좋은 수업은 좋은 수업이다: 효과적인 의학교육자들에 대한 내러티브 리뷰(Anat Sci Educ, 2015)

Good Teaching Is Good Teaching: A Narrative Review for Effective Medical Educators

Anthony C. Berman1,2*

도입

INTRODUCTION

- 역사적으로 교직과 효과적인 교사에 대한 많은 정의가 존재했고 지금도 존재한다. "교육은 다차원적이고 복잡한 활동"이기 때문에(Khandelwal, 2009) 그 효과를 정의하는 것은 상당히 어려운 것으로 입증되었다.

- 37년 전, Gage(1978)는 가르침은 "한 사람이 다른 사람에게 배우는 것을 용이하게 하기 위한 어떤 활동"이라고 간단히 말했다.

- Mursell(1954)이 일찍이 쓴 저자들은 효과적인 교사는 학생들에게 이해와 통찰력을 "극화하고 집중하기" 위해 언제 그리고 어떻게 가르치는 기회를 이용하는지를 본질적으로 알고 있는 교사였다고 썼다.

- 바(1961년)는 교사의 효과를 묘사할 수 있는 적절한 수단이 없어서 좌절했던 많은 사람들 중 하나였다.

- 펠리서(1984년)는 효과적인 가르침이 어떤 예술적 능력을 포함하고 있고 훌륭한 선생님들은 기본적으로 예술가라고 하지만, "우리가 훌륭한 가르침으로 인식하는 많은 것들은 과학적이거나 기술적인 본질이며, 쉽게 식별되고, 이해되며, 심지어 체계적으로 복제될 수 있다"고 주장했다.

- 그럼에도 불구하고, Ornstein(1993)은 "교사의 인간적인 면은 측정하기 어렵다"고 응답했는데, 이는 나중에 다니엘슨(2007)이 지지한 생각인데, 이는 일부 교사 특성이 관찰되기 보다는 추론되어야 하기 때문이다. 스트롱게(2007)는 이 유능한 교사를 "각 음악가로부터 최고의 연주를 이끌어내 아름다운 소리를 내는 교향악단 지휘자"에 비유했다.

- 보리히(2013년)는 '학생 성취를 촉진하기 위해 개인의 행동을 다른 정도로 혼합한다'는 교사를 '색깔과 질감을 그림으로 혼합해 일관성 있는 인상을 연출하는 예술가'에 비유했다.

- 효과적인 교사는 계속해서 "학생들 사이에서 높은 성취도를 일관되게 만들어 내는" 특성을 보이는 교사로 정의되기 때문에, 학생 성취도의 요소이다(Arends et al., 2001).

- There have historically been and still are many definitions of teaching and effective teachers. As “teaching is a multidimensional, complex activity” (Khandelwal, 2009), defining its effectiveness has proven to be quite difficult.

- Thirty-seven years ago, Gage (1978) made the simple statement that teaching is “any activity on the part of one person intended to facilitate learning on the part of another,” and

- authors as early as Mursell (1954) wrote that an effective teacher was one who inherently knew when and how to take advantage of teaching opportunities in order to “dramatize and focalize understanding and insight” in students.

- Barr (1961) was among many who were frustrated by the lack of an adequate means to describe the effectiveness of teachers.

- Pelicer (1984) argued that, although effective teaching incorporates a certain artistic ability and that good teachers are basically artists, “much of what we do recognize as excellent teaching is of scientific or technical nature and can be readily identified, understood, and even systematically replicated.”

- Nevertheless, Ornstein (1993) responded that “the human side of teaching is difficult to measure,” a thought later supported by Danielson (2007) because some teacher characteristics must be inferred rather than observed. Stronge (2007) likened the effective teacher to “a symphony conductor who brings out the best performance from each musician to make a beautiful sound,” and

- Borich (2013) compared a teacher blending “individual behaviors to different degrees to promote student achievement” to an “artist who blends color and texture into a painting to produce a coherent impression.”

- It is the element of student achievement, which has remained essential, because effective teachers continue to be defined as those who exhibit characteristics that “consistently produce high achievement among their students” (Arends et al., 2001).

