의학교육에서 사회적 정의: 포용으로는 충분하지 않다, 단지 첫 걸음일 뿐이다(Perspect Med Educ. 2022)

Social justice in medical education: inclusion is not enough—it’s just the first step

Maria Beatriz Machado · Diego Lima Ribeiro · Marco Antonio de Carvalho Filho

서론

Introduction

세계적으로 의과대학에 입학하기 위한 선발 과정은 종종 사실적 지식을 평가하는 것을 우선시하며, 이는 종종 비싸고 좋은 중등교육을 받은 부유한 가정의 학생들에게 이익이 된다[1,2,3]. 게다가, 중산층 학생들조차 증가하는 교육 부채로 어려움을 겪고 있기 때문에 의료 훈련과 관련된 비용은 저소득 가정의 사람들에게 엄청나게 비싸다. 관찰되는 결과는 낮은 사회경제적 지위를 가진 학생들을 배제하는 것으로, 소수 인종과 종종 겹치는 사회 집단이다[2, 4]. 이러한 [사회적, 인종적 분리]는 의료 분야가 스스로 갱신되는 것을 막고 사회 정의의 원칙과 양립할 수 없는 [특권의 순환]을 영속시킨다[3, 5, 6]. 이러한 선발 편향을 보완하기 위해 전 세계 의과대학들은 취약계층의 입학정원을 늘리는 포용정책을 마련하고 있다[2, 5, 6, 7, 8]. 그러나 이러한 학생들의 서로 다른 사회적, 경제적, 인종적 배경이 의과대학에서의 사회화 과정에서 어떻게 교차하고 상호작용하며 그들의 직업적 정체성 발달에 영향을 미치는지는 알려져 있지 않다[9]. 이러한 [취약한 사회 집단의 학생들이 의사가 되기 위한 궤적]을 어떻게 경험하는지 이해하는 것은 맞춤형 교육 및 지원 관행을 고안하는 데 필수적이다.

Globally, the selection processes for entering medical schools often prioritize assessing factual knowledge, which benefits students from wealthy families who have had access to good and often expensive secondary education [1,2,3]. Moreover, costs associated with medical training are prohibitive for people from low-income families as even middle-class students struggle with increasing educational debts. The observed result is the exclusion of students with low socioeconomic status, a social group that often overlaps with racial minorities [2, 4]. This social and racial segregation prevents the medical field from renewing itself and perpetuates a cycle of privilege incompatible with the principle of social justice [3, 5, 6]. To compensate for this selection bias, medical schools worldwide are creating inclusion policies to increase admissions from vulnerable social groups [2, 5,6,7,8]. However, it is unknown how the different social, economic, and racial backgrounds of these students intersect and interact during their socialization in medical school and influence their professional identity development [9]. Understanding how students from these vulnerable social groups experience their trajectory to becoming doctors is essential for devising tailored educational and supportive practices.

최근의 노력에도 불구하고, 전 세계적으로 여전히 의학계에서 대표성이 낮은 사회 집단이 있다[4, 7, 10]. 브라질에서는 2011년 한 연구에 따르면 [공립 의대생의 98%]가 최저임금보다 5배 높은 가족소득을 가지고 있으며, 6%만이 자신의 인종을 브라운 또는 블랙[11, 12]으로 자칭하였다. 그러나 [브라질 인구의 절반 이상]이 최저 임금/월 1회 미만으로 생활하며 인종을 브라운 또는 블랙[13]으로 자칭하고 있으며, 이는 미국(미국)[1, 10], 호주[14] 및 영국[3]에서 발견되는 인구 통계를 반영한다.

Despite recent efforts, there are still underrepresented social groups in medicine worldwide [4, 7, 10]. In Brazil, a 2011 study revealed that 98% of medical students in public universities had a family income five times higher than the minimum wage, and only 6% self-declared their race as Brown or Black [11, 12]. However, more than half of Brazil’s population lives on less than one minimum wage/month and self-declared their race as Brown or Black [13], which mirrors demographics around the world, including those found in the United States (US) [1, 10], Australia [14], and the United Kingdom [3].

의과대학에서 더 큰 사회적 다양성은 일반인들의 보살핌care을 개선하고 의대 학생들의 교육에 도움이 될 수 있다. 증거는 소수 민족 환자들이 같은 민족 출신의 의사의 치료를 받을 때 더 나은 집착과 치료 성공을 보인다는 사실을 뒷받침한다[1, 5, 15, 16, 17]. 또한, 더 다양한 환경에서 공부하는 의사들은 다른 인종 및 사회 그룹의 환자를 다루는 데 더 능숙하다[18, 19]. 따라서, 의과대학에서 소외된 사회 집단의 대표성을 높이는 것은 연대의 문제일 뿐만 아니라, 의료 서비스를 개선하고 사회 정의를 증진하기 위한 자산이다. 따라서 의료 교육에 대한 접근을 민주화하는 데 전념하는 여러 국가는 저소득 가정과 소수 인종 학생들의 입학을 촉진하는 정책을 채택했다[3, 7, 8]. 이러한 정책들이 다양성을 성공적으로 증가시켰음에도 불구하고, 불리한 사회적 배경의 학생들은 재정적 문제와 인종차별을 경험했고, 잠재적으로 그들의 사회적 및 직업적 통합을 방해했다[20, 21, 22, 23, 24].

Greater social diversity in medical schools could improve the care of the general population and benefit medical students’ education. Evidence supports the finding that ethnic minority patients have better adherence and treatment success when cared for by a doctor from the same ethnicity [1, 5, 15,16,17]. Additionally, doctors who study in a more diverse environment are more competent in dealing with patients from different racial and social groups [18, 19]. Therefore, increasing the representation of underserved social groups in medical schools is not only a matter of solidarity, but an asset to improve healthcare and promote social justice. Thus, several countries committed to democratizing access to medical education have adopted policies to facilitate the admission of students from low-income families and racial minorities [3, 7, 8]. Although these policies successfully increased diversity, students from disadvantaged social backgrounds experienced financial problems and racism, potentially hampering their social and professional integration [20,21,22,23,24].

본 연구는 브라질 의과대학에 입학한 저소득층 의대생들의 사회화 및 전문적 정체성 발달과 관련된 과제를 긍정정책을 통해 탐색한다.

This study explores the challenges related to the socialization and professional identity development of medical students from low-income families admitted to a Brazilian medical school through an affirmative policy.

방법들

Methods

이것은 리치 픽처스 방법론을 이용한 구성주의 패러다임에 기초한 단면적 질적 연구이다[25]. 캄피나스 대학교 의과대학 연구윤리위원회는 이 연구를 승인했다(CAAE: 91119118.1.0000.5404).

This is a cross-sectional qualitative study based on a constructivist paradigm using the Rich Pictures methodology [25]. The research ethics committee of the School of Medical Sciences of the University of Campinas approved the study (CAAE: 91119118.1.0000.5404).

우리는 브라질 상파울루 캄피나스 대학교(UNICAMP) 의과대학에서 이 연구를 수행했다. UNICAMP 선정 과정은 국가적인 두 단계 인지 테스트에 의존한다. 2018년에는 110명의 자리에 30676명의 지원자가 지원했다. 브라질의 중등 학교 시스템은 불평등하며, 부유한 가정의 학생들은 우수한 사립학교에 접근할 수 있고 대학에 진학할 기회가 증가했습니다 [26]. 대조적으로, 빈민가 한가운데에 있는 일부 주변 공립학교 학생들은 거의 입학하지 않는다[7, 11, 12].

We conducted this study in the School of Medical Sciences at the University of Campinas (UNICAMP), São Paulo, Brazil. The UNICAMP selection process relies on a national two-step cognitive test. In 2018, 30,676 candidates applied for 110 available positions. The secondary school system in Brazil is unequal, and students from wealthy families have access to excellent private schools and increased opportunities to attend universities [26]. In contrast, students from peripheral public schools, some in the middle of slums (“favelas”), are seldom admitted [7, 11, 12].

2011년, UNICAMP의 고등 학제간 훈련 프로그램(ProFIS)은 [캄피나스의 92개 중등학교에서 각각 학생들을 선발]하여, 대학 프로그램과 비슷한 준비 프로그램에 입학시키기 위해 만들어졌다. ProFIS 선택은 영역 매개 변수를 학생들의 학업 성과와 결합한다. [지역적 매개변수]는 빈민가에 위치한 학교를 포함한 모든 공립학교의 학생들의 입학을 보장하며, 이는 빈곤 가정으로부터의 포함inclusion을 보장하고 affirmative policies의 혁신을 나타낸다.

In 2011, the UNICAMP’s Higher Interdisciplinary Training Program (ProFIS) was created to select students from each of the 92 secondary public schools of Campinas to enter a college-like preparatory program. ProFIS selection combines a territorial parameter with students’ academic performance. The territorial parameter guarantees admission of students from all public schools, including those located in favelas, which assures inclusion from impoverished families and represents an innovation in affirmative policies.

