하나의 정답은 없다: 미세차별에 대한 이상적 수퍼바이저 반응에 대한 임상실습학생의 인식 질적연구(Acad Med, 2021)

No One Size Fits All: A Qualitative Study of Clerkship Medical Students’ Perceptions of Ideal Supervisor Responses to Microaggressions

Justin L. Bullock, MD, MPH, Meghan T. O’Brien, MD, MBE, Prabhjot K. Minhas, Alicia Fernandez, MD, Katherine L. Lupton, MD, and Karen E. Hauer, MD, PhD

다양성은 성공적인 기관의 필수적인 특성입니다. 1 의료 분야에서 다양성은 교육 경험을 향상시키고, 사회적 형평성을 증진하며, 환자 건강 결과를 개선합니다. 2-4 [다양성의 중요성을 잘 이해하고 있는 기관]은 [다양한 사회적 정체성 집단의 단순한 인구통계학적 대표성]을 넘어, [다양성을 기관 우수성의 기본으로 우선시하는 의미 있는 포용성]을 향해 기관 문화를 발전시킵니다. 1 그러나 의료기관은 다양한 개인을 포용하지 못하는 학습 환경으로 인해 이러한 이상에 미치지 못하고 있습니다. 특히 [유색인종 학생들]은 평가와 진학에서 [편견, 사회적 자본 감소, 인종 차별, 학습과 성과에 부정적인 영향을 미치는 미세한 공격] 등을 경험합니다. 5-8 의료계에서 빈번한 인종 및 성별 미세 공격의 해로운 결과에도 불구하고 임상 학습 환경을 개선하기 위해 미세 공격을 가장 잘 해결하는 방법에 대한 집단적 이해에는 여전히 격차가 있습니다. 9-11

Diversity is an essential characteristic of successful institutions. 1 In medicine, diversity enhances educational experiences in training, promotes social equity, and improves patient health outcomes. 2–4 Institutions with an advanced understanding of the importance of diversity move beyond mere demographic representation of multiple social identity groups to drive institutional culture toward meaningful inclusion where diversity is prioritized as fundamental to institutional excellence. 1 However, medical institutions fall short of these ideals, with learning environments that are not inclusive of diverse individuals. In particular, students of color experience biases in assessment and advancement, decreased social capital, racism, and microaggressions that negatively impact their learning and performance. 5–8 Despite harmful consequences of frequent racial and gender microaggressions in medicine, a gap remains in our collective understanding of how best to address microaggressions to improve the clinical learning environment. 9–11

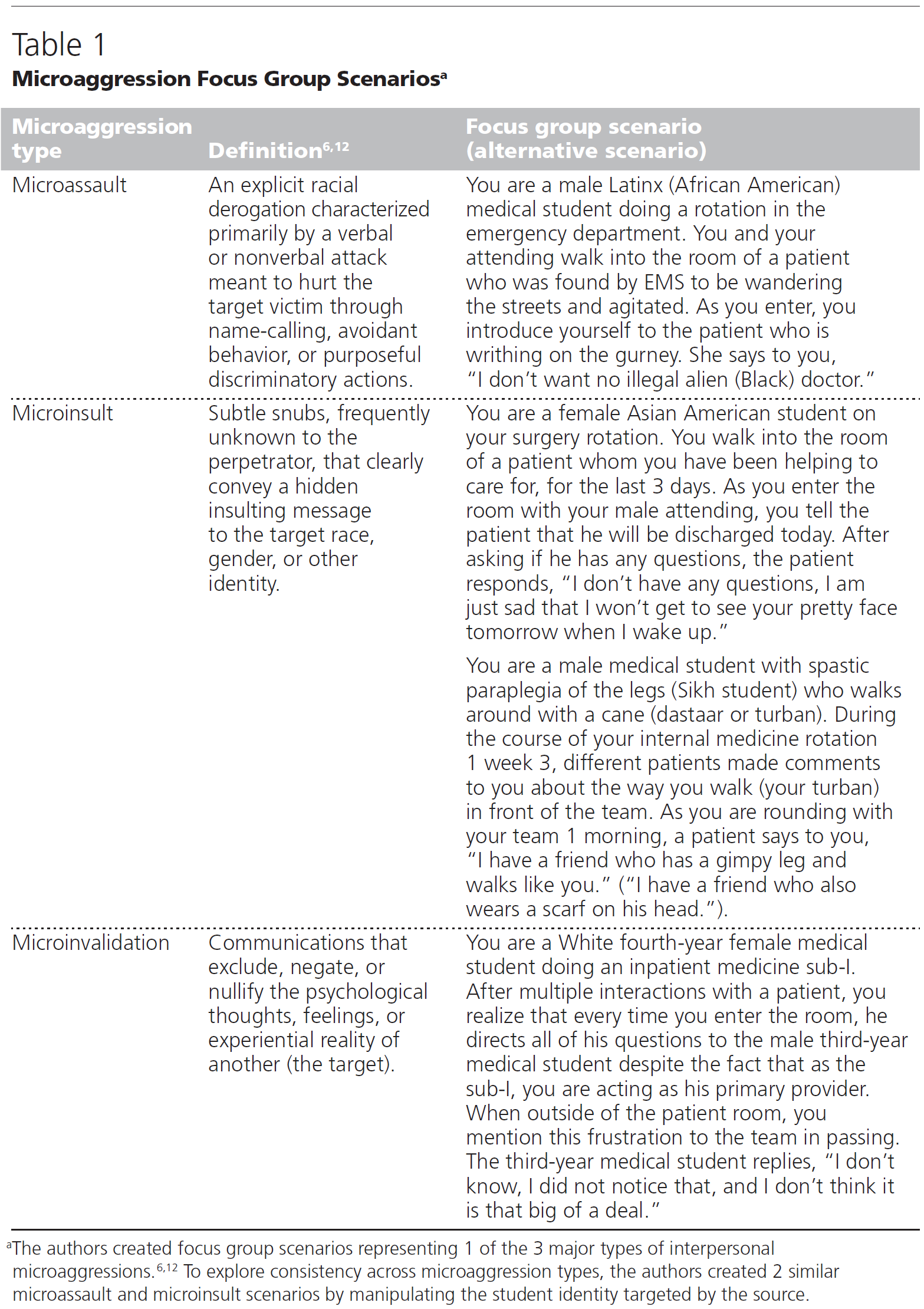

[미세 공격]은 [의도적이든 의도적이지 않든] 대상의 [정체성]에 대한 [적대감이나 부정적 감정]을 전달하는 [언어적, 행동적 또는 환경적 모욕감]을 의미합니다. 12 환자, 제공자, 동료 및 학습 환경 자체는 모두 임상 학습 환경에 만연하여 학습자, 제공자 및 환자에게 해를 끼치는 미세 공격의 일반적인 원인입니다. 9,10,13-15 Sue와 동료들은 [미세 폭행, 미세 모욕, 미세 무효화]6,12의 [세 가지 대인 관계 미세 공격의 유형]을 특징지었습니다(표 1 참조).

- 가장 심각한 형태인 [미세 폭행]은 대상에게 불쾌감을 주는 언어적 또는 비언어적 공격입니다(예: 인종으로 인해 소수인종 의료진의 진료를 거부하는 환자). 16

- [미세 모욕]은 가해자가 의도하지 않았더라도 대상을 비하하는 미묘한 발언입니다(예: 여성 의사를 간호사로 부르는 것).

- 마지막으로, [미시적 무효화]는 대상의 실제 경험을 부정하거나 무시하는 것입니다(예: 요즘 소수계 학생들은 미시적 공격에 너무 민감하다는 말).

Microaggressions are verbal, behavioral, or environmental indignities that communicate hostility or negativity—whether intentional or unintentional—toward a target’s identity(ies). 12 Patients, providers, peers, and the learning environment itself are all common sources of microaggressions, which pervade the clinical learning environment to the detriment of learners, providers, and patients. 9,10,13–15 Sue and colleagues characterized 3 types of interpersonal microaggressions: microassaults, microinsults, and microinvalidations 6,12 (see Table 1).

