CARDA: 보건전문직교육 연구에서 문헌분석의 가이드 (Med Educ, 2022)

CARDA: Guiding document analyses in health professions education research

Jennifer Cleland1 | Anna MacLeod2 | Rachel H. Ellaway3

1 소개

1 INTRODUCTION

'태초에 말씀이 계시니라'. 요한복음 1:1-3

‘In the beginning was the Word’. John 1:1–3

우리는 문서를 만들고, 문서를 사용하고, 문서를 보관하고, 문서를 주고받습니다. 집과 사무실에 있는 문서, 휴대하고 다니는 문서, 컴퓨터와 기타 디지털 기기에 있는 문서가 있습니다. 보내는 문서와 받는 문서가 있습니다. 현대 사회에 대한 우리의 지식과 현대 사회와의 상호 작용은 상당 부분 문서에 의해 매개됩니다. 정책 및 절차, 회의록, 보고서, 커리큘럼 맵, 시험지, OSCE 스테이션, 학습 사례 및 시뮬레이션 스크립트 등 수많은 문서를 생성하고 이를 통해 재인용되는 보건 전문직 교육(HPE)도 예외는 아닙니다. 문서는 HPE에 관련된 사람들의 일상적인 경험을 구조화하며, '어떤 것은 존재하게 하고 어떤 것은 부재하게 하며, 어떤 것은 보이게 하고 어떤 것은 보이지 않게 하는'(182페이지) 도구 역할을 합니다.1

We make documents, we use documents, we keep documents and we exchange documents. There are documents in your home and in your office, documents you carry with you and documents on your computer and other digital devices. There are documents you send and documents you receive. Our knowledge of and interactions with contemporary society are substantially mediated by documents. Health professions education (HPE) is no outlier in this regard as it generates and is reinscribed through, its many documents, including policies and procedures, meeting notes, reports, curriculum maps, examination papers, OSCE stations, learning cases and simulation scripts. Documents structure the everyday experiences of those involved in HPE, and they serve as tools ‘through which some things are made present, and others absent, some things visible and others invisible’ (p. 182).1

문서는 연구 관점에서 풍부한 정보를 제공할 수 있습니다. 실제로 문서는 과거 사건을 이해하는 데 있어 가장 좋은, 때로는 유일한 데이터 소스인 경우가 많습니다(예: 2). 마찬가지로 현재에도 사람, 사건, 사회적 관계, 권력에 대한 지식의 대부분은 문서를 통해 간접적으로 얻게 됩니다. 스미스3는 이를 '이러한 형태의 사회를 통치, 관리 및 운영하는 관행의 기본이 되는'(257쪽) '문서적 실재'라고 설명했습니다.

Documents can provide a wealth of information from a research perspective. Indeed, documents are often the best, and sometimes the only, source of data for understanding past events (e.g.,2). Similarly, in the present, much of our knowledge of people, events, social relations and powers arises indirectly, through documents. Smith3 described this as ‘documentary reality’ that ‘is fundamental to the practices of governing, managing and administration of this form of society’ (p. 257).

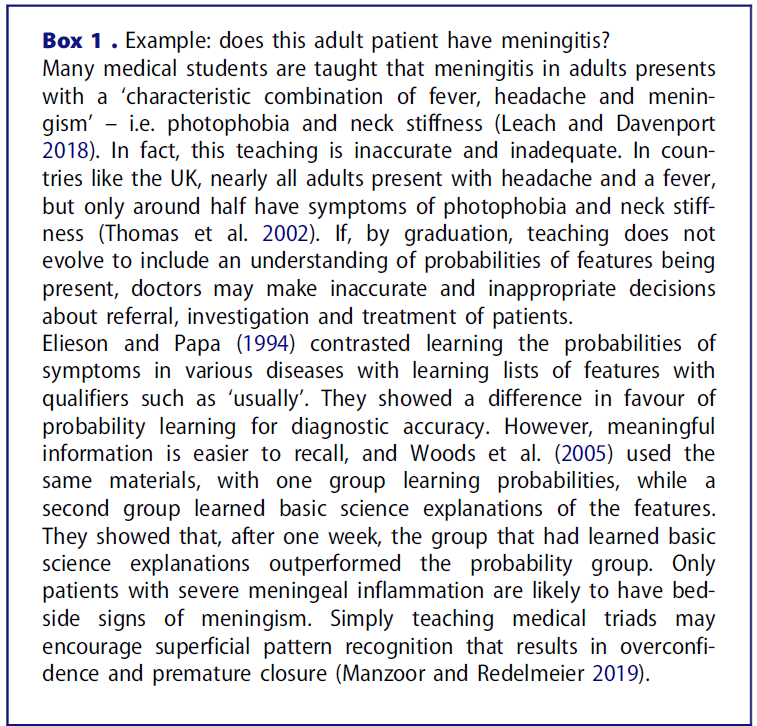

문서가 우리 주변에 존재함에도 불구하고(그리고 부분적으로는 그 때문에) 문서가 무엇인지, 또는 문서가 되어야 하는지에 대한 하나의 표준적이거나 포괄적인 정의는 없으며, 오히려 문서가 무엇인지에 대한 다양한 담론이 존재합니다. 예를 들어, 문서는 물리적 물건으로 정의될 수도 있고,4 정보 소스5로 정의될 수도 있으며,6 탐구 행위를 통해 탄생할 수도 있습니다(상자 1 참조).

Despite their ambient presence (and perhaps in part because of it), there is no one canonical or overreaching definition of what documents are or should be; rather, there are different discourses of what documents can be. For instance, a document can be defined as a physical item,4 an informational source5 or brought into being by the act of inquiry6—see Box 1.

박스 1: 문서란 무엇인가요?

Box 1: What is a document?

문서가 무엇인지, 또는 문서가 되어야 하는지에 대한 표준적이고 포괄적인 정의는 없으며, 문서가 무엇일 수 있는지에 대한 다양한 담론이 존재합니다. 문서는 텍스트 본문일 수도 있고, 텍스트 내용 외에 연구자가 관심을 가질 만한 특성(예: 이미지, 주석 또는 상호 참조의 사용)이 있는 인공물일 수도 있습니다. 오리어리4는 문서를 다음과 같이 분류했습니다:

There is no one canonical or overreaching definition of what documents are or should be; rather, there are different discourses of what documents can be. They can be bodies of text or they can be artefacts with qualities of interest to researchers beyond their textual content (such as the use of images, annotations or cross-references). O'Leary4 classified documents as follows:

- 공공 기록: 조직의 활동에 대한 공식적이고 지속적인 기록. HPE의 예로는 학생 성적표, 사명 선언문, 연례 보고서, 매뉴얼, 학생 핸드북, 전략 계획 및 강의 계획서 등이 있습니다.

- 개인 문서: 개인의 행동, 경험 및 신념에 대한 1인칭 서술. 예를 들면 달력, 이메일, 스크랩북, 블로그, Facebook 게시물, 근무일지, 사건 보고서, 반성문/일기, 신문 등이 있습니다.

- 물리적 증거: 연구 환경 내에서 발견된 물리적 물체. 예를 들면 전단지, 이메일, 포스터, 의제, 핸드북, 교육 자료 등이 있습니다.

- Public Records: The official, ongoing records of an organisation's activities. Examples from HPE include student transcripts, mission statements, annual reports, manuals, student handbooks, strategic plans and syllabi.

- Personal Documents: First-person accounts of an individual's actions, experiences and beliefs. Examples include calendars, e-mails, scrapbooks, blogs, Facebook posts, duty logs, incident reports, reflections/journals and newspapers.

- Physical Evidence: Physical objects found within the study setting. Examples include flyers, emails, posters, agendas, handbooks and training materials.

HPE의 맥락에서는 다음으로 구분할 수 있습니다(Ellaway 외., 2019).

- 교육 과정의 일부로 작성된 문서(예: 프로그램 평가, 강의 계획서 및 커리큘럼),

- 교육 과정에서 작성되었지만 교육 목적이 아닌 문서(예: 개인 파일, 조직 정책 및 웹사이트),

- 의학교육과 무관하게 작성된 문서(예: 소셜 미디어 게시물, TV 또는 영화 대본)

문서는 생성 방법과 목적, 보존 또는 큐레이션 방법, 캡처한 미디어, 생성 이후 복사, 필사, 편집 또는 수정 여부에 따라 다를 수 있습니다.

In the context of HPE, we might differentiate between

- documents that were created as part of educational processes (e.g., program evaluations, syllabi and curricula),

- documents created in education but not for educational purposes (e.g., personal files, organisational policies and websites), and

- documents created outside of medical education altogether (e.g., social media posts, TV or film scripts) (Ellaway et al., 2019).

Documents can differ in how they were produced and for what purposes, as well as how they were preserved or curated, what media they were captured on and whether they have been copied, transcribed, edited or redacted since their creation.

문서는 중립적인 것이 아니라 사회적으로 구성된 것입니다.7 문서의 사회성에 주목하면 누가, 어떤 목적으로, 어떤 맥락/사회적 위치에서 문서를 만들었는지에 주목하게 됩니다. 다시 말해, 문서는 단순히 문서에 포함된 정보 그 이상이며, 문서가 무엇을 나타내는지, 그리고 문서가 해석되고 사용될 수 있는 무수한 방식에 관한 문제이기도 합니다.

Documents are not neutral, they are socially constructed.7 Attending to the sociality of documents focuses attention on who created it, for what purposes and in what context/social situatedness. In other words, a document is more than the information it contains; it is also a matter of what it represents and the innumerable ways in which it might be interpreted and used.

연구자는 각 연구의 맥락에서 문서가 의미하는 바를 정의해야 합니다. Prior8는 ''문서'라는 단어는 어떤 종류의 물리적 또는 전자적 용기를 나타내는 명사로 사용되는 경향이 있지만... 어떤 대상을 문서로 표시하는 것은 그것이 담고 있는 내용이나 물리적 또는 전자적 형식이 아니라 정보의 전달자로서의 역할과 사용'이라고 주장했습니다(Briet9 및 Lund 참조).10 반면에 Ricoeur는 문서를 탐구 행위로 인해 생겨난다고 설명했습니다.6 이는 과학적 탐구에서 데이터의 정의와 더 일치하는데, 합법적인 출처의 독점 목록보다는 선택 및 분석 행위가 더 중요하다는 점입니다.

Researchers need to define what they mean by documents in the context of each study. Prior8 argued that ‘[T]he word “document” tends to be used as a noun to denote a physical or electronic container of some kind … however, what marks an object as a document is not what it contains nor its physical or electronic format, but its role and use as a conveyor of information’—see also Briet9 and Lund.10 Ricoeur on the other hand described documents as brought into being by the act of inquiry.6 This is more consistent with a definition of data in scientific inquiry: acts of selection and analysis matter more than exclusive lists of legitimate sources.

문서 분석(DA)은 일반적으로 텍스트 및/또는 이미지가 포함된 인쇄 또는 전자 문서를 포함하는 체계적인 연구를 포괄하는 용어입니다.11 DA는 연구 참여자로부터 정보를 직접 도출하지 않으므로 참여자의 반응이나 행동 변화 가능성을 제거하므로 비교적 방해가 적습니다.12 DA는 [과거 사건에 대한 역사적 분석과 비판적 이론적 관점의 표현]에서 [정책 및 이론 개발]에 이르기까지 다양한 용도로 사용될 수 있습니다. 그러나 많은 연구에서 문서가 엄격하고 논리적인 DA 방법론을 따르기보다는 '상대적으로 조용히 '현장'에 들어왔다가 나가는'(417쪽) 경향이 있습니다.5 구어에 비해 문서 기반 데이터를 과소평가하거나 DA 연구의 수행이나 보고에 거의 관심을 기울이지 않는 연구자들에 대한 비판도 있었습니다.13-16

Document analysis (DA) is an umbrella term for systematic research involving printed or electronic documents, typically containing text and/or images.11 It is relatively unobtrusive as it does not involve the direct elicitation of information from research participants and thus removes the potential for reaction or changed behaviour from participants.12 There are many possible uses of DA, ranging from historical analyses and articulations of critical theoretical perspectives on past events to policy and theoretical development. However, rather than following rigorous and logical DA methodologies, documents in many studies have tended ‘to enter and to leave the ‘field’ in relative silence’ (p. 417).5 There has also been criticism of researchers who under-privilege document-based data compared to the spoken word or who pay little attention to the conduct or reporting of DA studies.13-16

보건 전문직 교육(HPE) 실무, 토론 및 문화의 문서화 현실에 의도적으로 조율하고 DA를 사용하는 것은 HPE 연구에서 아직 개발되지 않은 풍부한 잠재력을 가지고 있으며, 이는 다른 연구자들이 더 깊이 탐구하도록 남겨둘 문제입니다. 그러나 이 연구의 계기가 된 것은 DA가 HPE 연구에서 제대로 개발되지 않아 엄밀성과 명확성이 부족하다는 가설이었습니다. 이 가설을 탐구하기 위해 메타 연구 검토 프로세스를 채택하여17 결과보다는 방법에 비판적으로 집중할 수 있었습니다. 따라서 이 연구는 더 나은 방법을 개척하기 위한 연구를 수행하기 위한 것이었습니다.18, 19

Deliberately attuning to the documentary reality of health professions education (HPE) practice, debate and culture and the use of DA holds a wealth of untapped potential in HPE research, a matter that we will leave others to explore in more depth. However, the trigger for this study was our hypothesis that DA has been underdeveloped in HPE research, with a resulting lack of rigour and clarity. To explore this hypothesis, we employed a meta-study review process,17 which allowed for a critical focus on methods rather than on outcomes. As such, this study was about conducting research on research to pioneer better methods.18, 19

방법론적 입장과 다양한 절차적 방법의 집합으로서 DA에 초점을 맞추기 위해 메타 방법 접근법을 채택했습니다.20 우리의 목표는 HPE 문헌에서 DA의 현재 상태를 설명하고, DA에 참여하는 연구자를 지원하는 방법을 파악하고, 우리 분야의 다른 방법과 비교할 수 있는 방법론적, 분석적, 보고의 엄격성 표준을 제안하는 것이었습니다. 이를 통해 HPE에서 문서 정보에 기반한 연구의 품질을 개선하는 데 기여하고자 했습니다.

Given our focus on DA both as a methodological stance and as a set of various procedural methods, we adopted a meta-method approach.20 Our aims were to describe the current state of DA in the HPE literature, to identify ways to support researchers engaging in DA and to propose standards of methodological, analytical and reporting rigour comparable to other methods in our field. Collectively, we sought to contribute to improving the quality of document-informed research in HPE.

이를 위해 다음과 같은 검토 질문을 던졌습니다:

To that end, the review questions were as follows:

1. HPE 연구 논문에서 DA는 어떻게 접근해 왔습니까?

2. HPER(보건 전문직 교육 연구)에서 현재 DA 관행의 강점과 약점은 무엇인가?

3. HPER에서 DA 관행을 강화하려면 무엇이 필요한가?

4. DA를 통해 해결할 수 있는 지식의 격차는 무엇입니까?

- How has DA been approached in HPE research papers?

- What are the strengths and weaknesses of current DA practices in HPER (health professions education research)?

- What is needed to strengthen DA practices in HPER?

- What are the gaps in our knowledge that could be addressed through DA?

2 방법론

2 METHODS

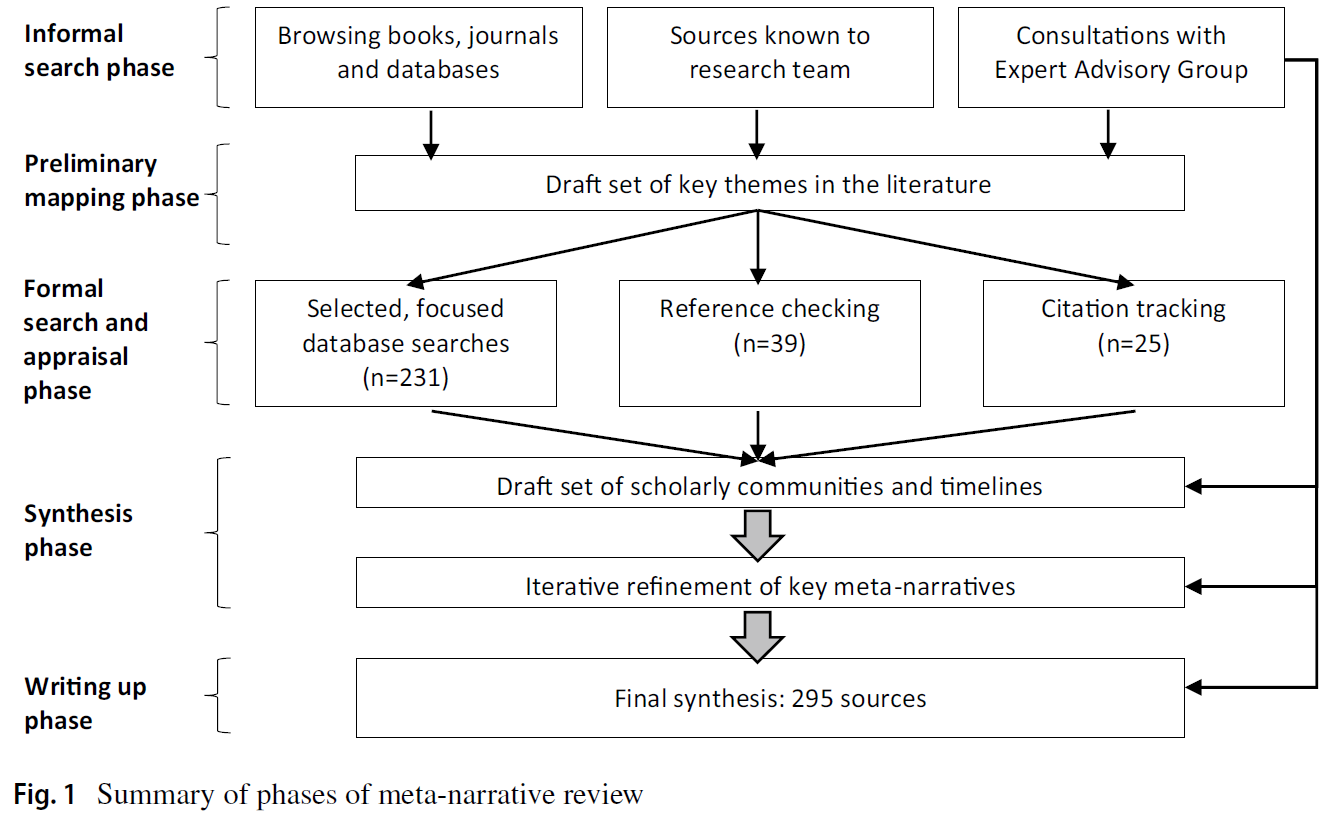

DA의 방법론적 입장과 절차적 방법에 초점을 맞추다 보니 범위 검토 접근 방식을 취하게 되었을 수 있습니다. 그러나 범위 검토Scoping review는 '연구 활동의 범위, 범위 및 성격을 검토'하고 '기존 문헌의 연구 공백을 파악'할 수 있지만,21 연구 과정을 명시적으로 고려하는 메타 연구의 초점과 구체성이 부족합니다. 따라서 우리의 연구 설계는 메타 연구에서 inform되었으며,17 '실질적 영역에서 연구의 이론, 방법 및 데이터 분석을 면밀히 조사하는 분석, 그리고 새로운 지식 창출에 적용하는 마무리로 종합'(2페이지)을 포함합니다.

- 분석과 관련하여 우리의 목표는 연구 목적으로 사용된 문서가 식별, 기술, 관리 및 분석된 방식을 종합하고 해석하는 것이었습니다. 즉, 메타 연구는 사용된 DA 방법의 인식론적 건전성(지식의 원천으로서 문서의 표현과 문서에서 도출된 지식 또는 이를 기반으로 한 지식 사이의 일치와 일관성)과 방법론적 적절성에 초점을 맞추었습니다.

- 종합 측면에서, 우리의 목표는 특히 강점과 한계, 문헌의 동향, 우리 분야에서 DA의 수행과 보고가 어떻게 개선될 수 있는지에 중점을 두고 HPER의 DA 연구에 대한 증거에 기반한 설명에 도달하는 것이었습니다.

Our focus on methodological stance and procedural methods in DA might have led us to take a scoping review approach. However, while scoping reviews can both ‘examine the extent, range and nature of research activity’ and ‘identify research gaps in the existing literature’,21 they lack the focus and specificity of meta-study, which explicitly considers research processes. Our study design was therefore informed by meta-study,17 which involves ‘analysis, the scrutiny of the theory, method, and data analysis of research in a substantive area, and culminates in synthesis, an application of that scrutiny to the generation of new knowledge’ (p. 2).

- With respect to analysis, our goal was to synthesise and interpret the ways in which documents used for research purposes had been identified, described, managed and analysed. This meant that our meta-study focused on the apparent epistemological soundness (an alignment and coherence between the articulation of documents as sources of knowledge and the knowledge that was derived from them or based upon them) and methodological appropriateness of the DA methods used.

- In terms of synthesis, our goal was to arrive at an evidence-informed description of DA research in HPER with a particular focus on its strengths and limitations, trends in the literature and how the conduct and reporting of DA in our field might be improved.

포지셔닝

Positionality

우리는 이 연구를 수행하면서 우리가 가져온 관점에 주목합니다. 이 연구는 HPER의 방법론과 이론에 대한 지속적인 논의를 바탕으로 개발되었으며, 처음에는 DA 연구를 수행한 저희의 경험을 바탕으로 했습니다.

- 보다 구체적으로, JC는 연구의 일환으로 문서 분석을 수행한 경험이 있고(예: Cleland 외.22, Patterson 외.23), 연구 내에서 DA를 사용한 박사 과정 학생을 감독한 경험이 있습니다(예: Coyle 외.24, Hawick 외.25).

- AM은 문제 기반 학습 연구(To 외.26 및 MacLeod 외1)와 리더십 직무 기술서 연구(Gorsky 외.27)에서 문서를 주요 소스로 사용하고 삼각 측량을 위해 DA를 사용한 초기 연구에서 DA를 주요 소스로 사용한 경험을 가지고 있습니다. 각각의 경우 문서 소싱, 관리 및 분석 방법과 관련하여 추가 설명의 기회가 있습니다.

- RHE는 연구의 일환으로 문서 분석을 수행한 경험이 있었는데28-30, 편집자이자 멘토로서의 다른 관점을 이 문제에 적용했습니다. 우리 자신의 DA 경험과 이 분야의 다른 사람들의 DA 작업을 읽으면서 일반적으로 DA 관행의 깊이와 엄격함을 개선하기 위해 노력했습니다.

We note the perspectives we brought to bear in undertaking this research. The study was developed from our ongoing discussions about methodology and theory in HPER and was based initially on our own experiences in conducting DA research.

- More specifically, JC had experience in conducting document analyses as part of her research (e.g., Cleland et al.22, Patterson et al.23) and in supervising doctoral students who used DA within their research (e.g., Coyle et al.24 and Hawick et al.25).

- AM had experience using DA as a primary source in earlier research where documents were used both as a primary source and to triangulate in studies of Problem Based Learning (To et al.26 and MacLeod et al1) and also as an object in studies of leadership job descriptions (Gorsky et al.27). In each case, there are opportunities for further explanation with respect to how documents were sourced, managed and analysed.

- RHE had experience in conducting document analyses as part of her research28-30 she brought other perspectives from being an editor and mentor to bear on the issue. It was both our own DA experiences and our reading of the DA work of others in the field that led us to seek to improve the depth and rigour DA practices in general.

프로세스

Process

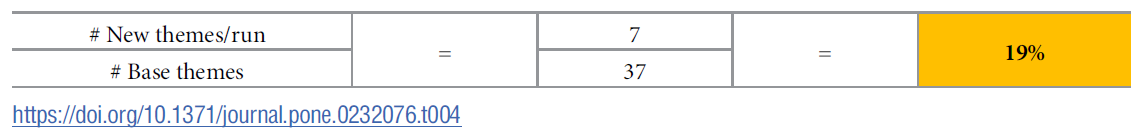

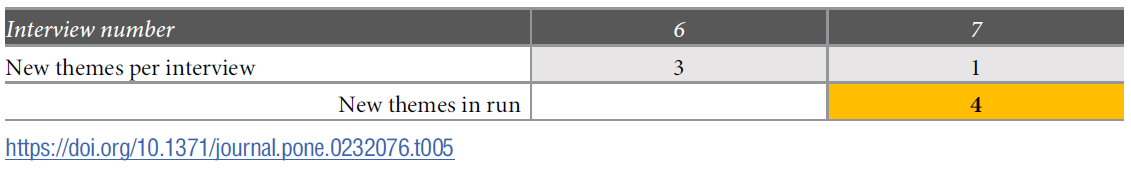

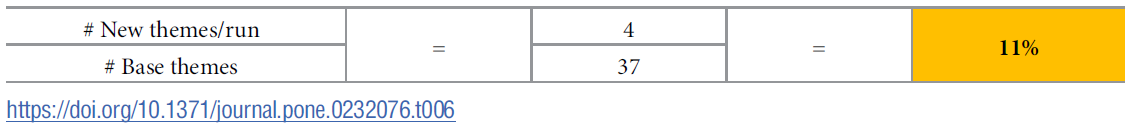

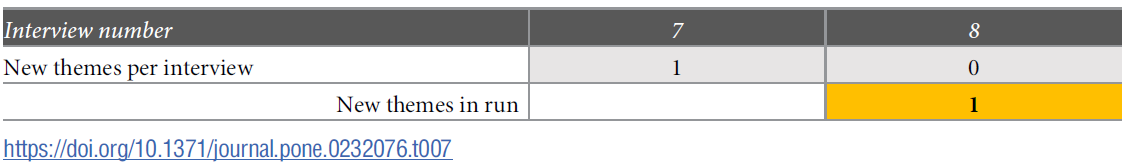

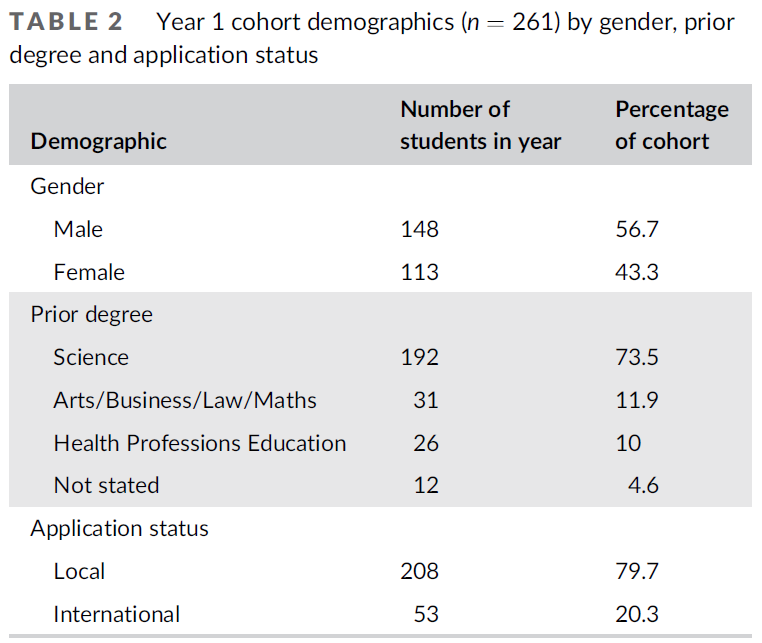

먼저 파일럿 검색을 실시하여 잠정 검색 전략을 테스트하고, 연구 질문을 구체화하며, 검토 범위를 계획하는 데 도움을 받았습니다. 2021년 7월 15일에 익명 모드에서 ['문서 연구' 및 '의학교육']이라는 용어로 Google Scholar를 사용하여 이 파일럿 검색을 실시했습니다. 그 결과 261개의 논문이 반환되었으며, 이 중 처음 50개의 관련성을 분석하여 6개의 논문(12%)을 식별했습니다. 이를 통해 학습한 후, 2021년 7월 16일에 PubMed와 ['문서 분석' 및 '의학 교육']을 사용하여 두 번째 파일럿 검색을 수행한 결과 53개의 논문이 반환되었습니다. 관련성을 검토한 결과, 14개의 논문은 HPE와 관련이 없는 것으로 제외되었고, 39개(74%)의 논문이 신뢰할 수 있는 것으로 나타났습니다. 이는 또한 대규모 메타 연구를 실행할 수 있을 만큼 충분한 HPE 연구에서 어떤 식으로든 DA를 사용했음을 시사합니다.

We first conducted a pilot search to test our provisional search strategy, refine our research questions and help us plan the scope of the review. We conducted this pilot search using Google Scholar in anonymous mode with the terms [‘document research’ AND ‘medical education’] on 15 July 2021. This returned 261 articles, of which the first 50 were analysed for relevance, identifying six articles (12%). Learning from this, we then conducted a second pilot search using PubMed and [‘document analysis’ AND ‘medical education’] on 16 July 2021, which returned 53 articles. Screening for relevance, 14 articles were excluded as not being relevant to HPE, leaving 39 (74%) that seemed credible. This also suggested that sufficient HPE studies had used DA in some way to render a larger meta-study viable.

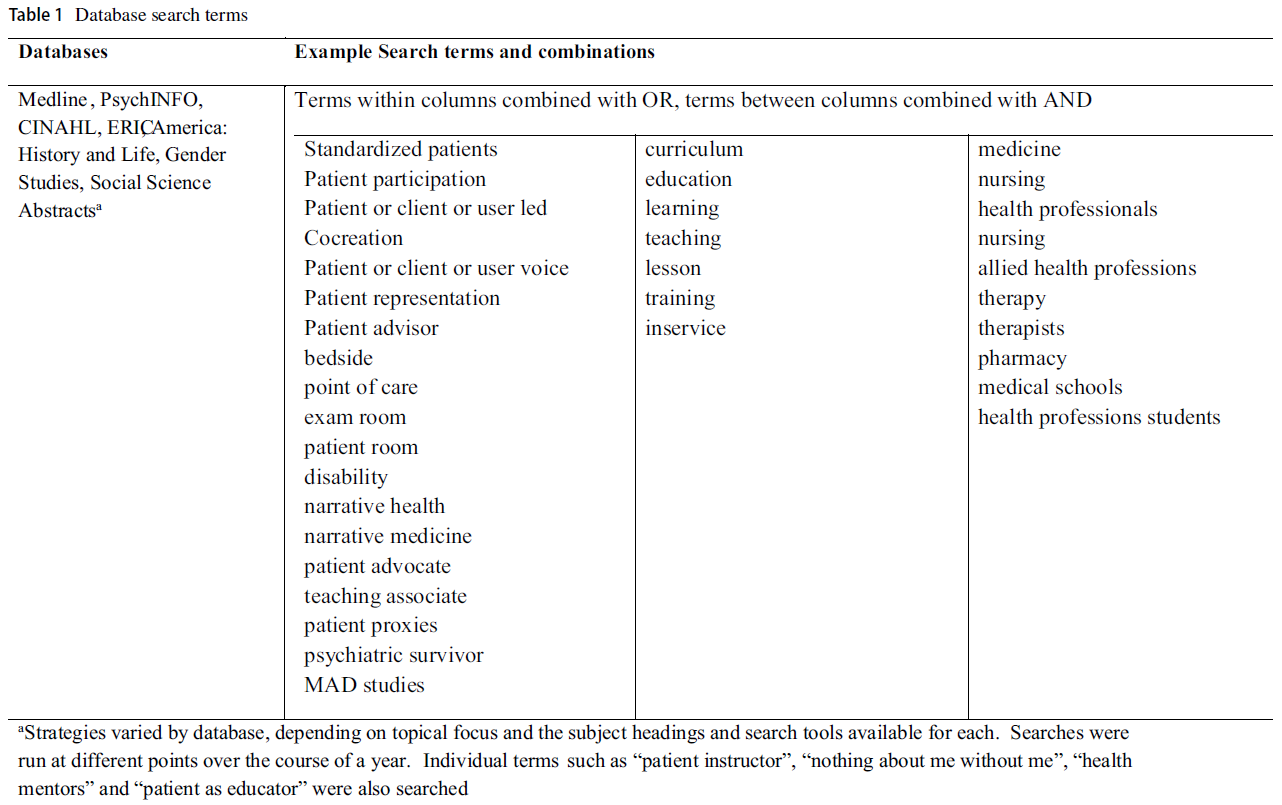

전체 검색을 위해 사서와 협력하여 검색 전략을 수립했습니다. 사서의 추천에 따라 범위를 '의학교육'에서 HPE에 대한 보다 광범위한 용어로 확장하고(부록 1a-1c 참조), MEDLINE, CINAHL, Scopus 및 ERIC을 포함하도록 검색을 확대했습니다. Google Scholar는 제외되었으며, 연구에 입력된 논문의 양과 일관성을 관리하기 위해 2000년 1월부터 2021년 10월까지 발표된 영어 논문으로 검색을 제한했습니다. 전체 검색 결과 1298개의 논문이 검색되었으며, 이 단계에서 285개의 중복 논문을 제거했습니다. 그런 다음 인용문을 Excel로 가져왔습니다.

