눈치보기: 의학 수련과정에서 과소대표된 여성의 경험(Perspect Med Educ. 2022)

“Walking on eggshells”: experiences of underrepresented women in medical training

Parisa Rezaiefar · Yara Abou-Hamde · Farah Naz · Yasmine S. Alborhamy · Kori A. LaDonna

서론

Introduction

서구 세계에서 의학 분야에서 여성의 대표성이 증가하고 있으며, 경우에 따라서는 동등함에도 불구하고, 여성들은 그들의 경력 향상에 있어 상당한 사회 문화적, 구조적 장애에 계속 직면하고 있다. 여성은 남성에 비해 의료 분야에서 직무 만족도가 낮고, 소진율이 높으며, 임금 불평등을 경험한다[2,3,4]. 전 세계적으로, 여성 의사들은 또한 학문적 경력을 추구하거나, 지도자 자리를 얻거나, 승진할 가능성이 적습니다 [5,6,7,8]. 그러나 불평등은 단일-이슈 현상이 되는 경우가 거의 없다. 증거에 따르면 그러한 도전은 의사 대표가 부족한 여성(UWiM)에게 복합적으로 작용한다. 예를 들어, 2009년과 2018년 사이에 미국 의과대학의 전체 전임 여성 교수진의 비율이 꾸준히 증가했지만, 대표가 부족하다고 간주되는 인종 또는 민족 출신 여성의 비율은 13%로 정체되었다[6].

Despite growing—and in some cases equal—representation of women in medicine across the Western world [1], women continue to face significant sociocultural and structural impediments to the advancement of their careers. Compared with their male counterparts, women experience lower job satisfaction, higher rates of burnout, and wage inequity in medicine [2,3,4]. Globally, women physicians are also less likely to pursue academic careers, attain leadership positions, or be promoted [5,6,7,8]. Inequity is rarely a single-issue phenomenon, however. Evidence suggests that such challenges are compounded for underrepresented women in medicine (UWiM). For example, although the overall proportion of full-time women faculty in US medical schools has increased steadily between 2009 and 2018, the percentage of women from a race or ethnicity considered to be underrepresented has stagnated at 13% [6].

최근의 형평성, 다양성 및 포용 노력은 부분적으로 의학에서 [과소 표현되는 것이 수반하는 복잡성]에 주의를 기울이지 않기 때문에 이러한 도전을 완화하지 못했다[9]. 예를 들어, "과소대표"의 개념화는 기관마다 매우 다양하다[10].

- 일부는 URiM을 "일반 인구의 수에 비해 의료 직업에서 과소 대표되는 인종 및 민족 인구"로 개념화하면서 AAMC의 정의를 그대로 채택한다[11].

- 다른 사람들은 URiM을 "인종, 민족, 사회경제적 지위, 건강 상태 또는 장애와 같은 개인적 특성이 의식적 또는 잠재의식적 편견이나 차별의 위험에 처한 개인"을 포함한다고 해석한다[10].

- 캐나다 의학부 협회(AFC)는 URiM에 대한 공식적인 정의를 가지고 있지 않다. 그럼에도 불구하고 AFMC 지도부는 프로그램이 원주민, 여성, 장애인 및 가시적 소수자를 포함한 지정 지분 그룹을 어떻게 지원하고 있는지를 측정하는 데 도움이 되는 "캐나다 의대를 위한 형평성 및 다양성 감사 도구"를 개발했다[12].

Recent equity, diversity, and inclusion efforts have not eased these challenges, in part because efforts do not attend to the complexities of what being underrepresented in medicine (URiM) entails [9]. For instance, conceptualizations of “underrepresented” vary widely across institutions [10].

- Some adopt the Association of American Medical Colleges definition verbatim, conceptualizing URiM as “racial and ethnic populations that are underrepresented in the medical profession relative to their numbers in the general population.” [11].

- Others interpret URiM to include “individuals whose personal characteristics, such as race, ethnicity, socioeconomic status, health condition, or disability, place them at risk for conscious or subconscious bias or discrimination” [10].

- In Canada, the Association of Faculties of Medicine of Canada (AFMC) does not have a formal definition of URiM. Nevertheless, AFMC leadership developed “the Equity and Diversity Audit Tool for Canadian Medical Schools” to help programs gauge how they are supporting designated equity groups, including Aboriginal peoples, women, persons with disabilities, and visible minorities [12].

URiM에 대한 [보다 광범위한 정의]는 지금까지 의료 교육 맥락에서 간과되고 충분히 탐구되지 않았던 가시적 및 보이지 않는 마커를 탐색하는 것의 [오랜 복잡성]에 고개를 끄덕인다[13]. 그러나 진정으로 의미가 있기 위해서는, [과소 표현의 정의]가 또한 어떻게 [가시적이고 보이지 않는 과소 표현된 정체성을 여러 개 갖는 것]이 [역사적으로 남성 우위적이고 이성적이며 유럽 중심적인 직업]에서 배우고 일하는 사람들을 위한 [소외를 복합할 수 있는지] 설명해야 한다. 1989년 페미니스트의 비판적 인종 학자인 킴벌레 크렌쇼는 [성별과 인종의 교차]로 인해 [흑인 여성]이 [[백인 여성]과 [흑인 남성]을 더한 것]보다 더 큰 차별을 경험한다는 사실을 설명하기 위해 [교차성]이라는 용어를 도입했다[16]. [젠더, 인종 또는 민족]을 [사회적 및 제도적 권력으로부터 분리]된 [단일monolithic 정체성]으로 접근하는 것은 "굴복이 중첩되는 시스템 내에서 그리고 페미니즘 및 반인종주의의 가장자리"에 위치할 수 있는 사람들을 효과적으로 지원하지 못할 위험이 있다[16].

More expansive definitions of URiM nod to the long-recognized complexities of navigating both visible and invisible markers [13], that have, so far, been overlooked and underexplored in the medical education context. However, to be truly meaningful, definitions of underrepresentation must also account for how having multiple visible and invisible underrepresented identities may compound marginalization for those learning and working in a historically male-dominant, heteronormative, and Euro-centric profession [14, 15]. In 1989, Kimberlé Crenshaw, a feminist critical race scholar, introduced the term intersectionality to account for the fact that, because of the intersection of their gender and race, Black women experience greater discrimination than both white women and Black men [16]. Approaching gender, race, or ethnicity as monolithic identities divorced from social and institutional power risks failing to effectively support those who may be located both “within overlapping systems of subordination and at the margins of feminism and antiracism” [16].

