온라인 의학교육에서 윤리적으로 가르치기: AMEE Guide No. 146 (Med Teach, 2022)

AMEE guide to ethical teaching in online medical education: AMEE Guide No. 146

Ken Mastersa , David Taylorb , Teresa Lodac and Anne Herrmann-Wernerd

서론

Introduction

COVID-19 및 긴급 원격 교육

Covid-19 and emergency remote teaching

2020년 코로나19 범유행으로 의료 교육이 대면 교수 및 학습에서 온라인 교수 및 학습으로 전례 없는 전환으로 이어졌다. 비록 의료 교육에서의 온라인 교수와 학습이 e-러닝의 형태로 수십 년 동안 존재했지만, 그것은 대개 세부적인 준비와 관리, 작은 단계, 파일럿 그리고 신중하게 통제된 성장으로 선행되어 왔다. 2020년 시프트는 달랐고 비상 원격 교육(ERT)으로 가장 잘 설명되었습니다.

In 2020, the Covid-19 pandemic led to an unprecedented shift in medical education from face-to-face teaching and learning to online teaching and learning. Although online teaching and learning in medical education had existed for several decades in the form of e-learning, it had usually been preceded by detailed preparation and management, small steps, pilots and then carefully-controlled growth (Ellaway and Masters 2008; Masters and Ellaway 2008). The 2020 shift was different and was best described as Emergency Remote Teaching (ERT) (Hodges et al. 2020).

Hodges 등이 설명했듯이 ERT(때로는 팬데믹 교육학)와 일반적으로 좋은 온라인 학습으로 간주되는 것 사이에는 많은 차이가 있지만, 본질적으로 ERT의 우선 순위는 교육 자료를 온라인으로 제공하고 연속성의 손실을 최소화하면서 수업을 시작하는 것이었다. 종종 교사들에 대한 지도가 거의 없는 상태에서, 목표는 [대면 교수 활동]을 온라인에 [동등한 것으로 대체함]으로써 가능한 한 [비슷하게 모방]하는 것이었다.

As explained by Hodges et al., there are many differences between ERT (sometimes called Pandemic Pedagogy (Schwartzman 2020)) and what is normally considered good online learning, but, in essence, the priority of ERT was to get the teaching materials online and get the classes up and running with as little loss of continuity as possible. Frequently, with little guidance to teachers, the aim was to mimic face-to-face teaching activities as closely as possible by replacing them with online equivalents (Stojan et al. 2021).

ERT는 필요했고, 많은 경우, 결과는 놀라웠다. 그러나, 문제는 신중한 사전 계획, 관리 및 파일럿의 사치 없이 일하는 것이 ERT의 요구 사항을 충족시키는 결과를 낳았지만, 일반적으로 e-러닝과 연관될 수 있는 확실한 기반이 부족하다는 것이다. 대부분의 경우, 상당히 이해할 수 있는 것은, 새로운 환경에서 학습의 반영과 확장을 위한 기회가 거의 없었다는 것이며, 불완전하게 해결된 문제들 중에는 온라인 학습에 내재된 윤리적인 문제들이 있다. Stojan 등의 검토는 많은 교사들이 윤리적 문제(특히 전염병으로 인해 교사 및 학습자에게 부과됨)에 대해 알고 있었음을 보여주지만, 이러한 복잡성에 대처할 수 있는 위치에 있는 경우는 거의 없었다. 또한 윤리적 딜레마에 대한 많은 해결책이 단기적인 것에 불과하다는 것을 깨달았다.

ERT was necessary, and, in many instances, the results were remarkable. A problem, however, is that working without the luxury of careful pre-planning, management and piloting has resulted in courses’ meeting the requirements of ERT, but lacking in the solid grounding that one would normally associate with e-learning (Stojan et al. 2021). In most instances, quite understandably, there was little chance for reflection and extension of learning in the new environment, and among the issues incompletely addressed are the ethical issues inherent in online learning. While Stojan et al.’s review does show that many teachers were aware of the ethical issues (specifically imposed upon teachers and learners because of the pandemic), they were seldom in a position to cope with these complexities. There was also the realisation that many solutions to ethical dilemmas were short-term only.

의료 e-러닝의 미래

The future of medical e-learning

비록 기관들은 대면 교육이 다시 한번 지배적인 교육 방식이 되는 미래를 바라볼 수 있지만, ERT의 경험은 온라인 교육이 가능하다는 것을 보여주었고, 어떤 경우에는 더 선호된다는 것을 보여주었다. 따라서 2020년 이전보다 더 큰 범위에서 e-러닝을 사용하고 싶은 교사와 학습자 모두의 욕구가 의심할 여지 없이 있을 것이다. (또한 COVID-19 변종, 미래의 새로운 바이러스 또는 더 나은 e-러닝으로 갑자기 전환해야 할 수 있는 다른 사건의 가능성을 고려해야 한다.) 하이브리드, HyFlex 또는 온라인을 막론하고, e-러닝의 형식이 무엇이든, 의료 e-러닝의 광범위한 사용은 ERT로 특징지을 수 있는 것보다 더 체계적이고 형식적일 것이다.

Although institutions may look to a future in which face-to-face education once again becomes the dominant mode of education, the experience of ERT has shown that online education is possible, and, in some cases, preferable, and so there will undoubtedly be a desire from both teachers and learners to use e-learning to an extent that was greater than pre-2020 (Stojan et al. 2021) (One should also consider the possibility of Covid-19 variants, future novel viruses or other events that may require a sudden shift to greater e-learning). Whatever the format of the e-learning, whether hybrid, HyFlex (Beatty 2007, 2019; Abdelmalak and Parra 2016), or entirely online, the widespread use of medical e-learning will become more structured and more formal than is characterised by ERT.

온라인 의료교육의 윤리

Ethics in online medical education

모든 의학 교육에서 윤리적 원칙(아래에서 더 자세히 설명)은 오랫동안 주목을 받아왔다. 공식적인 온라인 학습은 이러한 것들을 포함할 필요가 있을 뿐만 아니라, 온라인 환경이 새로운 윤리적 문제를 야기한다는 것을 인식해야 하며, 윤리적 의학 교육자는 이를 인식하고 온라인 교육이 윤리적으로 수행되도록 해야 할 것이다.

In all medical education, ethical principles (described in more detail below) have long received attention. Formal online learning not only needs to include these, but also has to recognise that the online environment introduces new ethical issues, and the ethical medical educator will need to be aware of these and ensure that online education is conducted ethically.

윤리적인 온라인 교육은 광범위한 교육적 이슈와 (때로는 흔한) 온라인 활동의 재평가를 필요로 한다. 예를 들어,

- 코스 관리 정보 문서의 작성과 그러한 정보의 전달,

- 기관이 관리하는 커뮤니케이션 시스템(예: LMS(Learning Management System)),

- 기관 외부의 통신 시스템(예: 개인 또는 상업용 모바일 앱, 소셜 미디어)

- 라이브 클래스 녹음,

- 자료 접근성,

- 전자 재료 품질(텍스트, 이미지, 비디오, 오디오 포함)

- 라이선스,

- 온라인 평가 및 감독,

- 코스 평가 및

- 학생 추적

Ethical online teaching requires a reassessment of a range of educational issues and (sometimes even common) online activities, such as

- the construction of course administration information documentation, delivery of such information,

- communication systems controlled by the institution (e.g. the Learning Management System (LMS)),

- communication systems outside the institution (e.g. private or commercial mobile apps, social media),

- live-class recording,

- material accessibility,

- electronic material quality (including text, images, video, audio),

- licensing,

- online assessment and proctoring,

- course evaluation, and

- student tracking.

또한 임상 교육 환경은 학생과 환자의 안전, 개인 정보 보호 및 기밀성을 포함하는 많은 새로운 복잡성을 열어준다.

In addition, the clinical teaching environment opens a host of new complexities involving student and patient safety, privacy and confidentiality.

그러나 이러한 활동과 관련된 윤리적 요구 및 관련 이상은 (의료 교육자들이 자신의 행동에 대한 현실적인 기대를 가지고 있고 과도한 부담을 갖지 않도록 하기 위해) [현실]에 맞춰 균형을 이루어야 한다.

These activities and the associated ethical needs and the associated ideals, however, should be balanced by reality, in order to ensure that medical educators have realistic expectations of their own behaviour and are not over-burdened.

이러한 가이드의 필요성 및 목적

The need for, and aim of, such a guide

안타깝게도, 윤리에 대한 언급이 거의 없는 온라인 교육을 다루는 전체 텍스트를 찾는 것은 드문 일이 아니다. 또한, 연구와는 달리, 의료 교육 기관이 온라인 강좌의 윤리를 구체적으로 검토하는 교육 윤리 위원회나 기관 검토 위원회(IRB)를 두는 것이 일상적이지 않기 때문에 온라인 강의로 전환하는 의료 교육자는 해결해야 할 윤리 문제에 대한 지침이 거의 남아 있지 않다.

Unfortunately, it is not unusual to find entire texts dealing with online education that have little mention of ethics at all. In addition, unlike research, it is not routine for medical education institutions to have Education Ethics Committees or Institutional Review Boards (IRBs) that specifically review the ethics of online courses, and so the medical educator transitioning to online teaching is left with little guidance on the ethical issues that need to be addressed.

온라인 의료 교육에서 윤리 지침이 필요하다는 점을 감안하여, 본 가이드의 목적은

- 교육자들이 온라인 교육이 최고의 윤리적 관행에 의해 가이드되도록 하기 위해

- 전임상 및 임상 의료 교육자에게 온라인 의료 교육의 윤리 문제에 대해 경고하고,

- 그들이 내려야 할 결정을 가이드하는 것이다.

In light of a need for ethical guidance in online medical education, the aim of this Guide is

- to alert pre-clinical and clinical medical educators to the ethical issues in online medical education and

- to guide them through the decisions that they will have to make

- in order to ensure that their online teaching is guided by the best ethical practices.

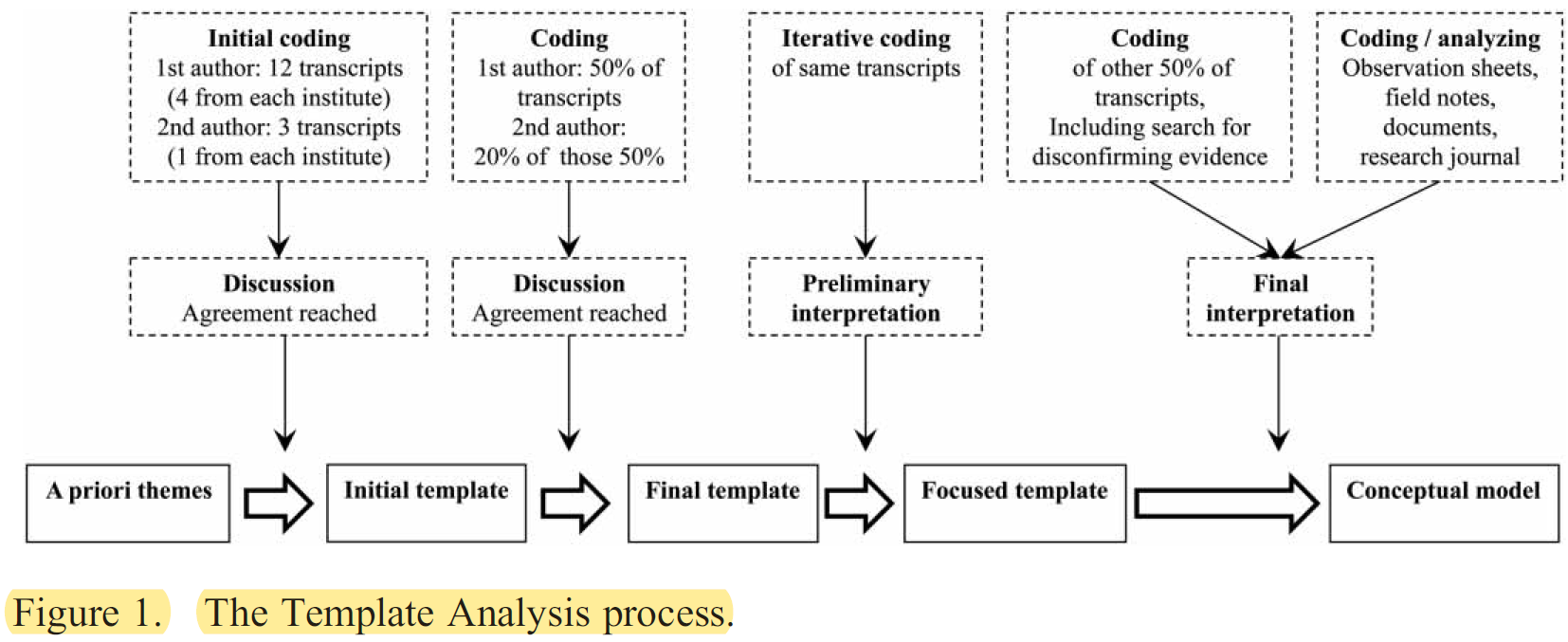

이 가이드는 가장 일반적으로 인용되는 [윤리적 원리에 대한 일반적인 소개]로 시작하여, 의학 교사가 새로운 온라인 과정을 구성하거나 온라인 환경을 위해 기존 ERT 또는 대면 과정을 수정하면서 겪게 될 일반적인 과정의 노선을 따라 구성될 것이다. 계획, 건설, 전달 및 평가의 요소가 맥락을 형성하며 기술 활동 내에서 설정된다. 그러나 본 가이드의 초점은 이러닝의 모든 측면에 초점을 맞추는 것이 아니라, 관련 활동에 의해 제기되는 윤리적 문제와 온라인 의학 교육의 맥락에서 접근하는 방법에 초점을 맞출 것이다.

The Guide will begin with a general introduction to the most commonly-cited ethical principles, and will then be structured along the lines of the general process that a medical teacher would go through as they construct a new online course or modify an existing ERT or face-to-face course for the online environment. The elements of planning, construction, delivery, and assessment will form the context, and will be set within the technological activities; the focus of this Guide, however, will not be on all aspects of e-learning, but rather on the ethical issues that are raised by the related activities, and how to approach them within the context of online medical education.

온라인 의학 교육에 적용할 수 있는 광범위한 윤리

The broad ethical principles applicable to online medical education

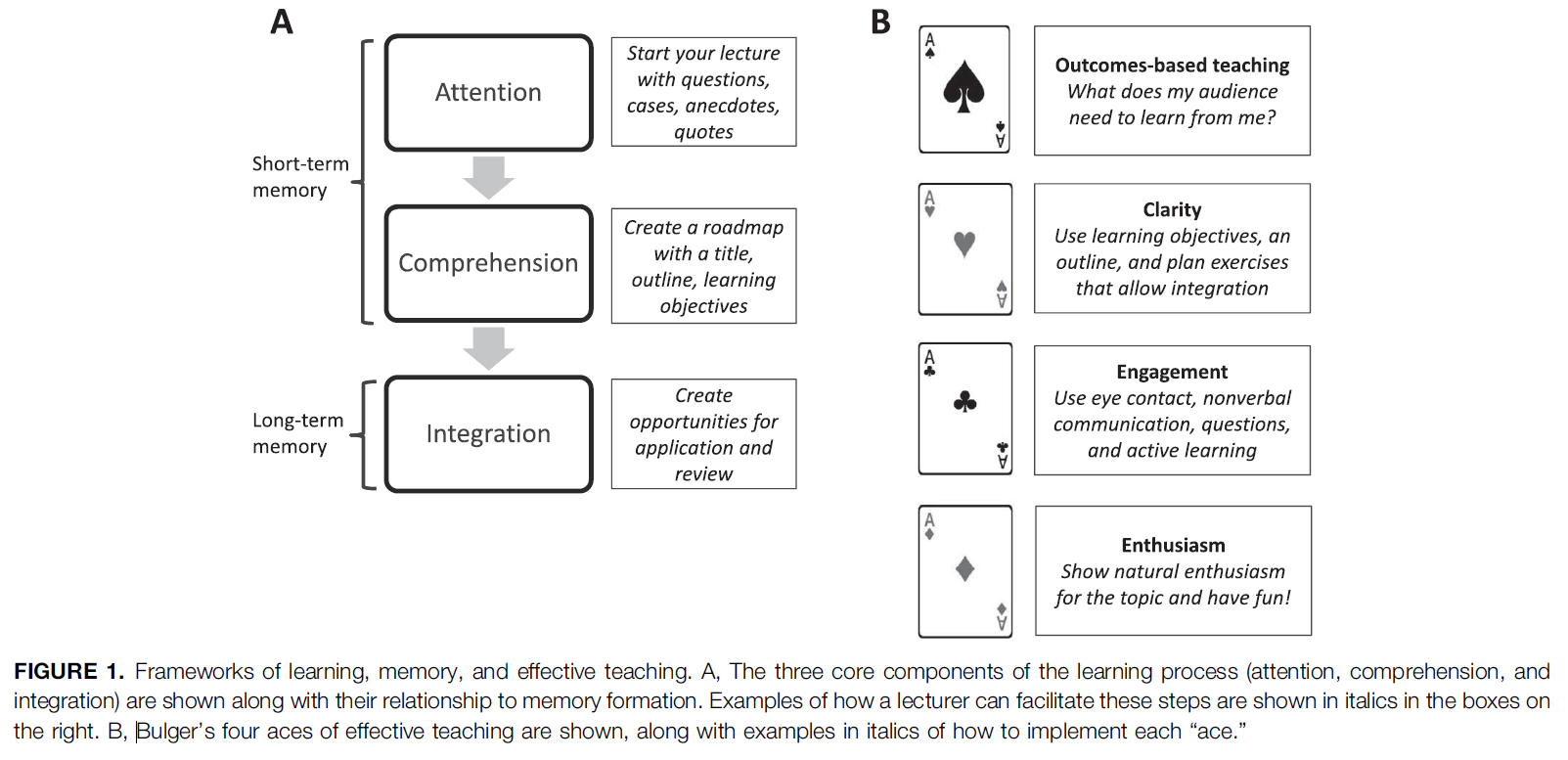

본 가이드는 온라인 의료교육에서 윤리행위의 실질적인 구현에 초점을 맞추고 있지만, 가장 관련성이 높은 윤리원칙과 온라인 의료교육에 미치는 영향을 개정할 필요가 있다. 실용적인 사용을 위해 이 목록을 짧게 유지했습니다. 보다 자세한 내용을 위해 독자는 국제의료정보학협회(IMIA) 건강정보전문가 윤리강령 (International Medical Informatics Association 2016) 및 (Anderson and Simpson 2007)과 같은 아이디어를 도출한 다른 텍스트를 참조하기를 원할 수 있다.

