학습 대화: 피드백과 디브리핑의 이론적 뿌리와 발현의 분석(Acad Med, 2020)

Learning Conversations: An Analysis of the Theoretical Roots and Their Manifestations of Feedback and Debriefing in Medical Education

Walter Tavares, PhD, Walter Eppich, MD, PhD, Adam Cheng, MD, Stephen Miller, MD, MEd, Pim W. Teunissen, MD, PhD, Christopher J. Watling, MD, PhD, and Joan Sargeant, PhD

의학교육에서의 경험 학습은 단순히 학습자에게 경험을 제공하는 것 이상의 것을 요구합니다. 학습자는 실습에 대한 개념을 강화하고 향후 수행에 영향을 미치는 방식으로 이러한 경험을 반성하도록 자극받아야 합니다.1-3 피드백 및 디브리핑은 이러한 반성적 작업을 촉진하는 핵심 요소로 자주 사용됩니다. 피드백은 [학습 대화]의 한 형태이며, [학습 대화]란 교육자가 [실제 또는 모의 임상 실습]에서 [학습자의 행동을 관찰한 정보]를 바탕으로 [향후 수행 능력을 향상]시키기 위해 실시하는 대화입니다.4,5 두 가지 모두에서 교육자는 학습자가 보인 행동에 주의를 기울이고, 처리하고, 통합한 다음 해석하여 향후 수행 능력을 향상시키기 위해 학습자와 대화 또는 정보 교환을 진행합니다. 그러나 피드백 및 디브리핑의 공통된 선행 요소와 의도에도 불구하고 피드백 및 디브리핑의 개념은 종종 서로 달라서 교육자와 학습자가 생산적으로 참여하려는 노력을 복잡하게 만들 수 있습니다.

Experiential learning in medical education demands more than simply providing learners with experiences. Learners must be stimulated to reflect on those experiences in ways that strengthen their conceptualizations of practice and impact their future performances.1–3 Feedback and debriefing are often used as key facilitators of this reflective work. Each is a form of learning conversation—a dialogue informed by an educator’s observations of a learner’s behavior in actual or simulated clinical practice, conducted with the intention of improving future performance.4,5 In both, the educator attends to, processes, integrates, and then translates the behaviors exhibited, to then engage in dialogue or exchange of information with the learner with the intent of improving future performance. But despite their common antecedents and intent, conceptualizations of feedback and debriefing frequently diverge, potentially complicating educators’ and learners’ efforts to engage productively with them.

피드백과 디브리핑은 정의하는 방식뿐만 아니라 교육 실무에서 시행하는 방법, 시기, 장소도 다양합니다.

- [피드백]을 주로 수련의가 환자 치료에 관여하는 환경에서 "수련의의 성과를 개선하기 위한 의도로 주어진 수련의의 관찰된 성과와 표준 간의 비교에 대한 구체적인 정보"를 제공하는 단방향 프로세스라고 정의합니다. Archer5는 이러한 단방향 프로세스에 의문을 제기하며, 대신 촉진, 양방향 커뮤니케이션 및 문화적 요구사항에 따라 피드백을 형성할 것을 제안합니다. 피드백에 대한 이러한 접근 방식은 의학교육의 디브리핑과 점점 더 유사해지고 있지만, 두 교육 전략은 처음에 서로 다르게 설명되고 구성되었지만 점점 더 유사해지고 있습니다.

- [디브리핑]은 게임과 항공 분야의 초기 연구에서 주요 사건을 설명하고 사고와 행동을 분석하여 새로운 이해를 향후 수행에 적용하는 것을 목표로 하는 촉진된 성찰 과정으로 정의되었습니다.7-9 피드백은 거의 모든 곳에서 발생할 수 있지만, 의학 교육에서의 디브리핑은 주로 시뮬레이션 상황에서 이루어졌습니다.4,10 환자 치료 에피소드 후 임상 사건 디브리핑은 피드백과 디브리핑 사이의 맥락적 구분이 어렵고,6,11-15 목적과 구조의 중복성을 강조하고 있습니다.

Feedback and debriefing diverge not only in how they are defined but also in how, when, and where they are enacted in educational practice.

- Van de Ridder et al6 define feedback as a unidirectional process that offers “specific information about the comparison between a trainee’s observed performance and a standard, given with the intent to improve the trainee’s performance,” mainly in settings where trainees are involved in patient care. Archer5 questions this unidirectional process, suggesting instead that feedback be shaped by facilitation, 2-way communication, and cultural requirements. This approach to feedback is increasingly similar to debriefing in medical education, even though at their origins, the 2 educational strategies were described and organized differently.

- Debriefing, in early seminal works from gaming and aviation, has been defined as a process of facilitated reflection, which aims to describe key events and analyze thoughts and actions to apply new understanding to future performance.7–9 Whereas feedback may occur almost anywhere, debriefing in medical education has been positioned mainly in simulated contexts.4,10 Clinical event debriefing after patient care episodes is challenging that contextual divide between feedback and debriefing,6,11–15 highlighting the overlap in purpose and structure.

공유된 목표에도 불구하고 피드백과 디브리핑을 둘러싼 담론은 크게 구분되어 있으며, 각각은 서로 영향을 미치거나 영향을 받지 않고 발전하고 있습니다.

- 예를 들어, 디브리핑에 대한 리뷰에서 Cheng 등10은 디브리핑의 특징은 "상호적이고 양방향적이며 성찰적인 토론"이라고 설명한 반면, 피드백은 "수신자의 행동에 대한 단방향 커뮤니케이션"이라고 정의했습니다.

- 마찬가지로 피드백에 대한 리뷰는 (피드백이 크게 다르지 않을 수 있다는 제안에도 불구하고.18 ) 디브리핑을 전혀 고려하지 않거나 디브리핑이 무엇을 제공할 수 있는지 고려하지 않고 증거를 종합하는 경우가 많습니다.6,16,17

피드백 및 디브리핑 담론의 기초가 되는 이론적 프레임워크은 [학습 대화]에서 발생하는 문제에 대한 해결책이 어떻게 그리고 왜 뚜렷하게 구분되어 나타나는지 설명해 줄 수 있습니다. 이러한 이론적 프레임워크는 필연적으로 후속 연구에 영향을 미쳐 일부 아이디어를 영속화하고 다른 아이디어를 무시하며 [학습 대화]를 논의하는 사람들을 파벌로 나누기도 합니다. 이러한 불필요한 분열은 의학교육자가 학습 효과를 향상시키는 방식으로 이러한 도전적인 대화를 정의하고 실행하는 방법을 제한할 수 있습니다. 따라서 의학교육 커뮤니티는 [학습 대화]를 재개념화할 필요가 있으며, 이러한 차이를 하나의 접근법으로 통합하는 것이 아니라 공유된 개념적 프레임워크의 잠재적 어포던스를 이해하고 고려해야 할 것입니다. 이러한 공유 프레임워크는 관련된 사람들, 그들의 교육적 요구, 학습 대화의 맥락과 상황에 반응하고 상호 작용하는 기능을 적절히 혼합하고 차별화해야 합니다.

