21세기의 미국 의사과학자 인력: 파이프라인 권고 (Acad Med, 2019)

U.S. Physician–Scientist Workforce in the 21st Century: Recommendations to Attract and Sustain the Pipeline

Robert A. Salata, MD, Mark W. Geraci, MD, Don C. Rockey, MD, Melvin Blanchard, MD, Nancy J. Brown, MD, Lucien J. Cardinal, MD, Maria Garcia, MD, MPH, Michael P. Madaio, MD, James D. Marsh, MD, and Robert F. Todd III, MD, PhD

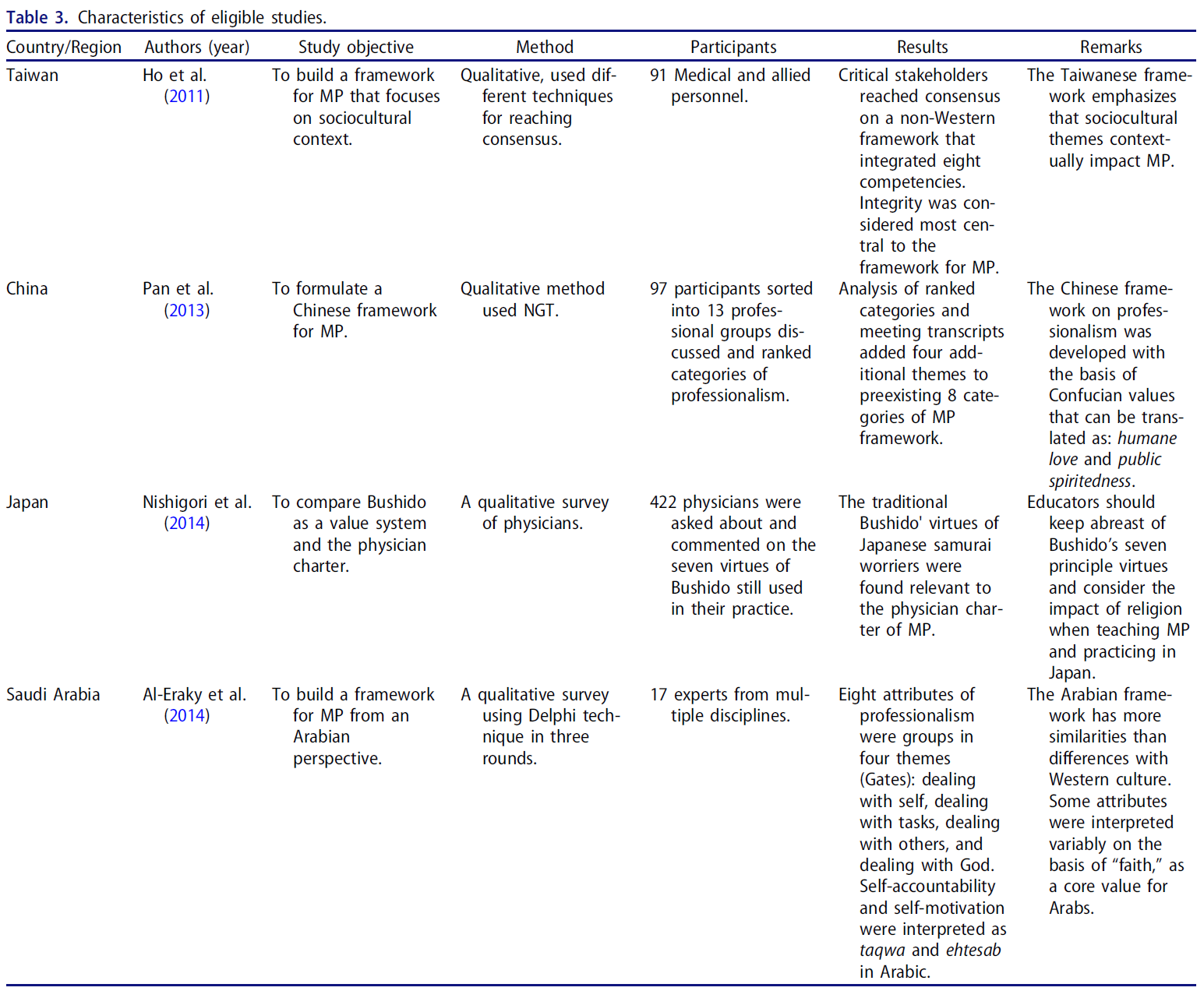

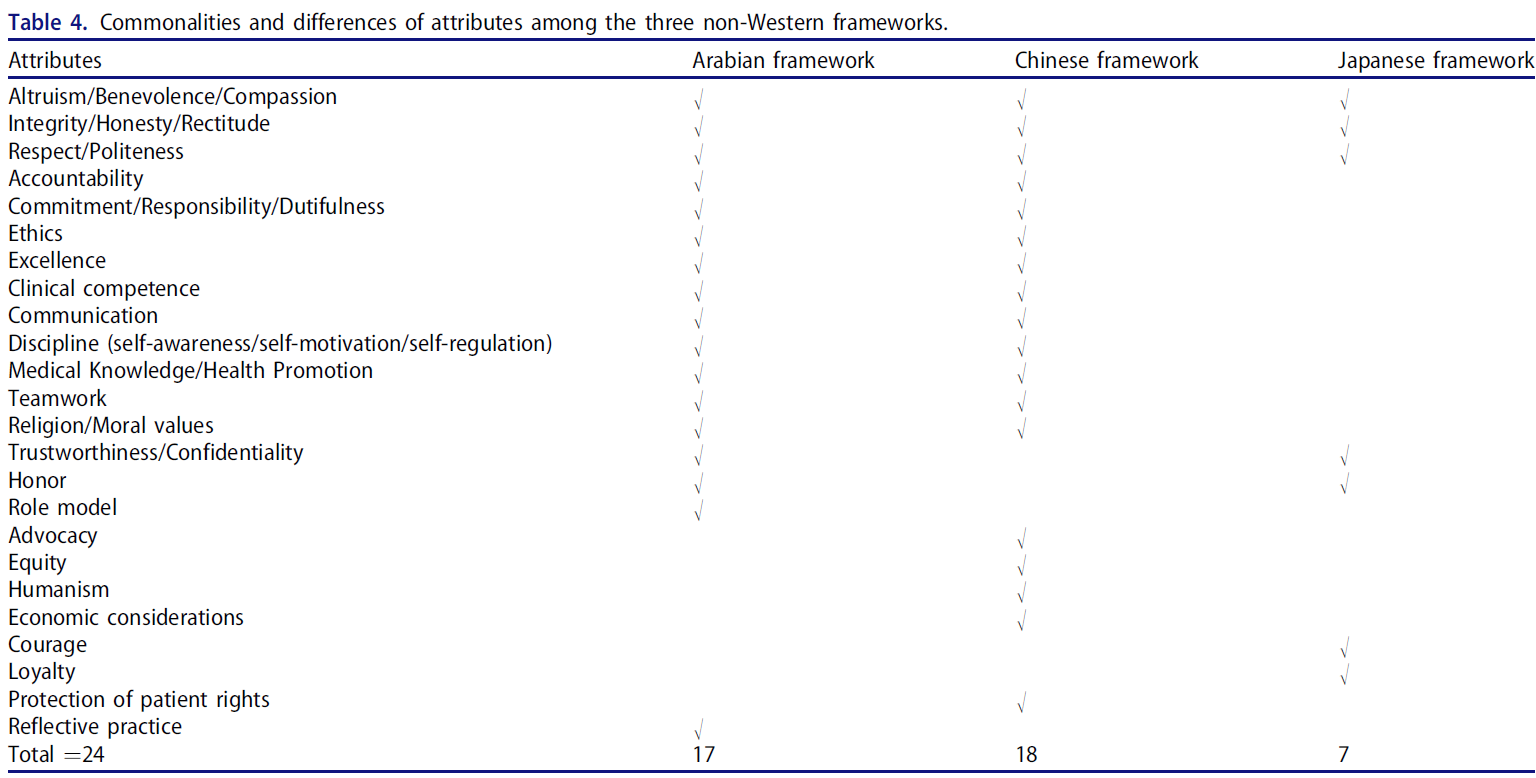

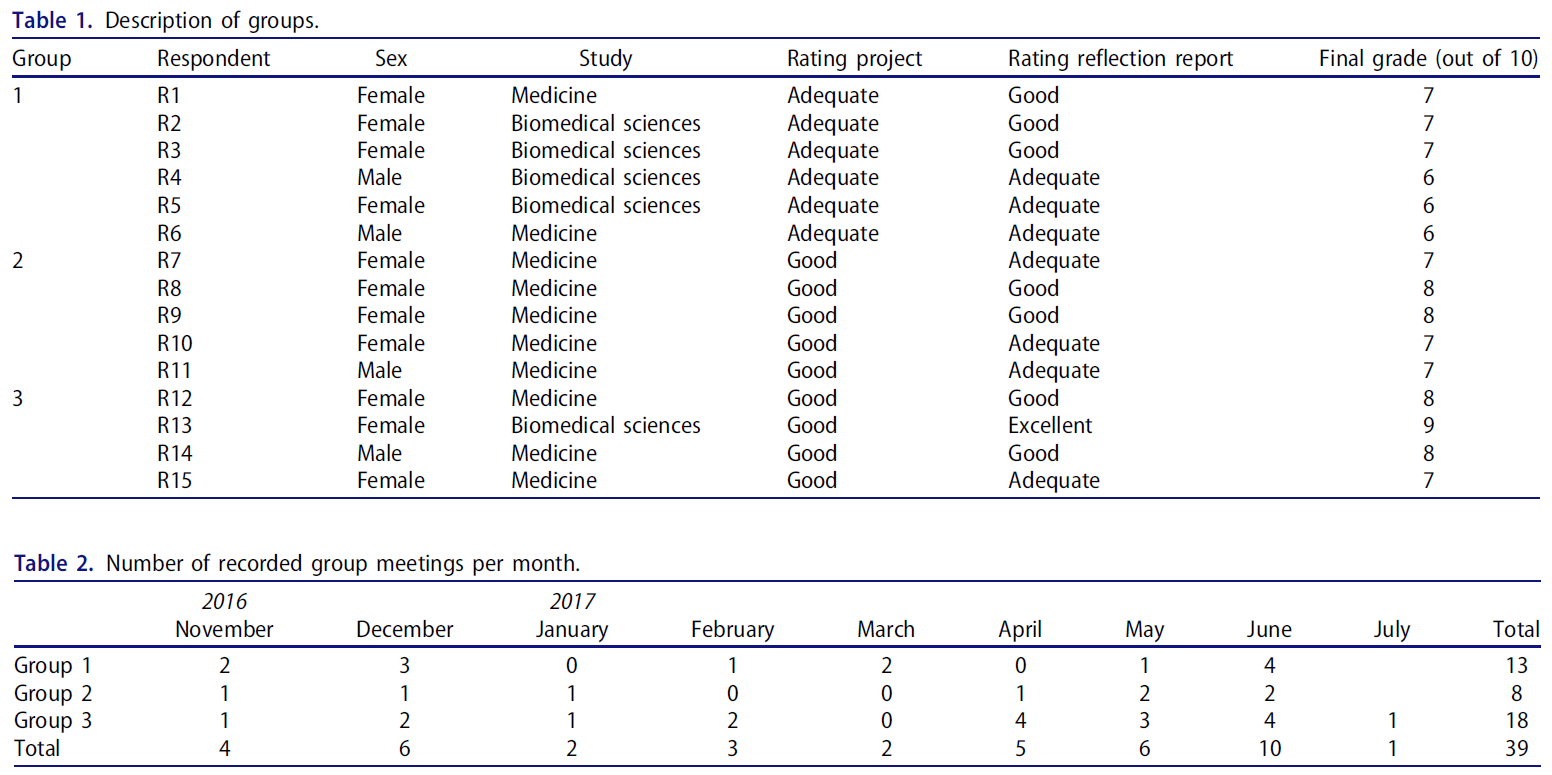

미국은 현재 미국의 의사-과학자(PS) 노동력의 기여로 인해 생물의학 연구에서 세계 선두를 달리고 있다. PS는 미국 전체 의사 노동력의 1.5%에 불과한 것으로 추정된다. 그러나 PS는 국가의 생의학 연구 노력에 매우 중요하다. 그들의 훈련 때문에, PS는 "임상 관찰을 실험 가능한 연구 가설로 전환하고 연구 결과를 의학 발전으로 변환하는 데 필수적인 힘"이다. 생의학 연구를 통해 특정 질병이 없어지고, 다른 질병에 대한 치료법이 발견되고, 생명을 구하는 의료 절차와 치료법이 개발되었다. 그러한 발견들은 수명 연장, 삶의 질 향상, 그리고 전 세계적으로 공중 보건의 향상으로 이어졌다.

The United States is currently the world’s leader in biomedical research,1 in large measure because of the contributions of the nation’s physician–scientist (PS) workforce.2–5 PSs are estimated to account for only 1.5% of the nation’s total physician workforce5; however, they are invaluable to the nation’s biomedical research effort.5–13 Because of their training, PSs are a “vital force in transforming clinical observations into testable research hypotheses and translating research findings into medical advances.”10 It is through biomedical research that certain diseases have been eliminated, cures for others have been discovered, and medical procedures and therapies that save lives have been developed.1–3,14,15 Such discoveries have led to the lengthening of life spans, quality of life improvements, and the betterment of public health throughout the world.1–7,13–15

중요한 것은, 생의학 연구를 통해 지금까지 이루어진 발전은 PS 인력들이 점점 더 빠른 속도로 인간 건강 증진에 더 큰 기여를 할 수 있도록 자리를 잡았다는 것이다. 1989년에 시작된 인간 게놈 프로젝트는 연구를 수행하기 위한 환경을 변화시켰고 건강 문제를 해결하기 위해 데이터를 공유하고 다학제적 접근법을 사용하는 시대를 열었다. 또한 팀 사이언스, 빅데이터, 정밀 의학에 기반을 둔 프로젝트에 문을 열었다. 이 세 가지 이니셔티브의 결과로 PS 인력들은 뇌를 더 잘 이해하고 그 장애를 치료하기 위해 설계된 혁신적 신경기술을 통한 뇌 연구와 같은 대규모의 조정된 생의학 연구 프로그램을 구현할 수 있다. 이것의 또 다른 예는 백만 명의 지원자들을 대상으로 한 종적 연구인 정밀의학 이니셔티브 코호트 프로그램으로, 질병의 약리유전학을 더 잘 이해하기 위해 이동 건강 기술을 사용하고 참가자들에게 그들 자신의 건강을 증진시킬 것이다. 마지막 예로, 모든 종류의 암을 예방하고, 발견하고, 치료하는 능력을 가속화하기 위해 빅데이터를 사용하는 국립 암 문샷이 있다.

Importantly, the advances made thus far through biomedical research have positioned the PS workforce to make greater contributions to the enhancement of human health at an increasingly faster pace. The Human Genome Project, which began in 1989, changed the landscape for conducting research and ushered in an era of sharing data and using multidisciplinary approaches to address health issues.16 It also opened the doors to projects based on team science, big data, and precision medicine. As a result of these three initiatives, the PS workforce is able to implement large-scale, coordinated biomedical research programs, such as the Brain Research through Advancing Innovative Neurotechnologies Initiative, which is designed to better understand the brain and treat its disorders.4,17 Another example of this is the Precision Medicine Initiative Cohort Program, a longitudinal study of one million volunteers, which will enhance understanding of microbiome science, using mobile health technologies to better understand the pharmacogenetics of disease and empowering participants to improve their own health.4,18 As a final example, there is the National Cancer Moonshot, which uses big data to accelerate the ability to prevent, detect, and treat all types of cancer.4,19

