아너(Honors)를 위하여: 임상실습 평가와 성적에 관한 학생의 인식 다기관 연구(Acad Med, 2019)

In Pursuit of Honors: A Multi-Institutional Study of Students’ Perceptions of Clerkship Evaluation and Grading

Justin L. Bullock, MPH, Cindy J. Lai, MD, Tai Lockspeiser, MD, MHPE, Patricia S. O’Sullivan, EdD, Paul Aronowitz, MD, Deborah Dellmore, MD, Cha-Chi Fung, PhD, Christopher Knight, MD, and Karen E. Hauer, MD, PhD

[임상 실습]을 준비하려면 학생들은 광범위하고 빠르게 확장되는 기술과 지식을 습득해야 합니다.1 동시에, 학생들은 특히 특정 전문과목에서 레지던트 자리를 차지하기 위한 경쟁이 치열해지고 있습니다.2,3 이러한 요구는 함께 [부담스러운 임상 학습 환경]을 조성하여 학습자에게 악영향을 미칠 수 있습니다.4 학생들의 스트레스를 유발하는 중요한 요인 중 하나는 [임상실습 성적]입니다.5,6 성적은 학생과 의과대학에 중요한 피드백을 제공하며, 레지던트 프로그램은 레지던트 선발 시 핵심 임상실습 성적에 의존합니다.7-9 성적 배정은 일반적으로 [시험 점수]와 [감독 교수 및 레지던트의 종합 평가]에 의해 결정됩니다. 그럼에도 불구하고 학생과 교육자 모두 성적의 공정성과 정확성에 의문을 제기합니다.4 "평가가 학습을 이끈다"는 교육자의 격언에 비추어 볼 때, 현재 평가 시스템에 대한 부정적인 인식은 학생의 동기 부여, 학습 행동, 성과에 부정적인 영향을 미칠 수 있습니다.10

Preparing for clinical practice requires students to acquire broad and rapidly expanding skills and knowledge.1 Simultaneously, students face increasing competition for residency positions, particularly in certain specialties.2,3 Together, these demands create a taxing clinical learning environment, which may adversely affect learners.4 One significant contributor to student stress is clerkship grading.5,6 Grades provide important feedback to students and medical schools, and residency programs rely on core clerkship grades in resident selection.7–9 Grade assignments are typically informed by examination scores and summative evaluations from supervising faculty and residents. Still, students and educators alike question the fairness and accuracy of grades.4 Drawing from the educator’s adage “assessment drives learning,” negative perceptions of the current assessment system may adversely affect students’ motivation, learning behaviors, and performance.10

임상실습 평가 및 채점에 대한 학생의 우려는 [다양한 요인]으로 인해 발생할 수 있습니다.

- 감독자는 평가 척도를 다양하게 해석하고 최고 성과에 대한 [공유된 정신 모델이 부족]할 수 있습니다.11-13

- 학생은 자신을 평가할 때 [감독자가 무엇을 중요하게 생각하는지 불확실]하게 느낄 수 있습니다.14

- 공정한 평가 시스템은 학생이 학습하고 [학습을 입증할 수 있는 충분한 기회]가 필요하고 [평가 및 채점에 투명한 기준을 사용]하며 [공평]해야 합니다.15,16

- 한 의과대학에서 실시한 한 연구에 따르면 학생의 38%만이 임상실습 평가가 공정하다고 생각하는 것으로 나타났습니다.17

- 수퍼바이저가 [수련생을 직접 관찰하지 않고 역량을 평가]하기 때문에 학생들은 평가의 정확성을 의심할 수 있습니다.18,19

- [편견] 또한 정확성을 위협하고 성적에 대한 회의론을 불러일으킵니다. 의학계에서 소외된 인종 또는 민족(UIM) 출신의 학생은 최고 성적을 받고 아너 소사이어티에 선발될 가능성이 낮습니다.20-22

Students’ concerns around clerkship evaluations and grading may arise from a variety of factors.

- Supervisors variably interpret assessment scales and may lack a shared mental model of top performance.11–13

- Students can feel uncertain about what supervisors value when evaluating them.14

- A fair assessment system requires sufficient opportunities for students to learn and demonstrate learning, uses transparent criteria for evaluation and grading, and is equitable.15,16

- One study at a single medical school found that only 38% of students felt that clerkship evaluation was fair.17

- Students may doubt the accuracy of their evaluations because supervisors evaluate trainees on competencies despite infrequent direct observation of those trainees.18,19

- Bias also threatens accuracy and raises skepticism around grades. Students from racial or ethnic groups underrepresented in medicine (UIM) are less likely to earn top grades and honor society selection.20–22

모든 학생은 임상실습 환경이 학습에 미치는 영향에 취약할 수 있습니다.

- [숙달 지향적 환경]은 학생들이 도전을 추구하고 장애물에 직면했을 때 성공하는 학습에 대한 적응적 접근 방식을 촉진합니다.23

- 반대로 [성과 지향적 환경]에는

- 학생들이 [겉으로 유능해 보일 수 있는 과제를 수행]하면 보상하는 "성과 접근 방식"과,

- 학생들이 [무능해 보일 수 있는 도전적인 상황을 회피]하게 만드는 "성과 회피 방식"이 포함됩니다.

- [숙달 중심]의 [합격/불합격 전임상 학습 환경]에서 [성과 중심]의 [단계별 채점 임상 학습 환경]으로 전환하면 학생이 숙달 중심의 행동을 경시하고 학습에 부정적인 영향을 미칠 수 있습니다.24

- [성과 중심]의 학습 문화는 학생의 정보 유지력과 만족도를 떨어뜨리고 소진을 증가시킬 수 있습니다.23,25

All students can be susceptible to influences of the clerkship environment on their learning.

- A mastery-oriented environment fosters adaptive approaches to learning in which students seek challenges and thrive when facing obstacles.23

- Conversely, performance-oriented environments include

- “performance approach,” which rewards students for performing tasks that they know will make them appear competent,

- and “performance avoid,” which encourages students to avoid challenging situations that could make them appear incompetent.

- The transition from a more mastery-oriented pass/fail preclinical learning environment to a more performance-oriented tiered grading clinical learning environment may cause students to deemphasize mastery-oriented behaviors and negatively affect learning.24

- A performance-oriented learning culture can decrease students’ retention of information and satisfaction and increase burnout.23,25

[UIM 학생과 비 UIM 학생 간의 성적 격차]는 [평가자의 편견을 넘어 임상실습 학습 환경의 다른 요인에 대한 고려]를 촉구하며, 이는 UIM 학생의 성과 저하에 고유하게 기여할 수 있습니다.21,26 [낙인찍힌 집단]의 취약한 구성원(예: 일반적으로 UIM인 인종/민족 학생)이 [자신이 속한 집단에 대한 낮은 기대치에 부합할 것을 걱정]할 때 [고정관념 위협]을 경험하게 됩니다. [고정관념 위협]은 인지 부하를 증가시키고 습득한 기술과 역량을 발휘하지 못하게 함으로써 집단 간 성과 차이를 악화시킵니다.27-29 인종, 성별, 나이와 관련된 고정관념 위협은 널리 연구되어 왔지만, 의대생 사이에서 고정관념 위협의 영향을 조사한 문헌은 부족합니다.28-32

Grading disparities between UIM and non-UIM students prompt consideration of other forces in the clerkship learning environment, beyond evaluator bias, which may uniquely contribute to poorer UIM student performance.21,26 When vulnerable members of stigmatized groups (e.g., students from races/ethnicities typically UIM) worry that they will conform to lower expectations for their group, they experience stereotype threat. Stereotype threat exacerbates group differences in performance by increasing cognitive load and inhibiting the display of acquired skills and competencies.27–29 While stereotype threats relating to race, gender, and age have been widely explored, a dearth of literature examines effects of stereotype threat amongst medical students.28–32

본 연구는

- (1) 임상실습 평가 및 채점의 공정성과 정확성에 대한 학생들의 인식을 조사하고,

- (2) 임상실습 학습 환경에 대한 학생들의 인식을 조사하고,

- (3) 이러한 인식과 학생의 성취도 사이의 관계를 평가하기 위해 설계되었습니다.

We designed this study to

- (1) examine students’ perceptions of the fairness and accuracy of clerkship evaluation and grading,

- (2) examine students’ perceptions of the clerkship learning environment, and

- (3) assess the relationship between these perceptions and students’ achievement.

방법

Method

설계

Design

이 연구는 여러 기관을 대상으로 한 횡단면 설문조사 연구입니다.

This is a multi-institutional, cross-sectional survey study.

