의학교육의 패턴과 패턴어 탐색(Med Educ, 2015)

Exploring patterns and pattern languages of medical education

Rachel H Ellaway1 & Joanna Bates2

소개 Introduction

의학 교육은 많은 다른 환경에서 이루어지며, 다양한 방법과 활동을 사용한다. 비록 지역 관행이 시간이 지남에 따라 다른 방향으로 발전하고 발전하는 경향이 있지만, 의학 교육은 guide and critique practice을 위한 연구에 의해 지원되는 점점 더 글로벌한 사업이다. 이러한 세계화 성장의 핵심 부분은 [일반적인 교육 관행(예: 포트폴리오 및 OSCE)]의 광범위한 채택뿐만 아니라 [공통 활동, 도구 및 관행(예: 문제 기반 학습, 주요 특징 질문 및 시뮬레이터)]의 개발 및 사용이었다.

Medical education takes place in many different settings and it employs a multitude of methods and activities. Although local practices tend to develop and evolve in different directions over time, medical education is an increasingly global undertaking, supported by research to guide and critique practice. A key part of this growing globalisation has been the development and use of common activities, tools and practices (such as problem-based learning, key feature questions and simulators) as well as the widespread adoption of generic educational practices (such as portfolios and OSCEs).

의학 교육 문헌은 이러한 테크닉이 (화학자가 분자를 지칭하는 것과 동일한 방식으로) 일반적이고 잘 정의된 실체인 것처럼 언급하는 경향이 있지만, 실제로는 교육적 실체educational entity는 사례마다 크게 다를 수 있다. 적어도 다른 맥락이 의미와 효과를 재구성하는 경향이 있기 때문이다.1 불행히도 [고려 중인 활동 및 활동이 일어난 상황이나 맥락]보다는 [활동에서 생성된 데이터]를 분석하는 데 더 중점을 둔 많은 연구가 있었다.2

Although the medical education literature tends to refer to these techniques as if they were generic and well-defined entities (in the same way that a chemist might refer to a molecule), in practice educational entities can vary greatly between instances, not least because different contexts tend to reconstruct their meaning and efficacy.1 Unfortunately there has been a great deal of research that has focused more on analysing data generated from activities than on the activity under consideration or the context or contexts within which the activity took place.2

우리가 의학 교육에 사용하는 일반 구조에서 이러한 구조를 사용하는 연구를 평가하거나 합성하려고 할 때마다 이 분산 문제는 복합적이다. 서로 다른 연구에서 고려되는 교육 활동과 기법이 동일한지, 공통점과 어떻게 다른지에 대해서는 거의 고려하지 않는 경우가 많다. 이는 다른 연구자, 구현자 및 리더에게 (비록 숨겨지거나 무시되는 경우가 많지만) 문제를 제시한다. 본 논문에서 우리는 [교육 활동, 시스템 및 맥락을 설명할 때 패턴과 패턴 언어를 보다 신중하게 사용하는 것]이 이러한 단점을 해결하고 의료 교육에 대한 학술활동을 진전시키고 확장할 수 있는 잠재력을 가지고 있다고 주장한다.

This problem of variance in the erstwhile generic constructs we use in medical education is compounded whenever we seek to appraise or synthesise studies employing these constructs. There is often little consideration as to whether the educational activities and techniques considered in different studies are the same, what they have in common and how they differ. This presents problems (although they are often hidden or disregarded) for other researchers, implementers and leaders. We argue in this paper that a more deliberate use of pattern and pattern language in describing educational activities, systems and contexts has the potential to address these shortcomings and to advance and expand scholarship in medical education.

패턴 및 패턴 언어

Patterns and pattern languages

패턴은 [우리 주변의 세계에서 우리가 인지하는 규칙]입니다. 예를 들어, 우리는 문, 신발, 그리고 수저의 패턴을 쉽게 인식합니다. 우리가 마주치는 각각의 문, 신발, 숟가락은 독특한 특성을 가지고 있지만, 그것들이 무엇이고 어떻게 작동하는지 즉시 알 수 있다. 실제로, 우리가 그것의 패턴을 인식하고 그에 대응하는 것은 일상 생활을 정의하는 특성defining characteristics이다. [패턴을 인식하는 것]은 [사물의 어포던스, 사물이 어떻게 작동하는지, 무엇을 할 수 있는지, 그리고 사물의 본질적인 특징들을 인식하는 것]이다. 패턴은 [정규성의 수학적 모델]이 아니라 [인식과 이해를 기반으로 하는 인지 현상]이며, 특히 복잡한 사회 및 기술 시스템에서 다양성과 모호성을 분석할parse 수 있다. 패턴에 대한 인식이 개인에게 특정될 수 있지만, 사회 체계는 부분적으로 패턴에 대한 공유된 이해와 레퍼토리에 의해 정의된다. 사회 시스템에의 참여는 그것의 패턴과 그에 수반되는 가정과 기질을 공유하는 것을 포함한다.

Patterns are regularities we perceive in the world around us. For example, we readily recognise the patterns of doors, shoes and cutlery. Although each door, shoe and spoon we encounter has unique properties, it is immediately apparent what they are and how they work. Indeed, it is a defining characteristic of everyday life that we recognise and respond to its patterns. Recognising a pattern is to perceive its affordances; how it works, what it can do and what its essential features are. A pattern is not a mathematical model of regularity, it is a cognitive phenomenon, based on perception and understanding, which allows us to parse variety and ambiguity, particularly in complex social and technical systems. Although the perception of a pattern may be specific to an individual, social systems are in part defined by a shared understanding and repertoire of patterns. Participation in a social system involves sharing its patterns and the assumptions and dispositions that accompany them.

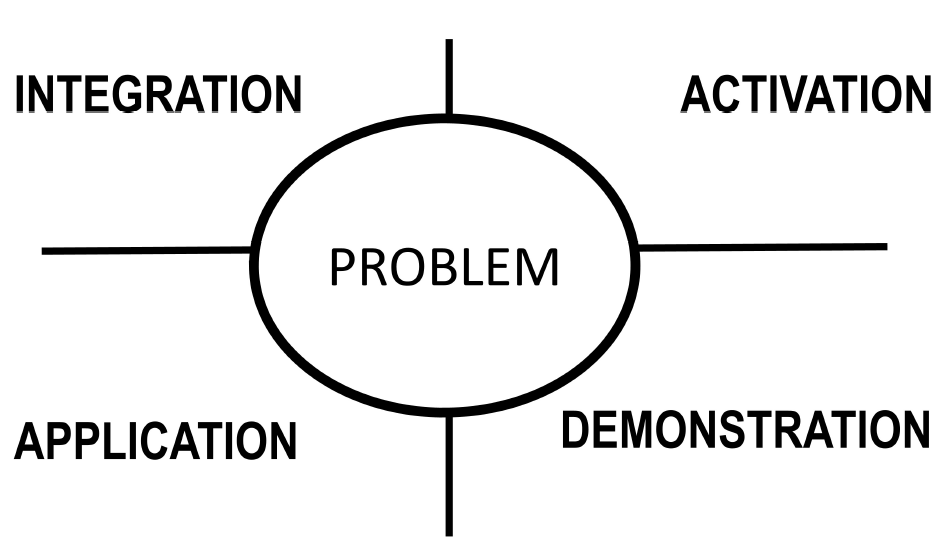

패턴과 패턴 언어의 통합에 대한 이론적 이해는 건축, 경영, 컴퓨터 과학을 포함한 다양한 학문 분야에서 나타났다. 건축이론가 크리스토퍼 알렉산더는 '패턴'을 [특정한 맥락, 그 맥락에서의 문제, 그 문제의 해결책 사이의 관계를 정의하는 규칙]이라고 묘사했다.3