Although this Guide focuses on the practical implementation of ethical behaviour in online medical education, it is necessary to revise the most pertinent ethical principles and their impact on online medical education. For practical ease of use, we have kept this list short. For more details, the reader may wish to consult other texts from which we have drawn ideas, such as the International Medical Informatics Association (IMIA) Code of Ethics for Health Information Professionals (International Medical Informatics Association 2016), and (Anderson and Simpson 2007).

- 투명성, 공개 및 사전 동의: 과정 레이아웃 및 요구 사항에 대한 완전한 공개, 데이터 수집, 저장, 공유 및 필요한 경우 동의가 제대로 전달되도록 보장합니다.

- 평등, 형평성, 다양성 및 접근성: 온라인 시스템이 학생들을 부당하게 차별하지 않도록 보장하고, 다양한 상황과 배경을 고려하며, 모든 학생들이 쉽게 교과서에 접근할 수 있도록 보장한다.

- 과잉을 방지하라: 학생에 대한 필요한 정보만 수집되도록 보장하라.

- 개인 정보 보호 및 보안: 교사와 기관이 개인 정보를 유지하고 학생과 환자에 대해 수집된 모든 정보를 안전하게 보호하기 위한 모든 합리적인 조치를 취하도록 보장하고 익명성을 유지합니다.

- 해를 끼치지 마라: 히포크라테스(Hippocrates 1957)에서 따온, 이것은 의학에서 일반적인 지침 원칙이다; 현대 해석은 신체적 해와 심리적 스트레스를 다룬다.

- 가능성: 그 기관이 성취할 수 있는 모든 것들로부터 윤리적 기준을 요구하도록 보장한다.

- Transparency, disclosure and informed consent: ensuring that there is full disclosure about the course layout and requirements, gathering, storage, sharing of data, and ensuring that consent when required, is truly informed.

- Equality, equity, diversity and accessibility: ensuring that the online system does not unfairly discriminate against students, take into account a diversity of circumstances and backgrounds, and ensures that the course materials are easily accessible by all students.

- Guard against excess: ensuring that only necessary information about students is gathered.

- Privacy and security: ensuring that the teacher and institution take all reasonable steps to keep private and secure all information gathered about students and patients, and maintains their anonymity.

- Do no harm: taken from Hippocrates (Hippocrates 1957), this is a common guiding principle in medicine; modern-day interpretations cover physical harm and psychological stress.

- Possibility: Ensuring that the institution requires an ethical standard from all that is possible to achieve.

아래 섹션에서는 이러한 항목과 특히 관련이 있는 영역을 살펴보겠습니다.

In the sections below, we will see the areas in which these are particularly relevant.

코스 계획

Course planning

법률, 지침 및 정책

Laws, guides and policies

코스를 설계하기 전에 코스 설계자는 윤리적인 코스 설계를 보장하기 위해 수용되어야 하는 다양한 표준을 알고 있어야 합니다. 이것들은 위에 열거된 가장 명백한 윤리적 문제와 관련이 있을 것이다. 다소 느슨하게, 이러한 표준은 [법률, 디자인 가이드 및 기관 정책]의 세 가지 그룹으로 나눌 수 있다.

Before designing a course, course designers should be aware of a range of standards that need to be accommodated in order to ensure the ethical course design. These will relate to the most obvious ethical issues as listed above. Rather loosely, these standards can be divided into three groups: laws, design guides, and institutional policies.

