졸업후 윤리 교육 프로그램: 체계적 스코핑 리뷰(BMC Med Educ, 2021)

Postgraduate ethics training programs: a systematic scoping review

Daniel Zhihao Hong1,2, Jia Ling Goh1,2, Zhi Yang Ong1,2, Jacquelin Jia Qi Ting1,2, Mun Kit Wong1,2, Jiaxuan Wu1,2, Xiu Hui Tan1,2, Rachelle Qi En Toh1,2, Christine Li Ling Chiang1,2, Caleb Wei Hao Ng1,2, Jared Chuan Kai Ng1,2, Yun Ting Ong1,2, Clarissa Wei Shuen Cheong1,2, Kuang Teck Tay1,2, Laura Hui Shuen Tan1,2, Gillian Li Gek Phua2,3, Warren Fong1,3,4, Limin Wijaya3,5, Shirlyn Hui Shan Neo2, Alexia Sze Inn Lee6, Min Chiam6, Annelissa Mien Chew Chin7 and Lalit Kumar Radha Krishna1,2,6,8,9,10*

소개

Introduction

"의료 행위를 규율하는 도덕적 의무"[1]를 지키기 위한 수단으로 간주되는 의사의 윤리 교육은 의료 행위가 직면한 윤리적 문제에 대처하기 위해 발전해 왔습니다. 기본적인 수준의 윤리 지식과 기술은 캐나다 왕립 의사 및 외과의 대학, 일반 의사회, 미국 가정의학회(AAFP), 의학전문대학원 교육 인증위원회(ACGME) 등의 인증 기관에서 규정하고 있지만, 많은 윤리 프로그램은 임상 실무의 요구에 민감하면서도 변화에 발맞추는 데 어려움을 겪어 왔습니다. 최근 미국의 레지던트 프로그램에서 가정의학과 의사에 관한 리뷰에서 의사들 사이에서 윤리 교육의 내용과 기간에 불가피한 차이가 있다는 사실이 드러났습니다[2].

Seen as a means of ensuring that “obligations of moral nature which govern the practice of medicine” [1] are maintained, ethics training amongst physicians have evolved to contend with ethical issues facing medical practice. Whilst basic levels of ethics knowledge and skills have been stipulated by accreditation bodies such as The Royal College of Physicians and Surgeons of Canada, The General Medical Council, the American Academy of Family Physicians (AAFP) and the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME), many ethics programs have struggled to keep pace with change whilst remaining sensitive to the demands of clinical practice. Inevitable variations in the content and duration of ethics education amongst physicians have been laid bare in a recent review pertaining to family physicians in residency programs in the United States [2].

법적 책임을 두려워하고 대중의 신뢰와 사회적 기대에 부응하기 위해 고군분투하는 의료계에서 의사에게 윤리 지식, 기술 및 전문직업적 행동을 효과적으로 교육하기 위한 리트머스 시험지[3-7]는 아마도 코로나19 팬데믹이었을 것입니다. 그러나 코로나19 팬데믹 기간 동안 의사의 의심스러운 행동과 임상적 결정에 대한 보고가 드러나면서 기존의 교육 프로그램을 점검하고, 윤리 교육 프로그램의 내용과 구조의 격차를 검토하며, 근거에 기반하고 임상적으로 관련성이 높은 학습자 중심 교육 이니셔티브를 업데이트하고 도입할 수 있는 기회가 되었습니다.

The litmus test for effectively educating physicians in ethics knowledge, skills and professional conduct in a medical field trepidatious of legal recourse and struggling to meet public trust and societal expectations [3–7] has perhaps been the COVID-19 pandemic. Yet, the surfacing of reports of questionable physician conduct and clinical decisions during the COVID-19 pandemic also offers an opportunity to take stock of prevailing education programs, review gaps in content and structure of ethics education programs as well as update and instil more evidence based, clinically relevant, learner centred education initiatives.

이 검토의 필요성

The need for this review

의사를 위한 윤리 교육 프로그램을 재구성하는 과정을 안내하기 위해, 동료 검토 문헌에서 현재 [졸업후교육 의학 윤리 교육 및 평가 프로그램]을 분석하는 체계적인 범위 검토를 제안합니다.

To guide this process of retooling ethics education programs for physicians, a systematic scoping review is proposed to analyse current postgraduate medical ethics training and assessment programs in peer-reviewed literature.

방법론

Methodology

이 체계적 문헌고찰(이하 SEBA의 SSR)[8-14]을 안내하기 위해 크리슈나의 체계적 근거 기반 접근법(SEBA)을 채택하고 광범위한 문헌을 면밀히 조사합니다[15-17]. 구성주의적 관점과 상대주의적 렌즈를 통해 SEBA의 SSR은 실무에 영향을 미치는 복잡하고 다양한 역사적, 사회문화적, 이념적, 맥락적 요인을 매핑하여 의과대학 졸업생들을 위한 의료윤리 교육 프로그램에 대한 전체적인 그림을 제공합니다[17-24].

We adopt Krishna’s systematic evidence-based approach (SEBA) to guide this systematic scoping review (henceforth SSRs in SEBA) [8–14] and scrutinise a broad range of literature [15–17]. With its constructivist perspective and relativist lens, SSRs in SEBA map the complex and diverse historical, socio-cultural, ideological and contextual factors that impact practice to provide a holistic picture of medical ethics training programs for graduates beyond medical school [17–24].

연구팀은 결과의 신뢰성을 더욱 높이기 위해 싱가포르국립대학교(NUS) 및 싱가포르국립암센터(NCCS)의 용루린 의과대학(YLLSoM)의 의학 사서, NCCS, 리버풀 완화치료연구소, YLLSoM 및 듀크-NUS 의과대학의 현지 교육 전문가 및 임상의(이하 전문가 팀)의 자문을 구했습니다. SEBA의 체계적 접근, 분할 접근, 직소 관점, , 퍼널링 프로세스, 토론 단계(그림 1. SEBA 프로세스)가 전체 연구 프로세스를 안내하는 데 사용되었습니다.

To further improve the reliability of the results, the research team consulted medical librarians from the Yong Loo Lin School of Medicine (YLLSoM) at the National University of Singapore (NUS) and the National Cancer Centre Singapore (NCCS), and local educational experts and clinicians at NCCS, Palliative Care Institute Liverpool, YLLSoM and Duke-NUS Medical School (henceforth the expert team). The Systematic Approach, Split Approach, Jigsaw Perspective, , Funnelling Process, and Discussion stages of SEBA (Fig. 1. The SEBA Process) were used to guide the entire research process.

1단계: 체계적 접근

Stage 1: Systematic approach

검토 제목 및 배경 결정

Determining the title and background of the review

연구팀은 전문가 팀과 현지 의료윤리 교육 프로그램의 이해관계자들과 협의하여 SEBA에서 SSR의 중요한 목표와 평가 대상 인구, 상황 및 의료윤리 교육 프로그램을 결정했습니다.

The research team consulted the expert team and stakeholders from a local medical ethics training program to determine the overarching goals of the SSR in SEBA as well as the population, context and medical ethics training programs to be evaluated.

연구 질문 파악

Identifying the research question

포함 기준[25]의 인구, 중재, 비교 및 결과(PICOS) 요소에 따라 1차 연구 질문은 "졸업후 의학 교육 프로그램은 윤리적 기술을 어떻게 가르치는가?"입니다. 두 번째 질문은 "핵심 주제는 무엇인가?" 및 "졸업후 의학교육에서 프로그램을 구성하는 데 사용되는 방법은 무엇인가?"입니다.

Guided by the Population, Intervention, Comparison and Outcome (PICOS) elements of the inclusion criteria [25], the primary research question is “How do postgraduate medical training programs teach ethical skills?” The secondary questions are “What are the core topics included?” and “What are the methods used to structure the program in postgraduate training?”

SEBA 방법론의 반복적 과정의 일환으로, 이 검토의 초기 결과를 논의할 때 전문가 팀은 윤리 교육 평가에 대한 데이터 부족을 해결하기 위해 현재의 윤리 평가 방법에 대한 연구를 수행할 것을 권고했습니다. 이에 따라 SEBA에서 두 번째 SSR이 수행되었습니다. PICOS의 지침에 따라 1차 연구 질문은 "졸업후교육에서 윤리 지식, 기술 및 역량은 어떻게 평가되는가?"입니다. 두 번째 질문은 "어떤 영역이 평가되는가?"입니다.