For our full search, we worked with a librarian to create a search strategy. On their recommendation, we expanded the scope from ‘medical education’ to a set of broader terms for HPE (see Supplementary Appendices 1a–1c), and we expanded the search to include MEDLINE, CINAHL, Scopus and ERIC. Google Scholar was omitted, and we limited the searches to English-language papers published from January 2000 to October 2021 as a way of managing the quantities and coherence of the papers entered into the study. This full search resulted in 1298 articles; 285 duplications were removed at this stage. Citations were then imported into Excel.

그런 다음 각 저자는 전체 텍스트를 읽기 전에 논문 그룹을 필터링하고, 라벨을 붙이고, 제목과 초록을 선별하여 포함하거나 제외한 이유에 대한 의견을 작성했습니다. 이 단계에서 의학 교육에 관한 논문이 아닌 경우, DA를 포함하지 않는 방법론이 포함된 경우, 문서를 참조했지만 해당 문서를 분석하지 않은 경우(예: 논평), 인터뷰 녹취록만 분석한 경우, 영어로 된 논문이 아닌 경우 논문을 제외했습니다. 논평이나 오피니언 기사는 DA와 관련된 내용일 경우 포함했습니다.

Each author then took a group of articles to filter, label and make comments on why she included or excluded them on title and abstract screening, before full-text reading. At this stage, we excluded articles if they were not on healthcare education, if they involved methodologies that did not include DA, if they referred to documents but did not analyse these documents (such as in commentaries), if the analysis was only of interview transcripts or if they were not in English. We included commentaries or opinion articles when they involved some sort of DA.

파일럿 검색을 통해 얻은 인사이트를 바탕으로 연구 질문 1과 2를 해결하기 위해 데이터 추출은 다음에 중점을 두었습니다.

- DA가 사용된 정도,

- DA의 목적,

- 사용된 DA 방법과 DA 적용 및 보고의 엄격성,

- 사용된 문서의 범위와 유형,

- 연구 질문 해결에 있어 DA의 유용성

이러한 초기 연역적 주제에 매핑된 데이터 추출 도구를 반복적으로 개발했습니다. 또한 Siegner 등이 제시한 정성적 DA의 유형을 참고했습니다.

- 맥락(문서가 연구 질문이나 문제에 대한 관련 배경을 제공함),

- 삼각측량(문서가 다른 데이터를 확증하는 수단으로 사용됨),

- 1차 출처(연구용 데이터),

- 연구 대상(사회적 맥락에서 특정 문서의 역할과 기능)

Based on the insights gained from the pilot search and to address study questions 1 and 2, data extraction focused on

- the extent to which DA had been employed,

- the purpose of DA,

- the DA methods used and the rigour with which DA was applied and reported;

- the range and types of documents used; and

- the utility of DA in addressing the research question.

We iteratively developed a data extraction tool mapped to these initial deductive themes. We also drew on Siegner et al’s31 typology of qualitative DA:

- contextual (documents provide relevant background on the research question or problem),

- triangulation (documents are used as a means of providing corroborating other data),

- primary source (the data for a study) and

- object of the research (the role and function of a specific document in its social context).

세 명의 저자가 처음 몇 개의 논문을 코딩하고 도구로 데이터를 추출한 후, 데이터 추출 도구의 흐름과 명확성을 위해 수정한 다음 선택한 모든 논문에 적용했습니다(보충 부록 2 참조). 이 도구는 추출 데이터의 추적 및 대조가 가능하도록 Qualtrics(유타주 프로보)를 사용하여 제공되었습니다.

Following the coding of the first few articles and data extraction into the tool by all three authors, the data extraction tool was modified for flow and clarity and then applied to all selected articles (see Supplementary Appendix 2). The tool was delivered using Qualtrics (Provo, UT) to allow for tracking and collation of extraction data.

데이터 추출이 완료되면 Qualtrics에서 리뷰를 다운로드하고 구조화된 응답을 표로 만들고 구조화되지 않은 응답을 대조했습니다. 세 팀원 모두 비정형 응답을 읽고 주요 이슈와 우려 사항을 코딩했습니다. 이 단계는 귀납적이고 해석적이며 반사적인 방식으로 진행되었으며, DA 상태에 대한 초기(선입견) 믿음을 코딩의 출발점으로 삼아 이후 데이터와의 접촉, 회의 및 토론을 통해 이러한 믿음을 지속적으로 재구성했습니다.32

Once the data extraction was complete, the reviews were downloaded from Qualtrics, the structured responses tabulated and the unstructured responses collated. All three team members read through the unstructured responses and coded for key issues and concerns. This step was inductive, interpretive and reflexive, using our initial (preconceived) beliefs about the state of DA as the starting point for coding and reconstructing these beliefs continuously through subsequent contact with the data, meetings and discussions.32

