의학적 실천과 학습에서 사회물질성: 중요한 것에 조음하기(Med Educ, 2014)

Sociomateriality in medical practice and learning: attuning to what matters

Tara Fenwick

'과학뿐 아니라 의학에도 예술이 있고, 따뜻함, 동정심, 이해력이

외과의사의 칼이나 화학자의 약보다 더 클 수 있다는 것을 기억할 것이다.

‘I will remember that there is art to medicine as well as science, and that warmth, sympathy, and understanding may outweigh the surgeon's knife or the chemist's drug’.

서론

Introduction

히포크라테스의 이 말은 이상적이고 확률적인 의료 관행을 제시하고 있으며, 이타적인 환자 중심성에 지나치게 초점을 맞추고 있고, 현대 기술 과학의 복잡성과는 크게 관련이 없다는 것으로 잘못 해석될 수 있다. 그러나 이 발췌문에서는 환자가 중심 초점으로 고립되어 있지 않다. 분명한 것은 나이프와 화학 물질에 더하여, 지식 그 자체, 감정과 의미와 의료행위에는 [광범위한 사회적 힘뿐만 아니라 물질적 힘]이 발동한다는 것이다. 예술과 과학에 대한 매력은 [이성적 확실성과 학문discipline]만큼이나 [창조적인 불확실성과 즉흥성에 의존하는 광대한 세계]를 불러일으킨다. 또한 히포크라테스는 이러한 힘들, 사회적, 물질적 관계들, 그리고 이러한 관계들 속에서 의사의 함축적 의미들 사이의 상호작용을 지적한다. 실제로 히포크라테스는 의사에게 이러한 광범위한 관계 속에서의 참여자로 행동할 윤리적 책임을 부과하고 있다(I will remember 이라는 표현).

Hippocrates may be misinterpreted as presenting an idealised and probabilistic medical practice, overly focused on altruistic patient-centredness and not terribly relevant to the complexities of contemporary technoscientific medicine. Yet in this excerpt the patient is not isolated as the central focus. What is clear is the invocation of broad social as well as material forces in medical practice and knowledge per se, emotion and meaning alongside the knife and the chemical. The appeal to art and science evokes vast worlds that rely upon creative uncertainty and improvisation as much as rational certainty and discipline. Further, Hippocrates points to interplay among these forces, the relationships among the social and material, and the implication of the doctor amidst these relations. Indeed, Hippocrates clearly imposes an ethical responsibility on the doctor – ‘I will remember’ – to act as a participant within these broad relations.

전문적 실천과 학습에 대한 연구에서는 일상 업무의 이러한 사회적 물질적 관계를 왜 중요한가, 그리고 일상적 실천에 영향을 미치는 미시적 역학에 대해 우리를 맹목적으로 볼 수 있는 추상적 개념들이 어떻게 선택될 수 있는가 하는 측면에서 더 정확하게 이해하는 것에 대한 관심이 증가하고 있다. 사회 물질적 접근 방식에서 일하는 교육자들은 의료종사자에게 [실무, 지식 및 환경]을 한데 묶는 이 [일상적인quotidian 물질적 디테일]을 유의하도록 권고한다. – 단순히 연결고리에 매우 가깝게 조율하는 것뿐만 아니라, 조정하고 즉흥적으로, 끼어들고, 새로운 가능성을 포착하는 것도 가능합니다.

In studies of professional practice and learning more generally, there is growing interest in understanding these sociomaterial relations of everyday work more precisely in terms of why matter matters, and how the abstractions that can blind us to the microdynamics that influence everyday practices can be unpicked. Educators working from sociomaterial approaches are encouraging new practitioners to attend to these quotidian material details that stitch together their practice, knowledge and environments – not just to attune very closely to the connections, but also to tinker and improvise, to interrupt, and to seize emerging possibilities.

현재 문제

Current Issues

Mann1이 주장했듯이, [맥락]은 의료 실습과 실제 학습에서 중요하다. Mann은 학습이 개인의 인지 처리의 관점에서만 고려될 수 없다는 것을 보여 온 광범위한 연구자들에 합류한다. [학습의 내용과 과정]은 [특정 상황과 환자, 사용 가능한 도구, 기술, 사회적 관계 및 기타 환경적 역동]에 따라 크게 변화한다. [지식 '획득'과 전이transfer]라는 전통적인 은유는 ['참여'와 공동체에서의 적극적인 관여]라는 이해로 대체되고 있다. Mann은 '실천 공동체'에 초점을 맞춘 전문 교육, 경험적 학습 및 위치된 학습 환경에서의 어포던스가 널리 보급된 것을 정확하게 기록한다. 그녀는 이러한 ['사회 문화적' 학습] 관점이 의학 교육에 특히 유익하다고 결론짓는다.

As Mann1 has argued, context is critical in medical practice and learning in practice. Mann joins a broad river of researchers who have been showing that learning cannot be considered solely in terms of individual cognitive processing. The content and process of learning change dramatically with particular situations and patients, the tools available, technologies, social relations and other environmental dynamics. Conventional metaphors of knowledge ‘acquisition’ and transfer are being replaced with understandings of ‘participation’ and active engagement in communities. Mann2 accurately documents the widespread uptake in professional education of focus on ‘communities of practice’,3 experiential learning and affordances in situated learning environments. She concludes that these ‘socio-cultural’ learning perspectives are particularly fruitful for medical education.2

실제로, [사회문화적 지향]은 [지식은 [과학에 의해 개발되고, 실무자에 의해 구현]되는 것이라는 [고정된 개념]]을 가로막는 것으로서, 전문직 연구 전반에 걸쳐 중요하게 여겨졌다. 그러나, 실천적 접근은 보수주의, 관리주의, 직장에서의 권력 관계의 제한된 분석뿐만 아니라, '공동체'와 전문적 업무에서의 실천에 대한 일반적이고 거의 낭만적인 개념으로 비판을 받아왔다.

Indeed, socio-cultural orientations have been important across professional studies for interrupting fixed notions of knowledge as developed by science and implemented by practitioners. However, the community of practice approach has been critiqued not only for its conservatism, managerialism and limited analysis of power relations in workplaces, but also for its generalised and almost romantic notions of both ‘community’ and practice in professional work.4, 5

추가 이슈는 더 자세히 개발될 것입니다.

- 첫째, 연구자들은 재료들이 능동적으로 실천과 지식을 구성하는 방법에 대해 훨씬 더 많은 인식을 요구해 왔다.

- 둘째로, 학생을 포함한 의료 종사자들이 직면하고 있는 실질적인 도전은 단지 다른 관점이나 의미뿐만 아니라 서로 다른 온톨로지, 즉 서로 다른 사회 물질 '세계'가 수행되고 있다는 측면에서 점점 더 이해되고 있다.

- 셋째, 증거 기반 프로토콜과 일상적인 실습 사이의 단절에 대한 구체적인 문제가 소개되어 의료 학습에서 이러한 일반 모델의 역할과 실습의 복잡성에서 정확히 무슨 일이 일어나고 있는지에 대한 의문이 제기된다.

이 절을 통해 알 수 있듯이, 이러한 문제를 해결하기 위해 고군분투하는 연구자들은 새로운 이론에 도달했다. 이것들은 여기서 사회 물질적 접근이라고 널리 언급되며, 다음 절에서 설명될 것이다. 먼저, 이러한 접근법으로 이어지는 현재 문제의 예를 살펴보자.

Further issues will be developed in more detail.

- Firstly, researchers have pressed for much more recognition of the ways that materials actively configure practice and knowing.

- Secondly, practical challenges facing medical practitioners including students are increasingly being understood in terms of different ontologies – different sociomaterial ‘worlds’ being performed – not just different perspectives or meanings.

- Thirdly, specific challenges about the disconnection between evidence-based protocols and everyday practice are introduced, raising questions about the roles of these general models in medical learning, as well as about what exactly is happening in the complexities of practice.

As we see throughout this section, researchers grappling with these issues have reached for new theories. These are broadly referred to here as sociomaterial approaches, and will be explained in the subsequent section. First, let us examine examples of current issues leading to these approaches.

놓치고 있는 것

Missing matter

물질matrerial(things that matter)은 종종 학습을 설명할 때 누락된다. 물질은 [인간 행동의 배경의 일부로 무시]되거나, [의식과 인식에 대한 선입견에서 무시]되거나, [인간의 의도와 설계에 종속된 그저그런brute 도구의 지위]로 밀려나는 경향이 있다. 그러나 의료 실무에서 항생제 및 진통제, 기관지 확장제 및 심전도, 카테터 및 복강경, 정책, 데이터베이스 및 프로토콜 등 특정 환경에서 사용할 수 있는 특정 종류의 재료와 그에 따른 권한의 가중치는 의료 지식뿐만 아니라 의료 지식도 근본적으로 형성한다. 맥락이 중요할 수는 있지만, 단순히 맥락을 [추상적인 컨테이너]로 이해하는 것은, 이 무수한 [비인간적 요소들]뿐만 아니라 맥락의 특정한 역학을 형성하는 [인간 요소들] 사이의 관계의 소란을 놓치는 것이다. 스톨리 박사는 환자의 안전이 종종 물질성에 대한 주의 부족으로 인해 위험에 처한다고 주장한다. 복강 내부에 밸브가 거의 남겨둘 뻔한 프로시져나, 가파른 기울기에서 마찰이 없는 테이블 매트를 가로질러 미끄러질 때 환자가 거의 떨어질 뻔한 사건을 포함하여, [환자, 보건의료인, 루틴과 함께 작용하는 물체 사이의 관계에서, 어떤 방식으로 서로를 변형시켜 위험한 상황을 만드는지]를 보여준다. 스들리는 의사들이 물질들이 실제로 어떻게 작용하는지에 대한 미시적인 세부사항들에 훨씬 더 익숙해지는 법을 배워야 한다고 주장한다.

Materials – things that matter – are often missing from accounts of learning. Materials tend to be ignored as part of the backdrop for human action, dismissed in a preoccupation with consciousness and cognition, or relegated to the status of brute tools subordinated to human intention and design. Yet clearly in medical practice, the particular kinds of materials available and the weight of authority ascribed to them in certain settings – antibiotics and analgesics, bronchodilators and electrocardiograms, catheters and laparoscopes, policies, databases and protocols – fundamentally shape practice as well as medical knowledge. Context may be critical, but to understand context simply as an abstract container is to miss the turmoil of relationships among these myriad non-human as well as human elements that shape, moment to moment, particular dynamics of context. Bleakley6 contends that patient safety is frequently put at risk precisely by lack of attention to materiality. His examples, which include that of a procedure in which a valve was almost left inside an abdominal cavity, and that of an incident in which a patient almost fell when a gel mat slid across a frictionless table mattress in a steep tilt, show how it is the relationships among objects acting together with patients, health personnel and routines that transform one another to create risky situations. Bleakley argues that doctors must learn to become much more attuned to the micro-details of how materials act in practice.6

'물질적 퍼포먼스'로서의 실질적인 과제

Practical challenges as material performances

의학교육의 주요 과제 중, 의과대학에서 의과대학으로의 주니어 의사들의 문제적 전환과 이러한 전환에 수반되는 오류에 대한 일반적인 위험은 친숙한 논의 주제이다.7 그러나, 최근의 연구는 물질적 세계가 어떻게 과도기를 수행하는 의사들의 학습에 관여하는지에 대해 더 가까이서 관찰했다. 예를 들어, Kilminster 등은 기존의 학습 모델들이 의대생들이 접하는 [일상적인 물질적 장벽]이나 [이러한 문제를 해결하기 위해 배우는 즉흥성]을 설명하지 않는다는 것을 발견했다. Orlikowski에 따라, 우리는 학생들의 정체성과 활동이 [특정한 행위를 구성하는데 작용하는 물질적 대상과 테크놀로지]와 관련하여 수행된다고 말할 수 있다.

