학습 고리: 적시 교수개발 개념화(AEM Educ Train. 2022)

The Learning Loop: Conceptualizing Just-in-Time Faculty Development

Yusuf Yilmaz PhD1,2,3,4 | Dimitrios Papanagnou MD, MPH5 | Alice Fornari EdD, RDN6 | Teresa M. Chan MD, FRCPC, MHPE, DRCPSC1,2,4,7,8

소개

INTRODUCTION

오늘날의 업무를 처리하기 위해 지식은 종종 '적시에', 그리고 사용 시점의 리소스를 통해 액세스됩니다. 따라서 학습 방식도 변화하고 있습니다. 구글에서 넷플릭스에 이르기까지, 적시성 있는 콘텐츠를 쉽게 검색할 수 있게 되면서 전 세계적으로 정보에 접근하는 방식과 그 지식을 받아들이는 방식이 바뀌었습니다. 이러한 변화는 (1) 광범위한 인터넷 연결, (2) 모바일 테크놀로지의 광범위한 채택, (3) 정보 관리의 최적화(예: 검색 도구 또는 온라인 지식 데이터베이스)라는 세 가지 근본적인 테크놀로지 변화로 인해 가능했습니다. 1 , 2 , 3 , 4 최근 코로나바이러스 감염증 2019(COVID-19) 팬데믹으로 인해 기존의 교육 및 학습 관행이 혼란에 빠지면서 많은 교육기관이 보다 효과적인 온라인 교육 방법을 찾아야 했습니다. 5 , 6 , 7

To navigate today's work, knowledge is often accessed “just‐in‐time” and through point‐of‐use resources. Consequently, the way we learn is changing. From Google to Netflix, the ease of searching for just‐in‐time content has changed the way we access information across the globe and how we expect that knowledge to be received. Three fundamental changes in technology have allowed for this shift: (1) widely available internet connectivity; (2) broad adoptions of mobile technology; and (3) optimization of information management (e.g., search tools or online knowledge databases). 1 , 2 , 3 , 4 Recently, the Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID‐19) pandemic disrupted our current practices of teaching and learning and forced many institutions to identify more effective ways of online education. 5 , 6 , 7

온라인 프로그램, 8 웨비나, 9 또는 e-모듈과 같이 전통적인 프로그램에 참여할 수 없는 응급의학 교수진을 지원하기 위한 새로운 리소스가 많이 등장하고 있습니다. 10 안타깝게도 이러한 프로그램은 상당한 시간 투자가 필요하며 일반적으로 수동적이고 비동기적인 방식입니다. 11 온라인 교수개발은 종종 기존 프로그램(예: 아카이브된 세션 녹화본 또는 대면 버전을 대체하는 가상 실습 커뮤니티)을 단순히 번역한 것으로, 교수개발을 진정으로 혁신하기 위해 새로운 테크놀로지의 어포던스를 충분히 활용하지 못한다는 단점이 있습니다. 11 , 12 , 13 , 14 그러나 이러한 경향이 변화하고 있음을 시사하는 문헌이 존재합니다. 11 Steinert 15는 교수개발을 "보건 전문가가 개인 및 그룹 환경에서 교사 및 교육자, 리더 및 관리자, 연구자 및 학자로서 지식, 스킬 및 행동을 개선하기 위해 추구하는 모든 활동"으로 정의합니다. 교수개발은 다양한 접근 방식을 활용하여 교육을 제공해야 합니다. 예를 들어,

- 온라인 교수개발은 실시간 소그룹 토론 대신 비동기식 블로그 기반 사례 토론으로 진행할 수 있습니다. 16

- 또는 회진 중 병동이나 응급실에 있는 바쁜 임상의 교육자를 대상으로 하는 대신 모바일 장치 애플리케이션(앱)을 개발하여 업무 중에도 교육에 참여할 수 있도록 할 수 있습니다. 17

- 라이브 강의 대신 트위터에서 트윗 채팅 18을 하거나 비동기식 채팅 기반 인큐베이터를 통해 디지털 방식으로 진행할 수도 있습니다. 8

- 교수개발에 대한 새로운 접근 방식은 휴대용 개별 디바이스를 통해 보다 개인화되고 쉽게 접근할 수 있는 방법을 제안합니다. 11

There are many emerging resources to support emergency medicine faculty who are unable to engage in traditional programming, such as online programs, 8 webinars, 9 or e‐modules. 10 Unfortunately, these require a significant time investment and are typically passive, asynchronous modalities. 11 Online faculty development can often have the disadvantage of being a simple translation of existing programs (e.g., archived recordings of sessions, or virtual communities of practice that replace in‐person versions) that do not fully harness the affordances of new technologies to truly transform faculty development. 11 , 12 , 13 , 14 There are trends that exist, however, within the literature that suggest this may be changing. 11 Steinert 15 defines faculty development as “all activities health professionals pursue to improve their knowledge, skills, and behaviors as teachers and educators, leaders and managers, and researchers and scholars, in both individual and group settings.” Faculty development should utilize multiple approaches to deliver education. For example,

- instead of a live small‐group discussion, online faculty development may be an asynchronous blog‐based discussion of a case. 16

- Or instead of trying to target busy clinician educators on the wards during rounds or in the emergency department, a mobile device application (app) can be developed to engage them while at work. 17

- Instead of a live course, a digital equivalent may take the form of a Tweet chat 18 on Twitter or an asynchronous chat‐based incubator. 8

- New approaches to faculty development suggest more personalized and ease of access through the handheld individualized devices. 11

교육 및 학습 시스템에 돌이킬 수 없는 영향을 미친 코로나19의 여파로 팬데믹 이후의 새로운 환경에 대비하여 교수개발에 대한 인식을 재검토하는 것은 유용하고 시의적절한 일입니다. 교육자들이 적시적소에 맞춰 교수개발을 성공적으로 재개념화하려면 어떻게 해야 할까요? 적시적소 접근 방식은 이러한 환경에서 교수개발을 위한 새로운 접근 방식을 제공할 수 있습니다. 이 백서에서는 교수진 전문성 개발에 적시적소 접근 방식을 통합하는 방법을 정의하는 새로운 조직 모델, 즉 JiTFD 학습 루프를 제안합니다.

In the wake of COVID‐19, which has irrevocably influenced systems of teaching and learning, it is both useful and timely to revisit our perceptions of faculty development for the new post‐pandemic landscape. How might educators successfully reconceptualize faculty development to fit into a just‐in‐time world? Just‐in‐Time (JiT) approaches may provide a new set of approaches to deliver faculty development in this environment. In this paper, we propose a new organizing model to define how we can incorporate JiT methods into faculty professional development: the JiTFD Learning Loop.

적시 접근법: 개요

JUST‐IN‐TIME APPROACH: AT A GLANCE

적시적소 접근법을 더 잘 정의하기 위해서는 먼저 몇 가지 질문을 고려해야 합니다.

- 먼저, 적시성이란 무엇을 의미할까요?

- 다음으로, 교수개발 콘텐츠를 가장 효과적으로 전달하려면 어떻게 해야 하며, 마이크로러닝과 마이크로콘텐츠는 어떤 방법이 될 수 있을까요?

- 또한, JiTFD는 어떻게 인증 및 평가될 수 있을까요? 마이크로 자격증명 및/또는 디지털 배지의 역할이 있나요?

- 교수개발을 위해 이러한 구성 요소를 어떻게 결합할 수 있을까요?

다음 섹션에서는 이러한 질문에 대한 답을 살펴보고, 이를 바탕으로 새로운 가이드 모델인 'JiTFD 학습 루프'를 소개합니다.

To better define JiTFD, we must first consider several framing questions. First, what is meant by just‐in‐time? Next, how might faculty development content be best delivered and how might Microlearning and Microcontent be a way forward? Also, how might JiTFD be credentialed and/or assessed? Is there a role for Micro‐credentials and/or Digital Badges? How do these components fit together to deliver faculty development? In the sections that follow, we will explore the answers to these questions, which will lead us to a new guiding model, which we have entitled the JiTFD Learning Loop.

교육을 위한 적시성 패러다임: 개념적 모델

THE JUST‐IN‐TIME PARADIGM FOR EDUCATION: A CONCEPTUAL MODEL

메리엄 웹스터 사전에서는 적시성(Just-In-Time, JiT)을 "필요한 만큼만 부품을 생산하거나 납품하는 제조 전략"으로 정의합니다. 19 학습, 교육 등 모든 것의 적시성을 결정하려면 종합적인 사고와 분석이 필요합니다. JiT는 원하는 콘텐츠에 쉽게 액세스할 수 있는 모든 환경이 갖춰진 기간 동안만 가능합니다. 교육적으로 JiT는 적시 학습, 20 , 21 적시 교육, 22 , 23 적시 훈련, 24 , 25 , 26 및 적시 피드백 등 여러 가지 이름으로 불려 왔습니다. 27 JiT의 다양한 사용으로 인해 개념과 그 적용에 대한 다양한 관점이 생겨났고, 이로 인해 간단하고 명확한 정의를 내리는 것이 어려워졌습니다. 그럼에도 불구하고 이러한 접근 방식은 모두 필요할 때 특정 요구 사항을 충족하는 것을 목표로 하고 있으며 적절한 리소스에 대한 접근을 수반합니다.

Merriam‐Webster dictionary defines just‐in‐time (JiT) as “a manufacturing strategy wherein parts are produced or delivered only as needed.” 19 Determining JiT of anything (i.e., learning, training) requires comprehensive thinking and analysis. JiT can only be situated for a time period where everything is in place to readily access the content desired. Educationally, JiT has had several names, including Just‐in‐Time Learning, 20 , 21 Just‐in‐Time Teaching, 22 , 23 Just‐in‐Time Training, 24 , 25 , 26 and Just‐in‐Time Feedback. 27 The various uses of JiT have led to the development of different perspectives of the concept and its applications, where it has become challenging to convey a simple, clear‐cut definition of JiT. Nonetheless, these approaches have all aimed to meet specific needs when required and have entailed accessing appropriate resources.

학습자가 특정 학습 리소스를 '푸시'하는 경우 외부 기관(예: 교육자)이 정보를 제공하는 반면, 학습자가 특정 리소스를 '풀'하는 경우 학습자가 필요에 따라 독립적으로 리소스에 빠르게 접근하고 찾을 수 있는 능력이 있어야 한다는 개념이 현대 교육 환경의 관련 개념입니다. 28

Related concepts in the modern educational landscape are the ideas of “push” and “pull” resources: when learners are “pushed” a specific learning resource, an external entity (e.g., educator) is providing them with information, whereas when learners can “pull” a specific resource, they must have the ability to quickly access and find the resource independently, on demand. 28

어떻게 하면 콘텐츠를 가장 잘 전달할 수 있을까요? 마이크로러닝 및 마이크로콘텐츠 활용

HOW MIGHT JiT CONTENT BE BEST DELIVERED? LEVERAGING MICROLEARNING AND MICROCONTENT

마이크로러닝은 학습자에게 짧은 콘텐츠를 연속적으로 제공하여 학습자가 자기 속도에 맞는 작은 단계를 통해 시간이 지남에 따라 코스 및 교육 성과를 성공적으로 달성할 수 있도록 도와줍니다. 29 , 30 2004년에 처음 정의된 마이크로러닝은 더 큰 학습 생태계를 발전시키기 위한 새로운 유형의 학습으로 인식되고 있습니다. 31 , 32 마이크로러닝은 통합되어 있지만 느슨하게 연결된 일련의 마이크로 콘텐츠가 포함된 학습 활동에 참여하는 것을 말합니다. 31 마이크로러닝은 집중적이고, 독립적이며, 분할할 수 없고, 구조화되어 있으며, 전달 방법에 따라 다양한 콘텐츠 유형(예: 텍스트, 비디오, 오디오)을 활용합니다. 33 , 34

Microlearning delivers short pieces of content, in succession, to learners to help them successfully accomplish course and/or training outcomes over time via small, self‐paced steps. 29 , 30 First defined in 2004, microlearning has been perceived as a new type of learning to develop the larger learning ecosystem. 31 , 32 Microlearning refers to engaging with learning activities that contain integrated, but loosely connected, series of microcontent. 31 Microlearning is focused, self‐contained, indivisible, structured and leveraged varied content types (e.g., text, video, audio), depending on the delivery method. 33 , 34

더 나은 마이크로러닝 경험을 제공하려면 마이크로콘텐츠가 필수적입니다. 닐슨 35은 이메일 및 웹 페이지와 같은 전자 정보에 이름, 헤더, 제목, 주제를 일관성 있게 할당할 필요성에 대해 작성자의 주의를 환기시키기 위해 '마이크로 콘텐츠'라는 단어를 처음 사용했습니다. 이러한 테크놀로지적 특징 덕분에 마이크로 콘텐츠는 최종 사용자 수준에서 더욱 유용해졌습니다. 콘텐츠를 찾는 것부터 소비하는 것까지, 사용자는 단기간에 마이크로 콘텐츠에 참여하고 상호 작용할 수 있습니다. 오늘날 이 용어는 일반적으로 콘텐츠 자체의 특성보다는 콘텐츠 전달 방식에 대한 보다 구조화된 접근 방식을 의미합니다. 36 따라서 마이크로러닝은 니즈를 파악하는 것부터 필요한 마이크로콘텐츠를 제공하는 것까지 전반적인 학습을 요약하고 안내합니다. 마이크로 콘텐츠의 조합을 통해 교사는 몇 시간이 걸리는 기존의 워크숍 참여 방식이 아닌, 적시에 필요한 방식으로 몇 분 안에 자신의 업무와 관련된 새로운 마이크로 스킬을 배울 수 있게 될 수 있습니다. 교대 근무가 끝날 때 연수생에게 어려운 피드백을 제공하고자 하는 신입 교수진을 상상해 보세요. 좋은 마이크로러닝 인프라가 있다면 이 교수진은 3분짜리 동영상과 코칭 접근법을 설명하는 인포그래픽을 검색하여 때마침 유용한 정보를 얻을 수 있을 것이라고 상상할 수 있습니다.

To provide better microlearning experiences, microcontent is essential. Nielsen 35 first used the word "microcontent" to draw writers’ attention to the need for consistency in allocating names, headers, headlines, and subject to electronic information, such as e‐mails and web pages. These technical features make microcontent more useful on the end‐user level. From finding content to consuming it, users may engage and interact with the microcontent in a short period of time. Today, the term typically refers to a more structured approach to how content should be delivered, rather than the nature of the content itself. 36 Microlearning, therefore, encapsulates and guides overall learning, from identifying a need to delivering the required microcontent. Through a combination of microcontent, it may be possible for teachers to learn new microskills relevant to their practice within minutes, in a just‐in‐time fashion, rather than the traditional investment of workshop participation, which may take hours. Imagine a new faculty member looking to provide difficult feedback to a trainee at the end of shift. One might imagine that with a good microlearning infrastructure, this faculty member could search for a 3‐min video and an infographic that outlines an approach to coaching that may come in handy, just in the nick of time.

