인터뷰 기반 연구에서 표본 크기 충분성의 특성화 및 정당화: 15년간 질적 건강연구의 체계적 문헌고찰(BMC Med Res Methodol. 2018)

Characterising and justifying sample size sufficiency in interview-based studies: systematic analysis of qualitative health research over a 15-year period

Konstantina Vasileiou1* , Julie Barnett1, Susan Thorpe2 and Terry Young3

배경

Background

질적 조사에서 [표본의 적절성]은 [표본 구성 및 크기의 적절성]과 관련이 있습니다. 이는 많은 질적 연구의 품질과 신뢰성을 평가할 때 중요한 고려 사항이며[1], 특히 [후기 실증주의 전통]에 속하고 [실재론적 존재론적 전제]를 어느 정도 고수하는 연구의 경우 타당성과 일반화 가능성을 평가할 때 중요한 의미를 갖습니다[2,3,4,5].

Sample adequacy in qualitative inquiry pertains to the appropriateness of the sample composition and size. It is an important consideration in evaluations of the quality and trustworthiness of much qualitative research [1] and is implicated – particularly for research that is situated within a post-positivist tradition and retains a degree of commitment to realist ontological premises – in appraisals of validity and generalizability [2,3,4,5].

[질적 연구의 표본]은 이 탐구 방식의 기본인 사례 중심 분석의 깊이를 뒷받침하기 위해 작은 경향이 있습니다[5]. 또한 질적 표본은 목적적 표본, 즉 조사 대상 현상과 관련된 풍부한 질감의 정보를 제공할 수 있는 능력에 따라 선택됩니다. 결과적으로 정량적 연구에 사용되는 [확률적 표본 추출]과 달리 [의도적 표본 추출][6, 7]은 '정보가 풍부한' 사례를 선택합니다[8]. 실제로 최근 연구에 따르면 질적 연구에서 무작위 샘플링에 비해 [의도적 샘플링의 효율성이 더 높다]는 사실이 입증되어[9], 질적 방법론가들이 오랫동안 주장해온 관련 주장을 뒷받침하고 있습니다.

Samples in qualitative research tend to be small in order to support the depth of case-oriented analysis that is fundamental to this mode of inquiry [5]. Additionally, qualitative samples are purposive, that is, selected by virtue of their capacity to provide richly-textured information, relevant to the phenomenon under investigation. As a result, purposive sampling [6, 7] – as opposed to probability sampling employed in quantitative research – selects ‘information-rich’ cases [8]. Indeed, recent research demonstrates the greater efficiency of purposive sampling compared to random sampling in qualitative studies [9], supporting related assertions long put forward by qualitative methodologists.

질적 연구에서의 표본 크기는 지속적인 논의의 주제였습니다[4, 10, 11]. 정량적 연구 커뮤니티는 표본 크기를 정확하게 설정하기 위해 비교적 간단한 [통계 기반 규칙]을 확립한 반면, 질적 연구의 표본 크기 결정 및 평가의 복잡성은 질적 연구의 특징인 [방법론적, 이론적, 인식론적, 이념적 다원주의]에서 비롯됩니다(심리학 분야에 초점을 맞춘 논의는 [12]를 참조하세요). 이는 항상 적용되는 명확한 지침에 반하는 것입니다. 이러한 어려움에도 불구하고 다양한 개념적 발전이 이 문제를 해결하기 위해 지침과 원칙을 제시하고 있으며[4, 10, 11, 13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20], 최근에는 표본 크기 결정에 대한 증거 기반 접근 방식이 경험적으로 논의를 뒷받침하려고 합니다[21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35].

Sample size in qualitative research has been the subject of enduring discussions [4, 10, 11]. Whilst the quantitative research community has established relatively straightforward statistics-based rules to set sample sizes precisely, the intricacies of qualitative sample size determination and assessment arise from the methodological, theoretical, epistemological, and ideological pluralism that characterises qualitative inquiry (for a discussion focused on the discipline of psychology see [12]). This mitigates against clear-cut guidelines, invariably applied. Despite these challenges, various conceptual developments have sought to address this issue, with guidance and principles [4, 10, 11, 13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20], and more recently, an evidence-based approach to sample size determination seeks to ground the discussion empirically [21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35].

본 연구는 참여자별 단일 인터뷰 질적 설계에 초점을 맞추어, 표본 크기와 관련된 정당화 관행에 대한 실증적 증거를 제공함으로써 질적 연구에서 표본 크기의 논의에 더욱 기여하고자 합니다. 다음으로 표본 크기 결정에 관한 기존의 개념적 및 실증적 문헌을 검토합니다.

Focusing on single-interview-per-participant qualitative designs, the present study aims to further contribute to the dialogue of sample size in qualitative research by offering empirical evidence around justification practices associated with sample size. We next review the existing conceptual and empirical literature on sample size determination.

질적 연구에서의 표본 크기: 개념적 발전과 실증적 조사

Sample size in qualitative research: Conceptual developments and empirical investigations

질적 연구 전문가들은 '몇 명'이라는 질문에 대한 정답은 없으며, 표본 크기는 인식론적, 방법론적, 실제적 문제와 관련된 여러 요인에 따라 달라진다고 주장합니다[36].

- 샌델로우스키[4]는 질적 표본의 크기는 연구 대상 현상에 대한 '새롭고 풍부한 질감의 이해'를 펼칠 수 있을 만큼 [충분히 크되], 질적 데이터의 '심층적인 사례 중심 분석'(183쪽)이 배제되지 않도록 [충분히 작을 것]을 권장합니다.

- 모스[11]는 각 사람으로부터 더 많은 사용 가능한 데이터를 수집할수록 더 적은 수의 참가자가 필요하다고 가정합니다. 그녀는 연구자가 연구 범위, 주제의 특성(예: 복잡성, 접근성), 데이터의 품질, 연구 설계와 같은 [매개변수를 고려]할 것을 권유합니다.

실제로 질적 면접에서 [질문의 구조 수준]은 생성되는 [데이터의 풍부함에 영향]을 미치는 것으로 밝혀졌기 때문에[37] 주의가 필요하며, 경험적 연구에 따르면 [인터뷰 후반부에 질문하는 개방형 질문]이 [더 풍부한 데이터를 생성하는 경향]이 있다고 합니다[37].

Qualitative research experts argue that there is no straightforward answer to the question of ‘how many’ and that sample size is contingent on a number of factors relating to epistemological, methodological and practical issues [36].

- Sandelowski [4] recommends that qualitative sample sizes are large enough to allow the unfolding of a ‘new and richly textured understanding’ of the phenomenon under study, but small enough so that the ‘deep, case-oriented analysis’ (p. 183) of qualitative data is not precluded.

- Morse [11] posits that the more useable data are collected from each person, the fewer participants are needed. She invites researchers to take into account parameters, such as the scope of study, the nature of topic (i.e. complexity, accessibility), the quality of data, and the study design.

Indeed, the level of structure of questions in qualitative interviewing has been found to influence the richness of data generated [37], and so, requires attention; empirical research shows that open questions, which are asked later on in the interview, tend to produce richer data [37].

이러한 지침 외에도 전문가들의 질적 연구 경험을 바탕으로 구체적인 수치적 권장 사항도 제시되고 있습니다.

- 예를 들어, Green과 Thorogood[38]은 상당히 구체적인 연구 질문으로 인터뷰 기반 연구를 수행하는 대부분의 질적 연구자의 경험에 따르면 분석적으로 관련된 하나의 참가자 '범주'에 속하는 20명 내외를 인터뷰한 후에는 새로운 정보가 거의 생성되지 않는다고 주장합니다(102-104페이지).

- Ritchie 등[39]은 개별 인터뷰를 사용하는 연구에서는 연구자가 분석 작업의 복잡성을 관리할 수 있도록 50명 이하의 인터뷰를 실시할 것을 제안합니다.

- 마찬가지로 Britten[40]은 대규모 인터뷰 연구의 경우 50~60명으로 구성되는 경우가 많다고 언급합니다. 전문가들은 또한 다양한 이론적, 방법론적 전통과 특정 연구 접근법(예: 근거 이론, 현상학)에 맞춘 수치적 지침을 제시했습니다[11, 41].

- 최근에는 모집단 내 테마의 빈도 추정치를 기반으로 선험적 표본 크기 결정을 지원하는 정량적 도구가 제안되었습니다[42]. 그럼에도 불구하고 이러한 보다 [수치 공식적인 접근 방식]은 '테마'의 개념적[43], 존재론적 지위[44]에 대한 가정과 샘플링, 데이터 수집 및 데이터 분석 프로세스에 따른 선형성[45]과 관련된 비판을 불러일으켰습니다.

Beyond such guidance, specific numerical recommendations have also been proffered, often based on experts’ experience of qualitative research.

- For example, Green and Thorogood [38] maintain that the experience of most qualitative researchers conducting an interview-based study with a fairly specific research question is that little new information is generated after interviewing 20 people or so belonging to one analytically relevant participant ‘category’ (pp. 102–104).

- Ritchie et al. [39] suggest that studies employing individual interviews conduct no more than 50 interviews so that researchers are able to manage the complexity of the analytic task.

- Similarly, Britten [40] notes that large interview studies will often comprise of 50 to 60 people. Experts have also offered numerical guidelines tailored to different theoretical and methodological traditions and specific research approaches, e.g. grounded theory, phenomenology [11, 41].

- More recently, a quantitative tool was proposed [42] to support a priori sample size determination based on estimates of the prevalence of themes in the population. Nevertheless, this more formulaic approach raised criticisms relating to assumptions about the conceptual [43] and ontological status of ‘themes’ [44] and the linearity ascribed to the processes of sampling, data collection and data analysis [45].

원칙적인 측면에서 링컨과 구바[17]는 [정보 중복성]의 기준에 따라 표본 크기를 결정할 것을 제안했는데, 즉 [더 많은 단위를 샘플링해도 새로운 정보가 도출되지 않을 경우 샘플링을 중단할 수 있다]는 것입니다. 정보 포괄성의 논리에 따라 Malterud 등[18]은 실용적인 지침 원칙으로 [정보력 개념]을 도입하여 표본이 제공하는 [정보력이 많을수록 표본 크기가 작아야 하고 그 반대의 경우도 마찬가지]라고 제안했습니다.

In terms of principles, Lincoln and Guba [17] proposed that sample size determination be guided by the criterion of informational redundancy, that is, sampling can be terminated when no new information is elicited by sampling more units. Following the logic of informational comprehensiveness Malterud et al. [18] introduced the concept of information power as a pragmatic guiding principle, suggesting that the more information power the sample provides, the smaller the sample size needs to be, and vice versa.

의심할 여지 없이, 표본 크기를 결정하고 그 충분성을 평가하는 데 가장 널리 사용되는 원칙은 [포화]입니다. 포화 개념은 경험적으로 도출된 이론 개발과 명시적으로 관련된 질적 방법론적 접근 방식인 근거 이론[15]에서 비롯되었으며 이론적 샘플링과 불가분의 관계에 있습니다. [이론적 표본 추출]은 [데이터 수집, 데이터 분석 및 이론 개발의 반복적인 프로세스]를 설명하며, 데이터 수집은 모집단의 사전 정의된 특성이 아닌 새로운 이론에 의해 관리됩니다. [근거 이론 포화(종종 이론적 포화라고도 함)]는 개발 중인 이론 범주(데이터가 아닌)와 관련이 있으며, '새로운 데이터를 수집해도 더 이상 [새로운 이론적 통찰력]을 얻지 못하거나 [핵심 이론 범주의 새로운 속성]이 드러나지 않을 때'[46페이지 113] 분명해집니다. 따라서 근거 이론에서 포화 상태는 [일반적인 데이터 반복에 대한 초점과 동일하지 않으며], 표본 추출의 적절성을 정당화하는 표본 크기에 대한 단일 초점을 넘어서는 것입니다[46, 47]. 근거 이론에서 표본 크기는 진화하는 이론적 범주에 따라 달라지기 때문에 [선험적으로 결정할 수 없습니다].

Undoubtedly, the most widely used principle for determining sample size and evaluating its sufficiency is that of saturation. The notion of saturation originates in grounded theory [15] – a qualitative methodological approach explicitly concerned with empirically-derived theory development – and is inextricably linked to theoretical sampling. Theoretical sampling describes an iterative process of data collection, data analysis and theory development whereby data collection is governed by emerging theory rather than predefined characteristics of the population. Grounded theory saturation (often called theoretical saturation) concerns the theoretical categories – as opposed to data – that are being developed and becomes evident when ‘gathering fresh data no longer sparks new theoretical insights, nor reveals new properties of your core theoretical categories’ [46 p. 113]. Saturation in grounded theory, therefore, does not equate to the more common focus on data repetition and moves beyond a singular focus on sample size as the justification of sampling adequacy [46, 47]. Sample size in grounded theory cannot be determined a priori as it is contingent on the evolving theoretical categories.

포화(종종 '데이터' 또는 '주제별' 포화도라는 용어로 사용됨)는 근거 이론의 기원을 넘어 여러 질적 커뮤니티로 확산되었습니다. '새로운 데이터 없음', '새로운 주제 없음', '새로운 코드 없음'과 다양하게 동일시되는 의미의 확장과 함께, 포화도는 질적 탐구에서 '황금 표준'으로 부상했습니다[2, 26]. 그럼에도 불구하고 모스[48]가 주장했듯이, 포화는 '질적 엄격성의 보증'으로 가장 자주 호출되지만, '우리가 가장 잘 모르는 것'(587쪽)입니다. 물론 연구자들은 포화도가 특정 유형의 질적 연구(예: 대화 분석, [49]; 현상학적 연구, [50])에 적용하기 어렵거나 적절하지 않다고 경고하는 반면, 다른 연구자들은 이 개념을 완전히 거부합니다[19, 51].