법률

Laws

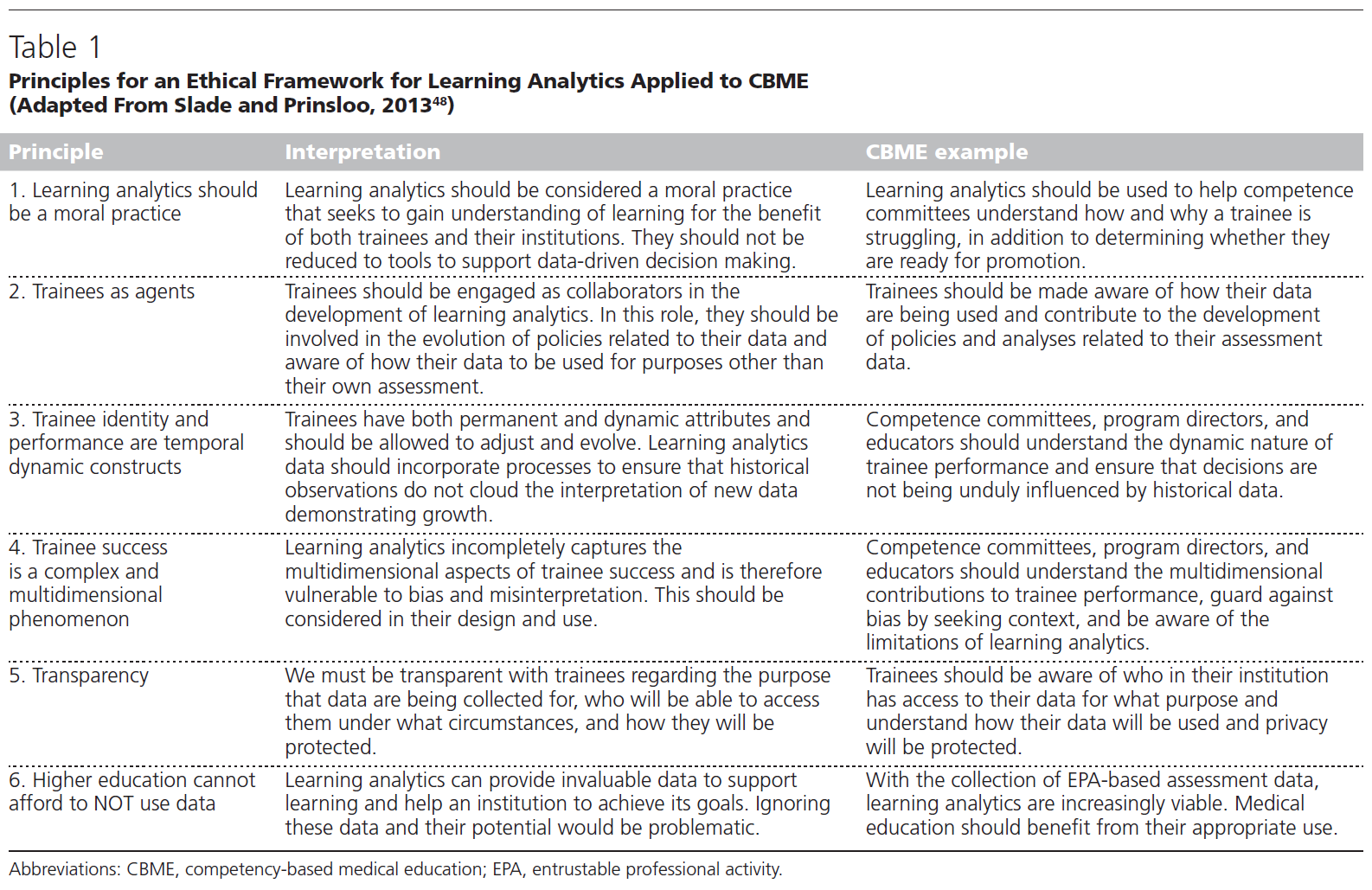

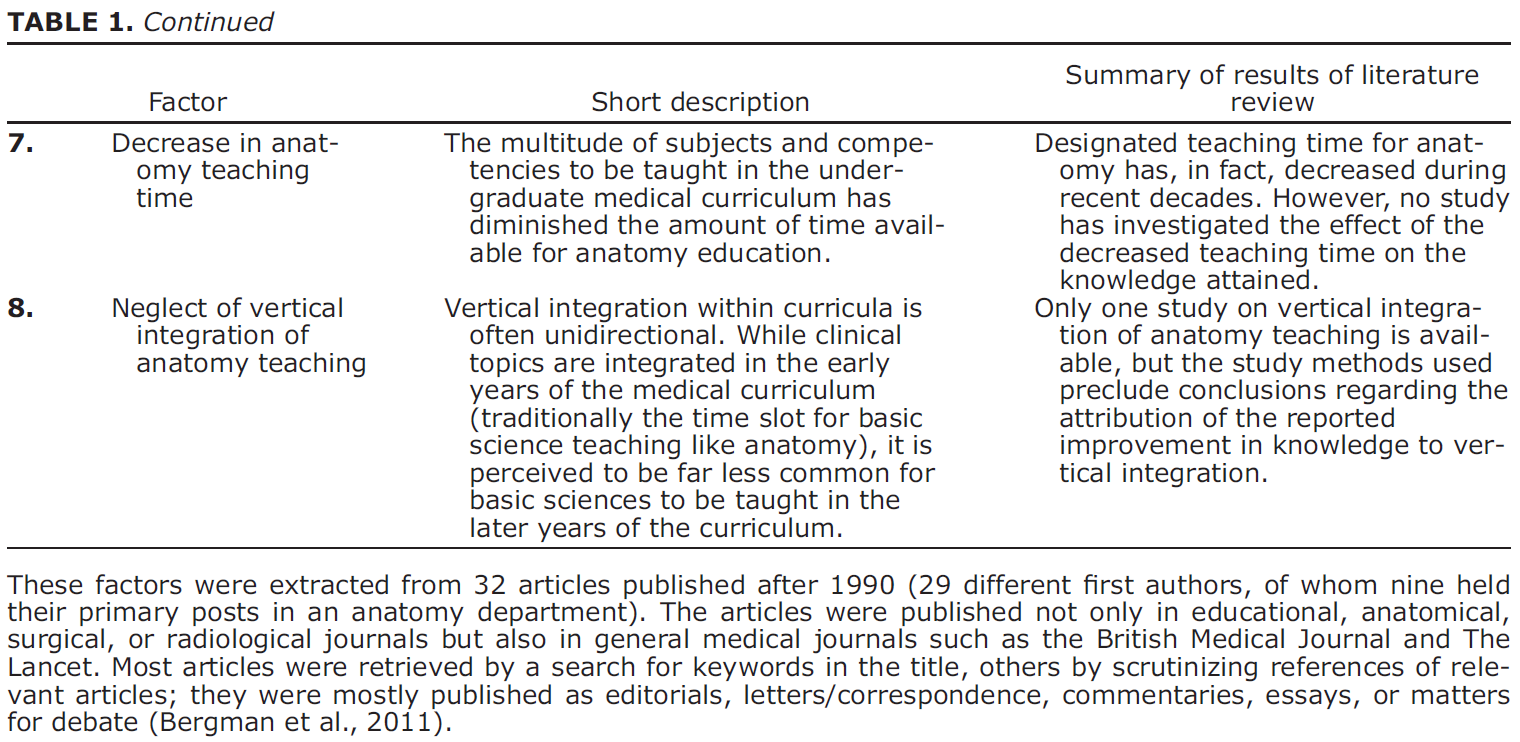

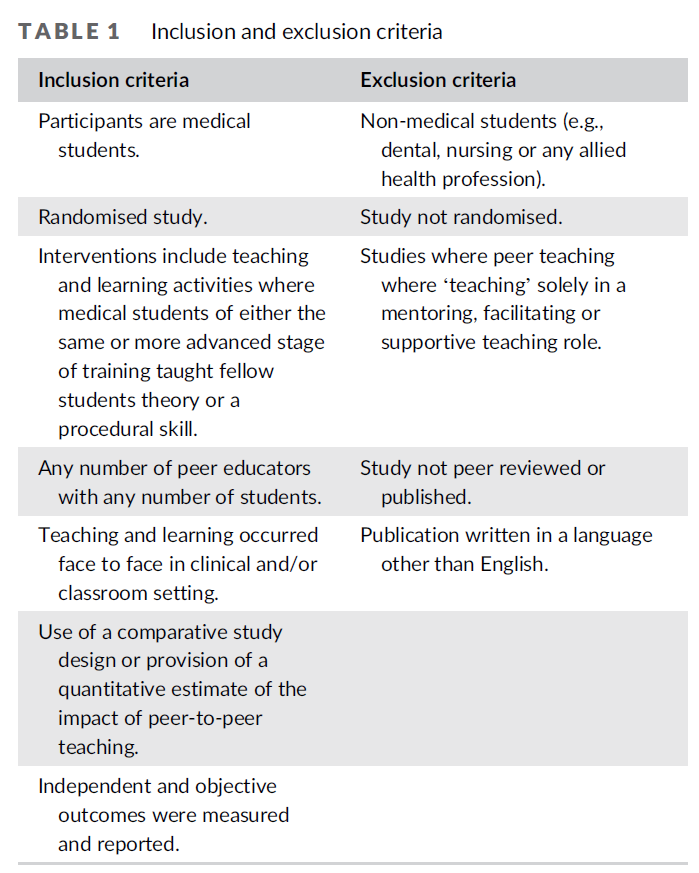

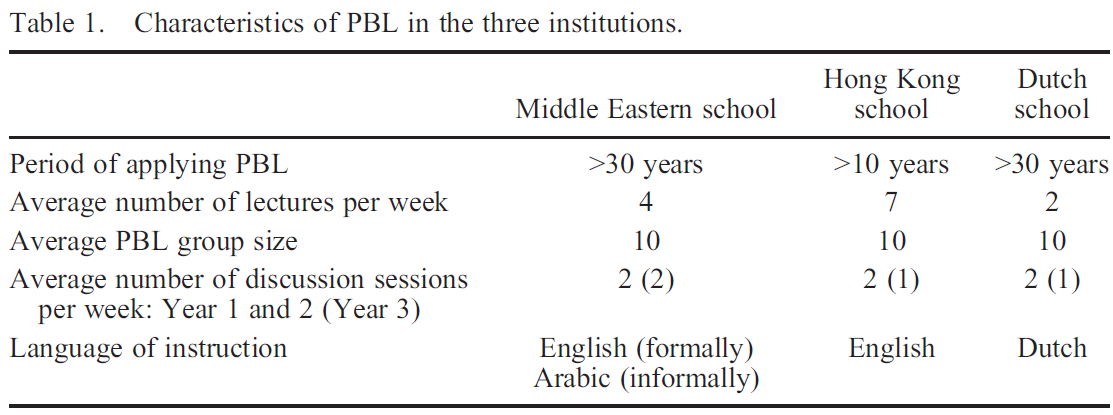

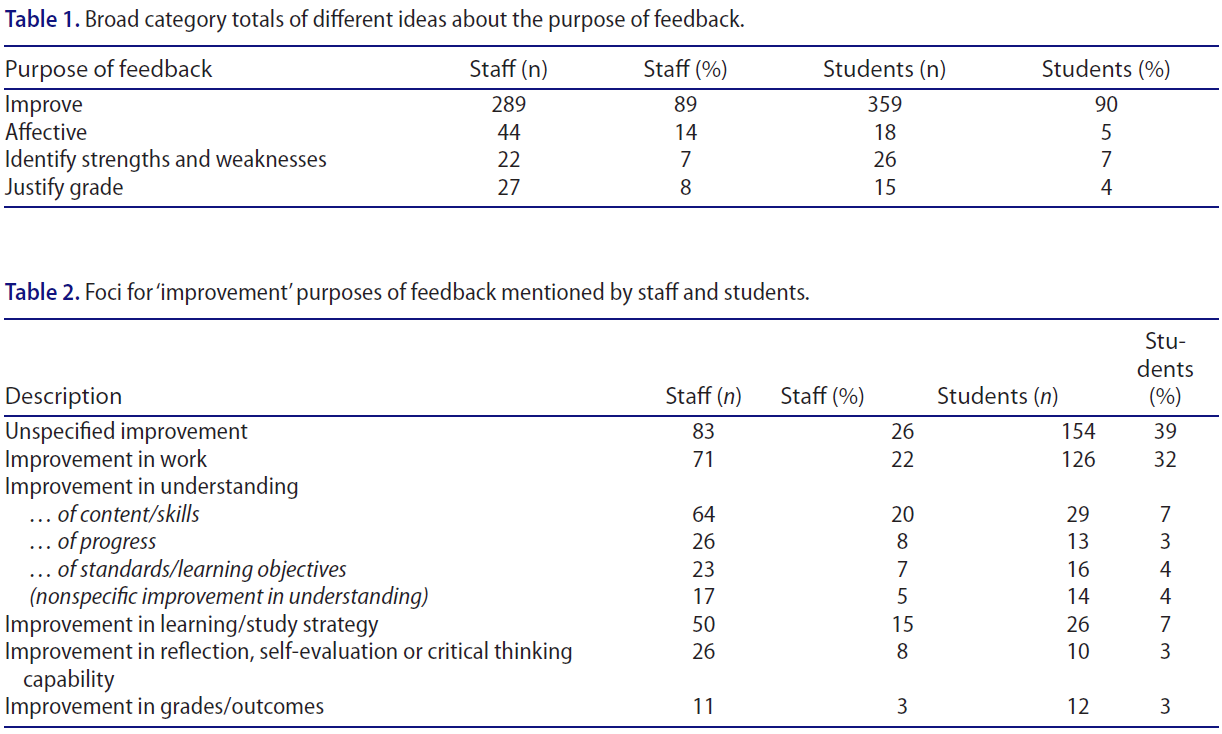

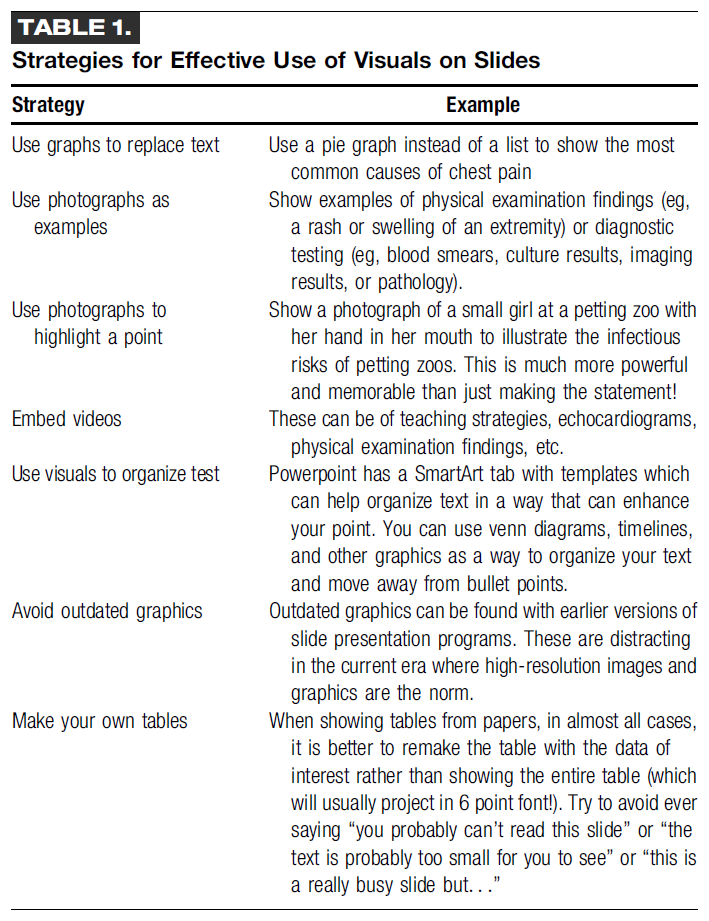

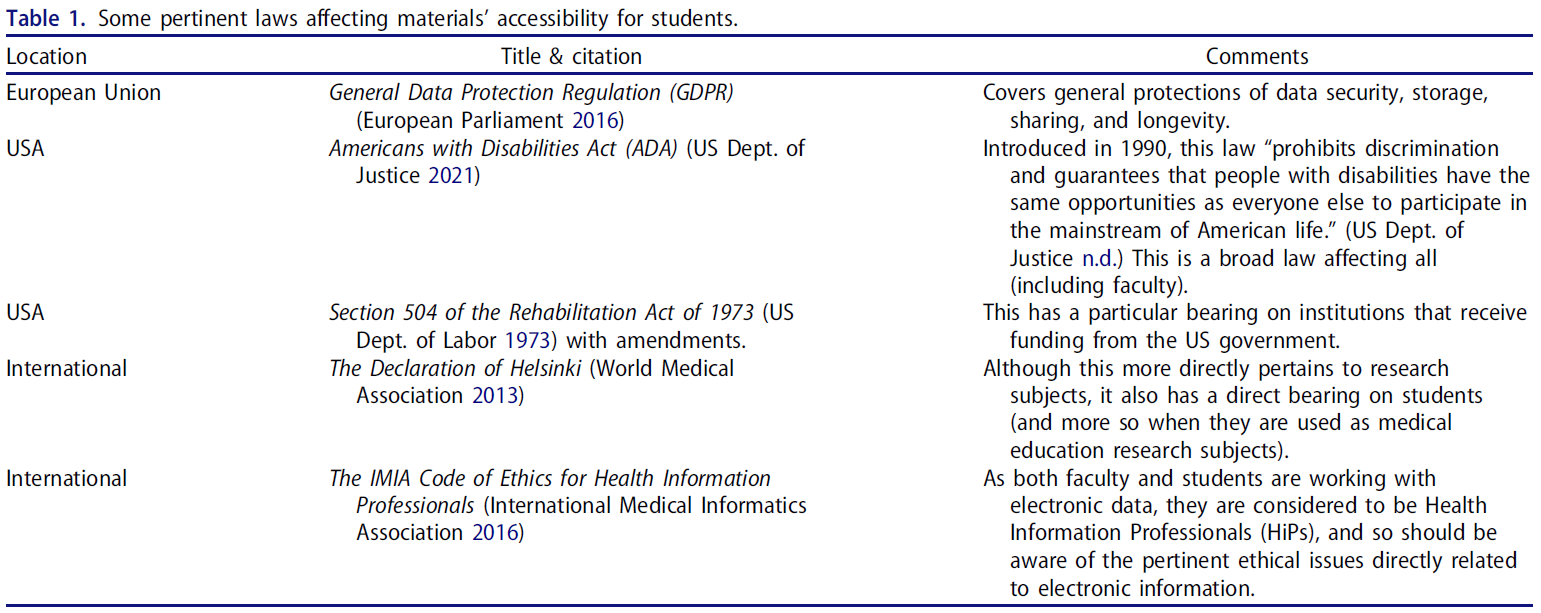

[관련 법]은 나라마다 다르므로, 모든 교사에게 적용되지 않을 수 있다. 그러나 의학교사가 이러한 법의 관할권 밖에 있는 경우에도 강좌를 설계할 때 유용한 지침이 될 수 있다. 표 1은 가장 관련성이 높은 법률의 목록을 보여줍니다.

The relevant laws differ from country to country, and so may not be applicable to all teachers. Even when the medical teacher falls outside the jurisdiction of these laws, however, they can be useful guides when designing courses. Table 1 gives a listing of some of the most pertinent laws.

In addition, some training is available through the Kansas Accessibility Resource Network (KASN) (free, with registration) (https://ksarn.org/free-training/) and extra tips from the University of Minnesota (https://accessibility.umn.edu/what-you-can-do/start-7-core-skills).

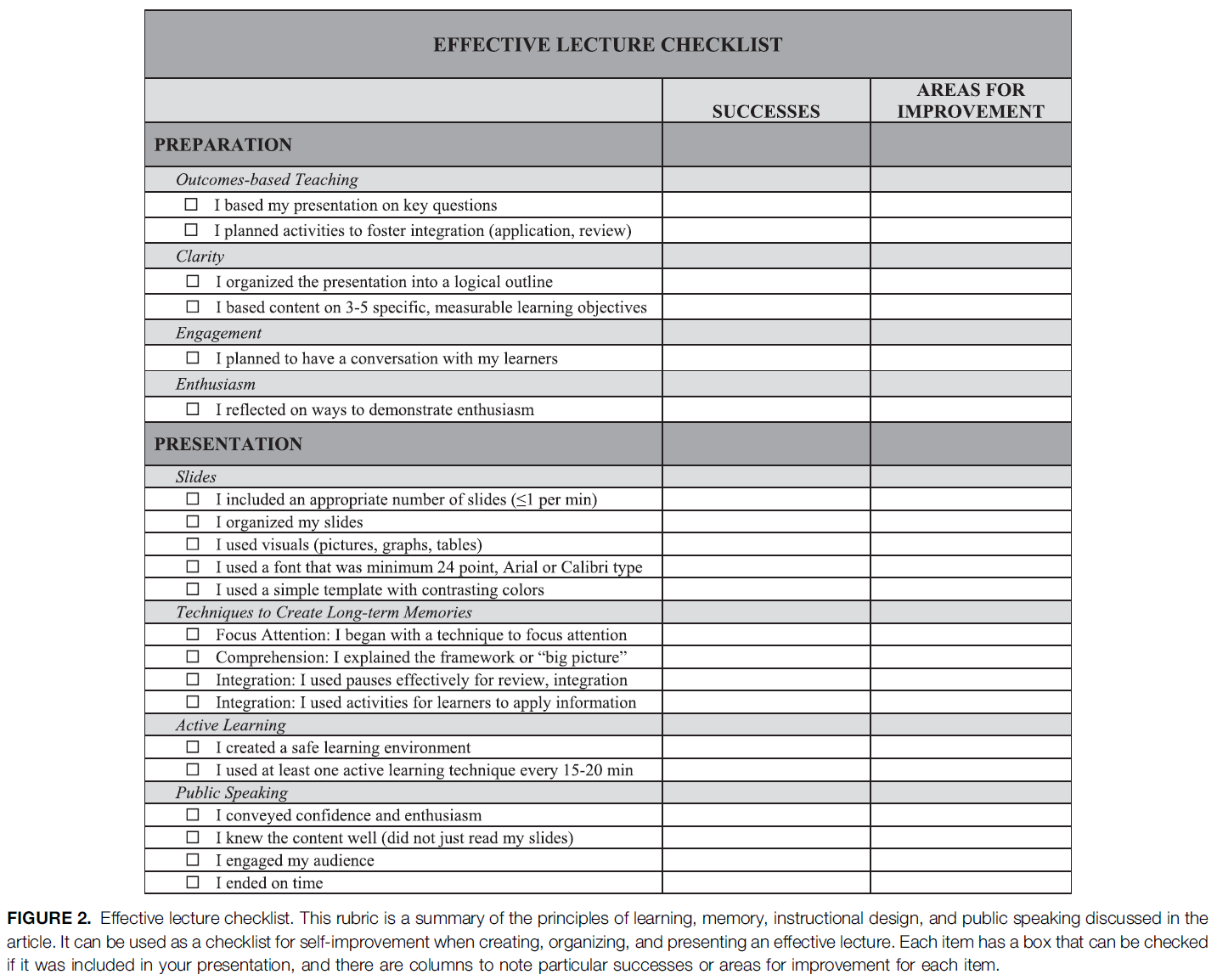

설계 가이드 및 루브릭

Design guides and rubrics

법률 외에도, 자신의 진로를 형성하는 데 도움을 줄 수 있는 몇 가지 [안내서와 루브릭]이 있다. 이들 중 대부분은 전반적인 과정 설계를 위해 설계되었지만, 대부분의 세부 사항은 자료의 접근성에 초점을 맞추고 있습니다. 특히 가치 있는 세 가지는 다음과 같다.

In addition to laws, there are several guides and rubrics that can be used to help shape one’s course. Most of these are designed for overall course design, but many of the specifics focus on the accessibility of materials. Three that will be of particular value are:

- 품질 문제(QM): (https://www.qualitymatters.org/. . . . . 이 사이트는 온라인 교육을 위한 매우 우수하고 포괄적인 도구 세트를 제공합니다. 최소한 고등 교육을 위한 그들의 루브릭(https://www.qualitymatters.org/qa-resources/rubric-standards/higher-ed-rubric. . . )은 개별 강사들이 자기 평가와 더 넓은 동료 평가를 위해 사용할 수 있다. 루브릭은 여행을 시작하는 사람에게는 부담스러울 수 있으므로 초보자는 천천히 진행하기를 원할 수 있습니다. ERT를 사용해 온 사람들에게는 QM 지침에 따라 귀하의 자료를 변환하는 것이 기본 윤리 기준을 충족하도록 하는 데 큰 도움이 될 것입니다(QM 사이트의 자료의 대부분은 무료가 아니며 저작권 제한).s가 존재하므로 사용자는 무엇을 사용할 수 있는지 알아야 한다).

- 앤스티 앤 왓슨의 루브릭(앤스티 앤 왓슨 2018)도 매우 유용하며 크리에이티브 커먼즈(CC BY-NC-SA 4.0) 라이센스를 통해 구입할 수 있다.

- QM 자료를 활용한 국가품질온라인학습표준(NSQ)(https://www.nsqol.org/. . . )도 심층 가이드를 제공한다.

- Quality Matters (QM): (https://www.qualitymatters.org/. . . . ). This site provides an extremely good and comprehensive set of tools for online education. At the very least, their rubric for higher education (https://www.qualitymatters.org/qa-resources/rubric-standards/higher-ed-rubric. . . . ) can be used by individual instructors for self-evaluation and for broader peer-evaluation. The rubric might be daunting for somebody starting on the journey, so novices may wish to progress slowly; for those who have been using ERT, conversion of your material according to QM guidelines will go a long way in ensuring that your course meets basic ethical standards (Much of the material on the QM site is not free, and copyright restrictions exist, so users should be aware of what may be used).

- Anstey and Watson’s rubric (Anstey and Watson 2018) is also very useful and is available through a Creative Commons (CC BY-NC-SA 4.0) licence.

- National Standards for Quality Online Learning (NSQ) (https://www.nsqol.org/. . . . ) which uses the QM material, also offers in-depth guides.

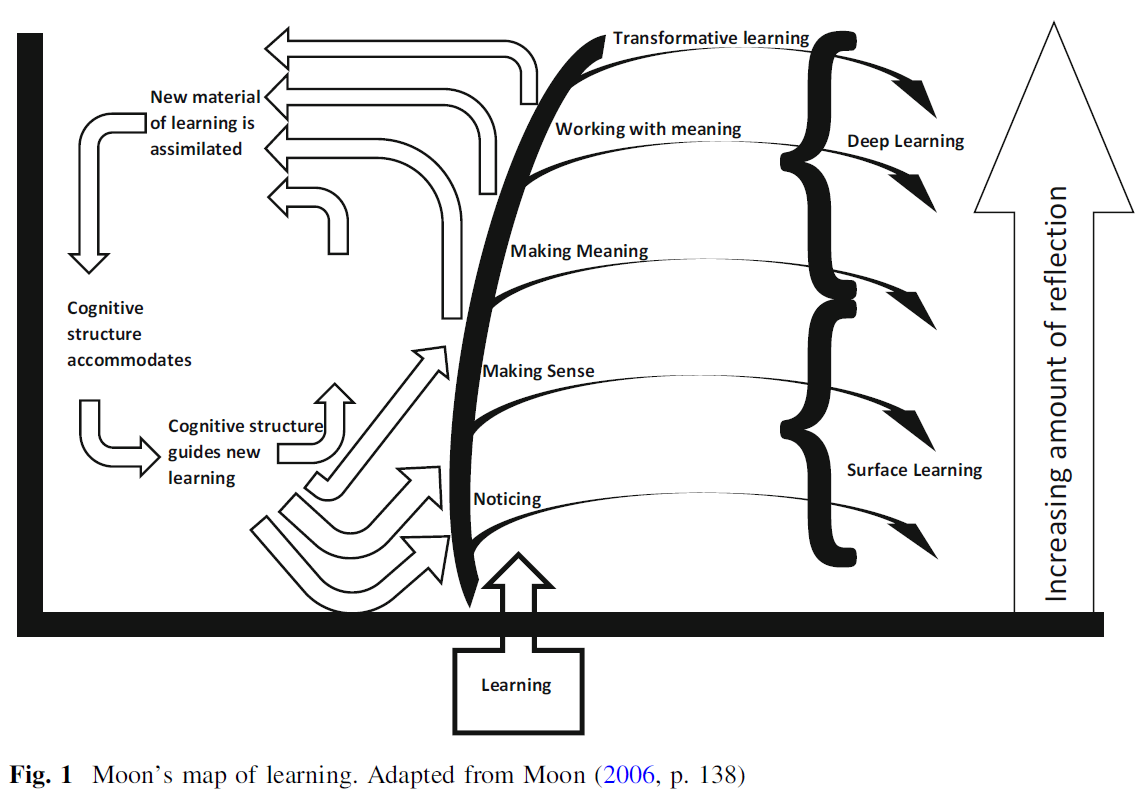

기타 표준 및 루브릭에 대한 논의는 (Martin et al. 2017)을 참조하십시오. 강사들이 루빅 기반 교육 설계에서 벗어나면서, 그들은 그들의 자료를 형식화formalize하고 또한 이러한 많은 루빅 뒤에 있는 원리들을 이해하기를 원할 수 있다. 이러한 경우 관련 이론에 익숙해지기 위한 유용한 출발점이 될 것이다.

For a discussion of other standards and rubrics, see (Martin et al. 2017). As instructors move away from rubric-based instructional design, they may wish to formalise their material, and also understand the principles behind many of these rubrics. For these, useful starting points for familiarising oneself with the pertinent theories would be (Clark and Mayer 2003; Sandars et al. 2015; Picciano 2021).

제도적 정책

Institutional policies

대부분의 기관은 데이터 보호, 개인 정보 보호, LMS의 구체적인 사용 등 전자 시스템의 올바른 사용을 다루는 정책을 가지고 있으며, 이러한 정책들을 교사와 학생 모두 잘 알고 있어야 해당 기관이 운영하지 않을 수 있다.

Most institutions have policies covering the correct use of their electronic systems, including data protection, privacy, and the specific usage of the LMS. It is necessary for both teachers and students to be aware of these so that they do not run afoul of the institution.

또한 개별 부서 및 과정에는 허용 가능한 행동에 대한 [추가 규칙]이 있을 수 있습니다. 모든 관련자들이 이것들을 인식하도록 하는 것이 중요하다. 각 부서는 교사와 학생들에게 알려야 하며, 커리큘럼 문서도 이를 참조하는 것이 좋을 것입니다(아래 약술). (학과에 이러한 사항이 없다면 윤리 교사가 이를 공식화하는 데 도움을 줄 수 있습니다.)

In addition, individual departments and courses may have extra rules regarding acceptable behaviour. It is important that all concerned are made aware of these. Departments should inform their teachers and students, and it would be a good idea for curriculum documents to refer to these also (as outlined below) (If departments do not have these, then the ethical teacher could take a hand in formulating them).

그러나 이 모든 것에서 [윤리적 행동에 대한 욕구와 현실적인 기대의 균형]을 맞추는 것도 중요하다. 대표적인 두 가지 예는 다음과 같다.

In all of these, however, it is also crucial to balance a desire for ethical behaviour with realistic expectations. Two typical examples are:

- 학생들이 다른 학생들로부터 투영된 용납할 수 없는 이미지에 노출되지 않도록 하는 것이 바람직하지만, 교사들은 우리가 온라인에서 가르칠 때, 우리는 학생들의 집에 있다는 것을 기억해야 한다. 결과적으로, 학생들이 그들의 삶의 측면의 이미지나 오디오를 의도치 않게 방송할 가능성이 있다. 그렇지 않으면 대면 교실에서 받아들일 수 없을 것이다. 이는 학생의 집에 있는 다른 사람들의 (고의적이거나 의도적이지 않은) 배경 간섭이나 단순한 잘못된 사건의 결과일 수 있습니다. 격한 반응보다는 교사와 기관의 이해심 있는 반응이 바람직할 것이다.

- While it is desirable to ensure that students are not exposed to unacceptable images projected from other students, teachers should remember that, when we teach online, we are in students’ homes. As a result, it is possible that students will unintentionally broadcast images or audio of aspects of their lives that would otherwise be unacceptable in a face-to-face classroom. This might be the result of (intentional or unintentional) background interference from other people in the student’s home or a simple ill-advised event. An understanding reaction from the teacher and institution, rather than a fierce response, would be preferable.

- [잘못된 생각ill-thought-out이나 광범위한 산업 소프트웨어 표준에 기반을 둔 제도적 온라인 행동 약관]은 교사와 학습자에게 심각한 결과를 초래할 수 있다. 예를 들어, [불쾌한 자료를 보내거나 받는 것]을 범죄로 만드는 것: 이것은 자동으로 LMS 과정 게시판이나 포럼에 게시된 메시지를 여는 것이 범죄라는 것을 의미한다. 따라서 범죄를 저지르는 것에 대한 유일한 확실한 예방 방법은 포럼에 게시된 내용을 절대 읽지 않는 것인데, 그렇게 되면 강좌의 교육적 가치를 즉시 떨어뜨립니다. 그런 정책이 존재한다면 이를 올바른 제도적 경로로 제기해 변화시키는 것이 현명할 것이다.

