설문에서 최대한을 얻어내기: 응답 동기부여 최적화하기(J Grad Med Educ. 2022)

Getting the Most Out of Surveys: Optimizing Respondent Motivation

Anthony R. Artino Jr , PhD

Quentin R. Youmans , MD, MSc

Matthew G. Tuck , MD, MEd, FACP

대학원 의학교육(GME)을 연구하는 사람들을 포함한 보건 전문 교육 연구자들은 설문 조사와 오랜 연애를 한다. 이러한 호감의 증거는 의학 교육 저널(Journal of Graduate Medical Education, JGME)에 게재된 최근 기사를 검토함으로써 찾을 수 있다. 우리가 집계한 바로는 2021년에 발간된 Original Research and Brief Report 기사 중 56%가 설문조사를 이용했다. 시간, 돈, 방법론적 전문지식의 한계를 포함하여 많은 GME 학자들이 직면한 제약을 고려할 때 이 큰 비율은 놀라운 일이 아니다. 결과적으로, 설문조사는 종종 GME 조사자들이 가장 접근하기 쉬운 연구 방법이다. 또한 설문조사는 일반적으로 GME 교육자들이 훈련생 평가와 프로그램 평가를 위해 사용한다. 이러한 이유로, 설문조사는 상당히 적응 가능하며, 신념, 가치, 태도, 인식 및 의견과 같이 측정하기 어려운 심리적 구조를 평가하는 효율적인 방법이 될 수 있다.

Health professions education researchers, including those who study graduate medical education (GME), have a long-standing love affair with surveys. Evidence of this fondness can be found by reviewing recent articles published in the Journal of Graduate Medical Education (JGME). By our count, 56% of Original Research and Brief Report articles published in 2021 used a survey. This large proportion is not surprising, considering the constraints that many GME scholars face, including limitations of time, money, and methodological expertise. Consequently, surveys are often the most accessible research method for GME investigators. In addition, surveys are commonly used by GME educators for trainee assessment and program evaluation. For these reasons, surveys are quite adaptable and can be an efficient way to assess hard-to-measure psychological constructs like beliefs, values, attitudes, perceptions, and opinions.1

광범위한 사용과 방법론적 유연성에도 불구하고 설문조사에는 [몇 가지 고유한 약점]이 있다. 여론조사, 사회학, 심리학과 같은 분야에서 수십 년 동안의 경험적 증거에 의해 뒷받침되는 한 가지 약점은 [낮은 수준의 응답자 동기가 질 낮은 데이터로 이어질 수 있다]는 것이다. GME에서 문제는 훨씬 더 심각할 수 있다. 전공의는 업무 외의 삶뿐만 아니라 임상 및 교육 책임을 포함하여 많은 경쟁적 시간 제약을 가지고 있기 때문이다. 이러한 제약 및 기타 제약 조건은 특정 GME 연구 또는 평가 노력의 장점에 관계없이 설문 조사를 우선해서 답하기 어렵게 만든다.

Notwithstanding their widespread use and methodological flexibility, surveys come with several inherent weaknesses. One weakness, supported by decades of empirical evidence in fields like public opinion polling, sociology, and psychology, is that low levels of respondent motivation can lead to poor-quality data.2 In GME the problem may be even more acute, as resident physicians have many competing time constraints, including clinical and educational responsibilities, as well as life beyond work. These and other constraints make prioritizing surveys difficult, regardless of the merit of any particular GME study or evaluation effort.

이러한 상황을 염두에 두고, 우리는 이 사설에서 [응답자의 동기 부여 문제]에 초점을 맞춘다. 동기 부여를 해결하기 위해 먼저 인식에 대해 논의하고 설문 조사를 완료할 때 참가자가 일반적으로 고려하는 사항을 강조합니다. 다음으로, 동기가 낮을 때 발생할 수 있는 몇 가지 응답 행동을 설명하여 낮은 품질의 설문 조사 데이터를 생성한다. 우리는 연구원이 응답자의 동기를 최적화하고 궁극적으로 더 정확하고 해석 가능한 설문 조사 데이터로 이어질 수 있는 설계 및 구현 전략으로 결론을 내린다.

