교육적 평가의 타당화: 시뮬레이션 등을 위한 프라이머(Adv Simul (Lond). 2016)

Validation of educational assessments: a primer for simulation and beyond

David A. Cook1,2,3* and Rose Hatala4

좋은 평가가 중요하며 시뮬레이션이 도움이 될 수 있습니다.

Good assessment is important; simulation can help

교육자, 관리자, 연구원, 정책 입안자, 심지어 일반 대중들도 건강 전문가 평가의 중요성을 인식하고 있습니다. 역량 기반 교육, 이정표 및 숙달 학습과 같은 트렌드 주제는 성과에 대한 필수 정보를 제공하기 위해 정확하고 시기 적절하며 의미 있는 평가에 달려 있습니다. 전문 역량 평가는 교육을 넘어 임상 실습으로 점차 확대되며, 초기 및 지속적인 전문 면허 및 인증 요건에 대한 지속적인 논의가 이루어진다. 일선 교육자와 교육 연구자는 임상 및 비임상 환경에서 의료 전문가의 방어 가능한 평가를 요구합니다. 실제로, 좋은 평가에 대한 필요성은 그 어느 때보다도 컸으며 앞으로도 계속 증가할 것입니다.

Educators, administrators, researchers, policymakers, and even the lay public recognize the importance of assessing health professionals. Trending topics such as competency-based education, milestones, and mastery learning hinge on accurate, timely, and meaningful assessment to provide essential information about performance. Assessment of professional competence increasingly extends beyond training into clinical practice, with ongoing debates regarding the requirements for initial and ongoing professional licensure and certification. Front-line educators and education researchers require defensible assessments of health professionals in clinical and nonclinical settings. Indeed, the need for good assessments has never been greater and will most likely continue to grow.

직장 기반 평가가 필수적이지만 [1–3] 시뮬레이션은 안전한 환경에서 특정 주제와 기술을 목표로 삼을 수 있기 때문에 보건 전문직 평가에서 중요한 역할을 하며 앞으로도 그럴 것이다 [4–6]. 시뮬레이션에서 평가 조건은 학습자 간에 표준화될 수 있으며 질병, 임상 상황 및 합병증의 스펙트럼을 조작하여, 예를 들어 [흔하지만 중요한 작업, 자주 보이지 않는 조건, 환자를 위험에 빠뜨릴 수 있는 활동 또는 특정 감정 반응을 유발하는 상황]에 초점을 맞출 수 있다[7, 8]. 따라서 시뮬레이션 기반 평가가 점점 일반화되고 있는 것은 놀랄 일이 아니다. 2013년에 발표된 리뷰에서는 시뮬레이션 기반 평가를 평가하는 400개 이상의 연구가 확인되었으며[9] 그 수는 확실히 증가했다. 그러나 동일한 검토에서는 이러한 평가를 뒷받침하는 증거와 그러한 증거를 수집하기 위해 설계된 연구(즉, 검증 연구)에서 심각하고 빈번한 결함을 확인했다. 좋은 시뮬레이션 기반 평가의 필요성과 현재 검증 노력의 과정과 산물의 결함 사이의 차이는 검증 과학의 현재 상태에 대한 인식을 높일 필요가 있음을 시사한다.

Although workplace-based assessment is essential [1–3], simulation does and will continue to play a vital role in health professions assessment, inasmuch as it permits the targeting of specific topics and skills in a safe environment [4–6]. The conditions of assessment can be standardized across learners, and the spectrum of disease, clinical contexts, and comorbidities can be manipulated to focus on, for example, common yet critical tasks, infrequently seen conditions, activities that might put patients at risk, or situations that provoke specific emotional responses [7, 8]. Thus, it comes as no surprise that simulation-based assessment is increasingly common. A review published in 2013 identified over 400 studies evaluating simulation-based assessments [9], and that number has surely grown. However, that same review identified serious and frequent shortcomings in the evidence supporting these assessments, and in the research studies designed to collect such evidence (i.e., validation studies). The gap between the need for good simulation-based assessment and the deficiencies in the process and product of current validation efforts suggests the need for increased awareness of the current state of the science of validation.

이 기사의 목적은 교육자와 교육 연구자를 위한 평가 검증에 대한 입문서를 제공하는 것입니다. 우리는 건강 전문가에 대한 시뮬레이션 기반 평가의 맥락에 중점을 두지만, 이 원칙은 다른 평가 접근법과 주제에도 광범위하게 적용된다고 믿는다.

The purpose of this article is to provide a primer on assessment validation for educators and education researchers. We focus on the context of simulation-based assessment of health professionals but believe the principles apply broadly to other assessment approaches and topics.

타당화는 프로세스입니다.

Validation is a process

[타당화]는 [평가 결과에 기초하여 해석, 사용 및 결정의 적절성을 평가하기 위해 타당성 증거를 수집하는 과정]을 의미한다[10]. 이 정의는 몇 가지 중요한 점을 강조합니다.

Validation refers to the process of collecting validity evidence to evaluate the appropriateness of the interpretations, uses, and decisions based on assessment results [10]. This definition highlights several important points.

첫째, 검증은 엔드포인트가 아닌 프로세스입니다. 평가에 "타당화됨"이라는 라벨을 붙이는 것은 타당화 검사 프로세스가 적용되었다는 것, 즉 증거가 수집되었다는 것만을 의미하며, 다음의 것들은 알려주지 않는다.

- 어떤 프로세스가 사용되었는가,

- 증거의 방향 또는 크기는 어떠한가(즉, 유리한가, 불리한가, 어느 정도까지 사용되었는가?),

- 어떤 gap이 남아 있는가, 또는

- 어떤 맥락(집단, 학습 목표, 교육적 설정)에 대한 증거.

First, validation is a process not an endpoint. Labeling an assessment as “validated” means only that the validation process has been applied—i.e., that evidence has been collected. It does not tell us

- what process was used,

- the direction or magnitude of the evidence (i.e., was it favorable or unfavorable and to what degree?),

- what gaps remain, or

- for what context (learner group, learning objectives, educational setting) the evidence is relevant.

둘째, 타당화는 다음 절에서 논의한 바와 같이 타당성 증거 수집을 포함한다.

Second, validation involves the collection of validity evidence, as we discuss in a following section.

셋째, 타당화와 타당성은 궁극적으로 (이러한 수치 점수 또는 서술적 의견[11]과 같은) 평가 데이터의 특정 해석 또는 사용을 의미하며, 이 해석에 근거한 결정을 의미한다. 우리는 임상 의학에서의 진단 테스트와 유추를 통해 이 점을 설명하는 것이 도움이 된다는 것을 발견했다[12]. 임상시험은 (a) 시험이 결정에 영향을 미치고 (b) 이러한 결정이 조치 또는 환자 결과에 의미 있는 변화를 가져오는 정도까지만 유용하다. 따라서, 의사들은 종종 "만약 그것이 환자 관리에 변화를 주지 않는다면 검사를 지시하지 말라"고 가르친다. 예를 들어, 전립선특이항원(PSA) 검사는 신뢰성이 높고 전립선암과 강하게 연관돼 있다. 그러나 전립선암 검진은 암이 없을 때 상승하는 경우가 많고, 검사가 불필요한 전립선 생체검사와 환자의 불안감을 유발하며, 종종 발견되는 암을 치료해도 임상 결과가 개선되지 않기 때문에 더 이상 널리 권장되지 않는다. (즉, 치료가 필요하지 않음). 즉, 많은 환자에서 부정적인/유해한 결과가 시험(검진)의 유익한 결과보다 크다[13–15].

Third, validation and validity ultimately refer to a specific interpretation or use of assessment data, be these numeric scores or narrative comments [11], and to the decisions grounded in this interpretation. We find it helpful to illustrate this point through analogy with diagnostic tests in clinical medicine [12]. A clinical test is only useful to the degree that (a) the test influences decisions, and (b) these decisions lead to meaningful changes in action or patient outcomes. Hence, physicians are often taught, “Don’t order the test if it won’t change patient management.” For example, the prostate-specific antigen (PSA) test has high reliability and is strongly associated with prostate cancer. However, this test is no longer widely recommended in screening for prostate cancer because it is frequently elevated when no cancer is present, because testing leads to unnecessary prostate biopsies and patient anxiety, and because treating cancers that are found often does not improve clinical outcomes (i.e., treatment is not needed). In other words, the negative/harmful consequences outweigh the beneficial consequences of testing (screening) in many patients [13–15].

그러나 PSA 검사는 전립선암을 진단하고 치료한 후에도 여전히 질병의 지표로 유용하다. 이 예를 교육 테스트(평가)와 의사 결정의 중요성에 반영하면 이러하다.

- (1) 만약 그것이 관리management를 바꾸지 않는다면, 시험을 하지 말아야 한다.

- (2) 하나의 목표 또는 설정에 유용한 시험은 다른 맥락에서 덜 유용할 수 있다.

- (3) 시험의 전반적인 유용성을 결정할 때 시험의 장기적인 결과와 다운스트림 결과를 고려해야 한다.

However, PSA testing is still useful as a marker of disease once prostate cancer has been diagnosed and treated. Reflecting this example back to educational tests (assessments) and the importance of decisions:

- (1) if it will not change management the test should not be done,

- (2) a test that is useful for one objective or setting may be less useful in another context, and

- (3) the long-term and downstream consequences of testing must be considered in determining the overall usefulness of the test.

평가 타당화가 중요한 이유는 무엇입니까?

Why is assessment validation important?

교육적 평가에 대한 엄격한 타당화는 최소한 두 가지 이유로 매우 중요하다.

Rigorous validation of educational assessments is critically important for at least two reasons.

첫째, 평가를 사용하는 사람들은 결과를 신뢰할 수 있어야 한다. 유효성 확인은 신뢰도(유효성)에 관한 간단한 예스/노 답변을 제공하지 않습니다. 오히려, 신뢰도나 타당성의 판단은 의도된 적용과 맥락에 따라 달라지며 일반적으로 정도의 문제이다. 타당화는 그러한 [판단]과 [남아있는 격차gaps]에 대한 비판적 평가를 할 수 있는 증거를 제공한다.

First, those using an assessment must be able to trust the results. Validation does not give a simple yes/no answer regarding trustworthiness (validity); rather, a judgment of trustworthiness or validity depends on the intended application and context and is typically a matter of degree. Validation provides the evidence to make such judgments and a critical appraisal of remaining gaps.

둘째, 새로운 객관식 문제, 척도 항목 또는 시험장이 사실상의 새로운 도구를 만들기 때문에 평가 도구, 도구 및 활동의 수는 본질적으로 [무한]하다. 그러나 주어진 교육자에게 평가가 필요한 관련 과제와 구성은 [유한]하다. 따라서 각 교육자는 자신의 즉각적인 요구에 가장 잘 맞는 평가 솔루션을 식별하기 위해 무수한 가능성을 분류하고 선별할 수 있는 정보가 필요합니다. 잠재적 해결책으로는 기존 평가도구 선택, 기존 평가도구 적응, 여러 평가도구의 요소 결합 또는 새로운 평가도구를 새로 생성 등이 있습니다 [16]. 교육자는 점수의 신뢰도뿐만 아니라 시험 시행과 관리 과정에서 발생하는 비용, 수용성, 타당성 등 물류 및 실무적 이슈에 대한 정보가 필요하다.