As part of the SEBA methodology’s iterative process, when the initial results of this review were discussed, the expert team advised that a study of current methods of assessing ethics be conducted to address the lack of data on assessments of ethics education. Thus, a second SSR in SEBA was carried out. Similarly guided by PICOS, the primary research question is “How is ethics knowledge, skills, and competencies assessed in postgraduate training?” The secondary question is “What domains are assessed?”

포함 기준

Inclusion criteria

연구팀은 전문가 팀의 안내에 따라 의료 윤리를 가르치고 평가하기 위한 SEBA의 SSR에 대한 포함 기준을 다음과 같이 만들었습니다(표 1).

Guided by the expert team, the research team created the inclusion criteria for the SSRs in SEBA for teaching and assessing medical ethics, as outlined (Table 1).

검색

Searching

전반적으로 두 검색에는 16명의 연구팀이 참여했으며, 이들은 검토를 위해 PubMed, Embase, PsycINFO 및 ERIC 데이터베이스에서 독립적으로 검색을 수행했습니다. 연구팀은 실행 가능하고 지속 가능한 연구 프로세스를 보장하기 위한 Pham, Rajic[26]의 접근 방식에 따라 일반적인 인력 및 시간 제약을 고려하여 1990년 1월 1일부터 2019년 12월 31일 사이에 출판된 논문으로 검색을 제한했습니다. 영어로 출판되었거나 영어 번역본이 있는 논문의 모든 연구 방법론이 포함되었습니다. 독립적인 검색은 2020년 2월 14일부터 2020년 4월 9일 사이에 수행되었습니다. 전체 PubMed 검색 전략은 추가 파일 1에서 확인할 수 있습니다.

Overall, both searches involved 16 members of the research team who carried out independent searches of PubMed, Embase, PsycINFO, and ERIC databases for the review. In keeping with Pham, Rajic [26]’s approach to ensuring a viable and sustainable research process, the research team confined the searches to articles published between 1 January 1990 and 31 December 2019 to account for prevailing manpower and time constraints. All research methodologies in articles published in English or had English translations were included. The independent searches were carried out between 14 February 2020 and 9 April 2020. The full PubMed search strategy may be found in Additional File 1.

그런 다음 연구팀은 최종 목록의 모든 제목을 독립적으로 검토하고, 검토에 포함될 개별 논문 목록을 비교하고, '합의된 합의 검증'을 사용하여 윤리 교육(그림 2.) 및 윤리 평가(그림 3)에 대해 분석할 최종 논문 목록에 대한 합의를 도출했습니다.The research team then independently reviewed all the titles on the final list, compared their individual lists of articles to be included in the review and employed ‘negotiated consensual validation’ to achieve consensus on the final list of articles to be analysed on the teaching of ethics (Fig. 2.) and assessing of ethics (Fig. 3).

2단계: 분할 접근법

Stage 2: Split approach

SEBA의 각 SSR에 대해 5명의 연구원으로 구성된 두 팀이 분석의 신뢰성을 높이는 데 초점을 맞춘 크리슈나의 분할 접근 방식에 따라 동시에 독립적으로 전체 논문을 검토했습니다[27, 28]. 첫 번째 팀은 브라운과 클라크[29]의 주제 분석 접근법을 사용하여 포함된 기사를 면밀히 조사했고, 두 번째 팀은 시에와 섀넌[30]의 지시적 콘텐츠 분석 접근법을 사용했습니다. 분할 접근법의 결과 간의 비교는 방법 삼각 측량을 제공하는 반면, 각 검토자가 동일한 데이터를 독립적으로 분석하도록 하는 것은 연구자 삼각 측량을 제공합니다[27, 28]. 삼각 측량은 외부 타당도를 높이고 이 접근법을 보다 객관적으로 만들 수 있습니다.

For each SSR in SEBA, two teams of five researchers concurrently and independently reviewed the full-text articles in keeping with Krishna’s Split Approach that is focused on enhancing the reliability of the analyses [27, 28]. The first team scrutinised the included articles using Braun and Clarke [29]’s approach to thematic analysis whilst the second team employed Hsieh and Shannon [30]’s approach to directed content analysis. Comparisons between the results of the Split Approach provides method triangulation whilst having each reviewer independently analyse the same data provides investigator triangulation [27, 28]. Triangulation augments external validity and allows this approach to be more objective.

브라운과 클라크(2006)의 주제별 분석 접근법

Braun and Clarke (2006)’s approach to thematic analysis

의사를 대상으로 의료 윤리를 가르치거나 평가하기 위한 선험적 프레임워크가 없는 상황에서, 우리는 의학에서 의료 윤리의 상황별 특성을 탐색하면서 다양한 목표와 다양한 학년, 경험, 전공을 가진 의사 집단에서 공통된 주제를 찾아내기 위해 브라운과 클라크의 주제 분석 접근법을 사용했습니다[29, 31-37]. 또한 통계적 풀링 및 분석의 사용을 방지하고[29, 38-42] 의료 윤리와 같이 사회문화적으로 영향을 받는 교육 과정에 대한 적절한 분석을 용이하게 하기 위해 포함된 논문들 사이에 존재하는 광범위한 연구 방법론을 수용합니다.

Without an a priori framework for either teaching or assessing medical ethics amongst physicians, we employed Braun and Clarke’s approach to thematic analysis to single out common themes across varying goals and populations of physicians of different grades, experiences and specialties whilst circumnavigating the context-specific nature of medical ethics in Medicine [29, 31–37]. It also accommodates for a wide range of research methodologies present amongst the included articles which prevents the use of statistical pooling and analysis [29, 38–42] and facilitates appropriate analysis of socio-culturally influenced educational processes such as medical ethics.

'코드'는 반복적인 단계별 주제 분석을 통해 텍스트의 '표면적' 의미로부터 구성되었습니다. 이러한 코드는 데이터를 가장 잘 표현할 수 있는 테마로 재구성되었습니다. 개별적으로 검토한 다음 그룹으로 검토했습니다. 그 후, 이 소팀원들은 각자의 개별 결과를 온라인으로 심의하고 최종 주제에 대한 합의를 도출하기 위해 '합의된 합의 검증'을 활용했습니다.

‘Codes’ were constructed from the ‘surface’ meaning of the text through a reiterative step-by-step thematic analysis. These were re-organised into themes that were best able to represent the data. They were reviewed individually and then as a group. Subsequently, the members of this sub-team deliberated their separate findings online and utilised ‘negotiated consensual validation’ to achieve consensus on the final themes.

Hsieh와 섀넌(2005)의 지시적 콘텐츠 분석 접근 방식

Hsieh and Shannon (2005)’s approach to directed content analysis

Hsieh와 섀넌의 지시적 내용 분석 접근법은 주제의 타당성을 높이고 브라운과 클라크가 상대적으로 모순된 데이터를 활용하지 못한 문제를 해결하기 위해 사용되었습니다.

Hsieh and Shannon’s approach to directed content analysis was employed to increase the validity of the themes and to address Braun and Clarke’s relative failure to engage contradictory data.

윤리 교육과 관련하여 두 번째 하위 팀은 Sutton [43]의 '학부 의학에서의 윤리 및 법 교육 및 학습'이라는 제목의 논문과 McKneally와 Singer [44]의 '임상의사를 위한 생명윤리 25'에서 코드와 범주를 도출했습니다. 임상 환경에서의 생명윤리 교육'.

With regards to the teaching of ethics, the second sub-team drew codes and categories from Sutton [43]’s article entitled ‘Ethics and law teaching and learning in undergraduate medicine’ and McKneally and Singer [44]’s ‘Bioethics for clinicians 25. Teaching bioethics in the clinical setting’.

윤리, 강령 및 범주 평가와 관련하여 Norcini, Anderson [35]의 '2018 좋은 평가를 위한 합의 프레임워크 초안', Veloski, Boex [45]의 '평가, 피드백 및 의사의 임상 수행에 관한 문헌의 체계적 검토'를 참조하세요: BEME 가이드 7'과 Watling과 Ginsburg[46]의 '평가, 피드백 및 학습의 연금술'이 사용되었습니다.

With regards to the assessing of ethics, codes and categories from Norcini, Anderson [35]’s ‘Draft 2018 Consensus Framework for Good Assessment’, Veloski, Boex [45]‘s ‘Systematic review of the literature on assessment, feedback and physicians’ clinical performance: BEME Guide No. 7′ and Watling and Ginsburg [46]’s ‘Assessment, feedback and the alchemy of learning’ were used.