With this landscape in mind, we focus on the issue of respondent motivation in this Editorial. To address motivation, we first discuss cognition and highlight what participants typically consider when completing a survey. Next, we describe several response behaviors that can occur when motivation is low, thereby resulting in low-quality survey data. We conclude with design and implementation strategies that can help researchers optimize respondent motivation and ultimately lead to more precise, accurate, and interpretable survey data.

설문조사 응답 프로세스

Survey Response Process

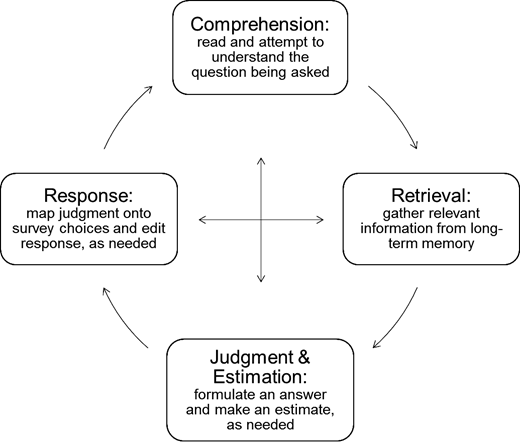

응답자의 동기를 이해하기 위해서는 먼저 [설문 응답의 심리]를 살펴보는 것이 도움이 된다. 설문 조사를 수행하는 인지 작업을 설명하는 데 사용되는 고전적인 프레임워크는 Tourangeau와 동료들의 응답 프로세스 모델이다(그림 참조). 그것은 응답자들이 설문조사를 할 때 4가지 인지 과정을 거치는 것을 제안한다.

- 첫째, 설문 항목을 이해하고 페이지에 있는 [단어의 의미를 해석]해야 한다(자체 조사에서).

- 다음으로, 그들은 장기 기억에서 항목에 대응하는 데 필요한 [관련 정보를 검색]해야 한다. 이 정보에는 과거 활동에 대한 구체적인 날짜나 주제에 대한 태도나 의견이 포함될 수 있습니다. 일반적으로 메모리에서 검색해야 합니다.

- 다음으로, 의견제출자들은 그 [정보를 판단에 통합하고, 경우에 따라서는 추정]할 필요가 있다. 예를 들어, 한 응답자는 작년에 얼마나 자주 헌혈을 했는지 보고할 것을 요청했고, 따라서 얼마나 자주 헌혈을 하는지에 따라 그 숫자를 추정할 필요가 있다. 만약 헌혈이 분기별로 실시된다면, 응답자는 작년에 헌혈한 횟수로 "4"를 추정할 수 있다.

- 마지막으로, 응답자들이 답변을 염두에 둔 후에는 [해당 답변을 설문조사에 보고하고 제공된 옵션에 따라 답변을 조정]해야 합니다. 위의 예에서 헌혈 빈도에 대한 응답 옵션이 "가끔" 또는 "자주"로 제시된 경우, 응답자는 자신의 대답 "4"를 가장 적절한 응답 범주로 변환해야 한다.

To understand respondent motivation, it is helpful to first examine the psychology of survey response. A classic framework used to describe the cognitive work of taking a survey is Tourangeau and colleagues' response process model (see Figure).3 It proposes that respondents move through 4 cognitive processes when taking a survey.

- First, they need to comprehend the survey item and interpret the meaning of the words on the page (in a self-administered survey).

- Next, they need to retrieve from their long-term memory the relevant information needed to respond to the item. That information could include specific dates for activities in the past, or an attitude or opinion about a topic. Generally, something must be retrieved from memory.

- Next, respondents need to integrate that information into a judgment and, in some cases, make an estimation. For example, a respondent asked to report how often they gave blood last year might not remember all instances and therefore would need to estimate the number based on how often blood drives are held. If blood drives are conducted quarterly, then the respondent might estimate “4” as the number of times they gave blood last year.

- Finally, once respondents have an answer in mind, they must report that answer on the survey and adapt their response based on the options provided. In the example above, if the response options for the frequency of blood donations are presented as “sometimes” or “often,” then a respondent would need to convert their answer “4” into what they believe is the most appropriate response category.

