의학교육에 대한 새로운 상상: 행동할 때 (Acad Med, 2013)

Medical Education Reimagined: A Call to Action

Charles G. Prober, MD, and Salman Khan

우리의 신념은 의과대학생에게 평생에 걸쳐 지식을 쌓을 수 있는 프레임워크를 제공해야 한다는 것이다. 그리고 생의학 혹은 의료의 특정 영역에 적성과 열정이 있는 학생은 그 분야를 더 깊이 추구해야 한다.

Our belief is that medical students should be provided a framework on which knowledge can be built over a lifetime of learning. And students who have aptitude and passion for developing a focus in a specific area of biomedicine or medical practice should pursue this area more deeply.

교실 뒤집기

Flipping the Classroom

The One World School House: Education Reimagined에서 살만 칸은 교육의 새로운 모델을 제시했다.

In The One World School House: Education Reimagined, one of us (S.K.) described a new model of education, informed in part by ongoing work with K–12 students.1

'거꾸로교실'에서 이전에 교실에서 가르치던 내용은 집에서 학습하고, 숙제는 동료와 함께, 교사의 지도하에 협력적으로 교실에서 수행한다.

There is a “flipping of the classroom”: Lessons previously taught in class are learned at home, and “homework” is performed in the classroom in collaboration with peersand guided by teachers.

의학교육에 대한 새로운 상상

Reimagining Medical Education

초중등교육에 대한 새로운 모델이 의학교육에도 적용가능할 것이다.

We believe that the model for reimagining K–12 education is equally relevant to medical education.

