효과적으로 질적연구 결과 섹션을 쓰는 세 가지 원칙 (Focus on Health Professional Education, 2021)

Three principles for writing an effective qualitative results section

S. Cristancho, C. J. Watling & L. A. Lingard

도입 Introduction

우리의 글쓰기와 학문적 글쓰기에 대한 가르침은 중요한 전제에 달려 있다. 괜찮은decent 연구 논문은 [연구study]를 보고하지만, 훌륭한great 연구 논문은 [이야기story]를 들려준다. 명확하게 하기 위해, 우리는 연구와 이야기가 더 두드러지는 연구 논문의 부분을 구분했습니다. 우리는 [이야기가 크게 도입/고찰]이고 [연구는 방법/결과]라고 말해왔다. 그러나 이러한 구분을 너무 엄격하게 적용하지 않는 것이 중요합니다. 좋은 결과 섹션은 결과를 보고할 뿐만 아니라 독자가 결과에 참여할 수 있도록 도와줍니다. 좋은 결과 섹션은 스토리와 공부의 요소가 모두 필요하고, 그것들을 공존시키는 것은 결과 섹션을 쓰기가 어려운 이유일 것이다. 본 논문에서, 우리는 질적 논문의 저자들이 결과 부분에서 연구/이야기 난제와 씨름하는 데 도움이 되는 세 가지 원칙인 과학적 스토리텔링, 진정성 및 주장을 논의한다.

Our writing, and our teaching about academic writing, hinges on a key premise—a decent research paper reports a study, but a great research paper tells a story (Lingard & Watling, 2016). For the sake of clarity, we have distinguished the sections of a research paper where study and story are more prominent. We have said that story is largely introduction/discussion and study is methods/results. It’s important, however, not to apply this distinction too rigidly—a good results section not only reports findings but also helps the reader to engage with them. A good results section needs elements of both story and study, and making them coexist is, likely, why a results section is so difficult to write. In this paper, we discuss three principles—scientific storytelling, authenticity and argument—to help writers of qualitative papers grapple with the study/story conundrum in their results sections.

원칙들

The principles

1. 과학적 스토리텔링

1. Scientific storytelling

"이야기"라는 단어는 과학과 함께 놓이기 불편한 단어이다. 과학은 그 자체로 설득력이 있다는 믿음 때문에 불편함을 만듭니다. 따라서, 연구 보고를 윤색하는 것처럼 보이는 것은 무엇이든 잘못인 것처럼 느껴집니다. 우리가 "이야기"라는 단어를 사용하는 것은 과학의 장식을 선호하기 위한 것이 아니라, 독자들이 [연구의 결과를 설득력 있게 만드는 것]이 무엇인지 쉽게 인식하도록 하기 위함이다. 과학적 스토리텔링의 원리는 그러한 목표를 향한 몇 가지 지침을 제공할 수 있습니다.

The word “story” sits uneasily alongside science (“Should scientists tell stories?,” 2013). It creates discomfort because of the belief that science is persuasive on its own. Therefore, anything that seems like embellishing the reporting of a study feels wrong. Our use of the word “story” is not to favor embellishment of science but, rather, to ensure that readers readily recognise what makes the results of a study compelling. The principle of scientific storytelling can offer some guidance towards such a goal.

많은 작가들이 직면하는 어려운 점은 [무엇이 당신의 결과를 구성하는지]를 결정하는 것이다. 만약 독자들이 여러분의 연구에 참여하도록 강요하는 것이 목표라면, 여러분의 결과 섹션은 여러분이 그 구성 요소의 목록보다 더 많이 연구하고 있는 문제에 대한 개념적인 이해를 그들에게 제공해야 합니다. 훌륭한 연구자들은 독자들에게 의미를 부여하기 위해 해석하고 맥락화하며, 그러한 맥락화는 과학적 스토리텔링의 기초가 된다.

A struggle many writers face is deciding what constitutes your results. If the goal is to compel readers to engage with your study, then your results section should offer them a conceptual understanding of the issue that you’re studying more than an inventory of its components. Good researchers interpret and contextualise to make meaning for their readers, and such contextualisation is the basis of scientific storytelling.

일반적으로 좋은 이야기는 환기시키고evocative, 참신하며 기억에 남아야 한다(Simmons, 2019).

- 과학적 스토리텔링에서, 환기시킨다는 것은 글이 감정을 자극한다는 것을 의미하지 않는다; 대신, 그것은 마음을 사로잡고 울려 퍼지게 하는 결과를 의미한다.

- 마찬가지로, 새롭다는 것이 항상 획기적인 발견을 제시하는 것은 아니다. 그것은 또한 알려진 현상에 대해 다른 관점을 제공하는 것에 관한 것이다.

- 그리고 기억에 남는다는 것은 독자들이 신문의 모든 세부사항을 기억할 것이라는 것을 의미하는 것이 아니라, 오히려 중요한 발견이 그들을 돋보이게 할 것이라는 것을 의미한다.

As a general rule, a good story should be evocative, novel and memorable (Simmons, 2019).

- In scientific storytelling, evocative doesn’t mean the writing stirs emotion (although it might); instead, it refers to results that captivate and resonate.

- Similarly, novel is not always about presenting a groundbreaking discovery. It is also about offering a different perspective on a known phenomenon.

- And memorable doesn’t mean that your readers will remember every single detail of the paper but, rather, that the key findings will stand out for them. How do you organise your story with these features in mind?

여기서부터 시작하는 것은 시작 단락입니다. 대부분의 질적 연구가 주제를 식별하는 것을 포함하기 때문에, 흔히 다음과 같이 시작하는 단락을 쓰는 경향이 있을 것이다: "우리는 다섯 가지 주제를 발견했다: 테마 1, 테마 2, … 테마 5. 주제 1은 … 주제 5는 … 각 주제는 참가자들의 인용문을 사용하여 아래에 설명되어 있습니다." 이러한 유형의 문단은 결과에 대한 큰 그림 설명을 제공하는 것으로 생각할 수 있지만 그렇지 않습니다. 이것은 테마의 목록입니다. 그리고 틀린 것은 아니지만, 할 이야기가 있는 것 같지는 않다. 대신 수치 경험에 대한 바이넘 외 연구진(2021)의 논문의 이 첫 단락을 생각해 보자.

A place to start is the opening paragraph. As most qualitative studies involve identifying themes, we might be inclined to write an opening paragraph that reads like: “We found five themes: theme 1, theme 2, … theme 5. Theme 1 refers to … theme 5 refers to … Each theme will be described below using quotes from participants”. You might think of this type of paragraph as providing a big picture description of the results, but it does not. That’s an inventory of themes. And while it is not wrong, it doesn’t feel like there is a story to be told. Consider instead this opening paragraph from Bynum et al.’s (2021) paper on experiences of shame.

참가자들이 묘사한 수치 경험은 개인과 그들의 환경 사이의 동시적이고 다층적인 상호작용으로 구성되었다. 이러한 상호작용의 의미를 모색하면서, 우리는 '불의 은유'를 통해 참가자들의 수치심을 이해하게 되었습니다. 불이 기질에 미치는 잠재적인 영향처럼, 수치심은 우리의 참가자들에게 깊은 영향을 미칠 수 있다: 대부분의 보고는 세계적으로 부정적인 자기 평가로 구성된 강렬하고, 음흉하고, 그리고/또는 매우 골치 아픈 수치 반응을 경험한다. 학생들은 스스로를 '좋지 않다'(P10), '전혀 가치가 없다'(P12), '부적절한 의대생'(P15), '작다'(P8, P11), '멍청하다'(P6)고 생각한다고 보고했다. "이름도 없는 이 부정적인 감정에 빠져드는 것 같았다"(P15)는 수치심의 감정적 경험이 종종 압도적이었다. 참가자가 겪어낸 수치심 경험의 기원에 대한 두 가지 광범위한 구조, 즉 수치심 유발자와 수치심 촉진자를 식별했다. (188쪽)

The shame experiences described by participants consisted of simultaneous, multi-layered interactions between the individual and their environment. In seeking the meaning of these interactions, we came to understand participants’ shame experiences through the metaphor of fire. Like the potential impact of fire on a substrate, shame could profoundly affect our participants: most reported experiencing intense, insidious and/or deeply troublesome shame reactions that consisted of globally negative self-assessments. Students reported viewing themselves as “no good” (P10), “completely worthless” (P12), “an inadequate medical student” (P15), feeling “small” (P8, P11) and feeling “stupid” (P6). The emotional experience of shame was often overwhelming: “I felt like I was drowning in this negative emotion that I didn’t have a name for” (P15). We identified two broad structures of the origins of participants’ lived experiences of shame: shame triggers and shame promoters. (p. 188)

이 단락을 읽으면, 여러분은 결과 파트에서 [수치심을 유발하고 촉진하는 것]을 다룰 것이라는 느낌을 받게 됩니다. 하지만, 그것이 다가 아닙니다. 저자들은 이 단락에 이야기 풍미를 불어넣기 위해 [두 가지 추가 전략]을 사용했다. 주제 간 관계가 [메타포의 형태로 묘사될 것이라는 기대]를 독자들에게 준비시키고, [메타포를 엿볼 수 있는 짧은 인용구]를 주입하는 동시에 독자들의 시선을 사로잡았다.

