부정의 바로잡기: 어떻게 여자 의과대학생이 주체성을 발휘하는가 (Adv Health Sci Educ Theory Pract. 2023)

Redressing injustices: how women students enact agency in undergraduate medical education

A. Emiko Blalock1 · Dianey R. Leal2

소개

Introduction

의학교육이 여성의 소외를 지속시키는 방식에 대한 최근의 연구는 오늘날 여성이 남성과 동등하게, 때로는 더 많은 수의 의과대학에 입학함에 따라 훨씬 더 중요해졌습니다(Kelly-Blake et al., 2018; Pelley & Carnes, 2020). 안타깝게도 여성 의대생의 경우, 의과대학의 오랜 남성적 문화, 즉 백인, 유럽 중심 및/또는 북미의 이상에서 비롯된 문화가 의대생의 의학 학습 및 실습 방식에 오랜 그림자를 드리우고 있습니다(참조; Phelan 외., 2010; Sharma, 2019). 이러한 전통은 남성을 의학의 지배적인 지식 보유자로 자리매김하여 여성의 목소리, 경험, 지식의 방식을 부차적인 것으로 만들었습니다(Babaria 외., 2009, 2012; Bruce & Battista, 2015; Drinkwater 외., nd; Ludmerer, 2020). 예를 들어,

- 의학교육의 학습 역학 및 숨겨진 커리큘럼은 종종 여학생에 대한 편향된 대우를 나타냅니다(Cheng & Yang, 2015; Dijkstra et al., 2008; Lempp & Seale, 2004).

- 또한, 학계 의학 분야에서는 남성 의사가 여성 의사보다 더 빠른 속도로 승진하는 경우가 많으며(Borges 외, 2012; Howell 외, 2017; Murphy 외, 2021; Richter 외, 2020),

- 여성이 가정을 꾸리기 시작하면 경력 발전에 불이익을 받기도 합니다(Butler 외, 2019; Winkel 외, 2021).

- 성별화된 상징, 역사, 전통은 여성 의대생들이 의학에 속하지 않는다고 느끼도록 만들거나(Balmer 외, 2020; Blalock 외, 2022; Levine 외, 2013),

- 남성이 지배하는 전문 분야를 여성이 지속하지 못하도록 막았습니다(Baptiste 외, 2017; Burgos & Josephson, 2014).

이러한 관행의 정점은 의학계에서 여성을 합법적이고 타당한 지식 보유자로 인정하지 않는 데 기여하며, 이러한 관행을 인식론적 불공평이라고 합니다.

Recent scholarship on the ways medical education perpetuates the marginalization of women has become vastly more important today as women enter medical school in equal and sometimes greater numbers to men (Kelly-Blake et al., 2018; Pelley & Carnes, 2020). Unfortunately, for women medical students their numbers alone do not change a long-standing masculine culture in medical school, a culture born from White, Eurocentric and/or North American ideals, casting a long shadow on how medical students learn and practice medicine (see; Phelan et al., 2010; Sharma, 2019). These traditions have positioned men as the dominant knowledge holders in medicine, rendering women’s voices, experiences, and ways of knowing as subaltern (Babaria et al., 2009, 2012; Bruce & Battista, 2015; Drinkwater et al., n.d.; Ludmerer, 2020). For example,

- learning dynamics and hidden curriculum in medical education often exhibit biased treatment of women students (Cheng & Yang, 2015; Dijkstra et al., 2008; Lempp & Seale, 2004).

- Moreover, the field of academic medicine frequently promotes men physicians at faster rates then women physicians (Borges et al., 2012; Howell et al., 2017; Murphy et al., 2021; Richter et al., 2020)

- while penalizing women in career advancement when they begin having families (Butler et al., 2019; Winkel et al., 2021).

- Gendered symbols, histories, and traditions have made women medical students feel they do not belong in medicine (Balmer et al., 2020; Blalock et al., 2022; Levine et al., 2013) or

- discouraged women from persuing specialties dominated by men (Baptiste et al., 2017; Burgos & Josephson, 2014).

The culmination of these practices contributes to dismissing women in medicine as legitimate and valid knowledge holders, a practice known as epistemic injustice.

인식론적 부정의는 종종 사회적 정체성(예: 여성, 소수자, 학생 등)에 근거하여 특정인을 정당한 지식 보유자로 인정하지 않거나 무시하거나 의심하는 관행입니다(Dotson, 2012; Fricker, 2011). 또한 인식론적 불공정은 아는 것과 모르는 것에 대한 차별의 순간에만 국한되는 것이 아니라 다른 합법적인 앎의 방식에 대한 무시도 포함합니다. Dotson(2012)은 인식론적 불공정은 "해석학적으로 소외된 공동체 내부에 존재하는 대안적 인식론, 반신화, 숨겨진 기록 등을 고려해야 한다"(31쪽, 원문 강조)고 설명합니다. 본질적으로 인식론적 불공정은 사회적 정체성에 기반한 개인의 지식을 즉각적으로 불신하는 행위이자 다른 방식의 앎에 대한 가능성을 지속적으로 무시하는 행위입니다.

Epistemic injustice is the practice of discrediting, ignoring, or doubting people as legitimate knowers often based on their social identity (e.g., women, minority, student, etc.) (Dotson, 2012; Fricker, 2011). Furthermore, epistemic injustice is not only confined to moments of discrimination about what one knows or does not know; it also includes a disregard for other legitimate ways of knowing. Dotson (2012) explains epistemic injustice must “account for alternative epistemologies, countermythologies, and hidden transcripts that exist in hermeneutically marginalized communities among themselves” (p. 31, emphasis in original). In essence, epistemic injustice is both the immediate discrediting of an individual’s knowledge based on their social identity and the act of persistently ignoring possibilities for other ways of knowing.

인식론적 부정의의 증거는 생명윤리 및 의학교육 학계에 잘 기록되어 있으며(Battalova 외., 2020; Blease 외., 2017; Carel & Kidd, 2014; Seidlein & Salloch, 2019), 의학계 여성에게 인식론적 부정의는 가부장적인 의학의 역사에서 기인한 형태로 만연해 있습니다. 이러한 남성 중심적 태도는 무의식적으로 이성과 합리성을 남성, 남성성, 남성다움에 부여하는 표현입니다(Lloyd, 1979; Samuriwo 외., 2020; Shaw 외., 2020). 남성을 이성적인("더 나은" 또는 "더 숙련된") 의사로 습관적으로 인식하는 것은 역사적으로 의학계에서 여성의 위치를 낮추고, 여성의 기여를 약화시키며, 여성의 전문직 진출을 선택적으로 제한해 온 이 분야에 광범위한 영향을 미칩니다(Roberts, 2020; Sharma, 2019). 이러한 관행을 종합하면 성별에 기반한 인식론적 불공정의 은밀하고 명백한 사례입니다(Tuana, 2017).

Evidence of epistemic injustice is well-documented in bioethics and medical education scholarship (Battalova et al., 2020; Blease et al., 2017; Carel & Kidd, 2014; Seidlein & Salloch, 2019), and for women in medicine forms of epistemic injustice are rampant and stem from a patriarchal history in medicine. These androcentric attitudes are manifestations of sub-consciously assigning reason and rationality to men, masculinity, and maleness (Lloyd, 1979; Samuriwo et al., 2020; Shaw et al., 2020). Habitually recognizing men as reasoned (read “better” or “more skilled”) physicians has far-reaching implications for the field, one that has historically discounted the place of women in medicine, undermined their contributions, and selectively limited their advancement in the profession (Roberts, 2020; Sharma, 2019). Combined, these practices are discreet and obvious examples of epistemic injustice based on gender (Tuana, 2017).

인식론적 불공정이 발생하는 경우, 여성 의사의 지식은 종종 의학에 대한 "올바른" 또는 "정확한" 지식에 대한 획일적인 이해와 비교됩니다. 여성이 이러한 형태의 규범적 지식을 입증하면 인식적 불공정의 형태를 회피할 수 있습니다. 예를 들어, 여성 의사는 보다 "남성적"인 행동을 취하거나 채택하거나 의학에서 정당한 것으로 인정되는 특성에 더 기꺼이 자신을 맞출 수 있습니다. 그러나 그렇게 하기 위해 여성은 자신의 커뮤니티와 문화, 심지어 자신에게서 비롯된 지식의 형태를 숨기거나 보류해야 할 수도 있습니다(Dotson, 2012). 따라서 의학계 여성이 순응을 통해 인식론적 불의에 저항할 때, 여성으로서의 사회적 정체성과 자신의 젠더 경험, 인종과 민족, 자신을 키워준 공동체에서 비롯된 지식, 즉 "반-신화와 숨겨진 기록"을 소홀히 하게 됩니다. 여성이 의학 분야에 가져다주는 중요한 지식을 인정하지 않는다면, 백인 남성으로서의 의사의 존재를 지속적으로 재생산하는 동시에 이 분야에서 지식으로 간주되는 것에 대한 한계를 강화함으로써 의료 분야는 빈곤해질 것입니다.

During events of epistemic injustice, women physicians’ knowledge is often compared to a monolithic understanding of a “correct” or “accurate” knowledge for medicine. If a woman demonstrates this form of normative knowledge, then they may evade forms of epistemic injustice. For example, women physicians may take on or adopt behaviors that are more “masculine” or align themselves more willingly to characteristics that are recognized as legitimate in medicine. However, to do so, women may be tasked with hiding or withholding the very forms of knowledge that arises from their communities and from their cultures, even themselves (Dotson, 2012). Thus, when women in medicine resist epistemic injustice through conformity, they neglect their social identity as women and the knowledge arising from their own gendered experiences, their race and ethnicity, and the communities that raised them—their “countermythologies and hidden transcripts” (Dotson, 2012, p. 31). Without acknowledging the important knowledges women bring to the field of medicine, the medical field will be impoverished by continually reproducing the presence of doctors as White men, while reinforcing limits on what counts as knowledge in the field.

인식론적 불공정의 프레임워크는 이러한 불공정을 바로잡을 수 있는 방법도 제공합니다. 이러한 불공정이 어떻게 발생하는지 분석하는 과정에는 인식적 불공정의 관행을 줄이고 궁극적으로 개혁할 수 있는 방안에 대한 가능성이 내재되어 있습니다(Dotson, 2012). 학생들의 의료 경험이 권력과 억압의 맥락에 놓여 있더라도(Chow 외, 2018; Vanstone & Grierson, 2021; Wyatt 외, 2021 참조) 인식론적 불공정을 시정할 수 있는 능력은 지식이 위치한 위치(예: 자신의 커뮤니티 내, 의료 분야 내, 학습 환경 내)와 밀접하게 연관되어 있습니다. 예를 들어, 유색인종 학생은 의과대학에서의 교육 경험에 자신의 지역사회와 배경에서 비롯된 관점이라는 혁신적인 관점을 가져옵니다(Solorzano & Delgado Bernal, 2001; Wyatt et al., 2018).

In its entirety, the framework of epistemic injustice also offers avenues to redress such injustices. Embedded in analyzing how such injustices occur are possibilities for ways to reduce and eventually reform the practice of epistemic injustice (Dotson, 2012). Even as students’ medical experiences are situated within the context of power and oppression (see, Chow et al., 2018; Vanstone & Grierson, 2021; Wyatt et al., 2021) their ability to redress epistemic injustices are tightly coupled with where their knowledge is situated (e.g., within their own communities, within the medical field, within a learning environment). For example, students of Color bring with them transformative perspectives into their educative experiences in medical school, perspectives originating from their own communities and backgrounds (Solorzano & Delgado Bernal, 2001; Wyatt et al., 2018).

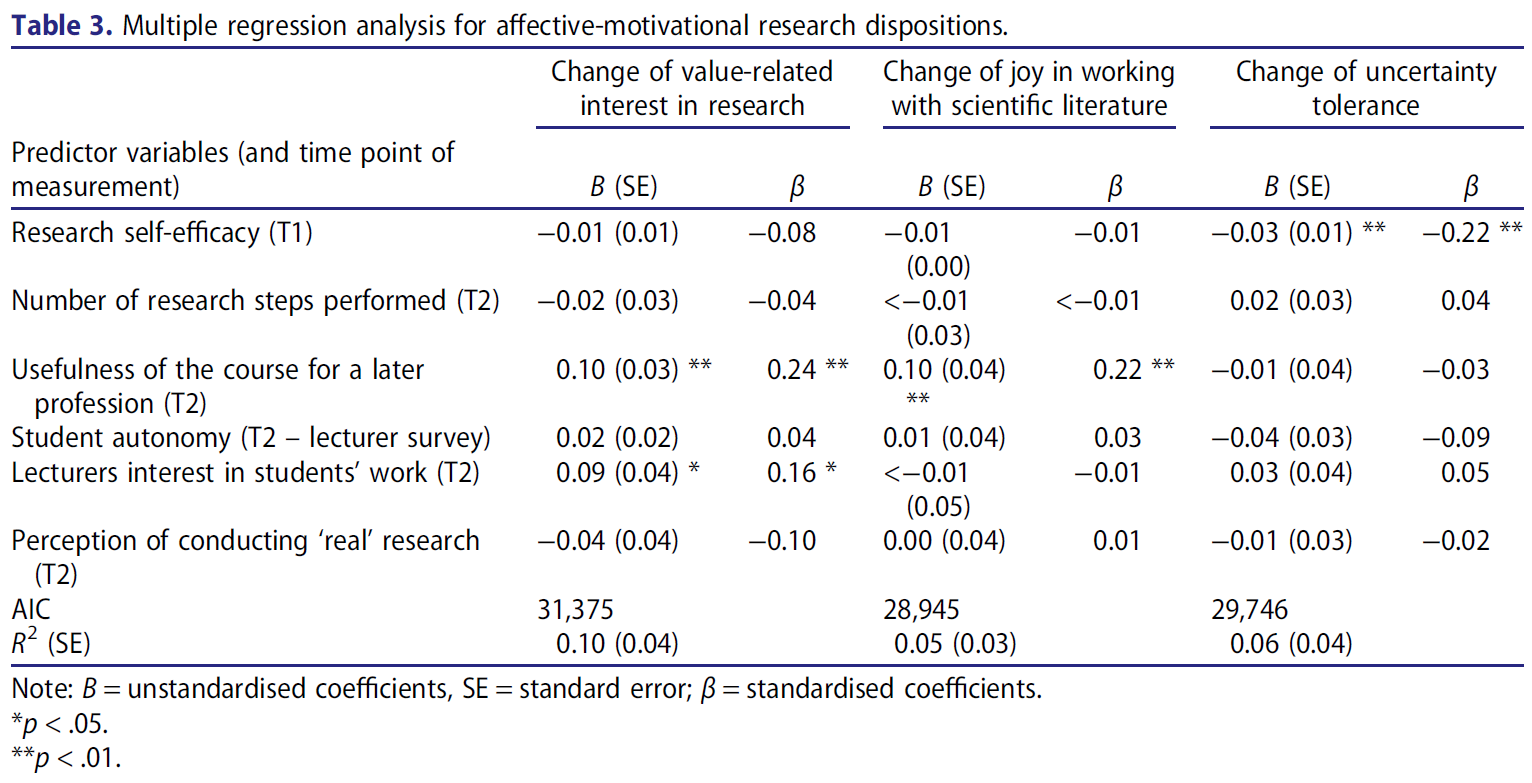

인식적 불공정의 형태에 맞서기 위해, 우리는 인식적 주체성의 개념을 활용하여 참가자의 행동을 해석합니다. 인식적 주체성이란 특정 커뮤니티 내에서 자신의 인식적 자원(예: 지식 체계, 학습, 관행 등)을 설득력 있게 활용하고 공유하는 개인의 능력을 말합니다(Dotson, 2012). 우리는 의학교육의 결핍된 내러티브에 대응하기 위해 의대생이 주체성을 발휘하는 순간에 초점을 맞췄습니다. 이러한 순간은 데이터 분석에 대한 우리의 접근 방식(페미니스트적, 주체적, Tuana, 2017 참조)과 인식론적 불공정의 개념적 틀을 전체적으로 사용하여 데이터를 제시하는 방법에 대한 의도적인 결정을 반영합니다(Dotson, 2012). 주체성은 참여자 경험에 대한 자산 기반 관점을 제공하며, 이는 의대생의 소진과 차별 경험에 대한 풍부한 문헌의 균형을 맞추는 데 도움이 됩니다(Daya & Hearn, 2018; Frajerman 외, 2019; Kilminster 외, 2007; Neumann 외, 2011; Orom 외, 2013). 의료 및 고등 교육 분야에서 도출한 기관의 역할은 (1) 관점 취하기(O'Meara, 2015), (2) 전략적 저항(Baez, 2000, 2011; Ellaway & Wyatt, 2021, 2022; Gonzales, 2018)으로 요약할 수 있습니다.

- 관점 취하기는 의대생이 목표를 달성하는 데 도움이 되는 상황과 자신에 대한 반사적 숙고를 의미하며, 이러한 반사적 숙고는 더 큰 사회적 요인에 의해 형성되고 배양된 내적 대화 또는 자기 대화입니다(O'Meara, 2015). 반면

- 전략적 저항은 의대생이 자신과 타인을 불법적인 지식인으로 만드는 제도적 구조에 저항하거나 이를 전복하려는 의도적인 전술을 말합니다(Baez, 2000, 2011; Ellaway & Wyatt, 2021; Gonzales, 2018).

To combat forms of epistemic injustice, we leverage the concept of epistemic agency to interpret actions of participants. Epistemic agency refers to a person’s ability to persuasively utilize and share their epistemic resources (e.g., knowledge systems, learnings, practices, etc.) within a given community (Dotson, 2012). We focused on moments of agency in medical students to counter deficit-narratives in medical education. These moments reflect both our approach to data analysis (feminist and agentic, see Tuana, 2017) as well as an intentional decision in how to present the data using the conceptual framework of epistemic injustice in its entirety (Dotson, 2012). Agency provides an asset-based perspective on participant experiences, one that helps balance the plentiful literature on medical student experiences of burn-out and discrimination (Daya & Hearn, 2018; Frajerman et al., 2019; Kilminster et al., 2007; Neumann et al., 2011; Orom et al., 2013). Drawn from the fields of medical and higher education, we frame agency as (1) perspective-taking (O’Meara, 2015), and (2) strategic resistance (Baez, 2000, 2011; Ellaway & Wyatt, 2021, 2022; Gonzales, 2018).