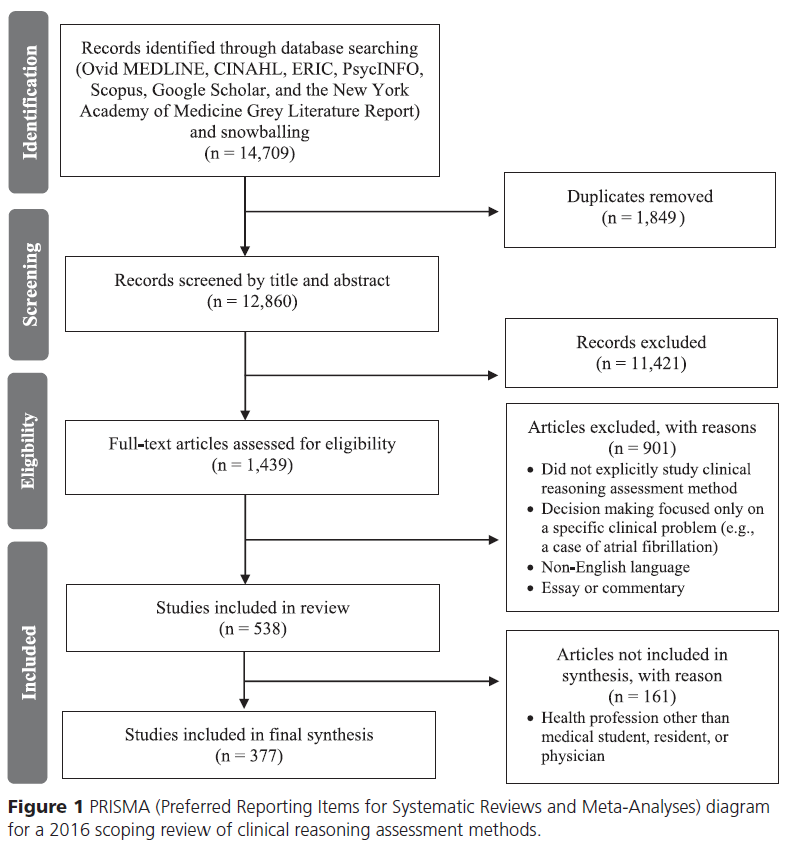

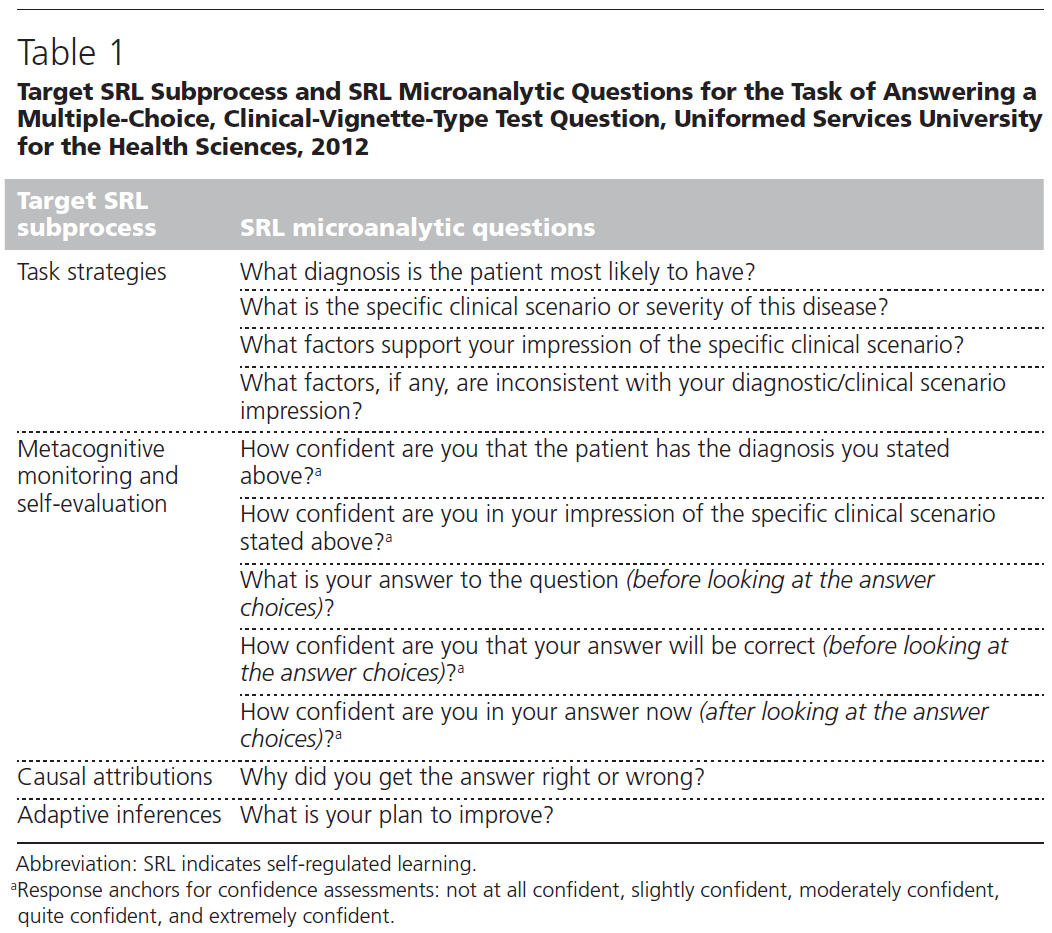

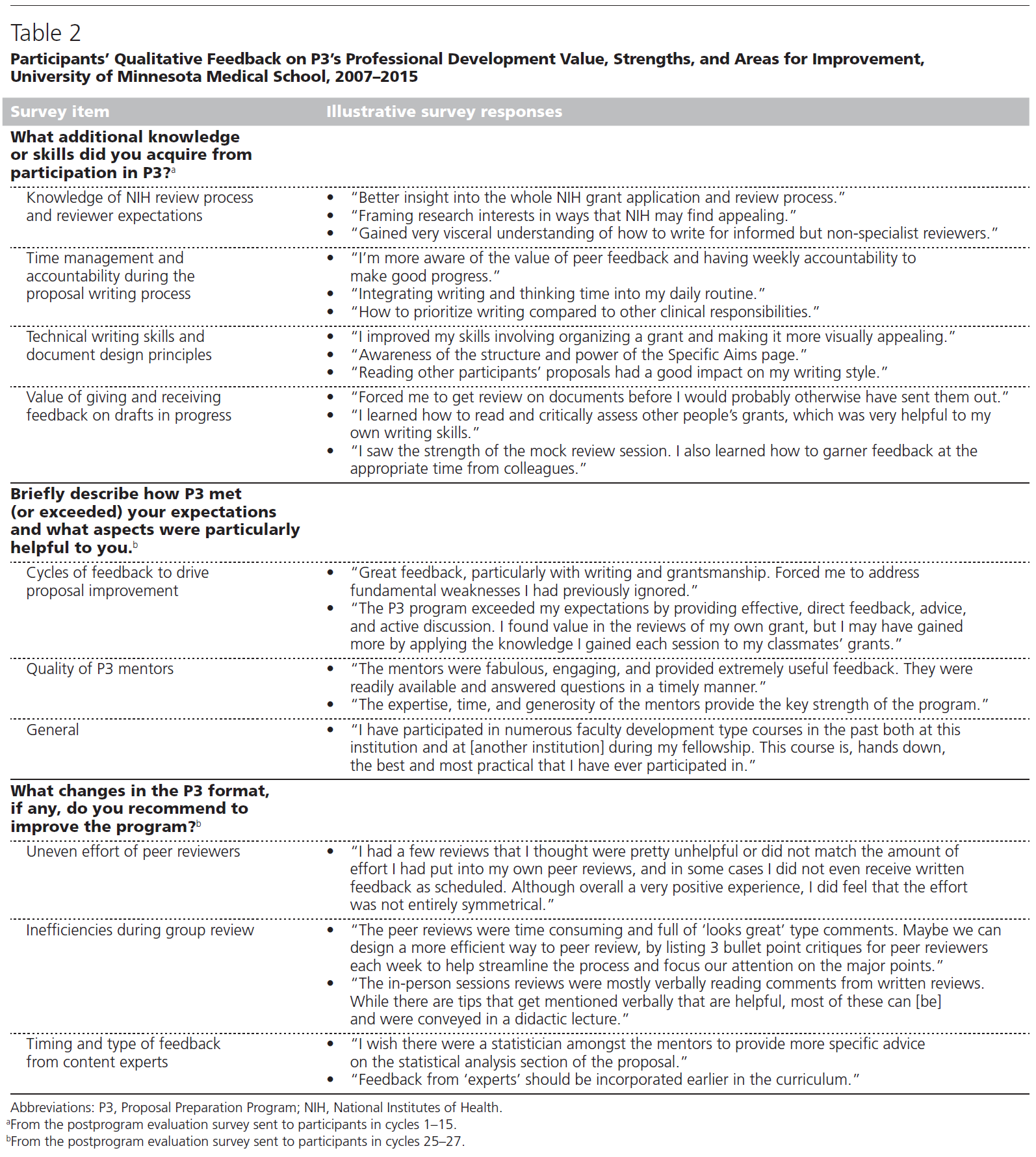

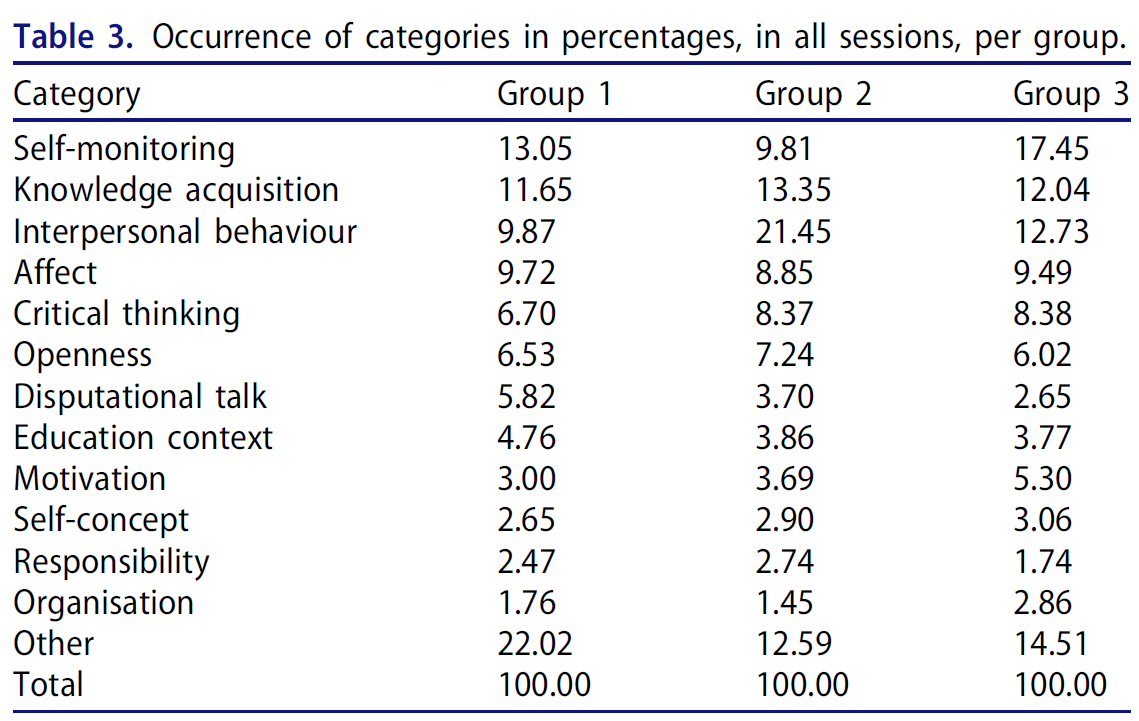

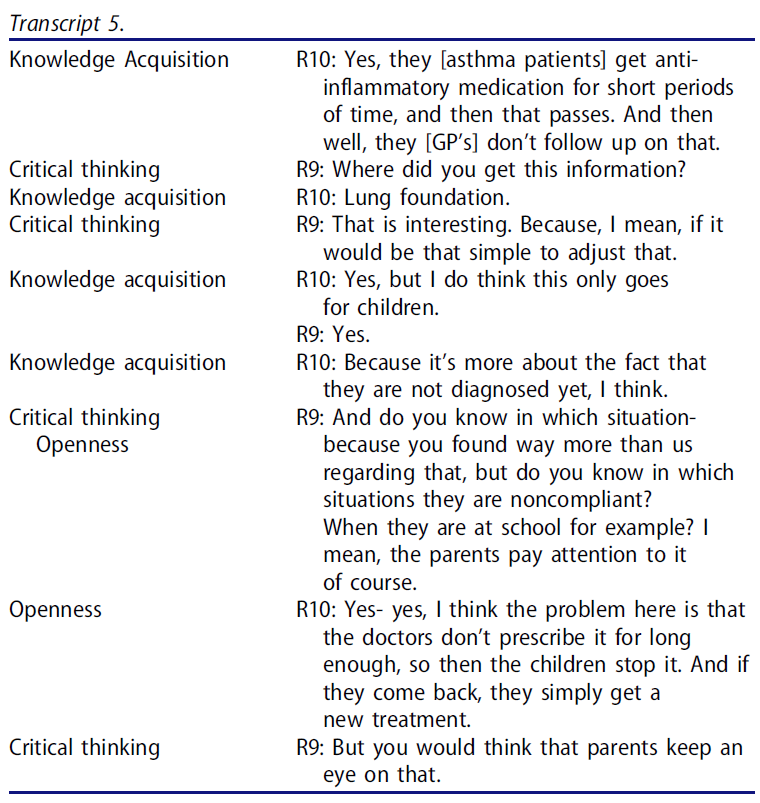

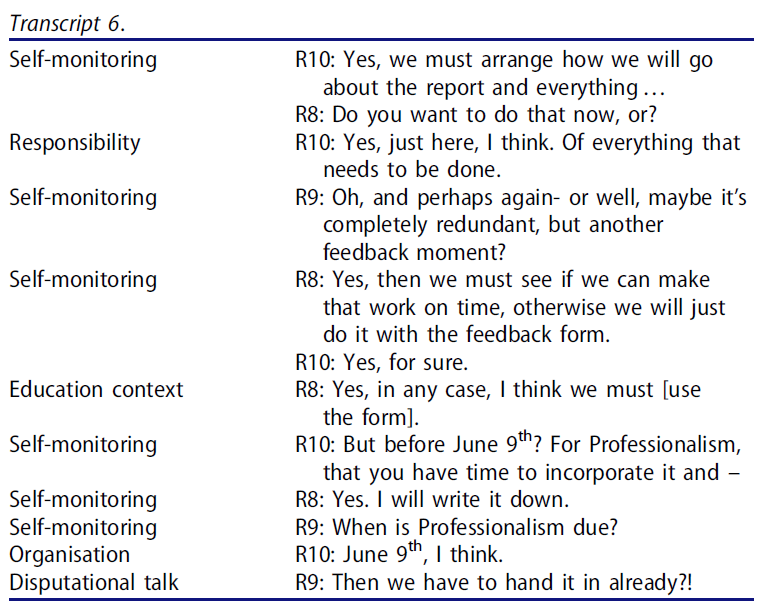

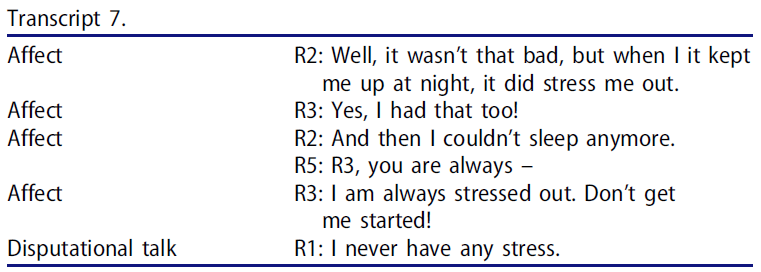

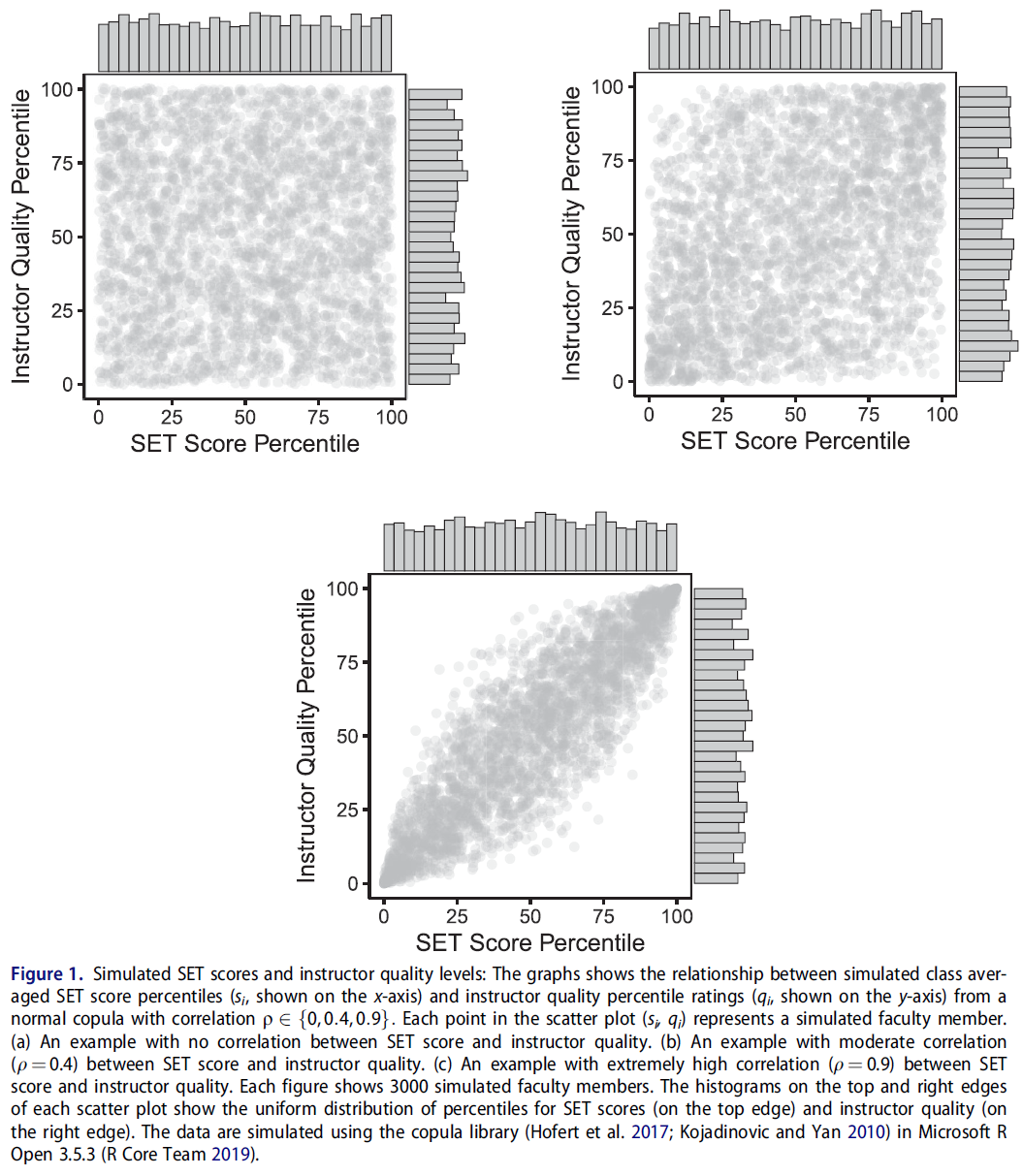

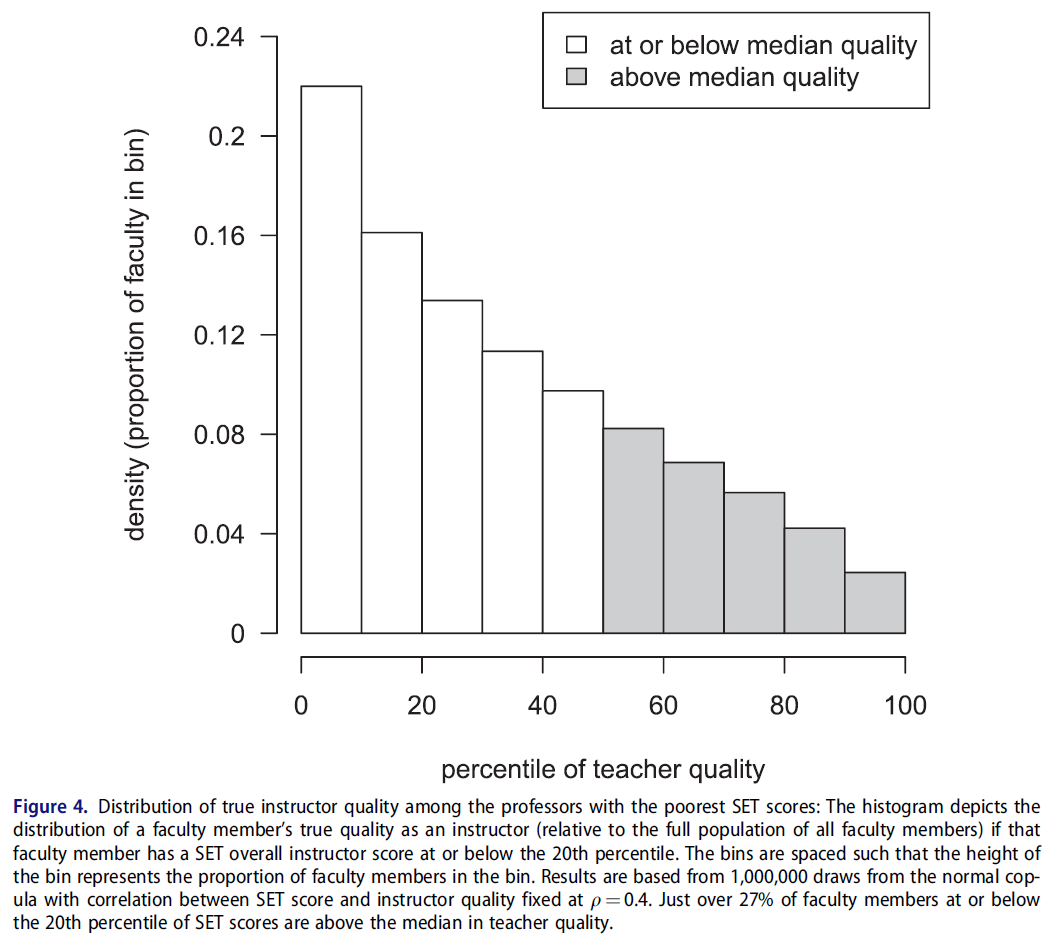

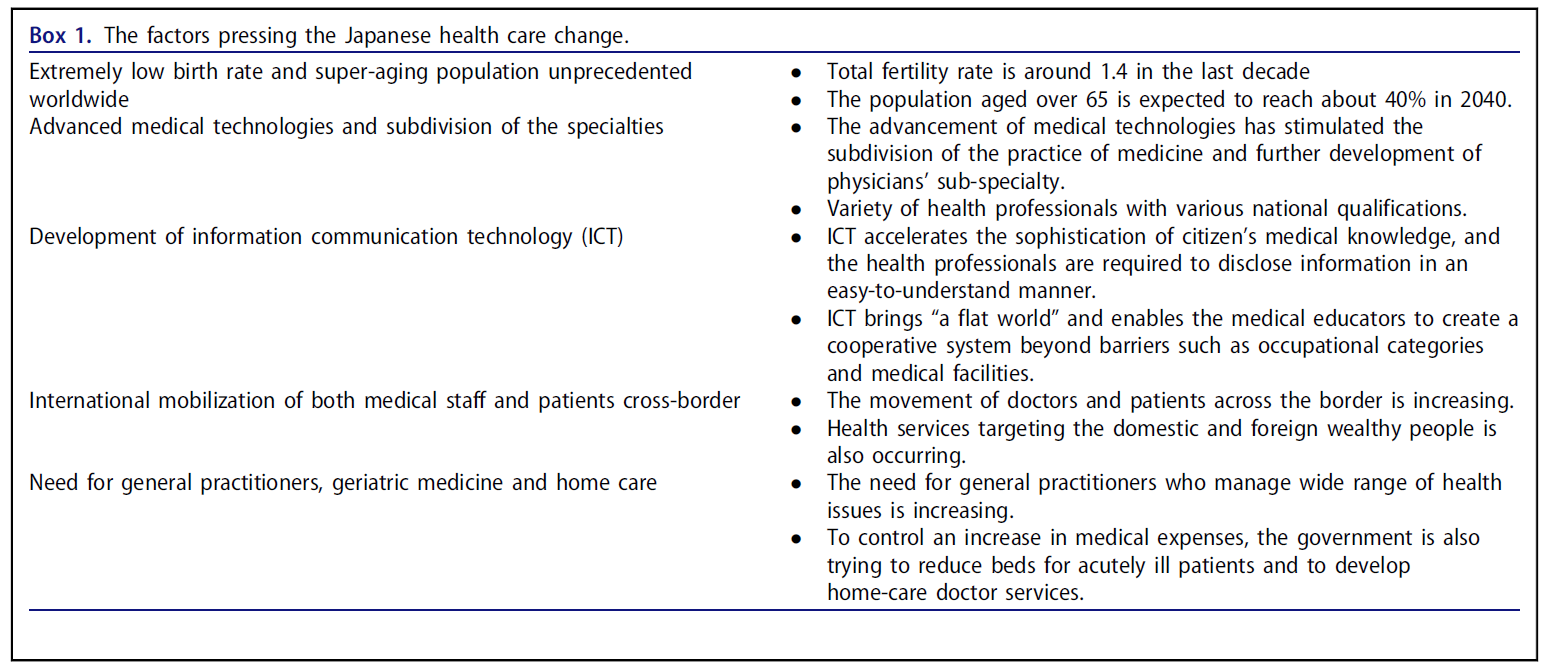

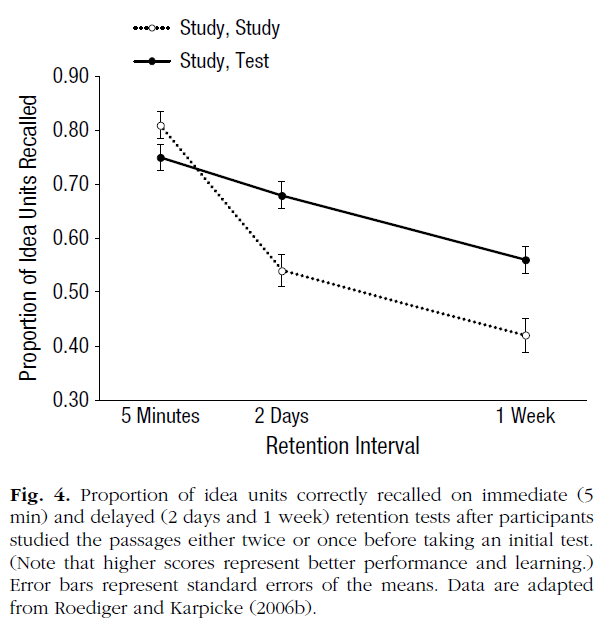

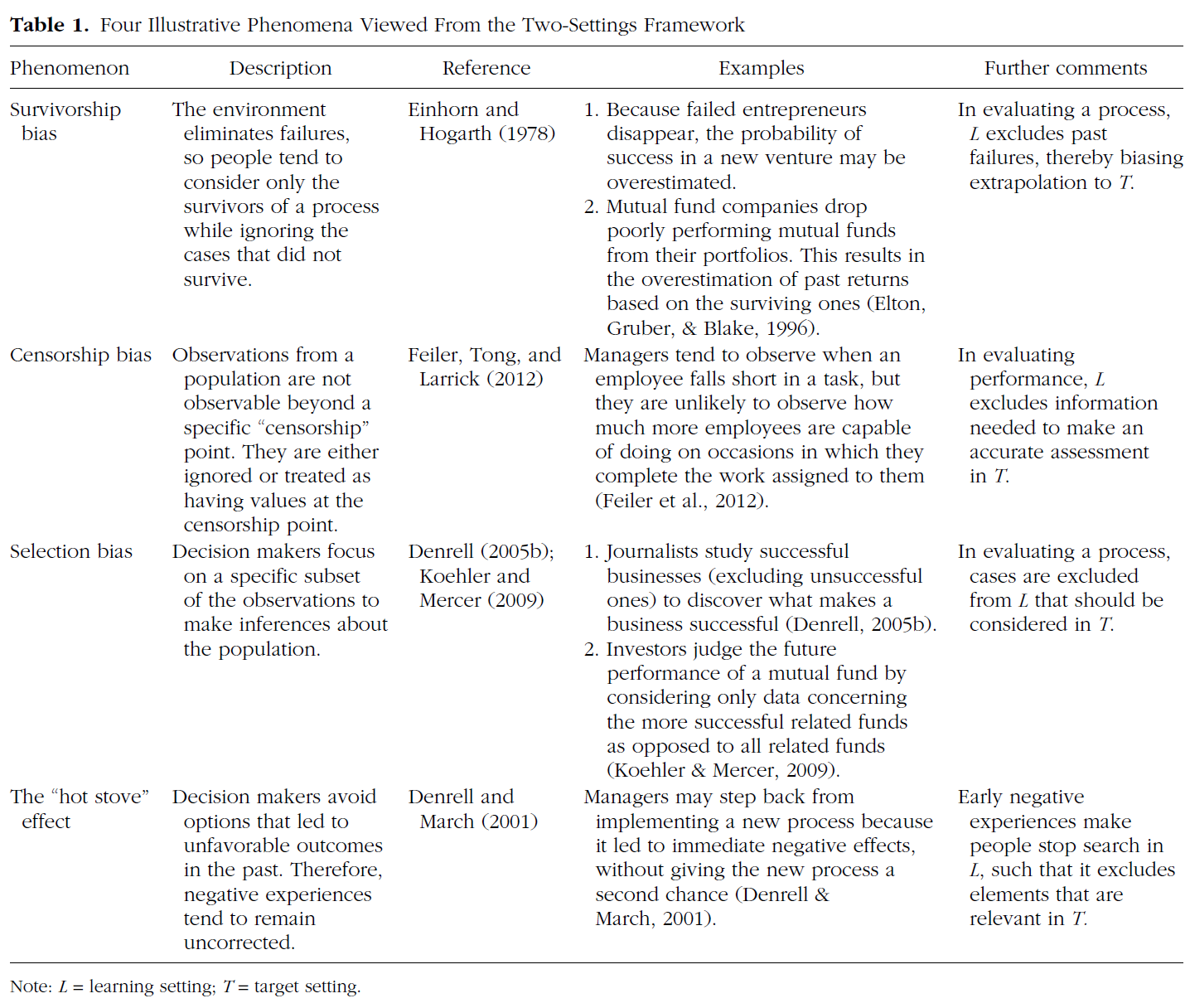

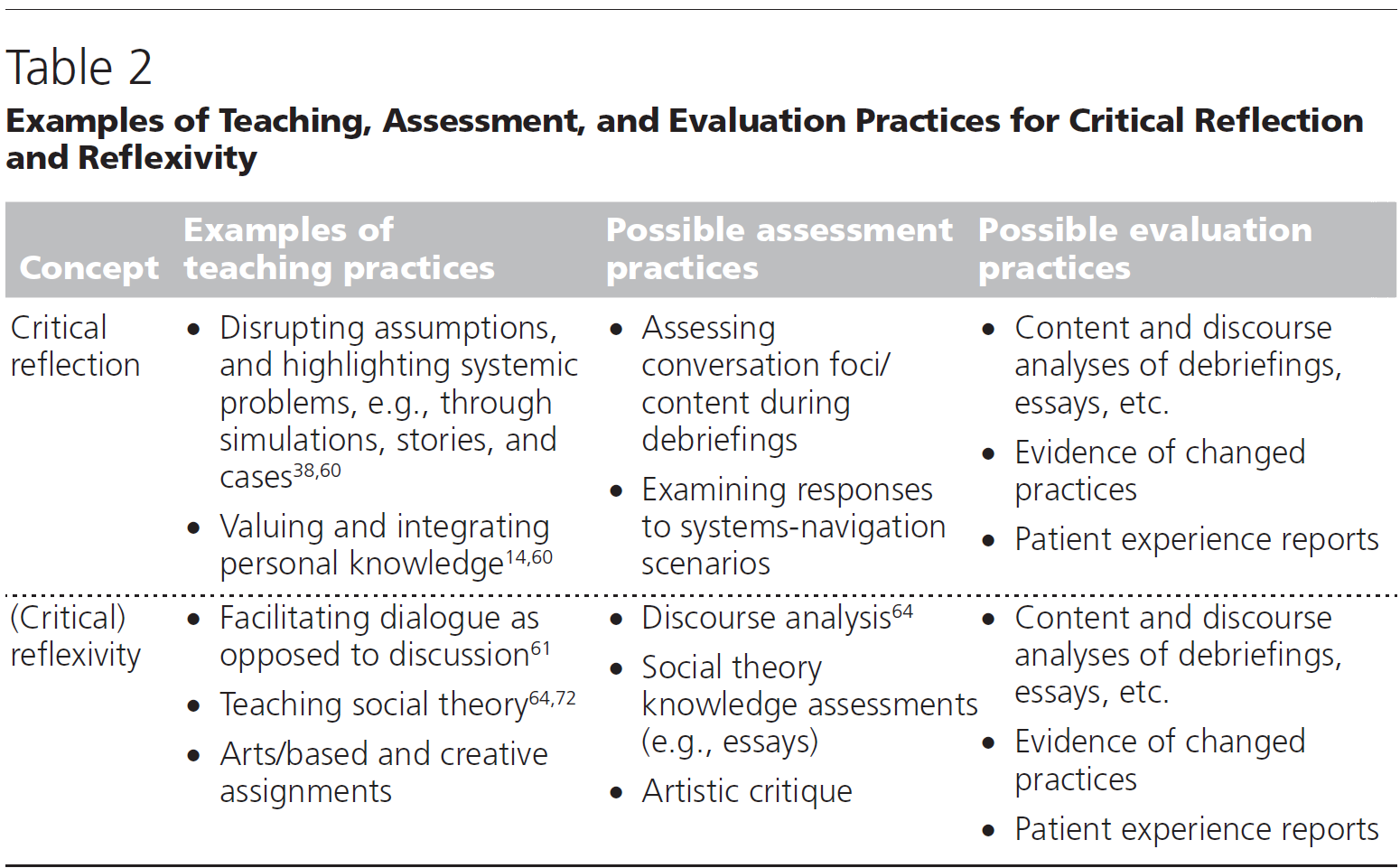

한국의 PS 노동력 유지에 대한 우려는 지난 40년 동안 정책 입안자들과 다른 사람들에 의해 공개적으로 제기되어 왔으며, 그러한 우려는 범위와 강도에 있어서 증가하고 있다. 젊은 의사들이 PS보다는 임상의나 임상의사-교육자로 경력을 쌓는 것을 선택함에 따라, 지난 몇 년 동안 PS 인력 규모가 감소해왔다. 아마도 더 큰 관심사는 현재 PS 노동력의 고령화이다. 2003~2012년 10년 동안 60세 이하 PS는 감소했고 61세 이상은 증가했습니다(그림 1 참조). 이 데이터는 놀랍습니다.

- (1) 새로운 PS의 인력진 진입과 지속적인 참여가 전례 없이 감소하고 있음을 시사한다.

- (2) 고위직원들은 은퇴를 연기했다.

PS 파이프라인 모델의 관점에서, 유입과 유출이 모두 감소하기 때문에, 시니어 인력들이 은퇴할 때 시스템이 갑자기 붕괴되기 쉽다.

Concerns about sustaining the nation’s PS workforce have been publicly voiced by policy makers and others for the past four decades,5–13 and those concerns are growing in scope and intensity.5–13,20 The size of the PS workforce has declined over the past several years,5 as young physicians choose to focus their careers on being clinicians or clinician–educators rather than PSs. Perhaps of even greater concern is the aging of the current PS workforce. During the 10-year period between 2003 and 2012, the number of PSs aged 60 or younger declined, while the number of those aged 61 or older rose (see Figure 1).5 These data are striking;

- they suggest that (1) the entry and sustained engagement of new PSs into the workforce are in unprecedented decline, and

- (2) senior members of the workforce have postponed retirement. In terms of a PS pipeline model, the decreased inflow and outflow renders the system vulnerable to collapsing suddenly as the senior workforce retires.

2007년과 2008년 동안 의대 교수 협회(APM)와 미국 의대 협회(AAMC)는 일련의 회의를 개최하여 기금 풀을 다음과 같이 확장하기 위한 권고안을 발표 및 배포하였다.

- 젊은 PS의 경력을 유지하고 육성합니다.

- 젊은 PS의 멘토링을 위한 접근 방식을 개선합니다.

- 여성 PS의 발전을 촉진한다.

- 미래 PS의 경력 개발을 식별하고 육성합니다.

