구색만 갖추기: 어거지로 하는 설문이 자료 퀄리티에 미치는 영향(EDUCATIONAL RESEARCHER, 2021)

Assessing Survey Satisficing: The Impact of Unmotivated Questionnaire Responding on Data Quality

Christine Calderon Vriesema1 and Hunter Gehlbach2

Social scientists, including educational researchers, have long maintained a love–hate relationship with surveys. On the one hand, surveys uncover respondents’ values, perceptions, and attitudes efficiently and at scale (Gehlbach, 2015; Gilbert, 2006; West et al., 2017). Surveys’ flexibility allows respondents to report on themselves (i.e., self-report measures), other individuals, or their perceptions of a whole class or community.

- 첫째, 일부는 참가자들이 양질의 답변을 제공하는 데 필요한 자기성찰 능력에 대해 의문을 제기한다. 예를 들어, Nisbett와 Wilson(1977a, 1977b)은 사람들이 자신의 선택을 이해하려는 잘못된 시도의 여러 예를 제공했다. 다른 것들은 응답자들이 존재하지 않는 정책에 대해 어떻게 쉽게 보고하는지, 따라서 사람들이 어떻게 그들이 가질 수 없는 의견을 보고하는지를 보여준다(Bishop et al., 1980).

- 두 번째 도전은 사람들이 자신의 태도를 알 수 있다는 것을 인정하면서도, 미묘한 힘이 응답자의 정확한 보고를 방해할 수 있다고 우려하는 비평가들로부터 발생한다. 이러한 힘에는 묵인 편향, 사회적 만족도, 바닥/천장 효과, 편향된 질문 표현, 대응 순서 효과 등과 같은 현상이 포함된다(예: Krosnick, 1999).

Yet, survey designers can delimit surveys to topics that respondents might reasonably have opinions on. Furthermore, they can design surveys to accord with many of the best practices that survey researchers have developed (Gehlbach & Artino, 2018). So, although these two potential problems with survey research as a methodology are real and need to be taken seriously, they are rarely insurmountable.

- 셋째, 잠재적으로 더 도전적인 것은 참가자들이 설문조사를 진지하게 받아들이려는 동기에 대한 우려이다. 가장 극단적인 형태로, 어떤 사람들은 아마도 지루하거나 웃기려는 시도로 거짓 대답을 하기 위해 적극적으로 노력하는 "장난꾸러기 응답자"가 될 수도 있다. Krosnick(1991)은 응답자들이 응답에 최선의 노력을 기울이지 못하는 더 온화하고 잠재적으로 더 보편적인 형태의 "구색만갖추기satisficing"을 설명한다. 이러한 동기 부여 문제는 충분히 일반적이어서 일부 연구자들은 성실성이라는 성격 특성을 측정하기 위한 수행 과제로 설문지에 대한 응답자의 노력(또는 그 부족)을 사용했다(Hitt et al., 2016; Zamarro et al., 2018).

As schools increasingly aim to inform their policies with survey data, this motivation problem presents a unique challenge. If respondents want to skip items, quit early, or speed through the survey by giving the same answer each time, researchers can do little to prevent it. Practitioners and policymakers face a complementary problem: They need to understand the pervasiveness of satisficing to determine to what extent satisficing affects data quality. We address both challenges by investigating satisficing in an ongoing, large-scale survey of elementary and secondary students’ social–emotional learning in California. This article outlines straightforward strategies for detecting, assessing, and accounting for satisficing in survey data. Within the larger literature around participant satisficing (e.g., Barge & Gehlbach, 2012; Hitt et al., 2016; Krosnick, 1991; Soland, 2018), we hope this study provides educational decision makers with accessible tools for identifying potentially problematic response patterns.

구색만 갖추기

Satisficing

- 첫 번째 합리적인 응답 옵션 선택,

- 제시된 모든 진술에 동의하는 것,

- 여러 항목에 걸쳐 동일한 옵션을 직선으로 반복적으로 선택하는 것,

- "모름" 또는 "해당되지 않는" 응답을 일관되게 선택하는 것을 포함할 수 있다(Barge & Gehlbach, 2012; Krosnick, 1991).

- selecting the first reasonable response option,

- agreeing with all the statements presented,

- selecting the same option repeatedly in a straight line across multiple items, and

- consistently selecting the “don’t know” or “not applicable” responses (Barge & Gehlbach, 2012; Krosnick, 1991).

Although some survey researchers have reported on participant satisficing, few systematically include these details. Barge and Gehlbach (2012) examined the effects of satisficing on the reliability of and associations between scales for two surveys administered to college students. The authors found that most students engaged in at least one form of satisficing (61% and 81% of students across the two surveys). This satisficing resulted in artificially inflated internal consistency estimates and correlations between scales. The pervasiveness of these practices and implications for data interpretation underscore the need to further explore survey satisficing and its potential consequences, especially for younger students who may struggle with how certain items are written (e.g., negatively worded items; Benson & Hocevar, 1985). This knowledge is particularly important now as large-scale data are increasingly used to guide decisions for policy and practice (Marsh et al., 2018).

- 조기종결

- 미응답

- 한줄긋기

Strategies for detecting satisficing include a range of methods that vary in complexity (Barge & Gehlbach, 2012; Steedle et al., 2019). Ideally, any set of procedures to address satisficing should be as broadly accessible as possible. Toward this end, we focus on three respondent behaviors that researchers, practitioners, and policymakers can assess within almost all survey-based data sets:

- early termination—when respondents fail to complete the full survey;

- nonresponse, or omitted items; and

- straight-line responding—when respondents select the same response option repeatedly (e.g., for at least 10 consecutive items).

