임상추론 교육을 위한 세 가지 지식-지향 교수전략: 자기설명, 개념매핑연습, 의도적 성찰: AMEE Guide No. 150 (Med Teach, 2022)

Implementation of three knowledge-oriented instructional strategies to teach clinical reasoning: Self-explanation, a concept mapping exercise, and deliberate reflection: AMEE Guide No. 150

Dario Torrea , Martine Chamberlandb and Silvia Mamedec

소개

Introduction

임상 추론은 의사의 성과와 결과적으로 환자 치료의 질에 중대한 영향을 미칩니다(Eva 2005; Norman 2005). 이러한 중요성에도 불구하고 최근까지 학부 및 대학원 프로그램에는 임상 추론을 가르치기 위한 구체적인 활동이 포함되어 있지 않았습니다. 전통적으로 학생과 수련의는 주로 견습과 경험을 통해 임상 추론을 배워야 했습니다(Graber 외. 2005). 최근 이러한 전통에 의문이 제기되고 있습니다. 의학교육 전반에 걸쳐 임상적 추론이 명시적이고 포괄적으로 다루어져야 한다는 공감대가 확산되고 있습니다(Kononowicz 외. 2020; Cooper 외. 2021). 그러나 이 목표를 향한 진전은 더딘 것 같습니다. 임상 추론은 학부 커리큘럼에 체계적으로 통합되어 있지 않은 경우가 많습니다(Trowbridge 외. 2015). 실제로 최근 설문조사에 참여한 대부분의 미국 의과대학에서는 임상 추론에 대한 구체적인 교육 세션이 부족한 것으로 나타났습니다. 결과적으로, 임상실습 책임자들은 학생들이 임상실습에 들어갈 준비가 충분히 되어 있지 않다고 생각했습니다(Rencic 외. 2017). 종단적 임상 추론 커리큘럼에서 무엇을, 언제, 어떤 교육 전략으로 가르쳐야 하는지에 대한 명확한 지침은 없습니다(Cooper 외. 2021).

Clinical reasoning critically influences physicians’ performance and, consequently, the quality of patient care (Eva 2005; Norman 2005). Despite its importance, until recently, undergraduate and postgraduate programs did not include specific activities for teaching clinical reasoning. Traditionally, students and trainees were expected to learn clinical reasoning largely through apprenticeship and experience (Graber et al. 2005). This tradition has recently been questioned. There is growing consensus that clinical reasoning should be addressed explicitly and comprehensively throughout medical education (Kononowicz et al. 2020; Cooper et al. 2021). However, progress towards this goal seems slow. Clinical reasoning is often not systematically integrated in the undergraduate curriculum (Trowbridge et al. 2015). Indeed, in the majority of US medical schools recently surveyed, specific teaching sessions dedicated to clinical reasoning are lacking. Consequently, clerkships directors considered students not being adequately prepared to enter the clinical clerkships (Rencic et al. 2017). There is no clear guidance on what to teach, when and with which instructional strategies in a longitudinal clinical reasoning curriculum (Cooper et al. 2021).

이러한 커리큘럼에 대한 최근 지침은 학습 과학의 증거로 뒷받침되는 교육 전략을 선택하여 과학적 접근 방식을 채택할 필요성을 강조하고 있습니다(Cooper 외. 2021). 또한 슈미트와 마메데(2015)는 내러티브 리뷰에서 전문성 개발의 여러 단계에서 임상 추론을 가르치기 위해 서로 다른 교육 전략이 필요할 수 있다고 주장합니다. 최근의 리뷰에서는 교육 활동의 목적이 콘텐츠 지식 개발인 지식 중심 접근법의 가치를 보여주었습니다(Schmidt and Mamede 2015; Prakash 외. 2019; Cooper 외. 2021). 이러한 리뷰에서는 이해를 구축하고, 지식 조직을 촉진하며, 성찰을 촉진하는 전략이 의대생의 임상 추론을 개선하는 데 효과적이라는 것을 보여주었습니다. 자기 설명(SE)과 의도적 성찰(DR)은 이러한 효과적인 지식 중심 교육 전략의 두 가지 예입니다(Schmidt and Mamede 2015; Prakash et al. 2019). 이 두 가지 전략은 임상 문제를 해결하기 위한 지식의 검색, (재)구성 및 적용을 촉진하며 임상 추론을 가르칠 때 함께 구현할 수 있는 상호 보완적인 학습 연습이 될 수 있습니다(Chamberland 외. 2020). 그러나 언어화와 반성이 임상 추론을 학습하는 데 중요한 과제인 경우, 지식을 시각적으로 표현하는 것이 복잡한 문제를 이해하는 데 특히 도움이 될 수 있습니다. 예를 들어, 개념 매핑으로 묘사된 지식의 그래픽 표현은 복잡한 사고를 가시화하여 임상 추론을 향상시키는 동시에 지식 조직과 의미 있는 학습을 촉진할 수 있습니다(Acton 외. 1994; Delany와 Golding 2014; Wu 외. 2016). 임상 추론 매핑 연습(CReSME)은 임상 추론 교육에 사용되는 개념 매핑 기법의 예시적인 예입니다(Torre 외. 2019).

Recent guidelines for such a curriculum have stressed the need to adopt a scientific approach by opting for instructional strategies supported by evidence from the learning sciences (Cooper et al. 2021). Moreover, Schmidt and Mamede (2015), in a narrative review, posit that different instructional strategies may be needed to teach clinical reasoning at different stages of expertise development. Recent reviews have shown the value of a knowledge-oriented approach in which the purpose of teaching activities is content knowledge development (Schmidt and Mamede 2015; Prakash et al. 2019; Cooper et al. 2021). These reviews have shown strategies that build understanding, foster knowledge organization, and promote reflection to be effective in improving medical students’ clinical reasoning. Self-explanation (SE) and deliberate reflection (DR) are two examples of these effective knowledge-oriented instructional strategies (Schmidt and Mamede 2015; Prakash et al. 2019). They both foster retrieval, (re-)construction, and application of knowledge to solve clinical problems and might be complementary learning exercises that could be implemented together in teaching clinical reasoning (Chamberland et al. 2020). Yet, if verbalization and reflection are critical tasks for learning clinical reasoning, a visual representation of knowledge may be particularly helpful in the understanding of complex problems. A graphic representation of knowledge depicted, for example, by concept mapping, may enhance clinical reasoning by making complex thinking visible, while fostering knowledge organization and meaningful learning (Acton et al. 1994; Delany and Golding 2014; Wu et al. 2016). The Clinical Reasoning Mapping Exercise (CReSME) is an illustrative example of a concept mapping technique used for the teaching of clinical reasoning (Torre et al. 2019).

이론과 경험적 데이터로 뒷받침되는 이 세 가지 교육 전략은 의대생에게 유용한 도구가 될 수 있습니다. 그러나 이러한 전략의 효과에 대해 보고된 여러 연구는 전략에 대한 일반적인 설명만 제공합니다. 이러한 전략을 활용하고자 하는 교사는 연구 논문에서 제공하는 개요와 전략을 실행하는 데 필요한 구체적인 단계 및 운영 측면 사이를 탐색해야 합니다. 따라서 이 가이드의 목적은 교육자에게 임상 추론을 가르치기 위해 이러한 전략을 사용하는 활동을 설계하고 학부 커리큘럼에 통합하는 데 대한 실질적인 조언을 제공하는 것입니다. 또한 전략을 적용하려는 현지 상황에 맞게 조정하는 데 도움이 될 수 있습니다. 조정은 종종 필요하지만 전략이 잘 작동하기 위한 필수 조건에 영향을 미쳐서는 안 됩니다(Mamede and Schmidt 2014; Chamberland 외. 2020). 실행에 대한 구체적인 지침은 교육자가 이러한 위험을 피하는 데 도움이 될 수 있습니다.

These three instructional strategies, supported by theory and empirical data, can be helpful tools for medical teachers. However, the several published studies reporting on their effectiveness provide only a general description of the strategies. Teachers interested in employing them would need to navigate between the overview provided by research papers and the concrete steps and operational aspects required for putting the strategies into practice. Therefore, the purpose of this guide is to provide educators with practical advice on the design of activities using these strategies for the teaching of clinical reasoning and their integration into the undergraduate curriculum. It may also help adapt the strategies to the local context where they are to be applied. Adjustments are often necessary but should not affect essential conditions for the strategies to work well (Mamede and Schmidt 2014; Chamberland et al. 2020). Specific instructions on the implementation may help educators avoid this risk.

임상 추론 교육에 대한 관심이 증가함에 따라 많은 교육 전략이 제안되었지만, 그 효과에 대한 조사가 수반되는 경우는 많지 않습니다(Schmidt and Mamede 2015; Lambe 외. 2016; Prakash 외. 2019). 우리는 많은 전략이 존재한다는 것을 알고 있으며 SE, CReSME 및 DR이 가장 효과적인 전략이거나 채택해야 할 유일한 전략이라고 주장하지 않습니다. 그럼에도 불구하고 이러한 전략을 선택한 이유는 중요한 이론적 원칙, 해당 전략의 사용을 뒷받침하는 경험적 증거, 우리 자신의 경험(Lambe 외. 2016; Prakash 외. 2019; Cooper 외. 2021), 그리고 학부 수준에서 임상 추론을 가르치는 종단적 및 발달적 접근 방식에 결합하여 적용할 수 있는 잠재력을 고려했기 때문입니다.

As interest in the teaching of clinical reasoning increases, many teaching strategies have been proposed though not so often accompanied by investigation of their effectiveness (Schmidt and Mamede 2015; Lambe et al. 2016; Prakash et al. 2019). We are aware that many strategies exist and are not arguing that SE, CReSME, and DR are the most effective ones or the only ones to be adopted. Nevertheless, we selected these strategies because of overarching theoretical principles, empirical evidence supporting their use, and our own experience with them (Lambe et al. 2016; Prakash et al. 2019; Cooper et al. 2021) and the potential for a combined application in a longitudinal and developmental approach to teaching clinical reasoning at the undergraduate level.