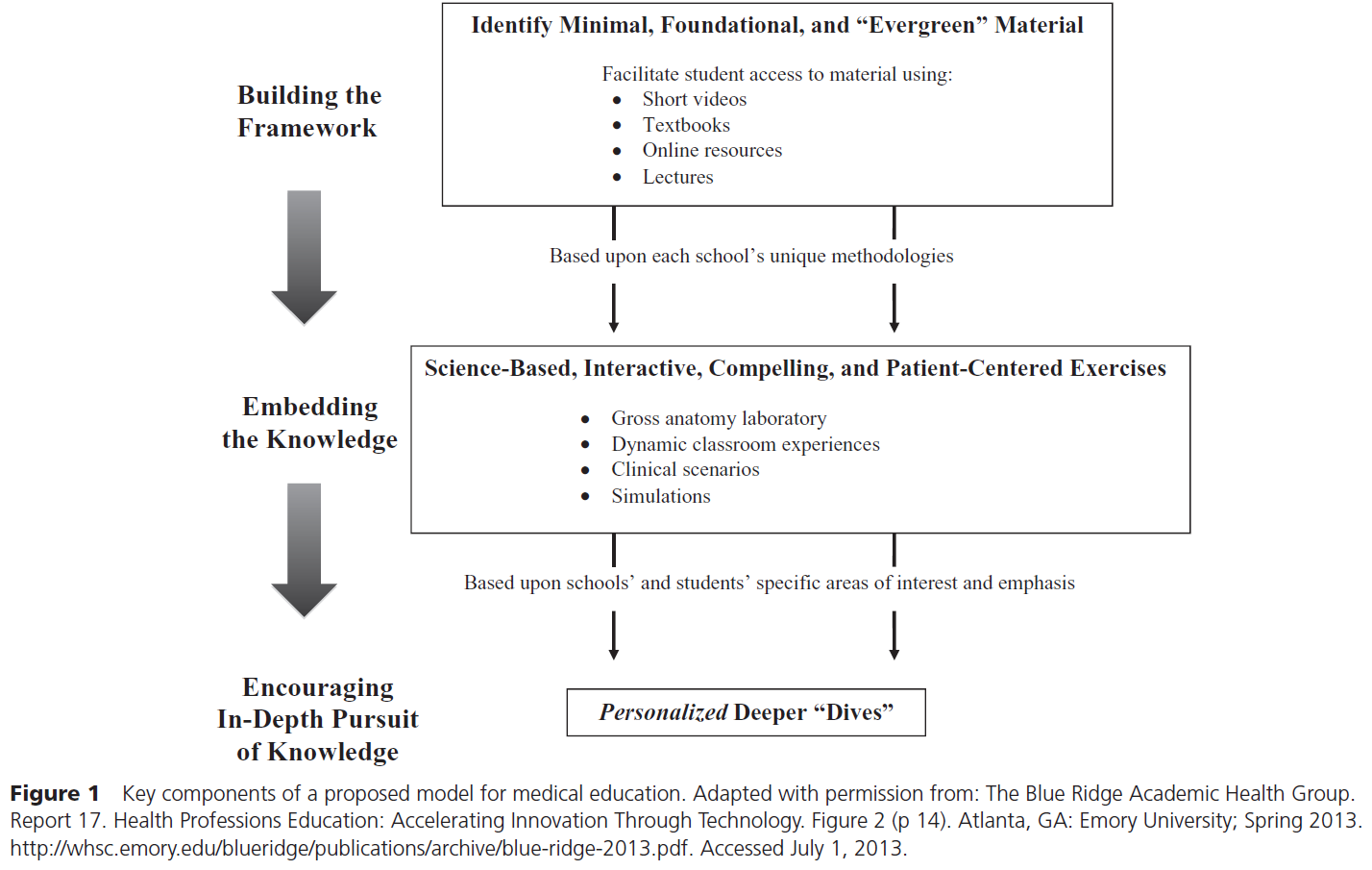

그림 1은 새로운 모델의 핵심 요소 세 가지를 그리고 있다.

Figure 1 depicts the three key components of our proposed model for medical education:

- 핵심지식의 프레임워크 확립 building a framework of core knowledge;

- 지식을 상호작용적인, 강렬한, 참여적 형태로 심기 embedding the knowledge in richly interactive, compelling, and engaging formats; and

- 일부 영역에서는 심화 학습 추구 encouraging in-depth pursuit of knowledge in some, but not all, domains.

핵심지식의 프레임워크 확립

Building a framework of core knowledge

우리가 제안하는 의학교육의 핵심 요소는 '필수 전임상 교육과정'이다. 이 교육과정은 이후 학습의 토대가 되며 진실(evergreen)인 것으로 알려진 것에 초점을 둔다.

The central element of our medical education proposal, depicted at the top of Figure 1, is the core preclinical curriculum. This curriculum should focus on medical knowledge that is foundational and known to be true (“evergreen”).

이 과정의 목표는 이후 수업에서 구성요소(building block)으로 역할을 할 수 있는 제한된 양의 필수적인 자료 배우는 것이다. 놀랍게도 핵심 교육과정은 국가적 차원에서 결정되는 것이 아니다. 핵심 교육과정은 유기적인 것으로, 비록 학교 간 상당히 높은 비율로 유사하더라도, 여러 시대에 따라 각 의과대학마다 새롭게 만들어지고 자라나는 것이다ㅏ.

Rather, a goal should be to identify a limited amount of critical material that serves as the building blocks for subsequent lessons. It is striking that such a core curriculum is not defined on a national basis. Core curricula tend to be organic, arising and growing over time at each medical school, even though a high proportion of core content will be similar between schools.

의과대학 핵심 교육과정을 통일시키는 주요 동력은 USMLE 내용이다.

The one unifying driver of medical schools’ core curricula appears to be the content of the USMLE.

의과대학 교육과정과 무관하게 학생들은 의과대학에서의 실라버스가 아닌 서드파티 교육자료를 가지고 이 시험을 준비한다.

Students, irrespective of their own medical school’s curriculum, typically prepare for these examinations by using third-party review material rather than their course syllabi.

학생들은 그들이 배운 교육과정이 표준화된 국가시험의 내용을 반영하지 못한다는 사실을 깨닫고 매우 좌절하거나 스트레스를 받는다. 스탠포드의 전임상과정의 학생을 대상으로 한 연구에서 73%의 학생이 교육과정의 내용과 USMLE step 1을 위해서 알아야 하는 내용 사이에 불합치가 스트레스의 주요 원인임을 지적했다.

