졸업후의학교육에서 역량중심의학교육(Med Teach, 2010)

Competency-based medical education in postgraduate medical education

WILLIAM F. IOBST1, JONATHAN SHERBINO2, OLLE TEN CATE3, DENYSE L. RICHARDSON4, DEEPAK DATH5, SUSAN R. SWING6, PETER HARRIS7, RANI MUNGROO8, ERIC S. HOLMBOE9 & JASON R. FRANK10, FOR THE INTERNATIONAL CBME COLLABORATORS

소개

Introduction

현재의 대학원 의학교육(PGME)은 [100년 전 존스 홉킨스의 오슬러, 할스테드 등이 설립한 이후 본질적으로 변하지 않았다는 비판]을 받아왔습니다. 그러나 의사가 실무에 투입될 수 있도록 준비하는 기간인 레지던트 교육은 1990년대 초부터 조용한 혁명을 겪어왔습니다. 1993년 영국에서 '내일의 의사'가 출범하면서(General Medical Council 1993, 2009) 의학교육의 기본 틀이 [시간 및 과정 기반 프레임워크]에서 [역량 기반 모델]로 전환되기 시작했습니다. 이러한 패러다임 전환에 대한 국제적인 수용은 이후 발표된

- CanMEDS 프레임워크(Frank 2005; Frank & Danoff 2007),

- The Scottish Doctor(Simpson et al. 2002; Scottish Deans' Medical Curriculum Group 2009),

- ACGME 성과 프로젝트(Swing 2007; Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education 2009a,b),

- Good Medical Practice(General Medical Council 2006),

- 호주 전공의 교육과정 프레임워크(Graham 외. 2007),

- 네덜란드 학부 의학교육 2009년 프레임워크(Van Herwaarden 외. 2009) 등이 발표되었습니다.

Postgraduate medical education (PGME), it its current form, has been criticized as being essentially unchanged from its founding by Osler, Halsted, and others at Johns Hopkins a century ago. However, residency education – the period of training that prepares physicians to enter practice – has undergone a quiet revolution since the early 1990s. With the launch of Tomorrow's Doctors in the United Kingdom in 1993 (General Medical Council 1993, 2009), the framework guiding medical education began to shift from a time- and process-based framework to a competency-based model. International acceptance of this paradigm shift is reflected by the subsequent release of

- the CanMEDS framework (Frank 2005; Frank & Danoff 2007),

- The Scottish Doctor (Simpson et al. 2002; Scottish Deans’ Medical Curriculum Group 2009),

- the ACGME Outcomes Project (Swing 2007; Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education 2009a,b),

- Good Medical Practice (General Medical Council 2006),

- the Australian Curriculum Framework for Junior Doctors (Graham et al. 2007), and

- the 2009 Framework for Undergraduate Medical Education in the Netherlands (Van Herwaarden et al. 2009).

역량 기반 교육으로의 전환은 이제 막 시작되었지만 관심이 커지고 있습니다. 이제 [규제 기관]은 기대치의 일부로 역량 달성에 대한 증명을 요구하고 있으며, 일부 국가에서는 이 요구사항이 인증 절차를 안내하고 있습니다. 오슬러의 '고등 의학교육 신학교'에 첫 수련의가 입학한 지 한 세기가 지난 지금, 역량 기반 의학교육(CBME)은 21세기 대학원 의학교육(PGME)을 정의하는 프레임워크가 될 것으로 기대됩니다. 이 백서에서는 PGME에 대한 역량 기반 접근 방식의 근거와 시사점, 장점과 과제, 역량 기반 비전을 실현하는 데 필요한 변화를 검토합니다.

Although the move to competency-based training has just begun, interest is growing. Regulatory organizations now require demonstration of attainment of competency as part of their expectations; in some countries, this requirement now guides accreditation processes. A century after the first trainees entered Osler's “seminary of higher medical education,” competency-based medical education (CBME) promises to become the defining framework for postgraduate medical education (PGME) in the 21st century. In this paper, we review the rationale and the implications of a competency-based approach to PGME, its advantages and challenges, and the changes needed to realize a more competency-based vision.

레지던트 교육을 개혁해야 하는 이유는 무엇인가요?

Why reform residency education?

전 세계적으로 레지던트 교육이 성공적으로 성장하지 않았다면 현대 의학 및 진료의 놀라운 성공은 불가능했을 것입니다. 이제 의과대학 졸업 후 실습 준비를 위한 집중적인 임상 교육은 [필수적인 과정]으로 여겨지고 있습니다. PGME는 이제 수천 명의 교사와 학습자가 지속적인 활동에 참여하는 거대한 전문 기업으로 성장했습니다. 오늘날의 의사들은 역사상 가장 높은 수준의 교육을 받았습니다. 그렇다면 [왜 PGME에 대한 새로운 접근 방식]을 고려해야 할까요? 현재 시스템의 약점은 만연한 시간 기반 패러다임에 있습니다. 전 세계적으로 레지던트 커리큘럼을 성공적으로 이수했는지 여부를 [습득한 능력이 아니라 로테이션에 소요된 시간으로 인식하는 경향]이 있습니다(Carraccio 외. 2002). 모든 졸업생이 진료에 대비할 수 있도록 보다 신뢰할 수 있는 방법을 찾는 것이 바로 CBME의 동기입니다.

Arguably, the incredible successes of modern medical science and practice would not have been possible without the successful growth of residency education worldwide. Intensive clinical training in preparation for practice is now considered imperative after medical school. PGME is now an enormous professional enterprise engaging thousands of teachers and learners in continuous activity. Today's physicians are the most highly educated in history. So why should we consider a new approach to PGME? The weaknesses of our current system lie in its pervasive time-based paradigm. Worldwide, there is a tendency to recognize the successful completion of a residency curriculum as time spent on rotations, as opposed to abilities acquired (Carraccio et al. 2002). Here lies the motivation for CBME: to find a more reliable way to ensure that every graduate is prepared for practice.

