보건의료전문직교육의 환자참여: 메타 내러티브 리뷰 (Adv Health Sci Educ Theory Pract. 2019)

Patient involvement in health professionals’ education: a meta‑narrative review

Paula Rowland1,2,3,4,5 · Melanie Anderson3 · Arno K. Kumagai6,7 · Sarah McMillan3 · Vijay K. Sandhu8 · Sylvia Langlois5

소개

Introduction

환자 활동은 커리큘럼을 설계하고 실행하는 사람들의 직접적인 권한에 속할 수도 있고 그렇지 않을 수도 있지만, 환자 및 교육에서 환자의 역할은 항상 교육자들의 관심사였습니다. 최근에는 "환자 참여"로 식별되는 프로그램에서 환자가 보건 전문직 교육에 참여하는 방식이 더욱 공식화되고 있습니다. 전문직 교육에서의 환자 참여 관행에 대한 실용적, 이론적, 윤리적 문제를 다루고자 하는 문헌이 점점 더 많아지고 있습니다. 그러나 환자 참여 의제(예: 건강 연구, 정책 또는 의료 서비스 설계에 대한 환자 참여)를 추구하는 다른 의료 분야와 마찬가지로, 교육에서의 환자 참여에 관한 문헌은 이론이 부족하고 경험적 증거보다는 이념적 진술에 불균형적으로 치우친다는 비판을 받아왔습니다(Regan de Bere와 Nunn 2016). 그 결과 다양한 문헌이 존재하고, 환자 참여의 목적에 대한 상충되는 조언이 있으며, 해당 분야에서 지식을 구축하는 방법에 대한 합의가 거의 이루어지지 않았습니다.

Patients—and their role in education—have always been of interest to educators, even as those patient activities may or may not have been in the direct purview of those designing and implementing curricula. Recently, the ways that patients are involved in health professions education has become more formalized in programs identified as “patient engagement”. There is a growing body of literature that seeks to address pragmatic, theoretical, and ethical questions about practices of patient engagement in professional education. However, in common with other health care fields that are also pursuing patient engagement agendas, (e.g. patient engagement in health research, policy, or health service design), the body of literature of patient engagement in education has been critiqued as under-theorized and disproportionately weighted towards ideological statements rather than empirical evidence (Regan de Bere and Nunn 2016). The result is a disparate body of literature, conflicting advice as to the purpose of patient engagement, and little consensus about how to build knowledge in the field.

이러한 개념적 문제를 해결하기 위해 많은 문헌 검토가 시도되었습니다(Jha 외. 2009a, Livingston과 Cooper 2004, Repper와 Breeze 2007, Spencer 외. 2000, Towle 외. 2010, Wykurz와 Kelly 2002). 이러한 각 리뷰는 이 분야가 일관되지 않은 정의와 용어의 배열로 특징지어지기 때문에 문헌 검색 프로세스의 어려움을 지적했습니다(Towle 외. 2010). 이전의 문헌 검토에서는 환자 참여를 공식 교육 과정의 적어도 한 단계로 정확하게 정의함으로써 이러한 어려움을 현명하게 해결했습니다(Jha 외. 2009a, Towle 외. 2010).

- 교육과정 의사 결정,

- 교육 프로그램 설계,

- 교육과정 전달,

- 학습자 평가 및/또는 프로그램 평가에 환자(또는 가족 및/또는 간병인)가 참여하는 것으

이러한 방법론적 결정으로 인해 [교육에 대한 환자 참여의 효과]에 대한 중요한 종합 보고와 함께 [교사로서의 환자]에 초점을 맞춘 문헌 검토가 이루어졌습니다(Jha 외. 2009a, 2010; Towle 외. 2010; Wykurz와 Kelly 2002).

A number of literature reviews have attempted to redress these conceptual problems (Jha et al. 2009a; Livingston and Cooper 2004; Repper and Breeze 2007; Spencer et al. 2000; Towle et al. 2010; Wykurz and Kelly 2002). Each of these reviews have noted the difficulty of the literature search process, as the field is characterized by an inconsistent array of definitions and terms (Towle et al. 2010). Previous literature reviews have sensibly addressed this difficulty by offering precise definitions of patient engagement as the involvement of patients (or their family members and/or caregivers) in at least one phase of the formal education process:

- curricular decision making,

- education program design,

- delivery of curriculum,

- assessment of learners and/or evaluation of programs (Jha et al. 2009a; Towle et al. 2010).

These methodological decisions have resulted in literature reviews focused on patients as teachers, with important syntheses reporting on the effectiveness of patient involvement in education (Jha et al. 2009a, 2010; Towle et al. 2010; Wykurz and Kelly 2002).

이러한 이전 검토에서 적용된 포함 및 제외 기준은 중요하고 방어할 수 있지만, [교사로서의 환자]에 초점을 맞추면 보건 전문직 교육에 대한 환자의 참여에 대한 대안적인 개념화가 필연적으로 모호해집니다. 그 결과, 보건 전문직 교육에 대한 환자 참여는 개념적으로 교사로서의 환자 참여라는 한 가지 가능한 환자 참여의 반복으로 축소되고, [환자가 지속적인 전문직 학습 과정에 참여하는 다른 방식]에 대한 맥락에서 제외됩니다. Bleakley(2014)가 말했듯이, 환자와 함께, 환자로부터, 환자에 대해 학습하는 과정을 전체 보건의료 전문직 교육 기업의 기초로 이해할 필요가 있습니다. 지금처럼 [교사로서 환자]라는 반복되는 역할에 초점을 맞추는 것은, 이러한 역할이 실제로 어떻게 제정될 수 있는지에 대한 정보를 제공할 수 있는 [풍부한 문헌을 고려하지 않은 채로 "새롭고 흥미로운 역할"(Stockhausen 2009)로 간주되는 반역사적 접근 방식]의 위험이 있습니다. 환자 참여 관행을 보건 전문직 학습에 대한 환자 참여에 대한 더 큰 논쟁과 딜레마의 맥락에 다시 넣음으로써 교육에서 환자 참여의 역할에 대한 새로운 통찰력을 얻을 수 있습니다. 이러한 인사이트는 현재 운영되고 있는 환자 참여 관행에 생산적으로 적용될 수 있을 뿐만 아니라 향후 교육 개혁, 특히 역량 기반 교육과 관련된 개혁에서 환자 참여에 대한 임박한 질문에도 적용될 수 있습니다.

While the inclusion and exclusion criteria being applied in these previous reviews are both important and defensible, the focus on patients as teachers necessarily obfuscates alternative conceptualizations of patients’ involvement in health professions education. The result is that patient engagement in health professions education is conceptually reduced to just one possible iteration of patient involvement—patients as teachers—and is taken out of context of the other ways in which patients participate in processes of ongoing professional learning. As Bleakley (2014) puts it, there is a need to understand processes of learning with, from, and about patients as foundational to the entire health professions education enterprise. To focus on current iterations of patients as teachers risks an ahistorical approach, where recent iterations of patient engagement are taken to be “new and exciting roles” (Stockhausen 2009) that do not take into account the rich bodies of literature that could inform how these roles might actually be enacted. By putting patient engagement practices back into context of larger debates and dilemmas about patient involvement in health professions learning more broadly, new insight might be garnered about the role of patient engagement in education. This insight might be productively applied to practices of patient engagement as they currently operate, but also impending questions about patient involvement in future educational reforms, specifically reforms related to competency based education.

이 검토의 목적은 다양한 연구 전통에서 [시간이 지남에 따라 보건의료 전문직 교육에 대한 환자 참여 문제가 어떻게 고려되어 왔는지 종합하는 것]이었습니다. 우리는 환자 참여에 대한 관심을 [환자 참여engagement]에 국한하지 않고 교육에 대한 [환자 참여involvement]라는 더 넓은 개념에 초점을 맞추기로 했습니다. 특히, 우리는 보건 전문직 교육에 대한 환자 참여에 관한 광범위한 지식 기반에 기여하는 다양한 연구 전통 내의 논쟁과 딜레마에 중점을 두었습니다. 따라서 보건 전문직 문헌의 모든 환자 참여 관련 출판물을 포괄적으로 요약하는 것을 목표로 하지 않았습니다. 우리는 환자 참여 연구에 대한 다양한 접근 방식과 이러한 접근 방식에 영향을 주는 다양한 철학적 가정 및 세계관을 포함하여 의미 있는 종합을 생성했습니다.

The objective of this review was to synthesize how questions of patient involvement in health professions education have been considered over time across various research traditions. We have chosen to focus on the broader concept of patient involvement in education, rather than restricting our interest to patient engagement. In particular, our focus was on the debates and dilemmas within the various research traditions that contribute a broader base of knowledge regarding patient involvement in health professions education. In this way, we did not aim to generate a comprehensive summation of all the patient involvement publications in the health professions literature. We generated a meaningful synthesis of various approaches taken to the study of patient involvement, including the various philosophical assumptions and world views that inform these approaches.

이 종합은 메타 내러티브 검토 프로세스를 사용하여 수행되었습니다(Greenhalgh 외. 2004, 2005, 2009; Wong 외. 2013). 메타 내러티브 검토의 근거는 아래에 자세히 설명되어 있습니다. 이 논문에서는 보건 전문직 교육에 대한 환자 참여와 관련된 세 가지 연구 활동의 동시적 흐름을 강조하는 연구 결과를 보고하고, 이러한 활동 흐름 사이의 다양한 긴장에 대해 논의합니다. 이 특별한 검토의 고유한 기여는 보건 전문직 교육에서 환자 참여와 관련된 연구 활동에 대한 비판적이고 해석적인 관점을 추가한 것입니다. 메타 내러티브 리뷰는 비교적 새로운 형태의 지식 종합이므로 분석을 제시하기 전에 그 방법론을 자세히 설명하고 설명하겠습니다.

The synthesis was conducted using a meta-narrative review process (Greenhalgh et al. 2004, 2005, 2009; Wong et al. 2013). The rationale for the meta-narrative review is described in more detail below. In this paper, we report on our findings—highlighting three concurrent streams of research activity related to patient involvement in health professions education—and we discuss the various tensions between these streams of activity. The unique contribution of this particular review is the addition of a critical and interpretive perspective of the research activity related to patient involvement in health profession education. As meta-narrative reviews are relatively new forms of knowledge synthesis, we will describe and explain its methodology in detail prior to presenting our analysis.

방법론: 지식 종합으로서의 메타 내러티브 리뷰

Methodology: meta-narrative review as knowledge synthesis

메타 내러티브 리뷰는 [서로 다른 연구자 그룹에 의해 서로 다르게 개념화되고 검토된 주제]를 위해 특별히 고안되었습니다(Wong et al. 2013). 2004년에 Greenhalgh 등이 개발한 메타 내러티브 리뷰는 연구 결과가 어떻게 생산되는지에 초점을 맞추고 있습니다(Greenhalgh 등 2005). 2004년부터 메타 내러티브 접근법은 아래 등을 조사하는 데 생산적으로 사용되어 왔습니다.

- 커뮤니티의 구성(Jamal 외. 2013),

- 전자 환자 기록 연구의 역설과 긴장(Greenhalgh 외. 2009),

- 서비스 조직에서 혁신의 확산(Greenhalgh 외. 2004)

The meta-narrative review is designed specifically for topics that have been differently conceptualized and examined by different groups of researchers (Wong et al. 2013). Developed by Greenhalgh et al. in 2004 (Greenhalgh et al. 2005), the focus of meta-narrative reviews is on how research findings are produced (Gough 2013). Since 2004, meta-narrative approaches have been productively used to examine (among other things)

- the constructs of community (Jamal et al. 2013),

- the paradoxes and tensions in electronic patient records research (Greenhalgh et al. 2009), and

- the diffusion of innovations in service organizations (Greenhalgh et al. 2004).

메타 내러티브 검토는 개인이 [상충하는 문헌을 이해하는 데 도움을 주기 위한 실용적인 목표]를 가지고 있습니다(Wong 외. 2013). 메타 내러티브 리뷰는 [특정 주제에 대한 지식]이 [연구 전통 내]에서 그리고 [여러 연구 전통에 걸쳐] 어떻게 발전해 왔는지에 관한 것입니다(Greenhalgh et al. 2005). 이는 보건 전문직 교육에 대한 환자 참여에 관한 기존의 모든 증거를 목록화하는 것과는 다릅니다. 대신, 이러한 형태의 지식 종합은 해당 학문 분야를 구성하는 다양한 전통에 존재하는 역사, 기본 가정, 주요 연구 결과와 관련이 있습니다. 여기서 [연구 전통]은 [공유된 가정]과 [선호되는 방법론]을 통해 연결된 일련의 연결된 연구로 간주됩니다(Wong et al. 2013). 메타 내러티브 검토는 다음을 역사적으로 살펴봅니다(Wong et al. 2013).

- [특정 연구 전통이 시간이 지남에 따라 어떻게 전개되어 왔는지],

- 이러한 [전통이 제기되는 질문의 종류]를 어떻게 형성했는지

- 이러한 [질문에 답하는 데 사용되는 방법]은 무엇인지

따라서 메타 내러티브 리뷰의 결과물은

- 아이디어의 다단계 구성의 지도이며

- 이러한 아이디어가 주제에 대해 알 수 있는 것에 어떤 영향을 미쳤는지에 대한 지도이다.

A meta-narrative review has a pragmatic goal, intended to help individuals make sense of a conflicting body of literature (Wong et al. 2013). A meta-narrative review is concerned with how knowledge of a particular topic has been developed within and across research traditions (Greenhalgh et al. 2005). This is distinct from cataloging all the existing evidence about patient involvement in health professions education. Instead, this form of knowledge synthesis is concerned with the history, guiding assumptions, and key findings that exist within the different traditions that comprise the scholarly field. Here, a research tradition is considered to be a series of linked studies that are connected through shared assumptions and preferred methodologies (Wong et al. 2013). A meta-narrative review looks historically at

- how particular research traditions have unfolded over time,

- how these traditions have shaped the kinds of questions being asked, and

- the methods that are used to answer those questions (Wong et al. 2013).

