어떻게 의과대학이 공감을 바꾸는가: '환자에 대한 공감'과의 사랑 및 이별 편지 (Med Educ, 2020)

How medical school alters empathy: Student love and break up letters to empathy for patients

William F. Laughey1 | Megan E. L. Brown1 | Angelique N. Dueñas1 | Rebecca Archer1 | Megan R. Whitwell1 | Ariel Liu2 | Gabrielle M. Finn1,3

1 소개

1 INTRODUCTION

의과대학에서 공감을 가르치는 것은 확인된 역사를 가지고 있다. 불과 10여 년 전, Hojat 등은 학생들이 환자 치료의 현실을 경험함에 따라 3학년 때부터 침식이 가속화되는 등 의대 기간 동안 학생들의 공감이 실제로 침식된다는 결론을 내린 영향력 있는 논문을 발표했다. 공감이 미래의 의사의 핵심 자질이라는 점을 감안할 때, 공감의 감소는 ('윤리적 침식' 문제의 일부이며) 충격적인 결과입니다. 비록 의대 중 공감을 측정하는 연구에 대한 최근 리뷰가 적어도 서구 국가에서 전반적인 추세는 확실히 공감 점수가 감소하는 것으로 나타났지만, 모든 정량적 연구가 동일한 결론에 도달한 것은 아니다.

Empathy teaching in medical school has a chequered history. Just over a decade ago, Hojat et al1 published an influential paper concluding that student empathy actually erodes during medical school, with erosion accelerating from third year onwards as students experience the realities of patient care. Given that empathy is a core quality for a future physician, empathic decline—part of the problem of ‘ethical erosion’2—is a shocking result. Not all quantitative studies have reached the same conclusion, though a recent review3 of studies that measure empathy during medical school found that, in Western countries at least, the overall trend is indeed for empathy scores to decline.

그러나 정량적 연구를 고려할 때, 공감을 측정하는 바로 그 노력이 복잡하거나 논란이 없는 것은 아니라는 것을 인식해야 한다. 공감의 구성 요소는 인지적 측면과 정서적 측면을 모두 포함하며, 일부 정의는 전적으로 인지적 특징에 중점을 두고 있지만, 다른 이들은 감정적 공명이 없는 공감이라고 주장하기도 한다. 따라서 공감을 측정하기 위한 모든 척도가 실제로 그렇게 하는 것은 아니다. 공감에는 인지적, 정서적 요소 외에도 행동적, 도덕적 요소도 있다. 또한 존재론적 관점에서 공감을 인지행동적 용어로 보아야 하는지, 습득해야 할 기술로 보아야 하는지, 아니면 한 인간이 다른 사람에게 빚지고 있는 자질인 '존재의 방식'으로 보아야 하는지에 대한 논쟁이 있다. 인지적, 정서적, 행동적, 도덕적 요소를 포함한 이러한 공감의 측면은 본 연구와 정보에 입각한 데이터 수집 및 분석에서 민감화 개념sensitizing concepts으로 작용한다.

In considering quantitative research, it should be recognised, however, that the very endeavour of measuring empathy is not without complication or controversy.4-6 Empathy is complex, its components include both cognitive and affective aspects, and while some definitions centre entirely on cognitive characteristics (including Hojat's1), others argue that empathy without emotional resonance may not be empathy at all.7 Therefore, not all scales that purport to measure empathy may actually do so.6 Besides cognitive and affective elements, empathy also has behavioural and moral components.7 Furthermore, in ontological terms, there is debate regarding whether empathy should be viewed in cognitive-behavioural terms, as a skill to be acquired, or as a personal attribute, a quality that one human owes to another, a ‘way of being’.8, 9 These facets of empathy—including cognitive, affective, behavioural and moral components—act as sensitising concepts10 within this study and informed data gathering and analysis.

의과대학이 학생 공감에 어떤 영향을 미치는지 조사하는 대안적 접근 방식은 질적 탐구 쪽으로 눈을 돌리는 것이며, 이러한 다면적인 개념의 뉘앙스를 탐구하는 데 더 적합할 것이다. 현재까지 질적 연구는 [숨겨진 커리큘럼]의 측면을 의대생들이 임상적 공감을 어떻게 보는지에 대한 핵심 영향력자influencer로 파악한다. 이러한 측면에는 다음이 포함된다.

- 긍정적 및 부정적 역할 모델링,

- 환자 관계 확립보다 생물의학 지식 습득을 우선 순위에 두는 것

- 환자 관여에 대한 암묵적 감정 규칙

- 대처 전략으로 냉소주의를 채택하는 것

질적 연구는 또한 다음에 의해 학생들의 공감이 어떻게 부정적인 영향을 받는지를 밝혀냈다.

- 시간의 압박,

- '어렵다'고 인식되는 환자,

- 스트레스 받는 근무환경,

- 성찰의 기회 부족

An alternative approach to investigating how medical school influences student empathy is to turn to qualitative enquiry, arguably better suited to exploring the nuances of such a multifaceted concept.11 To date, qualitative research identifies aspects of the hidden curriculum12 as key influencers of how medical students view clinical empathy. These aspects include

- positive and negative role modelling,

- the prioritising of acquiring biomedical knowledge over establishing patient rapport,

- the implicit emotional rules of engaging with patients and

- the adoption of cynicism as a coping strategy.13-15

Qualitative research has also identified how student empathy is adversely influenced by

- the pressures of time,

- patients who are perceived to be ‘difficult’,

- stressful working conditions and

- a lack of opportunity for reflection.14, 16-19

그러나 본 논문에서 다룬 연구 격차인 의학적 교육에 의한 공감의 형성방식과 공감감소 문제에 대한 질적 연구가 미흡하다는 것이 대체적인 의견이다.

However, it is generally agreed that there is insufficient qualitative research into how empathy is shaped by medical education, and the problem of empathic decline,11, 16 the research gap addressed in this paper.

우리는 이전에 의료 교육에서 전혀 활용되지 않았던 질적 탐구 형태인 사랑 및 이별 편지 방법론(LBM)으로 눈을 돌렸다.

We have turned to a form of qualitative enquiry never previously utilised in medical education—love and break up letter methodology (LBM).20, 21

연애와 이별 편지 방법론은 기술 기반 연구인 UX(User Experience)에 뿌리를 두고 있다. UX에서, 참가자들은 기술의 한 측면에 사랑과 이별의 편지를 쓰도록 요청 받는다. 글자는 다음 포커스 그룹 토론의 트리거가 됩니다. LBM은 정서적 영역을 포함하여 논의 중인 개념과 참가자의 관계를 이해하는 창의적인 방법이다. 우리는 LBM이 의대를 통해 학생들이 공감에 대해 얻는 긍정적이고 부정적인 감정을 이해하는 데 도움이 될 것이라고 추론했다. 특히 부정적인, 혹은 '헤어진' 감정은 윤리적 침식의 개념에 대한 유용한 통찰력을 제공할 수 있다. 이와 같이 LBM은 환자공감 실천을 통해 학생관계의 변화하는 성격을 이해하고자 하는 본 연구의 요구조건에 부합한다.

Love and break up letter methodology has roots in User Experience (UX), a technology-based research.22 In UX, participants are asked to write a love and break up letter to an aspect of technology. The letters form the triggers for the focus group discussion that follows. LBM is a creative way to understand participants' relationships with the concept under discussion, including affective domains. We reasoned that LBM would help us understand the positive and negative feelings that students acquire about empathy as they progress through medical school. The negative, or ‘break up’, feelings, in particular, may provide useful insight into the concept of ethical erosion.2 As such, LBM suits the requirements of this study, which aims to understand the changing nature of student relationships with the practice of empathy for patients.

우리의 주요 연구 질문은 [상급 의대생]들이 [환자에 대한 공감]이라는 개념과의 [변화하는 관계]를 어떻게 특징짓는가 하는 것이었습니다. 우리의 목표는 의과대학 과정을 거치면서 공감에 대한 그들의 감정이 어떻게 변하는지 탐구하는 것이다.

Our primary research question was how do senior medical students characterise their changing relationship with the concept of empathy for patients? Our aim is to explore how their feelings about empathy change as they progress through medical school.

2 방법

2 METHODS

2.1 연구 접근법

2.1 Research approach

본 연구에서는 [현실과 지식의 주관성과 사회성]을 강조하는 [상대론적 존재론]과 [사회구성주의 인식론]을 채택한다. 이는 [현실주의자realist], 또는 실증주의자의 양적 관점에서 진행된 대다수의 임상적 공감 연구와는 대조적이다. 후자는 공감의 변화를 측정하는 데 적합하지만, 이러한 변화가 왜 또는 어떻게 발생하는지에 대한 자세한 통찰력을 제공하지 못했다. 이 접근 방식 내에서, 우리는 성찰적 주제 분석을 선택하여 참여자의 경험을 해석하는 데 있어 연구팀의 적극적인 역할을 인정하는 방식으로 데이터를 분석하였다.

