의학교육연구실의 목적, 설계, 전망 (Acad Med, 2022)

The Purpose, Design, and Promise of Medical Education Research Labs

Michael A. Gisondi, MD, Sarah Michael, DO, MS, Simiao Li-Sauerwine, MD, MSCR, Victoria Brazil, MD, MBA, Holly A. Caretta-Weyer, MD, MHPE, Barry Issenberg, MD, Jonathan Giordano, DO, MEd, Matthew Lineberry, PhD, Adriana Segura Olson, MD, MAEd, John C. Burkhardt, MD, PhD, and Teresa M. Chan, MD, MHPE

의학 교육 연구원들과 임상의 교육자들은 장학금, 교육 기법의 개선, 그리고 직접 가르침을 통해 건강 관리의 미래를 이끈다. 그러나 역사적으로 학문적 승진academic promotion은 학습자를 교육하는 데 성공적이지 않고, 연구 생산성에만 국한되어 왔다. 의학 교육 연구자들이 새로운 지식을 발굴하고 의미 있는 학술적 결과를 만들어내지만, 학계에서는 자신의 연구를 연구로 인정하지 못하는 경우가 많은 것이 우리의 경험이었다. 이러한 편견은 의료교육 연구 경력을 추구하는 개인에 대한 제도적 지원과 승진 가능성에 부정적인 영향을 미친다.

Medical education researchers and clinician educators steer the future of health care through scholarship, refinement of educational techniques, and direct teaching. 1,2 However, academic promotion has historically been tied to research productivity alone and not success in educating learners. Though medical education researchers discover new knowledge and create meaningful scholarship, it has been our experience that many in academia fail to recognize their work as research. This bias negatively affects institutional support and the likelihood of promotion for individuals pursuing medical education research careers.

실제로 교육 연구자는 작업 본체를 생산하는 뚜렷하고 잘 확립된 연구 방법을 사용하나, 이는 생물 과학자의 연구와는 다르다(예: 교육 연구자는 백신 흡수를 옹호하는 교육자의 능력을 연구할 수 있지만 생물 과학자는 환자에 의한 백신 채택률을 연구할 수 있다). 3 불행하게도, 기초 과학과 임상 연구자들이 종종 더 나은 자금, 자원 및 존경을 받는 학교에서, 교육 연구는 저평가되고 있다. 웹사이트와 보조금 개요를 검토하면서, 우리는 국립 보건원 상과 같은 교외 연구비의 격차가 생물 과학자들에게 크게 유리하고, 교육 연구 보조금은 간접 비용을 거의 보상하지 않는다는 것을 발견했다. 실제로, 우리는 의료 교육 연구원들이 종종 일관되지 않은 자금 조달 메커니즘과 그들의 기관에서 매우 소수의 명백한 멘토들을 남겨둔다는 것을 발견했다.

In reality, education researchers employ distinct, well-established study methods that produce bodies of work unlike those of bioscientists (e.g., an education researcher might study trainees’ abilities to advocate for vaccine uptake, while a bioscientist might study rates of vaccine adoption by patients) but that are no less rigorous. 3 Unfortunately, education research is undervalued at schools where basic science and clinical investigators are often better funded, resourced, and respected. 4,5 In reviewing websites and grant outlines, we have found that disparities in extramural funding, such as National Institutes of Health awards, greatly favor bioscientists, and education research grants rarely cover indirect costs. In effect, we have found find that medical education researchers are often left with inconsistent funding mechanisms and few obvious mentors at their institutions.

[연구실Research labs]은 개별 연구자의 커리어를 지원하기 위한 유용한 프레임워크를 제공하지만, 우리는 그것들이 의학 교육에서 상대적으로 드물다고 믿는다. 우리는 [연구실Research labs]을 [특정 조건이나 문제를 연구하는 단일 또는 복수의 PI(주요 조사자)가 이끄는 부서 또는 기관 내의 별개의 연구팀으로 정의]한다. 그들은 종종 부서나 학교를 넘나들며 많은 조사원으로 구성된 [연구 센터, 협력체 또는 네트워크]보다는 작다. [연구실]은 PI가 연구를 수행하고, 강력한 지원 팀을 이끌고, 학생들을 훈련시키는 것을 돕기 위해 구성될 수 있다. 의학 교육 연구자들은 [연구실 모델]을 폭넓게 채택하지 않아왔으며, 대신 의학 교육 부서, 보건 전문 장학 단체 또는 다른 연구 기업과 같은 다양한 종류의 협력적 구성에 배치한다. 우리의 의견으로는, 이러한 조직 스펙트럼은 특정 기관의 문화적 압력과 자금 부족, 협력자, 연구 주제 및 부서 지원과 같은 현장의 공통적인 도전에서 비롯된다. 우리는 [교육 연구실]이 이러한 장벽을 극복하고, 연구를 촉진하고, 교육 프로그램을 강화하고, 과외 자금 지원을 위해 경쟁하기 위해 부서 내에서 의도적으로 설계될 수 있다고 믿는다.

Research labs provide a useful framework to support the careers of individual investigators, yet we believe they are relatively rare in medical education. We define a lab as a distinct research team within a department or institution that is led by a single or multiple principal investigators (PIs) who study specific conditions or problems. They are smaller than research centers, collaboratives, or networks, which often cross departments or schools and are composed of many investigators. Labs can be constructed to help a PI conduct their research, lead a robust supporting team, and train students. Medical education researchers have not broadly adopted the lab model, instead arranging themselves in different kinds of collaborative configurations, such as departments of medical education, health professions scholarship units, or other research enterprises. 6–9 In our opinion, this organizational spectrum results from cultural pressures at certain institutions and common challenges in the field, such as a lack of funding, collaborators, study subjects, and departmental support. 10 We believe that education research labs can be deliberately designed within departments by established investigators to overcome these barriers, catalyze research, enhance training programs, and compete for extramural funding.

본 논문에서는 [의료 교육 연구실]의 조직과 임무를 [연구 센터, 협력체 및 네트워크]와 같은 다른 더 큰 구조와 비교하여 설명한다. 우리는 또한 교육 연구실의 몇 가지 핵심 요소에 대해 논의한다. 의학 교육에 있어 상대적으로 참신함을 감안할 때, 우리는 자체 실험실 창설을 고려하고 있는 다른 교육 연구자들에 의해 고려될 수 있도록 연구실 구조를 강조한다.