- Microassaults, the most egregious form, are verbal or nonverbal attacks that offend the target (e.g., patient refusing care from minority providers due to race). 16

- Microinsults are subtle remarks which demean the target, even if unintended by the perpetrator (e.g., calling a female doctor a nurse).

- Finally, microinvalidations negate or dismiss the target’s lived experience (e.g., saying that minority students these days are too sensitive to microaggressions).

미세 공격은 심리적, 생리적 고통을 유발할 수 있습니다. 미세 공격은 우울 증상, 불안, 알코올 사용과 관련이 있으며 일중 코티솔 분비를 변화시킬 수 있습니다. 17-19 의대생들은 미세 공격이 인종적/민족적 [고정관념 위협]을 유발하고 악화시키는데, 이는 [자신이 속한 집단에 대한 부정적인 고정관념을 충족하는 것에 대한 두려움으로 인해 수행 능력이 저하되는 과정]이라고 보고된다. 10,20,21 [고정관념 위협]은 부정적인 감정을 유발하고 학생들의 인지 부하를 증가시키며, 핵심 사무직 성적을 낮추는 것과 관련이 있습니다. 10,22

Microaggressions may cause both psychological and physiological distress. They are associated with depressive symptoms, anxiety, and alcohol use and may alter diurnal cortisol secretion. 17–19 Medical students report that microaggressions trigger and exacerbate racial/ethnic stereotype threat, a process in which fear of fulfilling negative stereotypes about one’s group results in lower performance. 10,20,21 Stereotype threat, in turn, triggers negative emotions and increases students’ cognitive load, and is associated with lower core clerkships grades. 10,22

우리는 '소스', '타겟', '방관자'라는 용어를 사용하여 각각 [미세 공격자, 미세 공격의 수신자, 미세 공격의 목격자]를 지칭합니다. 23 권력에 초점을 맞춘 [비판적 인종 이론(CRT)]은 미세 공격의 영향과 효과적인 방관자 대응을 탐구하는 데 중요한 이론적 렌즈를 제공합니다. 24,25 [비판적 인종 이론]은

- 미국 사회에서 인종 차별을 일반적인 것(norm)으로 강조하고,

- 권력이 인종 차별적 상호작용을 매개하는 방식을 인식하며,

- 사람들이 인종 차별(예: 성차별, 계급 차별)과 교차하고 복합적으로 작용하는 여러 소외된 정체성을 가질 수 있다는 점을 인정합니다. 24

We use the terms “source,” “target,” and “bystander” to refer to the microaggressor, recipient of the microaggression, and witness to a microaggression, respectively. 23 Critical race theory (CRT), with its focus on power, offers an important theoretical lens through which we explore the impact of microaggressions and effective bystander responses. 24,25 CRT

- highlights racism as the norm in American society,

- recognizes how power mediates racially charged interactions, and

- acknowledges that people can have multiple marginalized identities that intersect and compound with racism (e.g., sexism, classism). 24

때때로 미묘하고 상황에 따라 달라질 수 있는 [미시적 공격]은 [개인에 따라 다양하게 해석]될 수 있습니다. 26 [방관자]는 동시에 [미세 공격의 목격자]이면서 [동시에 영향]을 받을 수 있습니다. 27 우리는 미세 공격으로 인해 피해를 입을 가능성이 가장 높은 대상의 관점과 해석을 우선시합니다. CRT는 학생들이 인종화된 교육 계층을 탐색하는 데 직면하는 [교차하는 어려움]을 인정합니다. [환자]가 [학생]에게 [미세 공격]을 가할 때, 학생은 [방관자인 감독자]에 비해 [교육적 지위가 낮고] 동시에 [미세 공격의 대상]이기 때문에 [교차하는 취약성]을 지니고 있으며, 학생은 또한 환자를 돌보는 사람으로서 팀원이 개입하지 않는 한 [계속 돌봐야 할 직업적 의무]를 느낄 수 있습니다.

Because of their sometimes subtle and context-dependent nature, microaggressions may be interpreted variably by different individuals. 26 Bystanders may simultaneously be witnesses to and impacted by a microaggression. 27 We prioritize the perspective and interpretation of the target as the person most likely harmed by the microaggression. CRT acknowledges the intersecting challenges students face navigating racialized educational hierarchies. When patients commit microaggressions against students, students hold intersecting vulnerabilities as they are simultaneously the microaggression target and low in educational status compared with bystander supervisors; students may also be caretaker for the patient and feel professionally obligated to continue caring unless a team member intervenes.

[의료 위계 구조의 최상위에 있는 교수진]은 [학생을 옹호할 수 있는 좋은 위치]에 있을 수 있지만, 학습자가 방관자 지원이 가장 필요할 때 [아무런 반응을 보이지 않음]으로써 미세 공격에 직면하는 경우가 많습니다. 9 많은 교수진은 편견과 차별에 대한 인식이 높아지면서 '살얼음판을 걷는 기분'이 들며, 잘못된 행동이나 말을 하다가 [학습자로부터 인종차별주의자나 성차별주의자로 낙인찍힐까 봐 불안감]이 커진다고 설명합니다. 28-30 안타깝게도 이러한 불편함과 두려움은 학습자의 요구를 충족시키지 못하고 포용적인 문화를 위한 노력을 방해하는 결과를 초래할 수 있습니다.

While faculty atop the medical hierarchy may be positioned well to advocate for students, they often meet microaggressions with inaction when learners most need bystander support. 9 Many faculty describe that their increasing awareness of bias and discrimination prompts feelings of “walking on eggshells,” with increased anxiety about doing or saying the wrong thing and being labeled as racist or sexist by learners. 28–30 Unfortunately, this discomfort and fear can result in failing to meet learners’ needs and thwart efforts toward inclusive culture.

[미세 공격에 대한 방관자의 개입]을 위한 다양한 기법이 제안되었는데, 여기에는 Sue의 미세 개입, Ackerman-Barger의 ARISE 프레임워크, Wheeler의 12가지 팁 등이 포함됩니다. 6,23,31-37 이러한 기법들은 일반적으로 [미세 공격을 인식하고, 대응할지 여부를 결정하고, 그 순간에 다양한 대응 기술을 사용하는 것]을 수반합니다. 23,32,37 이러한 접근법은 학습자를 대상으로 하는 미세 공격에 대응하기 위한 일반적인 지침을 제공하지만, 학습자를 위한 대응의 효과를 극대화하기 위해서는 대응의 영향에 대한 증거 기반 이해와 권장 사항이 필요합니다. 학습자에게 미치는 [미세 공격의 정서적, 인지적, 생리적 영향]과 [특정 미세 공격에 대한 대응 시기와 방법]을 결정할 때 고려해야 할 다각적인 요소는 [교육자가 최적의 방관자 개입에 대한 학습자의 관점을 이해하는 방법]에 대한 의문을 불러일으킵니다.

A variety of techniques for bystander interventions on microaggressions have been proposed, including Sue’s microinterventions, Ackerman-Barger’s ARISE framework, Wheeler’s 12-tips, and others. 6,23,31–37 These techniques generally entail recognizing a microaggression, deciding whether or not to respond, and employing various response techniques in the moment. 23,32,37 Though these approaches provide general guidance for responding to microaggressions targeting learners, there is a need for evidence-based understanding of the impact of responses and recommendations to maximize the effectiveness of responses for learners. The emotional, cognitive, and physiological impact of microaggressions on learners, as well as the multifactorial considerations underpinning a decision of when and how to respond to a given microaggression, prompt questions about how educators understand learners’ perspectives on optimal bystander interventions.

이 연구의 목적은 임상 실습에서 방관자 감독자가 미세 공격에 어떻게 대응해야 하는지에 대한 학생들의 관점을 탐구하는 것입니다. 연구 질문은 다음과 같습니다:

- (1) 학생을 대상으로 한 미세 공격에 대응하는 교수진의 주요 고려 사항에 대한 학생의 관점은 무엇인가?

- (2) 미세 공격에 대한 이상적인 감독자 대응의 주요 특징은 무엇인가?

