포화라는 위장 뒤에 숨은 것: 질적 인터뷰 자료와 견고함 (J Grad Med Educ, 2021)

Beyond the Guise of Saturation: Rigor and Qualitative Interview Data

Kori A. LaDonna, PhD . Anthony R. Artino Jr, PhD . Dorene F. Balmer, PhD

대학원 의학교육(GME)을 연구하는 이들을 포함한 보건직업 교육 연구자들이 교육 실천을 지도할 수 있는 근거 기반을 구축하고 있다. 지난 20년 동안 질적 연구자들은 수많은 경험적 발견을 해냈다. 그러나 좋은 질적 증거의 특징은 무엇인가?

Health professions education researchers, including those who study graduate medical education (GME), are building an evidence base to guide educational practice. Over the last 2 decades, qualitative researchers have generated a plethora of empirical findings. However, what are the features of good qualitative evidence?

엄격함 및 포화도

Rigor and Saturation

보건 직업 교육에서 질적 연구자는 "어떻게 교수진이 저성취나 실패를 탐색하는가?"1 또는 "왜 일부 의대생은 소아과에서 직업적 관심을 유지하는가?"2 그러한 질문에 답하기 위해 질적 연구 과정은 적절히 견고해야 한다. 일반화가능한generalizable 것이 아닌 전이가능한transferable 연구 결과를 도출한다.3 이는 연구 상황을 넘어서는 상황에서 생각을 촉발하고, 문제를 제기하며, 정보를 제공하거나, 실천을 바꾼다는 것을 의미한다. 이를 위해, 연구 결과는 타당하거나 신뢰할 수 있거나 대표적일 필요는 없지만, 신뢰할 수 있고, 공명적resonant이며 풍부해야 한다.3-6 이러한 기준의 주관성을 고려할 때, 일대일 인터뷰 방법을 사용하는 정성적 연구의 엄격성을 어떻게 평가하고 있는가?

In health professions education, qualitative researchers explore how and why questions, such as “How do faculty members navigate underperformance or failure?”1 or “Why do some medical students maintain a career interest in pediatrics while others do not?”2 To answer such questions, the qualitative research process must be appropriately robust to produce findings that are transferable rather than generalizable,3 which means that they provoke thought, raise questions, and inform or change practice in settings beyond the research context. To do this, findings do not need to be valid, reliable, or representative, but they do need to be credible, resonant, and rich.3–6 Given the subjectiveness of these criteria, how do we evaluate the rigor of qualitative research that uses one-on-one interview methods?

엄격함은 종종 주로 [포화] 상태에 달려있다고 가정되는데, 이는 일반적으로 면접이 더 이상 새로운 정보를 생성하지 않거나 연구자들이 "모든 것을 들었다"고 결정할 때 데이터 수집의 포인트로 이해된다. 포화라는 아이디어는 충분히 간단해 보이지만, 포화도가 의미하는 바에 대한 상당한 혼란은 언제 그것이 도달하는지(또는 도달하는지) 결정하는 것은 어게 한다. 실제로 정성적 인터뷰 기반 연구의 체계적인 분석은 저자들이 [포화]의 지표를 가변적이고 부적절하게 기술했으며, 검토자(그리고 아마도 그들 자신)에게 주장을 입증하기에 충분한 표본을 모집했다는 것을 확신시키기 위해 참가자 수에 종종 초점을 맞췄다는 것을 입증했다. 결과적으로, 많은 GME 연구자들은 그들의 연구에서 포화가 무엇을 의미하는지 설명하거나, 그들의 데이터가 실제로 포화되었다는 주장을 뒷받침하는 증거는 제공하지 않고, "우리는 아홉 번째 레지던트를 인터뷰한 후에 포화상태에 도달했다"와 같은 진술을 한다.

