학부의학교육에서 임상추론 교육과정 내용에 대한 합의문(Med Teach, 2021)

Consensus statement on the content of clinical reasoning curricula in undergraduate medical education

Nicola Coopera , Maggie Bartlettb , Simon Gayc , Anna Hammondd, Mark Lillicrape, Joanna Matthanf , Mini Singhg On behalf of the UK Clinical Reasoning in Medical Education (CReME) consensus statement group

소개

Introduction

임상 추론은 '임상의가 환자를 진단하고 치료하기 위해 데이터를 [관찰, 수집, 해석]하는 [기술, 과정 또는 결과]로 정의할 수 있습니다. 임상 추론은 [환자의 고유한 상황과 선호도, 진료 환경의 특성]과 같은 [맥락적 요인]과 상호작용하는 [의식적 및 무의식적 인지 작용]을 수반합니다'(Daniel 외. 2019).

Clinical reasoning can be defined as, ‘A skill, process, or outcome wherein clinicians observe, collect and interpret data to diagnose and treat patients. Clinical reasoning entails both conscious and unconscious cognitive operations interacting with contextual factors such as the patient’s unique circumstances and preferences and the characteristics of the practice environment’ (Daniel et al. 2019).

임상 추론은 특히 [진단 오류]와 관련하여 임상 실습에서 중요하기 때문에 교육자들이 관심을 갖는 주제입니다. 진단 오류는 흔한 질병에서 발생하는 경향이 있으며(Gunderson 외. 2020), 전 세계적으로 환자에게 예방 가능한 피해를 입히는 중요한 원인입니다(Tehrani 외. 2013; 세계보건기구 2016). [사용 가능한 모든 정보를 올바르게 종합하지 못하거나 신체 검사 결과 또는 검사 결과를 적절하게 사용하지 못하는] 등의 [인지적 실패]가 대부분의 [진단 오류]에 기여하는 것으로 밝혀졌습니다(Graber 외. 2005). 미국 의학 아카데미의 중요한 보고서인 '의료 진단의 개선'(2015)에 따르면 의료의 질과 안전을 개선하기 위한 노력에서 진단 및 진단 오류가 크게 인식되지 않고 있다고 합니다. 이 보고서는 학습 과학의 증거에 부합하는 교육적 접근 방식을 사용하여 진단 과정에서의 교육을 명시적으로 다루는 커리큘럼을 요구했습니다.

Clinical reasoning is of interest to educators because of its importance in clinical practice, particularly in relation to diagnostic error. Diagnostic errors tend to occur in common diseases (Gunderson et al. 2020) and are a significant cause of preventable harm to patients worldwide (Tehrani et al. 2013; World Health Organization 2016). Cognitive failures, such as failure to synthesise all the available information correctly or failure to use the physical examination findings or test results appropriately, have been found to contribute to the majority of diagnostic errors (Graber et al. 2005). The National Academy of Medicine’s seminal report Improving Diagnosis in Health Care (2015) found that diagnosis and diagnostic errors have been largely unappreciated in efforts to improve the quality and safety of healthcare. It called for curricula to explicitly address teaching in the diagnostic process using educational approaches that are aligned with evidence from the learning sciences.

학부 의학 커리큘럼은 병력 청취, 신체 검사, 감별 진단 등 [진단 과정의 기본 요소]에 대한 교육을 제공합니다. 그러나 학생과 대학원 수련생은 효과적인 임상 추론에 필요한 지식, 기술 및 행동을 경험과 견습을 통해 [암묵적으로 습득]하는 경우가 많습니다(Graber 외. 2018). 정확한 진단을 위해서는 역학, 기초 과학 및 임상의학에 대한 지식이 필요하지만, 임상 추론의 몇 가지 구성 요소가 설명되어 있습니다. 각 구성 요소에는 특정 지식, 기술 및 행동이 필요하지만 일부 커리큘럼에서는 명시적으로 강조되지 않을 수 있습니다. 예를 들면, 다음이 있습니다.

- 진단 검사 결과의 정확한 해석(Whiting 외. 2015),

- 진단 정확도와 상관관계가 있는 문제 표현 생성(Bordage 1994),

- 환자의 결과를 개선하는 공유된 의사 결정(미국 과학, 공학 및 의학 아카데미 2015)

미국 의과대학을 대상으로 실시한 한 설문조사에서 내과 임상실습 책임자의 84%는 학생들이 주요 임상 추론 개념에 대한 지식이 부족하거나 기껏해야 보통 정도 수준으로 임상실습에 들어갔으며, 대부분의 교육기관에서 이러한 주제에 대한 세션이 부족하다고 답했으며, 그 이유로 [시간과 교수진의 전문성 부족]을 꼽았습니다(Rencic 외. 2017). 진단과 관련된 교육에 관한 출판된 문헌을 검토한 Graber 등(2018)은 기존 교육 프로그램이 진단 안전에 관한 적절한 교육을 제공하지 못할 수 있음을 발견했습니다.

Undergraduate medical curricula provide instruction in the basic elements of the diagnostic process, for example taking a history, performing a physical examination, and generating a differential diagnosis. However, students and postgraduate trainees largely learn the knowledge, skills and behaviours required for effective clinical reasoning implicitly, through experience and apprenticeship (Graber et al. 2018). While accurate diagnosis requires knowledge of epidemiology, basic sciences and clinical medicine, several components of clinical reasoning have been described. They each require specific knowledge, skills and behaviours but may not be explicitly emphasised in some curricula. Examples include:

- accurate interpretation of diagnostic test results, which has been shown to be poor (Whiting et al. 2015);

- generating a problem representation, which correlates with diagnostic accuracy (Bordage 1994); and

- shared decision making, which improves outcomes for patients (National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine 2015).

In one survey of US medical schools, 84% of internal medicine clerkship directors indicated that students entered clinical clerkships with poor, or at best fair, knowledge of key clinical reasoning concepts and most institutions lacked sessions dedicated to these topics, citing lack of both time and faculty expertise (Rencic et al. 2017). In reviewing the published literature on education related to diagnosis, Graber et al. (2018) found that existing training programmes may not provide adequate education regarding diagnostic safety.

의과대학 및 대학원 수련 프로그램에서 임상 추론을 현재의 근거에 부합하는 [체계적인 접근 방식]을 채택하여 프로그램의 [각 학년별 과정에 명시적으로 통합된 방식으로 가르쳐야 한다]는 공감대가 확산되고 있습니다(Trowbridge 외. 2015). 그러나 임상 추론 문헌은 '단편적'으로 기술되어 있어(Young 등. 2018) 의학교육자가 접근하고 채택하기 어려울 수 있습니다. 전문가 합의와 최신 근거에 대한 검토를 바탕으로 무엇을 어떻게 가르쳐야 하는지를 모두 다루는 임상 추론 커리큘럼은 거의 존재하지 않습니다. 따라서 이 백서의 목적은 의학 교사, 커리큘럼 기획자 및 정책 입안자에게 학부 의학교육에서 임상 추론 커리큘럼의 내용에 대한 실질적인 권장 사항을 제공하는 것입니다. 이러한 권장 사항은 향후 연구를 위한 프레임워크도 제공할 수 있습니다. 임상 추론 평가 방법에 대한 실용적인 권장 사항은 다른 곳에서 발표되었습니다(Daniel 외. 2019).