이 코드는 포함된 논문을 검토하기 위한 프레임워크로 채택되었습니다. 기존 코드에 포함되지 않은 관련 데이터는 연역적 범주 적용을 통해 새로운 코드를 할당했습니다. 독립적인 연구 결과는 온라인에서 논의되었고, 최종 '코드북'에 대한 합의를 도출하기 위해 '협상된 합의 검증'이 다시 사용되었습니다.

These codes were adopted as a framework for reviewing the included articles. Any relevant data not captured by existing codes were assigned a new code through deductive category application. The independent findings were discussed online and ‘negotiated consensual validation’ was again used to achieve consensus on the final ‘code book’.

3단계: 직소 관점

Stage 3: The jigsaw perspective

분할 접근법의 결과와 반복적인 프로세스를 통해 도출된 결과를 한데 모아 데이터에 대한 균형 잡힌 관점을 확보했습니다. 여기서는 각 SSR 내의 공통 주제와 카테고리를 비교했습니다. 카테고리와 테마가 겹치는 부분을 결합하여 직소 퍼즐의 보완적인 조각을 모으는 것처럼 데이터에 대한 더 넓은 관점을 만들었습니다. 이 프로세스를 직소 관점이라고 하며, 일관성을 보장하기 위해 전문가 팀이 감독합니다.

The findings of the Split Approach and its reiterative process were then pooled together to ensure a well-rounded perspective of the data. Here, common themes and categories within each SSR were compared. Overlaps between the categories and themes were combined to create a wider perspective of the data, much like bringing together complementary pieces of a jigsaw. This process is called the Jigsaw Perspective and is overseen by the expert team to ensure consistency.

결과

Results

윤리 교육과 관련된 첫 번째 검색에서는 7669개의 초록이 검색되었으며, 573개의 전체 텍스트 논문이 검토되었고 66개의 논문이 포함되었습니다. 분할 접근법의 일부로 식별된 범주와 주제를 비교한 결과, 직소 관점을 사용하여 주제/카테고리로 결합된 유사한 범주와 주제가 발견되었습니다. 이러한 주제/범주에는 교육 목표, 내용, 사용된 교수법, 윤리를 가르치는 데 있어 조력자 및 장벽이 포함됩니다.

The first search involving the teaching of ethics retrieved 7669 abstracts, with 573 full-text articles reviewed and 66 articles included. Comparison of the categories and themes identified as part of the Split Approach revealed similar categories and themes which were combined into themes/categories using the Jigsaw Perspective. These themes/categories include the goals, content, teaching methods employed, and enablers and barriers to teaching ethics.

윤리 평가를 위해 검색을 통해 9919개의 초록이 확인되었고, 333개의 전문 논문이 검토되었으며, 29개의 논문이 포함되었습니다. 평가 방법에 대한 SEBA의 SSR의 분할 접근 방식은 평가되는 유형과 영역, 다양한 평가 방법의 장단점을 포함하는 세 가지 주제/범주를 드러냈습니다.

For the assessment of ethics, the search saw 9919 abstracts identified, 333 full-text articles reviewed and 29 articles included. The Split Approach from the SSR in SEBA of assessment methods revealed three themes/categories which included the types and domains assessed and the pros and cons of various assessment methods.

4단계: 퍼널링 프로세스

Stage 4: The funnelling process

또한, 세 번째 소팀은 포함된 논문의 중요한 논의 개념과 모순되는 견해가 포함되었는지 확인하기 위해 포함된 논문의 전문을 요약하고 표로 작성했습니다. 또한 표로 정리된 요약은 확인된 결과가 기존 데이터의 정확한 표현인지 확인하는 역할도 합니다. 윤리 교육 및 평가에 대한 표로 정리된 요약본은 각각 추가 파일 2와 3에서 확인할 수 있습니다. 연구팀은 전문가 팀의 감독 하에 퍼널링 프로세스에 따라 유사성과 중복되는 영역을 기준으로 SEBA의 두 SSR에서 주제/범주를 결합했습니다.

In addition, a third sub-team summarised and tabulated the included full-text articles to ensure that important concepts of discussion and contradictory views within the included articles were retained. The tabulated summaries also serve to verify that the results ascertained are an accurate representation of the existing data. The tabulated summaries for the teaching and assessing of ethics may be found in Additional File 2 and 3 respectively. Under the oversight of the expert team, the research team combined themes/categories from the two SSRs in SEBA based upon their similarities and their areas of overlap in keeping with the Funnelling Process.

두 검색에서 도출된 5가지 주제/카테고리는 목표와 목적, 콘텐츠, 교수법, 활성화 및 제한 요소, 평가 도구입니다.

The five funnelled themes/categories from the two searches are the goals and objectives, the content, pedagogy, enabling and limiting factors, and assessment tools.

목표 및 목적

Goals and objectives

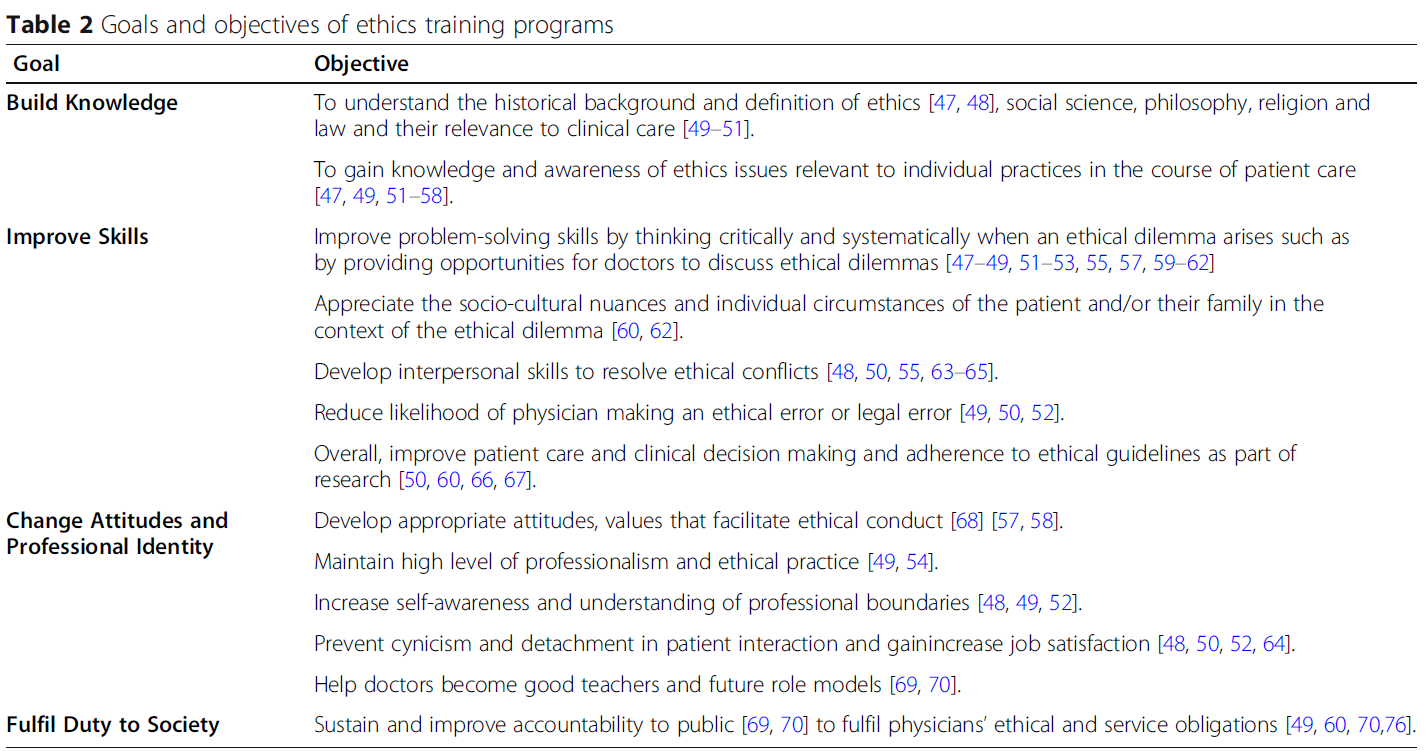

의사를 위한 윤리 교육 프로그램의 목표와 목적은 아래 표 2에 강조 표시되어 있습니다.

The goals and objectives of ethics training programs for doctors are highlighted in Table 2 below.