Rigor is often assumed to hinge largely on saturation, which is typically understood as the point in data collection where interviews are either no longer generating new information or when researchers determine that they have “heard it all.”7 While this idea seems simple enough, considerable confusion about what saturation means makes it difficult to determine when (or if) it is reached. Indeed, a systematic analysis of qualitative interview-based studies demonstrated that authors variably and inadequately described indices of saturation and often focused on participant numbers to try to convince reviewers (and perhaps themselves) that they have recruited a large enough sample to substantiate their claims.8 Consequently, many GME researchers make statements like “we reached saturation after the ninth resident was interviewed” without either describing what saturation means for their study or providing evidence to support the claim that their data were actually saturated.8

포화상태에서 충분상태로

Shifting From Saturation to Sufficiency

질적 데이터 세트는 반복 주제 패턴을 식별할 수 있으면서(깊이), 동시에 모순되는 예를 설명할 수 있을 만큼(너비) 충분히 포괄적이어야 한다. 단순히 포화는 참여자 수보다 더 많은 것에 좌우된다는 얘기다. 우리는 리뷰어들에게 주로 표본 크기에 초점을 맞춰 퀄리티를 평가하는 것은, 실제로는 기준을 충족하지 못한 데이터를 위장할 수 있음을 경고합니다. 사실, 연구 윤리에 대한 최근의 국제 연구는 연구자의 11%가 포화 같은 용어를 부적절하게 알고 있다고 인정했다는 것을 발견했고, 이는 보건 직업 교육에서 가장 흔한 의문스러운 연구 관행 중 하나가 되었다.9

A qualitative dataset should be comprehensive enough (depth) to both identify recurrent thematic patterns and to account for discrepant examples (breadth).7 In other words, saturation depends on more than the number of participants. We caution reviewers that appraisals of quality focused primarily on sample size may be a guise for data that do not meet these criteria. In fact, a recent international study of research ethics found that 11% of researchers admitted to knowingly using terms like saturation improperly, making it among the most common questionable research practices in health professions education.9

설상가상으로, 일부 질적 연구자들은 포화 상태에 도달하는 것이 가능한지에 대해 의문을 품기 시작했다.10-13 대신에, 많은 질적 연구자들은 충분성은 분석 과정의 엄격함(분석적 충분성)과 그것이 생성하는 데이터의 풍부함(데이터 충분성) 모두에 달려 있다는 것을 인식하면서 품질 발견을 충분하다고 설명하는 것으로 전환하였다. 데이터 세트를 [객관적인 포화점을 가진 스폰지]에 비유하는 포화상태와 달리, [충분성]의 개념은 (인간 경험의 고유성과 사회적으로 구성된 데이터의 특성을 모두 인정하는 연구 패러다임 내에서) 은유적으로 연구자들이 지속적으로 데이터 세트를 짜낼 수wring out 있음을 시사한다. 인터뷰 가이드를 반복적으로 수정하고, 새로운 참가자를 샘플링하며, 여러 차례의 데이터 생성 및 분석에 참여함으로써 새로운 이해도를 얻을 수 있습니다. 하지만 연구는 영원히 계속될 수 없습니다. 의지할 수 있는 검정력 분석이나 표본 크기 계산 없이, 어떻게 연구자들이 그들이 "모든 것을 들었다"는 것이 아니라, 그들이 [충분히 들었다는 것]을 설득력 있게 증명할 수 있을까?

To further complicate matters, some qualitative researchers have begun to question whether reaching saturation is even possible.10–13 Instead, many qualitative researchers have shifted to describing quality findings as sufficient, recognizing that sufficiency depends on both the rigor of the analytical process (analytical sufficiency) and the richness of the data it generates (data sufficiency). Unlike saturation, which likens a dataset to a sponge with an objective saturation point, the notion of sufficiency suggests that—within a research paradigm that acknowledges both the uniqueness of human experience and the socially constructed nature of data—researchers can metaphorically wring out their dataset, continuously dipping into a well of new understanding by iteratively revising interview guides, sampling new participants, and engaging in multiple rounds of data generation and analysis. But research studies cannot go on forever. Without power analyses or sample size calculations to rely on, how can researchers convincingly demonstrate not that they have “heard it all,”7 but that they have heard enough?