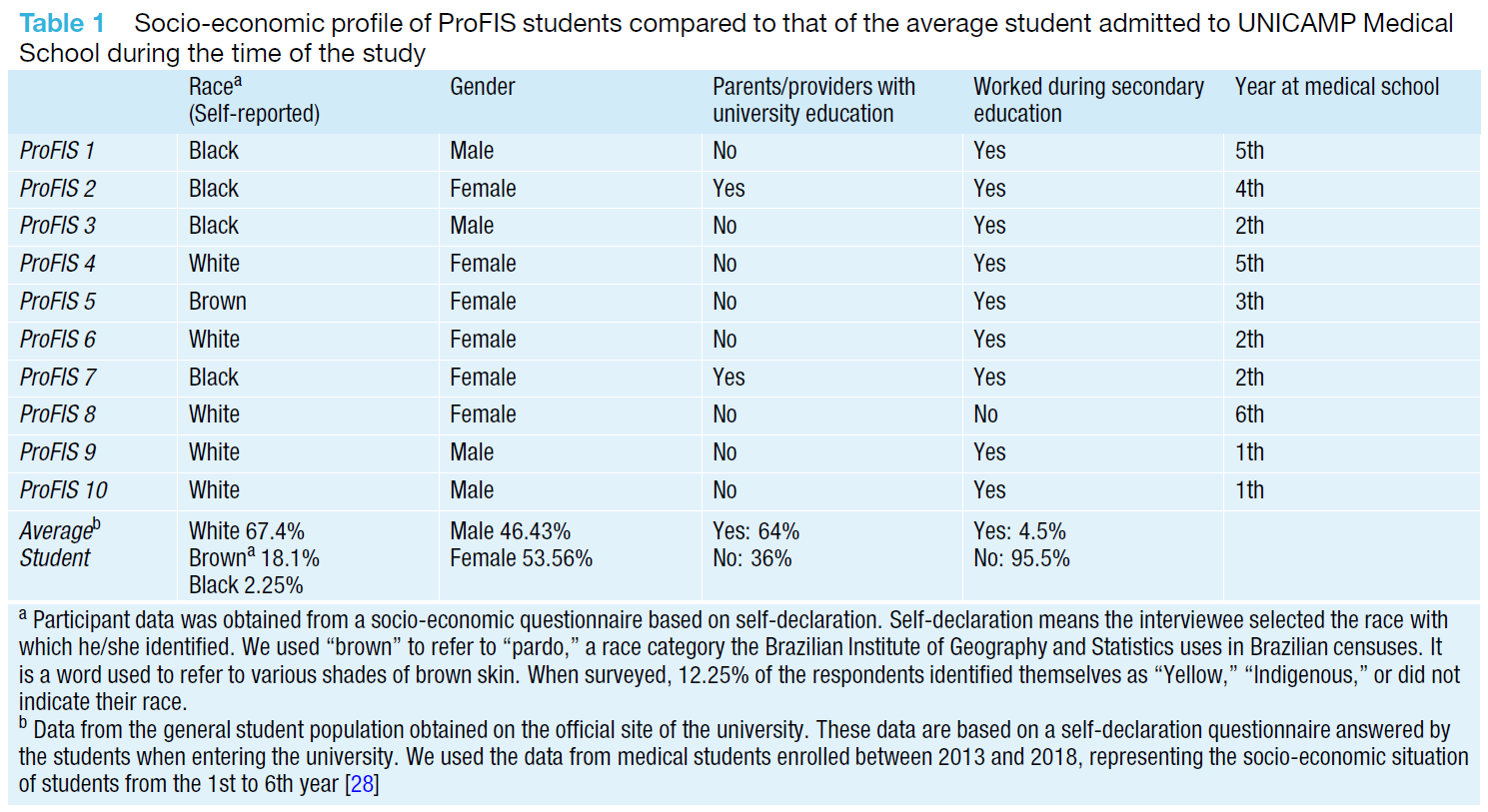

매년 120명의 학생들이 ProFIS를 통해 선발된다. 2년간의 프로그램을 마친 후, ProFIS 학생들은 그들의 선호, 순위, 장소의 가용성에 따라 유니캠프 과정 중 하나를 선택한다. 매년, 10명의 프로FIS 학생들은 의대에 입학할 수 있으며, 입학정원의 거의 10%를 차지한다[27]. ProFIS 학생들은 의대 학생들의 일반 인구와 다른 인종 및 사회경제적 배경을 가지고 있다(표 1).

Annually, 120 students are selected through ProFIS. After completing the two-year program, ProFIS students choose one of the UNICAMP courses to follow, according to their preferences, ranking, and availability of places. Every year, 10 ProFIS students are admitted to the medical school, representing almost 10% of its admissions [27]. ProFIS students have different racial and socioeconomic backgrounds than the general population of medical students (Tab. 1).

인종과 인종주의

Race and racism

우리는 인종이 생물학적 기반이 없는 [사회적 구조]라고 믿고 [28, 29] 피부색이 인간 조건의 한정자로 사용되지 않는 날을 희망합니다. 그러나 모순적으로 보일지 모르지만, 인종 차별과 싸우고 불평등을 줄이기 위한 보상 정책을 시행하기 위해서는 피부색이 사회적 결정요인으로 인식되어야 한다. 브라질의 흑인 운동은 흑인 학생들의 대학 입학률을 높이는 것을 목표로 하는 보상 교육 정책을 시행하기 위해 수십 년 동안 싸웠다[30].

We believe that race is a social construct with no biological foundation [28, 29] and hope for the day when skin color will not be used as a qualifier of the human condition. However, as contradictory as it may seem, to fight racism and implement compensatory policies to decrease inequality, skin color must be recognized as a social determinant. The black movement in Brazil fought for decades to enforce compensatory educational policies that target increasing the university admission of black students [30].

참가자, 연구팀 및 반사성

Participants, research team, and reflexivity

우리는 ProFIS의 다양한 학년 학생들이 사회화 경험에 대한 보다 포괄적인 개요를 갖도록 하기 위해 목적 있는 샘플링 전략을 사용했다. 10번의 인터뷰 후, 우리는 이론적 충분성에 도달했다[31]. 즉, 우리는 학생들의 [사회화의 다양한 측면(공식 및 비공식; 교실 내 및 임상 활동)], 그리고 이러한 활동이 학생들의 정체성 발달에 어떤 영향을 미치는지에 대한 충분한 정보를 얻었다.

We used a purposeful sampling strategy that included ProFIS students from different academic years to have a more comprehensive overview of their socialization experiences. After ten interviews, we reached theoretical sufficiency [31], i.e., we covered different aspects of students’ socialization (formal and informal; in-classroom and clinical activities), and obtained sufficient information about how these activities impacted students’ identity development.

연구팀은 임상교습 경력이 20년이고 리치픽처스 방법론에 정통한 의대생(MB), 임상교사(DLR), 교육혁신연구부교수(MACF)로 구성됐다. MB, DLR 및 MACF는 비슷한 사회적 배경을 가지고 있습니다. 이들은 모두 하위 중산층 가정 출신이며 참가자들의 경험 중 몇 가지 측면과 관련될 수 있으며, 이는 조사 결과를 이해하는 데 도움이 되었습니다. 또한, 저자들은 유니캠프를 졸업했지만 약 10년 안에 졸업했다. 이러한 종단적 이해는 학생들의 관점에 더해져 지난 20년 동안 소수민족 학생에 대한 기관의 문화가 어떻게 발전했는지에 대한 통찰력을 촉진시켰다. 감정적 과정인 경우가 많았던 만큼 저자들은 자신의 감정적 반응이 자료수집과 분석의 자격요건으로 작용하도록 성찰적 입장을 취했다.

The research team was composed of a medical student (MB), a clinical teacher (DLR), and an associate professor in innovation and research in education (MACF) who had 20 years of experience in clinical teaching and is familiar with the Rich Pictures methodology. MB, DLR, and MACF share a similar social background—they all come from lower middle-class families and could relate to several aspects of participants’ experiences, which helped them make sense of the findings. In addition, the authors graduated from UNICAMP but within a period of approximately ten years. This longitudinal understanding added to students’ perspectives to facilitate insights on how the institution’s culture regarding minority students evolved over the last 20 years. As it was often an emotional process, the authors took a reflective stance to guarantee that their emotional responses worked as qualifiers of data collection and analysis.

MB는 데이터 수집에서 위계 구조의 영향을 최소화하기 위해 학생들을 인터뷰했다. 연구팀은 [교육]을 사회 정의에 헌신하는 비판적 의식을 개발하기 위한 "해방" 과정으로 간주하는 [비판적 페다고지]의 개념을 따른다[32]. 선행연구팀인 연구팀은 사회적 포용을 바람직한 결과로 간주했다. 다양한 학생들은 의과대학의 종종 가부장적이고 인종차별적인 구조를 재고하고 새롭게 할 기회를 제공한다[33, 34]. 이러한 관점은 연구 프로토콜, 데이터 수집 및 데이터 분석의 정교화에 영향을 미쳤다.