In this article, we describe the organization and missions of medical education research labs as compared with other larger structures, such as research centers, collaboratives, and networks. We also discuss several key elements of education research labs. Given its relative novelty in medical education, we highlight the research lab construct for consideration by other education researchers who may be contemplating starting up labs of their own.

사례 예제

Case Examples

우리 저자 그룹은 조직, 규모, 또는 목적이 다른 팀을 이끄는 의학 교육 연구원으로 구성되어 있습니다. 우리는 기존의 전문적인 관계를 통해 편리하고 비공식적으로 모였습니다. 그들 사이의 차이점을 비교하기 위해, 우리는 각각 우리 팀 구조의 상세한 사례 예시를 제공했다. 우리는 조직 구조, 1차 연구 강조, 자금 조달 메커니즘, 기관 지원, 교육자 영향 및 성공에 대한 장벽을 포함하여 우리 팀의 정의 특성을 설명했습니다. 우리 중 몇 명(M.A.G., S.M., J.C.B., T.M.C.)은 설명을 검토하고 공통 특성에 따라 팀을 그룹화하고 다음과 같은 5가지 공통 유형의 연구 팀 구조를 만들었습니다.

- 단일 PI 연구소(단일 PI 리드가 있는 연구소)

- 여러 PI 연구소(일반적으로 같은 부서 내에 있는 소규모 PI 그룹이 이끄는 연구소)

- 연구 센터(여러 부서를 넘나들면서 해당 기관에서 여러 명의 연구자를 통합하는 대규모 단일 조직 기관. 이를 연구기관이라고도 할 수 있다.

- 연구 협력체(많은 기관에서, 그리고 많은 부서에서 온 대규모의 비기관 조사자 그룹)

- 연구 네트워크(많은 기관에 걸쳐 있는 연구자들의 느슨한 연합)

Our author group is composed of medical education researchers who lead teams that differ in organization, size, and/or purpose. We were conveniently and informally assembled through existing professional relationships. To compare the differences among them, we each provided detailed case examples of our team structures. We described the defining characteristics of our teams including the organizational structure, primary research emphasis, funding mechanisms, institutional supports, trainee impacts, and/or barriers to success. A few of us (M.A.G., S.M., J.C.B., T.M.C.) then reviewed the descriptions, grouped the teams based on common characteristics, and created 5 common typologies of research team structures:

- single PI labs (labs with a single PI lead),

- multiple PI labs (labs led by small groups of PIs, who are generally within the same department),

- research centers (large, single-institution entities that cross departments but aggregate multiple investigators at the institution; these may also be called research institutes),

- research collaboratives (large, noninstitutional groups of investigators who come from many institutions and may also come from many departments), and

- research networks (loose associations of investigators across many institutions).

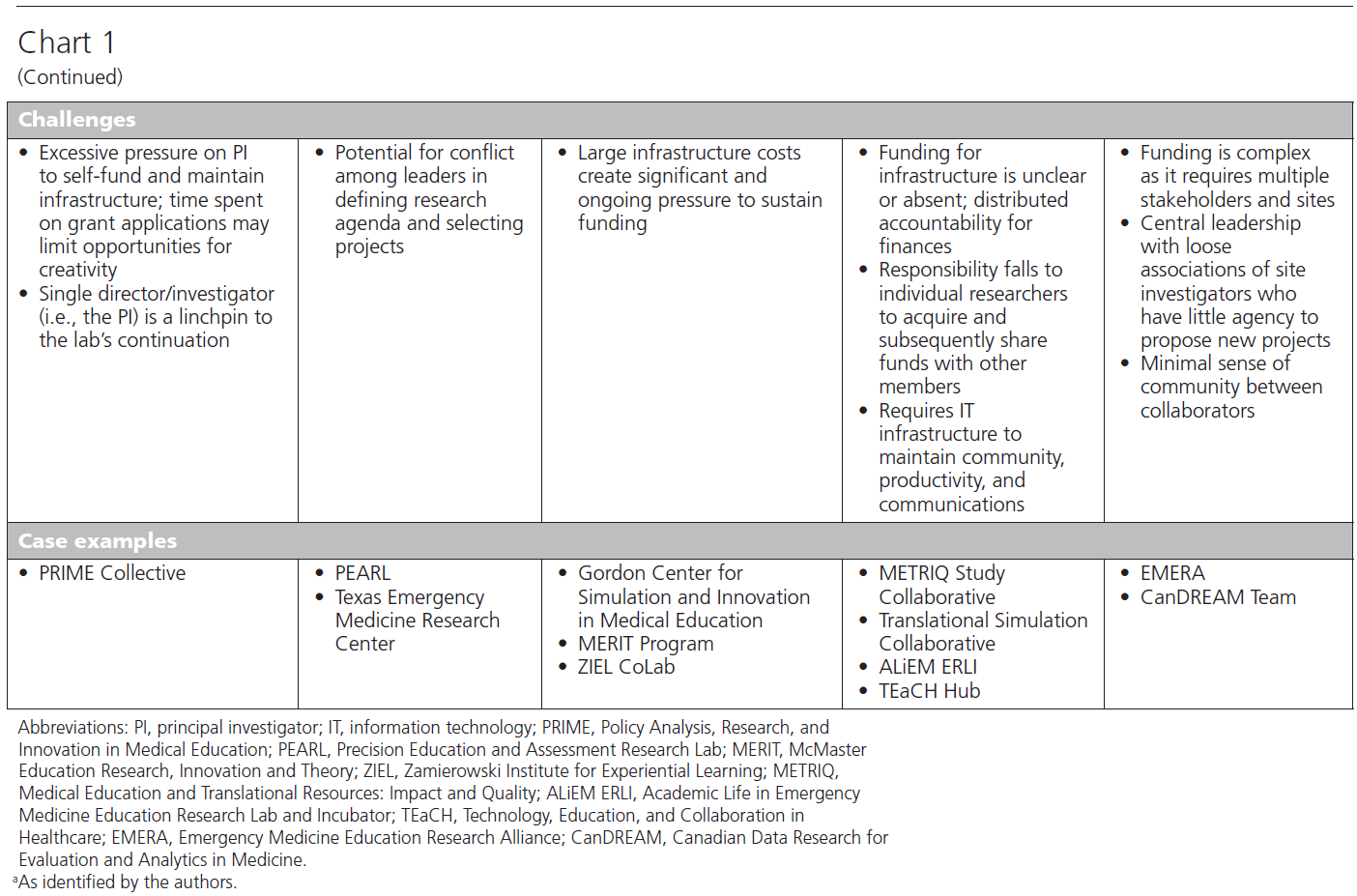

우리의 명명법은 [labs]라는 용어가 대규모 연구 센터, 협력체 및 네트워크와 구별되는 [단일 PI 또는 여러 PI 랩]을 지칭한다는 것이다. 도표 1과 그림 1은 이러한 의료 교육 연구 구조에 대한 개요를 제공한다. 우리는 아래의 다양한 구조를 간단한 예와 함께 설명하고 보충 디지털 부록 1의 각 연구 팀 구조에 대한 완벽한 사례 설명을 제공한다.