역량 기반 PGME란 무엇인가요?

What is competency-based PGME?

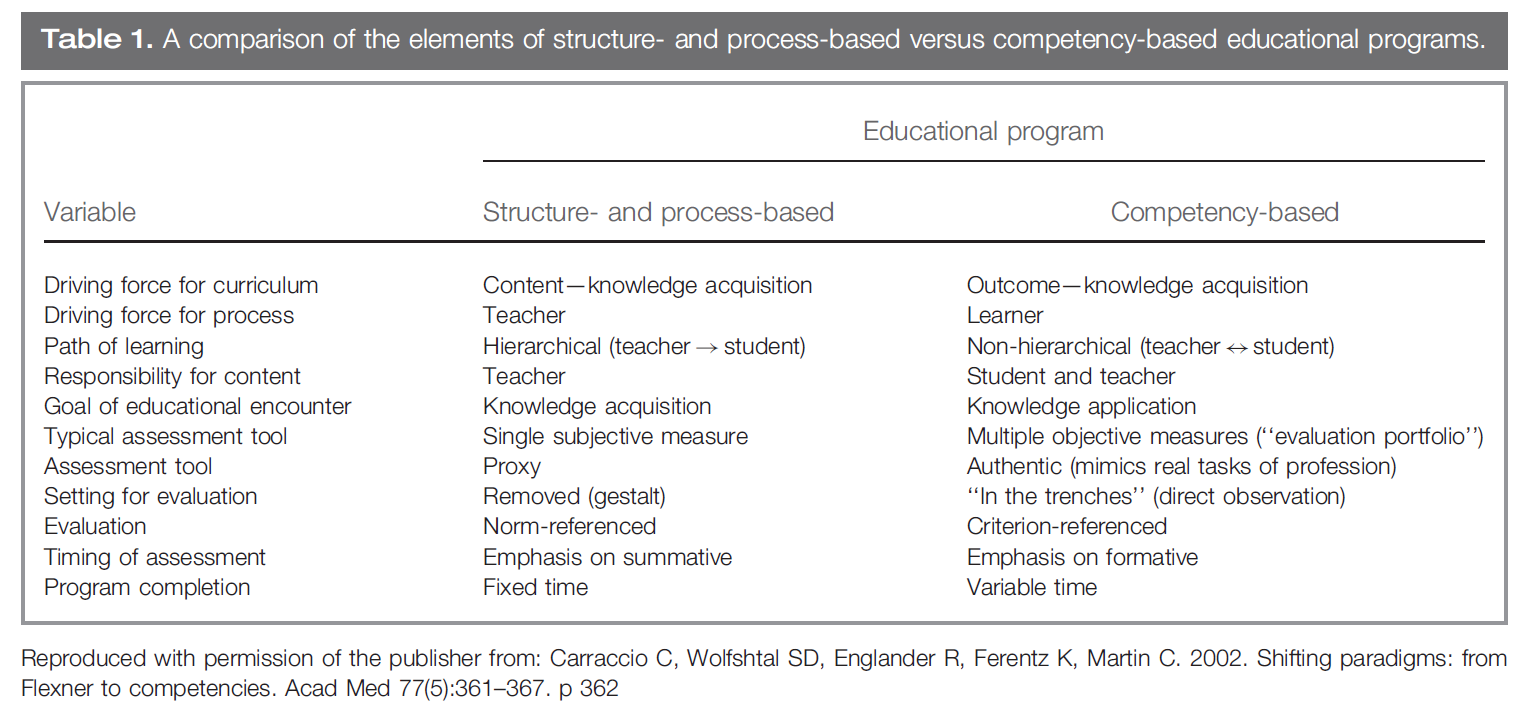

이 주제 호의 다른 부분(Frank 외. 2010)에서 자세히 설명했듯이, CBME는 교육 성과에 초점을 맞춥니다. 역량 기반 레지던트 패러다임에서 프로그램은 [새로 수련받은 의사]가 [진료의 모든 측면에 대해 유능하다는 것을 입증]해야 합니다. 이 접근 방식은 교사나 프로그램이 [어떻게 가르쳐야 하는지] 또는 학생이 그 목표를 달성하는 동안 [어떻게 배워야 하는지]를 규정하지 않습니다. 오히려 역량 기반 교육은 바람직한 [졸업생 능력을 명시적으로 정의]하고 이러한 [결과가 커리큘럼, 평가 및 평가의 개발을 가이드]할 수 있도록 합니다. 따라서 레지던트를 위한 CBME는 [정해진 기간을 강조하지 않고], 모든 필수적인 실무 측면에서 [이정표에서 이정표로 역량이 발전하도록 장려]합니다. 또한 CBME는 커리큘럼 목표인 지식뿐만 아니라 능력 추구에 있어서, [새로운 교육 방법], [경험 순서를 구성하는 데 있어 더 큰 유연성], [더 빈번한 평가], [전문 교수진의 의미 있는 감독], [교사와 수련의 모두의 더 큰 참여]를 요구합니다. 역량 기반 레지던트 교육은 수년간 임상 서비스를 제공하는 동안 [단순히 기회주의적인 학습]이 아니라 설계 단계부터 역량을 고려한 교육입니다. Carraccio와 공동 저자(2002)는 교육에 대한 접근 방식에서 CBME 패러다임 전환의 요소를 설명했습니다(표 1 참조).

