협력적 수행능력의 상호의존성 측정의 접근법(Med Educ, 2021)

A scoping review of approaches for measuring ‘interdependent’ collaborative performances

Stefanie S. Sebok-Syer1 | Jennifer M. Shaw2 | Farah Asghar3 | Michael Panza4 | Mark D. Syer5 | Lorelei Lingard6

1 소개

1 INTRODUCTION

임상 성과Clinical performance 는 근본적으로 협업적입니다. 그러나 임상 성과의 평가는 근본적으로 개인주의적이다. 이것은 의학 교육에 심오한 의미를 갖는 개념적 역설이다. 우리는 시스템, 팀 및 관계의 중요성을 인정하지만 전통적인 평가 모델을 사용하여 이를 설명하지는 못한다. 평가는 종종 [복잡한 수행능력의 인위적인 단순화]로 간주되지만, 우리는 [복잡한 수행능력의 진정성]을 풍부하게 하기 위해 고군분투한다. 우리는 평가 데이터에서 [설명되지 않은 '노이즈']가 더 높은 수준의 패턴을 반영할 수 있다고 의심하지만, 우리는 그것을 이해할 이론이 부족하다. 이 역설을 해결하기 전까지는 효과적인 협업 의료 제공에서 개인의 역할을 의미 있고 진정으로 나타내는 강력한 평가를 제공할 수 없다.

Clinical performance is fundamentally collaborative. However, the assessment of clinical performance is fundamentally individualist. This is a conceptual paradox with profound implications for medical education. We acknowledge the importance of systems, teams and relationships, but we fail to account for them with our use of traditional assessment models. Assessments are often regarded as artificial simplifications of complex performances, but we struggle to enrich their authenticity. We suspect that the unexplained ‘noise’ in assessment data may reflect higher-level patterns, but we lack theory to make sense of it. Until we address this paradox, we cannot provide individuals with robust assessments that meaningfully and authentically represent their role in effective collaborative healthcare delivery.

직장 기반 임상 환경에서 개인은 협업 팀의 일부로 작업하며, 성과는 한 사람에게만 쉽게 귀속될 수 없다. 이 과제를 해결하기 위해 노력하는 연구자들은 팀의 '집단적 역량', 감독자, 다른 팀 구성원 및 시스템 요소와의 훈련생의 '상호 의존성', 임상 팀 성과에 대한 훈련생의 기여에 대해 설명했다. 그러나 이러한 노력의 지배적인 배경은 독립적 성과에 대한 강한 집중과 암묵적인 가정을 가진 평가 담론으로 남아 있다. 그 밖의 모든 것은 많은 통계적 모델에서 독립성의 가정에 도전하고 개인의 역량을 문서화하는 주요 목표를 훼손하기 때문에, 전통적으로 '통계적으로 성가신 것'로 간주된다. 이 목표는 필요하지만 충분하지 않습니다. [개별 성과]는 서로를 [보완 또는 모순, 수렴 또는 발산, 정교화 또는 약화]할 수 있기 때문에, 높은 품질의 의료 서비스는 [성과 간의 관계]를 이론화하고 측정할 수 있어야 합니다.

In workplace-based clinical settings, individuals work as part of a collaborative team, and performance cannot easily be attributed to one person alone.1-3 Researchers grappling with this challenge have described the ‘collective competence’ of a team,4 the ‘interdependence’5 of trainees with supervisors, other team members and system factors,6 as well as the contribution of trainees to clinical team performance.7 Yet the dominant backdrop to these efforts remains an assessment discourse with a strong focus on—and tacit assumption of—independent performances.8-10 Anything else is conventionally viewed as a ‘statistical nuisance’11 because it challenges the assumption of independence in many statistical models and detracts from the primary goal of documenting the competence of individuals. This goal is necessary but insufficient: high-quality health care requires that we are able to theorise—and measure—relationships among performances because individual performances can complement or contradict, converge or diverge, elaborate or undermine each other.12

[상호 의존성]의 구성을 둘러싼 복잡성은 임상 성과의 개념적 역설과 함께 추가적인 도전을 제시한다. 다양한 분야의 연구자들이 다양한 의미를 전달하기 위해 '상호의존'이라는 용어를 사용하게 되면서 일반적인 모호성을 초래했다. 연구자들 사이의 용어와 접근 방식의 가변성은 평가를 더 어렵게 만드는 데 기여할 수 있다. 넓게 봐서, [상호의존성]은 [경험과 결과에 영향을 미치는 개인 간의 상호작용 패턴]으로 특징지을 수 있다. 이 연구의 목적과 특히 의료 교육에 적용하기 위해, 우리는 [상호 의존성]을 [협력적으로 작업하여, 개인의 성과를 내게 하거나afford, 제한하고contrain, 잠재적으로 더 광범위한 의료 팀의 실천을 형성할 수 있는 개인 간의 상호 작용 패턴]으로 특징지었다.

The complexity surrounding the construct of interdependence presents an additional challenge alongside the conceptual paradox of clinical performance. Researchers from numerous disciplines have used the term ‘interdependence’ to convey various meanings, leading to general ambiguity.13 The variability in both terminology and approaches among researchers may contribute to assessment challenges. Broadly, interdependence can be characterised as patterns of interactions among individuals that influence experience and outcomes.14 For the purposes of this work and application to medical education specifically, we characterise interdependence as patterns of interactions between individuals, working collaboratively, that can afford or constrain one's performance and potentially shape the practice of a broader healthcare team.

우리가 아는 바로는, 현재 의학 교육에서 더 큰 그룹의 일부로 함께 일하는 개인들 사이에 관계가 존재하는 성과를 특성화하고 측정하기 위한 단일 접근법은 존재하지 않는다. 그러나 다른 많은 분야는 협업 성과를 평가하는 과제와 씨름하고 있으며, 그들의 노력은 유망한 접근 방식을 조정하고 지속적인 지식 격차를 목표로 하는 측면에서 우리 자신에게 알려야 한다.

To our knowledge, no single approach currently exists in medical education to characterise and measure performances where relationships exist among individuals working together as part of a larger group. However, many other disciplines are grappling with the challenge of assessing collaborative performance, and their efforts ought to inform our own, both in terms of adapting promising approaches and targeting persistent knowledge gaps.

2 방법

2 METHODS

우리는 다음 연구 질문을 해결하기 위해 범위 검토를 수행했다. 협업적이고 상호의존적인 성과를 의미 있게 평가하기 위해 어떤 측정 접근법이 존재하는가? 범위 검토는 연구 영역을 뒷받침하는 핵심 개념과 이용 가능한 증거의 주요 출처 및 유형을 매핑한다. 그것들은 이전에 검토되지 않은 분야의 문헌을 검토할 때 유용하다. 후속 조사 결과 분석의 깊이는 검토의 목적에 따라 달라진다. 정량적 체계적 검토와 같은 다른 유형의 검토와 달리 [범위 검토]는 연구 증거의 품질을 평가하지 않는다. 그러나 개별 연구의 강점과 한계를 고려하고 기존 지식의 체계를 비판한다. 우리는 주제에 대한 문헌을 검토, 요약 및 합성하기 위해 아크시와 오말리의 5단계 범위 검토 방법론을 따랐고 이 접근법에 대해 인정된 엄격성 원칙을 따랐다. 우리의 해석은 Levac 등이 권고한 비공식 이해관계자 협의에 의해 강화되었다.

We conducted a scoping review to address the following research question: What measurement approaches exist to meaningfully assess collaborative, interdependent performance? Scoping reviews map the key concepts underpinning a research area and the main sources and types of evidence available. They are useful when reviewing literature in areas that have not been reviewed before. The depth of the subsequent analysis of findings depends on the purpose of the review. Unlike other types of reviews, such as quantitative systematic reviews, a scoping review does not appraise the quality of research evidence. However, it does consider the strengths and limitations of individual studies and critique the existing body of knowledge. We followed Arksey and O’Malley's five-stage scoping review methodology to review, summarise and synthesise the literature on a topic15 and followed accepted principles of rigour for this approach.16 Our interpretations were enriched by informal stakeholder consultations, as recommended by Levac et al.17

2.1 검색 전략

2.1 Search strategy

우리는 모든 분야에서 상호의존성의 구성을 측정하는 문헌을 식별하기 위한 검색 전략을 개발했다. 주요 용어: 협업 학습, 그룹 프로세스, 협력 행동, 교육 측정, 상호 작용 패턴, 팀워크, 다이애드 성과 모델링 및 그룹 성과 평가. 이러한 용어는 범위 검토 전문가의 권고에 따라 검토가 진행됨에 따라 수정 및 수정되었다.15 연구 사서의 지원을 받아 2018년 10월 ERIC, CINAHL, Academic Search Complete, PsycINFO 및 Medline의 5개 데이터베이스에 걸쳐 검색을 구현했다. Medline에 대한 검색 문자열은 부록 1에 설명되어 있습니다. 다른 모든 검색 문자열은 각 추가 데이터베이스의 구문 및 어휘로 변환되었습니다.

We developed a search strategy to identify literature on measuring the construct of interdependence from any discipline. Key terms included: collaborative learning, group process, cooperative behaviour, educational measurement, interaction patterns, teamwork, modelling dyad performance and assessing group performance. These terms were revised and adapted as the review progressed, as recommended by scoping review experts.15 With the support of a research librarian, we implemented the search in October 2018 across five databases: ERIC, CINAHL, Academic Search Complete, PsycINFO and Medline. The search string for Medline is included as illustration in Appendix 1. All other search strings were translated into the syntax and vocabulary of each additional database.

2.2 포함 및 제외 기준

2.2 Inclusion and exclusion criteria

우리는 모든 연도의 출판물과 이론 또는 응용 분야를 포함했다. 우리는 상호의존적 협업 성과의 측면을 측정하고 접근 방식이 어떻게 개발되었는지 이해할 수 있는 측정 또는 모델에 대한 충분한 세부 정보(복제할 수 있을 정도로)를 제공하는 작업을 추구했다.

We included any publications from all years and any domain of theory or application. We sought work that measured an aspect of interdependent collaborative performance and supplied sufficient details (ie enough to replicate) about the measure or model that we could understand how the approach was developed.

[개인의 성과만]을 측정하거나 [팀의 성과만]을 측정하는 작업은 제외했습니다. 팀 성과 측정과 상호의존적 성과 측정의 차이는 우리의 선정 과정에서 매우 중요했다. [팀 성과 측정 도구]는 [개별 구성원의 성과 격리 능력]을 제한하는 그룹 수준 결과에 초점을 맞춘다는 점에서 의료 훈련생 평가에 적합하지 않다. 초점의 측면에서, 그런 도구의 지향점은 팀 전체이다. 예를 들어, 의사소통의 차원은 일반적으로 개인에게 '환자 치료에 대한 팀원 간의 효과적인 의사소통이 있다'와 같은 진술에 동의하는 리커트 척도로 점수를 매길 것을 요청함으로써 평가된다. 이 구조는 개인의 기여를 포착하고 측정하는 방식으로 [둘 이상의 개인의 협력 결과를 조사하는 상호의존성 측정]과는 구별된다.

We excluded work that measured only individual performance or only team performance. The distinction between measuring team performance and measuring interdependent performance was critical to our selection process. Team performance measurement instruments are unsuitable for medical trainee assessment given their focus on a group-level outcome, which limits the ability to isolate the performance of individual members. In terms of focus, their orientation is the team-as-a-whole. For example, the dimension of communication is commonly assessed by asking individuals to score on a Likert scale their agreement with statements such as ‘There is effective communication between team members about patient care’.18 This construct is distinct from measures of interdependence, which examine a collaborative outcome from two or more individuals in a way that also captures and measures individual contributions.

특정 분야의 수많은 논문(예: 비즈니스 및 시뮬레이션)은 그룹 성과(예: 팀 성과, 응집력) 또는 개인 성과(예: 학습 인식)에 대한 유일한 초점을 고려할 때 제외되었습니다. 또한 측정 측면이 없는 작업(예: 커리큘럼 설명), 상호 의존성과 관련이 없는 교육적 측정(예: 전문가와 초보자 성과 간의 차이), 측정 애플리케이션을 설명하기 위한 경험적 데이터가 없는 완전한 개념적 작업, 영어 이외의 언어로 작업, 전체 원고를 얻을 수 없는 연구를 제외했다.

