인지 아키텍처와 교수 설계: 20년의 역사(Educational Psychology Review, 2019)

Cognitive Architecture and Instructional Design: 20 Years Later

John Sweller1 & Jeroen J. G. van Merriënboer2 & Fred Paas3,4

서론

Introduction

[인지 부하 이론]은 학습 과제에 의해 유도된 [정보 처리 부하]가 어떻게 학생들의 [새로운 정보 처리 능력]과 [장기 기억의 지식 구성]에 영향을 미칠 수 있는지를 설명하는 것을 목표로 한다. 그것의 기본적인 전제는 인간의 인지 처리가 (한 번에 제한된 수의 정보 요소만 처리할 수 있는 한정된) [작업 기억력에 의해 심하게 제한]된다는 것이다. 인지 부하는 인지 시스템에 불필요한 요구가 부과될 때 증가한다. 인지 부하가 너무 높아지면 학습과 전달을 방해한다. 그러한 요구에는 환경의 불필요한 방해뿐만 아니라 주제에 대해 학생들을 교육하기 위한 부적절한 교육 방법이 포함된다. 인지 부하는 본질적으로 복잡한 과목 정보를 강조하는 교육 방법과 같이 학습과 밀접한 과정에 의해 증가할 수 있다. 학습과 전달을 촉진하려면, 인지 부하를 잘 관리하는 것이 중요하다. 이는 사용 가능한 인지 능력의 한계 내에서 [학습과 무관한 인지 처리는 최소화]되고, [학습과 밀접한 인지 처리는 최적화]하는 것이다. (van Merrienboer et al. 2006).

Cognitive load theory aims to explain how the information processing load induced by learning tasks can affect students’ ability to process new information and to construct knowledge in long-term memory. Its basic premise is that human cognitive processing is heavily constrained by our limited working memory which can only process a limited number of information elements at a time. Cognitive load is increased when unnecessary demands are imposed on the cognitive system. If cognitive load becomes too high, it hampers learning and transfer. Such demands include inadequate instructional methods to educate students about a subject as well as unnecessary distractions of the environment. Cognitive load may also be increased by processes that are germane to learning, such as instructional methods that emphasise subject information that is intrinsically complex. In order to promote learning and transfer, cognitive load is best managed in such a way that cognitive processing irrelevant to learning is minimised and cognitive processing germane to learning is optimised, always within the limits of available cognitive capacity (van Merriënboer et al. 2006).

인지 부하 이론의 뿌리는 1982년으로 거슬러 올라갈 수 있지만,

- 이 이론에 대한 첫 번째 완전한 설명은 1988년 "문제 해결 중 인지 부하: 학습에 미치는 영향"이라는 기사에서 제시되었다. 이후 10년 동안 호주의 뉴사우스웨일스 대학과 네덜란드의 트벤터 대학에 위치한 소규모 연구진에 의해 많은 인지 부하 영향과 관련 교육 방법이 조사되었다.

- 이러한 긴밀한 협력은 1998년 Cognitive Architecture and Instructional Design(Sweller et al. 1998) 논문에 게재된 인지 부하 이론의 업데이트된 설명으로 이어졌다.

- 1998년 이후, 인지 부하 이론은 빠르게 교육 심리학 및 교육 설계 분야에서 가장 인기 있는 이론 중 하나가 되었고, 전 세계의 연구원들이 추가 개발에 기여했습니다.

- 1998년 기사는 현재 구글 스콜라에서 5000개 이상의 인용을 받아 교육 분야에서 가장 많이 인용된 기사 중 하나가 되었다.

The roots of cognitive load theory can be traced back to 1982 (Sweller and Levine 1982), but a first full description of the theory was given in the 1988 article Cognitive Load During Problem Solving: Effects on Learning (Sweller 1988). In the next decade, many cognitive load effects and associated instructional methods were investigated by a small group of researchers located at the University of New South Wales, Australia, and the University of Twente, the Netherlands. This close collaboration led to an updated description of cognitive load theory that was published in the 1998 article Cognitive Architecture and Instructional Design (Sweller et al. 1998). After 1998, cognitive load theory quickly became one of the most popular theories in the field of educational psychology and instructional design, with researchers from across the globe contributing to its further development. The 1998 article became one of the most cited articles in the educational field with currently over 5000 citations in Google Scholar.

이 후속 기사의 주요 목적은 1998년 기사를 출발점으로 삼고 미래 방향에 대한 설명을 종점으로 삼으면서 지난 20년 동안의 인지 부하 이론의 진화를 되돌아보는 것이다.

The main aim of this follow-up article is to reflect on the evolution of cognitive load theory over the past 20 years, taking the 1998 article as a starting point and a description of future directions as the end point.

인지부하 이론의 짧은 역사

Short History of Cognitive Load Theory

1998년 Cognitive Architecture and Instructional Design 논문는 인지 부하 이론의 개요와 그 일반 원리, 이론에 의해 생성된 7가지 인지 부하 효과의 설명과 인지 부하 측정과 관련된 이슈를 포함한 인간의 인지 구조에 대해 논의하였다. 아래에서는 1998년 기사에서 설명한 인간의 인지 구조와 원래의 인지 부하 영향을 간략히 재검토할 것이다.

The 1998 article Cognitive Architecture and Instructional Design discussed human cognitive architecture including an outline of cognitive load theory and its general principles, a description of seven cognitive load effects generated by the theory and issues associated with measuring cognitive load. Below, we will briefly revisit the human cognitive architecture and the original cognitive load effects described in the 1998 article;

1998년에 사용된 인지구조

Human Cognitive Architecture Used in 1998

1998년에 사용된 인지 구조는 그 당시 인간의 인식에 대한 우리의 지식을 반영했다. 그 아키텍처의 기본 구성 요소들, 작업 기억, 장기 기억 그리고 그들 사이의 관계는 잘 알려져 있었다. 비록 작업 기억과 장기 기억 사이의 복잡하고 비판적인 관계가 적어도 일부 독자들에게는 새로운 것처럼 보였지만, 작업 기억이 [정보의 출처가 외부 환경인지 장기 메모리인지 여부]에 따라 다르게 기능한다는 것을 의심하는 독자들에게는 새로운 것이었다. 또한, 인지 아키텍처에서 파생된 지시적 의미는 대부분 알려지지 않았다.

The cognitive architecture used in 1998 reflected our knowledge of human cognition at that time. The basic components of that architecture, working memory, long-term memory and the relations between them were well-known, although the intricate, critical relations between working and long-term memory seemed novel to at least some readers who doubted that working memory functioned differently depending on whether the source of the information was the external environment or long-term memory. In addition, the instructional implications derived from that cognitive architecture were largely unknown.

[작업 기억]의 용량과 지속 시간 한계는 밀러(1956년)와 피터슨 및 피터슨(1959년) 이후로 알려져 왔지만, 이러한 한계는 친숙한 정보가 아닌 [새로운 정보에만 효과적으로 적용]되었다는 사실은 대부분의 치료treatment에서 암시적으로 보였다. 새로운 정보를 다룰 때 작업 기억력의 한계는 대부분의 교육 권고사항에는 없었다. 이러한 권고안은, 특히 지시적 문제 해결의 사용과 관련하여, 마치 작업 기억의 특성이 무관한 고려사항인 것처럼 진행되었다. 실제로 대부분의 교육 권고사항에서는 작업 메모리에 대해 언급하지 않았습니다.

The capacity and duration limits of working memory have been known at least since Miller (1956) and Peterson and Peterson (1959), although the fact that these limits effectively applied only to novel, not familiar information, seemed more implicit rather than explicit in most treatments. The limitations of working memory when dealing with novel information were absent in most instructional recommendations. These recommendations, especially with regard to the use of instructional problem solving, proceeded as though the characteristics of working memory were an irrelevant consideration. Indeed, most instructional recommendations made no mention of working memory.

물론, [장기 기억]도 잘 알려져 있었다. 그럼에도 불구하고, 그것은 아마도 암기 학습과 관련이 있을 수 있기 때문에 교육 권고사항에서 거의 역할을 하지 않았다. 암기적 학습은 분명히 장기 기억에 정보를 저장해야 하는 반면, 장기 기억이 이해력을 가진 학습에 최소한의 역할을 하거나 전혀 역할을 하지 않는다는 가정이 있는 것처럼 보였다. 우리가 [학습할 때 장기 기억이 (이해와 일반적인 기술 형성을 통해) 중심적 역할을 한다고 강조한 것]은 인지 부하 이론의 특이한 측면이었다. 그 강조점은 1946년에 [체스 전문지식]에 대한 원래 연구가 출판된 드 그루트의 비평적인 작품에서 비롯되었다. 체스 기술은 기억되는 체스 보드 구성으로 완전히 설명될 수 있다는 그의 발견과 각각의 구성에 대한 최고의 움직임은 문제 해결 기술의 핵심 요소로 장기 기억을 지울 수 없는 것으로 배치했다. 지금까지 이 자리에 거의 없었다. 그러나 여전히, 이 연구결과가 교육설계에 가지칠 수 있음에도 불구하고, 교육적 권고사항이 장기기억의 역할에 중점을 둔 경우는 거의 없다.

Long-term memory was, of course, equally well-known in the literature. Nevertheless, it played almost no role in instructional recommendations perhaps because it may have been associated with rote learning. While rote learning obviously required the storage of information in long-term memory, there seemed to be an assumption that long-term memory played a minimal or no role in learning with understanding. Our emphasis on the central role of long-term memory when learning with understanding and in general skill formation was an unusual aspect of cognitive load theory. That emphasis derived from the critical work of De Groot (1965) whose original work on chess expertise was published in 1946. His finding that chess skill could be entirely explained by remembered chessboard configurations and the best moves for each configuration placed long-term memory indelibly as the central factor in problem-solving skill. This presence had heretofore been largely absent. Again, despite the ramifications of this finding for instructional design, few if any instructional recommendations placed any emphasis on the role of long-term memory.

[작업 기억]과 [장기 기억] 각각에 대해서는 잘 알려져 있지만, 그들 사이의 중요한 관계는 훨씬 덜 강조되었다. 작업기억은 새로운 정보를 다룰 때 용량과 지속시간이 제한되었지만 작업기억이 장기 기억에서 전송된 정보를 다룰 때 이러한 제한은 사실상 사라졌다. 장기 기억에서 많은 양의 조직화된 정보를 즉시 사용할 수 있게 되면 그러한 정보를 처리할 때 효과적으로 작업 메모리가 제한되지 않게 된다. 에릭슨과 킨치는 장기 작동 기억 이론에서 이 점을 반영했다. [(장기 기억에 저장된 정보에 의존하는) 전문지식]은 개인과 사회에 대한 교육의 변화적 결과를 반영하여 작업 기억에서 정보를 처리하는 능력을 변화시키고 우리를 변화시킨다. 학습자가 중요한 정보를 장기기억에 축적할 수 있도록 하는 것이 교육의 주요 기능이라는 것이다. 새롭기 때문에, 새로운 정보는 작업 기억의 한계를 고려하는 방식으로 제시되어야 한다. 이러한 과정들은 1998년에 인지 부하 이론의 교육적 영향을 초래한 인지 구조를 제공했다.

While working and long-term memory were well-known, the important relations between them were much less emphasised. Working memory was limited in capacity and duration when dealing with novel information but these limitations effectively disappeared when working memory dealt with information transferred from long-term memory. A ready availability of large amounts of organised information from long-term memory results in working memory effectively having no known limits when dealing with such information. Ericsson and Kintsch (1995) in their theory of long-term working memory, reflected this point. Expertise, reliant on information held in long-term memory, transforms our ability to process information in working memory and transforms us, reflecting the transformational consequences of education on individuals and societies. It follows that the major function of instruction is to allow learners to accumulate critical information in long-term memory. Because it is novel, that information must be presented in a manner that takes into account the limitations of working memory when dealing with novel information. These processes provided the cognitive architecture that led to the instructional implications of cognitive load theory in 1998.

인지부하의 범주

Categories of Cognitive Load

1998년에, 우리는 인지 부하의 세 가지 범주에 대해 논의했다: 내재적, 외부적, 그리고 본유적.

In 1998, we discussed three categories of cognitive load: intrinsic, extraneous and germane.

[내재적 인지 부하]는 [처리 중인 정보의 복잡성]을 의미하며, 요소 간 상호작용의 개념과 관련이 있다. 위에서 설명한 인간 인지 구조의 특성 때문에, 인간에 의해 처리되는 정보의 복잡성을 결정하는 것은 어렵다. 정보의 복잡성에 대한 대부분의 척도는 순전히 정보의 특성에 관한 것이다. 위에서 논의한 작업 기억과 장기 기억 사이의 관계 때문에 인간에 의해 처리되고 있는 정보를 언급할 때 그러한 조치들은 부적절하다. 장기 기억에 조직되고 저장된 정보는 저장되기 전의 동일한 정보와는 매우 다른 특성을 가지고 있다.