- (3) 이상적인 대응은 미세 공격의 유형에 따라 어떻게 다른가?

The purpose of this study is to explore students’ perspectives on how bystander supervisors should respond to microaggressions on clinical clerkships. The research questions are:

- (1) What are student perspectives on key considerations for a faculty member responding to a microaggression targeting a student?

- (2) What are the key features of an ideal supervisor response to a microaggression? and

- (3) How does the ideal response differ by type of microaggression?

방법

Method

디자인

Design

해석주의 패러다임에 기반한 이 질적 포커스 그룹 연구에서는 주제 분석의 프레임워크 방법을 사용하여 2020년 미국 내 임상실습생을 대상으로 [환자의 미세 공격에 대한 슈퍼바이저의 대응에 대한 의대생들의 인식]을 탐색했습니다. 38 올해는 인종적, 민족적 불평등으로 인한 국가적 사회 불안이 심각했던 해로, 이러한 맥락에서 데이터를 해석했습니다. 39,40

For this qualitative focus group study, based in an interpretivist paradigm, we employed the framework method of thematic analysis to explore medical students’ perceptions about supervisor responses to microaggressions from patients targeting clerkship students in the United States, 2020. 38 This year was notable for significant national social unrest because of racial and ethnic inequalities; our data are interpreted within this context. 39,40

연구팀에는 남아시아 의대생 1명, 흑인 레지던트 1명, 교수진 4명(백인 2명, 아메리카 원주민 및 백인 1명, 라티나 1명)이 참여했습니다. 모든 팀원은 샌프란시스코 캘리포니아 대학교(UCSF) 의과대학 출신으로 소수인종 학습자의 경험에 학문적 관심을 가지고 있었습니다. 모든 교수진은 의대생과 직접 협력합니다.

Our research team included 1 South Asian medical student, 1 Black resident, 4 faculty (2 White, 1 Native American and White, 1 Latina). All team members were from the University of California, San Francisco (UCSF) School of Medicine, with academic interests in the experience of minoritized learners. All faculty members work directly with medical students.

UCSF 기관윤리심의위원회는 이 연구를 면제 연구로 승인했습니다(IRB #20-29884).

The UCSF Institutional Review Board approved the study as exempt (IRB #20-29884).

환경 및 참가자

Setting and participants

연구 대상은 3개의 핵심 교육 시스템(4년제 대학 시스템, 공공 안전망 병원, 재향군인 의료 센터)과 여러 지역사회 기반 계열사를 보유한 주립 공공 기관인 UCSF였습니다. 2020년 3월에 재학 중인 모든 3학년 및 4학년(임상 실습 기간) 의대생이 참여할 수 있었습니다. 다양한 참여자를 확보하기 위해 의대생의 [다양성(의대생 중 소수자 33%, 여성 53%)을 고려하여 편의 표본 추출]을 사용했습니다. 2021학년과 2022학년 학급을 대상으로 매주 4회에 걸쳐 리스트서브 이메일을 통해 학생들을 모집했습니다. 이메일 초대는 관심 있는 학생들이 Qualtrics 웹 플랫폼으로 이동하여 인구 통계, 이메일 주소, 참석 가능 여부를 입력하도록 안내했습니다. 관심 있는 모든 학생을 포커스 그룹에 초대했습니다. 포커스 그룹 참가자에게는 20달러가 지급되었습니다.

The study site was UCSF, a state public institution with 3 core teaching systems (quaternary university system, public safety net hospital, and veterans’ affairs medical center) and multiple community-based affiliates. All third- and fourth-year (clerkship years) medical students during March 2020 were eligible to participate. We used convenience sampling, relying upon the diversity of the medical student body (33% underrepresented in medicine, 53% female) to ensure diverse participants. We recruited students through 4 weekly listserv emails to the classes of 2021 and 2022. The email invitation directed interested students to the Qualtrics web platform to enter their demographics, email address, and availability. We invited all interested students to a focus group. Focus group participants received $20.

데이터 수집

Data collection

반구조화된 포커스 그룹에서 참가자들은 [3가지 주요 대인관계 미세 공격 유형]을 대표하는 [4개의 미세 공격 시나리오]에 대해 논의했습니다(표 1 참조). 6,12 시나리오는 입원 환자 또는 응급실 환경에서 학생의 미세 공격 대상과 교직원의 방관자 상황을 묘사했습니다. 연구팀은 문헌 검토와 팀원들의 실제 경험을 바탕으로 시나리오를 설계했습니다. 미세 공격 유형 간의 일관성을 탐색하기 위해 [대상 학생의 신원을 조작하여 두 가지 유사한 미세 폭행 및 미세 모욕 시나리오]를 만들었습니다. 진행자(P.K.M.)는 모든 포커스 그룹을 시작하면서 [미세 공격의 정의]를 내리고, 학생들에게 미세 공격에 대응하는 방법에 대한 [교수진 교육을 만드는 것이 목적]임을 알렸습니다.

During semistructured focus groups, participants discussed 4 microaggression scenarios representing the 3 major types of interpersonal microaggressions (see Table 1). 6,12 Scenarios depicted a student microaggression target and faculty bystander in an inpatient or emergency department setting. The research team designed scenarios based on literature review and team members’ lived experiences. To explore consistency across microaggression types, we created 2 similar microassault and microinsult scenarios by manipulating the targeted student identity. The moderator (P.K.M.) began all focus groups by defining microaggressions and informing students that the purpose was to create faculty trainings on how to respond to microaggressions.

진행자 및 공동 진행자(J.L.B.)는 참여 자격이 없는 UCSF 의대 레지던트 4명을 대상으로 [파일럿 포커스 그룹]을 진행하기 전에 퍼실리테이터 교육을 받았습니다. 그런 다음 저자들은 공식적인 데이터 수집을 시작하기 전에 명확성을 높이고 중복성을 줄이기 위해 포커스 그룹 가이드를 수정했습니다. 최종 가이드는 부록 디지털 부록 1입니다. [공동 진행자]는 포커스 그룹이 진행되는 동안 주요 아이디어와 참가자 간의 상호 작용을 기록한 메모를 작성했습니다. 마지막 3개의 포커스 그룹에서는 각 사례에 대한 토론의 균형을 맞추기 위해 시나리오 순서를 뒤집었습니다. 데이터 수집은 관심 있고 참여 가능한 모든 학생이 참여한 후에 종료되었습니다. 마지막 포커스 그룹까지 새로운 주요 아이디어나 대응 전략이 논의되지 않았으며, 이는 주제와 수집된 데이터가 충분함을 나타냅니다. 41 모든 그룹은 Zoom을 통해 진행 및 녹화되었고, 전문적으로 전사되었으며, 분석 전에 비식별화 과정을 거쳤습니다.

The moderator and co-facilitator (J.L.B.) underwent facilitator training before conducting a pilot focus group with 4 UCSF Medicine residents ineligible for participation. Authors then revised the focus group guide to improve clarity and reduce redundancy before formal data collection began. The final guide is Supplemental Digital Appendix 1, available at https://links.lww.com/ACADMED/B157. The co-facilitator took notes documenting key ideas and interparticipant interactions during focus groups. We inverted scenario order for the final 3 focus groups to balance discussion of each case. Data collection ended after all interested and available students participated. By the final focus group, no new major ideas or response strategies were discussed, indicating sufficiency of themes and data collected. 41 All groups were conducted and recorded over Zoom, professionally transcribed, and deidentified before analysis.