A theoretical understanding of patterns and their aggregation into pattern languages has emerged in different academic disciplines, including architecture,3, 4 management5 and computer science.6 The architectural theorist Christopher Alexander described a ‘pattern’ as a rule that defines the relationships between a particular context, a problem in that context and a solution to that problem.3

예를 들어, 문은 어떻게 할 것인가의 문제에 대한 해결책이다.

- (i) 벽에 구멍을 만들어 우리가 그 동안 지나갈 수 있도록 한다.

- (ii) 사용하지 않을 때 구멍을 닫아 둔다

For instance, a door is a solution to the problem of how to

- (i) create an aperture in a wall through which we can pass while

- (ii) closing the aperture between uses.

패턴은 다른 컨텍스트에서 다른 방식으로 실현됩니다. 자동차 도어, 현관 도어 및 찬장 도어는 모두 문으로 인식 가능하지만, 이러한 도어가 사용되는 컨텍스트는 동일한 기본 패턴에 대해 서로 다른 변형을 요구합니다.

The pattern is realised in different ways in different contexts; car doors, front doors and cupboard doors are all recognisable as doors, but the contexts in which they are used require different variations on the same underlying pattern.

알렉산더의 패턴은 '패턴 언어'의 요소였는데, '패턴 언어'는 사용자들이 건물, 정원, 마을이라고 부르는 3차원 패턴 조합의 무한한 다양성을 만들 수 있게 해주는 시스템입니다. 패턴 언어는 생성적입니다. 그것은 우리에게 배열의 규칙을 알려줄 뿐만 아니라, (규칙을 충족하는 한) 우리가 원하는 만큼 배열을 구성하는 방법을 우리에게 보여준다.'

Patterns for Alexander were elements of a ‘pattern language’, a ‘system which allows its users to create an infinite variety of those three dimensional combinations of patterns which we call buildings, gardens, towns … the pattern language is generative. It not only tells us the rules of arrangement, but shows us how to construct arrangements – as many as we want – which satisfy the rules' 3.

알렉산더에게 [패턴 언어] 다음으로 구성되었다.

- 패턴의 어휘

- 서로 다른 패턴들이 어떻게 관련되는지에 대한 구문

- 패턴이나 패턴의 조합이 어떻게 특정한 문제나 도전에 대한 해결책을 제공할 수 있는지를 설명하는 문법

For Alexander, a pattern language consisted of

- a vocabulary of patterns,

- a syntax of how different patterns related to each other, and

- a grammar that described how a pattern or a combination of patterns could provide a solution to a particular problem or challenge.

예를 들어, 대부분의 건물들은 [벽, 지붕, 바닥, 창문 그리고 문 패턴]을 사용합니다; [어떻게 이 패턴들이 함께 사용될 수 있는지]를 명확하게 보여주는 것이 건물의 [패턴 언어]입니다. 결과적으로 나타나는 [패턴의 조합]은 [그 자체로 패턴]으로 인식될 수 있다; [패턴 언어]는 [패턴들이 어떻게 결합되어 새로운 패턴을 만들 수 있는지]를 설명할 수 있다. 알렉산더는 건축 패턴 언어의 어휘를 형성한 '링 로드', '물로의 접근', '먹는 대기'와 같은 253개의 건축 패턴을 확인했다.7

For instance, most buildings will employ wall, roof, floor, window and door patterns; it is the pattern language for buildings that articulates how these patterns can be used together. The resulting combinations of patterns may themselves be perceived as patterns (such as houses, garages and greenhouses); pattern languages can also describe how patterns can be combined to create new patterns. Alexander identified 253 architectural patterns, such as ‘ring roads’, ‘access to water’ and ‘eating atmosphere’ that formed the vocabulary for a pattern language of architecture.7

패턴 언어에 대한 알렉산더의 생각은 주로 물질적, 미적 문제에 대한 해결책과 관련이 있다. 비록 강의실, 시뮬레이터, 도서관과 같은 [물질 패턴material pattern]을 가지고 있지만, 의학 교육의 학술활동은 주로 [활동과 능력activity and capability]에 초점을 맞추고 있다. 그렇다면 알렉산더의 개념을 의학교육으로 어떻게 해석할 수 있을까요? [조직적 일상 이론Organizational routine theory]은 [활동의 패턴]에 특정한 초점을 두고 있으며, 따라서 그것은 이 문제에 반응하는 데 사용될 수 있는 개념적 도구를 제공한다.

Alexander's ideas of pattern languages are primarily concerned with solutions to material and aesthetic problems. Although it does have material patterns (such as lecture theatres, simulators and libraries), medical education scholarship focuses primarily on activity and capability. How then do we translate Alexander's concepts to medical education? Organisational routine theory has a specific focus on patterns of activity and as such it provides conceptual tools that can be used to respond to this problem.

Nelson과 Winter이 개발한 '루틴'이란 [반복적이고, 상대적으로 안정적이며, 그 루틴이 발생하는 조직을 정의하는, 조직적 맥락 내에서 발생하는 활동의 패턴]이다.5 조직 내의 개인과 그룹은 조직의 활동을 조정하는 데 도움이 될 수 있는 비교적 제한적이고 안정적인 [루틴 레퍼토리]에 의존하는 경향이 있다. 이러한 루틴은 조직 전체에 걸쳐 어느 정도의 행동 안정성을 제공할 수 있고, 관련 의사 결정 노력을 줄일 수 있으며, 조직의 지식organizational knowledge을 저장하는 데 도움을 줄 수 있다. 예를 들어, 일반적인 의료 교육 프로그램의 루틴에는 다음의 반복 활동이 포함된다.

- 강의(강의 및 문제 기반 학습),

- 평가(시험 및 OSCE),

- 행정(위원회 및 정책),

- 물류(스케줄링 및 재무 관리)

Developed from the work of Nelson and Winter,8 a ‘routine’ is a pattern of activity within an organisational context that is recurrent, relatively stable, and defining of the organisation in which it occurs.5 Individuals and groups within organisations tend to depend on a relatively limited and stable repertoire of routines that can help to coordinate the organisation's activities; these routines can afford a degree of stability of behaviour across the organisation, they can reduce the effort associated decision making, and they can help to store organisational knowledge.5 As an example, the routines of a typical medical education programme include the recurring activities of

- teaching (lecturing and problem-based learning),

- assessment (exams and OSCEs),

- administration (committees and policies), and

- logistics (scheduling and financial management).

