가이드라인: 의학교육에서 임상술기 직접관찰의 할 것, 하지 말 것, 모르는 것 (Perspect Med Educ, 2017)

Guidelines: The do’s, don’ts and don’t knows of direct observation of clinical skills in medical education

Jennifer R. Kogan1 · Rose Hatala2 · Karen E.Hauer3 · Eric Holmboe4

소개

Introduction

임상 술기를 직접 관찰하는 것은 역량 기반 의학교육의 핵심 평가 전략이지만, 모든 졸업생이 필수 영역에서 역량을 갖출 수 있도록 하는 것은 항상 의료 전문직 교육에 필수적이었습니다[1, 2]. 이 가이드라인에서는 다음과 같은 역량에 대한 정의를 사용합니다: '의학교육 또는 실습의 정의된 단계에서 특정 맥락에서 모든 영역에서 요구되는 능력을 보유하는 것[1]'. 이제 교육 프로그램과 전문과목은 관찰 및 평가할 수 있는 필수 역량, 역량 구성 요소, 발달 이정표, 성과 수준 및 위탁 가능한 전문 활동(EPA)을 정의했습니다. 그 결과, 학습자(의대생, 대학원 또는 대학원 수련의)가 의미 있고 진정성 있고 현실적인 환자 치료 및 임상 활동에 참여하는 동안 감독자가 관찰하는 직접 관찰이 점점 더 강조되는 평가 방법[3, 4]이 되고 있습니다[4, 5]. [직접 참관]은 의학교육 연락 위원회, 의학전문대학원 교육 인증위원회, 영국 파운데이션 프로그램과 같은 의학교육 인증 기관에서 요구합니다[6,7,8]. 그러나 그 중요성에도 불구하고 임상 술기에 대한 직접 관찰은 드물고 관찰의 질이 떨어질 수 있습니다[9,10,11]. 양질의 직접 관찰이 부족하면 학습에 중대한 영향을 미칩니다. 형성적 관점에서 학습자는 임상 술기 개발을 지원하기 위한 피드백을 받지 못합니다. 또한 학습자의 역량과 궁극적으로 환자에게 제공되는 치료의 질에 대한 종합적인 평가도 위태롭습니다.

While direct observation of clinical skills is a key assessment strategy in competency-based medical education, it has always been essential to health professions education to ensure that all graduates are competent in essential domains [1, 2]. For the purposes of these guidelines, we use the following definition of competent: ‘Possessing the required abilities in all domains in a certain context at a defined stage of medical education or practice [1].’ Training programs and specialties have now defined required competencies, competency components, developmental milestones, performance levels and entrustable professional activities (EPAs) that can be observed and assessed. As a result, direct observation is an increasingly emphasized assessment method [3, 4] in which learners (medical students, graduate or postgraduate trainees) are observed by a supervisor while engaging in meaningful, authentic, realistic patient care and clinical activities [4, 5]. Direct observation is required by medical education accrediting bodies such as the Liaison Committee on Medical Education, the Accreditation Council of Graduate Medical Education and the UK Foundation Program [6,7,8]. However, despite its importance, direct observation of clinical skills is infrequent and the quality of observation may be poor [9,10,11]. Lack of high quality direct observation has significant implications for learning. From a formative perspective, learners do not receive feedback to support the development of their clinical skills. Also at stake is the summative assessment of learners’ competence and ultimately the quality of care provided to patients.

이 백서에서 제안하는 가이드라인은 임상 술기 직접 관찰에 관한 문헌의 종합을 기반으로 하며, 학습자 감독자와 의학교육 임상 교육 프로그램을 담당하는 교육 리더 모두에게 실질적인 권장 사항을 제공합니다. 이 백서의 목적은

- 1) 일선 교사, 학습자 및 교육 리더가 직접 관찰의 질과 빈도를 개선하도록 돕고,

- 2) 직접 관찰에 대한 현재의 관점을 공유하며,

- 3) 이 분야를 발전시키기 위한 향후 연구 의제에 정보를 제공할 수 있는 이해의 격차를 파악하는 것입니다.

The guidelines proposed in this paper are based on a synthesis of the literature on direct observation of clinical skills and provide practical recommendations for both supervisors of learners and the educational leaders responsible for medical education clinical training programs. The objectives of this paper are to

- 1) help frontline teachers, learners and educational leaders improve the quality and frequency of direct observation;

- 2) share current perspectives about direct observation; and

- 3) identify gaps in understanding that could inform future research agendas to move the field forward.

방법

Methods

이 지침은 직접 관찰에 대한 연구 경험이 있고 임상 환경에서 학부(의대생) 및 대학원/대학원(레지던트/펠로우) 학습자를 가르치고, 관찰하고, 피드백을 제공한 실무 경험이 있는 2개국 4명의 의학교육자의 전문가 의견과 함께 기존 증거에 대한 서술적 검토[12]로 이루어졌습니다. 반복적인 프로세스를 통해 가이드라인을 개발했습니다. 특히 병력 청취, 신체 검사, 상담 및 시술 기술 관찰과 같이 학습자가 환자 및 그 가족과 상호작용하는 모습을 직접 관찰하는 것으로 범위를 제한했습니다. 고품질의 직접 관찰을 촉진하고 보장하는 권장 사항을 만들기 위해 일선 교사/감독자, 학습자, 교육 리더 및 상황을 구성하는 기관에 초점을 맞추었습니다.

This is a narrative review [12] of the existing evidence coupled with the expert opinion of four medical educators from two countries who have research experience in direct observation and who have practical experience teaching, observing, and providing feedback to undergraduate (medical student) and graduate/postgraduate (resident/fellow) learners in the clinical setting. We developed the guidelines using an iterative process. We limited the paper’s scope to direct observation of learners interacting with patients and their families, particularly observation of history taking, physical exam, counselling and procedural skills. To create recommendations that promote and assure high quality direct observation, we focused on the frontline teachers/supervisors, learners, educational leaders, and the institutions that constitute the context.

형성 평가와 총괄 평가 모두에 사용되는 직접 관찰을 다루었습니다. 평가의 단계는 연속적이지만,

- [형성 평가]는 학습자 성취도에 대한 증거를 도출하고 해석하여 교사와 학습자가 수업의 다음 단계에 대한 결정을 내리는 데 사용하는 저부담의 평가로 정의하고,

- [총괄 평가]는 행정적 결정의 주요 목적(예: 진도 진행 여부, 졸업 여부 등)을 위해 학습자를 평가하도록 고안된 고부담의 평가로 정의합니다[13].

다음은 제외했습니다

- 1) 모의 진료, 비디오 녹화 진료 및 기타 기술(예: 프레젠테이션 기술, 전문가 간 팀 기술 등)에 대한 관찰,

- 2) 실무 의사에 초점을 맞춘 직접 관찰,

- 3) 다른 형태의 작업장 기반 평가(예: 차트 감사)

직접 관찰의 중요한 측면은 관찰 후 학습자에게 피드백을 제공하는 것이지만, 피드백 가이드라인이 이미 발표되었기 때문에 피드백에 초점을 맞춘 가이드라인의 수를 제한하기로 합의했습니다[14].

We addressed direct observation used for both formative and summative assessment. Although the stakes of assessment are a continuum, we define

- formative assessment as lower-stakes assessment where evidence about learner achievement is elicited, interpreted and used by teachers and learners to make decisions about next steps in instruction, while

- summative assessment is a higher-stakes assessment designed to evaluate the learner for the primary purpose of an administrative decision (i. e. progress or not, graduate or not, etc.) [13].

We excluded

- 1) observation of simulated encounters, video recorded encounters, and other skills (e. g. presentation skills, inter-professional team skills, etc.);

- 2) direct observation focused on practising physicians; and

- 3) other forms of workplace-based assessment (e. g. chart audit).

Although an important aspect of direct observation is feedback to learners after observation, we agreed to limit the number of guidelines focused on feedback because a feedback guideline has already been published [14].

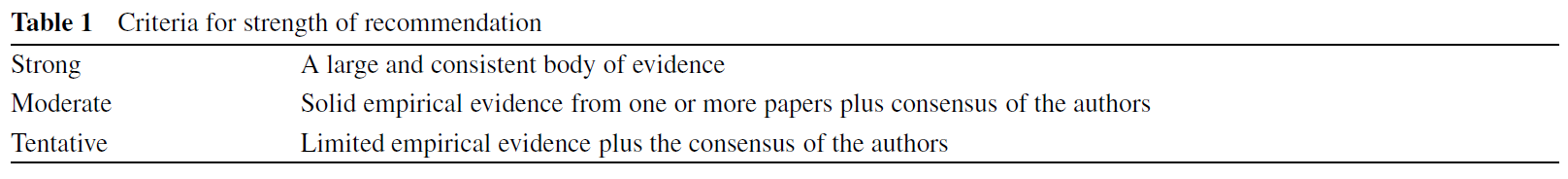

이러한 매개변수를 정의한 후 각 저자는 아래에 정의된 대로 해야 할 일, 하지 말아야 할 일 및 모르는 일 목록을 독립적으로 생성했습니다. 특히 '모르겠다'는 답변이 있을 경우 교육 관행을 바꿀 수 있는 항목에 초점을 맞추었습니다. 일련의 반복적인 토론을 통해 [해야 할 일, 하지 말아야 할 일, 모르는 일] 목록에 합의할 때까지 목록을 검토하고 토론하고 다듬었습니다. 그런 다음 항목은 4명의 저자가 나누어 담당했으며, 각 저자는 할당된 항목에 대한 찬성과 반대의 증거를 식별할 책임이 있었습니다. 주로 임상 술기의 직접 관찰에 초점을 맞춘 근거를 찾았지만, 근거가 부족한 경우 다른 평가 양식과 관련된 근거도 고려했습니다. 그런 다음 모든 저자가 증거 요약을 공유했습니다. 필요한 경우 근거에 따라 항목을 재분류하고 상충되는 근거가 있는 항목은 '잘 모름' 범주로 이동했습니다. 그룹 합의를 통해 이전 지침의 강도 지표를 사용하여 각 지침을 뒷받침하는 근거의 강도를 결정했습니다([14], 표 1). 직접 관찰이 아닌 평가 방식을 추정하여 얻은 증거는 보통 이상의 지지를 받지 못했습니다.

With these parameters defined, each author then independently generated a list of Do’s, Don’ts and Don’t Knows as defined below. We focused on Don’t Knows which, if answered, might change educational practice. Through a series of iterative discussions, the lists were reviewed, discussed and refined until we had agreed upon the list of Do’s, Don’ts and Don’t Knows. The items were then divided amongst the four authors; each author was responsible for identifying the evidence for and against assigned items. We primarily sought evidence explicitly focused on direct observation of clinical skills; however, where evidence was lacking, we also considered evidence associated with other assessment modalities. Summaries of evidence were then shared amongst all authors. We re-categorized items when needed based on evidence and moved any item for which there was conflicting evidence to the Don’t Know category. We used group consensus to determine the strength of evidence supporting each guideline using the indicators of strength from prior guidelines ([14]; Table 1). We did not give a guideline higher than moderate support when evidence came from extrapolation of assessment modalities other than direct observation.

결과

Results

원래 목록에는 개별 감독자, 학습자, 교육 프로그램을 담당하는 교육 리더의 세 그룹에 초점을 맞춘 지침이 있었습니다. 이 초기 목록에는 67개(해야 할 일 35개, 하지 말아야 할 일 16개, 잘 모르겠다 16개)의 항목이 있었습니다. 그룹 토론을 통해 유사하거나 중복되는 항목을 합쳐 33개로 줄였고, 중요하지 않다고 판단된 항목은 2개만 삭제했습니다. 교육 프로그램을 담당하는 교육 리더를 위한 지침에 학습자 중심의 항목을 포함시켜 중복 항목을 줄이고, 교육 리더가 학습자가 직접 관찰하고 피드백을 학습 전략의 일부로 통합하도록 활성화하는 학습 문화를 조성하는 것이 얼마나 중요한지 강조하기로 했습니다.

Our original lists had guidelines focused on three groups: individual supervisors, learners, and educational leaders responsible for training programs. This initial list of Do’s, Don’ts and Don’t Knows numbered 67 (35 Do’s, 16 Don’ts, 16 Don’t Knows). We reduced this to the 33 presented by combining similar and redundant items, with only two being dropped as unimportant based on group discussion. We decided to embed items focused on learners within the guidelines for educational leaders responsible for training programs to reduce redundancy and to emphasize how important it is for educational leaders to create a learning culture that activates learners to seek direct observation and incorporate feedback as part of their learning strategies.

