구름낀 푸른하늘: 의대생-전공의 이행에서의 지속적 긴장을 식별하고 미래의 이상적 상태 그리기(Acad Med, 2023)

Blue Skies With Clouds: Envisioning the Future Ideal State and Identifying Ongoing Tensions in the UME–GME Transition

Karen E. Hauer, MD, PhD, Pamela M. Williams, MD, Julie S. Byerley, MD, MPH,

Jennifer L. Swails, MD, and Michael A. Barone, MD, MPH

의학교육의 목적은 환자의 요구를 충족하고 점점 더 다양해지는 인구를 돌볼 수 있는 지식, 기술, 태도(역량)를 갖춘 의사를 양성하는 동시에 공익을 위해 봉사하는 의료계의 의무를 이행하는 것입니다. 1 의학교육은 또한 COVID-19 팬데믹과 조직적 인종차별을 포함하여 건강과 웰빙에 대한 현재의 도전에 맞설 준비가 된 강력한 인력을 확보하고 지원하기 위해 수련생과 의사의 웰빙에도 관심을 기울여야 합니다. 2,3 이러한 널리 지지되는 목표에도 불구하고 현재의 단계적 의사 수련 과정은 어려움을 겪고 있습니다. 4,5

- 교육 연속체 전반에 걸쳐 조정이 제대로 이루어지지 않고,

- 수련의 진도를 의료 요구에 맞추지 못하며,

- 여러 이해관계자에게 스트레스를 유발하고,

- 수련의와 교육자의 시간, 에너지, 자원을 과도하게 소비하는

The purpose of medical education is to prepare physicians with the knowledge, skills, and attitudes (competencies) to meet patient needs and care for an increasingly diverse population while fulfilling the medical profession’s obligation to serve the public good. 1 Medical education also needs to attend to trainee and physician well-being to ensure and support a robust workforce prepared to confront current challenges to health and wellness, including the COVID-19 pandemic and systemic racism. 2,3 Despite these widely endorsed aims, the current stepwise process of physician training

- suffers from poor coordination across the educational continuum;

- fails to align trainee progression with health care needs;

- creates stress for multiple stakeholders; and

- consumes excessive trainee and educator time, energy, and resources. 4,5

이러한 단점을 보여주는 특별한 문제점은 의과 대학에서 레지던트로 전환하는 과정입니다.

- [학생]들은 의과대학 4학년이 되면 교육적, 개인적 가치를 인식하지만,6 이 시기에는 주로 지원 절차에 집중합니다. 자기소개서와 2차 지원서 작성, 방문 로테이션 완료, 인터뷰 예약, 프로그램 방문을 위한 여행 등이 포함된 이 과정은 많은 재정적, 시간적 비용이 발생하며 재정적 여유가 있는 학생에게 유리합니다. 7-9 이 과정은 또한 전환에 관련된 다른 사람들에게도 부담을 줍니다.

- [의과대학 교육자]들은 재학생 및 예비 학생, 동료, 인증기관 사이에서 학교에 대한 우호적인 인식을 조성하기 위한 지속적인 노력의 일환으로 학생들이 원하는 레지던트 자리를 확보할 수 있도록 경쟁합니다.

- 한편 [레지던트 프로그램 디렉터, 직원 및 교수진]은 학생들이 많은 수의 지원서를 제출하도록 장려하는 시스템의 맥락에서 지원자에 대한 비슷한 수준의 정보가 포함된 수백 개의 지원서를 접수하고 처리합니다. 10

- 이러한 과중한 업무량을 관리하기 위해 교육계 리더들은 자기소개서 타겟팅, 추천서 구조화, 면접 제한 등 다양한 솔루션을 제안했습니다. 11-14 이러한 솔루션은 미국 의대 및 정골과 학생, 교육자, 레지던트 프로그램 디렉터 및 직원뿐만 아니라 미국 레지던트 자리를 확보하는 데 더 큰 장애물을 경험하는 국제 의대 학생 및 교육자에게도 지원 절차를 완화할 수 있는 잠재력을 가지고 있습니다. 14,15

그러나 의과대학에서 레지던트로의 전환을 개선하기 위한 공식적이고 대규모적인 노력은 없었습니다.

A particular pain point demonstrating these shortcomings is the transition from medical school to residency.

- While students recognize educational and personal value to the fourth year of medical school, 6 they largely focus this time on the application process. The process, which involves writing personal statements and secondary applications, completing visiting rotations, securing interviews, and traveling to visit programs, incurs high financial and time costs and advantages students with more financial resources. 7–9 The process also strains others involved in the transition.

- Medical school educators vie to ensure their students secure desired residency positions as part of their ongoing efforts to foster favorable perceptions of their school among current and prospective students, peers, and accreditors.

- Meanwhile, residency program directors, staff, and faculty receive and process hundreds of applications containing similarly glowing information about candidates, in the context of a system that incentivizes students to submit high numbers of applications. 10

- To manage this overwhelming workload, education leaders have proposed various solutions, including targeting personal statements, structuring letters of recommendation, and limiting interviews. 11–14 These solutions hold potential to ease the application process not only for U.S. medical and osteopathic students, educators, and residency program directors and staff but also for students and educators from international medical schools, who experience even greater hurdles to securing U.S. residency positions. 14,15

But there has been no formal, large-scale effort to improve the transition from medical school to residency.

학부 의학교육에서 대학원 의학교육 검토 위원회(UGRC)

Undergraduate Medical Education to Graduate Medical Education Review Committee (UGRC)

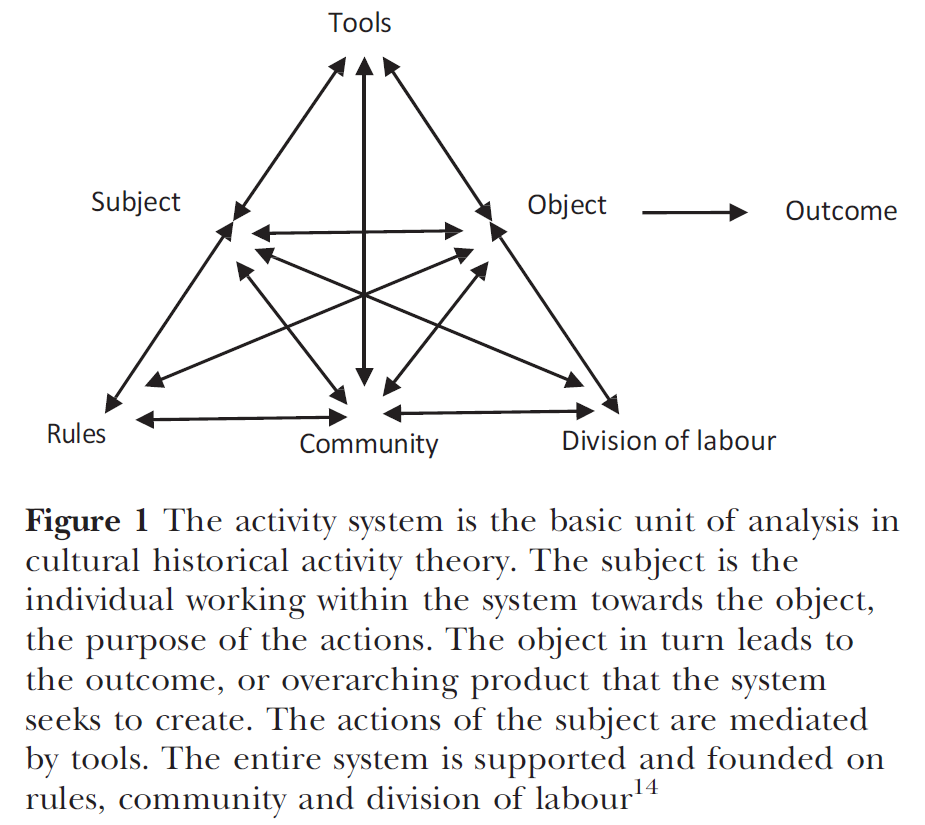

2020년에 발표된 USMLE 1단계 점수 보고가 합격/불합격 결과만으로 변경되면서 학부 의학교육(UME)에서 의학전문대학원(GME)으로의 전환을 학습자, 프로그램, 잠재적으로 의료계에 도움이 되는 방식으로 완화하고 개선하는 논의가 촉발되었습니다. 16,17 [교육 연속성을 개선하기 위해 노력하는 이해관계자들이 모여 수련의와 의사에 대한 감독, 교육, 평가에 중점을 두는 단체]인 의사 책임성 연합(CoPA)은 학부 의학교육-의학전문대학원 교육 검토위원회에 전환을 개선하기 위한 권고안을 작성하도록 의뢰했습니다. UGRC는 학습과 건강을 최적화하고 수련의가 공익을 위해 봉사할 수 있는 역량을 갖추도록 교육 연속성을 추구하는 데 이해관계자를 통합하는 것을 목표로, 비효율성과 이해관계자 간 이해관계가 상충하는 현재의 프로세스를 혁신하기 위해 대규모 변화 관리를 수반했습니다. 변화 관리에는 필요한 변화의 목적과 범위를 이해하여 다양한 이해관계자를 원하는 상태로 안내하는 강력한 비전을 만들어야 합니다. 18,19

The change in USMLE Step 1 score reporting to a pass/fail outcome only, announced in 2020, catalyzed discussions about easing and improving the transition from undergraduate medical education (UME) to graduate medical education (GME) in ways that would benefit learners, programs, and potentially health care. 16,17 The Coalition for Physician Accountability (CoPA), an organization that convenes stakeholders committed to improving the educational continuum and focuses on oversight, education, and assessment of trainees and physicians, charged the Undergraduate Medical Education to Graduate Medical Education Review Committee with crafting recommendations to improve the transition. The charge to the UGRC entailed large-scale change management to transform the current process, which is characterized by recalcitrant inefficiencies and competing stakeholder interests, with the goal to unify stakeholders in pursuing an educational continuum that optimizes learning and wellness and equips trainees to serve the public good. Change management requires understanding the purpose and scope of needed change to create a powerful vision that guides diverse stakeholders toward a desired state. 18,19

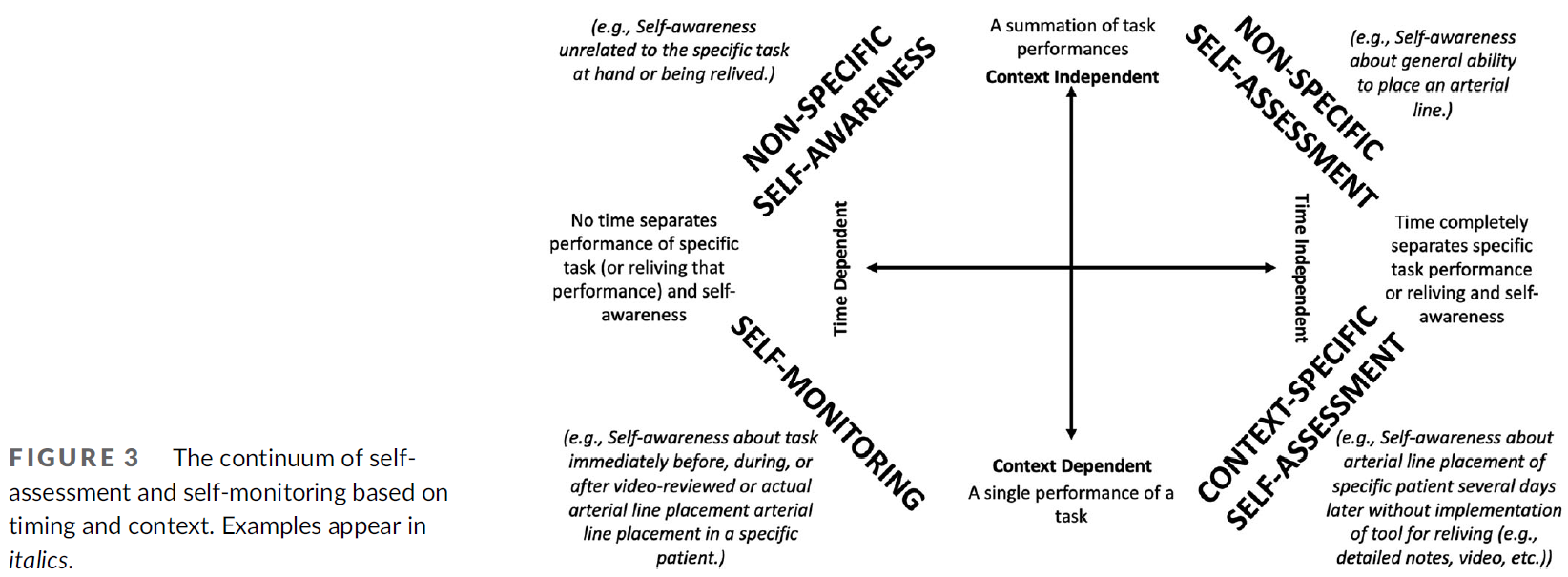

[공유된 비전]을 달성하려면 쉬운 해결책이 없는 UME-GME 전환의 현재 긴장을 인정해야 합니다. 상호 연결된 모든 우려 사항을 충분히 해결하지 못한 채 해결책에 조기에 집중하는 것을 피하기 위해 UGRC는 긴장을 해결하기보다는 인정하는 접근 방식인 양극성 사고를 채택했습니다. 20 양극성 사고는 의학 교육에서 학습자 평가의 긴장을 고려하는 데 유용한 프레임을 제공합니다. 21 양극성 또는 긴장은 서로 다른 장단점을 가진 스펙트럼의 두 극을 나타냅니다. 이해관계자의 서로 다른 가치관은 서로 다른 극의 상대적 장점에 대한 견해를 형성합니다. 조직이 수용의 태도와 긴장을 관리하려는 목표를 가지고 시스템 설계에 접근하면 복잡한 문제를 성공적으로 해결할 수 있습니다. 따라서 이 글의 목적은

- (1) UGRC가 구상하는 이상적인 상태를 제시하고

- (2) 양극성 사고를 사용하여 관리가 필요한 이상적인 시스템의 긴장을 이해하는 것입니다.

Achieving a shared vision requires acknowledging current tensions in the UME–GME transition that defy easy solutions. To avoid a premature focus on solutions that insufficiently address all interconnected concerns, the UGRC employed polarity thinking, an approach that acknowledges rather than solves tensions. 20 Polarity thinking provides a useful frame to consider tensions in learner assessment in medical education. 21 Polarities, or tensions, represent 2 poles of a spectrum with different advantages and disadvantages. Stakeholders’ different values shape their views of relative merits of different poles. When organizations approach systems design with an attitude of acceptance and a goal of managing tensions, they are positioned to succeed in tackling complex problems. Thus, the purpose of this article is to

- (1) present the ideal state envisioned by the UGRC and

- (2) use polarity thinking to understand tensions in the ideal system that will require management.

UGRC 방법

UGRC Methods

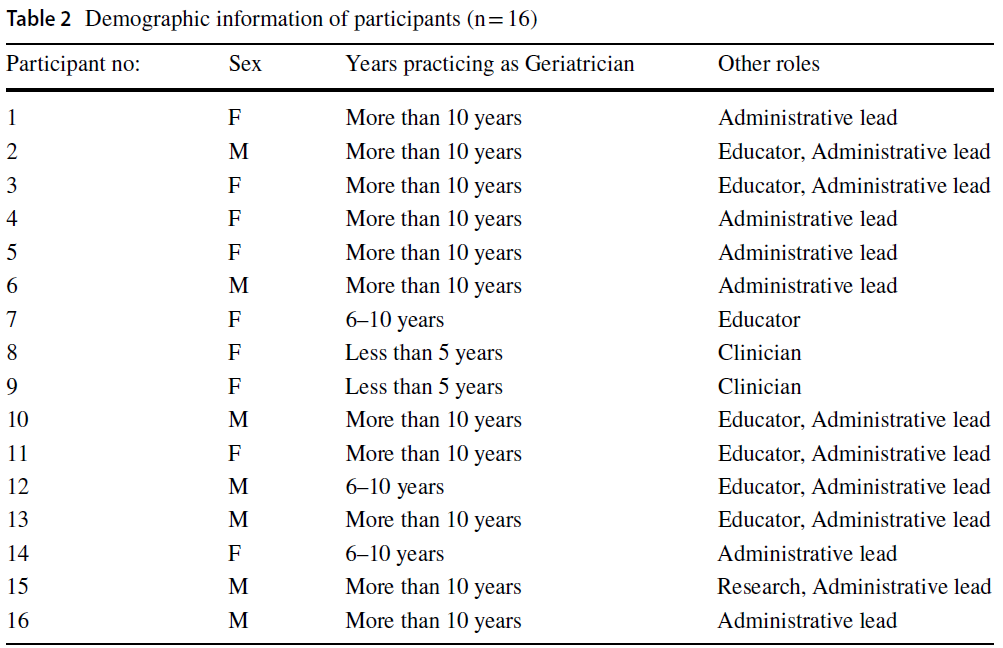

[학부 및 대학원 의학교육자, 국내 및 국제 의학교육 기관 회원, 일반인 회원, 학생, 레지던트, 의학박사 학위 수여 학교 및 정골의학 학교 대표 등 30명]으로 구성된 UGRC 위원들은 이상적인 상태의 전환을 위해 노력했습니다. 이상적인 상태를 구상하기 위해 UGRC는 문헌, 데이터 및 이해관계자 경험을 검토하여 UME-GME 전환의 문제점을 특성화했습니다. 결과 기반 교육의 원칙을 준수하면서22 UGRC는 현재의 우려 사항과 원하는 결과 사이의 격차를 해소하는 비전을 명확히 하기 위해 백워드 디자인 프로세스에 참여했습니다. 23

The 30 members of the UGRC included undergraduate and graduate medical educators, national and international medical education organizational members, public members, students, and residents, with representatives of MD-granting and osteopathic schools. To envision the ideal state, the UGRC reviewed literature, data, and stakeholder experience to characterize problems in the UME–GME transition. Adhering to tenets of outcomes-based education, 22 the UGRC engaged in a backward design process to articulate a vision that addresses the gap between current concerns and desired outcomes. 23

UGRC는 UME-GME 전환이 학습자, 교육자, 대중 등 모든 이해관계자에게 최적의 결과를 가져다주는 이상적인 상태를 성과로 정의했습니다. 24 이 "푸른 하늘" 접근 방식은 혁신을 불러일으키고 복잡한 문제를 해결하는 데 적합합니다. 25 회원들이 현상 유지에서 벗어나 대담하게 생각할 수 있는 충분한 시간을 갖도록 하기 위해 UGRC는 2개월 동안 UME-GME 전환을 위한 이상적인 상태를 개념화하는 데 전념했습니다. UGRC는 레지던트 지원 단계에 맞춰 4개의 작업 그룹을 구성하여 매치의 거래적 측면이 아닌 이상적인 전환 시스템을 구상했으며, 전환의 다음과 같은 측면을 포함했습니다:

- (1) 레지던트 준비도(예: 학생 진로 상담, 역량 평가),

- (2) UME 관점에서의 지원 및 선발 과정의 메커니즘(예: 학생과 학교의 지원 및 선발 경험)

- (3) GME 관점에서의 지원서 선발 과정의 메커니즘(예: 지원서 검토, 면접, 후보자 순위),

- (4) 매칭 후 최적화(예: 학습자의 의과대학에서 레지던트로의 전환 지원).

The UGRC defined outcomes as an ideal state in which the UME–GME transition produces optimal results for all stakeholders: learners, educators, and the public. 24 This “blue-skies” approach invites innovation and is well suited to addressing complex problems. 25 To ensure that members had adequate time to think boldly outside the status quo, the UGRC devoted 2 months to conceptualizing an ideal state for the UME–GME transition. The UGRC charged 4 work groups aligned with residency application stages to envision an ideal transition system, rather than just the transactional aspects of the Match, including the following aspects of the transition:

- (1) residency readiness (e.g., student career advising, assessing competence);

- (2) the mechanics of the application and selection process from the UME perspective (e.g., student and school experience with applications, interviews);

- (3) the mechanics of the application selection process from the GME perspective (e.g., application review, interviewing, candidate ranking); and

- (4) post-Match optimization (e.g., supporting learner transition from medical school to residency).

4개의 작업 그룹은 각각 7~8명으로 구성되었으며, 학생 및 레지던트 교육자, 기관 대표, 학습자, 일반인이 각 작업 그룹에 고루 분포되어 있습니다. 모든 작업 그룹에서 이상적인 상태를 위한 통일된 동인은 웰빙, 공익, 다양성, 형평성, 포용성에 대한 약속이었습니다.

Each of the 4 work groups included 7 to 8 members with student and resident educators, organizational representatives, learners, and members of the public distributed throughout the work groups. Unifying drivers for the ideal state across work groups were commitments to well-being; public good; and diversity, equity, and inclusion.

