질적연구 실용 가이드: Part 5: 일차의료 연구에서 공동-생성적 질적 접근: 경험-기반 공동 설계, 사용자-중심적 설계, 공동체-기반 참여적 연구 (Eur J Gen Pract. 2022)

Series: Practical guidance to qualitative research. Part 5: Co-creative qualitative approaches for emerging themes in primary care research: Experience-based co-design, user-centred design and community-based participatory research

Albine Mosera,b and Irene Korstjensc

소개

Introduction

수년에 걸쳐 저희는 감독 업무를 수행하면서 질적 연구가 많은 질문과 도전을 불러일으키는 경향이 있다는 사실을 발견했습니다. 질적 연구에 대한 실용적인 지침을 제공하기 위한 시리즈[1-4]의 다섯 번째 글인 이 글에서는 일차 진료 연구에서 새롭게 떠오르는 주제를 다루기 위한 세 가지 공동 창조적(그리고 대부분) 질적 접근 방식, 즉 진료의 질을 개선하기 위한 경험 기반 공동 설계, eHealth 리소스 개발 및 평가를 위한 사용자 중심 설계, 지역 건강을 협력적으로 개선하기 위한 지역사회 기반 참여 연구를 소개합니다.

Over the years, in our supervisory work, we have noticed that qualitative research tends to evoke many questions and challenges. This article, the fifth in a series aiming to provide practical guidance for qualitative research [1–4], introduces three co-creative (and mostly) qualitative approaches for addressing emerging themes in primary care research:

- experience-based co-design to improve the quality of care,

- user-centred design to develop and evaluate eHealth resources and

- community-based participatory research to improve local health collaboratively.

변화하는 1차 의료

A changing primary care

일차 의료는 만성 치료 및 노인 치료 제공 증가, 공동 의사 결정 및 사전 치료 계획, e- 및 mHealth, 예방 및 커뮤니티 케어, 간호사, 구급대원 및 관련 서비스와의 전문가 간 협업 등 변화하는 상황에 직면해 있습니다[5-8]. 이러한 변화는 일차 진료 연구에 영향을 미칩니다. 일반의는 본질적으로 환자 및 다른 전문가와 협력하여 일상 진료에서 복잡한 건강 문제에 대한 해결책을 모색하는 공동 창작자입니다. 그러나 공동 창작에 대한 '명시적' 개념은 국가 정책 맥락에 따라 일반의에게 익숙하지 않을 수 있습니다[9].

Primary care faces a changing context, including the increasing provision of chronic care and elderly care, shared decision-making and proactive care planning, e- and mHealth, preventive and community care, and interprofessional collaboration with nurses, paramedics and relevant services [5–8]. These changes have consequences for primary care research. By nature, general practitioners are co-creators in working with their patients and other professionals on seeking solutions for complex health issues in daily practice. However, the ‘explicit’ idea of co-creation may not be very familiar to general practitioners, depending on their national policy context [9].

공동 창조적 접근 방식

Co-creative approaches

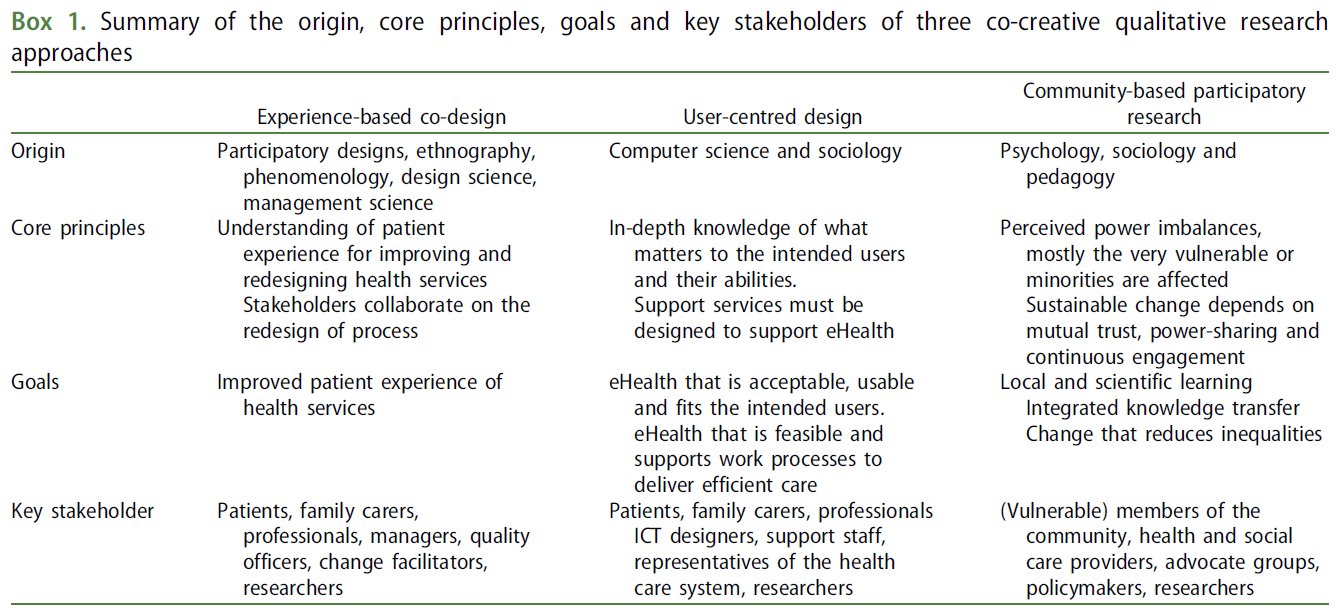

연구에서 공동 창작은 연구 연속체 전반에 걸친 반복적이고 비선형적인 프로세스와 이해관계자와 함께 일하는 학자들의 협력적인 지식 창출을 의미합니다[10]. 우리는 공동 창조적 질적 접근법이라는 용어를 포괄적인 개념으로 사용합니다. 세 가지 공동 창조적 접근법은 기원, 핵심 원칙, 목표, 이해관계자가 다르지만(상자 1) 공통점을 공유합니다.

- 이 접근법은 현실의 문제를 해결하는 데서 출발하여, 이해관계자의 참여와 이해관계자 간의 동등한 파트너십을 지원하고, 취약한 사람/지역사회에 권한을 부여하며, 실천과 연구 간의 격차를 해소합니다.

- 이들은 일반의 및 기타 1차 진료 전문가의 과학적 지식과 전문성을 보완합니다.

- 이들은 다양한 관점에서 요구, 경험, 열망, 이해관계 및 변화에 대한 인사이트를 제공합니다.

공동 창조적 접근 방식은 일차 진료에서는 비교적 생소하지만 병원, 정신과 치료 또는 사회 복지와 같은 다른 환경과 간호, 사회학 또는 발달 연구와 같은 학문 분야에서는 다소 친숙한 접근 방식입니다.

In research, co-creation means an iterative and non-linear process throughout the research continuum and the collaborative generation of knowledge by academics working alongside stakeholders [10]. We use the term co-creative qualitative approaches as an umbrella concept. The three co-creative approaches have different origins, core principles, goals and stakeholders (Box 1) but they share common ground.

- They start from solving a problem in practice, supporting stakeholder involvement and equal partnerships among the stakeholders, empowering vulnerable people/communities and bridging the gap between practice and research.

- They complement the scientific knowledge and expertise of general practitioners and other primary care professionals.

- They provide insights into needs, experiences, aspirations, stakes and changes from a multi-perspective.

Co-creative approaches are relatively novel to primary care but they are rather familiar in other settings such as hospitals, psychiatric care or social care and to disciplines such as nursing, sociology or developmental research.

공동 창작이 궁극적으로 효율성과 결과를 개선하고, 환자 만족도와 신뢰도를 높이며, 연구 역량을 강화할 수 있음을 시사하는 문헌이 점점 더 많아지고 있습니다[11]. 이는 일반의와 일차 진료 전문가가 제공하는 의료 서비스와 국민 건강을 개선하기 위한 상향식 접근 방식입니다[12]. 과학 문헌에서는 공동 설계, 공동 제작, 파트너십 접근법, 이해관계자 참여, 환자 및 대중 참여, 참여 연구 등 공동 창조라는 개념에 맞는 다양한 용어가 사용되고 있음을 알고 있습니다[13].