증거를 검토한 결과, 원래 '해야 할 일'로 정의된 4개 항목이 '모름'으로 이동되었습니다. 해야 할 일, 하지 말아야 할 일 및 잘 모름의 최종 목록은 개별 감독자에 초점을 맞춘 지침(표 2)과 교육 프로그램을 담당하는 교육 리더에 초점을 맞춘 지침(표 3)의 두 섹션으로 나뉩니다. 이 원고의 나머지 부분에서는 각 지침을 뒷받침하는 주요 근거와 이용 가능한 문헌에 근거한 지침의 강점을 제공합니다.

After review of the evidence, four items originally defined as a Do were moved to a Don’t Know. The final list of Do’s, Don’ts and Don’t Knows is divided into two sections: guidelines that focus on individual supervisors (Table 2) and guidelines that focus on educational leaders responsible for training programs (Table 3). The remainder of this manuscript provides the key evidence to support each guideline and the strength of the guideline based on available literature.

직접 관찰을 수행하는 개별 임상 감독자를 위한 근거가 포함된 가이드라인

Guidelines with supporting evidence for individual clinical supervisors doing direct observation

개별 슈퍼바이저가 해야 할 일

Do’s for individual supervisors

지침 1. 실제 임상 현장에서 실제 임상 업무를 관찰합니다.

Guideline 1. Do observe authentic clinical work in actual clinical encounters.

직접 관찰은 임상 현장에서 이루어지는 평가로서 임상 역량 평가를 위한 밀러 피라미드의 최상단에 있는 '해야 한다'의 평가를 지원합니다[15, 16]. 교육과 평가의 목표는 임상 환경에서 감독 없이 실습할 수 있는 의사를 배출하는 것이므로, 학습자는 임상 역량을 입증해야 하는 환경에서 관찰되어야 합니다. 실제 임상 상황은 시뮬레이션이나 역할극보다 더 복잡하고 미묘하며 다양한 맥락을 수반하는 경우가 많으므로 실제 임상 진료를 직접 관찰하면 이러한 복잡성을 탐색하는 데 필요한 임상 기술을 관찰할 수 있습니다[17].

Direct observation, as an assessment that occurs in the workplace, supports the assessment of ‘does’ at the top of Miller’s pyramid for assessing clinical competence [15, 16]. Because the goal of training and assessment is to produce physicians who can practise in the clinical setting unsupervised, learners should be observed in the setting in which they need to demonstrate clinical competence. Actual clinical encounters are often more complex and nuanced than simulations or role plays and involve variable context; direct observation of actual clinical care enables observation of the clinical skills required to navigate this complexity [17].

학습자와 교사는 임상 활동 참여를 통한 실습이 학습의 핵심임을 인식하고 있습니다[18,19,20]. [진정성]은 상황별 학습의 핵심 요소이며, 학습이 실제와 가까울수록 기술을 더 빠르고 효과적으로 학습할 수 있습니다[21, 22]. 또한 학습자는 실제 환자와의 만남과 그 환경이 시뮬레이션된 만남보다 더 자연스럽고 유익하며 흥미진진하다고 느끼며, 시뮬레이션된 만남보다 실제 만남에 대해 더 많은 준비를 하고 자율 학습에 대한 더 강한 동기를 표현할 수 있습니다[23]. 학습자는 시간이 지남에 따라 의미 있는 임상 진료에 참여하는 것을 관찰한 후 발생하는 평가와 피드백을 중요하게 생각합니다[24,25,26]. [진정한 만남의 예]로는 임상팀이 이미 병력을 확보한 환자에 대해 학습자가 병력을 작성하는 것을 지켜보는 것보다, 학습자가 초기 병력을 작성하는 것을 지켜보는 것을 들 수 있습니다.

Learners and teachers recognize that hands-on-learning via participation in clinical activities is central to learning [18,19,20]. Authenticity is a key aspect in contextual learning; the closer the learning is to real life, the more quickly and effectively skills can be learned [21, 22]. Learners also find real patient encounters and the setting in which they occur more natural, instructive and exciting than simulated encounters; they may prepare themselves more for real versus simulated encounters and express a stronger motivation for self-study [23]. Learners value the assessment and feedback that occurs after being observed participating in meaningful clinical care over time [24,25,26]. An example of an authentic encounter would be watching a learner take an initial history rather than watching the learner take a history on a patient from whom the clinical team had already obtained a history.

감독자는 학습자를 실제 상황에서 관찰하려고 노력할 수 있지만, 저자의 경험에 따르면 학습자는 관찰을 받을 때 비실제적인 실습(예: 환자 병력을 기록할 때 전자 건강 기록에 입력하지 않거나 더 집중적인 검사가 적절한데도 종합적인 신체 검사를 하는 등)을 기본값으로 설정할 수 있습니다. 관찰자 효과가 성과에 미치는 영향에 대해서는 논란의 여지가 있지만(호손 효과라고도 함)[11, 27], 관찰자는 학습자가 실제 업무 행동에 대한 피드백을 받을 수 있도록 학습자가 '평소에 하던 대로' 하도록 격려해야 합니다. 관찰자는 [호손 효과]에 대한 두려움을 임상 환경에서 학습자를 관찰하지 않는 이유로 사용해서는 안 됩니다[지침 18 참조].

Although supervisors may try to observe learners in authentic situations, it is the authors’ experience that learners may default to inauthentic practice when being observed (for example, not typing in the electronic health record when taking a patient history or doing a comprehensive physical exam when a more focused exam is appropriate). While the impact of observer effects on performance is controversial (known as the Hawthorne effect) [11, 27], observers should encourage learners to ‘do what they would normally do’ so that learners can receive feedback on their actual work behaviours. Observers should not use fear of the Hawthorne effect as a reason not to observe learners in the clinical setting [see Guideline 18].

지침 2. 관찰하기 전에 평가의 후과 및 성과를 포함하여 목표를 논의하고 기대치를 설정하여 학습자를 준비시킵니다.

Guideline 2. Do prepare the learner prior to observation by discussing goals and setting expectations, including the consequences and outcomes of the assessment.

목표 설정에는 학습자와 감독자 간의 협상이 포함되어야 하며, 가능한 경우 직접 관찰에서는 학습자가 가장 필요하다고 느끼는 것에 초점을 맞추어야 합니다. 학습자의 목표는 어떤 활동에 참여할지, 그리고 그러한 활동에 대한 접근 방식에 대해 학습자가 선택할 수 있도록 동기를 부여합니다. 잘 수행하고 '잘 보이는 것'보다는 [학습과 개선을 지향하는 목표]는 학습자가 직접 관찰에 수반될 수 있는 피드백과 교육을 더 잘 수용할 수 있도록 합니다[28, 29]. 학습자가 직접 관찰을 언제, 무엇을 위해 수행할지 자율적으로 결정하면 관찰에 대한 동기가 강화되고 수행 목표에서 학습 목표로 초점을 전환할 수 있습니다[30, 31]. 교사는 학습자의 목표를 묻고 이를 해결하기 위해 교육 및 관찰의 초점을 조정함으로써 이러한 자율성을 촉진할 수 있습니다. 예를 들어, 동일한 임상 상황 내에서 감독자는 학습자가 관찰 및 피드백의 초점(병력 기록, 의사소통 또는 환자 관리)을 선택할 수 있도록 함으로써 학습자를 위한 직접 관찰의 관련성을 높일 수 있습니다. 학습자의 목표는 프로그램 목표, 역량(예: 마일스톤) 및 특정 개인의 필요와 일치해야 합니다[지침 17 참조]. 모든 수준의 학습자에게 목표를 설정하도록 요청하면 어려움을 겪는 학습자에게 초점을 맞추기보다는 모든 학습자에게 개선의 중요성을 정상화하는 데 도움이 됩니다. 관찰자와 학습자 간의 협력적 접근 방식은 아래에 설명된 자기조절 학습 주기의 첫 번째 단계인 학습 계획을 촉진합니다[32]. 학습자는 특정 개인화된 목표를 식별하고 이를 위해 노력하라는 요청을 받아들이고, 그렇게 함으로써 학습에 대한 책임감을 심어줍니다[31].

Setting goals should involve a negotiation between the learner and supervisor and, where possible, direct observation should include a focus on what learners feel they most need. Learners’ goals motivate their choices about what activities to engage in and their approach to those activities. Goals oriented toward learning and improvement rather than performing well and ‘looking good’ better enable learners to embrace the feedback and teaching that can accompany direct observation [28, 29]. Learners’ autonomy to determine when and for what direct observation will be performed can enhance their motivation to be observed and shifts their focus from performance goals to learning goals [30, 31]. Teachers can foster this autonomy by soliciting learners’ goals and adapting the focus of their teaching and observation to address them. For example, within the same clinical encounter, a supervisor can increase the relevance of direct observation for the learner by allowing the learner to select the focus of observation and feedback-history taking, communication, or patient management. A learner’s goals should align with program objectives, competencies (e. g. milestones) and specific individual needs [see Guideline 17]. Asking learners at all levels to set goals helps normalize the importance of improvement for all learners rather than focusing on struggling learners. A collaborative approach between the observer and learner fosters the planning of learning, the first step in the self-regulated learning cycle described below [32]. Learners are receptive to being asked to identify and work towards specific personalized goals, and doing so instills accountability for their learning [31].

관찰하기 전에 관찰자는 평가의 후과에 대해서도 학습자와 논의해야 합니다. 관찰이 높은 수준의 평가가 아닌 피드백을 위해 사용되는 경우 이를 명확히 하는 것이 중요합니다. 학습자는 직접 관찰을 통해 얻을 수 있는 형성적 학습 기회의 이점을 인식하지 못하는 경우가 많으므로 이점을 설명하는 것이 도움이 될 수 있습니다[33].

Prior to observation, observers should also discuss with the learner the consequences of the assessment. It is important to clarify when the observation is being used for feedback as opposed to high-stakes assessment. Learners often do not recognize the benefits of the formative learning opportunities afforded by direct observation, and hence explaining the benefits may be helpful [33].

가이드라인 3. 학습자의 자기조절 학습 능력을 배양합니다.

Guideline 3. Do cultivate learners’ skills in self-regulated learning.

학습을 향상시키기 위한 직접 관찰을 위해 학습자는 개별 목표를 달성하기 위해 받은 피드백의 유용성을 극대화하는 전략을 사용할 준비가 되어 있어야 합니다. 자신의 학습 요구와 지식 및 성과 향상에 필요한 행동에 대한 인식은 직접 관찰의 가치를 최적화합니다. 자기조절 학습은 다음의 지속적인 주기를 설명합니다[32].

- 1) 학습을 위한 계획 수립,

- 2) 활동 중 자기 모니터링 및 학습과 성과를 최적화하기 위해 필요한 조정,

- 3) 활동 후 목표 달성 여부 또는 어려움의 위치와 이유에 대한 성찰

직접 관찰의 맥락에서의 예는 그림 1에 나와 있습니다. 직접 관찰의 맥락에서 발생하는 것처럼 활동 중에 소량의 특정 피드백을 제공하면 자기조절 학습이 극대화됩니다[34]. 훈련생은 피드백을 구함으로써 스스로 평가한 성과를 보강하는 정도가 다양합니다[35]. [직접 관찰과 피드백을 결합]하면 학습자가 받는 피드백의 양을 늘림으로써 이러한 문제를 극복하는 데 도움이 될 수 있습니다[프로그램 지침 18 참조].

For direct observation to enhance learning, the learner should be prepared to use strategies that maximize the usefulness of feedback received to achieve individual goals. Awareness of one’s learning needs and actions needed to improve one’s knowledge and performance optimize the value of being directly observed. Self-regulated learning describes an ongoing cycle of

- 1) planning for one’s learning;

- 2) self-monitoring during an activity and making needed adjustments to optimize learning and performance; and

- 3) reflecting after an activity about whether a goal was achieved or where and why difficulties were encountered [32].

An example in the context of direct observation is shown in Fig. 1. Self-regulated learning is maximized with provision of small, specific amounts of feedback during an activity [34] as occurs in the context of direct observation. Trainees vary in the degree to which they augment their self-assessed performance by seeking feedback [35]. Direct observation combined with feedback can help overcome this challenge by increasing the amount of feedback learners receive [see Program Guideline 18].

가이드라인 4. 중요한 임상 술기는 대리 정보를 사용하지 말고 직접 관찰을 통해 평가합니다.

Guideline 4. Do assess important clinical skills via direct observation rather than using proxy information.