정성적 발견의 충분성 평가

Evaluating the Sufficiency of Qualitative Findings

포화 개념의 한계를 고려할 때, [정보력information power]의 개념은 충분성 평가를 위한 더 나은 척도를 제공할 수 있다. 질적 발견이 충분한지를 결정하기 위해 정보력을 사용하는 것은 연구의 목적, 표본의 특수성, 이론의 사용, 분석 전략, 면접의 질에 따라 달라진다.

Given the limitations of the saturation concept, the notion of information power14 may provide a better gauge for evaluating sufficiency. Using information power to determine whether qualitative findings are sufficient depends on examining them alongside the aims of the study, the specificity of the sample, the use of theory, the strategy for analysis, and the quality of the interviews.

질적 연구자들은 뚜렷한 유리한 관점에서 현상을 조사하기 위해 다양한 분석 전략을 이용하는 많은 방법론적 접근법을 사용한다. 어떤 방법론은 몇 개의 개별 accounts에 대한 심층 분석을 위해 설계된 반면, 어떤 방법론은 여러 관점에서 현상을 분석하기 위해 더 큰 샘플을 필요로 한다.14 또한 특정한 잠재적 참여자 그룹을 대상으로 하는 [협소한narrower 연구 목표]를 가지고 있다면, 더 희박한 샘플로 데이터 충분성을 달성할 수 있다. 예를 들어 [텍사스와 뉴멕시코의 아동학대 동료들이 어떻게 인간 밀수업자에 의한 강간 혐의의 첫 사례를 관리하는지를 탐구하는 연구]는 [훨씬 광범위한 목적을 가진 연구(예: 북미 전역의 소아과 동료들이 아동학대를 보고할 때 그들의 감정을 어떻게 관리하는지)]보다 적은 참가자를 필요로 할 수 있다.

Qualitative researchers use a multitude of methodological approaches that draw on various analytical strategies to examine a phenomenon from a distinct vantage point. Some methodologies are designed to produce an in-depth analysis of a few individual accounts, whereas other methodologies require a larger sample to analyze a phenomenon from multiple points of view.14 Moreover, a narrower study aim with a targeted group of potential participants may allow for data sufficiency to be achieved with a leaner sample size. To illustrate, consider that a study exploring how child abuse fellows in Texas and New Mexico manage their first case of suspected rape by human smugglers may need fewer participants than a study with the much broader aim of examining how pediatrics fellows across North America manage their emotions when reporting child abuse.

충분성에 대한 요구사항은 또한 연구자의 의도가 [현상을 기술]하는 것인지, 아니면 [이론을 생성]하는 것인지에 달려있다. 예를 들어, 가상 학습에 참여하는 1학년 레지던트들에 대한 서술적 질적 연구는 가상 학습에 대한 적응에 대한 구성주의 근거이론(CGT) 탐구보다 더 적은 인터뷰 샘플과 덜 집중적인 분석 작업을 요구할 가능성이 높다. CGT에서, 강력한 이론화는 종종 [20회 이상의 심층 인터뷰]와 점점 더 해석적인 코딩의 여러 라운드에 의존한다.16,17 실제로, 충분성의 도달이라는 측면에서 [이미 선험적으로 존재하는 이론을 사용하여, 특정 연구 렌즈를 통해 현상을 조사하는 연구]는 [귀납적으로 이론을 구축하려는 연구]는 출발점이 서로 다르다. 따라서, [데이터 생성과 분석을 프레임화하기 위해 자기결정 이론19를 사용하는 연구]는 [정규 커리큘럼 밖에서 학습에 참여하려는 전공의의 동기에 대한 이론 생성을 목표로 하는 연구]보다 더 적은 인터뷰와 덜 해석적인 노동으로 충분할 것이다.

Requirements for sufficiency also depend on whether the researcher's intention is to describe a phenomenon or to generate theory. For example, a descriptive qualitative study15 of first-year residents engaging with virtual learning will likely require both a smaller sample of interviews and less intensive analytical work than a constructivist grounded theory (CGT)16,17 exploration of adaptations to virtual learning. In CGT, robust theorizing often relies on 20 or more in-depth interviews18 and multiple rounds of increasingly interpretive coding.16,17 Indeed, studies using theory a priori to examine a phenomenon through a specific research lens are at different starting points for reaching sufficiency than studies seeking to build theory inductively. Consequently, a study using self-determination theory19 to frame data generation and analysis will likely reach sufficiency with fewer interviews and less interpretive labor than a study aimed at generating theory about residents' motivation to engage in learning outside the formal curriculum.