Numerous articles from certain fields (eg business and simulation) were excluded given their sole focus on group outcomes19 (eg team performance, cohesiveness) or individual outcomes20 (eg perceptions of learning). We also excluded work with no measurement aspect (eg curriculum descriptions), educational measurement not related to interdependence (eg differences between expert and novice performance), wholly conceptual work with no empirical data to illustrate a measurement application, work in languages other than English, and studies where the full manuscript was unavailable.

2.3 심사 및 선정

2.3 Screening and selection

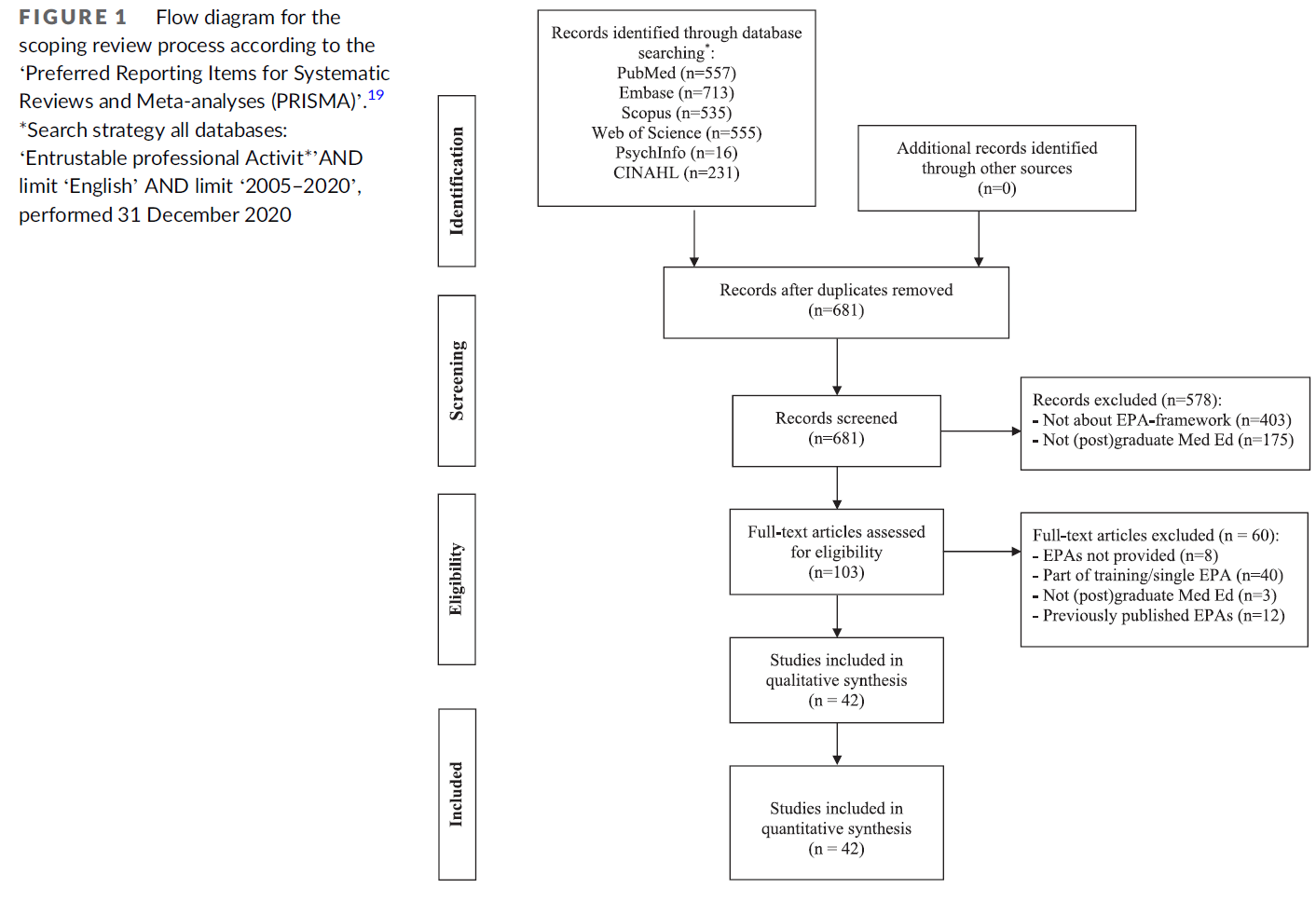

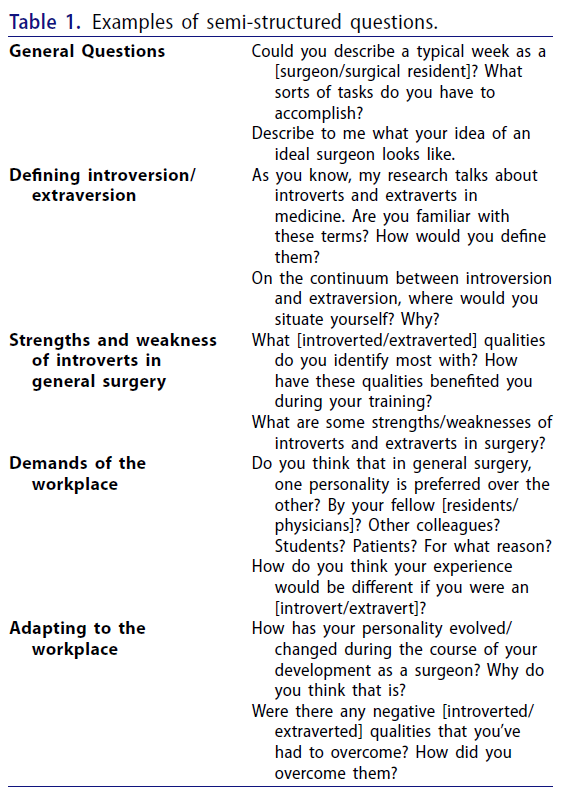

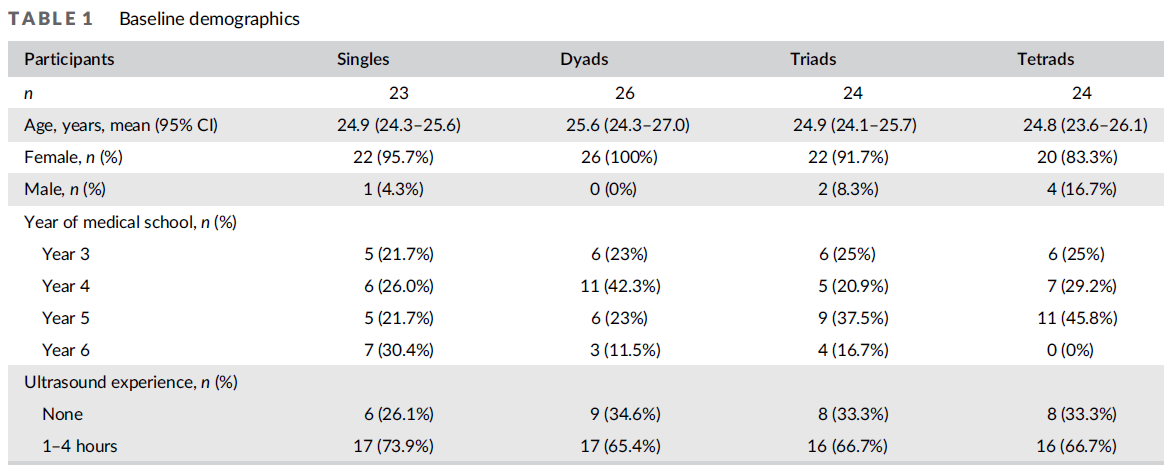