설문조사 응답 프로세스의 구성요소

응답자들이 네 가지 인지 과정을 작업하는 동안, 이리저리 뛰어다니고, [심지어 단계를 건너뛸 수 있다]는 것을 주목하는 것이 중요하다. 예를 들어, 한 사람이 작년에 의사를 얼마나 자주 봤는지 보고해 달라고 요청했는데, 기억에서 그 정보를 찾기 시작할 수도 있지만 물리치료사에게 가는 것이 고려되어야 하는지에 대해 궁금해했다. 그리고 나서 그들은 이해 단계로 돌아가서 단서를 찾기 위해 질문을 다시 읽을 수도 있다. 그런 다음 응답자는 제공된 응답 옵션에 기초하여 의사 방문 횟수가 적정한지에 대한 다른 단서를 찾기 위해 응답 단계로 점프할 수 있다. 이러한 방식으로, 설문 응답 프로세스는 비선형적입니다. 응답자들은 개별 설문 조사 질문을 탐색하고 응답하는 데 도움이 되도록 설문 조사에서 제공하는 상황별 단서를 사용합니다.

It is important to note that respondents may jump around, and even skip steps, while working through the 4 cognitive processes. For instance, a person asked to report how often they saw a physician last year might begin retrieving that information from memory but wonder if going to the physical therapist should be counted. They might then jump back to the comprehension step and reread the question to look for clues. The respondent might then jump forward to the response step to look for other clues about what a reasonable number of physician visits might be, based on the response options provided. In this way, the survey response process is nonlinear; respondents hop around and use contextual clues provided by the survey to help navigate and respond to individual survey questions.

이 네 가지 인지 단계에 대한 또 다른 중요한 점은, 과정 중에 어떤 지점에서 [마주치는 어려움이 오류를 발생]시킬 수 있다는 것이다. 예를 들어, 응답자들은 혼란스러운 문구나 전형적인 시각적 배치 때문에 질문을 오해하거나, 관련 정보를 잊어버려서 검색할 수 없거나, 정보에 입각한 답변을 하는 데 필요한 정보가 없기 때문에 정확한 판단을 할 수 없을 수 있다. 각 예제에서 [응답 오류]가 발생할 수 있으며 제공된 답변은 [부정밀하고, 부정확하며 조사 연구자가 해석하기 어려울 가능성]이 더 높습니다. 게다가, 응답자들은 설문 조사를 통해 일하는 동안 [인지적 지름길]을 취할 수 있고 종종 그렇게 한다. 즉, 응답자는 응답 프로세스(이해, 검색, 판단 및 추정 또는 보고)의 모든 단계에서 설문 응답 프로세스를 최적화할 수 없습니다. 대신에, 응답자들은 [정신적 에너지와 만족감을 보존하는 것]을 선택할지도 모른다.

Another important point about these 4 cognitive steps is that difficulties encountered at any point along the process can produce errors. For example, respondents might misunderstand a question because of confusing wording or atypical visual layout, not be able to retrieve the relevant information because they have forgotten it, or not be able make an accurate judgment because they do not have the necessary information to give an informed answer. In each example, response errors may occur, and the answers provided are more likely to be imprecise, inaccurate, and difficult for survey researchers to interpret. Furthermore, respondents can and often do take cognitive shortcuts while working through a survey. That is, at any step in the response process—comprehension, retrieval, judgment and estimation, or reporting—respondents may not optimize the survey response process. Instead, they may choose to conserve their mental energy and satisfice.4

동기 부여 및 Satisficing

Motivation and Satisficing

응답자의 동기부여에 대한 우려는 설문조사 설계 문헌에 오랫동안 설명되어 왔다. 20여 년 전, 크로스닉는 "단 하나의 질문에도 최적의 답을 생성하기 위해서는 많은 인지 작업이 필요하다"고 언급했다 이와 같이, 양질의 답변은 에너지를 소비하고 설문 조사 응답 프로세스를 최적화하도록 동기를 부여하는 응답자에게서 나오는 경향이 있다. 응답자들은 자기 표현에 대한 욕구, 지적 도전, 도움이 되고 싶은 욕구를 포함한 많은 요소들에 의해 동기 부여를 받는다. GME에서 주민들은 의무감과 전문성에서 설문에 참여하려는 동기부여를 받는다고 보고한다. 반면에, 개인적인 경험과 수십 년에 걸친 경험적 연구는 응답자들이 종종 설문 질문에 고품질의 답변을 제공할 동기가 없음을 말해준다. 크로스닉은 이 흔한 상황을 satisficing이라고 지칭한다.