설정

Setting

연구 기관은 서부의 다양한 지리적 위치와 공립/사립 현황을 대표하는 서부 교육 문제 그룹에 속한 미국 학교 6곳을 편의 표본으로 선정했습니다(표 1). 초대받은 학교 중 참여를 거부한 학교는 없었습니다. 6개 기관 심의위원회 모두 이 연구를 승인했습니다. 모든 학교는 학생들에게 가정의학과, 내과, 산부인과, 소아과, 정신과, 외과 임상실습을 이수하도록 요구했습니다. 일부는 추가적으로 요구되는 임상실습이 있었습니다. 이 연구에서 "우등"은 각 학교에서 달성할 수 있는 가장 높은 서클러십 성적을 의미합니다. 전국 의과대학과 마찬가지로 학교마다 우등상을 받을 수 있는 학생 비율, 종단 통합 서클럭의 존재 여부, 성적 부여 방식이 다양했습니다.33

Study institutions were a convenience sample of 6 U.S. schools in the Western Group on Educational Affairs, representing diverse western geographical locations and public/private status (Table 1). No invited schools declined participation. All 6 institutional review boards approved the study. All schools required students to complete family medicine, internal medicine, obstetrics–gynecology, pediatrics, psychiatry, and surgery clerkships (see Supplemental Digital Appendix 1 at https://links.lww.com/ACADMED/A720). Some had additional required clerkships. In this study, “honors” refers to the highest clerkship grade achievable at each school. Consistent with medical schools nationally, schools varied in the percentage of students allowed to receive honors, presence of longitudinal integrated clerkships, and method of grade assignments.33

참여 학생

Participating students

참여 대상은 핵심 임상실습 연도가 끝나는 모든 의대생이었습니다. 5개 학교에서 학생들은 해당 학교의 수석 조사자가 서명한 전자 설문조사 플랫폼에 대한 개별 이메일 링크를 받았습니다. 학교별 규칙에 따라 이메일 초대는 여섯 번째 학교의 학급 목록 서버로 보내야 했습니다. 응답하지 않은 응답자에게는 매주 최대 3회의 리마인더가 전송되었습니다. 설문조사는 공개 후 30일 동안 활성화되었습니다. 설문조사가 완료되면 참가자는 외부 웹사이트를 통해 이메일 주소를 제출하여 10달러 전자 기프트 카드를 받을 수 있었습니다. 데이터 수집 후, 연구에 관여하지 않은 데이터 분석가가 개인 식별 정보를 제거하고 참가자에게 무작위 식별 번호를 할당했습니다. 학생이 인구 통계 섹션을 작성하지 않았거나 임상실습을 3개 미만으로 완료한 경우 설문조사에서 제외되었습니다.

Eligible participants were all medical students at the end of the core clerkship year. At 5 schools, students received an individualized email link to an electronic survey platform (www.qualtrics.com), signed by the lead investigator of that school. School-specific rules required that the email invitation go to the sixth school’s class listserv. Nonrespondents received up to 3 weekly reminders. The survey was active for 30 days after release. Upon completion, participants could submit their email address via an outside website to receive a $10 electronic gift card. After data collection, a data analyst not otherwise involved in the study removed identifying information and assigned participants random identification numbers. Surveys were excluded if the student did not complete the demographics section or completed fewer than 3 clerkships.

이론적 모델 및 설문조사 개발

Theoretical model and survey development

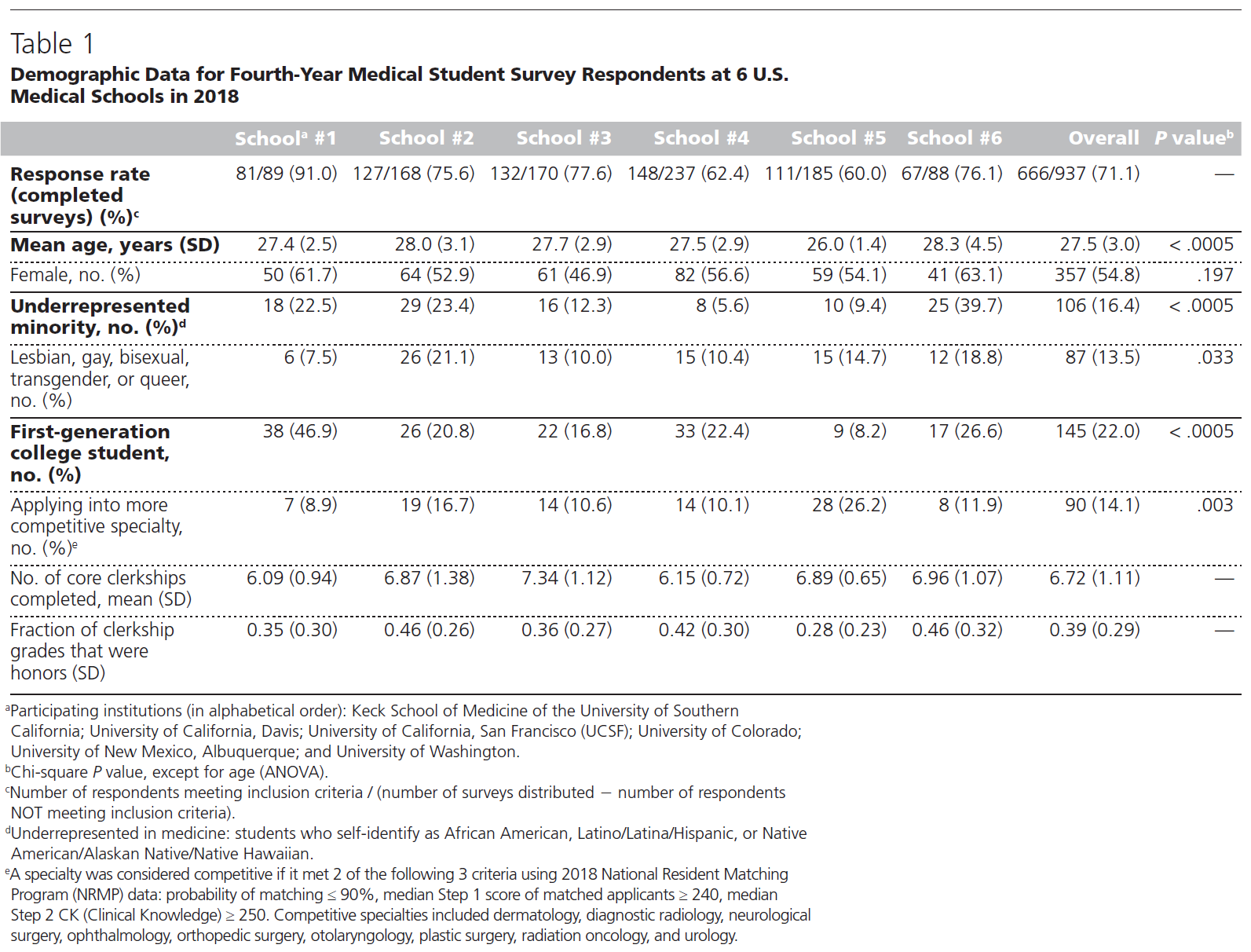

설문조사 개발 지침에 따라 설문조사를 개발했습니다.34 두 명의 저자(J.L.B., K.E.H.)가 문헌을 검토하여 학생들의 임상실습 성적에 대한 인식을 둘러싼 주요 이론, 증거 및 격차를 파악했습니다. 한 학교(캘리포니아대학교 샌프란시스코 캠퍼스[UCSF])에서는 의과대학 학장들과 함께 임상실습 채점에 관한 학생 타운홀을 개최했습니다. 문헌 검토와 타운홀 피드백을 바탕으로, 저희는 학생 평가의 공정성과 정확성, 학생의 동기 부여와 노력, 피드백에 대한 학생의 인식, 학생의 학습 환경, 학생의 성취 결과에 기여하는 요인에 대한 [학생의 인식에 대한 모델]을 개발했습니다(그림 1). 이 모델을 사용하여 2개의 연구 학교(UCSF, 콜로라도대학교 의과대학)에서 23명의 학생이 서면으로 또는 4개의 포커스 그룹 중 1개 그룹에서 피드백을 제공한 설문조사 항목을 개발하고 파일럿 테스트를 거쳤습니다. 최종 설문조사에는 적응 학습 척도(PALS) 및 고정관념 취약성 척도(SVS) 매뉴얼의 문항도 포함되었습니다.28,35 PALS 숙달, 수행 접근 방식, 수행 회피 교실 목표 구조 척도 및 SVS 고정관념 위협 항목을 "임상실습"을 참조하도록 수정했습니다. 파일럿 학생들에게 혼란을 줄 수 있는 이중 부정적 표현으로 인해 원래의 SVS 항목 3개를 제거했습니다.