- Institutional online behaviour terms and conditions that are ill-thought-out, or based on broad industry software standards, can have serious consequences for teachers and learners. For example, making it an offence to send or receive offensive material: this automatically means that opening such a message posted into the LMS course bulletin boards or forums is an offence. The only sure prevention method against committing an offence, then, is to never read anything posted into the forums, which immediately lessens the educational value of the course. If such policies exist, it would be wise to raise this with the correct institutional channels, so that they may be changed.

기관 행정 및 지원 구조

Institutional administrative and support structures

대면교육에서는 개별 교사가 혼자 근무하는 경우가 많고, 주변에는 행정 및 기술 인력이 상주해 학생들의 눈에 띄지 않는 경우가 많다. 그러나 온라인 교육에서 [교육 매체]는 윤리적 의무를 따르는 [테크니컬 및 기타 직원들]에 의해 통제되는데, 이것이 늘 교사의 교육적 필요와 일치하지는 않는다. 결과적으로, 아래에서 논의되는 많은 항목은 개별 교사 및 심지어 부서의 통제를 벗어날 수 있으며, [소프트웨어 및 파일 서버의 원활한 작동]이 주된 관심사인 다른 사람들과 신중하게 협상해야 할 필요가 있을 수 있다.

In face-to-face education, individual teachers frequently work alone, and administrative and technical staff are present on the periphery, frequently unobserved by students. In online education, however, the very medium of instruction is controlled by technical and other staff who may be guided by ethical imperatives that do not always align themselves with the pedagogic needs of the teachers. As a result, many of the items discussed below may be beyond the control of individual teachers and even departments, and may need to be delicately negotiated with others who see their prime concern as the smooth-functioning of software and file servers.

충돌 가능한 영역은 다음과 같습니다.

Areas of possible conflict may include:

- 온라인 교육을 거의 받지 않은 교사와 학생들은 [끊임없이 변화하는 환경]에 적응하고 적응해야 한다.

- 접근성을 용이하게 하기 위해 [추가적인 비표준 소프트웨어 및 플러그인, 글꼴, 레이아웃을 사용하고자 하는 교사의 욕구]는 LMS 주제 및 템플릿에 반할 수 있다.

- 교원 및 학생에게 [자체 하드웨어 및 소프트웨어 기술]을 교수 및 학습에 사용하도록 요구하는 기관

- 온라인 환경에 적용되고 효과가 있을 것으로 예상되는 [대면 교육에 적합하도록 발전된 기관의 시간표, 과정 섹션 및 강의 규모]

- [필요한 지원을 하지 않으면서], 교원 및 학생에게 기관의 기준 준수 요구,

- 윤리적 교육 윤리적 요건과 상충될 수 있는 [기관 및 교사의 데이터 관행].

- Teachers and students who are largely untrained in online education having to adapt and adjust to an ever-changing environment;

- Teachers’ desire to use extra non-standard software and plugins, fonts, layouts in order to ease accessibility, but which may be contrary to LMS themes and templates;

- Institutions’ requiring teachers and students to use their own hardware and software technology for teaching and learning;

- Institutions’ time tables, course sections and class sizes that have evolved to suit face-to-face teaching imposed into an online environment and expected to work;

- Institutions’ demands for standards on teachers and students without supplying the necessary support, and

- Institutions’ and teachers’ data practices that may conflict with ethical educationally ethical requirements.

임상 교육에서 환자와 관련된 다른 문제가 발생하며, 이 가이드의 뒷부분에서 다룹니다.

In clinical teaching, other issues around patients arise, and are dealt with later in this Guide.

소셜 미디어 및 타사 소프트웨어

Social media and third-party software

온라인 의학 교육은 소셜 미디어와 제3자 소프트웨어 및 웹 사이트를 사용함으로써 향상될 수 있는데, 일부는 일반적으로 교육적인 것으로 간주되지 않을 수 있으며, 일부는 다른 관할 지역의 윤리 원칙에 따라 지도될 수 있다. 독점, 자유 또는 오픈 소스 여부에 관계없이 소프트웨어 개발자와 공급업체는 소프트웨어 사용에 대한 데이터를 수집하기를 원할 수 있으며, 이러한 활동의 구체적인 내용은 소프트웨어의 약관에 묻혀 있을 수 있습니다. 의학교사와 기관은 이러한 조건을 인지하고, 이러한 조건에 기초하여 소프트웨어 적합성에 대한 결정을 내리는 것이 필수적이다. 학생들에게 우려할 만한 부분이 있다면 학생들에게 이를 알려야 한다.

Online medical education can be enhanced by the use of social media and third-party software and websites, some of which may not normally be considered educational, and some may be guided by ethical principles from other jurisdictions. Whether proprietary, free or open-source, software developers and vendors may wish to gather data about the use of their software, and the specifics of these activities may lie buried in the software’s Terms and Conditions. It is imperative that the medical teacher and the institution be aware of these conditions, and make decisions about the software suitability, based upon those conditions. If there are areas that may be of concern to students, the students should be made aware of this.

과정 설계 및 레이아웃

Course design and layout

투명성, 공개 및 사전동의 : 교육과정 개요

Transparency, disclosure and informed consent: Curriculum outline

물리적 과정 레이아웃을 고려하기 전에 [투명성, 공개 및 사전 동의]라는 윤리적 요구 사항을 충족해야 합니다. 이를 위해 [학생이 사용할 수 있는 커리큘럼 개요 문서]가 필요하며, 이를 통해 다음 사항을 명확하게 확인할 수 있습니다.

Before one can consider the physical course layout, it is necessary to meet the ethical requirements of transparency, disclosure and informed consent. To do this, one will require a Curriculum Outline document that is available to students, and clearly identifies:

- 과목의 표준적 특징들: 코스 설명, 필수 조건, 학습 목표, 출석 정책, 평가 정보, 주별/모듈별 세부 정보, 학생 참여 기대치, 최소 기술 요구사항, 코디네이터/강사/연락처 세부 정보 및 시간

- 만약 학생들이 다른 시간대에 있을 수 있다면, 스케줄은 그 모든 시간대에 시간을 주어야 한다(실용적이지 않을 정도로 많은 시간대가 있는 경우, 학생들이 접근할 수 있는 온라인 검색 테이블을 사용할 수 있다).

- 서머타임이 있다면 고려하십시오.

- The standard features of the course, such as the course description, pre-requisites, learning objectives, attendance policies, assessment information, week-by-week/module-by-module details, expectations of student participation, minimum technological requirements, and coordinator/instructor/s contact details and hours.

- If students may be in different time zones, then schedules must give times in all of those time zones (If there are too many to be practical, then one can use an online look-up table that students can access).

- Take into account any daylight-saving time changes.

- [온라인 상호 작용, 에티켓, 세션 기록 및 공유]와 관련된 기관 및 과목 정책입니다

- Institutional and course policies that relate to online interactions, netiquette, session recording and sharing.

- 학생 데이터의 수집 및 저장에 관한 기관 및 과정 관행. 이 항목에는 다음이 포함됩니다. 수집되는 데이터는 무엇인지, 수집되는 이유는 무엇인지, 저장 방법, 기간 및 공유(제3자 포함), 사이트 간 추적 및 데이터 비활용 적용 여부.

- Institutional and course practices regarding the gathering and storage of student data. This needs to cover:

- which data are collected, why they are collected, storage methods, duration and sharing (including with and by third parties), and whether any form of cross-site tracking and data de-anonymisation are applied.

투명성에 대한 윤리적 요구 사항을 충족시키기 위해, 학생들이 코스 개요 문서를 읽었다고 가정할 것이 아니라, 학생들이 가능한 한 정보를 얻을 수 있도록 코스 시작 시 수업과 논의해야 합니다. 적절한 기간(예: 1~2주) 내에 학생들은 이 문서의 모든 용어를 이해한다는 것을 전자적으로 표시해야 합니다. 코스 기간 동안 본 문서에 대한 중요한 변경 사항이 학생에게 표시되어야 합니다.

To meet the ethical requirements of transparency, rather than assume that the students have read the Course Outline document, it should be discussed with the class at the beginning of the course, so that students can be as informed as possible. Within a reasonable period (e.g. a week or two), students should electronically indicate that they understand all the terms of this document. Material changes to this document during the course’s term should be indicated to the students.

투명성, 공개 및 사전 동의: 실행

Transparency, disclosure and informed consent: Implementation

윤리 지침이 이해되면 [물리적 과정 설계 및 레이아웃에 구현]되어야 합니다. 많은 경우, 온라인 교사는 LMS 또는 그들이 제한된 통제권을 가진 다른 시스템 내에서 일하고 있을 것이다. 이에 따라 개별교사가 달성할 수 있는 성과에는 한계가 있겠지만, 위의 제도행정 및 지원구조에 관한 절에서 보듯이, 때때로 변화를 협상할 수 있다. 어떤 경우에는 교사가 교육 디자이너와 접촉할 수 있지만, 이것은 표준이 아니며, 교사들은 흔히 스스로 작업해야 한다.

Once the ethical guidelines are understood, they need to be implemented in the physical course design and layout. In many cases, the online teacher will be working within an LMS or other system over which they have limited control. As a result, there will be limits to what the individual teacher can accomplish, but, as indicated in the section on Institutional administrative and support structures above, sometimes changes can be negotiated. In some cases, teachers may have access to instructional designers, but this is not the norm, and teachers have to frequently work by themselves.

그럼에도 불구하고, 할 수 있는 많은 것들이 있다. 이 절에서는 [평등, 형평, 다양성 및 접근성]의 윤리적 원칙도 적절하며, 교육이 테크놀로지, 특히 개인별로 구입해야하는 테크놀로지에에 의존할 때 취약하고 불리한 학생들에게 더욱 중요해진다는 것을 기억해야 한다. 대부분의 경우, 이러한 원칙은 기술적으로 적용하기가 상당히 쉬우며, 이러한 조치를 올바로 이행하면 코스 자료의 접근성에 상당한 영향을 미칠 수 있습니다.

Nevertheless, there are many things that can be done. In this section, ethical principles of Equality, Equity, Diversity and Accessibility are also pertinent, and one should remember that the vulnerable and disadvantaged students become even more so when education relies on technology, especially personally-financed technology. In most cases, these principles are reasonably technically easy to apply, and the correct implementation of these actions can have a significant impact on course material accessibility.

화면 레이아웃

On-screen layouts

- 스크롤 대신 [탭]을 누릅니다. 일부 LMS는 학생들의 접근 속도를 늦추고 추가 대역폭을 사용하는 "죽음의 스크롤"로 알려져 있다. 탭으로 된 테마 또는 템플리트를 사용하면 학생 액세스 시간이 크게 향상되고 탐색이 쉬워집니다. 탭은 현재 주/주제, 이전 주/주제 및 검사와 같은 특수 항목을 나타내기 위해 컬러 코딩할 수도 있습니다.

- Tabs instead of scrolling. Some LMSs are known for their “Scroll of Death” which slows student access and also uses extra bandwidth. Using a tabbed theme or template significantly improves student access times and eases navigation. Tabs can also be colour-coded to indicate the current week/topic, previous weeks/topics, and special items such as examinations.

- 항목의 제목, 들여쓰기 및 간격. 이것들은 명확하게 읽을 수 있도록 나열된 항목이 많을 때 특히 중요하다

- Headings, indentation and spacing of items. These are especially important when there are many items listed so that they can be clearly read.

- 텍스트 글꼴 유형, 크기 및 색상. 색상은 모든 학생들이 본문을 쉽게 읽을 수 있도록 신중하게 사용해야 한다. 색상 조합 및 표준에 대한 일부 기술적 문제에 대한 소개는 WC3 지침(WC3 2016), 특히 섹션 1.4.1, 1.4.3, 1.4.4 및 (렐로와 빅햄 2017)을 참조하십시오. 보다 진보된 작업을 위해서는 재료 디자인 구글의 페이지(https://material.io/. . . )를 참조할 수 있다

- Text font type, size and colours. Colours should be used carefully, ensuring that all students can easily read the text. For an introduction to some of the technical issues on colour combinations and standards, see the WC3 Guidelines (WC3 2016), especially Sections 1.4.1, 1.4.3 and 1.4.4 and (Rello and Bigham 2017). For more advanced work, Google’s page on Material Design (https://material.io/. . . . ) can be consulted.

- 파일 형식 및 크기. 파일 형식과 파일 크기는 학생들이 액세스하는 파일에 필요한 소프트웨어와 다운로드에 대한 영향을 미리 알 수 있도록 항상 명확하게 표시되어야 한다

- File types and sizes. File types and file sizes should always be clearly indicated so that students are forewarned of necessary software and download implications for files they access.

- 비록 현재 연구가 결론을 내리지 못했지만, OpenDyslexic(https://opendyslexic.org/. . . )과 같은 무료 글꼴을 사용하는 것이 난독증을 가진 사람들이 더 쉽게 읽을 수 있도록 돕는다는 일화적인 보고가 있다. 난독증을 앓고 있는 학생들이 노트를 읽는 데 어려움을 겪고 있다면 글꼴과 플러그인을 설치하는 것을 추천할 수 있습니다.

- Although the current research is inconclusive, there are anecdotal reports that using a free font like OpenDyslexic (https://opendyslexic.org/. . . . ) helps people who have dyslexia to read more easily. If you have students with dyslexia, and they are struggling to read your notes, then you may consider recommending they install the fonts and plugins.

- 이렇게 생긴 글꼴은 굵은 글씨와 기울임꼴도 지원한다.

- The font looks like this, and supports bold and italics also.

- 특별 활동(퀴즈나 여분의 독서 자료 등)이 명확하게 표시되어야 한다

- Special activities, such as quizzes and extra reading materials should be clearly indicated.

- 화면 판독기는 이미지의 [<alt > 텍스트]를 읽을 수 있으므로 이미지를 명확하게 설명하기 위해 모든 이미지가 해당 텍스트를 포함해야 합니다. 이것은 항상 중요하지만, 이미지가 표준 텍스트 대신 사용되는 경우 특히 중요합니다. 이미지를 평가에 사용하는 경우, <alt > 텍스트가 질문의 답을 식별하지 않도록 주의해야 합니다

- Screen readers can read the < alt > text on images, so all images should contain such text in order to clearly describe the image. This is always important, but especially so if images are used in place of standard, written text. If images are used in assessments, care should be taken to ensure that the < alt > text does not identify the question’s answer.

- 가능한 경우 screen-reader를 사용하여 레이아웃을 테스트합니다. 유용하고 무료 화면 보호는 NVDA(https://www.nvaccess.org/. . . . . )이다

- If possible, test the layout with a screen-reader. A useful and free screen-reader is NVDA (https://www.nvaccess.org/. . . . ).

- 성별 문제, 특히 특정 성별 특정 대명사에 대한 선호가 고려되어야 한다. 임상 사례에서 성별은 관련 기준과 관련되어야 하며, 관련되지 않은 경우 균형을 유지해야 한다

- Gender issues, especially a preference for particular gender-specific pronouns, should be considered. In clinical cases, genders should be related to pertinent criteria, and, where not relevant, should be balanced.

- 전반적으로 직원, 학생 및 환자에 대한 논의는, 주제와 직접 관련이 없는 한 성별, 연령, 인종 등에 대한 구체적인 언급을 피해야 한다

- Overall, discussions about staff, students and patients in general, should avoid specific references to gender, age, race, etc., unless they are directly pertinent to the topic.

- 문화적으로 부적절한 온라인 교육에는 표준적이고 일반적인 모범 사례가 있을 수 있다. 문화적 민감성과 최상의 관행의 균형을 맞추기 위해(특히 관련 문화에 익숙하지 않은 경우) 문화 전문가와 학생들 스스로에게 상담해야 한다

- There may be standard and common best practices in online education that are culturally inappropriate. To balance best practice against cultural sensitivity (especially if one is unfamiliar with the relevant culture), one should consult with cultural experts and with the students themselves.

코스 및 자료 접근성

Course and materials accessibility

학생들이 교재를 쉽게 접할 수 있도록 하는 것이 필수적이다. 의료 실무에서 오랫동안 인정되어 왔듯이(Maxwell 1984), 서비스에 대한 접근성은 복잡한 과정이다. 학생이 자료에 액세스할 수 있도록 다음 단계를 수행할 수 있습니다.

It is essential to ensure that the teaching materials are easily accessible by students. As has long been recognised in medical practice (Maxwell 1984), accessibility to a service is a complex process. In order to ensure student access to materials, the following steps can be taken:

소프트웨어

Software

- [특수한 소프트웨어 도구]에 익숙하지 않은 학생은 강의 자료에 접근하고 참여하는 학생들의 능력에 즉각적인 부정적인 영향을 미칠 수 있습니다. 코스는 가능한 한 일반적으로 사용되는 도구를 사용해야 하며 새로운 도구에 대한 지침(노트 및 비디오 형식)을 제공해야 합니다. 또한 코스는 2개 이하의 동기식 비디오 교육 도구를 사용하도록 시도해야 한다.

- Student unfamiliarity with special software tools will have an immediate negative impact on students’ ability to access and engage with the course materials. As far as possible, the course should require the use of commonly-used tools, and should provide instructions (in the form of notes and videos) on any new tools. Courses should also attempt to use not more than two synchronous video instruction tools.

- 다양한 전달 방법과 도구를 사용하여 올바른 작업을 수행할 수 있지만, 특히 수업에서 도구를 동시에 사용할 때 학생들이 압도당하지 않도록 주의해야 한다

- While a variety of delivery methods and tools can be used to ensure that the correct tool is being used for the correct task, care should be taken to not overwhelm students, especially when tools are used simultaneously in a class.

- 학생들이 자료를 더 쉽게 활용할 수 있도록 비표준 파일 형식을 사용하지 않도록 주의해야 한다. 비표준 파일 형식을 사용하는 경우 해당 파일에 필요한 관련 무료 소프트웨어에 대한 링크가 제공되어야 하며, 해당 소프트웨어에 대한 기술 지원 및/또는 교육이 필요할 수 있습니다

- To ensure that students can more easily utilise the materials, care should be taken to avoid non-standard file types. If non-standard file types are used, then links to the relevant free software required for those files should be provided, and technical support and/or training on that software may be required.

- 비디오는 사용자의 선호에 따라 스트리밍과 다운로드가 모두 가능해야 한다

- Videos should be available to be both streamed and downloaded to meet the preference of the users.