Saturation – often under the terms of ‘data’ or ‘thematic’ saturation – has diffused into several qualitative communities beyond its origins in grounded theory. Alongside the expansion of its meaning, being variously equated with ‘no new data’, ‘no new themes’, and ‘no new codes’, saturation has emerged as the ‘gold standard’ in qualitative inquiry [2, 26]. Nevertheless, and as Morse [48] asserts, whilst saturation is the most frequently invoked ‘guarantee of qualitative rigor’, ‘it is the one we know least about’ (p. 587). Certainly researchers caution that saturation is less applicable to, or appropriate for, particular types of qualitative research (e.g. conversation analysis, [49]; phenomenological research, [50]) whilst others reject the concept altogether [19, 51].

이 분야의 방법론적 연구는 포화도에 대한 지침을 제공하고 포화를 '조작화'하고 증거하는 프로세스의 실제 적용을 개발하는 것을 목표로 합니다.

- 게스트, 번스, 존슨[26]은 60개의 인터뷰를 분석한 결과 12번째 인터뷰에 이르러 주제의 포화 상태에 도달했다는 사실을 발견했습니다. 이들은 표본이 비교적 동질적이고 연구 목표가 집중되어 있기 때문에 더 이질적인 표본과 더 넓은 범위를 대상으로 한 연구는 포화 상태에 도달하기 위해 더 큰 규모가 필요할 것이라고 지적했습니다.

- 이 질문을 다중 사이트, 다문화 연구로 확장한 Hagaman과 Wutich[28]는 연구 사이트를 가로지르는 메타 주제의 데이터 포화도를 달성하려면 20~40개의 인터뷰 샘플 크기가 필요하다는 것을 보여주었습니다.

- 이론 중심 내용 분석에서 Francis 등[25]은 사전 결정된 모든 이론적 구성에 대해 17번째 인터뷰에 데이터 포화 상태에 도달했습니다. 저자들은 포화도 지정의 근거가 되는 두 가지 주요 원칙을 추가로 제안했습니다.

- (a) 연구자는 1차 분석에 사용될 초기 분석 샘플(예: 10개의 인터뷰)을 선험적으로 지정하고,

- (b) 분석에서 새로운 주제나 아이디어를 얻지 못할 경우 추가로 수행해야 하는 인터뷰 수(예: 3개)를 중단 기준으로 정해야 한다는 것입니다.

- 투명성을 높이기 위해 프란시스 외[25]는 연구자가 포화 상태에 도달했다는 판단을 뒷받침하는 누적 빈도 그래프를 제시할 것을 권장합니다.

- 주제 포화도 비교 방법(CoMeTS)도 제안되었는데[23], 각각의 새로운 인터뷰 결과를 이미 나온 인터뷰 결과와 비교하여 새로운 주제가 나오지 않으면 '포화된 지형'이 확립된 것으로 간주합니다.

- 인터뷰 분석 순서는 데이터의 풍부도에 따라 포화 임계값에 영향을 미칠 수 있으므로, 콘스탄티노우 등[23]은 포화 상태를 확인하기 위해 인터뷰 순서를 바꾸고 다시 분석할 것을 권장합니다.

- 헤닝크, 카이저, 마르코니의 [29] 방법론 연구는 포화도를 지정하고 입증하는 문제에 대해 더 자세히 조명합니다.

- 인터뷰 데이터를 분석한 결과 코드 포화(즉, 추가 이슈가 식별되지 않는 지점)는 9번의 인터뷰로 달성할 수 있었지만 의미 포화(즉, 이슈의 차원, 뉘앙스 또는 통찰력이 더 이상 식별되지 않는 지점)는 16~24번의 인터뷰가 필요했습니다.

- 폭은 특히 유병률이 높고 구체적인 코드의 경우 비교적 빨리 달성할 수 있지만, 깊이는 특히 개념적인 성격의 코드의 경우 추가 데이터가 필요합니다.

Methodological studies in this area aim to provide guidance about saturation and develop a practical application of processes that ‘operationalise’ and evidence saturation.

- Guest, Bunce, and Johnson [26] analysed 60 interviews and found that saturation of themes was reached by the twelfth interview. They noted that their sample was relatively homogeneous, their research aims focused, so studies of more heterogeneous samples and with a broader scope would be likely to need a larger size to achieve saturation.

- Extending the enquiry to multi-site, cross-cultural research, Hagaman and Wutich [28] showed that sample sizes of 20 to 40 interviews were required to achieve data saturation of meta-themes that cut across research sites.

- In a theory-driven content analysis, Francis et al. [25] reached data saturation at the 17th interview for all their pre-determined theoretical constructs. The authors further proposed two main principles upon which specification of saturation be based:

- (a) researchers should a priori specify an initial analysis sample (e.g. 10 interviews) which will be used for the first round of analysis and

- (b) a stopping criterion, that is, a number of interviews (e.g. 3) that needs to be further conducted, the analysis of which will not yield any new themes or ideas.

- For greater transparency, Francis et al. [25] recommend that researchers present cumulative frequency graphs supporting their judgment that saturation was achieved.

- A comparative method for themes saturation (CoMeTS) has also been suggested [23] whereby the findings of each new interview are compared with those that have already emerged and if it does not yield any new theme, the ‘saturated terrain’ is assumed to have been established.

- Because the order in which interviews are analysed can influence saturation thresholds depending on the richness of the data, Constantinou et al. [23] recommend reordering and re-analysing interviews to confirm saturation.

- Hennink, Kaiser and Marconi’s [29] methodological study sheds further light on the problem of specifying and demonstrating saturation.

- Their analysis of interview data showed that code saturation (i.e. the point at which no additional issues are identified) was achieved at 9 interviews, but meaning saturation (i.e. the point at which no further dimensions, nuances, or insights of issues are identified) required 16–24 interviews.

- Although breadth can be achieved relatively soon, especially for high-prevalence and concrete codes, depth requires additional data, especially for codes of a more conceptual nature.

넬슨[19]은 포화도 개념을 비판하면서 개발 중인 이론의 견고성을 평가하기 위해 근거 이론 프로젝트에서 다섯 가지 개념적 깊이 기준을 제안합니다:

- (a) 이론적 개념은 데이터에서 도출된 광범위한 증거에 의해 뒷받침되어야 하며,

- (b) 상호 연결된 개념 네트워크의 일부임을 입증할 수 있고,

- (c) 미묘함을 입증하고,

- (d) 기존 문헌과 공명하고,

- (e) 외부 타당성 테스트에 성공적으로 제출할 수 있어야 합니다.

Critiquing the concept of saturation, Nelson [19] proposes five conceptual depth criteria in grounded theory projects to assess the robustness of the developing theory:

- (a) theoretical concepts should be supported by a wide range of evidence drawn from the data;

- (b) be demonstrably part of a network of inter-connected concepts;

- (c) demonstrate subtlety;

- (d) resonate with existing literature; and

- (e) can be successfully submitted to tests of external validity.

영양학[34], 보건 교육[32], 교육 및 보건 과학[22, 27], 정보 시스템[30], 조직 및 직장 연구[33], 인간 컴퓨터 상호작용[21], 회계 연구[24]에 이르기까지 다양한 학문 분야와 연구 영역에서 표본 크기 보고 및 충분성 평가의 관행을 조사하고자 한 다른 연구도 있습니다. 다른 연구에서는 박사 학위 질적 연구[31]와 근거 이론 연구[35]를 조사했습니다. 이러한 조사에서 불완전하고 부정확한 표본 크기 보고가 흔히 발견되는 반면, 표본 크기의 충분성에 대한 평가와 정당화는 훨씬 더 산발적으로 이루어지고 있습니다.

Other work has sought to examine practices of sample size reporting and sufficiency assessment across a range of disciplinary fields and research domains, from nutrition [34] and health education [32], to education and the health sciences [22, 27], information systems [30], organisation and workplace studies [33], human computer interaction [21], and accounting studies [24]. Others investigated PhD qualitative studies [31] and grounded theory studies [35]. Incomplete and imprecise sample size reporting is commonly pinpointed by these investigations whilst assessment and justifications of sample size sufficiency are even more sporadic.

Sobal[34]은 30년 동안 영양 교육 저널에 발표된 질적 연구의 표본 규모를 조사했습니다. 개별 인터뷰를 사용한 연구(n = 30)의 평균 표본 크기는 45명이었으며, 이들 중 표본 크기가 포화 상태에 도달했는지 여부를 명시적으로 보고한 연구는 없었습니다. 소수의 논문에서는 표본 관련 제한 사항(대부분 표본의 크기보다는 표본의 유형에 관한 것)이 일반화 가능성을 어떻게 제한하는지 논의했습니다. 20년간의 보건 교육 연구에 대한 체계적인 분석[32]에 따르면 인터뷰 기반 연구의 평균 참여자 수는 104명(인터뷰 대상자 범위는 2~720명)이었습니다. 그러나 40%는 참가자 수를 보고하지 않았습니다. 주요 정보 시스템 저널[30]에 실린 83건의 질적 인터뷰 연구를 조사한 결과, 질적 방법론자의 권고, 선행 관련 연구 또는 포화도 기준에 근거하여 표본 규모에 대한 방어가 거의 없는 것으로 나타났습니다. 오히려 표본 크기는 출판 저널이나 연구 지역(미국 대 유럽 대 아시아)과 같은 요인과 상관관계가 있는 것으로 나타났습니다. 이러한 결과를 바탕으로 저자들은 질적 정보 시스템 연구에서 표본 규모를 결정하고 보고할 때 보다 엄격해야 하며, 근거 이론(예: 20~30개 인터뷰) 및 단일 사례(예: 15~30개 인터뷰) 프로젝트에 대한 최적의 표본 규모 범위를 권장했습니다.

Sobal [34] examined the sample size of qualitative studies published in the Journal of Nutrition Education over a period of 30 years. Studies that employed individual interviews (n = 30) had an average sample size of 45 individuals and none of these explicitly reported whether their sample size sought and/or attained saturation. A minority of articles discussed how sample-related limitations (with the latter most often concerning the type of sample, rather than the size) limited generalizability. A further systematic analysis [32] of health education research over 20 years demonstrated that interview-based studies averaged 104 participants (range 2 to 720 interviewees). However, 40% did not report the number of participants. An examination of 83 qualitative interview studies in leading information systems journals [30] indicated little defence of sample sizes on the basis of recommendations by qualitative methodologists, prior relevant work, or the criterion of saturation. Rather, sample size seemed to correlate with factors such as the journal of publication or the region of study (US vs Europe vs Asia). These results led the authors to call for more rigor in determining and reporting sample size in qualitative information systems research and to recommend optimal sample size ranges for grounded theory (i.e. 20–30 interviews) and single case (i.e. 15–30 interviews) projects.

마찬가지로 조직 및 직장 연구 논문의 10% 미만이 방법론가, 선행 관련 연구 또는 포화도와 관련된 표본 크기 정당성을 제공했으며[33], 건강 관련 저널의 포커스 그룹 연구 중 17%만이 표본 크기(즉, 포커스 그룹 수)에 대한 설명을 제공했으며, [포화]가 가장 자주 인용된 논거였고 그 다음으로 [출판된 표본 크기 권장 사항]과 [실용적인 이유][22] 순으로 나타났습니다. 포화 개념은 교육 및 보건 과학 분야에서 가장 많이 인용된 51개의 연구 중 11개에서 사용되었는데, 이 중 6개는 근거 이론 연구, 4개는 현상학적 연구, 1개는 내러티브 탐구였습니다[27]. 마지막으로, 회계학 분야의 인터뷰 기반 논문 641편을 분석한 Dai 등[24]은 상당수의 연구가 정확한 표본 크기를 보고하지 않았기 때문에 더 엄격할 것을 요구했습니다.

Similarly, fewer than 10% of articles in organisation and workplace studies provided a sample size justification relating to existing recommendations by methodologists, prior relevant work, or saturation [33], whilst only 17% of focus groups studies in health-related journals provided an explanation of sample size (i.e. number of focus groups), with saturation being the most frequently invoked argument, followed by published sample size recommendations and practical reasons [22]. The notion of saturation was also invoked by 11 out of the 51 most highly cited studies that Guetterman [27] reviewed in the fields of education and health sciences, of which six were grounded theory studies, four phenomenological and one a narrative inquiry. Finally, analysing 641 interview-based articles in accounting, Dai et al. [24] called for more rigor since a significant minority of studies did not report precise sample size.

질적 연구의 엄격성에 대한 관심 증가(예: [52])와 질적 연구의 검증을 위한 보다 광범위한 방법론 및 분석 공개에도 불구하고[24], 표본 크기 보고 및 충분성 평가는 다양한 연구 영역에서 일관되지 않고 부분적으로만 이루어지고 있습니다.

Despite increasing attention to rigor in qualitative research (e.g. [52]) and more extensive methodological and analytical disclosures that seek to validate qualitative work [24], sample size reporting and sufficiency assessment remain inconsistent and partial, if not absent, across a range of research domains.

본 연구의 목적

Objectives of the present study

본 연구는 건강과 관련된 질적 연구에 초점을 맞추어 표본 크기 보고 및 정당성에 대한 관습과 관행에 대한 기존의 체계적 분석을 강화하고자 했습니다. 또한, 본 연구는 질적 표본 크기가 학문적 서술에서 어떻게 특징지어지고 논의되는지를 조사함으로써 이전의 경험적 조사를 확장하고자 했습니다. 질적 건강 연구는 의학과의 연관성으로 인해 종종 양적 정신을 반영하는 견해와 입장에 직면하는 학제 간 분야입니다. 따라서 질적 건강 연구는 표본 규모를 고려할 때 구체화되는 과학계의 근본적인 철학적, 방법론적 차이를 드러내는 데 도움이 될 수 있는 상징적인 사례입니다. 따라서 본 연구에서는 질적 건강 연구와 관련된 세 가지 다른 학문 분야인 의학, 심리학, 사회학을 기반으로 비교 요소를 통합했습니다. 질적 건강 연구에서 대중적이고 널리 사용되는 방법론적 선택일 뿐만 아니라 인터뷰 대상자 수로 정의되는 표본 크기에 대한 고려가 특히 두드러지는 방법이기 때문에 [단일 참가자당 인터뷰 설계]에 분석의 초점을 맞추기로 결정했습니다.