Intrinsic cognitive load referred to the complexity of the information being processed and was related to the concept of element interactivity. Because of the characteristics of human cognitive architecture described above, determining the complexity of information processed by humans is difficult. Most measures of informational complexity refer purely to the characteristics of the information. Such measures are inadequate when referring to information being processed by humans because of the relations between working and long-term memory discussed above. Information that has been organised and stored in long-term memory has very different characteristics for humans than the same information prior to it being stored.

이 논문의 독자들에게 영어 단어 'characteristics'과 그 로마자는 장기 기억에서 회수된 하나의 요소로 쉽고 무의식적으로 처리된다. 반면, 영어 읽기를 배우는 누군가에게 쓰여진 단어는 아직 장기 기억에 단일 요소로 저장되지 않았기 때문에 여러 개의 상호작용하는 요소로 작업 기억에서 처리되어야 한다. [복잡성 또는 요소 상호작용성]은 [정보의 성격과 정보를 처리하는 사람의 지식의 조합]에 좌우된다.

- 영어 읽기를 배우는 누군가에게, 'characteristics'이라는 단어를 구성하는 여러 개의 꼬불꼬불한 말을 해석하는 것은 작업 기억을 압도하는 매우 높은 요소 상호작용성 작업이 될 수 있다.

- 전문가에게, 동일한 구불구불한 선squiggles은 최소 요소 상호작용으로 인해 최소한의 인지 부하를 부과하는 단일 요소만 구성할 수 있다.

For readers of this paper, the English word ‘characteristics’ and its Roman letters are processed easily and unconsciously as a single element retrieved from long-term memory. For someone learning to read English, the written word must be processed in working memory as multiple, interacting elements because the written word has not yet been stored as a single element in long-term memory. Complexity or element interactivity depends on a combination of both the nature of the information and the knowledge of the person processing the information.

- For someone learning to read English, interpreting the multiple squiggles that constitute the word ‘characteristics’ may constitute a very high element interactivity task that overwhelms working memory.

- For an expert, the same squiggles may constitute only a single element that imposes a minimal cognitive load due to minimal element interactivity.

따라서, 내재적 인지 부하는 정보의 복잡성과 정보를 처리하는 사람의 지식에 의해 결정된다. 인간 인지 시스템의 이러한 특징들을 고려할 때, (제시된 정보의) 복잡성을 결정할 때 [(기존) 지식을 무시하는 측정]은 대부분 소용이 없다. 이 분석에 기초하여, 내재적 인지 부하는 학습해야 할 것을 변경하거나 학습자의 전문지식을 바꿈으로써만 바뀔 수 있다.

Accordingly, intrinsic cognitive load is determined by both the complexity of the information and the knowledge of the person processing that information. Given these characteristics of the human cognitive system, measures that ignore knowledge when determining complexity are largely useless. Based on this analysis, intrinsic cognitive load only can be changed by changing what needs to be learned or changing the expertise of the learner.

[외재적 인지 부하]는 정보의 본질적 복잡성에 의해 결정되는 것이 아니라, 정보가 어떻게 제시되고 학습자가 지시 절차에 의해 무엇을 해야 하는가에 의해 결정된다. 내재 인지 부하와 달리, 교육 절차instructional procedures를 변경하여 바꿀 수 있다. 1998년에는 요소 상호작용만이 내재 인지 부하와 관련이 있다고 가정했다. 그 결과, 외부 인지 부하(Sweller 2010)를 동일하게 결정한다는 것이 명백해졌다.

- 효과적인 교육 절차는 요소의 상호작용성을 감소시키는 반면

- 비효율적인 절차는 요소의 상호작용성을 증가시킨다.

Extraneous cognitive load is not determined by the intrinsic complexity of the information but rather, how the information is presented and what the learner is required to do by the instructional procedure. Unlike intrinsic cognitive load, it can be changed by changing instructional procedures. In 1998, it was assumed that element interactivity only was relevant to intrinsic cognitive load. Subsequently, it became apparent that it equally determines extraneous cognitive load (Sweller 2010).

- Effective instructional procedures reduce element interactivity while

- ineffective ones increase element interactivity.

[본유적 인지부하]는 학습에 필요한 인지부하으로 정의되었으며, 이는 (외재적 인지 부하가 아니라) 내재적 인지 부하를 다루는 데 사용되어야 하는 작업기억 자원을 가리킨다. 외부 인지 부하를 처리하는 데 더 많은 자원을 할애할수록 내재 인지 부하를 처리하는 데 더 적은 가용성이 제공되므로 학습량이 줄어들 것이다. 그런 점에서 [내재적 인지적 부하]와 [본유적 인지 부하]는 밀접하게 얽혀 있다.

Germane cognitive load was defined as the cognitive load required to learn, which refers to the working memory resources that are devoted to dealing with intrinsic cognitive load rather than extraneous cognitive load. The more resources that must be devoted to dealing with extraneous cognitive load the less will be available for dealing with intrinsic cognitive load and so less will be learned. In that sense, intrinsic and germane cognitive load are closely intertwined.

[본유적 인지 부하]의 이러한 특성은 1998년 논문에서 벗어난 것이다. 본 논문에서 우리는 본유적 인지 하중이 외부 하중을 대체하여 총 인지 하중에 기여한다고 가정했다. 현재, 우리는 [본유적 인지 부하]가 총 부하에 기여하기 보다는, 학습 과제의 본질적인instrinsic 정보를 처리하여, 외부 활동에서 학습과 직접 관련이 있는 활동으로 작업 기억 자원을 재배포한다고 가정한다. 이러한 변경의 필요성은 외부 하중이 감소되었을 때 게르마인 인지 하중이 단순히 외부 하중을 대체했다면 외부 하중의 감소에 따른 총 하중의 변화가 없어야 한다는 문제에서 비롯되었다. 수많은 경험적 연구에 따르면 외부 부하 감소에 따른 부하 감소가 나타났다. 현재 공식은 [본유적 인지 부하]가 그 자체로 부하를 부과하기 보다는, 직무의 외부적 측면에서 본질적 측면으로 [(부하의) 재분배 기능]을 가지고 있다고 가정함으로써 이 문제를 제거한다.

This characterisation of germane cognitive load is a departure from the 1998 paper. In that paper we assumed that germane cognitive load contributed to total cognitive load by substituting for extraneous load. Currently, we assume that rather than contributing to the total load, germane cognitive load redistributes working memory resources from extraneous activities to activities directly relevant to learning by dealing with information intrinsic to the learning task. The need for this alteration arose from the issue that if germane cognitive load simply replaced extraneous load when extraneous load was reduced, then there should be no change in total load following a reduction in extraneous load. Numerous empirical studies indicated a reduction in load following a reduction in extraneous load. The current formulation eliminates this problem by assuming that germane cognitive load has a redistributive function from extraneous to intrinsic aspects of the task rather than imposing a load in its own right.

1998년 보고한 지시효과

Instructional Effects Reported in 1998

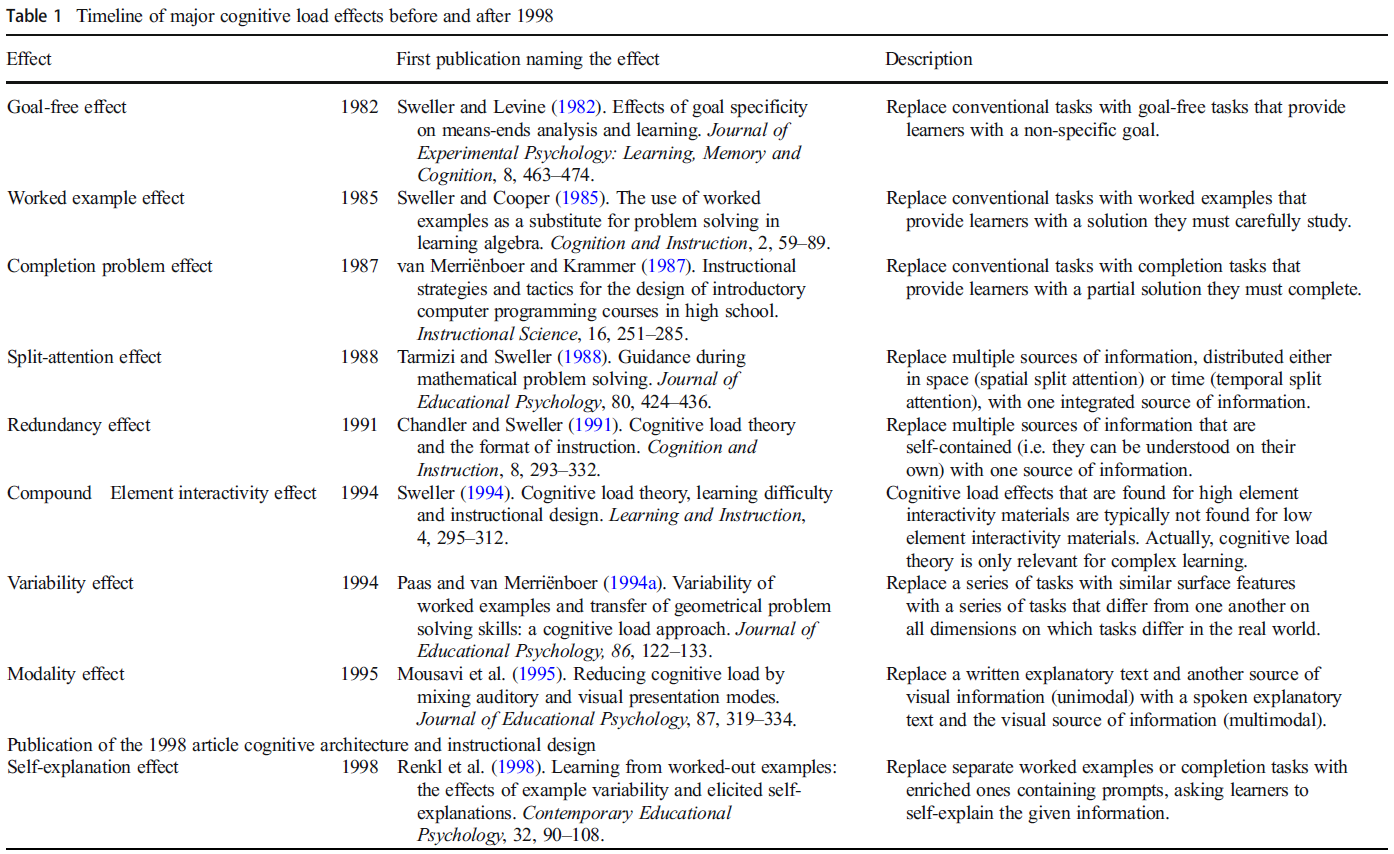

1998년 기사에서는 7가지 인지 부하 효과가 보고되었다(표 1의 상단 참조). [변동성 효과]를 제외한 이 모든 효과는 외부 인지 부하 감소와 관련된 요소 상호작용성의 감소에 기인한다. [변동성 효과]는 내재 인지 부하의 변화로 인한 것이다. 이러한 효과는 전 세계 여러 연구 센터에서 수행된 여러 번의 중복 실험과 다양한 재료 및 모집단을 사용한 실험에 기초했다. 그러나, 이러한 실험들 중 다수는 비교 인지 부하를 직접 측정하려고 시도하지 않았다. 오히려, 인지 부하 이론은 교육 기법을 생성하는데 사용되었고 이러한 기술이 학습 결과에 대한 기대 효과를 생성한다면 이론을 강화하는 것으로 가정되었다.

In the 1998 article, seven cognitive load effects were reported (see the upper part of Table 1). All of these effects with the exception of the variability effect were due to a reduction in element interactivity associated with a decrease in extraneous cognitive load. The variability effect is due to alterations in intrinsic cognitive load. These effects were based on multiple, overlapping experiments carried out in several research centres around the globe and using a variety of materials and a variety of populations. Yet, many of these experiments did not attempt to directly measure comparative cognitive load; rather, cognitive load theory was used to generate instructional techniques and if these techniques produced the expected effects on learning outcomes they were assumed to strengthen the theory.

표 1 1998년 이전과 이후의 주요 인지부하 영향의 연표

Table 1 Timeline of major cognitive load effects before and after 1998

목표 부재 효과

Goal-Free Effect

[목표 부재 효과]를 [목표-특이성 감소 효과] 또는 [목표 없음 효과]라고도 합니다. 그것은 기존의 문제들이 일반적으로 [수단-목표means-ends 분석]에 의해 해결된다는 관찰로부터 시작되었는데, 이런 문제해결 방식은 작업 메모리 용량에 유난히 "비싼" 프로세스이다. 왜냐하면 학습자는 작업 기억, 현재 문제 상태, 목표 상태, 그들 사이의 관계, 차이를 줄일 수 있는 문제 해결 연산자 및 하위 문제를 유지하고 처리해야 하기 때문이다. (예: 차량은 1분 동안 정지 상태에서 균일하게 가속됩니다. 그것의 최종 속도는 2km/min이다. 얼마나 멀리 이동했습니까?)