Within this study, we adopt a relativist ontology and social constructionist epistemology, which highlight the subjectivity and social nature of reality and knowledge.23-26 This is in contrast to the majority of clinical empathy research, which has been undertaken from a realist, or positivist, quantitative standpoint.11, 27-29 Whilst the latter is suited to measuring changes in empathy, it has not provided detailed insights into why or how these changes occur, questions better explored with a relativist, qualitative approach, adopted here. Within this approach, we have selected reflexive thematic analysis30, 31 to analyse our data in a way that acknowledges the active role of the research team in interpreting participant experiences.32

2.2 설정 및 참가자

2.2 Setting and participants

데이터는 HYMS 윤리 위원회(1902)의 승인에 따라 2019-20학년도 동안 헐 요크 의과대학(HYMS)에서 수집되었다. 모집은 의과대학 경험이 충분한 학생들이 연구 질문에 답할 수 있도록 객관적인 표본을 얻기 위해 4, 5학년 때부터 독점적으로 이루어졌다. HYMS는 850명(여 59%, 남 41%)의 학생이 재학 중인 중소규모 학교이다. 4학년과 5학년은 각각 147명(여 58%, 남 42%)과 132명(여 52%, 남 48%)이다. 모든 자발적 참여자(n = 21)는 포커스 그룹에 참여했지만, 이후 날짜를 맞출 수 없는 한 학생은 예외였다. 우리는 연구 질문에 맞추기 위해 전임 임상 배치 경험이 있는 학생들을 의도적으로 모집했다. 참여는 인센티브가 아닌 자발적이었고, 이메일, 소셜 미디어, 입소문을 통해 모집이 이루어졌다.

Data were collected at the Hull York Medical School (HYMS), during the academic year 2019-20, following approval from the HYMS ethics board (1902). Recruitment was exclusively from years 4 and 5 in order to obtain a purposive sample of students with sufficient experience of medical school to answer the research question. HYMS is a small-medium sized school with 850 students (59% female, 41% male). Years 4 and 5 have 147 (58% female, 42% male) and 132 (52% female, 48% male) students respectively. Every volunteer (n = 21) took part in the focus groups, with the exception of one student who subsequently could not make the date. We purposively recruited students with experience of full-time clinical placements, in order to align with our research questions. Participation was voluntary, not incentivised, and recruitment occurred via email, social media, and word of mouth.

2.3 데이터 수집

2.3 Data collection

포커스 그룹 참여에 앞서, 각 참가자는 익명의 인구 통계 데이터를 수집하기 위한 온라인 설문조사를 완료했다. 학생들은 공감에 대한 자신의 정의와 의과대학 재학 중 공감의 변화가 있었는지에 대해 고려하도록 요청받았다. 이러한 설문 질문은 후속 포커스 그룹 토론을 위해 학생들의 생각을 자극하기 위해 휴리스틱하게 작용했으며, 따라서 독립적인 결과로 보고되지 않는다.

Prior to focus group participation, each participant completed an online survey to collect anonymous demographic data. Students were prompted to consider their own definition of empathy and whether their empathy had changed during medical school. These survey questions acted heuristically to stimulate student thoughts for the subsequent focus group discussion, and so are not reported as standalone results.

포커스 그룹의 시작에서, 참가자들은 30분 동안 환자에 대한 공감을 위해 사랑과 이별 편지를 모두 쓸 수 있는 시간이 주어졌다. 편지 쓰기 프롬프트는 보충 자료로 제공됩니다. 그리고 나서 학생들은 그들의 편지를 큰 소리로 읽는 동안 연구원들은 후속 토론 프롬프트를 위해 메모를 했다. 각 포커스 그룹에는 적어도 두 명의 연구원이 참석했는데, 한 명이 퍼실리테이션을 하는 동안 다른 한 명은 현장 메모를 했다. 레터 리딩에 이어 진행자는 토론을 위해 레터에 의해 제기되는 반복 포인트를 강조했는데, 그 중 상당수는 동료들이 의견을 내고 서로의 기여를 논의하면서 학생 주도로 이루어졌다.

At the beginning of the focus group, participants were given 30 minutes to write both a love and a break up letter to empathy for patients. The letter writing prompts are provided as Supplementary Material. Students then read their letters aloud whilst researchers took notes for subsequent discussion prompts. At least two researchers were present at each focus group – one facilitated whilst the other took field notes. Following letter reading, the facilitator highlighted recurrent points raised by the letters for discussion, much of which was student-led, as peers commented and discussed one another's contributions.

4개의 포커스 그룹이 소집되었지만, 1개는 너무 작아서 분석에 포함시킬 수 없었다(마지막 순간에 결석한 학생은 2명만 참석했다는 의미). 총 3개의 포커스 그룹이 사용 가능했다. 이 세 그룹은 각각 7, 8, 5명의 학생으로 구성되어 있으며, 총 20명이었다. 토론 시간(편지 읽기 제외)은 각각 48분, 42분, 43분이었다. 포커스 그룹 1, 2는 대면 진행했지만 그룹 3은 코로나19로 인해 비디오 스트림으로 진행되었습니다. 포커스 그룹이 녹음한 오디오는 MW & WL에 의해 수동으로 변환되었습니다. 다른 정성적 연구와 마찬가지로, 우리는 (이미 사본이 있는) 편지 읽기 같은 일부 내용을 생략하고 집중적인 전사 전략을 선택했다. 모든 예시적인 인용문은 그대로 캡처되었다.

Four focus groups were convened, but one was too small to be included in the analysis (last minute absence meant only two students attended), leaving a total of three usable groups. These three groups comprised 7, 8 and 5 students respectively, total 20. Discussion times (excluding letter reading) were 48, 42 and 43 minutes respectively. Focus groups 1 and 2 were conducted face-to-face, but group 3 was conducted by video stream, due to COVID-19. Focus group recorded audio was manually transcribed by MW & WL. In common with other qualitative research,33, 34 we chose a focussed transcription strategy, omitting some content such as the reading of letters (where we already had copy). All illustrative quotes were captured verbatim.

2.4 데이터 분석

2.4 Data analysis

포커스 그룹 성적표와 연애편지와 이별편지를 함께 분석하였다. 브라운과 클라크가 자세히 설명하고 키거와 바르피오가 최근 요약한 과정에 따른 반사적 주제 분석이 수행되었다. 브라운과 클라크의 주제 분석 6단계는 다음과 같다.

- (a) 데이터를 숙지합니다.

- (b) 초기 코드 생성

- (c) 테마 검색;

- (d) 주제 검토

- (e) 테마 정의 및 이름 지정

- (f) 보고서 작성

연구자(WL, MB, MW, RA)는 포커스 그룹 대화록과 편지를 독립적으로 코딩하여 분석을 심화하도록 모든 데이터를 이중 코딩하였다. 코드북은 공유 Google 드라이브를 사용하여 구성되었으며 포커스 그룹을 분석하면서 귀납적 코드를 추가했습니다. 분석 및 연구자 토론은 각 포커스 그룹 이후 데이터 수집과 동시에 수행되었으며 그룹은 몇 주씩 분리되었다. 주제는 WL에 의해 서면 서술로 구성되었다. 그 팀은 '정보력'이 충족된 시점에 대해 논의하기 위해 정기적으로 만났다.

— 연구 연구 질문에 답하고 전이 가능한 결과를 생성하기에 충분한 표본 크기:

Focus group transcripts and love and break up letters were analysed together. Reflexive thematic analysis, following the process detailed by Braun and Clarke,30 and recently summarised by Kiger and Varpio31 was undertaken. Braun and Clarke's six steps of thematic analysis were adhered to:

- (a) Familiarise with data;

- (b) Generate initial codes;

- (c) Search for themes;

- (d) Review themes;

- (e) Define and name themes; and

- (f) Produce the report.

Researchers (WL, MB, MW, RA) independently coded focus group transcripts and letters, ensuring all data were double coded to deepen the analysis. The code book was formed using a shared Google drive and inductive codes were added as the focus groups were analysed. Analysis and researcher discussion were occurring contemporaneously with data collection, after each focus group, with the groups being separated by several weeks. Themes were constructed into a written narrative by WL. The team met regularly to discuss the point at which ‘information power32, 35 —a sample size sufficient to answer the study research question and generate transferrable findings—had been met.

2.5 반사적 고려사항 및 민감 개념

2.5 Reflexive considerations and sensitising concepts

우리의 접근 방식은 귀납적이었지만, 이론은 내내 논의되었다. 반사적 대화를 통해 정서적, 인지적, 행동적, 도덕적 요소를 포함한 광범위한 관점에 동의하면서 공감에 대한 개인적인 해석을 명확히 했다. 이 모든 것은 우리의 포커스 그룹 질문 및 데이터 분석을 구상한 [민감한 개념]을 형성했다. 예를 들어, 거의 필요하지 않았지만, 우리는 이러한 개념을 중심으로, 자발적인 논의가 수그러들 경우, 포커스 그룹 질문 프롬프트를 고안했다.