- 품질 저하 없이 다운로드 시간을 줄이기 위해 파일 크기를 최소로 유지하도록 주의해야 합니다. 이는 다운로드 시간이 영향을 받을 때 시간 제한 평가 중에 사용되는 경우 특히 중요합니다. 다음은 파일 최적화에 대한 몇 가지 팁입니다(부록 1: 언급된 소프트웨어 사용 방법에 대한 기술 지침은 기술 "사용 방법"을 참조하십시오).

- Care should be taken to keep file sizes to a minimum, in order to reduce download times, without compromising quality. This is especially important if these are used during time-restricted assessments when download times are affected. Here are some tips on file optimisation (See Supplementary Appendix 1: Technical “How To” for technical guidance on how to use the software mentioned):

- 모호한 미디어 파일은 어댑터(Mac 및 Windows용) 도구를 사용하여 보다 일반적인 파일 형식으로 변환해야 합니다.

- 이미지 품질을 저하시키지 않고 이미지를 줄여야 합니다. 무료 이미지 편집 소프트웨어 그림판.NET, Photopea 또는 TinyPNG를 사용할 수 있습니다. 게다가, 다소 빠르고 더러운 방법(유연성은 낮지만 기본은 한다)은 MS Office를 사용하는 것이다.

- PowerPoint 프레젠테이션을 비디오로 저장할 경우 화면 해상도를 낮추려면 파일 | 다른 이름으로 저장 대신 파일 | 내보내기를 사용하십시오.

- 모든 비디오 파일에는 명확한 자막이 있어야 한다. 무료 오픈 소스 비디오 편집기 Kdenlive는 자막을 삽입할 수 있다.

- 오디오 파일의 품질은 무료 오픈 소스 Audacity를 사용하여 향상될 수 있습니다.

- Obscure media files should be converted into more common file types by using the tool Adapter (for Mac and Windows).

- Images should be reduced without compromising image quality. Free image editing software Paint.NET, Photopea, or TinyPNG can be used. In addition, a rather quick-and-dirty way (with less flexibility, but it does the basics) is to use MS Office.

- If saving a PowerPoint presentation as a video, use File | Export (rather than File | Save As) so that the screen resolution can be reduced.

- All video files should have clear subtitles. The free, open-source video editor Kdenlive can insert subtitles.

- The quality of audio files can be improved using free, open-source Audacity.

- 모호한 미디어 파일은 어댑터(Mac 및 Windows용) 도구를 사용하여 보다 일반적인 파일 형식으로 변환해야 합니다.

- MS-Word에는 접근성 검사기가 내장되어 있습니다. 사용 방법과 MS-Word 문서에 보다 쉽게 액세스할 수 있도록 하기 위한 팁에 대한 자세한 내용은 https://support.microsoft.com/en-us/office/make-your-word-documents-accessible-to-people-with-disabilities-d9bf3683-87ac-47ea-b91a-78dcacb3c66d. . . .를 참조하십시오.

- MS-Word has an in-built accessibility checker. For more details on how to use it and tips for making your MS-Word documents more accessible, see https://support.microsoft.com/en-us/office/make-your-word-documents-accessible-to-people-with-disabilities-d9bf3683-87ac-47ea-b91a-78dcacb3c66d. . . . .

언어와 문화

Language and culture

- 준비된 자료의 [학생 언어 수준]은 수용되어야 한다. 이것은 명백한 피드백 없이 비동기 교육에 의존하기 때문에 특히 중요하다. 언어 확인의 경우, 언어 난이도를 확인하는 자동 시스템이 완벽하지는 않지만 유용하다. 자세한 내용은 부록 1을 참조하십시오.

- Student language levels in prepared materials need to be accommodated. This is especially important because of the reliance on asynchronous teaching without obvious feedback. For language-checking, although automatic systems that check language difficulty are not fool-proof, they are useful. See Supplementary Appendix 1 for details.

- 소재의 문화적 민감성은 수용될 필요가 있다. 특정 이슈는 특정 상황과 관련될 것이지만, 우리는 교사들에게 이슈에 대해 경고하는 과정을 시작할 몇 가지 논문을 추천할 수 있다. 여기에는 다음이 포함됩니다

- Cultural sensitivities of material need to be accommodated. The particular issues will be related to the specific circumstances, but we can recommend a few papers that will begin the process of alerting teachers to the issues. These include (Liu et al. 2010; Torras and Bellot 2017; Kumi-Yeboah 2018).

재료의 부피

Volume of the material

- 대면에서 온라인으로의 전환을 서두르는 가운데 대부분의 강사들은 자료를 모두 온라인으로 옮겼고 자료량도 거의 조정하지 않았다. 이것은 보건 전문가 자격을 얻기 위해 숙달되어야 할 자료이기 때문에 이해할 수 있다. 그러나 온라인 학습은 다른 수준의 집중력을 요구한다. 대면 회의와 온라인 회의 사이에 요구되는 집중도의 차이만 생각하면 되고 매일 몇 시간씩 온라인 수업을 듣는 것을 상상하면, 온라인 학습 피로감으로 이어진다. 이 때문에 전달량을 줄이고, 보다 간결하게 하며, 예시와 재미있는 일화를 적게 하고, 특히 1시간이 넘는 수업에서 쉬는 시간을 더 자주 줄 필요가 있다.

- In the rush to convert from face-to-face to online, most instructors moved all their material online and made few adjustments to the amount of material. This is understandable, as the view is that this is the material that needs to be mastered in order to qualify as a health professional. Online learning requires different levels of concentration, however. One only has to think of the differences in the concentration required between face-to-face meetings and online meetings and imagine attending several hours of online classes every day, leading to online learning fatigue. For this reason, it is necessary to reduce the amount of material delivered, be more succinct, have fewer illustrative examples and interesting anecdotes, and give more frequent breaks, especially in classes that go over an hour.

- 콘텐츠에 대한 논의는 시간, 특히 스크린 타임에 대한 논의로 이어진다. 팬데믹 이전에 연구자들은 연구 결과가 엇갈리지만 장시간 상영으로 인한 건강 영향에 대해 우려했다. 컴퓨터 비전 증후군(CVS), 디지털 눈의 피로(DES) 및 기타 신체적 문제가 광범위하게 연구되었으며, 일부는 화면 시간 연장과 강한 연관성을 보여주었다. 미국 검안학회는 20-20-20 규칙을 권장하고 있다("매 20분마다 20피트 떨어진 곳을 보려면 20초 휴식을 취하십시오."). 다른 많은 연구들은 의대생들의 과도한 인터넷 사용을 "중독"으로 규정할 정도로 의대생들이 온라인에서 보내는 시간의 양에 대해 우려했고, 현재의 취업 가이드는 매시간 5-10분 휴식을 권장하고 있으며, "이상적으로, 사용자는 휴식 시간을 선택할 수 있어야 한다."(HSE.d)

- The discussion of content leads to a discussion of time, specifically screen-time. Before the pandemic, researchers were concerned about the health impact of prolonged screen-time, although the results of studies are mixed (Victorin 2018; Orben and Przybylski 2019; Lanca and Saw 2020). Computer vision syndrome (CVS), digital eye strain (DES) and other physical problems have been widely studied, and some have shown a strong association with prolonged screen-time (Sheppard and Wolffsohn 2018; Al Tawil et al. 2020; Sánchez-Valerio et al. 2020). The American Optometric Association recommends the 20-20-20 rule (“take a 20-second break to view something 20 feet away every 20 minutes”)(AOA n.d.). Many other studies were concerned about the amount of time medical students spent online, even to the point of labelling heavy Internet usage by medical students as an “addiction” (Masters et al. 2021), and current employment guides recommend a 5–10 minute break every hour, and “Ideally, users should be able to choose when to take breaks.” (HSE n.d.)

- 스크린 타임 해악에 대한 이러한 우려를 고려할 때, 글로벌 의료 교육이 의료 교육 기관과 교사들에게 적합할 때 스크린 기반 학습으로 전환되어, 이전보다 훨씬 더 많은 온라인 시간으로 이어진 것은 이상하고 불안할 정도로 아이러니하다. 이전에는 수업 일정이 대면 시간을 위해 설계되었으며, 전환 과정에서 이러한 일정이 축소되었다는 징후는 없습니다. 스크린 타임 문제는 때때로 과장되었을 수 있고, "중독"은 제대로 정의되지 않은 것으로 나타났지만, 여전히 학생들이 화면을 보는 데 소비하는 시간의 양에 대한 우려가 있고, 윤리적인 의학 교사들은 그것을 인지해야 하며, 가능한 피해를 완화하기 위해서는 학생들(그리고 그들 자신)은 스크린 타임의 양이 적절할 필요가 있다.

- Given these concerns about screen-time harm, it is then strangely and disturbingly ironic that global medical education switched to screen-based learning when it suited medical education institutions and teachers, leading to far greater online time than before. Previously, class schedules had been designed for face-to-face time, and, in the transition, there is no indication that these were reduced (Stojan et al. 2021). While the screen-time issues may have sometimes been over-stated, and the “addiction” has been shown to be poorly defined, (Masters et al. 2021) there is still a concern about the amount of time students spend viewing a screen, and ethical medical teachers need to be aware of it, and require an appropriate amount of screen time from their students (and themselves), in order to mitigate possible harm.

제도적 문제 및 지원

Institutional issues and support

- 운영 체제(OS)의 범위와 함께, 기관은 어떤 것이 지원되는지 명확하게 표시해야 하며, 개별 교사들은 모든 자료가 공식적으로 지원되는 모든 OS가 액세스할 수 있는 형식으로 되어 있는지 확인해야 한다.

- With the range of Operating Systems (OSs), the institution needs to clearly indicate which are supported, and individual teachers must ensure that all materials are in a format that can be accessed by all of the officially-supported OSs.

- 학생들이 필요로 하는 전문 소프트웨어는 가능한 한 무료이거나 대학 라이센스로 보장되어야 한다(웹 기반의 경우 다른 브라우저에서 소프트웨어를 테스트하는 것도 필요하다). 그렇게 하지 않으면 윤리적 학생을 처벌하거나 불법 복제(및 고위험) 소프트웨어 버전을 얻으려는 학생들의 비윤리적인 행동을 조장한다.

- As far as possible, specialised software required by the students should be either free or covered by a University licence (If web-based, it is also necessary to test the software on different browsers). Failure to do so punishes the ethical student or encourages unethical student behaviour as they attempt to obtain pirated (and high-risk) versions of the software.

- 인용, 참조, 저작권 문제를 고려할 필요가 있다. 대면 교육에서, 일부 자유는 받아들여지고 용서된다; 온라인 과정에서는, 이것들은 더 엄격하게 시행될 것으로 기대되며, 이것들을 지배하는 규칙들은 우리가 학생들에게 기대하는 기준과 같거나 더 높아야 한다. 특히 저작권 문제는 법적 영향을 미칠 수 있으므로 기관의 법무 부서에 대한 접근이 필요할 수 있습니다. 어떤 경우에는 기관이나 심지어 주에서도 LMS 내에 남아 있는 한 저작권으로 보호된 자료를 사용할 수 있는 특별한 권리를 가지고 있다.

- Citing, referencing and copyright issues need to be considered. In face-to-face teaching, some liberties are taken and forgiven; in online courses, these are expected to be more strictly enforced, and the rules governing these should be of the same as, or higher than, the standard we expect from our students. Copyright issues, in particular, may have legal implications, so access to the institutions’ legal department may be required. In some instances, institutions or even states have particular rights to use copyrighted material as long as it remains within the LMS.

- 위의 요점과 관련하여, 귀하가 생산하는 자료의 지적 재산, 기관의 다른 부분에서 생산된 자료 및 생성된 데이터에 관한 기관의 규칙과 법률을 숙지하는 것이 필수적입니다. 이 문제들은 당신의 자료 사용에 심각한 결과를 초래할 수 있기 때문에, 이러한 문제들에 대해 애매한 확신을 얻는 것만으로는 충분하지 않다. 이는 환자 데이터를 다룰 때 점점 더 중요해지고 있습니다.

- Related to the above point, it is essential that you are familiar with your institutions’ rules and laws regarding the intellectual property of materials you produce, materials produced by other parts of the institution, and data that are generated. It is not enough to get vague assurances on these issues, as they can have serious consequences for your use of material. This becomes increasingly important when working with patient data.

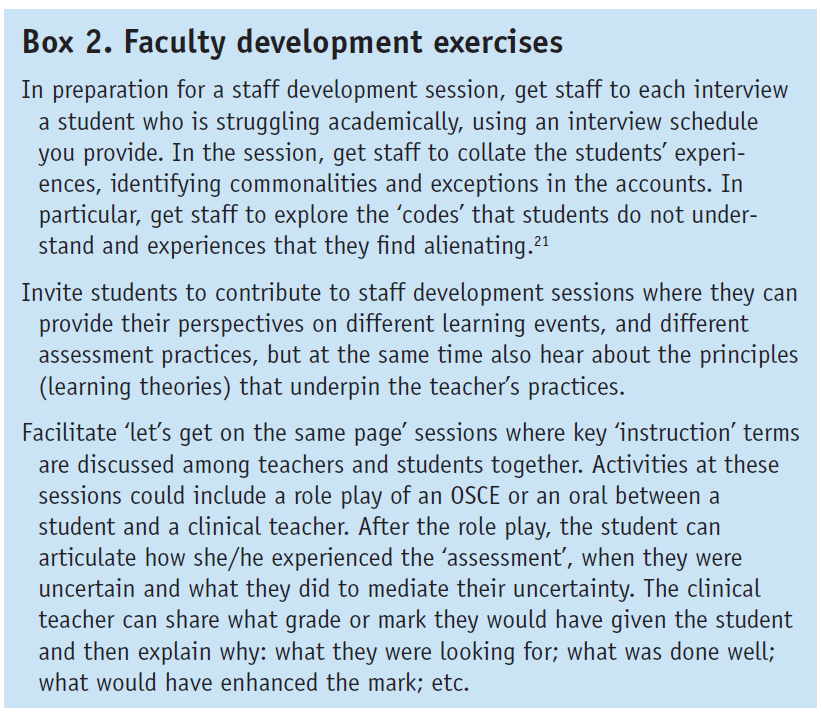

- ERT 동안, 많은 교사들은 온라인으로 가르치는 것이 그들의 교육 전략과 접근법에 대한 재평가를 필요로 하고, 온라인 가르치는 것은 그들이 훈련받지 않은 교육적 접근을 필요로 한다는 것을 깨달았다. 이에 따라 교육이론에 초점을 맞춘 교육 워크숍 및 기타 교육 개입이 요구될 것이다. 비록 제도적 지원에 초점을 맞추겠지만, 동료들의 동료 지지는 (non-judgmental한 방식으로 수행되는 한) 대학 지원의 접근과 함께 매우 귀중하다는 것이 입증될 수 있다. 이것들이 없다면, 교사들이 그들이 하고 있는 피해에 대해 알지 못한 채 그들의 예감을 따를 위험이 있다. 이는 교육 방법이 비표준 강의인 영역(예: PBL, TBL)에서 특히 중요합니다(이 가이드의 마지막 부분에서 조금 더 자세히 다룹니다).

- During ERT, many teachers came to realise that teaching online required a reassessment of their teaching strategies and approaches, and online teaching requires educational approaches for which they were not trained. As a result, educational workshops and other training interventions focusing on educational theory will be required. Although the focus will be on institutional support, peer support from colleagues can prove invaluable, as long as it is performed in a non-judgmental manner, with the approach of collegial support. Without these, there is the risk that teachers will follow their hunches, without being aware of the damage they are doing. This will be especially important in areas where the teaching methods are non-standard lectures (e.g. PBL, TBL) (This is dealt with in a little more detail near the end of this Guide).

- 위의 요점과 유사하게, 훨씬 더 많은 기술 지원과 교육을 이용할 수 있어야 합니다. 많은 직원이 스스로 기술적 트릭을 발견했지만, 부족한 부분을 보완하고 기술 사용에 대한 모범 사례로 전환해야 합니다. 그렇게 하지 않으면 기술 사용은 저조하고 심지어 유해한 결과를 초래할 것이다.

- Similar to the point above, far greater technical support and training will need to be available. Many staff will have discovered technical tricks for themselves, but there is a need to fill in the gaps and also to move towards best practices in the use of technology. Failure to do so will result in technology use, but poor, and even harmful, use.

자신의 프로필 보안

Securing one’s own profile

물질적 접근성을 보장하는 것과는 다소 대조적으로, 보안을 유지하는 윤리적 필요성이 있다. ERT 동안, 교수자들이 [업무와 관련된 목적으로 개인 기기를 사용하는 것]을 발견했고, 이것은 새로운 우려를 낳았다. 수행할 단계는 다음과 같습니다.

Somewhat contrasted to ensuring material accessibility, there is the ethical imperative of maintaining security. During ERT, medical teachers found themselves using their personal devices for work-related purposes, and this introduced new concerns. Steps to take include:

- 가정의 다른 거주자가 개인 기기를 사용할 수 없도록 하십시오. 기기가 있는 곳에서는 시간 초과와 함께 다른 프로파일이 존재하는지 확인하십시오.

- 가정용 장치 및 계정은 업계 표준 암호로 보호되어야 하며, 정기적으로 변경해야 합니다(또는 암호가 손상된 것으로 의심되는 경우). 이는 온라인 교육 시스템에 액세스하는 데 점점 더 많이 사용되는 모바일 장치에서 특히 중요하다.

- 특히 외장 드라이브에 저장된 경우 중요한 데이터는 모두 암호화해야 합니다.

- 홈 네트워크가 제대로 보호되고(최소한 방화벽이 활성화되어야 함), Wi-Fi 모뎀에 대한 액세스가 암호로 보호되어야 하며 Bluetooth 연결은 사용 중일 때만 활성화되어야 합니다.

- Ensure that private devices at home are not accessible to other residents in the home; where they are, ensure that different profiles exist on these, with time-outs.

- Home devices and accounts must be secured with industry-standard passwords, and these should be changed regularly (or if you suspect they have been compromised). This is particularly important for mobile devices that are increasingly used to access online education systems.

- All sensitive data, especially if stored on external drives, should be encrypted.

- Ensure that home networks are properly secured (at the very least, the firewall should be activated), access to Wi-Fi modems should be password-protected, and Bluetooth connections should be activated only when in use.