There is a growing consensus that medical schools and postgraduate training programmes should teach clinical reasoning in a way that is explicitly integrated into courses throughout each year of the programme, adopting a systematic approach consistent with current evidence (Trowbridge et al. 2015). However, the clinical reasoning literature has been described as ‘fragmented’ (Young et al. 2018) and consequently can be difficult for medical educators to access and adopt. Few published clinical reasoning curricula exist covering both what should be taught and how it should be taught, based on expert consensus and a review of current evidence. The purpose of this paper is therefore to provide medical teachers, curriculum planners and policy makers with practical recommendations on the content of clinical reasoning curricula in undergraduate medical education. These recommendations may also provide a framework for future research. Practical recommendations for clinical reasoning assessment methods have been published elsewhere (Daniel et al. 2019).

방법

Methods

이 백서의 권장사항은 영국 임상 추론 의학교육 그룹(CReME)의 회원들이 12개월에 걸친 일련의 회의를 통해 개발했습니다. CReME는 영국 의과대학의 절반 이상을 대표하는 사람들로 구성되어 있으며, 이들 중 다수는 학부 의학 커리큘럼과 임상 추론 교육에 대한 구체적인 책임도 가지고 있습니다. 권고안을 개발하기 위해 3단계 접근 방식이 사용되었습니다. 첫 번째 단계에서는 12개 의과대학의 20명이 하루 종일 회의에 참석하여 의과대학에서 제공해야 할 임상 추론 관련 교육 목록(무엇을 가르쳐야 할 것인가)을 파악했습니다. 제출된 모든 아이디어를 공유하고 토론하여 중복되는 내용을 제거하고, 토론 내용을 바탕으로 필요한 경우 추가 내용을 추가했습니다. 이 과정을 거쳐 30개의 아이디어가 기록되었습니다. 이러한 아이디어는 임상 추론 교육의 5가지 영역으로 분류한 다음 영국 일반 의학 교육 과정과 매핑했습니다.

The recommendations in this paper were developed by members of the UK Clinical Reasoning in Medical Education group (CReME) in a series of meetings over a twelve-month period. CReME consists of representatives from over half of UK medical schools, many of whom also have specific responsibility for undergraduate medical curricula and clinical reasoning education. A three-stage approach was used to develop the recommendations. In the first stage, 20 members from 12 medical schools attended a whole-day meeting to identify a list of clinical reasoning-specific teaching that should be delivered by medical schools (what to teach). All the submitted ideas were shared and discussed, duplicates removed, and further content added if required, based on the discussions. Following this process, 30 ideas were recorded. These were grouped into five domains of clinical reasoning education and then mapped against the UK General Medical Council’s ‘Outcomes for Graduates’ (General Medical Council 2018) to allow educators to see how they might fit into a curriculum mapping process.

두 번째 단계에서는 의대생의 임상 추론 능력 향상에 효과적인 교수 전략(교수법)을 파악하기 위해 문헌 고찰을 실시하였습니다. 문헌 고찰은 '임상 추론', '임상 의사결정', '진단 추론', '진단 의사결정', '의대생', '교육', '커리큘럼' 등의 용어를 사용하여 전자 데이터베이스 MEDLINE, PsycINFO, CINAHL, EMBASE, ERIC 및 Google Scholar를 통해 최근 30년 이내에 발표된 영어 논문을 대상으로 수행되었습니다. 의대생의 임상 추론 능력을 향상시키기 위해 고안된 교육 중재를 설명하고 경험적 결과를 기술한 영어 논문도 포함되었습니다. 학생/교수 평가 유무에 관계없이 임상 추론 교육에 대한 특정 접근법을 설명하는 논문은 제외되었습니다. 이러한 포함 및 제외 기준에 따라 27개의 적격 논문이 선정되었습니다. 포함된 연구들은 다양한 연구 설계를 사용하여 광범위한 전략을 설명했기 때문에 합의문을 알리기 위한 목적으로 연구 결과를 분류하고 설명하는 것 외에 체계적으로 정리하려는 시도는 하지 않았습니다. PRISMA 도표는 보충 파일 2에 나와 있습니다. 포함 기준을 충족하지 못했지만 인용된 근거(예: 리뷰 논문)도 권고안을 알리는 데 사용되었습니다.

In the second stage, a literature review was conducted to identify teaching strategies that are successful in improving the clinical reasoning ability of medical students (how to teach). The literature review was conducted of English language papers published within the last 30 years through the electronic databases MEDLINE, PsycINFO, CINAHL, EMBASE, ERIC and Google Scholar using the terms ‘clinical reasoning’ OR ‘clinical decision making’ OR ‘diagnostic reasoning’ OR ‘diagnostic decision making’ AND ‘medical students’ OR ‘teaching’ OR ‘curriculum’. English language articles that described a teaching intervention designed to improve clinical reasoning ability among medical students, which also described empirical findings, were included. Articles that merely described a particular approach to teaching clinical reasoning, with or without student/faculty evaluation, were excluded. These inclusion and exclusion criteria resulted in 27 eligible articles. The included studies described a wide range of strategies, using variable study designs, so no attempt was made to systematically organise the findings other than to categorise and describe them with the purpose of informing the consensus statement. A PRISMA diagram is shown in Supplementary File 2. Articles that did not meet the inclusion criteria but cited evidence (e.g., review articles) were also used to inform the recommendations.

마지막 단계에서는 이러한 연구 결과를 바탕으로 학부 임상 추론 커리큘럼의 내용에 대한 실질적인 권고안을 합의문 형태로 작성하여 합의문 그룹의 모든 구성원에게 배포하여 의견을 구했습니다. 이 최종 반복 과정은 이메일 토론을 통해 진행되었습니다. 그런 다음 최종 성명서를 작성하고 저자들이 승인했습니다.

In the final stage, practical recommendations for the content of undergraduate clinical reasoning curricula were made based on these findings in the form of a consensus statement and the text was circulated to all the members of the consensus statement group for comments. This final iterative process was undertaken through e-mail discussions. The final statement was then written and approved by the authors.