- Perspective-taking refers to medical students’ reflexive deliberations of a situation and of themselves that help them to advance goals—these reflexive deliberations are inner conversations or self-talk shaped and cultivated by larger societal factors (O’Meara, 2015).

- Strategic resisting, by contrast, refers to medical students’ intentional tactics to resist or subvert institutional structures that render them and others as illegitimate knowers (Baez, 2000, 2011; Ellaway & Wyatt, 2021; Gonzales, 2018).

이를 위해 이 연구의 목적은 두 가지입니다.

- (1) 여의대생의 경험에서 인식론적 불공정이 어떻게 나타나는지 이해하고,

- (2) 종종 여의대생을 정당한 지식인으로서 불신, 침묵 또는 자격을 박탈하는 환경에서 학습하는 여의대생의 주체적 경험을 설명하는 것입니다.

우리는 의료계에서 성평등과 성평등이 아직 완전히 실현되지 않았다는 점을 이해하면서 여의대생의 경험에 특히 초점을 맞춥니다(Butler et al., 2019; Dimant et al., 2019). 우리의 연구 결과는 여학생들이 불의에 맞서는 방식과 그들이 경험한 불의의 형태를 시정하기 위해 취하는 행동에 대한 설명을 제공합니다. 페미니스트 주체적 관점(Tuana, 2017)을 통해 우리는 지식이 다면적이고 개인과 공동체에 모두 존재하며, 가부장적 제도와 직업 내에서 여성의 존재가 여전히 인식되지 않는 경우가 많다는 점을 인식합니다(Sharma, 2019). 또한 지식이 정의되는 방식은 지식에 대한 규범적이거나 공유된 집단적 이해 또는 지배적인 집단이 지식으로 구독할 수 있는 내용보다 훨씬 더 큰 의미를 갖습니다. 따라서 이 백서에 대한 접근 방식의 핵심은 참여자가 누구인지, 어디에서 왔는지, 의대 경험에서 그 지식을 어떻게 구현하는지에 따라 파생된 지식을 인식하는 것입니다.

To this end, the purpose of this study is two fold:

- (1) to understand how epistemic injustice appears in women medical students’ experiences and

- (2) to describe the agentic experiences of women medical students who are learning in environments that are often discrediting, silencing, or disqualifying them as legitimate knowers.

We focus specifically on the experiences of women medical students while understanding that gender-equality and gender-equity in the health professions is yet to be fully realized (Butler et al., 2019; Dimant et al., 2019). Our results offer descriptions of the ways women students confront injustices and the actions they take to redress the forms of injustice they experienced. Through a feminist agentic lens (Tuana, 2017), we recognize knowledge as multifaceted and existing both within individuals and shared communities, and for women, often situated within a patriarchal system and a profession where their presence is still in large part, unrecognized (Sharma, 2019). Additionally, how knowledge is defined is much larger than a normative or shared collective understanding of knowledge, or what a dominant group may subscribe as knowledge. Thus, central to our approach to this paper is recognizing knowledges of our participants derived from who they are, where they come from, and how they enact that knowledge in the medical school experiences.

방법론적 설계

Methodological design

비판적 연구자로서(Denzin, 2015; Denzin & Lincoln, 1994), 우리는 모든 연구 질문을 사회의 더 큰 구조적 규범(예: 인종, 계급, 성별 등) 내에 위치시키고 더 큰 형평성을 추구하여 이러한 규범을 비판하고 변화시키려고 노력합니다. 방법론적으로, 이 연구는 참여자의 경험을 이야기함으로써 공유된 현상을 시간의 흐름에 따라 조사하는 내러티브 전통에 뿌리를 두고 있습니다(Clandinin, 2013; Clandinin & Connelly, 2000). 따라서 이 연구의 설계는 의과대학에 재학 중인 여성으로서 의사가 된 이야기를 들려주기 위해 동일한 공유 경험에 대해 질문하여 참가자들을 여러 번 참여시키는 것이었습니다.

As critical researchers (Denzin, 2015; Denzin & Lincoln, 1994), we situate any research question within the larger structural norms of society (e.g., race, class, gender, etc.) and seek to critique and transform these norms pursuant of greater equity. Methodologically, this study is rooted in the narrative tradition, one where a shared phenomenon is examined in and over time by storying participants’ experience (Clandinin, 2013; Clandinin & Connelly, 2000). Hence, the design for this study was to engage the participants multiple times, asking about the same shared experience to tell their story of becoming a doctor as women in medical school.

클랜디닌과 코넬리(2000)는 "내러티브 질문은 항상 자서전적 요소가 강합니다. 우리의 연구 관심사는 우리 자신의 경험 이야기에서 비롯되며 내러티브 탐구 플롯을 형성합니다."(121쪽). 저희 둘 다 유색인종 여성이고, AEB는 아시아계/백인 혼혈 여성이며, DRL은 라틴계 여성입니다. 우리의 정체성, 경험, 역사에는 인식론적 불의에 대한 우리 자신의 경험, 그리고 이러한 경험을 검증하기 위해 우리 커뮤니티와 서로를 어떻게 바라보았는지에 대한 수많은 줄거리(Polkinghorne, 1988)가 포함되어 있습니다. 의학 분야에서 여성의 경험은 남성과 크게 다르다는 점을 계속 강조할 필요성을 감안하여(Sharma, 2019), 이 연구는 여성이라고 밝힌 학생들을 대상으로 설계되었습니다. 22명의 참가자는 모두 시스 여성으로 자신을 밝히고 발표했지만, 향후 의학계의 젠더에 관한 연구를 통해 젠더의 개념이 확장되기를 바랍니다. 이 연구는 성별 문제에 기반을 두고 있기 때문에 참가자와 동료를 식별하기 위해 '여성female' 또는 '남성male'이라는 용어 대신 '여성woman'과 '남성man'이라는 용어를 사용했습니다. 참가자가 '여성' 또는 '남성'을 사용했을 때 따옴표에서 그 표현을 바꾸지 않았습니다. 또한, 연구자들은 결핍에 초점을 맞춘 연구에 대응하기 위해 내러티브에 대응하기 위해 노력하면서 참가자들이 직면한 불의를 시정하기 위해 취한 구체적인 행동을 찾았으며, 이러한 행동이 인종주의, 계급주의, 성차별적 구조의 한계 내에서 수행되었음을 이해했습니다(Acker, 1990; Nguemeni Tiako 외., 2021; Ray, 2019).

Clandinin and Connelly (2000) noted “narrative inquiries are always strongly autobiographical. Our research interests come out of our own narratives of experience and shape our narrative inquiry plotlines” (p. 121). For both of us, we are women of Color, AEB a biracial Asian/White woman and DRL a Latina woman. Our identities, experiences, and histories contain numerous plot-points (Polkinghorne, 1988) of our own experiences with epistemic injustices, and how we have looked to our own communities and one another to validate these experiences. Given the need to continue to emphasize that women’s experiences in medicine are vastly different from men (Sharma, 2019), this study was designed to look at students who identified as women. Although all 22 participants identified and presented as cis-women, we hope future work on topics of gender in medicine will expand the construct of gender. We use the term “woman” and “man” rather than “female” or “male” to identify participants and their peers since this study is grounded in issues of gender. When participants used “female” or “male,” we did not change their wording in their quotes. Further, as researchers committed to counter narratives to attend to deficit-focused research, we sought out specific actions participants took to redress the injustices they encountered, all the while understanding that these actions were performed within the confines of racist, classist, and sexist structures (Acker, 1990; Nguemeni Tiako et al., 2021; Ray, 2019).