Among the major challenges in medical education, the problematic transition of junior doctors from medical schools to wards and the general risks for error that accompany these transitions are a familiar topic of discussion.7 However, recent studies have attended more closely to how material worlds are involved in the learning of doctors undertaking transition. Kilminster et al.,8 for example, have found that conventional models of learning do not explain the everyday material barriers that medical students encounter or the improvisations they learn to work around these problems. We could say, following Orlikowski,9 that students’ identities and activities are performed into being, in relation with the material objects and technologies that act to configure particular practices.

[새로운 테크놀로지]는 (초보자들에게 뿐만 아니라) 지속적인 실질적인 도전을 제기한다. 이러한 구현은 여전히 합리주의적인 [습득-및-전이 모델]에서 진행되며, 종종 직원 워크숍(인쇄된 정보의 큰 바인더로 완성됨)에 이어 실제 구현을 모니터링하기 위한 평가까지 이어진다. 그러나 연구자들은 [구현의 실패]는 많은 물질적 요인에 달려 있으나, 그것은 거의 인식되지 못한다는 것을 발견했다. Allan은 환자 안전과 같은 새로운 통합 치료 경로가 종종 다른 논리를 따르고 다른 실천의 세계를 수행하는 기록 보관 공예품과 같은 기존의 물질적 인프라를 어떻게 방해하는지를 보여준다(범용화된 시스템이 아닌 개별화된 환자 기록). [새로운 시스템]은 말 그대로 [새로운 실천의 세계]를 도입하여, 상충되는 일련의 퍼포먼스를 생산한다. 그러나 임상의사들은 여러 퍼포먼스를 동시에 저글링하는 데 능숙하기 때문에, 앨런이 기록한 바와 같이, [서로 연결되지 않는 문서 기록물]이 쏟아져 나온다.

New technologies also pose continual practical challenges, and not only to novices. The implementation of these still tends to proceed from a rationalist acquire-and-transfer model, often through staff workshops (complete with large binders of printed information) followed up with appraisals to monitor implementation in practice. Yet researchers are finding that failure to implement relies on a host of material factors that are rarely acknowledged. Allan shows how new integrated care pathways, such as for patient safety, often interfere with existing material infrastructures such as record-keeping artefacts that follow a different logic and perform a different world of practice (individualised patient records rather than a universalised system).10 New systems literally introduce a new world of practice, producing a conflicting set of performances. Clinicians, however, are adept at juggling multiple performances simultaneously, and thus results the flurry of paper records that don't connect, as Allan10 documents.

또한, 전문직군 간 의료행위IPP는 의료 분야에서 주요 과제를 계속 제시하는데, 이는 [임상의사들 사이의 우선순위 및 언어, 중복되지만 결합되지 않은 서비스, 상호 신뢰 문제] 등과 관련이 있다. 이러한 문제에 대한 사회적, 문화적 해석을 넘어, 연구자들은 [전문 분야 간 실무에서 물질적 협상]에 점점 더 초점을 맞추고 있다. 그들은 특정 임상의사 그룹에게 특히 중요한 [기구나 텍스트]가, 어떻게 독특한 접근방식을 중개하거나, 심지어는 고정anchor시키는지 추적한다. 그들은 또한 서로 다른 실무자들이 서로 다른 방법, 다른 구체화된 관행 및 다른 인프라로 서로 다른, 심지어 상충되는 사회 물질 세계를 실제로 어떻게 수행하는지 보여준다. 이러한 연구는 현재 [서로 다른 물질적 '온톨로지'] 및 [의료종사자는 그 안에서 그리고 그것들 사이에서 일하는 법을 어떻게 배우는지]에 대해 중요한 질문을 제기하고 있으며, 그 내용은 나중에 더 언급될 것이다.

In addition, interprofessional practice continues to present major challenges in health care, which concern conflict in the priorities and languages of different clinicians, services that overlap but are not joined up, issues of mutual trust, and so forth. Moving beyond social and cultural interpretations of these issues, researchers have increasingly focused on material negotiations in interprofessional practice.11, 12 They trace how instruments or texts that have particular importance for different groups of clinicians mediate and even anchor their unique approaches. They also show how different practitioners actually perform different, even conflicting, sociomaterial worlds with different methods, different embodied practices and different infrastructures. These studies are now raising significant questions about different material ‘ontologies’ and how practitioners learn to work within and across them, about which more will be said later.

증거 기반 관행은 어디에서 왔는가?

Whence Evidence-Based Practice?

근거 기반 관행은 [통제, 즉 바람직한 결과를 도출하리라고 신뢰할 수 있는 표준화된 프로토콜]의 이상을 가정한다. 그러나 프로토콜은 [실천의 중요한 세부 사항을 추적]해보면, [종이에 나타나는 것보다, 또는 대부분의 실무자들이 인정하는 것보다] 훨씬 더 조건에 따라 달라짐contingent이 입증되었다. 실제로, [표준화된 관행]은 종종 일부 환경에서 문제가 있을 뿐만 아니라, 비판적이고 유연한 사고를 억제하는 퇴적된sedimented 패턴을 나타낸다. 예를 들어, 그루프먼은 이러한 퇴적된 패턴에서 얼마나 많은 의학적 진단 오류가 발생하는지 보여줍니다.

- 가용성 진단(자신의 물질적 현실에서 가장 빈번한 것으로부터 해결책을 제시함)

- 앵커링(물질적 현실을 가장 친숙하거나 바로 보이는 하나의 강력한 세부 사항과 결합한다),

- 또는 확증 편향(선입견이나 희망적 사고에 맞는 물질적 현실을 제시함)

Evidence-based practice presumes an ideal of control, of standardised protocols that can be relied upon to produce desirable results. Yet protocols have proven to be far more contingent when one traces the material details of practice than they ever appear on paper, or than most practitioners are prepared to admit.13, 14 Indeed, standardised practices often represent sedimented patterns that are not only problematic in some settings, but also stifle critical and flexible thinking. For example, Groopman15 shows how many patterns of medical diagnostic error accrue from these sedimented patterns, referring to

- availability diagnosis (selecting a solution from those most frequent in one's material reality),

- anchoring (framing material reality with one powerful detail that is most familiar or immediately visible), or

- confirmation bias (wanting material reality to fit one's preconceptions or wishful thinking).

슈베르트와 같은 다른 사람들은 [의료행위의 우발성contingency과 부분적 해결책]을 조사하여 [신체, 기구, 기타 상충되는 프로토콜, 조직 환경의 특정 물질적 제한]에 의해 [프로토콜이 어떻게 수정되는지]를 보여주었다. 네덜란드의 한 병원에서 당뇨병 관리를 관찰하는 그녀의 오랜 연구에서, Mol17은 임상 실습이 형태를 만들고 변화하는 것을 지켜봤고, 그것들이 '끝없이 구체적이고 놀랍다endlessly specific and surprising'고 결론지었다. 깔끔하고 체계적인 치료 계획 및 프로토콜에도 불구하고 일상적인 치료는 [다루기 힘든 물질에 지속적으로 적응]해야 합니다.

- 기술과 신체는 행동하지 않을 수 있다;

환자들은 실수하고 싶은 유혹을 받을 수 있다.

그리고 모든 종류의 지저분하고, 냄새나고, 피비린내 나고, 무섭고, 지루한 활동들은 하기 어렵다.

Others, like Schubert,16 have examined the contingency and partial solutions of medical practice, showing how any protocol becomes modified by particular material limitations of bodies, instruments, other conflicting protocols, and organisational settings. In her lengthy study observing diabetes care in a Dutch hospital, Mol17 watched clinical practices taking shape and shifting, and concluded that they were ‘endlessly specific and surprising’. Despite neat and systematic treatment plans and protocols, daily care must continually adjust to unruly materialities:

- technologies and bodies may not behave;

patients may be tempted to err,

and all sorts of messy, smelly, bloody, frightening and tedious activities are difficult to do.

Mol은 '과제를 숙달했더라도, 통제는 착각이다Control is an illusion even if you master the tasks'라고 결론짓는다. 거의 같은 방식으로 그루프만의 의사들은, 이용할 수 있는 의학 지식의 한계와 만일의 사태에 대한 불확실성이 있어서, 대부분 '그냥 만들어낸 것'이라고 주장한다. 그렇다면 지식, 기술, 증거 기반 프로토콜에 대한 숙달이 아니라면, 의료 관행이란 무엇일까요? 분명히, 물질은 중요하지만, 정확히 사회물질적 관점이 무엇이며, 이것들이 학습과 어떻게 관련이 있는가?

Mol concludes that ‘Control is an illusion even if you master the tasks’.17 In much the same way, Groopman's doctors claim they are, mostly, ‘just making it up’, given the limitations in available medical knowledge and the uncertainties of contingency.15 So if it is not mastery of knowledge, skill and evidence-based protocols, what then is medical practice? Clearly, materials matter, but what exactly are sociomaterial perspectives and how are these relevant to learning?

사회 물질적 관점

Sociomaterial Perspectives

사실, 다양한 이론들은 각각 다른 관점과 목적을 가진 '사회물질적(인 것)'이라고 기술될 수 있다. 이 간략한 기사의 목적은 이러한 이론에 걸쳐 공유된 특정 약속과 접근 방식에 대한 매우 일반적인 소개를 제공하는 것이다. 물론 이 전술의 위험은 유용한 이론적 세부사항과 토론이 불가피하게 모호해지고, 지나치게 단순화되거나 생략될 것이라는 점이다. 그러나 이러한 새로운 이론적 지형의 다른 지역에서 열린 의료 실무와 교육에 대한 기여의 범위와 질문을 지적하는 데 있어 얻을 수 있는 이점이 있다. 여기서는 특히 어떤 하나의 이론을 유일한 또는 '최고의' 사회 물질적 접근법으로 홍보하는 것은 피할 것이다.

In fact, a range of theories can be described as sociomaterial, each with distinct perspectives and purposes. The objective of this brief article is to provide a very general introduction to certain shared commitments and approaches across these theories. The danger of this tactic, of course, is that useful theoretical details and debates necessarily will be obscured, over-simplified or omitted. However, there are advantages to be gained in pointing to the range of contributions and questions for medical practice and education that are opened in different regions of this new theoretical landscape. This also avoids promoting any one theory in particular as the only or ‘best’ sociomaterial approach.