Our nomenclature is that the term labs refers to single PI or multiple PI labs, distinct from larger research centers, collaboratives, and networks. Chart 1 and Figure 1 provide an overview of these medical education research structures. We describe the different structures below with brief examples and provide complete case descriptions for each research team structure in Supplemental Digital Appendix 1 (at https://links.lww.com/ACADMED/B274).

단일 PI 연구소

Single PI labs

전통적인 기초과학 연구소와 유사하게, 이들 유닛은 [인프라를 유지하는 단일 PI]에 의존하여 연구 및 교육생을 지원한다. 성공적인 단일 PI 모델의 이점은 일반적으로 [명확한 연구 의제]와 [지속적인 연구비 지원]을 포함한다. 한계로는 개인 PI가 자체 자금을 계속 지원해야 한다는 압박과 연구소를 떠날 경우 연구소가 문을 닫을 가능성이 포함됩니다. 미시간 대학의 의학 교육의 Burkhardt 정책 분석, 연구 및 혁신(PRIME) 컬렉션은 단일 PI 연구소의 한 예이다. 이는 PI의 연구 활동을 그의 전반적인 목표와 일치시켜 의학교육의 정책분석, 연구, 혁신을 연구하고 잠재적인 멘티 및 협력자에 대한 그의 가시성을 높이려는 욕망에서 비롯되었다. 그것의 연구 의제는 "의학과 전문 교육의 힘을 더 큰 공공의 이익을 위해 활용하는 것"이다.

Similar to traditional basic science labs, these units rely on a single PI who maintains the infrastructure to conduct research and support trainees. Benefits of a successful single PI model generally include a clear research agenda and sustained grant funding. Challenges include the pressure on that individual PI to continue self-funding and a likelihood that the lab would close if they left the institution. The Burkhardt Policy Analysis, Research, and Innovation in Medical Education (PRIME) Collective at the University of Michigan is an example of a single PI lab. It stemmed from a desire to align the PI’s research activities with his overall goals to study policy analysis, research, and innovation in medical education and to increase his visibility to potential mentees and collaborators. Its research agenda is “to leverage the power of medical and professional education for the greater public good.” 11

여러 PI 랩

Multiple PI labs

이러한 연구소는 동일한 기관 및 일반적으로 [동일한 부서 내에서 공통의 연구 의제를 가진 소규모 PI 그룹]에 의해 주도됩니다. 연구실 내의 각 PI가 보조금을 시작하고 보유할 수 있기 때문에 그들은 [책임을 공유]하고 [재정적 탄력성을 증가]시켰다. 잠재적 어려움으로는 [연구 이니셔티브와 프로젝트 선정을 둘러싼 집단 갈등의 가능성]이 포함된다. Stanford University의 Precision Education and Assessment Research Lab(Pearl)과 Houston의 Texas University Health Science Center의 Texas Emergency Medicine Research Center는 여러 PI Lab의 두 가지 예입니다. PEARL은 서로 보완하고 다양한 관심사를 가진 연습생들의 멘토링을 가능하게 하는 독특한 기술과 배경을 가진 3명의 연구자가 지휘한다. 그것의 임무는 "의사를 위한 훈련을 개인화하는 최선의 방법을 연구함으로써 의학 교육의 정밀도를 정의하는 것"이다. 텍사스 응급 의학 연구 센터는 학습자를 교육하기 위한 기술 적용에 대해 비슷한 열정을 공유하는 두 명의 PI에 의해 만들어졌습니다. 그것의 연구 목표는 혁신적인 의료 교육 도구의 개발, 구현 및 영향을 측정하는 것이다.

These labs are led by a small group of PIs with a common research agenda at the same institution and generally within the same department. They have shared accountability and increased financial resilience, since each PI within the lab can initiate and hold grants. Challenges include the potential for group conflict surrounding research initiatives and selecting projects. The Precision Education and Assessment Research Lab (PEARL) at Stanford University and the Texas Emergency Medicine Research Center at the University of Texas Health Science Center at Houston are 2 examples of multiple PI labs. 12,13 PEARL is directed by 3 researchers with unique skills and backgrounds that complement one another and allow for the mentorship of trainees with diverse interests. Its mission is to “define precision in medical education by studying the best ways to individualize training for physicians [… to] optimize assessment methods to promote learning and [to] leverage technology to reimagine health professions education.” 12 The Texas Emergency Medicine Research Center was created by 2 PIs who share a similar passion for the application of technology to educate learners. Its research goals are to develop, implement, and measure the impact of innovative medical education tools. 13

연구소

Research centers

때때로 [연구 기관]이라고 불리는 이 그룹들은, [공통의 연구 의제를 공유하며, 여러 부서에 걸쳐 여러 명의 연구자를 지원하는, 기관 수준의 enterprises]이다. 연구소의 설립은 일반적으로 특정 조직 요건을 갖춘 [매우 형식적인 제도적 노력]이다. 그들은 보통 원활한 창업을 보장하기 위해 기부자 자금 또는 중앙 자금 지원을 받지만 장기적인 유지를 위해 상당한 지원이 필요하다. 몇몇은 학위를 수여할 수 있는 능력을 가지고 있거나 그들 자신의 내부 계층이나 승진 과정을 가지고 있다. 우리는 이 연구팀 설계의 3가지 예를 제시합니다.

- Gordon Center for Simulation and Innovation in Medical Education은 학습 및 평가를 위한 혁신 기술의 개발과 평가를 연구하기 위해 마이애미 대학교 우수 센터로 설립되었다. 고든 센터는 연방 보조금과 비연방 보조금을 조합하여 자체 자금을 지원하고 있으며, 최소 50%의 노력을 연구에 바치는 4명의 전임 PI를 보유하고 있다.