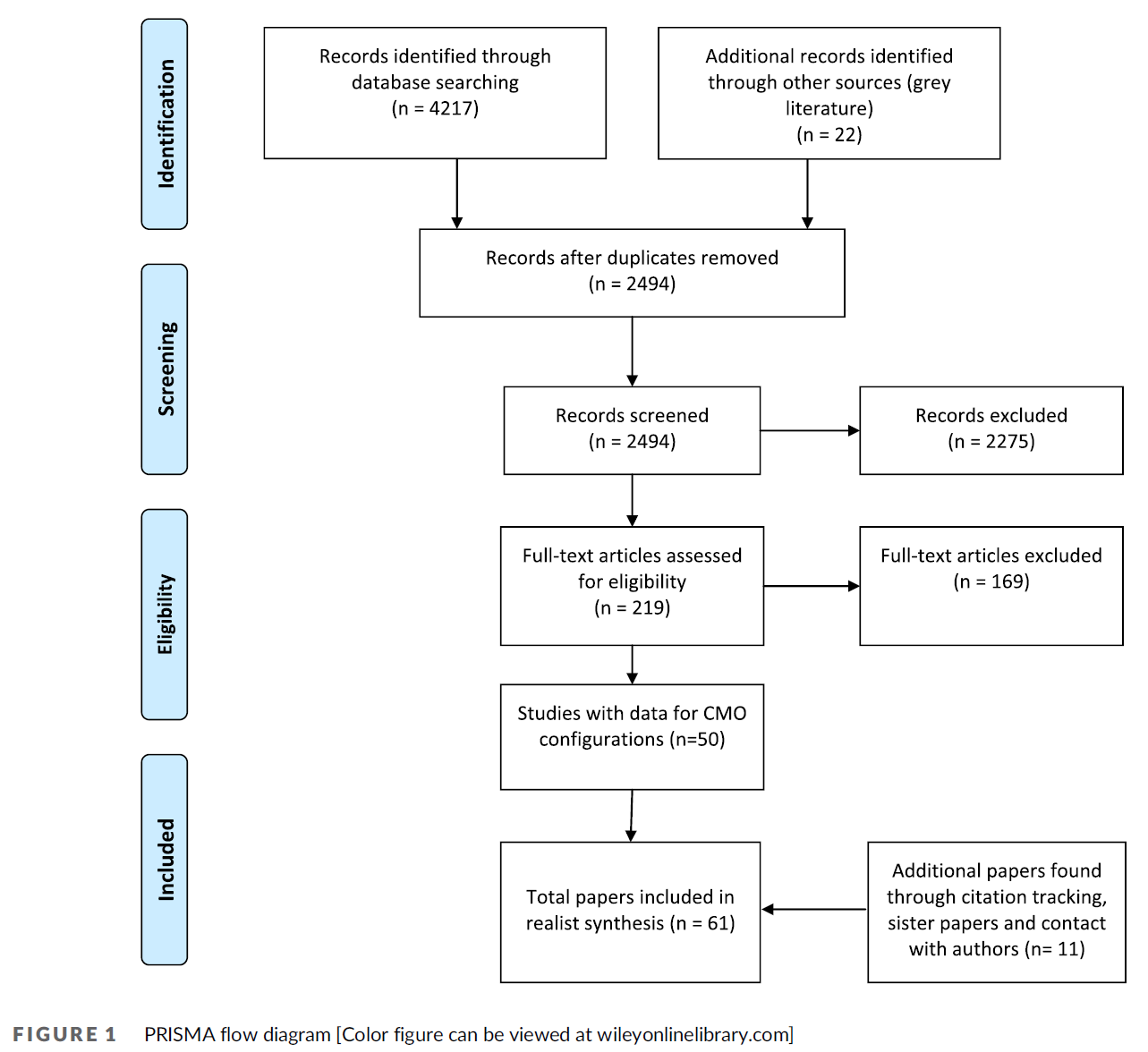

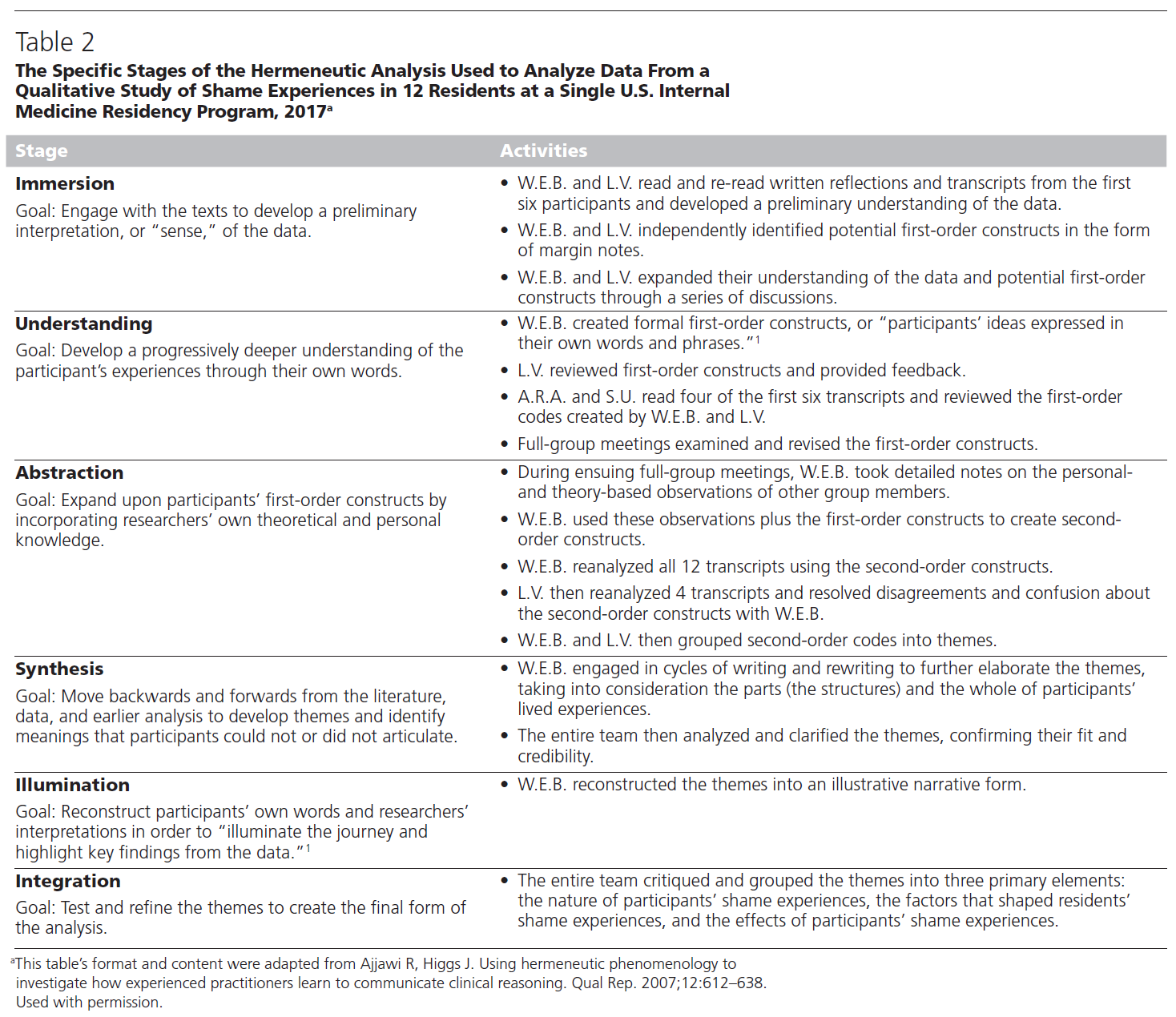

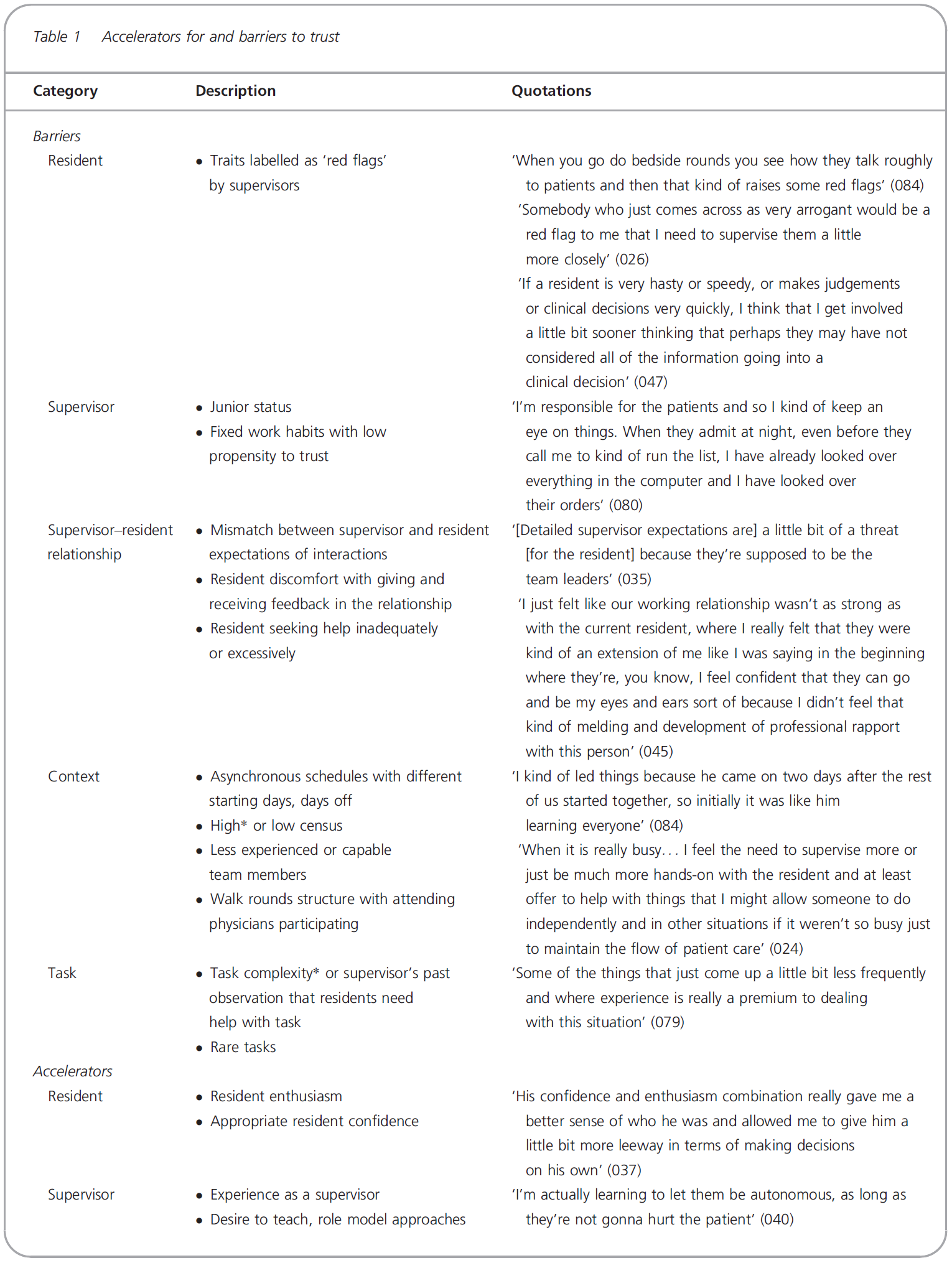

세 명의 저자(SSS, FA, JMS)가 포함 및 제외 기준을 적용하여 제목과 요약(n = 10254)을 선별했다. 전체 텍스트 스크리닝(n = 131) 다음에 두 명의 저자(SSS, MDS)가 나옵니다. 두 선별 단계에서 두 명의 훈련된 검토자가 포함 및 제외 기준을 반영하기 위해 개발한 선별 가이드를 사용하여 각 기록을 선별했다. 불일치는 세 번째 검토자에 의해 해결되었다. 총 24개의 인용구가 포함 기준을 충족했다. 2020년 10월, 우리는 동일한 절차에 따라 검색을 업데이트했다. 최종 숫자가 표시된 PRISMA 다이어그램은 그림 1에서 확인할 수 있습니다. 3명의 저자(SSS, JMS 및 MP)가 제목 및 요약(n = 1598)에서 각 레코드를 선별했으며, 3명의 저자(SSS, MP 및 MDS)는 전체 텍스트 선별 단계(n = 30)에 참여하여 추가로 2개의 인용문을 제공했다. 포함된 26개의 모든 기록의 서지 목록은 관련 참고 자료를 손으로 검색했다: 14개의 제목과 요약본이 상영되었지만, 전문으로 진행된 것은 없었다. 마지막으로, 7개의 기사가 주요 정보원에 의해 추천되었고 1개는 추출에 성공하여 우리의 범위 검토 총 27개의 기사가 되었습니다. 이 범위 검토에 포함된 문헌 목록은 표 1에서 확인할 수 있다.