The present study sought to enrich existing systematic analyses of the customs and practices of sample size reporting and justification by focusing on qualitative research relating to health. Additionally, this study attempted to expand previous empirical investigations by examining how qualitative sample sizes are characterised and discussed in academic narratives. Qualitative health research is an inter-disciplinary field that due to its affiliation with medical sciences, often faces views and positions reflective of a quantitative ethos. Thus qualitative health research constitutes an emblematic case that may help to unfold underlying philosophical and methodological differences across the scientific community that are crystallised in considerations of sample size. The present research, therefore, incorporates a comparative element on the basis of three different disciplines engaging with qualitative health research: medicine, psychology, and sociology. We chose to focus our analysis on single-per-participant-interview designs as this not only presents a popular and widespread methodological choice in qualitative health research, but also as the method where consideration of sample size – defined as the number of interviewees – is particularly salient.

방법

Methods

연구 설계

Study design

횡단면 인터뷰 기반의 질적 연구를 보고하는 논문을 구조적으로 검색하고 양적 및 질적 분석 기법을 모두 사용하여 적격 보고서를 체계적으로 검토 및 분석했습니다.

A structured search for articles reporting cross-sectional, interview-based qualitative studies was carried out and eligible reports were systematically reviewed and analysed employing both quantitative and qualitative analytic techniques.

(a) 동료 검토 프로세스를 따르고, (b) 저널 지표에 반영된 바와 같이 해당 분야에서 높은 수준과 영향력을 지닌 것으로 간주되며, (c) 질적 연구를 수용하고 출판하는 저널을 선정했습니다(추가 파일 1에는 질적 연구와 관련된 저널의 편집 입장과 가능한 경우 샘플 고려 사항이 제시되어 있습니다). 의학을 대표하는 영국의학저널(BMJ), 심리학을 대표하는 영국건강심리학저널(BJHP), 사회학을 대표하는 건강과 질병의 사회학(SHI) 등 각기 다른 학문 분야를 대표하는 세 개의 건강 관련 저널이 선정되었습니다.

We selected journals which (a) follow a peer review process, (b) are considered high quality and influential in their field as reflected in journal metrics, and (c) are receptive to, and publish, qualitative research (Additional File 1 presents the journals’ editorial positions in relation to qualitative research and sample considerations where available). Three health-related journals were chosen, each representing a different disciplinary field; the British Medical Journal (BMJ) representing medicine, the British Journal of Health Psychology (BJHP) representing psychology, and the Sociology of Health & Illness (SHI) representing sociology.

연구 식별을 위한 검색 전략

Search strategy to identify studies

각 개별 저널의 검색 기능을 사용하여 '인터뷰*' 및 '질적'이라는 용어를 사용했으며, 2003년 1월 1일부터 2017년 9월 22일(즉, 15년 검토 기간) 사이에 출판된 논문으로 결과를 제한했습니다.

Employing the search function of each individual journal, we used the terms ‘interview*’ AND ‘qualitative’ and limited the results to articles published between 1 January 2003 and 22 September 2017 (i.e. a 15-year review period).

자격 기준

Eligibility criteria

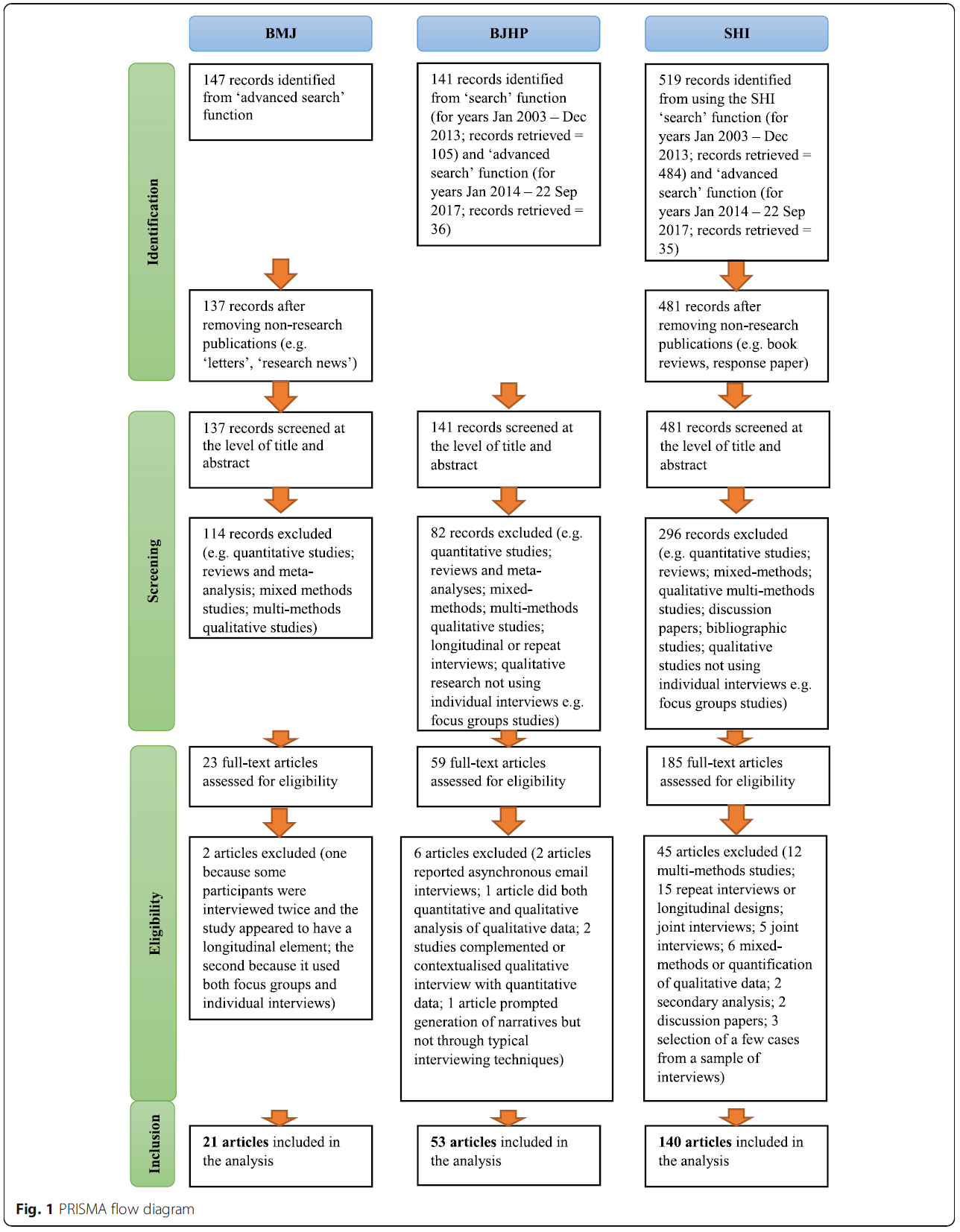

검토 대상에 포함되려면 논문이 단면 연구 설계를 보고해야 했습니다. 따라서 종단 연구는 제외되었지만, 광범위한 연구 프로그램 내에서 수행된 연구(예: 광범위한 민족지학의 일부로 임상시험에 중첩된 인터뷰 연구, 종단 연구의 일부)는 단 한 번의 질적 인터뷰만 보고한 경우 포함되었습니다. 데이터 수집 방법은 개별적이고 동시적인 질적 인터뷰여야 하며(즉, 그룹 인터뷰, 구조화된 인터뷰, 일정 기간에 걸친 이메일 인터뷰는 제외), 데이터를 질적으로 분석해야 합니다(즉, 질적 데이터를 정량화한 연구는 제외). 혼합 방법 연구와 두 가지 이상의 질적 데이터 수집 방법(예: 개별 인터뷰 및 포커스 그룹)을 보고하는 논문은 제외되었습니다. 그림 1은 PRISMA 흐름도[53]로, 검색 및 선별된 논문, 적격성 평가 논문, 리뷰에 포함된 논문의 수를 보여줍니다(추가 파일 2는 리뷰에 포함된 논문의 전체 목록과 고유 식별 코드(예: BMJ01, BJHP02, SHI03)를 제공합니다). 한 명의 리뷰 저자(KV)가 검색에서 확인된 모든 논문의 적격성을 평가했습니다. 의심스러운 경우, KV와 JB는 정기적인 회의를 통해 논문을 유지하거나 제외하는 것에 대해 논의하고 공동으로 결정을 내렸습니다.

To be eligible for inclusion in the review, the article had to report a cross-sectional study design. Longitudinal studies were thus excluded whilst studies conducted within a broader research programme (e.g. interview studies nested in a trial, as part of a broader ethnography, as part of a longitudinal research) were included if they reported only single-time qualitative interviews. The method of data collection had to be individual, synchronous qualitative interviews (i.e. group interviews, structured interviews and e-mail interviews over a period of time were excluded), and the data had to be analysed qualitatively (i.e. studies that quantified their qualitative data were excluded). Mixed method studies and articles reporting more than one qualitative method of data collection (e.g. individual interviews and focus groups) were excluded. Figure 1, a PRISMA flow diagram [53], shows the number of: articles obtained from the searches and screened; papers assessed for eligibility; and articles included in the review (Additional File 2 provides the full list of articles included in the review and their unique identifying code – e.g. BMJ01, BJHP02, SHI03). One review author (KV) assessed the eligibility of all papers identified from the searches. When in doubt, discussions about retaining or excluding articles were held between KV and JB in regular meetings, and decisions were jointly made.

데이터 추출 및 분석

Data extraction and analysis

데이터 추출 양식(추가 파일 3 참조)을 개발하여 (a) 논문에 대한 정보(예: 저자, 제목, 학술지, 출판 연도 등), (b) 연구의 목적, 표본 크기 및 이에 대한 정당성, 참여자 특성, 표본 추출 기법 및 저자의 표본 관련 관찰 또는 의견, (c) 데이터 분석 방법 또는 기술, 분석에 참여한 연구자 수, 소프트웨어 사용 가능성, 인식론적 고려 사항에 대한 논의 등 세 가지 영역의 정보를 기록했습니다. 각 논문의 초록, 방법 및 토론(및/또는 결론) 섹션은 모든 관련 정보를 추출한 한 명의 저자(KV)가 검토했습니다. 이는 논문에서 직접 복사했으며, 필요한 경우 의견, 메모 및 초기 생각을 기록했습니다.

A data extraction form was developed (see Additional File 3) recording three areas of information: (a) information about the article (e.g. authors, title, journal, year of publication etc.); (b) information about the aims of the study, the sample size and any justification for this, the participant characteristics, the sampling technique and any sample-related observations or comments made by the authors; and (c) information about the method or technique(s) of data analysis, the number of researchers involved in the analysis, the potential use of software, and any discussion around epistemological considerations. The Abstract, Methods and Discussion (and/or Conclusion) sections of each article were examined by one author (KV) who extracted all the relevant information. This was directly copied from the articles and, when appropriate, comments, notes and initial thoughts were written down.

기사에서 제공하는 표본 크기의 정당성을 조사하기 위해 귀납적 내용 분석[54]이 처음에 수행되었습니다. 이 분석을 바탕으로 질적으로 다른 표본 크기 정당화를 표현하는 범주를 개발했습니다.

To examine the kinds of sample size justifications provided by articles, an inductive content analysis [54] was initially conducted. On the basis of this analysis, the categories that expressed qualitatively different sample size justifications were developed.

또한 다음과 같은 측면에 대한 정량적 데이터를 추출하거나 코딩했습니다:

We also extracted or coded quantitative data regarding the following aspects:

- 학술지 및 출판 연도

- 인터뷰 횟수

- 참가자 수

- 표본 크기 정당성 유무(예/아니오)

- 특정 표본 크기 정당화 범주의 존재 여부(예/아니요) 및

- 제공된 표본 크기 정당화 항목의 수

- Journal and year of publication

- Number of interviews

- Number of participants

- Presence of sample size justification(s) (Yes/No)

- Presence of a particular sample size justification category (Yes/No), and

- Number of sample size justifications provided

이러한 데이터를 탐색하기 위해 설명적 통계 분석과 추론적 통계 분석이 사용되었습니다.

Descriptive and inferential statistical analyses were used to explore these data.

그런 다음 연구의 표본 크기에 대해 논의하거나 언급하는 모든 과학적 서술에 대해 주제별 분석[55]을 수행했습니다. 이러한 내러티브는 표본 크기를 정당화하는 논문과 그렇지 않은 논문 모두에서 분명하게 나타났습니다. 이러한 내러티브를 식별하기 위해 방법 섹션 외에도 검토된 논문의 토론 섹션을 조사하고 관련 데이터를 추출하여 분석했습니다.

A thematic analysis [55] was then performed on all scientific narratives that discussed or commented on the sample size of the study. These narratives were evident both in papers that justified their sample size and those that did not. To identify these narratives, in addition to the methods sections, the discussion sections of the reviewed articles were also examined and relevant data were extracted and analysed.