본질적 특성

ESSENTIAL CHARACTERISTICS

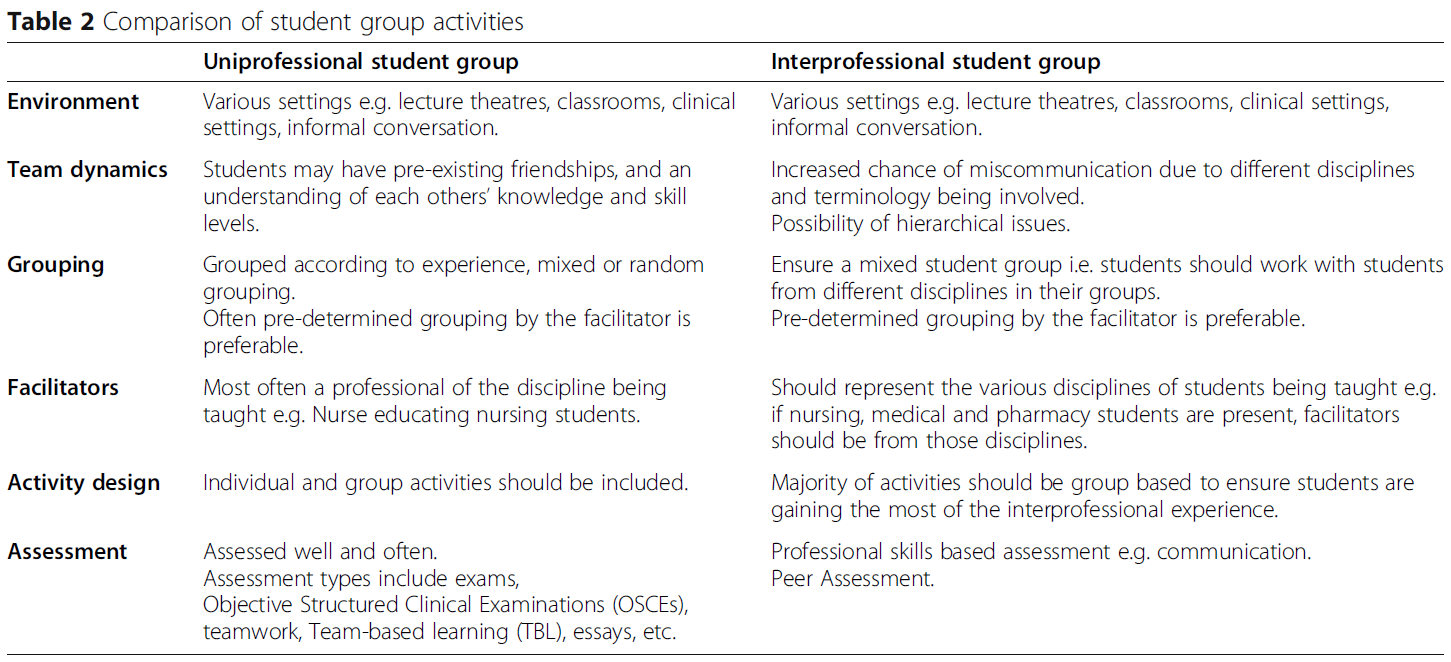

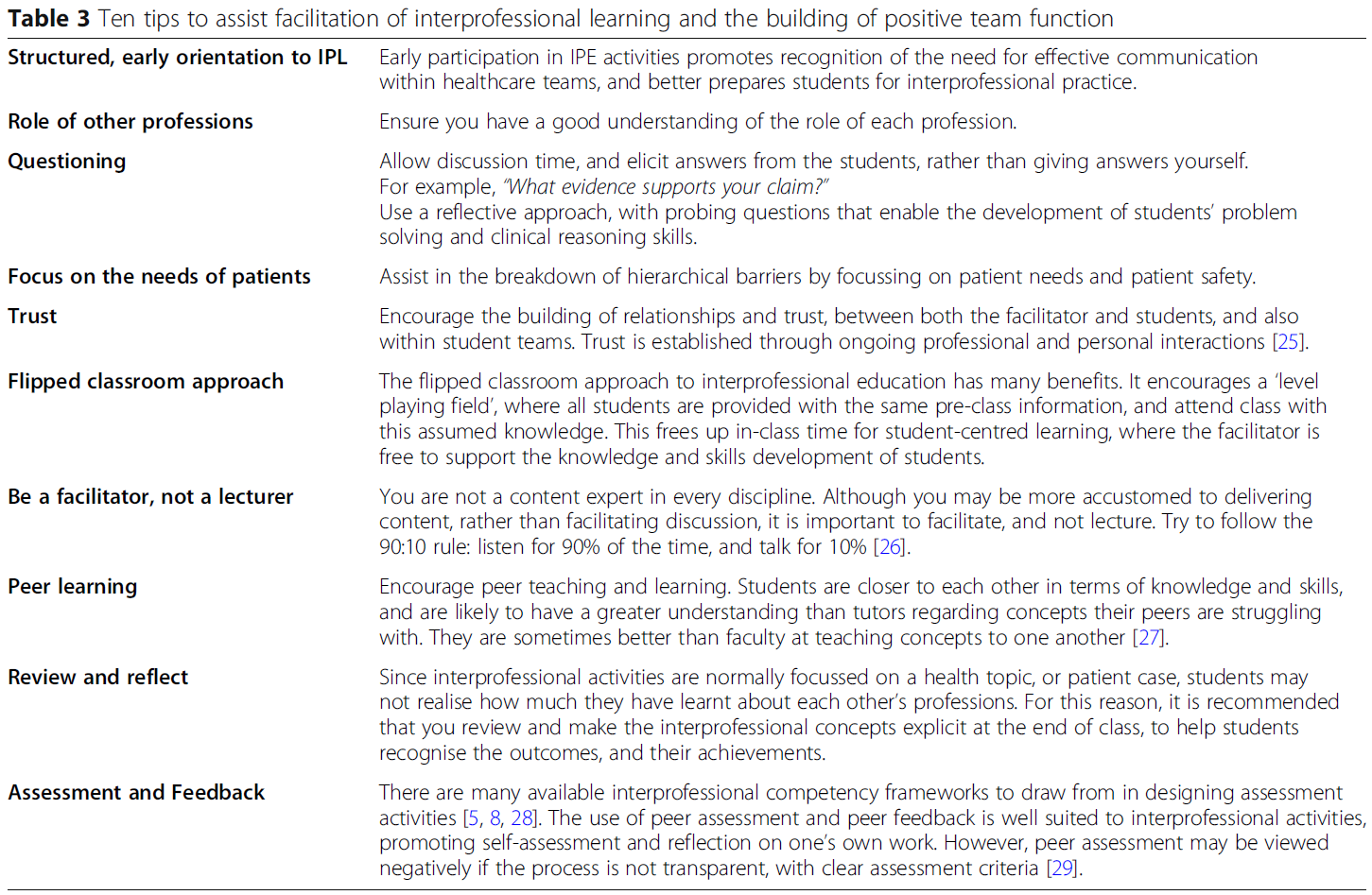

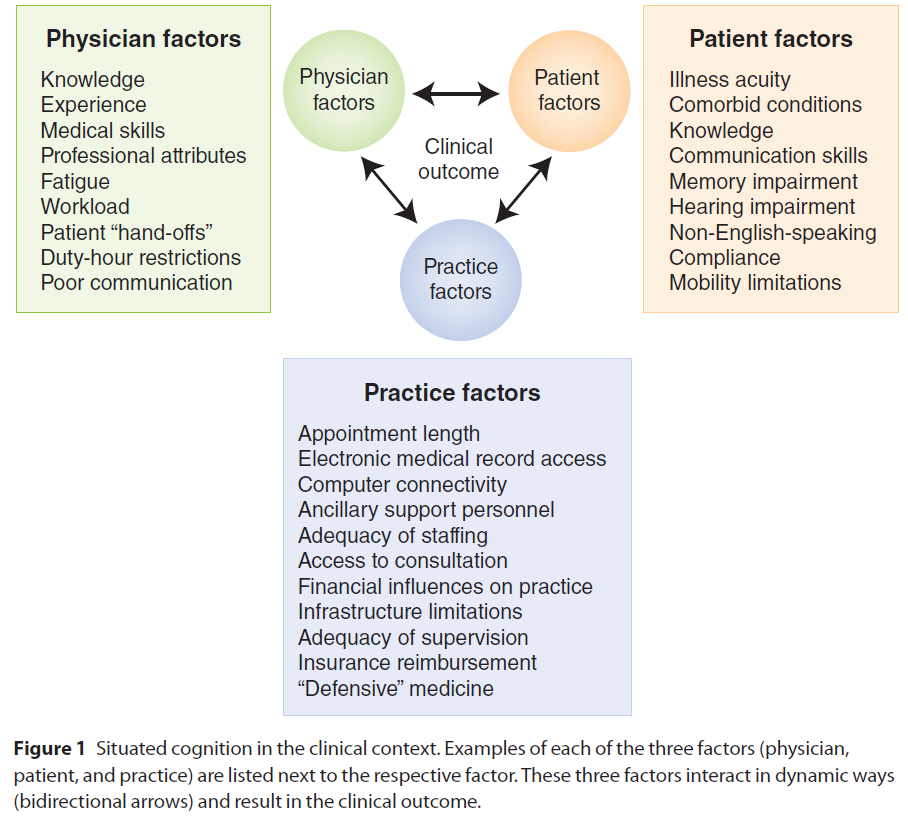

의대생들은 의대 교육 초기뿐만 아니라 여러 해 동안 공부한 동안에도 배울 것이 많다. 종종, 그들의 초기 선생님들은 그들이 의학 학위까지 이르는 필수 과정을 마쳤다는 이유만으로 효과적인 선생님으로 생각됩니다. 그러나, Haycock (1998)은 이러한 믿음에 동의하지 않았는데, 왜냐하면 그녀는 어떤 과정도 교사들에 의해 얻어진 학위가 학생들의 학습과 직접적으로 관련이 없다는 것을 발견했기 때문이다. 의료 교사가 효과적일 수 있도록 준비하고 이들을 생산적인 의료 학습 환경에 배치하는 것은 복잡한 작업이다. 교육 효과의 개발을 위한 단일 이론이나 접근법을 결정하거나 효과적인 교사에 대한 단일 설명을 작성하는 것이 가능하다면, 모든 종류의 학교들이 그러한 교사를 모든 학습 환경에 오래 전에 배치했을 것이라는 스트롱의(2007) 가설이었다. Medical students have much to learn, not only in the early years of their medical education but also throughout their many years of study. Often, their early teachers are thought to be effective teachers just because they have completed the required courses leading to a medical degree. Haycock (1998), however, disagreed with this belief, because she found that neither courses completed nor degrees earned by teachers correlated directly with student learning. Preparing medical teachers to be effective and placing them in productive medical learning environments is a complex task. If it would be possible to determine a single theory or approach for the development of teacher effectiveness or to craft a single description of an effective teacher, it was Stronge’s (2007) hypothesis that schools of all kinds would have long ago placed such a teacher in every learning environment.

학생들을 알아가는 것이 교사의 효과의 토대이다.

Getting to Know Your Students Is the Foundation of Teacher Effectiveness

브룩필드(2006)의 의견에서 [학습자를 아는 것]은 아마도 가장 중요한 요소일 것이다. "학습의 극대화를 위해, 교사들은 그들의 과목과 그에 수반되는 교육학뿐만 아니라 그들의 학생들도 알아야 한다."(Danielson, 2007). 그러므로, 학생들이 배우는 것은 수업에 가져오는 것에 영향을 받기 때문에, 그들을 알아가는 것은 매우 중요하다. 그들이 당신을 알게 하는 것도 중요합니다. 이 두 가지 과제를 모두 수행하는 가장 좋은 방법 중 하나는 학생들에게 많은 질문을 하고, 학생들이 여러분에게 많은 질문을 하도록 격려하며, 두 경우 모두 학생들이 말하는 것을 주의 깊게 듣는 것입니다.

Knowing your learners is perhaps the most important element in the opinion of Brookfield (2006). “To maximize learning, teachers must know not only their subject and its accompanying pedagogy, but also their students” (Danielson, 2007). It is, therefore, critical to get to know them (and what they already know), since what students learn is influenced by what they bring to class (Svinicki, 2004). It is also important to let them get to know you. One of the best ways to accomplish both of these tasks is to ask many questions of your students, to encourage your students to ask many questions of you, and to listen very carefully to what the students are saying in both instances.

매우 많은 다른 선생님들이 종종 짧은 시간 동안 각 학생들과 함께 참여하기 때문에, 따라서 교대 시간 사이에 환자를 진료할 때 사용되는 것과 유사한 "handoff" 절차를 개발할 필요가 있을 수 있다. 다시 말하지만, 시간이 많이 걸리지만, 과거에 학생들과 함께 일했던 선생님들은 미래에 이 같은 학생들과 함께 일하는 선생님들에게 가치가 있다는 것을 증명할 수 있는 통찰력을 가지고 있을지도 모른다.

Because so many different teachers are involved with each student for often short periods of time, it may, therefore, be necessary to develop a “handoff” procedure similar to those used when handing off patients between shift changes. Again it is time-consuming, but teachers who have worked with students in the past may have insights that could prove valuable to teachers working with these same students in the future.

모르는 것은 가르칠 수 없다

You Cannot Teach What You Do Not Know

간단히 말해서, 모르는 것은 가르칠 수 없다. 교육학적으로 성공하기 위해서는 [과목에서의 역량]과 [그 역량을 가지고 있다는 자신감]이 둘 다 필요하다. 상식적으로 '이해하지 못한 것은 가르칠 수 없다'는 간결한 진술을 한 클라크(1993)만큼 잘 말한 사람은 없다. 단순히 아는 것이 아니라, 선생님들은 그들의 과목을 너무 잘 알기 때문에 그들은 가장 복잡한 과목의 주제조차도 단순화할 수 있다. 그러나 교사는 모든 것을 알 필요가 없고 모든 것을 안다고 주장해서는 안 된다.

Quite simply, one cannot teach what one does not know. Both competence in the subject and confidence that you have that competence are necessary for pedagogical success. No one has ever said it better than Clark (1993), who made the concise statement that common sense dictates “one cannot teach what one does not understand.” But, in addition to simply knowing their subjects well, teachers should know their subjects so well that they are able to simplify even the most complex topics of the discipline. A teacher does not, however, need to know everything nor should a teacher ever claim to know everything.

학습 환경은 안전하고, 위협적이지 않으며, 긍정적이고, 협력적이어야 합니다.

The Learning Climate Should Be Safe, Nonthreatening, Positive, and Collaborative

교육 환경, 분위기 또는 분위기로도 알려진 학습 기후는 다면적이며 때로는 [교육 기관의 성격이나 정신]으로 표현되기도 한다(Holt and Roff, 2004). 이는 해당 기관 내에서 교육/학습 세팅의 톤으로 나타날 수 있으며, 학습 활동에 영향을 미치는 유형 및 무형 요소의 합계에 의해 제어됩니다. Loukas(2007)에 따르면, 학생들이 [친근하고, 초대하고, 지지하고, 또는 배제되고, 환영받지 못하며, 심지어 안전하지 않은] 것으로 인식되는 교육 환경을 설명하는 태도와 감정이 학습 환경을 설명한다.

Learning climate, also known as the educational environment, atmosphere, or ambiance, is multifaceted and is sometimes described as an educational institution’s personality or spirit (Holt and Roff, 2004). It can be manifested as the tone of any teaching/learning setting within that institution and is controlled by the sum total of the factors, both tangible and intangible, which impact the learning activity. According to Loukas (2007), attitudes and feelings describing educational settings, perceived by students as friendly, inviting, and supportive, or exclusionary, unwelcoming, and even unsafe, constitute a description of the learning climate.

학습 기후는 대학마다 많이 다를 뿐 아니라, 모든 학생들이 단일 기관이나 환경의 분위기를 항상 동일한 방식으로 인식하지는 않는다. [학습 풍토는 의과대학의 영혼]이라고 할 수 있기 때문에, 안전하고, 위협적이지 않으며, 긍정적이고, 학습자의 인식에 협력적일 때 가장 생산적이다. (Gen, 2001) 교사의 개입으로 일반적으로 바뀔 수 있다는 점에서 방의 온도와 같다. 최고의 교사들은 학습자들이 통제감을 가지고 있고 그들이 공정하게 평가받을 것이라고 느끼는 도전적이면서도 지지적인 분위기를 만들기 위해 끊임없이 노력한다. (Bain, 2004)

Learning climates can vary greatly, and the climate of a single institution or setting is not always perceived in the same way by all students. As a learning climate can be considered to be the very soul of a medical school, it is most productive when it is safe, nonthreatening, positive, and collaborative in the perception of the learners (Genn, 2001). It is like the temperature of the room, in that it can generally be altered via interventions by the teacher. The best teachers constantly work to create a challenging yet supportive atmosphere where learners have a sense of control and feel they will be evaluated fairly (Bain, 2004).

이러한 풍토의 근간에는 교사에 대한 학생 신뢰와 학생에 대한 교사신뢰가 있다. 유능한 교사는 학생들에 대한 신뢰가 두텁고, 학생들에게 솔직하고, 항상 세심한 배려와 존경심을 가지고 대함으로써 이러한 신뢰를 보여준다. 머셀(1954년)은 수년 전 "교실의 사회적 환경이 그곳에서 일어나는 학습에 막대한 영향을 끼친다"고 지적했다.