결과

Results

임상 추론 교육의 영역(무엇을 가르칠 것인가)

Domains of clinical reasoning education (what to teach)

합의된 의견은 임상 추론 교육의 다섯 가지 영역으로 분류되었습니다:

The agreed consensus ideas were grouped in to five domains of clinical reasoning education:

- 임상 추론 개념

- 병력 및 신체 검사

- 진단 검사 선택 및 해석

- 문제 식별 및 관리

- 공유된 의사 결정.

- Clinical reasoning concepts

- History and physical examination

- Choosing and interpreting diagnostic tests

- Problem identification and management

- Shared decision making.

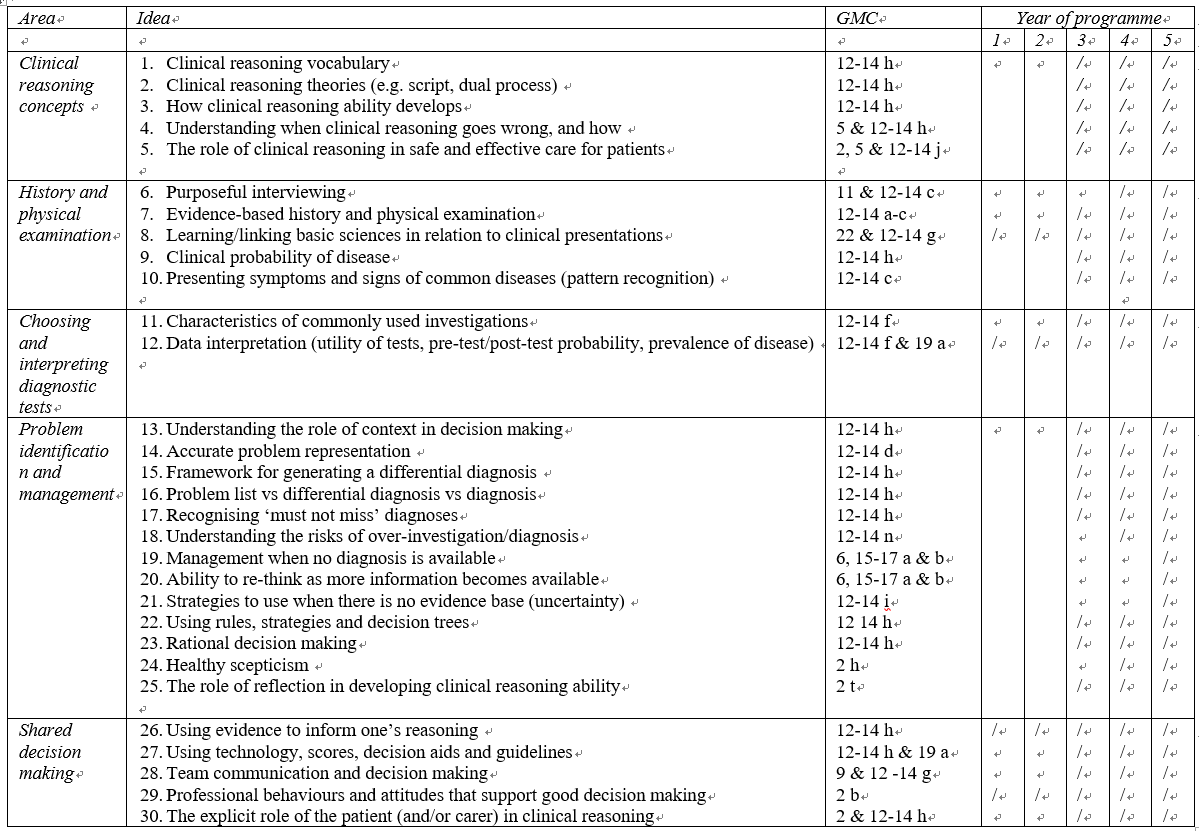

이러한 영역은 표 1과 아래 텍스트에서 자세히 설명합니다. 부록 파일 1에는 영국 일반의협의회의 '졸업생 성과'(일반의협의회 2018)에 매핑된 개별 합의 아이디어가 나열되어 있으며, 5년 프로그램 동안 언제 교육해야 하는지에 대한 제안도 포함되어 있습니다.

These domains are expanded on in Table 1 and in the text below. Supplementary File 1 lists the individual consensus ideas, mapped against the UK General Medical Council’s ‘Outcomes for Graduates’ (General Medical Council 2018), and also includes suggestions for when to teach during a 5 year programme.

임상 추론 개념

Clinical reasoning concepts

의미 있는 토론과 학습을 촉진하기 위해서는 교사와 학습자 모두 [임상 추론에 대한 정의, 어휘 및 개념]을 공유하는 것이 중요합니다(Wu 2018). 주요 이론(예: 스크립트, 이중 과정), 임상 추론 능력의 발달 과정, 진단 오류의 문제, 환자를 위한 안전하고 효과적인 치료에서 임상 추론의 역할, 인지 오류 및 임상 추론 과정 또는 결과를 손상시킬 수 있는 기타 요인은 의과대학에서 가르쳐야 하며 프로그램 전반에 걸쳐 과정에 통합되어 있어야 합니다.

It is important for both teachers and learners to have a shared definition, vocabulary and concepts for clinical reasoning in order to facilitate meaningful discussion and learning (Wu 2018). Key theories (e.g., script, dual process), how clinical reasoning ability develops, the problem of diagnostic error, the role of clinical reasoning in safe and effective care for patients, cognitive errors and other factors that may impair the clinical reasoning process or outcome should be taught in medical schools and integrated into courses throughout the programme.

병력 및 신체 검사

History and physical examination

[효과적인 의사소통 기술]은 환자, 친척 또는 보호자로부터 정보를 이끌어내고 신뢰를 얻는 데 필수적입니다. 학부 의학교육의 의사소통 커리큘럼 내용에 대한 영국 합의 성명서(Noble 외. 2018)는 의사소통 기술 개발을 위한 프레임워크를 제시하고 핵심 내용을 권장합니다. 또한 졸업 시점에 학습자는 환자의 병력이 환자 이외의 출처(예: 친척, 간병인, 구급차 시트, 의료 기록)에서도 나올 수 있다는 점을 인식해야 합니다. 학습자는 [의도적으로 정보를 수집]하고 [가설 중심의 질문]을 통해 환자의 증상을 탐색할 수 있어야 합니다(Hasnain 외. 2001). 이는 가설을 확인하거나 반박하기 위해 [신체 검사 결과를 예상]하고, 실제 진단에 도달하거나 새로운 가설을 생성하기 위해 결과를 도출하고 해석하는 [신체 검사 기동을 수행해야 하는 신체 검사로 확장]됩니다(Yudkowsky 외. 2009).