인증 또는 평가가 가능한가요? 마이크로 자격 증명과 디지털 배지 활용하기

CAN JiTFD BE CREDENTIALED OR ASSESSED? LEVERAGING MICRO‐CREDENTIALS AND DIGITAL BADGES

2010년 모질라 드럼비트 페스티벌에서 소개된 이후 디지털 배지, 즉 마이크로 크리덴셜에 대한 관심이 높아졌습니다. 37 , 38 마이크로 자격 증명은 배지의 마이크로 보상 시스템을 확장한 것으로, 교수진이 각자의 학업 환경에 맞는 새로운 전문 역량을 구축할 수 있는 방법을 제공하는 새로운 성취 기반 학습 프레임워크를 제공합니다. 마이크로 인증은 교직원에게 교육자나 학자가 필요로 하는 일상적인 스킬과 직접적으로 연결된 집중적이고 자기 주도적이며 상황에 맞는 전문 학습에 참여할 수 있는 기회를 제공합니다. 38 , 39 문헌에서 찾을 수 있는 교육자 마이크로 자격 증명을 정의하는 네 가지 주요 특징은 역량 기반, 개인화, 온디맨드, 공유가능/검증가능입니다. 39 , 40

Since its introduction at the Mozilla Drumbeat festival in 2010, interest in digital badges, or micro‐credentials, has increased. 37 , 38 An extension to this micro‐reward system of badging, micro‐credentials offer a new achievement‐based learning framework that provides faculty members with a way to build new professional competencies tailored to respective academic environment. Micro‐credentials provide faculty members the opportunity to participate in intensive, self‐paced, contextually‐relevant professional learning that is directly linked to everyday skills educators or scholars will require. 38 , 39 Four key features that are found within the literature define educator micro‐credentials: competency‐based, personalized, on‐demand, and shareable/verifiable. 39 , 40

디지털 마이크로 자격 증명은 학습자의 스킬, 전문 지식 및 역량을 설명, 확인, 식별 및 정의하기 위해 디지털 배지를 사용하는 것으로 구체화되었습니다. 39 , 40 여러 교육기관에서 학생들을 위한 디지털 배지 시스템을 도입함에 따라 마이크로 자격증명 및 관련 디지털 배지의 사용이 전 세계적으로 주목을 받고 있습니다. 41 마찬가지로 의료 교육에서도 역량 기반의 학습자 중심 교육을 위해 디지털 배지를 점점 더 많이 활용하고 있습니다. 42 이는 교수진 및 수련생 수준의 동료 학습에도 해당될 수 있습니다. 43 예를 들어 LinkedIn은 디지털 배지를 포함한 자격증을 표시하는 인터페이스를 제공합니다. 디지털 배지를 신청하고 사용자 프로필에 자신의 마이크로 자격 증명을 공유하면 더 큰 커뮤니티에 자신의 스킬과 업적을 보여줄 수 있는 방법을 제공합니다. 각각의 콘텐츠와 컨텍스트가 포함된 디지털 배지는 전 세계에 공개되며 인증 제공업체의 링크(예: Badgr, Credly)를 클릭 한 번으로 확인할 수 있습니다.

Digital micro‐credentialing has been embodied in the use of digital badges to explain, verify, identify, and define the learners' skills, expertise and capabilities. 39 , 40 With several institutions embracing a digital badge system for their students, the use of micro‐credentialing and related digital badges is gaining traction worldwide. 41 Similarly, health care education increasingly utilizes digital badges for competency‐based, learner‐centered education. 42 This may also be true for peer learning at the faculty and trainee levels. 43 LinkedIn, for example, provides an interface for displaying certifications, including digital badges. Claiming a digital badge and sharing one's micro‐credentials on a user profile provides a way of demonstrating one's skills and achievements to the larger community. Digital badges, with their respective content and context, are open to the world and can be verified with a single click on the certification provider's link (e.g., Badgr, Credly).