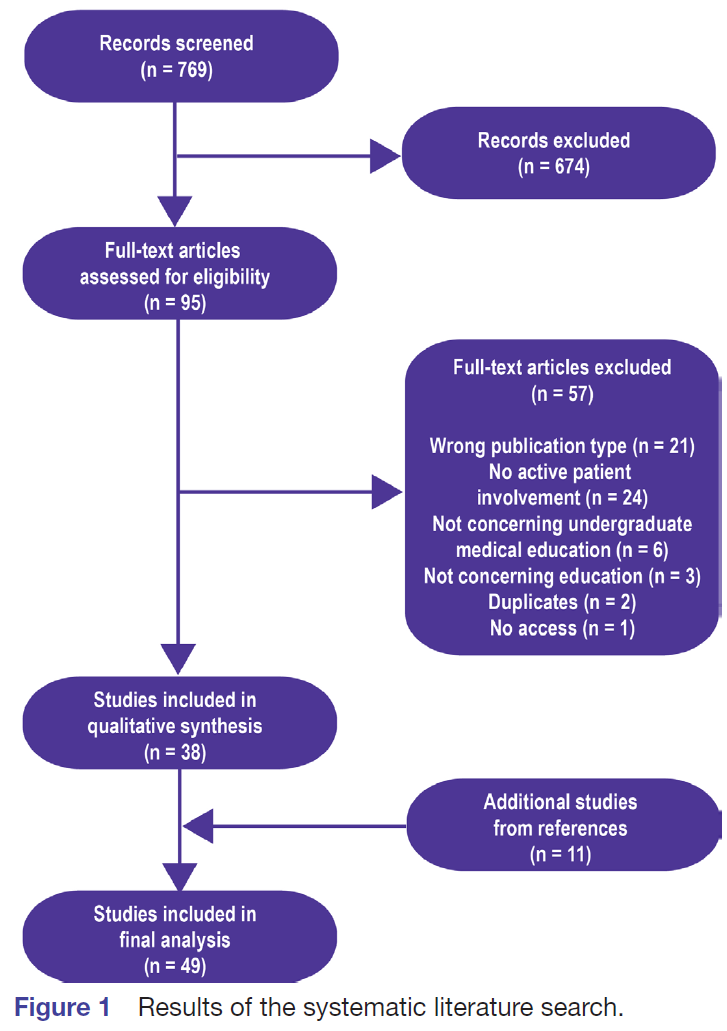

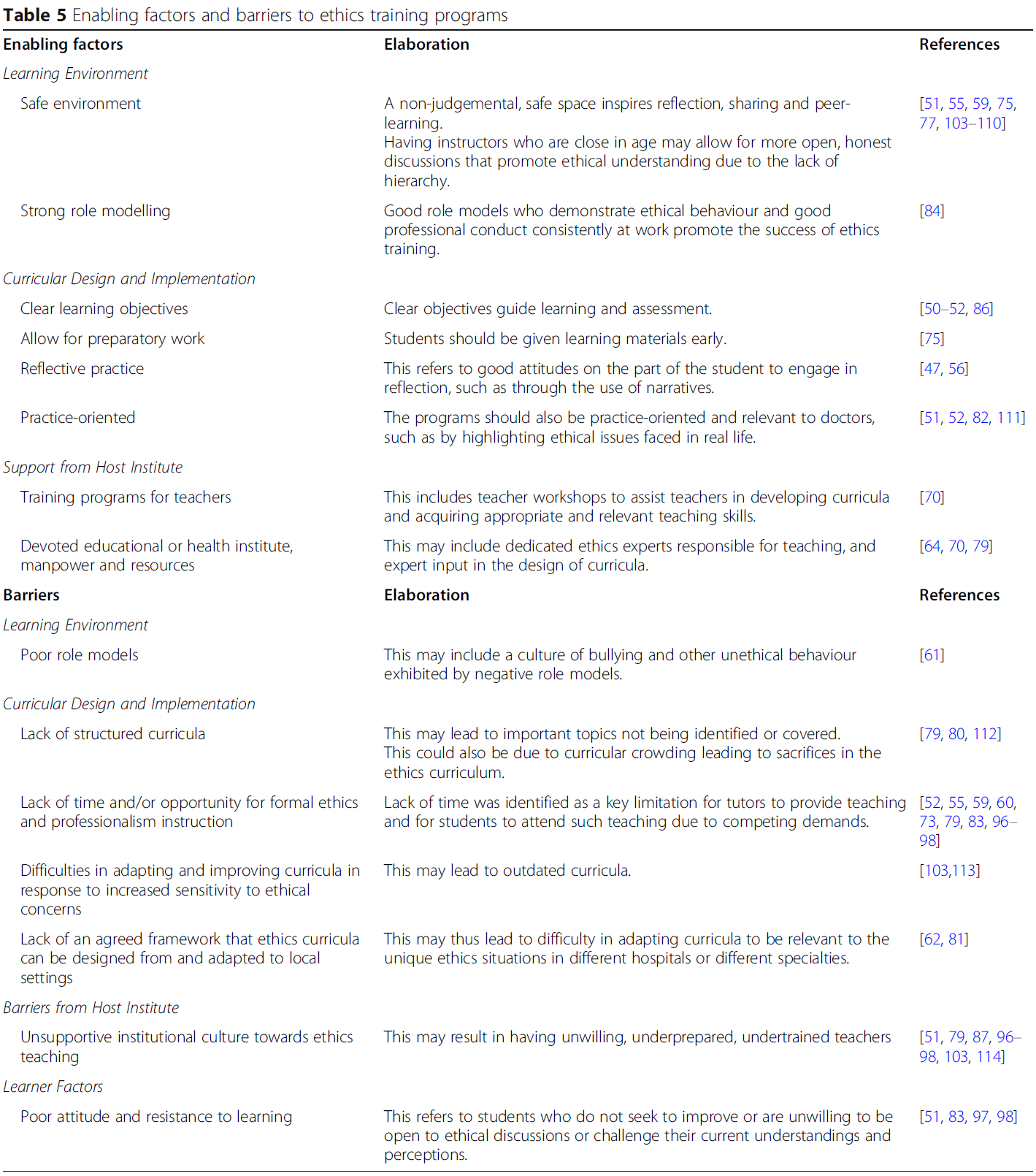

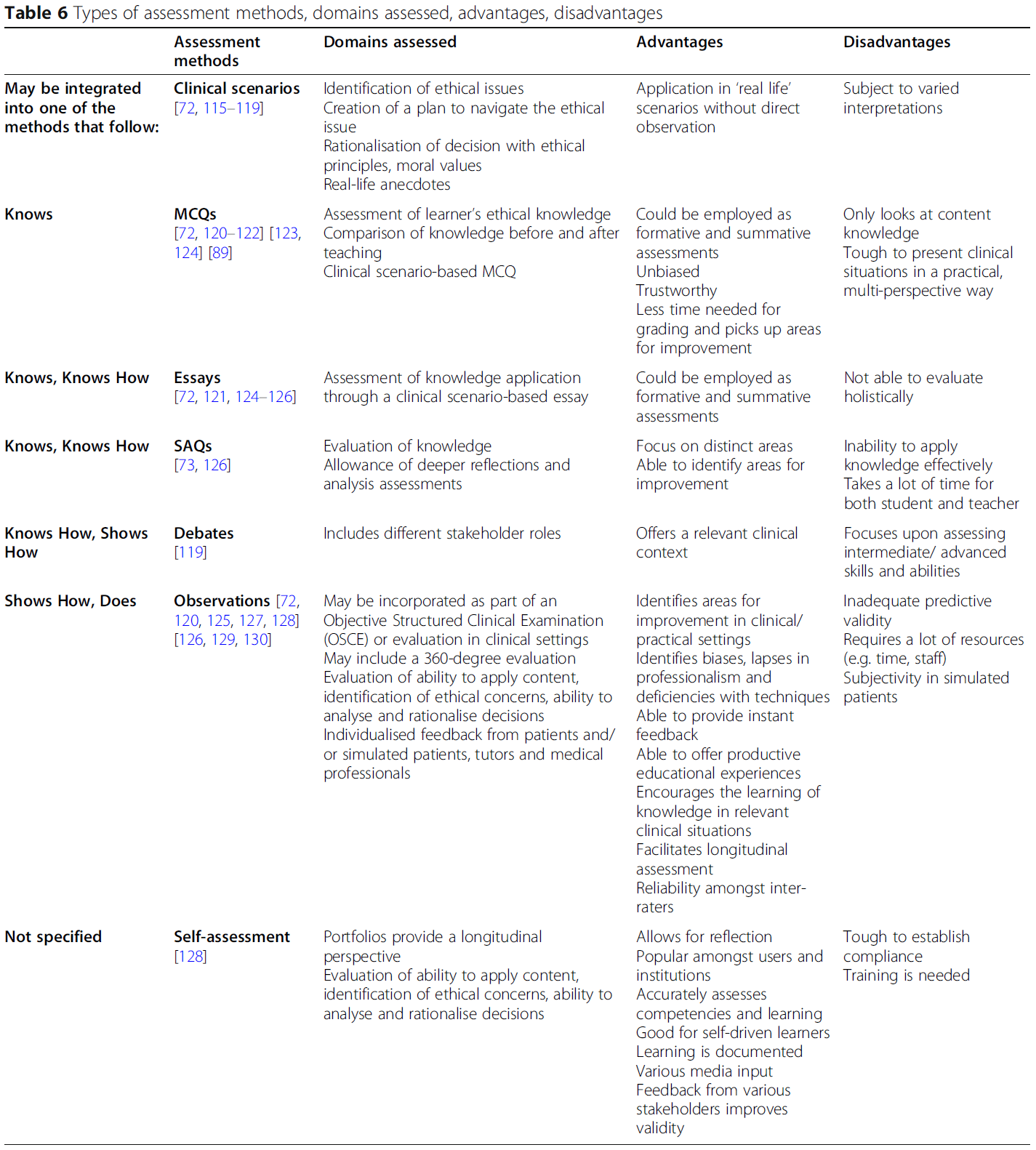

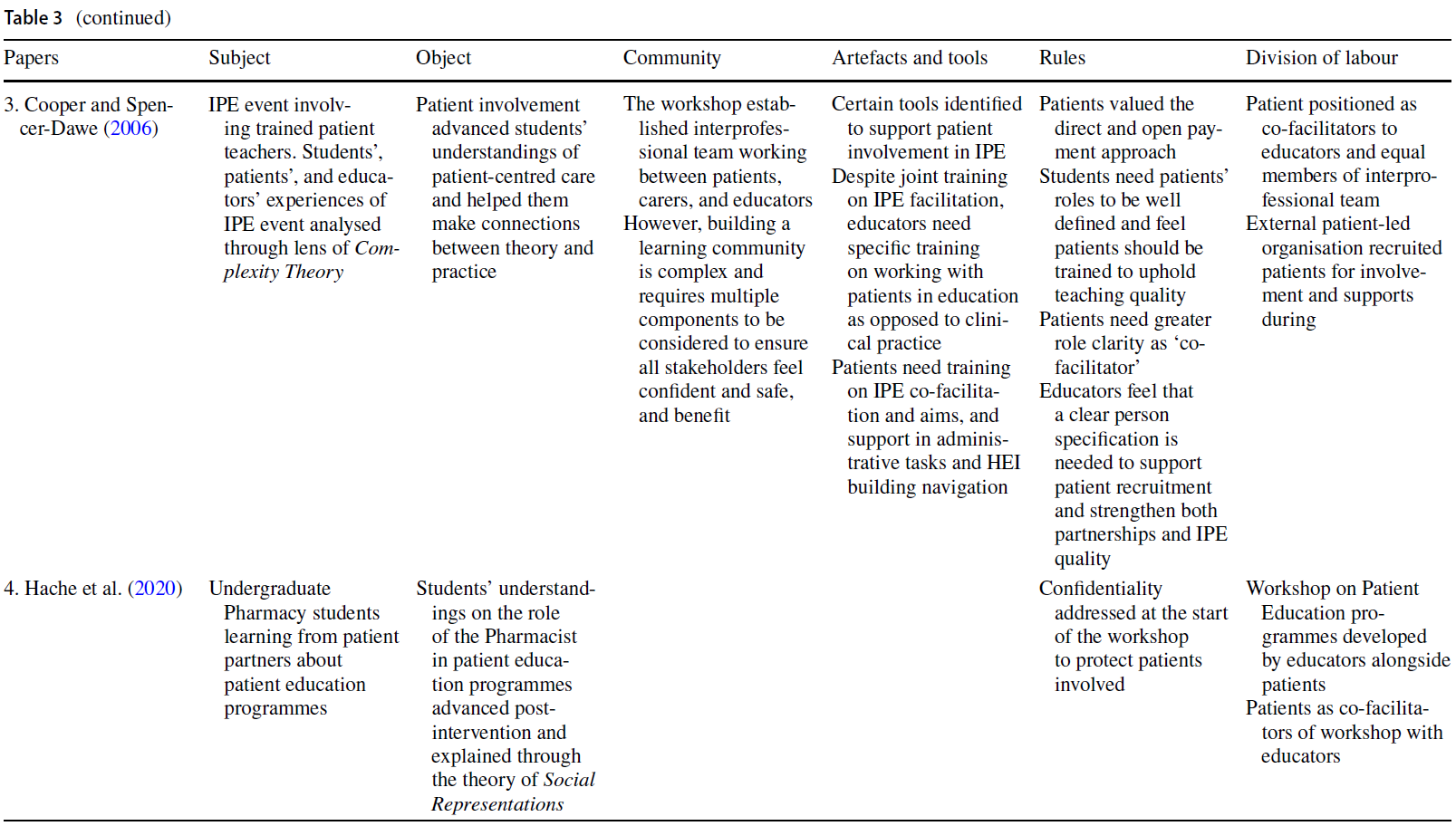

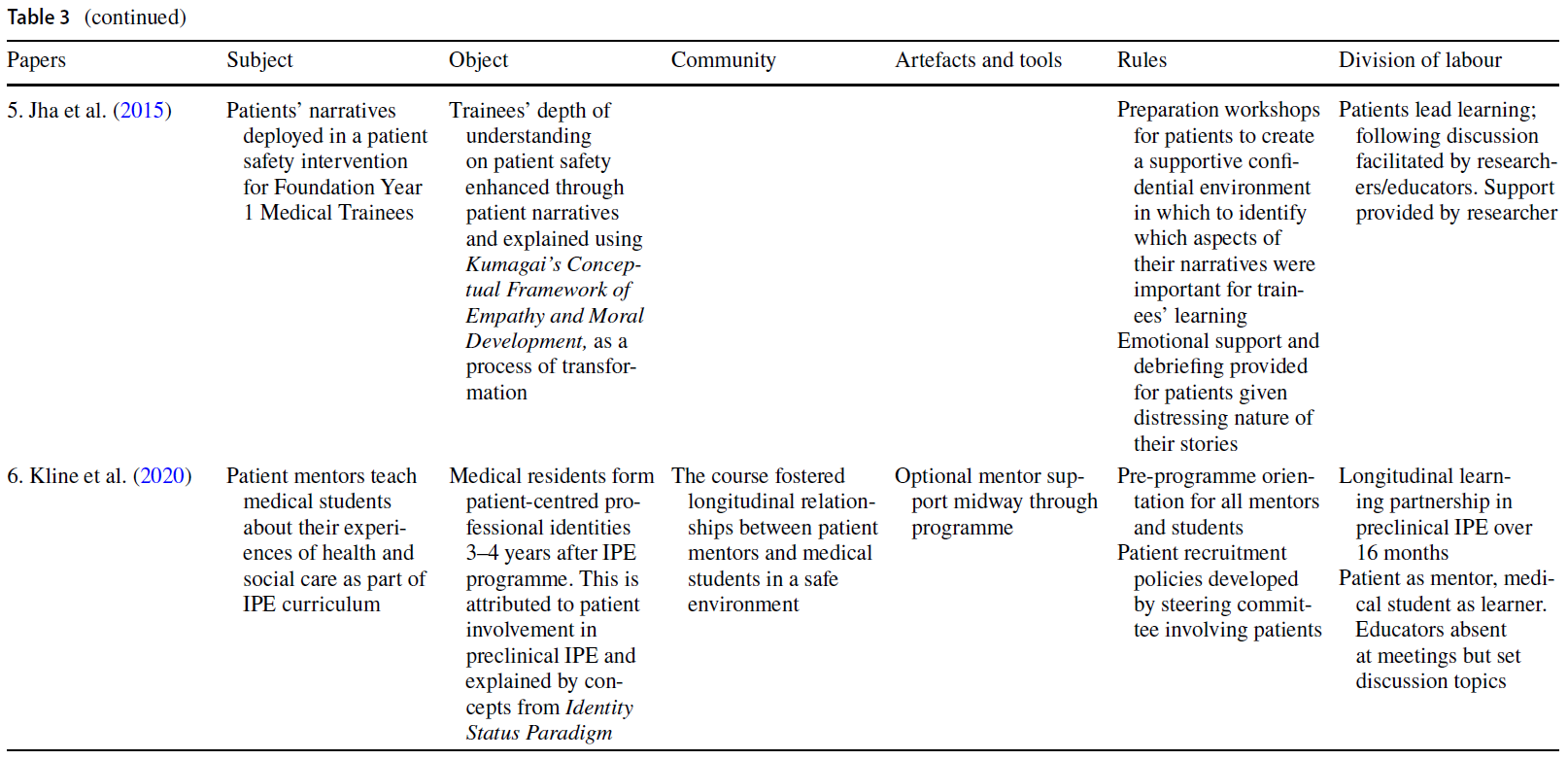

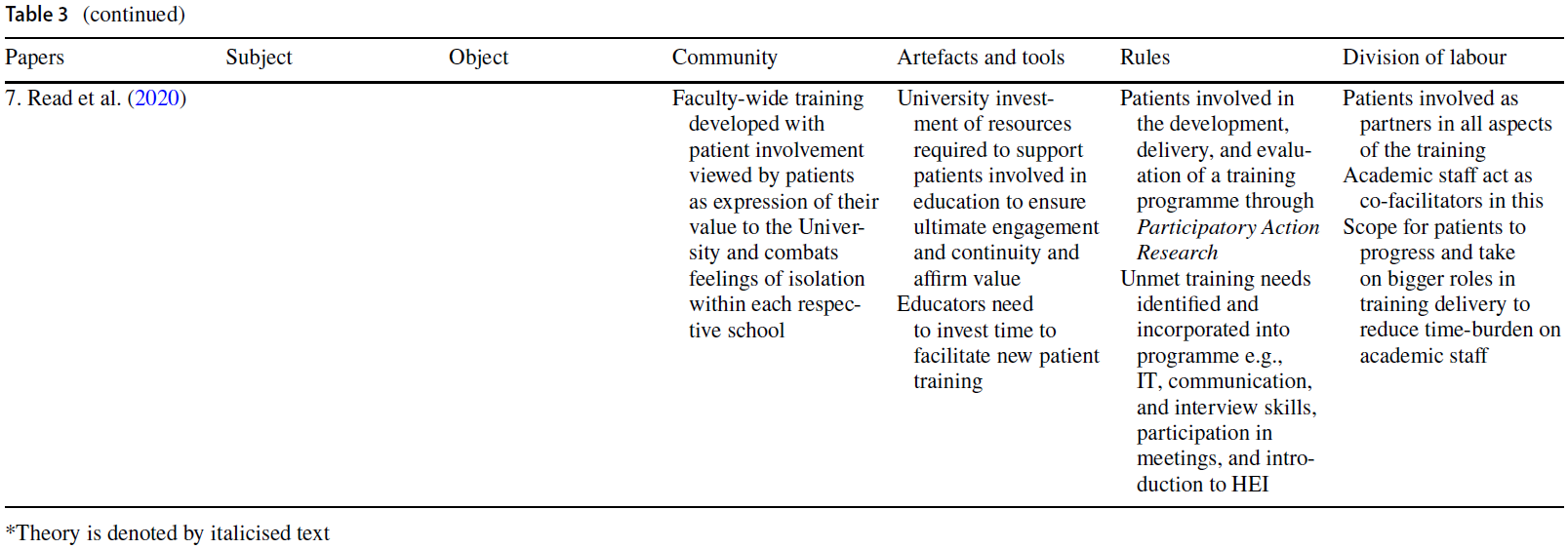

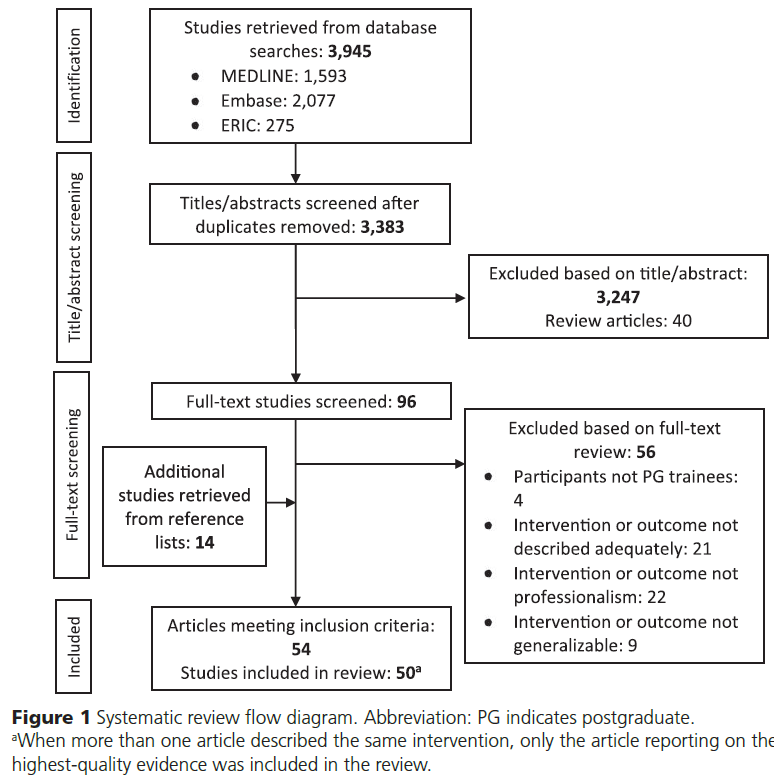

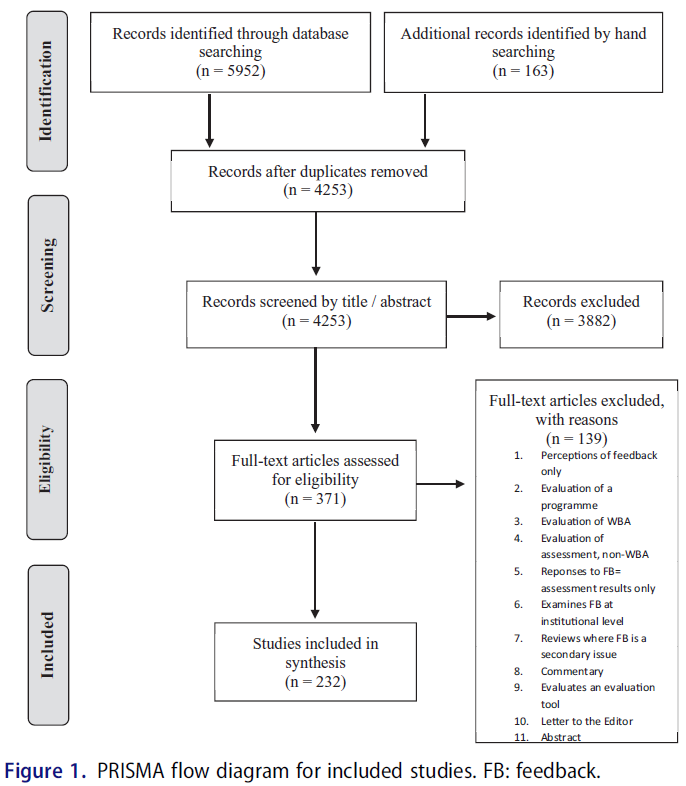

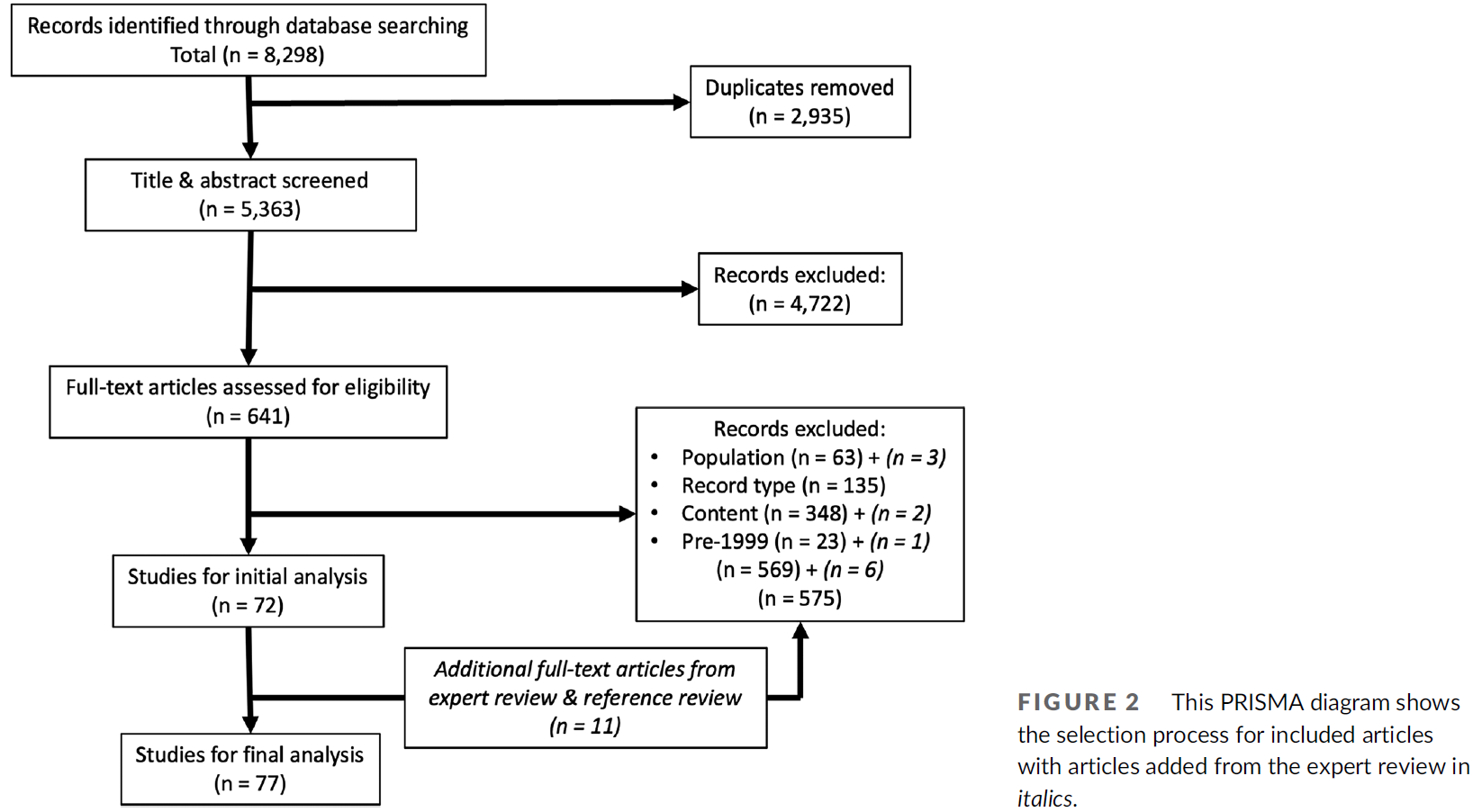

먼저, 각 작업 그룹은 전환의 각 부분에 대한 이상적인 상태를 개념화했습니다. 전체 UGRC는 각 이상적인 상태를 검토하고 구체화하여 그룹 간의 차이를 분석했습니다. 그런 다음 작업 그룹 리더는 복합적인 이상적인 상태를 생성했습니다. 복합 이상 상태의 타당성을 구축하고 시스템 설계를 성공적으로 안내하고 원하는 결과를 달성할 가능성을 높이기 위해 UGRC는 2020년 12월에 이 작업에 관심이 있는 103개 조직을 대상으로 설문조사를 통해 관련 이해관계자의 의견을 구했습니다. 주로 의대생(n = 10), 레지던트/펠로우(n = 1), 레지던트 프로그램 디렉터(n = 15), 사무직 디렉터(n = 8), 의료 협회(n = 11), 주 의사회(n = 53), CoPA 회원 단체(n = 5) 등이 참여했습니다. 32개의 응답을 받아 주제별로 정리했으며, 확인된 주제는 추가 구성 요소를 호출하지 않고 복합적인 이상적 상태 내용을 강화했습니다. 이상적인 상태 특성화는 이후 현재 상태와 이상적인 상태 사이의 격차를 탐색하고 이상적인 상태 구성 요소에 매핑된 권장 사항을 생성하는 UGRC 작업을 안내했습니다.

First, each work group conceptualized an ideal state for their portion of the transition. The entire UGRC vetted and refined each ideal state and analyzed discrepancies across groups. Work group leaders then generated a composite ideal state. To build validity of the composite ideal state and increase the likelihood that it will successfully guide system design and achieve desired outcomes, the UGRC sought relevant stakeholder input via a survey in December 2020 of 103 organizations interested in this work. These primarily represented medical students (n = 10), residents/fellows (n = 1), residency program directors (n = 15), clerkship directors (n = 8), medical associations (n = 11), state medical societies (n = 53), and CoPA member organizations (n = 5). We received 32 responses, which we organized thematically; the identified themes reinforced composite ideal state content without invoking additional components. The ideal state characterization subsequently guided UGRC work exploring gaps between current and ideal states and generating recommendations mapped to ideal state components.