분석

Analysis

4명의 연구자(J.L.B., P.K.M., M.T.O., K.E.H.)가 독립적으로 3개의 트랜스크립트를 읽고 오픈 코딩을 수행했습니다. 그런 다음 연구팀은 회의를 통해 제안된 코드에 대해 논의하고 분석 프레임워크를 개발하여 하나의 코드북을 만들었습니다. 다음으로 5명의 연구자 중 2명(J.L.B., P.K.M., M.T.O., K.L.L., K.E.H.)이 각 트랜스크립트를 개별적으로 코딩하고 토론을 통해 불일치하는 부분을 조정했습니다. 인터뷰는 Dedoose 버전 8.0.35(캘리포니아주 로스앤젤레스)를 사용하여 코딩했습니다. 코딩된 발췌문을 미시적 공격 시나리오별로 분류한 후, 각 시나리오에 대한 코드별로 발췌문을 합성했습니다. Microsoft Excel 버전 16.44(워싱턴주 레드몬드)를 사용하여 각 합성을 코드별(열별)로 마이크로 공격 시나리오를 담은 최종 프레임워크 매트릭스에 도표로 작성했습니다. 모든 연구원이 데이터의 최종 해석 및 요약에 참여했습니다. 참가자의 인용문과 함께 참가자가 스스로 밝힌 인종/민족을 표시했습니다.

Four researchers (J.L.B., P.K.M., M.T.O., K.E.H.) independently read and performed open coding of 3 transcripts. The research team then met to discuss their proposed codes, developed an analytic framework, and created a single codebook. Next, 2 of 5 researchers (J.L.B., P.K.M., M.T.O., K.L.L., K.E.H.) separately coded each transcript and reconciled discrepancies through discussion. Interviews were coded using Dedoose Version 8.0.35 (Los Angeles, California). After sorting coded excerpts by microaggression scenario, we synthesized excerpts by code for each scenario. We charted each synthesis into the final framework matrix which held microaggression scenario by code (column by row) using Microsoft Excel Version 16.44 (Redmond, Washington). All researchers participated in the final interpretation and summary of the data. We indicated participants’ self-identified race/ethnicity alongside their quotations.

반사성

Reflexivity

연구팀은 학생들의 응답에 대한 반성과 미세 공격에 대한 개인적인 경험이 참가자들의 응답과 어떻게 병치되는지에 대해 자주 논의했습니다. 이 프로젝트는 두 명의 팀원(J.L.B., M.T.O.)이 사무직 의대생에 대한 미세 공격 행위를 목격하고, 주치의(M.T.O.)가 미세 공격에 대응하고, 나중에 임상팀 전체가 이 경험을 디브리핑한 후 개념화되었습니다. 이 학생은 미세 공격 후 광범위한 반성은 도움이 되지 않는다는 피드백을 주었습니다.

The research team frequently discussed our reflections on students’ responses and how our personal experiences with microaggressions juxtaposed with participants’. This project was conceptualized after 2 team members (J.L.B., M.T.O.) witnessed a microaggression against a clerkship medical student; the attending (M.T.O.) responded to the microaggression, and the entire clinical team later debriefed the experience. The student gave feedback that extensive reflection after a microaggression was not helpful.

신뢰성

Credibility

분석이 끝난 후 모든 참가자에게 원고 결과 초안을 이메일로 보내 제시된 결과가 포커스 그룹 토론 및 임상 경험과 일치하는지에 대한 피드백을 요청했습니다. 10명의 참가자가 응답했으며, 모두 결과와 토론이 자신의 포커스 그룹을 정확하게 반영한다는 데 동의했습니다. [3명은 약간의 텍스트 수정을 제안했고, 한 참가자는 자신의 인용문과 인종/민족을 명확히 해 달라고 요청했습니다].

After the analysis, we emailed all participants a draft of the manuscript results and discussion for their feedback on whether the presented results felt consistent with their focus group discussions and clinical experiences. Ten participants responded: all agreed that the results and discussion accurately represented their focus groups. Three gave minor text edits, and one participant clarified her quotation and race/ethnicity.

결과

Results

설문조사 초대에 응답한 학생은 45명이었으며, 44명이 초대되었습니다(1명은 포커스 그룹 시간이 맞지 않아 참여하지 못함). [39명의 학생이 7개의 포커스 그룹에 참여했으며, 그룹당 5~7명의 학생이 참여했습니다]. 포커스 그룹은 평균 86분 동안 진행되었습니다(범위: 80-92분). 참가자들은 다양한 사회적 정체성을 가지고 있었습니다(표 2 참조). 15명(38%)의 참가자가 아시아계, 12명(31%)이 흑인, 5명(13%)이 라틴계, 17명(44%)이 백인, 1명(3%)이 아메리카 원주민, 1명(3%)이 중동계로 밝혀졌습니다. 13명(33%)의 참가자는 남성, 25명(64%)은 여성, 1명(3%)은 비이성애자, 15명(38%)은 성소수자로 밝혀졌습니다. 참가자들은 제공된 시나리오에 대해 토론하면서 임상 현장에서의 미세한 공격에 대한 자신의 경험에 대해서도 생각해 보았습니다. 아래 결과는 시나리오와 실제 경험을 바탕으로 한 학생들의 관점을 나타냅니다.

Forty-five students responded to our survey invitation; 44 were invited (1 was unavailable for any focus group times offered). Thirty-nine students participated in 7 focus groups, with 5 to 7 students per group. Focus groups lasted an average of 86 minutes (range: 80–92). Participants had a range of intersecting social identities (see Table 2). Fifteen (38%) participants identified as Asian, 12 (31%) Black, 5 (13%) Latinx, 17 (44%) White, 1 (3%) Native American, and 1 (3%) Middle Eastern. Thirteen (33%) participants identified as men, 25 (64%) women, and 1 (3%) nonbinary, and 15 (38%) as LGBTQ. As participants discussed the provided scenarios, they also reflected on their own experiences with microaggressions in the clinical workplace. Findings below represent students’ perspectives based on the scenarios and their lived experiences.

포커스 그룹 내에서 학생들은 미세 공격 사례의 대상이 된 정체성을 가진 사람들이 응답할 때까지 [논평을 미루는 것]으로 나타났습니다(성별에 기반한 미세 공격의 경우 남성은 여성에게, 인종에 기반한 시나리오의 경우 백인 학생은 유색인종 학생에게 미루었습니다). 참가자의 성적 지향에 따른 응답의 차이는 확인되지 않았지만, 이 주제를 다룬 시나리오는 없었습니다.

Within focus groups, students seemed to defer commenting until after those who self-identified with the identity targeted by the microaggression case responded (men deferred to women for gender-based microaggressions; White students deferred to students of color for race-based scenarios). We did not identify differences in responses based on participants’ sexual orientation, though none of the scenarios addressed this topic.

전반적으로 학생들은 [미세 공격이 발생하기 전에 감독자의 효과적인 대응이 시작되어야 한다]는 데 동의했습니다. 아래 결과는 두 가지 주제를 설명합니다:

- 방관자 고려 사항에 대한 학생의 인식.

- 감독자 조치

- 첫 번째 주제에서는 학생들의 인식을 3개의 하위 주제로 분류했습니다. 학생들은 미세 공격에 대한 대응으로 수퍼바이저가 교수 수퍼바이저와의 [사전 토론("사전 브리핑")]을 통해 수집한 학생의 선호도, [환자의 상황], 진료실 내 다양한 [대인관계 역학 관계] 등을 고려해야 한다고 생각했습니다.

- 두 번째 주제인 수퍼바이저의 행동에 대해 학생들은 미세 공격이 발생하는 동안 이상적인 수퍼바이저의 대응, 목격하는 것이 적절한 경우, 또는 방 밖으로 대응을 미루는 것이 적절한 경우, 마지막으로 미세 공격이 발생한 후 효과적인 대응에 대해 설명했습니다. 이러한 결과는 아래에 자세히 설명되어 있습니다. 인용문에는 참가자 번호, 본인 식별 인종/민족, 성별이 포함되어 있습니다.

Overall, students endorsed that effective supervisor responses began before microaggressions occurred. Results below describe 2 themes:

- Student perceptions of bystander considerations and

- supervisor action.

- For the first theme, we capture students’ perceptions in 3 subthemes. In response to a microaggression, students felt that supervisors should consider the student’s preferences, which ideally were gathered through anticipatory discussions (“pre-brief”) with their faculty supervisors, the patient’s context, and the various interpersonal dynamics in the room.

- For the second theme, supervisor action, students described ideal supervisor responses during the microaggression, when it was appropriate to bear witness, or defer response until outside the room, and, finally, effective responses after the microaggression. These results are detailed below. Quotations include participant number, self-identified race/ethnicity, and gender.