In this study, we operationalized straight-line responding as 10 consecutive items based on prior research (Barge & Gehlbach, 2012), and because it fit the context of this particular survey given the placement of reverse-scored items. Although it seemed plausible for students to respond similarly across multiple items within the same construct, the likelihood of 10 identical responses in a row spanning multiple constructs and reverse-scored items seemed vanishingly small. This operationalization also should help distinguish straight-lining from ostensibly similar cognitive biases, such as carryover effects. Straight-line responding helps respondents conserve cognitive effort. By contrast, carryover effects (Dillman et al., 2014) can occur when participants perceive similarities from one survey item to a subsequent item, thereby encouraging (overly) similar responses. Because multiple constructs are included in all 10-item sets within the survey, participants should see conceptual differences between items.

In sum, we operationalized satisficing as engaging in one or more of these three suboptimal response patterns: early termination, nonresponse, or straight-line responding. Although other approaches exist (e.g., Hitt et al., 2016; Robinson-Cimpian, 2014; Steedle et al., 2019), we focused on three straightforward, accessible strategies for systematically defining, calculating, and reporting satisficing in large-scale student survey data. By doing so, we hoped that these simple steps might be widely adopted by as many users of survey data as possible within their specific educational contexts.

연구 질문과 가설

Research Questions and Hypotheses

- (a) 학생들이 어느 정도까지 조사 satisficing에 참여했는지,

- (b) 어떤 형태의 satisficing이 조사 데이터에 가장 큰 위협이 되는지,

- (c) 이 전략이 조사 척도에서 학생들의 평균 점수에 어떻게 영향을 미칠 수 있는지 더 잘 식별하기 위해, 학생들이 한줄긋기를 할 때 가능성이 높은 응답 옵션이 무엇인지

- (d) 어떤 학생들이 가장 satisficing을 할 것 같은지

- (a) to what extent students engaged in survey satisficing,

- (b) which form of satisficing posed the largest threat to survey data,

- (c) which response option students were most likely to select when straight-lining in order to better discern how this strategy might affect students’ mean scores on the survey scales, and

- (d) which students were most likely to satisfice.

Informed by our exploratory pilot data and prior research, we tested the following prespecified hypotheses:

- 가설 1: 전체 표본의 최소 10%가 만족스러운 형태로 사용됩니다.

- 가설 2: 세 가지 유형의 만족도 조사 중 직선이 가장 많은 총 조사 항목에 영향을 미칩니다.

- 가설 3: 직선 라이닝은 데이터의 품질에 영향을 미칩니다. 구체적으로:

- 가설 3a. 직선을 이루는 참가자는 대부분 척도의 오른쪽에서 가장 극단적인 반응 옵션을 선택합니다.

- 가설 3b: 역점수 항목을 고려한 후 직선 응답은 네 가지 조사 척도의 평균 점수에 유의한 영향을 미친다.

- 가설 3a. 직선을 이루는 참가자는 대부분 척도의 오른쪽에서 가장 극단적인 반응 옵션을 선택합니다.

- 가설 4: 남학생이 여학생보다 만족도가 높을 것이다.

방법

Method

샘플

Sample

This study examined secondary data collected through the Policy Analysis for California Education’s CORE-PACE Research Partnership. We analyzed student responses to a set of social–emotional learning (SEL) items administered as part of a larger survey to several California school districts during the 2014–2015 and 2015–2016 school years. The full survey included SEL items followed by a set of school culture and climate items; however, the number of culture and climate items varied across districts and school years. Thus, we restricted our analyses to the SEL items.

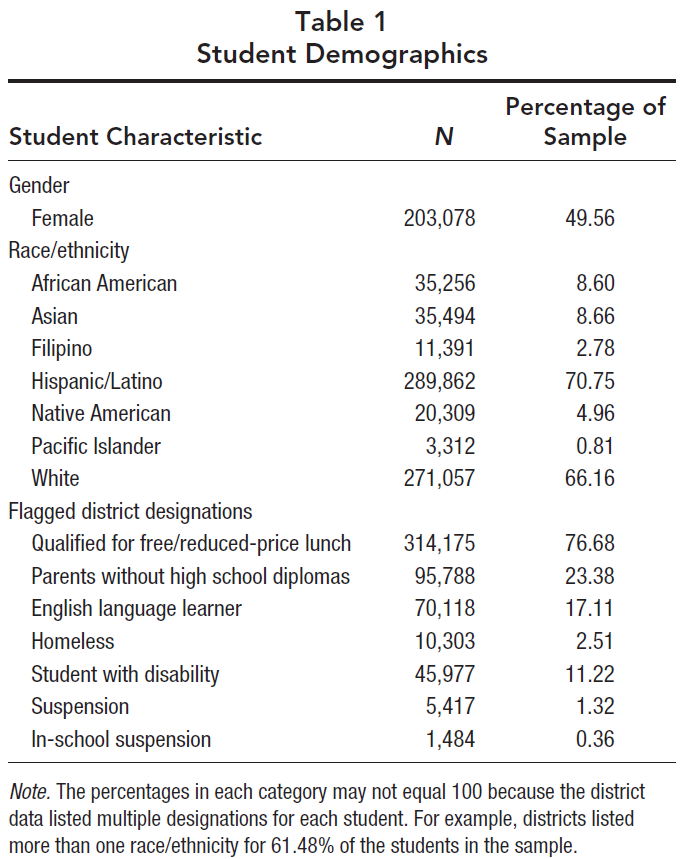

파일럿의 경우 2014-2015학년도 데이터에 대한 탐색적 분석을 수행했습니다. 이러한 분석은 2015-2016년 데이터에 대해 테스트한 사전 등록된 가설을 생성했다. 확인 연구를 위한 표본(N = 409,721)은 CORE 학군의 하위 집합에서 온 학생들을 포함했다. 2학년 2명을 제외한 학생들은 3학년부터 12학년까지 다양했다. 표본은 146,126명의 초등학생들, 125,747명의 중학생들, 그리고 137,838명의 고등학생들을 포함했다. 표 1은 학생 인구 통계의 완전한 설명을 제공한다.