Thus, the outputs of meta-narrative reviews are

- maps of multi-level configurations of ideas and

- how these ideas have influenced what can be known about a topic.

메타 내러티브 검토는 두 가지 이유로 선택한 방법론이었습니다.

- 첫째, 이 연구의 초기 단계부터 여러 연구팀이 서로 다른 방식으로 이 주제를 개념화하고 연구하고 분석했음을 알 수 있었습니다.

- 둘째, 우리의 주요 목표는 여러 분야에 걸친 상충되는 문헌을 이해하고 이러한 분야가 서로에게 어떤 영향을 미쳤는지 살펴보는 것이었습니다.

환자 참여를 역사적, 정치적, 사회적 담론에 내재된 사회적 혁신으로 이해할 필요가 있고 메타 내러티브 검토에 관한 국제 RAMESES 가이드라인(Wong 외. 2013)에 따라 메타 내러티브 검토를 방법론으로 선택했습니다. 메타 내러티브 검토에 참여하면서 우리는 잠재적인 개념적 긴장을 강조하고 이러한 긴장이 보건 전문직 교육 분야에서 환자 참여가 어떻게 계속 실행되고 연구될 수 있는지에 대한 함의를 해석하여 비판적인 종합을 제공하고자 했습니다.

Meta-narrative review was our methodology of choice for two reasons.

- First, from an early stage in this study it was evident that different research teams had conceptualized, studied and analyzed the topic in different ways.

- Second, our primary aim was to make sense of a conflicting literature that spanned many fields, and also look at how these fields have influenced one another.

Given the need to understand patient involvement as a social innovation embedded in historical, political, and societal discourses, and following the international RAMESES guidelines on meta-narrative reviews (Wong et al. 2013), the meta-narrative review was selected as the methodology of choice. In engaging in a meta-narrative review, we sought to offer a critical synthesis, highlighting potential conceptual tensions and interpreting the implications of these tensions for how patient engagement might continue to be practiced and researched in the health professions education field.

메타 내러티브 검토의 방법론을 채택할 때, 우리는 Greenhalgh 외(2005)가 처음 소개하고 나중에 메타 내러티브 검토를 위한 RAMES 출판 표준에 요약된 6가지 지침 원칙을 따랐습니다(Wong 외. 2013). 이러한 원칙에는 실용주의, 다원주의, 역사성, 논쟁, 반성성, 동료 검토가 포함됩니다.

In taking up the methodology of meta-narrative review, we also ascribed to the six guiding principles first introduced by Greenhalgh et al. (2005) and later summarized in the RAMESES publication standards for meta-narrative reviews (Wong et al. 2013). These principles include: pragmatism, pluralism, historicity, contestation, reflexivity, and peer review.

수집 절차 및 분석 전략

Collection procedures and analytical strategy

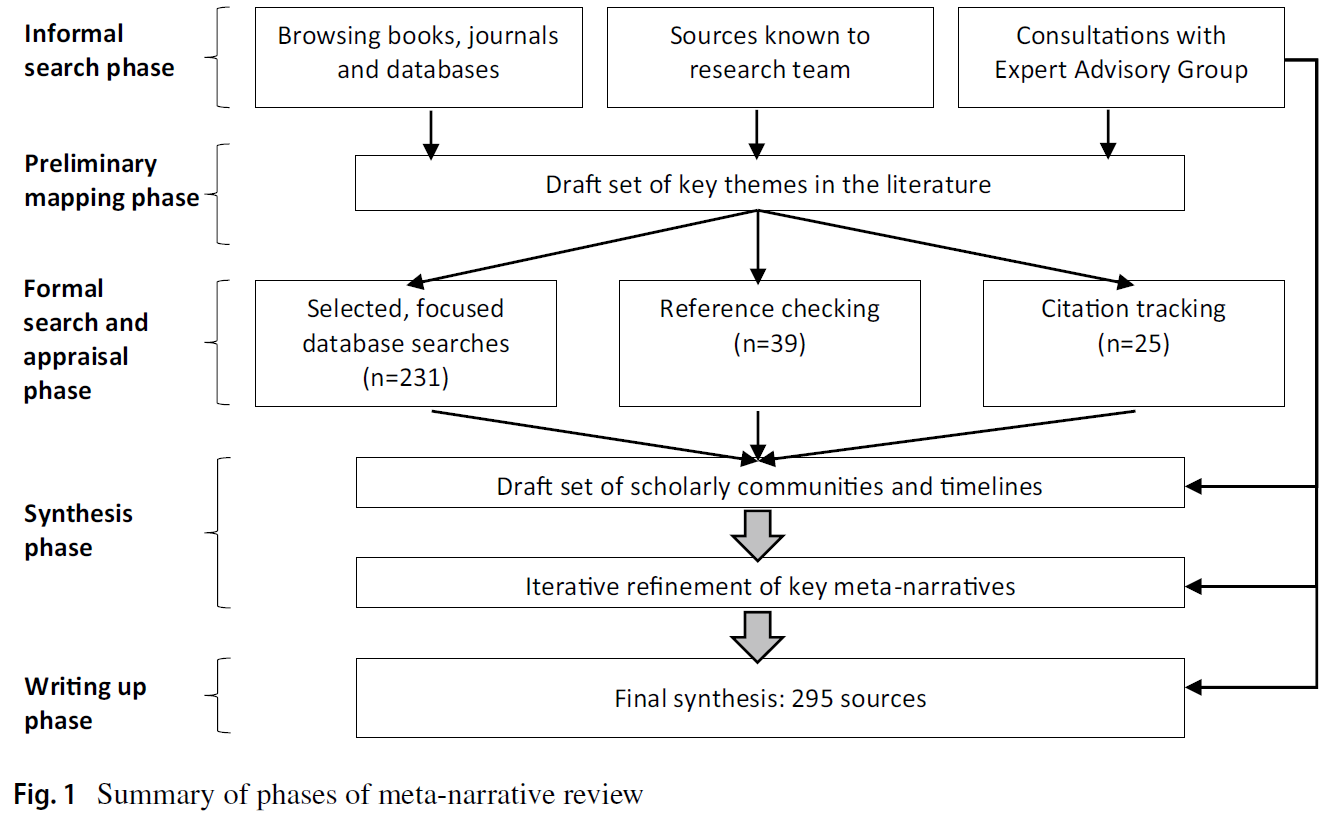

이 지식 종합의 절차는 RAMES에서 발표한 가이드라인을 따르며, (1) 아카이브 수집, (2) 분석, (3) 고차 개념 간의 교차점 해석이라는 세 가지 주요 단계를 통해 발전했습니다. 이러한 단계는 선형적인 순서로 제시되어 있지만, 분석 단계를 통해 아카이브의 추가 개발이 필요함을 알 수 있고, 고차 개념 간의 해석을 통해 추가 분석의 필요성을 알 수 있는 등 단계 간에 많은 중복과 상호 연결이 있었습니다. 그림 1은 포함된 텍스트의 1차 아카이브에 대한 수집, 선별 및 분석 과정을 보여줍니다. 검색 과정과 결과 분석 절차는 동료 검토의 기본 원칙에 따라 검토에 참여하도록 초청된 전문가 자문위원회와의 지속적인 협의를 통해 결정되었습니다. 자문위원회에는 환자, 보건 전문직 교육자, 사회과학 연구자가 포함되었습니다.

The procedures for this knowledge synthesis follow the guidelines published by RAMESES and evolved through three main phases: (1) collecting the archive, (2) analysis, and (3) interpreting intersections between higher order concepts. While these phases are presented in linear order, there was much overlap and interconnection between the phases such that stages of analysis informed the need for further development of the archive, interpretation between higher order concepts pointed towards the needs for further analysis and so on. Figure 1 displays the process of collection, screening, and analysis of the primary archive of texts included. The search process and resulting analytical procedures were informed through ongoing consultations with an expert advisory council that had been invited to participate in the review, adhering to the guiding principle of peer review. Members of the advisory council included patients, health professions educators, and social science researchers.

제외 기준은 실용주의 원칙, 즉 의도된 청중에게 가장 유용하고 이해도를 높일 가능성이 가장 높은 내용을 중심으로 검토해야 한다는 원칙에 따라 결정되었습니다(Wong et al. 2013). 이 검토에서는 임상 치료의 순간에 환자의 참여에만 관심이 있고 학습 또는 교육과 관련하여 명시적으로 연결 및/또는 이론화되지 않은 출처는 제외했습니다. 이 검토를 포함하기 위해 환자 교육 개발 시 환자 참여와 관련된 문헌도 포함하지 않았습니다. 그러나 방법론적 엄격성에 대한 분석에 따라 출처를 제외하지는 않았습니다. 저희는 여러 전통에 걸친 증거를 목록화하기보다는 어떤 종류의 주장이 가능한지에 더 중점을 두었습니다. 따라서 특정 분야에서 영향력이 있는 것으로 간주되는 출처는 특정 사고 방식을 보여주는 것으로 데이터 세트에 포함시켰습니다. 그 결과, 데이터 세트에 포함된 출처 중 일부는 해당 분야 내에서 논쟁의 여지가 있을 수 있습니다. 이러한 논쟁도 흥미롭습니다.

Our exclusion criteria were informed by the principle of pragmatism, namely that the review should be guided by what will be most useful to the intended audience(s), and what is most likely to promote sense-making (Wong et al. 2013). For this review, we excluded sources that were solely concerned with patient engagement in moments of clinical care and were not explicitly linked and/or theorized in relation to learning or education. For the purposes of containing this review, we also did not engage with the literature that is concerned with patient involvement in developing patient education. However, we did not choose to exclude sources based on an analysis of their methodological rigor. Our concern was less with cataloguing evidence across traditions, and more focused on what kinds of claims were possible to say at all. As such, if a source was considered to be influential within a particular field, it was included in our dataset as display of a particular way of thinking. The result may be that some of the sources included in our dataset may be contested within their own field. Those contestations are also of interest.

연구 초기에는 이 검토를 의학과 간호 등 한두 가지 의료 전문직으로 제한할지 여부도 고려했습니다. 하지만 전문직 간 교육 분야에서 환자 참여가 보편화되고 있다는 점을 고려하여 검색 전략을 전문직별로 제한하지 않기로 결정했습니다. 이 결정은 보건 전문직 교육 분야 전반에 걸쳐 어느 정도 의미 있는 결정을 내릴 수 있게 해주었지만, 원고의 한계 섹션에서 다룬 다른 개념적 딜레마를 야기했습니다.

Early in the study, we also considered whether we should limit this review to one or two health professions, namely medicine and nursing. Given the prevalence of patient involvement that is emerging in the field of interprofessional education, we chose to not limit our search strategy by profession. While this decision allowed a certain kind of sense-making across the field of health professions education, it introduced other conceptual dilemmas that we address in the Limitations section of the manuscript.