A growing body of literature suggests that co-creation can ultimately result in improved efficiencies and outcomes, increased patient satisfaction and trust and greater capacity for research [11]. It is a bottom-up approach to improve health services and the population’s health that general practitioners and primary care professionals serve [12]. We are aware that in scientific literature many different terms are used that fit our notion of co-creation such as co-design, co-production, partnership approaches, stakeholder engagement, patient and public involvement, and participatory research [13].

이해관계자

Stakeholders

공동 창조는 이해관계가 있는 사람들과의 파트너십을 통해 (연구) 문제를 정의하고, 중재를 개발 및 실행하며, (연구 및 실천) 결과를 평가 및 정의하는 것을 목표로 합니다.

- 이 글에서는 [이해관계자]를 특정 진료, 과정, 결정 및 건강 결과와 이를 뒷받침하는 근거에 명시적인 이해관계가 있는 사람으로 정의합니다.

- 일차 진료 연구의 일반적인 이해관계자는 환자, 가족 간병인, 연구자, 의료 전문가(관리자 포함), 옹호 단체 및 기타 관련 이해관계자(예: 지역 정책 입안자, 보험 회사)입니다.

그러나 공동 창작을 사용하는 모든 연구 프로젝트는 연구 문제를 정의하는 단계에서 [이해관계자 분석]이 필요합니다. 초기 프로젝트 멤버들은 가능한 모든 이해관계자에 대한 브레인스토밍으로 시작한 다음, 문제와 프로젝트에 대한 이해관계자의 권한, 영향력, 관심도에 따라 우선순위를 정합니다. 그리고 그들의 동기, 관심사, 입장, 기대치, 기대 이익을 탐색합니다[14].

Co-creation aims to define the (research) problem, develop and implement interventions and evaluate and define (research and practice) outcomes in a partnership with those who have a stake.

- For this article, we define stakeholders as those who have an explicit interest in a particular practice, process, decision and/or health outcome and the supporting evidence.

- Common stakeholders in primary care research are patients, family carers, researchers, care professionals (including managers), advocacy organisations and other relevant stakeholders (e.g. local policymakers, insurance companies).

However, every research project using co-creation requires a stakeholder analysis at the stage of defining the research problem. The initial project members start with a brainstorm of all possible stakeholders and then prioritise them according to their power over, influence on, and their interest in the problem and the project. They explore their motivations, interests, positions, expectations and expected benefits [14].

이 문서의 대상 독자 및 내용

Target audience and content of this article

이 논문은 이러한 공동 창작 디자인을 사용하고자 하는 연구자들과 이 방법론을 사용한 논문을 점점 더 많이 읽게 될 일반 실무자들에게 적합합니다. 그들은 우리의 소개를 '첫 데이트'라고 생각할 수 있습니다. 우리는 이러한 접근법의 맥락과 무엇을, 왜, 언제, 어떻게, 그리고 주요 실무적, 방법론적 과제에 대한 가능한 질문을 다룹니다. 1차 의료 및 기타 의료 영역에서 발표된 경험적 연구 사례와 추가 자료를 제공합니다.

This paper is relevant for researchers who want to use these co-creative designs and general practitioners who will increasingly read articles using this methodology. They might consider our introduction a ‘first date’. We address possible questions about the context and the what, why, when, and how of these approaches and their main practical and methodological challenges. We provide examples of published empirical studies in primary care and other health care domains and sources for further reading.

치료의 질을 개선하기 위한 경험 기반 공동 설계

Experience-based co-design to improve the quality of care

맥락

Context

고품질의 의료 서비스를 제공하는 것은 모든 1차 의료 전문가의 목표입니다. 치료의 질을 개선하는 고전적인 방법은 생의학적 및 심리사회적 결과, 기능 및 비용 효율성을 평가하는 것입니다[15]. 최근에는 의료 서비스 설계 과정에 환자, 가족 간병인, 대중을 적극적으로 참여시켜 환자 경험을 기반으로 의료의 질을 개선하는 방향으로 전환하고 있습니다. 의료 서비스의 질을 개선하기 위한 혁신적인 접근 방식 중 하나가 경험 기반 공동 설계입니다[16]. 이 접근법을 사용하여 발표된 경험적 연구에는 다음이 포함됩니다:

Providing high-quality care services is the goal of every primary care professional. Classic ways for improving quality of care are based on evaluating biomedical and psychosocial outcomes, functioning and cost-effectiveness [15]. In recent years, there has been a shift towards quality of care improvement based on patient experiences by actively involving patients, family carers and the public in the design process of health services. An innovative approach to improving the quality of care services is experience-based co-design [16]. Published empirical studies using this approach include:

- 사람들이 일차 진료에서 안전에 대해 발언할 수 있도록 지원: 공동 설계를 사용하여 복합 이환 환자를 위한 새로운 개입을 개발하는 데 환자와 전문가를 참여시킵니다[17].

- 경험 기반 공동 설계를 사용하여 환자 중심 암 치료 경로에서 대장암 및 유방암 고령자의 경험 개선 [18].

- 가보지 않은 길: 경험 기반 공동 설계를 사용하여 화상 부상 후 어린이와 가족의 정서적 여정을 매핑하고 서비스 개선 사항을 파악합니다[19].

- Empowering people to help speak up about safety in primary care: using co-design to involve patients and professionals in developing new interventions for patients with multimorbidity [17].

- Improving the experience of older people with colorectal and breast cancer in patient-centred cancer care pathways using experience-based co-design [18].

- A road less travelled: using experience-based co-design to map children’s and families’ emotional journey following burn injury and identify service improvements [19].

무엇?

What?

경험 기반 공동 설계의 목표는 환자, 가족 보호자, 전문가가 치료의 질을 개선한다는 공통의 목표를 향해 협력하는 것을 촉진하는 것입니다. 이 접근 방식은 사람들이 프로세스 또는 서비스를 경험하는 방식을 포착하고 이해하고자 하는 행동 연구의 한 형태입니다[16]. 경험 기반 공동 설계 접근 방식은 환자, 가족 간병인, 일반인, 전문가의 주관적이고 개인적인 감정을 의도적으로 끌어내어, (개인의 전반적인 경험을 형성하는 핵심 순간인) 터치포인트를 식별합니다. 경험 기반 공동 설계를 통해 환자, 가족 간병인, 일반인, 전문가가 파트너로서 서비스 또는 치료 경로를 공동 설계하여 경험을 바탕으로 치료의 질을 개선할 수 있습니다.

The goal of experience-based co-design is to facilitate collaborative work between patients, family carers and professionals towards a common goal – to improve the quality of care. This approach is a form of action research that seeks to capture and understand how people experience a process or service [16]. An experience-based co-design approach deliberately draws out the subjective, personal feelings of patients, family carers, the public and professionals to identify touchpoints – key moments that shape a person’s overall experience. Experience-based co-design enables patients, family carers, the public and professionals – as partners – to co-design services or care pathways to improve the quality of care based on experiences.

왜 그리고 언제?

Why and when?

의료 전문가는 종종 자신이 치료 프로세스를 개선하고 환자를 위한 가치를 창출할 수 있는 고유한 전문 지식을 가지고 있다고 생각합니다[16]. Berwick [20]은 전문가 우위에서 벗어나 공동 창조에 더 중점을 둘 것을 제안했습니다. 환자와 대중의 참여에 대한 관심이 증가하고 있으며, 이는 종종 보건 정책 이니셔티브와 의료 서비스 전반에 걸친 가치 공동 창출에 대한 지원으로 촉발됩니다.

Health care professionals often think they have the unique expert knowledge to improve care processes and create value for patients [16]. Berwick [20] proposed shifting away from professional dominance to a greater focus on co-creation. There is a growing interest in patient and public involvement, often triggered by health policy initiatives and support for co-creating value across health care.