Second, the number of assessment instruments, tools, and activities is essentially infinite, since each new multiple-choice question, scale item, or exam station creates a de facto new instrument. Yet, for a given educator, the relevant tasks and constructs in need of assessment are finite. Each educator thus needs information to sort and sift among the myriad possibilities to identify the assessment solution that best meets his or her immediate needs. Potential solutions include selecting an existing instrument, adapting an existing instrument, combining elements of several instruments, or creating a novel instrument from scratch [16]. Educators need information regarding not only the trustworthiness of scores, but also the logistics and practical issues such as cost, acceptability, and feasibility that arise during test implementation and administration.

또한 시뮬레이션 기반 평가는 그 정의상 "의미 있는meaningful" 임상 또는 교육적 결과의 대체물surrogate로 사용된다[17]. 우리는 [학습자들이 시뮬레이션된 환경에서 얼마나 잘 수행하는지]를 알고 싶은 것이 아니다; 우리는 그들이 실제 생활에서 어떻게 수행하는지 알고 싶다. 타당화에 대한 포괄적인 접근법에는 평가 결과가 다른 설정과 결과에 추정하는 정도를 평가하는 것이 포함된다[18, 19].

In addition, simulation-based assessments are almost by definition used as surrogates for a more “meaningful” clinical or educational outcome [17]. Rarely do we actually want to know how well learners perform in a simulated environment; usually, we want to know how they would perform in real life. A comprehensive approach to validation will include evaluating the degree to which assessment results extrapolate to different settings and outcomes [18, 19].

타당성 증거란 무엇을 의미하는가?

What do we mean by validity evidence?

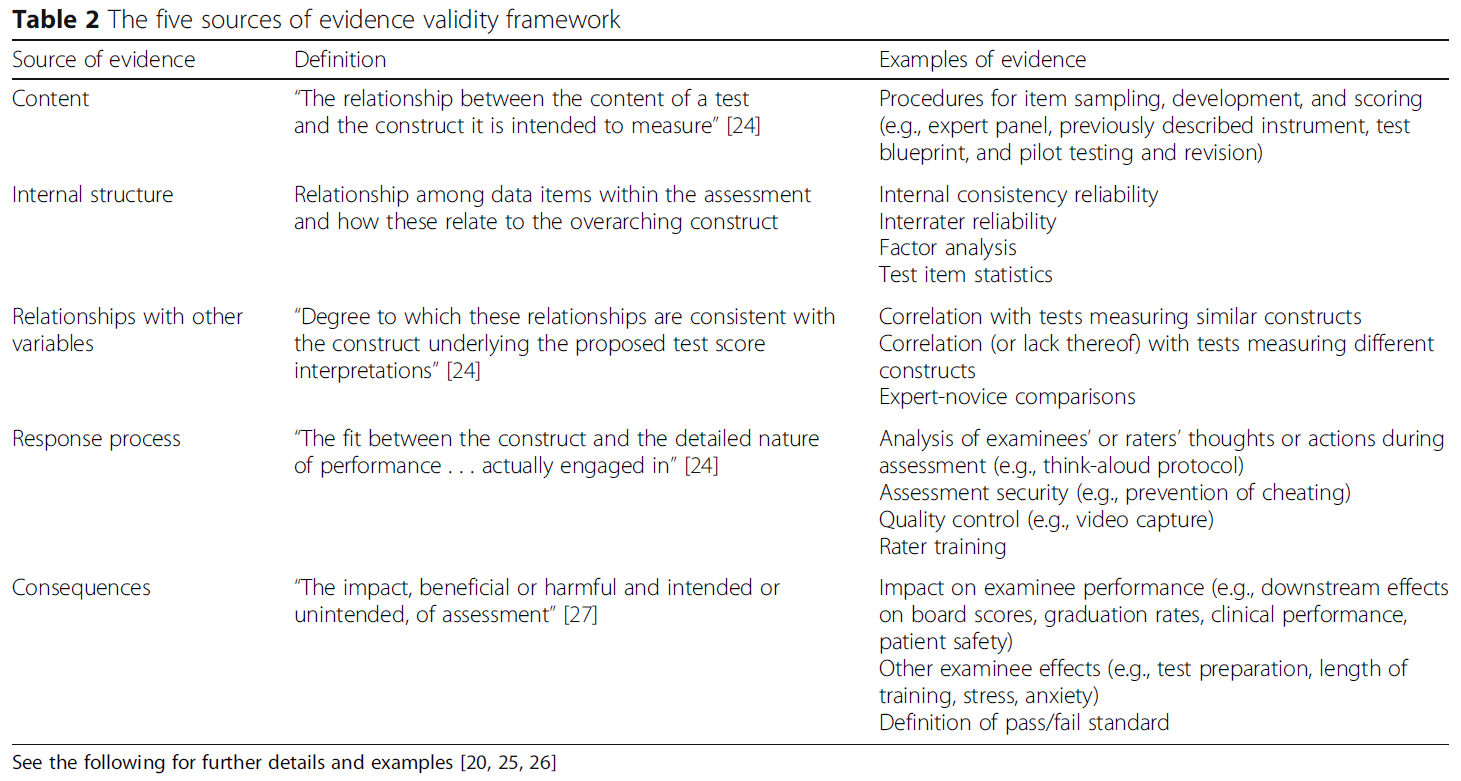

[고전적인 타당화 프레임워크]는 적어도 세 가지 다른 "유형"의 타당성을 식별했다: 내용, 구성, 준거. 표 1을 참조하십시오. 그러나 이러한 관점은 보다 미묘하면서도 통일된 실용적 타당성 관점으로 대체되었다[10, 12, 20]. 현대의 틀은 타당성을 [가설]로 보고, 연구자가 [연구 가설]을 지지하거나 반박하기 위해 증거를 수집하는 것처럼, 타당성 증거는 [타당성 가설]을 지지하거나 반박하기 위해 수집된다. 가설을 절대 증명할 수 없듯이, 타당성은 절대 증명할 수 없다. 그러나 증거가 축적됨에 따라 [타당성 주장을 지지하거나 반박]할 수 있다.

Classical validation frameworks identified at least three different “types” of validity: content, construct, and criterion; see Table 1. However, this perspective has been replaced by more nuanced yet unified and practical views of validity [10, 12, 20]. Contemporary frameworks view validity as a hypothesis, and just as a researcher would collect evidence to support or refute a research hypothesis, validity evidence is collected to support or refute the validity hypothesis (more commonly referred to as the validity argument). Just as one can never prove a hypothesis, validity can never be proven; but evidence can, as it accumulates, support or refute the validity argument.

최초의 현대적 타당성 프레임워크는 1989년 Messick에 의해 제안되었고 [21] 1999년 [22] 그리고 2014년 [23]에 이 분야의 표준으로 채택되었다. 이 프레임워크는 고전적 프레임워크와 부분적으로 중복되는 다섯 가지 타당성 증거의 출처를 제안한다[24–26]. (표 2 참조)

- 콘텐츠 증거(콘텐츠 유효성의 개념과 본질적으로 동일)는 평가 항목(시나리오, 질문 및 응답 옵션 포함)이 측정하고자 하는 구성을 반영하도록 하기 위해 취한 단계를 말한다.

- 내부 구조 증거는 신뢰성, 도메인 또는 요인 구조, 항목 난이도 등 개별 평가 항목과 주요 구성 요소 간의 관계를 평가한다.

- 다른 변수와의 관계 증거는 평가 결과와 다른 측정 또는 학습자 특성 사이의 연관성을 긍정 또는 부정, 강 또는 약하게 평가한다. 이것은 준거criterion 타당성과 구성construct 타당성에 대한 고전적인 개념과 밀접하게 일치한다.

- 반응 프로세스 증거는 문서화된 레코드(응답, 등급 또는 자유 텍스트 서술)가 관찰된 성능을 얼마나 잘 반영하는지 평가합니다. 응답 품질을 방해할 수 있는 문제에는 제대로 훈련되지 않은 평가자, 저품질 비디오 녹화, 부정행위 등이 포함된다.

- 결과 증거는 유익하거나 유해한 평가 자체와 그 결과로 발생하는 결정과 조치의 영향을 살펴봅니다 [27–29].

The first contemporary validity framework was proposed by Messick in 1989 [21] and adopted as a standard for the field in 1999 [22] and again in 2014 [23]. This framework proposes five sources of validity evidence [24–26] that overlap in part with the classical framework (see Table 2).

- Content evidence, which is essentially the same as the old concept of content validity, refers to the steps taken to ensure that assessment items (including scenarios, questions, and response options) reflect the construct they are intended to measure.

- Internal structure evidence evaluates the relationships of individual assessment items with each other and with the overarching construct(s), e.g., reliability, domain or factor structure, and item difficulty.

- Relationships with other variables evidence evaluates the associations, positive or negative and strong or weak, between assessment results and other measures or learner characteristics. This corresponds closely with classical notions of criterion validity and construct validity.

- Response process evidence evaluates how well the documented record (answer, rating, or free-text narrative) reflects the observed performance. Issues that might interfere with the quality of responses include poorly trained raters, low-quality video recordings, and cheating.

- Consequences evidence looks at the impact, beneficial or harmful, of the assessment itself and the decisions and actions that result [27–29].

교육자와 연구자는 평가 및 해당 결정과 가장 관련이 있는 증거를 확인한 후 이 증거를 수집하고 평가하여 타당성 주장을 공식화해야 한다. 불행하게도, 이 "5가지 근거 소스" 프레임워크는 증거 사이의 우선 순위를 정하거나, 증거를 선택하는 데 있어 불완전한 지침만을 제공한다.

Educators and researchers must identify the evidence most relevant to their assessment and corresponding decision, then collect and appraise this evidence to formulate a validity argument. Unfortunately, the “five sources of evidence” framework provides incomplete guidance in such prioritization or selection of evidence.

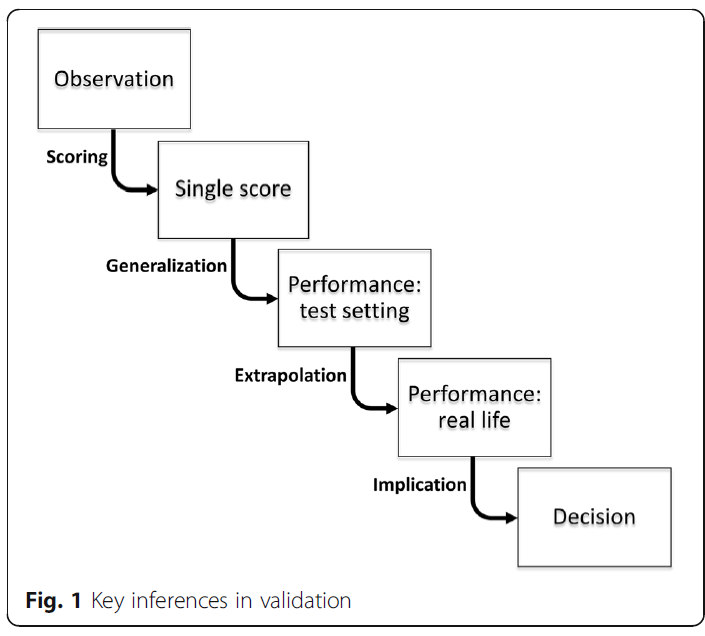

Kane의 최신 유효성 프레임워크는 평가 활동에서 4가지 주요 추론을 식별함으로써 우선순위 부여 문제를 다룬다(표 3). 고전적 또는 5가지 증거 소스 프레임워크에 익숙한 사람들에게 케인의 프레임워크는 용어와 개념이 완전히 새로워 처음에는 종종 도전적이다. 사실, 이 프레임워크를 학습할 때, 우리는 이전 프레임워크의 개념과 일치하려고 시도하지 않는 것이 도움이 된다는 것을 발견했다. 오히려, 우리는 모든 평가 활동에 관련된 단계들을 개념적으로 고려하는 것으로 혁신을 시작한다.