Despite shared objectives, the discourses surrounding feedback and debriefing remain largely distinct, each evolving without necessarily drawing on or affecting the other.

- For example, in a review of debriefing, Cheng et al10 suggested that the hallmark of debriefing is the “interactive, bidirectional, and reflective nature of discussion,” while characterizing feedback as “unidirectional communication about a recipient’s behavior.”

- Similarly, reviews on feedback often synthesize evidence without considering debriefing at all, or what it might offer,6,16,17 despite suggestions that they may not be all that different.18

The theoretical frameworks underlying feedback and debriefing discourses may explain the historical divide and how and why solutions to challenges with learning conversations emerge and remain distinct. These theoretical frameworks unavoidably influence subsequent research—perpetuating some ideas, ignoring others, and splitting those who discuss learning conversations into factions. This perhaps unnecessary divide may limit how medical educators define and enact these challenging dialogues in ways that enhance their learning impact. Thus, the medical education community may need to reconceptualize learning conversations, not necessarily to assimilate the differences into one approach but to understand and consider the potential affordances of a shared organizing conceptual framework. Such a shared framework should both blend and discriminate (as appropriate) features that are responsive to and interact with the people involved, their educational needs, and the contexts and circumstances of the learning conversations.

이 관점에서는 피드백 및 디브리핑과 관련된 [이론적 뿌리]와 그 [발현 양상]을 살펴봅니다. 이 두 가지 교육 전략을 선택한 이유는 오랜 역사, 광범위한 사용, 의학교육 연구에서 점점 더 많은 관심을 받고 있기 때문입니다. 그럼에도 불구하고 이 두 가지 교육 전략의 공통된 목적을 고려할 때, 각각의 개념에 대해 생각하고 연구해야 하는 이론적 및 상황적 정당성은 고유하다고 생각합니다. 그런 다음 의학교육 커뮤니티가 이러한 개념을 분리하여 [학습 대화]를 이해하려는 노력을 더 발전시킬 수 있는지, 아니면 각각의 교육적 기여를 통합하는 통일된 개념적 틀을 만들 수 있는지 질문합니다.

In this Perspective, we explore the theoretical roots and their manifestations as they relate to feedback and debriefing. We have selected these 2 educational strategies because of their long history, widespread use, and increasing focus in medical education research. Given their shared purpose, we nevertheless consider theoretical and contextual justifications for thinking about and studying each of these concepts as unique. We then ask whether the medical education community can better advance efforts to understand learning conversations by keeping these concepts separate or can, instead, create a unifying conceptual framework that integrates the educational contributions of each.

피드백: 이론적 뿌리와 그 발현

Feedback: Theoretical Roots and Their Manifestations

의학교육의 초기 피드백 전략은 부분적으로는 표준 이하의 성능을 보이는 기계 또는 장치를 피드백을 통해 수정하여 원하는 성능을 달성할 수 있는 교정적 접근법을 포함하는 생물학적 또는 공학적 개념적 프레임워크에서 비롯되었습니다. Ende19는 이 초기 개념을 간결하게 요약했습니다: "피드백은 수행의 결과를 시스템에 다시 삽입하여 시스템을 제어하는 것입니다." 그러나 엔데는 학습자의 관점과 목표, 효과적인 학습 지원 방법을 고려하는 인본주의 및 인지 이론을 바탕으로 피드백에 대한 이러한 접근 방식에 대한 우려를 제기하고 개선했습니다.19 그는 학습자에게는 주체성, 의지, 정서적 반응이 있기 때문에 피드백을 단순한 정보 공유로 개념화하는 것은 교육에 사용하기에 충분하지 않다고 보았습니다. 엔데는 경영학, 조직 심리학, 교육학의 개념적 틀을 바탕으로 피드백을 철학적으로 형성적인 것으로 포지셔닝하고 학습자의 반응과 사용에 대한 의존성을 강조했습니다. 이러한 발전은 피드백이 교사 중심적이고 여전히 단방향적이더라도, 학습자가 교육자의 '진단'을 올바른 것으로 보고 받아들이도록 하기 위해서는, 학습자가 성찰과 토론에 참여해야 한다는 가이드라인을 만들었습니다.

Early feedback strategies in medical education arose, in part, from biological or engineering conceptual frameworks involving corrective approaches, where machines or devices performing below a standard could be corrected using feedback to achieve the desired performance. Ende19 succinctly summarized this early notion: “Feedback is the control of a system by reinserting into the system the result of its performance.” However, Ende raised concerns about and then refined this approach to feedback by drawing upon humanist and cognitive theories that consider the views and goals of the learner and how effective learning can be supported.19 He viewed the conceptualization of feedback as merely information sharing to be insufficient for use in education, as learners have agency, volition, and emotional responses. Drawing on conceptual frameworks from business administration, organizational psychology, and education, Ende positioned feedback philosophically as being formative and also highlighted its dependence on learner reaction and use. The advances generated guidelines that were teacher centric and arguably still unidirectional but that also engaged learners in reflection and discussion—if only, perhaps, to have learners see and accept the educator’s “diagnosis” as correct.

나중에 Kluger와 DeNisi는 피드백의 다양한 효과에 대한 데모20를 통해 성과와 더불어 사람에 대한 관심의 중요성을 강조했습니다. 이들은 과제 관련 학습과 인간의 동기 부여에 관한 문헌을 바탕으로 자아감을 위협하는 피드백은 효과적일 가능성이 낮다는 피드백 개입 이론을 제안했습니다. 피드백은 심리적으로 안정감을 줄 수 있지만, 이는 자아나 사회적 지위에 대한 위협이 낮을 때만 가능하다고 제안했습니다. 이러한 상황에서는 실제로 학습자는 성과에 영향을 미치지 않더라도 더 많은 피드백을 원할 수 있습니다.20 저자들의 개념적 프레임워크는 성과 향상에 효과적이려면 피드백이 자아가 아닌 과제를 대상으로 해야 한다는 후속 가이드라인에 반영되어 있습니다.

Later, Kluger and DeNisi’s20 demonstration of the variable effects of feedback highlighted the importance of attending to the person in addition to the performance. Drawing on literature on task-related learning and human motivation, they proposed feedback intervention theory, which posited that feedback threatening to one’s sense of self is less likely to be effective. Feedback, they suggested, could prove psychologically reassuring, but only if threats to the self or to social status were low. In such circumstances, in fact, learners may seek more feedback, even if it does not affect performance.20 The authors’ conceptual framework is reflected in subsequent guidelines that feedback should target the task rather than the self to be effective in improving performance.