In reading this paragraph, you get a sense that the results will be about triggers and promoters of shame. However, that’s not all. The authors used two additional strategies to instill a story flavor in the paragraph. They prepared readers to expect that the relationships among themes will be described in the form of a metaphor, and they infused evocative short quotes to provide a glimpse of the metaphor, while at the same time, capturing readers’ attention.

문단을 여는 것만이 당신의 결과의 스토리를 묘사하는 유일한 방법은 아니다. [시각 지향적인 도표]를 사용하여 독자가 아이디어 간의 연결을 볼 수 있습니다. 다음은 예입니다.

Opening paragraphs are not the only way to portray the story of your results. In the event that you are more visually oriented, you could also use diagrams to help readers see the connections between your ideas. Here is an example:

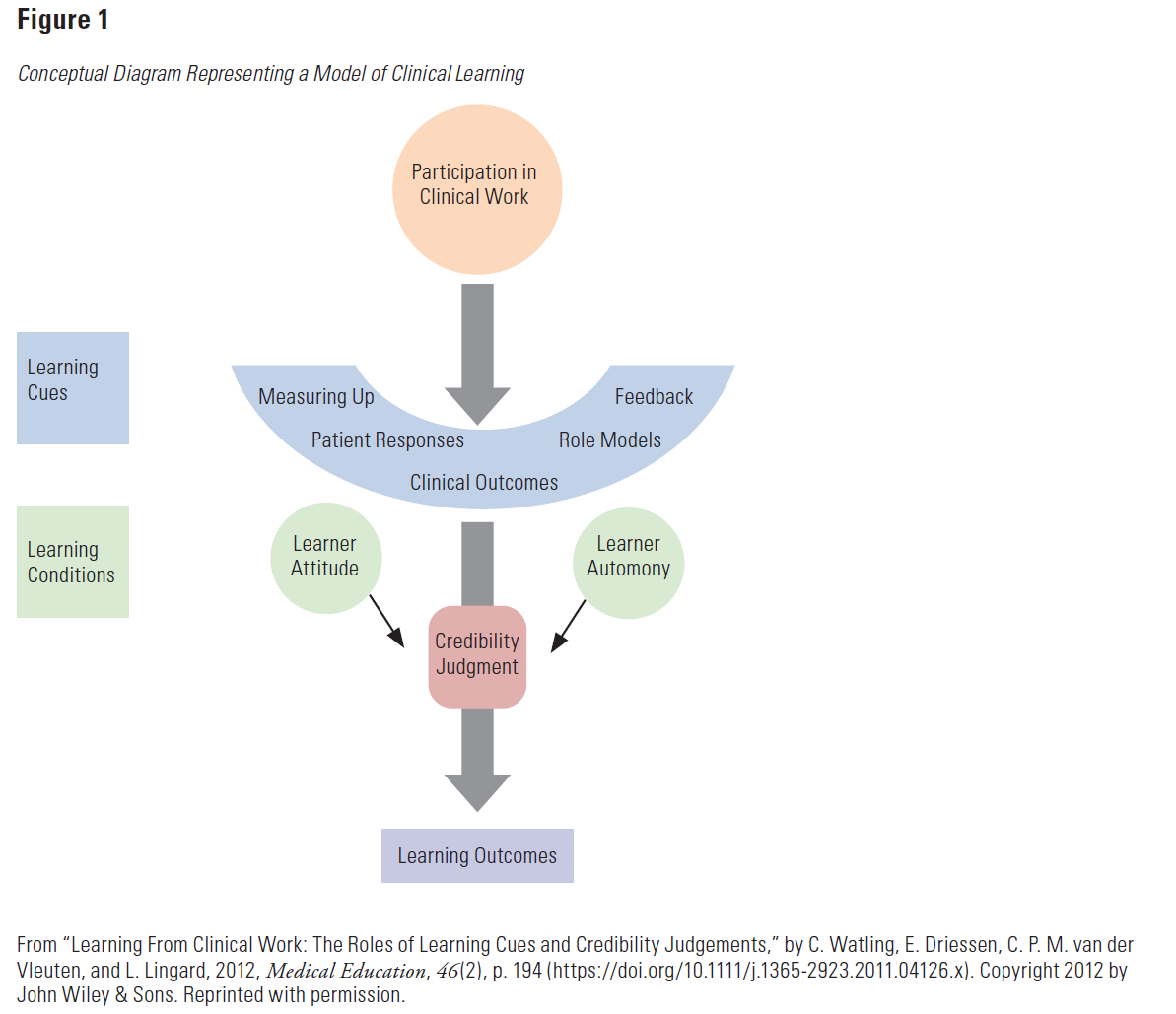

임상 학습 과정은 도표를 사용하여 표현되었다(Watling 등, 2012). 저자들은 모델의 각 핵심 요소를 입증하고자 했기 때문에 결과 섹션의 시작 부분에 도표를 포함하기로 명시했다. 그렇게 함으로써, 그 다이어그램은 독자들이 앞으로 다가올 것과 각각의 요소들이 어떻게 연결되어 있는지에 대한 방향을 제시하는데 도움을 주었다.

The process of clinical learning was represented using a diagram (Watling et al., 2012). Since the authors intended to evidence each key element of the model, they made the explicit decision to include the diagram at the beginning of the results section. By doing so, the diagram helped orient readers to what was to come and to how each element was connected.

시작 문단 및 도표는 [이야기의 큰 그림]을 그리는데 도움이 된다. 결과 섹션의 나머지 부분에서는 의도한 스토리가 스터디와 어떤 관련이 있는지 설명합니다. 시작하기 전에, 모든 주제가 과학 이야기에서 동등하게 표현되어야 하는 것은 아니라는 것을 기억하라. 모든 주제 간의 관계를 설명할 수 있지만, 때때로 하나의 핵심 주제를 중심으로 이야기를 진행하기로 결정할 수도 있습니다. 이것은 임의적인 결정이 아닙니다. 테마가 이야기를 의미 있게 진전시키는지, 그리고 그것을 뒷받침할 충분한 자료가 있는지 여부에 달려 있다. 이는 전통적인 결과 표시가 아니므로, 작성자들은 이 사례에서 예시된 바와 같이 의사결정을 명시적으로 표현하는 것을 고려해야 한다.

Opening paragraphs or diagrams help lay out the big picture of the story. The rest of the results section is about describing how your intended story relates to your study. To start, remember that not all themes must figure equally in a scientific story. While you could describe all the relationships among all your themes, sometimes you might decide to center your story around one key theme. This is not a random decision. It hinges on whether the theme(s) advances the story in a meaningful way and on whether you have enough data to support it. As this is not a traditional presentation of results, writers should consider explicitly articulating their decision making, as illustrated in this example.

우리는 두 가지 주요 발견을 확인했다. 첫 번째 범주는 아래에 설명된 원칙과 선호도의 한계인 핵심 범주입니다. 두 번째는 참가자들이 이러한 문턱에 직면했을 때 어떻게 반응했는지에 대한 이론적 프레임워크입니다. 연구 결과를 더 강력하게 표현해야 한다는 최근의 요구에 따라(26–28) 우리는 그 구축을 이끈 모든 범주와 코드를 요약하는 대신 [핵심적 이론 구조]를 환기하는 핵심 내러티브를 사용하기로 결정했다. (Apramian 등, 2015, 페이지 S71)

We identified two key findings. The first is the core category—thresholds of principle and preference—as described below. The second is a grounded theoretical framework of how our participants responded to encountering these thresholds. Following recent calls to represent research findings more powerfully (26–28) we have elected to use core narratives that evoke the central theoretical constructs rather than outlining all categories and codes that led to their construction. (Apramian et al., 2015, p. S71)

저자들은 결과 이야기를 '문턱 원칙과 선호'라는 핵심 주제에 집중하기로 했을 뿐만 아니라 그 구성 요소를 짧은 인용구가 아닌 내러티브의 형태로 설명하기로 했다. 아래의 주장의 원칙이 이 전략에서 확장될 것입니다.

