의학교육에서 자신감-역량 정렬과 자기확신의 역할: 개념 리뷰(Med Educ, 2022)

Confidence-competence alignment and the role of self-confidence in medical education: A conceptual review

Michael Gottlieb1 | Teresa M. Chan2 | Fareen Zaver3 | Rachel Ellaway4

1 | 소개

1 | INTRODUCTION

의심은 당신에게 동기를 부여할 수 있으니 두려워하지 마세요. 자신감과 의심은 양 끝에 있고, 당신은 둘 다 필요합니다. 그들은 서로 균형을 잡는다. –바바라 스트라이샌드

Doubt can motivate you, so don’t be afraid of it. Confidence and doubt are at two ends of the scale, and you need both. They balance each other out. –Barbra Streisand

지난 10년 동안 보건 직업 교육(HPE)에서 역량 기반 의료 교육에 대한 강조가 증가하고 있다. 이는 시간 기반 교육 및 평가에서 관찰 가능한 역량으로 관심이 이동했음을 반영한다. 관찰된 행동에만 기반한 역량에 대한 접근법은 [잘못된 인식과 속성]을 놓칠 수 있다.1 학습자가 역량에 대해 공개하거나 행동할 충분한 확신이 있는 경우에만 명확해질 것이다. 간단히 말해서, 오직 역량에만 집중하는 것은 자신감의 중요한 차원을 무시합니다.

There has been an increasing emphasis on competency-based medical education (CBME) in health professions education (HPE) in the last decade.1,2 T his reflects a shift of attention f rom t ime-based teaching and assessment to observable competence. Approaches to competence that are solely based on observed actions may miss aberrant perceptions and attributions,1 which will only become apparent if a learner is sufficiently confident to disclose or act on them.3 Simply put, focusing solely on competence neglects the important dimension of confidence.

자신감은 많은 것을 의미할 수 있지만, 일반적인 정의는 '사람이나 사물을 신뢰하거나 의지하는 마음가짐; 어떤 사실이나 문제에 대해 자신하거나 확신하는 마음가짐'이다. 자신감은 행동과 인식을 바꿀 수 있습니다. 불행하게도, 기술에 대한 개인의 자기평가는 형편없고, 이것은 자신감과 역량의 공통적인 불일치를 반영한다. 자기조절이 성과 개선의 한 방법으로 제안되었지만, 여전히 개인의 자신감과 기술에 대한 확실한 이해에 달려 있다.7 자신감과 역량이 맞지 않을 때 문제가 생긴다. 예를 들어, 자신감이 부족한 의사는 필요할 때 결정을 내리는 것을 망설일 수 있는 반면, 자신감이 부족한 의사는 그들의 행동의 결과에 무모하거나 맹목적일 수 있다. 두 가지 상황 모두 환자에게 해를 끼칠 수 있다.8,9 이와 비슷하게, 과소-자신감은 이미 알려진 정보에 과도한 시간을 소비할 수 있는 반면, 과다-자신감은 학습 기회를 놓치고 피드백에 대한 수용성이 저하될 수 있습니다. 안전한 임상 실천을 위해서는 훈련, 경험 및 임상 복잡성의 수준에 따라 적절한 수준의 자신감이 필요하다.

Confidence can mean many things, but a common definition is ‘the mental attitude of trusting in or relying on a person or thing; feeling sure or certain of a fact or issue’.4 Confidence can change behaviours and perceptions.5 Unfortunately, individual self-assessment of skills is poor,6 which reflects a common mismatch between confidence and competence. Although self-regulation has been proposed as a way of improving performance, it is still contingent on a robust understanding of one's confidence and skills.7 When confidence and competence are out of sync, problems arise. For instance, a physician who is underconfident may still hesitate to make decisions when needed, whereas an overconfident physician may be reckless or blind to the consequences of their actions; either situation could lead to patient harm.8,9 Similarly, underconfidence may lead to spending excessive time on information already known, while overconfidence may lead to missed learning opportunities and decreased receptivity to feedback. Safe clinical practice requires an appropriate level of confidence based on the level of training, experience and clinical complexity.

자신감은 스트레스, 불확실성, 감정, 인지 부하 및 그룹 역학을 포함한 많은 요인에 의해 영향을 받는다. 이러한 개별 차원이 어느 정도 주목을 받긴 했지만, 신뢰와 그것이 성과와 어떤 관련이 있는지 구체적으로 본 사람은 거의 없다.

Confidence is influenced by many factors including stress,10 uncertainty,11,12 emotion,13 cognitive load14 and group d ynamics.15 Although these individual dimensions have received some attention, few have specifically looked at confidence as a multidimensional construct and how it relates to performance.

2 | 방법

2 | METHODS

우리는 의학 교육뿐만 아니라 HPE 전반에 걸쳐 자신감과 역량에 대한 자신감의 교정을 탐구하기 위한 개념적 검토를 수행했다. 우리는 관심 있는 현상을 탐구하기 위해 문헌 검토와 이해관계자 협의를 이끌어내며 반복적인 발산 및 수렴 접근법(증거, 의견 및 이론의 차이점과 유사성을 탐구)을 채택했다.

We undertook a conceptual review16 to explore confidence and the calibration of confidence against competence not just in medical education but across HPE. We employed an iterative divergent and convergent approach (exploring differences and similarities in evidence, opinion and theory), drawing on a literature review and a stakeholder consultation to explore our phenomena of interest.17,18

2.1 | 팀

2.1 | The team

연구팀은 응급의학 분야의 임상 교육자 3명과 박사과정 과학자 1명으로 구성됐으며 이들 모두 HPE 분야의 연구자로 확인됐다. 임상의에게는, 한 명의 저자가 그녀의 첫 몇 년간의 임상 실습에 있었고, 두 명은 그들의 학문적인 경력에 더 가까웠다. 한 교육자는 그녀의 지역 역량 위원회에 참여했고 거의 10년 동안 CBME에 몰두해 왔다. 우리의 박사 교육 과학자는 HPE 연구의 여러 영역에 광범위하게 익숙하며 임상의 교육자들이 반사성과 이론에 대한 참여를 유지할 수 있도록 돕는 데 초점을 맞추고 있다. 우리는 과정 전반에 걸쳐 핵심 현상에 대한 가정과 개념화를 선언하고 해제함으로써 반사적인 구성 요소를 연구에 내장했다.

The study team was composed of three clinician educators in the field of Emergency Medicine and one PhD scientist, all of whom also identify as researchers within the field of HPE. For the clinicians, one author was in her first few years of clinical practice and two were further along in their academic careers. One educator has participated in her local competence committee and has been immersed in CBME for nearly a decade. Our PhD education scientist is broadly familiar with multiple domains of HPE research and focused on helping the clinician educators maintain their reflexivity and engagement with theory. We built a reflexive component into the study through declaring and unpacking our assumptions and conceptualisations of our core phenomena throughout the process.

2.2 | 팀 토론

2.2 | Team discussions

첫 번째 단계는 우리의 이론적 작업에 대한 민감한 개념으로 사용하기 위해 HPE 내부와 외부의 이론을 식별하기 위한 파일럿 문헌 검토를 포함했다. 반복적인 그룹 토론을 통해 확인된 용어에는 자기 효능감, 자가 평가, 직업적 정체성 형성, 쇤의 행동반영/행동반영25 개념 및 임포스터 증후군이 포함되었다. 이것은 우리의 초기 아이디어와 후속 문학 리뷰를 비계화 할 수 있게 해주었다. 다음으로, 우리는 협업 메모잉과 개념 쌓기를 사용하여 귀납적 추론과 연역적 추론을 번갈아 할 수 있는 일련의 대화식 토론에 참여했습니다. 우리의 목표는 명료성이 부족한 아이디어들을 질문하고 재구성하는 것뿐만 아니라 아이디어화와 이론적 합성을 지원하는 것이었습니다.

The first step involved a pilot literature review to identify theories from within and beyond HPE to use as sensitising concepts for our theoretical work.19 Terms identified through iterative group discussion included self-efficacy, 20 self-assessment, 7,21-23 professional identity formation,24 Schön's concepts of reflection-in- action/ reflection-on- action25 and imposter syndrome.26 This enabled us to begin scaffolding our initial ideas and subsequent literature reviews. Next, we engaged in a series of interactive discussions that allowed us to alternate between inductive and deductive reasoning using collaborative memo-ing and concept-building. Our goal was to support ideation and theoretical synthesis, as well as question and reframe ideas which lacked clarity.

