피드백 탐색의 예술과 술책: 임상실습 학생의 피드백 요청에 대한 접근(Acad Med, 2018)

The Art (and Artifice) of Seeking Feedback: Clerkship Students’ Approaches to Asking for Feedback

Robert Bing-You, MD, MEd, MBA, Victoria Hayes, MD, Tamara Palka, MD, Marybeth Ford, MD, and Robert Trowbridge, MD

학습자에 대한 피드백은 의학 교육 연구자에게 중요한 연구 영역으로 남아 있다. 의학 학습자를 위한 피드백에 대한 최근의 범위 검토는 문헌이 광범위하고 상당히 최근이며 고품질의 증거 기반 권고가 부족하다고 설명했다. 의학 학습자에게 제공된 피드백 내용에 대한 문헌을 통합 검토한 결과, 피드백 제공자가 부정적 피드백을 제공하는 것을 꺼리는 낮은 품질의 피드백과 관용 편향을 발견하여 학습자가 수년 동안 불만을 제기해 온 내용을 확인했다. 피드백 전달을 촉진하는 수십 년간의 교수개발 노력에도 불구하고 교수진의 부적절한 피드백 전달은 계속해서 발생하고 있다. 이러한 피드백에 대한 학습자의 지속적인 불만족의 문제는 [피드백 상호작용의 중요한 파트너로서 학습자]에게 관심을 옮겨 [적극적인 대화와 교류]에 대한 [사회구성주의적 관점]을 강조하고 있다. 우리는 "피드백은 말하는 것이 아니"며, 양방향 대화이고, "피드백은 정보의 일방적 전송에 해당한다"는 가정에 이의를 제기할 필요가 있다는 몰로이와 보드의 의견에 동의한다. 학습자가 찾는 이유와 피드백을 얻는 방법을 이해하는 것은 탐구의 중요한 영역입니다.

Feedback for learners remains an important area of study for medical education researchers.1–3 A recent scoping review on feedback for medical learners described the literature as broad, fairly recent, and lacking in high-quality, evidence-based recommendations.4 An integrative review of the literature on the content of feedback given to medical learners found low-quality feedback and leniency bias, in which feedback providers were reluctant to offer negative feedback,5 confirming what learners have complained about for years.6,7 The inadequate delivery of feedback by faculty has continued to occur despite decades of faculty development efforts promoting feedback delivery.8–10 The problem of this prolonged dissatisfaction of learners with feedback has shifted attention to the learner as a significant partner in the feedback interaction, emphasizing a socio-constructivist view of an active dialogue and exchange.11–13 We agree with Molloy and Boud14 that “feedback is not telling” but, rather, a two-way dialogue, and there is a need to challenge the assumption that “feedback constitutes a one-way transmission of information.” Understanding the reasons learners seek and the ways they obtain feedback is an important area of exploration.15

수의학과 학생들을 대상으로 한 연구에서 Bok 등은 학생들이 피드백을 추구하는 이유를 설명하는 요소들을 설명했다.

- 피드백 추구자의 이익(예: 부정적 판단 회피),

- 피드백 추구자의 특성(예: 특정 임상 영역에 대한 자신감),

- 피드백 제공자의 특성(예: 양호한 의사소통 기술).

[피드백의 개념적 모델]은 [피드백을 추구하는 동기요인]과 [피드백을 추구하는 행동의 결과]를 강조하는 조직심리학과 사회과학 문헌에 의해 알려졌다. 수의학과 학생들을 대상으로 한 후속 연구에서, 성적이 높은 학생들은 낮은 학생들에 비해 피드백을 추구하는 동기가 더 높고 자기 결정력이 더 높은 것으로 나타났다. 그러나 이러한 연구의 결과는 수의학과 학생들에 초점을 맞춘다는 점에서 제한적이었다.

In a study of veterinary medicine students, Bok et al16 described factors that explained students’ reasons for seeking feedback, including

- interests of the feedback seeker (e.g., avoidance of negative judgments),

- characteristics of the feedback seeker (e.g., confidence in a specific clinical area), and

- characteristics of the feedback provider (e.g., good communication skills).

Their conceptual model of feedback was informed by the organizational psychology and social science literatures, which emphasize the motivational factors for seeking feedback and the outcomes of feedback-seeking behaviors.17–19 A follow-up study, again with veterinary students, revealed that high-performing students were more motivated to seek feedback and demonstrated higher self-determination compared with low-performing students.20 However, these studies’ findings were limited by their focus on veterinary students.

의학교육에서 학생들의 피드백을 추구하는 행동에 관한 문헌과 주민들이 피드백을 추구하기 위해 사용하는 행동을 기술하는 최소한의 문헌에는 차이가 있다. Jansen과 Prins는 피드백을 추구하는 의료인들이 "학습 목표" 지향(새로운 기술과 지식에 대한 욕구) 대 "수행 목표" 지향(자신의 역량에 대한 긍정적인 평가와 부정적인 판단의 회피에 대한 욕구)의 경향을 가지고 있다고 설명했다. 이러한 의료 종사자들은 피드백과 관련된 세 가지 다른 비용을 인식했다.

- 자기 프레젠테이션 비용(학습자를 무능해 보이게 하는 피드백);

- 자아 비용(학습자의 자기 이미지에 맞지 않는 피드백);

- 노력 비용(학습자가 얻기 위해 너무 많은 노력이 필요하다고 느끼는 피드백).

Teunissen 등은 OB/GYN 전공의들이 ["문의inquiry" 접근법을 통해 직접 피드백을 요청]하거나, ["모니터링monitoring" 접근법을 통해 학습 환경에서 다른 사람들의 행동을 관찰함]으로써 피드백을 추구하는 방법을 설명했다. 곤트 외 연구진은 Teunissen 외 연구진과 유사한 피드백 추구 모델을 사용하여 트레이너의 감독 역할(즉, 지지 대 도구적 리더십 스타일)이 피드백 편익과 비용에 대한 외과 레지던트의 인식과 그에 따른 피드백 추구 행동에 영향을 미친다는 것을 발견했다.

In medical education, there is a gap in the literature regarding the feedback-seeking behaviors of students and minimal literature describing the behaviors that residents use to seek feedback.21–23 Janssen and Prins23 described feedback-seeking medical residents as having a tendency toward a “learning goal” orientation (desire for new skills and knowledge) versus a “performance goal” orientation (desire for positive assessments of one’s competence and avoidance of negative judgments).24–26 These medical residents perceived three different costs associated with feedback:

- self-presentation cost (feedback that makes the learner look incompetent);

- ego cost (feedback that does not fit the learner’s self-image); and

- effort cost (feedback that the learner feels requires too much effort to obtain).23

Teunissen et al22 described how OB/GYN residents sought feedback either by asking for it directly via an “inquiry” approach or by observing the behaviors of others in their learning environment via a “monitoring” approach.17 Gaunt et al,21 using a feedback-seeking model similar to that of Teunissen et al,22 found that the trainers’ supervisory role (i.e., a supportive vs. an instrumental leadership style) influenced surgery residents’ perceptions of feedback benefits and costs and their subsequent feedback-seeking behaviors.

의대생들의 피드백 추구 행동에 대해 생각할 때 피드백 과정의 개념화를 전환하면 추가적인 통찰력을 얻을 수 있다. Bowen 등은 피드백의 개념적 모델로 "교육적 동맹"(이러한 목표에 도달하기 위한 목표를 상호 이해하고 책임에 대해 합의하는 과정)을 사용하여 피드백에 대한 의대생들의 인식을 탐구했다. 그들은 "피드백 추구"를 세 가지 피드백 행동 중 하나로 설명했다. 다른 두 가지는 "피드백 인식"과 "피드백 사용"이었습니다. 각각의 행동은 학습자의 신념, 태도, 인식, 관계, 교사 속성, 학습 문화, 피드백 방식에 의해 영향을 받았다. 우리가 아는 한, 연구 당시 의대생들의 피드백 추구 행동을 설명하는 다른 발표된 연구는 없었다.

As we think about the feedback-seeking behaviors of medical students, shifting the conceptualization of the feedback process provides additional insight. Using the “educational alliance” (a process between parties to mutually understand goals and agree on responsibilities to reach these goals)27 as a conceptual model of feedback, Bowen et al1 explored medical students’ perceptions of feedback. They described “feedback seeking” as one of three feedback behaviors; the other two were “recognizing feedback” and “using feedback.” Each behavior was influenced by learner beliefs, attitudes, and perceptions; relationships; teacher attributes; learning culture; and mode of feedback. To the best of our knowledge, there were no other published studies describing medical students’ feedback-seeking behaviors at the time of our study.

Ashford 등은 조직심리학 문헌에서 [개인은 수동적으로 피드백을 받는 사람이 아니라]고 주장했다. 개인은 피드백을 자원으로 보고 다양한 이유와 선호에 따라 피드백을 구합니다. 의학 교육 문헌에서 피드백 추구자와 제공자 간의 능동적 대화, 동맹 또는 심지어 복잡한 춤으로서의 피드백의 새로운 개념 모델은 의대생과 전공의가 피드백 과정을 주도하도록 적극적으로 도와야 한다고 제안한다.

