신뢰와 통제 사이: 프로그램적 평가에서 교수의 평가에 대한 개념화(Med Educ, 2020)

Between trust and control: Teachers' assessment conceptualisations within programmatic assessment

Suzanne Schut1 | Sylvia Heeneman1,2 | Beth Bierer3 | Erik Driessen1 | Jan van Tartwijk4 | Cees van der Vleuten1

1. 소개

1. INTRODUCTION

의학교육에서 평가를 학습에 활용하는 것에 대한 관심이 높아지고 있으며 그 혜택에 대한 기대도 높다. 프로그램 평가는 [연속적인 평가 부담continuum of assessment stakes]을 제안함으로써 [형성적 또는 총괄적 평가 목적의 전통적인 이분법을 극복]하려고 시도한다. 이러한 일련의 평가 부담은 다양하다.

- 저부담 평가 (정보와 피드백을 통해 교사와 학습자를 유익하게 하고 지원하기 위한 빈번한 평가)

- 고부담 평가 (평가 데이터의 집계에 기초한 진행 결정)

Interest in using assessment for learning is increasing in medical education and expectations of its benefits are high.1 Programmatic assessment attempts to overcome the traditional dichotomy of assessment purposes as either formative or summative by proposing a continuum of assessment stakes.2, 3 This continuum of assessment stakes ranges from

- low (frequent assessments to benefit and support teachers and learners with information and feedback) to

- high (progress decisions based on the aggregation of assessment data).

저부담 평가의 주요 목표는 학습자의 진도를 지원하는 것입니다. 따라서 한 번의 낮은 평가 결과가 학습자에게 제한적이어야 합니다. 그러나 여러 평가 결과가 집계되면 학습자에게 상당한 영향을 미치는 높은 평가 수행 결정을 알리는 데 사용할 수 있습니다. 실제로 학습자는 학습에 도움이 되는 저부담 평가의 가치를 인식하지 못하는 경우가 많습니다. 대신, 그들은 저위험 평가의 잠재적인 종합 결과에 초점을 맞추는 경향이 있다. 이러한 이유로, 학습을 지원하기 위해 프로그래밍 방식의 평가를 사용하는 것은 여전히 어려운 일입니다.

The primary goal of low‐stake assessment is to support learners' progress. Thus, one low‐stake assessment should have limited consequences for learners. When multiple low‐stake assessments are aggregated, however, they can be used to inform high‐stake performance decisions that have substantial consequences for learners.4 In practice, learners often do not appreciate the value of low‐stake assessments to guide their learning. Instead, they tend to focus on the potential summative consequences of low‐stake assessments.5, 6 For this reason, using programmatic assessment to support learning remains challenging in practice.1, 7, 8

교사들은 (특히 프로그램 평가의 학습 잠재력을 충족시키거나 약화시키는 데 있어) 강력한 역할을 하는 것으로 보인다. 프로그램 평가의 많은 기본 원칙이 새로운 것은 아닐 수 있지만, [평가에 대한 체계적인 접근법]과 [두 가지 목적을 가진 평가 부담의 연속성]은 [전통적인 총괄평가 접근법]과 근본적으로 다르다.9 교사가 평가의 의미와 목적을 완전히 이해하지 못하거나 평가의 기본 철학에 동의하지 않는 경우, 저부담 평가와 저부담 평가의 잠재적 학습 이익은 사소해질 가능성이 높다.4 저부담 평가에서와 같이 평가 목적이 복잡하고 중첩된 상호 작용을 하는 경우, 평가 프로세스는 더욱 복잡해진다.

Teachers appear to play a particularly powerful role in fulfilling or undermining the learning potential of programmatic assessment.7 Although many of the underlying principles of programmatic assessment may not be novel, the systematic approach to assessment and the continuum of assessment stakes with dual purposes fundamentally differ from traditional, summative approaches to assessment.9 If teachers do not fully understand the meaning and purpose of assessment or do not agree with its underlying philosophy, low‐stake assessments and their potential learning benefits are likely to become trivialised.4 The complex and overlapping interplay of assessment purposes, such as in low‐stake assessments, adds to the already complicated assessment processes.10, 11

학부 교육의 맥락에서, 사무엘로비츠와 베인은 교사들이 근본적인 이유로 '변혁적' 평가방법에 저항할 수 있으며, 교육적 신념과 가치관을 바꿀 때까지 평가의 혁신을 수용하지 않을 수 있다고 경고한다.

In the context of undergraduate teaching, Samuelowicz and Bain13 warn that teachers may resist ‘transformative’ assessment methods for fundamental reasons and may not embrace innovation in assessment until they also shift their educational beliefs and values.14

더 나아가, 교사가 평가를 어떻게 개념화하는지는 [교육 이론이나 기관의 평가 정책]보다는, [교사 개인의 평가 경험]에 더 영향을 받는다. 이러한 신념과 실천 사이의 차이은 특히 교사가 [프로그램 평가에 사용되는 저부담 평가와 같은 이중 목적 평가]에 직면할 때 나타날 가능성이 높다. 예를 들어, 교사는 아래의 두 가지 역할 사이에서 중요한 딜레마를 경험할 수 있다.

- 학습자의 개발 및 촉진에 대한 지지자 역할

- 학습자의 성과와 성취도에 대한 평가자로서 판단의 책임.

Furthermore, teachers' assessment conceptualisations are often informed by their personal assessment experiences rather than by educational theory or the institution's assessment policies.10, 12 These differences between beliefs and practices are especially likely to emerge when teachers encounter dual‐purpose assessments,15 such as the low‐stake assessments used in programmatic assessment. For instance, teachers may experience significant dilemmas when navigating between

- their supportive roles as they monitor and facilitate learners' development and

- their judgemental responsibilities as assessors of learners' performance and achievement.1, 10, 16, 17

2. 방법

2. METHODS

우리는 교사들의 평가 개념화와 프로그램 평가 내의 평가 관계를 탐구하기 위해 구성주의자 근거이론 접근법을 사용했다.

We used a constructivist grounded theory approach19, 20 to explore teachers' assessment conceptualisations and assessment relationships within programmatic assessment.

2.1. 샘플

2.1. Sample

프로그램 평가에 대한 중요한 통찰력을 제공하는 것으로 알려진 고유한 연구 설정을 선택하기 위해 극단적인 사례 샘플링 전략을 채택했다.21 우리는 평가의 목적이 저부담과 고부담 모두인 상황에서, 교사가 저부담 평가를 사용해야 하는 연구 설정을 선택했다. 이러한 구현을 위한 포함 기준은 다음과 같다.

- (a) 학습 정보를 제공하기 위한 저부담 평가의 사용

- (b) 낮은 평가의 집계를 바탕으로 학습자의 진행 상황에 대한 높은 의사 결정을 내린다.

- (c) 최소 5년의 장기 프로그램 평가 시행

An extreme case sampling strategy was employed to select unique research settings known to provide significant insights about programmatic assessment.21 We selected research settings that required teachers to use low‐stake assessment in contexts in which assessments have both low‐ and high‐stake purposes. The inclusion criteria for these implementations were:

- (a) the use of low‐stake assessment to provide information for learning;

- (b) the making of high‐stake decisions on learners' progress based on the aggregation of those low‐stake assessments, and

- (c) a long‐term programmatic assessment implementation of at least 5 years.

해당 분야 전문가들의 이전 연구와 제안을 바탕으로 두 개의 의학전문대학원을 선정했다.

Based on previous research and suggestions by experts within the field, we selected two medical schools with graduate‐entry medical programmes:

- the Physician‐Clinical Investigator Programme at Maastricht University, the Netherlands (Setting A) and

- the Physician‐Investigator Programme at the Cleveland Clinic Lerner College of Medicine at Case Western Reserve University, Cleveland, Ohio, USA (Setting B).

이러한 의사-연구자 프로그램은 생물의학 연구와 임상 실습의 발전에 중요한 자기 주도 학습 기술을 주입하는 것을 목표로 한다. 두 프로그램 모두 역량 기반 학생(<50명의 학습자)의 소규모 코호트이며, 학습을 육성하기 위해 프로그램 평가 접근 방식을 사용한다. 두 프로그램의 구조와 특성은 표 1과 같다. 추가적으로, 두 프로그램 모두 다른 곳에 자세히 설명되어 있습니다.

