실제 임상실습 상황에서 교육자의 행동: 관찰 연구와 체계적 분석(BMC Med Educ, 2019)

Educators’ behaviours during feedback in authentic clinical practice settings: an observational study and systematic analysis

Christina E. Johnson1* , Jennifer L. Keating2 , Melanie K. Farlie3 , Fiona Kent4 , Michelle Leech5 and Elizabeth K. Molloy6

배경

Background

역량 기반 교육 및 프로그램 평가와 연계된 현대 임상 교육은 역량 평가를 위한 Miller의 프레임워크에서 최고 수준을 목표로 하는 작업장의 일상적인 작업에 대한 평가 및 피드백에 초점을 맞추고 있습니다[1,2,3]. 피드백은 학습과 성과에 가장 강력한 영향을 미치는 요소 중 하나입니다 [4,5,6,7,8]. 학습자가 다른 실무자의 비판, 추론, 조언 및 지원으로부터 이익을 얻을 수 있는 기회를 제공합니다. 이러한 협업을 통해 학습자는 성과 목표가 무엇이고 이러한 표준에 도달하는 방법에 대한 이해를 높일 수 있습니다[9, 10]. ['On the run' 또는 비공식 피드백]은 환자 치료를 제공하는 도중에 발생하는 짧은 피드백 조각을 의미합니다. [공식적인 피드백 세션]은 일반적으로 상급 임상의(교육자)와 학생 또는 하급 임상의(학습자)가 학습자의 성과를 보다 포괄적인 방식으로 논의하는 것을 의미한다. 공식적인 피드백 세션은 실습기간 중간 또는 실습기간 종료 평가 또는 작업장 기반 평가의 일부로 종종 발생합니다. 그러나 이 모델의 성공은 효과적인 피드백을 제공하는 일상적인 임상의에게 달려 있다. 효과적인 피드백의 어떤 구성 요소가 문헌에서 직장의 감독 관행으로 성공적으로 변환되었는지 그리고 그렇지 않은 구성 요소는 명확하지 않다. [Translation의 격차]에 대한 정보는 전문 개발 교육을 더 잘 목표로 삼거나 품질 피드백 행동을 구현하는 데 장애물을 극복하기 위한 전략을 설계하는 데 사용될 수 있다.

Modern clinical training, aligned with competency based education and programmatic assessment, is focused on assessment and feedback on routine tasks in the workplace, targeting the highest level in Miller’s framework for competency assessment [1,2,3]. Feedback is one of the most powerful influences on learning and performance [4,5,6,7,8]. It offers the opportunity for a learner to benefit from another practitioner’s critique, reasoning, advice and support. Through this collaboration, the learner can enhance their understanding of what the performance targets are and how they can reach those standards [9, 10]. ‘On the run’ or informal feedback refers to brief fragments of feedback that occur in the midst of delivering patient care. A formal feedback session typically refers to a senior clinician (educator) and student or junior clinician (learner) discussing the learner’s performance in a more comprehensive fashion. Formal feedback sessions often occur as a mid- or end-of-attachment appraisal or as part of a workplace-based assessment. However the success of this model relies on everyday clinicians providing effective feedback. It is not clear which components of effective feedback have been successfully translated from the literature into supervisory practice in the workplace, and which have not. Information on gaps in translation could be used to better target professional development training, or to design strategies to overcome impediments to implementing quality feedback behaviours.

병원에서 진정한 피드백을 [직접 관찰]한 연구는 드물다. [관찰 연구]는 일상적인 임상 교육에서 실제로 일어나는 일에 대한 주요 증거를 제공하기 때문에 매우 가치가 있다. [직접 관찰]은 활동을 관찰하는 연구자나 비디오 관찰을 통해 달성할 수 있다. 우리는 이전의 몇 가지 직접 관측 연구만 확인했다. 이는 공식 또는 비공식 피드백(외래 클리닉, 병동 또는 종합 시뮬레이션 임상 시나리오에 따른)을 포함하는 소수의 전문 분야(내부 또는 가족 의학)에서 주니어 학습자(의대생 또는 주니어 레지던트)를 포함한다. 추가적인 단일 연구에는 공식적인 애착 중간 또는 종료 피드백 동안 물리치료 학생들이 포함되었다[19]. [관찰 연구의 부족]은 시간 소모적인 특성, 바쁜 일정에 끼워진 피드백 회의와 일치하도록 관찰자나 비디오 녹화를 배치하는 것의 어려움 또는 관찰되거나 기록될 참가자의 침묵과 관련이 있을 수 있다. 이러한 연구들은 일반적으로 교육자들이 성과의 특정 측면에 대해 논평을 하고, 중요한 개념을 가르치고, 학습자가 어떻게 개선할 수 있는지 설명하거나 보여준다고 보고했다. 그러나 교수자가 말하는 시간이 대부분이고, 학습자에게 자기 평가를 요청하지만 응답하지 않으며, 수정 의견을 피하고, 일상적으로 실행 계획을 만들지 않습니다. 그러나 이러한 발견은 더 이상 현재의 관행을 반영하지 않을 수 있다. 또한 병원 환경에서 일하는 임상 교육자와 학습자의 다양성을 포착한 연구는 없었다.

Studies involving direct observation of authentic feedback in hospitals are rare. Observational studies are highly valuable, as they provide primary evidence of what actually happens in everyday clinical education. Direct observation can be achieved either by researchers observing the activity or via video-observation. We identified only a few previous direct observation studies: these involved junior learners (medical students or junior residents) in a few specialties (internal or family medicine) involving formal or informal feedback (in outpatient clinics, on a ward, or following summative simulated clinical scenarios) [11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18]. An additional single study involved physiotherapy students during formal mid- or end-of-attachment feedback [19]. The scarcity of observational studies may be related to the time consuming nature, difficulty in arranging observers or video recording to coincide with feedback meetings slotted into busy schedules, or the reticence of participants to be observed or recorded. These studies reported that typically educators make comments on specific aspects of performance, teach important concepts, and describe or demonstrate how the learner can improve. However educators tend to speak most of the time, ask the learner for their self-assessment but then do not respond to it, avoid corrective comments and do not routinely create actions plans. However these findings may no longer reflect current practice. In addition, no study captured the diversity of clinical educators and learners that work in a hospital environment.

따라서 우리는 직장 기반 학습 환경에서 [현대 교육자의 피드백 관행을 검토]하기 위해 자체 녹화된 비디오를 통해 병원 교육에서 진정한 공식 피드백 에피소드를 직접 관찰하기 시작했다. 이는 기회를 명확하게 하고 전문 개발 교육의 설계를 알릴 수 있다. 호주에서는 의료 전문 교육이 병원에 집중되어 입원 병동과 외래 진료소를 통합하고 있으며, 주요 전문 외래 환자 센터는 드물고 가족 의료 진료소는 상대적으로 작다. 바람직한 피드백 요소가 직업에 특정되지 않기 때문에 병원에 존재하는 다양성의 특징인 다양한 참가자를 모집했다. 우리는 완전한 피드백 상호작용을 포착하기 위해 공식적인 피드백 세션을 목표로 삼았다. 그런 다음 고품질 피드백을 위해 권장되는 관찰 가능한 일련의 교육자 행동을 사용하여 교육자 피드백 관행의 구성을 분석했다(표 1 참조) [20]. 이를 통해 덜 구조적이고 더 탐색적인 접근법이 사용되었던 이전 연구와 달리 포괄적인 행동 지표 세트를 사용하여 수집된 첫 번째 데이터 세트를 체계적으로 분석할 수 있었다. 이 프레임워크는 학습자의 참여, 동기 부여 및 개선을 지원함으로써 학습자의 결과를 향상시키는 것으로 간주되는 25가지 개별 관찰 가능한 교육자 행동을 개략적으로 설명한다(표 1 참조)[20]. 우리 팀의 이 초기 출판물은 학습자 결과를 향상시키기 위해 경험적 정보에 의해 입증된 교육자의 역할의 뚜렷한 요소를 식별하기 위한 광범위한 문헌 검토로 시작하여 관찰 가능한 행동으로 운영되고 전문가와 함께 델파이 프로세스를 통해 개선되는 방법을 설명했다.

Therefore we set out to directly observe authentic formal feedback episodes in hospital training, via self-recorded videos, to review contemporary educators’ feedback practice in workplace-based learning environments. This could then clarify opportunities and inform the design of professional development training. In Australia, health professions training is concentrated in hospitals, integrating both inpatient wards and outpatient clinics; major dedicated specialist outpatient centres are rare and family medicine clinics are relatively small. We recruited a range of participants, characteristic of the diversity present in hospitals, as desirable feedback elements are not profession specific. We targeted formal feedback sessions to capture complete feedback interactions. We then analysed the composition of educators’ feedback practice using a comprehensive set of observable educator behaviours recommended for high quality feedback (see Table 1) [20]. This enabled a systematic analysis of the first set of data gathered using a comprehensive set of behavioural indicators, in contrast to previous studies in which less structured and more exploratory approaches were used. This framework outlines 25 discrete observable educator behaviours considered to enhance learner outcomes by engaging, motivating and assisting a learner to improve (see Table 1) [20]. This earlier publication by our team described how these items were developed, starting with an extensive literature review to identify distinct elements of an educator’s role substantiated by empirical information to enhance learner outcomes, then operationalised into observable behaviours and refined through a Delphi process with experts.