Although our approach was inductive, theory was discussed throughout. Through reflexive conversations, we clarified our personal interpretations of empathy, agreeing on a broad-based view, including affective, cognitive, action and moral components. All of these formed the sensitising concepts10 around which we conceived our focus group questioning and data analysis: for example, although rarely needed, we devised focus group question prompts in case spontaneous discussion waned, which centred on these concepts.

3 결과

3 RESULTS

3.1 인구통계 및 배경 설문지 데이터

3.1 Demographics and background questionnaire data

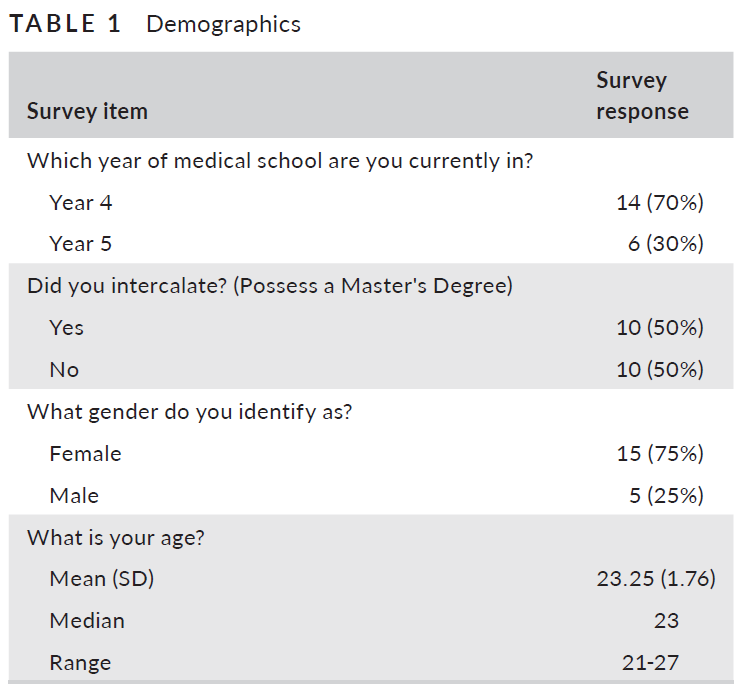

20명의 학생들은 주로 의학교육 4학년이었고, 15명의 여성과 5명의 남성이 참여했다. 표 1은 조사 데이터의 전체 세부 정보를 제공합니다.

The 20 students were primarily in their fourth year of medical education, 15 women and 5 men participated. Table 1 provides full details of survey data.

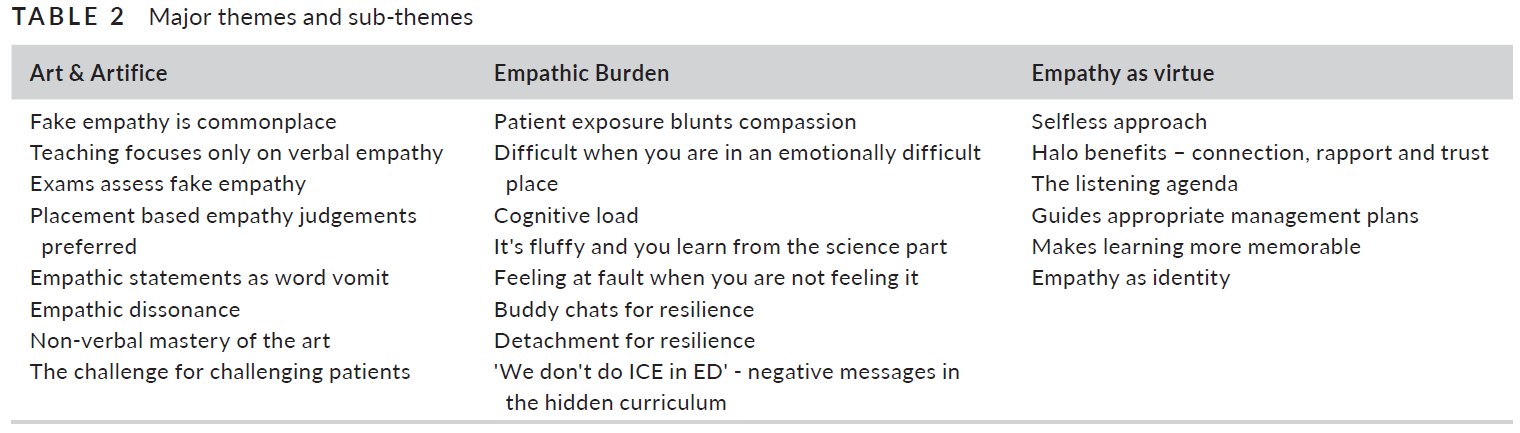

분석 결과 22개의 하위 테마와 3개의 주요 테마(표 2)가 생성되었습니다.

Analysis generated 22 sub-themes and three major themes (Table 2).

주요 주제는 예술과 기교로서의 공감, 공감 부담, 미덕으로서의 공감이었다. 결과는 이 제목 아래에 서술적으로 제시된다.

The major themes were

- empathy as art and artifice,

- empathic burden, and

- empathy as a virtue.

Results are presented narratively under these headings.

3.2 예술과 책략으로서의 공감

3.2 Empathy as art and artifice

학생들은 진정한 공감 소통이 [숙달을 위한 예술]이고, 그 [예술의 숙달]은 [장기적인 노력]이라는 것을 인식했습니다. 역설적이게도, 그들은 또한 임상적 공감의 실천에 많은 책략이 있다는 것을 인식했다.

Students recognised that true empathic communication is an art to master, and mastery of that art is a long-term endeavour. Paradoxically, they also recognised that there is much artifice in the practice of clinical empathy.

여러분의 작은 몸짓과 신호를 포착하는 것은 진정한 예술입니다. 제가 어떤 식으로든, 어떤 형태로든, 어떤 대가도 될 수 없지만, 계속 노력할 것입니다. 편지, 5학년 3반

Picking up on all your little gestures and signals is a true art that I am in no way, shape or form a master at, but will continue to work on. Letter, 5th year student, group 3난 그걸 속이고 있었어…. 아주 오랫동안 그러지 않겠다고 약속했던 건 알지만 더 이상 숨길 수 없어 편지, 4학년 학생, 1조

I’ve been faking it…. for so long. I know I promised I wasn't, but I can't hide it anymore. Letter, 4th year student, group 1

학습은 모의환자(SP)와 함께 형식적인 수업과 실습으로 시작됐고, 임상배치 체험이 이어져 실제 환자와의 공감을 관찰하고 실천할 수 있는 기회가 마련됐다. SP와의 세션은 실제 환자를 만나기 전에 연습할 수 있는 귀중한 기회를 제공했지만 [SP 시나리오의 허구성]과 [역할극의 당혹스러운 요소]가 한계로 보였다. 공식적인 가르침은 [비언어적 표현]보다는 [공감적 진술]에 중점을 둔 것으로 보고되었다.

Learning began with formal teaching and practice with simulated patients (SPs), followed by the experience of clinical placement, allowing opportunity to observe and practice empathy with real patients. Sessions with SPs afforded a valued opportunity to practice before meeting real patients, though the fictitious nature of SP scenarios and the embarrassment factor of role plays were seen as limitations. Formal teaching was reported to centre on empathic statements rather than non-verbal expression.

의과대학은 우리에게 공감을 가르칠 것입니다. 하지만 그것은 항상 언어적이고 우리가 전에 사용했던 공감을 매우 많이 가지고 있습니다. 하지만 그들은 당신의 끄덕임이나 눈맞춤 같은 것을 체크하지 않습니다. 그것은 정말 중요하지 않습니다. 토론, 5학년 학생, 그룹 3

Med school will teach us empathy but it's always verbal and there are so many types of empathy that we did use before, but they don't tick that box kind of, like your nod or your eye contact or whatever, it doesn't really matter. Discussion, Year 5 student, group 3

평가는 또한 공감 진술, 특히 객관적 구조 임상 검사(OSCE)에 초점을 맞췄고, 여기서 공감 기술은 [속임수]로 바뀌었다. 이런 고압적인 상황에서 말 그대로 '공감 상자 체크'를 하기 위해 학생들은 강제적이고 거짓된 공감 발언을 하는 것 외에는 대안이 없었다.

Assessments also focussed on empathic statements—particularly, Objective Structured Clinicals Examinations (OSCEs)—and here the art of empathy turned to artifice. In order to literally ‘tick the empathy box’ in these high-pressure situations, students had no alternative other than to make forced, fake empathic statements.