We developed a survey following guidelines for survey development.34 Two authors (J.L.B., K.E.H.) reviewed the literature to identify key theories, evidence, and gaps surrounding students’ perceptions of clerkship grading. One school (University of California, San Francisco [UCSF]) held a student town hall on clerkship grading with medical school deans. Based on the literature review and town hall feedback, we developed a model of students’ perceptions of the fairness and accuracy of clerkship assessment, student motivation and effort, perceptions of feedback, clerkship learning environment, and contributors to students’ achievement outcomes (Figure 1). Using this model, we developed and pilot-tested survey items at 2 study schools (UCSF, University of Colorado School of Medicine) with 23 students who provided feedback in writing or in 1 of 4 focus groups. The final survey also included adapted questions from the Manual for the Patterns of Adaptive Learning Scales (PALS) and the Stereotype Vulnerability Scale (SVS).28,35 We modified the PALS Mastery, Performance Approach, and Performance Avoid Classroom Goal Structure scales and SVS stereotype threat items to reference “clerkships.” We eliminated 3 original SVS items because of double-negative wording that confused pilot students.

[최종 106개의 설문조사 항목]은 참가자 인구통계, 자가 보고한 우등상 수상 횟수, 수강한 임상실습 횟수, 의도한 전공, 다양한 영역이 최종 성적에 미치는 영향에 대한 인식(0~10점), 채점에 대한 인식(공정성, 정확성) 및 임상실습 학습 환경(동기 부여, 고정관념 위협)이라는 가설 예측 변수에 관한 것이었습니다. 예측변인 질문은 5점 리커트 척도(매우 동의하지 않음[1] ~ 매우 동의함[5])를 사용했습니다. 개방형 질문 중 하나는 성적 향상을 위한 학생의 추천을 요청하는 질문이었습니다.

The final 106 survey items addressed participant demographics, self-reported number of honors earned, number of clerkships taken, intended specialty, perceived impact of various domains on their final grade (scored 0–10), and our hypothesized predictors: perceptions of grading (fairness, accuracy) and clerkship learning environment (motivation, stereotype threat). Predictor questions used a 5-point Likert scale (strongly disagree [1] to strongly agree [5]). One open-ended question solicited students’ recommendations to improve grading (see Supplemental Digital Appendix 2 at https://links.lww.com/ACADMED/A720).

요인 분석

Factor analysis

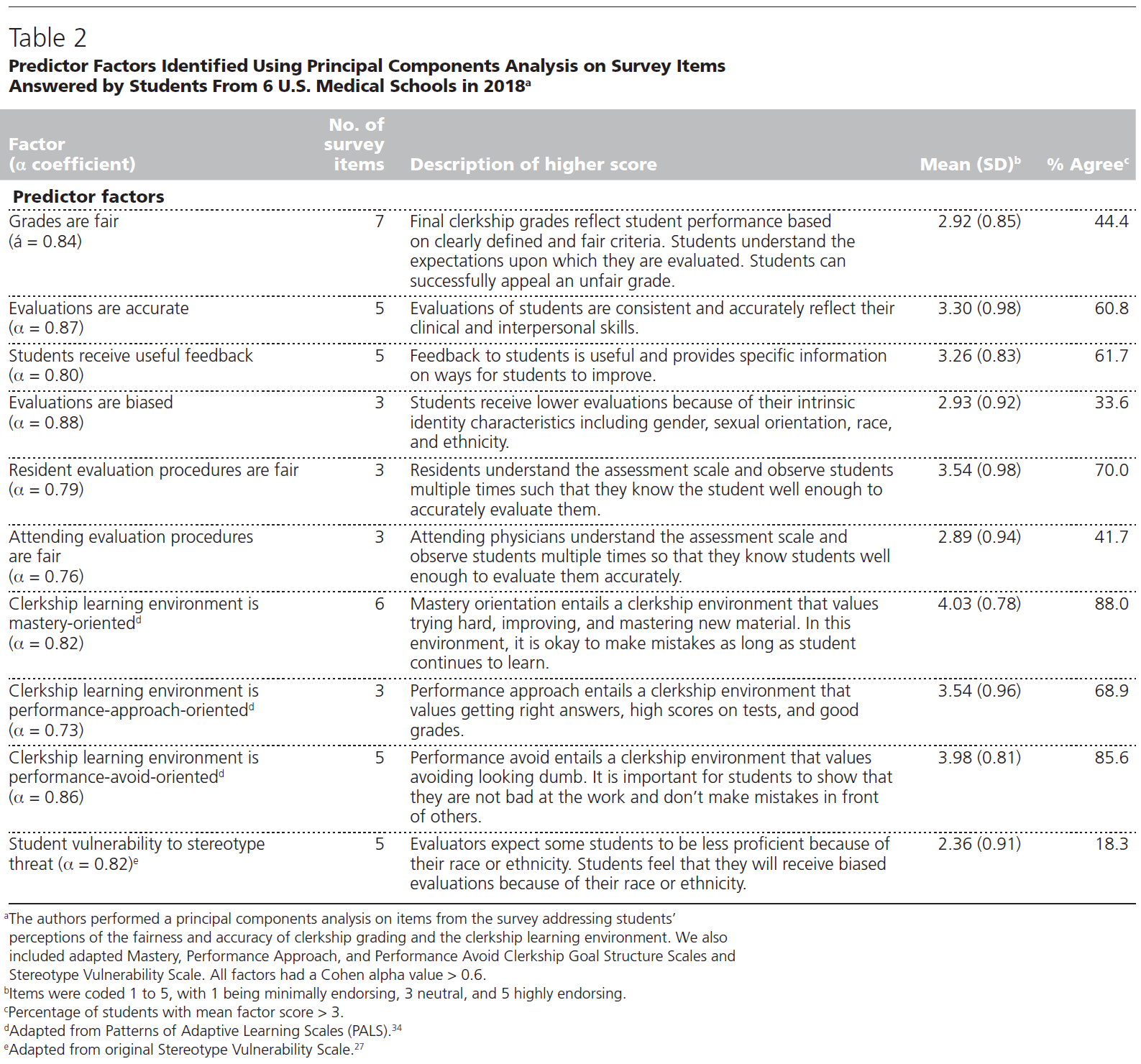

데이터 축소를 위해 주성분 분석을 사용하여 채점 및 임상실습 학습 환경의 공정성과 정확성에 대한 인식에 대해 리커트 척도 질문을 1~5개의 연속 변수로 처리했습니다. 바리맥스 회전을 사용하여 고유값이 1 이상인 요인을 유지하고 수렴하기 전까지 최대 25회 반복했습니다. 누락된 데이터는 쌍별 삭제를 사용했습니다. 카이저-마이어-올킨 검정은 0.80 이상으로 항목 간에 충분한 상관관계가 있음을 나타냅니다. 항목은 가장 큰 로딩을 기준으로 요인에 할당되었습니다. PALS 동기 부여 척도와 SVS는 이전에 검증되었고 약간의 수정에도 여전히 높은 내적 일관성을 보였기 때문에 주성분 분석에 포함되지 않았습니다.28,35 모든 요인에 대해 크론바흐 알파 계수와 비가중 평균 점수를 계산하여 크론바흐 알파가 0.6 이상인 요인만 유지했습니다. 모든 요인 적재량이 양수가 되도록 필요에 따라 항목을 리버스 코딩했습니다. 유지된 각 요인에 대해 해당 요인을 구성하는 항목의 평균과 동일한 연속 변수로 취급하여 척도 점수를 계산했습니다. 척도 점수의 경우 3점 미만은 "동의하지 않음", 3점 이상은 "동의", = 3점은 "중립"으로 분류했습니다. SVS 점수가 3점 이상이면 고정관념 위협에 취약한 것으로 나타났습니다.

We used principal components analysis for data reduction, treating Likert scale questions as continuous 1–5 variables for perceptions of fairness and accuracy of grading and clerkship learning environment. We used varimax rotation, retaining factors with an eigenvalue ≥ 1 and a maximum of 25 iterations before convergence. We used pairwise deletion for missing data. The Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin test was > 0.80, indicating sufficient correlation amongst items. Items were assigned to factors based on their largest loading. Because the PALS motivation scales and SVS were previously validated and still had high internal consistency with our minor modifications, they were not included in the principal component analysis.28,35 For all factors, we calculated the Cronbach alpha coefficient and nonweighted mean score, retaining factors with Cronbach alpha > 0.6. Items were reverse-coded as needed so that all factor loadings were positive. For each retained factor, we calculated a scale score, treated as a continuous variable equal to the mean of the items comprising the factor. For scale scores, we categorized < 3 as “disagree,” > 3 as “agree,” and = 3 as “neutral.” An SVS score > 3 indicated vulnerability to stereotype threat.