반복되는 속성을 가진 만큼 루틴도 마찬가지입니다. 루틴의 '일반적인 규칙과 절차는, 맥락을 가로질러 전달될 때 불완전하게 특정화incompletely specified되어야 한다… 루틴의 [전이가능성과 관련된 문제]는 [루틴의 필수적인 것과 주변적인 것]이 무엇인지 명확하지 않을 수 있기 때문에 발생한다.' 루틴의 instance(활동 패턴)는 다음에 의해 정의된다.

- 패턴 프로토타입의 어떤 측면이 존재해야 하는지만큼이나 어떤 측면을 생략할 수 있는지

- 패턴이 그 패턴으로 인식되어지기 위해 어떤 임계 질량critical mass이 존재해야 하는지

As much as they have recurring properties, routines' ‘general rules and procedures have to be incompletely specified when transferred across contexts … problems with the transferability of routines arise because it may not be clear what is essential about the routines and what is peripheral’.5 An instance of a routine (an activity pattern), is defined as much by what aspects of the pattern prototype can be omitted as by what aspects must be present, or what critical mass of elements must be present for the pattern to be recognisable as such.

이것은 비트겐슈타인의 '가족 유사 개념'과 유사하다. 비록 그들 모두가 공유하는 단 하나의 자질도 없을지라도 공통점을 기반으로 사물을 하나로 묶는 온톨로지적 경향을 말한다.

This parallels Wittgenstein's ‘family resemblance concept’9: an ontological tendency to group things together on the basis of what they have in common even though there may not be a single quality that they all share.

의학 교육에서는 이것이 거의 명시적인 개념이 아니지만, 오타와 대학에서 팀 기반 학습(TBL)의 철학적이고 절차적인 요소의 구현에 대한 바르피오 외 연구진들의 연구에 반영되어 있다.10 원래의 요소 중 일부는 TBL 구현에 보존되었고, 일부는 현지 상황에 맞게 변경되었으며, 일부는 생략되었다. 그들은 어떤 모델의 파생상품derivatives 또는 모든 파생상품에, 요소elevment의 일부 또는 전체가 존재하는지(또는 존재해야 하는지)에 대한, 우려보다 모델의 철학과 원칙에 충실하는 것이 더 중요하다고 결론지었다. 이것은 암묵적인 패턴 사고implicit pattern thinking의 한 예이다.

Although this is rarely an explicit concept in medical education, it is reflected in the study by Varpio et al. on the implementation of the philosophical and procedural elements of team-based learning (TBL) at the University of Ottawa.10 Some of the original elements were preserved in their TBL implementation, some were changed to suit local circumstances and others were omitted. They concluded that it was more important to be true to the philosophy and principles of the model (or, as we would argue, the pattern) than to be concerned over whether some or all of the elements were (or should be) present in any or all of its derivatives. This is an example of implicit pattern thinking.

우리는 의학교육에 많은 패턴이 있고, 패턴에 기초한 사고와 실천의 많은 예가 있다고 제안하지만, 그런 방식으로 인식considered되는 경우는 거의 없다. 이러한 패턴은 여러 가지 방법으로 의료 교육 분야를 정의하는 [공유 인식 레퍼토리]를 형성한다. (교과서, 지침서 및 보고서와 같은) 의학교육 전체를 고려하는 저작들은, 일반적으로 의학교육을 패턴과 루틴의 교차 시스템으로 모델링하기 보다는, 각각의 방법과 접근 방식으로 고립시킨다. 이 환원주의적 접근 방식은 패턴과 루틴이 교차하는 방식, 서로 구축되거나 결합될 수 있는 방식을 보는 우리의 능력을 제한한다. 또한 [패턴과 루틴에 기초한 의학 교육의 학술활동]은 [개념 간의 차이에만 초점을 맞추는 분류학적 관점]보다 더 포괄적이고 관계적일 가능성이 있다.

We suggest that there are many patterns in medical education and many examples of pattern-based thinking and practice, even though they are rarely considered as such. These patterns form a shared perceived repertoire (including but not limited to its routines) that in many ways defines the field of medical education. Works that consider medical education as a whole (such as textbooks, guides and reports) generally isolate different methods and approaches, rather than modelling medical education as a system of intersecting patterns and routines. This reductionist approach limits our ability to look at how patterns and routines intersect, build on each other, or can be combined. We also argue that a scholarship of medical education based on patterns and routines has the potential to be more inclusive and relational than taxonomic perspectives that focus only on the differences between concepts.

우리는 네 가지 명제를 중심으로 우리의 주장을 구성했다:

- 의학 교육의 패턴은 주로 학문적 의사소통을 통해 확립된다;

- 현대 의학 교육에는 패턴 사고의 상당한 암묵적 활용(활동 패턴으로서 루틴 포함)이 있다;

- 패턴 사고를 더 의도적으로 채택하지 못하는 것은 의학교육 학술활동(그리고 그것에 의해 형성되는 관행)에게 해롭다;

- 의학교육에서 패턴과 패턴 언어의 의도적인 사용은 학자와 실무자 모두에게 매우 생성적이고 자유로울 수 있는 잠재력을 가지고 있다.

We have structured our argument around four propositions:

- that patterns in medical education are primarily established through scholarly communication;

- that there is a significant tacit use of pattern thinking (including routines as activity patterns) in contemporary medical education;

- that the failure to employ pattern thinking more deliberately has been to the detriment of medical education scholarship (and the practices that are shaped by it); and

- that the deliberate use of patterns and pattern languages in medical education has the potential to be highly generative and liberating to scholars and practitioners alike.

패턴 사고 및 의료 교육

Pattern thinking and medical education

[패턴]은 [주요 요소]와 [그 요소들이 각기 다른 맥락에서 실현되는 방법]에 의해 정의됩니다. 이것은 각각의 개념이 구별되고 그것의 상위 개념의 관점에서 조직되는 [분류학적 세계관]과는 다르다. 우리는 문제 기반 학습(PBL)을 구문 분석하여 이를 설명할 수 있다.

- [분류학적 관점]에서 PBL은 소규모 그룹 학습(클래스 크기별로 조직됨) 또는 사례 기반 학습(관련 작업에 의해 조직됨) 또는 촉진 또는 독립 연구와 같은 다른 주요 특성의 하위 집합이다. 각 관점은 다른 관점과 함께 한정자로 정의되는 하나의 주요 특성에 기초한다.