전반적으로 대부분의 윤리 프로그램의 목표는

- 의과대학에서 다루는 주요 윤리적 원칙을 되새기고[51],

- 의사가 윤리적 딜레마에 대처할 수 있도록 준비시키며,

- 그렇게 할 수 있는 자신감을 향상시키는 것이었습니다[59, 71, 77].

일부 프로그램은 다음 섹션에서 다루는 내용에서 강조한 바와 같이 상황 및 전문 분야별 윤리적 딜레마를 소개하기도 했습니다[48, 53, 56, 70, 78-80].

Overall, the goal of most ethics programs was to

- refresh key ethical principles covered in medical schools [51],

- prepare physicians to tackle ethical dilemmas, and

- improve their confidence in doing so [59, 71, 77].

Some programs also introduced context and specialty-specific ethical dilemmas as highlighted in the next section on content covered [48, 53, 56, 70, 78–80].

다루는 콘텐츠

Content covered

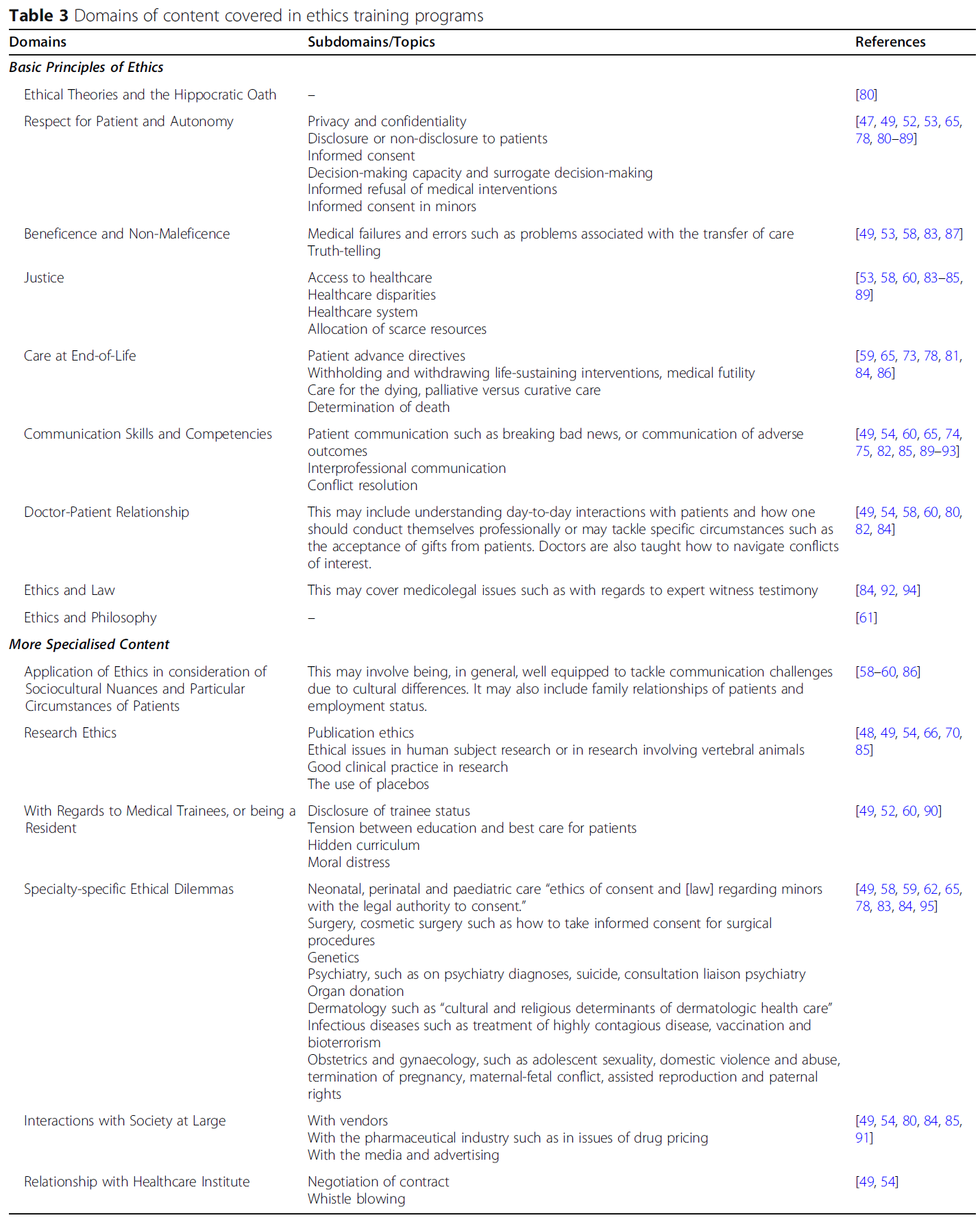

다루는 콘텐츠는 표 3에 요약되어 있습니다.

Content covered is outlined in Table 3.

대부분의 교육 프로그램은 다양한 주제를 다루고 있습니다.

Most training programs covered a varying number of topics.

Carrese, Malek [96]은 의사를 위한 윤리 교육과 의대생을 위한 윤리 교육에서 다루는 주제의 범위가 겹친다고 지적했지만, 저자들은 "레지던트에게 제공되는 교육 자료는 일반적으로 의대생을 위한 것보다 더 복잡하고 상황에 따라 달라질 수 있으며 윤리적 문제는 더 미묘하고 심도 있게 논의될 수 있다"고 설명합니다.

Whilst Carrese, Malek [96] noted an overlap in the range of topics covered in ethics training for doctors and those for medical students, the authors explain that “educational materials offered to residents can typically be more complex and contextual than those intended for medical students, and ethical issues can be more nuanced and discussed in greater depth”.

교수법

Pedagogy

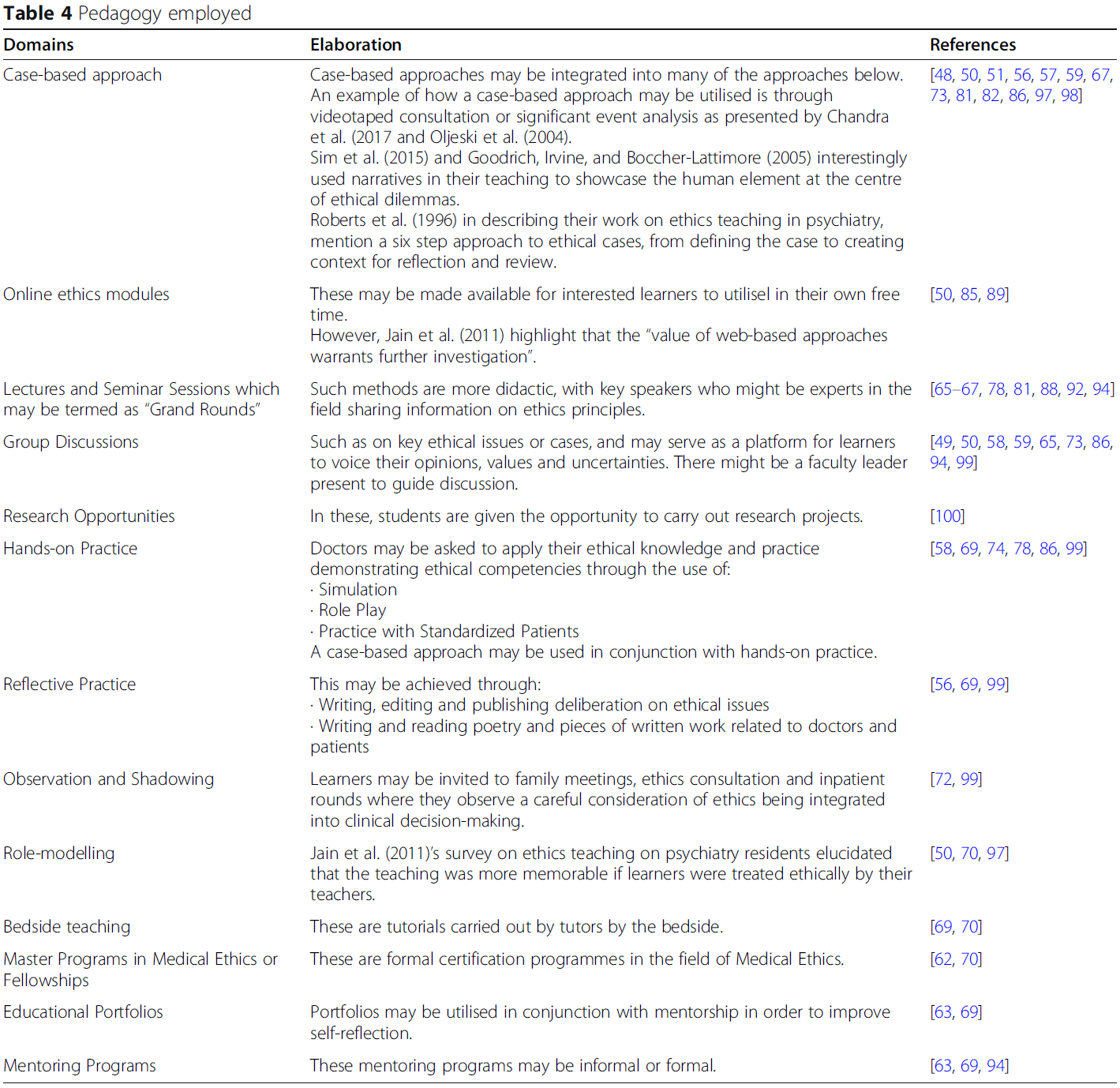

아래 표 4에는 다양한 교육법이 강조되어 있습니다.