MB interviewed the students to minimize the effect of hierarchy in data collection. The research team follows the concepts of critical pedagogy, which considers education as a “liberation” process towards developing a critical consciousness committed to social justice [32]. The research team, a priori, regarded social inclusion as a desirable outcome. Diverse students bring an opportunity to rethink and renew medical schools’ often patriarchal and racist structures [33, 34]. This perspective influenced the elaboration of the research protocol, data collection, and data analysis.

데이터 수집

Data collection

비공개 세션에서 MB는 참가자들에게 사회, 경제, 인종적 배경을 고려하여 의학 과정 동안 경험한 어려운 상황을 나타내는 [그림을 그리도록 지시]했다. 그 후, 학생들은 27분에서 69분 사이의 인터뷰에 응했다. 우리는 비언어적 기억을 활성화하고 "사회적으로 바람직한 답변" 현상을 최소화하기 위한 전략으로 [리치 픽처스]를 사용했다[35, 36]. 자료수집과 분석은 서로 정보를 주고받았으며 2018~2019년 8개월에 걸쳐 발생했으며, 반구조화된 인터뷰의 대본/주제는 자료수집 과정에 따라 진화했다. 우리의 프로토콜은 ESM(Electronic Supplementary Material)에 있는 부록 1에 자세히 설명되어 있습니다.

In a private session, MB instructed participants to draw a picture representing a challenging situation they experienced during the medical course, considering their social, economic, and racial background. Afterward, students were interviewed (in interviews ranging from 27–69 min). We used the Rich Pictures as a strategy to activate non-verbal memories and minimize the phenomenon of “socially desirable answers” [35, 36]. Data collection and analysis informed each other and occurred over eight months in 2018–2019, and the script/topics of the semi-structured interview evolved along the process of data collection. Our protocol is detailed in Appendix 1, found in the Electronic Supplementary Material (ESM).

데이터 분석

Data analysis

우리는 실천 공동체(CoP) 이론적 프레임워크에 기초하여 연역적 주제 분석[37]을 수행했다[38]. 코딩 프로세스를 안내하기 위해 CoP의 참여, 상상력 및 정렬 개념을 선험적 주제로 사용했습니다 [38]. 우리는 공동체 활동에 참여할 수 있는 능력으로 참여, 다른 구성원들과 연결되어 있다고 느끼면서 자신을 공동체의 일원으로 상상할 수 있는 능력으로 상상, 그리고 공동체의 가치와 행동 규범을 공유하고 내재화하는 과정으로 정렬을 고려했다[38] 데이터 분석 프로세스는 ESM의 부록 1에 자세히 설명되어 있습니다.

We performed a deductive Thematic Analysis [37] grounded on the Communities of Practice (CoP) theoretical framework [38]. We used CoP’s engagement, imagination, and alignment concepts as a priori themes to guide our coding process [38]. We considered engagement as the ability to get involved in community activities; imagination as a capacity to imagine oneself as a member of the community while feeling connected to other members; and alignment as the process of sharing and internalizing the community’s values and codes of conduct while learning to collaborate with other members [38]. Our data analysis process is detailed in Appendix 1 in the ESM.

결과.

Results

참가자들은 [학문과 사회활동을 할 경제적 수단이 부족하고, 인종과 사회경제적 편견에 시달리며, 집단의 일부를 느끼지 못하며, 동료와 임상감독관의 지배적인 상류사회 문화에 맞지 않기 때문에] 의료계와의 연계에 어려움을 겪고 있다. 반면에, 참가자들은 소외계층을 돌볼 때 환자와 더 가깝고 공감을 더 잘 보여줄 수 있는 것으로 인식한다. 이들은 공공의료체계를 파악하고 이에 맞춰 [자신이 받은 투자를 사회에 환원하고 싶은 강렬한 마음urge]을 느낀다.

Participants wrestle with connecting to the medical community because they

- lack the financial means to engage in academic and social activities,

- suffer from racial and socio-economic prejudice,

- do not feel part of the group, and

- do not fit the predominant upper social class culture of their colleagues and clinical supervisors.

On the other hand, participants perceive themselves as closer to patients and more capable of showing empathy when caring for underserved populations. They identify and align with the public healthcare system and feel the urge to pay back the investment they received to society.

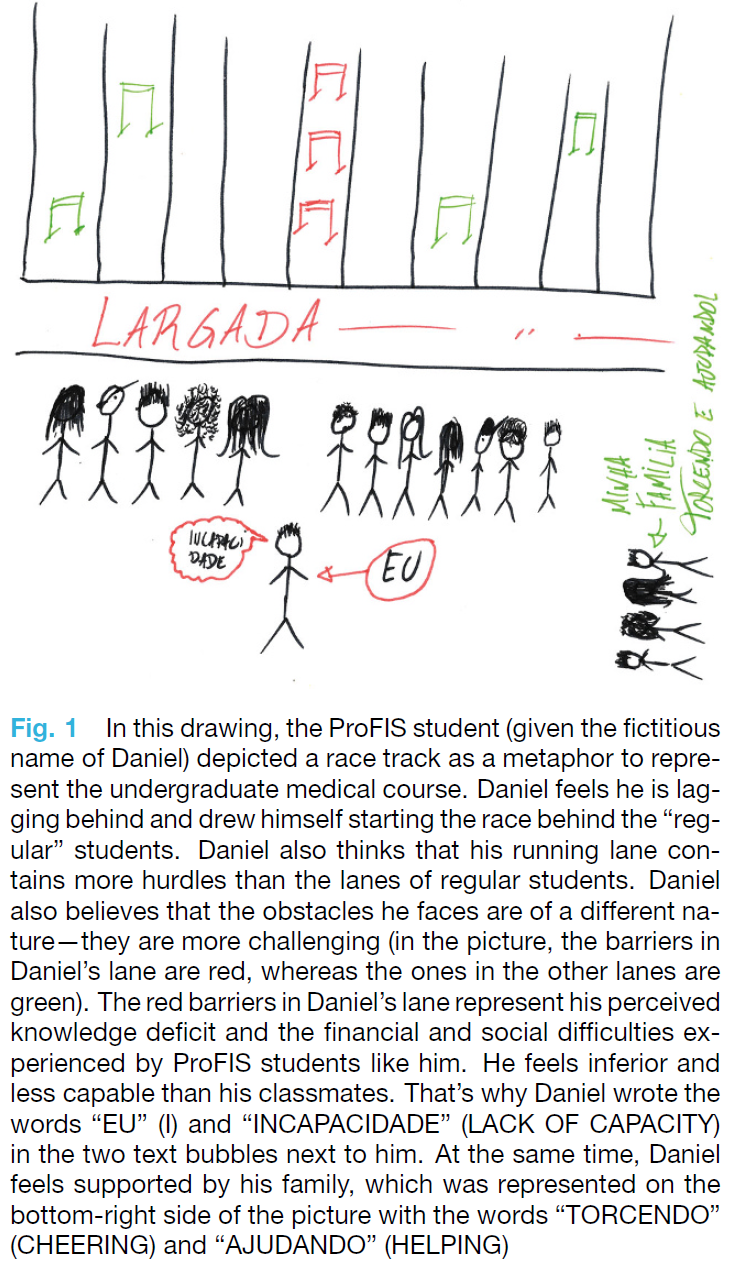

참가자들은 의과대학에서 경험한 어려운 상황을 공유할 때 강렬한 감정을 보여주었다. 종종 그들은 "숨쉬기 위해" 인터뷰를 중단해야 했고, 우는 에피소드도 흔했다. 학생들은 종종 그림에서 자신을 의학 교육 영역에 통합하거나 이해할 수 없는 외부인으로 묘사했다. 그 사진들은 학생들이 그들의 과거와 현재의 경험을 멈추고, 기억하고, 성찰할 수 있도록 함으로써 인터뷰의 유력한 촉진자 역할을 했다. 특정 사건에 초점을 맞추는 대신, 일부 학생은 학업 궤적을 은유적으로 표현하였다(그림 1). 이러한 은유적 성격은 참가자들의 의미 형성 과정을 탐구할 수 있는 창구를 제공했고, 이는 인터뷰 중과 후에 통찰력을 확장시켰다. 다음 섹션에서는 참가자들의 목소리를 증폭시키고 그들의 사회적, 경제적, 인종적 배경이 의료계에 대한 소속감에 어떤 영향을 미치는지에 대한 그들의 반성을 공유한다.