그들이 [UWiM이 되는 것의 의미와 영향]을 완전히 이해하지 못하는 한, 기관과 개인 의료 교육자들은 UWiM 교육생들의 개인적이고 전문적인 요구를 지원하기 위해 고군분투할 것이다. 의학 교육 학자들은 뉘앙스를 점점 더 요구하고 있지만, [과소 표현의 복잡성]은 여전히 탐구되지 않고 있다. 지금까지 우리가 아는 것은 [인종차별이나 성차별의 범위]를 정량화하는 데 초점을 맞추고 있다[19, 20]; 그러한 과소표현의 경험이 의사로서의 UWiMs의 인식에 [어떻게] 영향을 미치는지를 설명한 연구는 거의 없다. 이러한 이해에 따라 형평성, 다양성, 포용성 작업이 좌우되기 때문에 여성 교육생들이 의학에서 과소대표 개념을 어떻게 개념화했는지, 그들의 경험이 그들이 구상하는 진로에 어떤 영향을 미쳤는지를 조사하기 위해 정성적 탐구를 진행했다.

Unless they have a fulsome understanding of the meaning and impact of being UWiM, institutions and individual medical educators will struggle to support the personal and professional needs of UWiM trainees. Medical education scholars are increasingly calling for nuance, yet the complexities of underrepresentation remain underexplored [17, 18]. So far, the little we know focuses on quantifying the scope of racism or sexism [19, 20]; few studies have elucidated how such experiences of underrepresentation influence UWiMs’ perception of themselves as physicians [21,22,23,24]. Since equity, diversity, and inclusion work depends on such an understanding, we conducted a qualitative exploration to investigate how women trainees conceptualized underrepresentation in medicine and how their experiences influenced their envisioned careers.

방법들

Methods

모든 연구 절차는 교육 프로그램과 관련된 두 개의 학술 기관(의전 #H-05-20-5708 및 #M16-20-036)의 기관 연구 윤리 위원회에 의해 승인되었다.

All study procedures were approved by Institutional Research Ethics Boards at two academic institutions affiliated with the training program (Protocols # H-05-20-5708 and # M16-20-036).

모집

Recruitment

모집은 2020년 6월부터 9월까지 진행되었다. YAH와 FN은 부서 목록을 사용하여 캐나다의 가정의학 대학원 교육 프로그램에 등록된 모든 연수생(n = 159)에게 채용 이메일을 보냈다. 정의에 대한 합의가 부족하고 캐나다의 의료 연수생 인구 통계에 대한 데이터가 부족하다는 점을 고려하여[25], 우리는 대표성 부족을 정의하지 않기로 결정했다. 대신, 우리는 참가자들이 인종이나 민족뿐만 아니라 성 정체성, 성, 종교, 나이, 신체적 체격, 장애(보이는 것 또는 보이지 않는 것) 또는 사회경제적 지위(SES)와 같은 특성에 근거하여 UWiM으로 스스로 식별하도록 초대했다.

Recruitment took place between June and September 2020. Using a departmental list, YAH and FN sent a recruitment email to all trainees (n = 159) enrolled in a family medicine postgraduate training program in Canada. Given the lack of consensus around definitions and the dearth of data on medical trainee demographics in Canada [25], we elected not to define underrepresentation. Instead, we invited participants to self-identify as UWiM based not only on race or ethnicity, but also on characteristics such as gender identity, sexuality, religion, age, physical build, disability (visible or invisible), or socioeconomic status (SES).

데이터 수집

Data collection

우리는 풍부한 데이터를 생성하기 위해 "참가자들이 서로의 인식을 피드백하는" 방법인 그룹 인터뷰를 사용하여 데이터를 수집했습니다 [26, 페이지 100]. 그룹 인터뷰는 또한 YAH와 FN의 학술적 작업과 COVID-19 팬데믹 동안 UWiM 훈련생의 참여를 촉진했다. 구체적으로 연수생들의 학업일이 끝날 때 집단면접을 추가하는 것은 임상업무의 중단을 최소화하면서 여러 관점을 수집하는 이상적인 방법이었다.

We collected data using group interviews, a method where “participants feed off of each other’s perceptions”[26, p. 100] to generate rich data. Group interviews also facilitated both the scholarly work of YAH and FN and the participation of UWiM trainees during the COVID-19 pandemic—a global emergency disproportionately affecting women, particularly those identifying as underrepresented. Specifically, adding group interviews at the end of trainees’ academic day was an ideal method of collecting multiple perspectives with minimum interruption to their clinical duties.

10명의 연습생들이 YAH가 이끄는 3개의 그룹 인터뷰 중 하나에 참여하는 것에 동의했다. 코로나19 제약 때문에 고투미팅을 이용해 단체 인터뷰를 진행했다. 각 인터뷰는 2-5명의 참가자가 참여했으며 45분에서 140분 사이에 진행되었다. 반구조화된 가이드를 사용하여 YAH는 대화를 안내하기 위해 다음과 같은 중요한 질문을 제시했다.

Ten trainees consented to participate in one of three group interviews led by YAH. Because of COVID-19 restrictions, group interviews were conducted using GoToMeeting. Each interview was attended by 2–5 participants and lasted between 45 and 140 min. Using a semi-structured guide, YAH posed the following overarching questions to guide conversations:

- 1. 무엇이 당신을 UWiM이라고 정의합니까?

- 2. UWiM 정체성이 지금까지 훈련 경험에 어떤 영향을 미쳤습니까?

- 3. UWiM 정체성이 환자 및 의료 팀의 다른 구성원과의 상호 작용에 어떤 영향을 미쳤습니까?

- 4. UWiM으로서의 경험이 직업이나 직업 선택에 어떤 영향을 미친다고 생각하십니까?

- 1.What defines you as UWiM?

- 2.How has your UWiM identity influenced your training experience thus far?

- 3.How has your UWiM identity impacted your interactions with patients and other members of the healthcare team?

- 4.How do you perceive your experiences as a UWiM influence your professional or career choices?

모든 그룹 인터뷰는 NVivo 자동 전사 소프트웨어를 사용하여 오디오 녹음 및 전사되었다[27]. YAH와 FN은 녹취록의 정확성과 익명성을 보장했다.

All group interviews were audio-recorded and transcribed using NVivo automated transcription software [27]. YAH and FN ensured the accuracy and anonymization of transcripts.

데이터 분석

Data analysis

성찰적 주제 분석에 대한 브라운과 클라크의 [28] 6단계 접근법에 따라 팀원들은 독립적으로 대본을 읽고 데이터에 익숙해졌다. 다음으로, YSA는 일련의 팀 미팅을 통해 개선되고 확정된 예비 주제를 식별하기 위해 선택적 코딩에 참여했다. 마지막으로, YAH와 YSA는 전체 데이터 세트를 재코딩했다. 분석 과정 전반에 걸쳐, 팀 구성원들은 데이터 패턴을 식별하여 의학에서 과소 표현된 참가자들의 경험을 이해하는 것을 목표로 점점 더 해석적인 분석 '스토리라인'을 구성했다.

Guided by Braun and Clarke’s [28] six-phased approach to reflexive thematic analysis, team members independently read transcripts to familiarize themselves with the data. Next, YSA engaged in selective coding to identify preliminary themes that were refined and finalized over a series of team meetings. Finally, YAH and YSA re-coded the entire dataset. Throughout the analytical process, team members identified data patterns, constructing increasingly interpretive analytical ‘storylines’ aimed at understanding participants’ experiences of underrepresentation in medicine.

