학습자 동기부여를 촉진하기 위한 임상교육자의 가이드(AMEE Guide No. 137) (Med Teach, 2020)

The clinical educator’s guide to fostering learner motivation: AMEE Guide No. 137

Kayley M. Lyonsa , Jeff J. Cainb , Stuart T. Hainesc , Danijela Gasevicd and Tina P. Brocka

서론

Introduction

학습자의 의욕은, 학생으로부터 프로페셔널에 이르기까지, 그리고 강의실에서 시뮬레이션 실험실, 임상 배치에 이르기까지, 모든 교육 레벨에서 필수적입니다. 배우고자 하는 욕구가 없으면 학습자는 학습에 필요한 노력을 기울이지 않을 것이다. 강한 의욕을 가진 사람들은 더 많은 노력을 기울일 뿐만 아니라, 도전적인 개념이나 기술을 배울 때 생기는 불가피한 좌절에도 더 탄력적이다. 교실 안팎의 임상교육자는 학습활동 설계, 교육전략의 실시 및 긍정적인 학습환경의 조성을 통해 학습자의 동기부여에 중요한 역할을 합니다. 예를 들어, 건강 전문가 학생은 다양한 업무, 관리자의 열정, 그리고 그들이 받은 피드백의 질로 인해 배치에 더 많은 동기를 부여할 수 있습니다. 이 동기 부여로 인해 학생은 더 많은 책을 읽고, 추가적인 학습 활동에 참여하고, 더 나은 질문을 할 수 있습니다.

Learner motivation is essential at every level of education, from student to professional, and in every setting, from lecture halls to simulation laboratories to clinical placements. Without a desire to learn, learners will not put forth the necessary effort to learn (Bandura 1977; Cook and Artino 2016). Not only do individuals with strong motivation put forth more effort, but also they are more resilient to the inevitable setbacks that arise when learning challenging concepts or skills. Clinical educators, within and outside the classroom walls, play a key role in learner motivation through the design of the learning activities, implementation of instructional strategies, and creation of positive learning environments (Kusurkar et al. 2011b). For instance, a health professional student may find a placement more motivating due to the variety of tasks, enthusiasm of the supervisor, and quality of feedback they received. This motivation then may lead the student to read more, engage in additional learning activities, and ask better questions.

학습 과정에서 학습자의 노력, 관심 및 소유권에 영향을 미치는 것을 이해하려는 몇 가지 동기 부여 이론이 있습니다.

There are several motivation theories that attempt to understand what influences learner effort, interest, and ownership in the learning process.

- 자기결정이론은 학습자의 자율성(자신의 행동에 대한 통제), 역량(자기효율성), 관계성(소속감 및 유대감)에 대한 요구가 충족될 때 내적 동기부여가 촉진된다고 가정한다(Ryan과 Deci 2000b).

- 목표 지향 이론은 학습자의 성취 동기 부여에 영향을 미치는 것을 중심으로 합니다. 성과 목표(예: 높은 성적 획득)를 지향할 때, 학습자는 주로 다른 사람의 판단(예: 교육자의 평가)에 관심을 갖는다. 이와는 대조적으로, 숙달 목표 지향의 학습자는 학습한 내용의 본질적 가치에 의해 동기 부여됩니다.

- 귀인 이론은 학습자의 성공과 실패에 대한 해석이 중요하다는 것을 시사한다. 학습자들은 다양한 정도의 성공 또는 실패를 개인적인 노력, 타고난 능력, 다른 사람, 그리고 운 탓으로 돌린다. 이러한 속성은 차례로 미래의 성공 가능성에 대한 그들의 미래 믿음에 영향을 미친다(Weiner 1985).

- 기대-가치-비용 이론에 따르면, 동기 부여는 학습자가 성공할 것이라고 믿고(기대), 과제를 중요하게 인식하고(가치), 과제와 관련된 단점(비용)을 고려하는 정도에 의해 영향을 받는다(Barron and Hulleman 2015).

- 상황학습이론Situative learning theory은 학생들이 사회적 지위에 대한 욕구에 의해 동기부여를 받는다고 가정한다. 상황 학습 이론에서 중요한 것은 의료 공동체에서 존경받는 구성원이 되고자 하는 학습자의 욕구를 이용하는 것이다.

- Self-determination theory posits that internal motivation is fostered when learners’ needs are met for autonomy (control over one’s actions), competence (self-efficacy), and relatedness (sense of belonging and connectedness) (Ryan and Deci 2000b).

- Goal-orientation theory centers around what influences the learners’ motivations for achievement. When oriented toward performance goals (e.g. earning high grades), learners are primarily concerned about the judgment of others (e.g. the educator’s evaluation). In contrast, learners with a mastery goal orientation, are motivated by the intrinsic value of what is being learned (Elliot and Hulleman 2017).

- Attribution theory suggests that learners’ interpretations of their successes and failures are what matters. Learners attribute success or failure in varying degrees to personal effort, innate ability, other people, and luck. These attributions, in turn, influence their future belief in the likelihood of their future success (Weiner 1985).

- According to expectancy value cost theory, motivation is influenced by the degree to which the learner believes they will be successful (expectancy), perceives the task as important (value), and considers the task-related downsides (costs) (Barron and Hulleman 2015).

- Situative learning theory postulates that students are motivated by a desire for social standing. What matters in situative learning theory is tapping into the learner’s desire to be a respected member of the health care community (Lave and Wenger 1991).

학습자의 동기를 최적화하는 '실버블릿' 전략은 없지만, 70년 이상의 연구를 통해 학습자의 동기 부여에 대한 설득력 있는 증거가 제시되었습니다. 학습 의욕은 궁극적으로 학습자의 책임이지만, 교육자는 학습자의 동기 부여에 중요한 역할을 합니다. 저자는 스토리 사용, 사고방식 개입, 강사-학습자 관계 개선 등 학습자 동기를 높이기 위해 설계된 수많은 교육 개입을 요약했다(Lin-Siegler et al. 2016). 강사가 성공적으로 적용한 다른 전술로는 교육용 게임 사용(Klein과 Freitag 1991), 학습자와 관련된 콘텐츠 만들기(Frymier와 Shulman 1995), 관심을 끌기 위한 개념 트리 구현(Hirumi와 Bowers 1991) 등이 있다.

Although there is no ‘silver bullet’ strategy to optimise learner motivation, over 70 years of research has produced persuasive evidence on what motivates learners (Maslow 1943; Bandura 1977; Lepper et al. 2005; Cook and Artino 2016). Motivation to learn is ultimately the responsibility of learners; however, educators play an important role in influencing learner motivation. Authors have summarized numerous instructional interventions designed to increase learner motivation, including the use of stories, mindset interventions, and improving instructor-learner relationships (Lin-Siegler et al. 2016). Other tactics that instructors have applied successfully include using an instructional game (Klein and Freitag 1991), focusing on making content relevant to learners (Frymier and Shulman 1995), and implementing concept trees to gain attention (Hirumi and Bowers 1991).

임상 교육자의 과제

The challenge for clinical educators

보건 전문가 교육은 이론 기반의 입증된 학습 동기 부여 전략을 더 많이 적용하는 것으로부터 이익을 얻을 수 있습니다. 그러나, 학생 동기 부여 문헌의 대부분은 전문 용어에 익숙하고 학습 이론을 해석하는 데 익숙한 교육 심리학 독자들을 대상으로 하고 있다. 따라서 동기 이론과 연구는 많은 임상학 교육자들에게 덜 다가갈 수 있습니다. 또한, 학생 동기 부여 문헌은 크고 중복된다. 새로운 임상 교육자가 각각의 동기 이론이 학습 이론의 더 넓은 그림에 어떻게 들어맞는지 이해하는 것은 어려울 것이다. 또한, 임상 교육자는 다양한 교육 전략을 알고 있을 뿐만 아니라 각 교육 전략에 대해 누가, 무엇을, 어디서, 언제, 왜, 어떻게 이해해야 합니다. 이건 너무 벅찰 수 있어요.

Health professions education would benefit from a greater application of theory-based, research-proven learning motivation strategies. However, much of the student motivation literature is directed at an educational psychology audience who is familiar with the professional jargon and is comfortable with interpreting learning theory. Thus, motivation theory and research may be less approachable for many clinician educators. Also, student motivation literature is large and overlapping. It would be difficult for a new clinical educator to understand how each motivation theory fits into the broader picture of learning theories. Furthermore, to be successful, clinical educators need to not only know of a wide variety of instructional strategies, but also have an understanding of the who, what, where, when, why, and how for each instructional strategy. This can be overwhelming.

모티베이션 이론에 익숙한 은유 적용

Applying familiar metaphor to motivation theory

모티베이션 이론과 연구를 보다 접근하기 쉽게 하기 위해 모티베이션 이론과 연구를 의료 전문가에게 친숙한 언어로 번역했습니다. 약물요법 논문과 마찬가지로, 학생의 의욕을 촉진하기 위한 개입을 그 징후, 행동 메커니즘, 투여, 투여, 부작용, 모니터링 등을 기술한 전략 논문으로 분류했다. 표 1은 이들 용어를 비교한 것입니다.

