검은 백조를 찾아서: 의사국가시험 불합격 위험 학생 식별 (Acad Med, 2017)

In Search of Black Swans: Identifying Students at Risk of Failing Licensing Examinations

Cassandra Barber, MA, Robert Hammond, MD, FRCPC, Lorne Gula, MD, FRCPC, Gary Tithecott, MD, FRCPC, and Saad Chahine, PhD

[모든 학부 의학교육 프로그램이 안고 있는 끊임없는 어려움]은 의학 공부에 잘 적응하고 역량을 발휘할 수 있도록 성숙할 학습자를 선발하는 것이다. 그러한 학습자를 식별하기 위한 많은 방법이 존재하지만, 우리의 문헌 검색은 학생들의 결과를 예측할 수 있는 것으로 인용되지 않는다는 것을 밝혔다. 이러한 [신뢰할 수 있는 예측 도구의 부족]은 의대생 선발의 과학을 이해하기 어렵게 만든다. 프로그램과 교육자가 모든 학습자를 지원하는 데 전념하고 있지만, 조기 개입을 안정적으로 허용하는 방법은 프로그램이 자원을 재집중하고 개별 학생 결과를 개선하는 데 도움이 될 수 있다. 따라서 의대생 선발에서 의사 결정을 위한 수학적 예측 모델의 통합은 입학 및 의대 중 더 계산되고 정보에 입각한 결정을 가능하게 할 수 있다. 따라서 본 논문은 캐나다 국가 면허 시험에서 학습자의 실패 위험을 예측하기 위해 다단계 모델링의 사용을 탐구한다. 즉, 캐나다 의학 위원회 자격 시험 파트 1(MCCQE1).

A constant struggle all undergraduate medical education programs grapple with is selecting learners who will adapt well to medical studies and mature to achieve competency. While many methods exist to identify such learners, our search of the literature revealed that none are cited as being able to predict student outcomes. This lack of reliable predictive tools makes the science of medical student selection elusive. While programs and educators are committed to supporting all learners, a method that would reliably allow for early intervention could help programs refocus their resources and improve individual student outcomes. Thus, the integration of mathematical models of prediction for decision making in medical student selection may allow for more calculated and informed decisions at admissions and during medical school. This paper, therefore, explores the use of multilevel modeling to predict learners’ risk of failure on the Canadian national licensing examination—the Medical Council of Canada Qualifying Examination Part 1 (MCCQE1).

배경

Background

면허시험 점수를 예측하기 위해 상당한 연구가 진행되어 왔다. 이러한 연구는 주로 의과대학입학시험(MCAT) 점수, 학부 학점평균점수(GPA) 등 예비입학변수가 향후 학업성취도에 미치는 예측 타당성에 초점을 맞추었다. 그러나 [MCAT 점수와 학부 GPA의 예측력]은 [학생들이 졸업을 향해 나아가고, 학습이 인지적 측정에서 보다 임상적 측정으로 변화함]에 따라 점차 감소한다는 것이 잘 문서화되어 있다. 결과적으로, 많은 면허시험이 졸업에 가까워질 때까지 이루어지지 않기 때문에 의대생의 미래성과를 예측하는 데 사용될 때 이러한 변수들의 신뢰성은 불분명하다.

Considerable research has been conducted to predict licensing examination scores.1–15 These studies have focused predominantly on the predictive validity that prematriculation variables, such as Medical College Admission Test (MCAT) scores and undergraduate grade point average (GPA), have on future academic performance.1–4,16 However, it has been well documented that the predictive power of both MCAT scores and undergraduate GPAs decreases as students progress toward graduation and learning shifts from cognitive to more clinical measures.5 As a result, the reliability of these variables when used to predict the future performance of medical students is unclear, as many licensing examinations do not occur until closer to graduation.5,6

예를 들어, 캐나다에서 Eva 등은 입학 변수(복수 미니 면접 점수, 자전적 논술 점수, 학부 GPA)와 국가 면허 시험 성과 사이의 연관성을 조사했다. 본 연구는 2004년과 2005년에 다른 곳에서 의대에 입학하였으나 불합격된 재학생과 의대에 입학한 재학생의 성적의 차이를 비교하였다. 그들의 분석에 따르면, 입학한 학생들은 불합격된 학생들에 비해 국가 면허 시험에서 더 높은 점수를 받았다.

In Canada, for example, Eva et al7 examined the association between admissions variables (multiple-mini interview scores, autobiographical essay scores, and undergraduate GPAs) and performance on national licensing examinations. This study compared differences between the performance of matriculated students and those that were rejected but gained entry to medical school elsewhere in 2004 and 2005. Evidence from their analysis suggests that matriculated students had higher scores on national licensing examinations compared with those who were rejected.

2013년, Woloschuk 등은 임상실습과 레지던트 첫 해 동안 관찰된 임상 성과가 4개 코호트에 걸쳐 캐나다 의학위원회 자격심사 파트 2(MCCQE2)에서 합격/불합격 성과를 예측할 수 있는지 조사했다. 그들은 임상실습 평가와 1년차 전공의 평가등급은 유의미하지만 MCCQE2의 합격/불합격 예측 변수는 좋지 않다는 것을 발견했다. 마찬가지로, 2016년에 Pugh 등은 객관적 구조화 임상 검사(OSCE)와 국가 고위험 검사 사이의 연관성을 조사했다. 이 연구는 8개 코호트의 데이터를 사용하여 내과 레지던트 OSCE 진행 테스트의 점수와 캐나다 왕립 의과대학 내과 종합 객관 검사 점수를 비교했다. 상관관계 및 로지스틱 회귀 분석의 결과는 OSCE 진행 테스트 점수와 임상 역량의 전국 고부담 검사가 연관되었음을 시사한다. 이러한 결과는 OSCE progress test가 향후 국가 고위험 시험에 실패할 위험이 있는 거주자를 식별하는 데 사용될 수 있음을 시사한다.

In 2013, Woloschuk et al8 examined whether clinical performance observed in clerkships and during the first year of residency could predict pass/fail performance on the Medical Council of Canada Qualifying Examination Part 2 (MCCQE2) across four cohorts. They found that clerkship evaluations and year 1 residency ratings were significant but poor predictors of pass/fail performance on the MCCQE2. Similarly, in 2016, Pugh et al9 examined the association between objective structured clinical examinations (OSCEs) and national high-stakes examinations. Using data from eight cohorts, this study compared scores from an internal medicine residency OSCE progress test versus scores from the Royal College of Physicians and Surgeons of Canada Comprehensive Objective Examination in Internal Medicine. Results from their correlation and logistic regression analysis suggest that OSCE progress test scores and national high-stakes examinations of clinical competency were associated. These findings suggest that OSCE progress tests could be used to identify residents at risk of failing a future national high-stakes examination.

2010년 이후, 미국에서 수행된 여러 연구는 과정과 평가 점수와 같은 [의대생 수행 변수]가 실제로 [입학 전 데이터]보다 면허 시험 수행의 더 강력한 예측 변수라고 제안했다. 이러한 연구는 2학년 학생 수행 결과 변수가 초기 면허시험에서 미래의 학업 위험도를 예측하는 가장 좋은 예측 변수임을 시사한다.

Since 2010, several studies conducted in the United States have suggested that medical student performance variables, such as course and assessment scores, are actually stronger predictors of licensing examination performance than prematriculation data.10–12 These studies suggest that year 2 student performance outcome variables are the best predictors of future academic risk on initial licensing examinations.

2015년, Gullo 등은 [사전 입학 수학 및 과학 GPA]와 [MCAT 점수]가 결합되었을 때, 미국 의학 면허 시험(USMLE) 1단계 성과에 대한 강력한 예측 변수라는 것을 발견했다. 그러나 추가적으로 [의대 내 과정 관련 평가 결과]가 추가되었을 때, 모델의 전반적인 예측 능력은 크게 향상되었다. 마찬가지로 Glaros 등은 의과대학 1학년부터 얻은 성과 데이터를 이용하여 3개 코호트에 걸쳐 종합골격의학면허시험 레벨 1에서 초기면허시험 성과를 성공적으로 예측할 수 있었다. 또한, Coumarbatch 등은 USMLE 1단계 실패 위험에 있는 학생을 식별하기 위해 이항 로지스틱 회귀 모델과 수신기 작동 특성(ROC) 곡선을 사용했다. 그들의 결과는 커리큘럼 2학년 누적 평균과 MCAT 생물과학 점수가 모두 초기 면허 시험에 실패할 위험이 있는 학생들을 식별하는 데 중요한 예측 변수라는 것을 보여주었다.

In 2015, Gullo et al10 found that MCAT scores combined with prematriculation math and science GPAs were strong predictors of United States Medical Licensing Examination (USMLE) Step 1 performance. However, when additional internal course-related assessment outcomes were added, the overall predictive ability of their model improved significantly. Similarly, Glaros et al11 were able to successfully predict initial licensing examination performance on the Comprehensive Osteopathic Medical Licensing Examination Level 1 using performance data obtained from the first year of medical school over three cohorts. Additionally, Coumarbatch et al12 used binary logistic regression models and receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves to identify students at risk of failing the USMLE Step 1; their results showed that curricular year 2 cumulative averages and the MCAT biological sciences score were both significant predictors in identifying students at risk of failing initial licensing examinations.

위에서 설명한 연구는 위험에 처한 학생들을 식별하기 위해 동일한 중요한 목적을 해결하기 위해 유사한 방법론을 사용한다. 이 논문은 초기 면허 시험에 앞서 학생 위험을 식별하기 위해 5개의 코호트 및 예측 모델의 데이터를 사용하여 이 강력한 작업을 기반으로 한다. 또한 USMLE와 MCCQE 사이에는 기초 과학과 의료 전문가 콘텐츠 측면에서 (두 가지 모두 향후 실무에서 제공되는 의료 품질을 예측한 것으로 나타났다) 유사점이 있지만, 이 두 시험은 대체로 국가-특이적이다. 이로 인해 [미국 내에서 수행된 연구 결과]는 [캐나다 국가 면허 시험]에서 미래의 학생 저성적을 예측하는 데 덜 적용 가능하다.

The studies outlined above10–12 use similar methodologies to address the same important purpose—to identify students at risk. This paper builds on this robust work through the use of data from five cohorts and predictive models to identify student risk in advance of an initial licensing examination. Additionally, although there are parallels between the USMLEs and MCCQEs (both of which have been shown to be predictive of the quality of care provided in future practice17,18) in terms of basic science and medical expert content, these examinations are largely country specific. This makes results from studies conducted within the United States less applicable in predicting future student underperformance on Canadian national licensing examinations.

본 연구의 목적은 분석적 접근법을 사용하여 다음과 같은 연구 질문을 해결하는 것이었다. MCCQE1에 불합격할 위험을 예측하는 입학 변수와 커리큘럼 결과는 무엇입니까? 학생들의 실패 위험을 얼마나 빨리 예측할 수 있는가? 그리고 미래의 학생 위험 추정에 있어 예측 모델링이 어느 정도까지 가능하고 정확한가?

The purpose of our study was to address the following research questions using an analytic approach: Which admissions variables and curricular outcomes are predictive of being at risk of failing the MCCQE1? How quickly can student risk of failure be predicted? And to what extent is predictive modeling possible and accurate in estimating future student risk?

방법

Method

스터디 설정

Study setting

캐나다에서는 모든 의대생들이 졸업후 수련를 위한 교육 자격증을 취득하기 위해 MCCQE1을 응시한다. 이 검사는 일반적으로 MD 프로그램을 성공적으로 완료한 직후인 봄에 이뤄집니다. 캐나다 전역의 학부 의료 교육 커리큘럼 목표는 비슷하지만, 각 학교는 의대생 선발, 교육학적 접근, 평가 전략에서 자율적이다. 그러나 모든 캐나다 의과대학은 캐나다 의학부 협회가 정한 엄격한 인증 기준을 준수하며, 공식적인 인증 과정은 모든 의료 프로그램의 교육 요건이 품질, 내용 및 레지던트 및 전문 실습에 대한 준비 면에서 유사하다는 것을 보장한다.

In Canada, all medical students take the MCCQE1 to receive an educational license for postgraduate training. This examination is typically written during the spring immediately following the successful completion of an MD program. While the undergraduate medical education curriculum objectives across Canada are similar, each school is autonomous in its selection of medical students, pedagogical approach, and assessment strategies. However, all Canadian medical schools adhere to rigorous accreditation standards set forth by the Association of Faculties of Medicine of Canada, and the formal accreditation process ensures that the educational requirements of all medical programs are comparable in quality, content, and preparing students for residency and professional practice.19

이 연구는 매년 약 171명의 신입생을 입학시키는 캐나다의 중간 규모의 의과대학인 웨스턴 대학의 슐리치 의과대학에 위치해 있었다. 각 학생 코호트는 메인 캠퍼스(런던, 온타리오)와 분산 캠퍼스(윈저, 온타리오)로 나뉜다. 비록 지리적으로 떨어져 있지만, 이 캠퍼스들은 비슷한 교육 프로그램, 동등한 평가, 그리고 동일한 커리큘럼을 가지고 있다.

This study was situated at the Schulich School of Medicine & Dentistry, Western University, a midsized medical school in Canada that matriculates about 171 new students each year. Each student cohort is divided between two campuses: the main campus (London, Ontario) and the distributed campus (Windsor, Ontario). Although geographically separated, these campuses have comparable education offerings, equivalent assessments, and an identical curriculum.

슐리히 의과대학원 학부 교육과정은 4년제 환자 중심의 통합형 교육과정으로 대규모 강의, 소그룹, 실험실, 지도임상 경험으로 구성된다. 이 교육학적 접근 방식은 개인, 문제 기반 소그룹, 능동적 및 직접 강의실 학습을 취학 전 연도(1학년과 2학년)에 결합한다. 3학년은 1년 동안의 통합 사무직 경험으로 구성된 단일 과정으로 구성되며, 프로그램의 마지막 해(4학년)에는 학생들이 임상 경험을 쌓고 레지던시를 준비할 수 있는 캡스톤 전환 과정과 임상 선택 학습에 모두 참여합니다.

The undergraduate curriculum at Schulich School of Medicine & Dentistry is a four-year, patient-centered, integrated curriculum composed of large-lecture, small-group, laboratory, and supervised clinical experiences. This pedagogical approach combines individual, problem-based small-group, active, and direct classroom learning in the preclerkship years (years 1 and 2). Year 3 consists of a single course—a yearlong integrated clerkship experience—while in the final year of the program (year 4), students participate in both clinical elective learning and a capstone transition course, which serves to enable students to build on their clinical experiences and prepare for residency.