환자 및 대중 참여는 의료 서비스의 계획, 제공 및 평가에 환자, 가족 간병인 및 대중의 적극적인 참여를 수반합니다. 여기에는 환자 및 서비스 사용자 시작, 호혜적 관계 구축, 공동 학습, 재평가 및 피드백의 지속적인 프로세스가 포함됩니다[21]. 환자 참여는 개별 치료 및 치료에 대한 결정에 있어 개인 수준에서, 그리고 의료 서비스 제공에 대한 결정에 있어 집단 수준에서 이루어질 수 있습니다[22].

Patient and public involvement entail the active participation of patients, family carers and the public in planning, delivering and evaluating health care services. It involves the ongoing process of patient and service user initiation, building reciprocal relationships, co-learning and re-assessment and feedback [21]. Involving patients can happen at the individual level – in decisions about individual care and treatment – and at the collective level – in decisions about the delivery of care services [22].

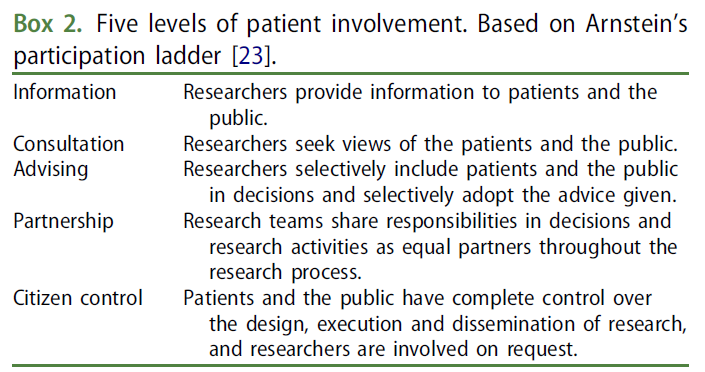

Arnstein[23]의 참여 사다리를 변형한 버전에 따라 정보, 상담, 자문, 파트너십, 시민 통제 등 다섯 가지 수준의 참여를 구분합니다(상자 2). 일차 진료 맥락에서 환자, 가족 간병인, 대중, 전문가가 적극적으로 참여함으로써 공동 설계는 이해관계자의 지식을 연결하여 진료의 질 우선순위 문제를 해결합니다.

Based on an adapted version of Arnstein’s [23] participation ladder, we distinguish five levels of involvement: information, consultation, advising, partnership and citizen control (Box 2). In the primary care context, by the active involvement of patients, family carers, the public and professionals, co-design connects the knowledge of stakeholders to address quality of care priority concerns.

어떻게?

How?

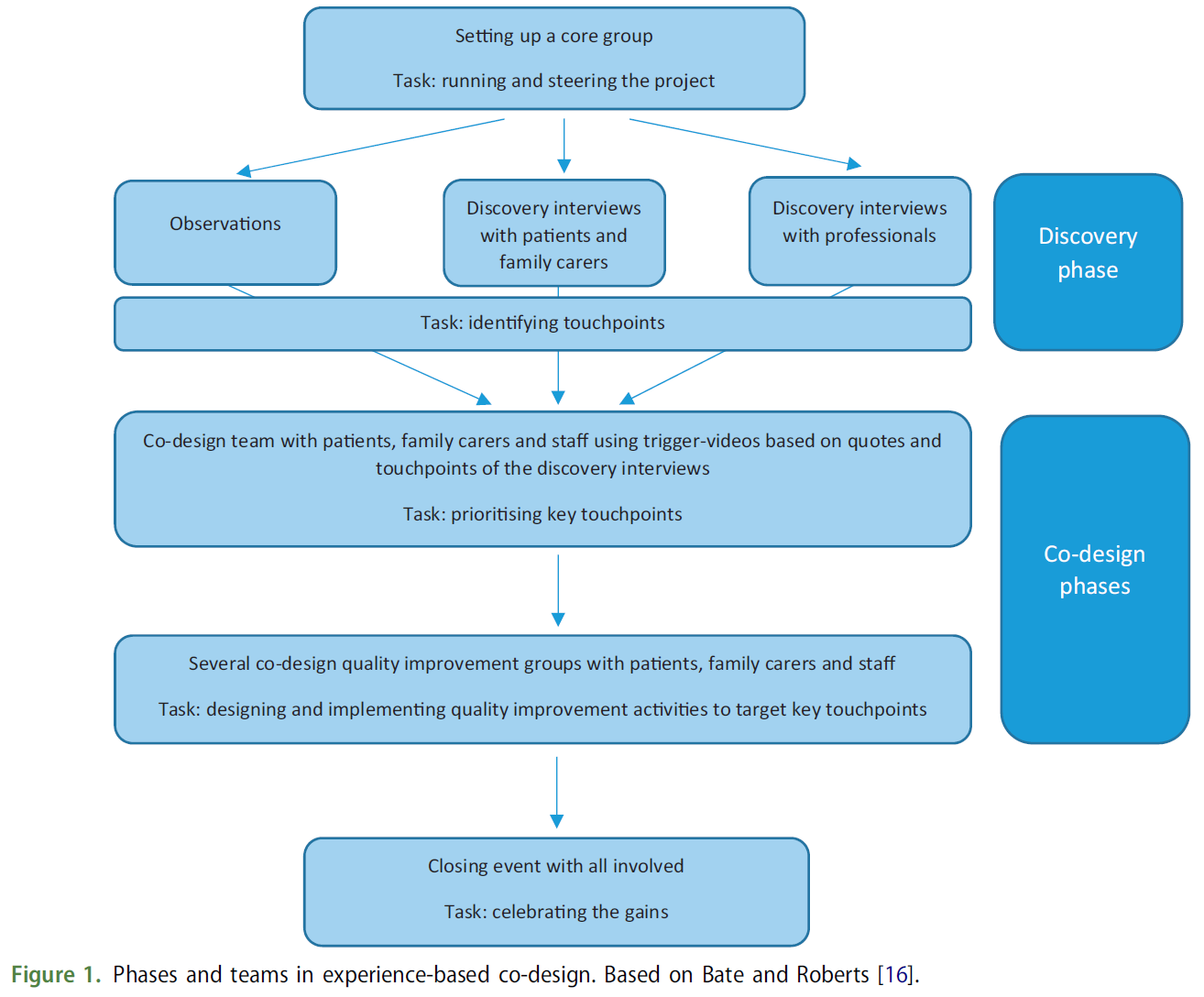

치료의 질을 개선하기 위한 경험 기반 공동 설계 프로젝트는 일반적으로 12개월 동안 진행되며[24], 이 프로세스에는 발견 및 공동 설계 단계가 포함됩니다[25](그림 1). 프로젝트의 시작은 프로젝트를 실행할 핵심 그룹을 구성하고 연구자를 모집하는 것입니다.

Experience-based co-design projects to improve the quality of care typically last 12 months [24], and the process contains discovery and co-design phases [25] (Figure 1). The start involves setting up a core group that runs the project and recruiting a researcher.

발견 단계는

- 개선할 서비스가 어떻게 작동하는지에 대한 귀중한 인사이트를 제공하는 [연구자의 관찰]로 시작됩니다. 이러한 인사이트는 연구자가 후속 인터뷰를 위해 민감하게 반응하는 데 도움이 됩니다.

- 발견 단계에서는 질병이 환자와 가족 간병인의 일상 생활에 미치는 영향을 탐색하고 학습하는 것을 목표로 하는 [발견 인터뷰]가 진행됩니다. 발견 인터뷰는 환자, 가족 간병인 및 전문가와 함께 의료 서비스 경험에 대해 실시하여 치료, 회복 및 복지에 중대한 영향을 미칠 수 있는 요구 사항에 대한 지식을 생성합니다.

- [접점]은 참여자의 경험을 바탕으로 파악됩니다. 인터뷰를 촬영하여 환자, 가족 보호자, 전문가 간의 대화를 유도하는 비디오를 제작합니다.

The discovery phase

- begins with observations by the researcher that provide valuable insights into how the service to be improved works. These insights are helpful to sensitise researchers for the subsequent interviews.

- The discovery phase proceeds with discovery interviews, which aim to explore and learn from the impact of illness on patients’ and family carers’ everyday lives. Discovery interviews – conducted with patients, family carers and professionals about their experiences with a health service – produce knowledge about needs that may significantly impact care, recovery and wellbeing.