이 가이드에서는 먼저 이러한 전략의 사용을 뒷받침하는 이론적 배경을 정리한 다음 각 전략에 대한 설명과 실제 적용을 살펴보고 마지막으로 이러한 전략을 통합하는 방법에 대한 제안을 제공합니다.

In this guide, we will first synthesize the theoretical background that supports the use of these strategies, then move to the description and practical application of each one, and finally provide suggestions on how to integrate them.

이론적 프레임워크

Theoretical framework

임상적 추론은 여러 이론적 프레임워크에 기반을 두고 있습니다(Schmidt 외. 1990; Charlin 외. 2000; Croskerry 2009; Durning 외. 2013). 이 백서의 목적상, 우리는 지식 조직, 스키마의 초기 형성, 질병 스크립트의 후속 개발 및 개선이라는 형태의 정보 처리 이론의 교리에 초점을 맞추고 있습니다(Schmidt 외. 1990). 영향력 있는 의학 전문성 발달 이론에 따르면 지식 개발과 조직화는 네 가지 발달 단계를 거쳐 진행된다고 주장합니다(Schmidt and Rikers 2007).

- 인과 네트워크 형성,

- 지식 캡슐화,

- 질병 스크립트 개발,

- 환자 사례를 통한 질병 스크립트 인스턴스화

Clinical reasoning is grounded in a number of theoretical frameworks (Schmidt et al. 1990; Charlin et al. 2000; Croskerry 2009; Durning et al. 2013). For the purpose of this paper, we focus on tenets of information processing theory in the form of knowledge organization, early formation of schemas and subsequent development and refinement of illness scripts (Schmidt et al. 1990). An influential theory of development of expertise in medicine argues that knowledge development and organization progress through four developmental stages:

- formation of causal networks;

- knowledge encapsulation;

- development of illness scripts; and

- instantiation of illness scripts by patient examples (Schmidt and Rikers 2007).

교육 첫 단계에서 의대생은 생의학 및 임상 과학을 연결하는 인과적 네트워크로 구성된 지식을 습득합니다. 질병은 병리 생리학적 메커니즘으로 설명되는 경향이 있으며, 학생들은 질병의 징후 및 증상과 그 인과 메커니즘 사이의 관계를 개발하려고 시도합니다. 이 단계에서 학생들은 관계의 의미를 설정하는 단어로 연결된 일련의 개념으로 구성된 명제적 네트워크 구조를 형성합니다.

In the first stage of their training, medical students acquire knowledge that is organized into causal networks linking biomedical and clinical sciences. Diseases tend to be explained by pathophysiological mechanisms, and students attempt to develop relationships between signs and symptoms of a disease and their causal mechanisms. At this stage, students form propositional network structures which comprise a series of concepts linked by a word that sets the meaning of their relationship.

학생들은 이 지식을 임상 문제 해결에 적용하면서 흔히 '캡슐화'라고 하는 단순화된 인과 모델을 개발하는 두 번째 단계로 이동합니다. 학생들은 병태생리학적 설명으로 연결된 개념을 캡슐화하는 보다 정교하고 고차원적인 지식 구조를 더 적게 만들기 시작합니다. 이렇게 캡슐화된 개념은 라벨이 붙고 질병 또는 증후군으로 분류되며, 더 많은 양의 임상 지식을 포괄하고 더 쉽게 검색하고 사용할 수 있습니다.

As students apply this knowledge to solve clinical problems, they move to a second stage which entails development of simplified causal models often referred to as ‘encapsulation’. Students begin to create a lower number of more refined, higher order knowledge structures that encapsulate concepts linked by pathophysiological explanations. These encapsulated concepts are labeled, and categorized into a disease or syndrome; they subsume a greater amount of clinical knowledge and can more easily retrieved and used.

임상 문제에 대한 경험이 증가함에 따라 학생들은 세 번째 단계로 진입합니다. 캡슐화된 개념은 더욱 재구성되고 궁극적으로 질병 스크립트로 재구성됩니다. 질병 스크립트는 프로토타입이거나 이전에 진료한 환자를 기반으로 한 임상 관련 정보의 풍부한 스키마입니다. 이러한 스크립트는 의사가 일련의 임상 징후 또는 증상이 있는 환자를 진료할 때 언제든지 활성화하고 검색할 수 있습니다(Schmidt & Boshuizen, 1993).

As experience with clinical problems increase, students enter a third stage. Encapsulated concepts are further restructured and ultimately reorganized into illness scripts. Illness scripts are rich schema of clinically relevant information, either prototypical or based on a patient previously seen. These scripts can be activated and searched at any time by the physician in response to a patient presentation with a set of clinical signs or symptoms (Schmidt & Boshuizen, 1993).

우리는 SE, CReSME 및 DR이 지식 구조 및 조직 개발 단계에 발판을 제공하고 실습을 최적화할 수 있는 교육 전략이라고 주장합니다. 올바르게 구현되면 학부 수준의 학생들 사이에서 임상적 추론의 발달을 촉진할 수 있습니다.

We argue that SE, CReSME, and DR are instructional strategies that can provide scaffold and optimize practice for the stages of development of knowledge structures and organization. If correctly implemented, they may promote the development of clinical reasoning among students at undergraduate level.

자기 설명

Self-explanation

SE란 무엇인가요?

What is it?

자기 설명은 학습 자료에 대한 이해를 심화시키고 자신의 지식을 모니터링할 목적으로 각 학생이 학습 자료를 사용하는 동안 스스로 설명을 제공하도록 요구하는 교육 기법입니다(Chi 외. 1994; Chi 2000). '

- '자기'라는 용어는 중요하며 SE의 두 가지 중요한 특징을 나타냅니다. 첫째, 설명은 학생에 의해 생성되고 둘째, 이러한 설명은 이 학생을 위해 제공됩니다. 이는 다른 사람을 가르치기 위해 설명을 제공하는 것과는 상당히 다릅니다(Renkl 및 Eitel 2019). 따라서 SE는 선험적으로 개별 학습 활동입니다.

- 설명이라는 용어를 명확히 하는 것도 중요합니다. 설명의 개념은 다양한 의미를 가질 수 있지만, SE 문헌에서는 일반적으로 학생이 기본 원리(원리 기반 SE)를 참조하여 문제의 요소를 설명하는 진술을 의미합니다(Renkl and Eitel 2019; Chi 2000).

SE is an instructional technique that requires each student to provide explanations for him/herself while engaging with a learning material in the purpose of deepening his/her understanding and monitoring his/her knowledge (Chi et al. 1994; Chi 2000).

- The term Self is important and refers to two critical features of SE. Firstly, the explanations are generated by the student and, secondly, these explanations are provided for this student. It is quite different from giving explanations to teach others (Renkl and Eitel 2019). SE is then, a priori, an individual learning activity.

- The term explanation is also important to clarify. Although the concept of explanation can have a variety of meanings, in the SE literature, it usually refers to statements expressed by the student that explains an element of the problem in reference to an underlying principle (principle-based SE) (Renkl and Eitel 2019; Chi 2000).

따라서 자기 설명은 단순히 thinking aloud 또는 텍스트의 일부를 반복하거나 의역하는 것이 아닙니다. SE가 학습에 미치는 이점은 학생들이 더 많은 SE를 생성할 때 증가하지만, 더 중요한 것은 문제의 요소와 기본 원리 또는 메커니즘을 연결하는 데 참여할 때 더욱 커집니다(Renkl 및 Eitel 2019).

So self-explaining is not simply thinking aloud, repeating or paraphrasing a segment of the text. The benefits of SE on learning are increased when students produce more SE but more importantly, when they engage in making links between the elements of the problem and underlying principles or mechanisms (Renkl and Eitel 2019).

SE는 학생의 지식이 여전히 심화 및 수정이 필요한 복잡한 문제나 덜 익숙한 문제에 유용한 것으로 보입니다(Chi 외. 1994; Wong 외. 2002; Chamberland 외. 2013). 학생이 문제를 완벽하게 이해하고 더 이상 학습할 여지가 없는 경우, 자기 설명에 참여해도 아무런 이점이 없습니다. SE는 지식을 구축하는 데 도움이 되며 지식을 자동화하지는 않습니다. 학생이 상호 연결되고 일관된 심층 지식을 개발할 수 있도록 지원하는 등 SE가 학습에 미치는 이점은 여러 영역에서 입증되었습니다(Chi 2000; Richey와 Nokes-Malach 2015). SE는 컴퓨터 기반 교육과 텍스트, 도표, 연습 문제, 풀어야 할 문제 등 다양한 학습 자료와 함께 사용되어 왔습니다.

SE appears to be useful for complex problems or less familiar, when the student’s knowledge still needs deepening and revision (Chi et al. 1994; Wong et al. 2002; Chamberland et al. 2013). If the student understands perfectly the problem and there is no room for more learning, there is no benefit of engaging in self-explaining. SE helps build knowledge and does not automatize it. The benefits of SE on learning such as supporting student’s development of deep interconnected and coherent knowledge, has been shown in several domains (Chi 2000; Richey and Nokes-Malach 2015). SE has been used in computer-based instruction and with different learning materials such as text, diagrams, worked-examples, and problems to solve.

의학에서 SE는 진단적 추론을 기르기 위한 교육 기법으로 학부생을 대상으로 실험적으로 연구되었습니다. 익숙하지 않은 사례를 풀면서 SE를 사용한 학생들은 추가 지시 없이 조용히 사례를 풀었던 학생들에 비해 더 나은 진단 성과를 보였습니다(Chamberland 외. 2011). 학생들이 생성한 SE의 내용 분석에 따르면 익숙한 사례에 비해 덜 익숙한 사례를 접할 때 더 많은 생의학 지식 또는 기본 메커니즘(원리 기반 SE)을 재활성화하여 질병 스크립트의 일관성을 높여 더 나은 진단을 내리는 데 도움이 될 수 있는 것으로 나타났습니다(Chamberland 외. 2013). 이는 진단 추론을 향상시키기 위해 학습하는 동안 생물 의학 지식을 임상 지식과 제공/연결하는 것이 중요하다는 이전 연구와 일치합니다(Wood et al. 2007).

