의학교육에서 기초의학 교수자의 전문직정체성형성 해체하기(Adv Health Sci Educ Theory Pract. 2022)

Deconstructing the professional identity formation of basic science teachers in medical education

Diantha Soemantri1,2 · Ardi Findyartini1,2 · Nadia Greviana1,2 · Rita Mustika1,2 · Estivana Felaza1,2 · Mardiastuti Wahid1,2 · Yvonne Steinert3

서론

Introduction

의과대학 교육과정 초기에 기초과학과 임상의학을 통합하는 것은 학습의 관련성과 유지성을 높이기 위한 의학교육의 핵심전략으로 여겨져 왔다. 이러한 통합은 또한 임상 실습에서 질병과 추론 과정에 대한 학생들의 이해를 촉진하는 데 중요하다. 그러나 기초과학 교사(BST)는 의학 교육에서 중요한 역할을 하지만, 많은 도전에 직면해 있다. 예를 들어, 일부 저자들이 언급했듯이, 임상과학의 급속한 발전을 고려할 때 기초과학 교수의 존재는 위협을 받고 더욱 축소될 가능성이 있다. 또한, 기본적인 의학 지식을 심층적으로 전달해야 하는 의무는 [암기]보다는 [지식 응용]에 초점을 맞추는 것과 마찬가지로, 교육을 더 [맥락적이고 실제와 관련성 있게 만들어야 하는 요구] 사항과 종종 충돌한다. 따라서 다음을 고려했을 때,

- [임상 실습에서 기초 과학의 기능에 대한 지속적인 논쟁],

- [교육 과정에서 기초 과학 교육을 위한 시간을 찾는 것]과 관련된 긴장감

- [의학 교육에서 교사의 진화하는 책임]

의료 교육에서 BST의 역할은 역동적으로 변화하고 있다.

Integrating basic science and clinical medicine early in the medical school curriculum has been considered a key strategy in medical education to increase the relevance and retention of learning (Brauer & Ferguson, 2015). This integration is also critical in facilitating students’ understanding of disease and reasoning processes in clinical practice (Bruin et al., 2005). However, although basic science teachers (BSTs) play a critical role in medical education, they face a number of challenges. For example, as some authors have stated, the existence of basic science teaching is likely to be threatened and further downsized given the rapid advancement of clinical sciences (Badyal & Singh, 2015). In addition, the obligation to impart basic medical knowledge in depth often clashes with the requirement to make teaching more contextual and relevant to practice, as does the tension between focusing on knowledge application rather than rote memorization (Grande, 2009). Thus, the role of BSTs in medical education has been changing dynamically given

- ongoing debates about the function of the basic sciences in clinical practice (Pangaro, 2010),

- the tensions related to finding time for basic science teaching in the curriculum (Finnerty et al., 2010), and

- the evolving responsibilities of teachers in medical education (Steinert, 2014; Harden & Lilley, 2018).

디킨슨 외 연구진(2020)이 그들을 부르는 [기초 과학 교사] 또는 의학 교육자들은 "주로 의료 전공 학생들에게 의과학을 가르치는 책임이 있는 교수진"이다. Dickinson 외 연구진(2020)은 교육과정 개발자, 평가자, 멘토, 연구자, 리더 및 관리자를 포함한 BST의 역할을 설명했으며, 이는 모두 정보 제공자의 역할을 넘어선다. BST는 또한 학생들의 [과학적 호기심을 길러주는 역할]을 하며, 위에서 언급한 바와 같이 학생들의 [추론 과정을 촉진]한다. 반면에, 수업에 대한 자신감의 부족, 특히 수업을 임상적 맥락과 연관시키는 것과 수업 개념의 부족은 일부 BST에 의해 [더 내용 지향적인 수업]으로 귀결되어, 기초 과학자들을 계속 괴롭히고 있다. 그러나, BST가 직면한 도전에도 불구하고, 그들의 역할에 대한 헌신은 BST가 자신을 어떻게 보고 표현하는지에 의해 영향을 받는다. 따라서 BST가 자신의 역할과 정체성을 어떻게 인식하는지 아는 것은 BST가 여러 책임을 수행할 수 있도록 지원하는 데 필수적이다.

Basic science teachers, or medical science educators as Dickinson et al. (2020) has called them, are “faculty members primarily responsible for teaching medical sciences to healthcare professions students” (p. 1). Dickinson et al. (2020) described the roles of BSTs, including that of curriculum developers, assessors, mentors, researchers, leaders, and managers, all of which go beyond the role of information providers. BSTs are also responsible for nurturing students’ scientific curiosity (Haramati, 2011), and as noted above, facilitating students’ reasoning processes. On the other hand, a lack of confidence in teaching, especially in relating teaching to the clinical context, and a conception of teaching, which has resulted in more content-oriented teaching by some BSTs (Laksov et al., 2008; McCrorie, 2000), continue to plague basic scientists. However, despite the challenges faced by BSTs, commitment to their roles is influenced by how BSTs view and present themselves (Dickinson et al., 2020; Haramati, 2011; McCrorie, 2000; van Lankveld et al., 2020). Therefore, knowing how BSTs perceive their roles and their own identities are essential in supporting BSTs to perform their multiple responsibilities.

정체성은 "외부 맥락 속에서 자아에 대한 이해와 자아에 대한 개념"으로 정의된다.

- [정체성 형성]은 [집단 차원의 사회화]뿐만 아니라 [개인 내에 존재하는 심리적 과정]을 포함한다.

- 따라서 [정체성]은 [개인이 경험을 얻음에 따라 많은 영향을 받고 변화하는 경향이 있는 동적 실체]이다.

- van Lankveld et al(2020)은 [교사 정체]성은 [자신에 대한 이해]일 뿐만 아니라, [교사와 주변 환경 간의 대화를 통해 끊임없이 형성되는 자신의 표현presentation]이라고 웅변적으로 결론 내렸다.

Identity has been defined as “an understanding of the self and a notion of that self within an outside context” (Beauchamp & Thomas, 2009, p. 178).

- Identity formation involves psychological processes that reside within the individual as well as socialization at the collective level (Jarvis-Sellinger et al., 2012).

- Identity, then, is a dynamic entity which is subject to many influences and tends to change as individuals gain experiences (Haamer & Reva, 2012; Wahid et al., 2021).

- van Lankveld et al. (2020) eloquently concluded that teacher identity is not only an understanding of oneself, but it is also a presentation of oneself which is constantly shaped through dialogue between the teacher and the surrounding environment.

의학 교사들, 특히 임상 교사들은 임상의, 학자들, 교사들로서 다른 역할들을 가지고 있으며, 연구들은 이러한 역할들이 종종 어떻게 충돌하는지 그리고 어떤 사람들에게는, 어떤 특정한 정체성이 다른 사람들보다 더 필수적이라는 것을 보여주었다. 기초과학과 임상교사의 전문적 정체성 형성(PIF)에 대한 이전 연구는 [교사 역할]이 그들의 [전문적 정체성]에 통합되는 것을 확인하고, [의사나 연구원과 같은 특정 역할 사이의 긴장감]을 탐구했다. 이 연구를 바탕으로 Wahid et al(2021)은 기초과학과 임상교사를 포함한 의학교사의 정체성을 살펴본 뒤, [사회화 요인]에 영향을 받고, [교사의 가치, 신념, 목표 탐색 및 미래 구상]에 의해 지원되는, [지속적이고 역동적인 정체성 형성 과정]을 보고했다.

Medical teachers, specifically clinical teachers, have different roles as clinicians, scholars and teachers, and studies have shown how these roles often conflict and how, for some, certain identities are more essential than others (van Lankveld et al., 2020). A previous study on the professional identity formation (PIF) of basic science and clinical teachers identified the integration of a teaching role into their professional identities and explored the tensions between certain roles such as medical doctors or researchers (Van Lankveld et al., 2017). Building on this work, Wahid et al. (2021) looked at the identity of medical teachers, including basic science and clinical teachers, and reported a continuous and dynamic process of identity formation, influenced by socialization factors and supported by exploration of the teachers’ values, beliefs, goals, and envisioning of the future.