데이터 및 분석

Data and analysis

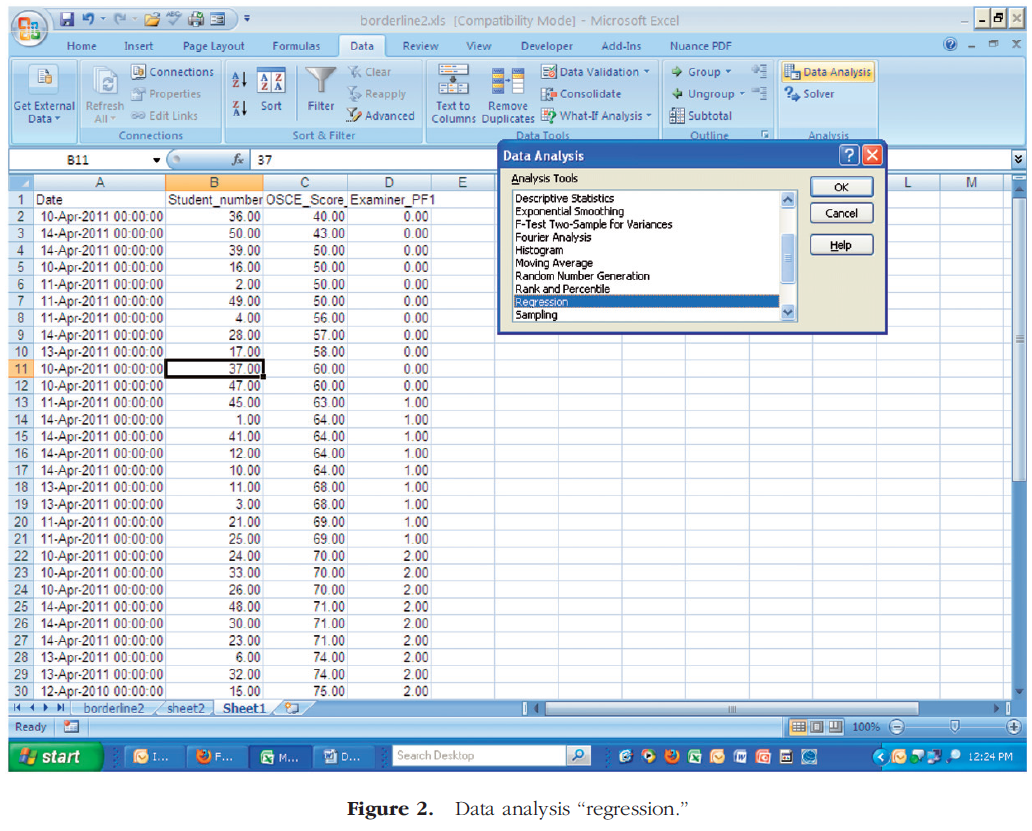

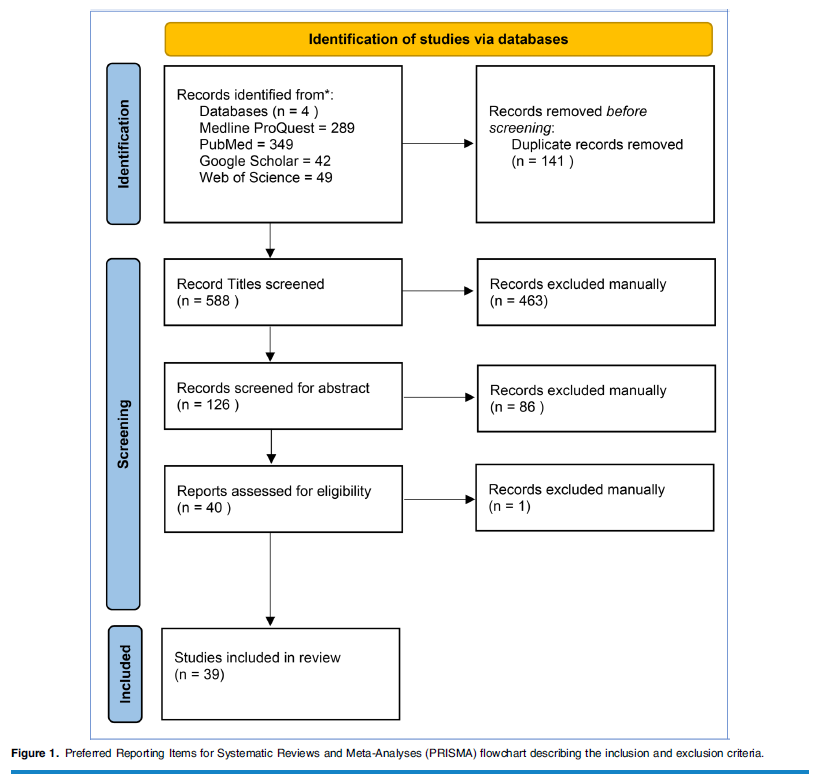

우리는 졸업생의 5개 코호트(2011~2015년)에서 20년간의 중복 데이터를 소급하여 수집했으며, 각 코호트는 4년의 데이터를 나타낸다. 계층적 선형 모델링(HLM)과 민감도 및 특수성 분석을 사용하여 입학 변수와 커리큘럼 결과 데이터를 분석하였다. 예측 모델을 개발하기 위해 HLM7(Scientific Software International, Inc., Skokie, Illinois)과 IBM SPSS 소프트웨어 버전 23(IBM Corporation, Armonk, New York)을 사용하여 모델의 정확도를 평가하고 수집한 데이터를 사용하여 미래의 고장 위험을 예측하는 데 사용할 수 있는지 여부를 결정했습니다.m 2016년 졸업생 코호트는 예측 모델의 정확성을 테스트하기 위한 유일한 목적으로 수집되었다.

We retroactively collected 20 years of overlapping data from five cohorts of graduating students (2011–2015), with each cohort representing four years of data. We analyzed admissions variables and curricular outcomes data using hierarchical linear modeling (HLM) and sensitivity and specificity analysis. We used HLM7 (Scientific Software International, Inc., Skokie, Illinois) to develop our predictive models and IBM SPSS software, version 23 (IBM Corp., Armonk, New York) to produce the area under the ROC curve (AUC) to evaluate the models’ accuracy and determine whether they could be used to predict future risk of failure, using data collected from the 2016 graduating student cohort, which was collected for the sole purpose of testing the accuracy of our predictive models.

계층적 선형 모델링

Hierarchical linear modeling

데이터의 본질적인 계층적 특성(즉, 학생이 코호트 내에 내포됨)을 설명하기 위해, 우리는 2단계 HLM을 사용하여 MCCQE1의 성능 결과를 분석하였다. HLM은 경제학에서 사회학, 발달 심리학에 이르기까지 다양한 분야에 걸쳐 사용되는 다변량 통계 기법이다.

To account for the intrinsic hierarchal nature of the data (i.e., students were nested within cohorts), we used a two-level HLM to analyze performance outcomes on the MCCQE1. HLM is a multivariate statistical technique developed in the early 1980s20–22 that has been used across multiple fields from economics to sociology and developmental psychology.

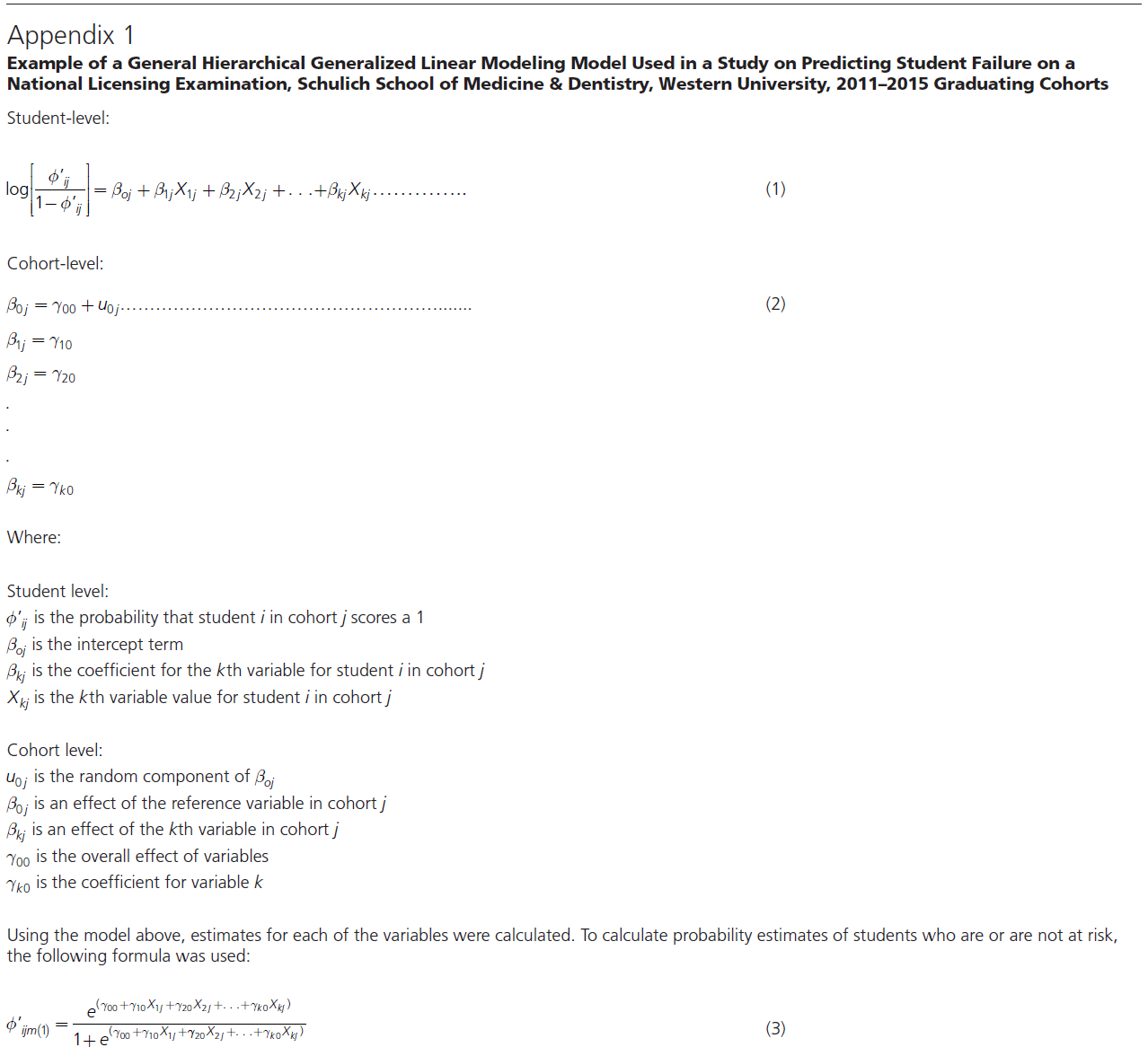

계층적 일반화 선형 모델(HGLM)은 HLM의 확장으로 데이터가 비정규 분포를 따르거나 결과가 이진일 때 적용된다. 이 연구는 학생이 MCCQE1에 실패할 위험이 있는지 없는지의 위험 확률을 조사하기 때문에 예측 모델을 생성하기 위해 HGLM을 사용했다.

Hierarchical generalized linear models (HGLMs) are extensions of HLM and applied when data are non-normally distributed or outcomes are binary. Because this study examines the probability of risk of whether a student is or is not at risk of failing the MCCQE1, we used HGLMs to produce our predictive models.

민감도 및 특이성 분석

Sensitivity and specificity analysis

HGLM 분석에서 생성된 예측 모델을 적용할 때 각 학생에 대해 [개별 확률]이 생성된다. 그런 다음 이러한 개별 확률을 민감도 및 특이성 분석을 사용하여 실제 이진 결과와 비교할 수 있습니다.

- 민감도는 실제 양성 비율이다. 즉, 위험하지 않은 것으로 확인된 모든 학생의 비율이 위험하지 않은 것으로 정확하게 식별되었다.

- 특이성은 실제 음성 비율이다. 즉, 위험으로 식별된 모든 학생의 비율이 위험으로 정확하게 식별되었습니다.

In applying the predictive models produced from the HGLM analysis, individual probabilities are produced for each student. These individual probabilities can then be compared with true binary outcomes using sensitivity and specificity analysis.23,24

- Sensitivity is the true positive rate—that is, the proportion of all students identified as not at risk who were correctly identified as not at risk.

- Specificity is the true negative rate—that is, the proportion of all students identified as at risk who were correctly identified as at risk.

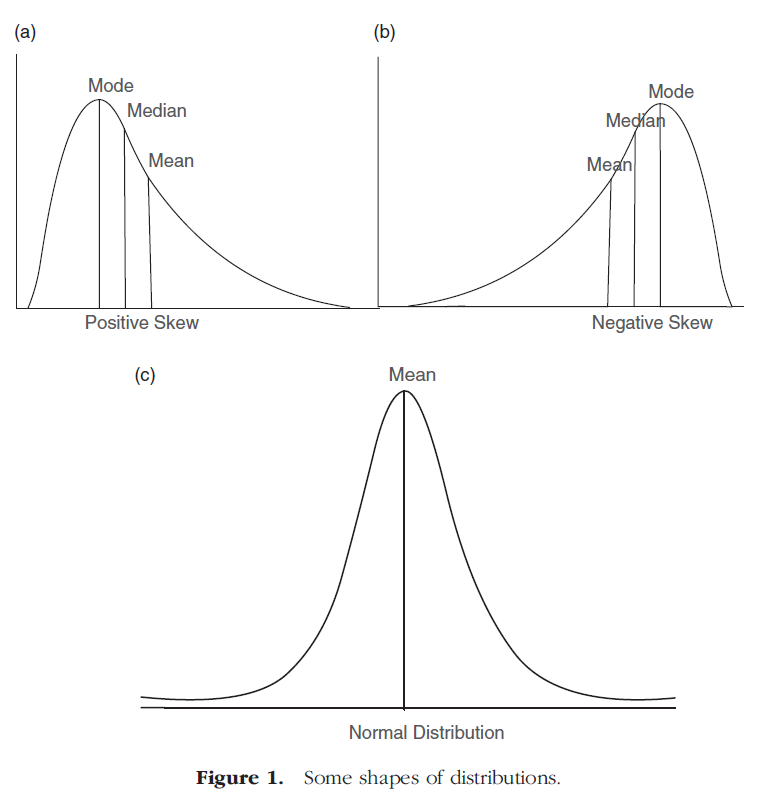

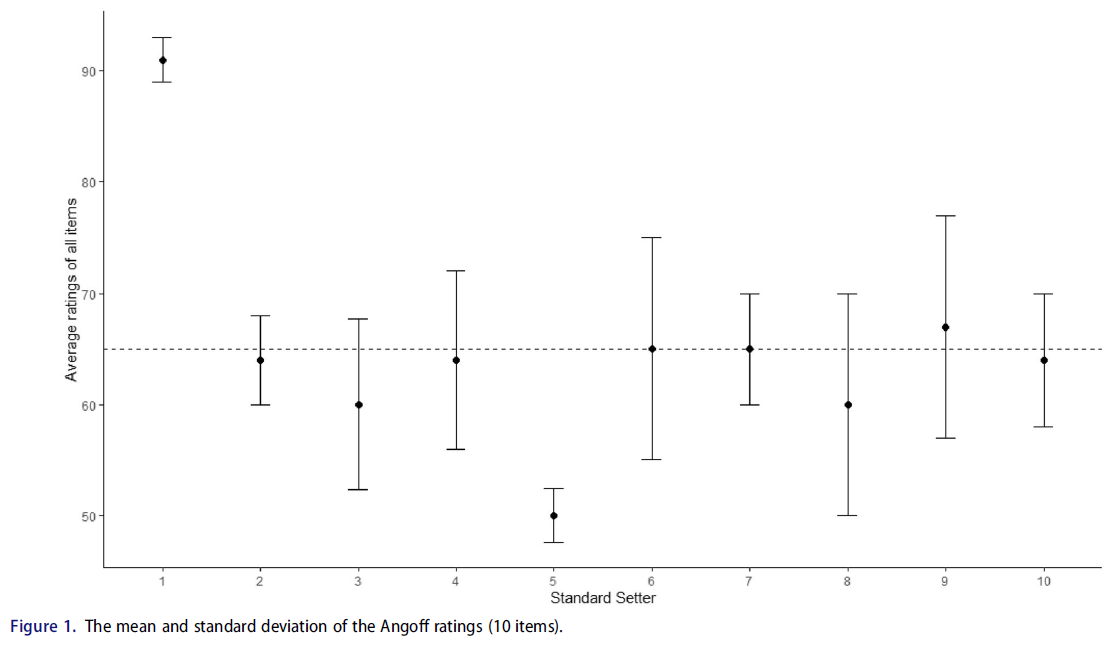

ROC 곡선은 로지스틱 회귀 분석 또는 방법을 통해 결정된 이항 분류의 정확도를 평가하기 위해 여러 분야에서 사용된다. 25,26 ROC 곡선은 수직축의 민감도를 수평축의 1-특이성으로 표시한다. 즉, 그들은 참 긍정과 거짓 긍정의 관계를 조사합니다. 이것의 일부로, AUC 값이 계산됩니다.27 AUC 값이 0.5이면 무작위 정확도를 나타내고, 값이 1이면 실제 결과에 대한 예측 결과의 완벽한 정확도를 나타냅니다. 즉, AUC가 1에 가까울수록 예측은 더 정확합니다.