- [패턴 관점]에서 PBL은 작은 그룹, 문제, 촉진, 독립 연구 등의 교차 패턴을 포함한다. 돌맨스 등은 PBL 내에서 [구성적 학습], [자기 주도적 학습], [협업 학습] 및 [상황 학습]을 포함한 다른 패턴 유사 구조를 식별했고, 슈미트 등은 [유연한 비계]와 [학습 조절]을 목록에 추가했다.

Patterns are defined by their key elements and the ways they are realised in different contexts. This is different from a taxonomic worldview where each concept is distinct and organised in terms of its parent concepts. We can illustrate this by parsing problem-based learning (PBL).

- From a taxonomic point of view PBL is a subset of small-group learning (organised by class size) or of case-based learning (organised by the tasks involved), or of other primary characteristics such as facilitation or independent research. Each perspective is based on one primary defining characteristic with the others as qualifiers.

- From a pattern perspective, PBL involves intersecting patterns of small groups, problems, facilitation, independent research and so on. Dolmans et al.11 identified other pattern-like constructs within PBL, including constructive learning, self-directed learning, collaborative learning and contextual learning, while Schmidt et al.12 added flexible scaffolding and regulation of learning to the list.

패턴 관점에서 PBL은 더 작은 패턴(작은 그룹, 문제 해결, 촉진, 독립적 연구)의 결합으로, 각각의 패턴은 다른 활동 패턴(시뮬레이션에서 작은 그룹, 의사소통 기술 훈련 등에서 '촉진')에서 발생할 수 있으며, 다른 조합으로 재구성하여 새로운 패턴을 만들 수 있다.

From a pattern perspective, PBL is a confluence of smaller patterns (small group, problem-solving, facilitated, independent research), each of which may occur in other activity patterns (‘small group’ in simulation, ‘facilitated’ in communication skills training, etc.) and can be reassembled in other combinations to create new patterns.13

어떤 하나의 패턴이 다른 패턴보다 우선primacy하지 않고, 각각의 PBL이 반드시 모든 패턴측면을 포함해야 하는 것은 아니지만, PBL의 한 가지 형태라고 할 만한 패턴의 instance이다. [분류학적 정의]는 차이와 구별을 강조하는 반면, [패턴 정의]는 각기 다른 패턴들 또는 패턴의 측면들을 결합함으로써 혼합hybrid될 수 있다. 예를 들어,

- 다중 미니 면접(MMI)은 거의 틀림없이 입학 면접과 OSCE의 hybrid of facets이고,

- 팀 기반 학습은 강의와 PBL에서 온 facets의 혼합이다.

패턴 사고는 활동 설계에 대한 이러한 암묵적 접근법을 더욱 명백하게 만들 것이다.

No pattern has primacy over any other and different instances of PBL in medical education may not necessarily involve all of its pattern's facets yet still clearly be an instance of that pattern by being considered to be a form of PBL. Whereas taxonomic definitions stress differences and distinctiveness, pattern definitions can be hybridised by combining patterns or facets from other patterns. For example, the multiple mini interview (MMI) is arguably a hybrid of facets from admissions interviews and OSCEs, and team-based learning hybridises facets from lecturing and PBL. Pattern thinking would make this implicit approach to activity design more explicit.

의학교육의 패턴은 정의상 그 분야에 관련된 사람들이 인식하고 공유하는 것이다. 실제로, 이러한 패턴을 인식하고 사용하는 것은 의학교육의 doxa를 정의내리는 측면 중 하나일 것이다. 패턴을 공유하려면 이름을 붙이고, 기술하고, 토론하고 적용해야 합니다. 의학교육에서 이 중 많은 부분이 논문, 발표 및 계획과 같은 학문적 행위(반드시 반드시 그렇지는 않다)에서 발생한다. 보다 구체적으로, 이러한 [학술적 커뮤니케이션에서 설정된 이상적인 형태]를 [새로운 교육적 맥락으로 변환]하려면 [패턴 사고]가 필요하며, 그 중 일부는 지역적으로 실용적이거나 바람직한 것에 대응하여 [수정되거나 생략]된다. 1, 10

The patterns of medical education are by definition perceived and shared by those involved in the field. Indeed, recognising and using these patterns is arguably one of the defining aspects of the doxa of medical education. For a pattern to be shared it needs to be named, described, discussed and applied. In medical education much of this is generated from (but not necessarily by) scholarly acts such as papers, presentations and plans. More specifically, translating the ideal forms set out in these scholarly communications into new educational contexts requires pattern thinking as the ideal forms are necessarily deconstructed to identify their key features, some of which are amended or omitted in response to what is locally practical or desirable.1, 10

따라서 패턴 사고는 본질적으로 적응적이고 번역적인 접근법이다. 새로운 맥락에서 새로운 종류의 활동이나 방법(또는 기존 형태의 새로운 변화)을 적용하는 것은 일정정도의 패턴 사고를 필요로 한다. 이러한 패턴 변이variation이 공유되고 논의되면, 가능한 변이variation이 탐색되며 패턴이 두꺼워지고, 패턴이 실현되는 많은 컨텍스트에 맞게 주요 기능을 적용할 수 있게 된다. 그것이 의학 교육 관행의 필수적인 부분임에도 불구하고, 이러한 현상은 거의 눈에 띄거나 인식되지 않기 때문에, Varpio 등에 의해 실존적 위기가 확인되었다. 우리는 패턴에 따른 다양한 실천 현실보다는 문헌에 제시된 [이상적 형태에 대한 패러다임적인 집착] 때문이라고 본다.

Pattern thinking is therefore an intrinsically adaptive and translational approach. Applying a new kind of activity or method (or a new variation of an existing form) in a new context requires a degree of pattern thinking. As these pattern variations are also shared and discussed, the pattern thickens as possible variations are explored, and its key features become malleable to suit the many contexts within which the pattern is realised. Despite its being an essential part of medical education practice, this phenomenon is rarely noticed or acknowledged, hence the existential crisis identified by Varpio et al.10 This is, we argue, partly due to a paradigmatic adherence to ideal forms set out in the literature rather than the pattern-variant realities of practice.

우리가 PBL 또는 임상교육을 [극도로 정밀해지는 이상적인 실행과 결과의 집합을 정의]하기 위해 결합combine하여 연구할 수 있다는 믿음은, [맥락의 가변성과 그것을 처리하는 데 필요한 패턴 사고를 수용하지 않기에] 본질적으로 제한적이다. Becker가 관찰한 바와 같이 '[특정 루틴이 여러 맥락을 가로지른 전이가능성의 한계]에 따르는 중요한 함의는 [보편적 모범 사례]와 같은 것은 존재할 수 없다는 것이다. 오로지 ["국지적" 최고의 솔루션]만이 가능하다'

The belief that we can research PBL or clinical teaching in ways that combine to define an increasingly precise set of ideal practices and outcomes is intrinsically limited without accommodating the variability of context and the pattern thinking required to deal with it. As Becker observes: ‘an importance consequence of the limits to the transferability of routines across contexts is that no such thing as a universal best practice can possibly exist. There can only be “local” best solutions’.5

이 문제는 효능 대 효과 논쟁에서도 반영됩니다. '효능efficacy은 [최적의 전달 조건]에서의 프로그램이나 정책의 유익한 효과를 의미하며, 효과effeictivness은 [보다 실제적인 조건]에서의 프로그램이나 정책의 효과를 의미한다.' 두 가지 접근 방식 모두 패턴 사고를 채택할 수 있지만, 효과 연구는 패턴 사고의 사용에 더 의존적이고 더 다루기 쉽다고 우리는 주장한다. 패턴 사고가 없는 상황에서, 동일한 구조를 investigate한 것으로 추정되는 연구를 연결하는 것은 기껏해야 의문스러운 작업일 뿐이다.