감독자는 평가할 술기를 직접 관찰해야 합니다. 실제로 감독자는 학습자의 임상 술기를 평가할 때 대리 정보를 기반으로 하는 경우가 많습니다. 예를 들어, 감독자는 학습자가 환자를 진찰하는 것을 듣고 병력 및 신체 검사 기술을 추론하거나 학습자와 팀과의 상호 작용을 기반으로 환자와의 대인관계 기술을 추론하는 경우가 많습니다[36]. 직접 관찰은 임상 수행 평가의 질, 의미, 신뢰성 및 타당성을 향상시킵니다[37]. 감독자와 학습자는 직접 관찰에 기반한 평가를 효과적인 평가자의 가장 중요한 특성 중 하나로 간주합니다[38]. 또한 학습자는 직접 관찰에 기반한 교육생에 대한 직접적인 정보에 근거할 때 교육 중 평가가 가치 있고 정확하며 신뢰할 수 있다고 생각할 가능성이 더 높습니다[39]. 예를 들어, 로테이션이 끝날 때 평가할 술기인 경우, 감독자는 로테이션이 진행되는 동안 학습자가 병력을 작성하는 것을 여러 번 직접 관찰해야 합니다.

Supervisors should directly observe skills they will be asked to assess. In reality, supervisors often base their assessment of a learner’s clinical skills on proxy information. For example, supervisors often infer history and physical exam skills after listening to a learner present a patient or infer interpersonal skills with patients based on learner interactions with the team [36]. Direct observation improves the quality, meaningfulness, reliability and validity of clinical performance ratings [37]. Supervisors and learners consider assessment based on direct observation to be one of the most important characteristics of effective assessors [38]. Learners are also more likely to find in-training assessments valuable, accurate and credible when they are grounded in first-hand information of the trainee based on direct observation [39]. For example, if history taking is a skill that will be assessed at the end of a rotation, supervisors should directly observe a learner taking a history multiple times over the rotation.

가이드라인 5. 실습을 방해하지 않고 관찰합니다.

Guideline 5. Do observe without interrupting the encounter.

관찰자는 가능한 한 학습자가 방해받지 않고 면담을 진행할 수 있도록 해야 합니다. 학습자는 자율성과 점진적인 독립성을 중요하게 생각합니다[40, 41]. 많은 학습자는 이미 직접 관찰이 학습, 자율성 및 환자와의 관계에 방해가 된다고 느끼고 있으며, 방해는 이러한 우려를 더욱 악화시킵니다[42, 43]. 학습자가 환자 치료에 참여하는 동안 방해하면 학습자의 구두 사례 발표(임상 추론에 대한 직접 관찰의 예)를 중단한 감독자에 대한 연구에서 볼 수 있듯이 중요한 정보가 누락될 수 있습니다[44]. 또한 평가자는 종종 자신의 존재가 학습자와 환자의 관계를 손상시킬 수 있다고 걱정합니다. 관찰자는 환자가 학습자를 우선적으로 바라볼 수 있도록 환자의 주변 시야에 위치하여 직접 관찰하는 동안 방해 요소를 최소화할 수 있습니다. 이러한 위치에서도 관찰자는 [학습자와 환자의 얼굴을 모두 볼 수 있어야 비언어적 단서를 식별]할 수 있습니다. 또한 관찰자는 학습자가 심각한 오류를 범하지 않는 한 학습자와 환자의 상호 작용을 방해하지 않음으로써 관찰자의 존재감을 최소화할 수 있습니다. 관찰자는 과도한 움직임이나 소음(예: 펜 두드리기)과 같이 주의를 산만하게 하는 방해 요소를 피해야 합니다.

Observers should enable learners to conduct encounters uninterrupted whenever possible. Learners value autonomy and progressive independence [40, 41]. Many learners already feel that direct observation interferes with learning, their autonomy and their relationships with patients, and interruptions exacerbate these concerns [42, 43]. Interrupting learners as they are involved in patient care can lead to the omission of important information as shown in a study of supervisors who interrupted learners’ oral case presentations (an example of direct observation of clinical reasoning) [44]. Additionally, assessors often worry that their presence in the room might undermine the learner-patient relationship. Observers can minimize intrusion during direct observation by situating themselves in the patient’s peripheral vision so that the patient preferentially looks at the learner. This positioning should still allow the observer to see both the learner’s and patient’s faces to identify non-verbal cues. Observers can also minimize their presence by not interrupting the learner-patient interaction unless the learner makes egregious errors. Observers should avoid distracting interruptions such as excessive movement or noises (e. g. pen tapping).

가이드라인 6. 인지적 편견, 인상 형성 및 암묵적 편견이 관찰 중에 도출된 추론에 영향을 미칠 수 있음을 인식합니다.

Guideline 6. Do recognize that cognitive bias, impression formation and implicit bias can influence inferences drawn during observation.

직접 관찰을 통해 도출된 평가의 타당성에는 여러 가지 위협이 있습니다. 평가자는 학습자를 관찰하기 시작하는 순간부터 즉각적인 인상을 형성하며(종종 적은 정보에 근거하여), 종종 빠르게(몇 분 내에) 수행 능력을 판단할 수 있다고 생각합니다[45, 46]. 이러한 빠른 판단, 즉 인상은 개인이 사람의 성격이나 행동에 대한 정보를 인지하고, 조직화하고, 통합하는 데 도움이 됩니다[47]. 인상 형성 문헌에 따르면 이러한 초기 판단이나 추론은 무의식적으로 빠르게 이루어지며 향후 상호 작용, 사람에 대해 기억하는 것, 미래 행동에 대해 예측하는 것에 영향을 미칠 수 있습니다[48]. 또한 학습자의 역량에 대한 판단은 다른 학습자와의 상대적 비교(대조 효과)에 의해 영향을 받을 수 있습니다[49]. 예를 들어, 실력이 부족한 학습자를 관찰한 후 한계 실력의 학습자를 관찰한 감독자는 이전에 실력이 뛰어난 학습자를 관찰했을 때보다 한계 실력의 학습자에 대해 더 호의적인 인상을 가질 수 있습니다. 관찰자는 이러한 편견을 인식하고 관찰된 행동에 근거하여 판단할 수 있도록 충분히 오래 관찰해야 합니다. 감독자는 [추론이 높은 인상]보다는 [추론이 낮고 관찰 가능한 행동]에 초점을 맞춰야 합니다. 예를 들어 학습자가 팔짱을 끼고 서서 나쁜 소식을 전하는 경우, 관찰 가능한 행동은 학습자가 팔짱을 끼고 서 있다는 것입니다. 이러한 행동은 상황에 대한 공감 부족 또는 불편함을 나타낸다는 추론 인상이 높습니다. 관찰자는 자신의 높은 수준의 추론이 정확하다고 가정해서는 안 됩니다. 오히려 비언어적 의사소통의 일부로서 팔짱을 끼는 것이 무엇을 의미하는지 학습자와 함께 탐구해야 합니다[가이드라인 16 참조].

There are multiple threats to the validity of assessments derived from direct observation. Assessors develop immediate impressions from the moment they begin observing learners (often based on little information) and often feel they can make a performance judgment quickly (within a few minutes) [45, 46]. These quick judgments, or impressions, help individuals perceive, organize and integrate information about a person’s personality or behaviour [47]. Impression formation literature suggests that these initial judgments or inferences occur rapidly and unconsciously and can influence future interactions, what is remembered about a person and what is predicted about their future behaviours [48]. Furthermore, judgments about a learner’s competence may be influenced by relative comparisons to other learners (contrast effects) [49]. For example, a supervisor who observes a learner with poor skills and then observes a learner with marginal skills may have a more favourable impression of the learner with marginal skills than if they had previously observed a learner with excellent skills. Observers should be aware of these biases and observe long enough so that judgments are based on observed behaviours. Supervisors should focus on low inference, observable behaviours rather than high inference impressions. For example, if a learner is delivering bad news while standing up with crossed arms, the observable behaviour is that the learner is standing with crossed arms. The high inference impression is that this behaviour represents a lack of empathy or discomfort with the situation. Observers should not assume their high-level inference is accurate. Rather they should explore with the learner what crossed arms can mean as part of non-verbal communication [see Guideline 16].

가이드라인 7. 관찰 후 피드백은 관찰 가능한 행동에 초점을 맞춰 제공하세요.

Guideline 7. Do provide feedback after observation focusing on observable behaviours.

직접 관찰 후 피드백은 이전에 발표된 모범 사례를 따라야 합니다[14]. 직접 관찰은 행동 계획과 관련된 시기적절한 행동 기반 피드백을 동반할 때 학습자가 더 잘 받아들일 수 있습니다[50]. 직접 관찰 후 피드백은 학습자의 즉각적인 우려 사항을 해결하고, 구체적이고 가시적이며, 학습자가 개선을 위해 앞으로 다르게 수행해야 할 사항을 이해하는 데 도움이 되는 정보를 제공할 때 가장 의미가 있습니다[31, 51]. 긍정적인 피드백은 학습자의 자신감을 향상시켜 학습자가 더 많은 관찰과 피드백을 구하도록 유도하기 때문에 학습자가 잘한 것을 설명하는 것은 중요합니다[31]. 피드백은 직접 대면하여 제공할 때 가장 효과적이므로 감독자는 대면 토론 없이 단순히 평가 양식에 피드백을 문서화하는 것을 피해야 합니다.

Feedback after direct observation should follow previously published best practices [14]. Direct observation is more acceptable to learners when it is accompanied by timely, behaviourally based feedback associated with an action plan [50]. Feedback after direct observation is most meaningful when it addresses a learner’s immediate concerns, is specific and tangible, and offers information that helps the learner understand what needs to be done differently going forward to improve [31, 51]. Describing what the learner did well is important because positive feedback seems to improve learner confidence which, in turn, prompts the learner to seek more observation and feedback [31]. Feedback is most effective when it is given in person; supervisors should avoid simply documenting feedback on an assessment form without an in-person discussion.

지침 8. 학습자가 피드백을 통합할 수 있도록 종단적으로 관찰합니다.

Guideline 8. Do observe longitudinally to facilitate learners’ integration of feedback.

교수자가 학습자를 시간이 지남에 따라 반복적으로 관찰하면 학습이 촉진되며, 이를 통해 전문성 개발에 대한 더 나은 그림을 그릴 수 있습니다. 학습자는 자신의 성과를 되돌아보고 [종적 관계]에서 학습 목표 및 목표 달성에 대해 감독자와 논의할 수 있을 때 매우 만족합니다[25, 31]. 종적 관계는 학습자가 자신의 학습 진행 상황을 목격하고 학습자로서의 더 넓은 관점에서 피드백을 제공할 수 있는 기회를 제공합니다[25]. 지속적인 관찰은 감독자가 학습자의 역량과 한계를 평가하는 데 도움이 될 수 있으며, 이를 통해 학습자에게 앞으로 얼마나 많은 감독이 필요한지 알 수 있습니다[52]. 유능하게 임상 활동을 수행하는 것이 관찰된 학습자에게 다음 임상 활동에서 더 큰 독립성을 가지고 이러한 활동을 수행할 수 있는 권리가 부여되면 자율성이 강화됩니다[53]. 숙련된 임상 교사는 개별 학습자의 목표와 필요에 맞게 교육을 조정하는 기술을 습득하며, 직접 관찰은 학습자 중심의 교육 및 감독 접근 방식에서 중요한 구성 요소입니다[54]. 동일한 감독자가 학습자를 종적으로 관찰할 수 없는 경우, 여러 교수진이 프로그램 수준에서 이러한 관찰 순서를 수행하는 것이 중요합니다.

Learning is facilitated by faculty observing a learner repeatedly over time, which also enables a better picture of professional development to emerge. Learners appreciate when they can reflect on their performance and, working in a longitudinal relationship, discuss learning goals and the achievement of those goals with a supervisor [25, 31]. Longitudinal relationships afford learners the opportunity to have someone witness their learning progression and provide feedback in the context of a broader view of them as a learner [25]. Ongoing observation can help supervisors assess a learner’s capabilities and limitations, thereby informing how much supervision the learner needs going forward [52]. Autonomy is reinforced when learners who are observed performing clinical activities with competence are granted the right to perform these activities with greater independence in subsequent encounters [53]. Experienced clinical teachers gain skill in tailoring their teaching to an individual learner’s goals and needs; direct observation is a critical component of this learner-centred approach to teaching and supervision [54]. If the same supervisor cannot observe a learner longitudinally, it is important that this sequence of observations occurs at the programmatic level by multiple faculty.

가이드라인 9. 많은 학습자가 직접 관찰을 거부한다는 점을 인식하고 이러한 주저함을 극복할 수 있는 전략을 준비합니다.

Guideline 9. Do recognize that many learners resist direct observation and be prepared with strategies to try to overcome their hesitation.