Not only did the authors decide to focus the story of the results on the key theme of “thresholds of principle and preference”, but they also chose to illustrate its components in the form of narratives, not short quotes. The principle of argument, below, will expand on this strategy.

문단이나 도표를 여는 용도, 주제 간 관계를 어떻게 탐구할 것인지 등을 고려하는 것 외에도, [결과 부분을 어떻게 마무리할지]에 대해서도 어느 정도 고민해야 한다. 요약 단락, 기억할 만한 인용문 또는 간단한 전환 문장을 사용할 수 있습니다. 자신의 선호도와 단어 수 제한과 상관없이, 중요한 것은 가장 취약한 지점weakest point으로 끝나지 않는 것입니다. 첫 번째 초안 후에 이야기의 흐름을 다시 돌아보는 습관을 들이고 수사적인 목적을 위해 재정렬하세요.

In addition to considering the use of opening paragraphs or diagrams and how you will explore the relationships among your themes, some thought should be given to the ending of the results section. You may use a summary paragraph, a memorable quote or simply a transition sentence. Regardless of your preference and word count limit, what’s important is that you don’t end with your weakest point. Make a habit of revisiting the flow of the story after your first draft, rearranging for rhetorical purposes.

과학적 스토리텔링의 원리를 이용하면서, 작가들이 마주치는 또 다른 어려움은 [결과와 토론 사이의 연결성]에 대해 결정하는 것이다. 저자는 잘못이 없다. 이런 어려움을 만드는 것은 질적 연구의 비선형성 때문이다. 질적 연구는 반복적이고 진화하는 것이다; 연구자들은 그들의 데이터를 읽고 해석하는 것 사이를 왔다 갔다 한다. 그리고 그것들을 작성하는 것도 마찬가지입니다. 이렇게 하면, 때때로 검토자로부터 해당 문장이 토론 섹션에 속하는지 궁금하거나 질문을 받을 수 있습니다. 보건전문교육(HPE) 논문의 전통적인 IMRD(서론, 방법, 결과, 토론) 구조에서 [결과 섹션]은 참가자들이 어떻게 경험했는가라는 질문에 답하고, [토론 섹션]은 참가자들의 경험을 알게 되었으니, 우리는 이 지식으로 무엇을 할 수 있는가라는 질문에 답한다.

In using the principle of scientific storytelling, another struggle writers encounter is deciding about the connection between the results and the discussion. The writer is not at fault here. What creates this struggle is the non-linear nature of qualitative studies. Qualitative studies are iterative and evolving; researchers go back and forth between reading and interpreting their data. And the same applies to writing them up. In doing so, you might sometimes wonder or get asked by a reviewer whether a statement belongs to the discussion section. In the traditional IMRD (Introduction, Methods, Results, and Discussion) structure for health professional education (HPE) papers, while

- a results section answers the question How did participants experience this?,

- a discussion section answers the question Now that we know about their experiences, what can we do with this knowledge?

결과 중 한 조각이 토론에 속하는지를 빠르게 점검해보는 요령은 [문장의 시제]를 확인하는 것입니다. 우리는 참가자들의 관점을 설명할 때 과거형을 사용하고, 우리의 해석을 제공할 때 현재형을 사용하는 경향이 있습니다. 만약 그러한 해석이 [참가자들이 말한 것을 어떻게 해야 하는지에 대한 권고]로 넘어가게 된다면, 당신은 경계를 넘은 것이다. 예를 들어, 아래 첫 번째 문장은 참가자들이 조정된 치료 계획을 해결책으로 식별했음을 암시한다. 두 번째 문장은 현재 시제로 인해 권고와 혼동될 수 있다.

A quick test to identify if a piece of the results belongs to the discussion is to check the tense of your sentences. We tend to use past tense when describing participants’ perspectives and present tense when providing our interpretation. If such interpretation slips into recommendations of what to do with what participants said, then you have crossed the boundary. For instance, the first sentence below implied that participants had identified the coordinated care plan as a solution. The second sentence, by virtue of its present tense, can be confused with a recommendation.

많은 참가자들이 환자의 의료 필요성의 반복적인 문제에 대한 "정밀한 해결책"으로서 조정된 진료 계획을 언급했다. 따라서 그러한 계획의 일상적인 채택은 전문가 간 의사소통을 개선하고 환자와 가족[작업의 시사점]의 관리에 있어 차질을 줄이기 위한 전략을 나타낼 수 있다.

Many participants spoke of coordinated care planning as a “sophisticated solution” to the recurring problem of patients’ healthcare needs “falling through the cracks” [participants’ experiences]. The routine adoption of such plans may, thus, represent a strategy to improve interprofessional communication and reduce disruptions in care for patients and families [implications of the work].

마찬가지로, 레퍼런스가 필요할 수도 있다고 생각되는 문장이나, 독자들이 그들의 실천에서 (적용)할 수 있는 것과 관련된 진술은 아마도 결과 섹션에 속하지 않을 것이다.

Similarly, if you write a statement that you think may need a reference, or a statement that has to do with what readers might do in their practice, those statements probably don’t belong in the results section.

이러한 빠른 테스트가 [결과 대 고찰]의 딜레마를 반드시 해결하는 것은 아니지만, 특히 결과와 토론이 관례적으로 혼합된 분야에서 온 경우 HPE 분야에서 글을 쓰는 연습에 자신을 적응시키는 데 도움이 될 것입니다. 최소한, 이 테스트들은 발견에 대한 묘사가 추천이나 함축적인 향을 가지고 있는지 자신에게 물어보거나 피드백을 요청하도록 유도해야 한다. 그런 경우 데이터로 돌아가서 소견으로 확인하거나 토론으로 이동해야 합니다.

While these quick tests will not necessarily solve the results versus discussion dilemma, it should help you orient yourself into the practices of writing in the HPE field, particularly if you come from a discipline where results and discussion are conventionally blended. At a minimum, these tests should prompt you to ask yourself or ask for feedback on whether a description of a finding has a recommendation or implication flavour. If so, then you should either go back to your data to confirm it as a finding or move it to the discussion.

2. 진실성—이야기에 가장 적합한 인용문 선택

2. Authenticity—selecting the best quotes for the story

연구에서 코딩하고 분석한 내용 중에서 가장 좋은 인용문을 선택하는 것은 보기보다 어렵습니다. 당신에게는 아마 선택지가 아주 많을 것이고, 그 중 일부는 당신이 꽤 좋아하는 것이다. [진실성의 원칙]은 각 인용문이 독자들에게 데이터의 지배적인 패턴에 대한 직접적인 접근을 제공하도록 당신의 선택을 안내할 수 있다. 진실성을 확보하려면 데이터에 대한 요점을 설명해주면서, 데이터 패턴을 나타내는 인용문을 선택하십시오.

Selecting the best quotes from among all those you’ve coded and analysed in your study is harder than it looks. You likely have a wealth to choose from, some of which you’re quite fond of. The principle of authenticity can guide your selection to ensure that each quote offers readers firsthand access to dominant patterns in the data. To achieve authenticity, select quotes that are illustrative of the point you’re making about the data, reasonably succinct and representative of the patterns in data.

인용문이 설명이 되는가?

Is the quote illustrative?

독자들은 여러분의 주장의 요점과 여러분이 증거로 제시한 인용문을 연결하기 위해 노력할 필요가 없습니다. 가장 좋은 인용구는 암묵적인 설명보다는 [명시적인 설명]입니다. 다음 예를 생각해 보십시오.

Readers should not have to work to connect the point in your argument and the quote you’ve offered as evidence. The best quote is an explicit illustration rather than an implicit one. Consider the following examples:

훈련 프로그램을 마친 뒤 참가자들은 "내가 내린 결정 중 가장 어려운 결정이었고, 하고 나니 기분이 나아지지 않았다"며 깊은 혼란과 방향감각을 드러냈다. (P5)

After leaving their training program, participants expressed profound confusion and disorientation: “It was the most difficult decision I’ d ever made, and I didn’t feel any better after making it”. (P5)

훈련 프로그램을 마친 뒤 참가자들은 자신들이 바라던 안도감이 바로 드러나지 않았다고 표현했다. "내가 내린 결정 중 가장 어려웠고, 하고 나니 기분이 나아지지 않았다." (P5)

After leaving their training program, participants expressed that the relief they’ d hoped for wasn’t immediately apparent: “It was the most difficult decision I’ d ever made, and I didn’t feel any better after making it”. (P5)

첫 번째 예에서, 인용문은 "혼란과 방향 상실"의 요점을 명시적으로 증명하지 않는다. 두 번째 예시는 인용문과의 연결을 타이트하게 만들고 있다.

