학부생 및 수련생이 피드백에 반응하는 렌즈로서 자기조절학습이론: BEME 스코핑 리뷰 (BEME Guide No. 66) (Med Teach, 2022)

Self–regulatory learning theory as a lens on how undergraduate and postgraduate learners respond to feedback: A BEME scoping review: BEME Guide No. 66

Muirne Spooner , Catherine Duane, Jane Uygur, Erica Smyth , Brian Marron, Paul J. Murphy and Teresa Pawlikowska

소개

Introduction

피드백은 오랫동안 학습자의 혁신적 변화에 영향을 미치는 핵심 요소로 간주되어 왔습니다(Black and William 1998; Hattie and Timperley 2007). 이전의 검토에 따르면 피드백의 효과는 다양하고 여러 이질적인 요인에 따라 달라지며(Kluger and DeNisi 1996; Winstone 외. 2017a), 학업 성취도가 주요 결과 측정치로 연구된 바 있습니다. 500개가 넘는 메타분석을 검토한 결과, 피드백이 학업 성취도에 미치는 주요 영향 중 하나로 밝혀졌습니다(Hattie 2008). 이는 Kluger와 DeNisi(1996)에 의해 뒷받침되었는데, 이들은 상호 작용의 [최대 1/3에서 피드백이 부정적인 영향을 미친다]는 점을 중요하게 강조했습니다. 해티와 팀퍼리는 네 가지 수준(과정, 과제, 자기 조절, 자기)에 따른 피드백을 강조했으며, 피드백의 목표가 효과성에 영향을 미치는 수준도 강조했습니다. 최근의 문헌에서는 [피드백 후 단계]와 [학습자의 경험]에 더 중점을 두고 있습니다. 이러한 논의는 [동기 부여 이론](Deci and Ryan 1985)과 피드백이 헌신과 성과 목표에 어떤 영향을 미칠 수 있는지를 중심으로 이루어졌습니다. Winstone 등(2017a)의 리뷰에서는 피드백에 대한 관점으로 '능동적 수신자'를 추가했는데, 그녀는 이 용어를 '피드백 프로세스에 적극적으로 참여하는 상태 또는 활동으로, 학습자의 근본적인 기여와 책임을 강조하는 것'이라고 설명합니다. 그녀는 능동적으로 피드백을 받는 학습자를 설명하기 위해 SAGE(자기 평가, 평가 리터러시, 목표 설정 및 자기 조절, 참여 및 동기 부여) 분류법을 제안합니다.

Feedback has long been considered as key in effecting transformational change in learners (Black and William 1998; Hattie and Timperley 2007). Earlier reviews show that the benefit of feedback is variable and dependent on a number of heterogeneous factors (Kluger and DeNisi 1996; Winstone et al. 2017a), with academic achievement the main outcome measure studied. A review of over 500 meta-analyses identifies feedback as one of the major influences on academic achievement (Hattie 2008). This was supported by Kluger and DeNisi (1996) who also importantly highlighted feedback had a negative effect in up to one-third of interactions. Hattie and Timperley emphasised feedback directed at four distinct levels (process, task, self-regulation, and self), with the level targeted influencing effectiveness. Recent literature turns more emphasis to the post-feedback phase and the learner’s experience. This discussion has centred on motivational theory (Deci and Ryan 1985) and how feedback can affect commitment and performance goals. Winstone et al’s (2017a) review has added ‘proactive recipience’ as a lens on feedback, a term she describes as the ‘state or activity of engaging actively with feedback processes, thus emphasizing the fundamental contribution and responsibility of the learner.’ She proposes the SAGE (Self-appraisal, Assessment literacy, Goal-setting and self-regulation, and Engagement and motivation) taxonomy to describe a proactive recipient of feedback.

[피드백과 성과 간의 관계]는 잘 연구되어 있지만, 학습자가 피드백과 상호작용하여 이러한 성과 변화에 영향을 미치는 방식에 대해서는 알려진 바가 적습니다. 이 리뷰에서는 피드백을 받은 후 학습자 내에서 일어나는 내부 재처리 변화에 관한 연구를 살펴봅니다. 이를 위해 [자기조절이라는 렌즈]를 사용하여 피드백에 대한 학습자의 반응을 고려합니다. [자기조절]이란

- 일련의 강력한 기술을 발휘하는 과제에 참여하는 스타일'입니다(Butler와 Winne 1995).

- '학생이 지식 업그레이드를 위한 목표를 설정하고,

- 목표에 대한 진전과 원치 않는 비용의 균형을 맞추는 전략을 선택하기 위해 숙고하며,

- 단계를 수행하고 과제가 발전함에 따라 참여의 누적 효과를 모니터링하는 등

While the relationship between feedback and performance is well researched, less is known about how learners interact with feedback to effect these changes in performance. This review explores research concerning the internal re-processing changes that occur within the learner following feedback. In doing so, we consider the learner’s response to feedback using the lens of self-regulation. Self-regulation is

- ‘a style of engaging with tasks in which students exercise a suite of powerful skills:

- setting goals for upgrading knowledge;

- deliberating about strategies to select those that balance progress toward goals-against unwanted costs; and,

- as steps are taken and the task evolves, monitoring the accumulating effects of their engagement’ (Butler and Winne 1995).

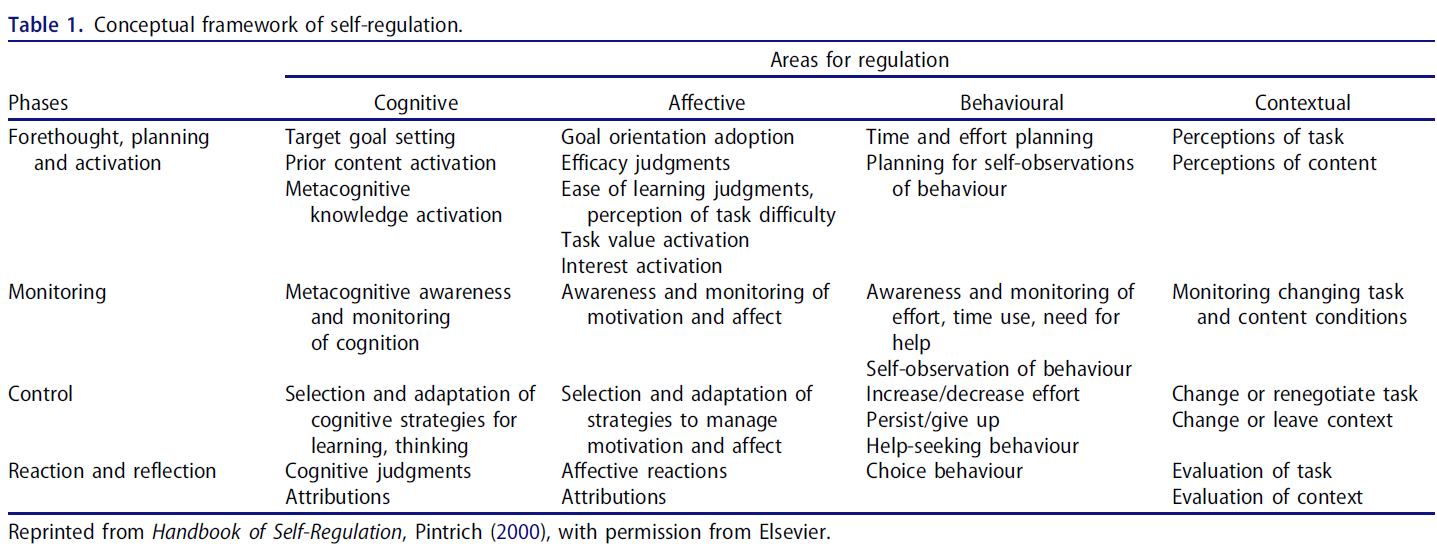

이 이론은 18세기 독일에서 등장하여 폰 훔볼트에게 기인한 광범위한 교육 및 사회 개념인 [빌둥]과 분명한 연관성을 가지고 있습니다. 이 개념은 학습자가 '지식의 형성이나 발달에 적극적으로 도움을 준 경우에만' 지식 또는 빌둥을 획득하는 교육적 현상을 말합니다. (노르덴보 2002). Pintrich(2000)는 SRL의 네 가지 주요 영역(인지, 정의, 행동, 맥락)과 네 가지 단계(사전 사고, 모니터링, 통제, 반응/반성)를 설명합니다(표 1). 중요한 점은 각 영역과 단계가 여러 활성화 지점을 가질 수 있고 이 모델의 다른 단계를 매개할 수 있기 때문에 이 표현이 순차적이지 않다는 것입니다. 자기조절 학습자는 능동적으로 활동을 계획합니다. 내부 및 외부 평가를 지속적으로 활용하여 진행 상황을 모니터링하며, 학습 효과를 강화하기 위해 전략과 행동을 재평가하고 수정하는 데 참여합니다. 피드백은 자기조절의 모든 단계에 영향을 미칠 수 있는 데이터의 원천 중 하나입니다.

This theory has clear associations with the broader educational and social concept of Bildung, which emerged in 18th-century Germany and is attributed to von Humboldt. This concept refers to an educational phenomenon by which the learner attains knowledge or Bildung ‘only if he or she has assisted actively in its formation or development.’ (Nordenbo 2002). Pintrich (2000) describes four main areas of SRL – cognitive, affective, behavioural, and contextual; and four phases – forethought, monitoring, control, and reaction/reflection (Table 1). Importantly this representation is non-sequential, as each area and phase can have multiple activation points and mediate other stages of this model. The self-regulated learner is proactively engaged in planning activities; continuously drawing on internal and external assessment to monitor progress, and re-evaluating and amending strategies and behaviours to potentiate learning gains. Feedback is one source of data that feeds into self-regulation and can affect any of its phases.

이전 리뷰에서는 피드백이 학업 성과와 어떤 관련이 있는지, 피드백에 가장 잘 참여할 수 있는 학습자의 특성은 무엇인지 등 몇 가지 주요 개념을 강조하는 귀중한 배경 지식을 제공했습니다.

Previous reviews have provided valuable background that highlights some key concepts: how feedback relates to academic performance and characterisation of the learner best positioned to engage with feedback.

이 리뷰에서는 자기조절 학습자의 맥락에서 피드백을 고려함으로써 교육자에게 피드백의 잠재력을 활용하고 학습자의 자기조절 학습을 최적화하기 위한 실용적인 접근 방식을 알려줍니다.

By considering feedback in the context of the self-regulated learner, this review informs educators on practical approaches to harnessing feedback potential and optimising learner’s self-regulated learning.

피드백 정의하기

Defining feedback

[피드백]에는 [피드백 이벤트]와 [피드백 메시지]라는 두 가지 표현이 있습니다.

- [피드백 이벤트]는 전달 기반 모델에서 [학습자 주도 및 학습자 중심]으로 개념이 발전해 왔습니다(Boud and Molloy 2013).

- [피드백 메시지]는 학습자와 교사 간의 상호 작용적이고 협력적인 대화로 상정합니다(Teunissen 외. 2007; Delva 외. 2013; Telio 외. 2015).

There are two distinct representations of feedback: the feedback event and the feedback message.

- The feedback event has evolved in conceptualisation from a transmission-based model to being learner-led and learner-centred (Boud and Molloy 2013).

- The latter envisions it as an interactive, collaborative dialogue between learner and teacher (Teunissen et al. 2007; Delva et al. 2013; Telio et al. 2015).

파일럿 검색 결과 [피드백에 대한 이해가 이질적인 것]으로 나타났기 때문에, 피드백 환경을 설명할 때 [다양한 피드백 목표와 형식]이 [학습자의 반응 방식에 미치는 영향]과 더불어, 이러한 현상을 그 자체로 강조하는 것이 적절했습니다. 피드백 연구의 이론적 토대는 심리학에서 비롯되었으며, Thorndike의 효과의 법칙(Thorndike 1927), 통제 이론(Carver and Scheier 1982), 예의 이론(Brown and Levinson 1987), 사회문화 이론(Lave and Wenger 1991), 동기 이론(Deci and Ryan 1985) 등 여러 이론이 기여하고 있습니다.

Pilot searches indicated heterogeneous understandings of feedback, so in describing the landscape, it was pertinent to highlight this phenomenon in its own right, in addition to how varying feedback aims and formats affect how learners react to it. The theoretical underpinning for feedback research stems from psychology, where multiple theories such as Thorndike’s Law of Effect (Thorndike 1927), Control Theory (Carver and Scheier 1982), Politeness Theory ((Brown and Levinson 1987), Socio-Cultural Theory (Lave and Wenger 1991) and Motivation Theory (Deci and Ryan 1985), contribute.

심리학 문헌은 실험 연구와 가설적 모델링을 제공하며, 종종 성적이나 결과(옳고 그름)로 피드백을 제공합니다. Kluger와 DeNisi(1996)의 리뷰에서는 피드백을 '성과에 대한 지식'으로 간주하고 등급으로 설명할 수 있는 예를 사용합니다. 이러한 유형의 피드백(단순히 응답의 정확성에 대한 정보)은 '결과 피드백'이라고도 불립니다(Butler and Winne 1995). 다른 개념에서는 [관찰된 성과]와 [원하는 성과] 사이의 [격차]를 해결하기 위한 피드백이 필요하며, 이는 메시지에 교정 또는 개발 요소가 포함되어 있음을 의미합니다(Ramaprasad 1983; Sadler 1989).

Psychology literature provides experimental studies and hypothetical modelling, frequently featuring feedback as grades or results (right/wrong). Kluger and DeNisi’s (1996) review considers feedback as ‘knowledge of performance,’ and uses examples that could be described as ratings. This type of feedback – simply information about the correctness of a response – has also been termed ‘outcome feedback’(Butler and Winne 1995). An alternative conception requires feedback to address a gap between observed and desired performance, implying the message includes some corrective or developmental element (Ramaprasad 1983; Sadler 1989).