At the foundation of such a climate is trust, both student trust of teacher and teacher trust of student. Effective teachers have a strong trust in their students, and they demonstrate this trust by being open and honest with students, always treating them with care and respect. Mursell (1954) noted many years ago that “the social setting of the classroom has an enormous influence on the learning that takes place there.”

이것은 오늘날의 의학 교실에서도 마찬가지이다. 의료지식과 기술 습득에 공동체 의식이 도움이 될 수 있다는 점에서 임상학습 환경에서 공동체 개발의 중요성을 Kost와 Chen(2015)이 뒷받침했다. Watling 외 연구진(2014)은 "(신뢰하는) 관계가 없으면 피드백이 신뢰할 수 있는 것으로 인식될 가능성이 낮아지고 따라서 수용되고 이행될 가능성이 낮아지기" 때문에 이러한 신뢰 관계를 구축하는 것도 중요하다고 생각했다. 효과적인 교사가 되고자 하는 교사(의학 또는 다른 교사)가 학생들이 성공할 수 있도록 최선의 가능성을 가진 분위기를 조성하는 데 의도적으로 노력하는 것은 이치에 맞을 것이다.

This is just as true in today’s medical classroom. The importance of developing community in the clinical learning environment was supported by Kost and Chen (2015) in that a sense of community can assist in the acquisition of medical knowledge and skills. Building such trusting relationships was also deemed important by Watling et al. (2014), because “without such relationships, feedback was less likely to be perceived as credible and thus less likely to be accepted and acted upon.” It would make sense for a teacher wanting to become an effective teacher (medical or otherwise) to deliberately work at establishing an atmosphere having the best possibility of enabling students to succeed.

확립된 기후는 학생들에게 중요한 만큼 staff들에게도 중요한데, 학생들의 성공 가능성에 큰 영향을 미치며, 의대 교사와 학생들의 학생, 그리고 의대 교사와 서로 간의 관계의 한 요인이다. (Gen, 2001) 공동체 의식을 기르는 것은, 실제로, 학생들의 성공을 촉진하는데 도움이 되고, 학생들의 성공은 언제나 모든 교육적 노력의 핵심bottomline이 되어야 한다.

The established climate, as important for staff as it is for students, greatly impacts the likelihood of student success and is a factor of the relationships between the medical teachers and their students and between medical teachers and each other (Genn, 2001). Building a sense of community does, indeed, help facilitate student success, and student success should always be the bottom line for any educational endeavor.

유능한 교사는 효과적인 질문 방법을 알아야 한다.

An Effective Teacher Must Know How to Effectively Ask Questions

Nicholl과 Tracy(2007)가 효과적인 질문을 가장 중요한 교육 기법 중 하나로 간주했기 때문에, 질문하는 데 능숙해지지 않고 효과적인 교사가 되는 것은 불가능하지는 않더라도 상당히 어려울 것이다. 따라서, 이러한 스킬 세트를 개발하고 학생 이해도를 높이기 위한 탐색 질문을 사용하는 것이 필수적입니다(Vasan 및 DeFouw, 2005).

It would be quite difficult, if not impossible, to become an effective teacher without first becoming adept at asking questions, as Nicholl and Tracey (2007) considered effective questioning to be one of the most important teaching techniques. Thus, developing this skill set, and using probing questions to enhance student comprehension (Vasan and DeFouw, 2005), along with practicing both the encouragement and answering of student questions, is essential.

보리히 (2013)에 따르면, 유능한 교사는 질문하는 방법뿐만 아니라 질문의 유형을 구별하는 방법도 알아야 한다.질문은 여러 수준에서 할 수 있지만, 가장 생산적인 질문은 생각을 자극하는, 개방적인, 탐구적인 질문이며, 학생들이 그들의 반응을 처리할 수 있는 충분한 대기 시간을 허용하는 것은 항상 중요하다. (Sachdeva, 1996; Nichol and Tracy, 2007) 의사들은 종종 질문을 던지는 데 꽤 능숙하지만, 환자 및/또는 학생들이 질문을 처리하고 답변할 수 있는 충분한 대기 시간을 남기는 것을 종종 잊을 수 있다. 오르슈타인의 진술서,"좋은 가르침의 본질은 좋은 질문과 관련이 있다"는 많은 존경 받는 교육자들의 강력한 지지를 받아 왔다.

According to Borich (2013), an effective teacher must not only know how to ask questionsbut also how to tell the difference between types of questions. Questions can be asked at many levels, but the most productivequestions are thought-provoking, open-ended, and probing, andit is always important to allow sufficient wait time for studentsto process their responses (Sachdeva, 1996; Nicholl and Tracey,2007). Physicians are often quite accomplished at asking ques-tions, but they can frequently forget to leave sufficient waittime for patients and/or students to process and answer thequestions that have been asked. Ornstein’s (1987) statement,“The essence of good teaching is related to good questioning,”has been strongly supported by many respected educators,

효과적인 질문자는 종종 콘텐츠 전문가보다 훨씬 더 나은 선생님이다. 생산적인 질문을 편안하고 효과적으로 하는 방법을 배우는 것은 다른 교육 분야와 마찬가지로 의학 교육자로서 일관성 있는 성공에 중요하다(Mazur, 2009). 쿡 외 연구진(2010)에 따르면 "아마 필요한 것은 침대 곁의 과학 전문가, 정답을 가진 사람이 아니라 생산적인 질문을 중시하는 문화일 것"이라고 한다. Kost와 Chen (2015)에 따르면, 의학 교육자들은 학습자 중심적인 질문 관행을 개발하기 위해 변화를 고려해야 한다.

An effective questioner is often a far better teacher than the content expert. Learning how to comfortably and effectively ask productive questions is just as critical to consistent success as a medical educator as it is in any other area of teaching (Mazur, 2009). According to Cooke et al. (2010), “Perhaps what is needed is not a science expert as the bedside, the person with the answers, but a culture that values productive questions.” According to Kost and Chen (2015), medical educators should consider making changes in order to develop questioning practices that are more learner-centered.

효과적인 질문은 모든 학습 환경의 전체 분위기를 제어하며, 효과적인 교사의 진단 도구의 기초를 형성하고, 사고를 촉진하고, 추론 능력의 개발을 촉진함으로써 다양한 건강 직업에서 학생 학습을 촉진하는 데 엄청난 도움을 준다. (Sachdeva, 1996; Nichol and Tracy, 2007).

Effective questioning controls the entire atmosphere of any learning environment, forming the basis of an effective teacher’s diagnostic tools and helping tremendously in facilitating student learning in all of the various health professions by prompting thinking and facilitating the development of reasoning ability (Sachdeva, 1996; Nicholl and Tracey, 2007).

학생들이 적극적으로 참여할 때 더 많은 것을 배운다.

Students Learn More When They Are Actively Involved

교육자들은 교육은 단순히 전통적인 강의를 통해 교사로부터 학생으로 정보를 전달하는 것 이상이라는 것을 배웠다(Mazur, 2009). 학생들은 그들이 적극적으로 참여할 때 더 많이 배우고 더 깊게 배운다. (Vasan and DeFouw, 2005) 실버먼(1996년)이 인용한 중국의 철학자이자 스승인 공자는 2400여 년 전 "내가 들은 것은 잊는다. 내가 본 건, 기억난다. 제가 하는 일은 이해해요." 훨씬 후, 치커링과 감슨(1987)은 "학생들은 수업시간에 앉아서 선생님들의 말을 듣고, 미리 꾸민 과제를 외우고, 답을 뱉는 것만으로 많은 것을 배우지 못한다"는 말과 함께 이 생각을 다시 찾았다. 줄(2002년)도 학생들이 '배움'을 하려면 '해야 한다'며 적극적인 학습의 필요성을 강조했다.

Educators have learned that education is more than simply transferring information from teacher to student via the traditional lecture (Mazur, 2009). Students simply learn more and learn more deeply when they are actively involved (Vasan and DeFouw, 2005). Confucious, the Chinese philosopher and teacher cited by Silberman (1996), was well aware of this over 2,400 years ago when he uttered the now famous, “What I hear, I forget. What I see, I remember. What I do, I understand.” Much later, Chickering and Gamson (1987) revisited this thought with the statement, “Students do not learn much just by sitting in classes listening to teachers, memorizing pre-packaged assignments, and spitting out answers.” Zull (2002) also emphasized the need for active learning, stating that students must “do” if they are to “learn.”

울프 외 연구진(2015)은 최근 여러 가지 추가적인 능동적 학습 전략(1분 논문, 생각 쌍 공유, 개념 지도, 조각, 생각 모자, 시뮬레이션)을 설명했다. 이는 지식 보유를 개선하고 "학습자의 요구를 전환하고 학습자의 적극적인 참여를 요구함으로써 수동적 학습보다 더 깊이 있는 이해"를 창출하는 데 도움이 될 수 있습니다. 능동적인 학습은 때때로 전통적인 훈련을 받은 교사가 교육 과정으로 통제력을 상실하게 만들 수 있지만, 학습은 관람 스포츠가 아니며 결코 관람 스포츠가 된 적도 없다! 의학 학습자들은 그들에게 주어진 새로운 정보를 실제로 적용하지 않는다면, 완벽한 오믈렛을 만드는 기술을 연습하는 것이 아니라, 그저 다른 사람들이 오믈렛을 만드는 것을 지켜보면서 완벽한 오믈렛을 만드는 법을 배우려는 요리사와 같을 것이다.

Wolff et al. (2015) recently described a number of additional active learning strategies (one-minute papers, think-pair-share, concept maps, jigsaw, thinking hats, and simulation), which can improve knowledge retention and help to create “a deeper understanding of material than passive learning can achieve by shifting the learner’s needs and requiring active participation of learners.” Active learning can sometimes cause a traditionally trained teacher to feel a loss of control with the instructional process, but learning is not and never has been a spectator sport! Without actually applying the new information presented to them, medical learners would be like chefs trying to learn how to make a perfect omelet by watching others make omelets (Hoffman, 2015) rather than by practicing the art of making a perfect omelet.

바산 외 연구원에 따르면 (2009, 2011) 및 Minhas 등(2012)은 해부학처럼 내용 밀도가 높은 자료를 학습하려고 할 때 학생들에게 능동적 학습이 특히 중요할 수 있다. 또한 학생으로서 팀 기반 및/또는 협력 학습 활동에 적극적으로 참여하는 것은 학생이 의료 팀의 일부로 더 효과적으로 참여할 수 있도록 준비하는 데 도움이 될 수 있으며, 팀 내에서 기능할 수 있는 능력은 의료 전문 분야에서 점점 더 중요해지고 있다 (Vasan 및 DeFouw, 2005; Vasan et al., 2009, 2010).1).