As elaborated elsewhere in this theme issue (Frank et al. 2010), CBME focuses on educational outcomes. In a competency-based residency paradigm, programs must demonstrate that the newly trained physician is competent for all aspects of practice. This approach does not prescribe how the teacher or program must teach or how the student must learn while achieving that goal. Rather, competency-based training explicitly defines desired graduate abilities and allows those outcomes to guide the development of curricula, assessment, and evaluation. CBME for residency therefore de-emphasizes fixed time periods and promotes the progression of competence from milestone to milestone in all of the essential aspects of practice. CBME also calls for new instructional methods, greater flexibility in organizing the sequence of experiences, more frequent assessment, meaningful supervision by expert faculty, and greater engagement of both teachers and trainees in the pursuit of abilities – not just knowledge – as the curricular goal. Competency-based residency education is competence by design, not merely opportunistic learning during years of providing clinical service. Carraccio and co-authors (2002) have described the elements of the CBME paradigm shift in the approach to training (see Table 1).

CBME의 커리큘럼 재조정

Realigning curricula in CBME

[전통적인 의학 대학원 교육]은 [기간과 커리큘럼 프로세스]를 중심으로 구성됩니다.

- 이는 '체류 시간'으로 정의되는 [기회주의적 접근 방식]으로, 정해진 기간 동안 개별 활동에 지정된 개월 수가 할당됩니다.

- [평가]는 학습자가 [특정 지식을 습득]했는지 여부를 명백하게 입증하는 데 중점을 두고, [기술과 태도의 습득]에 초점을 맞추는 경우가 훨씬 적습니다.

- [프로그램 평가]는 [과정의 문제(예: "모든 로테이션에 대한 목표가 있는가?" 또는 "교사 평가 양식이 있는가?")]에 초점을 맞추는 경향이 있습니다.

- [대다수의 학습자]는 [시간, 프로세스 및 커리큘럼 요건]을 충족하여 성공적으로 교육을 이수합니다.

- [이러한 요건이 충족]되면 학습한 내용을 실제 환자 진료에 적용할 수 있는 능력이 있는 것으로 [간주]되며, [실제로 해당 학습 내용을 의료 서비스 제공에 적용하는지 여부]는 평가하지 않습니다.

Traditional graduate medical education is structured around time frames and curricular processes.

- It is an opportunistic approach defined by “dwell time,” whereby a specified number of months is assigned to discrete activities over prescribed periods.

- To a large extent, assessment focuses overtly on demonstrating whether the learner has acquired specific knowledge; to a much lesser extent, it focuses on the acquisition of skills and attitudes.

- Program evaluation tends to focus on matters of process (e.g., “Are there objectives for every rotation?” or “Is there a teacher evaluation form?”).

- The vast majority of learners successfully complete their training by meeting time, process, and curricular requirements.

- When those requirements are met, the ability to apply what is learned to the actual delivery of patient care is assumed, without actually assessing whether the application of that learning to health care delivery occurs.

이와 대조적으로 역량 기반 교육은 의료 업무에 필요한 특정 [지식, 기술 및 태도의 적용을 성공적으로 입증하는 것]을 기반으로 합니다.

- 수련 내에서 진급을 위해서는 학습자가 [주요 발달 단계에서 역량을 입증]해야 합니다.

- 커리큘럼, 평가 도구 및 평가 시스템은 이러한 결과를 [달성하고 문서화]하기 위해 개발되었습니다.

- 이 수준의 평가와 평가는 실제 의료 서비스를 제공하는 동안 이루어져야 합니다. [밀러의 평가 피라미드]는 이 과정을 개념화합니다(1990). 이 모델에서 평가는 학습자가 "알고, 방법을 알고, 방법을 보여주거나, 할 수 있다"는 것을 입증할 수 있는 능력에 초점을 맞춥니다.

- 평가의 유형은 평가 대상 역량과 학습자의 학습 단계에 적합해야 하지만, CBME는 궁극적으로 이 피라미드의 맨 꼭대기에서 평가해야 합니다.

- 이를 위해서는 학습자가 [안전하고 효과적인 환자 치료를 제공할 수 있는 능력을 입증]해야 하며, 이는 [직접 관찰]을 통해 가장 잘 이루어집니다.

In contrast, competency-based training is based on the successful demonstration of the application of the specific knowledge, skills, and attitudes that are required for the practice of medicine.

- Progression in training requires that the learner demonstrate competence at critical stages of development.

- The curriculum, assessment tools, and evaluation system are developed to achieve and document this outcome.

- Assessment and evaluation at this level must occur during the actual delivery of care. Miller's pyramid of assessment conceptualizes this process (1990). In this model, assessments are directed at learners’ ability to demonstrate that they either “know, know how, show how, or do.”

- Although the type of assessment must be appropriate to the competency being assessed and to the learner's stage of learning, CBME ultimately requires assessment at the very top of this pyramid.

- This requires that learners demonstrate the ability to provide safe and effective patient care and is best accomplished through direct observation.

CBME는 [교육 또는 전문 경력]의 [다음 단계]로 나아가기 위한 [역량을 입증]해야 합니다.

- PGME 수준의 학습자 대부분은 궁극적으로 직접 환자 치료를 제공하게 되므로, 이들의 [평가 및 평가]는 [실제 치료 제공에 필요한 능력에 초점]을 맞추어야 합니다.

- [역량 임계값]은 평가자와 교육생 모두가 [명확하게 정의하고 이해]해야 하며, 교육생의 역량 여부를 신뢰성 있게 판단하기 위해서는 [평가가 정확]해야 합니다.

- 순수한 역량 기반 교육 프레임워크에서 [효과적인 평가를 해야]만 성공적인 역량 입증에 기반하여 학습자가 프로그램에서 [각기 다른 속도로 진급]할 수 있도록 합니다. 어떤 학습자는 더 빨리 발전하고 어떤 학습자는 더 느리게 발전할 수 있습니다.