To make motivation theory and research more approachable, we have translated motivation theory and research into language familiar to health professionals. Similar to medicine treatment monographs in drug compendia, we have categorized interventions for fostering student motivation into strategy monographs describing their indications, mechanism of action, administration, dosing, side effects, and monitoring. Table 1 compares these terminologies.

우리와 많은 다른 사람들은 과학을 배우는 것이 임상 과학보다 문화적이고 맥락에 의존적이라고 주장하지만(Brown et al. 1989), 임상 교육자들은 임상 과학에 대한 이해를 동기 부여 과학에 적용할 수 있다. 단순화하자면, 동기 부여는 소스, 프로세스, 영향력자 및 결과의 시스템으로 볼 수 있습니다. 동기 부여 결과(예: 노력)를 개선하는 최선의 방법은 [학습자 동기 부여와 관련된 요소를 신중하게 평가하고 목표로 하는 것]이다. 동기 부여에서 학습자의 행동과 관련된 요소는 학습, 과제, 환경, 동료 및 교육자에 대한 믿음일 수 있습니다. 예를 들어, 학생은 1차 진료에서 실습하기를 원하지만 중환자실에 대한 학습이 자신의 미래에 얼마나 중요한지 알지 못하기 때문에 중환자실 배치에 최소한의 노력을 기울일 수 있다. 따라서 의료 처치를 환자의 특징과 선호도에 맞게 개인화하는 것과 마찬가지로, 학습자의 동기를 개선하기 위한 전략은 시간이 지남에 따라 개인화되고 수정되어야 한다. 한 시점에서 학생에게 흥미를 주는 것은, 다른 시점에서는 효과가 없을지도 모른다. 한 학생에게 흥미로운 것은 다른 학생에게는 흥미롭지 않을 수 있다. 따라서 교육자는 학습자의 동기부여를 촉진하기 위한 전술의 종류뿐만 아니라 이러한 전술이 왜 어떻게 작동하는지 이해하는 것도 중요합니다.

Although we and many others argue that learning science is more cultural and context-dependent than clinical science (Brown et al. 1989), clinical educators can still apply their understanding of clinical science to the science of motivation. As a simplification, motivation can be viewed as systems of sources, processes, influencers, and outcomes. The best way to improve motivational outcomes (e.g. effort) is to carefully evaluate and target the factors related to learner motivation (Harackiewicz and Priniski 2018). In motivation, the factors related to learners’ behaviours may be their beliefs around learning, the task, the environment, their peers, and the educator. For example, a student may be putting forth minimum effort on a critical care placement because they want to practice in primary care and do not see how the learning about critical care will be important to their future. Therefore, akin to how medical treatments should be personalized to patient characteristics and preferences, strategies to improve learner motivation must be personalized and modified over time. What may engage students one day, may not work the next. What is interesting to one student, may not be interesting to another. Therefore, it is crucial for educators to not only know the types of tactics for fostering learner motivation but also to understand why and how these tactics work.

임상 교육자를 지원하기 위해 학습자의 동기를 촉진하는 개입을 Vansteenkiste 등의 작업에 따라 부분적으로 세 그룹으로 분류했다. 마찬가지로, 이러한 개입은 다양한 경로를 통해 학습자의 동기를 목표로 한다.

- 동기 부여 강도 증가— 특정 행동에 대한 학습자 [동기 부여 상태(강력, 양)]를 증가시키기 위한 개입

- 동기 부여 퀄리티 향상— 학습자의 [동기 부여 유형(즉, 활동에 참여하는 이유)]에 영향을 미치는 개입

- 동기 부여 노하우 향상— 자신의 동기 부여를 위한 [전술과 전략에 대한 학습자의 지식]을 높이기 위한 개입(즉, 동기 부여 규제 전략).

To assist clinical educators, we have categorized interventions that foster learner motivation into three groups based, in part, by work from Vansteenkiste et al. (2009). In the same way, these interventions target learner motivation via different pathways:

- Increasing motivation intensity—includes interventions to increase (i.e. strength, quantity) learner motivational state, willingness, and behaviour for a specific action (Vansteenkiste et al. 2009)

- Enhancing motivation quality—includes interventions to influence the type of motivation for the learner (i.e. why they are engaged in the activity).

- Improving motivation know-how—includes interventions to increase learner knowledge of tactics and strategies for motivating oneself (i.e. motivation regulation strategies).

다음 섹션에서는 기원, 메커니즘 및 결과를 포함한 각 치료 클래스의 기본 이론을 설명한다. 교육자가 사용할 수 있는 구체적인 전략(즉, 개입)과 이를 뒷받침하는 근거를 개략적으로 설명합니다. 임상 교육자가 다양한 환경(즉, 임상 배치, 강의실 및 온라인 학습)에서 개입을 구현하는 방법의 예를 설명한다. 각 섹션의 대응표에는 주요 용어, 표시, 일반 관리, 행동 메커니즘, 투여, 부작용, 모니터링이 정리되어 있다.

In the following sections, we describe the underlying theories of each therapeutic class including origins, mechanisms, and outcomes. We outline specific strategies (i.e. interventions) educators can use and the evidence to support them. We describe examples of how clinical educators may implement the interventions in different settings (i.e. clinical placements, the classroom, and online learning). In each section’s corresponding table, we outline key terms, indications, general administration, mechanism of action, dosing, side effects, and monitoring.

치료 클래스 1: 동기 부여 강도 증가

Therapeutic class 1: increasing motivation intensity

개요 및 이론적 기초

Overview and theoretical underpinnings

학습자 동기 부여의 강도(즉, 강도)는 다음에 의해 결정됩니다.

- 동기 부여 상태(예: '동기부여된 느낌이에요'),

- 특정 행동을 보여주는 것(예: 참여)

- 동기 부여 신념과 인식(예: '잘 할 자신이 있다')

The strength (i.e. intensity) of learner motivation is determined by

- the motivational state (e.g. ‘I feel motivated’),

- displaying certain behaviours (e.g. participation), and

- holding motivational beliefs and perceptions (e.g. ‘I’m confident I will do well’).

[동기부여의 신념과 인식]은 다음과 같습니다.

Motivational beliefs and perceptions include:

- 학습자의 과제 난이도 인식(McCaslin 및 Hickey 2001)

- 과제의 중요성 (Wigfield 등 2017)

- 교육자 배려에 대한 인식(1998년 Wentzel 및 Wigfield)

- 학습자 흥미 (Renninger 및 Hidi 2011)

- 자기 능력에 대한 인식 (Schunk and Pajares 2005).

- Learner perceptions of task difficulty (McCaslin and Hickey 2001)

- Task importance (Wigfield et al. 2017)

- Perceptions of educator caring (Wentzel and Wigfield 1998)

- Learner interest (Renninger and Hidi 2011)

- Perceptions of self-competence (Schunk and Pajares 2005).

긍정적인 [동기 부여 신념과 인식]은 [동기 부여 상태, 참여 및 행동]으로 이어집니다.

- [동기부여 신념과 인식]이 최적화되면 학습자는 학습에 대한 심층적 접근법을 사용하여 자신의 학습을 적응적으로 조절합니다. 예를 들어, 주제(예: 심장학)에 대한 관심이 발달한 학습자는 행동적으로 참여(예: 추가 자료 읽기)하고 해당 주제에 대한 미래 기회를 모색할 가능성이 높다. 학습자는 프롬프트 없이 질병 상태에 대해 읽고 추가적인 연습 기회를 요청할 수 있습니다.

- [동기부여 상태와 행동]은 또한 [가르침instruction]과 [학습자 성취] 사이의 중재자 역할을 합니다. 예를 들어, 행동 참여도가 높은 학습자는 더 높은 점수와 시험 점수를 달성하고 인턴쉽을 달성하며 환자 치료에 긍정적인 영향을 미칠 수 있다.

- [동기부여 신념과 인식]은 노력, 지속성 및 선택을 직접 예측하며, 이는 학교, 직장, 사회 환경 및 일상생활에서의 성공을 예측합니다(Marsh et al. 2017).

Positive motivational beliefs and perceptions lead to heightened motivational states, engagement, and behaviours (Wigfield and Guthrie 2000).

- When motivational beliefs and perceptions are optimized, learners use a deeper approach to learning (Heikkilä and Lonka 2006) and adaptively regulate their own learning (Paris and Turner 1994). For example, a learner with a developed interest in a subject (e.g. cardiology) is more likely to be behaviourally engaged (e.g. reading additional materials) and seek future opportunities in that subject (Renninger and Bachrach 2015). The learner might read about a disease state without prompting and ask for additional practice opportunities.

- Motivational states and behaviours also serve as a mediator between instruction and learner achievement (Wigfield and Guthrie 2000). For example, a learner with more behavioural engagement may then achieve higher marks and test scores, attain an internship, and positively affect the care of patients.