The diverse pedagogies are highlighted in Table 4 below.

이러한 교육 세션의 시기와 기간에는 큰 차이가 있습니다. 주최 기관이나 기관에서 운영하는 공식 교육은 몇 년[62, 82] 또는 하루[67]에 걸친 의무 교육 프로그램[80, 81]의 형태로 제공되는 경향이 있었습니다. 일부 프로그램은 매년 몇 시간 동안 진행되거나[58, 94], 더 광범위한 레지던트 교육 프로그램의 일부로 매달 또는 몇 달에 한 번씩 진행되기도 합니다[49, 59, 83].

There is great variation in the timing and duration of such training sessions. Formal teaching run by the host organisation or institution tended to come in the form of mandatory training programmes [80, 81] that span the course of a few years [62, 82] or a single day [67]. Some programs are held over a few hours each year [58, 94], or each month or every few months as part of a wider residency training program [49, 59, 83].

비공식 프로그램은 다과가 제공되고 위계가 최소화되는 보다 비공식적인 환경에서 이루어지는 경향이 있었습니다[49, 59].

Informal programs tended to be situated in more informal settings where refreshments are served and hierarchies are minimised [49, 59].

다양한 교육 프로그램은 목표를 달성하기 위해 여러 가지 접근 방식을 조합하여 활용했습니다[82]. 토론토 대학교의 하워드 맥닐리[70]는 공식적인 생명윤리 교육과 "윤리적 행동의 역할 모델링 및 윤리적 문제에 대한 병상 교육"의 통합에 대해 설명합니다. 이러한 조합의 영향은 소아과 프로그램 디렉터를 대상으로 윤리를 가르치는 방법에 대한 Lang, Smith[97]의 설문조사에서 잘 드러납니다. 의료 윤리 교육에 대한 Carrese, Malek [96]의 문헌 검토에서도 마찬가지로 공식, 비공식 및 숨겨진 커리큘럼의 시너지 효과를 강조했습니다[77].

Different training programs utilised a combination of approaches to meet their objectives [82]. At the University of Toronto, Howard, McKneally [70] describes integrating formal bioethics teaching with “role modelling of ethical behaviour and bedside teaching around ethical issues”. The impact of this combination is echoed by Lang, Smith [97]’s survey of paediatric programme directors on how ethics is taught. Carrese, Malek [96]’s literature review of medical ethics training similarly highlighted the synergistic nature of the formal, informal and hidden curricula [77].

다른 저자들은 의료 환경에서 팀 기반 업무의 복잡성을 설명하기 위해 다학제적 접근 방식을 사용할 것을 제안했습니다[59, 69, 73, 101, 102].

Other authors have proffered the use of a multidisciplinary approach to illustrate the intricacies of team based working in the healthcare setting [59, 69, 73, 101, 102].

활성화 요인 및 장벽

Enabling factors and barriers

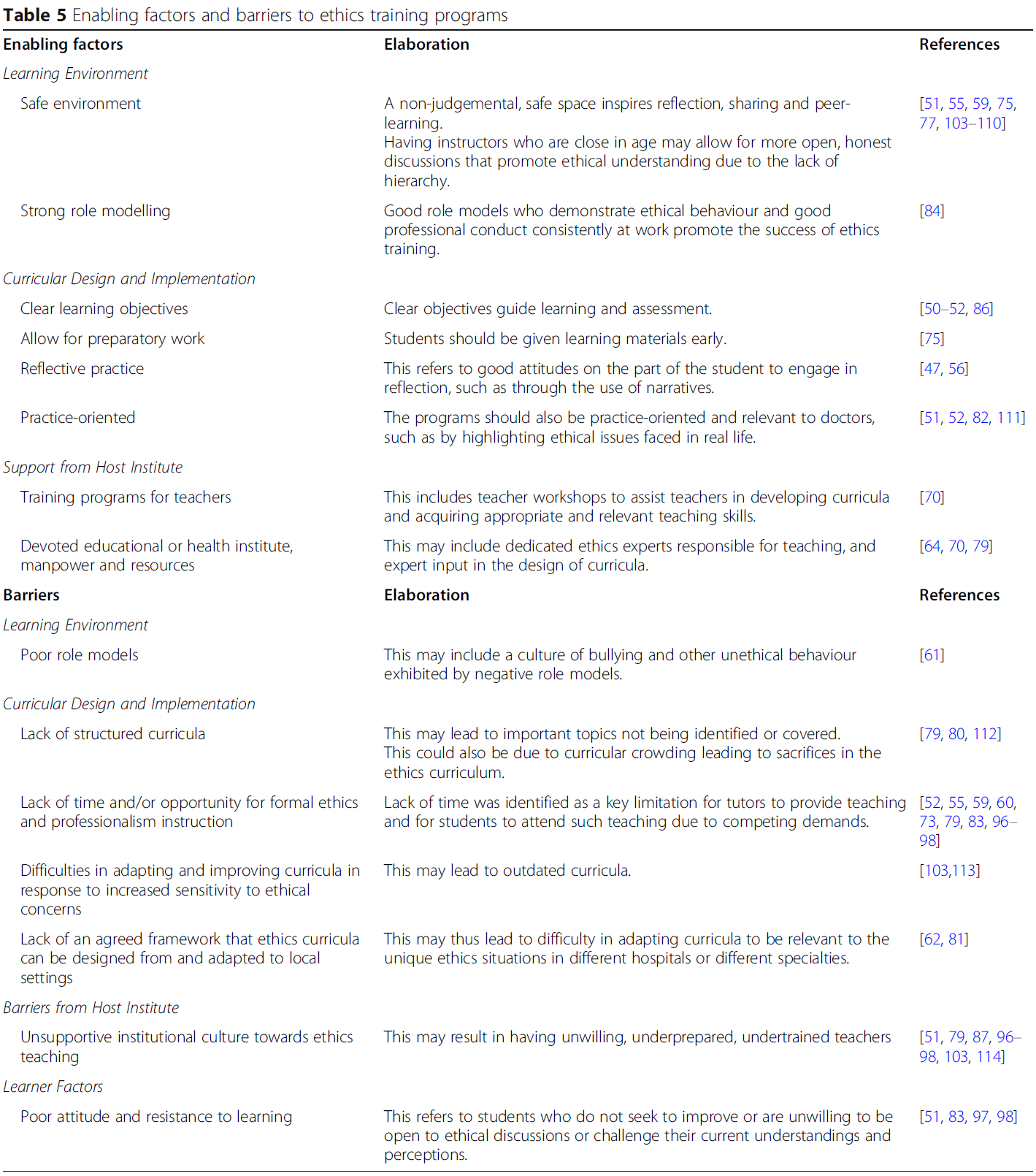

윤리 교육 프로그램의 성공적인 실행을 위한 지원 요인과 장벽은 다음과 같이 나타날 수 있습니다(표 5):

Enabling factors and barriers to the successful execution of ethics training programs may present themselves as follows (Table 5):

새로운 학습자들은 "임상 의학에 대한 노출이 제한적이거나 관련 가치에 대한 직업적 정체성이 아직 완전히 형성되지 않았기 때문에 윤리적 갈등의 실제적인 측면을 인식하지 못하는 경우가 많다"고 생각한 Grace와 Kirkpatrick [68]은 윤리적 사고를 실무에 적용하기 위해 윤리적 비네트 및 윤리적 추론 기법을 시범적으로 사용했습니다. 윤리 교육에 대한 외과 레지던트의 태도에 대한 Howard, McKneally [84]의 연구에 따르면 일반적으로 사례 토론과 윤리적 문제의 실제 적용에 대한 준비가 부족하고 상대적으로 경험이 부족하다는 인식이 드러났습니다.