Concerns about respondent motivation have long been described in the survey design literature. More than 2 decades ago, Krosnick4 noted that “a great deal of cognitive work is required to generate an optimal answer to even a single question.” As such, high-quality answers tend to come from respondents who are motivated to expend that energy and optimize the survey response process. Respondents are motivated by numerous factors, including their desire for self-expression, intellectual challenge, and a desire to be helpful. In GME, residents report being motivated to participate in surveys out of a sense of duty and professionalism.5 On the other hand, personal experience and decades of empirical research tell us that respondents are often unmotivated to provide high-quality answers to survey questions. Krosnick calls this common situation satisficing.4

Satisficing은 응답자들이 "기준을 타협하여, 에너지를 덜 소비하려고 하는 정도"이다. 즉, 응답자들은 [최적의 답변을 도출하기 위해 필요한 노력을 기울이기]보다는, 예를 들어 질문의 의미에 대해 [덜 생각]하고, 기억을 [덜 철저하게 검색]하고, 검색된 정보를 [부주의하게 통합]하고, 또는 응답을 [부정확하게 선택함]으로써 "적당히 좋은" 답변을 제공한다. 따라서, 가장 정확하고 최고의 답변(즉, 프로세스 최적화)을 생성하기 위해 응답 프로세스의 네 가지 인지 단계를 신중하게 수행하는 대신, 만족하는 응답자는 정신 에너지를 보존하고 만족스러운 답변만 제공하는 것에 만족한다. 경험적 증거는 제한적이지만, 우리는 GME 훈련생들의 고유한 시간과 맥락 제약을 고려할 때 Satisficing이 특히 널리 퍼질 수 있다고 의심한다.

Satisficing is the degree to which respondents “compromise their standards and expend less energy.”4 That is, rather than devote the necessary effort to generate optimal answers, respondents often give “good enough” answers by, for example, being less thoughtful about a question's meaning, searching their memory less thoroughly, integrating retrieved information carelessly, and/or selecting a response imprecisely. Thus, instead of carefully working their way through the 4 cognitive steps of the response process to generate the best, most precise answers (ie, optimizing the process), respondents who satisfice conserve their mental energy and settle for giving just satisfactory answers.4 Although empirical evidence is limited,5 we suspect that satisficing may be particularly prevalent for GME trainees given their unique time and context constraints.

실제로 Satisficing을 하면, 낮은 품질의 설문 조사 데이터로 이어지는 [여러 가지 응답 행동]이 발생합니다. 여기에는 다음이 포함됩니다

- (1) 서둘러 설문 조사를 통과하는 것;

- (2) 제일 처음 나오는 그럴듯한 답변을 선택합니다;

- (3) 평가에 제시된 모든 진술에 동의한다;

- (4) 동일한 옵션을 직선(일명 직선)으로 반복적으로 선택합니다;

- (5) 질문에 대해 실제로 생각하지 않고 "모름" 또는 "해당 없음"을 선택합니다

- (6) 설문 조사의 항목 또는 전체 섹션을 건너뜁니다.

Satisficing 는 중서부의 한 대규모 학술 의료 센터에서 설문 조사 행동에 대한 질문을 받은 주민의 말을 인용함으로써 전형적으로 나타난다: "대부분의 경우… 저는 정말로 기여할 것이 없고 단지 그것을 극복하고 싶기 때문에 중간을 끝까지 클릭할 것입니다." 이 진술이 시사하는 바와 같이, [응답 프로세스를 최적화하지 않는 응답자의 답변]은 suboptimal하며, 신뢰하기 어렵고, 의도한 용도에 타당할 가능성이 낮은 품질의 데이터를 초래한다.