이러한 인지적 관점은 피드백 과정이 사회적 규칙과 영향에 의해 구속되는 사회적 상호 작용으로 발생한다는 인식으로 보완되었습니다. 따라서 피드백 연구자들은 반두라(Bandura)의 사회 인지 이론,21 Boud22와 쇤(Schön)23이 제시한 성찰의 역할, 자기 평가의 한계에 주목했습니다.24 피드백의 개념은 [개인이 새로운 정보를 분석하고 기존의 지식과 경험 기반에 통합할 수 있도록 지원하는 프로세스]로 발전했습니다.25 일부에서는 다음을 주장했습니다

- 피드백이 학습자의 개인적 목표와 연결되어야 하고(인본주의적),

- 비판적 자기 성찰과 자기 모니터링을 촉진해야 하며(인지적),

- 피드백의 효과는 긍정적인 피드백 경험과 문화에 달려 있다(사회문화적).5

이러한 사회문화적 및 인지적 관점은 학습과 피드백을 조절하는 사회적, 전문적, 조직적 영향에 대해서도 관심을 기울였습니다.26,27 종합하면, 슈퍼바이저가 피드백 대화에 진정성 있게 참여하는 것이 학습자의 참여와 대화의 정보를 의미 있는 방식으로 수용하고 사용하는 데 중요한 것으로 인식되기 시작했습니다.

This cognitive perspective was supplemented with the recognition that feedback processes occur as social interactions, bound by social rules and influences. Thus, feedback researchers drew on the social cognitive theories of Bandura,21 the role of reflection articulated by Boud22 and Schön,23 and the limitations of self-assessment.24 The concept of feedback evolved as a process that supported individuals to analyze and integrate new information into an existing base of knowledge and experience.25 Some argued that

- feedback must link to the personal goals of the learner (humanistic),

- that it must promote critical self-reflection and self-monitoring (cognitive), and

- that its effectiveness further rests on a positive feedback experience and culture (sociocultural).5

These sociocultural and cognitive perspectives directed some attention toward the social, professional, and organizational influences that moderate learning and feedback as well.26,27 Taken together, authentic engagement of supervisors in feedback conversations became recognized as critical for learners’ engagement and their acceptance and use of the conversations’ information in meaningful ways.

이러한 이론적 뿌리를 바탕으로 특정 맥락에서 감독자-학습자 관계의 영향을 명시하는 피드백 대화 촉진 모델이 등장했습니다. 예를 들어, Sargeant 등28은 [관계, 반응, 내용, 코칭의 4가지 반복 단계]로 구성된 모델을 설명합니다. 각 단계는 학습자의 성과 데이터에 대한 [참여와 행동을 촉진]하기 위한 [개방형 반성적 질문]이 특징입니다. 이 모델은 다음 개념을 기반으로 합니다.

- 인본주의 이론(부정적 피드백의 잠재적 영향에 대한 이해 강조),

- 인지 이론(자기 성찰, 스키마 습득 및 행동 변화 강조),

- 정보에 입각한 자기 평가

이 모델은 학습자가 자신의 성과 데이터에 대한 대화에 참여하고, 비판적 자기 성찰과 자기 주도성을 촉진하고, 변화의 우선순위를 파악하고, 이를 달성하기 위한 계획을 수립하도록 하는 것을 목표로 합니다. 이 접근 방식은 성과 결과를 시스템에 다시 삽입하는 기계적인 접근 방식과는 크게 다릅니다. 다음 섹션에서 설명하겠지만, 이 모델은 디브리핑과 매우 유사합니다.

From these theoretical roots have emerged models of facilitated feedback conversations that make explicit the influence of the supervisor–learner relationship in a particular context. For example, Sargeant et al28 describe a model involving 4 iterative phases: relationship, reaction, content, and coaching. Each phase is characterized by open-ended reflective questions to promote learner engagement with, and action upon, their performance data. This model is based

- on humanistic theory (emphasizing understanding of the potentially limiting impact of disconfirming feedback),

- on cognitive theory (emphasizing self-reflection, schema acquisition, and behavior change), and

- on notions of informed self-assessment.

This model aims to engage learners in conversation about their performance data, to promote critical self-reflection and self-direction, to identify priorities for change, and to codevelop a plan to achieve it. This approach differs significantly from the more mechanical approaches of reinserting the results of the performance into the system. As we describe in the next section, this model bears more than a passing resemblance to debriefing.

디브리핑: 이론적 뿌리와 그 표현 방식

Debriefing: Theoretical Roots and Their Manifestations

[디브리핑]은 종종 구조화된 이벤트 후 학습 대화로 설명됩니다. 이 용어는 군사 작전, 중대한 사건 또는 충격적인 사건, 속임수가 발생한 심리 연구 등 다양한 유형의 사후 대화를 설명하는 데 사용되었습니다.8,29 교육적 맥락에서 디브리핑의 목적은 "체험 활동 중에 생성된 정보를 사용하여 학습을 촉진하는 것"이었습니다.8 Lederman8은 듀이의 연구를 바탕으로 디브리핑에는 통찰력을 생성하는 토론을 사용하여 이러한 경험을 처리하는 체험적 교육 방법론이 포함된다고 제안했습니다. 디브리핑의 정의는 학습자가 자신의 [경험과 그 의미에 대한 체계적인 분석]을 제공하는, [구조화되고 상호 작용적이며 성찰적인 토론]을 통해 학습자를 가이드하는 예측 가능한 프로세스를 강조합니다.10,13,30

Debriefing is often described as a structured postevent learning conversation. The term has been used to describe different types of postevent conversations, including those that followed military campaigns, critical incidents or traumatizing events, and psychological studies where deception occurred.8,29 In educational contexts, the purpose of debriefing has been to “use the information generated during the experiential activity to facilitate learning.”8 Lederman8 drew on Dewey’s work and suggested that debriefings involve experiential educational methodologies that incorporate processing those experiences using insight-generating discussions. Definitions of debriefing emphasize a predictable process of guiding learners following an experience in a structured, interactive, reflective discussion that offers a systematic analysis of their experience and its meaning.10,13,30

디브리핑 문헌의 대부분은 조직 맥락과 이론에 관한 주제에서 찾을 수 있습니다. 조직 이론은 조직의 구조를 최적화하기 위해 한때 조직의 규모, 기술 및 환경을 강조했습니다.31 이러한 접근 방식과 관련된 한계를 고려하면서 연구자들은 조직 구성원의 인지 및 동기 부여 방향, 즉 해석 체계가 어떻게 중요한지에 대해 인식하기 시작했습니다. 이러한 해석 체계는 가치, 신념, 직업 문화를 반영하고 형성하며 궁극적으로 구조적 변화와 얽혀 있는 행동에 영향을 미쳤습니다. 이러한 [개별적 해석 체계]라는 개념은 주어진 경험이 다양한 방식으로 해석되고 이해될 수 있다는 개념을 정당화했습니다. 관점 간에 충돌이 있을 경우 설명, 분석 및 적용을 포함하는 분석적 인지 과정을 통해 해결할 수 있습니다. 이 프로세스는 이러한 다양한 체계를 명시적으로 만들어 필요에 따라 비교하고, 설명하고, 수정할 수 있도록 합니다. 따라서 디브리핑은 학습자와 진행자 간의 공유된 이해를 달성하는 것을 목표로 합니다. 궁극적으로 교육자는 참가자의 "성찰적 역량과 자신의 행동을 분석하는 능력"을 높이려고 합니다.32