상호 작용 방법

Methods of interaction

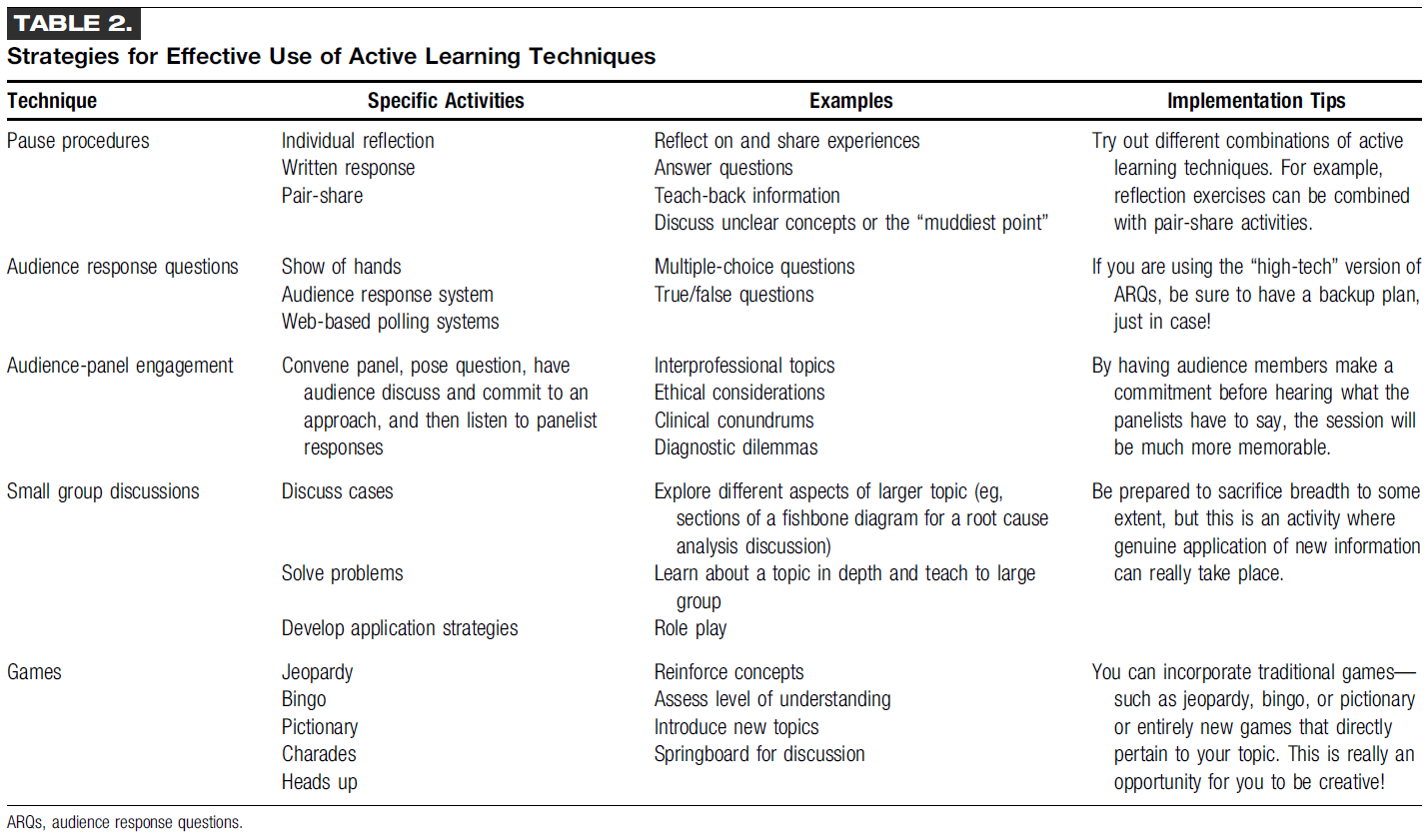

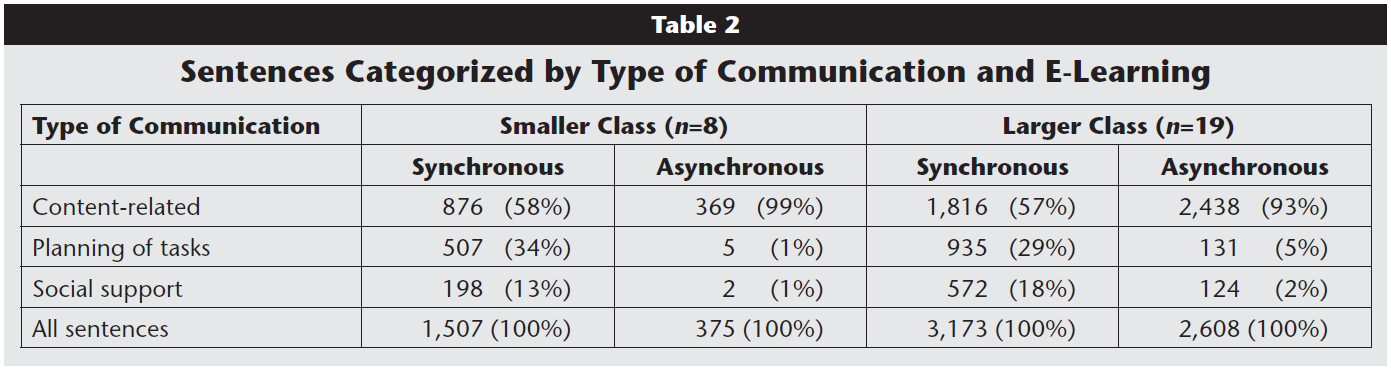

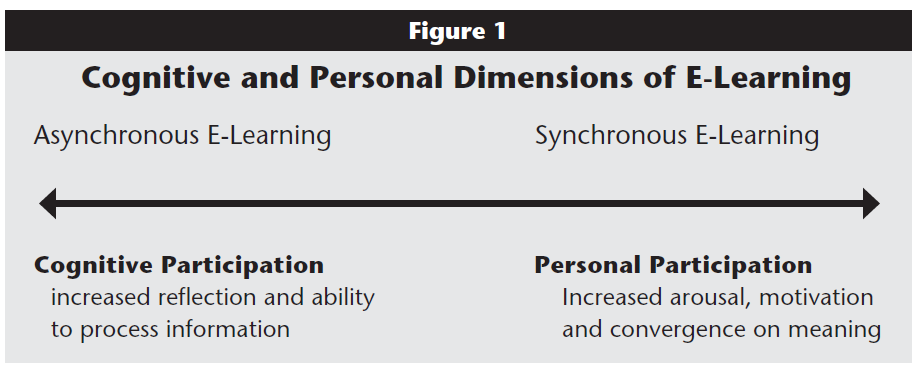

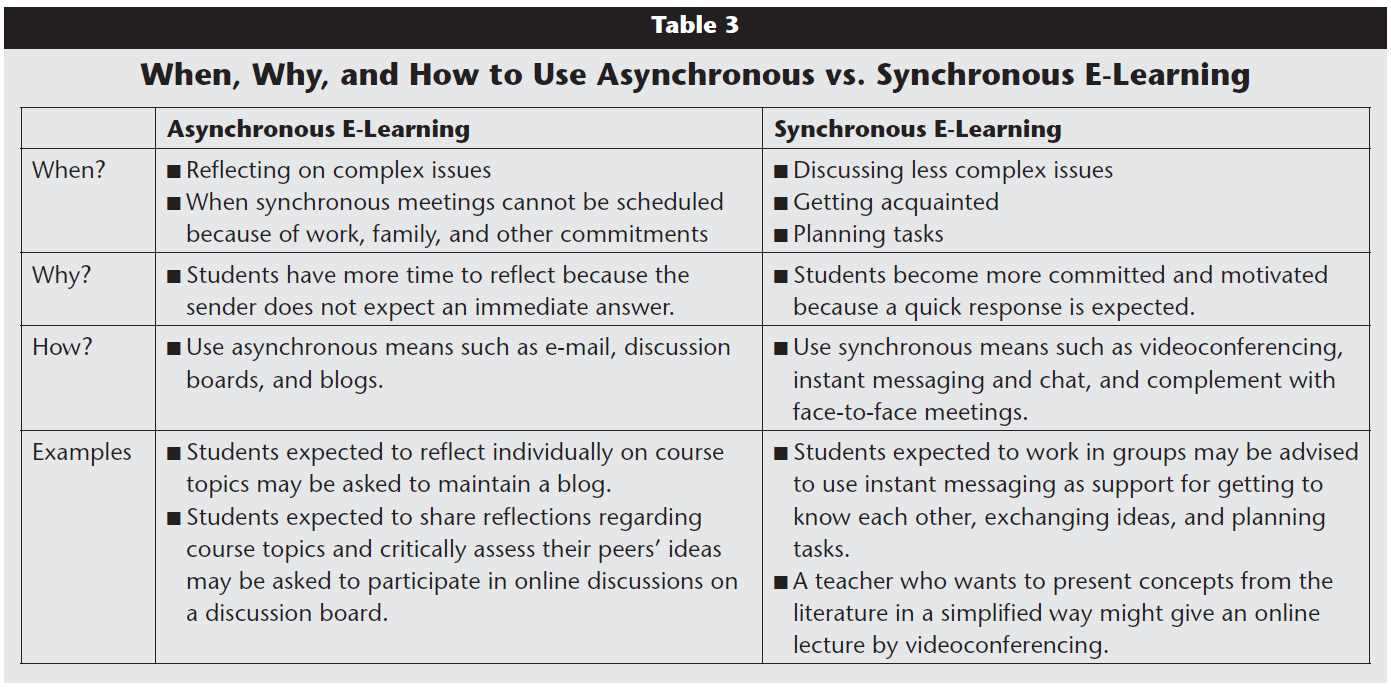

일반적으로 교육적 온라인 상호 작용에는 두 가지 방법이 있다.

- 동기식(일반적으로 Big Blue Button, Google Meet, Microsoft Teams 또는 Zoom과 같은 라이브 비디오 시스템을 통해 실시간 상호 작용), 일반적으로 대화형 강의 또는 대화형 강의의 형태(Stojan et al. 2021),

- 비동기식(예: 미리 만든 프레젠테이션 또는 비디오) 경우에

- 따라 두 가지를 동시에 사용할 수 있습니다.

In general, there are two methods of educational online interaction:

- synchronous (live interaction, usually through live video systems like Big Blue Button, Google Meet, Microsoft Teams or Zoom), usually in the form of an interactive or non-interactive lecture (Stojan et al. 2021), and

- asynchronous (e.g. pre-created presentations or videos).

- In some cases, both might be used simultaneously.

각 형식은 해결해야 할 윤리적 문제를 제기하며, 이 중 일부는 물리적 현실에 의해 결정된다. 예를 들어, Binks 등의 연구는 많은 학생들이 동기식 수업을 선호한다는 것을 보여주었다. 그러나 이 연구는 미국과 영국의 매우 자원이 풍부한 의과대학 학생들 사이에서 수행되었으며, 주로 PBL을 교수법으로 사용했다. 따라서, 그들은 전 세계 모든 교사들의 현실을 반영하지 않을 수 있다. 이것은 학생들이 전통적으로 도시 지역보다 기술적으로 자원이 부족하고 정전과 인터넷 장애에 더 취약한 시골 지역에 위치한 경우에 특히 적절하다. 그 결과, 비디오나 오디오가 내장된 파워포인트(또는 라이브 강의가 녹음되어 LMS에 게시됨)로 사전 녹화된 강의가 선호되기도 한다.

Each format raises ethical issues that need to be addressed, and some of these are dictated by physical reality. For example, a study by Binks et al. (2021) indicated that many students preferred synchronous classes. That study, however, was performed among students from some extremely well-resourced medical schools in the USA and UK, mostly using PBL as their teaching method; as such, they may not reflect the reality for all teachers across the Globe. This is particularly pertinent if students are located in rural areas that are traditionally technologically less well-resourced than urban areas, and more susceptible to power outages and Internet disruptions. As a result, pre-recorded lectures, either as video or PowerPoint with embedded audio (or live lectures that are then recorded and posted to the LMS) are sometimes preferable (Mann et al. 2020; Nkomo and Daniel 2021).

윤리적 온라인 교육을 위해서는 두 가지 선택사항이 모두 고려되어야 한다. 동기식으로 가르칠 때, 교수자 자신의 윤리적 행동이 가장 중요하다. 비록 자신의 윤리적 행동이 자동적으로 학생들의 윤리적 행동으로 바뀔 것이라고 믿는 것은 순진하지만, 비윤리적으로 행동하고 학생들에게 윤리적 행동을 요구하는 것은 위선적이다. 고려해야 할 문제는 다음과 같습니다.

For ethical online teaching, then, both options have to be considered. When teaching synchronously, your own ethical behaviour is paramount. Although it would be naïve to believe that one’s own ethical behaviour will automatically translate into ethical behaviour by students, it is hypocritical to behave unethically and demand ethical behaviour from your students. Issues to consider are:

수업 전

Prior to the class

- 출석, 주소 형식, 학생 및 환자 기밀 유지, 복장 규정, 행동, 마이크 및 비디오 설정, 참여, 휴식 등에 대한 모든 기대가 커리큘럼 개요(위에서 논의됨)에 명확하게 명시되어 있는지 확인합니다. 이 과정의 시작부에서, 학생들에게 수업에서 가장 중요한 것들을 상기시켜라.

- Ensure that all expectations about attendance, forms of address, student and patient confidentiality, dress codes, behaviour, microphone and video settings, engagement, breaks, etc. have been clearly stated in the Curriculum Outline (discussed above). In the earlier part of the course, remind students of the most important of these in the class.

- 세션을 녹화하려는 경우, 이 내용이 커리큘럼 개요에도 명시되어 있는지 확인하고 녹화를 켤 때 학생들에게 알려주십시오(많은 시스템에서 자동으로 녹화가 진행 중임을 알려주고 표시하지만, 이 내용도 구두로 명시해야 합니다). 일부 국가 및 기관은 정보에 입각한 동의와 관련하여 더 엄격한 법적 요구 사항(예: 종이)을 가지고 있을 수 있으며, 이러한 요구 사항 내에서 상호 작용을 수행해야 합니다.

- If you intend to record the session, ensure that this is also stated in the Curriculum Outline, and advise your students when you turn on the recording (Many systems do automatically advise and display an indication that recording is in progress, but you should verbally state this, also). Some countries and institutions may have stricter (e.g. paper) legal requirements regarding informed consent, and you will need to conduct your interactions within those requirements.

- 또한 커리큘럼 개요에 학생들의 활동 기록 및 학생들의 녹음 작업에 대한 행동에 대한 정보가 포함되어 있는지 확인합니다.

- Ensure that your Curriculum Outline also contains information about students’ recording of activities, and their behaviour regarding what they may do with your recordings.

- 초청된 모든 연사가 윤리적 문제에 대해 완전히 인식하고 이에 동의하는지 확인합니다.

- Ensure that any invited speakers are fully aware of the ethical issues, and are in agreement with them.

- 수업 시간보다 훨씬 전에 도착하여 수업 영역을 오픈할 시간을 가지십시오. 수업에 대한 링크가 작동하는지 확인합니다(테스트 학생 계정을 사용합니다. 일부 LMS에 있는 "학생 보기"를 신뢰하지 마십시오). 수업 중에 필요한 폴더, 파일 및 소프트웨어를 엽니다(특히 학생들을 기다리는 동안, 항상 마이크가 켜져 있고 화면이 브로드캐스트되고 있다고 가정하십시오. 그렇지 않으면 심한 충격을 받을 수 있습니다.)

- Arrive well before the time, so that you have time to open the class area, check that the link to the class is working (use a test student account for this – do not trust the “Student View” that exists in some LMSs), and open up any folders, files and software that you will need during the class (A tip, especially while waiting for students: always assume that your microphone is on and your screen is being broadcast, otherwise you may have a nasty shock).

- 일부 설정은 다른 기능에 영향을 미칩니다. 예를 들어 줌에서 포인트 투 포인트 암호화를 사용하면 컴퓨터에 녹화할 수 있지만 클라우드 녹화가 비활성화됩니다.

- Be aware that some settings affect other functionality. For example, in Zoom, using point-to-point encryption disables cloud recording although recording to your computer is still possible.

- 모든 파일을 다운로드하고 학생들이 수업 중에 다운로드하거나 액세스해야 하는 웹 사이트에 액세스합니다. 이렇게 하면 올바른 파일을 사용할 수 있고, 올바른 폴더에 파일을 저장할 수 있으며, 사이트가 작동하는지 확인할 수 있습니다. 개인 컴퓨터를 사용하는 경우 부적절한 파일이나 폴더가 표시되지 않는지 확인합니다.

- Download any files and access any websites that you will require the students to download or access during the class – this will ensure that the correct files are available, that you can put them in the correct folders, and that sites are functioning. If you are using your personal computer, ensure that no inappropriate files or folders are visible.

- 클래스에 대한 과정 이름과 주제를 제공하는 [보류 페이지]를 표시합니다(단순 PowerPoint 슬라이드일 경우에도). 이것은 학생들이 입장했을 때 올바른 수업에 있다는 것을 안심시킬 것이다.

- Display a holding page (even if it is simply a PowerPoint slide) that gives the course name and topic for the class. This will reassure students that they are in the correct class as they enter.

- 채팅 영역을 열고, 학생들이 문제가 있어 귀하에게 연락할 필요가 있을 경우 계속 주시하십시오(또한 학생이 교습 영역에 전혀 들어갈 수 없는 경우 다른 커뮤니케이션 채널을 모니터링해야 합니다).

- Open the chat area, and keep an eye on it in case students are having problems and need to contact you (Also ensure that you monitor other communication channels, in case the students cannot enter the teaching area at all).

- 모든 참가자를 "음소거"로 설정하지만, 선택한 경우 음소거 해제를 허용합니다.

- Set all participants to “mute,” but allow them to unmute if they choose.

수업중

During the class

- 비디오 카메라 전송에 대한 결정이 필요합니다. 비록 많은 학생들이 당신의 비디오 이미지를 보기를 선호하지만, 그것은 밴드 위드(band-with)를 사용하기 때문에, 수업을 시작하기 전과 시작할 때에만 카메라를 켜고 수업이 시작되면 그것을 끄기를 원할 수도 있다.

- A decision will need to be made on your video camera transmission. Although many students prefer to see your video image, it does consume band-with, so you may wish to have your camera on only before and as you start class, and then turn it off once the class begins.

- 학생 카메라 설정이 더 어렵습니다. 학생들의 카메라가 켜져 있으면 상호작용이 자주 개선되지만, 이것은 불필요하게 방해될 수 있다. 또한, 카메라를 켤 때 근로자들이 더 피곤하다는 연구 결과도 있다. 따라서 꼭 필요한 경우가 아니라면 학생들이 카메라를 끄도록 허용하는 것을 고려해야 한다. 여러분은 학교의 규칙, 개인적인 선호, 그리고 학생들의 바람의 균형을 맞출 필요가 있을 것입니다.