| 방향 및 프로세스 Orientation and Process |

|

| 1. 관찰된 성과를 기준으로 합니다. 1. Based on observed performance |

|

| 교육자의 논평은 관찰된 성과에 기초했다. The educator’s comments were based on observed performance |

|

| 2. 적시 피드백 2. Timely feedback |

|

| 교육자는 가능한 한 빨리 성과에 대해 논의하겠다고 제안했다. The educator offered to discuss the performance as soon as practicable |

|

| 3. 피드백 목적 명확 3. Feedback purpose clear |

|

| 교육자는 피드백의 목적이 학습자의 성과 향상을 돕는 것이라고 설명했습니다. The educator explained that the purpose of feedback is to help the learner improve their performance |

|

| 4. 비판적이지 않은 분위기 조성: '도움을 주기 위해 여기에 있다.' 4. Establish a non-judgmental atmosphere: ‘here to help’ |

|

| 교육자는 기술을 개발하는 동안 일부 측면이 개선될 것으로 기대되며 교육자는 비판이 아니라 도움을 주기 위해 여기에 있다고 지적했다. The educator indicated that while developing a skill, it is expected that some aspects can be improved and the educator is here to help, not criticise |

|

| 5. 피드백 프로세스를 명확히 하여 학습자가 무엇을 기대해야 하는지 알 수 있도록 합니다. 5. Clarify feedback process, so learner knows what to expect |

|

| 교육자는 피드백 토론을 위한 의도된 프로세스를 설명했습니다. The educator described the intended process for the feedback discussion |

|

| 학습자 중심의 초점 Learner-centred Focus |

|

| 6. 대화 장려 6. Encourage dialogue |

|

| 교육자는 학습자가 대화형 토론에 참여하도록 권장했습니다. The educator encouraged the learner to engage in interactive discussions |

|

| 7. 학습자의 우선순위를 찾습니다. 7. Seek learner’s priorities |

|

| 교육자는 학습자에게 관찰 및 피드백 토론을 위한 학습 우선순위에 대해 질문하고 응답했습니다. The educator asked the learner about their learning priorities for the observation and feedback discussion, and responded to them |

|

| 8. 학습자가 '스스로 해결'하도록 유도합니다. 8. Encourage learner to ‘work it out for themselves’ |

|

| 교육자는 피드백 토론 중에 학습자가 문제와 가능한 해결책을 고려하도록 권장했습니다. The educator encouraged the learner to consider the issues and possible solutions during the feedback discussion |

|

| 9. 학습자가 한계를 은폐하기보다는 학습에 집중하도록 유도합니다. 9. Encourage learner to focus on learning, rather than trying to cover up limitations |

|

| 교육자는 학습자가 해결책을 개발하는 데 도움을 줄 수 있도록 학습자가 어려움을 논의하고 성과에 대해 질문하도록 권장했습니다. The educator encouraged the learner to discuss difficulties and ask questions regarding the performance so the educator could help the learner to develop solutions |

|

| 10. 학습자의 정서적 반응을 인정하라 10. Acknowledge learner’s emotional response |

|

| 교육자는 학습자가 표현한 감정을 인식하고 적절히 대응하였다. The educator acknowledged and responded appropriately to emotions expressed by the learner |

|

| 11. '진심으로 관심을 갖는다' 11. ‘Best interests at heart’ |

|

| 교육자는 학습자에 대한 존경과 지원을 보여주었다. The educator showed respect and support for the learner |

|

| 성능 분석 Performance Analysis |

|

| 12. 자기평가의 가치를 명확히 한다. 12. Clarify the value of self-assessment |

|

| 교육자는 학습자가 자기 평가의 이점에 대해 무엇을 이해하고 명확하게 설명하는 데 도움을 주었는지 물었습니다. The educator asked what the learner understood about the benefits of self-assessment and helped clarify |

|

| 13. 학습자 자기 평가 13. Learner self-assessment |

|

| 교육자는 학습자에게 학습자 성과와 목표 성과 간의 주요 유사점과 차이점을 식별하도록 요청했습니다. The educator asked the learner to identify key similarities and differences between the learner’s performance and the target performance |

|

| 14. 목표 성과 및 추론 명확 14. Target performance and reasoning clear |

|

| 교육자는 학습자에게 목표 성과의 주요 특징을 명확히 설명하고 그 이유를 설명했습니다. The educator clarified with the learner key features of the target performance and explained the reasoning |

|

| 15. 명확한 성과 차이를 포함한 교육자 평가 15. Educator assessment, including clear performance gap |

|

| 교육자는 학습자의 성과와 목표 성과 간의 유사점과 차이점을 학습자에게 명확히 설명하였다. The educator clarified with the learner similarities and differences between the learner’s performance and the target performance |

|

| 16. 교육자는 몇 가지 중요한 문제에 대한 의견을 말합니다. 16. Educator comments on a few, important issues |

|

| 교육자의 의견은 성과 향상을 위한 주요 문제에 초점을 맞췄다. The educator’s comments focused on key issues for improving the performance |

|

| 17. 구체적인 사례('무슨 일이') 17. Specific instance (‘what happened’) |

|

| 먼저 교육자는 중립적인 언어를 사용하여 학습자가 한 일(행동, 결정 또는 행동)과 그 결과를 설명했습니다. First the educator described, using neutral language, what the learner did (action, decision or behaviour), and the consequences |

|

| 18. 교육자의 관점 명확 ('왜 중요한가') 18. Educator’s perspective clear (‘why it matters’) |

|

| 교육자는 학습자가 우려하는 이유를 포함하여 학습자의 행동에 대한 관점을 명확하게 설명했습니다. The educator clearly explained their perspective on the learner’s actions, including the reason for their concern |

|

| 19. 교육자는 학습자의 관점을 탐구한다('왜' 학습자는 자신이 했던 대로 행동했는가). 19. Educator explores learner’s perspective (‘why’ the learner acted as they did) |

|

| 교육자는 학습자의 관점과 추론을 탐구하여 학습자의 행동(예: 학습자가 무엇을 하려고 했는지, 고려된 옵션/어려움에 직면한 어려움)의 근거를 밝힙니다. The educator explored the learner’s perspective and reasoning to reveal the basis for the learner’s actions (e.g. what was the learner trying to do and options considered/ difficulties encountered) |

|

| 20. 사람이 아닌 행동에 집중하라 ('is'가 아닌 'did'에) 20. Focus on actions, not the person (‘did’ not ‘is’) |

|

| 교육자의 의견은 개인적 특성이 아닌 학습자의 행동에 초점이 맞춰졌다. The educator’s comments were focused on the learner’s actions not personal characteristics |

|

| 실행 계획 Action Plan |

|

| 21. 학습 우선순위 선택: 학습자에게 가장 유용한(중요하고 관련성 있는) 것 21. Select learning priorities: most useful (important and relevant) for the learner |

|

| 교육자는 학습자가 개선할 성과의 몇 가지 주요 측면을 선택할 수 있도록 도와주었습니다. The educator helped the learner to select a couple of key aspects of the performance to improve |

|

| 22. 실행 계획을 개발하라: 어떻게 해야 하는가! 22. Develop the action plan: how to do it! |

|

| 교육자는 학습자가 성과를 개선할 수 있는 방법을 연구하고 성과를 달성하기 위한 실질적인 단계를 명시할 수 있도록 도와주었습니다. The educator helped the learner to work how they could improve their performance and specify the practical steps to achieve it |

|

| 23. 학습자가 계획을 이해하는지 확인합니다. 23. Check the learner understands the plans |

|

| 교육자는 학습자가 학습 목표와 실행 계획을 이해했는지 확인하고, 이를 자신의 말로 요약하도록 요청했습니다. The educator checked if the learner understood their learning goals and action plan, by asking them to summarise it in their own words |

|

| 24. 학습자가 근거를 이해하고 있는지 확인합니다. '왜 더 나은지' 24. Checks the learner understands the rationale: ‘why it’s better’ |

|

| 교육자는 학습자가 학습 목표와 실행 계획의 근거를 이해했는지 확인했습니다. The educator checked if the learner understood the rationale for their learning goals and action plan |

|

| 25. 피드백의 영향을 검토할 기회 계획 25. Plan opportunities to review the impact of the feedback |

|

| 교육자는 학습자가 진행 상황을 검토할 수 있는 후속 기회에 대해 학습자와 논의했습니다. The educator discussed with the learner possible subsequent opportunities for the learner to review their progress |

|

우리는 학습자 중심의 패러다임을 강력하게 지지하지만, 교육자들이 학습자들이 안전함을 느끼고 참여하며 성공적으로 기술을 향상시킬 수 있는 여건을 조성하기 위해 영향력 있는 위치에 있기 때문에 피드백에서 교육자의 역할에 초점을 맞추기로 결정했다. 우리는 특정 피드백 에피소드가 관련된 개인, 맥락 및 문화에 의해 형성된다는 것에 동의하지만, 학습자의 동기와 성과를 향상시킬 수 있는 능력을 촉진하는 전략은 여전히 관련이 있다. [권장 피드백 행동]은 로봇 방식으로 구현하기 위한 것이 아니라, 상호 작용 전반에 걸쳐 가장 유용한 측면의 우선순위를 지정하여 특정 상황에 맞게 조정된다. 품질 피드백의 핵심 부분에는 목표 성과를 명확히 하고, 이 목표와 비교하여 학습자의 성과를 분석하며, 개선을 위한 실질적인 단계를 개략적으로 설명하고, 진행 상황을 검토하는 방법을 계획하는 것이 포함됩니다 [4, 9, 21]. 가장 중요한 주제는 안전한 학습 환경 내에서 동기 부여 촉진[22,23,24,25], 능동적 학습[26,27,28] 및 협업[29,30,31,32]을 포함한다[10,33,34].