3 결과

3 RESULTS

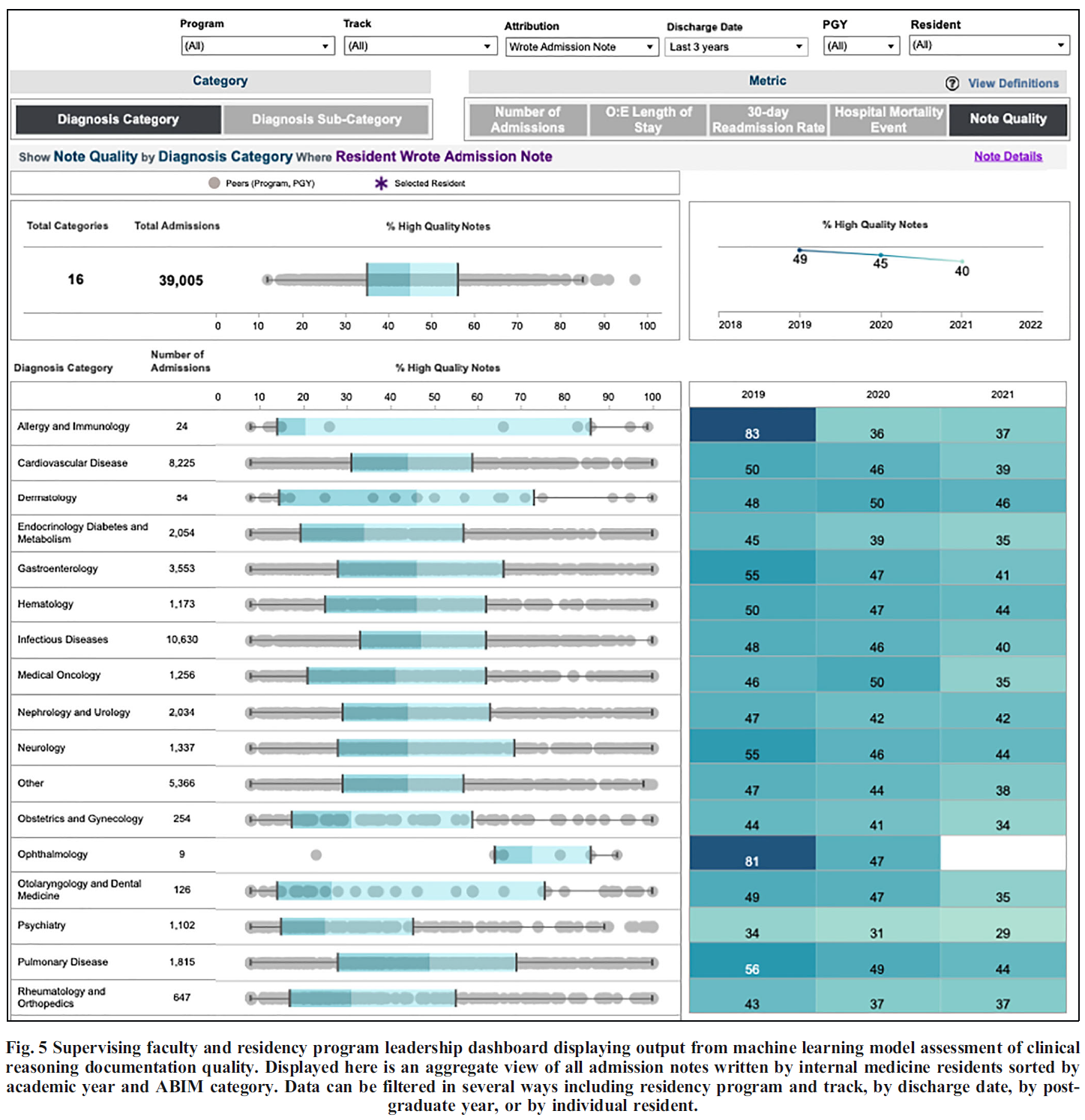

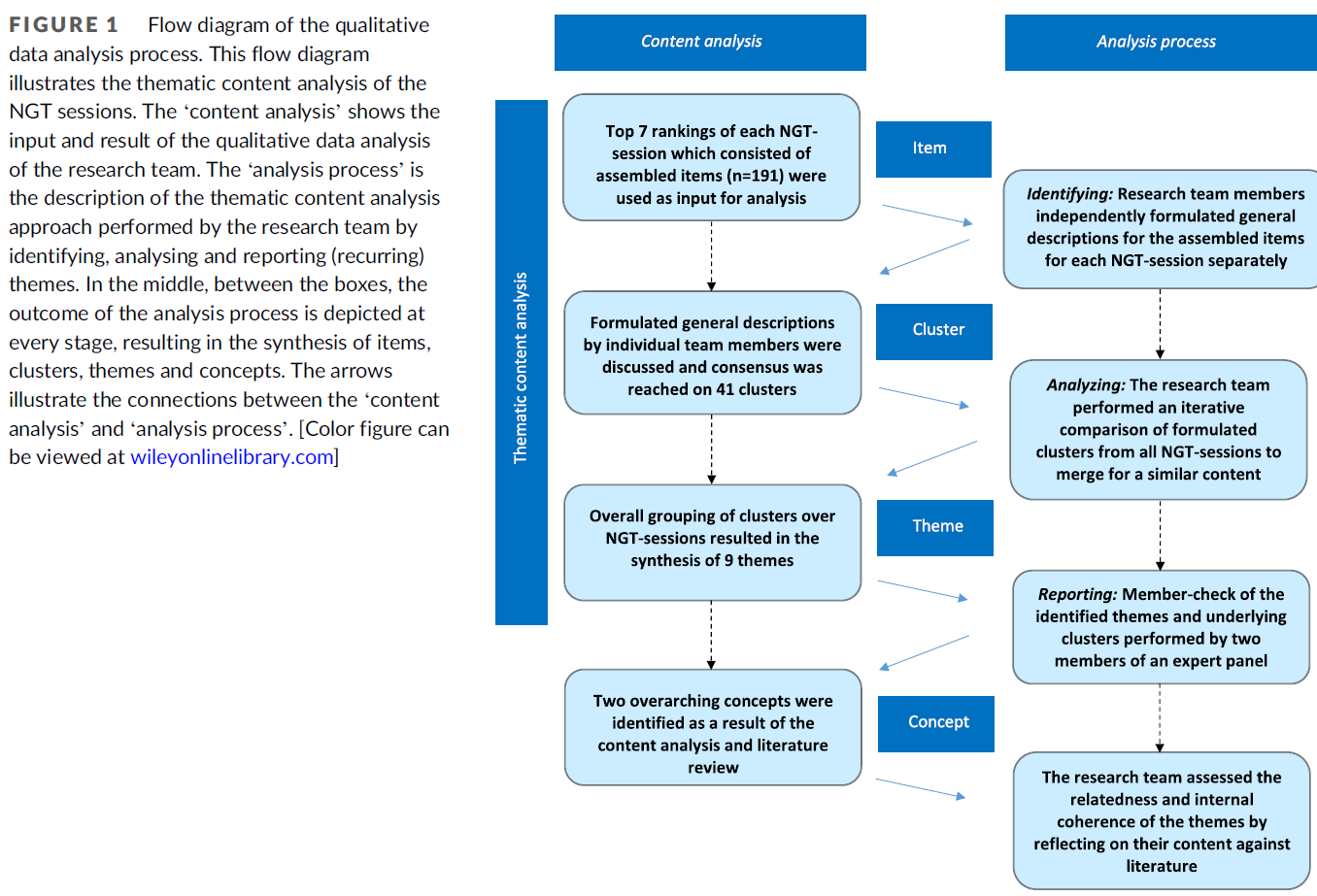

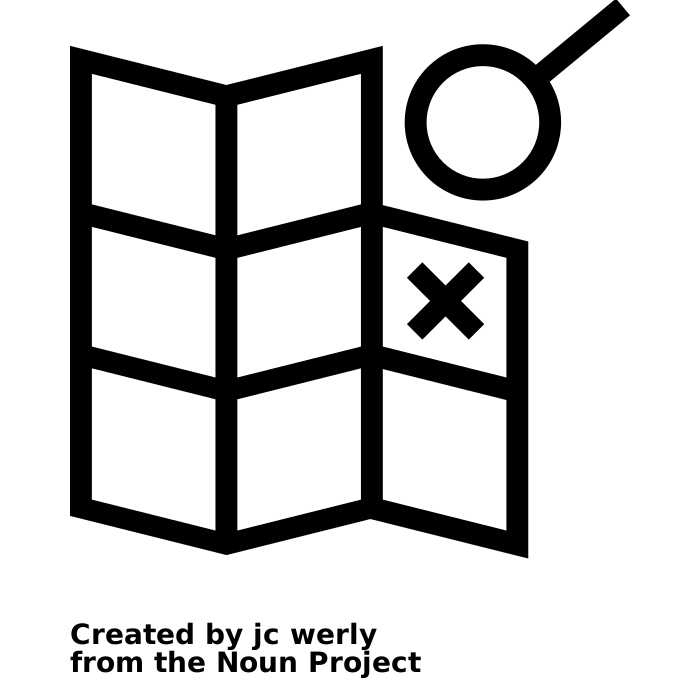

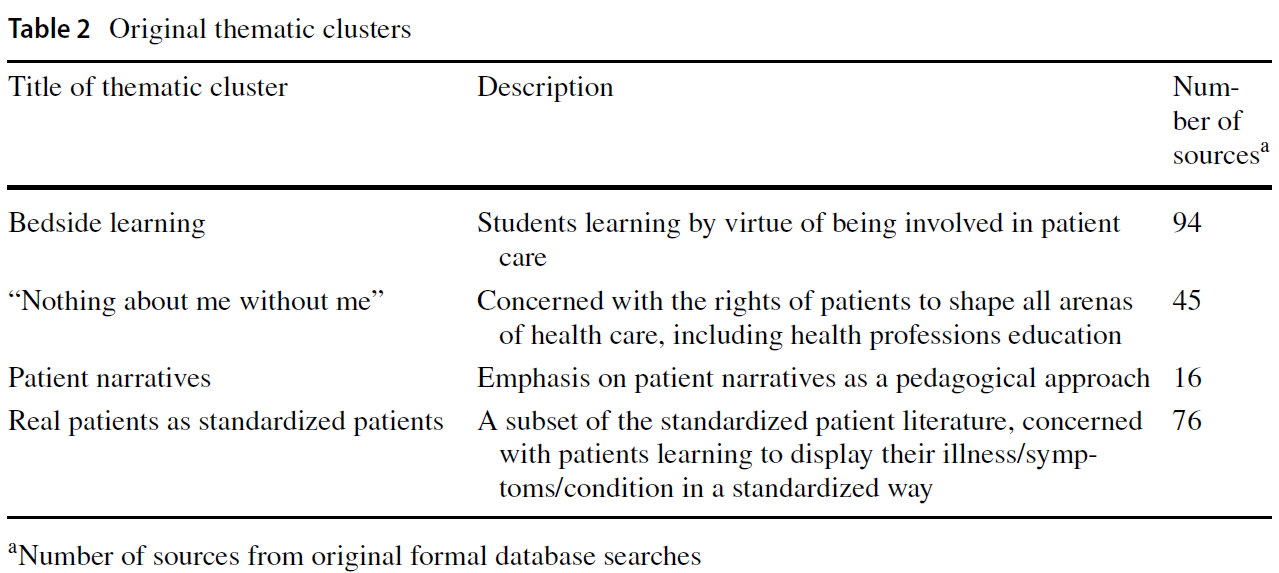

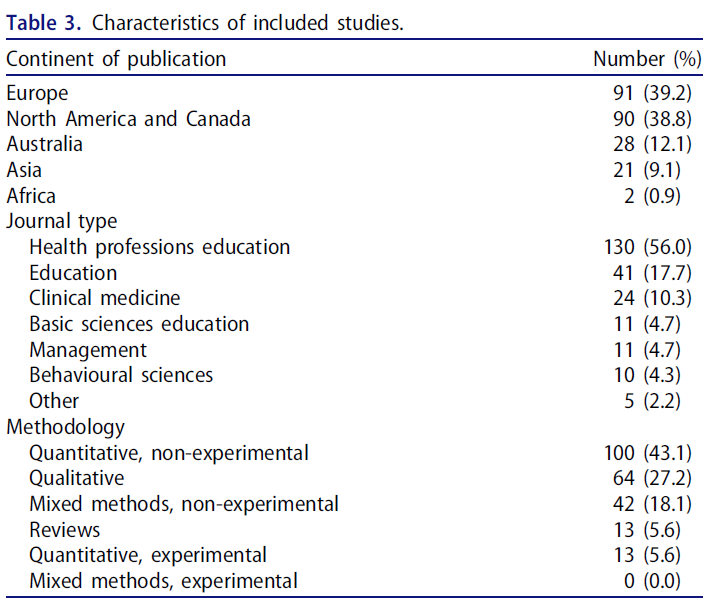

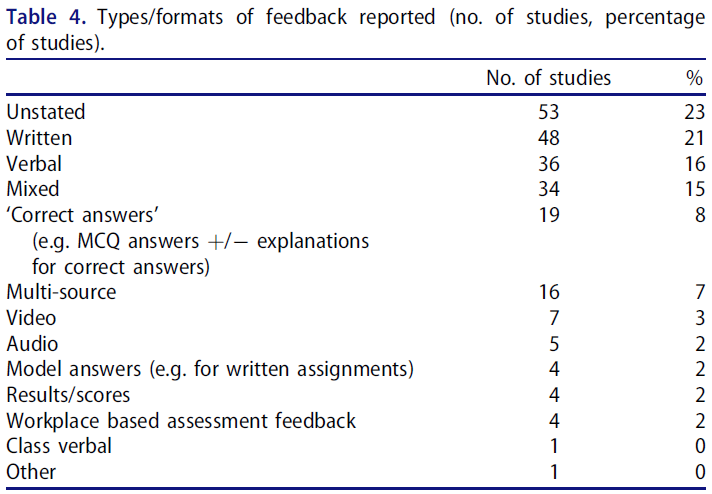

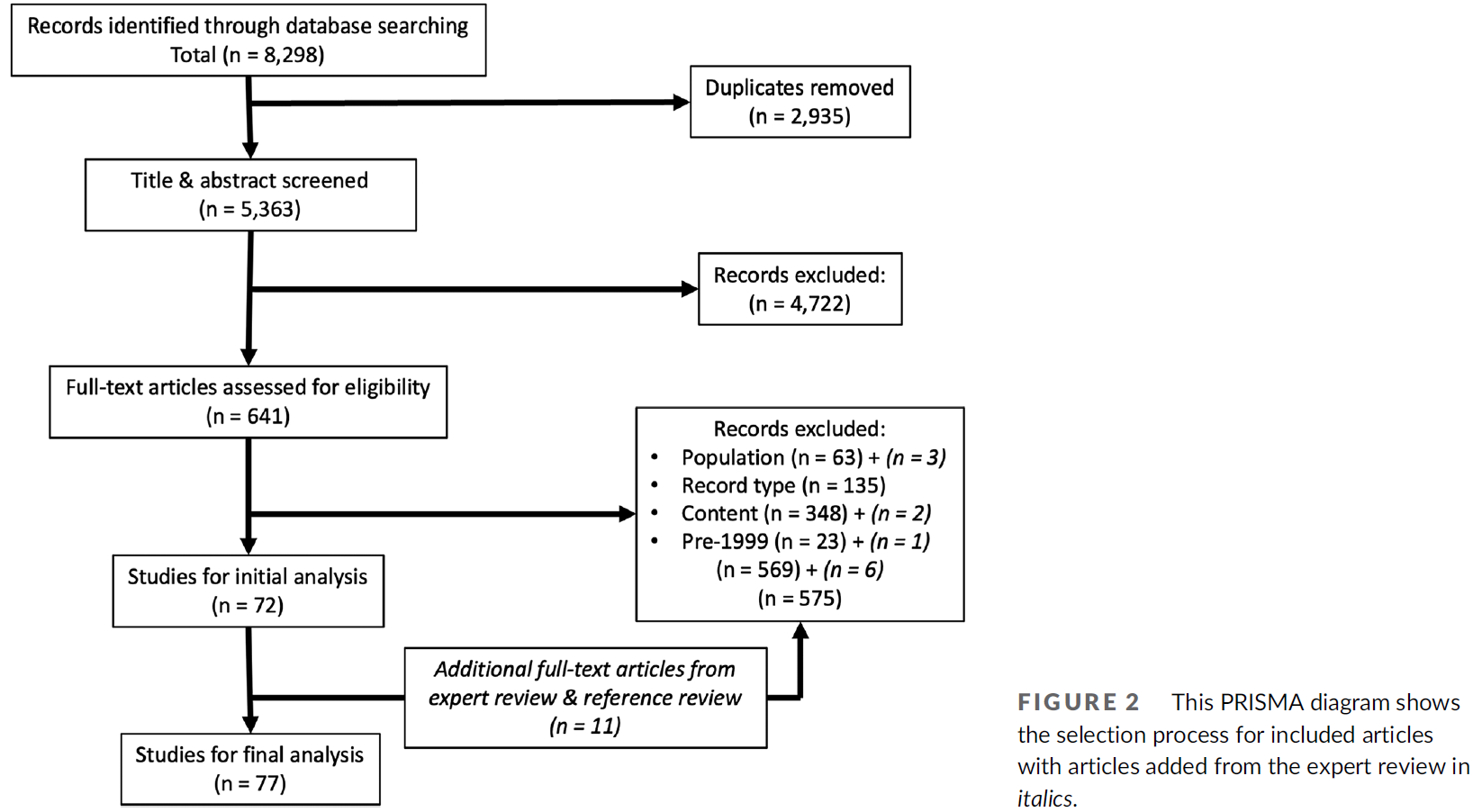

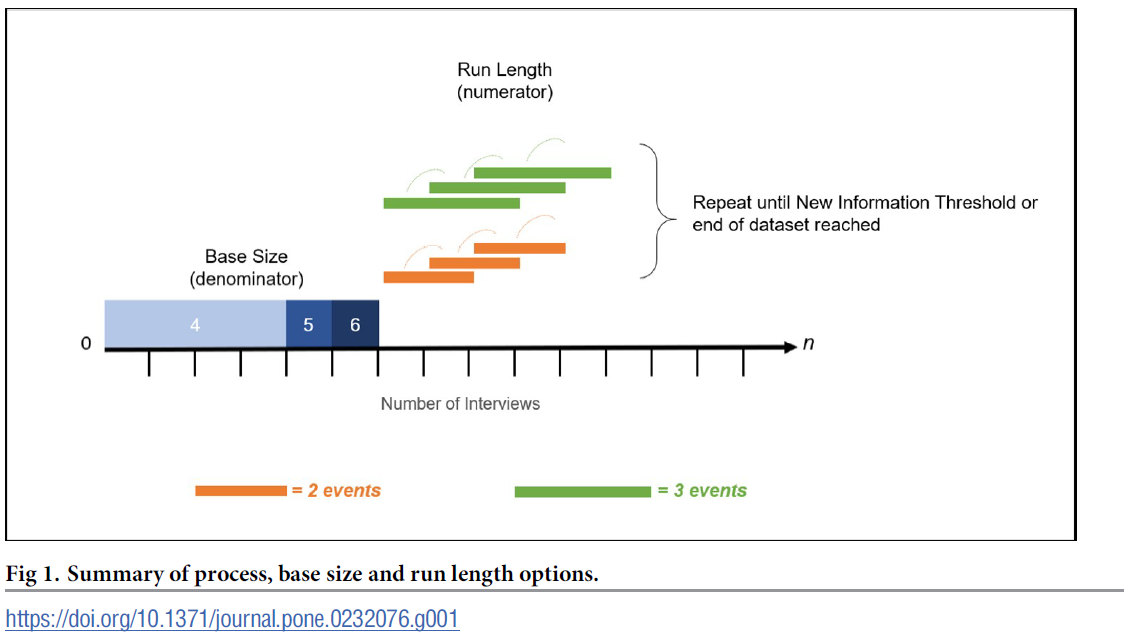

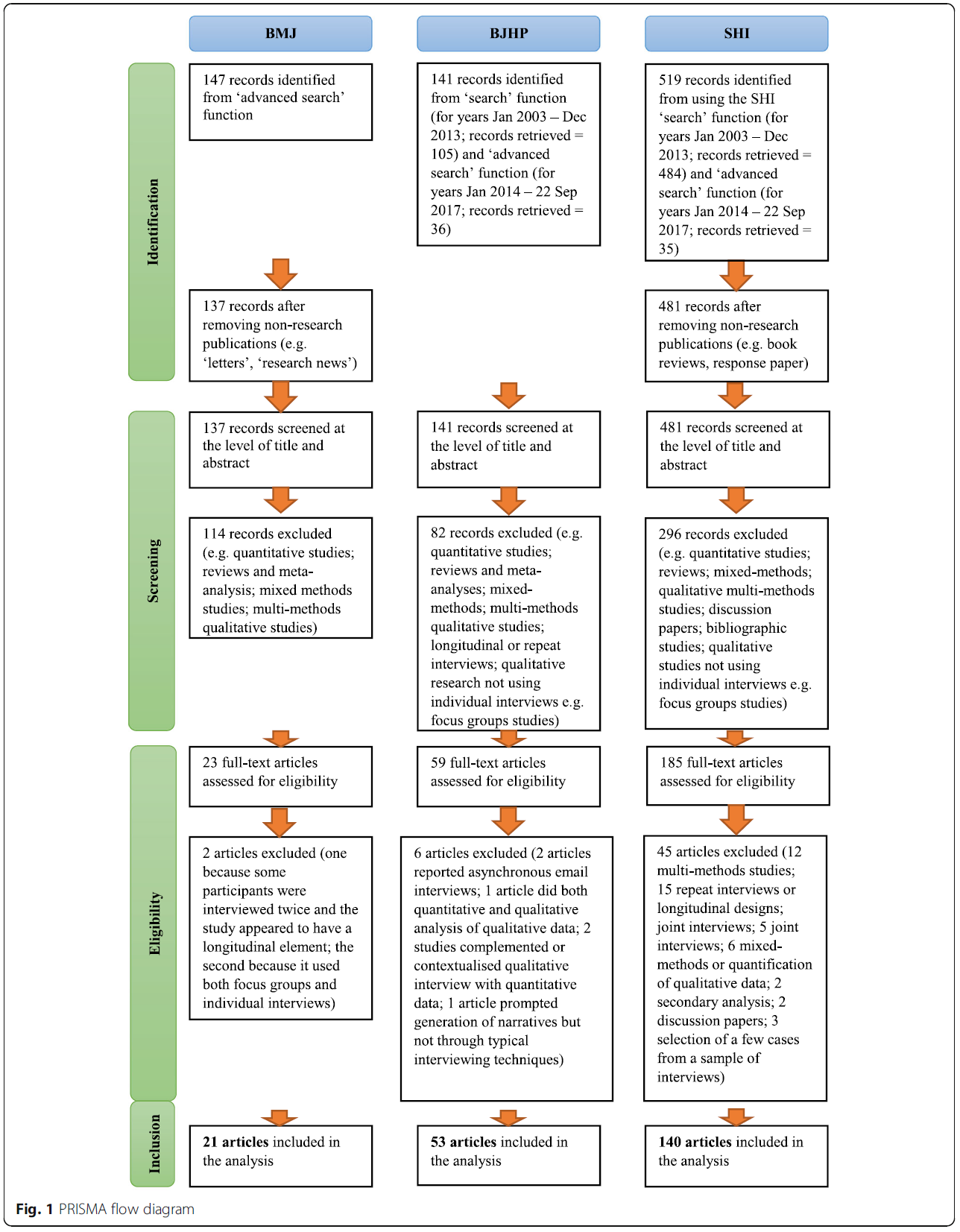

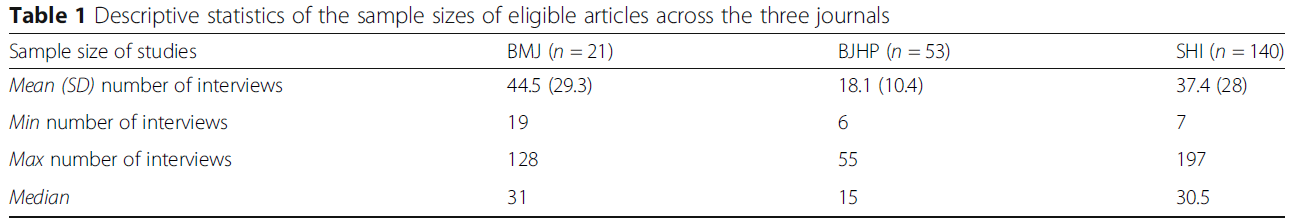

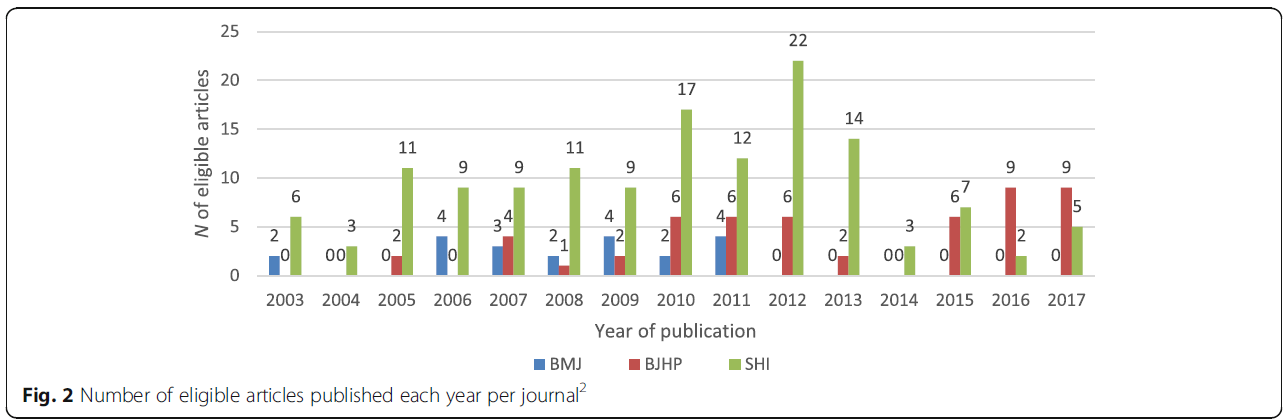

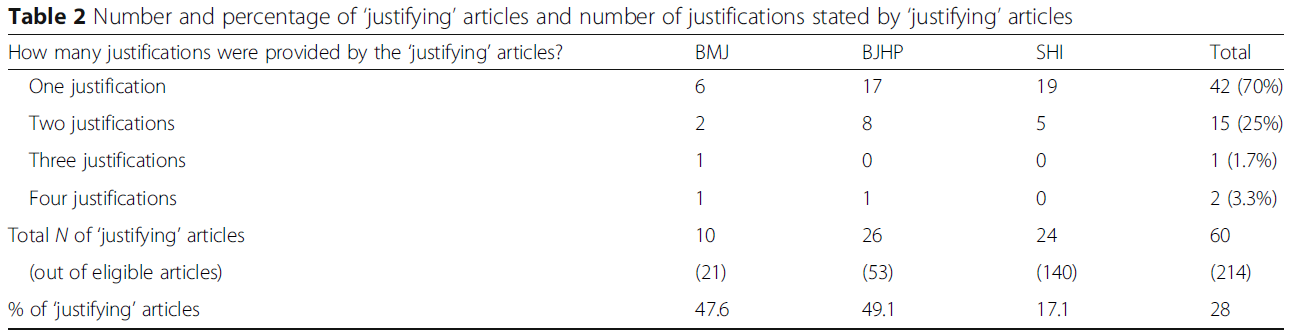

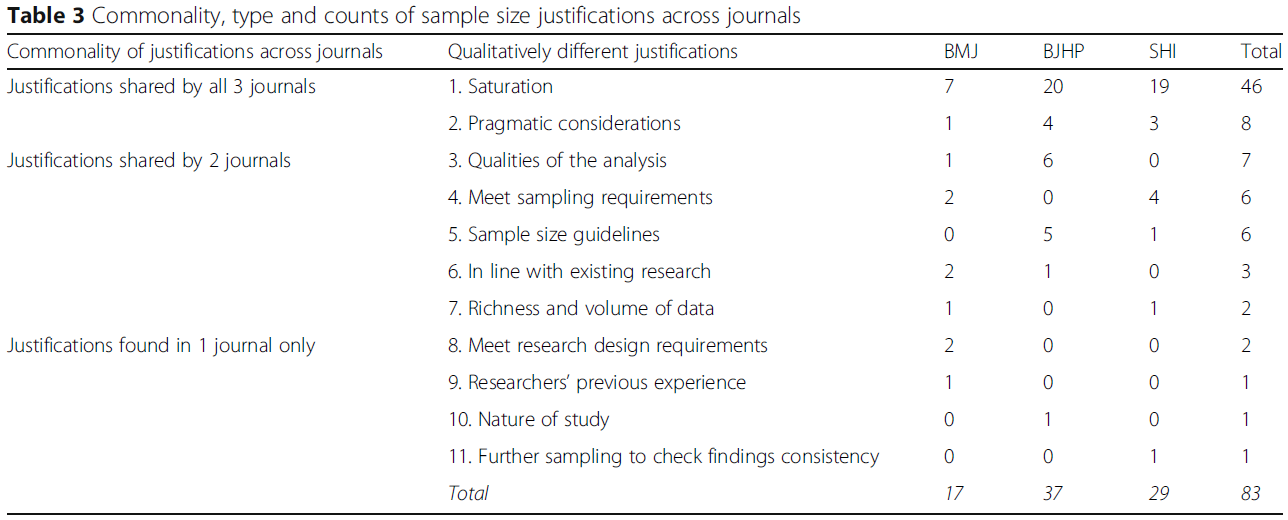

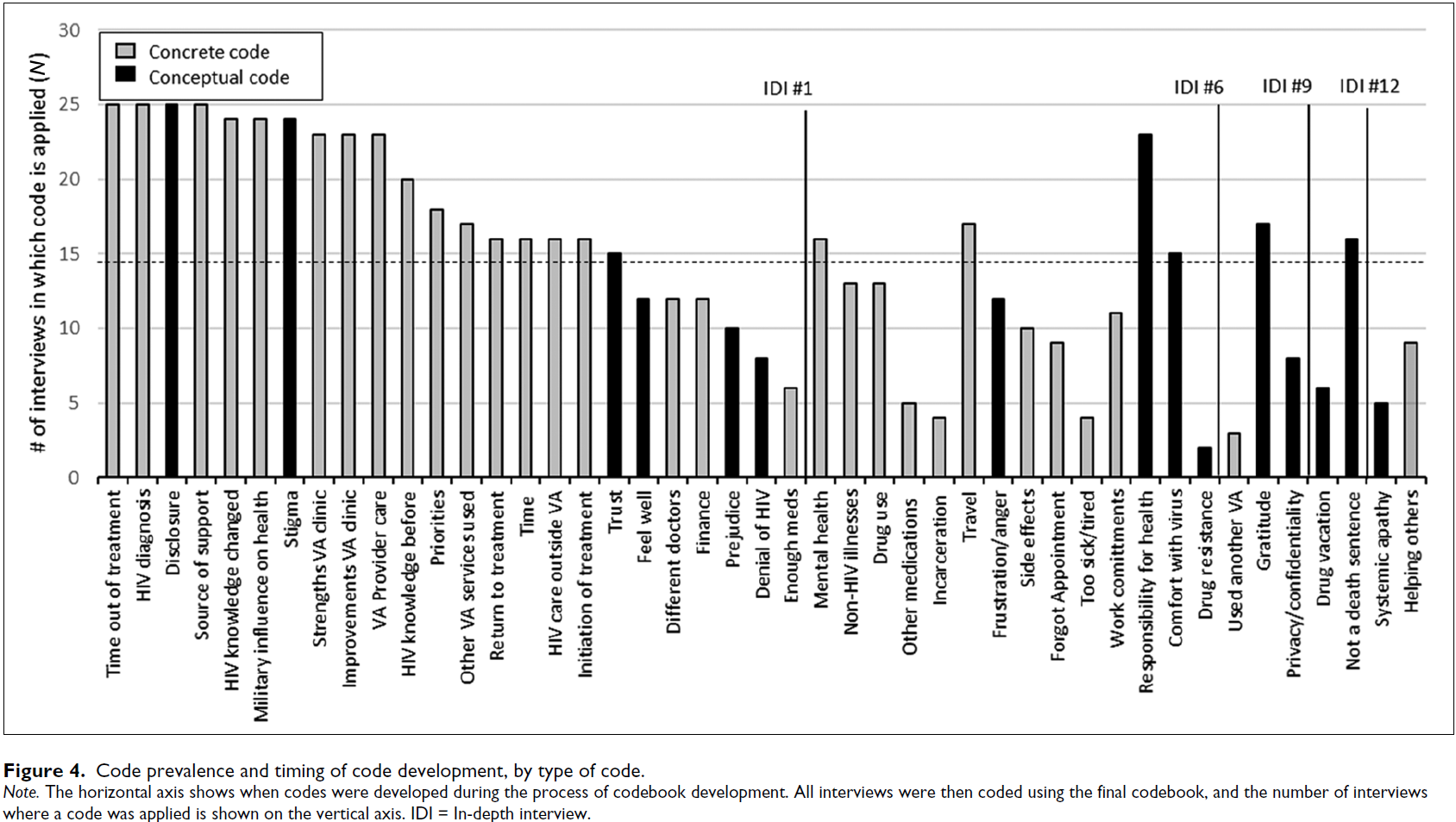

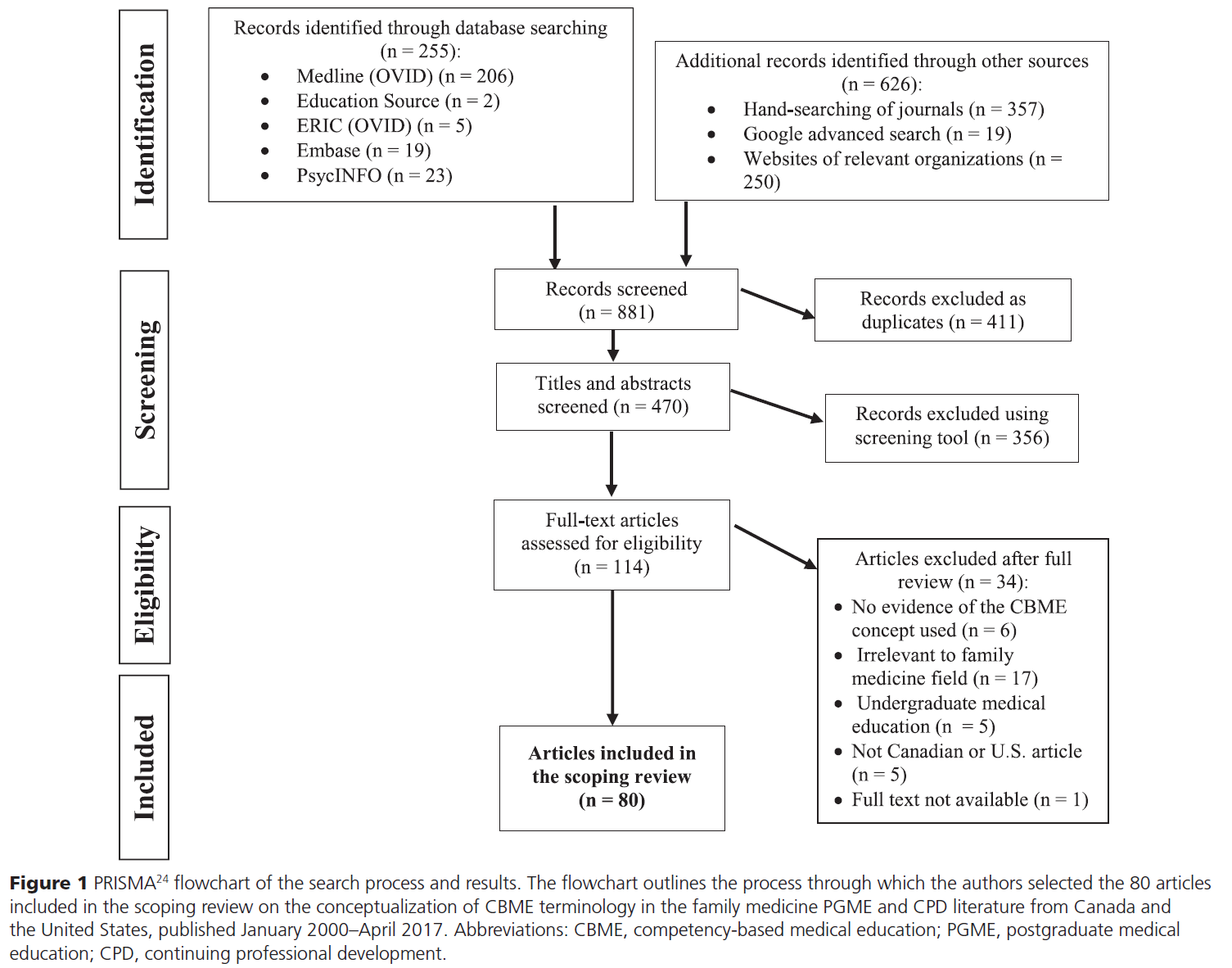

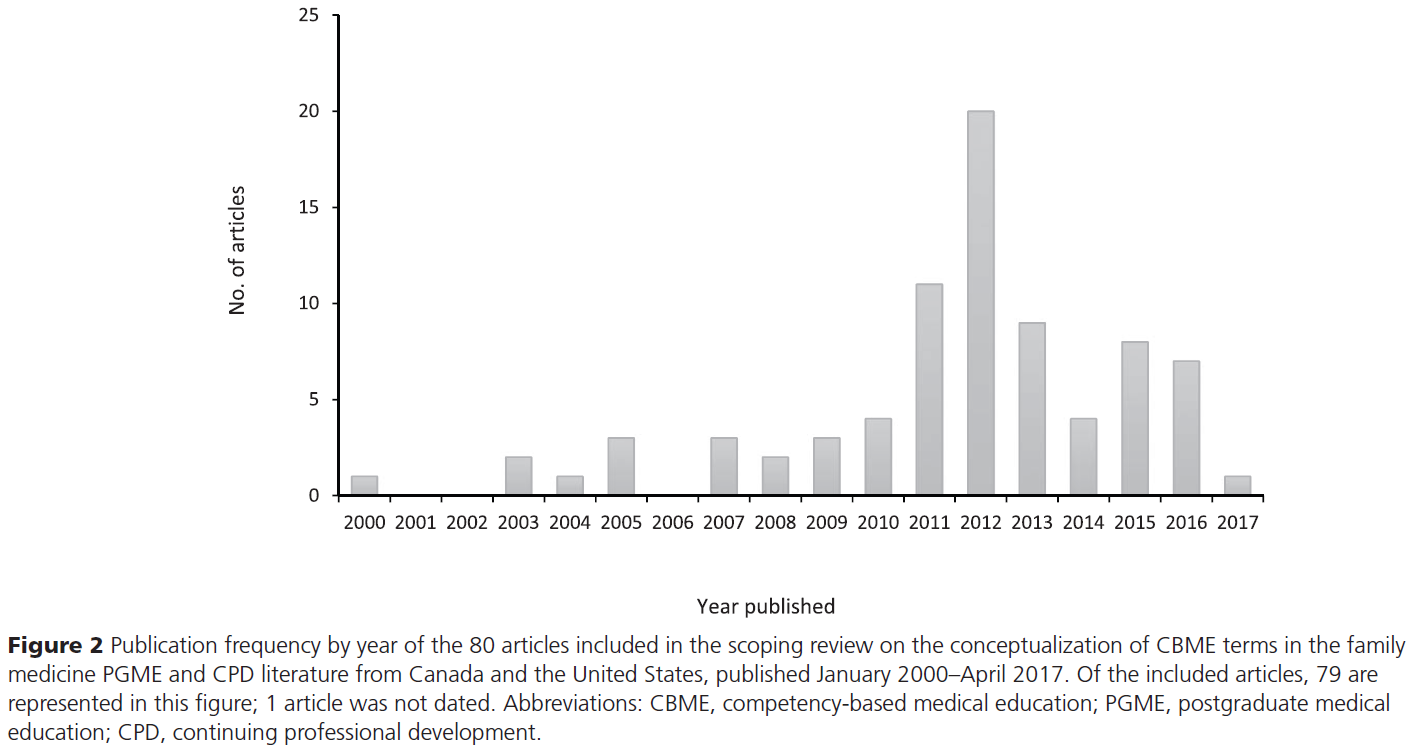

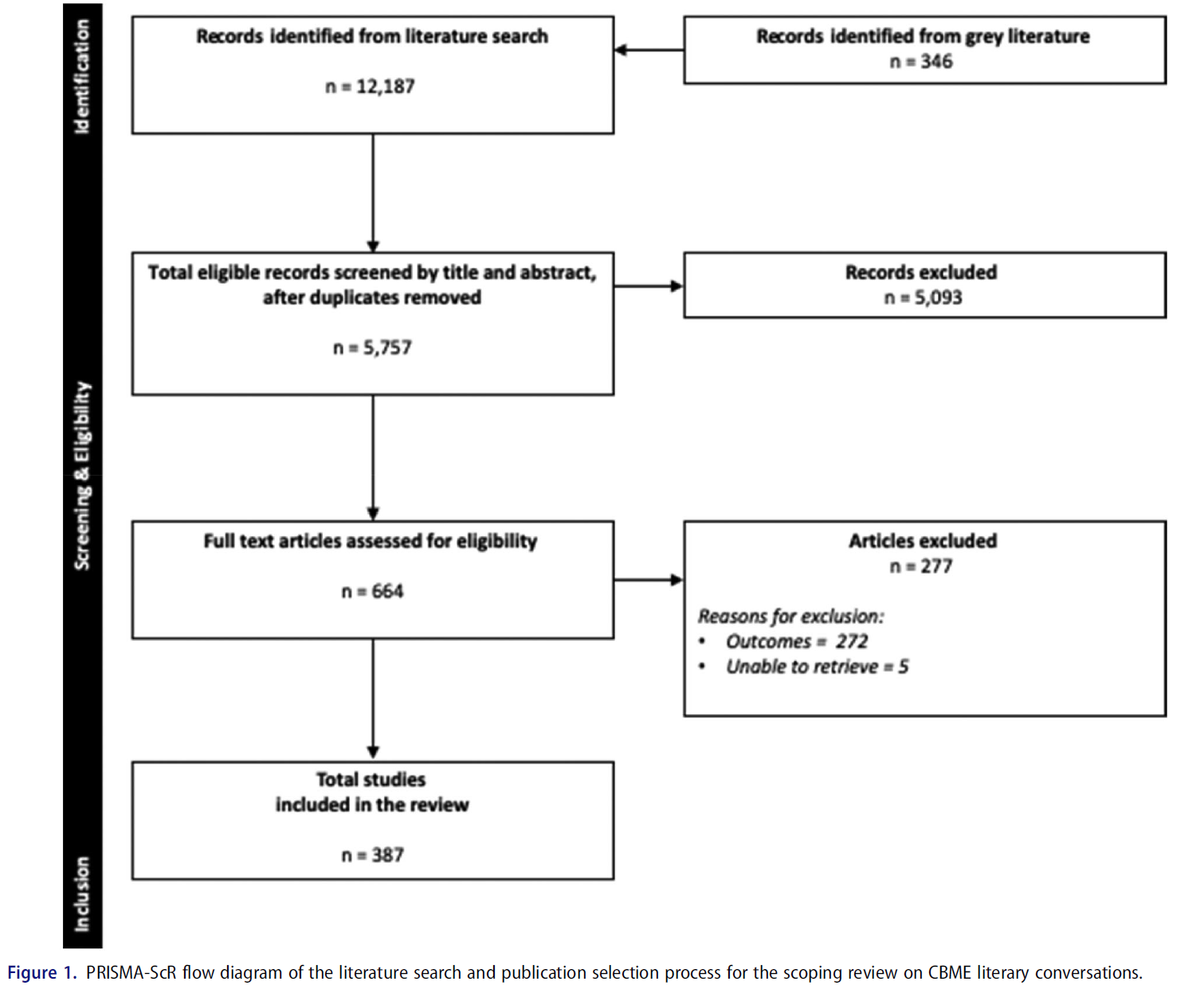

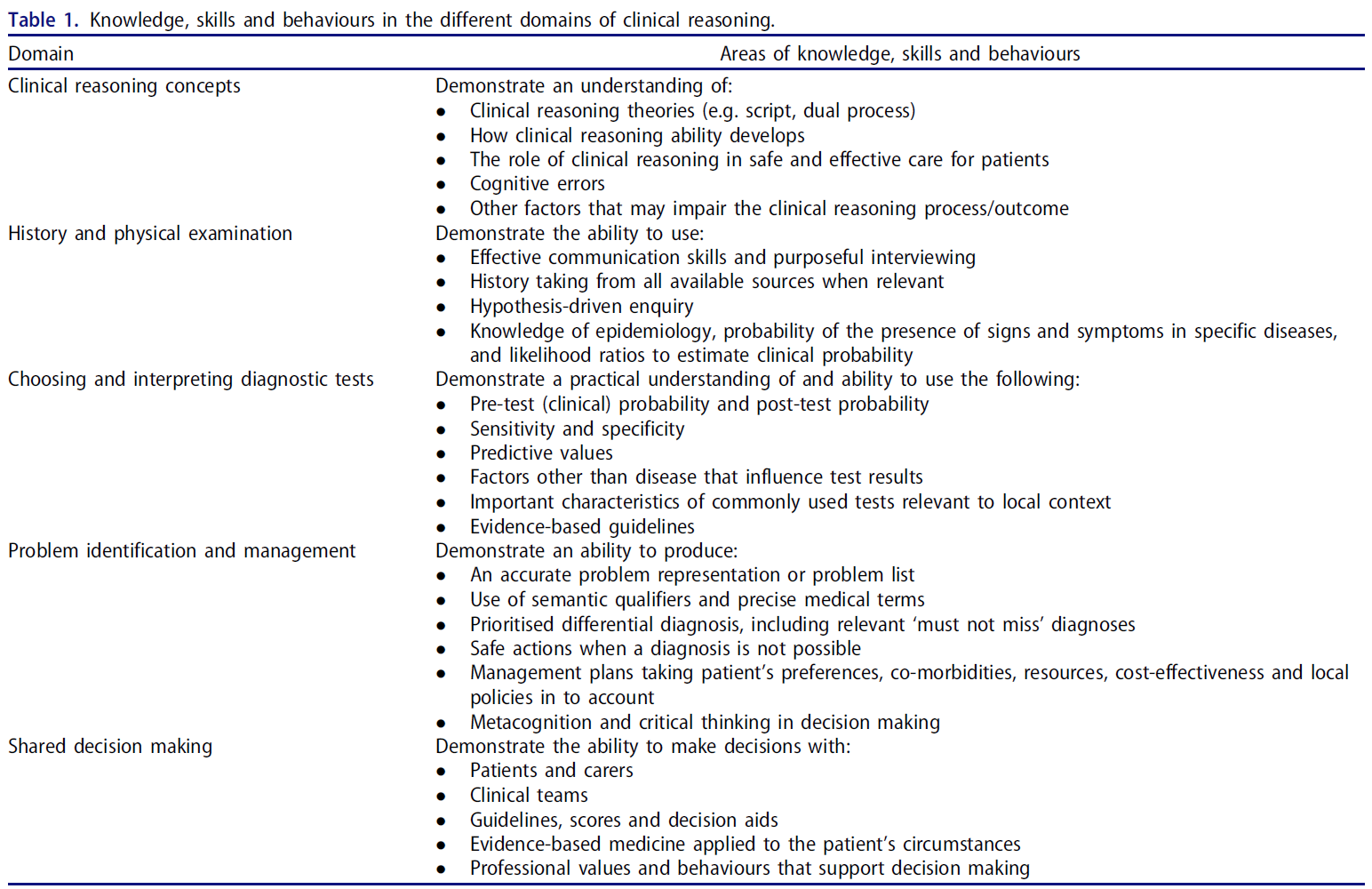

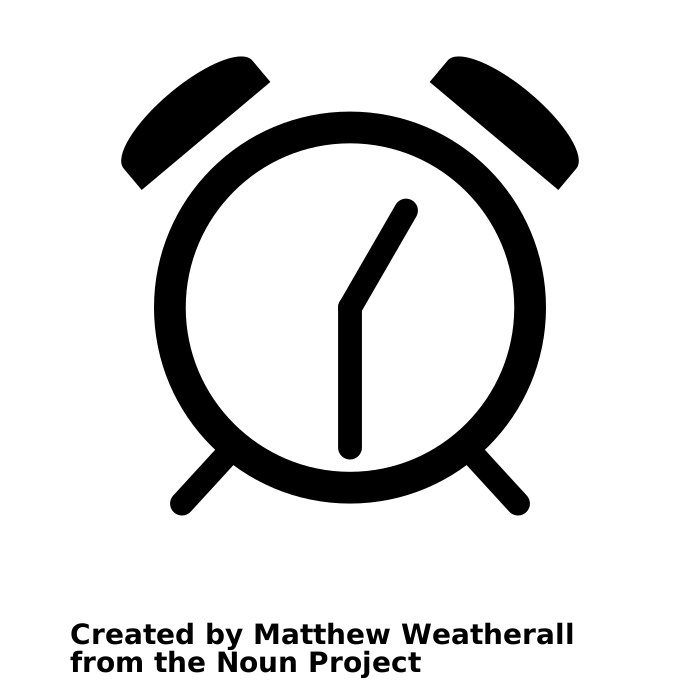

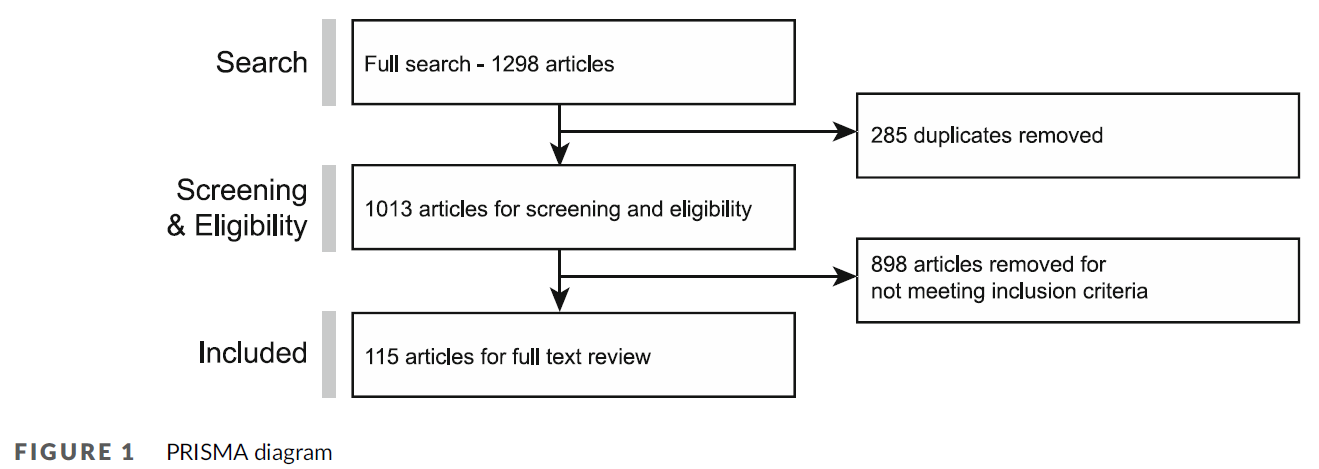

검색을 통해 확인된 1013개의 논문 중 898개의 논문이 포함 기준을 충족하지 못했습니다. 그 결과 115개의 논문이 리뷰에 포함되었습니다(리뷰 코퍼스를 구성하는 논문 목록은 그림 1 및 부록 3 참조).

Of the 1013 articles identified from the search, 898 did not meet our inclusion criteria. This left 115 articles for inclusion in the review—see Figure 1 and Supplementary Appendix 3 for the list of articles that made up the review corpus.

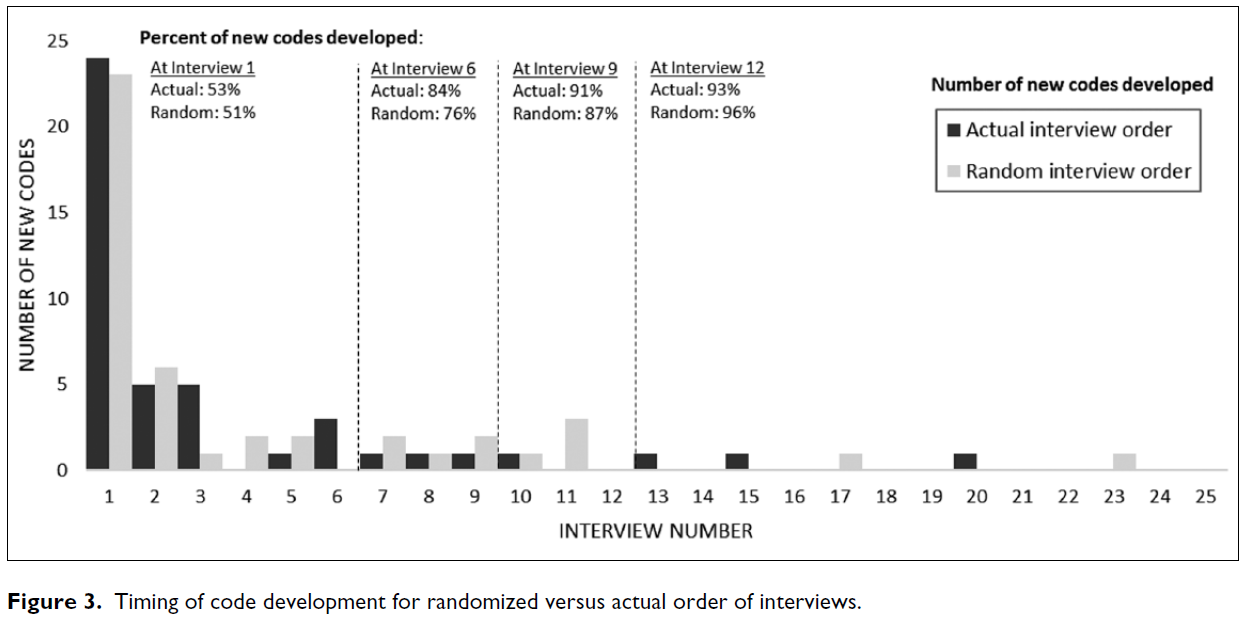

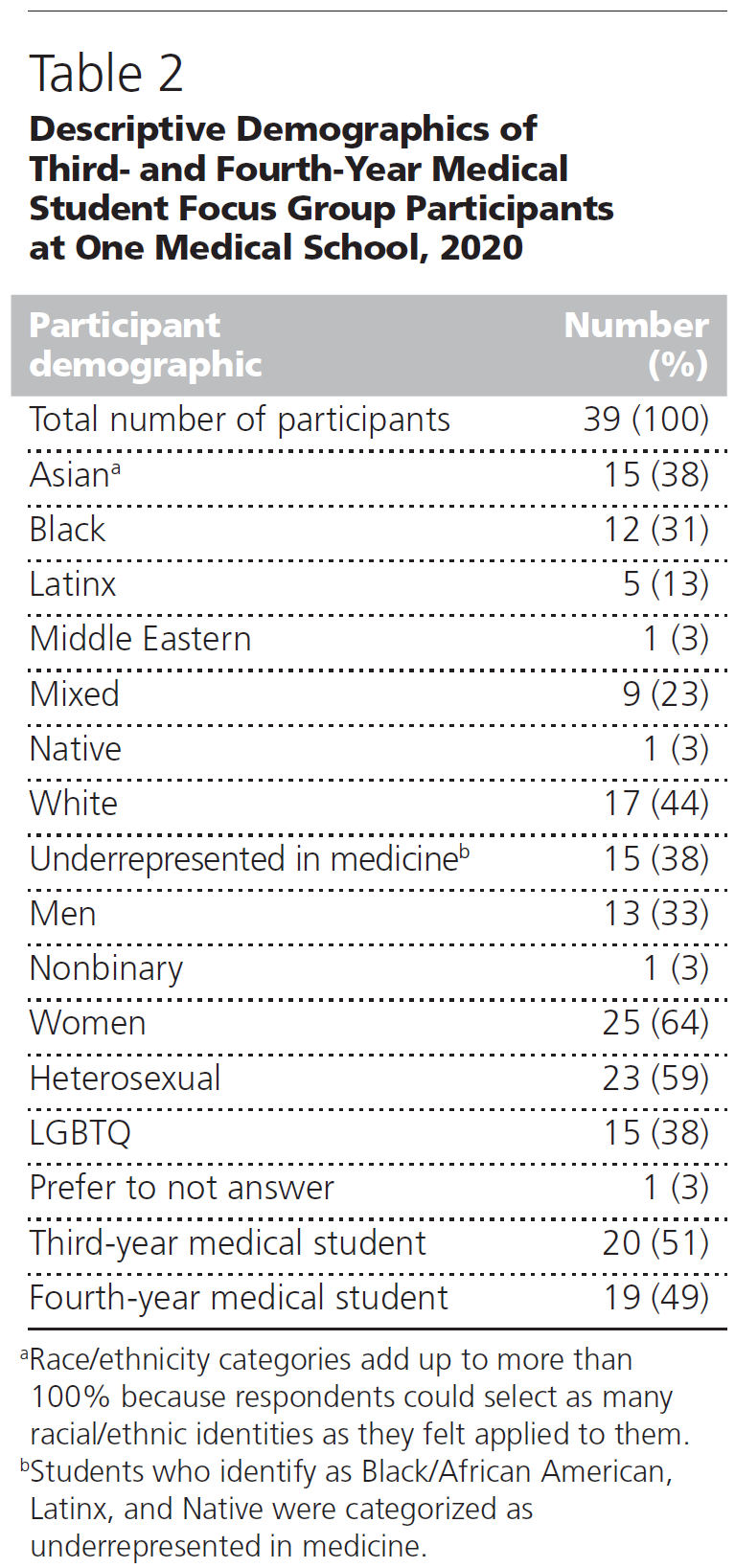

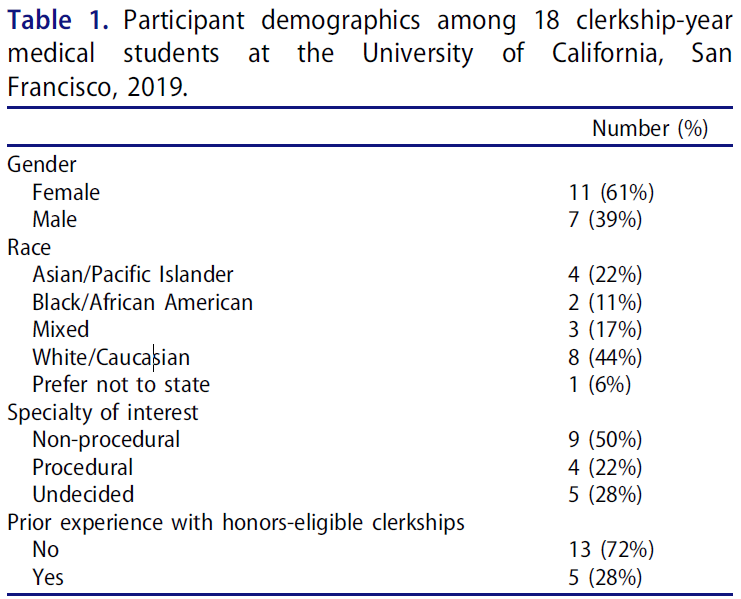

56편의 논문은 의학 교육(n = 20), 보건 과학 교육 발전(n = 9), 의료 교사(n = 9), 학술 의학(n = 6), 전문직 간 진료(n = 4), BMC 의학 교육(n = 5), 의학 교육에 대한 관점(n = 3, 이 저널은 2012년까지 영어로 출판되지 않음), 그리고 다양한 간호 저널에 20편의 논문이 추가로 실렸습니다. 몇몇 논문은 의학 전문 학술지(n = 10)에, 나머지는 다양한 기타 학술지에 게재되었습니다. 2000~2010년(n = 19)에 비해 2011~2021년(n = 96)에 DA 사용을 보고한 논문 수가 크게 증가했습니다. 63편의 논문은 단일 방법(DA만)이었고, 나머지는 혼합 방법 연구(MMR)였습니다. 이 중 22개는 DA와 인터뷰, 나머지 8개는 인터뷰와 포커스 그룹을 포함했습니다. 7건은 일반적으로 인터뷰와 함께 DA 및 설문조사 데이터를 포함했습니다(DA 및 설문조사 데이터만 사용한 논문은 1건뿐). 여러 연구에서 DA, 인터뷰(개별 또는 포커스 그룹), 관찰 등 다양한 데이터 소스를 사용했습니다. 저희가 확인한 연구 중 5건은 특정 정보를 찾기 위해 문서를 면밀히 검토한 후 설명적 또는 통계적 분석을 거친 정량적 연구였습니다.