내 생각에 너는 체크박스가 된 것 같아, '힘들겠다' '정말 답답하다' '이런 일을 겪어야 해서 미안하다'. 하지만 10분간의 OSCE에서, 내가 정말 신경 썼을까? 이게 정말 무슨 의미가 있었나요? 편지, 4학년 학생, 1조

I think you became a tick-box, ‘that must be hard’ ‘really frustrating’ ‘sorry you've had to go through this’. But in a 10-minute OSCE, did I really care? Did this really mean anything? Letter, 4th year student, group 1

학생들은 시험에서 [감정이입 진술을 위조하는 관행]과 같은 아이러니를 보았다. 시험이 [가짜 공감을 평가하는 것]이 되기 때문이다.

Students saw irony in the practice of faking empathic statements in examinations, as the examination then becomes an assessment of fake empathy.

그러니까 어차피 가짜일 거고 공감하는 척을 얼마나 잘하는지 평가하시는 거에요. 토론, 4학년 학생, 1조

So it's gonna be fake anyhow and you are assessing how good you are at faking empathy. Discussion, 4th year student, group 1

학생들은 시험공감과 실생활공감이 별개라는 것을 인식했다.

Students recognised that examination empathy and real-life empathy were two different things.

분명히 시험에서는 단어라고 생각합니다. 하지만 병동에서는 컨설턴트를 보면 정해진 문구보다는 환자들과 어떻게 지내는지가 중요하다고 생각합니다. 컨설턴트들은 진술 없이 여전히 매우 공감해 왔다. 토론, 5학년 2반

I think definitely for exams it's the words, but I think on the wards, if you watch consultants, it's how you are with the patients rather than set phrases. Consultants have still been very empathetic, without the statements. Discussion, 5th year student, group 2

이 문제는 [SP를 사용하는 것]으로부터 강화되었는데, SP는 이미 non-authentic한 OSCE 설정에 추가적인 인공적 요소를 추가했기 때문이다.

The problem was augmented by the use of SPs, which adds an additional layer of artifice to the already non-authentic OSCE setting.

나는 SP에게 진짜 공감을 보여주는 것은 정말 어렵다고 생각한다. 마치 모든 것이 가짜이고, 그들이 배우라는 것을 알고 있고, 그것이 진짜가 아니라는 것을 알고 있다. 토론, 5학년 2반

I think it's really hard with the SPs to show any real empathy, like it's all fake, you know they are actors, you know it's not real. Discussion, 5th year student, group 2

현재의 검사 기반 시스템을 [임상 배치 중에 병원 지도교사와 GP가 내린 판단으로 대체]하는 등 평가에 대한 대안적 접근법이 제시되었다.

Alternative approaches to evaluation were suggested, including replacing the current exam-based system with judgments made by hospital tutors and GPs during clinical placement.

공감에서의 속임수의 문제는 평가에 국한되지 않았다. 실제로, 학생들은 공감하는 말을 속이는 것이 [실제 환경에서도 흔한 관행]이라는 것을 자유롭게 인정했습니다. 대화의 공백을 메우기 위한 장치로 '힘드시겠어요'와 같은 말을 사용하는 것이 일반적인 주제였다.

The problem of artifice in empathy was not confined to assessment. Indeed, students freely acknowledged that faking empathic statements was common practice in real-world settings too. A common theme was the use of statements like ‘that must be difficult’ as a device to fill gaps in conversation.

그들은 약간 단어 토사물처럼 되기 시작한다.

They start to become a bit like word vomit …우리는 그것을 필러처럼 사용해왔습니다. 마치 여러분이 보통 멈췄을 때, 우리는 그것을 거기에 넣는 것을 배웠습니다. 토론 교류, 4, 5학년 학생, 2조

We have used it as our fillers, it's like, whenever you would have a normal pause, we have learned to put it in there. Discussion exchange, 4th & 5th year students, group 2

한 편지는 이것을 시로 표현했다:

One letter expressed this in poetry:

침묵은 시간이 생각할 수 있도록 많은 것을 말해준다.

탄산음료 같은 빈 충전재만 있는 게 아닙니다.

당신은 진정한 의미를 가질 수 있는 많은 잠재력을 가지고 있습니다.

하지만 강요된 말은 당신이 기울고 있는 방식입니다. 편지, 5학년 2반

Silence speaks volumes it allows time to think.

Not just empty fillers like a carbonated drink.

You have so much potential to really have meaning.

But forced words is the way you are leaning. Letter, 5th year student, group 2

가짜 공감이 감지되기 쉽다고 추론하면서, 학생들은 공허한 공감을 나타내는 말에 위화감을 느꼈습니다. 우리가 [공감적 불협화음]이라고 부르는 불편감입니다.

Reasoning that fake empathy is easy to detect, students felt a sense of discomfort around hollow empathic statements, a discomfort we have termed empathic dissonance.

제가 당신에 대해 가장 싫어하는 것은, 감정이입입니다. 우리가 거짓으로 말할 때, 우리는 진정성을 잃는다. 사람들은 이것과 그것을 바로 꿰뚫어 볼 수 있다… 그리고 나는 진심이 아닌 것처럼 보이고 싶지 않다. 편지, 4학년 학생, 1조

What I hate most of all about you, empathy, is when we are faking it, when we lose authenticity. People can see straight through this and its embarrassing… and I hate to seem not genuine. Letter, 4th year student, group 1

진정한 예술 공감 연습을 마스터하기 위해, 학생들은 [가장 가치 있는 교훈]은 [단어보다는 침묵에 있다]는 것을 나타낸다. 여기서 배우는 것은 모범적인 비언어적 의사소통을 보여주는 임상의사의 역할 모델에서 영감을 받아 공식적인 커리큘럼과 맞지 않는다.

In seeking to master the true art empathic practice, students indicate the most valuable lessons are more often in the silences rather than the words. Learning here is out-with the formal curriculum, inspired by clinician role models demonstrating exemplary non-verbal communication.

의대에서의 후반기를 향하면서 초점은 [당신이 말하는 것]에서 [당신이 말하는 방식]으로 바뀐다. … 목소리 톤을 바꾸고 조금 더 앉아서 눈을 마주칠 때처럼… 그리고 그것이 병원 의사들이 정말 잘하는 것입니다. 특히 완화의료 의사들 말입니다. 선배가 침대 옆에 무릎을 꿇는 의사들을 내가 보는 것만큼 자주 보는 것 같지는 않은데… 토론, 5학년 2반

The focus towards the later years in med school switches from what you say to how you say it… sort of when you change your voice tone and sit a bit further in making the eye contact… and that's what hospital doctors are really good at, especially… the palliative care physicians. I don't think I see doctors that senior get on their knees next to beds as often as I see them… Discussion, 5th year student, group 2

학생들은 또한 공감을 언제 적용할지를 선택하고 선택하는 법을 배우는 과정을 묘사했다. 어떤 환자들에게는 공감이 도전이였는데, 여기에는 자신을 도울 준비가 되어 있지 않은 사람들, 그리고 불평하거나 요구하거나 불친절해 보이는 사람들이 포함된다. [어려운 환자]에게는 당연히 공감능력이 더 어렵다는 인식과, 임상의가 이러한 상황에서 학생 공감능력에 악영향을 미쳐 [이러한 환자에 대한 학생의 냉소]를 증가시키고 있다는 인식 모두 있었다.

Students also described a process of learning to pick and choose when to apply empathy. For certain patients, empathy was a challenge, including those who seemed unprepared to help themselves and those who were otherwise complaining, demanding or unfriendly. There was both a sense that empathy is naturally more difficult for difficult patients, and also that clinicians were exerting an adverse influence over student empathy in these situations, increasing student cynicism in regard to these patients.

어려운 환자라고 생각되는 환자에게 공감하는 것은 어려울 수 있습니다. 토론, 4학년 학생, 2반

Patients you see as difficult, it can be difficult to be empathetic towards them… Discussion, 4th year student, group 2또한, 여러분은 더 냉소적이 될 수 있습니다. 만약 여러분이 GP에 있고 GP가 '이 환자가 병원에 오는 것은 정말 그들에게 도움이 되지 않는다'와 같다면 그것은 여러분의 공감을 반대로 영향을 미칩니다. 토론 교환, 5학년 학생 두 명, 그룹 3

Also, you can become more cynical as well… if you are in GP and the GP is like ‘this patient coming in just really doesn't help themselves’ then that impacts your empathy the other way… Discussion exchange, two 5th year students, group 3

3.3 감수해야 할 짐

3.3 Empathy as a burden to bear

[다른 사람의 이야기에 자신을 담는 행위]는 특히 [우울하거나 불행한 상황에 직면한 환자]를 본 후에 감당해야 할, 상당한 부담으로 판명되었다. 시간이 지남에 따라, 그들은 환자 이야기의 감정적인 측면에 더 많이 노출됨에 따라, 학생들은 그들이 적응을 하고 그들의 동정심 있는 반응을 무시한다는 것을 인식한다.

