이론, 잃어버린 인물? GP교육 연구논문에서 제시되는 방식에 따라 (Med Educ, 2019)

Theory, a lost character? As presented in general practice education research papers

James Brown,1,2 Margaret Bearman,3 Catherine Kirby,2,4 Elizabeth Molloy,5 Deborah Colville6 & Debra Nestel1,7

서론

Introduction

- 앨리스: '도대체 내가 누구야? 아, 정말 멋진 퍼즐이군요! … 제가 여기서 어느 쪽으로 가야 하는지 말씀해 주시겠습니까?'

Alice: ‘Who in the world am I? Ah, that's the great puzzle! … Would you tell me, please, which way I ought to go from here?’ - 체셔 고양이: '그것은 당신이 어디로 가고 싶은지에 따라 많이 다릅니다.'

The Cheshire Cat: ‘That depends a good deal on where you want to get to.’

(Alice in Wonderland, Lewis Carroll)1

소드는 [연구논문]을 ['드라마 속 인물'이라는 추상적인 개념을 가진 이야기]로 봐야 한다는 설득력 있는 주장을 펴고 있다. 그녀는 학술적 글쓰기에 대한 광범위한 리뷰를 기반으로 한다. 이런 관점에서 보면 의학 교육 연구 논문의 이야기에서 [이론]은 종종 [잃어버린 캐릭터]이다. 학자들은 이론의 역할에 있어서 종종 부재, 저개발, 어색함 또는 사소한 것으로 파악한다. 이상한 나라의 앨리스에 있는 체셔 고양이는 길을 잃은 사람들을 위한 현명한 조언을 가지고 있다: 우리가 누구이고 어떤 길을 가야 하는지 아는 것은 우리가 어디로 가고 싶은지에 달려 있다. 본 논문은 일반실천(GP) 교육연구의 스토리텔링에서 이론의 역할을 어디서 도출하고 싶은지에 대한 이야기다.

Sword makes a compelling argument for research papers to be viewed as stories with abstract concepts as ‘characters in a drama’.2 She bases this on an extensive review of academic writing. From this perspective, theory is often a lost character in the stories of medical education research papers. Scholars identify theory as frequently absent,3 underdeveloped4, 5 and awkward or trivial in its role.6, 7 The Cheshire Cat, in Alice in Wonderland ,1 has sage advice for the lost: knowing who we are and which way to go depends on where we want to get to. This research paper is a story about where we might want to get to in casting a role for theory in the storytelling of general practice (GP) education research.

이 논문을 이야기로 만들면서, 우리는 아리스토텔레스의 [고대 비극 이론]을 이야기의 가장 고귀한 형태로, 그리고 캠벨의 '단일 신화'에 대한 보다 현대적인 이론을 이용한다. 아리스토텔레스와 캠벨은 모두 도전으로 시작하여 미지의 세계로 들어가는 여정의 관점에서 이야기를 서술한다. 아리스토텔레스 8은 알려진 주인공과 청중에게 의미 있는 설정을 규정한다. 따라서 우리는 먼저 의학 교육 연구의 광범위한 서술과 GP 교육 연구의 주인공인 이론을 소개한다.

In crafting this paper as a story, we draw on Aristotle's ancient theory of tragedy as the most noble form of story8 and Campbell's more modern theory of the ‘monomyth’.9 Both Aristotle8 and Campbell9 describe story in terms of a journey that starts with a challenge followed by an entry into the unknown that results in a discovery and concludes in a change for both the story's protagonist and the audience or reader. Aristotle8 prescribes a protagonist that is known and a setting that is meaningful to the audience. We therefore first introduce our protagonist, theory, in the narrating of medical education research broadly, and GP education research specifically.

호지스와 쿠퍼는 이론을 다음과 같이 정의한다. '의미 있는 전체로서 전달되는 일련의 이슈에 대한 조직적이고 일관성 있고 체계적인 표현'. 이론의 성격은 세 가지 다른 관점에서 볼 수 있다.

- 첫 번째 관점, [범위scope]는 대통합 이론으로 시작하여, 시스템과 관련된 거시 이론, 특정 개입과 관련된 미시적 또는 프로그램 이론에 이르는 범위를 포함한다.

- 두 번째 관점은 [연구 패러다임]과 관련된 이론의 위치에 관한 것이다.

- 예를 들어, 후기 실증주의 패러다임에서 이론은 외부 불변의 진리의 표현으로 위치할 수 있다. 성인 학습 이론과 인본주의와의 정렬과 같이 문화적으로 받아들여지는 신념과 일치하는 이론은 이러한 방식으로 자리매김하는 데 도움이 된다.

- 대조적으로, 구성주의 패러다임에서 이론은 관심 있는 현상에 대한 임의의 수의 유용한 렌즈 중 하나로 위치할 수 있다. 이 관점은 이론이 목적에 부합하기 때문에 역할을 하는 이론에 대한 보다 실용적인 접근 방식을 가지고 있다.

- 세 번째 관점은 [인간이 되는 것이 무엇인가에 대해 취한 렌즈]를 말한다. 이러한 관점에서, Bladley 등은 의학 교육에서 널리 사용되는 세 가지 렌즈를 식별한다. 여기에는

- 사고, 감정, 행동의 과정에 초점을 맞춘 [인지-행동 기계론적 렌즈],

- 자신의 잠재력을 실현하는 개인에 초점을 맞춘 [휴머니즘적 렌즈],

- 학습의 사회적 맥락에 초점을 맞춘 [사회문화적 렌즈]가 포함된다.

Hodges and Kuper define theory as: ‘an organised, coherent, and systematic articulation of a set of issues that are communicated as a meaningful whole.’10 The character of theory can be viewed from three different perspectives.

> The first perspective, scope, embraces a range that extends from grand unifying theories to macro theories pertaining to a system, and to micro or programme theories pertaining to particular interventions.3, 11

> The second perspective concerns the position of the theory with respect to a research paradigm. For example, from a post-positivist paradigm, theory can be positioned as an expression of an external immutable truth.4 Theories that align with culturally accepted beliefs, such as adult learning theory and its alignment with humanism,12 lend themselves to being positioned in this way. By contrast, from a constructivist paradigm, theory can be positioned as one of any number of useful lenses on a phenomenon of interest.13 This view has a more utilitarian approach to theory in which a theory is cast a role because it fits a purpose.11, 14

> The third perspective refers to the lens taken on what it is to be a human. From this perspective, Bleakley et al. identify three prevalent lenses in medical education.6 These include a cognitive–behavioural mechanistic lens focusing on processes of thinking, emotion and behaviour,15, 16 a humanistic lens focusing on an individual realising his or her potential,17, 18 and a sociocultural lens focusing on the social context of learning.19

이론을 연구 이야기로 쓰는 것은 의학 교육 연구에서 [이론의 역할]에 대한 개념과 반드시 연관되어 있다.

- 리스와 몽루스는 이론을 [선험적인 방향을 제시]하고 [의미를 만들기 위한 프레임]으로 사용할 것을 권고한다. 하나의 틀로서, 이론은 여러 연구 프로그램에 걸쳐 교육 현상에 대한 이해를 증진시키는 일관성coherence을 제공할 수 있다.

- 비에스타 외 연구진은 [의미를 만드는 역할]에 이론을 캐스팅했다. 이 역할에서 그들은 이론에 대해 세 가지 가능한 과제를 식별한다: 인과관계 설명; 타당성에 대한 해석, 그리고 숨겨진 것을 가시화함으로써 해방.

- Malterud 등은 [신뢰성credibility]에 대한 이론의 중요성을 강조한다.

- 네스텔과 베어맨은 이론이 '사람들이 어떻게 배우고 어떻게 가르침이 집행되는지에 대한 이해'로서 조명을 제공한다고 주장한다.

이론은 연구 스토리에 기여하는 것뿐만 아니라 연구 자체의 대상이 되는 만큼 변화의 대상이 되어야 한다.

The writing of theory into a research story is necessarily entwined with conceptions of the role of theory in medical education research.

> Rees and Monrouxe recommend using theory as a frame to provide a priori orientation and for making meaning.3 As a frame, theory can provide coherence in advancing understanding of educational phenomena across multiple programmes of research.20

> Biesta et al. cast theory in a role in making meaning.21 In this role they identify three possible tasks for theory: causal explanation; interpretation for plausibility, and emancipation by making the hidden visible.21

> Malterud et al. highlight the importance of theory for credibility.22

> Nestel and Bearman suggest that theories provide illumination as ‘understandings of how people learn and how teaching is enacted’.11

As well as contributing to the research story, theory should be an object of change as it is subjected to the research itself.7, 23

학자들은 교육 연구자들이 질적 향상을 목적으로 이론과 그들이 창작하는 문헌에 등록할 것을 요구한다. 주요 의학전문지들은 연구논문이 이론에 대한 의미 있는 역할을 포함할 것으로 기대하고 있다. 2007년 주요 의학 교육 저널에 게재된 연구 논문들을 조사한 결과, 논문의 절반 가까이가 이론이나 개념적 틀을 명시적으로 포함하지 않은 것으로 나타났다.