- 이를 위해서는 [학습의 안내] 및 [평가 및 평가에 정보 제공]을 위하여 학습자에게 [교육 전반에 걸쳐 명확하게 정의된 목표]가 있어야 합니다. Green과 동료들이 개발한 내과 레지던트 교육에 대한 발달 이정표(2009)는 이러한 목표를 정의하는 방법의 한 예입니다.

- 이러한 [이정표]는 개별적인 행동 또는 발달의 중요한 지점을 설명하며, 이를 충족하면 평가자와 프로그램은 학습자가 진정으로 다음 단계의 교육으로 진행할 준비가 되었다는 것을 알 수 있습니다.

CBME requires the demonstration of competence to advance in training or to the next phase of a professional career.

- Because most learners at the PGME level will ultimately provide direct patient care, their assessment and evaluation should focus on the abilities needed for the actual delivery of that care.

- Competence thresholds must be clearly defined and understood by both assessor and trainee, and assessment must be accurate in order to reliably determine whether the trainee is competent.

- In a pure competency-based training framework, effective assessment would allow the learners to advance in a program at different rates on the basis of the successful demonstration of competency. Some learners would advance more quickly; others, to a point, would advance more slowly.

- This requires that learners have clearly defined targets throughout training to guide learning and inform assessment and evaluation. The developmental milestones for Internal Medicine residency training developed by Green and associates (2009) are one example of how these targets can be defined.

- These milestones describe discrete behaviours or significant points in development that, when met, allow evaluators and programs to know that a learner is truly ready to progress to the next stage of training.

교수자-학습자 관계 및 책임

Teacher-learner relationship and responsibilities

[전통적인 레지던트 교육 설계]에서는 학습이 [교사 주도]로 이루어집니다. [역량 기반 교육]에서는 [교사와 학습자 간에 책임이 공유되는 협업 과정]입니다.

- 이러한 협업을 위해서는 [학습자가 학습 계획을 결정하는 데 적극적으로 참여]해야 하며, 교사는 [빈번하고 정확한 형성 피드백을 제공]해야 합니다(Westberg & Hilliard 1993).

- 학습자에게 요구되는 핵심 기술에는 [자기 주도적 평생 학습, 자기 성찰 및 자기 평가]가 포함됩니다.

- Epstein과 동료들(2008)은 자기 평가를 "자신의 성과에 대한 데이터를 해석하고 이를 명시적 또는 암묵적 표준과 비교하는 과정"이라고 설명했습니다.

- 그러나 자기 평가는 성공적이고 지속적인 진료 개선, 우수성에 대한 헌신, 자기 모니터링에 매우 중요하지만, 많은 연구에서 [수련 중인 의사가 부정확한 자기 평가를 한다]는 사실이 입증되었습니다(Hodges 외. 2001; Davis 외. 2006).

- 자기평가는 [전문가 역할 모델] 또는 [수행의 모범]을 [수행 기준으로 사용]하거나, [여러 정보 소스를 사용]하여 완료하는 것이 가장 좋으며, [단독으로 완료해서는 안 됩니다].

- 후자는 학습자가 [외부 소스로부터 피드백]을 구하는 데 책임을 지고, 그 정보를 사용하여 "자기 주도적 평가 추구"라고 부르는 프로세스에서 [성과 개선을 안내하는 데 사용]하도록 요구합니다(Eva and Regehr, 2008).

- 이러한 [외부 정보 소스]의 예로는 다음 등이 있습니다.

- 여러 참관인으로부터 받은 피드백,

- 교육 중 시험 결과,

- 시뮬레이션 수행 결과

- 실습 감사에서 수집한 데이터

- 그러나 [교수진의 피드백]은 이러한 정보의 중요한 원천이며, 학습자를 [직접 관찰]해야 합니다. CBME 프레임워크에서 [교사와 학습자 간의 역동적인 상호 작용]은 이 과정을 분명히 촉진할 수 있습니다.

- 이러한 책임을 다하기 위해 프로그램은 [안전한 학습 환경]을 조성하고, 모든 참가자의 역할과 기대치를 명확하게 정의해야 합니다.

In a traditional residency design, learning is teacher driven. In competency-based training, it is a collaborative process in which responsibility is shared between teacher and learner.

- This collaboration requires that the learner be an active participant in determining a learning plan, and that the teacher provide frequent and accurate formative feedback (Westberg & Hilliard 1993).

- Critical skills required of the learner include self-directed and lifelong learning, self-reflection, and self-assessment.

- Epstein and colleagues (2008) have described self-assessment as “the process of interpreting data about our own performance and comparing them to an explicit or implicit standard.”

- However, although self-assessment is critical to successful and continuous practice improvement, commitment to excellence, and self-monitoring, many studies have demonstrated that physicians-in-training are inaccurate self-assessors (Hodges et al. 2001; Davis et al. 2006).

- Self-assessment is best completed using expert role models or exemplars of performance as performance criteria, or, alternatively, multiple information sources, and should not be completed in isolation.

- The latter requires that the learner take responsibility for seeking feedback from external sources and use that information to guide performance improvements in a process that Eva and Regehr (2008) have called “self-directed assessment seeking.”

- Examples of such external sources of information could include

- feedback solicited from multiple observers,

- in-training exam results,

- outcomes of simulation performance, and/or

- data gleaned from a practice audit.

- Feedback from faculty is, however, a critical source of such information and requires direct observation of the learner. The dynamic interaction between teacher and learner in a CBME framework can clearly facilitate this process.

- To meet this responsibility, programs must create safe learning environments and clearly define roles and expectations for all participants.

또한 CBME는 프로그램이 [적절한 학습자 감독]을 보장하도록 요구합니다.