[피드백 루프의 완성]이 강조되는데, 이 메시지는 후속 행동에 영향을 미쳐야 하며(Boud and Molloy 2013, van de Ridder 외. 2015), 개선된 성과에 대한 관찰이 이루어져야 합니다. 최근의 정의는 피드백 콘텐츠의 이러한 요소에 동의하지만 [프로세스에 중점]을 둡니다. 이들은 피드백을 개인 간 상호작용을 강조하는 사회문화적 현상으로 해석하며 학습자가 능동적인 참여자로 참여할 수 있는 상황을 요구합니다(Ramani 외. 2019). 우리는 연구 환경에서 진화하는 피드백의 특성을 반영하기 위해 검색 전략의 목적에 따라 피드백을 포괄적으로 정의합니다.

There is an emphasis on completion of the feedback loop – this message must effect a subsequent action (Boud and Molloy 2013; van de Ridder et al. 2015) and observation of the improved performance must occur. More recent definitions agree with these elements in the feedback content but also focus emphasis on process. They interpret feedback as a socio-cultural phenomenon with emphasis on inter-personal interaction and require circumstance that engages the learner as an active participant (Ramani et al. 2019). We are inclusive in our definition of feedback for the purposes of the search strategy, to reflect its evolving nature in the research landscape.

검토 방법론

Review methodology

이 범위 검토의 목적은 피드백의 사용과 피드백에 대한 반응에 관해 현재 알려진 내용을 매핑하고, 학습자가 학습 효과를 위해 피드백을 사용하는 과정에 피드백 렌즈를 집중하는 것이었습니다. 그 결과, 학습자가 후속 학습 접근 방식에서 [피드백을 어떻게 사용하고 피드백에 반응하는가]라는 사회 구성주의 패러다임을 기본 이론으로 채택하여 SRL을 채택했습니다.

The aim of this scoping review was to map what is currently known regarding the use of, and response to, feedback, and to focus the feedback lens on the learner’s process in employing feedback for their learning benefit. Consequently, it adopts a socio-constructivist paradigm, with SRL as the underpinning theory: How do learners use and respond to feedback in their subsequent approach to learning?

검색 전략

Search strategy

검토 질문과 관련하여 이용 가능한 연구의 광범위한 특성을 고려하여 범위 설정 방법론을 선택했습니다. 조안나 브릭스 연구소(JBI)의 범위 설정 방법론에 따라 3단계 검색 전략이 사용되었습니다(Peters 외. 2015). 첫 번째 단계는 Medline과 Embase의 초기 제한 검색이었습니다. 포함 기준은 학습자와 피드백의 상호작용을 설명하는 보고서로, 피드백을 받는 사람이 학부, 대학원 또는 평생 전문 교육 과정의 학습자(즉, 보건 전문직 교육에 국한되지 않는 모든 배경의 학습자)인 경우 영어로 작성된 것이어야 했습니다. 파일럿 검토를 통해 HPE에서의 피드백은 임상적 만남의 특성으로 인해 다른 맥락과 패러다임적으로 다르다는 것이 분명해졌으며, HPE 이외의 연구에서는 [대부분 서술형인, 구두 대면 피드백]에 대해 논의하는 경우가 거의 없었습니다. 따라서 이러한 맥락의 연구에서 학습자의 피드백 사용 및 반응에 미치는 영향이 다른지 확인하기 위해 이 검토에서는 학부, 대학원 또는 평생 교육 수준의 모든 학습자를 대상으로 한 연구를 포함합니다.

A scoping methodology was selected given the broad nature of available research related to the review question. A three-step search strategy was utilised, as per Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI) scoping methodology (Peters et al. 2015). The first step was an initial limited search of Medline and Embase. Inclusion criteria were: reports describing learner’s interaction with feedback, in the English language, where the recipients of feedback are learners at undergraduate, postgraduate, or in continuing professional education (i.e. learners from all backgrounds, not confined to health professions education). From our pilot review, it became apparent that feedback in HPE is paradigmatically distinct to other contexts due to the nature of clinical encounters; few studies outside HPE discuss verbal face-to-face feedback, which is mostly narrative. So in order to identify if studies in this context reported differing impacts on learner use and response to feedback, this review includes studies on all learners at undergraduate, postgraduate, or continuing education levels.

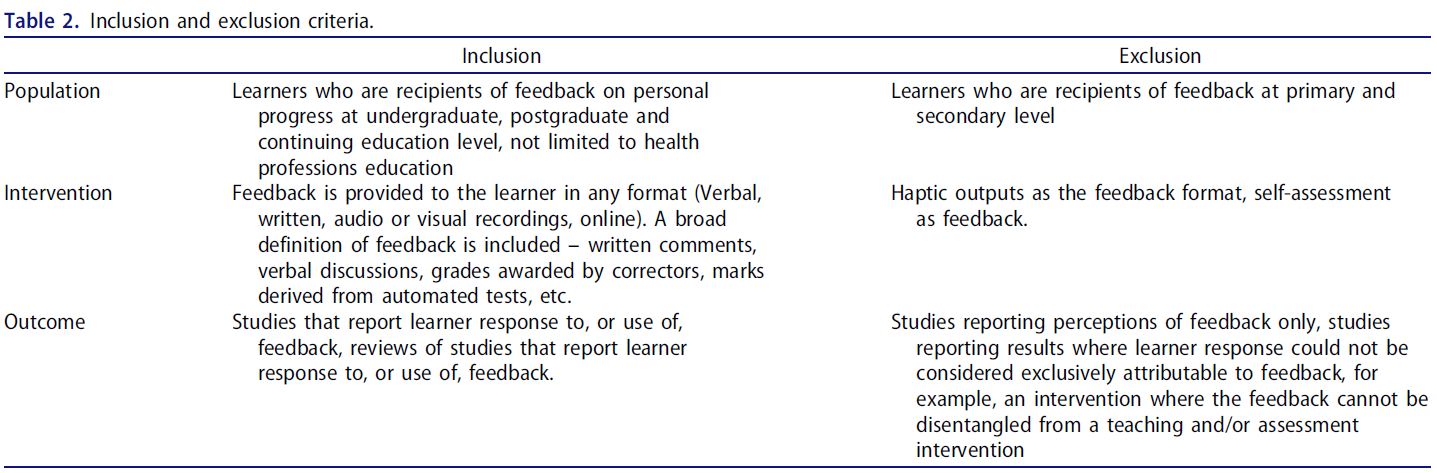

검색된 논문의 제목과 초록에 포함된 텍스트 단어와 논문을 설명하는 데 사용된 색인 용어에 대한 분석은 정보 전문가(PJM)의 도움을 받아 수행되었습니다. 이를 통해 모든 데이터베이스에서 검색된 키워드와 색인 용어를 식별할 수 있었습니다(보충 부록 1 참조). 파일럿 테스트를 거쳐 포함 및 제외 기준이 개발되었습니다(표 2). 검색된 데이터베이스는 다음과 같습니다: Medline, Embase, CINAHL, Web of Science, PsychINFO, Scopus. 검색은 데이터베이스 구축 초기부터 시작되었으며, 검색 문자열은 포괄성을 극대화하기 위해 개발되었습니다. 초기 검색은 2018년 5월에 수행되었으며 2020년 4월에 업데이트되었습니다. 연구 프로토콜(Spooner 2020)은 의학교육의 최고 증거(BEME) 웹사이트의 연구 리포지토리에 업로드되었습니다.

Analysis of text words in the title and abstract of retrieved papers, and of index terms used to describe the articles, was undertaken with the assistance of an information specialist (PJM). This led to the identification of keywords and index terms that were searched across all databases (see Supplementary Appendix 1). Following piloting, the inclusion and exclusion criteria were developed (Table 2). Databases searched were: Medline, Embase, CINAHL, Web of Science, PsychINFO, and Scopus. The search was from database inception and the search string was developed to maximise inclusivity. An initial search was undertaken in May 2018 and was updated in April 2020. A study protocol (Spooner 2020) has been uploaded into the study repository on the Best Evidence in Medical Education (BEME) website.

추가 연구를 위해 인용 검색(2단계)과 확인된 모든 보고서 및 논문의 참고문헌 목록 검색(3단계)을 수행했습니다. 전문을 검색할 수 없는 경우 해당 저자에게 사본을 요청했습니다. MS는 모든 초록의 선별, 데이터 추출 및 분석을 수행했습니다. 두 명의 검토자(CD 및 JU)가 Covidence에서 수행된 초록의 절반을 독립적으로 심사했습니다(Innovation nd). 세 번째 중재자(TP)는 합의를 통해 초기 코딩 차이를 해결할 수 있었습니다. 평가자 간 신뢰도는 Cohen의 카파를 사용하여 계산했습니다(McHugh 2012, 2013). 초록 심사 후 포함된 모든 연구의 전체 논문을 검색하여 포함 및 제외 기준에 따라 검토했습니다. 시범적으로 사용하고 반복적으로 개발한 수정된 BEME 코딩 시트를 사용했습니다(MS, BM, TP). X. 다양한 연구를 대상으로 표준화 작업을 수행한 후, 두 명의 연구 저자(MS와 BM)가 온라인 양식을 통해 코딩 시트에 포함된 모든 관련 연구에서 데이터를 독립적으로 추출했습니다. 이후 MS는 이를 엑셀 스프레드시트(부록 2, 추출된 데이터 요약)로 다운로드했습니다(TP 조정). 범위 검토이므로 연구의 질 평가는 수행하지 않았습니다.

Citation searching (step 2) and searching the reference lists of all identified reports and articles (step 3) for additional studies were performed. Where full-texts could not be retrieved, copies were requested from corresponding authors. MS undertook screening, data extraction, and analysis of all abstracts. Two reviewers (CD and JU) independently screened half of the abstracts undertaken in Covidence (Innovation n.d). A third arbitrator (TP) was available to resolve initial coding differences by consensus. Inter-rater reliability was calculated using Cohen’s Kappa (McHugh 2012, 2013). The full papers of all studies included after abstract screening were retrieved and reviewed against inclusion and exclusion criteria. We used a modified BEME coding sheet which was piloted and developed iteratively (MS, BM, TP). X. Following a standardisation exercise with a variety of diverse studies, two study authors (MS and BM) independently extracted data from all relevant studies in the coding sheet via an online form. MS subsequently downloaded this to an excel spreadsheet (Supplementary Appendix 2, Summary of extracted data) (TP moderated). Given that this is a scoping review, quality appraisal of studies was not undertaken.

결과

Results

설명적

Descriptive

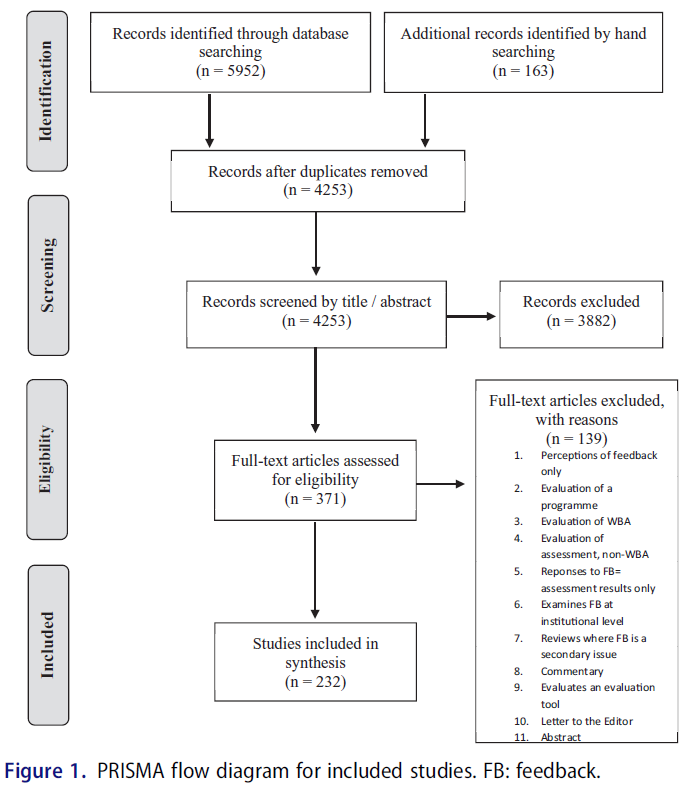

7번의 데이터베이스 검색을 통해 5952건의 인용을 검색했으며, 이중 4090건은 중복 제거를 완료했습니다. 인용 및 수작업 검색을 통해 163개의 초록이 추가로 확인되었습니다. 총 4253개의 초록을 선별한 후 371개의 전체 텍스트 연구를 검토하여 232개를 최종 종합에 포함시켰습니다. 그림 1은 연구 정보 흐름을 보여줍니다. 표 3에는 포함된 연구의 특징이 요약되어 있습니다. 대부분의 연구에는 유럽(91건)과 북미(90건)의 저자가 포함되었습니다. 70%(162건)는 최근 10년 사이에, 25%(57건)는 2000~2009년 사이에, 2.5%(6건)는 90년대, 나머지 3%(7건)는 그 이전 수십 년 사이에 발표되었습니다. 대부분의 연구(66.3%, n = 154)는 보건 전문직 교육 또는 임상 의학 분야에서 발표되었습니다. 연구의 43%(100건)는 정량적 연구였고, 27%(64건)는 정성적 연구였으며, 18%(42건)는 혼합 방법이었으며, 리뷰는 전체 연구의 6%(13건)를 차지했습니다. 평가자 간 신뢰도는 0.87(코헨 카파)이었습니다.

Seven database searches were done to retrieve 5952 citations, 4090 remained on de-duplication. A further 163 abstracts were identified via citation and hand searching. 4253 abstracts in total, were screened and 371 full-text studies were subsequently reviewed with 232 included in the final synthesis. Figure 1 shows the study information flow. Table 3 summarizes characteristics of the included studies. Most studies included authors from Europe (91) and North America (90). 70% (162) were published in the last ten years; 25% (57) between 2000 and 2009; 2.5% (6) in the nineties, and another 3% (7) in preceding decades. The majority of studies (66.3%, n = 154) were published in health professions education or clinical medicine. 43% (100) of the studies were quantitative; 27% (64) qualitative, with 18% (42) mixed methods; and reviews representing 6% (13) of all studies. Inter-rater reliability was 0.87 (Cohen’s Kappa).