For our pilot, we conducted exploratory analyses on the 2014–2015 school year data. These analyses generated the preregistered hypotheses that we tested on the 2015–2016 data. The sample (N = 409,721) for our confirmatory study included students from a subset of the CORE school districts (see the full list here: https://edpolicyinca.org/initiatives/core-pace-research-partnership). Except for two second graders, students ranged from Grades 3 through 12. The sample included 146,126 elementary school students; 125,747 middle school students; and 137,838 high school students. Table 1 provides a complete description of student demographics.

방안

Measures

절차들

Procedures

For each satisficing behavior, we determined whether respondents engaged in the specific response strategy or not (coded as 1 or 0, respectively). We operationalized early termination as ending the survey prior to completing the final survey item (i.e., Item 25). Nonresponse was operationalized as omitting at least one item in the survey prior to a respondent’s last completed item. This approach allowed us to avoid double-counting nonresponders and early terminators.

To identify straight-line responding, we analyzed the standard deviation for each sequential set of 10 items across the survey (e.g., Items 1–10, 2–11, 3–12, etc.). Standard deviations of zero for a given set indicated that the student selected the same response option for each of the 10 items. Thus, across the 16 possible intervals (i.e., the 16 sets of 10 sequential items), students qualified as straight-liners if they used the strategy at least once. Finally, we determined overall satisficing—whether a student satisficed at any point during the survey—by summing these three binary values; values greater than zero indicated that a student satisficed at some point during the survey. Please see Appendix B in the online supplementary materials (available on the journal website) for detailed descriptions of these calculations.

사전 등록된 결과

Preregistered Results

가설 1: 전체 만족도

Hypothesis 1: Overall Rate of Satisficing

We tested our first hypothesis that at least 10% of the sample would engage in survey satisficing by dividing the number of students who satisficed by the total number of participants. Our data supported the hypothesis with 30.36% of students engaging in at least one form of satisficing. The satisficing included 3.73% early termination, 24.99% nonresponse, and 5.38% straight-line responding. Some students engaged in multiple forms of satisficing (3.26% engaged in two forms, and 0.14% engaged in all three).

가설 2: 측량 영향

Hypothesis 2: Survey Impact

We hypothesized that out of the three response patterns, straight-line responding would affect the greatest number of total survey items. In contrast to nonresponse and early termination, which might affect as little as a single item, straight-line responding even once implicates a minimum of 10 items, by definition. The results supported our hypothesis in that students who straight-lined engaged in this behavior for a mean of 3.90 intervals (each interval represents a set of 10, potentially overlapping items; SD = 4.04). This average corresponds to selecting the same response option almost 13 items in a row. In comparison, average nonresponse corresponded to 1.77 skipped items, and average early termination resulted in ending 3.52 items early. Thus, even though more students engaged in nonresponse compared with straight-line responding (24.99% compared with 5.38%, respectively), fewer items were implicated by nonresponse.

가설 3a 및 3b: 직선 반응

Hypotheses 3a and 3b: Straight-Line Responding

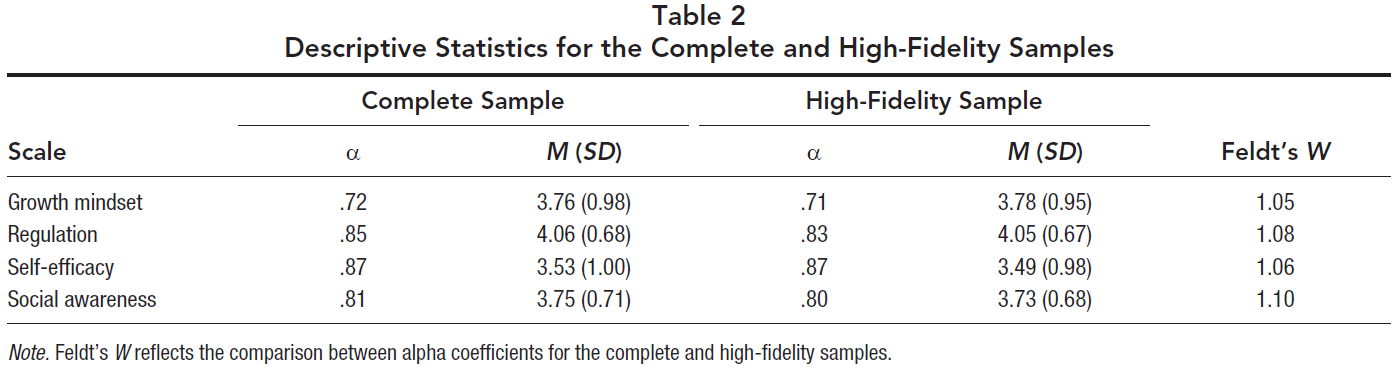

To examine whether straight-line responding affected students’ mean scores for the four scales (Hypothesis 3b), we conducted a series of two-sample t tests for each scale. We compared the complete sample with the high-fidelity sample (i.e., the sample after excluding respondents who straight-lined).1