ROC curves are used in multiple fields to evaluate the accuracy of a binary classification determined through logistic regression or methods.25,26 ROC curves plot the sensitivity on the vertical axis by 1 − specificity on the horizontal axis. In other words, they examine the relationship between true positives and false positives. As part of this, the AUC is calculated.27 An AUC value of 0.5 represents random accuracy, while a value of 1 represents perfect accuracy in predicted outcomes to true outcomes; that is, the closer the AUC is to 1, the more accurate the prediction.

변수 및 분석

Variables and analysis

예측 변수.

Predictive variables.

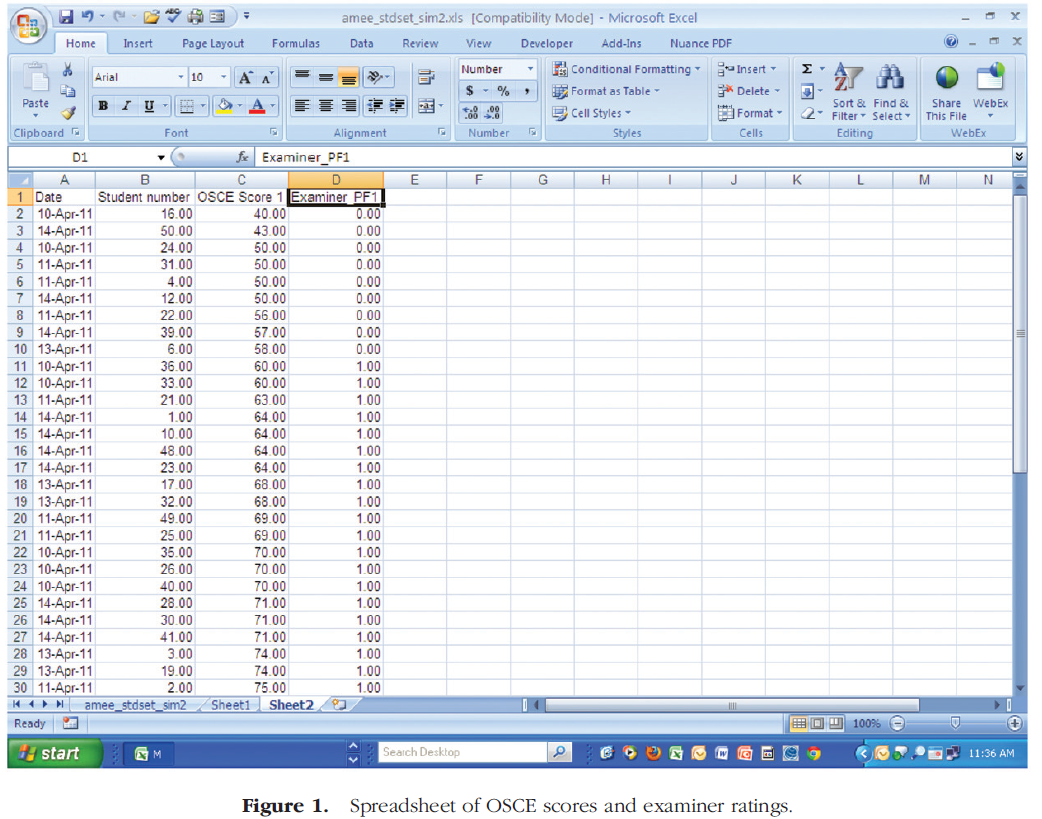

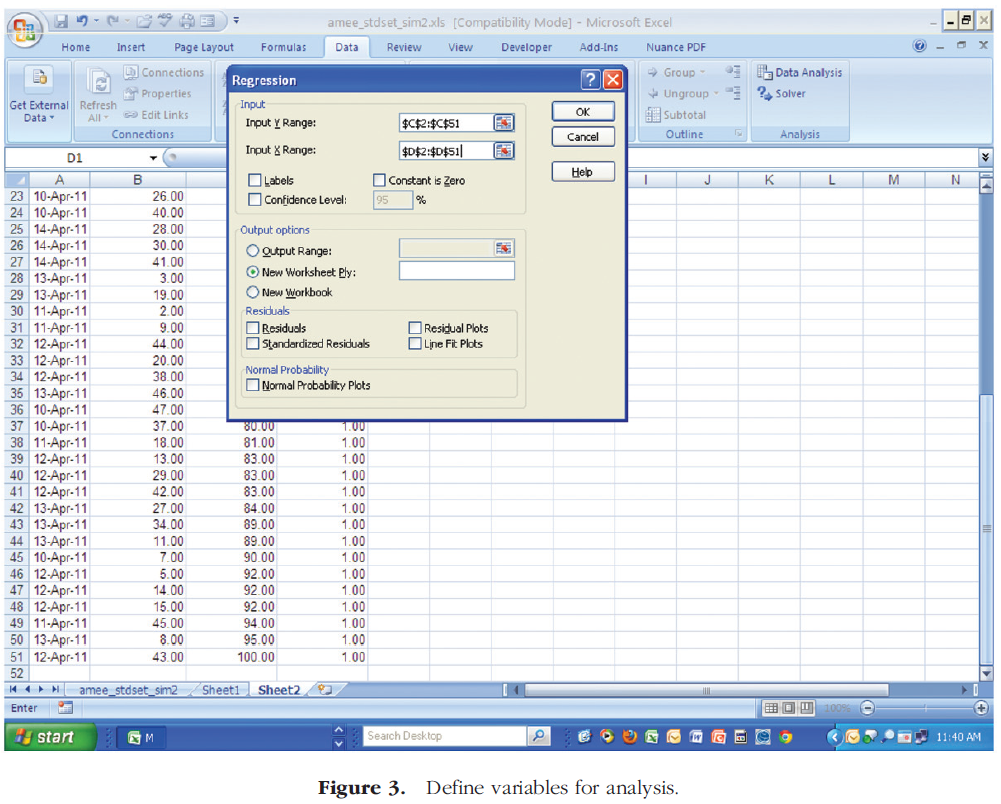

예측 변수로는 성별, 고등학교 교육 위치(농촌 대 도시), 학부 GPA, MCAT 점수(언어추론, 물리·생물과학), 입학 면접 점수, 캠퍼스 위치(런던 대 윈저), 그리고 커리큘럼 성과 결과(1차 및 2차 과정은 성적, 1차 및 2차 연도 누적 평균, 4차 연도 합계 OSCE 점수)를 의미한다. 과정 평균 성적은 각 과정 내 학생들의 전반적인 성과에 기초한다.

Predictive variables included the following measures: gender, location of high school education (rural vs. urban), undergraduate GPA, MCAT scores (verbal reasoning, and physical and biological sciences), admissions interview scores, campus location (London vs. Windsor), and curricular performance outcomes (years 1 and 2 course mean grades, years 1 and 2 cumulative averages, and year 4 summative OSCE score). Course mean grades are based on students’ overall performance within each course.

코호트 전체에서 관찰된 입학 연령의 변동이 최소였기 때문에 입학 연령은 분석에서 잠재적 예측 변수로 포함되지 않았다. 들어오는 코호트의 평균 연령은 23세였고, 입학 연령과 종속 변수 사이에는 아무런 상관관계가 없었습니다. 그러나 별도의 분석은 학생의 입학 연령, 졸업 시 연령 및 프로그램 기간(년)을 포함하도록 실행되었다. 이러한 분석은 MCCQE1의 학생 failure 위험에 대한 차이를 보여주지 않았으며, 따라서 이러한 변수는 계수 추정치(아래 참조)에 영향을 미치지 않았으며, MCCQE1의 불합격 위험에 대한 중요한 예측 변수가 아니었다.

Age at matriculation was not included as a potential predictor within our analysis because there was minimal variation in age at matriculation observed across the cohorts. The average age of our incoming cohorts was 23, and there was no correlation between age at matriculation and our dependent variable. However, separate analyses were run to be inclusive of student’s age at matriculation, age at graduation, and program duration (in years); these analyses showed no difference on student risk of failure on the MCCQE1, and therefore, these variables did not impact our coefficient estimates (see below) and were not significant predictors of being at risk of failing the MCCQE1.

총 21개의 프리클릭십 과정 중, 각각 특정 신체 시스템을 강조하는 과정 중에서, 우리는 분석에 1, 2학년 과정 3개를 포함시켰다. 이 과정들은 학부 교육과정 학장과의 자문을 바탕으로 2011~2016학년도 졸업식 코호트에 비해 내용이 비교적 안정적이고 난이도가 높은 것으로 파악됐다.

Of a total of 21 preclerkship courses,28 each emphasizing a specific physical system, we included three courses from years 1 and 2 in our analysis. These courses were identified on the basis of consultation with the undergraduate dean of curriculum as being relatively stable in content and difficulty over the 2011–2016 graduating cohorts.

종속 변수입니다.

Dependent variable.

종속 변수는 450의 컷오프 점수를 사용하여 MCCQE1에서 학생들의 실패 위험을 측정하는 이분법화된 변수이다. 전체적으로 MCCQE1의 전국 평균 점수는 500점, 표준 편차는 100점, 합격 점수는 427점이다. 확률 추정에서 주의를 기울이지 않기 위해 표준 편차의 절반 이상이 평균 아래로 떨어진 학생들을 포착하기 위해 450의 보수적인 컷오프 점수를 할당했다.

The dependent variable is a dichotomized variable measuring student risk of failure on the MCCQE1, using a cutoff score of 450. Overall, the MCCQE1 has a national mean score of 500, standard deviation of 100, and pass score of 427. To err on the side of caution in our probability estimates, we assigned a conservative cutoff score of 450 to capture students that fell more than half of a standard deviation below the mean.

MCCQE1은 두 파트로 구성되며, 필기시험에 기초한 척도 점수를 사용한다. 2015년 이전에는 1차 부분은 연도별로 동등화되었으며 2차 부분은 매년 재평가되었다. 2015년부터, 전체 시험은 매년 동등하다. 또한 시험에 합격하기 위해 필요한 최소 점수가 이전 50-950 등급의 컷오프 점수 390점에서 2015년에는 427점(이전 등급의 경우 440점)으로 변경되었다.

The MCCQE1 uses a scaled score based on a two-part written examination. Prior to 2015, the first part was equated from year to year and the second part was reestimated every year. Since 2015, the full examination is equated from year to year. There was also a change in the minimum score needed to pass the examination, from a previous cutoff score of 390 on the old 50–950 scale to 427 (which would have been 440 on the old scale), in 2015.

자격 시험으로 사용하는 것 외에도, MCCQE1은 캐나다의 학부 의료 프로그램에 대한 국가 표준 역할을 하며, 여러 기관에 걸쳐 학생들의 성과를 비교할 수 있다. 따라서 이 검사는 의료 지식과 임상 의사 결정을 모두 측정하는 높은 위험도의 종합 컴퓨터 기반 평가입니다.

Aside from its use as a qualifying examination, the MCCQE1 also serves as a national standard for undergraduate medical programs in Canada and allows student performance to be compared across institutions.29 This examination is, therefore, a high-stakes, summative computer-based assessment, measuring both medical knowledge and clinical decision making.29

모델 빌딩

Model building

우리는 반복적인 단계적 과정을 통해 예측 모델을 개발했다. 첫째, 성별, 고등학교 교육의 위치(농촌 대 도시), 캠퍼스 위치(런던 대 윈저) 등 학생 특성 변수를 살펴보았다. 예측특성변수가 결정된 후 학부 내신, 면접점수, MCAT점수 등 입시변수를 추가하였다. 마지막으로, 우리는 1학년과 2학년 평균 성적과 누적 평균, 4학년 종합 OSCE 점수와 같은 커리큘럼 결과를 한 번에 1년씩 추가했다. 우리의 예측 변수는 표준화된 변수와 표준화되지 않은 변수를 모두 포함했기 때문에, 우리는 각 변수에 대한 코호트 간의 그룹 평균 차이를 비교할 수 있도록 그룹 기반 센터링을 선택했다. 우리는 분석 단계에서 목록별 삭제를 사용하여 누락된 데이터가 있는 관측치를 제거했다. 본 연구에서 사용된 일반적인 HGLM 모델의 예는 부록 1에 제시되어 있다.

We developed predictive models through an iterative, stepwise process.30 First, we examined student characteristic variables such as gender, location of their high school education (rural vs. urban), and campus location (London vs. Windsor). After the predictive characteristic variables were determined, we added admissions variables, such as undergraduate GPA, interview scores, and MCAT scores. Lastly, we added curricular outcomes, such as years 1 and 2 course mean grades and cumulative averages and year 4 summative OSCE score, one year at a time. Because our predictive variables were inclusive of both standardized and unstandardized variables, we selected group-based centering to allow us to compare group mean differences across cohorts for each variable. We removed observations with missing data using listwise deletion at the analysis stage. An example of a general HGLM model used in this study is provided in Appendix 1.

다음으로, 각 변수 집합에 대한 계수를 추정하고 입학 1, 2학년 및 MCCQE1 이전(또는 MCCQE1 이전 5개월)에서 학생들의 실패 위험을 평가하기 위해 모델 내에서 식별된 변수를 사용하여 개별 예측 모델을 만들었다. 마지막으로, 이러한 모델은 MCCQE1 실패 위험에서 학생을 예측하는 정확성을 평가하기 위하여 AUC를 사용하여 각 코호트(2011-2015)에 개별적으로 적용되었다. 이러한 모델은 향후 위험을 예측하는 데 사용될 수 있는지 여부를 결정하기 위해 2016년 코호트에도 적용되었다.