The most recent validity framework, from Kane [10, 12, 30], addresses the issue of prioritization by identifying four key inferences in an assessment activity (Table 3). For those accustomed to the classical or five-evidence-sources framework, Kane’s framework is often challenging at first because the terminology and concepts are entirely new. In fact, when learning this framework, we have found that it helps to not attempt to match concepts with those of earlier frameworks. Rather, we begin de novo by considering conceptually the stages involved in any assessment activity.

평가는 객관식 시험 항목에 대한 답변, 실제 또는 표준화된 환자 인터뷰 또는 절차적 작업 수행과 같은 일종의 [수행performance]으로 시작한다.

- 이 관찰에 기초하여, 우리가 성능 수준을 반영한다고 가정하는 점수 또는 서면 서술이 문서화됩니다.

- 여러 점수 또는 서술이 결합되어 시험 환경에서 수행능력을 반영한다고 가정하는 전체 점수 또는 해석을 생성합니다.

- 시험 환경에서의 수행능력은 실제 환경에서 원하는 성능을 반영하는 것으로 가정한다.

- 그리고 그 성과는 의미 있는 결정을 내리기 위한 합리적인 근거를 구성한다고 가정한다(그림 1 참조).

An assessment starts with a performance of some kind, such as answering a multiple-choice test item, interviewing a real or standardized patient, or performing a procedural task.

- Based on this observation, a score or written narrative is documented that we assume reflects the level of performance;

- several scores or narratives are combined to generate an overall score or interpretation that we assume reflects the desired performance in a test setting;

- the performance in a test setting is assumed to reflect the desired performance in a real-life setting; and

- that performance is further assumed to constitute a rational basis for making a meaningful decision (see Fig. 1).

이러한 가정들 각각은 실제로 정당화될 수 없는 추론을 나타낸다.

- 성과의 문서화가 부정확할 수 있다. (점수 추론)

- 개별 점수의 합성은 원하는 시험 영역에 걸쳐 수행능력을 정확하게 반영하지 못할 수 있다(일반화 추론).

- 합성 점수는 또한 실제 수행능력을 반영하지 않을 수 있다(외삽 추론).

- 이 성능(시험 설정 또는 실제)은 원하는 결정을 위한 적절한 기반을 형성하지 못할 수 있다. (함의 또는 결정 추론)

Each of these assumptions represents an inference that might not actually be justifiable.

- The documentation of performance (scoring inference) could be inaccurate;

- the synthesis of individual scores might not accurately reflect performance across the desired test domains (generalization inference);

- the synthesized score also might not reflect real-life performance (extrapolation inference); and

- this performance (in a test setting or real life) might not form a proper foundation for the desired decision (implications or decision inference).

케인의 타당성 프레임워크는 이 네 가지 추론에 대한 정당성을 명시적으로 평가한다. 우리는 케인의 프레임워크에 대해 더 알고 싶은 사람들을 그의 설명[10, 30]과 그의 최근 작품 개요[12]에 언급한다.

Kane’s validity framework explicitly evaluates the justifications for each of these four inferences. We refer those wishing to learn more about Kane’s framework to his description [10, 30] and to our recent synopsis of his work [12].

교육자들과 연구원들은 종종 얼마나 많은 타당성 증거가 필요한지 그리고 새로운 맥락에서 도구를 사용할 때 이전 검증의 증거가 어떻게 적용되는지 묻는다. 불행하게도, 이러한 질문에 대한 대답은 잘못된 결정의 위험성(즉, 평가의 "부담stakes"), 의도된 사용 및 상황적 차이의 크기와 중요성을 포함한 몇 가지 요인에 따라 달라진다. 모든 평가가 중요해야 하지만, 일부 평가 결정은 다른 평가보다 학습자의 삶에 더 많은 영향을 미친다. 연구 목적으로 사용되는 평가를 포함하여 더 큰 영향력 또는 더 큰 위험성을 가진 평가는 증거의 양, 품질 및 범위에 대해 더 높은 기준을 가질 가치가 있다. 엄밀히 말하면, 타당성 증거는 그것이 수집된 목적, 맥락 및 학습자 그룹에만 적용된다. 기존 증거는 평가 접근법의 선택을 안내할 수 있지만 향후 해석과 사용을 지지하지는 않는다.

Educators and researchers often ask how much validity evidence is needed and how the evidence from a previous validation applies when an instrument is used in a new context. Unfortunately, the answers to these questions depend on several factors including the risk of making a wrong decision (i.e., the “stakes” of the assessment), the intended use, and the magnitude and salience of contextual differences. While all assessments should be important, some assessment decisions have more impact on a learner’s life than others. Assessments with higher impact or higher risk, including those used for research purposes, merit higher standards for the quantity, quality, and breadth of evidence. Strictly speaking, validity evidence applies only to the purpose, context, and learner group in which it was collected; existing evidence might guide our choice of assessment approach but does not support our future interpretations and use.

물론, 현실에서, 우리는 타당성 주장을 구성할 때 기존 증거를 일상적으로 고려한다. 오래된 증거가 새로운 상황에 적용되는지 여부는 상황 차이가 증거의 관련성에 어떻게 영향을 미칠 수 있는지에 대한 비판적인 평가를 필요로 한다. 예를 들어,

- 체크리스트의 일부 항목은 서로 다른 직무에 걸쳐 관련될 수 있는 반면, 다른 항목은 직무에 특정적일 수 있다.

- 신뢰성은 그룹마다 크게 다를 수 있으며, 일반적으로 더 동질적인 학습자 사이에서 더 낮은 값을 갖는다.

- [맥락의 차이(입원 환자 대 외래 환자), 학습자 수준(의대학생 대 시니어 전공의), 목적]의 차이가 내용, 다른 변수와의 관계 또는 결과에 대한 우리의 해석에 영향을 미칠 수 있다.

Of course, in practice, we routinely consider existing evidence in constructing a validity argument. Whether old evidence applies to a new situation requires a critical appraisal of how situational differences might influence the relevance of the evidence. For example,

- some items on a checklist might be relevant across different tasks while others might be task-specific;

- reliability can vary substantially from one group to another, with typically lower values among more homogeneous learners; and

- differences in context (inpatient vs outpatient), learner level (junior medical student vs senior resident), and purpose might affect our interpretation of evidence of content, relations with other variables, or consequences.

우리의 것과 유사한 맥락에서 수집된 증거와 다양한 맥락에서 일관된 발견은 우리의 타당성 주장을 구성하는 데 기존 증거를 포함하려는 우리의 선택을 뒷받침할 것이다.

Evidence collected in contexts similar to ours and consistent findings across a variety of contexts will support our choice to include existing evidence in constructing our validity argument.

타당성 논쟁은 무엇을 의미합니까?

What do we mean by validity argument?

케인은 네 가지 핵심 추론을 명확히 하는 것 외에도 사전 "해석-사용 주장argument" 또는 "IUA"와 최종 "타당성 주장"이라는 두 가지 뚜렷한 논쟁 단계를 강조함으로써 검증 과정에서 "주장"에 대한 우리의 이해를 진전시켰다.

In addition to clarifying the four key inferences, Kane has advanced our understanding of “argument” in the validation process by emphasizing two distinct stages of argument: an up-front “interpretation-use argument” or “IUA,” and a final “validity argument.”

위에서 언급한 바와 같이, 모든 해석과 사용(즉, 결정)은 다수의 가정을 수반한다. 예를 들어 가상 현실 평가의 점수를 해석할 때 시각적 표현, 시뮬레이터 제어 및 작업 자체를 포함한 시뮬레이션 작업이 임상적으로 중요한 작업과 관련이 있다고 가정할 수 있다.

- 채점 알고리즘이 해당 작업의 중요한 요소를 설명하는지 여부

- 교육자 성과를 신뢰성 있게 측정하기에 충분한 과제와 과제 간 다양성이 있는지 여부

- 훈련생들이 목표 점수를 달성할 때까지 계속 연습하도록 하는 것이 유익한지 여부

As noted above, all interpretations and uses—i.e., decisions—incur a number of assumptions. For example, in interpreting the scores from a virtual reality assessment, we might assume that the simulation task—including the visual representation, the simulator controls, and the task itself—has relevance to tasks of clinical significance;

- that the scoring algorithm accounts for important elements of that task;

- that there are enough tasks, and enough variety among tasks, to reliably gauge trainee performance; and

- that it is beneficial to require trainees to continue practicing until they achieve a target score.

이러한 가정들은 테스트할 수 있고 테스트해야 합니다! 많은 가정이 암묵적이며 증거를 수집하거나 조사하기 전에 이를 인식하고 명시적으로 진술하는 것이 필수적인 단계이다. 의도된 용도를 지정했으면 다음을 수행해야 합니다.

- (a) 가능한 한 많은 [가정을 확인]한다.

- (b) 가장 우려되거나 의심스러운 [가정에 우선 순위]를 매긴다.

- (c) 각 가정의 정확성을 확인하거나 반박할 [증거를 수집하는 계획]을 세우다

그 결과 우선 순위화된 가정과 원하는 증거 목록이 [해석-사용 주장]을 구성한다. 해석-사용 주장을 명시하는 것은 연구 가설을 진술하고 그 가설을 경험적으로 검증하는 데 필요한 증거를 명확히 하는 것과 개념적으로나 중요하다.

These and other assumptions can and must be tested! Many assumptions are implicit, and recognizing and explicitly stating them before collecting or examining the evidence is an essential step. Once we have specified the intended use, we need to

- (a) identify as many assumptions as possible,

- (b) prioritize the most worrisome or questionable assumptions, and

- (c) come up with a plan to collect evidence that will confirm or refute the correctness of each assumption.

The resulting prioritized list of assumptions and desired evidence constitute the interpretation-use argument. Specifying the interpretation-use argument is analogous both conceptually and in importance to stating a research hypothesis and articulating the evidence required to empirically test that hypothesis.

일단 평가 계획이 구현되고 증거가 수집되면, 우리는 증거를 합성하고, 이러한 발견을 원래의 해석-사용 논쟁에서 예상한 것과 대조하고, 강점과 약점을 식별하고, 이것을 [최종 타당성 주장]으로 증류한다. 타당성 주장은 해석과 용도가 실제로 방어할 수 있다는 것(또는 중요한 갭이 남아 있다는 것)을 다른 사람들에게 설득하려고 시도하지만, [잠재적 사용자들]은 [근거의 충분성]과 [bottom-line 평가]의 정확성에 관한 자신의 결론에 도달할 수 있어야 한다. 우리의 일은 변호사가 배심원 앞에서 사건을 주장하는 것과 비슷하다. 우리는 전략적으로 증거를 찾고 정리하고 해석하며 정직하고 완전하며 설득력 있는 주장을 제시하지만, 궁극적으로 의도된 사용과 맥락에 대한 타당성에 대한 판단을 내리는 것은 [잠재적 사용자]라는 "배심원jury"이다. [31]

Once the evaluation plan has been implemented and evidence has been collected, we synthesize the evidence, contrast these findings with what we anticipated in the original interpretation-use argument, identify strengths and weaknesses, and distill this into a final validity argument. Although the validity argument attempts to persuade others that the interpretations and uses are indeed defensible—or that important gaps remain—potential users should be able to arrive at their own conclusions regarding the sufficiency of the evidence and the accuracy of the bottom-line appraisal. Our work is similar to that of an attorney arguing a case before a jury: we strategically seek, organize, and interpret the evidence and present an honest, complete, and compelling argument, yet it is the “jury” of potential users that ultimately passes judgment on validity for their intended use and context. [31]

단일 연구가 특정 결정을 뒷받침하는 데 필요한 모든 타당성 증거를 수집할 가능성은 낮다. 오히려, 다른 연구는 일반적으로 논쟁의 다른 측면을 다룰 것이며, 교육자들은 그들의 맥락과 필요에 대한 평가 도구를 선택할 때 [증거의 전체성totality]을 고려할 필요가 있다.