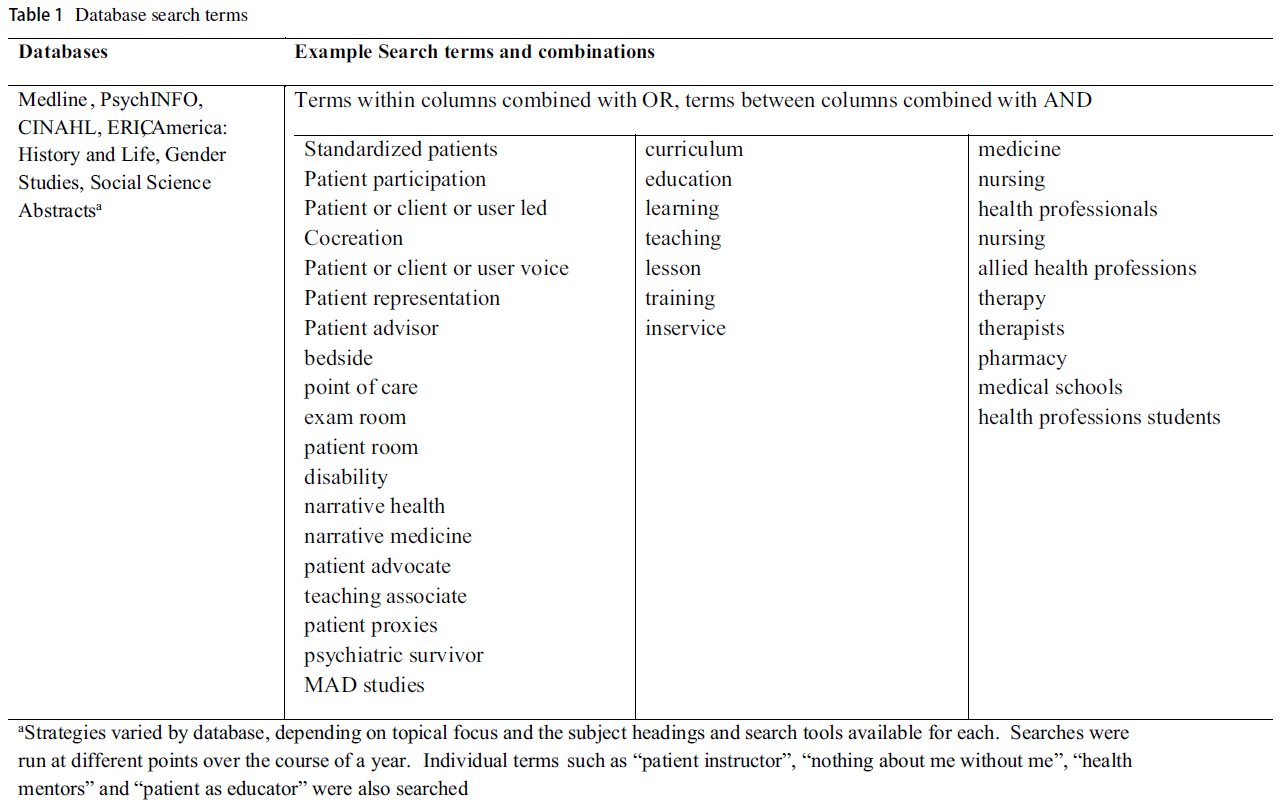

초기 데이터 수집에는 비공식적 및 공식적 검색 전략이 혼합되어 사용되었습니다. 2016년 9월부터 핵심 연구팀과 자문 위원회가 식별한 용어를 사용하여 Medline, PsycINFO, CINAHL, ERIC, 젠더 연구 데이터베이스, 사회학 초록, 미국 역사와 생활에 대한 초기 검색을 수행했으며, 각 데이터베이스의 주제 제목과 도구를 활용하여 관련성이 가장 높은 인용에 집중했습니다. 표 1은 초기 공식 검색에 사용된 검색어에 대한 개략적인 요약이며, 각 데이터베이스에 따라 다양하게 조정되었습니다. 제목과 초록의 관련성에 대한 초기 선별은 연구팀원 두 명(PR 및 SM)이 수행했습니다. 이 초기 선별 작업 이후, 두 명의 연구원이 주제별 클러스터를 만들어 나머지 아카이브를 정리했습니다(표 2 참조). 이 클러스터는 나머지 연구팀원들과의 지속적인 토론과 협업, 자문위원회의 자문을 통해 만들어졌습니다. 주제별 클러스터에 대한 합의에 따라 연구팀의 각 구성원(PR, SM, AKK, VS, SL)이 하나의 클러스터를 주도적으로 이끌었습니다. 정보 전문가(MA)와 협력하여 각 구성원은 특정 주제 클러스터를 정교화하거나 정보를 제공하거나 복잡하게 만드는 소스를 계속 검색, 요약 및 분석했습니다. 포함된 각 출처의 데이터 추상화에는 저자, 연도, 출판 장소, 주요 주장, 인용된 이론가/주요 출처 등이 포함되었습니다. 이 단계의 일환으로 각 수석 팀원은 주요 연구자, 중요하고 많이 인용되는 출처, 자주 함께 출판하는 저자를 파악했습니다. 이 작업은 검색어와 주요 출처에 대한 조언을 제공한 전문가 자문 패널의 자문과 함께 이루어졌습니다. 연결은 역사성 원칙에 따라 시간 경과에 따라 매핑되었습니다. 이러한 방식으로 다양한 연구 흐름을 만들어내는 주요 학술 커뮤니티를 밝혀내기 시작했습니다. 새로운 용어와 저자가 확인되면 추가 검색을 수행했습니다. 표 1에는 이러한 추가 검색어가 요약되어 있습니다.

Initial data collection included a mix of informal and formal search strategies. Starting in September of 2016, initial rounds of searches of Medline, PsycINFO, CINAHL, ERIC, Gender Studies Database, social studies abstracts and America history and life were performed using terms identified by the core research team and the advisory council, making use of the subject headings and tools available in each database to focus on the citations most likely to be relevant. Table 1 provides a high-level summary of the search terms used in the initial formal search, with various adaptions made for each database. Initial screening of titles and abstracts for relevance was conducted by two members of the research team (PR and SM). Following this initial screening, two of the investigators created thematic clusters to organize the remaining archive (see Table 2). These clusters were created through ongoing discussion and collaboration with the rest of the research team, and through consultation with the advisory council. Following consensus on the thematic clusters, each member of the research team (PR, SM, AKK, VS, SL) took leadership of a single cluster. In collaboration with the information specialist (MA), each member continued to search, summarize, and analyze sources that elaborated, informed, or complicated their particular thematic cluster. Data abstraction from each included source included: author(s), year, place of publication, main claims being made, and theorists/key sources cited. As part of this phase, each lead team member identified key researchers, seminal/highly cited sources, and authors that frequently published together. This was done in consultation with members of an Expert Advisory Panel who also provided advice on search terms and key sources. The connections were mapped out over time, following the principle of historicity. In this way, we started to elucidate key scholarly communities producing a range of research streams. Additional searches were performed as new terms and authors were identified. Table 1 summarizes these additional search terms.

검토를 진행하면서 '나 없이는 아무것도 없다'라는 문구가 역사적으로나 현재적으로 매우 중요한 의미를 지니고 있다는 사실을 알게 되었습니다. 따라서 우리는 이 문구를 역사적 맥락에 배치하기 위해 검색을 확장했습니다. Google Ngram과 Google 북스를 사용하여 '나 없이는 아무것도 없다'라는 문구를 시간 경과에 따라 추적했습니다. "나 없이는 나에 대해 아무것도 없다"에 대한 공식 데이터베이스 검색과 변형된 검색도 Embase, PsycINFO, Medline 및 ERIC에서 수행했습니다. 마지막으로 핵심 저자가 작성했거나 핵심 연구팀이 확인한 주요 논문을 인용한 논문을 찾기 위해 Web of Science를 사용했습니다. Greenhalgh와 Peacock(2005)의 의견에 동의하여, 우리는 공식 데이터베이스가 아닌 스노우볼링, 참고 문헌 목록 확인, 인용 검색을 통해 가장 유익한 검색 결과를 얻을 수 있었습니다.

As the review unfolded, it became clear that the phrase “nothing about me without me” had a great deal of historical and current salience. We therefore extended our search to help place the phrase in historical context. We used Google Ngram and Google Books to help track the phrase “nothing about me without me” over time. Formal database searches for “nothing about me without me” and variations were also performed in Embase, PsycINFO, Medline and ERIC. Finally, Web of Science was used to locate articles which were either written by key authors or which had cited key papers identified by the core research team. In agreement with Greenhalgh and Peacock (2005), we found our most fruitful searches were not in the formal databases, but were through snowballing, checking references lists, and citation searching.

한 해 동안 연구팀은 여러 차례 분석 세션을 가졌습니다. 데이터 세트 전반에 걸쳐 다양한 개념, 연구 설계, 주장이 제기되었기 때문에 [통계적 분석 전략]보다는 [내러티브 분석 전략]을 사용했습니다. 다양한 연구 전통을 포함하기로 한 이러한 결정은 [다원주의 원칙]에 부합하는 것입니다. 분석 세션을 통해 다양한 연구 커뮤니티의 경계를 파악했습니다. [논쟁이라는 기본 원칙]에 따라 분석 세션을 통해 다양한 커뮤니티 간의 연결과 경합, 합의의 주요 대상, 각 커뮤니티에서 지속되고 있는 다양한 논쟁을 강조하는 데 사용했습니다. 이러한 방식으로 네 가지 주제별 흐름은 해석의 시작점을 제공했습니다.

Over the course of the year, our research team met for several analysis sessions. Given the diversity of concepts, research designs, and claims being made across the dataset, we engaged in narrative, rather than statistical analytical strategies. This decision to include multiple research traditions is consistent with the principle of pluralism. Through our analytical sessions, we identified the boundaries of various research communities. Informed by the guiding principle of contestation, we used our analytical sessions to highlight connections and contentions between these various communities, key objects of consensus and various enduring debates occupying each of these communities. In this way, the four thematic streams provided an entry point into our interpretation.

이러한 매핑과 해석의 층위에서 우리는 보건 전문직 교육에 대한 환자 참여 분야를 구성하는 다양한 메타 내러티브를 설명하기 위해 상위 개념과 이러한 개념을 뒷받침하는 연구 전통을 명확히 표현하기 시작했습니다. 따라서 여기에는 문헌의 주제(예: 내러티브 의학, 병상 학습, "나 없이는 나에 대해 아무것도 없다", 표준화된 환자로서의 실제 환자)에서 중요한 패러다임 수준에서 작동하는 [메타 내러티브로 이동하는 추가적인 해석적 조작]이 필요했습니다.

From this layer of mapping and interpretation, we began to articulate the higher order concepts—and the research traditions enlivening these concepts—as an explication of various meta-narratives comprising the field of patient involvement in health professions education. Thus, this involved a further interpretive maneuver, moving from themes in the literature (i.e. narrative medicine, bedside learning, “nothing about me without me”, and real patients as standardized patients) to meta-narratives that operate at the level of overarching paradigms.

각 주제에 담긴 개념과 결론은 이러한 메타 내러티브의 맥락에 배치되었습니다. 따라서 우리의 종합 전략은 높은 수준의 추상화에서 작동했으며 다음을 검토해야 했습니다(Wong et al. 2013).

- (a) 기본 개념 및 이론적 가정의 공통점,

- (b) 기본 개념 및 이론적 가정의 차이점,

- (c) 다양한 패러다임 간의 상호 작용과 긴장,

- (d) 다양한 패러다임에 걸친 패턴 탐색

이러한 높은 수준의 추상화는 필연적으로 각 주제를 구성하는 뉘앙스의 일부를 잃게 하지만, 다른 방법으로는 불가능했던 방식으로 문헌을 개념적으로 연결할 수 있게 해주었습니다.

Concepts and conclusions held within each of the themes were put into context of these meta-narratives. Thus, our synthesis strategy operated at a high level of abstraction and required us to examine:

- (a) commonalities in underlying conceptual and theoretical assumptions,

- (b) differences across underlying conceptual and theoretical assumptions,

- (c) interplay and tensions between various paradigms, and

- (d) exploring patterns that span across various paradigms (Wong et al. 2013).

This high level of abstraction necessarily loses some of the nuance that occupies each theme, but allowed us to put bodies of literature into conceptual contact in a way that would not have been otherwise possible.

이 과정에서 우리는 연구자로서 우리 자신의 입장에 대해 반성했습니다. 주 저자는 다른 분야에서 환자 참여의 구조를 탐구해 온 조직학 학자입니다. 두 명의 구성원은 특히 내러티브 개념과 건강 멘토의 환자 역할을 활용하여 수년 동안 보건 전문직 교육 프로그램에서 환자 참여를 개발하고 실행해 왔습니다. 두 명은 보건 전문직 학생이었습니다. 한 명은 만성 질환, 장애를 앓고 있으며 다양한 자문 및/또는 옹호 단체에서 환자로 자원봉사를 한 경험이 있습니다. 마지막으로 정보 전문가가 연구팀의 핵심 멤버였습니다. 협업을 통해 우리는 환자 참여에 대한 우리만의 가정(환자 참여의 의미, 관심의 이유, 환자 참여가 '어떻게' 이루어져야 하는지, 어떻게 연구되어야 하는지)을 명시적으로 제시해야 했습니다. 예를 들어, 가장 유익한 분석적 결정 중 하나는 데이터 수집의 일부로 '적극적 대 소극적 환자 참여'에 대한 가정을 포함/제외 기준으로 삼지 않고, 대신 이 이분법을 해석적으로 접근하는 것이었습니다: 고려 중인 학계에서는 적극적 대 소극적 환자 참여라는 이분법을 어떻게 다루고 있을까요? 해석의 마지막 단계는 이 원고를 작성하는 것이었습니다. 즉, 우리가 집중할 메타 내러티브를 선택하고, 어떤 긴장을 조명하고, 단어의 제한을 고려할 때 어느 정도 깊이까지 다룰지 선택해야 했습니다.

Throughout the process, we were reflexive about our own position as researchers. The lead author is an organizational studies scholar who has explored constructs of patient engagement in other fields. Two members have spent many years developing and implementing patient engagement in health professions education programs, particularly making use of concepts of narrative and the patient role of Health Mentor. Two members were health professions students. One member also has experience of chronic illness, disability, and has volunteered as patient in various advisory and/or advocacy groups. Finally, our information specialist was a core member of the research team. Through our collaboration, we were required to make explicit our own assumptions about patient involvement (what it meant, why it was of interest, how it “should” be done, how it should be researched). For instance, one of our most fruitful analytical decisions was to release our assumptions about “active versus passive patient involvement” as an inclusion/exclusion criteria as part of the data collection, and instead engage with this dichotomy interpretively: how do the scholarly communities under consideration deal with this dichotomy of active versus passive patient involvement? Our final step of interpretation was to produce this manuscript. By this we mean that we were required to choose meta-narratives to focus on, which tensions to illuminate, and to what depth given the word limits available to us.

주요 결과: 의료 전문직 교육에 대한 환자 참여의 동시적 구축

Main findings: concurrent constructions of patient involvement in health professions education

캐나다의 저명한 의학교육자인 윌리엄 오슬러는 의료 전문직 교육에 대한 환자 참여와 관련된 모든 학계에서 두드러진 활약을 펼쳤습니다. 특히 뉴욕의 의학 아카데미에서 행한 그의 유명한 연설은 자주 인용되었는데, 그는 다음과 같이 선언했습니다: "의학 및 외과 분야의 후배 학생에게는 환자 없이 텍스트를 가르치지 않는 것이 안전한 규칙이며, 가장 좋은 가르침은 환자가 직접 가르치는 것입니다."(Towle and Godolphin 2011, 496쪽에서 인용). 그러나 이후 연구자와 교육자가 이 선언을 받아들이는 방식과 이와 관련하여 개발된 프로그램 및 기관은 모두 [학계 간의 차이]를 반영합니다. 다음 섹션에서는 보건의료 전문직 교육에 대한 환자 참여가 학문 분야와 연구 전통에 따라 이해되는 방식 중 세 가지에 대해서만 설명하겠습니다. 이 과정을 통해 다음을 살펴볼 것입니다.

- (a) '환자' 개념의 구성,

- (b) 보건 전문직 교육에 환자가 참여해야 하는 이유,

- (c) 해당 분야의 지식 창출과 관련된 연구 전통

William Osler, the well-known Canadian medical educator, featured prominently in all scholarly communities concerned with patient involvement in health professions education. In particular, his famous address to the Academy of Medicine in New York was frequently cited, where he declared: “for the junior student in medicine and surgery, it is a safe rule to have no teaching without a patient for a text, and the best teaching is that taught by the patient himself” (cited in Towle and Godolphin 2011, p. 496). However, the ways in which researchers and educators subsequently took up that declaration—and the programs and institutions developed in association with those constructions—all reflect distinctions between scholarly communities. In the following section, we will demarcate just three of the ways in which patient involvement in health professions education is understood across academic disciplines and research traditions. Through the process, we will explore:

- (a) constructions of the notion of “patient”,

- (b) rationales for patient involvement in health professions education, and

- (c) research traditions associated with generating knowledge in the field.