- Motivational beliefs and cognitions directly predict effort, persistence, and choices (Wigfield et al. 2017), which, in turn, predict success in school, the workplace, social settings, and daily living (Marsh et al. 2017).

모티베이션 강도를 높이기 위한 네 가지 개입

Four interventions to increase motivation intensity

동기 부여 강도를 높이기 위해 임상 교육자는 다음을 수행해야 합니다.

- 난이도가 적절한 학습 과제를 제공하다

- 학습자의 호기심과 흥미를 불러일으키다

- 열정을 모델링하고, 감정적 관심을 보여준다

- 과제의 관련성 및 유틸리티를 생성

To increase the level of motivation intensity, clinical educators should:

- Provide optimally challenging learning tasks

- Spark curiosity and interest among learners

- Model enthusiasm and show affective concern

- Create task relevance and utility

학습자 동기 부여의 강도를 높일 수 있는 이 치료 그룹 아래의 네 가지 예시적 개입에 대해서는 보충표 S1을 참조한다. 이 치료 수업에서 다른 개입 유형과 예는 학습자의 관심 증가(Harackiewicz와 Priniski 2018)와 자신의 역량에 대한 인식을 위해 찾을 수 있다.

See Supplementary Table S1 for four exemplary interventions under this therapeutic group that can increase the intensity of learner motivation. Other intervention types and examples, under this therapeutic class, may be found for increasing learner interest (Harackiewicz and Priniski 2018) and perceptions of their own competence (Bandura 1997).

난이도가 적절한 학습 과제를 제공

Providing optimally challenging learning tasks

학습자의 [과제 난이도에 대한 인식]이 중요합니다. 교육자는 학습 과제를 선택하고 설계할 때 너무 쉽지도, 너무 어렵지도 않다는 Goldilocks 원칙을 따라야 합니다.이 원칙은 도전적이면서도 부담스럽지 않아야 합니다. 예를 들어, 배치 감독자는 학생이 검토할 수 있도록 할당한 환자의 수와 복잡성을 최적화하여 학생의 과제가 줄어들수록 난이도를 높일 수 있습니다. 교실에서 교육자는 질문의 난이도를 최적화할 수 있습니다. 과제가 너무 쉬우면 학습자는 지루해지지만 너무 어려워질 수 있습니다. 학습자는 자제하거나 정신적 지름길을 택할 수 있습니다. 이 원칙은 온라인 학습에도 적용된다. 온라인 학습을 설계하는 한 가지 방법은 비디오 게임 이후 온라인 학습을 모델링하는 것이다. 비디오 게임은 학습자가 쉬운 과제를 숙달한 후에 난이도를 높인다. 예를 들어 온라인 모듈은 더 어려운 콘텐츠로 넘어가기 전에 마스터 퀴즈를 요구할 수 있습니다.

Learner perceptions of task difficulty matters (Paris and Turner 1994; McCaslin and Hickey 2001). When selecting and designing learning tasks, educators should follow the Goldilocks Principle of not too easy and not too hard—a task should be challenging, but not overwhelming. For example, placement supervisors could optimize the number and complexity of patients they assign for students to review, assigning more difficulty as the challenge decreases for the student. In the classroom, educators could optimize the difficulty of the questions they ask. If the task is too easy, learners may become bored, yet with too much difficulty; learners may withdraw or take mental shortcuts. This principle is also applicable to online learning. One way to design online learning could be modelling online learning after video games. Video games increase the level of difficulty after learners master easier tasks. For example, an online module could require mastery quizzes before moving onto content that is more difficult and subsequently more difficult quizzes.

최적의 난이도는 '몰입'으로 이어질 수도 있습니다. 이는 학습자가 경험하는 동기 부여의 몰입 상태로서, 시간 감각을 잃는 것이다. 예를 들어, 학습자는 몇 시간 동안 저널 기사를 검색하면서 질문에 대한 답을 찾으려고 열중할 수 있습니다. 학습자가 최적으로 도전적인 과제를 성공시키면, 그 결과는 역량 자기 인식의 증가입니다(예: 자신감, 자기 효율성).

Optimal challenges may also lead to ‘flow’ (Csikszentmihalyi 1997); an absorbing state of motivation that learners experience, losing their sense of time. For example, a learner may become absorbed trying to find an answer to a question, searching journal articles for hours. When a learner succeeds over an optimally challenging task, the result is an increase in their competence self-perceptions (e.g. confidence, self-efficacy) (White 1959; Marsh et al. 2017).

호기심과 흥미를 불러일으키다

Sparking curiosity and interest

학습자의 [관심과 호기심이 유발]되면 개인적 관심사가 잘 발달될 수 있습니다. 교육자는 학습 경험을 시작할 때 참신함, 놀라움 및 토론을 통해 학습자의 흥미를 유발하는 방법을 파악할 수 있습니다. 예를 들어, 임상 감독관이 임상 논쟁을 논의할 때 학습자의 관심이 최고조에 달할 수 있다. 교실 교육자는 학생들이 답을 밝히기 전에 질문에 대한 답을 예측하게 함으로써 놀라움을 줄 수 있습니다. 온라인 학습에서는 참신함이 자주 사용됩니다. 사실, 새롭게 인식되는 것은 교육 기술에 대한 학습자의 동기를 예측합니다. 그러나 '새로움 효과novelty effect'는 시간이 지날수록 희미해지는 것으로 알려져 있다.

If learner interest and curiosity is triggered, it may lead to well-developed personal interests (Renninger and Hidi 2011). At the beginning of the learning experience, educators may identify ways to spark learner interest through novelty, surprise, and debate. For example, learner interest may be peaked when clinical supervisors discuss clinical controversies. Classroom educators can create surprises by having students predict answers to questions before they reveal the answer. For online learning, novelty is often used. In fact, perceived novelty predicts learner motivation for education technology. However, the ‘novelty effect’ is known to fade over time (Jeno et al. 2019).

열정 모델링 및 정서적 관심 표시

Modelling enthusiasm and showing affective concern

[교육자와의 관계 및 교육자에 대한 인식]으로 인해 학습자의 동기 부여가 증가할 수 있습니다. 학습자는 열정적인 교육자에 대한 선호도를 설명하는 경우가 많습니다(Mitchell 2013). 주제에 대한 관심은 특히 학습자가 그 사람을 존중하거나 관련시킬 때 전염될 수 있습니다. 일화적으로, 많은 학습자들이 전직 교사의 열정 때문에 직업, 특기 또는 연습 환경을 선택했다고 말한다. 많은 교육자들은 그들이 왜 어떤 주제를 즐기거나 그것이 중요하다고 믿는지에 대해 이야기를 나눌 때 그들의 열정을 드러낸다. 예를 들어, 많은 학습자들은 그들의 학습을 실제 환자들과 연결하는 이야기에 감동합니다.

Learner motivation may increase due to their relationship with and perceptions of the educator. Learners often describe their preference for enthusiastic educators (Mitchell 2013). An interest in a topic can be contagious, especially when the learner respects or relates to that person. Anecdotally, many learners indicate they chose a profession, specialty, or practice setting due to a former teacher’s passion. Many educators often reveal their enthusiasm when they share their stories for why they enjoy a topic or believe it is important. For example, many learners are moved by stories connecting their learning to real patients.

교육자-학습자 관계의 또 다른 동기부여 측면은 학습자가 자신의 [교육자가 자신의 행복을 얼마나 아끼고 있는지]를 믿는 것입니다. 학습자는 교육자가 인간으로서 자신을 돌본다고 믿을 때 무의식적으로 존엄성과 소속감을 느낀다. 품위와 소속감은 학생 동기 부여의 기본이다. 품위나 소속감이 없다면, 학습자들은 주저하고 학습 주제나 환경이 '그들에게 맞지 않는다'고 생각하기 쉽다. 임상 현장에서 임상 교육자는 학생들을 체크하고 어떻게 지내는지 물어봄으로써 보살핌을 보여줄 수 있다. 강의실 교육자는 학생들의 학업과 시간 관리에 대한 압박감을 이해한다는 것을 보여줄 수 있습니다.

Another motivating aspect of the educator–learner relationship is how much a learner believes their educator cares for their well-being. Learners subconsciously feel dignity and belonging when they believe their educator cares for them as a person (Baumeister and Leary 1995). Dignity and belonging are fundamental to student motivation. Without dignity or belonging, learners are likely to withdraw and think the learning topic or environment is ‘just not for them.’ In clinical placements, clinical educators could show caring by checking in with students and asking them how they are doing. Classroom educators could show they understand students’ studying and time management pressures.

과제 관련성 및 유틸리티 생성

Creating task relevancy and utility

학습 과제의 관련성과 유용성에 대한 학습자의 인식이 동기 부여의 강도를 결정합니다. 학습자는 과제 가치에 대한 인식을 가지며, 다음을 통해 판단됩니다.