During 2007 and 2008, the Association of Professors of Medicine (APM) and the Association of American Medical Colleges (AAMC) held a series of conferences resulting in published and disseminated recommendations to expand the pool of funds to

- retain and foster the careers of young PSs,

- improve the approach for mentorship of young PSs,

- promote the advancement of women PSs, and

- identify and foster the career development of future PSs.12,13

PS에 대한 기존 국립 보건원(NIH) 지원에 대한 우려가 커짐에 따라, 2014년, 프랜시스 콜린스 소장은 의사-과학자 인력 워킹 그룹에 현재 커리어 서포트 메커니즘을 평가하고 개선을 위한 권고안을 제출하도록 요청했습니다. 2014년 6월, 작업 그룹은 여러 권고사항과 함께 보고서를 발표했는데, 무엇보다도 NIH에 다음과 같이 촉구했습니다.

- PS의 강력한 훈련을 지속합니다.

- [연방정부가 자금을 지원하는 의사 후 교육]에서 [더 많은 개인 대상 펠로우쉽을 포함]하는 쪽으로 균형을 옮깁니다.

- 신규 및 기성 조사원 간의 수상률award rates 격차를 지속적으로 완화한다.

- PS 인력의 강점을 평가하기 위해 엄격한 도구를 채택한다.5

In response to growing concerns about existing National Institutes of Health (NIH) support for PSs, in 2014, Director Francis Collins charged a Physician–Scientist Workforce Working Group to assess the current mechanisms of career support and make recommendations for improvement. In June 2014, the working group issued its report with a series of recommendations that, among other things, urged the NIH to

- sustain strong training of PSs,

- shift the balance in federally funded postdoctoral training for physicians to include more individual fellowships,

- continue to mitigate the gap in award rates between new and established investigators, and

- adopt rigorous tools to assess the strength of the PS workforce.5

이 워킹 그룹은 또한 약 14,000명의 PS의 현재 국내 인력을 유지하기 위해 "매년 약 1,000명의 개인이 파이프라인에 진입해야 할 것"이라고 추정했다. (이 계산은 "파이프라인에 진입"하는 사람들 중 절반이 성공하지 못할 것으로 가정한다.) 이는 [생의학 연구에서 세계적인 리더]로서 미국의 역할을 위협할 수 있기 때문에, 이 예측은 상당한 무게를 지니고 있다. 모세 외 연구진은 현재의 추세가 계속된다면 앞으로 10년 안에 중국이 이 역할을 맡을 것이라고 언급했다.

The working group also estimated that, to maintain the nation’s current workforce of approximately 14,000 PSs, “about 1,000 individuals will need to enter the pipeline each year.”5 (This calculation assumes that half of those who “enter the pipeline will not succeed.”)5 This projection carries with it significant weight because this could threaten the nation’s role as the global leader in biomedical research, as in 2015, Moses et al21 noted that, if current trends continue, China will assume this role within the next 10 years.