- The touchpoints are identified based on the experiences of participants. Interviews are filmed to develop a video to trigger a dialogue between patients, family carers and professionals.

연구자들은 영상을 편집할 때 진단, 치료, 후속 조치 등 특정 연대기 순서에 따라 품질 개선이 필요한 부분을 파악합니다. 환자 경험의 시각화는 비슷한 경험과 이야기를 가진 사람들을 (재)연결하는 데 도움이 되고 공동 설계 프로세스의 정서적, 인지적으로 강력한 출발점을 제공하기 때문에 비디오는 공동 설계 프로세스에서 중요한 촉매제 역할을 합니다[26].

In editing the video, researchers identify areas for quality improvement, often following a certain chronology, for example, diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. The video is an important catalyst in the co-design process as the visualisation of patient experiences helps (re)connect people with similar experiences and stories and offers an emotionally and cognitively powerful starting point for the co-design process [26].

다음으로, 공동 디자인 팀에서는 각 그룹(주로 환자, 가족 보호자, 전문가)별로 개별적으로 개선해야 할 다양한 영역의 우선순위를 정한 다음, 모든 그룹이 함께 모여 개선 방향을 논의합니다. 각 회의는 이전 단계에서 비디오로 촬영한 인용문을 통해 다양한 개선 영역을 발표하는 것으로 시작됩니다. 그런 다음 참가자들은 공동으로 3~4개 영역을 품질 개선의 핵심 우선순위로 선택합니다.

Next, the various areas for improvements are prioritised in the co-design team: separately within each group (mostly patients, family carers and professionals) and then with all the groups together. Each meeting starts with presenting the various areas for improvement, illustrated by videotaped quotes from the previous phase. Then, the participants jointly choose three or four areas as the key priority for quality improvement.

공동 설계 단계에서는 환자, 가족 보호자, 전문가로 구성된 소규모 실무 그룹인 공동 설계 품질 개선 그룹이 공동 설계 회의에서 강조된 핵심 우선순위 문제를 목표로 품질 개선 활동을 설계하고 실행합니다.

In the co-design phase, co-design quality improvement groups – small working groups of patients, family carers and professionals – design and implement quality improvement activities to target the key priority issues highlighted at the co-design meetings.

마지막으로 마무리 행사에서 개선 사항을 평가하고 공동 디자인 팀이 개선 사항을 공유하고 축하합니다. 경험 기반 공동 설계는 의료 서비스를 개선하고 변경 프로세스에 대한 과학적 인사이트를 제공하는 변경 접근 방식 및 프로세스입니다.

Finally, the improvements are evaluated in a closing event, and the gains are communicated and celebrated by the co-design team. Experience-based co-design is a change approach and process that improves health care and scientific insights into change processes.

사용자 중심 설계를 통한 eHealth 리소스 개발 및 평가

User-centred design to develop and evaluate eHealth resources

컨텍스트

Context

e헬스는 (디지털) 정보통신기술(ICT), 특히 인터넷 기술을 사용하여 건강 및 의료 서비스를 지원하거나 개선하는 것을 말합니다[27]. 이는 1차 진료의 질을 높이고 품질 보증, 교육 및 연구를 위한 고품질 데이터를 제공할 수 있는 포괄적인 가능성을 제공합니다[27]. 혁신적이면서도 타당한 연구 방법론은 eHealth의 지속적인 성공과 지속 가능성을 위한 전제 조건입니다[28]. 최종 사용자는 공동 제작 프로세스를 통해 전자 의료의 개발 및 구현에 참여해야 하며, 취약 계층과 전자 의료 문맹을 염두에 두고 설계해야 합니다. 적절한 접근 방식은 사용자 중심 디자인입니다.

eHealth is the use of (digital) information and communication technology (ICT), in particular internet technology, to support or improve health and health care [27]. It offers a comprehensive promise for a better quality of primary care and high-quality data for quality assurance, education and research [27]. Innovative but valid research methodology is a prerequisite for the ongoing success and sustainability of eHealth [28]. End-users need to be involved in the development and implementation of eHealth via co-creation processes, and design should be mindful of vulnerable groups and eHealth illiteracy. An appropriate approach is user-centred design.

이 접근 방식을 사용하여 발표된 경험적 연구에는 다음이 포함됩니다:

Published empirical studies using this approach include:

- 복잡한 환자를 위한 태블릿 대기실 도구를 사용자 중심으로 설계하여 1차 진료 방문 시 논의 주제의 우선순위를 정합니다[29].

- 향후 우울증 중증도를 예측하고 1차 진료에서 치료를 안내하기 위한 모바일 임상 예측 도구 개발: 사용자 중심 설계 [30].

- 생리적 출산의 보호자 양성: 네덜란드의 학생 조산사를 위한 교육 이니셔티브 개발 [31].

- User-centred design of a tablet waiting room tool for complex patients to prioritise discussion topics for primary care visits [29].

- Development of a mobile clinical prediction tool to estimate future depression severity and guide treatment in primary care: user-centred design [30].

- Creating guardians of physiologic birth: the development of an educational initiative for student midwives in the Netherlands [31].

무엇?

What?

사회 및 기술 디자인 과학에서 비롯된 사용자 중심 설계의 목표는 사용성이 매우 높은 eHealth 기술을 개발하는 것입니다. 이는 기술 및 조직 시스템을 평가, 설계 및 개발하는 방법으로, 설계 및 의사 결정 과정에 최종 사용자를 참여시킵니다[32]. 이 방법의 주요 특징은

- 문제 식별 및 솔루션 생성의 빠른 주기,

- 최종 사용자 특성에 대한 심층적 이해,

- 설계가 구체화되는 방식에 대한 최종 사용자의 영향,

- 전체 개발 프로세스 동안의 반복적 평가,

- 처음부터 구현 조건을 고려한다는 점입니다[33].

이상적으로 사용자 중심 설계는 환자, 가족 간병인, 전문가 및 직원, ICT 설계자, 의료 시스템 담당자, 기술 콘텐츠를 담당하는 연구자 등 모든 잠재적 이해관계자를 고려합니다. 그러나 최종 사용자는 대부분 환자, 가족 간병인, 전문가 및 직원입니다.

The goal of user-centred design, stemming from social and technological design sciences, is to develop eHealth technologies with very high usability. It is a method to assess, design and develop technological and organisational systems, which involves end-users in design and decision-making processes [32]. Its key features are

- rapid cycles of problem identification and solution creation,

- in-depth understanding of end-user characteristics,

- the influence of end-users on how a design takes shape,

- iterative evaluation during the entire development process, and

- accounting for the implementation conditions from the beginning [33].

Ideally, the user-centred design considers all potential stakeholders, for example, patients, family carers, professionals and staff, ICT designers, representatives of the health care system and researchers responsible for the content of the technology. However, the end-users are mostly patients, family carers, professionals and staff.

왜 그리고 언제?

Why and when?

e헬스 개발은 복잡한 건강 문제를 겪고 있는 사용자를 위해 새로운 기술과 서비스를 사용하는 경우가 많습니다. 사용자 중심 설계는 문제를 동시에 반복적으로 이해하고 해결함으로써 eHealth 개발을 지원합니다[33]. 최종 사용자가 직접 개입을 만들고 구현하는 데 참여하면 개입에 미묘한 요소가 통합되고 최종 사용자에게 영향을 미치는 건강의 사회적, 구조적, 환경적 결정 요인을 고려할 수 있습니다. 이러한 입력이 없었다면 이러한 요소는 연구자나 전문가에게 분명하게 드러나지 않았을 것입니다[33]. 사용자 중심 디자인으로 개발된 앱은 사용자 수용성, 안면 타당도, 사용자 친화성 및 활용도가 개선된 것으로 보고되었습니다[30]. eHealth의 채택과 지속적인 사용을 위해서는 사용자 친화적이고 최종 사용자의 동기, 가치, 요구 및 능력을 충족하며 의료 조직에 적합해야 합니다.