2.3 | 문헌검토 및 작성

2.3 | Literature review and writing

초기 개념화를 만든 후, 우리는 좀 더 심층적이고 표적화된 문헌 검토를 시작했다. 우리는 HPE 및 인접 도메인/분야(예: 심리학, 비즈니스, 비보건 전문직 교육)의 문헌을 활용하여 문제 공식과 새로 제안된 이론적 프레임워크에서 설명한 개념을 삼각측량하고 강화했다. 본 논문을 위해 검토한 개념의 전체 목록은 부록 S1에 포함되어 있다. 기사는 그룹 토론과 합의를 바탕으로 선정되었습니다. 그런 다음 기존 개요와 프레임워크를 텍스트와 그림으로 변환했습니다. 우리는 글의 흐름과 개념이 일치하고 반영될 수 있도록 논평, 토론, 편집을 통해 반복적인 수정에 참여했다. 우리는 식별된 주요 주제를 요약하기 위해 일반적인 공리를 만들었다.

After creating our initial conceptualisations, we began a more in-depth, targeted literature review. We utilised literature in the field of HPE and adjacent domains/fields (eg psychology, business, non-health professions education) to triangulate and augment the concepts that we described in our problem formulation and our new proposed theoretical frameworks. A full list of the concepts reviewed for this paper is included in the Appendix S1. Articles were selected based upon group discussion and consensus. We then converted the existing outlines and frameworks to text and figures. We engaged in iterative revisions through comments, discussion and edits to ensure that the flow and concepts were congruent and reflective of the literature. We created general axioms to summarise the key themes identified.

2.4 | 이해관계자 협의

2.4 | Stakeholder consultation

검토 범위 지정에 사용된 방법과 유사하게, 우리는 다음으로 전문가(예: HPE 분야의 과학자 및 학자)와 일선 개인(예: 임상의사 교육자, 동료 의사, 레지던트 의사 및 의대생)으로부터 잠정적 발견에 대한 조형적 피드백을 구했다. 기관, 국가, 전문성, 훈련 단계 등 다양성이 포함될 수 있도록 의도적으로 이해관계자를 선정했습니다. 이해관계자들에게 연락하여 원고 초안을 제공했다. 8명의 개인이 광범위한 서면 의견과 선택적인 화상 상담을 통해 잠정적인 결과에 대한 의견을 제공했습니다. 주로 설명과 다른 연구와의 교차에 초점을 맞춘 이러한 의견을 바탕으로, 우리는 시사점을 논의하고 피드백을 반영하기 위해 섹션을 다시 작성했다. 이해관계자 피드백의 한 예는 분산 신뢰에 대한 논의를 가시적인 사례로 확장하는 것이었다.

Similar to methods used in scoping reviews, we next sought formative feedback on our provisional findings from experts (eg scientists and scholars in the field of HPE) and frontline individuals (eg clinician educators, fellow physicians, resident physicians and medical students).27-29 We intentionally selected the stakeholders to include diversity of institution, country, specialty and stage of training. Stakeholders were contacted and provided a draft of the manuscript. Eight individuals provided their reflections on our provisional findings via extensive written comments and optional video consultation. Based on these comments, which focused primarily on clarifications and intersections with other research, we discussed the implications and rewrote sections to incorporate their feedback. One example of the stakeholder feedback was to expand the discussion of distributed confidence with a tangible example.

3 | 결과

3 | RESULTS

3.1 | 현상으로서의 신뢰도

3.1 | Confidence as a phenomenon

[확실성]은 주로 지식을 중심으로 구성된 인식론적 현상인 반면, [자신감]은 행동에 중점을 둔다. 무언가에 대해 확신하는 것은 [행동할 수 있는 자신감]을 만들 수 있습니다. 시간이 지남에 따라, 행동의 결과가 확신감을 강화한다면, 확신은 자신감을 시작하고 그것을 유지할 수 있다. 과학철학에서 [인식론적 자신감]은 [지식]과 [다른 조건에서 지식을 검증하는 능력]을 모두 반영한다. 인식론적 자신감은 (지식과 앎의 한계를 인식하는 온건한 덕목인) [인식론적 겸손]에 의해 조절되며, 그래야 한다. [인식론적 자신감]은 검증 가능한 확실성과 신뢰성을 반영해야 하지만, 자신감이 검증 가능성을 초과하면 오만이나 무모함으로 이어질 수 있다. 다른 때에는, 자신감이 검증 가능한 확신 아래로 떨어져 [소심함]이나 [불안정]으로 이어질 수 있다. 자신감은 주관적이고 감정적이며 해석적입니다. 그것은 이성이나 논리에 끌릴 수도 있고 끌리지 않을 수도 있는 것에 대한 게슈탈트 감각이다.

While certainty is an epistemic phenomenon primarily constructed around knowledge, confidence centres on action. Being certain about something can create the confidence to act.30,31 Over time, if the outcomes of the action reinforce the sense of certainty, then certainty can initiate confidence and sustain it.32 In the philosophy of science, epistemic confidence reflects both knowledge and the ability to verify that knowledge in different conditions.33 Epistemic confidence is (or should be) regulated by epistemic humility, a moderating virtue that recognises the limits of knowledge and knowing. Although epistemic confidence should reflect verifiable certainty and reliability, if confidence exceeds verifiability then it can lead to arrogance or recklessness. At other times, confidence may fall below verifiable certainty and lead to timidity or insecurity. Confidence is subjective, emotional and interpretive. It is a gestalt sense about something that may or may not draw on reason or logic.

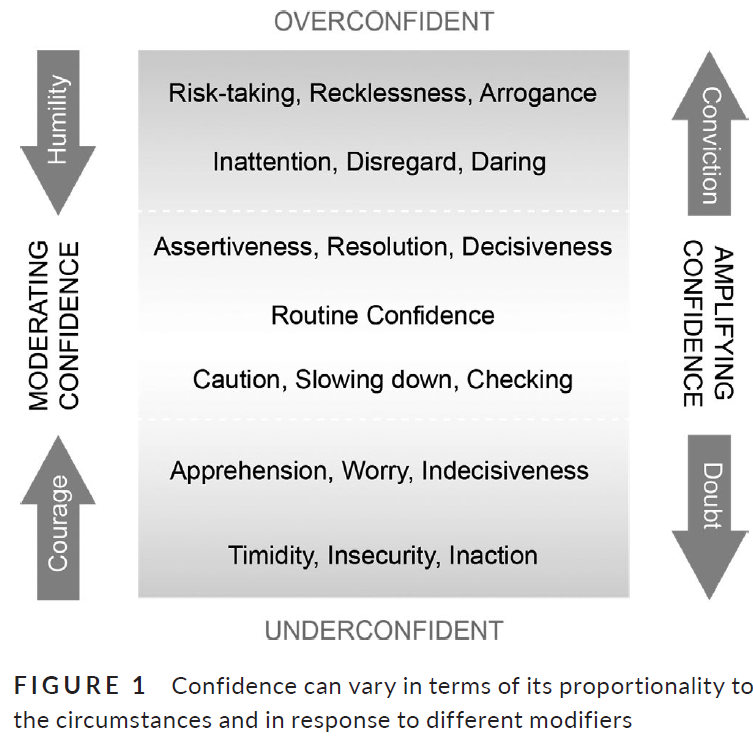

자신감은 역동적입니다(그림 1). 그것은 다른 modifier에 반응하여 빠르게 변할 수 있는데, 그 수식어 중 일부는 자신감(예: 용기, 확신)을 증폭시킬 수 있는 반면 다른 modifier들은 그것을 완화시킬 수 있다(예: 의심, 겸손). 더욱이, 자신감 수준은 개인이 처한 특정 상황의 역학을 반영해야 한다. 일상적인 신뢰도의 작은 차이(예: 비상 상황에서의 해결 또는 불확실성이 증가하는 상황에서의 주의)가 보장되는 반면, 신뢰의 상당한 초과나 부재(예: 명확성 앞에서의 소심함, 위험 앞에서의 무모함)는 피해야 한다.