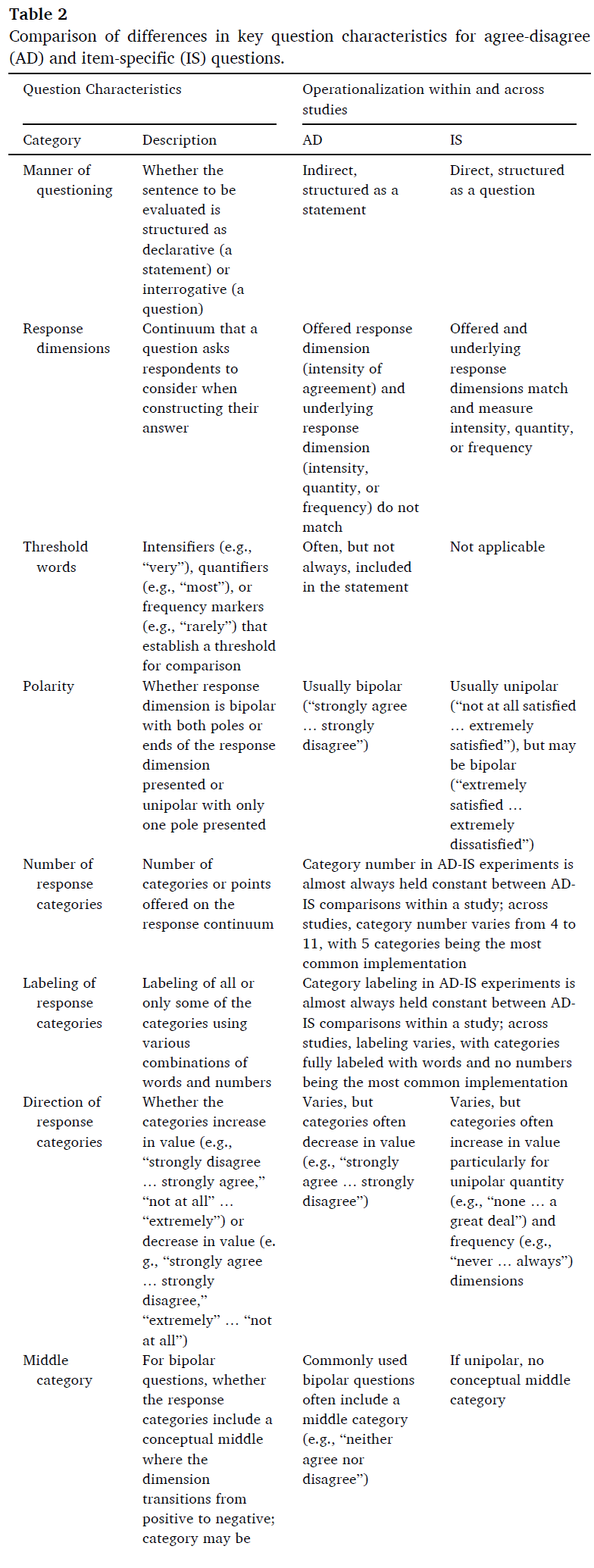

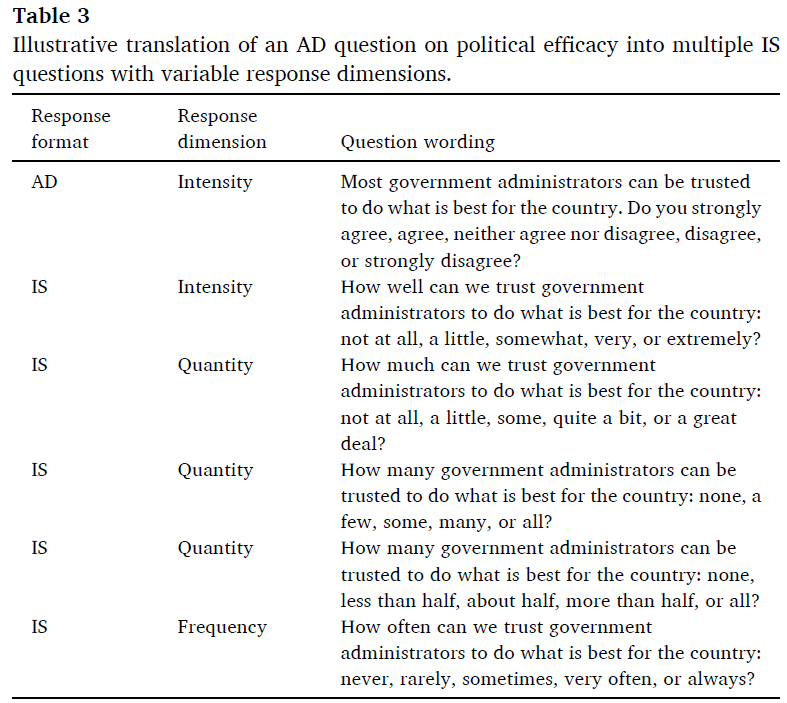

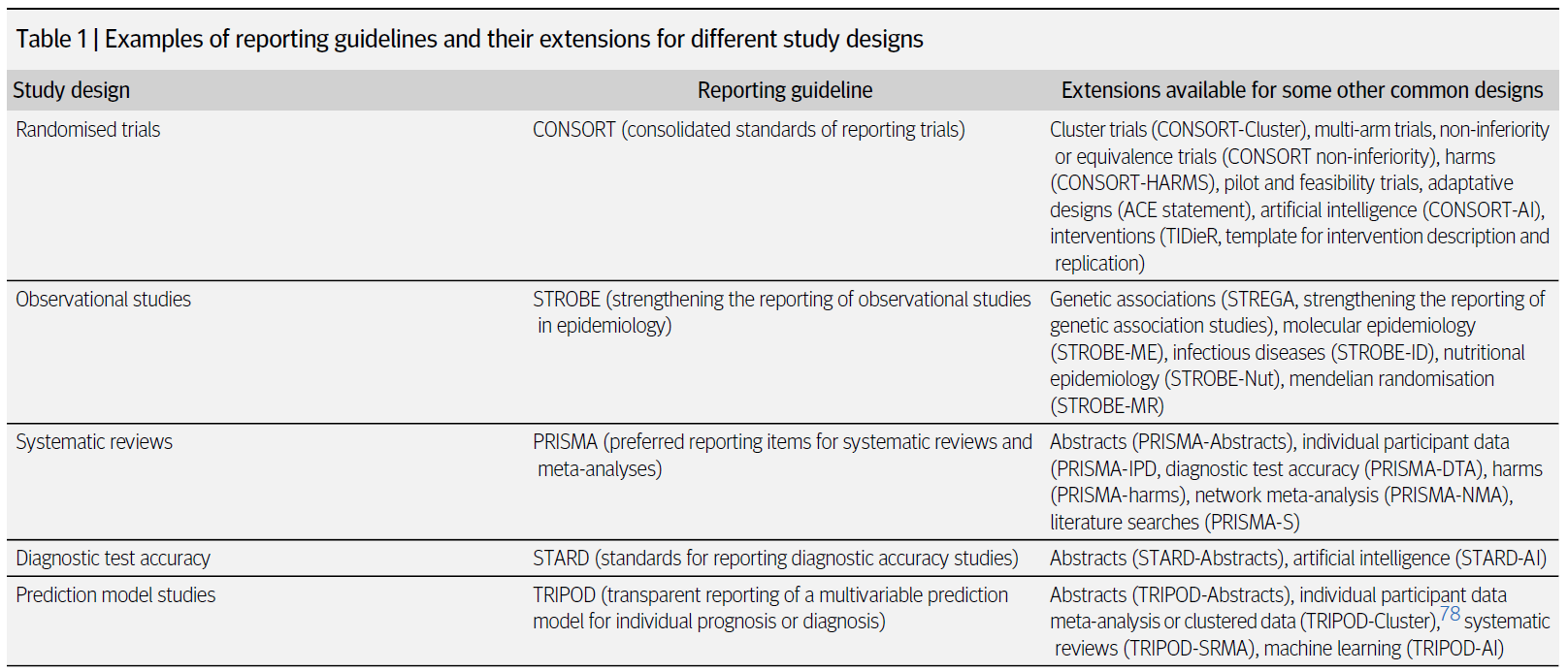

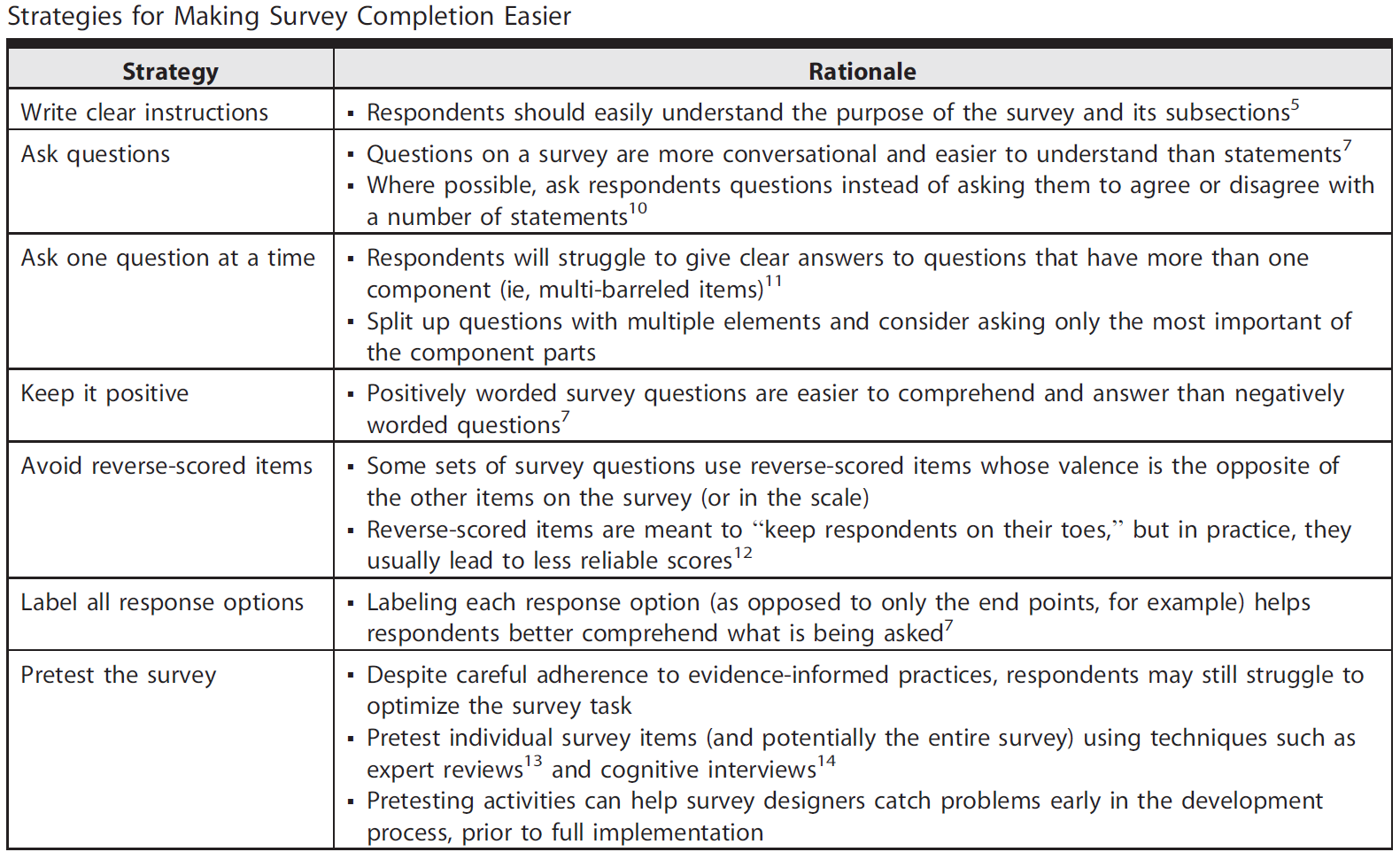

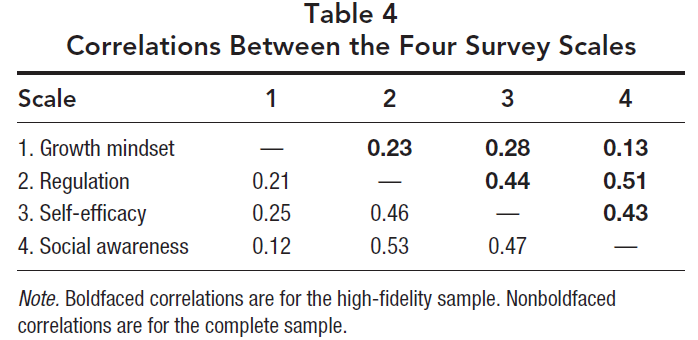

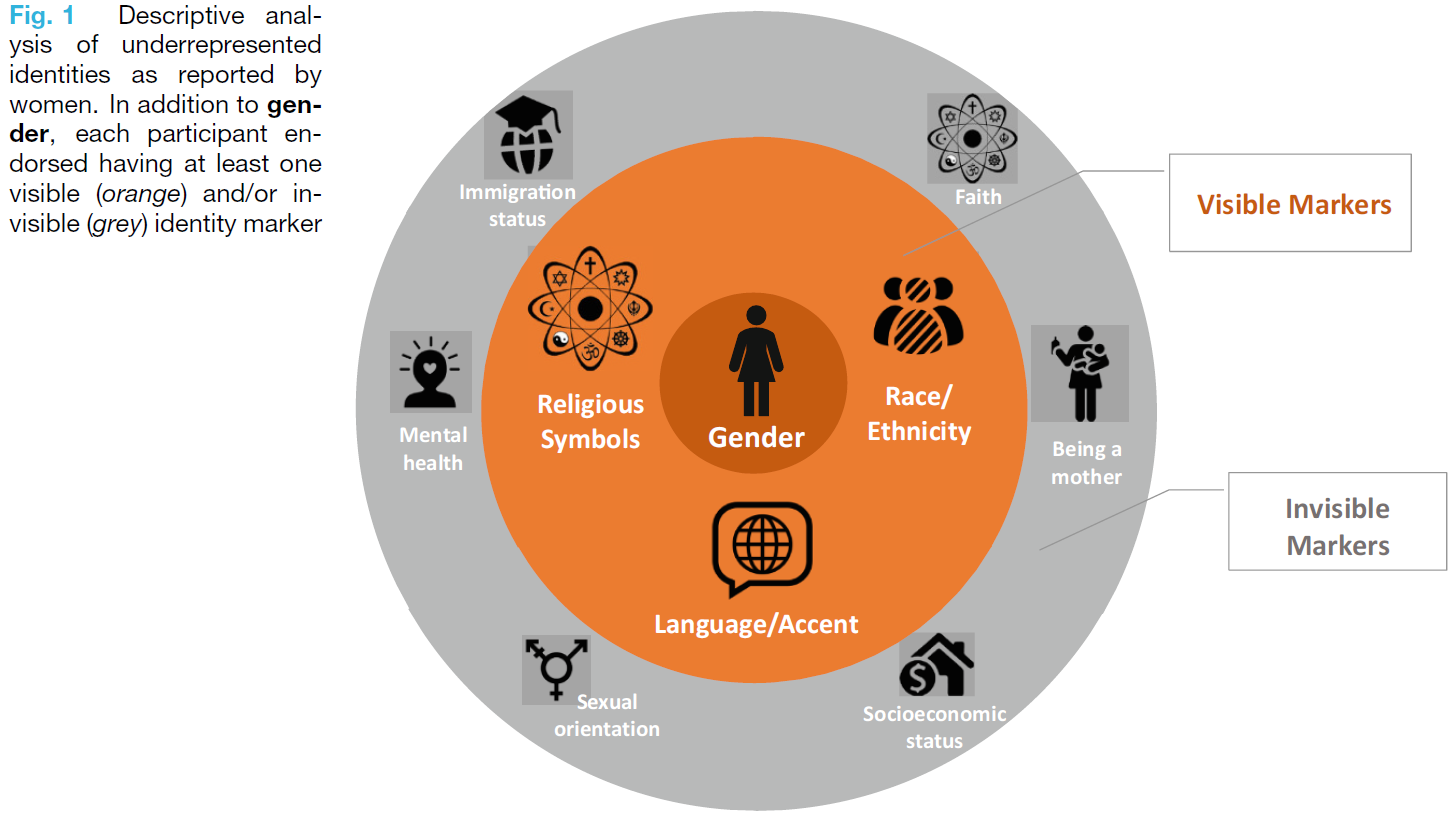

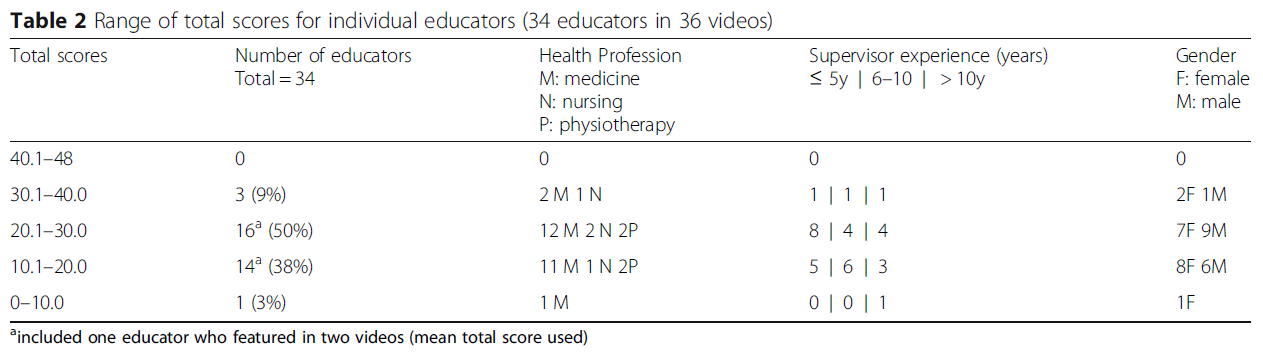

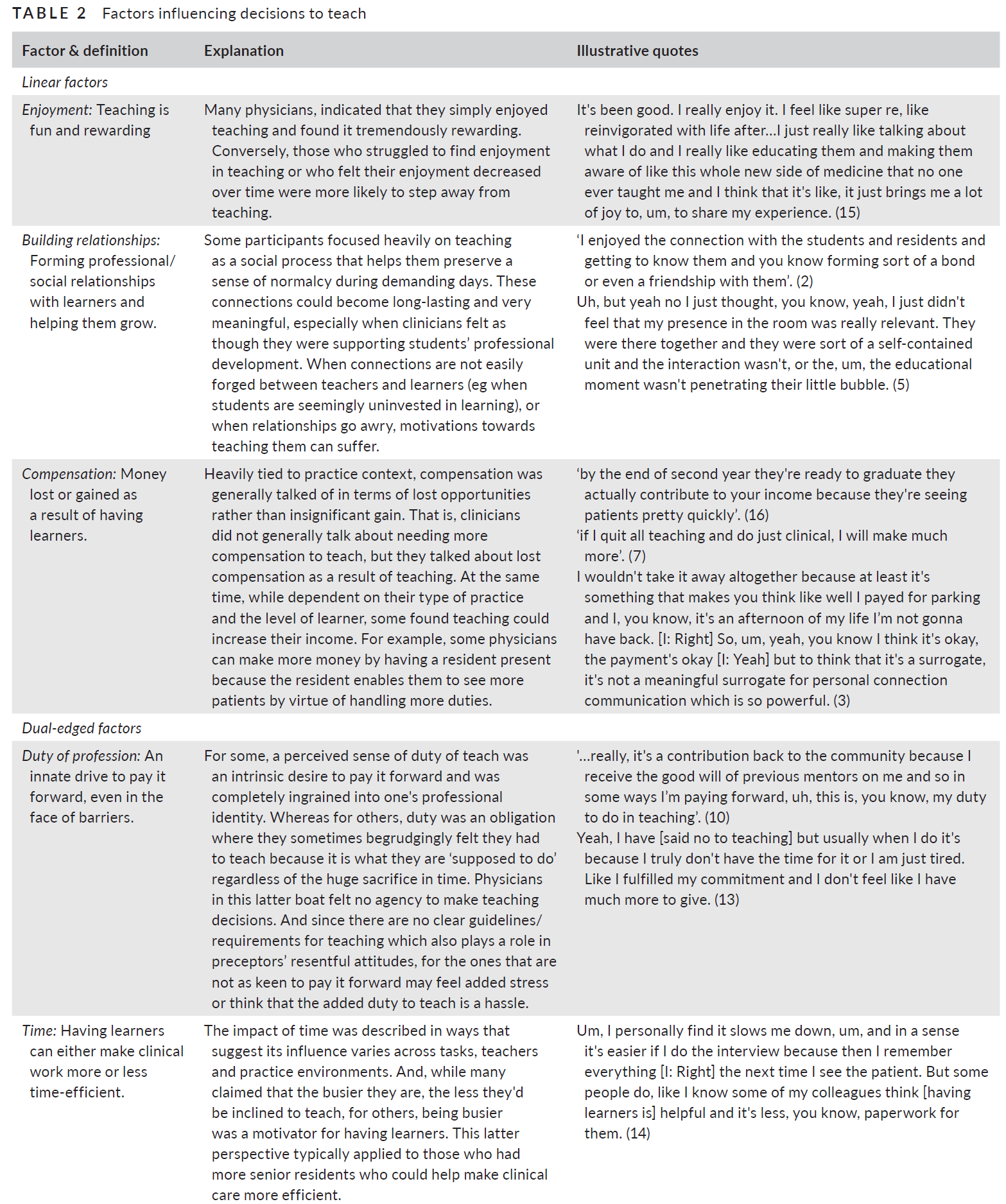

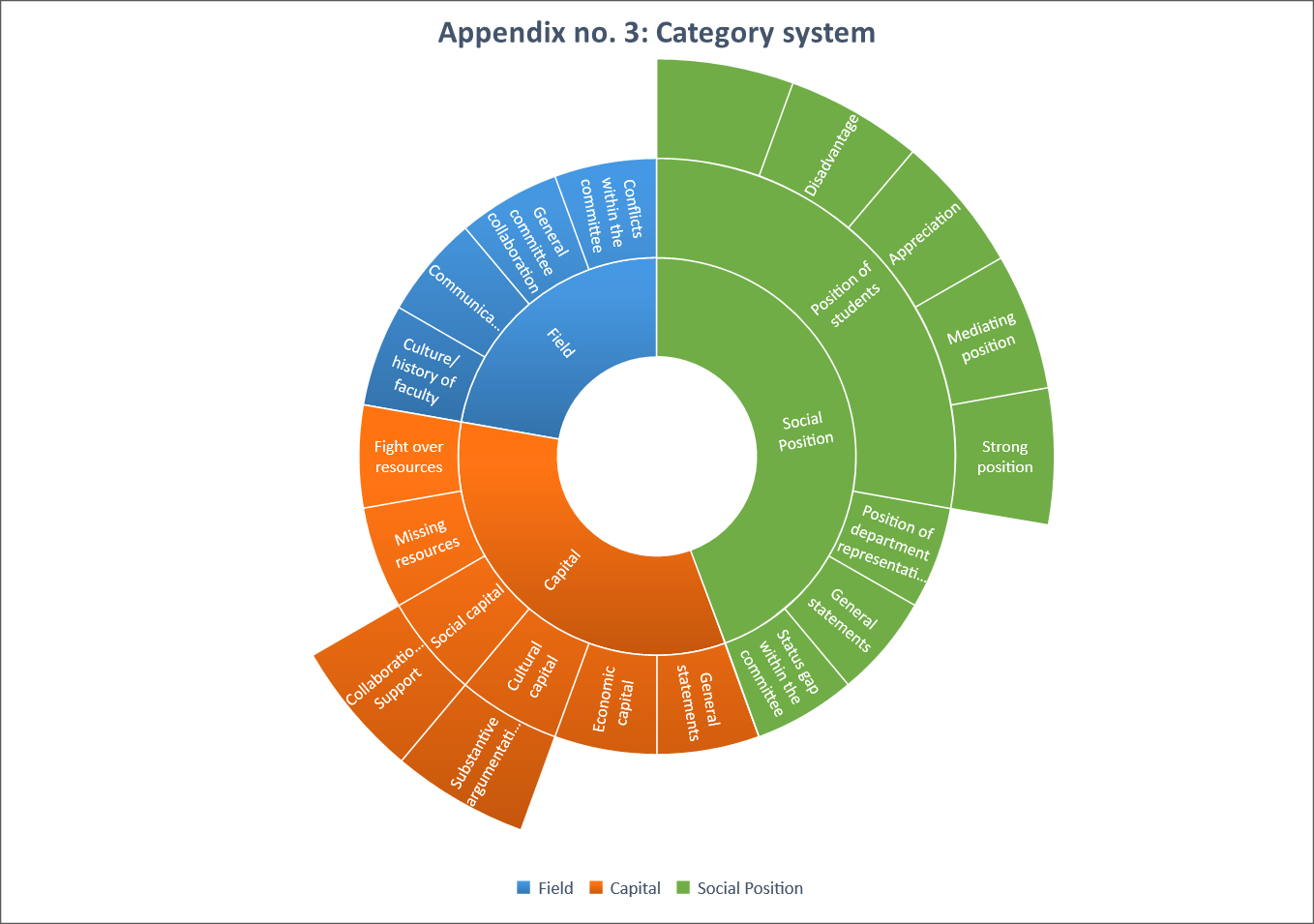

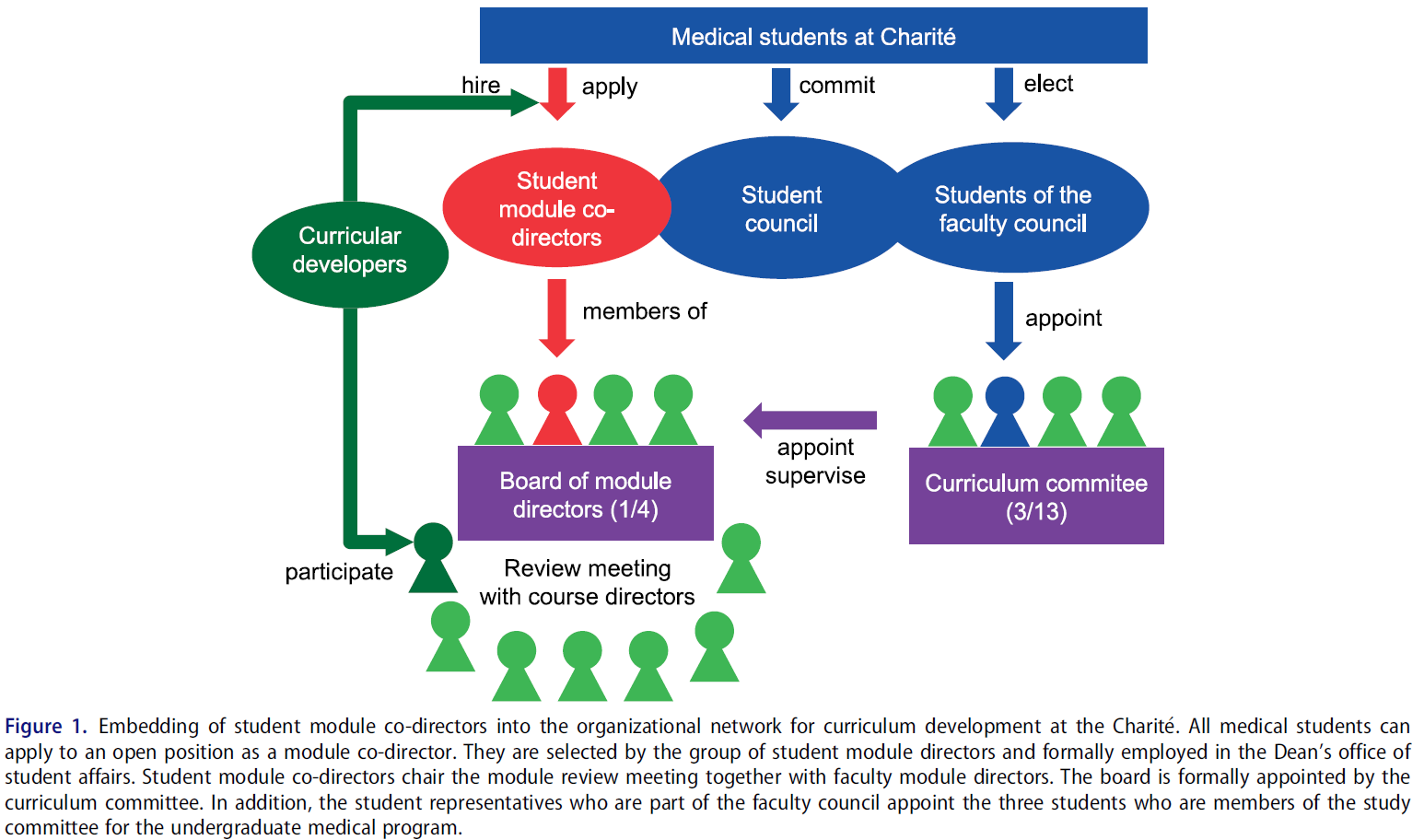

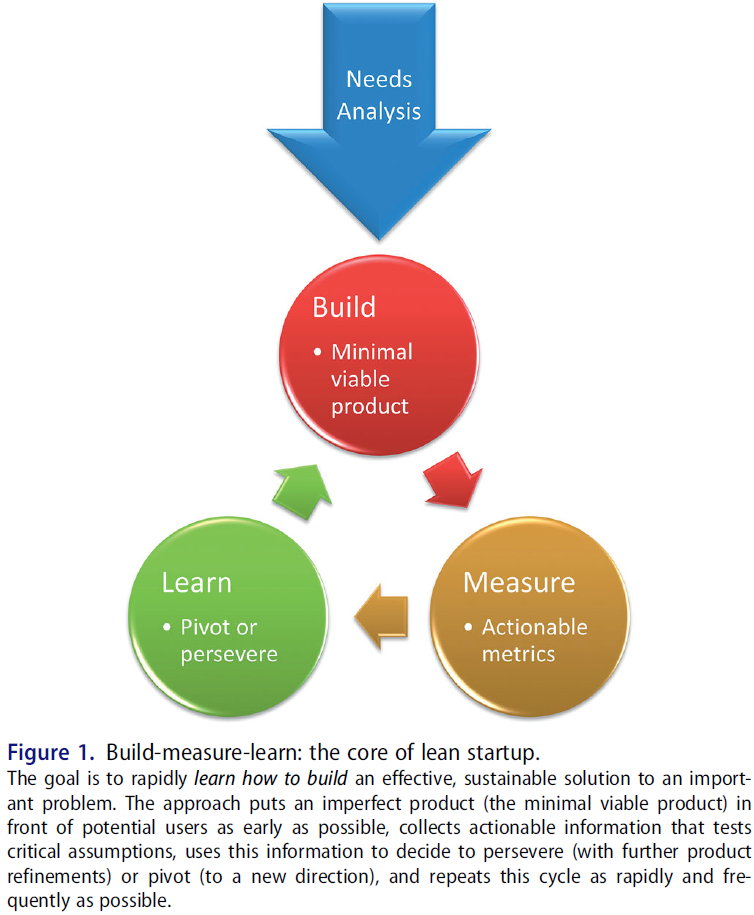

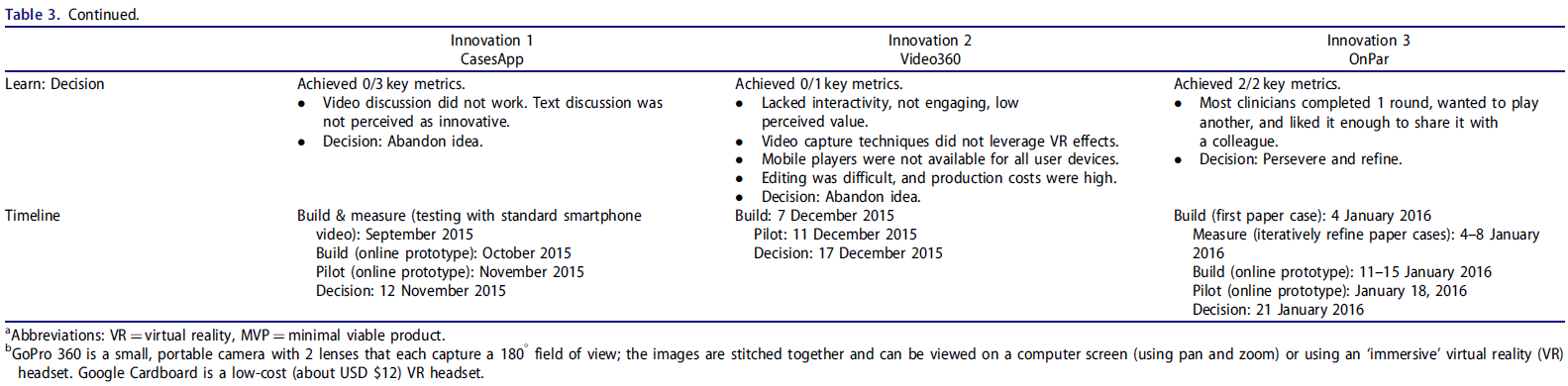

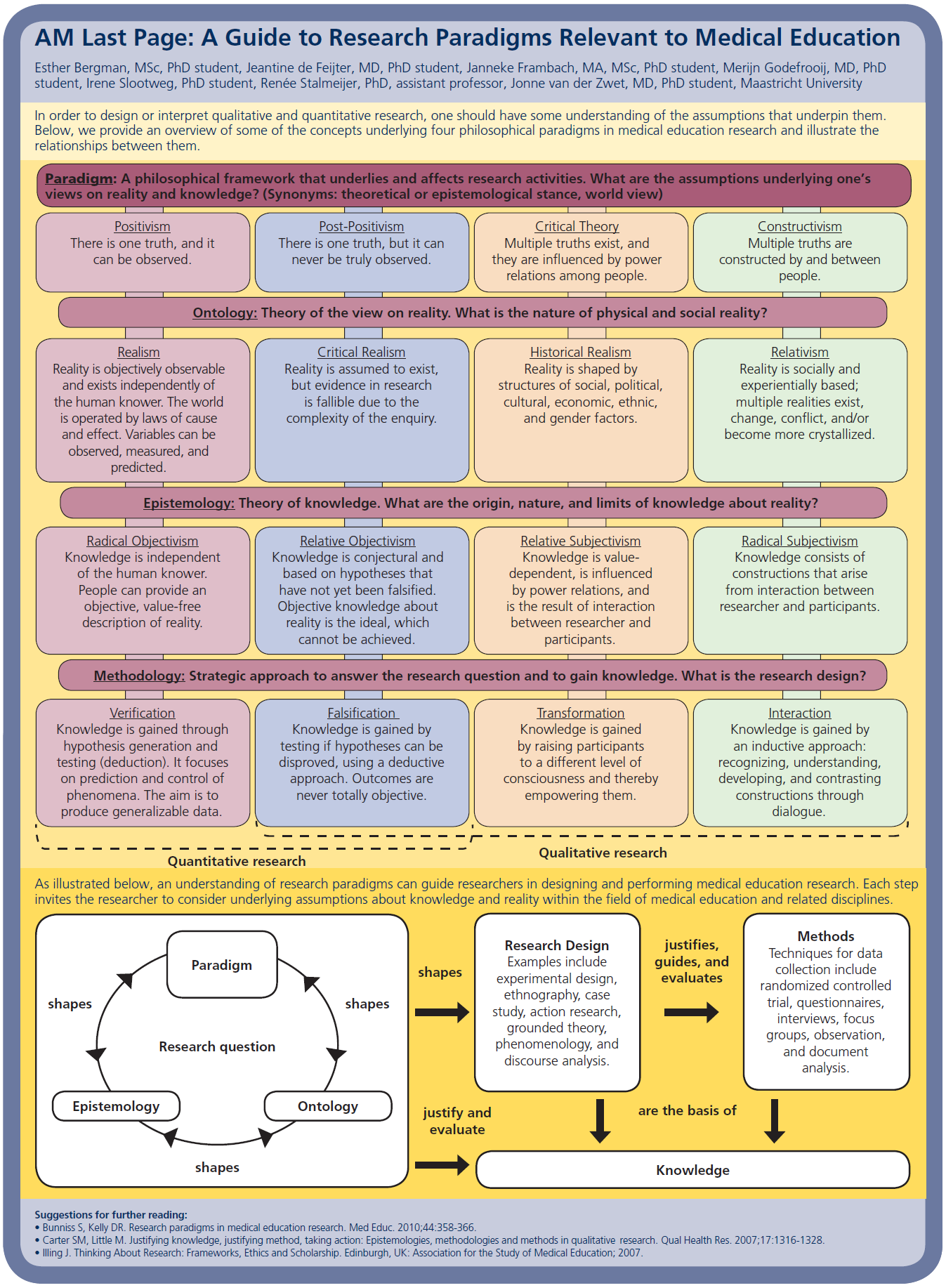

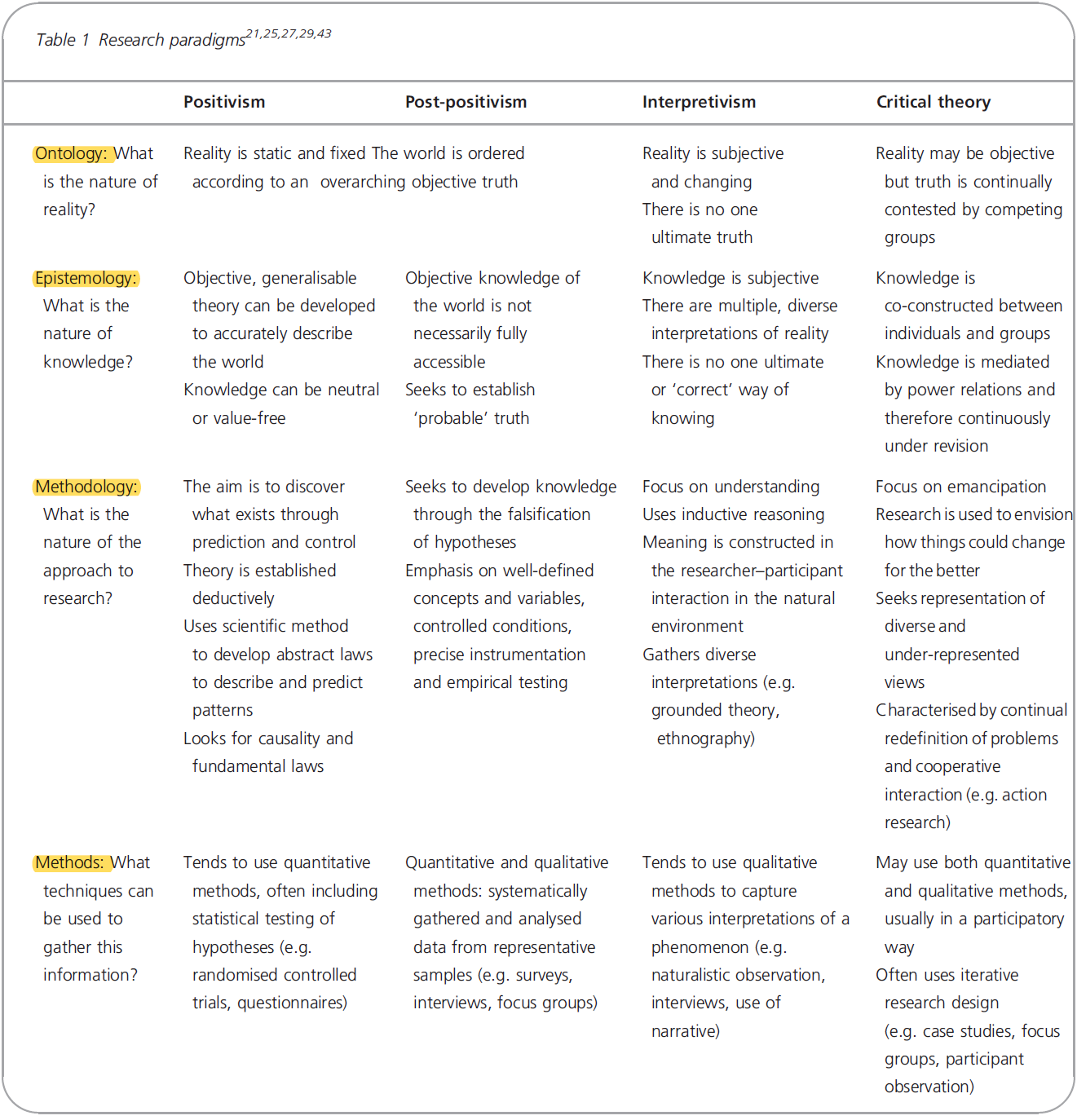