이상적 상태의 특성

Characterization of the Ideal State

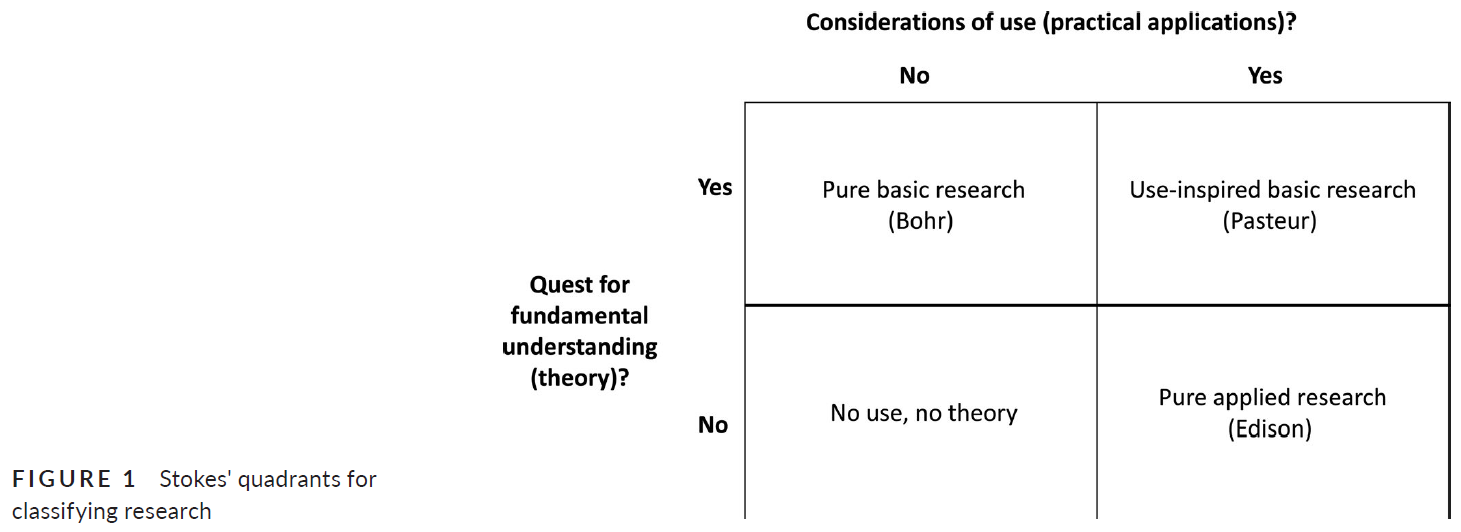

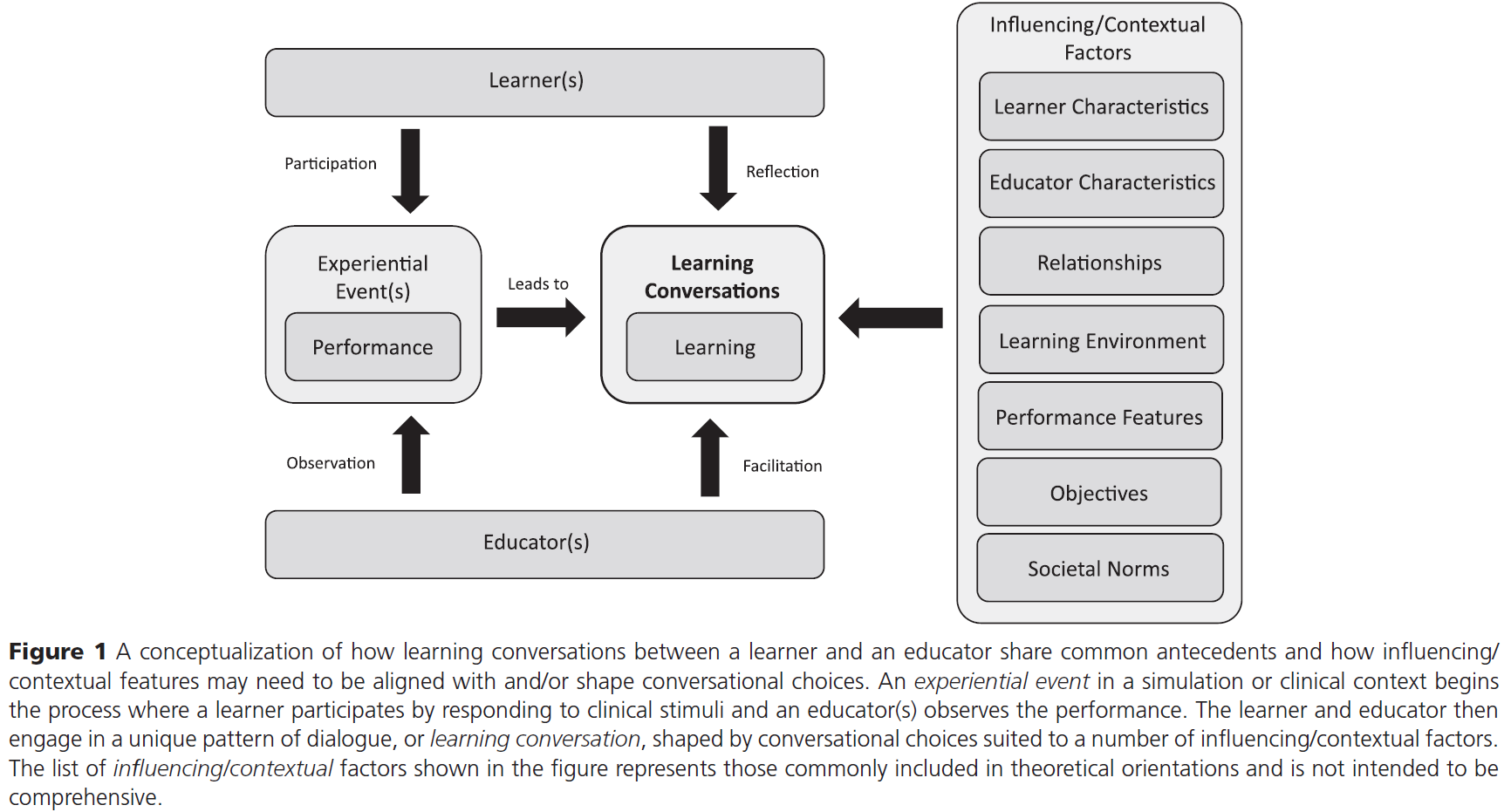

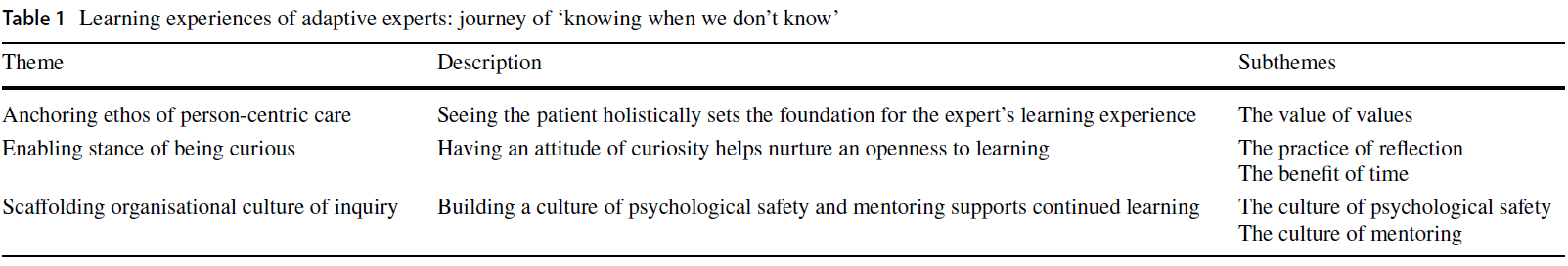

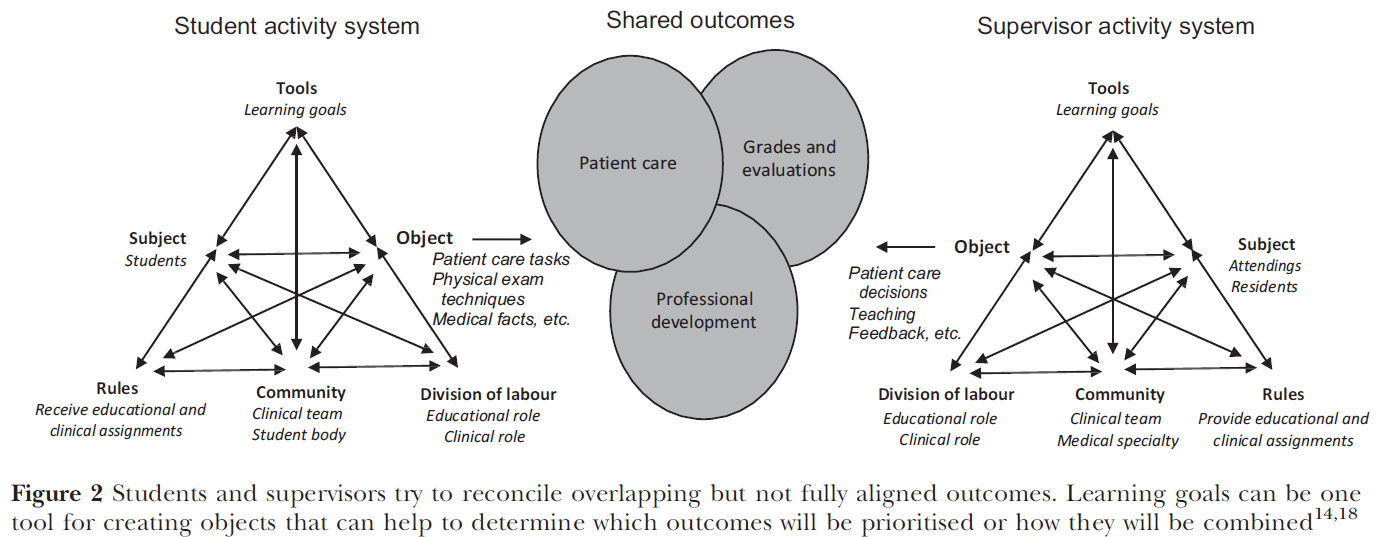

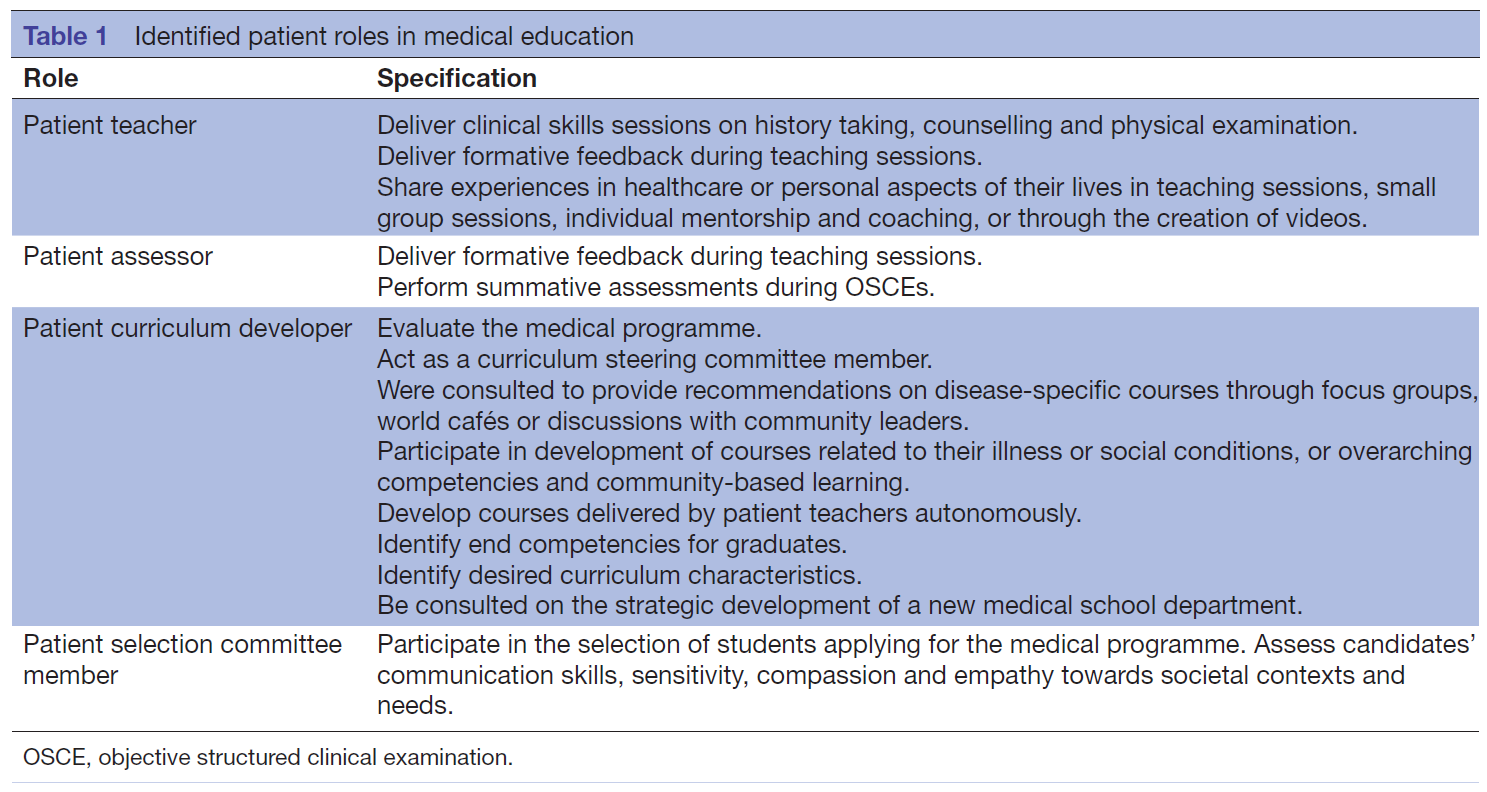

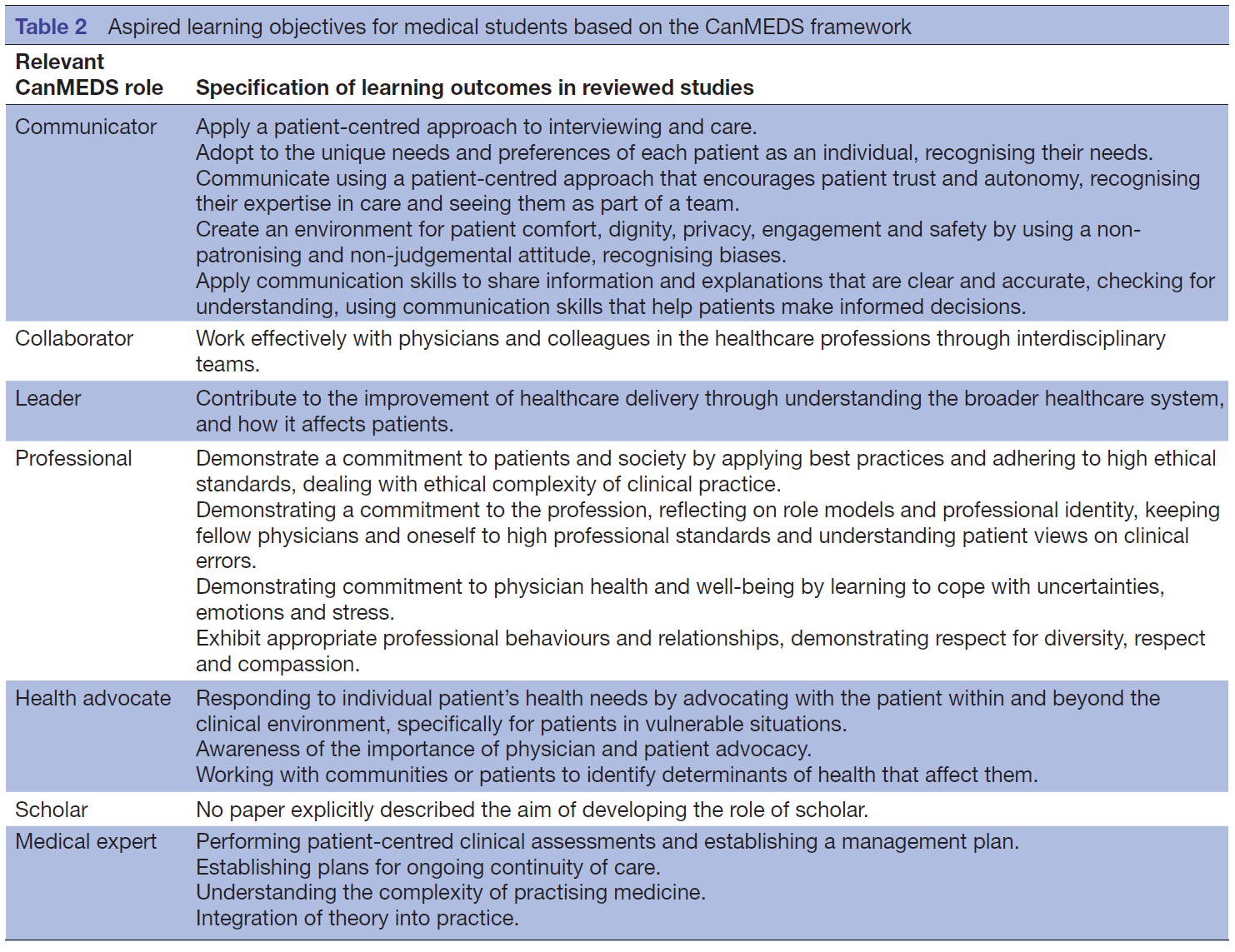

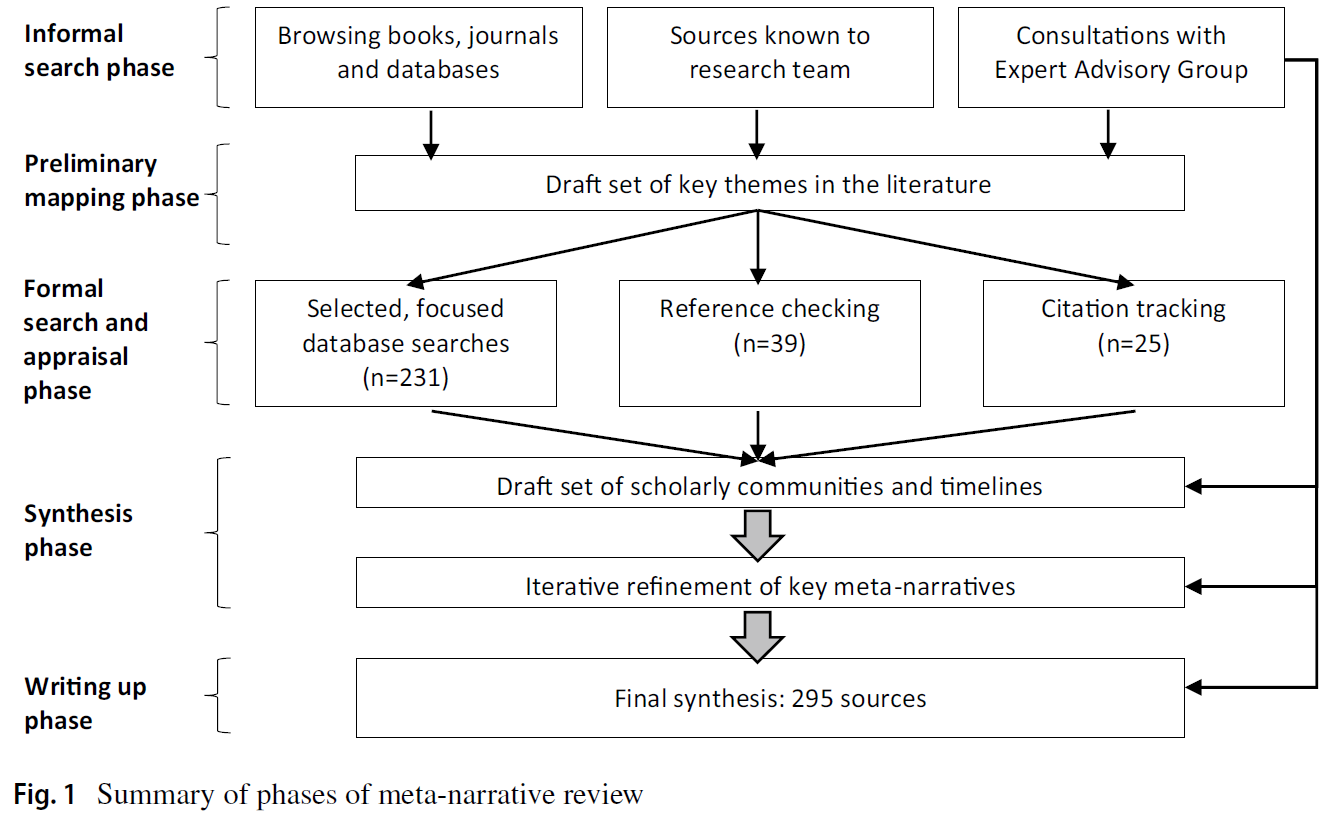