- 레지던트 근무시간에 관한 미국의학연구소의 보고서(2008)에서 권고한 바와 같이 인증기관, 후원기관, 수련 프로그램은 각 수련자의 수준과 전문성에 적합한 [측정 가능한 감독 기준]을 수립해야 합니다.

- 전통적으로 선임 학습자는 교육 기간 동안 더 많은 책임감을 가지고 후배 학습자를 가르치고 감독합니다. 교수진의 감독이 제한적으로 이루어지는 경우가 많습니다.

- 이러한 활동(교수진 슈퍼비전)은 학습자의 전문성 개발에 매우 중요한 것으로 간주되며, [학습 공동체]와 [수련 프로그램 문화]의 중요한 구성 요소로 여겨집니다(미국 내과학회 2009).

- 그러나 해당 분야의 전문가가 아닌 개인에 의한 코칭의 이점에 의문을 제기한 Ericsson과 동료들(1993)의 연구에도 불구하고, 상급 학습자가 하급 학습자를 감독하는 것은 상급 학습자가 실제로 감독을 제공할 수 있는 능력이 있는지에 대한 적절한 평가 없이 이루어지는 경우가 종종 있습니다.

- 또한, 교육 프로그램은 동료 학습자가 어려움에 처한 상황을 파악하고 해결하기 위해 학습자에게 지나치게 의존해서는 안 됩니다. [모든 수준의 학습자를 위한 적절한 슈퍼비전]은 학습을 풍부하게 하는 동시에 안전하고 효과적인 환자 치료를 제공할 수 있도록 보장할 수 있습니다.

CBME also requires that programs ensure adequate learner supervision.

- As recommended in the Institute of Medicine's report on resident work hours (2008), accrediting organizations, sponsoring institutions, and training programs should establish measurable standards of supervision for each trainee appropriate to his or her level and specialty.

- Traditionally, senior learners teach and supervise junior learners with increasing responsibility during training. Frequently, this occurs with limited faculty supervision.

- This activity is seen as critical to the learner's professional development and is believed to be a vital component of the learning community and culture of training programs (American Board of Internal Medicine 2009).

- However, despite work by Ericsson and colleagues (1993) that has called into question the benefit of coaching by individuals who themselves are not experts in the field, supervision of junior learners by advanced learners often occurs without adequate assessment of whether the more senior learner is actually competent to provide supervision.

- Moreover, training programs should not be overly dependent on learners to identify and remediate situations where peer learners are in difficulty. Appropriate supervision for all levels of learners can enrich learning while at the same time ensuring the delivery of safe and effective patient care.

평가에 대한 접근 방식

Approaches to assessment

[평가 프로세스]는 [학습자가 수련과정을 progress]하거나 [practice을 시작할 준비]가 되었는지에 대한 정보를 생성하는 데 사용되는 방법, 도구 및 프로세스로 구성됩니다. [평가Evaluation]는 커리큘럼의 유용성과 관련하여 이러한 데이터를 판단하거나 해석하는 것을 말합니다. 이번 호의 다른 곳에서 Holmboe와 동료들(2010)이 설명한 것처럼, CBME에는 [향상된 평가 도구와 프로세스]가 필요합니다.

The process of assessment comprises the methods, tools, and processes used to generate information about learners’ readiness to progress in training or start practice. Evaluation refers to the judgment or interpretation of those data as they relate to the utility of a curriculum. As described by Holmboe and colleagues (2010) elsewhere in this issue, CBME requires enhanced assessment tools and processes.

역량 기반 교육을 성공적으로 구현하려면 [모든 교수진]이 [역량 기반 실습을 이해하고 모범]을 보여야 합니다. 또한 교수진은 [커리큘럼 개발에 적극적으로 참여]해야 합니다. [평가 및 평가를 위해서는] 교수진이 의료 서비스를 제공하는 실습생을 [직접 관찰하는 구체적인 기술]을 개발해야 합니다. 시뮬레이션은 시간이 지남에 따라 역량 평가에서 점점 더 중요한 역할을 하게 될 것이지만, 학습자가 [진료를 제공하는 것을 직접 관찰하는 것]은 [평가 및 평가 프로세스의 초석]으로 남아 있을 것입니다. Carraccio와 동료들(2002)이 지적했듯이, 역량 기반 교육 및 훈련에는 직접 관찰이 필요하고 형성 평가의 빈도와 질이 높아지기 때문에 [교수진의 더 많은 참여가 필요]합니다.

The successful implementation of competency-based training will require that all faculty understand and model competency-based practice. Faculty must also be actively involved in curriculum development. Assessment and evaluation will require that faculty develop specific skills in the direct observation of trainees delivering care. Although simulation will likely play an increasingly important role in competency assessment over time, the direct observation of learners providing care will remain a cornerstone of assessment and evaluation process. As Carraccio and colleagues (2002) have noted, competency-based education and training requires greater involvement by faculty because of the need for direct observation and increased frequency and quality of formative assessment.

[환자를 면담하고, 진찰하고, 상담하는 기본 기술]은 효과적인 환자 치료에 필수적입니다. [직접 관찰]을 통해 이러한 기술을 평가하는 것은 [모든 역량 기반 평가 시스템에서 매우 중요한 부분]입니다. 안타깝게도 [대부분의 교수진]은 [신뢰할 수 있고 유효한 방식으로 직접 관찰을 수행할 준비]가 되어 있지 않습니다. 여러 연구에 따르면 많은 실무 의사와 교수진이 이러한 [(직접관찰)기술을 수행할 능력이 부족하다는 사실]이 입증되었습니다. 교수진은 이러한 [술기의 필수 구성 요소]를 배워야 할 뿐만 아니라, 이러한 술기를 수행하는 [학습자에 대한 유효하고 신뢰할 수 있는 평가를 제공하는 방법]도 배워야 합니다. 다행히도 수행 평가 문헌에 따르면 교수자 개발은 평가 오류를 줄이고 변별력을 개선하며 평가의 정확성을 향상시킬 수 있다고 합니다(이번 호의 Dath & Iobst 2010 참조).