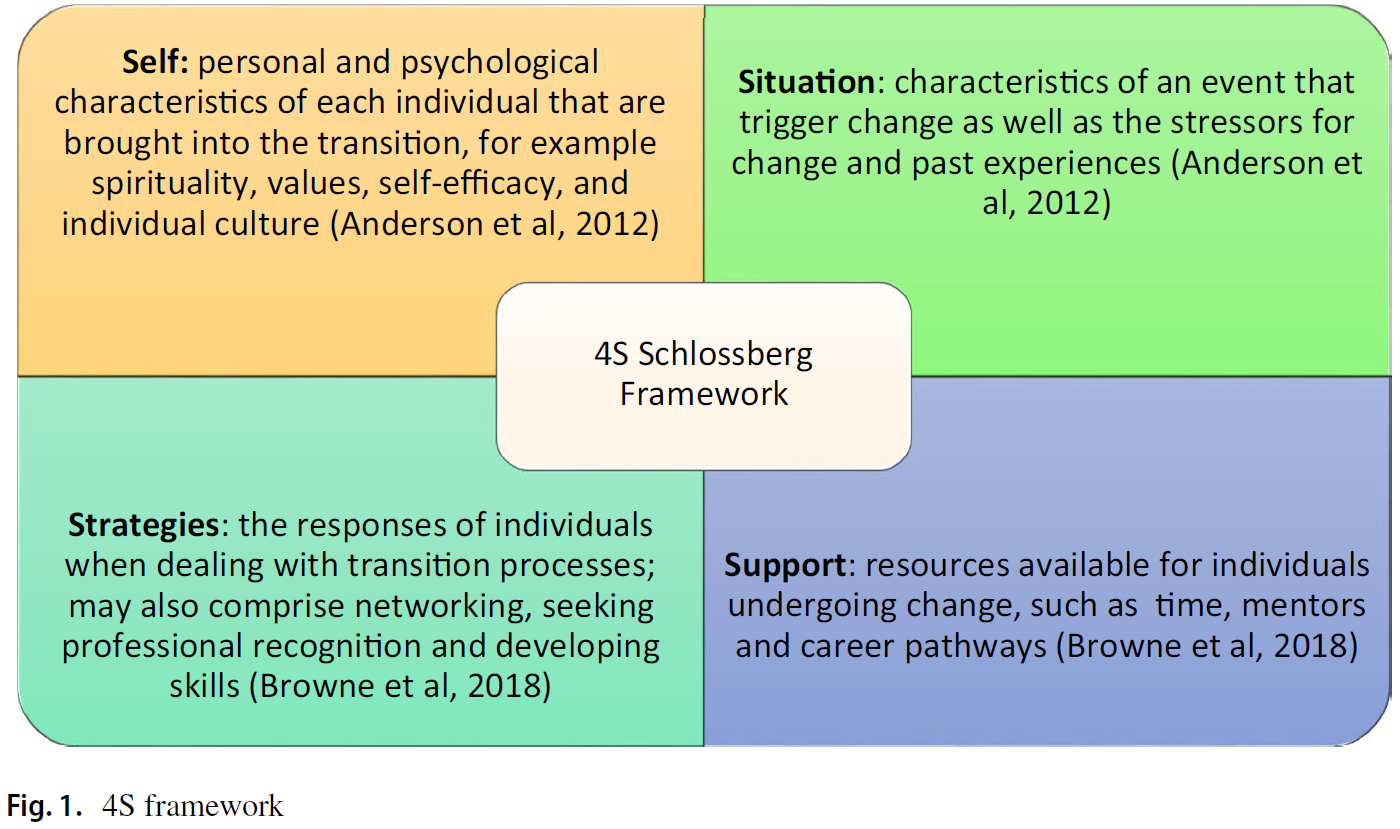

몇 가지 프레임워크는 PIF의 프로세스를 이해하는 데 도움이 될 수 있다. 사회화 이론에 기초한 하나의 프레임워크는 의사의 전문적 정체성 형성을 설명하고 사회화가 PIF에 미치는 영향을 강조하기 위해 사용되었다. Strong 외 연구진(2018)은 또한 [4S Schlossberg 프레임워크]가 교직원의 전문적인 발달을 조사하는 데 적합하다고 제안했다. 4S는 "상황, 자신, 지원 및 전략"을 나타냅니다(그림 1). [Schlossberg 프레임워크]는 [변화 과정에 대한 개인의 반응]을 설명하기 위해 [심리사회적 이행 이론]을 사용하고, 교사가 [의료 교육을 전문으로 하는 교육자로 전환하는 과정]과 관련이 있는 요소(즉, 개인적 가치, 네트워킹, 역할 모델, 멘토)를 탐구하기 위해 보건 전문 교육에 사용되어 왔다. . 이를 염두에 두고, 우리는 개인의 특성, 사회화 및 환경적 요인을 통합하고 자신과 타인 간의 대화의 결과로 끊임없이 진화하는 PIF의 지속적이고 동적인 과정을 고려할 때, 4S 슐로스버그 프레임워크가 BST의 PIF 과정을 설명하는 데 유용하다고 주장한다.