Developing eHealth often uses new technologies and services for users experiencing complex health problems. User-centred design supports developing eHealth by understanding and solving the problem simultaneously and iteratively [33]. If end users are engaged to create and implement interventions themselves, the interventions will incorporate nuanced factors and consider social, structural and environmental determinants of health that affect the end-users. Without this input, these elements would not have been evident to researchers or professionals [33]. Apps developed with user-centred design have reported improved user acceptance, face validity, user-friendliness and uptake [30]. Critical for eHealth’s uptake and continuous use is that it is user-friendly, meets end users’ motives, values, needs and abilities and fits into the organisation of care.

어떻게?

How?

사용자 중심 설계는 대부분 질적 또는 혼합 방법을 사용합니다[33].

- 문제 개발 주기에는 사용자 및 기타 출처에서 데이터를 수집하고 분석하여 문제와 요구 사항을 정의하는 과정이 포함됩니다.

- 솔루션 개발 주기에는 최종 사용자와 함께 프로토타입을 제작하고 테스트하기 위한 아이디어 창출이 포함됩니다.

이러한 주기 사이에는 반복적인 피드백 루프가 있습니다. 연구자와 개발자는 최종 사용자의 주요 요구 사항을 충족하는 e헬스 솔루션을 최종 확정하고 배포합니다.

User-centred design uses mostly qualitative or mixed methods [33].

- The problem development cycle involves gathering and analysing data from users and other sources to define problems and needs.

- The solution development cycle involves the generation of ideas to build and test prototypes with end-users.

Within and between these cycles, there are iterative feedback loops. Researchers and developers finalise and deploy an eHealth solution when it meets the end users’ key requirements.

사용자 중심 설계의 특정 유형은 교육(e-러닝) 프로그램 개발에 자주 사용되는 래피드 프로토타이핑입니다[34]. 여기에는 구현 및 평가를 위한 최종 프로토타입에 도달하기 위해 후속 프로토타입을 설계할 때 요구 사항 평가, 주요 이해관계자의 의견 및 피드백 단계가 중복적으로 포함됩니다.

A specific type of user-centred design is rapid prototyping, which is often used for developing educational (e-learning) programmes [34]. It involves overlapping stages of needs assessment, input and feedback from key stakeholders in designing subsequent prototypes to reach a final prototype for implementation and evaluation.

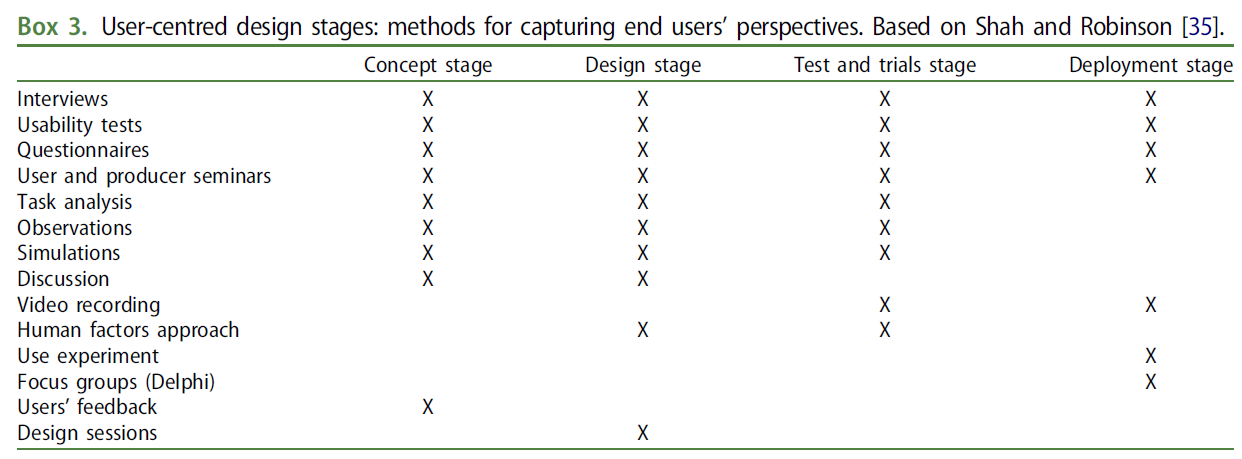

사용자 중심 설계 프로세스의 각 문제 및 솔루션 개발 주기 내 단계에 대한 다양한 설명이 존재하는데, 예를 들어 5단계 프로세스는 개념, 설계, 테스트 및 시험, 생산 및 배포 단계로 구성되며 최종 사용자는 생산을 제외한 모든 단계에 참여합니다[33,35](박스 3). 최종 사용자의 참여에 가장 많이 사용되는 방법은 사용성 테스트, 인터뷰 및 설문조사입니다. 다양한 단계에서 최종 사용자의 관점을 파악하는 것은 적용되는 방법에 따라 달라지므로 적절한 방법을 선택하는 것이 중요합니다[36]. 또한 모든 사용자와 그들의 활동, 실제 일상 환경, 기능적 한계, 무수한 정보 및 기술을 심도 있게 고려해야 합니다[35]. 예를 들어 조산사의 업무량이 많다는 점을 고려하여 연구자들은 포커스 그룹이 아닌 개별 인터뷰와 서면 피드백을 선택했습니다[31].

Various descriptions exist of the stages within each of the problem and solution development cycles in the user-centred design process, for example, a five-stage process consists of concept, design, testing and trials, production and deployment stages with end-users participating in all stages, except production [33,35] (Box 3). The methods most used for involving end-users are usability tests, interviews and questionnaire surveys. Since capturing end users’ perspectives at various stages depends on the method applied, selecting an appropriate method is important [36]. This also requires in-depth consideration of all users and their activities, their actual daily environment and their functional limitations, innumeracy and skills [35]. For example, considering midwives’ high workloads, researchers chose individual interviews and written feedback rather than focus groups [31].

고령자, 장애인 또는 특별한 도움이 필요한 사람을 포함하여 사용 가능한 최종 사용자의 경우 '사용자 대리인'이라고 하는 대리인이 개입할 수 있습니다[35]. 사용자 대리인이란 다른 사용자를 대신하여 작업을 수행할 수 있는 지식이나 권한을 가진 사용자를 말합니다. 사용자 대리자는 사용자에 대해 알고 있는 내용을 보고하거나 사용자가 어떻게 행동할지 역할극을 통해 보고합니다.

For less available end-users, including elderly people and people with disabilities and/or special needs, substitutes called ‘user surrogates’ might be involved [35]. A user surrogate is a user who has the knowledge or authority to perform tasks on behalf of another user. User surrogates report on what they know about the user or by role-playing how the user would behave.

지역 보건을 공동으로 개선하기 위한 커뮤니티 기반 참여 연구

Community-based participatory research to improve local health collaboratively

컨텍스트

Context

일차 진료 전문가는 종종 문화적 소수자나 빈곤한 지역사회와 같은 취약 계층을 대상으로 진료를 제공합니다. 이들은 라이프스타일 선택, 전기, 인생사, 교육 수준, 사회경제적 상황, 사회 및 물리적 환경의 영향을 받는 건강 문제로 어려움을 겪는 환자를 돌봅니다. 건강 격차를 해결하기 위한 연구 접근 방식은 커뮤니티 기반 참여 연구입니다. 이 방법은 접근하기 어렵거나 매우 취약한 지역사회에 주로 사용되어 왔습니다. 우리는 커뮤니티를 공유된 가치, 문화, 관습 또는 정체성과 같은 공통의 관심사를 가진 사람들의 그룹 또는 이웃, 지구 또는 지역과 같은 특정 지리적 영역에 거주하는 모든 사람들 또는 지리적 영역에 거주하는 공통의 관심사를 가진 사람들의 그룹으로 정의합니다.

Primary care professionals often provide care to vulnerable groups, such as cultural minorities and deprived communities. They care for patients who struggle with health problems affected by their lifestyle choices, biography, life events, educational level, socioeconomic situation and social and physical environment. A research approach to address health disparities is community-based participatory research. It has often been used for hard-to-reach or very vulnerable communities. We define community as a group of people with common interests – such as shared values, culture, customs or identity or as all people living in a particular geographical area – such as a neighbourhood, district or local area, or as groups of people with a common interest living in a geographical area.