Participants displayed intense emotions when sharing the challenging situations they experienced in medical school. Frequently, they had to pause the interview “to breathe,” and crying episodes were common. Students often portrayed themselves in the drawings as outsiders unable to integrate into or make sense of the medical education realm. The pictures functioned as potent facilitators of the interviews by allowing students to stop, remember, and reflect on their past and present experiences. Instead of focusing on a specific event, some drawings were metaphorical representations of students’ academic trajectories (Fig. 1). This metaphoric nature offered a window to explore participants’ meaning-making processes, which expanded the insights during and after the interviews. In the following sections, we amplify the participants’ voices and share their reflections on how their social, economic, and racial backgrounds influence their belongingness to the medical community.

이 그림에서 ProFIS 학생(가칭 다니엘)은 학부 의학 과정을 나타내는 은유로서 [경주 트랙]을 묘사했다. 다니엘은 자신이 뒤처져 있다고 느끼고 "일반" 학생들 뒤에서 경주를 시작하는 자신을 그렸다. 다니엘은 또한 자신의 달리기 차선이 일반 학생들의 차선보다 [더 많은 장애물]을 포함하고 있다고 생각한다. Daniel은 또한 그가 직면한 장애물은 다른 성질의 것이라고 믿는다 - 그것들은 더 도전적이다 (사진에서 Daniel의 차선의 장애물은 빨간색인 반면 다른 차선의 장애물은 녹색이다). Daniel의 차선의 빨간 장벽은 그가 인지한 지식 부족과 그와 같은 ProFIS 학생들이 겪는 재정적, 사회적 어려움을 나타냅니다. 그는 반 친구들보다 열등하고 능력이 떨어진다고 느낀다. 다니엘이 옆에 있는 두 개의 텍스트 버블에 'EU'(I)와 'INCAPACIDADE'(용량 부족)라는 단어를 쓴 것도 이 때문이다. 동시에 사진 오른쪽 하단에 'TORCENDO'(응원)와 'AJUDANDO'(도움)라는 글자로 표현된 가족의 지지를 느낀다.

In this drawing, the ProFIS student (given the fictitious name of Daniel) depicted a race track as a metaphor to represent the undergraduate medical course. Daniel feels he is lagging behind and drew himself starting the race behind the “regular” students. Daniel also thinks that his running lane contains more hurdles than the lanes of regular students. Daniel also believes that the obstacles he faces are of a different nature—they are more challenging (in the picture, the barriers in Daniel’s lane are red, whereas the ones in the other lanes are green). The red barriers in Daniel’s lane represent his perceived knowledge deficit and the financial and social difficulties experienced by ProFIS students like him. He feels inferior and less capable than his classmates. That’s why Daniel wrote the words “EU” (I) and “INCAPACIDADE” (LACK OF CAPACITY) in the two text bubbles next to him. At the same time, Daniel feels supported by his family, which was represented on the bottom-right side of the picture with the words “TORCENDO” (CHEERING) and “AJUDANDO” (HELPING)

상상력 -"우린 잘못된 곳에 있어"

Imagination—“We are in the wrong place”

ProFIS 학생들은 illegitimate함을 느끼고 미래의 의사로서 자신을 보기 위해 고군분투하는데, 이는 지역 의료계와 사회 전반에 반영된다. 자신을 의사로 상상하는 어려움은 세 가지 측면을 가지고 있다:

- 의료 환경과의 동일성 부족

- 낮은 자존감의 감정

- 인종과 사회적 차별의 경험.

ProFIS students feel illegitimate and struggle to see themselves as future doctors, a feeling reverberated by the local medical community and society in general. This difficulty in imagining themselves as doctors has three dimensions:

- a lack of identification with the medical environment,

- feelings of low self-esteem, and

- experiences of racial and social discrimination.

의료 환경과의 동일성 결여

Lack of identification with the medical environment

이러한 [정체성의 부족]은 ProFIS 의 학생들이 의과대학과 대학 환경을 꿈으로도 생각하지 않았기 때문에 의과대학에 입학하기 전에 시작된다. 일반적으로, ProFIS 학생들은 [대학 과정에 입학하는 가족의 1세대]를 대표하는데, 이것은 그들이 그들 자신, 과정, 동료, 그리고 환경에 대한 그들의 기대를 조절하는 데 어려움을 겪는다는 것을 의미한다. 이러한 기대치 조절의 어려움은 그들의 "올바른"(예상된) 행동이나 태도를 맥락과 문화에 맞게 예상하는 능력을 방해하기 때문에 좌절감을 느낄 가능성을 증가시킨다.

This lack of identification starts before entering medical school as ProFIS students have never considered the medical and university environments part of their reality, not even as a dream. In general, ProFIS students represent the first generation of their families to get into a university course, which means that they have trouble modulating their expectations about themselves, the course, their colleagues, and the environment. This difficulty in modulating expectations increases the chance of feeling frustrated because it hampers their capacity to anticipate the “right” (expected) behavior or attitude to match the context and culture.

ProFIS 가 없었다면, 저는 의대에 오지 못했을 것입니다. 첫째, 의대에 지원할 생각이 없었기 때문이다.나는 돈이 없었다. 나는 일하고 있었다. 그것은 나에게 괜찮았다. 세상에 대한 나의 시야는 너무 좁고 좁았다. 나는 낮에는 일하고 밤에는 학교에 가곤 했다. 그리고, 가르침이 매우 좋지 않았기 때문에, 나는 배우려고 노력하는 것에 흥분하지 않았다… 나는 시도조차 하지 않았다. (ProFIS 학생 번호 10 [PS 번호 10])

Without ProFIS, I would never have come to the Medical School. First, because I did not have the intention of applying for medical school, because [pause]—I did not have the money. I was working; it was OK for me. My vision of the world was too small, too narrow. I used to work during the day and go to school at night. And, because the teaching was not very good, I was not excited about making an effort to learn … I did not even try. (ProFIS student no. 10 [PS no. 10])

코스의 시작은 이러한 식별력 부족을 악화시킨다. ProFIS 학생들의 사회 현실은 의대생에 대한 일반적인 스테레오타입에 맞지 않는다. 이러한 차이는 [정당성legitimacy의 결여]로 인식되어 의료계에서의 그들의 참여를 방해한다. 그들은 자신들의 재정 상태에 대해 어색하고 당황스러워한다. 그들은 다르게 옷을 입고, 다른 것을 소유하고, 다른 경험을 하고, 다른 가치를 공언한다. 이러한 [충돌]은 소속되지 않았다는 감각을 유발하고, 그들의 사회적 연결과 네트워킹을 방해한다. 믿을 수 없다. 이 사람들처럼 (비프로)FIS)는 의과대학에서 승인을 받았고, 그 후 그들은 그것을 위해 차를 얻는다. 저는 22살이고, 제 가족 중 아무도 차를 가져본 적이 없어요, 한 번도!" (PS 3번)

The start of the course worsens this lack of identification. ProFIS students’ social reality does not fit the prevalent stereotype of medical students. This difference is perceived as a lack of legitimacy, which hampers their participation in the medical community. They feel out of place, awkward and embarrassed by their financial condition. They dress differently, possess different things, have different experiences, and profess different values. These clashes generate a sense of not belonging and hamper their social connections and networking. “It is unbelievable. Like, these guys (non-ProFIS’s) were approved in medical school, and then they get a car for that. I am 22 years old, and nobody in my family has ever had a car, never!” (PS no. 3).

다른 사회적 배경에서 온 ProFIS 학생들은 [다른 세계관, 우려, 그리고 정치적 이데올로기]를 가지고 있다. 그들은 사회적 불평등의 부담을 직접 경험했기 때문에 [사회 정의와 책임에 대한 확고한 의지]를 가지고 있으며, 의료 교육을 보다 공평한 의료 시스템을 향한 정치적 기업으로 이해한다.

Coming from a different social background, ProFIS students have different world views, concerns, and political ideologies. Since they have directly experienced the burden of social inequality, they have a solid commitment to social justice and accountability and understand medical education as a political enterprise towards a more equitable healthcare system.

그들(ProFIS 학생)은 세계관이 매우 다르다. 어떻게 설명해야 할지 모르겠어요. 하지만 나는 첫해 첫날에 그것을 기억한다. 이곳에 도착했을 때, 저는 사람들을 보았고, 그들이 제가 익숙했던 것과는 매우 다르다고 생각했습니다. 사고방식도 다르다. 나는 모른다. 어떤 사람들은 돔에 사는 것 같다. 그들은 아무것도 모른다. 그것은 주변 세계에 대한 인식 부족입니다, 아시죠? 심지어 그들이 가지고 있는 종류의 걱정까지. (PS no. 5)

They (non-ProFIS students) have a very different worldview. I don’t even know how to explain. But I remember that on the first day of the first year. When I arrived here, I looked at the people, and I thought they were very different from what I was used to. Different even in the way of thinking. I don’t know. It seems that some people live in a dome. They have no idea of anything. It is a lack of awareness of the world around, you know? Even the kind of concern they have. (PS no. 5)

낮은 자존감

Low self-esteem

"완벽한 폭풍"은 ProFIS 학생들의 자존감을 위협한다: 그들은 불안정하고 자금이 부족한 학교 출신이고, 교육 경험을 확장할 재정적 수단이 없으며, 그들의 친척들은 낮은 수준의 정규 교육을 받는다. 그들은 준비되지 않았고, 불안정하고, 의학 과정을 밟고, 직업적인 성공을 거두기엔 불충분하다고 느낀다. 의료 훈련의 경쟁적인 환경은 특히 ProFIS 학생들이 그들의 새로운 사회적, 학문적 현실에 적응하기 위해 씨름할 때 이러한 열등감을 강화한다. 뒤처진다는 이 느낌은 이미 의대생이 되기 위한 힘든 과정에 추가적인 압력을 가한다.