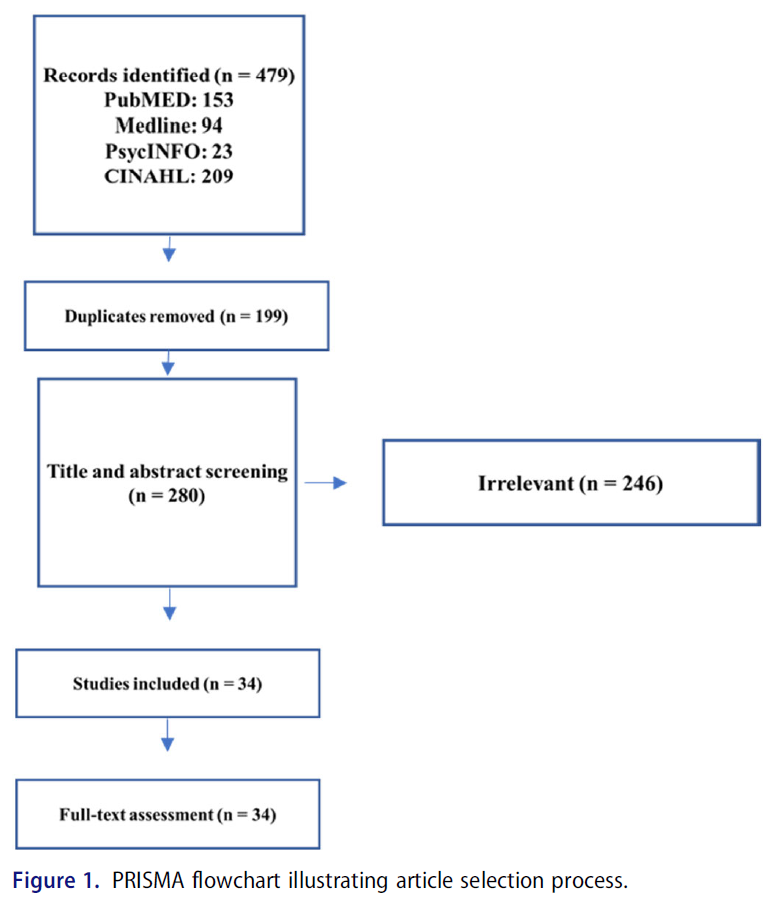

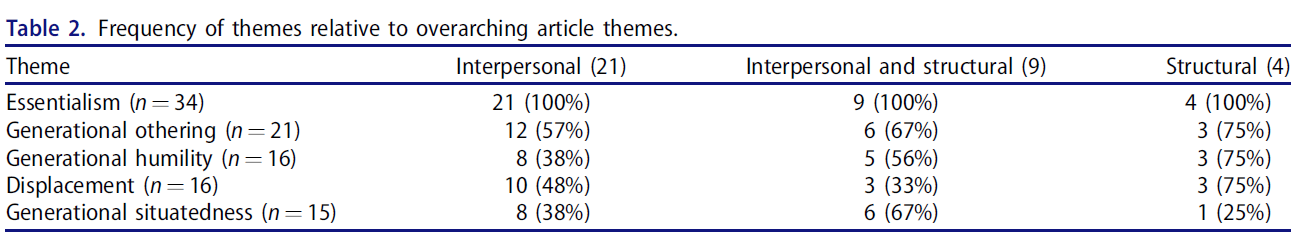

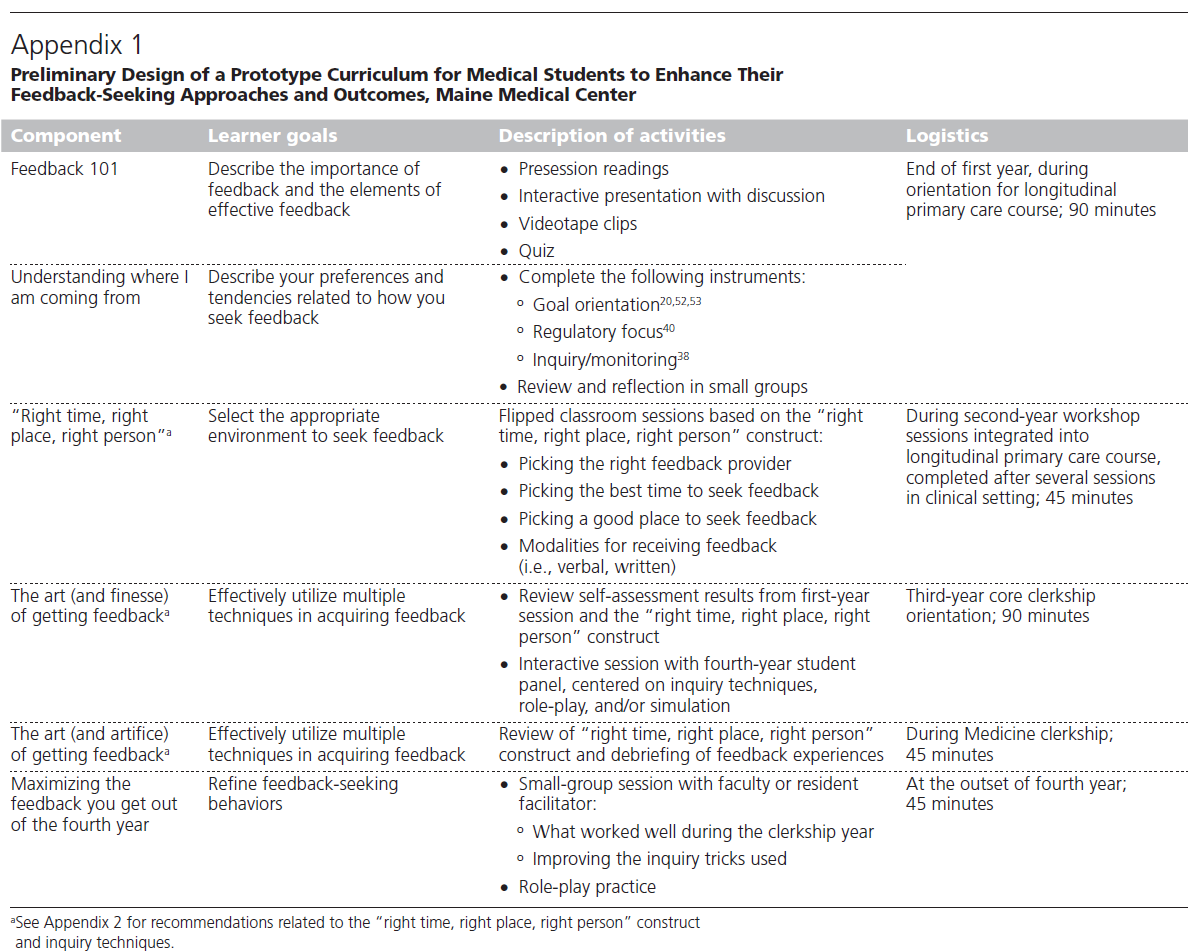

Several frameworks can help us to understand the process of PIF. One framework, based on socialization theory, has been used to explain the professional identity formation of doctors and highlights the impact of socialization on PIF (Cruess et al., 2014). Strong et al. (2018) also suggested that the 4S Schlossberg framework is suitable for examining the professional development of faculty members. The 4S stands for “situation, self, support and strategies” (Fig. 1). The Schlossberg framework utilizes psychosocial transition theory to explain individuals’ reactions to change processes (Anderson et al., 2012) and has been used in health professions education to explore the factors (i.e., personal values, networking, role models and mentors) related to the transition process of teachers into becoming educators who specialize in medical education (Browne et al., 2018). With this in mind, we argue that the 4S Schlossberg framework is useful to explain the PIF process of BSTs given the continuous and dynamic process of PIF which incorporates individual characteristics, socialization, and environmental factors (Cantillon et al., 2019; Steinert & MacDonald, 2015; van Lankveld et al., 2017) and constantly evolves as a result of dialogue between self and others (van Lankveld et al., 2020).

정체성은 교사의 직업적 삶에서 중요한 요소로 간주되고 의사결정에 영향을 미치지만, PIF는 BST보다 임상 교사를 위해 더 많이 탐구되었다. 의료 교육 과정에서 필요한 역할을 제정하고 여러 직무에 의미 있는 참여를 가능하게 하는 정체성의 중요성에도 불구하고, BST가 그들의 직업적 정체성 형성을 어떻게 인식하고 어떤 요소들이 그 명료성에 영향을 미치는지에 대해서는 거의 알려져 있지 않다. 따라서 와히드 외 연구진(2021)의 연구를 확장하여, PIF에 기여하는 요인을 탐색하는 데 도움이 될 수 있는 심리사회적 이행 이론에 기반한 또 다른 관련 프레임워크를 사용하여, [교사로서의 BST의 정체성]이 [어떻게 형성]되고, [어떤 요인이 PIF에 영향을 미치는지]에 대한 연구 질문을 해결하는 것을 목표로 했다.

Although identity is regarded as an important element in teachers’ professional lives and influences their decision-making (van Lankveld et al., 2020), PIF has been explored more for clinical teachers (e.g., Cantillon et al., 2019; Steinert & MacDonald, 2015) than for BSTs. Little is known about how BSTs perceive their professional identity formation and what factors influence its articulation, despite the importance of identity to enact their necessary roles in medical curricula and enable meaningful engagement in their multiple duties. Expanding on the work of Wahid et al. (2021), we therefore aimed to address the research questions of how the identity of BSTs as teachers is formed and what factors influence this PIF using another relevant framework based on psychosocial transition theory which can be helpful in exploring the factors which contribute to PIF.

방법들

Methods

맥락

Context

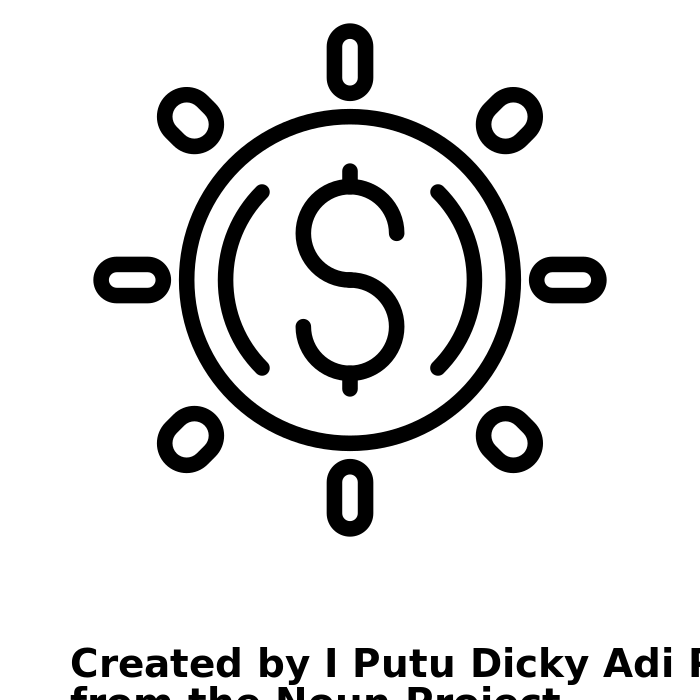

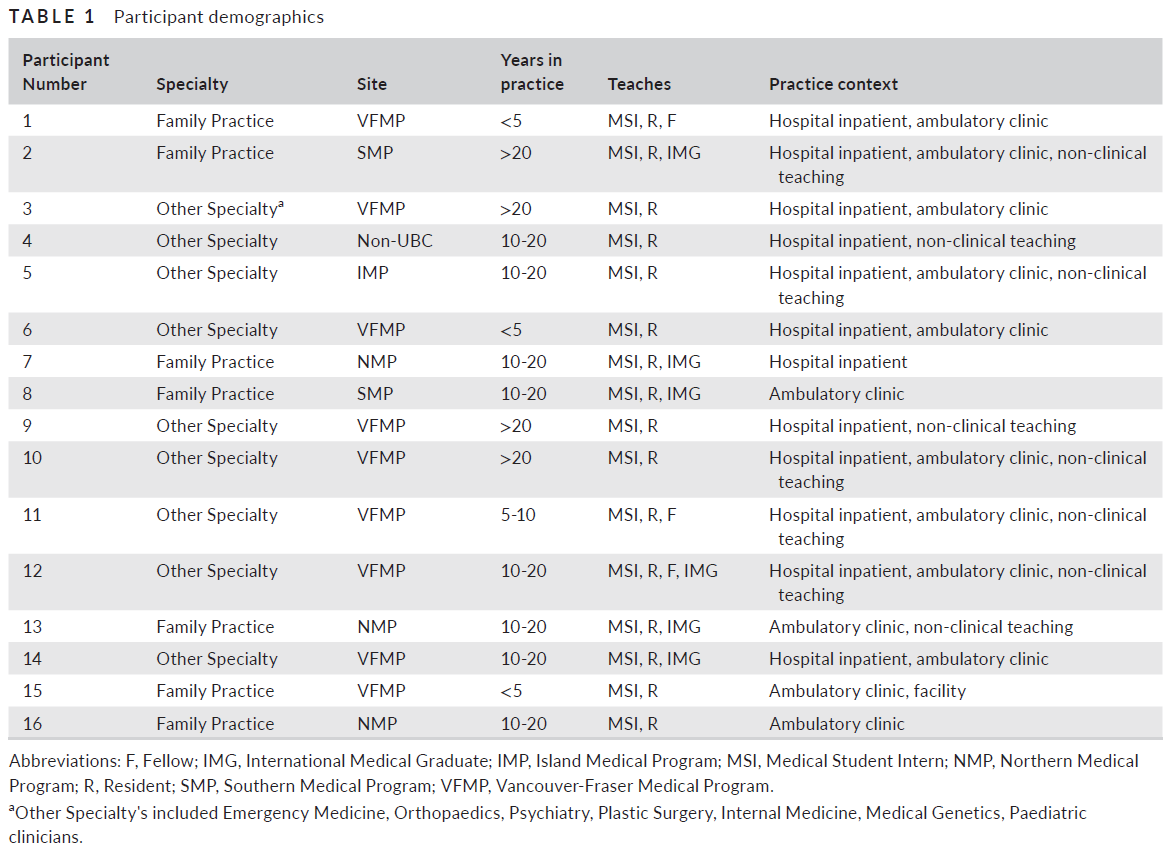

본 연구에는 인도네시아 의과대학 4곳, 공립학교 2곳, 사립학교 2곳의 기초과학 교사를 모집하였다. 인도네시아 의과대학의 대부분의 BST는 의학박사(Medical Doctor)와 생물의학 석사 학위를 가지고 있다. 일부 BST들은 여전히 일반 개업의로서 의학을 수행하고 있지만, 그들은 그들의 교수 역할 때문에 스스로를 BST라고 생각한다. 본 연구에서 BST의 특성은 임상 전 학부 의학 프로그램에서 강의한 연구 참가자 중 일부가 MD 학위를 보유한 반면, 일부는 보건 및 생명 과학 또는 사회 과학 대학원 학위를 보유한 Lankveld et al(2017) 연구와 상당히 유사했다. 본 연구에서 BST는 [주로 학부생 의학교육의 임상 전 단계에서 교육을 담당]한다. 교육 외에도, 우리의 맥락에서 BST는 그들의 전문 분야와 관련된 연구, 학술 작업 및 지역 사회 서비스를 수행해야 한다.

Basic science teachers in four Indonesian medical schools, two public schools and two private schools, were recruited to participate in this study. Most BSTs in Indonesian medical schools hold an MD (medical doctor) and a postgraduate degree in biomedical sciences. Some BSTs are still practicing medicine as general practitioners; however, they consider themselves BSTs because of their teaching roles. The characteristics of BSTs in this study were quite similar to those outlined in Lankveld et al.’s (2017) study in which some of the study participants who taught in the preclinical undergraduate medical programme held MD degrees, while some others held a postgraduate degree in health and life sciences or social sciences. The BSTs in this study are mainly responsible for teaching in the preclinical phase of undergraduate medical education. Aside from teaching, the BSTs in our context are required to conduct research, scholarly work and community service related to their areas of expertise.

설계 및 연구 참가자

Design and study participants

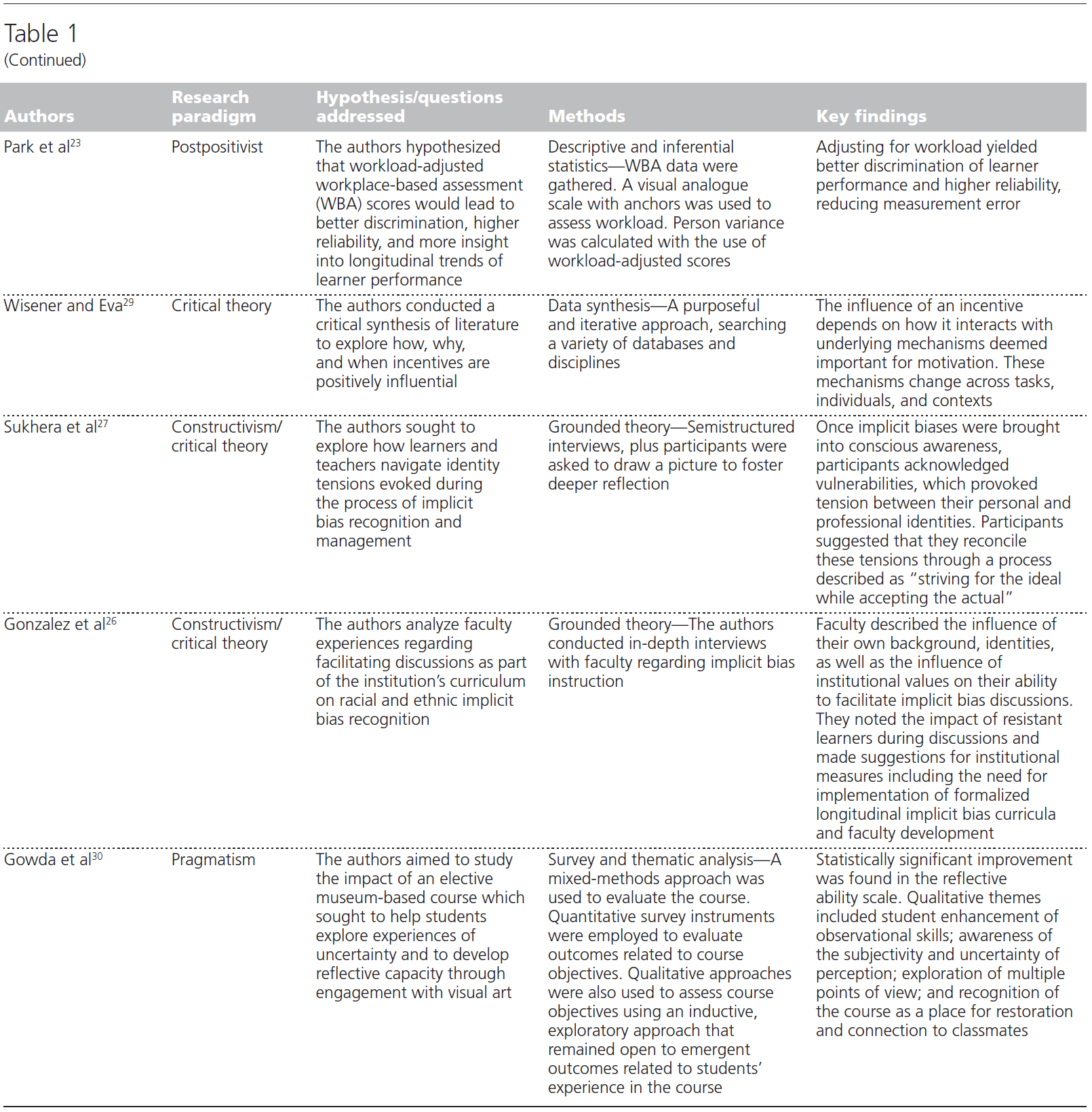

기초과학 교사의 전문적 정체성 형성을 탐색하기 위해 질적 서술이 사용되었다. 최대 변동 샘플링을 사용하여 기초과학과(예: 해부학, 생리학 및 약리학)의 표현, 교수 경험의 길이, 성별 및 대학원 학위(학력)를 기반으로 4개 학교에서 BST를 의도적으로 선택했다.

A qualitative descriptive (Sandelowski, 2000, 2010) was used to explore professional identity formation in basic science teachers. Maximum variation sampling was used to purposively select BSTs in the four schools, based on the representation of the basic science departments (e.g., anatomy, physiology and pharmacology), length of teaching experiences, gender and postgraduate degree (academic background).

데이터 수집

Data collection

참가자들의 동기부여, 경력개발, BST로서의 경험을 탐색하기 위해 부록에 제시된 것처럼 미리 정해진 질문을 이용하여 포커스 그룹 토론(FGD)을 각 의대에서 수행하였다. BST는 교육 경험(< 10년 또는 > 10년)에 따라 별도의 그룹으로 나뉘었다. 모든 참가자들은 FGD에 앞서 동의를 했다.

Focus groups discussions (FGDs), using predetermined questions (Wahid et al., 2021) as presented in the appendix, were conducted in each medical school aiming to explore participants’ motivations, career development, and experiences as BSTs. The BSTs were divided into separate groups based on the length of their teaching experiences (< 10 or > 10 years). All participants provided their consent prior to the FGDs.

데이터 분석

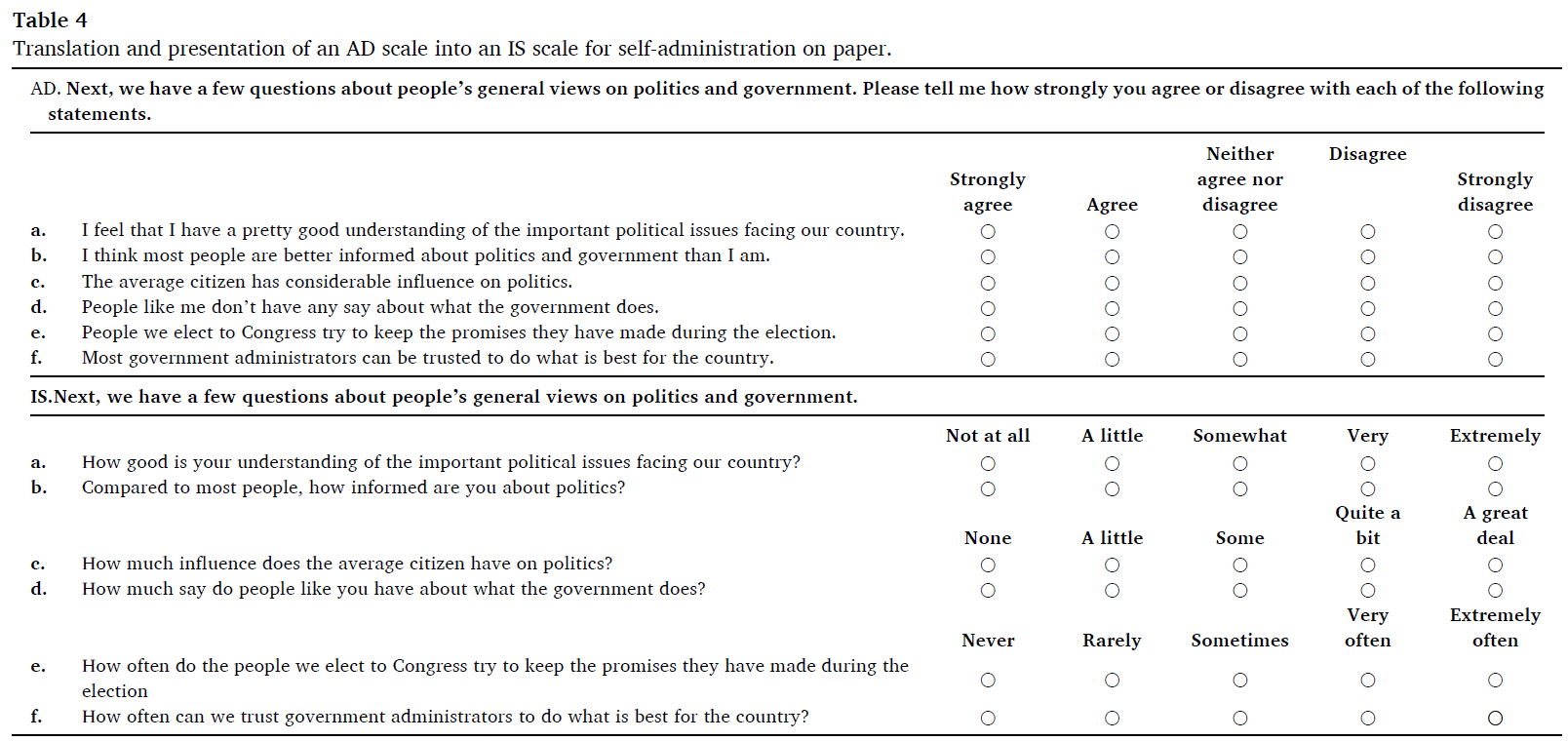

Data analysis

데이터 수집 및 분석의 반복적인 프로세스가 수행되었습니다. 포커스 그룹은 음성으로 녹음되고 말 그대로 전사되었다. 주제 분석을 위해, 우리는 먼저 텍스트에서 [주목할 만한 단어나 구를 식별]한 다음, 이러한 [단어/구문에서 관련 개념을 공식화]하는 SCAT(Steps for Coding and Theorization) 접근법(Otani, 2008)을 사용했다. 그런 다음 각 특정 개념을 기반으로 관련 하위 주제를 구성했다. 처음에는 네 명의 저자(MW, DS, RM, EF)가 핵심 주제와 하위 주제를 식별하고 논의하기 위해 [처음 두 개의 필사본에 대해 독립적인 주제 분석]을 수행했고, [이후 모든 저자가 다른 필사본을 분석]했다. 주제 분석에 이어 SCAT 접근법을 사용하여 얻은 각 하위 주제를 4S 프레임워크에 매핑하였다. 저자 DS와 NG는 각각의 하위 주제를 4S 구성요소("상황, 자체, 지원 및 전략")로 독립적으로 분류했고, 모든 불일치는 토론을 통해 해결되었다. 모든 저자들이 결과를 미세 조정하는 데 참여했다. 신뢰도를 높이기 위해 6명의 포커스 그룹 참가자와 구성원 확인을 수행하고, 감사 추적을 유지했으며, 반복적인 방식으로 주제와 하위 주제를 재검토하기 위해 연구자들 간의 지속적인 토론을 보장했다.