구성 요소는 어떻게 서로 맞물려 있나요? JiTFD의 학습 루프

HOW DO COMPONENTS FIT TOGETHER? THE LEARNING LOOP OF JiTFD

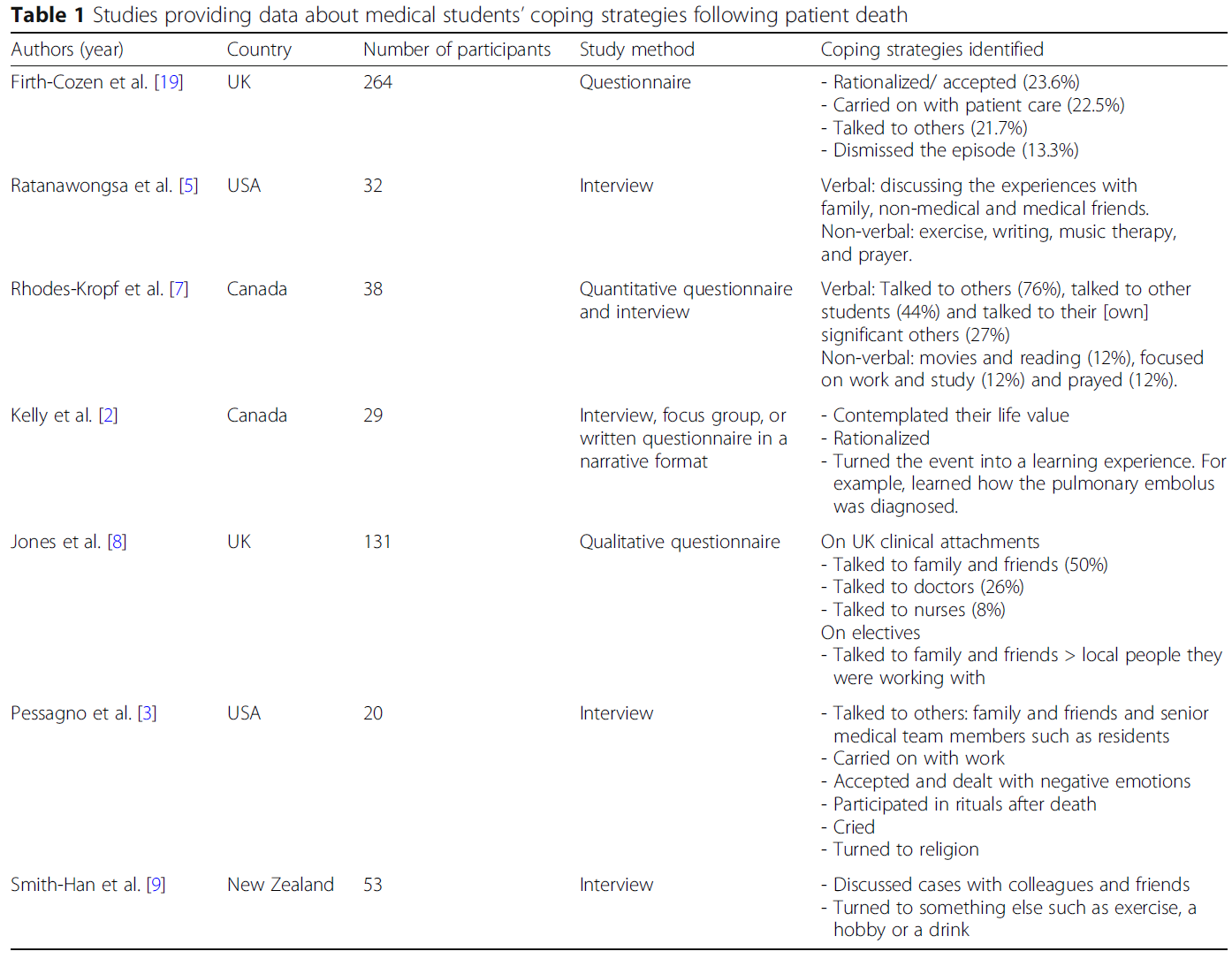

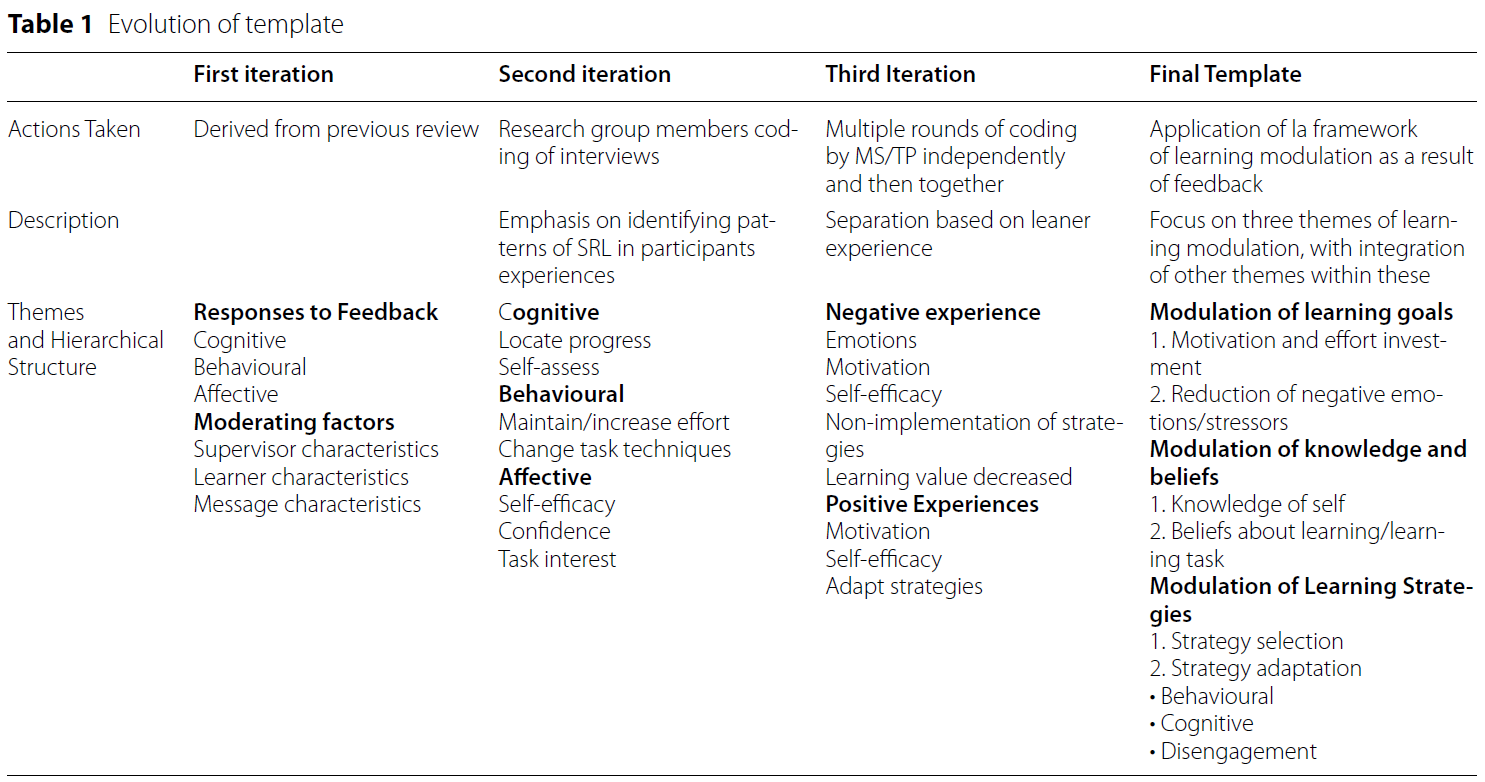

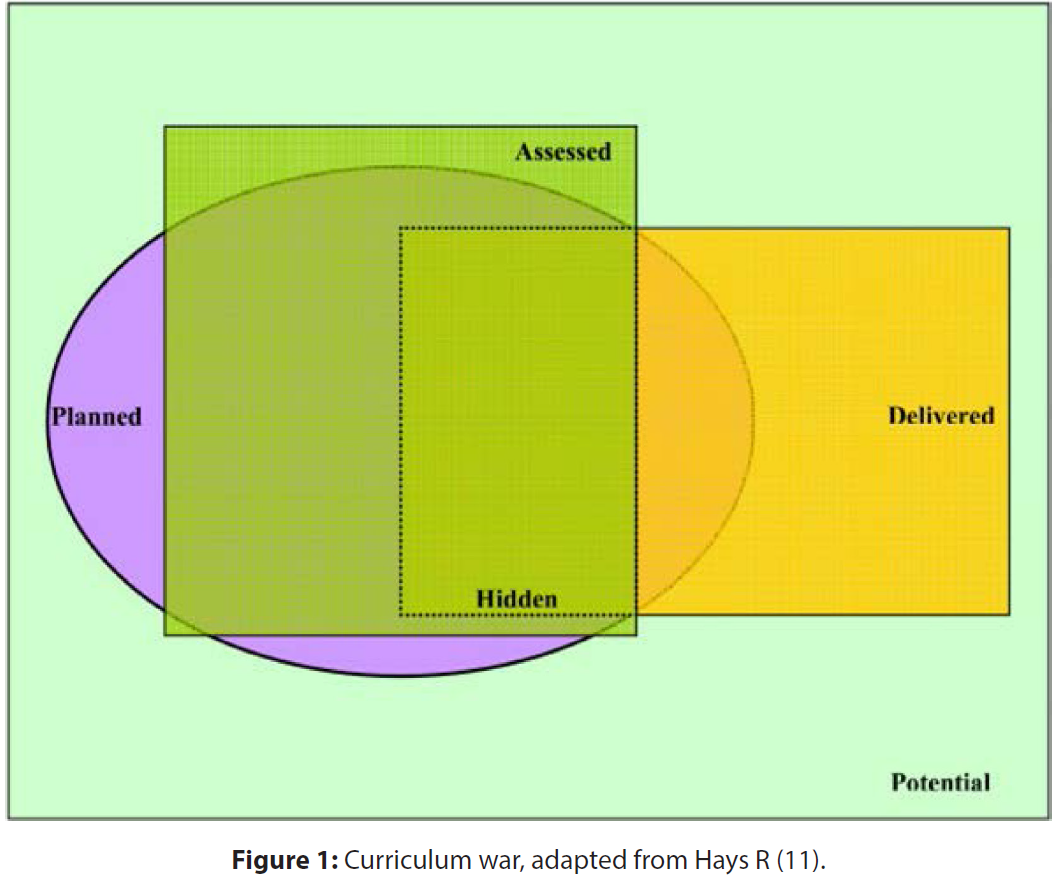

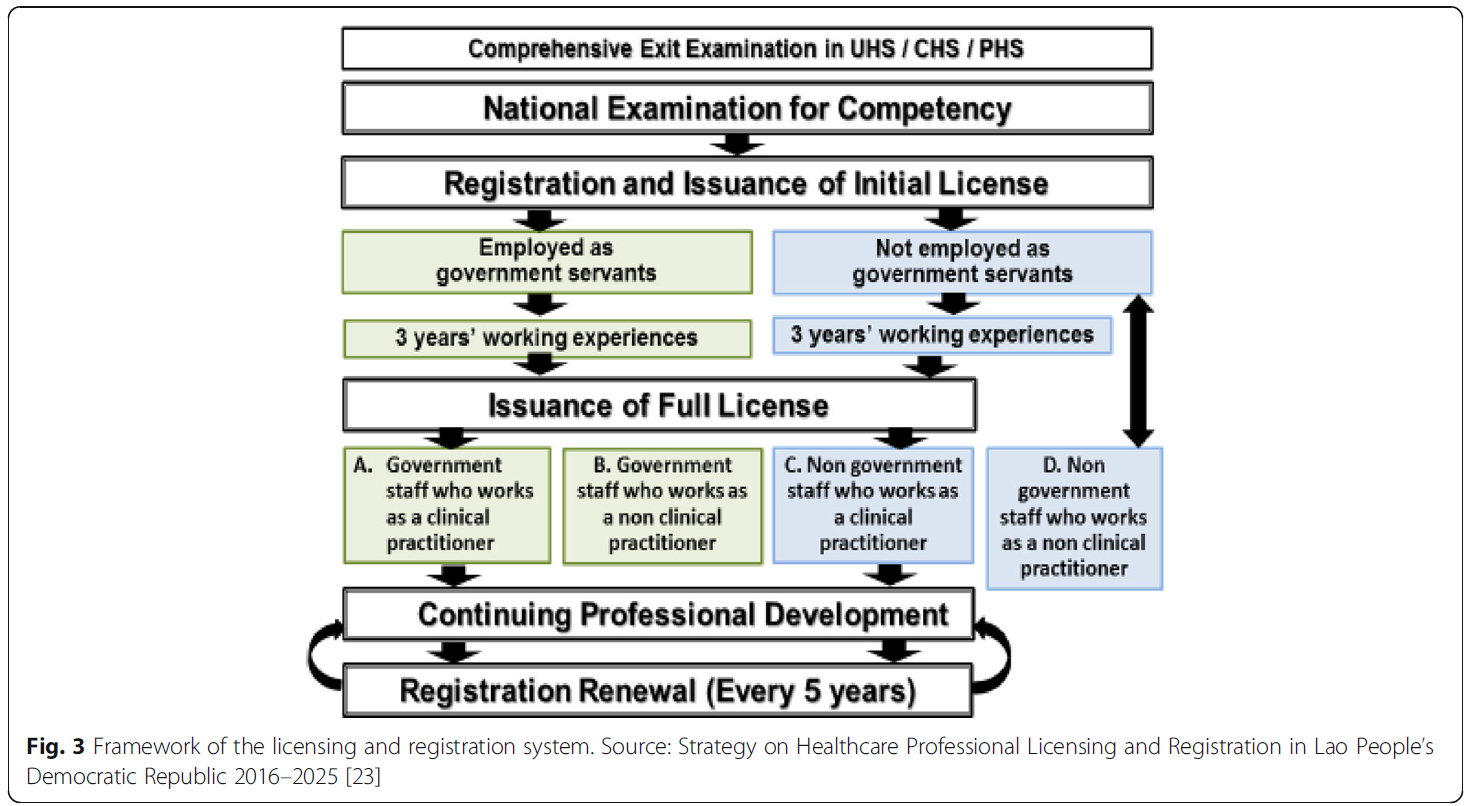

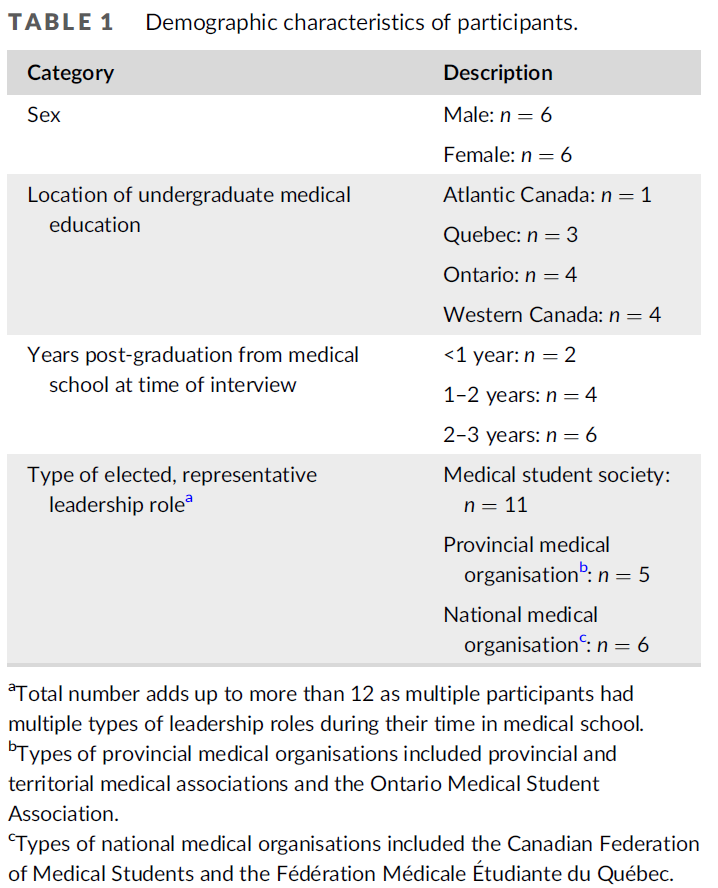

우리의 조직화 모델은 JiTFD의 학습 루프 개념입니다. 내재적 트리거(즉, 교육자가 스스로 감지한 필요)나 외재적 트리거(즉, 외부에서 교육자에게 공유된 개선 기회)를 통해 교수개발의 필요성이 확인되면, 다음의 세 가지 매개변수가 있어야 JiTFD가 실행될 수 있습니다.