Much of the debriefing literature can be traced to the topics of organizational contexts and theory. When thinking about optimizing an organization’s structure, organizational theory at one point emphasized an organization’s size, technology, and environment.31 In considering limitations associated with this approach, researchers began to appreciate how an organization’s members’ cognitive and motivational orientations—their interpretive schemes—mattered. These interpretive schemes reflected and shaped values, beliefs, professional culture, and ultimately actions, which were intertwined with structural change. This concept of individually held interpretive schemes legitimized the notion that a given experience can be enacted and understood in many ways. When there is a conflict between perspectives, resolution can be achieved through an analytical cognitive process involving description, analysis, and application. This process makes these different schemes explicit, allowing them to be compared, accounted for, and modified as needed. Debriefing thus aims to achieve a shared understanding between learners and facilitators. Ultimately, educators attempt to heighten participants’ “introspective capacities and their ability to analyze their own behavior.”32

디브리핑의 개념은 사회 심리학의 영향을 더 많이 받았습니다. 루돌프 등30 은 Bartunek,31 Lederman,8 Weick,33 등의 연구를 확장하여 사람들이 "내부 [인지 프레임]을 통해 외부 자극을 이해하는 방식"을 강조했습니다.30 이러한 이론적 고려는 학습자가 반드시 지식이 부족하거나, 정보가 필요하거나, 수행에 격차가 있는 것으로 간주하지 않았습니다. 대신, 모든 상호작용, 해석 및 행동은 피할 수 없는 순간적인 감각적 판단을 반영합니다. 학습자에게는 자신의 행동이 정확하고 정당한 것입니다. 학습 또는 성과 향상에는 사회적 맥락에서 발생하는 이러한 [숨겨진 인지 프레임]을 드러내어 이해한 다음 조정이 필요한지 여부를 결정하는 것이 포함됩니다. 강조점 또는 분석 단위는 구체적으로 행동이 아니라 그 행동으로 이어진 [인지 프레임(또는 해석 체계)]입니다.

The concept of debriefing has been further influenced by social psychology. Rudolph et al30 extended the work of Bartunek,31 Lederman,8 Weick,33 and others, highlighting how people “make sense of external stimuli through internal cognitive frames.”30 These theoretical considerations did not place the learner as necessarily lacking knowledge, needing information, or having gaps in performance. Instead, any interaction, interpretations, and behaviors reflect unavoidable in-the-moment sense making. To learners, their actions are correct and justifiable. Learning or performance improvement involves revealing these hidden cognitive frames occurring in social contexts to understand them and then determining whether they need to be adjusted. The emphasis, or unit of analysis, is not specifically the behavior but rather the cognitive frame (or interpretive scheme) that led to it.

의학교육에서 행동과 결과를 알려주는 해석 체계의 개념은 콜브의 경험적 학습 이론,1 쇤의 성찰 개념,23 의도적 연습34 및 숙달 학습에 대한 아이디어 등 피드백과 관련된 개념적 틀과 함께 자리 잡았습니다.35,36 예를 들어, 루돌프 등37 은 콜브를 인용하여 학습자가 다양한 관점에서 자신의 경험을 성찰하고 관찰하여 새로운 개념을 만들거나 미래의 맥락에서 사용할 수 있도록 기존 개념을 강화해야 한다고 주장했습니다. Fanning과 Gaba29는 Schön과 마찬가지로 개인이 "스스로 학습 경험을 분석하고, 이해하고, 동화할 수 있는 능력을 타고나지 않을 수 있기" 때문에 "경험 후 분석"(즉, 디브리핑) 또는 "경험 학습의 주기에서 안내된 성찰"이 필요하다고 제안했습니다.

In medical education, this concept of interpretive schemes informing actions and results became positioned alongside conceptual frameworks relevant to feedback, including Kolb’s experiential learning theories,1 Schön’s notions of reflection,23 and ideas about deliberate practice34 and mastery learning.35,36 Rudolph et al,37 for example, invoked Kolb to argue that learners need to reflect on and observe their experiences from many perspectives to create new concepts or strengthen existing ones for use in future contexts. Fanning and Gaba,29 aligning with Schön, suggested that “postexperience analysis” (i.e., debriefing), or “guided reflection in the cycle of experiential learning,” was necessary because individuals may not be “naturally capable of analyzing, making sense, and assimilating learning experiences on their own,” threatening reflective gains.

이러한 이론적 방향을 고려할 때 [디브리핑]은 [설명, 이해 및 유추, 일반화 및 적용]의 단계를 포함하는 [인지적 분석 활동]으로 부상했으며, 이러한 탐색에 대한 학습자의 반응을 강조합니다.4,38,39 이러한 분석적 접근 방식은 학습자의 반응이나 사회적 상호작용이 없는 것이 아니라 심리적으로 안전하고 지지적인 학습 환경을 구축하고 가혹한 판단을 최소화하는 데 중점을 두어 이를 설명하도록 특별히 구조화되어 있습니다. 심리적 안전감을 통해 디브리핑 대화는 성과를 기준에 맞추는 것이 아니라 수정이 필요할 수도 있고 필요하지 않을 수도 있는 특정 임상 상황에 대한 행동을 주도하는 근본적인 메커니즘을 이해하고, 드러내고, 정교화하는 데 집중할 수 있습니다.4,29,30 이 접근 방식은 학습자에게 궁극적으로 새로운 맥락에서 행동 변화를 촉진할 수 있는 정신 모델을 수정할 기회를 제공하는 것을 목표로 합니다. 디브리핑에는

- 행동에 대한 성찰을 촉진하는 분석적 선택이 포함되며,

- 이 때 학습자와 교수진이 공동으로 수행을 성찰하고,

- 행동의 근거를 탐색하고,

- 필요에 따라 수정하고,

- 개선 전략을 결정하는 시간을 갖습니다.36

효과적인 디브리핑은 학습한 교훈을 맥락화하고 일반화하여 향후 임상 환경에서 수행에 미치는 영향을 최적화할 수 있도록 합니다.

Given these theoretical orientations, debriefing has emerged as a cognitive analytical activity involving phases of description, understanding and analogy, generalization, and application, all the while emphasizing the learner’s response to such explorations.4,38,39 These analytical approaches are not devoid of learner reactions or social interactions but instead are structured specifically to account for them, through an emphasis on establishing a psychologically safe and supportive learning environment and minimizing harsh judgments. A sense of psychological safety allows debriefing conversations to become less about matching performance to criteria and more about understanding, revealing, and elaborating underlying mechanisms driving behavior for a given clinical situation, which may or may not need to be revised.4,29,30 This approach aims to afford learners the opportunity to modify mental models that would ultimately prompt behavior change in novel contexts downstream. Debriefing involves

- analytical choices facilitating reflection on action,

- where learners and faculty take time to jointly reflect on the performance,

- explore the rationale for actions,

- modify as necessary, and

- determine strategies for improvement.36

Effective debriefings contextualize lessons learned and also generalize them to optimize the impact on performance in future clinical environments.