피드백의 정의 및 형식

Feedback definition and format

조사 결과를 의미 있게 소개하기 위해 먼저 교육 환경에서 피드백이 어떻게 다양하게 해석되는지에 대한 검토 결과를 설명하겠습니다. [피드백이 정의되는 다양한 방식]과 피드백이 취하는 형식에 대해 설명합니다. 자기 조절 이론이 이 범위 검토에 사용된 렌즈이므로 [인지적, 정서적/동기적, 행동적 자기 조절 영역]에 따라 매핑을 설명합니다(그림 2에서 이러한 결과의 개념적 표현을 참조하세요).

To introduce the findings meaningfully, we will first delineate our review findings in terms of how feedback is variously interpreted in the educational landscape. The diverse ways that feedback is defined and the formats that it takes are described. As self-regulatory theory is the lens used for this scoping review, mapping is described according to areas of self-regulation, that is, cognitive, affective/motivational, and behavioural – see the conceptual representation of these findings in Figure 2.

피드백 정의

Feedback definition

14%(32개)의 연구에서 피드백에 대한 정의가 포함되어 있었습니다. 10%(22개)의 연구는 명시적인 정의는 없었지만 잘 알려진 모델을 참조했으며, 가장 흔하게는 Hattie와 Timperley(2007)의 모델을 사용했습니다. 76%의 연구는 정의가 없거나 특정 모델과 명확하게 일치하지 않았습니다. 정의가 제공된 경우 세 가지 그룹으로 하위 분류할 수 있습니다.

- 첫 번째 그룹은 '결과에 대한 지식'이라고 합니다(Kluger and DeNisi 1996). 나중에 Hattie와 Timperley에 의해 작업별 피드백으로 설명되었습니다. 쿨하비(1977)는 피드백을 '학습자에게 교수 반응이 [옳은지 그른지]를 알려주는 데 사용되는 수많은 절차 중 하나'라고 설명했습니다. 이러한 정의는 피드백을 수행과 관련된 정보로 개념화했지만 피드백의 맥락이나 목적은 언급하지 않았습니다. 이들은 [해석 없이 데이터를 전달하는 것]에 초점을 맞췄습니다.

- 두 번째 그룹은 피드백 데이터도 [특정 성과 표준과 관련되어야 한다]고 덧붙였습니다. 이 정의는 해티 모델의 [프로세스 수준]과 가장 잘 부합하며, '[실제 수준]과 시스템 매개변수의 [기준 수준] 사이의 [격차에 대한 정보]로서 어떤 방식으로든 그 [격차를 변경하는 데 사용]되는 정보'라는 라마프라사드(1983)의 정의를 떠올리게 합니다. 이 입장은 [비고츠키 이론의 관점]에서 피드백을 모델링합니다. 피드백은 [근위 발달 영역]에서 강화 도구입니다(비고츠키 1978).

- 세 번째 그룹은 피드백을 '격차를 좁히기 위한 정보'와 연결하지만, 새들러(Sadler 1989) 모델에 따라 '격차를 어느 정도 좁힐 수 있는 적절한 행동'을 추가로 요구합니다. 일부의 경우 이는 [평가적인 코멘트]를 의미하지만, 다른 일부는 [학습자-생성] 또는 [상호-생성된 실행 계획]을 제안하며, 최종적으로는 [학습자의 발전을 위한 개발 계획]을 포함한다는 점에서 전자의 정의와 구별됩니다.

14% (32) of studies included a definition of feedback. 10% (22) of studies had no explicit definition but referred to well-known models, most commonly that of Hattie and Timperley (2007). 76% of studies had neither a definition nor clear alignment to a specific model. Where definitions were provided, they could be sub-categorised into three groups.

- The first group is referred to as ‘knowledge of results’(Kluger and DeNisi 1996). It was later described as task-specific feedback by Hattie and Timperley. It is further described by Kulhavy (1977) as ‘any of the numerous procedures that are used to tell a learner if an instructional response is right or wrong.’ These definitions conceptualized feedback as information related to performance but did not refer to its context or purpose. They focus on the transmission of data without interpretation.

- A second group added that feedback data must also relate to a specific performance standard. This definition is best aligned with the process level in Hattie’s model and evokes Ramaprasad’s (1983) definition of ‘information about the gap between the actual level and the reference level of a system parameter which is used to alter the gap in some way.’ This stance models feedback in terms of Vygotskian theory; it is a potentiating tool in the zone of proximal development (Vygotsky 1978).

- The third group also links feedback with information to ‘narrow the gap’ but additionally requires ‘appropriate action which leads to some closure of the gap’ as per Sadler’s (Sadler 1989) model. For some, this means evaluative comments; others propose either a learner or mutually-generated action plan, the end result being a distinction from the former definition in that it includes a developmental plan for learner progression.

피드백 형식

Feedback formats

다양한 피드백 형식이 설명되었는데, 가장 일반적인 형식은 서면, 구두 또는 혼합 형식이었습니다(표 4). 피드백 형식은 하위 그룹의 정의와 관련된 몇 가지 패턴을 보였는데,

- 1그룹에서는 성적/결과에 대한 서면 또는 온라인 제공이 가장 많이 보고되었고,

- 3그룹에서는 양방향 대화가 포함된 대면 구두 만남이 가장 빈번하게 보고되었습니다.

다른 학과에 비해 보건 직업 교육에서는 구두 및 대면 피드백이 더 흔했습니다. 정서적 반응은 대면 피드백이 더 흔하게 보고되었습니다.

A number of feedback formats were described, the most common being written, verbal or mixed (Table 4). We highlight that feedback format showed some patterns related to the sub-group definitions,

- with written or online provision of grades/result the most commonly reported with group one, and

- face-to-face verbal encounters that included bi-directional dialogue reported most frequently for group three.

Verbal and face-to-face feedback were more common in Health Professions Education compared to other disciplines. The emotional response was more commonly reported face-to-face.

인지적 반응

Cognitive responses

[인지적 반응]을 보고한 연구에 따르면 피드백이 [학습자의 사고 과정을 변화]시켰다는 응답이 가장 많았으며, 명확성과 이해도 측면에서 가장 많았습니다(n = 96, 41%). 이러한 측면에서 피드백은 [개인의 강점과 약점을 파악]하고 [오류를 수정]하는 두 가지 주요 기능을 수행했습니다. 16건(7%)의 연구에서 피드백이 이해도에 미치는 부정적인 영향이 보고되었습니다. 학습자들은 [모호하거나 관련성이 없다고 생각되는 피드백]을 받을 때 좌절감을 느꼈습니다(Dawdy 외. 2014; Wardman 외. 2018). 피드백이 [너무 늦게 제공]되거나 [다른 모듈로 이전할 수 없는] 경우 피드백은 도움이 되지 않는 것으로 간주되었습니다(Harrison 외. 2016). 과제에 대한 감독자의 서면 코멘트와 같은 [단방향적 해설]도 학습자의 이해와 후속 피드백 활용에 장애가 되는 것으로 언급되었습니다. 피드백이 [간접적일 때 피드백을 오해]하는 경우가 더 많았습니다(Hyland와 Hyland 2001). 학습자는 명확성을 찾기 위해 감독자에게 다시 문의한다고 보고했습니다(Khowaja 외. 2014). 그들은 그러한 [해설의 행간을 읽어야 한다]고 느꼈다고 보고했습니다(Gleaves 외. 2008). 피드백이 [이해할 수 없는 것]으로 간주되면 참여도가 떨어지는 것으로 보고되었습니다. 한 연구에서 학생의 50%가 이해하기 어렵다고 생각하여 서면 피드백을 받지 못했습니다(Winter and Dye 2004). 간호학과 학생들은 [피드백을 해석할 수 없어] 무시하거나 접근하지 않는다고 설명했습니다(McSwiggan and Campbell 2017).

Studies reporting cognitive responses stated that feedback changed learners’ thought processes, most frequently in terms of clarity and understanding (n = 96, 41%). Feedback served two main functions in this respect: identifying an individual’s strengths and weaknesses, and error correction. 16 (7%) studies reported negative effects of feedback on understanding. Learners expressed frustration at receiving comments that they considered vague or irrelevant (Dawdy et al. 2014; Wardman et al. 2018). Feedback was considered unhelpful if provided too late to enact, or non-transferable to other modules (Harrison et al. 2016). Uni-directional commentary, for example, supervisors’ written comments on a written assignment, was also mentioned as a barrier to learner understanding and subsequent feedback use. Feedback was more often misunderstood when comments were indirect (Hyland and Hyland 2001). Learners reported returning to supervisors to seek clarity (Khowaja et al. 2014). They reported feeling they needed to read between the lines on such commentary (Gleaves et al. 2008). When feedback was deemed incomprehensible, disengagement is reported: in one study, 50% of students failed to pick up written feedback as they found it hard to understand (Winter and Dye 2004). Nursing students described feedback as being un-interpretable which meant they ignored or did not access it (McSwiggan and Campbell 2017).

피드백은 [수행 기준을 명확]하게 함으로써 이해에도 영향을 미쳤습니다. 학생들은 피드백을 통해 [평가 청사진을 해석]하여 시험 자료를 파악할 수 있었습니다(De Kleijn 외. 2013). 다른 학생들은 피드백이 [자신에 대한 기대치를 정의]해 주었다고 말했습니다(Chiu 외. 2014). 피드백이 명확하지 않은 경우도 있었습니다. 한 연구에 따르면 심리학 학부 3학년 학생과 지도교수는 [성과 기준에 대한 인식에 상당한 불일치]가 있는 것으로 나타났습니다(Norton and Norton 2001). 학부 심리학 학생들은 슈퍼바이저가 부정적인 피드백을 제공할 때 과제의 난이도를 과소평가한다고 느꼈습니다(Coleman 외. 1987).

Feedback also affected understanding by making performance standards clear. Students used feedback to interpret assessment blueprints to signpost exam material (De Kleijn et al. 2013). Others stated it defined expectations for them (Chiu et al. 2014). There were cases where feedback did not disambiguate. One study identified that third-year psychology students and supervisors had a significant mismatch in the perception of performance standards (Norton and Norton 2001). Undergraduate psychology students felt supervisors underestimated the task difficulty when providing negative feedback (Coleman et al. 1987).

40건(17%)의 연구에서 학습자가 [개인 학업 진도를 모니터링]하기 위해 피드백을 사용했다고 답했습니다. 38개(16%) 연구에서 [학습에 대한 성찰]이 보고되었습니다. 25개(11%) 연구에서 피드백을 통해 [실행 계획을 세웠다]고 응답했습니다. 마지막으로, [학습 전략의 변경 또는 계획된 변경]을 보고한 소수의 응답자(n = 20, 9%)가 있었으며, 시험관 관찰의 맥락에서 이를 보고한 경우는 거의 없었습니다. 예외적으로 과제 수행 중 여러 시점에서 참가자를 대상으로 미시 분석을 수행하여 학생의 [SRL 과정과 자기 효능감 신념의 변화]를 평가한 한 연구(Cleary 외. 2015)가 있었습니다. 이 연구에서는 부정적 피드백(정확/오류 모델)이 자기효능감 인식과 전략적 계획 및 메타인지 모니터링의 질을 저하시킨다고 보고했습니다.

Forty (17%) studies showed that learners used feedback to monitor their personal academic progress. Reflection on learning was reported in 38 (16%) studies. Feedback resulted in the creation of action plans in 25 (11%) studies. Finally, a minority reported changes or planned changes in learning strategies (n = 20, 9%) and few reported this in the context of examiner observation. An exception was one study (Cleary et al. 2015) evaluating shifts in students’ SRL processes and self-efficacy beliefs, by conducting microanalysis with participants at different points during a task. This reported that negative feedback (in a correct/incorrect model) led to decreased self-efficacy perception and quality of strategic planning and metacognitive monitoring.

대부분의 연구에서는 이러한 변화가 발생한 시점에 대한 보고가 없었습니다. 위의 연구에서는 '소리 내어 생각하기' 프로토콜을 사용하여 학습자의 자기 평가, 자신감 및 수행 전략에 대한 즉각적인 효과를 관찰했습니다(Cleary 외. 2015). 한 연구에서는 초기 피드백을 받은 지 3개월 후에 설문조사를 실시하여 학습자가 실제로 얼마나 많은 변화를 보였는지 확인했으며, 다른 연구에서는 1~2년 후에 피드백을 다시 방문하여 개입 이후 학습 활동의 변화에 대해 설명했습니다(Lockyer 등. 2003; Sargeant, Mann, Sinclair 등. 2008).

The majority of studies made no report on the timeline over which these changes occurred. In the above study, ‘think aloud’ protocols were used, observing immediate effects on learner self-assessment, confidence, and performance strategy (Cleary et al. 2015). Surgeons were surveyed 3 months after their initial feedback to determine how much change in practice they reported in one study; another described participants re-visiting the feedback one to two years later and recounting the changes in their learning activities since the intervention (Lockyer et al. 2003; Sargeant, Mann, Sinclair, et al. 2008).