결과

Results

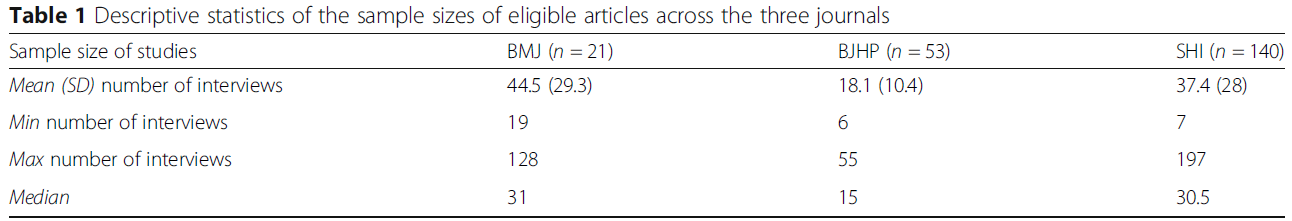

총 214개 논문(BMJ 21개, BJHP 53개, SHI 140개)이 검토 대상에 포함되었습니다. 표 1은 세 저널에서 검토한 연구의 표본 크기(인터뷰 수로 측정)에 대한 기본 정보를 제공합니다. 그림 2는 학술지별로 매년 출판되는 대상 논문 수를 보여줍니다.

In total, 214 articles – 21 in the BMJ, 53 in the BJHP and 140 in the SHI – were eligible for inclusion in the review. Table 1 provides basic information about the sample sizes – measured in number of interviews – of the studies reviewed across the three journals. Figure 2 depicts the number of eligible articles published each year per journal.

2012년 이후 BMJ에 게재된 질적 연구 논문이 현저히 감소했으며, 이는 질적 연구를 대상으로 하는 BMJ Open의 시작과 일치하는 것으로 보입니다.

The publication of qualitative studies in the BMJ was significantly reduced from 2012 onwards and this appears to coincide with the initiation of the BMJ Open to which qualitative studies were possibly directed.

유의한 Kruskal-WallisFootnote2 테스트에 따라 쌍으로 비교한 결과, BJHP에 게재된 연구의 표본 크기가 BMJ 또는 SHI에 게재된 연구보다 유의하게(p < .001) 작은 것으로 나타났습니다. BMJ와 SHI 논문의 표본 크기는 서로 크게 다르지 않았습니다.

Pairwise comparisons following a significant Kruskal-WallisFootnote2 test indicated that the studies published in the BJHP had significantly (p < .001) smaller samples sizes than those published either in the BMJ or the SHI. Sample sizes of BMJ and SHI articles did not differ significantly from each other.

표본 크기 정당화: 양적 및 질적 콘텐츠 분석 결과

Sample size justifications: Results from the quantitative and qualitative content analysis

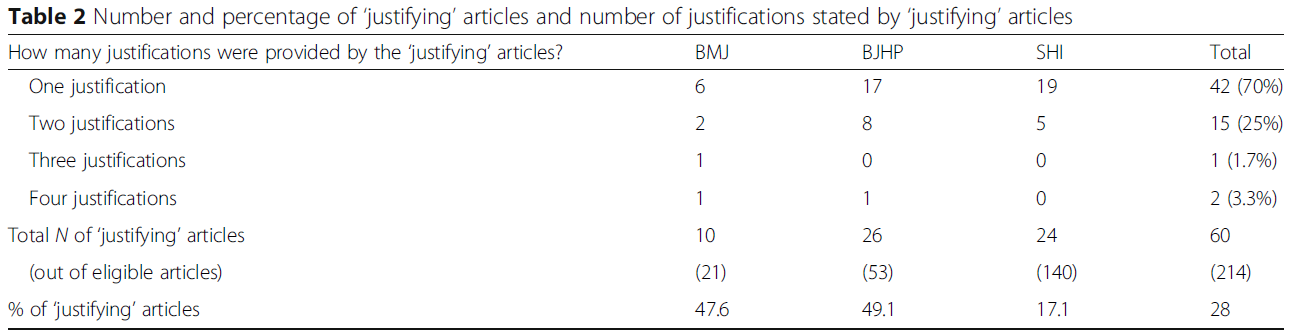

BMJ 논문 21편 중 10편(47.6%), BJHP 논문 53편 중 26편(49.1%), SHI 논문 140편 중 24편(17.1%)이 일종의 표본 크기 정당화를 제공했습니다. 표 2에서 볼 수 있듯이, 표본 크기를 정당화한 논문의 대부분은 한 가지 정당화를 제공했습니다(70%).

- 두 가지 정당화를 제공한 연구는 14건(25%),

- 세 가지 정당화를 제공한 연구는 1건(1.7%),

- 네 가지 정당화를 제공한 연구는 2건(3.3%)이었습니다.

Ten (47.6%) of the 21 BMJ studies, 26 (49.1%) of the 53 BJHP papers and 24 (17.1%) of the 140 SHI articles provided some sort of sample size justification. As shown in Table 2, the majority of articles which justified their sample size provided one justification (70% of articles);

- fourteen studies (25%) provided two distinct justifications;

- one study (1.7%) gave three justifications and

- two studies (3.3%) expressed four distinct justifications.

수행된 인터뷰 횟수(즉, 표본 크기)와 정당화 제공 사이에는 연관성이 없었습니다(rpb = .054, p = .433). 학술지 내에서는 맨-위트니 테스트 결과 BMJ와 SHI에서 '정당화' 및 '비정당화' 논문의 표본 크기가 서로 크게 다르지 않은 것으로 나타났습니다. BJHP에서는 '정당화' 논문(평균 순위 = 31.3)의 표본 크기가 '비정당화' 연구(평균 순위 = 22.7; U = 237.000, p < .05)보다 훨씬 더 컸습니다.

There was no association between the number of interviews (i.e. sample size) conducted and the provision of a justification (rpb = .054, p = .433). Within journals, Mann-Whitney tests indicated that sample sizes of ‘justifying’ and ‘non-justifying’ articles in the BMJ and SHI did not differ significantly from each other. In the BJHP, ‘justifying’ articles (Mean rank = 31.3) had significantly larger sample sizes than ‘non-justifying’ studies (Mean rank = 22.7; U = 237.000, p < .05).

논문이 게재된 저널과 정당화 제공 사이에는 유의미한 연관성이 있었습니다(χ2 (2) = 23.83, p < .001). BJHP 연구는 예상보다 훨씬 더 자주 표본 크기 정당성을 제공했으며(z = 2.9), SHI 연구는 훨씬 덜 자주 제공했습니다(z = - 2.4). 논문이 BJHP에 게재된 경우, 근거를 제공할 확률은 SHI에 게재된 경우보다 4.8배 더 높았습니다. 마찬가지로 BMJ에 게재된 경우, 표본 크기를 정당화하는 연구 확률은 SHI에 게재된 경우보다 4.5배 높았습니다.

There was a significant association between the journal a paper was published in and the provision of a justification (χ2 (2) = 23.83, p < .001). BJHP studies provided a sample size justification significantly more often than would be expected (z = 2.9); SHI studies significantly less often (z = − 2.4). If an article was published in the BJHP, the odds of providing a justification were 4.8 times higher than if published in the SHI. Similarly if published in the BMJ, the odds of a study justifying its sample size were 4.5 times higher than in the SHI.

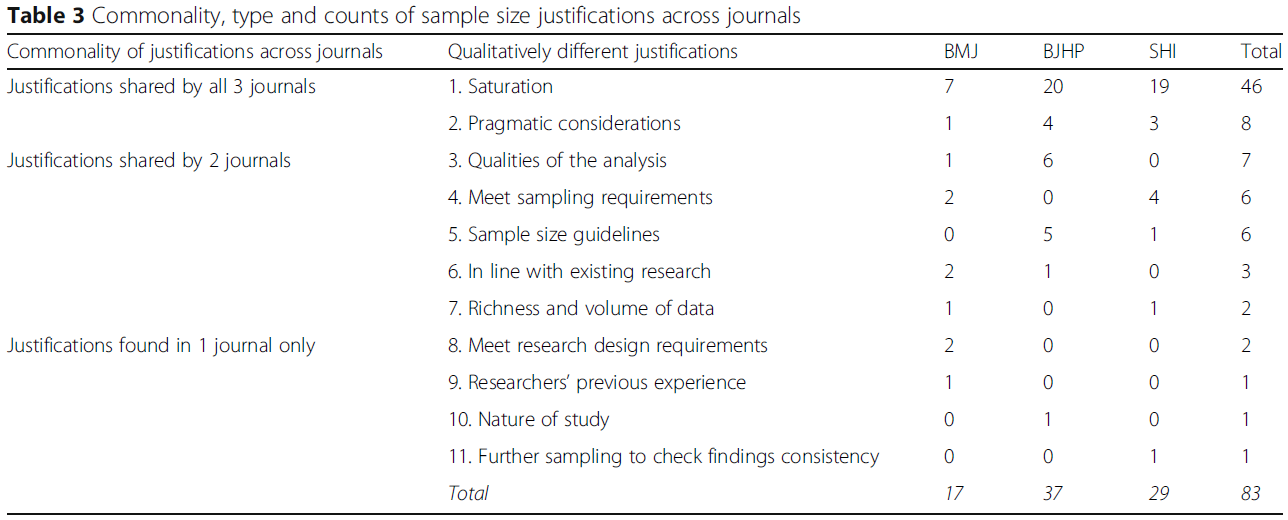

과학적 내러티브의 질적 내용 분석을 통해 11개의 서로 다른 표본 크기 정당성을 확인했습니다. 이에 대해서는 아래에 설명되어 있으며 관련 논문에서 발췌하여 설명합니다. 요약하자면, 세 저널에서 이러한 근거가 사용된 빈도는 표 3에 나와 있습니다.

The qualitative content analysis of the scientific narratives identified eleven different sample size justifications. These are described below and illustrated with excerpts from relevant articles. By way of a summary, the frequency with which these were deployed across the three journals is indicated in Table 3.

포화

Saturation

포화는 세 학술지 모두에서 표본 크기의 충분성을 정당화하기 위해 연구에서 가장 많이 사용된 원칙(전체 정당화의 55.4%)이었습니다. BMJ에서 데이터 포화도를 달성했다고 주장한 연구는 2건(BMJ17, BMJ18)이었으며, 포화도라는 용어를 명시적으로 사용하지 않고 설명적으로 언급한 논문은 1건(BMJ13)이었습니다. 흥미롭게도 BMJ13은 '비정상적/일탈적 관찰'을 찾고 연구 결과의 일관성을 확립하기 위해 포화 시점을 넘어선 데이터를 분석에 포함했습니다.

Saturation was the most commonly invoked principle (55.4% of all justifications) deployed by studies across all three journals to justify the sufficiency of their sample size. In the BMJ, two studies claimed that they achieved data saturation (BMJ17; BMJ18) and one article referred descriptively to achieving saturation without explicitly using the term (BMJ13). Interestingly, BMJ13 included data in the analysis beyond the point of saturation in search of ‘unusual/deviant observations’ and with a view to establishing findings consistency.

인터뷰 연구에 참여하기 위해 33명의 여성에게 연락을 취했습니다. 27명이 동의했고 21명(21-64세, 중앙값 40세)이 데이터 포화점에 도달하기 전에 인터뷰를 진행했습니다(한 번의 테이프 실패로 분석에 사용할 수 있는 인터뷰는 20건). (BMJ17).

Thirty three women were approached to take part in the interview study. Twenty seven agreed and 21 (aged 21–64, median 40) were interviewed before data saturation was reached (one tape failure meant that 20 interviews were available for analysis). (BMJ17).인터뷰의 약 3분의 2를 분석한 결과 새로운 주제는 발견되지 않았지만, 모든 인터뷰는 견해와 보고된 행동이 얼마나 특징적인지 더 잘 이해하고 비정상적이거나 일탈적인 관찰 사례를 더 수집하기 위해 코딩되었습니다. (BMJ13).

No new topics were identified following analysis of approximately two thirds of the interviews; however, all interviews were coded in order to develop a better understanding of how characteristic the views and reported behaviours were, and also to collect further examples of unusual/deviant observations. (BMJ13).

두 개의 논문은 데이터 포화도를 달성하기 위해 표본 크기를 미리 결정했다고 보고했습니다(BMJ08 - [기존 연구와 일치]하는 섹션의 발췌문 참조, BMJ15 - [실용적 고려 사항] 섹션의 발췌문 참조).

- 한 논문에서는 "분석에서 더 이상 반복되는 주제가 나타나지 않을 때"를 이론적 포화 상태(BMJ06)라고 주장한 반면,

- 다른 연구에서는 분석 범주가 매우 포화 상태이지만 이론적 포화 상태를 달성했는지 여부를 판단할 수 없다고 주장했습니다(BMJ04).

- 한 논문(BMJ18)은 포화도에 대한 입장을 뒷받침하기 위해 참고 문헌을 인용했습니다.

Two articles reported pre-determining their sample size with a view to achieving data saturation (BMJ08 – see extract in section In line with existing research; BMJ15 – see extract in section Pragmatic considerations) without further specifying if this was achieved.

- One paper claimed theoretical saturation (BMJ06) conceived as being when “no further recurring themes emerging from the analysis”

- whilst another study argued that although the analytic categories were highly saturated, it was not possible to determine whether theoretical saturation had been achieved (BMJ04).

- One article (BMJ18) cited a reference to support its position on saturation.

BJHP에서 6개의 논문이 데이터 포화 상태에 도달했다고 주장했고(BJHP21, BJHP32, BJHP39, BJHP48, BJHP49, BJHP52), 1개의 논문은 표본 크기와 데이터 포화 상태에 도달하기 위한 가이드라인을 고려할 때 포화 상태에 도달할 것으로 예상한다고 명시했습니다(BJHP50).

In the BJHP, six articles claimed that they achieved data saturation (BJHP21; BJHP32; BJHP39; BJHP48; BJHP49; BJHP52) and one article stated that, given their sample size and the guidelines for achieving data saturation, it anticipated that saturation would be attained (BJHP50).