정보력 모델은 [더 큰 표본이 더 나은 데이터와 같다]는 통념을 버린다. 따라서 충분성을 평가할 때는 양보다 인터뷰의 질이 더 중요합니다. 풍부한 데이터를 생성하기 위해 인터뷰는 대화식이어야 하고, 연구 주제에 초점을 맞추어야 하며, 전략적인 후속 질문이 필요하고, illustrative examples을 위한 프롬프트가 필요하다. 면접관 실력이 무엇보다 중요합니다. 면접관은 참가자와 공감대를 형성하고, 사려 깊은 성찰을 유도하며, 참가자의 순간적 반응과 진화하는 분석에 따라 연구 질문이 확대되거나 방향이 전환될 수 있도록 면접 가이드를 수정해야 한다. 질적 엄격함을 정량화하기는 어렵겠지만, [인터뷰 길이]가 표본 크기보다 정보 파워의 더 유용한 지표일 수 있음을 제안한다. 이 지침은 완벽하지 않으며 규범적으로 따라서는 안 되지만, [개방형 질문으로 1시간 이상 이어지는 6번의 심층 인터뷰를 한 경우]가 [표면 수준의 답변만 이끌어내는 10분짜리 인터뷰 20건]보다 풍부한 데이터를 산출할 가능성이 높다. 물론 면접 데이터가 풍부할 뿐만 아니라, [연구자의 개념, 실천, 문제에 대한 새로운 생각, 사고를 촉발하는 통찰력에 기여하는지]도 충분성이 진정으로 달성되었는지를 검증하는 방법이다.

The information power model dispels the myth that bigger samples equal better data. Thus, when evaluating sufficiency, interview quality matters more than quantity. To generate rich data, interviews must be conversational, focused on the research topic, and peppered with strategic follow-up questions and prompts for illustrative examples. Interviewer skill is paramount. Interviewers need to develop rapport with participants, invite thoughtful reflection, and adapt the interview guide to allow for research questions to expand or shift direction depending on participants' in-the-moment responses and the evolving analysis. While we hesitate to quantify qualitative rigor, we suggest that interview length may be a more useful indicator of information power than sample size. While this guidance is not foolproof and should not be followed prescriptively, 6 in-depth interviews with open-ended questions lasting an hour or more will likely yield richer data than twenty 10-minute interviews that elicit only surface-level responses. Of course, the true test of sufficiency is whether interview data are not only rich but also contribute new or thought-provoking insights into a GME concept, practice, or problem.

명확한 증거 가치 전달

Clearly Conveying Evidentiary Value

우리는 연구자들에게 학술적 글쓰기가 비효율적인 경우, 가장 강력한 질적 발견조차도 설득력이 없어 보이게 할 수 있다고 경고한다. 정보력은 정성 표본의 충분성을 평가하거나 정당화하는 데 유용하지만, [정성적 발견의 증거적 가치evidentiary value]는 풍부한 데이터와 엄격한 분석 그 이상이다. 여기에는 반드시 좋은 글쓰기가 필요하다. 출판을 위한 연구의 초안을 작성할 때, 연구 절차와 의사결정 과정을 투명하고 설득력 있게 만드는 책임은 저자에게 있다.8,22 연구자들은 [데이터가 충분한 이유]뿐만 아니라, [데이터가 어떻게 해석]되고, [어떻게 GME에 기여하는지]도 명확하고 설득력 있게 전달해야 한다. 주제가 연결되어 새로운 이해를 창출하는 것을 보여주지 못하고, 그저 이질적인 주제만 단순히 열거하는 것은 리뷰어와 독자에게 연구 결과가 의미 있다는 것을 납득시키지 못할 가능성이 높다. 결국, 검토자와 독자는 엄격한 질적 연구의 뉘앙스를 포착하지 못하는 정량적 기준의 부적절한 적용으로 인해 강력한 원고가 시들해질 수 있다는 것을 유념해야 한다.