According to Vasan et al. (2009, 2011) and Minhas et al. (2012), active learning can be especially important for students when they are attempting to learn such content-dense materials as anatomy. Furthermore, being actively involved in team-based and/or cooperative learning activities as a student can help prepare the student to participate more effectively as part of a medical team, and the ability to function within a team has become increasingly important within the healthcare professions (Vasan and DeFouw, 2005; Vasan et al., 2009, 2011).

수업을 안내하기 위해 구체적인 학습 목표가 필요합니다.

Specific Learning Objectives Are Needed to Guide Instruction

McKimm과 Stanwick(2009)이 관찰한 바와 같이, "의료 교육은 교육 개입의 결과로 학습자가 달성해야 하는 것을 설명하기 위해 목표, 학습 성과, 학습 목표, 역량 등 다양한 용어를 사용한다." 선택된 용어와 관계없이, 최근 연구(Wattling et al., 2014)는 의학교육이 의학 학습자를 위한 목표를 명확하게 정의하는데 어려움을 겪는 경우가 많다고 제안했다.

As observed by McKimm and Stanwick (2009), “Medical education uses a range of terms – aims, learning outcomes, learning objectives, competencies – to describe what learners should achieve as a result of educational interventions.” Regardless of the chosen term, a recent study (Watling et al., 2014) suggested that medical education frequently has difficulty in clearly defining objectives for medical learners

이러한 목표는 학생과 교사(Bassaw et al., 2003), 구체적이고 관찰 가능하며 측정 가능하고 평가 가능해야 한다. 또한 McKimm과 Stanwick(2009년)이 주장한 바와 같이, 그것들은 현실적이고 성취할 수 있어야 한다. 학생들에게 소통하고, 학습활동 내내 선생님의 집중을 받으며, 학습활동이 끝났을 때 학생이 실제로 무엇을 할 수 있어야 하는지에 대한 질문에 답할 수 있도록 단어화해야 한다(McKim과 Swanwick, 2009). 명확한 목표가 없다면, 어떤 특정한 교훈/활동이 달성되어야 하는지를 결정하거나 원하는 학습이 이루어졌는지 정확하게 평가하는 것은 불가능하다.

These objectives must be clear both to student and teacher (Bassaw et al., 2003), specific, observable, measureable, and assessable. In addition, as argued by McKimm and Stanwick (2009), they must be realistic and achievable. They should be communicated to students, focused on by the teacher throughout the learning activity, and worded so that they answer the question of what the student should be able to actually do when the learning activity has been completed (McKimm and Swanwick, 2009). Without clear objectives, it is impossible to determine what a particular lesson/activity is supposed to accomplish or to accurately assess whether the desired learning has taken place.

칸(1982년)은 "계획이 부족하면 대개 의식의 흐름 교육으로 이어지는데… 목표 없는 대화는 한 시간밖에 되지 않는다"고 확신했다. 계획은 엄격할 필요는 없지만(학습 활동이 침상 교육을 포함할 때는 엄격할 수 없다), 효과적인 교사는 계획이 어디로 향하고 있고 언제 교육 목적지에 도달했는지 알아야 한다. 스트롱(2007)은 좋은 계획을 효과적인 교육을 보장하는 것으로 여기지 않았지만, 그는 '분명 형편없는 계획이 덜 효과적인 교육으로 이어진다'고 확신했다.

Cahn (1982) was convinced that “lack of planning usually leads to stream-ofconsciousness instruction . . . amounting to nothing more than an hour of aimless talk.” Plans need not be rigid (and cannot be rigid when the learning activity involves bedside teaching), but effective teachers must know where they are headed and when they have reached their instructional destination. Although Stronge (2007) did not consider good planning to be a guarantee of effective instruction, he was definitely convinced that poor planning led to less effective instruction.

학생 학습에 대한 평가가 지침에 통합되어야 합니다.

Assessment of Student Learning Should Be Integrated Into Instruction

Dowie(2014)는 의학교육에서 의미 있는 평가를 학생의 의도된 학습에 대해 동시에 논의하지 않고는 논의할 수 없음을 확인했다. 정확하고 효과적인 평가는 교습에 중요하며 교습과 통합되어야 한다. 따라서 교사는 수시로 학생 학습을 확인하고 그에 따라 교습을 조정해야 한다.

Dowie (2014) confirmed that meaningful assessment in medical education cannot be discussed without simultaneously discussing the intended learning of the student. An accurate, effective assessment is important to instruction and should be integrated with instruction; so, teachers should frequently check for student learning and adjust instruction accordingly.

해부학 평가는 역사적으로 스폿터 검사(학생들이 고정된 구조를 식별해야 하는 곳, 땡시), 구두 시험, 필기 시험에 의존해왔지만, 학생들이 다양한 방식으로 학습한다는 인식에 따라 하이브리드 평가의 개발이 시작되었다(Smith and McManus, 2015).

Although anatomy assessment has historically relied on spotter examinations (where students have to identify a pinned structure), oral examinations, and written examinations, the development of hybrid assessment began in response to the realization that students learn in many different ways (Smith and McManus, 2015).

치커링과 감슨(1987년)이 상기한 것처럼 "학생들은 무언가 수행하고 개선을 위한 제안을 받을 수 있는 기회가 자주 필요하다"고 말했다. 평가assessment는 평가evaluation와 같지 않다는 것을 기억하는 것이 중요하다. 평가evaluation는 제품에 다른 사람의 가치를 부여하는 반면, 평가assessment는 학생이 명시한 학습 목표와 관련하여 무엇을 할 수 있는지를 결정하는 지속적인 과정이다.

As Chickering and Gamson (1987) reminded, “students need frequent opportunities to perform and receive suggestions for improvement.” It is important to remember that assessment is not the same as evaluation. Whereas evaluation is assigning another’s value to a product, assessment is an ongoing process of determining what a student can do in relation to the stated learning objectives.

"시험이 목표에 부합해야 하며, 목표가 시험에 부합해서는 안 된다."

“faculty should match the test to the objectives, not the objectives to the test.”

피드백은 학생 학습의 필수적인 부분입니다.

Feedback Is an Essential Part of Student Learning

일단 목표를 향한 학생들의 진보에 대한 평가가 이루어지면, 효과적인 교사의 다음 일은 그들이 이해하는 언어로 그 평가의 결과를 학생들에게 전달하는 것이다. 마흐무드와 다지(2004)에 따르면, 학습에서 피드백의 중요성은 꽤 오랫동안 선생님들에 의해 인식되어 왔다. "교사가 공평하게 피드백을 제공하고, 모든 학생이 자신의 업무에 대한 피드백을 받는 것이 중요합니다."(Danielson, 2007).

Once assessment of student progress toward objectives has been achieved, the next job of an effective teacher is to convey the results of that assessment to the students in language they understand. According to Mahmood and Darzi (2004), the importance of feedback in learning has been recognized by teachers for quite some time. “It is essential that teachers provide feedback equitably, that all students receive feedback on their work” (Danielson, 2007).

효과적인 교사는 "의도한 행동과 실제 행동 사이의 불일치를 인식하도록 설계된" 규칙적이고 건설적이며 구체적이고 정확한 피드백을 통해 학습 목표를 향한 구체적인 진행 상황을 학생들에게 알려야 한다(Bassaw et al., 2003). 학생들은 그들이 받는 피드백의 어조나 본질에 경시당했다고 느끼게 해서는 절대 안 된다. 오히려 확립된 학습 목표와 관련하여 성과를 개선하기 위해 긍정적인 프레임워크 내에서 도전을 받아야 한다(Lachman, 2015; van de Ridder et al., 2015).

An effective teacher should inform students of their specific progress toward the learning objectives (Pellicer, 1984) through regular, constructive, specific, and accurate feedback, designed “to recognize the discrepancy between intended and actual behavior” (Bassaw et al., 2003). Students should never be made to feel belittled by the tone or substance of the feedback they receive. Rather they should be challenged within a positive framework to improve their performance in relation to the established learning objectives (Lachman, 2015; van de Ridder et al., 2015).

피드백은 학습 활동 중(형식 피드백)과 학습 활동 종료 시(요약 피드백) 모두 제공되어야 합니다. 학습 과정에서 두 가지 점에서 모두 중요하지만, 알렉산더 외 연구진에 따르면, 이것이 가장 잘 허용되는 형성적 피드백이라고 한다. (2009년) 학생들은 주어진 상황에서 학습 부족에 대해 무언가를 할 수 있는 충분한 시간을 가지고, 자료를 어떻게 이해했는지 보고, 자신의 진도를 반 친구들과 비교한다. 스트롱(2007)에 따르면, "학생들의 학습 성과를 증가시키는 가장 강력한 수정 기술 중 하나"라고 한다. 또한, 마흐무드와 다지(2004)는 피드백이 없으면 학습자의 성과를 향상시키는 것이 불가능하다고 결론지었다. 다니엘슨(2007)은 가끔 웃는 얼굴, 격려의 눈짓, 그리고 안심시키는 몸짓의 이점을 지지했지만, 스크리븐(1994)은 가장 유익한 피드백은 특정 학생의 성취와 관련이 있다고 조언했다.

Feedback should be provided both during the learning activity (formative feedback) and at the conclusion of the learning activity (summative feedback). It is important at both points in the learning process, but it is the formative feedback that best allows, according to Alexander et al. (2009), students to see how they have comprehended the material and compare their progress with their classmates, with sufficient time to do something about a lack of learning in a given situation. It is definitely, according to Stronge (2007), “one of the most powerful modification techniques for increasing learning outcomes in students.” In addition, Mahmood and Darzi (2004) concluded that in the absence of feedback, it is impossible to improve learners’ performance. Danielson (2007) supported the benefit of occasional smiles, nods of encouragement, and reassuring gestures, but Scriven (1994) advised that the most beneficial feedback was related to specific student accomplishments.

피드백은 보통 효과적인 의료 교육의 필수적인 부분으로 받아들여지지만, 의학 교육자들은 종종 "학습자의 글로벌 지식에 대한 모호한 논평"의 제공에 만족한다(Watling et al., 2014). Archer(2010)는 피드백이 구체적이고, 정보에 입각한 외부 소스에 의해 순차적으로 촉진되고, 개별 학생의 개인적 속성보다는 학습 과제에 집중될 경우 의료 환경에서 피드백의 효과가 극대화된다는 생각을 지지했다. 실제로 Watling et al. (2014)에서 확인한 바와 같이, 여러 분야에서 학생들은 [명확하지 않거나 애매한 피드백]에 의해 좌절할 가능성이 가장 높다. 또한 경험이 풍부한 의료 교육자들은 "아무리 잘 의도되거나 잘 짜여져 있더라도 피드백이 지지적인 학습 환경 내에 있지 않으면 실패할 수도 있다"고 결론지었다(Watling et al., 2014).