Although the effect sizes were small, the complete sample had higher mean scores than the high-fidelity sample for: regulation, t(796909) = 9.68, p < .001, 99% CI 0.01, 0.02], Cohen’s d = 0.02; self-efficacy, t(794575) = 16.19, p < .001, 99% CI [0.03, 0.04], Cohen’s d = 0.04; and social awareness, t(795008) = 14.93, p < .001, 99% CI [0.02, 0.03], Cohen’s d = 0.03. The same pattern emerged for the growth mindset scale; however, the items were reverse scored. Students who straight-lined on the far right-hand side of the scale (i.e., selecting Response Option 5) endorsed the conceptual opposite of growth mindset. Thus, after accounting for the reverse-scored growth mindset items, we found that the growth mindset scores mirrored the pattern of the other scales. Specifically, the complete sample had lower scores than the high-fidelity sample, t(794700) = −6.51, p < .001, 99% CI [−0.02, −0.01], Cohen’s d = 0.01 (see Table 2). In sum, the pattern of how students engage in straight-line responding affected the overall mean scores for each construct.

가설 4: 만족자 식별

Hypothesis 4: Identifying Satisficers

We used a logistic regression to test our hypothesis that male students would be more likely to satisfice than female students. Results showed that the odds of satisficing were 16% higher for males than females (B = 0.15, SE = 0.01, odds ratio = 1.16, 99% CI [1.14, 1.18]).

탐색 결과

Exploratory Results

- 먼저 성별 외에 다른 학생 특성이 전반적인 만족도를 예측하는지 살펴보았다.

- 둘째, 직선 응답이 학생 하위 그룹 비교와 설문 조사의 심리학적 속성(예: 크론바흐의 알파 계수)에 미치는 영향을 추가로 조사했다

- 마지막으로, 우리는 학생들이 이러한 형태의 만족에 가장 자주 참여한다는 점을 고려하여 무응답을 더 자세히 탐구했다.2

Overall, our results showed the pervasiveness of student satisficing in our sample, with over 30% of students engaging in some form of satisficing and straight-line responding implicating the greatest number of items. While providing important confirmatory data, these preregistered hypotheses also raised additional questions that we pursued through a series of exploratory analyses. Specifically,

- we first explored whether other student characteristics in addition to gender predicted overall satisficing.

- Second, we further examined the effects of straight-line responding on student subgroup comparisons and the psychometric attributes of the survey (e.g., Cronbach’s alpha coefficients.)

- Last, we explored nonresponse in further detail, given that students engaged in this form of satisficing most frequently.2

탐색적 분석: 전반적인 만족도

Exploratory Analyses: Overall Satisficing

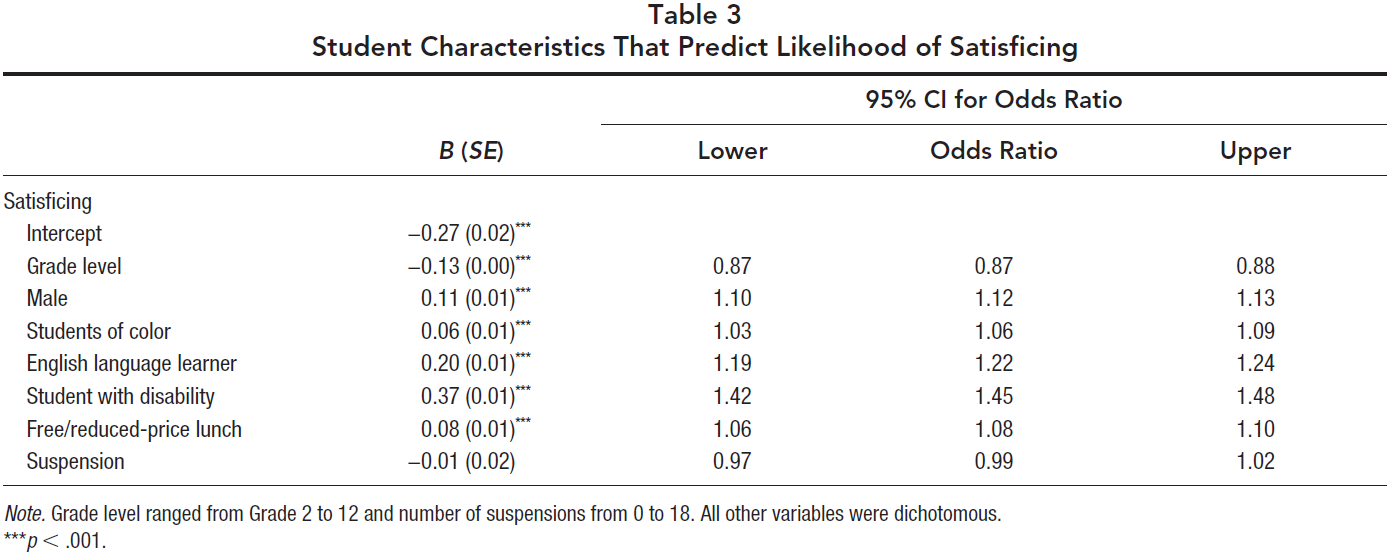

We fit a logistic regression model to examine whether other student characteristics also predicted survey satisficing. In addition to gender, we included race/ethnicity, grade, English Language Learner status, student with a disability status, free or reduced-price lunch qualification, and suspensions. Results indicated that odds of satisficing increased 6% for students of color, 8% for students qualifying for free or reduce price lunch, 22% for students classified as English language learners, and 45% for students with disabilities. Odds of satisficing decreased by 13% for students in younger grades. The number of suspensions did not predict student satisficing (see Table 3).