Fifty-six articles were in HPE journals including Medical Education (n = 20), Advances in Health Sciences Education (n = 9), Medical Teacher (n = 9), Academic Medicine (n = 6), The Journal of Interprofessional Care (n = 4), BMC Medical Education (n = 5) and Perspectives on Medical Education (n = 3, note this journal did not publish in English until 2012), plus an additional 20 articles in various nursing journals. Several articles were published in medical specialty journals (n = 10), and the remainder, in diverse other journals. There was a significant increase in the number of articles published reporting the use of DA in the period 2011–2021 (n = 96) compared to 2000–2010 (n = 19). Sixty-three articles were single method (DA only), and the others were mixed methods research (MMR). Of these, 22 involved DA and interviews, and a further eight involved interviews and focus groups. Seven included DA and survey data, usually along with interviews (only one paper used DA and survey data only). Several studies used many different sources of data, such as DA, interviews (individual or focus groups) and observations. Five of the studies we identified were quantitative, scrutinising documents for specific information, which was then subject to descriptive or statistical analysis.

문서 말뭉치, 연구 목적, 방법, 연구 결과, 문서 분석의 이론 및 메타학문 측면에서 메타 연구 내러티브 종합을 보고합니다.

We report our meta-study narrative synthesis in terms of the document corpus, purposes, methods, findings and theory and metascholarship in document analyses.

문서 코퍼스

Document corpus

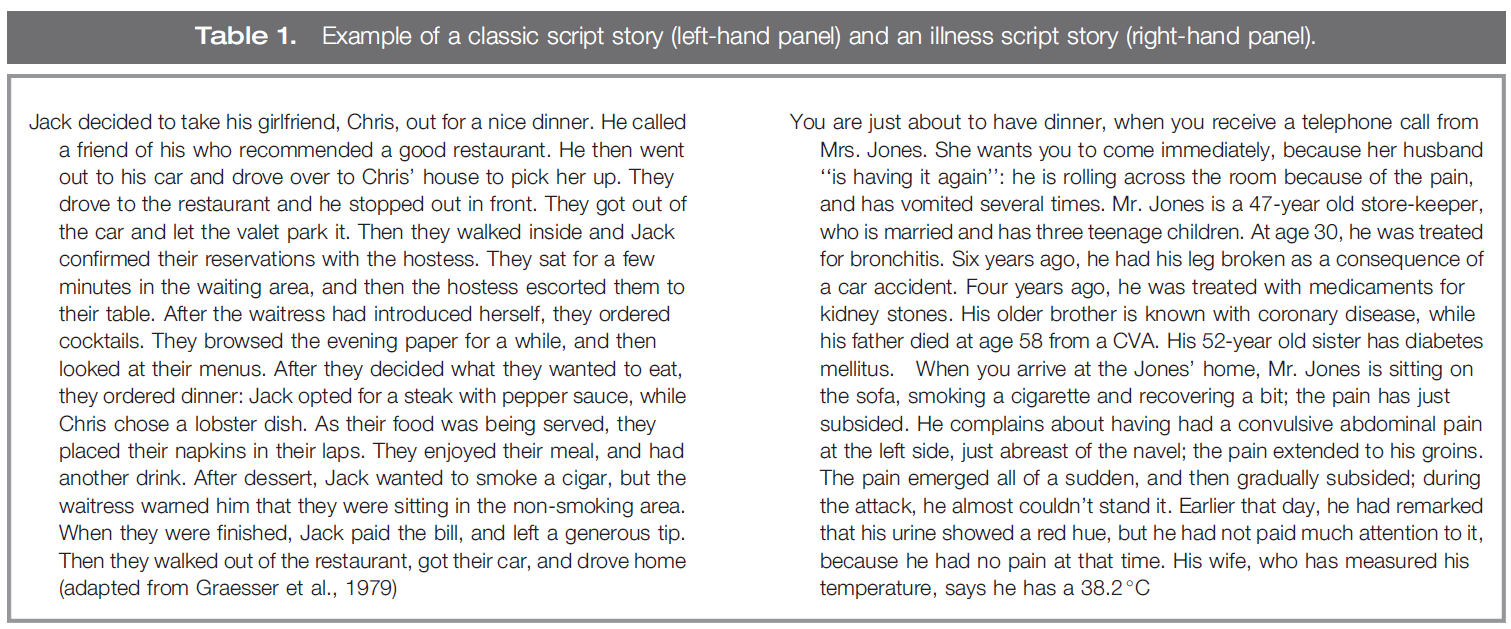

먼저 DA에 입력된 문서, 즉 '문서 말뭉치'(보충 부록 3)부터 시작합니다. 연구 이전에 존재했던 문서(예: 회의록 및 정책 문서)와 연구의 일부로 생산된 문서(예: 현장 노트 및 일기 항목)를 분석하는 데 한 가지 차이점이 있습니다. Charmaz33은 전자의 경우 '현존하는 텍스트'라는 용어를, 후자의 경우 '도출된 텍스트'라는 용어를 사용했습니다. 저희가 검토한 논문 중 단 2개(<2%)만이 연구에서 도출된 데이터를 사용했습니다. Voogt 등34은 정책 문서와 함께 참여자 QI 프로젝트 자료를 분석했고, Ruiz-Lopez 등35은 참여자의 저널을 분석했습니다. 인터뷰 녹취록과 같이 연구에서 생성된 데이터는 포함하지 않았습니다.

We start with the documents that were entered into the DA; the ‘document corpus’ (Supplementary Appendix 3). One distinction was between the analysis of documents that pre-existed the research (e.g., meeting minutes and policy documents) and documents that were produced as part of a study (e.g., field notes and diary entries). Charmaz33 used the term ‘extant text’ for the former and ‘elicited text’ for the latter. Only two (<2%) of the articles we reviewed used study-elicited data. Voogt et al.34 analysed participant QI project materials (alongside policy documents) and Ruiz-Lopez et al.35 analysed participants' journals. Note that we did not count study-generated data such as interview transcripts.

둘째, 문서 선정 방법, 포함된 문서 수, 분석된 문서의 특성에 대한 정보가 광범위하게 부족했습니다. 실제로 어떤 문서가 사용되었는지(또는 왜 포함되었는지 또는 어떻게 분석되었는지) 보고하지 않은 연구도 있었습니다(예: Brosnan36).

- 다음은 이러한 세부 사항 부족의 대표적인 예입니다: '검토 대상인 전문 규제 측면과 관련된 정책 보고서 또는 논평에 해당하는 텍스트가 포함된 경우'(731쪽).37

- 또 다른 예로, Wong38 은 다음과 같이 언급했습니다: '이용 가능한 모든 부서 및 프로그램 문서를 검토했다'(1211쪽)고 말했지만, 문서가 무엇인지, 문서 수가 얼마나 되는지, 그 밖의 다른 내용은 설명하지 않았습니다.

- 마찬가지로 '핵심 문서'라는 문구가 문서 포함에 대한 유일한 정당화였습니다. 그러나 이러한 핵심 문서가 무엇이고 왜 핵심 문서인지에 대한 정보가 없으면 포함된 문서의 품질이나 적절성을 평가할 근거가 없습니다.

Secondly, there was a broad deficit of information on how documents were selected, on how many documents were included and on the characteristics of the documents analysed. Indeed, some studies did not report what documents were used (or indeed why they were included or how they were analysed, e.g., Brosnan36).

- The following typifies this lack of detail: ‘texts were included if they constituted policy reports or commentary concerned with those aspects of professional regulation of concern to the review’ (p. 731).37

- As another example, Wong38 stated: ‘all available departmental and programme documents were examined’ (p. 1211) but did not describe what they were, how many there were, or anything else about them.

- Similarly, the phrase ‘key documents’ was the only justification for document inclusion. However, without information as to what these key documents were and why they were key, there are no grounds on which to assess the quality or appropriateness of the included documents.

DA 말뭉치의 구성에 대한 세부 정보가 부족하기 때문에, 우리가 말할 수 있는 것은 다음과 같은 대략적인 범주에 속하는 문서들이 포함되었다는 것입니다:

Given the lack of detail on the makeup of the DA corpus, the most we can say is that documents approximated to the following broad categories:

- 단일 교육기관 커리큘럼 문서. 예를 들어, Hawick 등은25 내부 보고서와 회의록을 분석하여 커리큘럼 개혁의 과정을 조사했습니다.

Single institution curricular documents. For example, Hawick et al.25 analysed internal reports and meeting minutes to examine the processes of curricular reform. - 다중 교육기관 커리큘럼 문서. 예를 들어 Steven 등39은 여러 영국 의과대학의 이비인후과 커리큘럼을 분석했습니다.

Multi-institution curricular documents. For example, Steven et al.39 analysed the otolaryngology curricula from multiple UK medical schools. - 정책 및 기타 공개 문서. 예를 들어, Razack 등40은 의과대학 선택에 대한 담론 분석을 위해 의과대학 웹사이트와 국가 규제 기관의 정책 문서를 조사했습니다. 프레데릭센41은 정해진 기간 내에 출판된 의사와 간호사를 위한 교과서를 분석했습니다(논문에서 교과서에 대한 세부 정보를 제공).

Policy and other public-facing documents. For example, Razack et al.40 examined the medical school websites and the policy documents of national regulatory bodies in a discourse analysis of medical school selection. Frederiksen41 analysed textbooks for doctors and nurses published within a defined time period (providing details of the textbooks in her paper). - 학생 또는 교수진 데이터(자기 성찰, 학습 로그, 온라인 토론 등). 예를 들어, Zaidi 등42은 온라인 토론의 텍스트를 분석하여 비판적 의식을 형성하는 데 있어 기존 다문화 토론의 강점과 한계를 정의했습니다.

Student or faculty data (self-reflections, learning logs, online discussions etc.). For example, Zaidi et al.42 analysed text from online discussions to define the strengths and limitations of existing cross-cultural discussions in generating critical consciousness.

목적

Purposes

- Siegner 등의 유형학을 사용하여 31개의 논문에서 삼각 측량 목적으로 DA를 사용한다고 명시적으로 설명했거나, 명시적으로 설명하지 않은 경우 전체 논문을 읽은 후 문서 사용을 그렇게 해석했습니다.

- 예를 들어, Hawick 외.25는 다음과 같이 말했습니다: '문서 분석의 목적은 다양한 데이터 소스와 방법을 사용하여 수렴과 확증을 추구하는 것이었다'.

- 20개의 기사에서 문서가 맥락적 목적으로 사용된 것으로 보였습니다.

- 그보다 적은 수(n = 16)의 논문이 문서를 연구 대상으로 사용했으며, 이들은 담화 분석 연구인 경향이 있었습니다.

- 나머지 논문(n = 48)에서는 사실 또는 맥락에 대한 주요 참고 자료로 문서가 사용되었습니다(우리가 알 수 있는 한).

- 예를 들어 보그스트롬 등43은 포트폴리오 콘텐츠를 조사하여 직업적 가치에 대한 언급을 식별하고 분석했습니다.

- 앤더슨과 갈리아르디44는 여성 건강 커리큘럼에 대한 내용 분석을 수행하여 관련 커리큘럼 내용을 파악했습니다.

- Waterval 등45 은 다양한 문서의 내용을 사용하여 연구 질문에 대한 정보를 얻었습니다.

- Using Siegner et al’s typology, 31 articles either explicitly described using DA for triangulation purposes or, where this was not made explicit, on reading the full article, we interpreted their use of documents as such.

- For example, Hawick et al.25 stated: ‘The aim of document analysis was to seek convergence and corroboration through the use of different data sources and methods’.

- In 20 articles, documents seemed to be used for contextual purposes.

- Fewer (n = 16) used documents as the object of the research, and these tended to be discourse analysis studies.

- In the other articles (n = 48), documents had been used (as far as we could tell) as primary reference sources on factual or contextual matters.

- For example, Borgstrom et al.43 examined portfolio content to identify and analyse references to professional values.

- Anderson and Gagliardi44 conducted a content analysis of women's health curricula to identify relevant curriculum content.

- Waterval et al.45 used the content of various documents to inform their research questions.

방법

Methods

문서에서 데이터를 추출하는 방법은 설명이 부족하고 모호한 경우가 많았습니다. 예를 들어, Sirili 등은46 탄자니아 교육 개혁의 정책 과정과 결과를 분석하는 데 사용한 문서를 명확하게 나열했습니다. 그러나 문서 데이터를 어떻게 관리하고 분석했는지에 대한 정보는 논문에서 찾아볼 수 없었습니다.

- 35편(30%)의 논문이 내용 분석, 프레임워크 분석 또는 주제 분석을 사용했다고 보고했지만, 이는 주로 기본적인 사실이나 세부 사항을 추출하는 데 그쳤으며, 권위나 명료성에 거의 주의를 기울이지 않았고 이러한 분석 기법의 사용 간에 별다른 차이를 발견할 수 없었습니다.

- 29개(25%) 논문은 어떤 종류의 담론 분석을 사용했다고 밝혔고, 24개(21%) 논문은 분석 접근법이나 방법론을 사용했다고 언급하지 않았습니다.

예를 들어, Fealy 외.37는 '검색된 모든 텍스트에 대해 문서 분석을 수행했다'(731페이지)고 명시했지만, 어떤 분석을 수행했는지에 대한 자세한 내용은 제공하지 않았습니다. 나머지 논문은 템플릿 분석(예: Chenot 및 Daniel47), 키워드 매칭(예: Wong 외.48) 등 다른 접근법을 사용했습니다.

How data were extracted from documents was often under-described and ambiguous. For example, Sirili et al.46 clearly listed the documents they used to analyse the policy process and outcomes of training reform in Tanzania. However, any information on how they managed and analysed the document data was lacking in the paper.

- Thirty-five articles (30%) reported using content, framework or thematic analyses, although this was often limited to extracting basic facts or details with little attention to their authority or articulation, and we found little distinction between the use of these analytic techniques.

- Twenty-nine (25%) articles stated that they used some kind of discourse analysis, while twenty-four (21%) did not mention having used any analysis approach or methodology.

For example, Fealy et al.37 stated ‘Documentary analysis performed on all retrieved texts’ (p. 731) but did not provide any detail of what was done. The remaining articles employed other approaches, including template analysis (e.g., Chenot and Daniel47) and keyword matching (e.g., Wong et al.48).

MMR 논문에서 대부분의 저자는 DA 사용에 대한 설명에 비해 그들이 사용한 다른 방법에 대해 훨씬 더 실질적인 설명을 제공했습니다. 예를 들어, 인터뷰와 문서를 데이터로 사용한 MMR 연구에서는 인터뷰 질문, 인터뷰 대상자, 인터뷰 횟수, 인터뷰 데이터 분석에 대해 명시적으로 설명한 반면, 문서에 대한 세부 사항(샘플링 방법 포함) 및 분석에 대한 설명은 부족했습니다. 예를 들어, 서덜랜드 등49 은 포커스 그룹의 수와 기간, 참가자 수, 포커스 그룹 데이터 분석에 대한 접근 방식을 명시했지만 문서의 수나 문서의 내용, 분석 방법에 대해서는 언급하지 않았습니다(질적 데이터 관리 소프트웨어에 문서를 입력했다고만 명시). 결과 섹션에는 문서 데이터가 제시되지 않았습니다. 다른 논문에서는 저자가 접근 방식을 구성하거나 수행한 방법을 설명하지 않고 단순히 문서 분석 접근 방식을 사용했다고 언급했습니다.

In the MMR articles, most authors provided much more substantive descriptions of the other methods they had used compared to their descriptions of using DA. For example, in MMR studies that used interviews and documents as data, the interview questions, who was interviewed, the number of interviews and interview data analysis were explicitly described, while parallel details about documents, including how they were sampled, and their analysis were lacking. To illustrate, Sutherland et al.49 specified the number and length of their focus groups, the number of participants and their approach to focus group data analysis but made no mention of the number of documents or what these were or how they were analysed (stating only that documents were entered into qualitative data management software). No document data were presented in the results section. In other articles, authors simply mentioned using a document analytic approach rather than describing how the approach was configured or conducted.

위에서 언급한 바와 같이, 29개 논문(25%)은 담화 분석 접근법을 사용했다고 명시적으로 언급했습니다. 그러나 전체 텍스트를 읽어보면 이러한 분석의 대부분은 내용 분석 또는 주제 분석으로 더 정확하게 설명할 수 있습니다. 비판적 담화 분석을 사용했다고 명시한 논문(n = 22) 중 19편이 푸코주의적 관점을 사용했으며, 이 중 16편은 같은 기관에 소속된 저자의 논문이었습니다. 담론 분석 논문에서는 대상 또는 객체와 다른 데이터와의 삼각 측량으로 처리된 문서를 검토했으며, 방법론적 지향이 명시되어 있어 엄밀성과 방법론적 일관성이 논의되고 분명했습니다.

As stated above, 29 articles (25%) explicitly stated that they took a discourse analysis approach. However, when we read the full texts, many of these analyses would be more accurately described as content or thematic analysis. Of those articles which were explicit about using critical discourse analysis (n = 22), 19 used a Foucauldian perspective and 16 of these were from authors associated with the same institution. In the discourse analysis articles, we reviewed documents that were treated as object or object plus triangulation with other data, and, as they had an explicit methodological orientation, rigour and methodological coherence was both discussed and apparent.

연구 결과 및 논의

Findings and discussions

검토한 논문 중 연구 결과의 맥락에서 문서나 그 내용을 명시적으로 설명한 논문은 거의 없었습니다. 오히려 제시된 증거는 고도로 일반화되었거나 MMR 연구의 경우 다양한 지식 주장을 설명 또는 방어하기 위해 다른 방법론적 흐름(예: 인터뷰 데이터)에서 주로 파생된 것이었습니다. 실제로 방법 섹션에서는 문헌을 언급했지만 결과나 논의에서는 명시적으로 언급하지 않은 경우도 있었습니다(예: 50). 유일한 예외는 문서가 유일한 데이터 소스인 담론 분석 기사였습니다. 고찰 섹션에서도 마찬가지로 문서의 품질, 중요성 또는 기타 특성이 연구 결과의 시사점, 추가 연구에 대한 시사점 또는 연구의 한계와 거의 고려되지 않았거나 연결되지 않았습니다. 이는 권위 있는 출처로서의 문서에 대한 신뢰도가 낮거나, 특히 MMR 연구에서 DA 스트림에 대한 연구자들의 일반적인 사각지대가 반영된 결과라고 볼 수 있습니다.

Very few of the articles we reviewed explicitly described their documents, or the content thereof, in the context of their findings. Rather, the evidence presented was either highly generalised or, in the case of MMR studies, largely derived from other methodological streams (e.g., interview data) to illustrate and/or defend their various knowledge claims. Indeed, at times documents were referred to in the methods section but not referred to explicitly in the results or discussion (e.g.,50). The only exceptions to this were the discourse analysis articles where documents were the lone data source. Similarly in discussion sections, the quality, significance or other characteristics of documents were rarely considered or linked to the implications of findings, implications for further research or limitations of the study. This suggests either a lower sense of confidence in documents as sources of authority or a further reflection of the common blind spots researchers have had regarding DA streams, particularly within MMR studies.

이론과 메타학술성

Theory and Metascholarship

대부분의 논문(담화 분석 제외)은 DA 이론이나 방법론적 문제에 대한 근거가 거의 또는 전혀 없었습니다. 대부분 DA 방법론은 이를 뒷받침하기 위해 방법론적 출처를 한두 번 인용하면서 언급되었는데, 가장 흔한 출처는 Bowen이었습니다.11 이러한 무성의함은 어떤 문서가 있는지, 문서와 관련된 연구자의 입장, DA 방법론의 도전과 논쟁 등에 대한 관심이 부족하다는 것을 반영합니다.

Most articles (discourse analyses excepted) had little or no grounding in DA theory or methodological concerns. Mostly, DA methodology was stated with one or two citations to a methodological source to back it up, most commonly Bowen.11 This casualness reflected a lack of attention to what documents might be, the position of the researcher in relation to the documents, the challenges and debates in DA methods and so forth.

또한 담론 분석 방법을 사용하는 논문과 커리큘럼 개혁에 초점을 맞춘 논문 중 이론적 렌즈를 사용하여 분석한 논문은 소수에 불과했습니다. 예를 들어,

- Ellaway 등은 담화 분석을 위해 Gee의51 개념적 틀을 사용했고,

- Razack 등은40 '푸코, 부르디외, 바흐친, 고프만의 성과 이론'을 활용했으며,

- Hawick 등은25 데이터의 측면을 강조하기 위해 '사악한 문제' 프레임워크52 를 적용했습니다.

Moreover, only a few articles, typically but not always those employing discourse analysis methods and those focused on curriculum reform, used a theoretical lens in their analysis. For instance,

- Ellaway et al. used Gee's51 conceptual framing for discourse analysis,

- Razack et al.40 drew on ‘Foucault, Bourdieu and Bakhtin … and the performance theories of Goffman’, while

- Hawick et al.25 applied the ‘wicked problem’ framework52 to highlight aspects of their data.

HPE 학자들은 학문적 연구에 더 많은 이론적 지향성을 요구해 왔으며,53 특히 그렇게 하지 않으면 연구 결과의 개념적 일반화 가능성이나 이전 가능성이 제한되기 때문입니다.54 일부 방법론이 이러한 요구에 부응했지만, 아직까지 DA에 실질적인 영향을 미치지는 않은 것으로 보입니다. 또한 DA 이론, DA 방법 또는 DA 과학 전체에 대한 기여에 대한 실질적인 고려는 거의 찾아볼 수 없었습니다.

HPE scholars have called for more theoretical orientation to scholarly work,53 not least because not doing so limits the conceptual generalisability or transferability of findings.54 While some methodologies have responded to this call, it seems that this has not yet touched DA in any substantial way. We also note that we found almost no substantive consideration of contributions to DA theory, DA methods or DA science as a whole.

예외

Exceptions

많은 누락에도 불구하고 DA를 수용하고 이를 잘 보도한 기사도 몇 개 발견했습니다. 그 중 눈에 띄는 논문은 Sundberg 등의 논문이었습니다.55 저자들이 사용한 문서뿐만 아니라 길이를 포함한 문서의 특성을 설명하는 방식에 감사했습니다. 또한 인터뷰와 문서 모두에 사용된 분석 접근 방식을 명시하고 분석의 각 측면에 대해 인터뷰 데이터와 문서 데이터를 모두 제시했습니다. 마지막으로, 연구진은 연구 질문과 관련된 소규모 문서 코퍼스의 한계에 대해 인정했습니다.

Despite the litany of omissions, we found some articles that had embraced DA and reported it well. One example which stood out was a paper by Sundberg et al.55 We appreciated the way the authors specified not only the documents they used but also described the characteristics of the documents, including the length. They also specified the analysis approach used for both their interviews and the documents and presented both interview and document data for each aspect of their analysis. Finally, they acknowledged possible limitations of the small corpus of documents relevant to their research question.

4 토론

4 DISCUSSION

HPE 연구 논문에서 DA는 어떻게 접근했습니까?

How has DA been approached in HPE research articles?

DA 연구에 사용된 문서는 기본 데이터 소스가 아닌 맥락적 및 삼각 측량 목적으로 자주 사용되었습니다. 즉, 대부분의 논문에서 문서를 정적이고 '유순한' 지식의 저장소로 개념화하여

- 문서가 '무엇을 하는가'보다는

- 문서가 무엇을 '말하는가'(내용),

- 문서가 어떻게 말하는가를 조사했습니다.8

We found that documents in DA studies were frequently used for contextual and triangulation purposes, not as a primary data source. This meant that most articles conceptualised documents as static and ‘docile’ containers of knowledge, examining

- what documents ‘say’ (content) and

- to a lesser extent how they say it,

- rather than what documents ‘do’.8

이러한 차이점에는 연구자가 문서에 관여하는 방식에 대한 암묵적인 변증법이 존재했습니다.

- 한편으로, 문서는 실험적으로 도출된 데이터와 유사한 방식으로 수집, 처리 및 분석되는 1차 데이터로 접근할 수 있습니다.

- 반면에 문서는 그 내용, 표현 방식, 권위에 대한 논란이 있을 수 있으므로, 덜 비판적이거나 직접적인 방식으로 접근할 수 있으며,

- 엄격하게 데이터로 간주되기보다는, 데이터를 성찰하는 데 사용될 수 있습니다.

There was an implied dialectic of researcher engagement with documents in these differences.

- On the one hand, documents may be approached as primary data that are collected, treated and analysed in similar ways to experimentally derived data.

- On the other hand, documents may be approached in a less critical or direct way such that their content, articulation and authority are moot, and they are used to reflect on data rather than being strictly considered as data.

문서의 내용을 조사하는 것도 분명 의미가 있지만, 문서의 의미나 중요성을 이해하는 데는 문서 작성, 생산 및 소비의 사회적, 물질적 현실이 매우 중요할 수 있다고 생각합니다. 이는 문서를 다음으로 취급해야 한다는 주장을 반영한 것입니다.

- 자원(독자에게 특정 환경, 조직, 사건 또는 사람에 대해 알려주는 의미, 정보원)으로서,

- 독립적인 인공물로서,56 그리고

- 잠재적으로 여러 온톨로지를 가진 '사회적 위치의 산물'(Scott57, 34쪽)

(문서의 위치성과 수사적 위치가 어느 정도는 채택된 방법론적 틀 안에 포함되곤 하는) 담론 분석 연구는 다소 예외였다. 예를 들어, Coyle 등24 은 데이터와의 관련성 측면에서 자신의 직업적, 개인적 배경을 밝히고, 서로 다른 삶의 과정, 교육 및 훈련이 문서에 대한 해석과 이 연구의 맥락 및 초점과 관련하여 자신의 입장을 어떻게 형성했는지에 대해 지속적으로 성찰했다고 언급했습니다.

While it is clearly meaningful to investigate the content of documents, we believe the social and material realities of document authorship, production and consumption can be of critical importance in understanding their meaning or significance. This reflects arguments that documents should be treated both

- as resources (meaning, sources of information that tell a reader about a particular setting, organisation, event or person),

- as stand-alone artefacts,56 and

- as ‘socially situated products’ (Scott57, p. 34) with multiple potential ontologies.

The exception, to an extent, was discourse analysis studies where the positionality and rhetorical positioning of the documents were (to some degree) included albeit within the methodological frame adopted. For example, Coyle et al.24 stated their professional and personal backgrounds in terms of relevance to the data and stated that they were continuously reflective about how their differing life courses, education and training shaped their interpretations of the documents and their positioning with respect to the study context and focus of this study.

현재 HPER의 DA 관행의 강점과 약점은 무엇인가요?

What are the strengths and weaknesses of current DA practices in HPER?

서두에서 언급했듯이, 그리고 이번 연구 결과에서 확인했듯이, DA의 활용 가능성은 매우 다양하며, 문서와 그 분석이 학술적 탐구 행위에 가치를 부여할 수 있는 이론적, 실제적 방법도 많습니다. 따라서 우리는 DA의 더 나은 사용이나 더 강력한 사용, 더 나쁜 사용이나 더 약한 사용이 있다고 말할 수 없습니다. 그보다는 DA가 사용된 연구 맥락에서 각각을 명확히 파악하고 평가해야 합니다. 이번 연구 결과는 글로벌 방법론적 규범에 따라 판단하기보다는 연구 내 공통 관심사에 초점을 맞추었기 때문에 이를 반영합니다.

As we mentioned in our opening and as our findings confirmed, there are many possible uses for DA and many theoretical and practical ways in which documents and analyses of them might lend value to acts of scholarly inquiry. We cannot say therefore that there are better or stronger uses or worse or weaker uses of DA. Rather, each should be articulated and appraised in the study context in which it was used. Our findings reflect this, as we focused on common concerns within studies rather than seeking to judge them against global methodological norms.

예를 들어, 연구를 시작하기 전부터 우려를 했음에도 불구하고(실제로 연구로 이어지기도 했습니다), 저희는 HPER에서 DA가 얼마나 제대로 보고되지 않는지에 놀랐습니다. 물론 예외도 있지만 전반적으로 다음을 보고하는 데에 있어 큰 허점이 있었습니다.

- 문서를 사용한 이유,

- 문서를 식별한 방법,

- 저자가 수행한 작업,

- 문서에서 발견한 내용에 대한

이는 특히 다른 방법 및 방법론에 비해 일관되게 DA를 덜 엄격하고 세부적으로 다루었거나, 적어도 덜 엄격하고 세부적으로 기술되거나 보고된 MMR 연구에서 두드러지게 나타났습니다. 이로 인해 투명성과 재현성에 대한 근본적인 문제가 발생하고 연구 결과가 의심스러워졌습니다. 부실한 보고는 문서 데이터의 '신뢰성'(예: 신뢰성 및 확인 가능성)을 평가하는 것을 불가능하게 만든다는 것은 잘 알려진 사실입니다58). MMR 연구 내의 다른 데이터 스트림에 대한 보다 실질적인 보고에 비해 반복적으로 DA 보고가 부족하다는 것은 인터뷰 기록의 주제별 분석과 비교하여 DA 방법 사용에 대한 자신감이나 역량이 부족하다는 것을 반영할 수 있습니다. 그러나 역량보다는 주의력 부족을 나타낼 수도 있습니다. 우리가 검토한 모든 논문이 각 저널에 게재되기 전에 일종의 동료 검토 과정을 거쳤으며, 그 과정에서 DA에 대한 설명이 부족하다는 지적을 받거나 수정되지 않았다는 사실이 이를 뒷받침할 수 있습니다. 따라서 이는 저자의 역량이나 집중력 때문이라기보다는 DA 학술활동에 대한 체계적인 부주의를 나타내는 것으로 보입니다.

For instance, although we had concerns leading into the study (indeed, they led to the study), we were still surprised at how poorly DA has been reported in HPER. Of course, there are exceptions, but, overall, there are major lacunae in terms of reporting on

- why documents were used,

- how documents were identified,

- what the authors did and

- what they found from the documents.

This was particularly apparent in MMR studies where DA was consistently treated with less rigour and attention to detail compared to other methods and methodologies (or at least it was described or reported with less rigour and detail). This created a fundamental problem of transparency and replicability and rendered findings suspect. It is well established that poor reporting makes it impossible to assess the ‘trustworthiness’ of the document data (e.g., credibility and confirmability58). The recurring paucity of DA reporting compared to the more substantive reporting of other data streams within MMR studies may reflect a lack of confidence or competence in using DA methods compared to, say, thematic analysis of interview transcripts. However, it may instead indicate a lack of attention rather than competence. This would be supported by the fact that all the articles we reviewed had passed some kind of peer review process before being published in their respective journals, during which the paucity of the description of DA had not apparently been challenged or corrected. This would seem therefore to indicate a systemic inattention to DA scholarship rather than one solely of author competence or focus.

HPER에서 DA 관행을 강화하기 위해 어떤 지침이나 표준이 필요하나요?

What guidelines or standards are needed to strengthen DA practices in HPER?