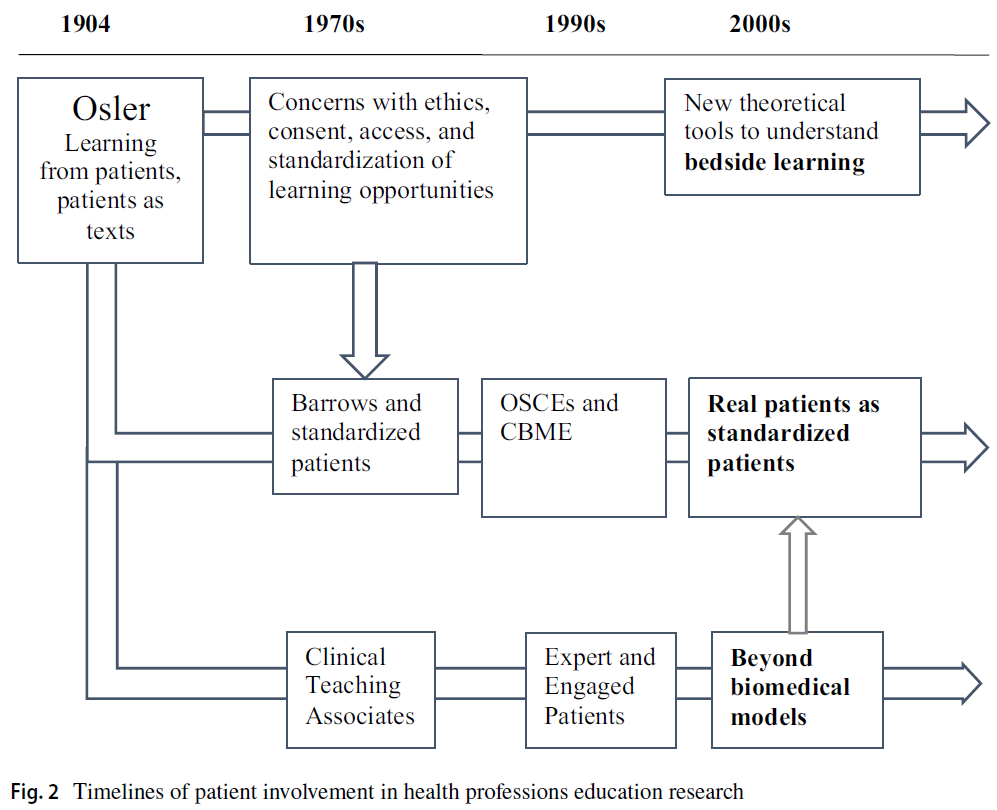

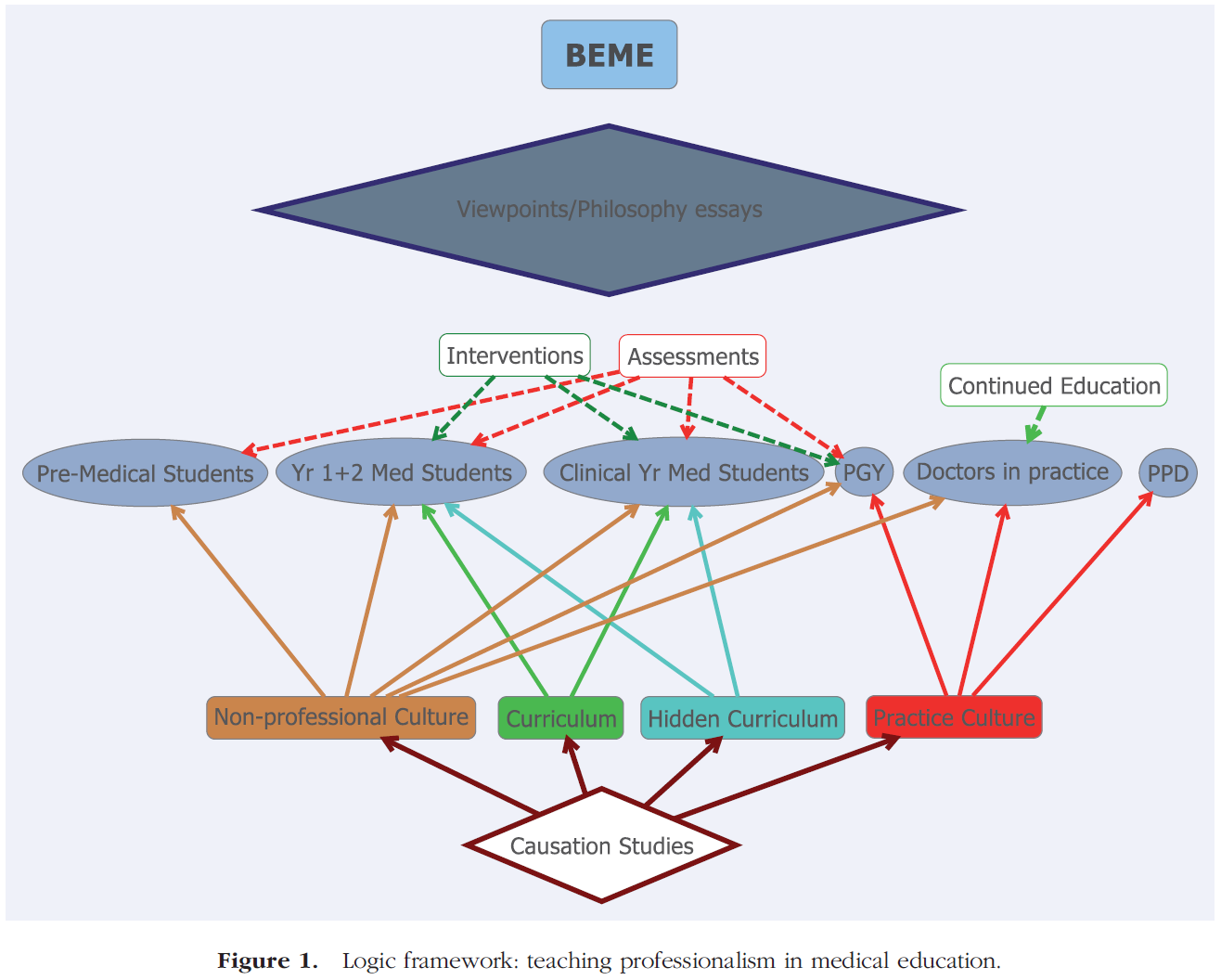

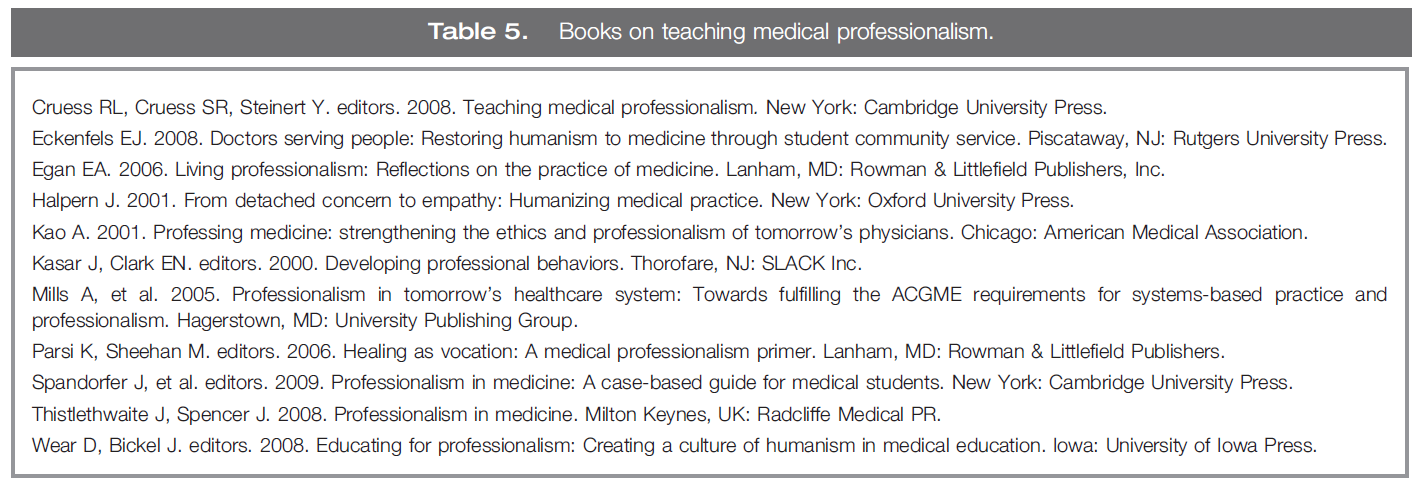

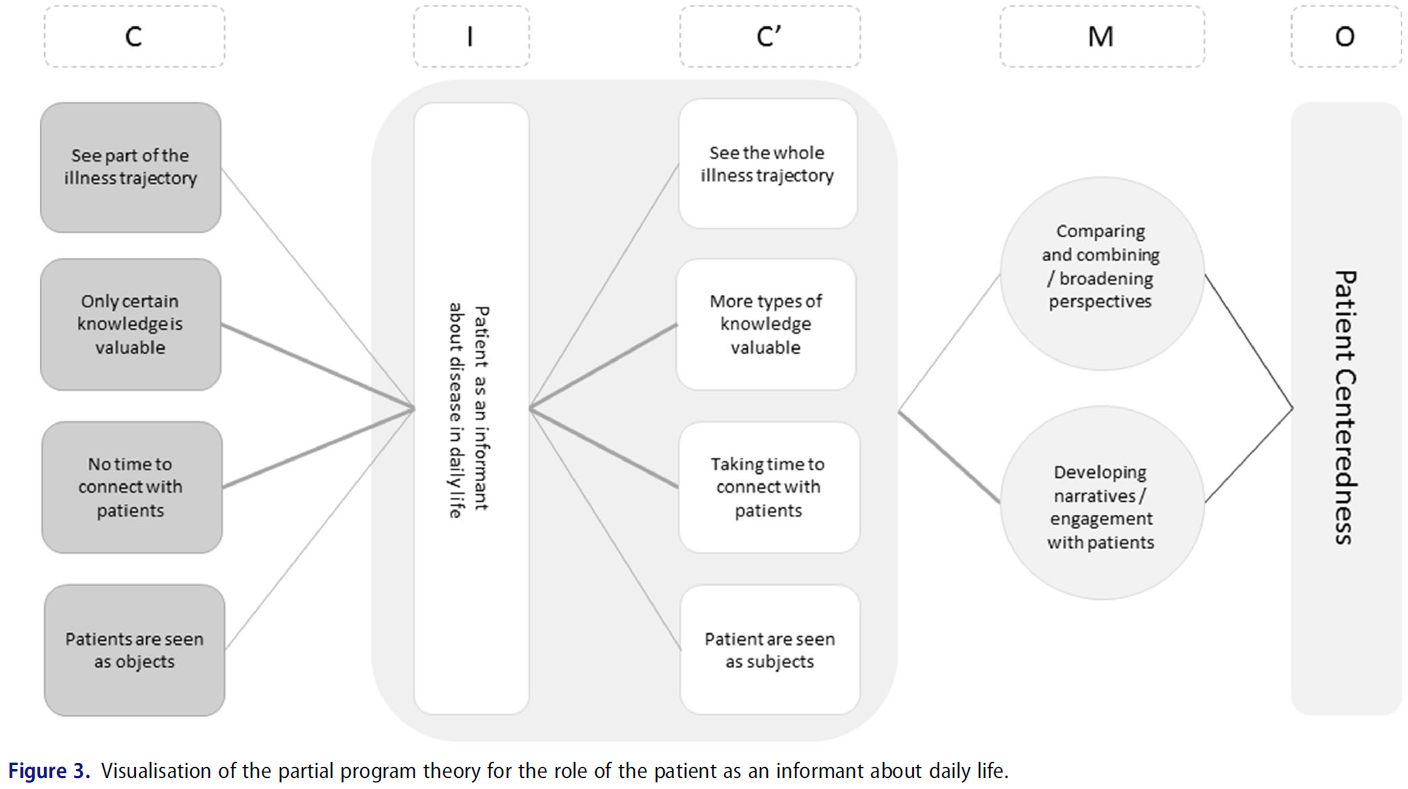

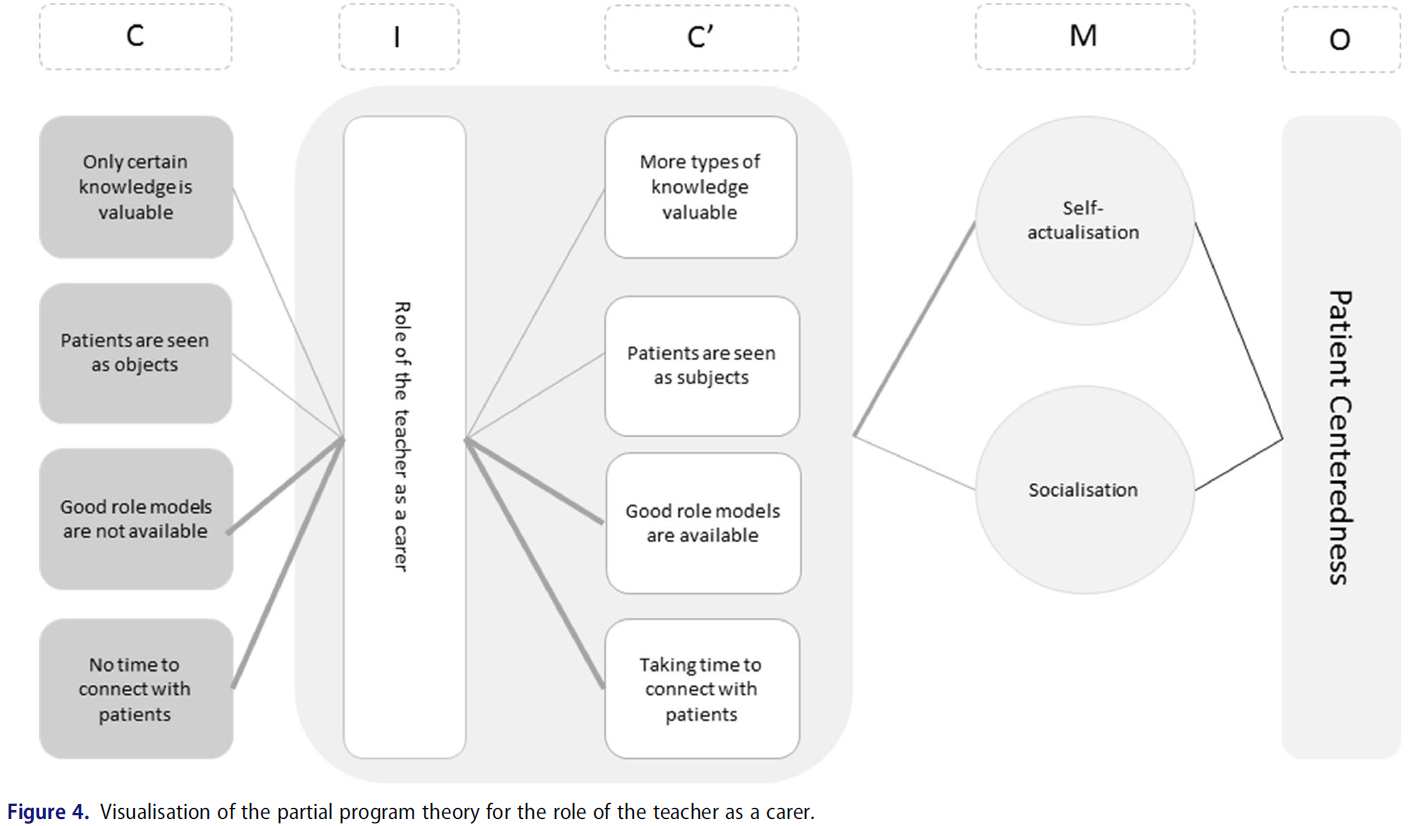

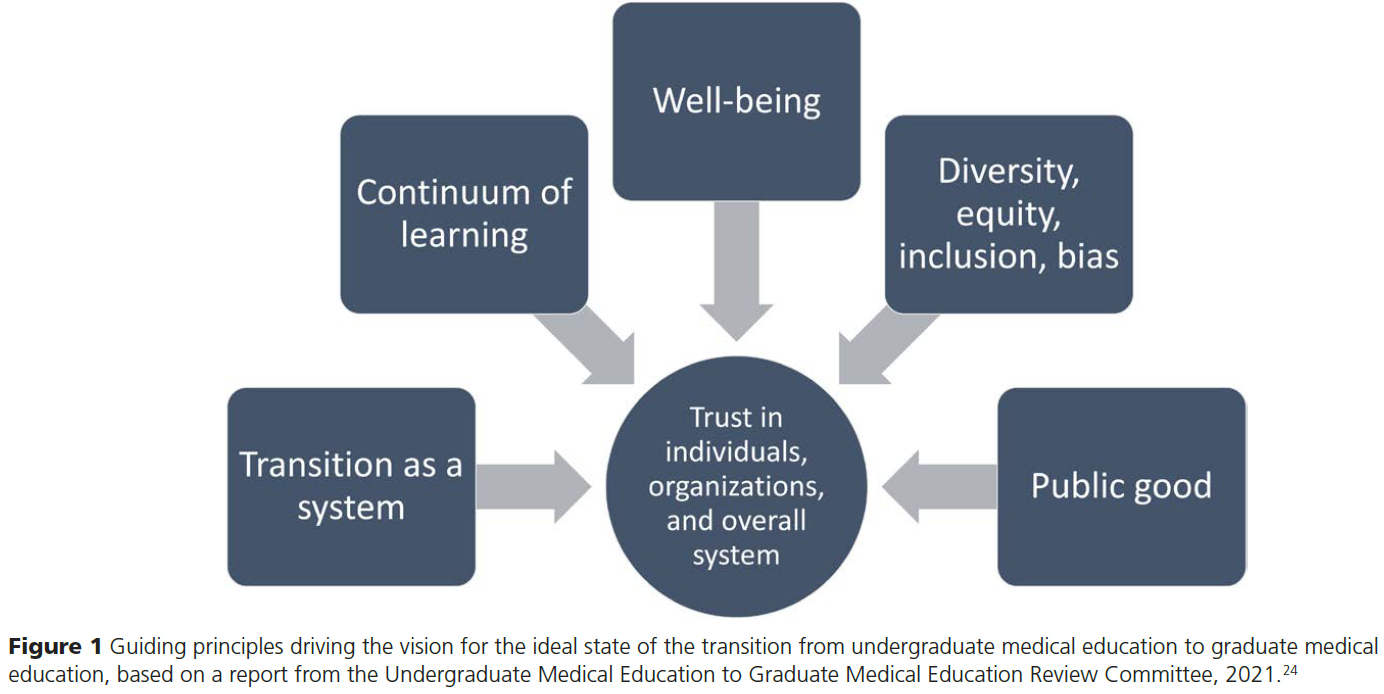

UGRC는 다음과 같은 핵심 가치에 중점을 둔 시스템으로 이상적인 상태를 구상했습니다(그림 1).