Scholars call for education researchers to enrol theory in their work and in the literature they generate for the purpose of enhancing quality.5, 10, 20 Key medical education journals expect research papers to include a meaningful role for theory.24, 25 A 2007 examination of research papers published in leading medical education journals indicated that close to half of papers did not explicitly include either a theory or a conceptual framework.26

연구 출판물에 이론의 더 나은 참여에 대한 요구는 이론의 본질과 사용 방법에 대한 연구자들 사이의 더 큰 이해의 필요성을 시사한다. 비스타 등은 [이론의 숙련된 사용]을 [이론적 감식안]이라고 한다. 이것은 주어진 맥락에서 어떤 이론이 연구 목적에 도움이 될 수 있고 그 이론이 어떻게 그 목적에 사용될 수 있는지를 인식하는 능력이다. Biesta 등은 [이론적 감식안]을 발전시키기 위해서는 먼저 이론이 현재 교육 연구에 어떻게 사용되고 있는지 알아야 한다고 제안한다. 우리가 이론이 연구에서 어떻게 사용되는지 알 수 있는 유일한 방법 중 하나는 그것이 연구 내러티브에 쓰여지는 방식을 통해서이다.

The call for better engagement of theory in research publications suggests a need for greater understanding amongst researchers of the nature of theory and how to use it.10 Biesta et al. identify the skilled use of theory as theoretical connoisseurship.21 This is the capacity to recognise which theory might serve the research purpose in a given context and how that theory might be used for that purpose. Biesta et al. suggest that to progress theoretical connoisseurship, we need first to know what and how theory is currently being used in education research.21 One of the only ways we can know how theory is used in research is through the way it is written into research narratives.

저희 연구팀은 교육이론, 연구이야기 작성, 가정의학 직업교육 연구 등에 관심이 있습니다. GP는 GP의 일이 개인과 공동체 내러티브에 의해 정의되는, 일상 생활의 평범한 세계에 위치한다. GP에 관한 직업교육은 주로 업무 중심이다. 의학교육 연구 문헌에 이론을 폭넓게 포함시켜야 한다는 요구에 따라 웹스터 등은 '가족의학 교육 연구에 더 많은 이론적 틀을 통합할 필요성'을 파악한다. 본 문헌 검토에서 우리의 전반적인 목표는 이론이 연구 내러티브에 어떻게 쓰여질 수 있는지 탐구함으로써 GP 직업 교육 연구에서 이론적 감각을 개발하는 것이다. 우리는 또한 GP 직업교육 연구의 문헌에서 이론의 사용을 이해하는 것이 의학 교육과 더 광범위하게 관련이 있다고 제안한다.

Our research team has an interest in education theory, the writing of research stories and GP, family medicine vocational education research. General practice is situated in the ordinary world of day-to-day living in which the work is defined by personal and community narratives.27, 28 General practice vocational education is principally work-based.29 In line with the call for the greater inclusion of theory in the medical education research literature broadly, Webster et al. identify ‘the need to incorporate more theoretical frameworks into family medicine education research’.30 Our overall aim in this literature review is to develop theoretical connoisseurship in GP vocational education research through exploring how theory can be written into its research narratives. We also suggest that understanding the use of theory in the literature of GP vocational education research is relevant to medical education more broadly.

우리의 조사 여정을 안내하기 위해, 우리는 과제를 구성하는 세 가지 관련 질문을 한다. GP 직업 연구 사례:

- 어떤 이론들이 명확한 역할을 부여받고 있는가?

- 이론에는 어떤 임무와 역할이 할당되어 있는가?

- 연구 이야기에서 이론이 제시되는 방식은 독자에게 어떤 영향을 미치는가?

To guide our investigative journey, we ask three related questions which frame the challenge. In GP vocational research stories:

- What theories are being given an explicit role?

- What tasks and roles are being assigned to theory?

- What impact does the way theory is presented in the research story have on the reader?

방법들

Methods

연구설계

Study design

GP 직업 연구에서 이론이 무엇과 어떻게 표현되는지를 조사하는 과제를 해결하기 위해, 우리는 체계적인 범위 문헌 검토를 선택했다.31 우리는 선택된 논문이 (연구팀의 선호에 부합하는 논문이 아니라) 현장에 의한 연구 이야기에서 이론의 사용을 포함하도록 보장하기 위해 논문 선택에 대한 헤르메네틱 접근 방식보다 [체계적인 접근 방식]을 취했다. 우리는 논문 샘플에 세 가지 분석 접근 방식을 사용했다.

- (i) 기술된 구성요소에 대한 내용 분석

- (ii) 이론에 할당된 역할과 이것이 어떻게 수행되었는지를 식별하기 위한 주제 분석, 그리고

- (iii) 이론 표현이 독자에게 미치는 영향을 고려하기 위한 휴리스틱 분석.

휴리스틱 분석은 다음과 같은 내용을 포함했다:

- 기사와의 참여,

- 독자로서의 경험에 대한 개별적 성찰, 그리고

- 이 경험에 대한 설명, 그리고 다른 연구원과의 대화.

In order to address the challenge of investigating what and how theory is represented in GP vocational research, we chose a systematic scoping literature review.31 We took a systematic rather than a hermeneutical approach32 to paper selection to ensure that our selected papers covered the uses of theory in research stories by those in the field rather than by those that aligned with the preferences of the research team. We used three analytic approaches to our sample of papers:

- (i) content analysis for the descriptive component;

- (ii) thematic analysis for identifying the roles assigned to theory and how this was done,33 and

- (iii) heuristic analysis for considering the impact of the representation of theory on the reader.34

The heuristic analysis involved the following:

- engagement with an article;

- individual reflection on our experience as a reader, and

- explication of this experience independently and then in conversation with another researcher.

우리의 주제 분석 및 휴리스틱 분석은 접근 방식에서 해석적이고 구성적이었으며, 데이터와 상호 작용할 때 우리 연구팀이 생성한 통찰력과 경험을 활용했다. 따라서 반사적으로 각 저자의 관련 관점을 제시한다.

Our thematic and heuristic analyses were interpretative and constructivist in approach and drew on the insights and experiences generated by our research team as they interacted with the data. We therefore reflexively35 present the relevant perspectives of each author.

JB는 일반 실무자이며 GP 직업교육 전달 및 연구에 관여합니다. 그는 GP 직업교육의 연구역량 구축에 관여하고 있다. JB는 현재 GP에서 해석적 접근법을 사용하는 업무 기반 학습에 중점을 둔 박사 후보이다. 이러한 맥락에서, 그는 이론 사용과 이론 구축에 관심이 있다.

JB is a general practitioner and involved in GP vocational education delivery and research. He is involved in building research capacity in GP vocational education. JB is currently a PhD candidate with a focus on work-based learning in GP using an interpretative approach. In this context, he is interested in theory use and theory building.

MB는 건강 전문 교육, 특히 질적 연구 분야에서 다년간의 경험을 가진 교육학자이자 교육 연구원이다. 그녀는 이론, 가장 최근에 실용 이론에 깊은 관심을 가지고 있다. 그녀는 또한 문학평론 방법론에 매료되었다.

MB is an educationalist and education researcher with many years of experience in health professional education and, particularly, in qualitative research. She has a keen interest in theory, most recently in practice theory. She is also fascinated by literature review methodology.

CK는 GP, 심리학, 교육 분야에서 양적, 질적 연구 경험을 가진 학제간 연구원이다. CK는 GP 교육 연구와 전문적 개발에 강한 관심을 가지고 있으며, 다양한 분야의 지식, 아이디어 및 전문 지식을 활용하고자 합니다.

CK is an interdisciplinary researcher with quantitative and qualitative research experience in GP, psychology and education. CK has a strong interest in GP education research and professional development, and seeks to draw on knowledge, ideas and expertise from across disciplines.

EM은 물리치료사이며 15년 이상 보건 전문 교육 분야에서 일해 왔다. EM은 직장 학습, 직업 전환 및 학습을 촉진하는 피드백과 평가의 역할에 대한 연구 관심을 가지고 있다. 그녀는 교육에서 사회적으로 내재된 현상을 조명하는 이론의 역할에 관심이 있다.

EM is a physiotherapist and has worked in health professions education for over 15 years. EM has research interests in workplace learning, professional transitions and the role of feedback and assessment in promoting learning. She is interested in the role of theory in illuminating socially embedded phenomena in education.

DC는 경험이 풍부한 임상의, 임상 교육자 및 학자이며, 페미니즘(들)을 포함한 많은 사회 문화 이론을 안과 수술 주제에 대한 GP 교육을 포함하여 자신의 교육 관행에 더 잘 통합하고자 합니다.

DC is an experienced practising clinician, clinical educator and scholar who seeks to better integrate many sociocultural theories, including feminism(s), into her own teaching practices, including GP education in the topic of ophthalmic surgery.

DN은 30년 이상의 경력을 가진 보건 전문 교육자이자 연구원이다. 그녀는 교육 이론과 교수진 개발에 특별한 관심을 가지고 있다. 그녀는 주로 연구에서 해석적 입장을 채택하고 훈련생과 감독관의 정체성 개발에 초점을 맞춘 GP 교육 연구 프로그램에 기여했다.

DN is a health professions educationalist and researcher with over 30 years of experience. She has a particular interest in education theory and faculty development. She mainly adopts an interpretative stance in research and has contributed to a programme of research in GP education with a focus on identity development in trainees and supervisors.