탐색적 분석: 직선 응답

Exploratory Analyses: Straight-Line Responding

Given that straight-line responding affected more total survey items than any other form of satisficing and affected students’ mean scores for the four scales, we pursued several follow-up questions for this specific form of satisficing. We focused on potential gender differences, differences in Cronbach’s alpha and correlation coefficients, and the pattern of straight-line responding.

성별 차이

Gender differences

- Female students reported higher

- self-regulation (Cohen’s d = 0.28 for complete, 0.27 for high fidelity),

- growth mindset after reverse-scoring the items (Cohen’s d = 0.04 for complete, 0.03 for high fidelity), and

- social awareness (Cohen’s d = 0.22 for complete, 0.22 for high fidelity) than male students.

- In contrast, male students reported higher

- self-efficacy than female students (Cohen’s d = 0.08 for complete, 0.10 for high fidelity).

Cronbach의 알파 및 상관 계수

Cronbach’s alpha and correlation coefficients

Second, we compared Cronbach’s alpha coefficients by using Feldt’s (1969) W statistic. As Table 2 shows, the alpha coefficients for growth mindset, regulation, self-efficacy, and social awareness were between .01 and .02 higher for the complete sample as compared with the high-fidelity sample; these findings correspond to a p value of less than .001 (see Table 2).

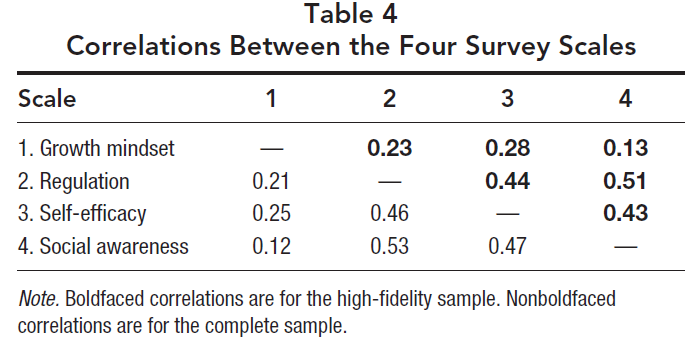

Third, we used Fisher’s z to compare the correlation coefficients between the complete sample and the high-fidelity sample. Correlations for growth mindset with regulation (z = −12.65), self-efficacy (z = −13.23), and social awareness (z = −5.12) were higher for the complete sample than the high-fidelity sample. The same pattern emerged when examining the correlations for regulation with self-efficacy (z = 13.20) and social awareness (z = 13.16), as well as the correlation between self-efficacy and social awareness (z = 21.80). All correlations were significant at p < .001 (see Table 4). In sum, the differences between the complete and high-fidelity samples for internal consistency and correlations between scales were small.

