'나는 이 공간에 있을 가치가 없어요': 의과대학생에게 수치의 근원(Med Educ, 2020)

‘I'm unworthy of being in this space’: The origins of shame in medical students

William E. Bynum IV1 | Lara Varpio2 | Janaka Lagoo3 | Pim W. Teunissen4

1 | 소개

1 | INTRODUCTION

'인간 경험에 편재하는 마스터 감성master emotion'(P34)으로 불려온 수치심은 개인에게 파괴적인 영향을 미칠 수 있다. 자신에 대한 전 세계적인 부정적 평가로 인해 수치심은 상당한 고통을 야기할 수 있으며 회피, 숨기기, 방어, 자책감을 조장할 수 있습니다. 의학 교육의 수치심 경험에 대한 겸손한 연구는 졸업후 의학 교육에 초점을 맞추었고, 연구들은 전공의의 수치심이 다음을 포함한 부정적인 결과를 유발하는 '감정적 사건'이 될 수 있다는 것을 보여준다: 심리적 고통(예: 번아웃), 고립, 직무 성과 저하, 공감 장애, 전문적이지 못한 행동 및 학습으로부터의 이탈.

Shame, which has been called 'a master emotion because of its ubiquity in human experience’(P34),1 can have devastating effects on individuals. Resulting from a global, negative evaluation of the self, shame can cause significant distress and promote avoidance, hiding, defensiveness and self-blame.2 The modest body of research on experiences of shame in medical education has focused on graduate medical education,3-6 with studies showing that shame in residents can be a ‘sentinel emotional event’6 that triggers negative outcomes, including psychological distress (eg, burnout), isolation, poor job performance, impaired empathy, unprofessional behaviour and disengagement from learning.5,6

그러나 수치심 경험은 레지던트 훈련에만 국한되지 않는다. 의대생들은 학대, 학업 투쟁, 과도기 등 많은 수치심을 유발하기 때문에 수치심에 노출되기 쉽다. 더 나아가 의대생들은 계급의 최하위에 있기 때문에, 학생들은 수치심 반응을 유발하는 상황에 노출되거나, 수치심이 유발되는 자기평가를 겪을 가능성이 높다. 수치심과 관련된 부정적인 결과를 고려할 때, 의대생들이 이러한 감정을 어떻게 경험하는지 이해하는 것이 필수적입니다.

However, shame experiences are not confined to residency training; medical students are likely susceptible to shame because they are exposed to many of the same shame triggers, including mistreatment,7 academic struggle and transition periods.8,9 Furthermore, medical students' position at the lower end of the medical hierarchy may expose them to situations and predispose them to self-evaluative tendencies that lead to shame reactions.10,11 Given the negative outcomes with which shame is associated, it is essential that we understand how medical students experience this emotion.

[교육적 안전]의 개념(심리적 안전이라는 용어에 기반한 표현으로써, 자신의 자기-이미지나 지위에 대한 부정적인 결과를 두려워하지 않고 업무에 참여할 수 있는 정도를 의미함)은 의대생들에게 수치심을 연구할 필요성을 더욱 강조합니다. Tsuei 등은 최근 '[교육적 안전]'을 다음과 같이 제안했다.

The notion of educational safety12—a term built upon psychological safety, or the degree to which an individual can engage at work without fearing negative consequences to their self-image or status13—further underscores the need to study shame in medical students. Tsuei et al recently proposed ‘educational safety’ as:

학습자가 자신의 투사된 이미지를 스스로 모니터링할 필요 없이, 학습 과제 참여에 진정하고 전적으로 집중할 수 있도록, 타인의 판단 의식에서 해방된 주관적 상태입니다.

The subjective state of feeling freed from a sense of judgment by others such that learners can authentically and wholeheartedly concentrate on engaging with a learning task without a perceived need to self-monitor their projected image.

쯔이 외 연구진 자료에 따르면 교육 안전은

- [다른 사람에게 역량을 발휘할 필요가 있다는 느낌]과 관련이 있다.

- 학생들이 타인의 기대에 반하여against 지속적으로 자기평가 한다고 느끼는 정도에 영향을 받습니다.

- 개인이 유능한 자기이미지를 보여줄 필요가 덜하다고 느낄 때 촉진됩니다.12

Tsuei et al's data suggest that educational safety

- is related to the feeling of needing to display competency to others;

- is affected by the degree to which students feel compelled to continuously self-assess against others' expectations; and

- is facilitated when an individual feels less need to present a competent self-image.12

(개인 스스로가 부족하고 무능하며 가치가 없다고 판단할 때 발생하는) 수치심은 교육 안전의 구조와 밀접하게 반비례한다. 수치심은 이탈, 고립, 심리적 고통, 판단의 공포를 초래하기 때문에, 수치심을 느끼는 사람은 교육 안전 수준이 낮다고 인식하기 쉽다. 마찬가지로, 교육 안전 수준이 낮으면 수치심의 위험이 높아질 수 있습니다. 그 결과 자기이미지에 부정적인 영향을 미치고 인식된 판단을 유발할 수 있습니다. 낮은 교육 안전과 높은 수치심의 환경에서는 학습, 환자 관리 및 웰빙에 잠재적으로 심각한 다운스트림 효과가 뒤따를 수 있습니다.

Shame—which occurs when an individual assesses themselves to be deficient, incompetent and/or unworthy2—is intimately and inversely linked with the construct of educational safety. Due to its tendency to cause disengagement, isolation, psychological distress and fear of judgment,6 an individual experiencing shame is likely to perceive low levels of educational safety. Likewise, low levels of educational safety—which may negatively impact self-image and cause perceived judgment—are likely to increase the risk of shame.14 In settings of low educational safety and high amounts of shame, potentially profound downstream effects on learning, patient care and well-being may follow.12,14,15

따라서, 교육적으로 안전한 환경을 조성하고, 의료 훈련에서 안전한 환자 관리를 보장하고, 학습자의 참여와 웰빙을 촉진하기 위해, 우리는 수치스러운 경험과 이를 전파하는 힘에 적응해야 합니다. 그러나 의대생들이 수치심을 어떻게 경험하고 이러한 경험이 어떻게 발전하는지에 대해서는 알려진 바가 거의 없다.

Thus, to facilitate educationally safe environments, ensure safe patient care in medical training and promote learner engagement and well-being, we must be attuned to the presence of shame experiences and the forces that propagate them. However, little is known about how medical students experience shame and how these experiences develop.

2 | 방법

2 | METHODS

2.1 | 헤르메네틱 현상학

2.1 | Hermeneutic phenomenology

해석적(헤르메네틱) 현상학은 어떤 현상을 묘사하고 그 근본적인 의미를 살아있는 경험의 맥락 안에서 전달하는 것을 목적으로 하는 질적인 방법론이다.16 헤르메네틱 현상학은 현상을 형성하는 '살아 있는 경험의 구조'를 통해 전달되는 현상의 의미에 대한 풍부한 설명을 만들어낸다.

Hermeneutic phenomenology is a qualitative methodology aimed at describing a phenomenon and conveying its underlying meaning within the context of lived experience.16 Hermeneutic phenomenology produces a rich description of the meaning of a phenomenon, conveyed through the ‘structures of lived experience’ that shape the phenomenon.17

우리는 해석적 현상학을 연구에 사용했다. 왜냐하면

- 해석적 현상학은 살아 있는 맥락에서 개인의 경험을 강조하기 때문이다.

- 해석적 현상학은 인간 경험의 숨겨진 측면을 드러내는 능력이 있기 때문이다.

- 해석적 현상학은 연구자들이 그 현상에 대해 살아 있는 경험을 분석 과정에 도입할 것을 요구하기 때문이다.

We used hermeneutic phenomenology in our research because of

- its emphasis on individuals' experiences in their lived contexts;

- its ability to reveal hidden aspects of human experience18; and

- its requirement that researchers bring their own lived experience with the phenomenon into the analytic process.19

이러한 특징들은 우리의 조사에 중요한 이유는 수치심은 맥락적으로 영향을 받는 감정이기 때문이다. 수치심은 종종 깊이 간직되어 있고 공개적으로 공유되거나 쉽게 이해되지 않습니다. 게다가, 우리는 개인으로서 우리를 형성하고 우리가 이 연구 프로그램에 참여하도록 동기부여하는 우리 자신의 수치스러운 경험들을 믿을 수 있게 분류할 수 없습니다.