- 학습의 연속성을 촉진하고,

- 관련된 사람들의 복지를 지원하고,

- 다양성을 증진하고,

- 편견을 최소화하고,

- 공익에 기여하고,

- 신뢰할 수 있는 정보와 결과를 제공

The UGRC envisioned a blue-skies ideal state as a system centered upon core values that

- facilitate the continuum of learning,

- support the well-being of those involved,

- promote diversity,

- minimize bias,

- serve the public good, and

- yield trustworthy information and results (Figure 1).

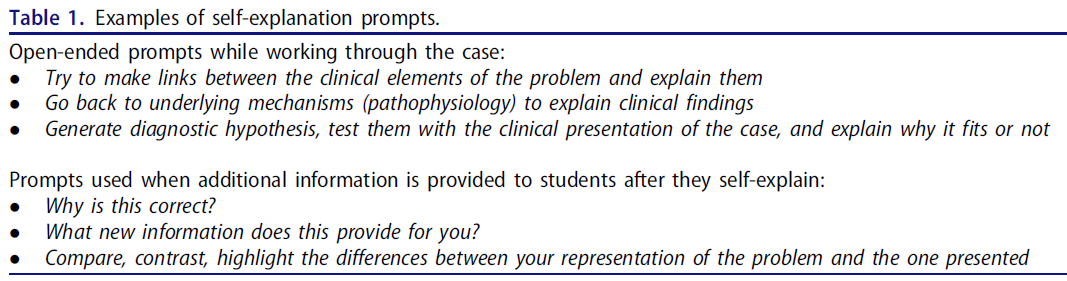

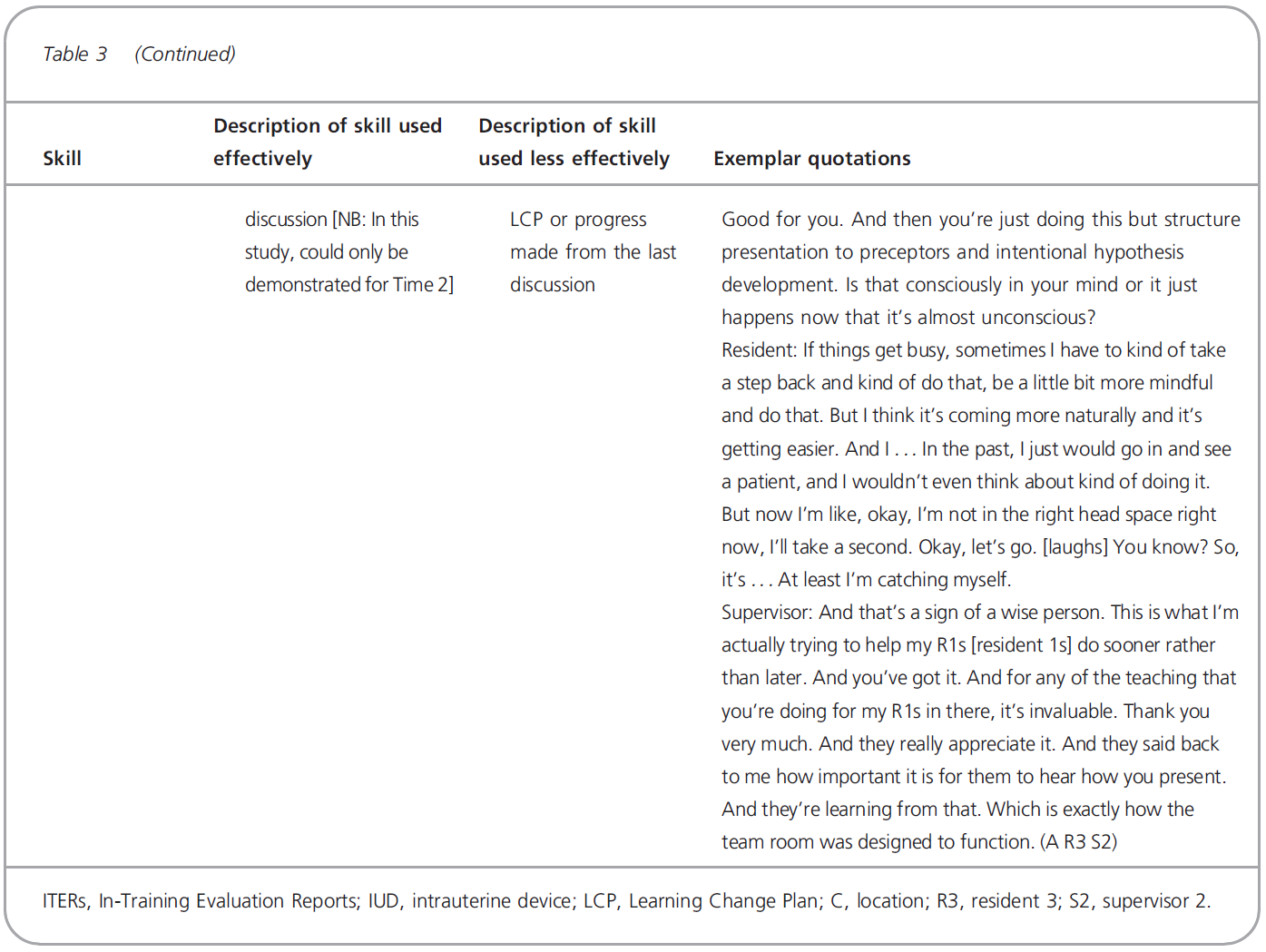

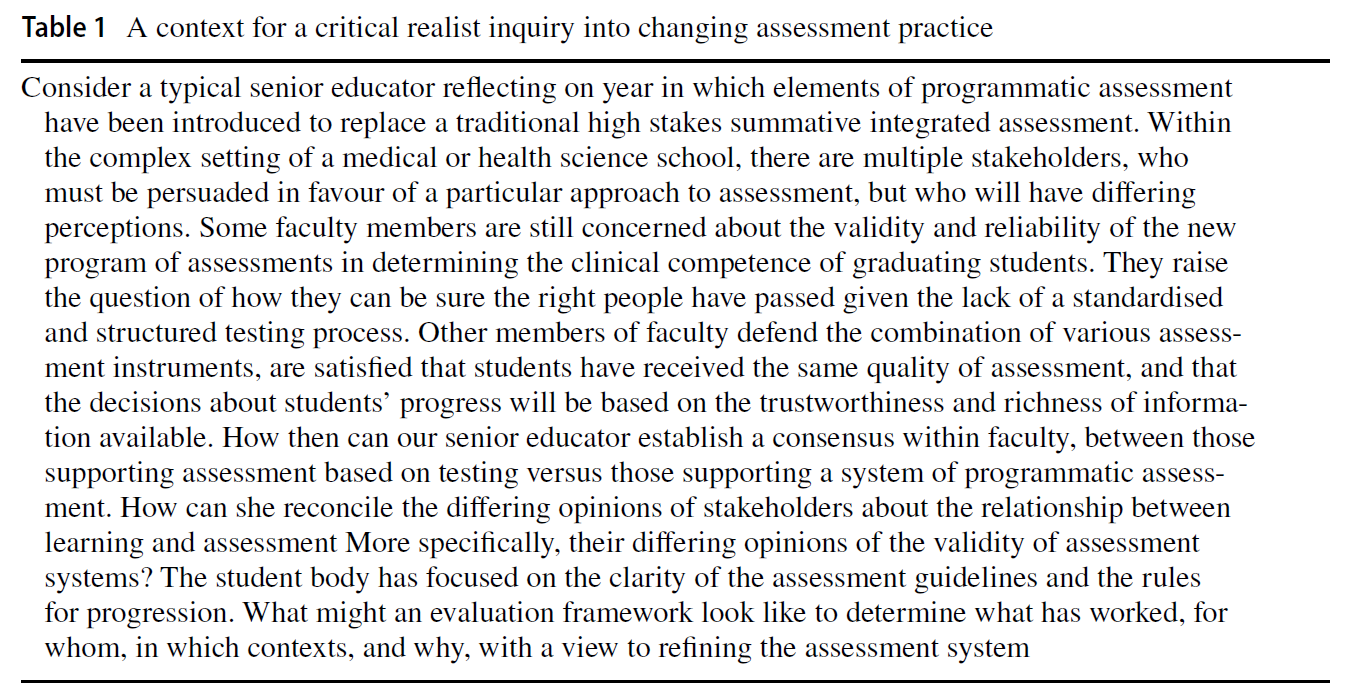

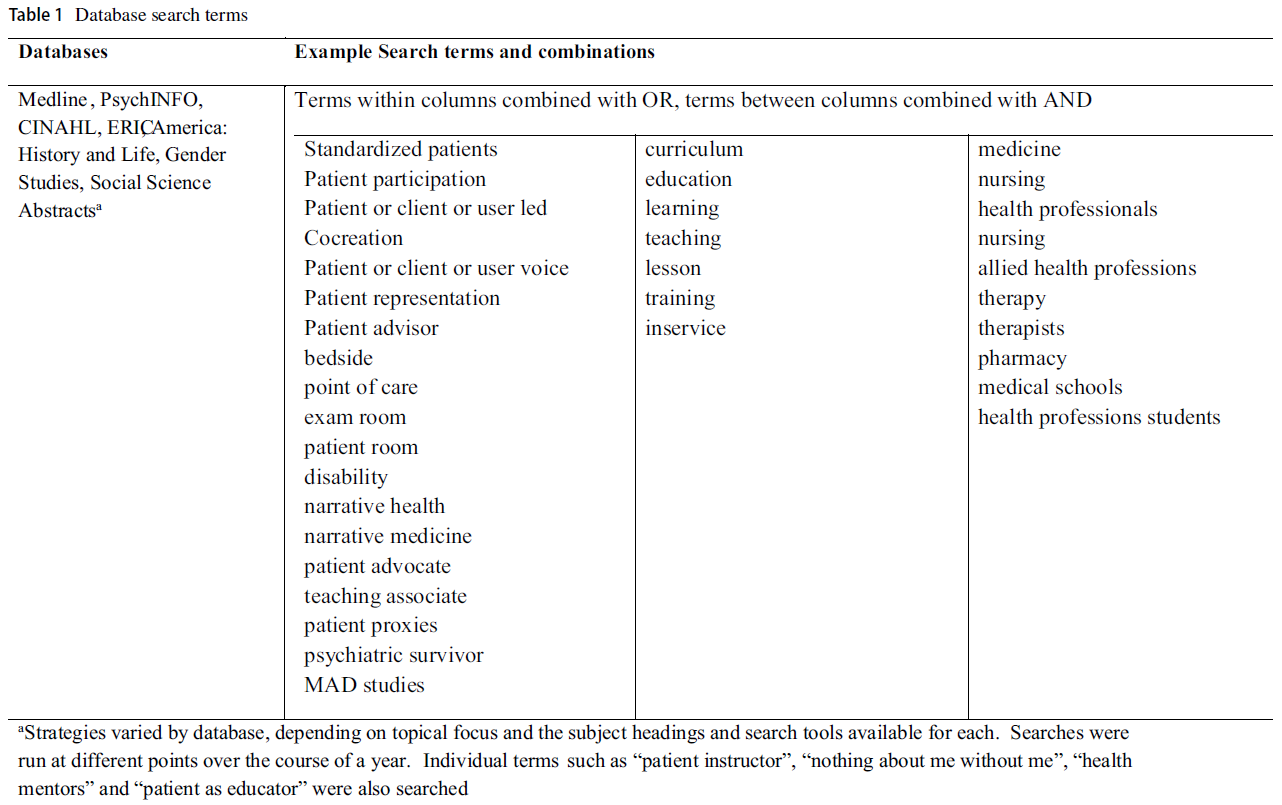

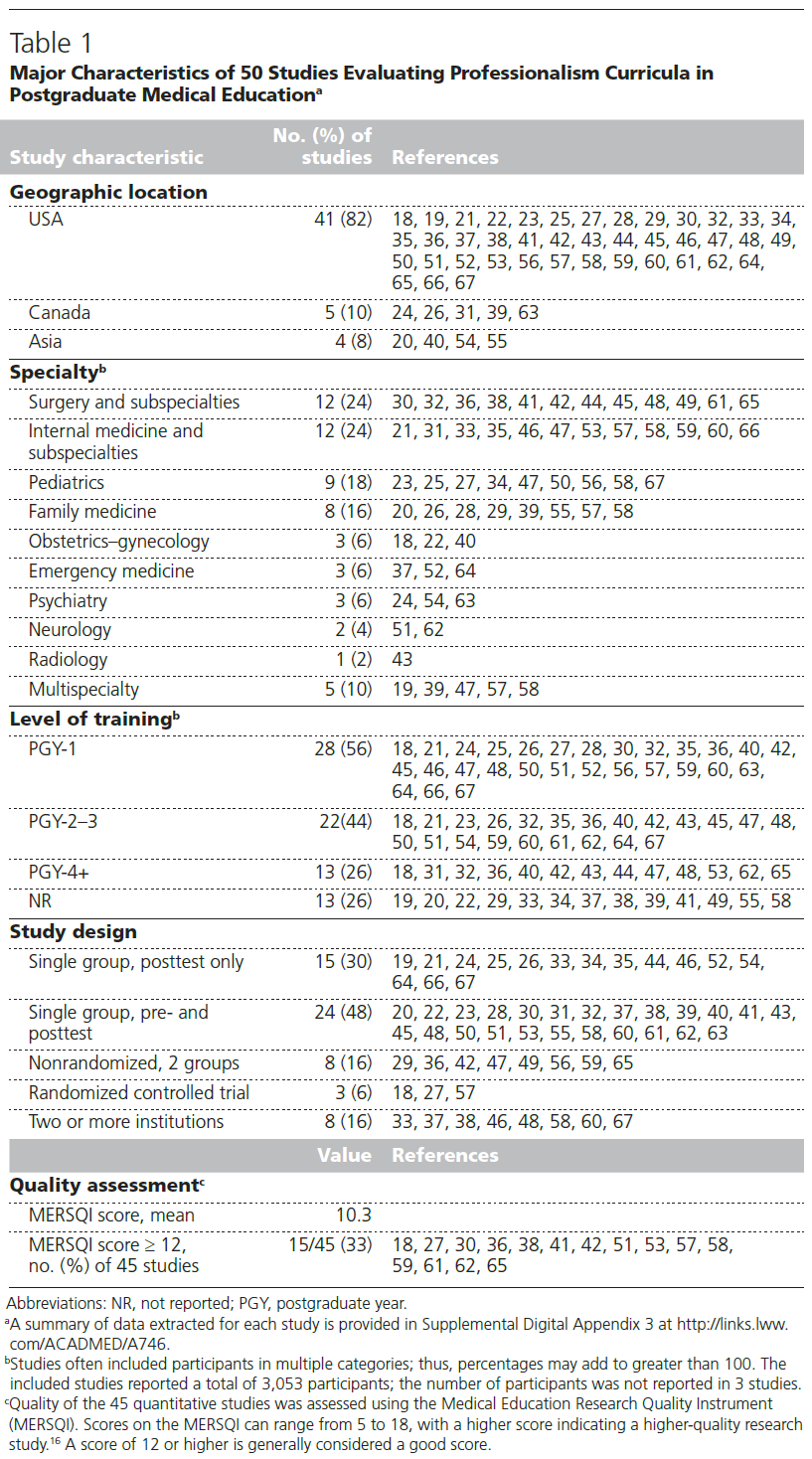

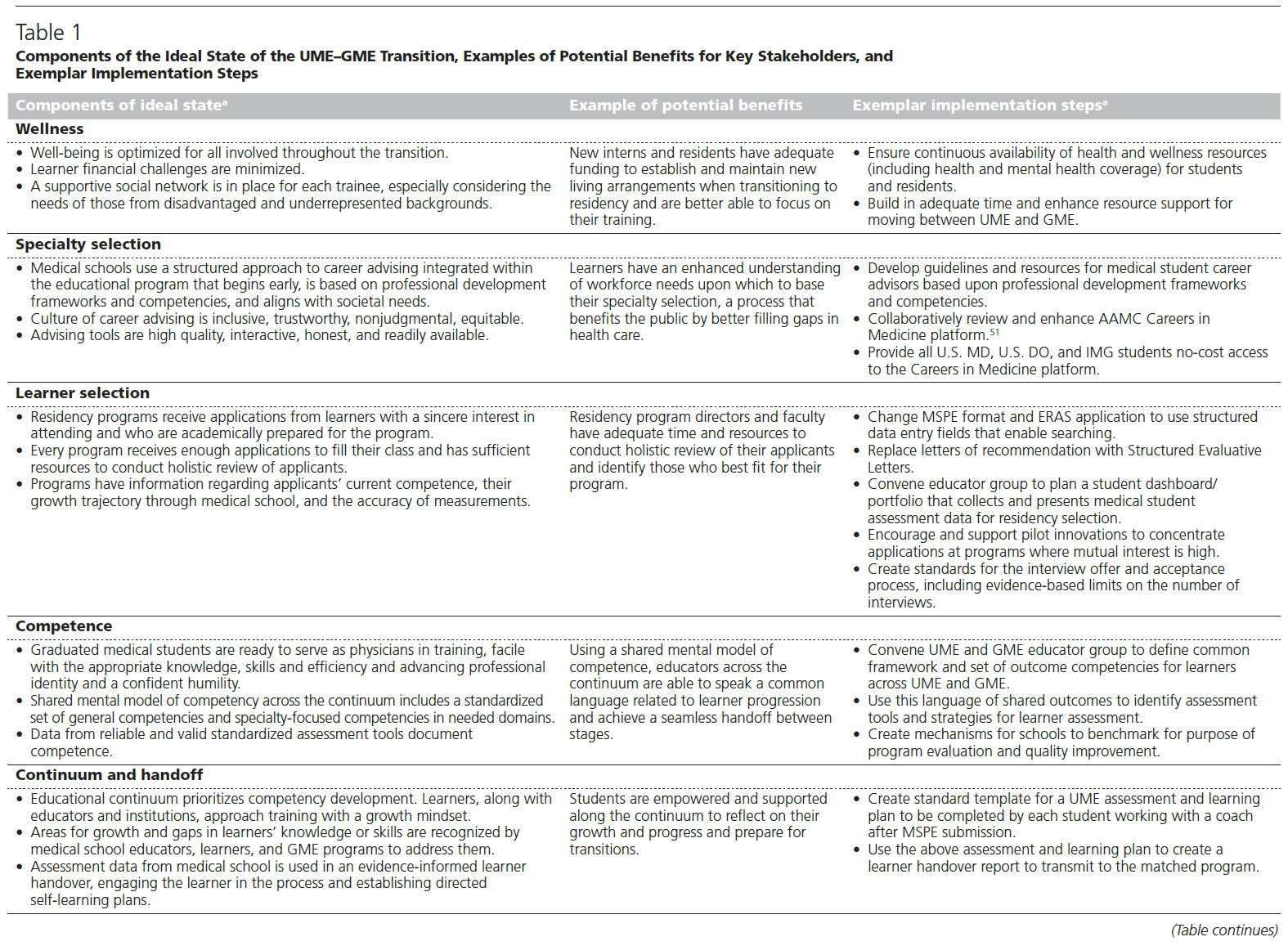

이상적인 UME-GME 전환은 공평하고 효율적이며 투명합니다. 24 표 1은 이상적인 전환이 학습자의 성장, 근거에 기반한 전문과목 선택, 역량 달성 및 개인 건강을 어떻게 지원하는지에 대한 개요를 제공합니다.

- 학습자는 개인의 강점과 학습 요구를 인식하고 직업적 정체성 형성을 최적화하는 방식으로 의과대학에서 적합한 레지던트 프로그램으로 진급합니다.

- 이 시스템은 학습자, 교육자 및 적절한 경우 규제기관을 위해 의미 있는 정보를 생성하는 도구를 사용하여 신뢰할 수 있는 역량 문서를 제공합니다.

- 이 시스템은 프로그램 디렉터와 후원 기관에 지속 가능한 학습자 중심 경험을 제공합니다.

- 이상적인 시스템은 의학교육 및 의료 시스템의 변화에 유연하게 적응할 수 있으며 지속적으로 개선됩니다.

- 재정, 교육, 환자 치료, 복지 등의 비용은 가치를 극대화하고 이해 상충을 인식하며 공익을 지원할 수 있는 적절한 규모로 책정되어야 합니다.