In medicine, SE has been studied experimentally in undergraduate students as an instructional technique to foster diagnostic reasoning. Students who used SE while solving lesser familiar cases showed better diagnostic performance when compared to students who had solved cases in silence without further instructions (Chamberland et al. 2011). Content analysis of SE generated by students indicated that when facing lesser familiar cases in comparison with familiar cases, they reactivated more biomedical knowledge or underlying mechanisms (principle-based SE), which could help them increase coherence of their illness scripts thus leading to better diagnosis (Chamberland et al. 2013). This is in line with previous studies showing the importance of providing/linking biomedical knowledge with clinical knowledge while learning to increase diagnostic reasoning (Wood et al. 2007).

진단적 추론을 키우기 위해 SE를 잘 설계한 활동은 학생들이 학습 자료를 사용하는 동안 다음을 요구할 것입니다.

- 사전 지식을 재활성화하고,

- 현재 지식을 정교화하고 설명을 제공하며,

- 문제의 임상 요소와 관련 기본 메커니즘 또는 원리를 연결하도록

결과적으로 학생은 질병에 대한 자신의 표현을 수정할 수 있을 뿐만 아니라 후속 학습을 안내하기 위해 지식의 모호성과 격차를 인식할 수 있습니다(Chamberland 외. 2015, 2020; 예시는 부록 1 참조).

A well-designed activity using SE to foster diagnostic reasoning will require students, while working with the learning material, to reactivate prior knowledge, to elaborate on current knowledge and provide explanations, making links between the clinical elements of the problem and relevant underlying mechanisms or principles. Consequently, it will allow the student to revise his/her representation of diseases as well as to recognize ambiguities and gaps in knowledge to guide subsequent learning (Chamberland et al. 2015, 2020; see Appendix 1 for an example).

SE를 준비하고 도입하는 방법은?

How to prepare and introduce SE?

SE는 독립적인 기법이 아니라 학습을 지원하기 위해 다양한 방식으로 통합될 수 있는 일반적인 지식 구축 전략입니다. 지금까지 학생들의 임상 추론 발달을 촉진하기 위한 SE 연구는 주로 학생들이 해결해야 하는 임상 사례를 학습 자료로 사용했습니다.

SE is not a stand-alone technique but rather a general knowledge building strategy that could probably be incorporated in many ways to support learning. So far, studies on SE to promote development of clinical reasoning among students have mainly used clinical cases that students were required to solve as learning materials.

학습 자료

Learning material

임상 사례

Clinical cases

- 학부생의 경우, 모든 임상 정보(전체 증례)를 제공하는 임상 증례를 통해 인지 부하를 관리하면서 SE에 참여할 수 있습니다.

- 자료를 설계할 때 학습자의 수준과 주어진 임상 문제에 대한 사전 지식을 고려합니다. 학생들은 문제와 관련된 질병에 대한 충분한 사전 지식이 있어야 하며, 일관된 질병 스크립트를 작성하고 이러한 질병에 대한 생의학 지식을 통합하는 초기 단계에 있을 것으로 예상됩니다.

- 임상 사례는 학생에게 적절한 수준의 난이도를 가져야 하며, 이를 통해 학생의 이해를 심화시키고 지식을 구축/수정할 수 있는 충분한 여지가 있어야 합니다(Chamberland 외. 2011, 2013).

- 케이스를 준비하려면 현재 활동을 담당하는 교사와 커리큘럼의 이전 관련 섹션을 담당하는 교사 간의 협력이 필요하며, 가능하면 비슷한 수준의 교육을 받은 학생을 대상으로 난이도를 테스트하거나 처음 사용한 후 체계적으로 모니터링하여 난이도를 검증할 수 있습니다.

- 사례는 종이 기반 형식 또는 전자 플랫폼에서 사용할 수 있습니다.

- For undergraduate students, clinical cases providing all the clinical information (whole case) allow them to engage in SE while managing cognitive load.

- Consider the level of the learners and their prior knowledge for a given clinical problem in designing the material: students should have sufficient prior knowledge on diseases relevant to the problem and expected to be at the early stage of building coherent illness scripts and integrating biomedical knowledge for these diseases.

- Clinical cases should be of appropriate level of difficulty for students so that there is enough room for deepening their understanding and build/revise their knowledge (Chamberland et al. 2011, 2013).

- Cases preparation then requires collaboration between teachers responsible of the current activity and of previous relevant sections of the curriculum; validation of the level of difficulty might be tested with students of similar level of training if possible or systematically monitored once first used.

- Cases can be used with a paper-based format or on an electronic platform.

SE에 대한 일반적 연구와 다른 영역의 연구를 고려할 때, 실습 사례(Dyer 외. 2015), 개념도, 컴퓨터 멀티미디어(텍스트 및 도표) 임상 사례, 라이브 또는 녹화된 강의 섹션 등 다양한 자료와 함께 SE를 사용하면 학생들에게 도움이 될 것으로 기대할 수 있습니다.

Considering the research on SE in general and in other domains, we could expect that students would benefit from using SE with a variety of materials such as worked examples (Dyer et al. 2015), concept maps, computer multi-media (texts and diagrams) serial-cues clinical cases, and sections of a live or recorded lecture.

학생에게 SE 소개하기

Introducing SE to students

SE는 학생들에게 어려운 과제이며 자발적으로 사용하지 않습니다. 학생들에게 SE에 대해 교육하는 것은 유익한 것으로 보입니다. 교육은 짧을 수 있지만 다음 등을 제공해야 합니다.

- SE의 정의와 사용 근거(학생들이 임상 추론과 관련된 지식을 쌓고 심화시키는 데 어떻게 도움이 되는지),

- 제안된 학습 자료로 학생이 직접 설명하는 예시, 학생들이 연습할 수 있는 기회

경험상 SE가 학습에 미치는 이점을 최적화하려면 학생은 SE가 평가 도구가 아닌 학습 전략이라는 점을 이해해야 합니다. SE는 정답을 제공하는 것이 아니며 구두 시험도 아닙니다. 학생은 '안전한 공간'에서 자신의 지식의 한계를 탐구하고 부족한 부분을 파악할 수 있도록 스스로 설명하면서 '학습하는 자세'를 취해야 합니다. 교사는 학생들의 참여를 극대화하기 위해 요구 사항을 명확히 해야 합니다. 선택 사항이 아닌 필수 사항으로 지정하고, 자기 설명에 소요할 최소한의 시간을 요구해야 합니다.

SE is a challenging task for students, and they do not use it spontaneously. Training students on SE appears beneficial. Training may be short but should provide:

- a definition of SE and rationale for using it (how it helps students build and deepen knowledge relevant to clinical reasoning);

- an example of a student self-explaining with the proposed learning material and opportunity for students to practice.

In our experience, in order to optimize the benefit of SE on learning, students must understand that SE is a learning strategy and not an assessment tool. SE is not about providing the right answer, nor it is an oral examination. Students must adopt a ‘learning position’ while self-explaining allowing them to explore the limits of their own knowledge and identify gaps in a ‘safe space’. Teachers should make the requirements clear to maximize students’ engagement: do not make it optional but mandatory and ask for a minimum time spent self-explaining.

과제를 어떻게 수행하나요?

How to perform the task?

SE는 선험적으로 개별 학습 활동입니다. 모든 학생이 새로운 학습 자료를 접할 때 자연스럽게 SE를 하는 것은 아닙니다. 활동 중에 프롬프트를 통합하면 더 많은 SE, 특히 원리 기반 SE를 생성하도록 장려할 수 있습니다. 예를 들어,

- 선택한 학습 자료가 해결해야 할 임상 사례인 경우, 학생에게 먼저 조용히 사례를 읽도록 하여 적절한 사전 지식을 다시 활성화할 수 있도록 도울 수 있습니다.

- 그런 다음 자료에 포함된 프롬프트에 따라 사례를 다시 살펴보면서 사례에 제시된 임상 결과를 체계적으로 스스로 설명하도록 초대합니다.

SE is a priori an individual learning activity. All students do not naturally self-explain when engaging with new learning materials. Incorporating prompts during the activity encourage them to generate more SE and in particular principle-based SE. For instance,

- if the learning material chosen is a to-be-solved clinical case, the student may be first invited to read the case in silence to help him begin reactivating appropriate prior knowledge.

- Then, going again through the case, guided by prompts included in the material, he is invited to self-explain systematically the clinical findings presented in the case.

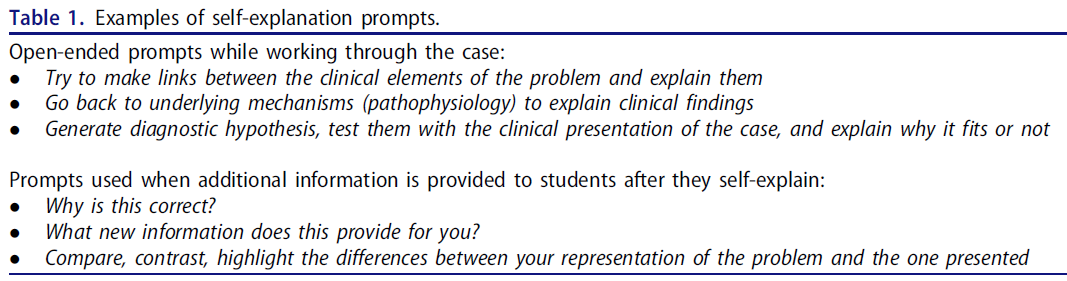

다양한 유형의 프롬프트는 구조 또는 지시성의 정도가 다릅니다(Wylie and Chi 2014; Renkl and Eitel 2019): 개방형 프롬프트는 학생이 생성된 SE의 유형을 제한하지 않고 사전 지식과 새로 제시된 정보를 연결하도록 장려합니다. 임상 사례에 사용할 수 있는 개방형 프롬프트의 예는 표 1에 나와 있습니다. 활동 중 또는 활동 후에 학생에게 다른 학생의 SE 사례 또는 문제 해결 방법과 같은 추가 리소스가 제공되는 경우, 학생이 이 새로운 정보에 참여하도록 유도하는 프롬프트가 도움이 될 수 있습니다(Nokes 외. 2011). 이러한 프롬프트의 예는 표 1에 나와 있습니다.