The goal-free effect is also called the reduced goal specificity effect or no goal effect. It is the oldest effect studied in the context of cognitive load theory (Sweller and Levine 1982). It started from the observation that conventional problems (e.g. A car is uniformly accelerated from rest for 1 min. Its final velocity is 2 km/min. How far has it travelled?) are typically solved by means-ends analysis, a process that is exceptionally expensive of working memory capacity because the learner must hold and process in working memory, the current problem state, the goal state, relations between them, problem-solving operators that could reduce differences and any sub-goals.

기존의 문제가 목표가 없는 문제로 대체될 때(예: 차량은 1분 동안 정지 상태에서 균일하게 가속됩니다. 그것의 최종 속도는 2km/min이다. 가능한 한 많은 변수의 값을 계산해보세요), 학습자는 단지 목표 상태가 제공되지 않는다는 이유만으로 현재 문제 상태와 목표 상태 간의 차이를 추출할 수 없다. 이제 그들은 마주치는 각 문제 상태를 고려하여, 적용할 수 있는 문제 해결 연산자라면 무엇이든 다 찾을 수 있다. 일단 연산자가 적용되면, 새로운 문제 상태가 생성되고 프로세스가 반복될 수 있습니다.

When conventional problems are replaced by goal-free problems (e.g. A car is uniformly accelerated from rest for 1 min. Its final velocity is 2 km/min. Calculate the value of as many variables as you can), learners are no longer able to extract differences between a current problem state and a goal state simply because no goal state is provided. They will now consider each problem state encountered and find any problem-solving operator that can be applied; once an operator has been applied, a new problem state has been generated and the process can be repeated.

[수단-목표 분석]은 지식 구성 프로세스와 거의 관련이 없는 반면, [목표가 없는 문제 해결]은 인지 부하를 크게 감소시키고 낮은 부하와 지식 구성에 필요한 해결책의 정확한 조합을 제공한다.

Whereas means-ends analysis bears little relation to knowledge construction processes, goal-free problem solving greatly reduces cognitive load and provides precisely the combination of low load and focus on solutions that is required for knowledge construction.

작업 예제 효과

Worked Example Effect

[작업된 예제]는 기존의 문제로 인한 인지 부하를 줄이고 지식 구성을 용이하게 하는 것을 목표로 한다. 작업 예제는 학습자가 주의 깊게 공부해야 하는 전체 문제 해결 방법을 제공합니다. 작업된 예제 효과는 대수학 영역에서 스웰러와 쿠퍼(1985)에 의해 처음 보고되었다. 기존의 문제와 대조적으로, [풀이된 예제]는 학습자의 주의를 문제 상태 및 관련 운영자(즉, 솔루션 단계)에 집중시켜 일반화된 솔루션을 유도할 수 있도록 한다. 따라서, 풀이된 예제를 공부하는 것은 실제로 동등한 문제를 해결하는 것보다 지식 구축과 전이라는 학습성과를 더 촉진할 수 있습니다.

Like goal-free problems, worked examples aim to reduce the cognitive load caused by conventional problems and to facilitate knowledge construction. Worked examples provide a full problem solution that learners must carefully study. The worked example effect was first reported by Sweller and Cooper (1985) in the domain of algebra. In contrast to conventional problems, worked examples focus the learners’ attention on problem states and associated operators (i.e. solution steps), enabling them to induce generalised solutions. Thus, studying worked examples may facilitate knowledge construction and transfer performance more than actually solving the equivalent problems.

작업된 예제 효과에 대한 매우 강력한 경험적 증거가 있지만, 중요한 제약 조건도 있다. 고전문가의 학습자에게 작업 예제는 덜 효과적이고 좋은 작업 예제의 설계는 어렵다. 예를 들어, 학습자가 다른 정보 소스를 정신적으로 통합하거나(아래의 [분산되 주의 효과] 참조) 중복 정보를 결합하도록 요구해서는 안 되기 때문이다 (아래의 [중복 효과] 참조). 예제를 통한 학습에 대한 연구 리뷰는 Renkl(2013)에 의해 제공된다.

Although there is very strong empirical evidence for the worked example effect, there are also important constraints: Worked examples are less effective for high-expertise learners and the design of good worked examples is difficult, for example, because they should not require the learner to mentally integrate different sources of information (see the split-attention effect below) or combine redundant information (see the redundancy effect below). A review of studies on learning from examples is provided by Renkl (2013).

부분완성 문제 효과

Completion Problem Effect

[풀이된 예제]의 잠재적인 단점은 학습자가 주의 깊게 학습하도록 강요하지 않는다는 것입니다. 따라서 Van Merrienboer와 Krammer(1987)는 컴퓨터 프로그래밍 입문 분야에서 [부분완성 문제]를 사용할 것을 제안했다. 그러한 문제들은 주어진 상태, 목표 상태, 학습자에 의해 완성되어야 하는 [부분적인 해결책]을 제공한다. 컴퓨터 프로그래밍 분야에서, 이것은 학습자들이 완성되어야 할 불완전한 컴퓨터 프로그램을 받는 것을 의미한다. [완전히 풀이된 예제]는 명시적으로 학습하도록 유도하지는 않는 반면, 학습자는 [부분완성 문제]에서 제공되는 [부분적으로 풀이된 예제]를 주의 깊게 공부하고 이해해야 한다. 그렇지 않으면 솔루션을 올바르게 완료할 수 없기 때문입니다.

A potential disadvantage of worked examples is that they do not force learners to carefully study them. Therefore, van Merriënboer and Krammer (1987) suggested the use of completion problems in the field of introductory computer programming. Such problems provide a given state, a goal state, and a partial solution that must be completed by the learners. In the field of computer programming, this means that the learners receive incomplete computer programs that need to be finished. Although fully worked examples do not explicitly induced learners to study them, learners must carefully study and understand the partial worked examples provided in completion problems because they otherwise will not be able to complete the solution correctly.

[부분완성 문제]는 [풀이된 예제]와 [전통적 문제] 사이의 가교로도 볼 수 있습니다. [풀이된 예제]는 완전한 솔루션의 완료 문제이고, [전통적 문제]는 부분적인 솔루션이 제시된 [부분완성 문제]입니다. 코스를 설계할 때, 이러한 서로 다른 솔루션 레벨은 거의 완전한 솔루션을 제공하는 완료 문제로 시작할 수 있도록 하며, 점진적으로 전체 또는 대부분의 솔루션이 학습자에 의해 생성되어야 하는 완료 문제로 작용할 수 있도록 합니다. 이 전략은 '완료 전략completion strategy'(1990년 반 메린보어 및 크라머)으로 알려졌으며 아래에서 설명될 guidance-fading effect의 선구자로 볼 수 있다.

Completion problems may also be seen as a bridge between worked examples and conventional problems: worked examples are completion problems with a complete solution and conventional problems are completion problems with a partial solution. When designing a course, these differing solution levels allow commencement with completion problems that provide almost complete solutions and gradually work to completion problems for which all or most of the solution must be generated by the learners. This strategy became known as the ‘completion strategy’ (van Merriënboer and Krammer 1990) and can be seen as a forerunner of the guidance-fading effect that will be described below.

주의 분할 효과

Split-Attention Effect

[주의 분할 효과]는 [풀이된 예제]에 대한 연구에서 비롯되어, Tarmizi와 Sweller(1988)에 의해 처음 보고되었다. 예를 들어, 지오메트리 영역의 [풀이된 예제]는 [다이어그램]과 이에 대한 [풀이법 설명 문장]으로 구성될 수 있습니다.

- [다이어그램]만으로는 문제에 대한 해결책에 대해 아무것도 드러내지 않으며,

- [풀이 문장]은 다이어그램과 통합되기 전까지는 학습자가 이해할 수 없습니다.

학습자들은 해결책을 이해하기 위해 두 가지 정보의 원천을 정신적으로 통합해야 하는데, 이 과정은 높은 인지 부하를 산출하고 학습을 방해하는 과정이다.

The split-attention effect stems from research on worked examples and was first reported by Tarmizi and Sweller (1988). For instance, a worked example in the domain of geometry might consist of a diagram and its associated solution statements.

- The diagram alone reveals nothing about the solution to the problem and

- the statements, in turn, are unintelligible for the learners until they have been integrated with the diagram.

Learners must mentally integrate the two sources of information in order to understand the solution, a process that yields a high cognitive load and hampers learning.

이러한 [주의 분할 효과]는 [다이어그램과 솔루션 문구를 물리적으로 통합]하여 정신적 통합을 불필요하게 만들고 작업 예제의 긍정적인 효과를 복원함으로써 예방할 수 있다. 주의 분할 효과는 정보 출처의 [공간적 조직]뿐만 아니라 [시간적 조직]과도 관련이 있다. 메이어와 앤더슨(1992)은 인지 부하를 줄이고 학습을 용이하게 하기 위해 애니메이션과 관련 내레이션이 일시적으로 조정되어야 한다는 것을 발견했다. 분할 주의 효과에 대한 최근 리뷰는 Ayres와 Sweller(2014)에 의해 제공되었습니다.

This split-attention effect can be prevented by physically integrating the diagram and the solution statements, making mental integration superfluous and reinstating the positive effects of worked examples. The split-attention effect not only relates to the spatial organisation of information sources but also to their temporal organisation. Mayer and Anderson (1992) found that animation and associated narration need to be temporally coordinated in order to decrease cognitive load and facilitate learning. A recent review of the split-attention effect is provided by Ayres and Sweller (2014).

중복 효과

Redundancy Effect

[주의 분할 효과]는 [풀이된 예제 효과]에서 나온 반면, [중복 효과]는 [주의 분할 효과]에서 나온 것입니다. 학습자가 독자적으로는 도움이 안 되지만, 통합된다면 이해에 도움이 되는 [두 가지 상호 보완적인 정보원]에 직면할 때 주의가 분산됩니다. 하지만 두 정보의 원천이 [서로에 대한 참조 없이] 스스로 포함되고 이해될 수 있다면 어떻게 될까? Chandler와 Sweller(1991)는 텍스트로 혈액의 흐름을 설명한 진술과 함께 심장, 폐 및 신체의 나머지 부분의 혈액 흐름을 보여주는 다이어그램을 사용했다. 따라서, 다이어그램과 문장은 동일한 정보를 포함하고 있으며 완전히 중복되었습니다. 이 경우 [다이어그램만를 제시]하는 것이, [두 개의 정보 출처를 함께 표시하는 것]보다 우월한 것으로 밝혀졌다.

While the split-attention effect grew out of the worked example effect, the redundancy effect, in turn, grew out of the split-attention effect. Split attention occurs when learners are confronted with two complementary sources of information, which cannot stand on their own but must be integrated before they can be understood. But what happens when the two sources of information are self-contained and can be understood without reference to each other? Chandler and Sweller (1991) used a diagram demonstrating the flow of blood in the heart, lungs and rest of the body together with statements that described this flow of blood in text. Thus, the diagram and the statements contained the same information and were fully redundant. It was found that only presenting the diagram was superior to presenting both sources of information together.

중복 효과가 발생하는 이유는, [학습자가 두 출처의 정보가 동일하다는 것을 발견하기 위해 노력을 들여 처리해야 하기 때문]입니다. 동일한 정보를 두 번 제공하는 것이 해를 끼치거나 심지어 이롭다는 가정 하에, 이 발견은 중요하지만, 직관적이지 않다. 문헌의 조사 결과, 중복 효과는 수십 년 동안 발견되고, 잊혀지고, 재발견되어 왔다. 1937년 초에, 밀러는 명사를 읽는 법을 배우는 어린 아이들이 단어들이 비슷한 그림과 함께 제시되기 보다는 혼자 제시된다면 더 많은 발전을 이루었다고 보고했습니다.

This redundancy effect is due to the fact that effortful processing is required from the learners to eventually discover that the information from the two sources is identical. This finding is important and counter-intuitive based on the assumption that providing the same information twice can do no harm or is even beneficial. Inspection of the literature shows that the redundancy effect has been discovered, forgotten and rediscovered over many decades: As early as 1937, Miller reported that young children learning to read nouns made more progress if the words were presented alone rather than in conjunction with similar pictures.

제시방식 효과

Modality Effect

1998년 기사에서 논의된 모든 인지 부하 효과는 [다룰 수 있는 요소의 수가 변경할 수 없다는 점]에서, [한 개인에 대해 작업 기억 용량이 고정되어 있다]고 가정했다. 하지만 유일한 예외는 [제시방식 효과]이다. 제시방식 효과는 작업 기억이 부분적으로 독립적인 프로세서로 세분화될 수 있다는 가정에 기초하며, 하나는 청각 작업 기억에 기초한 언어 자료와 다른 하나는 시각 작업 기억에 기초한 도표/그림 정보를 다룬다(예: Baddley 1992). 따라서 어느 한 프로세서만 사용하는 것이 아니라, [시각 및 청각]이라는 두 가지의 [작업 기억] 모두를 사용했을 때, 효과적으로 작업 기억 용량을 증가시킬 수 있다.

All cognitive load effects discussed in the 1998 article assumed that working memory capacity is fixed for a given individual in the sense that the number of elements that could be dealt with was unalterable, with the modality effect as an exception. The modality effect is based on the assumption that working memory can be subdivided into partially independent processors, one dealing with verbal materials based on an auditory working memory and one dealing with diagrammatic/pictorial information based on a visual working memory (e.g. Baddeley 1992). Consequently, effective working memory capacity can be increased by using both visual and auditory working memory rather than either processor alone.