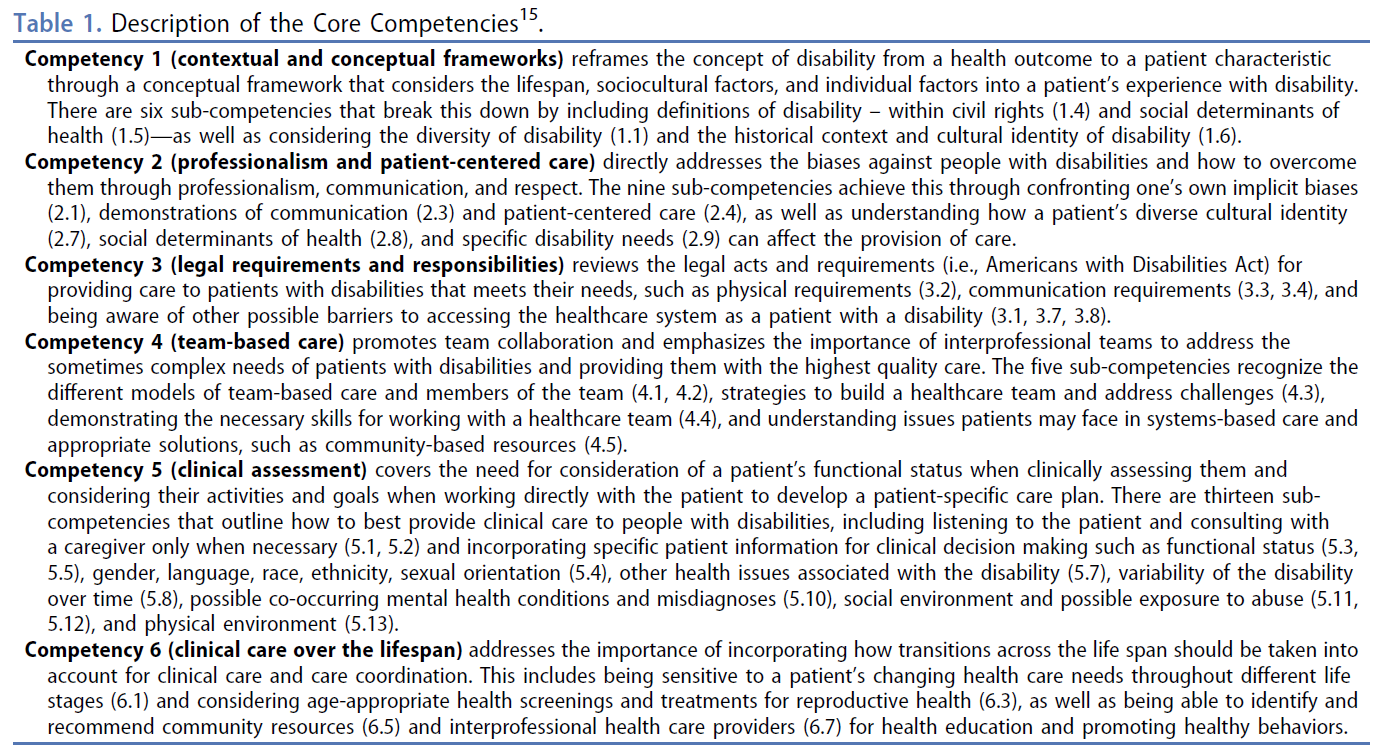

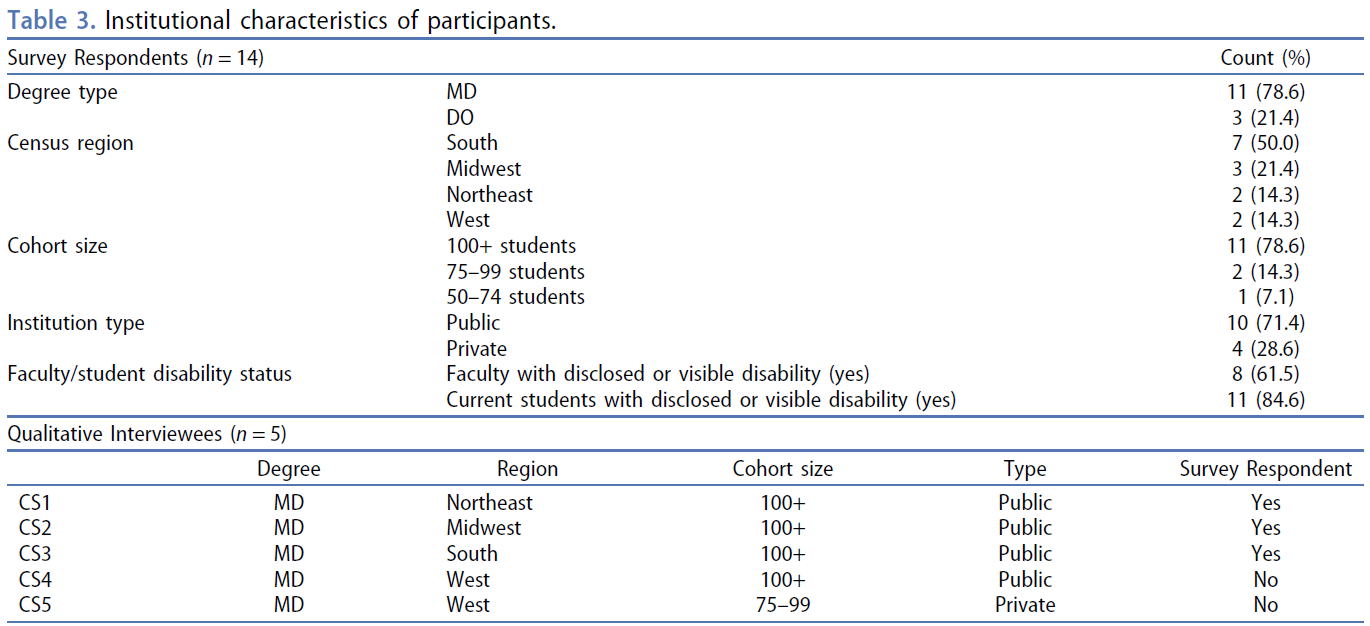

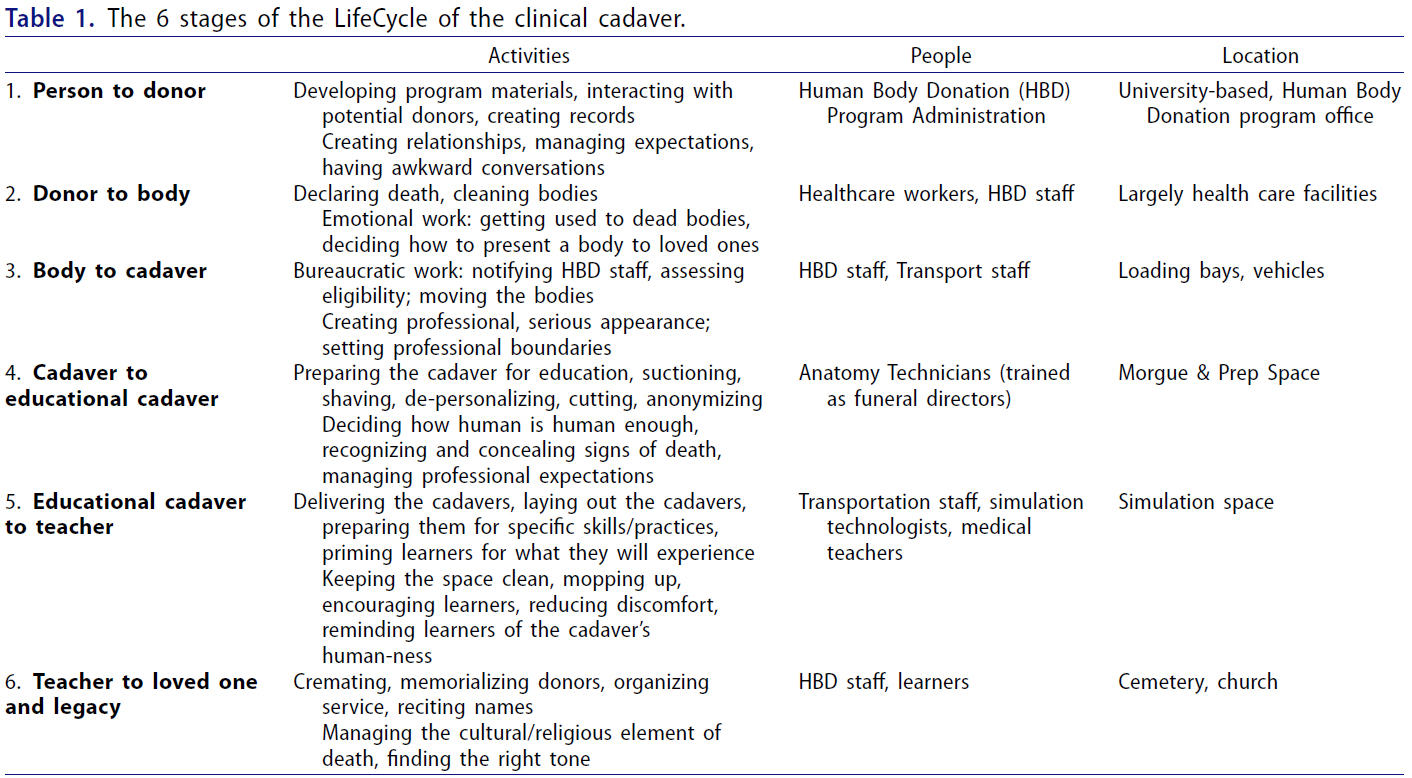

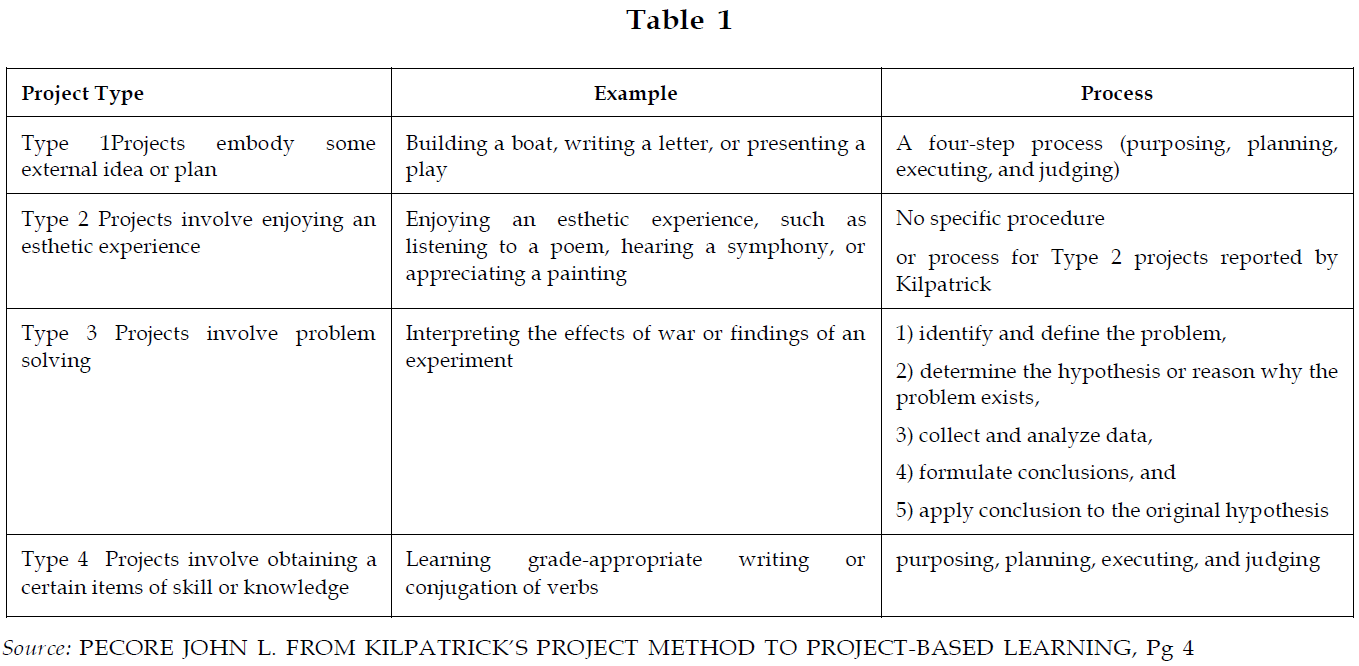

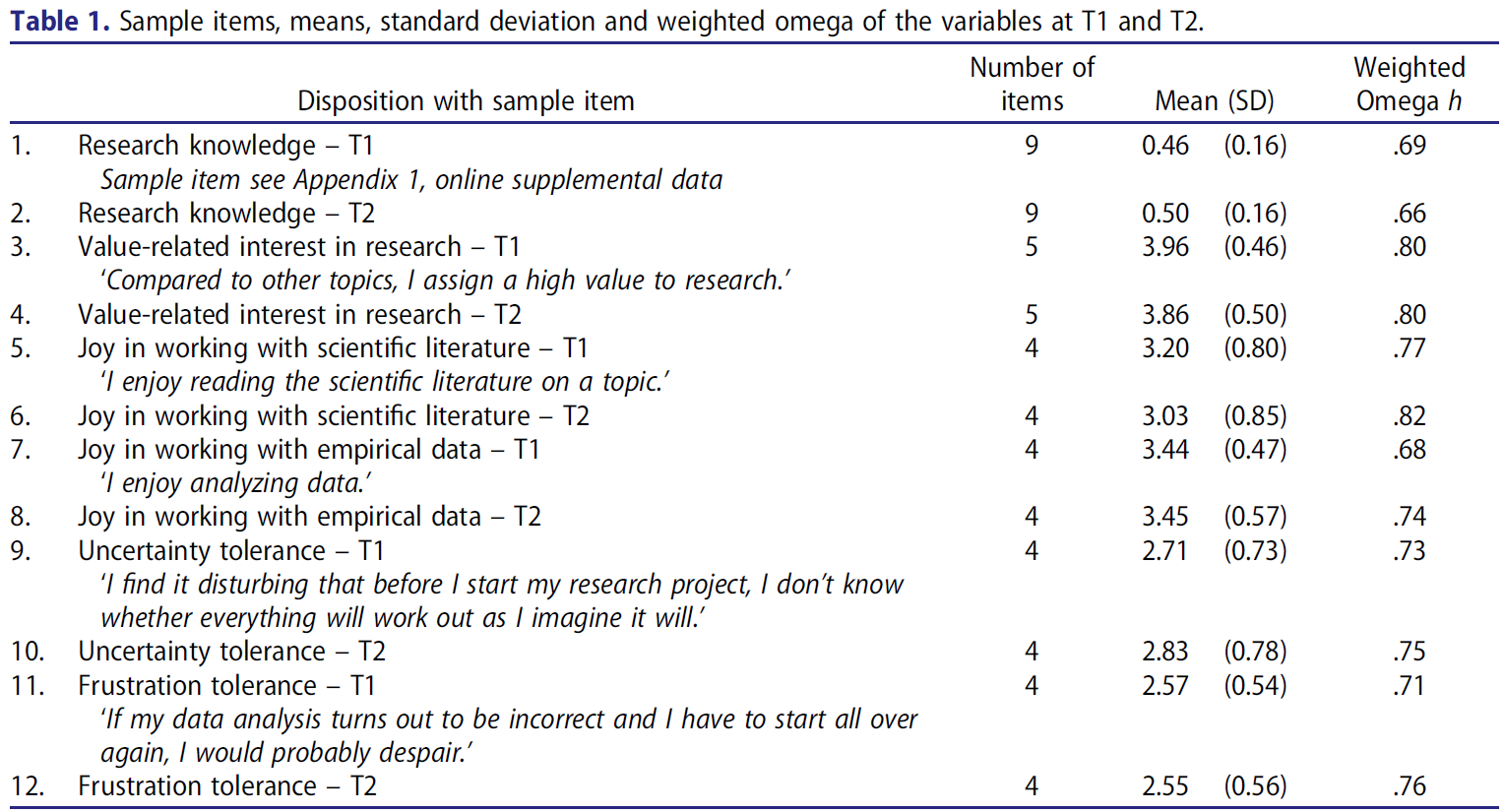

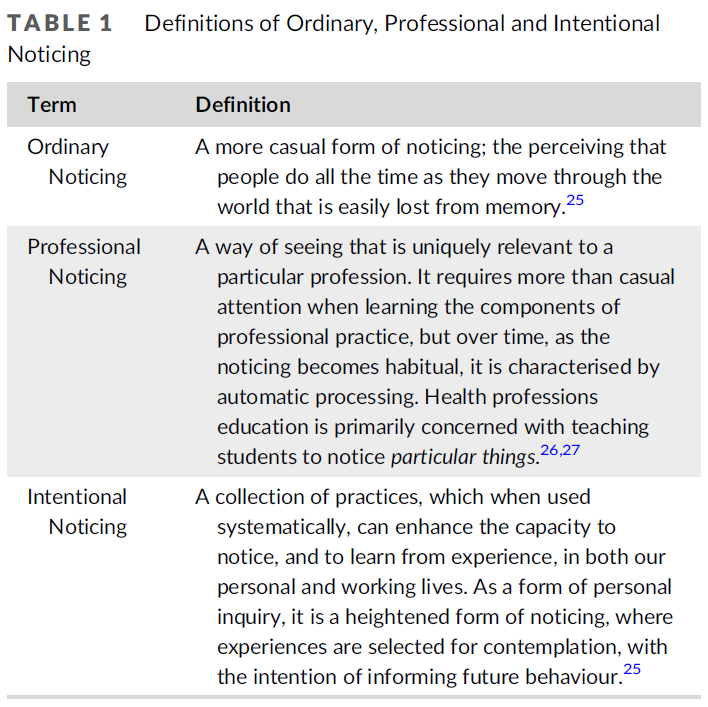

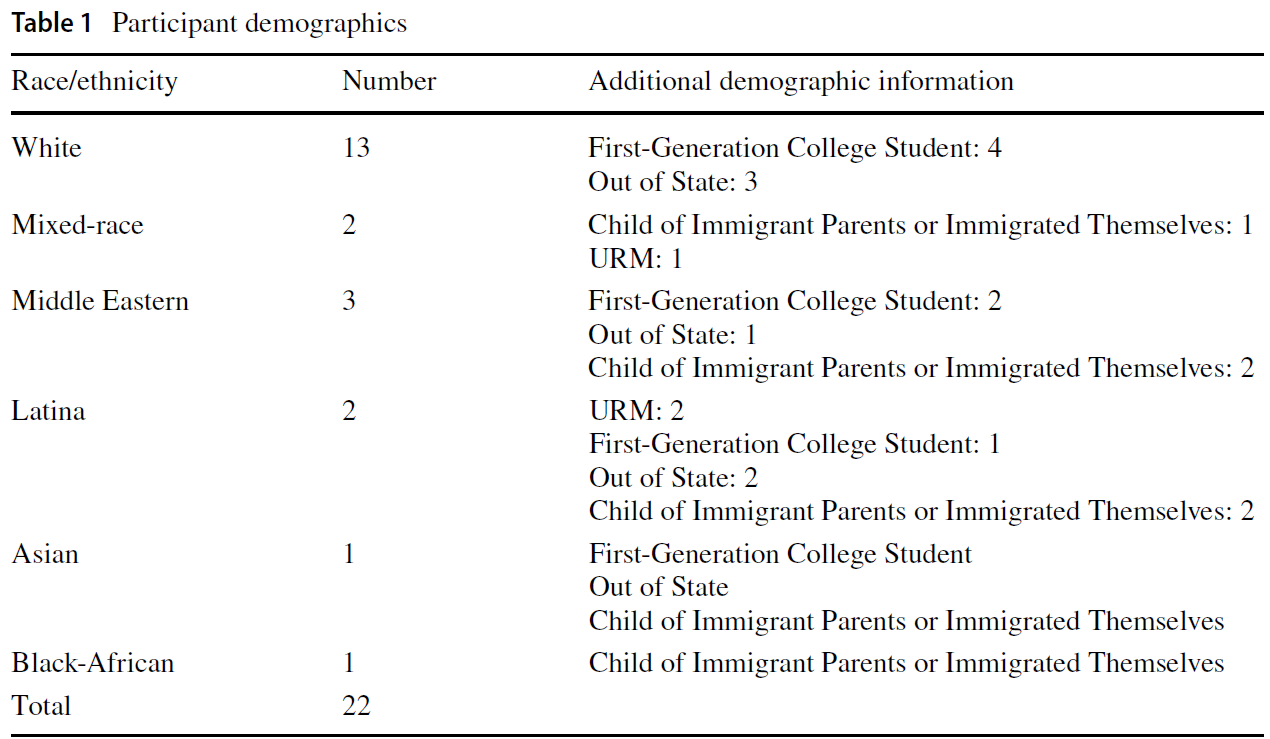

이 연구는 2020년 10월부터 2021년 5월까지 8개월에 걸쳐 진행되었으며, 내러티브 연구자들의 요청에 따라 시간의 흐름에 따른 현상을 탐구하기 위해 진행되었습니다. 우리는 참가자들에게 "어떻게 의사가 되어가고 있나요?"라는 질문을 던졌고, 시간의 흐름에 따른 변화를 관찰할 수 있는 가능성을 탐구하기 위해 8개월 동안 이 질문을 계속 이어나갔습니다(Balmer et al., 2021; Gordon et al., 2017). 모든 참가자는 미국 중서부에 있는 대규모 연구 대학의 동종요법 인체 의학 학교 출신입니다. 또한 이 연구는 코로나19 팬데믹으로 인해 극도로 혼란스러운 시기에 진행되었습니다. 참가자들은 인터뷰와 성찰을 통해 팬데믹에 대해 언급했으며, 일부는 의대 재학 중 원격 학습으로 인한 혼란을 언급했습니다. 연구 수행을 위해 대학과 학교 차원의 위원회를 통해 IRB 승인을 받았습니다. 대학 전체 리스트서브를 사용하여 모든 1학년 학생에게 약 200개의 이메일을 보내 여성으로 확인된 학생에게 참여를 권유했습니다. 22명이 8개월 동안 계속 참여하기로 동의했습니다. 이 22명의 학생은 인종과 민족, 국적과 이민자 신분 등 다양한 여학생 그룹을 대표합니다(표 1 참조). 또한 몇몇 참가자는 가족 중 처음으로 대학에 진학했는데, 이러한 사회적 정체성이 의과대학에서의 경험과 학생들이 받은 잠재적인 경제적 또는 사회적 네트워크 지원에 영향을 미쳤을 수 있습니다(Brosnan 외., 2016). 22명의 참가자 중 3명은 의학계에서 과소 대표되는 것으로 간주됩니다(URiM). 데이터 수집이 끝날 때 각 참가자에게는 75달러의 아마존 기프트 카드가 제공되었습니다. 많은 참가자가 이 인센티브에 대해 잊고 있었으며, 첫해에 자신의 경험을 공유하는 것이 카타르시스를 느꼈다고 말했는데, 이는 연구 참여를 유지하기 위해 스스로 선택한 것일 수도 있습니다.

This study took place over the course of eight months, from October 2020 to May 2021, to heed the call of narrative researchers to explore a phenomenon within and over time. Our phenomenon is the question we posed to our participants, “how are you becoming a doctor?” and we threaded that question throughout the eight-month period hoping to explore the possibilities of observing change throughout time (Balmer et al., 2021; Gordon et al., 2017). All participants are from a school for allopathic human medicine at a large research university in the Midwest United States. Additionally, this study took place during an extremely disruptive time due to the COVID-19 pandemic. Participants commented about the pandemic throughout interviews and reflections, and some noted the disturbance of remote learning during medical school. IRB approval was obtained through the university, as well as through the school level board for research conduct. Approximately 200 emails were sent to all first-year students using the college-wide listserv, inviting those who identified as women to participate. Twenty-two agreed to remain involved over the entirety of the eight months. These 22 students represent a diverse group of women students, in race and ethnicity, as well as nationality and immigrant status (See Table 1). Additionally, several participants were first in their family to attend college, a social identity that may have informed their experience of medical school and the potential economic or social network support these students received (Brosnan et al., 2016). Of the 22 participants, three are considered underrepresented in medicine (URiM). At the end of the data collection, each participant was offered a $75 Amazon Gift Card. Many participants had forgotten about this incentive and commented how sharing their experiences during their first year was cathartic, perhaps indicating some self-selection in maintaining engagement in the research study.