An iterative process of data collection and analysis was conducted. Focus groups were audio-recorded and transcribed verbatim. For the thematic analysis, we used a Steps for Coding and Theorization (SCAT) approach (Otani, 2008), whereby we first identified noteworthy words or phrases in the text and then formulated the relevant concepts from these words/phrases; we then constructed the relevant subthemes based on each particular concept. Initially, four authors (MW, DS, RM, EF) conducted independent thematic analysis on the first two transcripts to identify and discuss core themes and subthemes, after which all authors analyzed the other transcripts. Following the thematic analysis, each subtheme obtained using the SCAT approach was mapped onto the 4S framework (Anderson et al., 2012). Authors DS and NG independently grouped the subthemes into each of the 4S components (“Situation, Self, Support, and Strategy”) and any disagreement was resolved through discussion. All authors participated in fine-tuning the results. To enhance trustworthiness, we performed member checking with six focus group participants, kept an audit trail, and ensured a constant discussion among the researchers to revisit themes and subthemes in an iterative fashion.

결과.

Results

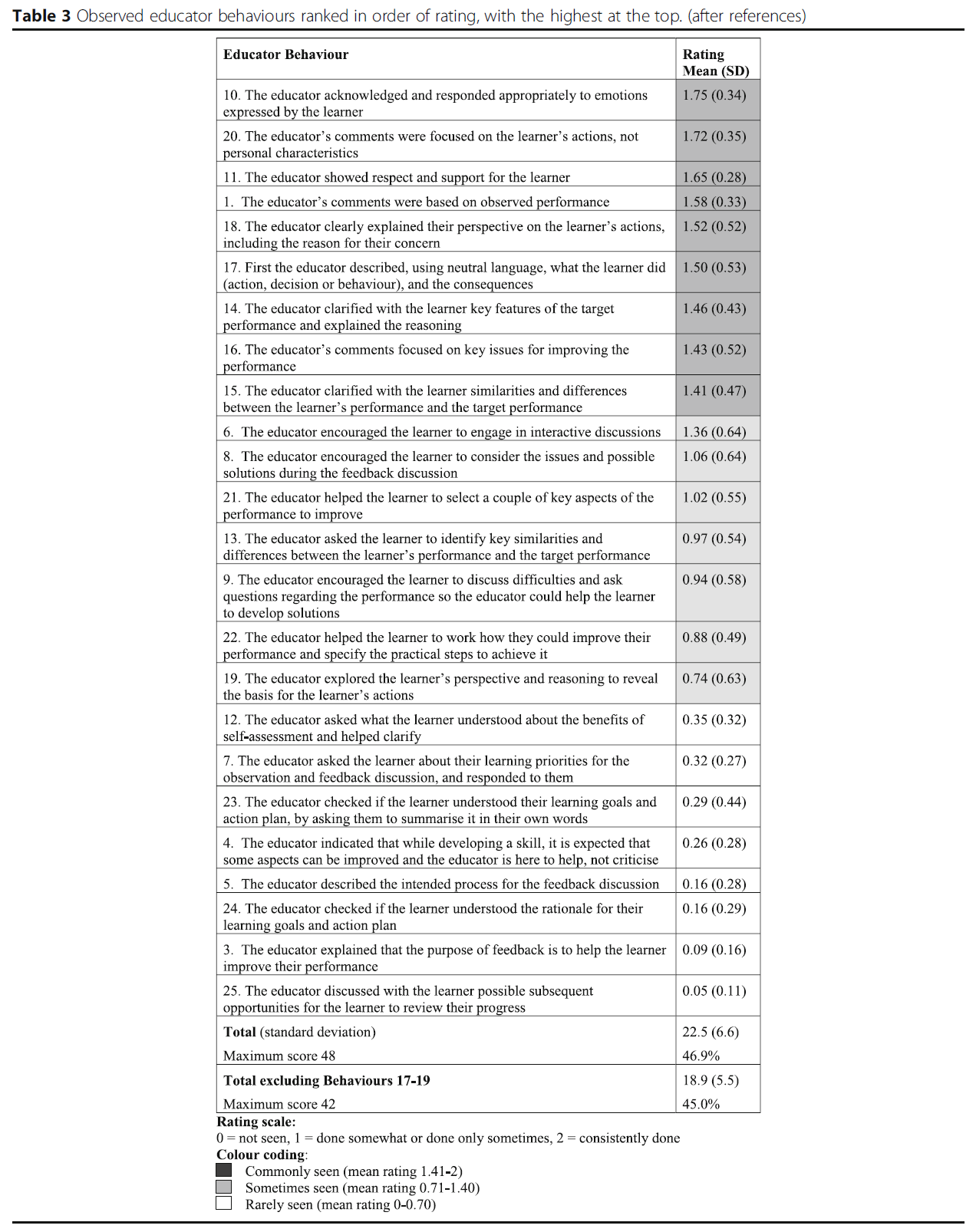

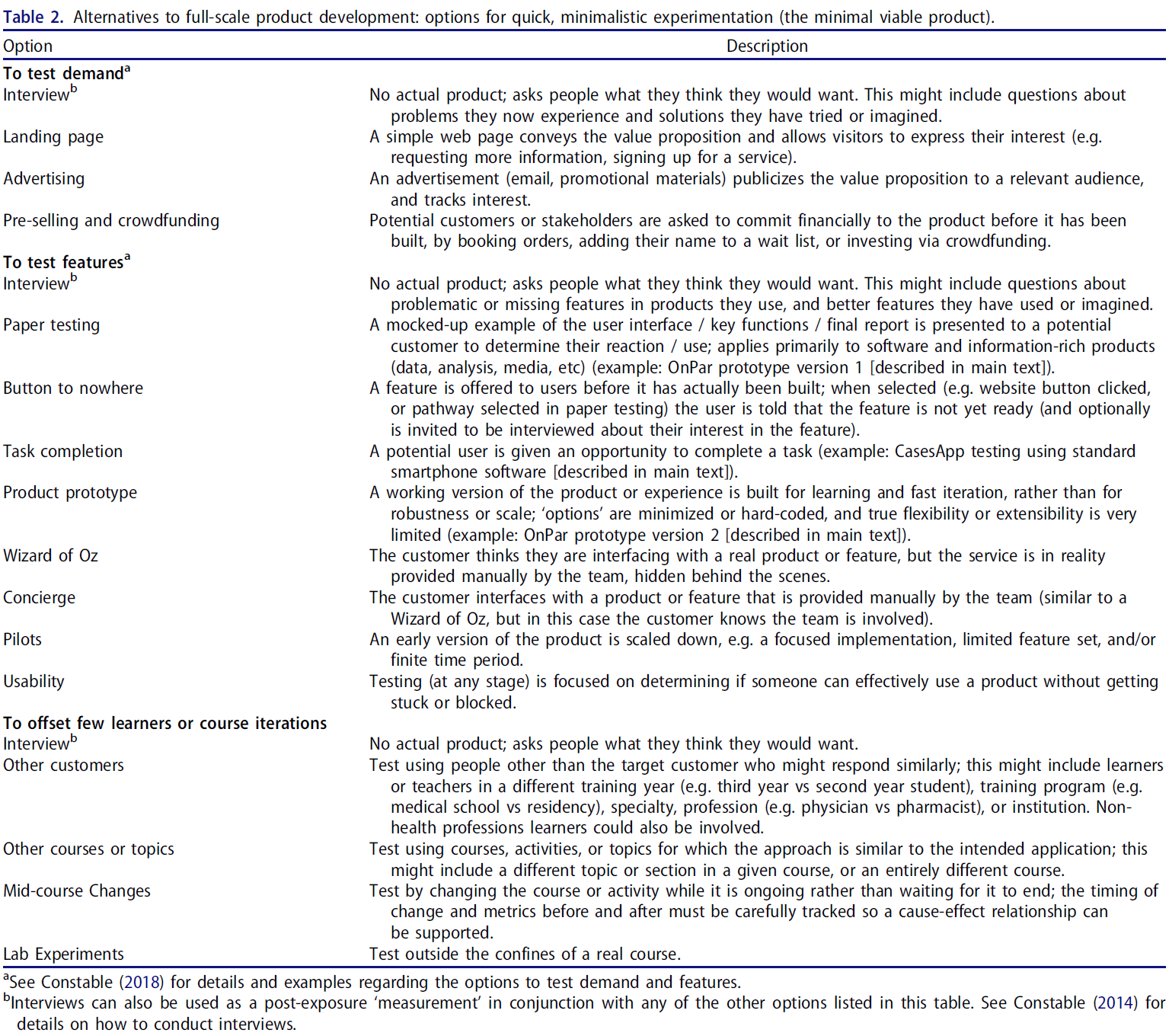

우리는 60명의 BST(이 중 68.3%가 여성)와 함께 9개의 포커스 그룹을 수행했다. 모든 기초과학 교사들은 의사였고 그들 중 대부분은 석사나 박사 학위를 가지고 있었다.

We conducted 9 focus groups with 60 BSTs (68.3% of whom were female). All basic science teachers were medical doctors and most of them held a master’s or PhD degree—24/60 (40%) and 23/60 (38%), respectively.

연구 참가자들은 자신이 처음 교사가 된 경위와 선택에 영향을 미친 요인이 무엇인지를 유창하게 설명했다. 참여자들의 내러티브를 바탕으로 연구 참여자들은 교사로서의 진로를 [의도적으로, 알면서도 선택하는 것]을 확인할 수 있었다. 또한 본 연구에서 BST는 교사로서의 역할과 의사로서의 역할 사이의 갈등을 인지하지 못하였다.

The study participants fluently described in detail how they first became teachers and what factors influenced their choice. Based on participants’ narratives, it was evident that the study participants purposively and knowingly chose their careers as teachers. As well, the BSTs in this study did not perceive conflicts between their roles as teachers and their roles as doctors.

저는 모든 상황에서 선생님이라고 소개합니다. 만약 사람들이 당신이 의사가 아니냐고 묻는다면, 저는 의사가 되는 것은 부업이라고 대답할 것입니다. 나는 주로 가르친다. (3JD > 10)

I introduce myself as a teacher in every situation. If people asked, were you not a doctor, I would answer that becoming a doctor is a side job. I mainly teach. (3JD > 10)저는 제 자신을 선생님이라고 소개하는 것을 선호합니다… 만약 제가 어디서 가르치는지 묻는다면, 저는 의학부라고 말할 것입니다. 기본적으로 나는 가르치는 것을 더 좋아해서 사람들에게 나는 선생님이라고 말한다. (2Y < 10)

I prefer to introduce myself as teacher… if I were to be asked where I teach, I would say faculty of medicine. Basically, I like teaching more, so I tell people that I am a teacher. (2Y < 10)