Next, individual predictive models were created using variables identified within our model to estimate the coefficients for each set of variables and assess student risk of failure at admissions, year 1, year 2, and pre-MCCQE1 (or five months prior to the MCCQE1). Lastly, these models were applied separately to each cohort (2011–2015) using AUCs to evaluate their accuracy in predicting students at or not at risk of failing the MCCQE1. These models were also applied to the 2016 cohort to determine whether they could be used to predict future risk.

이 연구는 웨스턴대학교 보건과학연구윤리위원회의 검토를 거쳐 면제 판정을 받았다.

This study was reviewed by the Health Science Research Ethics Board at Western University and was determined to be exempt.

결과.

Results

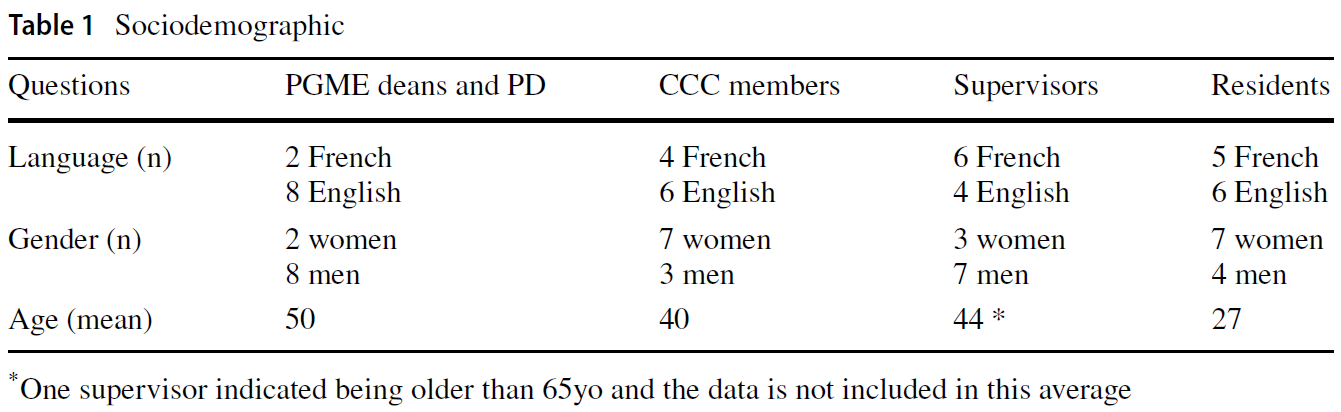

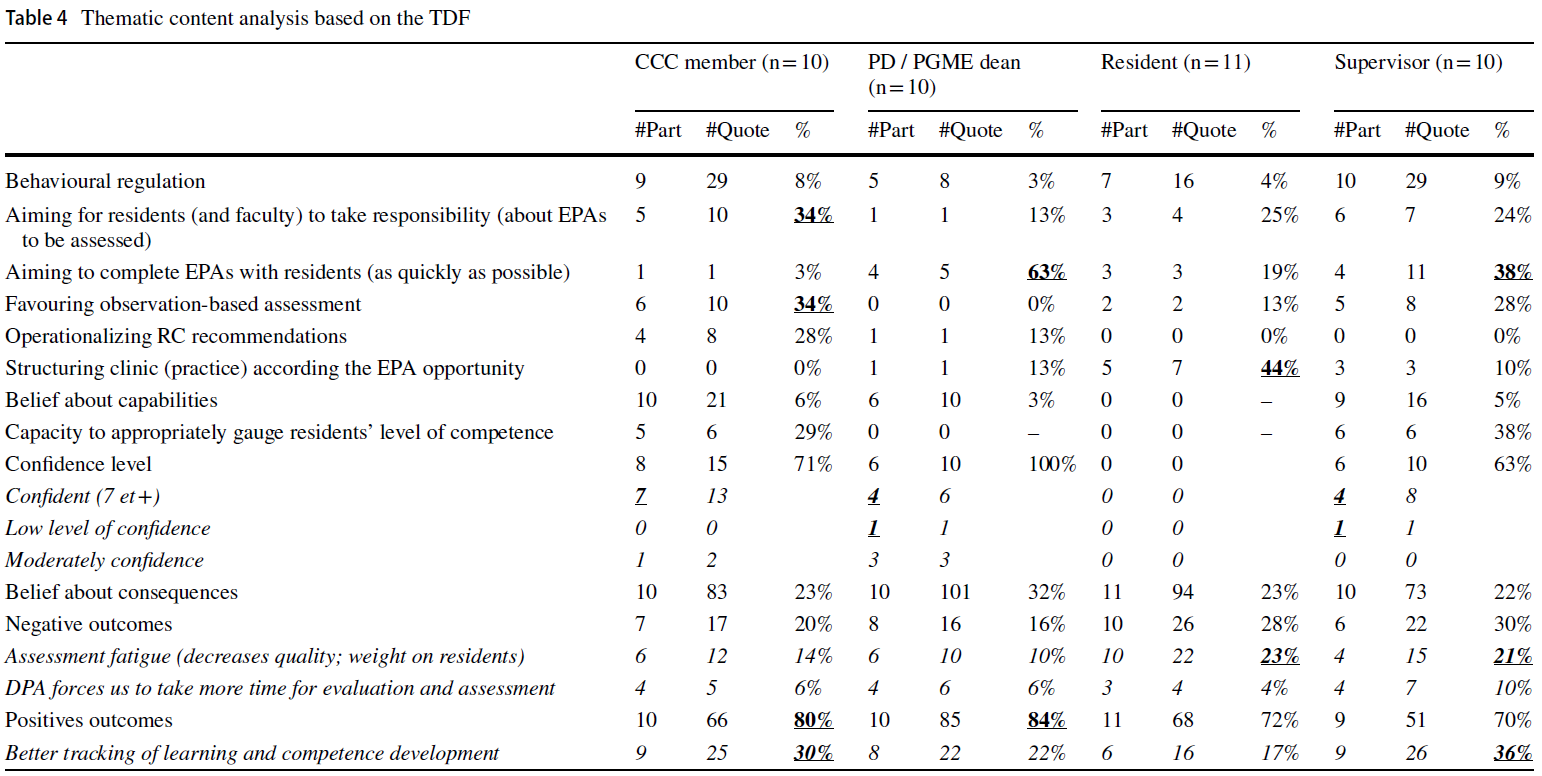

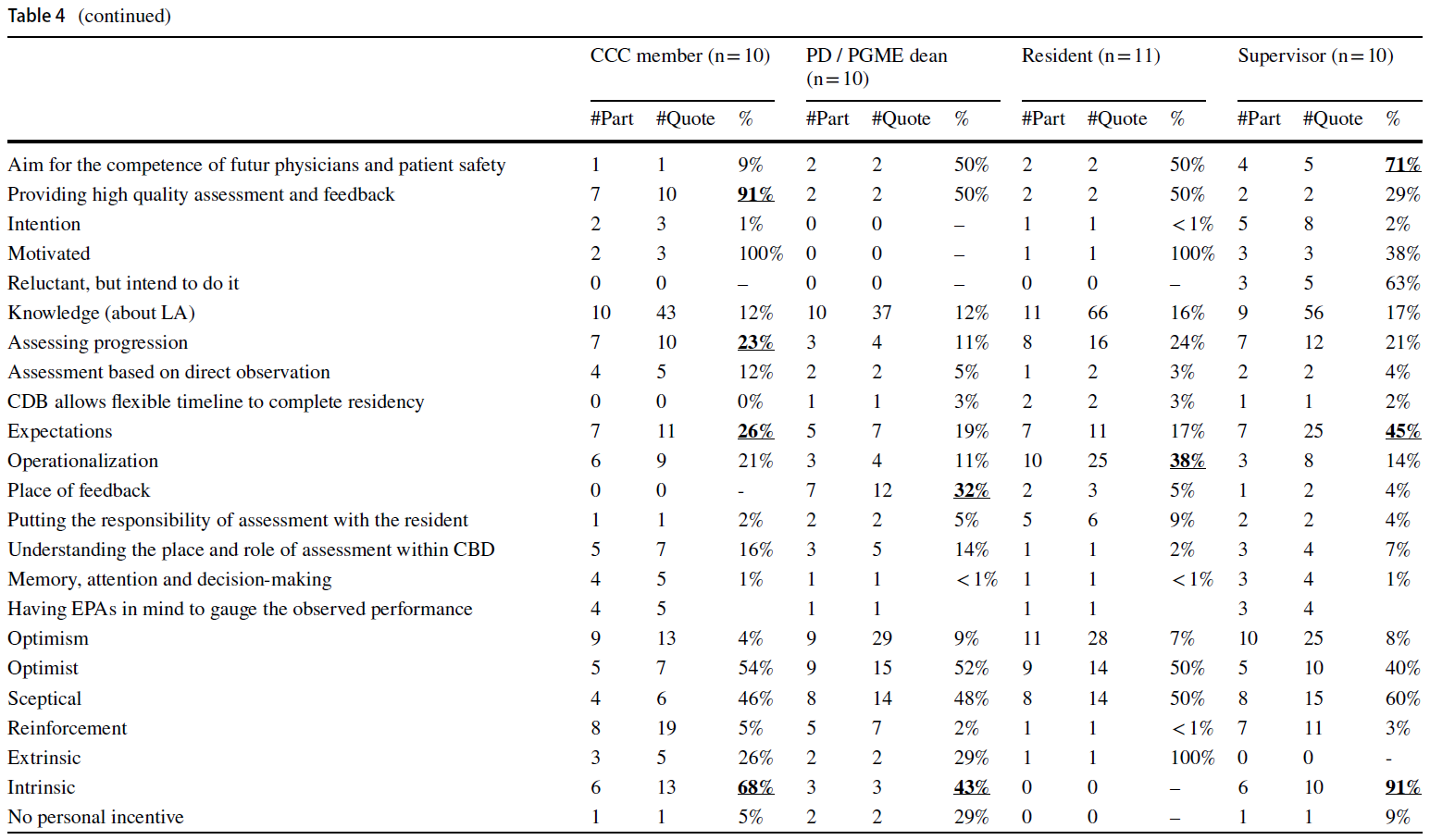

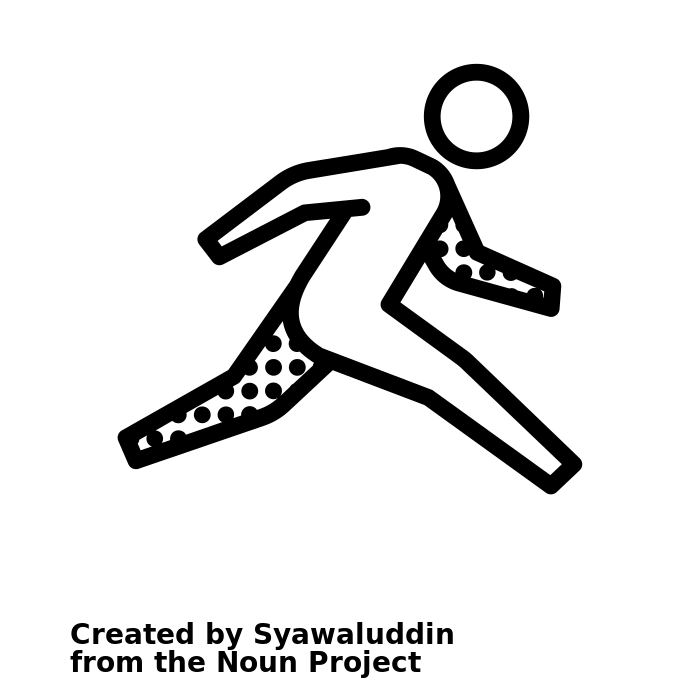

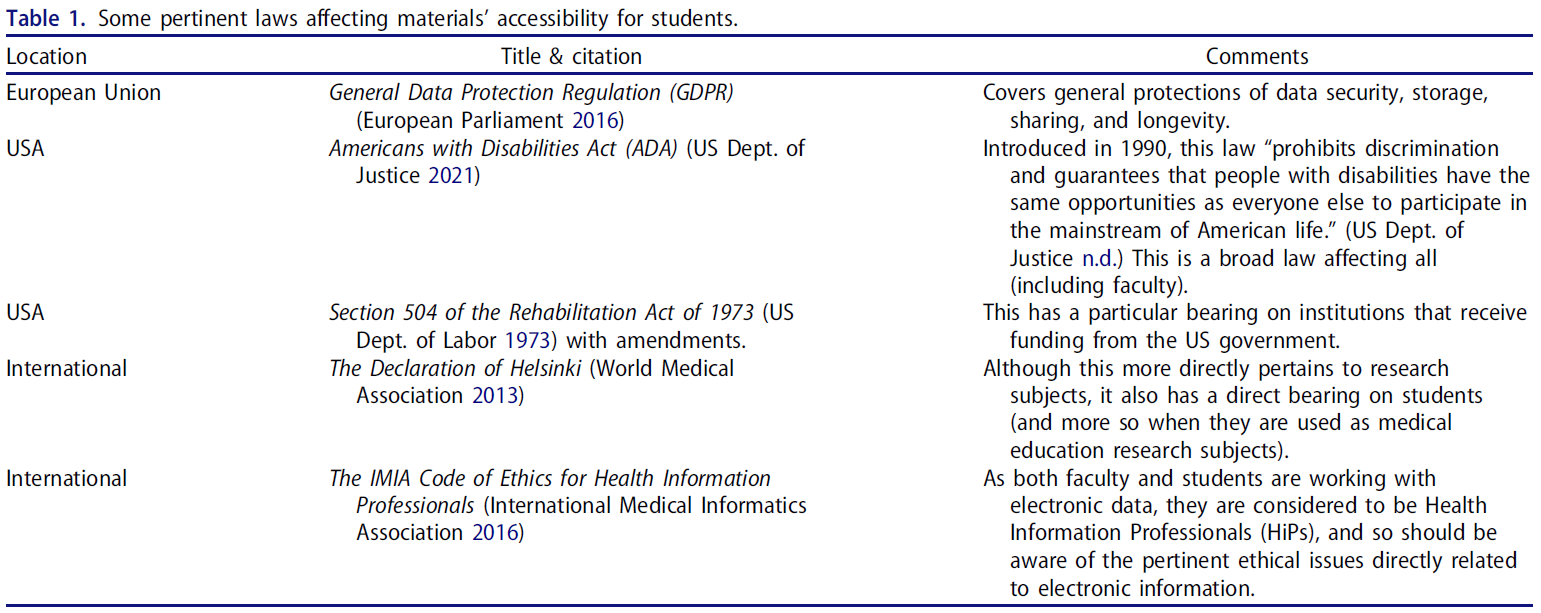