These characteristics are important to our investigation because shame is a contextually influenced emotion6 that is often deeply held and not openly shared nor easily understood. Furthermore, we cannot reliably bracket off our own shame experiences, which shape us as individuals and motivate us to engage in this program of research.

2.2 | 참가자 모집

2.2 | Participant recruitment

우리는 미국의 한 사립 의과대학에서 16명의 자원봉사자를 모집했습니다.

We recruited 16 volunteer participants from a private medical school in the United States.

2.3 | 반사율

2.3 | Reflexivity

학술 가정의학과 의사인 WB가 인터뷰를 진행하며 연구 과정의 모든 측면을 주도했으며 의학 교육의 수치심을 조사하는 연구 프로그램이 활발하게 진행되고 있다. 따라서 그는 의대생, 레지던트, 주치의 및 배우자로 경험했던 자신의 수치심 경험을 연구에 가져왔습니다. 이는 의대생들의 데이터가 전공의 자신의 경험 및 데이터와 어떻게 일치하고 다른지에 대해 WB를 민감하게 만들었다. 이런 데이터는 모두 이 연구의 이론적 및 개념적 분석에 도움이 되었다.

WB, an academic family medicine physician, conducted the interviews, led all aspects of the research process, and has an active program of research investigating shame in medical education. Accordingly, he brought his own experiences of shame—experienced as a medical student, resident, attending physician and spouse—to the study. This sensitised WB to how the data from medical students aligned with and differed from his own experiences and data collected in residents,6 both of which informed this study's theoretical and conceptual analyses.

JL은 가정의학과 레지던트이자 의대생으로서 수치스러운 경험을 통해 데이터 분석에 대한 관점과 기여도를 알게 되었습니다. PT는 산부인과 의사이자 의학 교육 분야의 연구자입니다. 그는 의대생, 레지던트, 주치의, 배우자로서의 수치스러운 경험을 이용했다. LV는 의학 교육 분야에서 10년 이상의 경력을 가진 박사 교육을 받은 자질 연구자입니다. LV는 임상의가 아니며 관리자로서 수치심을 경험하지 않았지만, 데이터에 대한 자신의 관점에 기여한 배우자, 부모, 친구 및 학자로서의 수치심을 여러 번 경험했습니다.

JL is a family medicine resident whose shame experiences as a resident and medical student informed her perspectives on, and contributions to, the data analysis. PT is a gynaecologist and researcher in the field of medical education. He drew on his shame experiences as a medical student, resident, attending physician and spouse. LV is a PhD-trained qualitative researcher with over 10 years of experience in the fiel d of medical education. LV is not a clinician and has not experienced shame as a care provider; however, she has experienced several shame experiences as a spouse, parent, friend and scholar that contributed to her perspectives on the data.

2.4 | 데이터 수집

2.4 | Data collection

우리는 각 참가자와 개별적으로 3부로 된 데이터 수집 프로세스를 수행했습니다. 2시간 동안의 단일 데이터 수집 세션에서, 참가자들은 먼저 성찰적 글쓰기(부록 S1)을 작성하도록 요청받았다. 그들은 심리학으로부터 수치심의 정의를 제공받았고 의과대학에서 수치심이 느껴질 때의 구체적인 경험에 대해 쓰라고 요청받았다.

We engaged in a three-part data collection process individually with each participant. In a single, 2-hour data collection session, participants were first asked to compose a written reflection ( Appendi x S1) . They were provi ded wi th a definition of shame from psychology and asked to write about a specific experience in medical school when they felt shame.

마지막으로, WB는 인터뷰 후 참가자가 정서적 고통의 존재 여부를 평가하고, 지지적 리소스(원하는 경우 당일 또는 일상적인 상담 포함)을 제공하고, 참가자의 연구에 대한 기여에 대한 통찰력과 감사를 제공하는 보고 기간을 통해 참가자를 이끌었다.

Finally, after the interview, WB led the participant through a debriefing period during which he assessed for the presence of emotional distress, provided resources for support (which included same-day or routine counselling if desired) and provided insights about, and appreciation for, the participant's contributions to the study.

2.5 | 데이터 분석

2.5 | Data analysis

이 과정에서 우리는 코딩 노트(데이터에 대한 이해의 진화를 위해 개발한 시각화 및 은유 포함)와 연구 회의록 작성을 통해 상세한 감사 추적을 유지했습니다. 우리는 해석적 방법을 고수했고 과거의 수치심 경험을 포함하여 데이터에 대한 우리의 반응을 공개적으로 논의함으로써 성찰성을 달성했습니다. 왜냐하면, 그녀의 해석적 철학자 마틴 하이데거에 따르면, 언어는 인간의 의식과 인식을 형성하기 때문이다, 22 우리는 참여자들이 수치심을 느낄 때 어떻게 자신을 묘사하는지, 그리고 그들이 이러한 감정을 설명할 때 사용한 은유 등을 포함하여, 우리는 참여자들이 사용하는 언어에 주의 깊게 주목했다. 첫 번째 연구에서 우리가 개발한 전문 지식과 이해력과 결합했을 때, 이 초점들은 데이터에 대한 효율적이고 깊은 몰입감을 촉진했습니다.

Throughout this process, we maintained a detailed audit trail through coding notes (including visualisations and metaphors we developed to frame our evolving understandings of the data) and written minutes of research meetings. We adhered to the hermeneutic method and achieved reflexivity by openly discussing our reactions to the data, including our own past shame experiences. Because, according to hermeneutic philosopher Martin Heidegger, language shapes human consciousness and perception,22 we carefull y attended to the language used by participants, including how they described themselves when feeling shame and the metaphors they used to explain these feelings. When combined with the expertise and understanding we developed in the first study,6 these foci facilitated an efficient and deep immersion into the data.

2.6 | 참가자 익명성 보호

2.6 | Protecting participant anonymity

참가자의 수치 경험의 독특한 특성은 독특한 문제를 제기했습니다. 어떻게 하면 참가자의 익명성을 보호하는 동시에 조사 결과에 대한 증거를 제공하기 위해 데이터를 보고할 수 있을까요? 참가자의 독특한 이야기나 장황한 발췌 데이터를 공유하는 것은 참가자를 알아볼 수 있게 하기 때문에 가능하지 않았다. 따라서 여러 참여자의 데이터에서 경험과 발췌한 내용을 통합하여 익명성을 유지하면서 수집된 데이터를 정확하게 보고하는 3가지 예시 내러티브를 구성하였습니다.

The idiosyncratic nature of our participants' shame experiences posed a unique challenge: how could we report our data to provide evidence of our findings while simultaneously protecting the anonymity of our participants? Presenting participants' unique stories or lengthy, verbatim data excerpts was not possible because sharing those data would render participants recognisable. Therefore, we constructed three illustrative narratives within which we integrated experiences and excerpts from multiple participants' data, simultaneously preserving their anonymity and accurately reporting the collected data.

원고를 완성한 후 참가자들에게 논문 최종 초안을 보내 익명을 지키면서 수치심 요소를 정확하고 진실하게 제시했는지를 물었다. 15명의 참가자가 만족스러운 익명화와 정확성을 확인했으며, 한 명은 우리가 채택한 사소한 제안을 요청했습니다.

After completing the manuscript, we sent participants the final draft of the paper and asked if we had correctly and truthfully presented elements of their shame experiences while also protecting their anonymity. Fifteen participants confirmed satisfactory anonymisation and accuracy, and one requested a minor suggestion that we adopted.

3 | 결과

3 | RESULTS

참가자들이 묘사한 부끄러움 경험은 개인과 환경 간의 동시적-다층적 상호작용으로 구성되었습니다. 이러한 상호작용의 의미를 찾으면서 우리는 불fire의 은유를 통해 참가자들의 수치심을 이해하게 되었습니다. 불이 기질에 미칠 수 있는 잠재적 영향과 같이, 수치심은 우리의 참가자들에게 깊은 영향을 미칠 수 있습니다: 대부분은 세계적으로 부정적인 자기 평가로 구성된 강렬하고, 음흉하며, 매우 골치아픈 수치 반응을 경험한다고 보고됩니다. 학생들은 자신을 '좋지 않다'(P10), '완전히 가치가 없다'(P12), '부적절한 의대생'(P15)이 '작다'(P8, P11), '멍청하다'(P6)고 말했다. 수치심의 감정적인 경험은 종종 압도적이었다.