데이터 분석은 참가자의 관점을 중앙 집중화하는 [Anderson이 설명한 페미니스트 인식론]을 사용하여 inform되어졌습니다 [29]. 데이터를 연역적으로 분석하기 위해 선행 이론 프레임워크를 사용하지 않았지만, 우리는 [임계 인종 이론]과 [교차성]에 민감했다[16, 30, 31]. 구체적으로, 우리는 참가자들이 자신의 정체성을 개념화하는 방법, 자신의 정체성을 인식하는 것이 훈련 경험에 어떻게 영향을 미쳤는지, 그리고 그러한 경험을 탐색하는 것이 전문가로서의 자아 인식과 그들이 구상하는 미래의 실천에 어떻게 영향을 미쳤는지에 대해 들었다.

Data analysis was informed using the feminist epistemology described by Anderson, which centralizes participants’ perspectives [29]. Although we did not use an a priori theoretical framework to deductively analyze the data, we were sensitized to critical race theory and intersectionality [16, 30, 31]. Specifically, we attended to how participants conceptualized their identities, how they perceived their identities influenced their training experiences, and how navigating such experiences affected their self-perceptions as professionals and their envisioned future practice.

반사율

Reflexivity

각 연구자의 개인적이고 전문적인 경험이 분석 과정에 어떻게 영향을 미칠 수 있는지 사려 깊게 고려하는 과정인 반사성은 질적 엄격성의 핵심 요소이다[32]. 우리는 풍부한 반사 계정을 전자 보충 자료의 표 1에 포함시켰다.

Reflexivity—a process of thoughtfully considering how each researcher’s personal and professional experiences might influence the analytical process—is a key component of qualitative rigor [32]. We have included a rich reflexive account in Table 1 of the Electronic Supplementary Material.

결과.

Results

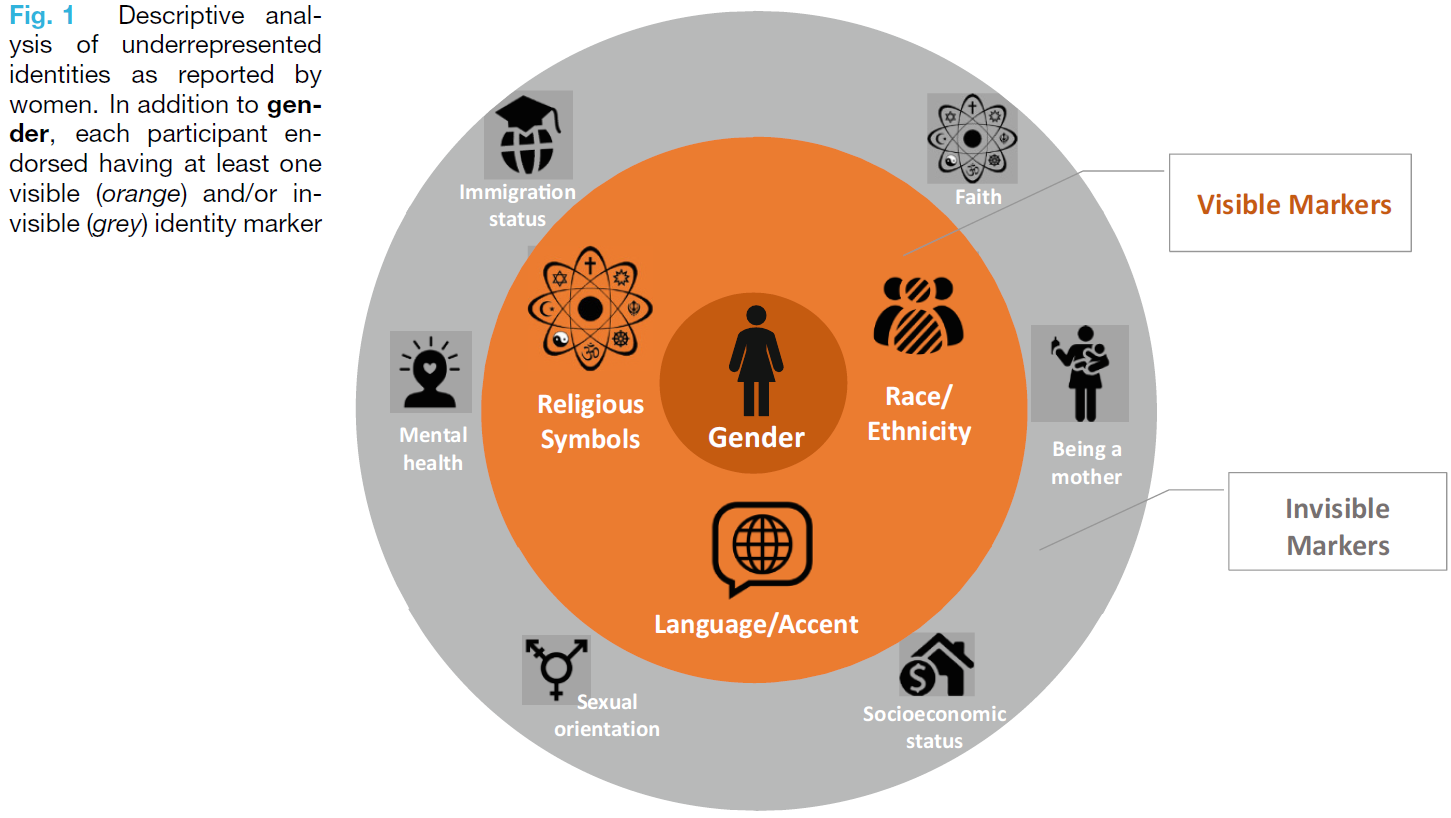

참가자들은 다양한 범위의 정체성에 기초하여 UWiM으로 확인되었다(그림 1). 참가자의 절반은 국제 의학 졸업생이었고 절반은 영어를 모국어로 보고했다. 8명의 참가자들은 인종, 민족(때로는 이름이나 억양으로 유추하기도 한다), 또는 히잡과 같은 종교적 상징 때문에 [가시적 소수집단]의 일원이라고 보고했다. 소외감을 느끼는 데 기여한 다른 [비가시적 정체성]에는 성적 지향, 종교, 낮은 SES, 정신 건강, 이민 지위, 모성이 포함되었다. 그들의 익명성을 보호하기 위해, 우리는 종종 교차하는 참가자들의 신원에 대한 추가적인 설명적 세부사항을 제공하지 않았다.

Participants identified as being UWiM based on a diverse range of identities (Fig. 1). Half of participants were international medical graduates and half reported English as their first language. Eight participants reported being a member of a visible minority because of race, ethnicity (sometimes inferred from one’s name or accent), or religious symbols such as the hijab. Other invisible identities that contributed to feeling marginalized included sexual orientation, religion, low SES, mental health, immigration status, and motherhood. To protect their anonymity, we have not provided additional descriptive details about participants’ often-intersecting identities.