A “perfect storm” threatens ProFIS students’ self-esteem: they come from precarious and underfunded schools, they do not have the financial means to expand their educational experiences, and their relatives have low levels of formal education. They feel unprepared, insecure, and insufficient to enter and follow the medical course and achieve professional success. The competitive environment of the medical training reinforces this feeling of inferiority, particularly when ProFIS students wrestle to adapt to their new social and academic reality. This feeling of lagging behind creates extra pressure on the already demanding process of becoming a medical student.

"와, 이 사람들처럼 되기 위해서라도 공부를 열심히 해야겠다"는 생각이 들었다. 사람들이 파티에 가는 동안, 나는 그들처럼 되기 위해 열심히 공부해야 해. 그리고 저는 제 인생 전체가 그랬다고 생각합니다. 이모는 항상 "너는 지금 공립대학에 있어. 수백만 명의 사람들이 당신과 경쟁하고 있습니다. 그리고 그들은 자원을 가지고 있습니다. 그들은 좋은 사립학교에서 공부했고, 더 나은 선생님들이 있었습니다. 그리고 넌 그런거 없어. 그래서, 여러분이 그들과 동등해지려면, 여러분은 두 배로 공부해야 할 것입니다." (PS No.1)

I felt like, “wow, I’m going to have to study hard to stand out or to be like these people.” While people are going to parties, I need to study hard to be like them. And I think my whole life has been like that. My aunt always said, “You are in a public university now. There are millions of people competing with you. And they have resources; they studied in good private schools, they had better teachers. And you don’t have that. So, for you to be equal to them, you’ll have to do twice as much.” (PS no. 1)

과정 중, [조직적으로 불신을 드러내고, ProFIS 학생들의 의견과 가치를 과소평가하는 동급생과 교사]들과의 상호작용이 낮은 자존감을 강화시키는 경우가 많다. ProFIS 학생들은 계속해서 자신의 가치를 증명해야 한다는 부담을 느낀다.

During the course, the interaction with classmates and teachers who systematically show distrust and underestimate ProFIS students’ opinions and values often reinforces their low self-esteem. ProFIS students continuously feel the burden to prove themselves valuable.

사람들은 내 말을 믿지 않는다. 그들은 항상 내가 사물에 대해 잘 모른다고 생각한다. 그래서, 만약 제가 주제나 아이디어와 관련된 말을 한다면, 사람들은 항상 제가 말하는 것을 평가절하할 것입니다. 혹은 그것이 진실이라고 믿지 않는 것. 다른 학생들과 하는 것과는 전혀 다릅니다. (PS no. 6)

People do not trust what I say. They always think that I do not know much about things. So, if I say something related to a subject, or an idea, there will always be people devaluing what I am saying. Or not believing that it is something true. Completely different from what they do with other students. (PS no. 6)

사회적 차별과 인종차별

Social discrimination and racism

일부 학생들은 교직원과 반 친구들로부터 차별을 느꼈습니다. affirmative policies 에 동의하지 않는 교사들이 반 친구들 앞에서 학생들을 모욕한다. 몇몇 상황에서, ProFIS 학생들은 대학에 쉽게 접근할 수 있다는 것이 그들이 대학에 있을 자격이 없다는 것을 의미한다는 생각에 직면했다. 다시, 이러한 경험은 [정당성이 부족하다는 느낌]을 강화한다.

Some students felt discriminated against by their faculty members and classmates. Teachers who disagree with the affirmative policies affront the students in the presence of their classmates. In several situations, ProFIS students were confronted with the idea that their facilitated access to the university meant they were less deserving to be there. Again, these experiences reinforce the feeling of lack of legitimacy.

학급 앞에서 ProFIS 에서 온 학생에게 물어보고 이런 긍정 정책에 동의하지 않는다며 우리에게 지시하는 연설을 시작한 교사가 있었다. 너무 노출된 것 같았어요. (PS No.1)

There was a teacher who asked in the front of the class who was from ProFIS and started giving a speech directed to us, saying that he did not agree with this affirmative policy. I felt super exposed. (PS no. 1)

자신을 [흑인]으로 식별한 모든 학생들은 주로 병원 내부에서 일어났던 인종차별과 관련된 도전적인 경험을 언급했다. [대학 병원에서 일하는 흑인 의사가 거의 없다는 사실]은 이미 이 학생들이 자신을 의료계의 일부로 상상하도록 도전한다. 그 외에도 인종차별의 경험들은 학생들이 미래에 일반 대중들이 그들을 의사로 보고 믿지 않을 것을 두려워하게 만든다.

All students who self-identified as black mentioned challenging experiences related to racism, which mainly occurred inside the hospital. The fact that few black doctors are working at the university hospital already challenges these students to imagine themselves as part of the medical community. Besides that, experiences of racism make students afraid that the general public will not see and trust them as doctors in the future.

흑인 전문직 종사자들은, 어떤 상황에서든, 그들의 영역이 무엇이든, 항상 이런 압박을 느낀다. 당신은 평범한 변호사가 될 수 없어요. 당신은 평범한 판사가 될 수 없어요. 당신은 평범한 의사가 될 수 없어요. 사회에서 인정받기 위해서는 흑인으로서 무엇을 하든 최고가 되어야 한다.(…) 내가 이 도시에서 최고의 정형외과 의사가 된다면 정말 멋질 것이다. 하지만 이것이 제가 최고의 정형외과 의사가 되고 싶은 이유는 아닙니다. 저는 최고의 정형외과 의사가 되고 싶습니다. 왜냐하면 제가 최고가 아니라면 사람들이 저를 단순히 흑인이라는 이유로 고용하지 않을 수도 있기 때문입니다.(PS No.2)

The black professional, in any situation, whatever their area, always feel this pressure. You cannot be an average lawyer. You cannot be an average judge. You cannot be an average doctor. To be recognized in society, as a black person, you need to be the best in whatever you do. (…) It would be really cool for me to be the best orthopedist in the city. But this is not the reason why I want to be the best orthopedist. I want to be the best orthopedist because if I am not the best, maybe people will not hire me simply because I am black. (PS no. 2)

인종차별은 또한 학생들이 의사로서의 역할에 대해 [칭찬을 받을 때 조차]도, 소속되지 않고 불법적이라는 느낌을 강화한다.

Racism also reinforces the feeling of not belonging and illegitimacy even when students are praised for their role as doctors.

주민들은 길에서 폭행을 당한 환자를 평가하고 있었고, 아무도 이유를 알지 못했고, 환자는 말을 할 수 없었다. 그래서, 그들은 조사를 위해 경찰을 불렀습니다. 그리고 경찰관들은 나를 의사라고 부르며 정중하게 인사를 했다. "안녕하세요, 의사 선생님." 그것은 나에게 큰 충격을 주었다. 왜냐하면 내가 길거리에 있을 때, 그들은 나를 그렇게 부르지 않기 때문이야, 알지? 막아서서 때리듯이. (PS no. 3)

The residents were evaluating a patient who had been assaulted on the street, and nobody knew the reason, and the patient could not speak. So, they called the cops to investigate. And the police officers greeted me respectfully, calling me doctor, “Good evening, doc.” It shocked me a lot. Because when I’m on the street, they do not call me that, you know? Like, they stop me, and they hit me. (PS no. 3)

계약 -"난 항상 지쳤어"

Engagement—“I’m always exhausted”

CoP 이론은 참여가 전문적 정체성을 개발하는 데 중요하다는 것을 암시한다[38]. 이러한 의미에서 ProFIS 학생들은 재정적인 어려움과 대학 지원의 부족으로 인해 사회적, 전문적 활동에 참여하기 위해 고군분투한다. 그들은 뒤처지고 소외된 기분을 느끼며, 이는 고뇌와 버림받은 감정을 유발한다.

The CoP theory implies that participation is crucial in developing a professional identity [38]. In this sense, ProFIS students struggle to engage in social and professional activities because of financial challenges and a lack of university support. They feel left behind and excluded, which triggers feelings of anguish and abandonment.