피드백과 마찬가지로 디브리핑에 대한 이해도 계속 발전하고 있습니다. 예를 들어, 저자들은 학습자에게 시간이 제한된 환경에서 자가 평가를 요청하는 형식(예: 플러스-델타)36과 의도적인 연습 및 숙달 학습 커리큘럼의 일부로 성과 기준을 강조하는 형식의 사용을 포함시켰습니다.39 전통적으로 디브리핑에 대한 기본 관점(예: 게임, 항공 및 시뮬레이션의 사후 이벤트)이 유보되었던 맥락에 이제 다른 개념과 접근 방식이 포함되고 있습니다. 디브리핑에 대한 보다 다양한 정의와 개념화는 디브리핑이 순전히 인지적 프레임에 기반하거나 시뮬레이션 기반 활동에만 국한된다는 매우 구체적인 생각에 도전하는 것으로 보입니다.40 디브리핑은 피드백과 뿌리가 다를 수 있지만, 이제 이론적 및 개념적 설명과 정당화에서 상당한 중복이 있을 수 있습니다.

Like feedback, understanding of debriefing continues to evolve. For example, authors have included the use of formats that ask learners to self-assess in time-limited settings (e.g., plus-delta)36 and that place emphasis on performance criteria as part of deliberate practice and mastery learning curricula.39 The contexts for which foundational views on debriefing had traditionally been reserved (e.g., postevents in gaming, aviation, and simulation) are now including other concepts and approaches. More diverse definitions and conceptualizations of debriefing seem to be challenging this once highly specific idea that debriefing is purely based on cognitive frames or purely situated in simulation-based activities.40 While debriefing may be rooted differently from feedback, there may now be significant overlap in the theoretical and conceptual descriptions and justifications.

피드백과 디브리핑 전통의 통합

Integrating the Feedback and Debriefing Traditions

비슷한 목표를 공유하고 있음에도 불구하고 피드백과 디브리핑의 개념은 문헌에서 서로 거의 독립적으로 발전해 왔습니다. 두 개념의 기원을 검토한 결과,

- (1) 각 개념은 서로 다른 이론적 뿌리에서 파생되어 연구, 발전 및 제정 방식에 차이가 있고,

- (2) 두 개념 모두 여러 가지 유사한 교육 이론을 활용하며 이러한 이론을 운영하는 방법으로 자리매김하고 있으며,

- (3) 피드백과 디브리핑을 연구하고 발전시키는 사람들이 유사한 인지 및 사회 이론을 활용하여 접근 방식을 개선하고 구조화한다는 점에서 현재 전통 간에 상당한 공통점이 존재한다는 것을 알 수 있었습니다.

이제 이러한 교육 전략을 학습 대화라는 단일 범주로 통합하고, 특정 교육적 용도나 이점을 위해 선택할 수 있는 리소스로서 구별되는 특징을 취급하는 것을 고려할 때가 되었다고 제안합니다.

Despite sharing similar objectives, the concepts of feedback and debriefing have evolved in the literature largely independent of one another. A review of their conceptual origins suggests that

- (1) each was derived from distinct theoretical roots, leading to variations in how they have been studied, advanced, and enacted;

- (2) both draw on multiple, often similar, educational theories, positioning themselves as ways of operationalizing those theories; and

- (3) considerable commonality between traditions now exists, in that those studying and advancing both feedback and debriefing are leveraging similar cognitive and social theories to refine and structure their approaches.

We propose that it is time to consider merging these educational strategies into a single category, learning conversations, treating any distinguishing features as resources from which to select for particular educational use or benefit.

피드백과 디브리핑의 뚜렷한 진화 경로는 이론만큼이나 상황에 따라 달라질 수 있습니다. 예를 들어, 의학 교육에서

- [디브리핑]은 [시뮬레이션]과 밀접한 관련이 있으며, 이는 디브리핑의 특징 중 일부를 설명할 수 있습니다. 시뮬레이션은 학습자의 심리적 안전을 확립하고 강화하는 의식을 쉽게 도입할 수 있는 통제된 환경을 제공합니다. 시뮬레이션을 통해 학습자의 행동에 대한 상세하고 때로는 비디오로 강화된 검토를 할 수 있는 기회는 의사 결정이 내려질 때 이를 해체하고 이해하는 과정을 더욱 지원합니다.

- 이와는 대조적으로 [피드백 접근 방식]은 더 [다양한 환경]에서 발전해 왔습니다. 예를 들어 임상 교육에서 피드백 대화는 역동적이고 체계적이지 않은 실제 환자 치료의 세계에서 즉석에서 이루어집니다. 따라서 피드백은 디브리핑과 같이 목적에 맞는 교육적 접근 방식으로 진화한 것이 아니라 다양한 환경과 맥락에서 사용되면서 그때그때 필요에 따라 발전해 왔습니다.

The distinct evolutionary paths of feedback and debriefing may be as much about context as about theory. In medical education, for example, debriefing’s strong foundational ties to simulation may explain some of its characteristic features. Simulation offers a controlled environment into which rituals that establish and reinforce psychological safety for learners can be readily introduced. The opportunities simulation creates for detailed and sometimes video-enhanced review of learner actions further support a process of deconstructing and understanding decisions as they are made. Feedback approaches, in contrast, have developed in a wider range of settings. In clinical education, for example, feedback conversations occur on the fly in the dynamic and less organized world of authentic patient care. Therefore, feedback has not evolved as a fit-for-purpose pedagogical approach like debriefing; rather, it has developed in fits and starts as its uses have played out across a range of settings and contexts.

이론적 기원과 맥락적 영향은 다르지만, 이 두 가지 전통은 사회적 맥락에서 인지 및 정서 영역을 대상으로 하는 관찰과 경험에 기반한 대화적 과정을 공유합니다.

- 두 가지 모두 형성적 활동이며 교육자가 학습자의 성과를 관찰하고,

- 표준을 기준으로 관찰내용을 공유하며,

- 학습자와 해당 성과, 관찰 내용, 표준 및 개선 방법에 대한 대화에 참여하게 합니다.

또한 두 전통 모두 학습자 안전의 역할, 관계, 신뢰, 신용의 영향, 문화와 가치의 영향 등 학습을 형성하는 사회적 측면에 대해 고민해 왔습니다.4,41-43 유사한 과제가 확인되었지만 역사적으로 연구자들은 최근까지 서로 다른 렌즈, 가치, 이론을 사용하여 각 방법을 탐구하고 개선해 왔으며, 그 결과 서로 다른 진화 경로를 밟아 왔습니다. 이제 이론적 지향에 존재하는 공통점을 고려할 때, 교육자들은 이제 [학습 대화]를 하나의 통합된 과학으로 탐구할 수 있는 전환점에 서 있습니다.

Despite their different theoretical origins and contextual influences, these 2 traditions share a dialogic process informed by observation and experience that targets cognitive and affective domains within social contexts.

- Both are formative activities and involve educators who observe learners’ performance;

- share their observations in reference to a standard; and

- engage the learner in a conversation about that performance, their observation, the standards, and how best to improve.