이 모든 관점이 공유하는 첫 번째는, [일상 업무에서 인간 활동과 맞물려 있는 역동적인 물질에 초점]을 맞추는 것이다. 이것은 Orlikowski9가 '사회와 물질의 구성적 얽힘'이라고 표현한 것이다.

'물질'은 유기적이고 무기적이며, 테크놀로지적, 자연적으로 존재하는 우리 삶의 모든 일상적 물질들을 말합니다:

- 살과 피, 형태와 체크리스트, 진단 기계와 데이터베이스, 가구와 패스워드, 눈보라, 죽은 세포 구역 등.

'사회적'은 상징과 의미, 욕망과 두려움, 문화적 담론을 의미한다. 물질적 힘과 사회적 힘 모두 일상적 활동을 이끌어내는 데 상호 연관되어 있다.

What all of these perspectives tend to share, first, is a focus on materials as dynamic and enmeshed with human activity in everyday practices. This is what Orlikowski9 describes as ‘the constitutive entanglement of the social and material’.

‘Material’ refers to all the everyday stuff of our lives that is both organic and inorganic, technological and natural:

- flesh and blood; forms and checklists; diagnostic machines and databases; furniture and passcodes; snowstorms and dead cell zones, and so forth.

‘Social’ refers to symbols and meanings, desires and fears, and cultural discourses. Both material and social forces are mutually implicated in bringing forth everyday activities.

이것은 [(비록 객체와 연결을 발달시키는 분리된 주체이지만) 객체와 주체가 [상호 작용inter-act]한다]는 가정을 넘어서는 관계에 대한 이해이다. 대신에, [사회 물질적 설명]은 물리학자 바라드가 자연, 기술, 인간성, 모든 종류의 물질의 이기종 요소들의 [내부 작용intra-action]이라고 설명하는 것을 조사한다. 이러한 [요소들과 힘들은 서로 [침투]하여 (그럼으로써 함께 작용하여)], 일상 생활의 [견고한, 분리된, 불변의 물체처럼 보이는 것]을 이끌어낸다. 파동이나 입자와 같은 것들은 우리가 일상적인 물질들을 관찰하고, 일하고, 의미를 만들기 위해 사용하는 바라드가 말하는 'apparatuses'에 따라 특별한 방식으로 나타난다. 우리가 apparatuses를 관찰하고 작업하면서, 우리는 주체와 객체를 정의하는 범주를 만듭니다. 물질의 이러한 '절단'은 (주체와 물체, 활동 및 현상)을 정의하는 경계를 만들지만 [새로운 가능성]을 열어준다. 인과관계를 [원인과 결과 사이의 선형적 관계]가 아니라, [놀라운 효과를 만들어내는 얽힘]을 지칭하는 것으로 다시 생각하는 것이다.

This is an understanding of relationships that pushes beyond assumptions that objects and subjects inter-act, as though they are separate entities that develop connections. Instead, sociomaterial accounts examine what the physicist Barad18 describes as the intra-actions of heterogeneous elements of nature, technologies, humanity and materials of all kinds. These elements and forces penetrate one another – they act together – to bring forth what appear to be the solid, separate, immutable objects of everyday life. Things like waves or particles emerge in particular ways according to what Barad18 calls the ‘apparatuses’ that we use to observe, work with, and make meaning of everyday materials. As we observe and work with them, we create categories that define subjects and objects. These ‘cuts’ in matter create boundaries that define (subjects and objects, activity and phenomena) but also open new possibilities. This is a rethinking of causality as referring to entanglements with surprising effects, not linear relations between causes and effects.

여러 이론이 공유하는 두 번째 이해는 이것이다. [모든 물질 또는 더 정확히 말하면, 모든 [사회물질적 객체objects]는 사실 [이질적인 집합체]라는 것입니다. 그것들은 자연적, 기술적, 인지적 요소들의 이질적인 모임이다. 모든 개체는 도구, 장비, 프로토콜 또는 증거에 관계없이 이러한 모임의 역사history를 [설계와 축적된 사용]을 협상할 때 포함시킨다. 의학이나 의학교육의 특정한 관행을 연구할 때, 연구자들은 특정한 요소들이 어떻게 그리고 왜 조립되는가, 왜 어떤 요소들은 포함되고 다른 요소들은 제외되는가, 그리고 가장 중요한 것은 요소들이 그들이 활동할 때 어떻게 변화하는지 묻는다. 스들리는 행위자-네트워크 이론(ANT)과 같은 분석을 위한 사회 물질적 프레임워크가, 의학 교육에 명백하게 유용함에도 불구하고, 사람과 사물 사이의 관계를 강조하는데 일반적으로 사용되지 않는 것에 놀랐다고 선언한다. 이러한 관계를 통해, 사람과 사물은 새로운 문제나 가능성을 만들기 위해 서로를 번역한다.

This is a second shared understanding: that all materials or, more accurately, all sociomaterial objects, are in fact heterogeneous assemblages. They are gatherings of heterogeneous natural, technical and cognitive elements. All objects embed a history of these gatherings in the negotiation of their design and accumulated uses, whether they are instruments, equipment, protocols or evidence. In examining particular practices of medicine or medical education, researchers ask how and why particular elements become assembled, why some elements are included and others excluded, and, most importantly, how elements change as they come together, as they intra-act. Bleakley6 declares that sociomaterial frameworks for analysis, such as actor–network theory (ANT), are so obviously useful to medical education he is surprised they aren't commonly used to highlight the relationships among people and objects. Through these relationships, people and objects translate one another to create new problems or possibilities.

셋째, 사회 물질적 관점은 인간과 비인간, 하이브리드 및 부품, 지식과 시스템 등 [모든 것을 연결과 활동의 효과]로 본다. 모든 것은 [관계의 거미줄]에서 수행된다. '행위자agents, 그들의 차원, 그들의 존재와 행동은 모두 그들이 관여하는 관계의 형태에 달려 있다.' 물질은 inert한 것이 아니라 enacted된다. Materials은 물질matter이며, 중요하다matter. 다른 유형의 사물 및 힘과 함께, [물질materials는 활동activity을 배제하고, 초대하고, 규제하기 위해 행동act]한다. 이것은 물체에 에이전시가 있다고 주장하는 것이 아니다. 바늘은 정맥에 저절로 들어가지 않는다. 그러나, 캐뉼러에서, 많은 것들이 의사의 손과 함께 결합되어 작용한다: 정맥 직경 및 벽 구성, 흐름, 바늘 크기, 이전 캐뉼러 부위, 박테리아, 환자 상태, 경쟁 병동 요구 등. 어떤 의료 행위도, 개인의 능력만의 문제가 아니며, 집합적 사회물질적으로 집행된다.

Thirdly, a sociomaterial perspective views all things – human and non-human, hybrids and parts, knowledge and systems – as effects of connections and activity. Everything is performed into existence in webs of relations: ‘the agents, their dimensions and what they are and do, all depend on the morphology of the relations in which they are involved’.19 Materials are enacted, not inert; they are matter and they matter. They act, together with other types of things and forces, to exclude, invite and regulate activity. This is not to argue that objects have agency: a needle does not hop into a vein by itself. Yet, in cannulation, many things act in assemblage with the doctor's hands: vein diameter and wall composition; flow; needle size; previous cannulation sites; bacteria; the patient's condition; competing ward demands, and so on. Any medical practice is a collective sociomaterial enactment, not a question solely of an individual's skills.

서로 다른 관심사와 접근 방식

Different interests, different approaches

보다 심층적인 탐구에 관심이 있는 사람들을 위해, 이러한 사회 물질적 관점에 대한 완전한 입문서는 다른 곳에서 이용할 수 있다. 전문적 실천과 학습에 대한 현대 연구에서 가장 자주 나타나는 것은 ANT와 '애프터 ANT', 실천 이론, 복잡성 이론, 새로운 지리학, '새로운 유물론' 및 활동 이론이다. 행위자-네트워크 이론은 후기구조주의 지향에서 등장하며, 라투르와 몰과 같은 주요 저자들 사이의 많은 내부적 경쟁을 감안할 때, 이론이라기보다는 감성의 확산 구름에 가깝다. '관계적 중요성', '물질적 기호학', STS(과학기술 연구), '사회-기술' 연구와 같은 문헌의 많은 용어들은 ANT와 core commitment을 공유한다. 그것의 지속적인 영향력은 네트워크화된 현실관이며, 특정한 활동, 사물 및 지식을 생성하기 위해 지속적으로 조립하고 재조립하는 '네트워크'의 동등한 기여자로서 인간과 비인간 요소를 급진적으로 다루는 것이다. 교육에 대한 ANT와 '애프터 ANT' 연구에 대한 장문의 토론을 이용할 수 있다.

For those who are interested in more in-depth exploration, a full primer to these sociomaterial perspectives is available elsewhere.20 Those that appear most frequently in contemporary research of professional practice and learning include ANT and ‘after-ANT’ approaches, practice theory, complexity theory, new geographies, ‘new materialisms’, and activity theory. Actor–network theory emerges from post-structural orientations, and is more of a diffuse cloud of sensibilities than a theory given its many internal contestations among key writers such as Latour21 and Mol.11, 17 Many terms in the literature, such as ‘relational materiality’, ‘material semiotics’, STS (science and technology studies) and ‘socio-technical’ studies share core commitments with ANT. Its lasting influences are a networked view of reality, and a radical treatment of human and non-human elements as equal contributors to the ‘networks’ that continually assemble and reassemble to generate particular activities, objects and knowledge. A lengthy discussion of ANT and ‘after-ANT’ studies in education is available.22

[복잡성 이론]은 상당히 다른 지향을 가지고 있다. 그것은 사회학에서가 아니라 주로 진화생물학과 물리학(사이버네틱스 및 일반 시스템 이론)에서 나타나는 또 다른 범위의 경쟁적 접근을 수용한다. Barad와 같은 복잡성 이론가들은 전문직 교육에 대한 연구에서 특히 영향력을 갖게 되었고, 우리가 아는 실천에서 '발현emergence', 회절 및 연결성의 역학을 연구할 것을 제안한다. 새로운 인간과 문화적 지형에 눈을 돌리면, 이 이론들은 그들이 어떻게 사회적 생산을 돕는지 보여주기 위해 전문적 실천의 물질적 공간과 장소를 조사하지만, 또한 인간의 활동과 의미에 의해 생산된다. 펜윅 등에서는 도린 매시, 데이비드 하비, 나이젤 트리프트, 앙리 르페브르와 같은 지리학자들이 널리 인용되고 있다. 그러나 교육에서 많은 관심을 끌고 있는 또 다른 연구 분야는 스스로를 '새로운 유물론new materialisms'을 언급하는 것으로 묘사하고 있다. 이들은 종종 특정 사회적, 물질적 힘이 어떻게 매우 다른 존재의 방식을 만들어내는지 조사하기 위해 immanence, 창의성, 집합성의 아이디어와 같은 철학자 질 들뢰즈의 아이디어에서 작업한다.