- 학습자는 다양한 환자 집단에 서비스를 제공하고, 격차를 최소화하며, 형평성을 높여 의료의 사회적 사명과 공적 계약을 이행할 준비가 되어 있습니다.

- 의학교육 및 의료 시스템이 인종차별과 유해한 편견의 영향을 최소화하기 위해 노력함에 따라, 다양성은 모든 전문 분야, 프로그램 및 지리적 영역에 걸쳐 존재하고 중요시됩니다.

- 교수진, 학습자 및 시스템 구조는 성장 마인드를 키우는 포용적인 학습 환경을 조성합니다.

- 의대생은 신뢰할 수 있고 수준 높은 조언을 통해 궁극적으로 자신의 커리어를 책임질 수 있는 역량을 갖추게 됩니다.

The ideal UME–GME transition is equitable, efficient, and transparent. 24Table 1 provides an overview of how the ideal transition supports learner growth, evidence-informed specialty selection, achievement of competence, and personal wellness.

- Learners progress from medical school to well-suited residency programs in a manner that recognizes their individual strengths and learning needs and optimizes professional identity formation.

- The system provides trustworthy documentation of competence using tools that generate meaningful information for learners, educators, and where appropriate, regulators.

- The system provides a learner-centered experience sustainable for program directors and sponsoring institutions.

- The ideal system is flexibly adaptable to changes in medical education and health care systems; it is continuously improved.

- Costs—financial, educational, patient care, well-being—are right-sized to maximize value, recognize conflicts of interest, and support the public good.

- Learners are prepared to serve diverse patient populations, minimize disparities, and elevate equity to fulfill medicine’s social mission and public contract.

- Diversity is present and valued throughout all specialties, programs, and geographic areas as medical education and health care systems act to minimize effects of racism and harmful bias.

- Faculty, learners, and system structure cultivate inclusive learning environments that foster a growth mindset.

- Medical students, supported by reliable and high-quality advising, are ultimately empowered to take responsibility for their career progression.

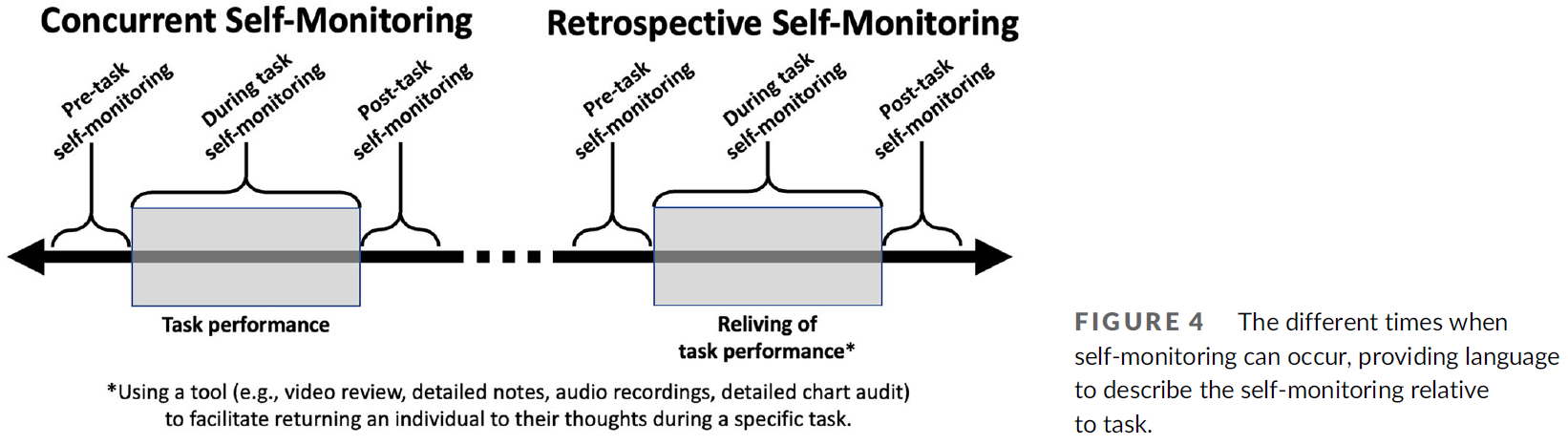

이 푸른 하늘의 비전은 매칭 전, 매칭 중, 매칭 후의 UME-GME 전환에 관한 것입니다. 위원회는 다음의 것들이 이상적인 상태에서 어떻게 나타날지 상상했습니다(표 1).

- 웰니스,

- 전공 선택,

- 학습자 선발,

- 역량,

- 연속성 및 핸드오프,

- 테크놀로지,

- 라이선스 및 자격 인증,

- 생애 전환,

- 레지던트 시작 및 레지던트 환경

이러한 열망적인 사고는 UGRC 회원들로 하여금 학습자(미국 의대 및 정골 의학 졸업생, 미국 시민권자 국제 의학 졸업생[IMG], 미국 외 IMG), UME 및 GME 교육자, 대중에게 혜택을 주기 위해 현재 생태계의 개선과 변화를 구상하게 만들었습니다.

This blue-skies vision attends to the UME–GME transition before, during, and after the Match. The committee envisioned how wellness, specialty selection, learner selection, competence, continuum and handoff, technology, licensing and credentialing, life transition, residency launch, and residency environment would manifest in an ideal state (Table 1). This aspirational thinking propelled UGRC members to envision enhancements and changes to the current ecosystem to benefit learners (medical and osteopathic U.S medical graduates, U.S. citizen international medical graduates [IMGs], and non-U.S. IMGs), UME and GME educators, and the public.

현재 상태의 긴장

Tensions in the Current State

UME-GME 전환의 [이상적인 상태에 대한 비전]과 [실제 현재 상태] 사이에는 격차가 존재합니다. 이러한 격차는 학습자, 교육자, 레지던트 프로그램 및 대중의 가치관이 서로 관련되어 있지만 다양한 목표를 가지고 있기 때문에 존재하며, 이러한 목표의 차이로 인해 현재 UME-GME 전환에서 잘못된 조정과 실패를 초래합니다. 이러한 불일치와 실패는 사려 깊은 관심과 행동, 옹호로 관리하고 해결하지 않는 한 당분간 지속될 근본적인 긴장에 기반을 두고 있으며, 쉽게 해결되지 않을 것입니다.

Gaps exist between the vision for an ideal state and the actual current state of the UME–GME transition. These gaps exist because learners, educators, residency programs, and the public value related yet varied goals, and the differences in these goals result in misalignment and failings in the current UME–GME transition. These misalignments and failings are grounded in underlying tensions that will persist for the foreseeable future and defy easy solutions unless they are managed and addressed with thoughtful attention, action, and advocacy.

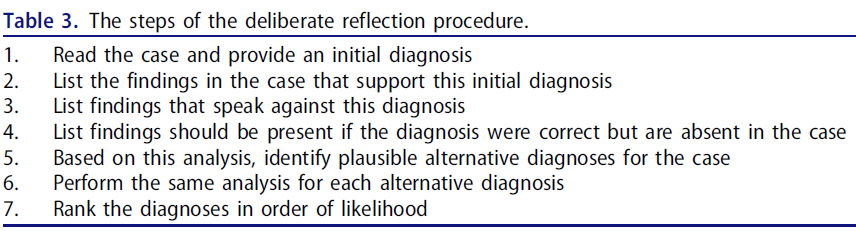

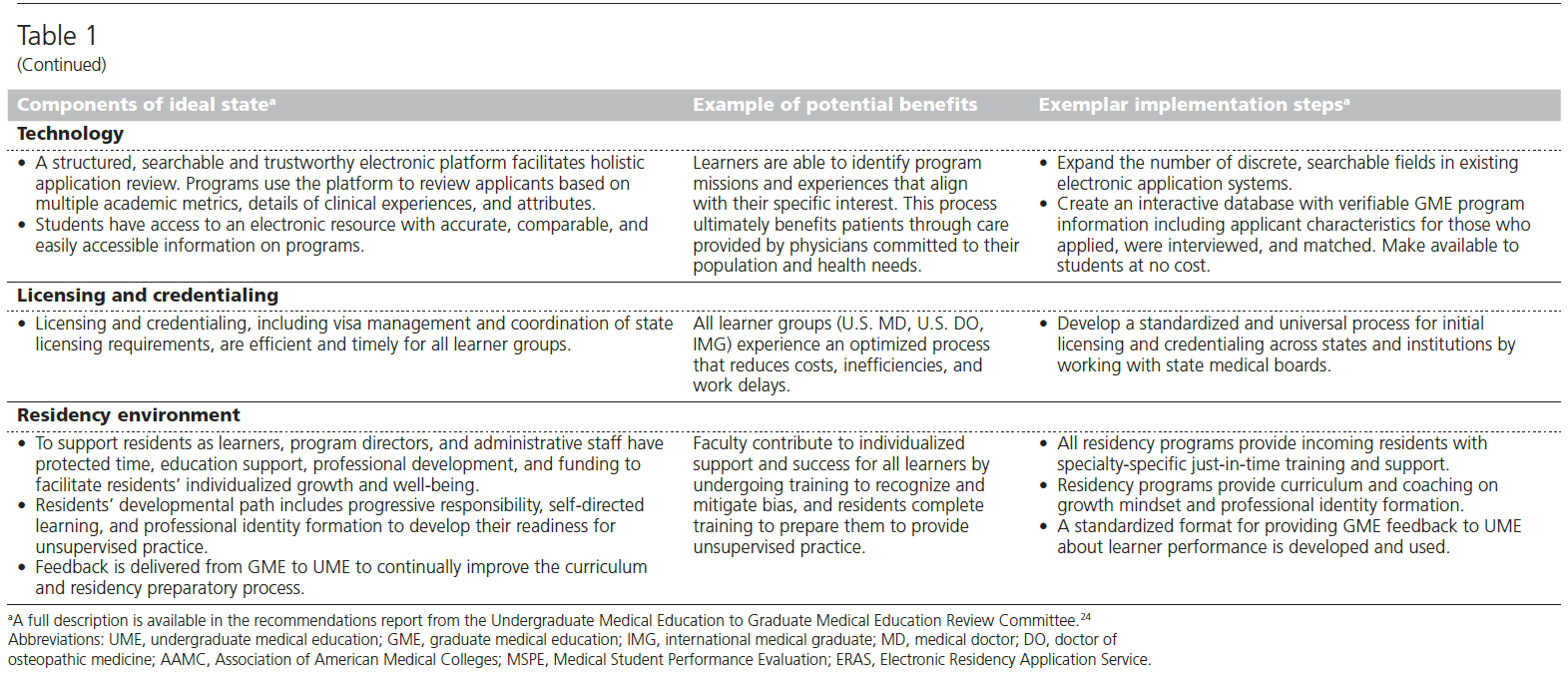

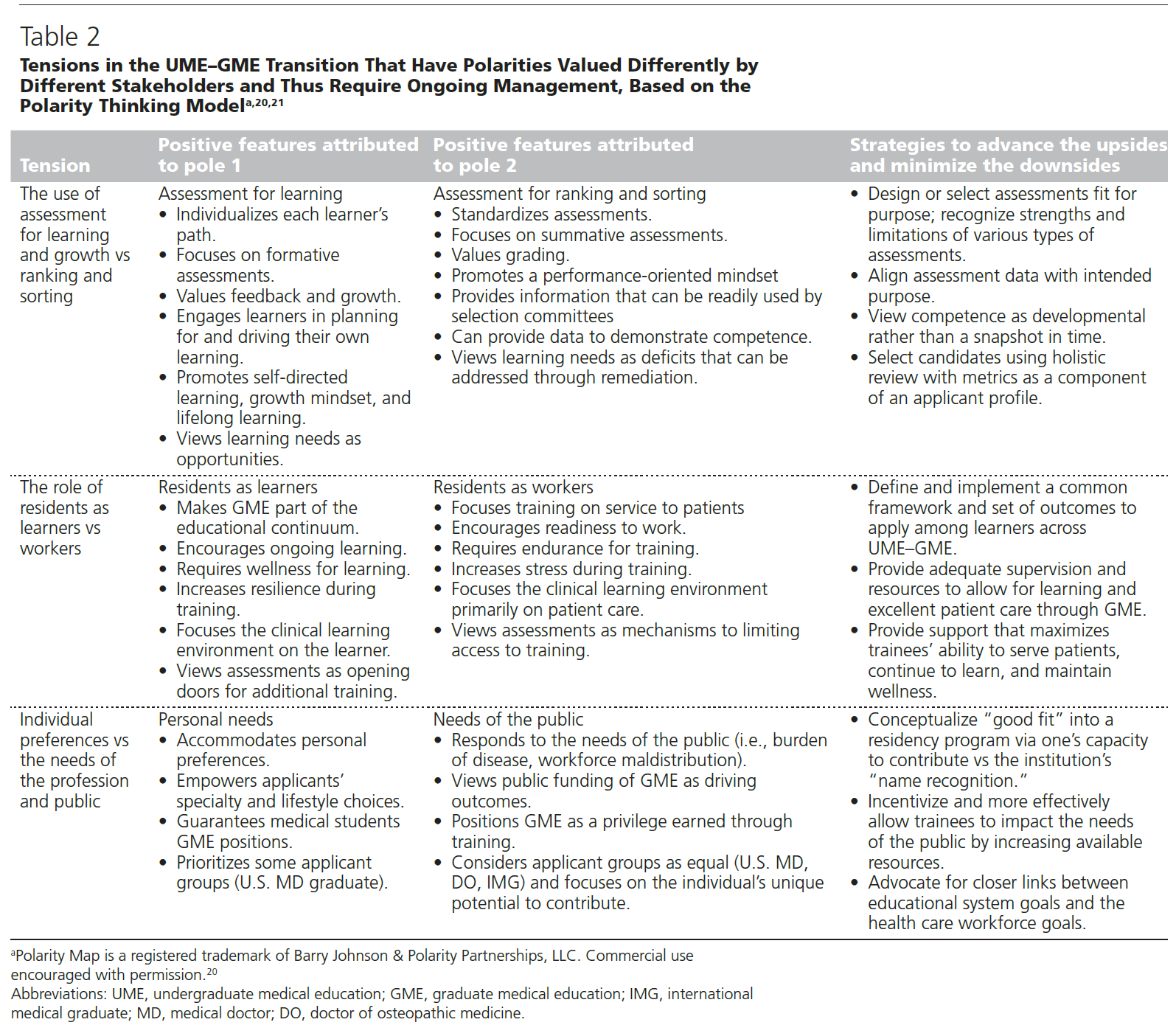

고베어츠와 동료들은 양극성 사고 모델을 설명하면서 긴장을 관리하기 위한 세 가지 단계, 즉 보기, 매핑, 탭핑/활용을 명확하게 설명합니다. 21

- 보기는 긴장의 존재를 인식하고 인정하는 것과 같습니다. 20,21

- 매핑은 긴장의 반대 극에 있는 긍정적인 측면과 부정적인 측면을 식별하는 것을 의미합니다.

- 태핑/활용에는 각 극의 장점을 극대화하고 단점을 최소화하기 위한 프로세스와 행동을 식별하는 것이 포함됩니다.

In describing the Polarity Thinking model, Govaerts and colleagues articulate 3 steps for managing tensions: seeing, mapping, and tapping/leveraging. 21

- Seeing equates to recognizing and acknowledging the existence of the tension. 20,21

- Mapping entails identifying positive and negative aspects of opposite poles of the tension.

- Tapping/leveraging involves identifying processes and actions to optimize upsides and minimize downsides of each pole.