The basic skills of interviewing, examining, and counselling patients are essential to effective patient care. Evaluating these skills using direct observation is a critical part of every competency-based evaluation system. Unfortunately, most faculty are not prepared to perform direct observation in a reliable and valid fashion. Multiple studies have demonstrated that many practising physicians and faculty members are not competent to perform these skills. Faculty must not only learn the essential components of these skills, but must also learn how to deliver valid and reliable evaluations of learners performing these skills. Fortunately, the performance appraisal literature suggests that faculty development can reduce rating errors, improve discrimination, and improve the accuracy of evaluation (see Dath & Iobst 2010, in this issue).

[직접 관찰을 위한 효과적인 교수자 개발]은 궁극적으로 프로그램 수준에서 평가의 신뢰성과 타당성을 향상시킬 수 있는 [직접 관찰에 대한 공유된 정신 모델 또는 이해 수준을 만드는 것]을 목표로 해야 합니다. 이러한 평가자 교육은

- [관찰할 역량의 필수 요소]에 대한 합의를 얻고,

- [해당 역량을 평가하는 기준을 표준화]하며,

- [관찰 빈도를 높이기 위한 전략을 개발]하는 데 중점을 두어야 합니다(Holmboe 2008).

Effective faculty development for direct observation must aim to create a shared mental model or level of understanding about direct observation that will ultimately enhance the reliability and validity of assessment at the program level. Such rater training should seek to gain agreement on the essential elements of the competency to be observed, standardize criteria for rating that competency, and develop strategies to increase the frequency of observations (Holmboe 2008).

일부에서는 CBME가 [의료 행위]를 [객관적으로 관찰 가능한 기준의 항목별 목록]으로 [축소reduce]한다고 주장하기도 합니다(Brooks 2009). 다른 사람들(Grant 1999)은 역량 [전체가 개별 부분보다 더 크며], 궁극적으로 환자 치료 제공에 있어 [역량의 입증]은 플레밍(1993)이 [메타 역량]으로 묘사한 것을 나타낸다고 관찰합니다.

- [메타역량]의 개념은 [실제 의료 환경에서 [안전하고 효과적인 진료]에 필요한 개인의 [지식, 기술, 태도]뿐만 아니라 [문화적, 사회적 맥락]의 복합적인 조합]을 인식합니다.

- 이러한 메타 역량을 평가하려면 다음이 필요합니다.

- 타당하고 신뢰할 수 있는 [다차원 평가],

- 여러 [데이터 포인트],

- 평가 정보를 [수집, 처리 및 조치]할 수 있는 강력한 시스템

- 신뢰할 수 있고 타당한 [메타역량 평가]를 위해서는 교수진 평가자가 [환자 치료 제공에 대한 깊은 지식과 경험]을 가지고 있어야 합니다.

- 또한 모든 참여자가 메타역량 평가가 [단순히 목록에 있는 항목에 체크하는 것 이상의 것]을 필요로 한다는 점을 이해해야 합니다.

- 메타 역량을 입증하려면 평가가 [유사한 상황에서 유능하게 수행할 수 있는 능력]을 다루어야 하며,

- 관찰된 성과를 [직접 평가하지 않은 실제 상황에서의 성과로 추정]할 수 있어야 합니다(Williams 외. 2003).

Some have argued that CBME reduces the practice of medicine to itemized lists of objective observable criteria (Brooks 2009). Others (Grant 1999) observe that the whole of competence is greater than its individual parts and that, ultimately, the demonstration of competence in the delivery of patient care represents what Fleming (1993) has described as meta-competency.

- The concept of meta-competency recognizes the complex mix of individual knowledge, skills, and attitudes, as well as cultural and social contexts, required for safe and effective practice in actual health care environments.

- Assessing such meta-competencies requires

- valid and reliable multi-dimensional assessment,

- multiple data points, and

- a robust system for collecting, processing, and acting on evaluation information.

- Reliable and valid meta-competency evaluation requires that faculty evaluators have deep knowledge and experience in the delivery of patient care.

- This also requires that all participants understand that the evaluation of meta-competency requires more than simply checking off items on a list. Attesting to meta-competency will require

- that evaluation addresses the ability to competently perform in a universe of similar situations and

- that observed performance can be extrapolated to performance in practice situations that are not directly evaluated (Williams et al. 2003).

절차적 교육을 제외하고 [전통적인 의학교육 모델]에서는 레지던트 평가에서 [직접 관찰 능력]을 우선시하지 않았습니다. 이 프레임워크의 [기본 평가]는 일반적으로 교육 경험 과정에서 개발된 [게슈탈트 평가]에 기반한 [로테이션 종료 시 평가]입니다.

With the exception of procedural training, the traditional model of medical education has not prioritized direct observation skills in residency evaluation. The foundational evaluation in this framework is typically end-of-rotation evaluation based on a gestalt evaluation developed over the course of the educational experience.

기준 참조 평가

Criterion-referenced assessment

[지식 적용에 대한 타당하고 신뢰할 수 있는 평가]는 CBME에서 매우 중요합니다. 이를 위해서는 [규범을 참조하는 평가 기준]이 아닌 [기준을 참조하는 평가 기준]이 필요합니다.

- [규범 참조 평가]에서는 평가자가 [즉각적이고 사용 가능한 학습자의 성과]를 사용하여 기준을 설정합니다. 이 접근 방식은 성과를 과대 평가하거나 과소 평가할 위험이 있습니다.