효과적인 대응을 위한 감독자의 고려 사항에 대한 학생의 관점

Student perspectives on supervisor considerations for an effective response

학생의 선호도: "사전 브리핑"을 통해 미세 공격에 대비하기.

Student preferences: Preparing for microaggressions through a “pre-brief.”

학생들은 각자의 정체성, 경험, 선호도를 가지고 왔기 때문에 [미세 공격에 대해 원하는 대응 방식이 달랐습니다](표 3 참조). 참가자들은 한 학생의 [선호도]를 다른 학생에게 적용하는 것에 대해 주의를 기울였습니다.

Because students brought their own identities, experiences, and preferences, their desired responses to microaggressions differed (see Table 3). Participants cautioned against extrapolating any one student’s preferences onto other students.

모든 학생에게 맞는 정답은 없습니다. 표준 운영 절차는 없습니다.... 어떤 개입이 상황에 가장 적합하거나 대상 학생의 피해를 최소화할 수 있는지 알 수 없다는 뜻이 아닙니다. 어떤 면에서는 겸손으로 표현할 수 있다고 생각합니다. (P37, 흑인/중동 여성)

There is no one size fits all. There is no standard operating procedure…. Doesn’t mean that we know what intervention would best suit the situation or minimize the harm to those that are targeted. I think in some ways it’s phrased as humility. (P37, Black/Middle Eastern woman)

포커스 그룹에서 반복적으로 제안된 이 문제에 대한 해결책 중 하나는 [사전 브리핑]이었습니다. 사전 브리핑은 함께 일하기 시작할 때 학습자와 감독자가 잠재적인 미세 공격에 대비할 수 있도록 토론하는 것을 의미합니다. 많은 학생이 효과적인 방관자 대응에 가장 중요한 요소는 [감독자가 사전 브리핑을 했는지 여부]라고 생각했습니다.

One solution to this concern proposed repeatedly across focus groups was to pre-brief. We use pre-brief to refer to discussion at the onset of working together which allowed the learner and supervisor to prepare for potential microaggressions. Many students believed that the most important contributor to an effective bystander response was whether the supervisor had pre-briefed.

감독자는 로테이션이 시작될 때 학생들과 미리 이러한 대화를 나누고, 자신이 인지한 미세 공격에 대처하는 방법에 대한 계획을 세워야 하며, 또한 자신이 인지하지 못한 미세 공격이 있는 경우 학생이 이를 전달할 수 있도록 [힘을 실어줄 수 있는 방법을 마련]해야 합니다. (P19, 흑인 남성)

Attendings should be having these conversations with their students in advance … at the beginning of a rotation and having a plan for how to address microaggressions that they recognize, but also … if there are microaggressions they don’t recognize, how the student can feel empowered to communicate that. (P19, Black man)

학생들은 [사전 브리핑]을 통해 감독자에게 [미세 공격에 대한 대응에 대한 선호도를 알리고], 실제로 자신을 지지하는 [방관자 대응을 장려]할 수 있다고 느꼈습니다. 수퍼바이저는 사전에 미세 공격에 대해 논의함으로써 학습자에게 학생의 [심리적 안전을 우선시한다는 신호]를 보냈습니다. 참가자들은 슈퍼바이저가 미세 공격의 표적이 될 가능성이 있어 보이는 학습자뿐만 아니라 [모든 학습자와 사전 브리핑을 해야 한다]고 강조했는데, 이는 학생들이 소외감을 느낄 수 있습니다. 사전 브리핑을 일대일로 해야 하는지, 임상 팀으로 해야 하는지, 이메일로 해야 하는지에 대한 합의가 이루어지지 않았습니다. 학생에게 선호도를 물어보는 것은 주치의에서 학생으로 권력을 이동시키고 학생이 자신의 필요를 가장 잘 알고 있다는 존중을 전달했습니다.

Students felt that pre-briefing allowed them to inform the supervisor of their preferences regarding responses to microaggressions and promoted bystander responses that were actually supportive for them. By discussing microaggressions in advance, supervisors signaled to learners that they prioritized students’ psychological safety. Participants emphasized that the supervisor should pre-brief with all learners, not simply those who appeared likely to be targeted with microaggressions, which might make students feel singled out. There was not consensus about whether the pre-brief should happen one-on-one, as a clinical team, or by email. Asking students for their preferences shifted power from the attending to the student and conveyed respect that the student knew what would best address their needs.

참가자들은 어텐딩이 팀의 의료 콘텐츠 전문가이기는 하지만, 미세 공격에 대응하는 데는 그에 상응하는 [전문성이 부족]할 수 있으며, [전문가에서 초보자로의 불편한 전환]이 [어텐딩의 비활동의 원인]이 될 수 있다고 지적했습니다. 또한 환자를 교육하는 데 필요한 [올바른 문화 용어에 익숙하지 않을 수]도 있습니다. 한 학생은 시크교의 관습적인 머리 장식인 다스타르를 언급하며 이렇게 말했습니다:

Participants noted that while attendings are content experts for medical care on the team, they may lack comparable expertise for responding to microaggressions, and that the uncomfortable shift from expert to novice might be a source of inaction for attendings. They may also be unfamiliar with the correct cultural terminology to educate patients. Referring to the dastaar, the customary Sikh headwear, one student said:

만약 그것이 내 문화가 아니라면 어텐딩으로서 '아, 이 학생에게 무슨 일이 일어나고 있는지 모든 사람에게 설명해야겠어'라고 말하는 것이 매우 이상하게 느껴질 수 있습니다. (P21, 백인 여성)

I would feel if that were not my own culture, I might as an attending have a hard time being like, “Oh, I’m going to explain what’s going on with this student for everyone,” because that would also feel very strange for me to do that. (P21, White woman)

이 경우, [사전 브리핑]은 주치의의 대응을 알리는 데 특히 중요하다고 느꼈습니다.

In this case, a pre-brief was felt to be especially important to inform attending response.

환자 컨텍스트.

Patient context.

학생들은 미세 공격에 대한 대응의 성격과 타이밍을 지시하기 위해 [임상적 맥락과 의학적 예민함]을 중요한 고려 사항으로 꼽았습니다. 예를 들어, 심하게 흥분한 환자를 설득하려고 시도하는 것은 미세 공격성을 완화할 가능성이 낮았습니다. 아프거나 혼란스러운 환자의 미세 공격은 관리자의 대응을 면제하는 것이 아니라 오히려 이상적인 대응의 타이밍과 특성을 바꾸어 놓았습니다.

Students identified clinical context and medical acuity as critical considerations to direct the nature and timing of a response to microaggressions. For instance, attempting to reason with an acutely agitated patient was unlikely to deescalate a microaggression. A microaggression from an ill or confused patient did not absolve the supervisor from responding, but rather, changed the timing and characteristics of the ideal response.

급성, 중환자인 경우.... 환자가 좀 더 안정될 때까지 이에 대한 언급을 보류하는 것이 개인적으로 더 괜찮을 것 같아요. (P12, 중국계 미국인 여성)

If they are acutely, critically ill…. I think it would be more okay with me personally to hold off on a comment about this for a time where they’re more stable. (P12, Chinese American woman)

학생들은 환자의 경과에 따라 [이상적인 대응 타이밍에 대해 신중하게 생각하기를 원했으며], 곧 퇴원할 예정이거나 향후 시술을 앞둔 환자에게 가혹한 대응을 하여 향후 치료를 받지 못하게 하고 싶지 않았습니다.

Students wanted to be thoughtful about the timing of an ideal response in the context of a patient’s course and did not want to deliver harsh responses to patients soon-to-be discharged or with upcoming procedures, so as not to dissuade them from seeking future care.

대인관계 역학.

Interpersonal dynamics.