Different types of prompts provide different degrees of structure or directedness (Wylie and Chi 2014; Renkl and Eitel 2019): open-ended prompts encourage students to make connections between prior knowledge and the new presented information without constraining the type of SE generated. Examples of open-ended prompts that could be used with clinical cases are provided in Table 1. If the student is provided with additional resource during or after the activity, such as an example of SE from another student or solution of the problem, prompts that invite students to engage with this new information may be helpful (Nokes et al. 2011). Examples of such prompts are provided in Table 1.

학생들은 SE를 어떻게 표현할까요?

- 임상 추론에 대한 SE는 학생들이 자신의 설명을 말로 표현하는 방식으로 가장 많이 연구되었습니다. 이는 구현에 추가적인 어려움이 될 수 있지만, 언어화는 학생에게 자연스러운 것으로 인식되며(Chebbihi 외., 2019), 학생의 추가적인 인지적 참여를 요구함으로써 침묵 속에서 스스로 설명하는 것과 비교할 때 학습을 향상시키는 것으로 보입니다(De Bruin 외., 2007).

- 또는 학생에게 SE를 작성하도록 요청할 수도 있습니다. SE 및 임상 추론에 대한 많은 연구에서 SE 과정에 대한 피드백이 제공되지 않았습니다. 이 문제는 실질적인 도전이 될 수 있습니다. 2년에 걸쳐 종단적 활동으로 SE를 구현한 경험에서 학생들은 SE 활동을 반복함으로써 SE를 연습하고 이 전략에 익숙해질 수 있었다고 보고했습니다.

- (교수자는) 학생들이 SE한 콘텐츠 지식에 대한 피드백을 제공할 수 있습니다. 연습 후 정확한 진단만 제공한 연구에서는 매우 유사한 후속 사례를 해결하는 데는 유용했지만 다른 사례에는 유용하지 않았습니다(Chamberland 외. 2019). SE에서 피드백의 역할에 대한 이 문제는 추가 연구가 필요합니다.

How will students express their SE?

- SE for clinical reasoning has been most studied with students verbalizing their explanations. Even though this might represent an additional challenge for implementation, verbalization is perceived as natural for students ( Chebbihi et al., 2019) and appears to improve learning when compared to self-explaining in silence (De Bruin et al. 2007) by requiring further cognitive engagement from the student.

- Alternatively, students may be asked to write their SE. No feedback on the process of SE has been provided in many studies on SE and clinical reasoning. This issue would represent a practical challenge. In our experience implementing SE with a longitudinal activity over 2 years, students reported that the recurrence of the SE activity allowed them to practice SE and get familiar with this strategy.

- Feedback on the content knowledge on which students self-explain may be provided. A study providing only the correct diagnosis after the exercise was useful to solve subsequent very similar cases but not for different cases (Chamberland et al. 2019). This issue of the role of feedback in SE needs further research.

SE를 커리큘럼에 통합하는 방법은 무엇인가요?

How to integrate SE into the curriculum?

SE와 임상 추론에 대한 연구는 주로 4년제 커리큘럼을 갖춘 의과대학에서 이루어졌으며, 3학년 의대생이 개별적으로 종이 증례 책자를 가지고 실습을 하는 방식으로 진행되었습니다. 그러나 학습자의 수준에 맞게 학습 자료가 조정된다면 현지 커리큘럼 설계에 따라 SE를 더 일찍 도입할 수도 있습니다. 5년 또는 6년 커리큘럼의 학교에서는 이미 강의 수업을 통해 질병에 대한 지식을 접했지만 임상 경험이 많지 않은 학생들을 참여시키는 것이 적절할 것입니다. 실제로 학부 수준에서 임상 추론을 가르치는 것에 대한 서술적 검토를 마무리하는 슈미트와 마메데의 제안은 SE가 초보 학생들에게 적합할 수 있다고 제안했습니다(슈미트 및 마메데 2015). 지금까지 실제 교육 상황에서 SE를 구현한 데이터는 아직 제한적입니다(Chamberland 외. 2020; Kelekar와 Afonso 2020).

Research on SE and clinical reasoning have mainly occurred in medical schools with a 4-year curriculum and involved third-year medical students in clerkship working individually with booklets of paper cases. However, SE may be introduced earlier depending on the local curriculum design as long as the learning material is adapted to the level of the learners. In schools with 5-or 6-year curricula, it would be appropriate to engage students who have already been exposed to knowledge of diseases through didactic activities but do not have much clinical experience with them. Indeed, Schmidt and Mamede’s proposal concluding their narrative review on teaching clinical reasoning at undergraduate level, suggested that SE could suit well novice students (Schmidt and Mamede 2015). So far, data on implementation of SE in authentical educational context are still limited (Chamberland et al. 2020; Kelekar and Afonso 2020).

SE는 선험적으로 개인의 건설적인 학습 활동이지만, 학생이 먼저 자신의 사전 지식을 가지고 작업하고 스스로 설명을 생성 할 수있는 충분한 공간이 제공된다면 다른 사람 (예 : 가까운 동료)과의 상호 작용을 추가하는 것이 유익 할 수 있습니다 (Chamberland et al. 2015, 2020). 실험 조건에서 동일한 사례에 대해 또래에 가까운 SE의 설명을 들었을 때 학생들의 진단 성능이 더욱 향상되었습니다(Chamberland 외. 2015). 후속 질적 연구에서 3학년 학생들은 후배 레지던트의 SE를 추가적인 외부 자원으로 사용했다고 보고했습니다. 짝지은 상호작용도 학습에 도움이 될 수 있습니다(Rotgans and Cleland 2021).

While SE is a priori an individual constructive learning activity, the addition of interactions with others (e.g. near-peers) (Chamberland et al. 2015, 2020) might be beneficial (Chi 2018) if the student is provided with enough space to work first with his/her own prior knowledge and generate for himself explanations. Under experimental conditions, diagnostic performance of students was further increased by listening to a near-peer SE on the same case (Chamberland et al. 2015). In a subsequent qualitative study, third-year students reported that they used the junior resident’s SE as an additional external resource. Interactions in dyads could also be beneficial for learning (Rotgans and Cleland 2021).

임상 추론 매핑 연습

Clinical reasoning mapping exercise

개념 지도란 무엇인가요?

What is it?

[개념 지도]는 의미를 만드는 단어 또는 명제로 연결된 상호 연관된 개념 집합을 그래픽으로 표현한 것으로, 개념 집합의 의미에 대한 학습자의 이해를 나타냅니다(Novak and Cañas 2006). 개념 맵을 사용한 연습은 지식 조직화와 비판적 사고를 촉진합니다(West 외. 2000; Torre 외. 2007; Daley와 Torre 2010). 교수자가 제공하는 지시성의 정도에 따라 두 가지 주요 매핑 전략이 개념 맵을 사용한 교수 및 학습에 사용될 수 있습니다(Ruiz-Primo 및 Shavelson 1996). 개념 지도의 지시성은 지도를 구성하기 위해 학습자에게 제공되는 정보의 양을 의미합니다.

- 저-지시성 맵(학습자 주도형)은 개념, 연결어, 맵의 구조가 학습자에 의해 구성되는 학습자에 의해 전적으로 생성되는 개념 맵이 특징입니다(Novak and Gowin 1984).

- 고-지시성 맵(교사 주도형)은 교사가 지도의 구성 요소(노드 또는 링크)를 개발한 다음 학생에게 노드의 내용을 채우고, 노드를 연결 단어로 연결하거나 두 가지를 조합하는 과제를 제공하는 기법입니다. (Schau와 Mattern 1997).

A concept map is a graphic representation of a set of interrelated concepts linked by meaning-making words or propositions that depicts the learner’s understanding of the meaning of a set of concepts (Novak and Cañas 2006). Exercises with concept maps foster knowledge organization and critical thinking (West et al. 2000; Torre et al. 2007; Daley and Torre 2010). Two main different mapping strategies, based on the degree of directedness provided by the instructor, can be used in teaching and learning with concepts maps (Ruiz‐Primo and Shavelson 1996). Directedness of a concept map refers to the amount of information that is provided to the learners for the construction of the map.

- A low degree of directedness (learner driven) map is characterized by a concept map that is entirely created by the learner in which concepts, linking words and structure of the map are constructed by the learner (Novak and Gowin 1984).

- A high degree of directedness map (teacher driven) is a technique in which components of the map (either nodes or links) are developed by the teacher and then provided to the student who has the task of filling in content of the nodes, connecting the nodes with linking words or a combination of both. (Schau and Mattern 1997).

CReSME는 높은 수준의 지시성을 가진 개념 지도입니다(Torre et al., 2019). CResME는 임상 및/또는 기초 과학 정보를 포함하는 노드를 사용하므로 학습자는 이러한 정보 노드를 정확하고 의미 있는 방식으로 연결하여 여러 영역에서 동일한 증상으로 나타나는 여러 질병의 주요 특징(예는 부록 2 참조)을 비교 및 대조할 수 있습니다.

The CReSME is a concept map with high degree of directedness (Torre et al., 2019). The CResME uses nodes that contain clinical and/or basic sciences information, requiring learners to connect these nodes of information in an accurate and meaningful way, allowing to compare and contrast, across multiple domains, key features of different diseases (see Appendix 2 for an example) presenting with the same complaint.

CReSME를 준비하고 도입하는 방법은 무엇인가요?

How to prepare and introduce the CReSME?

그 근거는 학생들에게 유사한 증상을 보이는 여러 질병의 전형적인 임상 특징을 비교하고 대조할 수 있도록 미리 구성된 스캐폴딩 구조를 제공하여 궁극적으로 동일한 증상을 보이는 질병에 대한 질병 스크립트 개발을 촉진하기 위한 것입니다.

The rationale is to provide students with a pre-constructed scaffolding structure to facilitate the comparing and contrasting of typical clinical features of different disease with a similar presentation, to ultimately foster the development of illness scripts for disease entities presenting with the same complaint.

학습 자료

Learning materials

- 사례 발표는 의도적으로 환자의 주요 불만 사항만 포함합니다. 예를 들어 55세 남성 환자가 급성 흉통을 호소한다고 가정해 보겠습니다.