2015년 11월, 학술 내과 연합(AAIM)은 의사 조사관 인력 재검토라는 컨센서스 컨퍼런스를 개최했다. 새롭고 진화하는 연구 영역과 학술 기관의 성공 경로. AAIM은 5개의 단체로 구성된 컨소시엄이다.

In November 2015, the Alliance for Academic Internal Medicine (AAIM) hosted a consensus conference, Re-examining the Physician Investigator Workforce: New and Evolving Areas of Research and Pathways to Success in Academic Institutions. The AAIM is a consortium of five organizations:

- the APM,

- Association of Subspecialty Professors,

- Association of Program Directors in Internal Medicine,

- Clerkship Directors in Internal Medicine, and

- Administrators of Internal Medicine.

이 컨퍼런스의 초점은 NIH 의사-과학자 인력 워킹 그룹에 주어진 것과는 달랐다. 즉, NIH 워킹 그룹의 주요 관심사는 NIH 프로그램과 정책에 영향을 미치는 문제를 다루는 것이었지만, AAIM 컨센서스 컨퍼런스의 주요 관심사는, 개개인의 경험과 관심에 기초한 커리어 초기 PS로부터의 투입으로, academic medical school에 영향을 미치는 문제를 다루는 것이었다.

The focus of this conference was different than the charge given to the NIH Physician–Scientist Workforce Working Group—that is, while the major concern of the working group was to address issues impacting NIH programs and policies, the major concern of the AAIM consensus conference was to address issues impacting academic medical schools, with input from early-career PSs based on their individual experiences and concerns.

이 컨퍼런스는 사상적 리더와 초기 경력 PS가 [생물의학 연구에 진지하게 참여할 가능성이 있는 개인을 조기에 식별하는 것과 관련이 있는 중요한 주제들]과 [이러한 개인의 커리어를 개발하기 위한 최적의 메커니즘]을 논의할 수 있는 기회를 제공했다. 또한, 이 회의의 목표 중 하나는 [PS를 유치하고 지원하는 데 있어 현재 걸림돌]을 확인하고 2016년 이후 [PS 인력을 유지하기 위한 새로운 권고안]을 개발하는 것이었다.

The conference provided an opportunity for thought leaders and early-career PSs to discuss a series of critical topics relating to the early identification of individuals with a potential for serious engagement in biomedical research, as well as optimal mechanisms for developing the careers of these individuals. Additionally, one of the goals of the conference was to identify current impediments to attracting and supporting PSs and to develop a new set of recommendations for sustaining the PS workforce in 2016 and beyond.

이 회의에는 100명 이상의 개인이 참석했으며, 학술 관리자, 학과 의장, 프로그램 책임자, 초기 경력 PS(아래 참조)와 국가 재단, NIH, 미국 국립 의학 아카데미, 제약 업계의 대표자들이 참석했다. 이 회의에는 10개의 의학 센터를 대표하는 14명의 초기 경력 PS가 참석했다. 그들 모두는 NIH 멘토링 경력 개발상 또는 보훈처 경력 개발상의 수상자였다. 모두 박사학위였고, 3명은 석사학위를 추가로 받았으며, 박사학위를 받은 사람은 없었다.

More than 100 individuals attended the conference, representing a cross-section of academic administrators, department chairs, program directors, and early-career PSs (see below), as well as representatives from national foundations, the NIH, the National Academy of Medicine, and the pharmaceutical industry. Fourteen early-career PSs attended the conference, representing 10 academic medical centers. All of them were recipients of either an NIH mentored career development award or a Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) career development award. All of them were MDs, 3 had additional master’s-level degrees, and none had a PhD.