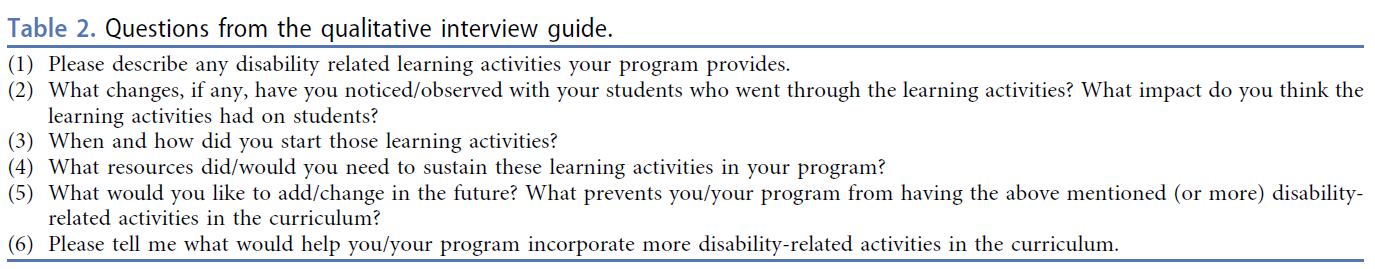

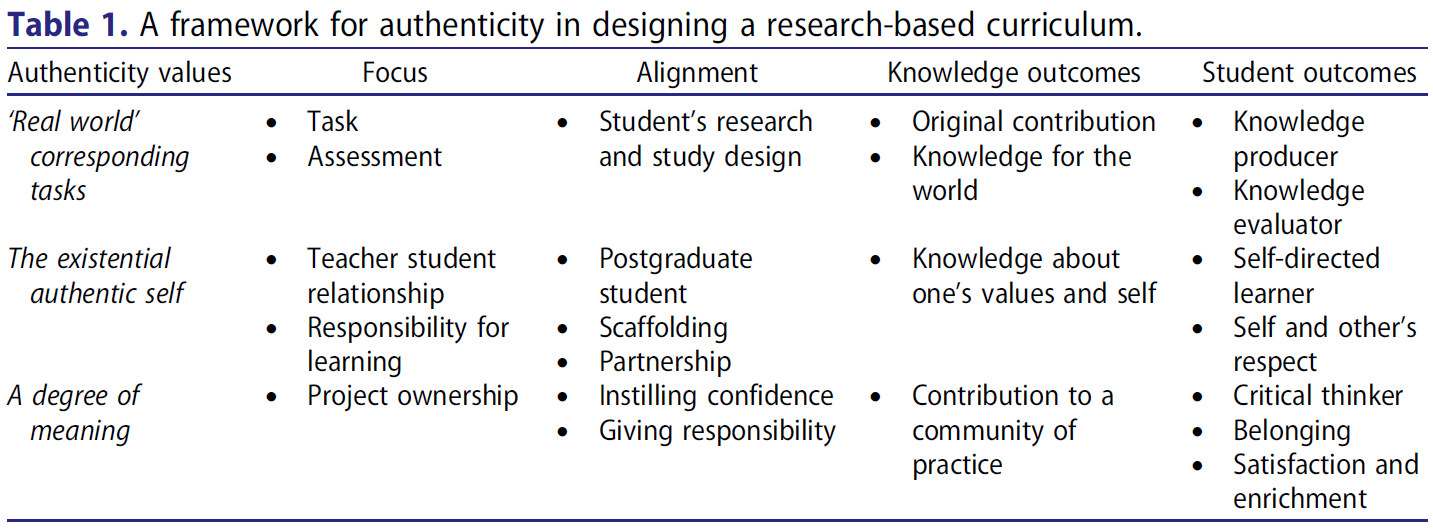

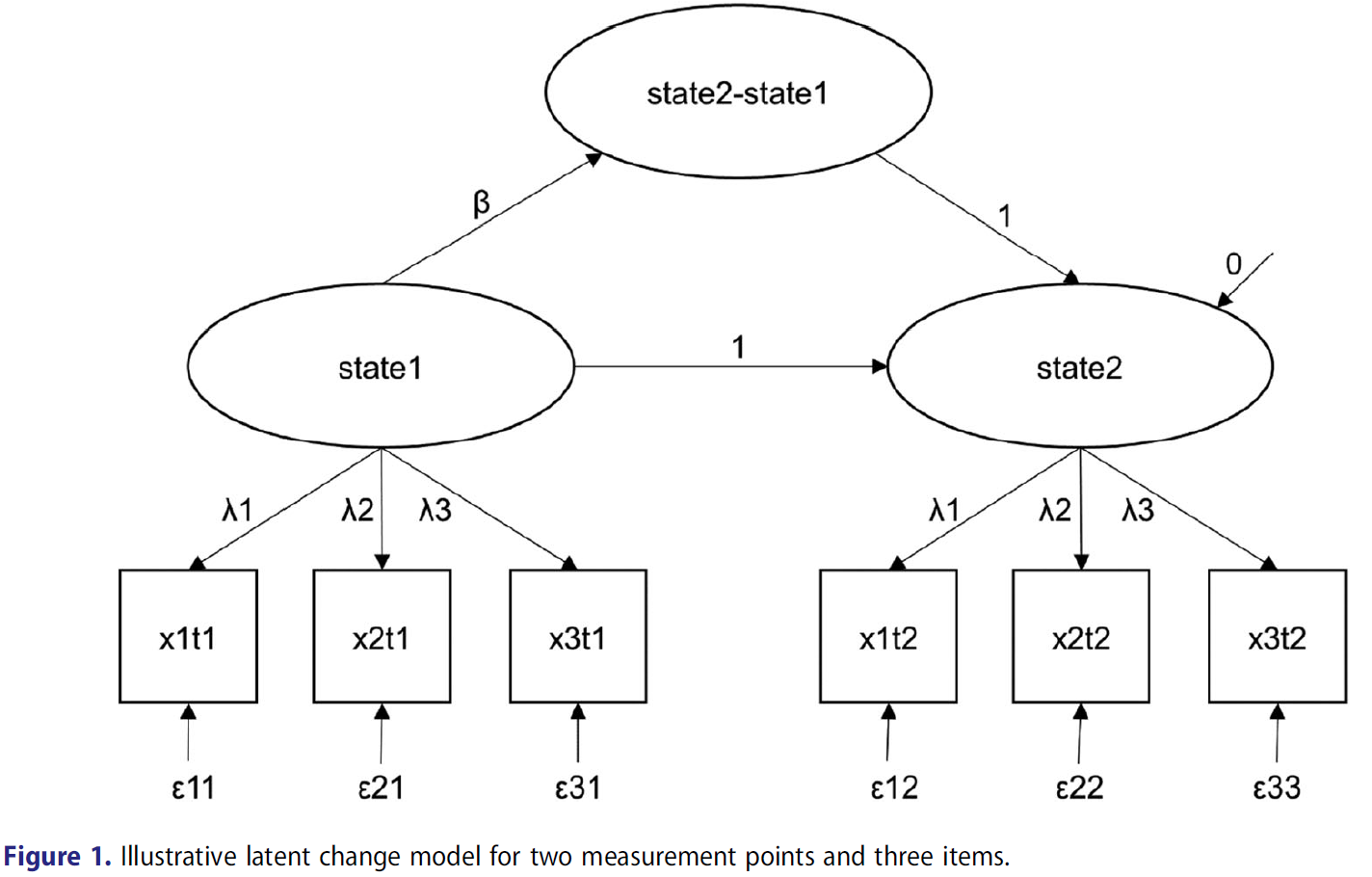

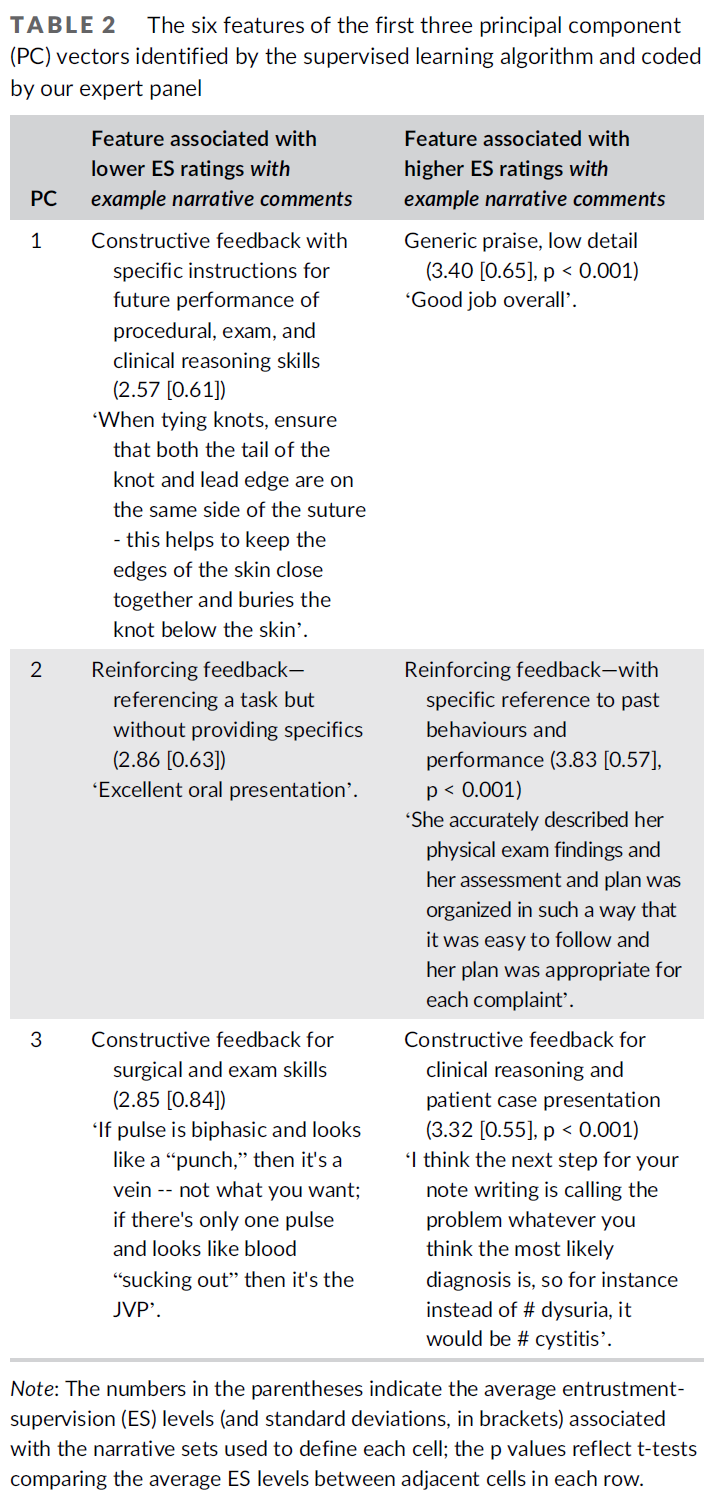

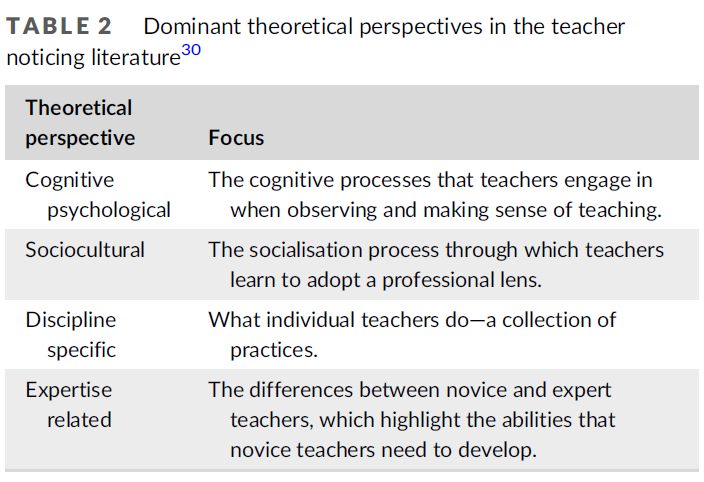

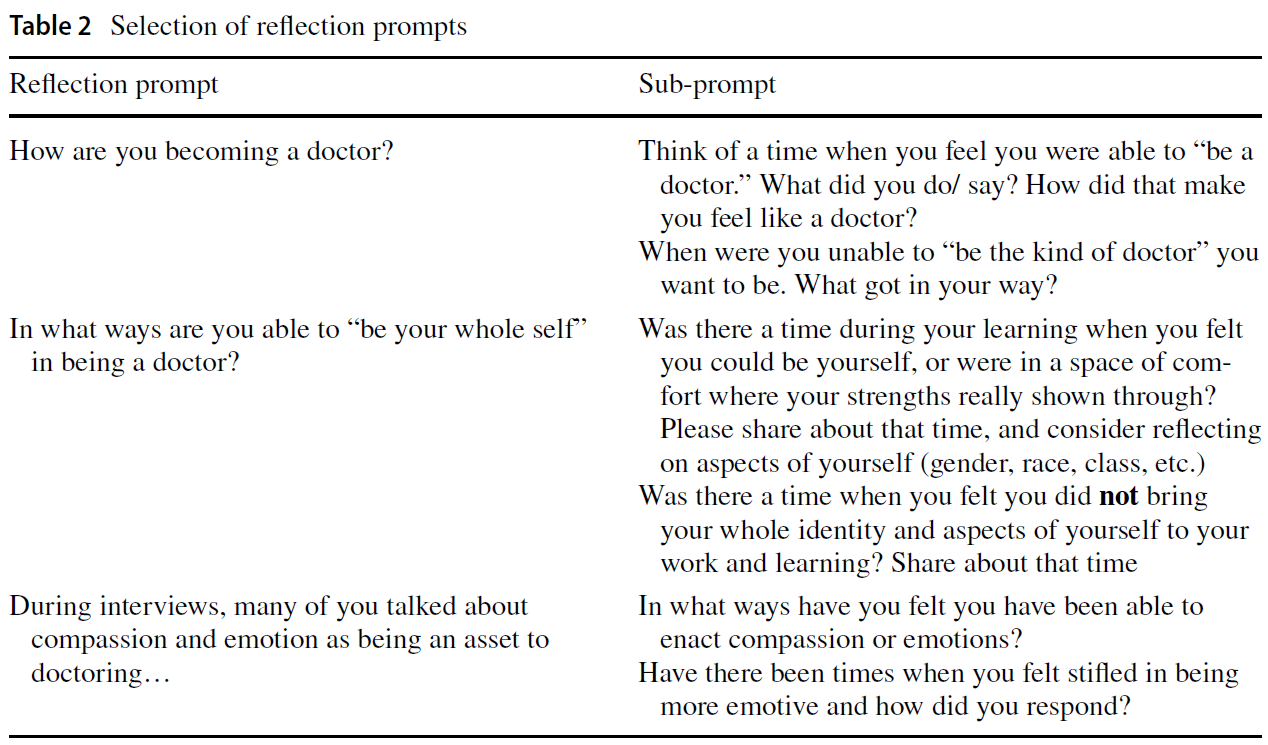

데이터 수집은 먼저 내러티브 전통(Clandinin & Connelly, 2000)을 사용하여 설계된 반구조화 인터뷰로 진행되었으며, 2020년 10월에 실시되었습니다. 내러티브 전통을 사용하여 인터뷰 질문을 만드는 것은 참여자의 이야기를 찾고 연구 조사 대상자에게 초점을 맞추는 것을 의미합니다. 따라서 내러티브 전통은 하나의 연구 질문에 답하기보다는 개인 및 가족 역사와 공유된 경험에 관심을 갖습니다(Clandinin & Connelly, 2000). 인터뷰는 AEB에서 수행했습니다. 인터뷰는 평균 45분 동안 진행되었습니다. 다음으로, 약 3주마다 참가자들에게 자신이 의사가 되는 과정을 중심으로 성찰문을 작성하도록 요청하고, 의사가 되는 과정에서 자신의 성별에 대해 더 깊이 성찰하도록 요청했습니다. (성찰 프롬프트 선택은 표 2 참조). 2020년 11월부터 2021년 4월까지 총 6차례에 걸쳐 반성문을 수집하여 총 105개의 반성문을 작성했습니다(참가자당 평균 4.7개). 모든 참가자는 최소 2개의 반성문을 제공했습니다. 2021년 5월에 각 참가자와의 최종 인터뷰가 진행되었으며, 인터뷰는 평균 45분간 진행되었습니다. 이 최종 인터뷰는 의과대학 1학년을 되돌아보고, 의사가 되기까지 자신의 지식과 정체성이 어떻게 영향을 미쳤는지에 대해 이야기하는 데 중점을 두었습니다.

Data collection proceeded first with semi-structured interviews, designed using the narrative tradition (Clandinin & Connelly, 2000) and performed in October 2020. Crafting interview questions using a narrative tradition means seeking out the story of participants and focusing on the people in the research inquiry. Thus, the narrative tradition is interested in personal and familial histories and shared experiences rather than answering a single research question (Clandinin & Connelly, 2000). Interviews were conducted by AEB. These interviews lasted on average 45 min. Next, approximately every three weeks, participants were asked to provide reflections largely centered around how they felt they were becoming doctors as well as asked participants to reflect more deeply on their gender in how they were becoming doctors. (See Table 2 for selection of reflection prompts). Six rounds of reflections were gathered from November 2020 to April 2021, making a total of 105 number of reflections (on average 4.7 per participant). All participants provided at least 2 reflections. A final interview in May 2021 with each participant was performed and lasted on average 45 min. This final interview was focused on looking back at their first year of medical school, and about how they felt their own knowledge and their identities informed how they were becoming doctors.

내러티브 분석

Narrative analysis

이 연구에서는 참가자들이 의사가 되는 과정을 어떻게 생각하는지 반복적으로 질문하는 데 중점을 두었습니다. 성별, 학습, 의학에 대한 직업적 사회화에 대한 폭넓은 경험에 대한 조사도 포함했기 때문에 인터뷰와 성찰을 통해 참가자들이 직면한 어려움과 기회, 때로는 희망적인 가능성에 대한 이야기를 이끌어냈습니다. (Anderson & Kirkpatrick, 2015)에서 설명한 것처럼, 이야기로서의 내러티브 탐구는 "단순한 사건의 목록이 아니라 화자가 시간과 의미에서 사건을 연결하려는 시도"(632쪽)입니다. 연구자로서 우리의 위치, 연구자로서의 성찰, 의대 여학생들의 비판적 작업과 노력을 높이려는 우리 자신의 노력을 바탕으로, 우리는 이 이야기를 인식론적 불의를 바로잡는 이야기로 서술합니다.

For this study, we focused on repeatedly asking how the participants felt they were becoming doctors. Since we also included probes about gender, learning, and broad experiences with professional socialization into medicine, interviews and reflections also elicited stories about challenges participants faced as well as opportunities and sometimes possibilities where they were hopeful. As (Anderson & Kirkpatrick, 2015) explain, narrative inquiry as story “is not just a list of events, but an attempt by the narrator to link them both in time and meaning” (p. 632). Based on our positionalities, reflexivity as researchers, and our own efforts to uplift the critical work and efforts of women students in medical school—we narrate this story as one about redressing epistemic injustice.

참여자들의 유효한 지식과 역사적, 문화적, 사회적 기원과 함께 그들의 경험에서 인식론적 불공정의 명백한 존재를 염두에 두고, 우리는 분석에 전체론적 접근 방식을 사용했습니다(Clandinin, 2013; Clandinin & Connelly, 2000; Konopasky et al., 2021). 전체론적 접근 방식은 개인의 역사를 고려할 뿐만 아니라 "체계적인 전체를 구성하는 이야기, 사건 또는 일련의 이야기와 사건 내의 연결에 초점을 맞추는" 접근 방식입니다(Konopasky 외., 2021). 이 논문의 체계적인 전체는 의과 대학 1학년 동안 참가자들이 인식론적 불의와 주체성 집행의 순간이었습니다. 우리는 먼저 데이터를 반복적으로 읽고 참가자의 초기 생활과 의대 재학 기간 동안 인식적 불공정의 순간을 중심으로 메모를 독립적으로 작성하는 것으로 시작했습니다(Richardson, 1997; Richardson & St. Pierre, 2000). 다음으로, 이번에는 의대 시절의 사건에 초점을 맞추어 인식적 불공정의 사례와 참가자들이 이러한 불공정에 어떻게 대응했는지에 대한 더 큰 내러티브를 구축하기 위해 다시 녹취록을 읽기로 했습니다. 여러 참가자들의 이야기를 읽으면서 정확히 같은 이야기는 아니더라도 비슷한 이야기가 공유되고 있음을 발견했습니다. 이러한 이야기를 정리하고 인식론적 부정의와 인식론적 주체성을 모두 포함하는 내러티브 아크arc를 개발하기 위해 우리는 중간 텍스트를 작성하기 시작했습니다.

Holding in mind the valid knowledge and historical, cultural, and social origins of our participants alongside the unmistakable presence of epistemic injustice in their experiences, we used a holistic approach to analysis (Clandinin, 2013; Clandinin & Connelly, 2000; Konopasky et al., 2021). A holistic approach considers personal histories, as well as “focuses on connections within a story, an event or even a series of stories and events that build a systematic whole” (Konopasky et al., 2021). The systemic whole for this paper were the moments of epistemic injustice and the enactment of agency on the part of the participants during their first year of medical school. We began by first performing repeated readings of the data and independently writing memos centered on moments of epistemic injustice during both the early lives of our participants and their time in medical school (Richardson, 1997; Richardson & St. Pierre, 2000). Next, we moved to reading transcripts again, this time focused on events during medical school to build the larger narrative of both instances of epistemic injustice and any connections to how participants responded to these injustices. Throughout readings we found similar if not the exact same story being shared by multiple participants. To organize these stories and develop a narrative arc including both epistemic injustice and epistemic agency, we moved to writing interim texts.