통계 분석

Statistical analysis

인구 통계에 대한 기술 통계를 계산했습니다. t 검정으로 연령의 차이를 평가했습니다. 다른 모든 하위 그룹 비교에는 카이제곱 테스트를 사용했습니다. 첫 번째 목표를 조사하기 위해 공정성과 정확성에 대한 학생들의 인식과 임상실습 학습 환경에서의 학생 경험에 대한 기술 통계를 계산했습니다. 성별 및 UIM 상태별 인식의 하위 그룹 비교를 위해 카이제곱 검정을 사용했습니다.

We calculated descriptive statistics for demographics. t Tests assessed differences in age. For all other subgroup comparisons, we used chi-square tests. To examine our first aim, we calculated descriptive statistics for students’ perceptions of fairness and accuracy and students’ experience in the clerkship learning environment. We used chi-square tests for subgroup comparisons of perceptions by gender and UIM status.

두 번째 목표인 학생 인구통계학적 특성과 인식 및 우등상 수상 간의 관계를 조사하기 위해 [다변량 회귀 분석]을 사용했습니다. 성적 정책의 학교 간 차이를 설명하기 위해 우등상 수상 비율, 해당 학생의 학교 우등상 수상 비율의 평균 및 표준 편차를 사용하여 z 점수를 계산하여 각 학생의 표준화된 우등상을 계산했습니다. 여기서 '우등상 획득'은 각 학생의 표준화된 우등상 값을 의미합니다. 예측 변수는 학생 인구 통계와 학생 인식(PCA 식별 요인, PALS, SVS)의 두 블록으로 입력했습니다. 인구통계학적 변수는 연속형인 나이를 제외하고 이분법으로 처리했습니다. 아프리카계 미국인, 라틴계 미국인, 라틴계 미국인, 히스패닉계 미국인, 아메리카 원주민, 알래스카 원주민, 하와이 원주민 또는 기타 태평양 섬 주민이라고 스스로 밝힌 UIM 학생들.36 2018년 전국 레지던트 매칭 프로그램 데이터를 사용하여 [경쟁이 심한 전문과목]은 매칭 확률 ≤ 90%, 매칭된 지원자의 1단계 점수 중간값 240 이상, 2단계 CK(임상 지식) 중간값 250의 3가지 기준 중 두 가지를 충족하는 것으로 정의했습니다(표 1). 회귀분석에서 16개의 비교를 설명하기 위해 Bonferroni 보정을 수행했으며, P값이 .003 이하인 경우 통계적으로 유의한 것으로 간주했습니다.41 분석에는 Windows용 IBM SPSS 통계 버전 23.0(IBM, Armonk, New York)을 사용했습니다.

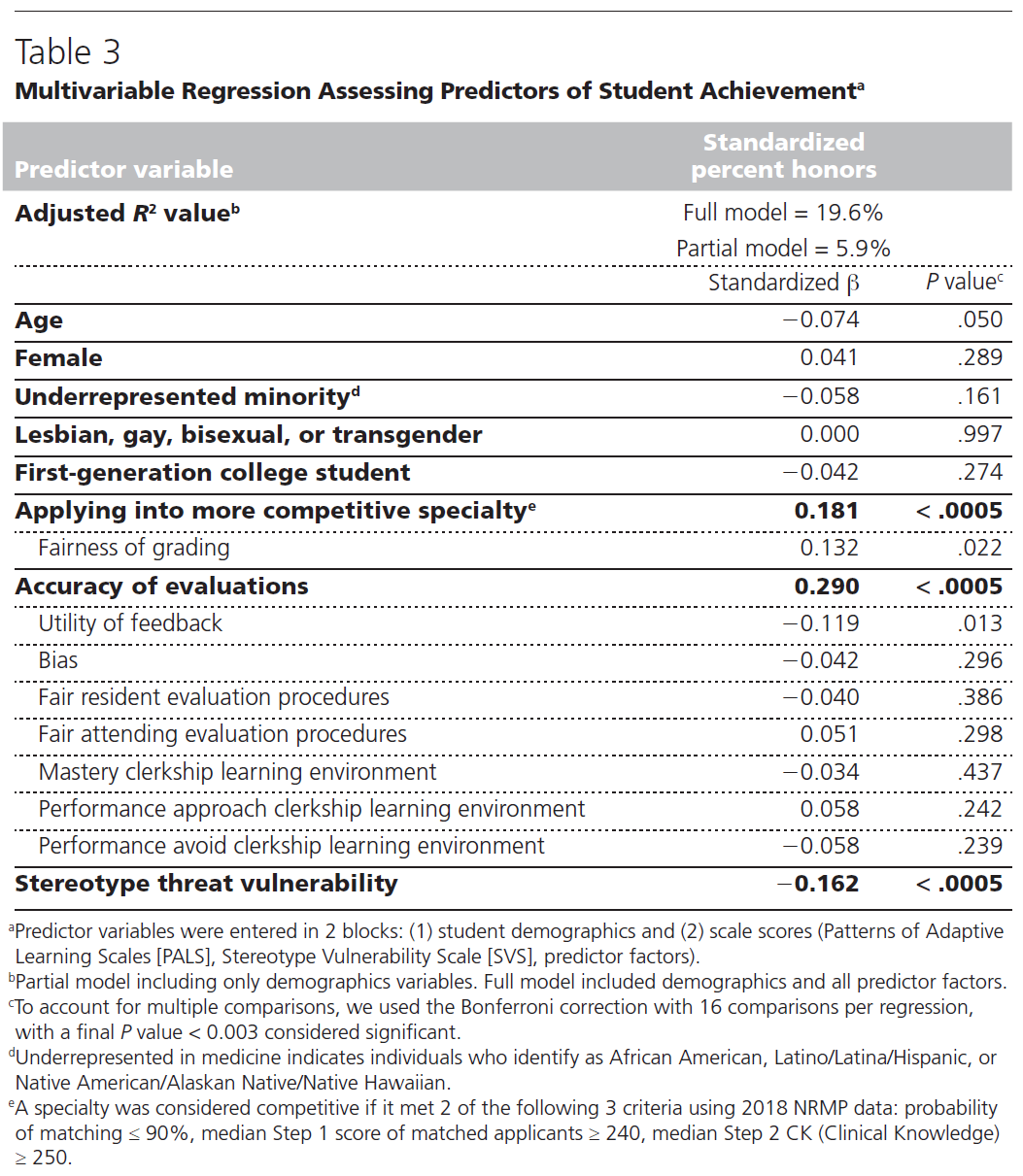

We used multivariable regression analysis to explore our second aim, the relationship between student demographics and perceptions and honors earned. To account for interschool differences in grading policies, we computed each student’s standardized honors by calculating a z score using the fraction of clerkships honored, mean and standard deviation of the fraction of clerkships honored for that student’s school. Hereafter, “honors earned” refers to each student’s standardized honors value. We entered predictor variables in 2 blocks: student demographics and student perceptions (PCA-identified factors, PALS, SVS). We treated demographic variables as dichotomous except age, which was continuous. UIM students self-identified as African American, Latino, Latina, Hispanic, Native American, Alaskan Native, Native Hawaiian, or other Pacific Islander.36 Using 2018 National Resident Matching Program data, competitive specialties were defined as meeting 2 of 3 criteria: probability of matching ≤ 90%, median Step 1 score of matched applicants ≥ 240, and median Step 2 CK (Clinical Knowledge) ≥ 25037–40 (Table 1). We performed a Bonferroni correction to account for 16 comparisons in the regression, with a P value ≤ .003 deemed statistically significant.41 We used IBM SPSS Statistics Version 23.0 for Windows (IBM, Armonk, New York) for analyses.

정성적 분석

Qualitative analysis

세 명의 저자(J.L.B., C.J.L., T.L.)가 콘텐츠 분석을 사용하여 댓글을 분석했습니다. 각 저자는 무작위로 추출한 50개의 댓글에서 귀납적으로 [코드북을 개발]했습니다. 토론을 거쳐 [코드를 하나의 코드북으로 통합]한 후 코딩 과정을 통해 [반복적으로 수정]했습니다. 2명의 저자가 Microsoft Excel을 사용하여 각 댓글을 독립적으로 코딩한 후 토론을 통해 불일치하는 부분을 조정했습니다. 코딩에 대한 토론과 코드 간의 관계에 대한 관심을 통해 핵심 주제와 하위 주제가 도출되었습니다. 코딩자 중에는 의대생, 임상실습 책임교수, 평가위원회 책임자가 포함되어 있었기 때문에 코드 조정은 자연스럽게 반성적 사고를 촉진했습니다. 학생의 코멘트 중 어떤 부분이 주어진 코드에 적용되는 코멘트 비율을 계산했습니다.