- 맵 콘텐츠는 동일한 주호소(급성 흉통)를 가진 질병에 대한 주요 정보가 포함된 미리 구성된 노드 집합으로 시각적으로 표시됩니다.

- 학습자는 연습의 맨 아래에 있는 빈 노드를 완성하여, 스크립트의 일부를 포함하는 노드 간의 일련의 정확한 연결과 일치하는 진단을 제공해야 합니다.

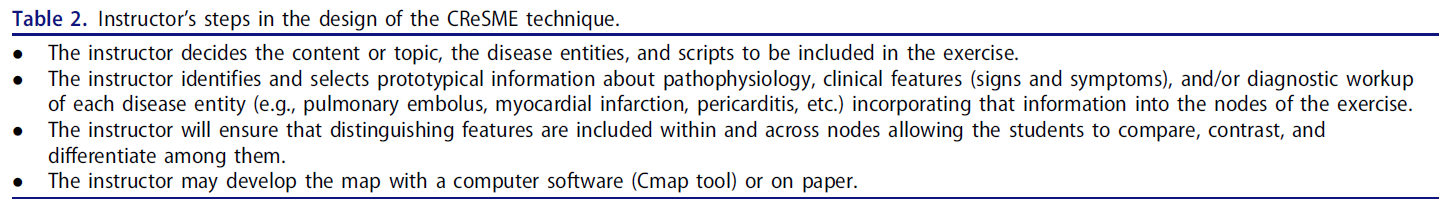

- 해결해야 할 완전한 임상 사례는 존재하지 않으므로, 환자의 주요 증상에 대한 감별 진단을 구성할 수 있는 3~5개의 질병 실체의 원형 구성 요소를 정확하게 식별하고 연결하는 것 외에는 하나의 정답이 존재하지 않습니다. 강사 CREsME 기법 설계의 단계는 표 2에 나와 있습니다.

- The case presentation purposefully entails only the chief complaint of a patient. For example, a 55-year-old male patient presenting with acute chest pain.

- The map content is displayed visually as a preconstructed set of nodes with key information about the diseases that all present with the same chief complaint (acute chest pain).

- The learner needs to provide a diagnosis consistent with a series of accurate connections among the nodes containing parts of the script, by completing the empty nodes at the bottom of the exercise.

- Since there is no complete clinical case-to-be-solved, there is not a single best answer but the accurate identification and connections of prototypical components of three to five disease entities that may constitute a differential diagnosis for the patient’s chief complaint. Instructor Steps in the design of the CREsME technique are provided in Table 2.

CReSME와 같이 지시성이 높은 개념 지도는 교사의 세심한 준비가 필요합니다.

- 실제로 개발하는 데 몇 시간이 걸릴 수 있으며, 콘텐츠의 정확성과 관련성 및 노드 간의 연결성을 보장하기 위해 교수진 그룹이 검토해야 합니다.

- 교수진은 가능한 모든 연결 고리를 파악하고, 적절한 난이도를 측정하고, 토론을 통해 합의에 도달해야 합니다.

- CReSME 기법을 학생들에게 소개해야 하며, 강사는 연습을 개발하거나 완료하는 목적, 코스 또는 학습할 자료에 어떻게 부합하는지 설명하고 화이트보드 또는 컴퓨터 매핑 시스템을 사용하여 해결하는 방법을 시연해야 합니다.

- 이전에 개발한 CReSME의 예시를 학생들에게 제시하여 학생들이 검토하고 질문하며 과제를 완료하는 방법을 이해할 수 있도록 하는 것이 도움이 됩니다. 그런 다음 학생에게 종이 또는 전자 방식으로 샘플 연습을 할 수 있는 기회를 제공해야 합니다. 이러한 입문 세션은 1~2시간 정도 소요될 수 있으며 필요한 경우 반복할 수 있습니다.

A high directedness concept map like the CReSME requires careful preparation by the teacher.

- Indeed, it may take a few hours to develop and should be reviewed by a group of faculty to ensure accuracy and relevance of the content and the connections among nodes.

- The faculty should identify all possible connections, gage the appropriate level of difficulty, and come to a consensus through discussion.

- the CReSME technique needs to be introduced to students and the instructor should explain the purpose of developing or completing the exercise, how it fits into the course or material to be learned, and demonstrate how to solve it on a whiteboard or using a computer mapping system (http://cmap.ihmc.us/).

- It is helpful to present the students with an example of a CReSME previously developed, so that they can review, ask questions, and understand how to complete the task. Subsequently, students should be given the opportunity to practice on a sample exercise, on paper or electronically. Such an introductory session may last 1–2 h and can be repeated if needed.

CReSME는 어떻게 수행하나요?

How to perform a CReSME?

학생들은 다양한 콘텐츠에 대한 CReSME를 이수하도록 배정될 수 있습니다. 콘텐츠는 기초 과학에서 임상 과학에 이르기까지 다양합니다. 대부분의 경우 기초 과학과 임상 과학 콘텐츠가 동일한 연습에 통합되어 있습니다(예: 미생물학, 약리학, 병태생리학, 임상적 특징 및 발열을 보이는 질병 개체의 진단 워크업을 통합한 연습). 경험상 20~30분은 학생이 하나의 CReSME를 완료하는 데 적당한 시간입니다. 그러나 이는 복잡성 수준, 연결해야 하는 노드 및 연결의 수, 학생이 비교하고 검토해야 하는 질병 엔티티의 수에 따라 달라질 수 있습니다. CReSME를 완성하는 것은 개별적으로 또는 소규모 학습자 그룹(그룹당 5~6명의 학생)이 공동으로 작업하여 수행할 수 있습니다. 마찬가지로, 그룹 개념 매핑(Torre 외. 2017; Peñuela-Epalza 및 De la Hoz 2019)과 마찬가지로, 각 그룹은 연습을 완료하고 다른 그룹과 그 근거를 공유할 수 있습니다. 그룹 환경에서 학생들은 서로 질문하고, 구체적이거나 더 어려운 연결고리에 대한 설명을 제공하고, 의미와 상호 이해를 공동으로 구성하는 과정에 참여할 수 있습니다.

The students can be assigned to complete a CReSME on a variety of contents Content may range from basic sciences to clinical sciences. Most often, basic and clinical sciences content are integrated within the same exercise (e.g. an exercise integrating microbiology, pharmacology, pathophysiology, clinical features, and diagnostic workup of disease entities presenting with fever). In our experience, 20–30 min is a reasonable amount of time for a student to complete one CReSME. But this will depend on its level of complexity, the number of nodes and connections that need to be made and the number of disease entities that will have to be compared and reviewed by students. The completion of a CReSME may be accomplished individually or by a small group of learners working collaboratively (five to six students per group). Similarly, to group concept mapping (Torre et al. 2017; Peñuela-Epalza and De la Hoz 2019), each group can complete the exercise and share their rationale with other groups. In a group setting, the students can ask questions to each other, provide explanations for specific or more challenging links and engage in a process of co-construction of meaning and mutual understanding.

이 교육 기법은 피드백의 기회를 제공합니다. 다음은 몇 가지 제안 사항입니다:

This instructional technique offers opportunities for feedback. Here are some suggestions:

- 교사는 학생들이 CReSME 결과를 공유하고 비교할 수 있는 세션을 계획하고, 제안된 근거와 정당성의 차이에 대해 토론하고 반성하며, 교사가 큰 소리로 생각하고 자신의 사고 과정을 모델링하여 정보 노드 간의 각 연결 집합에 대한 근거와 정당성을 설명할 수 있습니다. 이 과정을 녹화한 다음 학습자와 전자적으로 공유하면 학습자는 자신의 속도와 시간에 맞춰 액세스하여 들을 수 있습니다.

The teacher may plan a session where students can share and compare their CReSME results; discuss and reflect on differences in rationale and justifications proposed; the teacher can think aloud and model his or her thinking process, explaining the rationale and the justification for each set of connections among nodes of information. This process can be recorded and then shared electronically with the learners who can access it and listen to it at their own pace and time. - 교사는 학습자의 연습 문제를 검토한 후 일반적인 오해나 지식 격차를 파악하고 전체 학급을 대상으로 한 후속 교육 세션에서 해당 개념을 명확히 설명할 수 있습니다.

The teacher, after reviewing exercises from learners, may identify common misconceptions or knowledge gaps and clarify those concepts in a subsequent teaching session for the whole class. - 교사는 어려움을 겪고 있는 학생을 개별적으로 만나 특정 연결 또는 잘못된 링크의 근거에 대해 문의하고 구체적인 피드백을 제공할 수 있습니다.

The teachers can meet individually with struggling students, inquire about the rationale for specific connections or invalid links and provide specific feedback. - 교사는 '참조' CReSME를 개발하여 학생들과 공유하고 동기식 또는 비동기식 방식으로 완료한 연습과 비교하여 검토하도록 권장할 수 있습니다.

The teacher can develop and share with students a ‘reference’ CReSME and encourage them to review and compare it with their completed exercise in a synchronous or asynchronous manner.

커리큘럼에 CReSME를 통합하는 방법은 무엇인가요?

How to integrate the CReSME into the curriculum?

CReSME는 코스, 모듈 및 임상 실습 로테이션 전반에 걸쳐 기초 및 임상 과학을 통합하는 데 사용할 수 있습니다. 콘텐츠를 통합할 뿐만 아니라 시간이 지남에 따라 학생의 지식 구조 발달을 모니터링하는 데에도 종단적으로 사용할 수 있습니다. 다양한 콘텐츠로 임상 추론 매핑 연습을 구성하고 난이도를 높이면 시간이 지남에 따라 학습자의 성장과 궤적을 추적할 수 있습니다.

The CReSME could be used to integrate basic and clinical sciences, across courses, modules and clerkship rotations. It can be used longitudinally not only to integrate content but also to monitor the student development of knowledge structures over time. The construction of clinical reasoning mapping exercises with different content, and increasing level of difficulty may allow to follow the growth and trajectory of the learner over time.

의도적인 성찰

Deliberate reflection

DR이란 무엇인가요?

What is it?