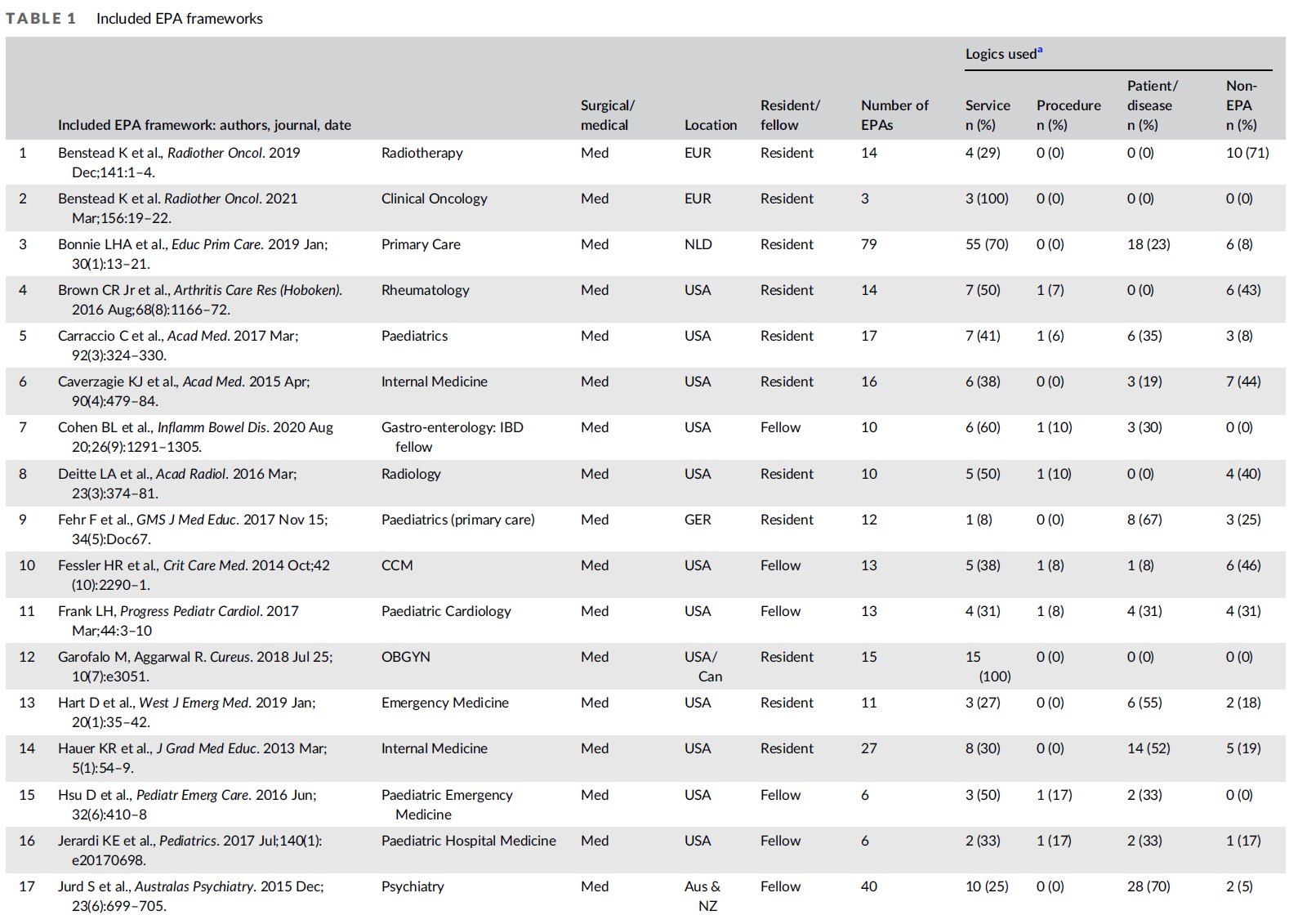

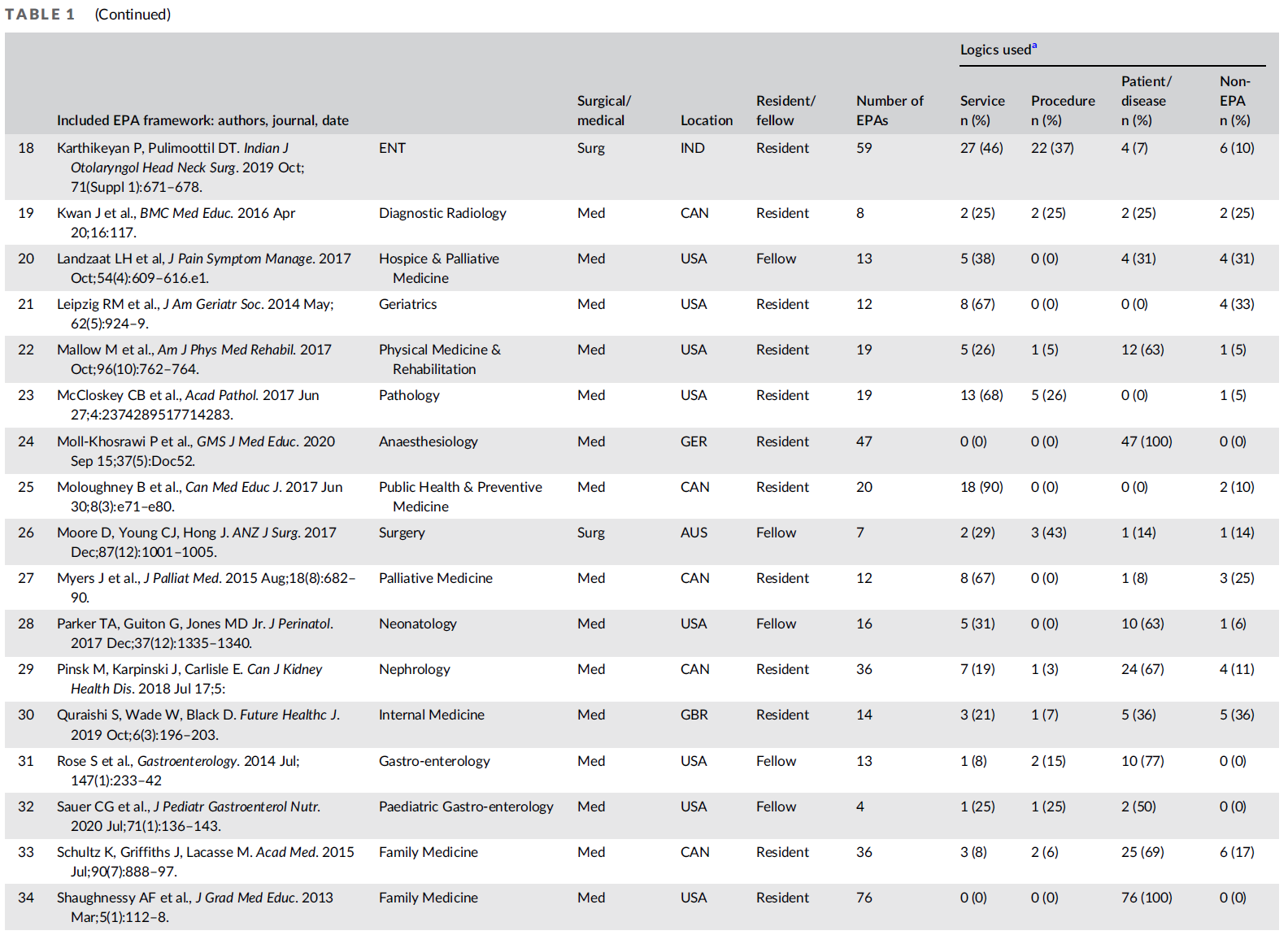

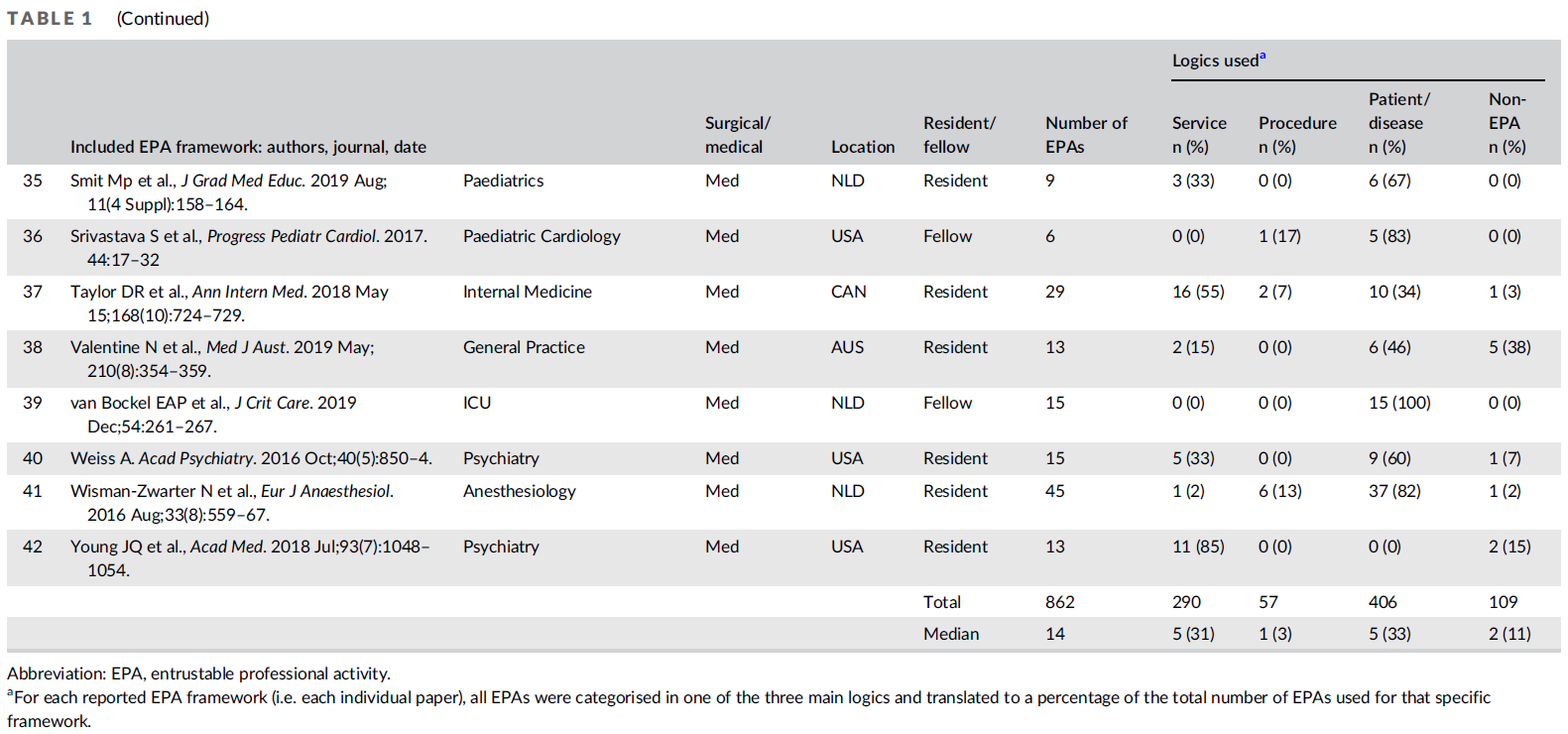

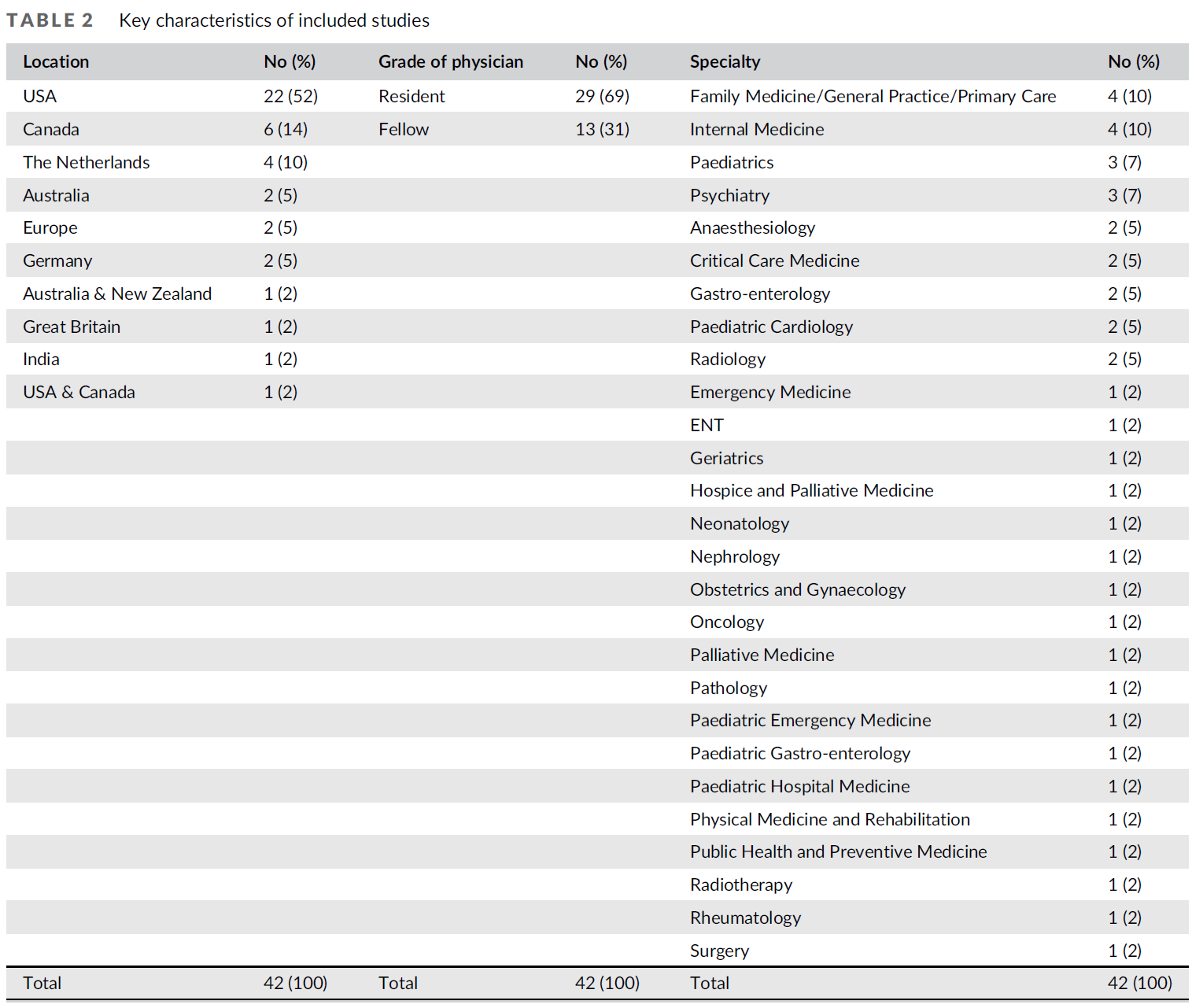

Three authors (SSS, FA and JMS) screened titles and abstracts (n = 10 254), applying inclusion and exclusion criteria. Full-text screening (n = 131) followed by two authors (SSS, MDS). At both screening stages, two trained reviewers screened each record using a screening guide we developed to reflect inclusion and exclusion criteria. Discrepancies were resolved by a third reviewer. A total of twenty-four citations met inclusion criteria. In October 2020, we updated the search following the same procedures. The PRISMA diagram with final numbers can be found in Figure 1. Three authors (SSS, JMS and MP) screened each record at the titles and abstracts (n = 1598), and three authors (SSS, MP and MDS) engaged in full-text screening stages (n = 30), yielding an additional two citations for inclusion. The bibliographies of all twenty-six included records were hand searched for relevant references: fourteen titles and abstracts were screened, but none progressed to full text. Finally, seven articles were recommended by our key informants and one made it through to extraction bringing our scoping review total to twenty-seven articles. A list of the literature included in this scoping review is available in Table 1.