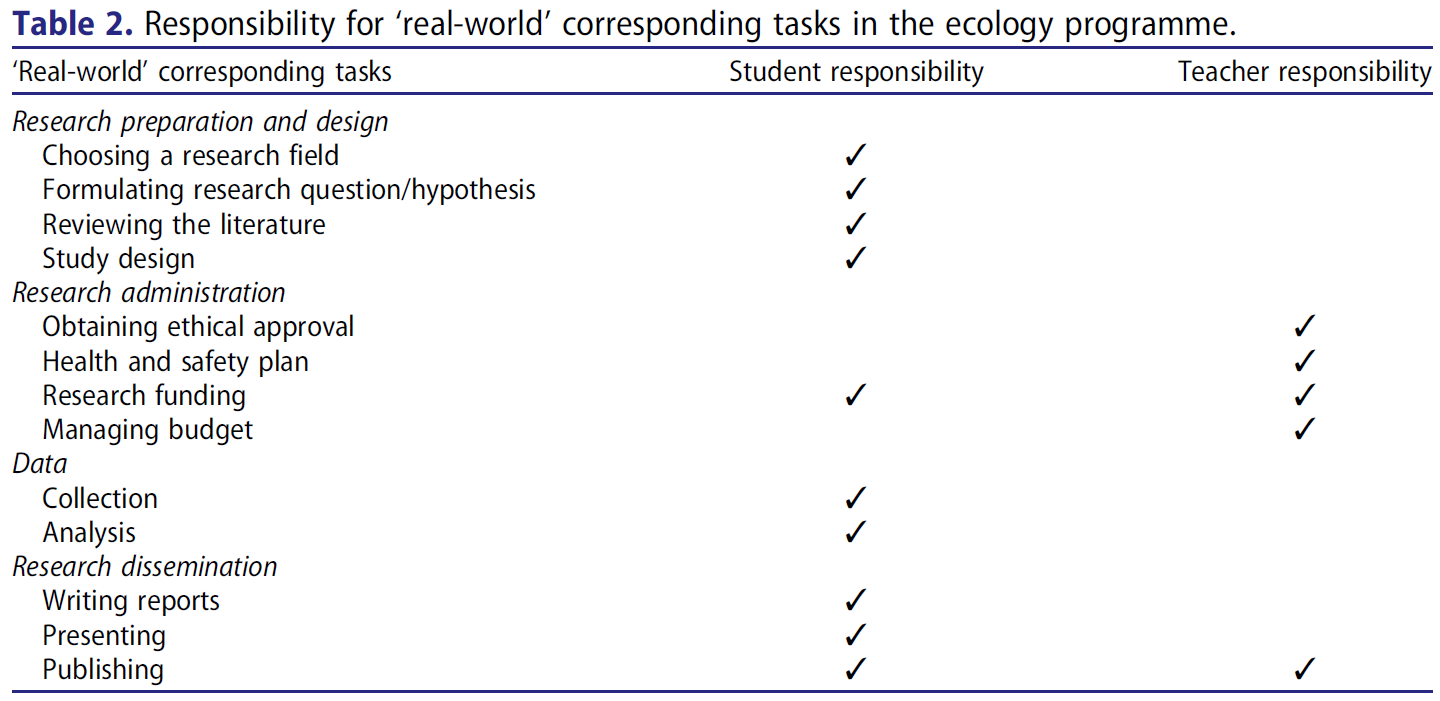

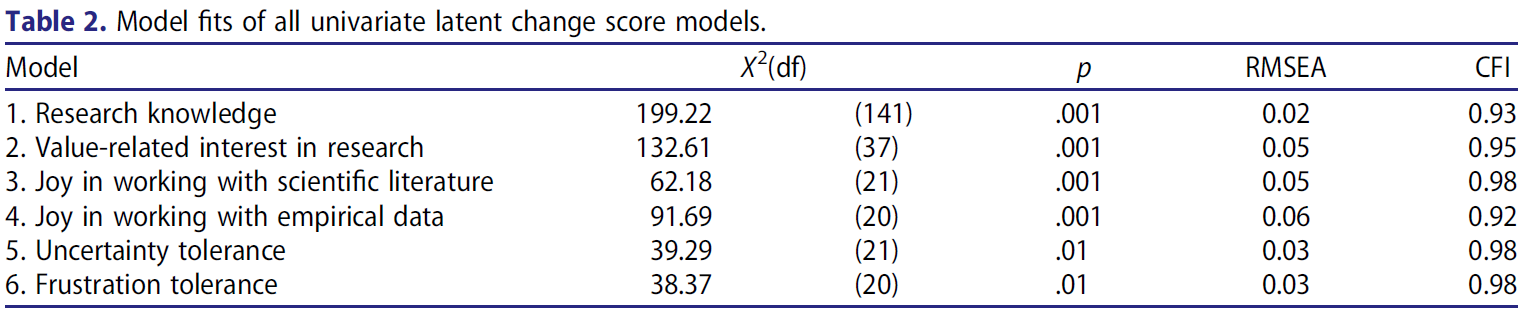

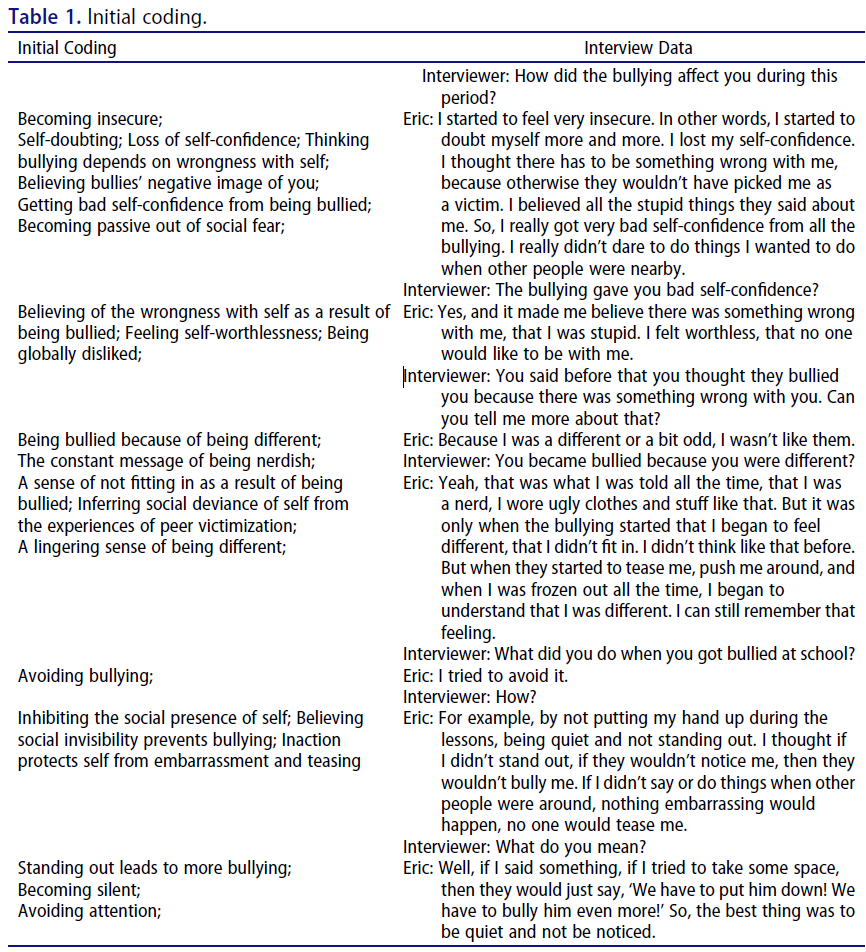

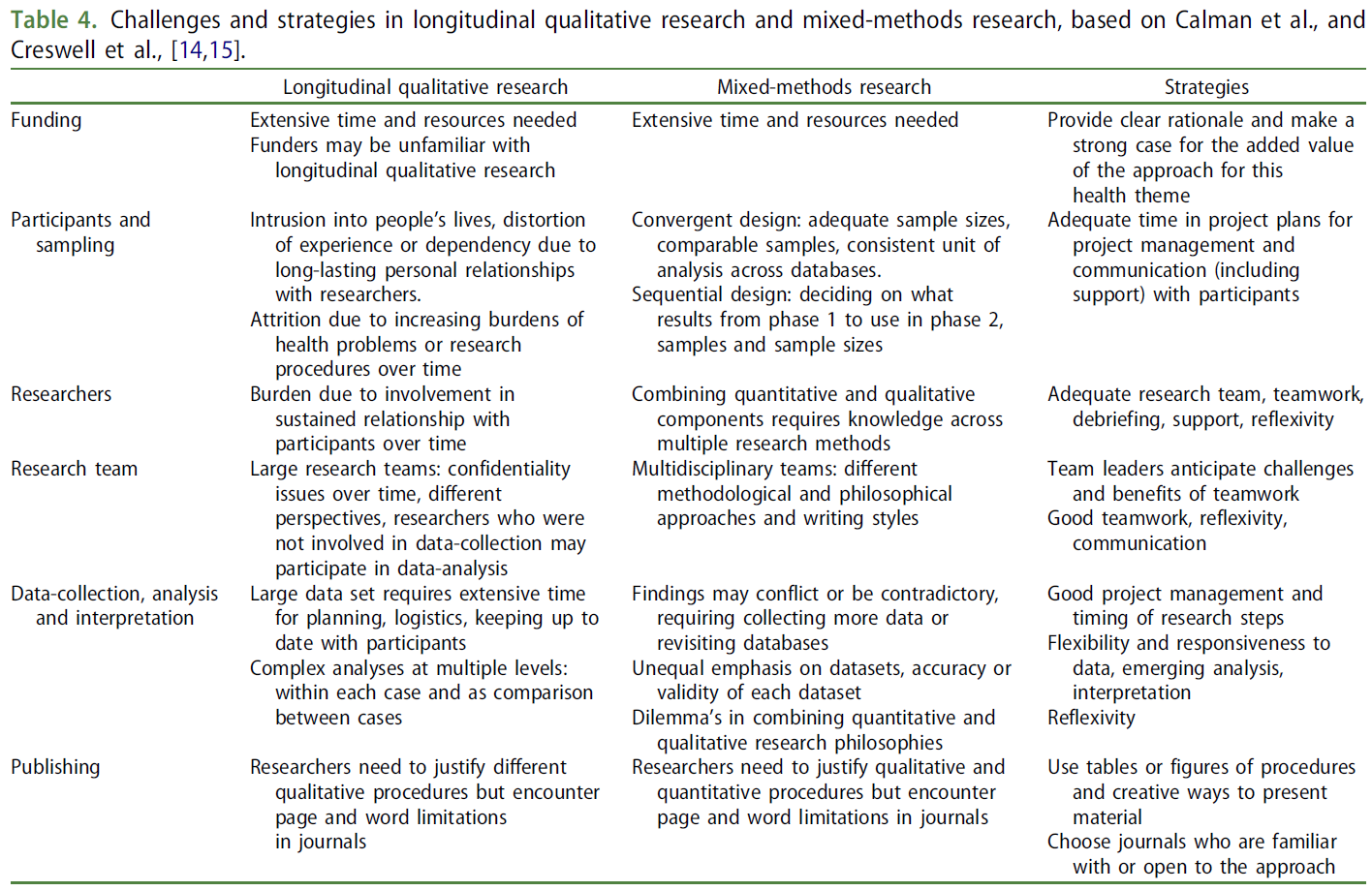

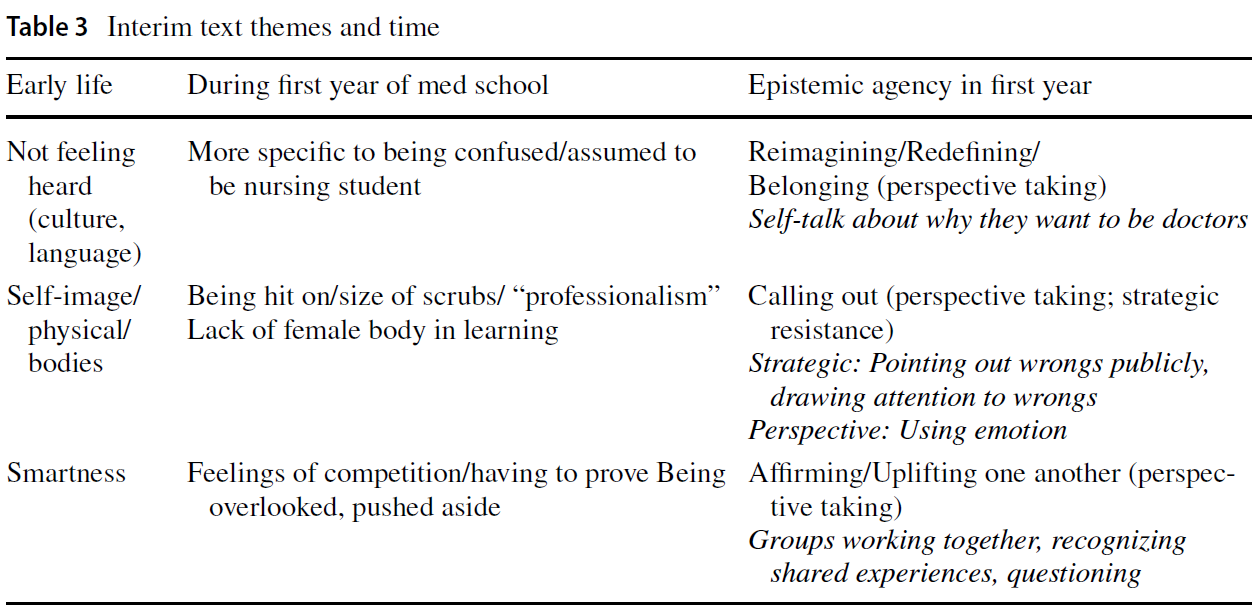

중간 텍스트는 연구 결과를 어떻게 정리할지, 어떤 이야기를 강조할지에 대한 가능성의 초안이었습니다(Clandinin & Connelly, 2000; St. Pierre & Jackson, 2014). 이 글들은 코딩과 코드 번들링의 첫 번째와 두 번째 단계(Saldaña, 2016)와 연구 결과의 최종 버전 사이의 텍스트, 즉 우리가 서로 협상하는 데 도움이 되는 글과 우리가 전한 이야기 사이의 텍스트 역할을 했습니다. 표 3 중간 텍스트 주제와 시간은 의료 환경에서의 인식론적 불공정에 대한 초기 경험, 의과대학에서의 인식론적 불공정의 순간, 불공정에 대응하는 인식론적 주체성의 사례를 정리한 최종 중간 텍스트의 한 예입니다. 각 열은 우리가 시간의 '플롯 포인트'라고 부르는 것을 나타냅니다. 각 행 안에는 불의 또는 기관에 따라 식별한 주제가 있습니다. 표에서 왼쪽에서 오른쪽으로 이동하면 이러한 불공정이 시간순으로 배치되고 참가자들이 불공정을 어떻게 시정했는지에 대한 예시가 표시됩니다. 각 행은 셀을 왼쪽에서 오른쪽으로 느슨하게 연결합니다. 조사 결과 발표에는 '초기 생애'의 구체적인 예가 포함되어 있지 않지만, 내러티브 분석을 위해 참가자의 생애 전체를 어떻게 끌어왔는지 설명하기 위해 이 부분을 열로 포함했습니다. 예를 들어, 간호사로 추정되거나 혼란스러웠던 경험은 일부 참가자가 의사 진료실에서 젊은 여성이라는 말을 듣지 못했던 초기 경험을 떠올리게 합니다. 마찬가지로, 참가자들이 추근대거나 수술복이 어떻게 보이는지 설명한 사례는 신체에 대한 초기 경험을 반영한 것입니다. 표 3은 연구 결과를 최종적으로 정리한 청사진입니다.

Interim texts were drafts of possibilities for how we organized our findings, and what stories we would emphasize (Clandinin & Connelly, 2000; St. Pierre & Jackson, 2014). They served as texts between first and second phases of coding and code bundling (Saldaña, 2016) and final versions of findings; writings that helped us make negotiations with one another and the story we told. Table 3 Interim Text Themes and Time is an example of one of our final interim texts that organizes early experiences of epistemic injustice in healthcare settings, moments of epistemic injustice in medical school, and examples of epistemic agency in response to injustices. Each column represents what we call “plot-points” in time. Within each row are the themes we identified according to injustices or agency. Moving from left to right on the table places these injustices in time and examples of how participants redressed injustices. Each row loosely connects the cells from left to right. Although our presentation of findings does not include specific examples of “early life,” we included this as a column to illustrate how we pulled on the entirety of a participant’s life to inform our narrative analysis. For example, being assumed to be a nurse or feeling confused are reminiscent of early experiences some participants shared of not being heard as young women in a doctor’s office. Similarly, instances of being hit on, or when participants described ways their scrubs looked were reflections of earlier experiences of their physical bodies. Table 3 was a blueprint for how our findings were finally organized.

연구 결과

Findings

지배적인 지식에 대한 실제적인 차이와 대안을 설명하기 위해 인식론적 불공정의 틀을 짜는 것은 개인이 불공정의 경험을 통해 어떻게 작동하는지에 대한 더 깊은 인식을 유도합니다. 또한, 인식론적 불공정에 대한 접근 방식은 개인의 역사, 개인적 경험, 특히 커뮤니티 지식을 포함하여 불공정이 개인 전체에게 어떻게 발생하는지 인식합니다. 아래 연구 결과는 의과대학 8개월 동안의 인식론적 불공정의 타임라인을 설명합니다. 이 조사 결과에 사용된 인용문은 22명의 참가자 표본을 대표합니다. 질적 내러티브 연구자로서 우리는 이 연구에 참여한 사람들의 더 큰 이야기를 반영하는 발췌문을 제공하고 다양한 참여자의 인용문을 제시하기 위해 노력했습니다. 먼저 참가자들의 경험의 배경을 제공하기 위해 불공정한 사례를 소개합니다. 이러한 사례는 교수진, 다른 남학생, 커리큘럼과의 상호작용 중에 발생했습니다. 다음으로, 참가자들이 인식적 불공정을 시정하고 자신에게 가해진 피해에 어떻게 대응했는지에 대해 이야기하는 인식적 주체성의 순간을 제공합니다. 불의를 바로잡기 위한 세 가지 가능성, 즉 자신이 의학계에 속해 있음을 재확인하고, 목소리를 내고, 서로를 격려하는 방법이 제시되었습니다.

Framing epistemic injustice to account for the very real differences and alternatives to dominant knowledges invites deeper recognition of how individuals are working through experiences of injustice. Additionally, our approach to epistemic injustice recognizes how injustices occur upon the whole person, inclusive of their history, personal experience, and especially their community knowledge. The findings below describe the timeline of epistemic injustice over an eight-month period of medical school. The quotes used in these findings are representative of the sample of 22 participants. As qualitative narrative researchers, we strive to provide excerpts that reflect the larger shared story of those in this study and ensure a variety of participant quotes were presented. We first introduce instances of injustice to provide a backdrop of the experiences of the participants. These instances occurred during interactions with faculty, other men students, and the curriculum. Next, we offer moments of epistemic agency, describing the ways the participants redressed epistemic injustice and talked about how they countered the harm they felt was being done to them. Three possibilities for redressing injustices are presented:

- reaffirming they belong in medicine,

- calling out and speaking up, and

- uplifting one another.