이 접근법을 사용하여 발표된 경험적 연구에는 다음이 포함됩니다:

Published empirical studies using this approach include:

- 마카시 개입의 참여형 개발 및 파일럿 테스트: 프랑스에서 사하라 사막 이남 및 카리브해 이민자의 성 건강 역량 강화를 위한 지역사회 기반 아웃리치 개입 [37].

- 벨기에의 동유럽 및 터키 커뮤니티에서 약물 사용 및 서비스 이용에 대한 연구에서 커뮤니티 기반 참여 연구 실시 [38].

- 네덜란드에서 건강과 사회의 통합을 개선하기 위한 커뮤니티 기반 참여 연구 [39].

- Participatory development and pilot testing of the Makasi intervention: a community-based outreach intervention to improve sub-Saharan and Caribbean immigrants’ empowerment in sexual health in France [37].

- Implementing community-based participatory research in the study of substance use and service utilisation in Eastern European and Turkish communities in Belgium [38].

- A community-based participatory research on improving the integration of health and social in the Netherlands [39].

무엇?

What?

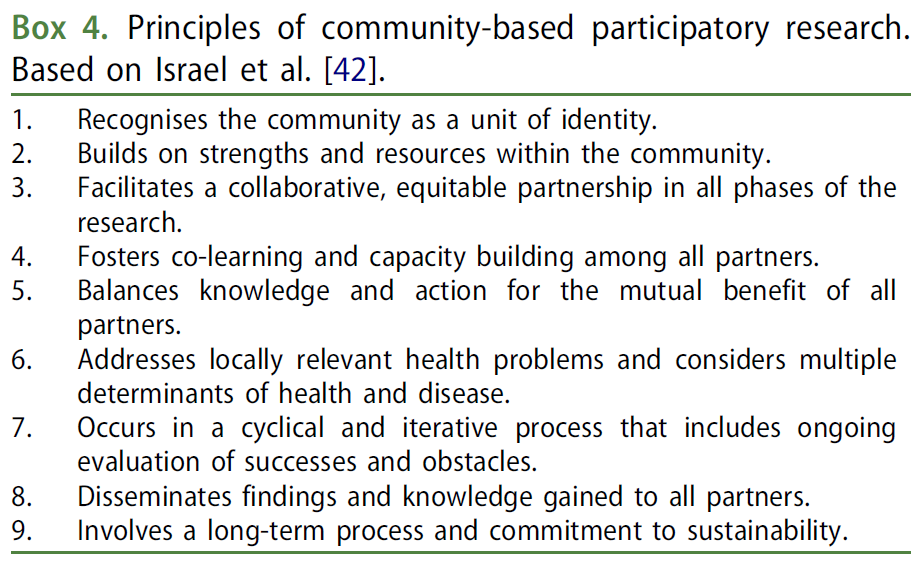

지역사회 기반 참여 연구의 목표는 교육, 실천 개선 또는 사회 변화를 가져오는 것입니다. 이는 지역적으로 관련된 건강 문제를 해결하고자 하는 연구에 대한 협력적 접근 방식입니다[40]. 커뮤니티 기반 참여 연구의 독특한 점은 다양한 커뮤니티 파트너가 참여하고 동등한 참여와 소유권, 호혜성, 공동 학습 및 변화를 위해 노력하는 데 중점을 둔다는 점입니다[41]. 이 접근 방식은 연구자와 커뮤니티 구성원을 요구 사항 평가 및 의제 설정, 의사 결정, 역량 구축, 지식 생성, 연구 결과의 실행 및 전파 등 연구 과정의 모든 측면에 참여시킵니다[42,43]. 지역사회 참여에 중점을 두기 때문에 지역사회 기반 참여 연구는 지역사회 파트너가 학술 파트너와 협력하여 지역사회에 영향을 미치는 건강 문제를 파악하고 해결할 수 있습니다(상자 4). 이는 변화로 이어질 수 있는 사회적 연결을 촉진하고 행동으로 이어질 수 있는 지식을 생산합니다[44].

The goal of community-based participatory research is to educate, improve practice or bring about social change. It is a collaborative approach to research, which seeks to address a locally relevant health issue [40]. What is unique to community-based participatory research is its emphasis on the diverse community partners involved and on striving for equal participation and ownership, reciprocity, co-learning and change [41]. This approach engages researchers and community members in all aspects of the research process, including needs assessment and agenda-setting, decision-making, capacity building, knowledge generation and the implementation and dissemination of findings [42,43]. Because of its focus on community engagement, community-based participatory research allows community partners working with academic partners to identify and address health problems affecting their communities (Box 4). It fosters social connections that can lead to change and produces knowledge that can lead to action [44].

왜 그리고 언제?

Why and when?

일차 진료에 대한 지역사회 참여는 1978년 알마-아타 선언[45]에서 시작되었으며, 이 선언은 사람들이 자신의 건강 관리 계획과 실행에 개별적으로나 집단적으로 참여할 권리와 의무가 있음을 명시했습니다. 연구 주제가 지역사회가 파악한 주요 이슈를 반영하도록 보장하고, 지역사회의 지혜를 활용하여 연구의 질, 타당성, 민감성을 개선함으로써 지역사회와 연구자 간의 신뢰를 증진하고, 연구 결과를 정책 및 실천으로 전환하는 과정을 개선하고, 지역사회 구성원의 연구 결과 활용도를 높이는 등의 이점이 있습니다[42]. 연구자들은 지역 사회와 함께 '상아탑' 연구라는 잘 설명된 문제를 해결하고 '현실 세계'에서 사회적 영향을 미칠 수 있습니다[46].

Community participation in primary care has its origins in the Alma-Ata Declaration of 1978 [45], which stated that people have the right and duty to participate individually and collectively in the planning and implementation of their health care. The benefits include the following: ensuring that the research topic reflects a major issue identified by the community; improving the quality, validity and sensitivity of the research by drawing upon community wisdom, thus promoting trust between communities and researchers; improving the translation of research findings into policy and practice; and enhancing uptake of the research findings by community members [42]. Researchers together with the local community might help address the well-described issue of ‘ivory tower’ research and have a social impact in the ‘real world’ [46].

어떻게?

How?