Complexity theory is quite different in orientation; it embraces another range of competing approaches emerging not from sociology, but chiefly from evolutionary biology and physics (as well as cybernetics and general systems theories). Complexity theorists such as Barad18 have become particularly influential in studies of professional education, and suggest that we examine dynamics of ‘emergence’, diffraction and connectivity in practices of knowing. Turning to new human and cultural geographies, these theories examine the material spaces and places of professional practice to show how they help produce the social, but are also produced by human activity and meaning. In professional education research as explained in Fenwick et al.20, geographers such as Doreen Massey, David Harvey, Nigel Thrift and Henri Lefebvre are widely cited. Yet another branch of studies that is gaining much traction in education describes itself as referring to the ‘new materialisms’.23, 24 These often work from the ideas of the philosopher Gilles Deleuze, such as those of immanence, creativity and assemblage, to examine how particular social and material forces bring forth very different ways of being.

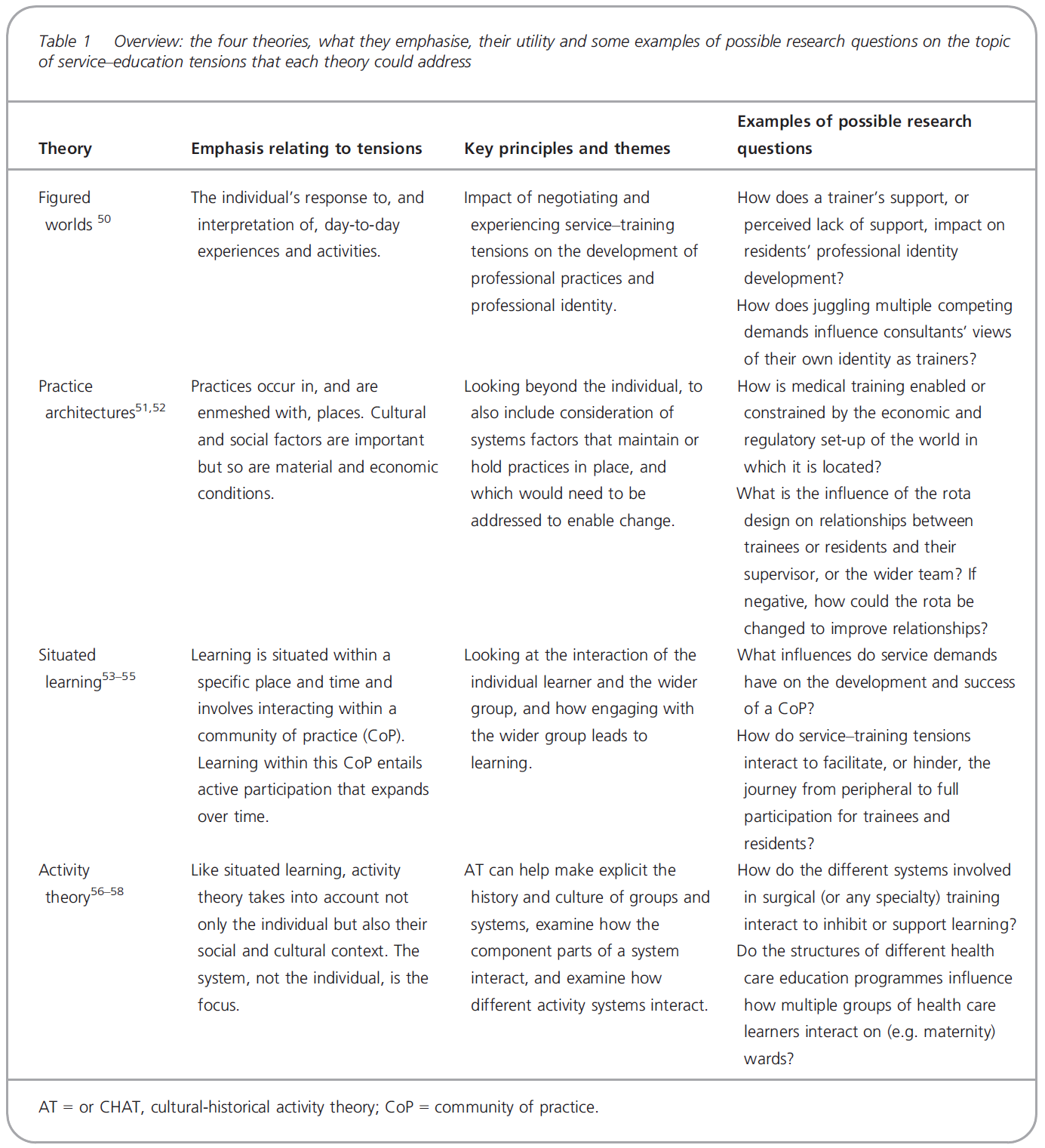

분명히 이 짧은 기사는 전문 학습 연구에서 점점 더 중요해지고 있는 'practice theory'을 홍보하는 것을 포함하여 사회 물질적 초점과 관련된 많은 추가적인 관점을 다룰 수 없다. 이 모든 이론의 한계에 대한 논의도 여기서 생략한다. 예상대로 비판과 반론자들이 넘쳐나고, 다른 곳에서 발견될 수도 있다. 그러나 배제된 한 가지 특히 두드러진 관점은 어느 정도 설명할 가치가 있다. 바로 [문화-역사 활동 이론, CHAT]으로, 엥게스트룀의 전문적인 연구에 가장 많이 관련되어 있다. 이 이론은 건강관리 연구에서 널리 채택되었고 방법론적으로 철저히 개발되었다. 그러나, 그것의 세계관과 지식의 본질은 여기서 설명하는 다른 이론 분야에서 채택된 입장과 질적으로 다르다.

- 첫째, 다른 것들은 본질적으로 후기구조주의적이고 비규범적인 반면, CHAT는 자본주의 생산의 관계와 활동 시스템의 내부 모순에 대한 구조적인 마르크스주의 설명에 뿌리를 두고 있다.

- 둘째로, CHAT는 인간 활동 시스템을 중재하는 데 도움이 되는 물질적 유물의 중요성을 인정하지만, 이것은 인간 활동(예: 노동, 문화적 규칙과 언어, 시스템에서 인간의 목적과 의미 등)에 대해 가지는 중심적 관심사에 이어 부수적인 것secondary이다.

Obviously this short article cannot address the many additional perspectives relevant to a sociomaterial focus, including those promoting ‘practice theory’, which are increasingly important in studies of professional learning.25, 26 Also omitted here are discussions of all these theories’ limitations. Critique and rejoinders abound, as one might expect, and may be found elsewhere.20 However, one particularly prominent perspective that has been excluded deserves some explanation: this is cultural–historical activity theory or CHAT, most associated in professional studies with Engeström.5 This theory has been widely taken up in health care research and is thoroughly developed methodologically. However, its views of the world and the nature of knowledge arguably differ qualitatively from the positions adopted by the other theory fields described here.

- Firstly, whereas the others are essentially post-structural and non-normative, CHAT is rooted in a structural Marxist explanation of the relations of capitalist production and the internal contradictions of activity systems.

- Secondly, whereas CHAT acknowledges the importance of material artefacts that help mediate human activity systems, this is secondary to its central concern for human activity, which encompasses the division of labour, cultural rules and languages, and the human purposes and meanings in the system.

따라서, CHAT는 의학 교육 연구자들에게 분명히 중요하지만, 그것의 다른 지향의 결과로, 그것은 이 기사를 위해 남겨지고 있다. 여기서 '사회 물질' 이론이 의미하는 것은 ANT, 복잡성 이론, 새로운 지리 및 새로운 물질주의에서 발생하거나 영향을 받는 이론이다. 이것들은 [실천]이란 [인간 이상의 것]이며, 활동과 학습을 이해하기 위해서는 [인간의 의미와 인간 에이전시에 대한 선입견을 넘어설 필요가 있다]는 가정으로부터 시작된다.

Thus, CHAT is clearly important for medical education researchers, but, as a consequence of its different orientation, it is being set aside for this article. Here, what is meant by ‘sociomaterial’ theories are those accruing from or influenced by ANT, complexity theory, new geographies and new materialisms. These begin with the assumption that practice is more than human, and that to understand activity and learning we need to move beyond preoccupations with human meanings and human agency.

물질이 어떻게 실무 및 프로토콜에 중요한가

How matter matters in practices and protocols

Barad는 다음과 같이 쓰고 있다: '앎을 실천하는 것은 세상을 재구성하는 [특정한 물질적 참여]에의 관여이다.'

Barad writes: ‘Practices of knowing are specific material engagements that participate in (re)configuring the world’.18

물질적 참여와 얽힘entanglement로서의 건강 관리 관행에 대한 면밀한 검토는 실제로 [실천이 고유한 사회 물질적 세계를 형성한다]는 것을 보여주었다. Mol11의 고전적인 연구는 실험실, 의사-환자 진료소, 방사선과, 수술실에서 제정된 이후, 하퇴부 동맥경화증의 치료법을 조사했다. Mol은 죽상동맥 경화증이 이러한 각각의 연습 환경에서 매우 다른 것으로 구체화되었다고 결론지었다. [방법, 담론, 기구의 고유한 집합]마다 서로 다른 세상을 만들었을 뿐만 아니라, 각 환경에서 다른 대상(즉 서로 다른 죽상동맥 경화증)을, 서로 다른 진단 및 치료와 함께 만들었다. 그런 다음 실용적인 질문은 우리가 어떻게 서로 다른 실천 속 앎(knowing-in-practice)세계를 결합할 수 있는지 언급하는데, 비록 그들이 그들 나름의 방법으로 [사회물질적 구성]을 통해 [다른 대상]을 생산하지만, 각각은 [같은 대상]에 관여하는 것처럼 보인다. 증거 기반 관행은 각 환경에서 기능하는 것은 의심의 여지가 없지만, 우리가 근본적인 차이를 이해하고 그들 사이에서 협상하려면 더 광범위하고 유연한 조정이 필요할 수 있다.

Close examination of health care practice as (socio) material engagement and entanglement has shown that, in fact, practices form unique sociomaterial worlds. A classic study by Mol11 examined the treatment of lower-limb atherosclerosis, following its enactment in the laboratory, doctor–patient clinic, radiology department and operating theatre. Mol11 concluded that atherosclerosis materialised as a very different thing in each of these practice settings. A unique assemblage of methods, discourses and instruments not only created a different world, but also produced a different object – a different atherosclerosis – in each setting, with different diagnostics and treatments. The practical question then refers to how we might patch together these different worlds of knowing-in-practice, which each appear to be engaging with the same object, even though they are producing a different object through the sociomaterial configurations of their own methods. Evidence-based practices are no doubt functioning in each setting, but a broader, more flexible attunement may be necessary if we are to appreciate fundamental differences and negotiate among them.