These physician‐investigator programmes aim to instil self‐directed learning skills critical for the advancement of both biomedical research and clinical practice. Both programmes are competency‐based, enrol small cohorts of students (<50 learners), and use programmatic assessment approaches to foster learning. The structure and characteristics of both programmes are shown in Table 1. Additionally, both programmes are described in detail elsewhere.5, 22, 23

우리는 기준과 최대 변동 샘플링 전략을 사용하여 의도적으로 참가자를 샘플링했다. 선정된 연구현장에 등록된 학습자 또는 주요 책임이 높은 평가로 학생을 안내하는 피드백 제공에 관련된 학습자를 대상으로 공식적인 책임을 지고 있는 교사를 초빙하였습니다.

We purposefully sampled participants using criterion and maximum variation sampling strategies. We invited

- teachers with formal responsibilities as assessors of low‐stake assessment tasks for learners enrolled in the selected research sites or

- those whose main responsibilities involved providing feedback to guide students towards high‐stake evaluation.

최대 변동은 다음을 기준으로 구되었다.

- (a) 프로그램에서 공식적인 역할(예: 튜터, 코치, 의사 고문/교수, 강사, 조정자, 강사/강사)

- (b) 저학점 평가 유형(예: 표준화된 강의 과정 시험, 논술, [학점] 과제, 직접 관찰),

- (c) 학습자와의 관계의 다양한 길이(짧은 만남에서 종적 관계에 이르기까지)

Maximum variation was sought based on:

- (a) formal role in the programme (eg, tutor, coach, physician advisor/mentor, lecturer, coordinator, preceptor/supervisor);

- (b) type of low‐stake assessment (eg, standardised in‐course tests, essays, [research] assignments, direct observations), and

- (c) variable lengths of relationships with learners (ranging from brief encounters to longitudinal relationships).

2.2. 데이터 수집 및 분석

2.2. Data collection and analysis

수석 조사관(SS)은 선별된 모든 참가자들에게 연구를 설명하고 현장에서 반구조적인 개별 인터뷰에 자발적으로 참여하도록 초대하는 이메일을 배포했다. 연구팀은 프로그램 평가와 교사 평가 개념화에 대한 이론적 토대를 바탕으로 개방형 질문으로 구성된 인터뷰 가이드를 설계했다. 이 인터뷰 가이드에는 참가자들에게 다음과 같은 질문이 포함되어 있습니다.

- (a) 프로그래밍된 평가 시스템 내에서 저수준 평가의 개념을 설명하고 반영한다.

- (b) 프로그래밍 평가에서 교사와 학습자의 역할과 책임을 논의한다.

- (c) 프로그램 평가의 맥락에서 학습자와의 상호 작용을 반영한다.

- (d) 평가와 학습에 대한 그들의 가치와 신념을 분명하게 표현한다.

The lead investigator (SS) distributed an email to all selected participants describing the study and inviting them to participate voluntarily in semi‐structured individual interviews on site. The research team designed an interview guide consisting of open‐ended questions based on theoretical underpinnings of programmatic assessment and teachers' assessment conceptualisations. This interview guide included questions that asked participants to:

- (a) describe and reflect upon the concept of low‐stake assessment within a programmatic assessment system;

- (b) discuss the roles and responsibilities of the teacher and learner in programmatic assessment;

- (c) reflect upon their interactions with learners in the context of programmatic assessment, and

- (d) articulate their values and beliefs about assessment and learning.

부록 S1은 초기 인터뷰 지침을 제공합니다. 면접은 프로그램 평가 시행 내 평가와 평가 부담에 초점을 맞췄지만, 참가자는 연구팀이 교사의 평가 개념화와 경험을 완전히 이해할 수 있도록 [과거 평가 경험을 되새기도록reflect upon] 장려했다. 모든 인터뷰는 직접적인 식별자 없이 녹음되고 문자 그대로 옮겨졌다.

Appendix S1 provides the initial interview guide. Although interviews focused upon assessment and assessment stakes within the implementation of programmatic assessment, participants were encouraged to reflect upon previous assessment experiences in order to help the research team fully understand teachers' assessment conceptualisations and experiences. All interviews were recorded and transcribed verbatim without direct identifiers.

데이터 수집과 분석은 반복적으로 수행되어 인터뷰 질문 및 후속 인터뷰에 대한 샘플링 전략의 수정에 필요한 적응을 가능하게 했다.

- 처음 네 번의 인터뷰는 초기 코드 개발을 목적으로 오픈 코딩 전략을 사용하여 SS와 SH에 의해 독립적으로 분석되었다. 각 인터뷰에 이어 SS와 SH는 코드와 코드 간의 관계에 대해 논의했습니다.

- 이러한 논의를 바탕으로, 초기 코드는 주요 개념 주제와 하위 테마 중심으로 구성되었다. 데이터를 조사하고 재조사함으로써 주요 범주 간의 관계를 탐구했다.

- 초기 코드는 예시와 반례가 있는 개념 코드로 진화했다. 연구팀(SS SH, BB, ED, JvT 및 CVDV)은 개념 코드를 논의하였다.

- 예비 분석을 자세히 설명하기 위해, 우리는 이론적 샘플링을 계속 사용하여 프로그램 평가에서 저부담 평가에 대한 추가 관점을 수집했다. 구체적으로는 교사들의 프로그램 평가 경험과 교사 배경(기초과학 배경을 가진 교사 대 임상의)을 바탕으로 표본을 확대했다.

- 이론적 충분성theoretical sufficiency에 도달할 때까지 데이터 수집과 분석은 계속되었는데, 이는 분석이 프로그래밍 평가의 맥락에서 교사의 평가 개념화를 이해할 수 있는 충분한 통찰력을 제공할 때까지 이러한 데이터 수집 과정을 계속했다는 것을 의미한다.

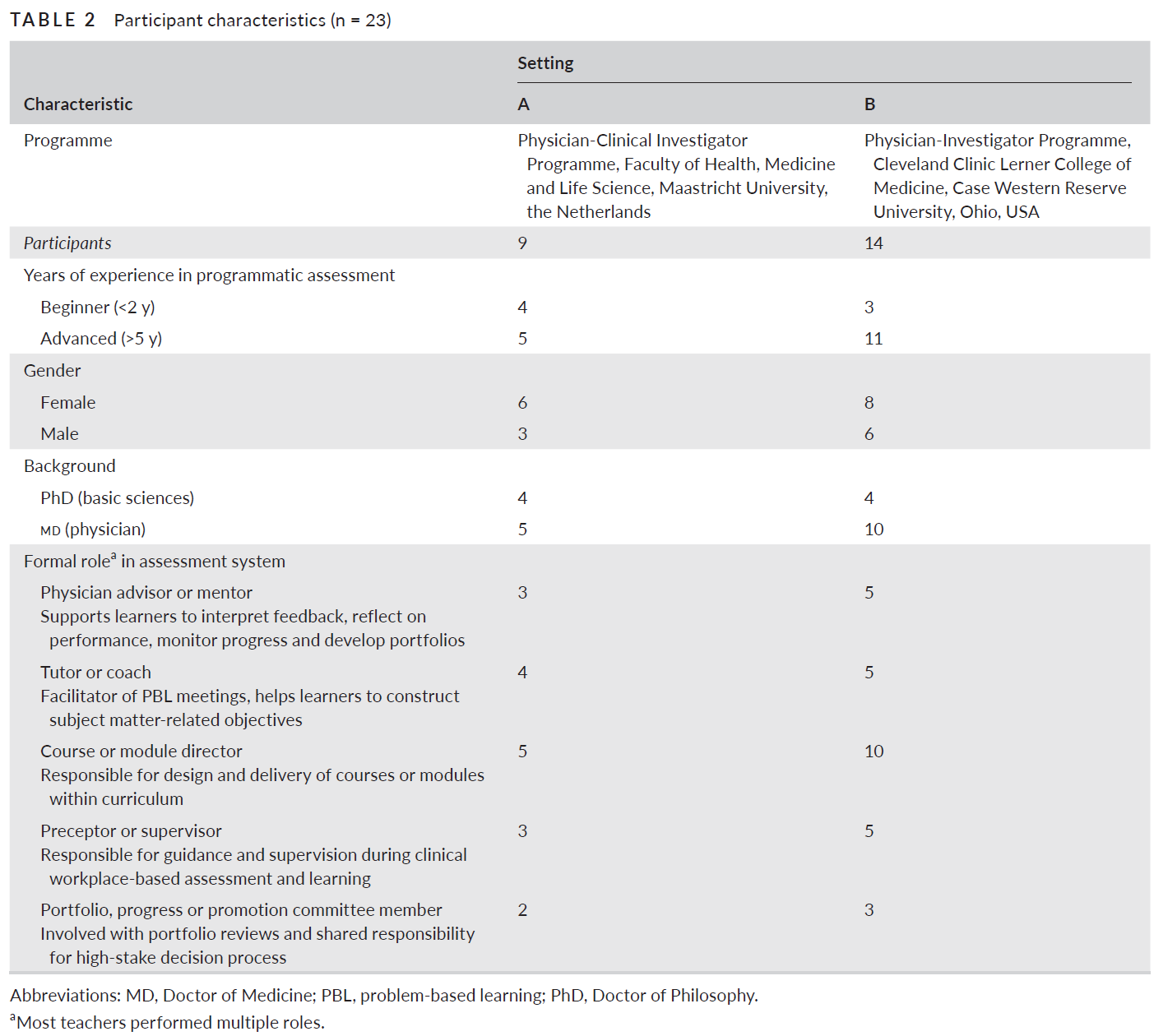

- 총 23명의 교사가 참여해 수석조사관(SS)과의 일대일 대면면접에 참여했으며, 표2는 이들 참가자의 특징을 요약한 것이다.