In the organizational psychology literature, Ashford et al28 have argued that individuals are not passive recipients of feedback. Individuals view feedback as a resource and seek feedback based on different reasons and preferences.17 In the medical education literature, the emerging conceptual models of feedback as an active dialogue,12 an alliance,1 or even a complex dance5 between feedback seekers and providers suggest that medical students and residents should actively help drive the feedback process.

의대생들이 선생님과의 피드백 교환에 적극적인 참여자가 될 수 있도록 교육 커리큘럼을 설계함에 있어 의대생들이 자신의 성과에 대한 피드백을 추구하는 이유와 그러한 피드백을 얻기 위한 방법을 조사하는 것이 중요하다고 생각했다. 우리의 의도는 다음과 같은 연구 질문에 초점을 맞추어 Bok et al 16의 작업을 확장하는 것이었다.

- (1) 의대생들은 임상실습 시기에 어떤 피드백을 추구하는 행동을 하는가?

- (2) 교직원과 학생의 관계는 임상실습 학생들의 피드백 추구 접근법에 어떤 영향을 미칩니까?

In designing an educational curriculum to help medical students be active participants in a feedback exchange with their teachers, we thought it was important to investigate the reasons medical students seek feedback about their performance and how they go about obtaining such feedback. Our intent was to extend the work of Bok et al16 with a focus on the following research questions:

- (1) What feedback-seeking behaviors do medical students use in the clerkship year? and

- (2) How does the faculty–student relationship affect the feedback-seeking approaches of clerkship students?

방법

Method

우리는 질적 연구 권고 보고 기준을 준수했다.

We followed the Standards for Reporting Qualitative Research recommendations.29

설정 및 참가자

Setting and participants

이 연구는 메인주 포틀랜드에 있는 독립적인 학술 의료 센터인 메인 메디컬 센터(MMC)에서 수행되었으며, 이는 터프츠 의과 대학의 2년 지역 분교 캠퍼스입니다. 일반적으로 매년 36명의 3학년 학생들과 36명의 4학년 학생들이 메인 트랙에 등록한다. 임상실습 학생들은 MMC에서 전통적인 6주에서 8주간의 입원 환자 블록 순환이나 MMC 또는 메인 주 전역의 9개 시골 지역 병원 중 하나에서 주로 외래 환자 중심의 종방향 통합 임상실습(LIC)을 이수한다. 시골 지역의 LIC 사이트는 일반적으로 한 번에 두 명의 임상실습 학생을 호스팅한다.

The study was carried out at Maine Medical Center (MMC), an independent academic medical center in Portland, Maine, which is a two-year regional branch campus for Tufts University School of Medicine. Typically, 36 third-year (clerkship) and 36 fourth-year students are enrolled in the “Maine Track” each year. The clerkship students complete either traditional, six- to eight-week inpatient block rotations at MMC or a nine-month, predominantly outpatient-oriented longitudinal integrated clerkship (LIC) at MMC or one of nine rural community hospitals throughout the state of Maine. The rural LIC sites typically host two clerkship students at a time.

2017년 3월, 메인 트랙 임상실습 학생들(n = 35)이 이메일로 초청되어 연구 인터뷰에 참여했다. 우리는 블록 로테이션과 LIC 학생을 거의 동일한 수의 모집하기 위해 목적적인 샘플링 접근법을 선택했다: LIC 학생 8명과 블록 로테이션 학생 1명이 처음 응답한 후, 우리는 반복적인 이메일 초대를 보내 로테이션 학생들의 참여를 증가시켰다. 연구 인터뷰는 2017년 4월~5월에 완료되었으며, 이는 학생들이 임상실습 학년에서 4학년으로 전환한 시기와 일치한다. 학생들은 연구의 기밀성을 알게 되었고, 참여 후 작은 금액의 기프트 카드를 받았다. MMC 기관 검토 위원회는 그 연구를 면제하는 것으로 결정했다.

In March 2017, Maine Track clerkship students (n = 35) were invited by e-mail to volunteer to participate in the study interviews. We chose a purposive sampling approach to recruit approximately equal numbers of block rotation and LIC students: After eight LIC students and one block rotation student responded initially, we sent repeat e-mail invitations to block rotation students to increase their participation. The study interviews were completed in April–May 2017, coinciding with the students’ transition from the clerkship year to the fourth year. The students were informed of the confidential nature of the study, and they received a gift card of a small value after their participation. The MMC Institutional Review Board determined the study to be exempt research.

스터디 디자인

Study design

이러한 질적 연구는 복 등이 강조한 조직심리학 문헌과 교육동맹의 틀에서 영감을 얻었다. 근거이론은 "연구 과정에서 이론을 생산하기 위해 데이터 수집과 분석 사이의 지속적인 상호작용을 요구하는" 질적 방법이다. 반구조화 면담과 자료분석을 위해 구성주의적 근거이론 접근법을 선택한 이유는 [자료에 대한 귀납적 분석이 특정 이론의 연역적 적용보다 적절하다]고 생각했기 때문이며, [연구자로서의 역할의 배경과 가정, 편향성을 인정]했기 때문이다.

This qualitative study was inspired by the organizational psychology literature,17–19 as highlighted by Bok et al,16 and the educational alliance framework.1,27 Grounded theory is a qualitative method “that calls for a continual interplay between data collection and analysis to produce a theory during the research process.”30 We chose a constructivist grounded theory approach for the semistructured interviews and data analysis because an inductive analysis of the data was thought to be more appropriate than a deductive imposition of a specific theory, and we acknowledged the backgrounds, assumptions, and biases of our roles as researchers.31

면접안내 및 절차

Interview guide and procedure

4개 질문 인터뷰 가이드는 Bok 등이 설명한 세 가지 주요 질문을 기반으로 했다.

- (1) 임상 작업 수행에 대한 정보를 찾는 이유는 무엇입니까?

- (2) 피드백을 구하는 방법에 영향을 미치는 요소는 무엇입니까?

- (3) 당신은 당신의 성과에 대한 정보를 어떻게 얻나요?

- 교사-학습자 관계가 피드백에 미치는 영향을 강조하는 최근 문헌 때문에 다음과 같은 질문을 추가했다.

(4) 교수진과의 관계가 피드백을 구하는 방식에 어떤 영향을 미칩니까?

The four-question interview guide was based on the three main questions described by Bok et al16:

- (1) Why do you seek information about your performance of a clinical task?

- (2) Which factors influence the way you seek feedback?

- (3) How do you obtain information about your performance?

- Because of the recent literature emphasizing the impact of the teacher–learner relationship on feedback,1,5,27 we added a question:

(4) How does your relationship with faculty influence the way you seek feedback?

각 인터뷰는 저자 중 한 명(R.B. [MMC 의학부] 또는 V.H. [MMC 가정의학부 교수])이 개인 사무실에서 전화로 진행한 두 번의 인터뷰를 제외하고 진행되었다. 이 저자들은 둘 다 질적 연구와 의학 교육의 피드백에 관한 연구 경험이 있으며, 임상실습에 시절에 참여한 학생들을 위한 지도자나 임살실습 책임자가 아니었다. 개별 인터뷰는 약 30분간 진행되었고 녹음되었다. 현장 노트는 인터뷰할 때마다 면접관이 작성했다. 녹음 테이프는 고용된 전사자에 의해 말 그대로 전사되었고, 학생들은 인터뷰가 전사된 순서에 따라 참가자 식별자 이니셜을 할당받았다. 이러한 이니셜은 결과에 보고된 대표적인 인용구와 함께 포함됩니다. 텍스트는 코딩 및 분석을 위해 정성적 연구 소프트웨어 시스템(NVIVO 10, QSR International, London, 영국)에 업로드되었다.

Each interview was conducted by one of the authors (either R.B. [chief of the MMC Department of Medical Education] or V.H. [a faculty member in the MMC Family Medicine Department]) in a private office setting, except for two interviews that occurred over the telephone. Both of these authors had experience in qualitative research and in research regarding feedback in medical education, and neither was a preceptor or clerkship director for the participating students during their clerkship year. The individual interviews lasted approximately 30 minutes and were audiotaped. Field notes were taken by the interviewer during each interview. The audiotapes were transcribed verbatim by a hired transcriptionist and deidentified, with students assigned participant identifier initials according to the order in which their interviews were transcribed. These initials are included with the representative quotes reported in the Results. The text was uploaded into a qualitative research software system (NVivo 10, QSR International, London, United Kingdom) for coding and analysis.

데이터 분석

Data analysis

인터뷰 녹취록은 초기 코드를 개발하기 위해 저자 중 두 명(R.B., V.H.)에 의해 독립적으로 검토되었다. 4개의 녹취록을 코딩한 후, 이 두 조사관은 코딩 체계를 검토하기 위해 만났고, 그 후 나머지 모든 녹취록을 각각 독립적으로 코딩했다. 지속적 비교 방법을 사용하여 코드로부터 테마를 개발하였다. 모든 기록의 코딩이 완료된 후, 두 조사관은 이론적 충분성이 달성되었으며(즉, 더 이상의 이론적 정보가 표면화되지 않음) 추가 인터뷰가 필요하지 않다는 데 동의했다. 세 번째 조사관(T.P.)은 모든 녹취록을 검토하여 데이터 분석의 철저성을 보장하고 추가 코드가 필요하지 않음을 확인했다. 다섯 명의 연구팀 구성원 모두가 만나서 코딩에서 주제를 해석하는 것에 대한 합의에 도달했다. 구성원 확인은 데이터 진위 여부를 평가하기 위해 인터뷰에 응한 첫 4명의 학생들에게 각각의 오디오 테이프와 관련 기록을 보내면서 수행되었다. 이 네 명의 학생들은 어떠한 수정이나 추가도 제안하지 않았다.