표준화된 프로토콜의 실제 사회 물질적 관행에 대한 연구는 사실, 엄격한 프로토콜조차도 항상 일종의 유연한 팅커링과 함께 독특한 방식으로 수행된다는 것을 발견했다. 급성 치료 환경에서 심폐소생술을 시행한 한 연구에서, 티머먼스와 버그는 80건 대부분의 경우에서 [프로토콜이 의도한 대로 지켜지지 않는다는 것]을 발견했다. 명시되지 않은 약물이 도입되었고, 절망적인 환자, 불안한 가족 또는 사용할 수 없는 장비의 경우 엄격한 지침이 변경되었다. 다시 말해서, 소위 표준이라고 불리는 것은, 실제로는 상호 작용interplay이며, 저자들이 '지역적 보편성local univerality'이라고 부르는 것에서 항상 새롭게 수행된다.

Research into the actual sociomaterial practice of standardised protocols has found that, in fact, even strict protocols are always performed in unique ways with a sort of flexible tinkering. In one study of cardiopulmonary resuscitation practice in acute care settings, Timmermans and Berg27 found that in most of 80 cases protocol was not followed as intended. Drugs not specified were introduced, strict directives were altered in instances of hopeless patients, anxious families or non-available equipment. In other words, so-called standards are actually interplays, always performed anew in what the authors call ‘local universality’.27

더욱이, 의료 행위 표준의 사회적 중요성을 더 광범위하게 조사하여, 티머먼스와 버그는 [프로토콜이란 것이 어떤 방식으로 일시적인 성취인지] 보여준다. 프로토콜 설계자, 기금 기관, 관련된 의사들의 다양한 그룹, 환자의 희망과 욕망, 조직 시설, 실험실 능력, 제약 회사 및 환자 자신의 장기 탄력성을 포함한 [여러 가지 궤적이 한 순간에 함께 모인다]. 실제로 이러한 [궤적은 수행 순간의 연속적인 내부 작용intra-actions을 통해 '결정화crystallised']된다. 연구에서, 우리는 인간과 인간이 아닌 다양한 에이전트들이 상호 작용하여 문제가 되는 것들을 포함한 특정한 결정화를 만들어내는 것에 전체적으로 주의를 기울일 필요가 있다. 이에 대한 한 가지 예는 수술 체크리스트의 사용 관행에서 찾을 수 있다. 이러한 프로토콜에 대한 논쟁에서 수술 오류의 53-70%가 수술실 밖에서 발생한다는 것이 지적되었다.

Furthermore, examining the sociomateriality of medical practice standards more broadly, Timmermans and Berg14 show how a protocol is a temporary achievement. Multiple trajectories come together in a moment, including protocol designers, funding agencies, the different groups of doctors involved, patients’ hopes and desires, organisational facilities, laboratory capabilities, drug companies, and the patients’ organs’ own resilience. In practice, these trajectories are ‘crystallised’ through continuous intra-actions in the moment of performance. In research, we need to attend holistically to the diverse agents, human and non-human, that interact to produce particular crystallisations, including those that are problematic. One example of this may be found in the practice of surgical checklist use. Among the debates around these protocols, it has been noted that 53–70% of surgical errors occur outside the operating room.28

환자 안전 결과를 개선하기 위해, 이러한 연구자들은 체크리스트에 대한 다학제적 입력(병동 의사, 간호사, 외과의사, 마취과 의사, 수술 보조)과 다양한 수술 관리 단계(수술 전, 수술 전, 회복 또는 집중 치료, 수술 후, 수술 후)에 대한 주의를 촉구했다. 이러한 단계에 걸쳐 연구자들은 다음과 같은 [체크리스트에 포함되어야 하는 다양한 물질적 네트워크]를 보여준다.

- 영상 연구 검토, 필요한 모든 장비 및 재료의 설명, 환자의 수술 측면의 표시, 수술 후 지침의 인도 및 퇴원 시 환자에게 약물 처방의 제공

To improve patient safety outcomes, these researchers have urged attention to the multidisciplinary inputs into the checklist (ward doctor, nurse, surgeon, anaesthesiologist, operating assistant) and the different stages of operative care (preoperative, operative, recovery or intensive care, postoperative). Across these stages, the researchers show the diverse material networks that should be included on the checklist:

- a review of imaging studies; an accounting of all necessary equipment and materials; the marking of the patient's operative side; the hand-off of postoperative instructions, and the provision of medication prescriptions to the patient at discharge.

사회물질적 접근법은 이처럼 [자연, 문화, 테크놀로지 사이의 미시적 관계]를 따르는 데 초점을 맞춘다. 중요한 가정은 이것들이 [우발적이고, 계속적이며, 항상 재연되고re-enact 있다]는 것이다. 사회물질적 접근법의 목표는 [무엇을 정의]하거나 [무엇이 되어야 하는지 규정]하기 위한 것이 아니라, '물질화matter-ing'의 과정, 즉 [사물과 가능성]이 지속적으로 [존재와 관계] 속으로 유입되는 과정을 면밀히 추적하는 것이다. 바라드의 용어로, '세계는 서로 다른 주권적agential 가능성의 실현에 있어서 의미와 형태를 획득하는 "mattering" 그 자체를 통해 지속적으로 열린 문제의 과정이다.

Sociomaterial approaches to practice focus on following these microdynamic relations among nature, culture and technology. The critical assumption is that these are contingent, ongoing and are always being re-enacted. The aim is not to define what is or to prescribe what should be, but to follow closely what emerges through processes of ‘matter-ing’, that is, processes by which things and possibilities are continually brought into being and into relationships. In Barad's terms, ‘the world is an ongoing open process of mattering through which “mattering” itself acquires meaning and form in the realisation of different agential possibilities’.29

이것의 한 가지 예는 기술이 새로운 형태의 의료 행위를 형성하는 방식에 있다.

- 샌델로프스키 박사는 환자의 신체에 대한 온정적 관리와 함께 환자의 신체에 대한 영상기술과 디지털 표현이 확산되면서, 간호 실습에서 터치의 중요성이 사라지고 있다고 주장한다.

- Johnson은 어떻게 특정한 테크놀로지가 다른 [의료 관행]뿐만 아니라 다른 [지식]을 불러일으키는지를evoke 보여준다. 그녀는 사회 물질 분석을 사용하여 실제로 미국과 스웨덴의 산부인과 시뮬레이터를 비교하며, 이러한 [시뮬레이터가 서로 다른 목적으로 구상되고 구성된다는conceived and constructed 점]에 주목한다. 존슨에게 이것은 모델 타당성이 무엇을 의미하는지에 대한 의문을 제기한다.

- 학생 의사와 시뮬레이터 사이의 '내부 작용'에 관하여

- 시뮬레이터 설계자와 의료 행위 사이의 '내부 작용'에 관하여

- (더 넓게는) 이렇게 구성된 관행을 통해 [여성의 신체가 어떻게 생산되는지]에 관하여

- 오를리코프스키가 전문적인 일에서 기술에 대한 그녀의 많은 연구를 통해 주장하듯이, 이 모든 논의의 요점은 [테크놀로지의 고유한 힘]이 아니라, [사람들이 실제로 테크놀로지에 관여할 때 수행되는 다양한 효과와 정체성]이다. 기술은 선험적으로 주어지지 않는 결과를 가진 물질이지만, 항상 실제에서 인간과의 상호작용을 통해 수행된다. 연구자는 사람과 테크놀로지 사이의 관계에서 일어나는 일에 집중해야 한다.

One example of this is in the ways that technologies are shaping new forms of medical practice.

- Sandelowski30 argues that the importance of touch in nursing practice is vanishing, along with compassionate care for patients’ material bodies, with the proliferation of imaging technologies and digital representations of patient bodies.

- Johnson31 shows how particular technologies evoke different knowledges as well as different medical practices. She uses a sociomaterial analysis to compare US and Swedish gynaecological simulators in practice, noting that these are conceived and constructed differently and for different purposes: each reflects and produces a different approach to bimanual pelvic examinations. For Johnson,31 this raises questions about what model validity means,

- about the ‘intra-actions’

- between student doctors and simulators, as well as

- between simulator designers and medical practice, as well as

- broader issues about how the female body is being produced through the practices configured here.

- about the ‘intra-actions’

- The point in all of these discussions, as Orlikowski9 argues through her many studies of technology in professional work, is not the inherent power of technology, but the different effects and identities that become performed when people engage with technology in practice. Technologies are materials with outcomes that are not given a priori, but are always performed through interaction with humans in practice.9 The researcher must focus on what goes on in the relationships among people and technologies.

그러나 어떠한 방식으로 이러한 효과 중에서 [일부 관행과 객체]는 표준화된 프로토콜과 같은 강력한 어셈블리로 안정되고 정착되는, 반면 다른 것들은 눈에 띄지 않게 되는가? 라투르는 [사실의 문제matter of fact]와 [우려의 문제matter of concern]를 구분한다.

- [사실의 문제]는 결정되고, 확실하고, 해결되었다고 가정되는 모든 것들이다. [어떻게 작동하는지 제대로 알지 못한 채 운전하는 자동차]처럼, 이런 것들은 [어떻게, 왜 만들어졌는지에 대한 비판적인 질문의 대상이 되지 못한 채]로 실제로 사용되는 '블랙박스'입니다. 블랙박스는 '사실들facts'일 수도 있지만, 일상 업무에서 [관행, 정책, 텍스트, 도구]일 수도 있다.

- [우려의 문제]는 이슈, 논란, 불확실성이다. 그러나 라투르와 다른 사회 유물론자들이 주장하듯이, [확정된 사실로 받아들여지는 관행]의 대부분의 것들은 [논쟁이 은폐되거나 가려져 있는, 실제로는 정말 관심을 가져야 할 문제]이다.

But how, among these effects, do some practices and objects become stabilised and entrenched as powerful assemblages – such as standardised protocols – while others go unnoticed? Latour21 delineates matters of fact from matters of concern.

- Matters of fact are all those things that are assumed to be decided, certain and settled. Like a car that we drive without really knowing how it works, these things are ‘black boxes’ that are used in practice without being subject to critical questioning about how and why they were constructed. Black boxes can be ‘facts’, but they can also be practices, policies, texts and tools in everyday work.

- Matters of concern are issues, controversies, uncertainties. Yet as Latour21 and other sociomaterialists12 contend, most things that are accepted as settled facts of practice are really matters of concern on which debate has been foreclosed or obscured.

사회-물질주의자의 목표는, 논쟁을 풀어내어, 마치 사실의 문제인 것처럼 가장하는 블랙박스를 여는 것이다. 이것은 우리가 학습을 [준비와 역량의 획득으로 인식하는 것]에서, 학습을 [조정, 반응 그리고 심지어 중단으로 보는 것]으로 전환해야 한다는 것을 암시한다.

The socio-materialist aim is to unpick the controversies and open the black boxes that masquerade as matters of fact. This suggests that we should turn from perceiving learning as preparation and the acquisition of competency, to seeing learning as attunement, response and even interruption.

실천과 학습에 대한 시사점

Implications for Practice and Learning

사회 물질적 관점에서는, [학습과 지식은 집행enactment]이며, 단순한 정신 활동이나 수용한 지식이 아니다. 결국, 정신mind라는 것은 [수많은 환경적 물질과의 지속적인 신경학적 연결의 역동]입니다. 사회 물질적 관점은 개인 학습에서 더 큰 사회 물질 집단으로, 그리고 젠슨이 설명하듯이 '인식론과 표현에서 실질적인 존재론과 성과주의로' 이동한다.