Data collection and analyses were performed iteratively, allowing for necessary adaptations to interview questions and modifications of the sampling strategy for subsequent interviews.20, 24

- The first four interviews were independently analysed by SS and SH using an open coding strategy with the aim of developing initial codes. Following each interview, SS and SH discussed the codes and relationships between codes.

- Based on these discussions, the initial codes were organised around key conceptual themes and sub‐themes. Relationships amongst major categories were explored by examining and re‐examining data.

- Initial codes evolved into conceptual codes, with examples and counter‐examples. The research team (SS SH, BB, ED, JvT and CvdV) discussed the conceptual codes.

- To elaborate upon our preliminary analysis, we continued the use of theoretical sampling to gather additional perspectives about low‐stake assessments in programmatic assessment. Specifically, we expanded our sample based on the teachers' experience in programmatic assessment and on teachers' backgrounds (teachers with basic science backgrounds versus clinicians).

- Data collection and analysis continued until theoretical sufficiency25 was reached, meaning that we continued this data collection process until the analysis provided enough insight to understand teachers' assessment conceptualisations in the context of programmatic assessment.

- In total, 23 teachers participated in one‐to‐one, in‐person interviews with the lead investigator (SS). Table 2 summarises the characteristics of these participants.

SS는 데이터 수집과 분석 과정에서 분석 메모와 도표를 만들어 과정이 논리적이고 체계적이 되도록 했다. 이 메모와 도표들은 연구팀 내에서 논의되었다. 데이터는 2018년 12월부터 2019년 5월 사이에 수집 및 분석되었다. 네덜란드 의학 교육 윤리 검토 위원회(NVMOmoERB 참조 2018.7.4)와 클리블랜드 클리닉 기관 검토 위원회(IRB 참조 18 ref1516)에서 윤리 승인을 받았다.

During data collection and analysis, SS created analytic memos and diagrams to ensure the process was logical and systematic. These memos and diagrams were discussed within the research team. Data were collected and analysed between December 2018 and May 2019. Ethical approval was obtained from the Dutch Association for Medical Education Ethical Review Board (NVMO‐ERB ref. 2018.7.4) and the Cleveland Clinic's Institutional Review Board (IRB ref. 18‐1516).

2.3. 성찰성

2.3. Reflexivity

우리는 연구자로서 이러한 데이터를 수집, 분석 및 해석하는 데 있어 우리가 한 역할을 인정한다. 편견을 완화하기 위해 다학제 연구팀으로 일했습니다. SS는 수석 연구원으로 활동했습니다. SS는 교육과학에 경험이 있고, 연구지 중 한 곳에서 교직원으로 일하며, 선정된 프로그램에 직접적으로 관여하지 않았다. ED와 CVDV는 의료 교육 및 평가 분야의 전문가입니다. 또한 CVDV는 의학 교육에서 프로그램 평가의 이론적 모델의 창시자 중 하나로 간주된다. SH는 보건 과학에 대한 공식적인 훈련과 경험을 가지고 있고, BB는 교수와 연구 방법에 대해 동등한 배경을 가지고 있다. SS와 BB는 모두 선정된 프로그램의 설계와 구현에 프로그램 디렉터로 참여하였으며, CVDV는 전문가로 참여하였다. SH와 BB는 데이터를 수집하는 동안 참가자들과 직접 접촉하지 않았다. JvT는 사회학자로 훈련을 받았으며 교사 교육 전문가입니다. JvT는 터널 비전과 확인 편향을 좌절시키는 데 도움이 되는 외부 관점을 제공하고 사례와 반례를 검토했으며 코드 구축과 데이터 해석 과정을 지원했다.

We acknowledge the roles that we, as researchers, played in collecting, analysing and interpreting these data. To help mitigate bias, we worked as a multidisciplinary research team. SS functioned as the lead researcher. SS has a background in educational sciences, works as a faculty member at one of the study sites, and had no direct involvement in the selected programme. ED and CvdV are experts in the field of medical education and assessment. Furthermore, CvdV is considered as one of the founding fathers of the theoretical model of programmatic assessment in medical education. SH has formal training and experience in the health sciences and BB has an equivalent background in teaching and research methods. Both SS and BB were involved as programme directors in the design and implementation of the selected programmes, as was CvdV as an expert. SH and BB had no direct contact with the participants during data collection. JvT is trained as a sociologist and is an expert in teacher education. JvT provided an outsider perspective to help thwart tunnel vision and confirmation bias, reviewed examples and counter‐examples, and supported the process of code construction and data interpretation.

3. 결과

3. RESULTS

그 결과, 교사들은 세 가지 다른, 그러나 관련성이 있는 방식으로 [평가의 목적]을 개념화하는 것으로 나타났다.

- (a) 학습을 자극하고 촉진하게 하기 위해,

- (b) 학습자를 다음 단계로 준비시키기 위해, 그리고

- (c) 교사 자신의 효과를 측정하기 위한 피드백으로 사용하기 위해,

The results showed that teachers conceptualise the purpose of low‐stake assessment in three different, yet related ways:

- (a) to stimulate and facilitate learning;

- (b) to prepare learners for the next step, and

- (c) to use as feedback to gauge the teacher's own effectiveness.

결과적으로 이러한 관점은 평가를 제공하거나 토론할 때 학습자에 대한 관여에 영향을 미쳤다.

Consequently, these views influenced their engagement with learners when providing or discussing assessments.

3.1. 저부담 평가의 개념화

3.1. Conceptualisations of low‐stake assessments

3.1.1. 학습 자극 및 촉진

3.1.1. Stimulating and facilitating learning

교사의 공식적인 위치(예: 튜터, 코치, 의사 조언자 또는 멘토, 과정 감독, 평가자, 교육자)의 차이에도 불구하고, 우리는 저부담 평가의 목적에 대해 [일차적으로 공유된 개념]은 [학습을 촉진하고 용이하게 하는 것]으로 식별했다. 이 개념은 [저부담 평가의 결과가 minimal하다는 점]에 영향을 받았다. '학습자는 이 평가로 fail을 받지 않는다', '등급이 매겨지지 않는다', '저부담 평가는 주로 성과 향상에 관한 것이다'와 같은 문장은 낮은 평가 개념을 반영할 때 참가자 모두가 내렸다. Grades의 사용은 고부담 평가와 밀접한 관련이 있었고, 대부분의 참가자들은 성적 배정이 학습learning에 이롭다고는 생각하지 않았다. 대신, Grades은 순위를 매기고 학습자를 비교하는 평가 목적과 연관되었다. 학습자가 [저부담 평가를 학습의 목적]으로 사용하게 하려면, 교수자는 학습 자극을 주고, 개선을 촉진하기 위해 학습자에게 서술적 피드백을 제공하는 것이 중요하다고 강조했습니다.