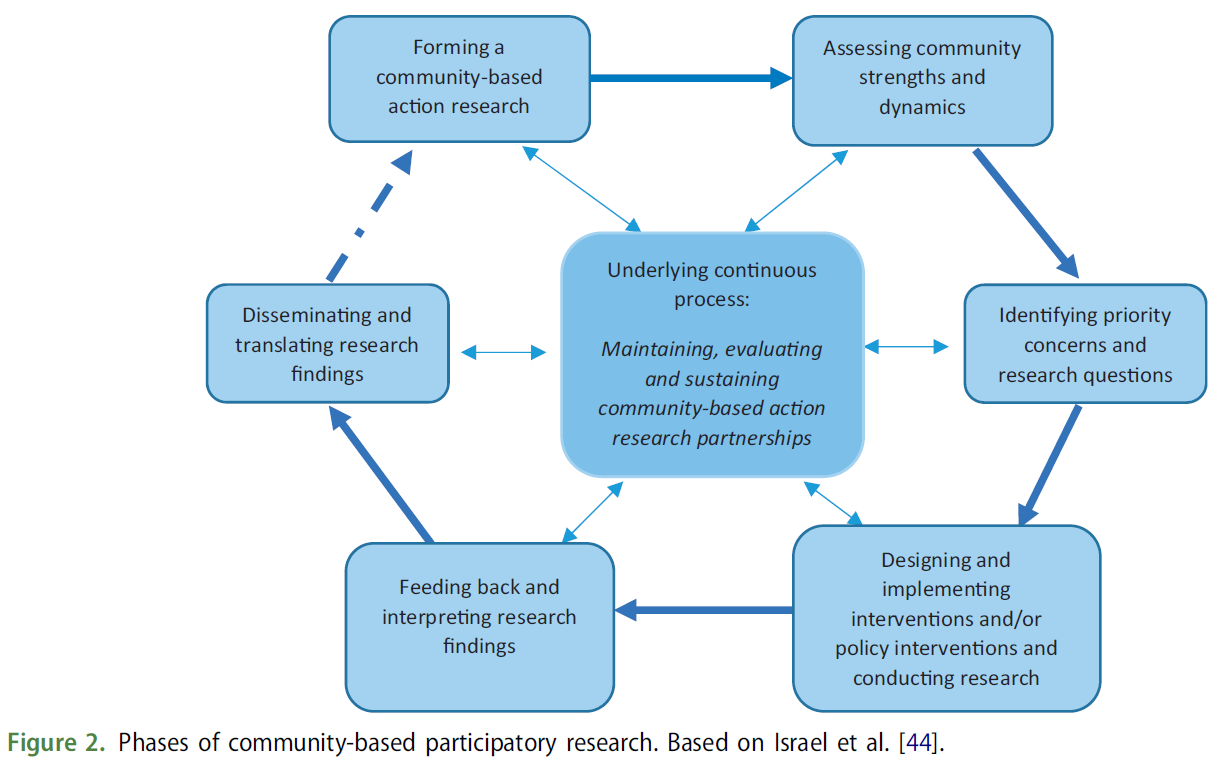

커뮤니티 기반 참여 연구는 질적 사례 연구, 환경 평가, 혼합 방법 연구, 무작위 대조 시험 등 다양한 방법론, 연구 설계 및 데이터 수집 방법을 사용할 수 있습니다. 일반적으로 7가지 단계가 있습니다[44](그림 2). 연구자와 지역 사회는 파트너로서 함께 일합니다.

Community-based participatory research can employ diverse methodologies, study designs and data collection methods, for example, qualitative case studies, environmental assessments, mixed methods research and randomised controlled trials. In general, there are seven phases [44] (Figure 2). Researchers and the local community work together as partners.

첫 번째 단계는 잠재적인 비학계 파트너를 발굴하는 활동을 포함하여 지역사회 기반 행동 연구 파트너십을 형성하는 것입니다. 파트너에는 환자, 가족, 멘토, 친구 등 대인관계 지원 네트워크, 환자는 아니지만 이 문제를 지지하거나 믿는 일반 대중, 의사, 보건 전문가, 행정가 등 환자 및/또는 환자의 대인관계 네트워크와 직접 교류하는 사람, 서비스 제공자, 정책 입안자 등 기타가 포함될 수 있습니다. 이 활동은 신뢰와 관계를 구축하고, 운영 규범과 지역사회 기반 행동 연구 원칙을 수립하여 형평성과 권력 공유를 보장하고, 연구 인프라를 구축하는 것을 목표로 합니다[43].

The first phase is forming a community-based action research partnership involving activities to identify potential non-academic partners. Partners might include the following: patients; interpersonal support networks, including family members, mentors and friends; members of the general public who are not patients but who support or believe in the issue; those who interface directly with patients and/or patients’ interpersonal networks, including practitioners, health professionals and administrators; and others, such as service providers and policymakers. The activities aim to build trust and relationships, establish operating norms and community-based action research principles to ensure equity and power-sharing and create an infrastructure for the research [43].

두 번째 단계는 커뮤니티의 강점과 역학을 평가하는 것입니다. 여기에는 다음을 발견하고 평가하는 것이 포함됩니다[45].

- 커뮤니티의 강점과 자원,

- 주요 문화 및 역사적 차원,

- 영향력 있는 조직,

- 커뮤니티의 권력 관계,

- 커뮤니티의 목소리를 듣기 위해 참여할 파트너

The second phase entails assessing community strengths and dynamics. This involves activities such as discovering and assessing

- the strengths and resources in the community,

- key cultural and historical dimensions,

- influential organisations,

- power relationships in the community and

- partners to be involved to ensure that the community voice is heard [45].

세 번째 단계는 우선순위 지역 보건 문제와 연구 질문을 파악하는 것입니다. 주요 활동은 지역사회 파트너가 지역사회에 영향을 미치는 것으로 경험하고 해결해야 할 주요 건강 문제를 식별하고 건강 문제와 그 기여 요인의 우선순위를 정하는 것입니다. 마지막으로 연구자와 커뮤니티 파트너는 연구의 주요 연구 질문을 공식화합니다.

The third phase is identifying priority local health concerns and research questions. Key activities are to identify the major health problems that community partners experience as affecting the community and that need to be addressed and prioritise health concerns and their contributing factors. Finally, the researchers and community partners formulate the key research questions for the study.

네 번째 단계는 공동으로 개입 및 정책 연구를 설계하고 수행하는 것입니다. 여기에는 연구 질문과 목표의 우선순위를 정하고, 연구 설계와 데이터 수집 방법을 선택하고, 가장 적절한 개입을 결정하는 것이 포함됩니다. 또한 연구 설계와 선택한 개입을 수행하는 방법을 결정하고, 마지막으로 평가에 동의하는 단계가 포함됩니다.

The fourth phase involves collaboratively designing and conducting interventions and/or policy research. This involves prioritising the research questions and goal, selecting the research design and data collection methods and deciding the most appropriate intervention. In addition, it involves determining how to carry out the research design and the intervention selected and, finally, agreeing on the evaluation.

다섯 번째 단계는 커뮤니티 내에서 결과를 피드백하고 해석하는 단계입니다. 여기에는 설문조사, 심층 인터뷰, 포커스 그룹 토론 등을 통해 얻은 (예비) 결과를 공유하고 커뮤니티 파트너가 결과를 이해할 수 있도록 참여시키는 등 데이터 분석이 포함됩니다.

The fifth phase is feeding back and interpreting the findings within the community. This involves data analysis: sharing (preliminary) findings from surveys, in-depth interviews, focus group discussions, etc. and engaging the community partners to make sense of the findings.

여섯 번째 단계는 연구 결과를 배포하고 번역하는 것입니다. 여기에는 커뮤니티와 공유하기 위해 가장 중요한 연구 결과를 파악하고, 연구 결과를 전달하고 번역하는 데 있어 커뮤니티의 역할을 파악하고, 연구 결과를 광범위한 개입과 정책 변화로 확산하고, 연구 결과를 발표하는 것이 포함됩니다. 이는 커뮤니티 기반 행동 연구 파트너십의 형성으로 이어질 수 있습니다.

The sixth phase is disseminating and translating the research findings. This involves identifying the most important findings for sharing with the community, the community’s role in communicating and translating the findings, disseminating the findings into broader interventions and policy changes and publishing the research results. This might lead to the formation of a community-based action research partnership.

모든 단계는 커뮤니티 파트너십을 유지, 지속 및 평가하는 지속적인 프로세스를 기본으로 공유합니다. 연구자와 커뮤니티 파트너는 협력 관계에 대해 성찰하고 장기적인 목표와 역량을 공유합니다. 이러한 모든 접근 방식은 파일럿 테스트 또는 개념 증명과 같은 일부 혼합 방법 연구를 통합할 수 있습니다[47].

All phases share an underlying continuous process of maintaining, sustaining and evaluating the community partnerships. The researchers and community partners are reflective about their working relationships and shared long-term goals and capacities. All these approaches might integrate some mixed-methods research such as pilot testing or proof-of-concept [47].

공동 창작 접근법을 적용할 때의 도전 과제

Challenges in applying co-creative approaches

공동 창작 연구 프로젝트에 대한 경험과 참고한 방법론 및 경험적 논문을 바탕으로 이러한 연구 프로젝트가 직면할 수 있는 실용적 및 방법론적 과제에 대한 간략한 개요를 제공합니다.

Drawing on our experience with co-creative research projects and based on the methodological and empirical papers we referenced, we provide a brief overview of practical and methodological challenges that such research projects may face.

실질적인 과제

Practical challenges

Unclear purpose and expectation

이해관계자와 연구자는 프로젝트의 목표가 무엇이며 공동 창작 과정이 왜 필수적인지 이해해야 합니다[40,46]. 이는 공동 창작 접근 방식의 각 단계에서 단계별로 작업하고 공유된 출발점을 설정하는 데 도움이 됩니다. 이때 연구자, 특히 연구책임자는 프로젝트의 범위와 예상 결과를 추적해야 합니다[44].