In sociomaterial perspectives, learning and knowing are also enactments, not simply mental activity or received knowledge. Mind, after all, is a dynamic of continuous neurological connections with the myriad matter of environments. Sociomaterial perspectives shift from an individual learning subject to the larger sociomaterial collective, and ‘from epistemology and representation to practical ontology and performativity’, as Jensen32 explains.

우리가 에이전시로 가득 찬 세상을 받아들일 때, 무언가를 할 때, 배움은 오로지 [지식적 표상을 습득함으로써 이 세상을 준비하는 것]만 강조하기보다, [그 자리in situ에서 현명하게 참여하는 과정]으로 바뀐다. 학습에서의 이슈는 다음과 같은 것이다.

- 어떻게 작은 변동과 놀라움에 적응할 수 있는지,

- 어떻게 해결된 것처럼 보이는 문제를 중단하고, [우려의 문제]에 대해 공개적인 논쟁을 벌이는지,

- 어떻게 자신과 타인이 창발하는 사회물질적 상황에 미치는 영향을 추적할지

- 어떻게 해결책을 즉흥적으로 만드는지

When we accept a view of the world full of agency, doing things, learning shifts from its sole emphasis on preparing for this world by acquiring knowledge representations, to a process of participating wisely in situ. Learning issues concern

- how to attune to minor fluctuations and surprises,

- how to interrupt matters that seem settled and hold open controversies for matters of concern,

- how to track one's own and others’ effects on the emerging sociomaterial situation, and

- how to improvise solutions.

알츠하이머병 치료법에 대한 그녀의 연구에서, 모저는 의료에서 물질적 집행을 알츠하이머병의 생의학 과학과 비교하는데, 우리는 그것의 특징적인 병리학적 변화로 대표되는 것에 대해 제한된 이해를 가지고 있다. (신경섬유 엉킴, 시냅스 손실, 세포사, 뇌수축 등이 질병 자체의 원인, 결과 또는 징후인지 알 수 없다.) 임상 실습용 교과서에서 인용한 모서는 하나의 긴장tension을 보여준다: 여기서 치료에서 알츠하이머 병의 '문제matter'는 개별 뇌의 병리학적 변화로 표현되는 것이 아니라, (보호자, 친척, 의료 종사자 및 환경을 포함하는) 인간 및 비인간 참여자 집단 간의 애착attachment으로 표현된다.

In her study of treatments for Alzheimer's disease, Moser12 compares the material enactments of medical practice with the biomedical science of Alzheimer's disease, in which we have limited understanding of what is represented by its characteristic pathological changes (we do not know if neurofibrillary tangles, synapse loss, cell death, brain shrinkage and so forth are causes, consequences or manifestations of the disease itself). Citing from textbooks for clinical practice, Moser12 shows a tension: here the ‘matter’ of Alzheimer's disease in treatment is not represented biomedically as pathological changes in individual brains, but as attachments among a collective of human and non-human participants that include carers, relatives, health practitioners and the environment.

그녀는 계속해서 다른 임상실천을 탐구합니다. 이 모든 것들이 [관계의 시스템]에 전제되어 있습니다. 관계에는 제약적인 관계도 있고(아세틸콜린에스테라아제 억제제 등) 또는 상호작용적 관계도 있다(네덜란드에서 개발된 마르테메오 커뮤니케이션 기반 치료제 등). 이러한 각각의 개입에서, 알츠하이머 병은 다르게 프레임화되고 제정된다. 모저의 핵심 질문은 어떤 방법이 가장 좋은가, 또는 어떤 알츠하이머 병의 제정이 가장 진실하거나 유효한가에 대한 것이 아니다. 대신, 그녀의 관심은 이렇나 것이다.

- 어떻게 서로 다른 [물질적 집행]들이 어떻게 서로 영향을 주고 간섭하는지,

- 무엇이 더 또는 덜 가시화되고 무엇이 더 또는 덜 현실적이 되는지,

- 어떻게 임상 실습의 일부로서 생물의학의 역할이 작용하는지

She goes on to explore other clinical practices, all of which are premised on a system of relationships, whether pharmaceutical (such as acetylcholinesterase inhibitors) or interactional (such as the so-called Marte Meo communication-based treatment developed in the Netherlands).12 In each of these interventions, Alzheimer's disease is framed and enacted – materialised – differently. Moser's key question is not about which method is best, or which enactment of Alzheimer's disease is the most true or valid.12 Instead, she is interested in

- how these different material enactments influence and interfere with one another,

- what becomes more or less visible and what becomes more or less real, and

- how the role of biomedicine works as part of the reality of clinical practice.12

아마도 의학 교육자들에게 특별한 관심사는 환자와 이용 가능한 기관의 치료와 함께 이러한 경쟁적인 버전과 그들의 토론을 중재해야 하는 일반 의사의 입장에 대한 모저의 강조이다. 이러한 중재mediation은 정치적 행위political practice이다. 즉, 논리적이고 분명한 방향의 의미라면, [진정한 선택real choice이란 없다]. 의사는 [각 결정에 수반되는 집행enactment의 일부]가 되고, [돌봄은 진화에 따라 집단에 지속적으로 조정되고 적응하는 과정]이다. 몰은 당뇨병 치료에 대한 연구에서도 비슷한 결론을 내립니다. '통제란 환상이며, 모든 요소들은 변덕스럽다'. 주요 업무는 '모든 것을 다른 모든 것에 맞추는 것이다. 무엇을 만지작거리고, 무엇을 고쳐야 할지가 명백한 경우는 거의 없다. 하려고 하는 일은 잘 안 될 수도 있다. 그러면 다른 것을 해봐야 한다. 계속 땜질을 해야 한다. 닥터링, 그리고 캐어링.' 그루프먼은 심장 생리학에서도 진단과 치료의 전체 사회 물질적 과정에서 나타나는 [예상치 못한 작은 신호에 밀접하게 지속적으로 주의를 기울이는 연습]이 연역적 추론보다 더 생산적일 수 있음을 보여준다.

Perhaps of particular interest for medical educators is Moser's highlighting of the position of the general practitioner, who must mediate these competing versions and their debates, alongside the unique contingencies of the patient and the available institutional care.12 This mediation is a political practice – there is no real choice in the sense of a logical and clear direction here. The doctor becomes part of the enactment with each decision, and care is a process of continuous attunement and adjustment to and with the assemblage as it evolves. Mol17 comes to a similar conclusion in her study of diabetes treatment, in which ‘control is illusionary and all the elements … capricious’. The main task, Mol17 learns, involves ‘attuning everything to everything else, one way or another. What to fiddle with and what to keep fixed, is rarely obvious. What you try to do may not work out. Try something else. Keep on tinkering. Doctoring. Caring’. Groopman15 shows that even in cardiac physiology, practices of attending closely and continuously to unexpected tiny signals emerging in the whole sociomaterial process of diagnosis and treatment can be more productive than deductive reasoning.

의학을 배우는 것은 [땜질의 기술art of tinkering]을 배우는 것을 포함할 수 있다. 의학은 [국지화된 사회물질적 실천, 즉흥작업, 우발적 협상의 집합]으로 간주될 수 있다. 의학교육은 다음을 더 자세히 살펴볼 수 있다.

- 특정 장소에서 전문가들이 일을 하는 방식에 가장 영향을 미치는 물질적 요소

- 어떻게 물질이 실천의 가능성을 제한하거나 향상시키는가

- 왜 특정 실천이 안정되고 강력해지며, 이러한 블랙박스가 문제를 일으킬 때는 언제인가

Learning to do medicine may then include learning the art of tinkering. Medicine can be appreciated as a set of localised sociomaterial practices, improvisations and contingent negotiations. Medical education can look more closely at

- the material elements that most influence the ways professionals in a particular place do their work,

- how materials limit or enhance possibilities for practice,

- why particular practices become stabilised and powerful and when these black boxes create problems.

학습, 특히 직장 학습은 다음 사항에 집중할 수 있습니다.

- 사소한 것, 심지어 일상적인 것, 요동, 기이한 실수를 다루는 것,

- 새로운 아이디어와 행동 가능성에 조음attuning하기 - 즉, 진행중인 물질 과정mattering process의 intra-action

- [창발하는 것]에 자신과 다른 사람이 미치는 영향을 알아차리기

- 불확실성 속에서 땜질하기,

- 논쟁과 소동을 막기 위해 실천의 블랙박스를 중단시키기

Learning, particularly workplace learning, can focus on:

- attending to minor, even mundane, fluctuations and uncanny slips;

- attuning to emerging ideas and action possibilities – the intra-actions of ongoing mattering processes;

- noticing one's own and others’ effects on what is emerging;

- tinkering amidst uncertainty, and

- interrupting black boxes of practice to hold open their controversies and disturbances.

전반적으로 사회 물질적 관점은 바라드의 말에 따르면

- '앎이란 직접적인 물질적 관여이며, 모여있는 것을 절단하는 것으로, 절단은 폭력을 가하지만, 가능성의 행위적agential 조건을 열어주어, 재작업한다.'

Overall, sociomaterial perspectives help to illuminate how, in Barad's words,

- ‘knowing is a direct material engagement, a cutting together-apart, where cuts do violence but also open up and rework the agential conditions of possibility’.33

결론들

Conclusions

[가능성을 여는 동시에, 무언가를 정의]하는 이 [절단의 역설paradox of the cut], [언제나 물질적으로 불확실한 이성적 확실성]은 의학에서 예술을 감상하는 우리의 출발점을 상기시킨다. 히포크라테스는 의료 윤리와 책임에 관심이 있었다. 이해와 공감을 촉진하는 데 있어서, 그는 분명히 [관계의 중요성]을 주장하고 있었다. 물론, 후속 토론은 환자의 요구에 더 민감하게 반응하도록 의사를 훈련시키는 것이 생물의학에서 역량의 핵심 가치를 위협하는지 여부에 대해 의문을 제기해 왔다. 그러나 히포크라테스의 경구는 [한 사람의 물질적 실천]에 있어서 [인간적 연결과 비인간적 연결 둘 다에 감사하는 것]으로 해석할 수도 있다. 히포크라테스는 과학과 예술을 함께 호출하면서, [이성적인 프로토콜]뿐만 아니라 [불확실성과 즉흥성을 위한 공간]을 허용하는 것의 중요성을 열어준다. 여기에는 작업 중인 수많은 시스템에 대한 조정과 이러한 시스템에 대한 의사 자신의 개입이 절개, 약물 치료, 측정 및 카테터화 시 필요하다.

This paradox of the cut that defines while opening possibilities, the rational certainty that is always materially uncertain, recalls our starting point of appreciating the art in the science of medicine. Hippocrates was concerned with medical ethics and responsibility. In promoting understanding and sympathy, he was clearly arguing for the importance of relationships. Of course, subsequent debates have wondered whether training doctors to be more responsive to patient needs threatens core values of competence in biomedical science. Yet it may also be possible to interpret Hippocrates as appreciating both the human and the non-human connections of one's material practice. His invocation of art alongside science opens the importance of allowing space for uncertainty and improvisation, as well as rational protocols. Here lies a call for attunement to the myriad systems at work, and practitioners’ own enmeshment within these systems when they cut open, drug, measure and catheterise bodies.