무사비 외 연구진(1995)은 기하학 학습에서 제시방식 효과를 최초로 시험한 사람이었다. 그들은 다이어그램을 통합된 필기 텍스트(즉, 시각적)와 제시하거나, 구어 텍스트(즉, 시각적)와 함께 제시했고, [제시방식 효과]로 인해 음성 텍스트와의 조합이 가장 효과적일 것이라고 가정했다. 그들은 실제로 그 이후로 많은 다른 실험에서 제시방식 효과가 재현되는 것을 발견했다. [제시방식 효과]는 [주의 분할 효과]를 처리하는 방법에 중요한 영향을 미친다. [주의 분할]이 발생하는 경우, [글자 정보]를 [청각 모드]로 표시하는 것이, [도표에 물리적으로 통합하는 것]보다 동등하거나 훨씬 더 효과적일 수 있다. 긴스(2005a)는 여전히 읽을 가치가 있는 양식 효과의 메타 분석을 제공했다.

Mousavi et al. (1995) were the first to test the modality effect in geometry learning; they presented a diagram either with integrated written text (i.e. visual) or with auditory, spoken text and they hypothesised that the combination with spoken text would be most effective due to the modality effect. They indeed found the modality effect that has since been replicated in many other experiments. The modality effect has important implications for how to deal with split-attention effects: if split attention occurs, presenting the written information in an auditory mode may be equally or even more effective than physically integrating it in the diagram. Ginns (2005a) provided a meta-analysis of the modality effect that is still worth reading.

변동성 효과

Variability Effect

문제 상황에 대한 [가변성]은, 유사한 특징을 식별할 수 있게 해주고, 관련성이 높은 특징을 관련성이 없는 특징과 구별할 수 있는 확률을 증가시키기 때문에, 학습자가 더 일반화된 지식을 구축하도록 유도할 것으로 예측할 수 있다. 즉, 가변성의 증가는 내재 인지 부하를 증가시켜 증가를 처리하기에 충분한 작업 기억 자원이 있는 경우 더 많은 것을 배울 수 있게 한다. 몇몇 연구는 [가변성]이 [연습 중 인지 부하]를 증가시킬 뿐만 아니라, [학습의 전이transfer]도 증가한다는 것을 보여주었다. 처음에 변동성 효과는 (이전에 보고된 모든 인지 부하 효과와) 모순되는 것으로 보였다. 왜냐하면 그것은 [인지 부하의 감소]가 아니라, [인지부하의 증가]와 '높은 학습성과'를 결합시켰기 때문이다.

Variability over problem situations is generally expected to encourage learners to construct more general knowledge, because it increases the probability that similar features can be identified and that relevant features can be distinguished from irrelevant ones. In other words, increases in variability increase intrinsic cognitive load allowing more to be learned provided there is sufficient working memory resources to handle the increase. Several studies showed that variability not only increased cognitive load during practice but also increased transfer of learning. Initially, the variability effect seemed to contradict all earlier reported cognitive load effects, because it combines an increase rather than a decrease of cognitive load with higher learning outcomes.

기하학 문제 해결 분야에서 파스와 판 메린보어(1994a)는 인지 부하 이론의 맥락에서 가변성 효과를 최초로 기술했다.

- 그들은 [높은 변동성]이 [인지 부하가 낮은 상황(즉, 완성된 예제를 통한 학습)]에서 학습과 전이에 긍정적인 영향을 미칠 것이라고 가정했다. 왜냐하면 그러한 상황에서는 변동성이 내재 인지 부하를 증가시켰다는 사실에 관계없이 총 인지 부하가 한계 내에 머물 것이기 때문이다.

- 대조적으로, 그들은 [높은 변동성]은 [인지 부하가 이미 높은 상황]에서 학습과 전이에 부정적인 영향을 미칠 것이라고 예측했다. 왜냐하면 총 인지 부하가 학습자의 작업 기억력에 과도한 부담을 주기 때문이다.

In the domain of geometrical problem solving, Paas and van Merriënboer (1994a) were the first to describe the variability effect in the context of cognitive load theory: They hypothesised that high variability would have a positive effect on learning and transfer in situations in which cognitive load was low (i.e. learning from worked examples), because in such situations the total cognitive load would stay within limits, irrespective of the fact that variability increased intrinsic cognitive load. In contrast, they predicted that high variability would have a negative effect on learning and transfer in situations in which cognitive load was already high (i.e. learning by solving conventional problems), because the total cognitive load would then overburden learners’ working memory.

실제로, 문제 형식(풀이된 예제, 전통적 문제)과 변동성(낮음, 높음) 사이의 기대했던 상호작용이 발견되었다. 이와 유사한 발견에 기초하여 학습에 생산적이지 않은 '외부적' 과정과 학습에 생산적인 '본유적' 프로세스에 의해 야기되는 부하 사이에 구별이 도입되었다. 수업instruction을 설계할 때 먼저 외부 인지 부하를 감소시켜야 하는 것은 유효하다. 하지만, 새로운 함의는, 총 인지 부하가 한계 내에 있다면, 외부 인지 부하의 감소는 본유적 인지부하의 증가가 동반되었을 때 훨씬 더 효과적일 수 있다.

Indeed, the expected interaction between problem format (worked examples, conventional problems) and variability (low, high) was found. Based on this and similar findings, a distinction was introduced between load that is caused by ‘extraneous’ processes not productive for learning and load that is caused by ‘germane’ processes and productive for learning. When instruction is designed, it should first decrease extraneous cognitive load, but as a new implication, instructional designs that are effective in decreasing extraneous cognitive load may become even more effective if they increase germane cognitive load, provided that total cognitive load stays within limits.

'인지 부하 이론의 발전 1998–2018' 섹션에서 설명될 것처럼, 이는 다양한 유형의 인지 부하를 측정하고 저마다의 처리를 증가시키는 것을 목표로 하는 새로운 효과를 식별하는 길을 열었다.

As will be described in the ‘Developments in Cognitive Load Theory 1998–2018’ section, this opened up the way for measuring different types of cognitive load and identifying new effects that explicitly aimed at increasing germane processing.

인지부하 이론의 발전

Developments in Cognitive Load Theory 1998–2018

지난 20년 동안 인지 부하 이론에서 주요한 발전이 있었다.

- 첫째, 진화 심리학에서 인간의 인지 구조를 위한 강력한 기초를 마련함으로써 그것의 이론적 기반이 강화되었다.

- 둘째, 4개 요소 교육 설계(4C/ID)는 더 긴 기간의 교육 프로그램 설계(강좌 또는 전체 커리큘럼)에 초점을 맞춘 쌍둥이 이론으로 개발되었다.

- 셋째, 연구는 소위 복합 효과, 즉 다른 단순한 인지 부하 효과의 특성을 바꾸는 효과를 포함한 일련의 새로운 인지 부하 효과를 산출했다.

- 네 번째이자 마지막으로, 다양한 유형의 인지 부하를 측정하기 위한 새로운 기기가 개발되었습니다. 우리는 진화 심리학에 기초한 이론적 발전을 고려하는 것으로 시작할 것이다.

There have been major developments in cognitive load theory over the last 20 years.

- First, its theoretical basis has been strengthened by laying a strong foundation for human cognitive architecture in evolutionary psychology.

- Second, four-component instructional design (4C/ID) has been developed as a twin theory focussing on the design of educational programs of longer duration (courses or whole curricula).

- Third, research yielded a series of new cognitive load effects, including the so-called compound effects, that is, effects that alter the characteristics of other, simple cognitive load effects.

- Fourth and finally, new instruments have been developed to measure different types of cognitive load. We will begin by considering theoretical developments based on evolutionary psychology.

진화심리학의 프리즘을 통해 본 인간의 인지구조

Human Cognitive Architecture Seen Through the Prism of Evolutionary Psychology

작업 기억과 장기 기억 사이의 복잡한 관계에 중점을 둔 1998년 버전의 인간 인지 구조는 우리가 어떻게 문제를 배우고, 생각하고, 해결하는지에 대한 중요한 측면을 제공했지만, 인간 인식에 대한 우리의 지식에 있어서 지속적인 진보는 초창기에 갖고 있던 개념이 확장될 필요성을 시사했다. 그 팽창의 대부분은 진화심리를 중심으로 돌아갔는데, 이것은 그 작업에 자극을 주었다.

While our 1998 version of human cognitive architecture, with its emphasis on the intricate relations between working memory and long-term memory, provided a critical aspect of how we learn, think and solve problems, the continual advances in our knowledge of human cognition indicated a need to expand that earlier conceptualisation. Much of that expansion revolved around evolutionary psychology which provided an impetus for that work.

생물학적으로 초등 지식과 중등 지식 사이의 Geary의 구별에 기초하여, [진화적 교육 심리학]은 우리가 이제 인지 부하 이론의 중심인 교육적으로 의미 있는 방식으로 정보를 분류할 수 있게 해준다. 생물학적으로 가장 중요한 지식은 우리가 [수없이 많은 세대를 거쳐 습득하도록 진화해 온 지식]이다. 이러한 지식의 범주는 인간에게 결정적으로 중요한 것을 제공해왔다.

- 예를 들어, 우리가 듣고 말하고, 얼굴을 인식하고, 기본적인 사회적 기능에 관여하고, 낯선 문제를 해결하고, 이전에 습득한 지식을 새로운 상황으로 이전하고, 일어날 수도 있고 일어나지 않을 수도 있는 미래 사건에 대한 계획을 세우거나, 우리의 현재 환경에 대응하도록 우리의 사고 과정을 규제할 수 있는 지식이다.

Based on Geary’s distinction between biologically primary and secondary knowledge (Geary 2008, 2012; Geary and Berch 2016), evolutionary educational psychology allows us to categorise information in instructionally meaningful ways that now are central to cognitive load theory (Sweller 2016a). Biologically primary knowledge is knowledge that we have evolved to acquire over countless generations. That category of knowledge tends to be critically important to humans providing,

- as examples, knowledge that allows us to listen and speak, recognise faces, engage in basic social functions, solve unfamiliar problems, transfer previously acquired knowledge to novel situations, make plans for future events that may or may not happen, or regulate our thought processes to correspond to our current environment.

인간은 이러한 매우 복잡한 인지 활동에 참여하는 것을 배워야 하지만, 그들의 중요성 때문에, 우리는 필요한 기술을 쉽고 [자동으로 습득하도록 진화]해 왔다. 결과적으로, 그것들은 대부분의 사람들에게 가르쳐질 수 없다.

Humans must learn to engage in these very complex cognitive activities but because of their importance, we have evolved to acquire the necessary skills effortlessly and automatically. Consequently, they cannot be taught to most people.

생물학적으로 [원초적primary 지식]은 [모듈식]이기에, 한 기술과 다른 기술과 관련된 인지 과정 사이에 거의 관계가 없다. 각각의 기술은 매우 다른 인지 과정을 요구하는 서로 다른 진화 시대에서 진화했을 것이다.

- 우리의 현재 환경에 대응하도록 우리의 사고 과정을 조절하는 우리의 능력은 의사소통을 위해 제스처를 사용하는 우리의 경향처럼 우리가 현대 인간이 되기 전에 진화했을 가능성이 있는 반면,

- 우리의 입술, 혀, 숨, 그리고 목소리를 말하기 위해 조직하는 우리의 능력은 훨씬 더 최근에 진화했을 가능성이 있다.

Biologically primary knowledge is modular with little relation between the cognitive processes associated with one skill and another (Geary 2008, 2012). Each skill is likely to have evolved in different evolutionary epochs requiring very different cognitive processes.

- Our ability to regulate our thought processes to correspond to our current environment is likely to have evolved before we became modern humans as did our tendency to use gestures to communicate, while

- our ability to organise our lips, tongue, breath and voice to speak is likely to have evolved far more recently.

생물학적으로 매우 많은 주요 기술들은 [일반적인 문제 해결 기술] 또는 심지어 [지식을 구성하는 우리의 능력]처럼 본질적으로 [일반적인 인지generic-cognitive 능력]이다. (Sweller 2015, 2016b; Tricot and Sweller 2014)

- [일반적인 인지 기술]은 우리가 본능적으로 습득하도록 진화한 기본적인 인지 기술입니다. 왜냐하면 그것은 매우 광범위한 인지 기능에 필수적이기 때문입니다.

- [일반적인 인식 기술]은 [특정한 주제 자체]보다는, 우리가 문제를 배우고, 생각하고, 해결하는 방법에 더 관심을 가지는 경향이 있다.

A very large number of biologically primary skills are generic-cognitive in nature such as general problem-solving skills or even our ability to construct knowledge (Sweller 2015, 2016b; Tricot and Sweller 2014).

- A generic-cognitive skill is a basic cognitive skill that we have evolved to acquire instinctively because it is indispensable to a very wide range of cognitive functions.

- Generic-cognitive skills tend to be more concerned with how we learn, think and solve problems rather than the specific subject matter itself.