- (1) 마이크로 콘텐츠의 존재,

- (2) 마이크로 콘텐츠(마이크로 러닝)를 통한 학습 참여,

- (3) 마이크로 자격 인증을 통한 평가

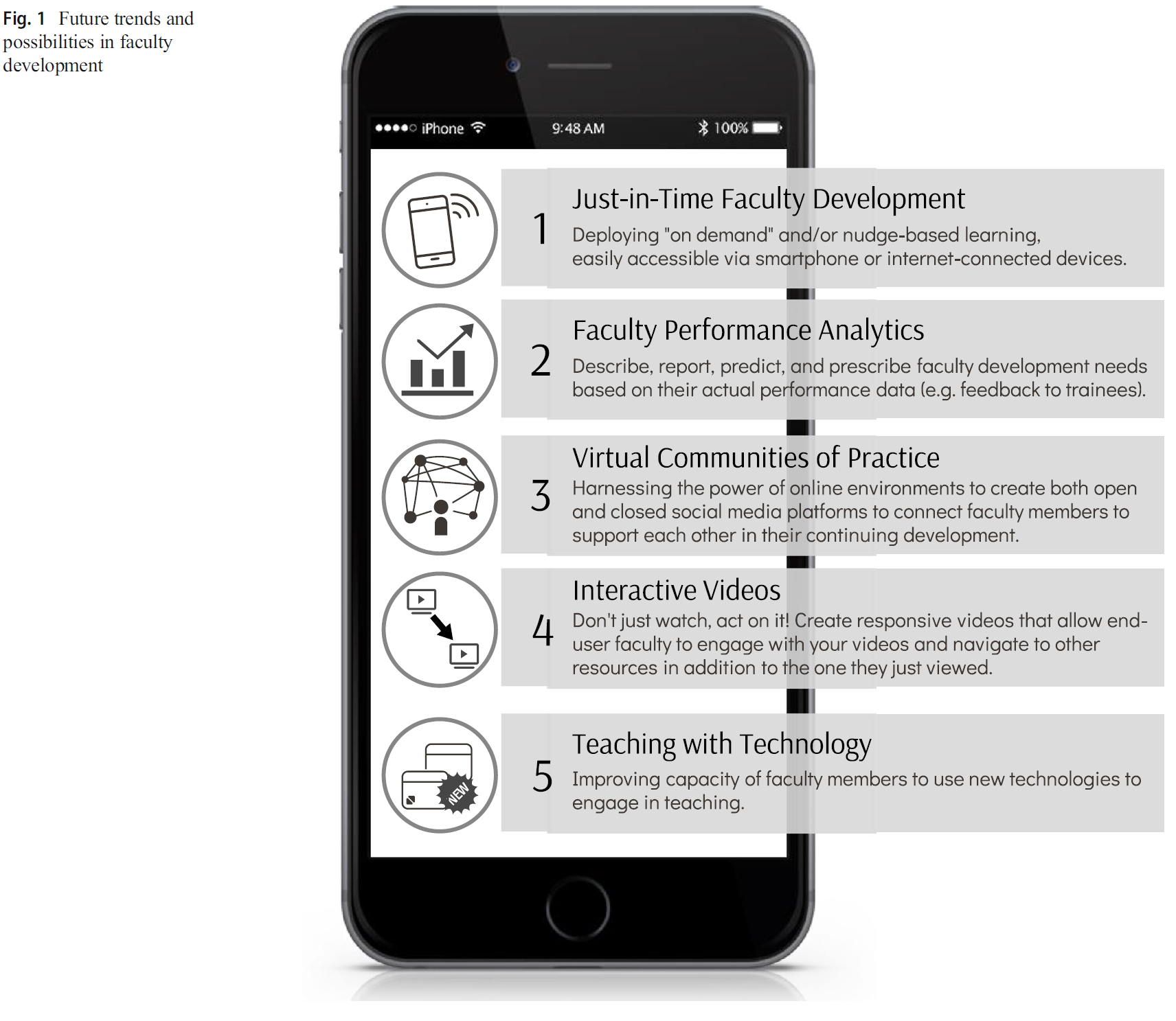

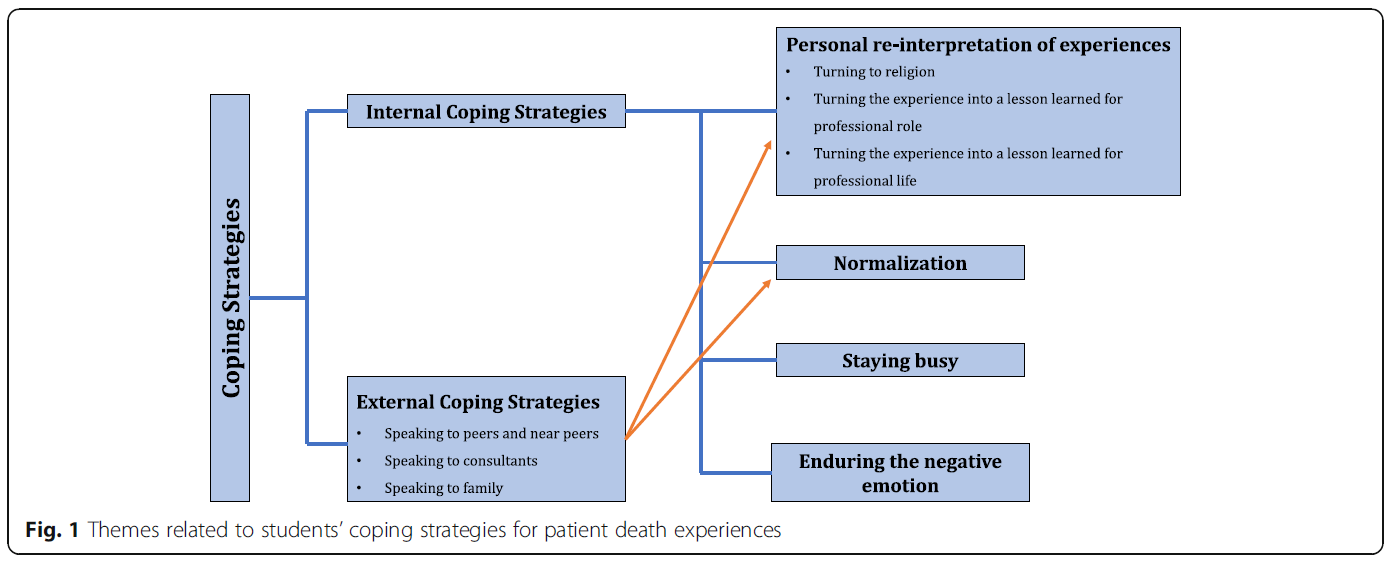

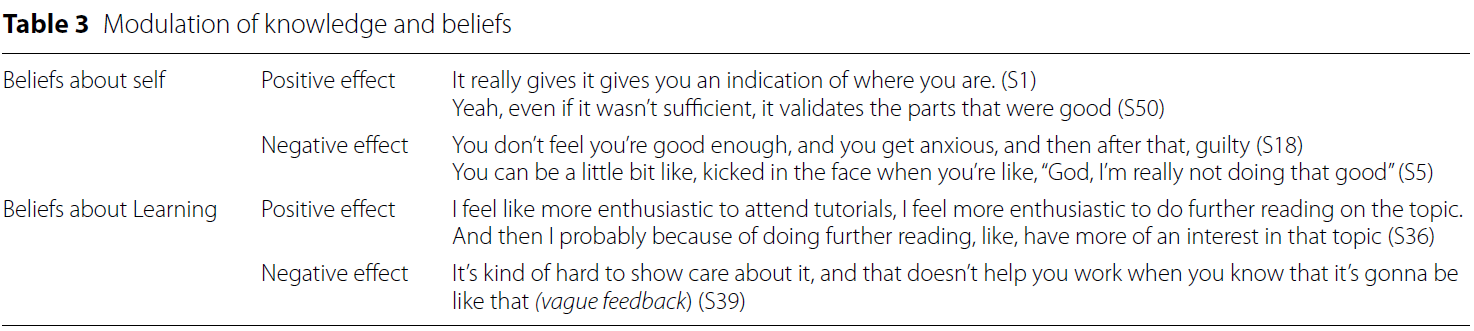

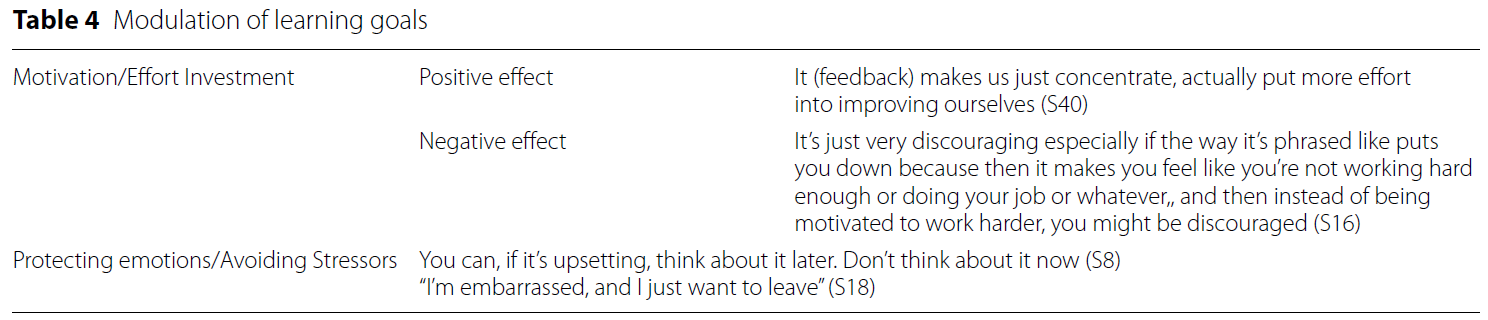

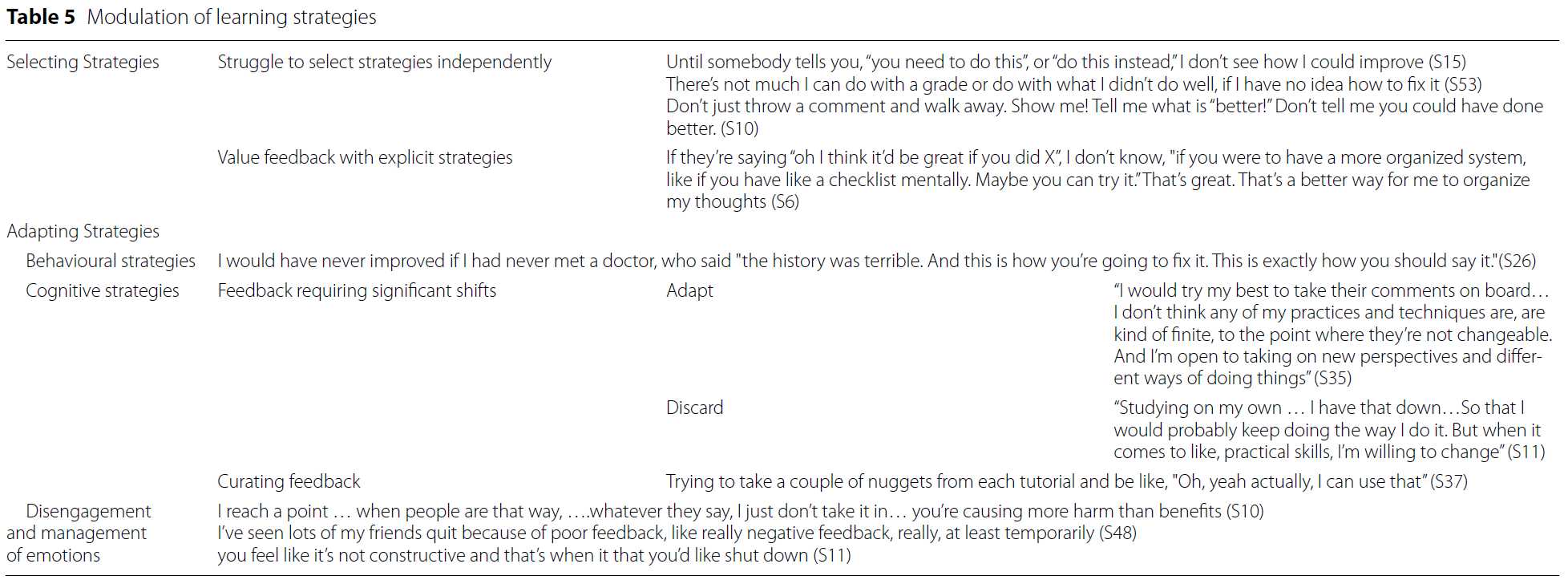

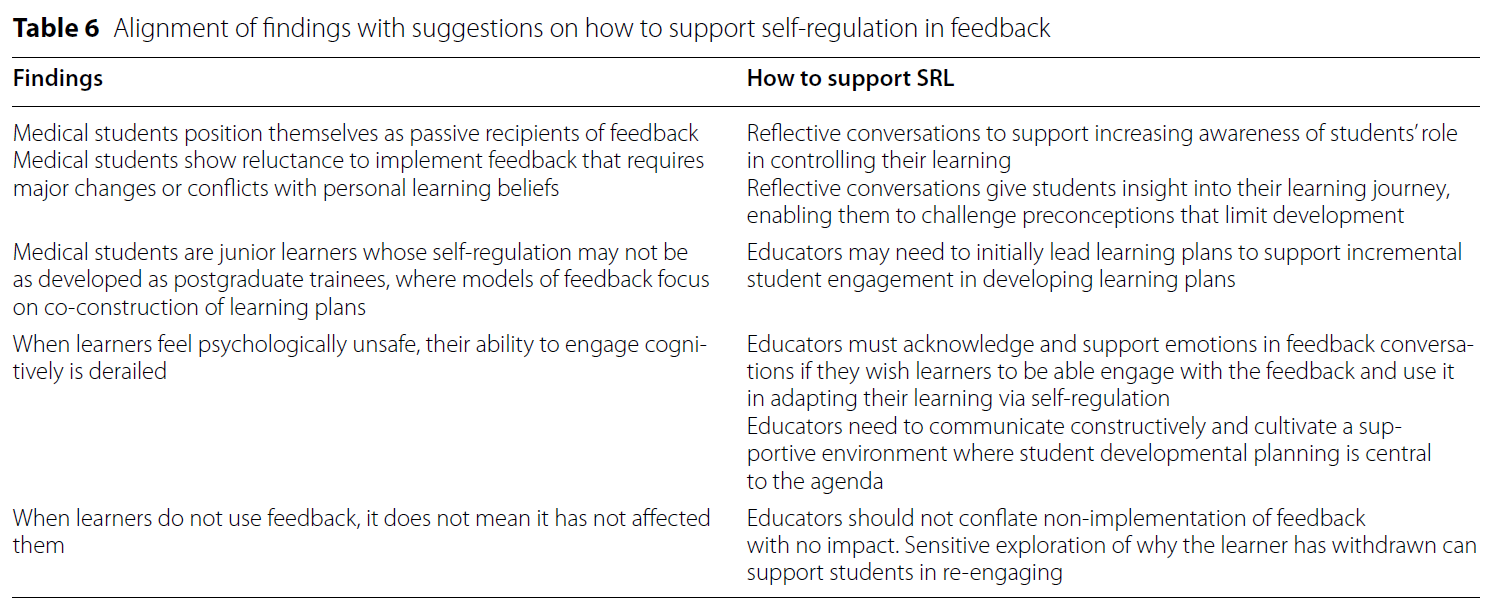

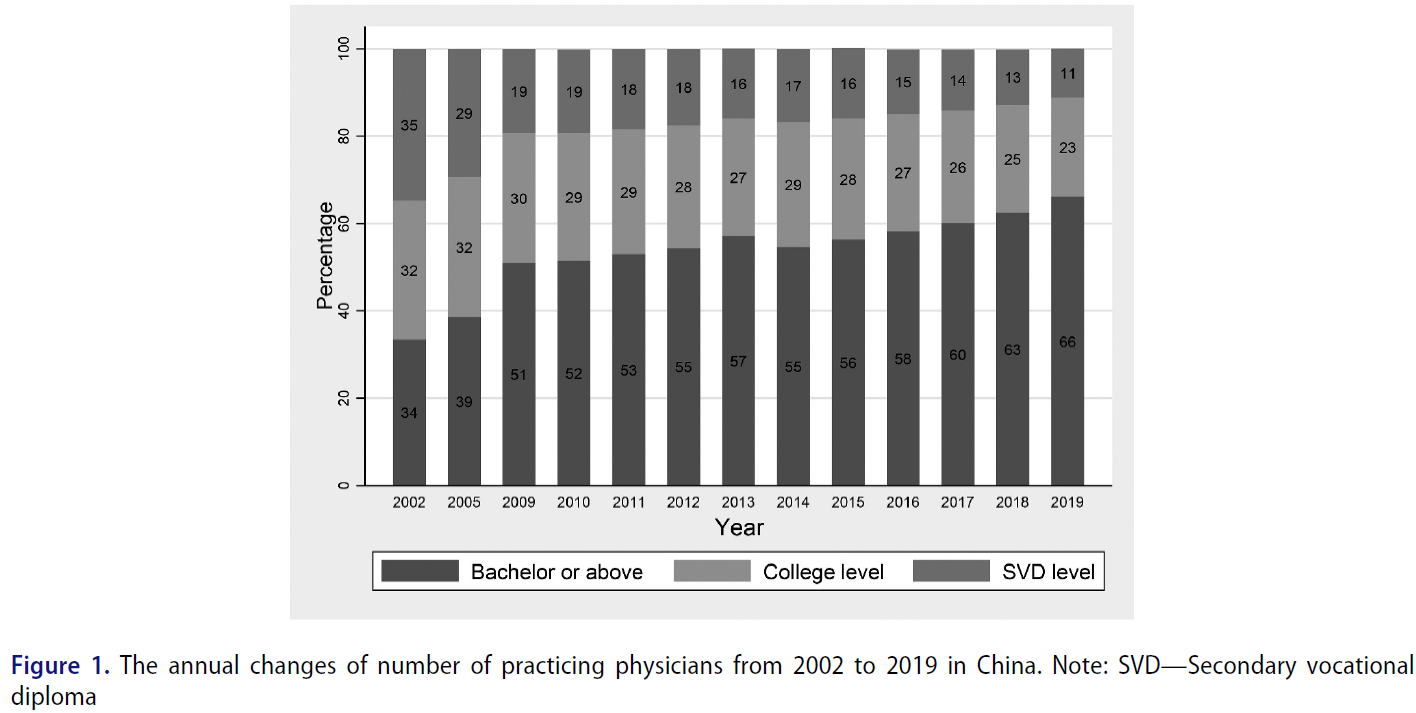

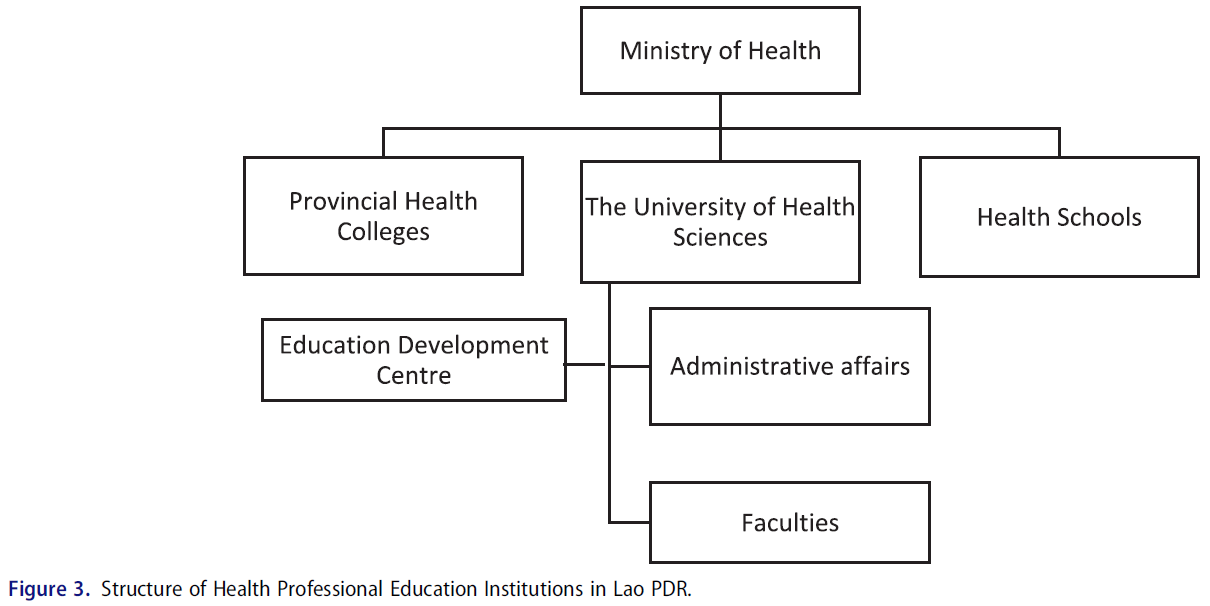

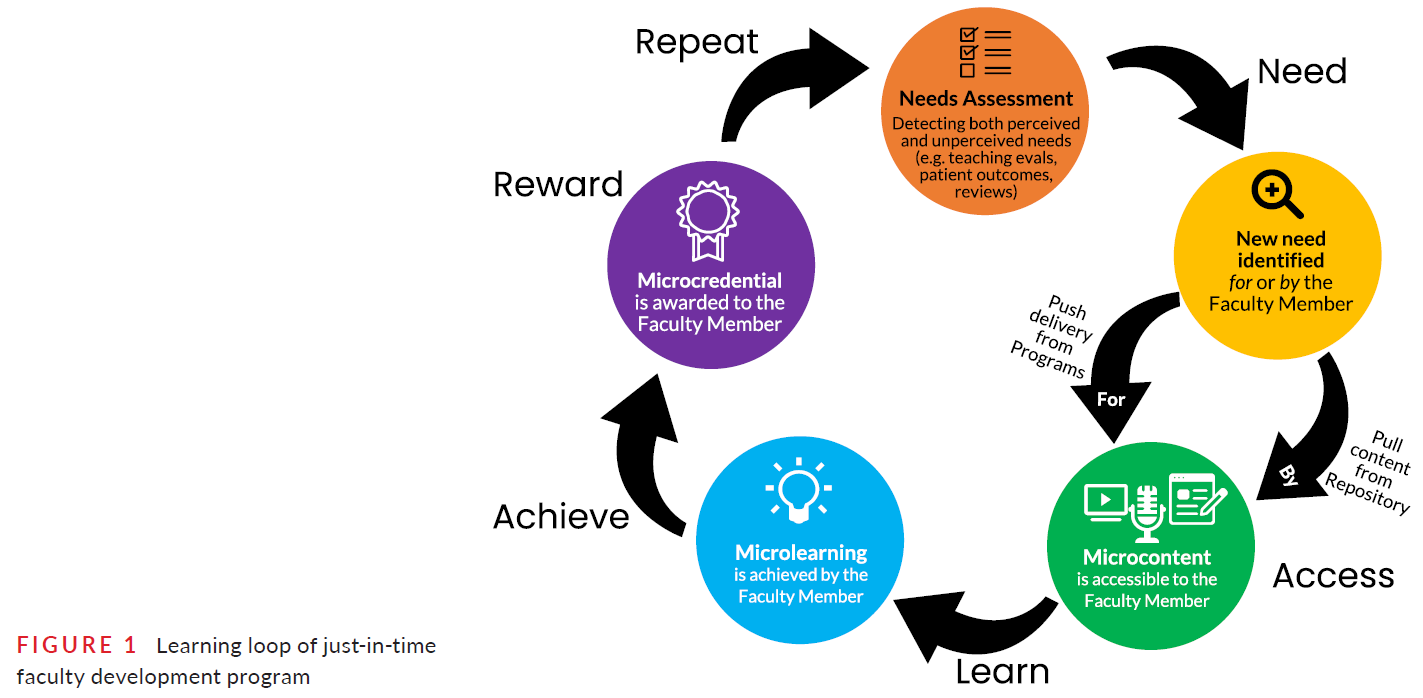

그림 1은 JiTFD가 어떻게 이루어질 수 있는지에 대한 개념화를 보여줍니다.

Our organizing model is the concept of the Learning Loop of JiTFD. Once the need for faculty development is identified, either through an intrinsic trigger (i.e., self‐identified need sensed by the educator) or extrinsic trigger (i.e., opportunity for improvement that is shared to the educator by an external source), three parameters are required to ensure JiTFD can take place:

- (1) existence of microcontent;

- (2) engagement in learning through microcontent (microlearning); and

- (3) assessment via micro‐credentialing.

Figure 1 depicts our conceptualization of how JiTFD may occur.