The act of putting yourself in somebody else's story proved a significant burden to bear, especially after a run of patients who were either depressed or facing unfortunate circumstances. Over time, as they became more exposed to the emotional aspects of patient stories, students recognise they undergo an adaptation, a blunting of their compassionate response.

난 끝이야, 끝이야. 난 더 이상 신경 안 써. 여러분은 매일, 환자 한 명 한 명, 눈물 한 방울을 흘리고 있습니다. 항상 할 수는 없어요. 편지, 4학년 학생, 1조

I am so done, so done. I just don't care anymore. You are draining… day after day, patient after patient, tears after tears. I can't do it all the time. Letter, 4th year student, group 1여러분은 공감할 수 있는 어려운 상황을 가진 환자들에게 노출되지만, 그것에 대해 무뎌져야 합니다. 그래서 그들을 사례로 더 많이 보세요. 토론, 4학년 학생, 3반

You're exposed to patients with difficult situations that you do empathise with, but you do have to become blunt to that, so see them more as cases. Discussion, 4th year student, group 3

어떤 상황에서는, 특히 정서적으로 '나쁜 곳'에 있는 경우, 공감 노력이 닿지 않는 것처럼 느껴졌다. 예를 들면, 학생 스스로가 평가의 압박으로 스트레스를 받거나, 원거리 배치에서 외로움을 느낄 때.

In some circumstances, the empathic effort felt out of reach, particularly if students themselves were in an emotionally ‘bad place’, for example when feeling stressed by the pressure of assessments, or lonely in a remote placement.

하지만 그 동안 너(=공감)에 대한 나의 감정은 시험받았고, 사실 3, 4학년 때 나는 너(=공감)에 대해 대부분 무시하고 잊어버렸어. 왜 그랬을까? 어쩌면 제가 의학에 대해 즐겼던 것을 잊었는지도 모릅니다. 어쩌면 우리가 배워야 할 터무니없는 양의 지식, 시험을 치르고, 아무도 없는 곳에 갇혀서 어떤 종류의 삶을 유지하는 것이 여러분보다 선례가 되었는지도 모릅니다. 편지, 5학년 1조

Along the way, however, my feelings towards you have been tested, in fact in 3rd and 4th year, I largely ignored and forgot about you. Why was this? Maybe I forgot what I enjoyed about medicine, maybe the ridiculous amount of knowledge we have to learn, the constant pressure of performing in exams, being stuck in the middle of nowhere and maintaining some sort of life took precedent over you. Letter, 5th year student, group 1

임상발표의 다양한 진단과 관리적 함의를 파악해야 하는 [인지부하]는 공감을 할 수 있는 공간을 적게 남겼다. 이와 관련하여 학생들은 '오토파일럿'에 대한 임상 추론의 상당 부분을 수행하는 숙련된 임상의에 비해 불이익을 느꼈습니다.

The cognitive load of grasping the various diagnostic and management implications of a clinical presentation left less space for empathy. With regard to this, students felt disadvantaged compared to experienced clinicians who do much of their clinical reasoning on ‘autopilot’.

...생각하는 시간의 압박도 있습니다. 그래서, 컨설턴트들과 함께, 그들의 주제를 알고 있는 좋은 사람들은 공감할 수 있는 그런 종류의 사고 시간을 가집니다. 그리고 그 상담, 즉 의학적 측면에서는 단지 2~3분 정도의 생각만 하면 됩니다. 토론 4학년 학생, 그룹 1

…there is also the thinking time pressure. So, with consultants, the nice ones, who know their subject back to front, they have that kind of thinking time to be empathetic and the consultation, the medical side of it, only takes like 2 or 3 minutes of their thinking. Discussion 4th year student, group 1

헤어진 편지들에서 특히 분명한 것은 ['시시한 것fluffy'으로서의 공감]의 개념이었다. 이것은 소중한 시간을 소비하고 평가를 통과하지 못하게 하는 [사소한 방해물]이다. 당신은 공감 부분이 아니라 과학 부분에서 배우는데, 왜 신경을 써야 하는가?

Especially apparent in the break up letters was the concept of empathy as ‘fluffy’, a trivial distraction that eats up precious time and does not get you through assessments—you learn from the science part, not the empathy part, so why bother?

우리가 추는 춤은 주요 이슈를 회피하고 끝없는 감정을 탐구하는 데 시간을 낭비하는 경향이 있다. 요점을 고수하고 잡다한 말fluff 없이 우리가 필요한 것을 말하는 것이 훨씬 간단하다. 편지, 5학년 2반

The dance we tend to do, skirting ‘round the main issue and wasting time exploring endless emotions. Much simpler just to stick to the point and say what we need without the fluff. Letter, 5th year student, group 2

일부 학생들은 공감해야 한다고 생각했을 때 공감을 경험하지 못한 것에 대해 잘못을 느끼고, 또 다른 공감 부담을 가중시켰다.

Some students were left feeling at fault for being unable to experience empathy when they thought they should, adding another layer of empathic burden.

공감은 또한 내가 나 자신이나 환자에 대해 [매우 다른 견해를 가진 사람들]과 같이 특정 환자들과 공감하려고 애쓸 때 죄책감을 느끼게 할 수 있다. 나는 어렵다고 느낀다. 편지, 4학년 2반

Empathy can also make me feel guilty when I struggle to empathise with certain patients such as those with very different views to my own or patients… I feel are difficult. Letter, 4th year student, group 2

학생들은 공감의 부담에 대처하기 위한 다양한 메커니즘을 가지고 있었다. 압도적으로, 가장 일반적인 대처 전략은 [또래 또는 가족과 함께 디브리핑]하는 것이었다. 다른 전략에는 정서적 고립이 포함되었고, 학생들은 순수하게 진료의 '과학'에 집중했다.

Students had a variety of mechanisms for coping with the burden of empathy. Overwhelmingly, the most common coping strategy was debriefing with peers or family. Other strategies included emotional detachment, with students concentrating purely on the ‘science’ of a consultation.

내 친구나 엄마랑 얘기하고 싶어 나는 어떤 기술도 있다고 생각하지 않는다. 그것은 단지 내가 어떤 속상한 상황에 대처하는 방법일 뿐이다. 토론, 4학년 학생, 3반

I feel like I would chat to my buddy about it, or my mum. I don't feel like there are any techniques, it's just how I would deal with any upsetting situation. Discussion, 4th year student, group 3만약 그들이 울면서 들어와서 여러분이 과학에 집중한다면, 여러분은 그것을 피할 수 있을 것입니다. 하지만 여러분이 공감과 아이디어, 우려, 기대에 정말 열심히 노력한다면, 여러분은 빨려들어갈 것입니다. 토론, 4학년 학생, 1조

If they come in crying and you just focus on the science bit then you kind of get around it… but then if you try really hard on the empathy and the ideas, concerns, expectations, you get sucked in. Discussion, 4th year student, group 1

일반적으로 학생들은 [의과대학의 자원]으로 눈을 돌리기 보다는 [그들 자신의 대처 전략]을 찾았다. 어떤 사람들은 그들이 대화할 수 있다고 느끼는 배치당 적어도 한 명의 튜터를 찾기를 희망했지만, 배치의 일시적 성격은 전문적인 관계를 구축하는 것을 더 어렵게 만들었다.

Generally, students found their own coping strategies rather than turning to the resources of the medical school. Although some hoped to find at least one tutor per placement that they felt they could talk to, the temporary nature of placements made building professional relations more difficult.

…. 만약 당신이 당신이 친하게 지내는 그 튜터를 찾을 수 있다면, 그래서 각 블록에 대해 당신은 때때로 하나를 찾을 수 있지만, 당신은 다음 블록으로 이동한다. 토론, 4학년 학생, 1조

…. if you can find that tutor you get along with, so for me each block you can sometimes find one, but then you move blocks. Discussion, 4th year student, group 1

공감교육의 [잠재 교육과정]을 탐색하는 것 자체가 부담으로 작용했다. 학생들은 [공식 교육과정]이 공감의 가치를 증진시키는 반면, [잠재 교육과정]은 이를 폄하하는 경우가 많은 상황에서 위선을 보았다. 학생들은 환자의 아이디어, 우려 및 기대(ICE)에 대한 논의를 [적극적으로 방해하는 감독관]과 함께 일하는 현실적 과제를 설명했습니다.

Navigating the hidden curriculum of empathic teaching proved a burden in itself. Students saw hypocrisy in a situation in which the formal curriculum promotes the value of empathy, whilst the hidden curriculum is often disparaging of it. Students described the real-world challenge of working with supervisors who actively discourage discussions of patient's ideas, concerns and expectations (ICE).

그는 매번 ICE를 한다고 우리를 꾸짖는다.