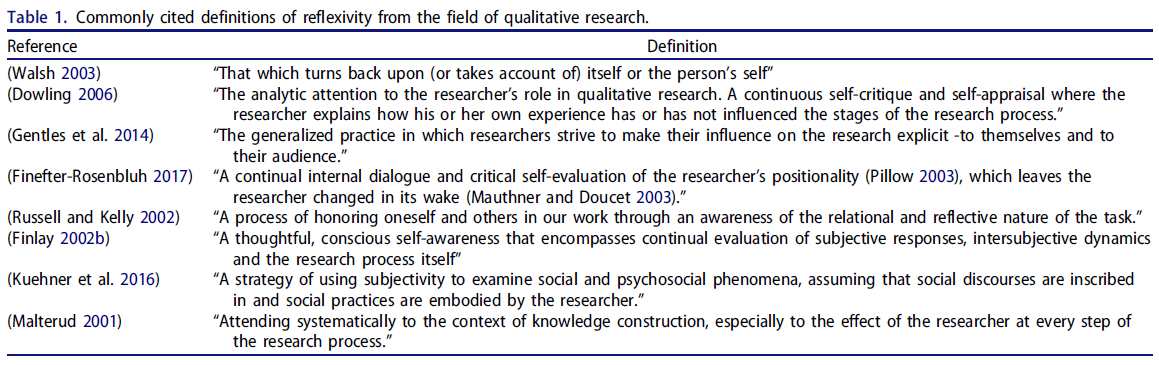

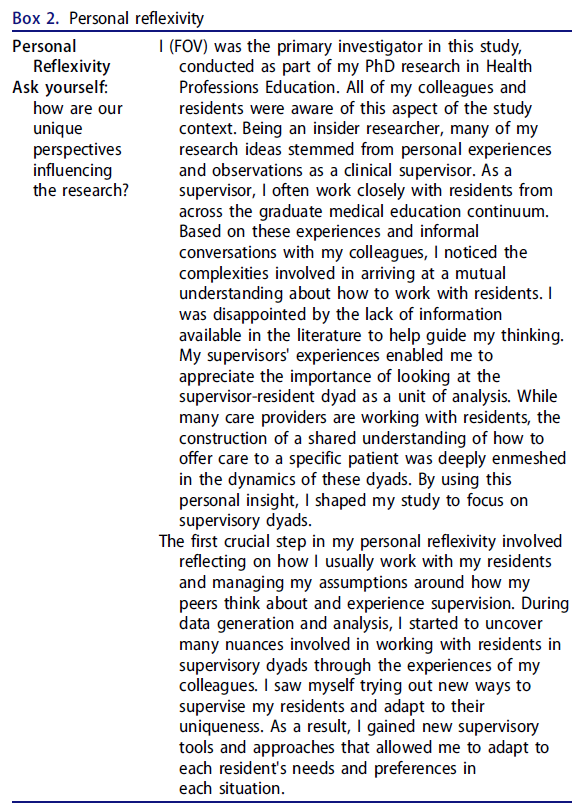

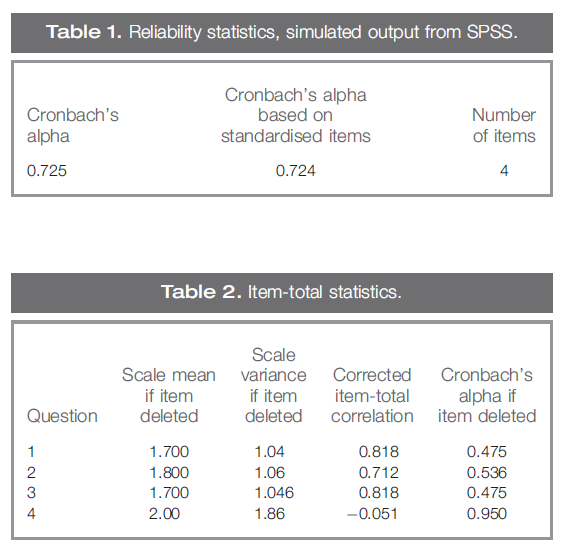

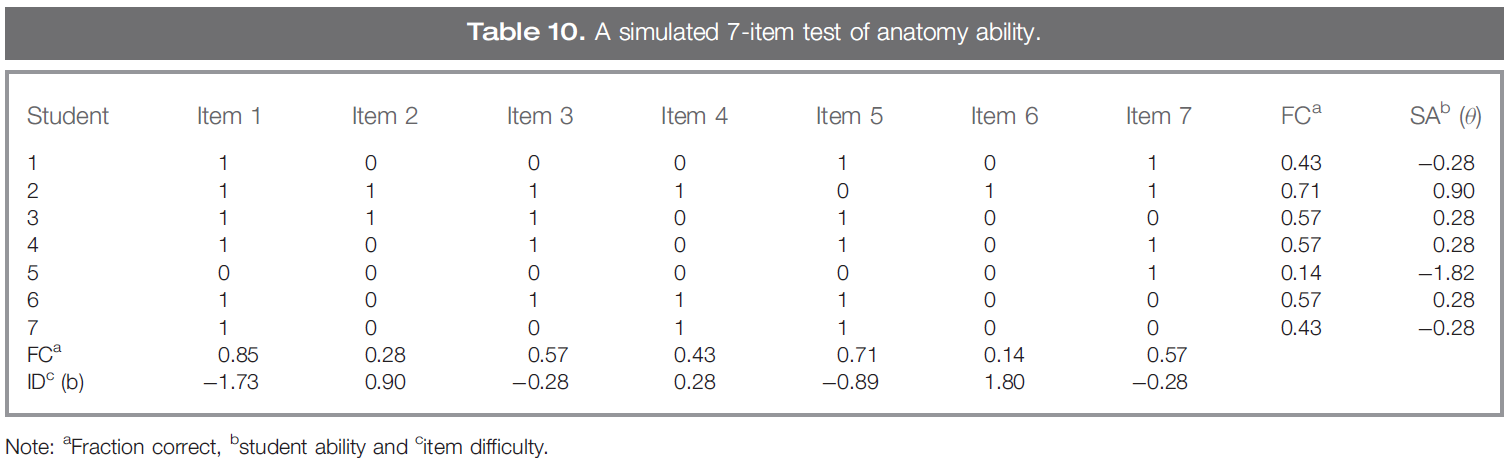

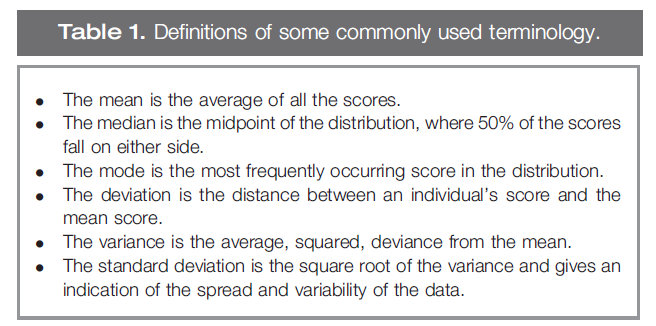

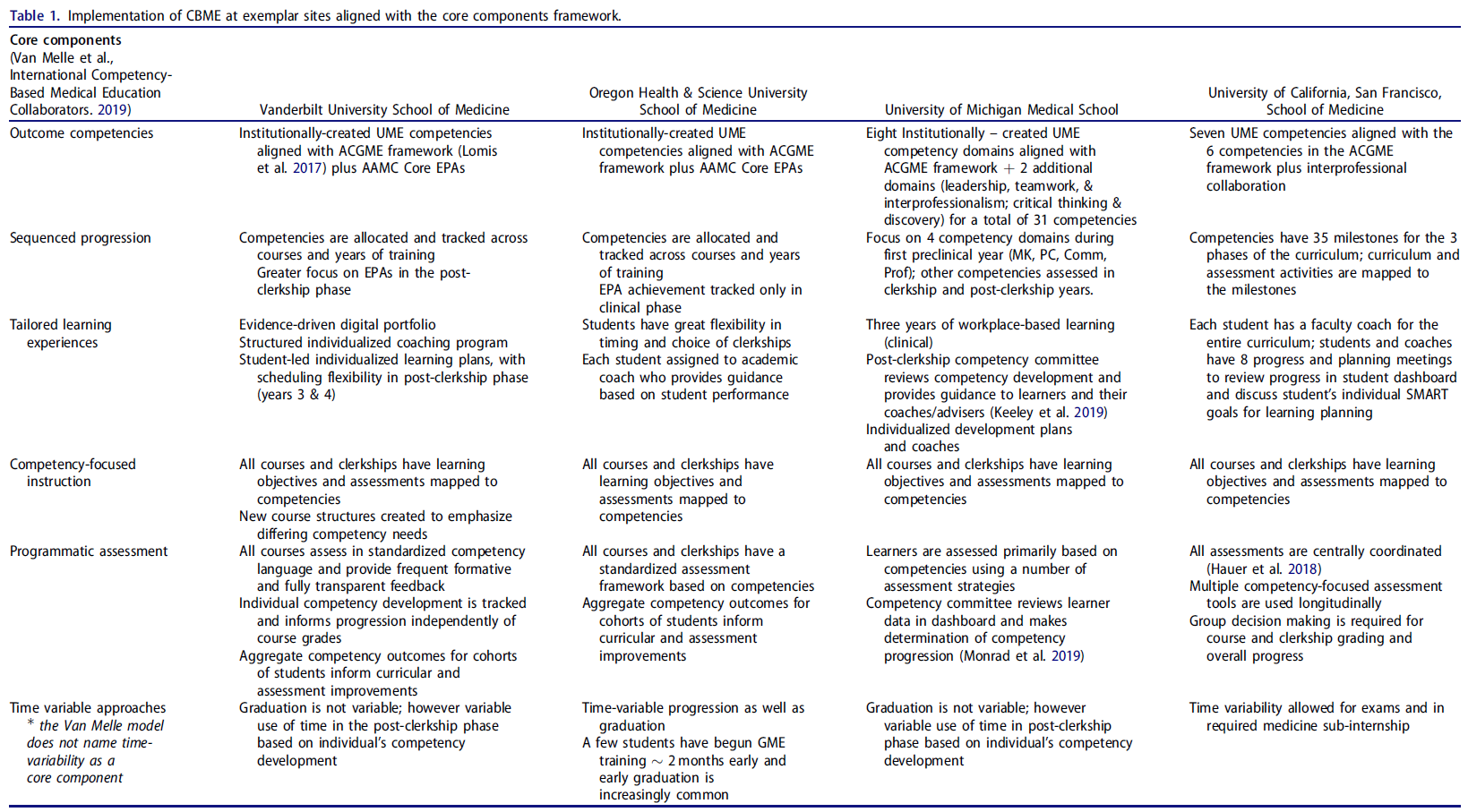

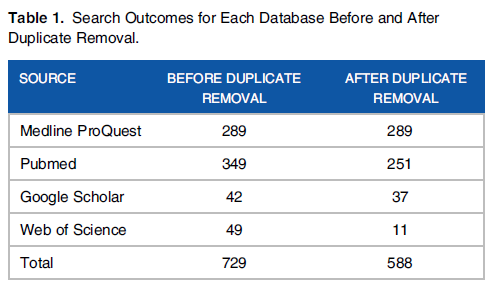

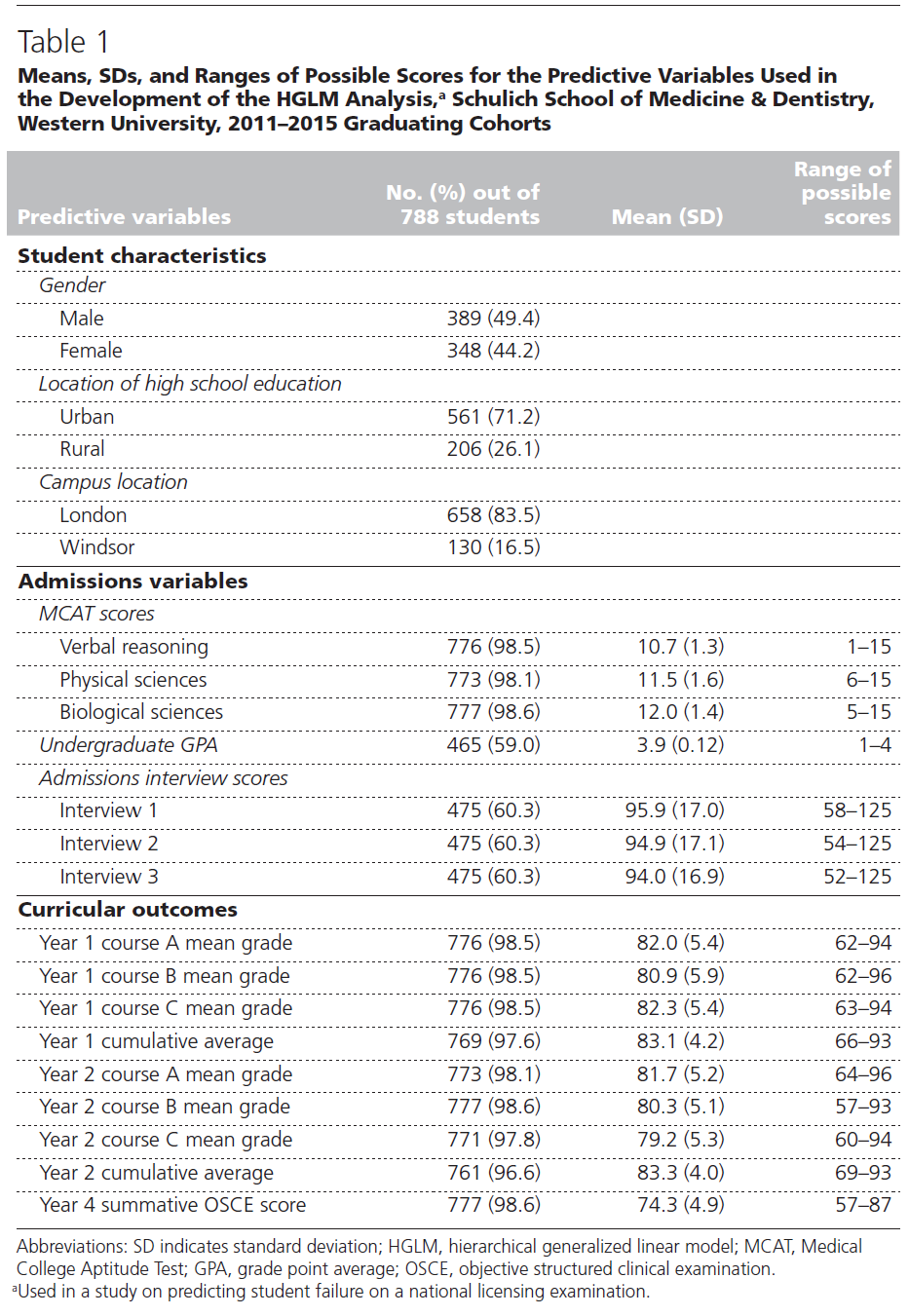

2011년부터 2015년까지 총 5개 졸업생의 코호트(각 코호트별 데이터 4년)에 걸쳐 20년간의 중복 데이터가 수집되었으며, 총 788명의 학생으로 구성되어 있다. 각 코호트의 학생 수는 147명에서 168명 사이였으며, 코호트당 평균 157명의 학생이 있었다. 표 1은 HGLM 분석 개발에 사용된 예측 변수에 대한 평균, 표준 편차 및 가능한 점수 범위를 제공한다.

In total, 20 years of overlapping data were gathered across five cohorts of graduating students (4 years of data from each cohort) from 2011 to 2015, comprising 788 students. The number of students in each cohort ranged from 147 to 168, with an average number of 157 students per cohort. Table 1 provides the mean, standard deviation, and range of possible scores for the predictive variables used in the development of the HGLM analysis.