이를 통해 각 학계에서 벌어지고 있는 다양한 논쟁과 딜레마를 조명할 것입니다.

Throughout, we will highlight various debates and dilemmas occupying each of the scholarly communities.

'참여된 환자'의 출현으로서의 환자 참여: 민주적이고 해방적인 근거

Patient involvement as emergence of the “engaged patient”: democratic and emancipatory rationales

2011년에 Towle과 Godolphin은 [환자 참여]의 정의를 [교육 과정의 설계, 제공 및/또는 평가에 적극적으로 참여하는 것]으로 사용하여 보건 전문직 문헌에서 환자 참여를 유용하게 종합했습니다. 이 종합을 통해 앞서 [참여의 타임라인]을 제시했습니다.

- 언급한 오슬러의 유명한 선언에서 시작하여

- 1970년대에 '임상 교육 보조원(CTA)'으로 발전하고,

- 1990년대에 환자 참여에 대한 보다 정치적으로 적극적인 역할로 이어졌으며,

- 최근에는 환자 전문성이 생의학 모델을 넘어 보건 전문직 교육을 발전시키는 데 도움이 되는 정당한 지식의 원천으로 인정받으면서 절정에 이르렀다.

우리의 종합은 비슷한 시기를 중심으로 이루어졌으며, 우리는 이를 "참여된 환자의 출현"이라고 명명했습니다.

In 2011, Towle and Godolphin usefully synthesized patient engagement in health professions literature, using the definition of patient engagement as active engagement in the design, delivery, and/or evaluation of curriculum. Through their synthesis, they presented a timeline of engagement,

- originating in Osler’s aforementioned famous declaration,

- evolving into “clinical teaching associates” (CTAs) in the 1970s,

- followed by a more politically active role for patient involvement in the 1990s, and

- culminating in a recent recognition of patient expertise as a legitimate source of knowledge that serves to move health professions education beyond the biomedical model.

Our synthesis distilled around a similar timeline, which we have labelled as “the emergence of the engaged patient”.

이 작업에서 참여된 환자는 특별한 의미를 가졌습니다.

- 첫째, 누구를 ['진짜' 환자]로 정의할 것인지에 대해 많은 논의가 있었습니다. [실제 환자]는 표현하고자 하는 질병 및/또는 상태를 직접 경험한 사람]으로 간주했습니다. 실제로 겪지 않은 증상이나 상태를 표현하기 위해 환자 역할극을 하는 사람은 "실제" 환자로 간주되지 않았으므로 이 범주에서 제외되었습니다(Towle 외. 2010). 따라서 [환자]와 [일반 대중] 사이에는 차이가 있었습니다. 또한, 이 연구 커뮤니티에서는 실제 환자가 "전문적인 가치 체계의 제약을 받지 않고 영향을 받지 않는"(O'Neill 외. 2006, 27쪽) [의료 전문가가 배제되는 경우]가 많았습니다.

- 둘째, 특정 질병 경험을 배제하기 위한 명백한 정의는 없었지만, 이 작업의 대부분은 만성 질환 문헌에서 자리 잡은 "전문가 환자"라는 개념(Muir and Laxton 2012; O'Neill 외 2006; Skog 외 2000; Towle and Godolphin 2011)과 [비판적 장애 연구] 및 [정신 건강 운동]의 "나 없이는 아무것도 없다"는 외침(Beecham 2005; Bollard 외 2012; Charlton 1998)에 기반하고 있었습니다. 만성 질환과 환자 전문성이 강조되면서 [급성 질환]을 경험하고 이후 완치된 환자를 '교사로서의 환자'로 간주할 수 있는지 여부가 명확하지 않았습니다. 이 구분은 이 원고의 뒷부분에서 논의하는 환자 참여에 대한 다른 이해와 대비되는 지점이 되기 때문에 주목합니다.

In this body of work, the engaged patient took on particular meaning.

- First, there was much discussion about who to define as a “real” patient. Real patients were considered to be those that have direct lived experience with the illness and/or condition they sought to display. People who role-play patients to express symptoms or conditions they do not actually have were not considered “real” patients and thus excluded from this category (Towle et al. 2010). Thus, there was a distinction between patients and general members of the public. Further, in this research community, health professionals were often excluded, where real patients “are not constrained and influenced by professional value systems” (O’Neill et al. 2006, p. 27).

- Second, while there were no overt definitions that served to exclude particular illness experiences, much of this body of work was anchored in notions of “expert patients” that have taken hold within the chronic illness literature (Muir and Laxton 2012; O’Neill et al. 2006; Skog et al. 2000; Towle and Godolphin 2011) and the “nothing about me without me” rallying cry of critical disability studies and mental health movements (Beecham 2005; Bollard et al. 2012; Charlton 1998). With the strong emphasis on chronic illness and patient expertise, it was not clear whether patients who had experienced acute illnesses that had subsequently resolved would be considered as “patients as teachers”. We draw attention to this demarcation, as it serves as a point of contrast to an alternate understanding of patient involvement discussed later in this manuscript.

이러한 작업은 보건 전문직 교육에 대한 [환자 참여에 대한 민주적 근거]의 영향을 강하게 받습니다. 여기서 [환자 참여]는 [환자가 자신의 신체와 경험에 대해 가르칠 수 있는 권리]로 정의되었습니다(Beadle 외. 2012; Jha 외. 2010; Robertson 외. 2003; Silverman 외. 2012). 이는 미래의 의료 직업을 형성할 교육 우선순위에 의미 있는 영향을 미칠 수 있는 권리로 발전했습니다(Towle and Godolphin 2011). 때때로 이러한 근거는 [교육 과정의 의사 결정권을 환자에게 이전]하거나 [교육자에서 환자로 권력을 이양하는 역할 모델]을 통해 의료 전문가 간의 기존 권력 관계를 파괴하려는 [해방적인 어조]를 띠기도 했습니다(Beecham 2005). 자주 인용되는 이론가로는 브라질의 교육자이자 철학자로 [비판적 교육학] 및 사회에서의 해방적 잠재력에 관심을 가진 것으로 유명한 파울로 프리에르(Paulo Friere)가 있습니다(Gutman 외. 2012; O'Neill 외. 2006). 또한, 이 연구에서 아른슈타인의 지역사회 참여 사다리에 대한 언급이 있었습니다(Beadle 외. 2012; McKeown 외. 2012). 원래 1960년대와 1970년대에 기존의 지역사회 참여 형태를 비판하기 위해 개발된 이 사다리는(Arnstein 1969), [의사결정 권한을 지역사회 구성원 스스로에게 부여하는 것을 특징]으로 하는 [더 높은 수준의 참여]를 권장합니다. 보건 전문직 교육의 맥락에 대입하면, [참여의 사다리를 올라간다는 것]은 [커리큘럼에 대한 의사 결정 권한]이 [교수진의 영역에만 머무르지 않고 환자에게로 확대된다는 것]을 의미합니다.

This body of work is strongly influenced by democratic rationales for patient engagement in health professions education. Here, patient engagement was framed as the right of patients to teach about their own bodies and experiences (Beadle et al. 2012; Jha et al. 2010; Robertson et al. 2003; Silverman et al. 2012). This was further translated into the right to meaningfully influence educational priorities that will shape health professions of the future (Towle and Godolphin 2011). At times, this rationale took on an emancipatory tone, explicitly attempting to disrupt existing power relationships between health professionals through shifting curricular decision-making power to patients and/or role-modelling the abdication of power from educators to patients (Beecham 2005). Frequently cited theorists included Paulo Friere (Gutman et al. 2012; O’Neill et al. 2006), a Brazilian educator and philosopher famously concerned with critical pedagogies and their emancipatory potentials in society. Further, it was only in this body of work that there was reference to Arnstein’s ladder of community engagement (Beadle et al. 2012; McKeown et al. 2012). Originally developed to critique existing forms of community engagement in the 1960s and 1970s (Arnstein 1969), this ladder recommends higher levels of engagement characterized by increased power for decision-making being placed in the domain of community members themselves. Translated into the context of health professions education, moving up the ladder of engagement implies increased powers of curricular decision making allocated to patients, rather than remaining exclusively in the domain of faculty members.

이 분야에서 벌어지는 논쟁과 딜레마는 이러한 [민주적이고 해방적인 이상]을 반영합니다. 따라서 연구자와 교육자들은 환자 대표성, 진정한(토큰주의가 아닌) 참여, 환자에게 제공되는 의사 결정의 양 결정, 이러한 참여 기회에 대한 환자의 경험에 관한 문제에 관심을 갖고 있습니다(McKeown 외. 2012; Rowland와 Kumagai 2018; Towle 외. 2010; Towle과 Godolphin 2011, 2015; Vail 외. 1996).

- 연구자들은 [환자 참여에 대한 학습자 경험]에도 관심을 가졌지만, 이러한 학습자 경험은 학습자의 경험에 대한 즐거움, 의료 전문가의 공감 수준에 미치는 영향 및/또는 학습자의 임상 기술 습득에 미치는 영향 측면에서 고려되는 경향이 있었습니다(Arenson 외 2012; Duggan 외 2010; Graham 외 2014; Hope 외 2007; Iezzoni and Long-Bellil 2012; Kumagai 2008).

- 다른 관심사로는 환자가 경험하는 치료 효과(McCreaddie 2002), 환자에 대한 보상의 윤리(Bollard 외. 2012), 다양한 장애를 겪고 있는 환자를 포함할 때의 현실적인 딜레마(Hope 외. 2007) 등이 있습니다. 이러한 작업은 [비판적 및 해석적 접근에 중점을 둔 질적 방법론]을 통해 제정되는 경향이 있었습니다.

- 환자가 교육자와 함께 출판물을 공동 저술한 증거가 있는 것은 이 작업의 결과물뿐이었습니다(Agrawal 및 Edwards 2013 참조).

The debates and dilemmas occupying this body of work reflect these democratic and emancipatory ideals. Thus, researchers and educators are concerned with questions of patient representation, authentic (as opposed to tokenistic) engagement, determining the amount of decision making afforded to patients, and patients’ experiences of these engagement opportunities (McKeown et al. 2012; Rowland and Kumagai 2018; Towle et al. 2010; Towle and Godolphin 2011, 2015; Vail et al. 1996).

- While researchers were also concerned with the learner experience of patient engagement, this learner experience tended be considered in terms of either the learner’s enjoyment of the experience, the effects on health professionals’ level of empathy and/or impact on learners’ acquisition of clinical skills (Arenson et al. 2012; Duggan et al. 2010; Graham et al. 2014; Hope et al. 2007; Iezzoni and Long-Bellil 2012; Kumagai 2008).

- Other matters of concern included the therapeutic benefits experienced by patients (McCreaddie 2002), the ethics of compensation for patients (Bollard et al. 2012), and the practical dilemmas of including patients who are experiencing various impairments (Hope et al. 2007). This body of work tended to be enacted through qualitative methodologies, with an emphasis on critical and/or interpretive approaches.

- It was only in this body of work where there was evidence of patients co-authoring publications with educators (see Agrawal and Edwards 2013).

환자 참여, "실제 환자", 표준화된 환자: 기술주의적 근거

Patient involvement, “real patients”, and standardized patients: technocratic rationales

'참여된 환자'와 관련된 업무와 '표준화된 환자로서의 실제 환자'와 관련된 업무 사이에는 많은 부분이 겹칩니다. "표준화된 환자로서의 실제 환자"라는 문구를 풀이하기는 다소 어렵습니다. 문헌에서는

- (a) 실제로 앓고 있지 않은 질병이나 상태를 묘사하기 위해 훈련을 받은 일반인과

- (b) 질병이나 상태를 표준화된 방식으로 묘사하기 위해 훈련을 받은 환자를 구분했습니다.

이 논문에서는 [후자]를 '표준화된 환자로서의 실제 환자'라고 부르며, 이러한 명칭에 내포된 다양한 역설과 딜레마를 인정합니다. 이 리뷰에서는 서로 다른 연구 전통을 조명하기 위해 연구 커뮤니티를 구분하여 다양한 문제 제기와 그에 따른 결론에 주의를 기울입니다. 따라서 의사 결정, 커리큘럼 설계 및 권력 공유와 관련하여 민주적이고 해방적인 우려를 공유하는 표준화 환자와 관련된 주장은 앞선 논의에서 고려됩니다. 실제로 [실제 환자]가 [표준화 환자로서의 경험]을 바탕으로 커리큘럼을 어떻게 형성할 수 있는지(그리고 형성해야 하는지) 관련 연구가 진행 중입니다(Nestel 외. 2008; Plaksin 외. 2016). 또한 정서적 및 신체적 안전을 포함하여 이러한 역할을 수행하는 환자의 경험에 대한 우려도 많습니다(Debyser 외. 2011; Krahn 외. 2002; Plaksin 외. 2016; Taylor 2011; Walters 외. 2003; Webster 외. 2012). 그러나 이러한 공유된 우선순위를 제쳐두고, '표준화된 환자로서의 실제 환자' 서술에는 논의할 가치가 있는 고유한 특징이 있습니다. 지금부터 이 연구, 즉 [표준화 환자로서의 실제 환자]에 대해 살펴보겠습니다.

There is much overlap between the body of work that is concerned with “engaged patients” and that involved with “real patients as standardized patients”. The phrase “real patients as standardized patients” is somewhat challenging to unpack. In the literature, a distinction was made between

- (a) members of the public who have received training in order to portray an illness or condition that they do not actually have and

- (b) patients who received training in order to portray their illness or condition in a standardized way.