Confidence is dynamic (Figure 1). It can change rapidly in response to different modifiers, some of which can amplify confidence (eg, courage, conviction) while others moderate it (eg, doubt, humility). Moreover, the level of confidence should reflect the dynamics of the specific situation that an individual finds themselves in. Small variances in routine confidence are often warranted (eg, resolution in the face of an emergency or caution in the face of growing uncertainty), 11 whereas significant excesses or absences of confidence should be avoided (eg, timidity in the face of clarity, recklessness in the face of risk).6,26,34

공리: 자신감은 우리가 현실에서 어떻게 행동하는지 형성하며, 현실과 밀접하게 일치할 때 최적화됩니다.

AXIOM: Confidence can shape how we act in our reality and is optimised when it closely corresponds to reality.

3.2 | 자신감

3.2 | Self-confidence

우리는 모두 자신감을 표현합니다; 다른 사람들, 교육 및 보건 시스템, 그리고 광범위한 기술 및 사회 시스템에. 그러나 교육 문헌에 대한 자신감은 자기 효능감, 즉 '특정 활동을 성공적으로 수행할 수 있다는 믿음'이라는 측면에서 더 자주 형성되어 왔다. 자기효능감은 종종 과제에 따라 다르지만, 긍정적이거나 부정적인 [자신감]의 축적은 개인의 전반적인 역량 감각을 형성할 수 있다. 그것은 또한 그들의 동기부여, 감정적 반응, 사고와 행동을 형성할 수 있다. 그동안 반두라 등이 '자기효능감'이라는 용어를 사용했지만, 우리는 그것이 사실상 자신감과 동의어라는 것을 발견했고, 일관성을 위해 후자를 사용했다. 자신감이 얼마나 중요한지는 개인이 감독 없이 주어진 일을 수행할 수 있는 책임이 얼마나 많은지에 달려있다. 우리에게 더 많은 선택권을 줄수록, 우리의 자신감은 더 중요하다. [더 개인주의적이고 모호함을 견뎌야 하는 맥락]은 [규칙 기반 또는 위계적 맥락]보다 더 많은 자신감을 요구할 수 있다. 따라서 자신감은 이러한 행동을 성공적으로 완수할 수 있는 능력뿐만 아니라 행동의 방향을 지시하는directing 것입니다.

We all express levels of confidence; in other people, in our educational and health systems and in our broader technical and societal systems. However, confidence in the educational literature has more often been framed in terms of self-efficacy, ‘the belief that one can successfully execute a specific activity’.35 While self-efficacy is often task-specific (ie one can be adept at one thing and inept at another), an accumulation of positive or negative confidences can shape an individual's overall sense of competence. It can also shape their motivation, emotional reactions, thinking and behaviours.5 While Bandura and others have used the term ‘self-efficacy’, we found that it was effectively synonymous with self-confidence, and we used the latter term for the sake of consistency. The degree to which self-confidence matters depends upon how much responsibility an individual is afforded to carry out a given task without supervision; the more options available to us, the more our self-confidence matters.5 Contexts that are more individualistic and tolerant of ambiguity may require more self-confidence than those that are more rule-based or hierarchical. Self-confidence is therefore about directing actions as well as the ability to complete these actions successfully.

자신감은 개인의 성격, 경험, 기대, 사회적 문화적 조건에 의해서도 형성된다. 개인의 이전 경험과 기준 자신감은 미래의 자신감을 알려주기 때문에 자신감이 긍정적이거나 부정적인 방식으로 스스로 쌓일 수 있다. 예를 들어, 자신을 이끌거나 믿도록 문화화된enculturated 사람은 그렇지 않은 사람보다 더 자신감을 가질 가능성이 높다. 낮은 사회적 지위에 있는 사람들은 (아무리 구성되어 있더라도) 자신감이 더 낮을 수 있으며, 특히 높은 사회적 지위에 있는 사람들(예: 교사 대 학습자, 전문가 대 비전문가)과 비교될 수 있다. 이러한 현상은 젠더, 성별, 인종, 민족성, 장애 및 사회-경제적 지위에 대한 사회적 불평등에 의해 더욱 악화될 수 있다. 예를 들어, 성별 간 자신감의 비대칭은 동등한 능력에서도 설명되었다. 이러한 능력에서 내면화된 자신감은 편견, 고정관념, 역할, 노동의 분할 및 보상에 의해 영향을 받을 수 있다. [지배적인 집단]에 속한 사람들은 종종 [덜 지배적인 집단]에 속한 사람들보다 더 큰 자신감을 갖게 된다.

Self-confidence is also shaped by an individual's character, experiences, expectations and social and cultural conditioning. An individual's prior experiences and baseline confidence can inform their future confidence, such that confidence can build upon itself in a positive or negative manner. For instance someone who has been enculturated to lead or believe in themselves is likely to have more self-confidence than someone who has not. Individuals of lower social standing (however constructed) may be conditioned or expected to have less confidence, particularly around and compared to those of higher social status (eg teachers vs learners, experts vs non-experts). 36 This phenomenon may be further exacerbated by social inequity around gender, sexuality, race, ethnicity, (dis)ability and socio-economic status. For example asymmetries of confidence between genders have been described even in light of equivalent abilities.37 I n t his c apacity, internalised self-confidence can be impacted by biases, stereotypes, roles, division of labour and rewards; those in more dominant groups are often afforded greater self-confidence than those in less dominant groups.

공리: 자신감은 직무에 특화되어 있지만 또한 개인의 자아 개념화, 주변 시스템 및 사회에 의해 불가분의 영향을 받습니다.

AXIOM: Self-confidence is task-specific but also inextricably influenced by the individual self-conceptualisation, the surrounding system and society.

3.3 | 관계 신뢰도

3.3 | Relational confidence

자신감은 학습자가 위치한 시스템뿐만 아니라 함께 일하는 개인들 간의 [관계 역학]을 반영할 수 있다. 팀 기반 환경에서는 여러 팀 구성원 간에 신뢰를 공유할 수 있으므로, [팀 구성원]은 개인 간 자신감 수준의 차이를 보완하거나 다른 팀 구성원의 기저 자신감 수준을 바꿔놓을 수 있습니다. 예를 들어, 더 젊은 주치의가 더 경험이 많은 간호사와 함께 일한다면 더 높은 자신감을 경험할 수 있다. 마찬가지로, 지도 의사가 도움을 주지 않는다면 학습자는 더 낮은 자신감을 경험할 수 있습니다. 주변 사람들에 대한 개인의 자신감은 또한 이러한 개인들이 계획하는 자신감에 의해 영향을 받을 수 있다. 따라서 개인의 내적 자신감이 반영되지 않을 수 있는 ['예측된 신뢰']와 그룹 역학의 산물로서 자신감이 어떻게 변화하는지 반영하는 ['분산된 신뢰']를 고려해야 한다.

Confidence can reflect the relational dynamics between individuals working together, as well as the system in which the learner is situated. In a team-based setting, confidence can be shared across multiple team members, allowing team members to compensate for differences in individual confidence levels or alter the baseline confidence among other team members. As an example, a more junior attending physician may experience increased confidence if they are working alongside a more experienced nurse. Similarly, a learner may experience more diminished confidence if their supervising physician is not supportive. A person's confidence in those around them may also be influenced by the confidence these individuals project. We should therefore consider ‘projected confidence’, which may not reflect an individual's internal confidence, and ‘distributed confidence’ that reflects how confidence changes as a product of the group dynamic.5,31

의료 지도자들(예: 의사, 교사)은 일반적으로 다른 사람들이 그들을 따르도록 자연스럽게 설득하는 자신감을 투영하도록 기대되지만, 부하들은 비판으로부터 그들 자신을 보호하기 위해 그들의 실제 자신감을 평가절하 할 수 있다. 이는 일부 교육생들이 현재 [CBME 환경을 고부담으로 보는 관점]으로 인해 복합적으로 해석될 수 있으며, 학습learning보다 성과performance를 중요시하는 인식이 반영되어 있다. 학습자는 학습 능력과 피드백을 받는 능력에 지장을 줄 수 있는 [과도한 자신감]은 피하면서, 적절한 수준의 자율성을 개발할 수 있는 [충분한 자신감]을 가져야 한다. 실제로, 자신감 부족을 감추기 위해 과도한 자신감을 보이는 학습자들은 역량의 위험뿐만 아니라 학습 기회를 더욱 제한하고 있을 수 있다.