In the first example, the quote doesn’t explicitly evidence the point of “confusion and disorientation”. The second example alters the lead up to the quote to tighten the connection.

때로는 작가로서 스스로가 할 수 없는 말을 인용구를 이용해 하고 싶을 때가 있다. 이 경우, 인용문은 당신의 주장을 입증하는 것이 아니라 당신을 대신해서 주장을 하는 것입니다. 다음 예를 들어 다음과 같습니다.

Sometimes, you may also want to use a quotation to say something that you, as the writer, can’t say yourself. In this case, the quote isn’t so much evidencing your point, it’s making a point on your behalf. Consider this example:

워크숍과 초청 연사와 같은 형평성 및 다양성 이니셔티브는 소수 교수진에 의해 "립 서비스"(P7)로 간주되었으며, 특히 기관의 더 큰 구조가 변경되지 않은 경우 더욱 그러했다.

Equity and diversity initiatives such as workshops and invited speakers were often viewed as “ lip service” (P7) by minority faculty, particularly if larger structures in the institution remained unchanged.

"립 서비스"라는 용어는 특히 소수 교수진 참가자의 입에서 나온 강력한 비판이다. 이것은 번역이 같은 영향을 미치지 않았을 때입니다. 독자들은 이러한 강한 입장이 참가자들로부터 직접 나온다는 것을 알아야 합니다.

The term “lip service” is a powerful critique, particularly coming from the mouth of a minority faculty participant. This is a moment where paraphrasing would not have had the same impact—readers need to know that this strong position comes directly from participants.

그 인용문은 간결합니까?

Is the quote succinct?

인터뷰 녹취록을 읽어본 사람이라면 그들이 구불구불하고 재귀적이며 타원과 갑작스러운 전환으로 가득 차 있다는 것을 안다. 이 때문에 요점을 설명하기 위한 짧은 인용문을 찾는 것이 어려울 수 있으며, 더 긴 인용문을 타이트하게 줄여야 합니다. 한 가지 조임tightening 기법은 주요 문구를 추출하여 인용문의 도입 문장에 통합하는 것이다.

Anyone who has ever read an interview transcript knows that they are meandering and recursive, full of ellipses and abrupt transitions. Because of this, it can be difficult to find a short quote to illustrate a point, and you need to tighten up a longer one. One tightening technique is to extract key phrases and integrate them into your own introductory sentence to the quote.

훈련 프로그램을 떠난 참가자들은 "어려운 결정"이었다고 반성을 했고, 직후에는 "기분이 나아지지 않았다."고 밝혔다 (P5)

Participants who had left their training program reflected that it was a “difficult decision”, immediately after which they “didn’t feel any better”. (P5)

또 다른 해결책은 줄임표를 사용하여 인용문의 일부를 오려냈다는 신호를 보내는 것입니다.

Another solution is to use the ellipsis to signal that you have cut part of the quote out:

대학원 훈련 경로는 "컨베이어 벨트처럼 단단하고 자동적이다. … 뛰어내릴 수는 있지만, 그 후에 다시 타는 것은 정말 쉽지 않습니다." (P13)

Postgraduate training pathways were described as “rigid and automatic, like … a conveyor belt. … You can jump off, but getting back on afterwards is really not easy”. (P13)

- 첫 번째 줄임표는 문장 중간에 무언가가 제거되었다는 신호입니다. 이 경우 이 누락된 자료는 내용을 추가하지 않았습니다. "그러니까, 알잖아요, 그 단어가, 내가 하려던 말은..."

- 두 번째 줄임표는 완전한 정지를 따르며, 따라서 적어도 한 문장이 제거되었거나 그 이상이 될 수 있다는 신호를 보낸다.

- The first ellipsis signals that something mid-sentence has been removed. In this case, this missing material did not add content: “like, you know, um, what’s the word I’m looking for, like you’re on a”.

- The second ellipsis follows a full stop, and therefore signals that at least one sentence has been removed and perhaps more.

줄임표를 사용할 때, 인용구의 의미에 중요한 뉘앙스를 가진 물질을 제거하지 않도록 주의하세요. 참가자가 원하는 바를 말할 때까지 단편적인 내용을 담아내는 것이 목적이 아니며, 목표는 전체 인용문의 요지에 충실한 표현입니다.

When using an ellipsis, be careful not to remove material that importantly nuances the meaning of the quote. The goal is not to snip bits and pieces until participants say what you want them to; it is a representation that remains faithful to the gist of the full quote.

앞의 예에서 알 수 있듯이, 여러분은 간결함을 돕기 위해 구술을 정돈하기를 원할지도 모릅니다. 인용문의 문구를 바꾸는 것은 항상 진실성 원칙에 위배될 위험이 있기 때문에 신중해야 한다. 인터뷰 전사본은 언어학자들이 "필러" 또는 "후회 표시자"라고 부르는 것, 소리 및 단어, 예를 들어 "아/어/음/좋아요/당신이 알고 있는/맞아요"(Tottie, 2016)로 가득 차 있다. 만약 당신이 담론과 서술적 분석을 한다면, 당신은 반드시 그러한 [망설임의 표현]조차도 의미의 일부로 분석하게 될 것입니다. 그러나 다른 연구 방법론에서는 언어적 특성이 참가자를 식별할 수 있게 한다는 우려와 같은 가독성 또는 윤리적 이유로 일부 "라이트 정리"를 선택할 수 있습니다(Corden & Sainsbury, 2006).

As the previous example shows, you may wish to tidy up oral speech to help with succinctness. Changing the wording of a quotation always risks violating the authenticity principle, so writers must do it thoughtfully. Interview transcripts are replete with what linguists refer to as “fillers” or “hesitation markers”, sounds and words such as “ah/uh/ um/like/you know/right” (Tottie, 2016). If you’re conducting discourse and narrative analysis, you will necessarily analyse such hesitations as part of the meaning. However, in other research methodologies, you may opt to do some “light tidying up” for readability or ethical reasons, such as the concern that linguistic features might make participants identifiable (Corden & Sainsbury, 2006).

마지막으로, 문장의 문법적 무결성을 유지하기 위해 인용구의 문구를 변경할 필요가 있을 수 있습니다. 작가들은 일반적으로 일관된 시제나, 동사와 주어 또는 대명사와 선행의 합치성을 위해 인용부호를 변경할 필요가 있다. 적절한 문법 흐름을 보장하기 위해 동사 시제를 과거에서 현재로 변경한 예에서와 같이 대괄호를 사용하여 이러한 변화를 나타냅니다.

Finally, you may need to alter the wording of a quote to maintain the grammatical integrity of your sentence. Writers commonly need to alter quotes for consistent tense or for agreement of verb and subject or pronoun and antecedent. Use square brackets to signal such changes, as in this example in which verb tenses were changed from past to present to ensure appropriate grammatical flow:

임상 감독관들은 "직접 관찰이 항상 가능한 것은 아니다.", 특히 "우리는 훈련생과 함께 일하지 않는다"와 "선배가 학생들의 직접적인 감독 중 일부를 하고 있다." (P2)

Clinical supervisors understood that “direct observation [isn’t] always feasible”, particularly in settings where “we [don’t] work side by side with the trainee” and “seniors [are doing] some of the direct supervision of the students. (P2)