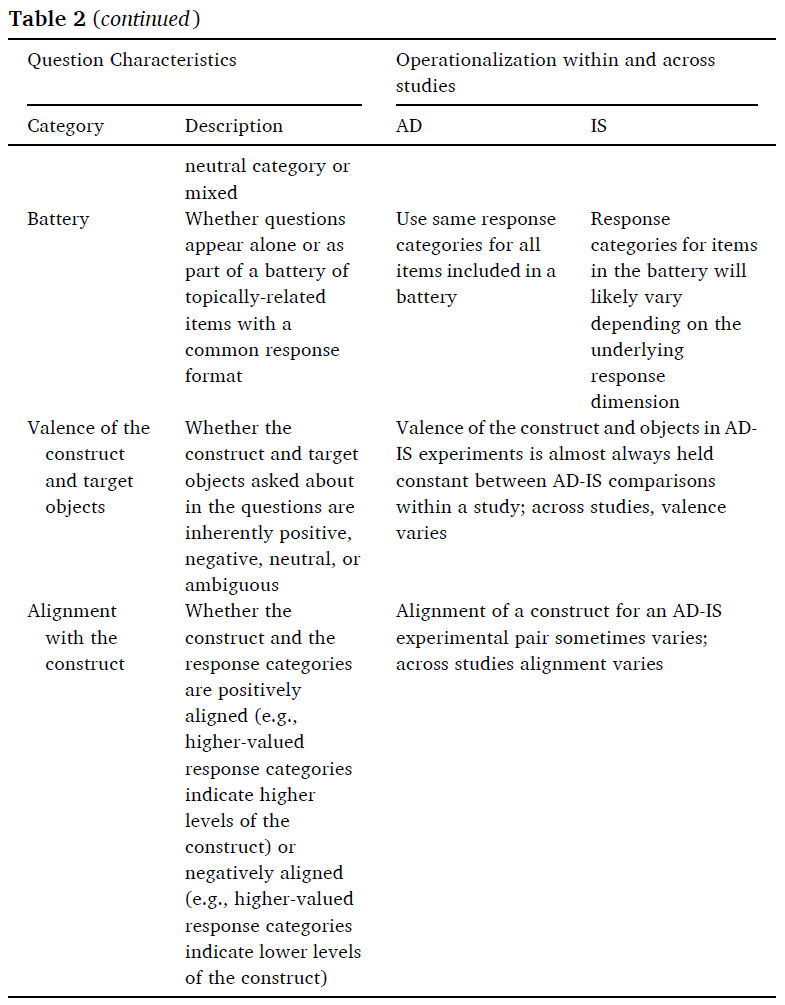

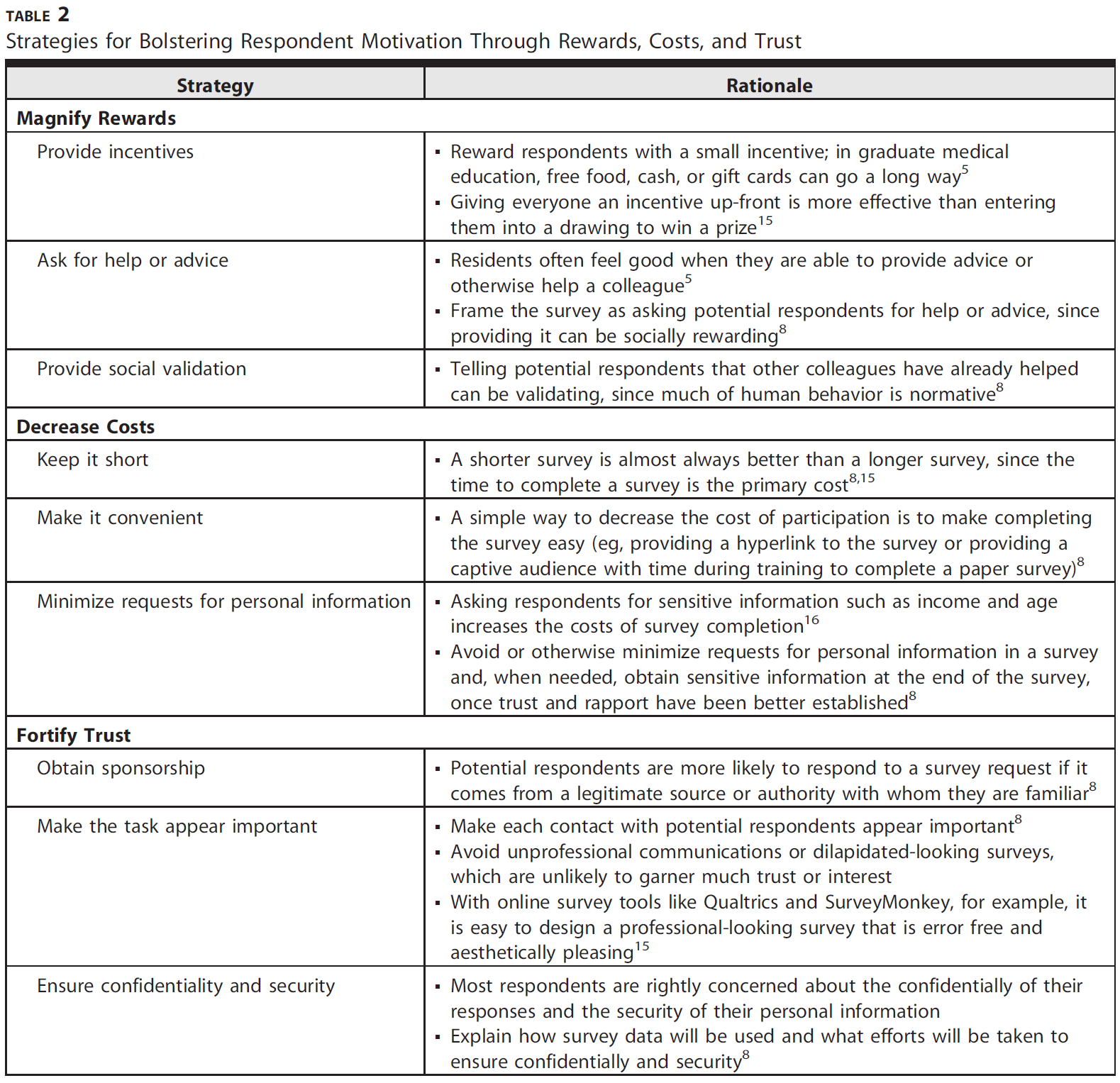

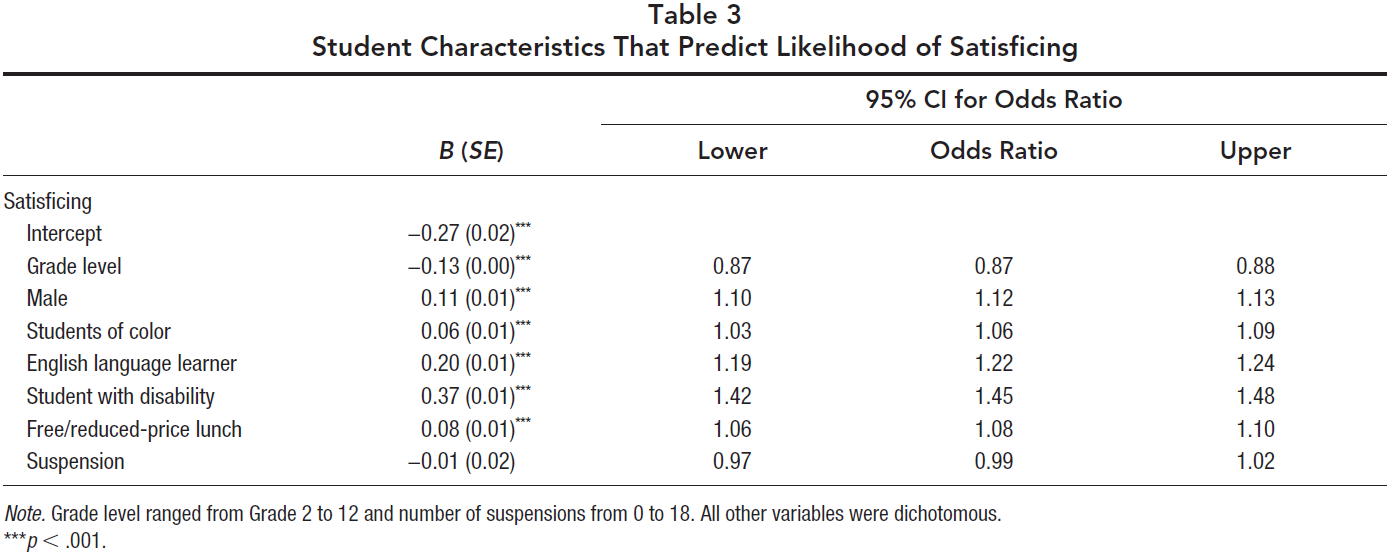

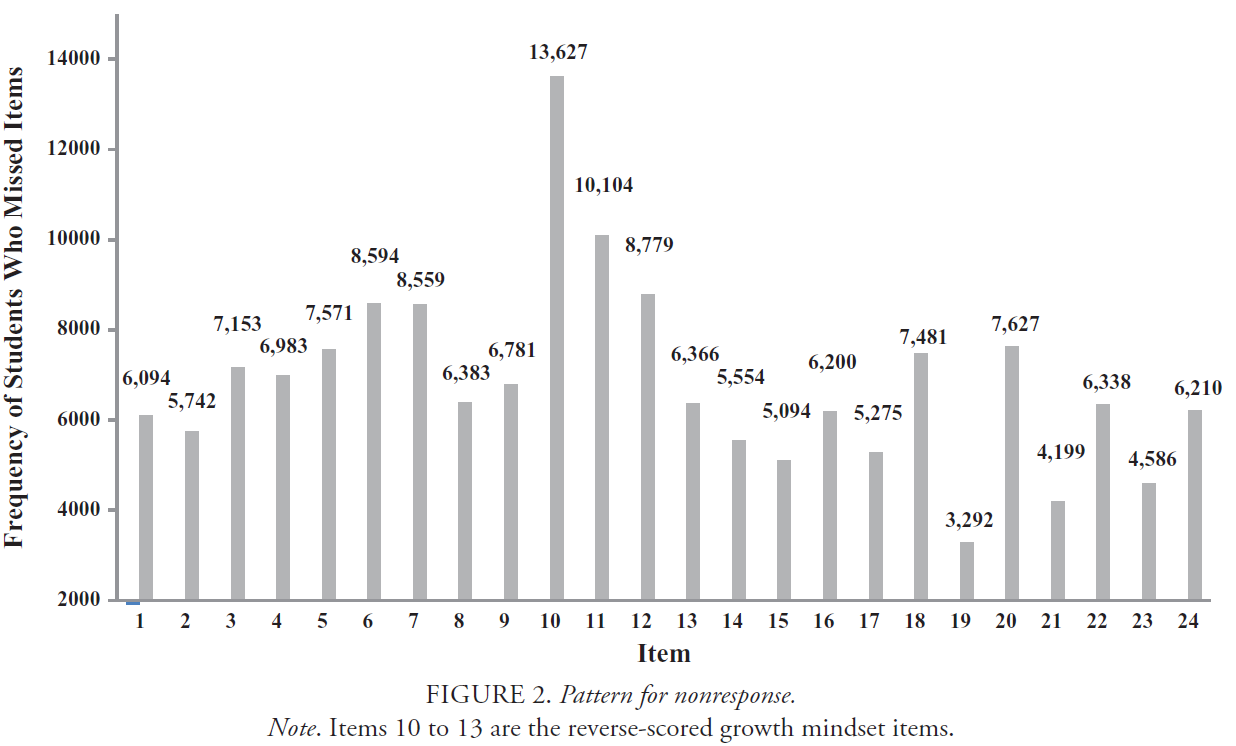

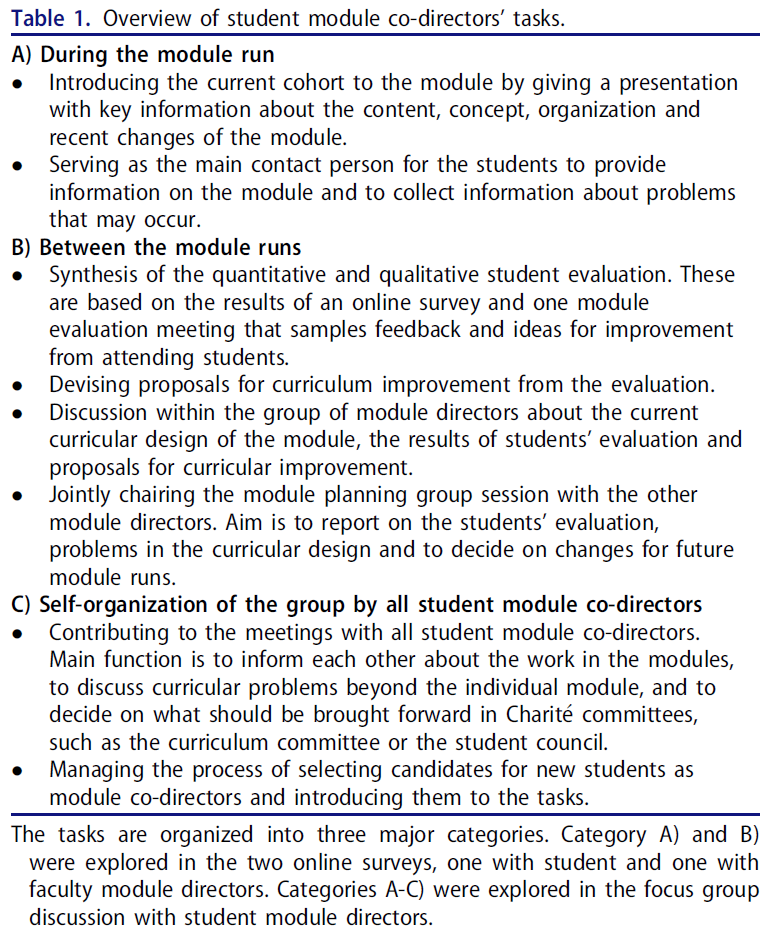

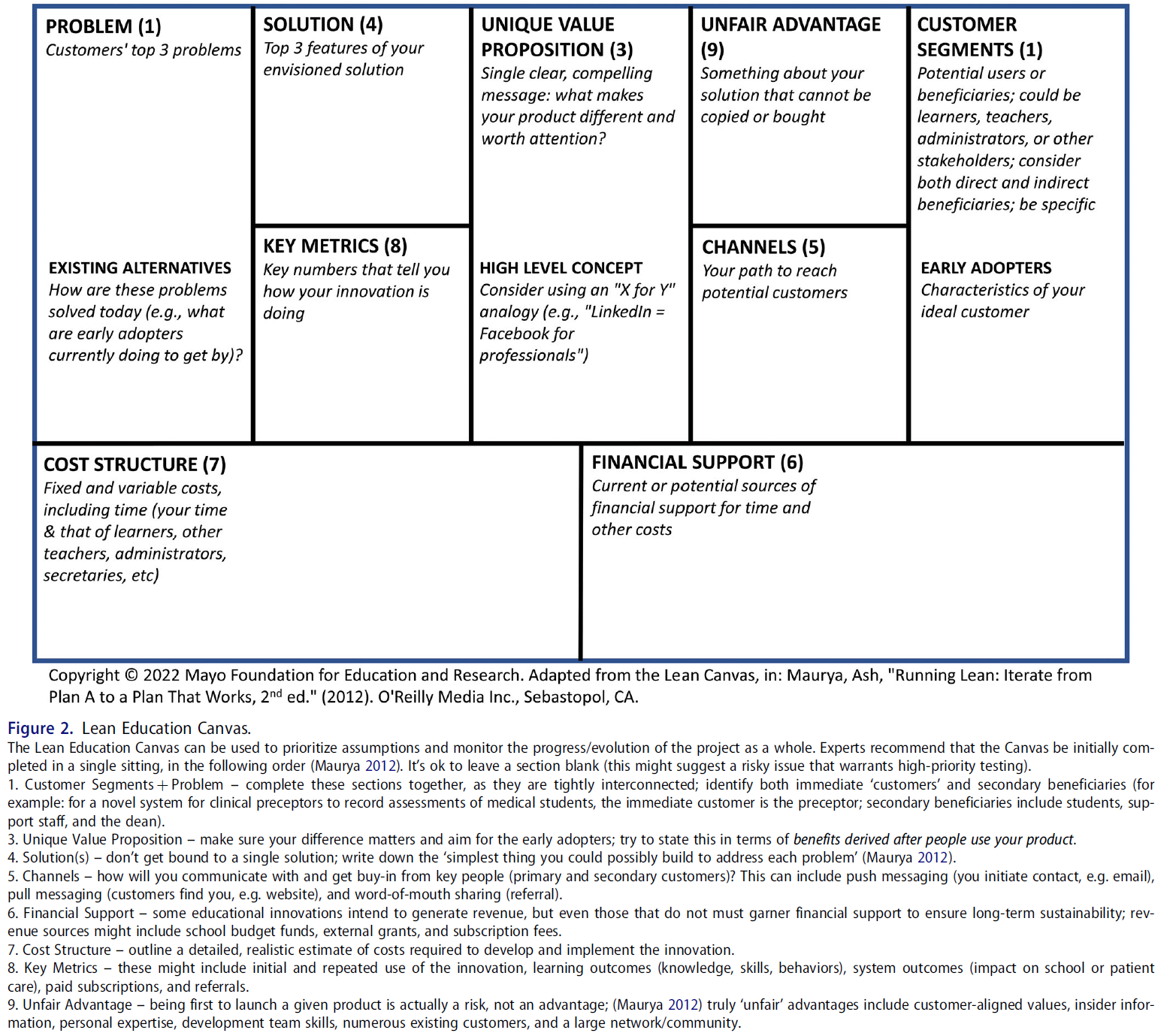

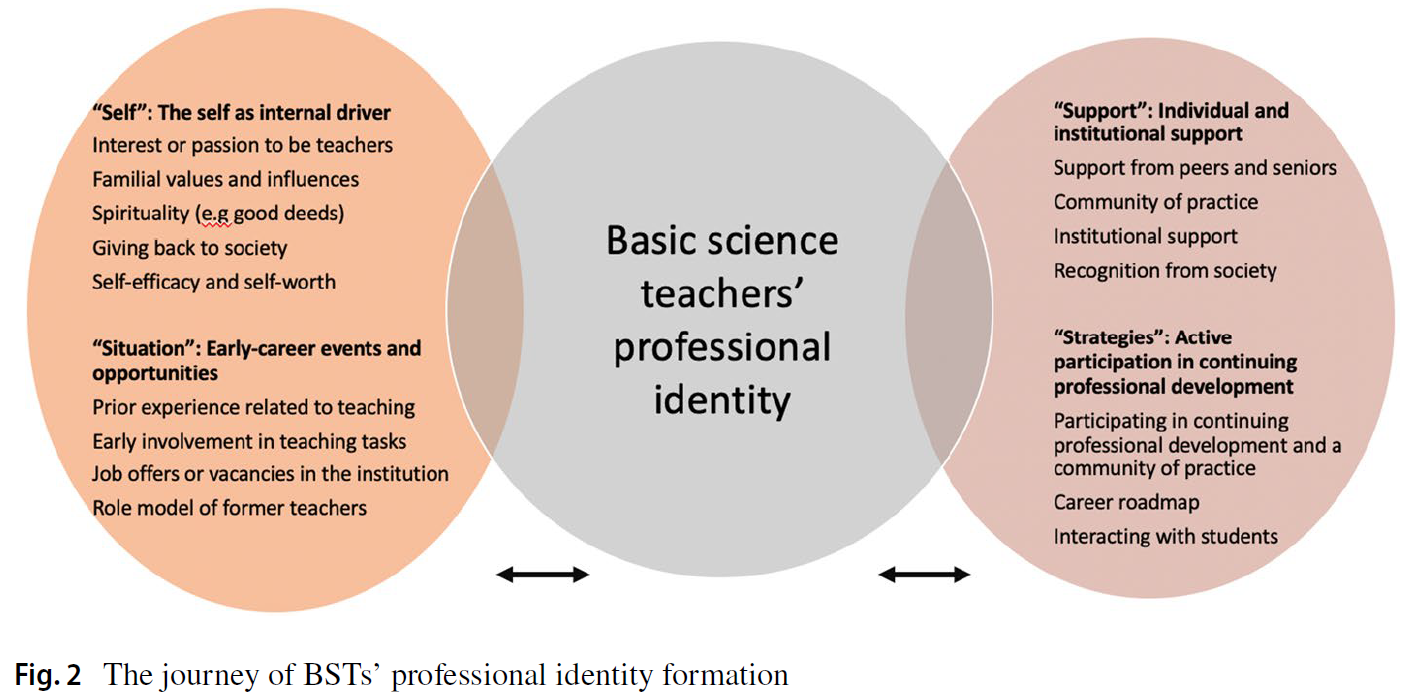

그림 2와 같이 BST의 PIF에 영향을 미친 다양한 요인들을 식별하고 4S 프레임워크에 매핑된 4개의 주제로 그룹화하였다. 각 4S 구성요소와 관련된 결과는 비식별화된 참가자(기관: 1-4, 이니셜: A, B 등)를 참조하는 대표적인 인용문과 코드를 제공한다. > 10년 또는 < 10년).

The different factors that influenced the PIF of BSTs were identified and grouped into four themes mapped onto the 4S framework, as presented in Fig. 2. The findings related to each of the 4S components are provided with representative quotes and codes referring to the de-identified participants (institution: 1–4; initials: A, B, etc.; > 10 or < 10 years).

BST는 "지원" 및 "전략" 구성요소에 비해, 자신의 동기와 초기 경력 경험을 설명하면서 "자신" 및 "상황" 구성요소와 더 쉽게 관련되는 것으로 보였다. 동시에 '전략'과 관련된 내용보다 '지원'에 대한 참가자들의 서술이 두드러졌다. 본 연구의 결과는 BST가 [내부적으로 주도]되며, BST로서 자신의 정체성 형성을 지원하고 성장하기 위한 다양한 전략에 적극적으로 참여하기보다는, [기존의 지원체계에 더 의존]하는 것으로 나타났다. 게다가, 참가자들은 [과학을 발전시키고 학문적인 일을 수행하는 것]보다 [가르치는 것]에서 그들의 역할에 대해 더 많이 이야기했다.

The BSTs seemed to more easily relate to “Self” and “Situation” components as they described their own motivations and early-career experiences, compared to the “Support” and “Strategies” components. At the same time, participants’ narratives about “Support” were more prominent than those related to “Strategy”. Findings of this study suggested that BSTs were internally driven and they seemed to rely more on existing support systems rather than actively take part in various strategies to support their identity formation and grow as BSTs. In addition, participants talked more about their roles in teaching than in advancing sciences and conducting scholarly work.

1.1.1 "자체": 내부 운전자로서의 자아

1.1.1 “Self”: The self as internal driver

BSTs의 내적 추진력은 개인이 주어진 상황에 어떤 영향을 미치는지, 그리고 자기효능감과 영성과 같은 개인적 특성과 심리적 자원과 관련이 있는 "Self"와 일치했다(Anderson et al., 2012). 본 연구는 교사가 되고 싶은 관심이나 열정, 가족적 가치와 영향, 영성, 사회에 환원하려는 욕구, 자기효능감과 자기가치를 포함하는 '자기'와 관련된 [5가지 요인]을 확인하였다.

BSTs’ internal drive matched the “Self,” which is related to what individuals bring to a given situation as well as their personal characteristics and psychological resources such as self-efficacy and spirituality (Anderson et al., 2012). This study identified five factors related to the “Self,” which included interest or passion to be a teacher, familial values and influences, spirituality, a desire to give back to society, and self-efficacy and self-worth.

[교사에 대한 열정]은 대부분의 교사들 사이에서 흔했지만, 일부 BST들은 가정에 교사가 있거나 교사가 되는 것이 매우 존중되기 때문에 교사가 되기를 원했기 때문에 [가족의 영향]도 두드러졌다.

Passion to teach was common among most teachers; however, family influences were also prominent, as some BSTs wanted to be teachers because there was a teacher in the family or being a teacher is highly respected.

그것은 부모님의 질문에서 시작되었다; 그들은 나의 이모들 중 한 명이 의학부의 직원이라는 것을 보고, 그들은 나에게 "그녀처럼 되고 싶니?" (1B < 10)

It began from my parents’ question; when they saw that one of my aunties is a staff member in a medical faculty, they asked me “Do you want to be like her?” (1B < 10)사람들은 내가 의사라는 것을 알지만, 내 딸은 그녀의 어머니가 선생님이라고 말한다. 한 번은, 그녀는 나의 박사 학위 졸업식에 참석하기 위해 중요한 활동들을 떠났다. 나에게 그것은 특별한 것이었다… 나는 내가 지금 하는 일이 그녀에게 큰 의미가 있다는 것을 알기 때문에 더욱 활기를 띠게 된다. (1U<10)

People know I am a doctor, but my daughter mentions that her mother is a teacher. One time, she left her important activities to attend my doctoral graduation. For me, that was something extraordinary… I become more spirited because I know what I do now means a lot to her. (1U<10)

[영성]은 또 다른 중요한 요소였는데, BST들이 가르치는 것이 하나님이 가르치는 좋은 관행과 일치하는 선행이라고 여겼기 때문이다.

Spirituality was another significant factor, as BSTs considered teaching a good deed, in line with the good practices taught by God.

처음부터 어머니는 내가 다른 사람들에게 유용하기를 원하셨다. 그것이 제가 그녀에게서 기억하는 것입니다. 그녀는 우리의 선행 중 하나가 다른 사람들에게 유용한 지식을 갖는 것이라고 강조했습니다. 그것이 제가 [선생님이 됨으로써] 찾고 있는 것입니다. (4KI<10)

From the very beginning, my mother wanted me to be useful for others. That is what I remember from her, she emphasized that one of our good deeds is to have knowledge that is useful for others… that is what I am looking for [by becoming a teacher]. (4KI<10)

일부 참가자들은 또한 [사회에 환원할 필요성]을 강조하여 교사가 되는 길을 선택했다. '자신'과 관련된 다른 요소로는 항상 좋은 롤모델이 될 수 없다는 약간의 우려가 있었지만, 교사가 됨으로써 얻어지는 [자기효능감과 자기가치감] 등이 있었다.