It is the latter that is referred to as “real patients as standardized patients” in this paper, even as we acknowledge the various paradoxes and dilemmas implied by such a label. In this review, we draw distinctions between research communities in order to illuminate disparate research traditions, attending to their various problem statements and their resultant conclusions. Therefore, those arguments related to standardized patients that share democratic and emancipatory concerns with decision-making, curricular design, and power sharing are considered in the preceding discussion. Indeed, there is a body of research concerned with how real patients could (and should) shape curricula as a result of their experience as standardized patients (Nestel et al. 2008; Plaksin et al. 2016). Further, there is much concern for the experience of patients acting in these roles, including their emotional and physical safety (Debyser et al. 2011; Krahn et al. 2002; Plaksin et al. 2016; Taylor 2011; Walters et al. 2003; Webster et al. 2012). However, taking those shared priorities aside, there are unique features of the “real patients as standardized patients” narrative that warrant discussion. It is to this body of work—real patients as standardized patients—that we turn to now.

여기서 우리는 [표준화]라는 개념을 구별되는 개념으로 강조합니다. 이 문헌을 역사적 맥락에서 살펴보면, 의대생의 임상 능력을 평가하기 위한 방법으로 모의 환자를 처음 사용한 의사인 하워드 배로우스 박사의 1960년대 연구를 알 수 있습니다(배로우스 1993; 크란 외. 2002). 시뮬레이션 환자의 도입은 의학 교육의 특정 딜레마를 해결하기 위한 것이었습니다.

- 표준 임상 교육의 일부로서 적절한 범위의 교육 사례에 대한 접근을 보장할 수 없다는 점,

- 임상 사례 전반에서 학습 기회의 일관성이 부족하다는 점,

- 예측 불가능성을 고려할 때 학생 평가의 형평성이 결여될 수 있다는 점(Bates and Towle 2012),

- 학생들이 의미 있는 환자 피드백을 받을 수 있는 기회가 부족하다는 점(Bokken et al. 2008) 등

따라서 시뮬레이션은 일련의 문제에 대한 해결책으로 개발되었습니다.

Here we highlight the notion of standardization as a distinguishing concept. Putting this body of literature into historical context points to the 1960s works of Dr. Howard Barrows, a physician who first made use of simulated patients as a way to examine the clinical skills of medical students (Barrows 1993; Krahn et al. 2002). The introduction of simulated patients was to address some particular dilemmas of medical education, namely:

- the inability to ensure access to a suitable range of teaching cases as part of standard clinical education,

- the lack of consistency of learning opportunities across clinical cases,

- the potential lack of equity in the assessment of students given that unpredictability (Bates and Towle 2012), and

- the opportunity for students to receive meaningful patient feedback (Bokken et al. 2008).

Thus, simulation was developed as a solution to a set of problems.

표준화된 환자 문헌은 시뮬레이션 환자 분야에서 역사적인 뿌리를 가지고 있지만, 우리는 결과적으로 [표준화] 개념을 강조하고자 합니다. 표준화 개념에는 각 학생이 정확히 유사한 모의 환자 시나리오를 접하게 될 것이라는 암묵적인 보증이 포함되어 있습니다. 시뮬레이션뿐만 아니라 표준화라는 추가적인 개념적 계층은 다음 두 가지 문제에 적용된 또 하나의 혁신이었습니다(Barrows 1993).

- (1) 학습 기회의 공정한 분배와

- (2) 학습자를 위한 평가 과정의 투명성

주목할 점은 이러한 문제 진술이 주로 학습자와 교육자의 관점에서 정의되었다는 것입니다.

While the standardized patient literature holds historical roots within the field of simulated patients, we wish to highlight the concept of standardization as consequential. Within the concept of standardization, there is implied assurance that each student will encounter an exactly similar simulated patient scenario. This additional conceptual layer—of standardization not just simulation—was a further innovation applied to the paired problems of

- (1) fair distribution of learning opportunities and

- (2) transparency of the assessment process for learners (Barrows 1993).

Of note, those problem statements were primarily defined from the standpoint of learners and educators.

[표준화 환자로서의 실제 환자]를 탐구하는 연구는 이러한 원래 문제 진술의 경계와 가장자리를 계속 탐색하면서 표준화 환자의 적절한 특성(Gall 외. 1984; Jha 외. 2010; Kroll 외. 2008; Long-Bellil 외. 2011; Stillman 외. 1980), 환자의 역할을 준비하는 적절한 방법(Jha 외. 2009b), 표준화 환자가 학생 학습에 미치는 영향을 평가하는 새로운 방법(Jha 외. 2009a)을 모색하고 있습니다. "표준화 환자로서의 실제 환자"에 대한 "능동적" 환자 참여에 대한 언급이 있지만, 이는 다른 교수자가 없을 때 가급적 교육에서 능동적인 역할을 수행하는 것을 의미하는 경향이 있습니다(Bokken 외. 2008). Jha 등(2009b)은 교육자와 학생이 이러한 [능동적인 교수 역할]을 중요하게 생각하지만, 커리큘럼 설계에서 환자의 역할이 반드시 필요하다고 생각하지는 않는다는 사실을 발견했습니다. 또한 근거 기반 의학 접근 방식에 익숙한 연구 설계를 사용하여 [표준화 환자의 유용성에 대한 근거 기반을 개발하려는 노력]이 분명히 있습니다. 이러한 작업에서 증거는 (학생에게) 부정적인 영향이 없는지, (학생에게) 긍정적인 영향이 있는지, (교육 기관에) 비용 편익이 있는지를 기준으로 고려됩니다(Allen 외. 2011, Asprey 외. 2007, Bokken 외. 2008, Davidson 외. 2001).

The body of research that explores real patients as standardized patients continues to explore the boundaries and edges of these original problem statements, exploring suitable characteristics of standardized patients (Gall et al. 1984; Jha et al. 2010; Kroll et al. 2008; Long-Bellil et al. 2011; Stillman et al. 1980), appropriate ways to prepare patients for their role (Jha et al. 2009b), and novel ways to evaluate the impact of these standardized patients on student learning (Jha et al. 2009a). There is reference to “active” patient involvement in the “real patient as standardized patient” body of work, but this tends to refer to active roles in teaching, preferably in the absence of other teachers (Bokken et al. 2008). Jha et al. (2009b) found that educators and students value this active teaching role, but do not necessarily see a role for patients in curriculum design. Further, there are clear efforts to develop an evidence base for the utility of standardized patients, using research designs that are familiar within evidence-based medicine approaches. In this body of work, evidence is considered along the lines of lack of negative impact (for students), the presence of positive impacts (for students), and cost benefits (for the educational institution) (Allen et al. 2011; Asprey et al. 2007; Bokken et al. 2008; Davidson et al. 2001).

그렇다고 해서 이러한 연구들이 [표준화 환자와 그들의 경험]에 둔감하다는 것은 아닙니다. 또한, 지식의 정치와 관련하여 누가 어떤 내용을 다루고, 환자를 어떻게 구성하며, 환자 경험에 대해 무엇을 표시하는지에 대해 [누가 결정하고 그러한 결정이 어떻게 이루어지는지에 대해 의문을 제기]하는 연구가 증가하고 있습니다(Taylor 2011). 이처럼 권력과 의사 결정에 대한 의문이 커지고 있음에도 불구하고 [증거의 개념은 주로 학습자, 교육자 및 교육 기관이 경험하는 영향의 종류에 한정]되어 있는 것으로 보입니다. 예를 들어, Allen 등(2011)은 표준화된 류마티스 관절염 환자로부터 교육을 받은 학생과 류마티스 전문의로부터 교육을 받은 학생의 학습 결과를 비교했습니다. Davidson 등(2001)은 신체 평가를 가르치는 두 가지 방법, 즉 [전통적인 교수진 교육 과정]과 [특별히 훈련된 표준화 환자가 가르치는 과정]을 비교하기 위해 동시 대조 시험을 설계했습니다. 두 저자 모두 학습 결과는 비슷하지만 표준화 환자 모델이 훨씬 더 비용 효율적이라는 결론을 내렸습니다. 비용 비교 및 대조군 임상시험 연구 설계의 사용은 "환자 파트너가 성공적으로 지속적으로 참여할 수 있도록 관리"하는 [자원 관리]의 개념화와 마찬가지로 환자 참여에 관한 이 연구의 고유한 특징입니다(Barr 외. 2009, 599페이지).

This is not to say that the studies are insensitive to standardized patients and their experiences. Further, there is a growing body of work that is concerned the politics of knowledge, questioning who decides—and how such decisions are made—about what content is addressed, how patients are constructed, what is being displayed about the patient experience (Taylor 2011). Despite these growing questions about power and decision-making, the concept of evidence seems largely to be reserved for the kinds of impacts experienced by learners, educators, and educational institutions. For example, Allen et al. (2011) compared learning outcomes for students receiving instruction from a standardized patient with rheumatoid arthritis and students receiving instruction from a rheumatologist. Davidson et al. (2001) also designed a concurrent controlled trial to compare two methods of teaching physical assessment: a traditional faculty-taught course and a course taught by specially trained standardized patients. Both sets of authors concluded that the learning outcomes were comparable, but the standardized patient model was far more cost effective. The use of cost comparisons and control trial research designs are unique to this body of research on patient involvement, as is the conceptualization of resource management, where “patient partners are managed for successful enduring engagement” (Barr et al. 2009, p. 599).

"참여형 환자의 출현"에 대한 앞 섹션에서 우리는 [해석적이고 때로는 비판적인 패러다임에 기반한 학술 커뮤니티]에 주목했습니다. 이와 대조적으로, 표준화 환자 분야에서는 [환자 참여에 대한 도구주의적 개념]을 활용하여 실증주의적 근거와 실험주의적 설계를 사용하여 [다양한 개입의 영향을 탐구하는 연구 커뮤니티]가 있습니다. 이미 언급했듯이 이 두 연구 커뮤니티와 다양한 가정 사이에는 중복되는 부분이 있습니다. 그러나 그 차이점을 강조할 가치가 있습니다. 특히, [학습 기회의 접근성 및 표준화 문제에 대한 기술주의적technocratic 대응]으로서 '표준화된 환자로서의 실제 환자'에 대한 역사적 근거는 여전히 중요한 의미를 지니고 있습니다. 이러한 [도구적 가정]은 항상 명시적으로 언급되지는 않았지만 [학습 경험의 품질, 재현성 및 표준화에 대한 많은 관심]을 통해 알 수 있습니다. [현재 및 미래의 환자에 대한 책무]는 [학습자에게 진정성 있고 의미 있으며 균등하게 분산된 학습 경험을 제공해야 한다는 책임감]을 통해 유추할 수 있습니다.

In the previous section on “the emergence of the engaged patient”, we drew attention to scholarly communities drawing on interpretive and sometimes critical paradigms. In contrast, there is a community of research in the field of standardized patients making use of instrumentalist notions of patient engagement, exploring the impacts of various interventions using positivist rationales and experimentalist designs. As already noted, there is overlap between these two research communities and their various assumptions. However, the distinctions are worth highlighting. In particular, the historical rationale for “real patients as standardized patients” as a technocratic response to a problem of access and standardization of learning opportunities remains consequential.

- These instrumental assumptions—not always explicitly stated—are visible in the great volume of concern displayed for the quality, reproducibility, and standardization of the learning experience.

- Accountability to present and future patients is inferred through a sense of responsibility for creating learning experiences that are authentic, meaningful, and equally dispersed for the learners.

치료와 학습의 얽힘으로서의 환자 참여: 사회문화적 학습

Patient involvement as entanglements of care and learning: sociocultural learning

의료 전문직 교육에서의 환자 참여에 대한 이전의 검토에서는 ["병상 학습" 또는 "임상 학습"]에 대한 고려가 제외되었는데, 여기서는 (학생 또는 환자가) [치료의 순간moments of care에 경험하는 학습]으로 정의됩니다(Monrouxe 외. 2009). "적극적인" 환자 참여가 일종의 교육적 역할을 적극적으로 추구하는 것을 의미한다는 점을 고려할 때(Towle 외. 2010), 이전 검토에서 침상 학습을 제외하는 것은 합리적입니다. 그러나 이 검토의 목적상, 우리는 보건의료 전문직 교육에 대한 환자 참여에 대한 고려를 역사적으로 영향력이 크고 오랫동안 지속되어 온 침상 학습에 대한 대규모 연구와 개념적으로 접촉하는 것이 중요하다고 생각했습니다. 이러한 작업은 너무 방대하여 이 특정 리뷰에서 심도 있게 다루기에는 무리가 있습니다. 대신 리뷰 논문, 많이 인용된 연구, 해당 분야에서 지속되고 있는 논쟁을 중심으로 살펴보았습니다. 병상 학습에 대한 설명은 1900년대 초부터 현재까지 지속되어 왔지만, 학습자-환자 접촉의 대부분은 더 이상 병상 옆에서 이루어지는 것이 아니라 지역사회 및 외래 환경에서도 발생한다는 인식이 확산되고 있습니다(Coleman and Murray 2002).

Previous reviews of patient engagement in health professions education have excluded considerations of “bedside learning”—or “clinical learning”—defined here as the learning experienced (by students or patients) during moments of care (Monrouxe et al. 2009). Given that “active” patient involvement has been taken to mean active pursuit of some kind of teaching role (Towle et al. 2010), the exclusion of bedside learning from previous reviews is sensible. However, for the purpose of our review, we deemed it important to put our consideration of patient involvement in health professions education in conceptual contact with the large, long-standing, and historically influential body of work on bedside learning. This body of work is too expansive to be considered in depth in this particular review. Instead, we engaged with review papers, highly cited pieces of work, and enduring debates in the field. While the descriptor of bedside learning has persisted from the early 1900s to current times, there is recognition that much of learner-patient contact is no longer at the side of a bed, but also occurs in community and ambulatory settings (Coleman and Murray 2002).