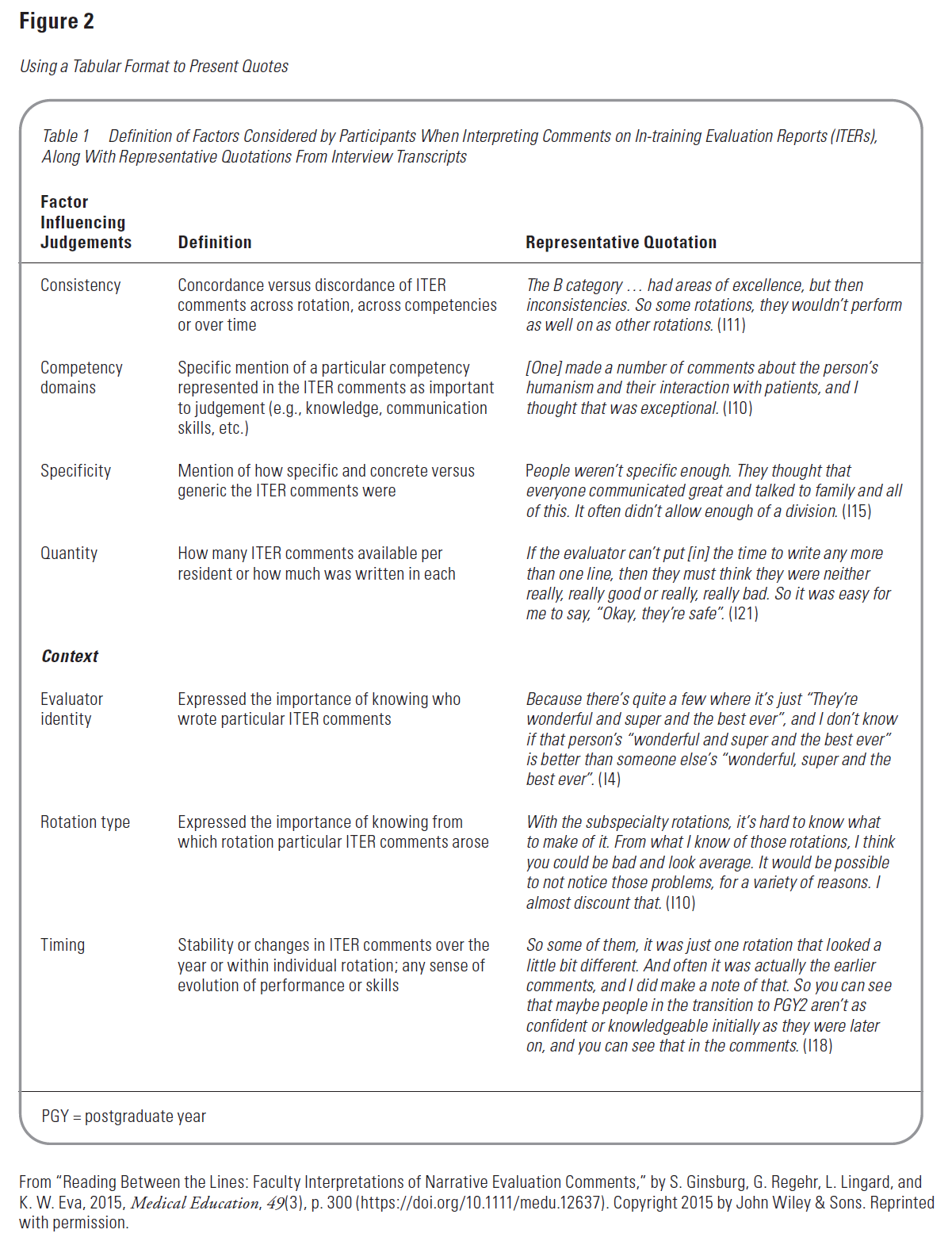

간결함을 위한 또 다른 전략은 인용문을 표에 넣는 것이다. 질적 연구자들은 표 형식이 주는 제약(그리고 '표'라는 것의 실승주의적 뿌리)에 대해 불평할 수 있지만, 복잡한 결과를 한눈에 보여주기 위해 전략적으로 사용될 수 있다. 이 예에서 긴즈버그 외 연구진(2015)은 참가자가 교육 중 평가 보고서에 대한 의견을 해석할 때 고려한 요소를 정의하고 설명한다(그림 2 참조).

Another strategy for succinctness is to put the quotes into a table. While qualitative researchers may chafe at the constraints (and positivist roots) of the table format, it can be used strategically to present complex results at a glance. In this example, Ginsburg et al. (2015) name, define and illustrate the factors their participants considered when interpreting comments on in-training evaluation reports (see Figure 2).

정성 분석의 주요 결과를 스냅샷하는 데 표를 사용할 수 있지만, 결과 본문에서 서술적 설명을 대체하거나 중복되어서는 안 됩니다. 이것은 의문을 제기한다: 어떤 인용구가 본문에 속하고 어떤 인용구가 표에 속할까? 결정하는 한 가지 방법은 "힘power"과 "증명proof" 인용구를 구별하는 것입니다.

- 파워 인용문은 가장 설득력 있는 인용문이며,

- 입증 인용문은 해당 인용문이 반복되었거나 다소 다면적이라는 추가 증거입니다(Pratt, 2008, 2009).

While tables can be used to snapshot the key findings from a qualitative analysis, they should not replace your narrative explanation in the body of the results, nor should they be duplicated. This begs the question: which quotes belong in the body and which belong in a table? One way to decide is to distinguish between “power” and “proof” quotes.

- Power quotes are the most compelling ones, the quotes that most effectively illustrate your points, while

- proof quotes are additional evidence that the point was recurrent or, perhaps, somewhat multifaceted (Pratt, 2008, 2009).

그 인용문이 대표적이니?

Is the quote representative?

모든 질적 연구자들은 그들이 빨리 논문을 작성하고 싶은 환상적인 인용문을 찾아냈다. 그러나 초안을 수정하다 보면 데이터가 잘못 전달되어 삭제되어야 하는 경우가 있습니다. 선택한 인용문은 데이터의 강력한 패턴을 반영해야 합니다. 모순되는 예는 중요한 목적을 수행하지만, 그 사용은 전략적이고 명확해야 합니다. 또한, 인용문 선택은 한 두 명의 매우 명확한 참가자로부터 나와서는 안 됩니다. 경우에 따라 차선의 또는 차차선의 모범적 예시문을 사용하더라도 여러 참가자에게 분산시킴으로써 데이터 집합 전체를 더 잘 표현할 수 있습니다.

Every qualitative researcher has identified a fantastic quote they just can’t wait to put into a paper. Sometimes, however, you discover as you revise the draft that it misrepresents the data, and it has to be removed. The quotes you choose should reflect strong patterns in the data. Discrepant examples serve an important purpose, but their use should be strategic and explicit. Furthermore, your quote selection shouldn’t come from the same one or two highly articulate participants. Distributing your choices across participants better represents the dataset as a whole, even if it means using the second- or third-best example in some instances.

주요 결과를 나타낼 인용문을 선택할 때 독자가 의미를 정확하게 추론할 수 있도록 충분한 맥락을 유지해야 합니다. 때때로 이것은 [참가자의 답변]뿐만 아니라, [면접관의 질문]도 포함한다는 것을 의미합니다. 그룹 토론에 중점을 두는 포커스 그룹 연구에서는 개별 의견을 추출하는 것보다 참가자 간의 교류를 인용하는 것이 필요할 수 있다. 다음의 공개된 예(Greenhalgh 등, 2004)는 이 기술을 설명한다.

As you select quotes to represent main findings, be sure that you retain sufficient context so that readers can accurately infer their meaning. Sometimes this means including the interviewer’s question as well as the participant’s answer. In focus group research, where the emphasis is on the group discussion, it might be necessary to quote an exchange among participants rather than extracting individual comments. The following published example (Greenhalgh et al., 2004) illustrates this technique.

그러나 부유하지 못한 학생들 사이에서는 높은 사회 계층과 특권 교육이 입학 과정에 유리하다는 인식이 강했다.

However, there was a strong perception among less affluent pupils that high social class and a privileged education would confer an advantage in the admissions process:

[왜 학생이 의대에 입학하는 것을 쉽게 느낄 수 있는지에 대한 질문에 대한 답변]

[in response to a question about why a pupil might find it easy to get into medical school]

"그녀의 자기 자신과 성적은... ...잘하면 면접을 보는 것처럼요."

“The way she carries herself and her grades . . . like at interview if she does well.”

"어떻게 스스로를 감당하겠어?"

[facilitator] “How would she carry herself?”

"각각, 제대로 말하고, 적절한 옷을 입고, 자신감이 넘친다."

“Respectively [sic], talking properly, and dressing appropriately, alot of confidence.”

"일반적인 억양이 아니라 제대로 말하세요."

“Not saying it in a common accent, say it properly.”

말을 잘하면 더 교육받은 것처럼 보일 것이다.(B학교 남학생들)

“If they speak well, then they’ ll look more well-educated.” (Boys from school B)

이 발췌문은 단일 참가자의 답변보다는 질문에 대한 그룹 참여를 효과적으로 나타냅니다.

This excerpt effectively represents the group engagement with the question rather than a single participant response.

3. 논쟁

3. Argument

예를 들어, 가장 대표적인 인용문조차도 스스로 설명하지는 않습니다. 글쓴이는 문법적으로나 수사적으로나 [인용문을 자신의 텍스트에 포함]해야 합니다. 문법 통합의 경우 인용된 자료는 인용되지 않은 자료와 동일한 문법 및 구두점 규정을 적용한다는 것만 기억하면 됩니다. 이 예제를 큰 소리로 읽어보십시오.