원래 의사의 진단 능력을 향상시키기 위한 도구로 개발 및 테스트된 DR은 임상 추론을 가르치기 위한 교육적 접근 방식으로도 활용되고 있습니다. 이 접근 방식은 임상 사례를 진단하는 동안 반성을 장려하고 안내하며, 학생들이 사례에 대한 대체 진단을 체계적으로 비교하고 대조하도록 요구합니다. DR의 목적은 임상 사례에 제시된(또는 관련된) 질병에 대한 정신적 표현의 발달을 촉진하여 향후 새로운 사례에서 질병을 접할 때 이를 더 쉽게 인식할 수 있도록 하는 것입니다.

DR, originally developed and tested as a tool to improve physicians’ diagnostic performance, has also been employed as an instructional approach for the teaching of clinical reasoning. The approach encourages and guides reflection during the diagnosis of clinical cases, requiring students to compare and contrast alternative diagnoses for the case in a systematic way. The purpose of DR is to foster the development of the mental representations of the diseases presented in (or related to) the clinical cases, making it easier to recognize them when they are encountered in new cases in the future.

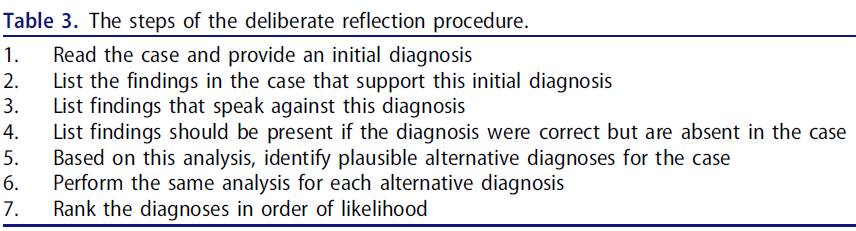

DR을 교육 기법으로 사용할 경우, DR은 학생들에게 임상 사례를 하나씩 제시하고 표 3에 설명된 일련의 단계에 따라 사례를 진단하도록 요구합니다. 일반적으로 학생들은 단계를 제시하는 표를 작성하여 사례를 되돌아봅니다. 이는 고려 중인 각 진단에 대한 찬성과 반대의 전체 증거를 동시에 시각화하는 데 중요한 역할을 합니다(예는 부록 3 참조).

When employed as instructional technique, DR presents students with clinical cases, one by one, and requires them to diagnose the case by following the series of steps outlined in Table 3. Usually, students reflect upon the case by filling in a table which presents the steps. This seems important to help visualize the whole evidence in favor and against each diagnosis under consideration simultaneously (see Appendix 3 for an example).

DR은 다음을 포함하는 의학에서의 5차원 반성적 진료 모델을 기반으로 합니다(Mamede and Schmidt 2004).

- (i) 의도적 귀납,

- (ii) 의도적 연역,

- (iii) 테스트 및 종합,

- (iv) 성찰을 위한 개방성,

- (v) 메타추론(메타추론)

DR 절차는 임상의가 사례에 대해 고려한 초기 진단의 근거를 비판적으로 조사하고, 가능한 대안을 검토하도록 안내함으로써 이러한 차원을 진단 프로세스에 '적용'합니다. 의사를 대상으로 한 연구에서 DR은 진단 오류를 줄이고, 추론의 편견에 대응하며, 성과를 개선하는 것으로 반복적으로 나타났습니다(Mamede 외. 2008, 2010). 여러 연구에서도 임상 추론 교육에 DR을 사용하는 것을 뒷받침하는 증거를 제시했습니다(Mamede 외. 2012, 2019, 2020; Myung 외. 2013; Ibiapina 외. 2014) 이러한 실험 연구에서 임상 사례로 실습하는 동안 DR을 사용한 학생들은 향후 진단 과제에서 감별 진단을 내리는 등 보다 전통적인 접근 방식을 사용하여 실습한 학생들보다 더 나은 성과를 냈습니다. DR의 이러한 긍정적인 효과는 질병 스크립트 개발에서 임상 문제에 대한 노출이 핵심적인 역할을 한다는 의료 전문성의 단계 이론(Schmidt 외. 1990)과 스키마 구성에 있어 사례 비교 및 대조가 이점을 제공한다는 심리학 연구(Gentner 외. 2009)와도 일치합니다. 그러나 기존의 거의 모든 경험적 증거는 실험실 조건에서 수행된 연구에서 나온 것이며, 실제 커리큘럼에서의 구현과 관련하여 검토해야 할 사항이 많이 남아 있습니다.

DR is based on a five-dimension model of reflective practice in medicine that involves:

- (i) deliberate induction,

- (ii) deliberate deduction,

- (iii) testing and synthesizing,

- (iv) openness for reflection, and

- (v) meta-reasoning (Mamede and Schmidt 2004).

The DR procedure ‘applies’ these dimensions to the diagnostic process by guiding clinicians through critical scrutiny of the grounds of the initial diagnosis considered for a case and the examination of possible alternatives. In studies with physicians, DR has repeatedly shown to reduce diagnostic errors, counteract bias in reasoning and improve performance (Mamede et al. 2008, 2010). Several studies have also provided evidence supporting the use of DR for the teaching of clinical reasoning (Mamede et al. 2012, 2019, 2020; Myung et al. 2013; Ibiapina et al. 2014) In these experimental studies, students who employed DR while practicing with clinical cases outperformed, in future diagnostic tasks, students who practiced by using more conventional approaches such as producing a differential diagnosis. This positive effect of DR is consistent with the stage theory of medical expertise (Schmidt et al. 1990), which attributes a key role to exposure to clinical problems in the development of illness scripts, and with psychological research showing the benefits of comparing and contrasting examples for the construction of schemas (Gentner et al. 2009). However, almost all existing empirical evidence comes from research conducted under laboratory conditions, and much remains to be examined regarding implementation in actual curricula.

DR을 준비하고 도입하는 방법은?

How to prepare and introduce DR?

DR은 학생들에게 다양한 임상 문제를 접하고 이러한 문제에 대한 대체 진단을 체계적으로 비교하고 대조할 수 있는 기회를 제공하기 위한 실습에 사용해야 합니다.

DR is to be used in exercises aimed at offering students the opportunity to encounter a variety of clinical problems and to systematically compare and contrast alternative diagnoses for these problems.

학습 자료

Learning materials

- 임상 양상은 비슷하지만 진단명이 다른 질병을 나타내는 3~5개의 임상 사례 세트(예: 흉통을 주요 증상으로 하는 서로 다른 질병). 유사한 질병을 나란히 배치하여 학생들이 유사점과 차이점을 식별하고 대체 진단을 구별하는 데 도움이 되는 소견에 대한 지식을 습득할 수 있습니다.

Sets of three to five clinical cases presenting diseases with similar clinical presentation but different diagnoses (e.g. different diseases with chest pain as chief complaint). Juxtaposing lookalike diseases allows students to identify similarities and differences between them and acquire knowledge of findings that help distinguish between alternative diagnoses. - 학생들은 이미 교육 활동을 통해 사례에 제시된 질병에 대한 지식에 노출되었지만 임상 경험이 많지 않아야 합니다. DR은 학생들이 이미 기억에 저장해 둔 지식을 동원하고 재구성하도록 촉진하는 방식으로 작동하기 때문입니다. 학생들이 반성 과제에 가져올 사전 지식이 충분하지 않으면 이 과제의 이점을 얻지 못합니다(Mamede et al). 반면에 학습자에게 사례가 너무 쉽거나 임상에서 이미 유사한 임상 증상을 보이는 환자를 많이 접한 경우, 질병 스크립트를 다듬을 여지가 없어 과제가 그다지 도전적이고 동기 부여가 되지 않을 수 있습니다.

Students should already have been exposed to knowledge of the diseases presented in the cases through didactic activities but do not have much clinical experience with them. This is so because DR works by mobilizing and fostering reorganization of knowledge that students already have stored in memory. When students do not have sufficient prior knowledge to bring to the reflection task, they do not benefit from it (Mamede et al). On the other hand, if cases are too easy for the learners and/or they have already encountered many patients with similar clinical presentation in clinical years, there is possibly no room for refining their illness scripts, and the task may be not so challenging and motivating. - DR에 대한 기존 연구는 학생들에게 진단에 도달하는 데 필요한 모든 정보를 제공하는 임상 사례를 사용했습니다. DR에는 상당한 정신적 노력이 필요하므로(Ibiapina 2014; Mamede 외. 2020), 합리적인 수준으로 유지되어야 합니다. DR 연습의 목표는 실제 사례의 복잡성을 재현하는 것이 아니라, 학생이 학습해야 하는 핵심 정보에 집중하는 것임을 명심하는 것이 중요합니다. 학생들이 커리큘럼을 진행함에 따라 사례 형식의 복잡성은 점차 증가할 수 있습니다. 그러나 예를 들어 학생이 진단에 도달하기 위해 필요한 정보를 독립적으로 수집해야 하는 사례에서 DR이 어떻게 작동할지는 아직 결정되지 않았습니다.

Existing research with DR has used clinical cases that provide students with all the information required to reach a diagnosis. DR involves considerable mental effort (Ibiapina 2014; Mamede et al. 2020), which should be kept at reasonable level. It is important to keep in mind that the goal of the DR exercise is not to replicate the complexity of real cases but rather focus on key information that the student is expected to learn. As students progress through the curriculum, complexity of the cases’ format may gradually increase. However, how DR would work, for example, with cases that require the student to independently gather the necessary information to reach the diagnosis, is still to be determined. - DR의 형식(아래 참조)에 따라 임상 사례는 반성 시 고려해야 할 대체 진단에 대한 단서와 함께 제시되어야 합니다.

Depending on the format of DR (see below), the clinical cases should be presented together with cues on the alternative diagnoses to be considered during reflection or not.

종이 기반 또는 가상 임상 사례의 사용 가능성, 임상 사례 준비 과정 및 교사의 역할과 관련하여 SE에 적용되는 사항은 DR 학습 자료에도 적합합니다.

What applies to SE regarding the possibility to use paper-based or virtual clinical cases, the process for the preparation of the clinical cases and the role of the teacher, is also pertinent for the learning materials for DR.