표 1에 나타난 바와 같이 변수별 학생 수는 변수별 가능한 점수 및 평균의 범위와 같이 다양하다. 그러나 각 변수 그룹 내의 표준 편차는 매우 유사합니다. 또한 전체 학생의 389명(49.4%)이 남학생이었고 348명(44.2%)이 여학생이었다.

As shown in Table 1, the number of students per variable varies, as do the ranges of possible scores and means for each variable. However, the standard deviations within each group of variables are very similar. Additionally, 389 (49.4%) of all students were male and 348 (44.2%) were female.

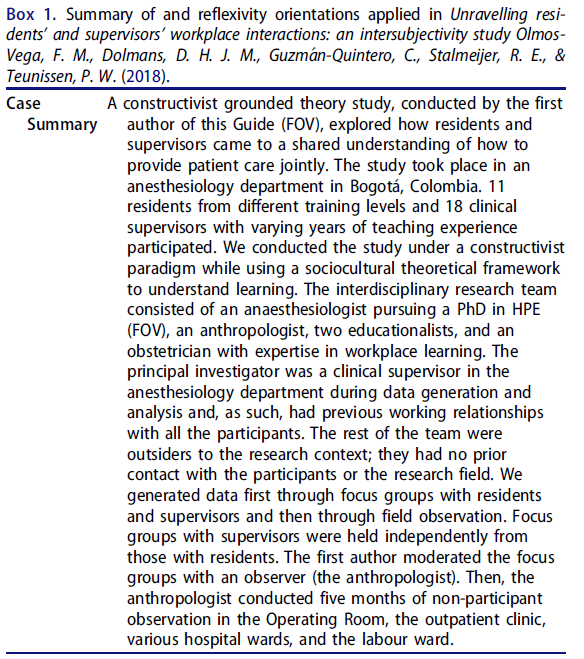

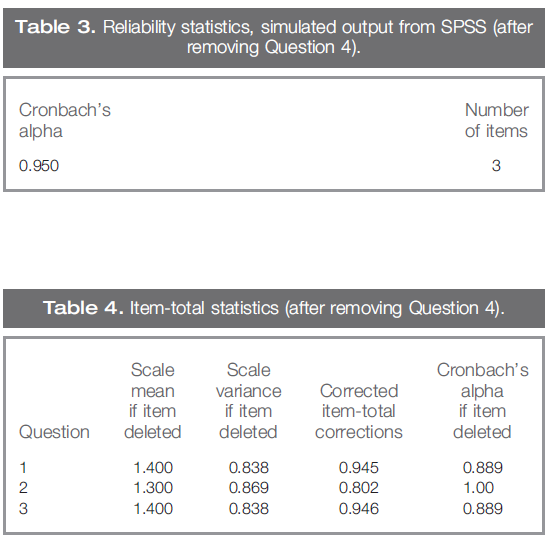

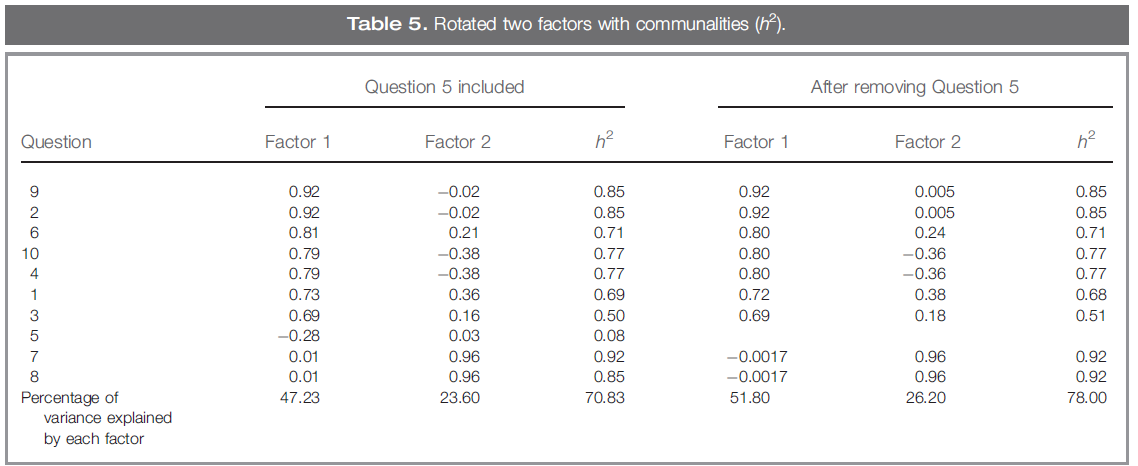

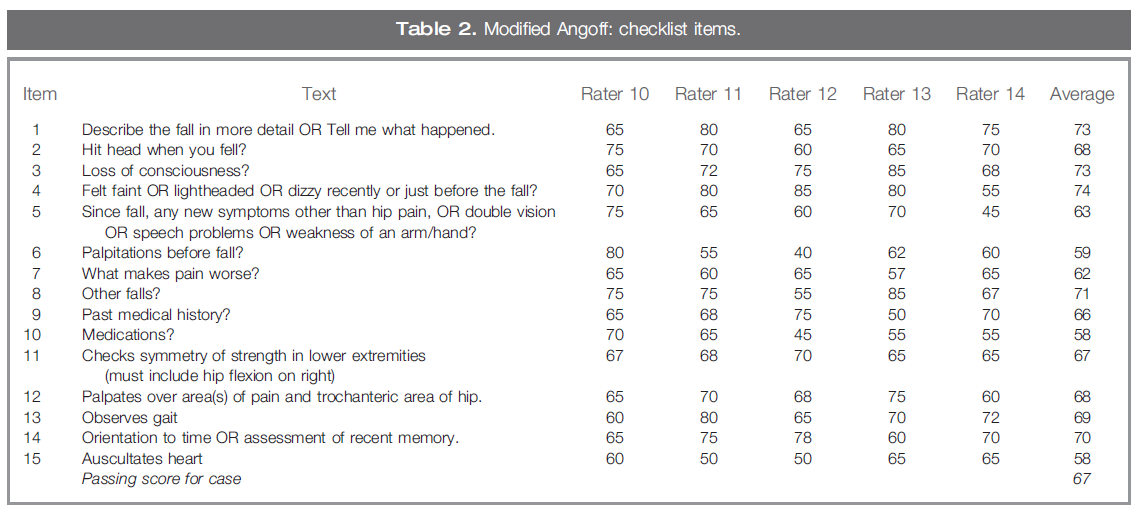

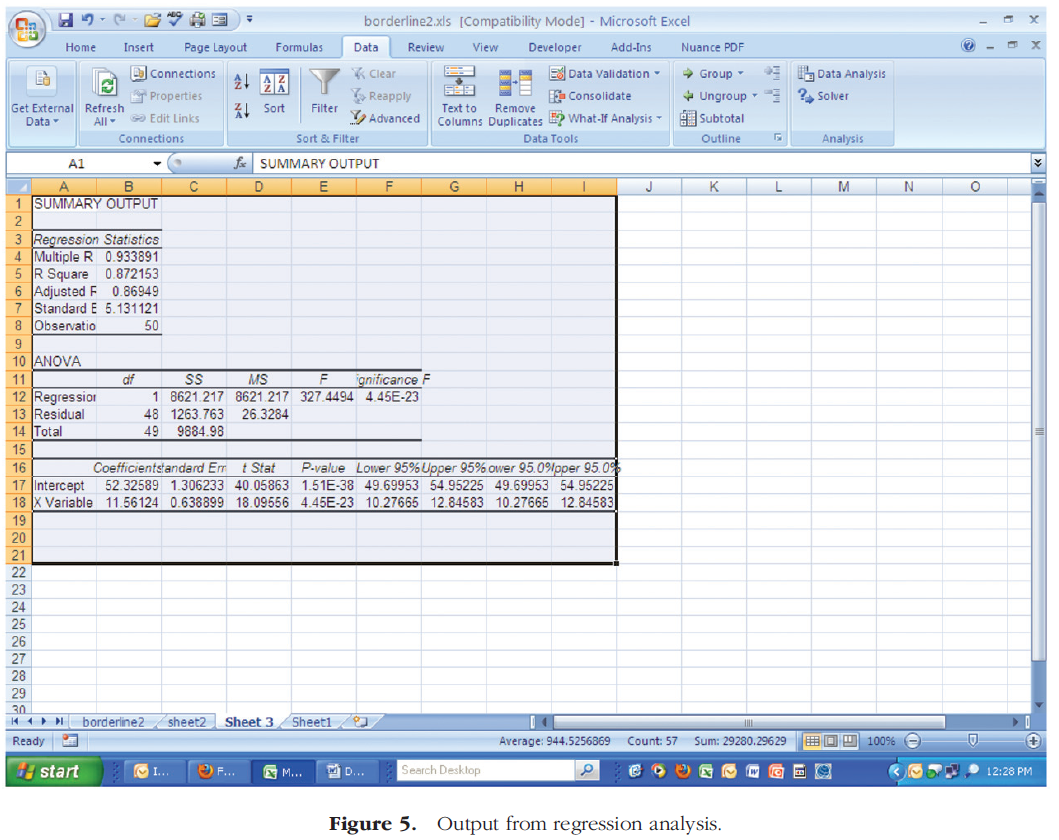

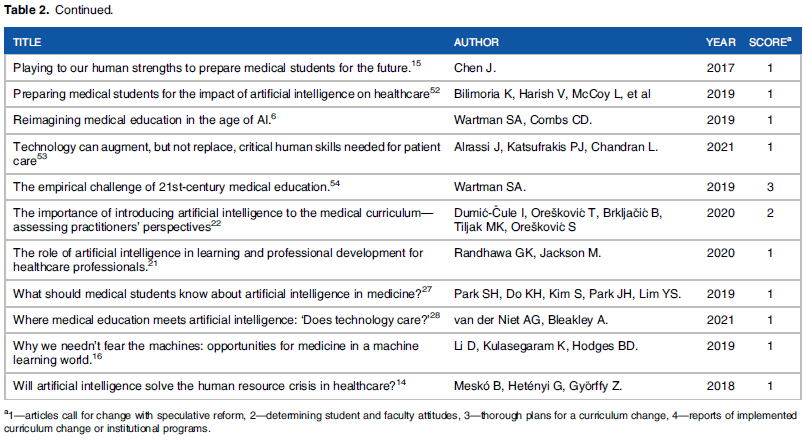

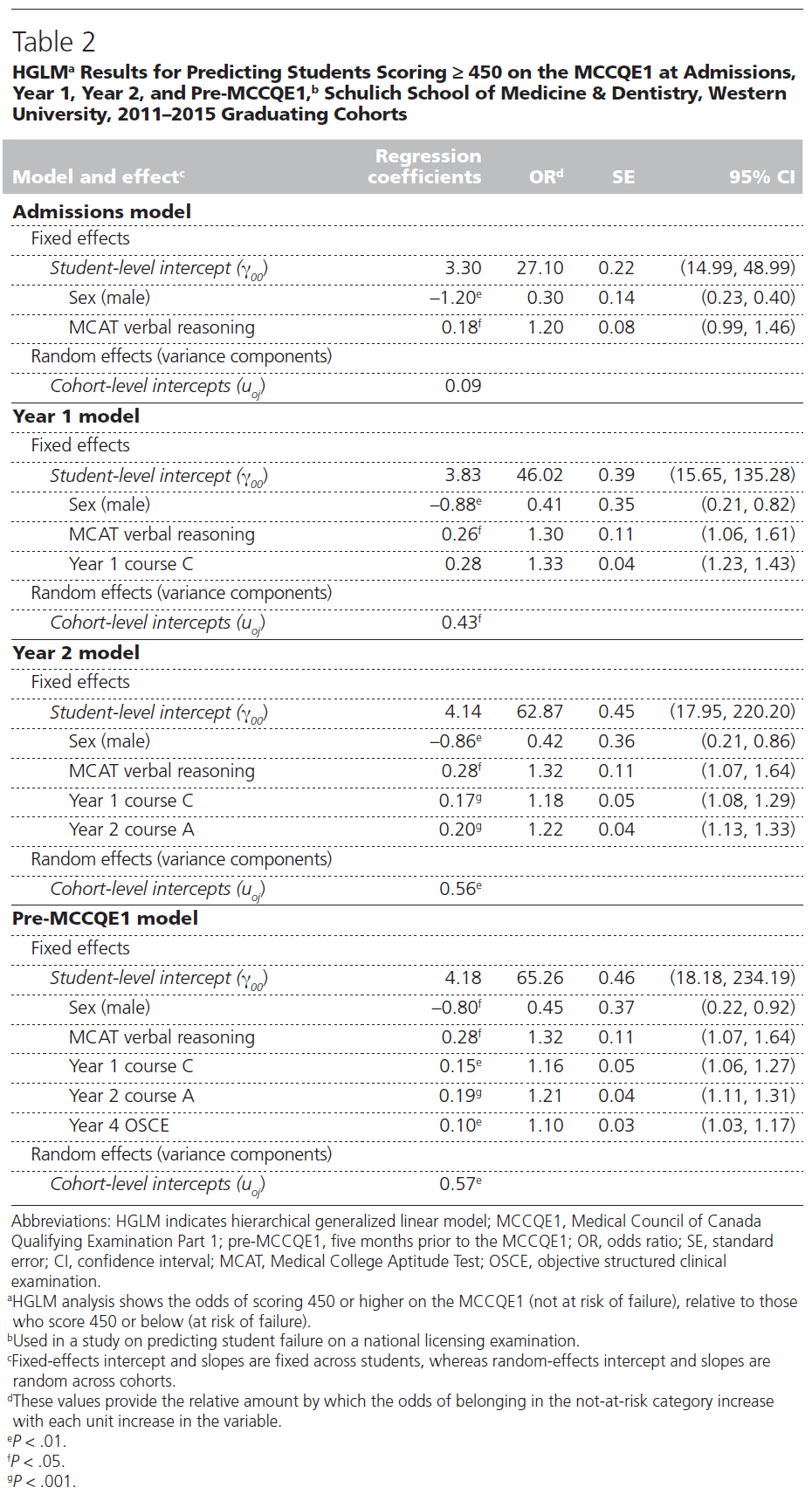

HGLM 분석의 결과를 기반으로, 우리는 다음 5가지 변수를 고장 위험에 대한 중요한 예측 변수로 식별할 수 있었다.

성별, MCAT 언어 추론 점수, 2개의 프리클래스 과정 평균 성적(1학년 과정 C와 2학년 과정 A), 4학년 합계 OSCE 점수(표 2).

On the basis of results from our HGLM analyses, we were able to identify the following five variables as significant predictors of being at risk of failure:

- gender,

- MCAT verbal reasoning score,

- two preclerkship course mean grades (year 1 course C and year 2 course A), and

- the year 4 summative OSCE score (Table 2).