학습 루프는 다음의 두 가지를 감지하는 요구 사항 평가로 시작됩니다.

- 인지한 요구 사항(즉, 교직원이 무엇을 학습해야 하는지 파악한 경우)과

- 인지하지 못한 요구 사항(즉, 교직원이 처음에 학습 요구 사항을 명확하게 파악하지 못했지만 어디서부터 시작해야 할지 결정한 경우)

이러한 개념은 이 문서의 뒷부분에서 자세히 설명합니다. 요구 사항이 확인되면 교직원은 설정된 요구 사항에 따라 콘텐츠에 접근하거나 콘텐츠를 받을 수 있습니다.

- 전자의 테크놀로지은 교직원이 '끌어오기' 작업을 시작하는 반면,

- 후자는 다양한 채널(예: 모바일 통지, 이메일)을 통해 교직원에게 직접 콘텐츠를 전달하는 '푸시'라고 할 수 있습니다.

마이크로 콘텐츠는 마이크로 학습을 단계적으로 지원하기 위해 마이크로 콘텐츠로 설계되며, 최종적으로 마이크로 자격 증명을 생성합니다. 마이크로 자격 증명을 획득하면 학습 루프를 성공적으로 완료했음을 의미하며, 이를 통해 교수자는 특정 목표를 향한 진행 상황에 대한 긍정적인 피드백을 받을 수 있습니다. 예를 들어, 학습 루프를 시작하는 학습 목표 및 확인된 요구 사항을 간단히 상기시키는 것이 피드백으로 작용할 수 있습니다. 반면에 학습 루프를 완료하지 못한 시도는 마이크로러닝 단계에서 해결해야 합니다. 교직원이 마이크로러닝 단계를 완료하지 못한 경우, 추가 탐색을 위한 지원 콘텐츠(예: 온라인 리소스, 추가 읽기 자료)와 같이 교직원의 필요에 대한 대체 솔루션을 제공해야 합니다. 그런 다음 다음 개발 요구 사항을 파악하기 위해 루프가 다시 시작됩니다.

The learning loop starts with a needs assessment that detects

- perceived faculty needs (i.e., when a faculty member has identified what to learn) and

- unperceived needs (i.e., when a faculty member does not see clearly the learning needs initially but still makes a decision for where to begin).

These concepts are explained in detail later in the article. Once a need is identified, faculty can access or receive the content for their established need.

- The former technique can be described as the “pull” action initiated by the faculty, whereas

- the latter is called the “push,” in which content is directly delivered to faculty through a variety of channels (e.g., mobile notifications, emails).

The content is designed as microcontent to support microlearning in small steps, and eventually yields a micro‐credential. Achieving a micro‐credential suggests the successful completion of a learning loop, which can provide the faculty member with positive feedback on progression towards their specific goals. For instance, the simple reminder of the learning objective and/or identified need initiating the learning loop could serve as feedback. On the other hand, unsuccessful attempts to finish the learning loop should be addressed in the microlearning step. When faculty fail to complete a microlearning step, faculty should be provided with alternate solutions to their needs, such as supportive content (e.g., online resources, further readings) for further exploration. The loop then starts over to identify the next developmental need.

적시 교수자 개발의 도전과 기회

CHALLENGES AND OPPORTUNITIES WITH JUST‐IN‐TIME FACULTY DEVELOPMENT

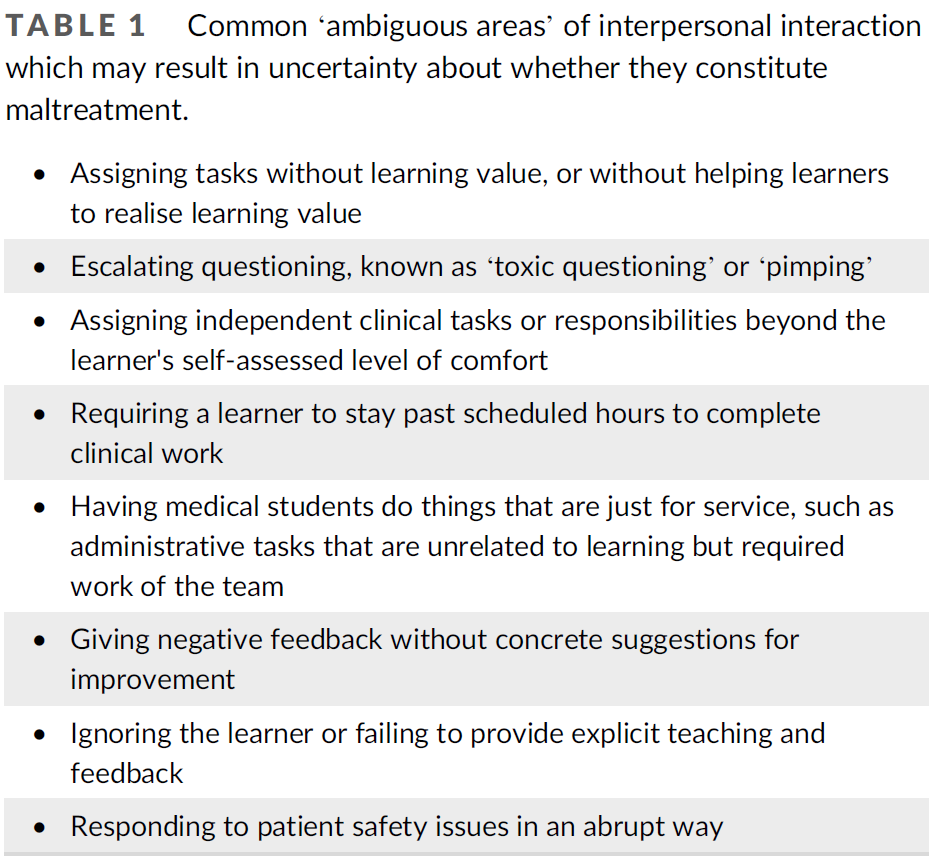

적시 교수 개발을 공식 프로그램에 성공적으로 통합하려면 먼저 고려해야 할 몇 가지 주요 고려 사항이 있습니다. 아래에서는 교수개발자가 JiTFD를 마이크로러닝 공간에 통합할 때 필요한 특정 지식과 스킬을 강조하는 네 가지 시나리오를 살펴봅니다.

If we are to successfully incorporate JiTFD into formal programming, there are several key considerations we must first consider. Below we explore four scenarios that highlight specific knowledge and skills that faculty developers will require when integrating JiTFD into the microlearning space.

-

새로운 것을 배우거나 특정 주제를 복습하고 싶어도 교수진은 바쁜 일정으로 인해 전문성 개발 세션에 참석할 시간이 없을 수 있습니다. 예를 들어, 새로운 교수진이 가상 임상 환경에서 강의할 준비를 하고 싶거나 새로운 환자 치료 환경에서 효과적으로 강의할 수 있는 방법을 검토하고 싶을 수 있습니다. 따라서 교수개발과 JiTFD는 교수진의 삶과 일치하고 호환되어야 합니다(예: 한입에 쏙 들어가는 크기, 모바일로 조정/검색 가능, 쉽게 검색 가능).

Despite wishing to learn something new or reviewing a specific topic, faculty members have busy schedules and may not have the time to attend professional development sessions. For example, a new faculty member may wish to prepare for teaching in a virtual clinical environment and may decide to review methods for effectively teaching in new patient care settings. Consequently, faculty development and JiTFD must be congruent and compatible with their lives (e.g., bite‐sized, mobile adaptable/retrievable, and easily searchable)-

●교수개발을 위한 핵심 콘텐츠가 확대되었습니다. 교수개발 프로그램의 범위, 내용 및 빈도가 학습의 원칙에 적절히 부합하도록 보장할 필요가 있습니다. 44 콘텐츠를 작은 단위로 나누어 인지 부하에 주의를 기울이면 교수개발 프로그램을 성공적으로 완료할 수 있습니다. 45

Core content for faculty development has expanded. There is a need to assure that the scope, content, and frequency of faculty development programs appropriately align with the principles of learning. 44 Attention to cognitive load, by dividing content into smaller chunks, will likely result in the successful completion of faculty development programs. 45 -

●전통적인 접근 방식의 또 다른 문제점은 교수진 참여자와 관련된 콘텐츠의 범위와 관련이 있습니다. 콘텐츠가 특정 시점의 필요 영역과 일치하지 않을 수 있습니다. 시간 및 가용성의 제한과 함께, 교수진은 특히 학업과 임상 책임의 균형을 맞추기 위해 교수진 개발 프로그램이 관련성이 없거나 시간을 잘 활용하지 못한다고 느낄 수 있습니다.

Another challenge of the traditional approach pertains to the scope with which content is relevant to the faculty participant. Content may not be congruent with their area of need at a specific point in time. Combined with limitations in time and availability, faculty may feel that faculty development programs are not relevant and/or a good use of their time, especially as they balance both academic and clinical responsibilities.

-

-

교수진은 서로 다른 우선순위와 다양한 관심사를 가지고 있습니다. 따라서 교수진이 중요하게 여기고 자신의 업무에 적용할 수 있는 콘텐츠를 제공할 수 있는 방법을 찾아야 합니다. 교수진의 자율성과 자기 결정을 촉진하기 위해 교수진 개발 프로그램에 선택권을 포함시켜야 합니다. 46

Faculty have different priorities and diverse interests. We must find a way to deliver content to faculty that they will value and find applicable to their responsibilities. Optionality should be embedded in faculty development programming to foster faculty autonomy and self‐determination. 46-

●교수개발은 학문적 생산성을 뒷받침하는 지식과 스킬의 핵심입니다. 교수진 개발에 관한 문헌은 교육자, 연구자 및 학자, 지도자 및 행정가로서 교수진의 개발을 강조하고 강조합니다. 47 이러한 개발 개입을 수행하기 위해 공식적 및/또는 비공식적 그룹 및/또는 개별 환경이 사용되어 왔습니다. 48

Faculty development is core to knowledge and skills that support scholarly productivity. Literature on faculty development emphasizes and stresses the development of faculty as educators, researchers and scholars, and leaders and administrators. 47 Formal and/or informal in‐group and/or individual settings have been used to carry out these developmental interventions. 48

-

-

교수진은 자신이 무엇을 배워야 하는지 항상 인지하지 못할 수도 있습니다. 우리는 '빅 데이터'와 분석의 힘을 활용하여 교수진이 인지하지 못한 학습 요구를 더 잘 파악하고 이를 해결하기 위한 지원을 제공할 수 있도록 도와야 합니다. Interfolio와 같은 성과 분석 및 도구 49는 인지되지 않은 요구 사항(예: 효과적인 피드백 제공 능력)을 강조한 다음 적시에 콘텐츠를 제공하는 데 도움이 될 수 있습니다.

Faculty may not always be cognizant of what they need to learn. We must harness the power of “big data” and analytics to help faculty better identify their unperceived learning needs and provide them with the support to address them. Performance analytics and tools, such as the Interfolio, 49 can help highlight unperceived needs (e.g., their ability to provide effective feedback) and then provide them with content, just‐in‐time.-

●적시 학습은 학습자가 실시간으로 자신의 학습을 스스로 조절할 수 있어야 합니다. 우리가 아는 한, 자기조절 학습자(SRL)가 되기 위한 능력을 향상시키고자 하는 교수진을 지원하는 리소스는 거의 없습니다. 50 마찬가지로, 교수진 개발 프로그램도 SRL 스킬과 공식적으로 연계되도록 설계되지 않았습니다. 우리의 JiTFD 개념 모델은 SRL을 기반으로 하며 지속적인 전문성 개발을 위한 수단으로 활용합니다.

Just‐in‐Time learning demands that learners are able to self‐regulate their learning in real time. To our knowledge, there are few resources to support faculty who want to refine their abilities to be self‐regulated learners (SRL). 50 Similarly, faculty development programs have not been designed to formally link to SRL skills. Our JiTFD conceptual model builds on SRL and leverages it as a means for ongoing professional development.

-

-

인간은 스스로를 평가하고 자기계발의 격차를 인식하는 데 효과적이지 못합니다. 51 자기 평가와 자기 조절 능력은 FD를 위한 몇 가지 "푸시" 전략을 통해 크게 향상됩니다:

As humans, we are not effective at assessing ourselves and perceiving personal development gap. 51 Our ability to self‐assess and self‐regulate benefits greatly from several “push” strategies for FD:-

●리소스 메뉴를 제공하여 지속적으로 사용할 수 있는 방식으로 콘텐츠를 배포합니다(예: MacPFD.ca는 대부분의 스트리밍 서비스와 유사하게 콘텐츠 유형별 비디오 아카이브를 만들어 교직원이 리소스를 검색할 수 있도록 합니다52 );

Provide a menu of resources, distributing content in continuously available manner (e.g., MacPFD.ca has created a video archive by content type, similar to most streaming services to allow faculty to surf through resources 52 ); -

●콘텐츠를 더 큰 프로그램으로 통합(예: 여러 가지 사용 사례를 안내하고 교직원으로서 가질 수 있는 다양한 요구 사항을 강조하는 필수 오리엔테이션 앱);

Fold content into larger programs (e.g., a mandatory orientation app that guides you through several use cases and highlights various needs you may have as a faculty member); -

●새로운 콘텐츠 개발에 대한 협업을 위한 동료 및 멘토 기반 권장 사항으로 FD에 사회적 학습 요소를 도입할 수 있습니다.

Peer‐ and/or mentor‐based recommendations for collaboration on the development of new content, which can introduce a social learning element to FD.

-

앞서 언급한 사항을 고려할 때, 교수개발을 위한 새로운 모델은 오늘날의 세계에서 교수진이 어떻게 성공할 수 있는지를 설명해야 합니다. 성인 교육에서 자기 주도적 학습은 매우 중요하지만, 학습 요구를 파악하고 그에 맞는 리소스를 찾는 문제는 어려울 수 있습니다. 이 모델은 식별된 성과 격차를 필요한 콘텐츠로 지속적으로 해결하므로 지속적인 전문성 개발을 제안합니다. 마찬가지로, 이 모델은 교육기관이 생애주기에 걸쳐 교수진을 육성할 수 있는 기회를 제공합니다. 53 우리는 아직 교수개발을 강화하기 위해 테크놀로지를 의미 있게 활용하지 못하고 있습니다.

Considering the aforementioned, a novel model for faculty development must describe how faculty thrive in today's world. Self‐regulated learning is critical at adult education while issues on identifying learning need and finding resources for that need could be challenging. The model suggests continuous professional development, as identified performance gaps are continuously addressed with needed content. Similarly, it affords institutions the opportunity to nurture their faculty across the lifecycle. 53 We have yet to capitalize on a meaningful usage of technology to augment faculty development.