학생들에게 DR 소개

Introducing DR to students

DR은 많은 노력이 필요하며(Ibiapina 외. 2014; Mamede 외. 2019), 학생들이 과제에 완전히 참여할 수 있는 기회를 극대화하려면 DR이 임상 추론에 미치는 잠재적 이점에 대해 알려주고 DR 테이블을 완성한 예를 보여줘야 합니다.

DR is effortful (Ibiapina et al. 2014; Mamede et al. 2019) and to maximize the chance that students engage fully in the task, they should be informed about the potential benefits from DR to clinical reasoning and shown examples of the completion of DR tables.

DR은 어떻게 수행하나요?

How to perform DR?

DR은 지금까지 학생들이 개별적으로 절차를 사용하여 연구해 왔지만 그룹으로 진행하지 못할 이유가 없으며 공동 학습의 이점도 얻을 수 있습니다.

DR has so far been studied with students using the procedure individually but there is no reason why it should not work in groups and even gain from the benefits of collaborate learning.

학생에게 제공되는 지침의 양이 다른 세 가지 형식의 DR 절차가 테스트되었습니다.

- 자유 성찰에서는 학생이 사례에 대해 고려해야 할 대체 진단을 스스로 생성해야 합니다(Mamede 외. 2012).

- 단서 성찰에서는 성찰 표에 그럴듯한 대안 진단이 제공되며, 학생은 그 결과를 기입하고 가장 가능성이 높은 진단을 최종 결정해야 합니다(Ibiapina 2014; Mamede 외. 2019, 2020).

- 마지막으로, 모델 성찰에서는 교사가 모든 요소를 채운 전체 반성표를 제시하고 학생이 이를 학습해야 합니다(Ibiapina 외. 2014; Mamede 외. 2019).

Three different formats of the DR procedure which vary in the amount of guidance provided to students have been tested.

- In free-reflection, students are required to generate by themselves the alternative diagnoses to be considered for the case (Mamede et al. 2012).

- In cued-reflection, the reflection table provides the plausible alternative diagnoses and the students are required to fill in the findings and make the final decision on the most likely diagnosis (Ibiapina 2014; Mamede et al. 2019, 2020).

- Finally, in modeled-reflection, the whole reflection table is presented, with all its elements filled in by teachers, and students are required to study it (Ibiapina et al. 2014; Mamede et al. 2019).

모델 반사에 필요한 정신적 노력은 단서 반사에 비해 낮지만, 전자는 교사의 준비 작업이 훨씬 덜 필요한 후자보다 학습에 더 유리하지 않습니다. 그러나 단서 반사가 자유 반사보다 더 유리한 것으로 보이지만, 이러한 연구에서 관찰 된 이점은 이전에 연구 된 질병 만 테스트에 포함되었다는 사실에서 비롯된 것일 수 있습니다. 아직 조사해야 할 부분이 많이 남아 있습니다.

Although the mental effort required by modelled-reflection is lower than that of cued-reflection, the former is not more advantageous for learning than the latter, which requires much less preparatory work from teachers. Cued-reflection seems, however, to be more beneficious than free-reflection, but the advantage observed in these studies may derive from the fact that only previous studied diseases were included in the tests. There is much to be investigated here yet.

DR에 대한 많은 연구에서 학생들에게 피드백이 제공되지 않았으며, 이는 새로운 지식이 제공되지 않더라도 지식 재구성을 통해 작용할 수 있음을 시사합니다. 그러나 레지던트들이 자신의 반성표와 전문가가 작성한 반성표를 비교하도록 한 최근 연구에서는 추론의 편향을 유도하는 것으로 알려진 조건에서 수행 능력을 향상시키는 절차를 보여주었습니다(Mamede 외. 2020). 이는 피드백을 통합하고 피드백에 대한 적극적인 반영을 통해 DR의 효과를 높일 수 있는 잠재력을 보여주는 신호일 수 있습니다. 다시 말하지만, 조사의 여지는 열려 있습니다.

No feedback has been provided to students in many studies on DR, suggesting that it may act through knowledge restructuring, even when new knowledge is not made available. However, a recent study in which residents were required to compare their own reflection tables with those filled in by experts showed the procedure to improve performance under conditions that are known to induce bias in reasoning (Mamede et al. 2020). This may be a sign of a potential to enhance the effect of DR by incorporating feedback and active reflection on the feedback. Again, open avenue for investigation.

DR을 커리큘럼에 통합하는 방법은 무엇인가요?

How to integrate DR into the curriculum?

원래의 형식에서 DR은 다른 활동과 독립적으로 수행되는 연습에 사용되었습니다. 그러나 임상 사례 실습을 기반으로 한 다른 교육적 접근 방식과 결합하여 지식 재구성 및 질병 스크립트 개선을 촉진할 수도 있습니다.

- 예를 들어, 셔브룩 대학교의 경험에서 SE와 DR이 함께 사용되었습니다.

- 또한 DR 연습에서 진단된 임상 문제와 관련된 지식 습득에 초점을 맞춘 학습 과제(예: 개인 또는 자율 학습, 소그룹 학습, 강의)와 함께 DR을 사용할 수 있습니다(예: 흉통의 감별 진단에 대한 강의를 시작할 때 흉통과 관련된 질환 사례 1~2개를 진단하는 데 DR을 활용).

- 최근 연구에 따르면 다른 학습 활동과 함께 DR을 사용하는 것을 지지하며, 문제의 감별 진단에 관한 텍스트를 학습하기 전에 임상 문제를 진단하기 위해 DR에 참여하는 것이 학습 참여를 촉진하고 학습 결과를 개선하는 것으로 나타났습니다(Ribeiro 외. 2019, 2021).

In its original format, DR has been used in exercises performed independently of other activities. However, it can also be combined with other instructional approaches based on practice with clinical cases to fostering knowledge restructuring and refinement of illness scripts.

- For example, SE and DR have been used in combination in the experience of the Sherbrooke University.

- Additionally, DR can be used in combination with a learning task (e.g. individual or self-study, small-group learning, lectures) focused on acquisition of knowledge relevant to the clinical problems diagnosed in the DR exercise (e.g. employing DR to diagnose one to two cases of diseases associated with chest pain in the beginning of a lecture on the differential diagnosis of chest pain).

- Recent research has supported the use of DR in combination with other learning activities, showing that engaging in DR to diagnose a clinical problem before studying a text on the differential diagnosis of the problem fosters engagement in learning and improves learning outcomes (Ribeiro et al. 2019, 2021).

세 가지 전략을 결합하고 순서를 정할 수 있는 기회 탐색하기

Exploring opportunities of combining and sequencing the three strategies

SE, CReSME, DR은 모두 의학의 전문성 습득 이론과 일치하므로(Schmidt 외. 1990), 학부 커리큘럼에서 이들의 조합 또는 시퀀싱을 통해 잠재적인 이점을 기대할 수 있습니다. 유사한 이론적 신념에 기반을 두고 지식 구축을 지향하지만 각 전략의 초점은 다르게 보일 수 있습니다.

- SE는 생물 의학 지식과 임상 지식 간의 연결을 촉진하고, 지식 캡슐화를 촉진하여, 질병 스크립트의 일관성을 향상시킬 수 있을 것으로 예상됩니다.

- CReSME는 새로운 질병 스크립트의 시각적 표현/비계를 제공하여 지식 캡슐화를 지원할 수 있으며, 학생들이 주어진 주요 불만 사항과 관련된 스크립트를 직접 작업할 수 있도록 조직화할 수 있습니다.

- DR은 여러 스크립트의 주요 특징을 비교하고 대조하는 절차를 활용하여 문제 해결에 적용하면서 질병 스크립트를 더욱 개발, 개선 및 강화할 수 있는 기회를 제공합니다.

Since SE, CReSME, and DR all aligned with the theory of expertise acquisition in medicine (Schmidt et al. 1990), we may expect potential benefits of their combination or sequencing in an undergraduate curriculum. It might be realized that although grounded in similar theoretical tenets and oriented toward knowledge building, the focus of each strategy appears different.

- SE fosters links between biomedical knowledge and clinical knowledge, presumably facilitates knowledge encapsulation and thus enhances coherence of illness scripts.

- The CReSME provides visual representation/scaffolding of emerging illness scripts, which might support knowledge encapsulation and organization allows students to work directly on their scripts relevant to a given chief complaint.

- DR provides opportunities to further develop, refine, and enrich illness scripts while applying them to solve problems by utilizing a procedure for comparing and contrasting key features of different scripts.

이러한 다양한 초점을 고려하여 SE, CReSME 및 DR은 커리큘럼에 따라 여러 가지 방식으로 결합되거나 순서대로 사용될 수 있습니다. 적절한 실행을 위해서는 현지 커리큘럼 설계를 고려하여 학생들이 이러한 전략을 활용할 수 있을 만큼 충분한 사전 지식을 갖추게 되는 시기를 파악해야 합니다.

- 예를 들어, 커리큘럼이 초기에 생물의학을 배우고 임상 과학을 배운 다음 임상 로테이션을 하는 전통적인 접근 방식을 채택하는 경우, 이러한 교육 전략은 시간이 지남에 따라 순차적으로 적용될 수 있습니다.

- 초기 학습자에게는 SE를 사용한 일련의 연습을,

- 중급 학습자에게는 CReSME를,

- 고급 학습자에게는 DR을 사용한 연습을 제공할 수 있습니다(Schmidt and Mamede 2015).

- 또는 학생들이 모든 유형의 지식과 기술(예: 생물 의학, 임상, 임상 기술, 치료법)을 통합적으로 습득해야 하는 문제 또는 임상 상황을 중심으로 구성된 커리큘럼에서는 세 가지 전략이 모두 조기에 구현될 수 있습니다.

- 예를 들어, 통합 커리큘럼을 채택하고 있는 셔브룩 대학교에서는 이미 1학기부터 SE와 DR을 결합한 활동을 시행하고 있습니다. 이 웹 기반 개별 활동은 프로그램의 첫 2년 동안 반복됩니다. 학생들은 세 가지 임상 사례를 해결하면서 다음 단계를 수행해야 합니다:

- 사례 읽기, 각 임상 소견에 대한 자기 설명 생성,

- 고의적 성찰 연습 완료,

- 교사가 작성한 DR 검토. (Chamberland 외. 2020, 2021).