The interview transcripts were independently reviewed by two of the authors (R.B., V.H.) to develop initial codes. After coding four transcripts, these two investigators met to review the coding scheme, and then each independently coded all the remaining transcripts. Themes were developed from the codes using the constant comparative method.32 After coding of all transcripts was complete, both investigators agreed that theoretical sufficiency33 had been achieved (i.e., no further theoretical information was surfacing) and that no additional interviews were necessary. A third investigator (T.P.) reviewed all of the transcripts to ensure thoroughness of the data analysis and that no additional codes were needed. All five research team members met to reach consensus on interpreting the themes from the coding. Member checking was conducted with the first four students interviewed by sending them their respective audiotapes and associated transcripts to assess for data authenticity.33 No revisions or additions were suggested by these four students.

결과.

Results

14명의 학생(남자 6명, 여자 8명)이 연구에 참여했다. 6명의 참가자는 블록 로테이션 학생이었고, 8명은 LIC 학생이었다. LIC 학생들 사이에서, 7개의 다른 병원 사이트들이 대표되었다.

Fourteen students (six men, eight women) participated in the study. Six participants were block rotation students, and eight were LIC students. Among the LIC students, seven different hospital sites were represented.

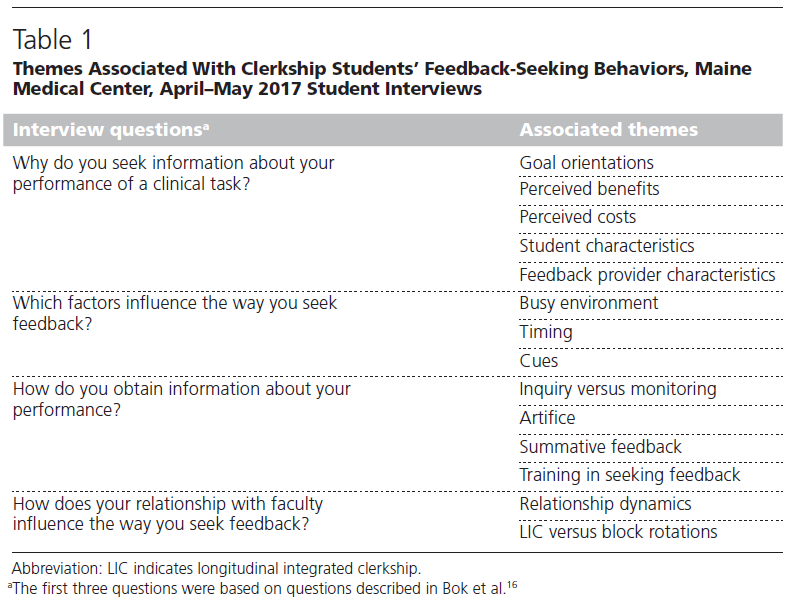

우리는 4개의 면접 질문과 14개의 관련 주제(표 1)의 제목으로 임상실습 학생들의 피드백 추구 행동에 대한 연구 결과를 제시한다. 다른 모델과 비교하여 새로운 관점에는 환경 요인, 큐잉, 기교 및 피드백 찾기 훈련이 포함된다.

We present our findings on clerkship students’ feedback-seeking behaviors under the headings of the four interview questions and the 14 associated themes (Table 1). New perspectives, compared with other models,1,16–19,27 include environmental factors, cueing, artifice, and training in seeking feedback.

임상 작업 수행에 대한 정보를 찾는 이유는 무엇입니까?

Why do you seek information about your performance of a clinical task?

목표 지향.

Goal orientations.

학생들은 종종 피드백을 추구하는 것이 그들의 기술을 향상시키거나 새로운 지식을 얻기 위한 수단이라고 묘사했다. 때때로 학생들은 자신의 역량에 대한 긍정적인 평가를 확인하고, 부정적인 평가를 피하기 위해 성과 목표로 피드백을 구한다고 지적했습니다.

Students often described seeking feedback as a means to improve their skills or acquire new knowledge. Occasionally, students indicated that feedback is sought as a performance goal to confirm a positive—and avoid a negative—assessment of their competence.

의대생으로서 실력과 지식을 향상시키는 것이 무엇보다 중요하다고 생각합니다. (CC)

I think first and foremost is to improve my skills and knowledge as a medical student. (CC)

[W]제가 원하는 것만큼 잘 하지 못했을 때 저는 그것을 시도했습니다. 그래서 일주일에 한두 번 남은 기간 동안 부탁을 하기 시작했는데, 그렇게 하지 않는 것이 너무 어리석은 일이었기 때문이다. (NN)

[W]hen I didn’t do as well as I wanted I kind of went for it.… So I started asking once or twice a week for the rest of the year, just because it was such a silly thing not to. (NN)

인식된 이점.

Perceived benefits.

그들의 지식과 기술을 향상시키기 위해 동기부여를 받는 것 외에도, 학생들은 더 나은 의사가 되고, 그들의 성적을 향상시키고, 그들의 성과에 대해 더 좋게 느끼는 것을 포함하여, 피드백을 추구함으로써 얻는 다양한 이점들을 인식했다.

Besides being motivated to improve their knowledge and skills, students perceived a variety of benefits from seeking feedback, including being a better doctor, improving their grades, and feeling better about their performance.

저는 이곳 의대에서의 시간과 제가 거기에 쏟은 모든 자원을 의사의 능력을 향상시키기 위한 시간으로 보고 있으며, 우리가 할 수 있는 가장 중요한 것은 좋은 피드백을 받는 것이라고 생각합니다. (JJ)

I view my time here in medical school and all the resources I’ve put into it as time to improve my ability in terms of doctoring and I think the most important thing we can do is just receive good feedback. (JJ)

평가받는 것이 우리 성적의 일부이기 때문에 피드백을 구합니다. 그래서 여러분이 어떤 입장에 서 있는지 아는 것은 좋은 일입니다. 그래서 성적은 피드백을 추구하도록 동기를 부여한다. (II)

I seek feedback because it is part of our grade to be evaluated. So it’s good to know kind of where you stand. So, grades motivate me to seek feedback. (II)

학생들은 피드백을 추구하는 것이 그들에 대한 다른 사람들의 인식된 이미지를 향상시킬 수 있다고 지적했다. 학생은 정보를 받기 위해서가 아니라 단순히 자신이 관련되었다는 것을 보여주기 위해 피드백을 요청할 수 있다.

Students pointed out that seeking feedback may enhance others’ perceived image of them. A student might ask for feedback not for the sake of receiving of information but, simply, to show that he or she was involved.

사람들에게 당신이 engage했다는 것을 알리는 것처럼...더 많은 피상적인 이유들이 있다. (JJ)

There are more superficial reasons … to let people know that you’re engaged. (JJ)

인식된 비용.

Perceived costs.

학생들은 피드백을 찾는 것의 이점 외에도 적극적으로 피드백을 찾는 것을 방해할 수 있는 잠재적인 비용을 언급했다.

Besides the benefits of seeking feedback, students cited potential costs of seeking feedback that could prevent them from actively seeking it out.

[W]기분이 좋지 않을 때는 피드백에 대해 더 긴장하고 피드백을 찾을 가능성이 적다고 생각합니다. (II)

[W]hen you’re not feeling great I think that also makes you more nervous about feedback and makes you less likely to seek feedback out. (II)

학생 특성.

Student characteristics.

학생들은 피드백을 추구하도록 동기를 부여하는 자신의 측면을 설명했다. 편안함을 느끼는 것이 중요해 보였다.

Students described aspects of themselves that motivated them to seek feedback. Feeling comfortable appeared to be important.

내가 더 편안하게 느꼈던 교수진은 일반적으로 피드백을 요청하는 것이 더 편안했다. 제 편안함에 영향을 준 것들은 제가 그 분야에서 얼마나 편안하게 느꼈는지에 대한 것이었습니다. (DD)

The faculty I felt more comfortable with I generally felt more comfortable asking feedback from. Things that influenced my comfort level were sort of broadly how comfortable I felt in the discipline. (DD)

비록 일부 학생들은 피드백을 구함으로써 적극적인 학습자가 되어야 한다고 생각했지만, 그들이 교수들에게 부담이 되는 것처럼 느끼는 것은 때때로 학생들이 피드백을 구하는데 방해가 되었다: "나는 아무도 괴롭히고 싶지 않다." (AA). 학생들은 주로 부정적인 피드백에 적응했고 긍정적인 피드백을 인식하지 못했다. 잘 하고 있지 않다고 생각하는 것은 일부 학생들이 피드백을 찾는 것을 피하도록 유도할 수 있지만, 이러한 상황은 다른 학생들이 피드백을 추구하도록 자극했다.

Although some students thought they should be active learners by seeking feedback, feeling as if they were a burden to faculty sometimes deterred students from seeking feedback: “I don’t want to bother anyone” (AA). Students were mainly attuned to negative feedback and not as cognizant of positive feedback. Thinking one was not doing well might prompt some students to avoid seeking feedback, but this situation provoked others to pursue feedback.