Effective communication skills are vital in eliciting information and gaining trust from a patient, relative or carer. The UK consensus statement on the content of communication curricula in undergraduate medical education (Noble et al. 2018) presents a framework and recommends key content for the development of communication skills. In addition, by graduation, learners should appreciate that a patient’s history may also come from sources other than the patient (e.g., relatives, carers, ambulance sheet, medical records). They should be able to purposefully gather information and explore patients’ symptoms through hypothesis-driven enquiry (Hasnain et al. 2001). This extends to the physical examination which should involve anticipating physical examination findings to confirm or refute hypotheses and performing physical examination manoeuvres to elicit and interpret findings in order to reach a working diagnosis or generate new hypotheses (Yudkowsky et al. 2009).

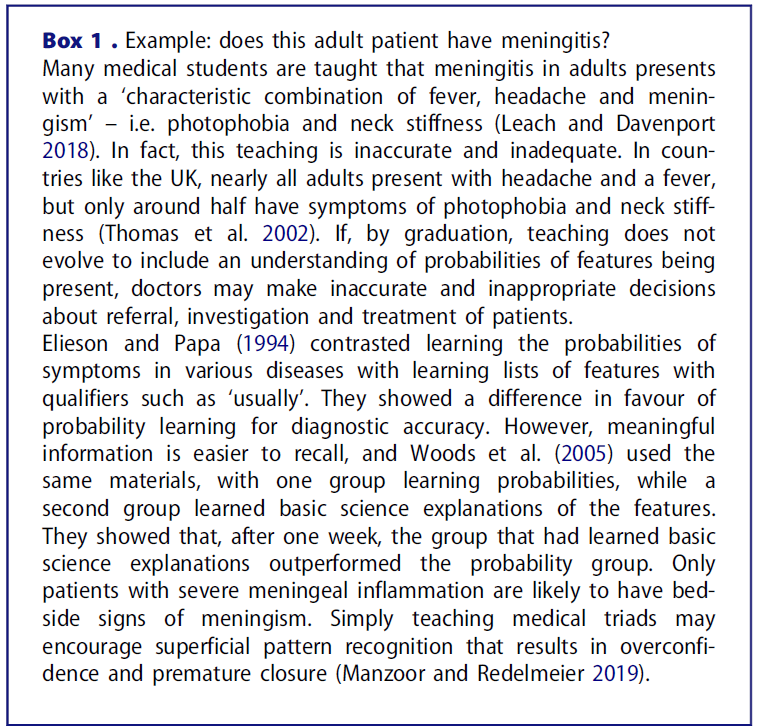

학습자는 역학에 대한 지식, 특정 질병에서 특정 증상 및 징후가 나타날 확률(상자 1의 예시 참조) 및 해당되는 경우 가능성 비율을 사용하여 [병력 및 신체검사의 데이터를 정확하게 종합]하여 [질병의 임상적 확률을 판단]할 수 있어야 합니다. 초기에는 질병에 대한 일반적인 설명과 간단한 특징 목록을 가르칠 수 있지만, 졸업할 때까지 학습자는 현지 상황과 관련하여 [많은 환자가 교과서에 설명된 질병의 전형적인 특징을 나타내지 않는다]는 것을 명확하게 이해해야 합니다(Manzoor 및 Redelmeier 2019). 학습자는 정상 결과와 부수적인 소견을 포함한 진단 검사 결과를 정확하게 해석하기 위해 질병의 임상적 확률을 추정할 수 있어야 합니다.

Learners should be able to accurately synthesise data from the history and physical examination to judge the clinical probability of disease using their knowledge of epidemiology, the probability of the presence of particular symptoms and signs in specific diseases (see example in Box 1) and likelihood ratios, where relevant. While typical presentations of diseases and simple lists of features may be taught in the early years, by graduation learners should have a clear understanding, relevant to their local context, that many patients do not present with the classical features of diseases as described in textbooks (Manzoor and Redelmeier 2019). Learners need to be able to estimate the clinical probability of disease in order to be able to accurately interpret diagnostic test results, including normal results and incidental findings.

진단 검사 선택 및 해석

Choosing and interpreting diagnostic tests

졸업 시 학습자는 [임상(검사 전) 확률, 민감도 및 특이도, 검사 후 확률, 질병 유병률, 예측값, 검사 결과에 영향을 미치는 질병 이외의 요인, 현지 상황과 관련된 일반적으로 사용되는 검사의 중요한 특징] 등의 개념에 대한 실질적인 이해를 입증할 수 있어야 합니다. 학습자는 많은 검사 결과가 임상 소견에 비추어 [해석이 필요하다는 것]을 알고 임상 추론 과정에서 이 지식을 적용할 수 있어야 합니다. 학습자는 특정 검사가 어떤 질문에 답할 수 있는지에 대한 지식을 바탕으로 조사를 제안할 수 있어야 하며, 적절한 조사에 관한 결정을 돕기 위해 근거 기반 지침 및 의사 결정 보조 도구를 사용할 수 있어야 합니다.

By graduation, learners should be able to demonstrate a practical understanding of concepts such as clinical (pre-test) probability, sensitivity and specificity, post-test probability, prevalence of disease, predictive values, factors other than disease that influence test results and important characteristics of commonly used tests relevant to their local context. Learners should know that many test results require interpretation in the light of clinical findings and they should be able to apply this knowledge during the clinical reasoning process. They should be able to suggest investigations based on knowledge of what question a particular test can answer, and be able to use evidence-based guidelines and decision aids to assist in their decisions regarding appropriate investigations.

문제 식별 및 관리

Problem identification and management

졸업 시 학습자는 [문제 표현을 정확하게 공식화]하고, 이를 바탕으로 ['반드시 놓치지 말아야 할' 진단을 포함하여 우선순위를 정하여 감별 진단을 구성]할 수 있어야 합니다. 때로는 [두 가지 이상의 문제]가 있을 수 있으며, 이러한 상황에서 학습자는 문제 목록을 구성할 수 있어야 합니다. 잠재적 진단을 생각하기 전에 [의미적 한정어와 정확한 의학 용어를 사용하여 문제를 명확하게 '캡슐화'하는 능력]은 사례와 관련된 장기 기억에서 지식을 구성하고 검색하는 데 도움이 되는 중요한 기술이며, 특히 복잡한 사례에서 진단 정확도를 높이는 것과 관련이 있습니다(Bordage 1994).

By graduation, learners should be able to accurately formulate a problem representation and, based on this, construct a prioritised differential diagnosis, including relevant ‘must-not-miss’ diagnoses. Sometimes there is more than one problem, and in these situations learners need to be able to construct a problem list. The ability to ‘encapsulate’ a problem clearly, using semantic qualifiers and precise medical terms, before thinking through potential diagnoses, is an important skill that helps to organise and retrieve knowledge from long term memory relevant to the case and is associated with higher diagnostic accuracy, particularly in complex cases (Bordage 1994).