The shame experiences described by participants consisted of simultaneous, multi-layered interactions between the individual and their environment. In seeking the meaning of these interactions, we came to understand participants' shame experiences through the metaphor of fire. Like the potential impact of fire on a substrate, shame could profoundly affect our participants: most reported experiencing intense, insidious and/or deeply troublesome shame reactions that consisted of globally negative self-assessments. Students reported viewing themselves as ‘no good’ (P10), ‘completely worthless’ (P12), ‘an inadequate medical student’ (P15) feeling ‘small’ (P8, P11) and feeling ‘stupid’ (P6). The emotional experience of shame was often overwhelming:

이름 없는 이 부정적인 감정에 빠져드는 것 같았어요. (P15)

I felt like I was drowning in this negative emotion that I didn't have a name for. (P15)

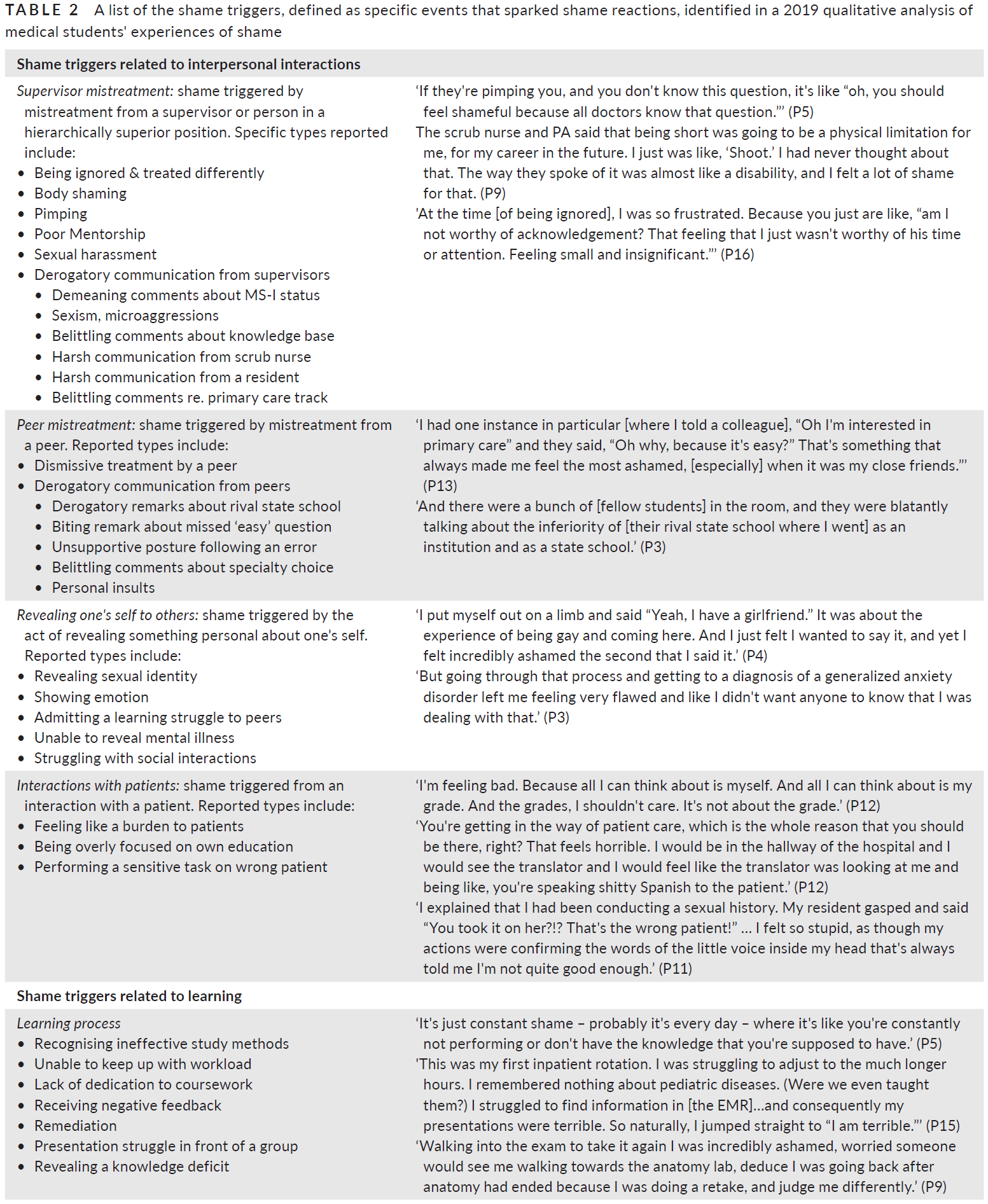

3.1 | 수치심 트리거

3.1 | Shame triggers

수치심 트리거는 우리가 스파크에서 화재가 발생한다고 인식하는 것처럼, 수치심 반응을 촉발하는 구체적인 사건, 행동 또는 사건이었다. 즉, 참가자들은 이러한 사건의 발생과 동시에 수치심(전 세계적으로 결함이 있거나 부족하거나 가치가 없다는 느낌)이 발달했다고 보고하였다.

Shame triggers, which we conceptualised as the sparks that initiated a fire, were the specific events, actions or incidents that precipitated shame reactions. In other words, participants reported that feelings of shame (ie, a sense of being globally flawed, deficient or unworthy) developed upon the occurrence of these events.

참가자들이 보고한 수치심 유발은 주로 다른 사람과의 상호작용과 학습과 관련이 있었다.

다른 사람과의 상호작용과 관련된 수치심 트리거는 네 가지 범주로 나뉩니다.

- 감독의사의 학대(예: 경멸적 발언, 신체 수치심),

- 동료의 학대(예: 무시적 취급, 경멸적 논평),

- 자신에 대한 개인적인 것을 다른 사람에게 드러내는 것(예: 성적 정체성 드러내기, 감정 드러내기)과

- 환자와의 상호작용에 대한 도전(예: 부담이 되는 느낌, 잘못된 환자에게 검사 수행)

Shame triggers reported by participants were primarily related to interactions with others and learning. Shame triggers related to interactions with others were broken into four categories:

- supervisor mistreatment (eg, derogatory comments, body shaming),

- peer mistreatment (eg, dismissive treatment, derogatory comments),

- revealing something personal about one's self to others (eg, revealing sexual identity, showing emotion) and

- challenging interactions with patients (eg, feeling like a burden, performing an examination on the wrong patient).

학습과 관련된 수치심 유발 요인은 두 범주로 나뉩니다.

- 학습 프로세스(예: 작업량을 따라가지 못하는 경우, 교정 중, 그룹 앞에서 고군분투하는 경우)와

- 평가(낮은 USMLE 1단계 점수, 명예롭지 않은 임상 성적 획득, 부정적인 피드백 받기)

Shame triggers related to learning were broken into two categories:

- struggle with learning processes (eg, inability to keep up with the workload, undergoing remediation, struggling in front of a group) and

- assessment (low USMLE Step 1 score, earning non-honours clinical grades, receiving negative feedback).

Table 2.