내가 더 힘들어하는 것처럼 느껴지는 로테이션이 피드백을 더 많이 요구한다는 것을 알게 되었습니다. 실제로 이 로테이션에서 조금 더 잘 할 수 있을 것입니다. (EE)

I found that rotations where I felt like I was struggling more I asked for feedback more … I actually would up doing a little better in these rotations. (EE)

피드백 공급자 특성.

Feedback provider characteristics.

학생들은 학생들이 피드백을 찾도록 유도하는 피드백 제공자의 몇 가지 특성을 강조했습니다. 예를 들어, 프롬프트 없이 자발적인 피드백을 제공하는 것입니다. 학생들은 자신의 관찰이나 좀 더 일반적인 의미에서 수집된 그러한 특성을 "내가 좋은 교육자라는 인상을 받는다면"(JJ)이라고 설명했다. 효과적인 피드백 제공자들은 "피드백을 주는 것에 열려있다" (II), "조금 더 차분하다" (BB), "교육에 대해 매우 사려깊다" (CC), "칭찬 샌드위치" (AA)와 같은 기술을 사용했으며 가르치는 것을 즐겼다. 학생들은 또한 그들이 더 잘하도록 밀어준 피드백 제공자들에게 감사했다.

Students underscored several characteristics of the feedback provider that would encourage the student to seek feedback—for example, giving spontaneous feedback without prompting. Students described such characteristics gathered from their observations or from a more general sense: “If I get the impression that they are a good educator” (JJ). Providers of effective feedback were “open to giving feedback” (II), “a little more calm” (BB), “very thoughtful about teaching” (CC), used techniques like a “compliment sandwich” (AA), and enjoyed teaching. Students also appreciated feedback providers who pushed them to do better.

그녀는 정말 수준이 높았어요. [S]그는 그녀가 당신이 더 잘하기를 응원하는 것처럼 느끼게 하면서 어떻게 하면 더 잘 할 수 있는지 말해줄 것이다. (BB)

She really had high standards.… [S]he would tell you how to make it better while all the time making it feel like she was rooting for you to do better. (BB)

학생들은 피드백 제공자의 성격에 대한 인식이 피드백을 구할지 여부와 그 방법에 영향을 미친다고 지적했다. 위협적으로 보이는 피드백 제공자들은 피했다. 학생들이 피드백을 구하도록 유도하는 긍정적 피드백 제공자 특성이 있었던 것처럼, 학생들이 해당 개인에게 피드백을 계속 구하고자 하는 욕구를 위축시키는 부정적 특성이 있었다.

Students indicated that their perception of the feedback provider’s personality had an impact on their decision whether to seek feedback and the ways in which they did so. Feedback providers who appeared to be intimidating were avoided. Just as there were positive feedback provider characteristics prompting students to seek feedback, there were negative characteristics that dampened students’ desire to continue to seek feedback from that individual.

나는 다른 성격 유형으로 사람들이 피드백을 적는 것이 얼마나 더 편안한지 확실히 알 수 있었다. (HH)

I could definitely see with different personality types how people would be more comfortable writing down feedback. (HH)

만약 내가 교수진과 나쁜 임상 경험을 했다면 나는 그들에게 피드백을 구하지 않았을 것이다. (II)

If I had a bad clinical experience with a faculty member I wouldn’t seek feedback from them. (II)

피드백을 구하는 방법에 영향을 미치는 요소는 무엇입니까?

Which factors influence the way you seek feedback?

바쁜 환경.

Busy environment.

몇몇 학생들은 때때로 정신없이 바쁜 임상 환경이 피드백을 추구하지 않는 데 영향을 미치는 강력한 요인이라고 언급했다.

Several students commented that the sometimes-frenetic clinical environment was a strong factor influencing them to not seek feedback.

만약 바쁘다면, 사람들이 방을 날아다니고 있다면. "저, 제가 제대로 했는지 알려주실래요?"같은 말은 안 할거에요 (LL)

If it was busy, if people are flying around the room. It’s crazy. I’m not going to say, “Hey, can you tell me if I did that correctly?” (LL)

타이밍.

Timing.

학생들은 임상 환경이 덜 바쁜 시간, 종종 하루나 한 주의 끝이 피드백을 받기에 더 최적의 시간이라고 설명했다. 학생들은 또한 적절한 비공식 피드백을 얻을 수 있는 추가적인 순간들을 강조했다.

Students described times when the clinical environment was less busy, often at the end of the day or week, as more optimal times to seek feedback. Students also highlighted additional moments when opportune informal feedback could be obtained.

피드백은 항상 하루에 함께하는 시간의 끝에 일어난다. (DD)

Feedback would always happen at the end of our time together on a day. (DD)

단서.

Cues.

학생들은 거주자나 교직원들과 일할 때 신호에 매우 익숙했다. 특정한 신호들은 [학생들이 학생의 이름을 배우거나 학생에게 관심을 보이는 것]과 같은 피드백을 얻도록 격려할 것이다.

Students were very attuned to cues when working with residents or faculty. Certain signals would encourage students to seek feedback, such as learning the student’s name or showing interest in the student.

만약 그들이 방에서 걸어나와 "오, 나는 네가 이런 짓을 했다는 것을 알아차렸다. 여기 당신이 작업할 수 있는 것이 있습니다."이라고 말했다. 그것은 정말로 다른 사람들이 하지 않는 방식으로 그들이 주의를 기울이고 있다는 신호였다. (CC)

If they walked out of a room and said, “Oh I noticed that you did this. Here’s a thing that I think you can work on.” That was really signaling me that they were paying attention in a way that other people were not. (CC)

당신은 당신의 성과에 대한 정보를 어떻게 얻나요?

How do you obtain information about your performance?

탐색 대 모니터링.

Inquiry versus monitoring.

학생들은 종종 다음과 같은 inquiry을 통해 자신의 성과에 대한 피드백을 얻었습니다. "야, 어떻게 된 것 같아? 다음 번에는 어떻게 다르게 해야 할까요?" (AA) 학생들이 묻는 질문은 일반적인 유형의 질문보다 더 구체적이었습니다. "이 특정 상황이 어떻게 진행되었다고 생각하십니까?" [T]주말이 되자 그것은 더 일반적이었다." (II)

Students often obtained feedback about their performance through inquiry—for example, asking: “Hey, how do you think that went? How should I do this differently next time?” (AA). Questions the students asked were typically more specific than a general type of inquiry: “How do you think this specific situation went?… [T]owards the end of the week it was more general.” (II)

학생들이 피드백을 얻기 위해 사용한 질문의 우선순위를 보고했지만, 학생들은 그들이 어떻게 수행하고 있는지 감지하기 위해 환경에서 다른 학습자를 관찰하는 것에 대해 종종 설명하지 않았다. LIC 학생들은 모니터링 할 수 있는 다른 학생이 많지 않았다.

Although students reported a preponderance of questions they used to obtain feedback, they did not often describe observing other learners in their environment to sense how they were performing. LIC students did not have many other students rotating with them whom they could monitor.

간접적 기술

Artifice.

일부 학생들은 "직접적으로 피드백을 요청한 적이 없다"(AA)고 지적했다. 대신, 그들은 피드백을 얻기 위해 "나는 항상 다른 것을 가지고 있고 그들이 피드백에 대해 이야기하도록 속이는 것을 좋아한다"(AA)와 같은 몇 가지 간접적이고 비조회적인 방법을 사용했다. 우리가 "똑똑하고 교묘한 기술: 독창성; 기발한 장치 또는 편법"으로 정의한 이러한 방법들은 [대화 스타터, 피드백 준비, 자기 비판적인 논평 사용]과 같은 기술을 포함했다.

Some students indicated that they “never asked for feedback directly” (AA). Instead, they used several indirect and noninquiry methods to get feedback—for example, “I always have something else and like trick them into talking about feedback” (AA). These methods—which we labeled as “artifice,” defined as “a clever or artful skill: ingenuity; an ingenious device or expedient”34—included such techniques as conversation starters, prepping for feedback, and using self-critical comments.

만약 누군가가 병력청취하는 나를 관찰할 것이라는 것을 안다면, 그들이 나를 관찰할 수 있다면, 나는 그들에게 피드백을 요청할 것이다. (JJ)

If I know somebody is going to be observing me in doing a history or something like that I might ask them for feedback right beforehand if they can observe me, give me feedback afterwards. (JJ)

[Y]여러분은 일종의 자기비하적인 발언으로 이끌 수 있습니다. "저는 정말로 제가 그 모든 것을 잘 하고 있다고 생각하지 않습니다.…" (FF)

[Y]ou can lead with a sort of self-deprecating statement saying, “I really don’t think I’m doing all that well with.…” (FF)

[G]나를 건설적으로 비판하도록 그들을 초대한다. 당신은 "내가 이것을 잘못했다고 생각한다" 또는 "나는 내가 어떻게 이것을 했는지 편안하지 않다"라고 말해야 한다. (AA)

[G]ive them an invitation to constructively criticize me. You have to say, “I think I did a bad job on this” or “I am not comfortable with how I did this.” (AA)

학생들이 사용한 다른 [간접적인 기법]에는 피드백 제공자를 칭찬하고, 문제에 대한 의견이나 접근 방식을 제공자에게 묻고, 피드백 제공자에게 감사하는 것이 포함되었다.