새로운 주제가 나타나지 않는 시점으로 정의되는 데이터 포화 상태에 도달할 때까지 모집을 계속했습니다. (BJHP48).

Recruitment continued until data saturation was reached, defined as the point at which no new themes emerged. (BJHP48).이전에는 질적 연구에서 데이터 포화 상태에 도달하기 위해 최소 12개 이상의 표본 크기가 필요하다고 권장되어 왔습니다(Clarke & Braun, 2013; Fugard & Potts, 2014; Guest, Bunce, & Johnson, 2006). 따라서 이 연구의 질적 분석과 규모를 위해 13개의 표본이 충분한 것으로 간주되었습니다. (BJHP50).

It has previously been recommended that qualitative studies require a minimum sample size of at least 12 to reach data saturation (Clarke & Braun, 2013; Fugard & Potts, 2014; Guest, Bunce, & Johnson, 2006) Therefore, a sample of 13 was deemed sufficient for the qualitative analysis and scale of this study. (BJHP50).

두 개의 연구는 [주제 포화]를 달성했다고 주장했고(BJHP28 - 표본 크기 가이드라인 섹션의 발췌문 참조, BJHP31), 이론 개발과 이론적 표본 추출을 명시적으로 다룬 한 개의 논문(BJHP30)은 [이론적 포화]와 [데이터 포화]를 모두 주장했습니다.

Two studies argued that they achieved thematic saturation (BJHP28 – see extract in section Sample size guidelines; BJHP31) and one (BJHP30) article, explicitly concerned with theory development and deploying theoretical sampling, claimed both theoretical and data saturation.

최종 표본 크기는 주제 포화(주제와 참여자의 의견이 반복되어 새로운 데이터가 더 이상 연구 결과에 기여하지 않는 것으로 보이는 지점)에 따라 결정되었습니다(Morse, 1995). 이 시점에서 데이터 생성이 종료되었습니다. (BJHP31).

The final sample size was determined by thematic saturation, the point at which new data appears to no longer contribute to the findings due to repetition of themes and comments by participants (Morse, 1995). At this point, data generation was terminated. (BJHP31).

5개의 연구는 포화라는 용어를 더 이상 명시하지 않고 포화도를 달성(BJHP05, BJHP33, BJHP40, BJHP13 - 실용적 고려 사항 섹션의 발췌문 참조)했거나 예상(BJHP46)했다고 주장했습니다. BJHP17은 포화라는 용어를 구체적으로 사용하지 않고 포화 상태에 도달한 상태를 설명적으로 언급했습니다. 테마의 포화 상태가 아닌 [코딩의 포화 상태]에 도달했다고 주장한 논문은 한 편(BJHP18)이었습니다. 포화 상태에 도달하지 않았다고 명시적으로 언급한 논문은 2건이었으며, 그 대신 [테마의 완성도](BJHP27)를 주장하거나 테마가 복제되고 있다는 주장(BJHP53)을 통해 표본 크기의 충분성을 논증했습니다.

Five studies argued that they achieved (BJHP05; BJHP33; BJHP40; BJHP13 – see extract in section Pragmatic considerations) or anticipated (BJHP46) saturation without any further specification of the term. BJHP17 referred descriptively to a state of achieved saturation without specifically using the term. Saturation of coding, but not saturation of themes, was claimed to have been reached by one article (BJHP18). Two articles explicitly stated that they did not achieve saturation; instead claiming a level of theme completeness (BJHP27) or that themes being replicated (BJHP53) were arguments for sufficiency of their sample size.

또한 포화점에 도달한 시점이 아니라 실용적인 이유로 데이터 수집이 중단되었습니다. 그럼에도 불구하고 데이터 분석이 끝날 무렵에도 하위 테마 내 뉘앙스가 여전히 나타나고 있었지만, 테마 자체는 복제되고 있어 완성도가 높다는 것을 알 수 있었습니다. (BJHP27).

Furthermore, data collection ceased on pragmatic grounds rather than at the point when saturation point was reached. Despite this, although nuances within sub-themes were still emerging towards the end of data analysis, the themes themselves were being replicated indicating a level of completeness. (BJHP27).

마지막으로, 한 논문에서는 [이론적 충분성]의 기준이 표본 크기를 결정한다고 주장하며 데이터 포화도 개념을 비판하고 명시적으로 포기했습니다(BJHP16).

Finally, one article criticised and explicitly renounced the notion of data saturation claiming that, on the contrary, the criterion of theoretical sufficiency determined its sample size (BJHP16).

원래 근거 이론 텍스트에 따르면, 데이터 수집은 새로운 발견이 없을 때까지(즉, '데이터 포화'; Glaser & Strauss, 1967) 계속되어야 합니다. 그러나 최근 이 과정에 대한 개정 논의에서는 데이터 수집이 완전한 과정인 경우는 드물며, 연구자는 데이터가 충분한 이론적 설명을 만들 수 있는 정도, 즉 '이론적 충분성'에 의존해야 한다고 주장하고 있습니다(Dey, 1999). 이 연구에서는 데이터 포화도를 찾기보다는 이론적 충분성을 기준으로 모집을 진행하기로 결정했습니다. (BJHP16).

According to the original Grounded Theory texts, data collection should continue until there are no new discoveries (i.e., ‘data saturation’; Glaser & Strauss, 1967). However, recent revisions of this process have discussed how it is rare that data collection is an exhaustive process and researchers should rely on how well their data are able to create a sufficient theoretical account or ‘theoretical sufficiency’ (Dey, 1999). For this study, it was decided that theoretical sufficiency would guide recruitment, rather than looking for data saturation. (BJHP16).

포화도 논증을 사용한 20개의 BJHP 논문 중 10개가 이 원칙과 관련된 인용을 하나 이상 사용했습니다.

Ten out of the 20 BJHP articles that employed the argument of saturation used one or more citations relating to this principle.

SHI에서는 한 논문(SHI01)이 저자의 판단에 따라 카테고리 포화를 달성했다고 주장했습니다.

In the SHI, one article (SHI01) claimed that it achieved category saturation based on authors’ judgment.

이 수치는 사전에 정해진 것이 아니라 샘플링 전략과 데이터 분석을 기반으로 '카테고리 포화'가 달성되는 시점에 대한 판단에 따라 결정되었습니다. (SHI01).

This number was not fixed in advance, but was guided by the sampling strategy and the judgement, based on the analysis of the data, of the point at which ‘category saturation’ was achieved. (SHI01).

3편의 논문은 포화도라는 용어를 사용하지 않거나 어떤 종류의 포화도(예: 데이터, 이론적, 주제적 포화도)를 달성했는지 명시하지 않고 포화도 달성 상태를 설명했으며(SHI04, SHI13, SHI30), 나머지 4편의 논문은 포화도를 달성했다고 명시적으로 언급했습니다(SHI100, SHI125, SHI136, SHI137). 2편의 논문은 데이터 포화를 달성했다고 명시했고(SHI73 - 표본 크기 가이드라인 섹션의 발췌문 참조, SHI113), 2편은 이론적 포화를 주장했으며(SHI78; SHI115), 2편은 주제별 포화를 달성했거나(SHI87; SHI139) 포화된 주제를 언급했습니다(SHI29; SHI50).

Three articles described a state of achieved saturation without using the term or specifying what sort of saturation they had achieved (i.e. data, theoretical, thematic saturation) (SHI04; SHI13; SHI30) whilst another four articles explicitly stated that they achieved saturation (SHI100; SHI125; SHI136; SHI137). Two papers stated that they achieved data saturation (SHI73 – see extract in section Sample size guidelines; SHI113), two claimed theoretical saturation (SHI78; SHI115) and two referred to achieving thematic saturation (SHI87; SHI139) or to saturated themes (SHI29; SHI50).

아래 설명된 범주에서 이론적 포화 상태에 도달하면 모집 및 분석이 중단되었습니다(링컨과 구바 1985). (SHI115).

Recruitment and analysis ceased once theoretical saturation was reached in the categories described below (Lincoln and Guba 1985). (SHI115).아래에 표시된 응답자의 인용문은 대표적인 것으로 선택되었으며 포화 된 주제를 보여줍니다. (SHI50).

The respondents’ quotes drawn on below were chosen as representative, and illustrate saturated themes. (SHI50).

한 기사에서는 표본 크기로 인해 주제별 포화도가 예상되었다고 언급했습니다(SHI94). [이론적 포화도를 정확히 파악하기 어렵다는 점]을 간략하게 언급하면서 SHI32(데이터의 풍부성 및 양 섹션의 발췌문 참조)는 "인터뷰 대상자들 사이에서 나타나기 시작한 높은 수준의 합의"를 근거로 표본 크기의 충분성을 옹호하며 인터뷰의 정보가 복제되고 있음을 시사했습니다. 마지막으로 SHI112(조사 결과의 일관성을 확인하기 위한 추가 샘플링 섹션의 발췌문 참조)는 [담론 패턴의 포화 상태]를 달성했다고 주장했습니다. 19개의 SHI 논문 중 7개가 [포화에 대한 입장을 뒷받침하는 참고 문헌을 인용]했습니다(세 저널에서 포화도에 대한 입장을 뒷받침하기 위해 논문에서 사용한 인용 문헌의 전체 목록은 추가 파일 4 참조).

One article stated that thematic saturation was anticipated with its sample size (SHI94). Briefly referring to the difficulty in pinpointing achievement of theoretical saturation, SHI32 (see extract in section Richness and volume of data) defended the sufficiency of its sample size on the basis of “the high degree of consensus [that] had begun to emerge among those interviewed”, suggesting that information from interviews was being replicated. Finally, SHI112 (see extract in section Further sampling to check findings consistency) argued that it achieved saturation of discursive patterns. Seven of the 19 SHI articles cited references to support their position on saturation (see Additional File 4 for the full list of citations used by articles to support their position on saturation across the three journals).

전반적으로 포화도 개념은 포화, 데이터 포화, 주제 포화, 이론적 포화, 카테고리 포화, 코딩의 포화, 담론적 주제의 포화, 주제 완성도 등의 용어로 표현되는 다양한 변형을 포괄하는 것이 분명합니다. 그러나 이러한 다양한 주장이 때때로 문헌을 참조하여 뒷받침되기는 하지만, 당면한 연구와 관련하여 입증되지는 않았다는 점에 주목할 필요가 있습니다.

Overall, it is clear that the concept of saturation encompassed a wide range of variants expressed in terms such as saturation, data saturation, thematic saturation, theoretical saturation, category saturation, saturation of coding, saturation of discursive themes, theme completeness. It is noteworthy, however, that although these various claims were sometimes supported with reference to the literature, they were not evidenced in relation to the study at hand.

실용적인 고려 사항

Pragmatic considerations

실용적 고려사항에 근거한 표본 크기 결정은 세 학술지 모두에서 두 번째로 자주 인용된 주장(전체 정당화 중 9.6%)이었습니다. BMJ에서는 한 논문(BMJ15)에서 시간 제약과 특정 연구 모집단에 접근하기 어렵다는 실용적인 이유를 들어 표본 크기 결정을 정당화했습니다.

The determination of sample size on the basis of pragmatic considerations was the second most frequently invoked argument (9.6% of all justifications) appearing in all three journals. In the BMJ, one article (BMJ15) appealed to pragmatic reasons, relating to time constraints and the difficulty to access certain study populations, to justify the determination of its sample size.

연구자들의 이전 경험과 문헌에 근거하여[30, 31] 각 사이트에서 15~20명의 환자를 모집하면 각 사이트의 데이터를 개별적으로 분석할 때 데이터 포화 상태에 도달할 것으로 예상했습니다. 시간 제약과 일부 재택 간호 서비스에서 간병인을 구하기 어려울 것으로 예상되어 사이트당 7~10명의 간병인을 목표로 설정했습니다. 이를 통해 전체적으로 75-100명의 환자와 35-50명의 간병인을 대상으로 표본을 추출했습니다. (BMJ15).

On the basis of the researchers’ previous experience and the literature, [30, 31] we estimated that recruitment of 15–20 patients at each site would achieve data saturation when data from each site were analysed separately. We set a target of seven to 10 caregivers per site because of time constraints and the anticipated difficulty of accessing caregivers at some home based care services. This gave a target sample of 75–100 patients and 35–50 caregivers overall. (BMJ15).

BJHP에서는 시간 또는 재정적 제약(BJHP27 - 포화 섹션의 발췌문 참조, BJHP53), 참여자 응답률(BJHP13), 인터뷰 대상자를 샘플링하는 고정된참여자 풀의 (따라서 제한된) 규모(BJHP18)와 관련된 실용적인 고려 사항을 언급한 논문이 4편 있었습니다.

In the BJHP, four articles mentioned pragmatic considerations relating to time or financial constraints (BJHP27 – see extract in section Saturation; BJHP53), the participant response rate (BJHP13), and the fixed (and thus limited) size of the participant pool from which interviewees were sampled (BJHP18).

우리는 더 이상 데이터를 수집해도 더 이상 주제가 나오지 않는 포화 상태에 도달할 때까지 인터뷰를 계속하는 것을 목표로 삼았습니다. 실제로 연구에 참여하겠다고 자원한 사람의 수에 따라 연구 모집이 중단되는 시점이 결정되었습니다(청소년 15명, 부모 15명). 그럼에도 불구하고 마지막 몇 번의 인터뷰를 통해 개념의 상당한 반복이 발생하여 충분한 샘플링이 이루어졌음을 알 수 있었습니다. (BJHP13).

We had aimed to continue interviewing until we had reached saturation, a point whereby further data collection would yield no further themes. In practice, the number of individuals volunteering to participate dictated when recruitment into the study ceased (15 young people, 15 parents). Nonetheless, by the last few interviews, significant repetition of concepts was occurring, suggesting ample sampling. (BJHP13).