- 다음으로, 맥마스터 교육 연구, 혁신 및 이론(MERIT) 프로그램은 원래 맥마스터 대학이 문제 기반 학습 커리큘럼을 설계할 때 지원하는 다중 PI 연구실이었다. 최근 MERITE는 의학 교육 연구에서도 견습생을 지원하는 연구 센터로 발전했다.

- 마지막으로, 캔자스 대학 의료 센터의 Jamierowski 체험 학습 연구소 내의 CoLab은 개별 제공자와 팀 성과를 조사합니다. CoLab의 설립은 사회 및 행동과학 전문지식의 필요성을 인식한 기관 리더십과 수혜자들에 의해 시작되었습니다.

Sometimes called research institutes, these groups are usually institution-wide enterprises that support multiple investigators across multiple departments who share a common research agenda. The establishment of a research center is generally a very formal institutional endeavor with specific organizational requirements. They are usually either donor-funded or centrally funded to ensure a smooth start-up but require significant support to sustain long term. Some have the capacity to grant degrees or have their own internal hierarchy or promotion process. We offer 3 examples of this research team design.

- The Gordon Center for Simulation and Innovation in Medical Education was established as a University of Miami Center of Excellence to study the development and evaluation of innovative technologies for learning and assessment. 14 The Gordon Center is self-funded through a combination of federal and nonfederal grants and has 4 full-time PIs who dedicate a minimum of 50% of their efforts to research.

- Next, the McMaster Education Research, Innovation and Theory (MERIT) Program 15 was originally a multiple PI lab that supported McMaster University in designing problem-based learning curricula. 16,17 Recently, MERIT evolved into a research center that also supports apprenticeships in medical education research. 2,18–20

- Finally, the CoLab within the Zamierowski Institute for Experiential Learning at the University of Kansas Medical Center examines individual provider and team performance. 21 The creation of CoLab was initiated by institutional leadership and benefactors who recognized the need for social and behavioral science expertise.

공동 연구

Research collaboratives

공식적인 [연구 센터]와 달리, 협력체은 [비공식적이고 더 비정형적이며, 대학 내의 부서나 학교에 걸쳐 같은 생각을 가진 연구자들 사이에서, 그리고 아마도 기관들 사이에서 더 유기적으로 발생]한다. [연구 센터]와 달리, 이것은 공식적인 제도적 구조가 아니다. 협업은 여러 PI를 보유하고 프로젝트별 팀을 구성하지만 새로운 벤처기업마다 구성원 자격을 변경할 수 있습니다. 이것은 다른 프로젝트를 후원하지만 같은 회원 그룹 내에 있는 연구 네트워크와는 대조적이다. 협력업체의 해결과제에는 [신뢰할 수 있는 자금 흐름]과 [의사소통을 위한 기술에 대한 의존도]가 포함됩니다.

In contrast to formal research centers, collaboratives are informal and more amorphous, arising more organically between like-minded researchers across departments or schools within a university, and possibly also between institutions. In contrast to research centers, they are not formal institutional structures. Collaboratives have multiple PIs and form project-specific teams but may change their membership with each new venture. This contrasts them from research networks, which sponsor different projects but within the same member group. Challenges for collaboratives include reliable funding streams and dependence on technology for communications.

여기서는 협업의 4가지 예를 강조합니다.

- 첫째, 의료 교육 번역 자료: METRIQ(Impact and Quality) Study Collaborative는 교육 및 번역 온라인 리소스를 개발, 측정 및 평가할 수 있는 방법을 연구하는 여러 기관의 연구자 파트너십입니다. METRIQ는 물리적인 집이 없으며, 오히려 여러 대륙에 걸쳐 수십 개의 프로젝트를 함께 완료한 협력자로 구성되어 있습니다.

- 둘째, 본드 대학의 TSC(Translational Simulation Collaborative)는 시뮬레이션을 통해 건강 관리를 개선하기 위해 노력하는 연구자들의 연결고리이다. 연구 협력의 초점은 번역 시뮬레이션 실습입니다. 따라서, 다양한 시뮬레이션 기법을 통해 의료 서비스 과제를 탐색하고, 잠재적 개선 사항을 테스트하며, 더 나은 의료 관행을 임상 운영에 포함시키는 것을 목표로 한다. TSC는 복잡한 재무 정리, 지적 재산권 문제 및 잠재적인 이해 상충을 가진 서로 다른 기관의 여러 연구 파트너들을 위한 포괄적인 조직 역할을 한다.

- 셋째, ERLI(Academic Life in Emergency Medicine Education Research Lab and Incubator)는 소셜 미디어 기술과 교육 연구자 멘토십에 중점을 둔 비영리 건강 전문 교육 기관 내 연구 협력체이다. ERLI는 대학과 제휴하지 않기 때문에 대부분의 전통적인 자금 조달 메커니즘에 적합하지 않다.

- 마지막으로, 의료 허브의 기술, 교육 및 협업은 기술, 교육 및 디지털 네트워크에 관심이 있는 6개 PI에 의해 조정된 국제 협업입니다. 허브의 핵심 원칙 중 하나가 수사관들 간의 경쟁보다는 투명성과 공유를 장려하는 것이기 때문에 공유된 학술 및 전문성 행동 강령이 있다.

We highlight 4 examples of collaboratives here.

- First, the Medical Education Translational Resources: Impact and Quality (METRIQ) Study Collaborative is a partnership of investigators at multiple institutions who study how educational and translational online resources can be developed, measured, and evaluated for quality. 22 METRIQ has no physical home, rather it consists of collaborators that span multiple continents and have completed dozens of projects together.

- Second, the Translational Simulation Collaborative (TSC) at Bond University is a nexus for researchers working to improve health care through simulation. 23 The focus of the research collaborative is translational simulation practice; thus, it aims to explore health services challenges, test potential improvements, and embed better health care practices into clinical operations through diverse simulation techniques. 24 TSC serves as an umbrella organization for multiple research partners from different institutions with complex financial arrangements, intellectual property issues, and potential conflicts of interest. 25

- Third, the Academic Life in Emergency Medicine Education Research Lab and Incubator (ERLI) is a research collaborative within a nonprofit, health professions education organization that focuses on social media technologies and education researcher mentorship. 26 ERLI is not affiliated with a university and therefore does not qualify for most traditional funding mechanisms; its funding has been largely philanthropic.