이 검토에서 우리가 관심을 갖는 것은 [서비스 제공의 순간]과 관련하여 [학습이 고려되는 순간]입니다. 우리가 구분하는 지점은 학습에 대한 환자의 "능동적" 또는 "수동적" 참여가 아니라 다음을 구분하는 것입니다.

- 환자가 [학습에 참여하기로 선택]했고, [자신의 교육 역할을 인식]하고 있는 시나리오(예: 임상 교육 동료, 커리큘럼 위원, 표준화 환자 등)

- 환자가 [치료를 받고 있으며] 이러한 [치료 관계에 학생이 참여함]으로써 학습에 참여할 수 있는 시나리오

이러한 입장은 또한 학습자와 환자가 서로를 통해, 서로로부터, 서로에 대해 동시에 학습할 수 있는 가능성을 열어주는데, 이는 Bleakley와 Bligh(2008)가 탐구한 개념입니다. 또한 [상호 학습의 순간]을 고려하면 환자가 학생과의 학습 관계에 참여하기 위해 특정 종류의 전문 지식을 보유할 필요가 없어집니다. 이러한 사고방식에 따르면 질병을 처음 경험하는 사람들도 학습 관계에 있다고 볼 수 있습니다. 학습 관계는 경험 및 만성 질환을 통해 전문성을 갖춘 환자들에게만 해당되는 것이 아닙니다. 마지막으로, [학습에 대한 환자의 적극적인 참여]가 일정 수준의 커리큘럼 의사 결정 및 직접적인 교육과 동일해야 한다는 가정을 제거함으로써, 우리는 (때로는 은유적인) 병상에서의 다양한 치료 및 학습에 대한 환자의 적극적인 참여를 개념화하는 연구자 그룹을 발견했습니다.

What is of interest to us in this review are those moments when learning is considered in relation to moments of service provision. The point of distinction we made is not between “active” or “passive” patient involvement in learning, but between

- scenarios where patients have chosen to participate in learning and are aware of their teaching roles (e.g. as clinical teaching associates, curriculum committee members, standardized patients etc.) and

- scenarios where patients are seeking care and may also be participating in learning by virtue of student participation in those care relationships.

This position also opens the possibility of learners and patients learning with, from, and about one another simultaneously, a concept explored by Bleakley and Bligh (2008). Further, considering moments of mutual learning also removes the necessity of patients having a particular kind of expertise in order to participate in a learning relationship with students. By this line of thinking, people experiencing illness for the first time are also in learning relationships. Learning relationships are not reserved for those patients with expertise by experience and/or chronic illness. Finally, by removing the assumption that active patient engagement in learning must equate to some level of curricular decision-making and/or direct teaching, we found a group of researchers conceptualizing active involvement of patients in various entanglements of care and learning at the (sometimes metaphorical) bedside.

병상 학습에 대한 환자의 참여는 현대 교육 병원 개념의 제도화에 원동력이 된 것으로 알려진 오슬러의 저서 '에콰니미타스(Aequanimitas)'에 그 근간을 두고 있습니다. 교육 병원은 원래 환자가 학생 학습에 참여하는 대가로 의료 서비스를 받는 '자선 병원'으로 시작되었습니다(Ludmerer 1983). 치료와 학습이 얽혀 있는 이 초기 모습에서 환자가 의료 전문가의 학습에 참여할 의무가 있는지에 대한 논쟁이 계속되고 있습니다(Waterbury 2001). 침상 학습의 본질에 대한 다른 지속적인 논쟁에는 아래 등이 포함됩니다(Bashour 외 2012; Celenza 외 2011; Chiong 2007; Draper 외 2008; Hubbeling 2008; Leinster 2004; Monrouxe 외 2009; Paull 2006).

- 환자 동의와 관련된 윤리적 문제,

- 학습 기회로서 환자에 대한 학생의 접근성 감소,

- 잠재 커리큘럼의 교묘한 효과를 포함한 선배 임상의의 환자 치료에 대한 역할 모델링 문제,

- 학습 요구와 환자 치료 요구의 균형을 맞추려는 학생들이 겪는 다양한 윤리적 딜레마

Patient involvement in bedside learning is anchored in Osler’s famous Aequanimitas, taken to be the impetus for the institutionalization of the modern concept of a teaching hospital. The teaching hospital originally emerged as a ‘charity hospital’, where patients received medical care in exchange for participating in student learning (Ludmerer 1983). From this early manifestation of entanglements of care and learning, there are continued debates about whether patients have a duty to participate in the learning of health professionals (Waterbury 2001). Other enduring debates about the nature of bedside learning include:

- ethical concerns related to patient consent,

- declining student access to patients as learning opportunities,

- problematic role modeling of patient care from senior clinicians including the insidious effects of hidden curricula, and

- the various ethical dilemmas experienced by students attempting to balance their learning needs against patients’ care needs (Bashour et al. 2012; Celenza et al. 2011; Chiong 2007; Draper et al. 2008; Hubbeling 2008; Leinster 2004; Monrouxe et al. 2009; Paull 2006).

이 리뷰에서 우리가 특히 관심을 갖는 것은 침대 옆 학습이 개념화되는 새로운 방식입니다. 이 문헌에서 우리는 [학습에 대한 구성주의 이론]을 볼 수 있습니다. 이는 환자를 교육 자료로 객관화하는 데 도움이 되는 이전의, 그리고 더 지배적이었던 침상 학습 접근 방식과는 대조적입니다. 임상 학습에 대한 이러한 대안적 개념화에서는 [학습자, 환자, 교수자 간의 삼자적 만남]에서 [상호 작용적 뉘앙스]에 초점을 맞추고, 이러한 관계적 공간에서 학습을 이해하는 방법으로 [학습에 대한 사회적 이론]을 사용합니다(Bleakley 2014; Bleakley와 Bligh 2008; Kumagai와 Naidu 2015). 우리가 강조하고자 하는 것은 바로 이러한 연구입니다. 여기에서는 합법적 주변적 참여(Lave and Wenger 1991), 실천 공동체(Wenger 1998), 활동 시스템에서의 확장적 학습에 대한 Engestrom의 개념(Engeström 1999), 행위자-네트워크 이론의 다양한 반복(Latour 2007; Law 1999; Mol 2010)에 대한 개념을 소개합니다. 이러한 이론적 방향의 공통점은 학습의 사회적, 물질적, 시간적, 맥락적 측면에 초점을 맞춘다는 점입니다(Fenwick and Edwards 2010).

What is of particular interest to us in this review are the emerging ways in which bedside learning is being conceptualized. It is in this body of literature that we see constructionist theories of learning. This in contrast to earlier—and more dominant—approaches to bedside learning that would serve to objectify patients into teaching materials. In this alternate conceptualization of clinical learning, there is a focus on the interactional nuances during triadic encounters between learners, patient and instructors, using social theories of learning as a way to make sense of learning in these relational spaces (Bleakley 2014; Bleakley and Bligh 2008; Kumagai and Naidu 2015). It is this body of research that we wish to emphasize. Here we see the introduction of concepts of legitimate peripheral participation (Lave and Wenger 1991), communities of practice (Wenger 1998), Engestrom’s notions of expansive learning in activity systems (Engeström 1999) and various iterations of actor-network theory (Latour 2007; Law 1999; Mol 2010). What these theoretical orientations share are a focus on the social, material, temporal, and contextual aspects of learning (Fenwick and Edwards 2010).

이는 역사적으로 개인의 인지적 성취로서의 학습에 초점을 맞춰온 [성인 학습 이론]과는 대조적입니다(Bleakley 2014). 사회 학습 이론은 개인에 초점을 맞추는 대신 [공유 지식, 사회적 정체성 개발, 집단적 감각 형성] 등의 개념을 활용하여 학습을 [단순히 지식의 습득]이 아니라 [특정 정체성을 채택]하여 [실천 공동체에 합법적으로 진입]하는 [사회화의 한 측면]으로 탐구합니다(Bleakley 2012). 이 이론적 틀에서 [환자는 의료 전문가와 함께 공통의 관심사로 묶인 활동 네트워크를 형성]하는 역할을 합니다. 물론 이러한 네트워크 내에서 행동하는 방법에 대한 긴장, 논쟁, 딜레마가 없다는 것은 아니지만, 이러한 긴장을 설명하는 것은 학습 현상을 이해하는 데 있어 중요한 부분이 됩니다(Fenwick and Edwards 2010). 이러한 이론적 장치를 활용하는 연구 설계는 심층 관찰과 비디오 민족지학적 연구가 주를 이루는 질적 연구 경향이 있습니다(Hamilton 2011).

This in contrast to theories of adult learning that have historically focused on learning as a cognitive accomplishment of an individual (Bleakley 2014). Instead of focusing on individuals, social learning theories draw on concepts such as shared knowledge, social identity development, and collective sense making as a means to explore learning not simply as acquisition of knowledge, but as an aspect of socialization, involving legitimate entry into a community of practice through the adoption of a particular identity (Bleakley 2012). In this theoretical framing, patients act along with health care professionals in forming a network of activity, held together by a common object of interest. That is not to say that there are not tensions, debates and dilemmas about how to act within these networks, but explicating these tensions becomes part of understanding the phenomenon of learning (Fenwick and Edwards 2010). Research designs making use of these theoretical apparatuses tend to be qualitative, with in-depth observations and video-ethnographic studies predominating (Hamilton 2011).

이 요약에서는 [구성주의 학습 이론에 초점을 맞춘 연구]라는 침대 옆 학습 문헌의 한 가지 흐름만을 강조합니다. 우리는 이 특정 학계가 침상 학습의 전체를 대표하지 않으며, 치료의 순간에 환자와 수련의 사이에 위험과 보상이 불균등하게 분배되는 환자들의 경험도 대표하지 않는다는 것을 알고 있습니다. 우리는 [유사한 가치관을 공유하지만 다른 이론적 입장에서 다양한 연구 질문에 접근하는 다른 학계 커뮤니티]의 이론적 기여와 병상 학습에 대한 이 메타 내러티브를 강조합니다.

In this summary, we emphasize just one stream of bedside learning literature: the body of work that focuses on constructivist theories of learning. We recognize that this particular scholarly community does not represent the whole of bedside learning—nor the experience of patients that find risk and rewards unevenly distributed between patients and trainees during moments of care. We highlight this one meta-narrative about bedside learning for the theoretical contributions being made and the juxtaposition from other scholarly communities sharing similar value statements, but approaching various research questions from a different theoretical stance.

메타 내러티브: 공통점과 긴장감

Meta-narratives: commonalities and tensions

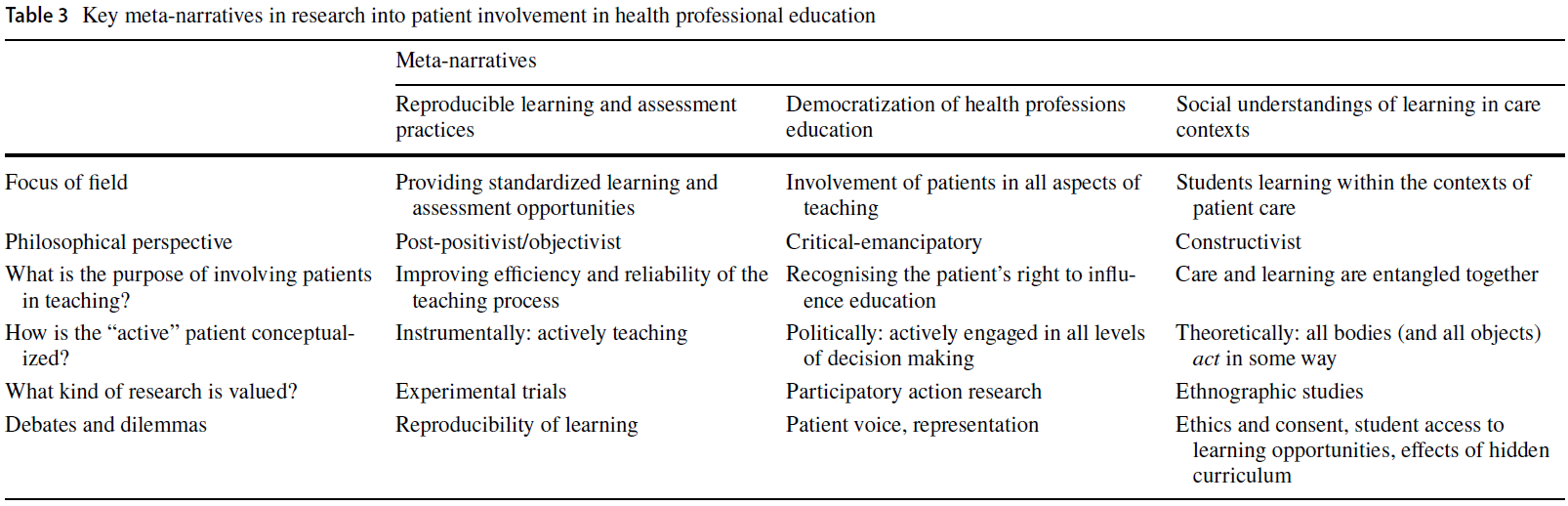

광범위하고 반복적인 프로세스를 사용하여 의료 전문직 교육에서 환자 참여와 관련된 광범위한 문헌을 수집했습니다. 참여 환자, 표준화 환자로서의 실제 환자, 병상 학습이라는 세 가지 학술 커뮤니티를 중심으로 분석 결과를 정리했지만, 종합에서 가장 중요한 것은 [이러한 각 커뮤니티를 움직이는 중요한 스토리라인]이며, 특히 [이러한 스토리라인(또는 메타 내러티브)이 서로 상호 작용하는 방식]에 주목했습니다. 이를 위해 각 학문적 전통을 뒷받침하는 주요 연구 질문과 딜레마, 그리고 적극적인 참여라는 다소 어울리지 않을 수 있는 개념에 대해 논의합니다. 문헌에서 [내러티브 주제를 다루는 것]에서 [메타 내러티브를 명확히 하는 것]으로의 전환은 개념적으로 중요합니다. 앞서 언급한 주제를 설명할 때 다양한 개념과 그 개념들이 서로 어떻게 연관되어 있는지에 주의를 기울였습니다. 메타 내러티브를 명확하게 표현하려면 [공통의 개념, 이론, 방법 및 도구를 공유하는 일관된 작업체]에 주의를 기울여야 합니다(Kuhn 1996). 여기에는 시간이 지남에 따라 다양한 공간과 장소에 걸쳐 실제 연구 커뮤니티 간의 경계와 상호 연결에 주의를 기울이는 것이 포함됩니다. [내러티브 주제]는 역사적으로 제시될 수 있지만, [메타 내러티브]에 주목하려면 역사, 맥락, 연결에 주목해야 합니다. 이미 살펴본 [개념적 주제]는 서로 상호 작용하지만, 다음에 설명하는 메타 내러티브는 이러한 주제에 단순히 매핑되지 않습니다. 설명하는 메타 내러티브는 이러한 [개념적 주제]를 고려할 뿐만 아니라 [다양한 연구 커뮤니티 간의 경계, 공유되는 개념, 커뮤니티 내부 및 커뮤니티 간에 존재하는 논쟁]도 함께 고려합니다. Greenhalgh 등(2004, 2005)의 연구를 바탕으로, 우리는 같은 학회에 참석하고, 저널에 실린 서로의 논문을 심사하고, 같은 연구비 지원 기관에 지원하는 연구자는 누구인가와 같은 질문을 던졌습니다. 이 과정에서 우리는 보건 전문직 교육에 대한 환자 참여의 더 큰 분야를 알려주는 다양한 메타 내러티브를 찾아내기 위해 내러티브 주제와 연구 커뮤니티를 연결하기 시작했습니다. 표 3은 메타내러티브에 대한 개괄적인 요약을 제공합니다.