지난 수십 년 동안, 그러한 기술의 중요성을 정확히 깨닫고 있는 많은 교육학자들은 [그것들을 가르쳐야 한다]고 주장해왔다. 그러한 캠페인은 실패하는 경향이 있는데, 그 이유는 기술이 중요하지 않기 때문이 아니라 인간에게 매우 중요하기 때문이다. 그래서 우리는 [교육 없이 자동적으로 그것들을 습득]하도록 진화해 왔다. 지난 세기에 일반적인 문제 스킬을 가르치는 데 엄청난 역점을 두었던 것이 한 예를 제공한다. [일반적인 인지 기술]에 대한 교육효과의 증거를 얻기 위해서는 [원거리 전이 시험]를 사용하여 무작위적이고 통제된 시험을 해야 한다. 일반적인 인식 기술의 근거는 광범위한 영역에서 성과를 향상시킬 것이며, 물론 [어떤 수행능력의 향상도 영역별 지식 때문이 아님을 확인하는 것]이 필수적이기 때문에 원거리 전이far transfer가 필요하다.

Over the last few decades, many educationalists, correctly realising the importance of such skills, have advocated that they be taught. Such campaigns tend to fail, not because the skills are unimportant but because they are of such importance to humans that we have evolved to acquire them automatically without instruction. The enormous emphasis on teaching general problem-skills last century provides an example. Evidence for the effectiveness of teaching generic-cognitive skills requires randomised, controlled trials using far transfer tests. Far transfer is required because the rationale of generic-cognitive skills is that they will enhance performance over a wide range of areas and, of course, it is essential to ensure that any performance improvement is not due to domain-specific knowledge.

생물학적인 [원초적primary 기술]의 습득은 [명시적인 교육 없이도, 자동적으로 무의식적]으로 일어나는 경향이 있지만, [기술의 사용]까지 [모든 맥락에서 무의식적으로 발생하는 것은 아니라는 점]에 유의해야 한다.

- 예를 들어, 우리는 명확한 노력 없이 무의식적으로 모국어를 말하는 것을 배우지만, 어떤 주어진 상황에서 적절한 의미를 가진 적절한 단어를 찾기 위해 상당한 노력을 필요로 할 수 있다.

우리는 생물학적으로 일차적인 지식을 특정 영역에서 사용하는 방법을 배울 필요가 있습니다. 이는 [생물학적 이차 지식biologically secondary knowledge]으로 이어집니다.

It should be noted that while the acquisition of biologically primary skills tends to occur automatically and unconsciously without explicit teaching, it does not follow that use of the skills occurs unconsciously in every context.

- For example, we learn to speak our native language unconsciously without explicit effort but may require considerable effort to find appropriate words with appropriate meanings in any given situation.

We need to learn how to use biologically primary knowledge in specific domains, which leads to biologically secondary knowledge.

[생물학적 이차 지식]은 [우리의 문화가 그것이 중요하다고 결정했기 때문에 우리에게 필요한 지식]이다. 생물학적 이차 정보의 예는 교육과 훈련 맥락에서 가르치는 [거의 모든 주제]에서 찾을 수 있다. 교육 기관들은 생물학적으로 2차적인 정보에 대한 지식을 습득하기 위한 사람들의 필요성 때문에 발명되었다.

Biologically secondary knowledge is knowledge we need because our culture has determined that it is important. Examples of biologically secondary information can be found in almost all topics taught in education and training contexts. Educational institutions were invented because of our need for people to acquire knowledge of biologically secondary information.

우리는 [2차 지식]을 습득하도록 진화해 왔지만, 그것은 [1차 지식]과는 매우 다르게 습득된다. 1차 지식과 관련된 경우를 제외하고, 보조 지식은 [모듈식]이 아니라, [단일한, 통일된single, unified 시스템]의 일부입니다. 통합된 시스템이기 때문에, 어떤 영역이든 관계없이 [생물학적 2차 지식의 획득]에는 상당한 유사점이 있다. 모든 2차 지식은 학습자의 의식적인 노력과 강사의 분명한 가르침을 필요로 하는 경향이 있다. (2차 지식이) 자동으로 획득되는 경우는 거의 없습니다.

We have evolved to acquire secondary knowledge but it is acquired very differently to primary knowledge. Except insofar as it is related to primary knowledge, secondary knowledge is not modular but rather, is part of a single, unified system. Because it is a unified system, there are considerable similarities in acquiring biologically secondary knowledge irrespective of the domain under consideration. All secondary knowledge tends to require conscious effort on the part of the learner and explicit instruction on the part of an instructor. It is rarely acquired automatically.

[일차 지식의 습득]과 [이차 지식의 습득] 사이의 차이는 [듣는 것]과 [읽는 것] 사이의 구별에 의해 예시될 수 있다.

- 위에서 말한 바와 같이, 우리는 수업료 없이 자동적으로 듣는 법을 배운다.

- 반면, 대부분의 사람들은 자동으로 읽는 법을 배우지 않는다. 수천 년 전에 읽기와 쓰기가 발명되었음에도 불구하고, 현대 교육이 출현하기 전까지 읽고 쓰는 법을 배운 사람은 거의 없었다.

The distinction between the two processes can be exemplified by the distinction between learning to listen and learning to read.

- As indicated above, we learn to listen automatically, without tuition.

- Most people do not learn to read automatically. Despite reading and writing having been invented thousands of years ago, few people learned to read and write until the advent of modern education very recently.

대부분의 [생물학적 일차 지식]과 관련된 [일반적 인지 기술]과는 달리, [생물학적 2차 지식]은 도메인별로 상당히 다르다(2015, 2016b; Tricot and Sweller 2014). 우리는 [일반적 인지 기술]을 사용하여 다양한 문제를 해결하는 방법을 배우도록 진화해 왔다. 하지만 우리는 특정한 단어를 영어나 중국어로 읽고 쓰는 방법이라든가, '(a + b)/c = d에서 a를 구하라'와 같은 문제를 풀 때 가장 좋은 첫 번째 움직임은 양쪽에 분모를 곱하는 것이라는 요령을 자동으로 배우게끔 진화하지 않았다. 이러한 영역별, 생물학적 2차 기술은 명시적으로 가르쳐야 하며, 적극적으로 학습해야 한다.

In contrast to the generic-cognitive skills associated with most biologically primary knowledge, biologically secondary knowledge is heavily domain-specific (Sweller 2015, 2016b; Tricot and Sweller 2014). We have evolved to learn how to solve a variety of problems using generic-cognitive skills. We have not specifically evolved to learn how to read and write a particular word in English or Chinese, or that the best first move when solving a problem such as (a + b)/c = d, solve for a, is to multiply both sides by the denominator on the left side. These domain-specific, biologically secondary skills need to be explicitly taught (Kirschner et al. 2006; Sweller et al. 2007) and actively learned.

대부분의 교육학자들은 직관적으로 [일반적 인지 기술]이 [영역-특이적 기술]보다 인간의 기능에 훨씬 더 중요하다는 것을 포착했으며, 이는 [일반적 인지 기술]을 상당히 강조하는 결과를 가져왔다. 그럼에도 불구하고, [영역-특이적 기술]은 상당히 가르칠 수 있는 것과 달리, 순수하게 [일반적 인지 기술]은 가르칠 수 없고, 그것들을 가르치려는 시도는 막다른 골목에 이르게 한다는 인식이 증가하고 있다.

Most educationists intuitively understand that generic-cognitive skills are far more important to human functioning than domain-specific skills and this understanding has led to a substantial emphasis on generic-cognitive skills. Nevertheless, there is an increasing recognition that while domain-specific skills are eminently teachable, purely generic-cognitive skills are not teachable and attempts to teach them lead to dead-ends (Sala and Gobet 2017).

과거에 [일반적 인지 기술]을 강조한 이유는, 생물학적으로 일차적인 지식과 이차적인 지식의 차이를 깨닫지 못했기 때문이다. [일반적 인지 기술]의 교육에 대한 강조는, 물론, 1998년에 [일반적인 문제 해결 기술]에 대한 교육이 인기를 얻으면서 함께 존재했습니다. 1998년 논문은 부분적으로 그 억양에 대한 반응이었다. 그 단계는 지났지만 다른 일반적인 인식 기술은 살라와 고베에서 알 수 있듯, 더 큰 성공을 거두지 못했다.

The previous emphasis on generic-cognitive skills is due to a failure to realise the distinction between biologically primary and secondary knowledge (Tricot and Sweller 2014). An accent on teaching generic-cognitive skills was, of course, present in 1998 with the popularity of teaching generic problem-solving skills. The 1998 paper was partially a reaction to that accent. That phase has passed but other generic-cognitive skills have replaced that emphasis with, as indicated by Sala and Gobet, no greater success.

게다가, 약 1세기 동안의 노력에도 불구하고, 원거리 전이 연구far transfer study에서 [영역 특이적 기술]을 초월하는 [일반적 인지 기술]을 가르칠 수 있다는 증거는 거의 나오지 않았다. 생물학적 [1차적, 일반적 인지 기술]을 습득하는 데에 '자연'스러운 것이었던 [최소한의 가이드]는, [쉽게, 무의식적, 자동적으로 습득되지 않는] 생물학적으로 [2차적, 영역-특이적 기술]의 습득에는 부적절했다.

Furthermore, despite about a century of effort, there is little evidence from far transfer studies, that generic-cognitive skills which transcend domain-specific areas can be taught. The ‘natural’, minimal guidance procedures used to acquire biologically primary, generic-cognitive skills are inappropriate for the acquisition of biologically secondary, domain-specific skills that tend not to be acquired easily, unconsciously and automatically.

우리는 위의 주장에서 [생물학적 1차 지식]과 [일반적 인지 능력]이 교육적인 문제와 무관하다고 결론내리지 말아야 한다. 생물학적으로 일차적이고 일반적인 인지 기술을 가르치려는 시도가 성공할지는 의심스럽지만, [생물학적 2차적 영역 특이적 기술]을 가르치는 데 도움을 주기 위해 사용될 수 있다(Paas and Sweller 2012)

- 예를 들어, 학생들은 문제해결 절차에 대한 지도를 받지 않고도 [무작위로 문제 해결 방법을 생성하는 방법]을 알 수 있지만, 어떤 방법이 어떤 영역에서 효과적일 것인가는 알지 못할 수 있다. [문제의 특정 클래스]에 [특정한 일반적 인지 기술]을 사용해야 한다고 학생들에게 지적하는 것은 교육적으로 효과적일 수 있다(유세프-샬랄라 외. 2014).

We should not conclude from the above argument that biologically primary knowledge and generic-cognitive skills are irrelevant to instructional issues. While we doubt that attempts to teach biologically primary, generic-cognitive skills will be successful, they can be used to assist in teaching biologically secondary, domain-specific skills (Paas and Sweller 2012).

- For example, students may know how to randomly generate problem solution moves without being instructed in the procedures to do so, but may not be aware of the domain-specific conditions where the technique might be effective. Pointing out to students that a generic-cognitive skill should be used on a particular class of specific problems can be instructionally effective (Youssef-Shalala et al. 2014).

게다가, 무엇이든 [가르치는 것]은 [1차 기술과 2차 기술의 조합]을 포함하며, 이 중에서 [2차 기술]만이 학습되는 유일한 부분이라는 것을 주목하는 것이 중요하다.

- 예를 들어, 의사들은 SBAR 방법을 사용하여 항상 상황, 배경, 평가 및 권고사항에 대해 보고함으로써 응급 팀에서 효과적으로 의사소통하는 방법을 배운다. 분명히, 의사들은 서로 말할 수 있기 때문에 SSAR 방법은 가르쳐질 수 있다. 하지만, 말하는 것이 [1차 지식]이기 때문에 의사들에게 일반적인 의미에서 서로 말하는 법을 가르치는 것은 말이 안 되지만, 특정한 SSAR 방법을 가르치는 것은 [2차 지식]이고 응급 상황에서 팀 의사소통에 매우 긍정적인 영향을 미칠 수 있다.

Furthermore, it is important to note that teaching anything involves a combination of primary and secondary skills with the secondary skill being the only part that is learned.

- For example, medical doctors are taught how to effectively communicate in an emergency team using the SBAR method, always reporting on the situation, background, assessment and recommendations (Beckett and Kipnis 2009). Obviously, the SBAR method can be taught because doctors are able to speak with each other. But, although it makes no sense to teach doctors how to speak with each other in a generic sense because this is primary knowledge, teaching them the specific SBAR method is secondary knowledge and might have a very positive effect on team communication in emergency situations.

인지 구조는 [생물학적 이차적 정보]를 처리하는 데 필요하며, 인지 구조는 (인지 부하 이론의 기초를 제공하는) [생물학적 일차적인 과정]으로 구성되어 있다. 이 프로세스는 모두 생물학적 진화의 정보 처리 절차(Sweller and Sweller 2006)를 모방하며, 자연 정보 처리 시스템을 구성하는 것으로 설명할 수 있습니다. 그것들은 생물학적으로 [5가지 기본 원리]로 설명될 수 있다. 이러한 원칙들은 인지 부하 이론의 지시 절차에 기초하는 인지 구조를 제공한다.