In practice, satisficing results in a number of response behaviors that lead to low-quality survey data: these include

- (1) rushing through a survey;

- (2) selecting the first reasonable answer;

- (3) agreeing with all statements presented on the survey;

- (4) selecting the same options repeatedly, in a straight line (so-called straightlining);

- (5) selecting “don't know” or “not applicable” without actually thinking about the question being asked; and

- (6) skipping items or entire sections of a survey.2

Satisficing is epitomized by this quote from a resident at a large Midwestern academic medical center who was asked about their survey behaviors: “A lot of the time… I'll just click the middle all the way through, because I have nothing really to contribute and I just want to get through it.”5 As this statement implies, answers from respondents who are not optimizing the response process are suboptimal and result in poor-quality data that are unlikely to be trustworthy, credible, or valid for their intended use.

Satisficing 완화 및 사려 깊은 응답 장려

Mitigating Satisficing and Encouraging Thoughtful Responses

만족스러운 결과로 발생하는 문제에 비추어 볼 때, GME 교육자와 연구자는 현상을 이해하고 데이터 품질에 대한 해를 완화하는 솔루션을 구현하기 위해 노력하는 것이 중요하다. 크로스닉은 [Satisficing 을 촉진하는 세 가지 조건]을 설명했다:

- (1) [과제]가 어려운 경우

- (2) [응답자의 능력] 또는 교육 수준이 낮은 경우

- (3) 응답에 대한 참가자의 [동기 부여]가 낮은 경우

대부분의 경우 [응답자의 능력과 교육 수준이 고정]되어 있습니다. 다행히도, GME 연구원들은 종종 고등학생들보다 [교육을 잘 받았기 때문]에 Satisficing할 가능성이 낮은 고능력 참가자들을 조사하고 있다. [과제의 난이도]와 [응답자의 동기 부여]에 관해서는, 조사 설계자는 사려 깊은 설계와 구현 관행을 통해 이러한 요인에 영향을 미칠 수 있으며 Satisficing을 상당히 완화시킬 수 있다.

In light of the problems that result from satisficing, it is important for GME educators and researchers to understand the phenomenon and work to implement solutions that mitigate harms to data quality. Krosnick4 described 3 conditions that promote satisficing:

- (1) greater task difficulty;

- (2) lower respondent ability or education level; and

- (3) lower participant motivation to respond.

In most cases, respondent ability and education level are fixed. Fortunately, GME researchers often are surveying high-ability participants who are well educated and thus less likely to satisfice than, for example, a high school student. As for task difficulty and respondent motivation, survey designers can influence these factors—and appreciably mitigate satisficing—through thoughtful design and implementation practices.6