학계의 많은 임상의-교육자들은 일상적인 임상 및 학업 업무 외에는 전문성 개발을 위한 시간이 제한되어 있습니다. 특히 팬데믹과 관련된 공중 보건 권고 사항이 빠르게 변화하는 불확실한 상황에서 대면 워크숍에 의존하려는 경우, 이러한 고급 학습자의 참여를 유도하는 효과적인 전략을 파악하는 것이 어려울 수 있습니다. 워크샵이 가상(예: Zoom)으로 제공되고 공간이 물류적으로 고려되지 않는 경우에도 참가자의 가용성을 고려한 동시 개최 시간을 찾는 것이 어려울 수 있습니다. 교수진 개발자는 바쁜 일선 임상 교육자 및 학자들을 그들의 생활에 가장 적합한 형식으로 참여시킬 수 있는 방법을 생각해야 합니다. 54 , 55 , 56 사용자(즉, 교수진)를 핵심에 두는 디자인적 사고 55 또는 디자인 기반 연구 57 , 58 접근 방식을 채택하는 것이 이러한 목적에 가장 적합할 수 있습니다. 이러한 사용자 중심의 디자인 방법론을 사용함으로써 교수진 개발자는 교수진의 경력 전반에 걸쳐 교수진의 성장을 지원하는 접근 가능하고 유용한 리소스를 구축하기 위한 새로운 전략을 수립할 수 있습니다.

In academic medicine, many of our clinician‐educators have limited availability for professional development outside of their daily clinical and academic duties. Identifying effective strategies to engage this advanced learner can be difficult if one is seeking to rely on in‐person workshops, especially with the looming uncertainty that surrounds these events with rapidly evolving public health recommendations related to the pandemic. Even when workshops are offered virtually (i.e., on Zoom) and space is not a logistical consideration, the ability to find a synchronous time that considers participants’ availability may be daunting. It is incumbent upon faculty developers to think of ways that will engage busy, frontline clinician educators and academics in formats that may best fit into their lives. 54 , 55 , 56 Adopting a design‐thinking 55 or design‐based research 57 , 58 approach that positions the user (i.e., the faculty member) at its core may be best suited for this purpose. By using these user‐centered design methodologies, faculty developers will be able to create new strategies for building accessible and useful resources that support faculty member growth throughout their careers.

JiTFD를 가능하게 하는 전달 시스템 및 테크놀로지

DELIVERY SYSTEMS AND TECHNOLOGY THAT WILL ENABLE JiTFD

온라인 학습이 학습 과정을 지배할 수 있으므로, JiTFD 제공자는 모바일 기기에서 탭 한 번으로 콘텐츠에 더 쉽게 접근할 수 있도록 학습 관리 시스템(LMS)에서 모바일 앱 사용을 활성화해야 합니다. 모바일 기기로 콘텐츠에 액세스하고 푸시 알림을 받으면 학습 참여도를 높일 수 있습니다. 이러한 방식으로 모든 로그와 기록이 시스템에서 수집되고 집계되어 모델의 구성 요소에 재사용되므로 온라인 도구는 JiTFD의 초석이 될 수 있습니다.

Since online learning can dominate the learning process, JiTFD providers should enable mobile app use on learning management systems (LMS) in order to provide better ease of access to the content with a single tap on a mobile device. Mobile access to content and push notifications of a mobile devices may support heightened engagement in the learning loop. In this way, online tools can become the cornerstone for JiTFD, as all logs and records are collected and aggregated in the system and reused for the components of the model.