- Student camera settings are more difficult. Although the interaction is frequently improved if students’ cameras are on, this may be unnecessarily intrusive. In addition, there is some research indicating that workers are more fatigued when cameras are on (“Zoom fatigue”) (Fauville et al. 2021; Shockley et al. 2021), so, unless it is absolutely necessary, one should consider permitting students to turn off their cameras. You will need to balance your institutions’ rules, personal preferences and the students’ wishes.

- 채팅 영역에서 묻는 질문에 답할 때는 질문에 답하기 전에 항상 학생의 이름을 사용하십시오. 법적, 제도적 또는 합의된 형태의 주소가 있을 수 있으며, 이러한 것들이 따라야 한다.

- When replying to questions asked in the chat area, always use the student’s name before answering the question. There may be legal, institutional, or agreed-to forms of address, and these need to be followed.

- 때때로, 학생들은 의견을 말하거나 질문을 하기 위해 손을 들 것이다. 이 점이 만족스럽게 해결된 후, 학생은 들어올린 손(때로는 "legacy hand"이라고도 함)을 제거하는 것을 잊어버릴 수 있습니다. 이것은 학생에게 약간의 당혹감을 줄 수 있기 때문에, 요점이 해결된 후에, 선생님은 수동으로 손을 내릴 수 있다(이렇게 할 것이라는 것은 온라인 수업 에티켓의 일환으로 학생들에게 알려져야 한다).

- Occasionally, a student will raise their hand to comment or ask a question. After the point has been satisfactorily addressed, the student may forget to remove the raised hand (sometimes termed a “legacy hand”). This can result in some embarrassment for the student, so, after the point has been addressed, the teacher can manually lower the hand (That the teacher will do this should be made known to the students as part of the online class etiquette).

- 소규모 그룹 작업을 사용하는 경우, 사용자(또는 튜터)가 각 그룹에 유사한 시간을 할애할 수 있는지 확인하십시오.

- If using any type of small group work, ensure that you (or tutors) are able to devote similar time to each group.

수업이 끝난 후

After the class

- 수강생에게 개인정보 유출을 요구하는 경우, 종단간(또는 지점간) 암호화가 가능한 시스템을 사용하고, 최종 녹취록에서 편집이 필요한지 확인한 후 수강생에게 게시한다.

- If the class requires students to divulge personal information, then use a system that permits end-to-end (or point-to-point) encryption, and check the final recording to see if it requires editing before posting it to the class.

- 일부 동기화 시스템은 자동 또는 수동 실시간 캡션을 허용하고, 다른 동기화 시스템은 미팅 후에 사용할 수 있는 텍스트 스크립트를 만듭니다. 비록 그 녹취록은 오류가 있을 것이지만, 선생님이 분명하게 말한다면, 그것은 놀랍도록 정확하다 (그러나, 몇몇 이름들은, 문제가 있을 수 있다). 시스템의 특성을 고려할 때, 이것은 범죄를 일으킬 가능성이 낮다; 만약 그렇다면, 간단한 검색-바꾸기로 이러한 문제를 해결할 수 있다).

- Some synchronous systems allow for automatic or manual live captions; others create a text transcript that is available after the meeting. Although that transcript will have errors, it is surprisingly accurate, if the teacher speaks clearly (Some names, however, may have problems. Given the nature of the system, this is unlikely to cause offence; if it does, then a simple Search-and-Replace can correct these).

- 수업이 끝난 후 가능한 한 빨리 녹음(및 대화록 및 대화 파일)을 수업에 사용할 수 있도록 해야 합니다.

- As soon as possible after the class, the recording (and the transcript and chat files) should be made available for the class.

- 수업 중에 기밀 또는 기타 허용되지 않는 자료 공개가 이루어진 경우 게시하기 전에 비디오를 편집해야 합니다. 유용하고 무료인 비디오 편집자는 Kdenlive(https://kdenlive.org. . . . . )이다.

- If, during the class, confidential or other unacceptable disclosure of material was made, then the video should be edited before posting. A useful and free video editor is Kdenlive (https://kdenlive.org. . . . ).

[비동기적]으로 가르칠 때는 파일 형식에 대한 위의 절을 참조하여 모든 파일을 볼 수 있도록 하십시오. 추가 사항:

When teaching asynchronously, please refer to the section above on file formats to ensure that all your files can be viewed. In addition:

- 사전녹화의 목적은 선생님에게 상황을 더 쉽게 만드는 것이 아닙니다. 어떤 경우에는, 자신의 존재를 유지하고 모든 학생들에게 필요한 자료의 접근성을 유지하는 것이 훨씬 더 어려울 것이다. 즉각적인 학생 피드백이 없다면, 초보자들이 너무 일찍 녹음을 준비하는 것은 현명하지 못하다. 왜냐하면 학생 피드백은 교사가 미래의 녹화를 위해 녹음 오류를 쉽게 수정할 수 있게 할 것이기 때문이다.

- The aim of pre-recording is not to make things easier for the teacher. In some cases, it will be a great deal harder to maintain one’s presence, and ensure that the necessary materials’ accessibility for all students is maintained. With no immediate student feedback, it is unwise for the novice to prepare recordings too far in advance, as student feedback will allow the teacher to easily correct recording errors for future recordings.

- 너무 뒤처진 학생들은 따라잡는 데 큰 어려움을 겪을 것이기 때문에, 학생들의 활동을 추적하고 즉각적인 조치를 취하는 것은 필수적이다.

- Tracking student activities, and taking immediate action, is essential (more on that below), as students who fall too far behind will have great difficulty in catching up.

- 녹화의 시작 화면에는 예상 시간과 이 클래스와 관련된 기타 활동이 정확하게 표시되어야 합니다. 이를 통해 학생들은 각 세션에 대한 시간을 적절하게 편성할 수 있고, 또한 미리 세션을 적절하게 준비할 수 있도록 할 것이다.

- The opening screen of the recording should give an accurate indication of the time expected, and any other activities that are associated with this class. This will allow students to properly budget their time for each session, and also to ensure that they can properly prepare for the session beforehand.

다른 교호작용도 고려해야 합니다. 정규 수업 외에도, 여러분은 다른 매체를 통해, 때로는 LMS에 내장되어 있고, 때로는 외부 매체를 통해 학생들과 상호 작용을 할 것입니다. 고려해야 할 몇 가지 사항은 다음과 같습니다.

Other interactions must also be considered. In addition to formal classes, you will have interactions with your students through other media, sometimes built into the LMS, and other times external. Some things to consider are:

- 자료에서 언어 수준에 대한 참조가 이미 이루어졌다. 포럼과 이메일을 통해 학생들과 소통할 때, 특히 모국어가 아닌 사용자(또는 다양한 배경의 모국어 사용자)가 예의 바른 언어 신호를 종종 놓치고, 쓰여진 텍스트를 읽을 때 무례하게 보일 수 있다는 것을 기억해야 한다. 표현을 극도로 조심해라. 필러 문구(예: "유감스럽지만…")가 혼동을 일으키지 않도록 하십시오.

- Reference has already been made to language levels in the materials. When communicating with students through forums and email, one must remember that courtesy language signals (which, in spoken interactions, would be identified in an audio tone) are often missed, especially by non-mother-tongue speakers (or mother-tongue speakers from a range of backgrounds), and may come across as rude when reading written text. Be extremely careful in your phrasing. Ensure that filler-phrases (e.g. “I’m afraid that….”) do not cause confusion.

- 학생들의 의사소통을 읽을 때, 마음을 열고 무례하게 보이는 것에 대해 화를 내는 것을 늦추세요. 일반적으로 사람들은 낯선 언어를 사용할 때 메시지에 집중하는 경향이 있고, 문법과 예의를 잃는다. "Please"와 같은 단어는 때때로 단어보다는 어조에 내포되어 있으므로, "I want..."는 "Please may i have..."와 동등합니다. 대부분의 언어와 마찬가지로 영어에서도 비슷한 의미의 단어와 구(예: "상관없어"/"상관없어"/"내 문제가 아니야"/"내 잘못이 아니야") 사이에 중요한 차이점이 존재하며, 이러한 중요한 차이점들은 모두에게 즉시 명백하지 않다. 게다가, 구어와 문자의 구별이 항상 명확한 것은 아니다 (그래서 문자 메시지 약어를 제외하고, "gonna"와 "wanna"와 같은 단어들은 어떤 사람들에게는 부적절하지만, 다른 사람들에게는 완벽하게 받아들여질 수 있다). 가장 안전한 방법은 항상 그 사람이 범죄를 의도하지 않았다고 가정하는 것이다.

- When reading your students’ communication, keep an open mind, and be slow to take offence at seeming rudeness. Generally, when people are using an unfamiliar language, they tend to focus on the message, and the grammar and courtesies are lost. Words like “Please” are sometimes implied in the tone rather than by a word, so “I want…” is an equivalent of “Please may I have…”. In English, as with most languages, there are important differences between similar-meaning words and phrases (e.g. “I don’t care”/“I don’t mind”; “It’s not my problem”/“It’s not my fault”), and these significant differences are not immediately apparent to all. In addition, the distinction between spoken and written is not always clear (so, apart from text-message abbreviations, words like “gonna” and “wanna” may be seen as inappropriate to some, but perfectly acceptable to others). The safest route is always to assume that the person does not intend offence.

- 비기관 메시징 앱은 전화 번호를 자주 표시하므로 개인 정보 보호라는 윤리적 문제가 있을 수 있습니다. 특히 유용한 무료 앱은 Band(https://band.us/en. . . )로, 다른 메시징 앱처럼 작동하지만 전화번호는 표시되지 않으며 교사들에게 유용한 다양한 추가 기능을 갖추고 있다. 앱을 사용할 때(외부 소프트웨어와 마찬가지로) 데이터 공유 정책이 잘 이해되고 허용될 수 있도록 주의해야 한다.

- Non-institutional messaging apps frequently display telephone numbers, so may have ethical issues of privacy. A particularly useful free app is Band (https://band.us/en. . . . ) which works like any messaging app, but does not display telephone numbers, and has a wide host of extra features that are useful for teachers. When using any app (as with any external software), one should take care to ensure that the data-sharing policies are well-understood and acceptable.

- 개인 전자 메일도 사용할 수 있지만, 과정 내용에 대한 학생 질문에 답변할 때 주의해야 합니다. 부당하게 혜택을 받는 학생이 없도록 (학생을 식별하지 않고) 질문을 과정 포럼 메시지에 복사하여 붙여넣고, 그 다음에 답을 제시합니다. 이렇게 하면 모든 학생이 질문과 대답을 볼 수 있을 뿐만 아니라 전자 메일로 보낸 쿼리의 중복 수도 줄어듭니다.

- Private email can also be used, but care should be taken when answering student questions about course content. To ensure that no student is unfairly advantaged, copy-and-paste the question (without identifying the student) into a course forum message, followed by the answer. This not only ensures that all students see the question and answer but also reduces the number of duplicates of emailed queries.

- 학생들이 모이는 너무 많은 온라인 영역에 접근하는 것을 경계하라, 왜냐하면 그것은 "소름끼치는 나무집 효과"로 이어질 수 있기 때문이다.

- Be wary of accessing too many online areas where your students congregate, as it can lead to the “creepy-treehouse effect.”

학생에 대한 피드백

Feedback to students

학생에 대한 피드백은 의학교육에서 중요한 부분이며, 온라인교육에서 더욱 중요한 역할을 한다. 왜냐하면 온라인교육은 학생들이 그 과정의 형성과 종합적 진행과 그들의 기술발달에 대해 제대로 알 수 있도록 하는 데 중요한 역할을 하기 때문이다. 이것은 과정의 많은 부분이 비동기적으로 학습되는 경우에 특히 중요하다. [학생의 발전을 보장하는 방식으로 피드백]을 수행하기 위해 다음과 같은 몇 가지 작업을 수행할 수 있습니다.

Feedback to students is a crucial part of any medical education (Harden and Laidlaw 2013), and is more so in online education, as it plays a vital role in ensuring that students are properly informed of their formative and summative progress in the course and their skills’ development. This is especially important if much of the course is taught asynchronously. To perform feedback in a manner that ensures student development, several things can be done:

- 라이브로 일대일 세션을 진행할 수 있으며, 이러한 세션은 가치가 있다는 것을 증명할 수 있습니다. 고려해야 할 몇 가지 문제:

- Live, one-to-one sessions can be held, and these can prove valuable. Some issues to consider:

- 가상 오피스 아워를 설정합니다. 이는 강좌가 정해진 구조를 가지고 있으며, 학생들이 이를 활용해야 한다는 점을 강조할 것이다.

- Set virtual office hours. This will emphasise that the course has a set structure, and students should utilise it.

- 많은 경우, 토론이 심도 있게 진행될 것이고, 여러분과 여러분의 학생 모두 필기보다는 토론에 집중하고 싶어할 것입니다. 만약 학생이 당신이 녹음을 만드는 것에 만족한다면, 녹음을 만들고 가능한 한 빨리 그 학생과 공유하세요.

- In many cases, the discussion will be in-depth, and both you and your student will want to concentrate on the discussion rather than taking notes. If the student is happy with your making a recording, then make one, and share it with that student as soon as possible.

- 암호화. 이러한 세션은 일반적으로 성적, 개인 성과 및 개인 정보에 대한 토론을 포함하므로 종단 간 암호화가 권장된다.

- Encryption. As these sessions will usually involve discussions around grades, personal performance, and possibly deeply personal information, end-to-end encryption is recommended.

- 실시간 일대다 세션도 중요합니다.

- Live, one-to-many sessions are also valuable:

- 과제와 시험에 대한 일반적인 피드백을 제공하기 위해.

- For giving general feedback on assignments and tests.

- 일대일과 유사하게 가상 사무실과 녹화가 선호된다.

- Similar to the one-to-one, the virtual office and recording is preferable.

- 일반적인 정기적인 피드백도 중요한 역할을 합니다.

- General, regular feedback also serves an important role:

- 매주 또는 최소 2주(모듈이 더 긴 경우)여야 합니다.

- This should be per week or, at the very least, fortnight (if modules are longer).

- 이 과정이 텍스트일 필요는 없으며, 미리 녹음된 오디오 및/또는 비디오 피드백이 대부분 비동기적으로 학습되는 경우 더욱 유용할 수 있습니다.

- This does not have to be text only, and pre-recorded audio and/or video feedback can be useful, more so, if the course is largely taught asynchronously.

- 이를 통해 다음 주에 예상되는 내용을 간략하게 소개할 수 있습니다.

- This can be used as a brief introduction of what to expect in the next week.

온라인 관리 및 상담

Supervision and counselling online

기관의 자원과 학생들의 선호에 따라 윤리 의학 교사의 접촉은 피드백을 넘어 더 깊은 감독과 상담의 영역으로 넘어가야 할 수 있다. 모든 기관은 자체적인 규칙과 정책을 가질 것이지만, 교사가 고려해야 할 몇 가지 요소들이 있다.

Depending on the institutions’ resources and students’ preferences, contact from the ethical medical teacher may have to go beyond feedback, and into areas of deeper supervision and counselling. Every institution will have its own rules and policies, but there are several factors that the teacher should consider:

- 학생들과의 정기적이고 예정된 모임은 온라인 수업의 중요한 요소이다. 그들은 학생들이 단순히 그들 스스로 일하는 것이 아니라 조직적인 활동의 일부라는 것을 깨닫도록 돕고, 선생님들이 그들의 학생들을 이해하도록 돕는다. 그것은 또한 학생들에게 단순히 학문적이지 않을 수도 있는 문제나 문제들을 제기할 수 있는 기회를 준다. 이러한 문제가 일대일 대화에서 제기되면 도움이 됩니다.

- Regular and scheduled meetings with students are an important element of online teaching. They help the student to realise that they are part of organised activity, not simply working on their own, and it helps teachers to understand their students. It also gives the students the opportunity to raise issues or problems which may not simply be academic. It is helpful if these issues are raised in a one-to-one conversation.

- 때때로, 학생들과 직접 접촉할 때와 마찬가지로, 우리는 [개별 학생과 더 긴밀하게 다뤄져야 하는 이슈가] 그룹 환경에서 노출되었다는 것을 깨닫는다. 이것은 개인적으로 다루는 것이 가장 좋다. 다음 그룹 또는 독립 활동 기간 동안 "브레이크아웃 룸"에 학생을 초대하는 것으로 충분할 수 있습니다. 만약 이것이 학생에게 관심을 끌거나 더 자세한 토론이 필요할 수 있다고 생각한다면, 차라리 개인 채팅 메시지, 문자 메시지 또는 이메일을 통해 학생을 개인 일대일 세션에 초대하십시오.

- Sometimes, just as in face-to-face contact with students, we realise that an issue has arisen, or been disclosed in a group setting which needs to be covered more closely with an individual student. It is best if this can be done privately. It might be sufficient to invite the student to join you in a “breakout room,” during the next period of a group or independent activity. If you feel that this may draw attention to the student, or may require a more detailed discussion, then rather invite the student to a private one-to-one session through a private chat message, text message or email.

- 이러한 세션은 반드시 암호화되어야 합니다.

- It is essential that these sessions are encrypted.

- 대부분의 기관들은 비록 기관들이 여러분이 대화에 대한 세부 사항을 제공하기를 기대할지 여부에 따라 다르지만, 여러분이 학생과 대화를 나눴다고 말하는 기록을 만들 것이라고 예상할 것이다. 일반적으로 대면 회의에서 적용되는 것과 동일한 방식으로 적용되는 [세 가지 고려 사항]이 있습니다.

- Most institutions would expect that you make a record saying that you had spoken with a student, although institutions vary as to whether they expect you to give any detail of the conversation. There are three considerations, that would apply in the same way that they would normally apply in face-to-face meetings:

- 학생은 어떤 정보를 기록하려고 하는지, 어떻게 사용될지, 누가 볼지를 항상 알고 있어야 하며, 학생의 동의가 있어야만 진행할 수 있습니다.

- The student must always know what information you are intending to record, how it will be used and who will see it, and you can only proceed with their consent.

- 만약 여러분이 더 유능하거나 경험이 많은 동료에게 추천하는 것이 도움이 될 것이라고 생각한다면, 여러분은 여러분 자신에게, 그리고 그 학생에게 분명히 할 필요가 있을 것입니다.

- You will also need to be clear to yourself, and to the student if you feel that a referral to a more competent or experienced colleague would be helpful.