And both traditions have grappled with social aspects that shape learning, such as the role of learner safety; the influence of relationships, trust, and credibility; and the impact of culture and values.4,41–43 Although similar challenges have been identified, historically, researchers have until recently explored and refined each method using different lenses, values, and theories, resulting in divergent evolutionary paths. Given the commonality that now exists in theoretical orientations, educators are now at a turning point where learning conversations can be explored as a united science.

피드백과 디브리핑의 기본 원칙은 서로 다르지만 중요한 방식으로 서로를 보완하기도 합니다. 예를 들어,

- [피드백]은 어떤 목표 성과 기준과 관련하여 행동에 대한 판단을 강조하는 반면,

- [디브리핑]은 무슨 일이 왜 일어났는지에 대한 참가자의 이해를 이해하려는 시도를 강조할 수 있습니다.

실제로 이 두 가지 프로세스는 피드백 및 디브리핑 상황 모두에서 다양한 정도로 존재할 수 있습니다. 개선해야 할 사항을 파악하면 학습자는 향후 성과 목표를 설정할 수 있으며, 현재 상황에서 발생한 일과 그 이유를 이해하면 학습자는 성과 목표를 지원하기 위해 자신의 행동을 수정할 수 있는 방법에 대한 통찰력을 얻을 수 있습니다. 이러한 뉘앙스를 인식하면

- (1) 교육자는 고유한 상황에 대응하여 대화 선택을 조정하는 능력을 향상시킬 수 있고,

- (2) 연구자는 학습 대화의 성공 요인 식별을 포함하여 연구 질문과 의제를 더 잘 묘사할 수 있으며,

- (3) 학습자와 최종 환자는 체험 이벤트에서 최적의 혜택을 받을 수 있습니다.

While the foundational tenets of feedback and debriefing differ, they also complement each other in important ways. For instance, feedback may emphasize a judgment of behavior with respect to some aspirational standard of performance, while debriefing may emphasize attempts to understand participants’ comprehension of what happened and why. In practice, these 2 processes are probably present to varying degrees in both feedback and debriefing situations. Knowing what needs to be improved allows learners to set goals for future performance, and understanding what happened in the current situation and why offers learners insights into how they can modify their behavior to support their performance goals. Recognition of these nuances may have several benefits

- (1) for educators, who may develop increased competence in tailoring their conversational choices in response to unique situations;

- (2) for researchers, who may now better delineate research questions and agendas, including the identification of success factors of learning conversations; and

- (3) for learners and their eventual patients, who may optimally benefit from the experiential event.

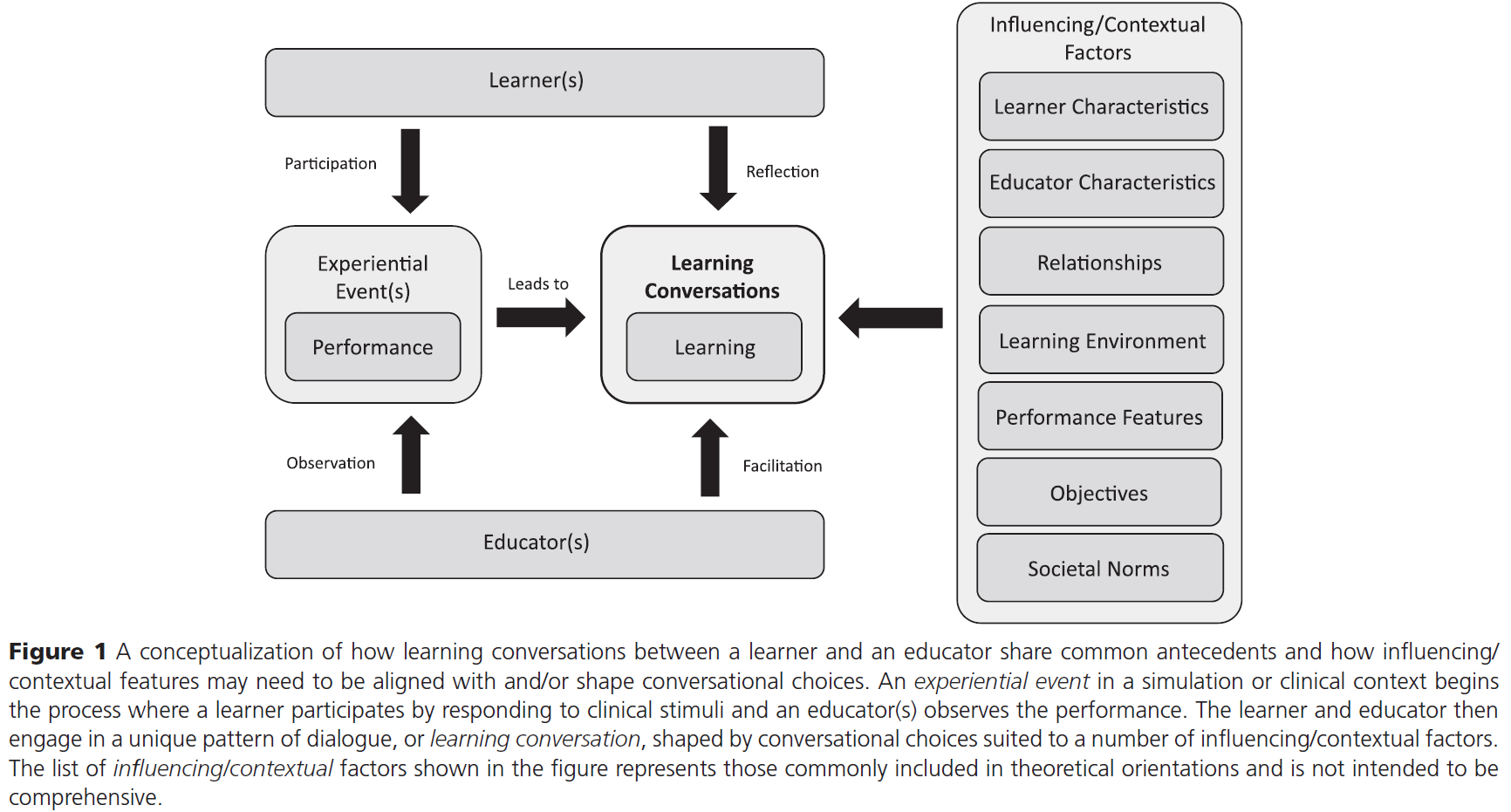

그림 1은 이 두 가지 피드백 및 디브리핑 프로세스를 결합한 결과를 보여주며, 유사한 [선행 요소](예: 행동적 체험 수행, 관찰자, 성찰)와 여러 [영향/상황적 요인]에 대응하여 성과 향상을 촉진하기 위한 특정 대화 전략을 통해 제정된 일반적인 대화 접근법으로 프레임을 구성합니다. 이러한 요소는 관련된 맥락 및 경험적 사건과 대화 선택의 기능적 및 이론적 일치 정도를 알려주는 일련의 '규칙'을 제공합니다. 현재 별개의 교육 활동 패턴으로 존재하는 피드백과 디브리핑을 [학습 대화]로 재구성함으로써, 우리는 이를 상호 보완적인 활동, 즉 미래의 성과를 개선하기 위한 정보 교환의 대화형 대화 프로세스를 포함하는 것으로 종합적으로 개념화합니다. 향후 연구 방향은 이러한 대화적 선택이 어떻게 최적으로 검토, 선택, 통합되는지, 그리고 주어진 경험적 사건에 어떤 방식으로 접근할 때 어떤 결정을 내려야 하는지를 탐구할 수 있습니다.