The cognitive architecture required to process biologically secondary information consists of biologically primary processes that provide a base for cognitive load theory. Together, the processes mimic the information processing procedures of biological evolution (Sweller and Sweller 2006) and can be described as constituting a natural information processing system. They can be described by five basic, biologically primary principles. These principles provide the cognitive architecture that underlies the instructional procedures of cognitive load theory.

정보 저장 원칙

The Information Store Principle

인간의 인식과 같은 [자연 정보 처리 시스템]은 우리의 복잡한 자연 세계에서 기능하기 위해 많은 양의 정보를 필요로 한다. [장기 기억]은 인간의 인식에 그런 구조를 제공한다. 우리는 생물학적으로 주요한 기능을 나타내는 정보를 장기 기억에 저장하거나 정리하는 방법을 사람들에게 가르칠 필요가 없다. 장기 기억은 1998년 논문에서 명확하게 표현되었다.

Natural information processing systems such as human cognition require a large store of information in order to function in our complex natural world. Long-term memory provides that structure in human cognition. We do not need to teach people how to store or organise information in long-term memory indicating its biologically primary function. Long-term memory was explicitly articulated in the 1998 paper.

차용 및 재조직 원칙

The Borrowing and Reorganising Principle

장기 기억에 저장된 방대한 양의 정보는 다른 사람들로부터 온다. 인간은 매우 사회적인데, 특히 [다른 사람들로부터 정보를 얻고, 다른 사람들에게 정보를 제공하는 절차] 츠면에서 강력하게 진화하였다는 점에서 그렇다. 그것은 생물학적으로 가장 중요한 기술이기 때문에, 우리는 자동적으로 우리가 우리의 삶 동안 다른 사람들로부터 정보를 제공하고 받을 것이라고 가정한다. 이 원칙은 명시적으로 언급되지는 않았지만 1998년 논문에서 어느 정도 가정되었다. 명확한 지시에 중점을 둔 인지 부하 이론은 이 원리를 중요시한다.

The vast bulk of information stored in long-term memory comes from other people. Humans are intensely social with powerfully evolved procedures for obtaining information from others and for providing information to others. Because it is a biologically primary skill, we automatically assume that we will provide and receive information from others during our lives. This principle was to some extent assumed in the 1998 paper, although it was not explicitly stated. Cognitive load theory with its emphasis on explicit instruction places prominence on this principle.

생성의 임의성 원리

The Randomness as Genesis Principle

장기 기억에 저장된 정보의 대부분은 다른 사람들로부터 얻지만, 만약 그 정보를 빌릴 수 있는 사람이 없다면, 그것은 생성될 필요가 있을 것이다. 새로운 정보는 문제 해결 중에 [무작위 생성 및 테스트 절차]를 사용하여 생성된다. [무작위 생성 및 테스트 절차]는 자신의 또는 다른 사람의 장기 기억에서 정보를 사용할 수 없는 경우에만 사용됩니다. 문제 해결사가 주어진 지점에서 어떤 동작을 수행해야 하는지를 나타내는 정보를 가지고 있지 않을 경우, 무작위로 동작을 생성하고 효과적인 동작을 유지하고 효과적인 동작을 포기한 상태에서 효과성을 시험하는 것 외에는 선택의 여지가 없다. 다시 말하지만, 이 절차는 생물학적으로 일차적이기 때문에 교육instruction이 필요하지 않습니다.

While most of the information stored in long-term memory is obtained from others, if no one is available from whom to borrow the information, it will need to be generated. Novel information is generated using a random generate and test procedure during problem solving. The procedure only is used when information is unavailable from one’s own or someone else’s long-term memory. When problem solvers do not have information indicating which moves should be made at a given point, they have no choice other than to randomly generate a move and test it for effectiveness with effective moves retained and ineffective ones jettisoned. Again, this procedure does not require instruction because it is biologically primary.

협소한 변화원칙

The Narrow Limits of Change Principle

인간의 인식을 다룰 때, 이 원리는 새로운 정보를 처리할 때 작업 기억력의 심각한 한계를 다룬다. 이 원리는 항상 인지 부하 이론의 중심이었고 1998년에 명확하게 설명되었습니다. 원리의 기본적인 가정은, 한 개인에 대해 일반적인 [작업 기억 용량]이 고정되어 있다는 것이다. 작업 기억력 고갈이 인지 노력 후에 발생하고 휴식 후에 회복된다는 최근의 증거와 함께(Chen et al. 2018) 그러한 용량 변화를 허용하도록 가정을 수정해야 한다. (이 문제는 '미래 방향' 섹션에서 자세히 설명합니다.)

When dealing with human cognition, this principle refers to the severe limitations of working memory when processing novel information. This principle has always been central to cognitive load theory and was clearly articulated as such in 1998. A basic assumption of the principle has been that for any given individual, general working memory capacity is fixed. With recent evidence that working memory depletion occurs after cognitive effort and recovers after rest (Chen et al. 2018), that assumption must be modified to allow such capacity variations. (This issue is discussed further in the ‘Future Directions’ section.)

환경정리 및 연계원칙

The Environmental Organising and Linking Principle

[작업 기억]은 새로운 정보를 처리하는 경우에는 제한이 생기지만, 익숙하고 조직된 정보가 장기 기억에서 처리될 때는 알려진 한계가 없다. 정보가 장기 기억에 저장되면 [환경적 단서]를 사용하여 해당 환경에 적합한 작업을 생성할 수 있습니다. 이러한 방식으로, 이 원칙은 [(특정) 환경에 적합한 행동을 관장하기 위해 사용될 지식]을 [장기 기억]으로 구성하는데 사용될 수 있다. 이미 조직되고 저장된 정보를 이러한 방식으로 사용하기 위한 추진력은 생물학적으로 가장 중요하며 교육비용tuition이 필요하지 않습니다. 이 원리는 인지 부하 이론의 1998년 버전에서 크게 강조되었다.

While working memory is limited when processing novel information, there are no known limits when familiar, organised information from long-term memory is processed. Once information is stored in long-term memory, environmental cues can be used to generate actions appropriate to that environment. In this manner, the previous principles can be used to construct knowledge in long-term memory that can be used to govern action that is appropriate to the environment. The impetus to use previously organised and stored information in this fashion is biologically primary and does not require tuition. This principle was heavily emphasised in the 1998 version of cognitive load theory.

이 인지 아키텍처는 (대부분의 교육 프로그램에서 다루는) [생물학적 2차, 영역-특이적 내용]을 다룰 때 [명시적 교육explicit instruction]의 중요성을 강조하는 [인지 부하 이론]의 기초를 제공한다. 또한 새로운 교육instructional 절차를 생성의 성공에 대한 설명을 제공한다. 교육은 명시적이어야 한다. 왜냐하면

- 우리는 [차용과 재조직의 원리]를 통해 다른 사람들로부터 직접 배우도록 진화해왔기 때문이다.

- [협소한 변경 원리]에 따라, 작업 메모리 로드는 주로 새로운 도메인별 정보를 처리할 때 발생하기 때문에 작업 메모리 로드를 줄이는 방식으로 구성될 필요가 있다.

- [차용과 재조직 원리]를 사용하여 다른 사람들로부터 정보를 얻는 것은, [창조의 임의성 원리]를 사용하여 정보를 직접 생성하는 방식에 비해 작업 기억 부하를 감소시킨다.

- [정보 저장 원리]를 통해 정보를 입수하여 장기 메모리에 저장하면 작업 메모리의 한계가 사라진다.

- [환경 구성 및 연결 원리]를 이용하여 작업 기억으로 정보를 다시 전송한다면, 적절한 작업을 수행할 수 있습니다.

This cognitive architecture, with its emphasis on the importance of explicit instruction when dealing with the biologically secondary, domain-specific content that is characteristic of most educational programs, provides a base for cognitive load theory and an explanation for its success in generating novel instructional procedures. Instruction should be explicit

- because we have evolved to learn directly from other people via the borrowing and reorganising principle.

- In line with the narrow limits of change principle, it needs to be organised in a manner that reduces working memory load because working memory load primarily occurs when processing novel, domain-specific information.

- Obtaining information from others using the borrowing and reorganising principle reduces working memory load compared to generating information ourselves using the randomness as genesis principle.

- Once information has been obtained and stored in long-term memory via the information store principle, the limitations of working memory disappear and

- the information can be transferred back to working memory using the environmental organising and linking principle to generate appropriate action.

4C/ID 및 인지 부하

4C/ID and Cognitive Load

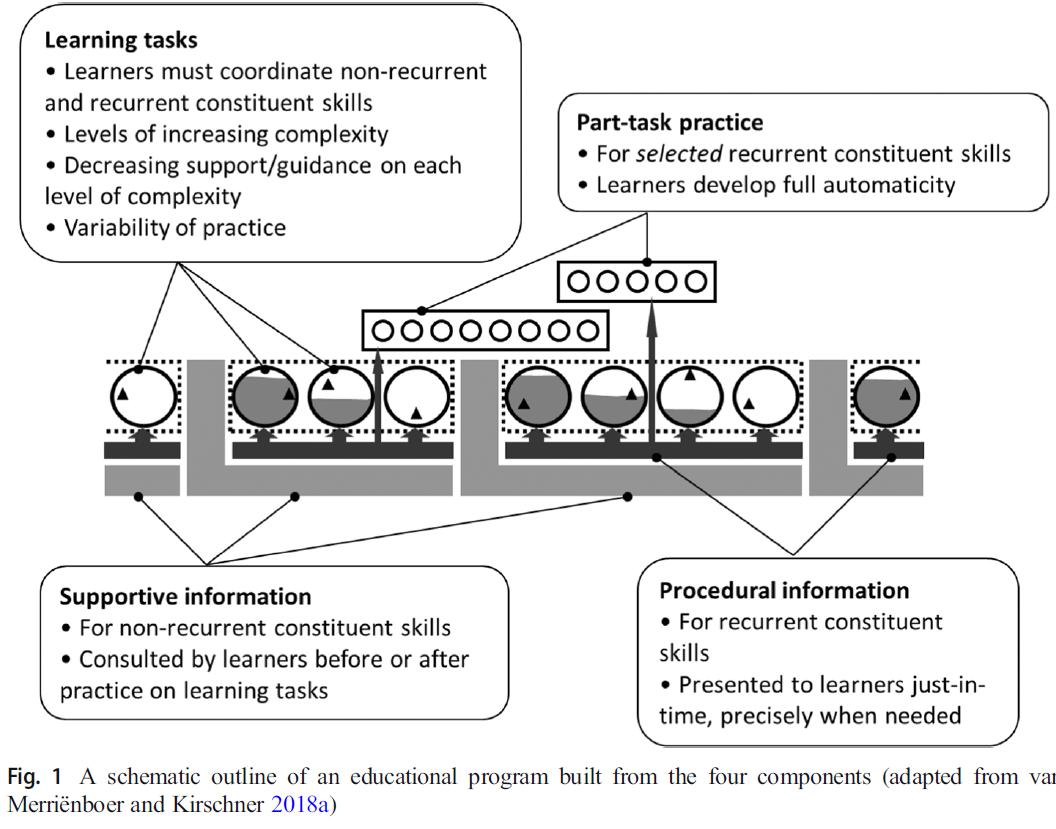

인지 부하 이론은 근거에 입각한 원칙을 제공한다. 이 원칙은 레슨, 텍스트와 그림으로 구성된 서면 자료, 교육용 멀티미디어(교육용 애니메이션, 비디오, 시뮬레이션, 게임)와 같이 [교육용 메시지] 또는 [비교적 짧은 교육 단위 설계]에 적용할 수 있다. 학습 및 교육 설계(예: Wickens 2008)보다는 작업장 성과에 초점을 맞춘 정신적 작업 부하 모델 및 멀티미디어 자료 설계에 배타적으로 초점을 맞춘 멀티미디어 학습 인지 이론(CTML; Mayer 2014)과 몇 가지 원칙을 공유한다. 인지 부하 이론과 정확히 동일한 인지 구조에 기초하고 완전히 병렬로 개발된 밀접하게 관련된 모델은 4개 요소 지시 설계(4C/ID)이다. 4C/ID 모델은 [더 긴 기간의 교육 프로그램 설계(예: 과정 또는 전체 커리큘럼)에 초점]을 맞추기 때문에 인지 부하 이론으로 중요한 확장을 제공한다.

Cognitive load theory provides evidence-informed principles that can be applied to the design of instructional messages or relatively short instructional units, such as lessons, written materials consisting of text and pictures, and educational multimedia (instructional animations, videos, simulations, games). It shares several of its principles with mental workload models, which focus on workplace performance rather than learning and instructional design (e.g. Wickens 2008), and with the cognitive theory of multimedia learning, which has an exclusive focus on the design of multimedia materials (CTML; Mayer 2014). A closely related model that is based on precisely the same cognitive architecture as cognitive load theory and that has been developed fully in parallel is four-component instructional design (4C/ID). The 4C/ID model provides an important extension to cognitive load theory because it focuses on the design of educational programs of longer duration (e.g. courses or whole curricula).