재정적 불이익

Financial disadvantage

ProFIS 학생들은 대부분 도시 외곽에 살기 때문에 대중교통을 이용하는데 3~4시간을 소비한다. 결과적으로, 그들은 공부하고 커리큘럼과 과외 활동에 참여할 시간이 더 적습니다. 일부 학생들은 가족의 수입을 보충하기 위해 돈벌이를 해야 할 수가 있다. 집에서도 공부할 수 있는 여건이 다르다. 예를 들어, 어떤 학생들은 안정적인 [인터넷 연결]이 없는 반면, 다른 학생들은 과정을 따라가는 데 [필요한 자료를 살 수 없다]. 의료행위의 아이콘인 [청진기를 구입하는 것조차 부담]스러울 수 있다. "저는 청진기를 사기 위해 다른 사람들보다 훨씬 더 많은 고통을 겪었습니다. 왜냐하면 내가 하나를 사러 갔을 때, 그것은 일종의 행사였기 때문이다. 열 명이 넘는 사람들이 우리 가족을 도와 청진기 하나를 샀다."(PS No.2).

ProFIS students spend 3 to 4 h in public transportation since most live on the city’s periphery. Consequently, they have less time for studying and engaging in curricular and extra-curricular activities. Some students need to work to complement family income. At home, the conditions to study are also different. For instance, some students do not have stable internet connections, while others cannot buy the necessary materials to follow the course. Even purchasing a stethoscope—the “icon” of the medical practice—may be a burden. “I suffered a lot more than other people to buy a stethoscope. Because when I went to buy one, it was a kind of event. More than ten people helped my family to buy one.” (PS no. 2).

학술행사에 참여하는 것 또한 경제적 자원이 부족하고, 좌절감과 불이익을 느끼기 때문에 도전이다. 장학금을 추구하는 것이 의학계의 핵심이기 때문에, ProFIS 학생들은 그들의 직업적 정체성을 기를 수 있는 가장 강력한 기회 중 하나를 거부당한다.

Engaging in academic events is also a challenge because they lack the economic resources, making them feel frustrated and disadvantaged. As pursuing scholarship is at the core of the medical profession, ProFIS students are denied one of the most potent opportunities to nurture their professional identity.

예를 들어, 의회와 다른 학문적인 것들입니다. 사람들은 "어떻게 congress에 가지 않을 수 있어?"라고 말한다. 저는 이렇게 말합니다. "여러분, 의회에 가는 비용을 생각해본 적이 있나요? 강의료도 내고 등록비도 내고 거기 가기 위해서도 돈을 내고, 나는 그들이 우리에게 이것이 얼마나 중요한지 보여주고 싶어하는 것을 이해한다. 하지만 그 중요성을 보여주기엔 충분하지 않다. 중요한 건 다들 알지만, 제가 참여할 수 있도록 중요성을 보여주는 것 말고는 어떻게 하실 건가요? (PS no. 6)

For example, congresses and other academic stuff. People say like, “How could you not go to the congress?” And I say like, “Guys, have you ever realized the costs of going to a congress? You pay for a lecture; you pay for registration; you pay to go there.” I understand that they (the teachers) want to show us how important this is. But it is not enough to show the importance. Everyone knows it is important, but what are you going to do besides showing me the importance so that I can participate? (PS no. 6)

ProFIS 학생들은 의료계 내부의 비공식 활동에 참여하는 것도 어렵다. 경제적 여건이 열악하고, 운동과 사회활동을 할 시간이 부족하며, 이는 집단과의 외로움과 단절감을 심화시키기 때문이다.

Joining informal activities inside the medical community is also challenging because ProFIS students lack the financial conditions and the time to engage in athletic and social activities, which intensifies the feeling of loneliness and disconnection from the group.

"아, 제가 더 복잡한 이유는… 이런 행사에 참석하는 사람들은… 훨씬 더… 글쎄요… 통합적이라는 것을 알기 때문입니다. 내가 거기에 있을 수 없기 때문에 통합의 부족을 느낀다."(PS No.3).

“Ah, it’s more complicated for me because I realize that … The guys who go to these events … they are much more … like … I don’t know … integrated. I feel this lack of integration because I can’t be there.” (PS no. 3).

불충분한 지원

Insufficient support

ProFIS 학생들에 따르면, 이 의과대학은 상류 사회 계층의 학생들을 다루는 데 익숙해 있는데, 이것은 저소득 가정의 학생들의 요구를 예상하는 데 있어서 그것의 커리큘럼 구조가 실패한다는 것을 의미한다. 그 대학은 학생들을 사회 경제적 프로필에 포함시키는 것에 진정한 관심이 없는 것처럼 느껴진다. "대학은 우리를 맞을 준비가 전혀 되어 있지 않다. 사람들이 우리를 무시하고 '언젠가 이 사람들은 여기 오는 것을 포기하고, 일이 예전으로 돌아갈 것이다.'라고 생각하는 것 같은 느낌을 준다.(PS No.2)

According to ProFIS students, the medical school is used to dealing with students from upper social classes, which means that its curricular structure fails in anticipating the needs of students from low-income families. It feels like the university does not have a genuine interest in including students with their socio-economic profile. “It (the university) is entirely unprepared to welcome us. It gives us a feeling that people are ignoring us and thinking, ‘someday, these people will give up on coming here, and things will go back to how they were before.’” (PS no. 2).

얼라인먼트: "나는 이 현실에서 왔다.—"나는 무언가를 돌려줘야 한다."

Alignment: “I came from this reality”—“I have to give something back”

비록 ProFIS 학생들은 자신을 공동체의 일원으로 상상하고 전문적이고 사회적인 활동을 하는 것에 어려움을 겪지만, 그들은 (스스로 그룹에 포함되기 위해 싸우도록 동기를 부여하기 위해 에너지와 열정을 제공하는) 강한 목적 의식을 가지고 있다. 과정 초반에 소외감을 느낀 후, 그들은 자신의 정당성을 발견하고 공공 의료 시스템의 가치와 목표에 연결되고 일치한다고 느끼며 자신에게 힘을 실어줍니다empower. 이런 맥락에서 비슷한 사회적 배경을 가진 환자들을 돌볼 수 있는 역량을 느끼는 것은 기쁨과 성취감의 원천이다.

Although ProFIS students struggle with imagining themselves as members of the community and engaging in professional and social activities, they have a strong sense of purpose that provides energy and enthusiasm to keep them motivated to fight to be included in the group. After feeling excluded at the beginning of the course, they discover their legitimacy and empower themselves by feeling connected and aligned with the values and aims of the public healthcare system. In this context, feeling competent to take care of patients with a similar social background is a source of joy and fulfillment.

빈약한 환자에 대한 공감 및 동일시 강화

Greater empathy and identification with poor patients

ProFIS 학생들은 사회적 불평등이 가난한 환자들에게 어떤 부담을 주는지에 대해 개인적으로 이해하고 있다고 믿는다. 그들은 공공 의료 시스템에 의존하고 의료 상담과 치료에 접근하기 위해 싸우는 것이 무엇을 의미하는지 알고 있다. 이러한 개인적 경험은 환자의 경험과 맥락에 대한 이해를 넓히고 공감력을 높여주고 환자 중심의 치료를 더 잘 채택할 수 있다고 느끼게 한다. 유능함을 느끼는 것은 그들의 자존감을 높이고 소속감을 회복시킨다. "우리가 공공 의료 시스템에서 돌볼 대부분의 사람들은 나 같은 사람들이다; 나는 이런 현실에서 왔다. 나는 내가 어디에서 왔는지 잊지 않았다. 나는 내가 누군지 안다…" (PS no. 6).

ProFIS students believe they have a personal understanding of how social inequality burdens poor patients. They know what it means to depend on the public healthcare system and fight to have access to medical consultations and treatment. These personal experiences expand their understanding of patients’ experiences and contexts, increasing their empathy and making them feel more capable of adopting patient-centered care. Feeling competent increases their self-esteem and rescues their sense of belongingness. “Most people who we are going to take care of in the public healthcare system are people like me; I came from this reality. I did not forget where I come from. I know who I am …” (PS no. 6).

더 큰 공감의 예로, 많은 참가자들은 [의사들이 환자의 사회 경제적 배경으로 인해 접근하기 어려운 치료를 처방한 상황]에 대한 개인적인 경험을 예시하였다. 이러한 경험들은 그들에게 환자의 사회적 현실을 평가하고 이해하는 것이 얼마나 중요한지를 가르쳐 주었다. 이러한 공유된 사회적 현실은 환자와의 관계를 강화하고 보다 동정심 있는 치료에 대한 그들의 헌신을 강화한다.

As an example of greater empathy, many participants brought up personal examples of situations in which doctors prescribed inaccessible treatments considering their socio-economic background. These experiences have taught them how important it is to assess and understand patients’ social reality. This shared social reality tightens their connections with patients and strengthens their commitment to a more compassionate care.