Figure 1 shows the results of combining these 2 processes of feedback and debriefing and frames them as having similar antecedents (e.g., behavioral experiential performances, observers, reflection) and as general conversational approaches enacted through specific conversational strategies to foster performance improvement in response to a number of influencing/contextual factors. These factors provide a set of “rules” that help inform the degree of functional and theoretical alignment of those conversational choices with the context and experiential event involved. By reframing feedback and debriefing—which exist currently as distinct patterns of educational activities—as learning conversations, we conceptualize them collectively as involving complementary activities, namely interactional conversational processes of information exchange to improve future performance. Future research directions may explore how these conversational choices are optimally examined, selected, and integrated and how decisions are to be made when approaching a given experiential event in one way or another.

관찰된 성과를 기반으로 성과를 개선하는 문제인 경우에는 피드백과 디브리핑의 구분이 덜 중요할 수 있습니다. 엘러웨이와 베이츠44는 패턴의 이론적 구성의 관련성을 정교하게 설명했습니다. 이들은 건축 이론가인 크리스토퍼 알렉산더의 연구를 바탕으로 다음과 같이 주장했습니다.

The distinction between feedback and debriefing may be less relevant when the problem is improving performance based on observed performance. Ellaway and Bates44 elaborated the relevance of the theoretical construct of patterns. Drawing on the work of architectural theorist Christopher Alexander, they argued that

[패턴 사고]는 개념과 일상의 경계가 어디인지, 시간이 지남에 따라 어떻게 발전하고 변화하는지 등 우리의 개념과 일상을 바라보는 새로운 방식을 제공합니다.

pattern thinking affords new ways of looking at our concepts and routines, such as where their boundaries are and how they develop and change over time.

[패턴의 관점]에서 사고하면 피드백과 디브리핑이 서로 다른 이론적 뿌리를 통해 파생된 패턴을 나타내며, 이는 특정 상황, 이러한 상황에서의 과제, 그리고 이러한 과제에 대한 적절한 해결책 간의 관계에서 비롯된다는 사실을 인식할 수 있습니다. 이러한 대화 전략이 발전해 온 방식을 고려할 때, 교육자가 피드백이나 디브리핑을 제공할지 또는 제공해야 하는지에 대한 미리 정해진 생각보다는 교육 상황과 주변의 영향 및 맥락 요인에 더 많은 영향을 받을 수 있음을 시사합니다. 예를 들어, 대화에는 다양한 개인(예: 학습자, 교육자, 동료), 다양한 상황(예: 시뮬레이션 실험실, 수술실, 외래 진료소), 성과 세부 사항 및 기타 수많은 영향 요인이 포함되므로 대화 선택의 관련성 또는 조정은 끊임없이 변화합니다. 피드백이나 디브리핑으로 분류하는 것이 아니라 이러한 상호 작용하고 영향을 미치는 요인이 가장 중요합니다. 이 새로운 '패턴'은 기능적, 이론적으로 정렬된 대화 선택지를 구분하는 데 도움이 될 수 있습니다. 앞으로 가장 가치가 있을 것으로 생각되는 것은 이러한 정렬의 역할과 기능, 그리고 학습 대화에 정보를 제공하는 방식입니다.

Thinking in terms of patterns allows us to recognize that both feedback and debriefing have represented patterns—derived through different theoretical roots—that result from their relationships between specific contexts, challenges in these contexts, and appropriate solutions to those challenges. Given the way in which these conversational strategies have evolved now suggests that it may be more about the educational situation and surrounding influences and context factors than any predetermined ideas about whether an educator is or should be preparing to provide feedback or debriefing. For instance, because the conversation involves different individuals (e.g., learners, educators, colleagues), different contexts (e.g., simulation laboratory, operating theater, outpatient clinic), as well as performance details and numerous other influencing factors, the relevance or alignment of conversational choices is ever-changing. It is these interacting and influencing factors that become paramount—not necessarily the categorization as feedback or debriefing. This new “pattern” may help to differentiate a selection of functionally and theoretically aligned conversational choices. It is the roles and function of this alignment and how they inform learning conversations that we think may be of most value moving forward.

이러한 접근 방식의 혼합과 대화 전략의 선택은 이전에 고려된 바 있습니다. 예를 들어, Eppich와 Cheng39은 디브리핑과 피드백에 대해 논의하면서 디브리핑이 피드백을 위한 포럼을 제공할 수 있다고 제안했습니다. 여전히 동일한 목표를 향한 별개의 구성 요소로 취급되지만, 집중 촉진, 학습자 자기 평가, 교수/지시 피드백을 포함하는 이들의 혼합 모델은 연구자들이 가장 적절한 전략을 선택하기 위해 사용할 수 있는 특정 어포던스(교육적 맥락, 학습자 특징, 수행 세부 사항)를 어떻게 사용했는지를 보여줍니다. 이론적 관점에서 두 가지 교육 전략이 어떻게 점점 더 유사해지는지 보여주는 데 기여했습니다.

This blending of approaches and the selection of conversation strategies has been considered previously. For example, Eppich and Cheng39 discussed debriefing and feedback and suggested that the former may provide a forum for the latter. Although still treated as distinct constructs toward the same goal, their blended model, which includes focused facilitation, learner self-assessment, and teaching/directive feedback, illustrates how researchers have used the specific affordances (i.e., educational contexts, learner features, performance details) available to them to select the most appropriate strategies. Our contribution is to demonstrate how from a theoretical perspective the 2 educational strategies are increasingly similar.

피드백과 디브리핑의 전통을 통합하는 것은 실질적인 이점을 제공할 뿐만 아니라, 학습 대화에 대한 다양한 접근 방식의 공통적인 취약성에 대한 연구의 관심을 집중시킵니다. 예를 들어, 모든 학습 대화에는 [학습자의 취약성]과 [위험 감수]라는 요소가 포함되므로 의미 있는 참여를 가능하게 하려면 학습자가 취약성을 안전하게 경험할 수 있도록 하는 접근 방식이 필요합니다. 디브리핑과 피드백을 학습 대화의 주제에 대한 변형으로 간주하면 의료 교육 커뮤니티에 이 중요한 문제를 해결할 수 있는 다양한 옵션을 제공할 수 있습니다. 시뮬레이션 환경에서 의료 교육자는 학습자가 충분히 참여할 수 있도록 디브리핑을 특징짓는 심리적 안전 확립 의식을 활용할 수 있습니다. 이러한 접근 방식이 불가능할 수 있는 실제 임상 환경에서는 의학교육자가 피드백의 핵심으로 점점 더 중요하게 여겨지고 있는 교사-학습자 관계를 활용하여 이러한 안전성을 구축할 수 있습니다.