2.4 데이터 도표 작성 및 분석

2.4 Data charting and analysis

우리는 선택된 기록의 특징을 도표화하기 위해 내용과 주제 분석의 방법을 사용하여 서술적 분석을 수행했다. 반복적인 프로세스에 따라, 우리(SSS, JMS, LL)는 데이터 추출을 조직하고 연구 질문 및 목적과 일치하는지 확인하기 위해 데이터 차트 양식을 개발, 파일럿 및 업데이트했다. 우리는 기사 유형, 분야, 적용 맥락, 방법, 이론적 개념, 측정 기법, 임상 훈련 맥락에 대한 조치의 적용 가능성, 그리고 그러한 적용과 관련된 촉진 및 제한 요인에 대한 각 기록을 분석했다. 세 명의 검토자(SSS, JMS, LL)가 독립적으로 각 레코드의 데이터를 차트화하여 정기적으로 회의를 열어 프로세스를 논의했다. 특정한 전문성이 필요한 경우, 세 번째 검토자도 기록을 도표화했습니다. 예를 들어, 고급 수학 공식을 포함하는 기록이 있는 경우, MDS는 이러한 전문성을 제공했습니다.

We conducted a descriptive analysis using methods from content and thematic analysis21 to chart the features of the selected records. Following an iterative process,16 we (SSS, JMS, LL) developed, piloted and updated a data charting form to organise data extraction and ensure it was consistent with the research question and purpose.10 We analysed each record for article type, discipline, context of application, method, theoretical concepts, measurement techniques, applicability of the measures to the clinical training context, and facilitating and limiting factors related to such application. Three reviewers (SSS, JMS, LL) independently charted the data for each record, meeting regularly to discuss the process. Where particular expertise was required, a third reviewer also charted the record: for instance, where a record included advanced mathematical formulas, MDS provided this expertise.

2.5 이해관계자 협의

2.5 Stakeholder consultation

우리는 범위 검토 방법론의 여섯 번째 단계인 이해관계자와의 협의를 수행했다. Levac 등의 권고에 따라 이 단계에 대한 명확한 목적을 설정하고 예비 지식 전달 메커니즘으로 처리했다. 우리의 목적은 세 가지였다: 검토에서 명백한 것을 놓친 것이 있는지 확인하고, 이해관계자에게 패턴에 대한 우리의 해석이 타당한지 탐구하고, 그 결과가 임상 훈련 환경에 어떻게 적용될 수 있는지에 대해 그들을 참여시키는 것이었다. 이해관계자 협의는 인터넷 기반 화상회의를 통해 이루어졌으며, 1개의 그룹 발표와 5개의 개별 토론이 포함되었다. 그룹 발표는 50명 이상의 의학 교육 연구 이사회 회원, 검토 후원자 및 협업 임상 상황에서 훈련생 성과를 평가하는 문제에 익숙한 의료 교육 분야의 리더들과 함께 했다. 의학교육평가 전문가 2명, 의학교육 경험이 있는 통계학자 2명, 검토(즉 사회심리학)에서 대표되는 학문인 사회심리학 학자 1명 등 이해관계자의 목적적 표본을 중심으로 5건의 개별 대화가 진행됐다. 개별적인 대화에 앞서, 이해 관계자들은 우리의 주요 연구 결과에 대한 비디오 프레젠테이션을 시청했고 또한 검토를 위해 추출 요약 표를 받았다. 두 명의 연구원(SSS, LL)이 개별 토론을 진행했고, 한 명은 손으로 쓴 메모를 했다.

We conducted a sixth stage of scoping review methodology: consultation with stakeholders. Following the recommendations of Levac et al,10 we established a clear purpose for this stage and treated it as a preliminary knowledge transfer mechanism. Our purpose was three-fold: to help identify whether we had missed anything obvious in the review, to explore whether our interpretation of patterns made sense to stakeholders and to engage them in reflecting on how the findings might apply to the context of clinical training environments. Stakeholder consultation took place over an Internet-based video conference and included one group presentation and five individual discussions. The group presentation was with 50+ members of the Society of Directors of Research in Medical Education, funders of the review and leaders in the medical education field who are familiar with the challenges of assessing trainee performance in collaborative clinical contexts. Five individual conversations took place with a purposive sample of stakeholders, including two medical education assessment experts, two statisticians with experience in medical education, and one scholar from social psychology, a discipline represented in the review (ie social psychology). Prior to individual conversations, stakeholders watched a video presentation of our main findings and were also sent the extraction summary table for review. Two researchers (SSS, LL) conducted the individual discussions, with one taking handwritten notes.

이 검토에서 공식적, 오디오 녹음 및 전사된 인터뷰에 대한 재정적 자원이나 윤리적 승인이 없었기 때문에, 우리는 참가자들에게 우리가 오디오 녹음도 안 하며, 말한 내용을 인용도 하지 않을 것이라고 알렸다. 따라서, 우리는 이해관계자 협의 단계의 전통적이고 인용된 '결과'를 제시하지 않는다. 오히려 이 단계를 사용하여 2020년 데이터베이스 검색 업데이트를 알리고 임상 환경에서 상호 의존적인 훈련생 성과를 측정하기 위한 연구 결과의 의미를 논의했다.

Given that we had neither financial resources nor ethical approval for formal, audiorecorded and transcribed interviews in this review, we informed participants that we would be neither audio recording nor using verbatim quotes. Therefore, we do not present conventional, quoted ‘results’ from the stakeholder consultation phase. Rather, we used this phase to inform our 2020 update of the database search and discussion of the findings’ implications for measuring interdependent trainee performance in clinical settings.

3 결과

3 RESULTS

검색은 2018년 10월에 수행되었으며 2020년 10월에 업데이트되었다. 스터디 선택 프로세스의 흐름도는 그림 1에 나와 있습니다. 최초 및 업데이트된 검색 결과 총 12732개의 기사가 검색되었습니다. 880건의 중복 배제 후 2명의 저자가 제목과 추상적 수준의 기사 11852건을 심사한 데 이어 포함·배제 기준에 반대하는 기사 161건에 대한 전문 심사가 이어졌다. 이해관계자 권고사항에 따라 추가 기사가 작성되었다. 총 27개 기사가 포함되도록 선정되었으며 각 기사의 관련 세부사항은 보충 자료 표 S1에서 확인할 수 있다.

Searches were conducted in October 2018 and updated in October 2020. A flow chart of the study selection process is provided in Figure 1. The initial and updated search resulted in a total of 12 732 articles. After the removal of 880 duplicates, two authors screened 11 852 articles at the title and abstract level, followed by a full-text review of 161 articles against the inclusion and exclusion criteria. Stakeholder recommendations yielded an additional article for inclusion; in total, twenty-seven articles were selected for inclusion and relevant details from each article are found in Supplementary Material Table S1.

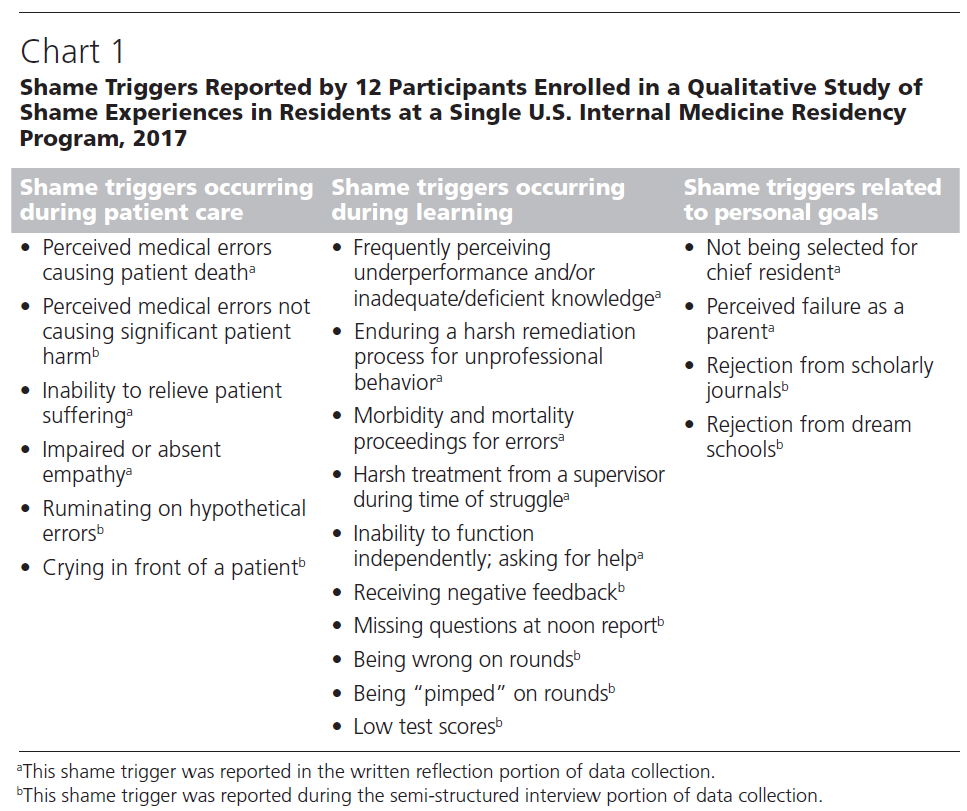

논문 유형과 관련하여, 18개의 포함된 연구는 경험적이었고 9개는 경험적 삽화가 있는 개념적이었다. 경험적 측정 접근법을 위해 기법은 (a) 서술적/탐색적, (b) 추론적/예측적의 두 가지 범주로 구분되었다.

- [서술적이고 탐색적인 접근법]은 데이터의 요약과 표현을 의미 있는 방식으로 제시함으로써 데이터에 대한 기본적인 이해를 제공한다.

- [추론적이고 예측적인 접근법]은 미래의 성능을 예측하고, 패턴을 설정하고, 데이터 간의 관계를 정량화할 수 있는 기회를 제공한다.

Regarding article type, eighteen included studies were empirical and nine were conceptual with an empirical illustration. For the empirical measurement approaches, techniques were divided into two categories: (a) descriptive/exploratory and (b) inferential/predictive.

- Descriptive and exploratory approaches provide a basic understanding of data by presenting summaries and representations of data in meaningful ways.

- Inferential and predictive approaches provide an opportunity to predict future performance, establish patterns and quantify relationships among data.

18개 연구의 대부분은 정량적 방법론을 사용했다. 예를 들어, 한 연구는 유쾌하고 갈등적인 상호작용 과제 동안 우울증이 있는 어머니-딸의 다이애드 사이의 생물행동 동기화의 장애를 평가하는 통제된 실험을 포함했다. 15개의 연구에서는 각 그룹 구성원에게 크레딧을 할당하고 특정 그룹 구성과의 차이를 속성화하기 위해 1차원 및 다차원 항목 응답 모델을 사용한 연구와 같은 모델 테스트 방법론을 사용하였다. 발리우드 산업 내의 복잡한 사회 구조의 일부로서 개인을 조사하기 위해 네트워크 분석을 활용한 연구를 포함한 두 가지 연구가 탐색적 연구였다. 나머지 9개 연구는 혼합 방법 접근법을 사용했다. 예를 들어, 한 연구는 사회 중심적 질적 인터뷰와 사회 그래프를 사용하여 노인들 사이의 사회적 통합을 보조 생활에서 측정했다.