눈에 보이든 보이지 않든 참가자의 정체성은 그들이 [전문직profession 전반에 걸쳐 친숙하고, 기대되거나, 일반적으로 받아들여지는 것]과 다르다는 보편적인 자기 인식(타자성otherness이라고 정의된 개념)을 낳았다[33]. 그러나, 참가자의 신원 표시가 보이는지 여부에 따라 다른 것의 경험과 시사점이 다르게 나타났다. 예를 들어, 인종차별을 당했거나 종교적 상징을 착용한 사람들은 명백한 차별 사례를 보고할 가능성이 더 높았다.

Participants’ identities, whether visible or invisible, resulted in a universal self-perception that they were different from what was familiar, expected, or generally accepted across the profession—a concept defined as otherness [33]. However, the experience and implications of otherness appeared to differ depending on whether participants’ identity markers were visible or not. For instance, those who were racialized or who wore a religious symbol were more likely to report overt instances of discrimination:

"저는 유색인종이기 때문에 환자들이 저로부터(지역 병원 두 곳)의 치료를 거부했습니다. 이로 인해 학습 기회가 사라지고 현장에서 이를 처리하는 방법을 모르는 직원들과의 상호 작용이 매우 어색해졌습니다."(P1, GI1)

“I’ve had patients refuse care from me at (two local hospitals) because I’m a person of colour. And that’s taken away learning opportunities and made for really awkward staff interactions who don’t know how to deal with that on the floor.” (P1, GI1)

반대로, [민족성, 성적 지향 또는 낮은 SES]와 같은 [덜 명백한 정체성 표지]를 가진 사람들은 그것의 직접적인 표적이 되기보다는 [편협한 행동을 목격]할 가능성이 더 높았다. 예를 들어, 혼합 인종으로서 "눈에 띄이지" 않은 참가자(P9, GI3)는 코로나바이러스 팬데믹의 맥락에서 동료들의 반중국 정서를 목격했다. 그녀는 다음과 같이 언급함으로써 동시에 다른 것과 겉으로 소속됨으로써 발생하는 해를 캡슐화했다.

Conversely, those with less readily apparent identity markers such as ethnicity, sexual orientation, or low SES were more likely to witness intolerant behaviour rather than be directly targeted by it. For example, a participant who did not “read as visibly” (P9, GI3) of mixed race witnessed anti-Chinese sentiment from colleagues in the context of the coronavirus pandemic. She encapsulated the harm caused by being simultaneously othered and outwardly belonging by noting:

"그런 정체성이 더 숨겨져 있다는 것은 많은 사람들이 내가 웃거나 그것에 동조할 것이라고 가정할 때, 실제로는 그것이 나에게 정말로 상처를 주거나 모욕적일 때 특정한 논평이나 농담을 하게 만들었다는 것이 흥미롭다." (P9, GI3)

“It’s interesting that having those identities being more hidden has caused a lot of people to make certain comments or certain jokes, assuming I’m going to laugh or go along with it, when in reality, that’s really hurtful or offensive to me.” (P9, GI3)

[타자성]은 임상 작업장의 [명백한 차별]뿐만 아니라, 참가자들이 [누구나 자기에게 잠재적 위협이 될 수 있다고 가정]하도록 자극한 지금까지의 삶의 경험에서 비롯되었다. 레즈비언이라고 밝힌 한 참가자는 비록 그녀가 환자와 충격적인 만남을 가진 적은 없지만, [동성애 혐오증이 만연하다는 것]은 [그녀가 누구든지 그녀에게 해를 끼칠 수 있다고 가정해야 한다는 것]을 의미한다고 설명했다. 그녀는 자신을 표적으로 삼을 수 있는 사생활의 측면을 언제 어떻게 숨겨야 할지 곰곰이 생각해 보았다.

Otherness resulted not only from overt discrimination in clinical workplaces, but also from prior life experiences, which primed participants to assume that anyone could be a potential threat. One participant identifying as lesbian described that, although she had not had a traumatic encounter with a patient, the pervasiveness of homophobia meant that she had to assume anyone could cause her harm. She ruminated on when and how to hide aspects of her personal life that might make her a target:

"저는 모든 환자와의 상호작용을 할 때 이러한 계산을 하고 있습니다… [제 아내에 대해 이야기하는 것이] 그들이 저를 어떻게 생각하는지에 영향을 미칠까요? 그것은 당신이 마음 한구석에서 하고 있는 정신적인 일일 뿐이다."(P7, GI2)

“I am doing those calculations with every patient interaction … Will [talking about my wife] affect how they think of me? It’s just the mental work that you’re doing in the back of your mind.” (P7, GI2)

실제로 모든 참가자는 [차별을 예상]하고 실제 또는 인식된 위협에 대한 [방어적 행동을 가정]하는 데 상당한 시간과 에너지를 소비했다. 많은 참가자들이 임상 환경에서 종교적 신념을 공개하는 것에 대해 우려를 표명했기 때문에, [종교]는 신분 표시기의 가시성 또는 투명성이 잠재적으로 해로운 경험을 조작하는 참가자들의 능력에 어떻게 다양하게 영향을 미쳤는지를 보여주는 중요한 예이다. 예를 들어, [성적 지향을 비공개로 함]으로써 잠재적 동성애 공포증에 반응한 참가자 7처럼, 참가자 4는 매우 유감스럽게도 환자를 advocating하는 것을 자제했다. 왜냐하면 [공통된 종교적 믿음을 드러내는 것]이 자신의 능력에 대한 인식을 편향시킬 것을 두려워했기 때문이다:

Indeed, all participants spent considerable time and energy both anticipating discrimination and assuming defensive behaviours against real or perceived threats. Since many participants expressed apprehension about disclosing religious beliefs in clinical environments, religion is a key example illustrating how the visibility or invisibility of identity markers variably affected participants’ abilities to maneuver potentially harmful experiences. For example, like Participant 7 who responded to potential homophobia by keeping her sexual orientation private, Participant 4 refrained, with great regret, from advocating for a patient because she feared that revealing shared religious beliefs would bias perceptions about her competence:

"한 환자는 자신이 로마 가톨릭 신자라는 이유만으로 DNR을 거부했다. 선임 스태프 의사와 간호사들이 내 앞에서 그것을 놀리고 있었다. 난 그냥 입을 다물었어. 아무 말도 하지 않은 이유는 만약 당신이 어떤 말을 한다면, 그들은 "아, 당신의 종교나 감정이 당신을 어떤 방향으로 이끌게 한다면 당신은 유능한 의사로서 어떻게 기능할 것인가?"라고 말할 수 있기 때문입니다."(P4, GI1)

“[A patient] refused the DNR simply because she said that she’s a Roman Catholic. The senior staff doctor and the nurses were making fun of that in front of me. I just shut my mouth. Didn’t say anything because if you say something, they might say, Oh, how would you function as a competent doctor if you let your religion or emotion lead you in a direction or another.” (P4, GI1)

이러한 [전략적 정체성 억압]은 [가시적 소수자 지위]를 가진 사람들에게는 더욱 복잡했다. 참가자들은 자신의 경험을 공유하면서 [자신의 정체성의 측면을 숨기는 능력]이 비록 힘을 잃기는 하지만, 동시에 모든 UWiM이 보편적으로 사용할 수 없는 특권이라는 것을 깨달았다.