논문 선택

Paper selection

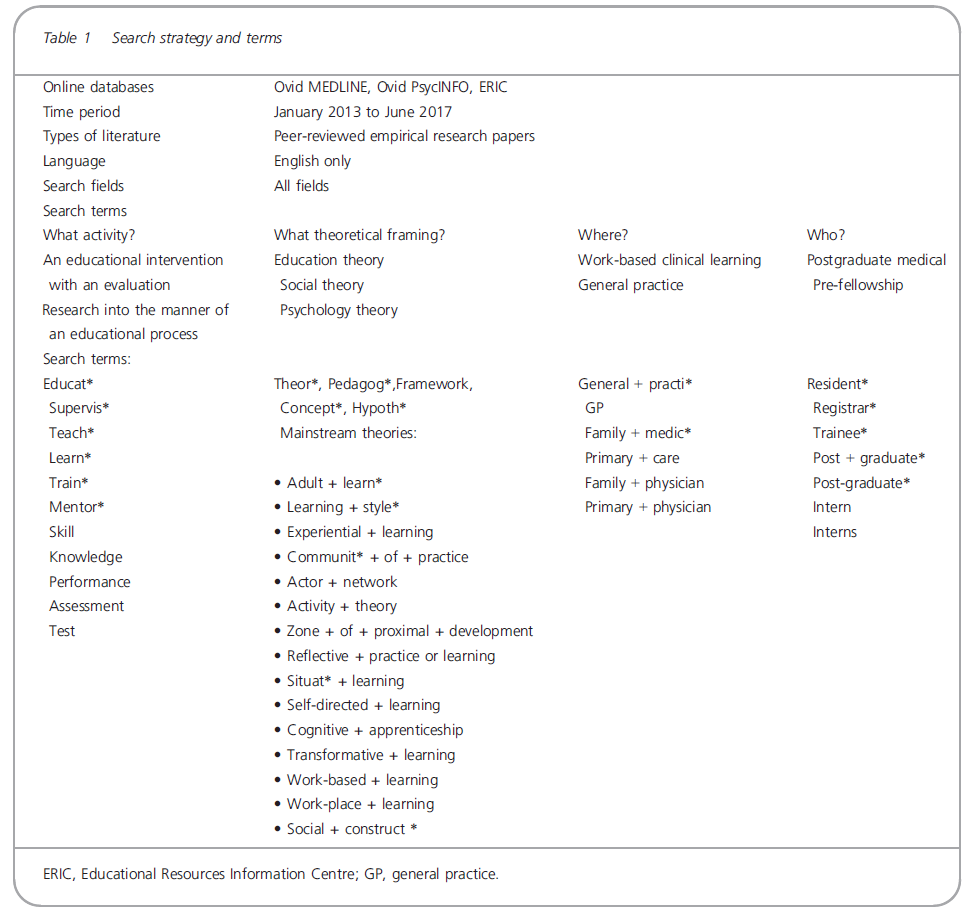

우리는 논문을 선정하기 위해 PRISMA(체계적 검토 및 메타 분석을 위한 선호 보고 항목) 지침을 따랐다(그림 1). 표 1에 자세히 나와 있는 검색어를 이용하여 Ovid MEDLINE, Ovid PsychINFO, ERIC(Educational Resources Information Center)를 검색하였다. 이 용어들은 GP 대학원 직업교육에서 이론을 명시적으로 언급한 발표된 연구 논문을 캡처하기 위해 고안되었다. 우리는 2013년 1월부터 2017년 6월까지 발표된 논문으로 검색을 제한했다. 검색어를 식별하기 위해 의학교육에서 이론 사용에 관한 최근 출판물에서 사용된 '이론' 용어를 살펴보았다. 우리의 기준을 충족시키는 알려진 논문들이 검색의 적절성을 판단하는 데 사용되었다. 팀(JB, MB, CK, EM, DC 및 DN)은 의도된 문헌에서 논문을 수집하는 목적을 달성할 수 있는 포함 및 제외 기준을 개발하기 위해 논문의 선택을 읽었다. 제외 기준은 그림 1에 자세히 설명되어 있다. 우리는 이론이 [교육 개입의 내용]만을 프레임하고, [개입의 교육적 과정]을 프레임하지 않기 위해 사용된 경우 그 논문을 제외했다. PRISMA 지침에 따라 두 명의 연구원(JB와 CK)은 제목별로, 추상별로, 그리고 나서 전체 논문을 읽음으로써 논문을 선별했다. 논문 포함에 대한 합의가 이뤄지지 않은 상황에서 연구팀(MB)의 제3의 멤버를 투입해 최종 결정을 가능하게 했다.

We followed the PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses) guidelines36 to select our papers (Fig. 1). We searched Ovid MEDLINE, Ovid PsychINFO and ERIC (Educational Resources Information Centre) using the search terms detailed in Table 1. These terms were designed to capture published research papers in GP postgraduate vocational education that explicitly referred to theory. We limited our search to papers published from January 2013 to June 2017 as this represented recency. We examined the ‘theory’ terms used in recent publications on theory use in medical education to identify search terms. Known papers that fulfilled our criteria were used to judge the adequacy of the search. The team (JB, MB, CK, EM, DC and DN) read a selection of papers to develop inclusion and exclusion criteria that would achieve our purpose of collecting papers from our intended literature. The exclusion criteria are detailed in Fig. 1. We excluded papers when theory was used to frame only the content of an educational intervention and not to frame the educational process of the intervention. Adhering to the PRISMA guidelines, two researchers (JB and CK) screened papers by title, by abstract and then by a reading of the full paper. Where consensus could not be reached on the inclusion of a paper, a third member of the research team (MB) was engaged to enable a final decision.

분석.

Analysis

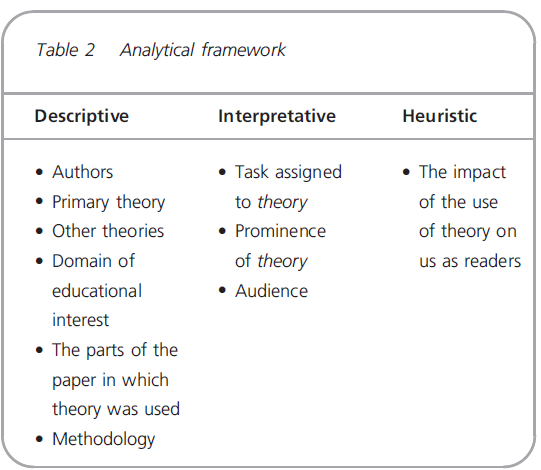

우리의 분석은 해석주의자와 구성주의자 관점에서 수행되었다. 우리는 데이터와 상호 작용하면서 반복적으로 분석 프레임워크를 구축하고 개념화를 개발했다. 우리의 범주는 연역적 및 귀납적 질문의 합성을 사용하여 개발되었습니다: 우리의 [범주의 개발]은 우리의 질문에 의해 프레임이 잡혔고, 교육 연구에서 이론의 역할에 대한 최근의 문헌을 읽음으로써 그리고 우리의 선택된 논문에서 이론이 표현되는 방법에 의해 알려졌습니다. 우리는 먼저 6개의 논문을 읽고 팀으로서 분석 범주의 초기 목록을 작성했다. 이러한 범주는 설명적, 해석적, 발견적이었으며 데이터에 대한 점진적 분석과 각자가 가져온 전문 분야별로 알려진 일련의 9개 회의에 걸쳐 다듬어졌다. 최종 분석 프레임워크의 구성 요소는 표 2에 자세히 설명되어 있습니다. 각 논문은 팀의 적어도 두 명이 분석했으며, JB는 자신이 작성한 두 개의 논문을 제외한 모든 논문을 분석했습니다.

Our analysis was undertaken from interpretivist and constructivist perspectives.35 We built an analytic framework iteratively as we interacted with the data and developed our conceptualisation. Our categories were developed using a synthesis of both deductive and inductive inquiry:37 our development of categories was framed by our questions, and informed by our reading of recent literature on the role of theory in education research and by the way theory was represented in our selected papers. We first read six papers and, as a team, developed an initial list of analytic categories. These categories were descriptive, interpretative and heuristic and were refined over a series of nine meetings informed by our progressive analysis of the data and by the areas of expertise we each brought. The component parts of our final analytic framework are detailed in Table 2. Each paper was analysed by at least two of the team; JB analysed all papers except two that he had authored.

사용된 이론을 확인한 후, 우리는 이것을 의학 교육에서 취해진 세 가지 이론적 관점에 대한 Bleakley 외 연구진의 유형론으로 분류했다.

- 인지-행동주의적;

- 인본주의적

- 사회문화적.

비록 우리는 이론들을 그들의 지배적인 관점으로 묶었지만, 우리는 이론들이 하나 이상의 관점을 취할 수 있다는 것을 인식했다.

Having identified the theories used, we grouped these to Bleakley et al.'s6 typology of three theoretical perspectives taken in medical education: cognitive–behavioural; humanistic, and sociocultural. Although we grouped theories to their dominant perspective, we recognised that theories may take more than one perspective.20, 38

우리는 저자들이 [이론이 무엇을 하도록 할당하고 있는지] 또는 [이론이 실제로 무엇을 하고 있는지] 확인함으로써 각 논문에서 이론에 할당된 작업을 결정했습니다. 그런 다음 우리는 [논문에서 이론에 할당된 과제]와 [캠벨의 '단신론monomyth' 이론에서 나온 전형적인 인물들의 과제] 사이의 유사점을 찾아냄으로써 [연구 이야기 내에서 역할을 가진 캐릭터로서의 이론의 개념화]를 발전시켰다. 캠벨은 위대한 이야기에는 각각 역할과 일련의 과제가 있는 전형적인 인물들이 있다고 이론화한다. 우리가 알아낸 과제와 유사한 역할을 가진 인물들은 다음과 같다:

- 도전을 하고 변화와 깨달음의 여정을 시작하는 '영웅' 또는 주인공.