Three authors (J.L.B., C.J.L., T.L.) analyzed comments using content analysis. Separately, each author inductively developed a codebook from a random sample of 50 comments. After discussion, we combined codes into a single codebook that we iteratively revised throughout the coding process. Using Microsoft Excel, 2 authors coded each comment independently and then reconciled discrepancies through discussion. Discussion of coding and attention to relationships among codes yielded key themes and subthemes. Code reconciliation naturally facilitated reflexivity as the coders included a senior medical student, clerkship director, and assessment committee director. We calculated the percentage of comments for which any portion of a student’s comment applied to a given code.

결과

Results

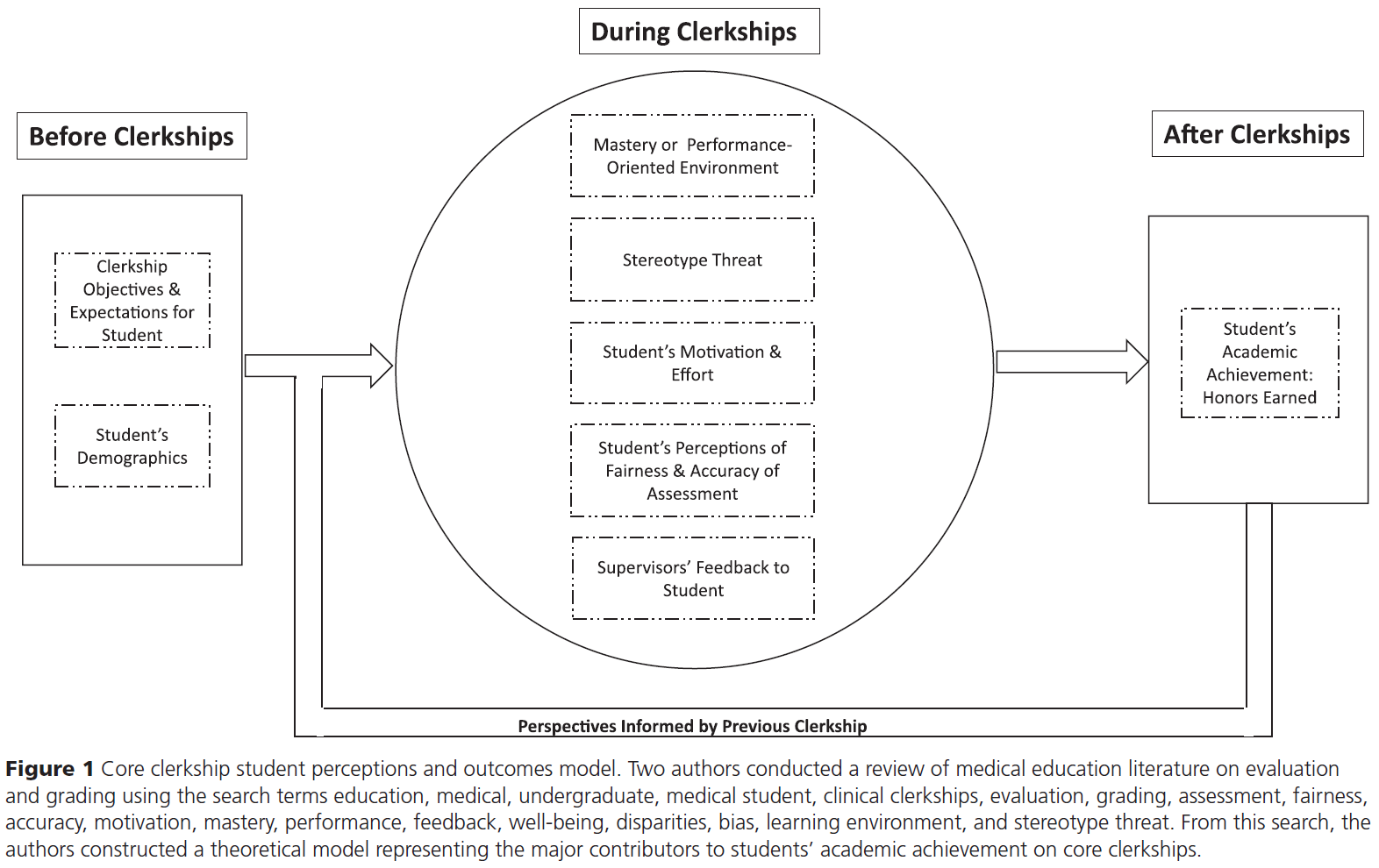

전체적으로 972명의 학생이 설문조사 초대를 받았고, 757명이 설문조사를 시작했으며, 701명이 설문조사를 완료했습니다. 35명의 학생이 제외 기준을 충족했습니다: 34명은 3개 미만의 임상실습을 이수했으며, 1명은 이수한 임상실습보다 더 많은 우등상을 받았다고 답했습니다. 최종 응답률은 666/937(71.1%)이었습니다. 참가자의 평균 연령(SD)은 27.5세(3.0)였으며, 54.8%가 여성, 16.4%가 UIM이었습니다(표 1). 이 비율은 2018년 전국 AAMC 의과대학 졸업생 설문조사 표본의 비율과 유사하며, 이 중 49.1%가 여성, 15.5%가 UIM이었습니다.42 응답자들은 평균 6.7회(1.1회)의 핵심 서클러십을 이수한 것으로 나타났습니다. 평균 연령, UIM 학생 비율, 경쟁이 치열한 전문 분야에 지원한 비율은 학교별로 통계적으로 유의미한 차이가 있었습니다(표 1).

Overall, 972 students received survey invitations, 757 began the survey, and 701 completed it. Thirty-five students met exclusion criteria: 34 had completed fewer than 3 clerkships, and 1 reported earning more honors than clerkships taken. The final response rate was 666/937 (71.1%). Participants’ mean age (SD) was 27.5 (3.0); 54.8% were women and 16.4% were UIM (Table 1). These percentages are similar to those in the national 2018 AAMC Medical School Graduate Questionnaire sample, among whom 49.1% were women and 15.5% were UIM.42 Respondents had completed a mean (SD) of 6.7 (1.1) core clerkships. There were small, statistically significant differences across schools for mean age, percentage of UIM students, and percentage applying into competitive specialties (Table 1).

최종 성적에 대한 영역의 중요성 인식

Perceived importance of domain on final grade

이 질문에 대한 응답입니다: 한 해 전체를 고려할 때, "귀하의 경험상 최종 임상실습 성적을 결정하는 데 다음 각 영역이 얼마나 중요합니까?"라는 질문에 대한 답변입니다. (보충 디지털 부록 3: https://links.lww.com/ACADMED/A720 참조), 학생들은 "호감도" 8.7/10점(SD = 1.7), "함께 일하는 특정 어텐딩" 8.7점(1.7), "함께 일하는 특정 레지던트" 8.5점(1.9)을 가장 높게 평가했습니다. '개선' 5.7점(2.7), '환자 및 가족과의 관계' 6.0점(2.7)을 가장 중요하지 않은 것으로 평가했습니다.

In response to the question: Considering the year as a whole, “in your experience, how important is each of the following in determining your final clerkship grade?” (see Supplemental Digital Appendix 3 at https://links.lww.com/ACADMED/A720),

students scored

- “being liked” 8.7/10 (SD = 1.7),

- “particular attendings you work with” 8.7 (1.7), and

- “particular residents you work with” 8.5 (1.9) highest.

They rated

- “improvement” 5.7 (2.7) and

- “rapport with patients and families” 6.0 (2.7) as least important.

성적 평가에 대한 인식

Perceptions of grading

회전된 PCA 구성 요소 매트릭스는 데이터 세트의 총 분산 중 64.9%를 차지했으며 6개의 예측 요인을 산출했습니다(표 2). 요인들의 내적 일관성은 높았습니다(크론바흐 알파 = 0.73-0.88). 학생들은 채점의 공정성에 대해 낮은 신뢰를 보였으며, 44.4%의 학생만이 평가가 공정하다고 동의했습니다. 임상실습 평가가 정확하거나 받은 피드백이 유용하다고 생각하는 학생은 3분의 2 미만이었습니다(각각 60.8%, 61.7% 동의). 70.0%의 학생이 레지던트 평가 절차가 공정하다는 데 동의한 반면, 주치의 평가 절차가 공정하다는 데 동의한 학생은 41.7%에 불과했습니다.