의과대학 내 인식론적 불공정 사례

Epistemic injustice in medical school

인식론적 불공정의 사례는 종종 참가자들이 의학을 추구하는 목적에 의문을 품게 만들었고, 때로는 이 분야에서 자신의 존재에 의문을 품게 만들었습니다. 그러나 무시당한다는 느낌을 받은 모든 상호작용이 명백한 것은 아니었습니다. 많은 참가자들은 도슨(2012)이 "불평등을 만들고 유지하는 사회 인식론적 구조..."(30쪽)로 인해 신뢰를 잃었다고 느낀 미묘한 순간을 설명했습니다. 의과대학에서 이러한 사회 인식론적 구조는 역사에서 파생된 문화로, 여성이 의과대학에 속하지 않는다는 수사를 유지합니다(Kang & Kaplan, 2019). 예를 들어, 한 참가자는 소그룹 학습 중 자신의 상호작용을 설명하면서 "명시적으로 언급되지 않았거나 현실이 아닐 수도 있지만, 때때로 남학생과 여학생 사이에 차이가 있는 것 같고, 때로는 남학생이 과학적 개념을 더 쉽게 이해할 수 있다는 명시되지 않은 암시가 있는 것 같다"고 반성했습니다. 이 참가자의 관찰은 성별이 학습 그룹에서 비언어적 상호 작용 중에도 한 성별을 다른 성별보다 우대하는 방식을 어떻게 형성할 수 있는지를 설명합니다. 이 참가자의 관찰에서 주목할 만한 점은 남성이 과학을 더 잘한다는 교육적 역학 관계를 경험한 결과 자신과 남성인 반 친구들 사이에서 느낀 '분리divide'였습니다. 이 참가자가 느낀 인식론적 불공평은 주로 성별에 근거한 것이었습니다. 그런 다음 그녀는 자신의 관찰이 '현실'인지 의문을 제기하고, 자신과 남성인 학생들 사이의 다른 대우에 대한 자신의 감정이 실제로 사실인지 숙고하면서 의과대학에서 자신의 지식과 위치에 의문을 제기해야 했습니다.

Instances of epistemic injustice often left participants questioning their purpose for pursuing medicine, and sometimes their presence in the field. However, not all interactions that led to feelings of being overlooked were explicit. Many participants described subtle moments of feeling divested of credibility due to, what Dotson (2012) refers to as the “socioepistemic structures that create and sustain situated inequality…” (p. 30). These socioepistemic structures in medical school are the cultures, derived from history, that maintain the rhetoric that women do not belong in medical school (Kang & Kaplan, 2019). For example, when describing her interactions during small group learning, one participant reflected, “Sometimes, although it is never explicitly stated or may not be reality, it does seem like there is a divide between the men and women medical students, and sometimes there appears to be this unstated undertone that the men have an easier time of understanding the scientific concepts.” This participant’s observation describes how gender may shape the way a learning group can privilege one gender over another, even during non-verbal interactions. Notable to this participant’s observation is the “divide” she felt between herself and classmates who are men, a result of experiencing the larger educative dynamic that men are better at science. The epistemic injustice this participant felt was largely based on her gender. She then questioned whether her observations were “reality” and pondered if her feelings about different treatment between herself and the students who are men was in fact true, an exercise in having to question her own knowledge and place in medical school.

다른 참가자들도 인식적 불공정의 사례를 공유하면서 자신이 의과대학에 속하지 않았다는 느낌을 공통적으로 드러냈습니다.

Other participants, when sharing instances of epistemic injustice, also disclosed the overarching sense that they did not belong in medical school.

항상 이곳에 속하지 않는다는 느낌이 들었습니다. 마치 우리가 여러분을 들여보낸 것처럼, 여러분은 본질적으로 이 공간에 속해 있는 것이 아니라 우리가 여러분을 들여보냈다는 것을 상기시켜줄 것입니다. 그리고 여러분 스스로도 그렇게 생각해야 합니다. 많은 남성, 특히 백인 남성은 자신이 이 공간에 속해 있다는 것을 상기시키기 위해 해야 하는 감정 노동을 이해하지 못한다고 생각합니다.

There’s always this feeling of just, you don’t quite belong here. Like you’ve been let in and we’re going to remind you that we let you in versus you just intrinsically belong in this space. And you have to remind yourself that you do. And I think a lot of men, particularly White men, don’t understand the emotional labor you have to do to remind yourself that you belong in this space.

이 참가자의 말은 성별에 따라 의과대학에 가면 안 된다고 은근히 또는 노골적으로 느꼈던 다른 참가자들의 많은 경험을 떠올리게 합니다. 이러한 경험은 참가자들이 의학을 추구해서는 안 된다고 느끼도록 만드는 인식론적 불공정을 나타냅니다. 한 구체적인 상호작용은 참가자들이 의과대학에서 교수진으로부터 질문을 받을 때 자신의 지식과 씨름하는 동시에 성별을 떠올리게 되는 과정을 보여줍니다:

This participant’s words recall many of the experiences of other participants, of feelings discreetly or overtly that they should not be in medical school largely based on their gender. These experiences are indicative of epistemic injustices, as participants would be made to feel they should not be pursuing medicine. One specific interaction demonstrates how participants grappled with their own knowledge in medical school when being questioned from faculty, while also being reminded of their gender:

저는 한 의사와 의사가 환자의 슬픔을 다루는 데 도움을 줄 수 있는 방법에 대한 아이디어를 논의하고 있었습니다. 저는 그분께 이 아이디어를 제시했고, 그분은 "계속 찾아보세요. 당신이 할 수 있는 일이 정말 많아요."라고 말해주었습니다. 나중에 제가 약리학의 기초 과학적 질문에 대한 아이디어를 제시했을 때 그가 한 말은 충격적이었습니다. 그는 저에게 "넌 똑똑한 애야. 네가 조사하기에 훨씬 더 좋은 질문이야."라고 말했죠. 저는 공중 보건과 사람들을 정서적으로 돌보는 것이 육체적으로 돌보는 것의 중요한 부분인 곳에서 왔습니다. 제 신념 체계 전체에 의문을 갖게 되었어요.

I was discussing an idea that I had with a physician, something on the topic of how physicians can help patients handle grief. I presented this idea to him and he told me, “keep looking. There are so many things that you could do.” So then when I presented to him later with an idea about a basic science question in pharmacology, the thing that he told me was shocking. He told me “you’re a smart girl. This is a much better question for you to investigate.” I come from a place where public health and taking care of people emotionally is a major part of taking care of them physically. It just made me question my entire belief system.

이 참가자는 교수진과의 상호작용을 통해 자신의 가치와 신념에 의문을 갖게 되었습니다. 유색인종 여성으로서 그녀는 자신의 인종과 성별과 함께 자신이 알고 있는 '똑똑함'을 사실로 바로잡아야 하는 상황에 직면했습니다. 게다가 공중 보건에 대한 이전 교육이 유효한지 여부에 대해서도 의문을 품었습니다. 이 참가자를 가장 힘들게 한 것은 아마도 [사람들을 돌보겠다는 헌신]과 [더 많은 "과학적 질문"을 추구해야 한다는 압박] 사이의 긴장감일 것입니다. 이 참가자에게는 이 두 가지 추구가 서로 상충되는 것이었습니다.

This participant’s interaction with her faculty member made her question her own values and beliefs. As a woman of Color, she was also faced with having to rectify her “smartness” with what she knows to be true, alongside her race and gender. Moreover, she questioned whether or not her previous education in public health was valid. Perhaps most frustrating for this participant was the tension between her commitment to care for people and pressure to pursue more “science questions.” For this participant these two pursuits were at odds.

참가자와 남성인 다른 학생들 간의 상호작용에서도 인식론적 불공평이 드러났습니다. 별도의 성찰에서 많은 참가자가 학습에 영향을 미친 사건을 설명했습니다. 한 유색인종 참가자는 시나리오를 설명했습니다:

Interactions between participants and other students who were men also introduced epistemic injustices. In separate reflections, many participants described an event that impacted their learning. One participant of Color described the scenario:

3주 전, 저는 신체 검사를 담당할 SIM 남성 파트너를 배정받았습니다. 우리는 함께 환자를 면담해야 했습니다. 그런데 그 남학생은 저를 기다리지 않고 바로 정보를 수집하기 시작했습니다. 그는 도를 넘었고 문진 부분만 하겠다고 말했음에도 불구하고 제게 말할 기회를 주지 않았습니다. 마침내 환자에게 "이제 신체검사를 실시하겠습니다"라고 말했고, 제가 청진기를 꺼내는 동안 남성 파트너는 대담하게도 환자에게 달려가 재빨리 장비를 챙겨서 신체검사를 시작했습니다. 그는 제가 마치 그의 서기인 것처럼 작은 발견 사항 하나하나를 중얼거리며 메모해 주었습니다. 저는 매우 충격을 받았습니다.

Three weeks ago, I was assigned a SIM male partner to perform a physical exam. We had to interview the patient together. But the male student did not wait for me, and he immediately began to gather information. He was overstepping and did not give me a chance to speak, even though he said that he will only do the history for the interview portion. I finally told the patient “I will now perform the physical exam” and as I was taking out my stethoscope my male partner had the audacity to run to the patient and quickly grab his equipment and begin performing the PE. He mumbled every little finding to me as though I was his scribe, just taking notes for him. I was very shook.

이 참가자는 옆으로 밀려나고 무시당하는 경험에 괴로움을 느꼈고, 동료 학생에게 심한 무례함을 느꼈습니다. 또한 이 참가자는 파트너와 환자 면담 진행 방식에 대해 합의한 후 환자와 면담실에 들어갔지만, 의대생으로서의 지식이 부족할 뿐만 아니라 도가 지나쳤다고 지적했습니다. 한 순간의 SIM 경험에서 인식론적 불공정은 성별에 따라 이 참가자의 의대생으로서의 자신감과 지식을 표적으로 삼았고, 그녀는 "흔들리는" 느낌을 받았습니다.

The experience of being pushed aside and talked over were distressful for this participant, making her face acute disrespect from her fellow classmate. Additionally, this participant pointed out she and her partner had come to an agreement about how the patient interview would proceed, and once in the room with the patient she was not only overstepped, but also minimized in her knowledge as a medical student. In one swift SIM experience, epistemic injustice targeted this participant’s confidence and knowledge as a medical student based on her gender and she left feeling “shook.”

인식론적 불공정은 커리큘럼에서 분명하게 드러나는 다른 학습 경험에서도 존재했습니다. 한 백인 참가자는 여성 환자를 성적으로 묘사한 필수 독서에 대해 설명했습니다. 이 참가자는 불쾌감을 느꼈을 뿐만 아니라 교수진이 자신과 여성인 다른 학급 친구들에 대해 어떻게 생각할지 혼란스러웠다고 말했습니다. "우리 중 많은 여성들이 매우 불쾌했습니다. 어떻게 이게 괜찮을 수 있죠? 여성 환자를 성적 대상화하지 않고도 이 자료를 가르칠 수 있는 다른 강의는 세상에 없었을까요?" 이 경험은 참가자들에게 피해를 입혔고, 다른 세 명은 반성문을 통해 이 시나리오를 공유하고 부적절하다고 생각되는 내용이 어떻게 학습에서 중립적인 것으로 제시될 수 있는지에 대해 의문을 제기했습니다. 다른 학습 사례에서도 참가자들은 학습에서 여성의 신체가 얼마나 적게 표현되었는지를 깨닫고 혼란을 겪었습니다.

Epistemic injustices were also present during other learning experiences, evident in curriculum. One White participant described required reading that portrayed a female patient in a sexualized manner. This participant shared how offended she felt, as well as confused about what faculty may think about her and her other classmates who were women. “A lot of us females were super offended, I mean, how is this okay? Is there no other article in the world that could have taught us the material without sexualizing a female patient?” This experience caused harm to participants and three others shared this scenario through their written reflections and questioned how something they believed inappropriate could be presented as neutral in learning. Other learning instances also stirred confusion for participants when they realized how little representation a woman’s body had in their learning.

저를 괴롭힌 몇 가지 사항이 있습니다. 예를 들어 신체검사를 해야 하는데 여성에게 신체검사를 하는 방법을 가르쳐주지 않았어요. 그리고 제 실습 파트너는 여자였어요. 그래서 다섯 번째 늑간 공간을 만질 때 말 그대로 가슴에 있는 그 부분을 만져야 하나요? 어떻게 해야 하나요? 브래지어를 들어 올려야 하나요? 브래지어 위로 해야 하나요? 사소한 질문이 너무 많아서 제대로 하고 있는지 확인하고 싶었어요. 하지만 가르쳐주지 않았어요. 그게 정말 중요하지 않나요? 그래서 제가 여성이라는 사실을 더 자각하게 되었죠.

There are some things that kind of bothered me. Like we had to do our physical exam, but they didn’t teach us how to do it on a woman. And my practice partner was a girl. And so when we feel for the fifth intercostal space, that’s literally on your breasts, like, are we supposed to touch it? How are we supposed to do it? Was I supposed to lift the bra up? Are we supposed to do it over the bra? There were so many little questions and we wanted to make sure we’re doing it right. But they didn’t teach us. And isn't that really important? So it made me more aware of being a woman.

백인 1세대 학생인 이 참가자는 신체 검사를 위해 여성의 몸을 어떻게 움직여야 하는지 모르는 것뿐만 아니라 학습 과정에서 여성의 신체에 대한 배려가 없는 것 같아 괴로웠습니다. 다른 방식의 앎과 학습에 대한 이러한 무시는 학생들의 의학 교육에서 여성을 신체적으로 "타자"로 젠더화하는 인식론적 불공정이 어떻게 나타날 수 있는지를 보여주는 예입니다. 이 경험을 통해 그녀는 자신의 성별에 대해 더 잘 인식하게 되었고, 자신의 신체가 의과대학에 속하지 않을 수 있으며, 더 나아가 의과대학에서 배울 만큼 중요한 신체로 간주되지 않을 수 있다는 생각을 증폭시켰습니다.

This participant, a White first-generation student, was troubled by both not knowing how to maneuver around a woman’s form for a physical exam, but also that there seemed not to be consideration for a woman’s body in her learning. This disregard for other ways of knowing (and learning) is an example of how epistemic injustice can appear in students’ medical training, gendering women physically as “other.” This experience made her more aware of her gender, amplifying how her body may not belong in medical school, and potentially worse, might not be considered a body important enough to learn about in medical school.

인식론적 주체성을 통한 인식론적 불공정의 시정

Redressing epistemic injustice through epistemic agency

참가자들은 의대 재학 중 인식론적 불공정을 겪었지만, 8개월이 지나면서 의대 재학 중 자신의 가치와 시스템 내에서 변화를 만드는 데 참여하는 것의 중요성을 인식하게 되었습니다. 참가자들은 남성인 다른 학생 및 교수진과 교류하고 정해진 커리큘럼을 배우는 과정에서 여성이라는 이유로 무시당하고 소외되는 느낌을 받았으며, 자신의 지식이 정당하지 않다고 느끼게 되었습니다. 또한 의사의 공감에 대해 연구하고 싶었던 참가자의 경우처럼 자신이 알고 있는 지식은 물론 새로운 지식조차도 가치가 없다고 느꼈습니다. 이러한 인식론적 불공정의 순간을 바로잡기 위해 참가자들은

- (1) 자신이 의과대학에 속한 이유를 되찾고,

- (2) 커리큘럼에서 배운 내용을 상기시키며,

- (3) 서로를 격려하기 위해 노력했습니다.

Although participants described encounters with epistemic injustice during medical school, over the course of eight months they came to recognize their own value in being in medical school as well as the importance of being a part of making change within the system. During interactions between themselves and other students and faculty who were men, and learning from prescribed curriculum, participants experienced feeling overlooked and marginalized because they are women; thus being made to feel their own knowledge was not legitimate. Furthermore, they described how their own way of knowing and even new ways of knowing (as in the case of the participant who hoped to research physician empathy) were not valuable. To redress these moments of epistemic injustice, participants worked to

- (1) reclaim why they belong in medical school,

- (2) call out their curricular materials, and

- (3) uplift one another.

의과대학에 소속된 이유 되찾기

Reclaiming why they belong in medical school

소속감을 느끼는 동시에 소외감을 느끼는 불안정한 감정으로 인해 많은 참가자가 의대를 선택한 이유를 다시 확인했습니다. 또한 참가자들은 자신이 이 분야에 가져온 지식을 상기하기 위해 노력했습니다. 참가자들은 반성적 숙고를 통해 자신이 왜 의대를 선택했는지 스스로에게 상기시키는 시간을 가졌습니다. 컬러의 한 참가자는 "저는 정말 힘을 얻었고, 제 '이유'는 개인으로서 그리고 리더십으로서 성장하고 싶다는 것입니다."라고 말했습니다. 다른 참가자들은 자신의 성별과 여성으로서 의학계에서 자신이 어떻게 소속되어 있는지 재확인했습니다:

The unsettled feeling between knowing they belong while also being marginalized led many participants to reaffirm why they chose to pursue medicine. Additionally, participants worked to remind themselves of the knowledge they brought to the field. Through reflexive deliberations, they shared how they spent time reminding themselves about why they pursued medical school. One participant of Color shared, “I feel really empowered… and my ‘why’ is I want to grow as an individual and in my leadership.” Others reaffirmed their gender and how they belong in medicine as women:

여성으로서의 경험과 제가 가지고 있는 모든 것이 환자와 대화하거나 학습하는 데 있어 가장 좋은 방법이 무엇인지 이해하는 데 도움이 될 수 있다고 생각합니다. 성장과 경험, 상호작용에 관한 모든 것.

I feel that my experience as a female and everything I have to bring to the table can help me understand what’s the best way to approach interactions or talking to patients or learning. Anything regarding growth and experiences and interactions.

마찬가지로 한 참가자는 "제 성별 때문에 정서적 보호자가 되어야 한다는 사회적 기대가 생겼고, 이는 환자와 상호작용할 때 그대로 드러납니다. 하지만 정서적 교감이 환자와의 만남에서 가장 만족스러운 요소라고 생각합니다."라고 말했습니다. 참가자들은 자신의 성별뿐만 아니라 성별과 관련된 더 큰 사회적 규범에 대해서도 자각하고 있었습니다. 간병인 및 보호자가 되는 것에 대한 기대는 참가자들이 의과대학에서 자신의 소속감을 상기시키고 정서적 연결을 가져다주는 역할을 다시금 상기시키는 특성이었습니다.