Stakeholders and researchers need to understand what the project goal is and why the process of co-creation is essential [40,46]. It helps to work step-by-step and establish a shared starting point in each phase of the co-creative approach. At the time, researchers, especially the principal investigator, need to keep track of the scope and expected outcomes of the project [44].

SKILLS, CAPACITIES AND FINANCIAL RESOURCES

일부 이해관계자는 자신의 개인적 이해관계를 넘어서는 관점을 채택할 기술이 부족할 수 있습니다[18]. 연구자는 다양한 프로젝트 단계 또는 연구 활동에서 다양한 이해관계자의 역량을 최적으로 활용해야 합니다. 일부 이해관계자, 특히 환자와 취약한 지역사회 구성원은 회의에 참여할 수 있는 자원이 부족할 수 있습니다[43,48], 예를 들어 대중교통이나 발언에 대한 자신감이 부족할 수 있습니다. 연구자, 특히 연구책임자는 공동 작성에 선호하는 참여 방식, 이해관계자에게 의미 있는 활동, 사용 가능한 시간, 조치, 시간 요구, 재정 자원의 균형을 맞춰야 합니다[44]. 연구책임자는 연구 프로젝트에 이해관계자 참여를 위한 예산을 적절히 책정하는 것이 중요합니다. 연구비 신청 시 이해관계자 참여, 특히 환자 및 대중 참여에 대한 예산을 명시적으로 책정해야 합니다(상자 5). 자금 지원자들은 종종 의미 있는 참여를 촉진하기 위해 예산이 신중하게 배분되었는지 확인합니다.

Some stakeholders might lack the skills to adopt a view beyond their personal stakes [18]. Researchers need to make optimal use of the various stakeholders’ capacities in different project phases or research activities. Some stakeholders, especially patients and vulnerable community members, might lack the resources to participate in meetings [43,48], for example, affording public transport or self-confidence to speak up. Researchers, especially principal investigators, need to balance preferred ways of engagement in co-creation, meaningful activities to stakeholders and the available time, enabling measures, time demands and financial resources [44]. It is important for principal investigators to budget for stakeholder involvement in their research projects adequately. When applying for research grants, stakeholder involvement, especially patient and public involvement should be explicitly budgeted (Box 5). Funders often check to ensure budgets have been thoughtfully allocated to promote meaningful participation.

MULTIPLE PERSPECTIVES AND CONFLICTS

심층 인터뷰, 포커스 그룹 토론, 워크숍 등을 통해 환자, 전문가, 관리자 등 다양한 출처에서 다양한 유형의 데이터를 수집합니다. 이러한 인식과 우려를 통합하고 우선순위를 정하는 것은 이해관계자와 연구자에게 어려운 과제입니다[49]. 서로 다른 의사결정 스타일, 가치, 우선순위, 언어 사용, 참여 이력, 인지된 권력 불균형, 경쟁 또는 이해관계자의 의견에 대한 피드백 부족으로 인해 갈등이 발생할 수 있습니다[40]. 연구자들은 민주적인 대화 과정, 공동 책임, 긍정적인 관계를 조성해야 합니다[38,39,41,46].

Various data types are collected during in-depth interviews, focus-group discussions, workshops etc., from different sources, for example, patients, professionals, and managers. The integration and prioritisation of these perceptions and concerns are challenges for stakeholders and researchers [49]. Conflicts may occur due to different decision-making styles, values, priorities, use of language, engagement history, perceived power imbalance, competition or lack of feedback on stakeholders’ input [40]. Researchers need to foster a democratic process of dialogue, shared responsibility and positive relationships [38,39,41,46].

방법론적 과제

Methodological challenges

Methodological quality

대부분의 이해관계자는 주로 프로젝트가 자신이 인지하는 건강 문제를 어떻게 해결할 것인지에 관심이 있는 반면, 연구자는 유효한 과학적 지식을 창출하기 위해 노력합니다. 연구자는 모든 연구 단계에서 실용적 관련성, 방법론적 품질, 타이밍의 균형을 맞추기 위해 유연성을 발휘해야 합니다[40,44,49].

Most stakeholders are primarily interested in how the project will address their perceived health issues, whereas researchers also strive for generating valid scientific knowledge. Researchers need to be flexible in all research steps in balancing practical relevance, methodological quality, and timing [40,44,49].

RESEARCH TEAM

공동 창작을 위해서는 연구팀에 다양한 역량이 필요합니다. 일반적으로 다학제 연구팀의 개별 연구자는 특정 연구 단계 또는 단계에서 자신의 전문성을 발휘합니다. 연구자들은 다양한 보건 분야 방법론적 역량, 사회적 역량을 통합하여 모든 이해관계자를 공동창출 과정으로 안내하는 연구팀을 구성해야 합니다[41,49]. 유연하고 시간이 많이 걸리며 때로는 예상치 못한 공동 창작의 특성으로 인해 시간 압박이 발생할 수 있습니다[43]. 연구자는 일을 완수하는 것과 연구 과정, 방법론적 품질, 이해관계자 관계 및 자신의 역할에 대한 성찰 사이의 균형을 유지해야 합니다[18].

Co-creation requires various competencies in the research team. Usually, individual researchers in multidisciplinary teams bring in their specific expertise in certain research phases or steps. Researchers need to compose a research team that integrates competencies from different health disciplines, methodological competencies and social competencies in guiding all stakeholders through the co-creation process [41,49]. The flexible, time-consuming and sometimes unexpected nature of co-creation might cause time pressure [43]. Researchers need to balance getting things done and reflecting on the research process, methodological quality, stakeholder relationships and their own role [18].

DIGITAL RESEARCH

넷노그래피[50], 다양한 공식 및 비공식 온라인 데이터 소스 사용, 디지털 데이터 수집 방법 및 대화형 디지털 도구와 같은 다른 질적 접근 방식이 본격적으로 개발되고 있습니다. 디지털 연구는 효율적인 데이터 수집과 관리를 지원할 수 있지만, 디지털 기술이 부족한 사람을 배제하는 등 불평등의 위험을 초래할 수도 있습니다[51]. 연구자들은 질적 연구에서 디지털화가 공동 창조적 접근 방식에서 유망한 방법이 될 수 있으므로 윤리적, 방법론적 문제를 고려해야 합니다.

Other qualitative approaches, such as netnography [50], use of various formal and informal online data sources, digital data collection methods and interactive digital tools are fully in development. Digital research might support efficient data collection and management but might also bring inequality risk, for example, exclusion of people lacking digital skills [51]. Researchers need to consider ethical and methodological issues in digitalisation in qualitative research because it might be a promising way forward in co-creative approaches.

| Box 5. Sources for further reading on stakeholder analysis and management, patient and public involvement and three co-creative qualitative approaches. Web sources on stakeholder analysis and management

|

Series: Practical guidance to qualitative research. Part 5: Co-creative qualitative approaches for emerging themes in primary care research: Experience-based co-design, user-centred design and community-based participatory research

PMID: 35037811

PMCID: PMC8765256

DOI: 10.1080/13814788.2021.2010700

Free PMC article

Abstract

This article, the fifth in a series aiming to provide practical guidance for qualitative research in primary care, introduces three qualitative approaches with co-creative characteristics for addressing emerging themes in primary care research: experience-based co-design, user-centred design and community-based participatory research. Co-creation aims to define the (research) problem, develop and implement interventions and evaluate and define (research and practice) outcomes in partnership with patients, family carers, researchers, care professionals and other relevant stakeholders. Experience-based co-design seeks to understand how people experience a health care process or service. User-centred design is an approach to assess, design and develop technological and organisational systems, for example, eHealth, involving end-users in the design and decision-making processes. Community-based participatory research is a collaborative approach addressing a locally relevant health issue. It is often directed at hard-to-reach and vulnerable people. We address the context, what, why, when and how of these co-creative approaches, and their main practical and methodological challenges. We provide examples of empirical studies using these approaches and sources for further reading.

Keywords: Primary care; co-creation; eHealth; patient and public involvement; qualitative research.