While we strongly endorse a learner-centred paradigm, we have chosen to focus on the educator’s role in feedback because educators are in a position of influence to create conditions that encourage learners to feel safe, participate and work out how to successfully improve their skills. We agree that specific feedback episodes are shaped by the individuals involved, the context and the culture, however strategies to promote a learner’s motivation and capability to enhance their performance remain relevant. Recommended feedback behaviours are not intended to be implemented in a robotic fashion but tailored to a particular situation by prioritising the most useful aspects throughout the interaction. The core segments of quality feedback include clarifying the target performance, analysing the learner’s performance in comparison to this target, outlining practical steps to improve and planning how to review progress [4, 9, 21]. Overarching themes include promoting motivation [22,23,24,25], active learning [26,27,28] and collaboration [29,30,31,32] within a safe learning environment [10, 33, 34].

연구 질문

Research question

본 연구에서 다루어진 연구 질문은 다음과 같다.

The research questions addressed in this study were:

- 병원 실무 환경에서 임상 교육자가 공식 피드백 세션에서 보여주는 행동은 무엇입니까?

- 이러한 행동이 공개된 피드백 권장 사항과 얼마나 밀접하게 일치합니까?

- What behaviours are exhibited by clinical educators in formal feedback sessions in hospital practice settings?

- How closely do these behaviours align with published recommendations for feedback?

방법들

Methods

연구 개요

Research overview

이 관찰 연구에서 선임 임상의(교육자)는 병원 환경에서 일상적인 임상 작업을 수행하는 주니어 임상의 또는 학생(학습자)을 관찰한 다음 후속 공식 피드백 세션 동안 자신들을 비디오로 촬영했다. 고품질 피드백에서 권장되는 일련의 교육자 행동을 기반으로 체크리스트를 사용하여 각 비디오를 분석했습니다(표 1 참조) [20].

In this observational study, senior clinicians (educators) observed junior clinicians or students (learners) performing routine clinical tasks in a hospital setting and then videoed themselves during the subsequent formal feedback session. We analysed each video using a check-list based on the set of educator behaviours recommended in high quality feedback (see Table 1) [20].

피드백 비디오는 2015년 8월과 2016년 12월 사이에 호주에서 가장 큰 대도시 교육 병원 네트워크 중 하나 내의 여러 병원에서 캡처되었다. 윤리 승인은 보건서비스(참고문헌 15,233L)와 대학 인간연구윤리위원회(참고문헌 2,015,001,338)에서 얻었다.

The feedback videos were captured at multiple hospitals within one of Australia’s largest metropolitan teaching hospital networks between August 2015 and December 2016. Ethics approval was obtained from the health service (Reference 15,233 L) and university human research ethics committees (Reference 2,015,001,338).

모집

Recruitment

의학, 간호, 물리치료, 직업치료, 언어치료, 사회복지 분야의 교육자(상급 임상의)와 그들과 함께 일하고 있는 학습자(추가 훈련을 받는 자격을 갖춘 보건 전문가 또는 학생)가 참여하도록 초대되었다. 전단지를 이용한 광범위한 연구 광고, 부서 관리 보조원이 배포한 이메일, 부서 회의에서의 짧은 프레젠테이션 및 보건 서비스 전반에 걸친 직원과의 대면 회의를 통해 광범위한 교육자를 구했다. 참여를 고려하기 위해서는 교육자가 광고에 응답하여 1차 연구원(CJ)에게 연락해야 했다. 교육자가 동의하면, 그들은 그들과 함께 일하는 모든 학습자들에게 전단지를 배포했고, 학습자들이 참여에 관심이 있다면 1차 연구원(CJ)에게 연락하라는 지침이 포함되어 있었다. 참가자들에게 롤링 광고를 통해 다양성을 추구했으며, 건강 직업 및 전문 분야, 성별 및 감독자 경험(교육자) 또는 훈련 수준(학습자) 등 주요 요인을 고려했다. 교육자와 학습자가 모두 동의한 후에는 두 사람에게 조언을 제공하고 일상적인 피드백 세션을 비디오로 녹화할 수 있도록 준비했습니다. 전체 피드백 만남을 기록하되, 시간은 약 10분을 목표로 설정하도록 요청받았지만 피드백 세션을 수행하는 방법에 대한 추가 지침은 제공되지 않았습니다. 참가자들은 비디오 분석에 사용된 고품질 피드백에 대해 권장된 25가지 교육자 행동을 보여주지 않았고, 현재 피드백 관행의 성격을 연구하는 것이 목적이었기 때문에 연구팀으로부터 피드백에 대한 다른 교육도 받지 못했다.

Educators (senior clinicians) across medicine, nursing, physiotherapy, occupational therapy, speech therapy and social work, and their learners (either qualified health professionals undertaking further training or students), who were working with them, were invited to participate. A broad range of educators were sought, via widespread advertising of the study using flyers, emails circulated by unit administration assistants, short presentations at unit meetings and face-to-face meetings with staff across the health service. To be considered for participation, an educator had to contact the primary researcher (CJ), in response to the advertisement. Once an educator consented, they distributed flyers to any learners working with them, with instructions to contact the primary researcher (CJ) if the learners were interested in participating. Diversity was sought by rolling advertising to participants, with consideration of key factors including health profession and specialty, gender and supervisor experience (educators) or training level (learners). Once an educator and a learner had both consented, the pair were advised and they made arrangements to video a routine feedback session. They were asked to record an entire feedback encounter and aim for a duration of approximately 10 minutes but were not given any additional instructions regarding how to conduct the feedback session. Participants were not shown the set of 25 educator behaviours recommended for high quality feedback used to analyse the videos nor given any other education on feedback from the research team, as the aim was to study the nature of current feedback practices.

동의하는 참가자들은 직장 기반 평가 또는 첨부 파일 종료 성과 평가와 관련된 다음 예정된 공식 피드백 세션에서 자신을 비디오로 녹화하기 위해 스마트폰이나 컴퓨터를 사용했다. 이 비디오는 이후 암호로 보호된 온라인 드라이브에 업로드되었으며 참가자들은 자신의 복사본을 삭제하라는 지시를 받았습니다. 비디오는 무작위 번호 생성기를 사용하여 번호가 매겨졌고 (이미지를 제외한) 비디오에는 개인 식별 정보가 포함되어 있지 않았다.

Consenting participants used a smart phone or computer to video-record themselves at their next scheduled formal feedback session related to either a workplace-based assessment or end-of-attachment performance appraisal. This video was subsequently uploaded to a password protected on-line drive and participants were instructed to delete their copy. The videos were numbered using a random number generator and the videos (other than the images) contained no personal identifying information.

비디오 분석

Video analysis

평가자 그룹은 감독 및 피드백에 대한 광범위한 경험이 있는 상급 교육/교육 연구 역할의 모든 보건 전문가(의료 2명, 물리치료 4명)였다. 각 평가자는 각 비디오를 독립적으로 분석하고 관찰 결과를 고품질 피드백을 위해 권장되는 25가지 교육자 행동과 비교했다(표 1 참조) [20]. 각 교육자 행동은 0 = 보이지 않음, 1 = 어느 정도 또는 가끔만 수행됨, 2 = 일관성 있게 수행됨으로 평가되었다.

The group of raters were all health professionals (two medical, four physiotherapy) in senior education/educational research roles with extensive experience in supervision and feedback. Each rater analysed each video independently and compared their observations with the set of 25 educator behaviours recommended for high quality feedback (see Table 1) [20]. Each educator behaviour was rated 0 = not seen, 1 = done somewhat or done only sometimes, 2 = consistently done.

사전 시범 연구에서, 우리는 그 기구를 사용하여 세 개의 비디오를 평가했다. 그런 다음 우리는 등급에 대해 논의하고 항목의 해석과 등급 척도의 사용에서 차이를 식별하기 위해 만났다. 일치를 장려하고 항목의 의미를 명확히 하는 전략이 개발되었다. 특히 '행동 2: 시기적절한 피드백을 확인했다.'는 교육자가 가능한 한 빨리 성과를 논의하자고 제안한 것은 관찰할 수 없었기 때문에 제외되었다. '행동 10: 학습자의 감정적 반응을 인정합니다'에 대해서, 교육자는 학습자가 표현한 감정을 인정하고 적절히 대응하였으며, 우리는 이것이 다음과 같은 상황에서 '2'(당연히 수행됨)로 평가되기로 결정했다.

- i) 학습자 감정의 암묵적 또는 명시적 지표(예: 불안 또는 방어)가 감지되고 교육자가 이를 인정하고 이에 주의를 기울인 경우 또는

- ii) 교육자와 학습자 사이의 이러한 정서적 균형이 교육자가 단서를 읽고 그에 따라 행동할 것을 요구한다고 가정한 것처럼, 만남 내내 정서적 균형이 관찰되었다.

결과적으로 총 항목 점수는 0에서 48 사이가 될 수 있습니다.

In a preparatory pilot study, we rated three videos using the instrument. We then met to discuss ratings and to identify differences in interpretation of items and the use of the rating scale. Strategies to encourage concordance and to clarify item meaning were developed. In particular we identified that Behaviour 2: Timely feedback: The educator offered to discuss the performance as soon as practicable was not observable, so it was excluded. For Behaviour 10: Acknowledge learner’s emotional response: The educator acknowledged and responded appropriately to emotions expressed by the learner, we decided that this would be rated as ‘2’ (consistently done) in the following situations

- i) if implicit or explicit indicators of learner emotion (such as anxiety or defensiveness) were detected, and the educator acknowledged, and attended to this, or

- ii) if emotional equilibrium was observed throughout the encounter, as we assumed that this emotional balance between educator and learner required the educator to be reading cues and acting accordingly.

Subsequently the total item score could range from 0 to 48.