It is unlikely that any single study will gather all the validity evidence required to support a specific decision. Rather, different studies will usually address different aspects of the argument, and educators need to consider the totality of the evidence when choosing an assessment instrument for their context and needs.

물론, 연구원들이 단순히 증거를 수집하는 것만으로는 충분하지 않다. 중요한 것은 증거의 양뿐만 아니라 관련성, 품질 및 폭이다. 점수 신뢰성에 대한 풍부한 증거를 수집한다고 해서 내용, 관계 또는 결과에 대한 증거가 필요하지 않습니다. 반대로, 기존의 증거가 견고하고 엄격한 항목 개발 과정과 같이 우리의 맥락에 논리적으로 적용될 수 있다면, 그러한 노력을 복제하는 것이 최우선 순위가 아닐 수 있다. 불행하게도, 연구자들은, 종종 가정의 중요성을 의도적으로 우선시하지 못하거나 [해석-사용 주장]을 완전히 건너뛰기 때문에, 가장 중요한 가정보다는 시험하기 쉬운 가정에 대한 증거를 보고할 수 있다.

Of course, it is not enough for researchers to simply collect any evidence. It is not just the quantity of evidence that matters, but also the relevance, quality, and breadth. Collecting abundant evidence of score reliability does not obviate the need for evidence about content, relationships, or consequences. Conversely, if existing evidence is robust and logically applicable to our context, such as a rigorous item development process, then replicating such efforts may not be top priority. Unfortunately, researchers often inadvertently fail to deliberately prioritize the importance of the assumptions or skip the interpretation-use argument altogether, which can result in reporting evidence for assumptions that are easy to test rather than those that are most critical.

검증에 대한 실용적인 접근 방식

A practical approach to validation

위의 개념들은 검증 과정을 이해하는 데 필수적이지만, 이 과정을 실용적인 방법으로 적용할 수 있는 것도 중요하다. 표 4에는 위에서 설명한 타당성 프레임워크(클래식, 메식 또는 케인)와 함께 작동할 수 있는 검증에 대한 하나의 가능한 접근법이 요약되어 있다. 이 섹션에서는 가상 시뮬레이션 기반 예를 사용하여 이 접근 방식을 설명합니다.

Although the above concepts are essential to understanding the process of validation, it is also important to be able to apply this process in practical ways. Table 4 outlines one possible approach to validation that would work with any of the validity frameworks described above (classical, Messick, or Kane). In this section, we will illustrate this approach using a hypothetical simulation-based example.

파트 태스크 트레이너를 사용하여 1학년 내과 레지던트에게 요추 천자(LP)를 가르치고 있다고 상상해 보십시오. 교육 세션이 끝나면 학습자가 실제 환자와 함께 안전하게 LP를 시도할 준비가 되어 있는지 평가하고자 합니다.

Imagine that we are teaching first year internal medicine residents lumbar puncture (LP) using a part-task trainer. At the end of the training session, we wish to assess whether the learners are ready to safely attempt an LP with a real patient under supervision.

1. 구성 및 제안된 해석을 정의합니다.

1.Define the construct and proposed interpretation

타당화는 관심 구인을 고려하는 것으로 시작한다. 예를 들어, 우리는 LP 표시와 위험에 대한 학습자의 지식, LP 수행 능력 또는 LP를 시도할 때 비기술적 기술에 관심이 있는가? 이들은 각각 다른 평가 도구를 선택해야 하는 서로 다른 구인이다. 지식을 평가하기 위해 객관식 질문(MCQ)을 선택할 수도 있고, 부분 작업 트레이너를 사용하여 절차적 스킬을 평가하기 위한 일련의 스킬 스테이션(OSATS) [32] 또는 소생 시나리오를 사용하여 선택할 수도 있습니다. 충실도가 높은 마네킹과 비기술적 기술(NOTECHS) 척도로 비기술적 기술을 평가하기 위한 공급자 팀[33].

Validation begins by considering the construct of interest. For example, are we interested in the learners’ knowledge of LP indications and risks, their ability to perform LP, or their non-technical skills when attempting an LP? Each of these is a different construct requiring selection of a different assessment tool: we might choose multiple-choice questions (MCQs) to assess knowledge, a series of skill stations using a part-task trainer to asses procedural skill with an Objective Structured Assessment of Technical Skills (OSATS) [32], or a resuscitation scenario using a high-fidelity manikin and a team of providers to assess non-technical skills with the Non-Technical Skills (NOTECHS) scale [33]

우리의 예에서, [구인]은 "LP 기술"이고 [해석]은 "학습자는 실제 환자에게 감독된 LP를 시도하기에 충분한 기본적인 LP 기술을 가지고 있다"는 것이다.

In our example, the construct is “LP skill” and the interpretation is that “learners have fundamental LP skills sufficient to attempt a supervised LP on a real patient.”

2. 의도된 결정을 명시합니다.

2.Make explicit the intended decision(s)

그러한 해석에 기초하여 [우리가 내릴 것으로 예상되는 결정]에 대한 명확한 생각이 없다면, 우리는 일관성 있는 타당성 주장을 만들 수 없을 것이다.

Without a clear idea of the decisions we anticipate making based on those interpretations, we will be unable to craft a coherent validity argument.

우리의 예에서, 우리의 [최우선 결정]은 [학습자가 실제 환자에게 감독된 LP를 시도할 수 있는 충분한 절차적 역량을 가지고 있는지 여부]이다. 대안적으로 고려할 수 있는 다른 결정에는 학습자에게 [피드백을 제공할 성과 지점을 식별]하거나, 학습자가 [다음 교육 단계로 승진할 수 있는지 여부]를 결정하거나, 학습자에게 [라이센스를 인증]하는 것이 포함됩니다.

In our example, our foremost decision is whether the learner has sufficient procedural competence to attempt a supervised LP on a real patient. Other decisions we might alternatively consider include identifying performance points on which to offer feedback to the learner, deciding if the learner can be promoted to the next stage of training, or certifying the learner for licensure.

3. 해석-사용 주장을 정의하고, 필요한 타당성 증거의 우선 순위를 정합니다.

3.Define the interpretation-use argument, and prioritize needed validity evidence

우리는 해석과 결정을 내릴 때, 많은 가정을 실행하며, 이것들은 검증되어야 한다. 주요 가정을 식별하고 우선 순위를 정하고 우리가 찾기를 원하는 증거를 예상하면 해석-사용 논쟁의 개요를 설명할 수 있다[30].

In making our interpretations and decisions, we will invoke a number of assumptions, and these must be tested. Identifying and prioritizing key assumptions and anticipating the evidence we hope to find allows us to outline an interpretation-use argument [30].

우리의 시나리오에서, 우리는 "합격"이 실제 환자에게 감독된 LP를 시도할 수 있는 능력을 나타내는 평가 도구를 찾고 있다. 우리는 이것이 기술 스테이션에서 학생들의 성과를 평가하는 의사를 포함할 것으로 예상한다. 이러한 맥락에 포함된 가정은 다음과 같다.

- 스테이션은 LP 성능에 필수적인 기술(무균 기술 또는 기구 취급에 대한 일반적인 기술 대)을 테스트하도록 설정되었고,

- 평가자가 적절하게 훈련되었으며,

- 서로 다른 평가자도 유사한 점수를 줄 것이며,

- 시험에서 더 높은 점수를 받은 학습자가 첫 번째 환자 대상 시도에서 더 안전하게 수행하게 될 것이다.

In our scenario, we are looking for an assessment instrument in which a “pass” indicates competence to attempt a supervised LP on a real patient. We anticipate that this will involve a physician rating student performance on a skills station. Assumptions in this context include

- that the station is set up to test techniques essential for LP performance (vs generic skills in sterile technique or instrument handling),

- that the rater is properly trained,

- that a different rater would give similar scores, and

- that learners who score higher on the test will perform more safely on their first patient attempt.

이러한 [가정을 지지하거나 반박해야 할 수 있는 증거]를 고려하고 케인의 프레임워크를 지침으로 삼아 다음과 같은 해석-사용 주장을 제안한다. 증거가 이미 수집됐는지, 직접 수집해야 할지는 현 단계에서 알 수 없지만 최소한 무엇을 찾아야 할지는 파악했다.

- (a)점수 매기기: 성능에 대한 관찰이 일관된 숫자 점수로 올바르게 변환됩니다. 증거는 기기 내의 항목이 LP 성능과 관련이 있고 평가자가 기기 사용 방법을 이해했으며 비디오 녹화 성능이 직접적인 관찰과 유사한 점수를 산출한다는 것을 이상적으로 보여준다.

- (b)일반화: 단일 성능의 점수는 테스트 설정의 전체 점수와 일치합니다. 증거는 우리가 성능을 적절하게 샘플링했다는 것(충분한 시뮬레이션 LP 수와 시뮬레이션된 환자 습관 변경과 같은 충분한 다양한 조건)과 성과 간 및 평가자 간(스테이션 간 및 평가자 간 신뢰성)을 이상적으로 보여줄 것이다.

- (c)외삽: 평가 점수는 실제 성과와 관련이 있습니다. 증거는 기기의 점수가 절차 로그, 환자 부작용 사건 또는 감독자 등급과 같은 실제 상황에서 다른 LP 성능 측정과 상관관계가 있다는 것을 이상적으로 보여준다.

- (d)함의: 평가는 학습자, 훈련 프로그램 또는 환자에게 중요하고 긍정적인 영향을 미치며 부정적인 영향은 미미합니다. 증거는 이상적으로 학생들이 평가 후에 더 준비가 되었다고 느끼고, 교정조치가 필요한 학생들은 이 시간이 충분히 소비되었다고 느끼고, 실제 환자의 LP 합병증은 시행 후 1년 동안 감소한다는 것을 보여줄 것이다.

Considering the evidence we might need to support or refute these assumptions, and using Kane’s framework as a guide, we propose an interpretation-use argument as follows. We do not know at this stage whether evidence has already been collected or if we will need to collect it ourselves, but we have at least identified what to look for.

- (a)Scoring: the observation of performance is correctly transformed into a consistent numeric score. Evidence will ideally show that the items within the instrument are relevant to LP performance, that raters understood how to use the instrument, and that video-recording performance yields similar scores as direct observation.

- (b)Generalization: scores on a single performance align with overall scores in the test setting. Evidence will ideally show that we have adequately sampled performance (sufficient number of simulated LPs, and sufficient variety of conditions such as varying the simulated patient habitus) and that scores are reproducible between performances and between raters (inter-station and inter-rater reliability).

- (c)Extrapolation: assessment scores relate to real-world performance. Evidence will ideally show that scores from the instrument correlate with other LP performance measures in real practice, such as procedural logs, patient adverse events, or supervisor ratings.