- Finally, the Technology, Education, and Collaboration in Healthcare Hub is an international collaborative coordinated by 6 PIs interested in technology, education, and digital networks. There is a shared academic and professionalism code of conduct, as one of the core principles of the hub is to encourage transparency and sharing, rather than competition, among investigators.

연구 네트워크

Research networks

덜 형식적인 [연구 협력체]와는 대조적으로, [연구 네트워크]는 [고도로 구조화된 경향]이 있으며, [연구 주제와 연구 프로젝트에 참여하는 기관의 수를 증가시키는 것을 목표]로 한다. [멀티센터 임상시험]은 종종 연구 네트워크 내에서 수행된다. 회원들은 이러한 임상시험에 참여함으로써 느슨하게 서로 제휴하고 있으며, 의사소통을 자주 하지 않을 수 있다. 자금 조달은 복잡하며, 사이트 리드는 전체 네트워크 내에 대리점이 거의 없을 수 있다. 여기서는 두 가지 예를 프로파일링합니다.

- 응급의학교육연구동맹(EMERA)은 노스웨스턴 대학교 응급의학 레지던트 졸업생들이 의학교육 연구에 관심을 가지고 설립한 단체이다. 회원들은 광범위한 공식적인 연구 훈련과 다양한 행정적 역할을 가지고 있다. EMERA의 임무는 응급의학의 교육적 모범 사례를 개발하는 것을 목표로 하는 다중 기관 연구를 수행하는 것이다.

- 둘째, RCPSC이 전국적인 역량 기반 의료 교육 평가 프레임워크를 시행하기 1년 전에 캐나다 의학 평가 및 분석을 위한 캐나다 데이터 연구(CanDREAM) 팀이 설립되었다. 세 명의 교육 연구원이 이 구현을 연구하기 위해 CanDREAM을 시작했고 캐나다의 거의 모든 의사 교육 프로그램에서 광범위한 교육자 네트워크를 빠르게 모집했습니다. 네 명의 연구원이 이 대규모 팀을 이끌고 새로운 도구를 개발하고, 기계 학습 혁신을 개발하며, 평가 기준을 검증한다.

In contrast to less formal research collaboratives, research networks tend to be highly structured and aim to increase the number of study subjects and participating institutions in research projects. Multicenter clinical trials are often conducted within a research network. Members are loosely affiliated with one another through participation in these trials and may communicate infrequently. Funding is complex, and site leads may have little agency within the overall network. We profile 2 examples here.

- The Emergency Medicine Education Research Alliance (EMERA) was established by a group of Northwestern University emergency medicine residency graduates with an interest in medical education research. 27 Members have a breadth of formal research training and diverse administrative roles. The mission of EMERA is to conduct multi-institutional research aimed at developing educational best practices in emergency medicine.

- Second, the Canadian Data Research for Evaluation and Analytics in Medicine (CanDREAM) Team was established 1 year before the Royal College of Physicians and Surgeons of Canada implemented a nationwide competency-based medical education assessment framework. 28 Three education researchers started CanDREAM to study this implementation and quickly recruited a wide network of educators from nearly all physician training programs in Canada. Four investigators lead this large team to develop new tools, develop machine learning innovations, and validate assessment rubrics.

실험실의 주요 요소

Key Elements of Labs

우리의 경험에서, 우리는 연구실 설립이 의학 교육 연구자들이 경험하는 잘 알려진 제도적 난제를 극복하기 위한 전략적 시도라는 것을 발견했다. 연구실 출범 자체가 교수 라인, 순위, 연구 서사에 따라 교외 자금과 PI 적격성에 대한 엄격한 요건을 갖춘 기관에서는 장애물이 될 수 있다. 우리는 연구실의 성공이 종종 연구자의 비전, 열정 및 정치적 의지에 의해 결정되며, 후원 기관의 초기 노력에서 거의 결과를 얻지 못한다는 것을 발견했다. 위에서 제시한 사례를 검토하면서, [의학 교육 연구실]을 위한 몇 가지 핵심 요소를 확인했습니다.

- 실험실 정체성의 중요성,

- 실험실 지정의 신호 효과,

- 필요한 인프라

- 실험실의 훈련 임무.

In our experience, we have found that the establishment of a lab is a strategic attempt at overcoming the well-recognized institutional challenges experienced by medical education researchers. Launching the lab can itself be a hurdle at institutions that have strict requirements for extramural funding and PI eligibility based on professoriate line, rank, and narrative of research. We have found that lab success is often predicated on the vision, passion, and political will of the investigators and rarely results from the nascent efforts of the sponsoring institution. In our review of the case examples presented above, we identified several key elements for medical education research labs:

- the importance of lab identity,

- the signaling effect of a lab designation,

- required infrastructure, and

- the training mission of a lab.

이러한 요소는 연구실을 다른 팀 구성(즉, 연구 센터, 협업 및 네트워크)과 차별화하는 것으로 나타납니다.

These elements appear to differentiate research labs from other team configurations (i.e., research centers, collaboratives, and networks).

실험실 아이덴티티의 중요성

Importance of lab identity

의학 교육 연구소는 표현형을 공유한다:

- 연구실은 단일 PI 또는 소규모의 선임 연구자 및 PI 그룹에 의해 운영되며,

- 이들은 집중적인 연구 라인을 가지고 있으며,

- 그들의 임무는 가르치는 것보다 연구이다.

우리는 마지막 특성이 연구소와 [교육센터] 또는 [교육협동조합]을 구분하는 결정적인 차이점이라고 본다. 예를 들어, 임상 교육을 주로 제공하는 [시뮬레이션 센터]는 연구에 학문적인 초점을 둔 [시뮬레이션 연구소]와 본질적으로 다르다. 의학 교육 연구소는 또한 PI의 진로를 검증하고 그들의 연구 초점을 명확히 할 수 있다. 우리의 경험에서, 연구자의 자기 개념은 교육 연구자에게 중요하다. 연구자의 본질적인 동기 및 발견에 대한 접근 방식을 생명과학 동료의 것과 일치시키기 때문이다. [PI, 교수 협력자 및 연구 교육생]과 같은 식별자identifier가 관계를 정의하고 멘토/멘티 역할을 명확히 합니다.

Medical education research labs share a phenotype:

- the lab is directed by a single PI or small group of senior researchers and PIs,

who have a focused line of research and

whose mission is research rather than teaching.