일부 학습자는 직접 관찰이 유용하다고 생각하지만[24, 55], 많은 학습자는 직접 관찰을 (주로 사용되는 평가 도구와 무관하게) '체크 박스 연습' 또는 커리큘럼상의 의무로 간주합니다[33, 56]. 학습자는 여러 가지 이유로 직접 관찰을 거부할 수 있습니다. 학습자는 직접 관찰이 [불안을 유발하고 불편하며 스트레스가 많고 인위적이라고 생각]할 수 있습니다[31, 43, 50, 57, 58]. 학습자의 저항은 교수자가 자신을 관찰하기에는 너무 바쁘고[43], 관찰할 시간이 있는 교수자를 찾는 데 어려움을 겪을 것이라는 믿음에서 비롯될 수도 있습니다[59]. 많은 학습자는 [직접 관찰이 피드백이 아닌 높은 수준의 평가에만 사용될 때] 교육적 가치가 거의 없다고 생각하며[60], 교육 및 개선 계획이 포함된 피드백 없이는 직접 관찰이 유용하지 않다고 생각합니다[59]. 한 연구에서는 미니 CEX의 일환으로 100회 이상의 피드백 세션을 오디오 녹음한 결과 교수진이 학습자와 함께 실행 계획을 세우는 데 거의 도움이 되지 않는 것으로 나타났습니다[61]. 학습자는 [교육 도구로서의 직접 관찰]과 [평가 방법으로서의 직접 관찰] 사이에 충돌이 있다고 인식합니다[57, 60]. 많은 학습자는 직접 관찰이 학습, 자율성, 효율성 및 환자와의 관계에 방해가 된다고 생각합니다[42, 43]. 또한 학습자는 자신의 학습을 촉진하기 위해 어려운 상황을 독립적으로 처리하는 것을 중요하게 생각합니다[62, 63].

Although some learners find direct observation useful [24, 55], many view it (largely independent of the assessment tool used) as a ‘tick-box exercise’ or a curricular obligation [33, 56]. Learners may resist direct observation for multiple reasons. They can find direct observation anxiety-provoking, uncomfortable, stressful and artificial [31, 43, 50, 57, 58]. Learners’ resistance may also stem from their belief that faculty are too busy to observe them [43] and that they will struggle to find faculty who have time to observe [59]. Many learners (correctly) believe direct observation has little educational value when it is only used for high-stakes assessments rather than feedback [60]; they do not find direct observation useful without feedback that includes teaching and planning for improvement [59]. One study audiotaped over a hundred feedback sessions as part of the mini-CEX and found faculty rarely helped to create an action plan with learners [61]. Learners perceive a conflict between direct observation as an educational tool and as an assessment method [57, 60]. Many learners feel that direct observation interferes with learning, autonomy, efficiency, and relationships with their patients [42, 43]. Furthermore, learners value handling difficult situations independently to promote their own learning [62, 63].

감독자는 직접 관찰에 대한 학습자의 [저항을 줄이기 위한 전략]을 사용할 수 있습니다. 학습자는 관찰을 수행하는 개인과 종적인 관계를 맺을 때 직접 관찰 과정에 참여할 가능성이 더 높습니다. 학습자는 감독자가 자신에게 투자하고, 자신을 존중하며, 자신의 성장과 발달에 관심을 갖고 있다고 느낄 때 더 잘 받아들입니다[31, 64]. 학습자는 일반적으로 관찰이 정기적으로 이루어질 때 직접 관찰에 더 익숙해지기 때문에 관찰은 자주 이루어져야 합니다[58]. [로테이션을 시작할 때 학습 및 기술 개발을 위한 직접 관찰의 역할에 대해 논의]하면 직접 관찰의 양이 늘어납니다[43]. 감독자는 학습자에게 직접 관찰할 수 있음을 알려야 합니다. 감독자는 직접 관찰이 피드백 및 개발을 위해 사용되는 경우와 더 높은 수준의 평가를 위해 사용되는 경우를 명시하여 학습자에게 관찰의 위험도를 명확히 알려야 합니다. 감독자는 학습자가 총괄 평가를 위한 직접 관찰보다 [형성 목적의 직접 관찰]을 더 긍정적으로 여긴다는 점을 기억해야 합니다[65]. 또한 학습자는 개인화된 학습 목표에 초점을 맞추고[31] 효과적이고 질 높은 피드백이 뒤따를 때 직접 관찰을 더 중요하게 여기고 참여할 가능성이 높습니다.

Supervisors can employ strategies to decrease learners’ resistance to direct observation. Learners are more likely to engage in the process of direct observation when they have a longitudinal relationship with the individual doing the observations. Learners are more receptive when they feel a supervisor is invested in them, respects them, and cares about their growth and development [31, 64]. Observation should occur frequently because learners generally become more comfortable with direct observation when it occurs regularly [58]. Discussing the role of direct observation for learning and skill development at the beginning of a rotation increases the amount of direct observation [43]. Supervisors should let learners know they are available for direct observation. Supervisors should make the stakes of the observation clear to learners, indicating when direct observation is being used for feedback and development versus for higher-stakes assessments. Supervisors should remember learners regard direct observation for formative purposes more positively than direct observation for summative assessment [65]. Additionally, learners are more likely to value and engage in direct observation when it focuses on their personalized learning goals [31] and when effective, high quality feedback follows.

개별 감독자가 하지 말아야 할 사항

Don’ts for individual supervisors

가이드라인 10. 피드백을 정량적 평가로 제한하지 마세요.

Guideline 10. Don’t limit feedback to quantitative ratings.

직접 관찰한 내러티브 코멘트는 학습자에게 풍부한 피드백을 제공합니다. 수치 평가가 포함된 평가 양식을 사용하는 경우 학습자에게 서술형 피드백도 제공하는 것이 중요합니다. 많은 직접 관찰 평가 도구는 평가자가 학습자의 수행을 설명하기 위해 숫자 등급을 선택하도록 유도합니다[66]. 그러나 수행 점수를 의미 있게 해석하려면 평가자의 추론에 대한 통찰력을 제공하는 서술적 코멘트가 필요합니다. 내러티브 코멘트는 역량 성취도에 대한 신뢰할 수 있고 방어 가능한 의사 결정을 지원할 수 있습니다[67]. 또한 내러티브 피드백은 건설적인 방식으로 제공될 경우 교육생이 수행 능력의 강점과 약점을 정확하게 파악하고 역량 개발을 안내하는 데 도움이 될 수 있습니다[46]. 직접 관찰 자체에 대한 증거가 부족하고 정량적 평가가 성적과 동일하지 않지만, 다른 평가 문헌에 따르면 학습자가 성적이나 코멘트와 함께 성적만 받았을 때 학습 이득을 보이지 않는다고 합니다. 학습자는 성적에 집중하고 코멘트를 무시하기 때문에 코멘트가 포함된 성적을 받을 때 학습 이득이 발생하지 않는다는 가설이 있습니다[68,69,70]. 반면, 성적 없이 코멘트만 받은 학습자는 큰 학습 이득을 보입니다[68,69,70]. [서술적 피드백이 없는 성적]은 학습자에게 개선을 자극할 수 있는 충분한 정보와 동기를 제공하지 못합니다[26]. 합격/불합격 등급이 특정 수치 등급보다 학생에게 더 잘 받아들여질 수 있지만[51], 전체 등급을 사용하면 피드백에 대한 수용도가 떨어질 수도 있습니다[71]. 직접 관찰 후 학습자와 평점을 공유하는 것의 장단점은 알려져 있지 않지만, 형성적 평가에 직접 관찰을 사용하는 경우 학습자가 강점 영역(잘 수행한 기술)과 개선이 필요한 기술을 설명하는 서술형 피드백을 받는 것이 중요합니다.

Narrative comments from direct observations provide rich feedback to learners. When using an assessment form with numerical ratings, it is important to also provide learners with narrative feedback. Many direct observation assessment tools prompt evaluators to select numerical ratings to describe a learner’s performance [66]. However, meaningful interpretation of performance scores requires narrative comments that provide insight into raters’ reasoning. Narrative comments can support credible and defensible decision making about competence achievement [67]. Moreover, narrative feedback, if given in a constructive way, can help trainees accurately identify strengths and weaknesses in their performance and guide their competence development [46]. Though evidence is lacking in direct observation per se and quantitative ratings are not the same as grades, other assessment literature suggests that learners do not show learning gains when they receive just grades or grades with comments. It is hypothesized that learning gains do not occur when students receive grades with comments because learners focus on the grade and ignore the comments [68,69,70]. In contrast, learners who receive only comments (without grades) show large learning gains [68,69,70]. Grades without narrative feedback fail to provide learners with sufficient information and motivation to stimulate improvement [26]. The use of an overall rating may also reduce acceptance of feedback [51] although a Pass/Fail rating may be better received by students than a specific numerical rating [71]. Although the pros and cons of sharing a rating with a learner after direct observation are not known, it is important that learners receive narrative feedback that describes areas of strength (skills performed well) and skills requiring improvement when direct observation is being used for formative assessment.

가이드라인 11. 학습자와 환자 모두의 허락을 구하고 준비하지 않은 상태에서 환자 앞에서 피드백을 제공하지 마십시오.

Guideline 11. Don’t give feedback in front of the patient without seeking permission from and preparing both the learner and the patient.

감독자가 환자 앞에서 직접 관찰한 후 학습자에게 피드백을 제공하려는 경우, 사전에 학습자와 환자의 허락을 구하는 것이 중요합니다. 피드백은 일반적으로 조용하고 사적인 장소에서 제공되며, 환자 앞에서 피드백을 제공하면 학습자와 환자의 관계가 손상될 수 있으므로 이러한 허락은 특히 중요합니다. 허가를 구하지 않았거나 허가를 받지 않은 경우 학습자는 환자 앞에서 피드백을 받아서는 안 됩니다. 그러나 예외적으로 환자가 안전하고 효과적이며 환자 중심의 치료를 받지 못하는 경우에는 즉시 중단해야 하며, 이러한 상황에서는 이러한 중단이 피드백의 한 형태임을 인식하고 학습자를 지지하고 비하하지 않는 방식으로 즉각 중단해야 합니다.

If a supervisor plans to provide feedback to a learner after direct observation in front of a patient, it is important to seek the learner’s and patient’s permission in advance. This permission is particularly important since feedback is typically given in a quiet, private place, and feedback given in front of the patient may undermine the learner-patient relationship. If permission has not been sought or granted, the learner should not receive feedback in front of the patient. The exception, however, is when a patient is not getting safe, effective, patient-centred care; in this situation, immediate interruption is warranted (in a manner that supports and does not belittle the learner), recognizing that this interruption is a form of feedback.

병상 교육은 학습자에게 효과적이고 흥미를 유발할 수 있지만[72, 73] 일부 학습자는 환자 앞에서 교육하는 것이 환자와의 치료 동맹을 약화시키고 긴장된 분위기를 조성하며 질문할 수 있는 능력을 제한한다고 느낍니다[73, 74]. 그러나 환자 중심주의 시대에는 피드백에서 환자 목소리의 역할과 중요성이 증가할 수 있습니다. 실제로 이전 연구에 따르면 많은 환자가 자신의 치료에 대해 논의할 때 의료진이 병상에 있기를 원한다고 합니다[75]. 직접 관찰의 맥락에서 환자와 치료 및 교육적 제휴를 가장 잘 구축하는 방법은 추가적인 주의가 필요합니다.

Although bedside teaching can be effective and engaging for learners, [72, 73] some learners feel that teaching in front of the patient undermines the patient’s therapeutic alliance with them, creates a tense atmosphere, and limits the ability to ask questions [73, 74]. However, in the era of patient-centredness, the role and importance of the patient voice in feedback may increase. In fact, older studies suggest many patients want the team at the bedside when discussing their care [75]. How to best create a therapeutic and educational alliance with patients in the context of direct observation requires additional attention.

개별 감독자의 경우 모름

Don’t Knows for individual supervisors

지침 12. 직접 관찰하는 동안 인지 부하가 미치는 영향은 무엇이며 이를 완화하기 위한 접근 방식은 무엇입니까?

Guideline 12. What is the impact of cognitive load during direct observation and what are approaches to mitigate it?