- (d)Implications: the assessment has important and favorable effects on learners, training programs, or patients, and negative effects are minimal. Evidence will ideally show that students feel more prepared following the assessment, that those requiring remediation feel this time was well spent, and that LP complications in real patients decline in the year following implementation.

우리는 타당화에서 이 처음 세 단계의 중요성을 아무리 강조해도 지나치지 않다. 제안된 해석, 의도된 결정(들) 및 가정과 그에 상응하는 증거를 명확하게 설명하는 것은 그 이후의 모든 것을 위한 단계를 집합적으로 설정한다.

We cannot over-emphasize the importance of these first three steps in validation. Clearly articulating the proposed interpretations, intended decision(s), and assumptions and corresponding evidence collectively set the stage for everything that follows.

4. 후보 평가도구 식별 및/또는 새 평가도구 생성/어댑트

4.Identify candidate instruments and/or create/adapt a new instrument

우리는 목표 구인과 개념적으로 일치하는 측정 형식을 식별한 다음, 우리의 요구에 부합하거나 적응할 수 있는 기존 도구를 검색해야 한다. 엄격한 검색은 최종 평가를 뒷받침할 내용 증거를 제공합니다. 적절한 기존 평가도구를 찾을 수 없는 경우에만 평가도구 개발을 해야 한다.

We should identify a measurement format that aligns conceptually with our target construct and then search for existing instruments that meet or could be adapted to our needs. A rigorous search provides content evidence to support our final assessment. Only if we cannot find an appropriate existing instrument would we develop an instrument de novo.

우리는 LP[34]에서 PGY-1의 절차적 역량 평가를 위한 체크리스트에 대한 설명을 찾는다. 체크리스트는 유사한 교육적 맥락에서 사용될 것이기 때문에 우리의 목적에 매우 적합한 것으로 보인다. 따라서 우리는 도구를 변경하지 않고 증거를 평가하는 작업을 계속합니다.

We find a description of a checklist for assessing PGY-1’s procedural competence in LP [34]. The checklist appears well suited for our purpose, as we will be using it in a similar educational context; we thus proceed to appraising the evidence without changing the instrument.

5.기존 증거를 평가하고 필요에 따라 새로운 증거를 수집합니다.

5.Appraise existing evidence and collect new evidence as needed

기존 증거는 그렇지 않지만, 엄밀히 말하면, 실제적인 목적을 위해 우리는 이 도구를 사용할지 여부를 결정할 때 기존 증거에 크게 의존할 것이다. 물론, 우리는 우리 자신의 증거도 수집하기를 원하겠지만, 우리는 현재 이용 가능한 것에 기초해야 한다.

Although existing evidence does not, strictly speaking apply to our situation, for practical purposes we will rely heavily on existing evidence as we decide whether to use this instrument. Of course, we will want to collect our own evidence as well, but we must base our initial adoption on what is now available.

우리는 기존의 증거를 찾는 것에서부터 타당성 주장에 대한 평가를 시작한다.

- 원본 설명[34]은 공식적인 LP 과제 분석과 전문가 합의를 통해 체크리스트 항목의 개발을 기술함으로써 채점 증거를 제공한다.

- 평가자 간 신뢰성이 우수하여 일반화 증거를 제공하고, 경험이 많은 거주자가 체크리스트 점수가 더 높았음을 확인함으로써 제한된 외삽 증거를 추가한다.

- 동일하거나 약간 수정된 체크리스트를 사용한 다른 연구는 좋은 평가자 간 신뢰성으로 추가 일반화 증거를 제공하며 [35, 36] 훈련 후 점수가 더 높고 [35, 37] 계측기가 실제 환자 LP를 평가하는 데 사용될 때 중요한 학습자 오류를 식별했다는 것을 보여줌으로써 외삽 증거를 제공한다[38].

- 또한 한 연구는 시뮬레이션 환경에서 역량을 획득하는 데 필요한 연습 시도 횟수를 계산하여 제한적인 함의 증거를 제공했다[37].

We begin our appraisal of the validity argument by searching for existing evidence.

- The original description [34] offers scoring evidence by describing the development of checklist items through formal LP task analysis and expert consensus.

- It provides generalization evidence by showing good inter-rater reliability, and adds limited extrapolation evidence by confirming that residents with more experience had higher checklist scores.

- Other studies using the same or a slightly modified checklist provide further evidence for generalization with good inter-rater reliabilities [35, 36], and contribute extrapolation evidence by showing that scores are higher after training [35, 37] and that the instrument identified important learner errors when used to rate real patient LPs [38].

- One study also provided limited implications evidence by counting the number of practice attempts required to attain competence in the simulation setting [37].

이러한 기존 연구에 비추어 볼 때, 우리는 이 도구를 처음 채택하기 전에 더 많은 증거를 수집할 계획을 세우지 않을 것이다. 그러나, 우리는 이행하는 동안, 특히 우리가 중요한 gap을 식별한다면, 우리 자신의 증거를 수집할 것이다. 즉, 유효성 검사 프로세스의 후반 단계에서 수집할 것이라는 의미이다.

In light of these existing studies, we will not plan to collect more evidence before our initial adoption of this instrument. However, we will collect our own evidence during implementation, especially if we identify important gaps, i.e., at later stages in the validation process; see below.

6. 비용을 포함한 실질적인 문제를 추적합니다.

6.Keep track of practical issues including cost

중요하지만 종종 제대로 평가되지 않고 연구되지 않은 검증의 측면은 개발, 구현 및 점수의 해석을 둘러싼 실제 문제와 관련이 있다. 평가 절차는 뛰어난 데이터를 산출할 수 있지만, 비용이 엄청나게 많이 들거나, 필요한 물류나 전문성이 현지의 가용 자원을 초과하는 경우 구현이 불가능할 수 있습니다.

An important yet often poorly appreciated and under-studied aspect of validation concerns the practical issues surrounding development, implementation, and interpretation of scores. An assessment procedure might yield outstanding data, but if it is prohibitively expensive or if logistical or expertise requirements exceed local resources, it may be impossible to implement.

LP 계측기의 경우, 한 연구[37]는 시뮬레이션 기반 LP 교육 및 평가 세션의 운영 비용을 추적했다. 저자들은 훈련된 비의사 평가자를 사용함으로써 비용을 줄일 수 있다고 제안했다. 우리가 그 기구를 시행하면서, 특히 새로운 타당성 증거를 수집한다면, 우리는 마찬가지로 돈, 인적 및 비인적 자원, 그리고 다른 실질적인 문제와 같은 비용을 모니터링해야 한다.

For the LP instrument, one study [37] tracked the costs of running a simulation-based LP training and assessment session; the authors suggested that costs could be reduced by using trained non-physician raters. As we implement the instrument, and especially if we collect fresh validity evidence, we should likewise monitor costs such as money, human and non-human resources, and other practical issues.

7.해석-사용 주장와 관련하여 타당성 인수를 공식화/합성합니다.

7.Formulate/synthesize the validity argument in relation to the interpretation-use argument

이제 우리는 원하는 해석과 결정(해석-사용 주장)을 뒷받침하기 위해 필요한 것으로 사전에 식별한 증거와 사용할 수 있는 증거(유효성 주장)를 비교한다.

We now compare the evidence available (the validity argument) against the evidence we identified up-front as necessary to support the desired interpretations and decisions (the interpretation-use argument).

우리는 합리적인 점수 매기기 및 일반화 증거, 외삽 증거의 차이(시뮬레이션과 실제 성능 간의 직접적인 비교가 이루어지지 않음) 및 제한된 함의 증거를 찾는다. 거의 항상 그렇듯이 해석-사용 주장과 사용 가능한 증거 사이의 일치는 완벽하지 않다. 일부 갭은 남아 있고, 일부 증거는 우리가 원하는 만큼 유리하지 않다.

We find reasonable scoring and generalization evidence, a gap in the extrapolation evidence (direct comparisons between simulation and real-world performance have not been done), and limited implications evidence. As is nearly always the case, the match between the interpretation-use argument and the available evidence is not perfect; some gaps remain, and some of the evidence is not as favorable as we might wish.

8.판단을 내리십시오. 그 증거가 의도된 사용을 뒷받침합니까?

8.Make a judgment: does the evidence support the intended use?

검증의 마지막 단계는 증거의 충분성과 적합성을 판단하는 것이다. 즉, 타당성 주장과 관련 증거가 제안된 해석-사용 주장의 요구를 충족하는지 여부.

The final step in validation is to judge the sufficiency and suitability of evidence, i.e., whether the validity argument and the associated evidence meet the demands of the proposed interpretation-use argument.

위에서 요약한 증거를 바탕으로, 우리는 타당성 주장이 그러한 해석을 뒷받침하고 합리적으로 잘 사용하고 있으며, 체크리스트는 우리의 목적에 적합한 것으로 보인다고 판단한다. 게다가, 비용은 지출된 노력에 비해 합리적인 것 같고, 우리는 평가자로서 훈련을 받기를 열망하는 시뮬레이션 실험실의 조수를 만날 수 있다.

Based on the evidence summarized above, we judge that the validity argument supports those interpretations and uses reasonably well, and the checklist appears suitable for our purposes. Moreover, the costs seem reasonable for the effort expended, and we have access to an assistant in the simulation laboratory who is keen to be trained as a rater.

우리는 또한 우리 기관에서 도구를 구현하면서 연구 연구를 수행하여 위에 언급된 증거 격차를 해소할 수 있도록 도울 계획입니다. 외삽 추론을 뒷받침하기 위해 시뮬레이션 평가의 점수를 진행 중인 작업 공간 기반 LP 평가와 상관시킬 계획이다. 또한 성과가 부진한 전공의에 대한 추가 훈련의 효과를 추적하여 시사점 추론을 다룰 것이다. 즉, 평가의 다운스트림 결과입니다. 마지막으로, 우리는 학습자 모집단의 평가자 간, 사례 간 및 내부 일관성 신뢰성을 측정하고 위에서 언급한 바와 같이 비용과 실제 문제를 모니터링할 것이다.

We also plan to help resolve the evidence gaps noted above by conducting a research study as we implement the instrument at our institution. To buttress the extrapolation inference we plan to correlate scores from the simulation assessment with ongoing workplace-based LP assessments. We will also address the implications inference by tracking the effects of additional training for poor performing residents, i.e., the downstream consequences of assessment. Finally, we will measure the inter-rater, inter-case, and internal consistency reliability in our learner population, and will monitor costs and practical issues as noted above.

동일한 평가도구를 다른 설정에 적용

Application of the same instrument to a different setting

사고 실험으로서, 만약 우리가 [같은 기구를 다른 목적과 결정에 사용]하기를 원한다면, 예를 들어, 신경과 수련생들이 [레지던시를 마칠 때 인증하는 고부담 시험의 일부]로서 위의 것들이 어떻게 전개될지 생각해 보자. 우리의 결정이 바뀌면, 우리의 해석-사용 주장도 바뀐다. 우리는 이제 [체크리스트의 "합격" 점수]가 [다양한 실제 환자에게 독립적으로 LP를 수행할 수 있는 능력]을 나타난대는 증거를 찾고 있을 것이다. 우리는 다른 또는 추가적인 타당성 증거를 요구할 것이다.