이러한 결과는 평균적으로 다른 모든 변수를 제어할 때 여성이 남성보다 MCCQE1에서 450점(즉, 실패 위험이 없는 경우)을 획득할 확률이 더 높다는 것을 보여주었다. 이 발견은 고부담 의학 시험에서의 성별 성과 격차가 줄어들고 있음을 시사할 수 있다. 그러나 이러한 성별 관련 성과격차를 더 살펴보기 위해서는 향후 연구가 필요하다. 또한 MCAT 언어 추론 점수(코호트의 평균에 비해)가 더 높은 학생, 1학년 과정 C와 2학년 과정 A의 평균 성적, 4학년 종합 OSCE 점수가 실패의 위험에 처하지 않을 확률이 더 높다.

These results showed that, on average, females have higher odds of scoring ≥ 450 on the MCCQE1 (i.e., of not being at risk of failure) than males, when controlling for all other variables. This finding may suggest that the gender performance gap on high-stakes medical examinations is narrowing. However, future research is needed to examine this gender-related performance gap further. Additionally, students with higher (relative to their cohort’s average) MCAT verbal reasoning scores, year 1 course C and year 2 course A mean grades, and year 4 summative OSCE scores have higher odds of not being at risk of failure.

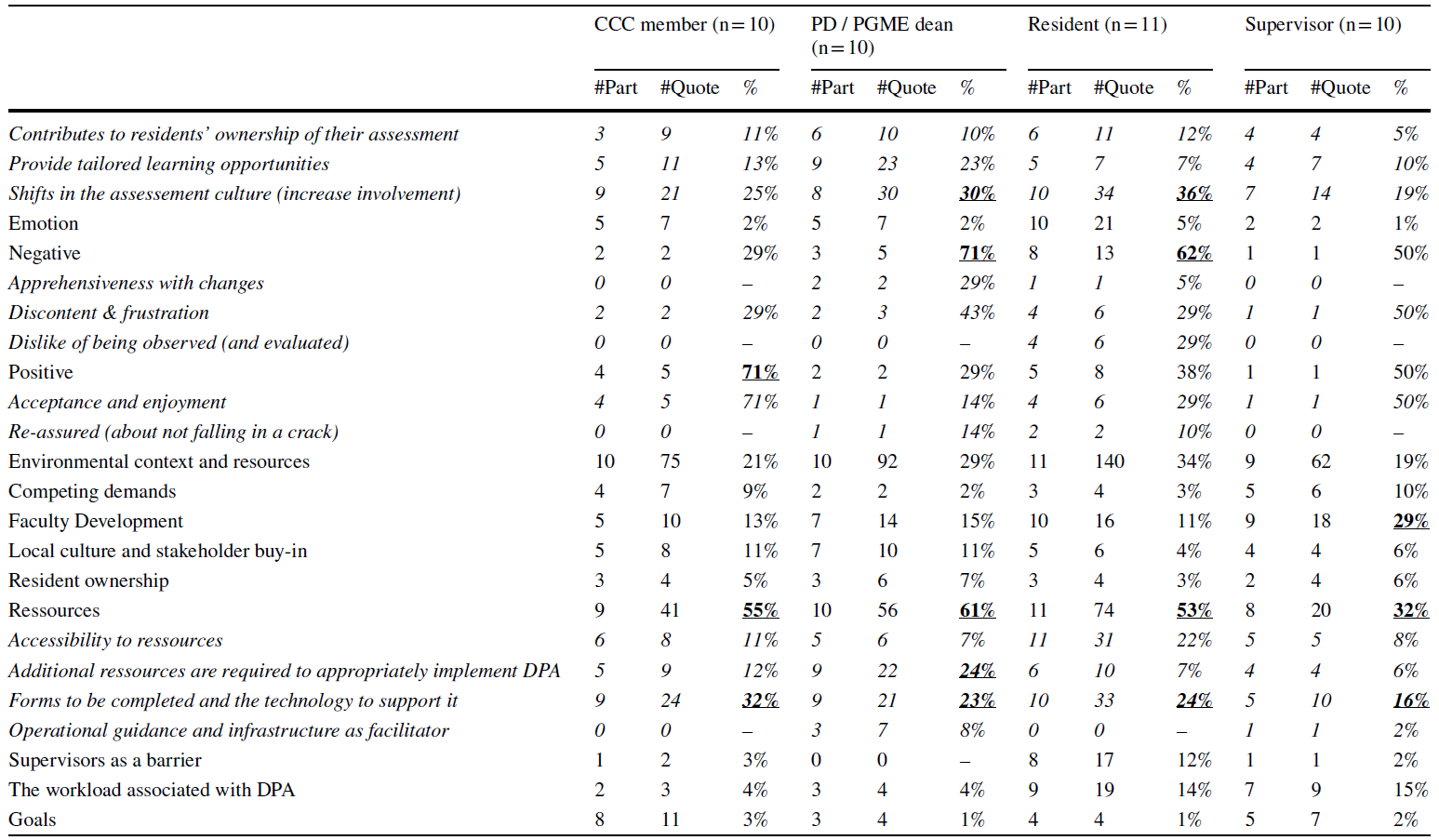

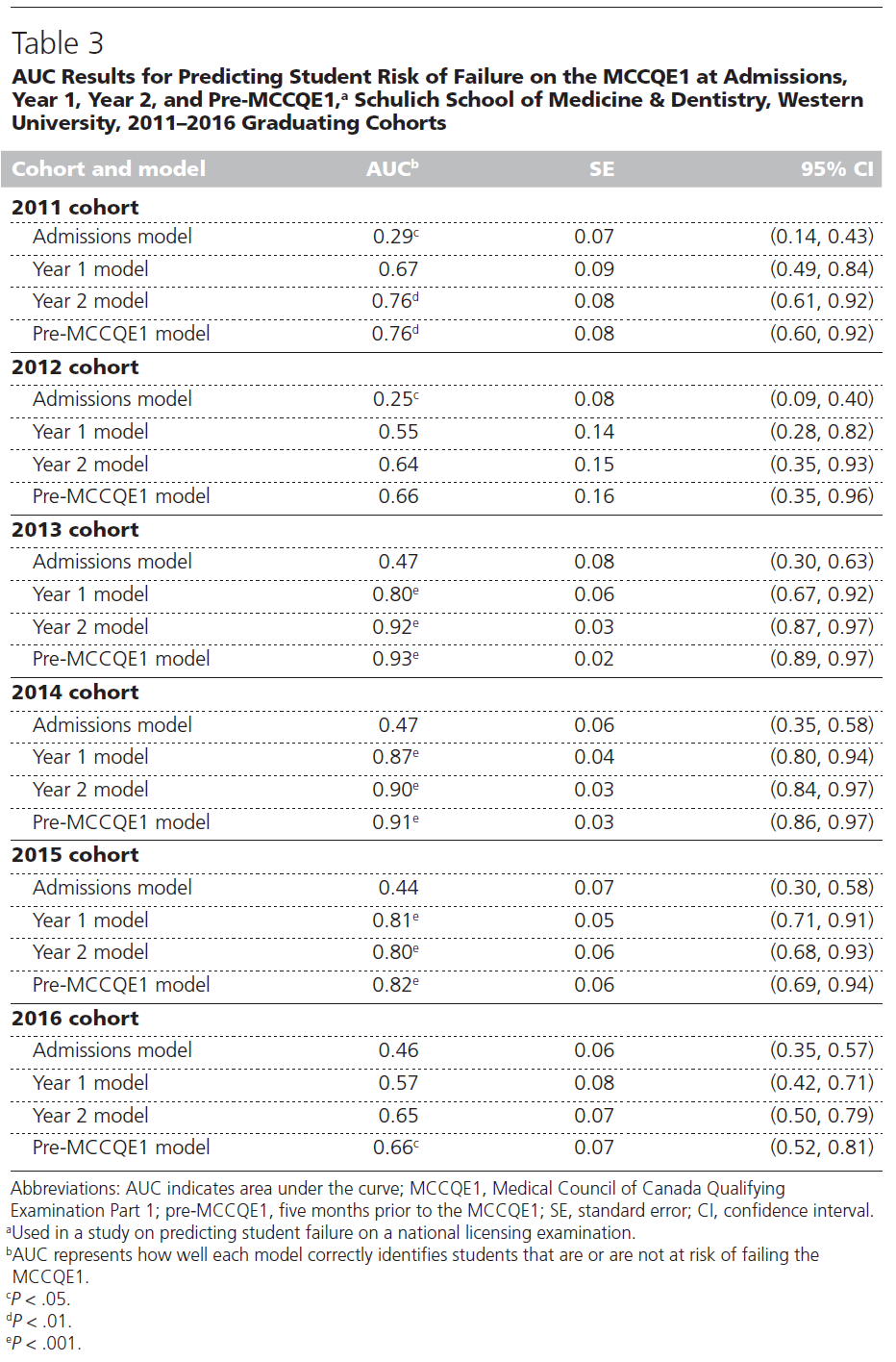

예측 모델(입학 1, 2학년 및 pre-MCCQE1 )을 개발한 후, 각 코호트의 데이터를 별도로 입력하여 학생들의 실패 위험을 얼마나 정확하게 예측했는지 조사했다. 그런 다음 2016년 코호트 데이터를 사용하여 미래 위험을 예측하는 모델의 정확도를 조사했다. 표 3은 AUC에서 계산된 모델 정확도 결과를 제공합니다.

After developing the predictive models (at admissions, year 1, year 2, and pre-MCCQE1), we examined how accurate we were in predicting student risk of failure by inputting data from each cohort separately. We then examined the accuracy of the models in predicting future risk using the 2016 cohort data. Table 3 provides the model accuracy results calculated from the AUC.

모델의 예측 정확도(AUC)는 다양하다. 전반적으로, pre-MCCQE1 model 은 학생의 실패 위험 예측에 가장 정확하며(AUC 0.66–0.93) 입학 모델은 MCCQE1 실패 위험의 정확한 예측 변수는 아니다(AUC 0.25–0.47). 1, 2, MCCQE1 이전 모델의 정확도는 2013년, 2014년 및 2015년 코호트에 대해 높은 수준의 정확도로 매년 다릅니다. 예를 들어, 2014년 코호트의 경우, 2년차 모델에서 AUC가 0.90(95% 신뢰 구간 0.84, 0.97)이었고, 이는 위험에 처한 학생들을 예측하는 강력한 능력을 보여주었다. 전반적으로, 2016년 코호트로 미래 성과를 예측하는 데 있어 모델은 덜 예측되었으며, 우리는 MCCQE1 이전 모델을 통해서만 유의미한 AUC를 달성할 수 있었다. 이는 모델이 위험에 처한 학생들을 정확하게 예측하는지 확인하기 위해 모델을 평가하고 수시로 업데이트할 필요가 있음을 시사한다.

The predictive accuracy (AUC) of the models varies. Overall, the pre-MCCQE1 model is the most accurate at predicting a student’s risk of failing (AUC 0.66–0.93), while the admissions model is not an accurate predictor of being at risk of failing the MCCQE1 (AUC 0.25–0.47). The accuracy of the year 1, year 2, and pre-MCCQE1 models varies from year to year, with high levels of accuracy for the 2013, 2014, and 2015 cohorts. With the 2014 cohort, for example, we had an AUC of 0.90 (95% confidence interval 0.84, 0.97) in our year 2 model, demonstrating a strong ability to predict students being at risk. Overall, the models were less predictive when it came to predicting future performance with the 2016 cohort, for which we were only able to achieve a significant AUC with the pre-MCCQE1 model. This suggests that the models need to be evaluated and updated from time to time to ensure that they are accurately predicting students at risk.

논의

Discussion

이 논문은 학부 의학 교육에서 예측 모델링의 가능성과 정확성에 대한 접근법과 증거를 모두 제공한다. 5개 코호트의 20년 데이터(각 코호트의 4년 데이터)를 사용하여 4개의 예측 모델을 개발하고 입학 1, 2학년 및 MCCQE1 이전에서 국가 면허 시험에 실패할 수 있는 학생 위험을 식별하는 데 있어 정확도를 측정했다. HGLM 분석의 결과는 국가 면허 시험인 MCCQE1에서 낙제할 위험이 있는 학생들을 예측하는 5가지 주요 입학 변수와 커리큘럼 결과를 확인했다. 이전 연구 결과와 유사하게, 우리 모델의 증거는 [입학 과정 동안 학생 위험을 식별하는 것은 불가능]하지만, [1학년 말]까지는 실패 위험이 있는 학생을 식별하고 모니터링하기 시작할 수 있음을 시사한다. 그러나 이러한 예측은 2년차 및 MCCQE1 이전에도 추가로 검증되어야 한다.

This paper offers both an approach and evidence of the possibility and accuracy of predictive modeling in undergraduate medical education. Using 20 years of data across five cohorts (4 years of data from each cohort), we developed four predictive models and measured their accuracy in identifying student risk of failing a national licensing examination at admissions, year 1, year 2, and pre-MCCQE1. Outcomes from our HGLM analysis identified five key admissions variables and curricular outcomes that are predictive of students at risk of failing the MCCQE1, a national licensing examination. Similar to findings from previous studies, evidence from our models suggests that, while it is not possible to identify student risk during the admissions process, we can begin to identify and monitor students at risk of failure by the end of year 1 studies.10–12 However, these predictions must be further validated in year 2 and again pre-MCCQE1.

우리의 AUC 분석 결과들은 이러한 모델의 예측 정확도가 코호트마다 달랐음을 시사한다. 그러나 모델에 더 많은 변수가 추가됨에 따라 정확도가 높아지면서 학생들의 실패 위험을 더 잘 예측할 수 있었다. 2013년, 2014년 및 2015년 코호트의 경우 높은 수준의 정확도로 학생들의 실패 위험을 예측할 수 있었습니다. 2016년 미래 학생 위험을 추정할 때 모델이 덜 예측된 것으로 밝혀졌지만, 여전히 MCCQE1 이전 모델을 사용하여 학생의 실패 위험을 어느 정도 정확하게 예측할 수 있어 학생의 역량 수준에 따라 개입이 가능하다. 코호트 간의 변동은 이러한 모델을 매년 평가하여 학생 모집단 내의 커리큘럼 변경이나 차이를 통제해야 할 수 있음을 시사한다.

Findings from our AUC analyses suggest that the predictive accuracy of these models varied among the cohorts. However, as more variables were added to our model, we were able to better predict student risk of failure with increasing levels of accuracy. For the 2013, 2014, and 2015 cohorts, we were able to predict student risk of failure with high levels of accuracy. While the models were found to be less predictive in 2016, when estimating future student risk, we were still able to predict student risk of failure with some accuracy using our pre-MCCQE1 model, allowing for intervention depending on the student’s level of competency. The variation among cohorts suggests that these models may need to be evaluated from year to year to control for any curricular changes or differences within student populations.

AUC에서 산출된 추정치는 내부적으로 학생들을 위험 범주(낮음, 중간 또는 높음)로 분류하기 위해 컷오프 점수를 생성하는 데 사용될 것이다. 그런 다음 1, 2학년 및 MCCQE1 이전 모델을 사용하여 여러 단계에서 학생 위험을 평가합니다. 어느 단계에서든 중간에서 고위험으로 확인된 학생은 사례별로 검토한다(학생 성과에 관한 다른 지원 문서도 고려된다). 그런 다음 학생의 필요에 따라 지원과 개입이 우선됩니다.