평가자는 학습자를 관찰하고 평가하는 동시에 환자를 진단하고 돌보려고 노력하면서 상당한 인지 부하를 경험할 수 있습니다[76]. [지각 부하]가 관찰자의 주의력을 압도하거나 초과할 수 있습니다. 이러한 과부하는 한 자극에 집중하면 다른 자극에 대한 지각이 손상되는 '부주의성 실명'을 유발할 수 있습니다[76]. 예를 들어, 학습자의 임상적 추론에 집중하는 동시에 환자를 진단하려고 하면 감독자가 학습자의 의사소통 기술에 주의를 기울이는 데 방해가 될 수 있습니다. 평가자가 평가해야 하는 차원 수가 증가하면 평가의 질이 떨어집니다[77]. 경험이 많은 관찰자는 학습자와 환자에 대한 휴리스틱, 스키마 또는 수행 스크립트를 개발하여 정보를 처리함으로써 관찰 능력을 향상시킵니다[45, 76]. 또한 고도로 숙련된 교수진은 더 강력한 스키마 및 스크립트와 관련된 노력이 감소하기 때문에 인지 부하를 줄이면서 강점과 약점을 감지할 수 있습니다[78]. [평가 도구 설계]도 인지 부하에 영향을 미칠 수 있습니다. 예를 들어, Byrne과 동료들은 인지 부하를 측정하기 위해 검증된 도구를 사용하여 마취를 유도하는 수련의에 대한 객관적인 구조화된 임상 시험을 위해 주관적인 평가 척도보다 20개 이상의 항목 체크리스트를 작성하도록 요청받았을 때 교수진이 더 큰 인지 부하를 경험하는 것으로 나타났습니다[79]. 시뮬레이션이 아닌 상황에서 직접 관찰하는 동안 인지적 부하가 미치는 영향과 관찰자가 중요한 요소만 평가하도록 평가 양식을 구성하여 평가할 항목 수를 제한하는 방법을 결정하기 위해서는 더 많은 연구가 필요합니다.

An assessor can experience substantial cognitive load observing and assessing a learner while simultaneously trying to diagnose and care for the patient [76]. Perceptual load may overwhelm or exceed the observer’s attentional capacities. This overload can cause ‘inattentional blindness,’ where focusing on one stimulus impairs perception of other stimuli [76]. For example, focusing on a learner’s clinical reasoning while simultaneously trying to diagnose the patient may interfere with the supervisor’s ability to attend to the learner’s communication skills. As the number of dimensions raters are asked to assess increases, the quality of ratings decreases [77]. More experienced observers develop heuristics, schemas or performance scripts about learners and patients to process information and thereby increase observational capacity [45, 76]. More highly skilled faculty may also be able to detect strengths and weaknesses with reduced cognitive load because of the reduced effort associated with more robust schemes and scripts [78]. Assessment instrument design may also influence cognitive load. For example, Byrne and colleagues, using a validated instrument to measure cognitive load, showed that faculty experienced greater cognitive load when they were asked to complete a 20 plus item checklist versus a subjective rating scale for an objective structured clinical examination of a trainee inducing anaesthesia [79]. More research is needed to determine the impact of cognitive load during direct observation in non-simulated encounters and how to structure assessment forms so that observers are only asked to assess critical elements, thereby limiting the number of items to be rated.

지침 13. 다양한 기술을 직접 관찰하기 위한 최적의 시간길이는 얼마입니까?

Guideline 13. What is the optimal duration for direct observation of different skills?

최근 직접 관찰 및 피드백 관련 문헌의 대부분은 바쁜 업무 환경에서 효율성을 높이기 위해 직접 관찰 시간을 짧고 집중적으로 유지하는 데 초점을 맞추고 있습니다[80]. 짧은 관찰은 환자를 만나는 시간이 짧은 임상 전문과목에 적합하지만, 다른 전문과목의 경우 긴 관찰을 통해서만 알 수 있는 진료의 관련 측면을 짧은 관찰로 놓칠 수 있습니다. 직접 관찰 및 피드백을 위한 시급한 질문 중 하나는 다양한 전문과목, 학습자 및 술기에 대한 최적의 면담 시간을 결정하는 것입니다. 최적의 면담 시간은 환자의 요구, 관찰 대상 과제, 학습자의 역량, 교수자의 과제에 대한 친숙도 등 여러 변수를 반영해야 할 것입니다[78, 81].

Much of the recent direct observation and feedback literature has focused on keeping direct observation short and focused to promote efficiency in a busy workplace [80]. While short observations make sense for clinical specialties that have short patient encounters, for other specialties relevant aspects of practice that are only apparent with a longer observation may be missed with brief observations. One of the pressing questions for direct observation and feedback is to determine the optimal duration of encounters for various specialties, learners and skills. The optimal duration of an encounter will likely need to reflect multiple variables including the patient’s needs, the task being observed, the learner’s competence and the faculty’s familiarity with the task [78, 81].

교육자/교육 지도자를 위한 근거가 있는 가이드라인

Guidelines with supporting evidence for educators/educational leaders

교육 지도자를 위한 지침

Do’s for educational leaders

지침 14. 관련 임상 기술과 전문성을 기준으로 참관자를 선정합니다.

Guideline 14. Do select observers based on their relevant clinical skills and expertise.

프로그램 디렉터와 같은 교육 리더는 관련 임상 기술과 교육 전문성을 기준으로 참관자를 선정해야 합니다. 공정하고 신뢰할 수 있는 평가를 위해서는 콘텐츠 전문성(모범 술기가 어떤 것인지에 대한 지식과 이를 평가할 수 있는 능력)이 전제 조건입니다[82]. 그러나 평가자는 종종 내용 전문성이 부족하다고 느끼는 술기를 직접 관찰하도록 요청받으며, 평가자는 체크리스트를 사용하여 자신의 임상 기술 부족을 보완할 수 있다고 생각하지 않습니다[83]. 또한 감독자 자신의 임상 기술이 학습자를 평가하는 방식에 영향을 미칠 수 있습니다[78]. 평가자의 특성이 평가자 자신의 역량 결핍의 결과인 경우[84], 평가자가 관찰 및 피드백 시 자신을 표준으로 삼는 경우 학습자도 동일한 결핍 또는 역량 장애를 습득할 수 있습니다[78,85,86,87,88,89,90]. 교수진은 종종 자신을 학습자 수행을 평가하는 기준(즉, 참조 프레임)으로 사용하기 때문에[82], 임상 술기 전문성을 기반으로 평가자를 선정하거나 평가자가 자신을 참조 프레임으로 사용하지 않고 유능하고 전문적인 수행을 인정할 수 있도록 평가자 교육을 제공하는 것이 중요합니다.

Educational leaders, such as program directors, should select observers based on their relevant clinical skills and educational expertise. Content expertise (knowledge of what exemplar skill looks like and having the ability to assess it) is a prerequisite for fair, credible assessment [82]. However, assessors are often asked to directly observe skills for which they feel they lack content expertise, and assessors do not believe using a checklist can make up for a lack of their own clinical skill [83]. Additionally, a supervisor’s own clinical skills may influence how they assess a learner [78]. When assessors’ idiosyncrasy is the result of deficiencies in their own competencies [84] and when assessors use themselves as the gold standard during observation and feedback, learners may acquire the same deficiencies or dyscompetencies [78, 85,86,87,88,89,90]. Because faculty often use themselves as the standard by which they assess learner performance (i. e. frame of reference), [82] it is important to select assessors based on their clinical skills expertise or provide assessor training so assessors can recognize competent and expert performance without using themselves as a frame of reference.

프로그램 수준에서는 특정 술기를 평가할 수 있는 [전문성을 갖춘 개인]에게 필요한 관찰 유형을 조정하는 것이 현명합니다. 예를 들어, 프로그램 디렉터는 심장 전문의에게 학습자의 심장 검사를 관찰하도록 요청하고 완화 치료 의사에게 학습자의 치료 목표에 대한 논의를 관찰하도록 요청할 수 있습니다. 학습자가 평가할 특정 술기에 대한 콘텐츠 전문 지식과 임상적 통찰력을 갖춘 평가자를 사용하는 것도 중요한데, 학습자는 이러한 개인의 피드백을 신뢰할 수 있고 신뢰할 수 있다고 생각할 가능성이 높기 때문입니다[20, 64]. 전문성이 부족한 경우 교수진의 역량 부족을 교정하도록 돕는 것이 중요합니다[91]. 평가와 관련된 교수진 개발은 이론적으로 교수진 자신의 임상 기술을 향상시키는 동시에 관찰 기술을 향상시키는 '일거양득'이 될 수 있습니다[91].

At a programmatic level, it is prudent to align the types of observations needed to individuals who have the expertise to assess that particular skill. For example, a program director might ask cardiologists to observe learners’ cardiac exams and ask palliative care physicians to observe learners’ goals of care discussions. Using assessors with content expertise and clinical acumen in the specific skill(s) being assessed is also important because learners are more likely to find feedback from these individuals credible and trustworthy [20, 64]. When expertise is lacking, it is important to help faculty correct their dyscompetency [91]. Faculty development around assessment can theoretically become a ‘two-for-one’—improving the faculty’s own clinical skills while concomitantly improving their observation skills [91].

평가자는 임상 술기 전문성 외에도 [다양한 교육 수준에서 학습자에게 기대할 수 있는 사항에 대한 지식]이 있어야 합니다[83]. 평가자는 교수 및 교육에 전념하고, 학습자의 성장을 촉진하는 데 투자하며, 학습자의 폭넓은 정체성과 경험에 관심을 갖고, 학습자를 신뢰하고 존중하며 돌볼 의향이 있어야 합니다[64][지침 28 참조].

In addition to clinical skills expertise, assessors also must have knowledge of what to expect of learners at different training levels [83]. Assessors must be committed to teaching and education, invested in promoting learner growth, interested in learners’ broader identity and experience, and willing to trust, respect and care for learners [64] [see Guideline 28].

가이드라인 15. 가능하면 직접 관찰을 위해 새로운 도구를 만들기보다는 기존의 타당성 근거가 있는 평가 도구를 사용합니다.

Guideline 15. Do use an assessment tool with existing validity evidence, when possible, rather than creating a new tool for direct observation.

직접 관찰을 기반으로 학습자의 수행을 평가하는 데 도움이 되는 많은 도구가 존재합니다[66, 92]. 교육자는 새로운 도구를 만들기보다는 가능하면 타당성 근거가 있는 기존 도구를 사용해야 합니다[93]. 교육자의 목적에 맞는 도구가 존재하지 않는 경우, 기존 도구를 수정하거나 새로운 도구를 만드는 방법이 있습니다. 직접 관찰을 위해 새로운 도구를 만들거나 기존 도구를 수정하려면 타당도 근거 축적을 포함하여 도구 설계 및 평가 지침을 따라야 합니다[94]. 필요한 타당도 증거의 양은 낮은 수준의 형성 평가보다 높은 수준의 총합 평가에 사용되는 도구의 경우 더 많을 것입니다.

Many tools exist to guide the assessment of learners’ performance based on direct observation [66, 92]. Rather than creating new tools, educators should, when possible, use existing tools for which validity evidence exists [93]. When a tool does not exist for an educator’s purpose, options are to adapt an existing tool or create a new one. Creating a new tool or modifying an existing tool for direct observation should entail following guidelines for instrument design and evaluation, including accumulating validity evidence [94]. The amount of validity evidence needed will be greater for tools used for high-stakes summative assessments than for lower-stakes formative assessments.

도구 설계는 평가자 응답의 신뢰도를 최적화하는 데 도움이 될 수 있습니다. 도구의 앵커 또는 응답 옵션은 수행을 평가하는 방법에 대한 지침을 제공할 수 있습니다. 예를 들어, 행동 앵커 또는 발달 수행의 스펙트럼을 따라 행동을 설명하는 이정표로 정의된 앵커는 평가자의 일관성을 향상시킬 수 있습니다[95]. 학습자에게 필요한 감독 정도 또는 감독자가 느끼는 신뢰도에 대한 감독자의 인상을 묻는 척도는 감독자가 생각하는 방식과 더 잘 일치할 수 있습니다[96]. 전체적인 인상은 긴 체크리스트보다 평가자 간에 성과를 더 안정적으로 포착할 수 있습니다[97]. 특정 [체크리스트]와 [글로벌 인상] 중 어떤 것을 선택할지, 그리고 그 사이의 모든 것을 선택할지는 주로 평가의 목적에 따라 달라집니다. 예를 들어, [피드백]이 주요 목표인 경우 (학습자가 세분화되고 구체적인 피드백을 받지 못한다면) [총체적 평가]는 거의 유용하지 않습니다. 어떤 도구를 선택하든, 도구가 서술적 코멘트를 위한 충분한 공간을 제공하는 것이 중요합니다[71][가이드라인 16 및 30 참조].

Tool design can help optimize the reliability of raters’ responses. The anchors or response options on a tool can provide some guidance about how to rate a performance; for example, behavioural anchors or anchors defined as milestones that describe the behaviour along a spectrum of developmental performance can improve rater consistency [95]. Scales that query the supervisor’s impressions about the degree of supervision the learner needs or the degree of trust the supervisor feels may align better with how supervisors think [96]. A global impression may better capture performance reliably across raters than a longer checklist [97]. The choice between the spectrum of specific checklists to global impressions, and everything in between, depends primarily on the purpose of the assessment. For example, if feedback is a primary goal, holistic ratings possess little utility if learners do not receive granular, specific feedback. Regardless of the tool selected, it is important for tools to provide ample space for narrative comments [71] [see Guideline 16 and 30].