- 도전을 밝히는 '선구(선발)자'

- 여정에서 영웅을 응원하는 '동맹자'

- 여정을 위한 안내와 도구를 제공하는 '멘토자'

We determined the tasks assigned to theory in each paper either according to what the authors said they were assigning theory to do or, more often, by identifying what theory was actually doing. Then we developed our conceptualisation of theory as a character with a role within a research story by looking for parallels between the tasks assigned to theory in our papers and the tasks of Campbell's archetypal characters from his theory of the ‘monomyth’.9 Campbell theorises that great stories have archetypal characters, each with a role and a set of tasks.9 The characters that held roles with parallels to the tasks we identified were:

- the ‘Hero’ or protagonist, who takes up a challenge and embarks on a journey of change and enlightenment;

- the ‘Harbinger’, who brings the challenge to light;

- the ‘Ally’, who supports the Hero on his or her journey, and

- the ‘Mentor’, who provides guidance and tools for the journey.

마지막으로, 이야기의 척도가 청중에게 미치는 영향이라는 아리스토텔레스의 견해에 따라, 8 우리는 독자인 우리가 논문의 이야기에 어떻게 반응하는지에 대해 각 논문에서 이론이 사용되는 방식의 영향을 휴리스틱하게 고려하였다.

Finally, following Aristotle's view that the measure of a story is its impact on its audience,8 we heuristically considered the impact of the way theory was used in each paper on how we, as readers, reacted to the story of the paper.34

결과.

Results

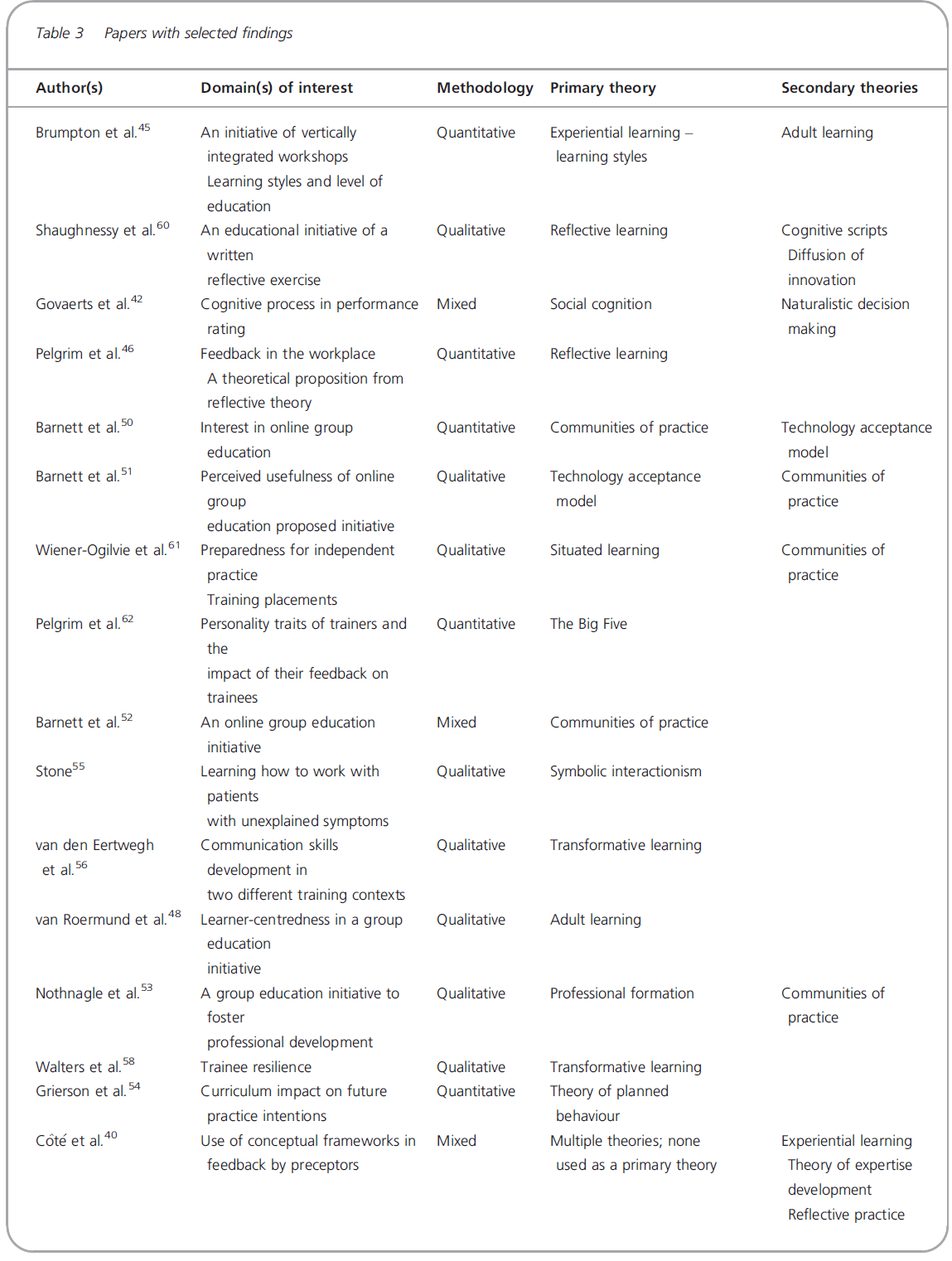

이론은 23편의 논문에 분명히 제시되었다. 선정 과정의 각 단계에서 확보한 논문이 그림 1에 자세히 나와 있습니다. 이론이 발견된 논문은 표 3에 우리의 발견 요소들과 함께 저자별로 나열되어 있다. 총 13편의 논문이 정성적 방법론을 사용하였고, 6편의 논문이 정량적 방법론을 사용하였으며, 4편의 논문이 혼합 방법을 사용하였다.

Theory was explicitly present in 23 papers. The papers secured at each stage of our selection process are detailed in Fig. 1. The papers in which theory was found are listed by author in Table 3 with elements of our findings. A total of 13 papers used a qualitative methodology, six used a quantitative methodology and four used mixed methods.

어떤 이론과 어떤 유형의 이론이 사용되었는가?

What theory and what type of theory were used?

이론은 우리가 선택한 논문에서 벵거의 '실천 공동체' 이론과 같은 단독 이론과 '반성적 실천에 대한 이론화'와 같은 이론영역으로 모두 사용되었다. 어떤 논문들은 하나의 이론에 관여한 반면, 다른 논문들은 주로 하나의 이론에 관여하고 다른 이론들을 부차적인 목적으로 사용했다. 두 논문은 하나의 이론을 강조하지 않고, 여러 이론에서 도출된 구조와 아이디어를 사용했다. 총 18개의 [단독 이론discrete theory]과 3개의 [이론 영역areas of theorising]이 사용되었다. 표 4에 자세히 설명되어 있으며, 각 이론은 이론의 주요 관점(인지적-행동적, 인본주의적 또는 사회문화적)의 유형론으로 분류된다. 가장 자주 취하는 관점은 휴머니즘적인 관점이다. 가장 일반적으로 사용되는 이론은 '성찰적 학습', '실천 공동체', '성인 학습'이었다.

Theory was used in our selected papers both as a discrete theory, such as Wenger's theory of ‘communities of practice’,39 and as areas of theorising such as ‘theorising on reflective practice’. Some papers engaged a single theory, whereas others primarily engaged one theory and used other theories for secondary purposes. Two papers used constructs and ideas drawn from multiple theories without emphasising any one theory.40, 41 A total of 18 discrete theories and three areas of theorising were used. These are detailed in Table 4, in which each theory is categorised to Bleakley et al.'s typology of a theory's primary perspective (cognitive–behavioural, humanistic or sociocultural).6 Perspectives, and then theories, are listed in order of their frequency of use as the primary perspective or primary theory. The most frequently taken perspective was a humanistic one. The most commonly used theories were those of ‘reflective learning’, ‘communities of practice’ and ‘adult learning’.

theory에 할당된 과제

Tasks assigned to theory

우리는 선택한 논문의 연구 이야기에서 이론에 할당된 [여섯 가지 다른 작업]을 확인했다. 이 발견은 대체로 우리가 논문에서 이론이 하는 것을 본 것에 의해 도출된 해석적 것이었다. 이론에 과제를 부여하는 데 있어서 명확한 논문은 거의 없었다. 6가지 작업은 다음과 같습니다.

- (i) 저자가 취한 위치와 얼라인하기.

- (ii) 연구 문제를 확인하기

- (iii) 아이디어를 전달하기 위한 수단

- (iv) 방법론적 도구 제공

- (v) 결과 해석

- (vi) 이론을 검토 대상으로 제시

We identified six different tasks assigned to theory in the research stories of our selected papers. This finding was largely an interpretative one derived by what we saw theory doing in the paper; few papers were explicit in assigning a task to theory. The six tasks were:

- (i) to align with a position taken by the author;

- (ii) to identify the research problem;

- (iii) to serve as a vehicle for an idea;

- (iv) to provide a methodological tool;

- (v) to interpret the findings, and

- (vi) to represent an object of examination.

하나의 논문에서, 이론은(때때로 하나 이상의 이론이) 여러 업무에 할당될 수 있었을 것이다. 작업 이론에 할당된 내용에서, 우리는 우리의 집합 안에 형식은 이론적의 일은 일의 모범을 보이는 기사를 참조합니다.

Within a given paper, theory might have been assigned multiple tasks, sometimes by using more than one theory. In detailing the tasks assigned to theory, we reference articles within our set that provide examples of theory undertaking that task.