Feedback is usually embraced as an essential part of effective medical education, but medical educators “often settle for the provision of vague commentary on learners’ global knowledge” (Watling et al., 2014). Archer (2010) supported the idea that the effect of feedback in a medical setting will be maximized if the feedback is specific, sequentially facilitated by an informed external source, and focused on the learning task rather than on the personal attributes of the individual student. Indeed, as confirmed by Watling et al. (2014), students in any field of learning are most likely to be frustrated by feedback that is nonspecific and/or vague. These experienced medical educators also concluded that “No matter how well intentioned or well crafted it is, feedback may be doomed to fail if it is not situated within a supportive learning climate” (Watling et al., 2014).

교사는 명확한 의사소통을 할 수 있어야 한다.

Teachers Must Be Able to Communicate Clearly

정보와 아이디어는 학생들뿐만 아니라 동료들에게도 분명하게 전달되어야 한다. Ornstein과 Lasley (2003)가 주장했듯이, 의사소통은 단지 대화만이 아니다. 비언어적 의사소통 (즉, 눈맞춤, 몸짓, 몸짓, 자세)은 말하는 것만큼 효과적인 의사소통에 중요하다. 경청은 의사소통의 한 부분으로 기억되어야 한다. 효과적인 교사는 항상 적극적인 청취를 요구하기 때문에 위협적이지 않은 방식으로 민감하게 듣는 것을 기억해야 한다. 커뮤니케이션의 모든 측면은 긍정적으로 프레임/패키지되어야 하며(van de Ridder et al., 2015) 학생이 주어진 교사와의 상호작용을 통해 학습해야 하는 경우 긍정적인 학생 성취(Borich, 2013)와 직접적인 상관관계가 있어야 한다. 또한 의료 교육자는 학생이 실습 영역에 들어갈 때 제공자-환자 관계 및 의료팀 효과의 발전에 중요한 효과적인 의사소통 습관과 기술을 모델링할 수 있다.

Information and ideas must be conveyed clearly not only to students but also to colleagues. Communication is not just talking, for as Ornstein and Lasley (2003) argued, nonverbal communication (i.e., eye contact, gestures, body movement, and posture) is just as important to effective communication as is speaking. Listening should be remembered as part of communication. Effective teachers must remember to listen sensitively in a nonthreatening manner, because effective teaching always requires active listening. All aspects of communication should be framed/packaged positively (van de Ridder et al., 2015) and should be directly correlated to positive student achievement (Borich, 2013) if students are to learn through interaction with a given teacher. In addition, medical educators can model the effective communication habits and skills that will be important to the development of provider–patient relationships and medical team effectiveness when the students enter their area of practice.

Bagnasco 외 연구진(2014)과 Herrmann 외 연구진(2015)은 간호학과 학생과 의대생 모두를 시뮬레이션 및 실험실 학습 활동을 위한 전문 트레이너로 통합함으로써 추가적인 이점을 얻을 수 있다고 제안했다. 의료 서비스 제공업체가 전문성 있는 의사 소통 접근 방식에 익숙해질 필요가 있기 때문입니다.

Bagnasco et al. (2014) and Herrmann et al. (2015) suggested further benefits might be gained by integrating both nursing students and medical students with an interprofessional team of trainers for simulation and laboratory learning activities, because of the need for healthcare providers to become comfortable with an interprofessional approach to communication.

Kirch and Ast(2015)는 전문직 간 교육(의료 제공자가 여러 분야에 걸쳐 협력적으로 작업하도록 교육)을 목표로 하는 짧은 교육 활동도 의료 사업자가 미래의 동료들과 의사소통 성공을 위해 설립하는 데 도움이 될 것이라고 결론지었다. 의료 분야에서의 협업과 팀워크에 대한 강조는 계속 확대될 것으로 보입니다(Lamb and Shraiky, 2013).

Kirch and Ast (2015) concluded that even brief educational activities aimed at interprofessional education (training health providers to work collaboratively across disciplines) would be helpful in setting healthcare providers up for communication success with their future colleagues, as it seems likely that the emphasis on collaboration and teamwork in healthcare will continue to expand (Lamb and Shraiky, 2013).

모든 교육 활동을 위해 학습 공간을 구성해야 합니다.

Learning Spaces Should Be Organized for All Instructional Activities

"최고의 교육 기법은 혼돈의 환경에서 가치가 없기 때문에" 어떤 학습 활동이 일어나든 원활한 운영을 위해 학습 환경을 구성해야 한다(Danielson, 2007). 따라서 효과적인 교사는 교실의 외관 및 구성, 교통 흐름, 가구 배치, 재료 유형, 자원 및 모든 참가자의 안전과 같은 것들을 고려하는 것이 효과적인 지침의 중요한 요소이다(Loukas, 2007; Leander et al., 2010; Lamb and Shraiky, 2013).

Learning environments should be organized for the smooth operation of whatever learning activity is to take place, because “the best instructional techniques are worthless in an environment of chaos” (Danielson, 2007). Thus, it is an important element of effective instruction for the effective teacher to consider such things as appearance and organization of the classroom, traffic flow, arrangement of furniture, types of materials, resources, and safety of all participants (Loukas, 2007; Leander et al., 2010; Lamb and Shraiky, 2013).

모든 발달 수준에서, 그러한 (물리적 공간의) 문제에 대해 신경쓰지 않는 것은 성공적인 교육을 방해할 수 있는 장벽으로 쉽게 이어질 수 있다. 최대한 효과적이 되고자 하는 교사는 어떤 물리적 변형을 해야 하고 또 할 수 있는지를 평가하고 반성하기 위해 항상 1차 교육기간 전에 학습환경을 방문하도록 노력하는 것이 좋다.

At any developmental level, absence of attention to such matters can easily lead to barriers that could inhibit successful instruction. Teachers wanting to become maximally effective are advised to always try to visit the learning environment in advance of the first instructional period in order to assess and reflect upon what physical modifications should and could be made.

대형 의학 강의실의 고정된 의자처럼 학습 환경을 원하는 대로 재배치할 수 없는 경우, 교사는 기존의 물리적 배열을 최대한 활용하기 위해 의도된 수업의 전달(교사에 대한 근접성 증가)을 수정하는 것을 고려해야 한다. 교사와 모든 학생 간의 의사소통에 대한 물리적 장벽을 최소화하고 학생 간의 상호작용 가능성을 최대화하기 위해 노력한다(Lander et al., 2010; Lamb and Shraiky, 2013). 아니면, 니콜과 트레이시 (2007년)에 의해 언급되었듯이, "교사는 세션을 위해 적절한 물리적 환경을 조성할 필요가 있습니다."

If the learning environment cannot possibly be rearranged as desired, such as the fixed chairs of a large medical lecture hall, the teacher should then consider modifying the intended delivery of instruction (as in increasing teacher proximity to the students) in order to better take the greatest possible advantage of the existing physical arrangement to minimize physical barriers to communication between teacher and all students and to maximize the potential for interaction between students (Leander et al., 2010; Lamb and Shraiky, 2013). Or, as stated by Nicholl and Tracey (2007), “The teacher needs to create the right physical environment for the session.”

긍정적인 태도/처분은 항상 학생들을 위해 모델링되어야 합니다.

Positive Attitudes/Dispositions Should Always Be Modeled for Students

어떤 교육전략이 선택되든 선택되지 않든, 다룰 내용을 얼마나 잘 이해하든, 또는 학생들을 알아가는 데 얼마나 많은 시간이 걸리든 간에, [학생 학습에 긍정적인 영향을 미칠 수 있는 능력에 대한 믿음]은 필수적이다. 열정(내용, 학생, 교단에 대한)은 매우 중요하다. 효과적인 교육에 대한 열의의 중요성은 Pratt와 Collins(2002)를 포함한 많은 사람들에 의해 설명되었다. 모델 열정에 더하여 슈미트와 핀치(1998)와 칸델왈(2009)은 전반적인 긍정적인 태도와 격려가 모든 수준에서 교사의 성공에 매우 중요하다고 선언했다.

Regardless of which instructional strategies are chosen or not chosen, how well one understands the content to be addressed, or how much time is taken in getting to know the students, the belief in one’s ability to positively impact student learning is essential. Enthusiasm (toward the content, the students, and the teaching act) is critical. The importance of enthusiasm to effective teaching was explained by many, including Pratt and Collins (2002). In addition to modeling enthusiasm, Schmidt and Finch (1998) and Khandelwal (2009) declared demonstrating an overall positive attitude and encouragement were extremely important to the success of a teacher at any level.

의학교육에서도 이러한 개인적 특성(Eluzbier and Rizk, 2001년)이 인턴과 레지던트들에게 특별한 선택을 할 때 상당한 영향을 미치는 것으로 나타났다. 효과적인 교사는 특히 환자에게 덜 유쾌한 결과를 수반할 수 있는 의학의 심각한 측면을 다룰 때 행복을 가장하거나 비현실적으로 기뻐해서는 안 되지만, 배움에 대한 열정은 전염성이 있고, 태도라는 것은 taught 되기보다는 caught 되는 것임을 기억해야 한다! 효과적인 의학 교육자가 학생들이 의학적 지식과 기술만큼이나 의학의 성공에도 태도가 중요하다는 것을 깨닫도록 돕는 것은 필수적이다. (Swartz, 2006)

In medical education, such personal characteristics were also found (Eluzbier and Rizk, 2001) to have significant influence on interns and residents as they made their specialty choices. An effective teacher ought not to feign happiness or be unrealistically joyous, especially when dealing with a serious aspect of medicine that could involve a less than pleasant outcome for a patient, but it should be remembered that enthusiasm toward learning is contagious and that attitudes are more easily caught than taught! It is essential for an effective medical educator to help students realize that their attitudes are just as important to their success in medicine as their medical knowledge and skills (Swartz, 2006).

교사가 변화하는 학생 학습 요구 사항을 충족할 수 있는 유연성

Flexibility Enables Teachers to Meet Changing Student Learning Needs

유능한 교사는 분명 학습 활동의 주요 조직자이지만, '조직성'은 경직성과 같지 않다. 교사가 항상 조직적인 것처럼 보여야 하지만, 일관적으로 성공한 교육자는 [회진 중에 발생하는 많은 침상 수업 기회 동안]뿐만 아니라 [교실에서 일어날 수 있는 교육 가능한 순간teachable moment]을 기반으로 하기 위해 학습 환경에서 일반적으로 경험하는 예기치 않은 사건에 대응해야 한다. 교육적 노력이 학생 학습을 촉진하지 않는 경우, 변화를 탐구해야 한다.