He tells us off for doing like ICE every time.네, ICE를 하면 문제가 생기죠 토론 교류, 4학년 학생, 1조

Yeah, we do ICE, we get into trouble. Discussion exchange, 4th year students, group 1병원에서는 ICE에 대해 이야기하면 낙담당하거나 서두르기 때문에 우리의 관점을 바꾸게 됩니다. 이는 분명히 그들의 관리를 바꾸지 않기 때문에 '내가 단지 그것을 위해 그것을 하고 있는 것인가?'라고 생각하게 만듭니다. 이것은 공감에 대한 우리의 관점을 바꾼다. 토론, 5학년 2반

In hospital it is discouraged or hurried along if you talk about ICE, so this does change our view, it makes you think ‘am I doing it just for the sake of it?’ as clearly it does not change their management. This changes our view on empathy. Discussion, 5th year student, group 2

3.4 미덕으로서의 공감

3.4 Empathy as a virtue

특히 러브레터를 통해 학생들이 공감을 '더 나은' 사람으로, 더 사심 없는 사람으로 만드는 미덕으로 본다는 것이 특히 분명했다.

It was particularly apparent, especially through love letters, that students see empathy as a virtue, something that makes you a ‘better’, more selfless person.

타인에 대한 생각, 걱정, 기대는 당신의 존재의 중심이며, 나의 이기적인 영혼을 당신에게 끌어당긴 것은 바로 그 사심 없는 마음입니다. 편지, 4학년 학생, 1조

Ideas, concerns, and expectations of others is the centre of your being, and it is that selflessness that has drawn my selfish soul to you. Letter, 4th year student, group 1

공감은 [관련 이익의 집합]과 일치했으며, 그 중 다수는 [선순환적 함의]를 가지고 있다. 학생들은 공감이 [환자와의 연결, 관계와 신뢰 구축, 경청 및 돌봄의제 수립, 환자를 사례나 질병이 아닌 사람으로 대하는 길]이라고 판단했다. 환자에 대한 이해도 향상되면 관리 계획을 조정할 수 있는 등 실질적인 이점도 얻을 수 있습니다.

Empathy was aligned with a collection of associated benefits, many of which also have virtuous connotations. Students reasoned empathy was the route to

- connecting with patients,

- building rapport and trust,

- establishing a listening and caring agenda and

- treating patients as people, not cases or diseases.

Improved understanding of patients also yields practical benefits, such as being able to tailor management plans.

환자와의 관계와 발전, 그리고 신뢰 관계를 구축할 수 있게 해주셔서 정말 좋습니다. 편지, 4학년 2반

I love how you enable me to build rapport and develop and a trusting relationship with patients. Letter, 4th year student, group 2공감은 지속적으로 제가 환자에게 더 나은 치료를 제공할 수 있도록 허락한다. 환자를 전체적으로 고려함으로써, 질병 이외의 복잡한 요구를 가진 누군가가... 당신이 없는 저를 상상하고, 그 숫자를 상상하세요. 편지, 4학년 3반

You continuously allow me to provide patients with better care …. through considering the patient as a whole, someone with complex needs other than a disease… imagine me without you, imagine the number. Letter, 4th year student, group 3

공감능력이 보다 효과적인 학습과 연결되었는데, 그 이유는 공감능력이 환자와의 교육적 만남을 더 기억에 남도록 만들기 때문이다.

Empathy was linked to more effective learning, largely because it made educational encounters with patients more memorable.

공감은 당신이 더 많은 공감을 가졌을 때의 경험을 기억하게 한다고 생각한다. 여러분이 무언가에 더 관심을 가질 때, 여러분은 그것을 더 잘 기억할 것입니다. 공감을 더 많이 할 때 학습에 도움이 된다고 생각해요. 토론, 4학년 학생, 1조

I just think it makes you remember experiences when you have more empathy involved. When you care more about something you are going to remember it better… I think it does help your learning when you have more empathy. Discussion, 4th year student, group 1

공감은 또한 전문적 정체성과 밀접한 관련이 있었고, 의대에 [입학하는 동기]와 그곳에 [남아 있는 이유] 둘 다로 보였다.

Empathy was also closely linked to professional identity and was seen both as a driver for entering medical school and reason for remaining there.

공감은 우리가 의대를 시작한 이유였습니다. 모든 예비 학생들은 동기부여와 필수품으로 인용했습니다. 편지, 5학년 2반

You were the reason we started medical school; cited by every prospective student as a motivator and a necessity. Letter, 5th year student, group 2공감과 함께라면 저는 이 정도 수준의 함정과 높은 수준을 따라잡을 수 있을 것 같습니다. 왜냐하면 궁극적으로 여러분이 제가 이 일을 하는 이유라는 것을 상기시켜주기 때문입니다. 편지, 4학년 학생, 1조

Together I think I can keep up with the pitfalls and heights of being in this degree, because ultimately you remind me that you're the reason why I’m doing this. Letter, 4th year student, group 1

4 토론

4 DISCUSSION

이 정성적 연구는 의과대학 4학년이 될 때까지 학생들이 환자에 대한 공감을 어떻게 느끼는지 이해하기 위해 LBM을 활용했다. 학생들이 보고한 이별 감정 중 일부를 고려하는 것은 특히 흥미롭다. 왜냐하면 이러한 감정들이 우리가 공감의 쇠퇴를 이해하는 데 도움이 될 수 있기 때문이다.

This qualitative study has utilised LBM to understand how students feel about empathy for patients by the time they reach the senior years of medical school. It is particularly interesting to consider some of the break up feelings that students reported, because these may help us to understand empathic decline.

아마도 가장 인상적인 발견은 [가짜 공감]과 관련이 있을 것이고, 학생들은 '그 말을 들으니 유감이다'와 같은 공감하는 진술이 종종 불성실하다는 것을 자유롭게 인정한다. 이는 배치와 평가 설정, 특히 OSCE 모두에 해당했다. 연구는 이전에 의료 교육 및 실습에서 가짜 공감을 강조했습니다. 또한, PA(Physicien Associate) 학생을 대상으로 한 연구는 OSCE의 공감 평가와 동일한 과제를 보고한다. 학생들은 문자 그대로 '공감 상자'를 클릭하도록 강요받고 그들이 진정으로 의도하지 않은 감정 표현을 억지로 외운다. PA학생에 대한 연구와 마찬가지로, 이 연구는 의대생들이 공감 부조화를 경험한다는 것을 확인했다. [공감 부조화]란 [진짜 의도하지 않은 공감의 진술을 하도록 강요당했을 때 학생들이 느끼는 불편함]을 뜻한다. 우리의 데이터는 또한 이러한 진정성 부족, 평가 시스템에 대한 좌절, 공감 부조화 문제가 공감 실천에 대한 일반적인 학생의 냉소를 키울 위험이 있음을 시사한다. 이러한 냉소주의는 다른 곳에서 보고되었고 학생들이 진정한 공감 실천에서 멀어지게 할 위험이 있다.

Perhaps the most striking finding relates to fake empathy, with students freely acknowledging that empathic statements like ‘I am sorry to hear that’ are often insincere. This was true both for placement and for assessment settings, particularly OSCEs. Research has previously highlighted fake empathy in medical education and practice.36-38 Furthermore, research with Physician Associate (PA) students38 reports identical challenges with the assessment of empathy in OSCEs: students feel compelled to literally ‘tick the empathy box’ and force out rote empathic statements that they do not truly mean. As with research on PA students, this study has identified that medical students experience empathic dissonance38—the discomfort students feel when are forced into making statements of empathy they do not truly mean. Our data also suggest that this lack of authenticity, frustration with the assessment system and the problem of empathic dissonance risk breeding a general student cynicism towards the practice of empathy. This cynicism has been reported elsewhere and risks turning students away from authentic empathic practice.13

[공감의 불성실성insincerity]에 대한 우리의 발견은 [공감적 진술]에 중점을 두고 있지만, 우리는 이러한 유형의 진술을 평가절하하고 싶지 않다. 진료에 관한 모델들은 [공감적 진술]의 authentic한 사용을 정확히 지지한다. 시뮬레이션된 환자(SP)를 사용한 연구는 인간 연결의 가치를 확인한다. 그러나, 이 같은 연구는 또한 [공허한 공감적 진술]이 흔하게 발견되고, 환자를 좌절시킬 위험이 있다는 것을 시사한다. 교육자들에게 [공감적 진술]에 대해 균형 잡힌 시각을 가지고, 그들의 장점뿐만 아니라 한계도 인정하면서, 또한 비언어적 의사소통의 가치를 증진시킬 것을 제안한다. 본 연구의 학생들은 환자의 머리맡에 무릎을 꿇는 시간을 갖는 임상의들의 바디랭귀지에 감명을 받았고, 이에 대한 지지는 공감적 경청을 중심으로 문헌에 나와 있다.