- 달성 가치 — 성공에 대한 상대적 중요성

- 효용 가치 — 미래에 대한 중요성

- 내재적 가치 — 작업에서 오는 지속적인 즐거움

The learner’s perceptions of the relevance and usefulness of the learning task determine the strength of their motivation (Eccles et al. 2005). Learners perceptions of task value and are determined by:

- Attainment value—relative importance for succeeding

- Utility value—importance for the future

- Intrinsic value—inherent enjoyment from task

흔히 볼 수 있는 관행과는 달리, 학습자에게 작업의 가치를 말해주기 보다는 보여주는 것이 중요합니다. 학습자에게 과제의 중요성을 "말하면" 역효과가 날 수 있습니다. 대신 임상 교육자는 중요성을 보여주거나 학습자가 과제의 가치를 옹호하도록 해야 합니다. 예를 들어, 임상 교육자는 포괄적인 환자 기록을 가져가고 이것이 어떻게 환자 결과를 향상시키는지 보여줄 수 있다. 강의실 교사 또는 교육 기술은 학습자가 주제 또는 과제가 현재 삶 또는 미래에 중요한 이유를 묻는 질문에 응답하도록 할 수 있습니다(즉, 학습자가 과제 가치를 옹호하도록 함).

Contrary to commonly seen practices, it is important to show learners the value of the task rather than tell them. Telling learners the importance of the task can backfire (Harackiewicz and Priniski 2018). Instead, clinical educators should either show the importance or have the learner advocate for the task’s value. For example, a clinical educator might demonstrate taking a comprehensive patient history and show how this led to an improved patient outcome. A classroom teacher or educational technology could have learners respond to prompts asking them why a topic or task is important to their current lives or their future (i.e. have learners advocate for task value).

치료 클래스 2: 동기 부여 품질 향상

Therapeutic class 2: enhancing motivation quality

개요 및 이론적 기초

Overview and theoretical underpinnings

학습자 모티베이션의 질은 학습자의 사고방식, 목표의 원천 및 능력에 대한 속성에 따라 결정됩니다. 동기 부여의 질은 참여, 노력, 지속성 및 장기적인 성과와 관련이 있습니다. 동기 부여 품질을 향상시키는 개입은 학습자의 학습 능력을 향상시킵니다.

- 역량의 가단성에 대한 신념(성장 마인드) (Dweck and Molden 2017)

- 자율성(예: 내적 동기 부여) (Ryan 및 Deci 2000b)

- 성과 목표와 균형을 이룬 내용 숙달을 향한 열망(즉, 숙달 목표와 성과 목표 지향) (Elliot 및 Hulleman 2017)

- 전문직 또는 학교 내에서의 정체성 형성(1991년 Lave 및 Wenger)

- 소속감 (1995년 바우미스터와 리어리)

- 노력과 전략이 학업 실패/성공과 인과 관계가 있다는 믿음(즉, 적응적 인과 귀인)(Perry and Hamm 2017).

The quality of learner motivation is determined by learners’ mindsets, sources for goals, and attributions for their competence. Motivation quality is associated with engagement, effort, persistence, and long-term achievement. Interventions that enhance motivation quality increase the learner’s:

- Belief that competence is malleable (i.e. growth mindset) (Dweck and Molden 2017)

- Autonomy (e.g. intrinsic motivation) (Ryan and Deci 2000b)

- Desire to achieve content mastery balanced with a focus on performance goals (i.e. mastery and performance approach goal orientation) (Elliot and Hulleman 2017), and

- Identity formation within a profession or school (Lave and Wenger 1991),

- Feelings of belonging (Baumeister and Leary 1995)

- Belief that their effort and strategy are causally related to their academic failures and successes (i.e. adaptive causal attributions) (Perry and Hamm 2017).

종종 학습자 [동기 부여의 질적 변화]는 [동기 부여 강도의 증가]와 관련이 있으며, 이는 다시 성과를 예측한다. 예를 들어,

- 내재적 동기(즉, 퀄리티)는 흥미, 흥분, 역량 자기 인식(즉, 강도)을 예측하여 [더 높은 지속성과 더 높은 성과]로 이어집니다.

- [목표 지향]은 [학습자가 학습 과제, 행동 및 전략을 인식하고 경험하고 선택하는 방법]에 영향을 미칩니다.

- 또한, [인과 귀인]은 [미래의 노력, 지속성 및 성과]를 결정합니다.

Often a shift in the quality of learner motivation is associated with increased motivation intensity, which in turn predicts performance.

- For example, intrinsic motivation (i.e. quality) predicts interest, excitement, competence self-perceptions (i.e. intensity) that leads to greater persistence and higher performance (Ryan and Deci 2000b).

- Goal orientations affect how learners perceive, experience, and choose learning tasks, behaviours, and strategies (Elliot and Hulleman 2017).

- Also, causal attributions determine future effort, persistence, and performance (Perry and Hamm 2017).

모티베이션 품질을 높이기 위한 네 가지 개입

Four interventions to enhance motivation quality

학습자 동기 부여의 질을 높이기 위해 교육자는 다음을 수행해야 한다.

- [자율성 촉진 및 구조화]

- 학습자의 [정체성 모순]을 해소

- 과제를 [일반적이고 개선 가능한 것]으로 프레이밍

- 목표에 대한 [숙달적 접근]을 유도

To elicit a higher quality of learner motivation, educators should:

- Promote autonomy and structure

- Address learner identity contraindications

- Frame academic challenges as common and improvable

- Elicit a mastery approach to learning goals

학습자 동기 부여의 질을 높일 수 있는 이 치료 그룹 아래의 네 가지 예시적 개입에 대해서는 보충표 S2를 참조한다. 권한과 책임의 균형, 학습자가 학문적 성공과 실패를 해석하는 방법, 내재적 동기를 높이기 위한 전술, 전문 커뮤니티 내에서 학습자의 정체성을 확립하는 다른 개입 유형 및 사례를 찾을 수 있습니다.

See Supplementary Table S2 for four exemplary interventions under this therapeutic group that can enhance the quality of learner motivation. Other intervention types and examples may be found for balancing authority with accountability (Engle and Conant 2002), re-training how learners interpret academic successes and failures (Weiner 1985), tactics to increase intrinsic motivation (Kusurkar et al. 2011a) and establishing an identity for learners within a professional community (Lave and Wenger 1991).

자율성·구조화 추진

Promoting autonomy and structure

자율성과 구조를 촉진하는 전략은 외적, 내적 동기 부여에 영향을 미칩니다.

- 외재적 동기 부여는 학습에 참여하려는 동기가 활동 외부에 있는 경우입니다.

- 내재적 동기 부여는 학습자가 활동을 본질적으로 만족스럽고 흥미롭고 즐거운 것으로 볼 때 더 높은 품질의 동기 부여 유형입니다.

Strategies to promote autonomy and structure influence extrinsic and intrinsic motivation.

- Extrinsic motivation is when the motive to engage in learning is external to the activity (Ryan and Deci 2000a).

- Intrinsic motivation, a higher quality type of motivation, is when the learner views activities as inherently satisfying, interesting, and enjoyable.

학생들이 모든 학습 활동에 의해 내재적 동기를 부여받을 것이라고 믿는 것은 비현실적이다. 교육자는 학습자가 내재적 동기 부여를 받은 학습자와 유사한 방식으로 행동하도록 유도하는 외재적 동기 부여자motivator를 제공할 수 있습니다(Ryan 및 Deci 2000b). 외재적 동기는 연속체에서 발생한다.

- 한 끝에서 학습자는 [외적인 보상이나 처벌 회피]에 의해서 동기 부여되며, 활동에 내재된 가치를 느끼지 못합니다.

- 다른 끝에서 학습자는 [활동의 본질적 가치]를 분명히 인식하지만, 외부적 보상이 없을 때 자발적으로 활동을 시작하지는 않을 것이다.

학습 태스크에 대한 자율성과 선택의 폭을 넓힘으로써 학습자는 자신의 고유한 관심사에 따라 이러한 활동을 구체화할 수 있습니다(Ryan 및 Deci 2000b).

It is unrealistic to believe that students will be intrinsically motivated by all learning activities. Educators can provide extrinsic motivators that prompt learners to behave in ways that are similar to learners who are intrinsically motivated (Ryan and Deci 2000b). Extrinsic motivation occurs on a continuum.

- At one extreme, the learner is only motivated by the extrinsic reward or avoidance of punishment and sees no inherent value in the activity.

- At the other end of the continuum, the learner clearly sees the intrinsic value of the activity, but would not otherwise voluntarily initiate the activity in the absence of an extrinsic reward.

Offering greater autonomy and choice over learning tasks allows learners the opportunity to shape these activities around their intrinsic interests (Ryan and Deci 2000b).

보다 자율적인 형태의 외적 동기를 유도하기 위해, 교육자들은 [구조를 제공]하면서 학습자의 [자율성을 촉진]해야 한다. 이 두 가지 교육 방식은 antagonistic하지 않다. 예를 들어,

- 임상에서는 수련생이 어떤 환자를 따르길 원하는지 선택할 수 있도록 허용할 수 있다(즉, 자율성). 그런 다음 수련생이 선택한 환자(즉, 구조)에 따라 자원을 사용하도록 지시할 수 있다.