때로는 진단을 내릴 수 없는 경우도 있으므로 학습자는 [진단의 불확실성을 관리하는 방법]을 배워야 합니다(Ilgen 외. 2019; Gheihman 외. 2020). 학습자는 졸업 시점에 이 환자에게 [가장 가능성이 높은 진단이 무엇인지, 안전하게 배제할 수 있는 진단은 무엇인지, 드물지만 반드시 배제해야 하는 심각한 진단은 없는지] 결정할 수 있어야 합니다(Murtagh 1990). 이러한 상황에서는 '이 환자의 상태가 얼마나 좋은가, 좋지 않은가' 또는 '선배 동료를 참여시켜야 하는가, 얼마나 긴급한가'와 같은 결정이 내려질 수 있으며, 고급 학습자에게는 이러한 상황에서 감독하에 결정을 내릴 수 있는 기회가 제공되어야 합니다.

Sometimes, it is not possible to make a diagnosis and learners must learn to manage diagnostic uncertainty (Ilgen et al. 2019; Gheihman et al. 2020). By graduation, learners should be able to decide what is the most likely diagnosis for this patient at this point in time, what can be safely excluded and whether there are any rare but serious diagnoses that must be excluded (Murtagh 1990). At such times the decision may be, ‘How well or unwell is this patient?’ or ‘Should I involve a senior colleague and how urgently?’ and advanced learners need to be provided with opportunities to make supervised decisions in these situations.

임상 추론 문헌에서는 결과가 진단으로 간주되는 경우가 많지만, 임상에서는 그렇지 않은 경우가 많습니다(Ilgen 외. 2016; Cook 외. 2018). 적절한 관리 계획의 개발은 때때로 문제 목록이나 감별 진단보다 더 복잡할 수 있습니다. [진단]은 환자의 증상과 징후 또는 진단 검사에 의해 결정되며, 여기에는 식별 가능한 문제, 해결책 및 상호 작용하는 요인의 범위가 한정되어 있습니다. 그러나 특정 진단에 대해 [다양한 잠재적 관리 옵션]이 있을 수 있으며, 모든 옵션이 적절할 수 있지만 환자 선호도, 동반 질환, 자원, 비용 효율성 및 지역 정책을 포함한 여러 요인에 따라 달라질 수 있습니다. 학습자는 관리 계획을 수립하는 과정에서 이러한 요소를 고려할 수 있어야 합니다(Cook 외. 2018).

In the clinical reasoning literature, the outcome is often considered to be the diagnosis, but this is often not the case in clinical practice (Ilgen et al. 2016; Cook et al. 2018). The development of an appropriate management plan may sometimes be more complex than that of a problem list or differential diagnosis. Diagnoses are determined by a patient’s symptoms and signs or diagnostic tests, in which there is a finite range of identifiable problems, solutions and interacting factors. However, for any given diagnosis, there may be numerous potential management options, all of which may be appropriate but dependent on a number of factors including patient preferences, co-morbidities, resources, cost-effectiveness and local policies. The learner needs to be able to take these factors into account in the process of formulating a management plan (Cook et al. 2018).

또한 학습자는 [메타인지적 지식과 비판적 사고]를 사용하여 성과를 개선할 수 있어야 합니다(Krathwohl 2002; Olson, Rencic 등, 2019). 영국에서는 시스템과 인적 요인에 중점을 둔 환자안전 교육이 학부 및 대학원 의학교육에서 확립되고 있지만(General Medical Council 2015), 효과적인 임상 추론을 위해서는 인지 전략에도 중점을 두어야 합니다. 가이드 반영은 진단 성과를 개선하고 임상 지식의 학습을 촉진하는 것으로 나타났으며(Chamberland 외. 2015; Prakash 외. 2019), 이 과정은 교육자가 촉진해야 합니다.

Learners should also be able to use metacognitive knowledge and critical thinking to improve their performance (Krathwohl 2002; Olson, Rencic, et al. 2019). In the UK, patient safety training, with a focus on systems and human factors, is becoming established in undergraduate and postgraduate medical education (General Medical Council 2015), but effective clinical reasoning also requires a focus on cognitive strategies. Guided reflection has been shown to improve diagnostic performance and foster the learning of clinical knowledge (Chamberland et al. 2015; Prakash et al. 2019) and this process should be facilitated by educators.

공유된 의사 결정

Shared decision making

학습자는 졸업할 때까지 [공동 의사 결정]에 필요한 기술을 개발해야 합니다. 공동 의사결정을 위해서는 [효과적인 의사소통과 타인의 가치를 파악하고 이해하는 능력]이 필요합니다(Elwyn 외. 2012; Fulford 외. 2012). [관리 의사결정]은 종종 환자 및 보호자와 공동으로 이루어지지만, [공유 의사결정은 팀, 근거 기반 지침, 기술, 점수 및 의사결정 보조 도구도 의미합니다]. 학습자는 실제 상황에서 지식은 '머릿속에 있는 것'이 아니라 사람, 컴퓨터, 책, 기타 도구 또는 도구를 통해 환경 전체에 분산되어 있다는 것을 이해해야 합니다(Artino 2013).

By graduation, learners need to develop the skills required for shared decision making. Shared decision making requires effective communication and the ability to identify and understand others’ values (Elwyn et al. 2012; Fulford et al. 2012). Management decisions are often co-produced with patients and carers, but shared decision making also refers to teams, evidence-based guidelines, technology, scores and decision aids. Learners should understand that in real world situations, knowledge is not something that is ‘all in your head’ but is distributed throughout the environment in people, computers, books, and other tools or instruments (Artino 2013).

또한 학습자는 팀워크, 다른 사람의 기여도 평가, 예의, 경청, 도움 요청, 명확한 의사소통(특히 환자 치료 인계 시), 진단 및 관리 과정에 환자 및 보호자 참여 등 의사 결정을 지원하는 전문적인 가치와 행동을 보여줄 수 있어야 합니다(미국 과학, 공학 및 의학 아카데미 2015).

Learners should also be able to demonstrate professional values and behaviours that support decision making, including teamwork, valuing the contributions of others, civility, listening, asking for help, clear communication (especially when handing over care of a patient), and involving the patient and/or carers in the diagnostic and management process (National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine 2015).

교육 전략(교육 방법)

Teaching strategies (how to teach)

의대생의 임상적 추론 능력을 향상시키기 위해 고안된 교육 개입을 설명하고 경험적 결과를 포함하는 27개의 연구가 확인되었습니다. 스키마/질병 스크립트를 가르치는 연구는 2건, 임상 의사 결정의 원리를 가르치는 연구는 3건, 소리 내어 생각하기, 브레인스토밍 또는 인지 매핑을 사용하는 전략은 4건, '인지적 강제 전략'(이 중 5건은 구조화된 반성을 사용)을 가르치는 연구는 7건, 피드백이 포함된 실습 사례는 11건이었다. 모두 단기적인 개입이었으며 장기적인 커리큘럼 접근법을 설명하는 사례는 없었습니다.