이것은 미래의 의학 교육을 옹호하는 사람들에게 반향을 불러일으키며, 그들은 [폭넓은 글로벌 감각]뿐만 아니라, 즉각적인 [국지적 사회물질적 관계]에 대한 조정을 강조한다. Hodges 등이 밝힌 의료 교육의 10가지 우선순위 중 많은 것은 지역 사회의 요구를 해결하면서 더 넓은 시스템에서 자신의 영향을 이해하는 것, 다양한 행위자와 환경과의 관계 조정, 학습 맥락의 다양화, 전문 분야 간 및 인트라 프랙티스의 진전에 초점을 맞추고 있다. [사회적 책임]은, 쿠퍼와 디온이 [기술과학]과 [환자의 높은 기대]라는 세계 속에서 실천이 이뤄지는 [의학교육의 '재민주화']를 요구하는 주요 주제이기도 하다.

This resonates with advocates for future medical education, who emphasise attunement to socio-material relations in immediate local as well as broader global senses. Among the 10 priorities for medical education articulated by Hodges et al.34 are many focused on understanding one's effects in wider systems while addressing local community needs, attuning to relationships with diverse actors and environments, diversifying learning contexts and advancing inter- and intraprofessional practice. Social responsibility is a major theme too in Kuper and D'Eon's call for a ‘re-democratisation’ of medical education that humanises practice in a world of technoscience and patients’ high expectations.35

이러한 주장이 [예술과 과학], [생물의학과 환자의 이해], 또는 [증거에 기반한 연습과 일상적인 즉흥 연주 사이]의 [이분법]을 만들거나 재현하자는 것이 아니다. 콘토스가 보여주었듯이, '환자 중심의' 공감형 바이오소셜 의학에 '환원론자' 바이오의학을 반대하는 것은 거짓 전쟁을 일으키고, 더 풍부한 가능성을 닫아버리는 것이다. 여기서 개략적으로 설명한 의료 관행과 학습의 현재 이슈는, [다양한 힘 사이의 상호 작용]과 [이것들이 함께 만들어내는 실천의 집행을 검토]하는 데 관심을 두고 있다. [사회물질적 관점]은 실제와 학습에서 특정 현실을 이끌어내는 [인간 및 비인간 관계의 모세혈관]을 추적하는, 동시에 [변화의 기회와 진입점]을 강조하는 방법을 제공한다. 그러한 관점에서, 실무자들은 모든 만남에서 이용할 수 있는 알려지지 않은 급진적인 미래 가능성뿐만 아니라 물질적 참여의 폭력성을 충분히 인식하도록 장려된다.

The argument is not about creating or recreating dichotomies between art and science, biomedicine and patient understanding, or evidence-based practice and everyday improvisation. As Kontos36 has shown, to pitch ‘reductionist’ biomedicine against ‘patient-centred’ empathic biosocial medicine is to create a false war and shut down richer possibilities. The current issues of medical practice and learning outlined here point instead to an interest in examining the interplay among these diverse forces, and the enactments of practice they produce together. Sociomaterial perspectives offer a way to trace the capillaries of human and non-human relationships that bring forth particular realities in practice and learning, while highlighting opportunities and entry points for change. With such a perspective, practitioners are encouraged to appreciate fully the violence of their material engagements as well as the unknown radical future possibilities that are available in every encounter.

Sociomateriality in medical practice and learning: attuning to what matters

PMID: 24330116

DOI: 10.1111/medu.12295

Abstract

Context: In current debates about professional practice and education, increasing emphasis is placed on understanding learning as a process of ongoing participation rather than one of acquiring knowledge and skills. However, although this socio-cultural view is important and useful, issues have emerged in studies of practice-based learning that point to certain oversights.

Methods: Three issues are described here: (i) the limited attention paid to the importance of materiality - objects, technologies, nature, etc.-- in questions of learning; (ii) the human-centric view of practice that fails to note the relations among social and material forces, and (iii) the conflicts between ideals of evidence-based standardised models and the sociomaterial contingencies of clinical practice.

Discussion: It is argued here that a socio-material approach to practice and learning offers important insights for medical education. This view is in line with a growing field of research in the materiality of everyday life, which embraces wide-ranging families of theory that can be only briefly mentioned in this short paper. The main premise they share is that social and material forces, culture, nature and technology, are enmeshed in everyday practice. Objects and humans act upon one another in ways that mutually transform their characteristics and activity. Examples from research in medical practice show how materials actively influence clinical practice, how learning itself is a material matter, how protocols are in fact temporary sociomaterial achievements, and how practices form unique and sometimes conflicting sociomaterial worlds, with diverse diagnostic and treatment approaches for the same thing.

Conclusions: This discussion concludes with implications for learning in practice. What is required is a shift from an emphasis on acquiring knowledge to participating more wisely in particular situations. This focus is on learning how to attune to minor material fluctuations and surprises, how to track one's own and others' effects on 'intra-actions' and emerging effects, and how to improvise solutions.

© 2013 John Wiley & Sons Ltd.