Students often express a high degree of frustration and stress when they recognize that their school’s curriculum does not mirror the content of standardized national examinations. In a recent survey of preclinical students at Stanford, 73% identified this perceived misalignment between curricular content and what they “needed to know for USMLE Step 1” as one of their major sources of stress (Porwal A, Newell G. Unpublished data. June 2012).

이는 의과대학 교육과정이 '시험을 위한 준비'가 되어야 한다고 말하는 것은 아니다. 오히려, 의과대학 교육과정과 NBME 사이에 신중한 합치를 이루어야 할 필요를 말하는 것이다. 이 목적을 위하여 우리는 의과대학 협력체를 구성하여 교육과정의 핵심 내용에 대한 합의된 의견을 대표할 수 있는 자료를 만들 책임을 갖도록 제안한다.

This is not to suggest that medical school curricula should be designed to “teach to the test.” Rather, there needs to be a conscious alignment between those responsible for creating medical school curricula and the National Board of Medical Examiners. To that end, we propose the creation of a medical school collaborative, charged with the identification of material that would represent a consensus opinion on the core content of the curriculum.

핵심 내용이 정해지면, 우리는 10분 정도의 짧은 비디오의 library를 만들 것을 권고한다. 학습자는 이것을 가지고 학교 교육과정이 조직된 것과 같은 순서로 학습 내용에 접근할 수 있다.

Following the identification of the core content, we further propose the creation of a library of short (~10 minute) videos that learners can use to access the content in an order consistent with the organization of their school’s curriculum.

여러 학교가 같은 내용으로 비디오를 만드는 것이 도움이 될 것이다. 학생들은 자신의 학습 스타일과 가장 잘 맞는 것을 선택할 것이고 시간이 지나면 '최고의 비디오'가 자연스럽게 드러날 것이다.

We believe that it would be advantageous for multiple schools to produce videos on the same core content. Students could select the version of the presentations most consistent with their learning style. Over time, the “best” videos would emerge.

학습자료는 시간이 지나면 업데이트되어야 하나, 이 과정은 필수 내용을 선정하는 과정에서 과학적 검증을 거친 것을 선택함으로써 최소화될 수 있다. 짧은 비디오 형태의 교육은 당대의 발견을 적절한 시기에 도입하는데 도움이 될 것이다.

Material would need to be updated over time, although this need would be minimized through the selection of core content that has withstood the test of scientific validation. The short video format would facilitate the timely introduction of contemporary discoveries.

지식을 상호작용적인, 강렬한, 참여적 형태로 심기

Embedding knowledge through interactive formats

두 번째 요소는 역동적 상호작용 세션이다.

The second defining element of our medical education proposal is the creation of dynamic interactive sessions.

이들 비디오는 SMILI의 일부일 뿐이다. SMILI 워킹그룹은 교수/학생/교육과학자/학습전문가/정보기술전문가 등으로 구성되어 있다. 우리의 핵심 목표는 수업을 보다 학생 중심의 상호작용적 형태로 진화시키고자 하는 교수를 돕는 것이다.

These videos are, in fact, only a fraction of our overall Stanford Medicine Interactive Learning Initiative (SMILI).3 Our SMILI working group includes faculty, students, educational scientists, learning specialists, and information technology experts. Our central goal is to support faculty who want to evolve their classes into a more student-centric, interactive format.

이러한 세션은 종종 서로 다른 전공의 교수들의 참여를 통해서 이득을 얻는다.

These sessions often benefit from the participation of faculty with different types of expertise,

비록 학생들은 교육과정 평가에서 수업을 개선할 다양한 지점을 찾아내지만, 141명의 응답자 중 82%는 기본적인 강의-기반 형태도바 이러한 형태의 모델을 더 선호한다. 가장 흔한 우려는 시간 관리이다. 학생들은 강의(또는 비디오)에 할당된 시간을 줄이지 않고 단순히 상호작용적 세션만 더하는 것을 가장 걱정한다.