정렬을 이론

Theory for alignment

이론에 할당된 가장 빈번한 작업은 논문에서 취한 관점과 이론을 정렬하는 것이었다. 이론적 정렬은 다음에 대해 수행될 수 있다. 연구의 맥락; 연구 방법론의 선택 또는 만들어진 결론. 독자로서, 우리는 [정렬]을 [저자의 관점에 독자를 민감하게 하거나 입장에 대한 신뢰를 주기 위해 수행되는 포지셔닝 방법positioning manoeuvre]이라고 보았다. 이러한 상황에서 언어는 이론이 '수용된 정통' 또는 '이상'의 지위를 부여하는데 사용될 수 있다. Ingham 등은 다음과 같이 논문을 발표했다.

The most frequent task assigned to theory was to align theory with a perspective taken in the paper. Theoretical alignment might be performed for: the context of the research;42 the choice of research methodology,43 or conclusions made.41 As readers, we experienced alignment as a positioning manoeuvre performed either to sensitise the reader to the author's perspective44 or to give credibility to a stance.45 In this positioning, language could be used to give the theory the status of an ‘accepted orthodoxy’ or an ‘ideal’.46 Ingham et al. opened their paper with:

성인 학습 이론의 적용은, 학습자 중심의 접근에 중점을 두고 있으며, 의학 교육에서 수십 년 동안 더 깊은 학습을 촉진하기 위해 필수적인 것으로 간주되어 왔다.

The application of adult learning theory, with its emphasis on a learner-centred approach, has for some decades in medical education been considered essential to facilitate deeper learning.47

이 오프닝으로, Ingham 등은 그들의 [논문의 목표]를 [성인 학습 이론]의 교리와 일치시키고, 이것을 [민감화하는 전략sensitising manoeuvre]으로 사용했다. 형용사 '본질적'을 사용하여 성인 학습 이론을 [노력하여 달성해야 할 이상]으로 위치시킨다. 논문의 뒷부분에서, 그들은 성인 학습 이론과 일치시킴으로써 그들의 결론을 정당화한다.

With this opening, Ingham et al.47 align the aim of their paper with the tenets of adult learning theory as a sensitising manoeuvre and, in using the adjective ‘essential’, position adult learning theory as an ideal to strive for. Later in the paper, they justify their conclusions by aligning them with adult learning theory:

이러한 행동은 학습자 중심의 성인 교육 접근법과 일치한다.

This behaviour is consistent with a learner-centred adult education approach.47

연구문제 파악을 위한 이론

Theory to identify the research problem

일부 논문은 [연구 문제를 식별]하기 위해 이론을 사용했다. Brumpton 등은 이러한 방식으로 [학습 스타일 이론]을 활용하여 수직적으로 통합된 교육 프로그램에서 [교수 스타일과 학습 스타일 간의 불일치에 문제가 있을 수 있다는 가능성]을 표시함으로써 경험적 학습 이론을 사용했다. Van Roermund 등은 [성인 학습 이론의 원리]를 사용하여 동료 디브리핑 워크숍에서 [교육자의 기대와 믿음]을 [피교육자의 기대와 신념]과 일치시키는 문제를 표시했다.

Some papers used theory to identify a research problem. Brumpton et al. used experiential learning theory in this way by drawing on theories of learning styles to flag the possibility that there may be a problem with a mismatch between teaching and learning styles in their vertically integrated education programme.45 Van Roermund et al. used the tenets of adult learning theory to flag the problem of matching the expectations and beliefs of educators with those of trainees in their peer debriefing workshops.48

아이디어의 매개체로서의 이론

Theory as a vehicle for an idea

단독 이론은 때때로 [아이디어나 개념의 매개체] 역할을 하는 임무를 맡기도 했다. 이러한 유형의 과제에 할당된 이론은 광범위한 통화currency를 가진 이론이었다.

- [성인학습이론]은 [학습자 중심주의 사상]의 매개체로 활용되었다.

- [경험학습]은 [실천의 맥락]에서 학습의 수단으로 이용되었고,

- [실천공동체 이론]은 [공동의 목적을 가지고 함께 일하는 사람들]을 전달하는 수단으로 이용되었다.

Discrete theories were sometimes tasked with serving as vehicles for ideas or concepts. Theories assigned this type of task were theories with broad currency.

Adult learning theory was used as a vehicle for the idea of learner-centredness.47, 48

Experiential learning was used as a vehicle for learning in the context of doing,40, 49 and

communities of practice theory was used as a vehicle for the idea of people working together with a common purpose.50-53

방법론적 도구를 제공하는 이론

Theory providing a methodological tool

어떤 저자들은 이론에게 [방법론적 도구]를 도입하거나 만드는 과제를 주었다. 여기에는 데이터 수집 도구, 유형학 도구 및 분석 도구가 포함됩니다.

- Grierson 등은 [계획 행동 이론]을 사용하여 GP 등록자의 향후 임상 실습을 위한 의도에 대한 데이터를 수집하기 위한 [설문지를 설계]했다.

- Keister 외 [드레퓌스의 기술 습득 모델]을 전공의 [발전과정progress을 채점]하기 위해 사용했습니다.

Some authors gave theory the task of introducing or crafting methodological tools. These included tools for collecting data, tools for typology and tools for analysis. Grierson et al. used the theory of planned behaviour to design a questionnaire to collect data on intentions for future clinical practice by GP registrars.54 Keister et al. used Dreyfus's model of skills acquisition for grading registrar progress.44

해석론

Theory for interpretation

비에스타 등은 이론이 '왜 사람들이 있는 그대로 말하고 행동하는가'에 대한 해답을 제공하는 방법으로 교육 연구에서 해석적 과제를 부여한다고 주장한다. 이러한 [해석 기능]의 예는 스톤이 의사들과 감독자들이 설명할 수 없는 의학적 증상을 다루는 방식을 이해하는 수단으로 [상징적 상호작용주의]를 사용한 것이다.

Biesta et al. suggest that theory is given interpretative tasks in education research as a way of providing an answer to ‘why people are saying and acting in the way that they are’.21 An example of this interpretative function was Stone's55 use of symbolic interactionism as a means of understanding the way that doctors and supervisors dealt with unexplained medical symptoms:

이 연구는 상징적 상호작용주의의 전통을 바탕으로 현실과 자아가 상호작용을 통해 알려지고 의사소통과 언어를 통해 표현된다는 기본적 가정을 가지고 있다.

This study is grounded in the symbolic interactionism tradition with its fundamental assumption that reality and the self are known through interaction and expressed through communication and language.55

검토 대상으로서의 이론

Theory as an object of examination

우리는 이론이 검토 대상으로 사용되는 두 가지 방법을 확인했다.

- 첫 번째는 연구를 위한 이론의 전반적인 유용성을 평가하는 데 있어 global한 것이었고,

- 두 번째는 이론적인 명제를 테스트하고 이론을 구축하고 확장하는 데 있어 particular한 것이었다.

Van den Eerweg 등은 의사소통 기술 학습에 대한 그들의 [연구 결과가 '변환적 학습 이론'과 일치한다고 판단]하며, 그 이론이 의사소통 기술 영역에서 추가 연구의 틀을 짜는 데 유용성이 있다고 결론지었다.

이론적 명제에 대한 시험은 [성찰이 행동의 변화를 이끈다는 '성찰의 이론']으로부터 명제를 검토했던 펠그림(Pelgrim) 등에 의해 수행되었다.

듀건 외 연구진은 의사-환자 의사소통에 대한 훈련생 성찰의 조사를 사용하여 이론 구축을 시도했다. 그들은 명시적과 암묵적 사이의 접점에 반성이 어떻게 자리 잡는지에 대한 표현으로서 [낚시꾼의 부유angler's float]에 대한 은유를 발전시키고 이러한 맥락에서 발생할 수 있는 긴장을 강조하기 위해 그들의 연구를 사용했다.

We identified two ways in which theory was used as an object of examination.

- The first was global in assessing the overall utility of a theory for a research purpose and

- the second was particular in testing a theoretical proposition, and building and extending a theory.

Van den Eerwegh et al. determined that their findings on learning communication skills were consistent with ‘transformative learning theory’ and hence concluded that the theory had utility for framing further research in the communication skills domain.56

Testing of a theoretical proposition was undertaken by Pelgrim et al., who examined the proposition from ‘theories of reflection’ that reflection leads to change in action.46

Duggan et al. endeavoured to theory build using an examination of trainee reflections on doctor–patient communication.57 They used their research to advance a metaphor of an angler's float as a representation of how reflection sits at the interface between the explicit and the tacit and to highlight the tensions that can occur in this context.

이론의 역할 특성 분석

Characterisation of the role of theory

이론이 캐릭터인 스토리로서의 연구 논문의 개념에서, 우리는 샘플에서 이론에 할당된 과제와 캠벨의 '단설 이론'에서 원형 캐릭터에 할당된 과제와 역할 사이의 유사점을 찾았다. 우리는 캠벨의 8개의 원형 캐릭터 중 4개와 의미 있는 유사점을 발견했다. 이러한 내용은 표 5에 자세히 나와 있습니다.

In our conception of a research paper as a story in which theory is a character, we looked for parallels between the tasks assigned to theory in our sample and the tasks and roles assigned to Campbell's archetypal characters in his ‘monomyth theory’.9 We found meaningful parallels with four of Campbell's eight archetypal characters. These are detailed in Table 5.

때때로 이론은 하나의 논문에서 두 개의 인물의 역할을 차지했습니다. 클레멘스 등은 실천이론 공동체를 '주역자'와 '멘토'로 분류했다. '주인공'으로서, 그 이론은 데이터에 의해 시험되었다. 이 이론은 데이터를 해석하는 데 사용되었다. 이것은 [이론이 연구에 정보를 제공]하고, [연구가 이론에 정보를 제공]해야 하는 필요성과 일치했다.