행동 반응

Behavioural responses

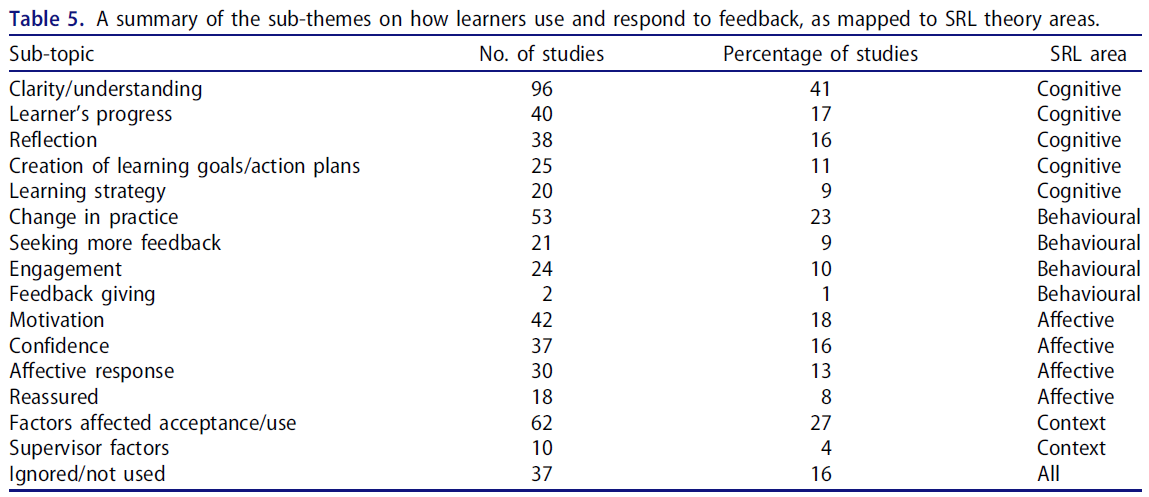

행동 영역에서 피드백 응답의 비율은 46.4%였습니다(표 5). 가장 흔한 결과는 [피드백이 실천의 변화로 이어진 경우]였습니다(n = 53, 23%). 가장 흔한 두 가지 결과는 참가자들이 피드백이 자신의 [관행에 변화]를 가져왔다는 데 동의했거나, 변화할 것이라고 답했거나, 이미 관행에 변화를 가져왔다는 것이었습니다. 그러나 이러한 변화의 성격은 드물게 추구되고 보고되었습니다.

- Sargeant 등(2007)은 다양한 출처의 피드백을 경험한 가정의학과 의사들을 인터뷰했습니다. 의사 소통에 대한 부정적인 피드백을 받은 응답자의 절반은 이러한 기술을 개선하기 위해 변화(설명에 더 많은 시간 할애, 질문 허용, 관련 교육 활동 참석)를 했다고 답했습니다.

- 네덜란드 컨설턴트들이 360도 피드백을 사용했을 때, 23명 중 11명이 성과 개선을 위한 구체적인 조치를 취했다고 보고했습니다(Overeem 외. 2009).

- 의대 1학년 학생들은 동료와 튜터로부터 업무 습관과 대인관계 기술에 대한 형성적인 피드백을 받았습니다. 지배적인 경향이 있다는 피드백을 받은 한 학생은 포트폴리오를 제출하면서 가시적인 행동 변화를 자세히 설명했습니다(Dannefer and Prayson 2013).

The percentage of feedback responses in the behavioural domain was 46.4% (Table 5). The most common outcome was feedback leading to a change in practice (n = 53, 23%). The two most common findings were that participants either agreed that feedback led to change in their practice, or they reported that they would change, or had already made changes in practice. The nature of these changes, however, were both infrequently sought and reported.

- Sargeant et al. (2007) interviewed family doctors who had experienced multi-source feedback. Having received negative feedback on their communication, half reported making changes (spending more time on explanation, allowing questions, attending relevant educational activities) to improve these skills.

- When Dutch consultants used 360-degree feedback, 11 of 23 reported making concrete steps towards performance improvement (Overeem et al. 2009).

- First-year medical students received formative feedback on work habits and interpersonal skills from peers and tutors. Following feedback indicating they had a tendency to dominate, one student’s portfolio submission detailed tangible behavioural changes(Dannefer and Prayson 2013).

연구들은 주로 학습자의 실제 변화에 대한 [자기보고]를 기술했습니다. 소수의 연구에는 [(타인에 의해) 관찰된 변화에 대한 데이터]가 포함되었습니다. 비디오로 녹화된 상담 및 피드백에 대한 사전 사후 연구에서 간호사는 환자의 도움 요청에 더 많은 주의를 기울이고(p <0.01), 더 많은 정보를 제공하며(p = 0.02), 혈압 측정에서 개선된 결과를 보였습니다[p <0.01; 21명(10%)](Noordman 외. 2014). 연구(21편, 9%)에 따르면 학습자는 주로 감독자의 [명확성을 높이기 위해 수행에 대한 더 많은 피드백을 구함]으로써 피드백에 반응하는 것으로 나타났습니다. [이전의 피드백 경험]이 학습자가 향후 학습에서 피드백 기회를 찾도록 자극하는 것으로 보고되기도 했습니다(Smither 외. 2005). 학습자 반응으로서의 [피드백 제공]은 2건(1%)의 연구에서만 보고되었습니다. 그럼에도 불구하고 피드백이 행동 변화를 보장하지는 않았습니다. 피드백이 [무시되거나, 무시되거나, 학습이나 실습에 적용되지 않았다]는 보고가 많았습니다(n = 37, 16%). 피드백이 실습에 영향을 미치지 않았다고 보고한 연구는 아래 컨텍스트에 설명되어 있습니다.

Studies mainly described learners’ self-reports of their change in practice. A small number of studies included data of observed changes. In a pre-post study of video-recorded consultations and feedback, nurses paid more attention to patients’ requests for help (p < 0.01), gave them more information (p = 0.02), and showed improvements in blood pressure measurement [p < 0.01; 21 (10%)] (Noordman et al. 2014). Studies (21, 9%) identified that learners responded to feedback by seeking more feedback on the performance, mainly to improve clarity from the supervisor. It was occasionally reported that previous feedback experiences enthused the learner to seek feedback opportunities in future learning (Smither et al. 2005). Feedback-giving as a learner response was only reported in 2 (1%) studies. Nonetheless, feedback did not guarantee behavioural change. A number of reports indicate it was ignored, disregarded, or not applied to learning or practice (n = 37, 16%). Studies that reported no effect of feedback on practice are discussed under Context

정서적 반응

Affective responses

[동기 부여와 자신감]은 [감정emotion 이외의 여러 요인에 의해 영향을 받는다]는 점을 고려하여 감정emotion과는 독립적으로 분류되었습니다(Deci and Cascio 1972; Carver와 Scheier 1982). 피드백은 86%의 연구에서 동기 부여(n = 42, 18%)에 긍정적인 영향을 미쳤습니다. 피드백의 특성 측면에서 [점수] 대 [코멘트]의 영향을 미치는지 조사한 여러 연구에서 대조적인 결과가 나왔습니다.

- 영어 작문 수업에서 피드백에 대한 연구에 참여한 참가자들은 [성적이 없는 내러티브 코멘트]가 더 동기 부여가 된다고 느꼈습니다(Lee et al. 2015).

- 레프로이(Lefroy et al. 2015)는 3학년 의대생들에게 코멘트, 성적 또는 두 가지를 모두 선택할 수 있는 옵션을 제공했는데, 후자(코멘트와 성적 둘 다)를 선택한 학생들은 성적을 받기 위해 개선하려는 동기가 더 강해졌다고 답했습니다.

- 그러나 Harrison 등(2016)은 학생들이 '기대 수준'의 성적을 받은 경우, 특히 많은 학생들에게 이 등급이 적용될 경우 더 이상 노력하지 않는다고 보고했습니다.

Motivation and confidence were categorised independently of emotion, considering psychological models of each are influenced by multiple factors other than emotion (Deci and Cascio 1972; Carver and Scheier 1982). Feedback affected motivation (n = 42, 18%) positively in 86% of studies. In terms of feedback characteristics, several studies explored if grades versus comments had an effect; with contrasting results.

- The participants in a study of feedback in English writing classes felt narrative without grades was more motivating (Lee et al. 2015).

- Lefroy (Lefroy et al. 2015) provided year 3 medical students with the option of comments, grades, or both, with those choosing the latter expressing that it prompted more motivation to improve to receive grades.

- However, Harrison et al. (2016) reported that if students received the grade ‘at the level expected,’ it demotivated them from further effort, particularly if this rating was applied to many students.

Van-Dijk와 Kluger(Van-Dijk and Kluger 2004, Van-Dijk and Kluger 2011)는 피드백의 동기가 [자기 조절 초점]에 따라 맥락화된다는 사실을 발견했습니다. 승진을 원하는 경우(성취 추구) 긍정적인 피드백이 부정적인 피드백보다 동기를 더 증가시키고, 안전을 추구하는 경우(실패 회피) 부정적인 피드백이 동기를 증가시킨다는 것이었습니다. Burgess와 Mellis(Burgess와 Mellis 2015)는 학생들이 [동료보다 지도 교수의 피드백]에 더 큰 동기를 느낀다는 사실을 확인했습니다. 한 연구에서는 [근속 기간이 긴 직원]이 근속 기간이 짧은 직원보다 피드백을 통해 동기 부여를 받을 가능성이 더 높다고 보고했습니다(Schürmann and Beausaert 2016).

Van-Dijk and Kluger (Van‐Dijk and Kluger 2004; Van-Dijk and Kluger 2011) found motivation from the feedback was contextualised by self-regulatory focus: if desiring promotion (pursuant of achievement), positive feedback increases motivation more than negative; if seeking security (avoiding failure), negative feedback increases motivation. Burgess and Mellis (Burgess and Mellis 2015) identified that students felt more motivated by feedback from academic supervisors than peers. One study reported that longer-serving employees were more likely to be motivated by the feedback than those with less experience (Schürmann and Beausaert 2016).

다수의 연구에서는 피드백이 동기 부여에 긍정적인 영향과 부정적인 영향을 모두 미친다고 보고했습니다(n = 13, 6%). 피드백이 동기를 저하시키는 경우, 유일하게 통일된 특성은 [부정적인 원자가 메시지]였습니다. 긍정적 원자가는 만족스러운 성과를, 부정적 원자가는 받아들일 수 없는 기준, 즉 비판을 나타냅니다. 피드백이 자신감에 영향을 미치는 것으로 보고된 연구는 37건(16%)으로, 33건(14%)은 자신감이 증가했다고 보고했고, 3건(1%)은 학습자가 자신감을 잃었다고 설명했으며, 1건의 연구에서는 피드백 후 학습자의 자신감 평가가 변하지 않았다고 보고했습니다. 동기 부여와 마찬가지로 자신감이 저하된 학습자의 경우 부정적인 피드백과 관련이 있었습니다.

A number of the studies reported feedback having both positive and negative effects on motivation (n = 13, 6%). Where feedback demotivated, the only unifying characteristic was negative valence messages.

- Positive valence indicates satisfactory performance,

- negative an unacceptable standard, that is, criticism

. Feedback was reported to affect confidence in 37 studies (16%), with 33 (14%) reporting an increase, 3 (1%) describing learners losing confidence, and 1 study where learner confidence ratings were unchanged post-feedback. As with motivation, for those where confidence deteriorated, it was associated with negative feedback.

피드백에 대한 정서적 반응(n = 30, 13%)이 빈번하게 나타났습니다. 효과는 원자가에 따라 고려되었습니다. 피드백은 [다양한 감정적 반응]을 불러일으켰으며, 그 중 가장 흔하게 보고된 것은 실망, 화, 스트레스, 분노였습니다. 기쁨, 만족과 같은 긍정적인 반응은 드물게 보고되었습니다(n = 5, 2%). 부정적인 감정이 더 널리 퍼져 있을 뿐만 아니라 학습자에게 미치는 영향과 관련하여 [훨씬 더 강한 용어로 기술]되었습니다.

- Duers와 Brown(2009)은 한 학생 간호사가 '갈기갈기 찢어질 것 같다'고 표현하며 어떻게 대처할 수 있을지 궁금해하는 내용을 인용했습니다.

- 분노를 보고한 연구는 과제에 대한 서면 해설을 받은 경험을 설명하는 액세스 프로그램의 성인 학생, 박사 과정 학생의 슈퍼비전 경험, 360도 피드백을 받은 MBA 학생 등 다양했습니다(Young 2000, Brett and Atwater 2001, Doloriert 외. 2012).

- 9건(4%)의 연구에서 학습자가 받은 피드백으로 인해 속상함을 느꼈다고 답했으며, 이 역시 다양한 학습자 프로필과 피드백 형식에 걸쳐 나타났습니다.

- HPE 학습자만이 피드백에 대한 반응으로 [굴욕감]을 느꼈다고 보고했습니다(Sargeant, Mann, van der Vleuten 외. 2008; Nofziger 외. 2010; Delva 외. 2013).

Affective responses to feedback (n = 30, 13%) were frequent. The effects are considered according to valence. Feedback prompted a range of emotional responses, of which the most commonly reported were disappointment, upset, stress, and anger. Positive reactions, for example, joy, satisfaction were infrequently reported (n = 5, 2%). In addition to negative emotions being more prevalent, they were described in much stronger terms with regards to their effects on the learner.

- Duers and Brown (2009) quote a student nurse describing being ‘torn to shreds,’ and wondering if they could cope.

- Studies reporting anger were diverse: mature students in an access programme describing their experience of written commentary on assignments, PhD students’ supervision experiences, MBA students receiving 360-degree feedback (Young 2000; Brett and Atwater 2001; Doloriert et al. 2012).

- 9 (4%) studies indicated that learners felt upset as a result of the feedback they received and again these traversed a variety of learner profiles and feedback formats.

- Only HPE learners reported humiliation in response to feedback (Sargeant, Mann, van der Vleuten, et al. 2008; Nofziger et al. 2010; Delva et al. 2013).

감정적 반응을 보고한 모든 연구에서 가장 흔한 특징은 부정적 원자가였습니다. 이와는 대조적으로, 단순히 피드백을 받을 수 있다는 것만으로도 긍정적인 정서적 반응이 나타났습니다. 학습자는 자신이 가치 있다고 느끼고 피드백을 받는 것을 [배려(Rowe 2011), 양육, 위로의 행위]로 해석한다고 설명합니다(Eide 외. 2016; Sudarso 외. 2016). 한 학생은 피드백을 주는 사람의 노력에 '튜터가 시간을 내어 자신의 과제에 세심하게 반응해 주었다는 생각에 눈물이 났다'고 말할 정도였습니다(Price et al. 2011).