Other indirect techniques that students used involved praising the feedback provider, asking the provider for their opinion or approach to a problem, and thanking the feedback provider.

[T]당신이 아주 잘한다는 걸 알아챘어요. 지식의 기반을 구축하려면 어떻게 해야 합니까? (EE)

[T]his is something I’ve noticed you do very well. What can I do to try to build that foundation of knowledge? (EE)

나는 그것을 종종 "당신은 어떻게 그렇게 했겠어요?"라고 표현한다. 그들은 종종 "이것이 당신이 한 일이고 이것이 내가 그것을 했을 방법이다."라고 채운다. (BB)

I often phrase it as like, “How would you have done that?” They often will end up filling in, “This is what you did and this is how I would have done it.” (BB)

[J]그저 감사하고 고맙다고 말하는 것이 피드백을 피드백이 계속 올 수 있도록 하는 좋은 방법이라고 생각합니다. (LL)

[J]ust saying thank you, being appreciative I think of feedback is a good way to make sure feedback will keep coming. (LL)

비록 학생들이 주로 구두 질문을 통해 피드백을 구했지만, 학생들은 또한 때때로 덜 위협적인 접근법으로 피드백을 얻기 위해 서면 또는 전자 매체를 사용한다고 지적했다.

Although students predominantly sought feedback through verbal inquiry, students also indicated they used written or electronic media to get feedback, sometimes as a less threatening approach.

총괄적 피드백.

Summative feedback.

대부분의 경우, 학생들은 [공식적 피드백 제공 접근법]이 [스스로 피드백을 구하는 것]만큼 도움이 된다고 생각하지 않았다. 공식적인 접근 방식에는 필요한 블록 중간 및 끝 회전 피드백, 3개월 및 6개월 LIC 평가 세션, 그리고 각 임상실습에서 DOC(직접 관찰) 카드 세트의 의무적인 교수진 완료가 포함되었다. (DOC 카드는 역사 체크리스트와 신체검사 요소와 같은 기본 역량을 다루었으며, 뒷면에 긍정적이고 건설적인 피드백을 위한 공간을 가지고 있었다.)

For the most part, students did not find the formal approaches to providing students with feedback to be as helpful as seeking feedback on their own. The formal approaches included required mid- and end-of-block rotation feedback, three- and six-month LIC evaluative sessions, and mandatory faculty completion of a set of DOC (direct observation) cards during each clerkship. (The DOC cards covered basic competencies, such as a checklist of history and physical examination elements, and had space for positive and constructive feedback on the back.)

3개월과 6개월의 피드백 중 일부는 도움이 되지 않았습니다. 일반적으로 "오, 그는 좋은 학생이고, 열심히 공부한다." … [D]제가 하고 있는 구체적인 일에 대해서는 언급하지 않았습니다. (EE)

Some of the feedback at three and six months wasn’t as helpful. Generally, “Oh, he’s a good student, he works hard.”… [D]idn’t mention specific things that I was doing. (EE)

대부분의 DOC 카드는 그다지 도움이 되지 않습니다. 건설적인 피드백의 좋은 루프와는 반대로 대부분의 작업인 것 같습니다. (KK)

Mostly DOC cards are not very helpful … it seems it’s mostly a task as opposed to a good loop of constructive feedback. (KK)

피드백을 찾는 교육.

Training in seeking feedback.

학생들은 [의대생들을 위한 교육]이 피드백을 구하는 데 도움이 될 것이라고 언급했고, 그들은 그러한 프로그램에서 학생들에게 무엇을 말할 것인지에 대한 조언을 제공했다. 학생들을 건설적인 피드백에 둔감하게 하는 것이 유익한 접근법으로 언급되었다.

Students indicated that training for medical students in seeking feedback would be helpful, and they offered advice as to what they would tell students in such a program. Desensitizing students to constructive feedback was mentioned as a beneficial approach.

저는 대학에서 꽤 잔인한 4학년 논문을 썼는데, 거기서 피드백을 많이 교환하고, 피드백을 받아 변화를 만드는 데 정말 익숙해졌어요. (NN)

I had a pretty brutal senior thesis year in college where we did a lot of exchanging feedback … that got me really used to taking in feedback and making changes with it. (NN)

[C]가끔은 조금 아플 때도 있다 그래서 피부가 두꺼워지면서 건설적인 피드백을 찾았던 것 같아요. (LL)

[C]onstructive [feedback] hurt a little bit sometimes. So I think as I got thicker skinned I guess, I looked for constructive feedback. (LL)

교수진과의 관계가 피드백을 구하는 방식에 어떤 영향을 미칩니까?

How does your relationship with faculty influence the way you seek feedback?

관계 역학.

Relationship dynamics.

학생들은 피드백을 추구하는 행동에 영향을 미치는 [피드백 제공자와의 관계]의 여러 측면을 설명했다. 학생들은 교직원들이 접근할 수 있을 정도로 충분히 강한 관계를 느껴야 했다.

The students described several aspects of their relationship with feedback providers that influenced their feedback-seeking behaviors. Students had to feel the relationship was strong enough such that faculty seemed approachable.

접근하기 쉬운 사람이 있다면. 피드백을 받는 것이 더 편하다고 느꼈다. 그 사람이 교육 친화적이라는 것을 알았다면… 당신은 그들로부터 피드백을 받고 싶을 것이다. (II)

If somebody is approachable. That I felt more comfortable getting feedback. If I knew that the person was education friendly … you want to seek feedback from them. (II)

그들이 동료라고 느끼거나 피드백 제공자와 공통점이 있다는 것은 피드백을 찾는 것이 더 쉬운 지원 관계를 촉진했다.

Feeling like they were colleagues or having something in common with a feedback provider facilitated a supportive relationship in which seeking feedback was easier.

[H]나는 그들과 많은 관계를 맺고 있다… 만약 우리가 더 많은 개인적인 것에 대해 이야기하게 된다면… 그런 식으로 피드백에 영향을 준다. (JJJ)

[H]ow much of a rapport I establish with them … if we got to talking about more personal things … in that way it influences the feedback. (JJ)

학생들은 [상호 신뢰감과 관계에 대한 관심caring]이 중요하다고 강조했다.

Students highlighted a sense of mutual trust and caring in the relationship as important.

그들이 실제로 당신이 더 나아지는 것을 보고 싶어한다고 느낄 때가 온다. 그것이 그들의 목표인 것처럼, 당신이 느낄 수 있는 것처럼. 그리고 그들은 당신과 함께 그 일에 관여하고 있어요. (DD)

There comes a point when you feel like they actually want to see you become better. Like that’s their goal, like you can feel it. And that they’re in on that with you. (DD)

학생들은 또한 피드백을 제공할 때 전공의와 교직원들이 그들에게 지나치게 친절하다는 것을 인식했고, 이것은 효과적인 피드백 의사소통을 방해했다.

Students also recognized that residents and faculty were too nice to them when getting around to providing feedback, and this inhibited effective feedback communication.

나는 때때로 [그들이 그렇게 일찍부터 나를 기분 나쁘게 하고 싶지 않아하는구나]고 느꼈다. 그들은 우리의 교사와 학습자의 관계를 바꾸고 싶어하지 않았다. 그들은 피드백을 주고 있는 사람의 감정을 상하게 하고 싶지 않기 때문에 피드백을 주고 싶지 않을 수도 있다. (BB)

I felt sometimes they didn’t want to make me feel bad that early on. They didn’t want to change our teacher–learner relationship. They might not like to give feedback because they don’t want to hurt the feelings of the person they’re giving it to. (BB)

LIC 대 블록 회전입니다.

LIC versus block rotations.

학생들은 학생들이 LIC에 비해 [블록 로테이션에 대한 교수진과의 상호작용이 훨씬 적었고], 블록 로테이션에서는 교수진보다 전공의들이 더 많은 피드백을 제공했으며, 학생들은 전공의들을 교수진이라기보다는 동료로 보았다는 점을 강조했다.

Students emphasized that students had much less interaction with faculty on the block rotations than the LIC, that residents provided more feedback than faculty on block rotations, and that students viewed residents more as peers than as faculty.

학생들이 받는 전공의 교육이 많거나, 오히려 전공의들이 수업을 많이 한다는 점에서, LIC와 블록이 조금 다르다고 생각합니다. (KK)

I think the block is a little bit different than the LIC in that there is a lot of resident education that the students get, or rather the residents do a lot of teaching. (KK)

LIC의 긴 기간과 현장에서의 적은 학습자는 교직원과의 더 나은 관계를 촉진하고 LIC 학생들에게 향상된 피드백 기회를 제공했다. 몇몇 학생들은 약 3~4개월 동안 교수진과의 관계가 피드백을 추구하는 행동을 촉진할 수 있을 정도로 견고하다고 지적했다.

The long duration of the LIC and fewer learners at the sites facilitated better relationships with faculty and enhanced feedback opportunities for LIC students. Several students indicated that approximately three to four months into the LIC, their relationships with faculty were solid enough to facilitate feedback-seeking behaviors.