4C/ID에 대한 최초의 설명은 1992년(van Merrienboer et al. 1992)과 4C/ID 모델에 대한 최초의 완전한 설명을 제공하는 복합 인지능력 훈련(Training Complex Cognitive Skills)이라는 책이 1998년 인지부하 논문(van Merrienboer 1997)과 같은 시기에 등장했다. 4C/ID 모델은 복잡한 기술이나 전문 역량 개발을 목표로 하는 학습 과정에서 높은 요소 상호작용성으로 특징지어지는 복잡한 학습을 독점적으로 다룬다.

- [4C/ID의 첫 번째 기본 가정]은 복잡한 기술에는 업무와 상황에 대해 일관되고 일상적으로 개발될 수 있는 'recurrent' 기술뿐만 아니라 문제 해결, 추론 및 의사결정에 의존적인 'non-recurrent' 기술이 포함된다는 것이다(반 메리언보어 2013).

- [두 번째 기본 가정]은 복잡한 기술 개발을 목표로 하는 과정이나 프로그램은 항상 네 가지 구성 요소로 구성될 수 있다는 것이다(그림 1 참조).

- (1) 학습 과제,

- (2) 지원 정보,

- (3) 절차 정보

- (4) 파트 과제 연습

The first description of 4C/ID appeared in 1992 (van Merriënboer et al. 1992) and the book Training Complex Cognitive Skills, which provided the first complete description of the 4C/ID model, appeared in the same period as the 1998 cognitive load article (van Merriënboer 1997). The 4C/ID model exclusively deals with complex learning, which is characterised by high element interactivity in a learning process that is often aimed at the development of complex skills or professional competencies.

- A first basic assumption of 4C/ID is that complex skills include ‘recurrent’ constituent skills, which are consistent over tasks and situations and can be developed into routines, as well as ‘non-recurrent’ constituent skills, which rely on problem solving, reasoning and decision-making (van Merriënboer 2013).

- A second basic assumption is that courses or programs aimed at the development of complex skills can always be built from four components:

- (1) learning tasks,

- (2) supportive information,

- (3) procedural information and

- (4) part-task practice (see Fig. 1).

학습 과제(그림 1의 빅 서클에 표시)는 가급적이면 실생활 과제를 기반으로 하며, 이러한 과제를 수행함으로써 학습자는 비반복 및 반복 구성 기술을 모두 습득하고 이를 조정하는 법을 배운다.

첫째, [내재적 인지 부하]를 관리하기 위해, 학습 과제는 복잡성 증가 수준에 따라 먼저 조직된다(그림 1의 일련의 학습 과제 주위에 점선 상자로 표시).

- 따라서 학습자는 간단한 학습 과제에서 일하기 시작하지만 전문 지식을 습득할수록 더 복잡한 과제(즉, 나선형 커리큘럼)를 수행한다.

둘째, [외재적 인지 부하]를 관리하기 위해 각 복잡성 수준에서 학습자 지원 및 지침이 점진적으로 감소한다(그림 1의 각 복잡성 수준에서 원의 채우기 감소로 나타남).

- 따라서 학습자는 처음에는 많은 지원과 지도를 받지만, 지원/지도를 받지 않고 특정 수준의 복잡성으로 학습 과제를 수행할 수 있을 때까지, 지원/지도를 점차적으로 감소하게 된다. 그 다음에야 학습자는 처음에 많은 지원/지도를 받는 더 복잡한 학습 과제를 계속 수행하게 된다. 이 모든 과정이 반복된다.

- 4C/ID 모델은 fading-guidance에 대한 몇 가지 접근방식을 설명하지만, [worked example] => [completion task] => [conventional task]로 이어지는 완수 전략이 특히 중요하다.

셋째, [본유적 처리]를 자극하기 위해, 과정이나 프로그램의 모든 학습 과제는 연습의 높은 가변성(각 학습 과제마다 위치가 다른 삼각형으로 표시)을 통해 학습자가 과제를 서로 비교하고 대조하도록 자극한다.

Learning tasks (indicated by the big circles in Fig. 1) are preferably based on real-life tasks and by performing these tasks learners acquire both non-recurrent and recurrent constituent skills and learn to coordinate them.

In order to manage intrinsic cognitive load, learning tasks are first organised according to levels of increasing complexity (indicated by dotted boxes around series of learning tasks in Fig. 1);

- thus, learners start to work on simple learning tasks but the more expertise they acquire the more complex the tasks they work on (i.e. a spiral curriculum).

Second, in order to manage extraneous cognitive load, learner support and guidance gradually decrease at each level of complexity (indicated by the diminishing filling of the circles at each level of complexity in Fig. 1);

- thus, learners first receive a lot of support and guidance but support/guidance gradually decreases until learners can perform the learning tasks at a particular level of complexity without support/guidance—only then, they continue to work on more complex learning tasks for which they initially receive a lot of support/guidance again, after which the whole process repeats itself.

- The 4C/ID model describes several approaches to fading-guidance but the completion strategy,

- from studying worked examples

- via completion tasks

- to conventional tasks, is a particularly important one.

Third, in order to stimulate germane processing, all learning tasks in a course or program show high variability of practice (indicated by the triangles at different positions in the learning tasks), stimulating learners to compare and contrast tasks with each other.

[지원 정보supportive information (그림 1의 L자 형태로 표시)]는 학습자가 학습 과제의 [비반복적 측면(예: 문제 해결, 추론, 의사결정)]의 수행을 배우는 데 도움이 된다. 그것은 영역이 어떻게 조직되고 (흔히 '이론'이라고 불린다) 도메인 내 과제들이 체계적으로 접근될 수 있는지를 설명한다; 그것은 [복잡성 수준]과 연결된다. 왜냐하면 더 복잡한 과제를 수행하기 위해서, 학습자들은 더 많은 또는 더 정교한 지원 정보를 필요로 하기 때문이다. 학습자가 이미 알고 있는 것과 학습 과제를 성공적으로 수행하기 위해 알아야 할 것 사이의 다리를 제공합니다. [학습 과제를 하는 것]과 [지원 정보를 공부하는 것]은 모두 지식 구축을 목표로 한다(순서, 귀납적 학습과 정교화를 통해).

Supportive information (indicated by the L-shapes in Fig. 1) helps learners learn to perform the non-recurrent aspects of learning tasks (i.e. problem-solving, reasoning, decision-making). It explains how the domain is organised (often called ‘the theory’) and how tasks in the domain can be systematically approached; it is connected to levels of complexity because for performing more complex tasks, learners need more, or more elaborated, supportive information. It provides a bridge between what learners already know and what they need to know to successfully carry out the learning tasks. Both the work on the learning tasks and the study of supportive information aim at knowledge construction (through, in order, inductive learning and elaboration).

[지원 정보supportive information ]는 일반적으로 [높은 상호작용 요소]를 가지기 때문에, 학습자가 학습 과제를 수행하는 동안에는 제공하지 않는 것이 바람직합니다. 학습과제를 수행하면서 동시에 지원 정보를 공부하는 것은 거의 확실히 인지 과부하를 일으킬 것이다. 그보다는, 학습자가 [학습 과제에 착수하기 전] 또는 적어도 [학습 과제에 대한 작업과는 별개]로 지원 정보를 제공하는 것이 가장 좋습니다. 이러한 방식으로 학습자는 작업 기억에서 나중에 활성화될 수 있는 장기 기억에서 지식 구조를 구성할 수 있으며 과제 수행 중에 추가로 재구성되고 조정될 수 있다. 이미 구성된 인지 구조를 검색하는 것은 작업 수행 중에 작업 기억에서 외부에 제시된 복잡한 정보를 활성화하는 것보다 인지적으로 덜 요구될 것으로 예상된다.

Because supportive information typically has high element interactivity, it is preferable not to present it to learners while they are working on the learning tasks. Simultaneously performing a task and studying the supportive information would almost certainly cause cognitive overload. Instead, supportive information is best presented before learners start working on a learning task, or, at least apart from working on a learning task. In this way, learners can construct knowledge structures in long-term memory that can subsequently be activated in working memory and be further restructured and tuned during task performance. Retrieving the already constructed cognitive structures is expected to be less cognitively demanding than activating the externally presented complex information in working memory during task performance.

[절차적 정보(위쪽 방향 화살표가 있는 검은색 빔으로 표시)]와 [부분 작업 연습(작은 원 시리즈로 표시)]은 학습자가 지식 자동화를 목표로 하는 학습 과제의 [반복적인 측면recurrent aspects]을 학습하는 데 도움이 된다.

- 절차 정보는 'how-to instruction'과 수정 피드백corrective feedback으로 구성되며,

- 절차 정보는 일반적으로 지원 정보보다 훨씬 낮은 상호작용 요소를 가지고 있다.

- 인지 부하 관점에서, 절차 정보는 학습자가 학습 과제에 대한 작업 중 just-in-time에 제시하는 것이 최선이다.

- 왜냐하면 (자동화의 한 하위 프로세스) [인지적 규칙의 형성]은 관련성 있는 정보가 이러한 규칙에 포함될 수 있도록 [작업 수행 중 작업 기억에서 활성화되어야 하기 때문이다.

- 예를 들어, 교사가 연습 중에 학습자에게 '학습자의 어깨너머로 보는 보조자' 역할을 하는 단계별 지시를 하는 경우이다.

Procedural information (indicated by the black beam with upward pointing arrows in Fig. 1) and part-task practice (indicated by the series of small circles in Fig. 1) help learners learn to perform the recurrent aspects of learning tasks—they aim at knowledge automation.

- Procedural information consists of ‘how-to instructions’ and corrective feedback and

- typically has much lower element interactivity than supportive information.

- From a cognitive load perspective, it is best presented just-in-time, precisely when learners need it during their work on the learning tasks,

- because the formation of cognitive rules (one subprocess of automation) requires that relevant information is active in working memory during task performance so that it can be embedded in those rules.

- That is, for example, the case when teachers give step-by-step instructions to learners during practice, acting as an ‘assistant looking over the learners’ shoulder’.

마지막으로, 특정 반복 작업recurrent task 측면의 [부분 작업 연습]은 인지적 규칙(자동화의 또 다른 하위 프로세스)을 더욱 강화할 수 있다.

- 일반적으로 [부분 작업 연습]에 과도하게 의존하는 것은 복잡한 학습에는 도움이 되지 않지만,

- 기본적이거나 중요한 반복 구성 기술(예: 초등교육의 곱셈표, 보건직업 프로그램의 의료기기 운영)을 완전히 자동화하면 전체 학습 수행과 관련된 인지 부하를 줄임으로써 작업 수행 및 학습에 필요한 처리 리소스를 확보할 수 있습니다.

Finally, part-task practice of selected recurrent task aspects may further strengthen cognitive rules (another subprocess of automation).

- In general, an over-reliance on part-task practice is not helpful for complex learning

- but fully automating basic or critical recurrent constituent skills (e.g. the multiplication tables in primary education, operating medical instruments in a health professions program) may decrease the cognitive load associated with performing the whole learning tasks and so free up processing resources for performing and learning non-recurrent task aspects.

1998년 이후 기술된 지시 효과

Instructional Effects Described After 1998

이 절은 1998년과 2018년 사이에 연구되고 보고된 가장 중요한 인지 부하 영향을 설명할 것이다. 표 1의 하단에 8개의 새로운 효과가 나열되어 있다. 그러나, 우리는 1998년 이전에 이미 알려져 있지만 1998년 기사에서 인지 부하 효과로 제시되지 않은 요소 상호작용 효과에 대해 논의함으로써 이 절을 시작할 것이다. [요소 상호작용 효과]를 앞에서 열거하지 않은 이유는, 이것이 '단순한' 효과가 아니라 다른 인지 부하 효과의 특성을 변화시키는 효과인 소위 [복합 효과compound effect]이기 때문이다. 1998년 기사에서는 [단순 효과simple effect]만 보고되었다. 복합 효과는 종종 다른 인지 부하 효과의 한계를 나타낸다. 아래에서 논의한 8개의 새로운 효과(요소 상호작용 효과 제외) 중 4개도 복합 효과로 분류되어 먼저 논의된다. 이러한 이론은 단순한 효과뿐만 아니라 단순한 효과의 범위를 제한하는 고차 효과를 포함하기 때문에 이것은 이론이 성숙해가는 표시maturing theory로 볼 수 있다.

This section will describe the most important cognitive load effects that have been studied and reported between 1998 and 2018. Eight new effects are listed in the bottom part of Table 1. We will, however, begin this section by discussing the element interactivity effect, an effect already known before 1998 but not presented as a cognitive load effect in the 1998 article. The reason for not previously listing the element interactivity effect is that it is not a ‘simple’ effect but a so-called compound effect, which is an effect that alters the characteristics of other cognitive load effects. In the 1998 article, only simple effects were reported. Compound effects frequently indicate the limits of other cognitive load effects. Four of the eight new effects (excluding the element interactivity effect) discussed below are also classified as compound effects and are discussed first. This may be seen as an indication of a maturing theory, because such a theory not only includes simple effects but also higher-order effects that limit the reach of simpler effects.