- [기준 참조 평가]에서는 [미리 정해진 기준]이 평가에 영향을 줍니다. 최근에 발표된 [내과 마일스톤]이 이러한 기준의 예입니다. 이러한 마일스톤은 [행동 기반]이며 레지던트가 프로그램에서 발전하고 [커리어의 다음 단계로 진입하는 데 필요한 지식, 기술 및 태도를 습득할 수 있도록 기준]을 제시합니다.

그러나 이러한 [이정표]는 기준을 참조한 평가에 정보를 제공할 수 있지만, "one size fits all" 평가 시스템을 의무화하지는 않습니다. 각 프로그램은 [고유한 임상 환경과 자원을 기반]으로 [기준 참조 평가를 촉진하는 평가 시스템]을 개발해야 합니다.

The valid and reliable assessment of knowledge application is critical in CBME. This requires criterion-referenced rather than norm-referenced standards of assessment.

- In norm-referenced evaluation, the evaluator uses the performance of immediate and available learners to establish criteria. This approach risks either overrating or underrating performance.

- In criterion-referenced evaluation, predetermined criteria inform evaluation. The recently released Internal Medicine Milestones are an example of such criteria. These milestones are behaviourally based and offer criteria to ensure that residents acquire the knowledge, skills, and attitudes necessary for advancing in their program and for entering the next phase of their careers.

However, while such milestones can inform criteria referenced evaluation, they do not mandate a “one size fits all” assessment system. Programs will need to develop assessment systems that facilitate criterion-referenced evaluation based on their unique clinical environment and resources.

평가 시기

Timing of assessment

평가는 [형성 평가] 또는 [총괄 평가]를 제공할 수 있습니다. 역량 기반 교육 시스템에서 [피드백을 제공하는 형성 평가]는 [학습자의 교육 과정 참여를 유도]하는 데 필수적입니다. 교육생은 형성 평가/피드백을 [받는 데 익숙]해져야 하며, 교수진은 이를 [자주 제공]해야 합니다. 프로그램은 이 과정을 위한 [안전한 교육 환경]을 조성하고 평가 및 피드백 제공을 위한 [다양한 기회]를 만들어야 합니다. 현재 대부분의 프로그램 평가 시스템에서 형성 평가를 자주 실시하는 것은 중요한 구성 요소가 아닙니다. 일반적인 로테이션 종료형 게슈탈트 평가는 실제 교육 경험과 시간적으로 근접한 시점에 제공되지 않기 때문에 학습자에게 즉각적이고 직접적인 피드백을 제공하는 데 성공할 수 없습니다.

Assessment can provide either formative or summative evaluation. In a competency-based education system, formative assessment that provides feedback is essential to guiding the learner's participation in the educational process. Trainees must become comfortable seeking formative assessment/feedback, and faculty must offer it frequently. Programs will need to cultivate a safe educational environment for this process and to create multiple opportunities for assessment and the delivery of feedback. Frequent formative assessment is currently not a significant component of most program evaluation systems. The typical end-of-rotation gestalt evaluation is not delivered in close temporal proximity to the actual educational experience, and so cannot succeed in providing immediate, direct feedback to the learner.

유연한 교육 기간

Flexible duration of training

CBME의 가장 큰 특징은 학습자가 입증된 능력에 따라 [자신의 속도에 맞춰 학습을 진행]한다는 것입니다. 안타깝게도 현재 널리 사용되고 있는 PGME의 구조는 여러 수준에서 순수한 역량 기반 교육 시스템의 도입을 어렵게 만듭니다. 옳든 그르든, 프로그램 디렉터들은 프로그램과 레지던트가 [점진적인 독립성]을 허용하면서 구조와 어느 정도의 감독이 필요한 성숙 과정을 통해 이익을 얻을 수 있다고 믿습니다(미국 내과학회 2009). 또한 이 과정에는 모든 학습자에게 [정해진 최소 교육 기간]이 필요하다고 생각합니다. 역량 기반 모델로 전환하면 [일부 레지던트의 조기 승진]과 [다른 레지던트의 승진 지연]으로 인해 이 과정이 중단될 위험이 있습니다. 그러나 [숙련된 학습자]는 역량을 입증하는 대로 진급해야 합니다. 한도 내에서 CBME는 [학습에 어려움을 겪는 학습자]에게도 구조화된 학습 환경에서 적절한 시간을 제공해야 합니다. 또한 CBME는 학습자가 특정 영역에서는 성취하고 다른 영역에서는 도전할 수 있음을 인식해야 합니다. 그러나 프로그램 졸업생이 안전하고 효과적인 환자 치료를 제공할 수 있도록 하기 위해서는 어떤 학습자도 [성급하게 시스템을 통과하도록 해서는 안 되며], 모든 학습자에게 원하는 역량을 개발할 수 있는 적절한 시간이 주어져야 합니다. 마지막으로, 현재의 PGME 자금 지원 시스템은 고정된 교육 기간을 기반으로 하고 있으며, [역량 기반의 유연한 시간 모델을 위한 자금 지원 전략]은 아직 제안되지 않았습니다. CBME가 발전하기 위해서는 전체 시스템의 재설계가 필요합니다. 이를 위해서는 교육 과정의 모든 수준에서 변화가 필요합니다.