Despite the differences in teachers' formal positions (eg, tutor, coach, physician advisor or mentor, course director, assessor, preceptor), we identified a shared primary conceptualisation of the purpose of low‐stake assessments as being to stimulate and facilitate learning. This conception was influenced by the perceived minimal consequences of low‐stake assessment. Statements like: ‘learners can't fail them,' ‘they are not graded’ and ‘low‐stake assessments are primarily about improving performance’ were given by all participants when reflecting on the concept of low‐stake assessments. The use of grades was strongly associated with high‐stake assessments, and most participants did not regard assigning grades beneficial for student learning. Instead, grades were associated with the assessment purposes of ranking and comparing learners. To enable learners to use low‐stake assessments for learning, teachers highlighted the importance of providing learners with narrative feedback in order to stimulate learning and facilitate improvement:

학생들의 석차는 나에게 별로 의미가 없다. 이런 환경에서 [학점을 사용하지 않는 프로그래밍식 평가]가 잘못될 염려가 별로 없으며, [학습자] 그들은 이 시스템으로 석차 등급을 받기 위해 영리하게 보이려고 노력하지 않는다고 생각합니다. (B5, 임상의)

The rank ordering of students is not that meaningful to me. […] In this environment [programmatic assessment without the use of grades] there is not a fear of being incorrect as much, I think, and they [learners] are not trying to look smart in order to get rank order grades with this system. (B5, clinician)

프로그램 수준에서 [성과나 개선에 대한 증거를 수집할 수 있는 기회의 수]는 교사의 평가 개념화와 학습 기회에 영향을 미쳤다.

At a programme level, the number of opportunities for collecting evidence on performance or improvement influenced teachers' assessment conceptualisations and opportunities for learning:

이 프로그램에는 단 한 번의 기회만 주어지기 때문에 진급 위원회는 학습자들이 포트폴리오에 이 평가 결과를 사용할 것으로 예상할 것이다.

There's only one chance in the programme, and so the progress committee will expect them [learners] to use it [the result of this assessment] in their portfolios, so that raises the stakes tremendously. (B7, basic scientist)

프로그램이 다수의 저부담 평가를 촉진하여야, 교사들은 자신들의 책임을 [학습자가 스스로 평가 근거의 경향이나 패턴을 발견하도록 지원하는 것, 성찰을 자극하는 것, 학습 목표와 잠재력에 도달하기 위한 학습자의 개선 계획을 가능하게 하는 것]으로 개념화할 수 있었다. 또한, 다수의 저부담 평가에 따른 결과는 제한적이라고 인식했기 때문에, 교사들이 학습자에게 정직하고 건설적인 피드백을 제공할 수 있는 더 나은 기회를 만들었다.

When the programme facilitated multiple low‐stake assessments, teachers conceptualised their responsibility as being to support learners in discovering trends or patterns in assessment evidence, to stimulate reflection, and to enable learners' improvement plans for reaching learning goals and perceived potential. Furthermore, multiple low‐stake assessments created better opportunities for teachers to provide learners with honest and constructive feedback because they perceived limited consequences:

왜냐하면 누군가 처벌받지 않고도 향상될 수 있다는 것을 안다면, 문제가 되는 것에 대한 정보를 주지 않을 이유가 없다. 반면 다른 환경에서는 '누구도 곤경에 빠뜨리고 싶지 않은 마음'때문에, 학습자가 잘하고 있는 것만 부각시키고, 잘 하지 못하는 것에 대해서는 침묵하는 습관이 생긴다고 생각한다.

I think it's liberating in a lot of ways, because if you know that somebody can improve without being punished, there is no reason to not give them the information about something that is problematic. Whereas I think that in other settings, it feels like people get into the habit of highlighting things that learners are doing well and just being quiet about things that are problematic because ‘I don't want anybody to get in trouble.' (B8, clinician)

3.1.2. 학습자 다음 단계 준비

3.1.2. Preparing learners for the next step

학습learning에 더하여, 교사들은 저부담 평가를 [학습자가 고부담 평가나 향후 실습을 대비할 수 있는 방법]으로 생각했다. 이러한 평가 개념화는 교사들이 학습을 촉진하는 방식에 큰 영향을 미쳤다. 교사들은 학습자들이 '적절한 준비를 하고 있는지' 확인하기 위해서는 보다 [직접적인 접근]이 필요하다고 생각했다. 중요한 것으로 여겨지는 것은 기초 과학자와 임상의 사이에 차이가 있었다.

In addition to learning, teachers also thought of low‐stake assessments as a way to prepare learners for high‐stake assessments or for future practice. This assessment conceptualisation strongly influenced how teachers facilitated learning: teachers thought a more directive approach was required to ensure learners were ‘properly prepared.' What was considered important differed between basic scientists and clinicians.

교육과정에서 [기초과학 관련 교육]를 담당하는 대부분의 교사는 지식평가를 강조했다. 그들은 지식을 역량에 필수적인 것으로 여겼고, 대부분의 학습자는 지식 테스트를 통과할 수 있어야 한다고 믿었다.

Most teachers with teaching tasks related to the basic sciences within the curriculum emphasised assessment of knowledge. They regarded knowledge as fundamental for competence, and most believed learners should be able to pass a knowledge test:

내가 보기에 이것들은 그들이 특정한 시점에서 취해야 할 중요한 장애물들이다. […] 만약 당신이 그 기준을 충족시킬 능력이 없다면, 당신은 충분한 지식과 통찰력을 가지고 있고, 이것은 결과를 가져올 필요가 있다. (A1, 기초과학명언)

In my view these are important hurdles which they [learners] have to take at certain points. […] If you are not capable of meeting those standards, you have insufficient knowledge and insights, which needs to have consequences. (A1, basic scientist)

그러나 [임상의]들은 [전반적인 임상 역량]에 초점을 맞추는 경향이 있었다. 지식 테스트는 중요하고 종종 근본적인 것으로 여겨졌지만, [지식의 차이는 학습자가 쉽게 고칠 수 있는 것]으로 인식되었다. 인터뷰한 많은 임상의에 따르면, 이러한 테스트는 학습자가 '실제' 임상 실습을 준비하는 데 덜 중요한 것으로 간주되었다.

Clinicians who participated in this study, however, tended to focus on overall clinical competence. Although knowledge testing was considered important and often fundamental, gaps in knowledge were perceived as being easy for learners to remediate. According to many of the clinicians interviewed, these tests were considered as less important for preparing learners for ‘real’ clinical practice:

나는 [지식 시험]은 [의사가 되는 것이 무엇을 의미하는지]를 반영하지는 못한다고 생각한다.

I don't think they [knowledge tests] reflect what it means to be a physician. (B4, clinician)

임상의는 주로 학습자를 향후 실습에 대비시키기 위해 저부담 평가(low-stake assessment)를 사용했다.

Clinicians used low‐stake assessment mainly to prepare learners for future practice:

저는 저부담평가가 평가를 준비하는 과정에서 학생들이 기술을 향상시키는 방법들 중 하나라고 생각합니다. 그렇게 함으로써 clinical years에 맞게 최적화하게 한다. (A3, 임상명언)

I think that is one of the ways that they improve their skills [by] preparing them and making sure they are optimised for [the] clinical years. (A3, clinician)

[외부의 고부담 지식 평가]가 포함된 경우에서는 예외가 발견되었습니다. 모든 교사는 학습자가 졸업 또는 면허 요건을 충족시키기 위해 높은 평가를 통과해야 한다는 것을 이해했으며, 평가의 의미가 있는지 여부에 관계없이 이러한 평가에 대한 준비를 중요하게 여겼습니다.

Exceptions were found when external, high‐stake knowledge assessments were involved. All teachers understood that learners must pass high‐stake assessments to meet either graduation or licensure requirements and considered preparing learners for such assessments an important responsibility, whether they considered the assessment meaningful or not:

3.1.3. 교사에 대한 피드백으로서 낮은 평가

3.1.3. Low‐stake assessments as feedback for teachers

저부담 평가가 teaching practice과 teacher themselves에 가지는 가치가 있었다. 교사들은 저부담 평가를 학습 목표 달성에 있어 학습자의 진행 상황을 진단하고, 교정 조치가 필요하다고 생각되는 학습자를 식별하며, 학습자의 수행 기준 달성을 모니터링할 수 있는 기회로 개념화했다. 일부 교사들은 평가가 개인적, 전문적 발전에 미칠 수 있는 상호적 이익을 높이 평가했으며, 이는 성찰적인 태도를 자극했다.

Low‐stake assessment also carried value for teaching practices and teachers themselves. Teachers conceptualised low‐stake assessments as representing opportunities to diagnose learners' progress in acquiring learning objectives, to identify learners they thought required remediation, and to monitor learners' achievement of performance standards. Some teachers appreciated the reciprocal benefits low‐stake assessment may have upon their personal and professional development, which stimulated a reflective attitude:

학생에게는 배움의 기회이지만, 저에게는 배움의 기회이기도 합니다. 그것은 또한 내가 무엇을 하고 있는지, 무엇을 개선할 수 있는지에 대해 생각하게 한다.