We believe that the last characteristic is a critical difference that distinguishes research labs from educational centers or teaching collaboratives. For example, a simulation center that primarily provides clinical training is inherently different from a simulation research lab that has a scholarly focus to its work. 8 A medical education research lab can also validate the career path of the PI and clarify their research focus. In our experience, the self-concept of investigator is important to education researchers, as it aligns their intrinsic motivations and approach to discovery with that of their bioscience colleagues. Identifiers such as PI, faculty collaborator, and research trainee define relationships and clarify mentor/mentee roles. 29

실험실 명칭의 신호효과

Signaling effect of a lab designation

과학자들이 종종 실험실을 가지고 있기 때문에, 의학 교육 연구실을 만드는 것은 병원과 십일조 지도자들에게 개인이 과학자로 보여져야 한다는 신호로 작용할 수 있다. 연구소의 브랜드 이미지는 "소비자"(즉, 과학 발표회 및 부서 회의에 참석하는 사람들)와 기금 모금, 연구실 웹사이트를 갖는 경험을 통해 더욱 만들어진다. [웹사이트]는 특히 기관 외부에 있는 사람들에게 보내는 [합법성에 대한 중요한 신호]이다. 게다가, 우리는 우리의 경험으로 일반적으로 [실험실 구조]가 의료계hall of medicine 내에서 더 잘 이해되며, 그들을 지휘하거나 구성원인 연구자들의 작업에 신뢰성을 더한다는 것을 발견했다. 우리는 "나는 X 조건을 연구한다"(연구자 개인의 업무와 능력을 나타낸다)와 "나의 연구소는 X 조건을 연구한다"(연구팀의 업무와 확장성을 나타낸다)라는 문구 사이에 강력한 신호 차이를 보았다. 이러한 시그널링은 단일 조사자보다 확립된 연구실을 찾을 가능성이 높은 기관 내 다른 사람들과의 협업 또는 멘토링 관계를 초래할 수 있다.

Since scientists often have a lab, the creation of a medical education lab can act as a signal to hospital and decanal leaders that an individual should be seen as a scientist. The brand image of a lab is further crafted through the experiences of having “consumers” (i.e., those who attend scientific presentations and department meetings), fundraising, and having lab websites. Websites are particularly important signals of legitimacy to those external to an institution. Furthermore, we find that in our experience the lab structure is generally well understood within the halls of medicine, adding credibility to the work of the researchers who direct or are members of them. We have seen a powerful signaling difference between the phrases “I study X condition” (signaling the work and capacity of an individual researcher) and “My lab studies X condition” (signaling the work and scalability of a research team). Such signaling may lead to collaborations or mentoring relationships with others in the institution, who are more likely to find established labs than a single investigator.

필요한 인프라

Required infrastructure

실험실 활동과 인력은 [재정적 지원]이 필요하며, 실험실 모델은 개별 조사자가 이용할 수 없는 자원을 제공할 수 있다. 연구실 직원 및 기타 필요에 대한 [자금]은 특별 보조금, 자선 기부, 자문 업무 및 직접 수당, 종자 기금, 보조금 및 교수 급여의 형태로 제도적 지원을 결합하여 추구된다. [후원 기관]은 일반적으로 실험실 관리자 및 관리 직원에게 급여 지원을 제공하지만 통계학자 또는 데이터 과학자와 같은 다른 상근 직원에게는 급여 지원을 제공할 가능성이 낮다. [실험실 인력]은 PI의 연구팀을 구성하고 연구 프로그램을 촉진하는 것을 돕는다. [사무실 공간 및 장비 요구 사항]은 연구 유형 및 조직 접근 방식에 따라 달라집니다. 교육연구실의 [스마트 디자인 및 전략적 자금 지원]은 불충분하거나 산발적인 교외 자금 지원, 연구 대상자 모집의 어려움 등 공통의 장벽을 직접 극복할 수 있다. 이러한 [초기 투자]는 공식적인 부서 지원 없이 어려움을 겪을 수 있는 PI의 성공을 보장할 수 있습니다. 또한, 강력한 인프라는 프로그램 연구자의 신뢰도와 교외 자금을 위해 경쟁할 수 있는 능력을 향상시킨다.

Lab activities and personnel require financial support, and the lab model may provide resources that are not available to individual investigators. Funding for lab personnel and other needs are sought through combinations of extramural grants, philanthropic gifts, consultancy work, and institutional support in the forms of direct stipends, seed funding, grants, and faculty salaries. Sponsoring institutions commonly provide salary support for lab managers and administrative staff but are less likely to do so for other full-time personnel, such as statisticians or data scientists. Lab personnel comprise the research team of a PI and help to catalyze a research program. Office space and equipment needs vary based on the type of research and organizational approach. Smart design and strategic funding of an education research lab can directly overcome common barriers, such as inadequate or sporadic extramural funding and difficulty recruiting study subjects. These initial investments can ensure the success of a PI who might otherwise struggle without such formal departmental support. Moreover, a robust infrastructure improves the credibility of programmatic researchers and their ability to compete for extramural funding.

연구소의 훈련 임무

Training mission of a lab

우리는 [연구 교육생]들이 있는 연구실에는 많은 장점이 있다고 믿는다. 차세대 교육 연구 학자들이 이러한 연구실에서 개발되고 있으며, 우리는 확립된 연구소가 후배 학자들이 성공하기 위해 필요한 멘토링과 인프라에 더 쉽게 접근할 수 있도록 할 수 있다는 것을 발견했다. 비록 연구실에 교육teach이 의무는 아니지만, 많은 사람들이 그들의 PI에서 교육 연구를 수행하는 것을 배우는 교육자들을 후원한다. 이 교육생들은 학생, 거주자, 동료, 그리고 후배 교직원들을 포함할 수 있다. PI 멘토들의 긍정적인 참여와 영향력은 훈련생들의 훈련 프로그램을 향상시킬 수 있다. 중요한 것은, 의학교육연구실에서 교육생들의 초점은, 다른 졸업후 의학교육 훈련 프로그램에서 볼 수 있는 단순한 임상교습이나 학습이론이 아닌, [교육연구방법과 학술활동]이다. 이러한 연수생들은 후원부서 밖에 소속되어 있는 경우도 있어, 연구실을 상호 풍부하게 하는 추가적인 협업으로 이어질 수 있다. 또한 학습자는 더 많은 학습자를 유치한다. 즉, 성공적인 연구 멘토링에 대한 기록은 유사한 관심사를 가진 다른 교육생 및 교수 협력자의 모집 장치 역할을 한다.