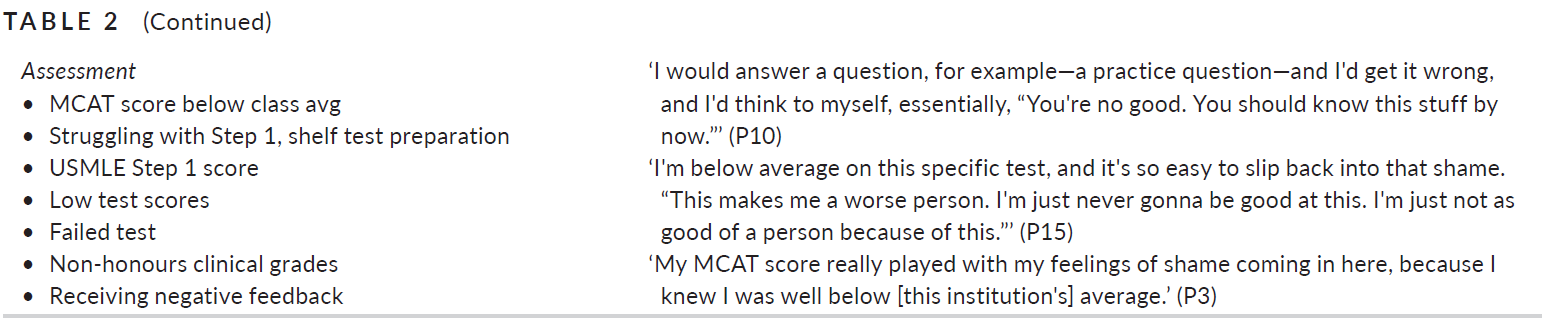

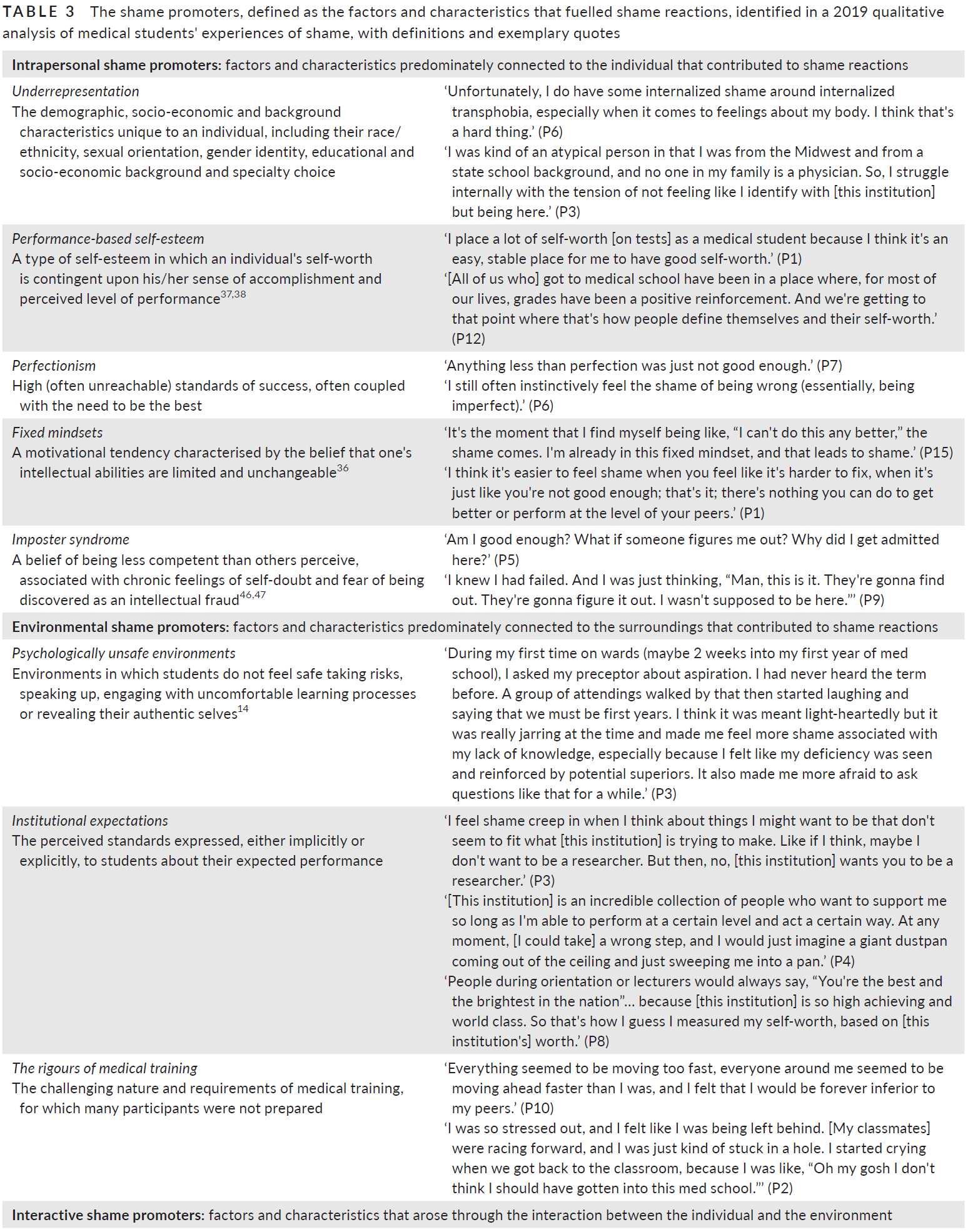

3.2 | 수치심 촉진자

3.2 | Shame promoters

우리가 화재 추진제로 개념화한 [수치심 촉진제]는 수치심 반응의 발생 위험을 높이거나 이미 촉발된 수치심 반응의 강도나 지속시간을 증폭시켰다.

Shame promoters, which we conceptualised as fire propellants, increased the risk of developing a shame reaction or amplified the intensity or duration of an already triggered shame reaction.

우리의 분석에 따르면 세 가지 유형의 수치심 유발자가 나왔다.

- 개인적 수치심 촉진자는 주로 개인과 연결되었고 과소 표현, 성과 기반 자존감, 완벽주의, 고정적 사고방식, 임포스터 증후군을 포함했습니다.

- 환경적 수치심 촉진자는 사람들은 주로 주변 환경과 관련이 있었고 심리적으로 안전하지 않은 환경, 기관의 기대, 의료 훈련의 혹독함을 포함했습니다.

- 관계적 수치심 촉진자는 개인과 환경 간의 상호작용에서 발생하였으며 타인과의 비교, 판단에 대한 두려움, 정체성 이동 및 소속감 저하를 포함하였다.

Our analysis yielded three types of shame promoters.

- Intrapersonal shame promoters were primarily connected to the individual and included underrepresentation, performance-based self-esteem, perfectionism, fixed mindsets and imposter syndrome.

- Environmental shame promoters were primarily connected to the surroundings and included psychologically unsafe environments, institutional expectations and the rigours of medical training.

- Interactive shame promoters arose from the interaction between the individual and their environment and included comparisons to others, fear of judgment, shifting identity and impaired belonging.

Table 3.

3.3 | 수치심 유발과 촉진자가 수치심 반응에서 어떻게 상호작용하는지

3.3 | How shame triggers and promoters interact in a shame reaction

수치심과 같은 복잡한 현상을 별개의 요소로 줄이는 것은 본질적으로 인위적인 과정이다. 참가자들의 생생한 경험 속에서 위의 요소들(예: 개인, 환경, 유발자 및 촉진자)은 복잡하고 혼합된 독특한 방식으로 상호작용하여 수치심을 유발합니다. 참가자들의 경험의 본질을 전달하기 위해 연구 참여자들이 공유하는 구체적인 수치심 경험의 측면을 포함하는 세 가지 내러티브를 만들었습니다. 이러한 내러티브는 우리가 식별한 모든 수치심 유발자 또는 촉진자를 묘사하지 않습니다(표 1과 2) 대신, 수치심으로 이어지기 위해 특정 요소들이 어떻게 상호작용할 수 있는지를 보여줍니다.

Reducing a complex phenomenon like shame into discrete elements is an inherently artificial process. Within the lived experience of our participants, the elements above (eg, the individual, environment, triggers and promoters) interacted in a complex, amalgamised and unique fashion to lead to shame. To convey the essence of our participants' experiences, we created three illustrative narratives wherein we have included aspects of the specific shame experiences shared by our research participants. These narratives do not depict all of the shame triggers or promoters that we identified (Tables 1 and 2); instead, they illustrate how specific elements can interact to lead to shame.

3.3.1 | 서술 #1: 과소표현, 임포스터 증후군 및 수치심

3.3.1 | Narrative #1: Underrepresentation, imposter syndrome, and shame

모니크의 수치스러운 경험은 학업 부진에서 비롯된다. 그러나 Monique의 수치 경험의 기원은 수많은 개인적, 환경적, 상호작용적 요인(즉 수치심을 조장하는 요인)에 의해 채워집니다. 과소대표는 모니크의 수치심에 가장 큰 기여자이다. 아프리카계 미국인이자 작은 주립대 출신의 1세대 대학생인 그녀의 배경은 의대에 입학할 만한 가치가 있다는 것을 증명해야 한다는 압박감을 증폭시켰다. underrepresented 배경을 가진 참가자도 비슷하게 다음과 같이 언급했다.