우리에겐... 모르겠어요... 우리가 더 동정심을 가지고 있다는 걸. 때때로 우리 [ProFIS] 학생들은 다른 [부자] 현실에서 온 친구들과 이야기합니다. 그리고… 그들이 공감하지 않는 것은 아닙니다… 하지만 저는 잘 모릅니다, 아마도, 제 피부에서 [환자들이 겪는 어려움]을 살았고, 저는 그것이 어떤 것인지 정확히 알고 있습니다, 아시죠? (PS no. 4)

It seems that we have a ... I don’t know … that we have more compassion. Sometimes we [ProFIS students] talk to friends who come from a different [wealthier] reality. And … it’s not that they’re not empathic … But I don’t know, maybe, I lived it [the difficulties experienced by patients] in my skin, and I know exactly how it is like, you know? (PS no. 4)

취약계층을 위한 봉사 의향상

Willingness to serve vulnerable populations

모든 ProFIS 학생들은 공공 의료 시스템에서 일하고 취약한 사람들에게 봉사하려는 의지를 보였다. 그들은 공립대학에서 의학을 공부할 수 있는 특권을 느끼고 소외된 지역사회의 환자들을 도우면서 사회에 보답하고 싶은 충동을 느낀다.

All ProFIS students showed a willingness to work in the public healthcare system and serve vulnerable populations. They feel privileged to study medicine in a public university and have the urge to pay the society back by helping patients from underserved communities.

나는 개인 병원에서 일하고 싶지 않고, 나는 SUS(브라질 공중 보건 시스템) 의사가 되고 싶고, 나는 항상 1차 진료소에서 일하고 싶다고 말했고… 그리고 우리 반의 ProFIS의 다른 사람들도 그것을 원한다. 우리는 항상 SUS에 의존해왔기 때문에, 나는 무언가를 돌려줘야 한다. 우리는 대학 등록금을 내지 않는다. 그래서 나는 공공 병원, 공공 장소에서 일할 것이다. (PS no. 7)

I don’t want to work at a private hospital, I want to be a SUS (Brazil public health system) doctor, I always said that I wanted to work in primary care … and the others from ProFIS in my class also want that. Because we have always depended on SUS, so, I have to give something back. We don’t pay for university. So, I will work at the public hospital, at a public place. (PS no. 7)

논의

Discussion

본 연구는 [저소득과 인종차별]이 어떻게 교차하여 학생들의 의료계 소속감을 저해하는지 조명한다. 그들의 다른 사회적 궤적과 지위는 사회 정의와 책임의 경로로서 다양성과 포용을 이해하지도 기념하지도 않는 엘리트주의 문화와 식민주의 권력 매트릭스와 충돌한다[39, 40]. 우리의 연구는 또한 [취약계층을 의대에 포함시키는 것]만으로는 충분하지 않다는 것을 분명히 하고 있다. 긍정적이고 보상적인 정책affirmative and compensatory policies에는 이러한 학생들의 의료계로의 [통합]을 지원하는 전략이 포함되어야 한다.

Our study sheds light on how low income and racism intersect to hamper students’ sense of belongingness to the medical community. Their different social trajectories and status clash against an elitist culture and a colonial power matrix that neither understands nor celebrates diversity and inclusion as pathways to social justice and accountability [39, 40]. Our study also makes it explicit that the inclusion of vulnerable social groups in medical school is not enough—affirmative and compensatory policies should include strategies to support the integration of these students into the medical community.

CoP 이론이 예상하는 바와 같이 [32, 33] 새로운 사람들은 관행을 갱신하고 편견에 의문을 제기함으로써 공동체가 더욱 발전하고 새로운 사회적 맥락에 적응할 수 있도록 한다. 그러나 이러한 변화는 이러한 새로운 사람들이 지역사회에 의해 합법적인 참여자로 받아들여지고 정회원 자격을 얻을 때까지 그들의 참여 수준을 높일 수 있도록 지원되어야만 일어날 것이다.

As the CoP theory anticipates [32, 33], newcomers are responsible for renewing practices and questioning prejudices, allowing the community to develop further and adapt to new social contexts. However, this transformation will only happen if these newcomers are accepted by the community as legitimate participants and supported to increase their levels of participation until achieving full membership.

[저소득 학생의 포용inclusion]은 여전히 특권, 인종 차별, 성차별, 식민지적 입장으로 특징지어지는 의료 문화의 보다 포괄적인 개혁을 향한 첫걸음이다[39, 41]. 이러한 포함은 의료계가 그것의 편협함을 반성하고 현재의 사회적 요구에 연결하고 대응하는 데 필요한 문화 개혁을 받아들일 수 있는 독특한 기회를 제공한다. 이 새로운 문화에서 의사나 의료 교육자가 되는 것은 시민권을 위한 활동가가 되는 것을 의미하며, 구조적 인종차별과 싸우고 취약한 인구와 동일시하며, 돌봄과 교육의 불평등을 우려하는 전문가이다[33]. 의과대학과 교육자들은 여전히 우리의 전문적이고 교육적인 공동체 내에 존재하는 억압의 시스템(인종차별, 성차별, 외국인 혐오 등)을 개혁할 수 있는 최고의 기회를 대표하는 학생들을 위한 안전한 환경을 조성할 책임이 있다[42].

The inclusion of low-income students is the first step towards a more comprehensive reform of the medical culture, which is still marked by privilege, racism, sexism, and a colonial stance [39, 41]. This inclusion offers the medical community a unique opportunity to reflect on its insularity and embrace the cultural reform necessary to connect and respond to current societal needs. In this new culture, being a doctor or medical educator means becoming an activist for civil rights, a professional who fights structural racism, identifies with vulnerable populations, and is concerned about inequality of care and education [33]. Medical schools and educators are responsible for creating safe environments for the students who represent our best opportunity to reform the systems of oppression (racism, sexism, xenophobia, etc.) that still exists inside our professional and educational communities [42].

실제적 함의

Practical implications

[취약한 사회 집단의 학생들을 지원]하는 것은 [재정 지원을 넘어서는 것]이어야 한다[20]. 의료 교육자와 리더는 의료 커뮤니티로의 통합을 촉진하기 위한 조건을 만들어야 합니다 [43, 44]. 이러한 통합은 학생들과의 [수평적 대화]와 [변화의 주체change agents가 되기 위한 학생들의 권한 부여empowerment]에 의존해야 한다[45].

- [권한을 느낀다는 것]은 그들의 가치를 인정하고 불의와 편견에 맞서 당당하게 말하는 것을 의미한다.

- [권한을 느낀다는 것]은 그룹에 동등하게 기여하는 지식 있는 사람들로서 동료들로부터 존중을 받는다는 것을 의미한다[46].

- [권한을 느낀다는 것]은 의료계 구성원들에게 그들의 정당성을 인정받는 것을 의미한다.

이러한 정당성 없이는, 그들은 전문적인 정체성을 배양하는 데 필요한 참여 수준에 도달할 수 없다[47]. 이러한 합법성은 또한 학생들의 현실을 변화시키기 위해 행동하려는 동기를 촉진하는 데 필수적이다[46].

Supporting students from vulnerable social groups should go beyond providing financial aid [20]. Medical educators and leaders must create the conditions to foster their integration into the medical community [43, 44]. This integration should rely on a horizontal dialogue with students and their empowerment to become change agents [45].

- Feeling empowered means having their values acknowledged and being comfortable to speak up against injustice and prejudice.

- Feeling empowered means being respected by their peers as knowledgeable people who equally contribute to the group [46].

- Feeling empowered means having their legitimacy recognized by the members of the medical community.

Without this legitimacy, they cannot reach the levels of participation needed to nurture their professional identities [47]. This legitimacy is also essential to fuel students’ motivation to act upon their realities to transform them [46].

지원적이고 성찰적인 역할 모델을 참여시키는 것은 필수적이다[23]. 감독관들은 학생들의 존재를 인정하고, 토론에 기여하도록 격려하고, 학생들의 목소리가 들리게 할 필요가 있다. 저소득층 학생들이 취약한 환자들과 더 강한 유대감을 느끼는 것에 자부심을 느낀다는 것을 아는 것은 공감능력이 실종되고 의사와 환자 관계가 차선책일 때 감독관들이 이러한 학생들에게 [주도권을 행사take the lead]할 수 있는 기회를 만들어준다. 그럼에도 불구하고, 이미 압도된overwhelmed 학생들에게 "주도권을 갖는 것taking the lead" 자체가 추가적인 부담이 되지 않는 것이 중요한데, 이 과정은 흔히 "소수자 세금"이라고 불린다[48]. "소수자 세금"은 "백인이 남성 중심의 제도적 환경 내에서 예외로 수반되는 일련의 추가 의무, 기대 및 도전"으로 정의될 수 있다[49].