Our rotated PCA component matrix accounted for 64.9% of the total variance in our dataset and yielded 6 predictor factors (Table 2). Factors had high internal consistency (Cronbach alpha = 0.73–0.88). Students had low confidence in the fairness of grading, with only 44.4% of students agreeing that assessment was fair. Less than two-thirds of students felt that clerkship assessment was accurate or that feedback received was useful (60.8% and 61.7% agreed, respectively). Whereas 70.0% of students agreed that resident evaluation procedures were fair, only 41.7% agreed that attending evaluation procedures were fair.

학생의 1/3(33.6%)이 채점이 편파적이라고 답했습니다. 여성이 남성보다 평가가 편파적이라고 인식하는 비율이 더 높았지만(64.4% vs 25.2%, P < .0005), 여성이 평가가 정확하다고 평가하는 비율도 더 높았습니다(69.2% vs 52.7%, P < .0005). 채점, 피드백의 공정성, 레지던트 및 참석 평가의 공정성에 대한 인식에는 성별 차이가 없었습니다. UIM 학생은 비 UIM 학생보다 평가가 편파적이라고 인식할 가능성이 더 높았습니다(48.1% vs 31.4%, P = .0001). 그 외에는 UIM 학생과 비 UIM 학생의 인식에 차이가 없었습니다.

One-third of students (33.6%) endorsed grading as biased. While more women perceived bias in evaluations than men (64.4% vs 25.2%, P < .0005), women also more commonly rated evaluations as accurate (69.2% vs 52.7%, P < .0005). There were no gender differences in perceptions of fairness of grading, feedback, or fairness of resident and attending evaluations. UIM students were more likely than non-UIM students to perceive bias in evaluations (48.1% vs 31.4%, P = .0001). Otherwise, UIM and non-UIM students’ perceptions did not differ (see Supplemental Digital Appendix 4 at https://links.lww.com/ACADMED/A720).

임상실습 학습 환경에 대한 인식

Perceptions of the clerkship learning environment

학생들은 임상실습 학습 환경이 숙달 및 성과 지향적이라고 압도적으로 지지했습니다(각각 88.0% 및 85.6%)(표 2). 임상실습 학습 환경이 성과 지향적이라고 답한 학생은 약간 더 적었습니다(68.9%). 성별이나 UIM 여부에 따른 임상실습의 숙련도 또는 성과 지향성에 대한 인식에는 하위 그룹 간 차이가 없었습니다.

Students overwhelmingly endorsed the clerkship learning environment to be both mastery- and performance-avoid-oriented (88.0% and 85.6%, respectively) (Table 2). Slightly fewer students endorsed clerkships as performance-approach-oriented (68.9%). There were no subgroup differences in perceptions of the mastery or performance orientation of clerkships by gender or UIM status.

전체적으로 학생 응답의 18.3%가 인종에 따른 고정관념 위협에 취약하다고 답했습니다. 여성과 남성은 고정관념의 위협을 비슷하게 인식했습니다. UIM 학생은 그렇지 않은 학생보다 고정관념 위협에 취약하다고 응답한 비율이 훨씬 높았습니다(55.7% 대 10.9%, P < .0005)(보충 디지털 부록 4: https://links.lww.com/ACADMED/A720 참조).

Overall, 18.3% of student responses indicated vulnerability to stereotype threat based on race. Women and men perceived stereotype threat similarly. UIM students were much more likely than non-UIM students to indicate vulnerability to stereotype threat (55.7% vs 10.9%, P < .0005) (see Supplemental Digital Appendix 4 at https://links.lww.com/ACADMED/A720).

우등상 수상에 따른 다변량 회귀 분석

Honors earned multivariable regression analysis

우등상은 더 [경쟁이 치열한 전문과에 지원]하는 것(베타 = 0.18, P < .0005)과 [평가가 더 정확하다고 인식]하는 것(베타 = 0.29, P < .0005)과 정(+)의 상관관계가 있는 것으로 나타났습니다(표 3). 명예 획득은 [고정관념 위협과 음의 상관관계]가 있었습니다(베타 = -0.162, P < .0005). 획득한 우등과 채점의 공정성에 대한 인식, 참석 또는 레지던트 평가 절차, 임상실습의 숙련도 또는 수행 환경에 대한 인식 간에는 유의미한 연관성이 없었습니다.

Honors earned was positively associated with applying into a more competitive specialty (beta = 0.18, P < .0005) and perceiving evaluations as more accurate (beta = 0.29, P < .0005) (Table 3). Honors earned was negatively associated with stereotype threat (beta = −0.162, P < .0005). There were no significant associations between honors earned and perception of grading fairness, attending or resident evaluation procedures, or perceptions of mastery or performance environment of clerkships.

정성적 분석

Qualitative analysis

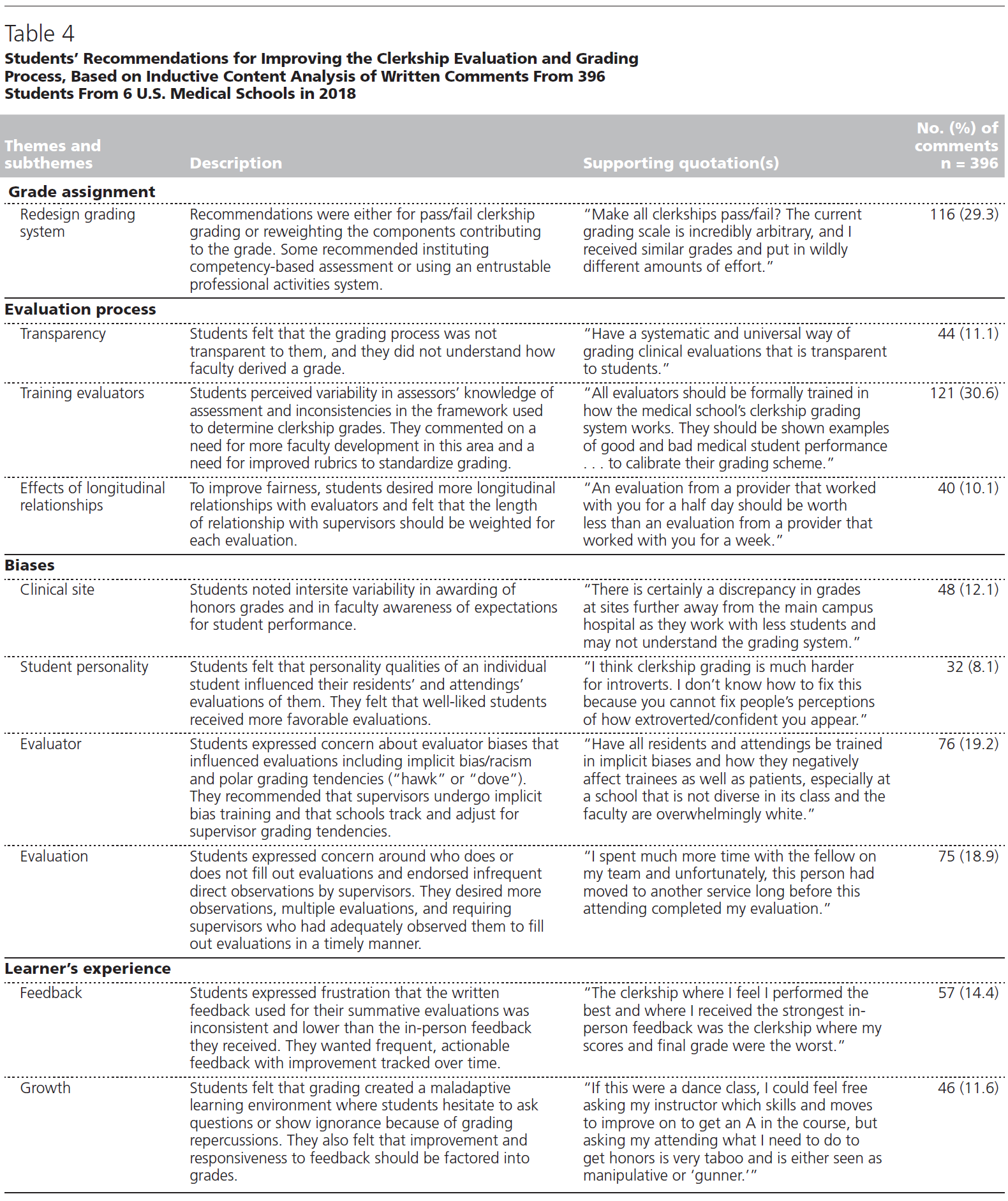

학생들의 의견은 [성적 부여, 평가 과정, 차등 채점의 원인이 되는 편향성, 학습자의 경험] 등 4가지 주제에 대해 다루었습니다(표 4).