분명히 LIC 대 블록 실습의 차이가 있었다. LIC에서 제 경험의 대부분은 외래 환자였는데, 이는 오늘날의 상황과는 다른 흐름을 가지고 있습니다. 입원 환자에 비해 환자 상황은 예측하기 어렵습니다. (EE)

There definitely was a LIC versus block difference. In the LIC most of my experience was outpatient, which has a different flow to the day … you know when people are going to be available, versus inpatient things are bit more unpredictable. (EE)

3개월쯤 되면 그들이 나를 꽤 잘 알고 내가 무엇을 잘하는지 알고 있다고 생각한다고 말할 것이다. (AA)

I’d probably say by three months I think they knew me pretty well and knew what I was good at. (AA)

논의

Discussion

우리의 정성적 연구 결과는 임상실습 연도의 의대생들의 피드백 추구 행동을 설명하고 임상실습 학생들의 피드백 추구 행동에 영향을 미치는 교수-학생 관계의 측면을 강조함으로써 의학 교육 문헌에 추가된다(표 1). 임상실습 학생들은 피드백을 추구하는 다양한 이유와 동기를 가지고 있었고, 종종 피드백의 인식된 [이익]과 [비용]을 저울질했다. 그들은 피드백을 찾는 기술을 향상시키면서 피드백 추구 접근법을 빠르게 진행되고 종종 혼란스러운 임상 학습 환경에 적응시키는 방법을 배웠다. 우리의 가장 참신한 발견은 학생들이 필요한 정보를 얻는 목표를 달성하기 위해 간접적이거나 비조회적인 피드백 추구 기술을 사용했다는 것입니다.

The findings of our qualitative study add to the medical education literature by elucidating the feedback-seeking behaviors of medical students in the clerkship year and by highlighting aspects of the faculty–student relationship that have an impact on clerkship students’ feedback-seeking behaviors (Table 1). Clerkship students had multiple reasons and motives for seeking feedback, and they often weighed the perceived benefits and costs of feedback. They learned how to adapt their feedback-seeking approaches to the fast-paced and often-chaotic clinical learning environment, as they advanced their skills in seeking feedback. Our most novel finding was that students also used indirect or noninquiry feedback-seeking techniques, which we labeled as “artifice,” to achieve the goal of getting the information they needed.

우리의 연구 결과는 조직 심리학 문헌과 교육 문헌의 피드백과 관련된 이론적 모델을 뒷받침한다. 임상실습 학년의 의대생들은 그들의 [지식과 기술을 향상시키기 위해] 피드백을 구했고, 그들의 역량에 대한 [긍정적인 판단을 받고 부정적인 판단을 피하기]를 원했다. 이러한 동기는 각각 [학습 목표 지향]과 [수행 목표 지향]을 반영한다. 피드백을 추구하는 것은 참여를 보여줌으로써 자신의 이미지를 홍보하는 것을 포함하여 학생들에게 [다양한 이점]을 가져다 주었다. 그러나, 학생들은 그들의 자아, 감정, 그리고 자기 표현에 대한 손상과 같은 [피드백 탐색의 비용]을 확인했다. 학생들이 피드백의 편익과 비용을 처리하는 방법은 규제 초점 이론에 의해 설명될 수 있는데, 이는 개인이 ["향상" 또는 "예방" 초점]을 가지고 있음을 시사한다. 의료 교육 현장 환경에서 규제 초점이 어떻게 예측 가치를 갖는지 설명했다. 다른 이론으로 Watling과 Harrison 등은 피드백에 대한 학생들의 인식과 반응이 종합 평가와 혼동되는 형태적 피드백에 의해 왜곡될 수 있다고 강조했다.

Our findings support theoretical models regarding feedback in the organizational psychology literature17–19 and the educational literature.35–37 Medical students in their clerkship year sought feedback to improve their knowledge and skills, while wishing to receive positive and avoid negative judgments about their competence. These motives reflect learning goal and performance goal orientations, respectively.24–26 Seeking feedback reaped various benefits for students,16 including promoting one’s image by showing engagement.28 However, students identified costs in seeking feedback, such as damage to their egos, feelings, and self-presentation.17,28,38 The ways in which students processed the benefits and costs of feedback may be explained by regulatory focus theory, which suggests that individuals have either a “promotion” or “prevention” focus.39,40 How regulatory focus has predictive value in medical education workplace settings has been delineated.41 As a different theory, Watling42 and Harrison et al43 have emphasized that students’ perceptions and reactions to feedback may be distorted by their confusing formative feedback with summative assessment.

의대생들이 피드백을 구하는 방식은 수의대 학생들과 완전히 비슷하지는 않았다. 우리 학생들은 주로 [탐구 방법]을 사용하고 [모니터링 방법]의 사용을 많이 설명하지 않은 반면, 수의학 학생들은 두 가지 방법을 모두 주요 전략으로 사용하였다. 비록 두 분야의 학습자들이 물질적으로 다를 수 있지만, 더 가능성 있는 설명은 학습 환경의 차이이다. 또한, 바쁜 임상 학습 환경에서 수의학과 학생과 의대생 모두 피드백을 구할 수 있는 최적의 시기를 결정할 수 있었습니다. 우리 학생들은 피드백을 찾는 것이 다소 도움이 될 것이라는 신호를 보내는 분위기와 같은 피드백 제공자의 단서를 관찰했다.

The manner in which our medical students went about seeking feedback was not entirely similar to that of veterinary students.16 Our students predominantly used an inquiry method and did not describe much use of a monitoring method,28 whereas veterinary students used both methods as main strategies. The reasons for this are unclear; although learners in the two fields may be materially dissimilar, a more likely explanation is differences in the learning environments. Also, in a busy clinical learning environment, both veterinary students16 and our medical students were able to determine the best timing to seek feedback. Our students observed for cues from the feedback provider, such as mood,15 that signaled that seeking feedback would be more or less beneficial.

이 연구에서 우리의 독특한 발견은 임상실습 학생들이 [직접적인 질문] 외에도 피드백을 얻기 위한 전략을 형성함으로써 학습 환경에 적응하는 능력이었다. 이 기술은 단순히 [간접적인 질문]을 사용하는 것이 아니라 다양한 [비질문적 전술]을 사용하는 것을 포함한다. 개별 학생들은 [자신에게 가장 잘 맞는 한 두 가지 전략]에 만족하는 것처럼 보였다. 우리는 "인공물"이라는 용어가 암시하는 것처럼 학생들이 의도적으로 조작하거나 기만적이라고 생각하지 않는다. 오히려, 이 중요한 발견은 학생들이 거의 피드백을 받지 못하는 상황에서 개발한 "지혜적인clever" 접근법을 반영한다.

Our unique finding in this study was the ability of clerkship students to adapt to the learning environment by fashioning strategies, besides direct inquiries, to obtain feedback. This artifice was not simply using indirect inquiries28 but also involved employing a variety of noninquiry tactics. Individual students seemed to settle on the one or two strategies that worked best for them. We do not believe that students are intentionally manipulative or deceptive, as the term “artifice” might imply. Rather, this important finding reflects the “clever”34 approaches students have developed in the face of receiving little feedback.

우리의 결과는 의대생의 피드백 추구 행동에 영향을 미치는 상호 관련 측면(예: 목표, 동기, 이점, 비용)이 있는 피드백 제공자와 수신자 간의 복잡한 관계 모델을 지원한다. 교수-학생 관계와 관련하여 추가한 네 번째 인터뷰 질문은 새로운 관점을 제공하기보다는 이전의 결과를 확인시켜 주었다. 그들의 임상실습 학년에 의대생들은 교직원들이 접근하기 쉽다는 것을 느낄 필요가 있다. 그들은 "예의바르고 관대한" 문화가 피드백의 장벽이 된다는 것을 인식한다. 교직원이 지지적이고 배려적이라고 느끼는 학생들과 달리, 교직원에 대한 부정적인 반응을 보이는 학생들은 [피드백 회피 전략]과 [교직원 신뢰도에 대한 인식이 떨어지는 경향]이 있다.

Our results support the model of a complex relationship5,27 between feedback provider and receiver which has interrelated aspects (e.g., goals, motives, benefits, costs) that affect the feedback-seeking behaviors of medical students. The fourth interview question we added regarding the faculty–student relationship confirmed previous findings rather than providing new perspectives. Medical students in their clerkship year need to feel that faculty members are approachable.1,44 They recognize that a culture of “politeness”45 and leniency5 becomes a barrier to feedback. In contrast to students who feel that faculty members are supportive and caring, students with negative reactions to faculty members46 tend toward feedback avoidance strategies and perceptions of poor faculty credibility.47

놀랄 것도 없이, LIC의 종단적 측면은 학생들이 교수진으로부터 피드백을 구하는 더 강한 관계를 더 쉽게 확립할 수 있도록 한다. 의대생들이 전통적인 입원 환자 블록 로테이션에 대해 충분한 피드백을 얻을 수 있지만, 그러한 피드백은 주로 (전공의보다 로테이션이 잦고 참석이 적은 교직원보다는) 전공의에게서 나온다. LIC 모델에 더 높은 품질의 피드백이 있을 수 있으며, 이는 부분적으로 블록 모델에 비해 피드백 기회가 증가한 것과 관련이 있을 수 있다. 또한 일반적인 입원 환자 블록 회전의 바쁜 임상 환경은 효과적인 피드백에 대한 장벽을 제시한다. 우리는 종단적인 멘토링과 조언을 통합하기 위해 의료 교육 모델을 크게 개혁하라는 어비 외 연구진의 요청을 지지한다.