[학생과 환자의 관계]는 감독자가 어떻게 대응해야 하는지 결정하는 데 있어 핵심적인 고려 사항이었습니다. 참가자들은 모든 환자가 학생(및 다른 팀원)의 정체성과 상호 작용하는 고유한 정체성, 경험, 선호도를 가지고 있다는 점을 인정했습니다. 학생들은 미세 공격의 유형에서 환자의 의도를 추론했습니다. 미세 폭행 시나리오는 주로 대상 학생에 대한 명백한 인종 차별 행위로 간주된 반면, 학생들은 미세 모욕과 미세 무효화에는 [맥락과 의도를 고려]했습니다. 예를 들어, 환자가 다른 팀원보다 한 팀원을 선호하는 경우, 일치하는 정체성을 가진 의료진이 환자에게 위안을 제공했다면 미세 공격으로 인식되지 않을 수 있습니다:

The student–patient relationship was a key consideration in deciding how supervisors should respond. Participants acknowledged that every patient comes with their own identities, experiences, and preferences that interact with students’ (and other team members’) identities. Students inferred patient intent from the type of microaggression. Microassault scenarios were largely viewed as an act of overt racism against the targeted student, whereas students considered context and intent for microinsults and microinvalidations. For instance, a patient’s preference for one team member over another may not be perceived as a microaggression if a provider of a concordant identity offered a source of comfort for a patient:

환자는 자신의 정체성과 일치하는 의료진에게 더 편안함을 느낄 것입니다..... 흑인 환자로서 팀에 흑인이 한 명 있다면 그 팀에 흑인 한 명이 있다고 생각할 수 있습니다.... 그 사람에게 질문을 하는 것이 더 편할 것 같습니다. (P31, 아프로라티나)

A patient’s going to be more comfortable with a practitioner that matches their identity…. I can think of, as a Black patient, if there’s a team and there’s a Black person there, one person in that team…. I’m going to feel more comfortable directing my questions to that person. (P31, Afrolatina)

일부 학생은 [환자 동맹을 우선시]하고, [대립이 학생과 환자 관계를 복잡하게 만들 수 있다]고 생각하여 [비대립적 대응을 선호]했습니다.

Some students preferred nonconfrontational responses because they prioritized their patient alliance and felt that confrontation could complicate the student–patient relationship.

감독자의 조치

Supervisor action

학생들은 [효과적인 감독자의 방관자적 대응]이 학생을 보호하고 검증할 수 있지만, 반드시 [환자의 신념을 바꾸는 것을 목표로 해서는 안 된다]고 주장했습니다. 효과적인 대응은 [미세 공격을 인정]하고, [안전한 학습 환경을 조성]하고, [동맹 관계를 제공]하고, [역할 모델링]을 보여주고, 필요한 경우 학생이 [유해한 상황에서 벗어날 수 있도록 하는 것]이었습니다(표 4 참조). 전부는 아니지만 많은 학생들이 즉각적인 대응을 원했습니다. 모든 학습자나 시나리오를 만족시키는 단일 반응은 없었기 때문에, 학생들은 "어텐딩이 매번 상황이 다르기 때문에 도구 상자에 다양한 각도가 있다는 것을 느끼는 것이 중요하다고 느꼈습니다."(P9, 백인 여성) 누군가를 이해하려면 때로는 여러 각도에서 여러 번 시도해야 할 때도 있습니다. 환자를 마주한 후, 학생들은 교직원과 일대일로 간단히 확인하여, [미세 공격성을 인정하고 학생이 추가적인 반성을 위한 시간을 원하는지], 또는 [전체 의료진에게 디브리핑을 원하는지] 물어본 후 둘 중 하나를 수행하는 것을 선호했습니다.

Students asserted that effective supervisor bystander responses would protect and validate the student but should not necessarily aim to change the patients’ beliefs. An effective response acknowledged the microaggression, promoted a safe learning environment, provided allyship, demonstrated role-modeling, and, when necessary, let students escape harmful situations (see Table 4). Many, but not all, students wanted a response in the moment. Because there was no single response that satisfied all learners or scenarios, students felt that it was important for “Attendings to feel that they have multiple angles in their toolbox, both because the context is different each time, but also it takes sort of multiple attempts at different angles sometimes to get through to someone” (P9, White woman). After the patient encounter, students preferred brief one-on-one check-ins with faculty to acknowledge the microaggression and ask whether the student wanted space for additional reflection, or to debrief with the entire medical team, before doing either.

미세 공격 중.

During the microaggression.

환자와 마주한 상태에서 효과적인 대응은 [짧고 직접적이며 환자를 공격하지 않는 것]이었습니다. 학생들이 제안한 순간적 대응의 예로는 학생의 임상적 가치 강조, 유머 사용, 환자 교육, 임상 치료에 집중하도록 방향 전환, 역할 명확화, 경계 설정 등이 있었습니다. 학생들은 환자에게 특정 방식으로 느끼는 이유를 설명해 달라고 요청하는 것이 효과적인지에 대해 토론했는데, 이 전략은 환자가 인종차별적 신념에 대해 설명하도록 유도할 위험이 있기 때문입니다.

- 미세 폭행의 경우, 학생들은 즉각적인 대응을 원하거나 환자가 임상적으로 안정된 경우 만남을 일시 중지하고 방을 나가기를 원했습니다. 명백한 미세 공격에도 불구하고 임상적으로 안정되어 방을 나갈 수 없는 경우, 학생들은 감독자가 짧고 직접적인 대응을 하고 학생이 나갈 수 있도록 허용할 것을 권장했습니다.

- 덜 심각하다고 인식되는 다른 미세 공격 유형의 경우, 일부 학생들은 아래에 설명된 대로 슈퍼바이저가 목격하는 것을 선호했으며, 팀이 그 자리를 떠날 때까지 적극적인 대응을 미뤘습니다. 다른 학생들은 당장의 대응 부족에 대해 경고했습니다.

Effective responses while still in the patient encounter were short, direct, and did not attack the patient. Examples of students’ proposed in-the-moment responses included: emphasizing the clinical value of the student, using humor, educating the patient, redirecting to focus on clinical care, clarifying roles, and setting boundaries. Students debated whether asking a patient to explain why they felt a certain way was effective, as this strategy risked prompting the patient to expound on racist beliefs.

- For microassaults, students wanted an immediate response or to pause the encounter to leave the room if the patient was clinically stable. If unable to leave the room due to clinical acuity despite a flagrant microaggression, students recommended that supervisors say a short, direct response and allow the student to step out.

- For other microaggression types perceived as less severe, some students preferred the supervisor to bear witness as described below, delaying active response until after the team left the encounter. Others cautioned against lack of response in the moment.

목격하기.

Bear witness.

우리는 "목격을 참아내다"라는 표현을 사용하여 [미세 공격을 파악하고 의도적으로 개입을 연기하는 것]을 의미합니다. 제공자는 의도적으로 교육생과 아는 표정을 주고받거나, 나중에 미세 공격에 대해 논의함으로써 방에서 목격할 수 있습니다. 그러나 학생이 명시적으로 이러한 선호를 밝히지 않는 한, 교육생은 미세 공격에 반응하지 않도록 주의해야 합니다.

We use the phrase “bear witness” to refer to identifying the microaggression and intentionally deferring intervention. A provider may bear witness in the room by intentionally exchanging a knowing look with the trainee or discussing the microaggression later. However, unless a student had explicitly stated this preference, students cautioned against not responding to microaggressions.

저에게 [반응하지 않는 것은] 일종의 문제처럼 들립니다. 우리는 피부가 거칠어도 괜찮고 사람들이 문제를 무시해도 괜찮습니다... 그냥 무시하고 넘어가자고 말하는 것과 같은 맥락으로 들립니다. 문제는 미세한 공격이 너무 자주 일어나서 결국에는 두꺼운 피부를 깨뜨리기 때문에 우리가 미세 공격에 대해 이야기하고 있다는 것입니다. (P26, 멕시코계 미국인 여성)

[Not responding] to me is kind of sounding like a problem. We’re okay with having tough skin and we’re okay with people ignoring the problem … sounds kind of like that’s the same, like let’s just ignore it and move on. The whole issue is that we’re talking about microaggressions because they happen so often that eventually they break your thick skin. (P26, Mexican American woman)

목격 후 학생들은 [만남 후 확인]이 매우 중요하다고 생각했습니다.