An effective teacher is definitely a master organizer of learning activities, but organization should not equal rigidity. Although a teacher should always appear to be organized, a consistently successful educator must respond to the unexpected events typically experienced in a learning environment in order to build on teachable moments that may arise, in the classroom as well as during the many bedside teaching opportunities occurring during rounds. If instructional efforts are not facilitating student learning, change should be explored.

성공적인 코치는 점수가 나지 않는 플레이를 지속적으로 요구해서는 안 되는 것처럼, 분명히 학생 학습의 극대화를 초래하지 않는 교육 계획을 고수해서는 안 된다. 게다가, 젤싱 외 연구진이 증명한 바와 같이. (2007) 의료 교육자는 학생들이 창의성, 환자에 대한 동정심, 리더십 능력 또는 학습에 대한 긍정적인 학생 인식을 개발할 수 있는 더 큰 기회를 제공할 수 있는 학습 접근법을 탐구하기 위해 커리큘럼과 커리큘럼 전달 모두를 자주 검토해야 한다. 필요한 수정과 조정을 허용하는 것이 중요하지만 유연성이 "혼란하고 일관성이 없거나 예측할 수 없는" 학습 환경으로 전환되어서는 안 된다(Oakes et al., 2012). 그것은 모든 분야의 교육자들에게 어렵지만 중요한 균형잡힌 행동을 만들어 준다.

As a successful coach should not continuously call plays that do not result in points being scored, one should never stick with instructional plans obviously not resulting in maximizing student learning. In addition, as demonstrated by Jelsing et al. (2007), medical educators should frequently examine both curriculum and curriculum delivery in an effort to explore learning approaches that may provide students with greater opportunity to develop creativity, compassion toward patients, leadership abilities, or positive student perception of learning. Allowing for necessary modification and adjustment is important, yet flexibility ought never to be transformed into a “confusing, inconsistent, or unpredictable” (Oakes et al., 2012) learning environment. It makes for a difficult, yet critical, balancing act for educators in all areas of study.

학생 학습 가능성을 극대화하는 멀티모달 접근 방식

A Multimodal Approach Maximizes the Likelihood of Student Learning

최대 학생 학습을 달성하기 위해, 특정 학생 모집단은 여러 교육 전략의 혼합에 노출되어야 한다. 왜냐하면 교육학을 다양화하는 것은 학생들의 두뇌의 다른 부분에서 활동을 촉발하는 경향이 있기 때문이다(Zull, 2002). 민하스 외 연구진(2012)은 다양한 교수 스타일을 멀티모달 접근법(강의와 연계하여 연습 문제 및 시각적 기반 학습)으로 결합하는 것이 학생들이 학부 해부학과 생리학 과정에서 배우는 것을 더 잘 가능하게 한다고 제안했다. 그러므로 교사의 기술 레퍼토리가 살아있는 실체가 되어야 한다. Jacobsen et al에 의해 논쟁되었다. (2008) 가장 효과적인 교사는 하나의 가장 좋은 방법이 없었기 때문에, 그들의 수업을 자주 바꾼 선생님들이었다. 레퍼토리에서 특정 교육 접근법을 선택할 때 학생들이 원하는 교육 목적과 교육 요구 모두를 고려해야 한다. 다양한 교육 방법을 사용하는 것은 학생들의 참여를 장려하고 교사들의 열정을 유지하는데 도움을 줄 수 있다.

In order to achieve maximum student learning, a given population of students should be exposed to a mix of instructional strategies, since varying one’s pedagogy tends to trigger activity in different parts of students’ brains (Zull, 2002). The findings of Minhas et al. (2012) suggested that combining various teaching styles into a multimodal approach (practice problems and visual-based lessons in conjunction with lectures) better enabled students to learn in undergraduate anatomy and physiology courses. Thus, a teacher’s repertoire of techniques ought to be a living entity. It was argued by Jacobsen et al. (2008) that the more effective teachers were those who frequently varied their instruction, because there really was no single best way. Both the desired instructional objective and the instructional needs of the students should be considered when selecting a specific teaching approach from one’s repertoire. Using a variety of instructional methods can encourage student participation and help maintain teacher enthusiasm.

강의는 여전히 자리를 갖고 있으며(드레이크와 파울리나, 2014) 의학교육의 주체로 남아있을 것이 틀림없지만, 강의에서 정보를 'covering'하는 것만으로 모든 건강관리 학생들에게 적용되는 의료지식이 'uncovering '되는 것은 아니라는 점을 명심해야 한다. 보건의료 학생에 대한 기대 학습 결과를 결정한 후, 바사 외 연구진(2003)은 이러한 목표에 부합하는 교육 방법의 채택을 권장했다. Schlomer 외 연구진(1997)은 의료 교육자들이 학습자와 교사 모두의 요구와 가용 자원에 기초해 레퍼토리에서 교육 전략을 선택하도록 권장했다.

Lectures still have a place (Drake andPawlina, 2014) and will no doubt remain as a staple of medi-cal education, but it should be remembered that “covering”information in a lecture will not always by itself lead to the“uncovering” of applicable medical knowledge for all health-care students. Once the have expected learning outcomes for to healthcare students been determined, Bassaw et al.(2003) encouraged the adoption of teaching methods match these objectives, and Schlomer et al. (1997) encour-aged medical educators to select teaching strategies from theirrepertoires based on the needs of both learner and teacher, aswell as on the available resources.

교사의 기대는 자성예언이 될 수 있다.

Teacher Expectations Can Become a Self-Fulfilling Prophecy

성공에 대한 높은 기대를 갖는 것은 유능한 교사들의 또 다른 중요한 특징이다. 교사들은 학생들이 성공하기를 끊임없이 기대하고 격려해야 한다. 베인(2004)이 상기시켰듯이, 유능한 교사들은 학생들이 배우고 싶어하고 배울 수 있다고 믿는다. 라이언과 쿠퍼(2012)는 학생들에 대한 교사들의 기대가 학생들의 성취와 밀접한 관련이 있는 것 같다고 단호하게 말했다. 치커링과 감슨(1987)에 따르면, 학생들이 높은 레벨이나 낮은 레벨에서 공연하기를 기대하는 것은 스스로 성취하는 예언이 될 수 있기 때문에, 이러한 높은 기대를 학생들에게 전달하는 것은 학생 수행의 필수적인 부분이다. 스트롱게(2007)는 "유능한 선생님은 모든 학생들이 배울 수 있다고 진정으로 믿기 때문에 이것은 단순한 슬로건이 아니다"라고 이 입장을 확인했다. 교사들은 또한 [학생들의 학습에 긍정적인 영향을 미칠 수 있는 자기자신의 능력]에 대해서도 높은 기대를 가질 필요가 있다.

Having high expectations for success is another critical characteristic of effective teachers. Teachers must constantly expect and encourage students to succeed. As Bain (2004) reminded, effective teachers believe students want to learn and are able to learn. Ryan and Cooper (2012) firmly stated teachers’ expectations for their students seem to correlate highly with students’ achievement. Communicating these high expectations to students is an essential part of student performance, since according to Chickering and Gamson (1987), expecting students to perform at either a high level or a low level can become a self-fulfilling prophecy. Stronge (2007) confirmed this position, because “the effective teacher truly believes that all students can learn – it is not just a slogan.” Teachers need also hold high expectations for themselves regarding their ability to have a positive impact on student learning.

유능한 교사는 항상 학생들을 과제를 지속위해 노력한다.

Effective Teachers Always Strive to Keep Students on Task

'과제를 하는 시간을 대체할 수 있는 것은 없다'(치커링·감슨, 1987년)는 만큼 교사들이 지속적으로 강조해야 할 사항이다. 효과적인 교사는 계획된 전체 교육 활동에서 학생들을 효율적으로 참여시키는 방법을 알아야 한다. 이것은 학생의 참여를 극대화하기 위한 원활한 전환을 계획하는 것이 각 학습 활동 전에 항상 고려되어야 하기 때문에, 자신의 내용을 이해하는 것을 넘어서는 것이다. 꽤 오랫동안, 효과적인 교사들이 학생들의 시간을 "덜 효과적인 교사들과 다르게" 사용한다는 것을 알고 있었다(Medley, 1982년). "더 효과적인 교사들은 그들의 활동에 낭비하는 시간이 적고, 과제에 더 많은 시간을 가졌다."(Evertson and Emer, 1982년). 간단히 말해서, 일반적으로 학생들의 학습량과 참여형 교육에 소요되는 시간 사이에는 직접적인 연관성이 있다. 모든 선생님들은 학습 활동 내내 학습자들이 최대한 참여하도록 하는 것이 필수적이다.

Since “there is no substitute for time on task” (Chickering and Gamson, 1987), it is something that should be continually emphasized by teachers. Effective teachers must know how to efficiently engage students throughout the entire planned instructional activity. This goes beyond having a grasp of one’s content, as planning smooth transitions in order to maximize student engagement should always be considered in advance of each learning activity. For quite some time, both researchers and practitioners have known that effective teachers used student time “differently than less effective teachers” (Medley, 1982) and that “more effective teachers had less wasted time in their activities and more time on task” (Evertson and Emmer, 1982). Simply stated, there is usually a direct connection between the amount of student learning and the amount of time spent on engaged instruction. It is essential that all teachers seek to keep learners maximally engaged throughout learning activities,

학생들의 자존감이 학업 성취도에 영향을 미칠 수 있다

The Self-Esteem of Students Can Have an Impact on Their Academic Achievement

과거의 성공처럼 미래의 성공을 낳는 것은 없으며, 콘텐츠 분야와 관련된 긍정적인(그러나 현실적인) 자아감각과 전반적인 학습과 같은 성공을 위해 학생들을 세우는 것은 없다. 자아 이미지와 학업 성취도(Ornstein과 Lasley, 2003) 사이에 분명한 직접적인 상관관계가 있다는 점을 고려할 때, 하나를 개선하면 자연스럽게 다른 하나를 개선할 수 있을 것이다. 학생들 사이에 능력의식을 고취시키기 위해 선생님이 할 수 있는 것은 무엇이든지 간에 학생들의 성취에 생산적인 영향을 미칠 수 있다.

Nothing breeds future success like past success, and nothing sets students up for success like having a positive (but realistic) sense of self related to the content area and to learning in general. Given there is an apparently direct correlation between self-image and academic achievement (Ornstein and Lasley, 2003), improving one would naturally seem to improve the other. Whatever a teacher can do to promote a sense of competence among students can have a productive impact on student achievement.

자존감이 높은 학생들은 [교실]에서 더 높은 수준에서 성취할 가능성이 높을 뿐만 아니라, [교실 밖]에서 계속 학습하려는 의욕도 더 강할 것으로 보인다. 따라서, 효과적인 의학 교육자는 학습을 계속하도록 동기를 부여해야 하며, 또한 일단 과정이 완료되고, 학위를 취득하고, 인증을 획득하면, 계속해서 학습 동기를 얻을 가능성이 가장 큰 학생들이 교실을 떠날 수 있도록 노력해야 한다.