- 일반화 (연령, 신체 습관 및 난이도에 영향을 미치는 기타 요인에 따라 달라지는 시뮬레이션된 환자에 대한 분석)

- 외삽 (시뮬레이션과 실제 성능 사이의 더 강력한 상관 관계 찾기) 및

- 함의 (예: 학습자를 독립적 실천을 위한 유능 또는 무능으로 정확하게 분류하고 있었다는 증거)

As a thought exercise, let us consider how the above would unfold if we wanted to use the same instrument for a different purpose and decision, for example as part of a high-stakes exam to certify postgraduate neurologist trainees as they finish residency. As our decision changes, so does our interpretation-use argument; we would now be searching for evidence that a “pass” score on the checklist indicates competence to independently perform LPs on a variety of real patients. We would require different or additional validity evidence, with increased emphasis on

- generalization (sampling across simulated patients that vary in age, body habitus, and other factors that influence difficulty),

- extrapolation (looking for stronger correlation between simulation and real-life performance), and

- implications evidence (e.g., evidence that we were accurately classifying learners as competent or incompetent for independent practice).

우리는 현재의 증거들이 이 주장을 뒷받침하지 않으며 다음 중 하나가 필요하다고 결론지어야 할 것이다.

- (a) 우리의 요구에 부합하는 증거를 가진 새로운 도구를 찾아라.

- (b) 새 도구를 만들고 처음부터 증거를 수집하기 시작합니다.

- (c) 공백을 메우기 위해 추가 타당성 증거를 수집합니다.

We would have to conclude that the current body of evidence does not support this argument and would need to either

- (a) find a new instrument with evidence that meets our demands,

- (b) create a new instrument and start collecting evidence from scratch, or

- (c) collect additional validity evidence to fill in the gaps.

이 사고 연습은 두 가지 중요한 점을 강조한다. 첫째, 의사 결정이 변경될 때 해석-사용 주장이 변경될 수 있다. 둘째, 기구 자체는 "유효"하지 않다. 오히려, 검증되는 것은 해석이나 결정이다. 동일한 증거에 기초한 타당성의 최종 판단은 제안된 결정마다 다를 수 있다.

This thought exercise highlights two important points. First, the interpretation-use argument might change when the decision changes. Second, an instrument is not “valid” in and of itself; rather, it is the interpretations or decisions that are validated. A final judgment of validity based on the same evidence may differ for different proposed decisions.

타당화에서 피해가야 할 일반적인 실수

Common mistakes to avoid in validation

당사 자체의 타당화 노력[39–41]과 타인의 작업[9, 25, 42]을 검토하면서 최종 사용자의 결과를 이해하고 적용하는 능력을 저해하는 몇 가지 일반적인 실수를 확인했습니다. 우리는 동료 검토자에게 경고하고, 독자를 좌절시키고, 도구의 사용을 제한하도록 보장된 10개의 실수를 제시한다.

In our own validation efforts [39–41] and in reviewing the work of others [9, 25, 42], we have identified several common mistakes that undermine the end-user’s ability to understand and apply the results. We present these as ten mistakes guaranteed to alarm peer reviewers, frustrate readers, and limit the uptake of an instrument.

1번 실수. 바퀴 재창조(매번 새로운 평가 작성)

Mistake 1. Reinvent the wheel (create a new assessment every time)

우리의 검토[9]는 대부분의 타당성 연구가 기존 도구를 사용하거나 채택하기보다는 새로 만들어진 도구에 초점을 맞춘다는 것을 발견했다. 그러나 대부분의 구조를 평가하는 도구가 이미 어떤 형태로 존재하기 때문에 학습자 평가를 시작할 때 완전히 처음부터 시작할 필요는 거의 없다. 기존 도구를 사용하거나 기존 도구를 사용하여 구축하면 도구를 새로 개발하는 수고를 덜 수 있고, 우리의 결과를 다른 사람의 이전 작업과 비교할 수 있으며, 다른 사람이 우리의 작업과 비교할 수 있으며, 해당 도구, 작업 또는 평가 양식에 대한 전체 증거 기반에 우리의 증거를 포함할 수 있다. OSATS [42], 복강경 수술의 기초 (FLS) [43] 및 기타 시뮬레이션 기반 평가에 대한 근거 검토[9]는 모두 근거 기반에 중요한 차이를 보여준다. 이러한 공백을 메우기 위해서는 동일한 평가에서 도출된 점수, 추론 및 결정에 대한 증거를 수집하는 데 초점을 맞춘 여러 조사관의 협업 노력이 필요하다.

Our review [9] found that the vast majority of validity studies focused on a newly created instrument rather than using or adapting an existing instrument. Yet, there is rarely a need to start completely from scratch when initiating learner assessment, as instruments to assess most constructs already exist in some form. Using or building from an existing instrument

- saves the trouble of developing an instrument de novo,

- allows us to compare our results with prior work, and

- permits others to compare their work with ours and

- include our evidence in the overall evidence base for that instrument, task, or assessment modality.

Reviews of evidence for the OSATS [42], Fundamentals of Laparoscopic Surgery (FLS) [43], and other simulation-based assessments [9] all show important gaps in the evidence base. Filling these gaps will require the collaborative effort of multiple investigators all focused on collecting evidence for the scores, inferences, and decisions derived from the same assessment.

실수 2. 타당화 프레임워크를 사용하지 않음

Mistake 2. Fail to use a validation framework

위에서 언급한 바와 같이, 검증 프레임워크는 증거의 선택과 수집에 엄격함을 더하고 그렇지 않으면 놓칠 수 있는 격차를 식별하는 데 도움이 된다. 어떤 프레임워크를 선택했느냐보다 더 중요한 것은 검증 노력에 프레임워크가 적용되는 시기(이상적으로 초기)와 방식(엄정하고 완전하게)이다.

As noted above, validation frameworks add rigor to the selection and collection of evidence and help identify gaps that might otherwise be missed. More important than the framework chosen is the timing (ideally early) and manner (rigorously and completely) in which the framework is applied in the validation effort.

3번 실수. 전문가와 초보자의 비교를 타당성 논쟁의 핵심으로 삼는다.

Mistake 3. Make expert-novice comparisons the crux of the validity argument

[경험이 적은 그룹의 점수]를 [경험이 많은 그룹의 점수]와 비교하는 것(예: 의대생 대 시니어 전공의)은 다른 변수와의 관계에 대한 증거를 수집하는 일반적인 접근법이다. 시뮬레이션 기반 평가 연구의 73%에서 보고되었다[9]. 그러나 이 접근법은 점수 차이가 의도된 구성과 무관한 무수한 요인에서 발생할 수 있기 때문에 약한 증거만을 제공한다[44]. 예를 들어, [봉합 능력]을 측정하기 위한 평가에서 실제로 [멸균 기술을 측정]하고 [봉합 능력 측정은 완전히 무시되었다]고 가정합니다. 만약 조사관이 3학년 의대생과 재학 중인 의사들 사이에서 실제로 이것을 시험한다면, 그는 아마도 주치의에게 유리한 상당한 차이를 발견할 것이고, 이 증거가 제안된 해석의 타당성(즉, 봉합 기술)을 뒷받침한다고 잘못 결론지을 수 있다.

Comparing the scores from a less experienced group against those from a more experienced group (e.g., medical students vs senior residents) is a common approach to collecting evidence of relationships with other variables—reported in 73% of studies of simulation-based assessment [9]. Yet this approach provides only weak evidence because the difference in scores may arise from a myriad of factors unrelated to the intended construct [44]. To take an extreme example for illustration, suppose an assessment intended to measure suturing ability actually measured sterile technique and completely ignored suturing. If an investigator trialed this in practice among third-year medical students and attending physicians, he would most likely find a significant difference favoring the attendings and might erroneously conclude that this evidence supports the validity of the proposed interpretation (i.e., suturing skill).

물론, 이 가상의 예에서, 우리는 어텐딩이 봉합과 멸균 기술 모두에서 의대생보다 낫다는 것을 알고 있습니다. 그러나 실제 삶에서, 우리는 [실제로 평가되고 있는 것]이 무엇인지에 대해서는 전지적 지식이 부족하다. 우리가 아는 것은 오로지 시험 점수이고, 동일한 점수는 어떤 수의 기본 구조를 반영하는 것으로 해석될 수 있다. 이 "교란confounding"의 문제(복수의 가능한 해석)는 그룹 간의 차이가 실제로 의도된 구조와 연결된다고 말하는 것을 불가능하게 만든다. 반면에 예상 차이를 확인하지 못하면 점수 무효의 강력한 증거가 될 수 있다.

Of course, in this hypothetical example, we know that attendings are better than medical students in both suturing and sterile technique. Yet, in real life, we lack the omniscient knowledge of what is actually being assessed; we only know the test scores—and the same scores can be interpreted as reflecting any number of underlying constructs. This problem of “confounding” (multiple possible interpretations) makes it impossible to say that any differences between groups are actually linked to the intended construct. On the other hand, failure to confirm expected differences would constitute powerful evidence of score invalidity.

쿡은 이 문제에 대한 확장된 토론과 설명을 제공했고, 다음과 같이 결론을 내렸다. "연구자들이 한계를 이해한다면, 그러한 분석을 수행하는 것은 잘못된 것이 아니다." … 이러한 분석은 [달라야 할 집단을 구별하지 못하거나] [차이가 없어야 할 곳에 차이를 발견하게 된다면] 가장 흥미로울 것이다. 가설상의 차이 또는 유사성의 확인은 타당성 주장에 거의 추가되지 않는다." [44]

Cook provided an extended discussion and illustration of this problem, concluding that “It is not wrong to perform such analyses, … provided researchers understand the limitations. … These analyses will be most interesting if they fail to discriminate groups that should be different, or find differences where none should exist. Confirmation of hypothesized differences or similarities adds little to the validity argument.” [44]

4번 실수. [가장 중요한 증거]보다는 [쉽게 접근할 수 있는 타당성 증거]에 초점을 맞춘다.

Mistake 4. Focus on the easily accessible validity evidence rather than the most important

검증 연구자들은 종종 쉽게 이용할 수 있거나 쉽게 수집할 수 있는 데이터에 초점을 맞춘다. 이 접근법은 이해할 수 있지만, 종종 한 소스에 대해 풍부한 유효성 증거가 보고되는 반면 동등하거나 더 중요할 수 있는 다른 소스에 대해서는 큰 증거 격차가 남아 있다. 그 예로는

- [내부 구조]를 무시하면서 [내용 증거]를 강조하거나,

- [평가자 간 신뢰성]이 더 중요할 때 [문항 간 신뢰도]를 보고하거나,

- 다른 변수와의 관계에 대해 [독립적인 측정과의 상관관계]보다는 [전문가-초심자 비교를 보고하는 것]이 있다.

우리의 검토에서, 우리는 306/417(73%)의 연구가 전문가와 초보자의 비교를 보고했고, 이 중 138(45%)은 추가 증거를 보고하지 않았다는 것을 발견했다. 이에 비해 별도의 측정으로 관계를 보고한 경우는 128명(31%), 내용증거 보고는 142명(34%), 점수 신뢰성 보고는 163명(39%)에 불과했다. 이러한 보고 패턴의 모든 이유를 알 수는 없지만, 적어도 부분적으로 일부 요소(예: 전문가-노바이스 비교 데이터)를 쉽게 얻을 수 있기 때문일 것으로 추측한다.

Validation researchers often focus on data they have readily available or can easily collect. While this approach is understandable, it often results in abundant validity evidence being reported for one source while large evidence gaps remain for other sources that might be equally or more important. Examples include

- emphasizing content evidence while neglecting internal structure,

- reporting inter-item reliability when inter-rater reliability is more important, or

- reporting expert-novice comparisons rather than correlations with an independent measure to support relationships with other variables.