We believe that there are many advantages for labs with research trainees. The next generation of education research scholars are developed in such labs, and we have found that established labs can make it easier for junior scholars to gain access to the mentorship and infrastructure that they need to become successful. Though labs are not mandated to teach, many sponsor trainees who learn to conduct education research from their PIs. These trainees can include students, residents, fellows, and junior faculty. The positive engagement and influence of PI mentors can enhance trainee’s training programs. Importantly, the focus for trainees in a medical education lab is education research methods and scholarship, not simply clinical teaching or learning theory as is seen with other postgraduate medical education training programs. In some cases, these trainees have affiliations outside the sponsoring department, which can lead to additional collaborations that reciprocally enrich the lab. Additionally, learners attract more learners; that is, a track record of successful research mentorship acts as a recruiting device for other trainees and faculty collaborators with similar interests.

창업 고려사항 및 지원 가능성

Start-Up Considerations and Likelihood of Support

우리는 최근 의학 교육 연구 경력을 지원하기 위해 혁신적인 조직 접근 방식을 개발하는 연구자들이 급증하는 것을 관찰했다. 왜 그럴까 하는 의문이 생긴다. 왜 실험실이나 더 큰 연구 구조가 그들의 성공을 위해 필요한가? 확실히 광범위한 교육 연구 주체와 투자 수익률을 계산하는 많은 방법(예: 지원금, 논문 발표, 프레젠테이션 전달)이 있다. 단일 PI 랩은 흔하지 않지만 고전적인 단위로 남아 있으며, (의료 교육 분야에서 종종 통합하기 어려운) 랩 인프라와 자금 지원에서 비롯되는 분명한 이점이 있다. 그러나, 우리는 이 최근의 확산에서 가치를 가져오는 다양한 규모와 범위의 다른 구조를 사용하는 것을 관찰했다. 자체 연구소를 설립할지 여부를 고민하고 있는 급성장하는 연구자에게 다음과 같은 의문이 제기된다. "어떤 전략이 최선입니까?" 의학 교육 연구자들이 그들의 생명과학 동료들이 사용하는 단일 PI 연구실을 거울로 삼아야 하는가? 아니면 의학 교육 연구자들이 그 분야에 대한 더 나은 접근법을 찾아내야 하는가? (실험실 시작 가이드는 그림 2를 참조하십시오.) 현재 우리는 연구실 모델이 부족한 것을 우려하는 바인데, 왜냐하면 [스스로 연구를 수행하는 단일 개인]은 훈련생도, 멘토링도, 미래 교육 과학자를 위한 파이프라인도 제공하지 않기 때문이다. 이러한 기회가 없다면, 훈련이 부족하기 때문에 미래에 의학 교육 실험실을 이끌 수 있는 사람이 없을 수도 있다.

We have observed a recent proliferation of investigators developing innovative organizational approaches to support their medical education research careers. The question arises: Why? Why are labs or larger research structures necessary for their success? There is certainly a wide array of education research entities and many ways to calculate return on investment (e.g., grant monies received, papers published, presentations delivered). The single PI lab is uncommon but remains a classic unit of analysis, with clear advantages that stem from lab infrastructure and funding that are often difficult to marshal in the medical education field. However, we observed in this recent proliferation the use of other constructs of various scales and scopes that bring value as well. 19 For the burgeoning researcher contemplating whether to establish a lab of their own, the question arises: “Which strategy is best?” Should medical education researchers mirror the single PI lab used by their bioscience colleagues? Or must medical education researchers identify a better approach for the field? (See Figure 2 for a lab start up guide.) The current scarcity of the lab model concerns us, as a single individual conducting research on their own yields no trainees, no mentoring, and no pipeline for future education scientists. Without these opportunities, there may be no one able to lead medical education labs in the future because of insufficient training.

교육 연구자를 조직 내에서 가장 잘 배치하기 위한 노력은 연구자와 그들의 소속 부서에 영향을 미친다. 우리의 경험에 따르면, [연구 협력체] 또는 [연구 네트워크]에 협력하는 연구원들은 [단일 PI 연구소]를 시작하는 데 필요한 지역 자원을 소진했기 때문에 그렇게 하는 경향이 있습니다. 그들은 처음부터 그러한 자원을 가지고 있었던 적이 없었거나 또는 그것들을 요청할 생각을 한 적이 없었습니다. 우리는 본 논문에서 검토한 다양한 연구소와 더 큰 연구 구조를 지역 연구 환경의 현실에 대한 측정된 반응으로 본다. 각 사례에서 선택한 경로는 특정 시간과 장소에서 사용할 수 있는 유일한 경로였을 수 있습니다. 우리의 사례에서 다양한 구성이 부서장들의 결정에 따라서 만들어진 것인지, 아니면 연구자들 스스로가 의사 결정자들을 중심으로 작업했기 때문에 발생했는지는 불분명하다.

Efforts to best position an education researcher within an organization have implications for the investigator and their home department. In our experience, researchers who align themselves with research collaboratives and networks tend to do so because they have exhausted the local resources necessary to start a single PI lab, they never had such resources to begin with, or they never thought to ask for them. We view the various labs and larger research structures reviewed in this paper as measured responses to the realities of local research environments. The paths chosen for each case example may have been the only one available at that specific time and place. It is unclear from our case examples whether the various configurations occurred in response to decisions by department leaders or because the investigators themselves worked around the decision makers.

또 다른 이론은 이러한 준비는 종종 [필요성]보다는 [편의성]에 의해서 만들어진다는 것이다. 아마도 [저비용의 외부 협력]은 department로 하여금 [의료 교육 연구자]를 지원할 책임을 더 쉽게 포기하도록 만들지도 모른다. 왜 그들이 지원해야 하는지, 얼마나 지원해야 하는지, 어떤 방식으로 지원해야 하는지, 그리고 어떤 목적으로 지원해야 하는지. 아무도 이런 질문을 하지 않고, 그저 외부에서 의학교육 연구 지원을 찾고 있다면, department는 이러한 질문에 대한 답변을 회피하게 되기 쉽다. 우리의 경험으로 볼 때, 이러한 질문에 대한 정직한 답변은 의료 교육 연구, 지원을 요청하는 개별 조사자 또는 둘 다에 대한 가치 판단을 나타낸다.

Another theory is that these arrangements are often made of convenience rather than necessity. Perhaps low-cost, external collaborations more easily allow departments to abdicate their responsibilities to support medical education researchers. Why should they support, how much should they support, in what ways should they support, and to what end should they support? It is easy for a department to avoid answering these questions if no one is asking them but instead looking externally for medical education research support. In our experience, honest answers to these questions represent value judgments about medical education research, the individual investigator seeking support, or both.