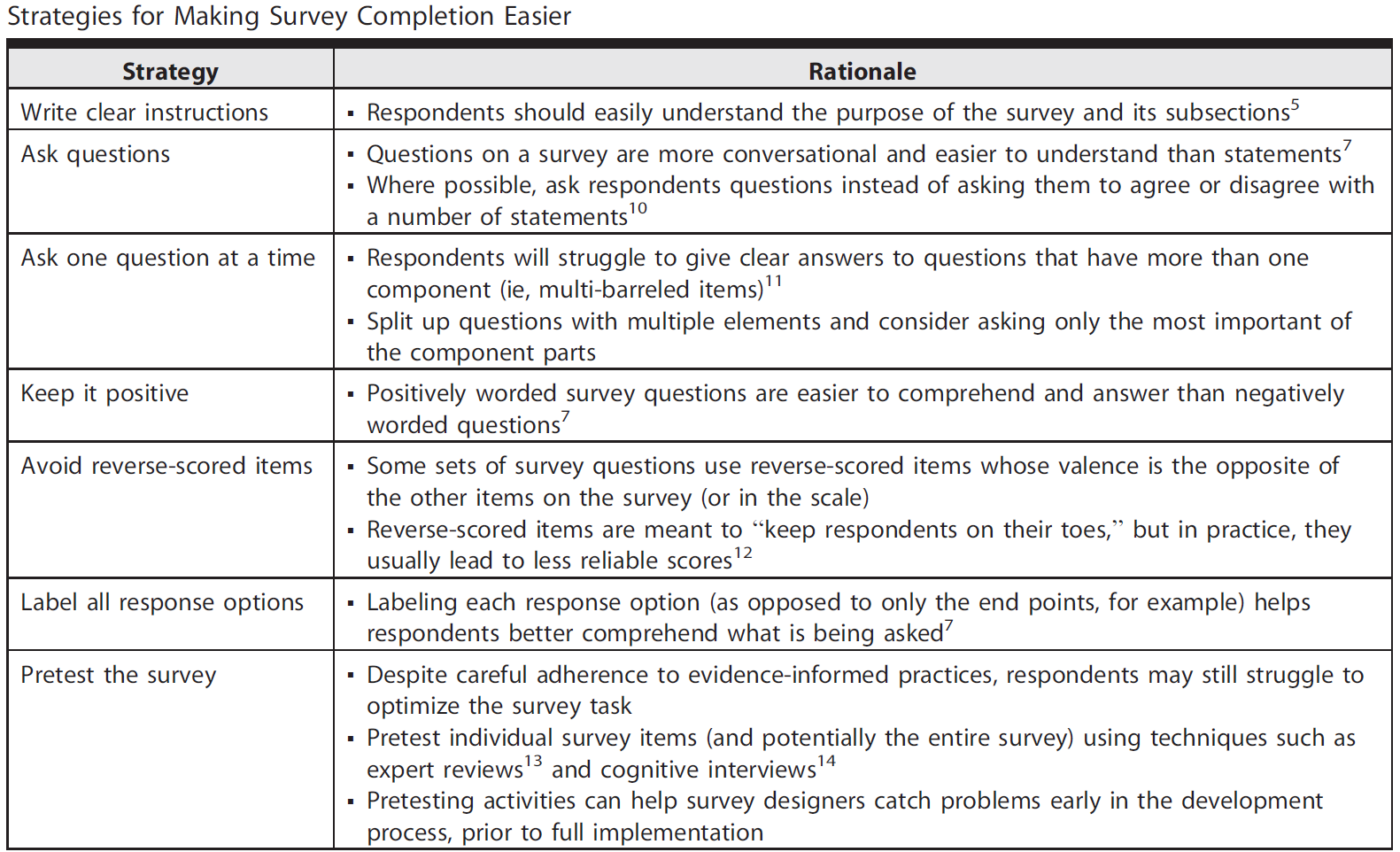

과제 난이도를 완화하는 것은 Satisficing을 완화하는 가장 중요한 방법이다. 설문조사의 경우, 설문조사를 완료하는 것이 과제입니다. 조사 설계자가 작업을 더 쉽게 하기 위한 최선의 접근법은 [근거에 입각한 모범 사례]를 따르는 것이다. 4가지 인지적 대응 과정을 통해 응답자가 자신의 길을 갈 수 있도록 지원하는 [양질의 설문지를 설계]하는 것이 목표다. 이러한 설계 관행이 다른 곳에서 자세히 설명되었지만, 우리는 표 1에서 GME 조사 설계자가 조사 완료 작업을 단순화하기 위해 사용할 수 있는 많은 [고수익high-yield 관행]을 강조한다.

Easing task difficulty is the most important way to mitigate satisficing. In the case of a survey, the task is completing the survey. The best approach for survey designers, to make the task easier, is to follow evidence-informed best practices. The goal is to design a high-quality survey that supports respondents as they work their way through the 4 cognitive response processes. Although these design practices have been articulated in detail elsewhere,1,7-9 we highlight in Table 1 a number of high-yield practices that GME survey designers can use to simplify the task of survey completion.