데이터 분석

Data analysis

그 데이터는 두 가지 관점을 제공했다.

- i) 개별 교육자의 관행: 고품질 피드백에서 권장되는 행동 중 몇 가지가 각 비디오에서 관찰되었으며

- ii) 교육자 그룹 전체에 걸친 관행: 어떤 행동이 일반적으로 수행되었는지.

비디오에서 볼 수 있는 각 개별 교육자의 실습을 특성화하기 위해, 각 항목의 점수를 평가자들 사이에서 평균화한 다음 합계하여 총점을 주었다. 전체 교육자 그룹에서 특정 교육자 행동이 얼마나 자주 관찰되었는지 설명하기 위해, 각 항목에 대한 평균 점수와 표준 편차를 모든 비디오에 걸쳐 계산했다[35]. 평가자 간 신뢰성을 평가하기 위해 Spearman's rho를 사용하여 각 비디오에 대한 총 점수를 검사자 쌍 간의 일치성에 대해 평가했다.

The data provided two perspectives

- i) on an individual educator’s practice: how many of the behaviours recommended in high quality feedback were observed in each video and

- ii) across the whole group of educators: which behaviours were commonly performed.

To characterise each individual educator’s practice seen in a video, the scores for each item were averaged across assessors and then summed to give a total score. To describe how commonly specific educator behaviours were observed amongst the whole group of educators, the mean score and standard devation for each item was calculated across all the videos [35]. To assess inter-rater reliability, total scores for each video were assessed for concordance between examiner pairs using Spearman’s rho.

결과.

Results

5개가 제외된 후 36개의 피드백 비디오를 분석할 수 있었다. 2개는 불완전하기 때문에(스마트폰 메모리 부족), 3개는 녹음의 기술적 오류 때문에(오디오 불분명, 시간 경과 포맷 사용, 참가자가 보이지 않음).

Thirty-six feedback videos were available for analysis after five were excluded: two because they were incomplete (insufficient smartphone memory) and three because of technical errors with recording (audio unclear, time-lapse format used, participants not visible).

비디오 참가자

Video participants

34명의 교육자가 참여했으며, 주요 특성(보건 직업 및 전문 분야, 감독자 경험 기간 및 성별)에 걸쳐 다양성을 갖추고 있습니다. 4명의 간호사, 4명의 물리치료사, 26명의 상급 의료진(3명의 마취사, 3명의 응급의사, 2명의 방사선사, 1명의 소아과 의사, 6명의 의사, 3명의 정신과 의사, 3명의 산부인과 의사, 1명의 안과의사, 4명의 외과의사)이 있었다. 여성 교육자는 18명(52.9%), 남성 교육자는 16명(47.1%)이었다. 교육자 경력이 5년 이하인 사람은 14명(41.2%), 6~10년 이상인 사람은 11명(32.3%), 10년 이상인 사람은 9명(26.5%)이었다.

Thirty-four educators participated, with diversity across key characteristics (health profession and specialty, length of supervisor experience and gender). There were four nurses, four physiotherapists and 26 senior medical staff (three anaesthetists, three emergency physicians, two radiologists, one paediatrician, six physicians, three psychiatrists, three obstetrician-gynaecologists, one opthalmologist and four surgeons). There were 18 (52.9%) female and 16 (47.1%) male educators. Fourteen (41.2%) educators had 5 years or less educator experience, 11 (32.3%) had six to 10 years and 9 (26.5%) had more than 10 years.

35명의 학습자가 주요 특성(건강 직업 및 전문 분야, 훈련 수준 및 성별)에 걸쳐 다양하게 참여했습니다. 수강생은 9명(25.7%), 사후자격 5년 이하 임상 9명(25.7%), 사후자격 6년 이상 임상 15명(42.9%), 상급 임상 2명(5.7%)이었다. 학습자는 23명이 여성(65.7%), 12명(34.3%)이었다. 모든 참가자들은 각각의 교육자들과 같은 보건 직업과 전문 분야에서 왔다.

Thirty-five learners participated with diversity across key characteristics (health profession and specialty, training level and gender). There were 9 (25.7%) students, 9 (25.7%) clinicians who were five years or less post-qualification, 15 (42.9%) clinicians 6 years or more post-qualification and 2 (5.7%) senior clinicians. Twenty-three learners were (65.7%) female and 12 (34.3%) were male. All participants were from the same health profession and specialty as their respective educators.

피드백 세션은 11개(30.6%)의 비디오에서 첨부파일 중간 또는 종료 평가와 25개(69.4%)의 비디오에서 특정 과제(절차적 기술, 임상 평가, 사례 토론 또는 발표 등)와 관련이 있었다. 피드백 세션 중 11회(30.6%)는 대학 또는 전문 의과대학 등 기관의 공식 피드백 양식을 사용하였으며, 대부분 첨부파일 중간 또는 첨부파일 종료 평가였다. 대부분의 평가는 형식적이었지만 일부는 프로그램적 평가 원칙에 따라 종적 훈련 프로그램의 구성요소로서 종합적이었다[3].

The feedback session was related to a mid- or end-of-attachment assessment in 11 (30.6%) videos and to a specific task (such as a procedural skill, clinical assessment, case discussion or presentation) in 25 (69.4%) videos. An official feedback form from an institution such as a university or specialist medical college was used in 11 (30.6%) of the feedback sessions, most of which were mid- or end-of-attachment assessments. Most of the assessments were formative but some were summative as a component of longitudinal training programs aligned with programatic assessment principles [3].

피드백 중 교육자 행동 분석

Analysis of educator behaviours during feedback

각 비디오는 4~6명의 평가자에 의해 분석되어 총 174개의 평가 세트를 제공했다(두 평가자에 의한 프로젝트의 예상치 못한 시간 제한 분석). 누락된 데이터는 드물었습니다(0.2%의 누락).

Each video was analysed by four to six raters providing a total of 174 sets of ratings (unexpected time constraints on the project limited analysis by two raters). Missing data were uncommon (0.2% ratings missing).

평가자 간 신뢰성

Inter-rater reliability

비교를 위한 데이터를 최대화하기 위해 모든 비디오를 분석한 평가자(4/6)에 대해 총 점수에 대한 평가자 간 신뢰성 범위를 계산했다. Spearman's rho는 0.62–0.73이었다. 나머지 두 평가자는 36개 동영상 중 10개(28%)와 21개(58%) 등급을 매겼으며, 평가자 간 신뢰도 분석에는 포함되지 않았다.

To maximise data for comparison, the inter-rater reliability range for total scores was calculated for raters (4/6) who analysed all the videos: Spearman’s rho was 0.62–0.73. The other two raters rated 10 (28%) and 21 (58%) of the 36 videos and were not included in the inter-rater reliability analysis.

개별 교육자의 피드백 실무

Individual educator’s feedback practice

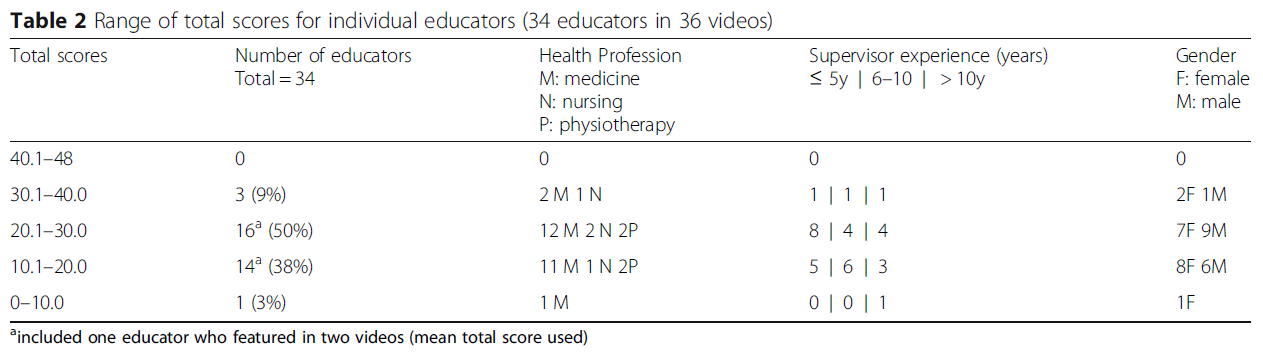

개별 교육자의 관행과 각 비디오에서 권장되는 교육자 행동 중 몇 가지가 관찰되었는지에 대해 자세히 알아보기 위해, 우리는 각 비디오에 대한 총 점수(관찰된 각 행동에 대한 등급의 합, 모든 평가자에 걸쳐 평균)를 계산했다. 총 점수는 최소 5.7점(11.9%)에서 최대 34.2점(71.3%)까지 다양했으며, 교육자들의 평균 점수는 최대 48점에서 22.5점(46.9%, SD 6.6)이었다. 보다 상세한 분석(표 2 참조)을 통해 사실상 모든 교육자(88%)가 총점이 10점에서 30점 사이인 것으로 나타났다. 비록 서로 다른 특성에 걸쳐 성과를 비교하는 것이 우리의 의도는 아니었지만(비교를 가능하게 하기 위해 각 그룹에 충분한 표본 크기가 필요함), 건강 전문가, 경험 및 성별이 점수 범위에 걸쳐 상당히 고르게 분포되어 있는 것으로 보였다.

To learn more about individual educator’s practice and how many of the recommended educator behaviours were observed in each video, we calculated a total score (sum of rating for each observed behaviour, averaged across all assessors) for each video. Total scores ranged from a minimum of 5.7 (11.9%) to a maximum of 34.2 (71.3%), with a mean score across educators of 22.5 (46.9%, SD 6.6), from a maximum possible score of 48. More detailed analysis (see Table 2) revealed virtually all the educators (88%) had a total score between 10 and 30. Although it was not our intention to compare performance across different characteristics (which would require sufficient sample sizes for each group, to enable comparisons), there seemed to be a fairly even spread of health professions, experience and gender across the score ranges.