- 백인이었던 참가자 7은 [자신의 성적인 면을 숨긴다는 것]은 UWiM의 지위를 완전히 숨길 수 있다는 것을 의미했다.

- 하지만 [히잡을 착용을 중단하는 것]이 도움이 될지 궁금했던 소외된 무슬림 참가자에게는 불가능한 일이다

Such strategic identity suppression was more complicated for those with visible minority status. In sharing their experiences, participants realized that the ability to conceal aspects of one’s identity, though disempowering, was simultaneously a privilege not universally available to all UWiM. For Participant 7 who was white, hiding her sexuality meant she could conceal her UWiM status entirely—an impossibility for a marginalized Muslim participant who wondered whether ceasing to wear hijab might help:

"저는 [히잡 때문에] 생각은 서구적이지만 민족적 외양을 보입니다. 이슬람 공포증이 있는 사람들이 있을 것이기 때문에 제가 분명히 이슬람교도처럼 보이게 하는 외모를 없애는 것이 더 나은 생각일까요? 저는 그것이 제 경력에 방해가 되는 것을 원하지 않습니다."(P10, GI3)“I am more Western-minded but more ethnic-looking [because of the hijab]. Is it a better idea if I sort of remove the look that makes me look very obviously Muslim, because some people will be Islamophobic? I don’t want that to stand in my way for my career.” (P10, GI3)

자신들의 민족성과 억양이 돋보인다고 보고한 참가자 4와 10에게 [눈에 띄는 종교적 상징을 제거]하거나, [종교적 소속을 숨기는 것]은 직장 차별을 방어하기 위한 부분적인 해결책에 불과했다. 모든 참가자들이 성별에 기반한 차별을 겪었지만, 타자성을 탐색하는 것의 부담은 [가시적 소수 집단의 구성원들]에게 더 컸다.

For Participants 4 and 10, who reported that their ethnicities and accents made them stand out, removing a visible religious symbol or concealing a religious affiliation were only partial solutions for shielding against workplace discrimination. Although all participants were privy to gender-based discrimination, the burden of navigating otherness was magnified for members of visible minority groups:

"당신[참가자 7]이 우리의 경험 사이에서 강조한 차이점은 당신에게 challenge가 될 수도 있는 자신의 정체성 부분을 거의 숨길 수 있다는 것입니다. 반면에 저에게는 안녕하세요, 저는 블랙입니다. 모두가 내가 흑인이라는 걸 알아. 그래서, 저는 여러분이 성적 정체성이라는 주제에 대해 달걀 껍질 위를 걷는 것처럼 느끼는 것이 믿을 수 없을 정도로 스트레스가 될 것이라고 생각합니다. 그리고 어떤 순간에 누군가 부적절한 말을 할지도 모릅니다. 반면에 저는 제 주변의 모든 사람들이 블랙니스에 대해 잘못된 말을 하지 않으려고 노력하는 것처럼 느껴집니다. 그리고 나는 누군가가 잘못된 말을 하기를 기다릴 뿐이다." (P6, GI2)

“The difference that you [Participant 7] highlighted between our experiences is that you can almost hide the part of your identity that may become a challenge, right. Whereas for me it’s like, hello, I’m Black. Everybody knows I’m Black. So, I think it must be incredibly stressful for you to feel like you’re walking on eggshells around the subject of sexual identity and that at any moment somebody might say something inappropriate. Whereas for me, I feel like everybody around me is walking on eggshells and trying not to say the wrong thing about Blackness. And I’m just waiting for someone to say the wrong things.” (P6, GI2)

참가자들의 차별과 타자성 경험은 [교수진의 지원 부재]로 인해 악화되었다. 특히, 그녀를 대신하여 옹호하는 한 교수진의 사례를 공유한 참가자는 없었다. 더 나쁜 것은, 교직원들이 그들의 권한을 개입시키는 데 실패함으로써 차별을 영구화했다는 것이다.

Participants’ experiences of discrimination and otherness were exacerbated by the absence of faculty support. Notably, no participant shared an example of a faculty member who advocated on her behalf. Worse, faculty members perpetuated discrimination by failing to use their authority to intervene:

"그것을 무시하는 사람들이 가장 좌절스럽다. 내가 방으로 걸어 들어가 눈물을 흘리며 걸어나오는 것이 괜찮다고 생각하는 사람들은 그냥 '걱정하지 마, 내가 그 환자 볼게'라고 말한다. 그건 도움이 안 돼요. 내가 그런 학대를 당했다는 사실을 인정하지 않는 것은 도움이 되지 않습니다."(P1, GI1)

“The ones that ignore it are the most frustrating. The ones that think it’s okay for me to walk into a room, walk out with tears in my eyes, and then just [say] ‘don’t worry about it, I’ll see that patient then.’ That’s not helpful. You not acknowledging the fact that I’ve gone through that abuse is not helpful.” (P1, GI1)

[차별, 타자성, 그리고 교수진의 옹호의 부족]에 대한 경험은 참가자들이 [그들의 professional paths을 어떻게 개념화하는지]에 지대한 영향을 미쳤다. 대부분은 더 안전하고 포괄적인 임상 및 학습 환경을 만드는 것을 목표로 하는 진로를 구상했다. 예를 들어, 정신 건강과 씨름하는 한 참가자는 미래의 훈련생들을 위해 개인적인 취약성을 제거하도록 동기를 부여받았다.

Experiences of discrimination, otherness, and the lack of faculty advocacy profoundly influenced how participants conceptualized their professional paths. Most envisioned a career path aimed at creating safer, more inclusive clinical and learning environments. For instance, a participant who struggled with mental health was motivated to de-stigmatize personal vulnerabilities for her future trainees:

"정신 건강과 관련된 일이 있다면, 디스트레스를 받는 사람으로서 [도움을 구하는 것]과 [벗어나는 것] 사이의 선을 긋는 것은 정말 어렵습니다. 내가 곧 staff이 될 거라는 걸 알아. 새로운 전공의들을 만나면 꼭 하고 싶은 말인 것 같아요… '스트레스를 받는다면 알려주세요'."(P2, GI1)

“If you have anything going on with mental health, it’s really difficult to tread the line between help seeking and coming off as a person who’s in distress. I know I’m going to be staff very soon. I think it’s something that I try and say when I meet new residents … ‘If you’re feeling stressed, let me know’.” (P2, GI1)

또한 참가자들은 [개인적 차별 경험]이 독특할 수 있지만, [소외받는다는 것]의[ 공통된 어려움]이 공통점을 확립한다는 인식으로 취약한 환자 집단에 봉사하고자 하는 강한 열망을 나타냈다.