- [성적 부여]의 경우, 많은 응답자가 최종 성적에 기여하는 요소에 [가중치를 부여]하거나, [합격/불합격 채점]을 사용할 것을 권장했습니다(의견의 29.3%). 역량 기반 평가를 도입하거나 위임가능 전문활동 시스템을 사용하자는 의견도 있었습니다.

- [평가 과정]에서 학생들은 평가자의 평가 지식과 학생 평가에 사용되는 프레임워크의 [variability]을 지적했습니다. 이들은 적절한 평가 기법에 대한 평가자 교육(30.6%)을 권장했습니다.

- [차등 채점의 원인이 되는 편견]을 해결하기 위해 암묵적 편견 교육 또는 평가자를 비교하는 제도적 시스템을 통해 평가자의 개인적 편견(19.2%)을 해결해야 한다는 의견도 있었습니다.

- [학습자의 경험]을 개선하기 위해 학생들은 보다 정기적이고 실행 가능한 피드백을 통해 학습을 지원하고(14.4%), 시간이 지남에 따라 추적하여 개선 사항을 평가하고 최종 성적에 반영하는 평가(11.6%)를 원했습니다.

Students’ comments addressed 4 themes: grade assignment, evaluation process, bias causing differential grading, and learners’ experience (Table 4).

- For grade assignment, many respondents recommended either reweighting components contributing to final grades or using pass/fail grading (29.3% of comments). Some recommended instituting competency-based assessment or using an entrustable professional activities system.

- In the evaluation process, students noted variability in assessors’ knowledge of assessment and frameworks used to evaluate students. They recommended training evaluators on proper evaluation techniques (30.6%).

- To address biases causing differential grading, some advocated addressing evaluators’ personal biases (19.2%) with implicit bias training or institutional systems to compare evaluators.

- To improve learners’ experience, students wanted assessment to support learning through more regular and actionable feedback (14.4%), tracked over time so that improvement was valued and incorporated into final grades (11.6%).

토론

Discussion

여러 기관이 참여한 이 연구에서 핵심 임상실습 평가 및 채점의 공정성에 대한 학생들의 신뢰도가 낮은 것으로 나타났습니다.

- UIM 학생의 절반 이상이 [고정관념에 의한 위협에 취약]하다고 답했으며, 이는 비 UIM 학생의 5배가 넘는 수치입니다.

- 당연히 현재 환경에서 [가장 성공한 학생들, 즉 더 많은 우등상을 받은 학생들]이 평가의 정확성을 더 높게 평가하고, 경쟁이 치열한 전문 분야에 지원할 계획이며, 고정관념 위협에 덜 취약하다고 답한 것은 당연한 결과입니다.

학생들의 서술형 의견은 평가 및 채점에 대한 변화에 대한 학생들의 열망을 뒷받침했습니다.

This multi-institutional study reveals low student confidence in the fairness of core clerkship evaluations and grading. More than half of UIM students endorsed stereotype threat vulnerability, a prevalence greater than 5 times that of non-UIM students. Perhaps unsurprisingly, students who were most successful in the current environment, defined by earning more honors, endorsed greater accuracy of evaluations, planned to apply in competitive specialties, and were less vulnerable to stereotype threat. Students’ narrative comments supported their desire for changes to evaluation and grading.

[Grading에 대한 학생들의 인식]은 학습에 중요한 영향을 미치므로 반드시 해결해야 합니다. 연구 결과에 따르면 학생들은 자신의 성적을 결정하는 가장 강력한 요인을 임상 역량과 별개로 인식하고 있습니다. [낮은 성적을 받은 학생]은 [불공정한 시스템]이나 [특정 팀원의 편차] 등 자신의 [외적 요인]으로 성적을 돌릴 수 있습니다.43,44 이러한 시나리오는 자기 효능감을 위협하고 학생의 노력, 행동 및 향후 학습에 부정적인 영향을 미칠 수 있습니다.25,43 이러한 문제를 해결하기 위해 참가자들은 [평가자 교육을 더 많이 받아야 한다]고 주장했습니다. 평가자 교육은 학생의 성과를 공정하고 정확하게 평가하는 데 필요하지만, [특정 환자를 마주하는 상황과 초점, 평가자 자체]에는 [변동성이 내재]되어 있습니다.13,45 평가자 간의 완벽한 신뢰성을 위해 노력하기보다는, 평가 프로그램에서 평가 데이터를 수집하고 종합하는 엄격한 방법을 개발하는 것이 더 적절한 목표입니다.46 그러나 적절한 직접 관찰은 강력한 평가의 필수 구성 요소이기도 합니다. 학생들이 [전공의의 평가]를 [주치의의 평가]보다 더 호의적으로 본다는 연구 결과는 [전공의]가 환자와 함께 일하는 학생들과 더 많이 직접 접촉하기 때문에 설명될 수 있습니다. 감독자, 특히 주치의의 관찰 횟수를 늘리고 주치의 평가자에 대한 학생의 경험을 개선하기 위한 다른 메커니즘을 모색하면 평가의 공정성에 대한 학생의 인식을 개선할 수 있습니다.

Students’ perceptions of grading have important implications for learning that should be addressed. Our results show that students perceive the strongest determinants of their grades as distinct from their clinical competence. Students who receive lower grades may attribute their grades to factors extrinsic to themselves such as an unfair system or variance of particular team members.43,44 This scenario threatens self-efficacy and can negatively affect students’ effort, behaviors, and future learning.25,43 To address these challenges, our participants advocated for more evaluator training. While rater education is necessary for fair and accurate assessment of students’ performance, there is inherent variability in the context and focus of particular patient encounters and evaluators themselves.13,45 Rather than striving for perfect reliability among raters, a more appropriate goal would be to develop rigorous methods of collecting and synthesizing assessment data in a program of assessment.46 However, adequate direct observation is also a necessary constituent of robust assessment. Our finding that students view residents’ evaluations more favorably than attendings’ may be explained by residents’ greater direct contact with students working with patients. Increasing the number of observations from supervisors, in particular attending physicians, and exploring other mechanisms to improve students’ experience with attending evaluators could improve students’ perceptions of the fairness of evaluations.

우리의 데이터는 현재의 평가 시스템이 학습 또는 성과를 촉진하는지에 대한 의문을 제기합니다.47 학생들은 [성과에 높은 가치]를 부여하는 반면, [개선에 대한 가치는 낮게 평가한다]고 느꼈습니다. '우등' 성적이라는 외재적 동기는 성과 중심의 학습 환경을 조장할 수 있습니다. 반면, "학습을 위한 평가"는 [관찰을 통해 학습 결과를 평가]하고, [시기적절하고 구체적인 피드백을 제공]하여, [평가를 학생의 학습으로 전환]할 때 발생합니다.9 이 시나리오는 장기적인 성과와 학습의 즐거움을 향상시키는 [숙달 지향적 학습자]를 양성합니다.23 참가자들은 [Grading 방식의 성적을 없애거나 역량 기반 접근 방식으로 변경]하여 [임상실습 평가 구조를 재설계]해야 [숙달 사고방식과 평생 학습을 촉진할 수 있다]고 권고했습니다.48,49 현재 [레지던트 배치에 성적이 중요한 것]은 이미 높은 압박감이 있는 임상실습 환경을 심화시키고 있습니다. 의과대학은 레지던트 선발에 활용되기 때문에 단계별 임상실습 성적을 없애는 것을 주저할 수 있습니다. 본 연구의 범위를 벗어나기는 하지만, 계층형 임상실습 성적이 레지던트 기간 동안의 성과를 효과적으로 예측한다는 사실을 뒷받침하는 자료는 별로 없다.50 [레지던트 프로그램의 총체적 검토 접근법]은 학생의 평가 및 채점 부담을 줄이고 레지던트 선발에 유용한 정보를 제공할 수 있는 가능성을 제공합니다.51

Our data raise questions about whether the current assessment system promotes learning or performance.47 Students felt that performance was highly valued, while improvement was minimally valued. The extrinsic motivation of an “honors” grade may promote a performance-oriented learning environment. In contrast, “assessment for learning” occurs when observations are used to both assess learning outcomes and provide timely, specific feedback, thereby transforming assessment into student learning.9 This scenario cultivates mastery-oriented learners with improved long-term performance and enjoyment of learning.23 Our participants’ recommendations to redesign the clerkship assessment structure by eliminating tiered grades or changing to a competency-based approach could better promote a mastery mindset and lifelong learning.48,49 Currently, the importance of grades for residency placement intensifies an already-high-pressure clerkship environment. Medical schools may hesitate to eliminate tiered clerkship grades because of their use during resident selection. While beyond the scope of our study, minimal data support that tiered clerkship grades effectively predict performance during residency.50 Holistic review approaches by residency programs offer promise to reduce evaluation and grading pressures for students and provide residencies useful information for selection.51

[고정관념 위협 취약성]은 성과에 대한 유의미한 부정적 예측 요인으로 나타났으며, 주로 UIM 학생들에게 영향을 미쳤습니다. 고정관념 위협 취약성을 통제한 후에도 UIM 상태는 성과에 대한 유의미한 예측 변수가 아니었습니다.