직선 응답 패턴

Pattern of straight-line responding

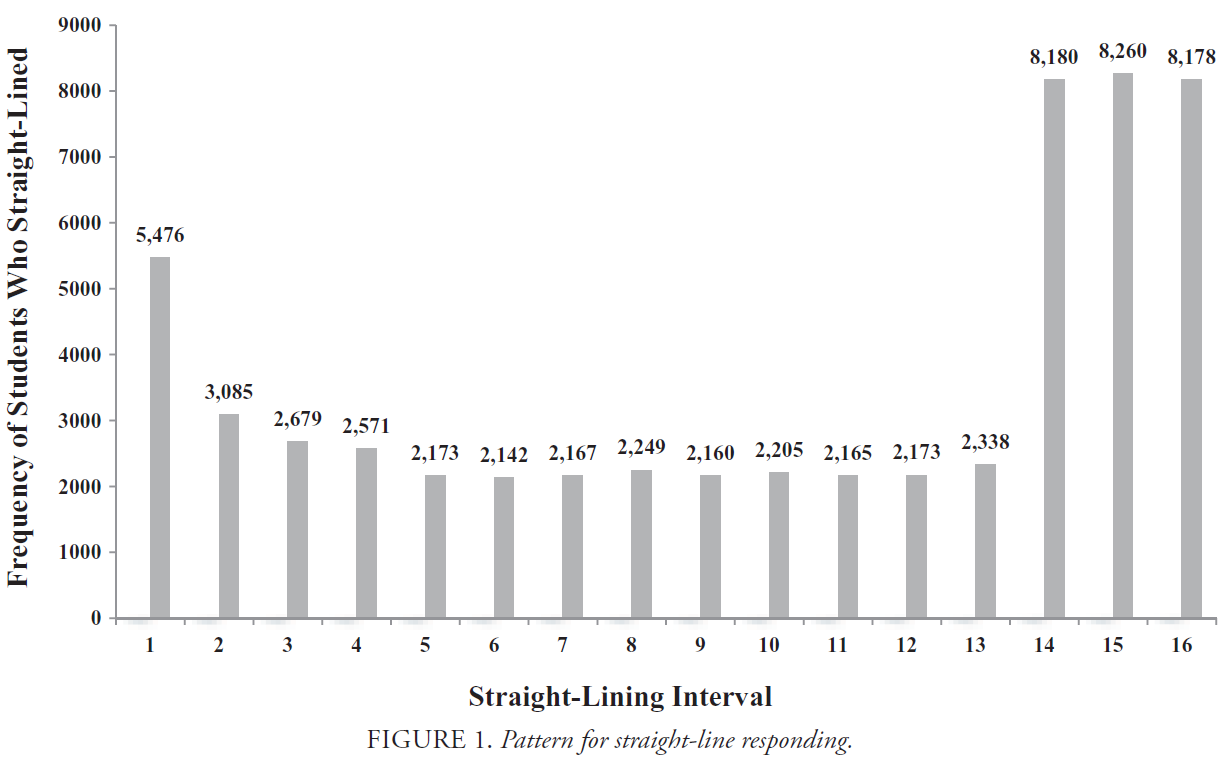

- 첫 번째 간격 이후 학생 직선(a)이 감소했고,

- (b) 다음 13 간격 동안 상당히 일정하게 유지되었지만

- (c) 조사의 마지막 세 간격 동안 증가했다는 것을 발견했다(그림 1 참조).

- (a) decreased after the first interval,

- (b) remained fairly consistent for the next 13 intervals

- but (c) increased during the last three intervals of the survey (see Figure 1).

탐색적 분석: 무응답

Exploratory Analyses: Nonresponse

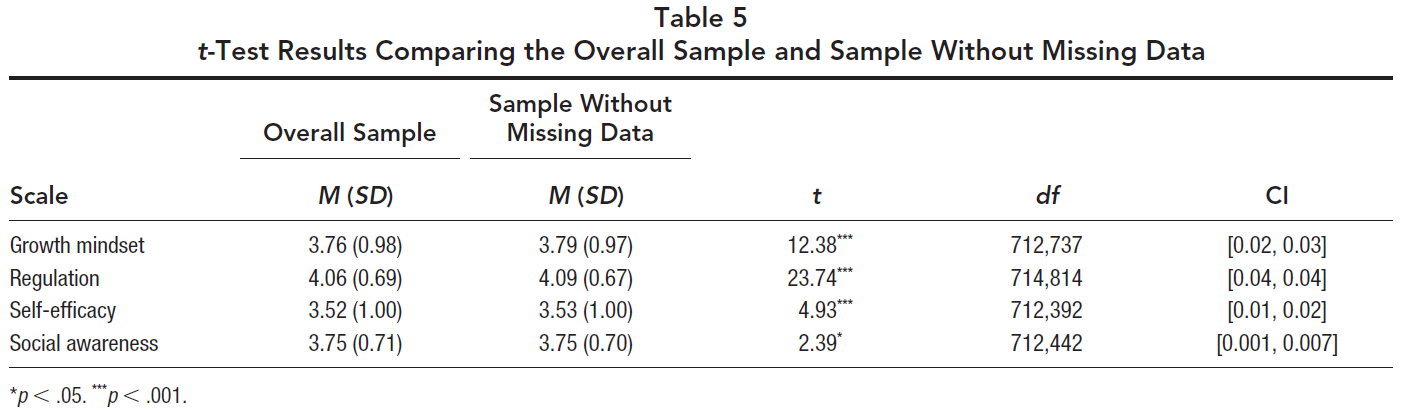

Our preregistered analyses indicated that straight-line responding implicated a greater number of survey items than nonresponse. However, given that nonresponse was the satisficing behavior most students engaged in, we pursued two exploratory analyses to examine (a) whether missing data also affected mean scores for the four scales and (b) the pattern of missing data.