Although the students identified a number of opportunities for improvement in course evaluations, 82% of 141 respondents favored this model of instruction when compared with a primarily lecture- based format (Ransohoff K, Xie J. Unpublished data. December 2012). The most common concern expressed by our students was time management. The students expressed concern about simply adding interactive sessions without concurrently reducing the amount of time allocated for didactic instruction (by video).

일부 영역에서는 심화 학습 추구

Encouraging in-depth pursuit of specific knowledge

학생들은 핵심 교육과정을 넘어선 'deep dive'를 하게 권장되어야 한다.

Students are encouraged to take “deep dives” beyond their core curriculum.

스탠포드의 scholary concentration는 deep dive의 한 사례이지만 이것만 있는 것은 아니다.

Examples of “deep dives” include, but are not limited to, what we currently offer students for their “scholarly concentration” pursuits at Stanford:

핵심은 학습자의 적성과 열정을 지지하고 다가가는 것이다.

The key is to tap into and support the individual learner’s aptitude and passion.

최근, Bruce Alberts는 "표면적 학습의 실패"를 강조하였다.

A recent editorial, authored by Bruce Alberts,4 the editor-in-chief of Science, underscored the “failure of skin-deep learning.” Alberts argues that we need to replace the current overview of subjects with a series of deep explorations. He cites research that demonstrates that “the most meaningful learning takes place when students are challenged to address an issue in depth.”4

Effecting Change Through Multi-Institutional Collaboration

협력적인, 다기관의 노력이 필요할 것이다.

Perhaps the result would not be a one-world medical school house but a collaborative, multi-institutional effort to reimagine medical education.

Acad Med. 2013 Oct;88(10):1407-10. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e3182a368bd.

Medical education reimagined: a call to action.

Author information

- 1Dr. Prober is senior associate dean for medical education and professor of pediatrics, microbiology, and immunology, Stanford School of Medicine, Stanford, California. Mr. Khan is founder and executive director, Khan Academy, Mountain View, California.

Abstract

The authors propose a new model for medical education based on the "flipped classroom" design. In this model, students would access brief (~10 minute) online videos to learn new concepts on their own time. The content could be viewed by the students as many times as necessary to master the knowledge in preparation for classroom time facilitated by expert faculty leading dynamic, interactive sessions where students can apply their newly mastered knowledge.The authors argue that the modern digitally empowered learner, the unremitting expansion of biomedical knowledge, and the increasing specialization within the practice of medicine drive the need to reimagine medical education. The changes that they propose emphasize the need to define a core curriculum that can meet learners where they are in a digitally oriented world, enhance the relevance and retention of knowledge through rich interactive exercises, and facilitate in-depth learning fueled by individual students' aptitude and passion. The creation and adoption of this model would be meaningfully enhanced by cooperative efforts across medical schools.

Comment in

- In reply to Goldberg and to Hurtubise et al. [Acad Med. 2014]

- Considerations for flipping the classroom in medical education. [Acad Med. 2014]

- Considerations for flipping the classroom in medical education. [Acad Med. 2014]

- PMID:

- 23969367

- [PubMed - indexed for MEDLINE]

'Articles (Medical Education) > ⓧ교수법, 피드백, 멘토링 (From Misc.)' 카테고리의 다른 글

| 재교육의 어려움: 이론적 방법론적 통찰 (Med Educ, 2013) (0) | 2016.03.10 |

|---|---|

| 상상해보자: 의학교육의 새 패러다임 (Acad Med, 2013) (0) | 2016.02.04 |

| "내가 의대에 적합한걸까?" 1학년 학생들의 확신결여 현상에 대한 이해(Med Teach, 2015) (0) | 2015.12.10 |

| 비공식적 학습용 웹사이트 분석(IJSDL, 2014) (0) | 2015.10.26 |

| "문제"학생: 이 문제는 누구의 문제인가? AMEE Guide No.76 (0) | 2015.07.21 |