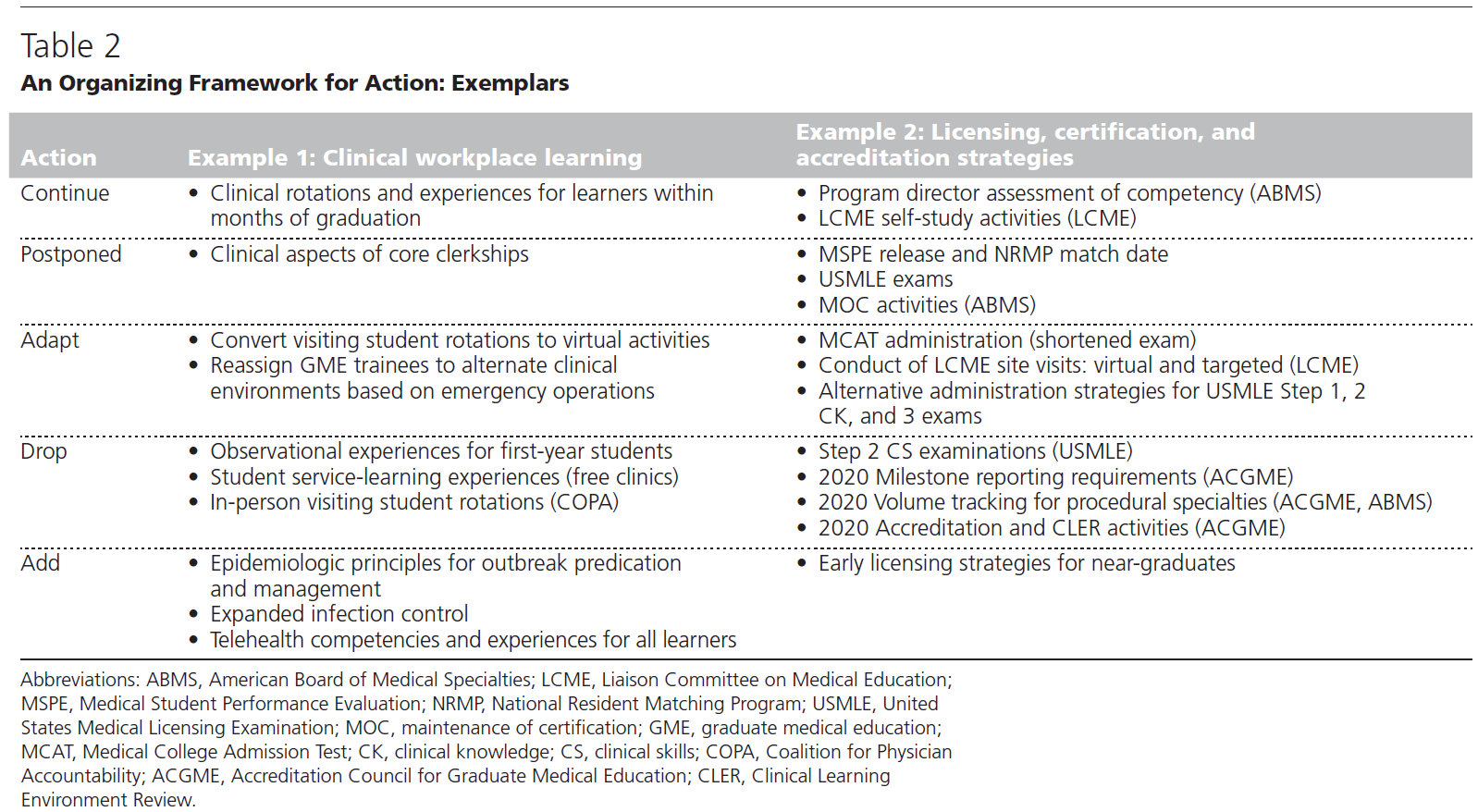

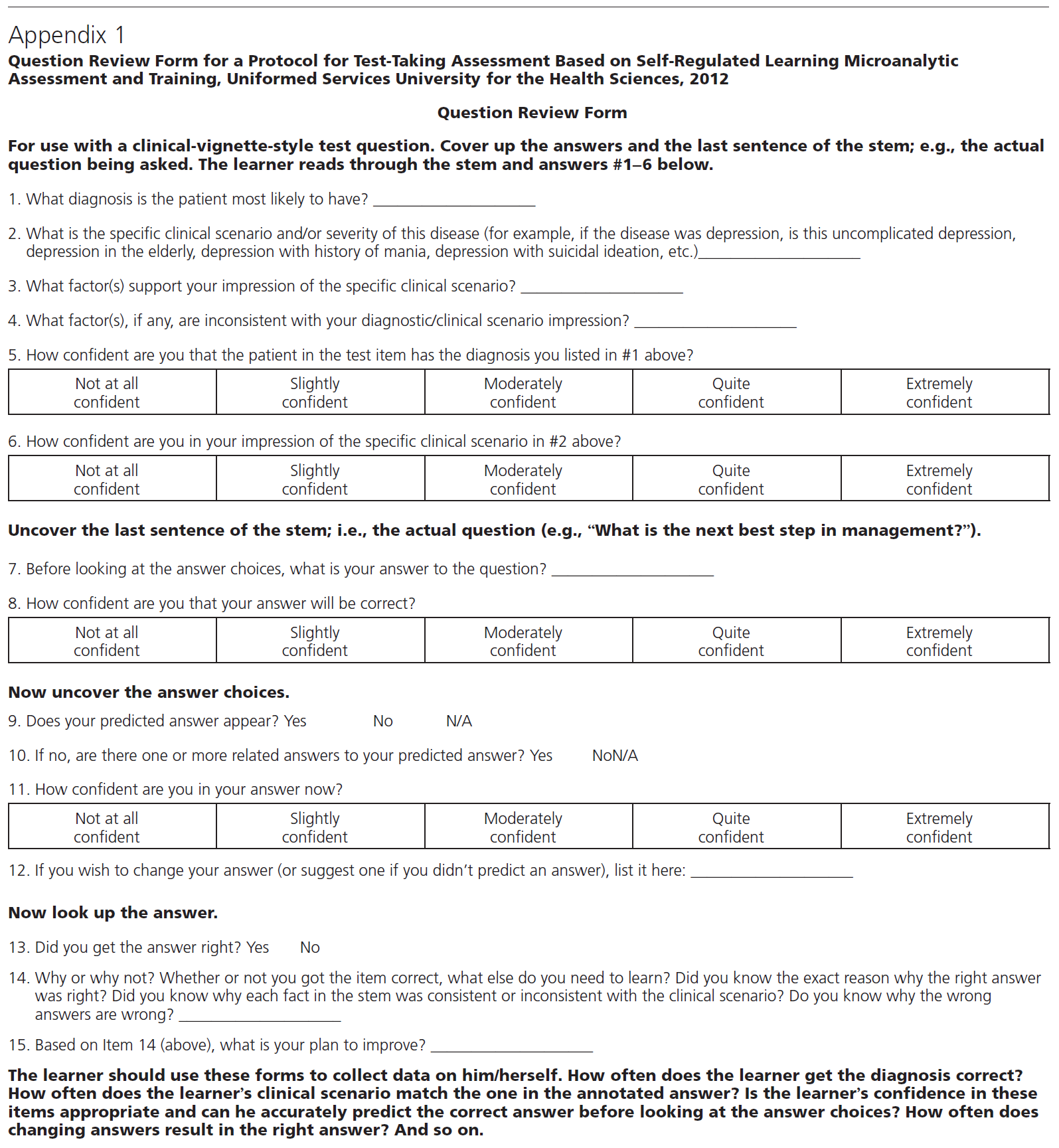

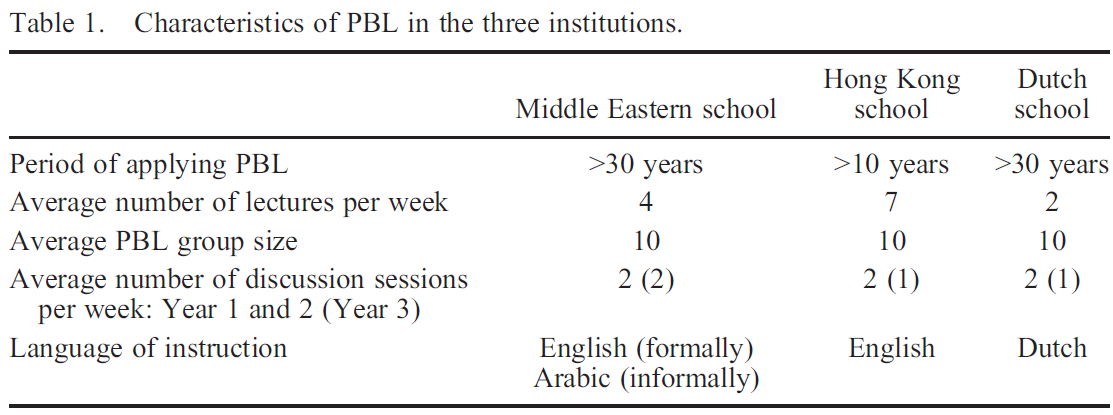

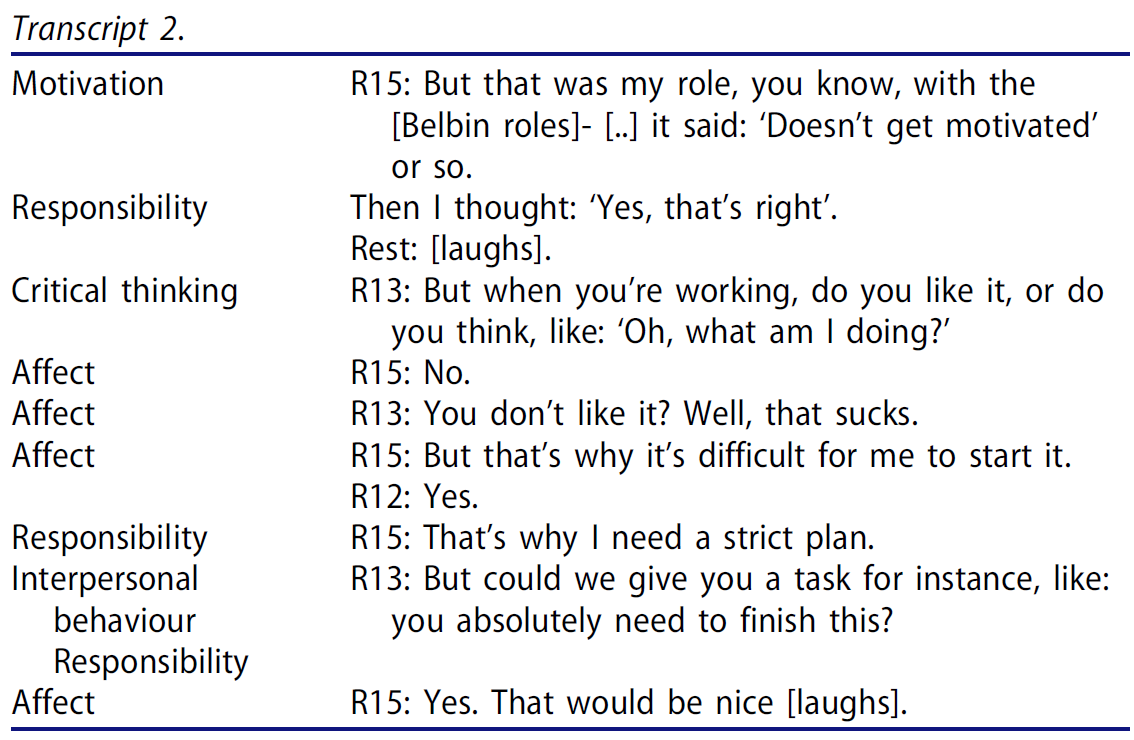

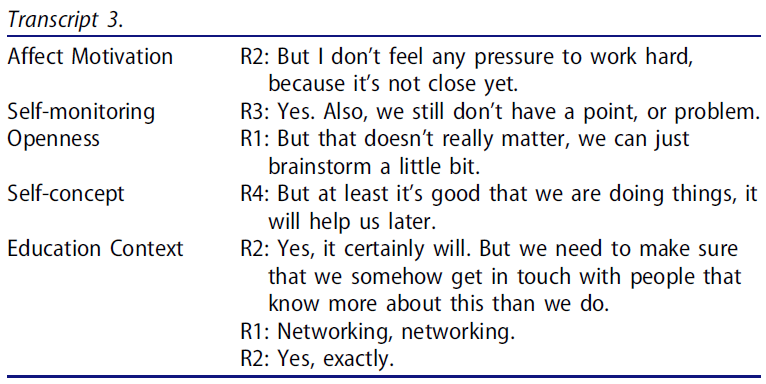

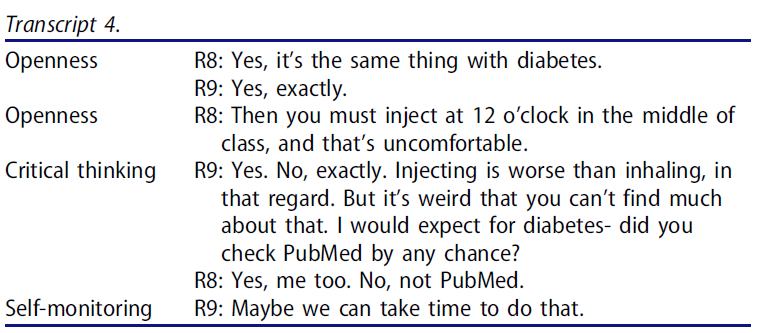

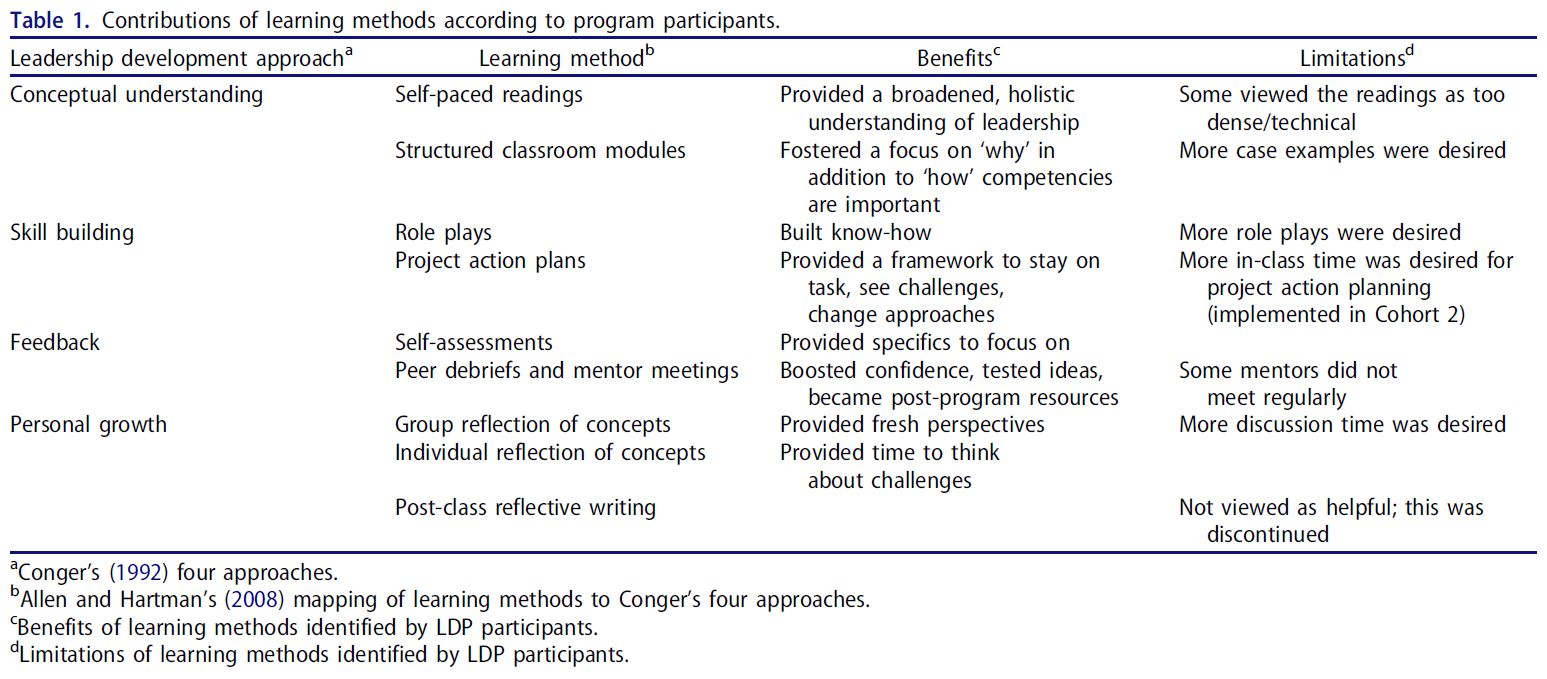

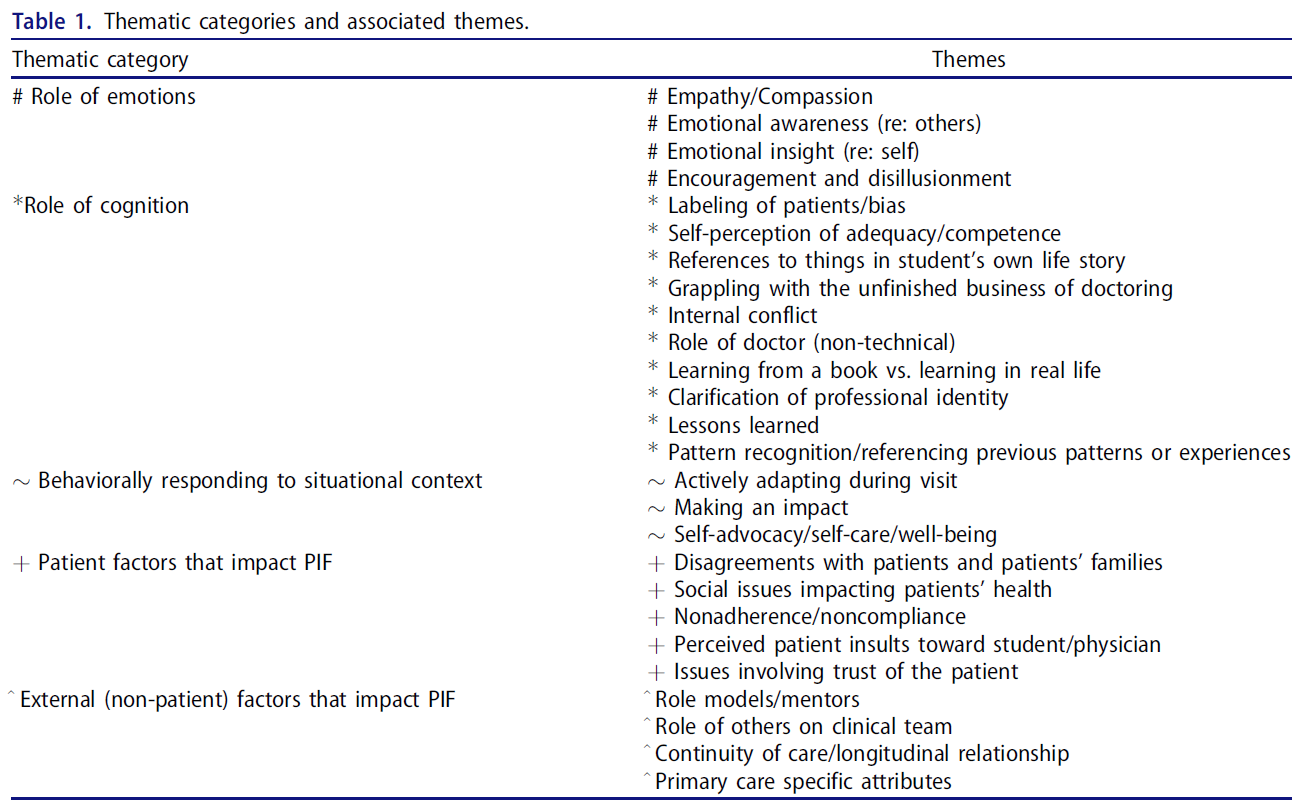

이 회의에는 10차례의 브레이크아웃 세션 동안 집중 토의할 핵심 주제에 대한 5차례의 전체 발표가 포함되었다. 각 브레이크아웃 세션은 국가의 PS 인력을 유지하고 잠재적으로 확장하는 것을 목표로 학술적 보건 지도자와 NIH 및 기타 기금 기관을 대상으로 한 일련의 권고안을 개발했다. 그런 다음 각 브레이크아웃 세션의 권장 사항이 모든 컨퍼런스 참석자에게 제시되었습니다. 특정 권고안에 대해 회의 참석자들 사이에 약간의 의견 차이가 있었지만, 이 관점에 포함된 권고안은 회의가 만장일치에 도달한 후 AAIM 이사회에 의해 승인되었다. 이러한 권장사항은 두 가지 주요 전략으로 분류됩니다.

- (1) PS 파이프라인으로의 진입 증가 및

- (2) PS 인력으로부터의 소모 감소(목록 1 참조)

The conference included five plenary presentations on key topics to focus discussion during its 10 breakout sessions. Each breakout session developed a series of recommendations targeted to academic health leaders and to the NIH and other funding agencies, with the goal of sustaining and potentially expanding the nation’s PS workforce. The recommendations from each breakout session were then presented to all of the conference attendees. Although there were slight differences of opinion among the conference participants on certain recommendations, the recommendations included in this Perspective are those on which the conference reached unanimous consensus and which were subsequently approved by the AAIM Board of Directors. These recommendations are categorized within two major strategies:

- (1) increasing entry into the PS pipeline and

- (2) reducing attrition from the PS workforce (see List 1).

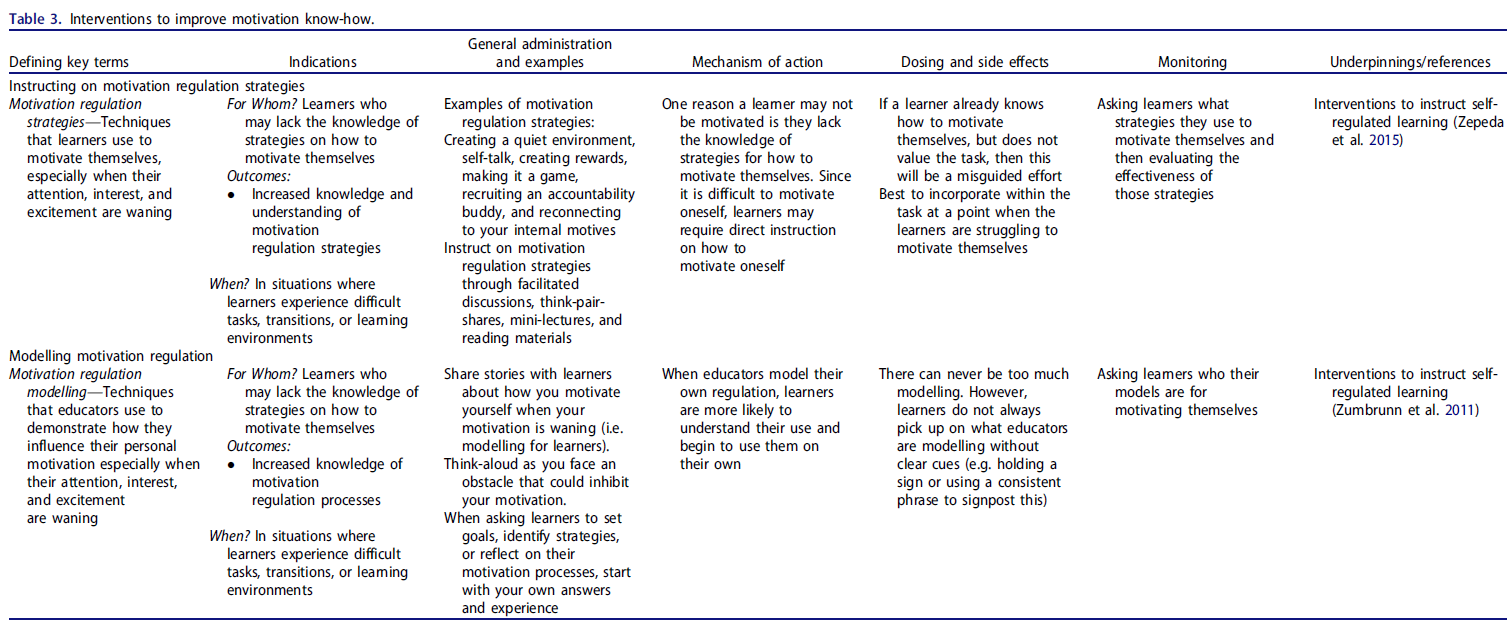

목록 1 PS Workforce에 대한 학술적 내과의사 컨센서스 컨퍼런스의 권고 사항, 2015년 11월

List 1 Recommendations of the Alliance for Academic Internal Medicine Consensus Conference on the PS Workforce, November 2015

PS 파이프라인 진입 증가

Increasing entry into the PS pipeline

- 젊은이들에게 생의학 연구의 가치와 생의학 진보에서 PS가 수행하는 중요하고 독특한 역할을 홍보합니다.

- 역할 모델 및 멘토 네트워크에 대한 액세스를 제공하는 프로그램의 광범위한 구현을 통해 다양한 모집단의 구성원을 PS로 모집 및 보유할 수 있습니다.

- 국제 PS가 미국에 들어와 미국 노동력의 일원으로 남을 수 있는 기회를 강화한다.

- PS 교육에서 효율성과 커리큘럼 모범 사례를 홍보합니다.

- MD/PhD 프로그램에 입학하지 않은 교육생을 위한 학부 및 대학원 연구 교육 기회를 강화합니다.

- Promote to young people the value of biomedical research and the important and unique role that PSs play in biomedical advances.

- Facilitate the recruitment and retention of members from diverse populations as PSs through widescale implementation of programs that provide access to a network of role models and mentors.

- Enhance opportunities for international PSs to enter and remain in the United States as members of the nation’s workforce.

- Promote efficiency and curricular best practices in the training of PSs.

- Enhance undergraduate and postgraduate research training opportunities for trainees who do not matriculate into MD/PhD programs.

PS 인력 소모 감소

Reducing attrition from the PS workforce

- "멘토 멘토링" 교육을 포함한 정형화된 멘토링 프로그램을 구현하고, 멘토링 결과에 대한 주기적인 검토를 수행합니다.

- [Training]에서 [독립적인 연구 커리어]로의 PS 전환을 지원하는 것을 특별히 목표로 하는 연구비 프로그램을 수립합니다.

- NIH 또는 VA 경력 개발 보조금을 수여받은 개인에 대한 학자금 대출 상환 기회를 확대합니다.

- 경력 개발 어워드로 지정된 멘토에게 급여 지원을 제공합니다.

- PS 간에 부서 전체의 급여 형평성을 보장합니다.

- 보호 시간 제공 및 필요한 경우 브리지 자금 지원을 통해 PS 교수진이 독립적인 연구자가 될 수 있는 안정적인 환경을 제공합니다.

- 생물의학 발전에 대한 PS의 기여에 대한 환경의 변화를 수용하고, P&T 의사결정 과정에 투명성을 유지하기 위해 P&T 기준을 재고한다.

- 산업계와의 파트너십 확대를 포함하여 연구 및 연구 자금 지원을 위한 새로운 방법을 모색합니다.

- PS 경력 개발 데이터 저장소를 구축합니다.

- Implement formalized mentoring programs, including “mentoring the mentor” training, and periodic reviews of mentoring results.

- Establish grant programs specifically targeted to supporting the PS transitioning from training to an independent research career.

- Expand student loan repayment opportunities for individuals who are awarded an NIH or a VA career development grant.

- Provide salary support for mentors named on career development awards.

- Assure department-wide salary equity among PSs.

- Provide a stable environment for PS faculty to become independent researchers through provision of protected time and, when necessary, bridge funding.

- Reconsider criteria for P&T to accommodate the changing environment for PSs’ contributions to biomedical advances and be transparent in P&T decision-making processes.

- Pursue new avenues for research and research funding, including expanding partnerships with industry.

- Establish a repository for PS career development data.

약자: PS는 의사-과학자, NIH, 국립보건원, VA, 보훈처, P&T, 승진 및 재임 기간을 나타냅니다.

Abbreviations: PS indicates physician–scientist; NIH, National Institutes of Health; VA, Department of Veterans Affairs; P&T, promotion and tenure.

이 합의문의 목적상, PS는 [전문적 노력의 대부분을, (학술기관, 정부기관, 산업 및 독립연구센터와 연구소에서 수행되는), 광범위한 생물 의학 연구의 연속체 내에서 정의된 영역에 바치는 의사]로 정의되었다. (기본, 번역, 임상, 역학, 결과 및 의료 교육 연구 포함) 이 사람들 중 많은 사람들은 MD에 더하여 과학 분야에서 전문 학위를 가지고 있으며, 임상의사로서의 자격으로 환자 치료를 계속 제공하고 있다.

For the purposes of this consensus statement, PSs were defined as physicians who devote the majority of their professional effort to a defined area within the broad continuum of biomedical research (inclusive of basic, translational, clinical, epidemiological, outcomes, and medical educational research) conducted in academic institutions, government agencies, industry, and independent research centers and institutes. Many of these individuals have a professional degree in the sciences, in addition to an MD, and continue to provide patient care in their capacity as clinicians.

PS 파이프라인 진입을 늘릴 기회

Opportunities for Increasing Entry Into the PS Pipeline

미국 내 PS를 늘리기 위한 전략 개발과 실행이 필수다. 이 목표를 달성할 수 있는 기회에는 생물의학 연구의 가치를 더 잘 촉진하고 조기에 홍보하는 것, PS 인력의 다양성을 증가시키는 것, 다양성을 증가시키기 위한 역할 모델과 멘토를 사용하는 것, PS 교육 프로세스의 합리화와 연구 교육 기회의 확대가 포함된다.

Developing and implementing strategies to increase the number of PSs in the U.S. workforce is essential. Opportunities to achieve this goal include

- facilitating better and early promotion of the value of biomedical research,

- increasing the diversity of the PS workforce,

- using role models and mentors to increase diversity, and

- streamlining the PS training process and expanding research training opportunities.

생물의학 연구의 가치를 더 낫고 조기에 홍보할 수 있도록 촉진

Facilitating better and early promotion of the value of biomedical research

아이들의 두뇌가 아직 개발되고 있는 중인 초등학교 때부터 생의학 연구의 가치를 홍보하는 것이 중요하다. 과학, 기술, 공학, 그리고 수학 (STEM)에서 학생들의 기술을 향상시키기 위한 프로그램을 시행하는데 초점을 맞추고 있음에도 불구하고, 미국은 선진국들 사이에서 표준화된 시험의 과학 점수에서 상위 20위 안에 들지 못하고 있다. 앨런과 케이먼은 이 낮은 순위가 부분적으로 연구와 혁신보다 운동선수와 연예인에 더 큰 가치를 두는 국가 전체에 기인할 수 있다고 주장한다. 생물의학 연구의 가치와 기존 STEM 프로그램의 목표를 효과적으로 홍보하기 위해서는 정부 기관, 지역사회 기반 조직, 민간 부문 연구 조직 및 학교 간의 협력이 필요하다.

It is important to promote the value of biomedical research as early as elementary school—while children’s brains are still being developed. Despite a focus on implementing programs to increase students’ skills in science, technology, engineering, and mathematics (STEM), the United States is not ranked in the top 20 on science scores from standardized tests among industrialized nations.22 Allen and Kamen23 argue that this low ranking can, in part, be attributed to the nation as a whole placing greater value on its athletes and entertainers than it does on research and innovation. Collaborations between government agencies, community-based organizations, private-sector research organizations, and schools are necessary to effectively promote both the value of biomedical research and the goals of existing STEM programs.