Engaging supportive and reflective role models is essential [23]. Supervisors need to acknowledge students’ presence, encourage them to contribute to the debate, and guarantee that their voices are heard. Knowing that low-income students feel proud of feeling a stronger connection with vulnerable patients creates opportunities for supervisors to empower these students to take the lead when empathy is missing and the doctor-patient relationship is sub-optimal. Nevertheless, it is crucial that “taking the lead” does not become an extra burden for already overwhelmed students, a process that is often called “the minority tax” [48]. “Minority tax” may be defined as “an array of additional duties, expectations, and challenges that accompany being an exception within white male-dominated institutional environments” [49].

또한, 대학은 통합을 최적화하기 위해 학생 및 환자와 동일한 사회 그룹의 [역할 모델]을 고용해야 한다. 교수진은 이러한 역할 모델을 쉽게 사용할 수 없을 때 이러한 통합 프로세스를 이끌 감독자를 준비해야 합니다. 첫 번째 단계는 감독자들이 자신의 편견과 암묵적인 편견을 [인식]하도록 돕는 것이다. 상호보완적 활동은 인식 창출 후 문화적 겸손을 자극하고 보상함으로써 [문화간 역량intercultural competencies] 개발을 목표로 삼아야 한다. [문화적 겸손]은 포론다 등에 의해 다음과 같이 정의되었다. "다양한 개인들과 기꺼이 교류한 후 개방성, 자기비판, 이기심, 자기반성과 비평의 통합의 과정. 문화적 겸손을 성취하는 것의 결과는 상호 권한 부여, 존중, 파트너십, 최적의 보살핌, 평생 학습이다.[50]. 따라서, 감독자들이 정의롭지 못할 때, 그들은 편안함을 느끼고 한 발짝 물러서서, 그들의 실수를 인식하고, 사과하는 데 동원되어, 그들 스스로가 그들의 실수로부터 배우고 미래의 교육적 또는 임상적 만남에서 그들의 행동을 바꿀 수 있는 기회를 줄 필요가 있다.

Additionally, universities should hire role models from the same social groups as their students and patients to optimize integration. Faculty development should prepare supervisors to lead this integration process when these role models are not readily available. The first step is to help supervisors become aware of their own prejudices and implicit bias. After creating awareness, complementary activities should target the development of intercultural competencies by stimulating and rewarding cultural humility. Cultural humility was defined by Foronda et al. “as a process of openness, self-awareness, being egoless, and incorporating self-reflection and critique after willingly interacting with diverse individuals. The results of achieving cultural humility are mutual empowerment, respect, partnerships, optimal care, and lifelong learning” [50]. Thus, when supervisors fail to be just, they need to feel comfortable and mobilized to step back, recognize their mistakes, and apologize, giving themselves a chance to learn from their mistakes and change their behavior in future educational or clinical encounters.

감독관만으로는 교육 시스템의 구조를 바꾸지 않는다. 의대 지도자는 통합 촉진을 위해 교육과정의 현대화와 디자인의 지침이 필요하다. 예를 들어, 우리의 결과는 어떻게 이 특정 의과대학이 저소득 학생들이 겪는 모든 어려움을 예상할 수 없었는지를 강조한다. 일반적으로 의과대학은 특권층 학생들을 다루며 대부분의 교과활동은 이러한 맥락에서 계획되기 때문에 놀라운 일이 아니다. 저소득층 학생들의 필요를 인식하기 위해서, 의과대학은 그들을 배울 수 있는 안전한 의사소통 채널을 열어야 한다. 이러한 니즈를 파악한 후, 학생들이 참여하는 조직 그룹은 통합을 목표로 하는 특정 프로젝트에 참여할 수 있습니다. 하지만, 학교에서 채택한 어떤 정책이나 조치도 학생들의 정체성을 보존하고, 그것들을 과도하게 노출시키지 않는 것not overexpose이 필수적이다. 저소득층 학생들은 이미 사회적 배제의 과정을 경험한 바 있으며, 자신의 사회 경제적 지위에 대해 부끄러움을 느낀다[20].

Supervisors alone do not change the structure of the educational system. Medical schools leaders need to guide the modernization of the curriculum and design to promote integration. For instance, our results highlight how this particular medical school could not anticipate all the challenges experienced by low-income students. It is unsurprising since, in general, medical schools deal with students from privileged backgrounds, and most curricular activities are planned within this context. To become aware of low-income students’ needs, medical schools should open a secure communication channel to learn about them. After understanding these needs, organizational groups with the participation of the students can work on specific projects targeting their integration. However, it is imperative that any policy or measure adopted by the schools preserve students’ identity and not overexpose them. Low-income students already experience a process of social exclusion and feel ashamed of their socio-economic status [20].

제한 사항

Limitations

우리의 연구는 의사가 되기까지의 모든 과정을 망라하는 학부생들로 한정되어 있었다. 또한, 사회적 포용의 과정은 매우 역동적이며, 우리는 저소득층 학생들의 통합에 대한 종단적 이해가 부족하다. 우리는 이 과정을 추적하고 정책 수립에 알리기 위해 종단 연구를 수행할 것을 제안한다. 우리는 또한 향후 연구가 졸업 후 저소득 배경의 의사들의 경험을 평가하여 그들의 진로에 대한 시사점을 더 탐구해야 한다고 믿는다.

Our study was limited to undergraduate students, which does not cover the whole process of becoming a doctor. Also, the process of social inclusion is hugely dynamic, and we lack a longitudinal understanding of low-income students’ integration. We suggest that longitudinal studies be conducted to track this process and inform policy-making. We also believe that future studies should evaluate the experiences of doctors from a low-income background after graduating, further exploring the implications for their careers.

결론

Conclusion

의학 교육자들은 취약한 사회 집단의 학생들이 포함됨으로써 오는 기회를 받아들여야 한다. 의학을 실천의 공동체로서, 저소득층 학생들을 이 공동체를 새롭게 할 수 있는 새로운 사람들로 생각한다면, 우리는 취해야 할 길은 이러한 학생들을 현재의 의료 문화에 맞게 만드는 것이 아니라, 공동체가 서로 다른 사회 집단과 계층의 기여를 할 수 있도록 스스로를 재정비하는 것이라고 믿는다.

Medical educators should embrace the opportunity brought by the inclusion of students from vulnerable social groups. Considering medicine as a community of practice and low-income students as the newcomers who may renew this community, we believe that the path to be taken is not to make these students fit into the current medical culture but to make sure that the community will reshape itself to allow the contribution of the different social groups and classes.

Perspect Med Educ. 2022 Aug;11(4):187-195. doi: 10.1007/s40037-022-00715-x. Epub 2022 May 23.

Social justice in medical education: inclusion is not enough-it's just the first step

PMID: 35604538

PMCID: PMC9391538

DOI: 10.1007/s40037-022-00715-x

Free PMC articleAbstract

Introduction: Medical schools worldwide are creating inclusion policies to increase the admission of students from vulnerable social groups. This study explores how medical students from vulnerable social groups experience belongingness as they join the medical community.

Methods: This qualitative study applied thematic analysis to 10 interviews with medical students admitted to one medical school through an affirmative policy. The interviews followed the drawing of a rich picture, in which the students represented a challenging situation experienced in their training, considering their socio-economic and racial background. The analysis was guided by the modes of belonging (engagement, imagination, and alignment) described by the Communities of Practice framework.

Results: Participants struggled to imagine themselves as future doctors because they lack identification with the medical environment, suffer from low self-esteem, aside from experiencing racial and social discrimination. Participants also find it troublesome to engage in social and professional activities because of financial disadvantages and insufficient support from the university. However, participants strongly align with the values of the public health system and show deep empathy for the patients.

Discussion: Including students with different socio-economic and racial backgrounds offers an opportunity to reform the medical culture. Medical educators need to devise strategies to support students' socialization through activities that increase their self-esteem and make explicit the contributions they bring to the medical community.

Keywords: Affirmative policies; Medical education; Professional identity; Social justice.

© 2022. The Author(s).

'Articles (Medical Education) > 대학의학, 조직, 리더십' 카테고리의 다른 글

| 만약 우리가 하던대로 한다면, 얻던대로 얻을 것이다: 아카데믹 메디신 다시 생각하기 (Med Teach, 2018) (0) | 2022.09.24 |

|---|---|

| 학부의학교육에 CBME와 개별화된 경로를 도입할 때 인프라와 조직문화의 결정적 역할(Med Teach, 2021) (0) | 2022.09.07 |

| 어떻게 의학교육이 건강 형평성을 후퇴시키는가 (Lancet, 2022) (0) | 2022.08.31 |

| 백인성에 직면하고 국제보건기관을 탈식민지화하기 (Lancet, 2021) (0) | 2022.08.31 |

| 현대의학은 식민지적 부산물이다: 의학교육연구의 탈식민지화 소개(Acad Med, 2021) (0) | 2022.08.31 |