전체 교육자 그룹에 걸쳐 특정 교육자의 행동 빈도

Frequency of specific educator behaviours across the whole group of educators

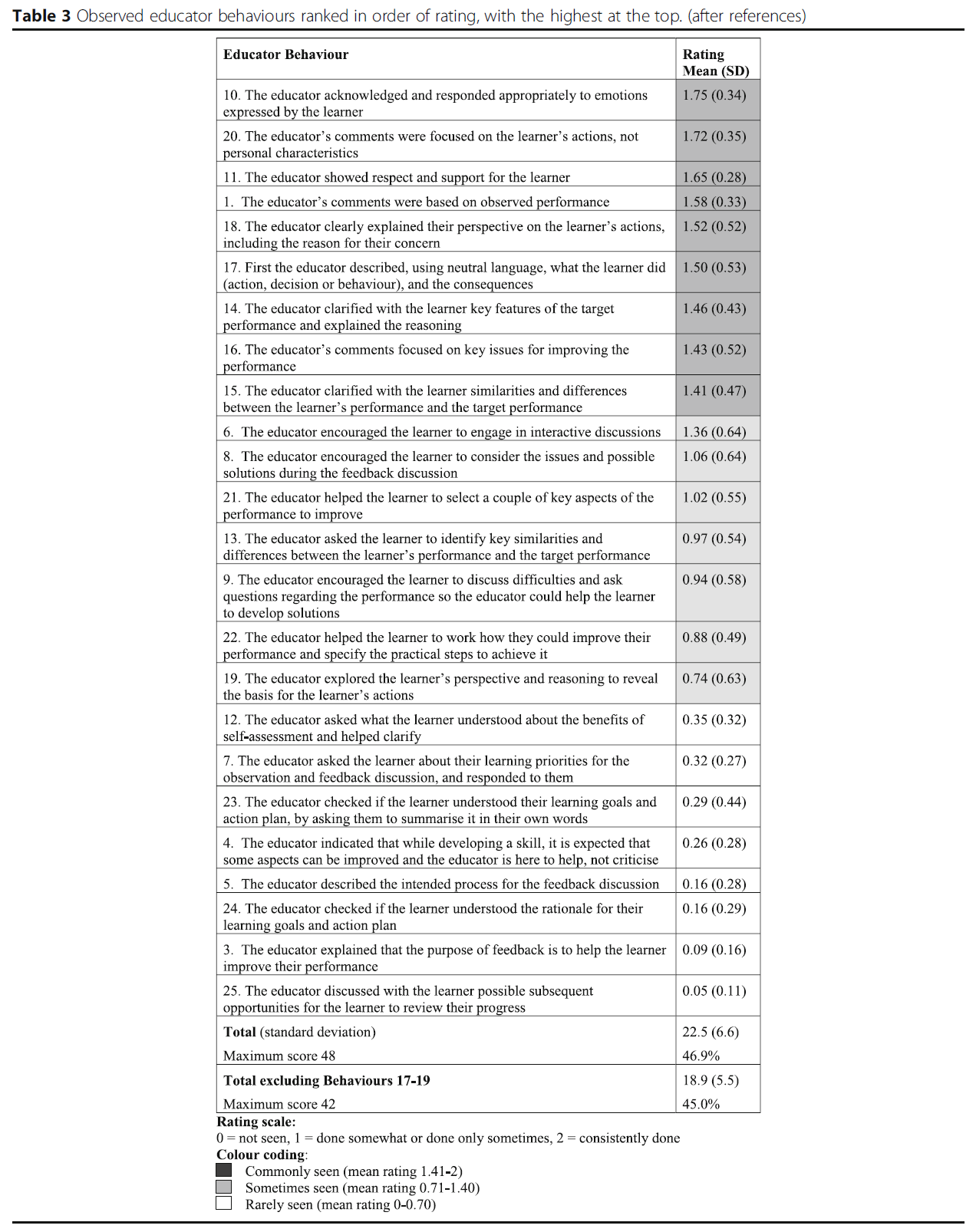

모든 참가자들 사이에서 구체적인 피드백 행동이 얼마나 자주 관찰되었는지 탐구하기 위해, 우리는 모든 비디오에서 각 행동에 대한 평균 평점 점수를 계산했다. 표 3은 각 행동에 대한 등급 평균(SD)을 가장 많이 관찰된 것부터 가장 적게 관찰된 것까지 순위를 매겼다. 일부 행동은 거의 모든 비디오(최고 평균 등급 1.75, 행동 10)에서 관찰된 반면, 다른 행동은 매우 드물게 관찰되었다(최저 평균 등급 0.05, 행동 25).

To explore how often specific feedback behaviours were observed amongst all participants, we calculated the mean rating score for each behaviour across all the videos. Table 3 displays the rating mean (SD) for each behaviour, ranked from most to least often observed. Some behaviours were seen in almost every video (highest mean rating 1.75, Behaviour 10) while others were very infrequently observed (lowest mean rating 0.05, Behaviour 25).

가장 흔하게 관찰되는 교육자 행동 중에서(상위 3위: 평균 평점 1.41–2.0), 학습자의 성과에 대한 교육자의 평가와 가장 관련이 있다. 교육자들은 일반적으로

- 학습자 성과에 대한 의견을 학습자의 행동(행동 1, 17, 20)과 연결시키고,

- 개선을 위한 중요한 측면(행동 16)에 초점을 맞추고,

- 학습자의 성과와 목표 성과 간의 유사점과 차이점(행동 15)을 설명하고,

- 무엇을 해야 하는지, 그 이유를 명확히 했다(행동 14).

일반적으로 볼 수 있는 다른 두 가지 행동은 안전한 학습 환경을 만드는 것과 관련이 있습니다. 여기에는 다음이 포함되었다.

- 존중과 지지를 보여주는 것(행동 11)

- 학습자가 표현하는 감정에 적절하게 반응하는 것(행동 10)

Amongst those educator behaviours most commonly observed (top third: mean rating score 1.41–2.0), most related to the educator’s assessment of the learner’s performance. Educators commonly

- linked comments regarding learner performance to the learner’s actions (Behaviours 1, 17, 20),

- focused on important aspects for improvement (Behaviour 16),

- described similarities and differences between the learner’s performance and the target performance (Behaviour 15), and

- clarified what should be done and why (Behaviour 14).

The other two behaviours commonly seen related to creating a safe learning environment. These included

- showing respect and support (Behaviour 11) and

- responding appropriately to emotions expressed by the learner (Behaviour 10)

교육자 행동의 중간 계층은 간헐적으로 나타났으며(평균 평점 0.71–1.40) 교육자들은 학습자들이 자신의 생각, 의견, 아이디어를 기여하고 불확실성을 드러내도록 장려하는 것과 관련이 있었다. 이것들은 포함되었다.

- 학습자가 대화형 토론에 참여하도록 유도합니다(행동 6).

- 스스로 해결하려고 노력한다(행동 8).

- 자신의 성과를 분석한다(행동 13).

- 행동의 배경에 있는 이유를 밝힙니다(행동 19).

- 어려움을 제기하고 질문을 한다(행동 9).

- 개선해야 할 가장 중요한 측면을 선택하는 데 참여한다(행동 21).

- 실행 계획을 통해 이를 수행하는 실질적인 방법(행동 22).

The middle band of educator behaviours were seen intermittently (mean rating score 0.71–1.40) and related to educators encouraging learners to contribute their thoughts, opinions and ideas, and to reveal their uncertainties. These included

- encouraging the learner to participate in interactive discussions (Behaviour 6),

- try to work things out for themselves (Behaviour 8),

- analyse their own performance (Behaviour 13),

- reveal the reasoning behind their actions (Behaviour 19),

- raise difficulties and ask questions (Behaviour 9), and

- participate in choosing the most important aspects to improve (Behaviour 21) and

- practical ways to do this through an action plan (Behaviour 22).

교육자 행동의 가장 낮은 범위는 거의 나타나지 않았으며(평균 평점 0–0.7) 주로 피드백 세션의 설정 및 종료와 관련이 있었다.

세션을 시작할 때, 안전한 학습 환경을 조성하기 위한 일환으로 권장되는 교육자 행동에는

- 피드백의 목적이 학습자의 향상을 돕는 것임을 명시적으로 설명하고(행동 3),

- 세션에 제안된 개요를 설명하고(행동 5)

- 실수는 학습 과정의 일부이며, 피할 수 없는 것임을 수용한다는 내용이 포함되었습니다. (행동 4).

세션 결론 또는 마무리의 일환으로,

- 권장되는 행동에는 학습 목표와 실행 계획에 대한 학습자의 이해를 확인하는 것(행동 23, 24),

- 진행 중인 학습을 촉진하기 위해 진행 상황을 검토할 수 있는 향후 기회에 대해 논의하는 것(행동 25)이 포함되었다.

그 밖에 거의 볼 수 없었던 교육자 행동으로는

- 학습자의 학습 우선순위를 통합한 교육자(행동 7)와

- 자기평가의 가치에 대한 학습자의 이해를 증진시키는 교육자(행동 12)가 있었다.

The lowest band of educator behaviours were rarely seen (mean rating score 0–0.7) and primarily related to the set up and conclusion of a feedback session.

At the start of the session, as part of creating a safe learning environment, the recommended educator behaviours included

- explicitly explaining that the purpose of the feedback was to help the learner improve (Behaviour 3),

- describing the proposed outline for the session (Behaviour 5), and

- stating their acceptance that mistakes are an inevitable part of the learning process (Behaviour 4).