It's a learning opportunity for the student, but, really, it's also a learning opportunity for me. It forces me to be reflective too, and think about what I'm doing, and what could be improved. (B4, clinician)

선생님들은 자신의 교육적 효과성에 대한 정보를 얻기 위해 저부담 평가들에 의존했다. 교사는 저부담 평가에서 학습자의 성과를 자신의 성과를 명시적이고 직접적인 지표로 인식하여 다음과 같이 평가하였다.

Teachers relied on low‐stake assessments to inform them about their effectiveness. Teachers perceived learners' performances on low‐stake assessments as explicit and direct indicators of their own performance, thereby making these assessments of higher stakes for teachers:

저에게는 [표준화된 지식 테스트]가 매우 중요한 순간이며, 학생들이 시험을 잘 볼 때 마음이 놓이고 매우 행복합니다. 내가 잘했다는 뜻이다.

For me it's [standardised knowledge test] a high‐stake moment, and I'm relieved and very happy when students perform well on the test. It means I did a good job. (A1, basic scientist)

이러한 관찰은 교사가 임상실습이나 로테이션 중에 개별 학습자를 감독할 때와 같은 임상적 맥락에도 적용된다.

This observation also applied to clinical contexts, such as when teachers supervised individual learners during a clerkship or rotation:

그래서 이 학생이 저와 함께 일해왔다는 사실이, 이 학생이 바로 여기 있다는 것이 나에 대한 어떤 반영reflection인 것 같다. 그래서 마치 부담이 더 크게 느껴지기도 한다. 우리는 이 학생을 다음 preceptor에게, 그리고 결국 현실 세계로 내보내기 때문이다. (B8, 임상의)

And so this idea that this person has worked with me and this is where they are, I feel like it is a certain reflection of me and so then it feels like the stakes are higher as part of it, we are sending them out to the next preceptor and in the end, into the real world. (B8, clinician)

3.2. 평가 관계에서 학습자와의 교사 참여

3.2. Teachers' engagement with learners in assessment relationships

3.2.1. 안전하지만 생산적인 관계 만들기

3.2.1. Creating safe but productive relationships

교사의 평가 개념화가 학습에 대한 평가 사용에 초점을 맞출 때, 교사들은 안전한 교사-학습자 관계를 만들어야 할 강한 필요성을 나타내며, 교사들은 이를 '돌봄', '따뜻함', '접근 가능', '동반자 관계'와 같은 단어를 사용하여 설명하였다. 교사들은 학습자들이 평가에 대한 인식이 다른 경우가 많다는 것을 알고 있었고, 교사들은 학습자들을 평가 시스템의 근본적인 철학에 대한 방향을 잡아야 할 책임이 있었다. 교사들은 학습자가 실패하거나 실수할 수 있는 '저부담' 학습 환경을 조성하고, 저부담 평가를 활용해 수행능력을 높이는 것이 자신들의 책임이라고 봤다. 교사들은 학습자와의 파트너십을 통해 기쁨을 얻었고, 프로그램 평가의 기본 철학이 (기존의 평가 방식보다) 실세계의 practice와 더 잘 부합한다고 여겼으며, 따라서 학습자와의 assessment practice는 더욱 의미 있고 관련성이 있었다.

When teachers' assessment conceptualisations focused on the use of assessment for learning, teachers indicated a strong need to create safe teacher‐learner relationships, which they described using words such as ‘care,' ‘warmth,' ‘accessible’ and ‘partnership.' Teachers were aware that learners often had different perceptions of assessment, and teachers took responsibility for orienting learners to the underlying philosophy of the assessment system. Teachers believed it was their responsibility to create a ‘low‐stake’ learning environment in which learners could fail or make mistakes, and to use low‐stake assessment to improve their performance. Teachers gained joy from partnering with learners and viewed the underlying philosophy of programmatic assessment as better aligned with real‐life practice than traditional assessment approaches, thereby making their assessment practices with learners more meaningful and relevant:

제가 하는 일은, 더 이상 수문장이 되거나 학생들이 졸업하지 못하게 하는 것이 아니라, 학생들이 성공할 수 있도록 돕는 것입니다. 이제 제 일은 '더 좋아지고 있나요?' 입니다. '넌 끝났어' 라고 말하는 것보다 그 역할에 대해 훨씬 더 기분이 좋다.

My job is not to be a gatekeeper anymore or keep students from graduating, but to help students be successful. My job now is: ‘Are you getting better?’ I feel much better about that role than [about] saying: ‘You are done.’ (B11, clinician)

그럼에도 불구하고, 교사들은 안전한 학습 환경을 유지하고 학습자와의 생산적인 작업 및 평가 관계를 유지하는 것 사이에서 올바른 균형을 이루는 데 초점을 맞췄다. 이것은 [교사-학습자 관계에서 일정 거리]를 요구하는 것으로 나타났다. 교사들은 이 관계가 전문적일 필요가 있다고 생각했다.

Nevertheless, teachers focused on striking the right balance between maintaining safe learning environments and preserving productive working and assessment relationships with learners. This appeared to require a certain distance in the teacher‐learner relationship. Teachers thought the relationship needed to be professional:

그들은 내 친구나 뭐 그런 사람들이 아니다. 나는 내가 접근하기 쉬운 것이 중요하다고 생각하지만,

일정한 경계선이 있다; 그것은 전문적인 관계를 유지해야 한다.

They [learners] are not my friends or anything. I think it's important that I'm approachable, but there are certain boundaries; it needs to stay a professional relationship. (A19, clinician)

모든 교사들은 평가의 맥락에서 학습자들에게 너무 가까이 가거나 지나치게 친숙해지지 않는 것에 대해 명백했다.

All teachers were explicit about not getting too close to or overly familiar with learners in the context of assessment; teachers wanted to minimise undue influences of their personal biases.

3.2.2. 통제력 확보 대 독립성 허용

3.2.2. Taking control versus allowing independence

학습자가 학습에 대한 책임을 질 수 있도록 하겠다는 의도를 교사들이 분명히 밝혔지만, 거의 모든 교사들은 [결국 평가 과정을 통제해야 한다]고 믿었다. 교사들은 이것이 그들의 공식적인 위계적 위치와 그들의 경험과 전문지식이 학습자들의 것과 비교한 자연스러운 결과라고 지적했습니다. 이러한 통제의 필요성은 [의도된 학습 목표]와 임상적 맥락에서 [환자 안전]에 관한 교사의 고부담 책임으로 더욱 강화되었다.

Although teachers were explicit about their intention to allow learners to take responsibility for learning, almost all teachers believed that, in the end, they should control the assessment process. Teachers indicated that this was a natural consequence of their formal hierarchal position and their level of experience and expertise compared with those of learners. This need for control was further augmented by teachers' high‐stake responsibility concerning intended learning objectives and, in a clinical context, patient safety:

하지만 내가 통제하고 있다. 내 말은, 그들이 배우고 있는지 확인하는 게 내 책임이라는 것이다[…] 해야 할 일과 배워야 할 일이 있습니다. 내가 그들에게 맡긴다면… 누가 알겠어요? 그래서, 나는 정말로 그것을 통제할 수 있어야 합니다. […] 누군가가 무언가를 할 수 있도록 허락하기 전에 그 일을 할 수 있는 기술을 갖추고 있는지 확인해야 한다. (B4, 임상의명언)

But I am in control. I mean, I am, you know it is my responsibility to make sure they are learning. […] There are things that need to be done and that they have to learn. If I left it to them… who knows? So, I really need to be able to control it. […] You have to make sure that someone is skilled in doing something before you allow them to do it. (B4, clinician)

프로그램 평가에서 [초보 교사]들은 경험이 많은 교사들보다 [평가 과정에 대한 더 많은 통제]를 원했다. 프로그램 평가 경험이 제한적인 이들은 자신의 지식과 프로그램 요구 숙련도, 평가 시스템 전체의 효율성에 대해 불확실성의 목소리를 높였다. 그 결과, 그들은 지침과 지원의 질에 대한 높은 압력을 인식하였고, 학습자가 프로그래밍 방식의 평가에 대한 경험이 부족하기 때문에 불이익을 받을 수 있다고 우려하였다. [학습자의 자율성을 명시적으로 중시하는] 경험이 풍부한 교사일수록, 학습자가 평가 과정을 추가로 통제할 수 있도록 하는 데 더 편안해 보였다. 이는 [학습자의 능력과 역량에 대한 교사들의 신념]에 크게 영향을 받았다.