Medical leaders (eg attending physicians, teachers) are typically expected to project confidence which naturally convinces others to follow them, while subordinates may downplay their actual confidence to protect themselves from criticism.38,39 T his c an b e c ompounded by the high-stakes view of the current CBME environment taken by some trainees, reflected in a perceived emphasis on performance over learning.38,40 In this capacity, learners must have sufficient confidence to develop appropriate levels and forms of autonomy, while avoiding overconfidence that may interfere with their ability to learn and receive feedback. Indeed, learners who exhibit excessive confidence to mask a lack of self-confidence may be further limiting their learning opportunities as well as risking dyscompetence.41

마지막으로 자신감의 [관계적 특성]은 자신감을 형성하는 많은 상황적, 우발적 요소에 반영된다. 예를 들어, 학습자가 엄격한 위계구조와 제한된 지원을 받는 부적응maladaptive 시스템에 있다면, 학습자의 자신감은 더 도움이 되는 학습 환경에 있을 때보다 더 낮을 수 있다. 그림 2는 반복 분석을 기반으로 신뢰도에 기여하는 몇 가지 주요 내부 및 외부 구성요소를 강조한다. [불확실성]이 클수록 자신감은 일상적이거나 단순한 상황보다 낮아지는 경향이 있다. 앞서 언급한 바와 같이 문화와 환경과 같은 맥락적 요소들이 모든 상황에 필연적으로 스며들기 때문에 그림 2에는 포함되지 않았다. 자신감은 [행동-후-성찰과 행동-중-성찰]에 의해서도 영향을 받는데, 그 결과 빠르게 진행할 때와 속도를 늦춰야 할 때를 조절할 수 있게 된다. 최악의 경우 자신감이 현실과 완전히 괴리될 경우 소시오패스(sociopathy)를 반영할 수 있다.

Finally, the relational nature of confidence is reflected in the many contextual and contingent factors that can shape it. For example, if the learner is in a maladaptive system with a strict hierarchy and limited support, their confidence may be lower than if they were in a more supportive learning environment. Figure 2 highlights some of the key internal and external components contributing to confidence based upon our iterative analyses. When there is greater uncertainty, confidence will tend to be lower than in routine or simple situations.11,12 As stated before, the contextual factors such as culture and environment inevitably permeate all situations, and thus have not been included in Figure 2. Confidence is also influenced by reflecting-on- action and reflecting-in- action, 42 moderating when one might proceed with ease or should slow down.7,43 In the worst-case scenario, it can reflect sociopathy if confidence becomes fully dissociated from reality.

공리: 자신감은 많은 외부 요인과 상황의 맥락에 의해 형성됩니다.

AXIOM: Confidence is shaped by many external factors and the context of the situation.

3.4 | 자신감 보정

3.4 | Calibrating confidence

우리는 자신감이 당면한 상황을 반영해야 한다고 주장해왔다; 개인의 자신감은 상황이 변함에 따라 변해야 한다. 우리는 또한 확실성certainty이 자신감에 대한 직접적인 아날로그는 아니지만, 자신감의 전구체precursor라고 제안했다. 일반적으로, 더 큰 확신을 가지게 되면, 자신감이 증가해야 한다. 그러나 자신감은 감정, 위계, 경험을 포함한 광범위한 외부 요인에 의해 수정될 수 있다. [자신이 처한 상황을 인지하고 해석하는 능력]은 [이러한 인식과 해석에 대해 행동하는 능력]과 직결된다. 이 단계가 중단되면 피드백 루프가 중단될 수 있습니다.

We have argued that confidence should reflect the circumstances on hand; an individual's confidence should change as their situation changes. We have also suggested that certainty is a precursor for, but not a direct analogue for confidence. Generally, with greater certainty, confidence should increase. However, confidence may be modified by a wide range of external factors including emotion, hierarchy and experience.44,45 The ability of an individual to perceive and interpret the situations they find themselves in is directly linked to their ability to act on these perceptions and interpretations. If any stage of this is interrupted, then the feedback loop can be disrupted.

자신감 수준은 다양한 심리 측정 도구를 사용하여 측정할 수 있습니다. 자신감 평가를 위한 검증된 도구는 많지만, 특정 애플리케이션(예: 근골격계 검사, 학생 학습 기술)으로 제한되는 경우가 많다. 따라서, 사용된 새로운 자신감 평가 도구에 대한 적절한 타당성 증거를 확립할 필요가 있을 것이다. 중요한 것은, 이 자신감 수준의 결과는 어느 정도 수준의 자신감이 특정 개인과 상황에 적합한지에 대한 이해를 필요로 한다는 것이다. 이러한 [비례성]과 [맥락화]는 비록 간접적이지만 CBME에서 자주 사용되는 위임 척도에 반영된다(예: CBME에서 자주 사용되는 위탁 척도에 대해 이야기하고, 설득하고, 만일의 경우를 대비해서 방에 있어야 하며, 거기에 있을 필요가 없다). 특정 도구와 별개로, 변화하는 상황에 대한 자신감을 설명할 수 있는 능력은 위임을 확립하는 데 어느 정도의 확실성이 필요하다.

Levels of confidence can be measured using different psychometric instruments.46-48 While there are a number of validated tools for assessing confidence, they are often limited to specific applications (eg musculoskeletal examination, student learning skills).47,48 Therefore, it would be necessary to establish proper validity evidence for any new confidence assessment tools used. Importantly, the ramifications of this confidence level require an understanding of what levels of confidence are appropriate to the particular individual and situation. This proportionality and contextualisation is reflected, albeit tangentially, in the entrustment scales often used in CBME (eg had to do, had to talk them through, had to prompt them, needed to be in the room just in case, did not need to be there).49,50 Regardless of the exact tool, the ability to account for confidence in response to changing circumstances, need and degree of certainty is a necessary part of establishing entrustment.

앞에서 언급한 많은 도구들은 자신감의 자기평가에 의존한다. 이들은 일반적으로 '전혀 자신감이 없다'와 '매우 자신감 있다'와 같은 용어로 고정될 수 있는 리커트 척도를 사용하여 측정된다. 자신감을 평가할 때, 우리는 [자신감self-confidence]과 [인지된 자신감]을 모두 고려하는 것이 중요하다고 믿는다. 전자의 관점에서 후자의 개념은 묘사된 자신감과 실제 신뢰도의 차이를 식별하고 적절한 경우 정렬을 유도하기 위해 고려될 수 있다(예: 과도한 자신감은 팀이 잘못된 정보에 의문을 갖지 않도록 이끈다). 인간이 자기 평가에 악명 높기로 악명 높은 것을 감안할 때, 적절한 수준의 자신감을 유지하는 것은 전적으로 개인에게 맡겨서는 해결하기 어려울 수 있다.

Many of the aforementioned tools rely upon self-assessment of confidence. These are typically measured using Likert scales that can be anchored by terms such as ‘not at all confident’ and ‘very confident’. When assessing confidence, we believe it important to consider both self-confidence and perceived confidence. The latter concept may be considered in light of the former to identify differences in portrayed versus actual confidence and guide alignment when appropriate (eg the perception of overconfidence leading the team to avoid questioning incorrect information). Given that humans are notoriously bad at self-assessment, maintaining appropriate levels of confidence can be challenging if left entirely to the individual to resolve.21-23,51,52