The majority of studies (ie eighteen) used quantitative methodology. For instance, one study involved a controlled experiment assessing disruptions in biobehavioural synchrony between depressed mother/daughter dyads during pleasant and conflict interaction tasks.22 Fifteen studies used model testing methodologies, such as a study using unidimensional and multidimensional item response models to assign credit to each group member and to attribute differences from specific group configurations.23 Two studies were exploratory studies, including one that utilised a network analysis to examine individuals as part of a complex social structure within the Bollywood industry.24 The remaining nine studies used mixed-method approaches. For example, one study used sociocentric qualitative interviews and sociograms to measure social integration among older adults in assisted living.25

논문 중에는 교육 9개, 심리 9개, 컴퓨터 과학 5개, 수학 2개, 생물학 2개 등 다양한 분야가 대표적이었다. 또한 온라인 학습, 스포츠 수행, 상담 및 시뮬레이션을 포함하여 연구에 따라 적용 맥락이 다양했다.

- 교육기사 중 하나는 [비동기식 토론집단을 연구하는 맥락에서 다단계 모델링을 적용한 실제 사례]를 제시했다.

- 심리학 분야의 논문은 [가상 그룹 내의 비공식적인 의사소통을 통한 네트워크 자기관련성network autocorrelation이 온라인 게임에서 개인의 작업 성취에 어떻게 영향을 미치는지] 탐구했다.

- 컴퓨터 과학 분야에서는 [협업에 대한 피드백을 통해 자기 성찰과 감각 만들기를 촉진하기 위해 학생들의 온라인 협업 관행]을 설명하고자 하는 글이 시도되었다.

- 수학 분야의 한 논문은 상호작용이 표본의 다른 개인과 비교하여 파트너를 더 유사하게 만드는지 여부를 조사했다.

- 마지막으로, 생물학 분야에서, 한 기사는 [스포츠 팀]을 기능적으로 통합된 '슈퍼 유기체'로 개념화하여 고도로 조정된 협력 선수들이 단일 사회 단위로 어떻게 집단적으로 작동할 수 있는지에 대한 설명을 제안했다.

Various disciplines were represented among the articles, including nine from education, nine from psychology, five from computer science, two from mathematics, and two from biology. Additionally, the context of application varied across studies, including online learning, sports performance, counselling, and simulation.

- Among the education articles, one presented a practical example of applying multi-level modelling in the context of studying asynchronous discussion groups.26 A

- An article from the discipline of psychology explored how network autocorrelation, via informal communication within a virtual group, affected an individual's task achievement in an online game.27

- From the computer science discipline, an article attempted to illustrate students’ online collaboration practices, in order to promote self-reflection and sense-making through feedback about collaboration.28

- An article from the mathematics discipline examined whether interactions cause partners to become more similar compared to other individuals in the sample.29

- Lastly, from the discipline of biology, an article conceptualised sport teams as functionally integrated ‘superorganisms’, proposing an explanation of how highly coordinated collaborating players might collectively operate as a single social unit.30

이론적 개념과 관련하여 세 가지 주요 범주가 나타났다. 다이애드에 초점을 맞춘 기사(8개 기사), 다이애드보다 큰 그룹(11개 기사), 네트워크(8개 기사).

Regarding theoretical concepts, three main categories emerged: articles focused on dyads (8 articles), groups larger than dyads (11 articles) and networks (8 articles).

세 가지 주요 이론적 범주에서 각각 다양한 핵심 개념이 등장했다.

- [다이애드]를 다룬 논문의 경우, 핵심 개념은 배우-파트너 상호작용 모델, 생물행동 동기화, 심리생물학적 조정, 협업 상호작용 유형, 긍정적 및 부정적 상호작용 유형, 누적 경험, 동기화, 일관성, 상호조절, 연결 및 교환 가능한 다이애드 멤버였다.

- [그룹]에 초점을 맞춘 기사와 관련하여, 핵심 개념은 협업 학습 모델, 입력-과정-결과 모델, 행위자-파트너 상호작용 모델, 영향력 및 시간적 의존성이었다.

- 마지막으로, [네트워크로서의 그룹]을 연구하는 논문의 경우, 핵심 개념은 정도 중심성, 초 유기체, 무작위 행렬 이론, 중앙 집중화, 상태 이론, 소셜 네트워크 이론 및 네트워크 자기 상관 모델이었다.

Various key concepts emerged from each of the three main theoretical categories.

- For articles addressing dyads, key concepts were the actor-partner interaction model,26, 31 biobehavioural synchrony,20 psychobiological attunement,20 collaborative interaction types,32 positive and negative reciprocity,28 cumulative experience,33 synchrony,34 coherence,31 coregulation,31 linkage31 and distinguishable vs. exchangeable dyad members.26

- Regarding articles that focused on groups, the key concepts were collaborative learning models,35 input-process-outcome models,36 actor-partner interaction model,26, 28 influence37 and temporal dependence.38

- Lastly, for articles studying groups as networks, key concepts were degree centrality,22, 34, 39-41 superorganism,27 random matrix theory,16 centralisation,36 status theory,38 social network theory22, 34, 36-38, 42 and network autocorrelation model.24

행위자-파트너 상호작용 모델과 중심성 정도degree centrality은 두 개 이상의 논문에서 나타난 유일한 이론적 개념이었다.

- 행위자-파트너 상호작용 모델은 적절한 통계 기법을 상호의존성의 개념적 관점과 결합하면서 이원적 관계를 나타낸다. 행위자 효과는 개인의 특성에 대한 척도가 그들 자신의 결과를 예측할 때 발생한다. 파트너 효과는 개인의 결과가 파트너의 이전 행동에 의해 예측될 때 발생한다. 이 핵심 개념은 심리학 분야의 두 기사에서 나타났으며, 둘 다 적용의 상담 맥락 안에 있었다.

- 소셜 네트워크 분석에서의 중심성 정도는 특정 노드가 포함하는 연결 수를 말하며, 네트워크에서의 중심성을 나타냅니다. 학위 중심성을 포함한 6개의 논문 중 4개는 심리학 분야에서 나왔고, 1개는 컴퓨터 과학 분야에서, 1개는 교육 분야에서 나왔다.

The actor-partner interaction model and degree centrality were the only theoretical concepts that appeared in more than one article.

- The actor-partner interaction model represents dyadic relationships while combining appropriate statistical techniques with a conceptual view of interdependence.43 The actor effects occur when a measure of individual's characteristics predicts their own outcome. The partner effects occur when an individual's outcome is predicted by a partner's earlier behaviour. This key concept appeared in two articles from the discipline of psychology, both within the counselling context of application.28, 44

- Degree centrality within social network analysis refers to the number of connections a specific node contains, indicating its centrality in a network. From the six articles that included degree centrality, four were from the discipline of psychology,22, 36-38 one from the discipline of computer science39 and one from the discipline of education.34

설명적 추출과 함께, 개념과 기법이 임상 맥락에 어떻게 적용될 수 있는지, 그리고 그러한 적용과 관련된 제한 또는 촉진 요인과 같은 해석적 추출 질문이 포함되었다. 우리는 다이애드 측정, 소셜 네트워크 매핑, 데이터 마이닝 및 기계 학습의 세 가지 반복 개념을 참조하여 해석적 추출 결과를 설명할 것이다. 이 세 가지 개념은 각각 여러 논문에 등장했으며 의학 교육에 잠재적으로 유익한 적용을 제공한다.

Alongside the descriptive extraction, interpretive extraction questions were included, such as how concepts and techniques might be applied to the clinical context, and the limiting or facilitating factors related to such application. We will illustrate the results of the interpretive extraction with reference to three recurring concepts:

- dyad measurement,20, 26, 28, 29, 31, 45

- social network mapping,22, 34, 36-39 and

- data mining and machine learning.24, 25, 32, 33, 38, 46, 47

These three concepts each appeared in multiple papers and offer potentially fruitful application to medical education.

[다이애드 측정]과 관련하여, 임상 결과의 얼마나 많은 부분이 전공의에게 기인하는지 분석하는 것과 같이, 감독자/전공의상호 의존성에 대한 작업을 추가하기 위해 측정 모델을 구축하는 데 접근법을 활용할 수 있다. 예를 들어, 한 기사는 개인 단위와 결합된 공연 단위로서 짝을 이룬 선수들 사이의 관계를 보여주는 경쟁적인 치어리더 공연을 포함했다. 한 가지 제한 요인은 고유한 쌍의 반복 성능을 얻을 수 없다는 것입니다. 촉진 조건은 정의되고 측정될 수 있는 결과(예: 시간 및 효율성)를 포함한다.

Regarding dyad measurement, approaches could be utilised to build measurement models to further our work on supervisor/resident interdependence, such as parsing out how much of a clinical outcome is attributable to a resident. For example, one article involved competitive cheerleading performances that demonstrated the relationships between paired athletes as individual and combined performing units.42 One limiting factor would be the inability to get repeat performances of unique pairs. A facilitating condition includes an outcome that can be defined and measured (eg time and efficiency).

[소셜 네트워크 매핑]과 관련하여 접근법을 사용하여 특정 임상 활동에 참여하는 개인을 매핑하여 상호의존성의 축이 가장 강한 위치(예: 중심성)를 입증할 수 있다. 예를 들어, 한 기사의 분석에는 팀의 성과에 가장 중요한 사람이 누구인지를 결정하기 위해 각 개별 행위자가 있는 시뮬레이션과 없는 시뮬레이션이 포함되었다. 잠재적 한계에는 각 개별 에이전트의 행동이 집단 성과에 동일하게 기여한다는 가정이 포함되며, 이는 임상 훈련 환경에서 적용되지 않을 수 있다. 촉진 요인에는 대학원 교육 프로그램에서 볼 수 있는 소규모 샘플(즉 ~ 30개) 사이의 효과 가능성이 포함된다.

Regarding social network mapping, approaches could be used to map individuals engaging in a particular clinical activity, demonstrating where the axes of interdependence are strongest (eg centrality). For example, analysis in one article involved simulations with and without each individual actor to determine who was most critical to the team's performance.39 A potential limitation includes the assumption that each individual agent's behaviour contributes equally to collective performance, which may not hold true in clinical training environments. A facilitating factor includes the possibility of effectiveness among smaller samples (ie ~30) such as might be seen in postgraduate training programmes.

[데이터 마이닝 및 기계 학습]과 관련하여, 클릭을 분석하기 위해 전자 건강 기록(EHR)과 같은 기존 데이터베이스와 함께 접근법을 사용할 수 있다. 예를 들어, 온라인 협업 글쓰기 과제와 관련된 한 기사는 수정 횟수와 수행된 변경의 길이를 정량화하여 학생들의 상호작용과 기여를 조사했다. 한 가지 잠재적인 제한 요소는 컴퓨터화된 데이터 환경의 필요성입니다. 또 다른 문제는 온라인 학습 연구에서 임상 환경으로 데이터를 변환하는 데 어려움이 있다는 것입니다. 연구자들은 간단하고 셀 수 있지만 관련성이 있고 의미 있는 EHR 작업을 식별할 필요가 있을 것이다. 촉진 요인에는 더 작은 샘플 크기(즉 ~100)로 다단계 모델링의 가능성이 포함된다.

Regarding data mining and machine learning, approaches could be used with existing databases, such as the Electronic Health Record (EHR), to analyse clicks. For example, one article involving online collaborative writings tasks examined students’ interactions and contributions by quantifying the number of revisions and the length of changes performed.44 One potential limiting factor is the necessity of a computerised data environment. Another is the difficulty in translating data from online learning studies to the clinical setting: researchers would need to identify simple and countable—yet relevant and meaningful—EHR actions. A facilitating factor includes the possibility of multi-level modelling with smaller sample sizes (ie ~100).