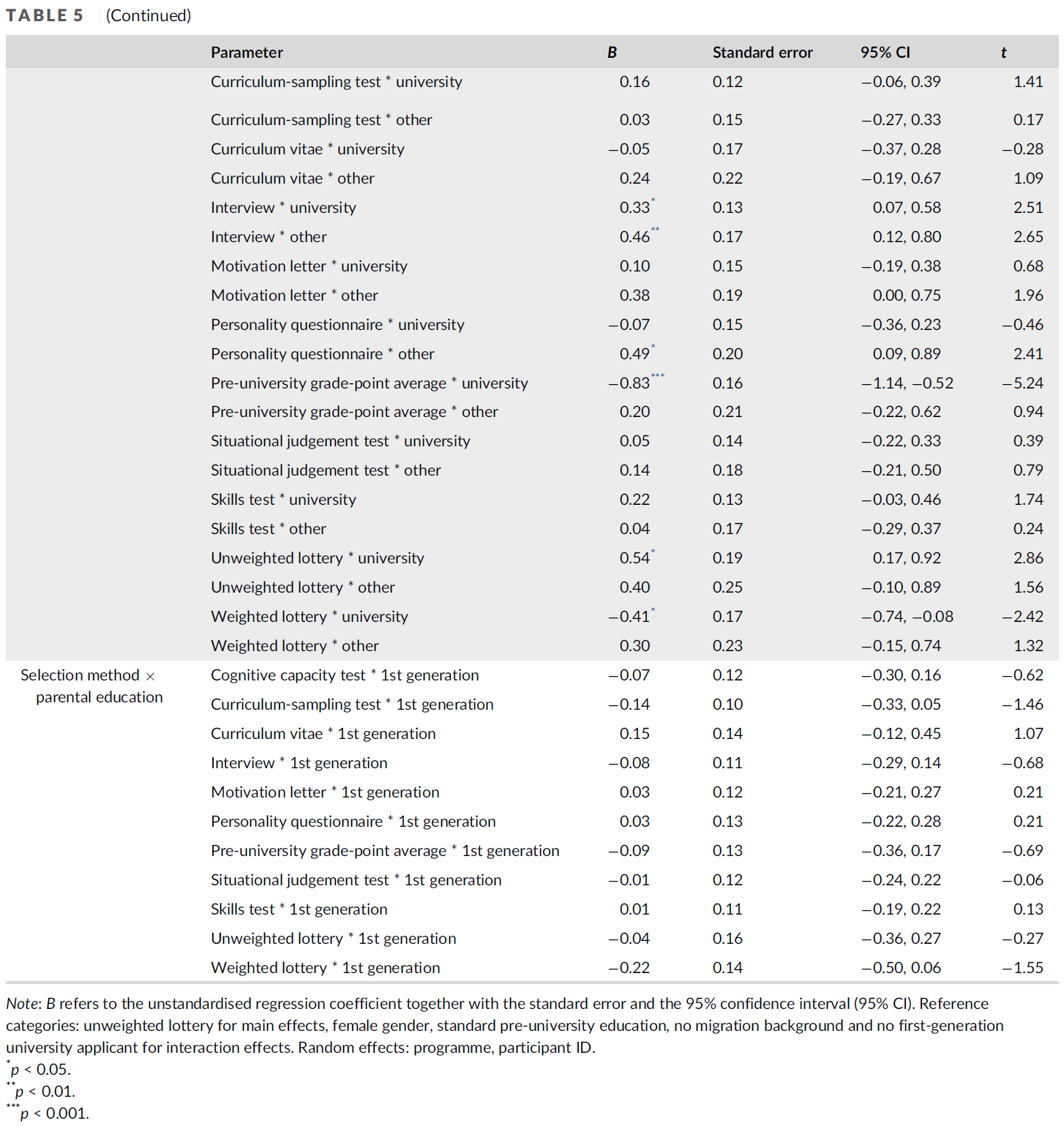

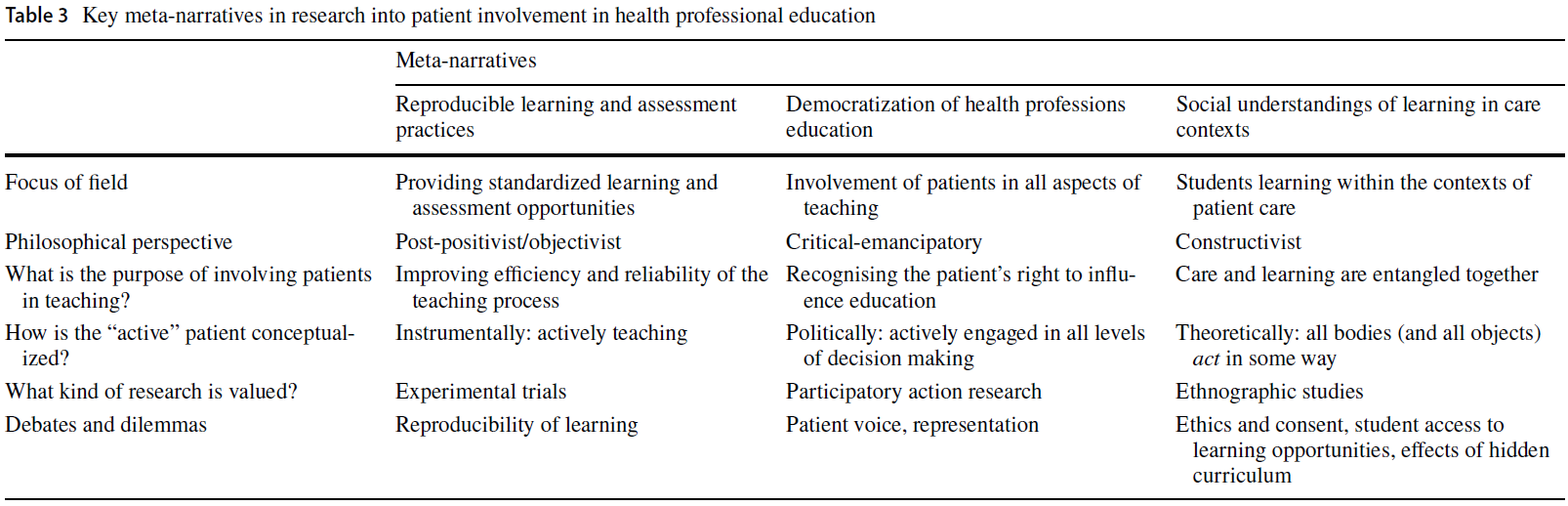

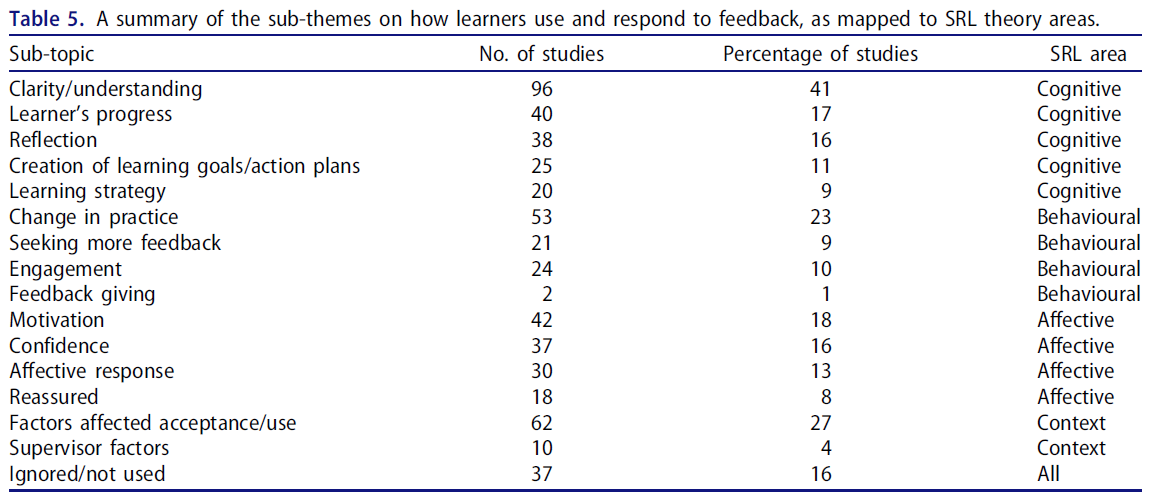

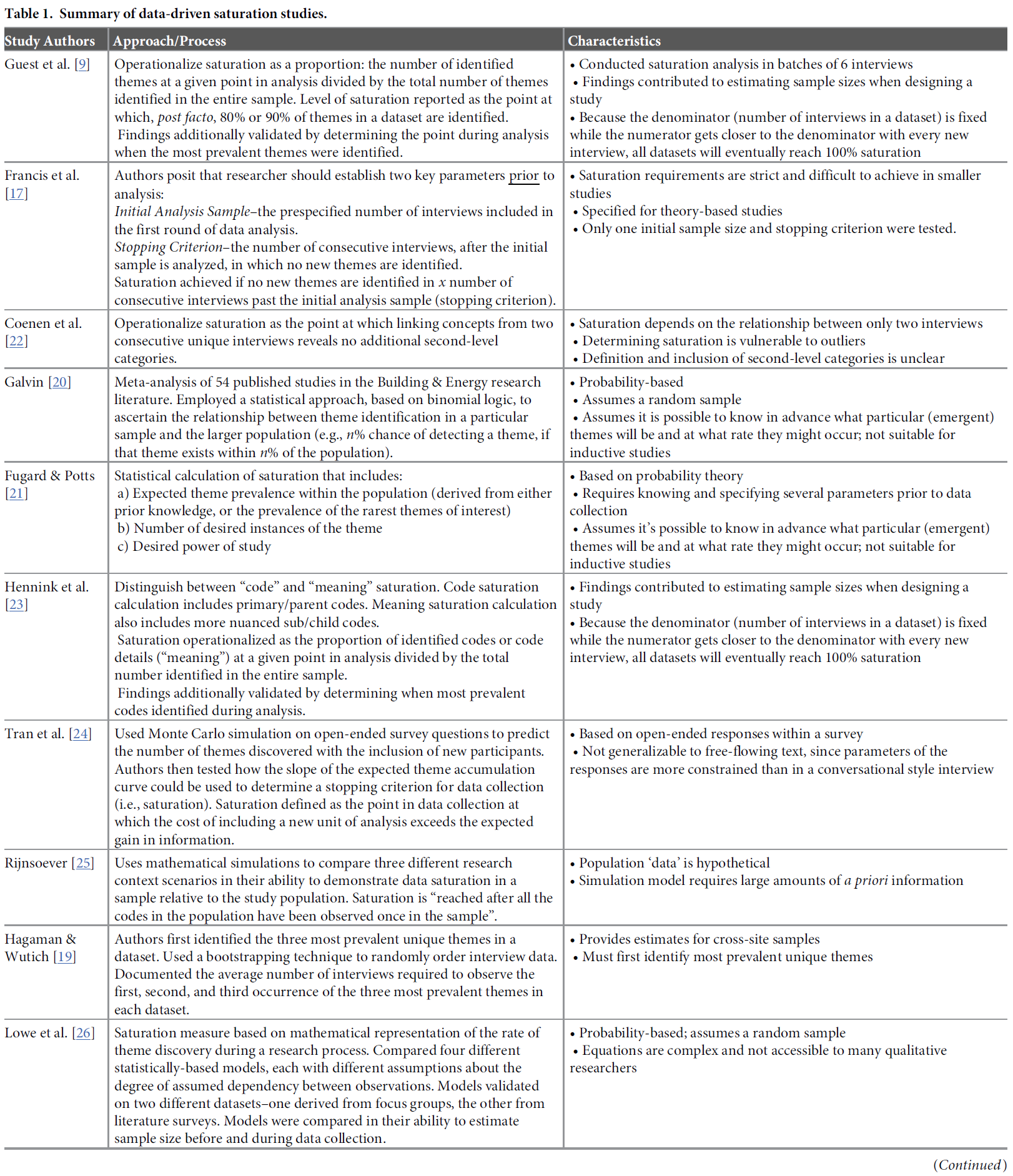

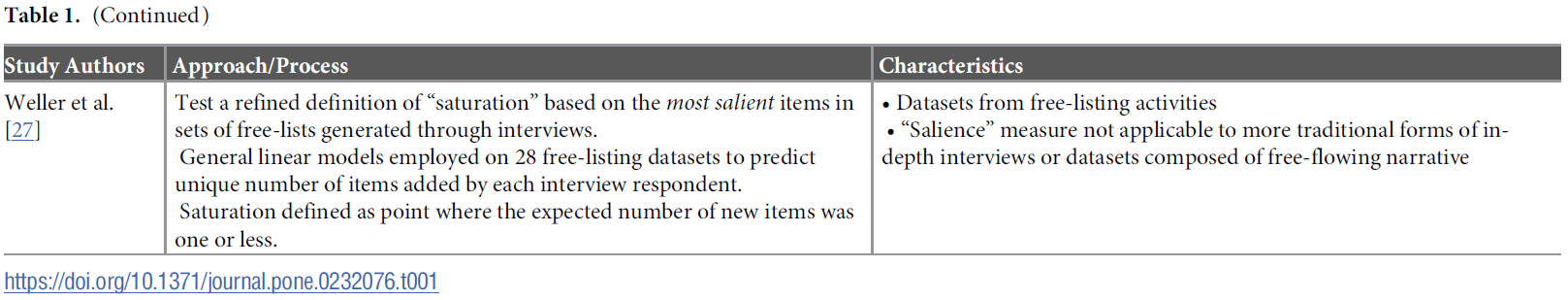

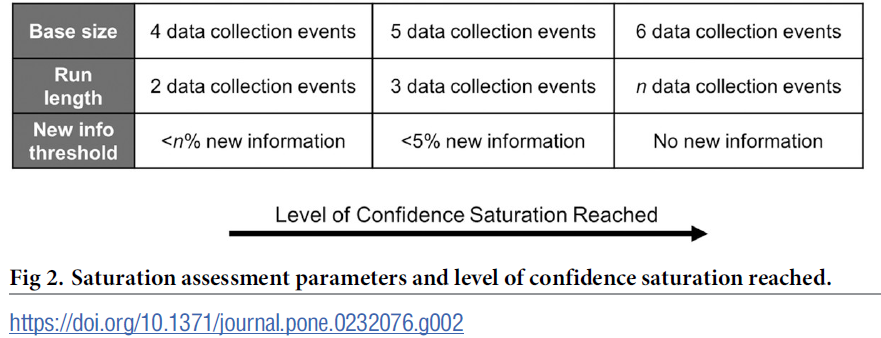

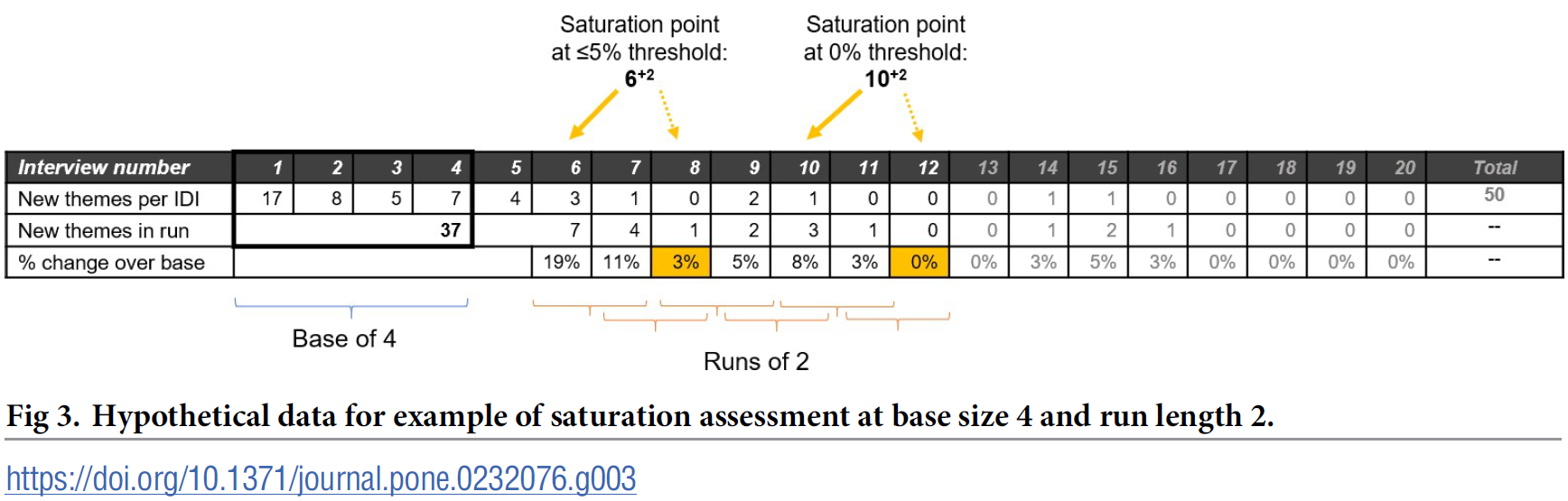

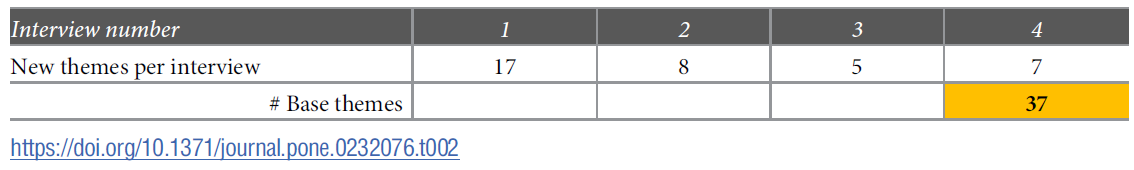

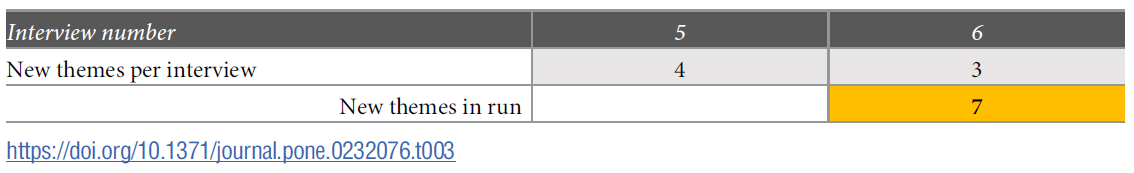

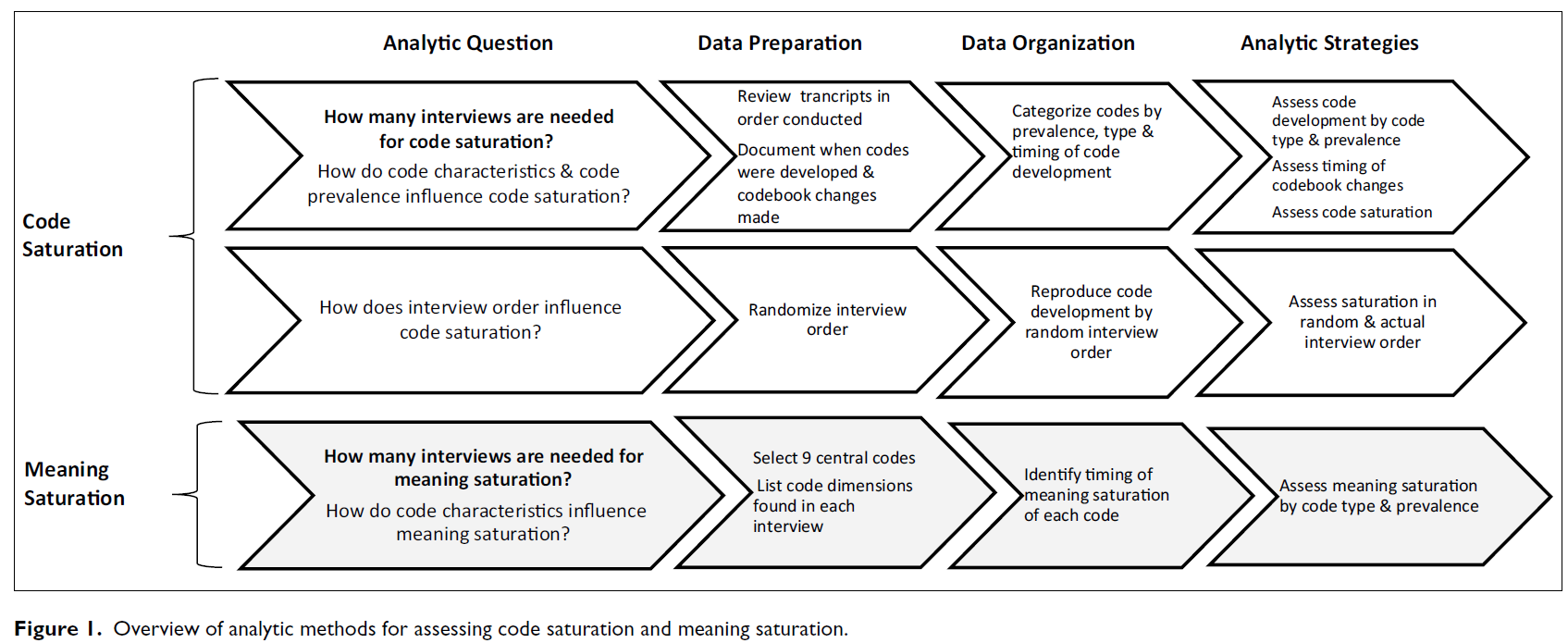

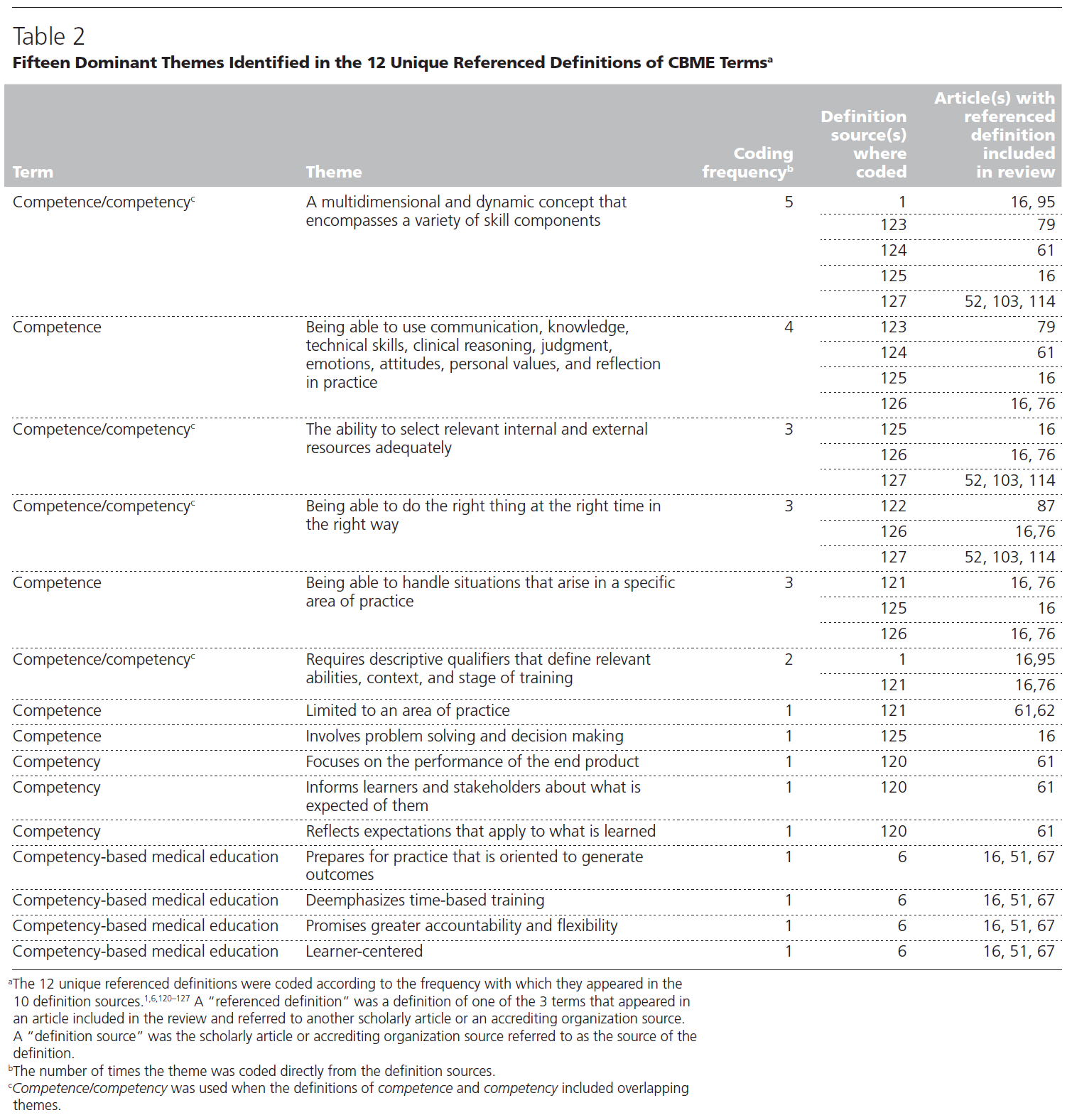

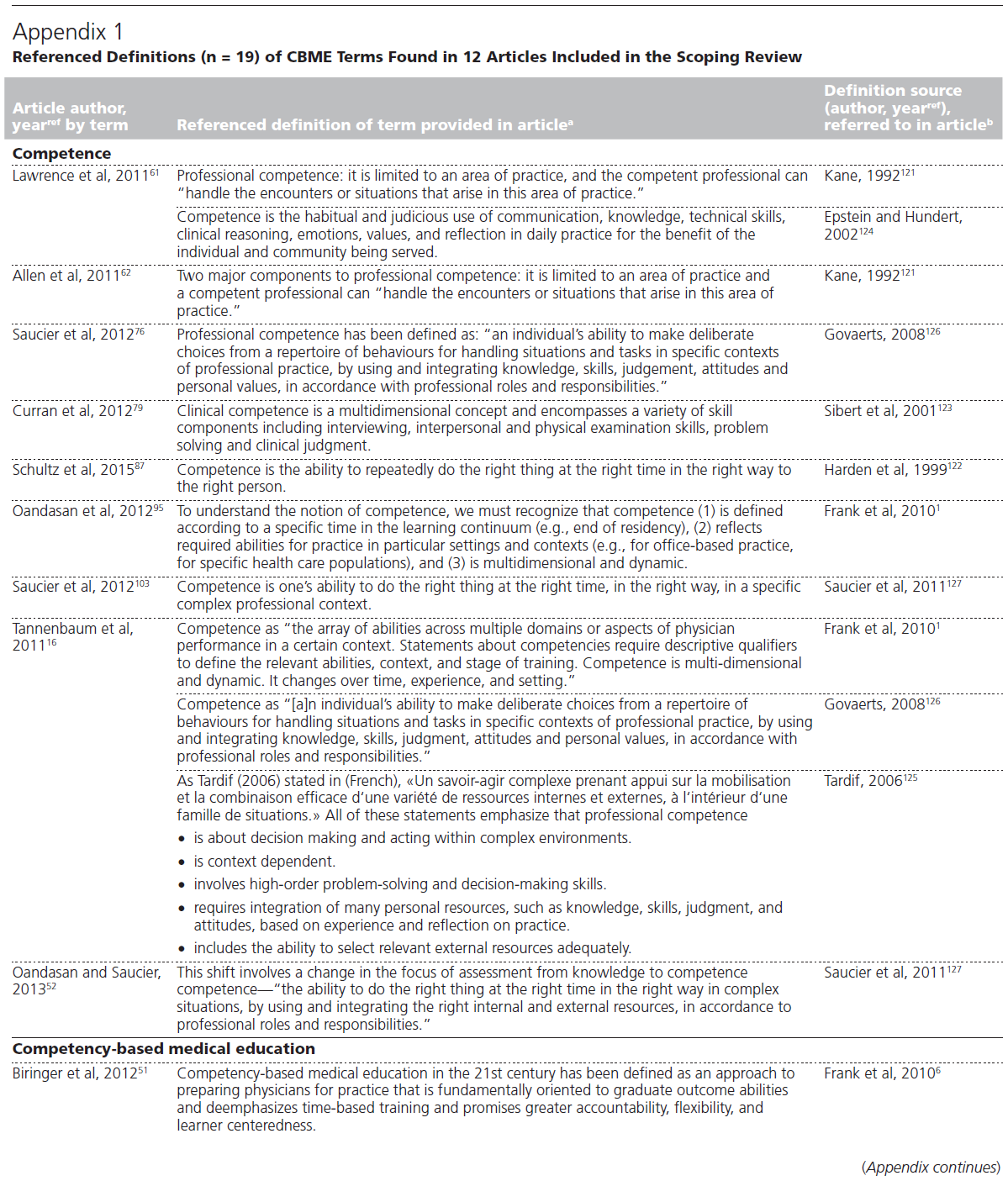

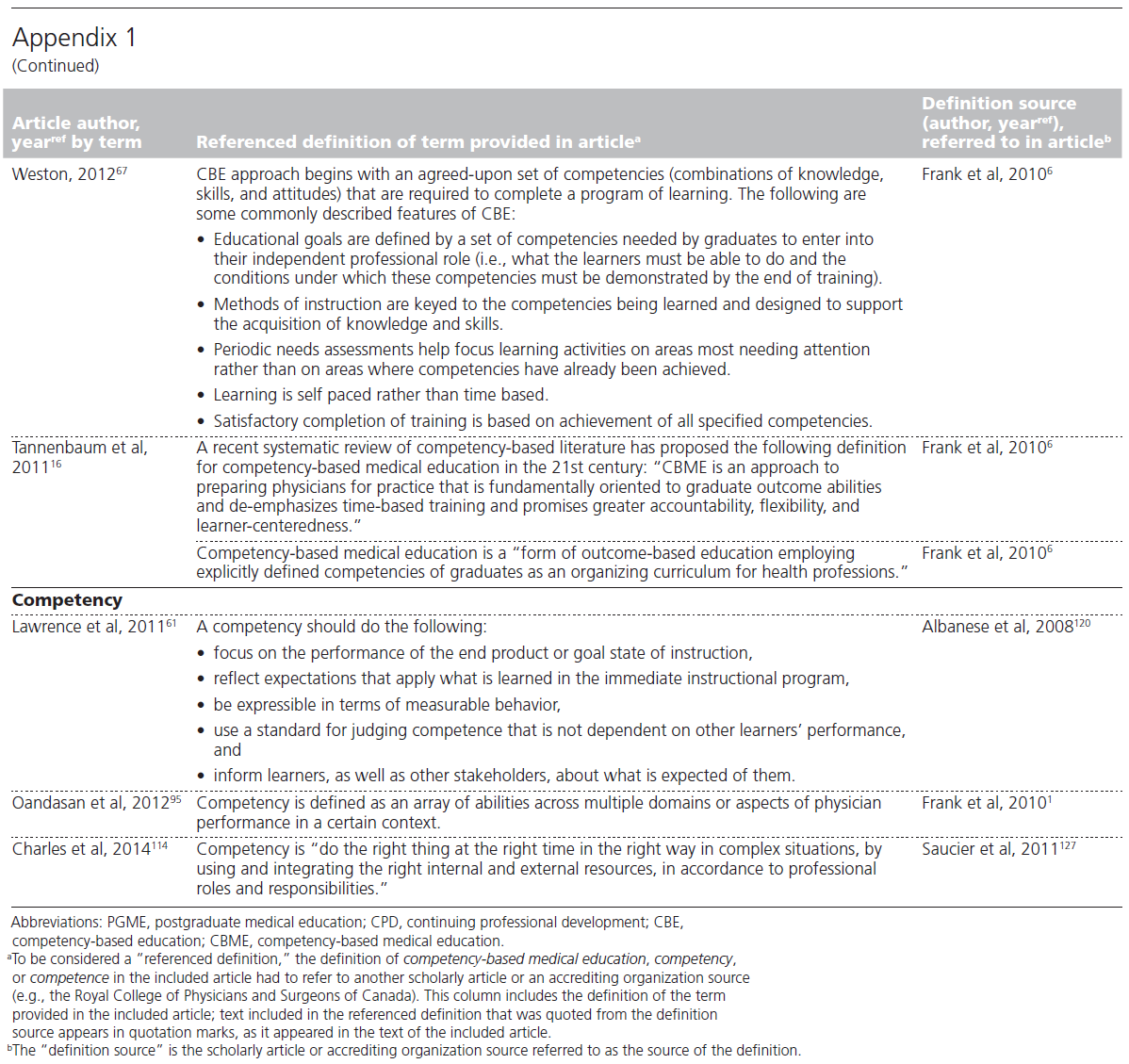

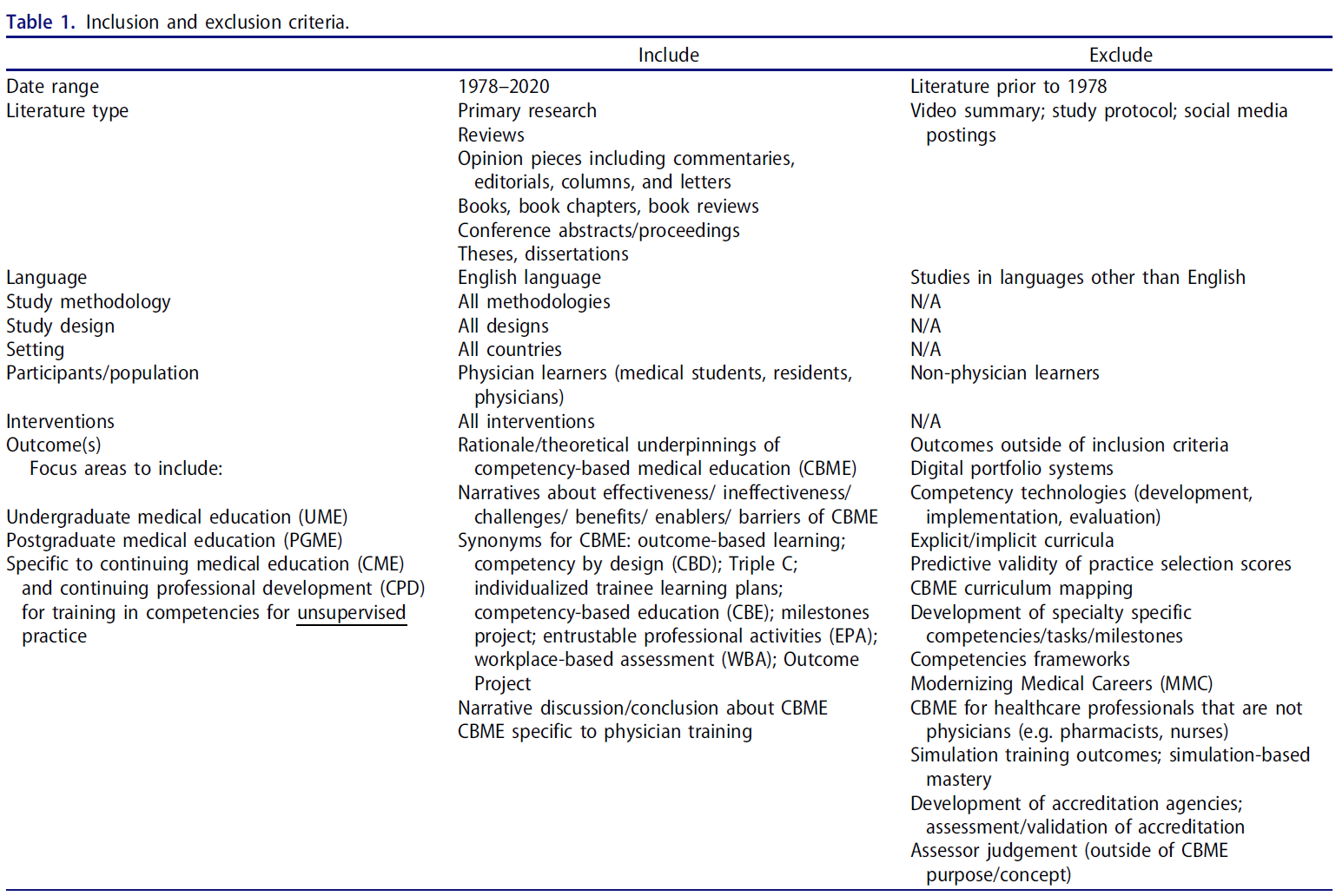

DA 보고에 대한 가이드라인과 기준이 필요합니다. 우리는 이 문제에 대해 오랫동안 논의한 끝에 일련의 지침과 검토 결과를 위한 출발점으로 PRISMA(체계적 문헌고찰 및 메타분석을 위한 우선 보고 항목) 프레임워크를 활용하기로 결정했습니다.59 PRISMA는 체계적 문헌고찰 보고를 안내하기 위해 개발되었고 DA와 SR 사이에는 많은 개념적, 절차적 차이가 있지만, 문헌 출처에서 자료를 식별, 선택, 추출, 분석 및 합성하는 것과 관련하여 명확성을 제공하는 원칙은 충분히 유사하여 그 사용을 보증하기에 충분했습니다. 말뭉치에서 일련의 기사를 평가하고 범주, 언어, 필수 및 선택적 요소를 해결하여 프레임워크의 초안을 작성하고 다시 작성했습니다. 수용 가능한 수준의 안정성(새로운 문제나 도전 과제가 발견되지 않음)과 기능성(검토 말뭉치의 샘플 기사에 쉽게 적용할 수 있음)을 달성한 후 검토 및 수정 프로세스를 종료했습니다.