Integrating the feedback and debriefing traditions not only provides practical benefits but also focuses research attention on the common fragilities of the various approaches to learning conversations. For example, all learning conversations involve elements of learner vulnerability and risk-taking, so making meaningful engagement possible demands an approach that makes it safe for learners to experience vulnerability. Viewing debriefing and feedback as variations on a theme of learning conversations offers the medical education community a range of options for addressing this critical issue. In simulated settings, medical educators may draw on the rituals of establishing psychological safety that characterize debriefing to allow learners to engage fully. In real clinical settings where such approaches may not be feasible, medical educators may draw instead on the teacher–learner relationship that is increasingly viewed as central to feedback to create this safety.

각 연구 전통은 각기 다른 관점에서 의미 있는 학습 대화에 참여해야 하는 과제를 탐구해 왔습니다. 그 과정에서 각 전통은 이러한 대화가 교육적 가치를 갖기 위해 필요한 조건에 대해 많은 것을 가르쳐 주었습니다. 서로 다른 강조점은 상호 보완적인 것으로 보이며, 의학교육은 이들의 주요 통찰력을 결합함으로써 많은 것을 얻을 수 있습니다. 예를 들어,

- 디브리핑 전통은 심리적 안전과 성찰을 유도하는 데 중점을 두는 반면,

- 피드백 전통은 관계, 신뢰성, 감정에 중점을 둡니다.

성과 향상을 촉진하려면 학습 대화를 진행할 때 이러한 요소를 종합적으로 고려해야 할 수 있습니다. 궁극적으로 체험 학습에는 여러 가지 영향 요인(그림 1 참조)과 이론적 정합성(즉, 대화 선택이 목적에 적합한 정도)을 고려한 이벤트 후 학습 대화가 포함되어야 합니다. 교육자는 두 모델 간의 일관된 특징뿐만 아니라 가장 적합한 대화 전략을 선택하기 위해 관련된 상황, 사람, 맥락을 감지하고 대응하는 접근 방식에 대한 역량을 개발해야 하며, 연구자는 이를 탐구해야 합니다.

Each research tradition has explored the challenge of engaging in meaningful learning conversations from a distinct perspective. In the process, each tradition has taught us much about the conditions necessary for such conversations to have educational value. Their different emphases appear complementary, and medical education has much to gain by combining their key insights. For example,

- debriefing traditions focus on psychological safety and guided reflection, while

- feedback traditions focus on relationship, credibility, and emotion.

Promoting performance improvement may need to consider these factors collectively when learning conversations are undertaken. Ultimately, experiential learning must include a postevent learning conversation that takes into account a number of influencing factors (see Figure 1) and theoretical alignment (i.e., the degree to which conversational choices are fit for purpose). Educators must develop competence in, and researchers must explore, not only the features that are consistent between the 2 models but also the approaches to detecting and responding to the circumstances, people, and contexts that are involved to select the most suitable conversational strategies.

요약

Summing Up

피드백과 디브리핑은 모두 참여형 학습 대화를 통해 성과 향상을 촉진하는 것을 목표로 합니다. 둘 다 인지적 영향과 사회적 영향의 미묘한 균형에 의존합니다. 여기서 설명한 크게 분리된 두 가지 연구 전통을 탐구하면서 의미 있는 학습 대화가 이루어지는 데 필요한 조건에 대한 인사이트를 발견했습니다. 그러나 의학교육계가 미래를 바라볼 때 이러한 전통을 통합함으로써 많은 것을 얻을 수 있습니다. 의학교육자들은 끊임없이 확장되는 다양한 상황과 환경에서 학습을 지원하기 위해 맞춤화할 수 있는 정교한 대화 전략 레퍼토리를 필요로 합니다. 이러한 전략을 연구하고 실행하는 통합적인 접근 방식은 이러한 요구를 충족하기 위한 진전을 가속화할 수 있습니다. 향후 연구에서는 피드백과 디브리핑을 학습 대화의 단일 범주에 통합하는 것이 이론적, 교육적, 실용적 타당성이 있는지에 대한 토론과 논의를 장려해야 합니다.

Both feedback and debriefing aim to stimulate performance improvement through engaged learning conversations. Both depend on a delicate balance of cognitive and social influences. The exploration of their largely separate research traditions that we have described here has unearthed insights into the conditions necessary for meaningful learning conversations to occur. As the medical education community looks to the future, however, much may be gained by integrating these traditions. Medical educators require a sophisticated repertoire of conversational strategies that can be tailored to support learning across an ever-expanding range of contexts and settings. An integrated approach to studying and enacting these strategies may accelerate progress toward meeting that need. Future research should encourage debate and discussion about whether integrating feedback and debriefing into the single category of learning conversations has theoretical, educational, and practical relevance.

Learning Conversations: An Analysis of the Theoretical Roots and Their Manifestations of Feedback and Debriefing in Medical Education

PMID: 31365391

Abstract

Feedback and debriefing are experience-informed dialogues upon which experiential models of learning often depend. Efforts to understand each have largely been independent of each other, thus splitting them into potentially problematic and less productive factions. Given their shared purpose of improving future performance, the authors asked whether efforts to understand these dialogues are, for theoretical and pragmatic reasons, best advanced by keeping these concepts unique or whether some unifying conceptual framework could better support educational contributions and advancements in medical education.The authors identified seminal works and foundational concepts to formulate a purposeful review and analysis exploring these dialogues' theoretical roots and their manifestations. They considered conceptual and theoretical details within and across feedback and debriefing literatures and traced developmental paths to discover underlying and foundational conceptual approaches and theoretical similarities and differences.Findings suggest that each of these strategies was derived from distinct theoretical roots, leading to variations in how they have been studied, advanced, and enacted; both now draw on multiple (often similar) educational theories, also positioning themselves as ways of operationalizing similar educational frameworks. Considerable commonality now exists; those studying and advancing feedback and debriefing are leveraging similar cognitive and social theories to refine and structure their approaches. As such, there may be room to merge these educational strategies as learning conversations because of their conceptual and theoretical consistency. Future scholarly work should further delineate the theoretical, educational, and practical relevance of integrating feedback and debriefing.

'Articles (Medical Education) > 교수법 (소그룹, TBL, PBL 등)' 카테고리의 다른 글

| ChatGPT의 등장: 의학교육에서 잠재력 탐색 (Anat Sci Educ. 2023) (0) | 2023.05.23 |

|---|---|

| 졸업후의학교육에서 피드백 활용을 개선하기 위한 코칭스킬 식별(Med Educ, 2019) (0) | 2023.04.23 |

| 밀레니얼의 학습을 촉진하기 위한 열두가지 팁(Med Teach, 2012) (0) | 2023.01.07 |

| 밀레니얼을 위한 의학교육: 해부학자들은 잘 하고 있는가? (Clin Anat, 2019) (0) | 2023.01.07 |

| 밀레니얼 학생 멘토링하기 (JAMA, 2020) (0) | 2023.01.07 |