상호의존성 측정과 관련된 다양한 주제들이 이해관계자들과의 대화에서 등장했다. 첫째, 이해관계자들은 이 검토의 필요성을 논의하면서 [현재 연구의 격차]를 언급했다. 그들은 [상호의존성 개념의 참신성novelty]을 접근법의 차이와 불일치의 핵심적인 이유로 보았다. 이해관계자들은 또한 여러 목적이 가능하며, 이 개념이 평가와 팀워크에 관한 광범위한 문헌에 어떻게 사용될 수 있는지에 대한 영향을 포함하여 [상호의존성 측정의 목적을 명확하게 정의할 필요]가 있음을 시사했다. 이해관계자들은 측정 분산을 설명하기 위해 이러한 접근방식을 사용할 수 있는 가능성에 대해 열정적이었으며 교수진/감독관 다이애드, 팀 및 임상 단위와 같은 임상적 맥락에서 다양한 수준에서 상호의존성의 영향을 조사하기 위한 사용에 관심이 있었다. 또한 이해관계자는 [다단계 모델링, 구조방정식모델링, 지시 비순환 그래프 및 소셜 네트워크 분석]을 포함하여, 상호의존성과 관련된 [다양한 통계적 접근방식의 장단점]에 대해 의견을 제시했다. 일부 강점에는 데이터 네스팅에 대한 설명이 포함되었고, 일부 약점에는 [통계적 배경이 거의 없거나 전혀 없는 교육자가 측정 모델에 접근할 수 있도록 하는 것]이 포함되었다. 측정할 수 없지만 의료 팀 내에 존재하는 복잡한 복잡성을 포착하기 위한 [질적 접근 방식을 유지하는 것의 중요성]도 강조되었다.

Various themes relating to the measure of interdependence emerged during conversations with stakeholders. Firstly, stakeholders mentioned the gap in current research, discussing the necessity of this review. They viewed the novelty of the concept of interdependence as a key reason for both the gap and the inconsistency in approaches. Stakeholders also alluded to the need to clearly define the purpose of an interdependence measure, given that multiple purposes are possible, with implications for how the concept could be used both for assessment and for the broader literature on teamwork. Stakeholders were enthusiastic about the potential to use these approaches to account for measurement variance and were interested in their use to examine the impact of interdependence at various levels in a clinical context, such as faculty/supervisor dyad, team and clinical unit. Additionally, stakeholders commented on the strengths and weaknesses of the various statistical approaches relating to interdependence, including multi-level modelling, structural equational modelling, directed acyclic graphs and social network analysis. Some strengths included accounting for nesting in data and some weaknesses included making the measurement models accessible to educators with little or no statistical background. The importance of retaining qualitative approaches to capture the intricate complexities that are immeasurable, yet exist within healthcare teams, was also emphasised.

마지막으로, 많은 이해관계자들은 상호의존성 측정이 프로그램 평가에 어떻게 적합한지, 그리고 그것을 [의학 교육에서 실용적이고 실현 가능하게 만드는 방법]에 대해 논의했다. 그들은 헬스케어는 상호의존성을 측정하기 위한 복잡한 맥락을 나타낸다는 것을 인식하였다. 따라서 몇몇은 임상 환경 내의 다이애드(예: 감독자 및 수습자)가 환자 치료 및 학습 결과와 같은 요인에 기초하여 교직원과 수습자를 쌍으로 구성할 수 있는 잠재력을 가지고 있기 때문에 상호 의존성의 구성을 측정하기 시작하는 데 가장 적절한 출발점일 수 있다고 제안했다.

Finally, a number of stakeholders discussed how an interdependence measurement might fit within programmatic assessment and how to make it practical and feasible in medical education. They recognised that health care represents a complex context for measuring interdependence because of the ever-changing group composition. Therefore, several suggested that dyads (eg supervisor and trainee) within clinical settings may be the most appropriate starting point to begin measuring the construct of interdependence because it has the potential to pair faculty members with trainees based on factors such as patient care and learning outcomes.

4 토론

4 DISCUSSION

이 검토는 상호의존성 측정과 관련하여 제한적으로 발표된 지식 기반을 발견했다. 대부분의 연구는 개인과 팀을 모두 고려하는 상호의존적 측정과 달리 개인 또는 팀 차원 측정을 대상으로 했기 때문에 선별 과정에서 제외되었다. 우리가 발견한 지식은 5개 학문분야와 6개 하위 분야의 기사와 함께 흩어져 있습니다. 의학 교육에서 지식은 특히 부족하며, 관련 기사는 단 두 개뿐이다. 우리가 검토한 기사들은 매우 다양한 이론적 개념을 사용했다. 그들은 또한 이론적 개념과 측정 기법 모두에 대한 [용어적 일관성이 부족하다]는 것을 보여주었다. 예를 들어, [연결, 관계, 상호작용 및 중심성 정도]과 같은 이론적 개념은 모두 [사람이나 사물 사이에 존재하는 상호의존적인 연결]을 가리킨다. 측정 기법 내에서 다단계 모델링, 계층적 선형 모델링 및 선형 성장 모델은 데이터가 독립적이지 않은 회귀 기반 모델에 대한 변형 용어이다. 여러 개념의 존재와 유사한 현상을 언급하기 위해 다른 용어를 사용하는 것은 개념이 연구에서 연구로 정제되지 않는 학문적 영역을 시사한다. 오히려, 비록 많은 분야의 학자들이 상호의존성을 측정하는 문제와 씨름하고 있지만, 그들은 아마도 다른 분야의 관련 이론이나 기술을 알지도 못하면서 평행선을 달리고 있다. 이러한 [용어적 문제]는 상호의존성(다중 상황에서 관련성이 있는 현상)을 포착하기 위한 새로운 측정 모델의 진화가 간헐적이고 누적되지 않으며 분리된 이유를 설명할 수 있다.

This review found a limited published knowledge base relating to the measurement of interdependence. The majority of studies were excluded during screening because they targeted either individual or team-level measurements, as opposed to interdependent measures which consider both the individual and team. The knowledge we did find is scattered, with articles from five disciplines and six sub-disciplines. Knowledge is particularly scarce in medical education, with only two relevant articles identified. The articles we reviewed employed a wide variety of theoretical concepts. They also demonstrated a lack of terminological consistency for both theoretical concepts and measurement techniques. For example, theoretical concepts such as links, relationships, interactions and degree centrality all refer to interdependent connections that exist between people or things. Within measurement technique, multi-level modelling, hierarchical linear modelling and linear growth models are variant terms for regression-based models where data are not independent. The presence of multiple concepts, and the use of different terms to refer to similar phenomena, suggest a scholarly domain in which concepts are not refined from study to study. Rather, although scholars from many fields are grappling with the problem of measuring interdependence, they are working in parallel tracks, perhaps not even aware of relevant theory or techniques from other disciplines. Together, these terminological issues might explain why the evolution of new measurement models to capture interdependence—a phenomenon of relevance in multiple contexts—has been intermittent, non-cumulative and segregated.

이 검토에 설명된 다양한 상호의존적 측정 기법은 임상 훈련 맥락에 대한 잠재력을 가지고 있다. 상호의존성을 단순한 '통계적 골칫거리' 이상으로 다루기 위한 전략들이 있다. 예를 들어, [다단계 모델링]은 서로 다른 수준의 변수를 통합하여 중첩된 데이터를 처리하기 위한 프레임워크를 제공하여 연구자가 개별 및 그룹 수준 요인을 모두 측정할 수 있도록 하기 때문에 유망하다. 비록 [측정 접근법]은 임상 훈련 상황에서 보통 가용한 샘플 수보다 더 큰 샘플 크기를 요구하지만, 우리는 중간 규모의 대학원 프로그램과 유사한 샘플을 사용한 몇 가지 연구를 발견했다.

Various interdependent measurement techniques described in this review have potential for the clinical training context. There are strategies to deal with interdependence as more than just a ‘statistical nuisance’. For example, multi-level modelling has promise as it provides a framework for dealing with nested data by incorporating variables at different levels, enabling researchers to measure both individual and group-level factors. And although measurement approaches often demand a larger sample size than is available in clinical training contexts, we did find some studies that used samples comparable to medium-sized postgraduate programmes.

그러나 여러 척도를 결합한 연구가 가장 흥미로울 수 있다. 예를 들어, 기술적 접근법(예: 네트워크 분석)과 예측 측정 접근법(회귀 기반 기술)을 결합하면 네트워크의 특성을 체계적으로 이해하고 네트워크 내에 존재하는 특정 상호의존성 패턴의 영향을 입증할 수 있는 조치를 만들 수 있는 기회를 제공한다.

However, research that combines multiple measures may be of most interest. For example, combining descriptive approaches (eg network analysis) with predictive measurement approaches (ie regression-based techniques) offers the opportunity to systematically understand the nature of a network and create measures that can demonstrate the impacts of specific patterns of interdependence that exist within it.

우리가 발견한 [기술적 접근법]과 [예측적 접근법]을 모두 결합한 측정 접근법의 가장 좋은 예는 Gin 등의 논문이다. 이 연구에서 저자들은 남녀 다이애드에 초점을 맞추고 다이애드 아이템 반응 이론(dIRT) 모델을 사용하여 스피드 데이팅 세션 동안 두 개인 사이에 존재하는 상호 작용을 포착했다. 저자들에 따르면, dIRT 모델은 이진 데이터의 측정을 위해 [문항 반응 이론]과 [사회적 관계]를 모두 활용한다. 그들은 이 접근법이 개별 접근법으로 측정할 수 없는 상호 매력과 같은 상호작용을 포착한다는 것을 발견했다. 또한 종속척도는 10점 등급 척도(이후 5점 척도로 압축됨)를 이용한 일련의 대응이었다. 이 결과 측정은 협력적인 직장 기반 환경에서 훈련생을 평가하는 데 가장 일반적으로 사용되는 위탁 척도 및 기타 등급 척도와 일치합니다. 간단히 말해서, 이 논문은 의료 교육 분야에서 상호 의존성을 측정하기 위한 중요한 고려 사항을 강조한다.

- (a) 다이애드로 시작한다(예: 감독관-의사-의사-의사 또는 의사-의료 보조자).

- (b) 개인 간의 상호 작용을 조사하기 위해 일종의 사회적 관계 또는 소셜 네트워킹 접근법을 사용한다.

- (c) 회귀 기반 모형을 사용하여 협업(또는 내포) 성능을 측정할 수 있도록 순서형 또는 비율 결과를 사용할 수 있습니다.

The best example we found of a measurement approach that combines both descriptive and predictive approaches is the paper by Gin et al.48 In this study, the authors focused on dyads of male and females and used a dyadic item response theory (dIRT) model to capture the interactions that exist between two individuals during speed dating sessions. According to the authors, the dIRT model utilises both Item Response Theory and Social Relations for the measurement of dyadic data.48 They found that this approach captured interactions, such as mutual attractiveness, that are not measurable by individual approaches. Furthermore, the dependent measure was a series of responses using a 10-point rating scale (which was later collapsed to a 5-point scale). This outcome measure is consistent with entrustment scales and other rating scales most commonly used to assess trainees in collaborative, workplace-based environments. In short, this paper48 highlights important considerations for measuring interdependence in the field of medical education:

- (a) start with dyads (eg supervisor-trainee, physician-nurse or physician-medical assistant);

- (b) use some sort of social relations or social networking approach to examine the interactions between individuals; and

- (c) have an ordinal or ratio outcome so that a regression-based model can be used to measure collaborative (or nested) performance.

4.1 의료 교육자를 위한 실제 권장 사항

4.1 Practical recommendations for medical educators

이 연구의 다음 단계는 [상호의존적 성과(예: 한 개인/기계가 수술 도구를 작동하고, 다른 개인이 카메라에 초점을 맞추고 비디오 영상을 해석하는 복강경 수술)]를 구성하는 임상 행동과 결정이 무엇인지 정확하게 식별하는 것이다. 이를 통해 우리는 기본적인 측면을 특성화하고 구조로서의 상호의존성에 대한 풍부한 이해를 개발할 수 있을 것이다. 우리의 훈련 모델이 훈련생과 교직원 간의 상호 의존성을 촉진하는 방식으로 설계되었다는 점을 고려할 때, 특히 의학 교육 맥락에서 이러한 격차를 탐구하는 것은 가치가 있다. 임상 훈련 내에서 상호의존성을 측정할 수 있는 가능성에 대해 생각할 때, 우리는 개별 훈련생이 의료 팀의 전반적인 성과에 어떻게 기여하는지를 반영하기 위해 교육 및 평가의 목표를 전환하는 것을 고려할 수 있다. 이를 위해서는 단일 점수 또는 결정에 초점을 맞추는 평가 시스템에서 벗어나 의료 팀 내에서 개인 및 상호의존적인 성과 측면을 모두 포착하는 평가를 만들어야 할 수 있습니다. 의료 교육자는 이 접근법을 지원하기 위해 다양한 데이터를 수집하고 이 검토에서 식별된 일부 측정 모델을 사용하여 분석할 수 있다. 마지막으로, 의료는 팀에서 수행되며 상호의존적 협업은 해당 팀 내에 존재한다. 따라서, 우리는 관련 영역에서 훈련생의 역량을 정확하게 평가하고 훈련생이 환자에게 제공하는 협업적인 팀 기반 치료에 대한 피드백을 제공하기 위해 상호의존성의 유효하고 신뢰할 수 있는 측정이 필요하다.