Stereotype threat vulnerability emerged as a significant negative predictor of performance, predominately affecting UIM students. UIM status was not a significant predictor of performance after controlling for stereotype threat vulnerability.

UIM 학생들이 직면한 문서화된 성적 편견 외에도, 이번 연구 결과는 고정관념 위협이 UIM 학생들의 학업 성취도를 더욱 저해할 수 있음을 뒷받침합니다.22,27 이 현상은 다른 곳에서 잘 설명되었음에도 불구하고 의대생들 사이에서는 조사되지 않았습니다. 의학교육에서 고정관념 위협의 범위와 의미를 이해하고 이에 대응하기 위한 개입을 설계하기 위해서는 더 많은 연구가 필요합니다. 고정관념 위협의 영향을 완화하기 위한 구체적인 전략으로는

- (1) 커뮤니티에 고정관념 위협의 개념을 도입하고,

- (2) 모든 커뮤니티 이해관계자를 참여시켜 정체성 안전을 증진하며,

- (3) 리더를 고정관념의 영향을 받는 그룹에 노출을 늘리는 것 등이 있습니다.52

In addition to the documented grading biases facing UIM students, our findings support that stereotype threat may further undermine UIM students’ academic achievement.22,27 Despite being well described elsewhere, this phenomenon has not been explored amongst medical students. More work is needed to understand the scope and implications of stereotype threat in medical education and to design interventions to counteract it. Concrete strategies to mitigate the effects of stereotype threat include

- (1) introducing the concept of stereotype threat to the community,

- (2) engaging all community stakeholders to promote identity safety, and

- (3) increasing exposure to leaders of the stereotyped group.52

이 연구에는 한계가 있습니다. 본 조사 결과는 임상실습 성적에 대한 학생의 관점을 포착한 것이므로 교육자의 의견은 다를 수 있습니다. 이 횡단면 설문조사는 인과관계를 보여주지 않습니다. 측정되지 않은 다른 요인들이 학생의 성과에 영향을 미칠 수 있습니다. 연구 대상 학교는 미국 내 한 지역에 위치하고 있어 다른 학교로 일반화할 수 없지만, 연구 집단은 인구통계학적으로 전국 학생과 유사했습니다. 우리는 PALS 교실 목표 구조와 SVS를 약간 수정했으며, 원래 척도가 서로 다른 집단에서 타당성을 보인다는 가정 하에 타당성을 가정했습니다. 설문조사 응답과의 상관관계를 파악하기 위해 성과 데이터를 수집하지 않았으며, 학생들의 전공 선호도는 시간이 지남에 따라 바뀔 수 있습니다. 마지막으로, 질적 결과는 학생들이 더 많은 질문을 통해 드러날 수 있는 임상실습 성적에 대한 추가 권장 사항이 있을 수 있고 모든 학생이 의견을 작성한 것은 아니므로 신중하게 해석해야 합니다.53

This study has limitations. Our results capture students’ perspectives on clerkship grading; educators’ opinions might differ. This cross-sectional survey does not show causation. Other unmeasured factors may contribute to student performance. Study schools are located in 1 U.S. region and may not generalize to other schools, although our study population was similar demographically to students nationally. We made small modifications to the PALS Classroom Goal Structures and SVS and assumed validity based on the original scales’ validity in distinct populations. We did not collect performance data to correlate with survey responses, and students’ specialty preferences may change over time. Finally, our qualitative results must be interpreted cautiously because students may have additional recommendations for clerkship grading that could have emerged with more questions, and not all students wrote comments.53

연구 결과에 따르면 많은 의대생들이 핵심 임상실습 기간 동안의 평가와 채점을 공정하다고 생각하지 않으며, 개선에 대한 보상보다는 성과를 장려하는 환경을 지지하는 것으로 나타났습니다. 평가와 채점에 대한 부정적인 인식은 학업 성취도 저하와 관련이 있습니다. UIM 학생은 임상실습 환경에서 추가적인 불리한 압력에 직면할 수 있습니다. 공정한 평가 시스템에는 평등과 형평성을 증진하는 정책과 절차가 필요합니다.54 본 모델(그림 1)에서 가설로 설정한 많은 기여 요인들이 학생 성과와 연관성을 보이지 않았지만, 이러한 영역에서의 차별적 인식은 학습 행동의 변화 또는 학생 복지와 같은 다른 영향을 미칠 수 있습니다.55,56 이러한 결과는 강력한 평가를 촉진할 뿐만 아니라 모든 학생의 학습을 가능하게 하는 학습 환경을 조성하기 위해 핵심 임상실습의 평가 문화를 재정의할 필요가 있다는 것을 뒷받침합니다.

Our findings demonstrate that many medical students do not view evaluation and grading during core clerkships as fair, and they endorse an environment that encourages performance rather than rewards improvement. Negative perceptions of evaluation and grading are associated with decreased academic achievement. UIM students may face additional adverse pressures in the clerkship environment. A fair assessment system requires policies and procedures that promote equality and equity.54 While many of the contributors hypothesized in our model (Figure 1) did not show associations with student performance, differential perceptions in these domains may have other effects such as changes in learning behaviors or student well-being.55,56 These results support a need to redefine the culture of assessment on core clerkships to create learning environments that not only facilitate robust assessment but also enable learning for all students.

Acad Med. 2019 Nov;94(11S Association of American Medical Colleges Learn Serve Lead: Proceedings of the 58th Annual Research in Medical Education Sessions):S48-S56. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000002905.

In Pursuit of Honors: A Multi-Institutional Study of Students' Perceptions of Clerkship Evaluation and Grading

PMID: 31365406

Abstract

Purpose: To examine medical students' perceptions of the fairness and accuracy of core clerkship assessment, the clerkship learning environment, and contributors to students' achievement.

Method: Fourth-year medical students at 6 institutions completed a survey in 2018 assessing perceptions of the fairness and accuracy of clerkship evaluation and grading, the learning environment including clerkship goal structures (mastery- or performance-oriented), racial/ethnic stereotype threat, and student performance (honors earned). Factor analysis of 5-point Likert items (1 = strongly disagree, 5 = strongly agree) provided scale scores of perceptions. Using multivariable regression, investigators examined predictors of honors earned. Qualitative content analysis of responses to an open-ended question yielded students' recommendations to improve clerkship grading.

Results: Overall response rate was 71.1% (666/937). Students believed that being liked and particular supervisors most influenced final grades. Only 44.4% agreed that grading was fair. Students felt the clerkship learning environment promoted both mastery and performance avoidance behaviors (88.0% and 85.6%, respectively). Students from backgrounds underrepresented in medicine were more likely to experience stereotype threat vulnerability (55.7% vs 10.9%, P < .0005). Honors earned was positively associated with perceived accuracy of grading and interest in competitive specialties while negatively associated with stereotype threat. Students recommended strategies to improve clerkship grading: eliminating honors, training evaluators, and rewarding improvement on clerkships.

Conclusions: Participants had concerns around the fairness and accuracy of clerkship evaluation and grading and potential bias. Students expressed a need to redefine the culture of assessment on core clerkships to create more favorable learning environments for all students.

'Articles (Medical Education) > 임상교육(Clerkship & Residency)' 카테고리의 다른 글

| 졸업후의학교육에서 역량중심의학교육(Med Teach, 2010) (0) | 2023.03.04 |

|---|---|

| 임상역량위원회가 교육을 강화하고 역량중심-시간변동 진급에 준비하는 모습 다시 그려보기(J Gen Intern Med. 2022) (0) | 2023.02.28 |

| 하나의 정답은 없다: 미세차별에 대한 이상적 수퍼바이저 반응에 대한 임상실습학생의 인식 질적연구(Acad Med, 2021) (0) | 2023.02.18 |

| 채점에서 학습을 위한 평가로: 핵심임상실습의 성적 제거 및 형성적 피드백 강화를 둘러싼 학생들의 인식(Teach Learn Med. 2021) (0) | 2023.02.18 |

| 관리추론: 보건전문직교육과 연구아젠다의 함의 (Acad Med, 2019) (0) | 2023.02.03 |