As part of the session conclusion or wrap-up, the recommended behaviours included

- checking a learner’s understanding of the learning goals and action plan (Behaviours 23, 24), and

- discussing future opportunities to review progress, to promote ongoing learning (Behaviour 25).

The other educator behaviours that were rarely seen included the educator

- incorporating the learner’s learning priorities (Behaviour 7) and

- promoting the learner’s understanding of the value of their self-assessment (Behaviour 12).

논의

Discussion

교육자의 피드백 관행에 대한 이 연구에서, 우리는 개별 교육자의 관행과 교육자 그룹 전체에서 구체적인 권장 행동이 얼마나 자주 관찰되는지 모두에서 상당한 차이를 발견했다. 이는 병원 기반 교육에서 공식 피드백 에피소드 동안 '현재 발생하는 일'에 대한 귀중한 통찰력을 제공한다. 이러한 통찰력은 상당한 영향을 미칠 수 있는 잠재력을 가진 교육자 개발에 대한 향후 연구의 기회를 명확히 한다. 또한 권장 행동은 교육자가 이러한 품질 표준을 이해하고 제정하는 데 도움이 될 수 있는 특정 전략의 레퍼토리를 제공한다.

In this study of educators’ feedback practice, we found considerable variation in both an individual educator’s practice and how frequently specific recommended behaviours were observed across the group of educators. This provides valuable insights into ‘what currently happens’ during formal feedback episodes in hospital-based training. These insights clarify opportunities for future research into educator development with the potential for substantial impact. Furthermore the recommended behaviours offer a repertoire of specific strategies that may assist educators to understand and enact these quality standards.

교육자 그룹 전체에서 관찰된 특정 권장 행동의 빈도

Frequency of specific recommended behaviours observed across the group of educators

우리는 교육자들이 일상적으로 학습자의 성과에 대한 평가를 제공하고 과제가 어떻게 보여야 하는지 설명하는 것을 발견했지만, 학습자들에게 자기 평가나 실행 계획의 개발을 간헐적으로 요청했을 뿐이다. 이는 학습자의 성과에 대해 [교육자의 분석이 지배적인 문화]를 반영하는 것으로 보인다[36]. 이러한 결과는 이전의 관찰 연구와 피드백 양식의 결과와 일치한다[11, 12, 17, 19, 37, 38, 39, 40]. 이는 이러한 누락이 수 년 전에 마지막으로 보고된 이후 임상 환경에서 일반적인 피드백 관행이 거의 동일하게 유지되었음을 시사한다.

We found that educators routinely gave their assessment of the learner’s performance and described what the task should look like, but only intermittently asked learners for self-assessment or development of an action plan. This seems to reflect a culture in which the educator’s analysis of the learner’s performance predominates [36]. These findings echo those from earlier observational studies and feedback forms [11, 12, 17, 19, 37,38,39,40]. This suggests that typical feedback practice in the clinical setting has remained much the same since these omissions were last reported years ago.

[자기 평가]는 자기 조절 학습 및 평가 판단의 핵심 요소이며, 이는 성찰, 독립 학습 및 성취를 촉진합니다 [28,29,30]. 학습자 자기 평가를 위한 초대장은 학습자에게 자신의 작업을 먼저 판단하고 자신이 가장 도움을 받고 싶어하는 것이 무엇인지를 나타낼 수 있는 기회를 제공합니다 [33, 41, 42]. 자기 평가는 학습자가 자신의 성과를 교육자보다 훨씬 더 높게 평가할 경우 교육자에게 부정적인 정서적 반응과 교육자의 의견에 대한 거부 가능성을 경고할 수 있다[43]. 자가 평가는 학습자가 관찰된 성과와 원하는 성과 표준에 대한 전문가의 이해를 바탕으로 이해를 교정함으로써 평가 판단력을 향상시킬 수 있는 기회를 제공한다. 학생 피드백 리터러시에 대한 최근 연구는 학습자가 피드백을 평가하고 해석하고 활용할 수 있도록 지원하기 위해, 양질의 작업 특성에 대해 논의할 수 있는 기회를 전략적으로 설계하는 것의 중요성을 강조했다[45].

Self-assessment is a key component in self-regulated learning and evaluative judgement, which promotes reflection, independent learning and achievement [28,29,30]. Invitations for learner self-asssessment provide learners with the opportunity to judge their work first and indicate what they most want help with [33, 41, 42]. Self-assessments can alert the educator to the potential for a negative emotional reaction and rejection of the educator’s opinion if the learner rates their performance much higher than the educator [43]. Self -assessment offer opportunities for learners to enhance their evaluative judgement by calibrating their understanding against an expert’s understanding of the observed performance and the desired performance standards [4, 44]. Recent work on student feedback literacy has highlighted the importance of strategically designing opportunities for learners to make judgements and discuss characteristics of quality work, to assist them to appreciate, interpret and utilise feedback [45].

[실행 계획]이 계속해서 자주 무시된다는 사실도 마찬가지로 심각한 주의를 기울여야 한다. 교육자가 학습자에게 실행 계획을 수립하도록 지원하고 안내하지 않는다면, 학습자는 피드백 정보를 성과 개선으로 전환하는 방법을 스스로 해결해야 하는 어려운 과제를 떠안게 됩니다[21]. 또한, 학습자들이 성과 격차에 대해 들었을 때, 개선 방법을 모른다면, 그들의 고통은 더 악화될 수 있다[46].

The fact that an action plan continues to be frequently neglected similarly warrants serious attention. If educators do not support and guide learners to create an action plan, learners are left with the difficult task of working out by themselves how to transform feedback information into performance improvement [21]. Furthermore, when learners hear about performance gaps, their distress may be exacerbated if they do not know how to improve it [46].

우리의 연구는 또한 이전에 문서화되지 않은 많은 누락된 피드백 기능을 식별했다. 하나는 [학습자의 동기, 이해 및 기술 개발]을 피드백의 초점으로 포지셔닝하는 것이다. 이 문헌은 학습자가 '원하고'(동기), '어떻게 할 줄 아는'(명확한 이해) 때만 변화를 성공적으로 구현할 가능성이 있음을 시사한다.

Our study also identified a number of missing feedback features, which have not been previously documented. One involves positioning the development of a learner’s motivation, understanding and skills as the focal point for feedback. The literature suggests that a learner is only likely to successfully implement changes when they ‘wish to’ (motivation) and ‘know how to’ (clear understanding) [9, 29, 47, 48].

[자기결정이론]은 학습자가 자신의 개인적 가치와 열망에 따라 무엇을 해야 할지 결정할 때 더 높은 성과와 더 높은 웰빙과 연관된 내재적 동기가 촉진된다고 주장한다. 이는 학습자를 의사결정자로, 교육자를 지침으로 하는 권장 교육자 행동에 의해 파악됩니다(표 1: 행동 7, 21, 22 참조). 학습자는 피드백이 신뢰할 수 있고 가치가 있다는 것을 스스로 확신해야 합니다(행동 1, 6, 7, 9, 20, 24) [8, 49, 50]. 교육자와 학습자 사이의 정보, 의견 및 아이디어의 자유로운 흐름은 맞춤형 조언과 좋은 의사 결정을 위한 기초로서 공유된 이해를 창출한다[51]. 또한, [목표 설정 이론]은 학습자의 동기가 성과 격차에 대한 명확한 시각, 학습자에게 구체적이고 달성 가능하며 가치 있는 성과 목표, 그리고 그들의 필요에 따라 실용적이고 맞춤화된 행동 계획에 의해 자극된다고 주장한다(행동 14, 15, 21, 22).

Self-determination theory argues that intrinsic motivation, which is associated with both higher performance and increased well-being, is promoted when a learner decides what to do, in line with their personal values and aspirations [23,24,25]. This is captured by recommended educator behaviours that position the learner as decision maker and the educator as guide (see Table 1: Behaviours 7, 21, 22). A learner must be convinced for themselves that the feedback is credible and valuable (Behaviours 1, 6, 7, 9, 20, 24) [8, 49, 50]. The free flow of information, opinion and ideas between the educator and learner creates a shared understanding, as a foundation for tailored advice and good decision making [51]. In addition, Goal Setting Theory asserts that a learner’s motivation is stimulated by a clear view of the performance gap, performance goals that are specific, achievable and valuable to the learner, and an action plan that is practical and tailored to suit their needs (Behaviours 14, 15, 21, 22) [22].

최근 피드백의 발전은 학습자가 피드백 정보를 처리하고 활용할 수 있도록 지원할 필요성에 초점을 맞추고 있습니다. 따라서 학습자는 자신의 성과를 '어떻게 향상시킬지' 알게 되어야 한다. 이것은 R2C2 피드백 모델에서 예시되며, 여기에는 학습자가 정보와 정보에 대한 반응을 탐색하고, 스킬 개발을 위한 효과적인 전략을 설계하는 데 도움을 주는 것이 포함됩니다. [사회 구성주의 학습 이론]은 학습자가 다른 사람과의 상호 작용을 통해 새로운 정보의 의미를 만드는 방법을 설명한다[52]. 이러한 능동적 학습을 촉진하기 위해 권장되는 교육자 행동에는 학습자가 자신의 성과를 분석하고 '자신을 위해 해결할 수 있는 문제'(행동 8, 12, 13), 학습자의 어려움이나 질문에 대한 질문(행동 9), 그리고 세션을 끝내기 전에 실행 계획에 대한 학습자의 이해를 확인하는 것이 포함됩니다. (행동 23, 24) [53].