This issue is also reflected in the efficacy versus effectiveness debate where ‘efficacy refers to the beneficial effects of a programme or policy under optimal conditions of delivery [and] effectiveness refers to effects of a programme or policy under more real-world conditions’.14 Although both approaches can employ pattern thinking, effectiveness research is more dependent on and, we argue, more tractable with the use of pattern thinking. In the absence of pattern thinking, connecting studies that are supposedly investigating the same construct is questionable at best.

또한, [체계적인 검토 및 메타 분석]과 같은 대규모 합성 활동은, [서로 다른 연구의 활동이 동일한 패턴이나 패턴을 구현하거나 구현하지 않는 방법을 일관성 있게 평가하고 모델링할 수단]이 없는 경우 취약해질 수 밖에 없다. 우리가 어떻게 [[패턴의 의도적인 사용]이라는 측면에서 의학 교육을 재평가할 것인가]라는 질문은 다시 [패턴 언어]를 고려하게 만든다.

Moreover, large-scale synthesis activities such as systematic reviews and meta-analyses are weakened without the means to consistently appraise and model how activities in different studies do or do not embody the same pattern or patterns. How we reappraise medical education in terms of a deliberate use of patterns brings us back to a consideration of pattern languages.

알렉산더에게 패턴 언어는 다음의 세 가지로 구성된다.

- 패턴의 어휘,

- 다른 패턴의 상호작용의 구문,

- 패턴 또는 패턴의 조합이 특정 문제나 과제에 대한 해결책을 제공할 수 있는 방법을 설명하는 문법

For Alexander a pattern language consists of

- a vocabulary of patterns,

- a syntax of how different patterns interact, and

- a grammar that describes how a pattern or a combination of patterns can provide a solution to a particular problem or challenge.

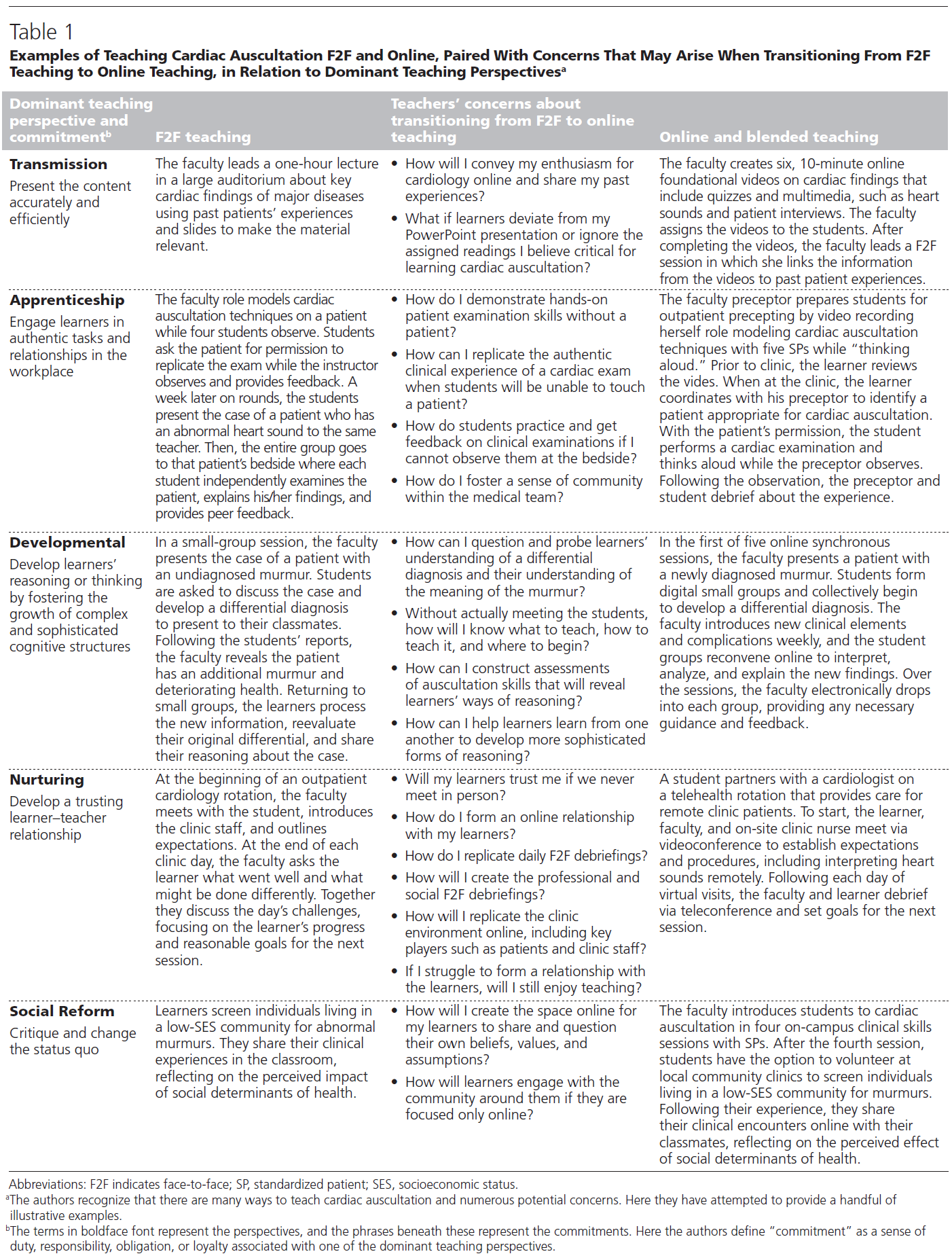

패턴 언어의 개발은 비록 한 분야 내에서 유도적이고 새로운 활동에 의해 알려졌지만, 실제와 학문에 사용되는 것에 대한 검토를 통해 더 체계적으로 접근할 수 있다. 이 주장을 설명하기 위해 우리는 4개의 현대 의학 교육 교과서 15-18장의 의학교육의 반복되는 패턴을 조사했다.