중요한 것은 도구의 타당도는 궁극적으로 도구의 사용자와 도구가 사용되는 맥락에 달려 있다는 것입니다. 평가자(예: 교수진)가 직접 관찰하는 것이 바로 도구라고 주장할 수 있습니다. 따라서 프로그램 책임자는 도구를 사용할 관찰자를 교육하는 것보다 도구를 설계하는 데 너무 많은 시간을 할애하는 경우가 많다는 점을 인식해야 합니다[지침 20 참조].

Importantly, validity ultimately resides in the user of the instrument and the context in which the instrument is used. One could argue that the assessors (e. g. faculty), in direct observation, are the instrument. Therefore, program directors should recognize that too much time is often spent designing tools rather than training the observers who will use them [see Guideline 20].

지침 16. 관찰자에게 직접 관찰하는 방법, 공유된 정신 모델과 공통 평가 기준을 채택하고 피드백을 제공하는 방법을 교육합니다.

Guideline 16. Do train observers how to conduct direct observation, adopt a shared mental model and common standards for assessment, and provide feedback.

감독자가 학습자를 관찰한 후 내리는 평가는 매우 다양하며, 같은 상황을 관찰하는 감독자라도 사용하는 도구에 따라 평가와 평가가 달라질 수 있습니다. 관찰자가 수행의 다양한 측면에 초점을 맞추고 우선순위를 정하고 수행을 판단하는 데 다른 기준을 적용하기 때문에 변동성이 발생합니다[46, 82, 98, 99]. 평가자는 또한 역량에 대한 서로 다른 정의를 사용합니다[82, 98]. 관찰자가 성과를 판단하는 데 사용하는 기준은 종종 경험적이고 특이한 방식으로 도출되며, 일반적으로 최근 경험의 영향을 받고[49, 82, 100], 첫인상에 크게 의존할 수 있습니다[48]. 평가자는 자신의 훈련과 수년간의 임상 및 교육 관행의 결과로 특이성을 개발합니다. 이러한 특성이 강력한 임상적 증거와 모범 사례에 근거한 경우 반드시 도움이 되지 않는 것은 아닙니다. 예를 들어, 평가자는 환자 중심 면담의 전문가로서 면담의 다른 측면을 배제하고 관찰하는 동안 그러한 행동과 기술을 크게 강조할 수 있습니다[47]. 뛰어난 성과 또는 매우 취약한 성과를 식별하는 것은 간단한 것으로 간주되지만, '회색 영역'의 성과에 대한 결정은 더 어렵습니다 [83].

The assessments supervisors make after observing learners with patients are highly variable, and supervisors observing the same encounter assess and rate the encounter differently regardless of the tool used. Variability results from observers focusing on and prioritizing different aspects of performance and applying different criteria to judge performance [46, 82, 98, 99]. Assessors also use different definitions of competence [82, 98]. The criteria observers use to judge performance are often experientially and idiosyncratically derived, are commonly influenced by recent experiences, [49, 82, 100] and can be heavily based on first impressions [48]. Assessors develop idiosyncrasies as a result of their own training and years of their own clinical and teaching practices. Such idiosyncrasies are not necessarily unhelpful if based on strong clinical evidence and best practices. For example, an assessor may be an expert in patient-centred interviewing and heavily emphasize such behaviours and skills during observation to the exclusion of other aspects of the encounter [47]. While identifying outstanding or very weak performance is considered straightforward, decisions about performance in ‘the grey area’ are more challenging [83].

[평가자 교육]은 이러한 직접 관찰의 한계를 극복하는 데 도움이 될 수 있지만 완전히 없애지는 못합니다.

Rater training can help overcome but not eliminate these limitations of direct observation.

[수행 차원 교육]은 참가자들이 관찰되는 [수행의 측면]과 [수행 평가 준거]에 대한 이해를 공유하는 평가자 교육 접근 방식입니다[9]. 예를 들어, 슈퍼바이저는 환자에게 약물 복용 시작에 대해 상담할 때 중요한 기술이 무엇인지 논의할 수 있습니다. 대부분의 평가자는 판단의 [스캐폴드 또는 중추 역할을 하는 프레임워크]를 환영합니다[83]. [성과 차원 교육]을 받은 수퍼바이저는 이 과정을 통해 평가 기준에 대한 [공유된 정신 모델]을 제공받음으로써 보다 표준화되고 체계적이며 포괄적이고 구체적인 관찰을 할 수 있고, 이전에는 주의를 기울이지 않았던 기술에 주의를 기울이며, 구체적인 피드백을 제공하는 자기 효능감을 향상시킬 수 있었다고 설명합니다[91].

Performance dimension training is a rater training approach in which participants come to a shared understanding of the aspects of performance being observed and criteria for rating performance [9]. For example, supervisors might discuss what are the important skills when counselling a patient about starting a medication. Most assessors welcome a framework to serve as a scaffold or backbone for their judgments [83]. Supervisors who have done performance dimension training describe how the process provides them with a shared mental model about assessment criteria that enables them to make more standardized, systematic, comprehensive, specific observations, pay attention to skills they previously did not attend to, and improve their self-efficacy giving specific feedback [91].

[기준 프레임 교육]은 평가자에게 [평가 차원과 관련된 적절한 기준을 제공]함으로써 관찰 및 평가 중에 성과에 대한 공통 개념화(즉, 기준 프레임)를 사용하도록 평가자를 교육함으로써 [성과 차원 교육]을 기반으로 합니다[101]. 비의료 성과 평가 문헌의 체계적 검토 및 메타 분석에 따르면 [기준 프레임 교육]은 중간 정도의 효과 크기로 평가 정확도를 크게 향상시키는 것으로 나타났습니다[101, 102]. 의학 분야에서 Holmboe 등은 표준화된 레지던트 및 환자와 함께 실제 실습을 포함한 8시간의 [기준 프레임 훈련 세션]이 개입 8개월 후 직접 관찰에서 관용을 약간 줄이고 정확도를 향상시킨다는 것을 보여주었습니다[9]. 그러나 짧은 평가자 교육(예: 반나절 워크숍)은 평가자 간 신뢰도를 개선하는 것으로 나타나지 않았습니다[103].

Frame of reference training builds upon performance dimension training by teaching raters to use a common conceptualization (i. e., frame of reference) of performance during observation and assessment by providing raters with appropriate standards pertaining to the rated dimensions [101]. A systematic review and meta-analysis from the non-medical performance appraisal literature demonstrated that frame of reference training significantly improved rating accuracy with a moderate effect size [101, 102]. In medicine, Holmboe et al. showed that an 8‑hour frame of reference training session that included live practice with standardized residents and patients modestly reduced leniency and improved accuracy in direct observation 8 months after the intervention [9]. However, brief rater training (e. g. half day workshop) has not been shown to improve inter-rater reliability [103].

교수진 개발 프로그램 책임자는 참가자가 교육 및 임상 업무에 평가자 교육을 적용할 수 있도록 하는 방법을 계획해야 합니다. 전략에는 참가자가 인지한 필요와 관련된 자료와 업무 맥락에서 적용 가능한 형식을 만드는 것이 포함됩니다[82, 104]. 교육 효과를 위한 [효과적인 교수진 개발]의 주요 특징에는 체험 학습, 피드백 제공, 효과적인 동료 및 동료 관계, 의도적인 커뮤니티 구축, 종단적 프로그램 설계 등이 포함됩니다[105, 106]. 동료 평가와 협업을 위해 서로 의지하는 교육자 간부 집단인 실무 커뮤니티를 개발하는 데 초점을 맞춘 교수진 개발은 평가자 교육에서 특히 중요하며 참가자들로부터 긍정적인 반응을 얻고 있습니다[91]. 그룹 교육은 교수진 개발의 중점을 개인에서 직접적인 관찰과 피드백에 투자하는 교육자 커뮤니티로 옮기는 것이 중요하다는 점을 강조합니다. 평가자는 직접 관찰 후 피드백을 제공할 때, 특히 건설적인 피드백을 제공할 때 긴장을 경험하기 때문에[107], 평가자 교육에는 [직접 관찰 후 효과적인 피드백 제공에 대한 교육]도 포함되어야 합니다[지침 32 참조]. 평가자 교육이 중요하지만, 평가자 교육에 대한 해답이 없는 질문이 여전히 많이 남아 있습니다[가이드라인 31 참조].

Directors of faculty development programs should plan how to ensure that participants apply the rater training in their educational and clinical work. Strategies include making the material relevant to participants’ perceived needs and the format applicable within their work context [82, 104]. Key features of effective faculty development for teaching effectiveness also include the use of experiential learning, provision of feedback, effective peer and colleague relationships, intentional community building and longitudinal program design [105, 106]. Faculty development that focuses on developing communities of practice, a cadre of educators who look to each other for peer review and collaboration, is particularly important in rater training and is received positively by participants [91]. Group training highlights the importance of moving the emphasis of faculty development away from the individual to a community of educators invested in direct observation and feedback. Because assessors experience tension giving feedback after direct observation, particularly when it comes to giving constructive feedback [107], assessor training should also incorporate teaching on giving effective feedback after direct observation [see Guideline 32]. While rater training is important, a number of unanswered questions about rater training still remain [see Guideline 31].

지침 17. 직접 관찰이 프로그램 목표 및 역량(예: 마일스톤)과 일치하는지 확인합니다.

Guideline 17. Do ensure direct observation aligns with program objectives and competencies (e. g. milestones).

명확하게 표현된 프로그램 목표와 목적은 [직접 관찰의 목적을 정의하기 위한 단계]를 설정합니다[93]. 정의된 평가 프레임워크는 학습자와 감독자의 교육 목표에 대한 이해를 조정하고 평가에 사용할 도구의 선택을 안내합니다.

- 프로그램 디렉터는 관찰할 실습의 구성 요소를 정의하는 분석적 접근법('분해하기')을 사용하여 목표와 목적을 정의할 수 있으며, 이를 통해 세부 체크리스트를 작성할 수 있습니다[108].

- 또한 [종합적 접근법]을 사용하여 유능하고 신뢰할 수 있는 실습에 필요한 업무 활동을 정의할 수 있으며, 이를 통해 위탁 등급과 같은 보다 총체적인 척도를 적용할 수 있습니다[109].

프로그램 디렉터는 감독자와 학습자가 직접 관찰을 위해 학습자 목표를 논의할 때 프로그램에서 사용되는 프로그램 목표, 역량, 마일스톤 및 EPA를 참조하도록 권장할 수 있습니다.

Clearly articulated program goals and objectives set the stage for defining the purposes of direct observation [93]. A defined framework for assessment aligns learners’ and supervisors’ understandings of educational goals and guides selection of tools to use for assessment.

- Program directors may define goals and objectives using an analytic approach (‘to break apart’) defining the components of practice to be observed, from which detailed checklists can be created [108].

- A synthetic approach can also be used to define the work activities required for competent, trustworthy practice, from which more holistic scales such as ratings of entrustment can be applied [109].

Program directors can encourage supervisors and learners to refer to program objectives, competencies, milestones and EPAs used in the program when discussing learner goals for direct observation.

지침 18. 학습자가 진정성 있게 연습하도록 유도하고 피드백을 환영하는 문화를 조성합니다.

Guideline 18. Do establish a culture that invites learners to practice authentically and welcome feedback.

대부분의 학습자는 성적과 고난도 시험에 중점을 두는 예비 대학 또는 학부 문화에서 의과대학에 입학합니다. 의과대학에서는 여전히 성적과 시험이 학습자의 행동을 크게 좌우할 수 있으며, 학습자는 여전히 낮은 비중의 평가를 학습 기회라기보다는 극복해야 할 총체적인 장애물로 인식할 수 있습니다. 학습자는 종종 학습 또는 성과에 대한 기대치에 대해 여러 가지 상충되는 메시지를 감지합니다[60, 110]. 그렇다면 현재 상황을 어떻게 [학습자 중심]으로 바꿀 수 있을까요?

Most learners enter medical school from either pre-university or undergraduate cultures heavily steeped in grades and high-stakes tests. In medical school, grades and tests can still drive substantial learner behaviour, and learners may still perceive low-stakes assessments as summative obstacles to be surmounted rather than as learning opportunities. Learners often detect multiple conflicting messages about expectations for learning or performance [60, 110]. How then can the current situation be changed to be more learner centred?

프로그램은 학습자에게 언제, 어디서 학습 문화가 낮은 위험도의 실습 기회를 제공하는지 명시적으로 파악하고, 학습자가 직접 관찰을 학습 활동으로 받아들일 수 있는 문화를 조성해야 합니다. 임상 교육 환경에서 학습자는 유능해 보이고 높은 점수를 받아야 한다는 압박감을 최소화하는 감독자가 학습 목표에서 다루는 술기를 수행하는 것을 관찰할 기회가 필요합니다[111]. 학습 방향(학습자 또는 숙달 목표 대 수행 목표)은 학습 결과에 영향을 미칩니다[112].