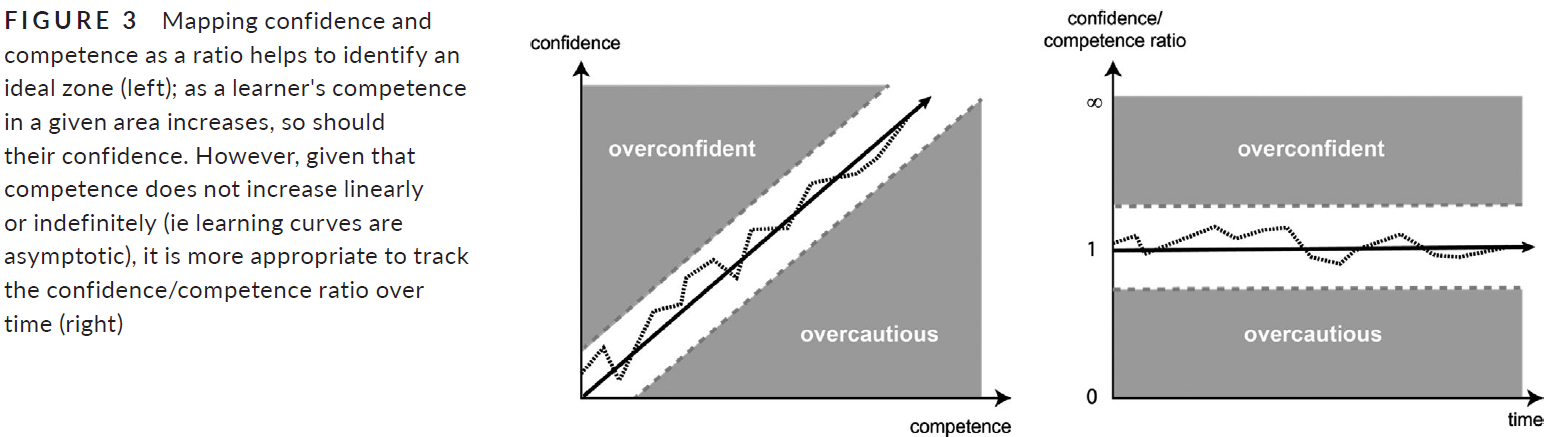

자신감은 [독립적인 변수나 구성으로서 측정하기보다는] 역량과 연결되어 있다고 생각할 수 있다. HPE에 대한 자신감과 역량의 상호작용은 오랫동안 고려되어 왔으며, 개인은 자신감과 역량이 분리될 때 문제가 있다고 본다. 역량과 자신감은 독립적으로 평가하기 어렵지만, 비율로 더 추적하기 쉬울 수 있다. 이는 주어진 기술에 대한 역량 점수에 대한 자신감의 비율(리커트 척도를 사용하여 평가)로 계산할 수 있다. 대안적으로, 교육자들은 자신감 앵커를 역량 앵커에 매핑하여 역량 단계를 통한 진행을 반영할 수 있습니다. 이상적으로는 자신감이 역량에 부합되어야 하며, 능력 있는 사람일수록 자신감이 있어야 하며, 그 반대의 경우도 마찬가지입니다(그림 3, 표 1). 다만 CCR이 잘못 보정됐을 때 문제가 발생할 수 있다.

Rather than measuring confidence as an independent variable or construct, we can consider it as being linked to (but not as a surrogate for) competence. The interaction of confidence and competence in HPE has long been considered,53-58 and individuals are viewed to be problematic when confidence and competence are decoupled.37 While competence and confidence are hard to assess independently,21,56 they may be more trackable as a ratio. This may be calculated as the ratio of self-confidence (assessed using a Likert scale) to a competence score for a given skill. Alternatively, educators could map confidence anchors to competence anchors, such that they mirror the progression through stages of competency. Ideally, confidence should align with competence, such that the more competent a person is, the more confident they are and vice versa (Figure 3, Table 1). However, it is when the CCR is miscalibrated that problems can arise.6,26,34

CCR은 일반적으로 [자신감을 역량에 따라오는 것]으로 표현하며, 자신감은 행동적 성향이고, 역량이 더 중요하고 필수적인 구조라고 본다. 주장의 핵심은 이 둘이 정렬되고 비례해야 한다는 것이다. 이들이 정렬하면 일이 예상대로 진행돼 자신감도 관심사로 후퇴한다. CCR이 과신이나 저신뢰로 표류할 때 우리는 균형을 다시 잡으려고 한다. 그러므로 우리는 자신감이 역량의 중재자라고 제안합니다. 연습생은 기술적으로 유능할 수 있지만 자신감이 부족하다면 그러한 잠재적 역량을 사용할 수 있는 능력이 손상되어 다음과 같은 일반적인 공식이 제시된다.

The CCR is typically articulated such that confidence needs to follow competence, with the former being a behavioural disposition, while the latter is the more critical and essential construct. The argument is that they should be aligned and proportional. When they are aligned, things proceed as expected and confidence recedes as a concern. It is when the CCR drifts towards overconfidence or underconfidence that we seek to re-establish the balance. We, therefore, suggest that confidence is a mediator of competence. A trainee might be technically competent but if they lack confidence then their ability to use that potential competence is compromised, suggesting a general formula such as:

예를 들어, 과신하는 학습자(높은 CCR 값)는 잘못된 진단 계획을 과도하게 추구하고 잠재적인 인지 편향을 무시함으로써 역량이 낮아질 수 있다. 한편 학습자의 임포스터 증후군(즉, 낮은 CCR 값)은 정답을 억제하거나 적절한 계획에서 벗어나 자신을 재추측하는 것으로 나타날 수 있다. 따라서 교육자와 전문가들은 독립적인 변수로서의 자신감보다는 CCR 구성에 더 집중해야 한다.

For example an overconfident learner (ie high CCR value) may manifest lower competence by over-aggressively pursuing an incorrect diagnostic plan and ignoring potential cognitive biases. Meanwhile, a learner's imposter syndrome (ie a low CCR value) may manifest with holding back on correct answers or second-guessing themselves out of an apt plan. Educators and professionals should therefore be more focused on the CCR construct than on confidence as an independent variable.

공리: 자신감은 역량과 함께 고려되어야 합니다.

AXIOM: Confidence must be considered in conjunction with competence.