Sometimes theory occupied two character roles in a single paper. Clement et al.43 placed communities of practice theory as both the ‘protagonist’ and the ‘mentor’. As the ‘protagonist’, the theory was tested by the data; as the ‘mentor’, the theory was used to interpret the data. This accorded with the imperatives for theory to inform research and for research to inform theory.

이론에 주어진 역할의 중요성

Prominence of the role given to theory

이론이 취하는 역할을 검토하면서, 우리는 중요한 주제로 이론에 부여된 '역할의 탁월성prominence of the role'을 확인했다. 우리는 역할의 중요도를 '카메오 캐릭터'에서 '주요 캐릭터'로 등급을 매겼다. 한 논문에서 하나 이상의 이론이 사용될 때, 각각의 이론은 다른 정도의 두드러짐을 줄 수 있다.

- [카메오 캐릭터]로서의 이론은 전형적으로 서론이나 토론에서 한 두 문장으로 나타났다.

- [주요 캐릭터]로서의 이론은 논문 전반에 걸쳐 중요한 존재였다.

중요성은 이론에 할당된 역할과 임무와 관련이 있었다. [카메오 역할]은 대부분 ('신뢰를 위한 정렬'이나 '아이디어의 매개체'라는 업무를 수행하며) '동맹' 역할을 했다. 월터스(Walters) 등은 변혁 이론의 카메오 역할을 맡았으며, 이 이론에 대한 간략한 언급을 통해 발견에 신뢰성을 더했다.

In examining the role taken by theory, we identified the ‘prominence of the role’ assigned to a theory as an important theme. We graded role prominence from ‘cameo character’ through to ‘major character’. When more than one theory is used in a paper, each theory may be given a different degree of prominence.

- A theory as a cameo character typically appeared in one or two sentences in either the introduction or the discussion.

- A theory as a major character was a significant presence throughout the paper.

Prominence was related to the role and tasks assigned to theory. Cameo roles were mostly as an ‘ally’ in the tasks of ‘alignment for credibility’ or as ‘a vehicle for an idea’. Walters et al. gave transformative theory a cameo role by making a brief mention of this theory to add credibility to a finding:58

이 연구는 또한 개인들이 주요 긴장을 관리하는 데 있어 그들의 편안함의 한계를 확장하기 위해 감독관에 의해 스트레칭될 수 있다는 것을 보여주었다. 이 발견은 사람들을 그들의 "지식의 가장자리"로 데려가는 것이 성장을 가져올 수 있다는 것을 인식하는 메지로의 변형적 학습 이론과 일치한다.58

This study also demonstrated that individuals can be stretched by supervisors to expand their limits of comfort at managing the key tensions. This finding is consistent with Mezirow's transformative learning theory which recognises that taking people to their “edge of knowing” can result in growth.58

[방법론적 도구의 원천]으로서의 이론의 사용, 또는 [검토의 대상]으로의 이론의 사용은 이론의 prominence를 더 높인다.

Use of theory as a source for a methodological tool or use of theory as an object of examination matched with greater prominence.

관객의 입장

Audience stance

이론 사용의 영향을 고려함에 있어 '관객 입장'이라는 주제를 유의미하게 파악하였다. 우리는 교육자-실천가, 교수진, 정책 입안자, 연구자 및 이론가의 5가지 청중 입장을 각각 확인했다. 몇몇 논문들은 그들의 의도된 청중들에 대해 분명히 말했지만 대부분은 그렇지 않았다.

- 논문의 대상 독자에 대해 명시되지 않은 경우, 논문의 관심 대상인 포커스 또는 주요 영역을 대상 독자의 지표로 사용했다(표 3).

- Nothnagle 등의 촉진 토론 그룹 검토와 같이, 초점이 이산 개입인 경우, 우리는 청중을 [교육자-의사]로 식별했다.

- 관심 영역이 Walter 등의 회복력 검사와 같이 [실용적인 관점에서 조사된 현상]이라면, 우리는 청중을 [교수진] 또는 [정책 입안자]로 파악했다.

- 관심 영역이 [방법론적인 문제]라면, 우리는 청중을 [연구자]로 식별했다. 예를 들어, Grierson 등은 '포괄적 실무에 참여하려는 의도'를 측정하는 도구를 개발하기 위해 계획된 행동 이론을 사용했다.

- 펠그림 등의 성찰 이론 검토와 같이 관심 영역이 [이론 개발]이었다면, 우리는 청중을 [이론가]로 받아들였다. 일부 신문들은 하나 이상의 초점을 맞추거나 둘 이상의 청중에게 말한다고 주장했다.

We identified the theme of ‘audience stance’ as significant in considering the impact of the use of theory. We identified five audience stances of, respectively, the educator–practitioner, the faculty member, the policymaker, the researcher and the theorist. Some papers were explicit about their intended audience; most were not.

- When the paper was not explicit about its intended audience, we used the focus or main domain of interest of the paper (Table 3) as an indicator of the intended audience.

- If the focus was a discrete intervention, such as in Nothnagle et al.'s examination of a facilitated discussion group,53 we identified the audience as educators–practitioners.

- If the domain of interest was a phenomenon investigated from a practical perspective, such as in Walter et al.'s examination of resilience,58 we identified the audience as faculty members or policymakers.

- If the domain of interest was a methodological issue, we identified the audience as researchers. For example, Grierson et al. used the theory of planned behaviour to develop a tool to measure ‘intention to engage in comprehensive practice’.54

- If the domain of interest was theory development, such as in Pelgrim et al.'s examination of theories of reflection,46 we took the audience to be theorists. Some papers took more than one focus or claimed to speak to more than one audience.

이론에 할당된 역할이 독자인 우리에게 어떤 영향을 미쳤는가?

What was the impact of the role assigned to theory on us as readers?

[이야기의 척도]란 [그것의 청중에게 미치는 영향]이라는 아리스토텔레스의 의무에 따라, 우리는 각 논문에서 이론이 사용되는 방식이 청중으로서 우리에게 미치는 영향을 조사했다. 우리가 경험한 영향은 이론의 역할과 그 역할이 할당된 방식, 역할의 중요성, 그리고 우리가 청중으로서 취한 자세의 융합이었습니다.

In line with Aristotle's imperative that the measure of a story is its impact on its audience,8 we examined the impact of the way theory was used in each paper on us, as an audience. The impact we experienced was a confluence of the role of theory and the way that role was assigned, the prominence of the role, and the stance we took as the audience.

이론에 할당된 역할의 명확성과 관련된 영향

Impact in relation to the clarity of the role assigned to theory

우리는 이론의 역할이 명확해졌을 때 이론과 더 쉽게 관계를 맺었다. 우리가 어떤 역할이 할당되고 있는지 추측하도록 남겨졌을 때 더 어려웠는데, 이는 대부분의 검토된 논문에서 그랬다. Govaerts 등의 논문은 이론이 논문에서 취할 역할을 명확히 한 연구의 좋은 예였다. 이 논문은 '개념적 프레임워크'에 대한 서론에서 한 부분을 할애했다. 이론의 선택 뒤에 있는 철학적 가정을 명확히 하는 것 또한 도움이 되는 방향 설정 기법이었다. 클레멘스 등은 사회문화 이론으로서 벵거의 실천공동체이론을 탐구하면서 이렇게 했다.

We engaged more easily with theory when its role was articulated. It was more difficult when we were left to guess what role was being assigned, which was the case in most of the reviewed papers. Govaerts et al.'s paper42 was a good example of a work that articulated the roles that theory would take in the paper. This paper dedicated a section within the introduction to the ‘conceptual framework’.42 Articulation of the philosophical assumptions behind the choice of theory was also a helpful orientating manoeuvre.4 Clement et al.43 did this in their exploration of Wenger's theory of communities of practice39 as a sociocultural theory.

이론에 주어진 역할의 중요성과 관련된 영향

Impact in relation to the prominence of the role given to theory

이론에 기인하는 역할의 중요성은 중요한 영향을 미쳤다. 독자로서 [이론이 논문의 이야기에 미치는 영향이 가장 큰 경우]는 (반 로어문드 등의 논문에서처럼) [이론이 일찍 소개되었으면서, 논문의 고찰에서도 여전히 활발한 캐릭터였을 때]이었다. 이론이 [카메오 캐릭터]였던 논문에서 우리는 이야기를 산만하게 하는, 이론의 덧없는 존재감만을 경험했다. 일부 논문은 서론에서 이론의 역할을 강하게 주었지만, 나머지 논문에서는 계속되지 않았다. 우리는 이것을 이야기의 잠재적인 동반자로서 이론을 제시하는 것으로 경험했고, 그 후 그들은 설명할 수 없이 사라진다.

The prominence of the role ascribed to theory had an important impact. As readers, the impact of theory on the story of the paper was most meaningful when theory was introduced early and was still an active character in the paper's concluding discussion, as in van Roermund et al.'s paper.48 In papers in which theory was a cameo character, we experienced the fleeting presence of theory as a distracting diversion from the story. Some papers gave theory a strong role in the introduction, which was not continued in the rest of the paper. We experienced this as presenting theory as a prospective companion for the story, who then inexplicably vanishes.