- 의대생에게 의사 결정의 원칙을 가르친다고 해서 성과가 개선되지는 않았습니다.

- 인지적 편향으로 인한 오류를 줄이기 위해 고안된 인지적 강제 전략을 가르치는 것 역시 성과를 개선하지 못했습니다.

- 그러나 질병 스크립트 교육, 소리 내어 생각하기/브레인스토밍 전략 사용, 구조화된 성찰, 피드백을 통한 사례 연습은 성과를 개선했습니다.

문헌 검토 결과에 대한 자세한 설명은 보충 파일 2에서 확인할 수 있습니다.

Twenty-seven studies were identified that included empirical findings and described a teaching intervention designed to improve the clinical reasoning ability of medical students. Two studies involved teaching schemas/illness scripts; three involved teaching the principles of clinical decision making; four used strategies that employed thinking aloud, brainstorming or cognitive mapping; seven taught ‘cognitive forcing strategies’ (five of which used structured reflection); and eleven used practice cases with feedback. All were short term interventions with none describing a long term curriculum approach.

- Teaching the principles of decision making to medical students did not improve performance.

- Teaching cognitive forcing strategies designed to reduce error from cognitive biases also did not improve performance.

- However, teaching illness scripts, using thinking aloud/brainstorming strategies, structured reflection, and practicing cases with feedback did improve performance.

A detailed description of the results of the literature review can be found in Supplementary File 2.

임상 추론 교육에 관한 광범위한 문헌에서 효과적인 임상 추론 능력 개발을 위해서는 [의학에 대한 공식적 지식과 경험적 지식이 핵심]이라는 데 동의하고 있습니다(Norman 외. 2006, 2017). 현재까지 사고 자체에 대한 교육(예: 이중 과정 이론, 인지적 편향 제거 전략 교육)이 그 자체로 진단 성과를 향상시킨다는 증거는 거의 없습니다(Sherbino 외. 2014; Smith and Slack 2015). 임상 추론 교육에 관한 문헌을 검토한 Schmidt와 Mamede(2015)는 임상 의사 결정에 관련된 [일반적인 사고 과정을 가르치는 교육적 접근 방식]은 [대체로 효과가 없는] 반면, [지식과 이해를 쌓는 것을 목표로 하는 교육 전략]은 [개선 효과를 가져온다]는 사실을 발견했습니다. 그러나 현재 진행 중인 연구 분야 중 하나는 반성적 전략의 사용입니다. 진단적 의사 결정 시 성찰이 단순히 기존 지식을 동원하는 수단인지, 아니면 이중 과정 이론(즉, 우리가 생각하는 방식)의 광범위한 틀 안에서 이해될 수 있는지는 현재 진행 중인 논쟁의 문제입니다(Norman 외. 2017; Prakash 외. 2019; Stanovich 2009).

In the wider published literature on teaching clinical reasoning, there is agreement that formal and experiential knowledge of medicine is central for the development of effective clinical reasoning ability (Norman et al. 2006, 2017). To date, there is little evidence to demonstrate that teaching about thinking itself (e.g., teaching dual process theory, cognitive de-biasing strategies) by itself improves diagnostic performance (Sherbino et al. 2014; Smith and Slack 2015). In a review of the literature on teaching clinical reasoning, Schmidt and Mamede (2015) found that educational approaches aimed at teaching the general thinking processes involved in clinical decision making were largely ineffective, whereas teaching strategies aimed at building knowledge and understanding led to improvements. However, one area of ongoing research is in the use of reflective strategies. Whether reflection during diagnostic decision making is simply a means of mobilising existing knowledge, or can also be understood within a broad framework of dual process theory (i.e. how we think), is a matter of ongoing debate (Norman et al. 2017; Prakash et al. 2019; Stanovich 2009).

의대생의 임상 추론 능력을 향상시키는 데 효과적인 것으로 입증된 교수 전략의 예는 표 2에 나열되어 있으며 아래에 자세히 설명되어 있습니다.

Examples of teaching strategies that have been demonstrated to be effective in improving the clinical reasoning ability of medical students are listed in Table 2 and expanded on below.

이해도를 높이는 전략

Strategies that build understanding

[의미 있는 정보]는 더 쉽게 기억하고 기억할 수 있습니다. [자기 설명/상술하기]는 의대생의 진단 능력을 향상시키고 학습자가 지식을 통합하는 데 도움이 되는 것으로 나타났습니다(Chamberland 외. 2011, 2015). [자기 설명]은 학습자가 사용하는 인지 과정, 즉 사전 지식과 새로운 지식의 고유한 매칭을 포함하기 때문에 [교수자의 설명]보다 성능이 뛰어납니다(Bisra 외. 2018). Woods 등(2005)은 증상 및 징후에 대한 기초 과학 메커니즘을 이해하면 의대생들의 진단 성과도 향상된다는 것을 보여주었습니다. 교사는 이해와 회상을 촉진하는 전략을 사용해야 합니다.

Meaningful information is easier to retain and recall. Self-explanation/elaboration has been shown to improve diagnostic performance in medical students and helps learners consolidate their knowledge (Chamberland et al. 2011, 2015). Self-explanation outperforms explanation by the instructor because of the cognitive processes learners use, which include their idiosyncratic matching of prior knowledge to new knowledge (Bisra et al. 2018). Woods et al. (2005) showed that understanding the basic science mechanisms for symptoms and signs also improved diagnostic performance among medical students. Teachers should use strategies that promote understanding as well as recall.

구조화된 반성을 사용하는 전략

Strategies that employ structured reflection

[구조화된 성찰] 또는 [안내에 따른 성찰]은 의대생의 진단 능력을 향상시키는 것으로 나타났습니다(Lambe 외. 2016; Prakash 외. 2019). 학습자에 비해 케이스가 더 복잡할 때 그 영향이 가장 큽니다(Norman et al. 2017). 구조화된 성찰의 예로는 '이것에 대한 증거는 무엇인가', '다른 것은 무엇일 수 있는가'와 같은 질문을 학생 스스로에게 하도록 유도하거나(Chew et al. 2016), 각 감별 진단과 양립하거나 양립할 수 없는 소견을 나열하도록 요청하는 것(Myung et al. 2013) 등이 있습니다. Mamede 등(2012, 2014)은 구조적 반성에 관한 두 가지 연구를 수행했는데, 두 연구 모두 임상 증례 진단을 연습하는 동안 [구조적 성찰]을 사용한 학생들이 일주일 후 같은 질병의 새로운 증례를 진단할 때 대조군보다 더 나은 성과를 보였다는 사실을 발견했습니다. 저자들은 '[증례로 연습하는 동안의 구조화된 성찰]이 임상 지식의 학습을 촉진하는 것으로 보인다'고 결론지었습니다.