Some participants also highlighted the need to give back to society and thus chose the path to become teachers. Other factors related to the “Self” included a sense of self-efficacy and self-worth obtained by becoming a teacher, although there was a slight concern about not always being able to be a good role model.

더 많은 연구를 진행할 수 있는 기회와 이 모든 것들... 선생님이 아니면 절대 못 받을 거야… 나는 돈 외에도 다른 것들이 있다고 생각하는데, 매슬로 피라미드에서 가장 높은 것은 사실 자존감이다. 그래서 내가 부자가 아닐 때도 자존감이 충족되고 그것이 나를 건강하고 영적이고 정신적으로 만들어 줄 수 있다. (3SV>10)

The opportunity to pursue further study and all of these… I will never get them if I am not a teacher… I think there are other things aside from money, the highest in the Maslow pyramid is actually self-esteem. So even when I am not rich, my self-esteem is fulfilled and it could make me healthy, spiritually and mentally. (3SV>10)교사가 되는 것에 대한 나의 가장 큰 두려움과 걱정은 과학적 관점이 아니라, 학생들이 내가 어떻게 행동하는지를 우러러보고, 말하고, 분노를 표현하고, 때로는 통제하기 매우 어려운 학생이나 갈등을 처리한다는 것을 깨닫는 것이다. (3H<10)

My biggest fears and concerns of being a teacher is not the scientific point of view, but realizing that students look up to how I behave, talk, express my anger, and deal with students or conflicts, which is sometimes very difficult to control. (3H<10)

1.1.2 "상황": 초기 경력 이벤트 및 기회

1.1.2 “Situation”: Early-career events and opportunities

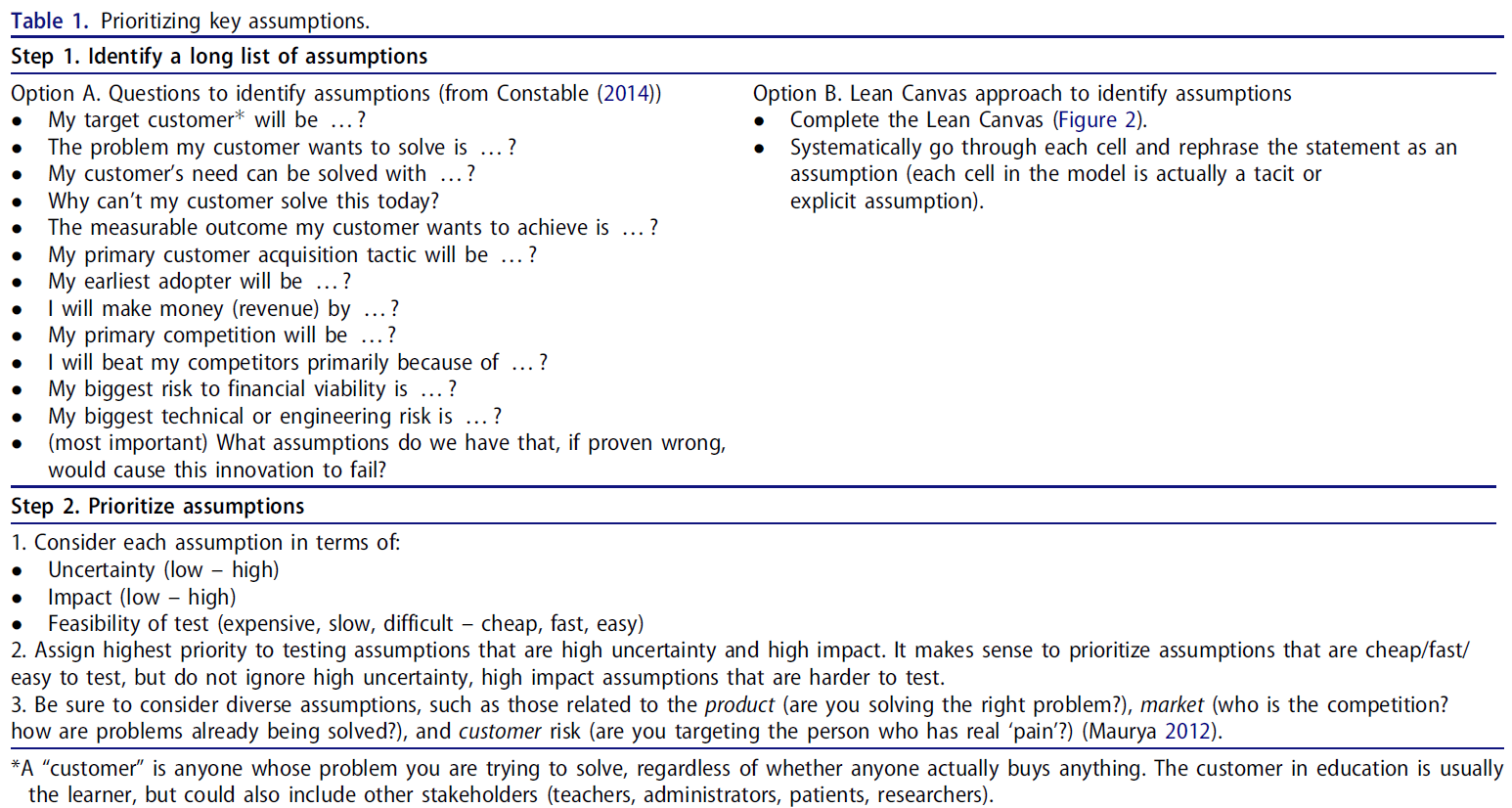

["상황"]은 [현재 의사결정에 영향을 미치는 과거 사건]을 의미한다(Anderson et al., 2012). 이 연구에서 '상황'은 교사가 되기로 한 결정에 영향을 미친 사건들을 포괄했다. BST의 PIF와 관련하여, [교사와 관련된 사전 경험, 교사 직무에 대한 조기 참여, 기관 내 일자리 제안 또는 공석, 전직 교사의 역할 모델링 등 4가지 요인]이 확인되었다.

“Situation” refers to past events that influence current decisions (Anderson et al., 2012). In this study, “Situation” encompassed events that influenced the decision to become a teacher. In relation to the PIF of BSTs, four factors were identified: prior experience related to teaching, early involvement in teaching tasks, job offers or vacancies in the institution, and role modeling of former teachers.

일부 교사들은 [중고등학생들을 가르친 경험]이 교사로서의 직업적 정체성을 형성하는 데 도움을 주었다고 보고했으며, 이와 함께 교직원이 되거나 커리큘럼을 개발하고 그룹 토론을 촉진하는 것과 같은 [교수 업무에 참여한 초기 경험]도 있었다.

Some teachers reported that their experiences in teaching junior or high school students helped shape their professional identity as teachers, along with early experiences of becoming teaching assistants in the faculty or being involved in teaching tasks, such as developing curricula and facilitating group discussions.

제가 한 학과의 조교가 되었을 때 저는 가르치는 것에 더 애착을 가졌습니다… 제 기술은 퍼실리테이터가 되었을 때 형성되기 시작했습니다. 나는 또한 학과에서 어려움을 겪고 있는 학생들을 도와달라는 요청을 받았다. (2RS > 10)

I was more attached to teaching when I became a teaching assistant in one department … My skills were starting to take form when I became a facilitator. I was also asked to help struggling students in the department. (2RS > 10)

그러나, 경력 초기에 [역할 모델]이 부족했음에도 불구하고 [각 기관의 교수직이 가능]하여 교사가 되기로 선택한 참가자들이 있었다.

However, there were some participants who opted to become teachers due to the availability of teaching positions in their respective institutions, despite a lack of role models early in their career.

제가 졸업할 때 한 학과에 교수 자리가 비어 있어서 그 학과에 지원하게 되었습니다. 그때는 졸업 후에 끝내야 하는 의무적인 일이 있어서 선생님이 되는 것도 의무적인 일로 간주될 수 있기 때문에 몇 년간 학과에 머물렀고, 그 후에 정규직 자리가 생겨서 지원했습니다. (3OR>10)

When I graduated, there was a vacant teaching position in one of the departments, so I applied to that department. At that time, there was compulsory work we had to complete after graduation, so I stayed in the department for a few years as becoming a teacher could also count as compulsory work, and then there was an opening for a permanent position, and I applied. (3OR>10)그때는 아무도 내 롤모델이 되지 않았는데 부서 운영을 맡겼을 때 혼란스러웠다. (4 N < 10)

It was confusing when I was entrusted to manage a department, while no one was my role model at that time. (4 N < 10)

1.1.2 "지원": 개인 및 기관 지원

1.1.2 “Support”: Individual and institutional support

Anderson 등(2012)은 "지원"을 [이행을 지속하는 데 사용할 수 있는 지원 또는 자원]으로 설명했으며, 본 연구에서는 교사가 되는 과정을 언급했다. 본 연구에서 BSTs의 PIF에 대한 지원은 교직 동료 및 선배, 실습 커뮤니티, 기관 및 사회의 지원을 포함하여 다양한 이해관계자로부터 나왔다.

Anderson et al. (2012) described “Support” as assistance or resources available to continue a transition, which in this current study referred to the process of becoming a teacher. In this study, the support for BSTs’ PIF came from different stakeholders, including support from their teaching colleagues and seniors, their communities of practice, the institution, and society.

일부 참가자들은 선배들을 따라다니며 역할 모델로 관찰할 수 있는 기회가 주어졌을 때 [선배 선생님들의 지지]를 느꼈다.

Some participants felt supported by senior teachers when they were given the opportunity to shadow their seniors and observe them as role models.

저는 후배 선생님들을 지도하고 제 경험을 공유하고 싶습니다. 후배 의사들은 멘토링을 받아야 할 것 같아요, 그렇지 않으면 어려움이 있을 거예요. 선배님들께 좋은 멘토링을 받았기 때문에 후배들의 멘토가 될 용의가 있습니다(2Y < 10)

I want to mentor junior teachers and share my experiences…. I think junior doctors need to be mentored, otherwise they will have troubles. I had good mentoring from our seniors, so I am willing to be a mentor for my juniors (2Y < 10)

교사들 사이에 [실천 공동체]가 존재하는 것도 BST의 정체성 발달을 지원하는 데 도움이 되었다. 이러한 [실천 공동체]는 참가자의 부서와 전문 조직 내에 존재했으며, 교사들이 자신의 교육 과제를 공유하고 동료들로부터 피드백을 받을 수 있는 기회를 제공했습니다. 비록 회원들이 시간적 제약 때문에 항상 참여하지는 않았지만, BST들이 서로 돕고 수업과 관련된 문제들을 논의하는 '장소'가 되었다. [제도적 지원]은 가용한 교수진 개발 활동, 경력 개발 기회, 명시적으로 명시된 성과 지표, 교직원 간 교육 과제 분배와 관련된 명확한 지침의 형태로 존재했다. 일부 참가자들은 또한 교사로서의 그들에 대한 [사회로부터 오는 인정]이 교사로서의 그들의 정체성을 강화시켰다고 느꼈다.

The existence of a community of practice amongst teachers also helped to support the BSTs’ identity development. These communities of practice existed within the participants’ departments and professional organizations and offered teachers an opportunity to share their teaching challenges and receive feedback from peers. The community of practice became the “place” for BSTs to help each other and discuss issues related to teaching, although members were not always engaged due to time constraints. The institutional support existed in the form of available faculty development activities, career development opportunities, explicitly stated performance indicators, and clear instructions regarding distribution of teaching tasks among staff. Some participants also felt that the recognition coming from society for them as teachers strengthened their identity as teachers.

만약 내가 그 기관에서 얻은 것에 대해 돌아본다면, 나는 큰 도움을 받을 것이다; 나는 더 많은 공부를 할 수 있고, 또한 몇몇 훈련이나 과정에 참석할 수 있다… 우리는 [많은 자원]을 매우 지원하므로 [자원]을 사용할지 여부가 문제입니다(4M < 10)

If I reflected on what I got from the institution, I was very supported; I could pursue further study, and I could also attend some training or courses… We are very facilitated [provided with many resources], so it is just a matter of whether we want to use them [resources] or not (4M < 10)"스파링 파트너"[교사가 토론하거나 건설적인 논쟁을 할 수 있는 파트너]가 있기 때문에 교육 기관에 들어오는 교사가 많아지면 우리의 학습 기회가 증가합니다(2RS > 10)

When there are more teachers coming into the institution, our opportunities to learn are increasing because there are “sparring partners” [partners with whom teachers can have discussion or constructive argument] (2RS > 10)가끔 학과 동료들이 학술활동, 강의, 연구 등으로 바빠서 일상적인 학과 활동을 위한 시간을 내기가 어렵다. 한편, 우리가 부서 활동에 참여하지 않는 한, 우리가 그들의 일부임을 느끼기 어렵다[소속감을 가지고 있다] (2H > 10)

Sometimes my colleagues in the department are busy with academic activities, teaching, researching, so it is difficult to make time for day-to-day department activities. Meanwhile, unless we get involved in department activities, it is difficult to feel how we are part of them [have the sense of belongings] (2H > 10)

1.1.3 "전략": 지속적인 전문성 개발에 대한 적극적인 참여

1.1.3 “Strategies”: Active participation in continuing professional development

"전략"은 [변화에 적응하기 위해 사용되는 방법]을 의미하며(Anderson et al., 2012), 교사가 전문적 정체성을 확립하고 강화하기 위해 제정한 조치 또는 대응을 포함한다. 이 구성요소에 해당하는 요인은 [지속적인 전문성 개발CPD]에 적극적으로 참여하는 것과 관련이 있으며, 여기에는 [실천공동체 참여]와 [진로 로드맵 수립(즉, 진로목표 및 승진목표 설정)]이 포함된다. [학생들과의 상호작용] 또한 이 구성요소에서 확인된 요인이었다.

“Strategies”, which refers to those methods used to adapt to change (Anderson et al., 2012), comprises actions or responses enacted by the teachers to establish and strengthen their professional identities. The factors that fell under this component related to active involvement in continuing professional development, which included participating in a community of practice and establishing a career roadmap (i.e., setting targets for career objectives and promotion). Interacting with students was also a factor identified under this component.

일부 참가자들은 학과 또는 다른 전문 조직 내의 [실천 공동체]에서 다른 교사들과 함께 학습하고 서로 피드백을 제공했다. 교사들은 또한 그들의 교수 기술을 발전시키고 가르칠 준비를 하기 위해 워크숍이나 연수회에 적극적으로 참여했다. 시간을 관리하기 위한 연구와 학습을 수행하는 것 또한 BST의 지속적인 전문성 발전을 위한 중요한 전략으로 확인되었다.

Some participants learned together with other teachers, and provided feedback to each other, in a community of practice within the department or other professional organization. Teachers were also actively engaged in workshops or training sessions to advance their teaching skills and prepare themselves to teach. Conducting research and learning to manage time were also identified as important strategies for BSTs’ continuing professional development.

교사들은 교육, 연구, 지역사회 봉사뿐만 아니라 관리까지 다양한 과제를 가지고 있다. 그리고 때때로 관리 업무는 더 많은 시간을 차지한다. 그래서 저는 한 번에 그 모든 작업을 해결하는 방법을 많이 배웠고, 가능한 시간 내에 완료하려고 노력했습니다(2RS > 10)

Teachers have multiple tasks, not only education, research and community service, but also management. And sometimes managerial work takes up more time. So, I learned a lot, how to tackle all those tasks in one time, and try to complete them within the available time frame (2RS > 10)

일부 참가자들은 교사로서 네트워크 개발, 학업 이정표 달성, 교수직 획득 등의 "커리어 로드맵"을 달성하기 위해 노력하는 것의 중요성을 표현했다.

Some participants expressed the importance of trying to accomplish their “career roadmap” as teachers, which included developing networks, achieving academic milestones, and obtaining professorship.

교육, 연구, 사회봉사 분야('tridharma')에서 각각의 실적을 보고 특정 벤치마크와 비교했을 때 기준을 완성하지 못해 자신감이 떨어진다는 것을 깨달았다. 그래서 이정표를 세우고, 교사로서 작은 성과를 추가해야 한다(2KN < 10)

I realized that when I saw my track record in each of the education, research, community service areas (“tridharma”) and compared them to a certain benchmark, I felt less confident since I had not completed the standards. So, I have to set the milestones, add small achievements as a teacher (2KN < 10)

[학생들과의 상호작용]도 교사의 정체성 형성에 도움이 되었고, 교사로서의 자기실현과 관련이 있었으며, 이는 학생들을 만나 감사함을 느끼면서 더욱 강화되었다.

Interacting with students also helped form the teachers’ identity and was related to their self-actualization as teachers, which was further reinforced by meeting students and feeling appreciated by them.

하지만 저는 또한 그들이 많은 질문을 하는 것을 좋아합니다. 비록 결국에는 제가 항상 확신할 수는 없기 때문에 우리가 함께 답을 찾아야 할 수도 있습니다. 나는 활동적인 학생들을 만나는 것을 좋아하는데, 특히 큰 반에서 활동적인 학생들을 좋아한다(4N > 10)

But I also like if they [students] ask many questions, although in the end, we may need to find the answers together since I am not always sure. I like meeting students who are active, especially those who are active in the large class (4N > 10)

논의

Discussion

이 연구는 기초과학자들이 문학에서 덜 탐구된 분야인 경력의 매우 초기 단계부터 의학 교사로서의 PIF에 대한 우리의 이해를 증진시킨다. 이 연구의 BST는 정체성 형성에 영향을 미치는 요인을 정교하게 설명할 수 있었고, 우리는 4S 슐로스버그 프레임워크에 따라 매핑했다. 이 연구는 [외부적인 상황]이 종종 이러한 선택을 강화시키지만, 개인이 직업에 진입하도록 유발하는 많은 [개인적 속성과 경험]이 어떻게 존재하는지 보여준다. Profession에 입문한 이후, BST로서 전문적인 정체성을 형성하기 위한 여정은 주로 [또래와 기관, 사회가 제공하는 지원]으로 이어지며, [구체적인 전략에 적극적으로 참여]함으로써 더욱 강화된다. 이 연구는 또한 참가자들이 어떻게 의도적으로 자신의 직업을 BST로 선택했는지를 보여준다.

This study furthers our understandings of the PIF of basic scientists as medical teachers from the very early stages of their careers, an underexplored area in the literature. The BSTs in this study were able to elaborate the factors influencing their identity formation, which we then mapped according to the 4S Schlossberg framework. This study shows how there are many personal attributes and experiences that trigger individuals to enter the profession, though external situations often strengthen this choice. Upon entering the profession, the journey to form a professional identity as a BST continues mainly with the support provided by peers, institutions and society, and it is further strengthened by active participation in specific strategies. This study also shows how the participants knowingly and purposively chose their careers as BSTs.

[자아(Self)]의 구성요소에는 여러 내재적 동기가 포함되어 있으며, 그 중 많은 부분은 보건학 교사의 직업적 정체성에 중요한 요소로 간주되었다. 이 연구의 BST들은 그들이 교사가 되기를 원한다는 것을 알고 그 분야에 들어갔다. 그러나 [교사가 되고 싶은 열정과 동기]와 같은 중요한 [내재적인 힘] 외에도, [교사와 관련된 사전 경험, 교사 직무에 대한 초기 참여, 전직 교사의 역할 모델, 그리고 직업 제안이나 공석]과 같은 ["상황"]은 BST의 전문직 여정의 진입을 특징짓는 데 도움이 되는 [외적인 요소]들을 형성했다. 또한 이러한 연구결과는 내재적 요인과 외적 영향 사이에서 동기부여와 대화의 중요성을 강조하였다.