마지막으로 세 개의 SHI 논문은 시간 제약 및 프로젝트 관리 가능성(SHI56), 제한된 응답자 및 프로젝트 리소스(SHI131), 시간 제약(SHI113)과 같은 실용적인 측면과 관련하여 표본 규모를 설명했습니다.

Finally, three SHI articles explained their sample size with reference to practical aspects:

- time constraints and project manageability (SHI56),

- limited availability of respondents and project resources (SHI131), and

- time constraints (SHI113).

표본의 크기는 주로 연구를 완료할 수 있는 응답자와 리소스의 가용성에 따라 결정되었습니다. 표본 구성은 가능한 한 맥락적 요인(예: 성별 관계 및 인종)이 질병 경험을 매개하는 방식에 대한 우리의 관심을 반영했습니다. (SHI131).

The size of the sample was largely determined by the availability of respondents and resources to complete the study. Its composition reflected, as far as practicable, our interest in how contextual factors (for example, gender relations and ethnicity) mediated the illness experience. (SHI131).

분석의 질

Qualities of the analysis

이 표본 크기 정당화(전체 정당화 중 8.4%)는 주로 BJHP 기사에서 사용되었으며, 집중적이고 관용적이거나 잠재적으로 초점을 맞춘 분석, 즉 [설명description을 넘어선 분석]에 대해 언급했습니다. 보다 구체적으로, 6개의 논문은 녹취록에 대한 집중적인 분석 및/또는 연구/분석의 관용적 초점을 근거로 표본 크기를 옹호했습니다. 이 중 4개 논문(BJHP02, BJHP19, BJHP24, BJHP47)은 해석적 현상학적 분석(IPA) 접근법을 채택했습니다.

This sample size justification (8.4% of all justifications) was mainly employed by BJHP articles and referred to an intensive, idiographic and/or latently focused analysis, i.e. that moved beyond description. More specifically, six articles defended their sample size on the basis of an intensive analysis of transcripts and/or the idiographic focus of the study/analysis. Four of these papers (BJHP02; BJHP19; BJHP24; BJHP47) adopted an Interpretative Phenomenological Analysis (IPA) approach.

본 연구에서는 각 참가자의 account을 탐색하기 위한 목적으로 10명의 표본을 사용했습니다(Smith et al., 1999). (BJHP19).

The current study employed a sample of 10 in keeping with the aim of exploring each participant’s account (Smith et al., 1999). (BJHP19).

BJHP47은 IPA 접근법 내에서 포화 개념을 명시적으로 포기했습니다. 다른 두 BJHP 논문은 주제 분석을 수행했습니다(BJHP34; BJHP38). 분석 수준 (즉, 피상적 인 설명 분석과 반대되는 잠재적 분석)은 개별 녹취록에 대한 집중적 인 분석이라는 주장과 함께 BJHP38에 의해 정당화로도 호출되었습니다.

BJHP47 explicitly renounced the notion of saturation within an IPA approach. The other two BJHP articles conducted thematic analysis (BJHP34; BJHP38). The level of analysis – i.e. latent as opposed to a more superficial descriptive analysis – was also invoked as a justification by BJHP38 alongside the argument of an intensive analysis of individual transcripts

그 결과 표본 크기는 주제별 분석에 사용되는 표본 크기 범위의 하위에 속했습니다(Braun & Clarke, 2013). 이는 각 녹취록에 대한 [상당한 성찰, 대화 및 시간을 확보하기 위한 것]으로, 피상적인 서술적 분석이 아닌 근본적인 아이디어를 파악하기 위해 사용된 [보다 잠재적인 수준의 분석]에 부합하는 것이었습니다(Braun & Clarke, 2006). (BJHP38).

The resulting sample size was at the lower end of the range of sample sizes employed in thematic analysis (Braun & Clarke, 2013). This was in order to enable significant reflection, dialogue, and time on each transcript and was in line with the more latent level of analysis employed, to identify underlying ideas, rather than a more superficial descriptive analysis (Braun & Clarke, 2006). (BJHP38).

마지막으로, 한 BMJ 논문(BMJ21)은 [분석 작업의 복잡성]을 언급하며 표본 규모를 옹호했습니다.

Finally, one BMJ paper (BMJ21) defended its sample size with reference to the complexity of the analytic task.

인터뷰의 깊이와 기간, 데이터의 풍부함, 분석 작업의 복잡성 때문에 30~35명의 인터뷰에 도달했을 때 모집을 중단했습니다. (BMJ21).

We stopped recruitment when we reached 30–35 interviews, owing to the depth and duration of interviews, richness of data, and complexity of the analytical task. (BMJ21).

샘플링 요건 충족

Meet sampling requirements

표본 추출 요건 충족(전체 정당화 이유 중 7.2%)은 두 개의 BMJ 논문과 네 개의 SHI 논문에서 표본 크기를 설명하기 위해 사용한 또 다른 논거였습니다. 특정 인터뷰 대상자 특성 측면에서 [최대 변동 샘플링을 달성]하는 것이 두 개의 BMJ 연구(BMJ02, BMJ16 - 연구 설계 요건 충족 섹션의 발췌문 참조)의 표본 규모를 결정하고 설명했습니다.

Meeting sampling requirements (7.2% of all justifications) was another argument employed by two BMJ and four SHI articles to explain their sample size. Achieving maximum variation sampling in terms of specific interviewee characteristics determined and explained the sample size of two BMJ studies (BMJ02; BMJ16 – see extract in section Meet research design requirements).

연령, 성별, 인종, 출석 빈도, 건강 상태의 다양성에 대한 샘플링 프레임 요건이 충족될 때까지 모집을 계속했습니다. (BMJ02).

Recruitment continued until sampling frame requirements were met for diversity in age, sex, ethnicity, frequency of attendance, and health status. (BMJ02).

SHI 논문과 관련하여 두 논문에서 표본 추출 전략에 근거하여 표본 수를 설명한 반면(SHI01-포화도 섹션의 발췌문 참조, SHI23), 한 논문에서는 [특정 관심 특성 측면에서 표본 이질성을 확보]하는 데 도움이 되는 표본 추출 요건이 인용되었습니다(SHI127).

Regarding the SHI articles, two papers explained their numbers on the basis of their sampling strategy (SHI01- see extract in section Saturation; SHI23) whilst sampling requirements that would help attain sample heterogeneity in terms of a particular characteristic of interest was cited by one paper (SHI127).

정량적 연구를 위한 모집 장소와 추가 목적 기준의 조합으로 104건의 2단계 인터뷰가 이루어졌습니다(인터넷(OLC): 21건, 인터넷(FTF): 20건, 체육관(FTF): 23건, HIV 검사(FTF): 20건, HIV 치료(FTF): 20건.). (SHI23).

The combination of matching the recruitment sites for the quantitative research and the additional purposive criteria led to 104 phase 2 interviews (Internet (OLC): 21; Internet (FTF): 20); Gyms (FTF): 23; HIV testing (FTF): 20; HIV treatment (FTF): 20.) (SHI23).실시된 50건의 인터뷰 중 30건은 스페인어에서 영어로 번역되었습니다. 연구 결과를 도출한 이 30명은 우울증 증상과 교육 수준의 이질성을 고려하여 번역 대상으로 선정되었습니다. (SHI127).

Of the fifty interviews conducted, thirty were translated from Spanish into English. These thirty, from which we draw our findings, were chosen for translation based on heterogeneity in depressive symptomology and educational attainment. (SHI127).

마지막으로, 인터뷰 횟수를 정당화하는 데 사용되지는 않았지만 [표본 추출 요건에 따라 표본 크기를 미리 결정한 논문]이 한 편 있었습니다(SHI10).

Finally, the pre-determination of sample size on the basis of sampling requirements was stated by one article though this was not used to justify the number of interviews (SHI10).

표본 크기 가이드라인

Sample size guidelines

5개의 BJHP 논문(BJHP28, BJHP38 - 분석의 질 섹션의 발췌문 참조, BJHP46, BJHP47, BJHP50 - 포화도 섹션의 발췌문 참조)과 1개의 SHI 논문(SHI73)은 [기존의 표본 크기 가이드라인 또는 연구 전통 내 규범]을 인용하여 표본 크기를 결정하고 이를 정당화하는 데 의존했습니다(전체 정당화 사례의 7.2%).

Five BJHP articles (BJHP28; BJHP38 – see extract in section Qualities of the analysis; BJHP46; BJHP47; BJHP50 – see extract in section Saturation) and one SHI paper (SHI73) relied on citing existing sample size guidelines or norms within research traditions to determine and subsequently defend their sample size (7.2% of all justifications).

표본 크기 가이드라인에서는 20~30건의 인터뷰가 적절하다고 제시했습니다(Creswell, 1998). 면접관과 메모 작성자는 20번의 면접을 완료한 후 주제 포화 상태, 즉 후속 면접에서 새로운 개념이 나오지 않는 지점(Patton, 2002)에 도달했다는 데 동의했습니다. (BJHP28).

Sample size guidelines suggested a range between 20 and 30 interviews to be adequate (Creswell, 1998). Interviewer and note taker agreed that thematic saturation, the point at which no new concepts emerge from subsequent interviews (Patton, 2002), was achieved following completion of 20 interviews. (BJHP28).데이터 포화(새로운 주제가 나오지 않는 지점)에 도달했다고 판단될 때까지 인터뷰를 계속했습니다. 연구자들은 반구조적 인터뷰 접근법을 사용할 때 이론적 포화 상태에 도달할 것으로 예상되는 대략적인 인터뷰 횟수 또는 실제 인터뷰 횟수로 30회를 제안했지만(Morse 2000), 이는 인터뷰 응답자의 이질성 및 탐구하는 문제의 복잡성에 따라 달라질 수 있습니다. (SHI73).

Interviewing continued until we deemed data saturation to have been reached (the point at which no new themes were emerging). Researchers have proposed 30 as an approximate or working number of interviews at which one could expect to be reaching theoretical saturation when using a semi-structured interview approach (Morse 2000), although this can vary depending on the heterogeneity of respondents interviewed and complexity of the issues explored. (SHI73).

기존 연구와 일치

In line with existing research

조사 대상 주제 분야의 출판 문헌의 표본 크기(전체 근거의 3.5%)는 2편의 BMJ 논문에서 자체 표본 크기를 결정하고 방어하기 위한 지침 및 선례로 사용되었습니다(BMJ08; BMJ15 - 실용적 고려 사항 섹션의 발췌문 참조).

Sample sizes of published literature in the area of the subject matter under investigation (3.5% of all justifications) were used by 2 BMJ articles as guidance and a precedent for determining and defending their own sample size (BMJ08; BMJ15 – see extract in section Pragmatic considerations).

연구 범위 내에서 데이터 포화도를 달성하고 충분한 후속 인터뷰를 진행하기 위해 매주 출소 예정인 수감자 목록에서 참가자를 추출하여 목표인 35건에 도달할 때까지 샘플링했으며, 이는 최근 연구[8-10]와 일치합니다. (BMJ08).

We drew participants from a list of prisoners who were scheduled for release each week, sampling them until we reached the target of 35 cases, with a view to achieving data saturation within the scope of the study and sufficient follow-up interviews and in line with recent studies [8–10]. (BMJ08).

마찬가지로 BJHP38(분석의 질 섹션의 발췌문 참조)은 표본 크기가 해당 분석 접근법을 사용하는 발표된 연구들의 표본 크기 범위 내에 있다고 주장했습니다.

Similarly, BJHP38 (see extract in section Qualities of the analysis) claimed that its sample size was within the range of sample sizes of published studies that use its analytic approach.

데이터의 풍부함 및 양

Richness and volume of data

BMJ21(분석의 질 섹션의 발췌문 참조)과 SHI32는 표본 크기의 충분성을 정당화하기 위해 수집된 데이터의 풍부함, 상세성, 양(전체 정당화 근거의 2.3%)을 언급했습니다.

BMJ21 (see extract in section Qualities of the analysis) and SHI32 referred to the richness, detailed nature, and volume of data collected (2.3% of all justifications) to justify the sufficiency of their sample size.

우편번호 추출을 통해 연락을 받은 잠재적 인터뷰 대상자가 더 많았음에도 불구하고 10차 인터뷰 이후에는 모집을 중단하고 이 표본 분석에 집중하기로 결정했습니다. 수집된 자료는 상당히 많았고, 연구의 집중적인 특성을 고려할 때 매우 상세했습니다. 또한 인터뷰 대상자들 사이에서 높은 수준의 합의가 이루어지기 시작했고, 어느 시점에서 '이론적 포화'에 도달했는지 또는 예외를 발견하기 위해 얼마나 많은 인터뷰가 필요한지 판단하기는 항상 어렵지만이 소규모 심층 조사의 목표를 충족시키기에 충분하다고 느꼈습니다 (Strauss and Corbin 1990). (SHI32).

Although there were more potential interviewees from those contacted by postcode selection, it was decided to stop recruitment after the 10th interview and focus on analysis of this sample. The material collected was considerable and, given the focused nature of the study, extremely detailed. Moreover, a high degree of consensus had begun to emerge among those interviewed, and while it is always difficult to judge at what point ‘theoretical saturation’ has been reached, or how many interviews would be required to uncover exception(s), it was felt the number was sufficient to satisfy the aims of this small in-depth investigation (Strauss and Corbin 1990). (SHI32).

연구 설계 요건 충족

Meet research design requirements

본 연구에서 채택한 연구 설계의 요건에 부합하는 표본 크기 결정(전체 정당화의 2.3%)은 2편의 BMJ 논문(BMJ16, BMJ08 - 기존 연구와 일치하는 섹션의 발췌문 참조)에서 사용된 또 다른 정당화였습니다.