- [숙달 지향적 학습자]는 학습을 위해 노력하고, 피드백을 요청하며, 도전을 수용하고, 개선을 축하합니다. 반대로

- [성과 지향적 학습자]는 유능해 보이고 실패를 피할 수 있는 기회를 찾습니다.

- 같은 기술이나 과제를 연습하고 재시도할 수 있고 노력과 개선에 대해 보상하는 문화는 숙달 지향성을 촉진합니다.

Programs should explicitly identify for learners when and where the learning culture offers low-stakes opportunities for practice, and programs should foster a culture that enables learners to embrace direct observation as a learning activity. In the clinical training environment, learners need opportunities to be observed performing the skills addressed in their learning goals by supervisors who minimize perceived pressures to appear competent and earn high marks [111]. Orientations to learning (learner or mastery goals versus performance goals) influence learning outcomes [112].

- A mastery-oriented learner strives to learn, invites feedback, embraces challenges, and celebrates improvement.

- Conversely, a performance-oriented learner seeks opportunities to appear competent and avoid failure.

- A culture that enables practice and re-attempting the same skill or task, and rewards effort and improvement, promotes a mastery orientation.

[학습을 희생하면서 성적, 완벽함 또는 정답을 강조하는 문화]는 학습자가 직접 관찰을 피하는 것처럼 실패를 피하기 위해 적극적으로 노력하는 부적응적인 '성과 회피' 목표를 조장할 수 있습니다[28]. 프로그램은 직접 관찰자가 정확성보다는 연습과 노력에 가치를 두는 커뮤니케이션 관행을 사용하도록 장려해야 합니다. 낮은 수준의 환경에서 직접 관찰 및 피드백을 수행하는 교사의 역할과 평가자의 역할을 분리하면 학습자가 이러한 구분을 명확히 알 수 있습니다. 또한 프로그램은 학습자에게 학습에 대한 개인적 선택권을 부여하고 학습자와 감독자 간의 종적 관계를 보장함으로써 학습자가 피드백을 잘 받아들이는 문화가 조성되도록 해야 합니다[14, 26].

A culture that emphasizes grades, perfection or being correct at the expense of learning can promote maladaptive ‘performance-avoid’ goals in which learners actively work to avoid failure, as in avoiding being directly observed [28]. Programs should encourage direct observers to use communication practices that signal the value placed on practice and effort rather than just on correctness. Separating the role of teacher who conducts direct observation and feedback in low-stakes settings from the role of assessor makes these distinctions explicit for learners. Programs should also ensure their culture promotes learner receptivity to feedback by giving learners personal agency over their learning and ensuring longitudinal relationships between learners and their supervisors [14, 26].

가이드라인 19. 직접 관찰을 가능하게 하거나 방해하는 시스템 요인에 주의를 기울이십시오.

Guideline 19. Do pay attention to systems factors that enable or inhibit direct observation.

[의료 실습 환경의 구조와 문화]는 직접 관찰에 대한 가치를 뒷받침할 수 있습니다. 수련생은 지도의가 언제, 어떤 활동을 관찰하는지에 주의를 기울이고 이를 바탕으로 어떤 교육 및 임상 활동을 중요하게 여기는지 유추합니다[42].

The structure and culture of the medical training environment can support the value placed on direct observation. Trainees pay attention to when and for what activities their supervisors observe them and infer, based on this, which educational and clinical activities are valued [42].

교육 환경 내에서 환자 중심 치료에 초점을 맞추면 [마이크로 시스템] 내에서 학습자와 감독자가 공유하는 임상 실습 과제를 통해 일상적인 임상 치료에 교육을 포함할 수 있습니다 [113]. 직접 관찰 과정에 대한 교수진의 동의는 학습을 위한 직접 관찰의 중요성에 대한 교육과 교수진이 병상에서 학습자와 함께 시간을 보낼 수 있는 일정 구조를 통해 얻을 수 있습니다[93]. 환자 간호를 수행할 때 직접 관찰을 수행하도록 교수진을 교육하면 이 작업이 효율적이고 질 높은 간호 및 교육에 필수적인 것으로 간주됩니다[114]. 이 교육 전략에 대한 환자와 가족의 선호도는 이 전략이 치료에 도움이 된다고 인식하고 있으며, 그 결과 임상의의 환자 만족도가 더 높아질 수 있음을 시사합니다[115, 116].

A focus on patient-centred care within a training environment embeds teaching in routine clinical care through clinical practice tasks shared between learners and supervisors within microsystems [113]. Faculty buy-in to the process of direct observation can be earned through education about the importance of direct observation for learning and through schedule structures that enable faculty time with learners at the bedside [93]. Training faculty to conduct direct observation as they conduct patient care frames this task as integral to efficient, high quality care and education [114]. Patient and family preferences for this educational strategy suggest that they perceive it as beneficial to their care, and clinicians can enjoy greater patient satisfaction as a result [115, 116].

교육 리더는 직접 관찰을 제한하는 [시스템 장벽]을 해결해야 합니다.

- 직접 관찰과 피드백을 위한 시간 부족은 직접 관찰을 가로막는 가장 흔한 장벽 중 하나입니다. 프로그램은 교육 및 환자 치료 시스템(예: 감독자:학습자 비율, 환자 센서스)이 직접 관찰 및 피드백을 위한 시간을 허용하도록 보장해야 합니다.

- 교육 병원의 더 큰 임상 진료 환경에 주의를 기울이면 직접 관찰을 촉진하기 위해 해결해야 할 추가적인 장벽을 발견할 수 있습니다.

- 현재의 수련 환경은 전자 건강 기록을 사용하여 컴퓨터로 빠르게 작업을 완료하는 데 집중하는 경우가 너무 많으며, 환자와 상호 작용하거나 교육 활동에 소요되는 수련의의 시간은 소수에 불과합니다[117, 118].

- 드물지 않게, 감독자-학습자 쌍이 자주 바뀌면 학습자가 피드백을 통합하고 개선 사항을 입증하기 위해 동일한 감독자가 오랜 시간 동안 관찰하기 어렵습니다[119].

- 프로그램 디렉터는 학습 환경에 대한 감독자와 학습자의 인식, 건설적인 피드백을 주고받는 능력, 학습자에 대한 판단의 공정성을 신뢰하는 능력을 향상시키는 종적 관계를 제공하는 커리큘럼 구조를 고려해야 합니다[26, 120, 121].

- 대학원 의학 교육에서 외래 연속성 경험을 재설계하면 이러한 직접 관찰 및 피드백을 위한 종단적 기회를 촉진할 수 있습니다[122].

Educational leaders must address the systems barriers that limit direct observation.

- Lack of time for direct observation and feedback is one of the most common barriers to direct observation. Programs need to ensure that educational and patient care systems (e. g. supervisor:learner ratios, patient census) allow time for direct observation and feedback.

- Attention to the larger environment of clinical care at teaching hospitals can uncover additional barriers that should be addressed to facilitate direct observation.

- The current training environment is too often characterized by a fast-paced focus on completing work at computers using the electronic health record, with a minority of trainee time spent interacting with patients or in educational activities [117, 118].

- Not uncommonly, frequent shifts in supervisor-learner pairings make it difficult for learners to be observed by the same supervisor over time in order to incorporate feedback and demonstrate improvement [119].

- Program directors should consider curricular structures that afford longitudinal relationships that enhance supervisors’ and learners’ perceptions of the learning environment, the ability to give and receive constructive feedback and trust the fairness of judgments about learners [26, 120, 121].

- Redesign of the ambulatory continuity experience in graduate medical education shows promise to foster these longitudinal opportunities for direct observation and feedback [122].

프로그램에 집중하지 않기

Don’ts focused on program

지침 20. 직접 관찰에 적합한 도구를 선택한다고 해서 평가자 교육이 필요 없다고 가정하지 마십시오.

Guideline 20. Don’t assume that selecting the right tool for direct observation obviates the need for rater training.

직접 관찰용 도구 사용자는 잘 설계된 도구는 평가자가 사용법을 모두 이해할 수 있을 정도로 명확할 것이라고 잘못 생각할 수 있습니다. 그러나 앞서 설명한 바와 같이, 어떤 도구를 선택하든 평가자는 도구를 사용하여 직접 관찰하고 관찰 내용을 기록하도록 교육받아야 합니다. 실제 측정 도구는 도구가 아니라 교수 감독자입니다.

Users of tools for direct observation may erroneously assume that a well-designed tool will be clear enough to raters that they will all understand how to use it. However, as described previously, regardless of the tool selected, observers should be trained to conduct direct observations and record their observations using the tool. The actual measurement instrument is the faculty supervisor, not the tool.

지침 21. 학습자에게 직접 관찰을 요청하는 책임을 전적으로 학습자에게만 지우지 마세요.

Guideline 21. Don’t put the responsibility solely on the learner to ask for direct observation.

학습자와 감독자는 직접 관찰 및 피드백이 이루어질 수 있도록 함께 책임을 져야 합니다. 학습자는 실제 임상 수행에 초점을 맞춘 의미 있는 피드백을 원하지만, [31, 39] 일반적으로 직접 관찰을 학습에 유용한 것으로 평가하는 것과 자율적이고 효율적으로 수행하기를 원하는 것 사이에서 긴장을 경험합니다[42]. 직접 관찰, [자율성, 효율성]이라는 두 가지 목표를 동시에 인정하면서 직접 관찰이 일상적인 활동의 일부가 되는 교육 문화로 바꾸면 학습자의 부담을 완화할 수 있습니다. 직접 관찰을 요청하는 학습자의 책임을 제거하거나 줄이고, 부분적으로 교수진과 프로그램의 책임으로 만드는 것은 이 학습 활동에 대한 [공동 책임]을 촉진할 것입니다.

Learners and their supervisors should together take responsibility for ensuring that direct observation and feedback occur. While learners desire meaningful feedback focused on authentic clinical performance, [31, 39] they commonly experience tension between valuing direct observation as useful to learning and wanting to be autonomous and efficient [42]. Changing the educational culture to one where direct observation is a customary part of daily activities, with acknowledgement of the simultaneous goals of direct observation, autonomy and efficiency, may ease the burden on learners. Removing or reducing responsibility from the learner to ask for direct observation and making it, in part, the responsibility of faculty and the program will promote shared accountability for this learning activity.

지침 22. 교수자가 교사와 평가자 사이에서 느끼는 긴장을 과소평가하지 마십시오.

Guideline 22. Don’t underestimate faculty tension between being both a teacher and assessor.

20년 전 마이클 J. 고든은 교수자가 교사(학습자에게 지도 제공)와 평가자(학습자가 성과 기준을 충족하는지 교육 프로그램에 보고)로서 겪는 갈등에 대해 설명했습니다[123]. 현재 역량 기반 의학교육의 시대에는 교수진이 [직접 관찰한 상황을 보고해야 하는 요구 사항이 증가함]에 따라 이러한 긴장이 지속되고 있습니다. Gordon의 해결책은 역량 기반 의학교육의 많은 발전 사항을 반영합니다. 학습자 중심의 두 가지 시스템을 개발하여 일선 교수진이 학습자에게 피드백과 지도를 제공하는 시스템과 교수자 중심의 시스템으로 최소한의 역량을 유지하지 못하는 학습자를 모니터링하거나 선별하여 추가 의사 결정 및 평가를 전문 표준위원회에 넘기는 것입니다[124, 125]. 프로그램은 역량 기반 의학교육에서 직접 관찰을 사용할 때 교수진의 이중적 입장에 민감해야 하며, 이러한 역할 갈등을 최소화하는 패러다임을 고려해야 합니다[126, 127].

Two decades ago Michael J. Gordon described the conflict faculty experience being both teacher (providing guidance to the learner) and high-stakes assessor (reporting to the training program if the learner is meeting performance standards) [123]. In the current era of competency-based medical education, with increased requirements on faculty to report direct observation encounters, this tension persists. Gordon’s solution mirrors many of the developments of competency-based medical education: develop two systems, one that is learner-oriented to provide learners with feedback and guidance by the frontline faculty, and one that is faculty-oriented, to monitor or screen for learners not maintaining minimal competence, and for whom further decision making and assessment would be passed to a professional standards committee [124, 125]. Programs will need to be sensitive to the duality of faculty’s position when using direct observation in competency-based medical education and consider paradigms that minimize this role conflict [126, 127].

가이드라인 23. 직접 관찰에 대한 학습 문화를 방해할 수 있으므로 모든 직접 관찰을 높은 위험도로 만들지 마십시오.