- 물론 학생들은 도움을 거절할 수 있다. 이 경우 지원이 제공되고 거부된 사실을 기록해야 합니다.

- Students can, of course, refuse help. In which case you will need to record the fact that support was offered and declined.

- 학생은 어떤 정보를 기록하려고 하는지, 어떻게 사용될지, 누가 볼지를 항상 알고 있어야 하며, 학생의 동의가 있어야만 진행할 수 있습니다.

보다 심층적인 접근성

Deeper accessibility issues

접근성의 중요한 윤리적 원칙은 이미 제기되었고, 그것은 위에서 논의된 것보다 훨씬 더 멀리 간다. 교재를 접근 가능하게 만드는 것이 첫 번째 단계이지만, 학생들이 필요한 교재에 접근할 수 있는 기술적 전문 지식, 훈련 또는 법적 권리가 없고 온라인 학습의 추가적인 상호 작용 요구를 이해하지 못하면 접근성이 저하됩니다. 다음 세 가지 문제를 더 자세히 고려해야 합니다.

The important ethical principle of accessibility has already been raised, and it goes much further than has been discussed above. Making teaching material accessible is the first step, but, if students do not have the technical expertise, training or legal right to access the required material, and do not understand the extra interaction demands of online learning, then accessibility is compromised. These three issues should be considered in more detail:

Student technical expertise

파일 및 사용 편의성에 대한 언급이 이미 이루어졌습니다. 모든 학생들이 자연스럽게 기술에 익숙하다는 것은 흔한 오류이다; 많은 학생들은 그렇지 않고, 많은 학생들은 그것에 관심이 없다. 또한, 일부 학생들은 고립된 지역에서 일하고 있으며, 컴퓨터 소프트웨어의 교육 자료에 쉽게 접근할 수 없거나 기술 지원을 받을 수 없을 것이다. 따라서, 학생들이 지원 자료와 교직원을 이용할 수 있는 것이 필수적이다. 많은 과제들이 휴일이나 밤늦게 제출되도록 설정되어 있기 때문에, 시간외 지원도 가능해야 한다(사실, 온라인 학생의 세계에서는 "근무시간"과 "시간외"의 개념이 막연히 익숙하지만 기묘하게 구식 개념이라는 것을 알아야 한다).

Reference has already been made to files and ease of use. It is a common fallacy that all students are naturally familiar with technology; many are not, and many have no interest in it. In addition, some students are working in isolated areas, and will not have easy access to instructional material on computer software or access to technical support. As a result, it is imperative that supporting material and staff are available to students. Given that many assignments are set to be submitted after holidays and/or late at night, after-hours support should also be available (In fact, the institution needs to be aware that, in the world of the online student, the concepts of “working hours” and “after-hours” are vaguely familiar, but quaintly old-fashioned concepts).

Student peer-work

매우 상호작용적인 온라인 과정은 포럼이나 공식 과제 영역에서 많은 양의 학생 작업을 발생시킬 수 있다. 이것은 형식적인 학생 동료 학습, 복습 및 평가를 위한 기회를 제공하지만, 학생들은 관련된 과정에 대해 적절하게 훈련되고 지도되어야 한다. 인터랙티브 화이트보드, 파워포인트 프리젠테이션 등 다양한 수업방식이 온라인 수업환경에서 적용될 수 있으므로, 학생 튜터student tutors는 온라인 수업에서 학생들과 상호작용하는 방법과 관련 정보를 전달하는 방법에 대해 교육을 받아야 한다. 또한 학생과 학생 튜터는 온라인 교육에 사용되는 소프트웨어(예: 줌 또는 마이크로소프트 팀)에 익숙해야 한다.

Highly-interactive online courses can generate a large amount of student work, either in the forums or in formal assignment areas. This does offer the opportunity for formative student peer-learning, reviewing, and assessment, but students must be properly trained and coached in the processes involved. Student tutors should be trained on how to interact with students in an online course and how to deliver the relevant information to them as different ways of teaching can be applied in the online teaching setting like interactive whiteboards, PowerPoint presentations, etc. Further, students and student tutors should familiarise themselves with the software used in online teaching (e.g. Zoom or Microsoft Teams).

Students’ accessing copyrighted references

학생들이 구매해야 하는 값비싼 소프트웨어를 사용하는 것을 피해야 하듯이, 유료 벽 뒤에 숨겨진 텍스트나 기사를 참조하는 것도 피해야 한다. 많은 경우, 대안이 없지만, 대학 도서관이 대리 서비스를 통해 학생들이 그들의 자료에 온라인으로 접근할 수 있도록 해야 한다. 만약 이것이 이루어지지 않는다면, 학생들은 이 자료들에 접근하기 위한 다른 방법들을 추구할 것이다.

Just as one should avoid using expensive software that should be purchased by students, one should also avoid referring to texts and articles that are hidden behind paywalls. In many cases, there is no alternative, but the department should then attempt to ensure that the university library, through a proxy service, allows the students online access to their materials. If this is not done, then students will pursue other means to access these materials.

임상 교육 관련 문제

Issues specific to clinical teaching

환자들은 종종 임상 수업에서 중요한 부분이다. 온라인 교육에 환자를 포함할 때, 선생님들은 몇 가지 특별한 점을 고려할 필요가 있다. 기억해야 할 몇 가지 사항:

Patients are often a crucial part of clinical teaching. When including patients in the online teaching, some special points need to be considered by the teachers. Some points to remember:

- 사용되는 소프트웨어는 데이터 보호의 형식을 충족해야 합니다(위에서 설명한 법률 및 정책 참조).

- The software used has to fulfil the formalities of data protection (see reference to the laws and policies outlined above).

- 교수자는 학생에게 각 세션에서 [환자 기밀]에 대해 상기시켜야 한다. 이것은 일반적인 기밀성을 넘어서며, [다른 사람이 학생과 함께 방에 있지 않도록 하는 것]과 [모니터의 배치]와 같은 문제까지도 포함합니다. 이러한 맥락에서, 학생들은 조용하고 방해받지 않는 장소에서 온라인 교육에 참여하도록 해야 한다.

- Students should be reminded of patient confidentiality by the teacher at each session. This exceeds the usual confidentiality and includes issues like ensuring no other person is in the room with the student and the placement of the monitor. In this context, students should ensure that they participate in online teaching while in a quiet and undisturbed place.

- 학생이 이 과정을 기록하는 것은 엄격히 금지되어 있다.

- Student recording of the process is strictly prohibited.

- 기관 녹화는 특별한 사정이 없는 한 금지되는 경우가 많다. 이러한 상황에서, 당신의 기관의 연구 윤리 원칙을 따르는 것이 가장 좋을 것이다.

- Institutional recording is frequently prohibited unless special circumstances exist. Under these circumstances, it would be best to be guided by your institutions’ research ethics principles.

- 모든 대학 규정 외에도 [LMS에 환자 비디오의 저장 및 제공에 관한 임상 현장별 규정]을 수용해야 한다.

- In addition to any university regulations, clinical site-specific regulations concerning storage and provision of patient videos in the LMS must be accommodated.

- 환자는 데이터 안전 또는 인간의 부정행위와 관련된 가능한 위험에 대해 informed 되어야 하며, 자신의 정체성을 보호하기 위해 취한 조치에 대해서도 알아야 한다(따라서, 정보에 근거한 동의 양식은 비록 조금 기술적이더라도 명시적이어야 한다).

- The patient needs to be informed about possible risks connected to data safety or human misconduct and also informed about the steps taken to protect their identity (As a result, the informed consent form needs to be explicit, even if a little technical).

- 환자들은 어떤 임상적 상황에서와 마찬가지로, 공동의 의사 결정 과정에 참여할 수 있도록 자신의 약속과 가능한 최악의 시나리오에 대해 완전히 알 필요가 있다.

- Patients need to be fully informed about their commitment and possible worst-case scenarios so that they can engage in the shared decision-making process as they would in any clinical situation.

- 어떤 형태의 온라인 병실 라운드에서든 교사와 학생의 개인 공간을 확보하는 것 외에도, [병원에 있는 사람들]은 종종 사생활(예: 침대 머리맡에 놓여 있는 사적인 편지)을 돌보는 것을 잊어버리기 때문에, 의도하지 않은 정보가 방송되는 것을 피하기 위해 환자의 개인 공간을 확보하는 데 많은 주의를 기울여야 한다.

- With any form of online ward-rounds, apart from securing the personal space of the teacher and the student, great care must be taken to secure the patients’ private space, in order to avoid unintended information broadcast, as people in hospitals frequently forget to take care of their privacy (e.g. a private letter lying on the bedside table).

- 개인 공간의 확보는 배경과 인근 환자 및 방문객으로부터 보호하는 것에도 적용된다. 대부분의 병원은 방마다 침대가 하나 이상 있고, 이웃과 방문객은 동의는커녕 자신도 모르게 촬영(혹은 엿듣기)될 수 있다.

- The securing of the personal space also applies to the background and protecting nearby patients and visitors. Most hospitals have more than one bed per room, and neighbours and visitors could unintentionally be filmed (or overheard) without their knowledge, let alone consenting.

- 더 기술적으로는, 온라인에서 병동회진을 가르칠 때, 다음과 같은 문제를 고려하기 위해 기술을 사전 테스트해야 한다.

- 임상 네트워크의 불안정성,

- 교수 네트워크와 임상 네트워크의 잠재적 비호환성

- 장비의 휴대성이 주는 편리성(예: 모바일 태블릿 또는 전화)과 기능 저하(예: 테이블 또는 전화기의 마이크가 일반적인 병원 배경 소리에 대해 환자의 목소리를 명확하게 포착하기에 충분하지 않음)의 균형을 맞추는 것

- On a more technical note, when teaching online ward-rounds, one should pre-test the technology to take into account issues like

- the instability of the clinical network,

- potential incompatibility of the teaching network and the clinical one, or

- balancing the convenience of easily transportable equipment (e.g. a mobile tablet or phone) against reduced functionality (e.g. microphone of the table or phone not good enough to capture a patient’s voice clearly against the usual hospital background sounds).

학생평가

Student assessment

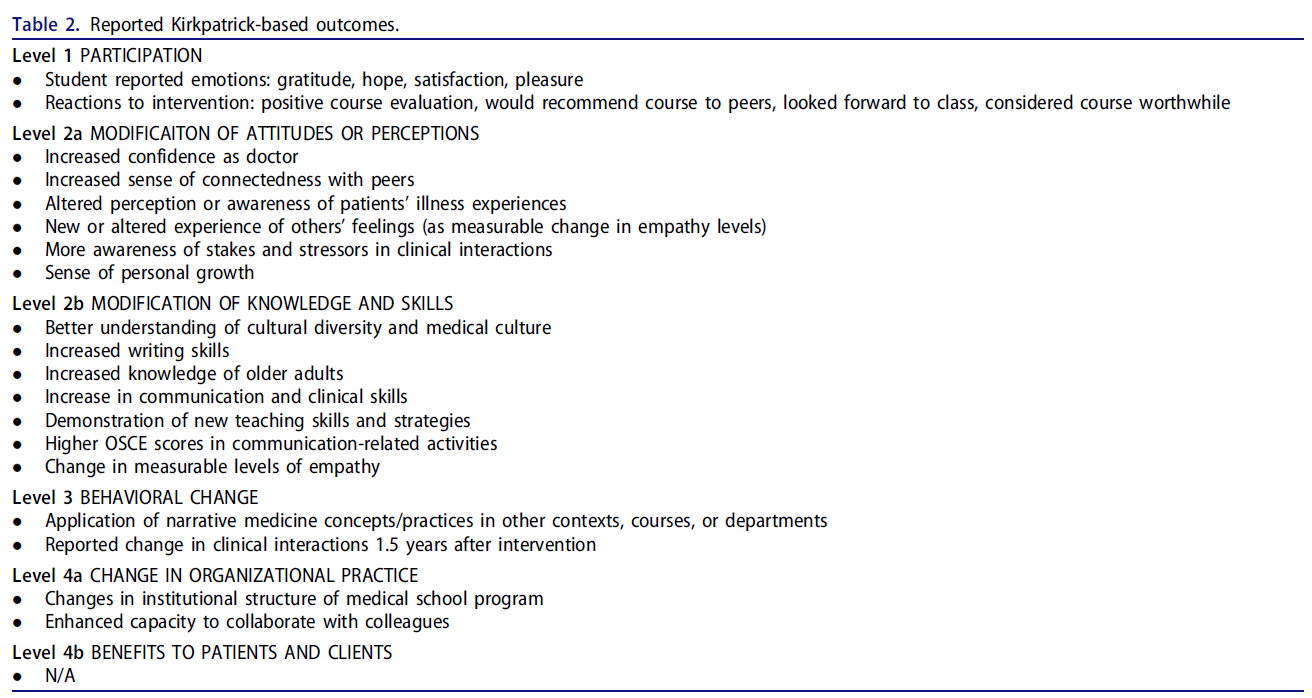

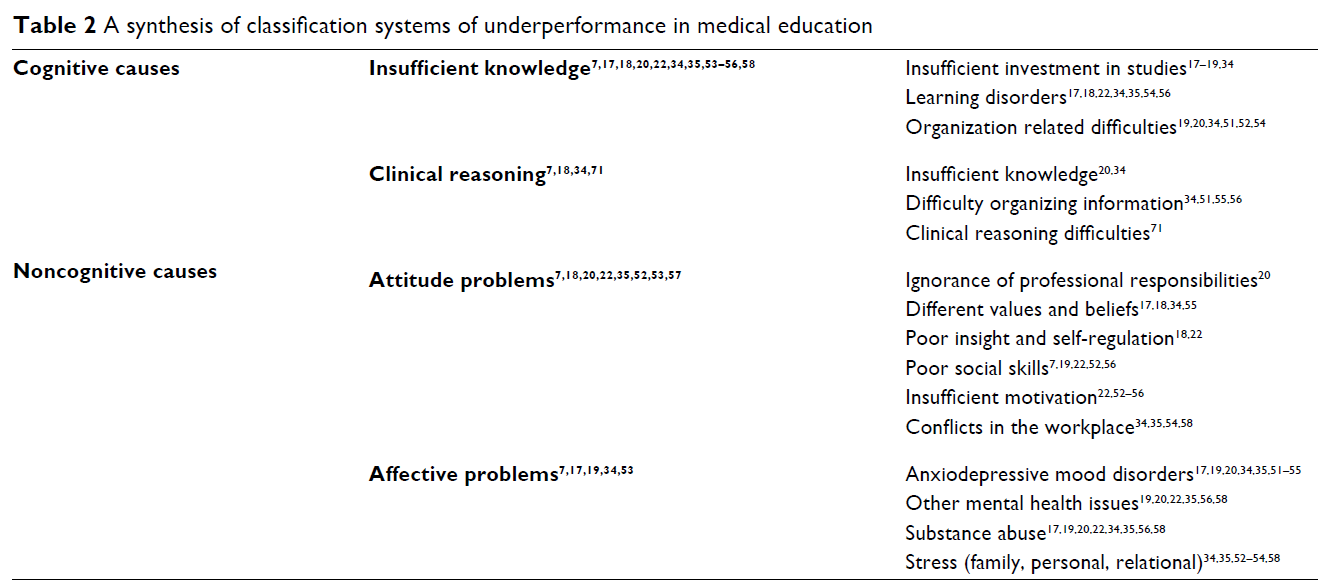

정확하고 유효한 평가를 갖는 것은 의학 교육에서 오랫동안 우려되어 왔으며, ERT는 특히 원격으로 완료된 온라인 평가와 같은 추가적인 합병증을 도입하여 많은 교육자들이 공정성과 타당성의 균형을 맞추기 위해 고군분투하게 만들었다. 학년 가중치, 학생식별, 지속적이고 반복적인 평가를 다루려고 시도한 다양한 지침이 소개되었다. 또한, 다음에 한 우려가 있었다.

- 평가 질문의 유형 (예: 교수진은 기존에 확립되어 있던, 과거에는 보호되었던 MCQ 은행을 잃음).

- 실습 시험(예: OSCE, OSPE, viva)을 더 많이 수행하는 방법

- 그룹 프로젝트 성적이 구성원들의 기여를 제대로 반영할 수 있도록 하는 방법

Having accurate and valid assessments has long been a concern in medical education, and ERT introduced further complications, specifically online assessments completed remotely, that left many educators struggling to balance fairness and validity. Various guidelines were introduced (e.g. (García-Peñalvo et al. 2021)) that attempted to deal with grade weightings, student identification, continuous and repeated assessment. In addition, there were concerns about

- the types of assessment questions (e.g. faculty now losing their well-established and previously-protected banks of MCQs),

- how to conduct more practical exams (e.g. OSCEs, OSPEs, vivas), and

- how to ensure that group project grades properly reflected the members’ contributions.

아마도 온라인 평가와 관련하여 해결되지 않은 가장 큰 윤리적 문제는 온라인 프록터링이다. 온라인 프록터링(일반 비디오 도구 또는 전문 소프트웨어에 의한)은 ERT 동안 초기에 널리 채택되었지만 많은 학교가 프록터링 수행량을 제거하거나 줄일 정도로 교직원과 학생들로부터 반발을 샀다(Feathers 2021). 윤리적 문제는 감독에 관한 것이라기보다는(학생들이 캠퍼스에 있을 때 수행되기 때문에), 학생의 집, 종종 침실과 같은 개인적인 공간에서의 사건들을 감시하고 기록하는 것과 함께 오는 사생활 침해입니다. 일반적인 관행은 학생의 침실을 기웃거리며 전체 환경을 조사하는 것이다. 이것은 대부분의 윤리적 교사들에게 분명히 혐오스러울 것이다 (비록 "동의"가 주어질지 모르지만, 이 동의는 대체로 강요에 의해 주어진다: 만약 학생들이 동의하지 않는다면, 그들은 학위를 마칠 수 없을지도 모른다).

Probably the greatest unresolved ethical issue related to online assessment is online proctoring. Online proctoring (either by common video tools or by specialised software) was initially widely adopted during ERT but resulted in a backlash from faculty and students (Feathers 2021) to the extent that many schools removed or reduced the amount of proctoring performed. The ethical issue is not so much proctoring (because that is performed when students are on campus), but a breach of privacy that comes with monitoring and recording events in a student’s home, frequently their very personal spaces, such as bedrooms. A common practice would be to survey the entire environment, essentially snooping in a student’s bedroom; this would surely be abhorrent to most ethical teachers (Although “consent” may be given, this consent is largely given under duress: if students do not agree, they might not be able to complete their degree).