The development of a pattern language, although informed by the inductive and emergent activities within a field, can also be approached more methodically through a review of what is used in practice and scholarship. To illustrate this assertion we examined the chapter titles of four contemporary medical education textbooks15-18 for recurring patterns in medical education.

교과서 챕터 제목을 단일 스프레드시트에 입력하고 주제와 제목을 비교했으며, 유사하거나 동일한 주제를 병합했으며, 유사한 패턴이 사용된 횟수를 계산했다(표 1 참조). 우리는 새로운 패턴이 확인되지 않을 때까지 이 과정을 반복했다. 이를 통해 우리는 이러한 패턴이 활동을 위한 상위 수준의 패턴과 차례로 관련된다는 점에 주목했다.

- 참가자가 수행하는 작업(문제 기반, 피드백 및 시뮬레이션),

- 참가자가 할 때 수행하는 역할(환자, 교사, 학생) 및

- 활동 패턴이 실현되는 상황(사회, 공동체 및 소그룹)

We entered the chapter titles of the textbooks into a single spreadsheet, we compared topics and titles, we merged similar or identical topics, and we counted the number of times similar patterns were used (see Table 1). We repeated this process until no new patterns were identified. In doing so we noted that these patterns were in turn associable with higher-level patterns for activity:

- what participants do (problem-based, feedback and simulation),

- the roles that participants play when they are doing it (patient, teacher and student), and

- the contexts in which the activity pattern is realised (bedside, community and small-group).

이 과정은 의학 교육 패턴 언어에 대한 흥미로운 후보 패턴 세트를 생성했지만, 그러한 언어에 포함될 수 있는 모든 패턴을 식별하지는 못했다. 예를 들어 통합, 위임가능성, 임상실습, 디브리핑, 역량 등과 같은 의료 교육에서 일반적으로 사용되는 패턴(적어도 의료 교육자로서의 경험에서)은 발견되지 않았다.

Although this process generated an interesting set of candidate patterns for a medical education pattern language, it did not identify all of the patterns that might be included in such a language. For instance, commonly used patterns in medical education (at least in our experiences as medical educators), such as integration, entrustability, clerkship, debriefing and competency, were not found.

그런 다음 패턴 언어에 대한 알렉산더의 개념을 탐구하기 위해 설명적illustrative 분석에 착수했다.3

- 어휘(구성 요소 패턴),

- 문법(구성 요소 패턴이 문제 또는 물질적 이득에 대한 해결책을 제공하는 방법) 및

- 구문(패턴이 더 넓고 추상적인 패턴과 어떻게 관련되는지)

We then undertook an illustrative analysis to explore Alexander's concepts of

- a pattern language's vocabulary (component patterns),

- its grammar (how the component pattern provides a solution to a problem or a material benefit) and

- its syntax (how a pattern is related to wider and more abstract patterns).3

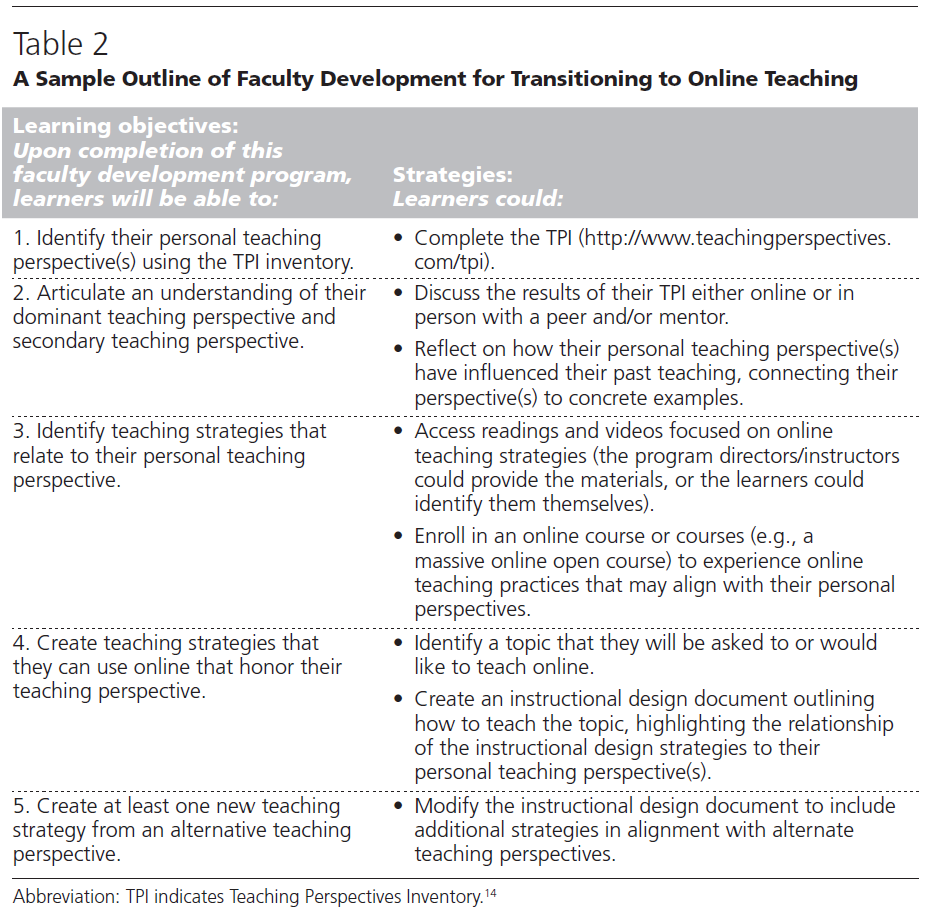

우리는 종적 통합 임상실습 (LIC)의 예를 들었고 기존의 연구 결과와 해석을 바탕으로 어휘, 문법 및 구문 요소를 식별했다(표 2 참조). 그렇게 함으로써 우리는 이러한 개념을 독립적 요소가 아닌 상호 연결된 패턴 언어의 일부로 이해하려고 할 뿐만 아니라 기본 메커니즘이 무엇인지 다시 강조해야 했다.

We took the example of the longitudinal integrated clerkship (LIC) and identified elements of vocabulary, grammar and syntax based on existing research findings and interpretations19-23 (see Table 2). In doing so we had to reappraise what the underlying mechanisms were as well as seeking to understand these concepts as part of an interconnected pattern language rather than as standalone elements.