Guidelines and standards for reporting DA are needed. We discussed this at length and decided to draw on the PRISMA (preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses) framework as a starting point for a set of guidelines as well as on the findings from our review.59 Although PRISMA was developed to guide reporting of systematic reviews and there are many conceptual and procedural differences between DA and SR, the principles of providing clarity with respect to identifying, selecting, extracting, analysing and synthesising material from documentary sources were sufficiently similar to warrant its use. We drafted and redrafted the framework based on evaluating a series of articles from the corpus, resolving categories, language and mandatory and optional elements. We ended the review and revision process once we had achieved acceptable levels of stability (no new issues or challenges were identified) and functionality (we found it easy to apply to sample articles from the review corpus).

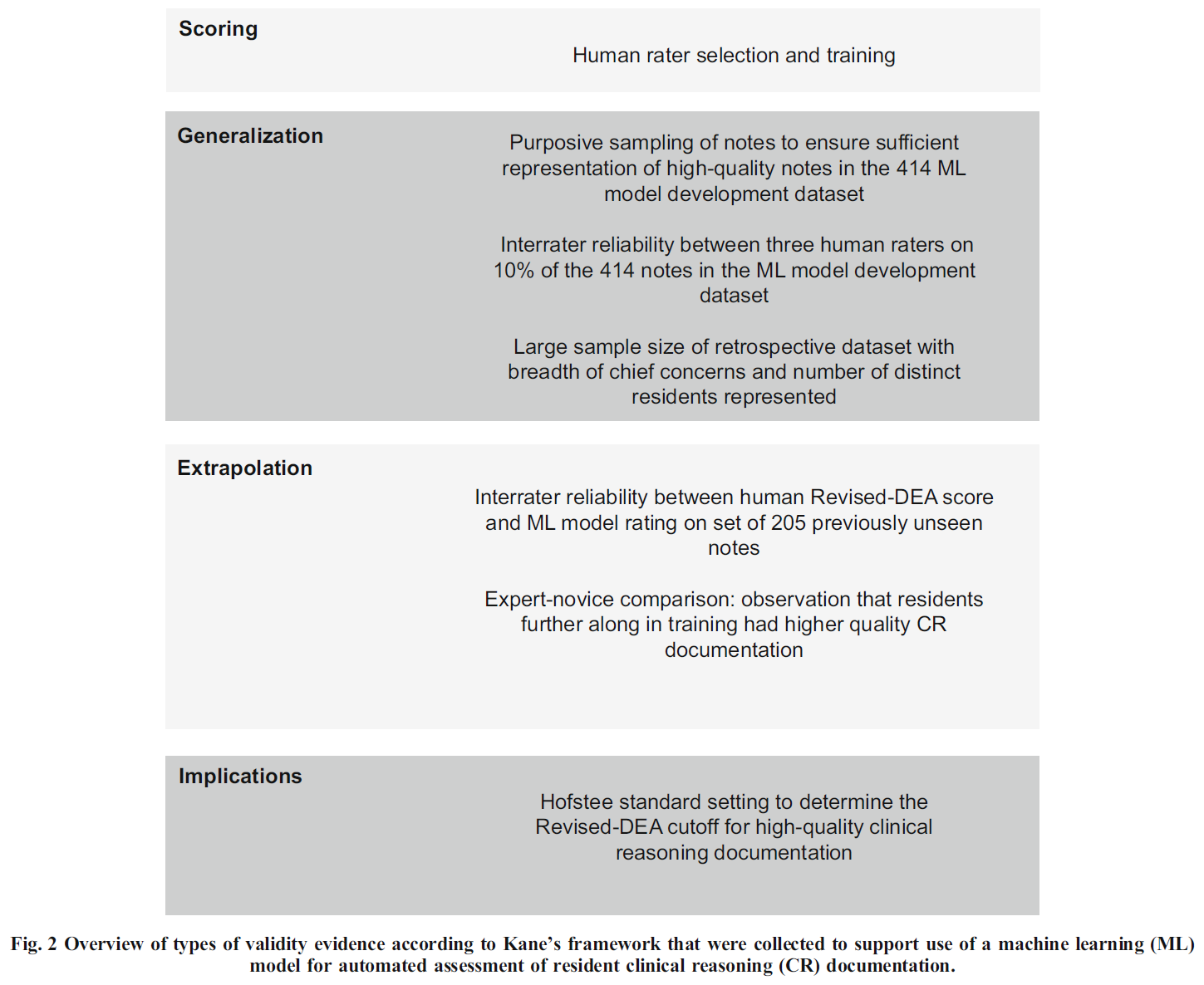

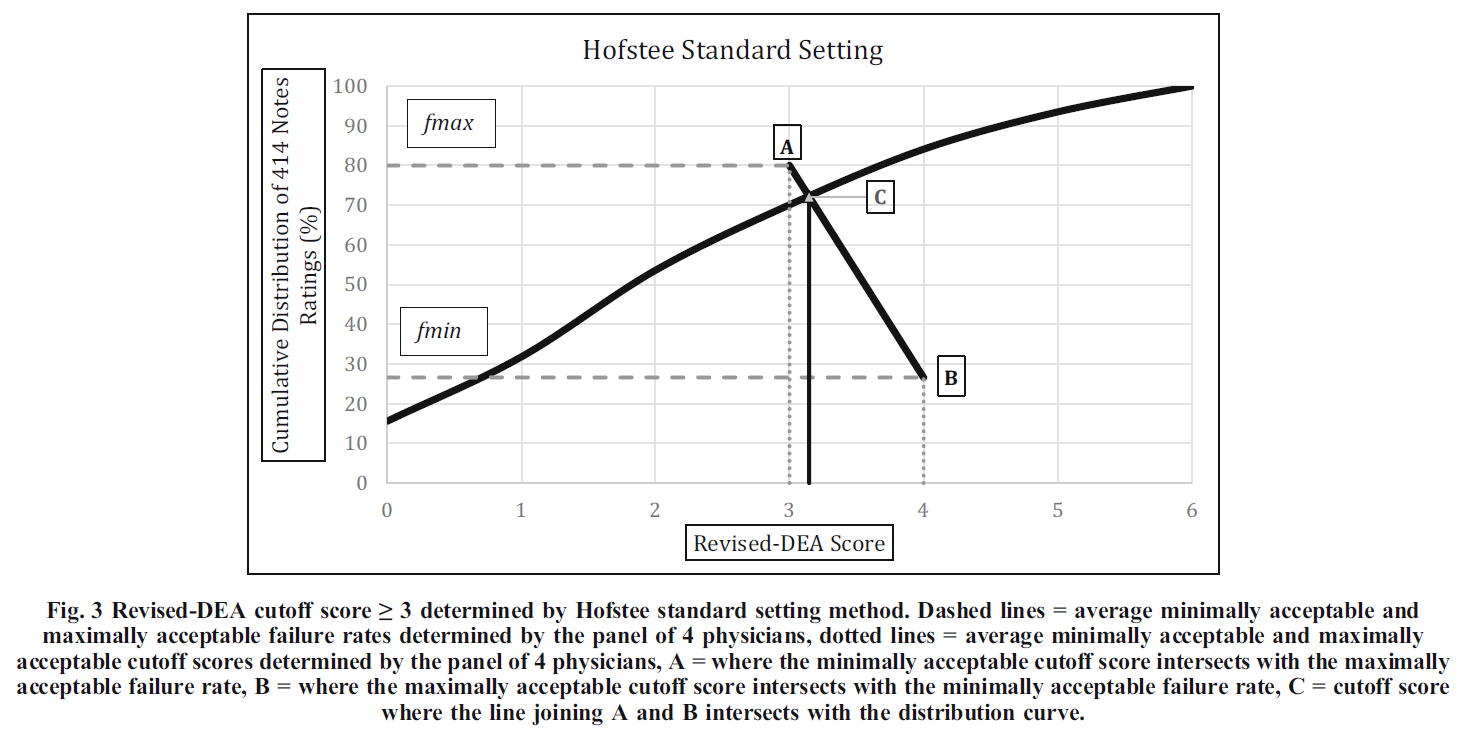

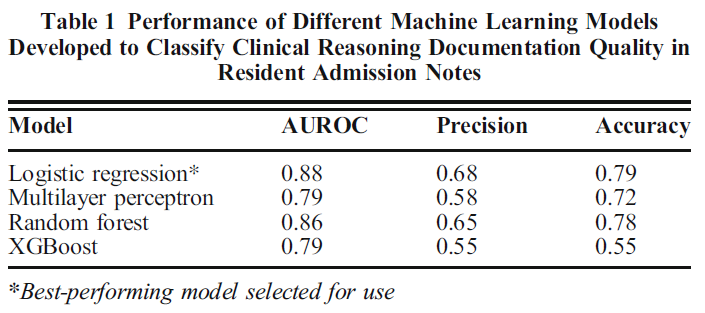

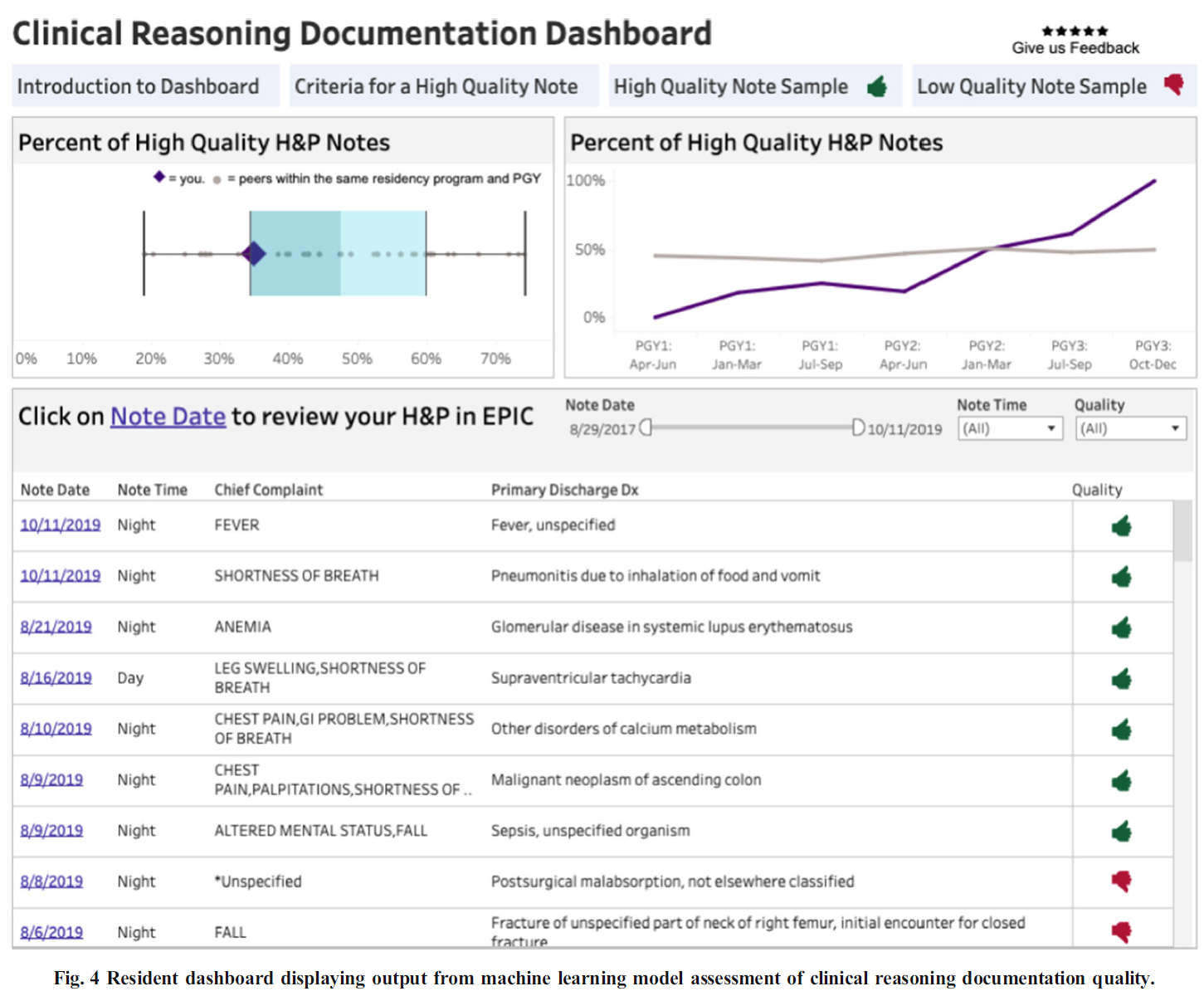

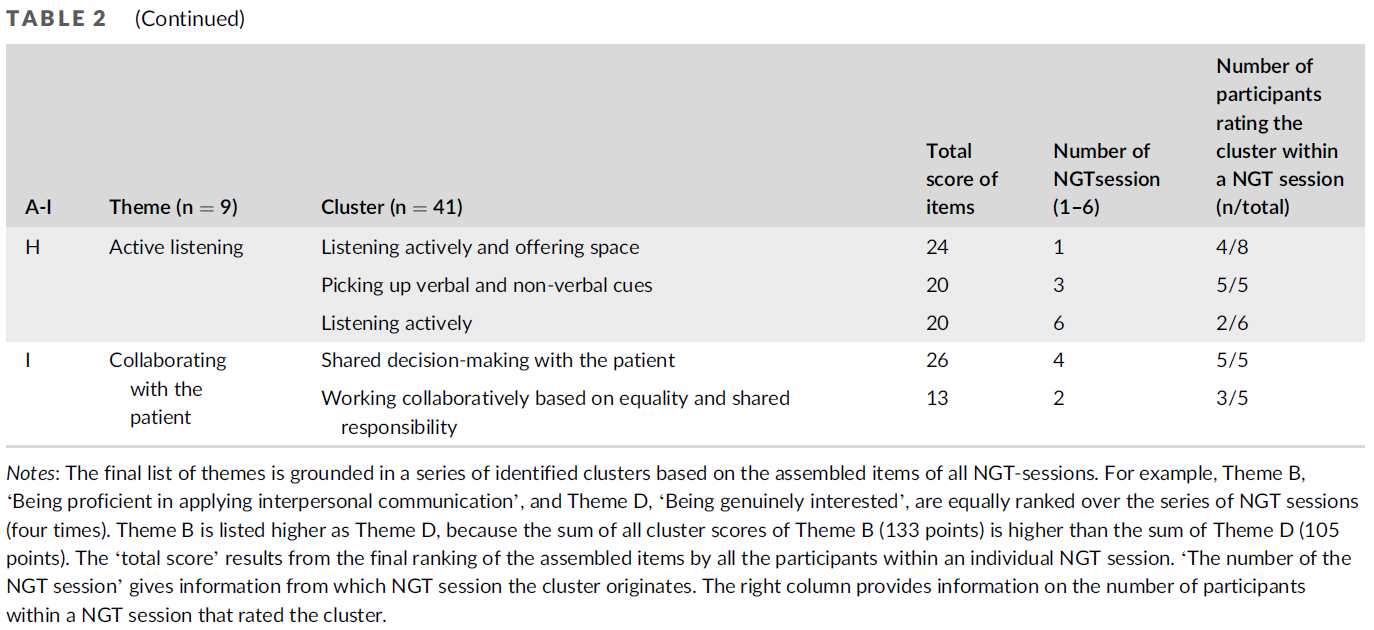

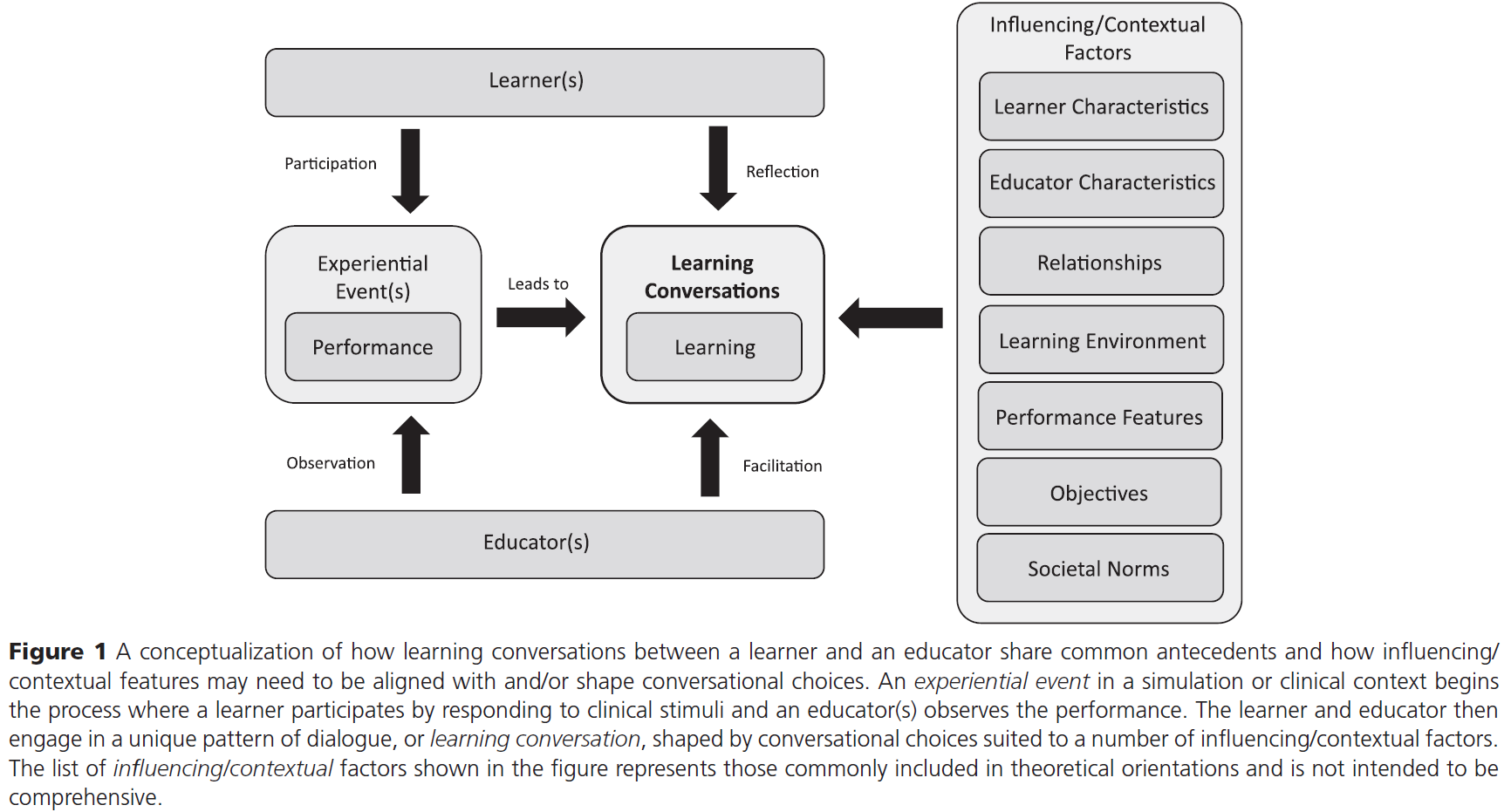

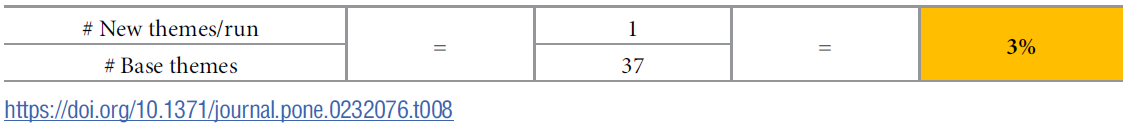

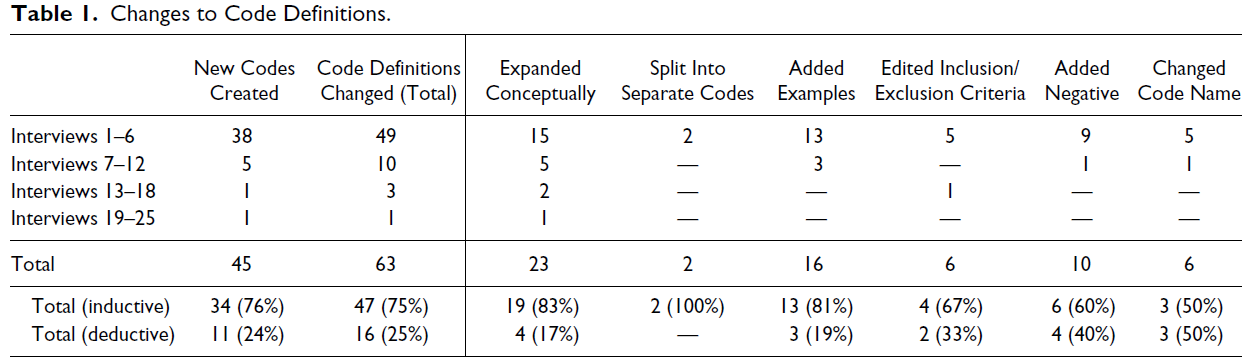

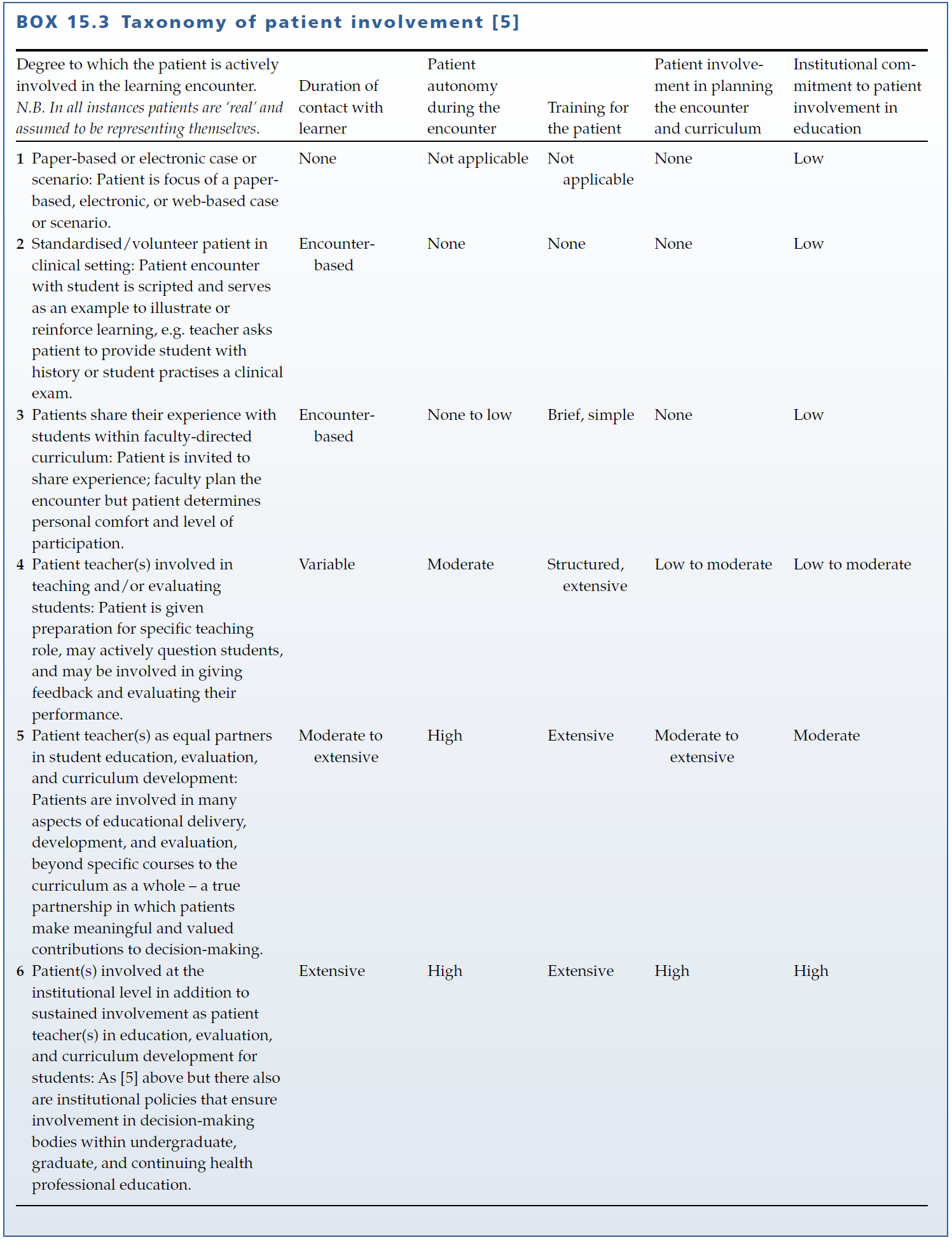

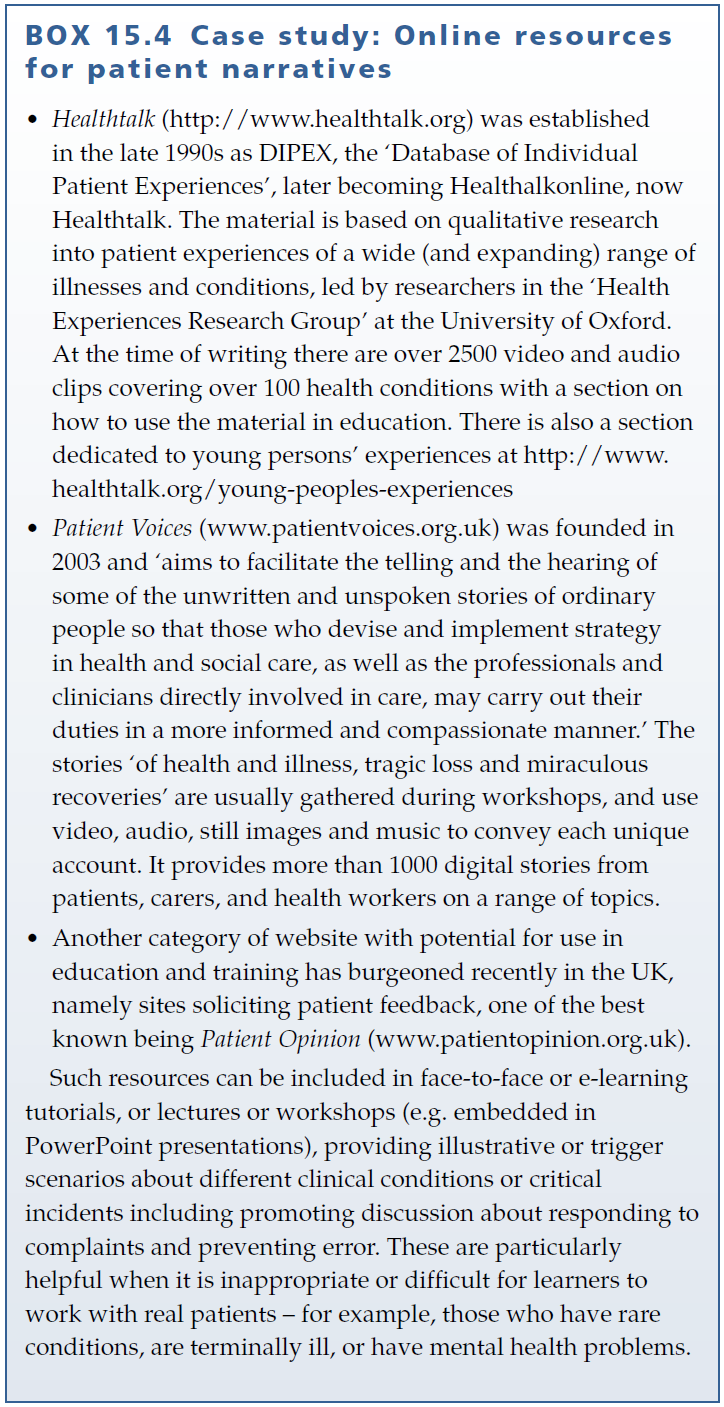

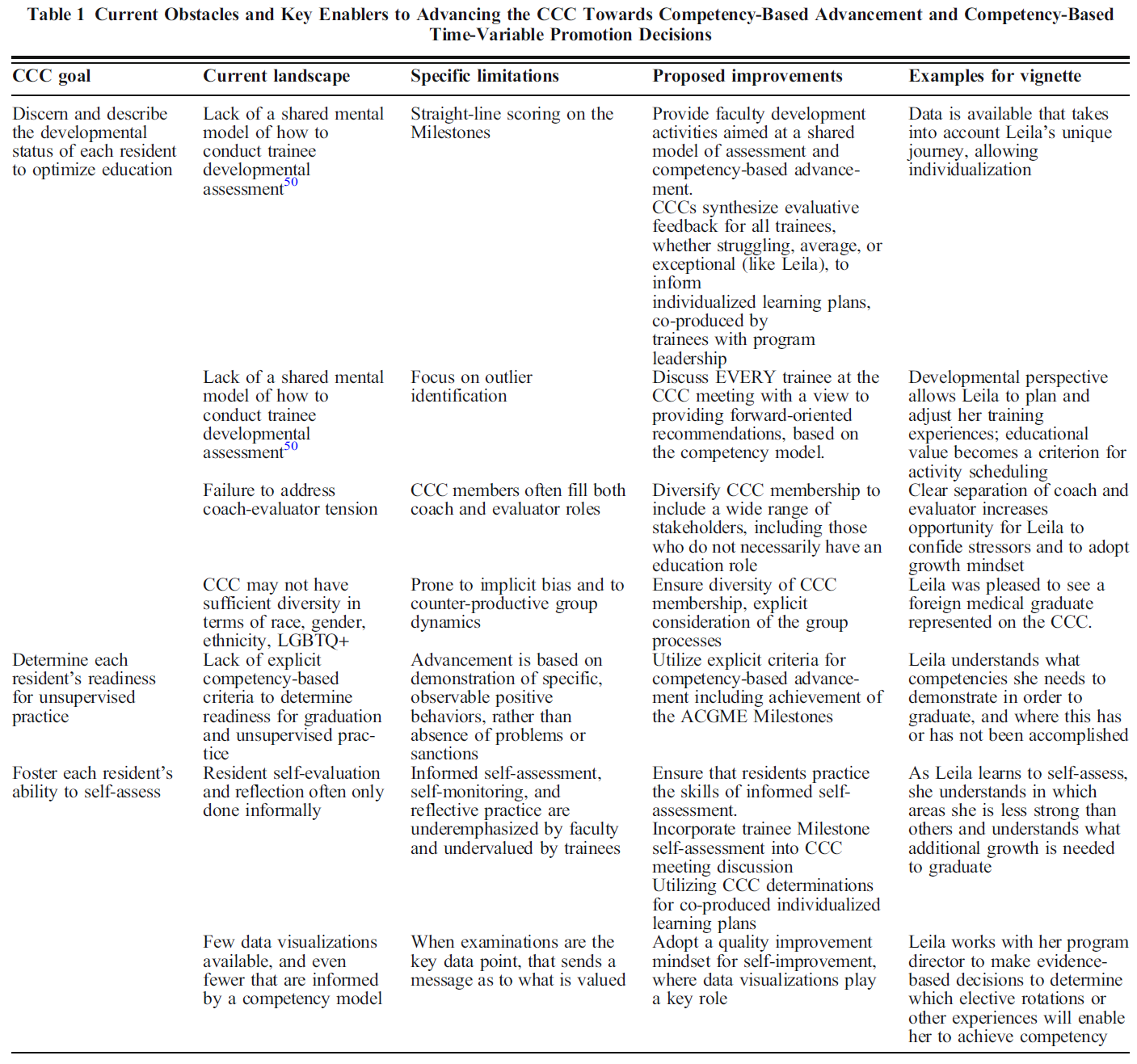

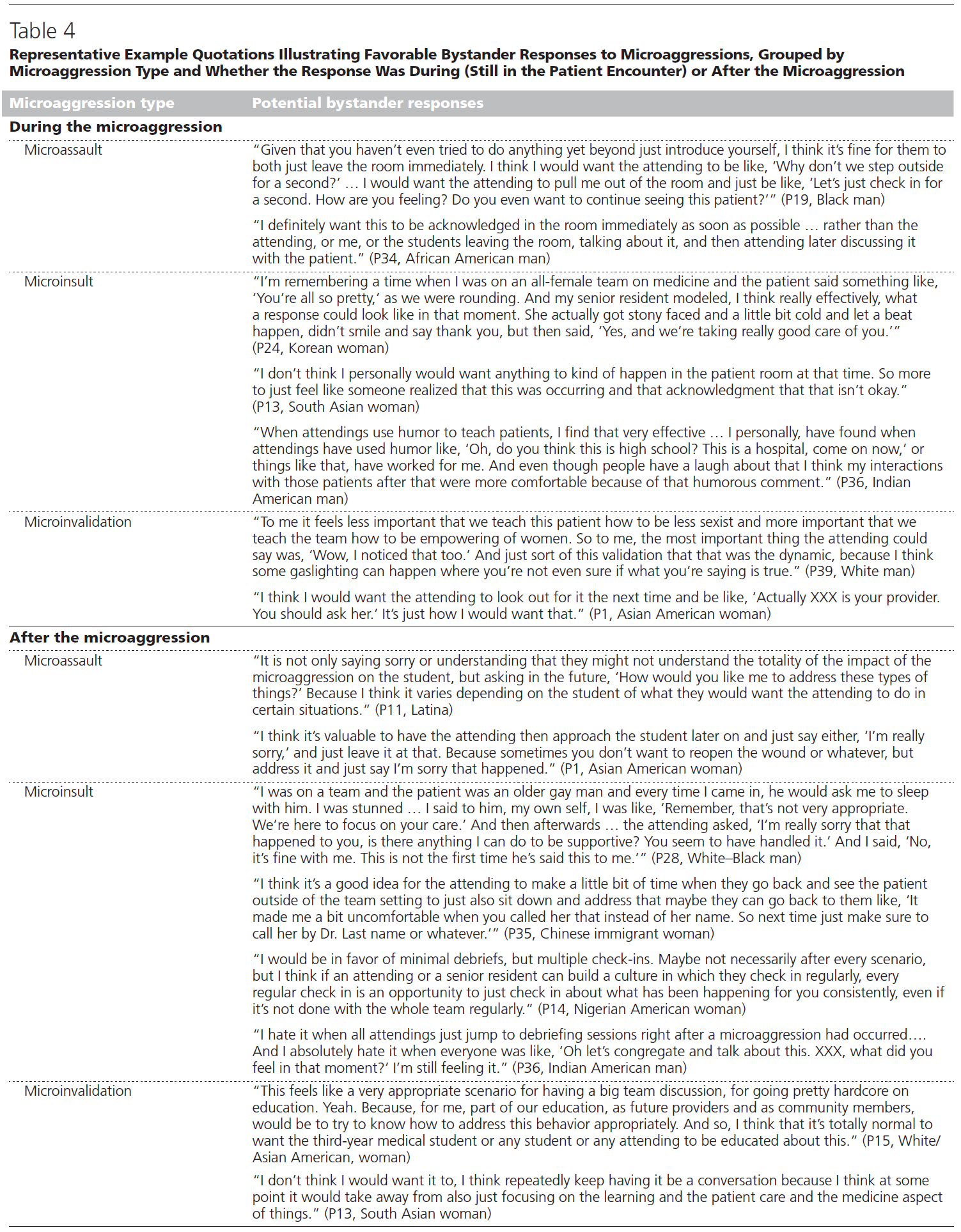

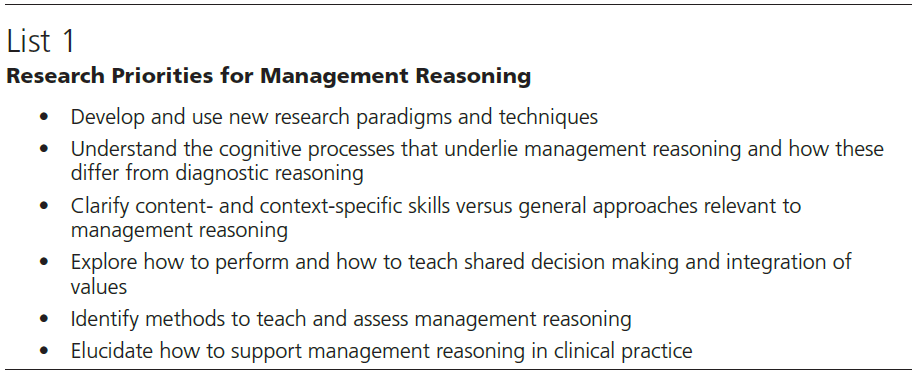

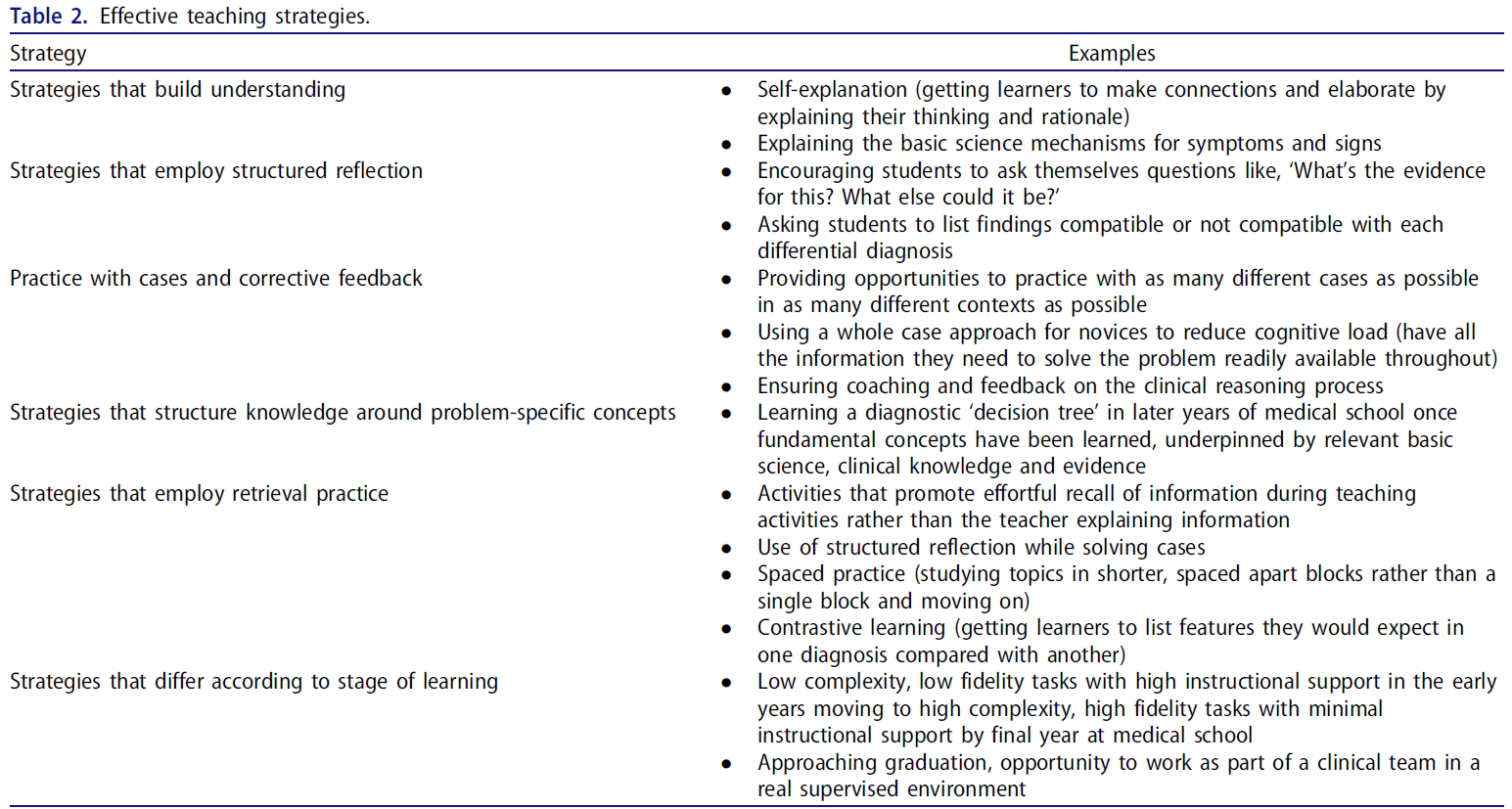

그 결과 도출된 프레임워크는 저자가 DA 보고를 안내하고 검토자가 DA 연구의 질을 평가할 수 있도록 체크리스트 형태로 표 1에 제시되어 있습니다. 이 체크리스트인 문서 분석 평가 및 보고 체크리스트(CARDA)(그림 60)는 엄격한 DA를 촉진하고 DA의 다양한 과정을 투명하고 완전하며 정확하게 보고하여 독자가 HPER 및 기타 주제 영역에서 문서 사용 및 분석 결과의 신뢰성을 평가하는 데 도움이 되도록 설계되었습니다.

The resulting framework is presented in Table 1, in the form of a checklist for authors to guide the reporting of DA and for reviewers to guide evaluations of the quality of DA studies. This checklist—the Checklist for Assessment and Reporting of Document Analysis (CARDA) (drawing on60) - is designed to facilitate rigorous DA and transparent, complete and accurate reporting of the various processes of DA, to help readers assess the trustworthiness of the findings from document use and analysis in HPER and other subject areas.

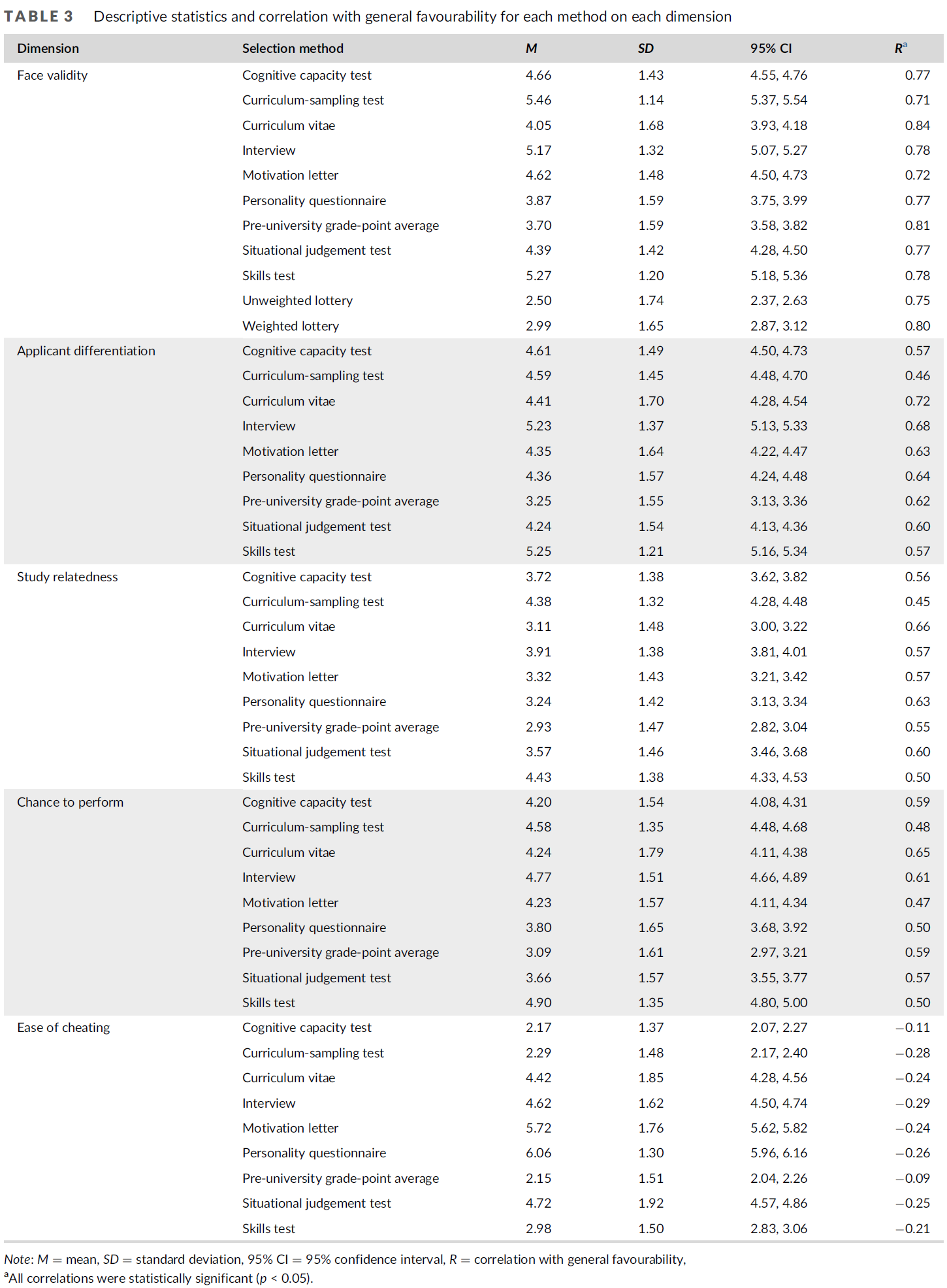

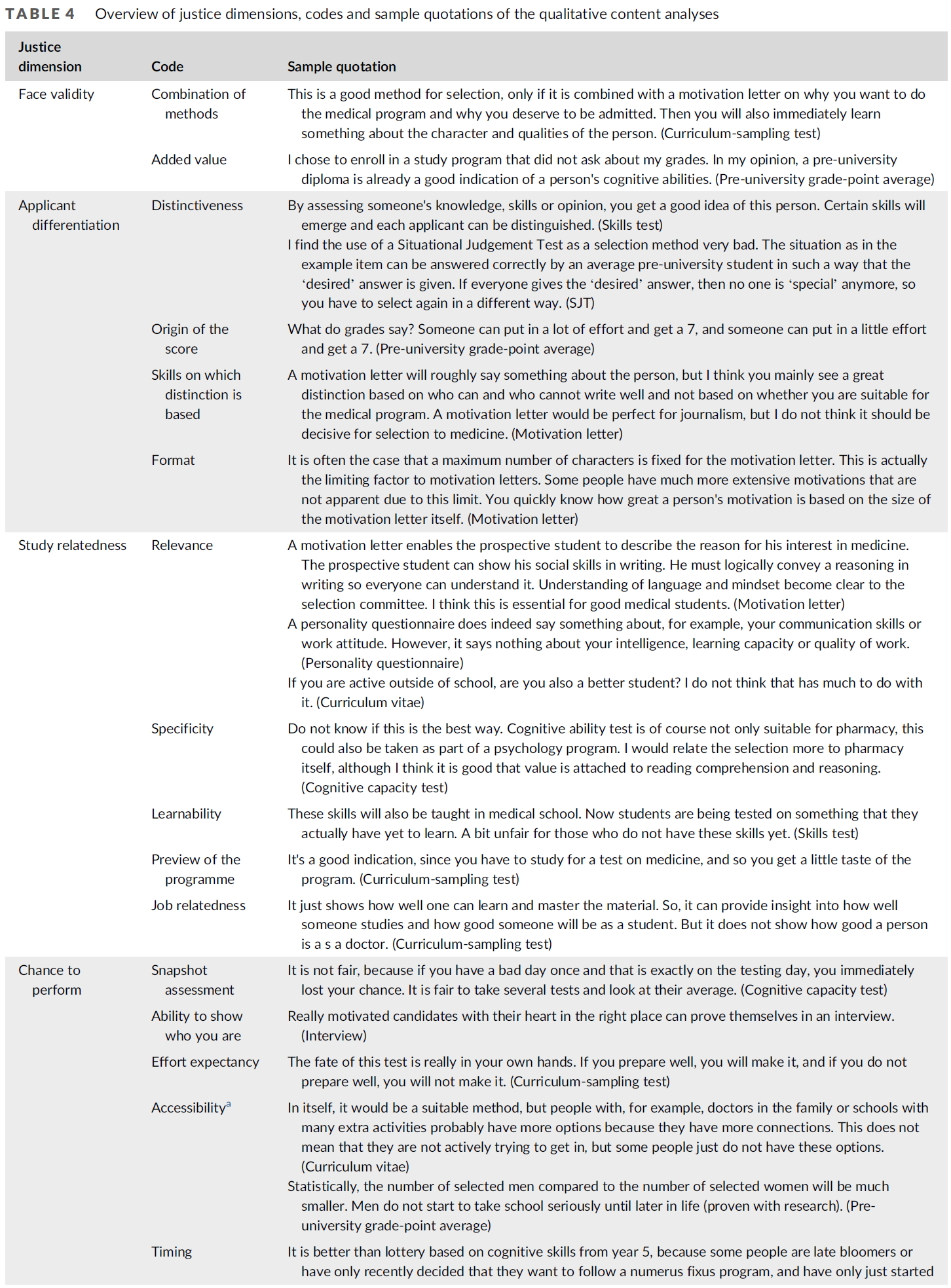

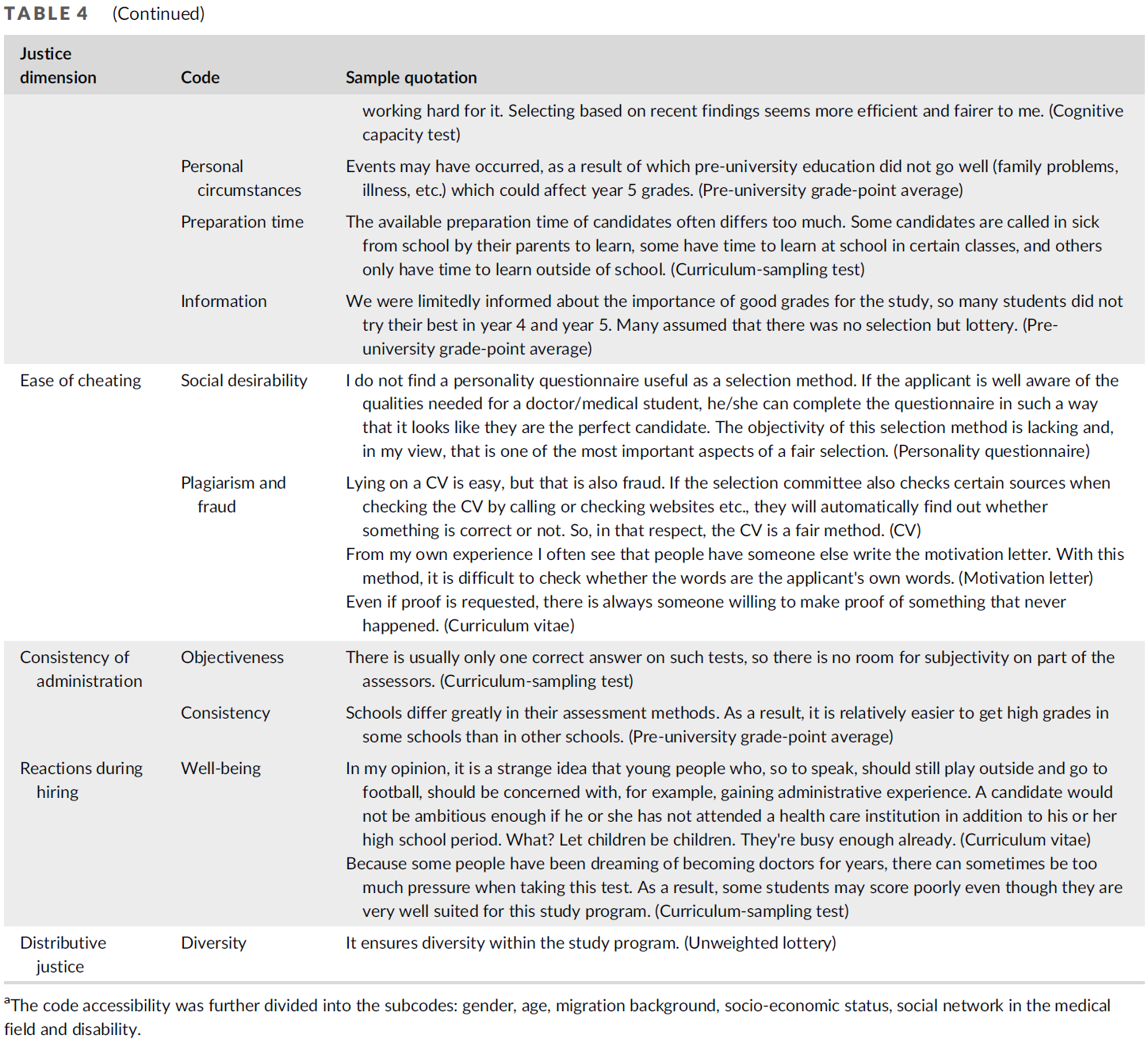

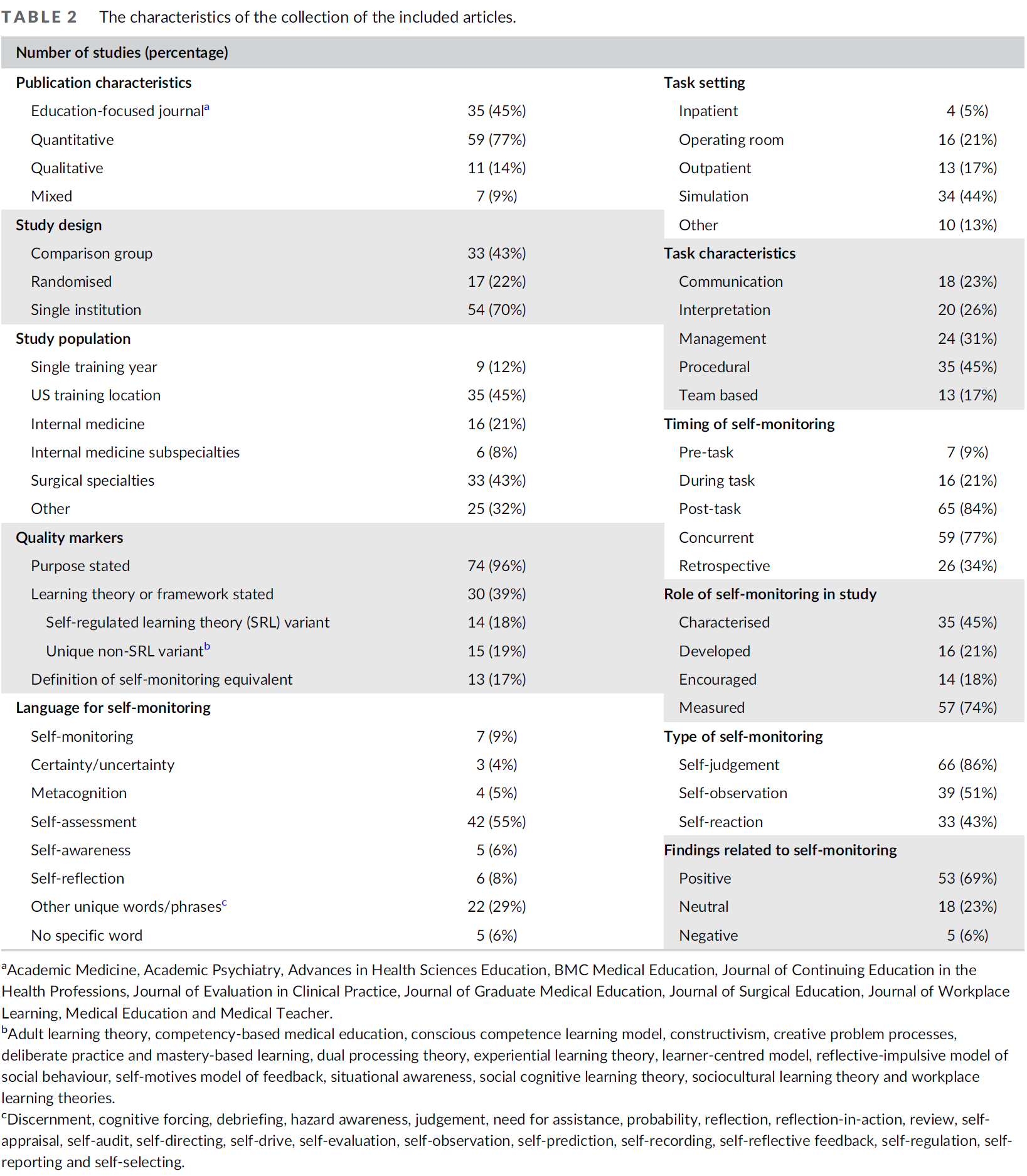

| Section and topic | Checklist item |

| Title | 문서 분석과 관련된 연구를 식별합니다. Identify the study involved in document analysis. |

| Abstract | 방법을 혼합(방법 나열) 또는 문서 분석 전용으로 식별합니다. Identify the methods as mixed (listing the methods) or solely document analysis. |

| Rationale | 연구에서 문서를 사용한 근거를 설명합니다. Describe the rationale for the use of documents in the study. |

| Objectives | 연구 목적 또는 연구 질문에 대한 명시적인 설명을 제공합니다. Provide an explicit statement of the research objective(s) or question(s) of the study. |

| Eligibility criteria | 이 특정 연구에서 데이터로 문서를 포함할 수 있는 자격 기준을 지정합니다. Specify the eligibility criteria for including documents as data in this specific study. |

| Document corpus | 말뭉치에 있는 문서의 성격을 지정합니다: - 얼마나 많은 문서가 있었는지. - 어떤 종류의 문서가 포함되었는지(예: 지역 커리큘럼 안내서, 국가 정책 문서). - 문서의 매체(인쇄물, 전자 문서 등). - 기존 문서가 사용된 문서의 원래 목적(예: 대상 고객, 누가, 언제, 왜 작성했는가?) 사용된 모든 문서에 대한 표 또는 이에 상응하는 문서(문서에 포함하거나 부록으로 포함)를 포함합니다. Specify the nature of the documents in the corpus:

|

| Document provenance | 해당 문서가 연구 전용 문서인지, 데이터 수집의 일환으로 작성된 문서(예: 현장 메모 및 일기 항목) 또는 기존(현존하는) 문서(예: 회의록, 안내서, 정책 또는 과거 문서)인지 명시합니다. State whether the documents were study-specific or elicited (created as part of data collection, e.g., field notes and diary entries) or existing (extant) documents (e.g., meeting minutes, prospectuses, policy or historical documents). 연구와 관련된 문서인 경우 구체적으로 명시합니다: - 문서가 어떻게 그리고 누구로부터 도출되었는지. - 연구자가 작성한 것인지 참여자가 작성한 것인지. 예를 들어, 일기나 반성적 글쓰기가 사용된 경우, 참여자 대상 그룹의 근거와 텍스트 작성과 관련하여 참여자에게 제공된 지침을 설명합니다. - 문서가 작성된 시기와 연구의 일부로 수집된 시기(예: 2020년 1월부터 2020년 12월 말까지)를 명시합니다. Where documents were study-specific, specify:

- 문서를 식별한 방법(예: 아카이브 또는 웹사이트 검색). - 적절한 경우, 사용된 필터 및 제한(예: 영어만, 특정 웹사이트만)을 포함하여 문서 식별을 위한 전체 검색 전략을 제시합니다. - 모든 검색의 데이터 제한과 이러한 데이터 제한의 근거를 제시합니다. Where existing documents were used, specify:

|

| Document collection and management | 문서 입수, 관리 방법 등 사용된 문서 중 공개적으로 사용 가능한 문서가 있는지, 어디서 찾을 수 있는지 보고합니다. How documents were obtained, managed etc. Report if any of the documents used are publicly available and where they can be found. |

| Document quality | 문서의 '품질'과 문서 품질과 연구 목표와의 관계를 고려합니다. 기존 문서의 경우: 문서가 완전한가? 문서에 공백이 있는가? 문서가 수정되었나요? 계획보다 더 많은 검색을 수행하거나 추가 문서에 의존해야 했습니까?11 일부 문서를 사용할 수 없거나 액세스할 수 없었는가? 도출된 문서의 경우: 참가자들이 의도한 대로 프로세스에 참여했습니까? 데이터가 포괄적이었습니까, 아니면 드물었습니까? 데이터를 도출하는 데 연구자의 노력이 얼마나 필요했으며, 연구자 개입(예: 잦은 알림)의 의미는 무엇인가요? Consider the “quality” of the documents and the relation of document quality to the study objectives. For existing documents:

|

| Reflexivity/positionality (may be placed in the methods or discussion section of your paper) | 연구자의 역할과 경험, DA 및 포지셔닝에 대한 경험. 문서(#8로 다시 연결되는 링크)와 연구자(들) 모두에서 포지셔닝의 잠재적 존재를 고려합니다. Role and experience of researchers, experience in DA and positionality. Consider the potential presence of positionalities, both in a document (links back to #8) and of the researcher(s). |

| Preliminary data analysis | 예비 또는 정리 데이터 분석에 대한 접근 방식, 문서에서 데이터를 수집하는 데 사용된 방법(예: 보웬의 "1차 문서 검토"[32페이지]11, 종종 주제별 또는 내용 분석의 변형 사용)을 명시합니다. 프로세스에 자동화 도구가 사용되었는지 명시합니다(예: AntConc 및 Wordsmith). Specify the approach to preliminary or organising data analysis, the methods used to collect data from the documents (e.g., Bowen's “first-pass document review” [p. 32]11; often using variations on thematic or content analyses). Specify if any automation tools were used in the process (e.g., AntConc and Wordsmith). |

| Document analysis | 어떤 방법론 또는 방법이 사용되었는지 분석 단계를 간략하게 설명하세요. 분석이 콘텐츠, 잠재적 콘텐츠, 언어학 또는 기타 문서 콘텐츠 또는 특성에 중점을 두었는지 설명하세요. 분석가가 분석 대상 문서의 콘텐츠, 스타일, 하위 텍스트 및 기타 차원에 어느 정도, 어떤 방식으로 몰입하거나 조율했나요? 이전 가능성을 보장하기 위해 이론적 렌즈를 사용했나요? 결과를 도출하기 위해 어떤 방식으로 결과를 종합했나요? Outline the analytical steps taken—what methodology or methods were involved? Explain whether the analysis focused on content, latent content, linguistics or some other document content or characteristics. To what extent and in what ways did analysts immerse or attune themselves to the content, style, subtexts and other dimensions of the documents they analysed? Was a theoretical lens used to ensure transferability? How were findings synthesised to arrive at findings? |

| Results directly relate to research questions or goals | 일반: 제시된 내용이 논리적 순서로 정리되어 있고 연구 질문과 일치하는지 확인합니다. General: ensure what is presented is set out in a logical order and aligns with the research question. |

| Findings directly relate to DA | 문맥, 삼각측량, 주요 데이터 소스 또는 연구 접근 방식의 대상 등 문서 데이터가 결과/결과의 근거가 된 방법을 명확히 설명합니다.31 따옴표를 사용하는 경우, 출판물을 참조할 때와 마찬가지로 문서에 대한 링크(예: 문서 이름 및 페이지 번호)를 제공합니다. Clarify how the document data informed the results/findings—including whether contextual, triangulation or as the primary data source or the object of the research approach.31 If using quotes, link back to the document as you would when referencing a publication (e.g., document name and page number). |

| Findings are balanced | 사용된 DA의 형태와 말뭉치의 성격에 따라 결과와 균형이 맞아야 합니다. MMR에서 DA 구성 요소는 연구 전체 내에서 가중치에 따라 결과에 표시되어야 합니다. Results and balanced and proportional to the form of DA used and the nature of the corpus In MMR, DA component should be represented in results according to its weighting within the study as a whole |

| Consequences for DA methods | 문서 분석이 연구에 무엇을 추가했는지 명확하게 설명해야 합니다. 연구가 DA에 무엇을 추가했나요? DA 사용의 강점과 한계를 고려합니다. Be clear about what the document analysis added to the study. What did the study add to DA? Consider the strengths and limitations of the use of DA. |

| DA in context | 다른 DA 연구의 맥락에서 결과에 대한 일반적인 해석을 제공하세요. Provide a general interpretation of the results in the context of other DA studies. |

| Overall | 제공된 세부 정보가 연구를 재현하기에 충분한가? 1. 연구를 재현할 수 있는가? 2. 연구의 모든 단계를 평가하는가? Are the details provided sufficient to

|

체크리스트의 유용성을 개선하기 위해 파일럿 테스트를 진행했지만, 추가 테스트의 여지가 있다는 점을 잘 알고 있습니다. 분명한 다음 단계는 질적 HPE 학자 및 저널 편집자와 함께 델파이 프로세스를 통해 내용을 계속 평가하고 개선하는 것입니다. 또한 DA에 종사하는 분들을 초대하여 DA 또는 혼합 방법 연구에서 CARDA의 실제 사용을 테스트해 보시기 바랍니다. 또한 다른 방법론 보고를 위한 지침과 체크리스트가 시간이 지남에 따라 발전해 온 것과 마찬가지로, 이러한 피드백이 체크리스트를 더욱 발전시키는 데 사용될 수 있다는 관점에서 학자들이 어떻게 사용했는지에 대한 토론에 참여하도록 초대합니다.