Monique's shame experience is triggered by academic underperformance. However, the origins of Monique's shame experiences are fuelled by numerous intrapersonal, environmental and interactive factors (ie, shame promoters). Underrepresentation is a central contributor to Monique's shame. Her background as an African-American and first-generation college student from a small state university has ratcheted up the pressure to prove herself worthy of admission to medical school. A participant from an underrepresented background similarly recounted:

다수의 참가자들은 인종적/민족적 소수자, 퀴어적/레즈비언적, 트랜스젠더, 공립대학에서 학부 과정 이수하고, 낮은 사회경제적 계층 출신, 특정 지역에서 성장 등이 자신들의 수치심 경험에 기여하는 형태로 과소표현의 형태를 보고하였다.

Multiple participants reported forms of underrepresentation as contributing to their shame experiences, including being a racial/ethnic minority, being queer/lesbian, being transgender, completing undergraduate studies at a public university, coming from a low socio-economic demographic and growing up in a certain region of the country.

의대에 도착한 모니크는 자신보다 남들이 똑똑하다고 인식하는 환경을 접하게 되고 자신과 비슷한 배경을 가진 사람들을 찾기 위해 고군분투하며 소속감과 자기 의구심, 자기 표현에 대한 거부감을 심화시킨다. 모니크의 수치심 반응은 1학기 내내 계속되는 추세인 1차 시험에서 평균보다 훨씬 낮은 점수를 받았을 때 불을 붙인다. 그녀의 수치심은 다른 학생들과 비교했을 때, 그리고 다른 참가자들에 의해 비슷하게 표현된, 덜 대표적인 학생이 되는 것의 무게로 인해 더욱 악화됩니다.

Upon arriving to medical school, Monique encounters an environment in which she perceives others as smarter than her, and she struggles to find people with similar backgrounds to hers, deepening her questions of belonging, feelings of self-doubt and unwillingness to express herself. Monique's shame reaction ignites when she scores well below average on the first test, a trend that continues throughout the first semester. Her shame feelings are further inflamed by comparing to other students and the weight of being an underrepresented student, tendencies similarly articulated by other participants:

모니크의 소속감을 더욱 악화시키고 수치심을 동반한 것은 의과대학 그녀가 기존에 소속되어있던 공동체와의 관계 상실과 지원 관계의 상실이었다. 한 아프리카계 미국인 참가자는 자신의 삶의 여러 영역에 소속감이 손상되고 수치심이 스며드는 경향을 비슷하게 반영했다.

Further exacerbating Monique's sense of impaired belonging and accompanying shame were the loss of supportive relationships and connection with the communities with which she was affiliated prior to medical school. An African-American participant similarly reflected on the tendency for impaired belonging and shame to seep into multiple areas of his life:

요약하자면, 모니크의 수치심은 의과대학에 입학하여 평균 이하의 시험 성적을 기록함으로써 촉발triggered되었다. 그녀의 수치심은 과소표현, 임포스터 증후군, 기관의 기대, 의료 훈련의 엄격함, 소속감 손상, 타인과의 비교와 관련된 현상으로 인해 촉진promoted되었다.

In summary, Monique's shame was triggered by arriving to medical school and making a below-average test score. Her shame was promoted by phenomena related to underrepresentation, imposter syndrome, institutional expectations, the rigours of medical training, impaired belonging and comparisons to others.

3.3.2 | 서술 #2: 성과 기반 자존감, 고정적 사고방식, 객관적 평가 및 수치심

3.3.2 | Narrative #2: Performance-based self-esteem, fixed mindsets, objective assessment, and shame

USMLE 1단계 시험을 준비하는 데 어려움을 겪으면서 John의 수치심이 촉발되었습니다. 그의 수치심의 근원은 자긍심의 원천, [그에 대한 다른 사람들의 인상]과 [다른 학생들과의 비교]에 있다. 이것들은 모두 수치심 촉진자promoter이다. 존은 '똑똑하게 보이는 것'에 높은 가치를 두는데, 이는 수행능력-기반 자기존중감을 나타내며, 초기 교육 경험에서 기인하는 성향이다.

John's shame is triggered by difficulty preparing for the USMLE Step 1 examination. The origins of his shame lie in his sources of selfworth, need to manage others' impressions of him and comparisons to other students—all shame promoters. The high value that John places on being seen as smart—and the degree to which his self-worth relies on feeling intelligent—indicates the presence of performance-based self-esteem, a tendency that some participants ascribed to early educational experiences:

자존감을 유지하기 위해 존은 시험에서 계속 좋은 점수를 받아야 하고, [다른 사람들이 그에게 가지는 인상]을 관리해야 한다는 압박감을 느낀다. 즉, 그들이 존을 똑똑하고 능력 있는 사람으로 보기를 바란다. 자신을 최고의 학생이라고 알게 하기 위해서, 그리고 이러한 이미지를 반 친구들에게 투영project하기 위해서, 존은 자주 자신을 다른사람과 비교하고, 다른사람을 능가해야 한다고 느낀다. 수많은 참가자들은 자존심을 강화하려는 것 때문에 비슷한 경쟁적 압박이 있었다고 보고했지만, [상대적 우월감을 느끼고자 하는 마음]이 수치심을 유발한다는 사실도 인정했습니다.

To maintain his self-esteem, John feels pressure to continue scoring well on tests and to manage the impressions that others have of him, namely that they see him as clever and capable. To know himself as a top student, and to project this image to classmates, John feels compelled to frequently compare himself against and outperform them. Numerous participants reported similar competitive pressures stemming from a need to bolster self-worth, but they also acknowledged that the need to feel superior drove feelings of shame:

John이 USMLE 1단계 준비과정에서 상당한 어려움을 겪을 때, 이러한 수치심 촉진자promoters들은 각각 큰 수치심 반응을 일으킵니다. 존은 주변 사람들이 모두 여유 있게 준비하고 있다고 생각하며, 어려움을 겪는 자신의 모습이 어떤 모습으로 비춰질지 깊은 우려를 가지고 있다. USMLE 1단계 점수에 대한 학교의 기대와, 이 시험점수가 그의 미래 커리어 계획에 미치는 영향력이 크다는 점이 수치심을 증폭시킨다. 복수의 참가자들은 1단계에서 높은 점수를 얻어야 한다는 강한 압박감을 보였으며, 그 원인에는 자문 학장, 학생들의 이전 수업, 종종 공표되는 학교 평균 등이 있었다. 이로 인해 한 참가자는 Step 1 시험을 '당신이 임포스터가 될지 훌륭한 레지던트 지원자가 될지, 그것을 만들거나 무너뜨리는 것 위대한 이퀄라이져'이라고 표현했다(P14).

When John encounters significant struggle preparing for USMLE Step 1, each of these shame promoters fuel a major shame reaction. John perceives that everyone around him is preparing with ease, and he has deep concerns over how he'll be viewed in the midst of his struggle. Amplifying his shame are the institution's expectations about USMLE Step 1 performance and the heavy influence the test has on his future career plans. Multiple participants reported intense pressure to achieve a high score on Step 1, the sources of which included advisory deans, prior classes of students and the oft-publicised school average. This caused one participant to describe the test as ‘the great equalizer [that] makes or breaks you as an imposter or a good residency applicant’ (P14).

존은 또한 Step 1 시험에서 어려움을 겪는 것이 '나는 시험을 잘 볼 수 있는 능력을 가지고 있지 않으며', 이것을 변화시키기 위해서 스스로 할 수 있는 것은 없다는 숨겨진 진실을 드러낸다고 믿는다. 이러한 [고정 마음가짐]의 증거로는 '느린 프로세서'(P3), '절대 나아지지 않을 것'(P4)과 '[성공할] 배경 없음'(P10)과 같은 느낌을 재조명한 다른 참가자들에게서 나타났다. [고정 마음가짐]은 수치심 트리거(예: 낮은 성과)가 [본질적으로 변하지 않는 자신의 부족한 점] 때문이라는 믿음을 심화시키는 것으로 나타났다.

John also believes that his struggle with Step 1 reveals a hidden truth: that he does not possess the ability to perform well on the test and that nothing he can do will change that. Evidence of this fixed mindset was present in other participants who recounted feeling like ‘a slow processor’ (P3), ‘never going to get better’ (P4) and ‘not having the background to [be successful]’ (P10). Fixed mindsets appeared to deepen the belief that a shame trigger (eg, low performance) was due to an inherent, unchangeable deficiency of the self:

요약하자면, John의 수치심은 낮은 모의고사 점수와 USMLE 1단계 준비 과정에서의 어려움으로부터 비롯되었습니다. 그의 수치심은 성과에 기초한 자존감, 판단에 대한 두려움, 제도적 기대, 타인과의 비교, 고정된 사고방식과 관련된 현상들에 의해 촉진되었다.

