터 분석을 결합하여 분야를 발전시키는 방법에 대한 몇 가지 예를 제공한다. 그러나 교육 과학자와 데이터 과학자의 긴밀한 파트너십은 (다른 전통, 가치, 그리고 다른 것들 사이에서 연구를 할 수 있는 동기 부여로 인해) 어려울 수 있다는 점에 유의해야 한다. 그럼에도 불구하고 향후 HPE에서의 데이터 과학 연구가 이론과 실제의 발전에 모두 관련될 수 있다면 협업이 중요할 것이다.

With an increased use of data science and ML in HPE, a more interdisciplinary collaboration among data scientists, quantitative researchers, and education scientists may be necessary to broaden the potential applications and ensure the continued advancement of theory in HPE. Studies demonstrating the utility of NLP (Burstein et al. 2014; Gierl et al. 2014; Baker 2010) offer some examples of how interdisciplinary approaches can bring together educational theory, qualitative research methods, ML, statistics, and data analytics to advance the field. However, it is important to note that close partnerships between education scientists and data scientists may be difficult due to different traditions, values, and incentives to do research among other things. Nonetheless, collaboration will be crucial if data science research in HPE in the future is going to be relevant to the advancement of both theory and practice.

이와 관련하여, 우리는 HPE 연구의 다른 영역에서 개발된 성공적인 [기존 학제간 파트너십] 중 일부에 주의를 돌릴 수 있다. 협력 관계의 유일한 유형은 아니지만, 데이터 엔지니어, 사회 과학자 및 임상 연구자가 함께 작업하여 실제 문제를 해결하고 이론에 기반을 둔 사용자 영감을 받은 연구를 생성하는 [학술-산업 협력]에서 한 가지 형태의 협업을 찾을 수 있습니다. [산업계]가 [재정 및 기술 자원]을 가지고 있을 수 있지만, [도메인 지식과 전문성]은 교육 과학자와 학자들이 가지고 있으며, 이는 파트너십과 협업을 개발하는 것이 향후 HPE 연구 내에서 데이터 과학과 ML을 성공적으로 통합하는 가장 중요한 예측 변수 중 하나가 될 수 있음을 의미한다.

In this regard, we may turn our attention to some of the successful existing interdisciplinary partnerships developed in other areas of HPE research. Although not the only type of partnership arrangement, one form of collaboration can be found within academic–industry partnerships, where data engineers, social scientists and clinician researchers, for example, work together to produce user-inspired research that solves a practical problem and is grounded in theory. Although industry may have the financial and technological resources, domain knowledge and expertise reside with education scientists and scholars, which means developing partnerships and collaborations may be one of the most important predictors of successfully integrating data science and ML within HPE research in the years to come.

이 저널의 25주년은 데이터 과학과 ML이 어떻게 HPE 분야에서 우리의 실천을 발전시키고 우리의 생각을 인도해 왔는지를 되돌아볼 수 있는 완벽한 시기인 것 같다. Norman과 Ellaway(2020)에 따르면, 건강 과학 교육의 진보는 여러 직업에 걸쳐 존재하는 시급한 교육 문제를 해결하고자 하는 열망에서 태어났다. 우리는 데이터가 가치 있는 상품인 HPE의 중추적인 지점에 있으며 우리 중 많은 사람들이 여전히 그것의 통화를 파악하고 있다. 혁신에 직면하여 과학적 탐구의 엄격함을 유지하기 위해, 데이터 과학 및 ML 접근 방식은 다른 접근 방식과 마찬가지로 존재론적 및 인식론적 가정의 맥락에서 검토될 필요가 있다. 우리가 다른 분야의 가치를 활용하고 보건 분야에서 이론과 실습을 계속 홍보하고 싶다면, 우리는 과학적 접근 방식을 확장하고 HPE 내에서 데이터 과학과 ML의 실용, 이론적, 인식론적 기여에 대한 담론을 계속해야 한다.

The 25th anniversary of this journal seems like a perfect time to reflect upon how data science and ML has evolved within the field of HPE to advance our practice and guide our thinking. According to Norman and Ellaway (2020), Advances in Health Sciences Education was born out of a desire to address pressing educational issues that exist across multiple professions. We are at a pivotal point in HPE where data is a valued commodity and many of us are still figuring out its currency. To retain rigor of scientific inquiry in the face of innovations, data science and ML approaches need to be reviewed in the context of their ontological and epistemological assumptions, just like any other approach. If we want to capitalize on the value of other disciplines, and continue to promote both theory and practice in the health professions, we need to expand our scientific approach and continue the discourse around the practical, theoretical, and epistemological contributions of data science and ML within HPE.

The role of data science and machine learning in Health Professions Education: practical applications, theoretical contributions, and epistemic beliefs

PMID: 33141345

Abstract

Data science is an inter-disciplinary field that uses computer-based algorithms and methods to gain insights from large and often complex datasets. Data science, which includes Artificial Intelligence techniques such as Machine Learning (ML), has been credited with the promise to transform Health Professions Education (HPE) by offering approaches to handle big (and often messy) data. To examine this promise, we conducted a critical review to explore: (1) published applications of data science and ML in HPE literature and (2) the potential role of data science and ML in shifting theoretical and epistemological perspectives in HPE research and practice. Existing data science studies in HPE are often not informed by theory, but rather oriented towards developing applications for specific problems, uses, and contexts. The most common areas currently being studied are procedural (e.g., computer-based tutoring or adaptive systems and assessment of technical skills). We found that epistemic beliefs informing the use of data science and ML in HPE poses a challenge for existing views on what constitutes objective knowledge and the role of human subjectivity for instruction and assessment. As a result, criticisms have emerged that the integration of data science in the field of HPE is in danger of becoming technically driven and narrowly focused in its approach to teaching, learning and assessment. Our findings suggest that researchers tend to formalize around the epistemological stance driven largely by traditions of a research paradigm. Future data science studies in HPE need to involve both education scientists and data scientists to ensure mutual advancements in the development of educational theory and practical applications. This may be one of the most important tasks in the integration of data science and ML in HPE research in the years to come.

Keywords: Artificial intelligence; Machine learning; Medical education research; Research in Health Professions Education; data science.

'Articles (Medical Education) > 의학교육연구(Research)' 카테고리의 다른 글

| 질적연구에서 성찰성(reflexivity)의 실용적 가이드: AMEE Guide No. 149 (Med Teach, 2022) (0) | 2022.09.14 |

|---|---|

| 의학교육의 출판과 지식생성에서 새는 파이프라인(Perspect Med Educ, 2022) (0) | 2022.08.28 |

| 심리학에서 이론의 위기: 어떻게 나아갈 것인가(Perspect Psychol Sci, 2021) (0) | 2022.08.26 |

| 이론, 잃어버린 인물? GP교육 연구논문에서 제시되는 방식에 따라 (Med Educ, 2019) (0) | 2022.08.26 |

| 불만족한 포화: 질적연구에서 포화된 샘플 크기에 대한 비판적 탐색(Qualitative Research, 2012) (0) | 2022.08.23 |