Not surprisingly, the longitudinal aspect of the LIC facilitates an easier establishment of stronger relationships in which students seek feedback from faculty.48 Although medical students may be able to obtain sufficient feedback on traditional inpatient block rotations, such feedback will be predominantly from residents rather than from faculty members, who transition often and are less present than residents. There may be a higher quality of feedback in the LIC model, which may be partly related to the increased opportunities for feedback compared with the block model. Also, the busy clinical environment of a typical inpatient block rotation presents a barrier to effective feedback. We support the call by Irby et al49 to significantly reform medical education models to incorporate longitudinal mentoring and advising.

실제적인 의미

Practical implications

교수진 피드백 역량을 개발하기 위한 역사적 접근 방식에 의문이 제기되었다. 교수진들이 학습자의 피드백 추구 능력을 증진하도록 권장하고 있지만, [최적의 피드백 교류]를 [공동으로 수행]하는 데 [적극적인 참여자]로서 의대생들에게 힘을 실어주는 데 관심을 기울여야 한다고 생각한다. Crommelink와 Anseel은 훈련 프로그램이 학습 목표 지향을 촉진하기 위해 설계되어야 한다고 제안했다. 우리는 이전에 효과적인 피드백을 받는 의대생을 지도하는 것이 가능하다는 것을 보여주었다. 밀라노 외 연구진은 임상실습 학생들이 피드백을 이끌어내는 방법에 대한 90분간의 워크숍을 거친 후 피드백을 얻는 긍정적인 태도의 변화를 보여주었다.

The historical approach for developing faculty feedback competencies has been called into question.14 Although faculty are encouraged to promote the feedback-seeking skills of learners,50 we believe attention should be given to empowering medical students as active participants in coproducing optimal feedback exchanges.1 Crommelinck and Anseel15 have suggested that training programs be designed to promote a learning goal orientation. We have previously shown that coaching medical students in receiving effective feedback is feasible.51 Milan et al44 have demonstrated changes in positive attitudes toward obtaining feedback after clerkship students underwent a 90-minute workshop on how to elicit feedback.