Whilst our findings regarding insincerity in empathy centre on the empathic statement, we do not wish to devalue this type of statement. Models of the consultation rightly support its authentic use.39 Research with simulated patients (SPs) confirms their value in establishing a human connection.40 However, this same research also suggests that hollow statements of empathy are easy to detect and risk frustrating the patient.40 We propose that educators take a balanced view on empathic statements, acknowledging their merits but also their limitations, whilst also promoting the value of non-verbal communication. Students in this study were impressed by the body language of clinicians who take the time to kneel by the patient's bedside, and there is support for this in the literature around empathic listening.40-42

['감정노동']과 [연민 피로]로서의 공감의 개념은 실제 임상의에 대한 연구에서 확립된다. 우리의 데이터는 또한 학생들이 [너무 많은 공감적 참여]가 [정서적 소진]으로 이어질 것을 두려워한다는 것을 확인시켜준다. 여기에 발표된 증거는 이 우려를 뒷받침하는 일부 연구와 반박하는 다른 연구로 모순된다. 그러나 [공감이 번아웃으로 연결될 위험이 있다는 단순히 인식]이 학생들을 환자에 대한 공감에서 멀어지게 할 수도 있다. 본 연구는 또한 학생들의 공감을 저해할 수 있는 유사한 잠재력을 가진 숨겨진 교육과정 내의 요소들을 강조한다. 의학교육이 '과학적인 것'을 우선시하는 경향과 임상실천에서 공감할 시간이 없음을 암시하는 부정적 역할모델링 등 일부 요인은 이전에 보고되었다.

The concepts of empathy as ‘emotional labour’43 and compassion fatigue44 are established in research with practising clinicians. Our data confirm that students also fear that too much empathic engagement leads to emotional burnout. Published evidence here is contradictory, with some research to support this concern45, 46 and other research to refute it.46 However, simply the perception that empathy risks burnout may turn students away from empathy for patients. This study also highlights factors within the hidden curriculum11 with similar potential to deter student empathy. Some factors have been previously reported, including the tendency for medical education to prioritise the ‘science stuff’47 and the negative role modelling that implies there is no time for empathy in the real world of clinical practice.38

또한 우리의 자료에서 그리고 이전에 PA 학생 연구에서 보고된 것은 의학교육의 경향으로 [일부 환자들은 공감할 자격이 있지]만, [다른 환자들은 공감할 자격이 없다]고 믿도록 학생들을 사회화하는 것이다. 학생들은 감독관들이 '어려운' 환자에 대해 하는 부정적인 논평에 영향을 받았다. 공감에 대한 그녀의 글에서, Halpern은 [의료진을 향한 도전적인 행동]이 때로는 [도움을 요청하는 외침]이라는 것을 상기시킨다. 샤피로는 내집단을 위한 공감을 유보하고, 외집단을 배제하지 말라고 경고한다. 모든 환자를 '무조건적 긍정적 존중'으로 대하라는 로저스의 문구는 완벽함을 위한 조언이지만, 교육자들이 학생들에게 소통할 수 있는 전문적인 기준으로 남아 있다.

Also evident in our data, and previously reported in PA student research,38 is the tendency of medical education to socialise students into the belief that whilst some patients ‘deserve’ empathy, others do not. Students were influenced by negative comments supervisors make about ‘difficult’ patients. In her writing on empathy, Halpern reminds us that challenging behaviours are sometimes a cry for help.48 Shapiro cautions against reserving empathy for in-groups and excluding out-groups.47 Rodgers’ phrase of holding all patients in ‘unconditional positive regard’49 is a counsel of perfection, but remains a professional standard for educators to communicate to students.

본 연구의 학생들은 회복탄력성에 대한 선행연구와 마찬가지로, 회복탄력성이 낮을 때 공감적 진료상담이 이루어지기 어렵다는 것을 알 수 있다. 특히 회복탄력성을 감소시킨 두 가지 요인은 [평가에 대한 스트레스]와 [원격 배치의 외로움]이었다. 외로움은 학생들이 동료들로부터 지지를 구하는 것을 확인한 주요 대처 전략에 반한다. 학생들은 학교의 자원보다 동료들에게 더 쉽게 의지했다. 교육자들은 또한 학생들이 배치를 통해 자주 로테이션할 때 임상 멘토를 찾기 어렵다는 것을 알아야 한다. 이것은 회복력에 부정적인 영향을 미칠 수 있으며 종적 통합 임상실습에 대한 잠재적인 논쟁거리이다.

As with previous research on resilience,44, 45, 50 students in this study indicate that when resilience is down empathic consulting is difficult to achieve. Two factors which particularly reduced resilience were the stresses of assessments and the loneliness of remote placements. Loneliness militates against the main coping strategy that students identified that of seeking support from peers. Students more readily turned to peers than to the resources of the school. Educators should also be aware that students find clinical mentors difficult to find when frequently rotating through placements. This may have adverse effects on resilience and is a potential argument for longitudinal integrated clerkships.51

[미덕으로서의 공감]이라는 주제는 학생들이 공감을 직업 정체성에 맞추고, 의학을 선택하는 주요 동기로 인용하면서 데이터를 통해 강하게 흘러갔다. 이러한 미덕적 측면은 임상적 공감의 진정한 본질과 그것이 의학 교육 내에서 어떻게 간주되어야 하는지에 대한 철학적, 존재론적 고려를 제기한다. 미덕이 특성, 즉 인간의 속성이라는 것을 감안할 때, 우리는 공감을 같은 방식으로 보아야만 할까요? 블룸의 분류학에서 공감은 기술보다 태도에 가까운가? 연구자들은 현대 의학 교육이 공감을 [기술]로서 가르치고 평가하는 데 너무 중점을 두고 있으며, 공감이 한 인간human being이 다른 사람에게 빚진owes to 자질이라는 개념을 과소평가한다고 주장해왔다.

The theme of empathy as a virtue ran strong through the data, with students aligning empathy to professional identity and citing it as a prime motivator for choosing medicine. These virtue aspects raise philosophical and ontological considerations as to the true nature of clinical empathy and how it should be regarded within medical education. Given that virtue is a trait, a human attribute, should we regard empathy in the same way? In terms of Bloom's taxonomy,52 is empathy closer to an attitude than a skill? Researchers have argued that contemporary medical education puts too much emphasis on teaching and assessing empathy as a skill and undervalues the notion that empathy is a quality that one human being owes to another.48

기술에서 벗어나 태도 또는 더 나은 속성으로 패러다임 전환을 통해 본 논의에서 제기된 몇 가지 문제에 대한 가능한 해결책을 제시합니다. OSCE의 경우, 교육자들은 공감의 '보여주기shows'와 '수행능력'를 평가하는 효용성을 재고할 수 있다. '보여주기shows'와 '수행능력'은 [정확히 OSCE가 밀러의 피라미드에서 차지하는 수준]이기 때문이다. [공감을 '존재의 방식'으로 여기는 교육자들]은 [동정심을 보이는 것] 만으로는 [진정한 공감 행위]와 동일시되지 않는다는 것을 인식하고, 두 가지를 혼동하는 평가를 거부할 가능성이 높다. 공감을 조금이라도 평가하려면 본 연구에서 학생들이 제안한 대로 튜터가 실제 임상 배치 판단을 선호할 것이다. 샤피로는 의학교육 내에서 [공감적 진료상담의 기풍]에 중점을 둔다면, 학생들은 현재 의학 문화에서 아웃그룹으로 간주되는 어렵고 도전적인 환자들에 대한 공감을 찾기 위해 더 많은 노력을 기울일 것이라고 주장한다. [공감의 미덕적 측면]을 재확인하는 것은 학생들이 숨겨진 교육과정 안에 내포된 다른 부정적인 메시지들을 극복하는데 유사하게 도움이 될 수 있다.

A paradigm-shift away from skills and towards attitudes—or perhaps better, attributes—presents possible solutions to some of the problems raised in this discussion. In the case of OSCEs, educators may reconsider the utility of assessing ‘shows’ and ‘performances’ of empathy, for ‘show’ and ‘performance’ is precisely the level the OSCE occupies in Miller's pyramid.53 Educators who regard empathy as a ‘way of being’8 are more likely to recognise that the mere show of compassion does not equate to the true act, and would reject an assessment that confuses the two.54 If empathy is to be assessed at all, our preference would be real-world clinical placement judgments made by tutors, as suggested by students in this study. Shapiro argues that if emphasis is made on committing to an ethos of empathic consulting within medical education, students would be more likely to stive to find empathy for those difficult and challenging patients who are currently regarded as outgroups in the culture of medicine.47 Reaffirming the virtue aspects of empathy may similarly help students overcome other negative messages implied within the hidden curriculum.