- 예를 들어, 통합 커리큘럼을 채택하고 있는 셔브룩 대학교에서는 이미 1학기부터 SE와 DR을 결합한 활동을 시행하고 있습니다. 이 웹 기반 개별 활동은 프로그램의 첫 2년 동안 반복됩니다. 학생들은 세 가지 임상 사례를 해결하면서 다음 단계를 수행해야 합니다:

Taking these different foci into consideration, SE, CReSME, and DR could be combined or sequenced in several ways along the curriculum. Proper implementation requires considering the local curriculum design to identify when students will have sufficient prior knowledge to be able to work with these strategies.

- For instance, if the curriculum adopts a more traditional approach, with early years of biomedical sciences followed by clinical sciences and then clinical rotations, these instructional strategies might be potentially sequenced overtime.

- A series of exercises with SE could be used with early learners,

- CReSME could be offered for intermediate learners,

- and more advanced learners would engage in exercises with DR (Schmidt and Mamede 2015).

- Otherwise, in a curriculum organized around problems or clinical situations in which students are expected to acquire all types of knowledge and skills (e.g. biomedical, clinical, clinical skills, therapeutics) in an integrated way, all the three strategies might be implemented early.

- For example, Sherbrooke University, with its integrated curriculum, has implemented an activity combining SE and DR as early as in the first semester. This web-based individual activity is recurrent over the first 2 years of the program. It requires students to work through the following steps while solving three clinical cases:

교사가 염두에 두고 있는 목표에 따라 두 가지 전략의 다른 조합을 만들 수도 있습니다. 그러나 SE, CReSME 및 DR은 학생에게 많은 노력이 필요하므로 동일한 연습에서 세 가지 전략을 모두 결합하는 것은 너무 어렵고 학습을 방해할 수 있는 수준으로 인지 부하를 가져올 수 있습니다. 종단적이고 반복적인 활동을 보장하면 학생들이 전략에 익숙해지고, 그 가치를 인식하고, 학습 잠재력을 최대한 활용하는 데 도움이 될 수 있습니다. 이러한 맥락에서 교사는 학습 자료(사례)를 커리큘럼에 따라 바람직한 난이도로 조정해야 함은 말할 필요도 없습니다.

Other combinations of two of the strategies may be made, depending on the goals that the teacher has in mind. However, since SE, CReSME, and DR are effortful for students, combining all three strategies within the same exercise might be too challenging and bring cognitive load to a level that could hinder learning. Ensuring longitudinal and recurrent activities might help students get familiar with the strategies, perceive their value and harness their full potential for learning. Perhaps needless to say, in this context, teachers must adapt the learning material (cases) to the desirable level of difficulty along the curriculum.

이러한 교육 전략을 다양한 방식으로 결합하여 구현하려면 커리큘럼에서 사용 가능한 시간, 학생 수, 교수진 리소스와 같은 상황적 제약도 고려해야 합니다. 이러한 요인으로 인해 활동의 구체적인 설계에 조정이 필요할 수 있습니다. 그러나 그렇게 하면서도 설계 과정 전반에 걸쳐 SE, CReSME, DR의 기본 철학과 핵심 원칙을 유지하는 것이 중요합니다(Cianciolo and Regehr 2019; Chamberland 외. 2020). 현지 상황에 맞게 조정하는 것은 항상 필요하지만, 기본 원칙에서 벗어나면 전략의 잠재적 이점을 손상시킬 수 있습니다.

The implementation of these instructional strategies, combined in different ways, will also need to consider contextual constraints, such as available time in the curriculum, number of students, faculty resources. These factors may require adaptations in the specific design of the activities. However, while doing that, it is crucial to uphold the underlying philosophy and core principles of SE, CReSME, and DR throughout the design process (Cianciolo and Regehr 2019; Chamberland et al. 2020). While adjusting to local circumstances is always necessary, deviating from the underlying principles compromises the potential benefits of the strategies.

이러한 전략의 사용과 실행에는 고려해야 할 몇 가지 문제가 있습니다.

- 첫째, 이러한 전략은 임상적 추론의 한 차원, 즉 지식에 초점을 맞춥니다. 그러나 임상적 추론은 다차원적인 구조이며 맥락적 요인에 의해 크게 영향을 받기도 합니다(Durning 외. 2012). 말할 필요도 없이, 지식 자체가 성공적인 임상 추론의 중요한 결정 요인이기는 하지만(Norman 외. 2017), 교사가 관심을 가져야 하는 유일한 차원은 아닙니다.

- 둘째, 난이도가 점점 높아지는 여러 임상 비네팅과 여러 임상 추론 매핑 연습을 개발하는 데는 시간이 많이 소요될 수 있으며 어느 정도의 교수자 개발이 필요할 수 있습니다. 그럼에도 불구하고 이러한 노력은 임상 추론 교육에서 점점 더 중요하게 인식되고 있는 시뮬레이션 사례 실습을 기반으로 한 학습 활동을 설정하는 것보다 더 까다롭지는 않을 것입니다(Schmidt and Mamede 2015). 또한, 여러 연습 문제를 생성한 후에는 학습자 및 커리큘럼 요구 사항을 충족하도록 쉽게 수정할 수 있습니다.

- 셋째, 이러한 전략을 사용하여 학습 효과를 극대화하려면 학생이 이러한 전략이 평가 도구가 아닌 학습 전략이라는 점을 이해하는 것이 중요합니다. 학생들은 이러한 전략을 사용하여 자신의 지식의 한계를 탐구하고, 사고 과정을 촉진하고, 의미 있는 학습을 구성하고, '안전한 공간'에서 격차를 식별해야 합니다.

The use and implementation of these strategies is bounded by several issues that deserve consideration.

- First, these strategies focus on one dimension of clinical reasoning, that is knowledge. However, clinical reasoning is a multidimensional construct and is also heavily affected by contextual factors (Durning et al. 2012). Perhaps needless to say, knowledge per se, though a critical determinant of successful clinical reasoning (Norman et al. 2017), is not the only dimension teachers should be concerned with.

- Second, the development of several clinical vignettes and multiple clinical reasoning mapping exercises with increasing levels of difficulty may be time intensive, and will likely require some degree of faculty development. Nevertheless, these efforts would not be more demanding than those involved in setting any learning activities based on practice with simulated cases, which has been more and more recognized as critical in the teaching of clinical reasoning (Schmidt and Mamede 2015). Furthermore, once a number of exercises have been created, they can be easily modified to meet learners’ and curricular needs.

- Third, to optimize the benefit on learning using these strategies, it is crucial that students understand that these are learning strategies and not assessment tools. Students should use these strategies to explore the limits of their own knowledge, promote their thinking processes, construct meaningful learning and identify gaps in a ‘safe space’.

결론

Conclusion

이 세 가지 임상 추론 교육 전략은 인과 관계 네트워크, 지식 조직화, 캡슐화 및 질병 스크립트 형성을 지원함으로써 공통된 이론적 원칙을 공유하므로 의료 전문성 개발의 여러 단계에서 임상 추론을 가르치는 데 효과적으로 사용될 수 있습니다. 임상 추론 학습 활동으로 이 방법만이 유일한 것은 아닙니다. 그러나 올바르게 구현한다면 임상 교사가 학습자의 임상 추론 발달을 촉진하는 데 중요한 도구가 될 수 있습니다.

These three clinical reasoning instructional strategies share common theoretical tenets by supporting development of causal networks, knowledge organization, encapsulation, and formation of illness scripts and therefore could be effectively used to teach clinical reasoning at different stages of medical expertise development. They are not the only clinical reasoning learning activities available. Yet, if correctly implemented, they can be a critical tool in the hands of clinical teachers to promote learners’ development of clinical reasoning.

Implementation of three knowledge-oriented instructional strategies to teach clinical reasoning: Self-explanation, a concept mapping exercise, and deliberate reflection: AMEE Guide No. 150

PMID: 35938204

Abstract

The teaching of clinical reasoning is essential in medical education. This guide has been written to provide educators with practical advice on the design, development, and implementation of three knowledge-oriented instructional strategies for the teaching of clinical reasoning to medical students: Self-explanation (SE), a Clinical Reasoning Mapping Exercise (CREsME), and Deliberate Reflection (DR). We first synthesize the theoretical tenets that support the use of these strategies, including knowledge organization, and development of illness scripts. We then provide a detailed description of the key components of each strategy, emphasizing the practical applications of each one by sharing specific examples. We also explore the potential for a combined application of these strategies in a longitudinal and developmental approach to teaching clinical reasoning at the undergraduate level. Finally, we discuss enablers and barriers in the implementation and integration of these teaching strategies while taking into consideration curricular needs, context, and resources. We are aware that many strategies exist and are not arguing that SE, CReSME, and DR are the most effective ones or the only ones to be adopted. Nevertheless, we selected these strategies because of overarching theoretical principles, empirical evidence supporting their use, and our own experience with them. We are hoping to provide practical advice on the implementation of these strategies to practicing educators who aim at developing an integrated approach to the teaching of clinical reasoning to medical students at different stages of their development.

Keywords: clinical reasoning; reflective learning; teaching methods.

'Articles (Medical Education) > 임상교육(Clerkship & Residency)' 카테고리의 다른 글

| 가능성과 불가피성: AI-관련 임상역량의 격차와 그것을 채울 필요성(Med Sci Educ. 2021) (0) | 2023.05.27 |

|---|---|

| 구름낀 푸른하늘: 의대생-전공의 이행에서의 지속적 긴장을 식별하고 미래의 이상적 상태 그리기(Acad Med, 2023) (0) | 2023.05.14 |

| 임상적 의사소통의 생각, 우려, 기대에 대한 비판적 고찰(Med Educ, 2022) (0) | 2023.04.23 |

| 매듭 묶기: 임상교육에서 학생의 학습목적에 관한 활동이론분석(Med Educ, 2017) (0) | 2023.04.16 |

| 건강 및 사회적 돌봄 교육에서 환자 참여에 대한 이론적 체계적 문헌고찰 (Adv Health Sci Educ Theory Pract. 2023) (0) | 2023.04.09 |