- 교실에서는 학생들이 자료를 배우고 성공하기 위해(구조) 적용할 수 있는 효과적인 학습 전략의 몇 가지 유형(즉, 자율성)을 설명할 수 있다.

- 온라인 플랫폼에서는 교육자가 단계별 지시(구조)를 제공하고 학습자가 이를 자신의 이익에 적용할 수 있는 유연성(자율)을 가질 수 있습니다.

To elicit more autonomous forms of extrinsic motivation, educators should promote learner autonomy while providing structure (Jang et al. 2010). These two instructional styles are not antagonistic (Jang et al. 2010).

- For example, a clinical supervisor may allow a trainee to choose which patients they would like to follow (i.e. autonomy) and then direct the trainee to resources depending on their choice (i.e. structure).

- In the classroom, an educator could describe several types (i.e. autonomy) of effective learning strategies that students could apply to learn the material and succeed (i.e. structure).

- In an online platform, educators could provide step by step directions (i.e. structure) and allow learners’ the flexibility to apply these to their own interests (i.e. autonomy).

학습자 정체성 모순 해결

Addressing learner identity contradictions

학습자 동기 부여의 가장 큰 요인 중 하나는 master practitioner로서의 정체성입니다. 학습자들은 미래 보건의료전문직으로서의 정체성을 지속적으로 형성하고 있으며, 보건의료전문직이 되는 것이 무엇을 의미하는지, 그리고 '좋은' 보건의료전문직이 되는 것이 무엇을 의미하는지를 생각한다. 이러한 자기-내레이션은 학생들이 취하는 연습과 그들이 내리는 결정에 영향을 미친다.

One of the largest drivers of learner motivation is their evolving identity as a master practitioner (Lave and Wenger 1991; McCaslin and Hickey 2001). Learners are continually forming their identity as a future health professional, what it means to be a health professional (e.g. a nurse, pharmacist), and what it means to be a ‘good’ health professional. These self-narrations influence the practices students take up and the decisions they make (Turner et al. 2014).

[모순]은 정체성 발달에 필수적이다. 교육환경과 누군가의 정체성 사이에는 모순이 있을 수 있다. 예를 들어, 만약 테크놀로지에 능숙하지 않다고 생각하면, 온라인 학습에 저항할 수 있다. 또한 학습자는 강의실이나 임상 환경 등 서로 다른 상황 간의 모순을 볼 수 있습니다. 보건 전문직 학생들은 궁극적으로 자신들을 미래의 의료종사자로 생각하기 때문에, 그들은 그들이 생각하는 어떤 수업 활동도 [관행의 규범에 위배된다고 생각한다면] 무시할 가능성이 높다. 교육자들은 그들이 교실에서 조언하는 것과 학생들이 실제로 관찰할 수 있는 것 사이의 모순에 대처하는 것이 중요하다. 임상실습에서 감독관은 [자신의 환경 또는 전문성]과 [학습자가 스스로를 구성원으로 간주하는 환경 또는 전문성] 사이의 모순을 해결할 수 있습니다. 예를 들어, 감염증의 임상 감독관은 덜 전문화된 진료 환경(예: 일차 진료소)에 대한 감염병 지식의 가치를 학습자에게 설명할 수 있다.

Contradictions are vital to identity development. There can be contradictions between an education setting and someone’s identity. For instance, if someone believes they are not adept at technology, they may resist online learning. Also, learners may see contradictions between different contexts such as in the classroom and in the clinical setting (Nolen and Ward 2008). As health professions students ultimately see themselves as future practitioners, they are likely to disregard any school activity they perceive contradicts the norms of practice. In the classroom, it is important for educators to address any contradictions between what they advise and what students may observe in practice. In clinical placements, a clinical supervisor may address contradictions between their setting or specialty and what setting or specialty the learners view themselves as a member. For example, a clinical supervisor in infectious disease may explain to their learners the value of infectious disease knowledge for less specialized practice settings (e.g. primary clinic).

학업 과제를 일반적이고 개선 가능한 것으로 구성

Framing academic challenges as common and improvable

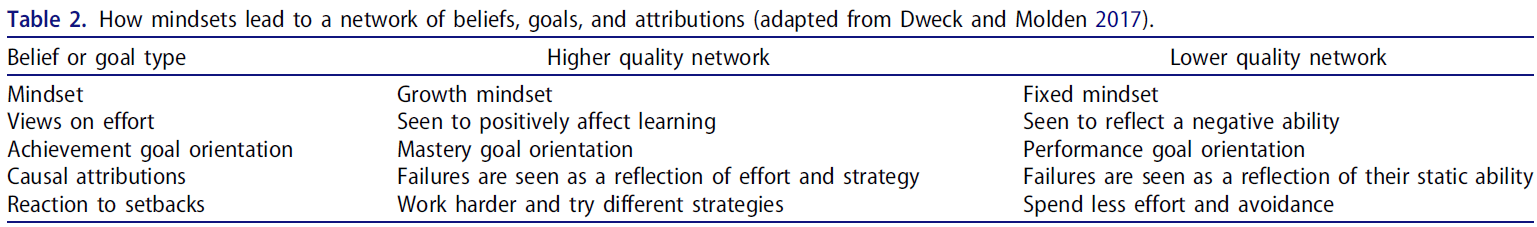

교육자들은 성장 마인드를 이끌어내기 위해 [학업적 도전을 흔하고 개선 가능한 것]으로 프레이밍해야 합니다. 성장 마음가짐이란 학습자가 더 많은 노력과 더 나은 전략이 성과를 향상시킬 것이라고 믿는 것입니다. 반면 고정 마음가짐은 역량은 정적이며 학습자는 잘 수행하거나 잘하지 못할 수 있다는 믿음입니다. 학습자는 노력을 긍정적으로 보고 더 깊은 학습 전략(예: 자가 테스트)을 사용할 용의가 있기 때문에 성장 마인드는 더 높은 품질의 동기 부여로 이어집니다. 사고방식은 동기부여 목적과 신념의 네트워크를 형성한다. 표 2를 참조해 주세요.

Educators should frame academic challenges as common and improvable to elicit a growth mindset (Dweck and Molden 2017). A growth mindset is when the learner believes, often unconsciously, that greater effort and better strategies will enhance their performance. A fixed mindset, in contrast, is the belief that competence is static and that learners either have the ability to perform well or not. A growth mindset leads to higher quality motivation because learners view effort positively and are willing to use deeper learning strategies (e.g. self-testing) (Blackwell et al. 2007). Mindsets shape a network of motivational goals and beliefs. See Table 2.

교육자는 교육생에 대한 피드백을 통해 학업 과제를 구상합니다. 학습자의 현재 과제와 관련하여 흔한coomon 어려움을 설명해줄 수도 있습니다. 예를 들어, 학습자에게 교육자도 학생일 때에는 역시 어려움을 겪었다고 말할 수 있다(예: 거부, 시간 관리 미흡, 항생제 이해 어려움). 또한, 학습자에게 개선할 수 있는 방법에 대한 피드백을 제공하고 학습자가 '아직' 도달하지 못했다는 것을 알려주면 과제는 개선 가능한 것으로 분류될 수 있습니다.

Educators frame academic challenges through their feedback to trainees. They may frame challenges as common by relating to learners’ current challenges. For example, they could tell the learner that they also struggled (e.g. rejection, poor time management, difficulty understanding antibiotics) when they were at the learner’s level. Also, challenges can be framed as improvable by providing learners with feedback on how they can improve and letting learners know they are not there ‘yet.’

숙달 접근적 목표 지향 도출

Eliciting a mastery approach goal orientation

[성취 목표]는 학습자가 역량을 추구하는 근본적인 이유입니다. [성취 목표]는 접근 또는 회피에 맞춰질 수 있습니다. 접근 지향(성공에 접근하는 것)은 회피 지향(실패 회피)보다 더 동기 부여가 된다.

- 접근 목표는 더 나은 수행, 기술 향상 또는 학습 시도와 같은 목표를 향해 노력하는 반면,

- 회피 목표는 학생들의 외모가 나빠지거나 기술이 저하되거나 실패하는 것을 방지하는 것입니다.

Achievement goals are the underlying reasons why learners pursue competence (Elliot and Hulleman 2017). Achievement goals can be oriented toward approach or avoidance. An approach orientation (i.e. approaching success) is more motivating than an avoidance orientation (i.e. avoiding failure).

- Approach goals are striving towards a goal such as performing better, improving skills, or attempting to learn, whereas

- avoidance goals are when students’ motive is to prevent looking bad, a decline in their skills, or failure (Elliot and Hulleman 2017).

예를 들어, 접근 지향을 가진 학생은 '이 과제에서 90%를 받고 싶다'고 말할 것이며, 회피 지향을 가진 학생은 '나는 이 과제에서 나쁜 점수를 받고 싶지 않다'고 말할 것이다.

For example, a student with an approach orientation might approach an assignment by saying ‘I want to get a 90% on this assignment’ compared to a student with an avoidance orientation might say ‘I don’t want to get a bad grade on this assignment.’