'Articles (Medical Education) > 교육이론' 카테고리의 다른 글

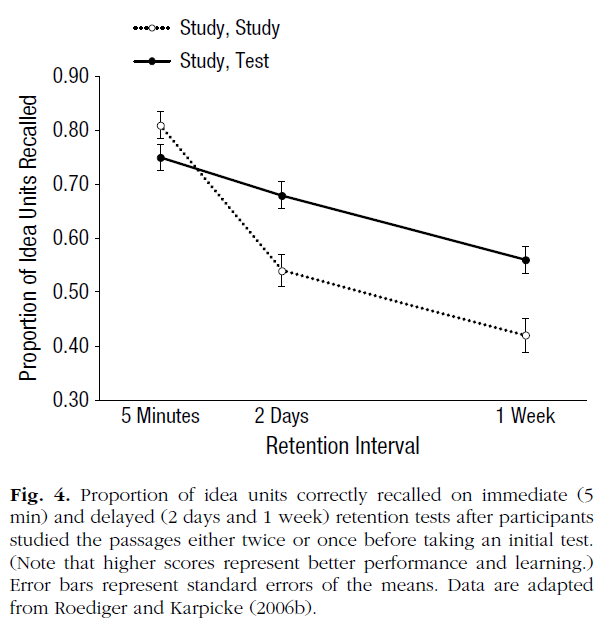

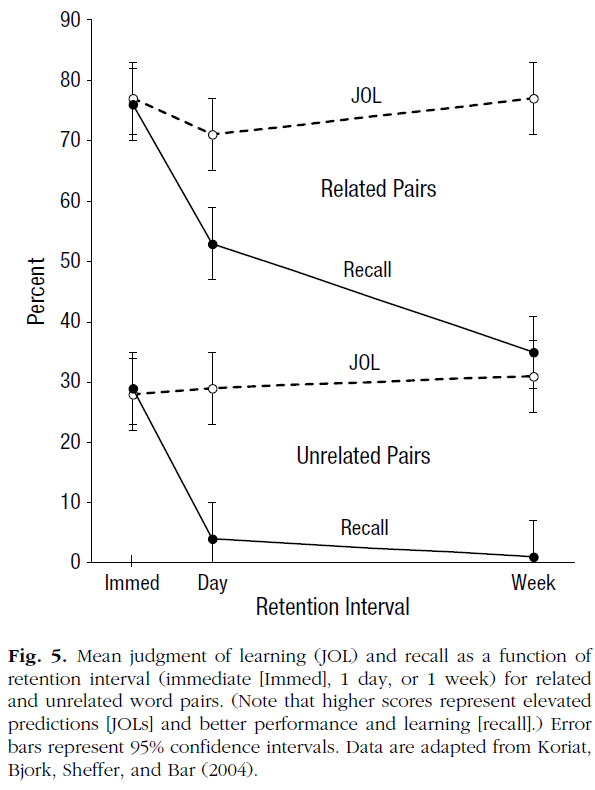

| 바람직한 어려움: 의도적으로 도전적인 학습의 이론과 적용(Med Educ, 2022) (0) | 2022.08.28 |

|---|---|

| 실천적 지혜, 의학교육의 잠자고 있는 특성? (Med Educ, 2019) (0) | 2022.08.12 |

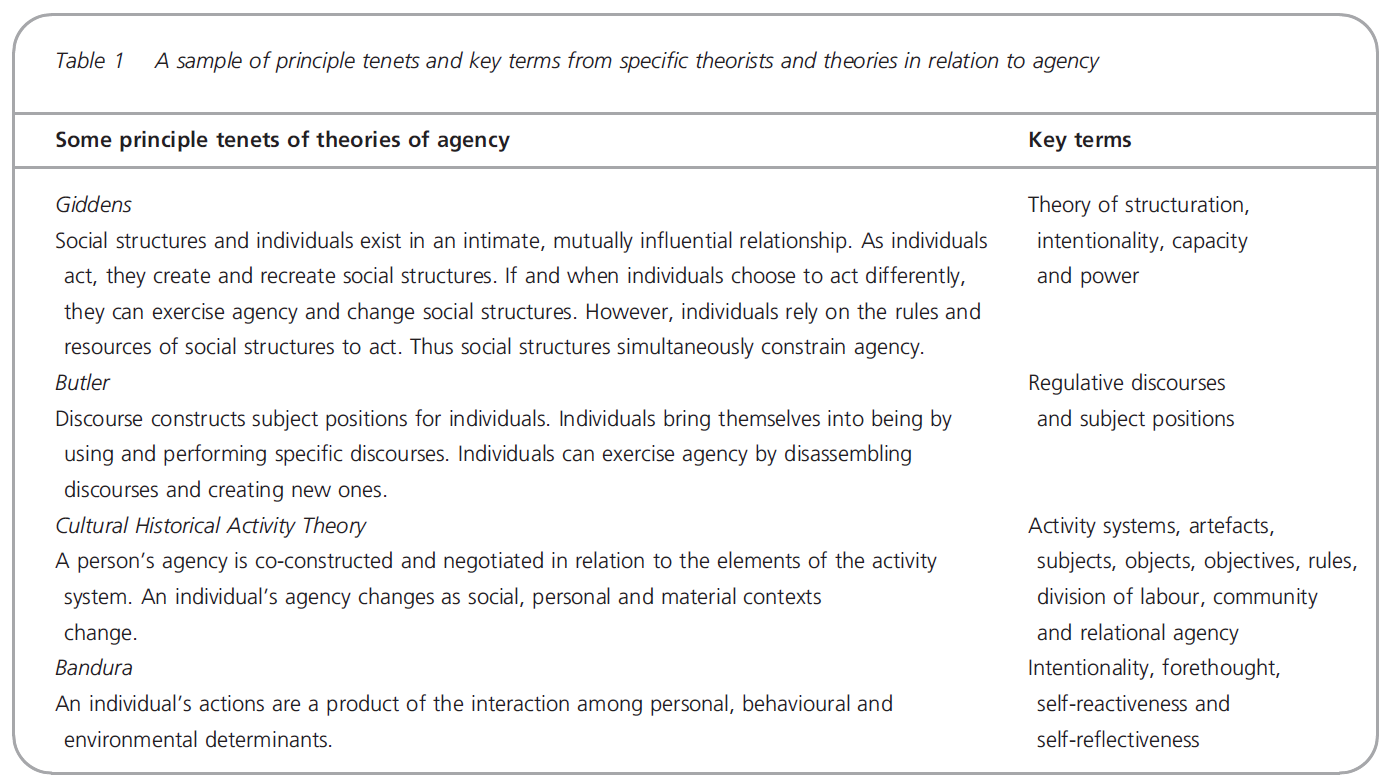

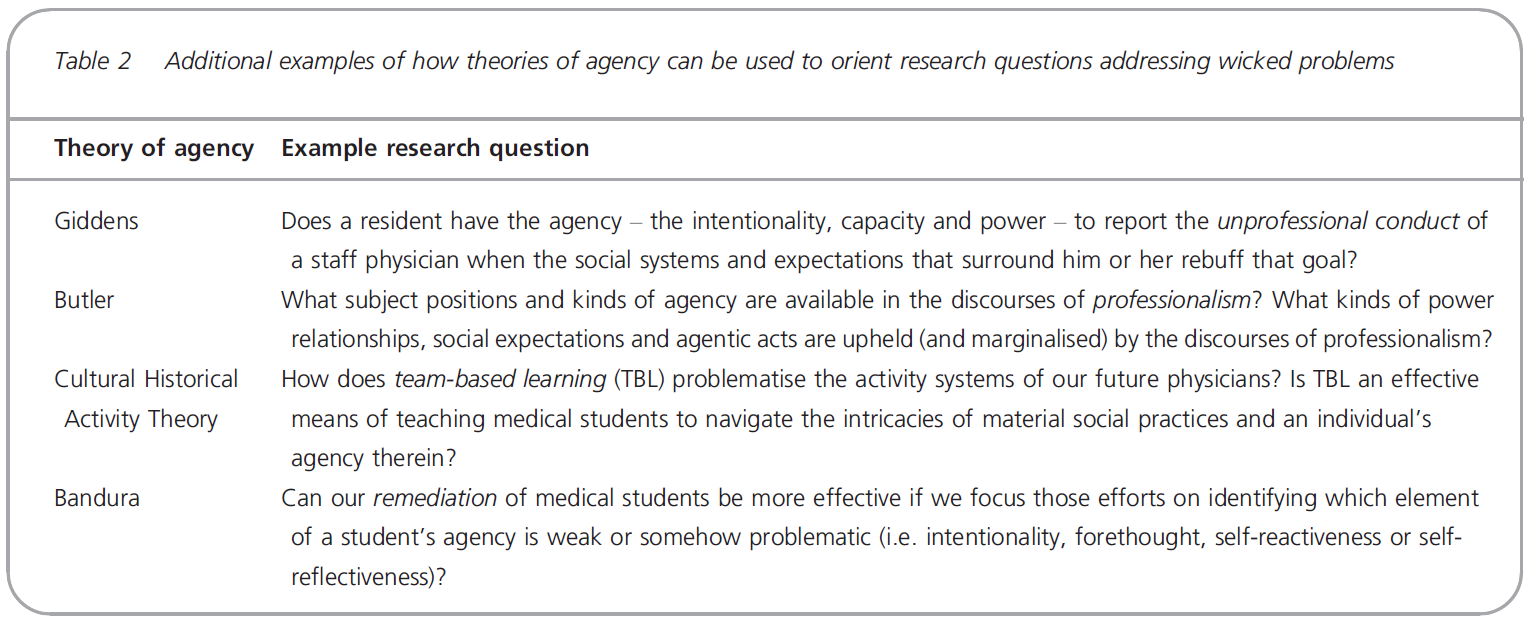

| 고약한 문제 씨름하기: 어떻게 행위자의 이론이 새로운 통찰을 줄 수 있는가(Med Educ, 2017) (0) | 2022.04.12 |

| 교육의 패러다임을 다시 그리기: 인식, 정렬, 다원성을 향하여 (Adv Health Sci Educ Theory Pract, 2021) (0) | 2021.11.13 |

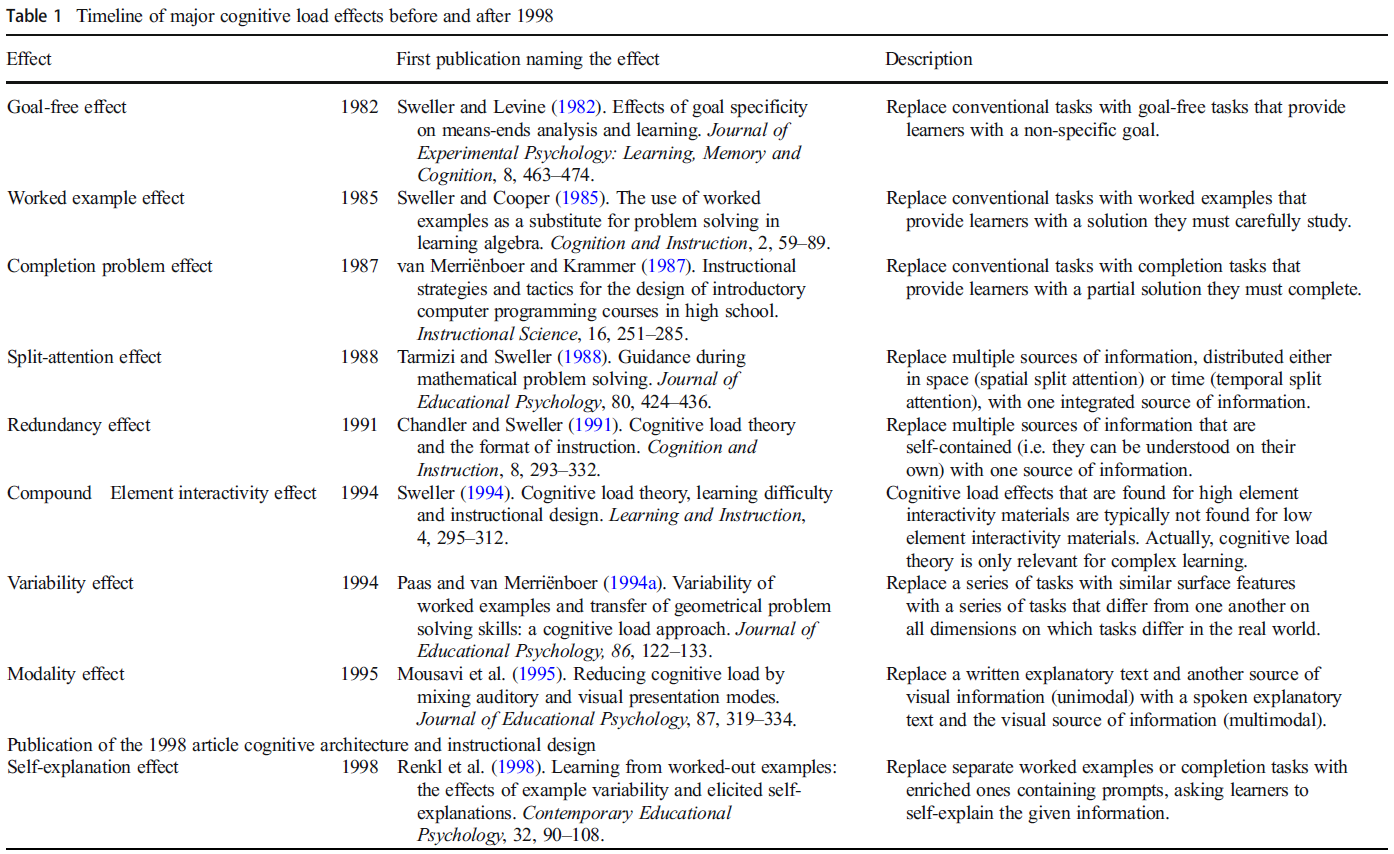

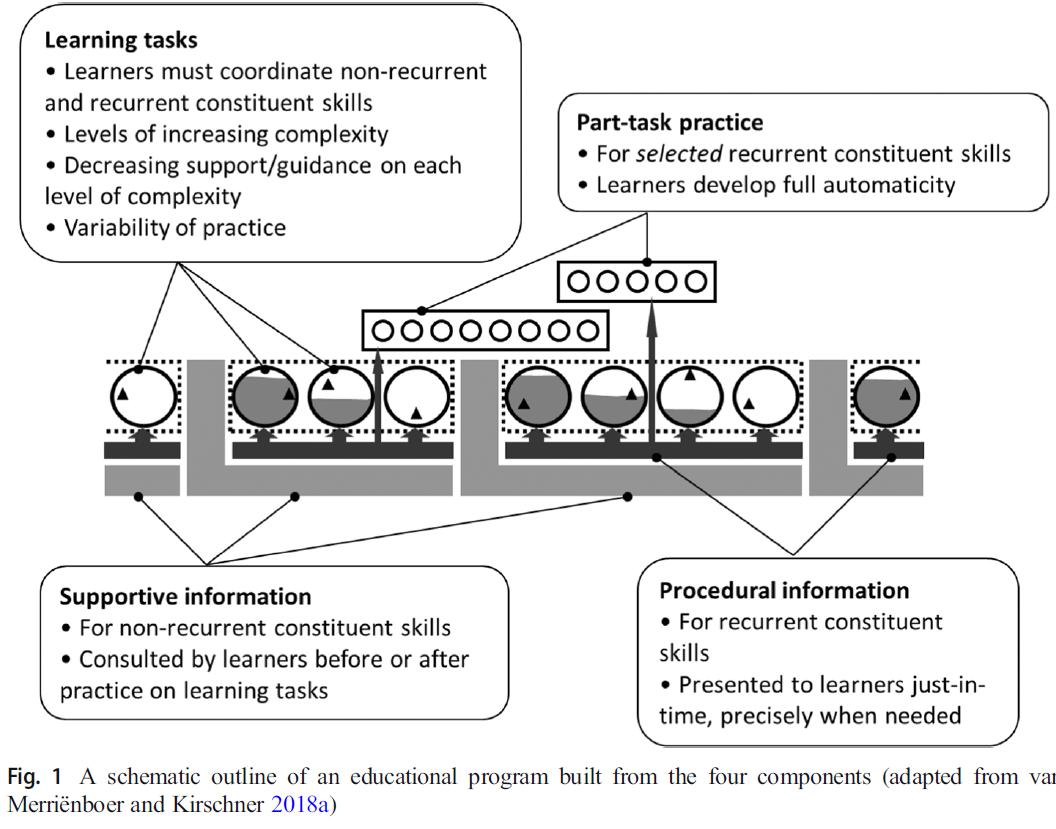

| 인지 아키텍처와 교수 설계: 20년의 역사(Educational Psychology Review, 2019) (0) | 2021.11.13 |