Structured or guided reflection has been shown to improve diagnostic performance in medical students (Lambe et al. 2016; Prakash et al. 2019). The impact is greatest when the case is more complex relative to the learner (Norman et al. 2017). Examples of structured reflection include encouraging students to ask themselves questions like, ‘What’s the evidence for this?’ and ‘What else could it be?’ (Chew et al. 2016), or asking students to list findings that are compatible or not compatible with each differential diagnosis (Myung et al. 2013). Mamede et al. (2012, 2014) performed two studies on structured reflection, both of which found that students who used it while practicing diagnosing clinical cases outperformed controls in diagnosing new examples of the same diseases a week later. The authors concluded that, ‘Structured reflection while practicing with cases appears to foster the learning of clinical knowledge.’

증례를 통한 연습과 수정 피드백

Practice with cases and corrective feedback

가능한 한 다양한 상황에서 [가능한 한 다양한 사례로 연습]하는 것이 학습에 매우 중요합니다(Eva 외. 1998). 그러나 연습만으로는 충분하지 않으며, 전문성을 개발하기 위해서는 수정 피드백, 노력, 코칭도 필요합니다(Ericsson 2004). 이를 위해서는 실수에 대한 토론이 장려되고 불확실성을 인정할 수 있는 안전한 학습 환경이 제공되어야 합니다(Eva 2009). 규칙적인 연습은 학습자가 질병 스크립트를 개발하는 데 도움이 되며(Schmidt 외. 1990), 이는 [일반적인 지식이 아닌 지식 조직화가 효과적인 임상 추론 능력의 핵심]이기 때문에 중요합니다(Lubarsky 외. 2015). 또한 사례를 단계적으로 드러내는 것보다 전체 사례 접근 방식('직렬 단서' 접근 방식)이 특히 초보자에게는 작업 기억에 대한 인지 부하를 줄이기 때문에 교육할 때 더 효과적이라는 증거가 있습니다(Schmidt and Mamede 2015).

Practice with as many different cases as possible in as many different contexts as possible is critical for learning (Eva et al. 1998). However, practice alone is insufficient; corrective feedback, effort and coaching are also required to develop expertise (Ericsson 2004). This requires the provision of a safe learning environment where discussion of mistakes is encouraged and where there is recognition of uncertainty (Eva 2009). Regular practice helps learners develop illness scripts (Schmidt et al. 1990), which is important because knowledge organisation rather than generic knowledge is key to effective clinical reasoning ability (Lubarsky et al. 2015). There is also evidence that a whole case approach, rather than revealing a case in stages (the ‘serial-cue’ approach) is more effective when teaching, especially for novices, because it decreases cognitive load on working memory (Schmidt and Mamede 2015).

문제 특이적 개념을 중심으로 지식을 구조화하는 전략

Strategies that structure knowledge around problem-specific concepts

성과가 높은 학습자는 비슷한 수준의 지식에도 불구하고 성과가 낮은 학습자와는 질적으로 다른 방식으로 지식을 구성합니다(Coderre 외. 2009). [문제 특이적 개념을 중심으로 지식을 구조화하는 것]은 [자발적인 유추적 전이], 즉 한 문제의 정보를 다른 맥락에서 다른 문제를 해결하는 데 사용하는 것을 촉진하는 것으로 나타났습니다(Needham and Begg 1991; Eva 외. 1998). 교육자는 졸업할 때까지 학습자가 다양한 일반적인 임상 프레젠테이션에 대해 조직화된 문제-특이적 지식(관련 지식 및 증거에 기반한 개념도 또는 의사결정 트리와 유사)을 습득할 수 있도록 지원해야 합니다.

High-performing learners organise their knowledge in a qualitatively different way to low-performing ones, despite similar levels of knowledge (Coderre et al. 2009). Structuring knowledge around problem-specific concepts has been shown to promote spontaneous analogical transfer – that is, the use of information from one problem to solve another problem in a different context (Needham and Begg 1991; Eva et al. 1998). By graduation, educators should facilitate learners in gaining organised problem-specific knowledge (akin to a concept map or decision tree, underpinned by relevant knowledge and evidence) for a range of common clinical presentations.

검색 연습을 활용하는 전략

Strategies that employ retrieval practice

여러 연구에 따르면 [정보의 장기 보존과 회상을 촉진하는 전략]이 성과를 향상시키는 것으로 나타났습니다(Eva 2009, Weinstein 및 Sumeracki 2019). 교수 및 학습 중에 정보를 열심히 기억하도록 촉진하는 전략은 진단 성과의 향상으로 이어집니다. 여기에는 구조화된 반성(Norman 외. 2017; Prakash 외. 2019), 저부담 퀴즈(Green 외. 2018; Larsen 외. 2009), 간격 연습(Kerfoot 외. 2007), 대조 학습(Ark 외. 2007) 등이 포함됩니다. 교육 및 학습 습관의 작은 변화만으로도 정보 유지 및 회상, 고차원적 사고 측면에서 상당한 이점을 얻을 수 있습니다(Dobson 외. 2018).

Several studies have shown that strategies that promote long term retention and recall of information improve performance (Eva 2009; Weinstein and Sumeracki 2019). Strategies that promote effortful recall of information during teaching and learning lead to improvements in diagnostic performance. These include structured reflection (Norman et al. 2017; Prakash et al. 2019), low stakes quizzing (Green et al. 2018; Larsen et al. 2009), spaced practice (Kerfoot et al. 2007) and contrastive learning (Ark et al. 2007). Small changes in instruction and study habits can yield significant benefits in terms of retention and recall of information and higher order thinking (Dobson et al. 2018).

학습 단계에 따라 달라지는 전략

Strategies that differ according to stage of learning

위의 모든 전략은 학습 단계에 따라 적절하게 조정되어야 하며 '나선형 커리큘럼' 내에서 개발되어야 합니다(Harden and Stamper 1999). 의학에서 의미 있는 학습을 하려면 상당한 인지적 처리가 필요하므로 학습자가 특정 과제를 다룰 때 [작업 기억에 사용되는 노력]을 고려하는 방식으로 교육을 구성해야 합니다(Van Merrienboer 및 Sweller 2010). 학습해야 할 각 역량에 대해 교육은 [복잡성이 낮고 충실도가 낮은 과제에 대한 높은 교육적 지원]에서 [충실도가 높고 복잡한 과제에 대한 최소한의 지원]으로 이동해야 합니다(Leppink and Duvivier 2016). 졸업이 가까워지면 학습자의 임상 추론 능력은 임상 팀의 일원으로 일하고 실제 임상 환경에서 감독을 받으며 의사 결정을 내리는 데 도움이 됩니다(Lefroy 외. 2017). 이러한 후기 교육 단계의 학습자는 [구조화된 디브리핑]을 통해 필터링되지 않은 사례에 노출되어야 합니다. 커리큘럼 설계와 평가 프로그램은 이러한 전환을 보장해야 합니다.