Additionally, participants expressed a strong desire to serve vulnerable patient populations—perceiving that while individual experiences of discrimination may be unique, the shared hardships of being marginalized established common ground:

"저는 도심의 건강을 정말 좋아하고 중독 치료제가 흥미롭다고 생각합니다. 나는 난민 건강이 매우 흥미롭다고 생각한다. 그리고 이것들은 모두 나에게 영향을 미치지 않는 분야들이다… 하지만 내 경험들 때문에, 나는 그들의 경험들을 이해하고 공감하기 위해 내 마음을 확장할 수 있을 것 같다." (P6, GI2)

“I really love inner city health and find addictions medicine interesting. I think refugee health is very interesting. And these are all areas that don’t affect me … But because of my experiences, I feel like I can sort of stretch my mind to understand and empathize with their experiences as well.” (P6, GI2)

하지만, 비록 참가자들이 공감과 이타주의로 의학을 가르치고 실천할 수 있는 힘을 부여받은 살아있는 역경에서 벗어났지만, [개인의 안전에 대한 필요성]에 의해 동기 부여된 것처럼 보였다. 이는 그들의 직업 선택은 또한 [차별로부터 스스로를 떨어뜨릴 수 있는 전문적인 공간을 개척하는 것]을 목표로 함을 뜻한다. 예를 들어, 참가자 7은 그녀의 현재 현실과 그녀가 청소년과 LGBTQ+ 환자들과 함께 일하는 것을 상상했던 미래를 비교했다. "나는 청소년 인구에 끌린다." (P7, GI2) 구체적으로, 그녀는 "당신과 같은 동맹자나 동일시하는 사람들을 찾는 것"(P7, GI2)이 환자뿐만 아니라 자신을 위한 진정하고 포용적인 방법으로 practice할 수 있도록 힘을 실어줄 것이라고 믿었다. 참가자 3은 안전에 대한 유사한 열망을 나타냈다. "나는 단지 내가 같은 생각을 가진 사람들 주변에 있고 이 [과잉 차별]에 대해 강조할 필요가 없는 환경으로 가고 싶다."(P3, GI1)

However, although participants emerged from lived adversity empowered to teach and practice medicine with empathy and altruism, their career choices also seemed motivated by a need for personal safety, aiming to carve out a professional space where they could insulate themselves from discrimination. For instance, Participant 7 contrasted her current reality with the future she envisioned working with adolescents and LGBTQ+ patients: “I’m drawn to the adolescent population” (P7, GI2). Specifically, she believed “finding your allies or people who identify like you” (P7, GI2) would empower her to practice in an authentic and inclusive way not only for patients but also for herself. Participant 3 expressed a similar desire for safety: “I just want to go to an environment where I’m around like-minded people and don’t have to stress about this [overt discrimination]” (P3, GI1).

논의

Discussion

UWiM 인터뷰 대상자들은 훈련 중에 현재 정의에서 과소 표현의 측면으로 항상 개념화되지 않는 [다양한 정체성 마커]를 설명했다. 참가자들의 설명은 UWiM 연습생들이 겪는 공개적이고 은밀한 차별의 빈도뿐만 아니라 학업 환경에서 자행되는 해악을 예측하고 회피하기 위해 그들이 소비하는 [상당한 인지적, 감정적 노동]에 대해서도 조명한다. 우리의 연구는 타자성과 차별이 어떻게 UWiM에게 의료 교육 환경을 억압적이고 적대적으로 만들 수 있는지 이해하는 데 매우 필요한 출발점을 제공한다.

UWiM interviewees described a variety of identity markers that made them feel othered during their training that are not always conceptualized as facets of underrepresentation in current definitions. Participants’ accounts shed light not only on the frequency of overt and covert discrimination UWiM trainees endure, but also on the considerable cognitive and emotional labor they expend to anticipate and deflect harms perpetrated in academic environments. Our study provides a much-needed starting point for understanding how otherness and discrimination may make the medical education environment oppressive and hostile for UWiM.

참가자들의 설명은 [권력과 특권이 지배적인 집단의 구성원들]이 [그들에게 강요하는 렌즈]를 통해 [피지배된 사람들이 어떻게 생각하고 행동하도록 강요하는지] 보여준다. 이에 대응하여 그리고 억압에 대한 생존 메커니즘으로서 소수 집단의 구성원들은 지배적인 문화의 렌즈를 통해 자신들의 정체성을 재정립할 수밖에 없는데, 이 현상은 1903년에 Du Bois[34]에 의해 아프리카계 미국인들의 맥락에서 설명되었고 더 나아가 데보라 그레이 화이트에 의해 인종화된 여성들을 포함하기 위해 "삼중의 의식"으로 발전했다. 흑인 여성에게만 초점을 맞춘 것이 아니라 캐나다의 맥락에서, 우리 참가자들의 경험은 [삼중의 의식]과 공명한다. 연구 참가자들은 다음과 같은 방식으로 다중의 '타자화된' 정체성을 조작했다[35].

- 잘 알려진 트라우마 반응(잠재적 위협에 대한 학습 환경의 초경계 또는 "과도한 스캔")에 engage하고

- 소속을 용이하게 하거나 공공연한 차별을 피하기 위해 정체성 측면을 은폐함으로써

Participants’ accounts demonstrate how power and privilege force subjugated populations to think and act through lenses that members of dominant groups impose on them. In response and as a survival mechanism to oppression, members of minority groups are forced to redefine their identity through the lens of the dominant culture, a phenomenon described by Du Bois [34] in 1903 in the context of African Americans and further developed as “triple consciousness” by Deborah Gray White to include racialized women. Though in the Canadian context and not solely focused on Black women, our participants’ experiences resonates with triple consciousness. Study participants maneuvered their multiple, ‘othered’ identities

- by engaging in well-known trauma responses [35], including

- hypervigilance or

- “excessive scanning” [36] of their learning environment for potential threats, and

- by concealing aspects of their identities to either facilitate belonging or to avoid overt discrimination [37,38,39].

그러나 [완전한 신분 은폐]는 [특권의 한 형태]로 언급되었다. 따라서 과소대표라고 식별하는 백인 여성은 확실히 직장 차별에 의해 피해를 입지만, 그들의 [백인성]은 [교차성 탐색의 부담을 덜어주는] "특수 조항, 지도, 여권, 코드북, 비자, 옷, 도구 및 백지 수표와 같이 [보이지 않는 무중력 배낭]"을 제공한다[40].

Full identity concealment was noted as a form of privilege, however. Thus, although white women who identify as underrepresented are certainly harmed by workplace discrimination, their whiteness affords “an invisible weightless knapsack of special provisions, maps, passports, codebooks, visas, clothes, tools and blank checks” that ease the burden of navigating intersectionality [40].