3.5 | CCR 및 CBME

3.5 | CCR and CBME

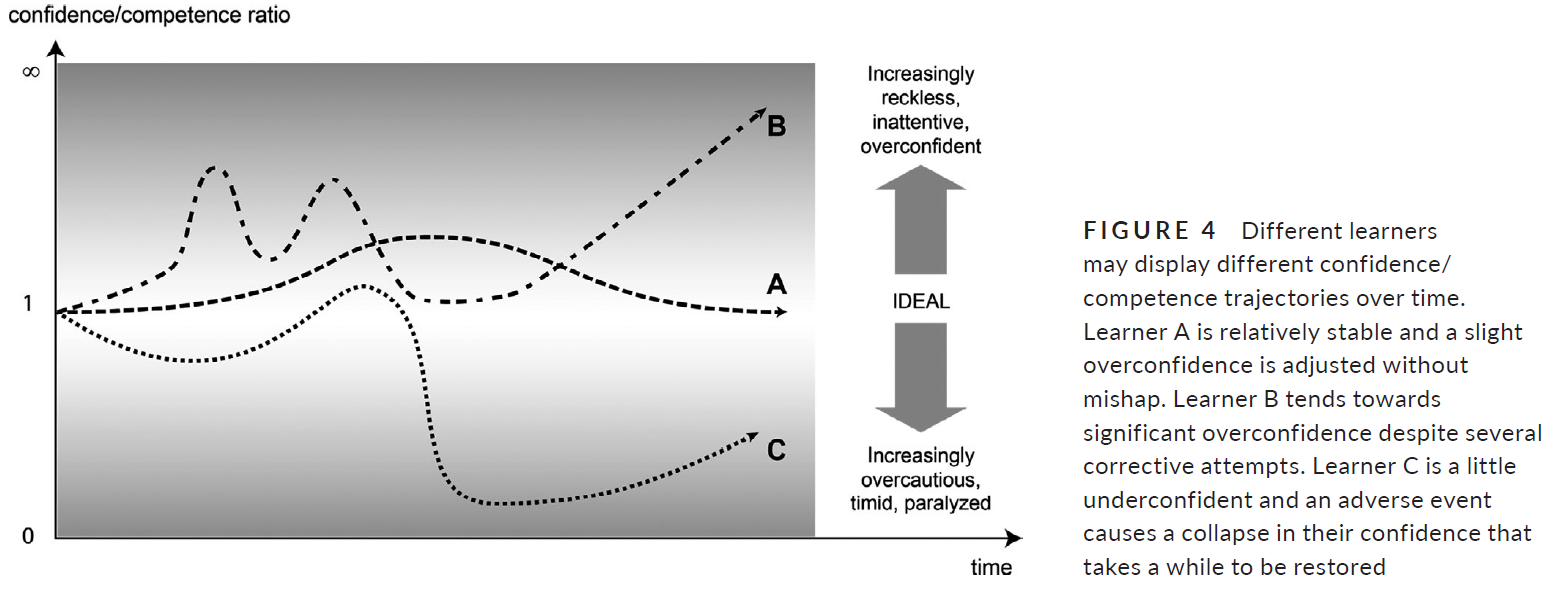

CCR은 역동적이다(그림 4). 과도한 자신감과 과소한 자신감의 균형을 유지하는 것이 목표다. 이상적인 CCR은 개인과 상황에 따라 약간 다를 수 있다. 개인 수준에서 일부 학습자는 약간 과하거나 자신감이 부족한 영역에서 탁월할 수 있으며, 이는 보다 균형 잡힌 팀을 만드는 데 도움이 될 수 있습니다. 또한 복잡한 의료 사례나 희귀 진단과 같은 일부 영역은 낮은 CCR을 필요로 할 수 있는 반면, 어떤 경우(예: 중요한 환자의 소생 유도, 새로운 리더십 위치)는 자신감을 표현하기 위해 더 높은 CCR을 필요로 할 수 있다. 임상의사 역량에 대한 현재 관점은 능력의 여러 영역이 있으며 각 영역에 대해 초보자에서 마스터까지 해당하는 스펙트럼이 있음을 시사한다. 따라서 자신감은 각 영역에 대한 역량의 정도를 반영하도록 adapt할 수 있어야 합니다. 그러나 이상적인 CCR에서 멀어질수록 CCR의 중앙으로 진로를 되돌려야 할 필요성이 커진다.

The CCR is dynamic (Figure 4). The goal is to maintain a balance between overconfidence and underconfidence. The ideal CCR may vary slightly by person and situation. At the individual level, some learners may excel in areas of slight over-or under-confidence, and this may in fact be beneficial for creating a more balanced team. Moreover, some areas such as complex medical cases or rare diagnoses may require a lower CCR, while other scenarios (eg leading a resuscitation of a critical patient, assuming a new leadership position) may need a higher CCR to portray confidence. The current view of clinician competence suggests that there are multiple domains of ability and for each domain there is a corresponding spectrum from novice to master.59 Thus, confidence must be able to adapt to reflect the degree of competence for each domain. However, as one drifts farther from their ideal CCR, there is a greater need to revert course back towards the centre of their CCR.

따라서 우리는 학습자를 평가할 때 자신감은 역량과 함께 추적되어야 한다고 주장한다. 이러한 측정은 지식 평가를 위한 시험 중 질문의 일부로, 그리고 시뮬레이션 사례 및 보다 포괄적인 학습자 평가 모델의 일부로써 실제 환자와의 만남에서 수집될 수 있다. 이는 CBME 내의 각 위탁 가능한 전문 활동(EPA)에 매핑되어 자신감과 역량이 각 구성요소에 대해 유사한 궤적을 따르도록 보장할 수 있다.

We therefore argue that confidence should be tracked alongside competence when assessing learners. These measurements could be gathered as part of the questions during examinations for knowledge assessment, as well as in simulation cases and real-life patient encounters as part of a more comprehensive learner assessment model. This could then be mapped to each entrustable professional activity (EPA) within CBME, ensuring that confidence and competence follow a similar trajectory for each component.

CCR의 deviation이 확인되면, 보다 균형 잡힌 CCR로 개인을 복귀시키기 위한 노력을 기울여야 한다. CCR의 교정 노력은 종종 역량 향상에 초점을 맞추고 있지만, 교정 및 일상적인 교육에서 자신감도 다루어야 한다고 제안한다. 자신감이 주체감과 밀접하게 묶여 있다는 점에서 지식에만 집중하는 것 또한 부족할 것이다. 오히려 CCR의 균형을 재조정하는 작업이 그들의 어려움을 해결하는 데 더 효과적일 수 있다. 대안적으로, 과신하는 학습자들이 [자신감이 과도한 부분을 파악할 수 있도록 돕는 것]은 그들이 더 열심히 생각하고 편견을 버리고 주어진 주제에 대한 더 깊은 이해를 찾도록 도전하게 할 수 있다.

When a deviation in CCR has been identified, efforts should be made to return the individual to a more balanced CCR. While remediation efforts are often focused on improving competence, we propose that confidence should be addressed in remediation as well as in day-to- day teaching. Given that self-confidence is intimately tied to one's sense of agency,20,30,60 concentrating on knowledge alone will also be insufficient. Rather, working to rebalance their CCR could be more effective in addressing their difficulties. Alternatively, helping overconfident learners identify where their confidence may be excessive may challenge them to think harder, discard biases and seek out a deeper understanding of a given topic.61-65

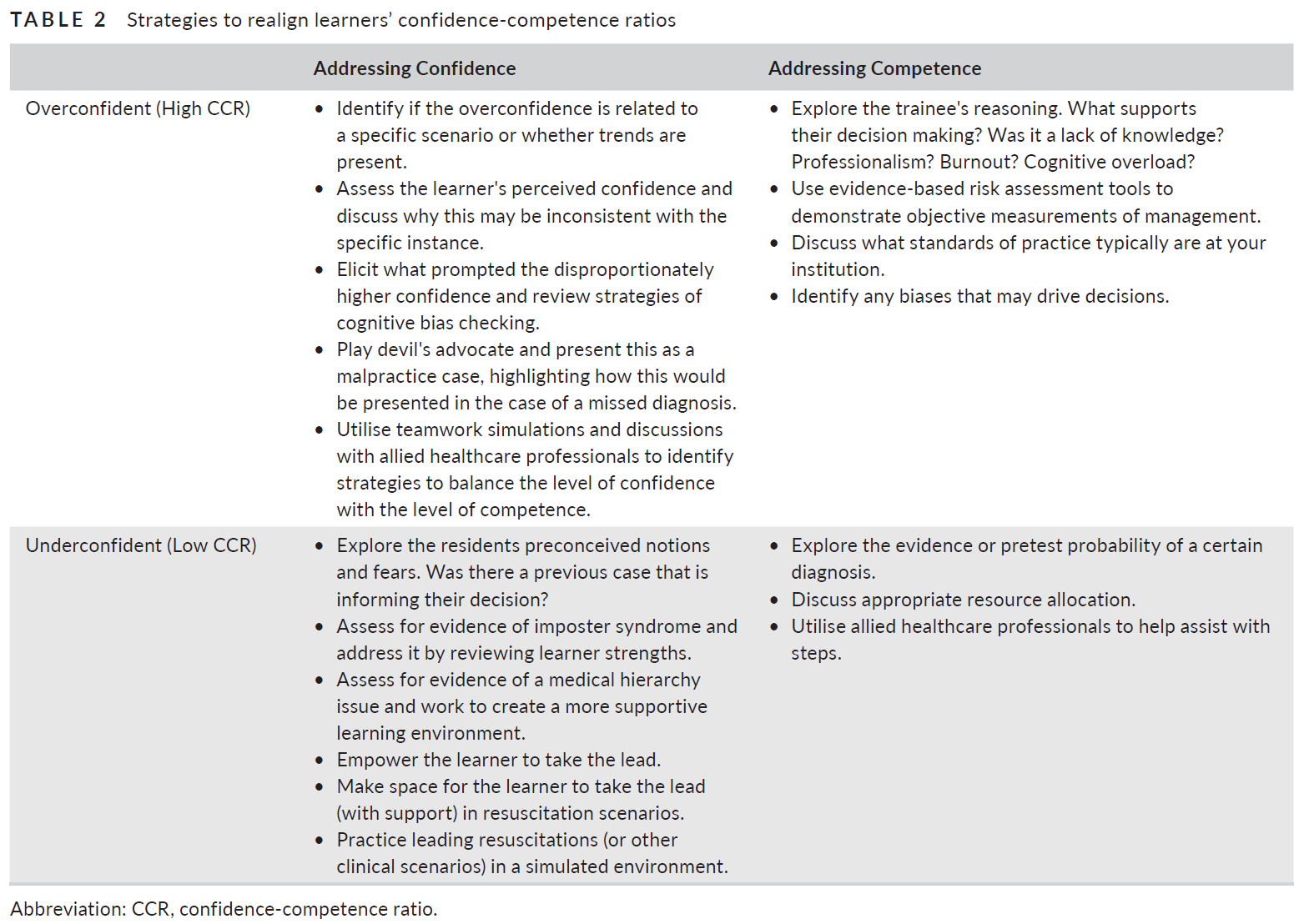

따라서 과소한 자신감과 과도한 자신감은 모두 학습자가 자신감과 역량 피드백 루프를 개발하도록 유도하는 것을 목표로 하는 목표targeted 피드백과 코칭 노력의 혜택을 받을 수 있습니다. 이를 위해 특정 사건 및 성과 데이터의 지원을 통해 학습자가 성공과 한계를 확인할 수 있도록 돕는 것은 특히 자신감과 역량의 정도를 연결하는 데 유용할 수 있다. 5,26,68-71 표 2는 학습자의 CCR 재정렬에 도움이 될 수 있는 전략을 제시한다.