In our review, we found that 306/417 (73%) of studies reported expert-novice comparisons, and 138 of these (45%) reported no additional evidence. By contrast, only 128 (31%) reported relationships with a separate measure, 142 (34%) reported content evidence, and 163 (39%) reported score reliability. While we do not know all the reasons for these reporting patterns, we suspect they are due at least in part to the ease with which some elements (e.g., expert-novice comparison data) can be obtained.

이것은 해석-사용 주장을 명확하고 완전하게 진술하고, 기존의 증거와 격차를 식별하고, 가장 중요한 격차를 해결하기 위해 증거 수집을 조정하는 것의 중요성을 강조한다.

This underscores the importance of clearly and completely stating the interpretation-use argument, identifying existing evidence and gaps, and tailoring the collection of evidence to address the most important gaps.

5번 실수. 점수 해석 및 사용보다는 평가도구에 집중

Mistake 5. Focus on the instrument rather than score interpretations and uses

위에서 언급한 바와 같이, 타당성은 평가도구의 속성이 아니라 점수, 해석 및 용도의 속성이다. [동일한 도구]를 [다양한 용도]에 적용할 수 있으며(PSA는 임상 검사 도구로 유용하지 않을 수 있지만, 전립선암 재발을 모니터링하는 데 계속 가치가 있다), 많은 타당성 증거는 상황에 따라 다르다. 예를 들어,

- 점수 신뢰성은 서로 다른 모집단에 걸쳐 크게 변할 수 있으며 [44],

- 외래 진료와 같은 한 학습 상황에 대해 설계된 평가는 병원이나 급성 치료 의료와 같은 다른 맥락과 관련되거나 관련되지 않을 수 있으며,

- OSATS 글로벌 등급 척도와 같은 일부 도구는 새로운 작업에 대한 평가에 쉽게 적용할 수 있지만, OSATS 체크리스트와 같은 것은 그렇지 않다 [42]

물론 의과대학과 같이 한 맥락에서 수집된 증거는 레지던트 훈련과 같은 다른 맥락과 적어도 부분적인 관련성을 갖는 경우가 많지만, 증거가 언제 어느 정도 새로운 환경으로 전이가능한지transfer에 대한 결정은 판단의 문제이며, 이러한 판단은 잠재적으로 잘못될 수 있다.

As noted above, validity is a property of scores, interpretations, and uses, not of instruments. The same instrument can be applied to different uses (the PSA may not be useful as a clinical screening tool, but continues to have value for monitoring prostate cancer recurrence), and much validity evidence is context-dependent. For example,

- score reliability can change substantially across different populations [44],

- an assessment designed for one learning context such as ambulatory practice may or may not be relevant in another context such as hospital or acute care medicine, and

- some instruments such as the OSATS global rating scale lend themselves readily to application to a new task while others such as the OSATS checklist do not [42].

Of course, evidence collected in one context, such as medical school, often has at least partial relevance to another context, such as residency training; but determinations of when and to what degree evidence transfers to a new setting are a matter of judgment, and these judgments are potentially fallible.

[해석-사용 주장]은 엄밀히 말하면 [의도된 적용의 맥락]을 명확히 하지 않고서는 적절하게 만들어질 수 없다. 연구자의 문맥과 최종 사용자의 문맥은 거의 항상 다르기 때문에 해석-사용 논쟁도 반드시 다르다. 연구자들은 [데이터 수집의 맥락]을 명확하게 명시함으로써 후속 작업의 활용을 촉진할 수 있다. 예를 들어, 학습자 그룹, 과제 및 의도된 사용/사용 범위, 그리고 자신의 연구 결과가 타당하게 적용될 수 있다고 믿는 범위를 제안함으로써.

The interpretation-use argument cannot, strictly speaking, be appropriately made without articulating the context of intended application. Since the researcher’s context and the end-user’s context almost always differ, the interpretation-use argument necessarily differs as well. Researchers can facilitate subsequent uptake of their work by clearly specifying the context of data collection—for example, the learner group, task, and intended use/decision—and also by proposing the scope to which they believe their findings might plausibly apply.

점수의 타당성에 대해 언급하는 것은 허용되지만, 위에 명시된 이유로, 그러한 점수의 의도된 해석과 사용, 즉 의도된 결정을 명시하는 것이 더 낫다. 우리는 연구자와 최종 사용자(교육자) 모두가 모든 검증 단계에서 해석과 사용을 명확히 할 것을 강력히 권장한다.

It is acceptable to talk about the validity of scores, but for reasons articulated above, it is better to specify the intended interpretation and use of those scores, i.e., the intended decision. We strongly encourage both researchers and end-users (educators) to articulate the interpretations and uses at every stage of validation.

6번 실수. 타당성 증거를 종합하거나 비평하지 못함

Mistake 6. Fail to synthesize or critique the validity evidence

우리는 종종 연구자들이 [증거를 합성하거나 평가하려는 시도 없이, 그저 보고하기만 하는 것]을 관찰했다. 교육자와 미래 연구자 모두 제안된 [해석-사용 주장]에 비추어 연구자가 [자신의 발견을 해석]하고, 이를 [이전 작업과 통합]하여 [현재 및 포괄적인 타당성 주장]을 만들고, [한계 및 지속적인 gap 또는 불일치를 식별]할 때 큰 이익을 얻는다. 교육자와 다른 최종 사용자도 증거에 익숙해져야 하며, 연구자의 주장을 확인하고 특정 상황에 대한 타당성에 대한 자체 판단을 공식화해야 한다.

We have often observed researchers merely report the evidence without any attempt at synthesis and appraisal. Both educators and future investigators greatly benefit when researchers interpret their findings in light of the proposed interpretation-use argument, integrate it with prior work to create a current and comprehensive validity argument, and identify shortcomings and persistent gaps or inconsistencies. Educators and other end-users must become familiar with the evidence as well, to confirm the claims of researchers and to formulate their own judgments of validity for their specific context.

7번 실수. 평가 개발을 위한 모범 사례 무시

Mistake 7. Ignore best practices for assessment development

평가 과제, 도구 및 절차의 개발, 개선 및 구현에 대한 책이 작성되었습니다 [23, 45–48]. 이러한 모범 사례를 고려하지 않고 평가를 개발하거나 수정하는 것은 경솔한 일일 것이다. 우리는 이것들을 요약할 수 없었지만, 우리는 건강 전문 교육자들에게 특별한 인상에 대한 두 가지 권고를 강조한다. 두 가지 모두 콘텐츠 증거(클래식 또는 5가지 소스 프레임워크 기준)와 일반화 추론(케인 기준)과 관련이 있다.

Volumes have been written on the development, refinement, and implementation of assessment tasks, instruments, and procedures [23, 45–48]. Developing or modifying an assessment without considering these best practices would be imprudent. We could not begin to summarize these, but we highlight two recommendations of particular salience to health professions educators, both of which relate to content evidence (per the classic or five sources frameworks) and the generalization inference (per Kane).

첫째, [작업 또는 토픽의 표본]은 원하는 수행능력 영역을 나타내야 한다. 보건 전문가 평가에서 반복적으로 발견되는 것은 [일반화 가능한 기술]이란 것은 거의 존재하지 않는다는 것이다. 한 과제에 대한 성과는 다른 과제에 대한 성과를 예측하지 못한다[49, 50]. 따라서 평가는 시나리오, 사례, 과제, 스테이션 등의 충분히 많고 광범위한 샘플을 제공해야 한다.

First, the sample of tasks or topics should represent the desired performance domain. A recurrent finding in health professions assessment is that there are few, if any, generalizable skills; performance on one task does not predict performance on another task [49, 50]. Thus, the assessment must provide a sufficiently numerous and broad sample of scenarios, cases, tasks, stations, etc.

둘째, 평가 응답 형식은 [객관화]와 [판단 또는 주관성]의 균형을 이루어야 한다[51]. 체크리스트와 글로벌 등급의 장점과 단점은 오랫동안 논의되어 왔으며, 둘 다 장단점이 있는 것으로 밝혀졌다[52]. 체크리스트는 원하는 행동에 대한 구체적인 기준과 형성적 피드백을 위한 지침을 개략적으로 설명하므로 평가 과제에 익숙하지 않은 평가자가 종종 사용할 수 있다. 그러나 체크리스트의 "객관성"은 대체로 착각이다. [53] [관찰된 행동에 대한 정확한 해석]은 여전히 [과제와 관련된 전문지식]을 필요로 할 수 있으며, 평가자에게 등급을 이분화하도록 강요하는 것은 정보의 손실을 초래할 수 있다. 또한 각 특정 작업에 대해 새로운 점검표를 작성해야 하며, 해당 항목은 종종 임상 역량을 보다 정확하게 반영할 수 있는 조치를 희생하여 철저성을 보상한다. 대조적으로, 글로벌 등급은 사용하기 위해 더 큰 전문지식이 필요하지만 성능의 더 미묘한 뉘앙스를 측정하고 여러 보완적 관점을 반영할 수 있다. 글로벌 등급은 또한 OSATS의 경우와 마찬가지로 여러 작업에 걸쳐 사용하도록 설계될 수 있다. 최근의 체계적 검토에서, 우리는 여러 연구에서 평균을 낼 때 글로벌 등급보다 체크리스트에 대한 등급 간 신뢰성이 약간 더 높았지만, 글로벌 등급은 항목 간 및 스테이션 간 신뢰성이 더 높았다[52]. 정성적 평가는 일부 학습자의 속성을 평가하기 위한 또 다른 옵션을 제공한다[11, 54, 55].

Second, the assessment response format should balance objectification and judgment or subjectivity [51]. The advantages and disadvantages of checklists and global ratings have long been debated, and it turns out that both have strengths and weaknesses [52]. Checklists outline specific criteria for desired behaviors and guidance for formative feedback, and as such can often be used by raters less familiar with the assessment task. However, the “objectivity” of checklists is largely an illusion; [53] correct interpretation of an observed behavior may yet require task-relevant expertise, and forcing raters to dichotomize ratings may result in a loss of information. Moreover, a new checklist must be created for each specific task, and the items often reward thoroughness at the expense of actions that might more accurately reflect clinical competence. By contrast, global ratings require greater expertise to use but can measure more subtle nuances of performance and reflect multiple complementary perspectives. Global ratings can also be designed for use across multiple tasks, as is the case for the OSATS. In a recent systematic review, we found slightly higher inter-rater reliability for checklists than for global ratings when averaged across studies, while global ratings had higher average inter-item and inter-station reliability [52]. Qualitative assessment offers another option for assessing some learner attributes [11, 54, 55].

8번 실수. 평가도구에 대한 세부 정보 생략

Mistake 8. Omit details about the instrument

의도된 용도를 뒷받침하는 타당성 증거와 지역 요구와 관련된 평가를 식별하는 것은 실망스러운 일이지만, 평가가 적용을 허용하기에 충분한 세부 사항을 명시하지 않았다는 것을 발견하는 것은 좌절스러운 일이다. 주로 누락되는 중요한 사항에는 다음이 있다.

- 평가도구 문항의 정확한 워딩,

- 채점 기준(rubric)

- 학습자 또는 평가자에게 제공되는 지침,

- 스테이션 배치에 대한 설명(예: 절차적 작업에 필요한 자료, 표준화된 환자 접견에서 참가자 교육)

- 사건의 순서.