To summarise, John's shame was triggered by his low practice scores and struggle to prepare for USMLE Step 1. His shame was promoted by phenomena related to performance-based self-esteem, fear of judgment, institutional expectations, comparisons to others and a fixed mindset.

3.3.3 | 서술 #3: 학대, 정체성 이동 및 수치심

3.3.3 | Narrative #3: Mistreatment, shifting identity, and shame

Peyton의 수치심은 상사의 학대(여러 참가자들이 보고한 수치심 유발)로 촉발되며 심리적으로 안전하지 않은 환경, 높은 개인적 성공 기대감 및 현재 로테이션에서 받는 평가의 고부담성 때문에 촉발됩니다. 사실 페이튼은 경쟁이 심한 레지던트 자리를 노리고 있고, 임상실습 첫 번째 해의 성적은 P/F로 판정되기 때문에, 임상 로테이션에서 Honor 이하의 성적을 받는 것은 사실상 실패Fail라고 믿고 있다.

Peyton's shame is sparked by mistreatment from a supervisor—a shame trigger reported by multiple participants—and fuelled by a psychologically unsafe environment, high personal expectations of success and the high-stakes nature of assessment on her current rotation. In fact, because Peyton is seeking a competitive residency, and because the first year is pass/fail, she believes that anything less than honours on a clinical rotation is a failure.

게다가, 페이튼은 항상 좋은 사랑을 받았기 때문에, 그녀는 주변 사람들과 교류할 수 있는 그녀의 능력에 큰 자부심을 부여한다. 환자와의 관계를 희생하면서라도, 점수를 잘 받고, 레지던트에게 호감을 받고자 하는 이 강렬한 욕구는 페이튼이 지금의 자신을 바라보는 방식(즉, 자신의 교육과 성적에 지나치게 신경을 쓰는 방식)과 페이튼이 의대에 입학했을 때 자신을 바라보는 방식(즉, 환자를 모든 것보다 우선하려는 욕구) 사이에 긴장을 불러일으킨다. '환자를 위해 자신을 완전히 바꿔야 한다'(P9)는 말처럼, 참여자들은 페이튼과 비슷한 정체성 변화가 수치심 경험을 촉진했다고 이야기했다.

Further, because Peyton has always been well liked, she attaches a great deal of self-worth to her ability to interact with those around her. This intense desire to receive a good evaluation and be liked by the resident, which come at the expense of her relationships with patients, creates tension between the way Peyton views herself now (ie, as overly concerned with her own education and grades) and the way Peyton viewed herself upon entering medical school (ie, as desiring to prioritise the patient above all else). Multiple participants reported similar identity shifts as promoting their shame experiences, including one who felt that ‘you have to completely change yourself for someone else, for the better of the patient’ (P9).

페이튼의 경험은 참가자가 보고한 수많은 수치심 유발 학대 중 하나로, 신체 수치심, 미세-공격성, '펌핑', 불필요하게 거친 커뮤니케이션, 지식 기반, 훈련 수준 또는 선택한 진로에 대한 비하 발언 등이 포함된다.

Peyton's experience is one of numerous types of shame-catalysing mistreatment reported by participants, including body shaming, microaggressions, ‘pimping’,23 unnecessarily harsh communication and disparaging comments about knowledge base, level of training or chosen career path.

참가자들은 또한 동료들로부터 수치심을 유발시키는 학대를 보고했으며, 이는 다음과 같은 형태를 취했다.

- 자신의 전공 선택 또는 학부 기관에 대한 경시.

- 직무 윤리에 대한 비판

- 시험에서 어려움을 겪은 후 지능에 대한 의심

- 개인적 삶의 선택에 대한 비판(예: 개인적 관계)

Participants also reported shame-triggering mistreatment from peers, which took the form of

- belittlement about their specialty choice or their undergraduate institution;

- critiques of their work ethic;

- questions about their intellect after struggling on a test; or

- criticisms about personal life choices (eg, personal relationships).

요약하자면, 페이튼의 수치심은 감독관의 학대mistreatment와 환자와의 단절로 촉발되었다. 그녀의 수치심은 심리적으로 안전하지 않은 환경, 소속감 손상, 완벽주의, 타인과의 비교, 정체성의 변화 등과 관련된 현상에 의해 촉진되었다.

In summary, Peyton's shame was triggered by supervisor mistreatment and disconnection with patients. Her shame was promoted by phenomena related to a psychologically unsafe environment, impaired belonging, perfectionism, comparisons to others and a shifting identity.

4 | 토론

4 | DISCUSSION

우리의 분석 과정을 통해 발전된 [불의 비유]는 참가자들의 수치심 반응의 기원의 복잡성과 의미를 이해하는 데 도움을 주었습니다. 이러한 은유를 통해 [의과대학의 경험]을 가연성combustible 물질로 개념화하고, 수치심이 발생하게 prime 되어 있다고 개념화할 수 있었다. 다시 말해, 많은 의대 학습자들에게 의대 환경을 탐색하는 것은 수치심을 경험할 수 있는 상당한 위험(필연적인 위험은 아님)을 야기하는 것으로 보입니다.

The metaphor of fire, developed throughout our analysis processes, helped us understand the complexity and meaning of the origins of participants' shame reactions. Through this metaphor, we came to conceptualise the medical school experience as being combustible and primed for the development of shame. In other words, for many medical learners, navigating the medical school environment appears to incur substantial—but not inevitable—risk of experiencing shame.

우리의 자료는 이러한 위험과 의대생들의 수치심 발달에 [환경적 요인]이 기여한다는 것을 강하게 시사하고 있습니다. 학대mistreatment는 강력하고 (학생과 전공의에게) 공통적인 수치심 트리거로서, 환경적 요인 중 하나입니다. 참가자가 보고한 괴롭힘, 체면치레, 핌핑, 모욕적 처우, 그리고 학문적 투쟁에 대한 지나치게 가혹한 반응은 유감스럽게도 의학 교육에서 흔하며, 학습 환경에서 불필요하게 수치심의 위험을 증가시키는 것으로 보인다. 본 연구에서는 강조하는, 현재 상당히 과소평가하고 있다고 생각하는 것은, 이러한 mistreatment가 의학 학습자에게 미칠 수 있는 엄청난 감정적 영향입니다. 실제로, 많은 참여자들은 때로는 다른 사람들을로부터, 교육학적 전략(예: 핌핑)을 가장하여, [상당한 권력이나 영향력을 가진 감독관]들의 손에 의해, 학대당하는 심대하고 장기간 지속된 수치심을 경험했습니다.

Our data strongly suggest that factors from the environment contribute to this risk and the development of medical students' shame. Mistreatment, a potent and common shame trigger in both our participants and residents,4-6 is one such environmental factor. The harassment, body shaming, pimping, derogatory treatment and overly harsh responses to academic struggle that our participants reported are unfortunately common in medical education24,34,35 and appear to unnecessarily increase the risk of shame in the learning environment. What our study emphasises—and what we believe is significantly underrecognised—is the overwhelming emotional impact this treatment can have on medical learners. Indeed, many of our participants experienced significant and prolonged shame upon being mistreated by others, sometimes under the guise of pedagogical strategy (eg, pimping) and often at the hands of supervisors with significant power or influence over them.

의대생들의 수치심은 단순히 환경의 특성 이상의 영향을 받는 것으로 보인다. 본 연구에서는 수많은 참가자들이 의학을 배우는 과정에서 정상적이고 충분히 있을 수 있는 사건(답을 틀리거나, 여러 사람 앞에서 struggle하거나, 부정적 피드백 을 받는 것 등)으로 촉발된 수치심 반응을 보고했습니다. 이러한 사건들이 수치심을 유발하는 경향은 고정된 사고방식의 존재와 성과에 기초한 자존감 같은 [개인적 특성]에 영향을 받는 것으로 보였다. 지적 능력은 고정되어 있고 바꿀 수 없다는 믿음으로 정의되는 고정(즉, 실체적entity) 마음가짐은 수치심의 위험을 증가시키는 것으로 보였으며(예: '나는 결코 충분히 똑똑하지 않을 것이다; 그러므로 나는 멍청하다'), 수치심 반응은 고정 마음가짐(예: '나는 멍청하다; 그러므로 결코 똑똑하지 않을 것이다')을 고착시키는 것으로 보였다.