Believing that new learners often “do not appreciate the practical side of ethical conflicts as they have had limited exposure to clinical medicine or have not yet fully formed a professional identity with its associated values,” Grace and Kirkpatrick [68] piloted ethical vignettes and ethical reasoning technique to acculturate ethical thinking into practice. Howard, McKneally [84]’s study of surgical resident’s attitudes towards ethics teaching revealed a general sense of being poorly prepared and relatively inexperienced for case discussions and practical application of ethical issues.

Carrese, McDonald [60]와 Chandra, Ragesh [69]도 윤리적 문제가 발생하더라도 제대로 모델링되지 않았고 교육 순간으로 거의 사용되지 않았다고 지적합니다.

Carrese, McDonald [60] and Chandra, Ragesh [69] also note that even in the event that ethical issues did arise, they were poorly modelled and rarely used as teaching moments.

평가 도구

Assessment tools

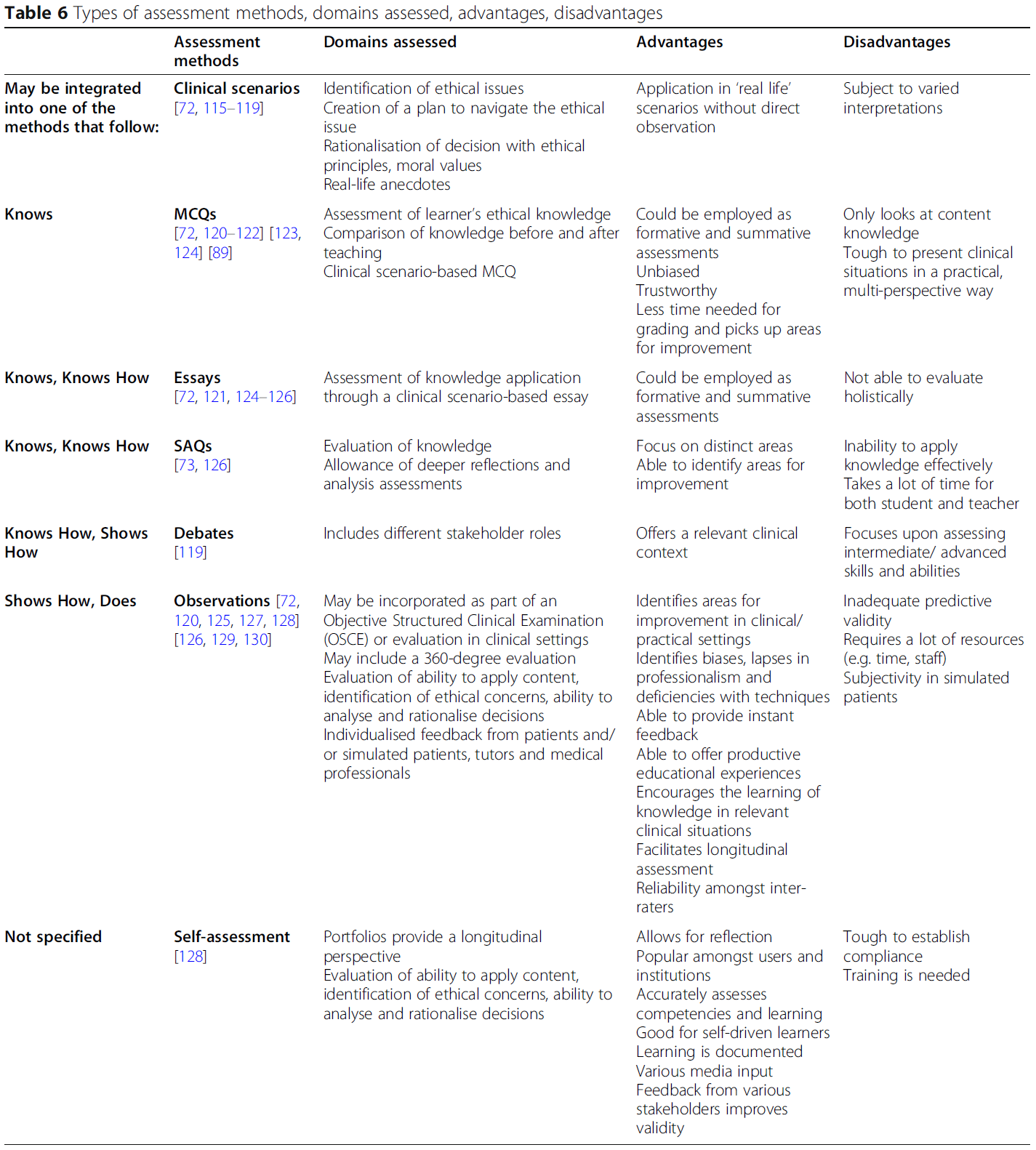

평가 도구는 사용되는 평가 방법의 유형, 평가되는 해당 영역, 장단점으로 구성됩니다(표 6). 이러한 평가 방법은 밀러의 임상 역량 피라미드에 매핑될 수 있습니다[131].

Assessment tools comprise the type of assessment method employed, corresponding domains assessed and their pros and cons (Table 6). These assessment methods may be mapped onto the Miller’s pyramid of clinical competency [131].

5단계: 5단계: SEBA의 SSR에 대한 토론 및 종합

Stage 5: Discussion and synthesis of SSRs in SEBA

의료 윤리 교육 및 평가에 경험이 있는 현지 교육자, 임상의, 연구자들과 함께 결과를 검토하고 자문을 구하여 이 검토의 완성도를 다시 한 번 확인했습니다. 작성된 내러티브는 STORIES(보건의료 교육에서의 근거 종합 보고에 대한 구조화된 접근법) 성명서[38] 및 근거 중심 의학 교육(BEME) 협력 가이드[39]에 따라 작성되었으며, 의사들의 윤리 교육 및 평가에 대한 이 새로운 검토는 여러 가지 통찰력을 보여줍니다. 여기에서는 쉽게 참조할 수 있도록 주요 결과 중 일부를 나열하고 특히 관심 있는 세 가지 영역을 자세히 살펴봅니다.

A review of the results and consultation with local educationalists, clinicians and researchers experienced in medical ethics teaching and assessment reiterated the completeness of this review. The narrative produced was guided by the STORIES (Structured approach to the Reporting In healthcare education of Evidence Synthesis) statement [38] and Best Evidence Medical Education (BEME) Collaboration guide [39].This novel review of teaching and assessment of ethics amongst physicians reveals a number of insights. Here we list some of the key findings for ease of reference and will delve into three areas of particular interest.

- 대부분의 윤리 프로그램의 공통적인 목표는 [윤리적 원칙에 대한 인식]과 [윤리적 딜레마를 재치 있고 전문적으로 해결하는 기술을 향상]시키는 것입니다. 그러나 최근의 논문들은 관행을 바꾸고, 태도를 형성하며, 사회적 및 직업적 의무를 충족하는 데 초점을 맞추고 있습니다.

- 윤리를 가르치고 평가하는 최근의 사례는 맥락 및 전공 관련 영향의 영향을 드러냅니다.

- 대부분의 프로그램의 핵심 요소는 다음에 관한 것이었습니다.

- 자율성, 유익성, 비악용성, 정의의 네 가지 원칙,

- 의사-환자 관계,

- 의사소통,

- 임종 간호

- 전공 분야 또는 맥락 특이적 정보 내용에는 다음이 포함됩니다.

- 연구 윤리,

- 전공 분야 관련 주제,

- 수련의 관련 고려 사항,

- 사회적 및 제도적 상호 작용

- 윤리를 가르치는 데는 여러 가지 접근법이 사용되었지만, 모두 학습자에게 그룹 토론에 선택적으로 참여하는 것부터 사례 토론 및 성찰을 유도하는 것까지 다양한 방식으로 지식을 적용할 수 있는 기회를 제공하는 데 중점을 두었습니다.

- 윤리 교육과 평가를 촉진하는 요소로는 체계적인 프로그램, 양육 문화, 우려 사항과 문의 사항을 논의할 수 있는 안전한 환경이 꼽혔습니다.