Both underconfidence and overconfidence may therefore benefit from targeted feedback and coaching efforts,5,66,67 with a goal of guiding learners to develop their own confidence-competence feedback loops. To that end, helping learners identify their successes and limitations with the support of specific incidences and performance data may be particularly valuable for linking confidence to their degree of competence.5,26,68-71 Table 2 sets out some strategies that could be employed to help realign learners’ CCR.

AXIOM: CCR은 시간이 지남에 따라 바뀔 수 있다. CCR을 측정하고 학습자와 협력하여 CCR을 이상적인 비율로 재조정하는 것이 중요합니다.

AXIOM: CCR is dynamic over time. It is important to measure CCR and work with learners to realign their CCR towards their ideal ratio.

4 | 토론

4 | DISCUSSION

본 논문에서, 우리는 HPE에서, 특히 CBME의 현재 컨텍스트 내에서 신뢰와 역량이 어떻게 연결되어 있는지 살펴보았다. In this paper, we have explored how confidence and competence are linked within HPE, specifically within the current context of CBME.

자신감과 역량의 관계는 [언어 행위 이론]과 [수행성performativity]의 개념의 맥락에서 볼 때 특히 흥미롭다. 예를 들어, 오스틴은 [말이 행동을 완성하는 역할을 할 수 있다]고 제안했다. 어떤 것을 선언함으로써, 그것은 실제로 특정한 경우에 행동을 구성할 수 있다(예를 들어, 환자를 입원시키거나 퇴원시키는 것을 선택한다). 이 개념은 버틀러에 의해 이와 관련된 권력과 정체성 형성에 대해 논의하기 위해 확장되었다. 이것에 비추어 볼 때, 자신감은 말에 영향을 미치며, 이는 나중에 행동을 유도할 수 있다. 따라서 CCR이 잘못 정렬되면 행위action에 직접적인 영향을 미칠 수 있습니다.

The concept of confidence and the relationship with competence is particularly interesting when viewed in the context of the speech act theory and the concept of performativity.72,73 For instance, Austin proposed that words could serve to consummate an action.72 By declaring something, it can actually constitute the action in certain cases (eg choosing to admit or discharge a patient). This concept was expanded upon by Butler to discuss the subsequent power and identity formation associated with this.73 When viewed in light of this, confidence influences speech, which can subsequently drive action. Therefore, when the CCR is misaligned, there can be a direct impact on action.

이는 신뢰와 CCR을 CBME에 대한 접근법에 반영해야 한다는 우리의 주장을 뒷받침한다. CCR 교정에 대한 적절한 관심이 없다면 역량 개발은 관리되기 어려울 것이다. 우리는 CCR이 CBME 프레임워크 내에서 일상적으로 평가되고 추적되어야 한다고 제안한다. 모의사례는 자신감과 역량에 대한 부수적인 평가로 수행될 수 있으며, 보다 표적화된 교정조치 전략을 안내할 수 있다. 피드백에는 역량만 고립해서 보기보다는 아닌 [자신감의 맥락에서 역량에 대한 논의]도 포함해어야 하며, CCR은 EPA에 통합되고 진급advancement 의사결정에 반영되어야 한다. 또한 CCR 불균형을 사용하여 '니어미스'를 식별하고 예측함으로써 나쁜 결과가 발생하기 전에 학습할 수 있는 순간을 식별할 수 있다. 정확하게 보정된 CCR은 학습자가 자신의 ZPD과 가장 잘 일치하도록 도와 성장률을 극대화할 수 있다.

This reinforces our argument that confidence and the CCR need to be factored into our approach to CBME. Without adequate attention to CCR calibration, the development of competency will likely be harder to manage. We propose that CCRs should be routinely assessed and tracked within the CBME framework. Simulated cases could be performed with concomitant assessments of confidence and competence, guiding more targeted remediation strategies. Feedback should include a discussion of competency in the context of confidence, as opposed to competency in isolation and CCRs should be incorporated into EPAs and factored into advancement decisions. Moreover, CCR imbalances could be used to identify and predict ‘near misses’, thereby identifying a teachable moment before a bad outcome occurs. An accurately calibrated CCR could also help a learner best align with their zone of proximal development to maximise their growth.74

추가 연구는 자신감 측정을 위한 이상적인 도구를 개발하는 것, 및 자신감이 상황에 따라 달라지는지 여부를 식별해야 한다(예: 시뮬레이션 사례, 절차, 실제 시나리오). 연구는 CBME 내의 CCR과 학습자와 환자의 결과에 영향을 미칠 수 있는 특정 CCR 임계값이 있는지 여부를 추가로 평가해야 한다. 이것은 어떤 CCR 수준이 개입이나 교정조치를 촉발해야 하는지를 알리는 데 사용될 수 있다. CBME에서 핵심 역할을 하는 기존의 임상 역량 위원회는 '신뢰 및 역량 위원회'로 재구성되어 학습자의 기술 집합에 대한 자신감을 평가하고 위임 의사 결정과 연결할 수 있다. 이는 아마도 CCBMC(역량 및 자신감 기반 의학교육)일지도 모른다.

Further research needs to identify the ideal tools for measuring confidence and whether this varies by situation (eg simulated cases, procedures, real-life scenarios). Studies should further assess CCRs within CBME and whether there are specific CCR thresholds that may impact outcomes for learners, as well as for patients. This could be used to inform what CCR levels should trigger interventions or remediations. The traditional clinical competency committees that play a key role in CBME could be reframed as ‘confidence and competency committees’, assessing learners' confidence in their skill sets and linking them to entrustment decisions—perhaps as part of CCBME (competency and confidence-based medical education).

또한 자신감을 가르치고 다른 사람들이 그들의 자신감을 스스로 교정하도록 지도하는 가장 효과적인 접근법이 무엇인지 결정해야 한다. 여기에는 개인화된 코칭 및 시뮬레이션 기반 전략이 포함될 수 있습니다. 자신감과 역량의 관계는 또한 우리의 학습자들 사이에 심리적 안전을 보장하고, 가짜 증후군과 이와 유사한 보증되지 않는 불안을 겪고 있는 사람들을 위한 완화 전략을 개발하는 것의 중요성을 강조한다.

Research should also determine what are the most effective approaches for teaching confidence and guiding others to self-calibrate their confidence. This could include personalised coaching and simulation-based strategies. The relationship between confidence and competence also emphasises the importance of ensuring psychological safety among our learners and developing mitigation strategies for those suffering from imposter syndrome and similar unwarranted anxieties.26

또한, 수련 종료 후 이를 지속적인 전문성 개발(CPD)에 통합하는 방법을 평가해야 한다. 현재 피드백은 종종 덜 강력하기 때문에 지속적인 임상 우수성 추구의 일환으로 개선이 필요한 영역을 식별하는 데 이상적인 영역을 제시한다. 향후의 노력은 훈련 후 신뢰도 보정을 위한 CPD 노력을 구축하고 지원하는 최선의 방법을 결정해야 한다. 여기에는 동료 관찰이나 레지던트 회의일 동안 환자 또는 외과 케이스의 공동 관리가 포함될 수 있다. 게다가, 전문 학회는 자격증 시험에 신뢰도 평가를 통합하는 것을 고려해야 합니다.