Although we pilot-tested the checklist to refine its usability, we appreciate that there is room for further testing. An obvious next step would be to continue to assess its content and refine it, perhaps via a Delphi process with qualitative HPE scholars and journal editors. We also invite those engaging in DA to test CARDA's use in practice in DA or mixed methods research. Moreover, we invite scholars to engage in discussion about how they used it, with the view that this feedback can be used to develop the checklist further—in the same way that guidelines and checklists for reporting other methodologies have evolved over time.

DA를 사용하면 어떤 지식의 격차를 해소할 수 있을까요?

What gaps in our knowledge could be addressed using DA?

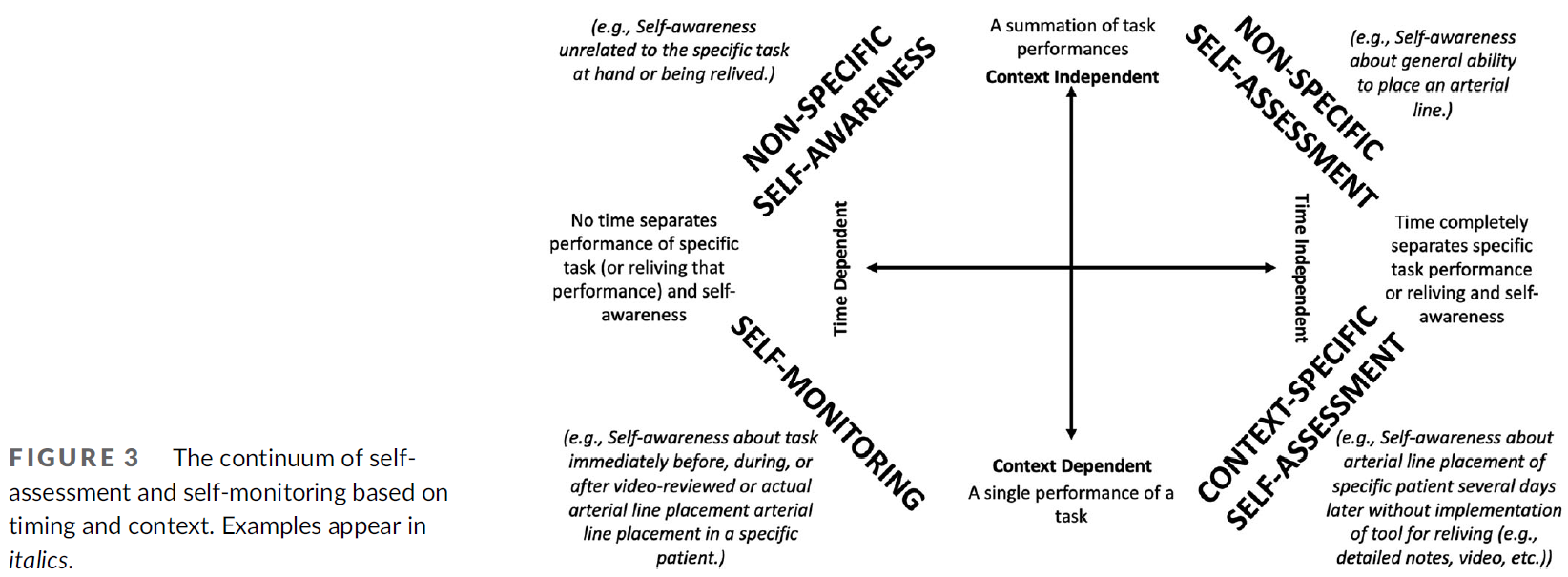

마지막 연구 질문은 DA를 통해 해결할 수 있는 지식의 격차를 파악하는 것과 관련이 있습니다. 물리적이든 물질적이든, 문서를 수동적인 정보 보유자 이상으로 개념화하면 HPER에서 데이터로서 문서가 가진 엄청난 잠재력을 활용할 수 있습니다. 예를 들어, 다양한 유형, 크기, 형태를 가진 문서는 여러 사회적 세계에 존재하고 이러한 세계 간의 커뮤니케이션을 연결하고 중재하여 여러 세계 간에 지식과 관점의 교환을 촉진하는 경계 개체 역할을 할 수 있습니다(예: 62). 즉, 주어진 텍스트가 어떻게 사용 및/또는 해석될지는 예측할 수 없습니다. 따라서 동일한 경계 개체라도 그것이 서식하는 세계에 따라 다르게 해석될 수 있습니다.

- 예를 들어, 일련의 인증 표준은 규정 준수를 입증해야 하는 사람들을 위한 거버넌스를 구성합니다.

- 커뮤니케이션 표준과 올바른 모양과 느낌을 준수하기 위해 인증 표준을 브랜딩하는 일을 맡은 사람들에게 이 문서는 일련의 업무 관련 작업을 수행하는 원동력이 됩니다.

- 수십 년 후 의료 기록 보관소에서 동일한 표준을 확인하는 사람들에게 이 문서는 한 시대의 우선순위를 나타내는 역사적 지표 역할을 합니다.

문서의 여러 복잡성을 파악하면 다양한 사회적, 물질적 행위자들이 원하는 프로젝트를 달성하기 위해 어떻게 협력하는지, 또는 서로 어떻게 충돌할 수 있는지 등 HPER의 지속적인 과제를 해결할 수 있는 새로운 관점을 발견할 수 있습니다. 예를 들어, 한 세기 전 플렉스너 개혁에 대한 슈레브의63 역사적 DA는 북미 의학교육의 발전에 있어 이 중요한 사건과 이전에는 연관되지 않았던 조작과 이념적 포지셔닝의 층위를 확인했습니다.

Our final research question related to identifying the gaps in our knowledge that could be addressed through DA. Whether physical or material, when we conceptualise a document as more than a passive holder of information, we can begin to leverage the tremendous potential of documents as data in HPER. For example, documents, of various types, sizes, and forms, can serve as boundary objects61 as they exist in multiple social worlds and serve to connect and mediate communication between those worlds, facilitating the exchange of knowledge and perspectives across them (e.g.,62). In other words, the ways in which a given text will be used and/or interpreted cannot be predicted. The same boundary object can therefore be interpreted differently, depending on the world it inhabits.

- A set of accreditation standards, for example, constitutes governance for those who must demonstrate compliance.

- For those tasked with branding the accreditation standards to comply with communications standards and the right look and feel, the document serves as an impetus to engage in a set of work-related tasks.

- For those who identify with the same set of standards decades later in a medical archive, the document serves as a historical indicator of the priorities of an era.

Attuning to the multiple complexities of documents can allow us to uncover new angles to address ongoing challenges of HPER, including how the various social and material actors involved cooperate to accomplish a desired project or how they may be in conflict with each other. For example, Schrewe's63 historical DA of the Flexner reforms of a century ago identified layers of manipulation and ideological positioning that have not previously been associated with this critical event in the development of medical education in North America.

이는 자연스럽게 디지털 문서에 대한 고려로 이어집니다. 의과대학 웹페이지를 분석한 몇몇 논문을 제외하고는 검토한 논문에서 디지털 문서에 대한 언급이 눈에 띄지 않는데, 디지털 문서가 제공하는 기회 때문에 많은 사람들이 디지털 문서를 다큐멘터리 연구의 미래로 칭송해 왔습니다. 그러나 디지털 문서는 '해석 과정에서 종종 보이지 않지만 중요한 역할을 하는 물질성을 지닌 고도로 매개된 대상'(1743쪽)입니다.64 디지털 문서가 인쇄 문서와 다르다는 점을 인식하면 '형태의 후과'(96쪽)에 대해 질문할 수 있습니다. 65 매체가 중요하다면 문서를 다루는 사람들은 '디지털 텍스트의 존재론적 지위... 디지털 텍스트가 제공하는 특정한 분석적 어포던스를 논의하는 미래의 작업의 근거가 될 것'(78쪽)을 고려해야 합니다.66 문서의 물성과 그 물성이 가능하게 하는 실천 사이의 관계에 대한 추가 고려는 디지털 인문학 분야에서 찾을 수 있습니다(예: Berry와 Fagerjord67 참조).

This leads naturally to the consideration of digital documents. Conspicuously absent in the articles reviewed—other than a few articles that analysed medical school webpages—digital documents have been extolled by many as the future of documentary research because of the opportunities they offer. However, digital documents ‘are highly mediated objects with a materiality that plays a significant, if often unseen contributory role in the interpretative process’ (p. 1743).64 Recognising that digital documents are different from print documents allows us to ask about the ‘consequences of form’ (p. 96).65 If the medium is important, those working with documents need to consider ‘the ontological status of digital text … that will ground future work discussing the specific analytical affordances offered by digital texts’ (p. 78).66 Further consideration of the relationships between the materiality of documents and the practices enabled by the materiality can be found in the field of digital humanities (see, for instance, Berry and Fagerjord67).

마지막으로, '역사가들은 필연적으로 현재에 배치된 설명을 통해 과거의 행동을 이해하려고 시도한다'(71쪽).68 HPE에 있는 수많은 문서와 문서는 과거 사건을 이해하는 주요 도구이지만, 보건 전문직 교육의 역사를 다룬 논문이 현저히 부족하다는 점에 주목했습니다. 단 9건(8% 미만)의 기사만이 일부 역사적 분석 요소를 포함하고 있었으며, 대부분 프로그램에 대한 단순한 설명에 그쳤습니다. 의학의 역사를 다룬 문헌은 중요하지만(실제로 의학의 역사에 초점을 맞춘 오랜 전통의 학술지[예: 의학 및 연합 과학사 및 의학사 저널]가 여러 개 있습니다), 보건 전문직 교육 분야의 역사적 뿌리와 시간의 흐름에 따른 발전에 주목하는 연구는 거의 없다는 점은 주목할 만합니다. 이 분야는 충분히 연구할 가치가 있는 분야입니다.

Finally, ‘historians attempt to understand past action through descriptions that are, by necessity, laid out in the present’ (p.71).68 The plethora of documents in HPE and documents are our primary tool for understanding past events, but we noted a significant absence of articles that dealt with the history of health professions education. Only nine articles (<8%) involved some element of historical analysis, and for the most part, these were simple descriptions of programs. While the literature addressing the history of medicine is significant (indeed there are several long-established journals focusing specifically on the history of medicine [e.g., Journal of the History of Medicine and Allied Sciences and Medical History], it is noteworthy that so little work in the field of health professions education attends to its historical roots and development over time. This is an area ripe for investigation.

이전 연구와의 비교

Comparison with previous research

연구 목적으로 문서의 장점을 강조한 것은 저희가 처음이 아닙니다. 또한 이를 위한 지침을 제공한 최초의 연구도 아닙니다(예: O'Leary4 및 Bowen11). 그러나 우리가 아는 한, 특정 분야 내에서 방법론적 프레임으로서 DA의 상태를 평가한 것은 이번이 처음입니다. 메타 리뷰 접근법을 사용하여 우리는 DA가 HPER에서 개념화, 제정 및 보고되는 방식에서 주요 문제를 식별할 수 있었습니다. 엄격성과 명확성이 부족한 이유 중 하나는 기존의 DA 지침이 유용하기는 하지만 '방법'에 대한 세부 사항을 충분히 제공하지 않았기 때문이라고 잠정적으로 판단했습니다. 이와 대조적으로, 본 검토의 면밀한 조사, 해석 및 비판을 통해 이전 지침(예: 오리어리4)을 기반으로 HPER 분야 및 잠재적으로 더 광범위하게 적용되는 DA의 방법론적 및 분석적 엄격성에 대한 증거에 기반한 기준을 설명할 수 있었습니다.

We are not the first to extol the virtues of documents for research purposes. Nor are we the first to offer guidance for doing so (e.g., O'Leary4 and Bowen11). However, to the best of our knowledge, this is the first evaluation of the state of DA as a methodological frame within a particular field. Using a meta-review approach, we were able to identify major issues in how DA has been conceptualised, enacted and reported in HPER. We tentatively suggest that part of the reason for the lack of rigour and clarity is that existing DA guidance, while useful, has not provided sufficient ‘how to’ detail. In contrast, the level of scrutiny, interpretation and critique in our review allowed us to build on previous guidance (e.g., O'Leary4), to delineate evidence-informed standards of methodological and analytical rigour for DA that apply to the field of HPER and potentially more broadly.

강점과 한계

Strengths and limitations

이 연구에 접근하는 우리의 입장이 이 연구의 과정과 보고에 영향을 미칠 수밖에 없었지만, 우리는 연구 방법과 결과, 그리고 연구에서 도출한 권고안을 개발하는 데 있어 투명성을 유지하기 위해 주의를 기울였습니다. 최근 Greenhalgh 등이 권고한 바와 같이,69 우리는 체계적 문헌고찰과 서술적 문헌고찰 방법을 상호보완적으로 사용했습니다. 특히, 검색 과정에 사서를 참여시켜 데이터베이스 선택과 적격 연구를 검색하기 위한 검색 전략 개발을 지원했습니다(예: 70). 검색, 선택, 관리 및 분석에 신중하고 엄격한 접근 방식을 사용했으며 검토 방법에 대한 감사 추적을 제공했습니다.71 '문서'와 '분석'은 연구 논문에서 일반적으로 사용되는 단어입니다. 최종 데이터 세트를 얻기 위해 포함 기준에 따라 식별된 논문을 면밀히 조사해야 했으며, 다른 사람들이 동의하지 않는 내용을 유지하거나 거부하는 결정을 내렸을 수도 있습니다. 그런 다음 이론적 이해를 증진하고 새로운 질문을 식별하기 위해 식별된 연구를 비판적으로 해석하여 DA가 어떻게 사용되었는지에 대한 통찰력을 수집하는 데 집중했습니다.72 이 후자의 과정은 검토된 논문에서 종종 제공되는 데이터가 부족하기 때문에 현실과 진실에 대한 우리 자신의 이해와 '문서 경험'(1118페이지)73에 상당 부분 의존했습니다.

Although our positionality in approaching this work will have inevitably shaped the process and reporting of this study, we were careful to be transparent in our methods and findings and in the development of the recommendations we made from the study. As recently recommended by Greenhalgh et al.,69 we used systematic and narrative review methods in a complementary manner. Specifically, we involved a librarian in the search process, to help with the selection of databases and the development of a search strategy to retrieve eligible studies (e.g.,70). We used a deliberate and rigorous approach for searching, selection, management and analysis and provided an audit trail of our review methods.71 ‘Document’ and ‘analysis’ are commonly used words in research articles. Close scrutiny of identified articles against the inclusion criteria was required to obtain the final dataset, and we may have made some decisions as to what to keep and what to reject with which others would disagree. We then focused on critically interpreting the identified studies to gather insight into how DA has been used, for the purpose of advancing theoretical understanding and identifying new questions.72 This latter process depended to a great extent on our own understandings of reality and truth and ‘document experience’ (p. 1118)73 given the paucity of data often provided in the reviewed articles.

우리는 HPER의 DA에 초점을 맞추었지만, DA 실무자에 대한 비평과 지침의 일환으로 광범위한 이론 및 절차 문헌을 활용했습니다. 이 과정에서 HPER에서 확인한 많은 강점과 약점이 다른 많은 분야에서도 발견된다는 점에 주목했습니다(예: Coffey56 참조). 우리는 DA에 대한 접근 방식에서 모범적인 분야나 학문을 발견하지 못했으며, 오히려 서로에게서 배울 점이 많은 것으로 보입니다.

Although our focus was on DA in HPER, we engaged broader theoretical and procedural literatures as part of our critique of and guidance to DA practitioners. In doing so, we noted that many of the strengths and weaknesses we identified in HPER are also to be found in many other disciplines (for instance, see Coffey56). We found no one field or discipline that was exemplary in their approaches to DA; rather, it would seem that there is much to be learned from each other.

5 결론

5 CONCLUSION

DA는 그 자체로 연구 도구로서, 그리고 HPER에서 혼합 방법 연구의 일부로서 많은 잠재력을 가지고 있습니다. 그러나 DA가 그 잠재력을 발휘하기 위해서는 엄격성과 보고 측면에서 개선되어야 합니다. 우리는 이를 위한 지침을 제공하고 해당 분야의 학자들이 DA를 어떻게 사용하는지에 대한 토론에 참여하도록 초대하며, 궁극적으로는 우리 분야에서 의미를 이해하고 구성하는 데 문서를 더 많이, 더 잘 사용하도록 보장하는 것을 목표로 합니다.

DA has much potential as a research tool in its own right and as part of mixed methods research in HPER. However, for it to fulfil its potential, DA must improve in terms of rigour and reporting. We offer guidance for doing so and invite scholars in the field to engage in discussions about how they use DA, with the ultimate aim of ensuring more and better use of documents for understanding and constructing meaning in our field.

CARDA: Guiding document analyses in health professions education research

PMID: 36308050

DOI: 10.1111/medu.14964

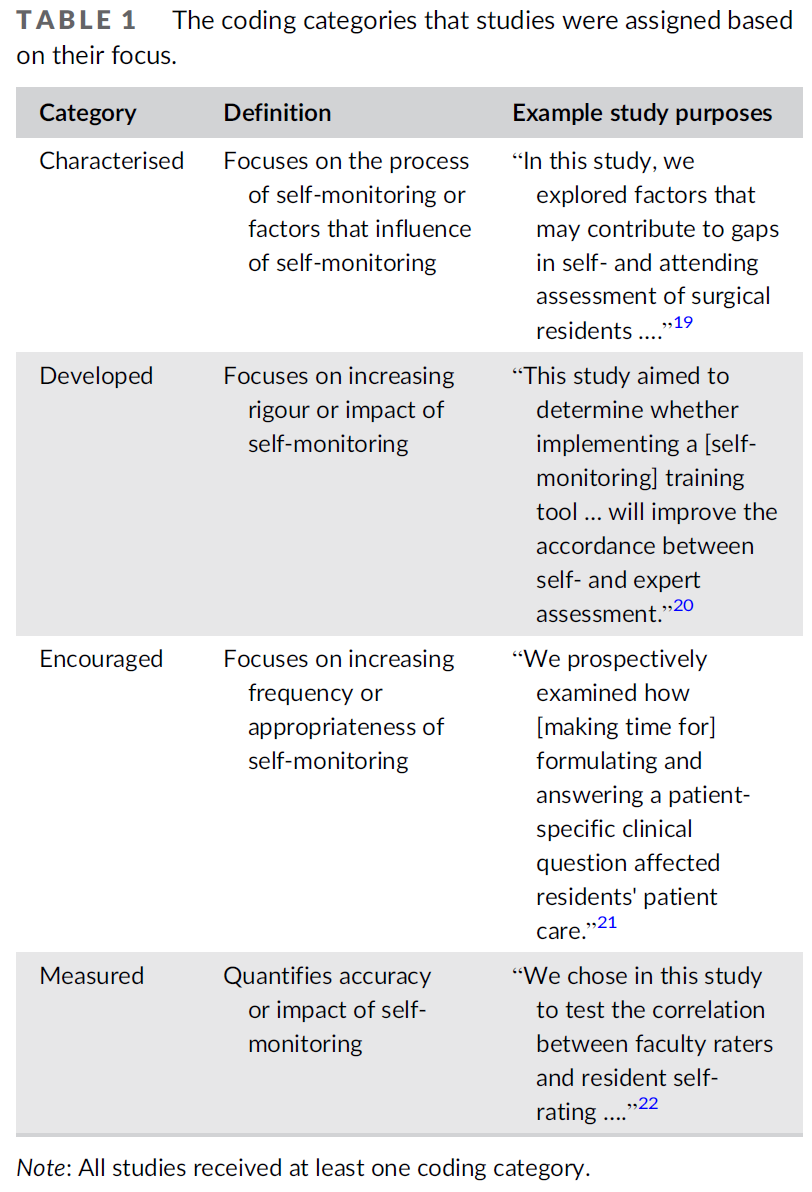

Abstract

Introduction: Documents, from policies and procedures to curriculum maps and examination papers, structure the everyday experiences of health professions education (HPE), and as such can provide a wealth of empirical information. Document analysis (DA) is an umbrella term for a range of systematic research procedures that use documents as data.

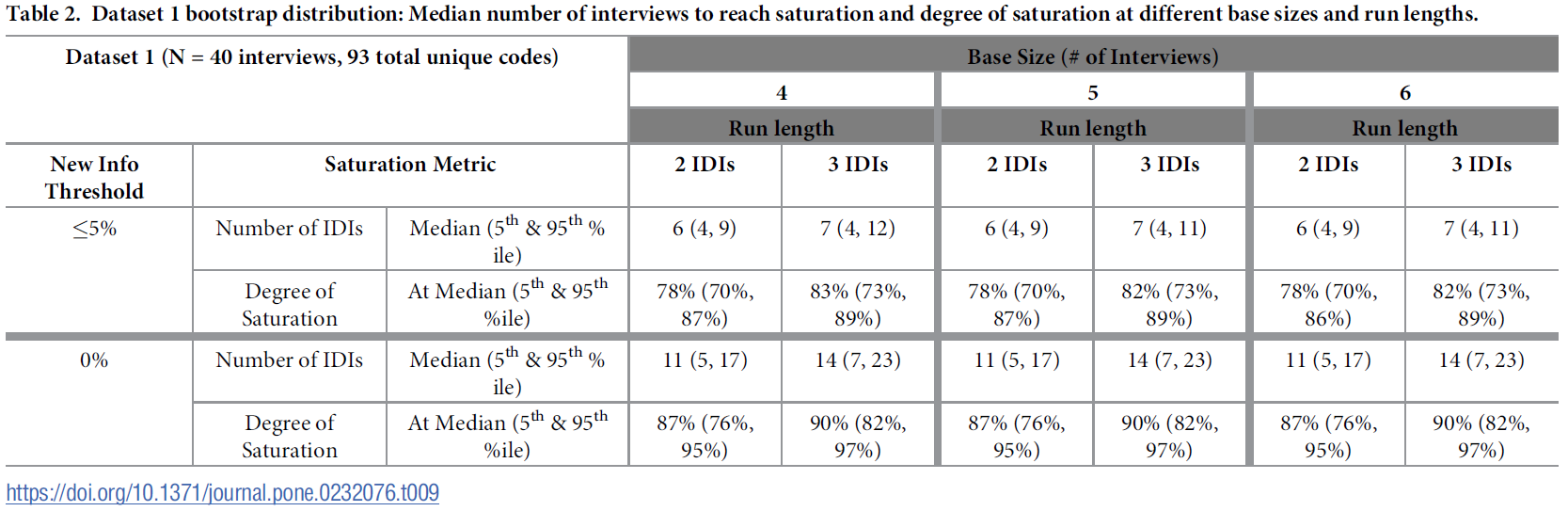

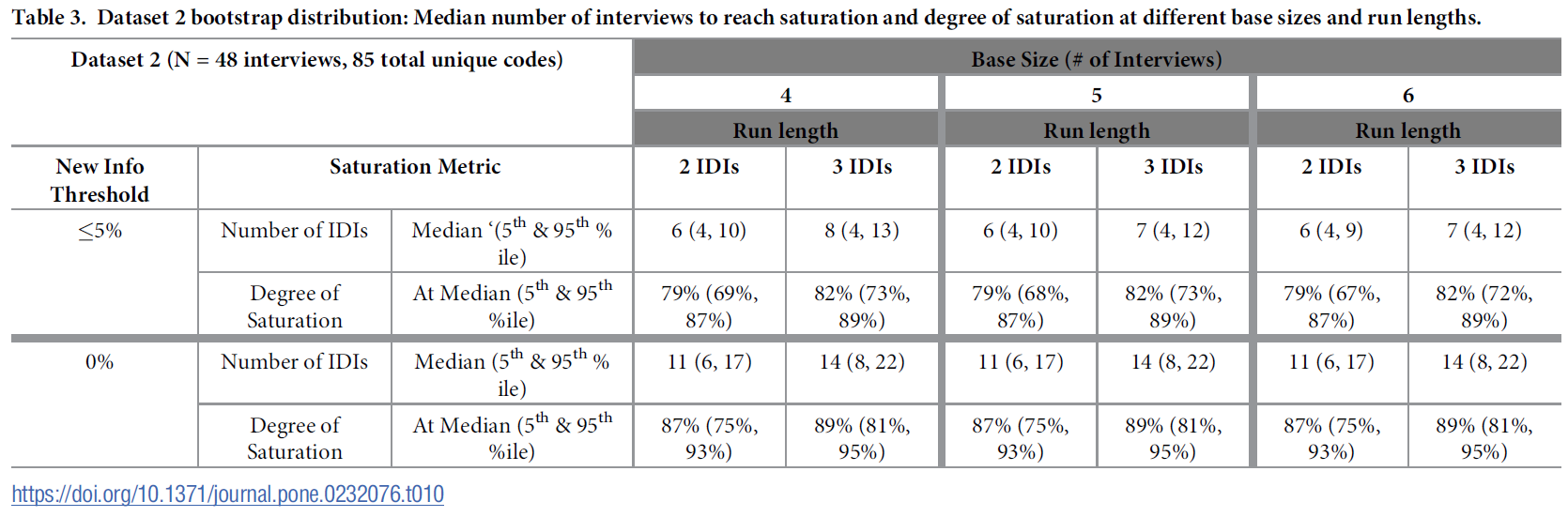

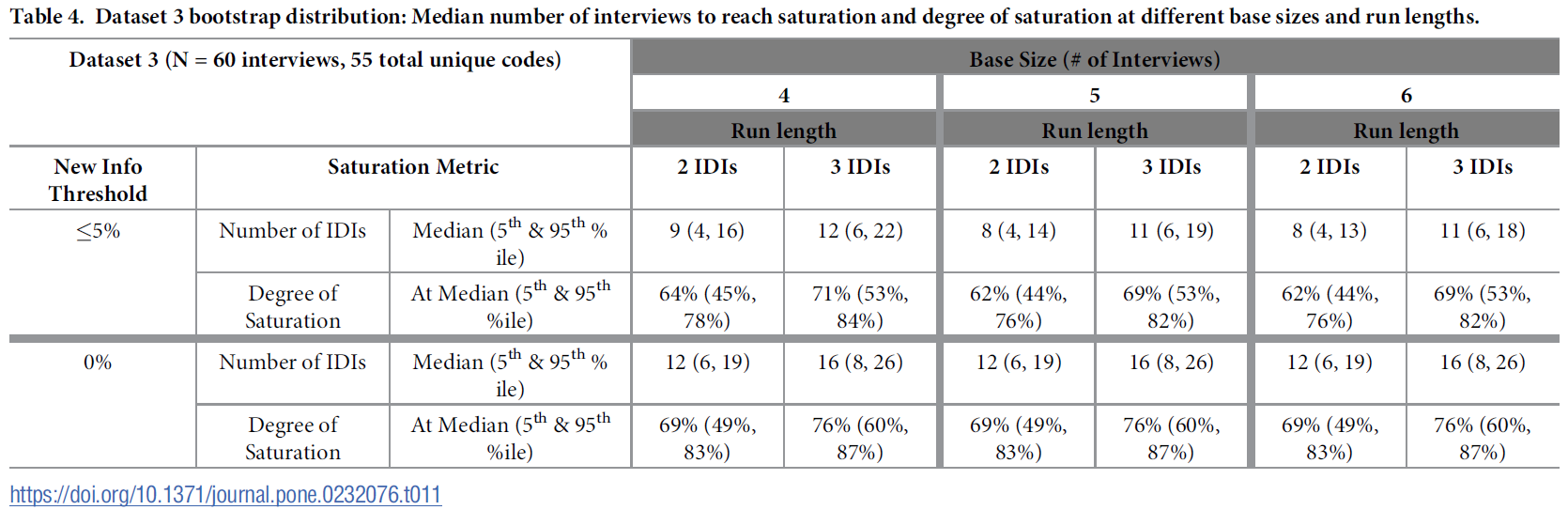

Methods: A meta-study review was conducted with the aims of describing the current state of DA in HPE, guiding researchers engaging in DA and improving methodological, analytical and reporting rigour. Structured searches were conducted, returns were filtered for inclusion and the 115 remaining articles were critically analysed for their use of DA methods and methodologies.

Results: There was a significant increase in the number of articles reporting the use of DA over time. Sixty-three articles were single method (DA only), while the others were mixed methods research (MMR). Overall, there were major lacunae in terms of why documents were used, how documents were identified, what the authors did and what they found from the documents. This was particularly apparent in MMR where DA reporting was typically poorer than the reporting of other methods in the same paper.

Discussion: Given these many lacunae, a framework for reporting on DA research was developed to facilitate rigorous DA research and transparent, complete and accurate reporting of the same, to help readers assess the trustworthiness of the findings from document use and analysis in HPE and, potentially, other domains. It was also noted that there are gaps in HPE knowledge that could be addressed through DA, particularly where documents are conceptualised as more than passive holders of information. Scholars are encouraged to reflect more deeply on the applications and practices of DA, with the ultimate aim of ensuring more substantive and more rigorous use of documents for understanding and constructing meaning in our field.

© 2022 Association for the Study of Medical Education and John Wiley & Sons Ltd.

'Articles (Medical Education) > 의학교육연구(Research)' 카테고리의 다른 글

| When I say ... 해석학적 현상학 (Med Educ, 2018) (0) | 2023.07.26 |

|---|---|

| 현상학이 어떻게 다른 사람의 경험으로부터 배우게끔 하는가(Perspect Med Educ, 2019) (0) | 2023.07.23 |

| 프레임워크 방법을 사용하여 다분야 보건연구에서 질적자료 분석하기(BMC Med Res Methodol. 2013) (0) | 2023.07.23 |

| 근거이론의 퀄리티를 추구하며 (QUALITATIVE RESEARCH IN PSYCHOLOGY, 2021) (0) | 2023.07.20 |

| 주제분석(TA)를 사용할 수 있나요? 그래야 하나요? 그러지 말아야 하나요? 성찰적 주제분석과 다른 패턴-기반 질적분석 접근(Couns Psychother Res. 2021) (0) | 2023.07.19 |