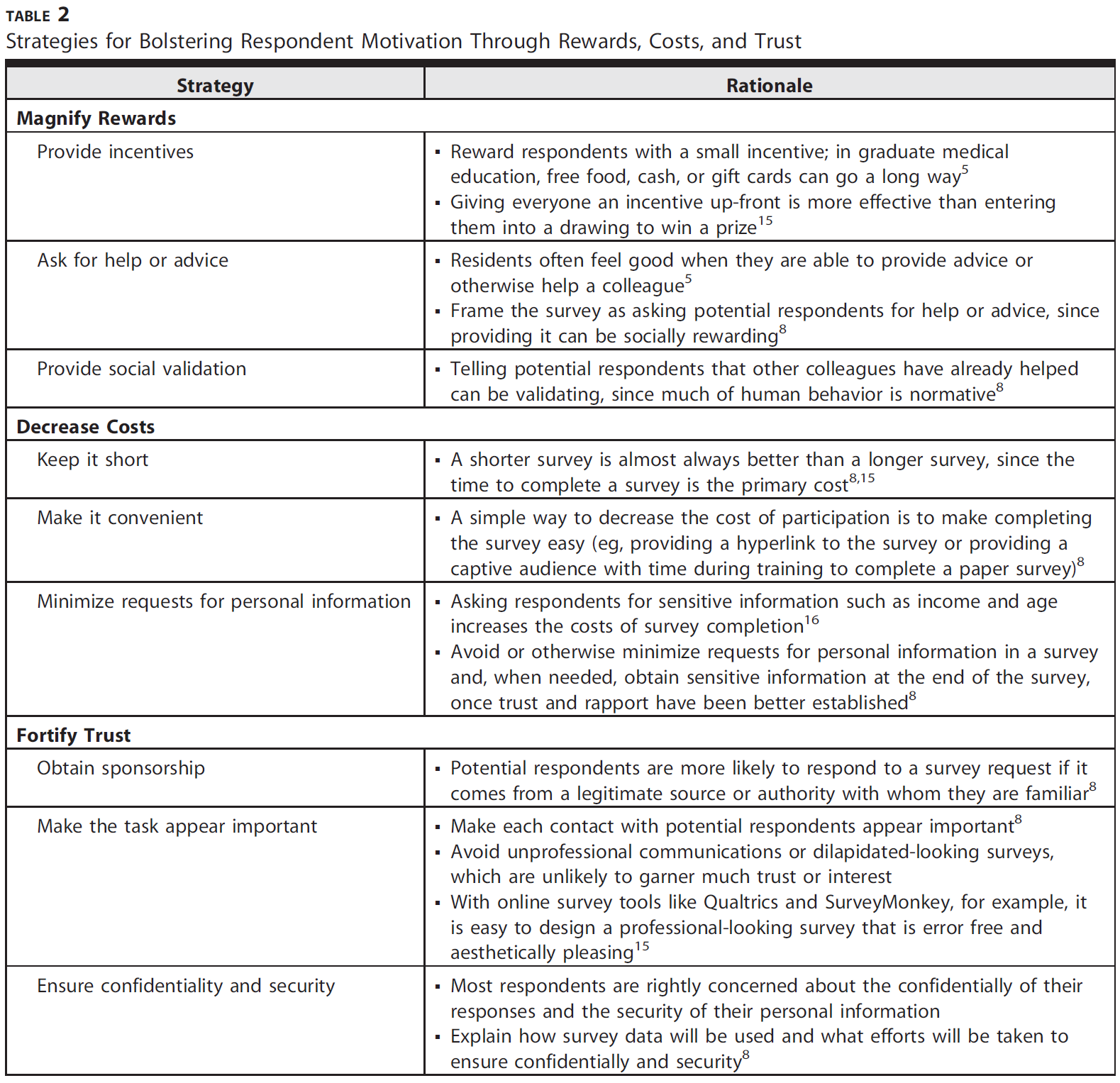

마지막으로, 설계자는 설문조사 요청을 [사회적 교환]으로 간주하여 응답자의 동기, 즉 [설문조사 초대를 수락하고, 설문조사를 시작하고, 응답 프로세스를 최적화하는 동기]를 직접 다룰 수 있습니다. 딜먼 등이 설명한 바와 같이, "사람들이 다른 사람의 요청을 따르는 것에 대한 [보상]이 결국에는 그 요청을 따르는 [비용]을 초과할 것이라고 믿고 신뢰한다면, 그들은 다른 사람의 요청을 따를 가능성이 더 높습니다." 즉, 잠재적 응답자들은 종종 [세 가지 주요 요인]을 고려합니다:

- 보상(이 설문 조사에 참여함으로써 얻을 수 있는 이점은 무엇입니까?),

- 비용(시간이 얼마나 걸립니까?)