Novice teachers in programmatic assessment desired more control of assessment processes than experienced teachers. Those with limited experience with programmatic assessment voiced uncertainties about their knowledge and proficiency with programme demands and the effectiveness of the assessment system as a whole. As a result, they perceived a high level of pressure on the quality of their guidance and support and feared that learners might be penalised as a result of their lack of experience with programmatic assessment. More experienced teachers, who explicitly valued learners' autonomy, seemed more comfortable with allowing learners to take additional control over assessment processes. This was strongly influenced by teachers' beliefs in learners' abilities and competencies:

나는 학생 개개인의 필요에 적응하는 것이 중요하다고 생각한다. 독립에 대한 필요성은 시간이 지남에 따라 증가한다.

I think it's important to adapt to individual student needs […], the need for independence grows over time. (A21, basic scientist)

3.2.3. 평가관계의 충돌

3.2.3. Conflicts in assessment relationships

교사들이 교사-학습자 평가 관계에서 인지할 수 있는 [잠재적 갈등]은, 교사들이 [문제가 있거나 저조한 학습자들]과 상호작용할 때 발생할 가능성이 가장 높은 것으로 보인다. 교사들은 학습자에게 건설적이거나 비판적인 피드백을 제공하는 것에 대해 불편함을 토로하였으며, 관계를 지속하는 것에 대해 우려했다.

The potential conflicts teachers were able to perceive in teacher‐learner assessment relationships seemed most likely to occur when teachers interacted with problematic or underperforming learners. Teachers voiced discomfort about providing learners with constructive or critical feedback and worried about preserving relationships:

'내가 [그들이 해야 할 일을 하지 않았다는 것]을 밝혀야 할 사람이다'라는 불편함이 내가 의학 교육자가 되기로 선택한 이유는 아니라고 생각한다.

I think that discomfort with ‘I'm the one that is going to have to identify that they haven't done what they're supposed to do,' is not why I chose to be a medical educator. (B8, clinician)

게다가, 교사들은 그들의 불편함을 느끼는 이유는, 어려움을 겪고 있는 학습자들을 위해 [추가적인 미팅과 더 광범위한 피드백]과 같은 더 많은 슈퍼비전을 제공할 필요가 있다는 필요성을 느끼기 때문이라고 말했다. 이로 인해 학습자 성과에 대한 최종 고부담 의사 결정에서 실제로 평가되는 것이 무엇인지에 대한 우려가 제기되었다. 즉, 교사의 멘토링과 피드백 기술인가? 아니면 학습자의 성과와 진전인가?

Furthermore, teachers attributed their discomfort to the perceived need to provide more supervision for struggling learners, such as additional meetings and more extensive feedback. This raised concerns about what would actually be assessed in the final high‐stake decision on learner performance: the teacher's mentoring and feedback skills or the learner's performance and progress?

[진급 위원회가 고부담 성과 결정에 대한 책임을 지고, 교사-학습자 평가 관계의 외부 당사자 역할을 할 때] 어려움을 겪고 있는 학습자와의 생산적인 작업 관계는 유지하기가 더 쉬웠다. 더욱이 교사들은 프로그램적 접근법에서 평가 결정을 공유된 책임shared responsibility으로 개념화하였는데, 이는 대부분 이전의 평가 경험에서 긍정적인 변화를 나타내는 것으로 인식되었다.

A productive working relationship with struggling learners was easier to maintain when progress committees assumed responsibility for high‐stake performance decisions and functioned as external parties to teacher‐learner assessment relationships. Moreover, teachers conceptualised assessment decisions within a programmatic approach as a shared responsibility, which most perceived as representing a positive change from their previous assessment experiences:

사람이 더 필요하다. 우리는 서로의 관점을 고쳐주고, 서로에게 도움이 되는 것을 제공한다. 그것은 또한 학생들을 위해 그것을 더 안전하게 만든다. […] 다수의 지혜가 소수의 지혜보다 낫다. (B11, 임상명언)

You need more people. We kind of correct each other's perspectives on things and offer things that are helpful. That also makes it safer for the student. […] The wisdom of several is better than the wisdom of some. (B11, clinician)

4. 토론

4. DISCUSSION

프로그램 평가 내의 평가 연속체는 이론적으로 하나의 극단('평가에 대한 학습적learning 개념')에서 반대 극단('평가에 대한 결산적accounting 개념')으로 흐르지만, 각각의 단일 저부담 평가는 이중의 목적을 가지고 있다. 대부분의 교사들은 저부담 평가의 [학습적 개념]에 초점을 맞췄다. 그러나 '학습'이 학습자의 고부담 평가 준비로 인식되고, 교사가 교사의 책무성을 강조하는 상황에서, 교사들은 [결산적 개념]으로 평가를 개념화하는 쪽으로 이동했고, 보다 지시적이고 통제적인 어조를 띠었다. [고부담 평가]로 평가를 개념화하게 되면 teaching to the test의 위험을 가지고 있었으며, (그 시험이 의미가 있건 없건) 특히 외부 고부담 평가가 결부된 상황에서 그러했다.

The assessment continuum within programmatic assessment theoretically flows from one extreme (the ‘learning conception of assessment’) to the opposite extreme (the ‘accounting conception of assessment’) yet holds a dual purpose in each single low‐stake assessment.2, 3 Most teachers focused on a learning conception of low‐stake assessment. However, when ‘learning’ was conceived as preparing learners for high‐stake assessment and when teachers emphasised teachers' accountability, teachers' assessment conceptualisations actually moved towards the accounting end of the continuum and carried a more directing and controlling tone. Such conceptualisations risk teaching to the test, whether it is considered meaningful or not, especially when external high‐stake assessments are involved.

Stiggins는 외부평가의 이러한 부정적인 영향을 설명하였는데, Stiggins는 [책무성accountability에 목적을 둔 중앙집중식 평가]가 개별 교사들의 교육정보 요구를 충족할 수 없으며, assessment practice을 경시trivialising할 위험이 있다고 언급하였다. 비록 본 연구 결과에 따르면, 프로그램 평가를 도입함으로써 교사의 초점을 [학습자가 시험을 통과하는데 필요한 지식과 기술의 수용성]에서 [지속적인 전문적 발전과 임상 역량]으로 전환시킬 수 있다는 것을 보여주었지만, 고부담 시험, 특히 표준화된 시험은 이 변화shift의 발생을 가로막을 수 있다.

This adverse impact of external assessment has been described by Stiggins,26 who notes that centralised assessment for accountability purposes cannot meet the instructional information needs of individual teachers and may run the risk of trivialising their assessment practices. Although the results showed that the implementation of programmatic assessment could enable a shift in teachers' focus on the acquiral of the knowledge and skills necessary for learners to pass a test to a focus on continuous professional development and clinical competence, high‐stake and especially standardised examinations could impede the occurrence of this shift.

이 연구의 결과는 또한 교사들이 [학습자의 수행과 진도를 바탕으로 자신의 교육 효과성을 측정]할 때, 저부담 평가의 이해관계가 교사들에게도 중요해진다는 것을 보여주었다. 이것은 왜 그렇게 많은 교사들이 양질의 학습자 성과와 수행 표준의 달성을 보장하기 위해 평가 과정을 통제하고자 하는지 설명할 수 있다. 본 연구의 교사들은 [학습자가 갖는 의존적인 입장]을 알고 있었으며, [교사-학습자 평가 관계를 설명할 때 역설을 표현]했다. 교사-학습자 파트너십, 학습자 독립성 및 학습자 자기 조절 능력에 대한 평가는 교사가 평가 과정의 통제를 줄이기에 충분하지 않은 것으로 보였다. 교사들은 [학습자의 수행능력이나 역량]이 ['좋은' 실천에 대한 교사의 인식이나 확립된 기준]과 일치해야만, [평가 과정을 통제할 수 있는 더 많은 권한을 학습자에게 부여empower했다]고 인정했다.

The results of this study further showed that the stakes of low‐stake assessment are just as much involved for teachers when teachers gauge their effectiveness based on learners' performance and progression. This may explain why so many teachers desire to control assessment processes to ensure high‐quality learner performance and achievement of performance standards. Teachers in our study were aware of the learner's position of dependency and expressed a paradox when describing teacher‐learner assessment relationships. The valuing of teacher‐learner partnerships, learner independence and learner self‐regulation abilities did not appear to be sufficient for teachers to lessen their control of assessment processes. Teachers admitted that they empowered learners to take more control over assessment processes only when the learner's performance or competence aligned with the teacher's perceptions of ‘good’ practice or established criteria.