Recent advances in feedback have focused on the need to assist learners to process and utilise feedback information, so they ‘know how to’ enhance their performance. This is exemplified in the R2C2 feedback model, which includes assisting a learner to explore the information, their reactions to it and to design effective strategies for skill development [30, 32, 51]. Social constructivist learning theory describes how a learner makes meaning of new information through interactions with others [52]. To promote this active learning, recommended educator behaviours include encouraging the learner to analyse their own performance and ‘work things out for themselves’ (Behaviours 8,12,13), enquiring about the learner’s difficulties or questions (Behaviour 9) and checking the learner’s understanding of the action plan before concluding the session (Behaviours 23, 24) [53].

본 연구에서 거의 볼 수 없는 효과적인 피드백의 또 다른 특징은, (교육자들이 전반적으로 학습자들에 대한 존중과 지지를 보였음에도 불구하고), 세션을 시작할 때 의도적으로 안전한 학습 환경을 설정하지는 않았다는 것이다. 최근의 문헌은 안전한 학습 환경을 촉진하고 교육 동맹을 구축하는 것의 중요성을 강화했다[34]. 이것은 교육자와 학습자가 확립된 관계가 없을 때 특히 중요한 전략이 될 수 있으며, 이는 짧은 배치와 학습자를 돌보는 다수의 감독자가 있는 현대 직장 훈련에서 점점 더 보편화되고 있는 것으로 보인다[54]. 과도한 불안은 사고, 학습, 기억에 부정적인 영향을 미친다. 피드백은 본질적으로 심리적으로 위험하다. 학습자의 한계가 노출되면, 교육자로부터 낮은 점수나 비판적 코멘트를 받거나, 학습자의 자아의식을 위협할 수 있다. Carless [10]은 피드백의 강력한 관계적, 정서적, 동기적 영향을 고려하여 신뢰의 중요한 역할을 강조했다. 교육자들은 자연적인 불안감에 대처하기 위해 "실수는 기술 습득 과정의 일부"이며, 비판적이 아니라 도움을 주고자 한다는 점을 분명히 할 수 있다[53]. 또한, 교육자가 피드백 세션에 대한 프로세스와 기대를 협상한 경우, 학습자가 앞으로 일어날 일을 모르거나 통제할 수 없을 때 발생하는 불안을 줄일 수 있다[30].

Another feature of effective feedback rarely seen in our study was educators deliberately setting up a safe learning environment at the start the session, although they showed respect and support for learners in general. Recent literature has reinforced the importance of promoting a safe learning environment and establishing an educational alliance [34]. This may be a particularly important strategy when the educator and learner do not have an established relationship, which seems to be increasingly commonplace in modern workplace training with short placements and multiple supervisors attending to learners [54]. Excessive anxiety negatively impacts on thinking, learning and memory [53, 55, 56]. Feedback is inherently psychologically risky; if a learner’s limitations are exposed, this can result in a lower grade or critical remarks from the educator, or threaten a learner’s sense of self [5, 33, 46]. Carless [10] highlighted the important role of trust in view of the strong relational, emotional and motivational influences of feedback. In an attempt to counter the natural anxiety, educators could be explicit that “mistakes are part of the skill-acquisition process” and that they desire to help, not to be critical [53]. In addition, if an educator negotiated the process and expectations for the feedback session, this could reduce the anxiety caused when the learner does not know, or have any control over, what is going to happen [30].

마지막으로 중요한 특징 중 하나는 [학습 활동의 고립]이었다. 우리 연구에서 학습자가 목표 기술을 어느 정도까지 성공적으로 개발할 수 있었는지 검토할 수 있는 시기와 방법에 대해 논의한 교육자는 없었다(행동 25). 이것은 모든 것 중에서 가장 낮은 순위의 행동이었다. Molloy와 Boud[9]는 [피드백 계획을 구현하고 후속 과제에서 진행률을 평가]할 수 있도록 [학습 활동을 연계하여 성과 개발을 촉진하는 것]의 중요성을 강조했다. 감독은 본질적으로 점점 더 단기적이고 단편적이기 때문에, 유사한 과제를 수행하는 평가를 받을 수 있는 또 다른 기회를 의도적으로 계획할 때 학습자와 협력하는 것이 중요한 목표로 보인다.

One final important feature was the isolation of the learning activity. In our study, no educator discused when or how the learner might be able to review to what extent they had been able to successfully develop the targeted skills (Behaviour 25); this was the lowest ranked behaviour of all. Molloy and Boud [9] have emphasised the importance of promoting performance development by linking learning activities, so that feedback plans can be implemented and progress evaluated in subsequent tasks. As supervision is increasingly short-term and fragmented in nature, collaborating with the learner in deliberately planning another opportunity to be assessed performing a similar task seems an important objective.

개별 교육자의 관행

Individual educator’s practice

우리 연구에서 발견된 개별 교육자의 점수 범위는 교육자들이 피드백에 대한 다양한 전문 지식을 가지고 있음을 시사한다. 교육자들은 비디오 분석에 사용된 권장 행동 목록을 보여주지 않았다. 공식적으로 테스트되지는 않았지만, 점수 범위에 걸친 감독자 경험의 확산에 기초하여 더 많은 경험이 더 큰 전문성을 부여한다는 징후는 데이터에 없었다(표 2). 우리는 우리 교육자들의 전문적인 개발 훈련에 대해 묻지 않았다. 잠재적으로 흥미롭긴 하지만, 이 정보는 권장되는 행동과 비교하여 현재 직장 관행을 평가하는 우리의 주요 목표와 밀접한 관련이 있었다. 교육 패러다임이 시간이 지남에 따라 상당히 변화하고 교육자의 행동이 학습자 시절에 사용된 방법을 부분적으로 반영할 수 있다는 점을 고려할 때, [피드백 접근법에서 관찰한 가변성]은 최근 발전에 초점을 맞춘 [전문적 개발이 지속적으로 필요함]을 강조한다.

The range in individual educator’s scores found in our study suggests the educators had variable expertise in feedback. Educators were not shown the check-list of recommended behaviours used in video analysis. Although not formally tested, there was no indication in the data that more experience conferred greater expertise, based on the spread of supervisor experience across the score ranges (Table 2). We did not ask about our educators’ professional development training. Although potentially interesting, this information was tangential to our primary goal of assessing current workplace practice against recommended behaviours. Given that education paradigms have changed considerably across time, and that educator behaviour may partly reflect methods used when they were learners, the observed variability in feedback approaches highlights the need for continuing professional development that focuses on recent advances.

[전문직 간에 현저한 점수 차이가 없다는 것]은 공식적인 만남 내의 피드백 기술이 다르다기보다는 비슷할 수 있다는 것을 시사한다. 따라서 [피드백 리터러시 교육]은 적어도 부분적으로 [보건 전문가 전체의 교육자를 위해 설계]함으로써 상당한 효율성을 얻을 수 있다. 그럼에도 불구하고, 이러한 기술이 비공식적인 피드백 만남 내에서 그리고 다양한 맥락에서 변화하는 정도는 더 많은 연구를 필요로 한다. 진료하는 임상의가 대부분의 [보건 전문 교육(선배 학생과 후배 임상의 모두)을 담당]하지만 [교육 및 훈련 역할에 대한 지정된 기준]은 드물다. 대조적으로 보건 전문가들은 그들의 [임상 기술]에 대해 수년간 훈련을 하고 신중하게 평가받는데 시간을 보낸다.

The lack of striking differences in scores between professions suggests that feedback skills within formal encounters may be more similar than different. Hence feedback literacy training could, at least in part, be designed for educators across the health professions, allowing significant efficiencies. Nevertheless, the extent to which these skills vary within informal feedback encounters and across different contexts requires more study. Practising clinicans are responsible for the majority of health professions training (both senior students and junior clinicians) and yet specified standards for their education and training role are rare. In contrast health professionals spend many years training and being carefully assessed on their clinical skills.

본 연구의 목적은 교육자가 학습자를 참여시키고 동기를 부여하며 학습자가 개선할 수 있는 교육자 행동에 대한 설명을 개발하고, [고품질 학습자-중심 피드백]을 생성하도록 지원하는 것입니다. 일단 임상의가 권고된 행동을 고려할 기회를 갖게 되면 누락된 요소를 실무에 도입하는 것이 상대적으로 쉬울 수 있다. 교육자에게 유용할 수 있는 전략 중 하나는 학습자와 함께 피드백을 비디오로 촬영한 후 목록을 사용하여 자신의 행동을 체계적으로 분석하는 것입니다. 이를 통해 교육자는 성찰적 학습과 목표 설정에도 참여할 수 있습니다 [57, 58]. 또한, 품질 피드백 관행을 재현하는 감독관의 문구나 비디오의 예는 교육자들이 고품질 피드백의 원칙을 새로운 의식으로 변환하는 데 도움이 될 수 있다. 제시한 일련의 행동은 포괄적이지만, [25가지 권장 행동]은 특히 신입 교육자에게 압도적으로 보일 수 있기 때문에, [우선순위를 정하거나 요약]하는 것이 유용할 수 있다.

The aim of our research is to assist educators in generating high quality learner-centred feedback, by developing descriptions of educator behaviours that could engage, motivate and enable learners to improve. It may well be that once clinicians have the opportunity to consider the recommended behaviours, it would be relatively easy for them to introduce missing elements into their practice. One strategy that might be valuable for educators would be to video their feedback with a learner and subsequently use the list to systematically analyse their own behaviours. This would enable educators to also engage in reflective learning and goal setting [57, 58]. In addition, exemplars of supervisors’ phrases or videos re-enacting quality feedback practices may help educators to translate the principles of high quality feedback into new rituals. The set of behaviours is comprehensive however it could be useful to prioritise or summarise them, as 25 recommended behaviours may seem overwhelming, especially to new educators.