Determination of sample size so that it is in line with, and serves the requirements of, the research design (2.3% of all justifications) that the study adopted was another justification used by 2 BMJ papers (BMJ16; BMJ08 – see extract in section In line with existing research).

우리는 다양한 사회적 배경과 인종, 다양한 유형의 자살 및 외상성 사망으로 인한 유가족으로 구성된 총 80명의 응답자[20]를 대상으로 다양하고 최대한의 표본을 확보하고자 했습니다. 다른 시점에 더 작은 표본을 인터뷰할 수도 있었지만(질적 종단 연구), 대신 수년 전에 유족이 된 사람과 최근에 유족이 된 사람, 다른 환경에 처한 유족과 고인과의 관계가 다른 유족, 영국의 다른 지역에 거주하는 사람, 다른 지원 시스템과 검시관 절차를 가진 사람들을 인터뷰하여 광범위한 경험을 추구하기로 결정했습니다(자세한 내용은 표 1과 2 참조). (BMJ16).

We aimed for diverse, maximum variation samples [20] totalling 80 respondents from different social backgrounds and ethnic groups and those bereaved due to different types of suicide and traumatic death. We could have interviewed a smaller sample at different points in time (a qualitative longitudinal study) but chose instead to seek a broad range of experiences by interviewing those bereaved many years ago and others bereaved more recently; those bereaved in different circumstances and with different relations to the deceased; and people who lived in different parts of the UK; with different support systems and coroners’ procedures (see Tables 1 and 2 for more details). (BMJ16).

연구자의 이전 경험

Researchers’ previous experience

연구자의 이전 경험(질적 연구 경험일 수 있음)은 BMJ15(실용적 고려 사항 섹션의 발췌문 참조)에서 표본 크기 결정의 근거로 사용되었습니다.

The researchers’ previous experience (possibly referring to experience with qualitative research) was invoked by BMJ15 (see extract in section Pragmatic considerations) as a justification for the determination of sample size.

연구의 성격

Nature of study

한 BJHP 논문에서는 표본 크기가 연구의 탐색적 성격에 적합하다고 주장했습니다(BJHP38).

One BJHP paper argued that the sample size was appropriate for the exploratory nature of the study (BJHP38).

이 연구의 탐구적 성격과 주제에 대한 근본적인 아이디어를 파악하는 데 중점을 두었기 때문에 8명의 참가자 표본이 적절한 것으로 간주되었습니다. (BJHP38).

A sample of eight participants was deemed appropriate because of the exploratory nature of this research and the focus on identifying underlying ideas about the topic. (BJHP38).

조사 결과의 일관성을 확인하기 위한 추가 샘플링

Further sampling to check findings consistency

마지막으로, SHI112는 담론 패턴의 포화 상태에 도달한 후, 연구 결과의 일관성을 확인하기 위해 추가 샘플링을 결정하고 수행했다고 주장했습니다.

Finally, SHI112 argued that once it had achieved saturation of discursive patterns, further sampling was decided and conducted to check for consistency of the findings.

연령별로 계층화된 각 그룹 내에서 담화 패턴의 포화 상태에 도달할 때까지 무작위로 인터뷰를 샘플링했습니다. 그 결과 67개의 인터뷰 샘플이 도출되었습니다. 이 샘플을 분석한 후, 연령별로 세분화된 각 그룹에서 무작위로 한 개의 인터뷰를 추가로 선정하여 조사 결과의 일관성을 확인했습니다. 이러한 접근 방식을 통해 주제 영역에서 '나', 주체성, 관계성, 권력에 대한 아동의 담론을 보다 주의 깊게 살펴볼 수 있었으며, 이 글에서 설명한 미묘한 담론적 변이를 발견할 수 있었습니다. (SHI112).

Within each of the age-stratified groups, interviews were randomly sampled until saturation of discursive patterns was achieved. This resulted in a sample of 67 interviews. Once this sample had been analysed, one further interview from each age-stratified group was randomly chosen to check for consistency of the findings. Using this approach it was possible to more carefully explore children’s discourse about the ‘I’, agency, relationality and power in the thematic areas, revealing the subtle discursive variations described in this article. (SHI112).

표본 크기를 논의하는 구절의 주제별 분석

Thematic analysis of passages discussing sample size

이 분석 결과 두 가지 중요한 주제 영역이 발견되었는데, 첫 번째는 표본 크기 충분성의 특징에 대한 변화, 두 번째는 표본 크기 부족으로 인한 인식된 위협과 관련된 것입니다.

This analysis resulted in two overarching thematic areas; the first concerned the variation in the characterisation of sample size sufficiency, and the second related to the perceived threats deriving from sample size insufficiency.

표본 크기 충분성의 특성

Characterisations of sample size sufficiency

분석 결과, 관련 의견과 논의를 제공한 논문에서 표본 크기에 대한 세 가지 주요 특징이 나타났습니다.

- (a) 대다수의 질적 연구(n = 42)는 표본 크기가 '작다'고 간주하고 이를 한계로 보고 논의했으며, 두 논문만이 작은 표본 크기를 바람직하고 적절한 것으로 간주했습니다.

- (b) 소수의 논문(n = 4)은 달성한 표본 크기가 '충분하다'고 선언했으며,

- (c) 마지막으로 소수의 연구 그룹(n = 5)은 표본 크기가 '크다'고 특징짓고 있었습니다.

'큰' 표본 크기를 달성하는 것이 보다 풍부한 결과를 도출할 수 있다는 점에서 긍정적으로 여겨지기도 했지만, 표본 크기가 큰 것이 바람직하기보다는 문제가 되는 경우도 있었습니다.

The analysis showed that there were three main characterisations of the sample size in the articles that provided relevant comments and discussion:

- (a) the vast majority of these qualitative studies (n = 42) considered their sample size as ‘small’ and this was seen and discussed as a limitation; only two articles viewed their small sample size as desirable and appropriate

- (b) a minority of articles (n = 4) proclaimed that their achieved sample size was ‘sufficient’; and

- (c) finally, a small group of studies (n = 5) characterised their sample size as ‘large’.

Whilst achieving a ‘large’ sample size was sometimes viewed positively because it led to richer results, there were also occasions when a large sample size was problematic rather than desirable.

'작다'고 하지만 왜 그리고 누구를 위한 것인가?

‘Small’ but why and for whom?

표본 크기가 '작다'고 명시한 다수의 논문은 암시적이거나 명시적인 정량적 기준 프레임워크에 반하는 결과를 초래했습니다. 흥미로운 점은 표본 크기로 데이터 포화도 또는 '이론적 충분성'을 달성했다고 주장한 3건의 연구에서 '작은' 표본 크기에 대해 논의하거나 한계로 지적했는데, 포화도의 질적 기준이 충족된 상황에서 [왜, 또는 누구를 위해 표본 크기가 작은 것으로 간주했는지에 대한 의문]을 가지게 한다.

A number of articles which characterised their sample size as ‘small’ did so against an implicit or explicit quantitative framework of reference. Interestingly, three studies that claimed to have achieved data saturation or ‘theoretical sufficiency’ with their sample size, discussed or noted as a limitation in their discussion their ‘small’ sample size, raising the question of why, or for whom, the sample size was considered small given that the qualitative criterion of saturation had been satisfied.

이번 연구에는 여러 가지 한계가 있습니다. 표본 크기가 작았고(n = 11), 새로운 주제가 나타나지 않을 만큼 충분히 컸습니다. (BJHP39).

The current study has a number of limitations. The sample size was small (n = 11) and, however, large enough for no new themes to emerge. (BJHP39).이 연구에는 두 가지 주요 한계가 있습니다. 첫 번째는 연구에 참여한 응답자 수가 적다는 점입니다. (SHI73).

The study has two principal limitations. The first of these relates to the small number of respondents who took part in the study. (SHI73).

다른 기사들은 표본의 크기가 작기 때문에 (비대표성, 편향성, 자기 선택 등 다른 구성적 '결함'과 함께) 표본에 결함이 있음을 인정하고 받아들이거나, 표본 크기가 작다는 이유로 비판을 받을 수 있음을 예상하는 것처럼 보였습니다. [상상 속의 청중(아마도 리뷰어 또는 독자)]은 정량적 연구의 원칙을 고수하는 경향이 있는 사람으로, 작은 표본이 문제가 될 수 있다는 인식을 나타내는 것이 중요한 사람인 것 같았습니다. 표본이 작다는 것은 종종 후회나 사과의 담론으로 포장된 한계로 해석되기도 했습니다.

Other articles appeared to accept and acknowledge that their sample was flawed because of its small size (as well as other compositional ‘deficits’ e.g. non-representativeness, biases, self-selection) or anticipated that they might be criticized for their small sample size. It seemed that the imagined audience – perhaps reviewer or reader – was one inclined to hold the tenets of quantitative research, and certainly one to whom it was important to indicate the recognition that small samples were likely to be problematic. That one’s sample might be thought small was often construed as a limitation couched in a discourse of regret or apology.

간혹 작은 규모를 한계로 표현하는 것은 [실증주의 프레임워크와 정량적 연구를 지지하는 입장]에 명시적으로 부합하는 경우가 있었습니다.

Very occasionally, the articulation of the small size as a limitation was explicitly aligned against an espoused positivist framework and quantitative research.

이 연구에는 몇 가지 한계가 있습니다. 첫째, 100건의 사건 샘플은 매년 발생하는 전체 심각한 사건 중 극히 일부에 불과합니다.26 우리는 전국적으로 초대장을 보냈지만 더 많은 사람들이 연구에 자원하지 않은 이유를 알 수 없습니다. 그러나 의료 사고에 대한 역학적 지식이 부족하기 때문에 적절한 표본 규모를 결정하는 것은 여전히 어려운 일입니다. (BMJ20).

This study has some limitations. Firstly, the 100 incidents sample represents a small number of the total number of serious incidents that occurs every year.26 We sent out a nationwide invitation and do not know why more people did not volunteer for the study. Our lack of epidemiological knowledge about healthcare incidents, however, means that determining an appropriate sample size continues to be difficult. (BMJ20).

양적 세계와 질적 세계를 구분하는 다양한 요건과 프로토콜 사이에서 [질적 연구자들이 명백하게 오락가락하고 있음]을 나타내는 몇 가지 사례에서, '작은' 표본 크기를 한계로 잠시 인정한 후, 경험의 복잡성을 포착하고 관용적으로 탐구하는 능력과 성공, 특히 풍부한 데이터를 생성하는 등 보다 질적인 근거로 연구를 옹호하는 논문이 있었습니다.

Indicative of an apparent oscillation of qualitative researchers between the different requirements and protocols demarcating the quantitative and qualitative worlds, there were a few instances of articles which briefly recognised their ‘small’ sample size as a limitation, but then defended their study on more qualitative grounds, such as their ability and success at capturing the complexity of experience and delving into the idiographic, and at generating particularly rich data.

이 연구는 규모는 제한적이지만 소득과 물질적 상황에 관한 남성의 태도와 경험에 내재된 복잡성을 포착하려고 노력했습니다. (SHI35).

This research, while limited in size, has sought to capture some of the complexity attached to men’s attitudes and experiences concerning incomes and material circumstances. (SHI35).소셜 네트워크에 대한 접근을 협상하는 것이 느리고 노동 집약적이기 때문에 우리의 숫자는 적지만, 우리의 방법은 매우 풍부한 데이터를 생성했습니다. (BMJ21).

Our numbers are small because negotiating access to social networks was slow and labour intensive, but our methods generated exceptionally rich data. (BMJ21).이 연구는 대표성이 없는 소규모 표본을 사용했다는 비판을 받을 수 있습니다. 선탠에 관한 연구에서 노년층이 무시되어 왔고, 피부가 고운 노년층이 피부암을 경험할 가능성이 가장 높으며, 여성은 일광욕을 할 때 건강보다 외모를 우선시한다는 점을 고려할 때, 이번 연구는 연구적 관심이 매우 필요한 인구통계학적 그룹에 대한 깊이 있고 풍부한 데이터를 제공합니다. (SHI57).

This study could be criticised for using a small and unrepresentative sample. Given that older adults have been ignored in the research concerning suntanning, fair-skinned older adults are the most likely to experience skin cancer, and women privilege appearance over health when it comes to sunbathing practices, our study offers depth and richness of data in a demographic group much in need of research attention. (SHI57).

'충분히 좋은' 표본 크기

‘Good enough’ sample sizes

달성한 표본 크기가 충분하다고 어느 정도 [자신감을 표명한 논문]은 4개에 불과했습니다. 예를 들어, SHI139는 주제 포화도에 대한 정당성을 제시하면서 낮은 응답률에도 불구하고 표본 크기의 충분성에 대한 신뢰를 표명했습니다. 마찬가지로 표본 크기의 정당성을 제시하지 않은 BJHP04는 낮은 응답률이 예상되었기 때문에 결국 충분한 수의 인터뷰 대상자를 모집하기 위해 더 큰 표본 크기를 목표로 삼았다고 주장했습니다.

Only four articles expressed some degree of confidence that their achieved sample size was sufficient. For example, SHI139, in line with the justification of thematic saturation that it offered, expressed trust in its sample size sufficiency despite the poor response rate. Similarly, BJHP04, which did not provide a sample size justification, argued that it targeted a larger sample size in order to eventually recruit a sufficient number of interviewees, due to anticipated low response rate.

대상 모집단 133명 중 23명(즉, 17.3%)의 제1형 당뇨병 환자가 참여에 동의했지만 4명은 이후 추가 연락에 응답하지 않았습니다(총 N = 19). 해당 연령대의 젊은이들의 바쁜 라이프스타일, 지리적 제약, 반구조화된 인터뷰 참여에 필요한 시간으로 인해 상대적으로 낮은 응답률이 예상되었기 때문에 더 많은 대상 표본을 통해 충분한 수의 참가자를 모집할 수 있었습니다. (BJHP04).