평균 차이

Mean differences

무응답 패턴

Pattern of nonresponse

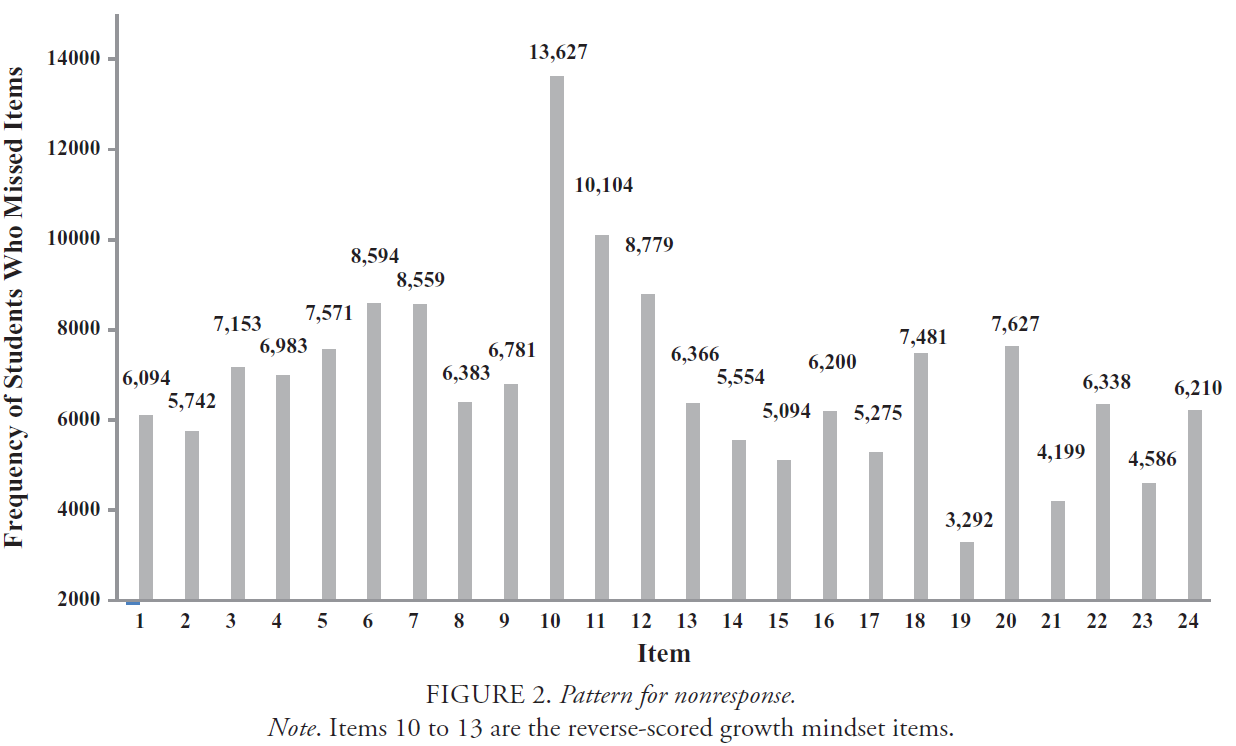

Similar to our analysis exploring the pattern of straight-line responding, we restricted our sample in this analysis to the students who completed the full survey (i.e., those who responded through to Item 25). Thus, Figure 2 shows the pattern of missing data across the first 24 items in the survey. The values represent the total missing responses for each item. The pattern suggests that students generally missed more items in the first half of the survey compared with the second half. The two most-missed items in the survey were Items 10 and 11, where there were 13,627 and 10,104 missing responses, respectively. Both items were reverse-scored growth mindset items.

논의

Discussion

이 기사에서, 우리는 고도로 훈련된 통계학자의 도움 없이도 다른 사람들이 이러한 단계를 쉽게 복제할 수 있도록 만족도를 정의하고 계산하기 위해 의도적으로 간단한 접근법을 취했다. 광범위한 satisficing에도 불구하고 데이터는 조기 종료, 무응답 및 직선 응답에 놀라울 정도로 robust한 것으로 나타났다. 우리는 우리의 연구 결과와 연구자, 실무자 및 정책 입안자가 응답자의 만족에 대응하여 무엇을 할 수 있는지 논의한다.

전체 만족도

Total Satisficing

설문조사 데이터에 미치는 영향

Impact on Survey Data

Of all three satisficing behaviors, student straight-line responding affected the greatest number of total survey items (almost 13 items on average) compared with nonresponse and early termination (1.77 and 3.52 items, respectively). We are reasonably confident that the students who straight-lined were not accurately reporting their attitudes because the survey included a set of reverse-scored items measuring growth mindset. The right-hand response option therefore signaled a fixed mindset—the conceptual opposite of growth mindset. Among straight-line responders, our survey results show that the students with the lowest growth mindset scores have the highest self-efficacy and regulation. These findings would be incongruous with the motivation research linking stronger growth mindsets with higher self-efficacy (Dweck & Master, 2009).

Moreover, because the students who straight-lined in our sample selected the response option on the far right-hand side almost half the time (M = 46.02%), this satisficing behavior affected students’ scores across the four scales. Yet, the relatively modest effect sizes suggested that, while significant, the differences between samples did not necessarily represent a substantial threat to interpretations of our findings. In our prespecified hypotheses, the Cohen’s d coefficients ranged from 0.01 to 0.04, falling below the 0.20 cutoff typically reserved for “small” effect sizes (Cohen, 1988). We obtained similar findings for our exploratory analyses (Cohen’s d coefficients from 0.001 to 0.06)—indicating that, in general, the means were not sufficiently different to warrant substantially different interpretations of our data. Of course, the magnitude of effect sizes ranges across research contexts—what may be small in one domain may represent a meaningful difference in others (Kraft, 2020). Moreover, some researchers argue that effect size cutoffs are relatively arbitrary and should instead be interpreted in terms of the consequences that the effects could cause (Funder & Ozer, 2019). Local contexts can therefore help guide when the differences are meaningful.

We also examined patterns in straight-line responding and nonresponse. Straight-line responding occurred more toward the end of the survey, whereas nonresponse happened more frequently in the first half. Of note is that the most frequently missed items were growth mindset items. This aligns with concerns about the growth mindset scale used in this SEL survey and its inclusion of reverse-scored items (Meyer et al., 2018). Using survey design strategies other than reverse-scoring items (e.g., interspersing items from different constructs throughout the survey rather than presenting all items from one scale at a time) may help to minimize respondent satisficing (Gehlbach & Barge, 2012) without adding the cognitive complexity required by the wording of reverse-scored items (e.g., Benson & Hocevar, 1985).

In sum, the findings of this study suggest that although survey data users need to be aware of how satisficing affects data quality in their respective samples, these behaviors may not always threaten the integrity of the overall results even when rates of satisficing are high. Users of survey data who want additional or different strategies for detecting satisficing that extend beyond the three assessed in this article (e.g., strategies described in Robinson-Cimpian, 2014; Steedle et al., 2019) will need to similarly determine to what extent the response behaviors affect the data in their specific educational context.

응답자 특성

Respondent Characteristics

연구자, 실무자 및 정책 입안자를 위한 권장 사항

Recommendations for Researchers, Practitioners, and Policymakers

- 첫째, 연구자, 실무자 및 정책 입안자는 설문 조사의 맥락 내에서 의미 있는 satisficing 의 정의를 결정해야 한다. 만족스럽게 정의하고 운영하기 위해 비교적 포괄적인 접근 방식을 취했지만, 일부 구역에서는 더 보수적인 접근 방식(예: 무응답을 하나가 아닌 네 개의 누락된 항목으로 정의)이 필요할 수 있다. 다행히도 다양한 정의를 만족하고 영향을 검토하는 테스트는 비교적 저렴한 비용으로 추가 분석을 수행하는 데 걸리는 시간에 불과합니다. 데이터 분석가들이 만족의 영향을 더욱 탐구함에 따라, 우리는 주어진 맥락에서 가장 합리적인 것이 무엇인지 보기 위해 다양한 정의를 테스트하는 것을 추천한다.