The “Self” components included several intrinsic motivations, many of which were seen as prominent factors in the professional identity of health sciences teachers in general (Snook et al., 2019). The BSTs in this study entered the field knowing that they wanted to be teachers. However, aside from important intrinsic forces such as passion and motivation to be a teacher, the “Situation,” such as prior experiences related to teaching, early involvement in teaching tasks, the role modeling of former teachers, and job offers or vacancies, formed the extrinsic factors that helped mark the entrance of BSTs into their professional journeys. These findings also highlighted the importance of motivation and dialogue between intrinsic factors and extrinsic influences (Cruess et al., 2015; Wahid et al., 2021).

본 연구는 ['지원']과 관련하여 [전문성 발전에 영향력이 있는 기관과 BST의 실천공동체, 멘토와 선배 동료, 사회의 지원]을 강조한다. 이러한 요인들은 임상 교사들의 PIF의 핵심이기도 한 사회화의 진행 과정에 구체적으로 기여했다. ['전략']에는 [후배 BST와 선배 교사의 짝짓기, 기존 롤모델에 대해 논의하고 성찰하는 계기가 된 멘토링 과정] 등의 접근법이 담겼다. 이 발견은 위계적이고 집단주의적인 문화에서 특히 강력할 수 있는 [시니어 BST의 멘토링 과정]을 공식화하고 명시하는 것이 유용할 수 있다는 관찰을 강조한다. 지속적인 전문성 개발, 학생들과의 상호작용, 진로 로드맵 수립과 같은 전략들도 BST에 의해 수행되었다. 흥미롭게도, 학생들과 상호작용하는 것은 직업적 정체성을 개발하기 위한 효과적인 전략으로 언급되었고 교사로서의 능력에 대한 BST의 인식에 기여할 수 있고 교사가 되기 위한 그들의 '진정한 소명'을 상기시킬 수 있다.

Regarding “Support,” this study underlines support from the institution and the BSTs’ community of practice, mentors and senior colleagues, and society as influential in professional development. These factors specifically contributed to the ongoing process of socialization, which is also at the core of the PIF of clinical teachers (Cantillon et al., 2016; Wahid et al., 2021). “Strategies” included approaches such as the pairing up of a junior BST with a senior teacher and the mentoring process which served as an opportunity to discuss and reflect on existing role models. This finding highlights the observation that it may be useful to formalize and make explicit the mentoring process from senior BSTs that can be particularly powerful in a hierarchical and collectivist culture (Hofstede, 2011). Strategies such as continuing professional development, interacting with students, and establishing a career roadmap, were also undertaken by the BSTs. Interestingly, interacting with students was mentioned as an effective strategy to develop professional identity and may contribute towards BSTs’ perceptions of competence as teachers (Deci & Ryan, 2012) and may remind them of their ‘true calling’ to become teachers.

이러한 결과를 바탕으로 [BST의 채용 시, 동기를 탐색]하고, [교사로서의 역할이 부여된 후 이러한 측면을 성찰하도록 유도하는 것]이 가치가 있을 수 있다. 즉, BST의 직업적 정체성에 대한 '자아'와 '상황'의 구성요소를 처음부터 인식할 수 있고, 이는 교육, 교육, 연구 및 지역사회 서비스에 대한 [조직의 비전과 사명에 교직원의 목표를 맞추는 데 도움]이 될 수 있다. 우리는 또한 교수진 개발 프로그램이 특히 BST의 역동적인 역할의 개발과 의료 커리큘럼에서 기초과학 역할의 본질과 중요성을 목표로 할 것을 권고한다. [채용부터 퇴직까지 기초과학 교사의 진로 로드맵]은 4S 요인을 고려하여 교사들이 다양한 현대적 역할을 수행할 수 있도록 도와주어야 한다. BST의 [PIF는 무엇보다 "Self"의 존재에 의해 영향]을 받기 때문에, 채용 및 유지 정책은 이를 고려해야 하며, 교수개발은 예를 들어 성찰을 통해 이러한 [자아 의식을 더욱 강화하는 것을 목표]로 해야 한다. [다양한 과거 사건]으로 인해 BST의 정체성이 강화된다는 점에서, BST의 [성찰적 실천을 육성하는 것을] 명시적 목표로 하는 교수개발 프로그램은 ["상황" 구성요소]를 강화하는 데 유용할 수 있다.

Based on these findings, exploring the motivations of BSTs during recruitment, and encouraging them to reflect on this aspect once they are given roles as teachers, may be worthwhile. That is, the institution can recognize the “Self” and “Situation” components of the BSTs’ professional identity from the start, which can help to align faculty members’ goals with the organization’s vision and mission in education, teaching, research and community services. We also recommend that faculty development programs specifically target the development of BSTs’ dynamic roles (Harden & Lilley, 2018) and the nature and importance of the basic science role in medical curricula (Dominguez & Zumwalt, 2020). The career roadmap for basic science teachers, from recruitment to retirement, should help teachers carry out various contemporary roles, considering the 4S factors. The PIF of BSTs is firstly influenced by the presence of “Self”; therefore, recruitment and retention policies should consider this, and faculty development should aim to further augment this sense of self, for example through reflection. A faculty development program with explicit aims to nurture the reflective practice of BSTs could also be useful to strengthen the “Situation” component, given that the identity of BSTs is reinforced by various past events.

본 연구를 통해 BST의 전문적 정체성은 다양한 교사 역할을 수행할 수 있는 역량을 개발하기 위한 [멘토링과 실천공동체, 지속적인 전문성 개발을 통해 '지원'과 '전략' 요인]에 의해 강화될 필요가 있음을 알 수 있다. 우리는 또한 기관이 부서, 연구 및/또는 교육에서 특정한 역할을 가진 부서 또는 BST의 전문성과 관련된 다른 전문 조직을 통해 보다 공식적인 실천 공동체의 설립을 지원할 필요가 있을 수 있다고 제안한다. 또한, [비공식적인 실천 공동체]는 BST가 의대생을 가르치기 위한 주제 내용을 맥락화하는 데 더 도움이 될 수 있다.

It is evident from this study that BSTs’ professional identity needs to be enhanced by “Support” and “Strategy” factors through mentoring, a community of practice, and continuing professional development to develop the abilities to enact various teacher roles. We suggest that the institution may also need to support the establishment of more formal communities of practice (Wenger et al., 2002), through departments, units with specific roles in research and/or education, or other professional organizations relevant to the BSTs’ expertise. Also, an informal community of practice can further help BSTs to contextualize their subject content for teaching medical students (Brauer & Ferguson, 2015; Gwee et al., 2010).

현재의 연구는 지금까지 이 주제를 탐구한 문헌의 희소성을 고려할 때 BSTs의 PIF에 대한 우리의 이해를 발전시켰다. 동시에 본 연구는 한 국가에서 수행되었기 때문에 그 한계를 인정한다. 또한, 본 연구에서 BST의 특성과 배경은 우리의 맥락에 특정될 수 있으므로 결과의 전달 가능성을 다른 맥락으로 제한할 수 있다. 그러나 이러한 발견들이 맥락에 따라 달라질 가능성이 있음에도 불구하고, 본 연구는 BST들이 스스로를 어떻게 보고 있는지, 교사로서 변화하는 역할을 수행하는 데 어떻게 지원받을 수 있는지에 대해 조명했다. 다양한 전략을 통해 교사와 학자로서 BST의 발전을 탐구하고 배양하기 위한 추가적인 경험적 연구는 가치가 있을 것이다.

The current study has advanced our understanding of the BSTs’ PIF, given the scarcity of literature that has explored this topic thus far. At the same time, we acknowledge the limitations of this study as it was conducted in one country. In addition, the characteristics and backgrounds of BSTs in this study may be specific to our context, thus limiting the transferability of the results to a different context. However, despite the fact that these findings are likely to be context-specific, the study has shed light on how BSTs view themselves and how they can be supported in carrying out their changing roles as teachers. Further empirical studies to explore and cultivate the development of BSTs as teachers and scholars through different strategies would be worthwhile.

결론

Conclusion

동적 역할이 주어진 BST의 PIF를 다루는 것이 중요하다. 4S 프레임워크의 렌즈를 통해 보면, BST의 PIF는 많은 다른 요소들의 영향을 받는 이행 과정이다.

- 이 과정은 [개인적인 요인]에 의해 촉발되고,

- 교육 과제에 대한 초기 참여와 전직 교사의 역할 모델링을 포함한 [초기 직업 상황]에 의해 더욱 활성화된다.

- ["자신"과 "상황"]의 요소는 모두 BST가 전문적인 교사가 되기 위한 [전략을 수립하도록 촉발]한다.

- 이러한 전문적 정체성을 형성하기 위한 전환 과정은 주로 [시니어, 동료, 기관 및 사회의 지원]에 의해 강화된다.

기초과학 교사의 PIF에 영향을 미치는 요인의 폭을 고려하여 BST의 변화된 역할을 포함하여 BST의 정체성을 육성하기 위한 교수진 개발 프로그램 및 지원 시스템을 구축해야 한다.

It is important to address the PIF of BSTs given their dynamic roles. Looking through the lens of the 4S framework, the PIF of BSTs is a transition process influenced by many different factors.

- The process is triggered by personal factors and

- further activated by early-career situations which including early involvement in teaching tasks and the role modeling of former teachers.

- Both the “Self” and the “Situation” components trigger the BSTs to enact strategies to become professional teachers.

- The transition process to form these professional identities is primarily enhanced by the support from seniors, peers, institutions and society.

A faculty development program and support system to foster the identity of BSTs, including their changing roles should be created by taking into consideration the breadth of factors influencing the PIF of basic sciences teachers.

Deconstructing the professional identity formation of basic science teachers in medical education

PMID: 35915274

Abstract

Purpose: The role of basic science teachers (BSTs) in medical education has been changing dynamically. Less is known, however, about how BSTs perceive their professional identity and what factors influence its formation. This study aims to explore how the professional identity of BSTs is formed and what factors influence this professional identity formation (PIF) using the 4S ("Situation, Self, Support, Strategies") Schlossberg framework.

Method: A qualitative descriptive study using focus groups (FGs) was conducted. Maximum variation sampling was used to purposively select BSTs. A rigorous thematic analysis was completed, including independent thematic analysis, intermittent checking and iterative discussions among researchers, and member checking.

Results: Nine FGs, involving 60 teachers, were conducted. The findings highlighted four major themes reflecting the 4S framework: the self as internal driver, early-career events and opportunities, individual and institutional support, and active participation in continuing professional development. Both the "Self" and the "Situation" components prompted the BSTs to utilize supports and enact strategies to become professional teachers. Although the BSTs in this study were primarily internally driven, they relied more on existing support systems rather than engaging in various strategies to support their growth.

Conclusion: It is important to address the PIF of BSTs given their dynamic roles. Looking through the lens of the 4S framework, PIF is indeed a transition process. A structured, stepwise faculty development program, including mentorship, reflective practice, and a community of practice designed to foster BSTs' identities, should be created, taking into consideration the diverse factors influencing the PIF of BSTs.

Keywords: 4S Schlossberg framework; Basic science teachers; Faculty development; Medical teachers; Professional identity formation.

© 2022. The Author(s), under exclusive licence to Springer Nature B.V.

'Articles (Medical Education) > 교수개발(Faculty Development)' 카테고리의 다른 글

| 임상실습의 수월성: 재능 분류하기가 아닌 재능 개발하기 (Perspect Med Educ, 2021) (0) | 2023.02.18 |

|---|---|

| 비서구 지역에서 의학 교수자의 전문직정체성형성(Med Teach, 2021) (0) | 2023.01.28 |

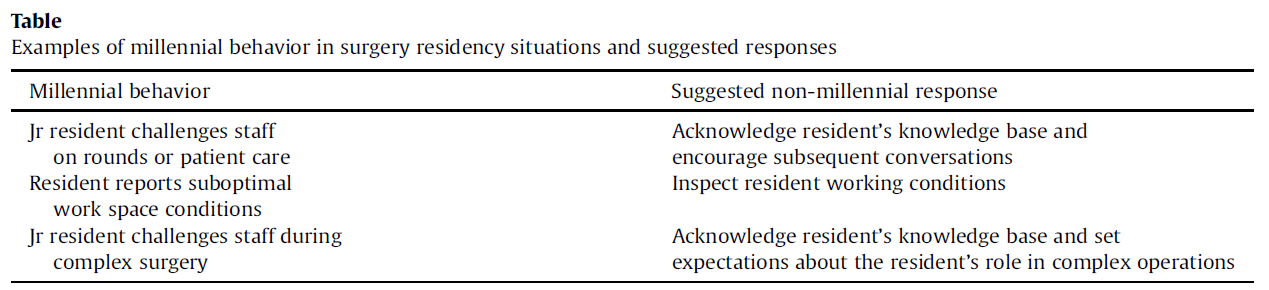

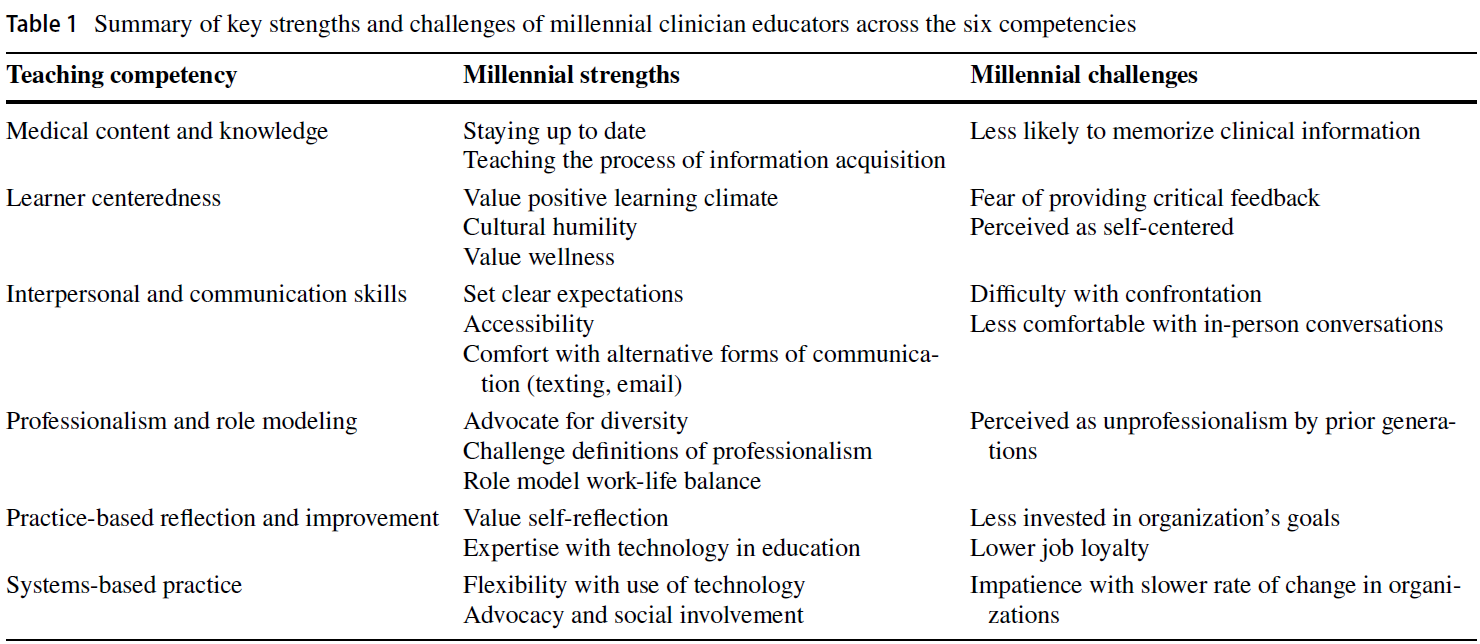

| 밀레니얼이 도착했다: 외과 교육자가 밀레니얼을 가르칠 때 알아야 할 것 (Surgery, 2020) (1) | 2023.01.13 |

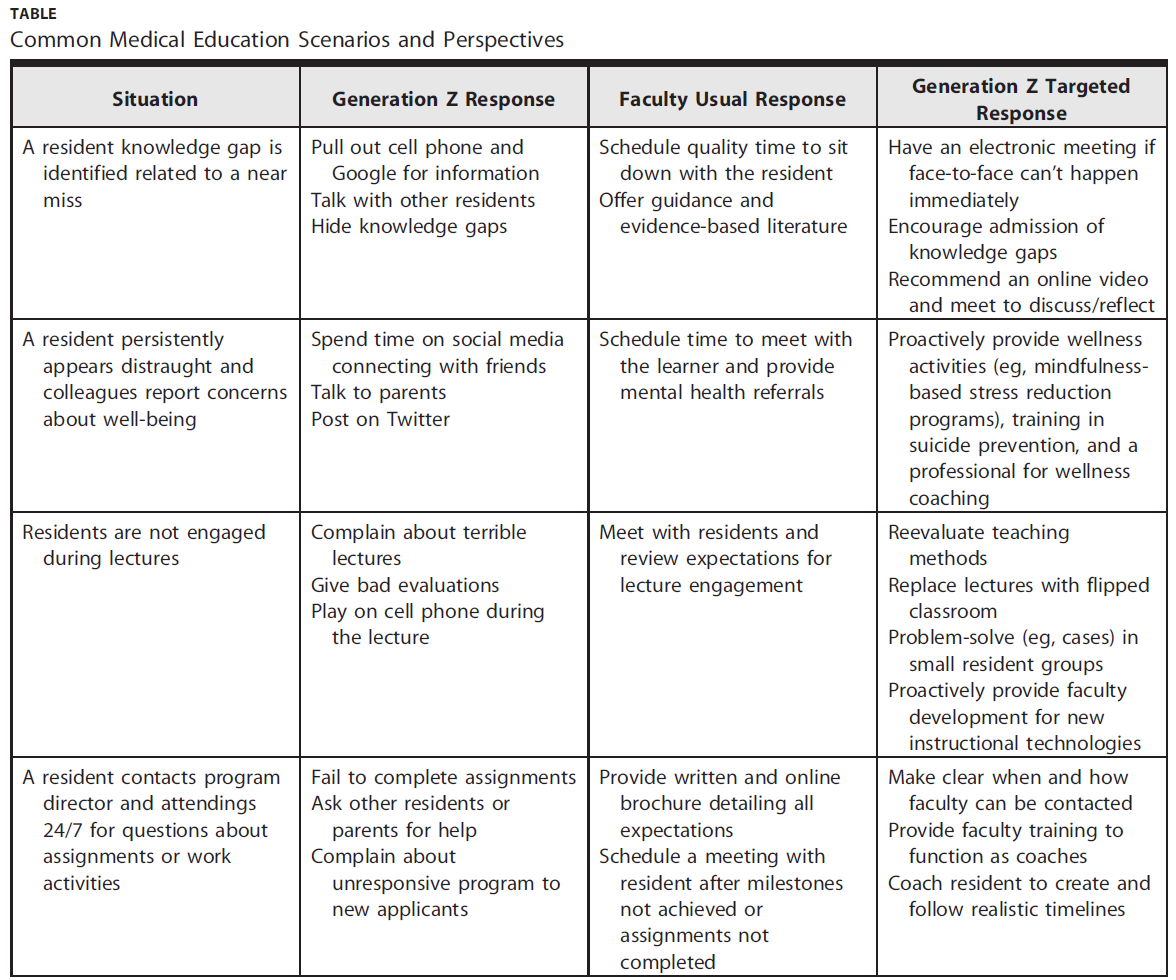

| 의학교육은 Z세대에 준비되었는가? (J Grad Med Educ. 2018) (0) | 2023.01.13 |

| 아이들은 문제 없다: 교육자의 새로운 세대 (Med Sci Educ. 2022) (0) | 2023.01.10 |