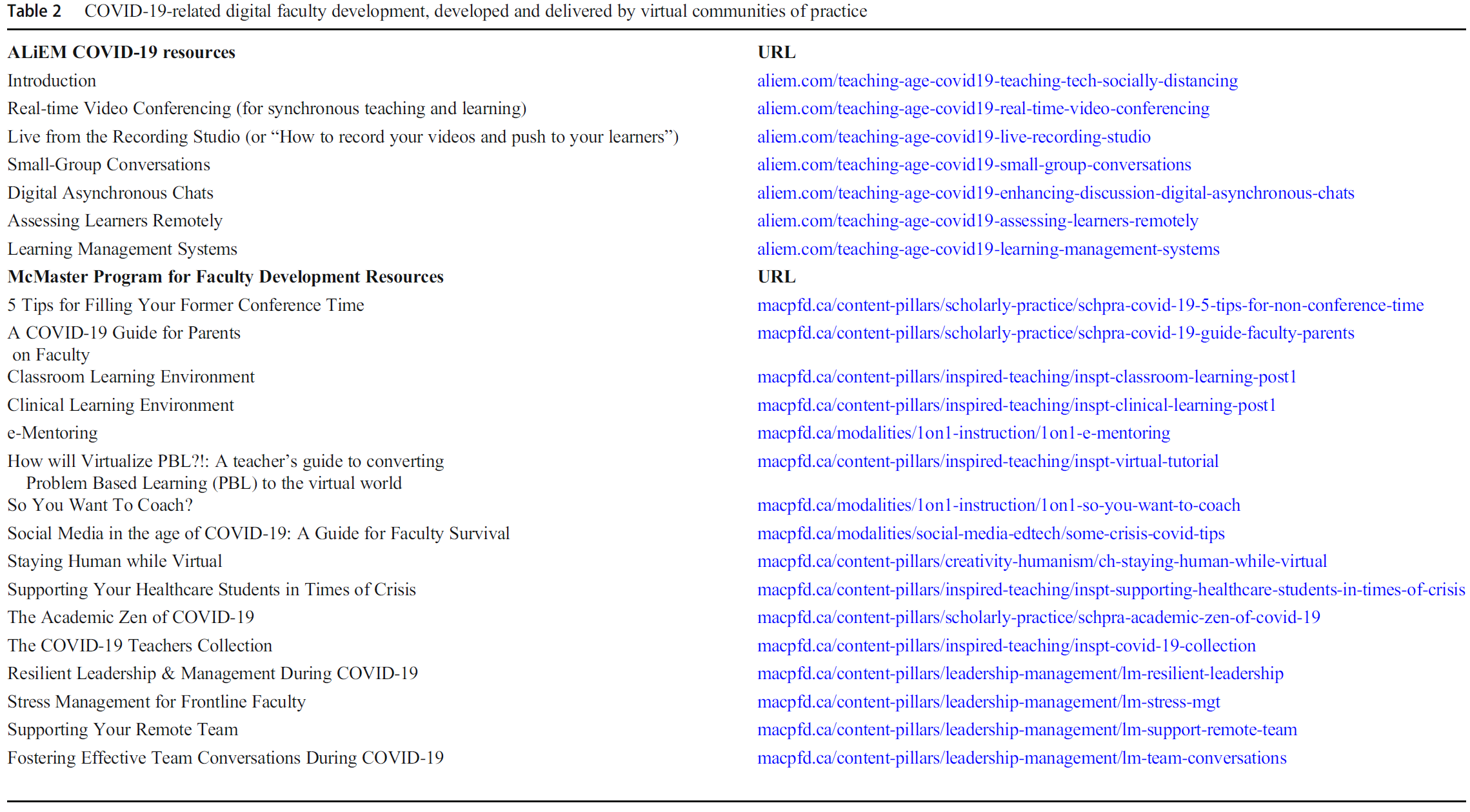

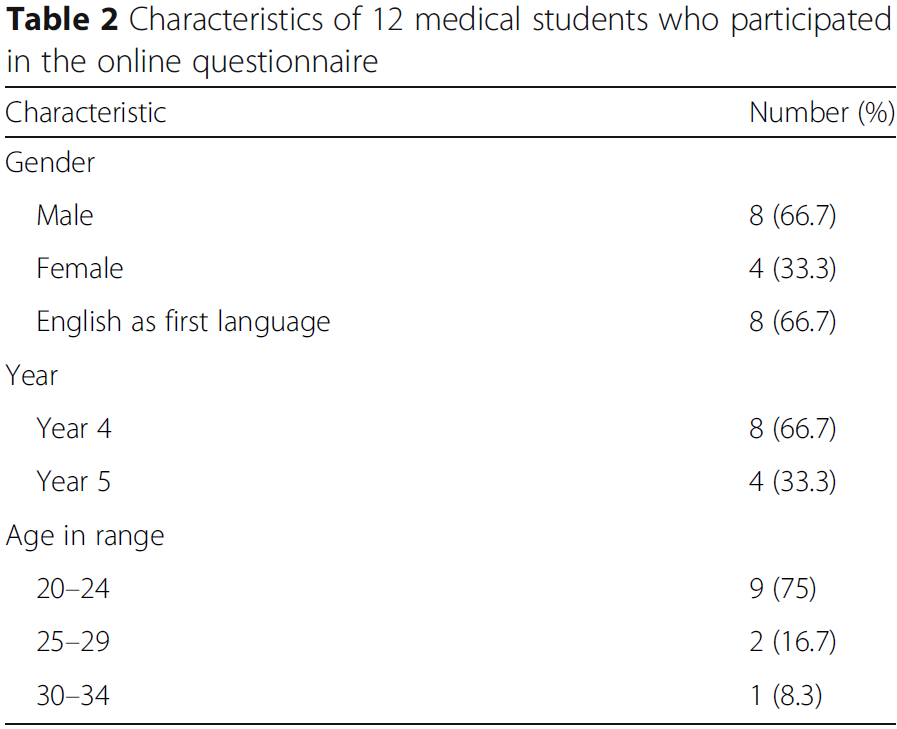

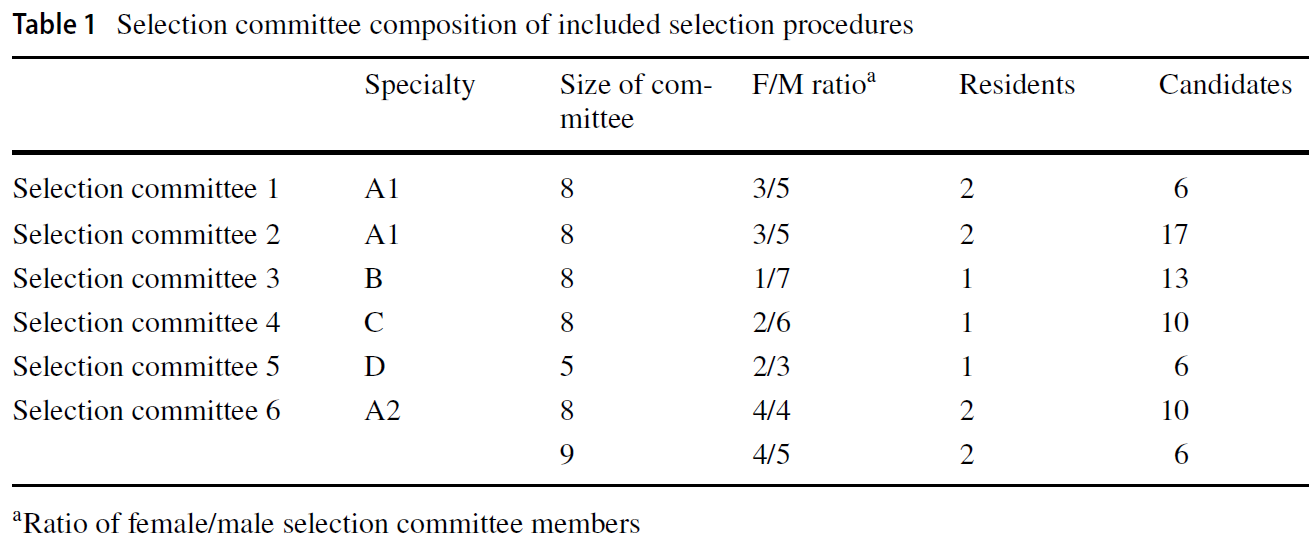

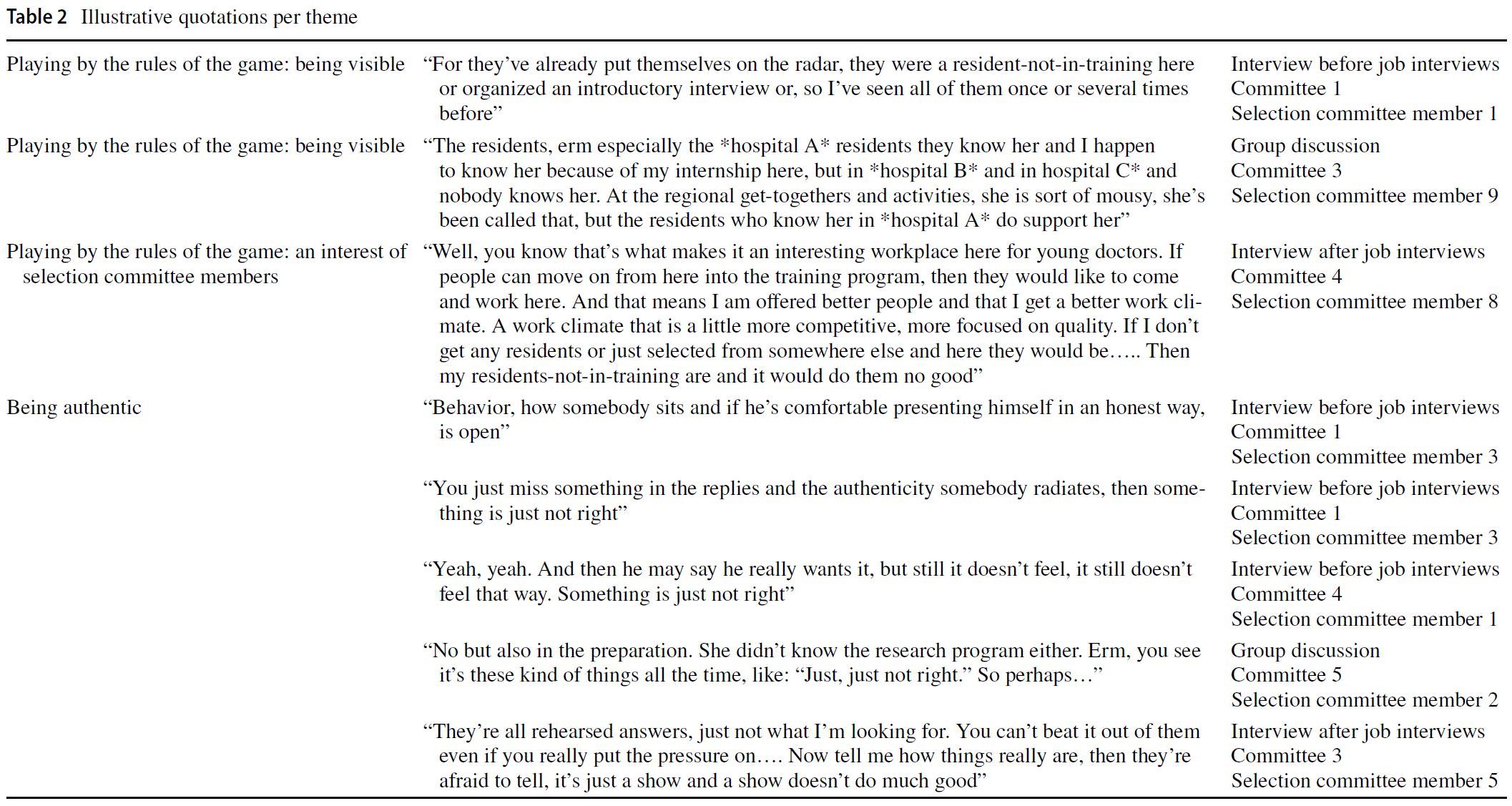

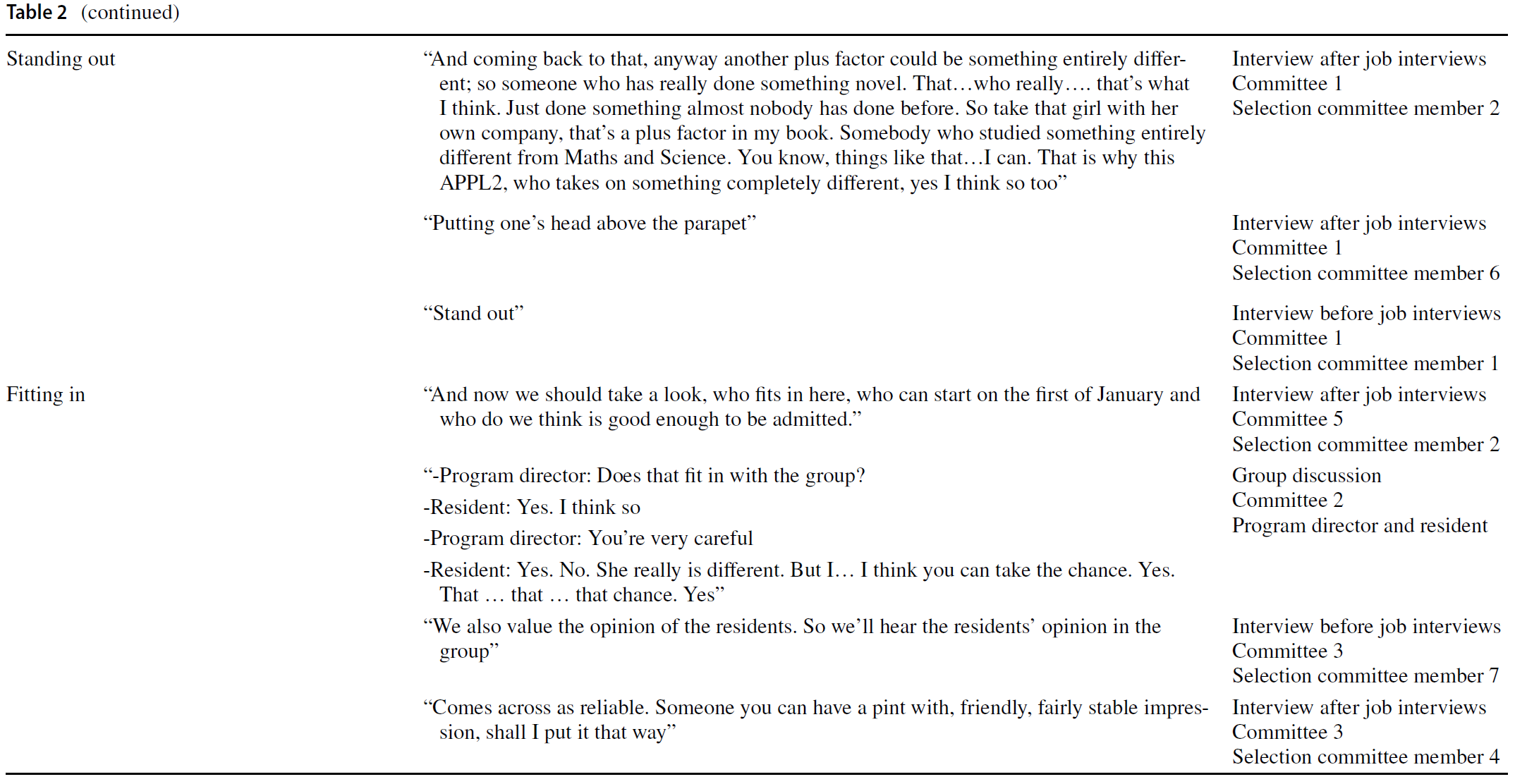

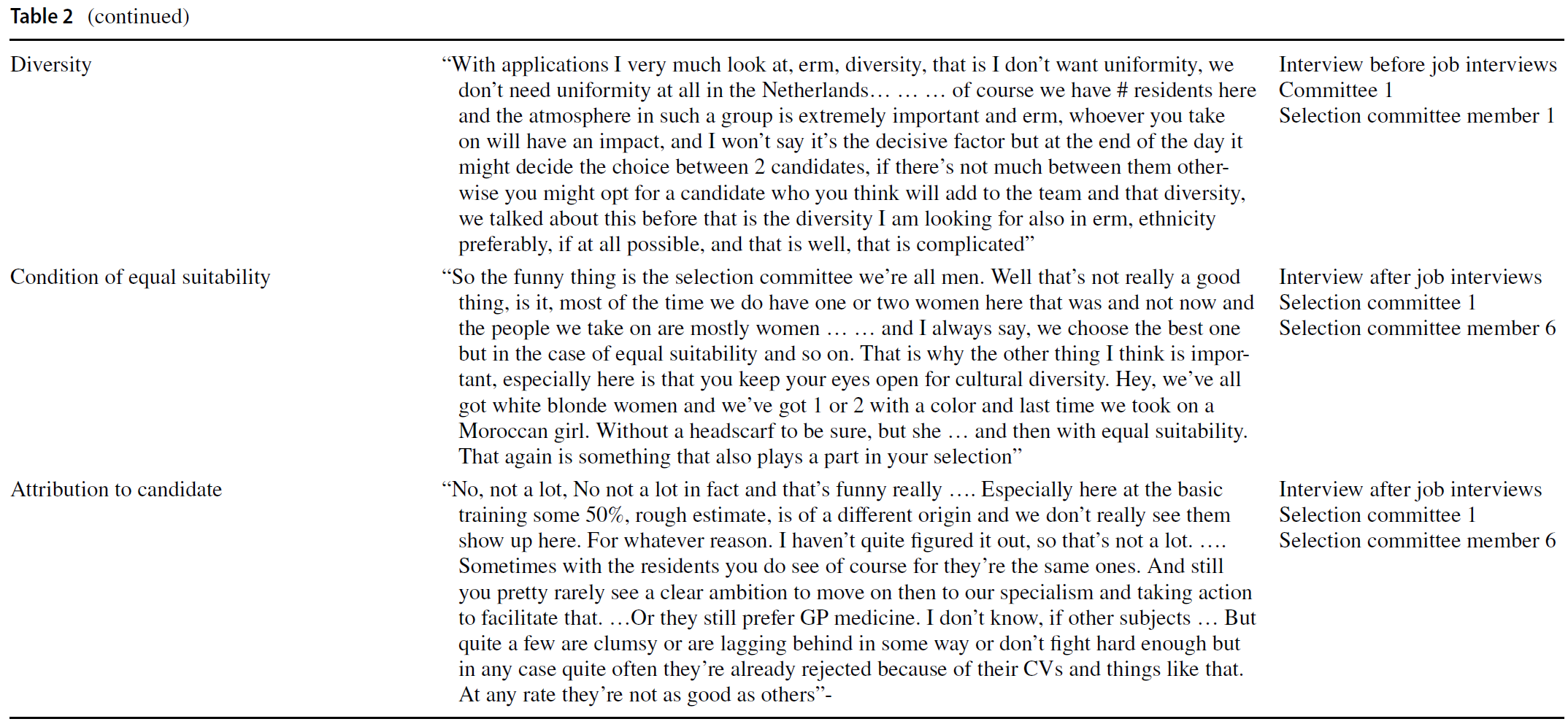

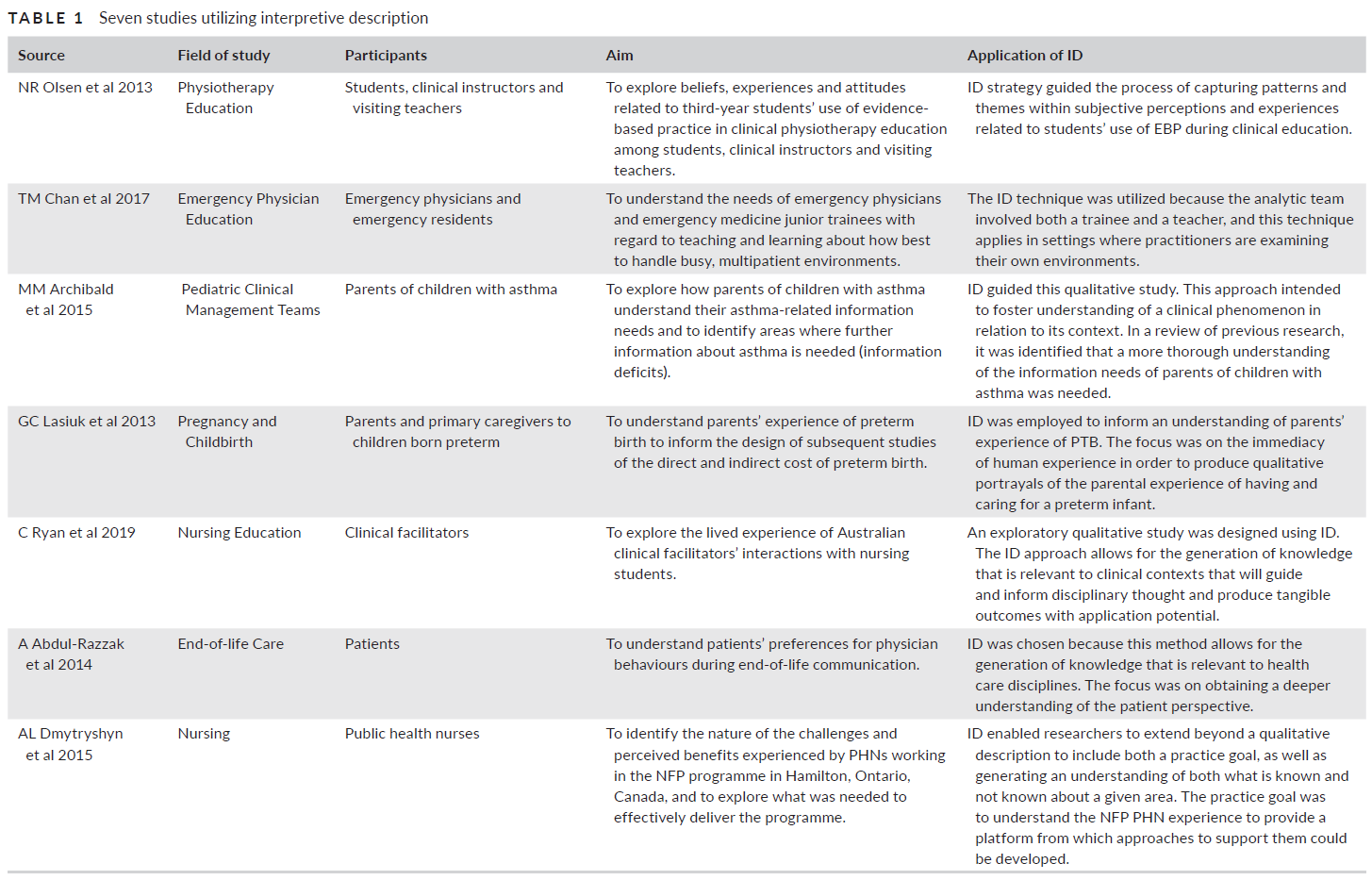

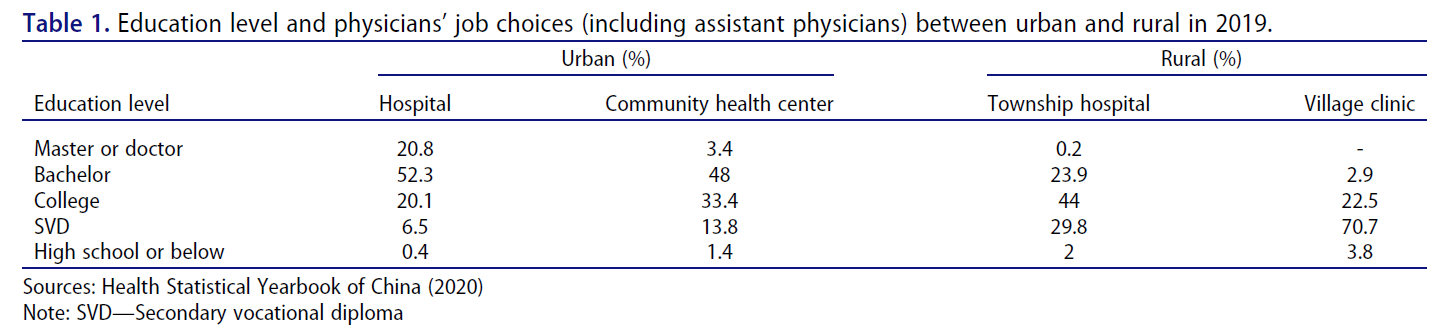

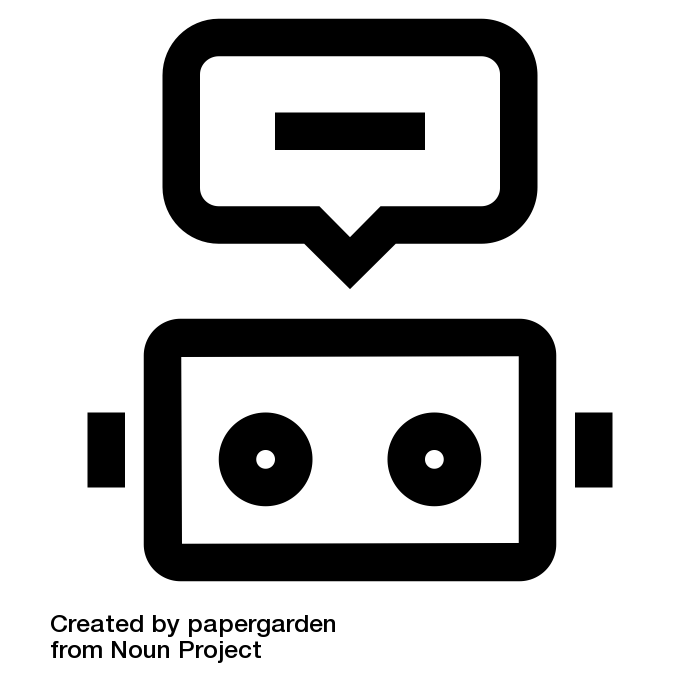

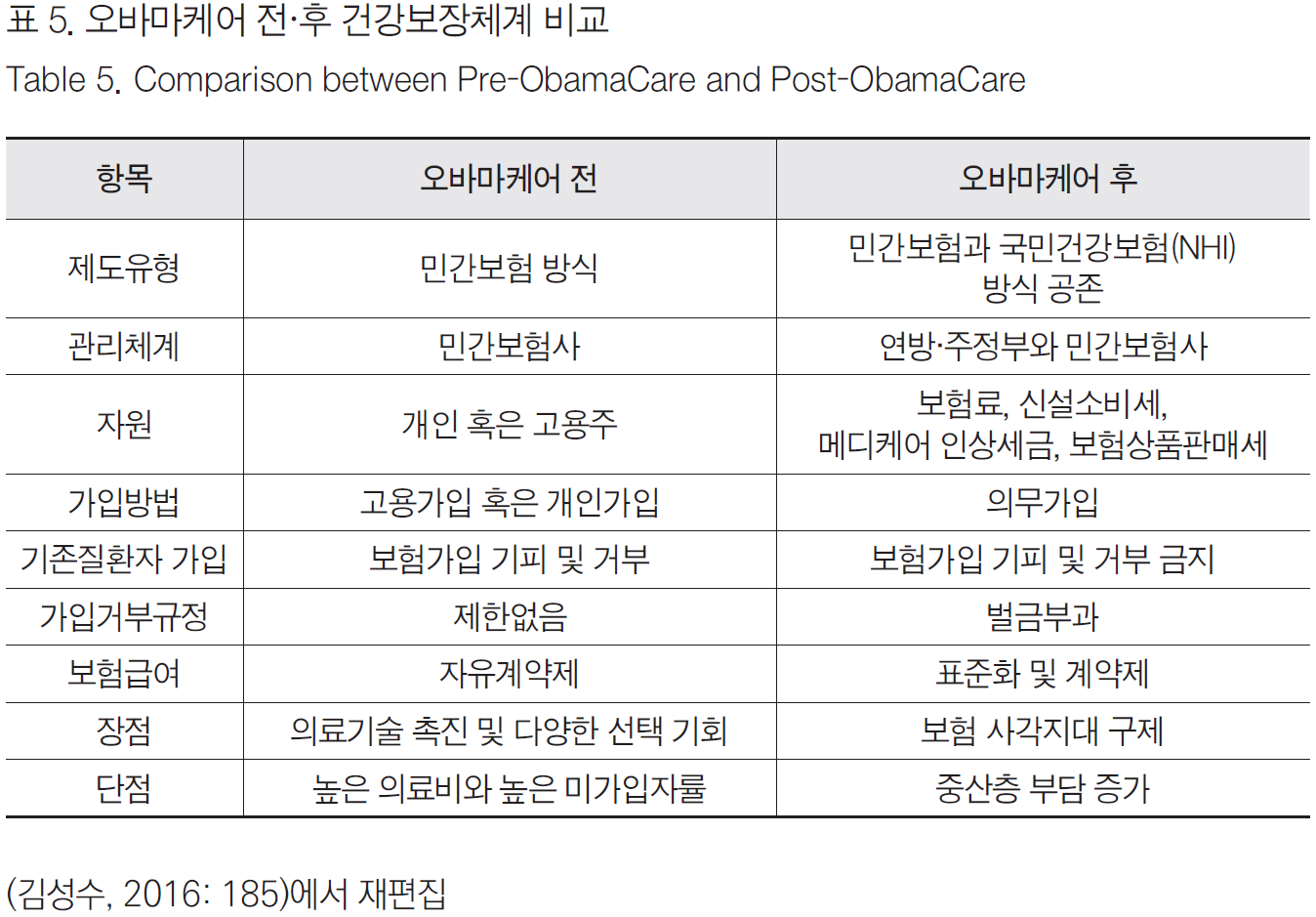

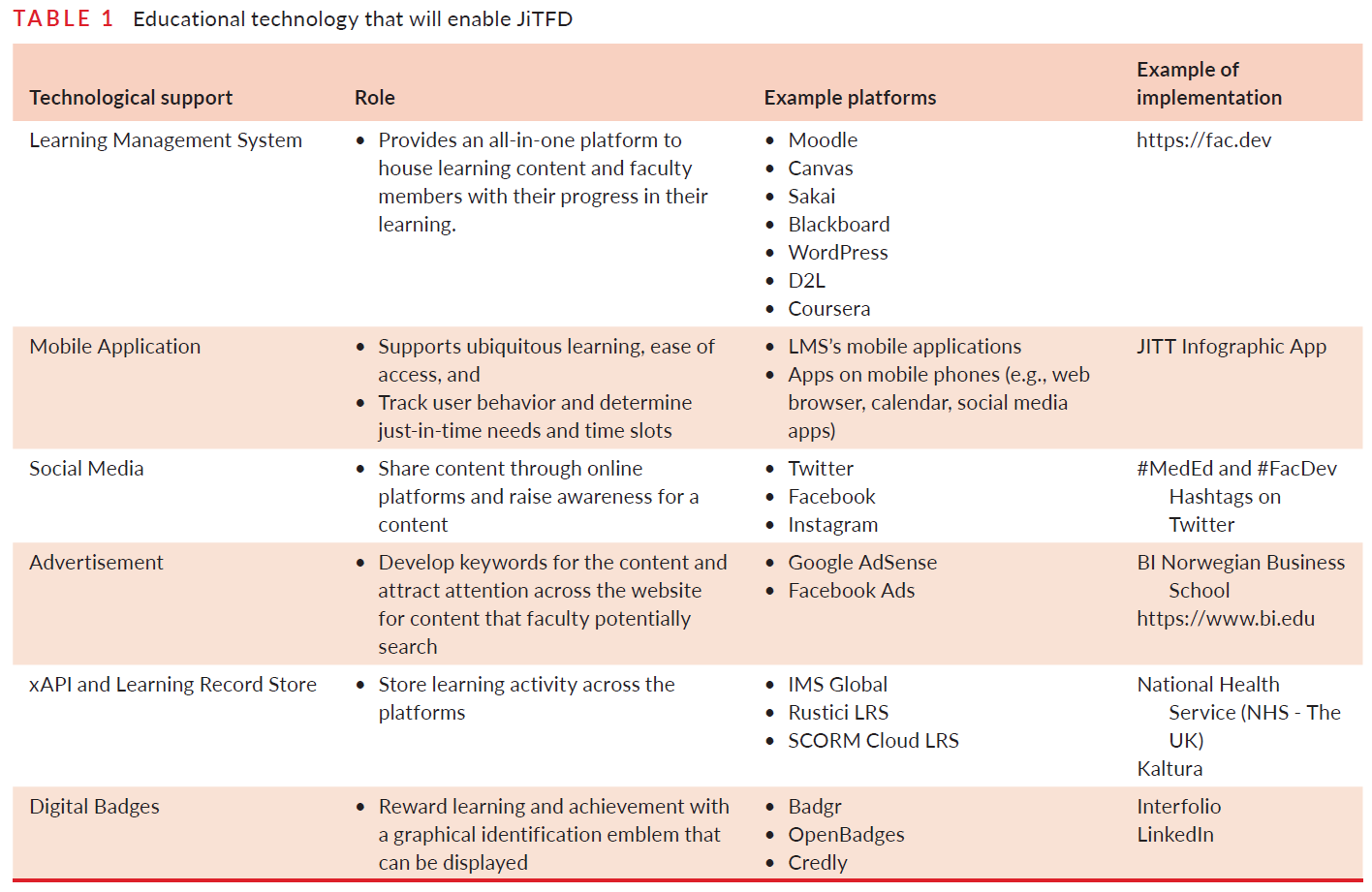

테크놀로지를 사용하여 JiTFD를 지원하는 것은 필수적입니다. 테크놀로지 수용과 혁신의 확산이 미치는 영향을 인정하지만,59 , 60 우리가 매일 사용하는 일반적인 접근 방식을 대상으로 하면서도 JiTFD가 가능합니다. 표 1은 자연스럽게 JiTFD를 지원할 수 있는 테크놀로지 도구를 정의하고 설명합니다. 이 목록은 최신 테크놀로지와 기기로 보강할 수 있지만, 여기서는 테크놀로지를 활용하여 JiTFD의 맥락에서 교수와 학습을 지원하는 방법에 초점을 맞추고자 합니다. 따라서 이 목록은 교수개발자가 즉시 사용할 수 있는 플랫폼에 대한 일반적인 설명과 예시를 나타냅니다.

Using technology to support JiTFD is essential. While we acknowledge the influence of technology acceptance and the diffusion of innovation, 59 , 60 JiTFD is possible while targeting common approaches that we use daily. Table 1 defines and explains technological tools that would naturally support JiTFD. While this list can be enhanced with the latest technologies and devices, we would rather focus on how to harness technology to support teaching and learning in the context of JiTFD. Therefore, the list represents a general description and example of the platforms immediately available to faculty developers.

제한 사항

LIMITATIONS

테크놀로지는 JiTFD의 필수적인 부분입니다.

Technology is an integral part of JiTFD

JiTFD 학습 루프는 교육에서 마이크로러닝과 추적 기능을 향상시킬 수 있는 주요 테크놀로지 발전을 전통적인 교수개발 분야와 연결하는 새로운 모델입니다. 우리는 테크놀로지의 가용성과 사용이 모든 사람에게 가능하지 않을 수 있음을 인정합니다. 반면, 코로나19 팬데믹 기간 동안 온라인 학습에 테크놀로지을 활용한 사례는 전 세계적으로 빠르게 요구되는 새로운 교육 및 학습 패러다임에 적응하는 데 테크놀로지이 어떻게 도움이 되는지 보여주었습니다. 따라서 테크놀로지를 교수개발을 강화하고 교수개발자에게 생애주기 전반에 걸쳐 교수진을 지원할 수 있는 최적의 전략을 알려주는 데 적용할 수 있을 것입니다.

The JiTFD Learning Loop is a new model that links key technological advancements that enable technology to enhance microlearning and tracking in education to the traditional field of faculty development. We acknowledge that technology availability and use may not be feasible for all. On the other hand, the use of technology for online learning during the COVID‐19 pandemic illustrated how technology helped us adapt to a new paradigm for teaching and learning—when it was quickly needed globally. Therefore, it is conceivable that technology could be adapted to enhance faculty development and inform faculty developers with more optimal strategies to support faculty across the life cycle.

비용 효율적인 솔루션을 제공하기 위해 사용 가능한 리소스의 용도를 변경해야 합니다.

Available resources need to be repurposed for JiTFD to provide cost‐effective solutions

무료 오픈 액세스 의학교육(FOAM) 운동은 평생 전문성 개발 61 , 62 , 63 및 대학원 의학교육(64 , 65 , 66 , 67)에 보편적으로 존재하며, 몇 가지 주목할 만한 이니셔티브와 교수진 개발 리소스(예: KeyLIME 팟캐스트, 68 국제 임상의사 교육자 블로그, 69 응급의학 학술 생활의 사례로 본 의학교육 시리즈, 16 MAX FacDev 이니셔티브 70 )가 있습니다. 강력한 리소스를 사용할 수 있지만, 공식적인 JiT 환경에서 리소스를 사용하는 것은 제한적입니다. 시간이 지남에 따라 지속 가능하려면 아카데미에서 FOAM 트렌드를 적절히 인정하고, 보상하고, 장려해야 하며 61 , 71 , 72 자원은 주기적으로 JiTFD를 위해 용도를 변경해야 합니다. 마찬가지로 테크놀로지 측면에서도 오픈 액세스 소프트웨어 운동에 동참하여 콘텐츠를 공동 제작할 수 있는 플랫폼을 협업하고 공유함으로써 테크놀로지 도구를 반복적으로 개발하는 데 드는 비용을 줄일 수 있습니다. 이 과정에서 교수개발자가 지식과 스킬을 공유하도록 유도하는 동시에 시간과 비용의 부담을 줄이면서 JiT와 성공적인 학습 루프를 지원할 수 있습니다.