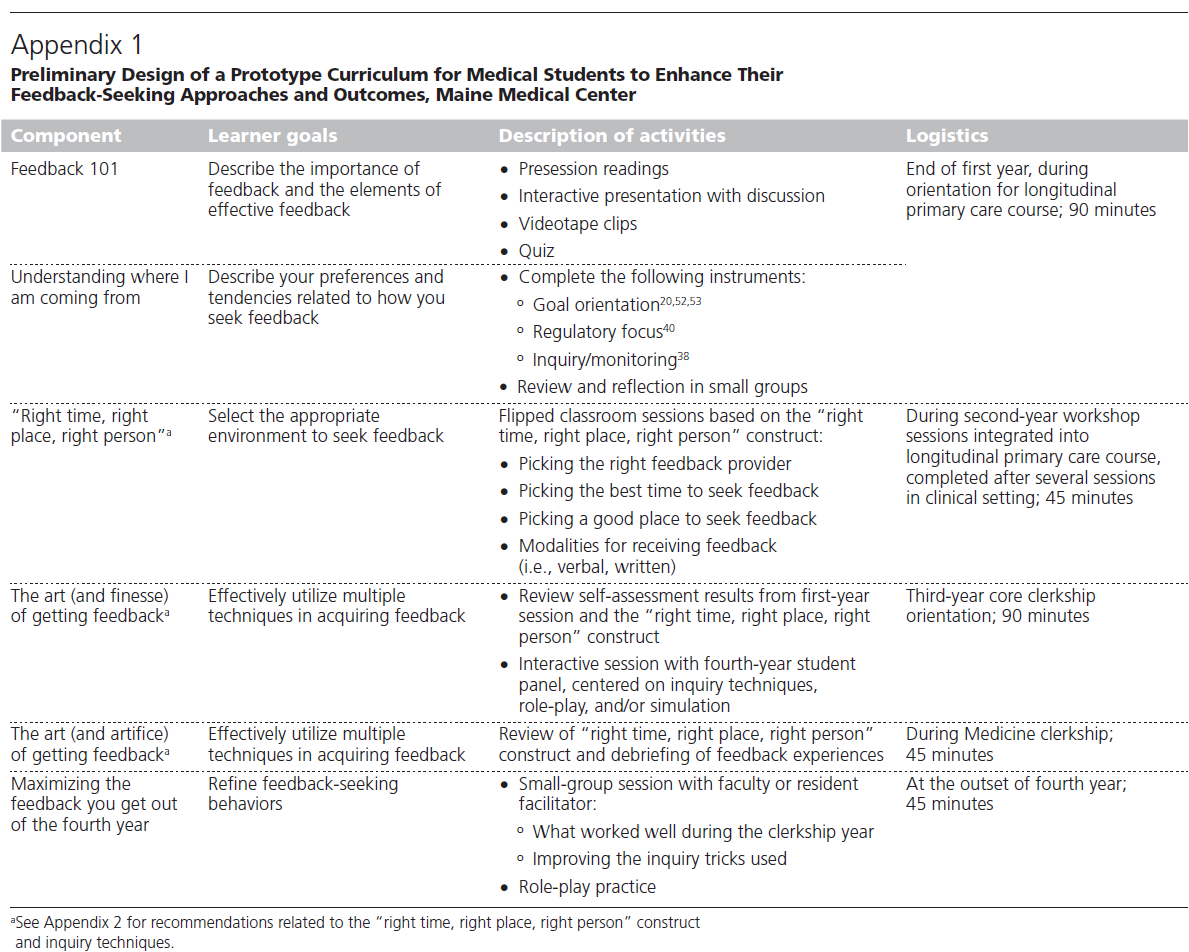

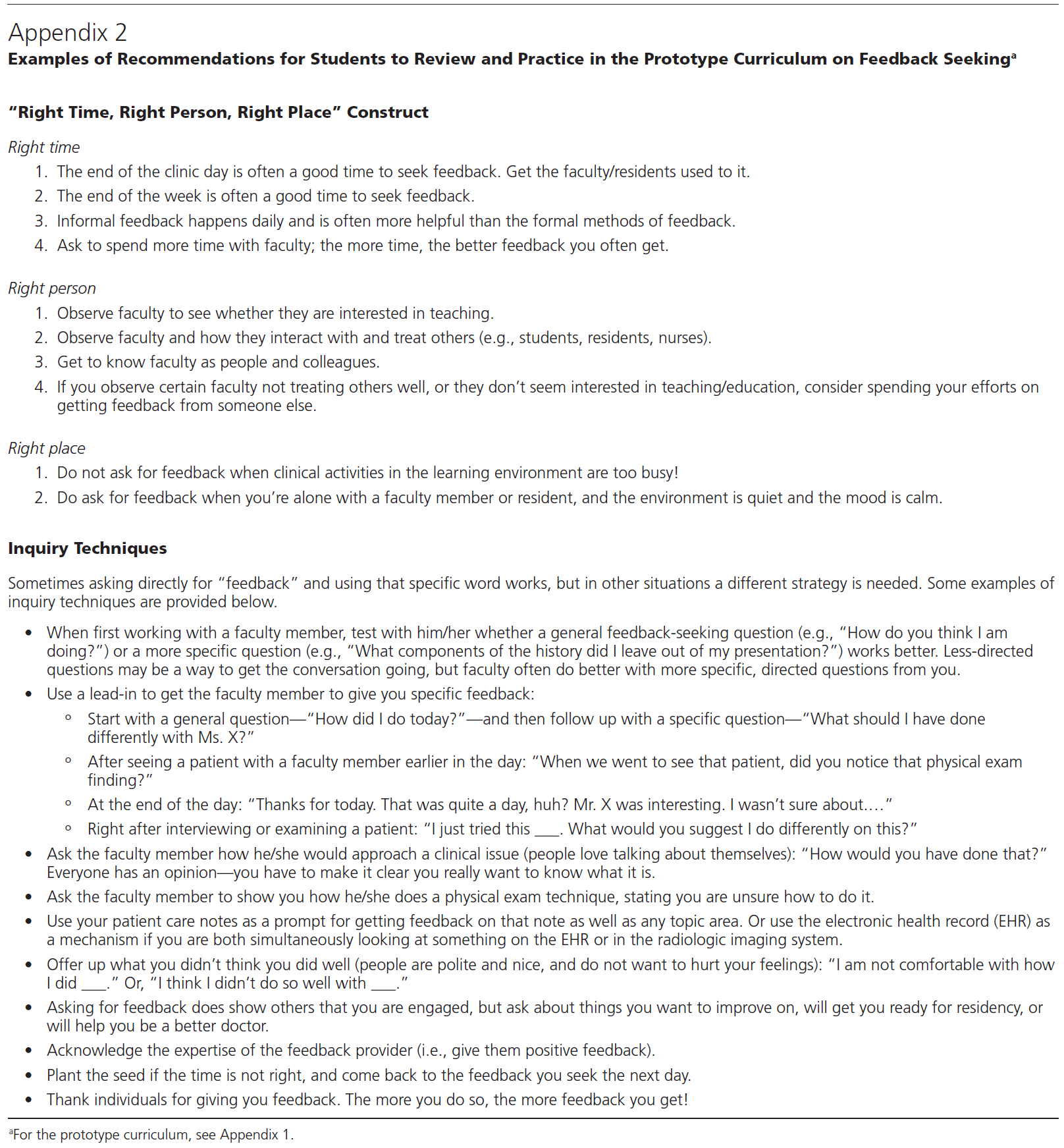

우리는 또한 교직원들이 단순히 학생들에게 피드백을 요청하고 자주 요청하라고 말하는 것을 넘어서야 한다고 믿는다. Boud와 Moloyy는 피드백 커리큘럼이 피드백 제공뿐만 아니라 자기 규제 촉진, 피드백 추구 기술에서의 연습, 수신 훈련과 같은 요소를 포함해야 한다고 제안했다. 본 연구의 결과와 위에서 강조한 목표지향성 및 교육동맹모형을 바탕으로 [의대생의 피드백 추구능력을 향상시키기 위한 종단적 교육과정의 원형]을 설계하였다(부록 1, 2). 교육과정은 [목표지향성에 대한 개인의 선호도, 탐구 대 모니터링 접근법, 규제 초점에 대한 평가와 자기반성]으로 시작된다. 구성 요소에는 건설적인 피드백에 대한 둔감화와 다른 학생들에게 유용한 것으로 입증된 피드백 기법에 초점을 맞춘 세션이 포함된다. 대화형 활동은 피드백을 받고 반영하는 방법을 강조할 수 있다. 이 커리큘럼의 구성 요소는 실험 연구에 의해 지원되어야 하며(그러나 개념 모델에 의해 잘 부양되고 있음) 일부 내용이나 방법은 논란의 여지가 있을 수 있다는 것을 완전히 인식하고, 우리는 이 프로토타입이 학생들이 적극적인 참가자로서 피드백을 찾는 방법을 개선하는 방법에 대한 논의를 촉진하기를 바란다.

We also believe that faculty need to go beyond just telling students to ask for feedback and to ask often. Boud and Molloy11 proposed that a feedback curriculum should include elements such as promoting self-regulation, practice in feedback-seeking skills, and training in receiving as well as providing feedback. Based on our findings in this study, and on the goal orientation and educational alliance models highlighted above,26,27 we designed a prototype of a longitudinal curriculum to enhance medical students’ feedback-seeking skills (Appendixes 1 and 2). The curriculum begins with an assessment of and self-reflection on an individual’s predilection to goal orientation,20,52,53 inquiry versus monitoring approaches,38 and regulatory focus.40 Components include desensitization to constructive feedback and a session focusing on the feedback artifice proven to be useful for other students. Interactive activities can emphasize how to receive and reflect on feedback. Fully recognizing that components of this curriculum need to be supported by experimental studies (but are well buoyed by conceptual models11) and that some of the content or methods may even be controversial, we hope this prototype will prompt discussion on methods to improve how students seek feedback as active participants.

한계

Limitations

우리 연구의 한계에 대해 반성적인 입장을 취할 때, 우리는 우리의 발견이 구성주의적 근거 이론 접근법의 위험인 우리 자신의 편견과 가정에 의해 제한되고 왜곡될 수 있다고 생각한다. 우리는 우리의 방법론적 과정이 강했다고 생각하지만, 한 가지 맹점은 의대생이나 교수진의 독특성일 수 있다. 우리는 다른 기관에서 두 그룹에 대한 연구가 서로 다른 결과를 초래할 수 있다는 것을 배제할 수 없다. 학생들이 자발적으로 인터뷰를 하였는데, 인터뷰를 하지 않은 학생들이 피드백 추구 접근법에 대한 인식이 다른지는 조사하지 않았다. 두 면접관은 참여 학생들과 직접적인 평가 역할이 없었음에도 학생들의 반응은 면접관의 리더십 역할에 영향을 받았을 수 있다. 인터뷰 가이드가 사용되었지만, 이 주제 영역에서 두 인터뷰어의 연구 경험 또한 우리의 해석을 편향시킬 수 있었다. 또한, 우리의 결론에 기초한 이론적 모델은 의학 교육 환경에서 개발되지 않았기 때문에 이러한 교육적 환경에 맞지 않을 수 있다. 우리는 프로토타입 교육 커리큘럼의 설계를 학생의 인식과 개념 모델에 기초했지만, 그러한 프로그램의 결과(예: 향상된 피드백 추구 기술)는 여전히 불확실하다. 학습 문화는 피드백 훈련 프로그램이 궁극적으로 얼마나 효과적인지에 중요한 역할을 할 수 있다.

In taking a reflective stance regarding limitations to our study,54 we think our findings could be limited and distorted by our own biases and assumptions, which is a risk with a constructivist grounded theory approach.31 Although we believe our methodologic processes were robust,29 one blind spot may be the uniqueness of our medical student or faculty populations. We cannot rule out that a study of either group at another institution may result in divergent findings. Students volunteered to be interviewed, and we did not investigate whether those who were not interviewed had differing perceptions of feedback-seeking approaches. Even though the two interviewers had no direct evaluation role with the participating students, the students’ responses may have been influenced by the leadership roles of the interviewers. Although an interview guide was used, the research experience of both interviewers in this topic area could also have biased our interpretations. Additionally, the theoretical models for the basis of our conclusions17–19,24 were not developed in medical education environments, so they may not fit this pedagogical environment. We based the design of our prototype educational curriculum on student perceptions and conceptual models,15,44,51 but the outcomes of such a program (e.g., improved feedback-seeking skills) remain uncertain. The learning culture may have a significant role in how effective any feedback training program eventually is.55

결론들

Conclusions

임상실습 학년의 의대생들은 피드백을 추구하는 많은 동기를 가지고 있으며, 피드백을 추구하는 행동을 조정하여 피드백 제공자와의 복잡한 대화 상호작용에 적극적으로 참여한다. 교직원과 학생의 관계는 복잡하고 학생들이 피드백을 얻기 위해 사용하는 접근법에 영향을 미친다. 학생들은 자신의 필요를 충족시키는 구체적인 피드백 정보를 얻는 기술(및 기교)을 점진적으로 개선하지만, 그들에게 훈련을 제공하는 것은 유익할 수 있다. 우리의 프로토타입 커리큘럼은 학생들의 피드백을 찾는 기술을 개발하는 데 도움이 될 수 있다.

Medical students in their clerkship year have many motives to seek feedback, and they adapt their feedback-seeking behaviors to actively participate in an intricate dialogic interaction with their feedback providers. The faculty–student relationship is complex and affects the approaches students use to seek feedback. Students gradually refine the art (and artifice) of obtaining the specific feedback information that meets their needs, but providing them training may be beneficial. Our prototype curriculum may facilitate the development of students’ feedback-seeking skills.

The Art (and Artifice) of Seeking Feedback: Clerkship Students' Approaches to Asking for Feedback

PMID: 29668522

Abstract

Purpose: As attention has shifted to learners as significant partners in feedback interactions, it is important to explore what feedback-seeking behaviors medical students use and how the faculty-student relationship affects feedback-seeking behaviors.

Method: This qualitative study was inspired by the organizational psychology literature. Third-year medical students were interviewed at Maine Medical Center in April-May 2017 after completing a traditional block rotation clerkship or a nine-month longitudinal integrated clerkship (LIC). A constructivist grounded theory approach was used to analyze transcripts and develop themes.

Results: Fourteen students participated (eight LIC, six block rotation). Themes associated with why students sought feedback included goal orientations, perceived benefits and costs, and student and feedback provider characteristics. Factors influencing the way students sought feedback included busy environments, timing, and cues students were attuned to. Students described more inquiry than monitoring approaches and used various indirect and noninquiry techniques (artifice) in asking for feedback. Students did not find summative feedback as helpful as seeking feedback themselves, and they suggested training in seeking feedback would be beneficial. Faculty-student relationship dynamics included several aspects affecting feedback-seeking behaviors, and relationship differences in the LIC and block models affected feedback-seeking behaviors.

Conclusions: Medical students have many motives to seek feedback and adapt their feedback-seeking behaviors to actively participate in an intricate dialogic interaction with feedback providers. Students gradually refine the art (and artifice) of obtaining the specific feedback information that meets their needs. The authors offer a prototype curriculum that may facilitate students' development of feedback-seeking skills.

'Articles (Medical Education) > 교수법 (소그룹, TBL, PBL 등)' 카테고리의 다른 글

| 밀레니얼 학생 멘토링하기 (JAMA, 2020) (0) | 2023.01.07 |

|---|---|

| 실제 임상실습 상황에서 교육자의 행동: 관찰 연구와 체계적 분석(BMC Med Educ, 2019) (0) | 2022.11.26 |

| 교육과정 변화 전후로 니어-피어 상호작용 동안 제공된 조언(Teach Learn Med. 2022) (0) | 2022.09.20 |

| 온라인 의학교육에서 윤리적으로 가르치기: AMEE Guide No. 146 (Med Teach, 2022) (0) | 2022.09.14 |

| When I say ... 페다고지(Med Educ, 2020) (0) | 2022.09.07 |