We warn researchers that ineffective scholarly writing can make even the most powerful qualitative findings appear unconvincing. While information power is useful for appraising or justifying the sufficiency of a qualitative sample, the evidentiary value of qualitative findings depends on more than rich data and rigorous analysis. It requires good writing. When drafting research for publication, the onus is on the authors to make their research procedures and decision-making processes transparent and convincing.8,22 Researchers need to clearly and compellingly convey not only why a dataset is sufficient, but also how data were interpreted and what they contribute to GME. Enumerating a list of disparate themes, rather than demonstrating how themes connect to generate new understanding, will likely fail to convince reviewers and readers that the findings are meaningful. In turn, reviewers and readers must be mindful that strong manuscripts may wilt under the inappropriate application of quantitative criteria that fail to capture the nuances of rigorous qualitative research.

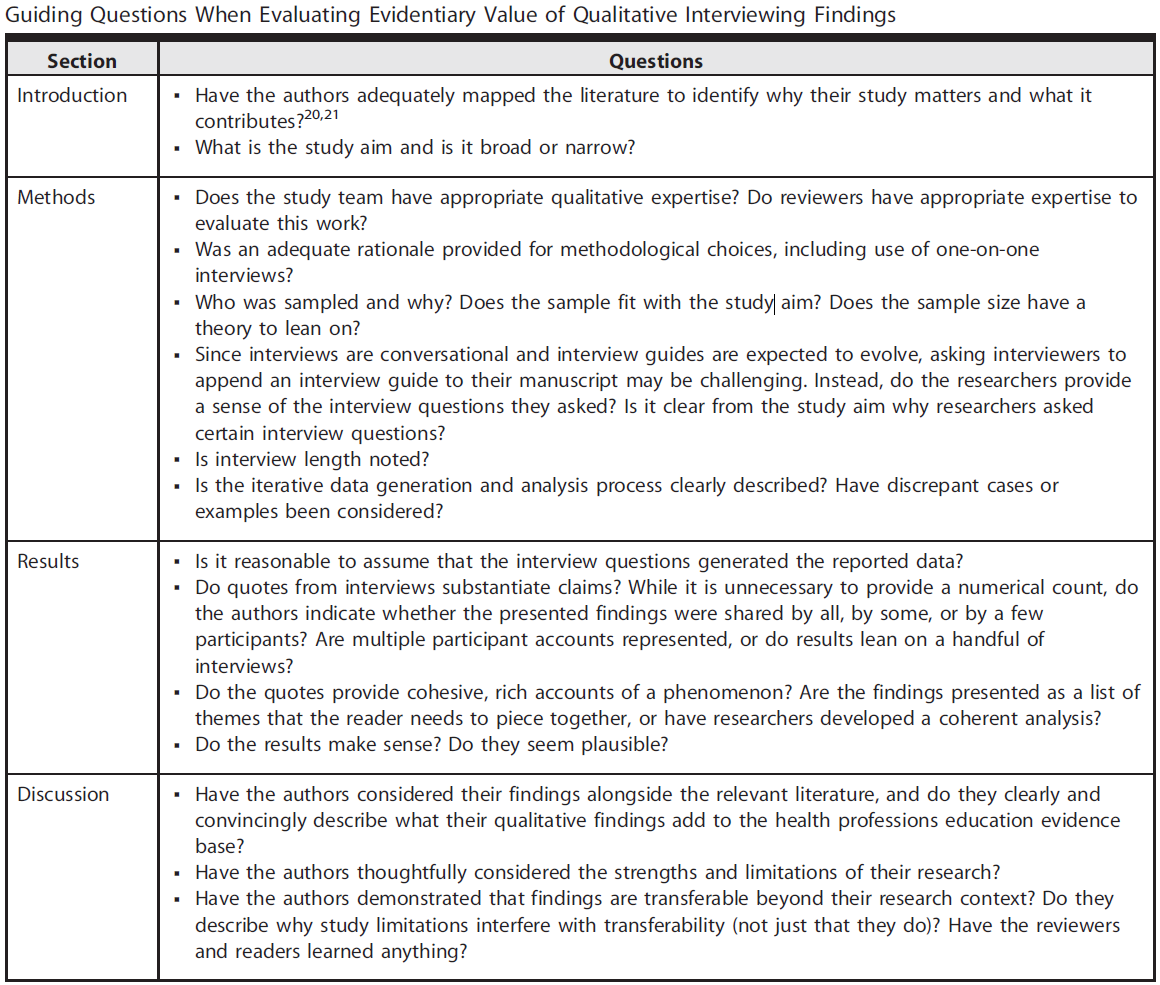

GME에서 질적 증거 기반을 강화하는 것은 [충분성을 입증]하고, [충분성을 적절하게 평가하는 것]에 달려 있다. 이 표에서 우리는 정성적 면접 결과의 증거 가치를 평가하거나 보고할 때 고려해야 할 일련의 안내 질문을 제공한다.

Boosting the qualitative evidence base in GME depends on both demonstrating sufficiency and evaluating it appropriately. In the Table we provide a set of guiding questions to consider when evaluating or reporting the evidentiary value of qualitative interview findings.

요약 Summary