The free open access medical education (FOAM) movement is universally present in continuing professional development 61 , 62 , 63 and postgraduate medical education, 64 , 65 , 66 , 67 with several notable initiatives and faculty development resources (e.g., KeyLIME podcast, 68 International Clinician Educator's Blog, 69 Academic Life in Emergency Medicine's Medical Education in Cases Series, 16 the MAX FacDev initiative 70 ). While robust resources are available, the use of the resources in a formal JiT environment is limited. The FOAM trend must be properly acknowledged, rewarded, and promoted in the academy to allow for sustainability over time 61 , 71 , 72 and resources must be periodically repurposed for JiTFD. Similarly, on the technology side, we can operate within the open access software movement to decrease the cost of repeatedly developing technological tools by collaborating and sharing platforms where content can be co‐created. In the process, this can prompt faculty developers to share knowledge and skills while lessening the burden of time and money as they support JiT and successful learning loops.

결론

CONCLUSION

저자들은 적시 교수개발 모델을 정의하여 교수진의 교수 및 학습 요구를 충족하고 보건 전문직 교육 분야에서 광범위하지만 종종 잘 알려지지 않은 이 개념에 대한 경계를 설정하기 위한 새로운 접근 방식을 소개합니다. 이러한 개념을 응급의학 교수개발 프로그램에 통합하는 것은 응급의학이 의학계 내에서 상대적으로 새로운 지위에 있고 디지털 학습과 관련하여 최첨단 전문 분야로 명성이 높기 때문에 특히 중요합니다.

The authors define the Just‐in‐Time Faculty Development model to introduce a new approach to meet faculty teaching and learning needs and to set boundaries for this wide, yet frequently underrepresented, concept in the field of health professions education. Integrating these concepts into faculty development programs for emergency medicine are especially important due to the specialty's relative new status within the house of medicine and its reputation as a leading‐edge specialty with regards to digital learning.

The Learning Loop: Conceptualizing Just-in-Time Faculty Development

PMID: 35224408

PMCID: PMC8848258

DOI: 10.1002/aet2.10722

Free PMC article

Abstract

Background: As technology advances, the gap between learning and doing continues to close-especially for frontline academic faculty and clinician educators. For busy clinician faculty members, it can be difficult to find time to engage in skills and professional development. Competing interests between clinical care and various forms of academic work (e.g., research, administration, education) all create challenges for traditional group-based and/or didactic faculty development.

Methods: The authors engaged in a synthetic narrative review of literature from several unrelated fields: learning technologies, medical education/health professions education, general/higher education. The aim for this review was to synthesize this pre-existing literature to propose a new conceptual model.

Results: The authors propose a new conceptual model, the Just-In-Time Learning Loop, to guide the development of online faculty development for just-in-time delivery.

Conclusions: The Just-In-Time Learning Loop is a new conceptual framework that may be of use to those engaging in online, digital learning design. Faculty developers, especially in emergency medicine, can integrate leading concepts from the technology-enhanced learning field (e.g., microlearning, micro-credentialing, badging) to create new types of learning experiences for their end-users.

Keywords: faculty development; microlearning; micro‐credential; online; self‐regulated learning; technology‐enhanced learning.

© 2022 by the Society for Academic Emergency Medicine.

'Articles (Medical Education) > 교수개발(Faculty Development)' 카테고리의 다른 글

| 교수자 개발을 위한 적시교육 인포그래픽 앱 (J Grad Med Educ. 2022) (0) | 2023.12.17 |

|---|---|

| 적시 보수교육: 인지되거나 인지되지 않은, 당기거나 미는(J Contin Educ Health Prof. 2022) (0) | 2023.12.15 |

| 테크놀로지-강화 교수개발: 미래의 트렌드와 가능성(Med Sci Educ. 2020) (0) | 2023.12.15 |

| 국제 교수개발에서 문화를 이해하고 포용하기(Perspect Med Educ. 2023) (0) | 2023.12.15 |

| ASPIRE 준거를 활용한 교수개발 및 학술활동의 프로그램적 접근 개발: AMEE Guide No. 165 (Med Teach, 2023) (0) | 2023.10.10 |