Not only are students with higher self-esteem more likely to achieve at higher levels in the classroom, but they are also likely to be more motivated to continue learning outside of the classroom. so, the effective medical educator must be motivated to continue learning and should also strive to have students leave the classroom with the greatest likelihood of continued motivation to learn once courses have been completed, degrees have been earned, and certifications have been achieved.

성찰은 교사와 학생 모두에게 지속적인 개선을 이끌 수 있다.

Reflection Can Lead to Continued Improvement for Both Teachers and Students

대니얼슨(2007)은 성찰의 사용이 교사들이 자신의 강점과 개선이 필요한 분야를 더 잘 이해하면서 다음 교육 경험을 능동적으로 준비할 수 있도록 함으로써 "진정한 성장과 우수성"을 이끌었다고 생각했다. 페라로(2000년)는 성찰이 경험이 부족한 교사나 베테랑 교사 모두에게 똑같이 도움이 된다고 생각했기 때문에, 모든 교사가 자신의 교무 수행에 대해 다른 사람에게 피드백을 구함으로써 그 잠재력을 활용해야 한다는 것이 논리적으로 보일 것이다.

Danielson (2007) considered that the use of reflection led to “real growth and therefore excellence” by allowing teachers to proactively prepare for their next instructional experiences with a better understanding of their strengths and their areas in need of improvement. Ferraro (2000) thought reflection to be equally helpful for both inexperienced and veteran teachers, so it would seem logical that all teachers should take advantage of its potential power by soliciting feedback from others regarding their teaching performances.

베인(2004)에 따르면, 교수는 자신의 교육에 대한 피드백을 얻기 위해 다양한 방법을 사용해야 한다. (학생뿐만 아니라 동료 및 감독관도 해당) 이러한 피드백을 수집한 후에는 받은 피드백에 따라 교육을 조정(또는 유지)하는 것을 고려해야 합니다. 모든 의료 종사자가 환자와 상호작용할 때 자신의 efficacy을 알고 있어야 하듯, 의료 교육자(다른 모든 분야의 교육자로서)도 학생들과 상호작용할 때 그 효능을 알고 있어야 한다(Sch€on, 1983; Lachman and Pawlina, 2006).

According to Bain (2004), they should use a variety of ways to obtain feedback (not only from students but also from peers and supervisors) on their teaching. Once such feedback has been collected, they should consider adjusting (or maintaining) their teaching according to the feedback they have received. All medical practitioners must be aware of their efficacy when interacting with patients, and medical educators (as educators in all other arenas) must also be aware of their efficacy when interacting with students (Sch€on, 1983; Lachman and Pawlina, 2006).

최근 연구(Wittich et al., 2013; Spampinato et al., 2014)와 마찬가지로 의학교육 영역에서도 학생들의 전문성 발달에 중요한 반영이 발견되었다. (2003)는 특히 집단 지원과 결합할 때 자기 성찰이 교직 효과의 향상으로 이어질 수 있다는 것을 발견했다.

Within the realm of medical education, just as recent studies (Wittich et al., 2013; Spampinato et al., 2014) have found reflection to be important in the development of professionalism within students, Lye et al. (2003) found that self-reflection, especially when combined with group support, can lead to improvement of teaching effectiveness.

전문성은 모든 수준의 교육에 있어서 중요한 요소이다.

Professionalism Is a Significant Factor in Teaching at All Levels

진정한 전문 교사의 문door은 물리적으로나 비유적으로나 항상 열려 있어야 한다. '전문직업성이라는 단어의 의미와 관련해 공통적인 근거가 없다'(에스코바-포니·포니·2006년)고 해도, 교사는 학생들이 쉽게 접근할 수 있어야 하고, 비유적으로 자기 분야의 중요한 발전에 따라 효과적으로 소통하고, 자기 분야 내에서 활발하게 활동하면서 문호를 개방해야 한다.폭넓게 읽고 동료들과 협력적으로 작업한다(Bain, 2004). "의료 전문성은 다면적인 구조"이며 "의료 교육의 필수 요소"로 간주된다(스팸피나토 외, 2014).

The door of a truly professional teacher should always remain open, both physically and figuratively. Although “there is no common ground regarding the meaning of the word professionalism” (Escobar-Poni and Poni, 2006), teachers should be easily approachable by their students, and figuratively, they should keep their doors open by communicating effectively, remaining active within their disciplines, following important developments in their fields, reading extensively, and working collaboratively with their colleagues (Bain, 2004). “Medical professionalism is a multifaceted construct” and is considered to be “an essential component of medical education” (Spampinato et al., 2014).

미국 내과의사 전문성 헌장에 따르면, 전문직업성은 "사회와의 의학 계약의 기초"로 선언되었다(ABIM Foundation et al., 2002; Cruess and Cruess, 2000; Paulina et al., 2006). Cruess and Cruess (1997)가 말한 "전문직 지위는 고유한 권한이 아니다" 그리고 "전문직의 본질은 모든 수준의 의학교육에서 가르쳐져야 한다"는 관념에 따라, 에스코바르-포니와 포니(2006)와 스와르츠(2006)는 전문직업성이 (전체 해부학에서 시작하여 학생들의 의학교육 내내 계속되어) 의대와 레지던시의 모든 측면에서 다루어져야 한다고 생각했다.

It was declared by the American Board of Internal Medicine’s Charter on Medical Professionalism to be “the basis of medicine’s contract with society” (ABIM Foundation et al., 2002; Cruess and Cruess, 2000; Pawlina et al., 2006). Following the Cruess and Cruess (1997) notions that “professional status is not an inherent right” and that “the substance of professionalism should be taught at all levels of medical education,” Escobar-Poni and Poni (2006) and Swartz (2006) considered professionalism to be something that should to be addressed in all aspects of medical school and residency, beginning with gross anatomy and continuing throughout students’ medical education.

스와르츠(2006년)가 밝힌 의학 전문성은 "히포크라테스 선서의 지시"를 수행하고 있으며, "수년에 걸쳐 획득된 연속체"이다. 무엇보다도, 의료 교육자들은 [롤모델링이 의대생이 전문 제공자가 되는 길을 교육하는 가장 일반적인 수단]으로 인식되듯, 전문가로서 학생들의 존경을 받기 위해 노력해야 한다. 또는 와인버거(2009년)가 확인한 것처럼 "전문직업성을 가르치는 방법에는 [의학의 예술과 과학에 모두 능통한 임상의사가 전하는 롤모델링]보다 더 좋은 방법은 없다"고 말했다.

Stated by Swartz (2006), professionalism in medicine “is carrying out the directives of the Hippocratic Oath” and, as such, “is a continuum acquired over a number of years.” Above all, medical educators should strive to be respected at all times by their students as professionals, since role modeling was found by Morihara et al. (2013) to be the most common means of educating medical students on their way to becoming professional providers. Or, as confirmed by Weinberger (2009), “there is no better way to teach professionalism than through the role modeling conveyed by a clinician who is masterful in both the art and the science of medicine.”

고찰

DISCUSSION

의학 학위를 가지고 있다고 해서 자동적으로 효과적인 의학 교육자가 되는 것은 아니다. 해부학 전문가가 된다고 해서 자동적으로 효과적인 해부학 교사가 되는 것은 아니다. 가르치는 것은 과학이면서 동시에 예술이다. 가르침의 예술과 과학은 모두 앞서 논의한 특징의 혼합에 의해 영향을 받으며, 예술과 과학은 모두 연습을 통해 의식적으로 발전할 수 있다. 가르치는 것은 쉽지 않다. 스트롱지(2007)에 따르면, "5단 스틱 시프트 자동차의 운전석에 오르는 것과 같다. 그 비효율적인 운전자는 가까스로 차를 운전할 수 있지만, 정지 표지판마다 엔진을 꺼버린다. 효과적인 드라이버는 효과적인 교사처럼 특정 목적지로 이동하는 목표를 놓치지 않고 여러 작업과 여러 의미를 능숙하게 동시에 처리합니다."

Having a medical degree does not automatically make one an effective medical educator; being an expert in anatomy does not automatically make one an effective anatomy teacher. Teaching is as much art as it is a science. Both the art and science of teaching are impacted by a mixture of the characteristics discussed earlier, and both the art and the science can consciously be developed through practice. Teaching is not easy. It is, according to Stronge (2007), “like getting into the driver’s seat of a 5-speed, stickshift automobile. The ineffective driver manages to get the car in gear, but cuts the engine off at every stop sign. The effective driver, like the effective teacher, adeptly and simultaneously handles multiple tasks and multiple meanings without losing sight of the goal of moving toward a specific destination.”

해리스(2000)는 이 과정을 야구공을 방망이로 꾸준히 치는 속일 정도로 복잡한 행동에 비유했다. 야구공을 치는 행위를 말로 표현하는 것은 어렵지 않지만, "타자가 플레이트에 나설 때 많은 변수가 집중된다"는 것이다. 각각의 특징은 퍼즐 조각으로 볼 수 있지만, 퍼즐을 맞추면 "효과적인 선생님의 초상화가 모양을 잡는다" (Stronge, 2007) 이러한 그림은 모두 [descriptor의 조합]으로 그려져야 합니다. 어떤 영역을 공부하든, 학습은 본질적으로 학습이며, "의학을 배우는 것은 다른 것을 배우는 것과 근본적으로 다르지 않다."(Flexner, 1910)

Harris (2000) likened the process to the deceivingly complex act of consistently hitting a baseball with a bat. The act of hitting a baseball is not hard to describe, but “when a batter steps up to the plate, many variables come into focus.” Each characteristic can be seen as a puzzle piece, but by putting the puzzle together, “a portrait of an effective teacher takes shape” (Stronge, 2007). Any such picture must be painted with a combination of descriptors. Regardless of the area of study, learning is essentially learning, and “learning medicine is not fundamentally different from learning anything else” (Flexner, 1910).

올슈타인과 래슬리(2003)는 우수한 교사를 학생들이 다룰 내용에 관계없이 학습하는지, 어떻게 학습하는지, 그리고 학생들이 학습하도록 확실히 하기 위해 해야 할 일은 모두 하는 사람이라고 묘사했다. 그들은 계속해서 학생들의 능력과 요구에 맞는 어떤 지시 활동이나 자료도 효과적일 수 있다고 강조했다. 바이머(2013)는 어떤 분야에서든 교사의 역할은 교사 가르침보다는 학생들이 배우는 것에 초점을 맞추는 것이어야 한다고 덧붙였다.

Ornstein and Lasley (2003) described excellent teachers as those who focus totally on whether and how students learn regardless of the content to be addressed, and who do anything they have to do in order to make certain that students learn. They went on to emphasize that any instruction matching activities and materials to student abilities and needs could be effective. Weimer (2013) added that the role of teachers in any discipline should be to focus on students learning rather than on teachers teaching.