Estimates produced from our AUCs will be used internally to create cutoff scores to classify students into risk categories (low, medium, or high). Student risk will then be assessed at multiple stages using our year 1, year 2, and pre-MCCQE1 models. Students identified as medium to high risk at any stage will be reviewed on a case-by-case basis (with other supporting documentation regarding student performance taken into consideration). Support and intervention will then be prioritized on the basis of student need.

프로그램적 관점에서, 이러한 결과는 교육자와 리더가 국가 면허 시험에 앞서, 효과적인 개입과 함께 조기 발견을 통해 학습자를 더 잘 지원하고, 미래의 학업 실패 위험을 최소화할 수 있는 잠재력을 가지고 있다. 프로그램은 학업 실패의 위험에 처한 학습자를 정확하게 식별하고 지원할 수 있는 신뢰할 수 있는 방법을 갈망한다. 이 연구는 예측 모델링이 어떻게 저성능을 식별하기 위해 사용될 수 있는지를 보여주는 사례이다. 데이터 중심 의사 결정과 투명성 및 책임성 증대에 대한 요구의 시대에 캐나다 의과대학은 학생 교육을 위한 정부 기금을 제공할 사회적 책임이 있으며, 입학 전에 학습자의 상대적 동질성을 고려할 때 리더는 효과적인 형성적 의사 결정을 지원하기 위한 도구를 중요시한다.

From a programmatic standpoint, these results have the potential to allow educators and leaders to better support learners and minimize risk of future academic failure through early detection, coupled with effective intervention, in advance of national licensing examinations. Programs thirst for a reliable way to accurately identify and support learners at risk of academic failure; this study serves as an example of how predictive modeling can be used to identify underperformance. In an era of data-driven decision making and demand for greater transparency and accountability, Canadian medical schools are socially accountable to deliver on government funding for student education, and, given the relative homogeneity of learners before matriculation, leaders value tools to support effective formative decision making.

5개 코호트에서 20년 이상의 데이터를 사용하여 다른 국가 간 연구와 일치하는 많은 발견을 확인할 수 있었다. 본 논문은 의과대학 1학년 내 잠재적 학업위험 학생을 능동적으로 식별하고 정량적으로 모니터링하기 위한 새로운 접근방식을 프로그램과 교육자에게 제공한다. 비록 우리의 연구 결과가 초기 면허 시험에 앞서 (AUC를 통해) 학생 실패에 대한 위험 점수를 정확하게 추정할 수 있었다는 것을 보여주지만, 우리가 다루고 싶은 몇 가지 제한이 있다.

Using over 20 years of data across five cohorts, we were able to confirm many findings consistent with other cross-national studies.10–12,16 This paper offers programs and educators with a new approach to proactively identify and monitor students at potential academic risk quantitatively within the first years of medical school. Even though our findings indicate that we were able to accurately estimate a risk score for student failure (via AUCs) in advance of an initial licensing examination, there are a few limitations we would like to address.

첫째, 우리 모델은 시간에 따른 변동성에 매우 민감하다. 이것은 매년 교육학적 변화와 학생 인구 차이를 모두 반영할 수 있지만, 추정을 더 어렵게 만든다. 그러나, 우리는 여전히 안정적인 학생 추정치가 우리의 예측에서 다소 정확하다는 것을 발견했다. 그럼에도 불구하고, 우리의 데이터는 이 접근법을 채택하는 학교가 커리큘럼 변화나 학생 인구 차이를 고려하여 이러한 모델을 주기적으로 업데이트할 필요가 있음을 경고할 필요가 있음을 시사한다. 또한, 우리의 결과는 분석을 통한 예측을 학습자를 식별하고 지원하기 위한 개입을 제공하기 위한 강력한 커리큘럼 거버넌스 도구로 인정하지만, 이러한 가능성에서 생성된 추정치는 코스 의장과 교직원의 다른 지원 문서와 함께 지침으로 사용되어야 한다. 마지막으로, 본 연구는 기관별 변수에 크게 의존한 것으로 보이지만(이러한 연구결과의 일반화 가능성을 제한할 수 있음), 모든 의과대학이 접근할 수 있고 예측을 위해 분석할 수 있는 변수를 포함하도록 예측 모델을 구성했다. 따라서 본 연구에서 제시한 방법론과 모델링이 다른 대학에서도 효과적으로 재현될 수 있을 것으로 판단된다.

First, our models are highly sensitive to variability over time. While this may be reflective of both pedagogical changes and student population differences from year to year, it makes estimation more challenging. However, we still found stable student estimates to be modestly accurate in our predictions. Nevertheless, our data suggest that schools adopting this approach need to be cautioned of a need for these models to be updated periodically to account for any curricular changes or student population differences. Additionally, while our results acknowledge prediction through analytics as a powerful curricular governance tool to identify and offer intervention to support learners, the estimates produced from these probabilities should be used as a guide, alongside other supporting documentation from course chairs and faculty as well as program governance indicators. Finally, although this study appears to have relied heavily on institution-specific variables (which could limit the generalizability of these findings), we constructed our predictive models to be inclusive of variables that all medical schools have access to and can analyze for prediction. As a result, we believe the methodology and modeling presented within this study could be effectively replicated at other universities.

결론들

Conclusions

학생 데이터에 대한 분석적 접근 방식을 사용하여, 실패 위험이 있는 학생을 조기에 식별하기 위한 노력으로, 우리는 주요 예측 변수를 체계적으로 식별하고 국가 면허 시험에서 향후 학생 성과를 예측하는 데 사용할 수 있는 방법론을 제공할 수 있었다고 믿는다. HGLM과 AUC 분석을 사용하여 프로그램 연구 초기에 MCCQE1에서 학생들의 학업 실패 위험을 정량화할 수 있었다. 이러한 유형의 모델에서 발견한 결과는 프로그램이 잠재적인 학업 위험에 있는 학생을 정량적으로 더 잘 식별하고 모니터링하며 맞춤형 조기(잠재적으로 이 핵심 경력 평가 전에 최대 3년) 개입 전략을 개발할 수 있도록 할 수 있다.

Using an analytic approach to student data, in an effort to identify students at risk of failure early on, we believe we were able to systematically identify key predictive variables and offer a methodology that could be used to predict future student performance on national licensing examinations. Through the use of HGLM and AUC analyses, we were able to quantify student risk of academic failure on the MCCQE1 early on within program studies. Findings from these types of models could enable programs to better identify and monitor students at potential academic risk quantitatively and develop tailored early (potentially up to three years prior to this key career assessment) intervention strategies.

새로운 MCCQE1의 향후 변경사항이 학생들의 성적과 시험에 들어가는 학생 위험을 예측하는 우리의 능력에 어떤 영향을 미칠 수 있는지 검토하기 위한 향후 연구가 필요하다. 우리는 또한 MCCQE1의 성별 성과 차이를 추가로 조사해야 한다고 제안한다. 마지막으로, 본 연구는 졸업 후 2년 후에 제공되는 MCCQE2에서 학생들의 실패 위험을 조사하기 위해 확장되어야 한다.

Future research is required to examine how forthcoming changes made to the new MCCQE131 may affect student performance as well as our ability to predict student risk going into the examination. We also propose that gender performance differences on the MCCQE1 should be further examined. Lastly, this study should be expanded to examine student risk of failure on the MCCQE2, which is offered two years post graduation.

결론적으로, 우리의 모델과 결과는 의과대학이 커리큘럼 내의 변수를 사용하여 면허 시험 결과를 더 잘 예측하기 위해 학생 데이터 검토에 분석적 접근 방식을 추가하는 것을 고려할 수 있음을 시사한다. 이것은 교육자들이 조기에 효과적으로 개입하고 잠재적인 위험에 처한 것으로 보이는 학생들에게 맞춤형 개입을 제공하게 할 수 있다. 이러한 모델은 프로그램이 미래의 학생 성과를 더 잘 예측할 수 있을 뿐만 아니라 프로그램 졸업생들을 자신 있게 식별, 지원 및 개선할 수 있도록 할 수 있는 잠재력을 가질 수 있다.

In conclusion, our models and results suggest that medical schools may wish to consider adding an analytic approach to student data review to better predict licensing examination outcomes using variables within their curriculum. This could lead educators to effectively intervene early and offer tailored interventions to students seen to be at potential risk. These models may have the potential to enable programs to not only better predict future student performance but also to allow them to confidently identify, support, and improve the quality of program graduates.

In Search of Black Swans: Identifying Students at Risk of Failing Licensing Examinations

PMID: 28953566

Abstract

Purpose: To determine which admissions variables and curricular outcomes are predictive of being at risk of failing the Medical Council of Canada Qualifying Examination Part 1 (MCCQE1), how quickly student risk of failure can be predicted, and to what extent predictive modeling is possible and accurate in estimating future student risk.

Method: Data from five graduating cohorts (2011-2015), Schulich School of Medicine & Dentistry, Western University, were collected and analyzed using hierarchical generalized linear models (HGLMs). Area under the receiver operating characteristic curve (AUC) was used to evaluate the accuracy of predictive models and determine whether they could be used to predict future risk, using the 2016 graduating cohort. Four predictive models were developed to predict student risk of failure at admissions, year 1, year 2, and pre-MCCQE1.

Results: The HGLM analyses identified gender, MCAT verbal reasoning score, two preclerkship course mean grades, and the year 4 summative objective structured clinical examination score as significant predictors of student risk. The predictive accuracy of the models varied. The pre-MCCQE1 model was the most accurate at predicting a student's risk of failing (AUC 0.66-0.93), while the admissions model was not predictive (AUC 0.25-0.47).

Conclusions: Key variables predictive of students at risk were found. The predictive models developed suggest, while it is not possible to identify student risk at admission, we can begin to identify and monitor students within the first year. Using such models, programs may be able to identify and monitor students at risk quantitatively and develop tailored intervention strategies.

'Articles (Medical Education) > 평가법 (Portfolio 등)' 카테고리의 다른 글

| 수행능력이 저조한 학생들도 행동-중-성찰 시에는 통찰력이 있다(Med Educ, 2017) (0) | 2022.09.30 |

|---|---|

| 역량 기반, 시간 변동 의학교육시스템의 평가를 위한 강화된 요구조건 (Acad Med, 2018) (0) | 2022.09.24 |

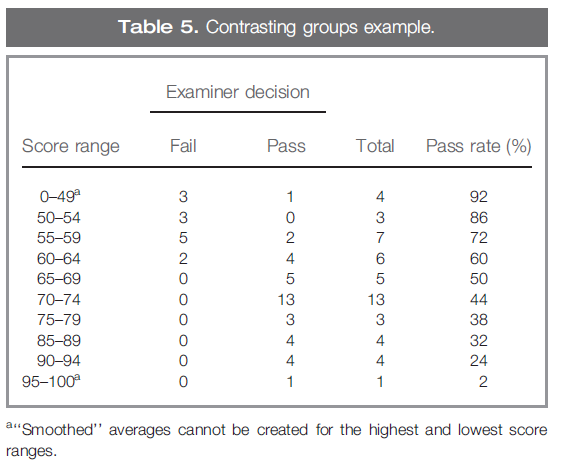

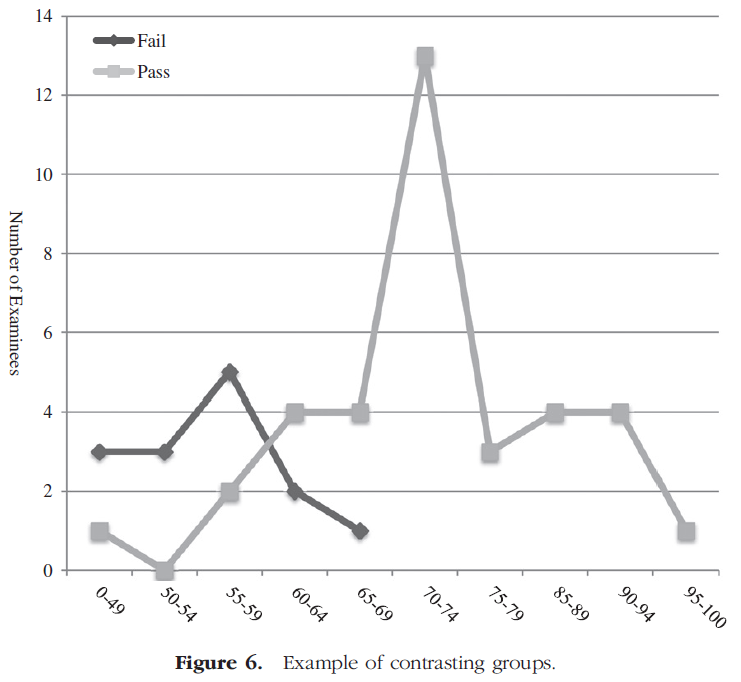

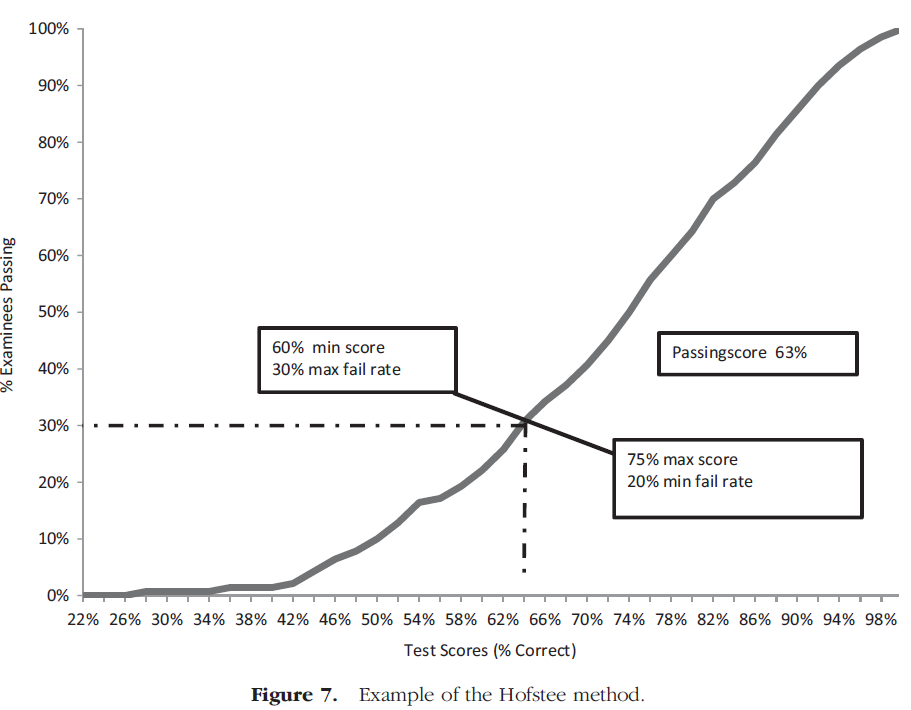

| 객관식 시험 자료의 사후 분석 - 고부담 시험 모니터링 및 개선: AMEE Guide No. 66 (Med Teach, 2012) (0) | 2022.09.09 |

| 객관식 시험의 사후 분석 AMEE Guide No. 54 (Med Teach, 2011) (0) | 2022.09.09 |

| 수행능력 기반 평가에서 합격선 설정 방법: AMEE Guide No. 85 (Med Teach, 2014) (0) | 2022.09.09 |