달성 목표는 [숙달 지향]과 [성과 지향]으로 더욱 구분됩니다. 숙달 지향이 강한 학습자는 일반적으로 학습 의욕이 더 강합니다. 학생들은 그들의 전문지식을 발전시키기 위해 숙달 목표를 만드는 반면, 성과 지향은 표준에 대한 능력을 달성하거나 증명하려는 욕구로 이어집니다. 예를 들어, 학생은 좋은 점수를 받고 싶어서(즉, 성과 목표) 또는 더 나은 의사가 되고 싶어서(즉, 숙달 목표) 시험을 위해 공부할 수 있습니다.

Achievement goals are further separated into mastery and performance orientations. Learners with a strong mastery orientation are typically more motivated to learn. Students create mastery goals to develop their expertise; whereas performance orientation leads to a desire to attain or demonstrate competence relative to a standard (Elliot and Hulleman 2017). For example, a student may study for a test either because they want to get a good grade (i.e. performance goal) or because they want to become a better physician (i.e. mastery goal).

교육자는 [TARGET 모델]과 학생 중심의 개입을 통해 숙달된 접근 목표의 방향을 도출할 수 있다. 보충표 S2를 참조한다. 교육자들이 숙달된 접근 방식을 도출하는 가장 직접적인 방법 중 하나는 평가를 통해서이다.

- 상벌은 성과 지향성을 이끌어냅니다.

- 개선의 기회는 숙달 지향성을 촉진합니다.

예를 들어, 임상 감독자는 훈련생에게 지속적인 피드백을 제공하고 등급이나 표준이 아닌 전문 지식 개발을 중심으로 개선 기회를 제안할 수 있습니다. 마찬가지로, 교실 교사와 온라인 모듈은 개선을 위한 형성적인 피드백을 제공하는 기준, 단계적 및 중간점 평가를 작성할 수 있습니다.

Educators can elicit a mastery approach goal orientation through the TARGET model (Ames 1992) and student-focused interventions (Elliot and Hulleman 2017). See Supplementary Table S2. One of the most direct ways for educators to elicit a mastery approach orientation is through assessment.

- Rewards and punishments elicit performance orientations.

- Opportunities for improvement foster mastery orientations.

For example, clinical supervisors can provide trainees ongoing feedback and suggest opportunities to improve framed around developing expertise rather than grades or standards. Likewise, classroom teachers and online modules may create baseline, stepwise, and midpoint assessments that provide formative feedback for improvement.

치료 클래스 3: 동기 부여 노하우 향상

Therapeutic class 3: improve motivation know-how

개요 및 이론적 기초

Overview and theoretical underpinnings

학습자는, 학습 과제를 의도적으로 증가시키거나 계속하는 것으로, 동기 부여의 레벨을 조절합니다(Wolters 2003). 동기 부여 노하우는 [학습자의 신념과 동기 부여에 대한 지식]과 관련이 있습니다. 여기에는 [학습자가 학습 동기를 얼마나 중요하게 생각하는지], [동기 부여가 어떻게 증가하고 유지되는지]에 대한 지식이 포함될 수 있습니다. 동기 부여 노하우에는 동기 부여 전략에 대한 지식뿐만 아니라 이러한 전술을 사용하는 방법, 시간 및 이유도 포함됩니다. 예를 들어, 동기부여가 떨어지면, 학습자는 자신에게 그 과제가 왜 중요한지를 상기시킬 수 있다.

Learners regulate their level of motivation by intentionally increasing or sustaining their effort in academic tasks (Wolters 2003). Motivation know-how relates to learners’ beliefs and knowledge of motivation. These may include how important learners believe motivation is for their learning and knowledge of how motivation is increased and sustained. (Wolters and Benzon 2013). Motivation know-how also includes knowledge of motivational strategies, as well as how, when, and why to use these tactics (Veenman et al. 2006). For example, when motivation wanes, learners may remind themselves why the task is important to them.

학습자에게 '노하우'(즉, 동기 규제)를 가르침으로써 학습자는 자신에게 동기를 부여하고, 지속하며, 노력을 늘릴 수 있는 더 나은 장비를 갖추게 될 것이다. 학습자가 적극적으로 동기를 조절하면 다음과 같이 됩니다.

- 향후 행동에 대한 목표를 설정한다(Boekaerts 1996).

- 자신의 동기 부여 상태, 신념 및 행동을 관찰한다(Wolters 및 Benzon 2013).

- 의도적으로 동기부여량을 늘리고, 양질의 동기부여를 유도하는 전략을 수립한다(울터스·벤존 2013)

- 미래의 성과를 조정하기 위한 과거의 동기 부여 상태, 신념 및 행동을 성찰한다(Hadwin et al. 2018).

By teaching learners motivation ‘know-how’ (i.e. motivation regulation), learners will be better equipped to motivate themselves, persist, and increase their effort (Kistner et al. 2010). When learners actively regulate their motivation, they:

- Create goals for their future behaviour (Boekaerts 1996)

- Observe their own motivational states, beliefs, and behaviours (Wolters and Benzon 2013)

- Intentionally enact strategies to increase their motivation quantity and elicit higher quality motivation (Wolters and Benzon 2013)

- Reflect on their past motivational states, beliefs, and behaviours to adjust future performance (Hadwin et al. 2018)

동기 부여 노하우를 개선하기 위한 두 가지 개입

Two interventions to improve motivation know-how

교육자는 다음을 통해 동기 부여 노하우를 개선할 수 있습니다.

- 동기 조절 전략의 교육

- 동기 조절을 모델링

Educators can improve motivation know-how by:

- Teaching motivation regulation strategies

- Modelling motivation regulation

표 3을 참조해 주세요. Wolters and Benzon (2013)은 또한 대학생들이 동기를 부여하기 위해 사용하는 다양한 유형의 전략을 연구하고 개요를 제시했습니다.

See Table 3. Wolters and Benzon (2013) have also studied and outlined different types of strategies that college students use to motivate themselves.

동기 조절 전략의 교육

Teaching motivation regulation strategies

동기부여 조절 전략을 사용함으로써, 학생들은 노력을 기울이고 교육 과제를 완료하려는 의지를 의도적으로 유지하거나 보완합니다. 이러한 전략은 다음과 같이 분류된다.

- 환경 구조화,

- 성과 목표의 조절,

- 숙달 목표의 조절,

- 자기 상벌,

- 가치의 조절

- 관심의 조절

Using motivation regulation strategies, students purposefully maintain or supplement their willingness to exert effort and complete an instructional task (Alexander et al. 1998; Wolters and Benzon 2013). These strategies have been classified as

- environmental structuring,

- regulation of performance goals,

- regulation of mastery goals,

- self-consequating,

- regulation of value, and

- regulation of interest (Wolters and Benzon 2013).

[환경 구조화] 전략에는 산만 제한, 설정 변경, 이상적인 시간에 공부하는 것이 포함됩니다. [자기 상벌]은 자신에게 학업을 마친 것에 대한 보상을 약속하는 것을 포함한다. 수행 목표, 숙달 목표, 가치 및 관심을 사용하여, 학생들은 의도적으로 상기시키고, 설득하고, 생각하고, 이러한 목표, 가치 또는 관심사와 연결시키는 데 관여합니다. 예를 들어, 학생은 의도적으로 학술 자료를 아는 것이 유용한 미래 상황에 연결할 수 있습니다. 대학생을 대상으로 한 조사에서, 학생들은 환경 구조화 전략과 성과 목표 전략을 가장 자주 보고하고, 작업 가치, 관심 또는 숙달 목표 전략을 덜 자주 보고했습니다(Wolters and Benzon 2013).

Environmental structuring strategies include limiting distractions, changing the setting, and studying at ideal times. Self-consequating includes promising oneself a reward for finishing academic work. Using performance goals, mastery goals, value, and interest, students purposefully engage in reminding, convincing, thinking, and connecting to these goals, values, or interest. For example, a student may purposefully connect the academic material to a future situation in which it would be useful to know the material. In a survey of college students, students most frequently reported environmental structuring strategies and performance goal strategies and less frequently employed task value, interest, or mastery goal strategies (Wolters and Benzon 2013).

학습자가 동기를 부여하는 데 어려움을 겪을 경우, 교육자는 무엇을, 언제, 왜, 그리고 어떻게 하는지를 포함한 동기 부여 전략에 대해 명시적으로 논의해야 합니다. 예를 들어, 교실 교육자는 온라인 학습 관리 시스템에 동기 부여 조절 전략을 강조하는 읽을거리를 게시할 수 있습니다. 임상 감독관은 학습자에게 장기적인 프로젝트 또는 학습(예: 보드 시험 학습)을 지속하는 방법을 가르칠 수 있습니다. 예를 들어, 그들은 학습자에게 언제, 왜, 그리고 어떻게 동기를 부여하는지 설명할 수 있다.