우리는 GME 연구자, 검토자 및 독자들이 인터뷰를 통해 얻은 정성적 발견을 평가할 때, [포화라는 미명을 벗어나야 한다]고 촉구한다. 이 사설에서는 질적 초보자가 질적 인터뷰 데이터의 증거적 가치에 대한 직감을 명확하게 표현하고 경우에 따라 확인할 수 있는 학문적 언어를 개발하는 데 도움이 되는 지침을 제공합니다. 그러나 질적 연구의 복잡성을 고려할 때 우리의 지침은 돌이 아닌 모래로 쓰여져 있다. 지도질문 목록(표)과 핵심참고문헌(박스)이 이러한 중요한 질적 이슈에 대한 보다 깊은 성찰과 학습을 촉진하기를 기대한다. GME 연구자, 검토자 및 독자들이 풍부함, 엄격함, 충분성, 정보력 등의 개념을 사려 깊게 사용하고 의심스러울 때는 질적 연구 전문가에게 조언을 구하도록 권장한다.

We urge GME researchers, reviewers, and readers to move beyond the guise of saturation when evaluating qualitative findings obtained from interviews. In this editorial, we provide guidance to help qualitative novices develop a scholarly language to articulate—and in some cases, check—their gut sense about the evidentiary value of qualitative interview data. However, given the complexities of qualitative research, our guidance is written in sand, not stone. We hope that the list of guiding questions (Table) and key references (Box) will promote deeper reflection and learning around these important qualitative issues. We encourage GME researchers, reviewers, and readers to thoughtfully use concepts like richness, rigor, sufficiency, and information power, and to seek advice from qualitative research experts when in doubt.

doi: 10.4300/JGME-D-21-00752.1. Epub 2021 Oct 15.

Beyond the Guise of Saturation: Rigor and Qualitative Interview Data

PMID: 34721785

PMCID: PMC8527935 (available on 2022-10-01)

'Articles (Medical Education) > 의학교육연구(Research)' 카테고리의 다른 글

| 템플릿 분석 하기 (Qualitative Organizational Research, Chapter 24) (0) | 2022.01.13 |

|---|---|

| 질적연구인터뷰 수행의 열두 가지 팁 (Med Teach, 2018) (0) | 2021.12.23 |

| 효과적으로 질적연구 결과 섹션을 쓰는 세 가지 원칙 (Focus on Health Professional Education, 2021) (0) | 2021.12.23 |

| 효과적인 문헌고찰 쓰기 파트2: 인용 테크닉(Perspect Med Educ, 2018) (0) | 2021.12.13 |

| 효과적인 문헌고찰 쓰기 파트1: 매핑 더 갭 (Perspect Med Educ, 2018) (0) | 2021.12.13 |