The most common feature of all studies reporting emotional reactions was negative valence. In contrast, simply the availability of feedback led to positive emotional responses. Learners describe feeling valued and interpreting the receipt of feedback as an act of caring (Rowe 2011), nurturing, and comforting (Eide et al. 2016; Sudarso et al. 2016). One student went so far as to say that the effort undertaken by the feedback-giver ‘brought tears to her eyes to think that her tutor had taken the time to respond carefully to her work’ (Price et al. 2011).

24개(10%) 연구에서 피드백은 학습 자료와 환경 모두에 대한 [참여도]에도 영향을 미치는 것으로 보고되었습니다. 교육, 수익 또는 의료 부문의 직원들은 [학습 리소스에 액세스]하고 피드백 후 [동료 및 상사와 피드백에 대해 논의]한다고 보고했습니다. 광범위하고 정확하며 긍정적인 피드백이 [성찰과 토론을 자극]할 가능성이 가장 높았습니다(Mulder 2013).

- 여러 저자(Brezis and Cohen 2004, Mains 외. 2015, Mains 외. 2015, Rana and Dwivedi 2017)는 자동 응답 시스템의 피드백을 받은 후 [코스 자료에 대한 참여도가 증가]했다고 보고합니다. 소수의 연구에서는 이러한 참여를 강화하는 요인을 자세히 설명합니다.

- Sargeant 등(2017)은 피드백 및 연습 개선(관계, 반응, 콘텐츠, 코칭)을 촉진하기 위한 R2C2 모델을 설명합니다.

- SRQ-L의 상대적 자율성 지수(RAI)로 확인된 성취도가 높은 학생과 자율적인 학습자는 피드백에 참여할 가능성이 가장 높았습니다(Liu 외. 2019).

Feedback was also reported to affect engagement both with learning material and environment, in 24 (10%) included studies. Employees in the education, profit, or healthcare sectors reported accessing learning resources and discussing feedback with colleagues and supervisors post-feedback. Extensive, precise, and positive feedback was most likely to stimulate reflection and discussion (Mulder 2013).

- Several authors (Brezis and Cohen 2004; Mains et al. 2015; Mains et al. 2015; Rana and Dwivedi 2017) report increased engagement with course materials following feedback from automated response systems. A small number of studies detail factors that potentiate this engagement.

- Sargeant et al. (2017) describe the R2C2 model for facilitating feedback and practice improvement (relationship, reaction, content, coaching).

- High-achieving students and autonomous learners, identified by the Relative Autonomy Index (RAI) of SRQ-L, were most likely to engage with feedback (Liu et al. 2019).

피드백이 [학습자를 안심시켰다]고 보고한 연구의 수는 18건(8%)이었으며, 이 중 14건(6%)은 의료 전문가 학생을 대상으로 한 연구였습니다.

- 윤리 석사 과정을 수행하는 중간 관리자는 안심 피드백을 정서적으로 지지하는 것으로 묘사했습니다(Eide 외. 2016).

- Harrison 등(2016)은 의대생들이 수치화된 성적을 중요하게 생각하며, 이러한 피드백이 제공되지 않을 때 안심이 부족하다고 느낀다고 보고했습니다.

- 피부과 수련의를 대상으로 한 연구에서 일부 수련의는 직장 기반 평가의 피드백을 안심할 수 있다고 느꼈고, 다른 수련의는 이를 부정적인 피해로 경험했으며, 이는 각각 긍정적인 가치와 부정적인 가치와 관련이 있었습니다(Cohen 등. 2009).

- 18개의 연구 중 대부분은 슈퍼바이저의 피드백에 대해 보고했지만, Burgess와 Mellis의 연구(Burgess and Mellis 2015)에 따르면 동료 피드백도 긍정적인 영향을 미칠 수 있다고 합니다.

The number of studies reporting that feedback reassured learners was 18 (8%), 14 (6%) of which were studies of healthcare professional students

- Middle managers undertaking an ethics master’s described reassuring feedback as emotionally supportive (Eide et al. 2016).

- Harrison et al. (2016) reported that medical students valued numerical grades and felt a lack of reassurance when these were not provided.

- In a study of dermatology trainees, some felt feedback from workplace-based assessments was reassuring; others experienced it as negative victimisation, these being associated with positive and negative valence respectively (Cohen et al. 2009).

- Of the 18 studies, most reported on feedback from supervisors, but a study by Burgess and Mellis (Burgess and Mellis 2015) indicated that peer feedback could also be affirming.

맥락

Context

많은 경우 [피드백에 대한 반응]은 학습자 [외부의 맥락적 요인]에 의해 영향을 받았습니다. 이는 [과제와 관련된 조건]이 [학습자의 자기 수정 및 후속 학습 행동에 기여]한다고 제안하는 자기 조절 학습 이론과 일치합니다. 이는 [학습자의 지각]과 [학습 상황]이 모두 학습자의 경험에 영향을 미친다는 [사회 구성적 관점]을 지지합니다. [외부 요인]을 다룬 연구는 대부분 [피드백 수용]의 상황에서 이루어졌습니다. 이러한 요인은 학습자 특성, 피드백 특성, 감독자 특성, 피드백 이벤트, 학습자-감독자 관계의 측면에서 논의되었습니다.

The response to feedback in many cases was affected by contextual factors external to the learner. This aligns with self-regulatory learning theory, which proposes that the conditions pertaining to the task contribute to the learner’s self-modification and subsequent learning actions. It supports a socio-constructive stance: both the learner’s perception and the learning situation will impact their experience. Studies that addressed external factors mostly did this in the setting of feedback acceptance. These are discussed in terms of

- learner characteristics,

- feedback characteristics,

- supervisor characteristics,

- the feedback event, and

- learner-supervisor relationships.

소수의 연구에서 [학습자의 특성]이 피드백 수용 증가와 관련이 있다고 설명했습니다. 그러나 일반적인 패턴은 존재하지 않았으며, 실제로 상반된 결과가 보고되었습니다.

- 호주 학부 간호사를 대상으로 한 연구에서는 여성, 외국 국적, 나이가 많은 학습자가 피드백을 더 잘 수용하는 것으로 나타났습니다(Carter 외. 2019).

- 피드백은 또한 고령의 인적 자원 및 마케팅 직원의 비공식 학습에 가장 큰 영향을 미쳤습니다(Schürmann and Beausaert 2016).

- 여성과 성취도가 높은 학부 3학년 의대생은 피드백을 더 자주 수집했습니다(Sinclair and Cleland 2007).

- Orsmond와 Merry(Orsmond and Merry 2013)의 연구에 따르면 성취도가 높은 학생들은 감독자의 피드백을 이해하기 위해 자기 평가, 동료 토론, 내부 보정을 더 많이 사용했으며, 피드백을 통해 타인 지시형에서 자기 주도형으로 진화했습니다. 성취도가 낮은 학생들은 이해의 증거 없이 피드백을 무시하거나 그대로 암기했습니다. 또한 피드백을 학습 목표에 반영할 가능성이 낮았으며, 피드백을 통해 확인되지 않더라도 자기 평가를 통해 목표를 설정하는 것을 선택했습니다.

- OSCE에서 최소한의 역량을 달성한 학생은 온라인 피드백을 이용할 가능성이 가장 낮았습니다(Harrison 외. 2013).

- 한 연구에 따르면 남성 학습자는 긍정적인 피드백을 받아들이고 부정적인 피드백을 무시할 가능성이 더 높은 반면, 여성 학습자는 피드백의 원자가에 관계없이 피드백에 더 많은 영향을 받는 것으로 나타났습니다(Roberts and Nolen-Hoeksema 1989).

A small number of studies described learner characteristics that were associated with increased feedback acceptance. However, no prevailing patterns existed; indeed, conflicting findings were reported.

- Female, non-national and older learners were more accepting of feedback as reported for Australian undergraduate nurses (Carter et al. 2019).

- Feedback was also most influential on the informal learning of older human resources and marketing employees (Schürmann and Beausaert 2016).

- Female and higher-achieving undergraduate third-year medical students collected feedback more frequently (Sinclair and Cleland 2007).

- Orsmond and Merry (Orsmond and Merry 2013) found that high-achieving students employed more self-assessment, peer discussion, and internal calibration in trying to make sense of supervisor feedback: they evolved from other-directed to self-directed via feedback. Low-achieving students either ignored or memorised feedback literally, without evidence of understanding. They were also less likely to incorporate feedback into their learning goals, opting to use self-assessment for creating their goals instead, even if this was disconfirmed by feedback.

- Students who achieved minimal competence in an OSCE were least likely to access online feedback (Harrison et al. 2013).

- One study reported that male learners were more likely to accept positive feedback and discount negative feedback; while female learners were more impacted by feedback, irrespective of feedback valence (Roberts and Nolen-Hoeksema 1989).

[피드백의 특성]도 수용에 영향을 미쳤습니다.

- 피드백이 너무 일반적이고 인지된 유용성이 부족하다고 느껴지는 경우 피드백을 수집하거나 수락하지 않았습니다(Sinclair and Cleland 2007, Price 외. 2011, Harrison 외. 2013, Jonsson 2013, Watling 외. 2013, McSwiggan and Campbell 2017).

- 학습자는 피드백을 사용하기 위해 피드백을 해독해야 한다고 느끼는 경우 피드백에 참여하지 않았습니다(Jonsson 2013; Winstone 외. 2017b).

- 일부 연구에서는 피드백 특성이 학습자의 사용에 영향을 미치는지에 대해 보고했습니다. 피드백 원자가가 매개 요인으로 확인되었습니다.

- 노프지거(Nofziger et al. 2010)는 피드백이 부정적일 경우 의대생이 실습에서 변화를 시도할 가능성이 더 높다고 보고했습니다.

- 그 반대도 있다. 즉 부정적인 피드백을 의도적으로 무시한 경우는 여러 연구에서 보고되었으며, 피드백이 실무 변화에 영향을 미치지 않는 몇 가지 이유 중 하나로 지적되었습니다(Sargeant 외. 2009, Eva 외. 2012, Delva 외. 2013).

- 부정적인 피드백을 받은 사람들을 대상으로 한 한 연구에서는 절반만이 피드백의 결과로 변화를 일으켰다고 답했습니다(Sargeant 외. 2007). 긍정적인 피드백을 받은 사람들은 그 피드백에 동의할 가능성이 더 높았습니다(Sargeant 외. 2003).

- 너무 권위적인 어조로 간주되는 피드백은 사용되지 않았습니다(Jonsson 2013).

Characteristics of the feedback also influenced acceptance.

- Feedback was neither collected nor accepted if felt to be too general and lacking in perceived utility (Sinclair and Cleland 2007; Price et al. 2011; Harrison et al. 2013; Jonsson 2013; Watling et al. 2013; McSwiggan and Campbell 2017).

- Learners disengaged from feedback where they felt they needed to decode it in order to use it (Jonsson 2013; Winstone et al. 2017b).

- Some studies reported on whether feedback characteristics affected learner usage. Feedback valence was an identified mediating factor.

- Nofziger (Nofziger et al. 2010) reported that medical students were more likely to undertake changes in their practice if feedback was negative.

- The opposite; where negative feedback was purposely ignored; was reported in a number of studies and is one of several reasons pinpointed where feedback did not effect any practice change (Sargeant et al. 2009; Eva et al. 2012; Delva et al. 2013).

- In one study of those who received negative feedback, only half reported making changes as a result of it (Sargeant et al. 2007). Those receiving positive feedback were more likely to agree with it (Sargeant et al. 2003). The feedback that was considered too authoritative in tone was not used (Jonsson 2013).

[피드백 제공자]는 학습자의 수용에 영향을 미치는 특성, 즉 감독자의 신뢰성, 인지된 전문적 역량, 대인관계 기술을 보여주었습니다(Bing-You 외. 1997; Watling 외. 2012).

- Sargeant는 360도 피드백에 대한 가정의의 반응을 연구한 결과, 환자로부터의 피드백을 받아들이고 동료로부터의 피드백에 동의하지 않을 가능성이 가장 높다는 사실을 발견했습니다(Sargeant 외. 2003; Sargeant, Mann, Sinclair 외. 2008)

- 중간 및 고위급 관리자는 같은 인종, 이성의 피드백을 받을 가능성이 더 높았습니다(Ryan 외. 2000).

- 피드백 상호 작용의 일부 특성은 수용성을 증가시켰습니다. Overeem 등(2009)은 여러 출처의 피드백을 받은 후 구체적인 목표를 제시하면 컨설턴트가 피드백을 사용하여 자신의 관행을 바꾼다고 설명합니다.

- 목표에 대한 대화가 중요했으며, 슈퍼바이저와 교육생 간에 목표 정렬이 이루어지지 않으면 향후 학습에서 피드백이 실행되지 않았습니다(Watling 외. 2014).

- 피드백 수용을 돕는 것으로 가장 많이 언급된 관행은 촉진된 성찰 또는 자기 성찰이었습니다.

- 대부분의 학생에게 서면 피드백 요약은 [비공식 피드백 토론]에 비해 중요하게 여겨지지 않았으며, 피드백 요약의 1/3은 한 번도 열람하지 않았습니다(Lefroy 외. 2017).

- 학생들은 점수(64%), 체크리스트(42%), 동영상(28%)을 검토하는 빈도는 감소했지만 학생-교수 디브리핑 회의가 진행되었을 때 모든 양식에 대한 검토가 향상되었습니다(p <0.001)(Bernard 외. 2017).

- 의사들은 부정적인 피드백을 처리하는 것이 어려웠지만 오랜 시간 숙고한 후 이를 받아들였다고 설명했습니다(Sargeant 외. 2009).

Feedback providers showed characteristics that affected learner acceptance: supervisor credibility, perceived professional competence, and interpersonal skills (Bing-You et al. 1997; Watling et al. 2012).