- 신뢰(초대 소스 및 제안된 데이터 사용을 신뢰합니까?).

표 2는 설계자가 보상을 확대하고 비용을 절감하며 신뢰를 강화하기 위해 사용할 수 있는 몇 가지 관행을 포함한다.

Finally, designers can directly address respondent motivation—the motivation to accept a survey invitation, start the survey, and optimize the response process—by viewing a survey request as a social exchange. As described by Dillman et al,8 “people are more likely to comply with a request from someone else if they believe and trust that the rewards for complying with that request will eventually exceed the costs of complying.” In other words, potential respondents often consider 3 primary factors:

- rewards (What will I gain by taking this survey?),

- costs (How much time will it take?), and

- trust (Do I trust the invitation source and the proposed data use?).

Table 2 includes several practices that designers can employ to magnify rewards, decrease costs, and fortify trust.

요약

Summary

고품질 설문 조사 결과는 응답 프로세스를 최적화하려는 동기를 가진 참가자들로부터 얻어집니다. 불행하게도, 많은 응답자들은 [동기가 없고], 그들의 [정신적 에너지를 보존하고], [satisfice하는 경향]이 있어서 "충분히 좋은" 대답에 만족한다. 설문조사를 통해 응답자의 생각을 이해하는 데 유용한 모델은 응답 프로세스 모델로, 다음과 같은 4가지 인지 단계를 설명합니다: 이해, 검색, 판단 및 추정, 대응. 이 모델을 사용함으로써 설문조사 개발자는 응답자의 [인지 작업을 예측]하고, [응답자의 satisfice하려는 성향을 완화]시킬 수 있다. 응답자의 동기 부여는 설문조사 완료에 따른 비용, 보상 및 신뢰를 고려함으로써 더욱 강화될 수 있습니다. 이러한 전략을 채택함으로써 연구자와 교육자는 응답자의 동기를 최적화하고 더 나은 품질의 설문조사 데이터를 수집할 수 있습니다. 또한, 우리는 조사자들이 조사 데이터 품질을 최적화하기 위해 거주자, 직원 및 교직원의 고유한 GME 인구를 위해 설계된 GME별 조사 전략을 연구할 것을 권장한다.

High-quality survey results come from participants who are motivated to optimize the response process. Unfortunately, many respondents are unmotivated and tend to conserve their mental energy and satisfice, thereby settling for “good enough” answers. A useful model for understanding how respondents think through a survey is the response process model, which describes 4 cognitive steps: comprehension, retrieval, judgement and estimation, and response. By using this model, survey developers can anticipate the cognitive work of respondents and mitigate respondents' tendencies to satisfice. Respondent motivation can be further bolstered by considering the costs, rewards, and trust involved in survey completion. By employing these strategies, researchers and educators can optimize respondent motivation and collect better-quality survey data. In addition, we encourage investigators to study GME-specific survey strategies, designed for the unique GME population of residents, staff, and faculty, to optimize survey data quality.

Getting the Most Out of Surveys: Optimizing Respondent Motivation

PMID: 36591428

PMCID: PMC9765912 (available on 2023-12-01)

'Articles (Medical Education) > 의학교육연구(Research)' 카테고리의 다른 글

| 주관적 평가를 측정할 때 동의-비동의 문항 사용의 재고(Res Social Adm Pharm. 2022) (0) | 2023.01.17 |

|---|---|

| 크리스마스 2022: 과학자: 크리스마스 12일째날, 통계학자가 보내주었죠(BMJ, 2022) (0) | 2023.01.15 |

| 구색만 갖추기: 어거지로 하는 설문이 자료 퀄리티에 미치는 영향(EDUCATIONAL RESEARCHER, 2021) (0) | 2023.01.15 |

| 의학교육의 패러다임, 가치론, 인간행동학 (Acad Med, 2018) (0) | 2022.11.13 |

| 혁신 - 의학교육원고의 핵심 특징 정의하기 (J Grad Med Educ. 2022) (0) | 2022.11.09 |