지금까지 자원이 부족해왔던 분야에서 얼마나 많은 연구소가 존재할 수 있으며, 존재해야 하는가? 의학 분야의 다른 분야들에 비해 미국에서 이용할 수 있는 의학 교육 연구 보조금은 매우 적다. 연구자들이 재정적으로 자립할 가능성이 낮은 연구 분야의 성장을 옹호하는 것이 옳기는가? 이러한 평가 질문은 학문적 의학에서 제자리를 찾으려는 잘 훈련된 의료 교육 연구자의 수가 증가하고 있는 실존적 위기를 나타낸다. 우리의 사례 예는 연구 정체성을 확립하는 방법에 대한 로드맵을 제공할 수 있지만, [왜, 언제, 또는 연구 정체성을 확립해야 하는지] 또는 [연구 정체성 확립에 얼마나 오래 걸릴 수 있는지]에 대한 로드맵을 제공하지는 않는다. 우리의 경험에 따르면, 실험실 설계에 대한 물류 결정이 내려지기 전에 그러한 결정들은 개인화되고 현재의 고용 상황에 맞춰져야 한다. 당연히 [교육 연구소를 위한 최선의 계획]은 [부서 및 기관 문화의 영향]을 받습니다. 단일 PI 랩을 시작하는 선택은 다른 분야의 랩이 현지에서 일반적인지 또는 기관이 그러한 혁신에 대한 욕구를 가지고 있는지에 따라 달라질 것이다. 이러한 조건(예: 자원이 풍부한 부서 및/또는 지원 기관 문화)이 없다면 교육 연구소를 시작하고 유지하는 데 필요한 지원이 불충분하고 그러한 연구소가 달성할 수 있는 성공은 미미할 수 있다고 생각합니다.

How many research labs can or should exist in a field with historically scarce resources? There are very few medical education research grants available in the United States compared with other disciplines in medicine. Is it even right to advocate for the growth of a research field in which investigators are unlikely to financially sustain themselves? These questions of valuation represent an existential crisis for the growing number of well-trained medical education researchers trying to find their place in academic medicine. Our case examples can provide roadmaps as to how to establish a research identity but not why or when one should or how long one might need to establish a research identity. In our experience, those decisions must be individualized and aligned to one’s current employment situation before any logistical decisions about lab design can be made. Unsurprisingly, the best conceived plans for an education research lab are subject to departmental and/or institutional culture. The choice to start a single PI lab will depend on whether labs in other disciplines are common locally or if the institution has an appetite for such innovation. Without these conditions (e.g., a well-resourced department and/or a supportive institutional culture), we feel that the necessary support to start and maintain an education research lab will be inadequate and that any successes such a lab may achieve may be meager.

결론들

Conclusions

의학교육연구소의 성공적인 출범은 비전과 전략을 전제로 한다. 연구자는 후원 기관 어디에도 이미 존재할 것 같지 않은 것을 기꺼이 만들어내야 하며, 역할 모델링을 본 표준 프로세스와 방법을 넘어서야 합니다. 새로운 연구소장은 기관 외부의 동료들로부터 모델과 도식을 찾아야 할 것 같은데, 우리는 이것이 이 기사를 통해 다소 쉬워졌기를 바란다. 우리의 경험에 따르면, [성공적인 구현]은 [연구소의 출범과 장기적인 생존 가능성 모두를 위한 전략적 계획, 이해관계자 분석의 신중한 사용, 강력한 정치적 감각]을 필요로 한다. 의료 교육 연구소의 사례 사례는 자체 연구소를 설립할 준비를 하는 조사관에게 교훈을 제공한다. 부서 리더들이 교육 연구실을 왜 그리고 얼마나 중시하는지, 그리고 이 평가가 궁극적으로 실험실의 설계와 성공 가능성을 지시하는지에 대한 의문들이 남아 있다.

We believe that the successful launch of a medical education research lab is predicated on vision and strategy. Investigators must be willing to create something that is unlikely to already exist anywhere in their sponsoring institutions, and they must move beyond the standard processes and methods they have seen role modeled. New lab directors will likely need to seek out models and schemas from colleagues outside their institution, something that we hope has been made somewhat easier by this article. In our experience, successful implementation requires

- a strategic plan for both the launch of the lab and its long-term viability,

- deliberate use of stakeholder analyses, and

- a strong political acumen.

Our case examples of medical education research labs offer lessons for investigators preparing to establish their own labs. Questions remain as to why and how much department leaders value education research labs and whether this valuation ultimately dictates the design of a lab and its likelihood of success.

The Purpose, Design, and Promise of Medical Education Research Labs

PMID: 35612923

Abstract

Medical education researchers are often subject to challenges that include lack of funding, collaborators, study subjects, and departmental support. The construct of a research lab provides a framework that can be employed to overcome these challenges and effectively support the work of medical education researchers; however, labs are relatively uncommon in the medical education field. Using case examples, the authors describe the organization and mission of medical education research labs contrasted with those of larger research team configurations, such as research centers, collaboratives, and networks. They discuss several key elements of education research labs: the importance of lab identity, the signaling effect of a lab designation, required infrastructure, and the training mission of a lab. The need for medical education researchers to be visionary and strategic when designing their labs is emphasized, start-up considerations and the likelihood of support for medical education labs is considered, and the degree to which department leaders should support such labs is questioned.

Copyright © 2022 by the Association of American Medical Colleges.

'Articles (Medical Education) > 의학교육연구(Research)' 카테고리의 다른 글

| 혁신 - 의학교육원고의 핵심 특징 정의하기 (J Grad Med Educ. 2022) (0) | 2022.11.09 |

|---|---|

| 의학교육연구자의 연구 패러다임 선택 가이드: 더 나은 연구를 위한 기반 만들기(Med Sci Educ. 2019) (0) | 2022.11.09 |

| 보건의료전문직 교육에서 리포팅 가이드라인의 사용과 가치(Acad Med, 2020) (0) | 2022.09.29 |

| 이름에 무엇이 있는가? 질적 서술 다시 보기 (Res Nurs Health. 2010) (0) | 2022.09.28 |

| 질적 서술(Qualitative Description)에 무슨 일이 있었는가? (Res Nurs Health. 2000) (0) | 2022.09.28 |