Using an expansive and iterative process, we collected a wide range of literature concerned with patient involvement in health professions education. While we organized the presentation of our analysis along the lines of three scholarly communities—concerned with the engaged patient, real patients as standardized patients, and bedside learning—what is of primary interest in our synthesis are the over-arching storylines that animate each of these communities, particularly as those storylines (or meta-narratives) interact with one another. To that end, we discuss the primary research questions and dilemmas fuelling each scholarly tradition and the possibly incommensurate notions of active engagement. The shift from addressing narratives themes in the literature to articulating meta-narratives is conceptually significant. In outlining the aforementioned themes, we attended to various concepts and how they related to one another. To articulate meta-narratives requires attention to coherent bodies of work that share common sets of concepts, theories, methods and instruments (Kuhn 1996). This involves attending to boundaries and interconnections between the actual research communities over time and across various spaces and places. Whereas the narrative themes can be presented as ahistorical, to attend to meta-narratives necessitates attending to history, context, and connections. While the conceptual themes already explored do interact with one another, the meta-narratives we describe next are not simply mapped onto those themes. The meta-narratives described take into account those conceptual themes, but also layer in the boundaries between various research communities, what concepts are shared, what debates exist within communities and across them. Building from Greenhalgh et al’s (2004, 2005) work, we asked questions such as: which of these researchers attend the same conferences, referee for each other’s papers on journals, apply to the same grant-giving bodies? In doing so, we started to interlay narrative themes and research communities in order to tease out various meta-narratives that are informing the larger field of patient involvement in health professions education. Table 3 provides a high-level summary of the meta-narratives.

오슬러의 역사적 유산에 기반을 둔 각 활동의 흐름은 [치료와 학습이 얽혀 있는 문제]와 씨름했습니다. 이는 원래 학생들, 더 나아가 교수진에게 가장 유익한 학습 경험이 어디에 위치해야 하는지에 대한 의문을 제기하는 학습의 문제였습니다. 환자들의 우려가 무시되었다는 것이 아니라, 더 나은 환자 치료를 위한 길은 더 나은 교육을 통해 매개될 수 있도록 구성되었다는 의미입니다. 침상 학습 전통은 학습을 치료 환경 내에 확고하게 위치시킴으로써 학습 딜레마를 해결했습니다. 병상 학습에 대한 강조는 수많은 새로운 기관을 탄생시켰으며, 오늘날에도 교육 병원 내 의료 인력 조직에서 여전히 볼 수 있습니다. 그러나 이 결정은 [환자 동의와 관련된 윤리적 딜레마]와 [학습 기회에 대한 학생의 접근성에 대한 현실적 우려] 등 다른 문제를 야기했습니다. 병상에서 치료와 학습을 분리하는 것이 불가능해지자 이러한 공간에 내재된 사회적 복잡성을 탐구할 수 있는 연구 전통이 발전했습니다. 일부의 경우 이러한 상황은 의료 환경 밖에서 시작된 학습에 대한 사회적 이론을 수용하는 것으로 발전했습니다.

Anchored in the historical legacy of Osler, each stream of activity wrestled with the entanglements of care and learning. This was originally framed as a problem of learning for the students—and by extension, the faculty members—bringing into question where the most fruitful learning experiences were to be located. This is not to say that patient concerns were ignored, but that the avenue to better patient care was constructed to be mediated through better education. The bedside learning tradition addressed the learning dilemma by firmly locating learning within the care settings. The emphasis on bedside learning germinated a host of new institutions, still visible in modern day organization of the medical workforce within teaching hospitals. However, this decision caused other problems to arise, including ethical dilemmas related to patient consent and pragmatic concerns about student access to learning opportunities. Given the impossibility of disentangling care and learning at the bedside, research traditions developed that could explore the inherent social complexity in these spaces. For some, this situation has evolved into embracing social theories of learning that have originated outside of health care settings.

[병상 학습]의 흐름을 이어온 교육자와 연구자들이 진료 환경 내에서 학습의 가치에 대한 기본 가정을 흔들지 않으면서 이러한 딜레마와 씨름하는 동안, 특정 교육자 그룹은 [시뮬레이션 환자]라는 새로운 교육 리소스를 도입하여 이러한 문제를 해결하려고 시도했습니다. 일부의 경우, 시뮬레이션 환자는 나중에 [표준화 환자]로 발전했습니다. 여기서 해결해야 할 문제는 주로 학생과 교육자의 문제였지만, 이 전략은 환자의 자발적 참여라는 메커니즘을 통해 환자 동의라는 까다로운 딜레마를 관리할 수 있는 길을 제공하기도 했습니다. 이러한 특정 윤리적 딜레마와 환자 안전 문제를 해결한 후에는 역량 및 역량 개발과 관련된 교육 활동을 더욱 강화할 수 있는 [표준화된 리소스]를 만드는 것과 관련된 [관행과 도구를 지속적으로 개선]하는 데 초점을 맞출 수 있습니다. 따라서 [교육적 자원으로서 표준화 환자]의 성공과 관련된 질문에 답할 수 있는 관련 연구 전통이 발전했습니다.

While educators and researchers that continued along the stream of bedside learning grappled with these dilemmas without destabilizing the foundational assumption of the value of learning within practice settings, a specific group of educators attempted to solve these problems by introducing a new educational resource: the simulated patient. For some, the simulated patient later evolved to become the standardized patient. Here, the problems to be solved were primarily the problems of students and educators, but this strategy also provided an avenue to manage the thorny dilemmas of patient consent through mechanisms of patient volunteerism. Having contained those particular ethical dilemmas and patient safety concerns, the focus could be placed on continuing to refine the practices and tools associated with creating a standardized resource that would bolster ever more educational activity related to competencies and competency development. Hence, an associated research tradition developed capable of answering questions related to the success of standardized patients as an educational resource.

그러나 표준화 환자 개발은 정치적 공백 상태에서 이루어진 것이 아니었습니다. 학회 외부에서도 병상 학습에 대한 대안을 제시하고자 하는 움직임이 동시에 일어났지만, 해결해야 할 문제는 반드시 학생이나 교수진에 국한된 것이 아니었습니다. 이러한 문제는 [더 큰 사회적 담론의 틀] 안에 놓여 있었습니다.

- 전문직에 대한 신뢰 약화

- 의료 시스템을 형성할 수 있는 환자의 권리

- 전문 지식의 한 형태로서 생생한 환자 경험에 대한 인식의 증가

However, the development of standardized patients was not occurring in a political vacuum. Coinciding movements outside of the academy also sought to provide alternatives to bedside learning, yet the problems to be solved were not necessarily those identified by students or faculty members. These problems were framed within a larger societal discourse of

- eroding trust in the professions,

- the rights of patients to shape health care systems, and

- a growing appreciation of lived patient experience as a form of expertise.

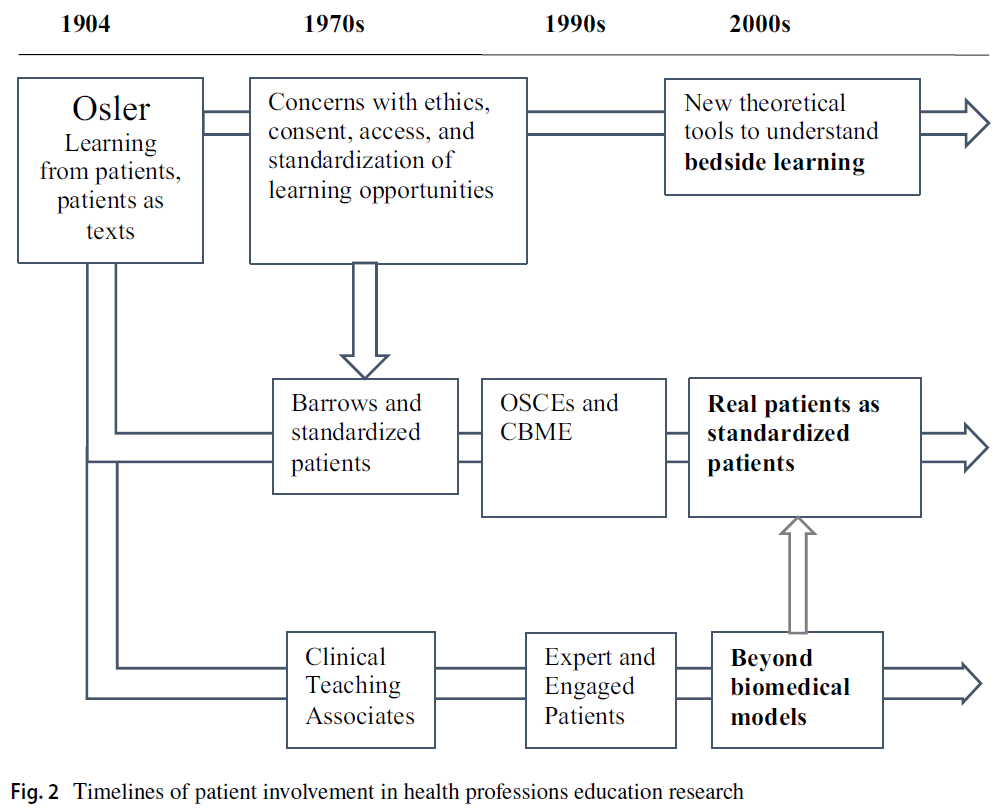

그림 2에서는 메타 내러티브가 시간이 지남에 따라 서로 상호 작용하는 것으로 표시되어 있습니다. 이러한 타임라인을 병렬로 제시하여 두 가지가 공존하고 있음을 명확하게 보여줍니다. 이는 메타내러티브를 선형적이고 명확하게 구분하는 표 3에 표시된 구분과는 대조적입니다. [수동적 참여]에서 [능동적 참여]로 이동하는 [하나의 목적론적 타임라인]이 아니라, 서로 다른 궤적을 가진 [여러 타임라인]이 존재합니다. 각 활동의 흐름은 [향상된 학습 경험을 통해 환자 치료를 개선한다는] [공통된 목표]를 공유합니다. 그러나 주요 연구 질문과 딜레마, 그리고 이를 해결하는 방식은 타임라인에 따라 다릅니다. 또한 한 가지 문제에 대한 해결책은 항상 새로운 문제를 야기하며, 교육자와 연구자들은 이를 적극적으로 추구합니다. 그 결과, 연구자들 사이에 공통 언어를 공유하는 것처럼 보이지만 잠재적으로 비교할 수 없는 개념으로 구체화될 수 있는 일련의 경계가 생겨납니다(Kuhn 1996).

In Fig. 2, we display the meta-narratives as interacting with one another over time. We have presented these timelines in parallel to demonstrate their co-existence in high relief. This is in contrast to the distinctions displayed in Table 3, which suggests linear and clear separation between meta-narratives. Rather than a single teleological timeline that moves from passive to active engagement, there are multiple timelines with different trajectories. Each stream of activity shares the declared aim of improving patient care through enhanced learning experiences. However, the primary research questions and dilemmas—and the ways they are addressed—are different across the timelines. Further, the solutions to one set of problems invariably create a new set of problems, vigorously pursued by educators and researchers. The result is a set of boundaries between researchers that potentially crystallize into incommensurable concepts that may go unnoticed, particularly as they appear to share common language (Kuhn 1996).