PS 인력의 다양성 증대

Increasing the diversity of the PS workforce

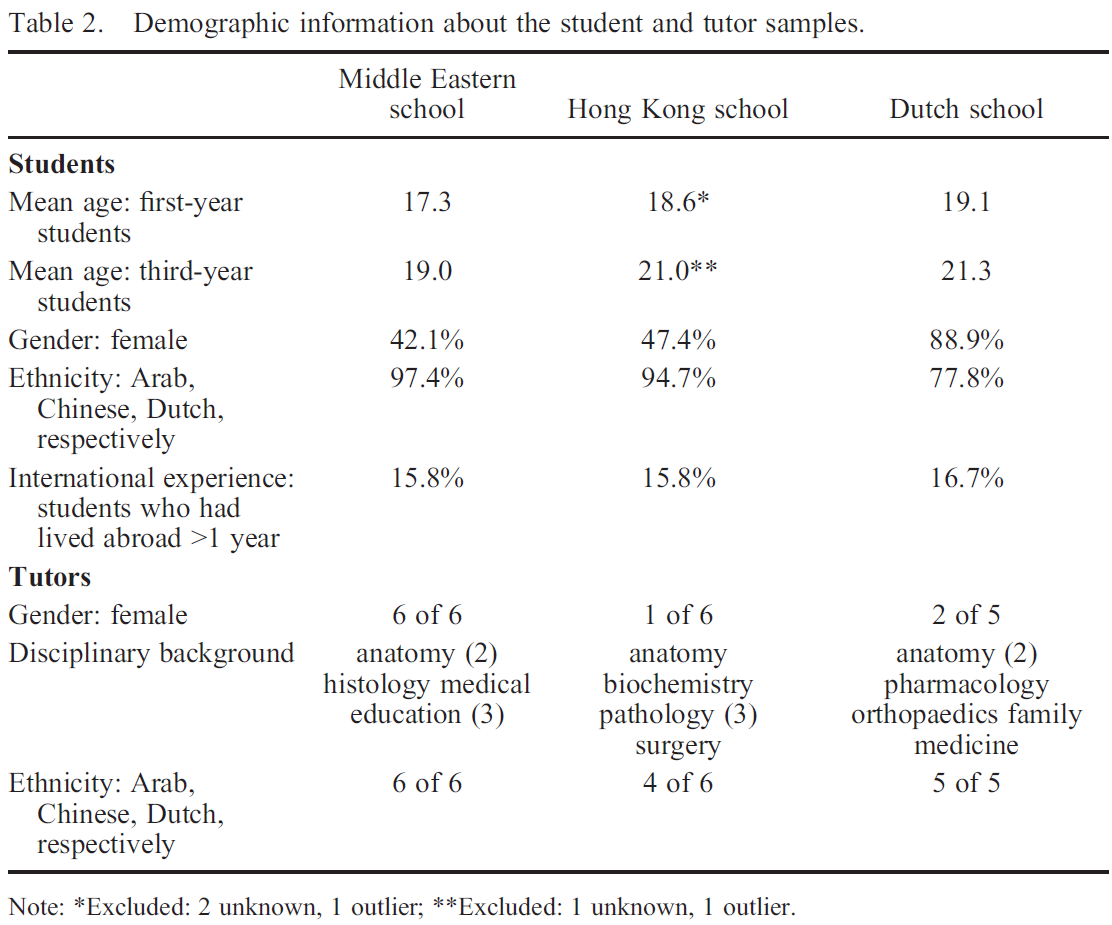

AAMC가 수집한 데이터는 PS 파이프라인의 다양성 부족을 보여준다. 2015년 의과대학 입학자 중 여성은 47.8%를 차지했다. 그러나, 지난 5년 동안, 그들은 국가의 MD/PhD 프로그램에 등록한 사람들 중 37%에서 38%를 지속적으로 차지해왔다.25 MD/PhD 파이프라인에서 여성의 낮은 대표성은 [시작부터 여성 지원자의 감소]와 [여성들 사이의 더 큰 이탈attrition 수준]을 반영한다. 여성이 MD/PhD 진로를 추구할 가능성이 낮은 이유에 대해 보고한 몇 가지 요인이 있는데, 여기에는 다음이 포함된다.

- 자녀 양육 또는 다른 가족 책임에 대한 우려,

- 남성 상대자에 비해 "경쟁에서 이길 필요"가 있다는 인식을 초래하는 직장의 편견,

- 여러 면에서 PS가 되기 위한 격려의 부족

- 역할 모델의 부족

Data compiled by the AAMC demonstrate a lack of diversity in the PS pipeline. In 2015, women accounted for 47.8% of those matriculating into medical school24; however, for each of the past five years, they have consistently accounted for between 37% and 38% of those enrolled in the nation’s MD/PhD programs.25 The lower representation of women in the MD/PhD pipeline reflects both fewer female applicants to start with and greater levels of attrition among women.26–28 There are several factors reported by women as to why they are less likely to pursue the MD/PhD career path, which include

- concerns about child rearing or other family responsibilities;

- a sense of bias in the workplace resulting in the perception that there is a need to “outcompete” relative to male counterparts;

- encountering, on multiple fronts, a lack of encouragement to become a PS; and

- a lack of role models.27–31

인종/민족의 대표성이 부족한 집단을 위한 파이프라인도 확대될 필요가 있다. 2014-2015년 미국 내 MD/PhD 프로그램 졸업생 616명 중 79명(12.8%)만이 인종/민족적으로 대표성이 낮은 집단 출신이라고 보고했다.

- 26명(4.2%)이 흑인 또는 아프리카계 미국인이라고 스스로 밝혔다.

- 히스패닉, 라틴계 또는 스페인계 혈통으로 12명(1.9%)

- 41명(6.7%)이 다인종/다인종이었다.

The pipeline for racial/ethnic underrepresented groups also needs to be expanded.8,32 Of the 616 graduates of MD/PhD programs in the United States during the 2014–2015 academic year, only 79 (12.8%) reported themselves as being from a racially/ethnically underrepresented group:

- 26 (4.2%) self-identified as black or African American;

- 12 (1.9%) as being of Hispanic, Latino, or Spanish origin; and

- 41 (6.7%) as multiple race/ethnicity.33

게다가, [다른 나라의 재능 있고 지망 있는 많은 수의 PS]들이 미국에서 연구 훈련에 들어가려고 시도하는 반면, 그들 중 소수만이 미국의 PS 노동력에 들어가는 데 성공하고 있다. 2015년 미국의 MD/PhD 프로그램에 입학한 626명 중 16명(2.6%)만이 미국 이외의 국가에서 왔다. 이 적은 수의 국제 대학 입학은 국가의 MD/PhD 프로그램의 절반 이하에 부과되는 자금 제한으로 부분적으로 설명될 수 있다. 즉, 연방정부에서 자금을 지원하는 의학 과학자 훈련 프로그램은 미국 시민들과 미국 영주권자들에게만 개방된다. 유학생이 미국에 입국하여 체류할 수 있는 기회를 강화하려는 노력을 포함하여 다양한 인구로부터 회원을 모집하고 유지하는 것을 촉진하는 것은 PS 인력을 늘리는 효과적인 전략이 될 수 있다.

Additionally, while large numbers of talented and aspiring PSs from other countries attempt to enter research training in the United States, only a small percentage of them are successful in entering the nation’s PS workforce.5 Of the 626 matriculates to the nation’s MD/PhD programs in 2015, only 16 (2.6%) came from countries outside the United States.34 This small number of international matriculates can be partially explained by funding restrictions imposed on slightly less than one-half of the nation’s MD/PhD programs—that is, the federally funded Medical Scientist Training Programs (MSTPs) are open only to U.S. citizens and permanent residents of the United States. Facilitating the recruitment and retention of members from diverse populations, including efforts to enhance opportunities for international students to enter and remain in the United States, could be an effective strategy for increasing the PS workforce.

역할 모델 및 멘토를 활용하여 다양성 증대

Using role models and mentors to increase diversity

롤모델과 멘토는 서로 다른 기능을 하며, 둘 다 PS 파이프라인 진입을 늘리는 데 중요합니다. Cruess 등에 따르면, [롤모델]은 "영감을 주고 모범을 보임으로써 가르칠 수 있다"고 한다. 롤모델은 예를 들어 스포츠 영웅, 연예인, PS가 될 수 있고, 다른 사람들에게 미치는 영향은 텔레비전 쇼나 그랜드 라운드 강의 동안처럼 쉽게 초등학교 교실에서 일어날 수 있다.

Role models and mentors function differently, and both are important to increasing entry into the PS pipeline. Role models, according to Cruess et al,35 can “inspire and teach by example.” Role models can be, for example, sports heroes, celebrities, or PSs, and their impact on others can occur in an elementary school classroom as easily as on a television show or during a Grand Rounds lecture.

롤모델에 대한 노출이 핵심입니다. 인종적/인종적으로 대표성이 낮은 고등학생을 대상으로 한 정성적 연구는 많은 학생들이 PS와 상호작용을 해본 적이 없다는 것을 보여주었다. 그들은 연구 경력을 고려하지 않은 근본적인 이유라고 목소리를 높였다. 더욱이, MD/PhD 의대생들을 대상으로 실시한 유사한 연구는 [일찍이 중학교 또는 고등학교의 역할 모델에 대한 노출]이 연구 커리어를 시작하려는 그들의 결정에 영향을 미친 것으로 나타났다. 학생들은 과학 과정 동안 마주친 역할 모델, 가족 내 PS에 대한 노출, 가족 건강 위기 동안 전문가에 대한 노출에 대해 말했다. 이러한 연구는 MD/PhD 파이프라인에서 인종/민족 차이를 해결하는 데 있어 롤 모델의 중요한 중요성을 강조한다.

Exposure to role models is key. Qualitative research of racially/ethnically underrepresented high school students revealed that many had never had interactions with a PS.30,36 They voiced this as an underlying reason for why they did not consider a research career. Furthermore, similar research conducted on MD/PhD medical students indicated that exposure to role models as early as middle and/or high school influenced their decisions to enter a research career.5,36 Students spoke of the role models they encountered during their science courses, exposure to PSs in their families, and exposure to professionals during a family health crisis. These studies emphasize the critical importance of role models in addressing racial/ethnic disparities in the MD/PhD pipeline.

파이체(Paice) 등에 따르면 [멘토]는 연습생이나 경험이 적은 동료와 '멘토가 명시적인explicit 쌍방향 관계를 활발히 하고 있다'는 점에서 롤모델과 다르다. 그것은 "시간이 지남에 따라 진화하고 발전하며 어느 한쪽이 종료할 수 있는 관계"이다. 국가연구멘토링네트워크(NRMN)와 같은 프로그램이 존재하여 특정 조사 영역뿐만 아니라 전문적 개발 영역에서도 멘토링을 제공한다. NRMN의 일부 프로그램은 "다양성, 멘토 관계 내에서의 포괄성 및 문화, 그리고 보다 광범위한 연구 인력 등의 혜택과 도전을 강조한다."

Mentors differ from role models, according to Paice et al,37 in that a “mentor is actively engaged in an explicit two way relationship” with a trainee or a less-experienced colleague. It is “a relationship that evolves and develops over time and can be terminated by either party.”37 Programs such as the National Research Mentoring Network (NRMN) exist to offer mentoring not only in specific areas of inquiry but also in areas of professional development. Some of the NRMN’s programs “emphasize the benefits and challenges of diversity, inclusivity and culture within mentoring relationships, and more broadly the research workforce.”38

PS 교육 프로세스 합리화 및 연구 교육 기회 확대

Streamlining the PS training process and expanding research training opportunities

생의학 연구를 위한 준비는 10년 이상의 학부, 의과대학, 대학원 교육을 필요로 하는 긴 과정이다. 이 과정을 가속화하기 위해, 연합 MD/PhD 커리큘럼(연방정부가 지원하는 MSTP 포함)은 의과대학 동안 의학 및 연구 훈련을 더 잘 통합하고 가속화하는 아이디어로 개발되었다. 2014년 전국 설문 조사 결과에 따르면 MD/PhD 프로그램 졸업생 중 80% 이상이 연구 지향적인 직업을 추구하는 것으로 나타났다. MSTP 등록(7년 이상의 의무)에 대한 대안으로, 의대생들 중 일부는 등록자들에게 (기관 또는 외부 자금 지원으로) 1년 동안의 멘토링 연구 경험을 제공하는 공식적인 연구 계약을 이용한다. 제한된 일화 데이터는 이러한 공식 연구 계획 중 일부의 효과를 뒷받침한다.

Preparation for a career in biomedical research is a lengthy process requiring well over a decade of undergraduate, medical school, and postgraduate training, which may include formal graduate education in a scientific discipline. To expedite this process, combined MD/PhD curricula (including federally funded MSTPs) were developed with the idea of better integrating and expediting medical and research training during medical school. The results of a national survey from 2014 show that these programs have had success with > 80% of MD/PhD program graduates pursuing research-oriented careers.39 As an alternative to MSTP enrollment (a commitment of over seven years),39 a subset of medical students take advantage of formal research tracts, which offer enrollees a one-year mentored research experience during medical school (with institutional or external funding support). Limited anecdotal data support the effectiveness of some of these formal research tracts.40,41

의과대학에서 연구 경험을 쌓은 후, 많은 졸업생들은 오랜 기간의 대학원 임상 및 연구 훈련으로 전문 교육을 이수하는 것을 선택한다. 이 과정을 가속화하기 위해, 이러한 [박사 후 경험을 간소화]하기 위한 보조 메커니즘이 개발되었습니다. 미국 내과의사회(Board of Internal Medicine)가 승인한 이러한 접근 방법 중 하나는 신속한 임상 훈련(그리고 종종 하위 전문 펠로우쉽)과 3년간의 멘토링된 박사 후 연구를 결합하는 레지던트 연구 경로이다. 짧은 임상 교육 기간(3년 대신 2년)에도 불구하고, 이러한 졸업생들의 임상 역량(보드시험 합격률로 측정)은 희생되지 않았으며, 80% 이상이 자금 지원을 받은 생물의학 연구를 계속했다. 다른 전공과목 학회(예: 소아과 및 병리학)도 유사한 간소화된 의사 후 교육 경로를 승인했다.

After gaining research experience in medical school, many graduates opt to complete their professional education with a lengthy period of postgraduate clinical and research training. To expedite this process, supplemental mechanisms have been developed to streamline this postdoctoral experience. One such approach, sanctioned by the American Board of Internal Medicine, is a residency research pathway which combines expedited clinical training (and often subspecialty fellowship) with three years of mentored postdoctoral research. Despite a shortened duration of clinical training (two years instead of three), the clinical competency (as measured by board exam pass rate) of these graduates was not sacrificed,42 and more than 80% went on to pursue funded biomedical research.43 Other medical specialty boards (e.g., pediatrics and pathology) have sanctioned similar streamlined postdoctoral training pathways.

마지막으로, 연구에 대한 새로운 관심을 가진 모든 의사들이 의과대학 이전 또는 그 동안 대학원 수준의 과학 훈련을 이수하지 않았기 때문에, 몇몇 연구집약적 의과대학은 [임상훈련의 후기 단계에 있는 의사나 주니어 교수진 중에서 엄선된 그룹에 이러한 엄격한 훈련을 제공하기 위한 공식적인 박사후 연구 훈련 프로그램](종종 MS 또는 PhD 학위까지 이어진다)을 개발했다.

Finally, because not all physicians with a budding interest in research have completed graduate-level scientific training prior to or during medical school, several research-intensive medical schools have developed formal postdoctoral research training programs (often leading to an MS or PhD degree) to provide this rigorous training to a select group of committed physicians who are in the later stages of clinical training or who are junior faculty.44–46

PS 파이프라인 진입을 늘리기 위한 권장 사항

Recommendations Aimed at Increasing Entry Into the PS Pipeline

PS 파이프라인 진입을 늘리기 위한 AAIM 컨센서스 회의 권고안은 다음과 같았다.

- (1) 젊은이들에게 생물의학 연구의 가치와 생물의학 진보에서 PS가 수행하는 중요하고 독특한 역할을 홍보한다.

- (2) 역할 모델 및 멘토 네트워크에 대한 액세스를 제공하는 프로그램의 광범위한 구현을 통해 다양한 모집단의 구성원을 PS로 모집 및 보유할 수 있습니다.

- (3) 국제 PS가 미국 노동력의 일원으로 미국에 입국하여 체류할 수 있는 기회를 강화한다.

- (4) PS 교육에서 효율성과 커리큘럼 모범 사례를 촉진한다.

- (5) MD/PhD 프로그램에 입학하지 않는 교육생을 위한 학부 및 대학원 연구 교육 기회를 강화한다(목록 1).

The AAIM consensus conference recommendations for increasing entry into the PS pipeline were to

- (1) promote to young people the value of biomedical research and the important and unique role that PSs play in biomedical advances;

- (2) facilitate the recruitment and retention of members from diverse populations as PSs through widescale implementation of programs that provide access to a network of role models and mentors;

- (3) enhance opportunities for international PSs to enter and remain in the United States as members of the nation’s workforce;

- (4) promote efficiency and curricular best practices in the training of PSs; and

- (5) enhance undergraduate and postgraduate research training opportunities for trainees who do not matriculate into MD/PhD programs (List 1).

젊은이들에게 생물의학 연구의 가치와 생물의학 발전에 있어 PS가 수행하는 중요하고 독특한 역할을 홍보합니다.

Promote to young people the value of biomedical research and the important and unique role that PSs play in biomedical advances

과학과 수학의 풍요를 제공할 뿐만 아니라, 어린 학습자들, 특히 소외된 배경을 가진 사람들에게 지원을 제공할 수 있는 혁신적인 교육 개입이 확립되어야 한다. 이를 위해 정부 기관, 지역사회 기반 조직, 민간 부문 연구 조직 및 학교 간의 협력을 장려해야 한다.

Innovative educational interventions should be established to provide enrichment in science and math as well as to provide support for young learners, especially those from disadvantaged backgrounds. To this end, collaborations between government agencies, community-based organizations, private-sector research organizations, and schools should be encouraged.

롤모델 및 멘토 네트워크에 대한 액세스를 제공하는 프로그램의 광범위한 구현을 통해 다양한 모집단의 구성원을 PS로 모집 및 유지

Facilitate the recruitment and retention of members from diverse populations as PSs through widescale implementation of programs that provide access to a network of role models and mentors

PS와 다른 전문가들로 구성된 롤모델 네트워크를 만들어 정기적으로 K-12 및 학부 수업을 방문하면 학생들이 생물의학 연구의 가치와 직업으로서의 생존 능력에 노출되는 데 도움이 될 것이다. 마찬가지로, NRMN과 같은 프로그램은 다양한 모집단의 구성원을 모집하고 유지하기 위해 널리 사용되어야 한다.

Creating a network of role models, comprising PSs and other professionals, to routinely visit K–12 and undergraduate classes would help expose students to the value of biomedical research and its viability as a career. Similarly, programs such as the NRMN should be widely used to recruit and retain members from diverse populations as they pursue training as PSs.

국제 PS가 미국에 입국하여 미국 노동력의 일원으로 체류할 수 있는 기회를 강화합니다.

Enhance opportunities for international PSs to enter and remain in the United States as members of the nation’s workforce

연구 상금과 보조금은 거주 상태에 따라 달라지는 경우가 많다. 외국 의대 졸업생들의 박사 후학을 후원하는 대학들은 미국 영주권 신청에 도움을 주어야 한다. 또한, NIH는 다른 정부 기관과 협력하여 국가 연구 서비스상 펠로우십, 교육 보조금 및 경력 개발상의 자격 요건에 대한 정책을 수정해야 한다. 여기에는 미국 대학원 유학을 위해 입학했지만, 아직 영주권을 부여받지 못한 외국 의과대학 졸업생도 포함해야 한다.

Research awards and grants are frequently dependent on residency status. Universities sponsoring foreign medical school graduates’ postdoctoral studies should provide assistance with applications for permanent residence in the United States. Additionally, the NIH should work with other government agencies to amend policies on eligibility requirements for its National Research Service Award fellowships, training grants, and career development awards to include graduates of foreign medical schools who have been admitted to the United States for postgraduate study but who have not yet been granted permanent resident status.