대부분의 연구자들은 다른 사람들이 그들의 창작물을 사용하고 그들의 출판물을 인용하기를 원한다.

필요한 세부 정보가 보고될 경우 이 문제가 발생할 가능성이 훨씬 높습니다. 온라인 부록은 기사 길이가 문제인 경우 인쇄 출판에 대한 대안을 제공합니다.

It is frustrating to identify an assessment with relevance to local needs and validity evidence supporting intended uses, only to find that the assessment is not specified with sufficient detail to permit application. Important omissions include

- the precise wording of instrument items,

- the scoring rubric,

- instructions provided to either learners or raters, and

- a description of station arrangements (e.g., materials required in a procedural task, participant training in a standardized patient encounter) and

- the sequence of events.

Most researchers want others to use their creations and cite their publications; this is far more likely to occur if needed details are reported. Online appendices provide an alternative to print publication if article length is a problem.

9번 실수. 시뮬레이터/평가 기구의 가용성이 평가를 주도하도록 합니다.

Mistake 9. Let the availability of the simulator/assessment instrument drive the assessment

교육자로서, 우리는 너무 자주 [수행능력 기반 평가]가 임상실습의 목표와 더 잘 일치함에도 불구하고, [임상실습 말 평가를 위해 기성 MCQ 시험을 보는 것]과 같처럼 [평가 도구의 가용성]이 평가 프로세스를 끌어나가게 방치한다. 이 문제는 시뮬레이터의 가용성이 교육 프로그램을 설계하고 교육 요구에 맞는 최적의 시뮬레이션을 선택하는 것과 반대로 교육 프로그램을 구동할 수 있는 시뮬레이션 기반 평가와 더욱 복잡하다[56]. 우리는 [우리가 가르치고 있는 구조]를 [그 구조를 가장 잘 평가하는 시뮬레이터 및 평가 도구]와 일치시켜야 한다.

Too often as educators, we allow the availability of an assessment tool to drive the assessment process, such as taking an off-the-shelf MCQ exam for an end-of-clerkship assessment when a performance-based assessment might better align with clerkship objectives. This issue is further complicated with simulation-based assessments, where the availability of a simulator may drive the educational program as opposed to designing the educational program and then choosing the best simulation to fit the educational needs [56]. We should align the construct we are teaching with the simulator and assessment tool that best assess that construct.

10번 실수. 평가도구를 '타당화된'이라고 명명

Mistake 10. Label an instrument as validated

계측기를 유효하다고 레이블링하는 데는 세 가지 문제가 있습니다.

- 첫째, 타당성은 도구가 아니라 점수, 해석, 결정의 속성이다.

- 둘째, 타당성은 정도의 문제이다. 예스냐 아니냐의 결정이 아니다.

- 셋째, 타당화는 엔드포인트가 아닌 프로세스입니다.

Validated라는 단어는 [프로세스가 적용되었다는 것]을 의미할 뿐이며, 프로세스에 대한 세부 정보를 제공하지 않으며 경험적 소견의 크기나 방향(지지 또는 반대)을 나타내지 않는다.

There are three problems with labeling an instrument as validated.

- First, validity is a property of scores, interpretations, and decisions, not instruments.

- Second, validity is a matter of degree—not a yes or no decision.

- Third, validation is a process, not an endpoint.

The word validated means only that a process has been applied; it does not provide any details about that process nor indicate the magnitude or direction (supportive or opposing) of the empiric findings.

시뮬레이션 기반 평가의 미래

The future of simulation-based assessment

우리는 시뮬레이션 기반 평가의 미래를 아는 척하지 않지만, 실현되기를 바라는 여섯 가지 야심찬 개발로 결론을 내린다

Although we do not pretend to know the future of simulation-based assessment, we conclude with six aspirational developments we hope come to pass.

1.우리는 일련의 학습자 평가의 일환으로 시뮬레이션 기반 평가를 더 많이 사용할 수 있기를 바란다. 시뮬레이션 기반 평가는 그 자체로 목표가 되어서는 안 되지만 일반적으로 더 빈번한 평가를 예상하고 시뮬레이션이 중요한 역할을 할 것으로 믿는다. 양식 선택은 먼저 주어진 상황, 즉 학습 목표, 학습자 수준 또는 교육적 맥락에서 최선의 평가 접근법이 무엇인지 고려해야 한다. 특히 조건과 내용의 표준화가 필요한 기술 평가에서 다양한 형태의 시뮬레이션이 해답이 될 수 있다.

1.We hope to see greater use of simulation-based assessment as part of a suite of learner assessments. Simulation-based assessment should not be a goal in and of itself, but we anticipate more frequent assessment in general and believe that simulation will play a vital role. The choice of modality should first consider what is the best assessment approach in a given situation, i.e., learning objective, learner level, or educational context. Simulation in its various forms will often be the answer, especially in skill assessments requiring standardization of conditions and content.

2.우리는 시뮬레이션 기반 평가가 [테크놀로지보다는 교육적 필요성에 더 명확하게 초점]을 맞추기를 바란다. 값비싼 마네킹과 가상현실 작업 트레이너가 역할을 할 수도 있지만 족발, 펜로즈 배수구, 나무 말뚝, 판지 마네킹은 더 많은 빈도와 더 적은 제약으로 사용될 수 있기 때문에 실제로 더 실용적인 유용성을 제공할 수 있다. 예를 들어, 이러한 저가 모델은 전용 시뮬레이션 센터보다는 가정이나 병동에서 사용할 수 있다. 고부가가치, 비용 의식이 높은 교육의 필요성을 고려함에 따라[57] 혁신적인 교육자들이 저기술 솔루션을 적극적으로 모색할 것을 권장한다.

2.We hope that simulation-based assessment will focus more clearly on educational needs and less on technology. Expensive manikins and virtual reality task trainers may play a role, but pigs feet, Penrose drains, wooden pegs, and cardboard manikins may actually offer more practical utility because they can be used with greater frequency and with fewer constraints. For example, such low-cost models can be used at home or on the wards rather than in a dedicated simulation center. As we consider the need for high-value, cost-conscious education [57], we encourage innovative educators to actively seek low-tech solutions.

3. 처음 두 가지를 바탕으로, 우리는 비용이 적게 들고 덜 정교하며 덜 거슬리고 덜 거슬리는 저부담 평가가 시뮬레이션과 작업장에서 모두 더 다양한 맥락에서 더 자주 수행되기를 바란다. 슈워츠와 반 데르 블류텐이 제안했듯이, 이 모델은 시간이 지남에 따라 아무리 잘 설계되었더라도 어떤 단일 평가보다 학습자의 완전한 그림을 그릴 것이다.

3.Building off the first two points, we hope to see less expensive, less sophisticated, less intrusive, lower-stakes assessments take place more often in a greater variety of contexts, both simulated and in the workplace. As Schuwirth and van der Vleuten have proposed [58], this model would—over time—paint a more complete picture of the learner than any single assessment, no matter how well-designed, could likely achieve.

4.새로운 평가 도구가 더 적게 생성되고 기존 도구를 지원하고 적용하기 위해 더 많은 증거를 수집하기를 바랍니다. 우리는 새로운 도구의 창조를 장려할 수 있는 힘을 높이 평가하지만, 연구자들이 [더 작은 집합의 유망한 도구]에 대해 타당성 증거를 확장하기 위해 노력을 모으고, [다른 맥락에서 그러한 도구를 평가]하여 [증거 공백을 연속적으로 메워간다면], 이 분야가 점점 더 빠르게 발전할 것이라고 믿는다.

4.We hope to see fewer new assessment instruments created and more evidence collected to support and adapt existing instruments. While we appreciate the forces that might incentivize the creation of novel instruments, we believe that the field will advance farther and faster if researchers pool their efforts to extend the validity evidence for a smaller subset of promising instruments, evaluating such instruments in different contexts, and successively filling in evidence gaps.

5.우리는 평가의 결과 및 시사점을 알려주는 더 많은 증거를 보기를 바란다. 이것은 아마도 가장 중요한 증거 자료일 것이지만, 가장 자주 연구되지 않는 것 중 하나이다. 평가의 결과에 대한 연구를 위한 제안이 최근에 발표되었다[27].

5.We hope to see more evidence informing the consequences and implications of assessment. This is probably the most important evidence source, yet it is among the least often studied. Suggestions for the study of the consequences of assessment have recently been published [27].

6.마지막으로, 우리는 해석-사용 주장의 더 빈번하고 명시적인 사용을 볼 수 있기를 바란다. 위에서 언급한 바와 같이, 이 초기 단계는 어렵지만 의미 있는 검증에 매우 중요하다.

6.Finally, we hope to see more frequent and more explicit use of the interpretation-use argument. As noted above, this initial step is difficult but vitally important to meaningful validation.

Validation of educational assessments: a primer for simulation and beyond

PMID: 29450000

PMCID: PMC5806296

DOI: 10.1186/s41077-016-0033-y

Free PMC article

Abstract

Background: Simulation plays a vital role in health professions assessment. This review provides a primer on assessment validation for educators and education researchers. We focus on simulation-based assessment of health professionals, but the principles apply broadly to other assessment approaches and topics.

Key principles: Validation refers to the process of collecting validity evidence to evaluate the appropriateness of the interpretations, uses, and decisions based on assessment results. Contemporary frameworks view validity as a hypothesis, and validity evidence is collected to support or refute the validity hypothesis (i.e., that the proposed interpretations and decisions are defensible). In validation, the educator or researcher defines the proposed interpretations and decisions, identifies and prioritizes the most questionable assumptions in making these interpretations and decisions (the "interpretation-use argument"), empirically tests those assumptions using existing or newly-collected evidence, and then summarizes the evidence as a coherent "validity argument." A framework proposed by Messick identifies potential evidence sources: content, response process, internal structure, relationships with other variables, and consequences. Another framework proposed by Kane identifies key inferences in generating useful interpretations: scoring, generalization, extrapolation, and implications/decision. We propose an eight-step approach to validation that applies to either framework: Define the construct and proposed interpretation, make explicit the intended decision(s), define the interpretation-use argument and prioritize needed validity evidence, identify candidate instruments and/or create/adapt a new instrument, appraise existing evidence and collect new evidence as needed, keep track of practical issues, formulate the validity argument, and make a judgment: does the evidence support the intended use?

Conclusions: Rigorous validation first prioritizes and then empirically evaluates key assumptions in the interpretation and use of assessment scores. Validation science would be improved by more explicit articulation and prioritization of the interpretation-use argument, greater use of formal validation frameworks, and more evidence informing the consequences and implications of assessment.

Keywords: Content Evidence; Lumbar Puncture; Validation Framework; Validity Argument; Validity Evidence.

'Articles (Medical Education) > 평가법 (Portfolio 등)' 카테고리의 다른 글

| 수행능력 기반 평가에서 합격선 설정 방법: AMEE Guide No. 85 (Med Teach, 2014) (0) | 2022.09.09 |

|---|---|

| 평가자의 합격선설정과정에 대한 이해와 수행능력을 지원하기 위한 피드백(Med Teach, AMEE Guide No. 145) (0) | 2022.09.07 |

| 테크놀로지-강화 평가: 오타와 합의문과 권고(Med Teach, 2022) (0) | 2022.08.18 |

| 논증 이론이 어떻게 평가 타당도에 정보를 제공하는가: 비판적 문헌고찰 (Med Educ, 2022) (0) | 2022.08.06 |

| When I say…응답 프로세스 타당도 근거(Med Educ, 2022) (0) | 2022.08.06 |