공약불가능의 관계 탐색: '능동적' 환자 참여 구축하기

Exploring incommensurabilities: constructing “active” patient engagement

한 가지 가능한 공약불가능의 관계는 "능동적" 환자 참여라는 개념입니다. 병상 학습에 대한 최근의 이론화(Bleakley 2014, Bleakley와 Bligh 2008)는 [환자를 사회 시스템의 일부로 위치시킬position] 수 있습니다. 이러한 이론에서는 "능동적" 또는 "수동적"인지에 대한 질문은 전적으로 관련이 없을 수 있습니다. 이러한 질문이 중요하지 않다는 것이 아니라 개념 자체가 같은 종류의 중요성을 지니지 않을 수 있다는 뜻입니다. 이러한 이론에서는 시스템 내의 모든 행위자가 학습에 관여합니다. 그러한 학습이 바람직한지 해로운지는 미리 정해져 있지 않지만, [수동성이라는 개념]은 이러한 질문을 추구하는 데 가장 유익한 방법이 아닐 수 있습니다. 예를 들어, 일부 사회 학습 이론에서는 [모든 유생물과 무생물]은 어떤 식으로든 능동적이라고 가정합니다(Latour 1999; Law 1999). 이러한 프레임워크에서는 [환자, 학습자, 교사, 책상, 창문, 정책 성명서, 평가 프로토콜, 환자 가운, 짧고 긴 흰 가운]이 [모든 것이 어떤 방식으로든 능동적]입니다. 따라서 사물이 행동하고 상호 작용하는 방식과 이러한 행동이 어떤 영향을 미치는지는 경험적 질문입니다. 이런 의미에서 [어떤 프로그램에는 활동적인 환자가 있고 어떤 프로그램에는 그렇지 않다]고 말하는 것은 같은 종류의 두드러짐을 갖지 않습니다. 이러한 이론을 기존 관행에 대한 비판으로 사용할 수 없다는 것은 아니지만(Latour 2004), 비판의 성격은 조사 전에 전제되지 않습니다. 차이점은 [참여의 본질에 대한 초기 가정]에 있으며, [참여가 어떻게 수행되어야 하는지]에 대한 가정을 괄호로 묶고, 대신 [관행이 실제로 어떻게 전개되고 있는지]에 경험적으로 초점을 맞출 필요가 있습니다(Broer et al. 2014).

One possible incommensurability is the notion of “active” patient engagement. Recent theorizations (Bleakley 2014; Bleakley and Bligh 2008) of bedside learning would position patients as part of social systems. The question of being “active” or “passive” may not be entirely relevant in these theorizations. This is not to say that these questions are not important, but that the concepts themselves may not hold the same kind of salience. In these theorizations, all actors within the system are implicated in learning. Whether the learning is desirable or detrimental is not predetermined, but the notion of passivity may not be the most fruitful way to pursue those questions. For example, in some social theories of learning, all animate and inanimate objects are active in some way (Latour 1999; Law 1999). In this kind of framing, patients, learners, teachers, desks, windows, policy statements, assessment protocols, patient gowns, short and long white coats are all active in some way. Thus, the ways in which objects act and interact, and to what effect these actions have, are empirical questions. In this sense, to say that some programs have active patients and some do not does not have the same kind of salience. This is not to say that these theorizations cannot be put to use as critique of existing practices (Latour 2004), but the nature of critique is not presumed prior to the investigation. The difference lies in the initial assumptions about the nature of engagement, requiring a bracketing of any assumptions about how it should be performed and instead focusing empirically on how practices are actually unfolding (Broer et al. 2014).

이와는 대조적으로, 최근 '교사로서의 환자'에 대한 일부 반복에서 [능동적 환자] 개념은 [능동적 환자]를 [의사 결정권 보유와 동일시]합니다. 권력에 대한 선형적 가정에 따르면, 아른슈타인의 사다리(Tritter and McCallum 2006)와 이 특정 참여 모델에서 개념적 계보를 찾을 수 있는 모든 [사다리형 모델]은 [환자에게 의미 있는 의사결정권을 적극적으로 이전하지 않는 모든 형태의 참여]는 [토큰주의]로 경험될 위험이 있습니다. 여기서 '능동적' 환자는 [의료의 정치]에 등록되어 있으며, 영향력 문제를 이해하기 위해서는 다른 이론이 필요합니다. 사회 과학자들은 환자 참여의 다른 분야에서 이러한 선형적 권력 개념화와 씨름하면서 진정한 참여를 거의 독점적으로 가시적인 형태의 의사 결정과 동일시하는 의도하지 않은 결과에 대해 의문을 제기해 왔습니다(Eakin 1984; Ocloo and Fulop 2012; Tritter 2009).

In contrast, the notion of active patient in some recent iterations of “patient as teacher” equates the active patient with holding decision-making power. Following the linear assumptions about power that animate Arnstein’s ladder (Tritter and McCallum 2006)—and all ladder-like models that might trace their conceptual lineage back to this particular model of engagement—any form of engagement that does not actively transfer meaningful decision-making power to patients risks being experienced as tokenistic. Here, the “active” patient is enrolled in the politics of healthcare, requiring a different set of theorizations to make sense of questions of impact. Social scientists have grappled with this linear conceptualization of power in other fields of patient engagement, raising questions about the unintended consequences of equating authentic engagement almost exclusively with visible forms of decision-making (Eakin 1984; Ocloo and Fulop 2012; Tritter 2009).

마지막으로, [표준화 환자 문헌]은 일부 의사 결정 영역에서 [참여 환자 문헌]과 겹칠 수 있지만, [표준화 환자 문헌]의 상당한 하위 집합은 ['적극적인 참여'가 적극적인 교육과 동일하다]고 가정합니다. 이는 [의사 결정 참여와 관련된 어떠한 가정도 요구하지 않으며], 환자와 교육자 간의 [권력 균형을 상대적으로 방해하지 않습니다]. '능동적' 환자가 교사로서 미치는 영향에 대한 문제를 해결하려면 실험주의적 사고에 적합한 [기술주의적 근거]가 필요합니다. 이를 위해 연구자 커뮤니티는 '능동적' 환자 참여의 개념을 '능동적' 참여에 수반되는 완전히 다른 정신 모델을 사용하여 배포할 가능성이 있습니다.

Finally, the standardized patient literature may overlap with the engaged patient literature in some decision-making spaces, but a substantive subset of the standardized patient literature assumes that “active engagement” equates to active teaching. This does not require any associated assumption about participating in decision-making and leaves the power balances between patients and educators relatively undisturbed. To address questions of impact of the “active” patient as teacher requires technocratic rationales that are amenable to experimentalist type thinking. To this end, there is a potential that communities of researchers are deploying the concept of “active” patient engagement with entirely different mental models of what “active” engagement entails.

따라서 보건 전문직 교육에서 환자 참여에 관한 문헌을 의미 있게 종합하는 데 따르는 어려움은 단순히 명명법의 문제가 아닐 수 있습니다. 유용한 종합을 만드는 것이 어렵다는 것은 [환자와 함께, 환자로부터, 환자에 관한 학습의 본질]에 대한 서로 다른 개념화를 반영하는 것일 수도 있습니다. 연구자와 교육자는 환자 참여가 여러 가지 방식으로 동시에 수행되는 여러 개념적 대상을 설명할 수 있습니다(Mol 1999). 이러한 다양한 수행 간의 결과는 의도하지 않은 결과에 대한 잠재력과 마찬가지로 항상 다를 수 있습니다. 예를 들어,

- 환자 참여가 [민주적인 방식]으로 수행되는 경우

- 환자의 목소리, 대표성, 대표성에 대한 질문이 중요해지지만(Rowland and Kumagai 2018),

- 학습자에 대한 책임(명시적인 학습 기회 원칙, 투명한 평가 관행, 공평한 학습 기회)은 덜 가시화될 수 있습니다.

- 환자 참여가 [기술적 노력]으로 수행되는 경우

- 학습자에 대한 책임이 보다 명시적으로 다뤄질 수 있지만,

- 환자에 대한 의도하지 않은 [가부장주의]가 지속될 수 있습니다.

- 환자 참여가 [해방적 노력]으로 수행될 때,

- [교육자의 완전한 기술적 전문성 실현]을 댓가로 [급진적 자율성의 가치]가 살아남을 수 있지만(Bleakley 2014),

- 다른 환자 참여 분야에서 탐구된 [상호 무력감]의 조건을 만들 수 있습니다(Broer et al. 2014).

Thus, the challenges of creating a meaningful synthesis of the literature on patient involvement in health professions education may not just be a problem of nomenclature. Instead, the difficulty of creating a useful synthesis may also reflect different conceptualizations about the nature of learning with, from, and about patients. Researchers and educators may be describing multiple conceptual objects (Mol 1999), where patient involvement is performed in multiple ways simultaneously. The outcomes between these various performances will invariably differ, as will their potential for unintended consequences. For example,

- where patient involvement performs as a democratic exercise,

- questions of patient voice, representation, and representativeness become relevant (Rowland and Kumagai 2018) but

- accountabilities to learners along the principles of explicit learning opportunities, transparent assessment practices, and equitable learning opportunities may be less visible.

- When patient involvement performs as a technical endeavour,

- accountabilities to learners may be more explicitly addressed, but

- unintended and unexplored paternalism towards patients may persist.

- When patient involvement performs as an emancipatory endeavour,

따라서 보건전문직 교육에서 환자 참여 분야의 지식을 지속적으로 구축하기 위해서는 이 분야가 동질적이지 않으며, [통일된 명명법을 만들려는 노력]만으로는 그 차이를 원활하게 해소할 수 없다는 점을 인식해야 합니다. 또한 교육자와 연구자는 한 패러다임에서 공명하는 영향력 매개변수를 사용하여 다른 패러다임에서 설계된 개입의 영향을 평가하는 등 [상응하지 않는 개념을 혼용하는 것에 주의]해야 합니다.

- 예를 들어, 대화적 개입의 영향을 결정하기 위해 [실험주의적 디자인]을 사용하는 것이 [두 인식론적 커뮤니티]를 진정으로 만족시킬 수 있는지는 의문입니다.

- "이 환자 참여 개입이 효과가 있는가?"라는 질문으로 조사를 시작하는 대신

- "환자 참여가 어떤 효과가 있는가?", "누구를 위한 것인가?", "어떻게 알 수 있는가?"라는 질문으로 시작하는 것이 현명할 수 있습니다.

따라서 우리는 보건 전문직 교육 분야의 환자 및 대중 참여 학술 및 연구에서 존재론적, 인식론적 문제를 더 많이 고려할 것을 촉구하는 Regan de Bere와 Nunn의 의견에 동의합니다(Regan de Bere와 Nunn 2016).

Therefore, to continue to build knowledge in the field of patient involvement in health professions education requires recognition that the field is not homogeneous, and the differences will not be rendered smooth through efforts to create uniform nomenclature. Further, educators and researchers should be cautious about mixing incommensurate concepts, using parameters of impact that resonate in one paradigm to evaluate the impact of interventions designed in another.

- For example, it is questionable whether using an experimentalist design to determine the impact of dialogical intervention can truly satisfy either epistemic community.

- Instead of starting an inquiry with the question “does this patient engagement intervention work?”,

- perhaps it is wise to start by asking “what work does patient engagement do?”, “for whom?” and “how will we know?”.

Thus, we are in agreement with Regan de Bere and Nunn as they call for more consideration of ontological and epistemological matters in patient and public involvement scholarship and research in the field of health professions education (Regan de Bere and Nunn 2016).

제한 사항

Limitations

이 검토의 목적을 위해, 우리는 교육자들이 보건 전문직 교육에서 환자 참여에 대한 다양한 개념화를 파악하고 씨름하는 데 도움이 되는 높은 수준의 추상화를 찾았습니다. 특정 의료 전문직으로 검색 범위를 제한하지 않았습니다. 한 예리한 검토자가 지적했듯이, 의료 전문직 간에는 차이가 있으며, 이러한 차이가 교육에 대한 환자 참여의 역사적 궤적에 미치는 영향도 중요합니다. 이러한 차이점, 이러한 차이점이 서로 어떻게 상호 작용하는지, 그리고 이러한 분석이 환자 참여에 대한 우리의 가장 중요한 관심사에 어떻게 영향을 미칠 수 있는지를 탐구하는 것은 이 특정 백서의 범위를 벗어났습니다. 향후 검토에서는 이러한 전문적 차이에 초점을 맞출 수 있습니다.

For the purpose of this review, we sought high level abstractions to help educators to grasp—and wrestle with—various conceptualizations of patient involvement in health professions education. We opted to not limit our search to any particular health profession. As an astute reviewer pointed out, the differences between health professions are consequential, as are the impacts of these differences on the historical trajectories of patient involvement in education. It was beyond the scope of this particular paper to explore those differences, how they interact with one another, and how such an analysis might inform our over-arching interest in patient involvement. Future reviews could focus on these professional differences.

또한 이 논문에서는 다양한 메타 내러티브 간의 높은 수준의 추상화와 상호 작용에 초점을 맞추기로 했습니다. 다양한 메타내러티브 내의 다양한 뉘앙스, 즉 각 메타내러티브에 유동성을 부여하는 모순, 논쟁, 딜레마 등을 다루는 것은 단일 원고의 범위를 넘어서는 것이었습니다. 따라서 이 백서에서 제시한 내용이 다소 직설적일 수 있다는 점을 인지하고 있습니다.

- 예를 들어, 표준화된 환자 문헌의 모든 연구가 효율성 및 재현성과 관련된 것으로 특징지을 수 없다는 점을 잘 알고 있습니다.

- 또 다른 예로, 우리는 다양한 사회적 학습 이론이 환자의 학습 및 다양한 진료 커뮤니티의 구성원을 적절히 설명하지 못하는 것 같은 딜레마에 대해 잘 알고 있습니다.

이 리뷰에 소개된 각 분야에는 분명 미묘한 차이와 논쟁이 존재합니다. 이 원고에서는 교육에 대한 환자 참여라는 더 큰 기업 전반에 걸쳐 대조를 탐구하기 위해 서로 경쟁하는 큰 아이디어를 전시하기로 결정했습니다. 향후 논문에서는 여기서 다룬 것보다 더 깊이 있는 패러다임 내 미묘한 차이를 탐구할 수 있습니다.

Further, in this particular paper, we have chosen to focus on high level abstractions and interactions among various meta-narratives. It was beyond the scope of a single manuscript to also address the various nuances within various meta-narratives: the contradictions, debates, and dilemmas that give each meta-narrative a sense of fluidity. As a result, we are aware that what we have presented in this paper is necessarily blunt.

- For example, we are aware that not all research in the standardized patient literature can be characterized as being concerned with efficiencies and reproducibility.

- As a further example, we appreciate the dilemmas of various social theories of learning that do not seem to adequately account for patients learning and/or membership in various communities of practice.