이렇게 [교사들이 [무엇이 good practice을 구성하는지]를 일방적으로 결정하는 것]은 [자기조절이라는 목표]와는 상충되는 것으로 보이며, 평가가 학습을 위해for 사용될 경우 역효과적으로 작용할 수 있다. 게다가, [교사가 통제에 대한 필요성을 느끼는 것]은 [학습자들이 종종 저부담 평가를 저부담으로 인지하지 못하는 이유]를 설명할 수 있다. 많은 학자들이 [학습과 평가 환경 내에서 행동하고, 통제하며, 선택을 할 수 있는 학습자의 능력]으로 정의되는 [학습자 행위자성agency]의 중요성을 강조하고 있다. 또한 학습자 스스로도 [학습을 위해 평가를 사용할 수 있는 행위자성agency의 중요성]을 제기하고 있다. 여기에도 [신뢰와 통제 사이의 긴장]이 여전하다. [학습을 위한 평가AoL를 촉진하게 하기 위해, 학습자가 안전한 저부담 환경을 누릴 수 있도록] 하려면, 교사들을 위한 [지지적 저부담 환경 조성]에도 집중해야 한다. 교사와 학습자 모두에게 이해관계가 걸려있으며, 단일 평가의 낮은 consequence만큼 간단하지 않다.

This unilateral determination by teachers of what constitutes good practice seems at odds with the objective of self‐regulation27, 28, 29 and could work counterproductively when assessment is intended to be used for learning. Furthermore, this need for control on the part of the teacher may explain why learners so often fail to perceive low‐stake assessments as being truly of low stakes and beneficial for their learning.5, 6, 7, 30 The importance of learner agency, defined as the learner's ability to act, control and make choices within the learning and assessment environment, is voiced by many scholars.1, 31, 32 Moreover, learners themselves have voiced the importance of agency to enable the potential of using assessment for their learning.7 Here too lingers the tension between trust and control. If we want learners to enjoy a safe low‐stake environment in order to facilitate assessment for learning, then we should focus on creating supportive low‐stake environments for teachers as well. Stakes are involved for both teachers and learners, and they are clearly not as straightforward as the low consequence of a single assessment.

교사들이 학습에 저부담 평가를 사용하도록 서포트하는 것으로 보이는 [두 가지 중요한 프로그램 평가 설계 특]징을 식별했다.

- (a) 다수의 저부담 평가를 사용하는 것. 특히 Grades를 사용하지 않는 것.

- (b) 독립적인 제3자를 평가 관계에 도입하는 진행 위원회의 실행.

The results also identified two important programmatic assessment design features that seemed to support teachers' use of low‐stake assessment for learning:

- (a) the use of multiple low‐stake assessments, especially those without the use of grades, and

- (b) the implementation of progress committees, which introduces an independent third party into the assessment relationship.

첫째, 다수의 저부담 평가와 다수의 평가자를 사용하는 원칙은 교사가 학습자에게 보다 정직하고 비판적인 피드백을 제공할 수 있게 해주었고, 의학교육의 '실패실패 failure to fail'에 비추어 볼 때 프로그래밍 평가 접근법의 유망한 설계 특징이다. 이전 연구에서는 [평가 증거가 서로 다른 맥락과 출처에서 근원했을originate 때], 진급 위원회와 학습자 모두 낮은 평가 증거의 품질을 더 높게 평가하는 것으로 나타났다. 따라서 [프로그램에서 제공되는 평가 증거 수집 기회의 숫자]는 복수의 이해관계자가 관여된 상황에서 [평가의 부담과 학습적 가치에 대한 인식]에 큰 영향을 미친다. 또한, 성적의 사용과 달리 [서술적 피드백의 강조]는 비교, 순위 및 경쟁이 아닌 숙달과 진보를 강조하기 때문에 학습 평가를 가능하게 하는 핵심 설계 요소로 인식되었다. 성적의 사용과 관련된 위험과 학습을 촉진하기 위한 서술적 피드백의 중요성은 다른 많은 사람들에 의해 강조되어 왔다.

First, the principle of using multiple low‐stake assessments and assessors enabled teachers to provide more honest and critical feedback to learners, which, in light of medical education's ‘failure to fail’33 is a promising design feature of the programmatic assessment approach. Previous research has shown that both progress committees and learners rate the quality of low‐stake assessment evidence more highly when assessment evidence originates from different contexts and sources.34 Thus, the number of opportunities for collecting assessment evidence provided by the programme strongly influences the perceptions of assessment stakes and learning value for the multiple stakeholders involved.7, 34 Furthermore, the emphasis on narrative feedback, as opposed to the use of grades, was perceived as a key design factor to enable assessment for learning because such feedback emphasises mastery and progress instead of comparison, ranking and competition. The risks associated with the use of grades and the importance of narrative feedback to promote learning have been highlighted by many others.1, 30, 35, 36, 37

둘째, 교사들은 평가의 맥락에서 학습자들과의 파트너십을 즐기고, 학습자들과 생산적인 업무 관계에 참여하기 위해 투자했습니다. 비록 일부 교사들에게 저부담 평가의 이중 목적이 불편한 결혼 생활unhappy marriage을 계속해서 나타낼 수 있지만, 우리의 결과는 역할 갈등이 꼭 필요한 것은 아님을 보여주었다. 프로그램 평가에서 다자 역할 멘토링에 대한 연구에서도 유사한 발견이 나타났습니다. 본 연구에서는, [어려움을 겪고 학습능력이 떨어지는 학습자]에 대해서만 갈등이 보고되었다. (임상 역량 위원회로도 사용되고 있는) [독립적인 진급 위원회의 운영]은 교사들이 평가 맥락에서 생산적인 교사-학습자 관계를 보존하면서, 이러한 갈등을 보다 쉽게 처리할 수 있는 기회를 만들었다.

Second, teachers enjoyed partnering with learners in the context of assessment and invested in engaging in productive working relationships with learners. Although for some teachers the dual purpose of low‐stake assessment may continue to represent an unhappy marriage, our results showed that a role conflict is not necessary. Similar findings emerged in a study on multiple‐role mentoring in programmatic assessment.38 Conflicts in our study were reported only in relation to struggling and underperforming learners. The implementation of independent progress committees, also in use as clinical competency committees,39 created opportunities for teachers to deal with this conflict more easily when preserving a productive teacher‐learner relationship in an assessment context.

우리의 연구 결과는 프로그래밍 방식의 평가의 다른 구현에 도움이 될 수 있다. 선생님들은 평가로 학습자에게 불이익이 가는 것에 대해 걱정합니다. 진급 위원회는 잘 조직되면 서포트, 전문지식, 그리고 무엇보다 프로그램 평가에 참여하는 [교사들을 위한 안전망]을 제공한다. 학생의 실패는 [집단적인 책임]이 되고, 학습자의 커리어는 [개인의 결정이나 제한된 스냅사진]에 의존하지 않는다. 이것은 교사들로부터의 압력의 일부를 제거해주는 것으로 보이며, 그들이 더 솔직한 건설적인 피드백을 제공할 수 있게 해주고, 장기간 참여prolonged engagement의 이점을 유지하면서도, 우려를 제기할 수 있게 한다. 나아가, 진급 위원회에 참여하는 것은 [평가 목표에 대한 교사들의 공통된 이해]에 기여하고, 프로그램 평가에서 평가자로서의 역할에 대한 교사들의 전문적인 발전에 도움이 되는 것으로 보인다.

Our findings may benefit other implementations of programmatic assessment. Teachers worry about disadvantaging learners with assessment. A progress committee, when organised well, provides support, expertise and, more importantly, a safety net for teachers involved in programmatic assessment. Failure of a student becomes a collective responsibility and learners' careers do not rest on decisions made by individuals or on limited snapshots. This seems to take some of the pressure from teachers and allows them to provide more honest constructive feedback or to raise concerns when preserving the benefits of prolonged engagement.4 Furthermore, participating in progress committees seems to contribute to teachers' shared understanding concerning assessment objectives and benefits teachers' professional development in their roles as assessors in programmatic assessment.