Likewise, one participant reflected, “my gender has raised me with societal expectations of being the emotional caretaker, and that comes through when I’m interacting with patients. But I believe the emotional connection is the most satisfying component of the patient encounter.” Participants were self-aware of their gender, as well as the larger societal norms connected to their gender. Expectations of being caregivers and caretakers were attributes these participants reclaimed as reminders as to how they belonged in medical school; to bring emotional connections.

정서적 측면 외에도 많은 참가자가 의과대학에 소속된 이유에 대한 더 큰 그림에 대해 논의했습니다. 이러한 큰 그림은 종종 참가자들이 제도적 문제에 대한 인식과 이러한 문제를 해결하기 위한 각자의 역할을 지적하는 것이었습니다. 한 URiM 참가자는 "지치고 패배감을 느끼는 날에는 내가 어떻게 지역사회를 위해 봉사할 수 있을지 자주 생각하게 됩니다. 의사가 다른 사람들의 삶에 긍정적인 영향을 미칠 수 있는 놀라운 잠재력을 떠올리게 됩니다."라고 말했습니다. 마찬가지로 다른 참가자도 "우리는 환자를 옹호할 수 있고 정말 열심히 노력할 수 있습니다. 하지만 결국 중요한 것은 환자와 어떻게 상호 작용하고 무엇을 하고 있는지, 환자와 함께 무엇을 위해 기꺼이 싸울 것인지입니다."라고 말했습니다. 따라서 참가자들은 자신의 이야기와 역사가 학습 방법과 의과대학에 있는 이유에 어떻게 영향을 미치는지 알게 되었습니다:

In addition to the emotional aspect, many other participants discussed the bigger picture of why they belonged in medical school. These bigger pictures often pointed to participants’ awareness of systemic challenges, and their individual roles in addressing these challenges. One URiM participant shared, “On days when I am feeling tired and defeated, I often think back to how I will serve as an advocate for my community. I am reminded of the incredible potential that a physician has to positively impact the lives of others.” Likewise, another participant shared, “We can advocate for our patients and we can try really hard. But at the end of the day, it is how we interact with our patients and what we're doing, what we're willing to fight for with them.” Thus, participants were aware of how their own stories and histories informed how they are learning, as well as why they are in medical school:

의과대학에서 우리를 형성하는 많은 배움은 학교 안에서만 일어나는 것이 아닙니다. 때로는 외부에서 경험하고 같은 반 친구들이 인생에서 겪은 일에 대해 이야기하는 것을 듣기도 합니다. 의사가 되기 전의 경험과 의료계에서 어떤 대우를 받았는지, 그리고 가족들이 어떤 대우를 받았는지가 의사로서 자신을 형성하는 데 많은 영향을 미친다고 생각합니다. 그리고 그것이 중요하다고 생각합니다.

A lot of the learning that happen that shape us in medical school or the stuff doesn’t even happen within school itself. Sometimes it’s our outside experience and listening to classmates talk about what they've gone through in their life. I think a lot of what shapes you as a physician is your experience prior to med school and how you have been treated and how your family has been treated in medicine. And I think that is important.

참가자들은 의료계의 더 큰 인식적 불공정을 예리하게 인식하고, 학습 여정에서 자신의 역사, 지식, 경험을 인식했으며, 의대 재학 중과 졸업 후 환자와의 상호작용이 더 큰 불공정과 불균형을 시정할 수 있는 방법임을 재확인했습니다. 또한 참가자들은 반성적 숙고를 통해 여성으로서 자신의 관점이 어떤 가치가 있는지 스스로 되새겼습니다.

Participants were acutely aware of the larger epistemic injustices in healthcare, recognized their own histories, knowledge, and experiences in their learning journeys, and reaffirmed ways that interactions they would have with patients during and after medical school would be the way could redress larger injustices and disparities. Furthermore, participants engaged in reflexive deliberations to remind themselves about ways their own perspectives as women were valuable.

커리큘럼 자료 불러내기

Calling out curricular materials

한 해 동안의 어려운 학습 경험은 학생들이 커리큘럼을 외쳐야 한다고 느끼는 방식을 강조했습니다. 학생들은 외치는 행위를 통해 전략적으로 저항하고, 자신의 권위를 주장하고, 자신이 직접 확인하고 경험한 인식론적 불의에 대응했습니다. 참가자들이 반성문과 최종 인터뷰에서 언급했던 문제가 되는 기사가 이러한 호소의 한 예입니다. 한 참가자는 "모욕적"이고 "여성 환자를 성적으로 묘사한" 동일한 기사를 다른 참가자는 용납할 수 없다고 지적했습니다: "남성 동료들이 여성 환자를 대하는 방법과 같은 허용 가능한 행동을 배운다고 생각하니 좋지 않다고 생각해요. 물론 그대로 두되, 이 글이 허용되지 않는 이유에 대해 소그룹과 대화를 나눈다는 내용을 넣으세요."라는 댓글이 달렸습니다.

Troubling learning experiences throughout the year highlighted how students felt they needed to call out the curriculum. Through the act of calling out, students engaged in strategic resisting, asserting their authority and countering the epistemic injustices they identified and experienced directly. One such example of calling out is the troubling article participants commented on in their reflections and final interview. The same article one participant described as “offensive” and “sexualizing a female patient,” another participant indicated as impermissible: “the thought of my male colleagues learning that’s acceptable behavior, like a way to treat a female patient I don’t think this is good. Sure leave it up, but put something that says have a conversation with a small group about why this article is not acceptable.”

기사에 댓글을 단 참가자들은 교수진에게 다가가 해당 기사의 적절성에 대해 대화를 시작했습니다. 궁극적으로 이들의 행동은 최종 목표를 달성하는 데 성공했지만, 이러한 행동은 또한 자신과 특정 교수진 사이에 더욱 긍정적이고 존중하는 상호 작용을 촉진했습니다.

Participants who commented on the article approached the faculty member, opening up a conversation about the appropriateness of the reading. Ultimately, their actions were successful towards their end-goals, but these actions also stewarded more positive and respectful interactions between themselves and this particular faculty member.

결국 그 글은 삭제되었습니다. 이 일을 계기로 저희는 정말 우리가 목소리를 낼 수 있다는 것을 느꼈습니다. 비록 우리는 의대생일 뿐이고 무엇을 해야 하고 무엇을 읽어야 하는지 지시를 받지만, 우리의 의견은 중요합니다. 그리고 목소리를 내기에 결코 늦지 않았습니다.

In the end, the article did get taken down. It really made us feel like we do have a voice. And even though we're just medical students and we're told what to do and what to read, our opinion does matter. And it's never too late to speak up.

참가자들은 자신의 가치와 지식으로 자신이 피해를 입었다고 느낀 부분을 바로잡을 수 있을 만큼 용감하고 신념이 있었습니다. 이를 통해 참가자들은 자신의 의견이 중요하고 자신의 지식이 정당하다는 것을 인식할 수 있었으며, 교수진이 경청하고 변화를 이끌어낼 수 있었습니다.

Participants were both brave enough and convicted by their own values and knowledge to redress how they felt harmed. This allowed participants to recognize their “opinion does matter” and their knowledge were legitimate, enough so for a faculty member to listen and make a change.

커리큘럼 자료를 불러오는 다른 사례는 더 미묘했으며, 참가자들이 시뮬레이션에서 스크립트화된 상호작용을 하는 동안 환자 상호작용에 대한 자신의 지식과 직관을 어떻게 활용했는지를 보여주었습니다. 참가자들은 반성적 숙고를 통해 자신의 지식과 경험을 불러일으켰고, 환자 시뮬레이션 중에 이를 활용하여 때때로 긴장되는 학습 경험에서 자신을 편안하게 하고 시뮬레이션된 환자를 편안하게 했습니다. 한 유색인종 참가자는 "커리큘럼이 모든 것을 체크리스트로 제시하고 환자 상호 작용에서 감정을 분리하는 것 같습니다."라고 말했습니다. 또 다른 백인 참가자는 체크리스트에 대한 다른 견해를 제시했습니다. "우리는 체크리스트를 사용하고 정서적 상담에 더 깊이 파고드는 데 중점을 두었습니다. 환자를 위로하는 것이 중요하지만 모든 환자가 그런 식으로 마음을 여는 것을 좋아하는 것은 아닙니다." 몇몇 참가자는 체크리스트를 사용하여 공감이나 연민을 이끌어내거나 환자 면담을 더 잘 수행하는 방법을 배우는 데 도움이 되었다고 말했습니다. 그러나 참가자들은 대인 관계에 대한 자신의 지식을 활용하고 이러한 지식을 임상 및 시뮬레이션 경험에 삽입하는 방법도 배웠습니다. 한 참가자는 다음과 같이 말했습니다,

Other instances of calling out curricular materials were more subtle and revealed how participants navigated their own knowledge and intuition about patient interactions during more scripted interactions in simulation. Through reflexive deliberations, they called upon their own sense of knowing and experience and used this during patient simulation to both put themselves at ease during sometimes nerve-racking learning experiences and put the simulated patient at ease. One participant of Color noted, “I feel a little like our curriculum presents everything as a checklist and detaches the emotion from our patient interactions.” Another White participant offered a different view of checklists, “A lot of our focus has been to use checklists and dig deeper into emotional counseling. While it is important to comfort patients, not all patients like to open up that way.” Several participants commented on using checklists to elicit empathy or compassion, or to help them learn how to better perform patient interviews. However, participants also learned how to draw on their own knowledge about interpersonal connections and insert this knowledge into their clinical and simulated experiences. One participant shared,

체크리스트는 분명히 환자와의 감정에 관한 것이고, 저는 실제로 환자와 교감하고 있습니다. 저는 환자와 소통하는 능력에 대해 보완을 받았고, 환자와의 만남에서 가장 만족스러운 요소는 정서적 연결이라고 생각하며, 이는 환자와 상호작용할 때 드러납니다."라고 말했습니다.

Clearly the checklists are about emoting with the patient, and I actually connect with the patient. I have been complemented on my ability to connect with them…and I believe the emotional connection is the most satisfying component of the patient encounter and this comes through when I’m interacting with them.

마찬가지로 다른 참가자는 "환자마다 개성이 다르기 때문에 반드시 지켜야 하는 체크리스트를 따르는 것이 항상 병상 매너를 가르치는 올바른 방법은 아닙니다. 저는 환자가 방문의 흐름을 결정하고 적응하고 기어를 바꿀 수 있도록 내버려둘 수 있었습니다." 마지막으로 한 참가자는 "[환자 면담은] 항상 제게 제2의 천직이었으며, 많은 SP가 제 연민으로 인해 잠재적으로 무서운 의학적 문제를 겪고 있는 환자에게 보살핌과 위로를 받았다고 큰 피드백을 주었습니다."라고 설명했습니다.

Similarly, another participant shared “Every patient is unique and following a checklist that we absolutely must stick to is not always the correct way to teach bedside manners. I’ve been able to let the patient decide the flow of a visit and adapt, and shift gears.” Finally, one participant explained, “[Patient interviewing] has always been second nature to me and many of the SPs have given me great feedback about how my compassion made them feel cared about and comforted them during a potentially scary medical problem.”

참가자들은 체크리스트를 읽거나 따라야 하는 학습 경험을 통해 자신의 지식과 경험을 쌓고, 그 지식과 경험을 행동으로 옮길 수 있었습니다. 다른 참가자들은 표준화 환자들로부터 격려적인 피드백을 받으면서 환자 면담을 수행하는 방법에 대한 자신의 개인적 지식을 재확인하여 환자로부터 주요 관심사를 이끌어내는 참가자들만의 방법을 지원받았습니다. 참가자들은 목소리를 내고 목소리를 높임으로써 받아들일 수 없는 커리큘럼 자료에 대해 전략적으로 저항하고 체크리스트와 기타 커리큘럼 자료를 환자 치료에 대한 접근 방식에 맞게 더 유연하게 만들 수 있는 방법을 고민하기도 했습니다.

Participants were able to shore up their own knowledge and experience during learning experiences that required reading or following checklists and put that knowledge and experience into action. Other participants received encouraging feedback from standardized patients, reaffirming their own personal knowledge about how to perform a patient interview, thereby supporting participants’ own way of eliciting chief concerns from patients. By speaking up and calling out, participants deployed strategic resistance to unacceptable curricular material, and also deliberated how they could make checklists and other curricular material more flexible towards their approach to patient care.

서로 격려하기

Uplifting one another

공동체의 고양감을 갖는 것은 참가자들이 인식의 불공정을 바로잡는 데 중요한 역할을 했습니다. 참가자들의 커뮤니티 형성은 주로 의과대학에서 여성이라는 공통된 경험을 중심으로 이루어졌습니다. 또한 특정 사건을 계기로 함께 모이게 되었습니다. 예를 들어, 한 백인 참가자는 짝을 지어 환자를 검사하는 실습에서 다른 참가자들이 옆으로 밀려난 경험이 있다는 사실을 알게 된 후, 그 경험에 대해 디브리핑하고 행동 계획을 수립했습니다.

Having a sense of communal uplift was an important part in how participants redressed epistemic injustices. Forming community for participants was primarily around their shared experience of being women in medical school. Their coming together was also ignited after specific incidences. For example, after learning that several others had experienced being pushed aside during a paired patient exam exercise, a White participant described how many of them debriefed about the experience and developed a plan of action.

어느 날 SIM에서 짝을 이루어 프리셉터 없이 환자 병력과 신체검사를 해야 하는 과제를 받은 적이 있었습니다. 그런데 제 친구로부터 파트너가 그 상황을 완전히 장악하고 자신이 어떤 작업도 할 수 없도록 했다는 이야기를 들었습니다. 그때 저는 우리 모두가 남성과 여성으로 나뉘어 있다는 사실을 깨달았습니다. 그 후 다른 친구로부터 같은 이야기를 들었는데, 그 친구 역시 남자 파트너가 전체 만남을 장악하고 있었습니다. 그리고 또 들었어요! 그리고 또 들었습니다! 너무 많은 사람들이 이런 일을 겪었기 때문에 저희는 말 그대로 "SIM의 위대한 스팀롤링"이라는 이름을 붙였을 정도로 심각한 문제였습니다. 언젠가 적어도 8명의 다른 여성들과 함께 테이블에 둘러앉아 우리의 경험에 대해 이야기하던 때가 기억납니다. 그들 중 다수는 언젠가 남성 동료와 비슷한 상황을 겪은 적이 있었습니다. 우리는 이것이 학습 경험에 방해가 된다는 데 동의했습니다. 저는 그 테이블에 앉아 똑똑하고 강인하며 동정심이 많은 여성들을 둘러보았습니다. 저는 물었습니다... 이렇게 해도 괜찮을까요? 그냥 이런 일이 일어나게 놔둘까요? 저는 이 문제를 어떻게 해결할 수 있을지 생각했습니다. 이런 일이 일어났을 때 여성으로서 나서서 무언가를 말해야 한다는 부담감을 갖거나. 아니면 우리 코호트의 남성들에게 그들이 하는 행동이 해롭다는 것을 가르치고 성별과 특권이 그들의 행동에 어떤 영향을 미치는지 인식하도록 돕습니다. 그래서 저는 두 가지를 모두 하면 어떨까 생각했습니다.

There was this one day in SIM where we were paired up and tasked to do a patient history and physical without a preceptor. And I heard from my friend that her partner had totally commandeered the encounter and didn’t allow her to do any of the tasks. It was then that I realized we were all broken into male-female pairs. I then heard this SAME story from another friend, whose male partner took over the entire encounter as well. And then I heard it again! And again! It was such a problem that we literally gave it a name, “The Great Steamrolling of SIM” because it had happened to so many of us. I remember one day, sitting around a table with at least 8 other women talking about our experiences. Many of them had a similar situation occur with a male colleague at some point or another. We agreed that this detracted from the learning experience. Sitting at that table, I looked around at this group of smart, strong, compassionate women. I asked… so are we okay with this? Do we just let this happen? I thought about how we could fix it. Either we put the burden on us as women to step up and say something when this is happening. OR we teach the males in our cohort that what they are doing is harmful and help them become aware of how their gender and privilege influence their behaviors. So I thought, what if we did both?

이 참가자는 많은 반 친구들이 감정적으로 힘들고 괴로운 경험을 겪은 후, 함께 모여 사건에 대해 공유했을 뿐만 아니라 이 사건을 해결하기 위한 계획을 세운 과정을 설명했습니다. 서로의 경험을 공유할 수 있는 커뮤니티를 형성함으로써 참가자들은 자신이 겪은 피해를 인식하는 동시에 자신의 지식과 정보를 검증할 수 있었습니다. 이 참가자는 같은 반 친구들을 똑똑하고 강인하며 자비로운 여성으로 묘사하면서 그들의 임계치와 공유된 경험이 남성 동료들에게 중요한 변화를 촉발할 수 있다는 것을 알았습니다. 또한 이 참가자는 이러한 성찰을 통해 유해한 상호 작용에 대한 자신의 지식이 어떻게 이용되어서는 안 되는지를 확인했습니다. 따라서 SIM의 위대한 스팀롤링을 경험한 참가자들은 존중하는 학습이 무엇인지에 대한 지식을 바탕으로 동료들을 교육함으로써 지속적인 문제를 해결할 방법을 함께 결정했습니다. 간단히 말해, 그들은 자신이 경험한 불공정을 바로잡기 위한 전략을 함께 세웠습니다.

This participant described how after an emotionally charged and distressing experience for many of her classmates, they came together to not only share what had happened but also make a plan to address this incident. By forming a community together where shared experiences could be heard, the participants were able to recognize the harm they had experienced while also validating their own knowledge and intelligence. As this participant described her classmates as smart, strong, compassionate women she knew their critical mass and shared experience could catalyze important change with their men peers. Furthermore, in this reflection, this participant also identifies how her knowledge about the harmful interaction should not be taken advantage of; thus, the participants who experienced The Great Steamrolling of SIM drew from their knowledge about what respectful learning is, and together decided how to address an ongoing problem by educating their peers. Simply, they came together with a strategy to redress the injustice they had experienced.