Additionally, studies should assess how to incorporate this into continuing professional development (CPD) after completion of training. As feedback is often less robust at this time,75 it presents an ideal arena to identify areas for improvement as part of the continuous pursuit of clinical excellence. Future efforts should determine how best to build and support CPD efforts to calibrate confidence post-training. This could include peer observation or co-management of patients or surgical cases during resident conference days. Moreover, professional societies should consider incorporating confidence assessment into certification examinations.

마지막으로, 자신감과 역량의 관계적인 측면은 흥미로운 탐구 영역입니다. 트레이너와 훈련생 사이의 관계는 개인의 자신감과 겉으로 보이는 자신감에 대한 외부 인식 사이의 관계뿐만 아니라 더 완전하게 검토하는 데 중요할 것이다. 분산된 신뢰도를 이해하고 조직과 팀에 걸쳐 공유된 신뢰의 상호작용을 이해하면 보다 효과적이고 균형 잡힌 팀을 구성할 수 있을 뿐만 아니라 팀을 활용하여 구성원 간의 신뢰 보정을 강화할 수 있는 방법을 알 수 있습니다.

Finally, the relational aspects of confidence and competence are an exciting area to explore. The relationships between trainers and trainees will be crucial to more fully examine, as well as the relationship between an individual's self-confidence and external perceptions of their apparent confidence. Understanding distributed confidence and the interaction of shared confidence across organisations and teams could inform the creation of more effective and balanced teams, as well as how teams can be utilised to strengthen confidence calibration across members.

5 | 제한사항

5 | LIMITATIONS

이 작품에는 몇 가지 한계가 있습니다. '과학의 상태' 논문으로서, 우리는 앞으로 이 연구의 영역에 직면하는 문제들을 추론적으로 탐색하고 반영하려고 노력해 왔다. 이 논문은 경험적으로 고려될 수 있는 것을 강조하기 위한 것이며, 이 시점에서 생겨나야 하는 과학적 연구를 대체하거나 대체하려고 하지 않는다. 또한 필드 내에서 잘 정의된 도메인을 조사하지 않기 때문에 체계적인 검토나 범위 지정 검토가 아니었습니다. 실제로 이러한 유형의 검토에 익숙한 사람들은 신흥 분야에서 이러한 유형의 지식 합성을 수행하는 것이 부적절하거나 시기상조라는 점에 주목한다.

This work has several limitations. As a ‘state of the science’ paper, we have sought to deductively explore and reflect on issues that face this domain of research going forward. This paper is meant to highlight what might be considered empirically and does not seek to supplant or replace the scientific work that must spring forth from this juncture. Additionally, this was not a systematic or a scoping review, as we are not looking to examine a well-defined domain within a field. Indeed, those with the familiarity of these types of reviews would note that in an emerging field it would be either inappropriate or premature to conduct these types of knowledge syntheses.

우리의 리뷰는 다른 사람들이 우리가 제기한 문제들을 고려하고 향후 작업을 위한 방법을 제안하도록 영감을 주기 위한 것이다. 우리는 또한 우리의 현재 개념이 이전의 많은 담론, 이론 및 탐구 영역과 겹친다는 것을 완전히 인정한다. 이 경우 HPE 분야 내에서 다른 저명한 업무 기관과의 연계를 끌어내고 연역적 과정을 통해 해당 분야를 발전시켜 이전에 왔던 아이디어를 결합하고 재방문하는 새로운 방법을 추가하는 것이 우리의 의도였다. 마지막으로, 우리가 포용력을 가지기 위해 노력해왔지만, 우리의 이론적이고 개념적인 제품들은 그 분야 전문가들로부터 피드백을 받는 작가팀의 공동 구성입니다. 그러므로 우리는 보건 분야와 그 너머에서 온 문헌에 대한 우리 자신의 인식에 의해 제한을 받는다.

Our review is meant to inspire others to consider the issues we have brought forth and suggest a way forward for further work. We also admit fully that our current concepts overlap with many preceding discourses, theories and areas of inquiry. It was our intention in this case to draw linkages to other prominent bodies of work within the field of HPE and advance the field through our deductive process, adding new ways to combine and revisit ideas that have come before. Finally, while we have tried to be inclusive, our theoretical and conceptual products are co-constructions of the authorship team with feedback from experts within the field. We are, therefore, limited by our own awareness of the literature from within the health professions and beyond.

6 | 결론

6 | CONCLUSION

자신감은 개인에서 사회 전반에 이르기까지 다양한 수식어와 상황에 의해 영향을 받을 수 있는 구조이다. CBME는 현재 주로 자신감에 중점을 두고 역량에 초점을 맞추고 있다. 그러나 자신감은 역량 평가의 필수 요소이며 CCR의 일부로 두 가지를 함께 고려하는 것이 중요하다고 생각한다. 이상적인 CCR에서 벗어나기 시작할 때 학습자가 어느 한 쪽에도 접근하지 않도록 이를 인식하고 개입하는 것이 중요하다. 향후 연구는 CCR을 평가하기 위한 전략, 신뢰도를 가르치고 자가 교정을 지도하기 위한 모범 사례 및 CBME, CPD 및 팀 간 CCR의 역할을 평가해야 한다.

Confidence is a construct that can be influenced by a variety of modifiers and circumstances, ranging from the individual to society at-large. CBME currently focuses primarily on competency with limited emphasis on confidence. However, confidence is an integral component of competency assessment and we believe it is important to consider them both in conjunction as part of the CCR. As one begins to deviate from the ideal CCR, it is important to recognise this and intervene to guide the learner to avoid approaching either extreme. Future research should evaluate strategies for assessing CCR, best practices for teaching confidence and guiding self-calibration, and the role of CCR in CBME, CPD and among teams.

doi: 10.1111/medu.14592. Epub 2021 Jul 20.

Confidence-competence alignment and the role of self-confidence in medical education: A conceptual review

PMID: 34176144

DOI: 10.1111/medu.14592

Abstract

Context: There have been significant advances in competency-based medical education (CBME) within health professions education. While most of the efforts have focused on competency, less attention has been paid to the role of confidence as a factor in preparing for practice. This paper seeks to address this deficit by exploring the role of confidence and the calibration of confidence with regard to competence.

Methods: This paper presents a conceptual review of confidence and the calibration of confidence in different medical education contexts. Building from an initial literature review, the authors engaged in iterative discussions exploring divergent and convergent perspectives, which were then supplemented with targeted literature reviews. Finally, a stakeholder consultation was conducted to situate and validate the provisional findings.

Results: A series of axioms were developed to guide perceptions and responses to different states of confidence in health professionals: (a) confidence can shape how we act and is optimised when it closely corresponds to reality; (b) self-confidence is task-specific, but also inextricably influenced by the individual self-conceptualisation, the surrounding system and society; (c) confidence is shaped by many external factors and the context of the situation; (d) confidence must be considered in conjunction with competence and (e) the confidence-competence ratio (CCR) changes over time. It is important to track learners' CCRs and work with them to maintain balance.

Conclusion: Confidence is expressed in different ways and is shaped by a variety of modifiers. While CBME primarily focuses on competency, proportional confidence is an integral component in ensuring safe and professional practice. As such, it is important to consider both confidence and competence, as well as their relationship in CBME. The CCR can serve as a key construct in developing mindful and capable health professionals. Future research should evaluate strategies for assessing CCR, identify best practices for teaching confidence and guiding self-calibration of CCR and explore the role of CCR in continuing professional development for individuals and teams.

© 2021 John Wiley & Sons Ltd and The Association for the Study of Medical Education.

'Articles (Medical Education) > 전문직업성(Professionalism)' 카테고리의 다른 글

| 전문직 정체성 형성 및 촉진을 위한 의학교육 현황과 고려점(KMER, 2021) (0) | 2022.02.23 |

|---|---|

| 한국 의사의 역사적 정체성 형성 (KMER, 2021) (0) | 2022.02.23 |

| '나는 이 공간에 있을 가치가 없어요': 의과대학생에게 수치의 근원(Med Educ, 2020) (0) | 2021.08.03 |

| 웰니스가 의사의 핵심 역량이 되어야 하는가? (Acad Med, 2020) (0) | 2021.07.31 |

| 임상술기와 지식의 학습과 전이에 있어서 감정의 역할(Acad Med, 2012) (0) | 2021.07.31 |