- Sargeant studied family physicians’ responses to 360-degree feedback and found that they were most likely to accept feedback from patients and to disagree with it from colleagues (Sargeant et al. 2003; Sargeant, Mann, Sinclair, et al. 2008)

- Middle and high-level managers were more likely to be receptive to feedback if it was from someone of the same race, and of the opposite gender (Ryan et al. 2000).

- Some characteristics of the feedback interaction led to increased receptivity. Overeem et al. (2009) describe consultants using feedback to change their practice if provided with concrete goals following multi-source feedback.

- Dialogue on goals was important, with feedback not being actioned in future learning if goal alignment did not occur between supervisor and trainee (Watling et al. 2014).

- The practice most commonly cited as aiding feedback acceptance was reflection, both facilitated or self-reflection.

- For most students, written feedback summary was not valued compared to informal feedback discussions – one-third of feedback summaries were never accessed (Lefroy et al. 2017).

- Students reviewed scores (64%), checklists (42%), and videos (28%) in decreasing frequency but the review of all modalities improved when student-faculty debriefing meetings were conducted (p < 0.001)(Bernard et al. 2017).

- Physicians described finding negative feedback difficult to process but accepting it following long periods of reflection (Sargeant et al. 2009).

피드백 수용의 중요한 매개 요인으로 [인간관계]가 자주 언급되었습니다.

- 돌로리어트(Doloriert) 등은 박사 과정 학생들의 피드백과 지도교수와의 경험을 조사했습니다(돌로리어트 외. 2012). 한 참가자는 관계적인 측면을 특히 간결하게 설명했습니다: '슈퍼바이저가 저와 함께 길을 걸어주기를 바랄 뿐입니다.'

- 여러 연구에서 감독자와의 친밀감, 종종 종적 관계의 맥락에서 피드백 수용을 촉진하는 것으로 언급되었습니다(Ryan 외. 2000; Veloski 외. 2006; Embo 외. 2010; Bates 외. 2013; Ramani 외. 2018).

- 일부 학생들은 피드백을 직접 관찰한 후, 이상적으로는 여러 번 관찰한 후 피드백을 더 신뢰한다고 합리화했으며, 이와 유사하게 수행이 관찰되지 않은 경우 피드백을 무시한다는 보고도 있었습니다(Eva 외. 2012; Watling 외. 2013; 2014).

- 학습자들은 이전에 긍정적인 피드백을 경험한 적이 있는 경우 향후 동일한 감독자에게 더 많은 피드백을 구하고, 부정적인 피드백을 경험한 감독자에게는 피드백을 피한다고 보고했습니다(Gaunt, Patel, Fallis 등, 2017).

Relationships were frequently cited as a crucial mediator of feedback acceptance.

- PhD students’ experiences of feedback and supervisors were explored by Doloriert et al (Doloriert et al. 2012). One participant described the relational aspect particularly succinctly: ‘You just want her to walk part of the way with me.’

- Familiarity with the supervisor, often in the context of a longitudinal relationship, was cited by several studies as promoting feedback acceptance (Ryan et al. 2000; Veloski et al. 2006; Embo et al. 2010; Bates et al. 2013; Ramani et al. 2018).

- Some students rationalised this: feedback was more credible following direct observation, ideally on multiple occasions; similarly, reports of discounting feedback where performance was unobserved occurred (Eva et al. 2012; Watling et al. 2013; 2014).

- Learners reported seeking more feedback from the same supervisor in the future when they had a prior positive feedback experience; and avoiding feedback from supervisors with whom they had a negative feedback experience (Gaunt, Patel, Fallis, et al. 2017).

토론

Discussion

이 리뷰에서는 학습자가 피드백에 어떻게 반응하고 이를 향후 학습에 활용하는지에 초점을 맞춘 232개의 연구를 확인했습니다. 자기조절의 관점에서 피드백에 대한 반응은 [인지적, 행동적, 정서적, 맥락적 반응]으로 인식할 수 있습니다. 이러한 범주 내에서 피드백은 학습을 지원하거나 방해하는 반응으로 이어집니다. 이 토론 섹션에서는 먼저 [정의의 이질성 문제]에 초점을 맞출 것입니다. 그런 다음 자기 조절이라는 렌즈를 통해 피드백에 대한 [학습자의 반응과 피드백 사용에 대한 이론적 고려 사항]을 논의할 것입니다. 그런 다음, 향후 학습을 강화하는 도구로서 피드백을 최적화하고자 하는 교육자를 위한 실질적인 [시사점]을 간략하게 설명합니다. 마지막으로 문헌에서 확인된 부족한 점과 향후 연구 방향에 대한 제안으로 마무리합니다.

In this review, we identified 232 studies that focus on how the learner responds to feedback and then uses it for their future learning. From the perspective of self-regulation, responses to feedback can be recognised as cognitive, behavioural, emotional, and contextual. Within these categories, feedback leads to responses that support or impair learning. In this discussion section, we will first focus on the issue of definition heterogeneity. We will then discuss theoretical considerations of learner response to and use of feedback, via the lens of self-regulation. We next outline practical implications for educators wishing to optimise feedback as a tool in potentiating future learning. We conclude with gaps identified in the literature and suggestions for future research directions.

대부분의 연구에서 [피드백에 대한 정의]나 [인정된 모델]을 제시하지 않았습니다. 피드백에 대한 세 가지 접근 방식이 전반적으로 확인되었습니다.

- 결과에 대한 지식,

- 성과 격차 해소를 위한 데이터,

- 실행 계획을 포함한 격차 해소를 위한 데이터

세 번째 정의의 경우, 일부는 관계 구축과 성장 의제 촉진에 중점을 두고 이 계획이 만들어지는 과정을 강조했습니다. 이러한 정의가 자기조절 학습과 관련하여 시사하는 바는 무엇일까요? [자기조절]은 학습자가 [학습 목표를 달성하기 위해 지속적으로 행동을 교정하고 조정하면서 능동적으로 과제를 계획하고, 모니터링하고, 반성하는 역동적인 과정]을 말합니다. The majority of studies did not provide a definition or recognised model of feedback. Three overall approaches to feedback were identified:

- knowledge of results;

- data to address a performance gap; and

- data to address a gap including an action plan.

With the latter, some emphasised the process by which this plan was produced, focussing on building a relationship and promoting a growth agenda. What are the implications of these definitions in terms of self-regulated learning? Self-regulation describes a dynamic process through which the learner actively plans, monitors, and reflects on tasks, with constant calibration and adjustment of actions to achieve their learning goals.

피드백을 [단순히 '결과에 대한 지식'(과제 관련)으로만 정의]할 경우, 달성한 성적이 [적절한 성취를 나타내는지 판단할 책임은 학습자에게] 있으며, 학습자가 '학습에 대한 판단'(JOL)을 결정하게 됩니다. 학습자는 자신의 진도를 이해하고, 알려진 것과 알려지지 않은 것을 평가하고, 다른 학습 과정 중에서 준비 상태와 진도를 측정할 수 있는 능력을 갖추고 있다는 것을 기대할 수 있습니다. [결과 피드백]은 '성취 상태 외에는 과제에 대한 추가 정보를 전달하지 않습니다'(Butler and Winne 1995). 따라서 [결과 피드백]만으로는 학습자가 [스스로 조절하는 방법에 대한 최소한의 외부 지침]만 제공합니다.

If feedback is confined by definition to merely ‘knowledge of results’ (task-related), the responsibility lies with the learner to decide if the grade attained represents adequate achievement – the learner determines the ‘judgment of learning’ (JOL). The expectation is that the learner possesses the ability to understand their progress, evaluate what is known and unknown, and gauge preparedness and progress, amongst other learning processes. It ‘carries no additional information about the task other than its state of achievement’(Butler and Winne 1995). Hence, outcome feedback alone provides minimal external guidance for a learner about how to self-regulate.

두 번째 정의인 '격차를 좁히는 정보'를 사용하면 과제 수행에 대한 [지시적instructive 또는 교정적corrective 코멘트]와 같은 [추가 세부 정보]가 제공됩니다. 이를 통해 학습자는 [향후 학습 계획]을 세우는 데 도움이 되는 [더 풍부한 모니터링 데이터]를 얻을 수 있습니다. 그러나 히긴스, 하틀리, 스켈튼(R. Higgins 외. 2001)이 지적한 바와 같이, 수정 가능한 요인을 파악하는 과정에서 학습자가 이러한 변화를 가져올 수 있는 전략으로 무장할 필요는 없으며, [계획을 세우는 것]만으로는 충분하지 않으며 학습자는 [계획을 실행하는 방법]을 알아야 합니다.

With the second definition – information that ‘narrows the gap’ – additional detail is given, for example, instructive or corrective comments on task performance. This provides the learner with richer monitoring data to inform future learning plans. However, as Higgins, Hartley and Skelton (R. Higgins et al. 2001) point out, the process of identifying remediable factors does not necessitate that the learner is armed with strategies to effect these changes – having the plan is not enough; learners need to know how to enact the plan.

세 번째 그룹은 이 문제를 다룬다: '피드백은 학습자가 기억에 있는 정보를 확인, 추가, 덮어쓰기, 조정 또는 재구성할 수 있는 정보로, 그 정보가 도메인 지식, 메타인지 지식, 자기 및 과제에 대한 신념, 인지 전술 및 전략 등입니다'(Winne and Butler 1994). 궁극적으로 자기 조절을 위해서는 참여 프로세스를 모니터링하고 생성된 정보에 따라 업데이트해야 하며, 이 경우 피드백이 필요합니다. 피드백이 자기조절 학습자에게 더 포괄적으로 제공될수록 학습자는 학습을 발전시키기 위한 적절한 전략을 더 잘 사용할 수 있습니다. 이러한 관점에서 이러한 정의는 학습자가 [정확한 판단]을 내리고 [학습에 가장 도움이 되는 인지 전략]을 선택하고 채택할 수 있도록 [최소한의 지원부터 가장 큰 지원]까지 [연속적인 연속체를 제공]합니다. 보다 효과적인 피드백은 피드백 메시지와 학습할 자료의 정보를 '주의 깊게' 처리하도록 유도합니다(Bangert-Drowns 외. 1991).

The third group addresses this issue: ‘feedback is information with which a learner can confirm, add to, overwrite, tune, or restructure information in memory, whether that information is domain knowledge, meta-cognitive knowledge, beliefs about self and tasks, or cognitive tactics and strategies’(Winne and Butler 1994). Ultimately self-regulation requires monitoring the processes of engagement and updating them based on information generated, which in this instance, is feedback. The more comprehensive the inputs from feedback to the self-regulated learner, the better they can employ appropriate strategies to evolve their learning. From this perspective, these definitions provide a continuum from least to most supportive of the learner, in making precise judgments and thereby in selection and adoption of cognitive strategies most conducive to learning. More effective feedback cues ‘mindful‘ processing of information in the feedback message and in the material to be learned (Bangert-Drowns et al. 1991).

검토한 논문에서 [피드백의 정의]가 [피드백 내용]과 [성과 목표]에 초점을 맞추고 있다는 점이 흥미롭습니다. 최근 몇 년 동안 전문가들은 [학습자의 성장을 목표]로 [학습자와 교사] 간에 [건설적인 관계를 형성하는 과정]에 초점을 맞춘 정의를 선호하고 있습니다(Ramani 외. 2019). 이러한 변화는 학습자 반응의 새로운 패턴을 드러낼 수 있습니다. 많은 연구에서 역사적 개념화를 반영하여 [평가 후 피드백(주로 총괄적 및 로테이션 종료 후)]에 대한 결과를 검토한 것은 주목할 만합니다. 이러한 연구들은 학습자의 인지적 반응에 집중했습니다. 최근 문헌의 연구들은 피드백을 다중 및 종단 평가의 입력으로, 지속적이고 형성적인 평가의 요소로, 또는 위의 두 가지를 조합하여 사용하는 등 보다 다양한 상황을 설명합니다. 이러한 진화는 연구들이 주로 질적 연구에 집중하고 학습자의 성장을 폭넓게 탐구하는 반응에 관심을 갖는 것에서 알 수 있습니다.

It is interesting that in the papers reviewed, definitions have focused on feedback content and performance endpoints. In recent years, experts have favoured definitions that concentrate on the process of creating constructive relationships between learner and teacher aiming for learner growth (Ramani et al. 2019). This shift may reveal new patterns in learner response. It is notable that many studies reviewed findings on post-assessment feedback (often summative and end-of-training) reflecting historical conceptualisation. These concentrated on learner cognitive responses. Studies from recent literature described more diverse circumstances;

- feedback as an input to multiple and longitudinal evaluations,

- as an element of continuous, formative assessments,

- or a combination of the above.

This evolution is evidenced in studies becoming predominantly qualitative and interested in response exploring learner growth in broader terms.

인지적 반응

Cognitive responses

연구의 거의 절반(n = 96, 41%)이 피드백이 [명확성과 이해도]에 영향을 미쳤다고 보고했으며, 대부분은 피드백이 학습자의 [강점과 약점]을 파악하는 데 도움이 되고 [예상 성과 기준]을 명확히 하는 등 두 가지 주요 하위 주제에 대해 긍정적인 효과를 보고했습니다.

Almost half of the studies (n = 96, 41%) reported that feedback affected clarity and understanding, the majority reporting a positive effect with two main sub-themes: feedback helped identify strengths and weaknesses in the learner and made expected performance standards clear.

피드백은 학습자의 [유능한 성과와 부족한 성과] 측면을 현미경처럼 들여다보는 역할을 합니다. 이는 관찰된 성과 기준과 바람직한 성과 기준 사이의 '격차'를 좁히기 위한 피드백의 개념화와 잘 맞아떨어집니다(Sadler 1989). 이 효과를 보고한 많은 연구에서 학습자가 역량의 특성을 인식하는 데 도움이 필요하다는 것을 확인했습니다. ['문제 소싱Trouble sourcing']은 학생이 [오류가 발생했을 때 정확한 라벨링]이 필요하거나, 피드백 상호작용을 통해 수정되지 않은 오해를 남기고 확장 학습의 기회를 놓칠 위험이 있다는 개념입니다(Rizan 외. 2014). 수행에서 강점과 부족한 영역을 강조하면 학습자에게 자기조절 주기의 여러 지점과 상호 작용할 수 있는 [정보]를 제공합니다.