The next step in this line of research is to precisely identify what clinical actions and decisions constitute interdependent performance (eg laparoscopic surgery where one individual/machine is operating the surgical tool while another individual is focusing the camera and interpreting video imaging). This will allow us to characterise fundamental aspects and develop a rich understanding of interdependence as a construct. Given that our training models are designed in ways that foster interdependence between trainees and faculty, exploring this gap specifically in medical education contexts is worthwhile. In thinking about the potential for measuring interdependence within clinical training, we might consider shifting the goal of education and assessment to reflect how individual trainees contribute to the overall performance of a healthcare team. This may require us to move away from an assessment system that focuses on a single score or decision and create assessments that capture both individual and interdependent aspects of one's performance within a healthcare team. Medical educators could collect a variety of data to support this approach and analyse it using some of the measurement models identified in this review. Finally, medicine is practiced in teams and interdependent collaborations exist within those teams; therefore, we need valid and reliable measures of interdependence to accurately assess trainees’ competence in associated domains and provide them with feedback about the collaborative, team-based care they provide to patients.

4.2 제한사항

4.2 Limitations

이 연구는 선정 과정에서 사용된 5개 데이터베이스의 기사로 제한된다. 우리가 발견한 기사들이 많은 분야와 하위 분야에 흩어져 있다는 점을 고려할 때, 우리는 다른 데이터베이스를 통해 추가 출처를 확인했을 가능성이 가능하다. 또한 포함 기준은 상호의존성에 대한 잠재적 대리인을 연구하는 분야를 제외했을 수 있다. 이 문헌에서 확인한 용어 불일치도 검색에 영향을 미쳤을 수 있다. 검색에서 키워드가 아닌 용어를 사용했기 때문에 관련 연구가 제외되었을 가능성이 있다. 특히 이 분야에서 '상호의존성'의 사용법이 상당히 생소하다는 점에서 의학교육에는 다른 글들이 존재하지만 우리의 검색어 이외의 용어를 사용하는 것은 아닌지 궁금하다. 팀 수준에서만 측정된 기사를 제외하기로 한 우리의 결정은 측정 세부사항이 불충분했던 기사를 제외하기로 한 결정이 관련 측정 접근법을 간과하게 만들었을 수도 있는 것처럼 '상호의존성'과 관련된 이론적 개념에 대한 통찰력을 제한할 수도 있다. 소셜 네트워크 분석이 샘플에서 반복적인 접근 방식이었지만, 이 논문들은 정도 중심성에 크게 초점을 맞춰 소셜 네트워크 분석의 전체적인 분석 접근 방식이 임상 훈련 환경에서 상호 의존성을 측정하는 데 어떻게 도움이 될 수 있는지에 대해 배울 것이 더 있음을 시사한다. 마지막으로, 우리의 검토는 포함된 기사의 품질 평가를 포함하지 않는다. 이러한 접근 방식 중 어떤 것이 효과적이고 실제적으로 얼마나 강력한지 평가하기 위한 추가 노력이 필요하다.

The study is limited to the articles from the five databases that were used in the selection process. Given that the articles we found were scattered across many disciplines and sub-disciplines, it is possible that we would have identified additional sources through other databases. Furthermore, inclusion criteria may have excluded disciplines that researched potential proxies for interdependence. The terminological inconsistency we identified in this literature may also have affected our search: it is possible that relevant studies were excluded because they used terms other than the keywords in our search. In particular, we wonder if other articles exist in medical education but use terminology outside our search terms, given that the usage of ‘interdependence’ is fairly new in this field. Our decision to exclude articles that only measured at the team level may also have limited our insight into theoretical concepts of relevance to ‘interdependence’, just as our decision to exclude those that had insufficient measurement detail may have caused us to overlook relevant measurement approaches. While social network analysis was a recurrent approach in our sample, these papers focused heavily on degree centrality, suggesting that there is more to be learned about how the full extent of analytical approaches in social network analysis might assist with measuring interdependence in clinical training settings. Finally, our review does not include a quality assessment of included articles; further efforts are needed to evaluate which of these approaches work and how robust they are in practice.

5 결론

5 CONCLUSION

팀 내에서 개인 간에 존재하는 상호의존성을 포착하기 위한 측정 접근법은 드물고 여러 분야에 걸쳐 분산되어 있다. 더욱이, 일관성 없는 개념적, 기술적 용어는 이 질문에 대한 지식의 축적을 제한할 수 있다. 이 검토는 연구자들이 상호의존성에 대해 어떻게 생각하고 있는지, 그리고 상호의존성의 어떤 측면이 측정 관점에서 중요한지를 강조한다. 다른 분야의 접근 방식이 임상 훈련 맥락에 대한 유망성을 가지고 있지만, 의료 교육 분야에서 단 두 가지 연구만 식별된다는 것은 이러한 맥락에서 응용 연구의 필요성을 시사한다.

Measurement approaches for capturing the interdependence that exists between individuals within a team are scarce and scattered across multiple fields. Furthermore, inconsistent conceptual and technical terminology may be limiting the accumulation of knowledge regarding this question. This review highlights how researchers are thinking about interdependence and what aspects of interdependence are important to consider from a measurement perspective. While approaches from other fields have promise for the clinical training context, the identification of only two studies in the field of medical education suggests a need for application studies in this context.

Med Educ. 2021 Oct;55(10):1123-1130. doi: 10.1111/medu.14531. Epub 2021 May 19.

A scoping review of approaches for measuring 'interdependent' collaborative performances

PMID: 33825192

DOI: 10.1111/medu.14531

Abstract

Introduction: Individual assessment disregards the team aspect of clinical work. Team assessment collapses the individual into the group. Neither is sufficient for medical education, where measures need to attend to the individual while also accounting for interactions with others. Valid and reliable measures of interdependence are critical within medical education given the collaborative manner in which patient care is provided. Medical education currently lacks a consistent approach to measuring the performance between individuals working together as part of larger healthcare team. This review's objective was to identify existing approaches to measuring this interdependence.

Methods: Following Arksey & O'Malley's methodology, we conducted a scoping review in 2018 and updated it to 2020. A search strategy involving five databases located >12 000 citations. At least two reviewers independently screened titles and abstracts, screened full texts (n = 161) and performed data extraction on twenty-seven included articles. Interviews were also conducted with key informants to check if any literature was missing and assess that our interpretations made sense.

Results: Eighteen of the twenty-seven articles were empirical; nine conceptual with an empirical illustration. Eighteen were quantitative; nine used mixed methods. The articles spanned five disciplines and various application contexts, from online learning to sports performance. Only two of the included articles were from the field of Medical Education. The articles conceptualised interdependence of a group, using theoretical constructs such as collaboration synergy; of a network, using constructs such as degree centrality; and of a dyad, using constructs such as synchrony. Both descriptive (eg social network analysis) and inferential (eg multi-level modelling) approaches were described.

Conclusion: Efforts to measure interdependence are scarce and scattered across disciplines. Multiple theoretical concepts and inconsistent terminology may be limiting programmatic work. This review motivates the need for further study of measurement techniques, particularly those combining multiple approaches, to capture interdependence in medical education.

© 2021 John Wiley & Sons Ltd and The Association for the Study of Medical Education.

'Articles (Medical Education) > 임상교육(Clerkship & Residency)' 카테고리의 다른 글

| 질환 스크립트의 30년: 이론적 기원과 실제적 적용(Med Teach, 2015) (0) | 2023.02.03 |

|---|---|

| 눈치보기: 의학 수련과정에서 과소대표된 여성의 경험(Perspect Med Educ. 2022) (0) | 2022.12.15 |

| 신뢰와 위험: 의학교육을 위한 모델 (Med Educ, 2017) (0) | 2022.11.06 |

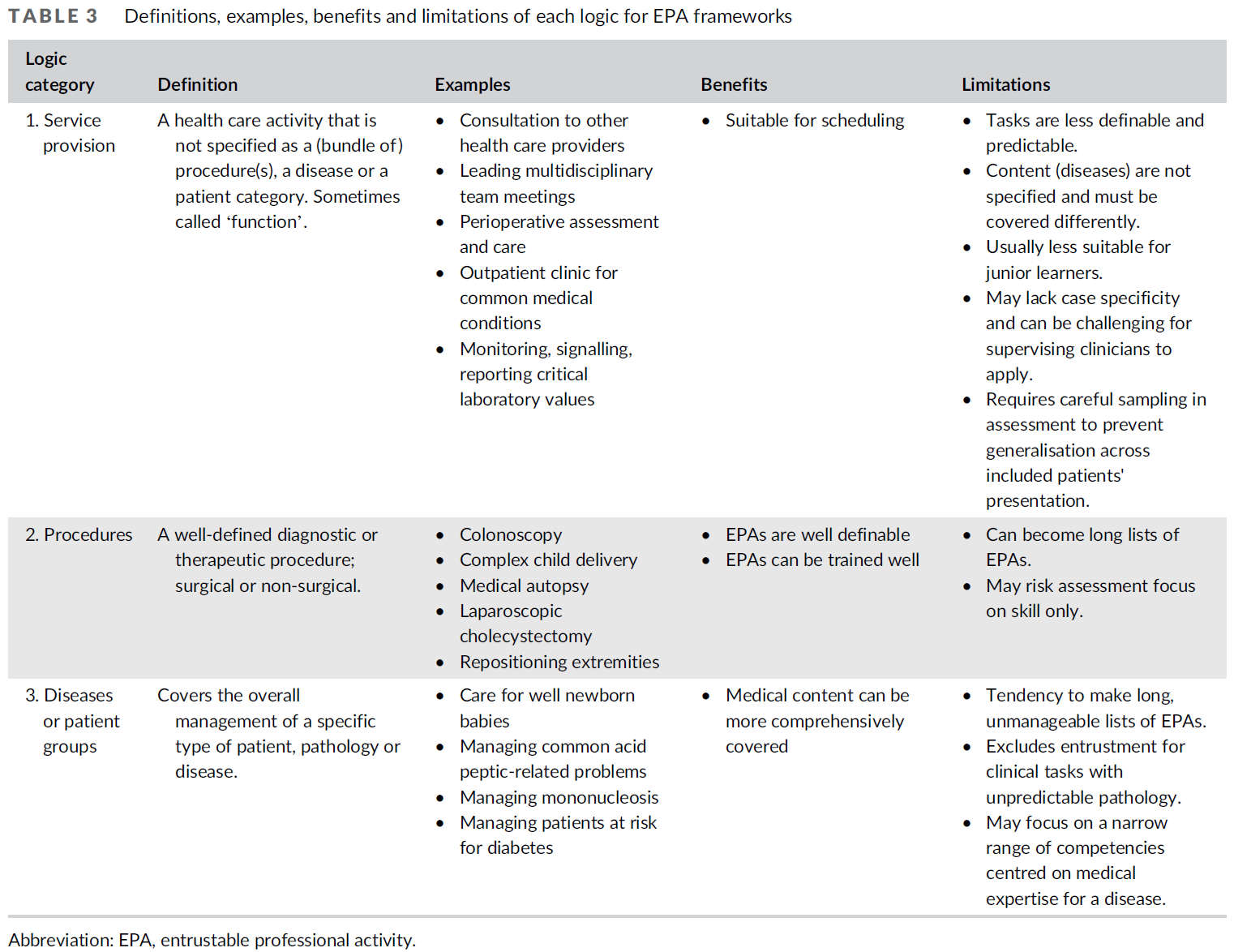

| EPA 프레임워크의 논리와의 고군분투 (Med Educ, 2022) (0) | 2022.11.06 |

| EPA 프레임워크의 논리: 스코핑 리뷰 (Med Educ, 2022) (0) | 2022.11.05 |