Shame in medical students appears to be influenced by more than just the nature of the environment. In our study, numerous participants reported shame reactions triggered by events considered normal and expected in the course of learning medicine, such as being wrong, struggling in public and receiving negative feedback. The tendency for these events to cause shame appeared to be influenced by personal characteristics such as the presence of fixed mindsets and performance-based self-esteem. Fixed (ie, entity) mindsets, defined as the belief that intellectual ability is fixed and unchangeable,36 appeared to increase the risk of shame (eg, ‘I'll never be smart enough do this; therefore, I'm stupid’), and shame reactions appeared to entrench fixed mindsets (eg, ‘I'm stupid; therefore, I'll never be smart enough to do this’).

많은 참가자들에게, [고정 마음가짐]의 존재는 정상적인 학습의 어려움을 자신에 대한 전체적인 무가치함이나 약점(수치심)의 증거로 변화시켰다. (개인의 자긍심이 성취감과 수행능력 인식 수준에 따라 좌우되는 자긍심의 한 유형으로 정의되는 )[수행능력-기반 자존감]도 연구에서 정상적인 학습 사건과 관련된 수치심을 증폭시켰다. 연구 결과에 따르면 관찰, 평가 및 수행능력 사이의 경계가 모호해지면 불안, 임포스터리즘, 자기-의심을 유발할 수 있습니다.27, 39 우리의 데이터는 이러한 발견을 반복하며 수치심을 목록에 추가할 것을 시사합니다.

For many participants, the presence of a fixed mindset turned a normal learning struggle into proof of global unworthiness or deficiency (ie, shame). Performance-based self-esteem, defined as a type of self-esteem in which an individual's self-worth is contingent upon their sense of accomplishment and perceived level of performance,37, 38 also amplified shame related to normal learning events in our study. Research has shown that the blurred lines between observation, assessment and performance can drive anxiety, imposterism and self-doubt.27, 39 Our data reiterate these findings and suggest that shame be added to the list.

이론적으로 수치심의 위험을 줄이기 위해서 [수행능력-기반 자존감]과 [고정 마음가짐]과 같은 특성은 [수정가능]하다 (아래 참조). 다만, 참가자가 수치심에 기여했다고 보고한 인종/인종, 성적 성향, 성 정체성, 종교적 신념, 고향, 학문적 혈통 등 [수정불가능]한 요인도 확인하였습니다. 중요한 것은 참가자들의 수치심을 자극한 것은 단순히 이러한 인구통계적 요인의 존재가 아니었다. 오히려, 이러한 인구통계학적 요인들이 (잘 표현되지 않는) 환경과의 상호작용을 통해 수치심이 유발되고 지속되었다. 우리의 underrepresent background을 가진 많은 참가자들에게, 면접 날이나 수업 첫날에 의과대학에 들어가는 것만으로도 상당한 수치심과 소속감에 대한 질문을 불러일으켰습니다. 일단 입학한 후에도, 자기-가치를 보호해주는 원천의 상실(예: 소셜 네트워크, 취미 및 가정과의 근접성), [새로운 문화 규범에 동화되어야 한다는 압박], 의대에 입학할 만큼의 [가치가 있음를 입증해야 한다는 압박]은 기존의 수치심을 증폭시키거나 새롭게 촉발시키는 데 도움을 주었다.

Characteristics such as performance-based self-esteem and fixed mindsets can theoretically be modified to reduce the risk of shame (see below). However, we also identified non-modifiable factors that participants reported as contributing to their shame, including race/ethnicity, sexual orientation, gender identity, religious beliefs, hometown and academic pedigree. Importantly, it was not simply the presence of these demographic factors that precipitated participants' shame. Rather, their shame was often triggered and sustained through interactions with an environment in which these demographic factors were underrepresented. For many of our participants from underrepresented backgrounds, simply walking into medical school on interview day or the first day of classes precipitated significant shame feelings and questions of belonging. Once enrolled, loss of protective sources of self-worth (eg, social networks, hobbies and proximity to home), pressure to assimilate to new cultural norms and the need to prove one's worthiness to be in medical school amplified existing shame or helped to trigger it anew.

마지막으로, 우리는 [표준화된 시험]과 [비표준화된 시험]을 모두 포함하여 [평가]가 참가자들의 수치심 경험에 상당한 영향을 미친다는 것을 발견했습니다. 객관적 평가가 동료와의 비교를 위한 명확한 측정 척도를 제공했을 뿐만 아니라, 많은 참가자는 객관적 수행능력의 실수를 스스로의 무가치함, 소속성 결여, 임포스터 증후군에 대한 결정적인 증거로 해석했다. 객관적 평가는 전공의에 대한 최근 연구에서 간헐적인 수치심 유발 요인이었지만, 객관적 평가에서 주관적 평가로의 전환(상대적 측정 막대 부족으로 정의됨)은 특히 객관적 지표 대신 지나치게 가혹한 자기 평가에 의존할 때 전공의의 수치심에 더 큰 기여를 했다.6 따라서 의대에서 자긍심을 평가하기 위해 객관적인 수행방안에 의존하는 것은 자긍심이 성과에 좌우되지만 객관적인 조치는 사라졌을 때 레지던트에서 정서적 고통을 선사할 수 있다.

Finally, we found that assessment—including both standardised and non-standardised testing—exerted substantial influence on our participants' shame experiences. Not only did objective assessment provide a clear measuring stick for peer-to-peer comparisons, but numerous participants interpreted lapses in objective performance as definitive proof of their perceived unworthiness, lack of belonging and imposter syndrome. While objective assessment was an infrequent shame trigger in the recent study on residents, the transition from objective to subjective assessment—defined by the relative lack of a measuring stick—was the greater contributor to resident shame, especially when they relied on overly harsh self-assessments in the place of objective markers.6 It is thus possible that relying on objective performance measures to assess self-worth in medical school presages emotional distress in residency when self-worth remains contingent on performance but objective measures disappear.

4.1 | 의과대학에서 수치심의 위험 해결 및 완화

4.1 | Addressing and mitigating the risk of shame in medical school

수치심의 위험을 줄이고, 수치심을 느끼는 학생들을 지원하고, 교육 안전을 강화하기 위해 우리는 제안합니다.

- (a) [진정한 포용성]을 보장하고, 우리의 학습 환경에서 [진정한 자기 표현]을 촉진한다.

- (b) [성장 마인드셋]을 촉진하고 성과가 아닌 [리허설]을 장려한다.

- (c) 우리 기관의 [학대 및 의도적인 수치심 주기shaming를 제거]하는 것.

To dampen the risk of shame, support students experiencing shame and enhance educational safety, we suggest

- (a) ensuring true inclusivity and promoting authentic self-expression in our learning environments,

- (b) facilitating growth mindsets and encouraging rehearsal, not performance, in our students and

- (c) eliminating mistreatment and intentional shaming in our institutions.

underrepresentation이 수치심을 유발할 수 있다는 사실을 감안할 때, 점점 더 다양한 학생들을 의과대학에 모집하려는 노력에도 불구하고, (우리가 아직) 진정한 소속감, 포용감, 진정한 자기표현을 촉진할 수 있는 환경을 조성하지 못하고 있을 수 있다고 생각합니다. 수치심의 위험을 줄이고 수치심의 회복력을 높이기 위해, 특히 URM의 학생들을 위해, 우리는 [자기표현]과 [개인적 정체성 형성]을 전문적 표준의 내면화(즉, 직업적 정체성 형성)와 같은 중요도로 높여야 합니다.

Given our finding that underrepresentation can promote shame, we believe, like others,40 that despite efforts to recruit increasingly diverse students into medical school, we may be failing to create environments that promote true belonging, inclusion and authentic self-expression. To reduce the risk of shame and promote shame resilience, particularly for students from underrepresented backgrounds, we should elevate self-expression and personal identity formation to the same level of importance that we ascribe to the internalisation of professional standards (ie, professional identity formation).41

[개인 정체성 형성]을 육성하기 위한 구체적인 이니셔티브는 다음을 포함할 수 있다.

- 학생들이 학습 환경 내에서 문화적, 개인적 정체성의 측면을 실제로 표현하고 통합할 수 있는 배출구 제공.

- 학생들이 자신의 정서적 경험을 공유할 수 있는 안전하고 지지적인 공간을 만듭니다.