A key distinguishing feature of CBME is that learners progress at their own rate in accordance with demonstrated ability. Unfortunately, the prevailing structure of PGME makes the adoption of a pure competency-based training system challenging at many levels. Rightly or wrongly, program directors believe that programs and residents benefit from a maturation process that requires structure and some degree of supervision while allowing for progressive independence (American Board of Internal Medicine 2009). They also believe that this process requires a fixed minimum period of training for all learners. Moving to a competency-based model risks disrupting this process by virtue of the early advancement of some residents and the delayed advancement of others. However, accomplished learners should advance as they demonstrate competence. Within limits, CBME should also provide appropriate time in structured learning environments for challenged learners. CBME must also recognize that a learner may be accomplished in certain domains and challenged in others. However, to ensure that program graduates can provide safe and effective patient care, no learner should be prematurely pushed through the system, and every learner should be given appropriate time to develop the desired competency. Finally, the current system of PGME funding is based on a fixed duration of training, and strategies to fund a competency-based, flexible-time model have yet to be proposed. For CBME to advance, a redesign of the entire system will be necessary. This will require change at all levels of the educational process.

프로그램 평가를 통한 인증 재조정

Realigning accreditation with program evaluation

CBME를 지원하기 위해 [인증 요건]은 점점 더 성과에 초점을 맞추고 있습니다. 예를 들어, ACGME 인증 내과 프로그램은 이제 [레지던트 성과 데이터 또는 결과]를 [개선의 근거]로 사용하여 [데이터에 기반한 교육 프로그램 개선의 증거]를 입증해야 하며, 학습자 및 프로그램의 성과를 모두 검증하기 위해 [외부 측정]을 사용해야 합니다(ACGME 2009b). 마찬가지로, 모든 캐나다 왕립 의사 및 외과의 대학 프로그램은 전통적인 시간 기반 로테이션과 전문 분야별 역량을 모두 입증해야 합니다(인증 위원회 2006).

In support of CBME, accreditation requirements have become increasingly focused on outcomes. For instance, ACGME-accredited Internal Medicine programs must now demonstrate evidence of data-driven improvements to the training program by using resident performance data, or outcomes, as a basis for improvement, and use external measures to verify both the learner's and the program's performance (ACGME 2009b). Similarly, all Royal College of Physicians and Surgeons of Canada programs require demonstration of both traditional time-based rotations and specialty-specific competencies (Accreditation Committee 2006).

변화에 따른 레지던트 재설계

Residency redesign as change

개별 이해관계자 수준에서 역량 기반 수련 모델로의 전환은 [전문가 정체성의 극적인 재정의]가 될 수 있습니다. 많은 교수진이 역량 기반 교육이 도입되기 전에 교육을 이수했습니다. 이러한 전문가에게 CBME는 미지의 영역이며, Carraccio와 동료들(2002)이 설명한 패러다임의 변화는 교수진이 교육자로서의 전문적 정체성의 잠재적 재정의에 직면하면서 심대한 상실감을 불러일으킬 수 있습니다.

At the level of the individual stakeholder, the transition to a competency-based training model can represent a dramatic redefinition of professional identity. Many faculty completed training before the era of competency-based training. For these professionals, CBME represents uncharted waters, and the paradigm shift described by Carraccio and associates (2002) can give rise to feelings of profound loss as faculty face the potential redefinition of their professional identities as educators.

결론

Conclusion

우리는 의학전문대학원 교육 커뮤니티가 CBME로의 진화를 수용해야 한다고 믿습니다. 이러한 전환에는 여러 가지 과제를 극복해야 합니다. 역량 기반 교육 프레임워크 구현의 중요성을 이해하는 것은 변화 과정의 시작에 불과합니다. 시간 및 프로세스 기반 시스템의 기존 인프라에서 변화를 촉진하면서 학습자의 요구를 충족할 수 있는 유연성을 확보하는 것이 중요합니다. 프로그램과 교육 현장의 다양성을 고려할 때 하나의 로드맵이 모든 프로그램에 적합하지는 않습니다. 역량 기반 교육이 궁극적인 목표이지만, 전환에는 특정 역량 기반 결과뿐만 아니라 시간 및 프로세스 구성 요소를 포함하는 중간 단계의 하이브리드 프레임워크가 포함될 가능성이 높습니다. 성공적인 실행을 위해서는 교육기관 고위 경영진의 지원과 프로그램 책임자 및 지역 수준의 주요 교수진 챔피언이 제공하는 [리더십이 매우 중요]합니다. 국가 차원에서 인증 및 주요 이해관계자 조직은 CBME가 현실화될 수 있도록 [PGME 정책 개혁과 적절한 자원을 위한 로비]를 계속해야 합니다.

We believe that the graduate medical education community must embrace the evolution to CBME. This transition will involve overcoming a number of challenges. Understanding the importance of implementing a competency-based training framework is only the beginning of the process of change. Allowing for the flexibility to meet the needs of the learner while promoting change in the existing infrastructure of a time-and-process based system will be critical. Given the diversity of programs and training sites, no single road map will fit all programs. Although competency-based training is the ultimate goal, the transition will likely include intermediate hybrid frameworks containing time and process components as well as specific competency-based outcomes. The support of senior institutional administration and the leadership provided by the program director and key faculty champions at the local level will be critical to successful implementation. At the national level, accreditation and key stakeholder organizations must continue to lobby for PGME policy reform and the appropriate resources to ensure that CBME becomes a reality.

Competency-based medical education in postgraduate medical education

1American Board of Internal Medicine, USA. wiobst@abim.org

PMID: 20662576

Abstract

With the introduction of Tomorrow's Doctors in 1993, medical education began the transition from a time- and process-based system to a competency-based training framework. Implementing competency-based training in postgraduate medical education poses many challenges but ultimately requires a demonstration that the learner is truly competent to progress in training or to the next phase of a professional career. Making this transition requires change at virtually all levels of postgraduate training. Key components of this change include the development of valid and reliable assessment tools such as work-based assessment using direct observation, frequent formative feedback, and learner self-directed assessment; active involvement of the learner in the educational process; and intensive faculty development that addresses curricular design and the assessment of competency.