고찰

Discussion

의학교육을 패턴의 관점에서 바라보는 것은 여러 가지 시사점을 준다. 무엇보다도, 그것은 우리가 사용하는 개념과 그것들을 사용하는 방법의 [번잡함]을 묘사하고 존중한다. 패턴 사고는 우리가 학습 활동, 방법 및 시스템을 구별되고 고정된distinct and fixed 레퍼토리로 보는 것에서 해방시킴으로써 분야로서의 의학 교육에 도움이 될 수 있다. 예를 들어, [문제 기반 학습]과 [공동체 지향 학습]은 문제 해결과 독립적 학습의 패턴을 공유할 수 있지만, 그룹의 크기나 학습이 촉진되는 방식과 같은 다른 패턴에서는 다르다. 패턴 관점에서 그들의 공통점은 명백해지고, 따라서 교육 혁신과 탐구의 재료로 접근 가능하다. 패턴 사고는 우리의 개념과 루틴을 보는 새로운 방법을 제공합니다. 예를 들어, 그들의 경계가 어디에 있는지, 그리고 시간이 지남에 따라 어떻게 발전하고 변화하는지와 같은.24

Conceiving medical education in terms of patterns has a number of implications for the field. First and foremost, it illustrates and respects the fuzziness of the concepts we use and the ways in which we use them. Pattern thinking can help medical education as a field by freeing us from seeing learning activities, methods and systems as a distinct and fixed repertoire. For instance, problem-based learning and community-oriented learning may share patterns of problem solving and independent study but differ in other patterns such as the size of the group or the ways in which learning is facilitated. From a pattern perspective their commonalities become apparent, and as such they become accessible as ingredients for educational innovation and exploration. Pattern thinking affords new ways of looking at our concepts and routines, such as where their boundaries are and how they develop and change over time.24

패턴 사고는 의학교육의 많은 실천, 모델 및 접근방식을 유연한 레퍼토리로 자리하게 한다situate. 이는 새로운 또는 새로운 도전과 요구에 대응하여 새로운 형태와 실천방식을 생성하는 데 사용할 수 있는 [적응적adapatable 팔레트]이다. 따라서 의학교육을 위한 패턴 언어는 의학교육 학술활동 전반에 통합적이고 전체적인 틀로 작용할 수 있다. 패턴과 패턴 언어 기법은 [우리가 의학 교육의 규칙성]과 [그러한 규칙성이 실현되는 방법의 다양성]을 체계적으로 식별하고 표현하도록 도와줌]으로써, 우리가 하는 일의 책무성을 개선할 수 있는 잠재력을 가지고 있다. 패턴과 패턴 언어는,

- 체계적인 검토에서 등가성의 많은 난제들을 해결할 방법을 제공하며,

- (용어, 기관, 학자가 달라져도) 시간에 따라 의학 교육 관행이 어떻게 변화하는지

- 수사학적 또는 담화 분석에 특정 패턴이 어떻게 사용되는지

- (패러다임으로서) 패턴이 의학교육의 실무와 연구가 지속적으로 진화하는 방식을 어떻게 지시하고 형성하는지

Pattern thinking situates the many practices, models and approaches of medical education as a flexible repertoire, an adaptable palette that can be used to generate new forms and practices in response to new or emerging challenges and needs. Pattern languages for medical education can therefore serve as a unifying and holistic frame for medical education scholarship as a whole. Pattern and pattern language techniques have the potential to improve the accountability of what we do by helping us to systematically identify and express the regularities of medical education and the variety in how those regularities are realised.

- They provide a way to address many of the challenges of equivalence in systematic reviews,25 and

- they could also be used to track how medical education practice changes over time (even when terminology, institutions, and scholars come and go),

- how certain patterns are used in rhetorical or discourse analyses, and

- how pattern (as paradigm) directs and shapes the way medical education practice and research continue to evolve.

패턴은 활동에서 나타납니다. 그 반대 순서가 아니다. 이것은 아이디어와 개념이, 단순히 세상을 묘사하는 것이 아니라, 새로운 사고 방식과 행동 방식을 만들어내는 다소 [델루지아적인 관점]입니다. 따라서 패턴 사고는 의료 교육 및 그 주변의 더 높은 수준의 혁신, 중요한 인식 및 시설을 활성화하고 지원할 수 있는 잠재력을 가지고 있다. 패턴 사고는 또한 일정 정도의 [모호성을 수반하는 사고]에 정당성을 부여하고, 이를 바탕으로 우리가 (종단실습, 지역사회 기반 프로그램, 이행, 멘토링과 같은) 엄격한 정의나 결과에 굴복하기보다는, 여러 활동을 새롭게 볼 수 있게 한다.

Patterns emerge from activity; they don't precede it. This is a somewhat Deleuzian perspective where ideas and concepts generate new ways of thinking and acting rather than simply describing the world. Pattern thinking therefore has the potential to energise and support greater levels of innovation, critical awareness and facility in and around medical education. Pattern thinking also confers legitimacy on thinking that includes a degree of ambiguity, which in turn allows us to look afresh at activities that don't yield to tight definitions or outcomes, such as longitudinal placements, community-based programmes, transitions and mentorship.

패턴의 기본 메커니즘에 대한 분석은 패턴 내에서 그리고 패턴 간에 새로운 연구 기회를 열 수 있는 잠재력을 가지고 있다. 의학교육 장학금에서 패턴 사고의 사용을 제안함으로써, 우리는 다양한 형태의 탐구와의 개념적 연관성을 인정해야 한다. 우리가 주장해 온 것처럼, 패턴은 딱딱한 정의에 관한 것이 아니다; 패턴은 [우리의 관행]과 [그 관행이 일어나는 상황에 대한 공유된 인식]에 관한 것이다. 따라서 패턴 사고는 의학교육에서 점차 증가하는 현실주의 방법과 잘 부합하며, 의학교육의 패턴과 규칙성에 대한 탐구를 통하여 의학교육 실천 및 연구의 여러 방법을 [현실주의 접근법]과 연결시켜준다.

An analysis of a pattern's underlying mechanisms (which are themselves patterns) has the potential to open up new research opportunities, both within a pattern and across patterns. In proposing the use of pattern thinking in medical education scholarship we should acknowledge the conceptual links with other forms of inquiry. As we have argued, patterns are not about hard definitions; they are about shared recognition of regularities in our practices and the contexts in which they take place. Pattern concepts, notably demi-regularities in the form of context-mechanism-outcome triads, are central to concepts of realist inquiry.26 Pattern thinking therefore aligns well with the growing use of realist methods in medical education practice and research, as well as connecting other methods with realist approaches through the exploration of patterns and regularities in medical education.

이것은 단순히 언어학이나 기호학의 문제인가? 언어는 학문적 담론의 주요 매체이고 따라서 이것이 우리의 주된 관심사였다. 그러나, 우리는 [언어란 의미적semiotic 표현을 위한 하나의 매개체일 뿐이며, 의학교육에는 패턴을 반영하고 패턴 사고에 굴복할 수 있는 잠재력이 있는 많은 다른 매체(건축, 시각, 계기, 행동 등)가 있다]는 야콥슨의 주장을 인식하고 동의한다.

Is this simply a matter of linguistics or semiotics? Language is the primary medium of scholarly discourse and this has therefore been our main focus. However, we recognise and agree with Jakobson's assertion that language is only one medium for semiotic expression27 and there are many other media (architectural, visual, instrumental, behavioural, etc.) in medical education that also reflect patterns and have the potential to yield to pattern thinking.