- 둘째, satisficing 행동이 결과 해석에 얼마나 영향을 미치는지 평가하기 위해 연구자, 실무자 및 정책 입안자가 satisficing 유무에 관계없이 데이터를 검토할 것을 권장한다. CORE 맥락 내에서, 직선 응답과 무응답은 결과의 주요 해석을 바꾸지 않았다. 예를 들어, 직선 응답 표본과 높은 충실도 표본 간의 차이의 크기는 매우 작았습니다. 그러나, 교육의 맥락 의존적 특성을 고려할 때, 이러한 결과는 교육 환경에 따라 달라질 수 있다. 또한 다른 유형의 분석은 다른 방식으로 영향을 받을 수 있다. 특정 부분군 비교(예: 학년 수준, 학교, 성장률 등) 또는 항목 구조와 관련된 분석(예: 요인 분석 기법)은 만족자의 포함 또는 제외에 더 민감할 수 있다. 따라서, 우리는 설문 조사 데이터 사용자가 다양한 분석 및 설정에 걸쳐 자체 설문 조사에서 만족도가 척도에 얼마나 영향을 미칠 수 있는지 조사할 것을 권장한다. 만족으로 인한 결과적 차이가 언제, 어디서, 왜 더 많이 나타나는지를 배우는 것이 앞으로 나아가는 중요한 지식이 될 것이다.

- 셋째, satisficing하는 모든 학생으로부터 모든 데이터를 제외하지 않는 것이 좋습니다. 대신, 연구자, 실무자 및 정책 입안자는 결함이 있는 데이터만 제거함으로써 더 많은 이익을 얻을 수 있다(즉, 목록별 삭제보다는 사례별 삭제). 특히, 직선 응답과 무응답은 학생들의 평균 점수에 영향을 미칠 수 있으므로, 데이터 분석가들이 이러한 두 가지 반응 패턴에 초점을 맞출 것을 제안한다. 결함이 있는 데이터를 제거하면 분석가들이 데이터 중심의 의사 결정을 지원할 때 잠재적으로 손상된 데이터와 함께 양질의 데이터를 낭비하지 않도록 하는 데도 도움이 될 것입니다. 그러나 이 과정의 일부로, 우리는 또한 데이터 분석가들이 먼저 데이터를 제외하는 것이 표본 모집단의 성격을 크게 바꾸지 않는다는 것을 확인하도록 권장한다(예: 불균형한 수의 특정 인구 통계 그룹을 제거함으로써).

- 넷째, 설문조사에 [역스코어 항목을 포함하는 것]은 직선 응답자를 탐지하기 위한 효과적인 전략으로 보일 수 있다. 그러나 우리는 이 전술을 사용하지 않아야 한다고 경고한다. 역스코어 항목은 척도의 신뢰성을 떨어뜨리고 참가자들이 답변하기 어렵다(Benson & Hocevar, 1985; Gehlbach & Brinkworth, 2011; Swain et al., 2008). 대신에 조사 설계자는 [서로 다른 구인의 항목을 분산시켜 삽입]하고(Gehlbach & Barge, 2012) [응답 옵션이 구인 특이적이도록 보장]하여 직선 응답을 완화할 수 있다(Gehlbach & Brinkworth, 2011).

- 항목을 [interspersing]하면 참가자가 동일하거나 유사한 구조의 항목을 서로 옆에 배치할 때 발생할 수 있는 고정 및 조정과 같은 인지 편향에 참여할 가능성이 줄어든다(Gehlbach & Barge, 2012).

- 또한 각 항목에 대해 [완전한 레이블이 지정된 응답 옵션]을 포함하고 항목과 응답 옵션 모두에서 동일한 구인별 언어를 사용하면 응답자들이 유사한 질문을 반복적으로 하는 것이 아니라 별개의 현상에 대해 설문조사가 질문한다는 점을 강화할 수 있다(Gehlbach, 2015).

- Interspersing items reduces the chances that participants will engage in cognitive biases, like anchoring and adjusting, which can occur when items from the same or similar constructs are placed next to each other (Gehlbach & Barge, 2012).

- Furthermore, including fully labeled response options for each item and using the same construct-specific language in both the items and response options can help to reinforce to respondents that the survey is asking about distinct phenomena as opposed to asking similar questions over and over (Gehlbach, 2015).

결론

Conclusion

Abstract

'Articles (Medical Education) > 의학교육연구(Research)' 카테고리의 다른 글

| 크리스마스 2022: 과학자: 크리스마스 12일째날, 통계학자가 보내주었죠(BMJ, 2022) (0) | 2023.01.15 |

|---|---|

| 설문에서 최대한을 얻어내기: 응답 동기부여 최적화하기(J Grad Med Educ. 2022) (0) | 2023.01.15 |

| 의학교육의 패러다임, 가치론, 인간행동학 (Acad Med, 2018) (0) | 2022.11.13 |

| 혁신 - 의학교육원고의 핵심 특징 정의하기 (J Grad Med Educ. 2022) (0) | 2022.11.09 |

| 의학교육연구자의 연구 패러다임 선택 가이드: 더 나은 연구를 위한 기반 만들기(Med Sci Educ. 2019) (0) | 2022.11.09 |