청중의 입장에 대한 영향

Impact in relation to the stance of the audience

청중입장은 연구이야기에서 이론의 성격 전개 깊이가 미치는 영향을 결정하였습니다. [초점이 이론에 있으면서, 이론가 청중에게 초점을 맞출 때], 이론의 캐릭터 개발이 복잡한 것은 가치 있었다. 그러나, 이것은 [교육 개입]에 대한 초점이나 [교육 실무자로서의 청중]이라는 맥락에서는 소외될alienating 수 있다. 빈과 드 라 크룩스의 논문은 이러한 긴장감의 한 예이다. 본 논문은 촉진된 동료 보고 그룹에서 사례 제시와 그룹 반영 사이의 전환을 검토했다. 이를 통해 저자들은 '지식의 인식론' 이론의 효용성을 검증하고, [성찰에 대한 이론]의 구축에도 관여했다. 이 두 번째 시도는 이론의 복잡한 탐구를 포함했다. 이 논문은 교육자를 청중으로 다루어야 한다고 명시적으로 주장했지만, 우리는 교육자-실천자의 관점에서 그것이 어려운 읽을거리라는 것을 발견했다. 그러나 그것은 이론가의 관점에서 읽는 것이 매력적이었다.

Audience stance determined the impact of the depth of development of the character of theory in the research story. Complex character development of a theory was valuable when the focus was theory and the audience theorists; however, this could be alienating in the context of a focus on an educational intervention and an audience of education practitioners. The paper by Veen and de la Croix was an example of this tension.49 This paper examined the transition between case presentation and group reflection in facilitated peer debriefing groups. In doing so, the authors49 tested the theory of ‘epistemics of knowledge’ for its utility and also engaged in building theory on reflection. This second endeavour involved complex exploration of theory. Although the paper49 explicitly claimed to address educators as an audience, we found it a challenging read from the perspective of an educator–practitioner. It was, however, engaging to read from the perspective of a theorist.

논의

Discussion

우리는 GP 직업교육 연구논문에서 어떤 이론이 역할을 부여받는지, 이러한 역할이 무엇인지, 그리고 이것이 이루어지는 방식이 독자에게 어떤 영향을 미치는지 규명하고자 했다. 총 21개의 다른 이론 또는 이론 영역이 선택된 23개의 논문에서 사용되었습니다. 이들 중 두드러진 것은 '성인학습이론', '실천공동체', '반성학습'으로, 모두 거시적 또는 중간적 이론이다. 인본주의적 관점을 가진 이론들이 지배적이었다. 이는 이러한 이론과 이 관점이 GP 교육 연구에서 특별한 의미를 가지고 있음을 시사한다. 이론들은 다음과 같은 역할을 위해 제출되었다.

- 민감화 하거나 신뢰도를 정당화하기 위한 이론적 정렬을 달성

- 아이디어의 매개체 역할

- 방법론적 도구 제공

- 해석 제시

- 검사 대상으로서 이론 제시

We sought to uncover which theories are assigned roles in GP vocational education research papers, what these roles are and how the ways in which this is done impact on the reader. A total of 21 different theories or areas of theorising were used in our 23 selected papers. Prominent amongst these were ‘adult learning theory’, ‘communities of practice’ and ‘reflective learning’, all of which are macro or middle-range theories.3, 11 Theories with a humanistic perspective were dominant. This suggests that these theories and this perspective have particular currency in GP education research. Theories were enlisted for the roles of:

- achieving theoretical alignment for sensitising or justifying credibility;

- serving as vehicles for ideas;

- providing methodological tools;

- giving interpretation, and

- representing objects of examination.

이러한 역할들은 다른 사람들이 제안한 역할과 일치한다. 예를 들면 특히 신뢰성에 대한 조정을 달성하기 위함이라든가, 해석 도구의 역할을 한다던가, 검토의 대상이 됨을 나타낸다. 우리는 할당된 역할에서 이론의 영향이 그 역할에 대한 명확성, 연구 이야기에서 이론이 얼마나 두드러졌는지, 독자의 입장에 달려 있다는 것을 확인했다.

These roles aligned with those suggested by others, particularly for achieving alignment for credibility,22 serving as an interpretative tool23 and representing an object of examination.7, 23 We established that the impact of theory in its allocated role depended on clarity about its role, how prominent theory was in the research story and the stance of the reader.

우리는 이론이 사용될 수 있는 방법을 식별함으로써 이론적 감지를 발전시키는 것을 목표로 했다. 이야기에서 역할에 대한 캠벨의 전형적인 특성을 적용함으로써, 우리는 역할이 이론에 어떻게 할당될 수 있고 이 역할이 연구 논문의 이야기에 어떻게 통합될 수 있는지에 대한 프레임워크를 제공한다. 넓은 의미에서, 이야기 속의 인물들은 등장, 전개, 그리고 출구를 필요로 한다. [카메오 출연]은 무의미하거나 산만해질 위험이 있다.

- 이론이 연구의 대상일 때, 그것은 [주인공]이다. 아리스토텔레스와 캠벨은 주인공이 여행이 시작되기 전에 관객들에게 친숙해지도록 권한다. 우리는 [서론]이 이 작업을 수행하는 부분이라고 제안한다. 그 여정은 변화 또는 새로운 통찰력을 가져와야 하며, 이는 [고찰]에서 분명해져야 한다.

- 이론이 credibility를 위해 사용되거나, 또는 아이디어의 전달 수단으로 사용될 때, 그것은 '동맹'으로서 기능한다. 동맹으로서 이론은 연구 이야기에서 주인공의 동반자이다. 따라서 도입부 또는 방법 섹션의 장면 설정에 나타나야 하며, 결론conclusion에 나타나야 한다.

- 이론이 [도전이나 문제를 식별]하는 데 사용될 때, 그것은 '항해자' 역할을 한다. 전조(항해자)들은 도입부에 강한 존재감을, 결론부에 강한 존재감을 필요로 한다.

- 이론이 [해석적 또는 방법론적 도구]로 사용될 때, 그것은 '멘토'로서 기능한다. 멘토 캐릭터는 신뢰받을 이유가 필요하기 때문에 연구 이야기에 처음 도입부에서 개발이 필요하다.

We aimed to progress theoretical connoisseurship by identifying the ways in which theory could be used. By applying Campbell's9 archetypal characterisation of roles in a story, we offer a framework for how a role might be assigned to theory and how this role might be integrated into the story of a research paper. In broad terms, characters in a story require an entry, development and an exit. Cameo appearances risk being meaningless or distracting.

- When theory is the object of the research, it is the protagonist. Both Aristotle8 and Campbell9 recommend that the protagonist be made familiar to the audience before the journey commences. We suggest that the introduction is the section in which this is done. The journey should bring a change or new insight, which should become clear in the discussion.

- When theory is used for credibility or as a vehicle for an idea, it functions as an ‘ally’. As an ally, theory is a companion for the protagonist in the research story. Therefore, it should appear in the scene setting of either the introduction or the methods sections and be present in the conclusion.

- When theory is used in identifying the challenge or problem, it functions as the ‘harbinger’. Harbingers need a strong presence in the introduction and a presence in the conclusion.

- When theory is used as either an interpretative or a methodological tool, it functions as a ‘mentor’. A mentor character needs reason to be trusted and therefore needs development when it is first introduced to the research story.

특정 역할에 대한 이론의 선택과 사용 방법은 분야와 관객에 따라 달라집니다. 이론이 신뢰성을 위해 또는 아이디어의 수단으로 사용되려면, 그 이론은 대상 독자와의 교류currency가 필요하다. 사용된 이론의 영향은 이론 뒤에 있는 철학적 가정을 명료화함으로써 뒷받침된다. 이는 이론이 인지-행동적 관점, 인문학적 관점 또는 사회문화적 관점에서 나오느냐에 따라 달라질 것이다. [이론적 개념화의 깊이]는 또한 [이론적으로 밀도 높은 탐색]에 대해서 [교육 실무자는 이론가와 같은 방식으로 참여할 수 없다는 사실]을 인식하며, 의도된 청중에 따라 달라야 한다.

The choice of theory for a particular role and how to use it depends on the field and the audience. If theory is to be used for credibility or as a vehicle for an idea, the theory requires currency with the target audience. The impact of the theory used is supported by articulation of the philosophical assumptions behind the theory.4 These will differ depending on whether the theory comes from a cognitive–behavioural perspective, a humanistic perspective or a sociocultural perspective.6 The depth of theoretical conceptualising should also be dictated by the intended audience in recognition of the fact that an education practitioner may not be engaged in the same way as a theorist by a theoretically dense exploration.

우리의 논문은, 그 자체로, 연구 이야기에서 이론의 특성을 보여주는 예이다.

이번 연구에서 [우리의 '주인공']은 [일반적인 구성generic constrcut으로서의 이론]이었다. 우리는 서론에서 그녀의 성격을 깊이 있게 했다. 탐사와 토론의 여정을 통해, 우리는 그녀가 다른 연구 이야기에서 어떻게 등장인물이 될 수 있는지에 대한 견해를 얻으려고 노력했다.

[우리의 '동맹']은 우리의 접근과 결론에 신뢰성을 주기 위해 사용한 아리스토텔레스의 시학이었다. 이 이론은 서론에서 도입되었고, 그 후 이야기의 후속 부분에 존재하기 위해 친숙해졌다.

[우리의 '멘토']는 캠벨의 '단일 신화' 이론이었고, 해석과 지도, 틀을 제공했다. 이 이론은 서론에서 소개되었고, 방법론 부분에서 친숙해졌으며, 발견과 논의에서 중요한 인물로 나타났다.

[우리의 '전조']은 의학 교육에서 이론의 사용에 관한 문헌이었다. 이것은 우리의 소개에서 두드러졌고 우리의 토론에서 잠깐 나타났다.