저부담 평가에 대해서 교사마다 서로 다르게 개념화한다면, 평가에 대해 다양한 믿음을 가질 가능성이 있다. 그리고 그 중 적어도 일부는 PA의 근본적인 평가 철학에 반할 수 있다. 학생들이 의료연수 중 많은 다양한 교사를 만나다 보니 프로그램에 사용되는 의도나 평가방법과 맞지 않는 평가에 대한 가치관이나 신념이 다른 교사를 만나게 될 가능성이 높다. 이는 학습자가 [양립할 수 없는 평가 목표나 메시지를 경험]하고, 냉소적으로 '그냥 해달라는 대로 해줘' 접근방식을 따르도록 유도할 가능성이 있으며, 이는 [학습을 위한 평가]의 의미 있는 활용을 방해할 수 있다. 더욱이, 교사들은 프로그램 평가와 같은 [복잡한 이중 목적 시스템]이 [그들의 근본적인 신념과 일치하지 않을 경우 거부하거나 무시]할 수 있다. 교수개발은 프로그램 평가의 기본 원칙과 교사의 평가 개념화에 초점을 맞춰야 한다. 이러한 원칙이 학습자와 평가 관계에 참여할 때 평가 실무에 영향을 미칠 수 있기 때문이다.

The different conceptualisations of low‐stake assessment indicate that teachers are likely to hold varying beliefs about assessment, at least some of which may be contrary to the underlying assessment philosophy advocated by its developers. As students encounter many different teachers during medical training, it is likely that they will encounter teachers with different values or beliefs about assessment that do not align with the intentions and assessment methods used in a programme. This risks the possibility that learners will have experiences of irreconcilable assessment objectives or messages and lead them to follow a cynical ‘give them what they want’ approach,13 which would hinder a meaningful uptake of assessment for learning. Moreover, teachers may resist or dismiss innovative assessment methods and complex dual‐purpose systems, like programmatic assessment, if these methods and approaches do not align with their fundamental beliefs about education and teaching.13 Faculty development should focus on the underlying principles of programmatic assessment and teachers' assessment conceptualisations as these may affect their assessment practices when engaging with learners in assessment relationships.

4.1. 제한사항

4.1. Limitations

우리의 연구결과는 여러 가지 한계점에 비추어 고려되어야 한다.

- 첫째, 이 연구는 두 가지 고유한 프로그램 평가 구현(즉, 동기 부여가 높은 학습자와 교사 모두를 선택한 기준을 사용한 작은 코호트 크기)을 포함했다. 우리는 미래의 연구와 실습을 안내하는 교훈이 될 수 있는 메커니즘에 대한 통찰력을 제공하는 능력을 고려하여 소위 극단적인 경우를 의도적으로 조사했다.

- 둘째, 평가는 학습자, 과제, 교사 및 상황 특성의 복잡한 상호 작용으로 다른 맥락으로의 일반화는 쉬운 일이 아니다. 교사의 역할과 책임은 프로그램, 기관, 문화적 맥락에 따라 다를 수 있다. 공식적인 역할과 평가 책임의 최대 변화를 의도적으로 추구함으로써, 우리는 프로그램 평가에서 교수와 평가의 근본적인 개념화에 초점을 맞췄다.

- 셋째, 이 연구는 교사들의 현실에 대한 인식을 탐구했습니다. 교사들이 믿고 실천했다고 보고한 것과 실제로 믿고 실천하는 것 사이에는 차이가 있을 수 있다.

- 마지막으로, 우리는 직접 요청 이메일에 대한 응답으로 참여를 자원한 교사들을 모집했기 때문에, 선택 편향을 도입했을 수 있습니다.

Our findings should be considered in the light of a number of limitations.

- First, this study included two unique implementations of programmatic assessment (ie, a small cohort size, using criteria that selected both highly motivated learners and teachers). We purposefully investigated these so‐called extreme cases in view of their ability to provide insight into the mechanisms underlying implementations, which can serve as lessons to guide future research and practice.19

- Second, assessment is a complex interaction of learner, task, teacher and context characteristics,40 which makes generalisations to other contexts challenging.41 Teachers' roles and responsibilities can vary amongst programmes, institutions and cultural contexts. By purposefully seeking maximum variation in formal roles and assessment responsibilities, we focused on the underlying conceptualisation of teaching and assessment in programmatic assessment.

- Third, this study explored teachers' perceptions of their reality. There may be differences between what teachers report they believe and intend to do versus what they actually believe and do.

- Finally, we may have introduced selection bias as we recruited teachers who volunteered to participate in response to a direct solicitation email.

5. 결론

5. CONCLUSIONS

교사들의 저부담 평가 개념화는 학습에만 초점을 맞추지 않는다. [교육 효과를 모니터링하기 위한 평가의 사용]은 교사의 [평가 행위]과 교사-학습자 [평가 관계]에 긴장을 조성할 수 있다. 평가 개념화에서 교사의 관점을 이해하는 것은 학습 실무에 대한 평가와 일치하도록 그러한 개념화에 영향을 미치거나 변경하기 위한 단계를 나타낸다. [다양한 평가법 및 평가자에 걸친 표본 추출]과 [진급 위원회 도입]은 장기 참여의 편익을 보존할 때 교사들이 학습에 이익을 주는 평가를 사용할 수 있도록 지원하는 프로그래밍 방식의 평가의 중요한 설계 특징으로 식별되었다.

However, teachers' conceptualisations of low‐stake assessments are not focused solely on learning. The use of assessment to monitor teaching effectiveness may create tension in teachers' assessment practices and the teacher‐learner assessment relationship. Understanding the position of teachers' assessments conceptualisations represents a step towards influencing and perhaps changing those conceptualisations to align with assessment for learning practices. Sampling across different assessments and assessors and the introduction of progress committees were identified as important design features of programmatic assessment that support teachers in using assessment to benefit learning, when preserving the benefits of prolonged engagement.

doi: 10.1111/medu.14075. Epub 2020 Apr 6.

Between trust and control: Teachers' assessment conceptualisations within programmatic assessment

PMID: 31998987

PMCID: PMC7318263

DOI: 10.1111/medu.14075

Free PMC article

Abstract

Objectives: Programmatic assessment attempts to facilitate learning through individual assessments designed to be of low-stakes and used only for high-stake decisions when aggregated. In practice, low-stake assessments have yet to reach their potential as catalysts for learning. We explored how teachers conceptualise assessments within programmatic assessment and how they engage with learners in assessment relationships.

Methods: We used a constructivist grounded theory approach to explore teachers' assessment conceptualisations and assessment relationships in the context of programmatic assessment. We conducted 23 semi-structured interviews at two different graduate-entry medical training programmes following a purposeful sampling approach. Data collection and analysis were conducted iteratively until we reached theoretical sufficiency. We identified themes using a process of constant comparison.

Results: Results showed that teachers conceptualise low-stake assessments in three different ways: to stimulate and facilitate learning; to prepare learners for the next step, and to use as feedback to gauge the teacher's own effectiveness. Teachers intended to engage in and preserve safe, yet professional and productive working relationships with learners to enable assessment for learning when securing high-quality performance and achievement of standards. When teachers' assessment conceptualisations were more focused on accounting conceptions, this risked creating tension in the teacher-learner assessment relationship. Teachers struggled between taking control and allowing learners' independence.

Conclusions: Teachers believe programmatic assessment can have a positive impact on both teaching and student learning. However, teachers' conceptualisations of low-stake assessments are not focused solely on learning and also involve stakes for teachers. Sampling across different assessments and the introduction of progress committees were identified as important design features to support teachers and preserve the benefits of prolonged engagement in assessment relationships. These insights contribute to the design of effective implementations of programmatic assessment within the medical education context.

© 2020 The Authors. Medical Education published by Association for the Study of Medical Education and John Wiley & Sons Ltd.

'Articles (Medical Education) > 평가법 (Portfolio 등)' 카테고리의 다른 글

| 의학교육의 프로그램적 평가가 헬스케어에서 배울 수 있는 것(Perspect Med Educ, 2017) (0) | 2021.12.10 |

|---|---|

| CBME에서 프로그램적 평가의 계획과 설계(Med Teach, 2021) (0) | 2021.12.05 |

| 프로그램적 평가를 위한 오타와 2020 합의문 - 2. 도입과 실천(Med Teach, 2021) (0) | 2021.12.02 |

| 평가프로그램에 대한 오타와 2020 합의문 - 1. 원칙에 대한 합의 (Med Teach, 2021) (0) | 2021.12.01 |

| 평가 프로그램의 철학적 역사: 변화해온 윤곽의 추적(Adv Health Sci Educ Theory Pract. 2021) (0) | 2021.11.18 |