그럼에도 불구하고, 참가자들의 계정은 차별의 트라우마와 임상 학습 환경에서 다른 것을 탐색하는 데 소요된 감정적 노동을 모두 보여주었다[41, 42]. 레지던트 훈련의 전형적인 스트레스를 관리하면서 참가자들의 학습 관심과 정서적 에너지는 [의사로서 자신이 되어야 할 사람과 맞지 않을 수도 있다는 신호]에 의해 끊임없이 우회divert되었다. 특히 리더십과 학문적 지위로 함축된 [권력이 대부분 백인 남성들의 손에 남아있는 학문적 환경]에서 말이다. 참가자들의 경험은 주로 백인 훈련 환경에서 흑인 의대생이 되는 것에 대한 대가를 설명하는 사설에서 Monnique Johnson이 최근 발표한 것과 공명했습니다: "저에게 있어서, 이러한 공간에서 상호작용을 해야 할 때 [제 전체가 유니폼이나 마스크]처럼 느껴졌습니다. 탈진은 [내 자신이 당당하고 진실되게 나 자신일 수 있는 공간]이 없고, [나와 공감할 수 있는 사람들이 충분하지 않은 것]에서 비롯됐다."

Nevertheless, participants’ accounts revealed both the trauma of discrimination and the emotional labor spent navigating otherness in clinical learning environments [41, 42]. While managing the typical stresses of residency training, participants’ learning attention and emotional energy were constantly diverted by signals that they may not fit who they are supposed to be as doctors, particularly in academic settings where power, connotated by leadership and academic rank, remains mostly in the hands of white men and, to a lesser extent, white women [6, 43,44,45]. Participants’ experiences resonated with those published recently by Monnique Johnson in an editorial explicating the toll of being a Black medical student in primarily white training environments: “For me, my whole being when I had to interact in these spaces felt like a uniform or a mask. Exhaustion came from not having a space to be unapologetically and authentically myself and not having enough people who could relate to me” [46].

참가자인 존슨 씨와 다른 사람들의 증언은 [학습 경험과 구조의 형평성]에 대한 의문을 제기한다. 기관 지도자들과 의료 교육자들은 대표자가 부족한 훈련생들이 훈련 중에 종종 침묵과 사일로에서 상당한 정체성 불협화음을 경험한다는 것을 인식해야 한다.

Testimonies by participants, Ms. Johnson, and others raise questions about the equity of learning experiences and structures. Institutional leaders and medical educators must recognize that underrepresented trainees experience significant identity dissonance during their training, often in silence and in silos.

또한 의학은 UriM 또는 UWiM으로 식별되는 훈련생이 [차별의 트라우마를 치유할 수 있는 충분한 공간을 제공하지 않는다]는 점을 유념해야 한다[47]. 지원을 받지 못한 참가자들은 자신의 개인적 정체성과 이상화된 직업 정체성 사이의 긴장을 관리하기 위해 홀로 남겨졌고, 평생 개인적, 경력적 결과를 초래할 수 있는 두려움과 배제에 뿌리를 둔 결정을 내렸다. UWiM 훈련생들이 차별에 직면했을 때 보고하고 그러한 경험이 그들의 직업 정체성과 의도된 직업 선택에 미치는 영향을 성찰하기 위해 신뢰할 수 있는 멘토의 지도 하에 안전한 공간이 필요하다. 비록 여성들, 특히 대표가 부족한 사람들은 그들의 경력을 육성하기 위해 숙련되고 동정적인 멘토가 필요하지만, 그들은 그것이 일어날 때 차별을 호소하고 여성들에게 개인적으로 그리고 직업적으로 영향을 미치는 차별적인 힘을 해체하기 위해 의미 있는 행동을 취할 수 있는 옹호자들이 더 필요하다.

We must also be mindful that medicine does not provide adequate space for trainees who identify as URiM or UWiM to heal from the trauma of discrimination [47]. Unsupported, participants were left alone to manage the tension between their personal and idealized professional identities, making decisions rooted in fear and exclusion that could have life-long personal and career consequences. Safe spaces—under guidance from trusted mentors—are required for UWiM trainees to debrief when encountering discrimination and to reflect on the impact of such experiences on their professional identity and intended career choices. Although women, particularly those who are underrepresented, need skilled and compassionate mentors to nurture their careers, they more so need advocates who are willing to both call out discrimination when it happens, and to take meaningful action to dismantle the discriminatory forces that impact women both personally and professionally.

[교수진 지지자]가 없는 상황에서, 참가자들은 [그들이 경험한 해악(명백한 차별과 문제가 되는 부작위 포함)을 바로잡기 위해 노력]하는 것처럼 보였다. 그들은 그들이 거부당한 멘토링, 옹호, 그리고 진정한 인간이 될 수 있는 기회를 제공할 수 있는 진로를 구상했다. 참가자들이 [봉사정신]으로 이런 불협화음에서 벗어나는 것은 존경할 만하지만, [잠재적인 단점]을 모르는 것 같았다. 예를 들어, [복잡한 심리사회적 및 의료 요구를 가진 사람들을 돌보는 것]은 [동정심 피로와 소진을 악화시킬 위험]이 있는 [시간 집약적인 작업]이다. 이는 여성 의사들 사이에서 이미 잘 문서화되어 있는 현상이다.

In the absence of faculty advocates, participants appeared driven to correct the harms—including blatant discrimination and problematic inaction—that they experienced. They envisioned a career path where they could provide the mentoring, advocacy, and opportunity to be authentically human that they were denied. Although it is admirable to emerge from such dissonance with a sense of service, participants seemed unaware of potential drawbacks. For example, caring for populations with complex psychosocial and health care needs is time-intensive work that risks exacerbating compassion fatigue and burnout—phenomena that are already well-documented among female physicians.

소외된 사람들에게 봉사하려는 욕구는 학계와 리더십에서 UWiM의 부족에 대한 또 다른 가능한 설명이 될 수 있다. 즉, 차별적 구조적 문제가 여성의 리더십 위치 달성 능력을 저해하는 "누출 파이프라인"을 생성하는 것으로 알려져 있지만[47] [불평등에 대한 트라우마 반응]은 [권력의 위치]로부터의 [자기 배제]로 이어질 수 있다. 참가자들이 진정으로 흥분하고 소외된 환자들과 훈련생들을 위한 훈련과 관리를 개선할 수 있는 진로를 시작할 수 있는 권한을 부여받은 것처럼 보였지만, 모든 의사들은 이 일을 할 수 있는 기술과 동기를 가지고 있어야 한다. 이것들은 문화적으로 유능한 의사가 되기 위한 기본적인 요소들이지만, UWiM 참가자들은 그것들을 전문화된 진로의 일부로 인식하는 것처럼 보였다.

The desire to serve marginalized populations may be another possible explanation for the paucity of UWiM in academia and leadership. That is, although discriminatory structural issues are known to create a “leaky pipeline” [47] that hinders women’s ability to attain leadership positions, the trauma response to inequities might lead to self-exclusion from positions of power. Although participants seemed genuinely excited and empowered to embark on a career path that would improve training and care for marginalized patients and trainees, all physicians should have the skillset and motivation to do this work. These are fundamental components of being a culturally competent physician, yet UWiM participants seemed to perceive them as part of a specialized career path—a problematic notion that should trigger both reflection and action.