- 윤리 교육에서 중요한 것은 역할 모델링, 사례 기반 토론, 윤리적 감수성 및 윤리적 문제 해결에 대한 교육입니다.

- 일반적으로 평가 방법이 부족합니다.

- The common objective across most ethics programs is to improve awareness of ethical principles and skills in resolving ethical dilemmas tactfully and professionally. More recent articles however focused on changing practice, shaping attitudes and meeting social and professional obligations.

- Recent accounts of teaching and assessing ethics reveal the impact of context and speciality related influences.

- The core elements of most programs concerned

- the four principles of autonomy, beneficence, non-maleficence and justice;

- the doctor- patient relationship;

- communication; and

- end of life care.

- Speciality or context specific information contents include

- research ethics;

- speciality related topics;

- trainee related considerations and

- social and or institutional interactions.

- There were a number of approaches employed to teach ethics yet all were focused upon providing learners with an opportunity to apply their knowledge in a variety of ways, ranging from optional participation in group discussions to guided case discussions and reflections.

- Factors facilitating ethics education and assessments were a structured program, a nurturing culture and a safe environment to discuss concerns and enquiries.

- Important in ethics training are role modelling, case-based discussions and instruction on ethical sensitivity and resolving ethical issues.

- There is a general lack of assessment methods.

각 교육 프로그램에는 고유한 차이가 있지만, 지식 구축에서 실천으로, 궁극적으로는 [학습자의 직업적 정체성]을 키우는 데까지 학습자를 안내하는 연속선상에 있다고 볼 수 있습니다. 실제로 많은 프로그램에서 학습자가 사회적 책임[49, 60, 70-76, 85]과 '실무 커뮤니티'[69, 70]에 대한 멤버십을 갖출 수 있도록 준비시키려고 노력합니다. 이는 크루스, 크루스[131]가 수정한 밀러 피라미드의 정점에 있는 "Is" 단계와 일치합니다. 이러한 가설에 대한 증거는 윤리 교육이 가르치는 내용과 방식에서 확인할 수 있습니다.

While there are inherent differences to each of the training programs, they may be seen to lie on a continuum of guiding the learner from knowledge building to practice and ultimately to nurturing the learner’s professional identity. Indeed, many programs seek to prepare learners for their societal responsibilities [49, 60, 70–76, 85] and their membership to their ‘community of practice’ [69, 70]. This would be consistent with Cruess, Cruess [131]’s “Is” level at the apex of their amended Miller’s pyramid. With this in mind, evidence for this posit is visible from the contents and manner that ethics education is taught.

교육 프로그램의 종단적 성격, 재교육 세션 및 자율성, 유익성, 비악의성, 정의, 임종 간호, 의사 환자 관계 및 치료 의무와 같은 '핵심' 주제를 포함하는 세션의 존재에 대한 면밀한 연구는 [일반적인 지식의 강화]를 시사합니다 [48, 50, 51, 56, 57, 59, 67, 73, 81, 82, 86, 97, 98]. 보다 전문화된 전공과목 지식, 임상 및 연구 콘텐츠의 도입은 [새로운 지식과 경험적 학습의 계층화]를 시사합니다. 이러한 [기존 지식에 대한 구축 과정]은 [의과대학에서 받은 교육과 임상 환경에서 윤리적 문제에 대한 인식을 심화하려는 노력]에 기반한 것으로 보이는 [교육의 종단적 특성]을 입증합니다. 이는 학습자를 교육하는 데 사용되는 방법에서도 입증됩니다. 교훈적인 강의, 온라인 비디오, 병상 윤리 토론은 사례 토론과 프레젠테이션으로 이어지며, 학습자는 지식과 자신감을 쌓고 윤리적 문제를 해결하는 데 지식과 기술을 적용할 수 있습니다[58, 69, 74, 78, 86, 99].

Careful study of the longitudinal nature of training programs, the presence of refresher sessions and/or sessions involving ‘core’ topics such as autonomy, beneficence, non-maleficence, justice, end of life care,the doctor patient relationship and the duty of care suggests a reinforcement of prevailing knowledge [48, 50, 51, 56, 57, 59, 67, 73, 81, 82, 86, 97, 98]. The introduction of more specialised speciality, clinical and research content suggests a layering of new knowledge and experiential learning. This process of building on prevailing knowledge evidences the longitudinal nature of training that would seem to build on training received in medical school and efforts to deepen appreciation of ethical issues in the clinical setting. This is also evidenced by the methods used to train the learners. Here didactic lectures, online videos and bedside ethics discussions give way to case discussions and presentations, allowing the learner to build their knowledge and confidence and apply their knowledge and skills in addressing the ethical issues [58, 69, 74, 78, 86, 99].

이러한 고려사항은 또한 대부분의 프로그램에서 사용하는 [나선형 커리큘럼의 수직적 측면]을 강조하고 지식 및 술기 평가의 중요성을 높입니다. 임종 간호와 특히 관련이 있거나 중환자실 배치와 같은 연명 치료 중단 및 보류에 대한 논의가 이루어지는 등 특정 진료 단계에 윤리 교육이 도입되었다는 증거는 윤리 교육 프로그램이 [수평적으로 통합]되어 있음을 시사합니다.

These considerations also highlight the vertical aspect of the spiral curriculum employed by most programs and raise the importance of knowledge and skills assessments. Evidence that ethical training is introduced at specific stages of practice such as during postings where end of life care is especially relevant, or where discussions of withdrawing and withholding life sustaining treatment, such as intensive care placements, suggest horizontal integration of the ethics training programs.

일반적인 지식을 바탕으로 상황에 맞는 학습을 통합하고자 하는 나선형 커리큘럼의 존재는 두 가지 고려 사항을 강조합니다. 첫 번째는 교육의 다음 단계로의 진도를 결정하기 위해 적절한 평가를 사용하는 것이고, 두 번째는 주최 기관의 프로그램 지원입니다.

The presence of a spiral curriculum that seeks to build on prevailing knowledge and integrate context specific learning highlights two considerations. The first is the use of pertinent assessments to determine progress to the next stage of the training and the second is the support of the program by the host organizsation.

교육 후에는 Norcini [132]가 제안한 것처럼 지식이 효과적으로 동화되고 적절하게 적용되었는지 확인하고 마이크로 크레딧을 촉진하기 위한 평가가 뒤따라야 합니다. 이와 함께 윤리 교육에서 명확한 위탁 가능한 전문 활동(EPA)을 수립할 필요성도 있는데, 현재로서는 실무의 다양성, 전문성, 사회 문화적 고려 사항 및 학습자의 일반적인 지식, 기술, 태도 및 경험 측면에서 학습자의 다양성을 고려할 때 추가 연구와 고려가 필요합니다[133]. 교육 포트폴리오의 일부로서 종단적 평가 프로세스의 필요성과 그것이 직업 정체성 형성(PIF) 개발에 미치는 영향에 대해서도 면밀한 조사가 필요합니다[131, 134].

Training should be followed by assessments to ensure that knowledge has been effectively assimilated and applied appropriately, and to facilitate micro-credentialling, as suggested by Norcini [132]. In tandem with this, there is also the need to establish clear Entrustable Professional Activities (EPA) s in ethics education which, at present, will require further research and consideration given the diversity of practice, specialities, socio-cultural considerations and learner variability in terms of their prevailing knowledge, skills, attitudes and experience [133]. The need for a longitudinal assessment process as a part of an education portfolio and their impact on the development of professional identity formation (PIF) also demands closer scrutiny [131, 134].

여기서 학습 포트폴리오는 학부 교육과 대학원 교육에서 윤리 교육을 원활하게 통합할 수 있으며[51, 83, 97, 98], 윤리 교육이 종단적 교육 경험의 일부라는 개념[4, 135]에 부합하여 PIF[131, 134]를 육성하는 데 도움이 될 수 있습니다. 포트폴리오는 윤리적 역량을 종단적으로 평가하는 데 유용한 평가 방식일 뿐만 아니라 지식 결핍을 인식하고 올바른 행동을 강화함으로써 지속적인 자기 학습을 촉진합니다[63, 136-143].

Here, learning portfolios will allow seamless integration between ethics training in undergraduate and postgraduate training [51, 83, 97, 98] and would be in keeping with the notion of ethics training being part of a longitudinal training experience [4, 135] that nurtures PIF [131, 134]. Portfolios not only serve as a valuable assessment modality for longitudinal evaluation of ethical competency but also promotes continuous self-learning through the recognition of knowledge deficits while reinforcing good behaviour [63, 136–143].