When learners have difficulty motivating themselves, educators should explicitly discuss motivation strategies including the what, when, why, and how (Veenman et al. 2006; Kistner et al. 2010). For example, classroom educators could post articles or readings highlighting motivation regulation strategies to their online learning management system. Clinical supervisors could instruct learners on how to persist with long-term projects or study (e.g. board exam studying). For example, they may explain to their learners when, why, and how they keep motivated.

동기 조절 모델링

Modelling motivation regulation

교육자는 동기 조절전략의 사용을 모델링하여 동기 조절을 암묵적으로 육성할 수 있다. 교육자가 전략을 사용하고 있다는 것을 명시적으로 언급하지 않더라도, [교육자의 행동]은 학습자가 동기 조절 행동과 전략을 채택하도록 이끌 수 있다. 예를 들어, 교실 교사는 게임화를 통해 학습의 지루한 측면을 더 즐겁게 만드는 전략을 모델링할 수 있다. 임상 감독관은 업무 가치의 조절을 모델링할 수 있다. 예를 들어, 환자 치료 활동 문서화와 관련된 비용(예: 시간, 노력)과 유익성(예: 팀워크 개선, 향후 방문을 위한 더 나은 데이터)이 비용을 초과하는지를 구두로 설명할 수 있다.

Educators may implicitly foster motivation regulation by modelling the use of motivation regulation strategies (Kistner et al. 2010). Without explicitly mentioning that the educator is using a strategy, an educator’s behaviour may lead learners to adopt motivation regulation practices and strategies. For example, a classroom teacher could model the strategy of making tedious aspects of learning more enjoyable through gamification. A clinical supervisor could model their regulation of task value. For example, they might verbalise the costs associated with documenting patient care activities (e.g. time, effort) and how the benefits (e.g. improved teamwork, better data for a future visit) outweigh the costs.

결론

Conclusion

동기 부여는 성공적인 배움의 열쇠입니다. 보건 전문 교육자들은 학습자 동기 부여의 중요성을 이해하고 있지만, 많은 교육자들이 동기 부여를 높이는 교육을 설계하고 전달하는 데 어려움을 겪고 있습니다. 다행히도, 학생들의 동기 부여에 긍정적인 영향을 미치는 것으로 증명된 증거 기반과 현장 검증 전략이 있다. 이 가이드는 약물 요약 비유를 사용하여 학습자 동기 부여의 강도를 높이고, 학습자 동기 부여의 질을 높이고, 학습자 자신의 동기 부여를 촉진하는 개입의 근거와 예를 제공한다.

Motivation is a key to successful learning. Health professions educators understand the importance of learner motivation; however, many have difficulty designing and delivering instruction that increases motivation. Fortunately, there are evidence-based and field-tested strategies that have been shown to positively influence student motivation. Using a drug compendia metaphor, this guide provides a rationale for and examples of interventions that increase the intensity of learner motivation, increase the quality of learner motivation, and promote learner regulation of their own motivation.

Interventions to Increase Motivation Intensity

| Defining Key Terms | Indications | General Administration and Examples | Mechanism of Action | Dosing and Side Effects | Monitoring | Underpinnings / References |

| Providing Optimal Challenging Learning Tasks |

||||||

| Optimal challenge - When a learner perceives a task as challenging but not overly difficult | For Whom? All learners Outcomes: · Improved competence perceptions · Use of deeper learning strategies · Deeper engagement When? In situations that require deep learning or understanding |

Increase task challenge (difficulty and complexity) by using real-world problems and constraints Decrease task challenge by breaking down tasks into pieces, allowing more time, or providing support and hints (e.g., an iterative paper) Continuously calibrate task challenge similar to video games - once learners master an easy level, they continue on to subsequently more difficult levels Predict learners’ perceptions of task difficulty by understanding their goals, previous experiences, and capabilities (e.g., conducting a baseline survey or interview) |

Learner perceptions of task challenge emerge in each moment, varying across learners and over time. Optimally difficult tasks produce “flow” – a stimulating motivation state and concentration |

With easy tasks, learners may experience boredom which limits learning Difficult tasks may be inaccessible for learners, inviting withdrawal, resentment, and short cuts |

Observe for deep vs. surface (i.e., going through the motions) engagement Observe for learner emotions – bored (i.e., the task is too easy) vs. overwhelmed (i.e., the task is too hard) |

Flow (Csikszentmihalyi 1997) Theories of motivation and self-regulation, interventions to invite motivation and regulation (McCaslin and Hickey 2001; Paris and Turner 1994) |

| Sparking Curiosity and Interest Among Learners |

||||||

| Curiosity - A natural desire to know more or engage in new situations because they are surprising or new Situational Interest - A content- specific state (e.g., I feel interested) Personal Interest - Content-specific trait (e.g., I am interested in chemistry) |

For Whom? All learners, especially those that are not engaged Outcomes: · Increased learner engagement and attention · If supported, sparking situational interest may evolve into personal interests · Increased effort and therefore, performance When? At the beginning of learning and then consistently to develop learners’ personal interests |

Gamification - Use principles from games including badges, levels, rewards, fail-safe environment, and friendly competition Create novelty and variety: Get novel ideas for teaching by following educators on Twitter, reading blogs, or browsing through education websites Create surprises by incorporating humour, unusual factors, Socratic questioning Stimulate "friendly controversies" by asking learners to vote or debate positions Connect content or activity to learners' current interests |

Surprise creates a disequilibrium that learners are curious to explore until they reach equilibrium What is interesting is always intrinsically motivating, but what is intrinsically motivating is not always interesting Interest states decrease cognitive load, allowing learners to take on greater complexity and difficulty |

Too much surprise or novelty may lead to feelings of being overwhelmed, inciting learners to disengage "Novelty effect" - Learners are initially interested in novel education elements, but this fades as the novelty effect wears off |

Observe for learners' attention or engagement Inventory learners' personal interests |

Theories of interest development and interventions to foster interest (Harackiewicz and Knogler, 2018) Educator development on sparking interest (Oyler et al., 2016) |

| Defining Key Terms | Indications | General Administration and Examples | Mechanism of Action | Dosing and Side Effects | Monitoring | Underpinnings / References |

| Modelling Enthusiasm and Showing Affective Concern |

||||||

| Modelling - Learners implicitly pick up information through observing others’ thinking, actions, process, and the consequences of those actions Enthusiasm - An authentic expression of excitement for the topic or activity Affective Concern - Learners feel like the educator cares for their well-being and personal development |

For Whom? All learners, especially those that may not be interested in the content or activity Outcomes: · Higher ratings of educator effectiveness · Related to educator well-being · Increased learner participation, effort, and intrinsic motivation, leading to higher achievement When? At the beginning to spark learners’ situational interest and after a difficult task |

Enthusiasm for learning and affective concern for the learner should be shown by instructors, near-peers (resident to a student), actual peers, and practicing professionals Share stories of what the material or activity means to you Conclude learning with a preview of what is to come next. This increases interest and demonstrates your enthusiasm to see the learners again. Apply concepts using examples that are either interesting to you or the learners. At times, the educator’s enthusiasm may spark a new interest for learners. (Re-)activate your own enthusiasm by thinking about how learners may use the content in the future or what initially engaged you in the topic. |

Learners internalize the values and attitudes of those they admire and relate to "Emotional contagion" – The emotions of one person can unconsciously influence others’ emotions. Learners perceptions of educators’ affective concern for them contributes to learner feelings of belonging |

Learners are adept at perceiving when an educator is being inauthentic or authentic. Educators may develop burn-out or negative attitudes if they spend too much energy falsely maintaining enthusiasm. Optimally, learners should share in the responsibility of being enthusiastic. “Distracting details” –Learners may disengage if they do not perceive the examples as relevant. |

Learners generally comment on educator enthusiasm in learners evaluations of teaching Observe for learners' attention or engagement |

Educator development on enthusiasm (Mitchell, 2013) Interventions to support feelings of belonging (Baumeister and Leary 1995) |

| Creating Task Relevance and Utility |

||||||

| Relevance - What learners believe is useful to their current personal lives Utility - What learners believe will be useful in the future |

For Whom? All learners Outcomes: · Use of deeper-level learning strategies · Increased engagement and interest in the topic · Influences learners’ choice to pursue future opportunities When? In situations where learners may question the value of the material or activity |

Eliminate content that is not relevant nor useful for learners Improve the "real world" nature of the tasks and activities (e.g., use real-world problems in class). “Task-value interventions” - Show, don't tell! Show them examples (e.g., news stories, articles) of the relevance or usefulness of the content or activity. "Saying-is-believing effect" - The tendency for learners to believe messages that were freely advocated by the learner. For example, ask the learners, in discussion or in writing, why the content or activity is important to their own lives, others, or the community. |

“Exchange value” – Learners constantly evaluate whether and to what extent to participate in an activity based on costs and benefits. For example, only studying material on the exam. Learners determine importance by thinking about the "real world.” Is it realistic? Is it aligned with their goals? Is this what they need to know and be able to do? |

If everything is labelled as important, then nothing becomes important If learners don't think content or activity is relevant or useful, they will go through the motions (i.e., surface-level engagement) |