장점과 한계

Study strengths and limitations

우리 연구의 강점은 '실제로 무슨 일이 일어나는지'를 밝히고 역량 평가를 위한 밀러의 프레임워크의 최상위 수준을 목표로 하기 위해 일상적인 임상 실습에서 실제 피드백 에피소드의 자체 녹화 비디오 관찰을 포함한다. 참가자들은 병원 실습의 특징인 다양한 임상 교육자 그룹을 포함했다. 교육자의 피드백 관행은 경험적으로 도출된 포괄적인 25가지 관찰 가능한 교육자 행동 세트를 활용하여 체계적으로 분석되었다.

Strengths of our study include self-recorded video-observations of authentic feedback episodes in routine clinical practice, to reveal ‘what actually happens’ and target the top level of Miller’s framework for competency assessment. Participants involved a diverse group of clinical educators, characteristic of hospital practice. The educators’ feedback practices were systematically analysed utilising an empirically derived, comprehensive set of 25 observable educator behaviours.

우리의 연구에는 여러 가지 한계가 있다. 36명의 참가자 중 작은 표본은 단일 보건 서비스 기관에서 추출한 것이지만, 여러 병원이 있는 호주에서 가장 큰 것 중 하나이다. 참가자들은 연구에 자원했고(이로 인해 자원하지 않은 사람들보다 더 강한 기술을 가진 교육자와 학습자의 일부가 되었을 수 있다), 참가자들은 자신의 성과를 기록하여 잠재적으로 우리의 데이터를 지나치게 낙관적으로 만들었다. 이러한 요인들은 우리의 연구 결과의 일반화 가능성을 제한한다. 피드백 중 교육자 행동 평가에 교육자 행동 설명을 적용할 때, 비율 일관성에 약간의 변화가 있었다. 이것에 대한 한 가지 이유는 교육자의 행동 묘사에 대한 다른 해석일 수 있다. 향후 연구에서는 관찰 가능한 행동과 지원 정보에 대한 설명을 세분화하고, 평가자 간의 합의를 최적화하기 위한 추가적인 관행과 논의를 수행하는 데 관심을 기울일 것이다.

There are a number of limitations to our study. The small sample of 36 participants were from a single health service, although it is one of the largest in Australia with multiple hospitals. Participants volunteered (which may have resulted in a subset of educators and learners with stronger skills than those who did not volunteer) and participants recorded their own performances, potentially making our data overly optimistic. These factors limit the generalisability of our findings. In the application of the educator behaviour descriptions to the assessment of educator behaviour during feedback, there was some variation in rater consistency. One reason for this could be different interpretations of the educator behaviour descriptions. In future research, attention will be directed to refining the descriptions of observable behaviours and supporting information, accompanied by additional practice and discussion to optimise consensus amongst raters.

비록 비디오 평가자들이 단지 두 개의 건강 전문가들(의사 두 명과 물리치료사 네 명)을 대표했지만, 이것이 그들의 직업을 넘어 교육자들의 행동에 대한 분석에 영향을 미칠 가능성을 제기할 수 있지만, 우리는 이것을 뒷받침할 수 있는 그럴듯한 주장을 볼 수 없다. 많은 교육자들이 (대학, 병원 또는 전문대학의) 공식 피드백 양식을 사용했습니다. 지침에 따라 이 양식을 완성하려고 하는 것은 교육자들의 행동에 영향을 미쳤거나 인지적으로 상당히 까다로울 수 있기 때문에 교육자들의 주의를 산만하게 했을 수 있다. 그러나 피드백 모범 사례가 학습자 평가 루빅과 동시에 발생할 수 없는 설득력 있는 이유는 없습니다. 또한 교육자-학습자 쌍은 일부 품질 피드백 행동, 특히 기대 설정 및 신뢰 확립과 관련하여 발생했을 수 있는 초기 피드백 대화를 할 수 있었지만 비디오에 캡처되지 않았다.

Although video raters represented only two health professions (two physicians and four physiotherapists), which could raise the possibility that this might influence their analysis of educators’ behaviours beyond their own profession, we cannot see a plausible argument to support this. A number of educators used official feedback forms (from university, hospital or specialty college). Trying to complete these forms in accordance with their instructions, may have influenced educators’ conduct or may have distracted educators’ attention, as they can be quite cognitively demanding. However, there are no compelling reasons why best practice in feedback could not occur in parallel with any learner assessment rubric. In addition, educator-learner pairs could have had earlier feedback conversations, during which some of the quality feedback behaviours may have occurred, particularly relating to setting up expectations and establishing trust, but were not captured on video.

결론들

Conclusions

우리의 연구는 공식적인 피드백 세션 동안, 교육자들이 일상적으로 학습자의 성과에 대한 분석을 제공하고, 과제가 어떻게 수행되어야 하는지 설명하며, 대화 내에서 존중하고 지지한다는 것을 보여주었다. 이들은 모두 품질 피드백의 가치 있고 권장되는 구성 요소입니다. 그럼에도 불구하고 다른 바람직한 행동은 거의 관찰되지 않았다. 종종 누락되었던 중요한 요소들

- 피드백 세션을 시작할 때 의도적으로 안전한 학습 환경을 조성한다(세션의 목적, 기대 및 가능한 구조를 명시적으로 명시함으로써).

- 자기 평가를 장려한다.

- 학습자의 동기 부여 및 이해를 활성화합니다.

- 실행 계획을 수립하고, 후속 성과 검토를 계획합니다.

Our study showed that during formal feedback sessions, educators routinely provided their analysis of the learner’s performance, described how the task should be performed, and were respectful and supportive within the conversation. These are all valuable and recommended components of quality feedback. Nevertheless, other desirable behaviours were rarely observed. Important elements that were often omitted included

- deliberately instigating a safe learning environment at the start of the feedback session (by explicitly articulating the purpose, expectations and likely structure of the session),

- encouraging self-assessment,

- activating the learner’s motivation and understanding,

- creating an action plan and planning a subsequent performance review.

이는 학습자가 성과 정보를 이해하고 통합하고 행동하도록 돕는 것의 중요성과 관련하여, [피드백 연구의 많은 발전]이 [일상적인 임상 교육에 영향을 미치지 않았음]을 시사한다. 우리의 연구는 보건 전문 교육 커뮤니티 전반에 걸쳐 교육자 피드백 기술 개발을 위한 귀중한 목표를 명확히 한다. 그러나 이러한 권장 교육자 행동의 구현이 설계된 대로 학습자 결과를 향상시키는지 여부를 조사하기 위해 추가 연구가 필요하다.

This suggests that many advances in feedback research, regarding the importance of assisting learners to understand, incorporate and act on performance information, have not impacted routine clinical education. Our research clarifies valuable targets for educator feedback skill development across the health professions education community. However further research is required to investigate whether implementing these recommended educator behaviours results in enhanced learner outcomes, as designed.

Educators' behaviours during feedback in authentic clinical practice settings: an observational study and systematic analysis

PMID: 31046776

PMCID: PMC6498493

DOI: 10.1186/s12909-019-1524-z

Free PMC article

Abstract

Background: Verbal feedback plays a critical role in health professions education but it is not clear which components of effective feedback have been successfully translated from the literature into supervisory practice in the workplace, and which have not. The purpose of this study was to observe and systematically analyse educators' behaviours during authentic feedback episodes in contemporary clinical practice.

Methods: Educators and learners videoed themselves during formal feedback sessions in routine hospital training. Researchers compared educators' practice to a published set of 25 educator behaviours recommended for quality feedback. Individual educator behaviours were rated 0 = not seen, 1 = done somewhat, 2 = consistently done. To characterise individual educator's practice, their behaviour scores were summed. To describe how commonly each behaviour was observed across all the videos, mean scores were calculated.

Results: Researchers analysed 36 videos involving 34 educators (26 medical, 4 nursing, 4 physiotherapy professionals) and 35 learners across different health professions, specialties, levels of experience and gender. There was considerable variation in both educators' feedback practices, indicated by total scores for individual educators ranging from 5.7 to 34.2 (maximum possible 48), and how frequently specific feedback behaviours were seen across all the videos, indicated by mean scores for each behaviour ranging from 0.1 to 1.75 (maximum possible 2). Educators commonly provided performance analysis, described how the task should be performed, and were respectful and supportive. However a number of recommended feedback behaviours were rarely seen, such as clarifying the session purpose and expectations, promoting learner involvement, creating an action plan or arranging a subsequent review.

Conclusions: These findings clarify contemporary feedback practice and inform the design of educational initiatives to help health professional educators and learners to better realise the potential of feedback.

Keywords: Effective feedback; Feedback; Formative feedback; Health professions education; Professional development.

'Articles (Medical Education) > 교수법 (소그룹, TBL, PBL 등)' 카테고리의 다른 글

| 밀레니얼을 위한 의학교육: 해부학자들은 잘 하고 있는가? (Clin Anat, 2019) (0) | 2023.01.07 |

|---|---|

| 밀레니얼 학생 멘토링하기 (JAMA, 2020) (0) | 2023.01.07 |

| 피드백 탐색의 예술과 술책: 임상실습 학생의 피드백 요청에 대한 접근(Acad Med, 2018) (0) | 2022.11.26 |

| 교육과정 변화 전후로 니어-피어 상호작용 동안 제공된 조언(Teach Learn Med. 2022) (0) | 2022.09.20 |

| 온라인 의학교육에서 윤리적으로 가르치기: AMEE Guide No. 146 (Med Teach, 2022) (0) | 2022.09.14 |