4.1 제한 사항

4.1 Limitations

본 연구의 주된 한계는 한 기관에 국한되어 있다는 것이다. 비록 통합 커리큘럼과 커뮤니케이션 교육이 많은 다른 서양 학교들과 비슷할 것으로 예상하지만, 가르침에 관한 일부 연구 결과는 이 학교에 특별할 수 있다. 우리는 학교가 커뮤니케이션 교육에 널리 채택된 [캘거리 캠브리지 모델]을 사용하고, 대부분의 학교에서 비슷하게 사용되는 SP와의 세션을 포함하여 초기에 대학 기반 커뮤니케이션 교육을 집중하는 관행을 기반으로 한다. OSCE를 통한 커뮤니케이션 능력 평가는 다른 기관에서도 널리 채택되고 있다. 예를 들어, HYMS 학생들은 1학년, 2학년, 3학년 때 종합 OSCE를 가졌다. LBM 방법론은 데이터 수집이 포커스 그룹에서만 이루어졌다는 것을 의미했으며, 이는 이러한 그룹의 공공성에 대해 우려하는 일부 학생들의 보다 민감한 기여를 방해했을 수 있다. 우리의 코호트는 여성이 남성보다 더 많은 공감을 보인다는 증거를 고려할 때, 여성 대 남성 비율이 3:1이었다. 이것은 또한 소견의 전달 가능성에 영향을 미칠 수 있다.

The principle limitation of this research is that it is confined to one institution. Some findings regarding teaching may be specific to this school, although we anticipate its integrated curriculum and communication teaching are similar to many other Western schools. We base this assumption on the school's use of the widely adopted Calgary Cambridge55 model for communication teaching, and the practice of concentrating university-based communication teaching in the early years, including sessions with SPs, which are similarly utilised in the majority of schools.56 The assessment of communication skill through OSCEs is also widely adopted in other institutions—for context, HYMS students had summative OSCEs in 1st, 2nd and 3rd years. LBM methodology meant data collection was exclusively from focus groups, which may have hindered more sensitive contributions from some students concerned about the public nature of these groups. Our cohort had a female to male ratio of 3:1, given the evidence that females demonstrate more empathy than males,57, 58 this may also affect the transferability of findings.

5 LBM 반사

5 LBM REFLECTIONS

의학 교육 연구에서 LBM의 첫 번째 사용이기 때문에, 우리는 방법론에 대한 간략한 반성을 제공한다.

As this is the first use of LBM has in medical education research, we offer brief reflections on the methodology.

사랑과 이별의 편지는 여기서 의인화, 은유, 과장, 심지어 시를 포함한 고조되고 비유적인 언어를 요구한다. 이 글은 더 다채롭다. 그것은 흥미와 참여를 높이며, 그렇지 않으면 추상적인 주제가 될 수 있는 것에 대한 토론을 부추긴다. 그 편지들은 또한 우리의 연구 분석에 우리를 참여시켰다. 창의적인 글쓰기는 더 풍부한 메시지를 전달하고 더 풍부한 메시지는 분석을 위한 더 풍부한 데이터로 변환됩니다. LMB는 [모든 그룹 구성원이 초기 음성을 가질 수 있도록] 하여, 조용한 구성원이 수다스러운 구성원에 의해 가려질 수 있는 포커스 그룹의 한계를 완화한다. [큰소리로 편지를 읽는 것]도 토론이 이어질 수 있는 쇄빙선 역할을 한다. 마지막으로, 편지는 포커스 그룹 내용을 보완합니다. 즉, 분석을 위한 증가된 데이터를 제공합니다.

Love and break up letters call for heightened, figurative language, here including personification, metaphor, hyperbole, even poetry. This writing is more colourful. It elevates interest and engagement, fuelling discussion around what could otherwise be an abstract topic. The letters also engaged us in our research analysis. Creative writing communicates richer messages and richer messages translate to richer data for analysis. LMB allows all group members to have an initial voice, mitigating a limitation of focus groups that quieter members may be over-shadowed by talkative ones.59 Reading letters aloud also acts as an icebreaker for the discussion to follow. Finally, the letters supplement the focus group transcripts: they provide increased data for analysis.

물론 한계가 있다. 사랑과 이별의 편지는 본질적으로 이분법적이어서 극적 대립에 초점을 맞추고 그 사이의 회색 음영을 희생시킨다. 포커스 그룹 진행자들은 이것을 유념할 필요가 있다. 진행자들은 또한 창의적인 글쓰기를 경계하고 그들의 편지를 읽는 것을 부끄러워하는 참가자들에게 민감할 필요가 있다. 실제 수준에서, 쓰기 과제는 본 연구에서 20-30분을 추가하여 포커스 그룹의 기간을 연장한다.

Of course, there are limitations. By their nature, love and break up letters are dichotomous, risking a focus on polar opposites and sacrificing shades of grey between. Focus group moderators need to be mindful of this. Moderators also need to be sensitive to participants who are wary of creative writing and embarrassed to read their letters. On a practical level, the writing task extends the duration of the focus group, adding 20-30 minutes in this study.

6 결론

6 CONCLUSION

본 연구는 의과대학 재학 중 환자에 대한 학생 공감의 질적 변화를 확인한다. 학생들은 먼저 [공감적 진술]을 배우고 나서, 그들의 의사소통 연습을 [더 자연스러운 어구 및 비언어적 표현]을 포함하도록 진화시킨다. 그러나 그들은 또한 현재의 평가 방법에 의해 악화되는 문제인 [공감적 진술을 위조하는 법]을 배운다. [연민적 의사소통의 장벽]에는 [공감 부담, 부정적인 역할 모델링, 어려운 환자에게 연민적 접근 방식을 채택하는 문제]가 포함된다. 이러한 장벽에도 불구하고, 학생들은 계속해서 공감을 미덕으로 인식하고 기술에 숙달된 임상의로부터 긍정적인 동기를 얻는다. 조사 결과를 바탕으로 교육자의 주요 요점을 제시합니다(표 3).

This study confirms qualitative changes in student empathy for patients during their time in medical school. Students first learn empathic statements and then evolve their communication practice to incorporate more natural turns of phrase and non-verbal expression. However, they also learn to fake empathic statements, a problem exacerbated by current assessment methods. Barriers to compassionate communication include empathic burden, negative role modelling and the challenges of adopting a compassionate approach for difficult patients. Despite these barriers, students continue to identify with empathy as a virtue and take positive motivation from those clinicians who demonstrate mastery of the art. Based on our findings, we include key points for educators (Table 3).

표 3. 교육자의 주요 사항

Table 3. Key points for educators

|

How medical school alters empathy: Student love and break up letters to empathy for patients

PMID: 33128262

DOI: 10.1111/medu.14403

Abstract

Introduction: Medical education is committed to promoting empathic communication. Despite this, much research indicates that empathy actually decreases as students progress through medical school. In qualitative terms, relatively little is known about this changing student relationship with the concept of empathy for patients and how teaching affects it. This study explores that knowledge gap.

Methods: Adopting a constructivist paradigm, we utilised a research approach new to medical education: Love and Breakup Letter Methodology. A purposive sample of 20 medical students were asked to write love and break up letters to 'empathy for patients'. The letters were prompts for the focus group discussions that followed. Forty letters and three focus group discussions were thematically analysed.

Results: The three major themes were: art and artifice; empathic burden; and empathy as a virtue. Students were uncomfortable with the common practice of faking empathic statements, a problem exacerbated by the need to 'tick the empathy box' during examinations. Students evolved their own empathic style, progressing from rote empathic statements towards phrases which suited their individual communication practice. They also learned non-verbal empathy from positive clinician role-modelling. Students reported considerable empathic burden. Significant barriers to empathy were reported within the hidden curriculum, including negative role-modelling that socialises students into having less compassion for difficult patients. Students strongly associated empathy with virtue.

Conclusions: Medical education should address the problem of inauthentic empathy, including faking empathic s in assessments. Educators should remember the value of non-verbal compassionate communication. The problems of empathic burden, negative role modelling and of finding empathy difficult for challenging patients may account for some of the empathy decline reported in quantitative research. Framing empathy as a virtue may help students utilise empathy more readily when faced with patients they perceive as challenging and may promote a more authentic empathic practice.

© 2020 John Wiley & Sons Ltd and The Association for the Study of Medical Education.

'Articles (Medical Education) > 전문직업성(Professionalism)' 카테고리의 다른 글

| 세대적 상황성: 보건의료전문직에서 세대적 고정관념에 도전하기 (Med Teach, 2022) (0) | 2023.01.10 |

|---|---|

| 뒤를 돌아보고 앞으로 나아가기: 의과대학 1학년의 포트폴리오 글쓰기에 대한 메타-성찰(Acad Med, 2018) (0) | 2022.12.15 |

| 초기 임상실습에서 전문직정체성형성 이해하기: 새로운 프레임워크(Acad Med, 2019) (0) | 2022.08.17 |

| 보건전문직 교육에서 공감: 무엇이 효과적이며, 격차와 개선 영역은? (Med Educ, 2022) (0) | 2022.08.10 |

| 의과대학에서 전문직업성 기르기: 1990년과 2019년 사이 교육과정의 체계적 스코핑 리뷰(Med Teach, 2020) (0) | 2022.08.09 |