PS 교육의 효율성 및 커리큘럼 모범 사례 촉진

Promote efficiency and curricular best practices in the training of PSs

연구 분야에서 진로에 대한 의지를 입증한 교육생은, 의과대학 재학 중 정식 MD/PhD 프로그램 및 전공의 수련 중 전공/세부전공 연구 경로 조정과 같이 교육 과정을 단축하고 능률화하는 교육 이니셔티브를 최대한 활용할 것을 강력히 권장해야 한다. MSTP에 대한 지속적인 NIH 자금후원이 제공되어야 한다.

Trainees who have demonstrated a commitment to careers in research should be strongly encouraged to take full advantage of educational initiatives that shorten and streamline the training process, such as formal MD/PhD programs during medical school and coordinated residency/subspecialty research pathways during postgraduate training. Continued NIH funding for MSTPs should be provided.

MD/PhD 프로그램에 입학하지 않은 교육생을 위한 학부 및 대학원 연구 교육 기회 강화

Enhance undergraduate and postgraduate research training opportunities for trainees who do not matriculate into MD/PhD programs

연구에 관심이 있지만 공식적인 MD/PhD 프로그램에 등록되지 않은 의대생은 1년 동안 멘토링된 연구 경험에 참여하는 것을 고려해야 한다. 전문 교육(예: 하위 전문 펠로십) 또는 하위 교수로서 연구를 추구하는 데 관심을 보이는 임상 교육을 받은 의사는 석사 및/또는 박사 학위를 받을 수 있는 공식적인 연구 훈련 기회에 참여하는 것을 고려해야 한다. 현재 이러한 학부 및 대학원 교육 프로그램의 효과에 대한 발표된 데이터가 제한적이므로, 이러한 대안 연구 커리큘럼에 대한 포괄적인 조사(졸업자의 내용, 지원 메커니즘 및 경력 결과 포함)는 관련 전문 기관이 수행해야 한다. 예를 들어 AAIM이나 AAMC, 프로그램 리더가 소집하고 모범 사례를 교환할 수 있는 메커니즘이 제공되어야 한다.

Medical students who have an interest in research but who are not enrolled in a formal MD/PhD program should consider participating in a one-year mentored research experience. Clinically trained physicians who develop an interest in pursuing research later in their professional education (e.g., subspecialty fellowship) or as junior faculty should consider participating in formal research training opportunities that may lead to a master’s and/or doctoral degree. Currently, there are limited published data on the effectiveness of these undergraduate and postgraduate training programs,40,41,44–46 so comprehensive surveys of these alternative research curricula (including content, mechanisms of support, and career outcomes of graduates) should be conducted by relevant professional organizations, such as the AAIM or AAMC, and a mechanism for program leaders to convene and exchange best practices should be provided.

PS 인력의 소모 감소를 위해 해결해야 할 요인

Factors to Address to Reduce Attrition From the PS Workforce

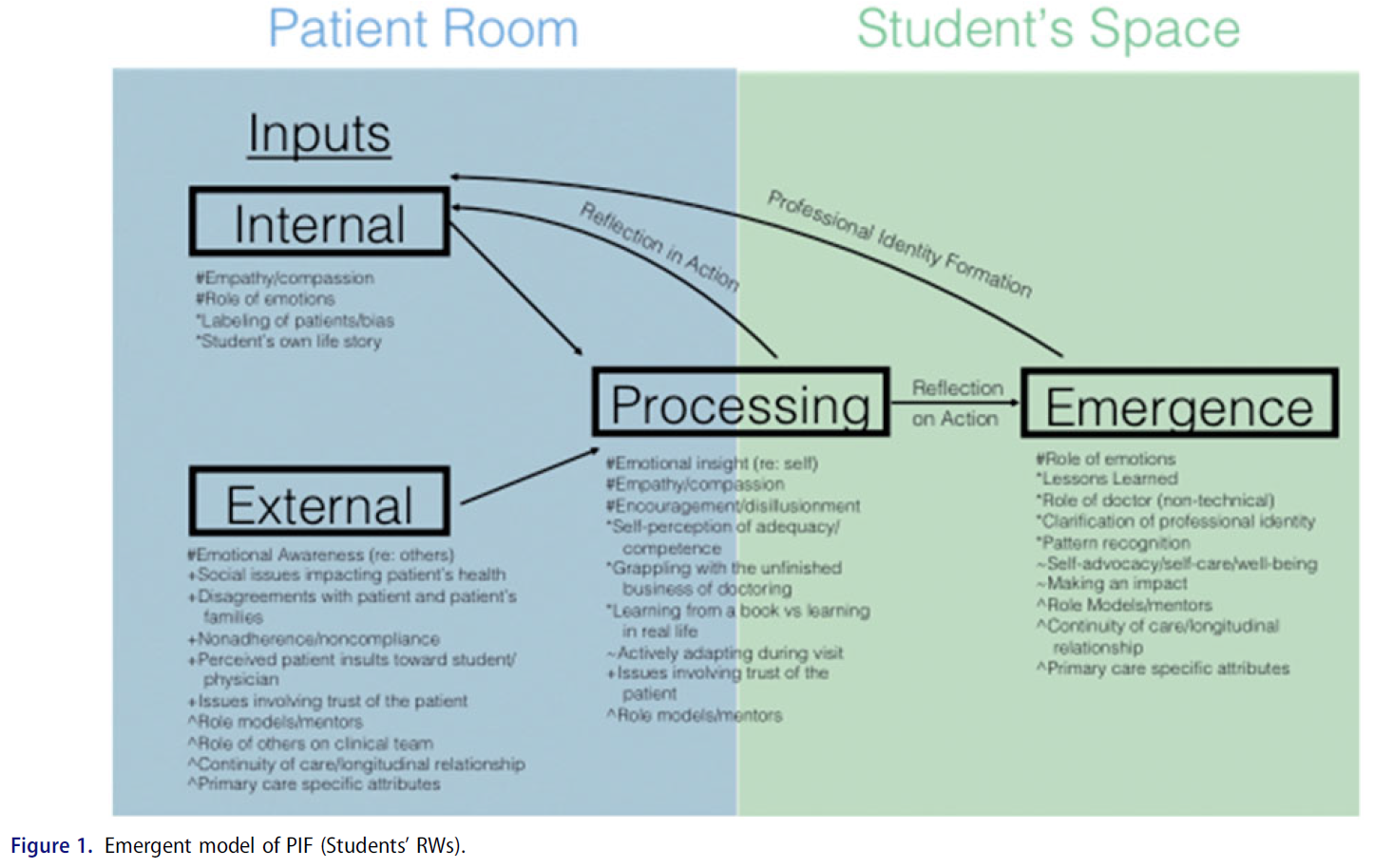

많은 PS들, 특히 그들의 경력 초기와 중간 단계에 있는 사람들은 전임 임상 실습에 들어가기 위해 생물의학 연구 기회를 추구하려는 그들의 원래 계획을 두고 떠난다. Attrition 사유는 다양하고 복잡하지만, 학계로부터 PS의 Attrition와 인과적으로 연결될 수 있는 식별 가능한 요인은 다음과 같다.

- 부적절한 멘토링,

- PS로서의 성공에 대한 편협한 인식,

- 외부 지원을 위한 경쟁이 치열해지고 있습니다.

- 재정적 압박,

- 불충분한 제도적 지원, 그리고

- 일과 삶의 균형에 대한 어려움

Many PSs, especially those in the early and middle stages of their careers, leave behind their original plans to pursue biomedical research opportunities to enter full-time clinical practice. Reasons for attrition are numerous and complex; however, there are identifiable factors that can be causally linked to the attrition of PSs from academia, including

- inadequate mentoring,

- a narrow perception of success as a PS,

- increasing competition for external support,

- financial pressures,

- inadequate institutional support, and

- difficulties with work–life balance.

부적절한 멘토링

Inadequate mentoring

독립적으로 자금을 지원하는 PS로서 성공을 달성하는 것은 어려울 수 있습니다. 강력하고 적극적인 멘토링은 그 성공의 중요한 요소이다. 멘토-연수생 다이애드가 멘토십의 전통적인 모델이었지만, 몇몇 기관들은 중앙 집중식 감독, 멘토 지원 및 경력 개발을 제공하기 위해 고안된 이니셔티브를 개발했다. 확립된 연구자는 연구를 수행하는 전문 지식을 가지고 있지만, 견습생을 적극적으로 지도하는 데 필요한 기술을 개발하기 위해 추가적인 교육 지원을 요구할 수 있다. 연구 멘토 양성 프로그램이 효과가 있는 것으로 나타났다. 그러한 프로그램은 모든 의과대학에서 시행되어야 하며 진로 협상, 보조금 작성, 원고 출판, 일과 삶의 균형과 같은 분야의 공식화된 훈련을 포함해야 한다. 가정 기관, NIH 및 기타 기금 기관은 시간과 보상 측면에서 멘토에게 적절한 자원을 할당해야 한다.

Achieving success as an independently funded PS can be challenging. Strong, active mentoring is a crucial element of that success.43 While the mentor–apprentice dyad has been the traditional model of mentorship, several institutions have developed initiatives designed to provide centralized oversight, mentorship support, and career development. Established researchers, while having the expertise to perform research, may require additional educational support to develop the skill set needed to actively mentor an apprentice. Training programs for research mentors have been shown to be effective.47–49 Such programs should be implemented in all medical schools and should include formalized training in areas such as career negotiation, grant writing, publication of manuscripts, and work–life balance.47 Home institutions, the NIH, and other funding agencies should allocate adequate resources to mentors in terms of both time and compensation.

PS로서의 성공에 대한 좁은 인식

A narrow perception of success as a PS

[성공적인 PS는 NIH가 벤치 또는 초기 중개연구를 위한 PI로 자금을 지원받는다]는 인식이 많다. 하지만, 이 개념은 NIH와 다른 사람들이 가정한 [광범위한 PS의 정의]를 고려하지 않으며, 또한 다학제 연구팀이 빅데이터를 사용하고 정밀의학 이니셔티브를 발전시켜야 하는 [연구 분야 내에서의 진화]도 고려하지 않는다. 그럼에도 불구하고, 성공적인 PS를 구성하는 이러한 오래된 개념은 연구 자금과 승진 및 테뉴어(P&T)에 대한 결정에 있어서 부정적인 경력 결과를 초래할 가능성을 계속 제기한다. 따라서, 연구비 지원 기관과 AMC 모두 [PS로서 성공을 구성하는 것]에 대한 더 광범위한 기준을 개발할 필요가 있을 것이다.

A widely held view is that a successful PS is funded by the NIH as a principal investigator for bench or early translational research.50 This notion does not take into account the broader definition of a PS as posited by the NIH and others,5 nor does it take into account the evolution occurring within the research arena that requires multidisciplinary research teams to use big data and advance precision medicine initiatives. Nonetheless, these antiquated notions of what constitutes a successful PS continue to pose the possibility of negative career consequences when it comes to decisions about research funding and promotion and tenure (P&T). Accordingly, both funding agencies and academic medical centers will need to develop broader criteria for what constitutes success as a PS.50

외부 지원 경쟁 심화

Increasing competition for external support

NIH가 지원하는 R01 보조금에 대한 PS의 최초 수상률은 2012년에 14%로 사상 최저였다. NIH로부터 보조금을 받기 위한 과정은 경쟁이 치열해졌고, 모든 연구 프로젝트 보조금에 대한 전반적인 성공률은 1997년 31%에서 2014년 18%로 떨어졌다. 자금을 성공적으로 확보하거나 지속하지 못하는 것은 흔하지만 예측할 수 없는 일이다. 그로 인해 발생하는 [다른 진로 경로와 비교했을 때에 연구자가 가지는 취약성]의 감각이 소모attrition에 기여할 수 있다. NIH가 훈련에서 독립 연구 경력으로 전환하는 동안 PS를 용이하게 하기 위해 K99/R00 Pathways to Independence Award 이니셔티브와 유사한 프로그램을 수립해야 한다는 강력한 논거를 제시한다.

The first-time award rate among PSs for an NIH-funded R01 grant was 14% in 2012, an all-time low.5 The process to receive a grant from the NIH has become more competitive, with overall success rates for all research project grants dropping from 31% in 1997 to 18% in 2014.5 The failure to successfully obtain or continue funding is a common yet unpredictable occurrence. The resulting sense of researcher vulnerability, as compared with other career pathways, can contribute to attrition. It makes a strong case for the NIH to establish a program similar to its K99/R00 Pathway to Independence Award initiative to facilitate PSs during their transition from training to an independent research career.

학술 기관들은 연방 및 주 기관, 전문 협회 및 사회, 제약 산업을 포함한 민간 부문과 같은 다른 자금 공급원과의 제휴를 고려할 필요가 있다. 빅데이터가 성장하면서 구글, 아마존과 같은 기업과 제휴할 기회도 존재한다. PS에게 이러한 다양한 자금 출처에 접근할 수 있는 지식과 도구를 제공하기 위해서는 효과적인 멘토링과 경력 개발이 필요할 것이다.

Academic institutions need to consider partnering with other sources of funding, such as federal and state agencies, professional associations and societies, and the private sector, including the pharmaceutical industry. With the growth of big data, opportunities also exist to partner with companies such as Google and Amazon. Effective mentorship and career development will be needed to provide PSs with the knowledge and tools to be able to access these diverse funding sources.

재정적 압박

Financial pressures

의대와 대학원 교육 동안, 임상 실습에서의 경력에 비해, PS 커리어를 선택할 때 따르는 재정적 디스인센티브가 있다. 즉, 교육 부채에 대한 부담이 훨씬 더 커지고 안정적인 유급 고용에 대한 자격이 상당히 지연될 가능성이 있다. 비록 MD/PhD 학생이 펠로우십을 통해 지원을 받는다고 해도, 의사 후 연구 훈련과 함께 의과대학 훈련의 상당한 기간(7년 이상)은 생물의학 연구 분야에서 가장 헌신적인 젊은 과학자를 제외한 모든 과학자들을 멀어지게 하기에 충분하다. 아무리 좋은 시나리오라도 PS는 36세에 테뉴어 트랙의 후보자가 된다. 그러나 많은 PS는 테뉴어 트랙 포지션에 대한 수요가 공급을 초과하기 때문에 몇 년 더 포스닥의 지위를 유지한다. 종종, 그들의 조교수로의 고용과 임명은 공식적으로 또는 비공식적으로 NIH의 성공적인 자금 지원(예: K 또는 R 상)에 좌우되지만, MD가 첫 R01을 받은 PS의 평균 연령은 43.8세이다. MD/PhD를 가진 사람들의 평균 연령은 44.3세이다. 많은 PS는 첫 번째 교직원 임명을 시작할 때 큰 부채 부담을 가지고 있는데, 이 상황은 상당한 재정적 압박을 유발하고 가족의 안정적인 지원을 위한 수단을 제공하지 못한다.

During both medical school and postgraduate training, there is a financial disincentive to pursue a PS career relative to a career in clinical practice—that is, there is the potential for a much greater burden of educational debt and a significant delay in eligibility for stable, paid employment.7,51,52 Even if an MD/PhD student is supported through a fellowship, the significant duration of medical school training (seven years or longer), coupled with incremental postdoctoral research training, is sufficient to sway all but the most committed young scientists away from a career in biomedical research. In a best-case scenario, a PS becomes a candidate for a tenure-track position at the age of 36.5 However, many PSs retain their postdoctoral status for several additional years because the demand for tenure-track positions exceeds the supply.52 Often, their employment and appointment as assistant professor are formally or informally contingent on successful funding from the NIH (such as a K or R award), yet the average age of PSs with an MD receiving their first R01 is 43.8 years; for those with an MD/PhD, the average age is 44.3 years.5 Many PSs have large debt burdens when beginning their first faculty appointment, a situation that creates substantial financial duress and does not provide the means for the stable support of a family.

제도적 지원 부족

Inadequate institutional support

제도적 지원은 여러 가지 형태를 취할 수 있으며 임상의사나 박사 연구자와 같은 다른 사람과 비교할 때 PS의 고유한 요구의 결과인 경우가 많다. PS는 연구에 소비하거나 연구 자금 확보에 적용할 수 있는 시간에 영향을 미치는 증가하는 양의 임상 수익을 창출해야 한다. 비슷하게, PS는 종종 임상의 동료들보다 적은 임금을 받으며 종종 외부 자금을 통해 그들의 급여와 연구팀의 다른 사람들의 급여의 많은 부분을 충당할 것으로 기대됩니다. 불행하게도, 그들이 소속된 기관은 외부 자금 부족이 발생할 때, [브리지 연구비 지원]을 제대로 제공하지 않는 경우가 많다. 마지막으로, PS에 대한 P&T 지표는 종종 시대에 뒤떨어지고 팀 과학에 대한 기여, 독립 PS로서의 경력을 확립하는 데 계속 증가하는 시간 또는 빅 데이터, 정밀 의료 및 팀 과학 분야에서 충족되어야 하는 요구를 고려하지 않는다.

Institutional support can take several forms and is often the result of the unique needs of PSs when compared with others, such as clinicians or PhD researchers. PSs are asked to generate increasing amounts of clinical revenue, which affects the time they can spend on their research or apply to securing research funding.52 Similarly, PSs are often paid less than their clinician counterparts and are often expected to obtain a large portion of their salary, and the salaries of others on their research team, through external funding. Unfortunately, their home institutions are often not optimally forthcoming with bridge funding when lapses of external funding occur.7 Finally, the metrics for P&T for PSs are often outdated and fail to take into account contributions to team science, the ever-increasing length of time needed to establish a career as an independent PS, or the demands that will need to be met within the arenas of big data, precision medicine, and team science.

일과 삶의 균형에 대한 어려움

Difficulties with work–life balance

PS는 일반적으로 그들 중 많은 수가 가정을 꾸리고 있는 시점에서 노동력으로 들어가고 있다. 일과성 비경력적 책임(예: 가족 및 건강 문제)은 종종 PS가 일시적으로 인력에서 이탈할 것을 요구할 수 있다. PS들이 소속된 기관은 직장과 가정의 경쟁적인 요구를 수용하고, 가능한 한 유연한 옵션을 제공하며, 결과적으로 PS 직원의 경력 궤적이 악영향을 받지 않도록 해야 한다. [세대 차이]는 후배들에게 매력적이지 않은 작업 환경으로 이어질 수 있다. 예를 들어, 현재 의대에 입학하는 개인과 하위 교수로 학계에 입학하는 사람들은 일과 삶의 균형을 점점 더 중요하게 생각한다. 이러한 가치 체계를 뒷받침하는 연구들은 일과 삶의 균형을 이루는 것이 스트레스, 감정적 피로, 그리고 소진을 줄일 수 있다는 것을 증명했다.