Even an illustrative, representative quote does not speak for itself—writers must incorporate the quote, both grammatically and rhetorically, into their own text. For grammatical incorporation, you need only remember that quoted material is subject to the same sentence-level conventions for grammar and punctuation as non-quoted material. Read this example aloud:

사무국장들은 "전문성 문제가 반복될 때 아마 그 역할에서 가장 어려운 부분일 것"이라며 비전문적인 행동을 바로잡기 위해 고군분투했다(P8)

Clerkship directors struggled to remediate unprofessional behavior, “ it’s probably the most difficult part of the role, when you come across a recurring professionalism problem.” (P8)

쉼표를 사용하여 인용구를 작가의 문장에 결합하면 쉼표 스플라이스와 런온 문장이 생성되는데, 이는 눈이 즉시 인식하지 못하더라도 귀가 들을 가능성이 높다. 인용구를 삽입한 문장을 큰 소리로 읽어서 문법적 편입을 확인하세요. 간단한 수정은 [쉼표를 콜론으로] 바꾸는 것입니다.

Using a comma to join the quote to the writer’s sentence creates a comma splice and a run-on sentence, which your ear likely hears even if your eye doesn’t instantly recognise it. Read aloud sentences where you’ve inserted a quote to check grammatical incorporation. A simple correction is to replace the comma with a colon.

사무국장들은 비전문적인 행동을 바로잡기 위해 고군분투했다. "전문성 문제가 반복되는 것이 그 역할에서 가장 어려운 부분일 것이다." (P8)

Clerkship directors struggled to remediate unprofessional behavior: “ it’s probably the most difficult part of the role, when you come across a recurring professionalism problem.” (P8)

[콜론]은 인용된 물질을 통합하기 위한 기본 메커니즘입니다. 그리고 그것은 문법적으로 많은 시간을 충분합니다. 그러나, 그것이 항상 수사적으로 충분한 것은 아니다. 왜냐하면 독자에게 [연구자가 하려는 말]과 [인용된 말] 사이의 관계를 유추하게 남겨두기 때문이다. 인용문이 글쓴이의 논점을 완벽하게 전달할 때, 콜론은 충분할 뿐만 아니라 인용문을 산만하게 집중 조명한다. 하지만, 인용문은 당신의 논점을 완벽하게 만드는 경우는 거의 없다; (인용문을 이해하는 데에는) 보통 약간의 추론이 필요하며, 독자들은 작가가 의도하는 바를 추론하지 못할 수도 있다. 독자들이 자신만의 해석을 하도록 내버려둘 것이 아니라, 작가들은 그들의 해석을 분명하게 해야 한다. 이러한 맥락화는 모로(2005)가 해석과 인용의 "균형balance"이라고 부르는 것을 달성하기 위한 요건이다.

The colon is a default mechanism for integrating quoted material. And it suffices grammatically much of the time. However, it doesn’t always suffice rhetorically, because it leaves the reader to infer the relationship between the point being made and the quoted illustration. When the quote perfectly makes the writer’s point, the colon not only suffices, it spotlights the quote without distraction. However, only rarely do quotes perfectly make your point; usually some inference is required, and readers might not infer what the writer intends. Instead of leaving readers to come to their own interpretations, writers should make explicit their interpretation. Such contextualising is a requirement for achieving what Morrow (2005) calls the “balance” of interpretation and quotation.

연구자들의 해석과 인용문 사이에 이러한 균형을 이루기 위한 많은 기술들이 있다. 다음 예에서 콜론 앞의 자료가 견적서에 대해 점진적으로 더 많은 맥락화를 제공하는 방법에 주목하십시오.

There are many techniques for achieving this balance between researcher interpretations and supporting quotations. Note in the following examples how the material before the colon provides progressively more contextualisation for the quote:

한 주민은 "표준 훈련 경로에서 벗어날 수 있지만, 다시 타는 것은 보장되지 않습니다."라고 말했다. (P21)

One resident said: “You can get off the standard training pathway, but getting back on isn’t guaranteed”. (P21)

한 주민은 "표준적인 훈련 경로에서 벗어날 수 있지만, 다시 승선하는 것은 보장되지 않는다."라고 단언했다. (P21)

One resident asserted: “You can get off the standard training pathway, but getting back on isn’t guaranteed”. (P21)

포커스 그룹의 한 주민은 훈련 경로가 CBME[역량 기반 의료 교육]의 맥락에서 개별화되고 유연하다는 생각에 동의하지 않았다. "표준 훈련 경로에서 벗어날 수 있지만, 다시 복귀하는 것은 보장되지 않습니다." (P21)

One resident in the focus group disagreed with the idea that training pathways were individualised and flexible in the context of CBME [competency-based medical education]: “You can get off the standard training pathway, but getting back on isn’t guaranteed”. (P21)

포커스 그룹 참가자들은 CBME의 맥락에서 훈련 경로의 유연성에 대해 토론했다. 일부는 훈련이 "더디게 갈 필요가 있거나 더 빨리 갈 수 있거나, 거주자의 길에서 조금 벗어나고 싶은 경우" (P19) 반면 다른 이들은 "표준 훈련 경로에서 벗어날 수 있다"고 주장했다. 하지만 다시 탈 수 있다는 보장은 없습니다." (21)

Focus group participants debated the flexibility of training pathways in the context of CBME. Some anticipated that training “can be adjusted, for if you need to go slower or you’re able to go faster or you want to do something a bit off the beaten path of residency” (P19), while others contested that “you can get off the standard training pathway, but getting back on isn’t guaranteed”. (P21)

증가하는 문맥화는 중립적인 "말한said"을 사용하는 첫 번째 예와 참가자의 어조를 감지하기 위해 "주장된asserted"을 사용하는 두 번째 예 사이의 동사 변화에서 시작된다. 세 번째는 [포커스 그룹 토론의 맥락]에 그것을 배치함으로써 인용문의 의미를 더욱 해석한다. 네 번째 예시는 두 개의 인용구를 [문장의 서술 구조에 직접 통합]하여 참여자들 사이에서 일어나고 있는 토론을 보여준다. 그리고 콜론을 사용하지 않음으로써, 마지막 예는 작가가 인용문을 그들의 논증에 엮기 위해 더 열심히 일하도록 강요한다. 이러한 직조는 [인용문의 의미를 수사적으로 강하게 통제]한다.

The increasing contextualisation begins with a shift in verb between the first example, which uses the neutral “said”, and the second example, which uses “asserted” to give a sense of the participant’s tone. The third interprets the meaning of the quote even more by situating it in the context of a focus group debate. The fourth example integrates two quotes directly into the narrative structure of the sentence to show the debate that was occurring among participants. And by not using a colon, the last example forces the writer to work harder to weave the quotes into their argument. Such weaving exerts strong rhetorical control over the quote’s meaning.

초안을 쓸 때는 때는 기본적으로 콜론을 사용하는 편이 낫다. 각각의 조각을 어떤 자리에 고정하는 데 이상적이다. 하지만 수정할 때는 더 다양하고 스타일을 지향하세요. 이렇게 하면 결과 섹션이 점-콜론-인용, 점-콜론-인용, 점-콜론-인용 등의 로봇적 운율을 넘어 향상되고 인용문이 여러분이 주장하는 요점을 뒷받침하고 발전시킬 수 있습니다.

Use the default colon when you’re drafting—it’s perfect for just getting the pieces into place. But when you revise, aim for more variety and style. This will elevate your results sections beyond a robotic cadence of point-colon-quote, point-colon-quote, point-colon-… . And it will ensure that the quotes support and develop the points you’re making.