- 학습 환경을 최적화하고 [microaggression 및 공공연한 인종차별]과 같은 수치심 유발에 직면한 학생들을 지원하기 위한 암묵적 편견, allyship, 반인종주의에 대한 교수 훈련.

- 부족한 학생들의 경험을 공감하고 지원할 수 있는 멘토의 존재를 보장합니다.

Specific initiatives to nurture personal identity formation could include

- providing outlets for students to authentically express and integrate aspects of their cultural and personal identities within the learning environment;

- creating safe, supportive spaces for students to share their emotional experiences;

- faculty training on implicit bias,42 allyship43 and anti-racism44 to optimise the learning environment and support students confronted with shame triggers such as microaggressions and overt racism; and

- ensuring the presence of mentors who can relate to and support the experiences of underrepresented students.45

이러한 노력이 underrepresented 학생들에게 집중될 수 있지만, 기관의 모든 구성원들에게까지 확대되어야 한다.

While these efforts may focus on underrepresented students, they should extend to all members of the institution.

[성장 마음가짐] 구축과 [학습을 (성과가 아닌) 리허설rehearsal로 재구성하는 것]은 학업적 어려움으로 인한 수치심의 위험을 줄이기 위한 두 가지 전략이다. 연구에 따르면 적어도 일시적으로만이라도 자신의 고유 역량에 대한 개인의 사고방식이 바뀔 수 있다.36 교육자는 아래 활동을 통해 성장 마음가짐을 촉진할 수 있다.

- 현실적인 기대치를 유지하고,

- 학업적 고군분투를 성장 기회로 재구성하고,

- 학습 환경에서 심리적 안전성을 확립하고,

- 근본적인 수치심을 탐색하고 해소하는 것.

Establishing growth mindsets36 and reframing learning as rehearsal, not performance, are two strategies to reduce the risk of shame in the midst of expected academic struggle. Research indicates that individuals' mindsets about their inherent capabilities can be changed, at least temporarily.36 Educators can facilitate growth mindsets by helping learners

- maintain realistic expectations,

- reframing academic struggle as a growth opportunity,

- establishing psychological safety in the learning environment and

- identifying and addressing underlying shame.

또한 학습자에게 수행perform이 아닌 리허설을 권장함으로써 탐색, 투쟁, 실패를 허용하고, 동시에 이러한 어려움에 내재된 학습 가치를 강조합니다.

Furthermore, by encouraging learners to rehearse—rather than perform—we grant them permission to explore, struggle and fail, simultaneously emphasising the learning value inherent in this struggle.

의학교육의 공동 목표가 [역량있고, 참여적이며, 공감적이고, 회복탄력적인] 의사를 배출하는 것이라고 가정할 때, 우리 교육 시스템에서 수치심을 유발하는 학대(특히 의도적으로 부과된 학대)는 설 자리가 없으며, 반드시 제거되어야 합니다. 그러나 이러한 행동의 근절을 복잡하게 만드는 것은 우리가 확인한 많은 [수치심 유발자와 촉진자]가 어느정도 의학과 의학교육의 문화에 내재되어 있을 수 있기 때문이다. 학대, 가혹한 교육방법, 포괄성 결여, 높은 수준의 경쟁, 성과에 대한 과도한 의존, 완벽주의, 개인 정체성 형성에 대한 낮은 강조 등이 그것이다. 수치심 치료를 없애기 위한 노력과 함께 의학에서 수치심 문화가 존재할 가능성을 고려하고 탐구해야 한다.

Assuming that our shared goal in medical education is to produce competent, engaged, empathic and resilient physicians, shame-inducing mistreatment—especially that levied intentionally—has no place in our education system and must be eliminated. Complicating the eradication of these behaviours, however, is the degree to which many of the shame triggers and promoters we identified may be embedded in the culture of medicine and medical education, including mistreatment, harsh teaching tactics, lack of inclusivity, high levels of competition, excessive reliance on objective measures of performance, perfectionism and low emphasis on personal identity formation. Alongside efforts to eliminate treatment intended to shame, we should consider and explore the potential existence of a shame culture in medicine.

4.2 | 한계

4.2 | Limitations

5 | 결론

5 | CONCLUSION

사실, 그것은 정상적인 인간의 감정이기 때문에, 수치심의 위험을 완전히 없애는 것이 우리의 목표가 되어서는 안 되며, 그렇게 할 수도 없습니다. 대신 우리는 이러한 위험의 원인을 식별하고 불필요한 위험 요소를 제거하며 학습자가 남아 있는 위험 요소에 완전하고 확실하게 참여할 수 있도록 지원해야 합니다.

In fact, because it is a normal human emotion, complete elimination of the risk of shame should not—and likely cannot—be our goal. We should instead strive to identify the sources of this risk, eliminate those that are unnecessary and support learners in fully and authentically engaging with those that remain.

12. Tsuei SH, Lee D, Ho C, Regehr G, Nimmon L. Exploring the construct of psychological safety in medical education. Acad Med. 2019;94(11S):S28-S35.

Med Educ. 2021 Feb;55(2):185-197.

doi: 10.1111/medu.14354. Epub 2020 Sep 13.

'I'm unworthy of being in this space': The origins of shame in medical students

William E Bynum 4th 1, Lara Varpio 2, Janaka Lagoo 3, Pim W Teunissen 4

Affiliations collapse

Affiliations

- 1Department of Family Medicine and Community Health, Duke University School of Medicine, Durham, NC, USA.

- 2Department of Medicine, Uniformed Services University, Bethesda, MD, USA.

- 3Duke Family Medicine Residency Program, Department of Family Medicine and Community Health, Duke University School of Medicine, Durham, NC, USA.

- 4School of Health Professions Education, Maastricht University, Maastricht, The Netherlands.

- PMID: 32790934

- DOI: 10.1111/medu.14354Abstract

- Objectives: Shame results from a negative global self-evaluation and can have devastating effects. Shame research has focused primarily on graduate medical education, yet medical students are also susceptible to its occurrence and negative effects. This study explores the development of shame in medical students by asking: how does shame originate in medical students? and what events trigger and factors influence the development of shame in medical students?Results: Data analysis yielded structural elements of students' shame experiences that were conceptualised through the metaphor of fire. Shame triggers were the specific events that sparked shame reactions, including interpersonal interactions (eg, receiving mistreatment) and learning (eg, low test scores). Shame promoters were the factors and characteristics that fuelled shame reactions, including those related to the individual (eg, underrepresentation), environment (eg, institutional expectations) and person-environment interaction (eg, comparisons to others). The authors present three illustrative narratives to depict how these elements can interact to lead to shame in medical students.

- Conclusions: This qualitative examination of shame in medical students reveals complex, deep-seated aspects of medical students' emotional reactions as they navigate the learning environment. The authors posit that medical training environments may be combustible, or possessing inherent risk, for shame. Educators, leaders and institutions can mitigate this risk and contain damaging shame reactions by (a) instilling a true sense of belonging and inclusivity in medical learning environments, (b) facilitating growth mindsets in medical trainees and (c) eliminating intentional shaming in medical education.

- Methods: The study was conducted using hermeneutic phenomenology, which seeks to describe a phenomenon, convey its meaning and examine the contextual factors that influence it. Data were collected via a written reflection, semi-structured interview and debriefing session. It was analysed in accordance with Ajjawi and Higgs' six steps of hermeneutic analysis: immersion, understanding, abstraction, synthesis, illumination and integration.

- © 2020 John Wiley & Sons Ltd and The Association for the Study of Medical Education.

'Articles (Medical Education) > 전문직업성(Professionalism)' 카테고리의 다른 글

| 한국 의사의 역사적 정체성 형성 (KMER, 2021) (0) | 2022.02.23 |

|---|---|

| 의학교육에서 자신감-역량 정렬과 자기확신의 역할: 개념 리뷰(Med Educ, 2022) (1) | 2022.01.14 |

| 웰니스가 의사의 핵심 역량이 되어야 하는가? (Acad Med, 2020) (0) | 2021.07.31 |

| 임상술기와 지식의 학습과 전이에 있어서 감정의 역할(Acad Med, 2012) (0) | 2021.07.31 |

| 의과대학이라는 형상화된 세계에서 의사가 되기 전 정체성 저술하기(Perspect Med Educ, 2018) (0) | 2021.07.28 |