Guideline 23. Don’t make all direct observations high stakes; this will interfere with the learning culture around direct observation.

대부분의 직접 관찰은 높은 위험도가 아니라 교수자가 학습자의 일상 업무에 대한 지침을 제공할 수 있도록 진정한 환자 중심 진료에 대한 낮은 위험도의 평가로 수행해야 합니다. 직접 관찰의 장점 중 하나는 학습자가 실제 임상 업무에 어떻게 접근하는지 볼 수 있는 기회이지만, 관찰 행위로 인해 성과가 변경되면 이점이 상쇄될 수 있습니다[128]. 학습자는 자신의 성과가 변경될 정도로 관찰과 관련된 '이해관계'에 매우 민감합니다[11, 31]. 직접 관찰에 대한 레지던트의 인식에 대한 질적 연구에서 레지던트들은 관찰자를 기쁘게 하기 위해, 그리고 성과가 채점된다고 생각하기 때문에 임상 스타일을 바꾼다고 보고했습니다. 직접 관찰은 학습자의 목표를 환자 중심 진료에서 성과 중심 진료로 전환했습니다[11]. 또 다른 연구에서 레지던트들은 직접 관찰에 대한 '이해관계'가 없기 때문에(관찰과 관련된 대화는 관찰자와 학습자 사이에만 이루어짐) 임상 수행의 진정성을 높이는 데 도움이 된다고 인식했습니다[31].

Most direct observations should not be high stakes, but rather serve as low-stakes assessments of authentic patient-centred care that enable faculty to provide guidance on the learner’s daily work. One of the benefits of direct observation is the opportunity to see how learners approach their authentic clinical work, but the benefits may be offset if the act of observation alters performance [128]. Learners are acutely sensitive to the ‘stakes’ involved in observation to the point that their performance is altered [11, 31]. In a qualitative study of residents’ perceptions of direct observation, residents reported changing their clinical style to please the observer and because they assumed the performance was being graded. The direct observation shifted the learner’s goals from patient-centred care to performance-centred care [11]. In another study, residents perceived that the absence of any ‘stakes’ of the direct observation (the conversations around the observations remained solely between observer and learner) facilitated the authenticity of their clinical performance [31].

지침 24. 직접 관찰을 사용하여 중요한 종합 결정을 내릴 때는 너무 짧은 시간 동안 너무 적은 수의 평가자에 의한 너무 적은 수의 직접 관찰에 근거하여 결정하지 말고 직접 관찰 데이터에만 의존하지 마십시오.

Guideline 24. When using direct observation for high-stakes summative decisions, don’t base decisions on too few direct observations by too few raters over too short a time and don’t rely on direct observation data alone.

단일 임상 성과에 대한 단일 평가에는 잘 설명된 한계가 있습니다:

- 1) 평가는 단 한 명의 평가자의 인상을 포착하고

- 2) 임상 수행은 단일 콘텐츠 영역으로 제한되는 반면 학습자는 평가의 내용, 환자 및 맥락에 따라 다르게 수행합니다[129, 130].

평가의 일반화 가능성을 높이려면 다양한 콘텐츠(예: 진단 및 술기) 및 맥락에서 학습자의 수행을 관찰하는 평가자의 수를 늘리는 것이 중요합니다[131, 132]. 또한 특정 시점의 학습자의 임상 수행은 감정 상태, 동기 부여 또는 피로와 같은 외부 요인에 의해 영향을 받을 수 있습니다. 따라서 일정 기간 동안 관찰한 내용을 캡처하면 보다 안정적으로 성과를 측정할 수 있습니다.

A single assessment of a single clinical performance has well-described limitations: 1) the assessment captures the impression of only a single rater and 2) clinical performance is limited to a single content area whereas learners will perform differentially depending on the content, patient, and context of the assessment [129, 130]. To improve the generalizability of assessments, it is important to increase the number of raters observing the learner’s performance across a spectrum of content (i. e. diagnoses and skills) and contexts [131, 132]. Furthermore, a learner’s clinical performance at any given moment may be influenced by external factors such as their emotional state, motivation, or fatigue. Thus, capturing observations over a period of time allows a more stable measure of performance.

평가 프로그램에서 여러 평가 도구(예: 의학 지식 테스트, 모의 상황, 직접 관찰)에서 수집한 정보를 결합하면 단일 평가 도구보다 학습자의 역량을 더 균형 있게 평가할 수 있습니다[133, 134]. 역량은 다차원적이며, 단일 평가 도구로는 모든 차원을 하나의 형식으로 평가할 수 없습니다[130, 135]. 이는 평가 도구를 뒷받침하는 타당성 논거를 검토할 때 분명하게 드러나는데, 단일 평가 도구의 경우 항상 논거의 강점과 약점이 존재합니다[136, 137]. 역량에 관한 의사결정에 도움이 되는 최상의 증거를 제공하는 도구를 신중하게 선택하는 것이 중요합니다[136, 137]. 예를 들어, 기술 숙련도를 평가하는 것이 목표인 경우, 프로그램은 시술의 적응증, 금기 사항 및 합병증에 대한 지식 테스트와 시뮬레이션 실험실의 파트별 트레이너를 사용한 직접 관찰 및 실제 임상 환경에서의 직접 관찰(환자와의 의사소통과 더불어 학습자의 기술 숙련도를 평가할 수 있는 곳)을 결합할 수 있습니다.

Combining information gathered from multiple assessment tools (e. g. tests of medical knowledge, simulated encounters, direct observations) in a program of assessment will provide a more well-rounded evaluation of the learner’s competence than any single assessment tool [133, 134]. Competence is multidimensional, and no single assessment tool can assess all dimensions in one format [130, 135]. This is apparent when examining the validity arguments supporting assessment tools; for any single assessment tool, there are always strengths and weaknesses in the argument [136, 137]. It is important to carefully choose the tools that provide the best evidence to aid decisions regarding competence [136, 137]. For example, if the goal is to assess a technical skill, a program may combine a knowledge test of the indications, contraindications and complications of the procedure with direct observation using part-task trainers in the simulation laboratory with direct observation in the real clinical setting (where the learner’s technical skills can be assessed in addition to their communication with the patient).

모름

Don’t Knows

가이드라인 25. 학습자의 독립성과 효율성이라는 가치를 훼손하지 않으면서 학습자가 관찰을 요청하도록 동기를 부여하는 프로그램은 무엇입니까?

Guideline 25. How do programs motivate learners to ask to be observed without undermining learners’ values of independence and efficiency?

직접적인 관찰/피드백과 자율성/효율성을 동시에 중시하는 학습 문화를 조성하는 데 따르는 어려움에 대해 논의되었지만, 이 문제에 대한 해결책은 명확하지 않습니다. 잠재적인 접근 방식으로는 교수진을 대상으로 짧은 만남에 대한 직접 관찰을 장려하고(따라서 효율성에 미치는 영향을 최소화), 교수진의 일상 업무에 직접 관찰의 근거를 두는 것이 있습니다[66, 129]. 그러나 이러한 전략은 직접 관찰에 더 많은 시간이 필요한 역량(예: 전문적 행동, 협업 기술 등)과는 반대로 짧은 관찰이 가능한 특정 업무에 직접 관찰을 집중하는 의도하지 않은 효과를 가져올 수 있습니다[60]. 또 다른 해결책은 환자 회진, 인수인계, 병원 또는 외래 환자 퇴원, 클리닉 프리셉팅 등과 같은 일상 업무에 직접 관찰을 포함시키는 것입니다. 기존 활동을 활용하면 일부 전문 분야 및 프로그램에서 발생하는 것처럼 학습자가 직접 관찰을 요청해야 하는 부담을 줄일 수 있습니다. 예를 들어, 맥마스터의 응급의학과 레지던트 프로그램에서는 관찰 영역을 공식화하여 각 응급실 교대 근무 시 감독자가 직접 관찰하는 시스템을 활용하고 있습니다[138]. 학습자가 관찰을 요청하도록 동기를 부여하는 추가 접근 방식을 식별하는 것이 중요합니다.

While the difficulties in having a learning culture that simultaneously values direct observation/feedback and autonomy/efficiency have been discussed, solutions to this problem are less clear. Potential approaches might be to target faculty to encourage direct observation of short encounters (thus minimizing the impact on efficiency) and to ground the direct observation in the faculty’s daily work [66, 129]. However, these strategies can have the unintended effect of focusing direct observation on specific tasks which are amenable to short observations as opposed to competencies that require more time for direct observation (e. g. professional behaviour, collaboration skills etc.) [60]. Another solution may be to make direct observation part of daily work, such as patient rounds, hand-offs, discharge from a hospital or outpatient facility, clinic precepting and so forth. Leveraging existing activities reduces the burden of learners having to ask for direct observation, as occurs in some specialties and programs. For example, McMaster’s emergency medicine residency program has a system that capitalizes on supervisors’ direct observation during each emergency department shift by formalizing the domains for observation [138]. It will be important to identify additional approaches that motivate learners to ask for observation.

가이드라인 26. 전문과목은 어떻게 직접 관찰의 초점을 환자가 중요하게 여기는 임상 진료의 중요한 측면으로 확대할 수 있습니까?

Guideline 26. How can specialties expand the focus of direct observation to important aspects of clinical practice valued by patients?

환자와 의사는 임상 진료의 측면의 상대적 중요도에 대해 의견이 다릅니다. 예를 들어, 환자는 건강 관련 정보의 효과적인 전달의 중요성을 더 높게 평가합니다[139]. 평가자가 가장 중요하게 생각하거나 가장 편한 것만 관찰하는 경우, 직접 관찰의 초점을 임상 진료의 모든 중요한 측면으로 어떻게 확장할 수 있을까요[42]? 역량 기반 의료 교육에서 프로그램은 특정 술기를 강조하는 로테이션을 활용하여 관찰 빈도가 낮은 영역으로 직접 관찰의 초점을 확대할 수 있습니다(예: 일반 내과 입원 환자에서 관절 검사를 관찰하는 대신 류마티스내과 로테이션을 사용하여 학습자의 근골격 검사 술기를 직접 관찰하는 것). 분명한 것은 모든 사람이 모든 것을 관찰하기를 기대하는 것은 실패한 접근 방식이라는 것입니다. 각 전문과목별로 직접 관찰의 초점을 확대하여 환자가 중요하게 여기는 임상 치료의 측면을 포괄하는 방법을 배우기 위한 연구가 필요합니다. 많은 교수진 개발 프로그램은 교수진 개인만을 대상으로 하며, 조직 내 프로세스나 문화적 변화를 목표로 하는 프로그램은 상대적으로 적습니다[106]. 따라서 이러한 유형의 프로세스 변화를 목표로 하는 교육 리더를 위한 교수진 개발이 필요할 것으로 보입니다.

Patients and physicians disagree about the relative importance of aspects of clinical care; for example, patients more strongly rate the importance of effective communication of health-related information [139]. If assessors only observe what they most value or are most comfortable with, how can the focus of direct observation be expanded to all important aspects of clinical practice [42]? In competency-based medical education, programs may take advantage of rotations that emphasize specific skills to expand the focus of direct observation to less frequently observed domains (e. g. using a rheumatology rotation to directly observe learners’ musculoskeletal exam skills as opposed to trying to observe joint exams on a general medicine inpatient service). What seems apparent is that expecting everyone to observe everything is an approach that has failed. Research is needed to learn how to expand the focus of direct observation for each specialty to encompass aspects of clinical care valued by patients. Many faculty development programs target only the individual faculty member, and relatively few target processes within organizations or cultural change [106]. As such, faculty development for educational leaders that target these types of process change is likely needed.

지침 27. 프로그램은 어떻게 위험 부담이 크고 빈번하지 않은 직접 관찰 평가 문화를 위험 부담이 적고 형성적이며 학습자 중심적인 문화로 바꿀 수 있는가?

Guideline 27. How can programs change a high-stakes, infrequent direct observation assessment culture to a low-stakes, formative, learner-centred culture?

형성적 평가에 직접 관찰을 집중하는 것의 중요성은 이미 설명했습니다. 그러나 높은 수준의 빈번한 직접 관찰 평가 문화를 낮은 부담의, 형성적이고, 학습자 중심의 직접 관찰 문화로 바꾸는 데 도움이 되는 추가적인 접근 방식이 여전히 필요합니다[140]. 평가 빈도를 높이고, 학습자가 평가를 요청할 수 있도록 권한을 부여하고[141, 142], 학습자에게 피드백 및 코칭을 위한 평가가 중요하다는 점을 강조하는 전략과 그 영향을 탐구하는 연구가 필요합니다[143,144,145]. 평가 프로그램의 설계, 모니터링 및 지속적인 개선에 학습자를 효과적으로 참여시키는 방법도 추가 연구가 필요합니다[146].