의학교육을 위한 하나 이상의 패턴 언어를 의도적으로 개발하고 사용하는 것에도 한계가 있다. 패턴에 대해 체계적으로 작업하는 데 필요한 노력은 물론, 패턴 언어가 얼마나 안정적이고 현재적이며 광범위하게 적용될 수 있는지에 대한 도전과 같은, 우리가 이미 설명한 실용적이고 개념적인 문제가 있다. 패턴 사고 역시 [우리가 서로 다른 패턴에 대한 인식을 공유하는 정도]에 의해 제한된다. 패턴은 문화적인 측면뿐만 아니라 패러다임적인 측면도 있을 수 있으며, 본질적으로 사회적으로 구성되며, 시간이 지남에 따라 그리고 맥락 사이에서 변화할 수 있다. 비록 모든 개념적 프레임워크가 대체로 다 그렇긴 하지만, 패턴 언어를 개발하고 사용하는 것 역시 우리의 생각을 제약시킬 수도 있고, 우리의 편견을 재현하거나 증폭시킬 수도 있으며, 또는 특정 의제를 다른 의제보다 더 진전advance시킬 가능성이 있다.

The deliberate development and use of one or more pattern languages for medical education also has its limitations. There are the practical and conceptual challenges we have already described, not least the effort needed to methodically work with patterns, and the challenge of how stable, current and widely applicable a pattern language can be. Pattern thinking is also limited by the extent to which we have a shared perception of different patterns. Patterns may be paradigmatic as well as cultural, and as such intrinsically socially constructed and subject to change over time and between contexts. Although this is arguably true of any conceptual framework, there is the potential for the development and use of a pattern language to act as a constraint on our thinking, to reproduce or even amplify our biases, or to advance certain agendas over others.

패턴을 절대적인 것이 아니라, [잠정적이고 유동적인 것으로 두는 것]은 이러한 문제를 해결하는 데 도움이 될 수 있지만, 패턴의 사용이 의학 교육에 가져올 수 있는 정밀도를 제한하기도 한다. 그러나 이러한 한계는 패턴 사고의 본질적인 한계라기보다는 의학 교육에 내재되어 있을 수 있다. 의학 교육을 위한 보다 명시적인 패턴 언어를 개발할 때, 우리는 [언어와 문화를 공유하는 지역] 간 용어와 개념의 변화뿐만 아니라, [언어와 문화가 상당히 다른 지역]으로부터 유입되는 variance을 염두에 두어야 한다. 실제로, 패턴 사고는 이러한 variance를 보다 명백하고 다루기 쉽게 만드는 데 도움이 될 수 있습니다. 우리는 의학 교육의 단 하나의 고정된 패턴 언어에 동의할 수 없을지도 모른다. 실제로 우리는 많은 [언어와 방언dialects]들이 있다는 것을 발견할지도 모른다. 의학교육의 맥락에서 패턴과 패턴 언어를 탐구하는 데는 분명히 해야 할 일이 많다.

Positioning patterns as provisional and fluid rather than as absolutes can help to address this, although it also limits the precision that the use of patterns can bring to medical education. These limits may, however, be intrinsic to medical education rather than an essential limitation of pattern thinking. In developing a more explicit pattern language for medical education we should be mindful of the variation in terms and concepts between regions that share the same (or similar) language and culture as well as the variances that flow from quite different languages and cultures. Indeed, pattern thinking may help to make these variances more explicit and tractable. We may not be able to agree on a single fixed pattern language of medical education, indeed we may find that there are many languages and dialects. There is clearly much to be done in exploring pattern and pattern language in the context of medical education.

결론

Conclusions

Regehr는 최근 의학 교육 연구에서 '어떤 것이 효과가 있는가'를 항상 증명하고 가장 단순한 일반 가능한 개념을 사용하여 이러한 증명들을 추구한 지배적인 사고에 도전했다. 그는 '교육의 과학은 [일반적인 문제]에 대한 [더 나은 일반 가능한 해결책]을 만들고 공유하는 것이 아니다. 그보다는 우리가 직면한 문제에 대해 더 나은 사고 방식을 만들고 공유하는 것이다'라고 이야기했다. 이 과제에 대한 우리의 해결책은 의학교육에서 패턴과 패턴 언어를 신중하고 체계적으로 사용하는 것이다.

Regehr recently challenged the dominant thinking in medical education research that sought always to prove whether something ‘works’ and that used the simplest most generalisable concepts in its pursuit of these proofs, suggesting instead that: ‘the science of education is not about creating and sharing better generalisable solutions to common problems, but about creating and sharing better ways of thinking about the problems we face’.28 Our solution to this challenge is the deliberate and systematic use of patterns and pattern languages in medical education.

Med Educ. 2015 Dec;49(12):1189-96.

doi: 10.1111/medu.12836.

Exploring patterns and pattern languages of medical education

Rachel H Ellaway 1, Joanna Bates 2

Affiliations collapse

Affiliations

- 1University of Calgary, Community Health Sciences, Calgary, Alberta, Canada.

- 2University of British Columbia, Faculty of Medicine, Vancouver, British Columbia, Canada.

- PMID: 26611184

- DOI: 10.1111/medu.12836Abstract

- Context: The practices and concepts of medical education are often treated as global constants even though they can take many forms depending on the contexts in which they are realised. This represents challenges in presenting and appraising medical education research, as well as in translating practices and concepts between different contexts. This paper explores the problem and seeks to respond to its challenges.Results: The authors argue that the deliberate and systematic use of patterns and pattern languages in describing medical educational activities, systems and contexts can help us to make sense of the world, and the pattern languages of medical education have the potential to advance understanding and scholarship in medical education, to drive innovation and to enable critical engagement with many of the underlying issues in this field.

- Methods: This paper explores the application of architectural theorist Christopher Alexander's work on patterns and pattern languages to medical education. The authors review the underlying concepts of patterns and pattern language, they consider the development of pattern languages in medical education, they suggest possible applications of pattern languages for medical education and they discuss the implications of such use. Examples are drawn from across the field of medical education.

- © 2015 John Wiley & Sons Ltd.

'Articles (Medical Education) > 교수법 (소그룹, TBL, PBL 등)' 카테고리의 다른 글

| 효과적인 강의 만들고 발표하기 (J Contin Educ Health Prof, 2020) (0) | 2021.08.05 |

|---|---|

| 동기적 & 비동기적 이러닝(EDUCAUSE Quarterly, 2008) (0) | 2021.07.28 |

| 이러닝 - 새장 속의 새 또는 날아오르는 독수리? (Med Teach, 2008) (0) | 2021.05.21 |

| 효과적인 강의: 실천을 이론으로 - 내러티브 리뷰(Med Sci Educ, 2021) (0) | 2021.05.21 |

| 교육의 죽지 않는 고정관념들 (Educational Leadership, 2021) (0) | 2021.05.13 |