After bearing witness, students considered a postencounter check-in critically important.

미세 공격 후.

After the microaggression.

학생들은 환자와의 만남을 떠난 후 미세 공격성에 대한 감독자의 논의가 [학생과 개별적으로 이루어져야 하는지] 아니면 [팀으로 이루어져야 하는지]에 대해 숙고했습니다. 대부분의 학생은 추가적인 그룹 토론이 학생에게 치유가 될지 여부를 논의하기 위해 [짧은 개인 상담]을 선호했습니다. 일부는 [팀과 함께 감정을 확인하는 것]이 중요하다고 생각했지만, 많은 학생들은 그룹 토론이 [트라우마나 공연적인 느낌을 줄 수 있는 소모적인 대화]로 이어져, 다른 사람들이 자신의 감정을 표현하고 동조자로 보일 수 있지만, 실제로 학생에게 도움이 되지 않을 수 있다고 우려했습니다. 학생들은 주치의가 그 순간 처리하고 싶지 않은 스트레스가 많은 [사건을 강제로 재현하도록 강요하지 않는 것이 필수적]이라고 느꼈습니다. 환자로부터 미세 폭행을 당하거나 잦은 미세 공격을 받은 학생은 수퍼바이저가 해당 학생을 다른 환자에게 재배치할 수 있는 옵션을 제안해 주기를 원했습니다. 수퍼바이저는 [재배치가 실력을 반영하는 것이 아니며 학생 평가에 해가 되지 않는다는 점을 명확히 하는 것이 중요했습니다]. 마지막으로, 일부 학생은 환자가 더 이상 혼란스러워하거나 화를 내지 않았을 때 다시 돌아와서 감독자 및 환자와 미세 공격에 대해 논의한 긍정적인 경험을 이야기했습니다.

Students deliberated whether the supervisor’s discussion of the microaggression after leaving the patient encounter should happen individually with the student or as a team. Most students preferred a brief private check-in to discuss whether further group discussion would be healing for the student. While some felt that validating emotions with the team was important, many worried that group discussion might invite an exhausting dialogue that could feel retraumatizing or performative, allowing others to express their emotions and appear as allies but not actually helping the student. Students felt it was imperative that attendings avoid forcing them to relive a stressful event that they did not want to process at that moment. Students subjected to a microassault or frequent microaggressions from a patient wanted their supervisor to propose the option of reassigning the student to a different patient. It was important for supervisors to clarify that reassignment was not a reflection of skill and would not harm student evaluations. Finally, some students recounted positive experiences returning to discuss the microaggression with the supervisor and patient when the patient was no longer confused or angry.

토론

Discussion

이 연구는 의대생이 선호하는 의대생 대상 미세 공격에 대한 [지도 교수의 대응 방식과 경험]에 대해 설명합니다. 학생들은 [단순한 일률적인 대응을 거부]했습니다. 오히려 학생의 선호도, 미세 공격의 맥락 등 교수진이 대응할 때 고려해야 할 다양한 고려 사항을 확인했습니다. 이들이 선호하는 방관자 대응은 [의사 결정권을 대상 학생에게로 전환하는 전략]을 나타냅니다.

This study describes medical students’ preferences for and experiences with faculty supervisor responses to microaggressions targeting clerkship students. Students rejected a simple one-size-fits-all response. Rather, they identified a variety of considerations which they felt faculty members should weigh in responding, including student preferences and microaggression context. Their favored bystander responses represented strategies to shift decision-making power toward targeted students.

[방관자 미세 공격 개입 가이드(B-MIG, 그림 1)]는 연구 참여자의 관점에서 선호하는 방관자 대응을 시각적으로 표현한 것입니다. 참가자들은 수퍼바이저가 모든 의대생에게 [함께 일하기 시작할 때] 미세 공격에 대한 대응 방식을 선호하는지 묻고, 각 미세 공격이 [발생한 후 간단히 다시 한 번 확인]할 것을 권장했습니다. 학생들은 모든 교수 지도교수가 모든 미세 공격에 대해 [어느 시점에는 짧게라도 대응해야 한다]는 데 동의합니다. B-MIG는 미세 공격에 대응하기 위한 개인 또는 교수진 개발의 발판이 되는 대응 가이드로 사용할 수 있지만, 학생과 상황에 맞게 대응을 계속 조정해야 하므로 처방전이 될 수는 없습니다. 감독자는 미세 공격 발생 시 서로를 지원하는 방법에 대한 팀 토론에 참여하기 위한 지침으로 B-MIG를 사용하는 것을 고려할 수 있습니다.

The Bystander Microaggression Intervention Guide (B-MIG, Figure 1) is a visual representation of the preferred bystander response from the perspective of our study participants. Participants recommended that supervisors ask all medical students for their preferences for responding to microaggressions at the onset of working together and to check-in again briefly with them after each microaggression. Students agree that all faculty supervisors should respond, even if briefly, to all microaggressions at some point. The B-MIG can be used as a response guide to scaffold personal or faculty development for responding to microaggressions; it cannot be a prescription because of the ongoing need to adapt responses to student and context. Supervisors can consider using the B-MIG as a guide to engage in team discussions around how to support one another in the event of a microaggression.

[학생의 희망에 초점을 맞춘 방관자 대응]은 교육 안전 환경을 조성할 수 있습니다. Tsuei 등은 [교육적 안전]을 "학습자가 자신의 투사된 이미지를 스스로 모니터링할 필요 없이, 학습 과제에 진정으로 전적으로 집중할 수 있도록, 타인의 판단으로부터 자유로움을 느끼는 주관적인 상태"로 정의했습니다. 42 미세 공격에 대한 학생 중심의 효과적인 개입을 실행하면 고정관념 위협과 이와 관련된 인지적 및 정서적 부하를 줄일 수 있습니다. 10,21,22 감독자의 사전 브리핑을 통해 신뢰감과 편안함을 느꼈다는 여러 참가자의 의견을 반영하여, [사전 브리핑]은 모두에게 더 유리한 학습 환경을 조성하는 데 중요한 도구로 간주합니다. 학생마다 선호하는 방식이 다르기 때문에, 모든 미세 공격에 대응하는 단일 전략이 모든 학생을 최적으로 지원하지는 못할 가능성이 높습니다. 다른 방관자 대응 문헌을 바탕으로 사전 브리핑에 대한 권장 사항은 휠러 등의 연구, 특히 "개방성과 존중의 문화를 미리 확립하라"는 권장 사항을 가장 잘 설명합니다. 11,32 임상팀에서 사전 브리핑을 시행한 제한된 경험에 따르면 일부 학생은 [미세 공격 대응에 대한 선호도를 확신하지 못했습니다]. 이 토론을 다시 살펴보면 학생들은 미세 공격에 대한 경험을 되돌아보고 향후 미세 공격에 대한 선호도를 수정할 수 있습니다. 사전 브리핑의 언어, 타이밍, 구조를 최적화하려면 더 많은 작업이 필요합니다.

Bystander responses centered on students’ wishes can foster an environment of educational safety. Tsuei et al defined educational safety as “the subjective state of feeling freed from a sense of judgment by others such that learners can authentically and wholeheartedly concentrate on engaging with a learning task without a perceived need to self-monitor their projected image.” 42 Implementing effective student-centered interventions to microaggressions may reduce stereotype threat and its associated cognitive and affective load. 10,21,22 Reflecting on multiple participants who described a sense of trust and comfort from supervisor pre-briefs, we view the pre-brief as a critical tool to foster a more favorable learning environment for all. Because student preferences differ, a single strategy for responding to all microaggressions is unlikely to optimally support all students. Building on other bystander response literature, the recommendation to pre-brief best elaborates upon the work of Wheeler et al, specifically the recommendation to “establish a culture of openness and respect upfront.” 11,32 In our limited experience implementing the pre-brief on our clinical teams, some students are unsure of their preferences regarding microaggression responses. Revisiting this discussion allows students to reflect on experiences with microaggressions and revise their preferences for future microaggressions. More work is needed to optimize the language, timing, and structure of the pre-brief.