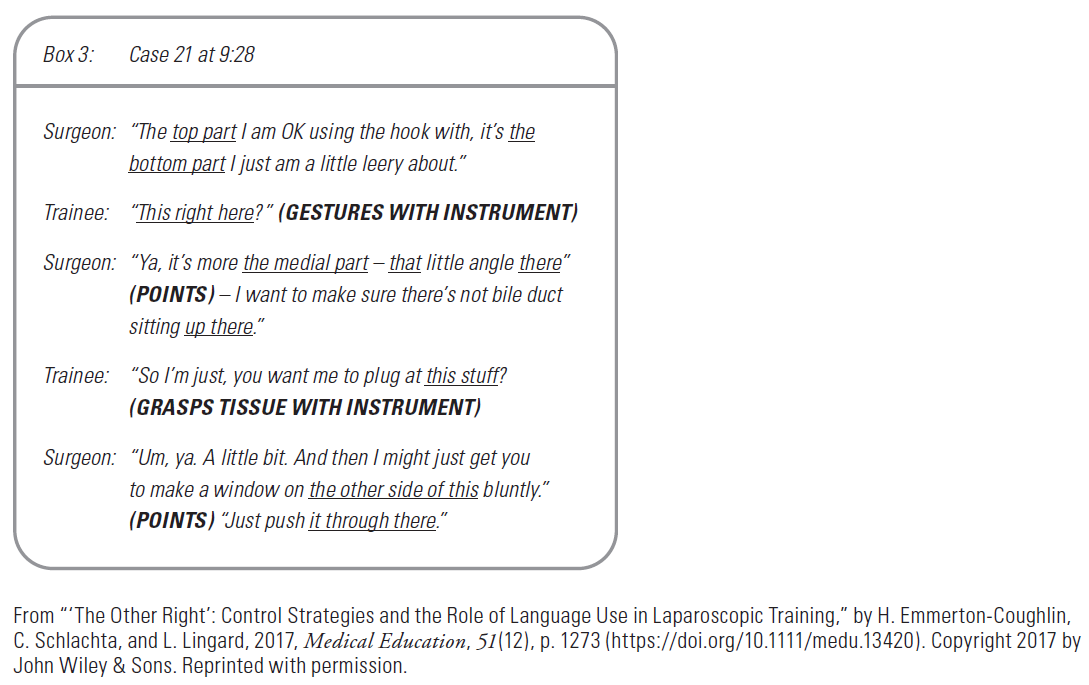

때때로 당신은 자신의 문장에 통합할 수 없는 더 긴 인용구를 포함하기를 원할 것이다. 이러한 인용문은 독자들에게 인터뷰의 분위기를 느낄 수 있게 하거나 아이디어들 사이의 복잡한 상호관계를 엿볼 수 있게 할 수 있으며, 당신은 이러한 차원을 잃어버릴 정도로 그것들을 자르고 싶어하지 않을 것이다. 하지만, 인용문이 길어질수록 독자의 관심이 당신이 의도한 것과는 다른 무언가에 걸릴 가능성이 더 커진다는 것을 명심하라. 결과 작성에 있어 이러한 모순을 방지하기 위해 인용 샌드위치 기법(인용문 앞의 문맥에 적용하고 그 뒤의 해석을 요약하는 것)을 고려하십시오. 다음 그림(Emerton-Coughlin et al., 2017)에서 비디오 발췌문 필사본은 3번 박스에서 설명되는 내용과 포인트에 대한 자세한 분석을 제공하는 요약 텍스트로 구성된다.

Sometimes you will want to include a longer quote that cannot be integrated into your own sentence. Such quotes can offer readers a sense of the mood of the interview, or a glimpse of the complex interrelationship among ideas, and you don’t want to cut them back to the point that this dimension is lost. Keep in mind, though, that the longer the quote, the greater the chance that the reader’s attention will snag on something other than what you intend. To guard against this source of incoherence in your results writing, consider applying the “quotation sandwich” technique (Graff & Birkenstein, 2018) to contextualise before the quotation and summarise your interpretation after it. In the following illustration (Emmerton-Coughlin et al., 2017), the transcription of a video excerpt is set off in Box 3, sandwiched by introductory text that sets up what’s being illustrated and summary text that provides detailed analysis of the point:

다음 예는 통제 역학의 양방향 특성을 보여줍니다. 의사가 수술 기법을 수정하라는 지침을 시작합니다(상자 3 참조).

The next example typifies the bidirectional nature of control dynamics. The surgeon initiates an instruction to modify the surgical technique (see Box 3).

외과의사의 지침을 올바르게 이행하려면 훈련생이 올바른 표현을 해석해야 합니다. "상단 부분"과 "하단 부분"이 있습니다. 훈련생은 다시 데히스를 사용하여 "이것이 바로 여기입니까?"라고 응답하고 주어진 지침에 대한 자신의 해석을 확인하기 위해 현지화 기동을 합니다. 외과의는 명령을 승인한 다음 추가 정보와 추가 지시로 자신의 신체적 제스처 동작을 추가하며 더 정교하게 다듬는다. 이는 핵심 구조물인 담관을 식별하고 보호하는 것과 관련된 고난도의 순간 동안 교육생이 강사에게 준 엄격한 수준의 통제를 강조합니다.

Correct implementation of the surgeon’s instruction relies on the trainee’s correct interpretation of the deictic expressions: “the top part” and “the bottom part”. The trainee responds, again using deixis, “This right here?” and pairs with it a physical localising manoeuvre in order to confirm her interpretation of the instruction given. The surgeon ratifies and then goes on to further refine the instruction with additional information and additional deictic instruction, adding his own physical gesturing manoeuvre. This back and forth highlights a concession by the trainee of a tight degree of control to the instructor during this high-stakes moment involving the identification and protection of a key structure, the bile duct.

이 예제는 또한 인용문의 내용을 단순히 반복하지 않고 요약하는 방법을 보여줍니다. 독자는 이미 인용문을 읽었는데, 인용문은 지시적인 표현들을 강조하기 위해 주석을 달았다. 그 뒤의 텍스트는 이 교환의 "양방향성"에 대한 시작점을 예시하며, 예제의 진행 상황에 대한 설명에서 "대응", "확인", "뒤로"와 같은 용어를 사용한다.

This example also demonstrates how to summarise the quote without simply repeating what it says. The reader has already read the quote, which is annotated to highlight the deictic expressions. The text after it exemplifies the opening point about “the bidirectional nature” of this exchange, by using terms such as “responds”, “confirms”, “ratifies” and “back and forth” in the explanation of what’s going on in the example.

한 요점을 뒷받침하기 위해 여러 개의 인용문을 사용하는 것은 피해야 합니다. 여러 인용구를 사용하는 편이 더 좋은 경우는 단 하나의 인용구만으로는 정당하지 않은 층위나 뉘앙스가 있을 때 뿐이다

Using multiple quotations to support a single point should be avoided. More is only better when there are layers or nuances that a single quote doesn’t do justice to.

웰니스(Wellness)는 참가자들에게는 미묘한 아이디어였습니다.

Wellness was a nuanced idea for our participants:

"걸어다니는 좀비가 되지 않기 위해 규칙적으로 먹고, 잠을 자는 것." (P2)

“Eating regularly, getting some sleep, so that you’re not a walking zombie.” (P2)

"건강하지 않을 때, 불안하거나 우울할 때, 인간관계가 고통받고 있을 때, 곁에 있을 수 없다는 것을 깨닫는다."(P11)

“Recognising when you’re not well, you’re anxious or depressed, your relationships are suffering, you’re impossible to be around.” (P11)

"기본적인 행복이요, 제게 더 이상 기쁨이 없는 것처럼요? '나는 임상적으로 우울하다'가 아니라 '나는 내 작품에 더 이상 없을 뿐이다.' (P12)

“Basic happiness, like is there any joy in this anymore for me? Not, ‘I’m clinically depressed’ but sort of, ‘I’m just not present in my work anymore.’” (P12)

"미묘한 아이디어"라는 표현이 독자에게 여러 인용문이 이러한 뉘앙스를 보여주기 위한 것임을 경고하지만, 이 예는 독자로 하여금 [인용문 사이의 (비어있는) 공간을 스케치를 하도록] 만든다. 다음과 같이 바꾸는 것이 수사적으로 더 효과적이다.

While “nuanced idea” alerts the reader that the multiple quotes are intended to demonstrate this nuance, this example makes the reader do the work of sketching in the space between the quotes. The following revision is more rhetorically effective.

웰니스(Wellness)는 우리의 참가자들에게는 미묘한 아이디어였다. 많은 이들이 "걸어다니는 좀비가 되지 않기 위해 규칙적으로 먹고, 잠을 자는 것"의 중요성을 인정하는 가운데, 참가자들의 설명에서 신체 건강의 차원이 두드러졌다(P2). 정신건강도 특히 "건강이 좋지 않을 때, 불안하거나 우울할 때, 인간관계가 고통받고 있을 때, 곁에 있을 수 없을 때" (P11)에 대해 논의했습니다. 건강은 또한 신체적, 정신적 건강에 대한 전통적인 개념을 넘어 "기본적인 행복, 나에게 더 이상 기쁨이 없는가?"라는 질문으로까지 확장됩니다. '나는 임상적으로 우울하다'가 아니라 '나는 더 이상 내 일에 있지 않을 뿐이다' (P12).