Review

Anat Sci Educ. Jul-Aug 2015;8(4):386-94.

doi: 10.1002/ase.1535. Epub 2015 Apr 22.

Good teaching is good teaching: A narrative review for effective medical educators

Affiliations collapse

Affiliations

- 1Master of Arts in Teaching Program, School of Education, Hamline University, Saint Paul, Minnesota.

- 2Mayo Clinic College of Medicine, Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minnesota.

- PMID: 25907166

- DOI: 10.1002/ase.1535

Abstract

Educators have tried for many years to define teaching and effective teachers. More specifically, medical educators have tried to define what characteristics are common to successful teachers in the healthcare arena. The goal of teacher educators has long been to determine what makes an effective teacher so that they could do a better job of preparing future teachers to have a positive impact on the learning of their students. Medical educators have explored what makes some of their colleagues more able than others to facilitate the development of healthcare professionals who can successfully and safely meet the needs of future patients. Although there has historically been disagreement regarding the characteristics that need be developed in order for teachers to be effective, educational theorists have consistently agreed that becoming an effective teacher is a complex task. Such discussions have been central to deciding what education at any level is really all about. By exploring the literature and reflecting upon the personal experiences encountered in his lengthy career as a teacher, and as a teacher of teachers, the author reaches the conclusions that teaching is both art and science, that "good teaching is good teaching" regardless of the learning environment or the subject to be explored, and that the characteristics making up an effective medical educator are really not much different than those making up effective educators in any other area.

Keywords: anatomy teachers; characteristics of effective educators; effective teachers; good teaching; medical education; medical educators; student learning.

© 2015 American Association of Anatomists.

'Articles (Medical Education) > 교수법 (소그룹, TBL, PBL 등)' 카테고리의 다른 글

| PBL에서 심층 및 표면학습: 문헌 고찰(Adv in Health Sci Educ, 2016) (0) | 2021.05.08 |

|---|---|

| 이론과 설계기반연구가 PBL의 실천과 연구를 어떻게 성숙시킬 것인가(Adv Health Sci Educ Theory Pract, 2019) (0) | 2021.05.01 |

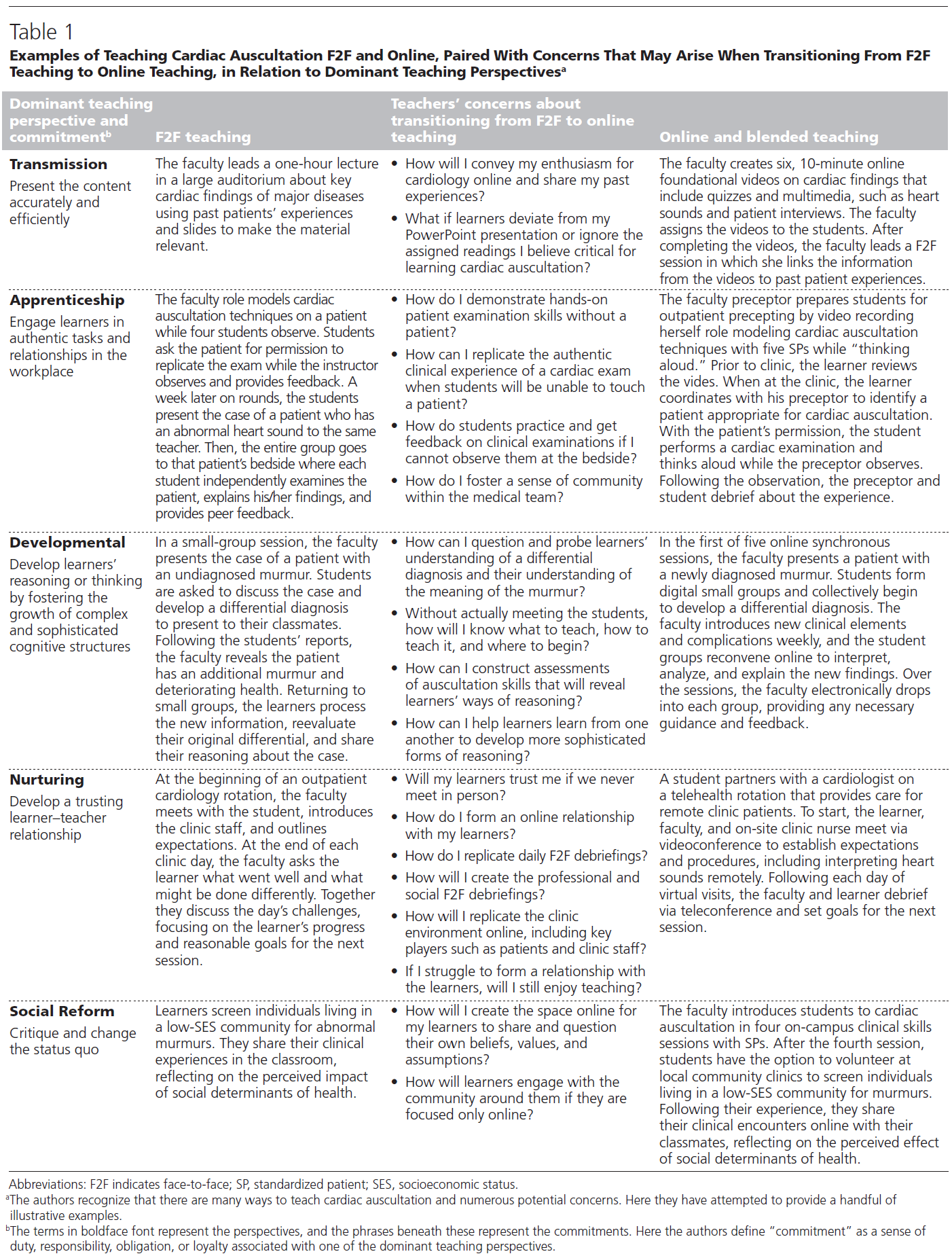

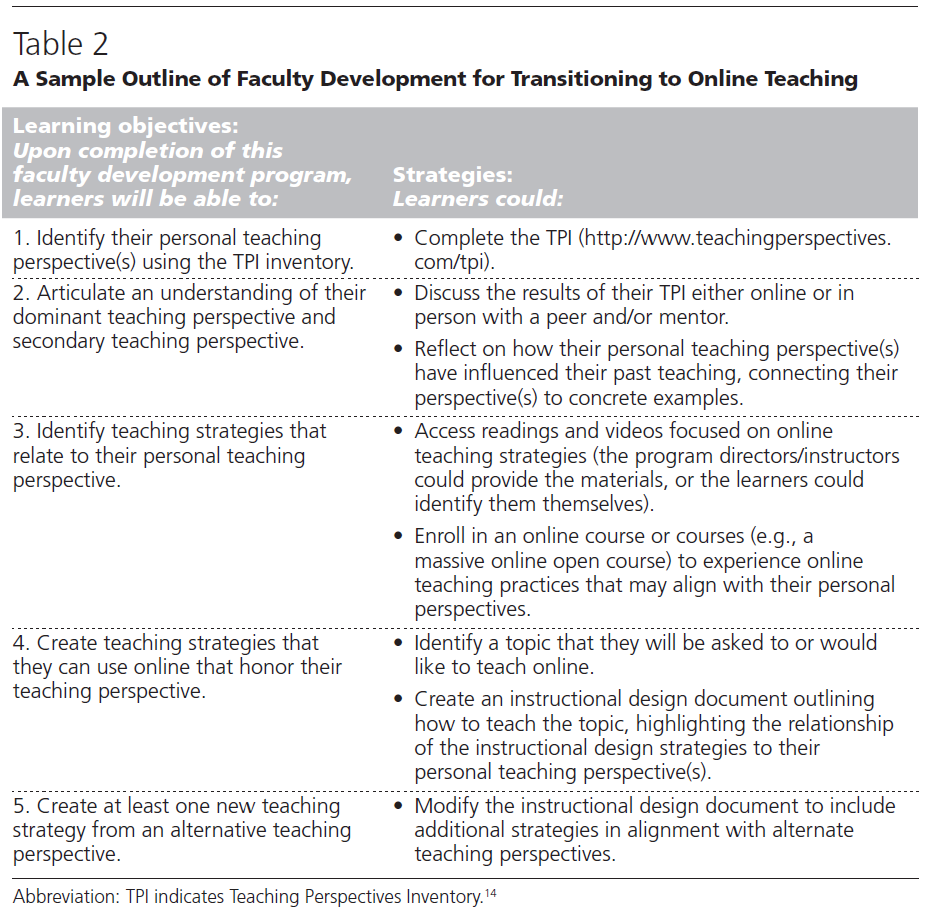

| 온라인 수업으로 전환에서 너 자신을 존중하라 (Acad Med, 2018) (0) | 2021.03.18 |

| 저의 멘토가 되어주실래요? 네 가지 원형(JAMA Intern Med, 2018) (0) | 2021.02.13 |

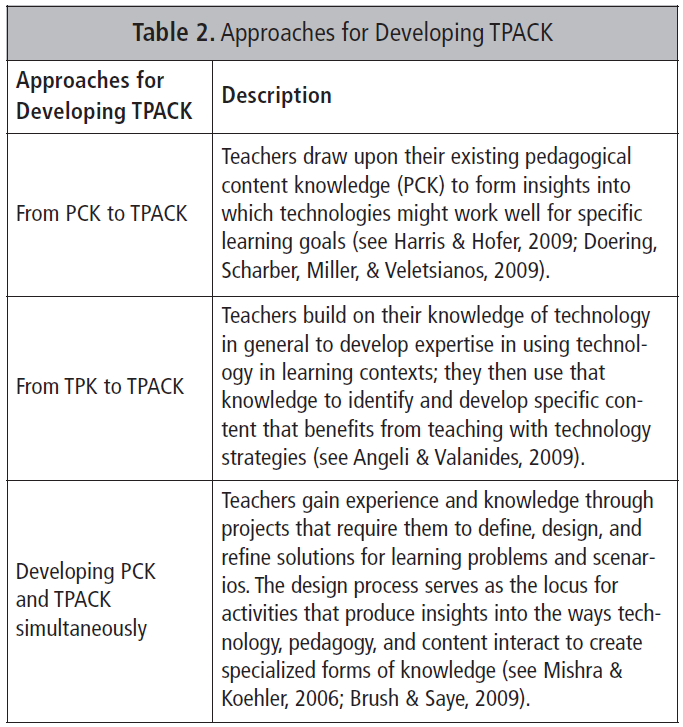

| 기술적내용적교육적지식(TPACK)은 무엇인가? (0) | 2021.02.13 |