우리의 분야는 GP 교육 연구였고, [우리의 청중]들은 그들의 연구에 이론을 사용할 사람들, 특히 GP 교육 연구였다. General practice은 목적을 달성하기 위해 넓은 관점의 미각을 이용하는 절충적인 훈련이다. 환자의 이야기가 무엇보다 중요한 훈육이기도 하다. 그러므로 우리는 이야기의 은유를 선택했고 우리의 목적을 달성하기 위해 하나 이상의 이론에 의존했다.

Our paper, in itself, is an example of the characterisation of theory in a research story.

Theory as a generic construct was our ‘protagonist’. We gave depth to her character in our introduction. Through our journey of exploration and discussion, we endeavoured to gain a view on how she might be a character in other research stories.

We recruited Aristotle's poetics8 as an ‘ally’ to give credibility to our approach and our conclusions. This theory was introduced and made familiar in the introduction to then be a presence in the subsequent sections of the story.

Campbell's theory of the ‘monomyth’9 was our ‘mentor’, providing interpretation, guidance and a framework.3 This theory was introduced in the introduction, made familiar in the section on methodology and appeared as a significant character in the findings and discussion.

Our ‘harbinger’ was the literature on use of theory in medical education. This had prominence in our introduction and appeared briefly in our discussion.

Our field was GP education research and our audience those who would use theory in their research, particularly GP education research. General practice is an eclectic discipline that draws on a broad palate of perspectives to serve its ends. It is also a discipline in which the narrative of the patient is paramount.27 We therefore chose the story metaphor and drew on more than one theory to meet our ends.

이번 연구 여정의 장점이 곧 한계다. 우리는 GP 교육 연구를 우리의 설정으로 선택했고 우리의 시험을 과거 5년으로 제한했다. 이것은 우리가 분석적인 깊이를 추구할 수 있도록 샘플을 제한했다. GP 연구는 필연적으로 의학교육의 다른 분야와 관련될 수도 있고 그렇지 않을 수도 있는 그 자체의 맥락적 특성을 가지고 있다. 우리는 GP 교육 연구가 그 자체로 중요한 분야이며, 또한 이 분야의 연구에서 도출된 결론은 보다 광범위한 관련성을 가지고 있다고 믿는다. 단 5년의 기간 내에 출판된 작품을 검토하기로 한 우리의 결정은 변화하는 환경의 변화에 대해 언급할 수 없게 만든다. 이론의 사용에 대한 보다 장기적인 관점은 이론의 사용의 미래 방향에 대한 통찰력을 제공할 수 있다. 우리의 검색어는 논문이 포함되기 위해 이론에 대해 명시적으로 언급할 것을 요구했다. 이것은 암묵적인 이론적 지향이 검토되지 않았다는 것을 의미했다. 이는 이론적 기반이 가정될 가능성이 더 높은 실증주의 패러다임에서 정량적 논문에서 벗어난 샘플의 가중치를 초래했을 가능성이 높다.3 정성적인 논문이 우리의 선택을 지배했다. 우리는 이론의 사용을 검토하면서 해석적 접근법을 취했고, 이것은 우리가 가지고 있는 관점과 논문을 읽는 우리의 반응을 끌어낼 수 있게 해주었다. 그러나 이것은 다른 사람들의 해석과 반응과 일치하지 않을 수 있다. 다른 사람들이 문학에서 이론의 사용에 대한 그들 자신의 경험과 비교하여 우리 해석의 진실성과 유용성을 판단하는 것이다. 우리가 하는 권고안은 그 결과에 대한 우리의 해석으로부터 도출된다. 우리의 구성주의적 접근 방식에 따라, 우리는 우리의 결론이 많은 정당한 관점 중 하나에서 나온다는 것을 인식한다. 우리의 관심은 이론이 연구 글쓰기에서 표현되는 방식이었다. 우리는 그 이론이 연구 자체에서 사용되는 방식이나 그것이 사용된 엄격함을 조사하지 않았다. 이것들은 추가 연구에 유용한 분야일 것이다.

The strengths of this research journey are also its limitations. We chose GP education research as our setting and confined our examination to the past 5 years. This limited our sample to enable us to pursue analytical depth. General practice education research inevitably has its own contextual characteristics that may or may not pertain to other areas of medical education. We believe that GP education research is an important field in itself and also that conclusions drawn from research in this area have relevance more broadly. Our decision to examine works published within a period of only 5 years makes us unable to comment on changes in what is likely to be a changing environment. A more longitudinal view on the use of theory may offer insights to future directions of the use of theory. Our search terms required that a paper make explicit mention of a theory in order to be included. This meant that implicit theoretical orientations were not examined. This is likely to have resulted in the weighting of our sample away from quantitative papers in a positivist paradigm in which theoretical underpinnings are more likely to be assumed.3 Qualitative papers dominated our selection. We took an interpretative approach in examining the use of theory and this enabled us to draw on the perspectives we held and on our reactions to reading the papers. However, this may not align with the interpretations and reactions of others. It is for others to judge the veracity and usefulness of our interpretation against their own experiences of the use of theory in the literature. The recommendations we make are drawn from our interpretation of the findings. In line with our constructivist approach, we recognise that our conclusions come from one of many justifiable perspectives. Our interest was the way in which theory was represented in research writing. We did not examine the way that theory was used in the research itself or the rigour with which it was used. These would be useful areas for further research.

결론들

Conclusions

왕은 매우 진지하게 "처음부터 시작해서 끝까지 계속하세요. 그리고 나서 멈추세요."라고 말했다.

“Begin at the beginning,” the King said, very gravely, “and go on till you come to the end: then stop.” (Alice in Wonderland, Lewis Carroll)1

우리의 집중적인 검토는, 우리의 연구 이야기에서 [이론이 잃어버린 캐릭터가 될 필요가 없다]는 것을 시사한다. 이론을 의미 있게 캐스팅하면 중요한 역할을 할 수 있게 만들 수 있다. 이론이 연구 이야기에 영향을 미치려면 우리가 선택한 역할에 대해 숙고하고 이론을 선택한 이유에 대해 명확히 설명하며, 우리의 연구 이야기에서 이론의 특성화에 주의를 기울일 필요가 있다. 이러한 차원에 걸쳐 명시함으로써, 교육 연구자들은 그들의 연구 글쓰기의 응집력 있는 품질을 더할 수 있고, 다른 사람들이 그들의 연구 이야기에 이론을 쓰는 것을 도울 수 있는 통찰력을 제공할 수 있다. 이를 통해 이론적 감식력을 향상시킬 수 있다.

Our focused review suggests that theory does not need to be a lost character in our research stories. Casting theory meaningfully enables it to take a significant role. For theory to have impact on the research story, we need to be deliberate about the role we choose to give theory and explicit about the reasons for our choice of theory, and to attend to the characterisation of theory in our research story. By being explicit across these dimensions, education researchers can both add to the cohesive quality of their research writing and provide insights to help others in writing theory into their research stories. Through this, theoretical connoisseurship may be progressed.

Theory, a lost character? As presented in general practice education research papers

PMID: 30723929

DOI: 10.1111/medu.13793

Abstract

Objectives: The use of theory in research is reflected in its presence in research writing. Theory is often an ineffective presence in medical education research papers. To progress the effective use of theory in medical education, we need to understand how theory is presented in research papers. This study aims to elicit how theory is being written into general practice (GP) vocational education research papers in order to elucidate how theory might be more effectively used. This has relevance for the field of GP and for medical education more broadly.

Methods: This is a scoping review of the presentation of theory in GP vocational education research published between 2013 and 2017. An interpretive approach is taken. We frame research papers as a form of narrative and draw on the theories of Aristotle's poetics and Campbell's monomyth. We seek parallels between the roles of theory in a research story and theories of characterisation.

Results: A total of 23 papers were selected. Theories of 'reflective learning', 'communities of practice' and 'adult learning' were most used. Six tasks were assigned to theory: to align with a position; to identify a research problem; to serve as a vehicle for an idea; to provide a methodological tool; to interpret findings, and to represent an object of examination. The prominence of theory in the papers ranged from cameo to major roles. Depending on the way theory was used and the audience, theory had different impacts. There were parallels between the tasks assigned to theory and the roles of four of Campbell's archetypal characters. Campbell's typology offers guidance on how theory can be used in research paper 'stories'.

Conclusions: Theory can be meaningfully present in the story of a research paper if it is assigned a role in a deliberate way and this is articulated. Attention to the character development of theory and its positioning in the research story is important.

© 2019 John Wiley & Sons Ltd and The Association for the Study of Medical Education.

'Articles (Medical Education) > 의학교육연구(Research)' 카테고리의 다른 글

| HPE에서 데이터 사이언스와 머신러닝의 역할: 실용적 적용, 이론적 기여, 인식론적 신념(Adv Health Sci Educ Theory Pract. 2020) (0) | 2022.08.27 |

|---|---|

| 심리학에서 이론의 위기: 어떻게 나아갈 것인가(Perspect Psychol Sci, 2021) (0) | 2022.08.26 |

| 불만족한 포화: 질적연구에서 포화된 샘플 크기에 대한 비판적 탐색(Qualitative Research, 2012) (0) | 2022.08.23 |

| 편집자에게 '오케이'를 얻어내기 위한 저자 답변서 쓰기(J Grad Med Educ, 2019) (0) | 2022.08.22 |

| 의학교육 출판에서 저자 순서: 실용적 가이드를 찾아서(Teach Learn Med, 2019) (0) | 2022.08.22 |