PSs are generally entering the workforce at a time when many of them are also starting families. Episodic noncareer responsibilities (e.g., family and health issues) can often demand that PSs temporarily remove themselves from the workforce. PSs’ home institutions need to accommodate the competing demands that work and family often present, provide flexible options whenever possible, and ensure that the career trajectories of their PS faculty are not adversely affected as a result. Generational differences may lead to work environments that are unappealing to junior faculty. For example, individuals now entering medical school and those entering academia as junior faculty increasingly value a balance between work and life. Supporting this value system, studies have demonstrated that achieving a work–life balance can reduce stress, emotional exhaustion, and burnout.47,53,54

PS 인력 소모 감소를 위한 권장 사항

Recommendations Aimed at Reducing Attrition From the PS Workforce

PS 파이프라인의 소모 감소를 위한 AAIM 컨센서스 컨퍼런스 권고안은 다음과 같았다.

The AAIM consensus conference recommendations for reducing attrition from the PS pipeline were to

- (1) "멘토 양성" 교육을 포함한 정형화된 멘토링 프로그램 구현 및 멘토링 결과의 주기적인 검토

- (2) 교육에서 독립적 연구 경력으로의 PS 전환을 지원하는 것을 특별히 목표로 하는 보조금 프로그램을 수립한다.

- (3) NIH 또는 VA 경력 개발 보조금을 수여받은 개인에 대한 학자금 대출 상환 기회를 확대한다.

- (4) 경력개발상(Career Development Awards)에 등재된 멘토에게 급여 지원을 제공한다.

- (5) PS 간 부서 전체의 급여 형평성을 보장한다.

- (6) 보호 시간 제공 및 필요한 경우 교량 자금 지원을 통해 PS 교수진이 독립적인 연구자가 될 수 있는 안정적인 환경을 제공한다.

- (7) 생물의학 발전에 대한 PS의 기여에 대한 환경의 변화를 수용하고 P&T 의사결정 과정에 투명성을 유지하기 위해 P&T 기준을 재고한다.

- (8) 산업계와의 파트너십 확대를 포함한 연구 및 연구 자금 지원을 위한 새로운 방법을 추구한다.

- (9) PS 경력 개발 데이터 저장소(목록 1)를 구축한다.

- (1) implement formalized mentoring programs, including “mentoring the mentor” training, and periodic reviews of mentoring results;

- (2) establish grant programs specifically targeted to supporting the PS transitioning from training to an independent research career;

- (3) expand student loan repayment opportunities for individuals who are awarded an NIH or a VA career development grant;

- (4) provide salary support for mentors named on career development awards;

- (5) ensure department-wide salary equity among PSs;

- (6) provide a stable environment for PS faculty to become independent researchers through provision of protected time and, when necessary, bridge funding;

- (7) reconsider criteria for P&T to accommodate the changing environment for PSs’ contributions to biomedical advances and be transparent in P&T decision-making processes;

- (8) pursue new avenues for research and research funding, including expanding partnerships with industry; and

- (9) establish a repository for PS career development data (List 1).

"멘토 멘토링" 교육을 비롯한 정형화된 멘토링 프로그램 구현 및 멘토링 결과 주기적 검토

Implement formalized mentoring programs, including “mentoring the mentor” training, and periodic reviews of mentoring results

정형화된 멘토링 프로그램은 멘티 뿐만 아니라 궁극적으로 교수진의 성공을 통해 기관의 명성을 높일 수 있다. 따라서 팀 기반, 다세대, 다기관 및 다문화 멘토링 그룹은 기관의 하위 교수진에게 광범위하고 긍정적인 영향을 미칠 수 있다. 멘토링 주제는 여러 분야를 다루어야 한다. 구체적인 연구 주제 외에도, 멘토링은 연구의 책임있는 수행, 연구비 지원서 작성, 원고 출판, 리더십, 경력 협상 및 일과 삶의 균형 등에 대해 제공되어야 한다. 멘토 양성 및 멘토링 결과의 주기적인 평가는 기관의 멘토링 프로그램의 필수 구성 요소가 되어야 한다.

Formalized mentoring programs may help not only the protégé but may also ultimately enhance the reputation of the institution through the successes of its faculty. Team-based, multigenerational, multi-institutional, and multicultural mentoring groups, therefore, could have a wide-reaching and positive impact on an institution’s junior faculty members. Mentoring topics should cover several areas; in addition to specific research topics, mentoring should be provided on the responsible conduct of research, grant writing, publication of manuscripts, leadership, career negotiation, and work–life balance. Training of mentors and periodic evaluations of mentoring results should be required components of an institution’s mentoring program.

교육에서 독립적 연구 경력으로의 PS 전환을 지원하기 위한 특별 보조금 프로그램 수립

Establish grant programs specifically targeted to supporting the PS transitioning from training to an independent research career

전환 기간은 젊은 PS에게 특히 취약한 시기이며, PS가 [Training에서 독립적인 연구 커리어로 전환되는 시기]는 이탈Attrition 현상이 발생할 가능성이 더 높은 시기이다. NIH는 현재의 K99/R00 프로그램과 유사한 이 전환 단계에서 PS를 보호하기 위해 특별히 지정된 기금을 적립해야 한다. NIH 연구 섹션은 많은 예비 데이터를 수집하지 않았을 수 있는 매우 유망한 개인을 수용하기 위해 그들의 기대를 재보정할 필요가 있다.

Periods of transition are a particularly vulnerable time for young PSs, and the period when a PS is transitioning from training to an independent research career is one in which attrition may be more likely occur. The NIH must set aside funds specifically designated for PSs with the purpose of protecting them in this transition phase, similar in nature to the current K99/R00 program. NIH study sections need to recalibrate their expectations to accommodate highly promising individuals who may not have amassed a large body of preliminary data.

NIH 또는 VA 경력 개발 보조금을 받은 개인에 대한 학자금 대출 상환 기회 확대

Expand student loan repayment opportunities for individuals who are awarded an NIH or a VA career development grant

많은 PS는 많은 양의 학자금 대출 채무를 축적했는데, 이것은 학계를 떠나 더 수익성이 높은 직업을 가지기로 한 결정에 영향을 미칠 수 있다. NIH 대출 상환 프로그램은 생물의학 연구 경력을 쌓기 위해 자격을 갖춘 의료 전문가를 모집하고 유지하는 것을 돕기 위해 고안되었습니다. 이러한 대출 상환 프로그램 참여자들은 연구 경력을 더 오래 유지하고, 더 많은 연구 보조금을 신청하고 수령하며, 독립적인 조사원이 될 가능성이 더 높은 것으로 나타났다. PS에 대한 대출 상환 기회가 강화되어야 한다.

Many PSs have amassed large amounts of student loan debt, which can factor into their decision to leave academia for a more lucrative profession. NIH loan repayment programs are designed to help recruit and retain highly qualified health professionals into biomedical research careers. Participants in these loan repayment programs have been shown to remain in research careers longer, apply for and receive more research grants, and be more likely to become independent investigators.55 Loan repayment opportunities for PSs should be enhanced.

경력개발상에 선정된 멘토에 대한 급여 지원 제공

Provide salary support for mentors named on career development awards

멘토 경력 개발 상을 받은 젊은 조사원들은 주로 다른 일정이 멘토링 일정보다 우선하기 때문에, 그들은 종종 그들의 멘토들과 함께 보낸 시간을 그들의 기금 기관에 과도하게 보고한다고 지적한다. NIH와 다른 기금 기관은 멘토가 독립적인 연구 경력을 확립하려는 젊은 연구원들의 개발에 수행하는 중요하고 시간이 많이 걸리는 역할을 인식할 필요가 있다. 멘토는 자신의 시간에 대한 보상을 받아야 하며, 자신의 노력과 생산성에 대해 보고할 때 멘토링에 소요된 시간의 비율을 공식적으로 기록할 수 있어야 합니다.

Young investigators with mentored career development awards note that they often overreport the time spent with their mentors to their funding agency,5 mainly because their mentors’ other commitments sometimes take precedence over their mentoring needs. The NIH and other funding agencies need to recognize the important and time-consuming role that mentors play in the development of young investigators looking to establish independent research careers. Mentors should be compensated for their time and allowed to formally record the percentage of time spent mentoring when reporting on their levels of effort and productivity.

PS 간 부서 전체의 급여 형평성 보장

Assure department-wide salary equity among PSs

몇몇 의과대학에서 급여 형평성이 해결되지 않은 채로 남아 있다는 것은 널리 인식되고 있으며, 특히 젠더 간 불평등의 가장 높은 원인이 된다. 부서 의장은 급여 정책을 투명하게 하고, 급여 지급자에게 급여 지급을 제안할 때 급여 분배와 스타트업 패키지에 대해 논의해야 하며, 이후 정기적으로 부서 직원들에게 급여 분배를 보고해야 한다.

It is widely recognized that salary equity remains unresolved in several of the nation’s medical schools, with gender as the highest source of disparity.56,57 Department chairs should be transparent in their salary policies, discuss salary distribution and startup packages when offering a salaried position to a PS, and report salary distributions to department faculty on a periodic basis thereafter.

보호 시간 제공 및 필요한 경우 브리지 자금 지원을 통해 PS 교수진이 독립적인 연구자가 될 수 있는 안정적인 환경 제공

Provide a stable environment for PS faculty to become independent researchers through provision of protected time and, when necessary, bridge funding

PS의 경력 개발은 장기적인 투자입니다. 소득 발생은 수년 단위의 latency period 이후에야 증가한다. 부서 의장과 그 기관은 젊은 PS의 기능과 궤적에 대한 광범위한 비전을 수용하고 이러한 지연을 반영하는 장기 예산을 구성해야 한다. 여기에는 멘토링 감독, 경력 개발 프로그래밍, 보조금 검토, 동료에서 교직원으로의 전환을 위한 자금 지원 등이 포함될 수 있다. 새로운 PS 교수진들이 [연구 경력을 발전]시키면서, 동시에 [자신의 급여를 지원할 수 있을 만큼 충분한 임상 수익을 창출]할 수 있다는 기대는 비현실적이다. 또한 부서 의장은 PS 교수진의 장기적인 일과 삶의 균형을 수용할 수 있는 유연한 옵션을 제공하는 것을 적극적으로 고려해야 한다.

The career development of a PS is a long-term investment; income generation usually increases only after a latency period that is measured in years. Department chairs and their institutions must embrace a broad vision of the function and trajectory of the young PS and construct a long-term budget that reflects this delay. This may include providing mentorship oversight, career development programming, grant reviews, and funding support for the transition from fellow to faculty.58 The expectation that new PS faculty members can generate clinical revenue sufficient to support their salaries while simultaneously developing their research careers is unrealistic. Additionally, department chairs should actively consider providing flexible options to accommodate their PS faculty members’ long-term work–life balance.

생물의학 발전에 대한 PS의 기여에 대한 환경의 변화를 수용하고 P&T 의사결정 과정에 투명성을 유지하기 위해 P&T 기준을 재고한다.

Reconsider criteria for P&T to accommodate the changing environment for PSs’ contributions to biomedical advances and be transparent in P&T decision-making processes

팀 기반 연구는 P&T 심의에서 적절하게 평가되어야 한다. 전통적으로 개별 연구는 금본위제였지만, 지식의 진보가 여러 분야의 기여를 필요로 하는 시대에 팀 기반 연구는 점점 더 일반화되고 중요해지고 있다. P&T 위원회는 현재의 연구 방향을 뒷받침하기 위해 연구자의 필수 기여자로서의 지위를 인정하고 누가 주 연구원으로 지명되든 간에 성공적으로 자금을 지원받은 보조금 제안을 장학금의 증거로 간주하는 정책을 개발해야 한다. 팀 과학 연구의 모델 내에서, 논문의 1저자 자리를 위한 경쟁에 대한 강조는 없어야 한다deemphasized. 마지막으로, 승진 및 종신 재직권 수여에 추가 시간이 필요한 PS에 대한 P&T 고려사항은 패널티 없이 제공되어야 한다.

Team-based research must be valued appropriately in P&T deliberations. Traditionally, individual research has been the gold standard; however, team-based research is becoming increasingly common and more important in an era where advancement of knowledge requires the contributions of multiple disciplines. In support of the current direction of research, P&T committees must develop policies that recognize a researcher’s status as an indispensable contributor and consider a successfully funded grant proposal as evidence of scholarship regardless of who is named as the principal investigator. Within the model of team science research, competition for first-author position on a publication should be deemphasized. Finally, P&T considerations for PSs needing additional time for promotion and the award of tenure should be provided without penalty.

산업계와의 파트너십 확대를 포함한 연구 및 연구 자금 지원을 위한 새로운 방법 모색

Pursue new avenues for research and research funding, including expanding partnerships with industry

비록 NIH가 PS에 대한 대부분의 연구 지원을 제공하지만, 그것이 유일한 지원원으로 여겨져서는 안 된다. 다른 연방 및 주 정부 기관 외에도 민간 및 공공 재단, 전문 사회 및 협회, 산업 및 외국 소스도 연구에 기꺼이 자금을 대려고 한다. 빅 데이터 이니셔티브가 보편화됨에 따라 기관들은 상호 이익이 될 수 있는 파트너십을 수용할 수 있게 될 것입니다.

Although the NIH provides the majority of research support for PSs, it should not be considered the only source of support. In addition to other federal and state agencies, private and public foundations, professional societies and associations, industry, and foreign sources are often willing to fund research. As big data initiatives become more commonplace, institutions would be well served to accommodate partnerships that can be mutually beneficial.

PS 커리어 개발 데이터 저장소 구축

Establish a repository for PS career development data

PS에 대한 [연구 커리어 개발 과정의 개선을 위한 합리적인 계획을 세울 수 있는 자료]가 부족하다. 데이터 저장소는 향후 의사 결정을 위한 강력한 기반을 제공합니다. 최소한 리포지토리는 다음을 포함해야 합니다.

- (1) 사용된 훈련 경로에 대한 설명

- (2) 외부 연구비 지원,

- (3) 성공적으로 지원된 외부 연구비,

- (4) 모든 교육을 완료한 후 최소 5년 동안 수집된 PS에 대한 임명 및 고용 데이터.

There is a paucity of data with which to make rational plans for improvement in the research career development process for PSs. A data repository would provide a strong foundation for future decisions. At a minimum, the repository should include

- (1) a description of training pathways used,

- (2) external grant applications,

- (3) external grants successfully funded, and

- (4) appointment and employment data for PSs collected for a period of at least five years after completion of all training.

요약

Summary

PS 노동력의 적절한 평가는 생물의학 연구의 세계 리더로서의 미국의 지위를 유지하는 데 매우 중요하다. 앞으로, 학술 기관, 정부, 그리고 민간 부문은 직업 선택으로서 생물의학 연구의 일반적인 분야를 홍보하기 위해 협력해야 한다. K-12 교육 시스템의 과학 및 수학 커리큘럼의 향상과 현재 노동력에서 대표성이 부족한 다양한 그룹에 대한 직업 선택으로서의 PS의 홍보도 있어야 한다.

The proper valuing of the PS workforce is critical to maintaining the status of the United States as the world leader in biomedical research. Moving forward, academic institutions, the government, and the private sector must work together to promote the general field of biomedical research as a career option through the enhancement of science and math curricula in the K–12 education system and the promotion of the PS as a career choice to diverse groups that are currently underrepresented in the workforce.

학문의학은 또한 팀 과학, 빅데이터, 정밀의학을 육성함으로써 생물의학 발전이 달성되는 새로운 방식을 수용해야 하며, 이러한 시책에 관여하는 연구자들이 인정받을 수 있는 메커니즘을 확립해야 한다. 강력하고 실행 가능한 멘토 프로그램을 통해 젊은 PS 교수진을 지원하고 바람직한 독립 연구 경력을 확립하는 데 필요한 지원을 제공하는 조치가 시행되어야 한다. 학계는 관심 있는 젊은 의사들이 연구 경로를 추구하도록 장려하고 모든 진로가 번창하도록 강력한 수준의 지원을 제공하는 효율적인 진로를 만들고 감독해야 한다. 마지막으로, 산업 및 기타 원천과의 새롭고 창의적인 파트너십은 생물의학 발전에 자금을 지원하는 데 도움이 될 수 있다.

Academic medicine must also embrace the new ways in which biomedical advances are achieved by fostering team science, big data, and precision medicine, and must establish mechanisms for researchers involved in these initiatives to be recognized. Measures must be implemented to support young PS faculty through strong, viable mentorship programs and the provision of the support necessary to establish desirable independent research careers. Academia must create and oversee efficient career tracks that encourage interested young physicians to pursue a research pathway and provide robust levels of support so that all career pathways will flourish. Finally, new and creative partnerships with industry and other sources could help fund biomedical advances.

U.S. Physician-Scientist Workforce in the 21st Century: Recommendations to Attract and Sustain the Pipeline

PMID: 28991849

PMCID: PMC5882605

DOI: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000001950

Abstract

The U.S. physician-scientist (PS) workforce is invaluable to the nation's biomedical research effort. It is through biomedical research that certain diseases have been eliminated, cures for others have been discovered, and medical procedures and therapies that save lives have been developed. Yet, the U.S. PS workforce has both declined and aged over the last several years. The resulting decreased inflow and outflow to the PS pipeline renders the system vulnerable to collapsing suddenly as the senior workforce retires. In November 2015, the Alliance for Academic Internal Medicine hosted a consensus conference on the PS workforce to address issues impacting academic medical schools, with input from early-career PSs based on their individual experiences and concerns. One of the goals of the conference was to identify current impediments in attracting and supporting PSs and to develop a new set of recommendations for sustaining the PS workforce in 2016 and beyond. This Perspective reports on the opportunities and factors identified at the conference and presents five recommendations designed to increase entry into the PS pipeline and nine recommendations designed to decrease attrition from the PS workflow.

'Articles (Medical Education) > 대학의학, 조직, 리더십' 카테고리의 다른 글

| When I say … 다양성, 평등, 포용(DEI) (Med Educ, 2022) (0) | 2022.08.06 |

|---|---|

| 내리막길로 깡통 차기 - 의과대학이 자기조절에 실패한다면 (NEJM, 2019) (0) | 2022.05.24 |

| 변화 외에는 다른 선택이 없다: COVID-19이후 의학교육의 미래 (Acad Med, 2022) (0) | 2022.04.07 |

| 학술의학에서 여성의 동등함 추구: 역사적 관점(Acad Med, 2020) (0) | 2022.04.06 |

| 의학교육을 위한 평등한 학습환경 만들기: 사회적 정체성의 편향과 교차(Med Educ, 2021) (0) | 2022.03.28 |