Twenty-three people with type I diabetes from the target population of 133 (i.e. 17.3%) consented to participate but four did not then respond to further contacts (total N = 19). The relatively low response rate was anticipated, due to the busy life-styles of young people in the age range, the geographical constraints, and the time required to participate in a semi-structured interview, so a larger target sample allowed a sufficient number of participants to be recruited. (BJHP04).

다른 두 논문(BJHP35, SHI32)은 연구의 범위(즉, '소규모 심층 조사'), 목적 및 성격(즉, '탐색적')에 따라 충분하다고 주장한 표본 수를 연구의 특정 맥락과 연결시켰습니다. 그럼에도 불구하고 표본 크기가 충분하다는 주장은 표본 크기가 클수록 과학적으로 더 생산적이라는 인정과 병치될 때 때때로 약화되었습니다.

Two other articles (BJHP35; SHI32) linked the claimed sufficiency to the scope (i.e. ‘small, in-depth investigation’), aims and nature (i.e. ‘exploratory’) of their studies, thus anchoring their numbers to the particular context of their research. Nevertheless, claims of sample size sufficiency were sometimes undermined when they were juxtaposed with an acknowledgement that a larger sample size would be more scientifically productive.

이 탐색적 연구에는 표본 규모가 충분했지만, 사회경제적 지위가 낮고 인종적 다양성이 더 많은 참가자를 포함하여 더 다양한 표본을 확보하면 더 많은 정보를 얻을 수 있을 것입니다. 또한 표본이 더 크면 더 다양한 플랫폼에서 운영되는 더 많은 대표 앱을 포함할 수 있습니다. (BJHP35).

Although our sample size was sufficient for this exploratory study, a more diverse sample including participants with lower socioeconomic status and more ethnic variation would be informative. A larger sample could also ensure inclusion of a more representative range of apps operating on a wider range of platforms. (BJHP35).

'대규모' 표본 크기 - 약속인가 위험인가?

‘Large’ sample sizes - Promise or peril?

포화도에 대한 정당성을 제공한 세 논문(BMJ13, BJHP05, BJHP48)은 모두 표본 크기가 '크다'고 특징짓고, 이러한 불충분성이 더 풍부한 데이터와 연구 결과를 제공하고 일반화 가능성을 높인다는 긍정적인 측면을 설명했습니다. 그러나 일반화 유형(BJHP48)은 더 이상 명시되지 않았습니다.

Three articles (BMJ13; BJHP05; BJHP48) which all provided the justification of saturation, characterised their sample size as ‘large’ and narrated this oversufficiency in positive terms as it allowed richer data and findings and enhanced the potential for generalisation. The type of generalisation aspired to (BJHP48) was not further specified however.

이 연구는 중요하지만 연구가 부족한 주제에 대해 비교적 많은 전문가 정보 제공자 표본이 제공한 풍부한 데이터를 사용했습니다. (BMJ13).

This study used rich data provided by a relatively large sample of expert informants on an important but under-researched topic. (BMJ13).질적 연구는 환자의 관점에서 임상 문제를 이해할 수 있는 독특한 기회를 제공합니다. 이 연구는 다양한 지역에서 모집된 대규모의 다양한 표본을 사용했으며 심층 인터뷰를 통해 결과의 풍부함과 일반화 가능성을 높였습니다. (BJHP48).

Qualitative research provides a unique opportunity to understand a clinical problem from the patient’s perspective. This study had a large diverse sample, recruited through a range of locations and used in-depth interviews which enhance the richness and generalizability of the results. (BJHP48).

일부 질적 연구자들은 '큰' 표본 규모를 지지하고 중요하게 생각하지만, IPA의 심리학 전통에서는 '큰' 표본 규모는 규범에 반하는 것이므로 정당화될 필요가 있었습니다. IPA를 채택한 4건의 BJHP 연구는 모두 ['작은' 표본 크기의 적절성 또는 바람직성]을 표명하거나(BJHP41; BJHP45), 일반적인 표본 크기보다 더 큰 표본 크기를 포함하는 이유를 서둘러 설명했습니다(BJHP32; BJHP47). 예를 들어, 아래의 BJHP32는 IPA 연구에서 어떻게 큰 표본 크기를 수용할 수 있는지, 그리고 이것이 실제로 특정 연구 목적에 어떻게 적합한지에 대한 근거를 제공합니다. 비규범적 표본 크기 선택에 대한 설명을 강화하기 위해 유사한 표본 크기 접근법을 인용한 이전 IPA 연구를 선례로 사용합니다.

And whilst a ‘large’ sample size was endorsed and valued by some qualitative researchers, within the psychological tradition of IPA, a ‘large’ sample size was counter-normative and therefore needed to be justified. Four BJHP studies, all adopting IPA, expressed the appropriateness or desirability of ‘small’ sample sizes (BJHP41; BJHP45) or hastened to explain why they included a larger than typical sample size (BJHP32; BJHP47). For example, BJHP32 below provides a rationale for how an IPA study can accommodate a large sample size and how this was indeed suitable for the purposes of the particular research. To strengthen the explanation for choosing a non-normative sample size, previous IPA research citing a similar sample size approach is used as a precedent.

소규모 IPA 연구는 대규모 표본으로는 불가능한 심층 분석을 가능하게 합니다(Smith et al., 2009). (BJHP41).

Small scale IPA studies allow in-depth analysis which would not be possible with larger samples (Smith et al., 2009). (BJHP41).IPA는 일반적으로 소수의 트랜스크립트를 집중적으로 조사하지만, 이번 연구는 (우리가 아는 한) 영국에서 이 집단에 대한 최초의 질적 연구이고 개요를 얻고자 했기 때문에 더 다양한 표본을 모집하기로 결정했습니다. 실제로 스미스, 플라워스, 라킨(2009)은 IPA가 대규모 집단에 적합하다는 데 동의합니다. 그러나 심층적인 개인주의적 분석에서 한 그룹의 사람들이 공유한 경험에서 공통된 주제를 도출하고 이를 통해 인터뷰에서 드러나는 주제 간의 관계망을 이해하는 데 사용할 수 있는 분석으로 강조점이 바뀝니다. 이 대규모 IPA 형식은 오탐 연구 분야의 다른 연구자들에 의해 사용되었습니다. 베일리, 스미스, 휴이슨, 메이슨(2000)은 24명의 참가자를 대상으로 염색체 이상에 대한 초음파 검사에 대한 IPA 연구를 수행했으며, 참가자의 수가 많을수록 더 정교하고 일관된 설명을 도출할 수 있다는 사실을 발견했습니다. (BJHP32).

Although IPA generally involves intense scrutiny of a small number of transcripts, it was decided to recruit a larger diverse sample as this is the first qualitative study of this population in the United Kingdom (as far as we know) and we wanted to gain an overview. Indeed, Smith, Flowers, and Larkin (2009) agree that IPA is suitable for larger groups. However, the emphasis changes from an in-depth individualistic analysis to one in which common themes from shared experiences of a group of people can be elicited and used to understand the network of relationships between themes that emerge from the interviews. This large-scale format of IPA has been used by other researchers in the field of false-positive research. Baillie, Smith, Hewison, and Mason (2000) conducted an IPA study, with 24 participants, of ultrasound screening for chromosomal abnormality; they found that this larger number of participants enabled them to produce a more refined and cohesive account. (BJHP32).

BJHP에서 발견된 IPA 논문은 '작은' 표본 규모를 옹호하고 '큰' 표본 규모를 문제 삼고 옹호한 유일한 사례입니다. 이러한 IPA 연구는 표본 크기 충분성의 특성화가 '객관적인' 표본 크기 평가의 결과라기보다는 연구자의 이론적, 인식론적 약속의 함수일 수 있음을 보여줍니다.

The IPA articles found in the BJHP were the only instances where a ‘small’ sample size was advocated and a ‘large’ sample size problematized and defended. These IPA studies illustrate that the characterisation of sample size sufficiency can be a function of researchers’ theoretical and epistemological commitments rather than the result of an ‘objective’ sample size assessment.

표본 크기 불충분으로 인한 위협

Threats from sample size insufficiency

위에서 살펴본 바와 같이, 표본 크기에 대해 언급하는 대부분의 논문은 동시에 [표본 크기가 작고 문제가 있다]고 지적했습니다. 저자가 단순히 '작은' 표본 규모를 연구의 한계로 언급하는 것이 아니라 작은 표본 규모가 어떻게 그리고 왜 문제가 되는지에 대한 설명을 이어가는 경우, 연구의 두 가지 중요한 과학적 특성인 결과의 일반화 가능성과 타당성이 위협을 받는 것으로 보였습니다.

As shown above, the majority of articles that commented on their sample size, simultaneously characterized it as small and problematic. On those occasions that authors did not simply cite their ‘small’ sample size as a study limitation but rather continued and provided an account of how and why a small sample size was problematic, two important scientific qualities of the research seemed to be threatened: the generalizability and validity of results.

일반화 가능성

Generalizability

표본이 '작다'고 응답한 사람들은 이를 [결과의 일반화 가능성이 제한적이라는 점]과 연결지었습니다. 표본과 관련된 다른 특징들(종종 일종의 구성적 특수성)도 [일반화 가능성의 제한]과 관련이 있었습니다. 논문에서 어떤 형태의 일반화를 언급했는지 항상 명시적으로 표현된 것은 아니지만(BJHP09 참조), 일반화는 대부분 명목상의 개념, 즉 표본에서 더 넓은 연구 집단('대표성 일반화' - BJHP31 참조)으로 추론할 수 있는 가능성과 관련된 것이었고 다른 집단이나 문화에 대한 일반화는 덜 자주 언급되었습니다.

Those who characterised their sample as ‘small’ connected this to the limited potential for generalization of the results. Other features related to the sample – often some kind of compositional particularity – were also linked to limited potential for generalisation. Though not always explicitly articulated to what form of generalisation the articles referred to (see BJHP09), generalisation was mostly conceived in nomothetic terms, that is, it concerned the potential to draw inferences from the sample to the broader study population (‘representational generalisation’ – see BJHP31) and less often to other populations or cultures.

표본이 적고 두 그룹 모두 대상 여성의 대다수가 참여했지만 일반화 가능성을 가정할 수 없다는 점에 유의해야 합니다. (BJHP09).

It must be noted that samples are small and whilst in both groups the majority of those women eligible participated, generalizability cannot be assumed. (BJHP09).이 연구의 한계를 인정해야 합니다: 상대적으로 소수의 참가자와의 인터뷰를 통해 얻은 데이터이므로 모든 환자와 임상의에게 일반화할 수 있는 것은 아닙니다. 특히 환자는 일반적으로 COFP 진단이 확인되는 2차 진료 서비스에서만 모집되었습니다. 따라서 이 표본은 전체 환자, 특히 치과 서비스에 의뢰되지 않았거나 퇴원한 환자를 대표하지 않을 가능성이 높습니다. (BJHP31).

The study’s limitations should be acknowledged: Data are presented from interviews with a relatively small group of participants, and thus, the views are not necessarily generalizable to all patients and clinicians. In particular, patients were only recruited from secondary care services where COFP diagnoses are typically confirmed. The sample therefore is unlikely to represent the full spectrum of patients, particularly those who are not referred to, or who have been discharged from dental services. (BJHP31).

일반화라는 용어를 명시적으로 사용하지 않았지만, 두 개의 SHI 논문은 '작은' 표본 크기가 '참여자의 설명으로부터 추정할 수 있는 범위'(SHI114) 또는 '결과로부터 광범위한 결론을 도출할 수 있는 가능성'(SHI124)에 제한을 가한다고 언급했습니다.

Without explicitly using the term generalisation, two SHI articles noted how their ‘small’ sample size imposed limits on ‘the extent that we can extrapolate from these participants’ accounts’ (SHI114) or to the possibility ‘to draw far-reaching conclusions from the results’ (SHI124).

흥미롭게도 소수의 논문만이 [질적 연구와 일치하는 일반화 유형], 즉 [관용적 일반화](즉, 사례로부터 그리고 사례에 대해 만들 수 있는 일반화[5])를 암시하거나 언급했습니다. 모두 사회학 분야에 발표된 이 논문들은 '작은' 규모에도 불구하고 다른 맥락에 대한 논리적, 개념적 추론을 이끌어내고 지식을 발전시킬 수 있는 잠재력을 가진 이해를 생성할 수 있다는 측면에서 연구 결과를 옹호했습니다. 한 논문(SHI139)은 [명목적(통계적) 일반화]와 [관용적 일반화]를 명확하게 대조하면서, 통계적 일반화 가능성이 부족하다고 해서 질적 연구의 연구 표본을 넘어서는 관련성이 무효화되지는 않는다고 주장했습니다.

Interestingly, only a minority of articles alluded to, or invoked, a type of generalisation that is aligned with qualitative research, that is, idiographic generalisation (i.e. generalisation that can be made from and about cases [5]). These articles, all published in the discipline of sociology, defended their findings in terms of the possibility of drawing logical and conceptual inferences to other contexts and of generating understanding that has the potential to advance knowledge, despite their ‘small’ size. One article (SHI139) clearly contrasted nomothetic (statistical) generalisation to idiographic generalisation, arguing that the lack of statistical generalizability does not nullify the ability of qualitative research to still be relevant beyond the sample studied.

또한 이러한 데이터는 의료화 분석을 발전시킬 수 있는 추론을 도출하기 위해 통계적으로 일반화할 수 있는 데이터일 필요는 없습니다(Charmaz 2014). 이러한 데이터는 추가적인 가설을 생성할 수 있는 기회로 볼 수 있으며 의료화 프레임워크의 고유한 적용입니다. (SHI139).