All of the above need to be tailored appropriately to different stages of learning and developed within a ‘spiral curriculum’ (Harden and Stamper 1999). Meaningful learning in medicine requires substantial cognitive processing, so instruction should be structured in a manner that takes into account the effort being used in working memory when learners are dealing with particular tasks (Van Merrienboer and Sweller 2010). For each competency to be learned, instruction should move from high instructional support on low complexity, low fidelity tasks through to minimal support on high fidelity, high complexity tasks (Leppink and Duvivier 2016). Approaching graduation, learners’ clinical reasoning abilities benefit from working as part of a clinical team and making decisions in a real but supervised clinical environment (Lefroy et al. 2017). Learners in these later stages of training should be exposed to unfiltered cases with structured debriefing. Curriculum design and its assessment programme must ensure this transition.

결론

Conclusion

임상 추론 교육은 의학교육, 인지 심리학, 진단 오류 및 의료 시스템 문헌에서 그 기원을 찾을 수 있습니다(Olson, Singhal 외. 2019). 다양한 분야의 여러 이론이 임상 추론에 대한 연구에 영향을 미치며(Ratcliffe 외. 2015), 무엇을 어떻게 가르쳐야 하는지에 대해 밝혀줍니다. 그러나 이러한 단편적인 문헌은 의학교육자가 접근하기 어렵고 일상적인 진료에 의미 있게 적용하기 어려울 수 있습니다. 이 백서의 목적은 모든 의과대학에 유용하고 각기 다른 지역 상황에 맞게 적용할 수 있는 실용적인 권장 사항을 제공하는 것입니다.

Clinical reasoning education has origins in the medical education, cognitive psychology, diagnostic error and health systems literature (Olson, Singhal, et al. 2019). A number of theories from diverse fields inform research on clinical reasoning (Ratcliffe et al. 2015), shedding light on what should be taught and how. However, this fragmented literature can be difficult for medical educators to access and adopt meaningfully into their daily practice. The purpose of this paper is to provide practical recommendations that will be of use to all medical schools and can be adapted to different local contexts.

모든 의과대학에서 지식, 기술 및 행동을 가르치지만, 목적에 맞는 커리큘럼 설계를 통해 가르치는 내용, 가르치는 방법, 가르치는 시기에 세심한 주의를 기울이면 임상적 추론 발달을 보다 효과적으로 촉진할 수 있다는 좋은 증거가 있습니다. 그렇다고 해서 반드시 추가 교육 시간이 필요한 것은 아닙니다. 대신, 교육에 대한 구체적인 접근 방식을 구상하고 권장하며, 이를 위해서는 교수진 개발 프로그램이 필요할 수 있습니다. 임상 추론 기술을 가르치기 위해 고안된 독립형 모듈은 성공할 가능성이 낮습니다. 임상 추론은 학부 및 대학원 의학 교육 과정 전반에 걸쳐 수평적, 수직적으로 명시적으로 통합되어 발달적 방식으로 진행되어야 합니다.

While all medical schools teach knowledge, skills and behaviours, there is good evidence that careful attention to what is taught, how it is taught, and when it is taught can facilitate clinical reasoning development more effectively, through purposeful curriculum design. This does not necessarily require additional teaching time. Instead, a specific approach to teaching is envisaged and recommended, and this is likely to require a programme of faculty development. Stand-alone modules designed to teach clinical reasoning skills are unlikely to be successful. Clinical reasoning should be explicitly integrated, both horizontally and vertically, into courses throughout undergraduate and postgraduate medical training in a developmental fashion.

Supplementary File 1: What to teach consensus ideas with duplicates removed, organised in to broad CR areas, and mapped against the GMCs ‘Outcomes for Graduates’.

Suggestions for when to teach during a 5 year programme are in the right hand columns.

Consensus statement on the content of clinical reasoning curricula in undergraduate medical education

PMID: 33205693

Abstract

Introduction: Effective clinical reasoning is required for safe patient care. Students and postgraduate trainees largely learn the knowledge, skills and behaviours required for effective clinical reasoning implicitly, through experience and apprenticeship. There is a growing consensus that medical schools should teach clinical reasoning in a way that is explicitly integrated into courses throughout each year, adopting a systematic approach consistent with current evidence. However, the clinical reasoning literature is 'fragmented' and can be difficult for medical educators to access. The purpose of this paper is to provide practical recommendations that will be of use to all medical schools.

Methods: Members of the UK Clinical Reasoning in Medical Education group (CReME) met to discuss what clinical reasoning-specific teaching should be delivered by medical schools (what to teach). A literature review was conducted to identify what teaching strategies are successful in improving clinical reasoning ability among medical students (how to teach). A consensus statement was then produced based on the agreed ideas and the literature review, discussed by members of the consensus statement group, then edited and agreed by the authors.

Results: The group identified 30 consensus ideas that were grouped into five domains: (1) clinical reasoning concepts, (2) history and physical examination, (3) choosing and interpreting diagnostic tests, (4) problem identification and management, and (5) shared decision making. The literature review demonstrated a lack of effectiveness for teaching the general thinking processes involved in clinical reasoning, whereas specific teaching strategies aimed at building knowledge and understanding led to improvements. These strategies are synthesised and described.

Conclusion: What is taught, how it is taught, and when it is taught can facilitate clinical reasoning development more effectively through purposeful curriculum design and medical schools should consider implementing a formal clinical reasoning curriculum that is horizontally and vertically integrated throughout the programme.

Keywords: Consensus; clinical reasoning; curriculum; medical education; undergraduate.

'Articles (Medical Education) > 임상교육(Clerkship & Residency)' 카테고리의 다른 글

| 채점에서 학습을 위한 평가로: 핵심임상실습의 성적 제거 및 형성적 피드백 강화를 둘러싼 학생들의 인식(Teach Learn Med. 2021) (0) | 2023.02.18 |

|---|---|

| 관리추론: 보건전문직교육과 연구아젠다의 함의 (Acad Med, 2019) (0) | 2023.02.03 |

| 질환 스크립트의 30년: 이론적 기원과 실제적 적용(Med Teach, 2015) (0) | 2023.02.03 |

| 눈치보기: 의학 수련과정에서 과소대표된 여성의 경험(Perspect Med Educ. 2022) (0) | 2022.12.15 |

| 협력적 수행능력의 상호의존성 측정의 접근법(Med Educ, 2021) (0) | 2022.11.17 |