이상적인 슈퍼바이저의 반응에 대한 참가자들의 인식은 [권력의 중심]을 [슈퍼바이저에서 학습자 쪽으로 이동]시킵니다. 프렌치와 레이븐의 6가지 권력 기반(합법적, 전문적, 정보 제공적, 보상적, 강압적, 경건적)은 사회적 권력 이동을 조사하는 데 유용한 프레임워크로 구성됩니다. 43-45

- 지도 어텐딩은 의대생에 대한 권한을 가진 [합법적인 권력]을 가지고 있습니다.

- [전문적 권력]은 주치의가 알고 있는 것으로 추정되는 내용을 기반으로 하며, [정보적 권력]은 다른 사람과 공유하는 정보에서 비롯됩니다. 46

- 미세 공격이 발생한 후 사전 브리핑을 한 후 학생의 의사를 집행하는 수퍼바이저는 학생을 미세 공격 경험에 대한 전문가로 취급하고 [합법적 권력과 전문적 권력]을 학생에게 효과적으로 이전한 것입니다. 학생이 선호하는 미세 공격 대응 방법을 감독자에게 알릴 때, 학생은 감독자가 조력자가 될 수 있도록 정보 권한을 이전합니다. 37,46

- 학생의 환자 돌봄 중단 결정이 평가에 영향을 미치지 않는다는 것을 확인함으로써, 감독자는 [보상 권력과 강압적 권력]을 무력화할 수 있습니다.

- 학생을 대상으로 한 [미세 공격에 대응하지 않는 감독자]는 학생들이 롤모델로서 감독자에 대한 믿음을 잃게 되어 [참조적 권력]을 잃을 수 있습니다. 교수진이 학생의 선호도를 물어봄으로써 학생에게 힘을 실어주자는 제안은 자기 평가와 자기 비판에 대한 평생의 노력으로 정의되는 "문화적 겸손"을 예시하며, 수련의-수퍼바이저 역학 관계의 권력 불균형을 바로잡고 상호 유익하고 가부장적이지 않은 임상 및 옹호 파트너십을 발전시키는 것입니다. 47

Our participants’ perceptions of ideal supervisor responses shift the bases of power from supervisors toward learners. French and Raven’s 6 bases of power (legitimate, expert, informational, reward, coercive, and reverent) constitute a useful framework to examine social power shifts. 43–45

- A supervising attending holds legitimate power with authority over the medical student.

- Expert power is based upon what an attending is presumed to know,

- while informational power comes from the information that one shares with others. 46 A supervisor who pre-briefs and then enacts a student’s wishes after a microaggression has treated the student as expert in their own experience of microaggressions and effectively transferred legitimate and expert power to the student. When students inform supervisors of their preferred microaggression response, they transfer informational power to facilitate supervisors’ ability to be allies. 37,46

- By confirming that a student’s decision to discontinue caring for a patient will not impact their assessment, supervisors can neutralize reward and coercive power.

- Supervisors who do not respond to microaggressions targeting students may lose referent power as students lose faith in them as role models. The suggestion that faculty empower students by asking for their preferences exemplifies “cultural humility,” defined as lifelong commitment to self-evaluation and self-critique, redressing the power imbalances in the trainee–supervisor dynamic, and developing mutually beneficial and nonpaternalistic clinical and advocacy partnerships. 47

이 연구에는 한계가 있습니다. 이 단일 기관 연구 참여자의 결과가 모든 의대생의 생각이나 경험을 대변하는 것은 아닙니다. 가능한 모든 미세 공격에 대해 다루지 않았습니다. 다양한 사회적 정체성이 교차하는 학생들을 포함했지만, 소수로 결론을 도출하고 학생 기밀을 침해할 위험이 있으므로 학생 인구통계를 기반으로 한 별도의 분석은 수행하지 않았습니다. 마지막으로, 학생의 관점에서 바라본 이 연구는 감독자가 실제로 미세 공격에 대응하는 것에 대해 어떻게 생각하는지 알려주지 않습니다.

This study has limitations. Findings from participants in this single-institution study do not represent the thoughts or experience of all medical students. We did not address all possible microaggressions. We included students with a range of intersecting social identities but did not do separate analyses based on student demographics due to the risk of drawing conclusions with small numbers and violating student confidentiality. Finally, this study from the student perspective does not tell us how supervisors actually think about responding to microaggressions.

앞으로 저희 팀은 미세 공격에 대응하는 감독자의 관점을 조사하고 있습니다. 또한 교수진 개발에서 B-MIG의 역할을 연구하고 가이드를 더욱 개선하는 것도 중요할 것입니다.

Looking forward, our team is investigating supervisors’ perspectives on responding to microaggressions. It will also be important to study the role of the B-MIG in faculty development and further refine the guide.

결론

Conclusions

이상적인 방관자 대응은 학생의 선호도와 미세 공격의 맥락을 통합합니다. 학생의 선호도는 미세 공격에 대한 사전 간략한 토론을 통해 가장 잘 드러납니다. B-MIG는 학생들이 선호하는 미세 공격 대응을 시각적으로 표현한 것입니다. 효과적인 개입은 교육적 안전을 증진하고 학생 대상에게 유리한 방향으로 힘의 역학을 변화시킵니다.

An ideal bystander response incorporates students’ preferences and microaggression context. Student preferences are best revealed through a pre-brief discussion of microaggressions. The B-MIG is a visual representation of students’ preferred microaggression response. Effective interventions promote educational safety and shift power dynamics in favor of the student target.

Acad Med. 2021 Nov 1;96(11S):S71-S80. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000004288.

No One Size Fits All: A Qualitative Study of Clerkship Medical Students' Perceptions of Ideal Supervisor Responses to Microaggressions

PMID: 34348373

Abstract

Purpose: This study explores medical students' perspectives on the key features of ideal supervisor responses to microaggressions targeting clerkship medical students.

Method: This single-institution, qualitative focus group study, based in an interpretivist paradigm, explored clerkship medical students' perceptions in the United States, 2020. During semistructured focus groups, participants discussed 4 microaggression scenarios. The authors employed the framework method of thematic analysis to identify considerations and characteristics of ideal supervisor responses and explored differences in ideal response across microaggression types.

Results: Thirty-nine students participated in 7 focus groups, lasting 80 to 92 minutes per group. Overall, students felt that supervisors' responsibility began before a microaggression occurred, through anticipatory discussions ("pre-brief") with all students to identify preferences. Students felt that effective bystander responses should acknowledge student preferences, patient context, interpersonal dynamics in the room, and the microaggression itself. Microassaults necessitated an immediate response. After a microaggression, students preferred a brief one-on-one check-in with the supervisor to discuss the most supportive next steps including whether further group discussion would be helpful.

Conclusions: Students described that an ideal supervisor bystander response incorporates both student preferences and the microaggression context, which are best revealed through advanced discussion. The authors created the Bystander Microaggression Intervention Guide as a visual representation of the preferred bystander microaggression response based on students' discussions. Effective interventions promote educational safety and shift power dynamics to empower the student target.

Copyright © 2021 by the Association of American Medical Colleges.

'Articles (Medical Education) > 임상교육(Clerkship & Residency)' 카테고리의 다른 글

| 임상역량위원회가 교육을 강화하고 역량중심-시간변동 진급에 준비하는 모습 다시 그려보기(J Gen Intern Med. 2022) (0) | 2023.02.28 |

|---|---|

| 아너(Honors)를 위하여: 임상실습 평가와 성적에 관한 학생의 인식 다기관 연구(Acad Med, 2019) (0) | 2023.02.18 |

| 채점에서 학습을 위한 평가로: 핵심임상실습의 성적 제거 및 형성적 피드백 강화를 둘러싼 학생들의 인식(Teach Learn Med. 2021) (0) | 2023.02.18 |

| 관리추론: 보건전문직교육과 연구아젠다의 함의 (Acad Med, 2019) (0) | 2023.02.03 |

| 학부의학교육에서 임상추론 교육과정 내용에 대한 합의문(Med Teach, 2021) (0) | 2023.02.03 |