한계

Limitations

타자성과 차별에 대한 경험은 독특하게 해로우므로, 이러한 해악을 탐구하는 것을 목표로 하는 질적 데이터 세트가 "포화"되는 것이 불가능하다[48]. 우리는 그룹 환경에서 편안하게 공유하지 못한 정보를 보류했을 수 있는 한 캐나다 학술 기관의 10명의 여성 표본이 의학의 다른성에 대한 불완전한 이해를 생성한다는 것을 인정한다. 그러나 참가자들의 풍부하고 감성적인 계정은 UWiM이 탐색해야 하는 복잡성을 이해하는 데 매우 귀중한 뉘앙스를 제공했다. 질적 소견은 일반화하기보다는 이전 가능한 것을 의도하기 때문에 성별 정체성과 실습 환경에 걸쳐 연수생과 교직원에게 반향을 일으킬 수 있다. 더 많은 연구가 시급하며, 현재 UWiM의 교차성과 전문적 정체성 형성의 관계를 이해하기 위한 전국적인 연구에 착수하고 있다.

Experiences of otherness and discrimination are uniquely harmful, rendering it impossible for a qualitative dataset that is aimed at exploring these harms to become “saturated” [48]. We acknowledge that a sample of 10 women from one Canadian academic institution, who may have withheld information they did not feel comfortable sharing in a group setting, generates an incomplete understanding of otherness in medicine. However, participants’ rich and emotive accounts provided invaluable nuance for understanding the complexities that UWiM must navigate. Because qualitative findings are intended to be transferable rather than generalizable, findings may resonate with trainees and faculty members across gender identities and practice settings. More research is urgently needed, and we are currently embarking on a national study to understand the relationship between intersectionality and the professional identity formation of UWiM.

결론

Conclusion

많은 훈련생들에게, 명백한 차별과 타인의 감정은 학업 환경에서 항상 존재하는 위협이다. [형평성, 다양성, 포용성]을 목표로 하는 [정책과 개인의 행동]은 억압을 악화시키는 [과소대표의 복잡성]을 고려해야 한다. 의학부는 지역적 및 역사적 맥락을 고려하여 의학에서 과소 표현 개념화에 대한 사려 깊은 접근법으로부터 이익을 얻을 것이다. [정의와 정책]이 [공평하고 포용적이라는 것을 보장하는 것]은 다음에 달려있다.

- 훈련생으로 대표되는 [눈에 보이는 정체성]과 [보이지 않는 정체성]의 폭에 대한 [포괄적으로 이해하는 것]

- 의학에서 [과소 표현에 대한 진화하는 개념화]가 역사적으로 소수화된 그룹을 지원하기 위한 노력을 희석시키지 않도록 [인구 통계 데이터를 계층화하는 것]

For many trainees, overt discrimination and feelings of otherness are ever-present threats in academic environments. Policies and individual actions aimed at equity, diversity, and inclusion must consider the complexities of underrepresentation that exacerbate oppression. Faculties of medicine would benefit from a thoughtful approach to conceptualizing underrepresentation in medicine, taking local and historical contexts into account. Ensuring that definitions and policies are equitable and inclusive depends

- on both a comprehensive understanding of the breadth of visible and invisible identities represented by trainees and

- on stratifying demographics data to ensure that any evolving conceptualizations of underrepresentation in medicine do not dilute efforts aimed at supporting historically minoritized groups [11].

대학원 프로그램과 개별 교육자들은 [훈련 환경]이 [문화적으로 안전]할 뿐만 아니라 "[의사]로서 발달하는 자신의 정체성을 이해할 수 있는, sense-making 과정을 용이하게 하는 교육학적 공간"으로 육성할 의무가 있다. 우리는 의학 교육계가 마야 안젤루 박사의 지시에 귀를 기울일 것을 촉구한다. "당신이 더 잘 알 때까지 당신이 할 수 있는 최선을 다하라. 그럼 네가 더 잘 알 때, 더 잘 하라." 우리의 참가자들은 모든 훈련생들이 번창할 수 있는 포용적 학습 환경을 옹호하기 위해 그들의 힘과 특권을 사용함으로써 교직원들이 "더 잘하기" 위해 필요한 비판적 인식을 형성했습니다.

Postgraduate programs and individual educators have a duty not only to ensure that training environments are culturally safe but also that they foster “the pedagogical space to facilitate sense-making processes … thereby enabling [trainees] to understand their own developing identities as doctors” [49]. We urge the medical education community to heed Dr. Maya Angelou’s instruction to “do the best you can until you know better. Then when you know better, do better” [50]. Our participants generated the critical awareness necessary for faculty to “do better” by using their power and privilege to advocate for an inclusive learning environment where all trainees can thrive.

"Walking on eggshells": experiences of underrepresented women in medical training

PMID: 36417160

PMCID: PMC9684928

DOI: 10.1007/s40037-022-00729-5

Free PMC article

Abstract

Introduction: Medicine remains an inequitable profession for women. Challenges are compounded for underrepresented women in medicine (UWiM), yet the complex features of underrepresentation and how they influence women's career paths remain underexplored. This qualitative study examined the experiences of trainees self-identifying as UWiM, including how navigating underrepresentation influenced their envisioned career paths.

Methods: Ten UWiM family medicine trainees from one Canadian institution participated in semi-structured group interviews. Thematic analysis of the data was informed by feminist epistemology and unfolded during an iterative process of data familiarization, coding, and theme generation.

Results: Participants identified as UWiM based on visible and invisible identity markers. All participants experienced discrimination and "otherness", but experiences differed based on how identities intersected. Participants spent considerable energy anticipating discrimination, navigating otherness, and assuming protective behaviours against real and perceived threats. Both altruism and a desire for personal safety and inclusion influenced their envisioned careers serving marginalized populations and mentoring underrepresented trainees.

Discussion: Equity, diversity, and inclusion initiatives in medical education risk being of little value without a comprehensive and intersectional understanding of the visible and invisible identities of underrepresented trainees. UWiM trainees' accounts suggest that they experience significant identity dissonance that may result in unintended consequences if left unaddressed. Our study generated the critical awareness required for medical educators and institutions to examine their biases and meet their obligation of creating a safer and more equitable environment for UWiM trainees.

Keywords: Family Medicine; Medical education; Medical training; Underrepresented women.

© 2022. The Author(s).

'Articles (Medical Education) > 임상교육(Clerkship & Residency)' 카테고리의 다른 글

| 학부의학교육에서 임상추론 교육과정 내용에 대한 합의문(Med Teach, 2021) (0) | 2023.02.03 |

|---|---|

| 질환 스크립트의 30년: 이론적 기원과 실제적 적용(Med Teach, 2015) (0) | 2023.02.03 |

| 협력적 수행능력의 상호의존성 측정의 접근법(Med Educ, 2021) (0) | 2022.11.17 |

| 신뢰와 위험: 의학교육을 위한 모델 (Med Educ, 2017) (0) | 2022.11.06 |

| EPA 프레임워크의 논리와의 고군분투 (Med Educ, 2022) (0) | 2022.11.06 |