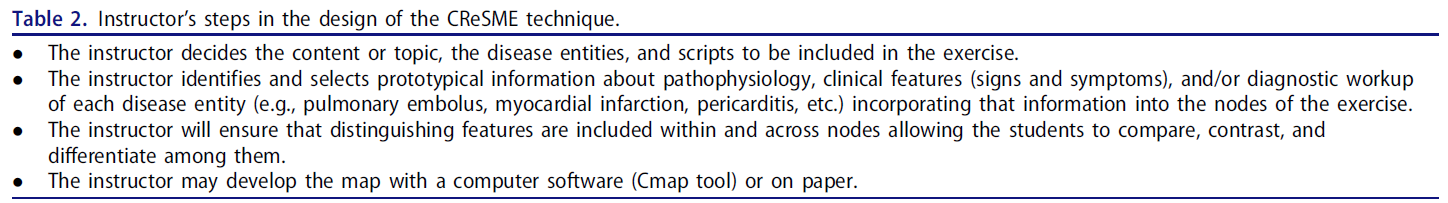

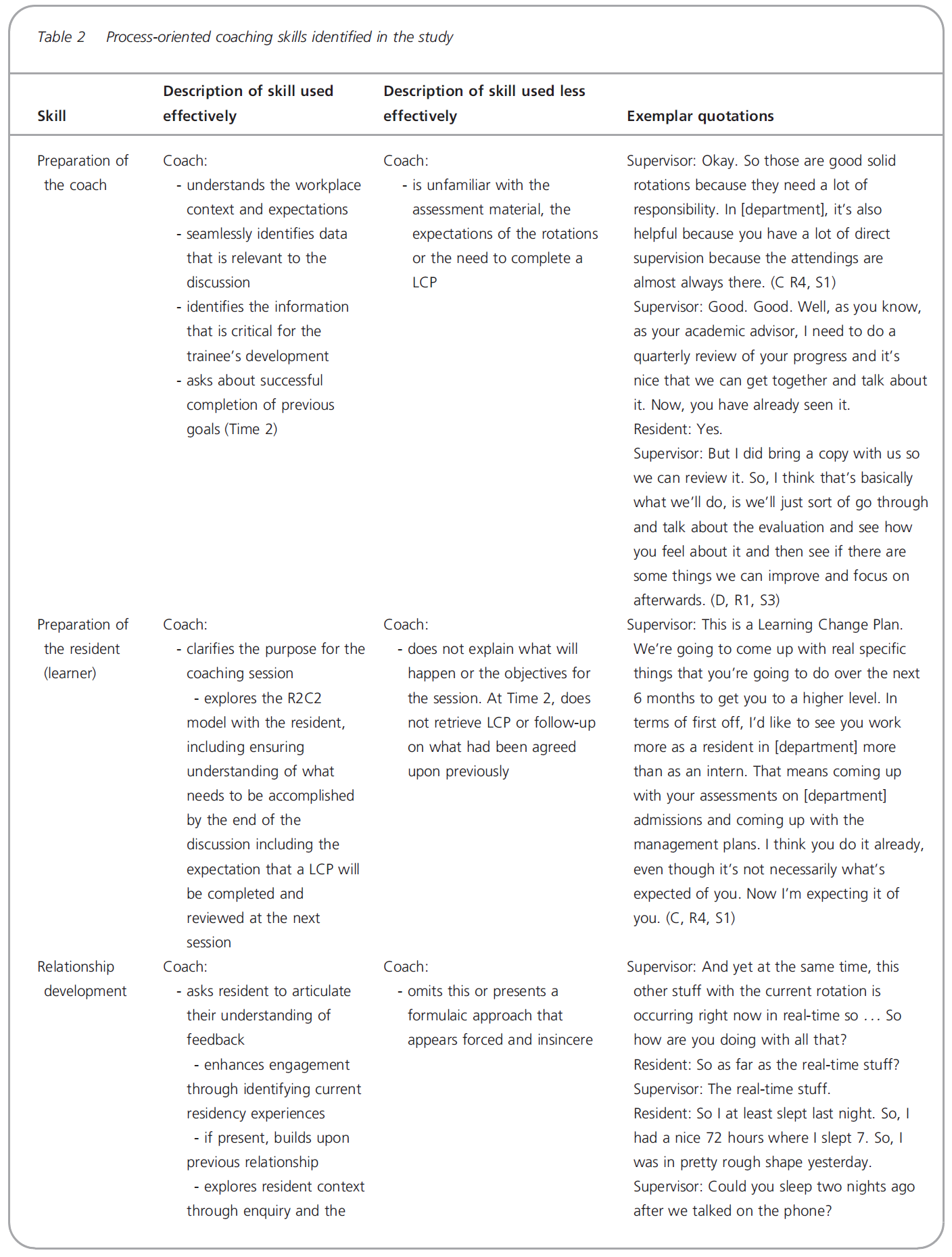

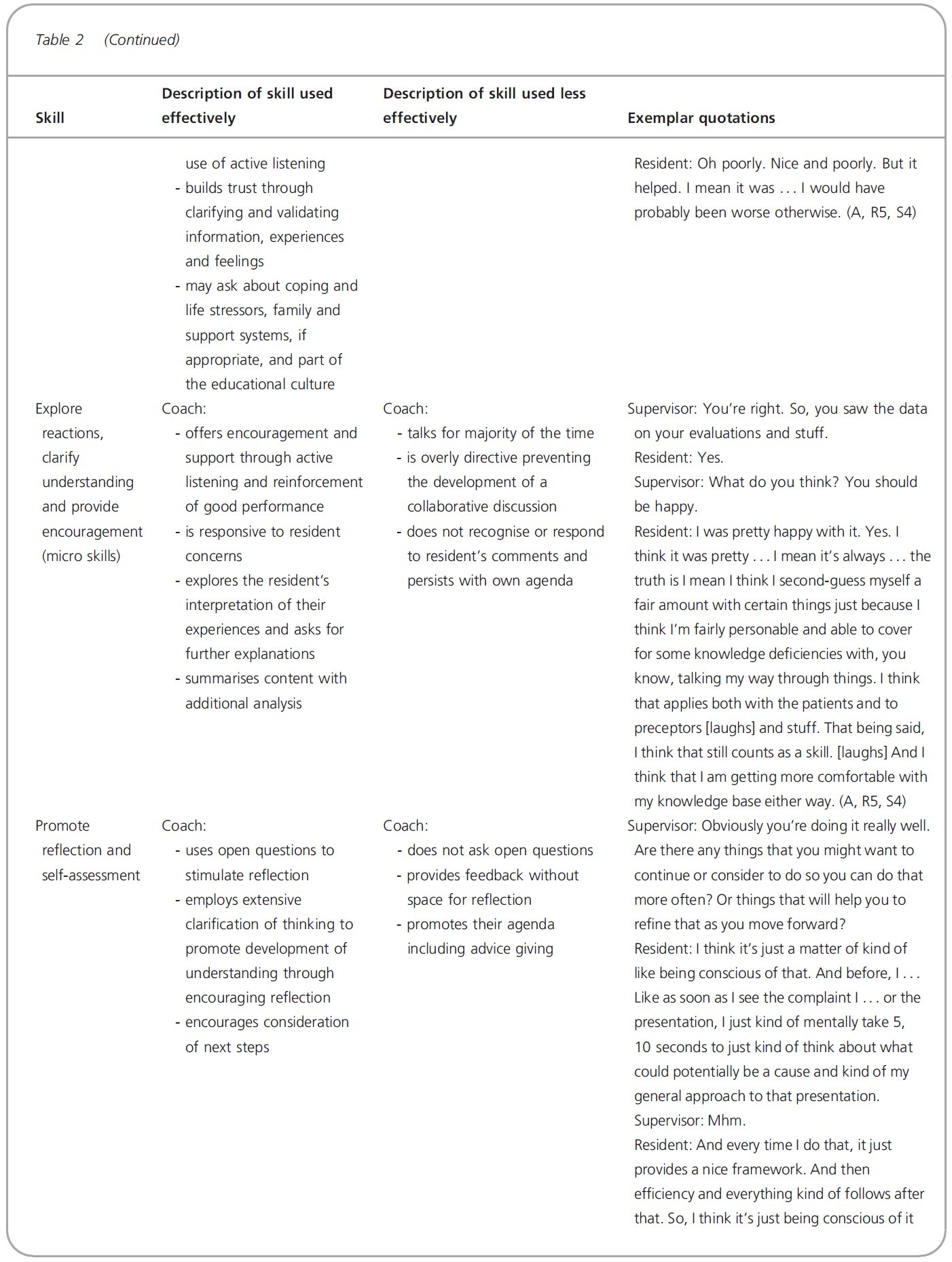

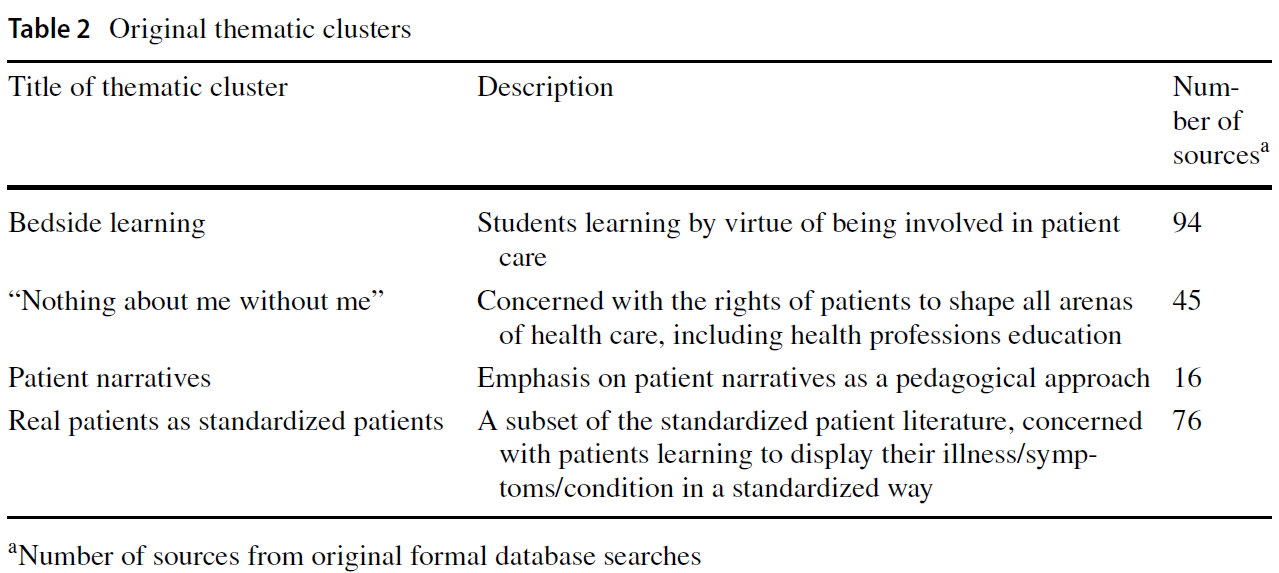

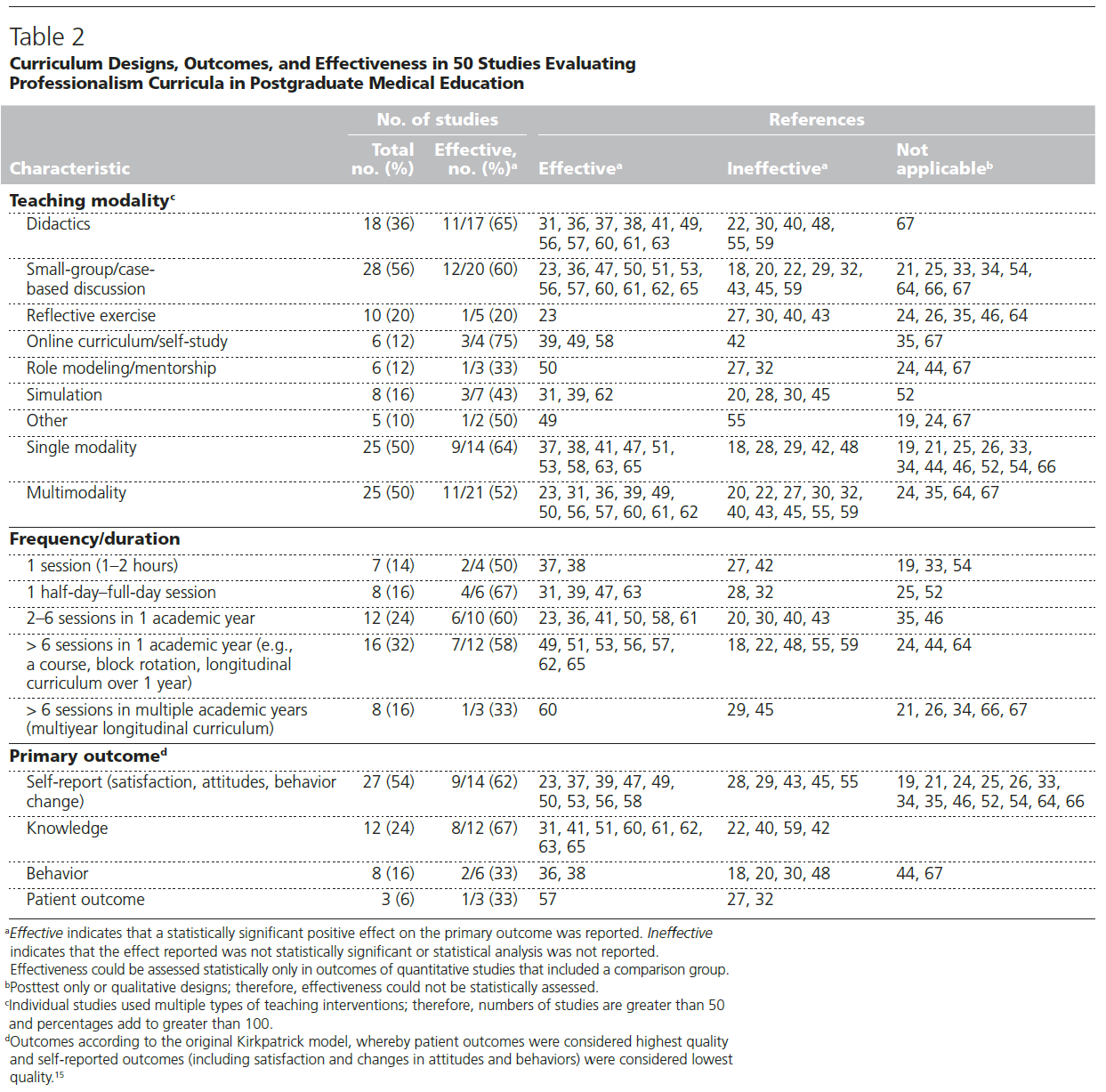

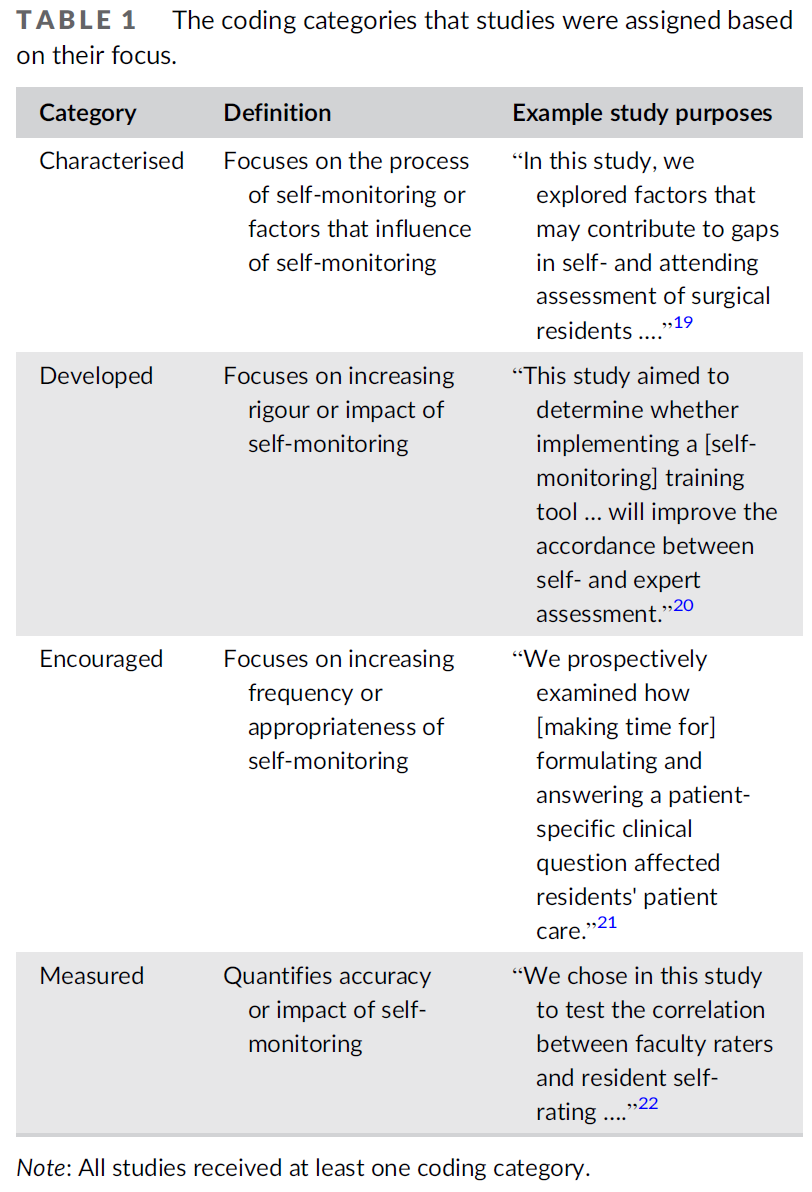

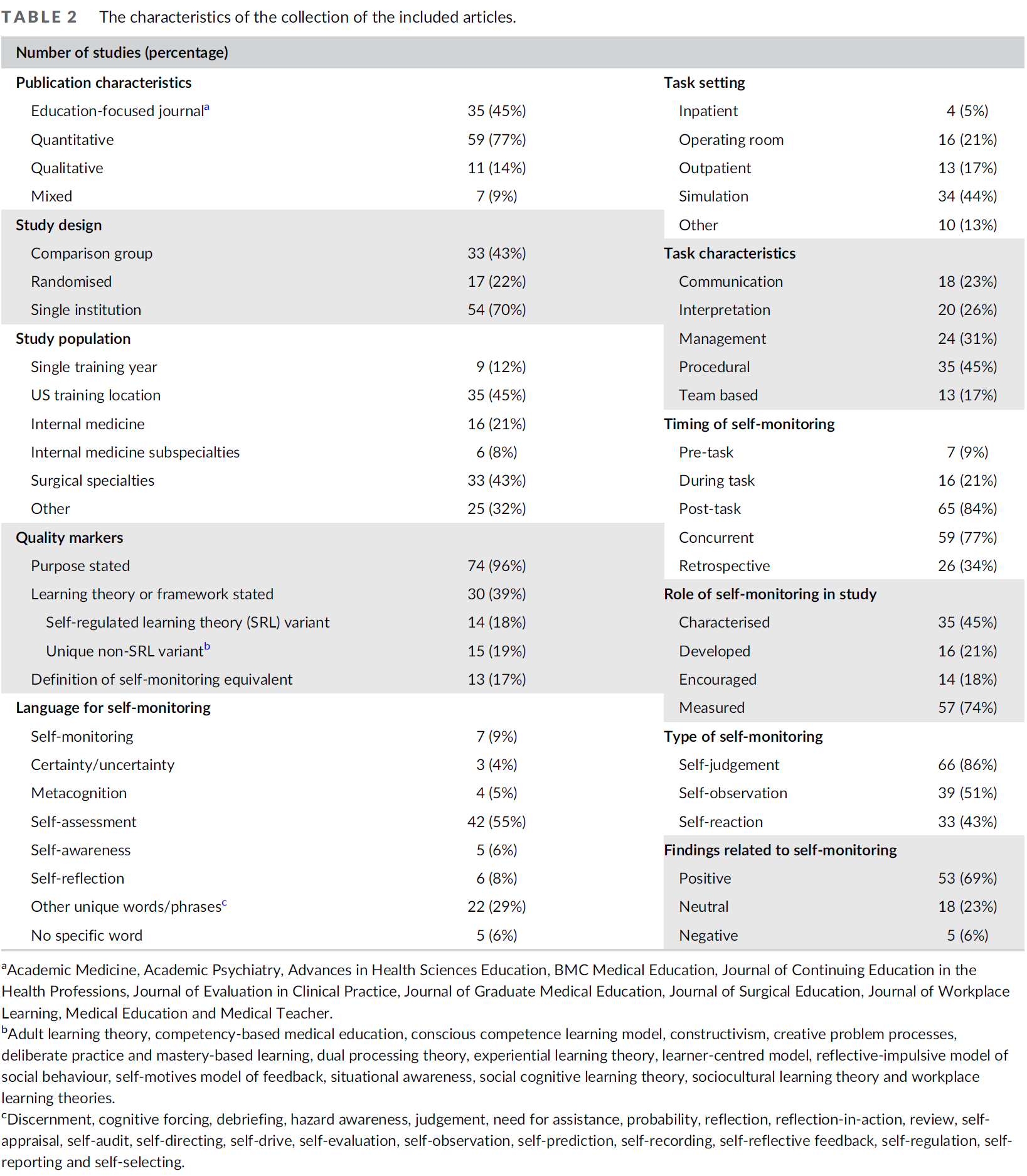

아래에서는 문헌 검토와 UGRC 논의 참여를 바탕으로 파악한 UME-GME 전환의 3가지 핵심 긴장에 대해 설명합니다("보기"). 부록 디지털 부록 1은 각 긴장에 대한 극성 지도("매핑")를 보여줍니다. 표 2는 '양립' 관점("활용/활용")을 통해 긴장과 이를 관리할 수 있는 기회를 설명합니다. 우리는 교육 시스템과 전반적인 의료 시스템의 복잡한 상호 작용으로 인한 긴장을 포함하여 다른 긴장이 존재한다는 것을 인정합니다.

Below, we describe 3 central tensions in the UME–GME transition that we identified based on our review of the literature and participation in UGRC discussions (“seeing”). Supplemental Digital Appendix 1 at https://links-lww-com-ssl.access.hanyang.ac.kr:8443/ACADMED/B324 shows the polarity map for each tension (“mapping”). Table 2 describes tensions and opportunities to manage them through a “both-and” lens (“tapping/leveraging”). We acknowledge that other tensions exist, including some driven by complex interactions of the educational system and overall health care system.

학습과 성장을 위한 평가의 목적과 순위 및 서열화를 위한 평가의 목적 비교

The purpose of assessment for learning and growth versus ranking and sorting

의학교육자들은 자신의 지속적인 성장과 개선에 전념하는 의사를 대중에게 제공하고자 합니다. 의학 발전의 속도와 대부분의 의사가 정규 교육 이후에 경력을 쌓는 현실을 고려할 때, 평생 학습과 성장 마인드를 촉진하는 기술과 행동은 필수적입니다. 26-28 그러나 레지던트 선발 과정에서는 학생과 학교가 최고 성과자를 구별할 방법을 모색함에 따라 [성장 관련 행동]보다 [성과 관련 행동]이 더 강조되고 있습니다. 마찬가지로, 레지던트 지원서를 많이 받는 프로그램 디렉터들은 지원자의 학업 기록을 구별하고 신속하게 순위를 매기고 분류할 수 있는 의미 있는 평가 데이터를 찾고 있습니다.

Medical educators aspire to provide the public with physicians dedicated to their own continuous growth and improvement. Given the speed of medical advances and reality that the majority of physicians’ careers occur after formal education, skills and behaviors that promote lifelong learning and growth mindset are essential. 26–28 However, the residency selection process emphasizes performance-related behaviors more than growth-related behaviors as students and schools seek ways to distinguish top performers. Similarly, program directors receiving high numbers of residency applications seek meaningful assessment data to distinguish among the academic records of candidates and enable quick ranking and sorting.

이러한 현상은 학습자들 사이에 고정된 사고방식을 조장하고 평가 데이터에서 잠재적으로 잘못된 추론(예: 높은 시험 점수가 양질의 환자 치료를 예측한다는 것)을 가능하게 합니다. 사고의 리더와 교육 학자들은 평가가 성장을 위한 도구로 사용되기보다는 무기화되고 있다고 경고해 왔습니다. 29 UME-GME 전환 과정에서 관리되지 않은 이러한 긴장은 의과대학 전체에서 평가가 사용되고 평가되는 방식을 형성했습니다.

- 레지던트 지원 시 신뢰도가 높은 총괄적 표준 객관식 시험에 초점을 맞추다 보니 순위 매기기와 분류에는 덜 유용하지만 학습이나 환자 진료에는 더 가치 있는 평가(예: 실무 기반 평가)의 개발과 채택이 부족해졌습니다. 30

- 수치 점수의 작은 차이는 오차 범위 내에 있는 것으로 공개적으로 보고됨에도 불구하고 과도하게 해석됩니다. 31

- 또한, 점수가 의도하지 않은 목적으로 사용될 경우, 시험 성과에 대한 잘못된 능력주의가 발생하여 성장 지향성을 소멸시키고 의학의 다양성과 포용성을 제한할 수 있습니다. 32,33

This current state manifests in the promotion of a fixed mindset among learners and enables potentially incorrect inferences from assessment data (e.g., that high exam scores predict quality patient care). Thought leaders and education scholars have warned that assessments are being weaponized rather than used as a tool for growth. 29 This unmanaged tension across the UME–GME transition has shaped how assessments are used and valued throughout medical school.

- The focus on high-reliability summative, standardized, multiple-choice question exams as key currency in residency applications shortchanges the development and adoption of assessments that are less useful for ranking and sorting but more valuable for learning or patient care (e.g., workplace-based assessments). 30

- Small differences in numeric score performance are overinterpreted despite these being publicly reported as within margins of error. 31

- Furthermore, when scores are used for purposes for which they were not designed, a false meritocracy develops around examination performance that can extinguish growth-orientation and limit diversity and inclusion in medicine. 32,33

의학교육자는 평가 목적을 중심으로 두 극의 장점을 모두 발전시킬 수 있도록 평가 목표를 재구성해야 합니다. 신뢰도와 정밀도가 높은 평가 형식을 "목적에 맞는" 방식으로 사용하여 중요한 전환점에서 중요한 판단을 내릴 수 있습니다. 레지던트 프로그램 지도부가 인정하지 않는 국제학교 출신 지원자 등 GME 지원자에 대한 자세한 정보나 맥락이 부족한 경우, 면허 시험 점수는 의학 지식에 대한 최소한의 역량을 보장합니다. 임상의가 진단 테스트 데이터를 사용하여 해석하고 의사 결정을 내리는 것처럼 교육자는 현재 평가 형식의 강점과 한계(즉, 응시자에 대해 무엇을 나타낼 수 있고 무엇을 나타낼 수 없는지)를 이해하고 준수하기 위해 노력해야 합니다. 총체적인holistic 검토를 수행할 때 "목적에 맞는" 평가 데이터를 활용하면 지원자를 학습 및 경력 목표에 적합한 GME 프로그램에 매칭한다는 명시된 목표에 더 가까워질 수 있습니다. 그렇게 하지 않으면 레지던트 선발의 행정 업무량을 관리하기 위해 평가 데이터를 부적절하게 사용하는 일이 지속되고, 지원자 수를 줄이고 총체적holistic 검토를 수행하기 위한 프로그램 리소스를 강화할 필요성을 피할 수 없게 됩니다.

Medical educators must reframe goals for assessment to advance the upsides of both poles around assessment purpose. Assessment formats with high reliability and precision can be used in a “fit-for-purpose” manner to inform high-stakes judgments at significant transition points. When more detailed information or context about a GME applicant is less available (e.g., for an applicant from an international school unrecognized by residency program leadership), licensing examination scores ensure minimum competence in medical knowledge. Educators should commit to understanding and adhering to strengths and limitations of current assessments formats (i.e., what they can and cannot represent about candidates), just as clinicians interpret and make decisions using diagnostic test data. Leveraging assessment data as “fit-for-purpose” when conducting holistic review will get us closer to our stated goal that candidates match into GME programs well suited to their learning and career goals. Not doing so perpetuates the inappropriate use of assessment data to manage the administrative workload of residency selection and avoids the need to reduce application numbers and enhance resources for programs to conduct holistic review.