그러나 효과적인 윤리 교육 프로그램을 위해서는 레지던트 프로그램, 의료 기관 및 교육 기관이 전담 자원, 인력 및 교수진 교육을 할당하는 등 지원이 필요합니다[64, 70, 79]. 주최 기관은 이러한 교육을 조율하고 프로그램의 궤적을 세심하게 감독해야 합니다. 마찬가지로 중요한 것은 임상의가 '진료 커뮤니티'에서 자신의 역할과 책임을 인정하고 받아들이도록 하는 노력이 필요하다는 것입니다[144]. 선택된 주제는 제한된 시간 내에 실용적이고 실현 가능하면서도 임상 실무와 관련이 있어야 합니다[52, 55, 59, 60, 73, 79, 83, 96-98].

Yet an effective ethics training program requires support fromresidency programs, healthcare institutes and educational institutes through the allocation ofallocating dedicated resources, manpower and faculty training [64, 70, 79]. The host organisation must orchestrate this training and provide careful oversight of the program's trajectory. Perhaps just as important is that there are efforts to ensure that clinicians acknowledge and adopt their roles and responsibilities in their ‘communities of practice’ [144]. The topics chosen should be practical and feasibly covered within the limited time allotted yet be relevant to clinical practice [52, 55, 59, 60, 73, 79, 83, 96–98].

또한 프로그램과 주최 기관은 핵심 가치를 전파하고 "의료 기관의 일상 생활에 이러한 가치를 적극적으로 통합"하는 인프라를 도입하여 윤리적 분위기를 조성해야 합니다[145]. 윤리적 분위기는 직업적 정체성 형성에 도움이 될 것입니다[131, 134, 146].

The programs and host organisations must also instil a nurturing ethical climate through the dissemination of core values and introduction of infrastructure that “proactively incorporates these values in the daily life of the healthcare organi[z]ations” [145]. An ethical climate would aid in professional identity formation [131, 134, 146].

한계점

Limitations

대학원 의학 교육에서 윤리 교육에 관한 다양한 문헌을 살펴보고자 했지만, 각 논문을 더 깊이 있게 연구할 수 있음은 분명합니다. 이러한 한계는 주로 현재의 교육 접근 방식과 커리큘럼, 프로그램 수행 및 평가 방식에 대한 보고가 불완전하기 때문입니다.

Whilst it was our intention to appreciate the range of available literature on ethics education in postgraduate medical education, it is evident that each paper could be studied in greater depth. This limitation is mainly due to incomplete reporting of the current training approaches and their curriculum, as well as the way in which the programs are is carried out and evaluated.

또한, 선택된 논문의 범위가 주로 북미와 유럽에서 작성된 논문에서 비롯되었습니다. 따라서 다양한 지리적 경계를 가로지르는 다양한 문화가 고려되지 않았기 때문에 이러한 연구 결과의 적용 가능성에 한계가 있습니다.

Furthermore, the range of selected articles chosen originates from papers that were largely written in North America and Europe. This limits the applicability of these findings, as the different cultures across the different geographical boundaries are not accounted for.

그러나 이러한 한계에도 불구하고 이 범위 검토는 Arksey와 O'Malley [21], Pham, Rajic [26], Levac, Colquhoun [147]이 주장한 엄격함과 투명성을 바탕으로 수행되었습니다. 서지 관리 프로그램인 Endnote를 사용하여 여러 데이터베이스의 모든 인용을 적절히 설명할 수 있었습니다.

However, despite these limitations, this scoping review was carried out with the necessary rigour and transparency advocated by Arksey and O’Malley [21], Pham, Rajic [26], and Levac, Colquhoun [147]. The use of Endnote, a bibliographic manager, ensured that all the citations from the different databases were properly accounted for.

결론

Conclusion

우리는 이 범위 검토의 결과 분석이 전 세계 대학원 의료 환경의 교육자 및 프로그램 설계자와 관련이 있을 것이라고 믿습니다. 그러나 접근 방식, 내용 및 질 평가에 대한 합의가 부족하고 관점의 차이가 있으며 윤리, 의사소통 및 전문성 간의 내재적 연관성을 탐구할 필요가 있다는 점[63, 148, 149]은 의학에서 의사소통 기술과 전문성을 향상시키는 데 초점을 맞춘 프로그램을 포함시키는 것을 정당화합니다. 또한 학습자의 다양한 특성, 환경, 경험 수준, 특정 의료 시스템 및 문화 속에서 윤리에 대한 EPA를 수립하기 위한 연구를 더 많이 수행해야 합니다. 또한 대학원 환경에서 윤리 실습에 대한 포트폴리오 설계, 실행 및 평가와 PIF 및 마이크로 크레딧에 대한 연구도 진행되어야 합니다.

We believe the analysis of our findings in this scoping review will be relevant to educators and program designers in postgraduate medical settings around the world. However, the lack of consensus and difference in perspectives regarding the approach, content and quality assessments as well as the need to explore the inherent link amongst ethics, communication and professionalism [63, 148, 149] justifies inclusion of programs focused on enhancing communication skills and professionalism in medicine. In addition, more needs to be done to research on establishing EPAs in ethics amidst the diverse characteristics of learners, their settings and their levels of experience as well as the particular healthcare system and culture that they practice in. Research should also look into portfolio design, implementation and assessment of PIF and micro-credentialling in ethics practice in the postgraduate setting.

Postgraduate ethics training programs: a systematic scoping review

PMID: 34107935

PMCID: PMC8188952

DOI: 10.1186/s12909-021-02644-5

Abstract

Background: Molding competent clinicians capable of applying ethics principles in their practice is a challenging task, compounded by wide variations in the teaching and assessment of ethics in the postgraduate setting. Despite these differences, ethics training programs should recognise that the transition from medical students to healthcare professionals entails a longitudinal process where ethics knowledge, skills and identity continue to build and deepen over time with clinical exposure. A systematic scoping review is proposed to analyse current postgraduate medical ethics training and assessment programs in peer-reviewed literature to guide the development of a local physician training curriculum.

Methods: With a constructivist perspective and relativist lens, this systematic scoping review on postgraduate medical ethics training and assessment will adopt the Systematic Evidence Based Approach (SEBA) to create a transparent and reproducible review.

Results: The first search involving the teaching of ethics yielded 7669 abstracts with 573 full text articles evaluated and 66 articles included. The second search involving the assessment of ethics identified 9919 abstracts with 333 full text articles reviewed and 29 articles included. The themes identified from the two searches were the goals and objectives, content, pedagogy, enabling and limiting factors of teaching ethics and assessment modalities used. Despite inherent disparities in ethics training programs, they provide a platform for learners to apply knowledge, translating it to skill and eventually becoming part of the identity of the learner. Illustrating the longitudinal nature of ethics training, the spiral curriculum seamlessly integrates and fortifies prevailing ethical knowledge acquired in medical school with the layering of new specialty, clinical and research specific content in professional practice. Various assessment methods are employed with special mention of portfolios as a longitudinal assessment modality that showcase the impact of ethics training on the development of professional identity formation (PIF).

Conclusions: Our systematic scoping review has elicited key learning points in the teaching and assessment of ethics in the postgraduate setting. However, more research needs to be done on establishing Entrustable Professional Activities (EPA)s in ethics, with further exploration of the use of portfolios and key factors influencing its design, implementation and assessment of PIF and micro-credentialling in ethics practice.

Keywords: Ethics curriculum; Ethics education; Ethics training program; Medical ethics; Physicians; Postgraduate medical education; SEBA; Scoping review; Systematic scoping review.

'Articles (Medical Education) > 전문직업성(Professionalism)' 카테고리의 다른 글

| 의학교육이 인공지능을 만나는 곳: 테크놀로지가 돌봄을 할 수 있을까? (Med Educ, 2020) (0) | 2023.05.25 |

|---|---|

| 보건의료전문직 교육에서 인공지능의 윤리적 사용: AMEE Guide No. 158 (Med Teach, 2023) (0) | 2023.05.11 |

| 프로페셔널리즘 달성에 의료윤리교육의 필수적 역할: 로마넬 보고서(Acad Med, 2015) (0) | 2023.04.13 |

| 의학교육에서 프로페셔널리즘 교육: BEME Guide No. 25 (Med Teach, 2013) (0) | 2023.04.06 |

| 졸업후교육에서 프로페셔널리즘 교육: 체계적 문헌고찰 (Acad Med, 2020) (0) | 2023.04.06 |