- 이를 통해 내부의 '앎의 느낌'(FOK)과 '학습의 판단'(JOL)을 [외부 엔드포인트에 매핑]할 수 있습니다.

- 학습자는 자신의 역량 수준에 대한 슈퍼바이저의 평가를 받으면 효능감과 학습 용이성(EOL)에 대한 판단을 내릴 수 있습니다.

피드백이 [혼란을 야기하고 이해도를 악화시킨다]고 보고한 연구들은 피드백이 모호하거나, 구체적이지 않거나, 전달이 불가능하고, 양방향 대화가 불가능하다는 반복적인 특징과 관련이 있었습니다. Orsmond 등(2000)은 [성취도가 높은 학생]이 [성취도가 낮은 학생]보다 감독자의 피드백을 이해하기 위해 자기 평가, 동료 토론, 내부 보정을 더 많이 사용하며, 즉 학습을 스스로 조절한다는 사실을 발견했습니다. 연구진은 [성취도가 높은 학생]들이 피드백을 통해 타인 주도형에서 [자기 주도형으로 진화]했다는 점에 주목했습니다. 이는 교육자들에게 [학습자의 특성]과 [제공된 피드백] 중 어느 것이 더 결정적인 요소인가라는 질문을 던집니다. 자기 조절을 지원하는 피드백을 제공하면 모든 학생이 높은 성취도를 달성할 수 있을까요? 만약 그렇다면, SRL을 촉진하는 피드백을 조기에 제공하면 더 효과적인 학습자를 만들 수 있다는 것이 실무에 시사하는 바가 있습니다.

Feedback served as a microscope on aspects of the learner’s competent and deficient performance. This fits well with conceptualising feedback to ‘narrow the gap’ between observed and desirable performance standards (Sadler 1989). Many studies reporting this effect identified that learners need assistance with recognising the characteristics of competency. ‘Trouble sourcing’ is the concept that the student needs precise labelling of an error when it occurs, or risks leaving a feedback interaction with uncorrected misunderstanding while missing the opportunity for expansive learning (Rizan et al. 2014). Highlighting strong and deficient areas in performance provides the learner with information that can interact with multiple points in the self-regulation cycle.

- It allows mapping of internal ‘feeling of knowing’ (FOK) and ‘judgment of learning’ (JOL) to an external endpoint.

- They can make efficacy and ease of learning (EOL) judgements once they are equipped with the supervisor’s evaluation of their competency level.

Those studies which reported feedback causing confusion and worsening understanding associated it with recurring characteristics: feedback was ambiguous, non-specific, or non-transferable, and bi-directional dialogue was not available. Orsmond et al. (2000) found that that high-achieving students employed more self-assessment, peer discussion, and internal calibration to make sense of supervisor feedback than low-achieving students, that is, they self-regulated their learning. They noted that high-achievers evolved from being other-directed to self-directed, via feedback. This poses the question for educators: which is the determining factor – the learner’s traits or the feedback provided? Can all students become high-achieving if given feedback that supports self-regulation? If this is the case, the implication for practice is that early provision of feedback which facilitates SRL can create more effective learners.

'인지적' 범주의 두 번째 결과인 피드백이 [평가 기준을 명확하게 함으로써 이해를 돕는다]는 사실은 평가 리터러시(평가 리터러시)라고 불립니다(Winstone 외. 2017a). 그녀는 학습자가

- (a) 평가와 학습 간의 관계와 학습자에게 기대되는 바를 이해하고,

- (b) 암묵적 또는 명시적 채점 기준에 따라 자신과 타인의 작업을 평가하며,

- (c) 피드백에 사용되는 용어와 개념을 이해하고,

- (d) 평가와 피드백을 위한 적절한 기술과 이를 적용할 시기를 알아야 한다고 설명합니다.

The second finding in the ‘cognitive’ category – that feedback aided understanding by making assessment criteria clear – has been termed assessment literacy (Winstone et al. 2017a). She describes that the learner must

- (a) understand the relationship between assessment and learning, and what is expected of them;

- (b) appraise their own and others’ work against implicit or explicit grading criteria;

- (c) understand the terminology and concepts used in feedback and

- (d) know suitable techniques for assessing and giving feedback, and when to apply them.

'평가' 리터러시라고 불리지만, 첫 번째 항목을 제외한 모든 항목은 다른 상황에서의 피드백과 관련될 수 있다는 점을 인식하고 있습니다.

- 니콜과 맥팔레인-딕(Nicol and Macfarlane-Dick 2006)은 최적의 피드백은 '좋은 성과(목표, 기준, 기대 기준)가 무엇인지 명확히 하는 데 도움이 되며, 학생이 학습 목표를 식별하는 데 사용할 수 있는 전략을 개괄적으로 설명'한다고 선언합니다.

- 다른 곳에도 적용된다. [피드백의 모호성]은 퍼실리테이션, 명확성을 위한 감독자 미팅, 피드백을 효과적으로 풀고 '사용'하기 위한 성찰 연습을 통해 해결되었습니다(Sargeant 외. 2009; Embo 외. 2010).

- 또 다른 제안은 피드백 리터러시를 최적화하기 위해 더 많은 자기 평가를 통해 학생의 평가 기술을 강화하는 것입니다.

While termed ‘assessment’ literacy, it is recognised that, with the exception of the first, all of these points can relate to feedback in other situations.

- Nicol and Macfarlane-Dick (Nicol and Macfarlane‐Dick 2006) declare that optimal feedback ‘helps clarify what good performance is (goals, criteria, expected standards),’ and outline strategies that could be used in helping students identify learning targets.

- These are applied elsewhere; feedback ambiguity has been addressed via facilitation, meeting supervisors for clarification, reflection exercises to effectively unpack and ‘use’ feedback (Sargeant et al. 2009; Embo et al. 2010). Another suggestion is strengthening students’ evaluative skills via more self-assessment to optimise feedback literacy.

그러나 [감독자가 사용하는 용어가 다를 경우] 피드백에 대한 어려움은 문해력을 넘어서는 것입니다. 이러한 문제는 자주 발생하는 것으로 보입니다.

- 학습자는 감독자와 비교하여 [표준에 대한 인식에 상당한 불일치]가 있을 수 있습니다(Norton 및 Norton 2001).

- 학습자는 특히 [익숙하지 않은 학문적 전문 용어]로 인해 '이해'에 어려움을 겪을 수 있습니다(Hounsell 1987).

- 학생들은 감독자의 피드백을 의도한 것과는 [상당히 다른 의미로 받아들입니다](Chanock 2000). 교사가 [의도적으로 모호한 표현을 사용]하는 경우, 즉 [헤징, 간접적 또는 완화된 표현]를 사용하는 경우 더 큰 문제가 발생합니다(Hyland and Hyland 2001).

- Yorke(2003)는 '기대되는 표준, 커리큘럼 목표 또는 학습 결과에 대한 진술은 일반적으로 그 안에 담긴 풍부한 의미를 전달하기에 불충분하다'고 지적합니다.

- Ginsburg 등(2015)은 평가에 사용되는 [서술형 평가에 '숨겨진 코드'가 사용되어 다양한 해석의 위험]을 초래할 수 있다고 설명합니다.

평가 과제 난이도, 진행 상황 모니터링, 인지 전략 선택, 시간 및 노력 할당 등 다양한 [자기조절 행동]을 실행하기 위해서는 [피드백이 명확하고 눈에 띄는 성과 결과와 명시적으로 연결]되어야 합니다. 이번 연구 결과에 따르면 피드백을 통해 목표가 명확해지고 목표에 대한 방향이 명확해질 수 있지만, 이는 [피드백 과정과 품질]에 따라 크게 달라집니다.

However, the challenges with feedback transcend literacy, if the supervisor is speaking a different language. This appears to occur frequently.

- Students can have a significant mismatch in their perception of standards compared with supervisors (Norton and Norton 2001).

- Learners may experience difficulty ‘making sense,’ in particular due to unfamiliar academic jargon (Hounsell 1987). Students take a significantly different meaning from supervisor feedback than what was intended (Chanock 2000).

- A further challenge lies when teachers are purposefully ambiguous – if hedging, indirectness, or mitigation are employed (Hyland and Hyland 2001).

- As Yorke (2003) notes, ‘statements of expected standards, curriculum objectives or learning outcomes are generally insufficient to convey the richness of meaning that is wrapped up in them.’

- Ginsburg et al. (2015) describes a ‘hidden code’ employed in written comments used in evaluations, leading to a risk of variable interpretations.

In order to employ a number of self-regulation actions – evaluation task difficulty, monitoring progress, selection of cognitive strategies, and allocation of time and effort – feedback must be clear and explicitly linked to salient performance outcomes. Our results indicate that while feedback can make the goalposts visible and the direction towards them clearer; this is highly dependent on the feedback process and quality.

학습자는 [진행 상황을 자기 모니터링하기 위해 피드백을 사용]한다고 설명합니다. 피드백은 자기조절 학습자가 적용한 전략이 원하는 결과를 달성했는지 판단하는 데 [필요한 인풋 중 하나]입니다. 피드백이 사용되는 방식은 [인풋 품질]에 직접적인 영향을 받습니다. [명확하고 투명한 피드백]은 이해도를 높이고 학습자가 객관적인 기준과 개인적인 목표에 따라 자신의 성과를 보정할 수 있도록 합니다. 이를 통해 학습자는 [메타인지적으로 강화, 수정 및 조정]할 수 있습니다. 학습자들은 피드백을 통해 [자기 모니터링에 대한 인센티브]를 받는다고 설명하므로(Price 외. 2010; Mann 외. 2011), 피드백은 [시간이 지남에 따라 자기 규제 행동을 종적으로 촉진]할 수 있습니다. 우수한 피드백 프레임워크가 있음에도 불구하고, (Nicol and Macfarlane-Dick 2006, Hattie and Timperley 2007, Sargeant 외. 2015) 연구에 따르면 이해에 부정적인 영향을 미치는 피드백 경험이 보고되어 이론과 실제 사이에 잠재적인 격차가 있음을 나타냅니다.

Learners describe using feedback for self-monitoring of progress. Feedback is one input that the self-regulated learner requires to determine if the strategies they apply have achieved the desired outcome. How feedback is used is directly affected by input quality. Clear, transparent feedback enhances understanding and allows the learner to calibrate their performance against both objective standards and personal goals. This then allows them to metacognitively reinforce, correct and adjust. Learners describe being incentivised to self-monitor by feedback (Price et al. 2010; Mann et al. 2011), thus it can catalyse self-regulatory actions longitudinally over time. Despite the availability of excellent feedback frameworks, (Nicol and Macfarlane‐Dick 2006; Hattie and Timperley 2007; Sargeant et al. 2015) studies report feedback experiences that negatively affect understanding, indicating a potential gap between theory and practice.

[성찰]은 모든 영역(인지, 정서, 행동)에서 수행되는 모니터링 및 반응 단계에 필요하기 때문에 [모든 자기 조절의 기초]가 됩니다. 이는 학습자가 나중에 피드백을 생산적으로 활용할 수 있도록 피드백에 대한 초기의 부정적인 반응을 관리하는 데 강력한 처리 도구로 작용할 수 있습니다(Sargeant, Mann, Sinclair 외. 2008). 일부 연구에 따르면 건설적인 성찰을 위해서는 전문가의 촉진이 필요하다고 합니다(Macafee 외. 2012).

Reflection is at the basis of all self-regulation, as it is required for monitoring and reaction phases to be undertaken in any area (cognitive, affective, and behavioural). It may act as a powerful processing tool in managing initial negative reactions to feedback in order for the learner to make productive use of it at a later stage (Sargeant, Mann, Sinclair, et al. 2008). Some studies indicate that constructive reflection requires expert facilitation (Macafee et al. 2012).

[학습 전략 변경 계획]은 이 범주에서 확인된 최종 결과입니다. 이는 [자신의 성과, 목표 및 환경을 지속적으로 재평가하고 원하는 목표를 달성하기 위해 조정하는 역동적인 학습자]라는 [SRL 이론의 핵심적인 실제 결과]를 요약합니다. 이 요소를 피드백에 대한 학습자의 반응으로 명시적으로 보고한 연구(n = 19, 8%)가 거의 없다는 점은 주목할 만합니다. 이는 연구 설계에서 피드백에 대한 반응으로서 학습 과정의 장기적인 변화를 탐구하지 않았기 때문일 수 있습니다. 이는 연구자와 교육자 모두에게 고려해야 할 사항입니다. [프로그램 방식의 평가 모델]이 널리 보급됨에 따라 학습자가 학습 활동을 수정하기 위해 내부적으로 피드백을 처리하는 방법도 외부화해야 한다는 점에서 모든 이해관계자의 피드백에 대한 투자가 활발해지고 있습니다.

Planning to change learning strategies is the final outcome identified in this category. It sums up the key practical outcome of SRL theory: the dynamic learner who constantly revaluates their performance, goals, and environment, and adjusts to effect desired goals. It is notable that few studies (n = 19, 8%) reported this element explicitly as a learner response to feedback. This may be because study designs have not explored the long-term changes in learning processes as a response to feedback. This is a consideration for researchers and educators alike. With programmatic assessment models becoming more widespread, there is heavy investment in feedback from all stakeholders: how learners internally process feedback to modify learning activities needs to be externalised.