학습자 대 근로자로서의 레지던트의 기능

The function of residents as learners versus workers

GME 프로그램의 교육 목표와 현대 의료 시스템에서 레지던트의 기대치 사이의 단절은 '학습자'와 '근로자'를 겉보기에는 반대되는 극에 놓이게 합니다. 근무 시간 제한에도 불구하고 많은 임상 학습 환경은 여전히 번아웃을 유발하고34 체계적인 학습과 성찰을 위한 시간을 제한적으로만 허용합니다. 의료 시스템의 대규모 임상 운영을 유지하기 위해 GME 선발이 지속적인 학습을 희생하면서까지 즉각적인 인력 준비에 지나치게 집중되고 있습니다. 취업 준비성에 대한 이러한 강조로 인해 의과대학은 교육에 중요한 다른 역량을 가르치거나 평가 또는 보고하거나 절차적 기술이나 더 복잡한 임상 과제와 같이 졸업생이 아직 학습 중인 영역에 대해 보고하는 데 인센티브를 받지 못하고 있습니다. 35-37 UME 교육자들은 학생들이 완전한 역량을 갖추지 못한 것으로 비춰질 수 있는 정보를 보고하는 것을 두려워합니다. 부록 디지털 부록 2에는 이러한 긴장에 대한 극성 지도가 나와 있습니다.

Disconnect between the educational goals of GME programs and the expectations of residents in modern health care systems places “learners” and “workers” on seemingly opposite poles. Despite work-hour restrictions, many clinical learning environments still contribute to burnout 34 and afford only limited time for structured learning and reflection. To maintain high-volume clinical operations of health systems, GME selection has become overly focused on immediate workforce readiness at the expense of ongoing learning. Because of this emphasis on work-readiness, medical schools are disincentivized to teach, assess or report on other competencies that are also critical to training, or report on areas where graduates are still learning, such as procedural skills or more complex clinical tasks. 35–37 UME educators fear reporting information that may portray students as less than fully competent and jeopardize their match. Supplemental Digital Appendix 2 at https://links-lww-com-ssl.access.hanyang.ac.kr:8443/ACADMED/B324 shows the polarity map for this tension.

교육자는 양쪽 극의 장점을 모두 인식하여 이러한 긴장을 관리해야 합니다. UME와 GME는 UME-GME 전환 과정에서 학습자에게 적용되는 공통 프레임워크와 공통 역량 세트를 함께 정의하고 구현해야 합니다. 신규 레지던트는 첫날부터 업무에 기여할 수 있어야 하며, 점진적으로 독립적인 역할을 수행할 수 있도록 충분한 감독과 학습 기회를 제공하는 환경도 제공되어야 합니다. 레지던트 시작을 위한 현실적인 역량에 대해 UME와 GME를 더 잘 연계하고, 전환 전반에 걸쳐 개별화된 학습과 지원을 제공하는 학습자 인수인계를 통해 지속적인 학습자 개발을 가능하게 할 것입니다. 38 효과적인 시스템은 성과에 대한 반성, 경험을 통한 학습 및 개선에 대한 시연을 포함하여 양질의 임상 성과 및 환자 치료 결과와 관련된 모든 역량 영역에서 연속성을 따라 교육 성과를 식별하고 평가해야 합니다. 39 서비스와 교육에 대한 "양립적" 관점을 강조하면 성장 지향성을 촉진하고 학습자 사이에서 잠재적으로 파괴적인 성과 사고방식과 완벽주의를 제한할 수 있습니다. 이러한 교육 과정은 지속적인 회복탄력성과 교육에 대한 공동체 의식을 촉진합니다. 40 보건 시스템 전체는 교육 시스템이 주민들이 학습하고 개인 지식의 격차를 메울 수 있는 시간을 제공하는 데 필요한 재정 및 기타 자원을 제공해야 할 책임이 있습니다. 41

Educators must manage this tension by recognizing the upsides of both poles. UME and GME must together define and implement a common framework and a common set of competencies that apply to learners across the UME–GME transition. New residents should be expected to contribute to the workforce on day 1, and in turn, they should also be afforded an environment with ample supervision and learning opportunities to scaffold their progressively independent roles. Better alignment of UME and GME on realistic competencies for starting residency, along with learner handovers that inform individualized learning and support across the transition, will enable continued learner development. 38 An effective system should identify and value educational outcomes along the continuum in all competency domains related to high-quality clinical performance and patient care outcomes, including demonstration of reflection upon performance, learning through experience, and improvement. 39 Emphasizing the “both/and” view of service and education will promote growth orientation and limit potentially destructive performance mindsets and perfectionism among learners. Such a training path promotes enduring resilience and a sense of community around education. 40 The health system as a whole is responsible for providing the financial and other resources needed for the educational system to afford time for residents to learn and fill the gaps in their individual knowledge. 41

개인의 선호도와 직업 및 대중의 필요성 비교

Individual preferences versus needs of the profession and public

UME-GME 전환 과정에서 누구의 요구가 우선인지에 대한 긴장은 지속될 것입니다.

- 한 쪽 극에는 통제에 대한 개인적 선호, 뛰어난 학벌, 미래 교육 기회, 교육 부채 상환 능력, 생활 방식에 대한 우려로 인한 개인의 요구가 있습니다.

- 다른 극에는 전체 의학교육 시스템이 책임을 져야 하는 대중을 포함한 더 광범위한 시스템의 요구가 있습니다.

Within the UME–GME transition, the tension of whose needs are primary will persist.

- On one pole are the needs of the individual, driven by personal preferences for control, distinguished academic pedigree, opportunities for future training, ability to repay educational debt, and lifestyle concerns.

- On the other pole are the needs of the broader system, including the public to whom the whole medical education system is accountable.

이러한 상황은 선호하는 프로그램에서 선호하는 전공분야에 대한 수련을 계속하고 일치하지 않는 우려되는 결과를 피할 수 있는 [개인들의 자격entitlement]으로 나타날 수 있습니다.

- 광범위한 의료 수요보다 의대생의 개인적 선호를 우선시하는 시스템은 환자에게 불이익을 줍니다.

- 또한 경쟁과 계층 구조는 의료계의 핵심 가치는 아니지만,42,43 UME-GME 전환의 많은 측면에서는 경쟁적 우위를 중요시합니다. 44

- 경쟁은 능력과 잠재력이 아니라 레지던트 또는 의사 성과와 관련이 의심스러운 특성에 근거하여 지원자 간의 계급class 차이를 유발합니다(예: 정골 의학 학교 또는 국제 의과 대학 출신 학생은 매치에서 절대적으로 불리함).

- 이러한 계급 차이로 인해 지속되는 고정관념은 정골 의대 또는 국제 의대 출신 학생들이 경쟁이 치열한 전문과목이나 프로그램에 매칭될 가능성이 낮기 때문에 의료 수요에 비해 의사의 지리적 및 전문과목 불균형을 조장합니다. 45 부록 디지털 부록 3은 이러한 긴장에 대한 양극성 지도를 보여줍니다.

These circumstances may manifest as individual entitlement to continue one’s training in a preferred specialty at a preferred program and avoid the feared outcome of not matching.

- A system that prioritizes the personal preferences of medical students over broader health care needs disadvantages patients.

- Furthermore, although competitiveness and hierarchy are not core values of the profession, 42,43 many aspects of the UME–GME transition value competitive advantage. 44

- Competition prompts class differences among applicants, based not on ability and potential but rather on characteristics that are doubtfully related to residency or physician performance (e.g., students from osteopathic schools or international medical schools are categorically disadvantaged in the Match).

- Stereotypes perpetuated from these class differences promote geographic and specialty maldistribution of physicians compared with health needs, as students from osteopathic or international medical schools are less likely to match into competitive specialties or programs. 45 Supplemental Digital Appendix 3 at https://links-lww-com-ssl.access.hanyang.ac.kr:8443/ACADMED/B324 shows the polarity map for this tension.

개인과 집단의 목표가 공존하는 보건의료 분야와 마찬가지로, 지원자의 개인적 선호와 집단적 요구 사이의 긴장은 UME-GME 전환에서도 지속될 것이므로 관리가 필요합니다. 이러한 긴장의 장점은 적절하게 조정된 인센티브와 공존할 수 있습니다. 개인이 특정 센터와 프로그램에 재능을 집중하기보다는 기술과 재능을 분산하도록 장려하고 인센티브를 제공해야 합니다. 사회적 불의에 맞서 싸우고자 하는 강한 동기를 가진 레지던트 지원자는 자원이 풍부한 학술 보건 센터 대신 작은 도시의 프로그램에 적합할 수 있습니다. 재정적 인센티브와 부채 탕감 프로그램을 만들어 지원자가 원하는 경력을 쌓을 권리를 침해하지 않으면서도 인력 부족 지역에서 수련과 실습을 선택하도록 장려할 수 있습니다. 46

Just as in health care, where individual and population goals coexist, tension between applicants’ personal preferences and collective needs will persist in the UME–GME transition and therefore must be managed. The upsides of this tension can coexist with properly aligned incentives. Individuals should be encouraged and incentivized to distribute skills and talent rather than to concentrate talents in select centers and programs. A residency applicant with strong motivation to combat social injustices may find an appropriate fit in a small urban program instead of a well-resourced academic health center. Financial incentives and debt relief programs can be created that encourage applicants to choose to train and practice in shortage areas without compromising their right to try for a desired career path. 46

토론

Discussion

이 원고는 권고 보고서에 요약된 UGRC의 푸른 하늘 비전을 통해 설명된 이상적인 UME-GME 전환을 개괄적으로 설명합니다. 24 이상적으로 이러한 전환은 학습자, 교육자 및 대중의 교육 및 복지 요구를 충족하는 조율되고 효율적인 시스템 내에서 이루어져야 합니다. 또한, 모든 학습자가 다양한 환자와 인구의 의료 요구를 충족할 수 있는 의사가 될 수 있는 기회를 가질 수 있도록 전환 과정 전반에 걸쳐 형평성을 증진해야 합니다. 또한 UGRC는 의과대학 및 레지던트 커리큘럼이 핵심 교육 콘텐츠로서 성장 마인드와 직업적 정체성 형성에 중점을 두어 의사가 UME-GME 전환과 실무에 적응하고 자신의 지식과 기술을 발전시킬 수 있도록 준비시킬 것을 명시적으로 권고합니다.

This manuscript outlines an ideal UME–GME transition articulated through the UGRC blue-skies visioning that is outlined in its recommendations report. 24 Ideally, this transition should occur within a coordinated, efficient system that meets the educational and wellness needs of learners, educators, and the public. Furthermore, equity should be promoted throughout the transition to ensure that all learners have opportunities to become physicians equipped to meet the health care needs of diverse patients and populations. The UGRC also explicitly recommends that medical school and residency curricula should focus on growth mindset and professional identity formation as core educational content to prepare physicians to adapt and advance their knowledge and skills through the UME–GME transition and into practice.

전환 시스템에서 혁신적인 변화가 일어나기 위해서는 내재된 긴장을 정의하고 관리하는 것이 매우 중요합니다. 지속적이고 새로운 과제를 해결하려면 역동적인 시스템 내에서 견제와 균형을 통해 세심한 모니터링, 관리, 협력이 필요합니다. 현재 목적과 재정적 인센티브가 서로 다른 개인, 프로그램, 조직의 이해관계가 더 잘 조율되면 일방적인 옹호보다는 이러한 긴장에 대한 균형 잡힌 시각이 촉진될 것입니다. 이러한 재조정을 촉진하기 위해 UGRC는 UME-GME 전환 시스템의 지속적인 품질 개선을 관리하기 위한 감독 위원회를 구성할 것을 권고했습니다.

For transformative change to occur in the transition system, it is critically important to define and manage its inherent tensions. Ongoing and emerging challenges require careful monitoring, management, and collaboration with checks and balances within a dynamic system. Greater alignment of individual, program, and organizational interests—all of which are currently misaligned in purpose and financial incentives—will promote balanced views of these tensions rather than one-sided advocacy. To promote this needed realignment, the UGRC has recommended that an oversight committee be created to manage continuous quality improvement of the UME–GME transition system.

평가의 목적(학습 대 순위 및 분류)과 레지던트의 역할(학습자 대 근로자)을 둘러싼 긴장은 교육 연속체 전반에 걸친 공통 역량 프레임워크, 역량과 연계된 평가, 구조화된 학습자 인계인수에 대한 주요 UGRC 권장 사항을 통해 해결됩니다. 이러한 공통 결과 프레임워크를 정의하기 위해서는 UME 및 GME 교육자 그룹이 협력하여 공통의 "목적에 맞는" 평가 도구 및 전략의 선택과 추가 개발을 가이드하는 데 사용해야 합니다. 필수 술기를 수행하는 학습자를 직접 관찰하는 것을 강조하는 평가는 현재 사용 가능한 점수 및 성적보다 피드백을 향상시키고 레지던트 성과를 예측하는 데 더 나은 정보를 생성할 수 있습니다. 44,47 학생이 멘토와 함께 작성한 후 새로운 레지던트 프로그램 디렉터와 함께 다시 방문하는 [매칭 후 개별화된 학습 계획]은 UGRC 권장사항에 언급된 대로 레지던트로의 전환을 보다 효과적으로 안내하는 데 사용될 수 있습니다.

Tensions around the purpose of assessment—for learning versus for ranking and sorting—and around the role of residents—as learners versus workers—are addressed through key UGRC recommendations for a common competency framework across the educational continuum, assessments aligned with competencies, and structured learner handovers. A collaborative UME and GME educator group is needed to define this common outcomes framework, which should then be used to guide the selection and further development of common “fit for purpose” assessment tools and strategies. Assessments that emphasize direct observation of learners conducting essential skills can enhance feedback and generate better information to predict residency performance than currently available scores and grades. 44,47 A post-Match individualized learning plan that a student creates with a mentor and then revisits with their new residency program director can be used to more effectively guide the transition to residency, as noted in the UGRC recommendations.

개인적 이익과 집단적 이익 사이의 긴장을 해소하기 위해 UGRC는 전문과목에서 인력 및 다양성 평가를 실시하여 어떤 유형의 수련의와 의사가 어디에 필요한지 결정하고 공평한 채용 관행을 위한 교육에 참여할 것을 권장합니다. 필요한 변화를 유도하기 위해 교육자들은 사회 정의, 건강 및 재정적 목표에 봉사하는 자체 인력을 강화하기 위한 일부 경쟁력 있는 전문과목 및 프로그램의 노력을 바탕으로 성공적인 채용에 대한 관점을 확장할 수 있습니다. 48,49

To address the tension around individual versus collective good, the UGRC recommends that specialties conduct workforce and diversity evaluations to determine which types of trainees and physicians are needed and where and engage in training for equitable recruitment practices. To prompt needed change, educators can expand their view of a successful recruitment by building on efforts of some competitive specialties and programs to strengthen their own workforce in service to social justice, health, and financial aims. 48,49

투명성과 형평성을 증진하기 위해 UGRC는 학생과 지도교수가 레지던트 프로그램 지원자의 특성, 초대, 인터뷰 및 결과에 대한 검색 가능한 데이터베이스에 액세스할 수 있어야 한다고 권장합니다. 또한 UGRC는 단순히 선택적 개선 사항으로 제공되는 것이 아니라 모든 프로그램에서 UME 및 GME 학습자에게 웰니스 지원을 의무화할 것을 권장합니다. 이러한 지원에는 UME 프로그램에서 GME 프로그램으로 전환하는 데 필요한 시간과 리소스, 간소화된 초기 라이선스 절차가 포함되어야 합니다.

To promote transparency and equity, the UGRC recommends that students and advisors should have access to a searchable database about residency program applicant characteristics, invitations, interviews, and outcomes. The UGRC also recommends that wellness supports be required for UME and GME learners across programs, not simply offered as optional enhancements. These supports should include time and resources for moving from a UME to GME program and streamlined initial licensing procedures.

이상적인 상태는 단기간에 또는 타협 없이 달성할 수 없습니다. 이러한 장밋빛 비전은 비현실적이거나 비현실적인 것으로 간주되는 콘텐츠에 대한 질문을 불러일으킬 것입니다. 모두를 위한 복지를 최적화하고 모든 지원자가 전공의 수련을 위한 충분한 준비와 신뢰를 갖출 수 있을까요? 환자 안전에 있어 무사고라는 이상적인 개념과 마찬가지로, 열망하는 이상적인 상태를 설명하는 것은 교육적 변화를 주도합니다. 이러한 장밋빛 비전을 달성하기 위해서는 작은 변화와 조기 승리가 중요하며, 지속적인 유연성과 적응도 필요합니다.

An ideal state cannot be achieved quickly or without compromise. This blue-skies vision will prompt questions about content deemed impractical or unrealistic. Can we optimize well-being for all and ensure every applicant is fully prepared and trustworthy for residency? Like the ideal concept of zero harm in patient safety, 50 describing the aspirational ideal state drives educational change. To achieve this blue-skies vision, small changes and early wins will be critical, as will ongoing flexibility and adaptation.

이 원고는 UME-GME 전환의 주요 긴장을 탐구하지만, 저자들은 다른 긴장도 존재한다는 것을 인식하고 있습니다. 예를 들어, UGRC는 의사 지불 및 급여 문제를 그룹의 책임 범위를 벗어난 것으로 파악했습니다. 이상적인 상태를 상상하는 것은 당연히 아직 존재하지 않는 시스템을 상상하는 것을 수반하며, 따라서 현재 증거 기반에는 이러한 이상을 달성하는 데 필요한 단계를 뒷받침할 증거가 부족합니다. 이상적인 상태로 나아가기 위해서는 결과를 입증하고 증거 기반을 구축하기 위한 점진적인 연구가 필요합니다. UGRC는 UME-GME 전환 전반에 걸쳐 형평성을 우선시하지만, 블루 스카이 시스템조차도 모든 참여자에게 공평한 결과를 보장하지 못할 수 있음을 인식하고 있습니다.

While this manuscript explores major tensions in the UME–GME transition, authors recognize that other tensions exist as well. For example, the UGRC identified challenges in physician payment and salary as beyond the scope of the group’s charge. Envisioning the ideal state naturally entails imagining a system that does not yet exist, and as such, the evidence base currently lacks evidence to support the steps needed to achieve this ideal. To move toward the ideal state, incremental research is needed to demonstrate outcomes and build the evidence base. Despite prioritizing equity throughout the UME–GME transition, the UGRC recognizes that even a blue-skies system may not ensure equitable outcomes for all participants.

결론적으로, UGRC는 학습 및 건강 목표를 달성하는 데 필요한 시스템 설계를 안내하는 이상적인 상태를 구상했습니다. UGRC 회원들은 지속되는 주요 긴장을 인식했습니다.

- 평가의 목적: 순위 및 분류 지원 대 학습 지원

- 교육생의 역할: 학습자 대 근로자

- 개인의 필요와 희망 대 공동의 이익

학습자와 교육자는 이러한 긴장을 제거하거나 해결할 수는 없지만, 이를 인식하고 여러 이해관계자의 관점에 대한 협력과 개방성을 통해 이를 관리하는 데 다시 집중해야 합니다. 학습자와 프로그램 간의 적합성을 최적화하는 조율되고 효율적인 UME-GME 전환이라는 더 큰 비전에 대한 공동의 약속은 이를 달성하기 위해 필요할 수 있는 희생과 타협을 정당화합니다. 웰빙, 다양성, 형평성, 포용성, 공익에 대한 의료계의 약속에 초점을 맞추는 것은 시스템을 보다 이상적인 상태로 이끄는 데 매우 중요합니다.

In conclusion, the UGRC has envisioned an ideal state to guide system design needed to achieve learning and health goals. UGRC members recognized key tensions that persist around

- the purposes of assessment to support ranking and sorting versus learning,

- the roles of trainees as both learners and workers, and

- the needs and wishes of the individual versus the collective good.

While learners and educators cannot eliminate or solve these tensions, they must recognize them and refocus on managing them through collaboration and openness to multiple stakeholder perspectives. A shared commitment to the larger vision of a coordinated and efficient UME–GME transition that optimizes fit between learners and programs justifies the sacrifices and compromises that may be required to achieve it. Maintaining focus on medicine’s commitments to wellness, diversity, equity, inclusion, and the public good will be critical to guide the system toward a more ideal state.

Blue Skies With Clouds: Envisioning the Future Ideal State and Identifying Ongoing Tensions in the UME-GME Transition

PMID: 35947473

Abstract

The transition from medical school to residency in the United States consumes large amounts of time for students and educators in undergraduate and graduate medical education (UME, GME), and it is costly for both students and institutions. Attempts to improve the residency application and Match processes have been insufficient to counteract the very large number of applications to programs. To address these challenges, the Coalition for Physician Accountability charged the Undergraduate Medical Education to Graduate Medical Education Review Committee (UGRC) with crafting recommendations to improve the system for the UME-GME transition. To guide this work, the UGRC defined and sought stakeholder input on a "blue-skies" ideal state of this transition. The ideal state views the transition as a system to support a continuum of professional development and learning, thus serving learners, educators, and the public, and engendering trust among them. It also supports the well-being of learners and educators, promotes diversity, and minimizes bias. This manuscript uses polarity thinking to analyze 3 persistent key tensions in the system that require ongoing management. First, the formative purpose of assessment for learning and growth is at odds with the use of assessment data for ranking and sorting candidates. Second, the function of residents as learners can conflict with their role as workers contributing service to health care systems. Third, the current residency Match process can position the desire for individual choice-among students and their programs-against the workforce needs of the profession and the public. This Scholarly Perspective presents strategies to balance the upsides and downsides inherent to these tensions. By articulating the ideal state of the UME-GME transition and anticipating tensions, educators and educational organizations can be better positioned to implement UGRC recommendations to improve the transition system.

Copyright © 2022 by the Association of American Medical Colleges.

'Articles (Medical Education) > 임상교육(Clerkship & Residency)' 카테고리의 다른 글

| 임상진료상황에서 능숙한 의사소통가의 특징 식별하기(Med Educ, 2022) (0) | 2023.06.30 |

|---|---|

| 가능성과 불가피성: AI-관련 임상역량의 격차와 그것을 채울 필요성(Med Sci Educ. 2021) (0) | 2023.05.27 |

| 임상추론 교육을 위한 세 가지 지식-지향 교수전략: 자기설명, 개념매핑연습, 의도적 성찰: AMEE Guide No. 150 (Med Teach, 2022) (0) | 2023.05.11 |

| 임상적 의사소통의 생각, 우려, 기대에 대한 비판적 고찰(Med Educ, 2022) (0) | 2023.04.23 |

| 매듭 묶기: 임상교육에서 학생의 학습목적에 관한 활동이론분석(Med Educ, 2017) (0) | 2023.04.16 |