Observe whether learners are going through the motions or going above and beyond (i.e., their level of engagement) Inventory what learners perceive as relevant and useful |

Expectancy-value-cost theory, interventions to improve task value (Renninger and Hidi 2011; Harackiewicz and Priniski, 2018) Communities of Practice theory (Lave and Wenger 1991) |

Interventions to Enhance Motivation Quality

| Defining Key Terms | Indications | General Administration and Examples | Mechanism of Action | Dosing and Side Effects | Monitoring | Underpinnings / References |

| Promoting Autonomy and Structure |

||||||

| Autonomy - When learners wholeheartedly endorse their own actions. The opposite is controlling Structure - Providing clear information to learners about expectations and how to achieve learning outcomes. The opposite is chaos and confusion. |

For Whom? All learners Outcomes: · Intrinsic motivation · Self-reported and observed engagement When? As often as possible |

Provide learners with choices Nurture learners personal interests and responsibility for their own learning Direct learners with “can,” “may,” and “I invite you to” rather than “must,” “need,” and “should.” Explain to learners what it takes to reach the desired outcomes Provide consistent step-by-step directions and smooth transitions |

When autonomy and structure are both provided, the basic human needs to feel autonomous and competent are supported Autonomy Support Activates learner interest, goals, curiosity, and sense of challenge Learners will see their successes as earned by them and experience their own free will, resulting in intrinsic motivation Structure Support Learners feel greater control over academic challenges (i.e., internal locus of control), resulting in greater confidence (i.e., self-efficacy) |

Too much autonomy may require more educator oversight, coordination, and grading Too little autonomy may lead learners to feel controlled and dependent, leading to frustration, boredom, and defensiveness Too much structure may lead to boredom and reliance on structure Too little structure leads to being overwhelmed, confused, or lost which may lead to taking short cuts and use of surface learning strategies |

Observe or have learners report on their level of engagement Observe for mediating processes—frustration, boredom, and surface learning strategies |

Self-determination theory, interventions for supporting autonomy and competence (Ryan and Moller, 2018; Jang, Deci, Reeve, 2010) |

| Defining Key Terms | Indications | General Administration and Examples | Mechanism of Action | Dosing and Side Effects | Monitoring | Underpinnings / References |

| Addressing Learner Identity Contradictions |

||||||

| Identity contradictions - Misalignments between one's identity and an activity. Also, contradictions between different contexts such as the classroom and clinical practice |

For Whom? Leaners who hold an identity that contradicts with the content area or learning environment (e.g., a learner who does not identify with a specialty) Outcomes: · Learner choices · Deeper engagement · Intrinsic motivation When? In situations that lead to identity contradictions |

Bring in a speaker that learners identify with currently (near peer) or in the future (practicing professional). Have the speaker discuss the value of the activity Create a hybrid across the two contradictions (e.g., having school-based faculty visit clerkships, having clinicians co-teach certain topics) Address learners misconceptions that they internalized from previous experiences, popular culture, and their social network (e.g., through a class discussion) |

A deep motive of learners is becoming a part of a community of practice (e.g., hospital, clinic). This drives their participation and choices in activities, formulating their identity When a topic or activity contradicts a learners current identity, they will complete the least amount of work as possible. However, this mechanism can be overruled by appealing to learners' future identities, especially their identity to be a "good" health professional. |

If a learner believes the educator is overinflating the importance of a topic, they may lose trust in the educator If a learner believes the educator is telling them what to do or how to be, they may become defensive |

Observing for surface versus deep engagement Ask learners what they do not enjoy or value about the task - it might unearth identity contradictions |

Situative motivation (Nolen et al., 2015) Communities of Practice Theory (Lave and Wenger, 1991) Motivational Filters (Horn and Campbell, 2015) |

| Framing Academic Challenges as Common and Improvable |

||||||

| Academic challenges - Events that learners interpret as challenging or failure (e.g., low marks, critical feedback) |

For Whom? · Those who may lack successful models (e.g., first-generation University students, under-represented identities) · Low performers who endorse a fixed theory of intelligence (i.e., fixed mindset) Outcomes: · Malleable theory of intelligence (i.e., growth mindset) · Increase feelings of belonging, leading to more intrinsic motivation · Increased marks and persistence · Decreased attrition When? During tough transitions or first perceived failures |

"Framing interventions" · Frame challenges as common and improvable (e.g., provide statistics or quotes from more senior learners illustrating that challenges to adjusting to the learning environment are common and can be overcome) · Share your personal stories of overcoming challenges in academia or practice · Have learners write about (or discuss) how to overcome academic challenges "Mindset interventions" Share and assign reading materials framing intelligence as malleable |

Some learners will interpret challenges or failure as evidence that they lack intelligence, don't belong in an area, or are "just not a certain type of person" (e.g., critical care person) Framing challenges as common supports learner belief that they belong even though they failed. Framing challenges as improvable supports the belief that they can achieve but require more effort and better strategies |

If the interventions are not provided during a period of transition or challenge, the interventions may be seen as another academic exercise |

Listen to how learners discuss their challenges or failures. Do they see them as permanent or improvable? Common or unique to them? Inventory learners implicit theories of intelligence (i.e., mindsets) |

Interventions to support feelings of belonging and relatedness (Jang, Deci, Reeve, 2010; Baumeister and Leary, 1995) Growth mindset interventions (Harackiewicz and Priniski, 2018) |

| Defining Key Terms | Indications | General Administration and Examples | Mechanism of Action | Dosing and Side Effects | Monitoring | Underpinnings / References |

| Eliciting a Mastery Approach Goal Orientation |

||||||

| Mastery approach goal orientation - The underlying reason or goal for learning is to further master a task or develop competence Performance goal orientation - The underlying reason or goal for learning is to outperform their peers (e.g., good marks, higher reputation) |

For Whom? All learners Outcomes: · Elicits a mastery approach goal orientation · Increased self-efficacy and interest · Improved marks · Decreased anxiety and failure avoidance When? In situations where a mastery approach goal orientation is required for complex, long-term learning |

The TARGET model for classroom structure · Tasks: Optimally challenging, interesting · Authority: Learners participate in decisions · Recognition: In a private setting · Grouping of learners: Mixed-ability · Evaluation: Based on self-improvement · Time: Flexible "Student-focused" interventions · Reframe assessments as an opportunity to learn · Define goal orientations and have learners discuss the advantages of a mastery orientation · Teach deeper learning strategies (e.g., self-testing, explaining topics to others) |

Learners may have both a mastery and performance orientation Learners may have a performance orientation in one unit and a mastery orientation in another Learners underlying reason(s) for learning (i.e., orientation) leads to different patterns of behaviour. Mastery orientation leads to the use of deeper learning strategies, deep engagement, and seeing challenges as motivating. |

Too much mastery without performance: Learners may lack the strategy or spend too much time on interesting material to attain higher performance Too much performance without mastery: Learners may take short cuts or do the bare minimum, therefore decreasing their long-term learning needed to succeed in the future If instruction on mastery goals is perceived by learners as only advising them to "try harder," they may feel defensive that the educator does not understand how hard they are trying |

Have learners take a goal orientation inventory Observe for expressions of their orientation (e.g., deep vs. surface level learning strategies) |

Achievement goal orientation interventions (Ames, 1992; Elliot and Hulleman, 2017) |

doi: 10.1080/0142159X.2020.1837764. Epub 2020 Nov 2.

The clinical educator's guide to fostering learner motivation: AMEE Guide No. 137

PMID: 33136450

Abstract

Motivation theory and research remain underused by health professions educators. Some educators say it can seem too abstract. To address this, we applied health care language to learner motivation theories. Using a familiar metaphor, we examined the indications, mechanism of action, administration, and monitoring of learner motivation interventions. Similar to the treatment monographs in medicine compendia, we summarized each motivation intervention in the form of a monograph. The purpose of this guide is for health professions educators to develop an understanding of when (i.e. indication) and how (i.e. mechanism of action) learner motivation interventions work. With this information, they can then access ready-to-implement strategies (i.e. administration) to increase their learner interest and assess the effects of these interventions (i.e. monitoring).

Keywords: Motivation; clinical educators; engagement; health professions students; medical students.

'Articles (Medical Education) > 교수법 (소그룹, TBL, PBL 등)' 카테고리의 다른 글

| 의학교육에서 동료지원학습(PAL): 체계적 문헌고찰과 메타분석(Med Educ, 2021) (0) | 2022.03.30 |

|---|---|

| 침묵 또는 질문? 학생-중심 교육에서 토론 행동의 문화간 차이(Studies in Higher Education, 2014) (0) | 2022.03.26 |

| 학습 대 수행: 통합적 문헌고찰 (Perspectives on Psychological Science, 2015) (0) | 2022.03.18 |

| 피드백의 심리적 안전: 무엇이며, 교육자들은 어떻게 배우는가? (Med Educ, 2020) (0) | 2022.03.12 |

| 학업적 어려움을 겪는 의과대학생 및 전공의를 위한 개입 (BEME Guide No. 56) (Med Teach, 2019) (0) | 2022.03.11 |