행동 반응

Behavioural responses

'행동' 측면에서 피드백은 실제로 변화를 가져왔고, '행동'과 '맥락' 영역 모두에서 '통제'와 '반응' 단계에 반영된 더 많은 피드백을 추구하게 되었습니다. 이는 [피드백 이후 행동]이 [개인의 내부 처리]로만 설명할 수 없고 [환경과의 상호작용이 필요하다]는 것을 전달하기 때문에 중요한 중첩입니다. [부정적인 피드백]을 무시하고 신뢰할 수 없는 것으로 치부하여 결국 관찰된 행동에 아무런 변화를 가져오지 못했다는 보고가 여러 차례 있었습니다. 이는 학습자가 인지적 조절 영역에서 모니터링할 때 이러한 데이터를 제외하기로 선택했기 때문으로 설명할 수 있습니다. 다르게 해석하자면, 피드백은 받아들였지만 동기/정서 영역에서 목표 지향 채택에 부정적인 영향을 미친다고 해석할 수 있습니다. 분명한 것은 피드백이 상호 작용하여 궁극적으로 [미래의 시간과 노력 계획 및 실행에 영향]을 미칠 수 있는 몇 가지 [메커니즘]이 있다는 것입니다. 이는 행동과 관련된 두 번째 발견으로 이어지며, [피드백]이 [추가 피드백을 구하게 된다는 것]입니다. 학습자는 재보정의 일부에 추가 데이터 입력이 필요하다고 판단할 수 있습니다. 피드백은 학습자가 이전의 노력을 포기하도록 부추길 수 있습니다. 이는 한 연구에서만 관찰되었는데, 부정적인 피드백은 일부 포기로 이어졌습니다(Young 2000). 피드백의 결과로 취해지는 외부 행동(실행의 변화, 피드백 추구)은 학습자가 내린 내부 결정의 일부에 불과할 수 있습니다. 교육자로서 피드백의 결과를 행동의 측면에서만 고려하면 학습에 대한 투자를 과소평가할 위험이 있습니다.

In terms of ‘behaviour,’ feedback led to change in practice, and to more feedback-seeking, which are reflected under the ‘control’ and ‘reaction’ phases, both in the ‘behaviour’ and also the ‘context’ areas. This is an important overlap as it conveys how the actions are undertaken after feedback cannot be singularly explained by the individual’s internal processing, but require an interaction with the environment. There were multiple reports of negative feedback being discounted, dismissed as not being credible, and ultimately leading to no changes in observed behaviours. This could be explained by the learner choosing to exclude these data when monitoring, at the cognitive area of regulation. It could be otherwise interpreted that the feedback is accepted, but then negatively affects goal orientation adoption at the motivation/affect area. What is clear is that there are several mechanisms by which feedback can interact to ultimately affect future time and effort planning, and implementation. This leads to the second finding related to behaviour; that feedback led to seeking further feedback. The learner may decide that part of their re-calibration requires additional data inputs. Feedback may incite learners to abandon prior efforts; this was seen in only one study, negative feedback led to some giving up (Young 2000). The external actions are taken as a result of feedback – changes in practice, feedback-seeking – probably represent a fraction of the internal decisions which the learner made. As educators, we risk under-estimating the learning investment undertaken if we consider feedback outputs in terms of behaviours alone.

정서적 반응

Affective responses

피드백에 대한 동기 부여 반응을 보고한 연구의 85%가 동기 부여가 증가했다고 설명했습니다. 긍정적인 동기 부여 반응과 관련된 특정 유형의 피드백은 없었습니다. 실제로 연구에 따르면 피드백의 내용이나 가치에 관계없이 [피드백을 받는 것만으로도 동기 부여가 되는 것]으로 나타났습니다(Lizzio and Wilson 2008; Eide et al. 2016). 이는 학습자의 성과 기준에 관계없이 학습자의 노력을 인정해 주었기 때문입니다. 이는 학습을 사회적으로 맥락화된 것으로 간주할 때에도 마찬가지입니다. [교수진과의 긍정적인 관계]는 학습에 도움이 됩니다(Drew 2001). 여러 연구에서 부정적인 피드백을 건설적으로 처리하고 학습 목표를 지속하는 데 [정서적 지원]이 중요하다고 언급합니다(Treglia 2008; Rowe 2011; Taylor 외. 2011). 피드백이 학습 의욕을 떨어뜨리는 경우, 대개 부정적인 피드백이나 실험 연구의 맥락에서 이루어졌습니다. 이러한 실험은 학습자가 촉진 또는 예방에 초점을 맞출 수 있다고 제안하는 [조절 초점 이론](Higgins and Silberman 1998)에 기초했습니다. 이는 드웩의 [동기부여 이론](드웩과 레겟 1988) 및 데시와 라이언의 [자기 결정 이론](데시와 라이언 1985)과 겹치는 부분이 있습니다. 이러한 연구에 따르면 예방에 초점을 맞출 때는 부정적인 피드백이 동기 부여를 증가시키는 반면, 승진에 초점을 맞출 때는 긍정적인 피드백이 동기 부여에 더 큰 영향을 미칩니다. 그러나 동기는 관계적이고 역동적인 경향이 있으며, 자기조절 학습자의 현실은 이러한 구성된 모델보다 재현성이 떨어질 수 있습니다. 학습자와 학습자에게 요구되는 복잡한 과제는 promotion과 prevention이라는 [양극화된 범주]에 거의 들어맞지 않습니다. 많은 연구의 내러티브는 학습자가 자기 개발과 외부 성과 기준 충족이라는 두 가지 목표 사이에서 균형을 맞추기를 희망하는 현실을 시사합니다.

85% of the studies that reported motivational response to feedback described increased motivation. There were no specific types of feedback associated with positive motivational reactions. Indeed, studies indicated that merely receiving feedback, irrespective of the content or valence, was motivating (Lizzio and Wilson 2008; Eide et al. 2016). This was due to acknowledging learners’ effort, irrespective of their performance standard. This follows when considering learning as socially contextualized – positive relationships with academic staff are supportive of learning (Drew 2001). Multiple studies mention emotional support as crucial to process negative feedback constructively and persist with learning goals (Treglia 2008; Rowe 2011; Taylor et al. 2011). Where feedback was demotivating, it was usually in the context of negative feedback or experimental studies. Such experiments drew on regulatory focus theory (Higgins and Silberman 1998) which proposes that the learner can have either a promotion or prevention focus. This overlaps with Dweck’s motivational theory (Dweck and Leggett 1988) and Deci and Ryan’s self-determination theory (Deci and Ryan 1985). These studies suggest that with prevention focus, negative feedback increases motivation, while positive feedback is more motivating in a promotion focus. However, motivation tends to be relational and dynamic and the reality of the self-regulated learner may be less reproducible than these constructed models. Learners, and the complex tasks demanded of them, rarely fit polarised categories of promotion and prevention. The narrative in many of the studies suggests a reality where learners hope to balance both self-development and meeting external performance standards.

자신감이 피드백의 영향을 받은 대부분의 연구에서 [자신감이 향상]되었습니다. 자신감 향상과 동기 부여 강화는 일반적으로 공존했습니다. 학습자가 모니터링 소스를 입력하면 자신의 FOK와 EOL을 평가할 수 있습니다. 피드백은 이 두 가지를 개선하여 자존감을 높일 수 있습니다. 이 영역은 잠재적으로 목표 지향 및 후속 시간 및 노력 계획과 상호 작용할 수 있으므로 자기조절 학습에서 이 둘의 조합은 의미가 있습니다.

Most studies where confidence was affected by feedback, led to improvements. Increased confidence and enhanced motivation commonly co-existed. As the learner inputs monitoring sources, they can evaluate their FOK and EOL. Feedback can ameliorated both, supporting self-esteem. This domain potentially interplays with goal orientation and subsequent time and effort planning and so the pairing makes sense in self-regulated learning.

이 리뷰는 피드백에 대한 정서적 반응은 흔한 일이면서 강렬하다는 것을 나타냅니다. 이전 리뷰에서는 학습자가 피드백에 반응하는 방법의 주요 특징으로 이를 강조하지 않았습니다. 자기조절 학습 이론은 [동기/정서]에 중요성을 부여합니다. 이 이론은 학습 전략의 진화를 결정할 때 정서를 인지 및 행동 영역과 함께 배치합니다. [긍정적인 정서]는 학습을 촉진하는 반면, [부정적인 정서]는 학습을 억제하는 등 정서와 학습 사이의 연관성은 잘 확립되어 있습니다(Fredrickson 2001). SRL 모델은 피드백 입력이 [단순히 감정적 반응을 유발]하는 것이 아니라 학습자의 [향후 학습 전략에 영향]을 미쳐 [특정 감정의 재발을 반복하거나 피할 수 있다]고 간주합니다. 피드백은 '자신에 대한 정보이며, 감정적으로 충전되어 있기' 때문에 강한 감정을 유발할 수 있습니다(Ashford와 Cummings 1983). [부정적인 감정]은 더 자주, 더 생생하게 보고되며, 때로는 광범위한 영향을 설명하기도 합니다. 학습자의 지속적인 개인적 반응을 설명할 뿐만 아니라 피드백 사용에도 상당한 영향을 미쳤습니다. 부정적인 정서적 반응은 일반적으로 받은 [피드백을 거부하거나 부분적으로만 수용하는 것]과 관련이 있었습니다(Sargeant, Mann, Sinclair 등, 2008). [자신감과 자존감에 대한 해로운 영향]도 보고되었습니다(Lizzio와 Wilson 2008). 이론적 관점에서 부정적인 원자가 감정이 피드백과 심오한 상호작용을 하는 이유에 대한 여러 가지 제안이 있기 때문에 이는 주목할 만합니다. 자신의 자기 평가에 반할 수 있는 데이터를 받는 것은 어려운 일입니다(Porter 외. 1974; Mann 외. 2011). 이는 학습자가 학습을 지원하는 피드백의 긴장과 자기 인식에 대한 위협 사이의 균형을 맞출 필요가 있음을 시사합니다. 반대로 피드백은 학습자의 주관적인 반응을 완화하는 기능을 할 수도 있습니다. 평가는 감정적으로 이루어지며 피드백은 불안한 학습자의 자기 평가보다 더 균형 잡힌 시각을 제공할 수 있습니다(Munro와 Hollingworth 2014).

This review indicates that affective reactions to feedback are both commonplace and intense. Previous reviews have not highlighted these as a major feature of how learners respond to feedback. Self-regulatory learning theory assigns significance to motivation/affect. It situates emotion alongside cognitive and behavioural areas, in determining the evolution of learning strategy. The connection between emotion and learning is well established: positive valence emotions are associated with facilitating learning, while negative valence inhibits learning (Fredrickson 2001). The SRL model considers that feedback inputs do not just provoke emotional reactions, but that a learner’s future learning strategies will be influenced to replicate or avoid specific feelings re-occurring. Feedback may provoke such strong feelings because ‘it is information about the self, it is emotionally charged’ (Ashford and Cummings 1983). Negative emotions are reported more frequently, and in more vivid terms, sometimes describing far-reaching effects. In addition to describing enduring personal reactions in the learner, they also had significant effects on their use of feedback. Negative emotional reactions were commonly associated with rejection of received feedback or only partial acceptance (Sargeant, Mann, Sinclair, et al. 2008). Deleterious effects on confidence and self-esteem were also reported (Lizzio and Wilson 2008). This is notable as, from a theoretical perspective, there are multiple proposals for why negative valence emotions interact profoundly with feedback. It is challenging to receive data that may counter one’s self-assessment (Porter et al. 1974; Mann et al. 2011). It suggests that the learner needs to balance the tension of feedback supporting learning with the threat it presents to self-perception. Conversely, feedback can function to temper a learner’s subjective reaction. Evaluation is emotionally charged and feedback may offer a more balanced view than the self-assessment of an anxious learner (Munro and Hollingworth 2014).

[감정적 비용]은 [학습자의 선택을 지배]하고 향후 학습 활동을 좌우할 수 있습니다(Trope and Neter 1994). 실무 관점에서 피드백을 받는 사람에게 [감정이 미치는 영향을 고려]하는 것이 중요한 이유는 무엇일까요? 이러한 [긴장을 인정하고 공감하는 맥락을 개발하는 것]은 피드백 전달의 전제 조건입니다. 그렇지 않으면 교수자는 학습자가 피드백을 잘 받아들이지 않을 뿐만 아니라 피드백을 회피할 위험이 있습니다. 학습자는 [수정 피드백을 요청하거나 받을 준비]가 되기 전에 [일정 수준의 편안함, 경험 및 자신감]을 경험해야 합니다(Eva 외. 2012). 학습자는 처음 감정을 표출한 후 이를 극복할 수 있는 능력을 보유할 수도 있습니다(Quinton and Smallbone 2010). 예를 들어, 상호작용에서 [격려적인 대화를 제공하는 등 감독자 의존적 요인]이 피드백으로 인해 유발된 [부정적인 감정을 중재]할 수 있습니다(Lizzio and Wilson 2008). 추가 연구에 따르면 가혹하고 비판적인 피드백을 학습자가 유용하다고 생각하는 정보로 변환하는 데 있어 감독자와 수신자 간의 목표 정렬이 중요하다고 합니다(Watling et al. 2014). R2C2 모델은 대화를 포함하고 관계에 초점을 맞춤으로써 학습자가 피드백 대화에 참여하는 것을 입증했습니다(Sargeant 외. 2018). 마음챙김 감독자는 피드백 관련 감정의 건설적인 처리를 촉진할 수 있습니다. 마지막으로, 감정, 특히 부정적인 원자가는 이러한 연구에서 피드백에 대한 일반적인 반응이었지만 여전히 과소 보고되고 있을 가능성이 높습니다. 여러 연구에서 학생들이 피드백과 관련된 동기 및 정서를 관리하기 위한 수단으로 [선택적 필터링]을 채택하는 것으로 나타났습니다. 학생들은 자기 보호 필터링을 통해 이득(펌핑)을 유도하는 피드백을 선택적으로 찾고 피해를 피하기 위해 피드백을 구하는 행동을 변경했습니다(Trope and Neter 1994; Quinton and Smallbone 2010; Gaunt, Patel, Rusius 외. 2017).