Wellness was a nuanced idea for our participants. Dimensions of physical health were prominent in participants’ explanations, with many acknowledging the importance of “eating regularly, getting some sleep, so that you’re not a walking zombie” (P2). Mental health was also discussed, in particular “recognising when you’re not well, you’re anxious or depressed, your relationships are suffering, you’re impossible to be around” (P11). And wellness was also understood to extend beyond the conventional notions of physical and mental health, into questions of “basic happiness, like is there any joy in this anymore for me? Not, ‘I’m clinically depressed’ but sort of, ‘I’m just not present in my work anymore’” (P12).

이 버전에서 작가는 독자를 위한 이 세 인용구 사이의 관계를 설정하면서 '물리적', '정신적', '그 너머'를 명시적으로 명명한다.

In this version, the writer explicitly names “physical”, “mental” and “beyond” as they establish the relations between these three quotes for the reader.

우리가 논의할 마지막 예는 결과를 설명하기 위해 복합 내러티브를 사용하는 것입니다. 복합 서술은 여러 인터뷰나 관찰로부터 얻은 데이터를 사용하여 하나의 상세한 이야기를 들려준다. 복합 내러티브는 인용구가 아니다; 그것들은 구성이고, 따라서 작가들에게 상당한 수준의 수사적 통제를 제공한다. 그것들을 효과적으로 사용하기 위해서, 작가들은 그 구성 요소들이 무엇을 나타내는지 그리고 발견을 설명하기 위해 어떻게 사용되는지를 설명하면서 독자들의 방향을 잡아야 한다. 다음 단락은 그러한 지향성이 어떻게 보일 수 있는지를 보여준다.

The final example we will discuss is the use of composite narratives to illustrate your results. A composite narrative uses data from multiple interviews or observations to tell a single, elaborated story. Composite narratives are not quotations; they are constructions and, thus, offer writers a significant degree of rhetorical control. To use them effectively, writers must orient readers, explaining what the composites represent and how they are used to illustrate findings. The following paragraph illustrates how such orienting might look.

데이터 분석 결과를 바탕으로 3가지 복합 내러티브가 생성되었는데, 참가자들의 3가지 구분된 그룹 각각에 대해, GP 교육을 마친 직후 학문적 역할에 입문한 GP들이 전임 임상을 원하지 않는다고 결정한 경험의 복합체인 '내러티브 1, '알렉스'l post; 교육이나 연구에 관심을 가지고 학문적 역할에 입문한 GP의 경험을 종합한 서사 2, '로빈', 그리고 경력 중후반에 학계에 입문한 GP의 경험을 종합한 서사 3, '조'로, 임상 실습에 대한 대안을 모색하고 있다.무식한 일 경험이 스스로 식별된 성별 범주를 넘나들었다는 것을 반영하여, 이러한 서술에 성 중립적인 이름이 할당되었다. 연구 결과는 복합 서술에서 발췌한 것으로 설명된다. (McElhinney & Kennedy, 2021, 페이지 3)

Based on the findings of the data analysis, three composite narratives were produced, one for each of the three distinct groups of participants identified: Narrative 1, ‘Alex’, a composite of the experiences of GPs who had entered an academic role immediately after completion of GP training, having decided that they did not want a full-time clinical post; Narrative 2, ‘Robin’, a synthesis of the experiences of GPs who entered an academic role mid-career, having been a GP partner, with an interest in education or research; and Narrative 3, ‘Jo’, synthesising the experiences of GPs who entered academia mid to late career, looking for an alternative to clinical practice to run in parallel to clinical work. Gender-neutral names were assigned to these narratives, reflecting that the experiences crossed self-identified gender categories. The findings are illustrated with excerpts from the composite narratives. (McElhinney & Kennedy, 2021, p. 3)

Willis (2019)에 따르면, 복합 내러티브은 세 가지 주요 이점을 제공한다:

- 원자적인 범주나 주제보다 복잡하고, 위치된 설명을 제공한다;

- 익명성을 보장한다;

- 효용성과 접근성을 극대화할 수 있다. 특히 학계 밖의 독자들을 위한 질적 연구 결과.

필자는 복합물이 주요 데이터의 톤과 내용에 충실하도록 보장해야 하며 복합 서사를 작성하기 위한 적절한 절차를 따라야 한다. 그들의 결과를 설명하기 위해 복합 사례를 시도하는 데 관심이 있는 저자들의 경우, 아파르미안 외 연구진(2015)과 팩 외 연구진(2020)은 이 접근방식을 사용하는 두 가지 다른 방법을 보여준다.

According to Willis (2019), composite narratives offer three main advantages:

- they present complex, situated accounts rather than atomistic categories or themes;

- they ensure anonymity; and

- they may maximise the utility and accessibility of qualitative findings, particularly for readers outside academia.

Their main limitation relates to authenticity—the writer must ensure that the composite is faithful to the tone and content of the primary data and should follow appropriate procedures for creating their composite narrative. For writers interested in trying a composite case to illustrate their results, Apramian et al. (2015) and Pack et al. (2020) demonstrate two different ways of employing this approach.

복잡성의 인정

An acknowledgement of complexity

우리는 효과적인 질적 결과 섹션의 작성을 안내하는 데 도움이 되는 세 가지 원칙을 제시했습니다: 스토리텔링, 진실성 및 논쟁. 이러한 원칙들을 고정된 규칙으로 보아서는 안 된다. 많은 요인들이 이러한 요인들이 어떻게 적용될 수 있는지에 영향을 미칩니다. 연구 방법론은 중요하다. 예를 들어, 서술적 탐구, 구성주의 기반 이론 및 비판적 담론 분석은 각자 바람직한 방식이 다를 것이다. 저널도 중요합니다. 많은 경우 이러한 원칙을 성공적으로 적용하는 방법을 이해하려면 반드시 참조해야 할 저자 지침이 있습니다.

We have offered three principles to help guide the writing of an effective qualitative results section: storytelling, authenticity and argument. These principles should not be viewed as static rules. A number of factors influence how they might be applied. Research methodology matters; for example, narrative inquiry, constructivist grounded theory and critical discourse analysis will look—and sound—distinct. The journal also matters. Many have author guidelines you should consult to understand how to adapt these principles successfully.

마지막으로, 역사는 중요합니다. 질적 연구가 정당성을 얻으면서 우리 분야의 관습이 변화하고 있다. 방법론적 용어가 변화하고 있는 것처럼(Varpio 등, 2017) 결과를 제시하는 관례도 변화하고 있다. 이 원고를 작성하면서 우리의 논문을 되돌아보면서, 우리는 우리의 접근 방식의 변화를 깨달았다. 예를 들어, 우리는 각 주제 범주의 인스턴스 수를 열거하는 테이블을 더 이상 거의 사용하지 않는다(Lingard, 2004). 그러나 20년 전에는 데이터 코딩에 관련된 여러 연구자에 대한 평가자 간 신뢰도 계수를 포함시키는 것이 흔한 일이었다. 따라서 이러한 원칙을 지침으로 사용하고, 설득력 있는 질적 결과 섹션을 만들 때 수사적 상황에 주의를 기울이십시오.

Finally, history matters. Conventions in our field are changing over time as qualitative research gains legitimacy. Just as methodological terms are shifting (Varpio et al., 2017), so too are conventions for presenting results. Looking back at our papers in the writing of this manuscript, we realised shifts in our own approaches. For instance, we rarely use tables enumerating the number of instances of each thematic category (Lingard, 2004) anymore, but that was commonplace 20 years ago, as were inter-rater reliability coefficients for multiple researchers involved in coding data. So use these principles as a guide, and stay attentive to your rhetorical situation as you work to craft a compelling qualitative results section.

Abstract

'Articles (Medical Education) > 의학교육연구(Research)' 카테고리의 다른 글

| 질적연구인터뷰 수행의 열두 가지 팁 (Med Teach, 2018) (0) | 2021.12.23 |

|---|---|

| 포화라는 위장 뒤에 숨은 것: 질적 인터뷰 자료와 견고함 (J Grad Med Educ, 2021) (0) | 2021.12.23 |

| 효과적인 문헌고찰 쓰기 파트2: 인용 테크닉(Perspect Med Educ, 2018) (0) | 2021.12.13 |

| 효과적인 문헌고찰 쓰기 파트1: 매핑 더 갭 (Perspect Med Educ, 2018) (0) | 2021.12.13 |

| 질적연구의 일반화가능성: 오해, 기회, 권고(Qualitative Research in Sport, Exercise and Health, 2018) (1) | 2021.11.23 |