서로를 고양하는 것은 대인관계와 관찰을 통한 상호작용에서도 나타났습니다. 한 백인 참가자는 자신이 수업 시간에 대답할 때 "이건 틀린 것 같지만..."이라는 말을 계속 사용하는 것을 알아차린 다른 학생으로부터 어떻게 지지를 받았는지 공유했습니다. 그녀는 이렇게 설명했습니다,

Uplifting one another also came in more interpersonal and observational interactions. One White participant shared how she felt supported by another student who noticed her continued use of prefacing her class-time answers with “this is probably wrong but…” She described,

저는 제 자신을 보호하기 위해 답변 앞에 '이것이 옳은지 잘 모르겠습니다'와 같은 문구를 넣었습니다. 하지만 같은 반 친구는 자신도 비슷한 감정을 경험했으며 미래의 여성 의사로서 자신을 과소평가하지 말고 우리 자신과 잠재력을 의심하지 말아야 한다고 말했습니다. 저는 그 친구의 말에 전적으로 동의하며, 제 답변이나 설명에 자기 의심을 앞세우지 않으려고 노력하고 있습니다. 여의대생들도 비슷한 감정을 경험하는 것은 매우 흔한 일이라고 생각하지만, 우리는 이런 이야기를 자주 하지 않습니다. 우리는 자신이 부족해 보일까 봐 약해 보이거나 연약해 보이고 싶지 않아요.

I preceded my answers with statements like ‘I’m not sure if this is right’ to shield myself. But my classmate shared that she had also experienced similar feelings, and that as future female physicians we need to stop selling ourselves short and stop doubting ourselves and our potential. I completely agree with her and I’ve been making an effort to stop prefacing my answers or explanations with self-doubt. I think it's very common for female medical school students to experience similar feelings, however we don't often talk about these things. We don't want to seem weak or vulnerable in fear of being seen as less than.

이 고양의 순간은 나약하고 연약하다는 느낌을 공유한 두 참가자 간의 간단한 대화에서 비롯되었으며, 한 참가자는 다른 참가자에게서 이를 발견했습니다. 두 사람은 함께 이러한 어려움을 극복하고 보다 적극적인 태도를 통해 변화를 일으키거나 보다 명확한 전략적 주체성과 저항을 구현하기 위해 노력했습니다.

This moment of uplift came from a simple conversation between two participants, one who shared the same challenges of feeling weak and vulnerable, and noticing this in another. Together, they worked through these challenges and worked to make changes or enact clearer strategic agency and resistance by being more assertive.

토론

Discussion

이 연구는 여의대생들의 경험에서 인식론적 불공정에 대한 설명을 제시하고 이러한 불공정을 시정하기 위해 학생들이 어떻게 노력했는지에 대한 설명을 제공하는 것을 목표로 했습니다. 인식론적 불공정의 틀을 통해 참가자들이 배웠던 교육 공간과 상호 작용에 대한 배경을 제시하고, 참가자들이 종종 유효한 지식인valid knowers으로서 불신을 받는 과정을 설명했습니다. 참가자들이 이러한 불의에 대응하는 방식은 스스로의 관점을 취하거나 자기 대화를 통해, 그리고 보다 중요한 전략적 저항 행위를 통해 이루어졌습니다. 관점 취하기와 전략적 저항을 통해 학생들의 주체성이 확립되었지만, 이러한 인식론적 부당함과 학생들의 반응은 다층적입니다. 학생들의 주체적 행동은 의료계의 더 큰 거시적 부조리를 조명합니다. 예를 들어, 자신이 왜 의과대학에 속해 있는지 스스로에게 상기시키는 것은 참가자들이 자신의 영향력 영역에 대한 인식과 의과대학에서 경험하는 많은 어려움이 체계적이라는 것을 이해하는 것을 정확히 보여줍니다.

This study aimed to present descriptions of epistemic injustice in the experiences of women medical students and provide accounts about how these students worked to redress these injustices. Through the framework of epistemic injustice, we offered a backdrop for the educative spaces and interactions the participants learned in, describing how participants were often discredited as valid knowers. The ways participants countered these injustices were through both their own perspective taking or self-talk, and more critical acts of strategic resistance. While their agency was enacted through perspective-taking as well as strategic resistance, these epistemic injustices and the students’ reactions are multi-layered. The agentic behavior of the students illuminates the larger macro-injustices of the medical profession. For example, reminding themselves why they belong in medical school pinpoints participants’ awareness of their sphere of influence and their understanding that many of the challenges they experience in medical school are systemic.

참가자들은 의대를 선택한 이유에 대한 자신의 신념을 되새기며 어떤 의사가 될 것인지, 누구를 위해 봉사할 것인지, 왜 의대에 왔는지에 대한 중요한 지식을 가지고 있음을 스스로에게 상기시켰습니다. 이러한 성찰은 의과대학의 지배적이고 남성 중심적인 문화에도 불구하고(또는 때로는 그럼에도 불구하고) 학생들이 자신의 목표를 향해 나아가는 데 도움이 되었습니다. 또한 참가자들은 자신이 의학에 속해 있다는 것을 어떻게 알았는지에 대해 열정적으로 이야기했지만, 미래의 의사로서 자신의 특별한 위치에 대해 순진하지 않았습니다. 참가자들은 또한 자신만의 노하우를 활용하여 처음에는 처방에 의존하던 환자 진료 방식을 조정하고 특정 상황에서는 개선하기도 했습니다. 참가자들은 환자 면담 체크리스트와 같은 암기식 학습 경험을 통해 자신과 환자 간의 관계를 형성하고 공감하며 궁극적으로 배려하는 의사소통을 이끌어내는 방법에 대한 직관에 귀를 기울였습니다. 다시 말하지만, 이러한 일상적인 학습 경험을 통해 참가자들이 나눈 내면의 대화는 그들의 인식론적 지식과 수완을 반영하는 것이었습니다. 그들은 스스로를 신뢰하며 일부 학습 상황에서 자신의 접근 방식이 유효하다는 점을 강조했습니다.

Participants pulled on their own beliefs about why they pursued medicine, reminding themselves that they held important knowledge about what kind of doctor they would become, who they would serve, and why they came to medical school. These were reflexive deliberations and helped them advance in their goals, despite (or at times in spite of) the dominating androcentric culture of medical school. Moreover, while participants spoke passionately about how they knew they belonged in medicine, they were not naïve about their singular position as future physicians. Participants also used their own ways of knowing to tweak and in certain situations, improve a patient encounter that had initially been prescriptive. They used rote learning experiences such as checklists for patient interviews as opportunities to listen to their intuitions about how to relate, empathize, and eventually elicit caring communication between themselves and patients. Again, the inner conversations participants had during these more routine learning experiences were a reflection of their epistemic knowledge and their resourcefulness. They trusted themselves, reinforcing that their approaches in some learning situations were valid.

참가자들은 관점을 취하는 것 외에도 보다 전략적인 이니셔티브를 통해 인식의 불공정을 바로잡았습니다. 참가자들은 서로를 의지하여 공동의 소외를 인식하고 이러한 공동의 소외를 변화시키기 위해 집단적으로 행동할 수 있는 커뮤니티를 구축했습니다. '위대한 심 스팀롤링' 기간 동안 참가자들은 서로 협력하여 자신의 지성을 고양하고 이러한 사례가 종식될 수 있도록 행동했습니다. 마찬가지로, 몇몇 참가자는 부적절한 학문적 독서에 대해 의견을 제시하고 결국 교수진에게 접근하여 이 독서에 대해 논의했습니다. 이러한 행동은 참가자들이 자신을 불법적인 지식인으로 만드는 더 큰 구조에 저항하는 동시에, 특히 교수진이 경청할 뿐만 아니라 동일한 행동action in-kind으로 응답했을 때 합법적인 지식인이 될 수 있도록 하기 위해 사용한 구체적인 전술이었습니다. 인식론적 불공정의 영역에 놓일 때, 이러한 주체적 행동은 더 큰 시스템적 변화가 일어나야만 인식될 수 있습니다. Dotson(2012)은 인식론적 불공정을 해결하기 위해서는 "진정한 차이를 인식하기 위해 일종의 '세계 여행'이 필요하다"고 주장합니다(Dotson, 2012, 34-35쪽). 이러한 종류의 세계 여행은 "대화와 대화를 넘어서는 것"으로, 다른 앎의 방식을 소중히 여길 뿐만 아니라 상황에 따라 다른 앎의 방식이 더 적합할 때를 이해하고 인식하는 데 헌신해야 합니다.

In addition to perspective taking, participants redressed epistemic injustices through more strategic initiatives. They drew on one another to build a community that could both recognize shared marginalization and collectively act to change this shared marginalization. During “The Great SIM Steamrolling” participants worked with one another, both uplifting their own intelligence and then acting to ensure instances such as this would end. Likewise, several participants commented on an inappropriate academic reading, and eventually approached the faculty member to discuss this reading. These actions were concrete tactics participants used to both resist the larger structure that rendered them as illegitimate knowers, while also enabling them as legitimate knowers, particularly when faculty not only listened but responded with action in-kind. When placed within the realm of epistemic injustice, these agentic behaviors may only be recognized once larger systemic change takes place. Dotson (2012) argues that addressing epistemic injustice “demands a kind of ‘world’-traveling…[where] we come to appreciate genuine differences” (Dotson, 2012, pp. 34–35). This kind of world-traveling “extends beyond conversation and dialogue;” it requires commitment to not only valuing other ways of knowing but also to understanding and recognizing when other ways of knowing (and coming to know) are a better fit given the context.

의학교육의 맥락에서 세계 여행은 의학계에서 여성이 다수를 차지한다고 해서 성 고정관념이 뿌리 깊게 박힌 문화가 바뀌지 않는다는 것을 이해하는 것을 의미할 수 있습니다.

- 더 넓은 관점에서 세계 여행은 의과대학의 리더십 역할에서 성별 및 인종적 다양성을 추구하거나 캠퍼스 전체 행사에 더 다양한 초청 연사를 초청하기 위해 의도적으로 노력하는 것을 의미할 수 있습니다.

- 보다 미시적인 관점에서 세계 여행은 학생들과 그들의 배경과 문화에 대해 배우는 시간을 갖거나 학생들이 소외되거나 차별받았던 경험을 이야기할 때 경청하는 것을 의미할 수 있습니다.

세계 여행은 학생들의 지식 구현을 지원하는 학습 환경을 구축하고 학생들이 중요한 지식의 형태를 활용하도록 장려하는 것을 의미할 수 있습니다(Rocha 외., 2022; Wyatt 외., 2018). 이러한 격려란 학생들에게 자신의 경험이 의과대학에서 학습하는 방식을 어떻게 형성하는지 묻거나, 의학에 대한 자신의 역사가 커리큘럼과 상호작용하는 방식에 어떤 영향을 미칠 수 있는지에 대해 생각해 보도록 유도하는 것을 의미합니다. 학생들의 이러한 중요한 지식을 인정하고 육성하는 것은 학생들 자신의 직업적 정체성 개발에 도움이 될 수 있으며, 의사가 되는 개인적, 공동체적 이유를 강화할 수 있습니다. 세계 여행은 의대생이 '백지 상태'가 아니라는 마음가짐으로 교육과 학습에 접근하는 것을 의미하며(퍼거스 외, 2018), 의사로서 자신의 정체성을 배우고 개발하는 방법을 알려주는 풍부한 경험을 가져올 수 있습니다. 교수법을 개선하고자 학생들과 상호작용하고 가르치는 사람들은 인식론적 불공정의 렌즈를 사용하여 의과대학의 보다 공식적인 교육 및 학습에 잠재되어 있거나 무언의 또는 숨겨진 형태의 커리큘럼이 어떻게 내재되어 있는지 조사하는 것을 고려할 수 있습니다(Milem 외., 2012; Nazar 외., 2015).

In the context of medical education, world-traveling can mean understanding that a majority representation of women in medicine will not change a culture deeply embedded with gender stereotypes.

- From a broader standpoint, world-traveling can mean pursuing more gender and racial diversity in leadership roles in medical colleges or making intentional efforts to invite more diverse guest speakers to all-campus events.

- From a more micro-standpoint, world-traveling can mean taking time to learn about students and their backgrounds and cultures or listening when students bring up experiences of being marginalized or discriminated against.

World-traveling can mean establishing learning environments that support students’ embodiment of their knowledge and further encouraging students to draw on their important forms of knowledge (Rocha et al., 2022; Wyatt et al., 2018). This encouragement means asking students how their own experiences may be shaping how they learn material in medical school or inviting students to reflect on ways their history with medicine may be informing how they interact with curriculum. Acknowledging and fostering these important knowledges in students may aid in their own professional identity development and strengthen their personal and communal reasons for becoming doctors. World-traveling can mean approaching teaching and learning with the mindset that medical students are not “blank slates” (Fergus et al., 2018) and bring with them a wealth of experience that inform how they learn and develop their own identities as physicians. Those who interact and teach students seeking to improve their teaching practice might consider engaging the lens of epistemic injustice to examine ways latent and unspoken or hidden forms of curricula are embedded in more formal teaching and learning in medical school (Milem et al., 2012; Nazar et al., 2015).

이 연구에 참여한 여학생들이 보여준 에이전시는 공유된 경험을 해결하거나 개선하기 위해 함께 노력하는 지식인 커뮤니티를 반영합니다. 또한, 이들의 에이전시는 보다 긴밀한 소규모 그룹에 속해 학습 경험을 공유하던 첫 해에 공유되었습니다. 이와 같은 공동 대리인 관행은 수습 기간에는 불가능할 수도 있지만, 이 연구 참여자들의 집단적 대리인(Beier et al., 2016; Lockie, 2004)을 인식하면 커리큘럼의 내용과 설계뿐만 아니라 첫해와 향후 몇 년 동안 동시에 많은 학습자에게 영향을 미칠 수 있는 능력에 대한 관점을 전환하는 데 도움이 됩니다. 이러한 접근 방식은 인식론적 변화를 달성하기 위해서는 관련된 모든 사람의 의도적이고 공동의 노력과 다양한 형태의 인식론적 불공정을 가려낼 수 있는 능력이 필요하다는 Dotson(2012)의 주장에 귀를 기울이는 데 도움이 됩니다. 'the 올바른' 앎의 방식에서 'a 올바른' 앎의 방식으로 사고방식을 전환하는 것은 학생들의 개인적, 직업적 발전에 중요한 이점을 가져올 수 있습니다. 의대생들의 집단적 주체성은 향후 의과대학에서 교육과 학습을 위한 중요한 수단이 될 수 있을 뿐만 아니라, 공유된 공동의 경험 안에서 개인의 경험의 균형을 맞추는 데에도 도움이 될 수 있습니다. 또한, 권력을 가진 사람들이 인식적 불공정의 만연을 제한하기 위해 어떻게 더 큰 구조적 변화와 공동의 대리성을 지원할 수 있는지에 대한 추가적인 연구도 필요합니다. 이 연구에서 살펴본 참여자들의 주체성 사례와 그들의 주체성을 엿보는 것이 제도화될 가능성이 있는 더 큰 공평한 변화를 촉진하는 촉매제가 되기를 바랍니다(Carr et al., 2017; Sugarman & Martin, 2011).

The agency the women students in this study demonstrated reflects a community of knowers working together to address/redress a shared experience. Furthermore, their agency was shared during their first year, a time when they were in more close-knit small groups and shared learning experiences. These same practices of communal agency may not be possible in clerkship years, but recognizing the collective agency (Beier et al., 2016; Lockie, 2004) of the participants in this study helps shift perspectives on ways curriculum is networked not just in its content and design, but also in its ability to impact a large group of learners simultaneously in their first-year and potentially in future years. This approach helps heed Dotson’s (2012) call that achieving epistemic change requires intentional and concerted efforts among all involved, and an ability to sift through multiple forms of epistemic injustice. Shifting mindsets from “the” correct way of knowing to “a” correct way of knowing can have important benefits for students in their own personal and professional development. Collective agency on the part of medical students may be an important avenue for future work on teaching and learning in medical school, as well as balancing individual experiences within a shared communal experience. Additionally further work on understanding how those in power may support larger structural changes and communal agency to limit the pervasiveness of epistemic injustice is also needed. We hope the examples of agency on the part of our participants, and the glimpses of their agency in this study may also catalyze larger equitable change that has the possibility to become institutionalized (Carr et al., 2017; Sugarman & Martin, 2011).

Adv Health Sci Educ Theory Pract. 2023 Aug;28(3):741-758. doi: 10.1007/s10459-022-10183-x. Epub 2022 Nov 17.

Redressing injustices: how women students enact agency in undergraduate medical education

PMID: 36394683

PMCID: PMC9672615

DOI: 10.1007/s10459-022-10183-x

Free PMC article

Abstract

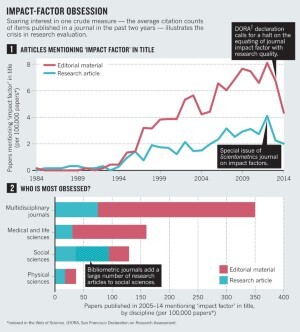

This study presents descriptions of epistemic injustice in the experiences of women medical students and provides accounts about how these students worked to redress these injustices. Epistemic injustice is both the immediate discrediting of an individual's knowledge based on their social identity and the act of persistently ignoring possibilities for other ways of knowing. Using critical narrative interviews and personal reflections over an eight-month period, 22 women students during their first year of medical school described instances when their knowledge and experience was discredited and ignored, then the ways they enacted agency to redress these injustices. Participants described three distinct ways they worked to redress injustices: reclaiming why they belong in medicine, speaking up and calling out the curriculum, and uplifting one another. This study has implications for recognizing medical students as whole individuals with lived histories and experiences and advocates for recognizing medical students' perspectives as valuable sources of knowledge.

Keywords: Agency; Epistemic injustice in medicine; Longitudinal qualitative research; Women medical students.

© 2022. The Author(s), under exclusive licence to Springer Nature B.V.

'Articles (Medical Education) > 인문사회의학(의사학, 의철학 등)' 카테고리의 다른 글

| 의료시스템과학 등장의 역사적 배경: 1910년대부터 2010년대까지의 미국 의료 체계 개혁과 의학교육을 중심으로(Korean J Med Hist, 2023) (0) | 2023.11.16 |

|---|---|

| 의학교육에서 의료인문학의 가치: 의사학을 중심으로 (Korean J Med Hist, 2022) (1) | 2023.11.16 |

| 갭에 마음쓰기: 성찰의 여러 이점에 관한 철학적 분석(Teach Learn Med, 2023) (0) | 2023.08.26 |

| 반대편-질환에-존재함: 의학교육과 임상진료의 현상학적 존재론(Teach Learn Med, 2023) (0) | 2023.08.25 |

| 우리는 돌보기에: 의학교육의 정신에 대한 철학적 탐구(Teach Learn Med, 2022) (0) | 2023.08.25 |