요소 상호작용 효과

Element Interactivity Effect

이 효과는 1998년에 이미 알려져 있었지만 복합 효과로서 인지 부하 효과로 분류되지는 않았다(스웰러 1994 참조). [요소 상호작용이 높은 정보]를 사용하여 얻을 수 있는 효과가 [요소 상호작용이 낮은 자료]를 사용했을 때 사라지거나 역효과로 나타나는 것을 의미한다. 요소 상호작용은

- [전문성 역전 효과]를 입증할 때 발생하는 전문성 수준을 변경하거나(아래 설명 참조)

- 더 높거나 낮은 수준의 요소 상호작용을 통합하기 위해 학습자료를 변경함으로써 변경될 수 있다.

This effect was already known in 1998 but as a compound effect, it was not classed as a cognitive load effect (see Sweller 1994). It occurs when effects that can be obtained using high element interactivity information disappear or reverse using low element interactivity material. Element interactivity can be altered either

- by altering levels of expertise as occurs when demonstrating the expertise reversal effect (see description below) or

- by changing the material to incorporate either higher or lower levels of element interactivity.

학습자가 높은 요소 상호작용에서 낮은 요소 상호작용으로 처리해야 하는 정보의 변경으로 인해 변경된 교육적 이점의 예는 Chen 외(2015, 2016, 2017)에서 찾을 수 있다. 그들은 학생들이 문제를 풀기 위해 배워야 하는 [고-요소 상호작용성 수학 자료]를 사용하여 전통적인 예제 효과를 얻었다. 대조적으로, 학생들이 수학적 정의를 배워야 했던 [저-요소 상호작용 자료]는 역효과를 낳았다. 적절한 반응을 이끌어 내도록 요구된 학생들은 올바른 반응을 보인 학생들보다 더 많이 배웠다.

Examples of changed instructional advantages due to changing information that learners must process from high to low element interactivity may be found in Chen et al. (2015, 2016, 2017). They obtained a conventional worked example effect using high element interactivity mathematical material in which students had to learn to solve problems. In contrast, low element interactivity material in which students had to learn mathematical definitions yielded a reverse worked example effect. Students who were required to generate an appropriate response learned more than students who were shown the correct response.

전문성 역전 효과

Expertise Reversal Effect

본질적으로, [전문성 역전 효과]는 [요소 상호작용 효과]의 변형이다. 1998년 이전까지, 인지 부하 효과는 높은 요소 상호작용 정보를 처리하는 초보 학습자를 사용하여 얻었다. [전문성이 증가]하면, 요소 상호작용성은 [환경 구성 및 연결 원리]로 인해 감소합니다.

- 전문지식이 증가함에 따라, [여러 요소로 구성된 개념과 절차]는 (적절한 환경에서 사용하기 위하여 작업 기억으로 전달되는) [단일 요소]로 장기 기억에 저장될 수 있다.

- 여러 상호작용 요소를 다루는 초보자를 위해 설계된 교육 절차는 전문지식이 증가하고 상호작용 요소가 장기 기억에 저장된 지식 구조에 내장됨에 따라 역효과를 낼 수 있다.

결과적으로, 전문지식이 증가함에 따라 위의 효과는 처음에는 크기가 감소했다가 사라지고 결국 역전될 수 있다(Kalyuga 등, 2003, 2012). 예를 들어, worked examples는 초보자에게 이익이 된다. 지식이 증가함에 따라, 문제를 해결하는 연습은 부정적인 영향을 끼치기 보다는 점점 더 중요해지고 있다.

The expertise reversal effect is, in essence, a variant of the more general element interactivity effect (Chen et al. 2017). The pre-1998 cognitive load effects can be obtained using novice learners processing high element interactivity information. With increases in expertise, element interactivity decreases due to the environmental organising and linking principle.

- Concepts and procedures that consisted of multiple elements can, with increases in expertise, be stored in long-term memory as a single element that is transferred to working memory for use in appropriate environments.

- Instructional procedures designed for novices dealing with multiple, interacting elements can be counterproductive as expertise increases and the interacting elements become embedded in knowledge structures held in long-term memory.

As a consequence, with increasing expertise, the above effects first decrease in size, then disappear, and can eventually reverse (Kalyuga et al. 2003, 2012). For example, worked examples benefit novices. With increasing knowledge, practice at solving problems becomes increasingly important rather than having negative effects.

가이드-페이딩 효과

Guidance-Fading Effect

[가이드-페이딩 효과]는 [요소 상호작용 효과] 및 [전문성 역전 효과]와 밀접하게 관련되어 있으며, [중복성 효과]가 중심인 또 다른 [복합 효과coumpound effect]이다.

- 초보자에게는 추가 정보 또는 작업 예제 연구와 같은 특정 활동이 필수적일 수 있습니다.

- 전문지식이 증가함에 따라 이러한 동일한 활동이 중복될 수 있으며 불필요한 인지 부하를 부과할 수 있다.

- 어느 시점을 지나면, worked example를 공부하는 것은 역효과를 낼 수 있으므로, faded out되고, 그냥 문제로 대체되어야 한다.

The guidance-fading effect is another compound effect that is closely related to the element interactivity and expertise reversal effects and for which the redundancy effect is central too.

- For novices, additional information or particular activities such as studying worked examples may be essential.

- With increases in expertise, these same activities may become redundant and impose an unnecessary cognitive load.

- Past a certain point, studying worked examples may be counterproductive and they should be faded out and replaced by problems.

이 일반적인 원칙은 [학습자들이 점진적으로 해당 영역에서 더 많은 전문지식을 습득하는 더 긴 기간의 교육 프로그램]에 특히 중요하다. 예를 들어, 그것은 1학년 학생들을 위한 교육 방법이 3학년 학생들을 위한 교육 방법과 다를 필요가 있다는 것을 나타낸다. 3학년 학생들은 영역에 대한 훨씬 더 많은 지식을 갖고 있기 때문이다.

- [요소 상호작용 효과]는 낮은 요소 상호작용 대 높은 요소 상호작용 자료와 관련이 있고,

- [전문성 역전 효과]는 낮은 전문성 학습자와 높은 전문성 학습자와 관련이 있는 반면,

- [지침 페이딩 효과]는 긴 교육 프로그램에서 [프로그램의 시작]과 [프로그램의 끝]의 비교와 관련이 있다.

This general principle is particularly important for educational programs of longer duration, in which learners gradually acquire more expertise in the domain; it indicates, for instance, that instructional methods for first-year students need to be different from instructional methods for third-year students, simply because third-year students have much more knowledge of the domain.

- Whereas the element interactivity effect pertains to low element interactivity versus high element interactivity materials, and

- the expertise reversal effect pertains to low expertise learners and high expertise learners,

- the guidance-fading effects thus pertains to the beginning of a longer educational program versus the end this program.

지침 페이딩 효과의 전조forerunner는 완료 전략completion strategy으로, 여기서 교육 프로그램은 작업 예제를 제공하는 것으로 시작하고, 학습자가 솔루션의 점점 더 큰 부분을 완료해야 하는 완료 문제가 뒤따른다

A forerunner of the guidance-fading effect is the completion strategy, where the educational program starts with providing worked examples, followed by completion problems for which the learners must complete increasingly larger parts of the solution and ending with conventional problems (van Merriënboer and Krammer 1990).

일시적 정보 효과

Transient Information Effect

[일시적 정보]는 학습자에게 제공되긴 하나, 몇 초 후에 사라지는 정보입니다(예: 음성 텍스트, 교육용 비디오 또는 애니메이션).

- [비-일시적 정보(예: 그림이 있는 서면 텍스트)]의 경우, 모든 정보는 학습자가 동시에 사용할 수 있으며 필요할 때 다시 검토할 수 있다.

- [일시적 정보]의 경우, 학습자가 [후속 처리를 위해 작업 기억에 정보를 적극적으로 유지]시켜야 하므로, 외부 인지 부하가 늘어나고, 따라서 학습을 저해한다

Transient information is information that is presented to learners but disappears after a few seconds, for example, in spoken text or in instructional video or animation (Leahy and Sweller 2011).

- For non-transient information (e.g. a written text with pictures), all information is available to the learner at the same time and may be revisited when needed;

- for transient information, it may be necessary for the learner to actively retain information in working memory for later processing which increases extraneous cognitive load and so reduces learning.

이러한 부정적인 효과를 극복하기 위해 [자기-페이싱] 또는 [분할]과 같은 많은 보완적 전략을 사용할 수 있습니다.

- [자기 페이스 효과]는 학습자에게 교육 애니메이션의 속도에 대한 제어권을 주는 것이 유익하다는 것으로 보고되었다. 아마도 그것이 이 정보의 일시적인 특성을 다루는 데 도움이 되기 때문일 것이다.

- [분할 효과]는 분할된 애니메이션(즉, 중간중간 정지된 부분으로 분할된)이 초보 학습자에게는 연속 애니메이션보다 효율적이지만, 사전 지식이 높은 학습자에게는 그렇지 않다는 것을 발견했다.

- 마지막 예로, 마지막 예로 Leahy와 Sweller(2011, 2016)는 [제시양식modality 효과]에 대한 [일시적 정보]의 상호작용 효과를 보고했다.

- [시청각 정보의 짧은 부분]은 시각 정보만 있는 경우보다 효과적이었다(예: 전통적인 양식 효과).

- 그러나 [시청각 정보의 긴 부분]은 청각적 부분에 유지시켜야 할 [일시적 정보]가 너무 많아서, 시각 정보보다 덜 효과적이었다.

To overcome these negative effects, a number of compensatory strategies are available such as self-pacing or segmentation.

- The self-pacing effect was reported by Mayer and Chandler (2001), who found that it was beneficial to give learners control over the pace of an instructional animation, probably because it helps them deal with the transient nature of this information.

- The segmentation effect was reported by Spanjers et al. (2011), who found that segmented animations (i.e. segmented in parts with pauses in between) were more efficient than continuous animations for novice learners, but not for learners with higher levels of prior knowledge.

- As a final example, Leahy and Sweller (2011, 2016) reported an interaction effect of transient information on the modality effect:

- short pieces of audio-visual information were more effective than visual information only (i.e. traditional modality effect), but

- longer pieces of audio-visual information were less effective than visual information only because of the abundance of transient information in the longer, auditory piece.

자기 관리 효과

Self-Management Effect

[자기 관리 효과]는 가장 최근의 효과 중 하나이다. [자기 관리 효과]는 학생들이 자신의 인지 부하를 관리하기 위해 [CLT 원칙을 스스로 적용하도록 가르칠 수 있다]는 가정에 기초한다. 이상적으로 학생들은 인지 부하를 고려하여 설계된 자료에만 접근해야 한다. 그러나 현실에서 인터넷은 누구나 정보를 만들고 공유할 수 있어서, 학생들은 [인지 부하를 고려하지 않은 상태로 설계된 저품질의 학습 자료]에 직면하게 될 가능성이 더 높다. 자신의 인지 부하(인지 부하에 대한 자기 관리)를 위해 CLT 원칙을 직접 적용하도록 학습된 학생이, [CLT 원칙에 기초한 일관성 있고 잘 구성된 학습 자료의 교육 시스템에만 노출된 학생]보다 잘못 설계된 자료를 처리할 준비가 더 잘 되어 있다고 가정할 수 있다.

One of the most recent effects, the self-management effect, is based on the assumption that students can be taught to apply CLT principles themselves to manage their own cognitive load. Ideally, students should only have access to materials that have been designed with a consideration of cognitive load. However, in reality, the Internet enables information to be created and shared by anyone, which makes it more likely that students will be confronted with low-quality learning materials that have not been designed with any consideration of cognitive load. It can be hypothesised that students who are taught to apply CLT principles themselves to manage their own cognitive load (self-management of cognitive load) are better equipped to deal with these badly designed materials than students who are only exposed to an education system of consistent, well-structured learning materials based on CLT principles.

지금까지 자기 관리 효과는 [주의 분할 학습 자료]로만 연구되어 왔다. 일반적으로 자가 관리 효과를 조사하는 연구는 두 단계로 구성된 세 가지 실험 조건을 비교하였다.

- 첫 번째 단계에서는 두 가지 실험 조건의 학생들이 멀티미디어 학습 자료를 분할 주의 형식으로 공부한다.

- 자기 관리 조건에서 학생들은 예를 들어 텍스트와 도표를 재구성하여 자신의 인지 부하를 스스로 관리하는 방법을 배운다.

- 세 번째, 신체적으로 통합된 조건에서 학생들은 강사가 관리하는 신체적으로 통합된 형식으로 동일한 자료로부터 배웁니다.

- 두 번째 단계에서는 세 가지 조건 모두에서 학생들은 다른 영역에서 동일한 분할 주의 학습 자료를 받는다. 자기관리 효과를 입증하는 가장 중요한 연구결과는 리콜 및 편입시험의 자기관리 조건에서 학생들의 우수한 성적에 반영된다.

Until now, the self-management effect has only been studied with split-attention learning materials. Typically, studies investigating the self-management effect compare three experimental conditions and consist of two phases (see Roodenrys et al. 2012; Sithole et al. 2017).